The cover image was rejuvenated by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The cover image was rejuvenated by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

'Natural History is the appointed handmaiden of Religion, enabling us to feel and

in some humble proportion to appreciate how closely and how carefully the

well-being and happiness of all creatures has been provided for,—how admirably

they are severally adapted to their respective stations and employments, and how

wonderfully every part of their economy is made subservient to the general good.

This is the true spirit in which the aquarïst ought to work, and this is the end

and object of his science.'—Rhymer Jones.

1 & 2 Valves of PHOLAS SHELL

3 Pholas crispata, with siphons extended

4 COMMON BRITTLE STAR (Ophiocoma rosula) From Nature, showing the progressive growth of new rays

5 COMMON CROSS-FISH (Uraster rubens)

TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

LORD BROUGHAM AND VAUX,

CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH,

ETC., ETC., ETC.,

THIS LITTLE VOLUME

Is Inscribed,

AS A TRIFLING TOKEN OF RESPECTFUL ADMIRATION

FOR

UNIVERSALLY RECOGNISED GREATNESS.

| CHAPTER I. | PAGE |

| ON THE PLEASURES DERIVED FROM THE STUDY OF MARINE ZOOLOGY. | |

| Introduction—Two classes of readers—Marine zoology as an | |

| amusement—The botanist and his pleasures—Entomological | |

| pursuits—Hidden marvels of nature—The little | |

| Stickleback—Conclusion, | 17 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| A GLANCE AT THE INVISIBLE WORLD. | |

| Microscopic studies—When to use the microscope—Modern | |

| martyrs of science—Infusoria—Use of Infusoria—Distinction | |

| between plants and animals—Vorticella—Rotatoria—Wheel | |

| animalcules—Mooring Thread of Vorticellæ—A | |

| compound species of Vorticella described—Zoothamnium | |

| spirale of Mr. Gosse—Nature's scavengers, | 27 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| SEA ANEMONES. | |

| Animal-flowers—A. mesembryanthemum—'Granny,' Sir J. Dalyell's | |

| celebrated anemone—Original anecdote—A. troglodytes—How | |

| to capture actiniæ—A roving 'mess.'—An intelligent | |

| anemone—Diet of the actiniæ—Voracity of these | |

| zoophytes—Defence of certain species—Actiniæ eating | |

| crabs—Their reproductive powers—Size of the 'crass.'—The | |

| Plumose anemone—Its powers of contraction, | 45 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| EDIBLE CRAB—SHORE CRAB—SPIDER CRAB, ETC. | |

| The Partane—Its character defended—Crustaceous demons—The | |

| wolf and the lamb—Interesting anecdote—Reason and | |

| instinct—Anecdote of the Shore crab—'The creature's run | |

| awa''—A crustaceous performer—The Fiddler crab—A little | |

| prodigal—Singular conduct of the Shore crab—The minute | |

| Porcelain crab—Maia squinado—Hyas araneus—Maia and | |

| C. mænas—Anecdote—The common Pea crab—Pinna and | |

| Pinnotheres—The Cray fish—Masticatory organs of | |

| crabs—Fishing for crabs—Crab fishers, | 63 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| HERMIT CRABS. | |

| Enthusiastic students of nature—Aristocratic Hermit | |

| crabs—Swammerdam—Hermit crab and its | |

| habits—Anecdote—The Hermit in a fright—Soldier crab and | |

| Limpet—A crustaceous Diogenes—Prometheus in the tank—The | |

| martyr Hermit crab—The author's pet Blenny—Anecdote, | 89 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| EXUVIATION OF CRUSTACEA (THE PHENOMENA OF CRABS, ETC., | |

| CASTING THEIR SHELLS). | |

| The Tower of London—A crustaceous armory—The author's | |

| experience on the subject—Reamur and Goldsmith—Rejected | |

| shells of crabs—Anecdote—Hint to the young | |

| aquarian—Exuviation described from personal observation | |

| in several instances—Renewal of injured limbs—Frequency | |

| of exuviation—Effect of diet on crustacea—Exuviation | |

| arrested—Exuviation of the Hermit crab—How the process | |

| is effected, | 109 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| PRAWNS AND SHRIMPS. | |

| Habits of the Prawn—The Common Shrimp—How to catch | |

| shrimps—Conclusion, | 135 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| ACORN-BARNACLES—SHIP-BARNACLES. | |

| The Common Barnacle described—Exuviation of the | |

| Balani—Anecdote—The Ship Barnacle—Barnacle | |

| Geese, | 143 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| PHYLLODOCE LAMINOSA (THE LAMINATED NEREIS). | |

| A rainy day at the sea-shore—Laminated Nereis—Its | |

| tenacity of life—Its unsuitableness for the aquarium—How | |

| the young annelids are produced—Evidence of a French | |

| naturalist, | 151 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| THE FAN-AMPHITRITE. | |

| Its renewal of mutilated organs—How to accommodate this | |

| annelid in the tank—The 'case' of the | |

| Fan-Amphitrite, | 159 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| THE COMMON MUSSEL. | |

| Dr. Johnson and Bozzy—Habits of the Mussel—Marine | |

| 'at homes'—The Purpura and its habits—Enemies of the | |

| Mussel—Anecdote—Construction of the beard (or | |

| Byssus)—Author's experience—Anecdote of the | |

| mussel—Muscular action of its foot—Threads of the | |

| beard—The bridge at Bideford—Anecdote—The | |

| Mussel tenacious of life—The beard not poisonous—M. | |

| Quatrefage—Mussel beds of Esnandes—Branchiæ of the | |

| Mussel—Food of this bivalve, | 163 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| TEREBELLA FIGULAS (THE POTTER). | |

| Anecdote of the Potter—Its cephalic tentacula—Construction | |

| of its tubular dwelling—Terebella littoralis—Curious | |

| anecdote—Branchial organs of this annelid, | 189 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| ACALEPHÆ (MEDUSÆ, OR JELLY-FISH). | |

| Introduction—Jelly-fish—Whales' | |

| food—Lieutenant Maury—Appearance of the Greenland | |

| Seas—Sir Walter Scott—The girdle of Venus—The | |

| Beröe—Pulmonigrade acalephæ—Portuguese | |

| man-of-war—Hydra-tuba—Alternation of | |

| generations—Dr. Reid—Modera-formosa—Cyanea | |

| capillata—Conclusion, | 201 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| DORIS EOLIS, ETC. | |

| Anecdote—Young Dorides—Doris spawn—Nudibranchiate | |

| gasteropoda—Dr. Darwin—Mr. Gosse—A black | |

| Doris—Bêches de mer—A Chinese dinner—Bird's | |

| nest soup, and Sea-slug stew, | 221 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| THE CRAB AND THE DAINTY BEGGAR. | |

| Anecdote—The Pholas and Shore-crab—The | |

| hyaline stylet—The dainty beggar—The | |

| gizzard of the Pholas—Of what use is the stylet? | 233 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| THE PHOLAS, ETC. (ROCK-BORERS). | |

| Pholades at home—Habits of the Pholas—P. | |

| crispata—The pedal organ—Finny gourmands—How is | |

| the boring operation performed?—Various theories on | |

| the subject—Mr Clark, Professor Owen—The Pholas at | |

| work—The boring process described from personal | |

| observation—Author's remarks on the subject—Pholas | |

| in the tank—Conclusion, | 241 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| THE SEA-MOUSE. | |

| The Sea-mouse—Bristles of the aphrodite—Its | |

| beautiful plumage (?)—Its weapons | |

| of defence—The spines described—Shape of the | |

| aphrodite, &c., | 263 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| STAR-FISHES, ETC. | |

| The Coral polypes—The Lily-stars—St. Cuthbert's | |

| beads—Pentacrinus europæus—Rosy feather star | |

| Ophiuridæ—Brittle-stars—Ophiocomo-rosula— | |

| British asteridæ—Uraster rubens—Habits of this | |

| species—Submarine Dandos—Sir John Dalyell—Professor | |

| Jones—Star-fish feeding on the oyster—Bird's foot | |

| Sea-star—Luidia fragillissima—Cushion-stars— | |

| Professor Forbes, | 269 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| SEA-URCHINS. | |

| Sea Urchins in the tank—Growth of the Echinus—Its | |

| hedgehog-like spines—Suckers and pores—Ambulacral | |

| tubes—Professor Agassiz—Movements of the | |

| Echinus—Pedicellariæ—Masticatory | |

| apparatus—Common Egg Urchin—Echinus sphæra—How | |

| to remove the spines—'Do you boil your sea eggs?'—The | |

| Green-pea Urchin—The Silky-spined Urchin—The | |

| Rosy-heart Urchin, | 287 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| THE SEA-CUCUMBER. | |

| Its unattractive appearance out of water—Trepang—Several | |

| varieties eaten by the Chinese—Common Sea Cucumber—Habits | |

| of the Holothuriæ—Their self-mutilation and renewal of | 301 |

| lost parts, | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| THE APLYSIA, OR SEA-HARE. | |

| Anecdote—The Sea Hare plentiful at North Berwick—Its | |

| powers of ejecting a purple fluid at certain times—Sea | |

| Hares abhorred by the ancients—Professor Forbes—Spawn | |

| of the Aplysia, | 307 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| SERPULÆ AND SABELLÆ. | |

| Tubes of the Serpulæ—Dr. Darwin—The harbour | |

| of Pernambuco—Its wonderful structure—Reproduction of | |

| the Serpulæ—Sabellæ—Their sandy tubes, &c., | 313 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| THE SOLEN, OR RAZOR FISH. | |

| How it burrows in the sand—How specimens are | |

| caught—Cum grano salis—Bamboozling the Spout | |

| Fish—Amateur naturalists, and fishermen at the | |

| sea-shore, | 321 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| A GOSSIP ON FISHES—INCLUDING THE ROCKLING, SMOOTH BLENNY, | |

| GUNNEL FISH, GOBY, ETC. | |

| Punch's address to the ocean—Old blue-jackets and the | |

| 'galyant' Nelson—The ocean and its inhabitants—Life | |

| beneath the wave—Fishes the happiest of created things—A | |

| fishy discourse by St. Antony of Padua—Traveller's ne'er | |

| do lie?—The veracious Abon-el-Cassim—Do fishes possess | |

| the sense of hearing—Author's experience—An intelligent | |

| Pike fish—Dr. Warwick—The Blenny in its native | |

| haunts—A 'Little Dombey' fish—Anecdote—The | |

| Viviparous Blenny—The Gunnel fish—Five-bearded | |

| Rockling—Two-spotted Goby—Diminutive Sucker-fish— | |

| Montagu's Sucker—The Stickleback—Its nest-building | |

| habits described—Conclusion, | 327 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| ON THE FORMATION OF MARINE AQUARIÆ, ETC. | |

| Mimic oceans—Practical hints on marine | |

| aquariæ—Various tanks described—The 'gravity | |

| bubble'—Evaporated sea-water—Aquariæ in | |

| France—Sea-water a contraband article across the | |

| Channel—An aquarium on a fine summer's day—The | |

| Lettuce Ulva—Author's tank—'Excavations on a | |

| rocky shore'—Tank 'interiors'—Various centre | |

| pieces—New siphon—Aquariæ difficult to keep in | |

| hot weather—How to remove the opacity of the | |

| tank—New scheme proposed—Conclusion, | 353 |

As every fresh branch of investigation in natural history has a tendency to gather around it a rapidly accumulating literature, some explanation may probably be looked for from an author who offers a new contribution to the public. And when, as in the present instance, the writer's intentions are of an humble kind, it is the more desirable that he should state his views at the outset. Nor can the force of this claim be supposed to be lessened, from the gratifying fact, that the present writer has already received a warm welcome from the public.

But, before entering upon any personal explanations, it may not be out of place, in an introductory chapter such as the present, to bring under review some of the objections which have been, and still continue to be urged against this, in common with other departments of study, which are attempted to be made popular. No branch of natural history has been subjected to more disparaging opposition, partly, it must be owned, from the misplaced enthusiasm[20] of over zealous students, than that of marine zoology.

There are two classes of readers, different in almost all other respects, whose sympathies are united in dislike of such works as this. The one, represented by men distinguished for their powers of original research, are apt to undervalue the labours of such as are not, strictly speaking, scientific writers. There is another class who, from the prejudice of ignorance, look upon marine zoology as too trivial, from the homeliness and minuteness of its details. The wonders of astronomy, and the speculations suggested by geological studies, nay, the laws of organization as exhibited in the higher forms of animal life, are clear enough to this class of readers; but it is not easy to convince them that design can be extracted from a mussel, or that a jelly-fish exhibits a marvellous power of construction.

Now, in my belief, the opposition of the better educated of these two classes of readers is the more dangerous, as it is unquestionably the more ungenerous. If Professor Ansted, when treating of the surprising neglect of geology, could thus express himself—'How many people do we meet, otherwise well educated, who look with indifference, or even contempt on this branch of knowledge,'—how much oftener may the student of the humble theme of marine zoology bewail the systematic depreciation of persons even laying claim to general scientific acquirements.[21] This may be illustrated by an observation, made in a northern university, by a celebrated professor of Greek to a no less celebrated professor of natural history. The latter, intently pursuing his researches into the anatomy of a Nudibranche lying before him, was startled by the sudden entrance of his brother professor, who contemptuously advised him to give up skinning slugs, and take to more manly pursuits.

There is one light in which the study of marine zoology may be regarded, without necessarily offending the susceptibilities of the learned, or exciting the sneers of the ignorant. The subject may be pursued as an amusement—a pastime, if you will; and it is in no higher character than that of a holiday caterer, that the author asks the reader's company to the sea-side. No lessons but the simplest are attempted to be conveyed in this little volume, and these in as quiet and homely a style as possible.

Even in the light of an amusement, the author has something to say in behalf of his favourite study. He believes it to be as interesting, and fully as instructive as many infinitely more popular. For example: The sportsman may love to hear the whirr of the startled pheasant, as it springs from the meadow, and seeks safety in an adjoining thicket. I am as much pleased with the rustling of a simple crab, that runs for shelter, at my approach, into a[22] rocky crevice, or beneath a boulder, shaggy with corallines and sea-weed. He, too, while walking down some rural lane, may love to see a blackbird hastily woo the privacy of a hawthorn bush, or a frightened hare limp across his path, and strive to hide among the poppies in the corn-field; I am equally gratified with the sight of a simple razor-fish sinking into the sand, or with the flash of a silver-bodied fish darting across a rock-pool.

Nay, even the trembling lark that mounts upwards as my shadow falls upon its nest among the clover, is not a more pleasant object to my eye, than the crustaceous hermit, who rushes within his borrowed dwelling at the sound of footsteps. In fact, the latter considerably more excites my kindly sympathies, from its mysterious curse of helplessness. It cannot run from danger, but can only hide itself within its shelly burden, and trust to chance for protection.

Neither the botanist nor the florist do I envy. The latter may love to gather the 'early flowrets of the year,' or pluck an opening rose-bud, but, although very beautiful, his treasures are ephemeral compared with mine.

'Lilies that fester, smell far worse than weeds.'

But I can gather many simple ocean flowers, or weeds that—

'Look like flowers beneath the flattering brine,'

whose prettily tinted fronds will 'grow, bloom, and[23] luxuriate' for months upon my table. They do not want careful planting, or close attention, or even—

'Like their earthly sisters, pine for drought,'

but are strong and hardy, like the pretty wild flowers that adorn our fields and hedge-rows. In the pages of an album, I can, if so disposed, feast my eyes for years upon their graceful forms, whilst their colours will remain as bright as when first transplanted from their native haunts by the sea-shore.

The entomologist delights to stroll in the forest and the field, to hear the pleasant chirp of the cricket in the bladed grass, to watch the honey people bustling down in the blue bells, or even to net the butterfly as it settles on the sweet pea-blossom, while I am content to ramble along the beach, and watch the ebb and flow of the restless sea—

or search for nature's treasures among the weed-clad rocks left bare by the receding tide.

A disciple of the above mentioned branch of natural history will dilate with rapture upon the wondrous transformations which many of his favourite insects undergo. But none that he can show surpasses in grandeur and beauty the changes which are witnessed in many members of the marine animal kingdom. He points to the leaf, to the bloom upon the peach, brings his microscope and bids me peer in,[24] and behold the mysteries of creation which his instrument unfolds. 'Look,' he says, pointing to the verdant leaf, 'at the myriads of beings that inhabit this simple object. Every atom,' he exultingly exclaims, 'is a standing miracle, and adorned with such qualities, as could not be impressed upon it by a power less than infinite!' Agreed. But has not the zoologist equal reason to be proud of his science and its hidden marvels? Can he not exhibit equal miracles of divine power?

Take, as an example, one of the monsters of the deep, the whale; and we shall find, according to several learned writers, that this animal carries on its back and in its tissues a mass of creatures so minute, that their number equals that of the entire population of the globe. A single frond of marine algæ, in size

may contain a combination of living zoophytic beings so infinitely small, that in comparison the 'fairies' midwife' and her 'team of little atomies' appear monsters as gigantic, even as the whale or behemoth, opposed to the gnat that flutters in the brightest sunbeam.

Again: in a simple drop of sea-water, no larger than the head of a pin, the microscope will discover a million of animals. Nay, more; there are some delicate sea-shells(foraminifera) so minute that the[25] point of a fine needle at one touch crushes hundreds of them.

Lastly, How fondly some writers dwell upon the many touching instances of affection apparent in the feathered tribe, and narrate how carefully and how skilfully the little wren, for example, builds its nest, and tenderly rears its young. I have often watched the common fowl, and admired her maternal anxiety to make her outspread wings embrace the whole of her unfledged brood, and keep them warm. The cat, too, exhibits this characteristic love of offspring in a marked degree. She will run after a rude hand that grasps one of her blind kittens, and, if possible, will lift the little creature, and run away home with it in her mouth. Now, whether we look at the singular skill of the bird building its nest, the hen sitting near and protecting its brood, or the cat grasping her young in its jaws, and carrying them home in safety, we shall find that all these charming traits are wonderfully combined in one of the humblest members of the finny tribe, viz., the common stickleback,—the little creature that boys catch by thousands with a worm and a pin,—that lives equally content in the clear blue sea or the muddy fresh water pool.

The author now finds that he has been much[26] too prolix in these preliminary observations to leave himself space for a lengthened explanation of his reasons for again intruding upon the public. These are neither original nor profound. But he cannot help expressing an earnest hope that he may get credit from old friends, and perhaps from some new, for wishing to show that the book of nature is as open as it is varied and inexhaustible; and that, however jealously guarded are many of the great secrets of organization, a knowledge of some of the most familiar objects tends to inspire us alike with wonder and with awe.

'There is a great deal of pleasure in prying into this world of wonders, which

Nature has laid out of sight, and seems industrious to conceal from us.... It

seems almost impossible to talk of things so remote from common life and the

ordinary notions which mankind receive from the blunt and gross organs of sense,

without appearing extravagant and ridiculous.'—Addison.

It is hardly possible to write upon marine zoology without either more or less alluding to those many objects, invisible to the naked eye, which call for the use of the microscope; and it seems equally difficult for any one who has been accustomed to this instrument to speak in sober terms of its wonderful revelations. The lines of Cowper, as the youngest student in microscopic anatomy will readily acknowledge, present no exaggerated picture of ecstasy:—

It is proper, however, to notice that a serious objection has been urged against the use of the microscope by young persons, namely, the injurious effects of its habitual use upon the eyesight.

So far as my experience goes, I cannot deny that this objection is well founded. Since I have begun to use the instrument, I am obliged, if I wish to[30] view distinctly any distant object, to distort my eyes somewhat to the shape of ill-formed button-holes puckered in the sewing. Some individuals, I am aware, foolishly affect this appearance, from the notion that it exhibits an outward and visible sign of their inward profundity of character. In my own case this result may have arisen from my having worked principally at night or in the dusk. 'As to the sight being injured by a continuous examination of minute objects,' writes Mr. Clark, a most scientific naturalist, 'I can truly say this idea is wholly without foundation, if the pursuit is properly conducted; and that, on the contrary, it is materially strengthened by the use of properly adapted glasses, even of high powers; and in proof I state, that twenty years ago I used spectacles, but the continued and daily examination of these minutiæ (foraminifera) has so greatly increased the power of vision, that I now read the smallest type without difficulty and without aid. The great point to be attended to is not to use a power that in the least exceeds the necessity; not to continue the exercise of vision too long, and never by artificial light; and to reserve the high powers of certain lenses and the microscope for important investigations of very moderate continuance. The observant eye seizes at a glance the intelligence required; whilst strained poring and long optical exertions are delusive and unsatisfactory, and produce those fanciful imaginations of objects which[31] have really no existence. The proper time for research after microscopic objects is for one hour after breakfast, when we are in the fittest state for exertion.'

Mr. Lewes, again, speaking to the same point, viz., the eyes being injured by microscopic studies, says:—'On evidence the most conclusive I deny the accusation. My own eyes, unhappily made delicate by over-study in imprudent youth, have been employed for hours daily over the microscope without injury or fatigue. By artificial light, indeed, I find it very trying; but by daylight, which on all accounts is the best light for the work, it does not produce more fatigue than any other steadfast employment of the eye. Compared with looking at pictures, for instance, the fatigue is as nothing.'

In spite of the foregoing assertions, I feel it my duty to caution the student against excess of labour. Let him ride his hobby cautiously, instead of seeking to enrol his name among the martyrs of science, of whom the noble Geoffry St. Hilaire, M. Sauvigny, and M. Strauss Dürckheim, are noted modern examples. Each member of this celebrated trio spent the latter part of his existence in physical repose, having become totally blind from intense study over the microscope. But setting aside the evils of excess, we must bear witness to the intense delight which this pursuit affords when followed with moderation.

As my aim is merely to give the reader a taste of the subject, and whet his appetite for its more extensive pursuit at other sources, I shall confine my remarks to a few of those creatures which are readily to be found in any well-stocked aquarium. The number of animalculæ and microscopic zoospores of plants, invisible to the naked eye, with which such a receptacle is filled, even when the water is clear as crystal, is truly marvellous. These animals mostly belong to the class Infusoria, so called from their being found to be invariably generated in any infusion, or solution of vegetable or animal matter, which has begun to decay. Now, the water in an aquarium which has been kept for any length of time necessarily becomes more or less charged with the effete matter of its inhabitants, which, if allowed to accumulate, would soon render the fluid poisonous to every living thing within it. This result is happily averted by the Infusoria, which feed upon the decaying substances in solution, while they themselves become in their turn the food of the larger animals. Indeed, they constitute almost the sole nutriment of many strong, muscular shell-fish, as pholas, mussel, cockle, &c.; and doubtless help to maintain the life of others, such as actiniæ, and even crabs, which, as is[33] well known, live and grow without any other apparent means of sustenance. Thus the presence of Infusoria in the tank may be considered a sign of its healthy condition, although their increase to such an extent as to give a milky appearance to the water, is apt to endanger the well-being of the larger, though delicate creatures. The peculiar phenomenon alluded to arises from decaying matter, such as a dead worm or limpet, which should be sought after and removed with all possible speed. The whereabouts of such objectionable remains will be generally indicated by a dense cloud of Infusoria hovering over the spot. The milkiness, however, although it may look for the time unsightly, is ofttimes the saving of the aquarium 'stock.' When these tiny but industrious scavengers have completed their task of purification, they will cease to multiply, and mostly disappear, leaving the water clear as crystal. I believe it is the absence or deficient supply of Infusoria that sometimes so tantalizingly defeats the attempts of many persons to establish an aquarium. Pure deep-sea water, although never without them, often contains but very few, hence great caution is necessary not to overstock the tank filled with it, otherwise the animals will die rapidly, although the water itself appears beautifully transparent.

Of Infusoria there are many species. They are nearly all, at one stage or other of their existence, extremely vivacious in their movements; so much so,[34] indeed, that it becomes a matter of difficulty to observe them closely. Some have the power of darting about with astonishing velocity, others unceasingly gyrate, or waltz around with the grace of a Cellarius; while not a few content themselves by, slug-like, dragging their slow length along. The last are frequently startled from their propriety and aplomb by the rapid evolutions of their terpshicorean neighbours. Some, again, grasping hold of an object by one of their long filaments, revolve rapidly round it, whilst others spring, leap, and perform sundry feats of acrobatism that are unmatched in dexterity by any of the larger animals.

I may here observe that the motions and general structure of many of the microscopic forms of vegetation, so much resemble those of some of the infusoria, that it has long puzzled naturalists to distinguish between them with any degree of certainty. The chief distinction appears to lie in the nature of their food. Those forms which are truly vegetable can live upon purely inorganic matter, while the animals require that which is organized. The plants also live entirely by the absorption of fluid through the exterior, while the animalculæ are capable of taking in solid particles into the interior of the body. Their mode of multiplication, and the metamorphoses they undergo, are much alike in both classes, being, during one stage of their existence, still and sometimes immovably fixed to stones, sea-weed, &c., and at another[35] freely swimming about. Notwithstanding the similarities here stated, the appearance of certain of the species is as various as it is curious. One of the commonest species of the Infusoria (Paramecium caudatum) is shaped somewhat like a grain of rice, with a piece chipped out on one side, near the extremity of its body. It swims about with its unchipped extremity foremost, rotating as it goes. During the milky condition of the water (before alluded to), these creatures swarm to such a degree, that a single drop of the fluid, when placed under the microscope, appears filled with a dense cloud of dancing midges. Another (Kerona silurus) may be said to resemble a coffee-bean, with a host of cilia, or short bristles, on the flat side. These are used when swimming or running. But perhaps the most singular and beautiful of all the infusorial animalcules are the Vorticellæ, which resemble minute cups or flower-bells, mounted upon slender retractile threadlike stalks, by which they are moored to the surface of the weeds and stones. They are called Vorticellæ on account of the little vortices or whirlpools which they continually create in the water, by means of a fringe of very minute cilia placed round the brim of their cups. These cilia are so minute as to require a very high microscopic power to make them visible, and even then they are not easily detected, on account of their extremely rapid vibration, which never relaxes while the animal is in full vigour. On[36] the other hand, when near death, their velocity diminishes, and ample opportunity is afforded for observing that the movements consist of a rapid bending inwards and outwards, over the edge of the cup. This is best seen in a side view. The action is repeated by each cilium in succession, with such rapidity and regularity that, when viewed from above, the fringe looks like the rim of a wheel in rapid revolution. A similar appearance, produced by the same cause, in another class of animalcula, of much more complex structure than the Vorticellæ, has procured for it the name of Rotifera, or wheel-bearers. The result of this combined movement of the cilia is, that a constant stream of water is drawn in towards the centre of the cup, and thrown off over the sides, when, having reached a short distance beyond the edge, it circles rapidly in a small vortex, curling downwards over the lips. These currents are rendered evident by floating particles in the water. The possession of these vibratile cilia is not peculiar to this class of animals; indeed, there is good reason to believe that there is scarcely a living creature, from the lowest animalcule, or plant germ, up to man himself, that is not provided with them in some part or other. In many of these Infusoria the cilia constitute the organs of locomotion; while in the higher forms they serve various other purposes, but chiefly that of directing the flow of the various internal fluids through their proper channels. But the peculiar[37] and perhaps most wonderful organ of the Vorticella, is its stalk or mooring thread. This though generally of such extreme tenuity as to be almost invisible with ordinary microscopes, yet exhibits a remarkable degree of strength and muscular activity in its movements, which apparently are more voluntary than those of the cilia. Its action consists of a sudden contraction from a straight to a spiral form with the coils closely packed together, by which the head or bell is jerked down almost into contact with the foot of the stalk; after a few seconds the tension seems gradually relaxed, the coils are slowly unwound, and the stalk straightens itself out. This action takes place at irregular intervals, but it is seldom that more than a minute elapses between each contraction. It (the contraction) invariably happens when the animal is touched or alarmed, and is, consequently, very frequent when the water swarms with many other swimming animalcula. When it takes place the flower-bell generally closes up into a little round ball, which opens out again only when the stalk becomes fully extended. From this we might almost infer that some animalcule, or other morsel of food, had been seized and retained within the cup; moreover, that the contraction of the stalk assisted in securing or disposing of the prey. This, however, is uncertain.

The motions of the Vorticella do not seem much affected by the stalk losing hold of its attachment;[38] but the result of such an accident taking place is that the cilia cause the animal to swim through the water, trailing its thread behind it, and the contraction of the latter merely causes it to be drawn up to the head.

There are various species of Vorticellæ. That just described is the simplest, consisting merely of a hemispherical ciliated cup, attached to a single thread. It is barely visible to the naked eye. But there is a compound species which I have this year found to be extremely abundant in my aquarium,—whose occupants, both large and small, it excels in singularity and beauty. In structure it is to the simple Vorticella what a many-branched zoophyte is to an Actinia. My attention was first drawn to the presence of this creature by observing some pebbles and fronds of green ulva thickly coated with a fine flocculent down. On closer inspection this growth appeared to consist of a multitude of feathery plumes, about one-sixteenth of an inch in height, and individually of so fine and transparent a texture as to be scarcely discernible to the unassisted sight. On touching one with the point of a fine needle it would instantly shrink up into a small but dense mass, like a ball of white cotton—scarcely so large as a fine grain of sand. In a few seconds it would again unfold and spread itself out to its original size. By carefully detaching a specimen with the point of a needle or pen-knife, and transferring[39] it, along with a drop of water upon a slip of glass, to the stage of the microscope, a sight was presented of great wonder and loveliness:—

Let the reader imagine a tree with slender, gracefully curved, and tapering branches thickly studded over with delicate flower-bells in place of leaves. Let him suppose the bells to be shaped somewhat between those of the fox-glove and convolvolus, and the stem, branches, bells, and all, made of the purest crystal. Let him further conceive every component part of this singular structure to be tremulous with life-like motion, and he will have as correct an idea as words can give of the complex form of this minute inhabitant of the deep. Moreover, while gazing at it through the microscope, the observer is startled by the sudden collapse of the entire structure. The lovely tree has shrunk together into a dense ball, in which the branching stem lies completely hidden among the flower-bells—themselves closed up into little spherules, so closely packed together that the entire mass resembles a piece of herring-roe. This contraction is so instantaneous that the mode in which it is accomplished cannot be observed until the tree is again extended. As the re-extension takes place very slowly, we are enabled to observe that each branchlet has been coiled in a spiral form, like the thread of the simple Vorticella previously[40] described; and also that the main stem, above the lowest branch, was coiled up in the same way, but not so closely, and that the part below the lowest branch had, curiously enough, remained straight. Sometimes, in large and numerously branched specimens, one or two of the lowest members do not contract at the same time with the rest, but do so immediately afterwards, as if they had been startled by the shrinking movements of their neighbours. Sometimes these lowest branches will contract alone, while all the others remain fully extended,—a fact that would almost seem to indicate that they possessed an independent life of their own.

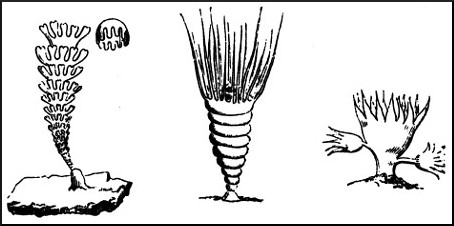

In the accompanying engraving I have attempted faithfully to portray one of these wonderful creatures. Fig. 1 represents it fully extended, while Fig. 2 indicates its collapsed form. There is another curious circumstance which I have fortunately observed in connection with this Vorticella, a description of which will perhaps be interesting to the reader. I allude to the casting off of what may be called the fruit of the tree. When this event takes place, the buds (or fruit) dart about with such rapidity, that it is almost impossible to keep them in the field of view for the briefest space of time. A represents the enchanted fruit hanging on the tree; B shows it as it swims about.

Although not exactly fruit, it is, no doubt, the means by which the Vorticellæ are propagated, for it[41] is known that many fixed zoophytes, and even some plants, produce free swimming germs or spores, which afterwards become fixed, and grow up into forms like those which produced them. In some of the branching zoophytes (Coryne, Sertularia, &c.), the germs are exactly like little medusae, being small, gelatinous cups fringed with tentacula, by means of which they twitch themselves along with surprising agility. In this Vorticella, however, it is more like one of the[42] ciliated Infusoria. The first one that I saw attached I conceived to be a remarkably large bell, with its mouth directed towards me, but the cilia with which it appeared to be fringed were unusually large and distinct. The movements of these appendages being comparatively slow, it was most interesting to watch them as they successively bent inwards and rose again, like the steady swell of a tidal wave, or an eccentric movement in some piece of machinery, making a revolution about twice in a second, and in the opposite direction to the hands of a clock. Suddenly the tree contracted, when, to my surprise, I observed the bell, which not an instant before appeared attached, now floating freely in the water, its ciliary movements not being in the least interrupted. Presently, however, they became brisker, the bell turned over on its side, and, ere the tree had again expanded, darted out of view, not, however, before I had remarked that it was not a bell, but a sphere flattened on one side, and having its circular ring of cilia on the flat side, with only a slight depression in the middle of it. There also appeared to be a small granular nucleus immediately above this depression, the rest of the body being perfectly transparent. I afterwards saw several others attached to the tree, each seated about the centre of a branch; but none of these were so fully developed. They were like little transparent button mushrooms, and had all more or less of a nucleus on the side by which they[43] were attached. On only one of these did I detect any cilia.

Mr. Gosse, in his 'Tenby,' gives a picture of an animal exceedingly like what I have described; but from his account of it, there seems to be some doubt of their identity. He calls it 'Zoothamnium spirale,' because the insertions of the branches were placed spirally around the main stem, like those of a fir-tree. In my specimens the branches were set alternately on opposite sides of the main trunk, and the whole was curved like a drooping fern leaf or an ostrich feather, the bells being mostly set on the convex side.

In conclusion, let me mention that it is an error to suppose, as many persons do, that putrid water alone contains life. Infusoria occur, as before hinted, in the clear waters of the ocean, in the water that we drink daily, and also in the limpid burn that flows through our valleys, or trickles like a silver thread down the mountain side.[1]

Let it be remembered, too, that Infusoria, when found in either do not themselves constitute the impurity of fresh or salt water; they merely act as 'nature's invisible scavengers,' whose duty it is to remove all nuisances that may spring up; and most unceasingly do these tiny creatures labour in the performance of their all-important mission of usefulness.

1 Sir J. G. Dalyell's celebrated ACTINIA (Drawn from Nature Jan. 1860.)

2 A. CRASSICORNIS

3 CAVE DWELLER (A. troglodytes)

No marine objects have become more universally popular of late years than Sea Anemones. Certainly none better deserve the attention which has been, and is daily bestowed upon them by thousands of amateur naturalists, who cannot but be delighted with the wondrous variety of form, and the beauteous colouring which these zoophytes possess.

A stranger could scarcely believe, on looking into an aquarium, that the lovely object before him, seated motionless at the base of the vessel, with tentacula expanded in all directions, was not a simple daisy newly plucked from the mountain side, or it may be a blooming marigold or Anemone from some rich parterre—instead of being, in reality, a living, moving, animal-flower.

One great advantage which the Actiniæ possess over certain other inhabitants of the sea-shore, at least to the eye of the naturalist, is the facility with which specimens may be procured for observation and study. Scarcely any rock-pool near low water[48] mark but will be found to encompass a certain number of these curious creatures, while some rocky excavations of moderate size will at times contain as many as fifty. Should the tide be far advanced, the young zoologist need not despair of success, for, by carefully examining the under part of the boulders totally uncovered by the sea, he will frequently find specimens of the smooth anemone, contracted and hanging listlessly from the surface of the stone, like masses of green, marone, or crimson jelly.

The Actiniæ, and especially examples of the above mentioned species, are extremely hardy and tenacious of life, as the following interesting narrative will prove.

The late Sir John Dalyell writing in 1851, says, 'I took a specimen of A. mesembryanthemum (smooth anemone) in August 1828, at North Berwick, where the species is very abundant among the crevices of the rocks, and in the pools remaining still replenished after the recess of the tide. It was originally very fine, though not of the largest size, and I computed from comparison with those bred in my possession, that it must have been then at least seven years old.'

Through the kindness of Dr. M'Bain, R.N., the writer has been permitted to enjoy the extreme pleasure of inspecting the venerable zoophyte above alluded to, which cannot now be much under thirty-eight years of age!

In the studio of the above accomplished naturalist, 'Granny' (as she has been amusingly christened) still dwells, her wants being attended to with all that tenderness and care which her great age demands.

Sir J. Dalyell informs us that during a period of twenty years this creature produced no less than 344 young ones. But, strange to say, nearly the fortieth part of this large progeny consisted of monstrous animals, the monstrosity being rather by redundance than defect. One, for instance, was distinguished by two mouths of unequal dimensions in the same disc, environed by a profusion of tentacula. Each mouth fed independently of its fellow, and the whole system seemed to derive benefit from the repast of either. In three years this monster became a fine specimen, its numerous tentacula were disposed in four rows, whereas only three characterize the species, and the tubercles of vivid purple, regular and prominent, at that time amounted to twenty-eight.

From the foregoing statement we learn that this extraordinary animal produced about 300 young during a period of twenty years, but, 'wonder of wonders!' I have now to publish the still more surprising fact, that in the spring of the year 1857, after being unproductive for many years, it unexpectedly gave birth, during a single night, to no less than 240 living models of its illustrious self!

This circumstance excited the greatest surprise and pleasure in the mind of the late Professor Fleming, in whose possession this famous Actinia then was.

Up to this date (January 1860) there has been no fresh instance of fertility on the part of Granny, whose health, notwithstanding her great reproductive labours and advanced age, appears to be all that her warmest friends and admirers could desire. Nor does her digestive powers exhibit any signs of weakness or decay; on the contrary, that her appetite is still exquisitely keen, I had ample opportunity of judging. The half of a newly opened mussel being laid gently upon the outer row of tentacula, these organs were rapidly set in motion, and the devoted mollusc engulphed in the course of a few seconds.

The colour of this interesting pet is pale brown. Its size, when fully expanded, no larger than a half-crown piece. It is not allowed to suffer any annoyance by being placed in companionship with the usual occupants of an aquarium, but dwells alone in a small tank, the water of which is changed regularly once a week. This being the plan adopted by the original owner of Granny, is the one still followed by Dr. M'Bain, whose anxiety is too great to allow him to pursue any other course, for fear of accident thereby occurring to his protegée.

A portrait of Granny, drawn from nature, will be found on Plate 2.

A. troglodytes[2] (cave-dweller) is a very common, but interesting object. The members of this species are especial favourites with the writer, from their great suitableness for the aquarium. They vary considerably in their appearance from each other. Some are red, violet, purple, or fawn colour; others exhibit a mixture of these tints, while not a few are almost entirely white. There are certain specimens which disclose tentacula, that in colour and character look, at a little distance, like a mass of eider-down spread out in a circular form. A better comparison, perhaps, presents itself in the smallest plumage of a bird beautifully stippled, and radiating from a centre. The centre is the mouth of the zoophyte, and is generally a light buff or yellow colour. From each corner, in certain specimens, there branches out a white horn that tapers to a very delicate point, and is oft times gracefully curled like an Ionic volute, or rather like the tendril of a vine.

In addition to the pair of horns alluded to, may sometimes be seen a series of light-coloured rays, occurring at regular intervals around the circumference of the deep tinted tentacula, and thereby producing[52] to the eye of the beholder a most pleasing effect.

As a general rule, never attempt to capture an anemone unless it be fully expanded, before commencing operations. By this means you will be able to form a pretty accurate estimate of its appearance in the tanks. This condition of being seen necessitates, of course, its being covered with water, and, consequently, increases the difficulty of capturing your prize, especially when the creature happens to have taken up a position upon a combination of stone and solid rock, or in a crevice, or in a muddy pool, which when disturbed seems as if it would never come clear again.

It is, in consequence, advisable to search for those situated in shallow water, the bottom of which is covered with clean sand. When such a favourable spot is found, take hammer and chisel and commence operations. Several strokes may be given before any alarm is caused to the anemone, provided it be not actually touched. No sooner, however, does the creature feel a palpable vibration, and suspect the object of such disturbance, than, spurting up a stream of water, it infolds its blossom, and shrinks to its smallest possible compass. At same time apparently tightens its hold of the rock, and is, indeed, often enabled successfully to defy the utmost efforts to dislodge it.

After a little experience, the zoologist will be able[53] to guess whether he is likely to succeed in getting his prize perfect and entire; if not, let me beg of him not to persevere, but immediately try some other place, and hope for better fortune.

Although apparently sedentary creatures, the Actiniæ often prove themselves to be capable of moving about at will over any portion of their subaqueous domain. Having selected a particular spot, they will ofttimes remain stationary there many consecutive months. A smooth anemone that had been domesticated for a whole year in my aquarium thought fit to change its station and adopt a roving life, but at last 'settled down,' much to my surprise, upon a large mussel suspended from the surface of the glass. Across both valves of the mytilus the 'mess.' attached by its fleshy disc, remained seated for a considerable length of time. It was my opinion that the mussel would eventually be sacrificed. Such, however, was not the case, for on the zoophyte again starting off on a new journey, the mollusc showed no palpable signs of having suffered from the confinement to which it had so unceremoniously been subjected.

The appearance of this anemone situated several inches from the base of the vessel, branching out from such an unusual resting-place, and being swayed to and fro, as it frequently was, by the contact of a passing fish, afforded a most pleasing sight to my eye. Indeed, it was considered for a while one of the 'lions' of the tank, and often became an object[54] of admiration not only to my juvenile visitors, but also to many 'children of larger growth.'

There is a curious fact in connection with the Actiniæ which deserves to be chronicled here. I allude to the apparent instinct which they possess. This power I have seen exercised at various times. The following is a somewhat remarkable instance of the peculiarity in question.

In a small glass vase was deposited a choice A. dianthus, about an inch in diameter. The water in the vessel was at least five inches in depth. Having several specimens of the Aplysiæ, I placed one in companionship with the anemone, and was often amused to observe the former floating head downward upon the surface of the water. After a while it took up a position at the base of the vase, and remained there for nearly a week. Knowing the natural sluggishness of the animal, its passiveness did not cause me any anxiety. I was rather annoyed, however, at observing that the fluid was becoming somewhat opaque, and that the Dianthus remained entirely closed, and intended to find out the cause of the phenomena, but from some reason or other failed to carry out this laudable purpose at the time. After the lapse of a few days, on looking into the tank, I was delighted to perceive the lace-like tentacula of the actinia spread out on the surface of the water, which had become more muddy-looking than before.

I soon discovered that the impurity in question[55] arose from the Aplysia (whose presence in the tank I had forgotten) having died, and its body being allowed to remain in the vessel in a decaying state. The deceased animal on being removed emitted an effluvium so intolerably bad that it seemed like the concentrated essence of vile odours. The water, of course, must have been of the most deadly character, yet had this most delicate of sea-anemones existed in it for several consecutive days.

In order further to test how long my little captive would remain alive in its uncongenial habitation, I cruelly refused to grant any succour, but must own to having felt extremely gratified at perceiving, in the course of a few days, that instead of remaining with its body elongated to such an unusual extent, the Dianthus gradually advanced along the base, then up the side of the vessel, and finally located itself in a certain spot, from which it could gain easy access to the outer atmosphere.

After this second instance of intelligence (?) I speedily transferred my pet to a more healthy situation.

Having procured a small colony of Actiniæ, you need be under no anxiety about their diet, for they will exist for years without any further subsistence than is derived from the fluid in which they live. Yet strange as the statement will appear to many persons, the Actiniæ are generally branded with the character of being extremely greedy and voracious.[56] 'Nothing,' says Professor Jones, 'can escape their deadly touch. Every animated thing that comes in contact with them is instantly caught, retained, and mercilessly devoured. Neither strength nor size, nor the resistance of the victim, can daunt the ravenous captor. It will readily grasp an animal, which, if endowed with similar strength, advantage, and resolution, could certainly rend its body asunder. It will endeavour to gorge itself with thrice the quantity of food that its most capacious stomach is capable of receiving. Nothing is refused, provided it be of animal substance. All the varieties of the smaller fishes, the fiercest of the crustacea, the most active of the annelidans, and the soft tenants of shells among the mollusca, all fall a prey to the Actiniæ.'

This is a sweeping statement, and, although corroborated by Sir J. Dalyell and others, is one that requires to be received with a certain degree of caution. It most certainly does not apply to A. bellis, A. parisitica, A. dianthus, troglodytes, or any other members of this group; and to a very limited extent only is it applicable to A. coriacea or A. mesembryanthemum.

As may readily be conceived, the writer could not keep monster specimens, such as are often found at the sea-shore; but surely if the statement were correct that, as a general rule, the actiniæ eat living crabs, the phenomenon would occasionally occur with[57] moderate-sized specimens, when kept in companionship with a mixed assembly of crustaceans. Yet in no single instance have I witnessed a small crab sacrificed to the gluttony of a small anemone.

With regard to A. mesembryanthemum, A. bellis, and A. dianthus, they get so accustomed to the presence of their crusty neighbours, as not to retract their expanded tentacula when a hermit crab, for instance, drags his lumbering mansion across, or a fiddler crab steps through the delicate rays, like a sky terrier prancing over a bed of tulips.

Thus much I have felt myself called upon to say in defence of certain species of Actiniæ; but with regard to A. crassicornis, I must candidly own the creature is greedy and voracious to an extreme degree.

Like many other writers, I have seen scores of this species of Actiniæ that contained the remains of crabs of large dimensions, but at one time considered that the latter were dead specimens, which had been drifted by the tide within reach of the Actiniæ, and afterwards consumed. That such, indeed, was the correct explanation in many instances I can scarcely doubt, from the disproportionate bigness of the crabs as compared with the anemones, but feel quite confident, that in other instances, the crustacea were alive when first caught by their voracious companions.

To test the power of the 'crass.,' I have frequently[58] chosen a specimen well situated for observation, and dropped a crab upon its tentacula. Instantly the intruding animal was grasped (perhaps merely by a claw), but in spite of its struggles to escape, was slowly drawn into the mouth of its captor, and eventually consumed. In one case, after the crab had been lost to view for the space of three minutes only, I drew it out of the Actinia, but although not quite dead, it evidently did not seem likely to survive for any length of time.

In collecting Actiniæ great care should be taken in detaching them from their position. If possible, it is far the better plan not to disturb them, but to transport them to the aquarium on the piece of rock or other substance to which they may happen to be affixed. This can in general be done by a smart blow of the chisel and hammer.

Should the attempt fail, an endeavour should be made to insinuate the finger nails under the base, and so detach each specimen uninjured. This operation is a delicate one, requiring practice, much patience, and no little skill. We are told by some authors that a slight rent is of no consequence, since the anemone is represented as having the power of darning it up. It may be so, but for my part I am inclined in other instances to consider the statement more facetious than truthful. In making this remark, I allude solely to the disc of the animal, an injury to which I have never seen repaired. On the[59] other hand, it is well known that certain other parts may be destroyed with impunity. If the tentacula, for instance, be cut away, so great are the reproductive powers of the Actiniæ, that in a comparatively short space of time the mutilated members will begin to bud anew.

'If cut transversely through the middle, the lower portion of the body will after a time produce more tentacula, pretty near as they were before the operation, while the upper portion swallows food as if nothing had happened, permitting it indeed at first to come out at the opposite end; just as if a man's head being cut off would let out at the neck the bit taken in at the mouth, but which it soon learns to retain and digest in a proper manner.'

The smooth anemone being viviparous, as already hinted, it is no uncommon circumstance for the naturalist to find himself unexpectedly in possession of a large brood of infant zoophytes, which have been ejected from the mouth of the parent.

There is often an unpleasant-looking film surrounding the body of the Actiniæ. This 'film' is the skin of the animal, and is cast off very frequently. It should be brushed away by aid of a camel-hair pencil. Should any rejected food be attached to the lips, it may be removed by the same means. When in its native haunts this process is performed daily and hourly by the action of the waves. Such attention to the wants of his little[60] captives should not be grudgingly, but lovingly performed by the student. His labour frequently meets with ample reward, in the improved appearance which his specimens exhibit. Instead of looking sickly and weak, with mouth pouting, and tentacula withdrawn, each little pet elevates its body and gracefully spreads out its many rays, apparently for no other purpose than to please its master's eye.

A. mesembryanthemum (in colloquial parlance abbreviated to 'mess.'), is very common at the sea-shore. It is easily recognised by the row of blue torquoise-like beads, about the size of a large pin's head, that are situated around the base of the tentacula. This test is an unerring one, and can easily be put in practice by the assistance of a small piece of stick, with which to brush aside the overhanging rays.

A. crassicornis grows to a very large size. Some specimens would, when expanded, cover the crown of a man's hat, while others are no larger than a 'bachelor's button.' Unless rarely marked, I do not now introduce the 'crass.' into my tanks, from a dislike, which I cannot conquer, to the strange peculiarity which members of this species possess, of turning themselves inside out, and going through a long series of inelegant contortions. Still, to the young zoologist, this habit will doubtless be interesting to witness. One author has named these large anemones 'quilled dahlias;' and the expression is so[61] felicitous, that if a stranger at the sea-side bear it in mind, he could hardly fail to identify the 'crass.,' were he to meet with a specimen in a rocky pool. Not the least remarkable feature in connection with these animal-flowers, is the extraordinary variety of colouring which various specimens display.

A. troglodytes, is seldom found larger than a florin. Its general size is that of a shilling. From the description previously given, the reader will be able to make the acquaintance of this anemone without any trouble whatever.

A. dianthus (Plumose anemone), is one of the most delicately beautiful of all the Actiniæ; it can, moreover, be very readily identified in its native haunts. Its colour is milky-white,—body, base, and tentacula, all present the same chaste hue. Specimens, however, are sometimes found lemon-coloured, and occasionally of a deep orange tint. Various are the forms which this zoophyte assumes, yet each one is graceful and elegant.

The most remarkable as well as the most common shape, according to my experience, is that of a lady's corset, such as may often be seen displayed in fashionable milliners' windows. Even to the slender waist, the interior filled with a mass of lace-work, the rib-like streaks, and the general contour, suggestive of the Hogarthian line of beauty, the likeness is sustained.

When entirely closed, this anemone, unlike[62] many others, is extremely flat, being scarcely more than a quarter of an inch in thickness; indeed, so extraordinary is the peculiarity to which I allude, that a novice would have great difficulty in believing that the object before him was possessed of expansive powers at all, whereas, in point of fact, it is even more highly gifted in this respect than any other species of Actiniæ.

'With a smart rattle, something fell from the bed to the floor; and disentangling

itself from the death drapery, displayed a large pound Crab.... Creel Katie made

a dexterous snatch at a hind claw, and, before the Crab was at all aware, deposited

him in her patch-work apron, with a "Hech, sirs, what for are ye gaun to let gang

siccan a braw partane?"'—T. Hood

1 EDIBLE CRAB

2 EDIBLE CRAB, casting its shell, from Nature

3 SPIDER CRAB

4 COMMON SHORE-CRAB

5 MINUTE PORCELAIN-CRAB

The foregoing motto, extracted from a humorous tale by 'dear Tom Hood,' which appeared in one of his comic annuals,—or volumes of 'Laughter from year to year,' as he delighted to call them,—may not inaptly introduce the subject of this chapter.

The term partane is generally applied in Scotland to all the true crabs (Brachyura). An esteemed friend, however, informs me that in some parts it is more particularly used to denote the Edible Crab (Cancer pagurus), which is sold so extensively in the fishmongers' shops. However that may be, there is no doubt it was a specimen of this genus that Creel Katie so boldly captured.

Now this crab, to my mind, is one of the most interesting objects of the marine animal kingdom, and I would strongly advise those of my readers who may have opportunities of being at the sea-side to procure a few youthful specimens. Its habits, according to my experience, are quite different from those of its relative, the Common Shore-Crab (Carcinus[66] mænas), or even the Velvet Swimming-Crab (Portunus puber). Unlike these, it does not show any signs of a vicious temper upon being handled, nor does it scamper away in hot haste at the approach of a stranger. Its nature, strange as the statement may appear to many persons, seems timid, gentle, and fawn-like.

On turning over a stone, you will perhaps perceive, as I have often done, three or four specimens, and, unless previously aware of the peculiarity of their disposition, you will be surprised to see each little fellow immediately fall upon his back, turn up the whites of his eyes, and bring his arms or claws together,—

making just such a silent appeal for mercy as a pet spaniel does when expecting from his master chastisement for some faux pas. One of these crabs may be taken up and placed in the hand without the slightest fear. It will not attempt to escape, but will passively submit to be rolled about, and closely examined at pleasure. Even when again placed in its native element, minutes will sometimes elapse before the little creature can muster up courage to show his 'peepers,' and gradually unroll its body and limbs from their painful contraction.

Most writers on natural history entertain an opinion totally at variance with my own in regard to the poor Cancer pagurus, of whom we are speaking.[67] By some he is called a fierce, cannibalistic, and remorseless villain, totally unfit to be received into respectable marine society. Mr. Jones relates how he put half a dozen specimens into a vase, and on the following day found that, with the exception of two, all had been killed and devoured by their companions; and in a trial of strength which speedily ensued between the pair of 'demons in crustaceous guise,' one of these was eventually immolated and devoured by his inveterate antagonist. Sir J. Dalyell mentions several similar instances of rapacity among these animals. Now, these anecdotes I do not doubt, but feel inclined, from the results of my own experience, to consider them exceptional cases.

When studying the subject of exuviation, I was in the habit of keeping half a dozen or more specimens of the Edible Crab together as companions in the same vase; but except when a 'friend and brother' slipped off his shelly coat, and thus offered a temptation too great for crustaceous nature to withstand, I do not remember a single instance of cannibalism. True, there certainly were occasionally quarrelling and fighting, and serious nocturnal broils, whereby life and limb were endangered; but then such mishaps will frequently occur, even in the best regulated families of the higher animals, without these being denounced as a parcel of savages.

Compared to Cancer pagurus, the Shore-Crab appears in a very unamiable light. When the two are[68] kept in the same vase, they exhibit a true exemplification of the wolf and the lamb. This, much to my chagrin, was frequently made evident to me, but more particularly so on one occasion, when I was, from certain circumstances, compelled to place a specimen of each in unhappy companionship. Here is a brief account of how they behaved to each other: The poor little lamb (C. pagurus) was kept in a constant state of alarm by the attacks of her fellow-prisoner (C. mænas) from the first moment that I dropped her in the tank. If I gave her any food, and did not watch hard by until it was consumed, the whole meal would to a certainty be snatched away. Not content with his booty, the crabbie rascal of the shore would inflict a severe chastisement upon his rival in my favour, and not unfrequently attempt to wrench off an arm or a leg out of sheer wantonness. To end such a deplorable state of matters, I very unceremoniously took up wolf, and lopped off one of his large claws, and also one of his hind legs. By this means I stopped his rapid movements to and fro, and, moreover, deprived him somewhat of his power to grasp an object forcibly. In spite of his mutilations, he still exhibited the same antipathy to his companion, and, as far as possible, made her feel the weight of his jealous ire. Retributive justice, however, was hanging over his crustaceous head. The period arrived when nature compelled him to change his coat. In due time the[69] mysterious operation was performed, and he stood forth a new creature, larger in size, handsomer in appearance, but for a few days weak, sickly, and defenceless. His back, legs, and every part of his body were of the consistency of bakers' dough. The lamb well knew her power, and though much smaller in size than her old enemy, she plucked up spirit and attacked him; nor did she desist until she had seemingly made him cry peccavi, and run for his life beneath the shelter of some friendly rock. Without wishing to pun, I may truly say the little partane came off with eclat, having my warmest approbation for her conduct, and a claw in her arms as token of her prowess. I knew that when wolf was himself again there would be a scene. Reprisals, of course, would follow. Therefore, rather than permit a continuance of such encounters, I separated the crabs, and introduced them to companions more suited to the nature of each.

The difference exhibited in the form and development of the tail in the ten-footed Crustacea (Decapoda)—as for instance, the crab, the lobster, and the hermit-crab—is so striking that naturalists have very appropriately divided them into three sections, distinguished by terms expressive of these peculiarities of structure: 1st, Brachyura, or short-tailed decapods, as the Crabs; 2d, Anomoura, or irregular tailed, as the Hermit-crabs; 3d, Macroura, or long-tailed, as Lobster, Cray-fish, &c.

It is to a further consideration of a few familiar examples of the first mentioned group that I propose to devote the remainder of this chapter.

Few subjects of study are more difficult and obscure than such as belong to the lower forms of the animal kingdom. However carefully we may observe the habits of these animals, our conclusions are too often apt to be unsound, from our proneness to judge of their actions as we would of the actions of men. As a consequence, an animal may be pronounced at one moment quiet and intelligent, and at another obstinate and dull, while perhaps, if the truth were known, it deserves neither verdict.

For my own part, the more I contemplate the habits of many members of the marine animal kingdom, the more am I astounded at the seeming intelligence and purpose manifested in many of their actions. Prior, apparently, must have been impressed with the same idea, for he says, speaking of animals,—

This train of thought has been suggested to my mind by viewing the singular conduct of a Shore-Crab, whom I kept domesticated for many consecutive months. Three times during his confinement he cast[71] his exuvium, and had become nearly double his original size. His increased bulk made him rather unfit for my small ocean in miniature, and gave him, as it were, a loblolliboy appearance. Besides, he was always full of mischief, and exhibited such pawkiness, that I often wished he were back again to his sea-side home. Whenever I dropped in a meal for my Blennies, he would wait until I had retired, and then rush out, disperse the fishes, and appropriate the booty to himself. If at all possible, he would catch one of my finny pets in his arms, and speedily devour it. Several times he succeeded in so doing; and fearing that the whole pack would speedily disappear, unless stringent measures for their preservation were adopted, I determined to eject the offender. After considerable trouble, his crabship was captured, and transferred to a capacious glass.

The new lodging, though not so large as the one to which for so long a time he had been accustomed, was nevertheless clean, neat, and well-aired. At its base stood a fine piece of polished granite, to serve as a chair of state, beneath which was spread a carpet of rich green ulva. The water was clear as crystal; in fact, the accommodation, as a whole, was unexceptionable. The part of host I played myself, permitting no one to usurp my prerogative. But in spite of this, the crab from the first was extremely dissatisfied and unhappy with the change, and for hours together, day after day, he would make frantic[72] and ineffectual attempts to climb up the smooth walls of his dwelling-place. Twice a day, for a week, I dropped in his food, consisting of half a mussel, and left it under his very eyes; nay, I often lifted him up and placed him upon the shell which contained his once-loved meal; still, although the latter presented a most inviting come-and-eat kind of appearance, not one particle would he take, but constantly preferred to raise himself as high as possible up the sides of the vase, until losing his balance, he as constantly toppled over and fell upon its base.

This behaviour not a little surprised me. Did it indicate sullenness? or was it caused by disappointment? Was he aware that escape from his prison without aid was impossible, and consequently exhibited the pantomime, which I have described, to express his annoyance, and longing for the home he had lately left?

Thinking that perhaps there was not sufficient sea-weed in the glass, I added a small bunch of I. edulis. Having thus contributed, as I believed, to the comfort of the unhappy crab, I silently bade him bon soir. On my return home, I was astonished by the servant, who responded to my summons at the door, blurting out in a nervous manner, 'O sir! the creature's run awa!' 'The creature—what creature?' I inquired. 'Do ye no ken, sir?—the wee crabbie in the tumler!'

I could scarcely credit the evidence of my sight[73] when I saw the 'tumler' minus its crustaceous occupant. The first thought that occurred to me was as to where the crab could be found. Under chairs, sofa, and fender, behind book-case, cabinet, and piano, in every crevice, hole, and corner, for at least an hour did I hunt without success. Eventually the hiding-place of the fugitive was discovered in the following singular manner: As I sat at my desk, I was startled by a mysterious noise which apparently proceeded from the interior of my 'Broadwood,' which, by-the-by, I verily believe knows something about the early editions of 'The battle of Prague,' The strings of this venerable instrument descend into ill-disguised cupboards, so that at the lower part there are two doors, or, in scientific language, 'valves.' On opening one of these, what should I see but the poor crab, who, at my approach, 'did' a kind of scamper polka over the strings. This performance I took the liberty of cutting short with all possible speed. On dragging away the performer, I found that his appearance was by no means improved since I saw him last. Instead of being ornamented with gracefully-bending polypes, he was coated, body and legs, with dust and cobwebs. I determined to try the effect of a bath, and presently had the satisfaction of seeing him regain his usual comely appearance. The next step was to replace him in his old abode; and having done so, I felt anxious to know how the creature had managed to[74] scale his prison walls. The modus operandi was speedily made apparent; yet I feel certain that, unless one had watched as I did, the struggles of this little fellow, the determination and perseverance he exhibited would be incredible.

After examining his movements for an hour, I found, by dint of standing on the points of his toes, poised on a segment of weed, that he managed to touch the brim of the glass. Having got thus far, he next gradually drew himself up, and sat upon the edge of the vessel. In this position he would rest as seemingly content as a bird on a bush, or a schoolboy on a gate.

My curiosity satisfied, the C. mænas was again placed in the vase, and every means of escape removed.

Here let me mention that I still had a Fiddler-Crab in my large tank, who had formerly lived in companionship with the shore-crab above mentioned. With 'the fiddler' I had no fault to find; he was always modest and gentle, and gave no offence whatever to my Blennies. He never attempted to embrace them, nor to usurp their lawful place at the table, nor even to appropriate their meals. On the contrary, he always crept under a stone, and closely watched the process of eating until the coast was clear, when he would scuttle out, and feed, Lazarus-like, upon any crumbs that might be scattered around.

Although so modest and retiring, I soon discovered[75] that this little crab possessed an ambitious and roving disposition. This made him wish to step into the world without, and proceed on a voyage of discovery—to start, indeed, on his own account, and be independent of my hospitality, or the dubious bounty of his finny companions. Taking advantage on one occasion of a piece of sandstone that rested on the side of the aquarium, he climbed up its slanting-side, from thence he stepped on to the top of the vessel, and so dropped down outside upon the room floor. For nearly two days I missed his familiar face, but had no conception that he had escaped, or that he wished to escape from his crystal abode. It was by mere accident that I discovered the fact.

Entering my study, after a walk on a wet day, umbrella in hand, I thoughtlessly placed this useful article against a chair. A little pool of water immediately formed upon the carpet, which I had no sooner noticed, than I got up to remove the parapluie to its proper place in the stand, but started back in surprise, for in the little pool stood the fugitive fiddler moistening his branchiæ.

Taking up the little prodigal who had left my protection so lately, I soon deposited him in a vase of clear salt water. After a while, thinking it might conduce to the happiness of both parties, I placed him in companionship with his old friend, Carcinus mænas. This, like many other philanthropic projects, proved a complete failure. Both creatures,[76] once so harmless towards each other, seemed suddenly inspired by the demon of mischief. Combats, more or less severe, constantly occurring, in a few days I separated them.

The 'fiddler' I placed in the large tank, where he rested content, and never again offered to escape—evidently the better of his experience. Not so his old friend, who still continued obstinate and miserable as ever. In his case I determined to see if a certain amount of sternness would not curb his haughty spirit. For two days I offered him no food, but punished him with repeated strokes on his back, morning and evening. This treatment was evidently unpleasant, for he scampered about with astonishing rapidity, and ever endeavoured to shelter himself under the granite centre-piece. When I thought he had been sufficiently chastised, I next endeavoured to coax him into contentment and better conduct. My good efforts were, however, unavailing. Every morning I placed before him a newly-opened mussel, but on no occasion did he touch a morsel. All day he continued struggling, as heretofore, to climb up the side of his chamber, trying by every means in his power to escape. This untameable disposition manifested itself for about a week, but at the end of that time, on looking into the vase, I saw the crab seated on the top of the stone, his body resting against the glass. I then took up a piece of meat and placed it before[77] him. To my surprise he did not run away as usual. Having waited for some minutes, and looking upon his obstinacy as unpardonable, I tapped him with a little stick—still he never moved. A sudden thought flashed across my mind; I took him up in my hand, examined him, and quickly found that he was stiff and dead!

There is a little crab, Porcellana longicornis, or Minute Porcelain-Crab, frequently to be met with in certain localities.