The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Antiquarian Magazine & Bibliographer; Vol. 4, July-Dec 1884, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Antiquarian Magazine & Bibliographer; Vol. 4, July-Dec 1884 Author: Various Editor: Edward Walford Release Date: July 25, 2016 [EBook #52641] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ANTIQUARIAN MAGAZINE *** Produced by Chuck Greif, Barbara Tozier, Bill Tozier and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

EDITED BY

Edward Walford, M.A.,

Formerly Scholar of Balliol College, Oxford, and late Editor of “The Gentleman’s

Magazine,” &c.

VOLUME VI.

July-December, 1884.

London:

DAVID BOGUE, 27, KING WILLIAM STREET,

CHARING CROSS, W.C.

The Gresham Press.

——

UNWIN BROTHERS,

PRINTERS,

LONDON AND CHILWORTH.

| Page | |

| THE GREAT YARMOUTH TOLHOUSE | 2 |

| ARCHITECTURAL DETAILS FROM SOUTHWELL MINSTER | 49 |

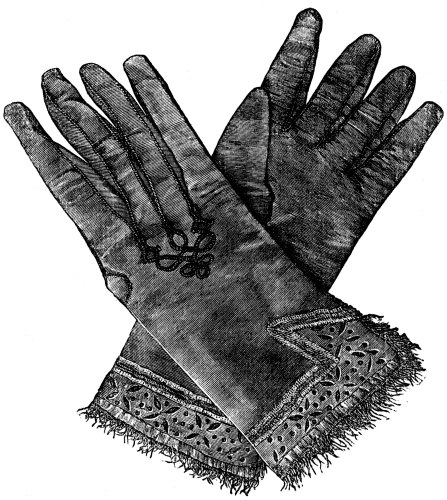

| GLOVES OF SHAKESPEARE, IN THE POSSESSION OF MISS BENSON | 102 |

| SEAL OF THE BOROUGH OF SEAFORD | 154 |

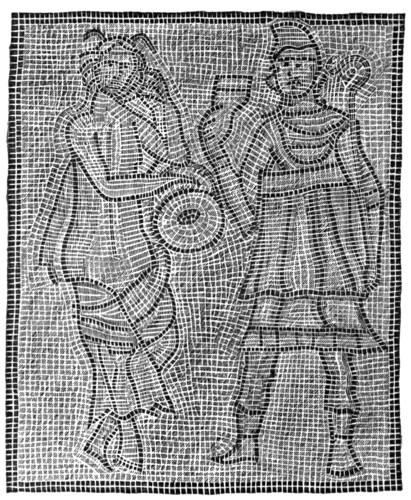

| TESSELLATED PAVEMENT DISCOVERED AT THE ROMAN VILLA NEAR BRADING | 206 |

| THE OLD PALACE, RICHMOND | 258 |

REAT YARMOUTH possesses a building of considerable antiquarian

interest. This is known by the somewhat unsuggestive name of the

Tolhouse. Its relation to the collection of tolls is referred to in many

old documents; but since this was but one of many uses to which it was

devoted, and far from a primary one, it is highly probable that, like

the Tolbooth of Edinburgh, its name is derived from its use in a greater

degree as the common prison of the town.

REAT YARMOUTH possesses a building of considerable antiquarian

interest. This is known by the somewhat unsuggestive name of the

Tolhouse. Its relation to the collection of tolls is referred to in many

old documents; but since this was but one of many uses to which it was

devoted, and far from a primary one, it is highly probable that, like

the Tolbooth of Edinburgh, its name is derived from its use in a greater

degree as the common prison of the town.

The building is spoken of by the old local historian, Manship, in 1619, who states that it was used in his time as the Borough Gaol, and had been so used from the time of the granting of the Charter by King John to the Burgesses. There are also records, which are referred to in Palmer’s “Perlustrations of Great Yarmouth,” of the very early use of the building as a gaol by the burgesses. A gaol for prisoners was also granted by Henry III. in 1261.

Apart from this, the building has been used for almost every municipal purpose, though it has never been actually a town-hall, for Great Yarmouth, like many other corporations, possessed a town-hall over or beside the entrance to the churchyard. Here various courts were held. The bailiffs were accustomed to receive their tolls or dues in the great chamber on the first floor. It was called the Host House, from a peculiar local custom. The accounts for the herrings, the staple article of commerce of the town in old days as now,{4} that were caught by foreign fishermen, and sold by their “hosts,” or salesmen of the town to whom they were consigned, had to be settled in the great chamber, and their “heightening money” paid. It was used also as their apartment of state by the local authorities; and there are many records of the quarrels over the questions of precedence with the deputies of the Cinque Ports when they paid official visits here.

It is for these most varying uses that the Tolhouse of Great Yarmouth is unique among our municipal antiquities, for England has not its counterpart elsewhere. Its history affords evidence of a most interesting nature of the growth and development of the authority of the town, no different it may be from what has taken place in other corporations, but illustrated here by the actual building.

The structure also is the original erection in all its essential features. Its walls are of early thirteenth century date, thus indicating its existence prior to 1261. It has a picturesque external staircase of open woodwork, giving access from the street to the level of the first floor, where the “Great Chamber” is situated, access being gained through a doorway of Early English moulded work; while the lobby of approach is lighted by a two-light open arcade, of somewhat later date. A very quaint figure of Justice, with sword and scales, stands on a projecting buttress; and the high-pitched roof, and the general features of the design, are both of considerable artistic interest. Internally, the Great Chamber has lost its open roof, which was replaced by a flat ceiling, probably in 1622, when it was “fitted up for assemblies.” The windows, too, are square-headed, with wood frames and mullions; but there are several features of the original work of great beauty, while others peep temptingly from the plastering and whitewash of more recent days.

Below the Hall is the “pit,” or common hold, wherein prisoners were thrust indiscriminately, and chained to a horizontal beam, which has long since disappeared. In this portion of the building the doors are iron-bound, and very solidly framed.

The recent history of the building deserves more than passing reference. On the completion of the handsome new town-hall the few recent uses even of the Tolhouse were no longer needed, and the demolition of the building was decided upon. The local antiquaries, however, being fully alive to the great interest of the building in relation to its forming a part, so to speak, of the history of the town, strove to prevent this loss occurring. Their persevering efforts have been eminently successful. Not only has the Town Council{5} reconsidered the proposal, but it has finally handed the building over to trustees, to be devoted to some useful purpose. Thus has an example been set to other lovers of our ancient buildings elsewhere.

The trustees have undertaken to repair the building, and they are now seeking to raise a fund for defraying the cost of this much-needed work. The building is in a sadly dilapidated state. It has been surveyed by Mr. E. P. Loftus Brock, F.S.A., architect, of London, and in his hands, and in those of a local firm of architects, it may be reasonably concluded that none but really necessary works will be carried out. The intention is, indeed, to repair the building only, and to retain all its ancient features.

The rough-cast, covering and hiding the ancient walling, will be taken off, the great hall will have its flat ceiling removed, and some approach made to the open appearance it formerly possessed; the walls will be strengthened where needed, the roofs made watertight, and general works of cleansing and repair done. No attempt whatever will be made to alter the structural appearance.

The trustees have undertaken their duties on public grounds, in the belief that, in these days when the removal of an ancient building is so greatly deplored, funds will not be wanting to uphold it for all time.

Subscriptions will be gladly received by C. S. Ade, Esq., Treasurer of the Fund (Messrs. Gurney & Co., Great Yarmouth); or by F. Danby-Palmer, Esq., Honorary Secretary, also at Great Yarmouth.

THE following details of sundry carvings on the misericordes still remaining in the choir of the collegiate church of St. Lawrence at Ludlow, in Shropshire, may interest such of our readers as are students of church architecture:—

North Side. (Read from West to East.)

1. A (left) and B (right), a rose. C (centre), four roses.

2. A and B, a padlock (or stirrup?). C, an eagle with two cords entwined behind.

3. A and B, floriated ornament. C, an angel holding a trumpet.

4. A and B, floriated ornament. C, king’s head, whiskers and beard flowing.

5. A and B, an animal holding a band in its mouth. C, a stag kneeling, a band behind it.{6}

6. A, two figures opposite each other; the left one has pointed shoes, the right one has his right arm raised as if to strike the other figure, and an animal is arising from under him. B, a floriated ornament. C, a mitred bishop in a pulpit preaching to birds; the bishop has a donkey’s face.

7. A and B, three feathers. C, the same, larger.

8. A and B, mitres on many-pointed stars. C, mitred bishop’s head, labels flying.

9. A and B, a face, from whose mouth two oak sprigs, right and left, issue. C, a stag, with a crowned collar round its neck attached to a chain, sitting on its haunches biting a band or flat snake.

10. A, a pot with two handles, on a fire. B, floriated ornament. C, two figures fighting; a third figure on the right is trying to hold one of the other figures; the left figure is sitting on the ground, as if knocked down; his head is broken off.

11. A and B, a fish with its tail in its mouth. C, a mermaid holding a circular mirror in its right hand, looking at it; the left hand four fingers broken off.

12. A, devil seated, holding a scroll. B, figure of a woman coming out of a pair of gaping jaws, the hinder parts of a man disappearing head foremost into the jaws; there are seven teeth in the upper jaw and three in the lower jaw. C, a man, whose head is broken off, carrying a naked female slung over his shoulders, one leg on either side of his head; her head and body hang down behind; she has a head-dress, a necklace from which is a pendant, and a ribbed jug or scroll in her left hand, her right hand is open, showing the palm; opposite the man, on the right, is a figure evidently meant to personate the Devil; he has wings, and is playing the bagpipes.

13. A and B, a winged beast. C, the same, with head-piece and five bands round its waist, terminating in the wings; there are eight balls or buttons on, and between these bands in front of the figure.

14. A and B, figure of a man, probably dancing; he holds a round thing like a cymbal in the right hand, the other is holding a branch; one knee is on the ground; it has pointed boots; part of the head and left foot below the knee of A is broken off. C, a woman’s head with head-dress, scowling, showing open ugly mouth and four teeth; the body of the dress is low, cut square; some thinner article of dress is beneath, concealing bare skin.

South Side. (West to East.)

1. A, ring, formed by two circles entwined. B is gone. C, rose {7}on a ——?

2. A and B, a head in a cloth or shroud. C, a man seated in cap and gown, holding a band.

3. A and B, a four-legged table, a barrel, end upwards, in centre, showing the bung in the middle; on one side is a jug or flagon, on the other a cup or chalice with a cover. C, two figures, men, kneeling; both heads are gone; a barrel on a bracket-shelf appears to be supported on one knee of each; one knee of each is on the ground.

4. A and B, floriated ornament. C, a woman drawing liquor from a barrel into a jug which she is holding; on the left of the barrel another barrel, on the right a jug on a shelf below; the figure has a mallet attached to a girdle round his waist.

5. A and B, a cock’s head. C, animal with wings, on its haunches.

6. A and B, pretty floriated ornament. C, remains of the trunk of an animal surrounded with the remnants of birds, broken off.

7. A a pack-horse; three of its legs are gone. B, a bag with a rose on centre, from which are suspended two smaller roses; below bag is a cushion, tasselled. C, two pairs of wrestlers wrestling; on left a figure is looking on.

8. A, pot with three feet and two handles, through which is a loose cord, on some burning fagots. B, trunks of two animals slung on a pole. C, a woman seated in a chair, holding hands and feet to fire which is in front of her.

9. A and B, floriated ornament. C, a swan standing.

10. A and B, a sparrow. C, an owl.

11. A and B, a woman’s head with head-dress. C, the same, with additional loose piece of material on top of her head, hanging over her shoulders.

12. A and B, floriated ornament. C, a man with a pack on his back, strapped on over his shoulders; he is pulling up his right boot with his hands; the boots are pointed.

13. A,B and C, floriated ornament.

14. A, a figure with pointed shoes, seated on a four-legged stool; both arms are gone. B, a wrist and hand from a cloud, on which, under the wrist, is a hammer, holding a pestle and mortar; beneath the hammer is a thigh bone, a skull, a skull, and a thigh bone; beneath these is a perpendicular altar tomb, with a spade and shovel crossed; the shovel is standing on the ground in front of the tomb, and has a T handle, the spade having a circular one. C, a figure with a row of beads on top of coat from shoulder to shoulder, and{8} wears a belt; on the left is a barrel on a shelf; under this is a pair of pattens hung on wall, and below these a pair of bellows, also hung on the wall; a hammer lies by his right foot on the left; all on the left-hand side are gone.

R. C. Hope, F.S.A.

By the Rev. H. H. Moore, M.A.

PART II.

(Continued from Vol. V. p. 282.)

THE characters of Warwick and of Edward IV. were so similar up to a certain point, and beyond that so opposite, their fortunes were so closely intertwined up to a certain time and afterwards were so fatally antagonistic, that they must be considered together awhile. The virtues of the one shine the brighter, and the defects of the other loom the darker by contrast; and the juxtaposition of the two figures in history makes the contrast all the more striking. In Warwick we see the nobler and more antique form of chivalry; in Edward we see chivalry modernised and debased by the additions of a voluptuousness more vicious than refined, and of a selfishness Italian in its intensity, and Machiavellian in its policy. Equally brave and distinguished for personal prowess in the field, Warwick joined to the courage the magnanimity of the lion, while Edward showed the cruelty as well as the fierceness of the tiger. But Edward greatly excelled Warwick, as well as all the other captains of his day, in generalship. His boldness, which cared for no odds however great, which shunned no danger however desperate, would have seemed mere foolhardiness, had not his marvellously quick perception, sagacious judgment, and tremendous energy, made prudence foolish and boldness prudent. His confidence in his own powers, which made them ten times more formidable, was fully justified by the results of nine pitched battles, in which victory never left his standard. But as soon as the opposition was overcome which had roused his energies into so fierce an activity, he abandoned himself to luxurious habits and indulgence in amorous and convivial pleasures. They who had seen him awhile ago delighting like a war-horse in the sound of the battle, would never expect such “a martial man to become soft fancy’s slave.” Yet so it was; terrible as Cæsar in war, in peace he was another Antony, and would risk{9} the loss of an empire for a woman’s smile. His generous affection for Elizabeth Woodville would be a bright spot in his character, had he not sullied it by his numerous amours and gross licentiousness. While Edward thus stained his character as much by his wantonness in peace as by his cruelty in war, Warwick, who despised such pleasures, won from both equally honourable laurels. The young King’s Court was no genial place for his severe manliness; and the disgraceful match-making and place-hunting by which the Queen’s relatives and friends were acquiring power, not only disgusted, but also alarmed him for the power of his family and of the old nobility. Edward and Warwick were equally proud, but Warwick’s was the pride of conscious worth, Edward’s the pride of an arbitrary will. More kingly than the King himself, Warwick overshadowed the throne with his greatness. To him Edward knew that he owed his crown, but he felt that he was strong enough to keep it without his help. His gratitude was swallowed up in the humiliation of his dependence, for he felt that he was not a king when Warwick was by. Accordingly, all his efforts were directed to abase that power which made him feel like a subject in his own realms. Warwick’s fall would, he knew, be the death-blow to his order; and, once determined on this policy, not even fear of Warwick moved this wonderful man, whose hand never hesitated to execute what his heart dared to design. He saw that the age was with him, while Warwick and the men of whom he was the type were behind the age. He knew also the advantage which his own character and talents gave him over Warwick. The latter was honest, unsuspecting, incapable of intrigue as he was indisposed to it; and though he joined to these soldier’s qualities a soldier’s sagacity also, yet he was no match for Edward, and fell an easy victim to his perfidious heart and scheming brain. And when outraged honour and insulted pride made him desert the Yorkist cause, which he had served and supported for years, and range himself with those whom he had most injured and who most hated him, he fell as easy a victim to the same man’s charmed sword. And Edward did prove himself strong enough to reign alone. No man was better fitted for his age and his circumstances; and this is shown by his popularity, vigorous even during Warwick’s life and while growing under his shade. Victor everywhere and at all times, Edward had won the heart of the nation even before he gained the throne. The painful tragedy of his father’s death, his own youth, beauty, princely bearing and accomplishments, excited the sympathy and admiration of the people on his earliest{10} appearance on the stage on which he was to play so great a part. His successful fortunes in war, and Warwick’s support, had commended young Edward to a people who had nothing to lose in losing Henry VI., and who hoped at least to gain peace and security under the protection of an arm which promised to be as strong to hold as it had been to acquire. Their minds, sickened by the gloom and horrors of war, were refreshed by the sight of their young King throwing himself with all the ardour of his nature into the light amusements and pleasures of peace; the citizens were charmed by his affability, their wives and daughters by his gaiety and gallantry. A new nobility, the mushroom growth of an hour, sprang up to sun itself in his smiles, to help him in the pursuit of pleasure, to increase the attractions of peace and of a Court. The commercial towns, and especially London, were pleased with a monarch who enriched them by his magnificent and sumptuous expenditure, and who gave a more liberal encouragement to commerce than they had known before. But two classes stood aloof and sullen: the old nobility, who felt that they were losing both their place and power in the Court and in the State; and those of the people who felt that, whether York or Lancaster were uppermost, they equally lost their rights, and failed to better their condition. The battlefields of Barnet and Tewkesbury rendered this dangerous element harmless for the future, and Edward, now able to breathe more freely than he had done heretofore, gave himself up without restraint to the impulses of his passions. His life henceforth became one voluptuous revel. The people were more ready to turn with him and his courtiers to pleasure than to criticise and condemn their vices; and so, in peace as in war, Edward’s sail was filled by the favouring breath of popularity. His love for his children and care for their education, his courteousness, his wisdom in weakening the power of the nobility, his encouragement of commerce, and his statesmanship, enlightened for those days, are all good points in Edward’s favour, and should be valued at their proper worth; but the possession of the ordinary virtues, and the performance of the ordinary duties of a prince and a parent, cannot fully redeem and make up for his extraordinary vice, perfidiousness, selfishness, and cruelty; and in the opinion of an age that is not dazzled by his fortune and ability, Edward’s hard, worldly, fleshly nature cannot be deemed worthy of admiration.

Richard III. and Henry VII. are but little concerned in the actual conduct of the civil war; not at all in its origin, but chiefly in furthering its effects, or reaping its fruits; but few words therefore need{11} be spent on them here, as it is their policy rather than their personal characters that is of chief interest. The same terribly precocious development of an unscrupulous will and of a heart steeled against mercy, marks the character of Richard III. as that we have seen in Edward IV. The school of civil war in which he had been trained taught him to despise the barriers which could be removed by the shedding of blood, and none ever showed greater aptness in improving on the lessons he had learned. He equalled Louis XI. in dissimulation, in cunning, in statesmanship; he equalled his brother Edward in fearlessness and inflexible purpose; he surpassed him in learning and mental culture. In the estimation of some minds the special pleading of Horace Walpole and others may have succeeded in clearing Richard’s name of the crimes imputed to him, but the majority in this age, as in Richard’s own, who do not demand positive proofs of everything, but judge by the laws of probability, cannot help feeling (rightly or not) a moral certainty of his guilt.

The character of Henry VII. was admirably adapted to heal the sores and bind the wounds caused by the long civil war. Sufficiently bold, if necessity demanded it, he was yet disinclined to war; cold and cautious in temperament, he was little tolerant of any disturbing element of passion, and greatly averse to violent and extreme measures which might derange the stability and order of his government. Eminently practical in his views of men and of affairs—in this ushering in the modern order of rulers and of statesmen—he preferred the reality to the show of power, peace to war, order to misrule, wealth to poverty, domestic security to foreign aggrandisement.

The unfortunate Richard, Duke of York, hesitating when he should have been bold, and bold when he should have hesitated, with a heart that could not keep pace with his ambition, without the wisdom to justify his pretensions by the Right which is derived from Might, not sufficiently scrupulous to resist temptation, and too scrupulous to win the prize that tempted, ensuring his son’s success by his own failure; the amiable, generous, unsuspecting Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester; the wily, avaricious, scheming Suffolk; the bold, grasping, passionate Cardinal Beaufort; the accomplished courtier, boon companion, and skilful general, Montacute (brother to Warwick); George, Duke of Clarence, unstable as water, changeable as the wind, uniting a weak head to a bad heart; Earl Rivers, accomplished, brave, learned, and a patron of learning, the type of the modern nobleman; the high-spirited, unfortunate son of Margaret; Lord Hastings, the gay gallant, the daring knight, the sage in the council, the scholar in{12} the study; all these and many more helped to swell the list of the horrid deeds, or served to supply the victims of those bloodstained times.

By Mrs. C. G. Boger.

(Continued from Vol. V. p. 228.)

PART II.—AT CAMELOT.

ARTHUR had arrived at man’s estate, and his people would fain that he should take a wife, so that, if, like his uncle, Aurelius Ambrosius, he were taken from them, he might, unlike him, leave an heir of his own blood. Among the petty kings of the West was Leodogran, King of Cameliard, a county represented at this day by Camelot or Cadbury-fort, and a cluster of other places in the east of Somerset, whose names are derived from the same root: North and South Cadbury, Queen’s Camel, West Camel, and Castle Cary. Leodogran’s kingdom had been beset by the invaders, and overrun with wild beasts: Arthur had come to his help and rescued his dominions. So it came to pass that when his people spake to him of marriage, Guinivere, the fair daughter of Leodogran, came to his mind, and he asked her of her father. The King of Cameliard was well pleased, and with his daughter’s hand he promised him his greatest treasure, the Table round, and made him his heir.

But Guinivere, in her pride of youth and beauty, had little noted her father’s deliverer, and scarce glanced at the young knight, who paid her none of the homage she thought her due, and who was ever engrossed in earnest consultations with her father on the state of the kingdom, on knights and wars, on castles and sieges; and so it came to pass that when Launcelot, Arthur’s best and most trusted knight, was sent by him to fetch her home, she, never doubting but that the King would have come himself, thought Launcelot was Arthur, and when she saw him her heart leapt to his. But when she came to see her pure and stainless lord, he seemed cold and passionless beside{13} Launcelot; and he, who had no thought of guile and loved when he trusted, and trusted when he loved, gave them unconsciously opportunities of meeting, and Guinivere’s heart passed more and more from Arthur, and attached itself more and more passionately to Launcelot. For Arthur was taken up with affairs of state, and with his beautiful dream of the Knights of the Round Table. In this order none was higher than other; and here, in his Palace of Camelot, built by Merlin’s magic power in a single night, he would assemble a hundred and fifty knights of noble birth, pure and stainless like himself, and the Knights bound themselves by solemn oaths to keep the rules of the order. They were as follows:—

1. That every knight should be well armed and furnished to undertake any enterprise wherein he was employed by sea or by land, on horseback, or on foot.

2. That he should be ever prest (ready) to assail all tyrants or oppressors of the people.

3. That he should protect widows and maids, restore children to their just rights, repossess such persons as without just cause were exiled, and with all his force maintain the Christian faith.

4. That he should be a champion for the public weal, and as a lion repulse the enemies of his country.

5. That he should advance the reputation of honour and suppress all vice, relieve the afflicted by adverse fortune, give aid to Holy Church, and protect pilgrims.

6. That he should bury soldiers that wanted sepulture, deliver prisoners, ransom captives, and cure men hurt in the services of their country.

7. That he should in all honourable actions adventure his person, yet with respect to justice and truth, and in all enterprises proceed sincerely, never failing to use the utmost force of body and labour of mind.

8. That after the attaining of an enterprise he should cause it to be recorded, to the end the fame of the fact might ever live to the eternal honour and renown of the noble order.

9. That if any complaint were made at the court of this mighty king, of perjury and oppression, then some knight of the order whom the King should appoint ought to revenge the same.

10. That if any knight of foreign nation did come into the Court, with desire to challenge or make any show of prowess (were he single or accompanied) those knights ought to be ready in arms to make answer.{14}

11. That if any lady, gentleman, or widow, or maid, or other oppressed person did present a petition declaring that they were or had been in this or other nations injured or offered dishonour, that they should be graciously heard, and without delay one or more knights should be sent to take revenge.

12. That every knight should be willing to inform young princes, lords, and gentlemen, in the orders and exercises of arms, thereby not only to avoid idleness, but also to increase the honour of knighthood and chivalry. Such were the rules which, combined with the disturbed state of the country, caused that—

It may, as I have before stated, have been probably the taking of Winchester by the Saxon Cerdic in 515 which caused Arthur to concentrate his forces in the Western Peninsula. Cameliard was now his, in right of his wife. He determined therefore to fortify his kingdom, and at the three extreme points to place strong castles, which he strengthened by every available means. These points were Caerleon on Usk, which guarded the Sabrina or estuary of the Severn, and St. Michael’s Mount at the extreme south-west; but the post of danger and therefore of honour was held by Camelot. He pitched with an experienced eye upon this great Belgic fortress, situated in one of the most fertile and picturesque parts of South Somerset, as the place where the great stand must be made. The shape of the mound is irregular, neither quite round nor square; part of it was hewed from the solid rock, its circumference is about a mile. Four deep ditches in concentric rings with as many ramparts of earth and stones form the primary defences: these are further strengthened by a series of zig-zag terraces on inclined planes, so constructed that the besieged, though he retreated from his assailants, could still make a desperate resistance. On the top of this fortified mount is a moated mount or Prætorium, enclosing a space of at least twenty acres; and here Merlin raised the enchanted Palace of Camelot. The spot must have been well-nigh impregnable in days when artillery was unknown.

Here, then, was Arthur’s great rallying point; hither the persecuted fled for protection, the wronged for redress, the patriotic to assist in the defence of their county. Every possibility of defence and adornment was lavished here; and here were held, specially at Whitsuntide, chapters of the order of the Knights of the Round Table. Here, in intervals of peace, were held the mimic games of{15} warfare, and from here, after a time of repose, they issued forth again and again against the heathen hordes. Within the Greater Triangle was a smaller and more sacred one; its three points were the Tor Hill at Glastonbury, the Mons Acutus or Montacute, and Camelot itself; lines drawn from point to point made an equilateral triangle, each side being twelve miles in length. This twice, trebly guarded territory was defended by saintly shield from invasion, and from any noxious or venomous creature.

It was the year 520 A.D. Exactly one hundred years had elapsed since the last Roman soldiers left Britain a prey to their enemies. But what a different Britain it was now. It is true the enemy were in the land, and held the greater part of it, but the Britons were no longer helpless or hopeless. From the towers of Camelot Arthur led forth an army full of confidence and eager for the fray; he led them beyond the bounds of Gladerhaf, for he would not that this beloved land should be soiled by the heathen’s tread. At Mount Badon, in Wiltshire, was fought the great battle in which Arthur was victorious, and the onward march of the Saxons was stayed for the time. At Camelot watch and ward was kept; from its summit could be seen the Mendip Hills, in the West of Somerset, the Blackdown summits in Devonshire, and the Bristol Channel on the south. Twelve great battles did Arthur fight; the eleventh is said by some to have been fought near Camelot, but I hold rather that the traces of a great conflict, which have been discovered there, took place in more recent times, when the Saxon dominion was extending itself still further to the West. For Gladerhaf remained British till after Arthur’s time, nor did Glastonbury pass under the Saxon sway till after they too had embraced Christianity, and conquerors and conquered knelt together at the same shrine.

The tale of King Ryence’s challenge belongs partly to Caerleon and partly to Camelot. It may be found in full in Mallory’s “King Arthur,” and also in a ballad preserved in “Percy’s Reliques of Ancient Poetry.” King Ryence, a potentate of North Wales, sent to Arthur at Caerleon to demand his beard, as he needed one more to make up the tale of twelve Royal beards, with which to “purfle his mantle.” If it were refused, he would slay him, and lay waste his country. Arthur, who was then young, answered that his beard would scarce answer for the purpose he required it, but threw back his threat upon himself. Shortly afterwards Ryence was brought as a prisoner to Camelot, and Arthur seems to have been content with this humiliation, and to have retaliated no further upon him.{16}

Amongst the treasures brought by Joseph of Arimathea to Britain were two of priceless worth; one, a thorn taken from our Lord’s brow, the other the cup from which the Lord drank at the last supper. The first was planted by Joseph, and slips from it planted in various places still remain, which, according to all contemporary folk-lore, flower invariably on old Christmas Eve (the Epiphany). But still more precious was the Sangreal, or cup, out of which our Lord drank at the last supper. It had been preserved for ages at Glastonbury, but on account of the grievous sins which prevailed, and the disordered state of the country, it had been caught away. But now a rumour arose, no one knew how or where, that the Sangreal had been seen again, and here seemed the salve for all their wounds, the cure for all their troubles, the talisman which was to preserve them from all ill; so men were waiting and wondering for what was to come to pass, they knew not what.

Pentecost had come, and a chapter of the order of the Knights of the Round Table was held as usual at Camelot. The knights were assembled in the great hall of the Castle. Anon a cracking and crying as of thunder was heard, and they thought the palace would break asunder. In the midst entered a sunbeam more clear by seven times than ever they saw day. Then the knights beheld each other fairer than they had ever seen them before, and no knight might speak a word for a great while, and each man looked on the other as they had been dumb. Then entered into the hall the holy grail, covered with white samite; but none might see it, nor who bare it, and all the hall was filled with sweet odours, and the holy vessel departed suddenly, and they wist not whence it came.[1]

Dumb were they all for a time; then spoke the light and foolish Sir Gawaine, and took an oath that he would go on a quest for the Sangreal, and would search for it, at least a year and a day, until he found it. Then the other knights swore to the same. It was with bitter grief that Arthur learned the vow, for well he knew that high and holy gifts are given by God to those who are in their ordinary way of duty, as the angels came to the shepherds whilst they kept their sheep, and that this wild quest would but disperse the knights throughout the land, while they neglected the work that God had set them, viz., the defence of their own land against the heathen. Then said the King: “I am sure at this quest of the Sangreal shall all of ye of the Round Table depart, and never shall I see you{17} whole together again, therefore will I see you all whole together in the meadow of Camelot, for to joust and tourney, that after your death men may speak of it, that such good knights were wholly together on such a day. So were they all assembled in the meadow, both more and less.”

Arthur’s last tournament was held, and the maiden-knight, Sir Galahad, won the honours of the day. Then, when the tourney was over, the whole assembly went to the Minster, and there, for the last time, joined all together in holy rites of prayer and praise. Then said the King to Sir Gawaine: “Alas! ye have well nigh slain me with the vow and promise that ye have made, for through you ye have bereft me of the fairest fellowship and the truest knighthood that ever were seen together in any realm of the world, for when they shall depart from hence I am sure that all shall never meet more in this world, for then shall many die in this quest, and so it forethinketh me a little, for I have loved them as well as my life.” The next morning the knights rode out of Camelot. But the story of their adventures does not belong to Somerset.[2]

Behind all this bravery and fair seeming, however, was rising a dark cloud, which did more to break up Arthur’s Table-round than even the quest of the Sangreal; for rumours had long been rife that Guinivere was unfaithful, and that his best-beloved knight, Sir Launcelot, was the partner of her sin. It was long ere they reached Arthur, who was so guileless that he could not believe in the guilt of those he loved; but at last it became too manifest, and Guinivere’s flight made the unfaithfulness of his wife and his friend patent to the King. Guinivere’s first flight was to Glastonbury; and in a life of Gildas, written by Caradoc of Lancarvon, we are told that whilst he (Gildas) was residing at Glastonbury, Arthur’s Queen was carried off and lodged there, that Arthur immediately besieged the place, but, through the mediation of the Abbot and of Gildas, consented at length to receive his wife again and to depart peaceably.[3] When this first flight took place we are not told; but after a time, and when the rebellion of his nephew, Mordred, took place, Guinivere fled again, this time to Amesbury, in Wiltshire. There she was professed{18} a nun. After her death her body was carried to rest at Glastonbury by Sir Launcelot himself, she having prayed that she might never see him again in life. And when she was put into the earth, Sir Launcelot swooned, and lay long upon the ground. A hermit came and awaked him, and said: “Ye are to blame, for ye displease God with such manner of sorrow-making.” “Truly,” said Sir Launcelot, “I trust I do not displease God, for He knoweth well mine intent, for it was not, nor is for any rejoicing of sin; but my sorrow may never have an end. For when I remember and call to mind her beauty, her bounty, and her nobleness, that was as well with her King, my lord Arthur, as with her; and also when I saw the corpse of that noble King and noble Queen so lie together in that cold grave, made of earth, that sometime were so highly set in most honourable places, truly mine heart would not serve me to sustain my wretched and careful body also. And when I remember me, how through my default, and through my presumption and pride, that they were both laid full low, the which were ever peerless that ever were living of Christian people. Wit ye well,” said Sir Launcelot, “this remembered of their kindness, and of mine unkindness, sunk and impressed so in my heart, that all my natural strength failed me, so that I might not sustain myself.”

The rebellion of his nephew Mordred brought strife and war into the hitherto carefully guarded peninsula. Mordred maintained that Arthur was no son of Uther Pendragon; and that he himself was the rightful heir, so Arthur had to turn his arms against his own people. It was at Camelford, near the north coast of Cornwall, that he fought his last fight; he was wounded to the death, for his skull was, as we shall see, pierced with ten wounds. Then, after the episode of the flinging away of the sword Excalibur, when Sir Bedivere saw “the water, wap, and waves waun,” a barge hoved to the bank; in it were ladies with black hoods, and one was Morgan la Fay, King Arthur’s sister. Then the barge floated to the shores of Gladerhaf, and there, to the vale of Avilion,[4] they took him to heal him of his grievous wound. And so men said that Arthur was not dead, but by the will of our Lord Jesus Christ was in another place; and men say that he will come again. I will not say that it shall be so, but rather I will say, that here in this world he changed his life. But many men say that there is written upon his tomb this verse:—{19}

And thus leave we him here, and Sir Bedivere with the hermit that dwelled in a chapel beside Glastonbury.[5]

(To be continued.)

A.D. 1212 AN. 13 John.[6]

BY M. T. PEARMAN.

THIS inquisition is subsequent to that printed by Hearne, in the “Liber Niger,” but some years earlier than any of the lists in the “Testa de Nevill.” The Inquisition itself is in italics.

Ricardus de Kanuill[7] de hereditate uxoris sue, pro Willelmo Basset. vii. mil.

The manors he held, by service of seven knights, or as seven knights’ fees, were Coleman and Uxbridge, Middlesex; Picheleshorne, Bucks; Burncestre (Bicester); Stratton Audley and Wrechwike, Oxon; Ardington, Berks; and Compton, Wilts.

Thurstañ Bassett, vi. milites et tres partes militis.

Walterus Pippard, 6 m. et de maritagio uxoris sue in Gathampton 1 m. et quintam partem per Cartam Regis.

In Rotherfield Peppard one fee; in Latchford, in Haseley, two fees; both these places in Oxon. The other three fees were in Pichecote, Wengrave, Rowsham, Briddeshorn, Weedon, Solebury, Stincele (Stewkley), Littlecote, and Wanyngdon, all in Bucks.

Gathampton, in Goring, Oxon, was held by one-fifth of a fee, the remainder being remitted.

Amauricus filius Roberti de Suleham, 4 m.

His fees were in Sulham, Burghfield, and Carswell (near Faringdon) Berks; Henton in Chinnor, Oxon; Adwell and Britwell, Oxon; Bradwell, Bucks; and Ikenham, Middlesex.

Willelmus Paynell, 4 m.

Walterus Crok, 4 m.

These fees were in Redburne (Rodburne-Cheyney), one; in Draycot-Foliat, one and a half fee. The Manor of Aselbir or Haselbury, Walcot, Cockelbergh, Assheby, and Fouleswyk, Wilts.

Robertus de Mara, 3 m.

Two fees were in Heyford-Warren and Baldon-with-Watecumbe, Oxon; and one fee in Bottclydon (Bottleclaydon), Bucks; and Chirton, Gloucestershire.

Hugo de Malo Almeto, 3 m. in Chaugrave.

Hugh de Malhannei, or Malo Almeto, held the Manor of Chalgrave, Oxon.

Ruelent Huscarl, 3 m.

In Purlegh (Purley), and Foulescote, Berks; in Beddington and Chessington, Surrey; and Brightwell, Oxon.

Henricus de Thayden, 3 m. Willelmus de Archis, 3 m.

In Esthorp, Crondewell, Wodehamme and Blagegrave, Bucks.

Warinus filius Geroldi, 2 m. et dimid.

In Whitchurch, Heyford-Warren, Oxon, and Clopham, Beds.

Robertus filius Roger est quietus pro 1 m. per cartam Regis de 2 m. et dimid.

He had one knight’s fee in Huere or Evere, probably Iver, Bucks.

Abbas de Bruere est quietus per cartum Regis de ii. milites et dimid.

This was for the Abbey itself in Oxon; and for its Granges, situate at Tretton, Tangele, Nethercote, and Sanderbrok, Gloucestershire.

Alanus Basset de hereditate uxoris sue, 2 milit.

In Vasterne or Wasterne, Wootton (Basset), and Brodeton, Wilts.

Hugo de Druual, 2 m.

H. Druval held Goring, Oxon, as two fees.

Thomas filius Ricardi, 2 m.; et de hereditate uxoris sue, 2 milit.

Alanus de Valonies, 2 m.

In Sobinton, Bucks. Shabbington (?).

Henricus Ffolliot, 2 m. in Roulesham.

(Rowsham) Oxon.

Walterus Ffoliot, 2 m. & in Clopton quartam partem m.

Probably one fee in Chilton, and the other in Winterburne and Mildhall, Wilts. Clopton is probably Clopcott, as in T. de N.

Milo Neirenuit pro parte sua de terra que fuit Galfridi de Bella Aqua, 2 m. He had one fee in Tydende, or Tydovre, Wilts, half one fee in Lynley, near Aston Rowant, Oxon, and half fee in Fleetmarston, Bucks.

Radulphus de Anuers, 2 m.

R. Danvers had one fee in Dorney.{21}

Galfridus Chausie, 1 m. et dimid. et Rex acquietat ei per cartam, dimid. mil.

Manor of Mapledurham-Chausy, or Parva M., Oxon, and Garsington in same county.

Yensi Malet, 1 m. et dimid.

In Quenton, Bucks.

Galfridus filius Reinfrei, 1 m. Johannes filius Hugonis, 1 m. Ricardus Morin, 1 m.

Newnham-Murren, Oxon.

Hamo Carbonell, 1 m.

This was in Dychend, Oxon, but where?

Andreas de Bellocampo, 1 m.

Probably in Crowlton and Thenford, Northants.

Simon Barre, f.m.[8]

In Stanton Barry, Bucks.

Rogerus de Stanf’, f.m.

In Saunterdon, Bucks.

Willelmus filius Galfridi, f.m. Walterus de Harenuill, f.m. Alex, filius Ricardi, f.m.

In Rycot, Oxon.

Robertus Corbet, f.m. in dalneye.

In Dalleg, Middlesex. Dawley near Hayes?

Willelmus Basset f.m. et in Hispedine quarta pars milit.

Fee in Oakly, near Brill, Bucks. He held the Manor of Ipsden Basset, in Ipsden, Oxon, by a quarter knight’s fee.

Alanus filius Roland, dimid. m.

In Aston-Rowant, Oxon.

Robertus de Thorinio, dimid. m.

In Turkden, Gloucestershire.

Robertus Hayer, debet I napa’ vel 3 sol ad scaccariu’ per cartam, 1 m.

This was petit serjeantry. He presented a table-cloth worth 3s., or else 3s. at the Exchequer, in lieu of scutage for one knight’s fee. The Holding was at Pushill, or Pishill, Oxon.

Walterus Crok, 4 m.

Apparently a repetition.

Galfridus de Mara, dimid. m. in dudecot.

In Didcot, Berks.

Petrus de Bixe, dimid. m.

Regin. Angerid, dimid. m.

In Holecombe, Oxon.

Galfridus filius Angod. dimid. m.

In Wycomb, Bucks.

Laurencius de Scaccario, dimid. m. In Stokenchurch, Oxon. He had likewise half a fee in Stivele (Stewkley), Bucks.

Radulphus Dairell, dimid. m.

In Hanworth, Middlesex.

Willelmus de Wodemundest, 4ta f.m.

One-fourth of a knight’s fee in Wormsley, Oxon.

Milo de Morlie, quarta f.m.

Nethercot, or Nethercourt, in Lewknor, Oxon.

Henricus Barnard, 5ta f.m. Willelmus de Kingestone, 5ta f.m.

In Kingston, near Aston Rowant, Oxon.

Warinus Pynell, 5ª f.m. Robertus de Rotham, 4ta partem m.

In Wycomb.

Willelmus de Druual, 5ª f.m. Robertus de Burgfeld, quintā, f.m.

In Stoke, Oxon.

Elias de Glynant quintā, f.m. Radulphus de Porta, 5ta f.m. Johannes de Cheney de terris, G. de bella aqua cum uxore dimid. m.

In “T. de N.” J. de C. is said to have 2 m. as his share of Geoffrey Bellew’s land, but that was some years subsequently. He then had one fee in Fleet-Marston, Bucks, and Linley, Oxon.

Willelmus filius Galfridi f.m. in Hedesoner. Hedsor.

Robertus Naparius, f.m. sed quietus est per cartam.

This is the same serjeanty as Robert Hayer’s, given above. R. Naparius, the table-cloth man, married Hayer’s daughter.

Novum Ffefamentum eiusdem honoris. De nouo ffefamento.

Robertus de veteri ponte dimid. Wicumbe, 1 m.

Robert de Vipont had a fee in Wycomb.

Alanus Basset al’ dimid. wimunde ville p. 1 m.

A. B. had the other half of the vill of Wycomb as a knight’s fee.

Simon de Pateshall, Wottesdon. Manor of Wottesdon or Wotthesdam.

Joh. Rabuz equum, saccum, et Brocham in exercitu Wall’ ad Custum Regis post primam noctem.

His service was to find a horse, sack, and broach on an expedition into Wales, the king finding him in provisions, or probably keeping him and his horse after the first night. It was a personal service to the Sovereign; the sack containing eatables and the can or pitcher drink for the king’s use.

By J. H. Round, M.A.

PART III

(Continued from Vol. V. page 287.)

BEFORE tracing the working of this process in the similar case of ceaster, it may be as well to dispose etymologically of port. I have avowedly restricted myself, in this paper, to port as it occurs in “port-reeve.” But Professor Skeat, in his “Etymological Dictionary” (p. 457), while wholly ignoring, it would seem, its meaning in this and the similar compounds, assigns to the Anglo-Saxon “port,” not merely the derivation direct from portus, but an identity of meaning with that word. And in support of that meaning, “a harbour, haven,” he aptly adduces Alfred’s translation of Bede, in which “to tham porte” means “to the haven.” Here, however, it might perhaps be urged that Alfred was influenced in his choice of the term by the “portus” in the original before him. It need not follow that when not so influenced, he would have spoken of a haven as a “port.” Moreover, it is possible, and indeed probable, that the original sense of “port” was replaced by that narrower one of a “haven” or “sea-port,” which it had certainly come to bear by Middle English days, in consequence of that recurrence to Latin models, in which Alfred had himself led the way, and which would lead to what might almost be termed a re-introduction of the word into the language, fresh from the Latin itself.

But again, Alfred might have been influenced in his style by the Welshman, “Asser, my bishop.”[9] For though the Welsh, as I have said, adopted “portman” in the sense of a “trader” from the A. S., they had in their own word porth the equivalent at once of porta and portus. Of its use in the former sense we have an illustration, as Mr. Barnes has pointed out (Arch. Jour. xxii. 232), in the Welsh version of Matthew vii. 13:—“ehang yw’r porth, a llydan yw’r fford,” (“wide is the gate, and broad is the way “), where in the A. S. version the word used is geat. Its use in the latter is familiar.

This brings us to a consideration of such terms as the “Westport” and “East-port” of Wareham, and the “Newport Gate” of Lincoln. The survival, at Wareham, of “port” in the sense of gate, is ingeniously attributed by the above writer to a direct derivation from the Welsh porth, rather than from the Latin porta. At{24} Lincoln, on testing Mr. Freeman’s statement that the gate was actually known simply as “The New Port” (Norm. Conq. iv. 212), I can find no evidence whatever for it.[10] If, therefore, as seems to be the case, “Newport Gate” has always been its name, within historic times, the inference is surely not that which has been drawn by Mr. Freeman in his paper on Lincoln,[11] but rather that the “barbarian” conquerors, ignoring the meaning of the “port” (porta), spoke of the Roman “porta” by their own word “geat,” distinguishing it from the other gates by the prefix “Newport,” and thus producing the, at first sight, unmeaning pleonasm, “Newport Gate,” just as Thorney Island, Mersea Island, &c., are pleonasms formed by the addition of “Island,” when the ea or ey (“Island”) no longer possesses a meaning.

We see, then, that the Latin porta failed to pass direct into our language in the form of port (“a gate”). It was, indeed, as Professor Skeat has shown, imported at a much later period, but then only through the French porte, and not direct from the Latin. But it could not, even so, succeed in establishing its position in the language. Found not unfrequently in the Elizabethan age, both in poetry and in classical prose, it lingered on, as a classical affectation, even so late as the Civil War, when we find it used of a city-gate, in a military sense, by such writers as Sprigge and Carter. A sure proof of its disuse is afforded shortly after this by the substitution of “port hole” for “port,” a pleonasm which, like those above quoted, implies that the original word no longer retained its meaning.

(To be continued.)

An Old Play-Bill—The following is a copy of the first play-bill issued from Drury-lane Theatre: “By His Majesty’s Company of Comedians, At the new Theatre in Drury-lane, This day, being Thursday, April 8th, 1663, Will be acted, a Comedy called THE HVMOVROVS LIEVTENANT. The King, Mr. Wintersel; Demétrivs, Mr. Hart; Selevcvs, Mr. Bvrt; Leontivs, Major Mohvn; Lievtenant, Mr. Clun; Celia, Mrs. Marshall. The play will begin at three o’clock exactly. Boxes 4s. Pitt 2s. 6d. Middle-Gallery 1s. 6d. Upper Gallery 1s.”{25}

By Cornelius Walford, F.S.S., Barrister-at-Law.

PART IV.

Chapter XXXII.—The Gilds of Lincolnshire.

THE Gilds of this county were not only very numerous, but they were regarded as important in several respects. I shall give some account of them under the several towns wherein they flourished. There were also many village Gilds.

Boston.—In this ancient town were various Gilds of great note, but the materials for detailed history have only been preserved in exceptional cases.

Gild of the Blessed Mary.—This appears to have ranked first amongst the Boston Gilds, and is believed to have been the Gilda Mercatoria of Boston, although its constitution in considerable part was ecclesiastical. The earliest mention of this Gild appears to be in 1393. The Gild itself was probably founded earlier—certainly other Gilds of earlier date existed in the town. The first Patent was granted to it at the date just named. Another Patent is dated in 1445, and a third in 1447. In this last year, Henry VI. granted a licence to “Richard Benynton and others that they should give to the Aldermen of the Gild of the Fraternity of the Blessed Mary of Boston, in the County of Lincoln, five messuages, thirty-one acres of land, and ten acres of pasture in Boston and Skirbeck.” Another Patent grant was issued to this institution in 1483. This Gild had a Chapel, called the Chapel of our Lady, in the Parish Church.

In 1510, Pope Julius II. in a “Pardon” granted to the town, provided that whatsoever Christian people, of what estate or condition soever, whether spirituall or temporall, would aid and support the Chamberlain or substitute of the aforesaid Gilde, should have five hundred years of pardon!

Item, to all brothers and sisters of the same Gilde was granted free liberty to eate in the time of Lent, or other fast-days, eggs, milk, butter, cheese, and also flesh by the counsell of their ghostly father and physician, without any scruple of conscience.

Item, that all partakers of the same Gilde, and being supporters thereof, which once a quarter, or every Friday or Saturday, either in the said Chappell or any other Chappell of their devotion, shall say a Paternoster, Ave Maria, and creed, or shall say or cause to be{26} said masses for souls departed in pains of purgatory, shall not only have the full remission due to them which visite the Chappell of Scala Cæli, or of St. John Latern [in Rome]; but also the souls in purgatory shall enjoy full remission and be released of all their paines.

Item, that all the souls of the brothers and sisters of the said Gilde, also the souls of their fathers and mothers, shall be partakers of all the prayers, suffrages, alms, fastings, masses and mattens, pilgrimages, and all other good deedes of all the holy Church militant for ever.

This pardon—and many such pardons, indulgences, grants and relaxations, were issued by Popes Nicholas V., Pius II., Sixtus, as well as Julius II.—was through the request of King Henry VIII., 1526, confirmed by Pope Clement VII.

It appears that at the time Pope Julius granted his “Bull” the Gild maintained seven priests, twelve ministers, and thirteen beadsmen; and also seems to have supported a grammar school. “The seats or stalls (says Thompson in his “Collections,” &c., 1820) on the south side of the chancel of the church were no doubt erected for the use of the master and bretheren of this establishment.” At the dissolution (1538) this college, as it was then called, was valued at £24.

The Guildhall of this establishment is yet remaining, and is used by the Corporation for their corporate and judicial proceedings. Beadsman-lane, adjoining the Guildhall, was no doubt inhabited by the beadsmen belonging to this institution; and the ancient buildings in Spain-lane were, it is very probable, the warehouses of the merchants. The possessions of this Gild were given to the Corporation in 1554, first of Mary.

Gild of St. Botolph.—It is recorded that in 1349 (23rd Edward III.) a patent was granted for making a Gild in the town of St. Botolph—the ancient name of Boston. And also that in the same year Gilbert de Elilond gave to the Aldermen, &c., of the Gild of St. Botolph certain lands and tenements in that town. Another patent in behalf of this institution was granted in 1399.

In 1403, Henry IV. granted a licence to Thomas de Friseby and others, that they might give to the Aldermen and brethren of the Gild or fraternity in Boston one messuage, forty acres of land, and twenty acres of meadow with the appurtenances “which they held of the Lord of Bello-monto for services, &c.” In 1411, the King granted a licence to Richard Pynchebek and others, that they should{27} give to Richard Lister, master of the Gild or fraternity in the town of St. Botolph, certain lands, &c.

It is not known who founded this Gild; what was the extent of its possessions; or the particular object of its institution. “It is most probable, however (says Thompson), that it was founded by a Company of merchants, and that its objects were entirely of a mercantile nature.” There is no account of any hall or other buildings belonging to this Gild.

Gild of Corpus Christi.—The first mention of this Gild is in 1389, when a patent was issued for the “Guild or Fraternity of Corpus Christi in St. Botolph.” Another patent was granted in 1392 for an Alderman, &c., of this Gild; a third grant bears date 1403. King Henry V. granted a licence in 1413 to John Barker, chaplain, and John Wellesby, chaplain, that they should give to the Alderman and brothers and sisters of the Gild of Corpus Christi, in the town of St. Botolph, two messuages with certain lands, &c., in Boston and Skirbeck. In 1414 another patent was granted to this Gild.

Mr. Thompson considers that this was in all probability a religious Gild. At the dissolution it was called a “College,” and its valuation, as given both by Dugdale and Speed, was £32. The situation of the hall of this institution was contiguous to Corpus Christi-lane, in Wide Bargate. No remains of any buildings, &c., belonging to it were visible in 1820.

Gild of the Apostles St. Peter and St. Paul.—The earliest record of this Gild is in 1393, when a patent was issued “for the Gild or Fraternity of the Apostles St. Peter and St. Paul, in the Church of St. Botolph in the Town of St. Botolph.” A second grant is dated 1448.

This appears to have been a religious establishment, and to have had a chapel, or at least an altar, in the parish church of St. Botolph. It was called a college at the dissolution, and was valued at £10 13s. 4d. It is supposed that St. Peter’s-lane, in Wide Bargate, had probably some connection with this Gild.

The charter of Philip and Mary, dated 1554, vested the possessions of this institution in the Corporation.

St. George’s Gild.—This was founded prior to 1403, for in that year a patent grant was issued in confirmation of a licence for the formation of this fraternity. In 1415 a patent was granted for the keeping or governing of the Gild of St. George in the town of St. Botolph.{28}

This appears to have been a trading company, no mention being made of it at the dissolution.

The hall of this Gild was standing in 1726 at the bottom of St. George’s-lane, on the west side of the river.

Gild of Holy Trinity.—Patent grants to this fraternity were issued in 1409 and 1411.

It appears from documents in the archives of the Corporation of Boston that Stephen Clerke, warden and keeper of the fraternity of the Holy Trinity, in the town of St. Botolph, together with the brethren and sisters thereof, did surrender to Nicholas Robertison, mayor, and the other burgesses of the new borough of Boston, all the estates, effects, and property of the said fraternity whatsoever, by deed under the common seal of their Gild, dated 22nd of July, in the 37th of Henry VIII. (1546). This surrender was formally made in a house then called the Trinity Chamber, which was most probably the hall or Gild of the fraternity. Its site is unknown. The possessions of this Gild were confirmed to the Corporation by Philip and Mary A.D. 1554; as were those of the St. Mary, St. Peter, and St. Paul Gilds, at the same time, “the better to support the Bridge and Port of Boston.”

It is more than probable that these Gilds played an important part in connection with the great fairs held in this town, but no evidence is at hand.

Craft Gilds.—During the sixteenth and early in the seventeenth century, various Craft Gilds were founded in the borough. Of these, particular mention is made of the following: 1555, the Company of Cordwainers and Curriers established; 1562, the Tailors’ Company; 1576, the Glovers’ Company; 1598, the Smiths’, Farriers’, Braziers’, and Cutlers’ Companies; 1606, the Butchers’ Company established.

These Craft Gilds were founded and conducted on the usual model of the period, as may be seen by the constitution of the Cordwainers’ Company. This Company was authorised, and its regulations sanctioned by the Mayor, Aldermen, and Common Council of the borough in 1855, the following being the substance of its regulations:—

There should be elected on the Monday before the Feast of St. Martin, by the said Company, two wardens, who should choose a person as beadle, to be attendant on the said wardens.

The officers were to be presented before and sworn in by the Mayor for the time being, on the feast day of St. Andrew, to serve their respective offices for one whole year.

The said wardens should have authority over all manner of{29} persons using the occupation or mystery of cordwainer in the said borough of Boston.

That no person or persons should set up within the said borough as cordwainers until such time as they could sufficiently cut or make a boot or shoe, to be adjudged by the said wardens, and were made free by the Mayor, Aldermen, &c., of the said borough, upon pain of forfeiting £3 6s. 8d., to be paid to the use of the Company: or to suffer imprisonment; this fine or imprisonment to be levied as often as any person should attempt the same.

If any foreigner, or person who did not serve his apprenticeship in the said borough, should be admitted to his freedom by the Mayor, &c., that he shall then pay to the wardens £3 6s. 8d. before he should be admitted a fellow of the said Company.

That no fellow of this Company, his journeymen or servants, should work on the Sabbath-day, either in town or country.

That the wardens of the said Company should have power once a month at least, or oftener if required, to search throughout the whole Company of Cordwainers and Curriers for unlawful wares or leathers.

There is no reference here to any powers of searching the stalls at the fairs for “unlawful wares;” but it is not improbable that such a power was exercised by the wardens of these Craft Gilds.

(To be continued.)

“Clapham Chronicle.”—J. M. Kemble edited as a boy at school a little newspaper, a sheet of about six inches square, printed by himself from a diminutive hand press, and aping the style of the daily journals. I [i.e., C. J. M.] have a file of them still, “Edited by John Mitchell Kemble, printer, No. 1, Desk-row.” (See C. Dickens’ “Life of Charles J. Matthews,” vol. i. p. 34.)

Civic Conviviality in 1759.—Mr. J. H. Round communicates the following: “The Mayor was also empowered [23 Nov. 1759] to give a grand Banquet at the ’Change to the Duke of Grafton and the officers of the Suffolk militia. The Suffolk militia then lay at Leicester, officered by the first characters in that county. It was then considered the most elegant and costly treat ever given by the corporation, and one the most inebriating. Mr. Mayor [Nicholas Throsby], at night, was assisted by the duke downstairs; and the duke soon after was assisted to his carriage by the town servants: there not being a soul left in the room capable of affording help to enfeebled limbs—Field Officers and Aldermen, Captains and Common Council, were perfectly at rest; all were levelled by the mighty power of wine.” (Throsby’s “History of Leicester” (1791), p. 162.){30}

History and Description of Corfe Castle. By Thomas Bond. E. Stanford. 1884.

We have here a book to which we can conscientiously pay a high tribute of praise. The noble ruins of mediæval castles in which England is so pre-eminently rich have rarely found competent historians, for the reason that while, on the one hand, their architecture is a special study, and understood by only a very few, who have made it their own subject; on the other hand, those who have thus acquired the necessary general knowledge are too often lacking in the special local knowledge, which is, in such cases, absolutely essential. Mr. Bond, however, has unquestionably succeeded in combining these two qualifications. In the present work he gives us, in an enlarged and final form, the results of those valuable researches on the castle, of which the outline has previously appeared in the third edition of Hutchins’ “Dorset,” and in his paper read before the Archæological Institute in 1866. The chief point which Mr. Bond has throughout sought to establish is the early date of the actual keep, which, as he shows, may with good reason be assigned to the days of the Conqueror. In this last controversy the most important point is the locality of the “Castellum de Warham,” mentioned in “Domesday.” Mr. Bond identifies it, beyond the shadow of a doubt, with Corfe Castle itself. Mr. Freeman’s unfortunate attempt to defend his own identification of it with the later and infinitely less important fortress of Wareham Castle is utterly shattered by Mr. Bond’s arguments, though he does not, strangely enough, allude to Mr. Freeman’s contention, which will be found under “Wareham,” in his work on “English Towns and Districts.”

We gladly call attention to the valuable searches made by Mr. Bond among original MS. authorities in the Public Records, especially the instructive “Fabric Rolls.” The careful excavations which he has been permitted to make have also led to important results, and, in short, we have in his book the fruits of long and patient study on the spot, combined with an unsparing and yet critical use of all available sources of original information.

We must not omit to notice the excellent plans and illustrations, with which the volume is liberally adorned, and which, by their great clearness, are admirably adapted to their purpose.

Mediæval Military Architecture in England. 2 vols. By G. T. Clark. Wyman. 1884.

It is with a feeling of real gratitude that we welcome this noble work. The prolonged labours of “Castle Clark” have long been familiar to antiquaries, and no archæological meeting at any spot that could boast a castle has seemed complete without the presence of “the great master of military architecture,” as Mr. Clark has been justly termed by Professor Freeman: to whom, by the way, these volumes are dedicated, as having been issued “at his suggestion.” It has long been a matter of natural regret that the valuable results of Mr. Clark’s researches should have been so widely scattered as to render them, for practical purposes, inaccessible to the student. In these volumes they have now been collected, gathered together from many quarters, such as the “Transactions” of the national and local Archæological societies, the Builder, and, not least, the scarce volume known as “Old London,” from which Mr. Clark has been allowed to reproduce his important monograph on the Tower.{31}

The work begins with twelve introductory chapters, of which we may select, as of special interest, that on “earthworks of the post-Roman and English periods,” an obscure subject, on which Mr. Clark has here collected much instructive information. Three chapters deal with “the Castles of England and Wales at the latter part of the twelfth century,” and we can only regret that a subsequent chapter has not been devoted to the period of the Charter (1213-1223), when these fortresses played so large and important a part in the struggle. These chapters are succeeded by more than one hundred papers on various castles and works, not confined to England alone, as could be gathered from the title, but including many in Wales, Borthwick Tower in Scotland, and, beyond the Channel, the typical strongholds of Arques and Coucy, together with the famous Château-Gaillard. The plans and diagrams, so all-essential in a work dealing with these subjects, are bestowed with no sparing hand, and there are not a few illustrations of a less severe character.

The drawback incident to such a work as this is the great area which it has to cover. Not only a very wide knowledge of history, but also much special local knowledge is needed to secure a satisfactory result. It must be confessed that Mr. Clark has been more successful in the structural than in the historical portion of his theme. Nor have his views on the former always escaped challenge. His statements as to Pevensey were questioned at the time, and his account of Colchester, both of the structure and of its history, has been very gravely impugned. It is somewhat strange that, in this case, Mr. Clark has repeated, without correction, his statements, as he has inserted, in his account of the Tower, the important discovery of two fireplaces on the second stage, since the paper was originally written. We may also note that, notwithstanding the admiration which Messrs. Freeman and Clark profess for one another, their views are often very contradictory, as, for instance, on Norwich Castle, on the character of pre-Conquest keeps, on the earthworks at Lincoln, and on Richard’s Castle.

But while it is necessary to sound a note of warning, it is almost ungrateful to criticise a work which will be recognised as indispensable to every student of English history in the middle ages. Few studies could throw more light on the social life of the two centuries succeeding the Norman Conquest. When we learn that, of the papers reprinted in these volumes, that on Caerphilly was originally issued no less than half a century ago, we may form some idea of the duration of Mr. Clark’s labours, and may congratulate him on being not only the worthy successor of the painstaking and indefatigable Mr. King, but the greatest authority we have ever had on Mediæval Military Architecture.

Cowdray: the History of a Great English House. By Mrs. Charles Roundell. Bickers & Son. 1884.

This handsome quarto volume possesses something more than local interest; it is the history of a house which was one of the most characteristic examples of Tudor architecture, and of a family which for several generations was conspicuous in the history of the times. Cowdray House stood close to Midhurst, in West Sussex; but it was burned down towards the end of the last century, and little now remains of the once magnificent pile but ivy-clad walls. With the mansion perished several invaluable historical treasures—among them the sword of William the Conqueror, his coronation robe, and the oft-disputed Roll of Battle Abbey. The house was full of rare and curious things, and contained a large number of family portraits of the Lords of Cowdray, whose fortunes{32} were founded by Sir Anthony Browne, the friend and confidant of Henry VIII., and whose son, on the marriage of Queen Mary with Philip of Spain, was created Viscount Montague, a title which became extinct on the death of the ninth Lord in 1797. According to tradition, it was at Battle Abbey, where Sir Anthony Browne and his family were established within three months of its surrender to the Crown, that the famous “curse of Cowdray” was invoked. The story runs that while Sir Anthony was holding his first great feast in the Abbots’ Hall, “a monk made his way through the crowd of guests, and, striding up to the daïs on which Sir Anthony sat, cursed him to his face. He concluded with the words, ‘By fire and water thy line shall come to an end, and it shall perish out of the land.’ ” Two hundred and fifty years afterwards the curse was fulfilled, for Cowdray was burned down, and the eighth Lord Montague and his two nephews were all drowned. Misfortune seems to have been the lot of Lord Montague’s family from the first to the last, and the climax came with the burning of Cowdray; the last Viscount was a monk, who obtained the Papal dispensation to marry and continue the line; but he, too, died childless, and the male line of the Brownes of Cowdray became extinct. Mrs. Roundell thus describes the present appearance of the ruins of Cowdray: “Above the great gateway the face of the clock still remains, with its hands still pointing to the hour at which it stopped; by the door is the old bell, and the original staples which held the doors to the gateway. The kitchen still contains the enormous dripping-pan, five feet long and four feet wide, and the great meat-screen and meat-block. Among these relics of old Cowdray are lying a fine mirror-frame, a chandelier, and Lady Montague’s harp, on which are the words, ‘H. Naderman, à Paris.’ ”

It only remains to add that Mrs. Roundell has treated her subject exhaustively, but in a plain, unvarnished manner, and that the book is illustrated with reproductions, by a photographic process, of some old views of Cowdray.

Life and Times of William IV. By Percy FitzGerald, M.A., F.S.A.

This is rather a sample of book-making by a gentleman who can do better work, and has done it. The account of King William’s early years is dull and heavy; and that of the first Reform Bill contains nothing that has not been told before. His accounts of Holland House and its “set” (where he has had Macaulay to draw upon), and of the French emigrés in London after the Revolution of 1830, and of the chief dandies and ladies of fashion who hung about Lady Blessington, are the most interesting parts of the book.

1. Luther and the Cardinal. Translated by Julie Sutter. 2. Homes and Haunts of Luther. By John Stoughton, D.D. 3. Luther Anecdotes. By Dr. Macaulay. Religious Tract Society. 1883.

Certainly the enterprising publishers who call themselves the Religious Tract Society were not behindhand in contributing to the Luther Festival last year. The story of one of the bravest men in history (let us not hesitate to call him so) has seldom been more worthily enshrined than in the books now lying on our table. The “anecdotes” are an unambitious attempt to unite in a connected form the various stories told of Luther at various periods of his life. “Homes and Haunts of Martin Luther” is evidently written in the true spirit of the loving and faithful chronicler. We follow the great Reformer from the mines of Eisènach to the princely castle of the Wartburg; from the quiet of the Wittenberg monastery to the fierce conflict of the Diet of Worms.{33} Everywhere Mr. Stoughton describes the life and doings of his hero with the tender reverence of an ardent admirer. A noticeable feature of the book is the elegance of the illustrations, which are artistically drawn and carefully engraved. The foregoing treat of the general story of Luther’s life; in the work entitled “Luther and the Cardinal,” we have a graphic historical picture of the memorable struggle between the Reformer and one of the greatest of the Papal adherents, Cardinal Albrecht, Elector and Archbishop of Mainz. It is written almost in the style of an historical novel, except that no imaginary personage or event is introduced. Pastor Metschmann thoroughly warms to his task when he describes in the latter part of the book the fierce retribution wreaked upon the Cardinal by Luther for the judicial murder of poor Hans von Schömtz, and he is appreciatively and carefully interpreted by his translator.

Hanley and the House of Lechmere, by the late Mr. E. P. Shirley (Pickering), is a book to which much interest attaches, as the last (and indeed posthumous) work of one of the most noble and worthy of scholars and gentlemen. It is partly topographical, as giving an account of the parish of Hanley Castle; it is also partly architectural, and partly genealogical; and in all these three qualifications Mr. Shirley shone pre-eminent. The old seat of the Lechmere family, now known as Severn End, is one of those fine old timbered mansions which are scattered so thickly up and down the western and north-western counties from Gloucester to Lancaster; and it appears that the mansion must have ranked a century ago high among the houses of its class. Its general structure, its tapestries, its pictures, its painted glass, all serve to show this. The greater part of the volume is taken up with the diary of Sir Nicholas Les Lechmere, recording the history of the family from the days of the first two Edwards down to the reign of William and Mary, in fact to within a year of his own death in 1701. The entries exhibit to us the domestic pursuits,—pleasures, as well as the public duties of a worthy man and upright judge. A manuscript of Dr. Thomas, quoted by Nash, in his “History of Worcestershire,” observes of the Lechmeres: “This family came out of the Low Countries, served under William the Conqueror, and obtained lands in Hanley, called from them Lechmere’s Place, and Lechmere’s Fields. Lech is a branch of the Rhine, which parts from it at Wyke, in the province of Utrecht, and running westward falls into the Maes before you come to Rotterdam.” “Some foundation for the supposed foreign origin of the name,” remarks Mr. Shirley, “is derived from the fact that all the earlier ancestors of the Lechmeres used the prefix de, which was afterwards dropped; and as, with the exception of Lechmere Heath in Hertfordshire, there is no place of that name in England, we may, perhaps, conclude that Dr. Thomas’s theory is the right one. There can be no reasonable doubt that the progenitor of the venerable House of Lechmere was seated in the parish of Hanley not long after the Conquest, and, after all, it may not be impossible that he was the Roger who held under Gislebert, at the time of the Domesday survey.” Mr. Shirley’s work, we may add, is illustrated with a view of the western front of Severn End, as it appeared in 1803, taken from a sketch by the late Sir Edmund Lechmere; whilst the pages of the volume are enriched with numerous carefully-executed coats of arms of the Lechmeres, and their several impalements through marriage. The arms of Lechmere, Gules, a fess, and in chief two pelicans vulning themselves, or—“may be taken as an early instance of what is called canting heraldry, Lech, in old{34} Breton, meaning love, and mere, of course, mother,—a play upon the name symbolised by the pelican wounding herself and feeding her young with her blood.”