| Main Index | Previous Volume | Next Volume |

|

"We talked of pipe-clay regulation caps— Long twenty-fours—short culverins and mortars— Condemn'd the 'Horse Guards' for a set of raps, And cursed our fate at being in such quarters. Some smoked, some sighed, and some were heard to snore; Some wished themselves five fathoms 'neat the Solway; And some did pray—who never prayed before— That they might get the 'route' for Cork or Galway." |

|

CHAPTER

XI

Cheltenham—Matrimonial Adventure—Showing how to make love for a friend CHAPTER XII Dublin—Tom O'Flaherty—A Reminiscence of the Peninsula CHAPTER XIII Dublin—The Boarding-house—Select Society CHAPTER XIV The Chase CHAPTER XV Mems Of the North Cork CHAPTER XVI Theatricals CHAPTER XVI b (The chapter number is a repeat) The Wager CHAPTER XVII The Elopement |

It was a cold raw evening in February as I sat in the coffee-room of the Old Plough in Cheltenham, "Lucullus c. Lucullo"—no companion save my half-finished decanter of port. I had drawn my chair to the corner of the ample fire-place, and in a half dreamy state was reviewing the incidents of my early life, and like most men who, however young, have still to lament talents misapplied, opportunities neglected, profitless labour, and disastrous idleness. The dreary aspect of the large and ill-lighted room—the close-curtained boxes—the unsocial look of every thing and body about suited the habit of my soul, and I was on the verge of becoming excessively sentimental—the unbroken silence, where several people were present, had also its effect upon me, and I felt oppressed and dejected. So sat I for an hour; the clock over the mantel ticked sharply on—the old man in the brown surtout had turned in his chair, and now snored louder—the gentleman who read the Times had got the Chronicle, and I thought I saw him nodding over the advertisements. The father who, with a raw son of about nineteen, had dined at six, sat still and motionless opposite his offspring, and only breaking the silence around by the grating of the decanter as he posted it across the table. The only thing denoting active existence was a little, shrivelled man, who, with spectacles on his forehead, and hotel slippers on his feet, rapidly walked up and down, occasionally stopping at his table to sip a little weak-looking negus, which was his moderate potation for two hours. I have been particular in chronicling these few and apparently trivial circumstances, for by what mere trifles are our greatest and most important movements induced—had the near wheeler of the Umpire been only safe on his fore legs, and while I write this I might—but let me continue. The gloom and melancholy which beset me, momentarily increased. But three months before, and my prospects presented every thing that was fairest and brightest—now all the future was dark and dismal. Then my best friends could scarcely avoid envy at my fortune—now my reverses might almost excite compassion even in an enemy. It was singular enough, and I should not like to acknowledge it, were not these Confessions in their very nature intended to disclose the very penetralia of my heart; but singular it certainly was—and so I have always felt it since, when reflecting on it—that although much and warmly attached to Lady Jane Callonby, and feeling most acutely what I must call her abandonment of me, yet, the most constantly recurring idea of my mind on the subject was, what will the mess say—what will they think at head-quarters?—the raillery, the jesting, the half-concealed allusion, the tone of assumed compassion, which all awaited me, as each of my comrades took up his line of behaving towards me, was, after all, the most difficult thing to be borne, and I absolutely dreaded to join my regiment, more thoroughly than did ever schoolboy to return to his labour on the expiration of his holidays. I had framed to myself all manner of ways of avoiding this dread event; sometimes I meditated an exchange into an African corps—sometimes to leave the army altogether. However, I turned the affair over in my mind—innumerable difficulties presented themselves, and I was at last reduced to that stand-still point, in which, after continual vacillation, one only waits for the slightest impulse of persuasion from another, to adopt any, no matter what suggestion. In this enviable frame of mind I sat sipping my wine, and watching the clock for that hour at which, with a safe conscience, I might retire to my bed, when the waiter roused me by demanding if my name was Mr. Lorrequer, for that a gentleman having seen my card in the bar, had been making inquiry for the owner of it all through the hotel.

"Yes," said I, "such is my name; but I am not acquainted with any one here, that I can remember."

"The gentleman has ony arrived an hour since by the London mail, sir, and here he is."

At this moment, a tall, dashing-looking, half-swaggering fellow, in a very sufficient envelope of box-coats, entered the coffee-room, and unwinding a shawl from his throat, showed me the honest and manly countenance of my friend Jack Waller, of the __th dragoons, with whom I had served in the Peninsula.

Five minutes sufficed for Jack to tell me that he was come down on a bold speculation at this unseasonable time for Cheltenham; that he was quite sure his fortune was about to be made in a few weeks at farthest, and what seemed nearly as engrossing a topic—that he was perfectly famished, and desired a hot supper, "de suite."

Jack having despatched this agreeable meal with a traveller's appetite, proceeded to unfold his plans to me as follows:

There resided somewhere near Cheltenham, in what direction he did not absolutely know, an old East India colonel, who had returned from a long career of successful staff-duties and government contracts, with the moderate fortune of two hundred thousand. He possessed, in addition, a son and a daughter; the former, being a rake and a gambler, he had long since consigned to his own devices, and to the latter he had avowed his intention of leaving all his wealth. That she was beautiful as an angel —highly accomplished—gifted—agreeable—and all that, Jack, who had never seen her, was firmly convinced; that she was also bent resolutely on marrying him, or any other gentleman whose claims were principally the want of money, he was quite ready to swear to; and, in fact, so assured did he feel that "the whole affair was feasible," (I use his own expression,) that he had managed a two months' leave, and was come down express to see, make love to, and carry her off at once.

"But," said I, with difficulty interrupting him, "how long have you known her father?"

"Known him? I never saw him."

"Well, that certainly is cool; and how do you propose making his acquaintance. Do you intend to make him a "particeps criminis" in the elopement of his own daughter, for a consideration to be hereafter paid out of his own money?"

"Now, Harry, you've touched upon the point in which, you must confess, my genius always stood unrivalled—acknowledge, if you are not dead to gratitude—acknowledge how often should you have gone supperless to bed in our bivouacs in the Peninsula, had it not been for the ingenuity of your humble servant—avow, that if mutton was to be had, and beef to be purloined, within a circuit of twenty miles round, our mess certainly kept no fast days. I need not remind you of the cold morning on the retreat from Burgos, when the inexorable Lake brought five men to the halberds for stealing turkeys, that at the same moment, I was engaged in devising an ox-tail soup, from a heifer brought to our tent in jack-boots the evening before, to escape detection by her foot tracks."

"True, Jack, I never questioned your Spartan talent; but this affair, time considered, does appear rather difficult."

"And if it were not, should I have ever engaged in it? No, no, Harry. I put all proper value upon the pretty girl, with her two hundred thousand pounds pin-money. But I honestly own to you, the intrigue, the scheme, has as great charm for me as any part of the transaction."

"Well, Jack, now for the plan, then!"

"The plan! oh, the plan. Why, I have several; but since I have seen you, and talked the matter over with you, I have begun to think of a new mode of opening the trenches."

"Why, I don't see how I can possibly have admitted a single new ray of light upon the affair."

"There are you quite wrong. Just hear me out without interruption, and I'll explain. I'll first discover the locale of this worthy colonel—'Hydrabad Cottage' he calls it; good, eh?—then I shall proceed to make a tour of the immediate vicinity, and either be taken dangerously ill in his grounds, within ten yards of the hall-door, or be thrown from my gig at the gate of his avenue, and fracture my skull; I don't much care which. Well, then, as I learn that the old gentleman is the most kind, hospitable fellow in the world, he'll admit me at once; his daughter will tend my sick couch—nurse—read to me; glorious fun, Harry. I'll make fierce love to her; and now, the only point to be decided is whether, having partaken of the colonel's hospitality so freely, I ought to carry her off, or marry her with papa's consent. You see there is much to be said for either line of proceeding."

"I certainly agree with you there; but since you seem to see your way so clearly up to that point, why, I should advise you leaving that an 'open question,' as the ministers say, when they are hard pressed for an opinion."

"Well, Harry, I consent; it shall remain so. Now for your part, for I have not come to that."

"Mine," said I, in amazement; "why how can I possibly have any character assigned to me in the drama?"

"I'll tell you, Harry, you shall come with me in the gig in the capacity of my valet."

"Your what?" said I, horror-struck at his impudence.

"Come, no nonsense, Harry, you'll have a glorious time of it—shall choose as becoming a livery as you like—and you'll have the whole female world below stairs dying for you; and all I ask for such an opportunity vouchsafed to you is to puff me, your master, in every possible shape and form, and represent me as the finest and most liberal fellow in the world, rolling in wealth, and only striving to get rid of it."

The unparalleled effrontery of Master Jack, in assigning to me such an office, absolutely left me unable to reply to him; while he continued to expatiate upon the great field for exertion thus open to us both. At last it occurred to me to benefit by an anecdote of a something similar arrangement, of capturing, not a young lady, but a fortified town, by retorting Jack's proposition.

"Come," said I, "I agree, with one only difference—I'll be the master and you the man on this occasion."

To my utter confusion, and without a second's consideration, Waller grasped my hand, and cried, "done." Of course I laughed heartily at the utter absurdity of the whole scheme, and rallied my friend on his prospects of Botany Bay for such an exploit; never contemplating in the most remote degree the commission of such extravagance.

Upon this Jack, to use the expressive French phrase, "pris la parole," touching with a master-like delicacy on my late defeat among the Callonbys, (which up to this instant I believed him in ignorance of;) he expatiated upon the prospect of my repairing that misfortune, and obtaining a fortune considerably larger; he cautiously abstained from mentioning the personal charms of the young lady, supposing, from my lachrymose look, that my heart had not yet recovered the shock of Lady Jane's perfidy, and rather preferred to dwell upon the escape such a marriage could open to me from the mockery of the mess-table, the jesting of my brother officers, and the life-long raillery of the service, wherever the story reached.

The fatal facility of my disposition, so often and so frankly chronicled in these Confessions—the openness to be led whither any one might take the trouble to conduct me—the easy indifference to assume any character which might be pressed upon me, by chance, accident, or design, assisted by my share of three flasks of champagne, induced me first to listen—then to attend to—soon after to suggest—and finally, absolutely to concur in and agree to a proposal, which, at any other moment, I must have regarded as downright insanity. As the clock struck two, I had just affixed my name to an agreement, for Jack Waller had so much of method in his madness, that, fearful of my retracting in the morning, he had committed the whole to writing, which, as a specimen of Jack's legal talents I copy from the original document now in my posession.

"The Plough, Cheltenham, Tuesday night or morning, two o'clock—be the same more or less. I, Harry Lorrequer, sub. in his Majesty's __th regiment of foot, on the one part; and I, John Waller, commonly called Jack Waller, of the __th light dragoons on the other; hereby promise and agree, each for himself, and not one for the other, to the following conditions, which are hereafter subjoined, to wit, the aforesaid Jack Waller is to serve, obey, and humbly follow the aforementioned Harry Lorrequer, for the space of one month of four weeks; conducting himself in all respects, modes, ways, manners, as his, the aforesaid Lorrequer's own man, skip, valet, or saucepan—duly praising, puffing, and lauding the aforesaid Lorrequer, and in every way facilitating his success to the hand and fortune of—"

"Shall we put in her name, Harry, here?" said Jack.

"I think not; we'll fill it up in pencil; that looks very knowing."

"—at the end of which period, if successful in his suit, the aforesaid Harry Lorrequer is to render to the aforesaid Waller the sum of ten thousand pounds three and a half per cent. with a faithful discharge in writing for his services, as may be. If, on the other hand, and which heaven forbid, the aforesaid Lorrequer fail in obtaining the hand of _____, that he will evacuate the territory within twelve hours, and repairing to a convenient spot selected by the aforesaid Waller, then and there duly invest himself with a livery chosen by the aforesaid Waller—"

"You know, each man uses his choice in this particular," said Jack.

"—and for the space of four calendar weeks, be unto the aforesaid Waller, as his skip, or valet, receiving, in the event of success, the like compensation, as aforesaid, each promising strictly to maintain the terms of this agreement, and binding, by a solemn pledge, to divest himself of every right appertaining to his former condition, for the space of time there mentioned."

We signed and sealed it formally, and finished another flask to its perfect ratification. This done, and after a hearty shake hands, we parted and retired for the night.

The first thing I saw on waking the following morning was Jack Waller standing beside my bed, evidently in excellent spirits with himself and all the world.

"Harry, my boy, I have done it gloriously," said he. "I only remembered on parting with you last night, that one of the most marked features in our old colonel's character is a certain vague idea, he has somewhere picked up, that he has been at some very remote period of his history a most distinguished officer. This notion, it appears, haunts his mind, and he absolutely believes he has been in every engagement from the seven years war, down to the Battle of Waterloo. You cannot mention a siege he did not lay down the first parallel for, nor a storming party where he did not lead the forlorn hope; and there is not a regiment in the service, from those that formed the fighting brigade of Picton, down to the London trainbands, with which, to use his own phrase, he has not fought and bled. This mania of heroism is droll enough, when one considers that the sphere of his action was necessarily so limited; but yet we have every reason to be thankful for the peculiarity, as you'll say, when I inform you that this morning I despatched a hasty messenger to his villa, with a most polite note, setting forth that a Mr. Lorrequer—ay, Harry, all above board—there is nothing like it—'as Mr. Lorrequer, of the __th, was collecting for publication, such materials as might serve to commemorate the distinguished achievements of British officers, who have, at any time, been in command—he most respectfully requests an interview with Colonel Kamworth, whose distinguished services, on many gallant occasions, have called forth the unqualified approval of his majesty's government. Mr. Lorrequer's stay is necessarily limited to a few days, as he proceeds from this to visit Lord Anglesey; and, therefore, would humbly suggest as early a meeting as may suit Colonel K.'s convenience.' What think you now? Is this a master-stroke or not?"

"Why, certainly, we are in for it now," said I, drawing a deep sigh. "But Jack, what is all this? Why, you're in livery already."

I now, for the first time, perceived that Waller was arrayed in a very decorous suit of dark grey, with cord shorts and boots, and looked a very knowing style of servant for the side of a tilbury.

"You like it, don't you? Well, I should have preferred something a little more showy myself; but as you chose this last night, I, of course, gave way, and after all, I believe you're right, it certainly is neat."

"Did I choose it last night? I have not the slightest recollection of it."

"Yes, you were most particular about the length of the waistcoat, and the height of the cockade, and you see I have followed your orders tolerably close; and now, adieu to sweet equality for the season, and I am your most obedient servant for four weeks—see that you make the most of it."

While we were talking, the waiter entered with a note addressed to me, which I rightly conjectured could only come from Colonel Kamworth. It ran thus—

"Colonel Kamworth feels highly flattered by the polite attention of Mr. Lorrequer, and will esteem it a particular favour if Mr. L. can afford him the few days his stay in this part of the country will permit, by spending them at Hydrabad Cottage. Any information as to Colonel Kamworth's services in the four quarters of the globe, he need not say, is entirely at Mr. L.'s disposal.

"Colonel K. dines at six precisely."

When Waller had read the note through, he tossed his hat up in the air, and, with something little sort of an Indian whoop, shouted out—

"The game is won already. Harry, my man, give me the check for the ten thousand: she is your own this minute."

Without participating entirely in Waller's exceeding delight, I could not help feeling a growing interest in the part I was advertised to perform, and began my rehearsal with more spirit than I thought I should have been able to command.

That same evening, at the same hour as that in which on the preceding I sat lone and comfortless by the coffee-room fire, I was seated opposite a very pompous, respectable-looking old man, with a large, stiff queue of white hair, who pressed me repeatedly to fill my glass and pass the decanter. The room was a small library, with handsomely fitted shelves; there were but four chairs, but each would have made at least three of any modern one; the curtains of deep crimson cloth effectually secured the room from draught; and the cheerful wood fire blazing on the hearth, which was the only light in the apartment, gave a most inviting look of comfort and snugness to every thing. This, thought I, is all excellent; and however the adventure ends, this is certainly pleasant, and I never tasted better Madeira.

"And so, Mr. Lorrequer, you heard of my affair at Cantantrabad, when I took the Rajah prisoner?"

"Yes," said I; "the governor-general mentioned the gallant business the very last time I dined at Government-House."

"Ah, did he? kind of him though. Well, sir, I received two millions of rupees on the morning after, and a promise of ten more if I would permit him to escape—but no—I refused flatly."

"Is it possible; and what did you do with the two millions?—sent them, of course—."

"No, that I didn't; the wretches know nothing of the use of money. No, no; I have them this moment in good government security.

"I believe I never mentioned to you the storming of Java. Fill yourself another glass, and I'll describe it all to you, for it will be of infinite consequence that a true narrative of this meets the public eye—they really are quire ignorant of it. Here now is Fort Cornelius, and there is the moat, the sugar-basin is the citadel, and the tongs is the first trench, the decanter will represent the tall tower towards the south-west angle, and here, the wine glass—this is me. Well, it was a little after ten at night that I got the order from the general in command to march upon this plate of figs, which was an open space before Fort Cornelius, and to take up my position in front of the fort, and with four pieces of field artillery—these walnuts here—to be ready to open my fire at a moment's warning upon the sou-west tower; but, my dear sir, you have moved the tower; I thought you were drinking Madeira. As I said before, to open my fire upon the sou-west tower, or if necessary protect the sugar tongs, which I explained to you was the trench. Just at the same time the besieged were making preparations for a sortie to occupy this dish of almonds and raisins—the high ground to the left of my position—put another log on the fire, if you please, sir, for I cannot see myself—I thought I was up near the figs, and I find myself down near the half moon."

"It is past nine," said a servant entering the room; "shall I take the carriage for Miss Kamworth, sir?" This being the first time the name of the young lady was mentioned since my arrival, I felt somewhat anxious to hear more of her, in which laudable desire I was not however to be gratified, for the colonel, feeling considerably annoyed by the interruption, dismissed the servant by saying—

"What do you mean, sirrah, by coming in at this moment; don't you see I am preparing for the attack on the half moon? Mr. Lorrequer, I beg your pardon for one moment, this fellow has completely put me out; and besides, I perceive, you have eaten the flying artillery, and in fact, my dear sir, I shall be obliged to lay down the position again."

With this praiseworthy interest the colonel proceeded to arrange the "materiel" of our dessert in battle array, when the door was suddenly thrown open, and a very handsome girl, in a most becoming demi toilette, sprung into the room, and either not noticing, or not caring, that a stranger was present, threw herself into the old gentleman's arms, with a degree of empressement, exceedingly vexatious for any third and unoccupied party to witness.

"Mary, my dear," said the colonel, completely forgetting Java and Fort Cornelius at once, "you don't perceive I have a gentleman to introduce to you, Mr. Lorrequer, my daughter, Miss Kamworth," here the young lady courtesied somewhat stiffly, and I bowed reverently; and we all resumed places. I now found out that Miss Kamworth had been spending the preceding four or five days at a friend's in the neighbourhood; and had preferred coming home somewhat unexpectedly, to waiting for her own carriage.

My confessions, if recorded verbatim, from the notes of that four weeks' sojourn, would only increase the already too prolix and uninteresting details of this chapter in my life; I need only say, that without falling in love with Mary Kamworth, I felt prodigiously disposed thereto; she was extremely pretty; had a foot and ancle to swear by, the most silvery toned voice I almost ever heard, and a certain witchery and archness of manner that by its very tantalizing uncertainty continually provoked attention, and by suggesting a difficulty in the road to success, imparted a more than common zest in the pursuit. She was little, a very little blue, rather a dabbler in the "ologies," than a real disciple. Yet she made collections of minerals, and brown beetles, and cryptogamias, and various other homeopathic doses of the creation, infinitessimally small in their subdivision; in none of which I felt any interest, save in the excuse they gave for accompanying her in her pony-phaeton. This was, however, a rare pleasure, for every morning for at least three or four hours I was obliged to sit opposite the colonel, engaged in the compilation of that narrative of his "res gestae," which was to eclipse the career of Napoleon and leave Wellington's laurels but a very faded lustre in comparison. In this agreeable occupation did I pass the greater part of my day, listening to the insufferable prolixity of the most prolix of colonels, and at times, notwithstanding the propinquity of relationship which awaited us, almost regretting that he was not blown up in any of the numerous explosions his memoir abounded with. I may here mention, that while my literary labour was thus progressing, the young lady continued her avocations as before—not indeed with me for her companion—but Waller; for Colonel Kamworth, "having remarked the steadiness and propriety of my man, felt no scruple in sending him out to drive Miss Kamworth," particularly as I gave him a most excellent character for every virtue under heaven.

I must hasten on.—The last evening of my four weeks was drawing to a close. Colonel Kamworth had pressed me to prolong my visit, and I only waited for Waller's return from Cheltenham, whither I had sent him for my letters, to make arrangements with him to absolve me from my ridiculous bond, and accept the invitation. We were sitting round the library fire, the colonel, as usual, narrating his early deeds and hair-breadth 'scapes. Mary, embroidering an indescribable something, which every evening made its appearance but seemed never to advance, was rather in better spirits than usual, at the same time her manner was nervous and uncertain; and I could perceive by her frequent absence of mind, that her thoughts were not as much occupied by the siege of Java as her worthy father believed them. Without laying any stress upon the circumstance, I must yet avow that Waller's not having returned from Cheltenham gave me some uneasiness, and I more than once had recourse to the bell to demand if "my servant had come back yet?" At each of these times I well remember the peculiar expression of Mary's look, the half embarrassment, half drollery, with which she listened to the question, and heard the answer in the negative. Supper at length made its appearance; and I asked the servant who waited, "if my man had brought me any letters," varying my inquiry to conceal my anxiety; and again, I heard he had not returned. Resolving now to propose in all form for Miss Kamworth the next morning, and by referring the colonel to my uncle Sir Guy, smooth, as far as I could, all difficulties, I wished them good night and retired; not, however, before the colonel had warned me that they were to have an excursion to some place in the neighbourhood the next day; and begging that I might be in the breakfast-room at nine, as they were to assemble there from all parts, and start early on the expedition. I was in a sound sleep the following morning, when a gentle tap at the door awoke me; at the same time I recognised the voice of the colonel's servant, saying, "Mr. Lorrequer, breakfast is waiting, sir."

I sprung up at once, and replying, "Very well, I shall come down," proceeded to dress in all haste, but to my horror, I could not discern a vestige of my clothes; nothing remained of the habiliments I possessed only the day before—even my portmanteau had disappeared. After a most diligent search, I discovered on a chair in a corner of the room, a small bundle tied up in a handkerchief, on opening which I perceived a new suit of livery of the most gaudy and showy description and lace; of which colour was also the coat, which had a standing collar and huge cuffs, deeply ornamented with worked button holes and large buttons. As I turned the things over, without even a guess of what they could mean, for I was scarcely well awake, I perceived a small slip of paper fastened to the coat sleeve, upon which, in Waller's hand-writing, the following few words were written:

"The livery I hope will fit you, as I am rather particular about how you'll look; get quietly down to the stable-yard and drive the tilbury into Cheltenham, where wait for further orders from your kind master,

"John Waller."

The horrible villany of this wild scamp actually paralysed me. That I should put on such ridiculous trumpery was out of the question; yet what was to be done? I rung the bell violently; "Where are my clothes, Thomas?"

"Don't know, sir; I was out all the morning, sir, and never seed them."

"There, Thomas, be smart now and send them up, will you?" Thomas disappeared, and speedily returned to say, "that my clothes could not be found any where; no one knew any thing of them, and begged me to come down, as Miss Kamworth desired him to say that they were still waiting, and she begged Mr. Lorrequer would not make an elaborate toilette, as they were going on a country excursion." An elaborate toilette! I wish to heaven she saw my costume; no, I'll never do it. "Thomas, you must tell the ladies and the colonel, too, that I feel very ill; I am not able to leave my bed; I am subject to attacks—very violent attacks in my head, and must always be left quiet and alone—perfectly alone—mind me, Thomas—for a day at least." Thomas departed; and as I lay distracted in my bed, I heard, from the breakfast room, the loud laughter of many persons evidently enjoying some excellent joke; could it be me they were laughing at; the thought was horrible.

"Colonel Kamworth wishes to know if you'd like the doctor, sir," said Thomas, evidently suppressing a most inveterate fit of laughing, as he again appeared at the door.

"No, certainly not," said I, in a voice of thunder; "what the devil are you grinning at?"

"You may as well come, my man; you're found out; they all know it now," said the fellow with an odious grin.

I jumped out of the bed, and hurled the boot-jack at him with all my strength; but had only the satisfaction to hear him go down stairs chuckling at his escape; and as he reached the parlour, the increase of mirth and the loudness of the laughter told me that he was not the only one who was merry at my expense. Any thing was preferable to this; down stairs I resolved to go at once—but how; a blanket I thought would not be a bad thing, and particularly as I had said I was ill; I could at least get as far as Colonel Kamworth's dressing-room, and explain to him the whole affair; but then if I was detected en route, which I was almost sure to be, with so many people parading about the house. No; that would never do, there was but one alternative, and dreadful, shocking as it was, I could not avoid it, and with a heavy heart, and as much indignation at Waller for what I could not but consider a most scurvy trick, I donned the yellow inexpressibles; next came the vest, and last the coat, with its broad flaps and lace excrescenses, fifty times more absurd and merry-andrew than any stage servant who makes off with his table and two chairs amid the hisses and gibes of an upper gallery.

If my costume leaned towards the ridiculous, I resolved that my air and bearing should be more than usually austere and haughty; and with something of the stride of John Kemble in Coriolanus, I was leaving my bed-room, when I accidentally caught a view of myself in the glass; and so mortified, so shocked was I, that I sank into a chair, and almost abandoned my resolution to go on; the very gesture I had assumed for vindication only increased the ridicule of my appearance; and the strange quaintness of the costume totally obliterated every trace of any characteristic of the wearer, so infernally cunning was its contrivance. I don't think that the most saturnine martyr of gout and dyspepsia could survey me without laughing. With a bold effort, I flung open my door, hurried down the stairs, and reached the hall. The first person I met was a kind of pantry boy, a beast only lately emancipated from the plough, and destined after a dozen years' training as a servant, again to be turned back to his old employ for incapacity; he grinned horribly for a minute, as I passed, and then in a half whisper said—

"Maester, I advise ye run for it; they're a waiting for ye with the constables in the justice's room!" I gave him a look of contemptuous superiority at which he grinned the more, and passed on.

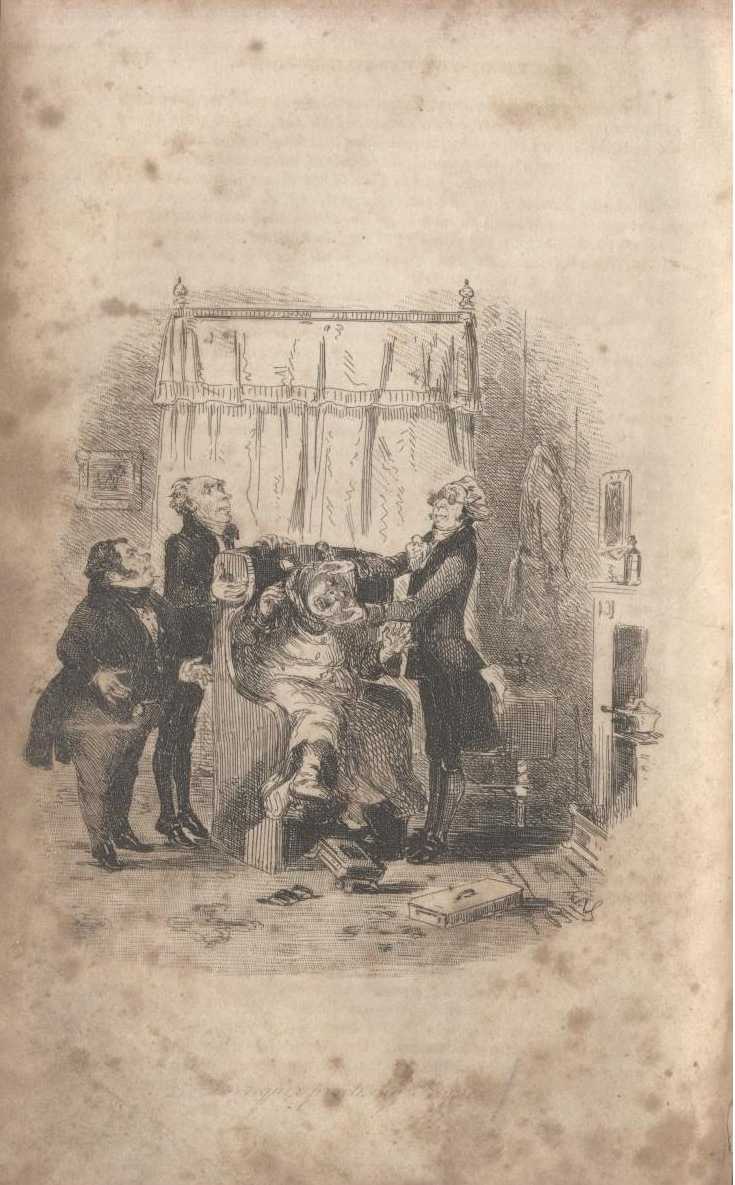

Without stopping to consider where I was going, I opened the door of the breakfast-parlour, and found myself in one plunge among a room full of people. My first impulse was to retreat again; but so shocked was I, at the very first thing that met my sight, that I was perfectly powerless to do any thing. Among a considerable number of people who stood in small groups round the breakfast-table, I discerned Jack Waller, habited in a very accurate black frock and dark trowsers, supporting upon his arm—shall I confess—no less a person than Mary Kamworth, who leaned on him with the familiarity of an old acquaintance, and chatted gaily with him. The buzz of conversation which filled the apartment when I entered, ceased for a second of deep silence; and then followed a peal of laughter so long and so vociferous, that in my momentary anger I prayed some one might burst a blood-vessel, and frighten the rest. I put on a look of indescribable indignation, and cast a glance of what I intended should be most withering scorn on the assembly; but alas! my infernal harlequin costume ruined the effect; and confound me, if they did not laugh the louder. I turned from one to the other with the air of a man who marks out victims for his future wrath; but with no better success; at last, amid the continued mirth of the party, I made my way towards where Waller stood absolutely suffocated with laughter, and scarcely able to stand without support.

"Waller," said I, in a voice half tremulous with rage and shame together; "Waller, if this rascally trick be yours, rest assured no former term of intimacy between us shall—"

Before I could conclude the sentence, a bustle at the door of the room, called every attention in that direction; I turned and beheld Colonel Kamworth, followed by a strong posse comitatus of constables, tipstaffs, , armed to the teeth, and evidently prepared for vigorous battle. Before I was able to point out my woes to my kind host, he burst out with—

"So you scoundrel, you impostor, you damned young villain, pretending to be a gentleman, you get admission into a man's house and dine at his table, when your proper place had been behind his chair.—How far he might have gone, heaven can tell, if that excellent young gentleman, his master, had not traced him here this morning—but you'll pay dearly for it, you young rascal, that you shall."

"Colonel Kamworth," said I, drawing myself proudly up, (and I confess exciting new bursts of laughter,) "Colonel Kamworth, for the expressions you have just applied to me, a heavy reckoning awaits you; not, however, before another individual now present shall atone for the insult he has dared to pass upon me." Colonel Kamworth's passion at this declaration knew no bounds; he cursed and swore absolutely like a madman, and vowed that transportation for life would be a mild sentence for such iniquity.

Waller at length wiping the tears of laughter from his eyes, interposed between the colonel and his victim, and begged that I might be forgiven; "for indeed my dear sir," said he, "the poor fellow is of rather respectable parentage, and such is his taste for good society that he'd run any risk to be among his betters, although, as in the present case the exposure brings a rather heavy retribution, however, let me deal with him. Come, Henry," said he, with an air of insufferable superiority, "take my tilbury into town, and wait for me at the George, I shall endeavour to make your peace with my excellent friend, Colonel Kamworth; and the best mode you can contribute to that object, is to let us have no more of your society."

I cannot attempt to picture my rage at these words; however, escape from this diabolical predicament was my only present object; and I rushed from the room, and springing into the tilbury at the door, drove down the avenue at the rate of fifteen miles per hour, amid the united cheers, groans, and yells of the whole servants' hall, who seemed to enjoy my "detection," even more than their betters. Meditating vengeance, sharp, short, and decisive on Waller, the colonel, and every one else in the infernal conspiracy against me, for I utterly forgot every vestige of our agreement in the surprise by which I was taken, I reached Cheltenham. Unfortunately I had no friend there to whose management I could commit the bearing of a message, and was obliged as soon as I could procure suitable costume, to hasten up to Coventry where the __th dragoons were then quartered. I lost no time in selecting an adviser, and taking the necessary steps to bring Master Waller to a reckoning; and on the third morning we again reached Cheltenham, I thirsting for vengeance, and bursting still with anger; not so, my friend, however, who never could discuss the affair with common gravity, and even ventured every now and then on a sly allusion to my yellow shorts. As we passed the last toll-bar, a travelling carriage came whirling by with four horses at a tremendous pace; and as the morning was frosty, and the sun scarcely risen, the whole team were smoking and steaming so as to be half invisible. We both remarked on the precipitancy of the party; for as our own pace was considerable, the two vehicles passed like lightning. We had scarcely dressed, and ordered breakfast, when a more than usual bustle in the yard called us to the window; the waiter who came in at the same instant told us that four horses were ordered out to pursue a young lady who had eloped that morning with an officer.

"Ah, our friend in the green travelling chariot, I'll be bound," said my companion; but as neither of us knew that part of the country, and I was too engrossed by my own thoughts, I never inquired further. As the chaise in chase drove round to the door, I looked to see what the pursuer was like; and as he issued from the inn, recognised my "ci devant host," Colonel Kamworth. I need not say my vengeance was sated at once; he had lost his daughter, and Waller was on the road to be married. Apologies and explanations came in due time, for all my injuuries and sufferings; and I confess, the part which pleased me most was, that I saw no more of Jack for a considerable period after; he started for the continent, where he has lived ever since on a small allowance, granted by his father-in-law, and never paying me the stipulated sum, as I had clearly broken the compact.

So much for my second attempt at matrimony; one would suppose that such experience should be deemed sufficient to show that my talent did not lie in that way. And here I must rest for the present, with the additional confession, that so strong was the memory of that vile adventure, that I refused a lucrative appointment under Lord Anglesey's government, when I discovered that his livery included "yellow plush breeches;" to have such "souvenirs" flitting around and about me, at dinner and elsewhere, would have left me without a pleasure in existence.

Dear, dirty Dublin—"Io te salute"—how many excellent things might be said of thee, if, unfortunately, it did not happen that the theme is an old one, and has been much better sung than it can ever now be said. With thus much of apology for no more lengthened panegyric, let me beg of my reader, if he be conversant with that most moving melody—the Groves of Blarney—to hum the following lines, which I heard shortly after my landing, and which well express my own feelings for the "loved spot."

|

Oh! Dublin, sure, there is no doubtin', Beats every city upon the say. 'Tis there you'll see O'Connell spouting, And Lady Morgan making "tay." For 'tis the capital of the greatest nation With finest peasantry on a fruitful sod, Fighting like devils for conciliation, And hating each other for the love of God. |

Once more, then, I found myself in the "most car-drivingest city," en route to join on the expiration of my leave. Since my departure, my regiment had been ordered to Kilkenny, that sweet city, so famed in song for its "fire without smoke;" but which, were its character in any way to be derived from its past or present representative, might certainly, with more propriety, reverse the epithet, and read "smoke without fire." My last communication from head-quarters was full of nothing but gay doings —balls, dinners, dejeunes, and more than all, private theatricals, seemed to occupy the entire attention of every man of the gallant __th. I was earnestly entreated to come, without waiting for the end of my leave—that several of my old "parts were kept open for me;" and that, in fact, the "boys of Kilkenny" were on tip-toe in expectation of my arrival, as though his Majesty's mail were to convey a Kean or a Kemble. I shuddered a little as I read this, and recollected "my last appearance on any stage," little anticipating, at the moment, that my next was to be nearly as productive of the ludicrous, as time and my confessions will show. One circumstance, however, gave me considerable pleasure. It was this:—I took it for granted that, in the varied and agreeable occupations which so pleasurable a career opened, my adventures in love would escape notice, and that I should avoid the merciless raillery my two failures, in six months, might reasonably be supposed to call forth. I therefore wrote a hurried note to Curzon, setting forth the great interest all their proceedings had for me, and assuring him that my stay in town should be as short as possible, for that I longed once more to "strut the monarch of the boards," and concluded with a sly paragraph, artfully intended to act as a "paratonnere" to the gibes and jests which I dreaded, by endeavouring to make light of my matrimonial speculations. The postscript ran somewhat thus—"Glorious fun have I had since we met; but were it not that my good angel stood by me, I should write these hurried lines with a wife at my elbow; but luck, that never yet deserted, is still faithful to your old friend, H. Lorrequer."

My reader may suppose—for he is sufficiently behind the scenes with me—with what feelings I penned these words; yet any thing was better than the attack I looked forward to: and I should rather have changed into the Cape Rifle Corps, or any other army of martyrs, than meet my mess with all the ridicule my late proceedings exposed me to. Having disburthened my conscience of this dread, I finished my breakfast, and set out on a stroll through the town.

I believe it is Coleridge who somewhere says, that to transmit the first bright and early impressions of our youth, fresh and uninjured to a remote period of life, constitutes one of the loftiest prerogatives of genius. If this be true, and I am not disposed to dispute it—what a gifted people must be the worthy inhabitants of Dublin; for I scruple not to affirm, that of all cities of which we have any record in history, sacred or profane, there is not one so little likely to disturb the tranquil current of such reminiscences. "As it was of old, so is it now," enjoying a delightful permanency in all its habits and customs, which no changes elsewhere disturb or affect; and in this respect I defy O'Connell and all the tail to refuse it the epithet of "Conservative."

Had the excellent Rip Van Winkle, instead of seeking his repose upon the cold and barren acclivities of the Kaatskills—as we are veritably informed by Irving—but betaken himself to a comfortable bed at Morrison's or the Bilton, not only would he have enjoyed a more agreeable siesta, but, what the event showed of more consequence, the pleasing satisfaction of not being disconcerted by novelty on his awakening. It is possible that the waiter who brought him the water to shave, for Rip's beard, we are told, had grown uncommonly long—might exhibit a little of that wear and tear to which humanity is liable from time; but had he questioned him as to the ruling topics—the proper amusements of the day —he would have heard, as he might have done twenty years before, that there was a meeting to convert Jews at the Rotunda; another to rob parsons at the Corn Exchange; that the Viceroy was dining with the Corporation, and congratulating them on the prosperity of Ireland, while the inhabitants were regaled with a procession of the "broad ribbon weavers," who had not weaved, heaven knows when! This, with an occasional letter from Mr. O'Connell, and now and then a duel in the "Phaynix," constituted the current pastimes of the city. Such, at least, were they in my day; and though far from the dear locale, an odd flitting glance at the newspapers induces me to believe that matters are not much changed since.

I rambled through the streets for some hours, revolving such thoughts as pressed upon me involuntarily by all I saw. The same little grey homunculus that filled my "prince's mixture" years before, stood behind the counter at Lundy Foot's, weighing out rappee and high toast, just as I last saw him. The fat college porter, that I used to mistake in my school-boy days for the Provost, God forgive me! was there as fat and as ruddy as heretofore, and wore his Roman costume of helmet and plush breeches, with an air as classic. The old state trumpeter at the castle, another object of my youthful veneration, poor "old God save the King" as we used to call him, walked the streets as of old; his cheeks indeed, a little more lanky and tendinous; but then there had been many viceregal changes, and the "one sole melody his heart delighted in," had been more frequently called in requisition, as he marched in solemn state with the other antique gentlemen in tabards. As I walked along, each moment some old and early association being suggested by the objects around, I felt my arm suddenly seized. I turned hastily round, and beheld a very old companion in many a hard-fought field and merry bivouack. Tom O'Flaherty of the 8th. Poor Tom was sadly changed since we last met, which was at a ball in Madrid. He was then one of the best-looking fellows of his "style" I ever met,—tall and athletic, with the easy bearing of a man of the world, and a certain jauntiness that I have never seen but in Irishmen who have mixed much in society.

There was also a certain peculiar devil-may-care recklessness about the self-satisfied swagger of his gait, and the free and easy glance of his sharp black eye, united with a temper that nothing could ruffle, and a courage nothing could daunt. With such qualities as these, he had been the prime favourite of his mess, to which he never came without some droll story to relate, or some choice expedient for future amusement. Such had Tom once been; now he was much altered, and though the quiet twinkle of his dark eye showed that the spirit of fun within was not "dead, but only sleeping,"—to myself, who knew something of his history, it seemed almost cruel to awaken him to any thing which might bring him back to the memory of by-gone days. A momentary glance showed me that he was no longer what he had been, and that the unfortunate change in his condition, the loss of all his earliest and oldest associates, and his blighted prospects, had nearly broken a heart that never deserted a friend, nor quailed before an enemy. Poor O'Flaherty was no more the delight of the circle he once adorned; the wit that "set the table in a roar" was all but departed. He had been dismissed the service!!—The story is a brief one:—

In the retreat from Burgos, the __ Light Dragoons, after a most fatiguing day's march, halted at the wretched village of Cabenas. It had been deserted by the inhabitants the day before, who, on leaving, had set it on fire; and the blackened walls and fallen roof-trees were nearly all that now remained to show where the little hamlet had once stood.

Amid a down-pour of rain, that had fallen for several hours, drenched to the skin, cold, weary, and nearly starving, the gallant 8th reached this melancholy spot at nightfall, with little better prospect of protection from the storm than the barren heath through which their road led might afford them. Among the many who muttered curses, not loud but deep, on the wretched termination to their day's suffering, there was one who kept up his usual good spirits, and not only seemed himself nearly regardless of the privations and miseries about him, but actually succeeded in making the others who rode alongside as perfectly forgetful of their annoyances and troubles as was possible under such circumstances. Good stories, joking allusions to the more discontented ones of the party, ridiculous plans for the night's encampment, followed each other so rapidly, that the weariness of the way was forgotten; and while some were cursing their hard fate, that ever betrayed them into such misfortunes, the little group round O'Flaherty were almost convulsed with laughter at the wit and drollery of one, over whom if the circumstances had any influence, they seemed only to heighten his passion for amusement. In the early part of the morning he had captured a turkey, which hung gracefully from his holster on one side, while a small goat-skin of Valencia wine balanced it on the other. These good things were destined to form a feast that evening, to which he had invited four others; that being, according to his most liberal calculation, the greatest number to whom he could afford a reasonable supply of wine.

When the halt was made, it took some time to arrange the dispositions for the night; and it was nearly midnight before all the regiment had got their billets and were housed, even with such scanty accommodation as the place afforded. Tom's guests had not yet arrived, and he himself was busily engaged in roasting the turkey before a large fire, on which stood a capacious vessel of spiced wine, when the party appeared. A very cursory "reconnaissance" through the house, one of the only ones untouched in the village, showed that from the late rain it would be impossible to think of sleeping in the lower story, which already showed signs of being flooded; they therefore proceeded in a body up stairs, and what was their delight to find a most comfortable room, neatly furnished with chairs, and a table; but, above all, a large old-fashioned bed, an object of such luxury as only an old campaigner can duly appreciate. The curtains were closely tucked in all round, and, in their fleeting and hurried glance, they felt no inclination to disturb them, and rather proceeded to draw up the table before the hearth, to which they speedily removed the fire from below; and, ere many minutes, with that activity which a bivouack life invariably teaches, their supper smoked before them, and five happier fellows did not sit down that night within a large circuit around. Tom was unusually great; stories of drollery unlocked before, poured from him unceasingly, and what with his high spirits to excite them, and the reaction inevitable after a hard day's severe march, the party soon lost the little reason that usually sufficed to guide them, and became as pleasantly tipsy as can well be conceived. However, all good things must have an end, and so had the wine-skin. Tom had placed it affectionately under his arm like a bag-pipe and failed, with even a most energetic squeeze, to extract a drop; there was no nothing for it but to go to rest, and indeed it seemed the most prudent thing for the party.

The bed became accordingly a subject of grave deliberation; for as it could only hold two, and the party were five, there seemed some difficulty in submitting their chances to lot, which all agreed was the fairest way. While this was under discussion, one of the party had approached the contested prize, and, taking up the curtains, proceeded to jump in—when, what was his astonishment to discover that it was already occupied. The exclamation of surprise he gave forth soon brought the others to his side; and to their horror, drunk as they were, they found that the body before them was that of a dead man, arrayed in all the ghastly pomp of a corpse. A little nearer inspection showed that he had been a priest, probably the Padre of the village; on his head he had a small velvet skull cap, embroidered with a cross, and his body was swathed in a vestment, such as priests usually wear at the mass; in his hand he held a large wax taper, which appeared to have burned only half down, and probably been extinguished by the current of air on opening the door. After the first brief shock which this sudden apparition had caused, the party recovered as much of their senses as the wine had left them, and proceeded to discuss what was to be done under the circumstances; for not one of them ever contemplated giving up a bed to a dead priest, while five living men slept on the ground. After much altercation, O'Flaherty, who had hitherto listened without speaking, interrupted the contending parties, saying, "stop, lads, I have it."

"Come," said one of them, "let us hear Tom's proposal."

"Oh," said he, with difficulty steadying himself while he spoke, "we'll put him to bed with old Ridgeway, the quarter-master!"

The roar of loud laughter that followed Tom's device was renewed again and again, till not a man could speak from absolute fatigue. There was not a dissentient voice. Old Ridgeway was hated in the corps, and a better way of disposing of the priest and paying off the quarter-master could not be thought of.

Very little time sufficed for their preparations; and if they had been brought up under the Duke of Portland himself, they could not have exhibited a greater taste for a "black job." The door of the room was quickly taken from its hinges, and the priest placed upon it at full length; a moment more sufficed to lift the door upon their shoulders, and, preceded by Tom, who lit a candle in honour of being, as he said, "chief mourner," they took their way through the camp towards Ridgeway's quarters. When they reached the hut where their victim lay, Tom ordered a halt, and proceeded stealthily into the house to reconnoitre. The old quarter-master he found stretched on his sheep-skin before a large fire, the remnants of an ample supper strewed about him, and two empty bottles standing on the hearth—his deep snoring showed that all was safe, and that no fears of his awaking need disturb them. His shako and sword lay near him, but his sabertasche was under his head. Tom carefully withdrew the two former; and hastening to his friends without, proceeded to decorate the priest with them; expressing, at the same time, considerable regret that he feared it might wake Ridgeway, if he were to put the velvet skull-cap on him for a night-cap.

Noiselessly and steadily they now entered, and proceeded to put down their burden, which, after a moment's discussion, they agreed to place between the quarter-master and the fire, of which, hitherto, he had reaped ample benefit. This done, they stealthily retreated, and hurried back to their quarters, unable to speak with laughter at the success of their plot, and their anticipation of Ridgeway's rage on awakening in the morning.

It was in the dim twilight of a hazy morning, that the bugler of the 8th aroused the sleeping soldiers from their miserable couches, which, wretched as they were, they, nevertheless, rose from reluctantly—so wearied and fatigued had they been by the preceding day's march; not one among the number felt so indisposed to stir as the worthy quarter-master; his peculiar avocations had demanded a more than usual exertion on his part, and in the posture he had laid down at night, he rested till morning, without stirring a limb. Twice the reveille had rung through the little encampment, and twice the quarter-master had essayed to open his eyes, but in vain; at last he made a tremendous effort, and sat bolt upright on the floor, hoping that the sudden effort might sufficiently arouse him; slowly his eyes opened, and the first thing they beheld was the figure of the dead priest, with a light cavalry helmet on his head, seated before him. Ridgeway, who was "bon Catholique," trembled in every joint—it might be a ghost, it might be a warning, he knew not what to think—he imagined the lips moved, and so overcome with terror was he at last, that he absolutely shouted like a maniac, and never cased till the hut was filled with officers and men, who hearing the uproar ran to his aid—the surprise of the poor quarter-master at the apparition, was scarcely greater than that of the beholders—no one was able to afford any explanation of the circumstance, though all were assured that it must have been done in jest—the door upon which the priest had been conveyed, afforded the clue—they had forgotten to restore it to its place—accordingly the different billets were examined, and at last O'Flaherty was discovered in a most commodious bed, in a large room without a door, still fast asleep, and alone; how and when he had parted from his companions, he never could precisely explain, though he has since confessed it was part of his scheme to lead them astray in the village, and then retire to the bed, which he had determined to appropriate to his sole use.

Old Ridgeway's rage knew no bounds; he absolutely foamed with passion, and in proportion as he was laughed at his choler rose higher; had this been the only result, it had been well for poor Tom, but unfortunately the affair got to be rumoured through the country—the inhabitants of the village learned the indignity with which the Padre had been treated; they addressed a memorial to Lord Wellington—inquiry was immediately instituted—O'Flaherty was tried by court martial, and found guilty; nothing short of the heaviest punishment that could be inflicted under the circumstances would satisfy the Spaniards, and at that precise period it was part of our policy to conciliate their esteem by every means in our power. The commander-in-chief resolved to make what he called an "example," and poor O'Flaherty—the life and soul of his regiment—the darling of his mess, was broke, and pronounced incapable of ever serving his Majesty again. Such was the event upon which my poor friend's fortune in life seemed to hinge—he returned to Ireland, if not entirely broken-hearted, so altered that his best friends scarcely knew him; his "occupation was gone;" the mess had been his home; his brother officers were to him in place of relatives, and he had lost all. His after life was spent in rambling from one watering place to another, more with the air of one who seeks to consume than enjoy his time; and with such a change in appearance as the alteration in his fortune had effected, he now stood before me, but altogether so different a man, that but for the well-known tones of a voice that had often convulsed me with laughter, I should scarcely have recognised him.

"Lorrequer, my old friend, I never thought of seeing you here—this is indeed a piece of good luck."

"Why, Tom? You surely knew that the __ were in Ireland, didn't you?"

"To be sure. I dined with them only a few days ago, but they told me you were off to Paris, to marry something superlatively beautiful, and most enormously rich, the daughter of a duke, if I remember right; but certes, they said your fortune was made, and I need not tell you, there was not a man among them better pleased that I was to hear it."

"Oh! they said so, did they? Droll dogs—always quizzing—I wonder you did not perceive the hoax—eh—very good, was it not?" This I poured out in short broken sentences, blushing like scarlet, and fidgeting like a school girl with downright nervousness.

"A hoax! devilish well done too,"—said Tom, "for old Carden believed the whole story, and told me that he had obtained a six months' leave for you to make your 'com.' and, moreover, said that he had got a letter from the nobleman, Lord _____ confound his name."

"Lord Grey, is it?" said I, with a sly look at Tom.

"No, my dear friend," said he drily, "it was not Lord Grey—but to continue—he had got a letter from him, dated from Paris, stating his surprise that you had never joined them there, according to promise, and that they knew your cousin Guy, and a great deal of other matter I can't remember—so what does all this mean? Did you hoax the noble Lord as well as the Horse Guards, Harry?"

This was indeed a piece of news for me; I stammered out some ridiculous explanation, and promised a fuller detail. Could it be that I had done the Callonbys injustice, and that they never intended to break off my attention to Lady Jane—that she was still faithful, and that of all concerned I alone had been to blame. Oh! how I hoped this might be the case; heavily as my conscience might accuse, I longed ardently to forgive and deal mercifully with myself. Tom continued to talk about indifferent matters, as these thoughts flitted through my mind; perceiving at last that I did not attend, he stopped suddenly and said—

"Harry, I see clearly that something has gone wrong, and perhaps I can make a guess at the mode too: but however, you can do nothing about it now; come and dine with me to-day, and we'll discuss the affair together after dinner; or if you prefer a 'distraction,' as we used to say in Dunkerque, why then I'll arrange something fashionable for your evening's amusement. Come, what say you to hearing Father Keogh preach, or would you like a supper at the Carlingford, or perhaps you prefer a soiree chez Miladi; for all of these Dublin affords—all three good in their way, and very intellectual."

"Well, Tom, I'm yours; but I should prefer your dining with me; I am at Bilton's; we'll have our cutlet quite alone, and—"

"And be heartily sick of each other, you were going to add. No, no, Harry; you must dine with me; I have some remarkably nice people to present you to—six is the hour—sharp six—number ___ Molesworth-street, Mrs. Clanfrizzle's—easily find it—large fanlight over the door—huge lamp in the hall, and a strong odour of mutton broth for thirty yards on each side of the premises—and as good luck would have it, I see old Daly the counsellor, as they call him, he's the very man to get to meet you, you always liked a character, eh!"

Saying this, O'Flaherty disengaged himself from my arm, and hurried across the street towards a portly middle-aged looking gentleman, with the reddest face I ever beheld. After a brief but very animated colloquy, Tom returned, and informed that that all was right; he had secured Daly.

"And who is Daly?" said I, inquiringly, for I was rather interested in hearing what peculiar qualification as a diner-out the counsellor might lay claim to, many of Tom's friends being as remarkable for being the quizzed as the quizzers.

"Daly," said he, "is the brother of a most distinguished member of the Irish bar, of which he himself is also a follower, bearing however, no other resemblance to the clever man than the name, for as assuredly as the reputation of the one is inseparably linked with success, so unerringly is the other coupled with failure, and strange to say, that the stupid man is fairly convinced that his brother owes all his success to him, and that to his disinterested kindness the other is indebted for his present exalted station. Thus it is through life; there seems ever to accompany dullness a sustaining power of vanity, that like a life-buoy, keeps a mass afloat whose weight unassisted would sink into obscurity. Do you know that my friend Denis there imagines himself the first man that ever enlightened Sir Robert Peel as to Irish affairs; and, upon my word, his reputation on this head stands incontestably higher than on most others."

"You surely cannot mean that Sir Roert Peel ever consulted with, much less relied upon, the statements of such a person, as you described you friend Denis to be?"

"He did both—and if he was a little puzzled by the information, the only disgrace attaches to a government that send men to rule over us unacquainted with our habits of thinking, and utterly ignorant of the language—ay, I repeat it—but come, you shall judge for yourself; the story is a short one, and fortunately so, for I must hasten home to give timely notice of your coming to dine with me. When the present Sir Robert Peel, then Mr. Peel, came over here, as secretary to Ireland, a very distinguished political leader of the day invited a party to meet him at dinner, consisting of men of different political leanings; among whom were, as may be supposed, many members of the Irish bar; the elder Daly was too remarkable a person to be omitted, but as the two brothers resided together, there was a difficulty about getting him—however, he must be had, and the only alternative that presented itself was adopted —both were invited. When the party descended to the dining-room, by one of those unfortunate accidents, which as the proverb informs us occasionally take place in the best regulated establishments, the wrong Mr. Daly got placed beside Mr. Peel, which post of honor had been destined by the host for the more agreeable and talented brother. There was now no help for it; and with a heart somewhat nervous for the consequences of the proximity, the worthy entertainer sat down to do the honors as best he might; he was consoled during dinner by observing that the devotion bestowed by honest Denis on the viands before him effectually absorbed his faculties, and thereby threw the entire of Mr. Peel's conversation towards the gentleman on his other flank. This happiness was like most others, destined to be a brief one. As the dessert made its appearance, Mr. Peel began to listen with some attention to the conversation of the persons opposite; with one of whom he was struck most forcibly—so happy a power of illustration, so vivid a fancy, such logical precision in argument as he evinced, perfectly charmed and surprised him. Anxious to learn the name of so gifted an individual, he turned towards his hitherto silent neighbour and demanded who he was.

"'Who is he, is it?' said Denis, hesitatingly, as if he half doubted such extent of ignorance as not to know the person alluded to.

"Mr. Peel bowed in acquiescence.

"'That's Bushe!' said Denis, giving at the same time the same sound to the vowel, u, as it obtains when occurring in the word 'rush.'

"'I beg pardon,' said Mr. Peel, 'I did not hear.'

"'Bushe!' replied Denis, with considerable energy of tone.

"'Oh, yes! I know,' said the secretary, 'Mr. Bushe, a very distinguished member of your bar, I have heard.'

"'Faith, you may say that!' said Denis, tossing off his wine at what he esteemed a very trite observation.

"'Pray,' said Mr. Peel, again returning to the charge, though certainly feeling not a little surprised at the singular laconicism of his informant, no less than the mellifluous tones of an accent then perfectly new to him. 'Pray, may I ask, what is the peculiar character of Mr. Bushe's eloquence? I mean of course, in his professional capacity.'

"'Eh!' said Denis, 'I don't comprehend you exactly.'

"'I mean,' said Mr. Peel, 'in one word, what's his forte?'

"'His forte!'

"'I mean what his peculiar gift consists in—'

"'Oh, I perceave—I have ye now—the juries!'

"'Ah! addressing a jury.'

"'Ay, the juries.'

"'Can you oblige me by giving me any idea of the manner in which he obtains such signal success in this difficult branch of eloquence.'

"'I'll tell ye,' said Denis, leisurely finishing his glass, and smacking his lips, with the air of a man girding up his loins for a mighty effort, 'I'll tell ye—well, ye see the way he has is this,'—here Mr. Peel's expectation rose to the highest degree of interest,—'the way he has is this—he first butthers them up, and then slithers them down! that's all, devil a more of a secret there's in it.'"

How much reason Denis had to boast of imparting early information to the new secretary I leave my English readers to guess; my Irish ones I may trust to do him ample justice.

My friend now left me to my own devices to while away the hours till time to dress for dinner. Heaven help the gentleman so left in Dublin, say I. It is, perhaps, the only city of its size in the world, where there is no lounge—no promenade. Very little experience of it will convince you that it abounds in pretty women, and has its fair share of agreeable men; but where are they in the morning? I wish Sir Dick Lauder, instead of speculating where salmon spent the Christmas holidays, would apply his most inquiring mind to such a question as this. True it is, however, they are not to be found. The squares are deserted—the streets are very nearly so—and all that is left to the luckless wanderer in search of the beautiful, is to ogle the beauties of Dame-street, who are shopkeepers in Grafton-street, or the beauties of Grafton-street, who are shopkeepers in Dame-street. But, confound it, how cranky I am getting—I must be tremendously hungry. True, it's past six. So now for my suit of sable, and then to dinner.

Punctual to my appointment with O'Flaherty, I found myself a very few minutes after six o'clock at Mrs. Clanfrizzle's door. My very authoritative summons at the bell was answered by the appearance of a young, pale-faced invalid, in a suit of livery the taste of which bore a very unpleasant resemblance to the one I so lately figured in. It was with considerable difficulty I persuaded this functionary to permit my carrying my hat with me to the drawing-room, a species of caution on my part—as he esteemed it—savouring much of distrust. This point however, I carried, and followed him up a very ill-lighted stair to the drawing-room; here I was announced by some faint resemblance to my real name, but sufficiently near to bring my friend Tom at once to meet me, who immediately congratulated me on my fortune in coming off so well, for that the person who preceded me, Mr. Jones Blennerhasset, had been just announced as Mr. Blatherhasit—a change the gentleman himself was not disposed to adopt—"But come along, Harry, while we are waiting for Daly, let me make you known to some of our party; this, you must know, is a boarding-house, and always has some capital fun—queerest people you ever met—I have only one hint—cut every man, woman, and child of them, if you meet them hereafter—I do it myself, though I have lived here these six months." Pleasant people, thought I, these must be, with whom such a line is advisable, much less practicable.

"Mrs. Clanfrizzle, my friend Mr. Lorrequer; thinks he'll stay the summer in town. Mrs. Clan—, should like him to be one of us." This latter was said sotto voce, and was a practice he continued to adopt in presenting me to his several friends through the room.

Miss Riley, a horrid old fright, in a bird of paradise plume, and corked eyebrows, gibbetted in gilt chains and pearl ornaments, and looking as the grisettes say, "superbe en chrysolite"—"Miss Riley, Captain Lorrequer, a friend I have long desired to present to you—fifteen thousand a-year and a baronetcy, if he has sixpence"—sotto again. "Surgeon M'Culloch—he likes the title," said Tom in a whisper—"Surgeon, Captain Lorrequer. By the by, lest I forget it, he wishes to speak to you in the morning about his health; he is stopping at Sandymount for the baths; you could go out there, eh!" The tall thing in green spectacles bowed, and acknowledged Tom's kindness by a knowing touch of the elbow. In this way he made the tour of the room for about ten minutes, during which brief space, I was according to the kind arrangements of O'Flaherty, booked as a resident in the boarding-house—a lover to at least five elderly, and three young ladies—a patient—a client—a second in a duel to a clerk in the post-office—and had also volunteered (through him always) to convey, by all of his Majesty's mails, as many parcels, packets, band-boxes, and bird-cages, as would have comfortably filled one of Pickford's vans. All this he told me was requisite to my being well received, though no one thought much of any breach of compact subsequently, except Mrs. Clan—herself. The ladies had, alas! been often treated vilely before; the doctor had never had a patient; and as for the belligerent knight of the dead office, he'd rather die than fight any day.

The last person to whom my friend deemed it necessary to introduce me, was a Mr. Garret Cudmore, from the Reeks of Kerry, lately matriculated to all the honors of freshmanship in the Dublin university. This latter was a low-sized, dark-browed man, with round shoulders, and particularly long arms, the disposal of which seemed sadly to distress him. He possessed the most perfect brogue I ever listened to; but it was difficult to get him to speak, for on coming up to town some weeks before, he had been placed by some intelligent friend at Mrs. Clanfrizzle's establishment, with the express direction to mark and thoroughly digest as much as he could of the habits and customs of the circle about him, which he was rightly informed was the very focus of good breeding and haut ton; but on no account, unless driven thereto by the pressure of sickness, or the wants of nature, to trust himself with speech, which, in his then uninformed state, he was assured would inevitably ruin him among his fastidiously cultivated associates.

To the letter and the spirit of the despatch he had received, the worthy Garret acted rigidly, and his voice was scarcely ever known to transgress the narrow limits prescribed by his friends. In more respects that one, was this a good resolve; for so completely had he identified himself with college habits, things, and phrases, that whenever he conversed, he became little short of unintelligible to the vulgar—a difficulty not decreased by his peculiar pronunciation.

My round of presentation was just completed, when the pale figure in light blue livery announced Counsellor Daly and dinner, for both came fortunately together. Taking the post of honour, Miss Riley's arm, I followed Tom, who I soon perceived ruled the whole concern, as he led the way with another ancient vestal in black stain and bugles. The long procession wound its snake-like length down the narrow stair, and into the dining-room, where at last we all got seated; and here let me briefly vindicate the motives of my friend—should any unkind person be found to impute to his selection of a residence, any base and grovelling passion for gourmandaise, that day's experience should be an eternal vindication of him. The soup—alas! that I should so far prostitute the word; for the black broth of Sparta was mock turtle in comparison—retired to make way for a mass of beef, whose tenderness I did not question; for it sank beneath the knife of the carver like a feather bed—the skill of Saladin himself would have failed to divide it. The fish was a most rebellious pike, and nearly killed every loyal subject at table; and then down the sides were various comestibles of chickens, with azure bosoms, and hams with hides like a rhinoceros; covered dishes of decomposed vegetable matter, called spinach and cabbage; potatoes arrayed in small masses, and browned, resembling those ingenious architectural structures of mud, children raise in the high ways, and call dirt-pies. Such were the chief constituents of the "feed;" and such, I am bound to confess, waxed beautifully less under the vigorous onslaught of the party.

The conversation soon became both loud and general. That happy familiarity—which I had long believed to be the exclusive prerogative of a military mess, where constant daily association sustains the interest of the veriest trifles—I here found in a perfection I had not anticipated, with this striking difference, that there was no absurd deference to any existing code of etiquette in the conduct of the party generally, each person quizzing his neighbour in the most free and easy style imaginable, and all, evidently from long habit and conventional usage, seeming to enjoy the practice exceedingly. Thus, droll allusions, good stories, and smart repartees, fell thick as hail, and twice as harmless, which any where else that I had ever heard of, would assuredly have called for more explanations, and perhaps gunpowder, in the morning, than usually are deemed agreeable. Here, however, they knew better; and though the lawyer quizzed the doctor for never having another patient than the house dog, all of whose arteries he had tied in the course of the winter for practice—and the doctor retorted as heavily, by showing that the lawyer's practice had been other than beneficial to those for whom he was concerned—his one client being found guilty, mainly through his ingenious defence of him; yet they never showed any, the slightest irritation—on the contrary, such little playful badinage ever led to some friendly passages of taking wine together, or in arrangements for a party to the "Dargle," or "Dunleary;" and thus went on the entire party, the young ladies darting an occasion slight at their elders, who certainly returned the fire, often with advantage; all uniting now and then, however, in one common cause, an attack of the whole line upon Mrs. Clanfrizzle herself, for the beef, or the mutton, or the fish, or the poultry—each of which was sure to find some sturdy defamer, ready and willing to give evidence in dispraise. Yet even these, and I thought them rather dangerous sallies, led to no more violent results than dignified replies from the worthy hostess, upon the goodness of her fare, and the evident satisfaction it afforded while being eaten, if the appetites of the party were a test. While this was at its height, Tom stooped behind my chair, and whispered gently—

"This is good—isn't it, eh?—life in a boarding-house—quite new to you; but they are civilized now compared to what you'll find them in the drawing-room. When short whist for five-penny points sets in—then Greek meets Greek, and we'll have it."

During all this melee tournament, I perceived that the worthy jib as he would be called in the parlance of Trinity, Mr. Cudmore, remained perfectly silent, and apparently terrified. The noise, the din of voices, and the laughing, so completely addled him, that he was like one in a very horrid dream. The attention with which I had observed him, having been remarked by my friend O'Flaherty, he informed me that the scholar, as he was called there, was then under a kind of cloud—an adventure which occurred only two nights before, being too fresh in his memory to permit him enjoying himself even to the limited extent it had been his wont to do. As illustrative, not only of Mr. Cudmore, but the life I have been speaking of, I may as well relate it.