VOL. III.

2 vols. 8vo. 32s.

IRELAND UNDER THE TUDORS.

WITH A SUCCINCT ACCOUNT OF THE EARLIER HISTORY.

By RICHARD BAGWELL, M.A.

Vols. I. and II.

From the First Invasion of the Northmen to the year 1578.

London: LONGMANS, GREEN, & CO.

IRELAND UNDER THE TUDORS

WITH A SUCCINCT ACCOUNT OF THE

EARLIER HISTORY

BY

RICHARD BAGWELL, M.A.

IN THREE VOLUMES

VOL. III.

LONDON

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

AND NEW YORK: 15 EAST 16th STREET

1890

All rights reserved

By a mistake which was not the author’s, the title-pages of its first instalment described this book as being in two volumes. A third had, nevertheless, been previously announced, and this promise is now fulfilled. The Desmond and Tyrone rebellions, the destruction of the Armada, the disastrous enterprise of Essex, and two foreign invasions, have been described in some detail; and even those who speak slightingly of drum and trumpet histories may find something of interest in the adventures of Captain Cuellar, and in the chapter on Elizabethan Ireland.

A critic has said that your true State-paper historian may be known by his ignorance of all that has already been printed on any given subject. If this wise saying be true, then am I no State-paper historian; for the number of original documents in print steadily increases as we go down the stream of time, and they have been freely drawn upon here. But by far the larger part still remains in manuscript, and the labour connected with them has been greater than before, since Mr. H. C. Hamilton’s guidance was wanting after 1592. Much help is given by Fynes Moryson’s history. Moryson was a great traveller, whose business it had been to study manners and customs, who was Mountjoy’s secretary during most of his time in Ireland, and whose brother held[Pg vi] good official positions both before and after. Much of what this amusing writer says is corroborated by independent evidence. Other authorities are indicated in the foot-notes, or have been discussed in the preface to the first two volumes. Wherever no other collection is mentioned, it is to be understood that all letters and papers cited are in the public Record Office.

It has not been thought generally necessary to give the dates both in old and new style. The officials, and Englishmen generally, invariably refused to adopt the Gregorian calendar, but the priests, and many Irishmen who followed them, naturally took the opposite course. As a rule, therefore, the chronology is old style, but a double date has been given wherever confusion seemed likely to arise.

It has often been said that religion had little or nothing to do with the Tudor wars in Ireland, but this is very far from the truth. It was the energy and devotion of the friars and Jesuits that made the people resist, and it was Spanish or papal gold that enabled the chiefs to keep the field. This volume shows how violent was the feeling against an excommunicated Queen, and, whether they were always right or not, we can scarcely wonder that Elizabeth and her servants saw an enemy of England in every active adherent of Rome.

At first the Queen showed some signs of a wish to remain on friendly terms with the Holy See, but she became the Protestant champion even against her own inclination. Sixtus V. admired her great qualities, and invited her to return to the bosom of the Church. ‘Strange proposition!’ says Ranke, ‘as if she had it in her power to choose; as if her past life, the whole import of her being, her political position and attitude, did not, even supposing her conviction not to be sincere, enchain her to the Protestant cause. Elizabeth returned no answer, but she laughed.’

The Elizabethan conquest of Ireland was cruel mainly[Pg vii] because the Crown was poor. Unpaid soldiers are necessarily oppressors, and are as certain to cause discontent as they are certain to be inefficient for police purposes. The history of Ireland would have been quite different had it been possible for England to govern her as she has governed India—by scientific administrators, who tolerate all creeds and respect all prejudices. But no such machinery, nor even the idea of it, then existed, and nothing seemed possible but to crush rebellion by destroying the means of resistance. It was famine that really ended the Tyrone war, and it was caused as much by internecine quarrels among the Irish as by the more systematic blood-letting of Mountjoy and Carew. The work was so completely done that it lasted for nearly forty years, and even then there could have been no upheaval, but that forces outside Ireland had paralysed the English Government.

My best thanks are due to the Marquis of Salisbury for his kindness in giving me access to the treasures at Hatfield, and to Mr. R. T. Gunton for enabling me to use that privilege in the pleasantest way.

Marlfield, Clonmel,

March 17, 1890.

OF

THE THIRD VOLUME.

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| REBELLION OF JAMES FITZMAURICE, 1579. | |

| PAGE | |

| Papal designs against Ireland | 1 |

| James Fitzmaurice abroad | 3 |

| The last of Thomas Stukeley | 6 |

| Defencelessness of Ireland | 8 |

| Ulster in 1579 | 9 |

| Fitzmaurice invades Ireland | 10 |

| Manifestoes against Elizabeth | 13 |

| Attitude of Desmond | 17 |

| Nicholas Sanders | 17 |

| Murder of Henry Davells | 20 |

| The Geraldines disunited | 22 |

| Death of Fitzmaurice | 23 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

| THE DESMOND REBELLION, 1579-1580. | |

| English vacillation | 25 |

| Progress of the rebellion | 26 |

| Last hesitations of Desmond | 28 |

| Desmond proclaimed traitor | 31 |

| Youghal sacked by Desmond | 33 |

| Ormonde’s revenge | 35 |

| The Queen is persuaded to act | 38 |

| Irish warfare | 40 |

| Pelham and Ormonde in Kerry | 42 |

| [Pg x]Maltby in Connaught | 43 |

| State of Munster | 44 |

| Ormonde’s raid | 48 |

| Rebellion of Baltinglas | 51 |

| A Catholic confederacy | 52 |

| Results of Pelham’s policy | 54 |

| Low condition of Desmond | 57 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| THE DESMOND WAR—SECOND STAGE, 1580-1581. | |

| Arrival of Lord-Deputy Grey | 59 |

| The disaster in Glenmalure | 60 |

| Consequences | 63 |

| Spanish descent in Kerry | 65 |

| Siege and surrender of the Smerwick fort | 72 |

| The massacre | 74 |

| State of Connaught | 79 |

| An empty treasury and storehouses | 79 |

| The Earl of Kildare’s troubles | 80 |

| Confusion in Munster | 83 |

| Raleigh | 85 |

| Ormonde superseded | 87 |

| Death of Sanders | 89 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| THE DESMOND WAR—FINAL STAGE, 1581-1582. | |

| Partial amnesty—William Nugent | 91 |

| Maltby in Connaught | 92 |

| John of Desmond slain | 93 |

| Savage warfare | 96 |

| Recall of Grey | 97 |

| William Nugent’s rebellion | 99 |

| Ormonde is restored | 101 |

| How ill-paid soldiers behaved | 102 |

| Desmond’s cruelty | 103 |

| General famine | 104 |

| Abortive negotiations | 105 |

| The rebels repulsed from Youghal | 107 |

| Ormonde shuts up Desmond in Kerry | 107 |

| Last struggles of Desmond | 108 |

| Ormonde and his detractors | 110 |

| Death of Desmond | 113 |

| [Pg xi]The Geraldine legend | 114 |

| CHAPTER XL. | |

| GOVERNMENT OF PERROTT, 1583-1584. | |

| Case of Archbishop O’Hurley | 116 |

| Spanish help comes too late | 118 |

| Murder of Sir John Shamrock Burke | 119 |

| Trial by combat | 121 |

| First proceedings of Perrott | 122 |

| Sir John Norris and Sir Richard Bingham | 124 |

| The Church | 125 |

| Munster forfeitures | 126 |

| The Ulster Scots | 127 |

| A forest stronghold | 131 |

| Proposed University | 131 |

| Hostility of Perrott and Loftus | 134 |

| State of the four provinces | 135 |

| CHAPTER XLI. | |

| GOVERNMENT OF PERROTT, 1585-1588. | |

| The MacDonnells in Ulster | 138 |

| Perrott’s Parliament | 140 |

| Composition in Connaught | 147 |

| Perrott’s troubles | 148 |

| The Desmond attainder | 149 |

| The MacDonnells become subjects | 150 |

| Bingham in Connaught | 151 |

| The Scots overthrown in Sligo | 154 |

| Perrott’s enemies | 157 |

| Irish troops in Holland—Sir W. Stanley | 161 |

| The Irish in Spain | 163 |

| Prerogative and revenue | 165 |

| Bingham and Perrott | 166 |

| Perrott leaves Ireland peaceful | 168 |

| The Desmond forfeitures | 169 |

| CHAPTER XLII. | |

| THE INVINCIBLE ARMADA. | |

| Unprepared state of Ireland | 172 |

| Sufferings of the Spaniards—Recalde | 173 |

| Wrecks in Kerry, Clare, and Mayo | 174 |

| [Pg xii]Wrecks in Galway | 176 |

| Alonso de Leyva | 177 |

| Wrecks in Sligo | 180 |

| Adventures of Captain Cuellar | 183 |

| Spanish account of the wild Irish | 185 |

| Summary of Spanish losses | 188 |

| Tyrone and O’Donnell | 190 |

| Wreck in Lough Foyle | 191 |

| Relics and traditions | 192 |

| The Armada a crusade | 193 |

| The last of the Armada | 194 |

| CHAPTER XLIII. | |

| ADMINISTRATION OF FITZWILLIAM, 1588-1594. | |

| Ulster after the Armada | 196 |

| O’Donnell politics | 197 |

| The Desmond forfeitures—Spenser | 198 |

| Raleigh | 199 |

| Florence MacCarthy | 200 |

| The MacMahons | 201 |

| Bingham in Connaught | 203 |

| O’Connor Sligo’s case | 208 |

| Bingham and his accusers | 210 |

| Sir Brian O’Rourke | 212 |

| Mutiny in Dublin | 217 |

| Tyrone and Tirlogh Luineach | 218 |

| Rival O’Neills | 220 |

| Rival O’Donnells | 221 |

| Hugh Roe O’Donnell | 222 |

| Tyrone and the Bagenals | 223 |

| CHAPTER XLIV. | |

| ADMINISTRATION OF FITZWILLIAM, 1592-1594. | |

| Escape of Hugh Roe O’Donnell | 226 |

| O’Donnell, Maguire, and Tyrone | 227 |

| Trial and death of Perrott | 228 |

| Spanish intrigues | 233 |

| Fighting in Ulster | 234 |

| Recall of Fitzwilliam | 236 |

| Tyrone’s grievances | 237 |

| Fitzwilliam, Tyrone, and Ormonde | 238 |

| Florence MacCarthy | 240 |

| [Pg xiii]Remarks on Fitzwilliam’s government | 241 |

| CHAPTER XLV. | |

| GOVERNMENT OF RUSSELL, 1594-1597. | |

| Russell and Tyrone | 242 |

| Russell relieves Enniskillen | 244 |

| Tyrone generally suspected | 245 |

| The Wicklow Highlanders—Walter Reagh | 246 |

| Feagh MacHugh O’Byrne | 247 |

| Recruiting for Irish service | 248 |

| Soldiers and amateurs | 250 |

| Sir John Norris | 251 |

| The Irish retake Enniskillen | 252 |

| Murder of George Bingham | 253 |

| Tyrone proclaimed traitor | 254 |

| Quarrels of Norris and Russell | 255 |

| Ormonde and Tyrone | 255 |

| Bingham, Tyrone, and Norris | 256 |

| Death of Tirlogh Luineach O’Neill | 258 |

| Tyrone’s dealings with Spain | 258 |

| A truce | 259 |

| O’Donnell overruns Connaught | 260 |

| Liberty of conscience | 261 |

| Confusion in Connaught | 263 |

| Elizabeth on the dispensing power | 264 |

| Norris and Russell | 265 |

| Story of the Spanish letter | 267 |

| Spaniards in Ulster | 268 |

| Bingham in Connaught | 268 |

| Bingham leaves Ireland | 271 |

| Crusade against English Protestants | 272 |

| Disorderly soldiers | 273 |

| Death of Feagh MacHugh | 274 |

| Dissensions between Norris and Russell | 276 |

| Bingham in disgrace | 278 |

| CHAPTER XLVI. | |

| GOVERNMENT OF LORD BURGH, 1597. | |

| Last acts of Russell | 280 |

| Norris and Burgh | 282 |

| Burgh attacks Tyrone | 283 |

| Failure of Clifford at Ballyshannon | 285 |

| Gallant defence of Blackwater fort | 286 |

| Death of Burgh | 287 |

| Death of Norris | 288 |

| [Pg xiv]Belfast in 1597 | 289 |

| Disaster at Carrickfergus | 290 |

| Tyrone and Ormonde | 291 |

| Brigandage in Munster | 292 |

| Florence MacCarthy | 293 |

| CHAPTER XLVII. | |

| GENERAL RISING UNDER TYRONE, 1598-1599. | |

| Bacon and Essex | 294 |

| The Blackwater fort | 295 |

| Battle of the Yellow Ford | 297 |

| Panic in Dublin | 300 |

| The Munster settlement destroyed | 301 |

| The Sugane Earl of Desmond | 302 |

| Spenser, Raleigh, and others | 305 |

| The native gentry and Tyrone | 307 |

| Religious animosity | 308 |

| Weakness of the Government | 309 |

| O’Donnell in Clare | 310 |

| Tyrone in Munster | 311 |

| CHAPTER XLVIII. | |

| ESSEX IN IRELAND, 1599. | |

| Essex offends the Queen | 313 |

| His ambition | 315 |

| Opinions of Bacon and Wotton | 316 |

| Great expectations | 318 |

| Evil auguries | 320 |

| Sir Arthur Chichester | 321 |

| Essex in Leinster | 323 |

| In Munster | 324 |

| Siege of Cahir | 325 |

| Deaths of Sir Thomas and Sir Henry Norris | 326 |

| Harrington’s defeat in Wicklow | 328 |

| Failure of Essex | 331 |

| Anger of the Queen | 332 |

| Death of Sir Conyers Clifford | 336 |

| Essex goes to Ulster | 339 |

| Essex makes peace with Tyrone | 340 |

| The Queen blames Essex | 342 |

| Who goes home without leave | 343 |

| Harrington’s account of Tyrone | 344 |

| Reception of Essex at court | 346 |

| Negotiations with Tyrone | 347 |

| Folly of Essex | 348 |

| [Pg xv]Liberty of conscience | 349 |

| CHAPTER XLIX. | |

| GOVERNMENT OF MOUNTJOY, 1600. | |

| Raleigh’s advice | 351 |

| Tyrone’s Holy War in Munster | 352 |

| Arrival of Mountjoy and Carew | 353 |

| Tyrone plays the king | 354 |

| Ormonde captured by the O’Mores | 355 |

| Carew in Munster—Florence MacCarthy | 360 |

| Docwra occupies Derry | 361 |

| Carew in Munster | 363 |

| O’Donnell harries Clare | 365 |

| Mountjoy and Essex | 366 |

| James VI. | 368 |

| The Pale | 369 |

| The midland counties | 370 |

| Mountjoy bridles Tyrone | 372 |

| Progress of Docwra | 373 |

| Relief of Derry | 375 |

| Spaniards in Donegal | 376 |

| Carew reduces Munster | 377 |

| The Queen’s Earl of Desmond | 379 |

| The end of the house of Desmond | 384 |

| CHAPTER L. | |

| GOVERNMENT OF MOUNTJOY, 1601. | |

| Mountjoy and the Queen | 386 |

| Final reduction of Wicklow | 387 |

| Mountjoy and Essex | 388 |

| Confession of Essex—Lady Rich | 389 |

| The last of the Sugane Earl | 391 |

| Mountjoy in Tyrone | 392 |

| Plot to assassinate Tyrone | 393 |

| An Irish stronghold | 394 |

| Brass money | 395 |

| CHAPTER LI. | |

| THE SPANIARDS IN MUNSTER, 1601-1602. | |

| The Spaniards land at Kinsale | 398 |

| Mountjoy in Munster | 399 |

| The Spaniards come in the Pope’s name | 400 |

| The siege of Kinsale | 401 |

| O’Donnell joins Tyrone | 403 |

| [Pg xvi]Spanish reinforcements | 404 |

| Irish auxiliaries | 406 |

| Total defeat of Tyrone | 408 |

| Kinsale capitulates | 411 |

| Importance of this siege | 414 |

| Great cost of the war | 415 |

| CHAPTER LII. | |

| THE END OF THE REIGN, 1602-1603. | |

| The Spaniards still feared | 417 |

| The Queen’s anger against Tyrone | 418 |

| Carew reduces Munster | 419 |

| Siege of Dunboy | 421 |

| Death and character of Hugh Roe O’Donnell | 425 |

| Last struggles in Connaught | 426 |

| Progress of Docwra in Ulster | 427 |

| The O’Neill throne broken up | 428 |

| Last struggles in Munster | 429 |

| O’Sullivan Bere | 430 |

| Submission of Rory O’Donnell | 432 |

| Tyrone sues for mercy | 433 |

| Famine | 434 |

| Tyrone and James VI. | 435 |

| Death of Queen Elizabeth | 437 |

| Submission of Tyrone | 438 |

| Elizabeth’s work in Ireland | 439 |

| CHAPTER LIII. | |

| ELIZABETHAN IRELAND. | |

| Natural features | 441 |

| Roads and strongholds | 442 |

| Field sports | 444 |

| Agriculture | 445 |

| Cattle | 445 |

| Fish | 447 |

| Trade and manufactures | 447 |

| Wine, ale, and whisky | 448 |

| Descriptions of the people | 450 |

| Tyrone’s soldiers | 451 |

| Costume | 452 |

| Conversion of chiefs into noblemen | 453 |

| Bards and musicians | 454 |

| Tobacco | 455 |

| Garrison life | 456 |

| [Pg xvii]Spenser and his friends | 457 |

| CHAPTER LIV. | |

| THE CHURCH. | |

| Elizabeth’s bishops | 459 |

| Forlorn state of the Church | 460 |

| Zeal of the Roman party | 461 |

| Bishop Lyon | 463 |

| Position of Protestants | 464 |

| Papal emissaries | 465 |

| Protestant Primates | 466 |

| Miler Magrath | 468 |

| The country clergy | 469 |

| Trinity College, Dublin | 470 |

| Irish seminaries abroad | 472 |

| Early printers in Ireland | 473 |

| Toleration—Bacon’s ideas | 474 |

| Social forces against the Reformation | 475 |

| INDEX | 477 |

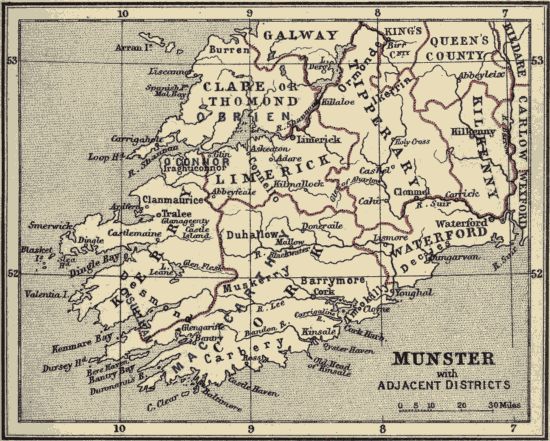

| MUNSTER | To face p. 24. |

| ULSTER | To face p. 244. |

| Page 18, line 12 from bottom, for provided to Killaloe read provided to Killala. |

| Page 56, bottom line, before Sanders insert and. |

| Page 384, line 4 from bottom, for Butler read Preston. |

IRELAND UNDER THE TUDORS.

REBELLION OF JAMES FITZMAURICE, 1579.

Sidney’s departure had been partly delayed by a report that Stukeley’s long-threatened invasion was at last coming. The adventurer had been knighted in Spain, and Philip had said something about the Duchy of Leinster. The Duke of Feria and his party were willing to make him Duke of Ireland, and he seems to have taken that title. At Paris Walsingham remonstrated with Olivares, who carelessly, and no doubt falsely, replied that he had never heard of Stukeley, but that the king habitually honoured those who offered him service. Walsingham knew no Spanish, and Olivares would speak nothing else, so that the conversation could scarcely have serious results. But the remonstrances of Archbishop Fitzgibbon and other genuine Irish refugees gradually told upon Philip, and the means of living luxuriously and making a show were withheld. ‘The practices of Stukeley,’ wrote Burghley to Walsingham, ‘are abated in Spain by discovery of his lewdness and insufficiency;’ and he went to Rome, where the Countess of Northumberland had secured him a good reception. ‘He left Florida kingdom,’ said Fitzwilliam sarcastically, ‘only for holiness’ sake, and to have a red hat;’ adding that he was thought holy at Waterford for going barefooted about streets and churches. ‘It is incredible,’ says Fuller, ‘how quickly he wrought himself through the notice into the favour, through the court into the chamber,[Pg 2] yea, closet and bosom, of Pope Pius Quintus.’ An able seaman, Stukeley was in some degree fitted to advance the Pontiff’s darling plan for crushing the Turks. The old pirate did find his way to Don John of Austria’s fleet, and seems to have been present at Lepanto. His prowess in the Levant restored him to Philip’s favour, and he was soon again in Spain, in company with a Doria and in receipt of 1,000 ducats a week.[1]

There was much movement at the time among the Irish in Spain, and the air was filled with rumours. Irish friars showed letters from Philip ordering all captains to be punished who refused them passages to Ireland, and the Inquisition was very active. One Frenchman was nevertheless bold enough to say that he would rather burn than have a friar on board, and those who sought a passage from him had to bestow themselves on a Portuguese ship. In 1575 Stukeley was again at Rome, and in as high favour with Gregory XIII. as he had been with his predecessor. The Pope employed him in Flanders, where he had dealings with Egremont Radcliffe. That luckless rebel had bitterly repented; but when he returned and offered his services to the queen, she spurned them and bade him depart the realm. From very want, perhaps, he entered Don John’s service, and when that prince died he was executed on a trumped-up charge of poisoning him. Stukeley was more fortunate, for he had then left the Netherlands, and Don John took credit with the English agent for sending him away. Wilson was equal to the occasion, and said the gain was the king’s, for Stukeley was a vain ‘nebulo’ and all the treasures of the Indies too little for his prodigal expenditure. It would be interesting to know what passed between the two adventurers, the bastard of Austria and the Devonshire renegade; between the man who tried to found a kingdom at Tunis, and talked[Pg 3] of marrying Mary Stuart, conquering England, and obtaining the crown matrimonial, and the man who, having dreamed of addressing his dear sister Elizabeth from the throne of Florida, now sought to deprive her of the Duchy of Ireland. Like so many who had to deal with this strange being, perhaps the governor of the Netherlands was imposed upon by his vapourings and treated him as a serious political agent. After leaving Brussels he went to Rome, well supplied with money and spending it in his old style everywhere. At Sienna Mr. Henry Cheek thought him so dangerous that he moved to Ferrara to be out of his way. At Florence the Duke honoured Stukeley greatly, ‘as did the other dukes of Italy, esteeming him as their companion.’ But he was without honour among his own countrymen, and they refused a dinner to which he invited all the English at Sienna except Cheek.[2]

James Fitzmaurice was already at Rome. He had spent the best part of two years in France, where he was well entertained, but where he found no real help. He received supplies of money occasionally. The Parisians daily addressed him as King of Ireland, but nothing was done towards the realisation of the title. Sir William Drury’s secret agent was in communication with one of Fitzmaurice’s most trusted companions, and his hopes and fears were well known in Ireland. At one time he was sure of 1,200 Frenchmen, at another he was likely to get 4,000; and De la Roche, who was no stranger in Munster, was to have at least six tall ships for transport. De la Roche did nothing but convey the exile’s eldest son, Maurice, to Portugal, where he entered the University of Coimbra. Sir Amyas Paulet had instructions to remonstrate with the French Court, and the old Puritan seems to have been quite a match for Catherine de Medici; but there was little sincerity on either side. The Queen-mother’s confidential agent confessed that all was in disorder,[Pg 4] and that the French harbours were full of pirates and thieves, but she herself told Paulet that De la Roche had strict orders to attempt nothing against England. Having little hope of France, Fitzmaurice himself went to Spain, where his reception was equally barren of result. The Catholic King was perhaps offended at the Most Christian King having been first applied to, and at all events he was not yet anxious to break openly with his sister-in-law.[3]

But at Rome, Fitzmaurice was received by Gregory with open arms. He was on very friendly terms with Everard Mercurian, the aged general of the Jesuits, who was, however, personally opposed to sending members of the order to England, Ireland, or Scotland; a point on which he was soon overruled by younger men. What the life of a Jesuit missionary was may be gathered from a letter written to the General about this time.

‘Once,’ wrote Edmund Tanner from Rosscarbery, ‘was I captured by the heretics and liberated by God’s grace, and the industry of pious people; twelve times did I escape the snares of the impious, who would have caught me again had God permitted them.’

But the harvest, though hard to reap, was not inconsiderable. Tanner reported that nobles and townsmen were daily received into the bosom of Holy Church out of the ‘sink of schism,’ and that the conversion would have been much more numerous but that many feared present persecution, and the loss of life, property, or liberty.

This chain still kept back a well-affected multitude, but the links were worn, and there was good hope that it soon would break.[4]

We know from an original paper which fell into the hands of the English Government, what were Fitzmaurice’s modes and requirements for the conquest of Ireland. Six thousand armed soldiers and their pay for six months, ten[Pg 5] good Spanish or Italian officers, six heavy and fifteen light guns, 3,000 stand of arms with powder and lead, three ships of 400, 50, and 30 tons respectively, three boats for crossing rivers, and a nuncio with twenty well-instructed priests—such were the instruments proposed. He required licence to take English ships outside Spanish ports, and to sell prizes in Spain. Property taken from Geraldines was to remain in the family, and every Geraldine doing good service was to be confirmed by his Holiness and his Catholic Majesty in land and title. Finally, 6,000 troops were to be sent to him in six months, should he make a successful descent.

As sanguine, or as desperate, as Wolfe Tone in later times, he fancied that England could be beaten in her own dominion by such means as these. Sanders, who was probably deceived by his Irish friends as to the amount of help which might be expected in Ireland, had no belief in Philip, whom he pronounced ‘as fearful of war as a child of fire.’ The Pope alone could be trusted, and he would give 2,000 men. ‘If they do not serve to go to England,’ he said, ‘at least they will serve to go to Ireland; the state of Christendom dependeth upon the stout assailing of England.’[5]

Stukeley appears to have got on better with Fitzmaurice than with Archbishop Fitzgibbon, which may have been owing to the mediation of Sanders or Allen. The Pope agreed to give some money, and Fitzmaurice hit upon an original way of raising an army. ‘At that time,’ says an historian likely to be well informed about Roman affairs, ‘Italy was infested by certain bands of robbers, who used to lurk in woods and mountains, whence they descended by night to plunder the villages, and to spoil travellers on the highways. James implored Pope Gregory XIII. to afford help to the tottering Catholic Church in Ireland, and obtained pardon for these brigands on condition of accompanying him to Ireland, and with these and others he recruited a force of[Pg 6] 1,000 soldiers more or less.’ This body of desperadoes was commanded by veteran officers, of which Hercules of Pisa (or Pisano) was one, and accompanied by Sanders and by Cornelius O’Mulrian, Bishop of Killaloe. Stukeley kept up the outward show of piety which he had begun at Waterford and continued in Spain, and he obtained a large number of privileged crucifixes from the Pontiff, perhaps with the intention of selling them well. It must be allowed that an army of brigands greatly needed indulgence, and fifty days were granted to everyone who devoutly beheld one of these crosses, the period beginning afresh at each act of adoration. Every other kind of indulgence might seem superfluous after this, but many were also offered for special acts of prayer, a main object of which was the aggrandisement of Mary Stuart.

Stukeley was placed in supreme charge of the expedition, which seems to have been done by the desire of Fitzmaurice, and the titles conferred on him by Gregory were magnificent enough even for his taste. He took upon himself to act as mediator between some travelling Englishmen and the Holy Office, and having obtained their release he gave them a passport. This precious document was in the name of Thomas Stukeley, Knight, Baron of Ross and Idrone, Viscount of Murrows and Kinsella, Earl of Wexford and Carlow, Marquis of Leinster, General of our Most Holy Father; and the contents are certified ‘in ample and infallible manner.’ Marquis of Leinster was the title by which Roman ecclesiastics generally addressed him.[6]

Stukeley left Civita Vecchia early in 1578, and brought his ships, his men, and his stores of arms to Lisbon, where he found nine Irish refugees, priests and scholars, whom Gregory had ordered to accompany him. He called them together, and, with characteristic grandiosity, offered a suitable daily stipend to each. Six out of the nine refused, saying: ‘They were no man’s subjects, and would take no stipend from anyone but the supreme Pontiff, or some king or great[Pg 7] prince.’ This exhibition of the chronic ill-feeling between English and Irish refugees argued badly for the success of their joint enterprise. After some hesitation, Sebastian of Portugal decided not to take part in this attack on a friendly power, and he invited the English adventurer to join him in invading Morocco, where dynastic quarrels gave him a pretext for intervention. Secretary Wilson was told that Stukeley had no choice, ‘the King having seized upon him and his company to serve in Africa.’ Sebastian had also German mercenaries with him. There was a sort of alliance at this time between England and Morocco, Elizabeth having sent an agent, with an Irish name, who found the Moorish Emperor ‘an earnest Protestant, of good religion and living, and well experimented as well in the Old Testament as in the New, with great affection to God’s true religion used in Her Highness’s realm.’ Whatever we may think of this, it is easy to believe that the Moor despised Philip as being ‘governed by the Pope and Inquisition.’ But it is not probable that this curious piece of diplomacy had much effect on the main issue. Stukeley warned Sebastian against rashness, advising him to halt at the seaside to exercise his troops, who were chiefly raw levies, and to gain some experience in Moorish tactics. But the young King, whose life was of such supreme importance to his country, was determined to risk all upon the cast of a die. The great battle of Alcazar was fatal alike to the Portuguese King and the Moorish Emperor. Stukeley also fell, fighting bravely to the last, at the head of his Italians. It may be said of him, as it was said of a greater man, that nothing in his life became him so much as his manner of leaving it.[7]

The Geraldine historian, O’Daly, says Fitzmaurice landed in Ireland entirely ignorant of Stukeley’s fate, but this statement is contradicted by known dates. Nor can we believe that if Stukeley had come with his Italian swordsmen while[Pg 8] Fitzmaurice lived, it would have fared ill with the English—that a little money and less blood would have sufficed to drive them out of Ireland. Yet it is probably true that the battle of Alcazar was of great indirect value to England. Sebastian left no heir, and the Crown of Portugal devolved on his great-uncle, Cardinal Henry, who was sixty-seven and childless. The next in reversion was Philip II., whose energies were now turned towards securing the much-coveted land which nature seemed to designate as proper to be joined with Spain. For a time, however, it was supposed that he would heartily embrace the sanguine Gregory’s schemes, and rumours were multiplied by hope or fear.

Lord Justice Drury knew that the lull in Ireland was only temporary, but Elizabeth made it an excuse for economy, and disaffected people, ‘otherwise base-minded enough,’ were encouraged to believe that the government would stand anything rather than spend money. By refusing to grant any protections, and by holding his head high, Drury kept things pretty quiet, but he had to sell or pawn his plate. He hinted that, as there was no foreign invasion, her Majesty might continue to pay him his salary, and save his credit. Meanwhile, he had some small successes. Feagh MacHugh made his submission in Christ Church cathedral, and gave pledges to Harrington, whom he acknowledged as his captain. Desmond and his brother John came to Waterford and behaved well, and a considerable number of troublesome local magnates made their submissions at Carlow, Leighlin, Castledermot, and Kilkenny; twenty-nine persons were executed at Philipstown, but the fort was falling down, and this was little likely to impress the neighbouring chiefs. Drury’s presence alone saved it from a sudden attack by the O’Connors. But a son of O’Doyne’s was fined for concealment, and his father took it well, so that it was possible to report some slight progress of legal ideas. Meanwhile there was great danger lest the Queen’s ill-judged parsimony should destroy much of what had been done in Sidney’s time. Thus, the town of Carrickfergus had been paved and surrounded by wet ditches; the inhabitants had, in consequence, been increased[Pg 9] from twenty to two hundred, forty fishermen resorted daily to the quay, and sixty ploughs were at work. But over 200l. was owing to the town, the garrison were in danger of starving, and it was feared that ‘the townsmen came not so fast thither, but would faster depart thence.’[8]

Tirlogh Luineach O’Neill was now old and in bad health. It was again proposed to make him a peer; but this was not done, since it was evident that a title would make fresh divisions after his death. There were already four competitors, or rather groups of competitors, for the reversion; of whom only two were of much importance. Shane O’Neill’s eldest legitimate son, known as Henry MacShane, was supported by one legitimate and five illegitimate brothers, and Drury’s idea was ‘by persuasion or by force of testoons’ to make him a counterpoise to the Baron of Dungannon, whose ambitious character was already known. The bastardy of the baron’s grandfather had been often condoned by the Crown, but was not forgotten and might be turned to account. Against the advice of his leeches old Tirlogh was carried forty miles on men’s shoulders, to meet Bagenal at Blackwater, and said he was most anxious to meet Drury. Dungannon, who expected an immediate vacancy, begged hard for 200 soldiers, without which the MacShanes would muster twice as many men as he could. He promised not to go out of his own district as long as the old chief lived. Drury temporised, since he could do nothing else, and tried what effect his own presence in the North might have. The suddenness of his movement frightened Tirlogh, who got better, contrary to all expectation, and showed himself with a strong force on the top of a hill near Armagh, refusing however to come in without protection. This Drury refused on principle, and Tirlogh’s wife, who was clever enough to see that no harm was intended, tried in vain to bring her husband to the Viceroy’s camp. Meanwhile he and the Baron became fast[Pg 10] friends, and the latter proposed to put away O’Donnell’s daughter, to whom he was perhaps not legally married, and to take Tirlogh’s for his wife. Drury made him promise not to deal further in the match; but his back was no sooner turned than the marriage was celebrated, and the other unfortunate sent back to Tyrconnell. At the same time Tirlogh gave another of his daughters to Sorley Boy MacDonnell’s son, and the assistance of the Scots was thus supposed to be secured. There were rumours that Fitzmaurice would land at Sligo, and a general confederacy was to be looked for. Fitton, who had been long enough in Ireland to know something about it, saw that the Irish had great natural wits and knew how to get an advantage quite as well as more civil people, and that Tirlogh, like the rest of his countrymen, would submit while it suited him and no longer.[9]

After Stukeley’s death James Fitzmaurice continued to prepare for a descent on Ireland. After his return from Rome he went to France, where he joined his wife, son, and two daughters. He then spent nearly three months at Madrid with Sanders, and obtained 1,000 ducats for his wife, who was then in actual penury at ‘Vidonia’ in Biscay. But he could not see the king, and professed himself indifferent to help from Spain or Portugal. ‘I care for no soldiers at all,’ he said to Sanders; ‘you and I are enough; therefore let me go, for I know the minds of the noblemen in Ireland.’ Some of Stukeley’s men, with a ship of about 400 tons, had survived the Barbary disaster. O’Mulrian, Papal Bishop of Killaloe, came to Lisbon from Rome with the same men and two smaller vessels, and by the Pope’s orders Stukeley’s ship was given to them. Sanders accompanied the bishop, and there seem to have been about 600 men—Italians, Spaniards, Portuguese, Flemings, Frenchmen, Irish, and a few English. It was arranged that this motley crew should join Fitzmaurice at Corunna, and then sail straight to Ireland. A Waterford merchant told his wife that the men were very[Pg 11] reticent, but were reported to be about to establish the true religion. When questioned they said they were bound for Africa, but the Waterford man thought they were going to spoil her Majesty’s subjects. Meanwhile Fitzmaurice was at Bilbao with a few light craft. The largest was of sixty tons, commanded by a Dingle man who knew the Irish coast, but who ultimately took no part in the expedition. William Roche, who had been Perrott’s master gunner at Castlemaine, and James Den of Galway, were also retained as pilots. A little later Fitzmaurice had a ship of 300 tons, for which he gave 800 crowns, several small pieces of artillery, 6,000 muskets, and a good supply of provisions and trenching tools. The men received two months’ pay in advance.

Fitzmaurice’s one idea was to raise an army in Munster, and he told an Irish merchant who thought his preparations quite inadequate, that ‘when the arms were occupied’ he made no account of all the Queen’s forces in Ireland. He was accompanied by his wife and daughter and about fifty men, who were nearly all Spaniards. Sanders went to Bilbao after a short stay at Lisbon, and two merchants, one of Waterford and one of Wexford, who came together from the Tagus to the Shannon, reported that a descent was imminent. ‘The men,’ they said, ‘be willing; they want no treasure, they lack no furniture, and they have skilful leaders.’ To oppose a landing the Queen had one disabled ship in Ireland, and there were no means of fitting her out for sea.[10]

The French rover, De la Roche, in spite of Catherine de Medici’s assurance, seems to have co-operated with Fitzmaurice. John Picot, of Jersey, bound for Waterford with Spanish wine, was warned at San Lucar by a Brest man that De la Roche and Fitzmaurice spoiled everyone they met. To avoid them Picot kept wide of the coast; nevertheless he fell in[Pg 12] with eight sail 60 leagues N.W. of Cape St. Vincent. They fired and obliged him to lower a boat, and then robbed him of wine, oil, raisins, and other things of Spain. Picot saw twelve pieces of cannon in De la Roche’s hold, but was warned significantly not to pry under hatches again. The Jerseymen were beaten, the St. Malo men spared, and all were told, with ‘vehement oaths and gnashing of teeth,’ that if they had been Englishmen they would have been thrown overboard—a fate which actually befell the crew of a Bristol vessel two or three days later. Finding that Picot was going to Ireland, his captors said they would keep company with him; but thick weather came on, and by changing his course, he got clear within twenty-four hours. A few days after Fitzmaurice was in Dursey Sound with six ships, and others were sighted off Baltimore. He picked up a fisherman and bade him fetch in Owen O’Sullivan Bere, but that chief refused, and three days later the invading squadron cast anchor off Dingle.[11]

The portreeve and his brethren went off to speak with the strangers next morning. Some Spaniards whom they knew refused to let them come on board, and they sent at once to Desmond for help. The preparations for resistance were of the slightest. The constable of Castlemaine reported that he had only five hogsheads of wheat, two tuns of wine, three hogsheads of salmon, and some malt; and that he was dependent for meat upon such bruised reeds as Desmond and Clancare. There were neither men nor stores at Dublin, and no hope of borrowing even 500l. Cork had but five barrels of inferior powder, and no lead. At Waterford there were only 2,000 pounds of powder. All that Drury could do was to write letters charging the Munster lords to withstand the traitors, but a fortnight passed before he himself could get as far as Limerick.[12]

Mr. James Golde, Attorney-General for Munster, writing from Tralee, thus describes the manner of Fitzmaurice’s landing, which took place on the day after his arrival at Dingle:—

‘The traitor upon Saturday last came out of his ship. Two friars were his ancient-bearers, and they went before with two ancients. A bishop, with a crozier-staff and his mitre, was next the friars. After came the traitor himself at the head of his company, about 100, and went to seek for flesh and kine, which they found, and so returned to his ships.’[13] On the same day they burned the town, lit fires on the hills as if signalling to some expected allies, and then shifted their berths to Smerwick harbour, taking with them as prisoners some of the chief inhabitants of Dingle. At Smerwick they began to construct a fort, of which the later history is famous. It was believed that Fitzmaurice expected immediate help out of Connaught. ‘Ulick Burke is obedient,’ said Waterhouse; ‘but I believe that John will presently face the confederacy.’ Drury could only preach fidelity, and commission Sir Humphrey Gilbert to take up ships and prosecute the enemy by sea and land.[14]

Fitzmaurice brought to Ireland two printed proclamations—one in English for those who spoke it and were attached to the English crown, the other in Latin for the Irish and their priests.

The first paper sets forth that Gregory XIII. ‘perceiving what dishonour to God and his Saints, &c.... hath fallen to Scotland, France, and Flanders, by the procurement of Elizabeth, the pretensed Queen of England; perceiving also that neither the warning of other Catholic princes and good Christians, nor the sentence of Pope Pius V., his predecessor, nor the long sufferance of God, could make her to forsake her schism, heresy, and wicked attempts; now purposeth (not without the consent of other Catholic potentates) to deprive[Pg 14] her actually of the unjust possession of these kingdoms, &c.’ Any attack on the Crown of England is disclaimed; the usurper was alone aimed at, and the help of the English Catholics was considered certain. The Catholics were everywhere, but ‘Wales, Chestershire, Lancastershire, and Cumberland’ were entirely devoted to the old faith, and their proximity to Ireland increased their importance. Throughout England the husbandmen—the raw material of every army—were ‘commonly all Catholics.’ Elizabeth had a few friends indeed, but she would be afraid to send them away from her, and if Ireland remained united, all must go well. One great crime of Queen Elizabeth was her refusal to declare an heir-apparent; by espousing the cause of that heir, whose name is not mentioned, the reward of those who worship the rising sun might fairly be expected. Fitzmaurice explained that the Pope had appointed him general because he alone had been present at Rome, but that he intended to act by the advice of the Irish prelates, princes, and lords, ‘whom he took in great part for his betters.’ And his appeal ends thus: ‘This one thing I will say, which I wish to be imprinted on all our hearts, if all we that are indeed of a good mind would openly and speedily pass our faith by resorting to his Holiness’ banner, and by commanding your people and countries to keep no other but the Catholic faith, and forthwith to expel all heresies and schismatical services, you should not only deliver your country from heresy and tyranny, but also do that most godly and noble act without any danger at all, because there is no foreign power that would or durst go about to assault so universal a consent of this country; being also backed and maintained by other foreign powers, as you see we are, and, God willing, shall be; but now if one of you stand still and look what the other doth, and thereby the ancient nobility do slack to come or send us (which God forbid), they surely that come first, and are in the next place of honour to the said nobility, must of necessity occupy the chief place in his Holiness’ army, as the safeguard thereof requireth, not meaning thereby to prejudice any nobleman in his own dominion or lands, which he otherwise rightfully[Pg 15] possesseth, unless he be found to fight, or to aid them that do fight, against the Cross of Christ and his Holiness’ banner, for both which I, as well as all other Christians, ought to spend our blood and, for my part, intend at least by God’s grace, Whom I beseech to give you all, my lords, in this world courage and stoutness for the defence of His faith, and in the world to come life everlasting.’[15]

The whole document is a good example of the sanguine rhetoric in which exiles have always indulged, and of the way in which the leaders of Irish sedition have been accustomed to talk. The part assigned to continental powers and to English Catholics in the sixteenth century, was transferred to the French monarchy in the seventeenth, and to the revolutionary republic in the eighteenth; and now, in the nineteenth, it is given to the United States of America, and to the British working-man.

A translation of the shorter paper may well be given in full:—‘A just war requires three conditions—a just cause, lawful power, and the means of carrying on lawful war. It shall be made clear that all three conditions are fulfilled in the present case.

‘The cause of this war is God’s glory, for it is our care to restore the outward rite of sacrifice and the visible honour of the holy altar which the heretics have impiously taken away. The glory of Christ is belied by the heretics, who deny that his sacraments confer grace, thus invalidating Christ’s gospel on account of which the law was condemned; and the glory of the Catholic Church they also belie, which against the truth of the Scriptures they declare to have been for some centuries hidden from the world. But in the name of God, in sanctification by Christ’s sacraments, and in preserving the unity of the Church, the salvation of us all has had its chief root.

‘The power of this war is derived first from natural, and then from evangelical, law. Natural law empowers us to defend ourselves against the very manifest tyranny of heretics,[Pg 16] who, against the law of nature, force us, under pain of death, to abjure our first faith in the primacy of the Roman Pontiff, and unwillingly to receive and profess a plainly contrary religion; a yoke which has never been imposed by Christians, Jews, or Turks, nor by themselves formerly upon us. And so since Christ in his gospel has given the help of the kingdom of heaven—that is, the supreme administration of his Church—to Peter, Gregory XIII., the legitimate successor of that chief of the Apostles in the same chair, has chosen us general of this war, as abundantly appears from his letters and patent (diploma), and which he has the rather done that his predecessor, Pius V., had deprived Elizabeth, the patroness of those heresies, of all royal power and dominion, as his declaratory decision (sententia), which we have also with us, most manifestly witnesseth.

‘Thus we are not warring against the legitimate sceptre and honourable throne of England, but against a she-tyrant who has deservedly lost her royal power by refusing to listen to Christ in the person of his vicar, and through daring to subject Christ’s Church to her feminine sex on matters of faith, about which she has no right to speak with authority.

‘In what belongs to the conduct of the war, we have no thoughts of invading the rights of our fellow-citizens, nor of following up private enmities, from which we are especially free, nor of usurping the supreme royal power. I swear that God’s honour shall be at once restored to Him, and we are ready at any moment to lay down the sword, and to obey our lawful superiors. But if any hesitate to combat heresy, it is they who rob Ireland of peace, and not us. For when there is talk of peace, not with God but with the Devil, then we ought to say, with our Saviour: I came not to bring peace on earth, but a sword. If then we wage continual war to restore peace with God, it is most just that those who oppose us should purchase their own damnation, and have for enemies all the saints whose bones they spurn, and also God himself, whose glory they fight against.

‘Let so much here suffice, for if anyone wishes to understand the rights of the case he need but read and understand[Pg 17] the justice and reasonableness of the fuller edict which we have taken care should be also published.’[16]

In these papers the arguments derived from the right to liberty of conscience, which all Protestants should respect, and from the Papal claims which all Protestants deny, are blended with no small skill; but Fitzmaurice, while demanding liberty of conscience for himself, expressly denies it to those who disagree with him.

There can be no doubt that Desmond was jealous of James Fitzmaurice; and historians well-affected to the Geraldines have attributed the latter’s rebellion to the ill-feeling existing between them. It is said that Lady Desmond, who was a Butler, had prevented her husband from making any provision for his distinguished kinsman. It was reported to Drury that Fitzmaurice had called himself Earl of Desmond on the Continent, and that this would be sure to annoy the Earl, whose pride was overweening. But this does not seem to have been the case. Fitzmaurice is not called Earl either in his own letters or in those written to him. The general of the Jesuits addresses him as ‘the most illustrious Lord James Geraldine’; the Pope speaks of him as James Geraldine simply, and so he calls himself, sometimes adding ‘of Desmond.’ But that he should have been appointed general of a force which was to operate in Desmond’s country was quite enough to excite suspicion. No sooner did the news of his arrival reach the Earl than he wrote to tell Drury that he and his were ready to venture their lives in her Majesty’s quarrel, ‘and to prevent the traitorous attempts of the said James.’ He had nevertheless been in correspondence with Fitzmaurice, and had urged his immediate descent upon the Irish coast some eighteen months before.[17]

Not less important than Fitzmaurice was Dr. Nicholas[Pg 18] Sanders, who acted as treasurer of the expedition. He was known by the treatise De Visibili Monarchia which Parker said was long enough to wear out a Fabius, and almost unanswerable, ‘not for the invincibleness of it, but for the huge volume.’ Answers were nevertheless written which no doubt satisfied the Anglican party, but the Catholic refugees at Brussels thought so highly of Sanders that they begged Philip to get him made a cardinal.

The English were then in disgrace at Rome, where the appointment of a Welshman as Rector of the new college had caused a mutiny among the students, and Allen doubted whether his own credit was good, but it was upon him that the red hat was at last conferred. To Sanders must be ascribed most of what was written in Fitzmaurice’s name, and that was a small part of what fell from his prolific pen. Queen Elizabeth, said the nuncio, was a heretic. She was childless, and the approaching extinction of Henry VIII.’s race was an evident judgment. She was ‘a wicked woman, neither born in true wedlock nor esteeming her Christendom, and therefore deprived by the Vicar of Christ, her and your lawful judge.’ Her feminine supremacy was a continuation of that which the Devil implanted in Paradise when he made Eve Adam’s mistress in God’s matters.’ When a knowledge of Celtic was necessary Sanders’s place might be taken by Cornelius O’Mulrian, an observant friar, lately provided to the see of Killaloe, or by Donough O’Gallagher, of the same order, who was provided to Killaloe in 1570. Letters in Irish were written to the Munster MacDonnells, Hebridean gallowglasses serving in Desmond, whom Fitzmaurice exhorts to help him at once—‘first, inasmuch as we are fighting for our faith, and for the Church of God; and next, that we are defending our country, and extirpating heretics, barbarians, and unjust and lawless men; and besides that you were never employed by any lord who will pay you and your people their wages and bounty better than I shall, inasmuch as I never was at any time more competent to pay it than now.... We are on the side of truth and they on the side of falsehood; we are Catholic Christians, and they are heretics; justice is with us, and[Pg 19] injustice with them.... All the bonaght men shall get their pay readily, and moreover we shall all obtain eternal wages from our Lord, from the loving Jesus, on account of fighting for his sake.... I was never more thankful to God for having great power and influence than now. Advise every one of your friends who likes fighting for his religion and his country better than for gold and silver, or who wishes to obtain them all, to come to me, and that he will find each of these things.’[18]

In the letter written by Sanders to Desmond in Fitzmaurice’s name, the Earl is reminded that the latter ‘warfareth under Christ’s banner, for the restoring of the Catholic faith in Ireland.’ Then, flying into the first person in his hurry, he says His Holiness ‘has made me general-captain of this Holy War.’ There are many allusions to Christ’s banner and to the ancient glories of the Geraldines, and the epistle ends with a recommendation to ‘your fellows, and to all my good cousins your children, and to my dear uncle your brother, longing to see all us, all one, first as in faith so in field, and afterwards in glory and life everlasting.’

A like appeal was made to the Earl of Kildare, and we may be sure that none of the Munster lords were forgotten. Friars were busy with O’Rourke, O’Donnell, and other northern chiefs, and the piratical O’Flaherties brought a flotilla of galleys, which might have their own way in the absence of men-of-war. Three of Fitzmaurice’s ships sailed away, and were expected soon to return with more help. Thomas Courtenay of Devonshire happened to be at Kinsale with an armed vessel, and was persuaded by his countryman Henry Davells, one of the Commissioners of Munster, to come round and seize the remaining Spanish ships. Courtenay seems not to have been in the Queen’s service; like so many other men of Devon, he was probably half-pirate and half-patriot. To cut out the undefended vessels from their anchorage was[Pg 20] an easy and congenial task, and thus, to quote another Devonian, ‘James Fitzmaurice and his company lost a piece of the Pope’s blessing, for they were altogether destituted of any ship to ease and relieve themselves by the seas, what need soever should happen.’ The O’Flaherties sailed away with the two bishops on Courtenay’s arrival, but Maltby afterwards found their lair upon the shores of Clew Bay. One was promptly hanged by martial law; a second, who had property to confiscate, was reserved for the sessions, and a third was killed for resisting his captors; the rest were to be hanged when caught. Fitzmaurice had with him at Smerwick but twenty-five Spaniards, six Frenchmen, and six Englishmen, besides twenty-seven English prisoners whom he forced to work at the entrenchments. Provisions were scarce, and the whole enterprise might have collapsed had it not been for a crime which committed the Desmonds irretrievably.[19]

On hearing of the landing in Kerry Drury had despatched a trusty messenger to confirm the Earl and his brother in their allegiance. The person selected was Henry Davells, a Devonshire gentleman who had served Henry VIII. in France, had afterwards seen fighting in Scotland, and had long lived in Carlow and Wexford, where he was well known and much respected. His countryman Hooker, who knew him, says he was not only the friend of every Englishman in Ireland, but also much esteemed by the Irish for his hospitality and true dealing. ‘If any of them had spoken the word, which was assuredly looked to be performed, they would say Davells hath said it, as who saith “it shall be performed.” For the nature of the Irishman is, that albeit he keepeth faith, for the most part, with nobody, yet will he have no man to break with him.’ The same writer assures us that the mere fact of being Davells’ man would secure any Englishman a free passage and hospitable reception throughout Munster and Leinster. He was equally valued by Desmond[Pg 21] and Ormonde, an intimate friend of Sir Edmund Butler, and on such terms with Sir John of Desmond, whose gossip he was and whom he had several times redeemed out of prison, that the latter used to call him father. Davells now went straight to Kerry, saw the Earl and his brothers, whom he exhorted to stand firm, and visited Smerwick, which he found in no condition to withstand a resolute attack. Returning to the Desmonds he begged for a company of gallowglasses and sixty musketeers, with whom and with the aid of Captain Courtenay, he undertook to master the unfinished fort. Desmond refused, saying that his musketeers were more fitted to shoot at fowls than at a strong place, and that gallowglasses were good against gallowglasses, but no match for old soldiers. English officers afterwards reported that sixty resolute men might have taken Smerwick, and were thus confirmed in their belief that Desmond had intended rebellion from the first, and that Fitzmaurice, whose ability was undeniable, would not have taken up such a weak position without being sure of the Earl’s co-operation. But religious zeal might account for that.

Davells, who was accompanied by Arthur Carter, Provost Marshal of Munster, and a few men, started on his return journey, prepared no doubt to tell Drury that nothing was to be expected of the Desmonds. John of Desmond, accompanied by his brother James and a strong party, followed to Tralee, surrounded the tavern where the English officers lay, and bribed the porter to open the door. Davells and Carter were so unsuspicious that they had gone to bed, and allowed their servant to lodge in the town. When Davells saw Sir John entering his room with a drawn sword he called out, ‘What, son! what is the matter?’ ‘No more son, nor no more father,’ said the other, ‘but make thyself ready, for die thou shalt.’ A faithful page cast himself upon his master’s body; but he was thrust aside and Sir John himself despatched Davells.

Carter was also killed, and so were the servants. In a curious print the two Englishmen are represented as sleeping in the same bed. Sir John holds back the servant with his[Pg 22] left hand and transfixes Davells with the right, while Sir James goes round, with a sword drawn, to Carter’s side. Outside stand several squads of the Desmond gallowglasses, and armed men are killing Davells’ followers, while Sanders appears in two places, carrying the consecrated papal banner, hounding on the murderers, and congratulating the brothers on their prowess. According to all the English accounts Sanders commended the murder as a sweet sacrifice in the sight of God, and two Irish Catholic historians mention it. But Fitzmaurice was a soldier, and disapproved of killing men in their beds. There is no positive evidence as to Desmond. Geraldine partisans say he abhorred the deed, but he never punished anyone for it, and Sir James was said to have pleaded that he was merely the Earl’s ‘executioner.’ Desmond accepted a silver-gilt basin and ewer, and a gold chain only a few days after the murder.[20]

‘Landed gentlemen,’ says Sidney Smith, ‘have molar teeth, and are destitute of the carnivorous and incisive jaws of political adventurers.’ The Munster proprietors held aloof with the Earl of Desmond, ‘letting “I dare not” wait upon “I would,”’ while the landless men followed his bolder and more unscrupulous brother. When Fitzmaurice disembarked, Desmond had 1,200 men with him; shortly after the murder of Davells he had less than 60; but Sir John was soon at the head of a large force. The activity of Maltby not only prevented any rising in Connaught, but also made it impossible for Scots to enter Munster. He lay at Limerick waiting till Drury was ready, and when the latter, who was ill, came to Limerick at the risk of his life, it was Maltby who[Pg 23] entered the woods and drove the rebels from place to place. For a time Fitzmaurice and his cousin kept together, though it may be that the latter’s savagery was disagreeable to the man who had seen foreign courts, and who was evidently sincerely religious, though the English accused him of hypocrisy. According to Russell, who gives details which are wanting elsewhere, the two marched together unopposed into the county of Limerick, where one of Sir John’s men outraged a camp-follower. Fitzmaurice ordered him for execution, but Sir John, ‘little regarding the Pope’s commission, and not respecting murder or rape,’ refused to allow this, and Fitzmaurice, seeing that he could not maintain discipline, departed with a few horsemen and kernes, nominally on a pilgrimage to Holy Cross Abbey, really perhaps to enter Connaught through Tipperary and Limerick, and thus get into Maltby’s rear. In doing so he had to pass through the territory of a sept of Burkes, of whom some had been with him in his former enterprise. Fitzmaurice was in want of draught animals, and took two horses out of the plough. The poor peasants raised an alarm, and at a ford some miles south of Castle Connell the chief’s son Theobald, who was learned in the English language and law, and who may have had Protestant leanings, appeared with a strong party. He was already on the look-out, and had summoned MacBrien to his aid.

Fitzmaurice urged Burke to join the Catholic enterprise; he answered that he would be loyal to the Queen, and a fight followed. Burke had but two musketeers with him, one of whom aimed at Fitzmaurice, who was easily known by his yellow doublet. The ball penetrated his chest, and feeling himself mortally wounded, he made a desperate dash forward, killed Theobald Burke and one of his brothers, and then fell, with or without a second wound. ‘He found,’ says Hooker characteristically, ‘that the Pope’s blessings and warrants, his agnus Dei and his grains, had not those virtues to save him as an Irish staff, or a bullet, had to kill him.’ The Burkes returned after the death of their leader, and, having confessed to Dr. Allen, the best of the Geraldines breathed[Pg 24] his last. Lest the knowledge of his death should prove fatal to his cause, a kinsman cut off Fitzmaurice’s head and left the bare trunk under an oak—an evidence of haste which shows that there was no great victory to boast of. The body was nevertheless recognised, carried to Kilmallock, and hanged on a gibbet; and the soldiers barbarously amused themselves by shooting at their dead enemy. ‘Well,’ says Russell, ‘there was no remedy—God’s will must be done, punishing the sins of the father in the death of the son. Fitzmaurice made a goodly end of his life (only that he bore arms against his sovereign princess, the Queen of England). His death was the beginning of the decay of the honourable house of Desmond, out of which never issued so brave a man in all perfection, both for qualities of the mind and body, besides the league between him and others for the defence of religion.’[21]

[1] Strype’s Annals, Eliz. lib. i. ch. i. and ii. i. Walsingham to Cecil, February 25, 1571, and Burghley to Walsingham, June 5, both in Digges’s Complete Ambassador. Lady Northumberland to Stukeley, June 21, 1571, in Wright’s Elizabeth. Answers of Martin de Guerres, master mariner, February 12, 1572; Examination of Walter French, March 30; report of John Crofton, April 13.

[2] Stukeley to Mistress Julian (from Rome) October 24, 1575, in Wright’s Elizabeth, Motley’s Dutch Republic, part v. ch. v.; Strype’s Annals, Eliz. book ii. ch. viii.; Wilson to Burghley and Walsingham, February 19, 1577, and to the Queen, May 1, both in the Calendar of S. P. Foreign; Henry Cheek to Burghley, March 29, 1577; Strype’s Life of Sir John Cheek. Stukeley left Don John at the end of February, 1577.

[3] Intelligence received by Drury, February 19, 1577, and April 16; Examination of Edmund MacGawran and others May 10; Paulet to Wilson, August, 1577, in Murdin’s State Papers.

[4] Edmundus Tanner Patri Generali Everardo, October 11, 1577, in Hogan’s Hibernia Ignatiana.

[5] Sanders to Allen, Nov. 6, 1577 (from Madrid) in Cardinal Allen’s Memorials; James Fitzmaurice’s instruction and advice (now among the undated papers of 1578) written in Latin and signed ‘spes nostra Jesus et Maria, Jacobus Geraldinus Desmoniæ.’

[6] This passport, given at Cadiz in April, 1578, ‘by command of his Excellency,’ is in Sidney Papers, i. 263. O’Sullivan’s Hist. Cath. lib. iv. cap. xv. O’Daly’s Geraldines, ch. xx. Strype’s Annals, Eliz. book ii. ch. xiii.

[7] Letter signed by ‘Donatus Episcopus Aladensis,’ David Wolf the Jesuit, and two other Irish priests, printed from the Vatican archives in Brady’s Episcopal Succession, ii. p. 174. Edmund Hogan to Queen Elizabeth (from Morocco) June 11, 1577; Dr. Wilson to——, June 14, 1578, in Wright’s Elizabeth.

[8] Drury to Walsingham, Jan. 6 and 12, 1579; to Burghley, Sept. 21, 1578; Drury and Fitton to Burghley, Oct. 10, 1578; Fitton to Burghley, Feb. 22, 1579. Note of services &c., town of Knockfergus in Carew, ii. p. 148.

[9] Drury to Walsingham, Jan. 6, 1579 (enclosing an O’Neill pedigree); to Burghley, Jan. 6 and Feb. 11, 1579; to the Privy Council, March 14; Fitton to Burghley, Feb. 12, 1579.

[10] Patrick Lumbarde to his wife (from Lisbon) Feb. 20, 1579; Nic. Walshe to Drury, Feb. 27; Declaration of James Fagan and Leonard Sutton, March 23; Drury to Walsingham, March 6; Desmond to Drury, April 20; Examination of Dominick Creagh, April 22, and of Thomas Monvell of Kinsale, mariner, April 30.

[11] July 17, 1579. Examination (at Waterford) of John Picot of Jersey, master, and Fr. Gyrard, of St. Malo, pilot, July 24; Lord Justice and Council to the Privy Council, July 22; Sir Owen O’Sullivan to Mayor of Cork, July 16; Portreeve of Dingle to Earl of Desmond, July 17. The story of the Bristol crew is told in Mr. Froude’s 27th chapter, ‘from a Simancas MS.’

[12] Lord Justice and Council to the Privy Council with enclosure, July 22, 1579; Waterhouse to Walsingham, July 23 and 26; Mayor of Waterford to Drury, July 25.

[13] James Golde to the Mayor of Limerick, July 22, 1579.

[14] Desmond, abp. of Cashel (Magrath), and Wm. Apsley to Drury, July 20, 1579; Waterhouse to Walsingham, July 23 and 24; Commission to Sir H. Gilbert, July 24; James Golde to the Mayor of Limerick, July 22.

[15] The signature is ‘In omni tribulatione spes mea Jesus et Maria, James Geraldyne.’

[16] These two declarations are at Lambeth. In the Carew Calendar, they are wrongly placed under 1569, when Pius V. was still alive. They are printed in full in the Irish (Kilkenny) Archæological Journal, N.S. ii. 364.

[17] Desmond to Drury, July 19, 1579; Russell. The letter from Desmond’s servant, William of Danubi, to Fitzmaurice, calendared under July 1579 (No. 37) certainly belongs to the end of 1577, just after Rory Oge had burned Naas.

[18] James Fitzmaurice to Alexander, Ustun, and Randal MacDonnell, July, 1579; these letters, with translation, were printed by O’Donovan in Irish (Kilkenny) Archæological Journal, N.S. ii. 362; Strype’s Parker, lib. iv. cap. 15, and the appendix; Sanders to Ulick Burke in Carew, Oct. 27, 1579. In Cardinal Allen’s Memorials is a letter dated April 5, 1579, in which Allen calls Sanders his ‘special friend.’

[19] Fitzmaurice to Desmond and Kildare, July 18, 1579; Waterhouse to Walsingham, July 24; notes of Mr. Herbert’s speech, Aug. 3; Maltby’s discourse April 8, 1580; Hooker in Holinshed.

[20] Hooker and Camden for the English view of Desmond’s conduct; Russell and O’Daly for the other side, and also O’Sullivan, ii. iv. 15. The picture is reproduced in the Irish (Kilkenny) Archæological Journal, 3rd S. i. 483. In his 27th chapter Mr. Froude quotes Mendoza to the effect that Davells was Desmond’s guest; but Hooker says distinctly that he ‘lodged in one Rice’s house, who kept a victualling-house and wine tavern.’ In a letter of Oct. 10, 1579, Desmond says his brother James was ‘enticed into the detestable act.’ E. Fenton to Walsingham, July 11, 1580; Lord Justice and Earl of Kildare to the Privy Council, Aug. 3, 1579. Examination of Friar James O’Hea in Carew, Aug. 17, 1580. Collection of matters to Nov. 1579.

[21] Irish Archæological Journal, 3rd S. i. 384; Four Masters; Camden; Hooker; O’Sullivan, ii. iv. 94. Waterhouse to Walsingham, Aug. 3 and 9, 1579. Fitzmaurice fell shortly before Aug. 20. O’Sullivan calls the place Beal Antha an Bhorin, which may be Barrington’s bridge or Boher. This writer, who loves the marvellous, says a Geraldine named Gibbon Duff, was tended among the bushes by a friendly leech, who bound up his eighteen wounds. A wolf came out of the wood and devoured the dirty bandages, but without touching the helpless man. The Four Masters, who wrote under Charles I., praise Theobald Burke and regret his death.

THE DESMOND REBELLION, 1579-1580.

Sir John of Desmond at once assumed the vacant command, and Drury warned the English Government that he was no contemptible enemy, though he had not Fitzmaurice’s power of exciting religious enthusiasm, and had yet to show that he had like skill in protracting a war. The Munster Lords were generally unsound, the means were wanting to withstand any fresh supply of foreigners, and there could be no safety till every spark of rebellion was extinguished. The changes of purpose at Court were indeed more than usually frequent and capricious. English statesmen, who were well informed about foreign intrigues, were always inclined to despise the diversion which Pope or Spaniard might attempt in Ireland; and the Netherlands were very expensive. Moreover, the Queen was amusing herself with Monsieur Simier. Walsingham, however, got leave to send some soldiers to Ireland, and provisions were ordered to be collected at Bristol and Barnstaple. Then came the news that Fitzmaurice had not above 200 or 300 men, and the shipping of stores was countermanded. On the arrival of letters from Ireland, the danger was seen to be greater, and Walsingham was constrained to acknowledge that foreign potentates were concerned, ‘notwithstanding our entertainment of marriage.’ One thousand men were ordered to be instantly raised in Wales, 300 to be got ready at Berwick, extraordinary posts were laid to Holyhead, Tavistock, and Bristol. Money and provisions were promised. Sir John Perrott received a commission, as admiral, to cruise off Ireland with five ships and 1,950 men, and to go against the Scilly pirates when he had nothing better to do. Then[Pg 26] Fitzmaurice’s death was announced, and again the spirit of parsimony prevailed. The soldiers, who were actually on board, were ordered to disembark. These poor wretches, the paupers and vagrants of Somersetshire, and as such selected by the justices, had been more than a fortnight at Bristol, living on bare rations at sixpence a day, and Wallop with great difficulty procured an allowance of a halfpenny a mile to get them home. The troops despatched from Barnstaple were intercepted at Ilfracombe, and all the provisions collected were ordered to be dispersed. Then again the mood changed, and the Devonshire men were allowed to go.[22]

The Earl of Kildare, who was probably anxious to avoid fresh suspicion, gave active help to the Irish government, ‘making,’ as Waterhouse testified, ‘no shew to pity names or kindred.’ He exerted his influence with the gentry of the Pale to provide for victualling the army, and he accompanied the Lord Justice in person on his journey to Munster. The Queen wrote him a special letter of thanks, and Drury declared that he found him constant and resolute to spend his life in the quarrel. The means at the Lord Justice’s disposal were scanty enough:—400 foot, of which some were in garrison, and 200 horse. He himself was extremely ill, but struggled on from Limerick to Cork, and from Cork to Kilmallock, finding little help and much sullen opposition; but the arrival of Perrott, with four ships, at Baltimore seemed security enough against foreign reinforcements to the rebels, and Maltby prevented John of Desmond from communicating with Connaught. Sanders contrived to send letters, but one received by Ulick Burke was forwarded, after some delay, to the government, and Desmond still wavered, though the Doctor tried to persuade him that Fitzmaurice’s death was a provision of God for his fame. ‘That devilish traitor Sanders,’ wrote Chancellor Gerrard, ‘I hear—by examination of some persons who were in the forts with him and[Pg 27] heard his four or five masses a day—that he persuaded all men that it is lawful to kill any English Protestants, and that he hath authority to warrant all such from the Pope, and absolution to all who can so draw blood; and how deeply this is rooted in the traitors’ hearts may appear by John of Desmond’s cruelty, hanging poor men of Chester, the best pilots in these parts, taken by James, and in hold with John, whom he so executed maintenant upon the understanding of James his death.’ No one, for love or money, would arrest Sanders, and Drury could only hope that the soldiers might take him by chance, or that ‘some false brother’ might betray him. Desmond came to the camp at Kilmallock, but would not, or could not, do any service. Drury had him arrested on suspicion, and, according to English accounts, he made great professions of loyalty before he was liberated. The Irish annalists say his professions were voluntary, that he was promised immunity for his territory in return, and that the bargain was broken by the English. Between the two versions it is impossible to decide. The Earl did accompany Drury on an expedition intended to drive John of Desmond out of the great wood on the borders of Cork and Limerick. At the place now called Springfield, the English were worsted in a chance encounter, their Connaught allies running away rather than fight against the Geraldines. In this inglorious fray fell two tried old captains and a lieutenant, who had fought in the Netherlands, and the total loss was considerable. Drury’s health broke down after this, and instead of scouring Aherlow Woods the stout old soldier was carried in a litter to his deathbed at Waterford. As he passed through Tipperary, Lady Desmond came to him and gave up her only son as a hostage—an unfortunate child who was destined to be the victim of state policy.

Sir William Pelham, another Suffolk man, had just arrived in Dublin, and was busy organising the defence of the Pale against possible inroads by the O’Neills. He was at once chosen Lord Justice of the Council, and the Queen confirmed their choice.

Drury was an able and honest, though severe governor,[Pg 28] and deserves well of posterity for taking steps to preserve the records in Birmingham Tower. Sanders gave out that his death was a judgment for fighting against the Pope, forgetting that Protestants might use like reasoning about Fitzmaurice.[23]

Maltby was temporary Governor of Munster by virtue of Drury’s commission, and had about 150 horse and 900 foot, the latter consisting, in great measure, of recruits from Devonshire. He summoned Desmond to meet him at Limerick, and sent him a proclamation to publish against the rebels. The Earl would not come, and desired that freeholders and others attending him might be excepted from the proclamation. Maltby, who had won a battle in the meantime, then required him to give up Sanders, ‘that papistical arrogant traitor, that deceiveth the people with false lies,’ or to lodge him so that he might be surprised. Upon this the Earl merely marvelled that Maltby should spoil his poor tenants. ‘I wish to your lordship as well as you wish to me,’ was the Englishman’s retort, ’and for my being here, if it please your Lordship to come to me you shall know the cause.’ It did not please him, and the governor made no further attempt at conciliation.[24]

The encounter which gave Maltby such confidence in negotiation took place on October 3 at Monasternenagh, an ancient Cistercian abbey on the Maigue. The ground was flat, and Sir William Stanley, the future traitor of Deventer, said the rebels came on as resolutely as the best soldiers in Europe. Sir John and Sir James of Desmond had over 2,000 men, of which 1,200 were choice gallowglasses, and Maltby had about 1,000. Desmond visited his brothers in the early morning, gave them his blessing, and then withdrew to Askeaton, leaving his men behind.

‘He is now,’ said Maltby, ‘so far in, that if her Majesty[Pg 29] will take advantage of his doings his forfeited living will countervail her Highness’s charges; and Stanley remarked that the Queen might make instead of losing money by the rebellion. After a sharp fight, the Geraldines were worsted, and the Sheehy gallowglasses, which were Desmond’s chief strength, lost very heavily. The two brothers escaped by the speed of their horses and bore off the consecrated banner, ‘which I believe,’ said Maltby, ‘was anew scratched about the face, for they carried it through the woods and thorns in post haste.’ Sanders, if he was present, escaped, but his fellow-Jesuit, Allen, was killed. In a highly rhetorical passage Hooker describes this enthusiast’s proceedings, and likens his fall to that of the prophets of Baal. Maltby’s commission died with Drury, and he stood on the defensive as soon as he heard of the event.[25]

Ormonde had been about three years in England, looking after his own interests, and binding himself more closely to the party of whom Sussex was the head. Disturbance in Munster of course demanded his presence, and he prepared to start soon after the landing of James Fitzmaurice. ‘I pray you,’ he wrote to Walsingham, ‘do more in this my cause than you do for yourself, or else the world will go hard.’