Copyright, 1896, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, JANUARY 14, 1896. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xvii.—no. 846. | two dollars a year. |

It was a dark, murky night when George reached the headquarters at West Point. He had been delayed often in the journey, having been forced to hide in the woods to avoid meeting stragglers from the guerilla forces, and once he saw a man ride to the top of a hill behind him and shadow his eyes with his hat. His horse was almost worn out when he had reached the American outposts. Here, however, there was no detention. He had passports that would take him across the river, where the forces that were making feints of threatening the British defences above the city were stationed.

After leaving the protection of the American arms he was to proceed on foot and enter the British lines as best he could, and there demand to be brought before the officials to whom he had despatches.

It is a strange thing that even the strongest and frankest natures often have the gift of dissembling when confronted with danger or necessity. A half-dozen times as George had ridden through the woods he had thought of[Pg 254] giving up the project. General Washington knew nothing of it, he felt sure, and Colonel Hewes was known more for his brilliancy and dash than for his caution. It seemed hardly possible that any scheme of such tremendous importance as the capture of the British General could be successful; the plotting could not go on under the very eyes of the English; they would surely suspect something, and he knew what the fate of a spy would be. He remembered the brave Nathan Hale, but was animated none the less by the memory of this hero's last words, and the sorrow that he had expressed at having "but one life to give for his country." The question of right or wrong involved George did not weigh long in his mind, and, to tell the truth, the mystery of the adventure had strongly tempted him from the first.

No one would have recognized our young Lieutenant as he stepped from the boat into the glare of a lantern on the eastern shore of the Hudson—for he had been ferried across the river, the very night of his arrival at West Point. His brown hair was dyed black and straggled about his shoulders. Instead of his long blue coat, he wore a gray jacket and a short plum-colored waistcoat buttoned tightly to the throat; his legs were encased in heavy riding-breeches, and stiff leather gaiters came up to his knees. The big pouch in his pocket was filled with the precious English guineas, and sewed on the inside lining of his waistcoat were the despatches.

The story of supposed hardships that he had faced in coming down from Albany he had learned by heart, but it was hard for George to change the soldierly carriage of his shoulders. He was stamped with the imprint of military service. However, by placing a button in the sole of his left boot, he reminded himself of the limp which Richard Blount was supposed to have.

The next day, at early dawn, he began his trip, and late in the afternoon he rested at a farm-house, keeping out of sight as much as possible. When darkness came on, under the guidance of a Lieutenant Peck of a Connecticut regiment, he rode away once more southward toward the city.

It was almost four o'clock in the morning when Lieutenant Peck stopped. The latter, out of delicacy, had asked no questions, and George had felt in no mood for conversation. Their journey had been made in silence.

"Here is the lone oak," said the Lieutenant, "and here I am to leave you and take back the horses. This road will carry you to the British lines. I wish you all success in your dangerous enterprise, for I can guess, sir, what hardships and sacrifices you will have to make. God speed you."

George had dismounted. He shook the other's hand, thanked him, and hastened down the road. The papers that were sewed inside his clothes crinkled as he walked. He almost felt as if his courage would give out. What was he going to face? Was he not being made the victim of a wild, reckless enthusiast?

Nevertheless he would not back out. It was not in the Frothingham blood to turn. The family motto was "Onward." He would be true to it.

As he walked ahead he kept making up his mind what he would say and how he would appear. He was supposed not to be a country bumpkin, but a youth of some education and appearance. He was not to go into hiding when he reached the city, but to live openly, and to spend money lavishly on the soldiers. He was not to talk overly much, but to listen carefully, and to await the orders that he would receive, and act, when the time came, with promptness and fearlessness. He had been going over for the hundredth time the tale of his imaginary and wonderful passage through the American lines; and had traversed perhaps eight or ten miles from the spot where he had separated from Lieutenant Peck, when he saw some men with guns on their shoulders crossing from the woods to the left of the road.

It was growing light, and it was evident from their movements that they had detected him. Now a strange fear came into his mind. If they were English, all would be right and well; but if they were Americans, it would be hard for him to explain. It was good that this idea came to him, for it made him act as a fugitive naturally would. He walked on as if he had discovered nothing until he had placed the big trunk of a tree between himself and the strangers standing on the hill-side, two of whom were advancing toward him. Then he backed carefully away, still keeping the tree between him and the approaching figures, until he reached the stone wall at the road-side. He cleared this at a bound, and falling on his hands and knees, crawled along in the direction he had been pursuing. At last he found a patch of underbrush, and worked his way into it cautiously as a skulking Iroquois might. Peering out through the branches of a small pine he could clearly see the men that were walking toward the tree behind, which he apparently had taken shelter, up the road. He could see their surprised gestures when they found no one was there. He saw them searching the ground for footprints, as there had been a slight snow-fall, and of course his having walked backwards did not betray him at first glance. He hoped that they were Englishmen, but could not tell, for their uniform was a nondescript one like the Americans. Suddenly, as he watched the slope from his hiding-place, he saw the flash of a red coat, and then another. The man near the road shouted something back to the top of the hill. It was evident that George had come across an English outpost, and as it was now quite day-light, he could see, down the road, a number of horses being led out of a weather-beaten gray barn.

So Lieutenant Frothingham, now "Richard Blount," of Albany, stepped from his hiding-place, and walked boldly out to the road-side and seated himself on the stone wall.

For some reason the party who was searching the bushes further up had not discerned him, but the man in the red coat had, and was seen coming swiftly down the hill. The other joined him also, and soon the two were within speaking distance.

"Stand and deliver!" said the first, with his hand upon the butt of a large pistol that he carried in his belt.

"If you will pardon me," returned George, affecting a careless air, "I had just as lief sit for awhile; and as to delivering, I have come a long way to do it."

"What mean you?" said the man, stepping across the road and coming closer. The others had by this time come down also, and our young hero found himself confronted by a group of curious faces. The nondescripts had proved to be Tory irregulars.

"I mean just this," said George: "you are English—John Bulls, are you not? I am Richard Blount, of Albany. I have some letters for General Howe and his Lordship; and I have crawled, walked, and stolen through the American lines, and it is my desire to reach New York. Anything that you can do for me I am sure will be appreciated by my family and the gentlemen I wish to see."

The officer laughed and advanced. "I am happy to meet you, sir," he said. "How did you do it?"

"I kept to the woods mostly, and used some Indian tactics, doubtless," answered George.

"He knows them well," broke in a voice. "See how he escaped us up the road."

"I feared you were Yankees," was "Mr. Blount's" rejoinder. "I will be grateful to you, sir, if you will bring me to where I can get a Christian meal, for I am half famished, and no dissembling."

He descended from his perch on the stone wall and approached the officer.

"Here are my credentials, sir," he said, unbuttoning his coat and showing the letters sewed into the lining. "If you can hasten me on my way to the city and recommend me to a tailor, for I am a stranger there, I shall be greatly in your debt."

"'Twill be a pleasure, sir," said the officer, glancing at the first paper George had extended. "Will you give us the honor of breakfasting with our mess? We are quartered in the farm-house yonder."

George accepted, and the two young men walked down the road.

To his surprise, George had sunk his own individuality. He had no idea that it would be so easy or so interesting. He seemed to feel that he was Richard Blount. He limped[Pg 255] beside the officer down the road, and chatted freely about the difficulties of his trip from Albany. There's a difference between lying and acting, and our young Lieutenant, though he did not know it, or perhaps had but discovered it, was an actor through and through.

He had caution enough not to embroider his narrative too freely, but stuck closely to the main idea that he had memorized; and he found that it was very easy to answer questions with questions—a common trick in America, the subtlety of which had not seemed to penetrate the English mind.

He found also, to his surprise, that he entertained the others by his assumption of a dry vein of humor.

"I might as well have Richard amuse them," he thought to himself, and made some remark about one of the thin horses which was being groomed in the front yard.

The officer laughed and ushered him into the little room.

A handsome young man in his shirt sleeves was bending over the open fireplace cooking something in a frying-pan. He looked over his shoulder as George and the party entered.

The young spy started. He remembered where he had seen this young man before; he had dined with him at Mr. Wyeth's.

"What have we here?" asked the officer.

George's heart beat once more quite freely.

"A hungry man," he responded, before any one could speak, "who would stand you a bottle of Madeira for your mess of pottage."

The other laughed, and soon Richard Blount was introduced. They inquired over and over again concerning the strength of the American forces, and, to tell the truth, the numbers did not suffer curtailing at George's hands.

"Why, for three days," he said, "I appeared to be crawling through the midst of an army."

"You did it well," responded one of the officers; "but, by the Dragon, you look a little like an Indian."

"'Tis no disgrace, sir," George answered quickly, affecting to be angered at the other's tone. "'Tis an honor to be allied to the chiefs of our Northern tribes. Perhaps you did not know—" He stopped.

"Pardon me," said the one who had last spoken. "I did not mean it as you have taken it. It was through my ignorance I spoke, as you assume."

After the meal, which gave some excuse for shortening the conversation, George asked to be sent down to the city.

"Can't you send me with a guard of honor?" he asked. "I will pay well for it."

"I cannot spare the men," answered the first officer, politely, who appeared to be in command of the picket, "but your neighbor on the right is going to town. He will accompany you, and save you the trouble of explaining and drawing out your papers at every cross-road."

"Thank you for the offer," said George. "And can you recommend the best inn that has a good cellar and table? for it seems to me that I have lived on parched corn for the last twelvemonth."

In a short time he was mounted on a spare horse, and was plying his conductor with questions as they traversed the streets of the town of Harlem and passed over the undulating hills dotted with handsome residences that adorned Manhattan Island. As they came into the city the ravages of the fire were visible to the westward; almost one-third of the town had suffered. There appeared to be soldiers, soldiers everywhere. They were quartered in every house, barracked in every large building. They passed a gloomy-looking structure that had once been "The City Farms."

"For what do they use that?" inquired George.

"'Tis jammed to the top with 'rebel' prisoners," replied the officer. "I wish they could tow it out into the river and sink it there."

George flushed hotly, but said nothing, and they made their way from the King's Road into one of the cross streets.

"You had best stop at the 'City Arms,'" said the officer. "I will come to-morrow myself to conduct you to General Howe."

"Thank you most kindly," said George. "But I must get some clothes first. I could not appear before the honorable gentlemen in this costume."

"Do you intend seeking an appointment?" inquired his companion.

"No," answered George; "I am lame."

The officer reddened, for he was a gentleman. "I hope I shall see you to-morrow then," he said. "Good-rest to you."

They had halted before the inn with the broad verandas. The whole scene looked very natural. Some church bell struck the hour, and a finely emblazoned coach came bowling down Broadway. Red and the mark of the crown were everywhere. George walked into the inn and called for the landlord. Taking the handsomest room in the house, and kept to it, feigning fatigue, the rest of that afternoon; how odd it seemed to Mr. Richard Blount! When he came down for his dinner he noticed that the landlord was unusually polite, and called him at once by name. He could not help but smile, for he remembered how he had watched this fat palm-rubbing individual stand in his doorway when he and his brother William had gone on that well-remembered walk about the city only a few years before.

"Ah! Mr. Blount," said the landlord, "we are glad to have you here. I know your family in Albany well, and your father has often been a guest under my roof. My humble regards to him."

"Indeed!" said George. "Have you seen any of my people lately?"

"Your uncle, of course," the landlord responded.

George's heart almost stopped beating. What if this uncle were in New York at present? How foolish it was for him to have undertaken any venture so certain of detection and surrounded with so many obstacles!

"Oh, yes, yes!" went on the landlord. "He told me you were coming."

"I wish I could see him," said George—adding to himself, "From a place where he could not see me."

"He will be away for some time. He has gone to Connecticut," said his host.

"Ah! indeed!" quoth young Frothingham, with a sigh of relief. Then he added, below his breath, "I wish it were Kamchatka. I forgot that I had an uncle. This will never do." But the humor of the situation struck him, and he smiled.

Sitting near a window he watched the groups passing up and down the street. How easy it had been; no danger had confronted him as yet. Everything seemed to fall into his hands. He began to whistle softly to himself; then suddenly stopped and fairly shivered. The air he had been whistling was "The White Cockade." He remembered how that tune and "Yankee Doodle" had stirred the half-starving soldiers on the banks of the Delaware. And this reminded him of something else.

"Take care, Richard Blount, take care," he said, "or your Yankee blood will get the better of you."

He wrinkled his forehead in a perplexed way for a minute, and placed his hand inside his coat. Yes, there it was, sewed up with the rest—the letter of poor Luke Bonsall to his mother. It would be a sad thing to break the news, but it was a trust. At last he went up stairs to his room, and ripped the letters from his waistcoat lining. He had pasted the cipher alphabet on a stiff bit of leather which hung from a cord around his neck. Tacked loosely over it, so as to hide it carefully, was a miniature of none other than Aunt Clarissa in her days of youth and beauty. It was the only one he could procure, and a safe hiding-place it would have made, for no one would have thought of looking back of a lady's portrait, and especially Aunt Clarissa's, for an important Yankee cipher. The magnifying-glass was covered with snuff in his small round snuff-box. He lit a candle, and began to write carefully and laboriously. It was late at night when he had finished. His chamber window opened upon a sloping roof which was bordered by a high stone wall. It was but the work of a moment to slip from the wall to the ground. He found himself in Waddell Lane. The despatch which he had written with the aid of the hieroglyphics was safe in his pocket, and now for the post-box of the conspirators.

A group of drunken soldiers reeled by him. One was singing at the top of his voice. From the light of a window at his elbow George saw that it was Corporal McCune, whom he remembered as the tall soldier to whom he and his beloved brother had asserted their loyalty to the King when on their first trip to the city.

What surprised George the most as he walked along was the smoothness with which everything had worked. Perhaps Colonel Hewes's reputation for rashness was entirely undeserved. Though he did not know exactly as yet what the project was in which he was to be a factor, yet, inflamed by the excitement, he could not doubt its successful accomplishment.

What the morrow would bring forth it was hard to tell. In the letter which he had written, or, better, printed, he had told his name, who had sent him, what he had come for, where he was stopping—in fact, had given an accurate description of himself and his supposed individuality. The letter added that he was waiting for his course of action to be determined upon by any orders he might receive.

It had again commenced to snow, and the board sidewalk was already covered with the downy film of white. How well he remembered everything! He knew the little shop across the way with the tops and candy jars in the window. And here was the blacksmith's, where he had stood in the doorway, with his arm around William's shoulder, and watched the sparks fly, and heard the anvil sing and clang. Oh, what good times they were! Would he ever have his arm around his brother's shoulder again, or would he ever feel the comforting touch of William's arm about his own? Thoughts began to rush through his mind, and the harder he thought the faster he walked.

But here he was at the orchard; here was the picket-fence. Now he recalled the signal, for he bent down and picked up a branch. He broke it into three pieces, and placed the first piece behind the third picket, the second behind the sixth, and the third behind the ninth. Colonel Hewes had instructed him to do this as a signal to the others of his safe arrival. Then he walked to the turn-stile and stopped for a minute, his heart beating fast. Even in the darkness, although objects at a distance were most indistinct, he could see that footprints had been lately made in the snow ahead of him. He stepped through the turn-stile, keeping his eyes on the footprints ahead of him; they ran to the second tree and stopped! Now, strange to say, the tracks ahead led directly to the trunk of the second tree, and instinctively George felt that whoever it was that made them was not far off. Without apparently raising his head, he glanced up with his eyes, stumbling at the same time in a way that might account for the slight halt. Yes, he had seen it plainly. There was a figure sitting cross-legged on the lower branch, so close that he could have touched it with a stick. On an occasion like this thoughts must be quick, and George did the best thing that he could have done, for he hastened across the orchard as if nothing had occurred. When he reached the other side and the little lane that ran from some farm buildings, he turned about the corner of a hay-stack.

It was not hard for him to work himself a little way into the damp, yielding hay. He waited patiently, and his patience was rewarded, for, following the footprints that he had made, came a thick-set, muffled figure in a voluminous cape. How a man as large as that could ever hoist himself up on the branch of an apple-tree seven feet from the ground so easily and so noiselessly he could not see, nor could he make out the stranger's features. He was muffled to the eyes. When he had passed, the young spy drew himself cautiously out of the hay, and walked after the retreating footsteps, bending over, and keeping well behind the piles of hay and fodder. But the other's hearing must have been acute, for he paused.

"What's that, I say?" came an intense voice.

George thought he detected a sharp metallic clicking. It was the cocking of the hammer of a pistol.

The only answer to the man's hail, however, was the quick, half-frightened barking of a dog.

"Get out, you beast!" said the voice, and a bit of stick struck the ground where George was crouching on all-fours.

Further down the street the man passed by a lighted window. He turned down his collar, and if George had been there, he would have been most astounded.

It was Rivington, the King's Printer!

The year 1881 was a great date in North Pole exploration. The most influential civilized nations sent out a dozen scientific parties to study the peculiarities of those desolate regions as accurately as can be determined without paying a visit to the centre of that mysterious territory.

The Swedish explorers made their headquarters at Cape Thorsden, on the southeastern island of the Spitzberg archipelago. This expedition, led by Mr. Elkholm, a distinguished physicist attached to the celebrated Upsal University, achieved considerable success. The members returned home in good condition, after having wintered in an excellent observatory, collected a large number of important readings, and carrying back hundreds of photograms, minerals, and specimens of vegetable and animal life in that far northern land.

The youngest member of this party was Mr. Samuel A. Andrée, son of an apothecary in business near Stockholm, and a graduate of the Swedish Polytechnic School. At that moment Mr. Andrée had not completed his twenty-fifth year. He had been appointed a member of the scientific staff through the influence of the Baron Nordenskjöld, the greatest living Scandinavian polar explorer, and an intimate friend of the Swedish King. Mr. Andrée's special duty on this first expedition was to keep track of Sir William Thomson's (now Lord Kelvin) electrometers, and to report on other scientific peculiarities.

Mr. Andrée is a genuine offspring of the famous sea-kings. He is very tall, powerfully built, with a prominent forehead, blue eyes, and a forest of fair early hair, and is endowed with great muscular strength. As for his mental capacities, he is a talented writer and speaker, and can converse in German and English as fluently as in his native tongue, while he speaks French well enough to make himself easily understood by an audience. Mr. Andrée's practical education has not been neglected, and he knows how to use a hammer, a file, or a chisel as well as any trained workman. On account of his manual acquirements he was selected by the chief of the exploring party to keep the registering apparatus in order, a difficult and painful operation during the terrific cold of the dreary polar nights.

Before he had attained his thirtieth year Mr. Andrée received the appointment of chief engineer of the Swedish Patent-Office. It is probable that he would have devoted[Pg 257] the whole of his life to the performance of these attractive official duties had he not felt, during his wintering in the northern regions, the irresistible spell of a more risky and enticing vocation. When he visited me in Paris last summer on his way to the International Geographical Congress, held in London, he confessed that it was in the presence of those grand and impressive scenes he had resolved to win for his native country the fame of having reached the North Pole first.

It was in 1889 that Mr. Andrée decided to make balloon ascensions. Receiving aid from a Swedish scientific fund and from the Stockholm Academy of Sciences, he had the Swea built in Paris, under the supervision of the Swedish Minister. (Swea is the poetic name for Sweden.) This balloon measured 30,000 cubic feet. Mr. Andrée's first ascension took place from Stockholm on July 15, 1893. He was quite alone in the car, and this enabled him to reach an altitude of 11,000 feet, after having passed successively through two layers of clouds, accurately ascertained the direction of the wind prevailing at several levels, and studied other important scientific matters, which have proved valuable to students in all branches of science the world over. He published a graphic account of his first experiences in the Aftonbladet, one of the most influential papers in Sweden, to which he had previously been a popular contributor. In this account he described his sensations as soon as he had lost sight of land, and also when he perceived that he would be immersed in the sea unless he found a serviceable breeze that would carry him towards land. Fortunately the breeze came in time.

ANDRÉE'S GUIDING SAIL.

ANDRÉE'S GUIDING SAIL.

On October 19th of the same year Mr. Andrée made another ascension, in the course of which almost any inexperienced aeronaut would have been lost. As soon as he had passed through a layer of clouds, which up to that moment had entirely concealed the earth from view, he saw that he was passing at an immense distance from land over the very centre of the Baltic. With a calm hand he gently lowered his guide-rope, and observed that the friction on the water was greatly diminishing the velocity with which the wind was carrying the Swea away from the sea-ports, where he could reasonably expect to be rescued by casual ships. Then he tried to reduce the velocity even more by attaching two sacks of ballast to the end of his guide-rope. This simple combination, conceived under the pressure of a great danger, led him to a discovery. He found that he could make the balloon turn slightly to the right or left by using a sail when lowering the guide-rope, not only on sea, but on a vast expanse of land. Mr. Andrée tried this important experiment during an ascension made on July 14, 1894, at Gottenburg. The change of course that he obtained with a moderate-sized sail and a heavy guide-rope was estimated from ten to thirty degrees, not only as shown by his compass, but also according to the testimony of competent persons who had witnessed this extraordinary ascension, when, for the first time, a man had made a balloon sail on the wind.

IN THE CAR OF THE SWEA.

IN THE CAR OF THE SWEA.

An eventful ending was reserved for this ascension, during which the young Swedish engineer had so cleverly combined the force of the wind with the friction it generates, and utilized both for varying at will the direction of the balloon to the right or left from the air current. The sun was fast declining when Mr. Andrée conceived for the first time this great idea, which may prove so useful for reaching the North Pole. He soon observed a small island straight ahead in the direction he was then following, and at once threw out a sack of ballast. His guide-rope was freed from the waves in an instant, and the Swea darted forward at a rapid rate for the desired land. Ten minutes had not elapsed when Mr. Andrée saw, with a feeling of deep satisfaction and even rapture, the shore lying about a hundred yards directly under his feet. Then he threw his whole weight on his valve-rope, hundreds of cubic feet of gas instantly escaped, the Swea struck land with a shock, and the car was overturned. Our aeronaut, to his great satisfaction, was thrown, at full length on the ground.

Being young in the art of balloon management, Mr. Andrée could not imagine how quickly events happen in aerial navigation. Before he could grasp a rope the Swea had vanished in the air, and he was left alone on the island, without any food or covering, exposed to the cold of those latitudes during a long and dismal October night. Naturally enough, he found in his pocket a box of matches, for the manufacture of these useful objects is a specialty in his native country. He gathered a few dry weeds and dead shrubs and lighted a fire. While warming his tired and hungry body he had plenty of time to meditate over the hardships of his unenviable position. The island, which seemed allotted to him by fate, was not two furlongs long and one wide, and had no water. It was one of the thousand rocky and barren islets composing the Finnish archipelago, and there was but slight possibility that any vessel sent from Sweden could discover his retreat in time to save him from the most terrible of fates, death from hunger and thirst.

As soon as the sun was up on the following morning Mr. Andrée ran to the crest of a little rocky eminence, and kept screaming at the top of his voice for more than an hour. Then he sat down exhausted and burst into tears. Finally his swollen eyes perceived a cloud of smoke upon the horizon. Surely it must be a steamer! No doubt the steamer was rapidly nearing the island! The unfortunate aeronaut[Pg 258] wrecked from the skies was about to be rescued! In his joy he danced and resumed his screamings. For a while he was elated. He had some right to believe that he had been seen from the deck, as the ship was steering straight towards the island. But the vessel changed its course, and in spite of the balloonist's piercing cries, disappeared.

This unlucky departure would have driven many a resolute man to despair. For Mr. Andrée it was a lesson. He at once understood that it was impossible for any one on a vessel to see a human figure on this desolate island, and that he must contrive a more showy signal than his body, notwithstanding he was tall and strongly built. After having meditated for half an hour—an eternity under the circumstances—he made a sort of stout stick by tying together with weeds a lot of branches torn from the shrubs. At the end of this stick he attached his trousers, and waved them wildly over his head, after having mounted to the top of the hill.

ANDRÉE'S ESCAPE FROM THE ISLAND.

ANDRÉE'S ESCAPE FROM THE ISLAND.

This unnamed island where Mr. Andrée was left is situated a few miles from Brunskär, which has two houses. One of the two is owned by a tailor, who goes around once or twice a week in a boat to visit his customers, who are dispersed over the archipelago. Of course the tailor's eyes were attracted by the sight of a pair of trousers floating in the air, and he rowed to the spot to see what such a signal meant. And this is how Mr. Andrée was restored to life, and thus enabled to pursue his grand idea of reaching the North Pole in a balloon.

Having given some idea of Mr. Andrée's career, and shown a few traits of his energetic character, I purpose, as soon as possible, to tell my young readers the story of the preparations he is now making for this great aerial voyage, which is attracting the interest of scientific people all over the world. Mr. Andrée will start on this perilous voyage some time this year, probably in July, if he can get all things ready by that time. His friend, Mr. Elkholm, will accompany him, and it is not impossible that the explorers may land somewhere in America, after having passed, perhaps, over the North Pole, or at least very near it.

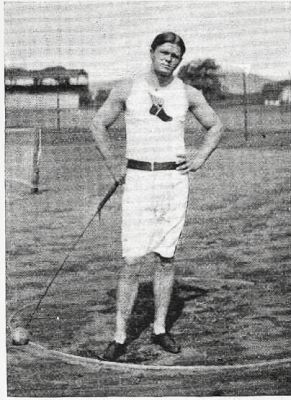

SAMUEL A. ANDRÉE.

SAMUEL A. ANDRÉE.

With very slight change one may convert the same material into several varieties of fancy bread. Southern cooks understand this so well that they frequently set aside a mixture, after having supplied the breakfast-table with griddle-cakes, only to have it reappear at luncheon in quite different guise—as "pone," muffins, egg-bread, or "pop-overs." If kept in a cool place an ordinary batter will remain sweet for twenty-four hours, and the addition of an egg or a spoonful of baking-powder will quickly restore its lightness.

By way of proving the many-sidedness of certain mixtures, let us see how the use of muffin-cups, waffle-irons, and frying-pan will alter results, and turn out for us "Virginia puffs," "Aunt Sally's waffles," and "bell fritters." The necessary ingredients for all three dainties are: 1 quart of milk; 1½ pints of flour (half a pint to be set aside for fritters, which require more than puffs or waffles); 4 eggs; a table-spoonful of butter and lard combined; a heaping teaspoonful of baking-powder; a small teaspoonful of salt.

The Virginia puffs will require everything except the half-pint of flour reserved for fritters.

Set aside a coffee-cup of milk, and put the rest in a farina-kettle over a brisk fire.

Sift a pint of flour into a bowl. Gradually pour over it the coffee-cup of cold milk, heating until it becomes a smooth paste. By this time the remainder of the milk will be hot enough (it must not boil) to stir little by little into the paste. Next add the butter, lard, and salt, then the baking-powder mixed in a little dry flour.

Now beat, beat, beat with a big spoon and plenty of muscle, for the success and puffiness of your puffs depend largely on the amount of energy expended on them.

Whisk the whites of two eggs to a stiff froth. Beat the whites of two and yolks of three together, very light, and beat them into the batter, the frothed whites last.

Have your muffin-cups hot and well buttered. Pour in the mixture, and bake twenty to twenty-five minutes in a quick oven. Serve the moment they are up to the top of the cups and a nice brown color, otherwise they will fall and grow sodden.

The same receipt, minus baking-powder and lard, makes excellent waffles. If you like them thick and soft, fill the irons well with batter. If they are preferred thin and crisp, use less. Should they still seem too solid, thin with a little milk.

The secret of good waffles is the cooking. The irons must be constantly turned over a steady fire to prevent blistering or scorching and to give to both sides an appearance of evenness. Never wait to bake a quantity, but serve as fast as the iron turns them out.

When you have reached the point mentioned in directions for Virginia puffs where the quart of milk has been stirred into a pint of flour, leave the paste to grow cold. Before dinner beat in the four eggs and a half-pint of dry flour.

These fritters are delicious with a hot sauce for dessert, but may be metamorphosed into an entrée by the addition of bananas, apples, or apricots, cut small and stirred lightly into the batter at the last moment before frying.

Put a pound or more of best leaf lard in a deep iron skillet, and let it come to a boil. Dip the fritter mixture up in a large kitchen spoon. Hold over the skillet, and cut it from the spoon with a knife. It will fall into the hot lard somewhat in the form of the bowl of the spoon. The name "bell" implies that they should not be flat and shapeless, but nicely rounded.

I used to think that Fido was a most exciting pet;

He'd come up in the morning and beneath the bed-clothes get,

And play that he was savage, and go biting at my toes;

But now he doesn't scare me—little Fi no longer goes.

I used to think our gardener a hero great and grand,

The biggest man of all the big in all our great big land;

But now I take no stock in him; he doesn't interest,

Although to make a wonder he just tries his level best.

You see, somebody gave me, not so very long ago,

A little book of fairy tales—it's wonderful, you know,

To read about the fearful things they do in books like that.

And it's what's made old Fido and the gardener seem flat.

I want a dragon for a pet—a dragon big and fierce—

That feeds on fire and powder, with a glance that seems to pierce,

I sort of don't get wrought up by old Fido when I read

Of how that fierce old dragon takes in lions for his feed.

And as for John the garden man, he doesn't seem to me

One half the hero that one time I thought that he must be,

For he don't kill off giants, like Hop o' my Thumb and Jack,

And all my liking for his tales is growing very slack.

So, daddy, get a dragon that will jump into my bed

Each morning when the sun comes up, and sniff about my head

The way old Fido does, and let the market garden go

To some real ogre-killer, like Great Jacky was, you know.

t was a very hot day even for Cuba. Every living thing moved listlessly. The great Spanish flag, hanging from the tall slender staff just inside the gate of the fort, drooped like the wings of a tired bird. The sentries were almost gasping for breath. In the barracks the men grumbled and railed at the fate which had brought them from home and friends to fight in a country where fever thinned their ranks far more effectively than did the bullets of the insurgents.

On a slight hill about a mile from the fort a man and a youth were lolling lazily on the ground. The lad was about eighteen years of age, tall, well-built, and unmistakably an American. His companion, a native Cuban, was at least thirty years old, short, but with a frame denoting immense strength.

They had been watching the fort for an hour or more through a powerful field-glass, and following closely the movements of the sentries on the wall nearest them.

"Pah!" said the lad at last, "they're only a lot of boys."

The man smiled at him meaningly, and the lad blushed.

"I know," he continued, hesitatingly, "that you're thinking I'm just a boy too; but," proudly, "I'm an American."

"So," answered the man, softly; "and had I a few score such lads as you in my command I'd strike a great blow for Cuba to-day."

"How, Captain Marto?" was the eager question.

"By taking yonder fort by storm," was the quiet reply.

The youth's father was a prisoner in the fort, and the incidents which led up to his capture may be here described. For five years Mr. Hinton, a native of Pennsylvania State, had resided with his son Ben in Havana, where he carried on business as a general merchant. His wife had died while on a visit to her old American home. Among Cubans Mr. Hinton was well known as a sympathizer in their cause. Immediately on receipt of the news in Havana that General Antonio Maceo had taken the field he decided to lend his active aid to the Cuban leader. Not wishing his son to share in the dangers of a struggle in which he knew that the Spaniards would show no mercy to any who took up arms against them, Mr. Hinton had suggested that Ben go back to relatives in America. This proposition the lad stoutly opposed. Ben knew by heart the stories of the brave efforts which the Cubans had so often made in their attempts to throw off the Spanish yoke. The names of Maceo, Gomez, Marto, and other revolutionists were held in high estimation by him, and, with that intense love of freedom inherited by every American boy, he had determined, long before he knew his father's views on the subject, to strike a blow in the coming struggle for Cuban independence. His father was at last compelled to consent to Ben's accompanying him.

Accordingly, one evening Mr. Hinton, Marto, and Ben left Havana secretly. By travelling at night, and lying concealed during the day in the huts of natives, and sometimes in the woods, they reached the outskirts of the province of Puerto Principe. Here, at the little village in which Marto was born, thirty natives joined them. Marto was elected captain of the band. Feeling somewhat secure, on account of their numbers, the band travelled through the country by day, taking the most direct route for Maceo's camp. But one morning they were suddenly surrounded by an overwhelming force of Spanish soldiers. With desperate courage, Captain Marto, Ben, and some twenty-five men cut their way out of the cordon of soldiers and sought safety in flight.

It was not until the Spaniards gave up the chase that any one noticed that Mr. Hinton was not with the party. Poor Ben was in a frenzy, and, but for Captain Marto and a couple of men restraining him by force, would have rushed back to the scene of the conflict to seek for his father. Wiser counsel prevailed, however, and towards evening a man who joined the party brought comparative happiness to Ben by the report that he had watched from the woods a party of Spanish soldiers marching along with an American prisoner in their midst. The description of the prisoner tallied so closely with that of Mr. Hinton as to leave no doubt of his identity.

Then Marto, who loved Mr. Hinton as a brother, had determined that, at whatever cost, his American friend must be rescued.

"Why," he had said to Ben, "I dare not go to Maceo without him, and I would not if I could. Tho General is expecting him, and will give him a command as soon as he arrives at the camp."

"Which," Ben had answered, gloomily enough, "will never be."

"Which," Marto had retorted, somewhat testily, "must and will be."

Two days after the fight they located the fort which was the headquarters of the soldiers who had attacked them, and it was this Ben and Captain Marto were watching when our story opens. The band had spent three days in the neighborhood, but as yet had not even succeeded in letting the prisoner know that his friends had not totally deserted him.

The fort was a very rude affair, the walls being constructed of two thicknesses of logs with earth packed between. An earthen embankment ran around the inner side of the walls, and at such a height that when the soldiers appeared on it their bodies from the waist up offered a splendid target to an enemy. Some two hundred and fifty men formed the garrison, and they were quartered in a huge two-storied log barracks in the centre of the enclosed ground. In front of the barracks, and about twenty feet from it, was a small hut, in which Ben and Captain Marto, by the aid of the field-glass, had learnt Mr. Hinton was confined.

Continuing their conversation, Captain Marto and Ben had decided that the attempted rescue must be made that night. They knew that the great heat would have a depressing effect on the Spaniards, and they knew also that after nightfall not more than three sentries patrolled the walls of the fort. Many plans were discussed whereby success might reasonably be expected to attend their venture, but the one upon which it was finally decided to act was suggested by Ben.

MARTO GRASPED THE SENTRY AND THREW HIM OVER THE WALL.

MARTO GRASPED THE SENTRY AND THREW HIM OVER THE WALL.

In accordance with that plan, after the night was well advanced, Captain Marto and Ben, with eight men, lay in the shadows under the eastern wall of the fort. They listened until they heard the sentry walk past the position they occupied, and then Marto, mounting upon the shoulders of two of the men, scrambled to the top of the wall. He dropped softly to the embankment, and lay as close to the logs as he possibly could. Shortly the sentry came along on his return patrol, humming a Spanish song. He did not notice the prostrate form until he almost trod upon it. It was then too late to give a warning, for Marto sprang up, and with all the strength of which he was capable, struck the man full on the mouth, and followed this up immediately by grasping him around the waist and fairly throwing him over the wall. Here a dozen hands quickly grasped the soldier, who was gagged and bound before he could utter a cry.

Then one by one the Cubans with Ben scrambled up, and the whole ten made a rush for the small hut. Three sleepy guards were cut down in a few seconds, the door of the building was forced open, and Mr. Hinton was led out by his son.

"Dad! dear old Dad!" cried Ben.

"Ben! my boy!" was the answer, and the voices of father and son betrayed deep emotion.

At this moment a shot was fired, and a sentry on the western wall fell. Instantly a tremendous hubbub arose within the barracks, and the Spaniards, some of whom had already been aroused by the scuffle with Mr. Hinton's guards, began to pour out of the building. All were armed, though many were only half dressed; but before they had time to load their rifles the remaining Cubans, who had got into the ground by way of the western wall, joined Captain Marto and those with him, and the little band of twenty-five flung themselves on the Spaniards.

While the fighting was going on Ben suddenly found himself thrust against something, which proved to be the flag-pole, and, looking up, discovered the Spanish flag waving overhead. The idea at once occurred to him to take advantage of the laxity of discipline among the Spanish troops. He hauled on the ropes, but for some reason they would not work. Placing his clasp-knife between his teeth, he climbed the staff, until he clasped the folds of the flag with his left hand; then he was compelled to sever the halyards with his knife.

From his airy perch Ben turned his eyes in the direction of the struggle. He could barely distinguish the outlines of the surging mass of men. But high above the din of oaths and cries in Spanish, the clash of bayonet, sword-blade, and the favorite Cuban weapon, the machete, arose the exulting cry: "Cuba libre! Cuba libre!"

The lad's soul was thrilled. "Surely," he muttered to himself, "Cuba for the Cubans will soon be a fact and not a dream. But they must retire."

Even as the word left his lips, a single long shrill note from a whistle pierced the air. It was a prearranged signal, and it came none too soon; for now, somewhat recovered from the suddenness of the attack, the Spaniards, realizing the small force opposed to them, were driving the Cubans back by sheer weight of numbers.

At the signal, however, the Cubans retired with surprising swiftness, carrying with them the bodies of several of their comrades who had fallen. As they passed the staff Ben slipped down amongst them, the flag bundled up under his left arm. The gate had already been opened by two Cubans, who had been assigned that duty. The whole band rushed through, three or four men in mere bravado lingering to pull the gate to after them.

As they fled several Spaniards mounted the embankment and sent a volley after them, one bullet striking Ben's left arm. A little cry of pain escaped him, but he clinched his teeth, and grasping the flag still tighter, hurried on.

No pursuit was made, and after placing two miles between themselves and the fort, a halt was called. Torches were lit, and by their fitful glare it was found that of the Cubans who had to be carried away none were dead, although in some cases the wounds were serious. When Ben produced the flag, all stained with his own blood, the impulsive Cubans showered such praise upon him that the lad felt almost shamed. His father said very little, but Ben knew by the silent hand-shake and the care for the wounded arm that Mr. Hinton was proud of his son.

The rest of the journey to Maceo's camp partook of the nature of a triumphal procession. The news of the gallant deeds of Marto's little band roused the whole countryside, and in a few weeks' time what had formerly been a quiet district was in arms against the Spaniard.

When Maceo's camp was reached Mr. Hinton, Marto, and Ben were at once conducted into his presence. He began to compliment Marto, but the latter interrupted respectfully.

"Sir, it was my gallant comrade here," pointing to Ben, "who planned the affair and captured the flag. To him the honor is due."

General Maceo stepped up to Ben and clasped the lad's right hand warmly in his own.

"What can I do for you, my hero?" he asked.

"Let me continue to fight in your cause," was the modest answer.

And, under the immediate command of his father, Ben Hinton is still fighting for Cuba.

Grace Wainwright, a slender girl in a trim tailor-made gown, stepped off the train at Highland Station. She was pretty and distinguished looking. Nobody would have passed her without observing that. Her four trunks and a hat-box had been swung down to the platform by the baggage-master, and the few passengers who, so late in the fall, stopped at this little out-of-the-way station in the hills had all tramped homeward through the rain, or been picked up by waiting conveyances. There was no one to meet Grace, and it made her feel homesick and lonely. As she stood alone on the rough unpainted board walk in front of the passenger-room a sense of desolation crept into the very marrow of her bones. She couldn't understand it, this indifference on the part of her family. The ticket agent came out and was about to lock the door. He was going home to his mid-day dinner.

"I am Grace Wainwright," she said, appealing to him. "Do you not suppose some one is coming to meet me?"

"Oh, you be Dr. Wainwright's darter that's been to foreign parts, be you? Waal, miss, the doctor he can't come because he's been sent for to set Mr. Stone's brother's child's arm that he broke jumping over a fence, running away from a snake. But I guess somebody'll be along soon. Like enough your folks depended on Mr. Burden; he drives a stage, and reckons to meet passengers and take up trunks, but he's sort o' half baked, an' he's afraid to bring his old horse out when it rains—'fraid it'll catch the rheumatiz. You better step over to my house 'long o' me; somebody'll be here in the course of an hour."

Grace's face flushed. It took all her pride to keep back a rush of angry, hurt tears. To give up Paris, and Uncle Ralph and Aunt Hattie, and her winter of music and art, and come to the woods and be treated in this way! She was amazed and indignant. But her native good sense showed her there was, there must be, some reason for what looked like neglect. Then came a tender thought of mamma. She wouldn't treat her thus.

"Did a telegram from me reach Dr. Wainwright last evening?" Grace inquired, presently.

The agent fidgeted and looked confused. Then he said coolly: "That explains the whole situation now. A despatch did come, and I calc'lated to send it up to Wishin'-Brae by somebody passing, but nobody came along goin' in that direction, and I clean forgot it. It's too bad; but you step right over to my house and take a bite. There'll be a chance to get you home some time to-day."

At this instant, "Is this Grace Wainwright?" exclaimed a sweet, clear voice, and two arms were thrown lovingly around the tired girl. "I am Mildred Raeburn, and this is Lawrence, my brother. We were going over to your house, and may we take you? I was on an errand there for mamma. Your people didn't know just when to look for you, dear, not hearing definitely, but we all supposed you would come on the five-o'clock train. Mr. Slocum, please see that Miss Wainwright's trunks are put under cover till Burden's express can be sent for them." Mildred stepped into the carryall after Grace, giving her another loving hug.

"Mildred, how dear of you to happen here at just the right moment, like an angel of light! You always did that. I remember when we were little things at school. It is ages since I was here, but nothing has changed."

"Nothing ever changes in Highland, Grace. I am sorry you see it again for the first on this wet and dismal day. But to-morrow will be beautiful, I am sure."

"Lawrence, you have grown out of my recollection," said Grace. "But we'll soon renew our acquaintance. I met your chum at Harvard, Edward Gerald, at Geneva, and he drove with our party to Paris." Then turning to Mildred: "My mother is no better, is she? Dear, patient mother! I've been away too long."

"She is no better," replied Mildred, gently, "but then she is no worse. Mrs. Wainwright will be so happy when she has her middle girl by her side again. She's never gloomy, though. It's wonderful."

They drove on silently. Mildred took keen notice of every detail of Grace's dress—the blue cloth gown and jacket, simple but modish, with an air no Highland dressmaker could achieve, for who on earth out of Paris can make anything so perfect as a Paris gown, in which a pretty girl is sure to look like a dream? The little toque on the small head was perched over braids of smooth brown hair, the gloves and boots were well-fitting, and Grace Wainwright carried herself finely. This was a girl who could walk ten miles at a stretch, ride a wheel or a horse at pleasure, drive, play tennis or golf, or do whatever else a girl of the period can. She was both strong and lovely, one saw that.

What could she do besides! Mildred, with the reins lying loosely over old Whitefoot's[Pg 262] back, thought and wondered. There was opportunity for much at the Brae.

Lawrence and Grace chatted eagerly as the old pony climbed hills and descended valleys, till at last he paused at a rise in the path, then went on, and there, the ground dipping down like the sides of a cup, in the hollow at the bottom lay the straggling village.

"Yes," said Grace, "I remember it all. There is the post-office, and Doremus's store, and the little inn, the church with the white spire, the school-house, and the manse. Drive faster, please, Mildred. I want to see my mother. Just around that fir grove should be the old home of Wishing-Brae."

Tears filled Grace's eyes. Her heart beat fast.

The Wainwrights' house stood at the end of a long willow-bordered lane. As the manse carryall turned into this from the road a shout was heard from the house. Presently a rush of children tearing toward the carriage, and a chorus of "Hurrah, here is Grace!" announced the delight of the younger ones at meeting their sister. Mildred drew up at the doorstop, Lawrence helped Grace out, and a fair-haired older sister kissed her and led her to the mother sitting by the window in a great wheeled chair.

The Raeburns hurried away. As they turned out of the lane they met Mr. Burden with his cart piled high with Grace's trunks.

"Where shall my boxes be carried, sister?" said Grace, a few minutes later. She was sitting softly stroking her mother's thin white hand, the mother gazing with pride and joy into the beautiful blooming face of her stranger girl, who had left her a child.

"My middle girl, my precious middle daughter," she said, her eyes filling with tears. "Miriam, Grace, and Eva, now I have you all about me, my three girls. I am a happy woman, Gracie."

"Hallo!" came up the stairs; "Burden's waiting to be paid. He says it's a dollar and a quarter. Who's got the money? There never is any money in this house."

"Hush, Robbie!" cried Miriam, looking over the railing. "The trunks will have to be brought right up here, of course. Set them into our room, and after they are unpacked we'll put them into the garret. Mother, is there any change in your pocket-book?"

"Don't trouble mamma," said Grace, waking up to the fact that there was embarrassment in meeting this trifling charge. "I have money;" and she opened her dainty purse for the purpose—a silvery alligator thing with golden clasps and her monogram on it in jewels, and took out the money needed. Her sisters and brother had a glimpse of bills and silver in that well-filled purse.

"Jiminy!" said Robbie to James. "Did you see the money she's got? Why, father never had as much as that at once."

Which was very true. How should a hard-working country doctor have money to carry about when his bills were hard to collect, when anyway he never kept books, and when his family, what with feeding and clothing and schooling expenses, cost more every year than he could possibly earn? Poor Doctor Wainwright! He was growing old and bent under the load of care and expense he had to carry. While he couldn't collect his own bills, because it is unprofessional for a doctor to dun, people did not hesitate to dun him. All this day, as he drove from house to house, over the weary miles, up hill and down, there was a song in his heart. He was a sanguine man. A little bit of hope went a long way in encouraging this good doctor, and he felt sure that better days would dawn for him now that Grace had come home. A less hopeful temperament would have been apt to see rocks in the way, the girl having been so differently educated from the others, and accustomed to luxuries which they had never known. Not so her father. He saw everything in rose-color.

As Doctor Wainwright towards evening turned his horse's head homeward he was rudely stopped on a street corner by a red-faced, red-bearded man, who presented him with a bill. The man grumbled out sullenly, with a scowl on his face:

"Doctor Wainwright, I'm sorry to bother you, but this bill has been standing a long time. It will accommodate me very much if you can let me have something on account next Monday. I've got engagements to meet—pressing engagements, sir."

"HERE I AM,YOUR MIDDLE DAUGHTER, DEAREST."

"HERE I AM,YOUR MIDDLE DAUGHTER, DEAREST."

"I'll do my best, Potter," said the doctor. Where he was to get any money by Monday he did not know, but, as Potter said, the money was due. He thrust the bill into his coat pocket and drove on, half his pleasure in again seeing his child clouded by this encounter. Pulling his gray mustache, the world growing dark as the sun went down, the father's spirits sank to zero. He had peeped at the bill. It was larger than he had supposed, as bills are apt to be. Two hundred dollars! And he couldn't borrow, and there was nothing more to mortgage. And Grace's coming back had led him to sanction the purchase of a new piano, to be paid for by instalments. The piano had been seen going home a few days before, and every creditor the doctor had, seeing its progress, had been quick to put in his claim, reasoning very naturally that if Doctor Wainwright could afford to buy a new piano, he could equally afford to settle his old debts, and must be urged to do so.

The old mare quickened her pace as she saw her stable door ahead of her. The lines hung limp and loose in her master's hands. Under the pressure of distress about this dreadful two hundred dollars he had forgotten to be glad that Grace was again with them.

Doctor Wainwright was an easy-going as well as a hopeful sort of man, but he was an honest person, and he knew that creditors have a right to be insistent. It distressed him to drag around a load of debt. For days together the poor doctor had driven a long way round rather than to pass Potter's store on the main street, the dread of some such encounter and the shame of his position weighing heavily on his soul. It was the harder for him that he had made it a rule never to appear anxious before his wife. Mrs. Wainwright had enough to bear in being ill and in pain. The doctor braced himself and threw back his shoulders as if casting off a load, as the mare, of her own accord, stopped at the door.

The house was full of light. Merry voices overflowed in rippling speech and laughter. Out swarmed the children to meet papa, and one sweet girl kissed him over and over. "Here I am," she said, "your middle daughter, dearest. Here I am."

Poor Bobby's sick! Dear little lad,

He's got a pain; it hurts him awful bad.

Just see his face!

In every line of it a trace

Of how he suffers from that pain.

What's that? His plate is back again

For buckwheat cakes? Oho, I see!

'Tis nearly nine o'clock. Ho!—hum!—tell me

What is this woe

That lays poor Bobby low

Each morning just at school-time, yet so fleet is?

Is it the olden time Nineoelockitis

That as a boy I had so frequently?

That comes at half past eight, and seems to last

From then till nine, or say a quarter past,

And then departs, and leaves him all the day

With twice the strength with which to go and play?

Oh—well—if this be so

I'll worry not. The symptoms well I know.

Only, instead of cakes to cure his ills,

Take him a spoon and fill it up with squills,

And by to-morrow

I doubt he'll suffer from his present sorrow.

Napoleon and his army of soldiers were marching across the Alps in Switzerland before descending into Italy upon that famous campaign in which all Italy bowed low to the French conqueror. Up the long steep slopes the soldiers toiled in the shadow of the frowning and overhanging cliffs. Here and there patches of bare rock appeared, where the snow had been swept off by the fierce gusts of wind. For miles the army was strung along the roads, and wearily the men walked as they struggled with the heavy cannon. These cannon were mounted on improvised sleds, and the soldiers pulled them over the snow with ropes. At times one of the sleds would slip and tumble over a precipice, carrying with it a number of the men who were dragging it along. The air was bitterly cold, and many of the soldiers died on the road, or from weakness fell off the cliffs, to be dashed to pieces on the rocks below.

An officer had been riding back and forth along his command most of the day, helping here and encouraging there, and by kindly acts urging his men to bravely laugh off their despondency. Cold, frozen, poorly clad, and with but little to eat, such conditions were too crushing to arouse much enthusiasm among the soldiers, but a faint cheer time and again reached this officer's ears as he shouted his commands.

Darkness was gathering fast, and it was desirable that this officer's detachment should reach a small plateau some distance ahead before camping for the night. In order to reach this it was necessary to cross a narrow dangerous part of the road with a sharp descent of some hundred feet on one side and the walls of a cliff on the other.

The officer stood at the narrowest part directing the way. Most of the detachment had passed the spot and three cannon had already made the passage. The last one, larger than any of the others, was being slowly but surely worked over, when there was a sudden sinking of the snow, several shouts, and the heavy iron cannon commenced toppling over the cliff.

"Throw a rope over the end there, quick!" shouted the officer, at the same time grasping the rope attached to the forward end. But it was too late, or else the frozen hands of the soldiers prevented their working lively, and all but two of those having hold of the rope that was attached dropped it in fear of being pulled over the cliff.

Down it went into the black depths of the narrow crevice between the mountains, and with it went the two men who had kept their hold, and also the brave officer, for when the others had dropped the rope it had become entangled in his feet. A short, despairing cry was all that rose on the night air to tell the tale of those three deaths. Napoleon's soldiers were too accustomed to such sights and the hopelessness of an attempt at rescue to do more than shudder and move stubbornly on. Through many such scenes the army made its way over the Alps.

Many years later, in the summer of 1847, a party of people were taking a pleasure trip through Europe, and had stopped at one of the small villages at the foot of the mountains. From here they made occasional trips, exploring the surrounding neighborhood. In the party was a geologist, who was making studies of the geological formations of the Alps. Such work took him into unfrequented spots.

On one of these expeditions he wandered one day into a narrow chasm and slowly worked along, making notes of the walls of stone that rose above his head, seemingly coming together where he could see a narrow rift of light. As he stumbled along, now and then stopping to examine a loose stone, he came across a log-shaped rock. Upon closer inspection, however, he saw it was an old rusty cannon, and sitting down upon it, he fell to musing how it came there.

He had noted that the cannon was of a make used during Napoleon's time, and concluded that it must be one of those that were lost over the precipice when the great general had crossed into Italy. Stooping down, he poked into its mouth, mechanically scraping out the dirt that had accumulated there, and idly thought of the brave soldiers of those days. Suddenly he noticed a leathern book, in fairly good condition, lying in the little heap of dirt he had scraped out. Picking it up he opened it and found it full of papers. Thinking then that it was of no great importance, he placed it in his pocket and retraced his steps to the village. That evening he examined its contents, and among some papers relating to an old estate he found the following scrawl:

"I, one of Napoleon's officers, fell from the cliff above, dragged over by a rope attached to this cannon. The two men that fell with me were instantly killed, as I have not heard them moan nor seen them move. My leg and left arm are broken, and I know that I am hurt internally. Fortunately, I struck but once while falling, and then this soft bed of snow prevented instant death. I have enough strength left to write this and stick it into the mouth of the cannon, for possibly some one may discover it. My papers and such as will prove the right to certain property will be found in the leathern book, and I beg the finder will place them in the hands of the proper owners. My strength is leaving me and I must stop—" (Here followed the signature.)

Among the papers was found the right to an estate of considerable value, and when, after great difficulty, the descendants and owners were traced, it was discovered that the family had suffered more or less privation from the loss of these papers, restored after so many years.

SUNDAY MORNING MUSTER OF THE CREW.

SUNDAY MORNING MUSTER OF THE CREW.

Above all, it means unceasing vigilance. It is said that a man who rides often over the same road can fall asleep in the saddle and still travel it safely. Such a man would be drummed out of the steamship service. Every man who has to do with the sailing of an ocean greyhound must be on the alert every moment of his tour of duty. No matter how many scores of times he may have sailed over the route between New York and Southampton, he must be constantly on the lookout for all that he can read in sea and sky, or in the earth beneath the sea. For two things he is responsible—the safety and speed with which the journey is made. Nothing else appeals to him. The greatest orator of the finest singer in the world might appear and perform on deck, and I doubt whether the men on the bridge would see him or hear him. The ship is like a great cannon-ball that has been shot out of one port to strike the other. The officers of the ship are to make that cannon-ball go true to the mark without deviating in the least degree from the course. That duty is so absorbing that nothing else can be allowed to interfere with it.

Gales cannot stop nor fogs hinder the swift passage of the transatlantic liner. She flies onward with what seems to be an entire disregard of storms. But these things are not disregarded. They are grappled with and fought against, and man triumphs over the fury of the elements. Nothing is left to chance. Every emergency that experience or imagination can suggest is prepared for and studied out long in advance. Friends sometimes ask the captain of a great ship if the nervous strain does not exhaust him; if he is not depressed by the responsibility for so many hundreds of lives and so many millions of dollars worth of property. The answer to that question is always no. If the captain were to give himself up to such reflections he would be unfit for his position. The captain's experience is long and varied before he becomes master of an ocean greyhound. His responsibility is small at first, but constantly grows greater, until he is no more worried by it than you would be worried by having to drive a pair of ponies.

THE PROMENADE DECK OF THE "NEW YORK."

THE PROMENADE DECK OF THE "NEW YORK."

The best ships of to-day are gigantic compared with the best of twenty or even fifteen years ago. The New York is 565 feet long, and of 63 feet beam. She extends 27 feet beneath[Pg 264] the water. These mere figures do not convey much of an impression of her size. If she should be lifted out of the water, however, she would fill Broadway, from curb-stone to curb-stone, from Chambers Street to Park Place, and a man standing on her bridge could easily look into the fifth story of the houses on either side. A ship of this size costs more than two millions of dollars. Her engines have power equivalent to that of 20,000 horses. The crew of the New York averages 400 men all the year around. There are 70 in the navigating department, 180 in the engine department, and the rest are in the steward's department.

Just as the government of the city of New York is divided among the Mayor, Aldermen, and boards and commissioners of various departments, so the administration of a giant steamship is divided into specialties. The Mayor is the chief officer of the city. The Captain is the chief officer of the ship. He is more than that. From the time she leaves port until she enters port he is master of the life and liberty of every person aboard the ship, as well as of all the property in it. He is an autocrat. Of course he must administer his authority wisely. Unwise autocrats don't last long, whether afloat or ashore.

LOOKOUT IN THE FORETOP.

LOOKOUT IN THE FORETOP.

The head of each department is responsible for all that goes on in it. The first officer is at the head of the crew, or navigating department. The chief engineer directs everything connected with the engines. The chief steward has full control of all that has to do with the comfort of the passengers and crew. Each of these chiefs makes a written report at noon every day. Thus the Captain is kept informed of everything pertaining to the ship's welfare.

Every one of the senior officers of the ship is a duly qualified master, capable of taking her around the world if need be. The day is divided into "watches," or tours of duty, of four hours each. One junior officer is on the bridge with each senior officer on duty. The senior officer directs the ship's course. He never leaves the bridge while he is on watch. Should he do so he would be dismissed at once. There is no excuse possible. It would be just as if he had died suddenly. His friends would all feel sorry, but nothing could be done to help him. Two seamen are always on watch in the bow of the ship, and two more in the fore-top. Twice as many are on the lookout in thick weather. Observations are taken every two hours. In the good old sailing-ship days the Captain was content to "take the sun" at noon every day. If the sky was cloudy for a day or two, it really didn't matter much, for he could jog along on dead reckoning. But on an ocean greyhound, rushing over the course between New York and Europe at the rate of more than twenty miles an hour, it is highly important that the ship's position be known all the time. Fog may come down at any moment, observations may not be obtainable for ten or twelve hours. The positions of more than one hundred stars are known. By observing any one of these the ship's whereabouts can be ascertained in a few minutes. Of course the "road" becomes more or less familiar to a man who crosses the ocean along the same route year after year. Yet this familiarity never breeds contempt or any carelessness. No man knows all the influences that affect the currents of the ocean. You may find the current in one place the same forty times in succession; on the forty-first trip it may be entirely changed. Sometimes a big storm that has ended four or five hours before the steamship passes a certain place may have given the surface current a strong set in one direction. There is no means of telling when these influences may have been at work save by taking the ship's position frequently.

Those of you who are familiar with boat-racing know how often a race is lost by bad steering. The cockswain who lets his shell drift to one side and then to the other loses much valuable time in getting back to the course. You know that from the start of the race he has his eye fixed on a certain mark, and that he steers straight for that mark. It is the same way with the Captain of a steamship. His mark is the port on the other side of the ocean. He aims at it all the time. If his ship should go astray only for one hour she would lose valuable time getting back to her course. Every unnecessary mile travelled not only causes loss of time, but waste of coal, and wear and tear of machinery, ship, crew, etc.

Great caution must be used at all times, but especially on nearing the land. Old-fashioned ships use the lead and hand-line for finding the depth of water and nature of the bottom, so that by referring to the chart the navigator can tell just where he is. That apparatus is too clumsy for the swift steamship. We use Sir William[Pg 265] Thompson's sounding-machine while the ship goes at full speed. A brass tube is fastened to the end of a piano-wire line. When this is lowered to the bottom the pressure of the water is exactly registered on a glass tube—somewhat resembling a thermometer—which is fastened inside the tube of brass. Upon reading the amount of pressure we know the exact depth. A cup on the end of the brass tube brings up a specimen of the bottom.

THE GREYHOUND IN A FOG—A CLOSE SHAVE.

THE GREYHOUND IN A FOG—A CLOSE SHAVE.

By taking soundings frequently when nearing the land, knowing the ship's course and her position at the last observation, one can prick out her track on the chart even in the heaviest fog. One never can tell what slant of tide or current is silently sending the ship toward the shore, so soundings are taken every fifteen minutes.

The presence of a pilot on board is no excuse for the Captain whose ship gets into trouble. The lives of the fifteen hundred persons on board, the value of the cargo, which is always very great, and of the vessel herself, which is worth at least two millions, all are in his hands. But, as I said before, the responsibility never worries him. He simply watches everything closely. The heads of departments report to him every day, and should any emergency arise, he is kept informed of every new occurrence.

How is it possible, we are often asked, to steer such a great vessel as the modern ocean liner? Steam and electricity have made the work almost seem like play. The senior officer on the bridge can tell at any moment just how fast the ship is going, how many revolutions the port and starboard screws are making per minute, just at what angle the rudder is set—in one word, all about the ship's progress. This is all reported to him on automatic registering machines.

You know, of course, that the ocean greyhound of to-day is a twin-screw ship—that is, that instead of being driven through the water by one propeller, she has two—one on each side of the end of her keel. Each screw is worked by its own set of engines. These engines are entirely independent of each other. The rudder is moved to one side or the other by steam or hydraulic power. Should the rudder become useless from any cause, it is possible to steer the ship by these screws. Most of you know that you can steer a row-boat by putting more force on one oar than on the other. If you want to turn sharply you back-water with one oar and row ahead with the other. So it is with these screws. By backing one screw and going ahead with the other, the ship can be turned around almost within her own length, as the phrase is. The ordinary vessel that loses her rudder is in a sad fix. The twin-screw ship simply needs a little extra care in handling. In fact, it has happened more than once that an ocean greyhound has been steered for more than a thousand miles straight into port while the rudder was useless.

It is easy to appreciate the necessity for making fast time across the ocean when you remember that each idle moment means a loss of earning power. The vessel costs $2,000,000. She will be worn out, say, in ten years. Her value will be very small. So that every moment of her ten good years must be made to tell. Suppose her navigators should be so careless as to let her wander one hour's journey off her course. Another hour would be lost bringing her back. That would mean a clear loss of two hours. Mathematical experts could tell you exactly what that loss would amount to. All we know is that not one instant shall be thrown away.

COALING.

COALING.

Perhaps you have been aboard one of the largest ships coming up the bay from Sandy Hook to New York. Have you noticed the churned-up white water that flows away behind her? Watch it, and you will observe that now on one side, now on the other, the foam ceases to flow so thickly. This shows that one screw or the other has almost stopped for a moment.[Pg 266] The ship-channel coming up the bay is so narrow and shallow that at certain low stages of the tide a great steamship drags the water along with her body, just as your own body can drag the water in a bath-tub. The result is that the rudder has very little effect in guiding the ship. Under such circumstances the screw on one side or the other is slowed so as to steer the vessel.