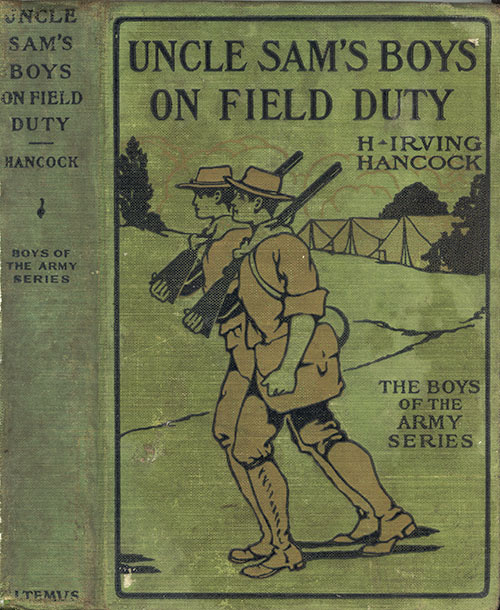

"Let Me Look at That Bolt."

Frontispiece.

OR

Winning Corporal's Chevrons

By

H. IRVING HANCOCK

Author of The Motor Boat Club Series, The High School Boys' Series, The West Point Series, The Annapolis Series, Uncle Sam's Boys in the Ranks, Uncle Sam's Boys as Sergeants, Etc.

Illustrated

PHILADELPHIA

HENRY ALTEMUS COMPANY

Copyright, 1911, by

Howard E. Altemus

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | A Squad-room Misunderstanding | 7 |

| II. | On the Great Summer Hike | 29 |

| III. | Soldier Hal Marches as a Prisoner | 47 |

| IV. | The Joking Scout | 54 |

| V. | The Corporal With the Sheepish Grin | 65 |

| VI. | Raynes Finds a Patriotic Ally | 77 |

| VII. | Bears and Other Troubles | 90 |

| VIII. | In the Midst of the "Hostiles" | 97 |

| IX. | Planning for the Night Attack | 103 |

| X. | Trappers and Trapped | 113 |

| XI. | That C Company Corporal Eats Crow | 119 |

| XII. | The Call to Deadly Work | 130 |

| XIII. | The Appointment With Supreme Danger | 138 |

| XIV. | Meeting Blick in Earnest | 145 |

| XV. | The Battle of Their Lives | 155 |

| XVI. | Captain Cortland "Makes a Speech" | 162 |

| XVII. | Rounding Up the Missing Leave Men | 171 |

| XVIII. | Dowley Eggs On a Catspaw | 184 |

| XIX. | A Dispute in the Guard House | 192 |

| XX. | Promotion Flies in the Air | 202 |

| XXI. | The Price of Being a Man | 211 |

| XXII. | Two Young Corporals Send Out the "C. Q. D." | 227 |

| XXIII. | The Wind Changes Its Course and Blows | 235 |

| XXIV. | Conclusion | 246 |

Uncle Sam's Boys on Field Duty

"I SEE by the paper——" began Private Green, looking up.

Instantly the doughboys in the squad room turned loose on him.

"You can never believe what you read in the papers," broke in Private Hyman.

"Cut it and study your guard manual!" yelled another.

"Is it going to rain to-night, rookie?"

"Let him alone. He wants to prove that he can read," jeered another, which witticism brought a swift flush to the face of Private Green.

For Green was as verdant as his name. He was a new recruit, just in after his probationary period at a northwestern recruit rendezvous. He was so green, in fact, that the men in the squad room, and throughout B Company of the Thirty-fourth United States Infantry accused the young fellow of having joined the[Pg 8] Army so that he could get a wall of bayonets between his own inexperienced self and the bunco men.

The young recruit's mistake lay in pretending to know a lot more than he really did know. He had been put through the unmerciful hazing that always awaits a very "fresh" rookie, or recruit, but even that had taught him little. Private Green was always looking for the chance to prove to his new comrades among the regulars of the Thirty-fourth that he knew something after all. This afternoon his trouble had taken the form of trying to find something in a two-days' old newspaper on which he could discourse for the enlightenment of the other men.

"I see by the paper," continued Private William Green, as soon as his tormentors would let him proceed, "that we of the United States are now manufacturing the biggest and finest guns in the world."

"Meaning cannon?" quizzed Private Hyman innocently.

"Sure," nodded Private William Green.

"Take that over to the red sheds," jeered one soldier.

"What do we of the infantry care about the red legs and their troubles?" demanded Hyman, as though affronted.

For the "doughboys," or infantrymen, of the[Pg 9] regular Army, affect supreme scorn for all other arms of the service. In especial do they profess contempt for the artillerymen, or red legs, this latter epithet being derived from the fact that red is the artillery color, and that the officers and non-commissioned officers of the artillery wear red side stripes on their trousers.

"But think what it means to this country," insisted Private William Green,"when we manufacture the biggest guns in the world."

"And we have also the loudest-mouthed and noisiest members in the peace societies," remarked Private Hal Overton, laughingly.

"What have peace-spouters got to do with big guns?" demanded Private William Green rather stiffly.

"Why, you see," explained Hal,"the peace advocates look for the millennium."

"The mill—what kind of mill?" inquired Green, with unlooked-for interest, for Private Willie had been employed in a grist mill before enlisting.

"The mil-len-nium," explained Private Overton patiently, though with a twinkle in his eyes.

"Never heard of that mill," replied Private Green rather disdainfully. "What's it for?"

"Why, you see, Greenie—pardon me, I mean Willie," continued Hal Overton, while the other soldiers in the squad room, scenting fun, remained[Pg 10] silent, "it's like this: The millennium is the age that may come some time. The peace-spouters tell us that the millennium is coming in two weeks from autumn. That millennium is the age when all war will be abolished and soldiers will have to go to work."

"What's all that got to do with what I was talking about?" demanded Private Green, bewildered and half offended.

"Wait, and Overton will tell you," warned Hal's chum, Noll Terry, who stood by looking decidedly trim and handsome in his spotless khaki uniform.

"Of course you know all about Armageddon?" resumed Hal.

"Never heard of him," retorted Green suspiciously, for he saw the amused looks in the faces of some of the soldiers standing about. "Say—hold on! Is Army-gid-ap——"

"Armageddon," corrected Hal quietly.

"Is that the name of the new breakfast food that the rainmaker (Army surgeon) was trying to have sprung on the bill of fare of our company mess?"

"Oh, no," Hal assured him. "Nothing as bad as that. You see, Greenie—Willie, I mean—while the peace-howlers lay all of their bets on the millennium being just over the fence, there's another crowd of high-brow thinkers who look[Pg 11] forward to the great battle when all the armies of the world will be present. That battle is going to be the one grand fight of all history, and the armies of one half of the world are going to get a sure thrashing from the armies of the other half. Any way you look at it, it's surely going to be a big scrap, Willie, and after that maybe all soldiers will be too tired to fight any more. Now, for that great battle the high-brows have invented the name of Armageddon. Don't forget the name, Willie—Armageddon. It's going to be the biggest fight the world ever saw—the only real fight in history, as we'll look back at it afterwards."

"But what has all this got to do with what I was reading from the paper?" insisted Private Green.

"Why, don't you see, if we're making the biggest and finest guns, and Armageddon comes on, it'll be just like robbing a baker's wagon for us to win Armageddon. On the other hand, if millennium runs in first, and we don't need the guns, then we win, too. We've got the biggest guns for Armageddon, and the noisiest peace-howlers for the millennium. Armageddon or millennium, it's just as good a bet either way, for the United States is bound to win, going or coming."

Private William Green didn't see more than a[Pg 12] tenth part of the point, but the laugh that followed got on his nerves.

"You fellows are nothing but a lot of horse-play idiots," he growled, rising and stalking away.

As he made his way through the little fringe of soldiers something happened to Private William Green, but Hal Overton was the only disinterested person who happened to see it.

William had joined the Army after toiling and saving for some four years. Green had saved his money, and hoped to save a lot more. He was known to have about four hundred dollars in cash, which he had so far declined to deposit with the Army pay-master. Where he kept this money was not known, beyond the fact that he sometimes carried it on his person.

Just as William was passing through the group of soldiers a hand ran expertly up under the loose hem of Private Green's blouse. A wallet left Green's right-hand hip pocket, coming away with the intruding hand. Then Private Dowley slipped the wallet into his own trousers' pocket.

Hal saw and acted with his usual quickness.

"Don't do that, Dowley," Hal advised, moving forward and resting a hand on Private Dowley's shoulder.

"Don't do what?" demanded Dowley, turning[Pg 13] scowling eyes on Hal.

"Give him back his wallet, Dowley. That's carrying a joke too far."

"I haven't——" was as far as Private Dowley got when Private William Green, who was twenty-two years old, tall, raw-boned, freckled and sandy haired, heard the word and clapped a hand to his own hip pocket.

"I've been touched—robbed—right in the heart of United States forces!" yelled Private Green, turning and staggering back.

"Give it back to him, Dowley," urged Hal.

"What do you mean? To say that I——" sputtered Dowley, clenching his fists as though he meant to hurl himself at Hal Overton.

But Private William himself settled the problem by hurling himself weakly at Dowley and running his hands over his comrade's clothing.

"There it is," yelled William. "My wallet—right in Dowley's trousers' pocket."

"Of course," nodded Private Hal. "Dowley did it as a joke, but it looks like carrying a joke too far."

Dowley, seeing that further denial was useless, broke into a guffaw. Then he thrust a hand into his pocket, producing the wallet. William Green pounced upon it with an exclamation of joy.

"I wanted to string Greenie," explained Dowley[Pg 14] hoarsely, "but Overton had to go to work and spoil it all."

"The joke was in bad taste," observed Private Hyman quietly. "We don't want any work of that sort here, even for fun."

"What I marvel at," remarked Hal innocently, "is how you did the thing in such a smooth, light-fingered way, Dowley."

"Light fingered? You hound!" raged Dowley, his eyes blazing. "Do you mean that I did the trick with the skill of a crook?"

He placed himself squarely before the young soldier, crowding him back and glaring into Overton's eyes.

The other soldiers in the room found suddenly a new interest in the scene. Young Overton wasn't quarrelsome; he was the soul of good nature, in fact, but he knew how to fight when he had to do it.

"Stop walking on my feet," counseled Hal, giving Dowley a slight push that sent him backward a step.

"What did you mean?" insisted Dowley, who was working himself into a greater rage with every second.

"It's time to ask what you mean," retorted Hal.

"You called me a light-fingered crook, because I played a joke on Greenie," roared Dowley.[Pg 15] "And I'm going to make you eat talk like that."

"You're putting a wrong construction on my words," returned Hal quietly.

"You called me a light-fingered crook, didn't you?" demanded Dowley hotly.

"I spoke of your performance as a light-fingered trick."

"That's the same thing," raged the older man.

"Is it?"

"Don't play baby, and don't crawfish," sneered Dowley, scowling. "You know what you meant."

"And you seem to think you know, too."

"We must break this up," whispered Private Hyman to Noll Terry, Hal Overton's soldier chum. "I don't want to see him get hurt."

"What do you care about Dowley?" asked Noll, shrugging his shoulders.

"Dowley be hanged!" retorted Hyman. "It's your kid friend I'm thinking about."

"Oh, he won't get hurt," retorted Noll with cheery assurance.

"Your friend is pretty handy with his fists, I know, but Dowley is a big fellow, an older man, with more fighting judgment; and I miss my guess if Dowley hasn't had a big lot of practice in rough-and-tumble in all the bad spots of life."

"Will you take back and apologize for what[Pg 16] you said?" insisted Dowley.

"If I said anything I shouldn't have said," replied Hal quietly.

"You're a liar, a cur and——"

"Stop that!" objected Hal Overton, yet without raising his voice.

"Apologize, then! Do it handsomely, too."

"You've said too much to be entitled to any apology now," Hal assured the scowling soldier.

"Apologize, or I'll——"

"Going to start now?" Hal queried smilingly.

"Yes, you——"

Dowley made a rush, with both fists clenched. Hal nimbly sidestepped, putting up his own guard at the same time.

"Attention!" shouted a soldier.

Instantly both prospective combatants dropped their hands. The door of the squad-room had opened, and now there entered a young officer, handsome and resplendent in his new fatigue uniform. Unlike the khaki-clad enlisted men, this officer was attired in the blue uniform. Down the outer side of either leg of his trousers ran the broad white stripe of the commissioned officer of infantry. On his shoulders lay the plain shoulder strap, without bars or other device, proclaiming the young man to be a second lieutenant. He was a handsome[Pg 17] young fellow of twenty-two, erect, fine of bearing and every inch of him an intense soldier.

"Where is Sergeant Hupner?" asked Lieutenant Prescott. His glance, as he made the inquiry, appeared to be directed to Private Hal Overton.

"I don't know, sir," Hal answered respectfully.

"And neither of the corporals berthed in this squad room are present, either?"

"No, sir."

No displeasure was apparent in the young lieutenant's tone. There was no reason why the corporals, as well as the sergeant, should not be absent at this moment, if they chose. The officer's query was made only for the purpose of securing information.

"You are Private Overton?"

"Yes, sir."

"When Sergeant Hupner returns be good enough to say to him that I wish to see him at my quarters. Any time before the call for parade will do."

"Very good, sir."

"If Private Overton is not here when Sergeant Hupner returns, any other man may deliver my message," continued Lieutenant Prescott. "That is all. Good afternoon, men."

The young lieutenant turned and strode from[Pg 18] the squad room.

"Somehow," mused Private Hyman, "it takes West Point to turn out a real soldier, doesn't it? No matter how good a man is, or how long he spends in learning the soldier trade, he's never quite the same unless he has the West Point brand on him."

"That's nothing to do with my affair," growled Private Dowley. "Now, Kid Overton, I'll attend to your case."

"Oh, cut it, Dowley," grumbled Private Hyman. "Get out and keep out, or we'll find a blanket and give you a little excitement. Eh, boys?"

"I'm going to polish off this kid for his insults to me," insisted Dowley sulkily.

"Bring the blanket, boys," muttered Hyman wearily.

From several of the men came a gleeful whoop as they started in various directions. It looked like business of a different sort now, and Dowley was not too blind to see it.

"Oh, all right, if you're all going to butt in to save this kid doughbaby from his just deserts. But he'll get his later on," snarled Private Dowley.

"I'm all ready now. There's no time like the present," smiled Hal.

But two of the soldiers were coming back with[Pg 19] blankets. There's not an atom of fun—for the victim—in being tossed in a blanket, so Dowley started for the door.

It banged behind him. Two minutes later it banged again, this time closing on big Private Bill Hooper.

"Birds of a feather—you all know the rest," chuckled Private Hyman, winking at some of his comrades in B Company. A general laugh answered.

"Why didn't you let Dowley have his fun?" asked Private Hal Overton good-humoredly.

"Because, Hal," replied Hyman, "Dowley is a big, ugly, dangerous man. You're spunky; you're all grit, and I don't know any kid who can handle himself as well as you do. But Dowley is in another class."

"You'll do well, after this, Hal," murmured Noll Terry, when the chums were by themselves at one end of the room, "to keep your eyes open. I shall do the same."

"Why?" Overton wanted to know.

"Well, you've made an enemy of Dowley."

"Perhaps."

"Don't treat it as lightly as that," warned Noll Terry with great earnestness. "Dowley isn't a man to forget even a fancied injury. You noticed that Bill Hooper went out soon after[Pg 20] Dowley, didn't you?"

"Yes; but what of it?"

"Hooper hates you; he has hated you for a long time, and Dowley has just learned to hate you. Now, you may be sure those two birds of a feather will flock together."

"Let 'em," laughed Hal indifferently.

"For what purpose will they flock together?" persisted Noll. "They now have a common interest in making life miserable for you."

"Just for my one remark to Dowley?" smiled Hal.

"I tell you Dowley is the kind of man who takes offense easily, and then can't make himself forget. Look there, quick!"

Noll, who had been half facing one of the end windows of the squad room, suddenly nudged Hal, then pointed.

"Do you see that pair over yonder, just going through under the trees?" queried Noll Terry dryly.

"Hooper and Dowley," nodded Hal.

"What do you suppose has brought that pair together so quickly after the scene here? They're drawn together by a common interest—in you."

"Let 'em talk about me, if they like," proposed Hal coolly.

"Do you imagine they're getting together[Pg 21] just to talk about you?" demanded Private Terry half indignantly. "Wake up, Hal; keep your eyes open, and I'll do the same. They're two, but we are two, also. If you don't go to sleep, Hal, I think we can prove ourselves equal to anything that that pair may try to do. But you don't want to forget that they are certainly plotting to do something to get you into trouble. Whatever gets you into trouble also puts a bad mark on your record as a soldier and threatens to interfere with your promotion."

"If Hooper and Dowley get busy along those lines," muttered Hal, his eyes blazing, "they'll find that they have a sure fight on their hands."

"That's the way to talk, old fellow," approved Noll Terry, his eyes shining eagerly. "And don't think I'm foolish, either, in the warning that I'm giving you."

"Thank you, Noll; I guess it will be as well to be ordinarily alert, where that pair are concerned. It never does any fellow harm to have his eyes open at all times."

Readers of the previous volume in this series, "Uncle Sam's Boys in the Ranks," will need no introduction to Privates Hal Overton and Noll Terry, of the Thirty-fourth United States Infantry, stationed at Fort Clowdry, in the lower Rockies of Colorado.

Hal and Noll were bright, typical American[Pg 22] boys when, at the age of eighteen, back in their New Jersey home town, they decided that their careers in life were to be found through enlisting in the Army.

It was in April that they enlisted, after which they were sent to a recruit rendezvous near New York City. At the recruit rendezvous the two young "rookies," as recruits are commonly termed in the service, were whipped very thoroughly into shape.

While at the recruit rendezvous the two rookies distinguished themselves by preventing the desertion of a corporal who was in arrest. For this service they were commended in orders.

On the way to their regiment in Colorado the boys were present when an attempt was made to hold up the United States mail train. An Army officer, Major Davis, of the Seventeenth Cavalry, ordered them to assist him in resisting an attack on the mail car. In the encounter that followed some of the train robbers were shot, others then surrendering to Major Davis. That same night Major Davis wired the colonel of the Thirty-fourth, speaking of the young recruits in high terms for their prompt obedience and their grit under trying circumstances. So Overton and Terry, on joining their regiment the next morning, found themselves in high favor.

Of course the young soldiers had to endure the usual amount of "hazing" when they took[Pg 23] up their new life in the squad room. But this they did with a combination of grit and good humor that soon won them the respect of the older soldiers.

Then came a period of great excitement on the post. Despite the fact that an entire battalion of the Thirty-fourth was stationed at Fort Clowdry, a gang of burglars visited the quarters of married officers on dark nights, and invariably succeeded in getting away with substantial booty.

It was young Private Overton who, when on sentry duty up in officers' row, was first to detect the burglars as they were leaving a house that they had robbed. Before the guard arrived Private Hal Overton had a spirited battle with the decamping thieves. One of them turned out to be Tip Branders, a young bully who had once lived in the home town of Hal and Noll. Branders had robbed his own mother and had drifted west, falling in with bad company. Hal and Noll then remembered a rock-strewn, distant part of the post where they had once met Tip, and there they led a squad of soldiers, under an officer. Here, after another brief but spirited battle, the escaped burglars had been caught; and here also all the booty stolen from the quarters along officers' row was recovered.

Both young soldiers had now received great[Pg 24] credit for their daring and clever work. Moreover, both had gone on rapidly in the thorough learning of their new work as soldiers of the regular Army.

And now the month of August had come around. Both young soldiers were now on the high road to efficiency and success in their strenuous new life.

Readers of the "High School Boys' Series" and the "West Point Series" will be quick to recognize another young man who has been briefly introduced in the opening of this present volume—Lieutenant Dick Prescott, a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, and just recently appointed to his regiment, the Thirty-fourth. With Lieutenant Prescott was Lieutenant Greg Holmes, who will be remembered as Prescott's close chum in the High School and West Point days.

Prescott we now find as second lieutenant of B Company; Holmes was now second lieutenant of C Company of the same battalion of the Thirty-fourth.

Both were splendid young officers, and manly to the core. In the few days that Lieutenants Prescott and Holmes had been at Fort Clowdry they had made a fine impression on the enlisted men. Soldiers are quick to judge and estimate[Pg 25] the worth of their officers.

Sergeant Hupner soon entered the squad room. The first sergeant being absent for a couple of days, Hupner was acting first sergeant. To him Hal gave Lieutenant Prescott's message.

"I'll go up to the lieutenant's quarters at once," nodded Hupner. "He's a fine young officer, isn't he?"

"Yes," agreed Private Overton. "But I haven't yet met any but mighty fine officers in the service, so the lieutenant isn't any cause of surprise to me."

Hupner was back within twenty minutes.

"Attention," he called. "Men, in the absence of the captain and first lieutenant until Wednesday, Lieutenant Prescott is company commander. He has just notified me, as acting first sergeant, to inform the men that B and C Companies march from the post on Friday for a two weeks' period of training in field duty. Every man will promptly see to it that all his field outfit is in proper order. Any man wishing further instruction or advice will apply to me at any time up to our departure."

Then Sergeant Hupner hurried forth to acquaint the men in the other squad rooms of B Company with the news.

"Field work? Hurrah!" shouted Private Terry, always eager to experience new phases[Pg 26] of the soldier's life.

"You've never been off on field work, have you?" asked Hyman dryly.

"No; that's why I'm so pleased about it," Noll answered.

"And that's the only reason," added Hyman. "Take it from me that it's a period of hard work, tedious marching, blistered feet, aching muscles and all but crumbling bones. It's nothing but a big, torturesome hike through the mountains."

"I'll enjoy it," insisted Private Terry.

"Wait," advised Hyman.

Soon after the buglers of the post were sounding first call to afternoon parade. It was not until the men were falling in ranks that Bill Hooper and the morose Dowley heard about the coming tour of field duty.

"That will be our chance," muttered Hooper to Dowley, after the men had been dismissed at the conclusion of parade. The two were again by themselves, their scheming heads together.

"I don't believe the chance will be as good off in the field as it will be here at barracks," grunted Dowley.

"That's because you haven't been in the Army long enough to know," retorted big Bill Hooper.

"Blast the Army!" snarled Dowley.

"However did you come to enlist, anyway?"[Pg 27] asked Hooper curiously.

"I had reasons of my own," replied Dowley shortly.

"Did the sheriff have anything to do with those reasons?" grinned Hooper darkly.

"Don't get too curious!" warned the other.

"Oh, I'm not nosey," laughed Hooper. "And we can't afford to quarrel. We're both pledged to getting Overton kicked out of the service."

"Are you sure that he and Terry really expect to work their way up to becoming commissioned officers?"

"I have it on the best of authority," declared Private Hooper.

"Whose?"

"Their own."

"Did they tell you so?"

"Not they! Those kids are too close-mouthed for that. At least, they didn't tell me direct, and I don't believe they've told any other enlisted men on the post. But I heard them talking it over, one day when they didn't know I was around. They expect to be made corporals before their first year is out. In three years they hope to be sergeants, and then they scheme to take the enlisted men's examination for commissions as second lieutenants."

"Lieutenants? Shave-tails?" guffawed Dowley. "Hooper, they'll never even be corporals.[Pg 28] It's a bob-tail discharge for theirs!"

Second lieutenants, when their commissions are very new, are often referred to as "shave-tails." A "bob-tail" is a dishonorable discharge, after court-martial. To a real soldier a "bob-tail" means unspeakable disgrace.

"A bob-tail for theirs—yes, sir," repeated Private Dowley. "And I'm genius enough to bring it about!"

"Perhaps you won't need my help, for you sure are some smart," suggested Bill Hooper in a tone of pretended admiration.

"I'm smart enough to see that you'd drop out and use me as the catspaw," growled Private Dowley. "None of that, Bill! You'll stand right by and do half of the dirty work in exchange for half of the satisfaction. Between us we'll give that fool Overton a new middle name, and that middle name will be 'Bob-tail'!"

FROM up the mountain road one of a little group of officers ahead sent back an informal signal.

"B Company fall in!" called out Lieutenant Dick Prescott.

"C Company fall in!" followed Lieutenant Greg Holmes.

These two young West Pointers had been left temporarily in command of the companies with which they served.

Some hundred and eighty men rose from their by no means soft seats on the ground along the trail and fell into single file.

Another hand signal came down the trail.

"B Company forward, route step, march!" commanded Lieutenant Prescott.

"C Company forward, route step, march," echoed Lieutenant Holmes a moment later.

Tortuously the line moved forward once more. To one well up in the air that long line might have looked like a thin serpent trailing its way up the mountain side. But it was a very real, human line.

Each private soldier carried rifle, bayonet, cartridge belt, intrenching tool, canteen, haversack[Pg 30] and blanket roll. It was a heavy pack. In addition, men here and there carried either a pick or a shovel.

Noll was carrying an extra shovel just now. Hal Overton had no such extra pack to-day, but all the day before he had toiled along with a pick added to the rest of his equipment.

What have soldiers to do with a pick and shovel? Theoretically these two companies now engaged on field duty were marching through a hostile country. After a battle the pick and shovel may be used for the work of burying slain comrades. Such tools are also useful in the swift digging of trenches in which to fight.

It was past the middle of the afternoon now, and the day of the week Monday. This little column was winding up the third day of its work in field.

As B Company traveled tediously along, Hal Overton was nineteenth man from the first sergeant. Noll was twentieth; directly behind Terry marched Private Hyman.

"Terry?" called Hyman in a low tone.

"Yes?" returned Noll.

"How do you like field work now?"

"Fine."

"You're a cheerful liar," growled Private Hyman.

"No, I'm not," laughed Noll. "I'm telling[Pg 31] the truth."

"You really enjoy this hike?"

"Yes; and so does Hal."

"Huh! He's a bigger liar than you are."

"What's that human calamity behind you howling about?" demanded Private Overton.

"He's intimating that the truth isn't in us because we claim to like field duty."

"Hyman always was a bake-house soldier," laughed Hal cheerily.

"What's that kid saying about me?" demanded Hyman.

"Overton says," reported Noll, not very accurately, "that he can't understand why you're in the Army at all. He says that one of your temperament could find a job in civil life that would suit you much better."

"What job is that?" asked Hyman.

"Nurse girl," grinned Terry.

"For that," threatened Hyman, "I'll put salt in that kid's coffee to-night."

The conversation was carried on in a low tone of course. Troops in the field, marching at route step, are allowed to carry on quiet conversations when not supposed to be near the enemy.

"You want to look out for Hyman, Hal," Noll passed word forward.

"Why?"

"He says you stole his bacon from his haversack this morning and he's going to set a steel trap in his haversack to-night."

"Hyman doesn't know the truth when he halts it on sentry post," Overton retorted. "Hyman hasn't had any bacon in his haversack since we started from Fort Clowdry."

"How do you know?" demanded Private Hyman, who happened to overhear this statement.

"Because I've gotten up every night and looked through your haversack for bacon," declared Private Overton unblushingly.

"I heard to-day why you joined the Army," grunted Hyman.

"Yes?" grinned Hal.

"Sure! You had some trouble with the sheriff at home over stealing the flowers from the cemetery and selling them to get cigarette money. You're a nice one, Overton, to be entrusted with government property!"

"Oh, come, now, Hyman," Hal laughed back. "That wasn't so bad as your case. You enlisted because the judge said you'd either have to go to jail for robbing the Salvation Army's Christmas boxes, or else turn soldier."

Half a dozen men in the long line were laughing now.

"I'll fix you for that when you're asleep to-night,"[Pg 33] growled Hyman.

"Yes; I notice you never do anything to a fellow when he's awake," jeered Private Hal.

The two men were not on bad terms, nor in any danger of becoming so. This was merely an instance of the way soldiers "josh" one another.

The sun was now disappearing behind the western hill tops. It would be daylight, however, for more than two hours to come.

Fifty minutes after this last start Lieutenant Prescott again received a hand signal from the officers on ahead.

"B Company halt; fall out," ordered the young West Pointer.

Holmes repeated the command to C Company.

The head of the line had halted near a grove through which a brook bubbled along on its way to the stream down in the canyon to the right of the trail.

"The officers are going to inspect the grove as a site for camp," was the word that passed back along the line.

"A soldier's first duty," quoth Hal, as he sank upon the ground, "is to make himself as comfortable as he can."

Noll, too, dropped to the ground, and Hyman followed the example.

"Overton, I'll have to borrow some of that[Pg 34] baby powder of yours to-night," sighed Hyman.

"For your complexion?" grinned Hal.

"No; to put in my shoes. This mountain hike has my feet in bad."

"I'll tell you what you ought to do, just before every big hike," laughed Hal.

"Don't tell me anything about the hospital," murmured Hyman disgustedly. "I tried that, day before we left Fort Clowdry, but the rainmaker warned me that if I tried to make hospital report, he'd see to it that I was left on thin gruel diet for a month."

"The rainmaker knew his business," mocked Hal. "And I've heard another yarn about that rainmaker."

"What?"

"After a malingerer gets his thin gruel down the rainmaker gives him a stiff dose of syrup of ipecac, and the gruel comes up again."

"There's no show for a man in the Army nowadays," sighed Hyman, who, with all his pretense at "kicking," was a keen soldier and dependable man.

In every regiment are some soldiers who would shirk every arduous duty if it were possible. The favorite device, with such men, is to turn malingerer—that is, to pretend illness and gain admission to hospital, which means a solid rest while comrades are working hard. But the successes[Pg 35] of malingerers in the way of shirking have made Army surgeons keener, also. Lucky is the suspected malingerer who doesn't get put on thin diet and fed nauseating medicines.

From the group of officers ahead on the trail came Captain Freeman and First Lieutenant Ray of C Company.

"Mr. Holmes," called Captain Freeman, "let C Company fall in and take up the march again."

Young Lieutenant Holmes instantly gave the order to fall in. A moment later C Company moved off at the route step.

"What does that mean?" Hal asked Hyman.

"Oh, some new scheme that the officers have hatched up," replied Hyman. "There'll probably be a sham engagement on between C and our company to-morrow."

"We're lucky if it doesn't take place in the night," grunted another soldier.

"Well, my man, suppose it does?" demanded Sergeant Hupner, appearing behind the "kicker." "What do you suppose these manœuvres are for? They're to teach you the soldier's trade. They're to fit you so that, in actual war, you'll know what to do under any given conditions. The better you know your trade, in war, the better chances you have to come out of the war alive. This field duty, which[Pg 36] so many of you dislike, is for the training of every officer and man in the very things he does in war time. The better every officer and man understands them the better is each fellow's chance of keeping alive in war time. Those of you who grumble ought to be ashamed of yourselves. Look around you at some of the older soldiers who've seen service, and you'll find they never kick."

"B Company fall in!" rang the order, this time from Captain Cortland.

But the march was to be a short one. The command was led into the grove and halted. The order to pitch camp was given. Now a lively scene followed.

As the outer covering of his blanket roll each soldier carries a flap of canvas, which constitutes one half of a shelter tent, as it is officially termed. The soldier's name for it is dog tent or pup house. Each man also carries two jointed sticks. One pair of sticks is jointed to form the front pole of the tent, the other the rear pole. In front of the tent site a peg is driven, and a cord passed from this peg up over the front pole, across to the rear pole, and down to a peg at the rear. Now the two flaps of canvas are fitted over this frame and the tent is up.

"Let's beat the company to it, Noll?" breathed Hal in his bunkie's ear. In the Army[Pg 37] the "bunkie" is the man with whom the tent is shared. Usually two bunkies become close chums, even if they were not before joining the service.

"We've done it," breathed Hal, as he and Noll straightened up and gazed about them. "That takes the crimp out of a few veterans."

"Get a hike on, some of you men!" called First Sergeant Gray briskly. Then he turned to glare mildly at Hooper and Dowley, who were finishing last.

Corporal Cotter, his own tent up with Corporal Reynolds, turned to look down the company street.

"Hooper, you and Dowley are going to hear something," predicted the corporal dryly.

"That's done well enough," grumbled Dowley, glancing at his tent.

Captain Cortland stood at the head of the company street glancing down.

"One tent forward out of alignment," called the company commander, then stepped down the street. "Who are the men that occupy this tent?" he demanded, halting.

"My tent, sir," mumbled Hooper.

"And mine, sir," added Dowley.

"Don't you men know how to erect a tent in alignment with the street front?" inquired Captain Cortland. "Take it down. Corporal Cotter,[Pg 38] stand by to see that these men set up their tent in soldierly fashion."

"I told you you'd hear something," remarked Cotter.

"Aw, what's the use of being so finicky about a tent a quarter of an inch out of alignment?" grumbled Hooper.

"The tent is more than that out of alignment," returned the corporal. "And there's every use in the world in performing every duty in the most soldierly fashion."

"Say," began Dowley argumentatively.

"Silence, and get on with your work," ordered Corporal Cotter sharply. "Hooper, you're close to thirty-five years old. Dowley, you're around thirty. Yet those two kids, Overton and Terry, are only eighteen, and they beat you at every point in soldierliness."

"Soldiering is a kid's game," growled Dowley.

"The best men we get in the Army are those we catch young," retorted Corporal Cotter. "Stop! Tighten that cord a whole lot more." "How does that suit you, Corp?" demanded Dowley when, at last, the sulky bunkies had again finished their task.

"Address me as Corporal, not Corp," returned Cotter stiffly.

"Well, Corporal, how do you like the set of[Pg 39] our tent now?" insisted Private Dowley.

"It looks better this time," assented the corporal. "But, after this, you men, instead of sneering at the kids of the company, will do well to show yourselves as good men."

"We're always getting the kids rubbed into us," growled Hooper.

"Because they're head and shoulders over you both as soldiers," rejoined Corporal Cotter, turning on his heel. "Even William Green is a lot ahead of you as a soldier."

As Dowley turned to glance scowlingly up the street he caught the glance of Captain Cortland, glancing once more down the street.

"Your tent is in proper alignment this time, men," nodded the company commander, and went away.

Now the creaking of heavy wagons was heard along the trail, accompanied by the loud voices of the drivers. The expedition was accompanied by six heavy wagons, each drawn by four mules.

"Water in the brook; wood two hundred yards southeast!" shouted Lieutenant Prescott, who had been sent scouting for these necessities. On pitching camp the first task is always to learn where wood and the best drinking water can be found in the neighborhood. Often the water close at hand is forbidden for cooking and drinking purposes in favor of clear water at[Pg 40] a distance.

Three of the approaching wagons continued along the trail, while the other three turned in at the side of the grove.

Corporal Reynolds and four men were detailed to unload and put up the eight-by-ten khaki-colored tent that was to be occupied by the three company officers.

"I notice that the wide stripes don't care about sleeping in pup-houses," grumbled Hooper to his bunkie.

"Wide-stripe" is the nick-name sometimes given an officer on account of the fact that the side stripe down the trousers' leg of the blue uniform is much broader than that worn by the non-commissioned officer. Privates wear no stripes on the trousers' leg, with the exception of musicians, who wear two very narrow parallel stripes.

Soon after the erection of the little village of tents, the soldiers scattered, though they soon returned with bundles of fire wood.

"You had better go and chase the stuff for our fire, Bill," proposed Dowley.

"Chase it yourself," retorted Hooper.

"Not this trip," retorted Dowley. "It's up to you this time."

Hooper swore that he wouldn't, but it ended by his starting tardily after fagots. Dowley[Pg 41] was already gaining the ascendancy over Private Bill and making a half servant of him.

Presently some forty fires were blazing brightly in an irregular line at a distance of some yards from the line of dog-tents. American soldiers were preparing their evening meal in the field. The operation was an extremely simple one. First, each soldier dropped a handful of coffee beans into his agate drinking cup. With the butt of the bayonet he crushed these beans, the fineness depending upon his skill. Then from the canteen each man poured water enough nearly to fill the cup, which was then set on the fire for boiling.

By the time that the coffee had boiled for a few minutes each soldier returned his cup to the ground beside him. A dash of cold water from his canteen was sufficient to "settle" the coffee.

Now, each man placed two or three strips of bacon in his frying pan and laid it on the coals. While these morsels were sizzling the soldier turned his attention to sweetening his coffee. Then, when the bacon was cooked to his satisfaction, each man brought out his field hard tack, munching alternately on biscuit and meat.

"Yesterday was Sunday, and we had raised biscuits, roast beef and potatoes, with real gravy," grunted Dowley. "If a stingy government[Pg 42] would give us more wagons we could have that every day."

"In war time," broke in Sergeant Hupner, "you might feel lucky if you saw the Army oven working once in a month. I've been there, and I've had to live for weeks on bacon, hard tack and coffee. Sometimes we didn't have the coffee or the bacon, either."

"That's a dog's life," grumbled Dowley.

"No; it's a man's life, at need, but only a man can stand it in the field," returned the sergeant gravely.

After supper many of the men smoked, but Hal and Noll, as they did not indulge in the weed, strolled down toward the trail.

"Isn't this great?" breathed Hal Overton, staring off over the distant mountain tops. "The field duty, I mean."

"It's great, and I wouldn't have missed it for anything," agreed Noll. "But it would do no good to try to tell anything of the sort to fellows like Hooper and Dowley."

"They're bad eggs," muttered Hal. "I wonder how such men ever got past with their references and managed to be accepted for the service."

"It is queer," nodded Noll. "But neither will stay in the service beyond the first enlistment."

"Yet they conduct themselves just well[Pg 43] enough to escape any real censure from the company officers."

First Sergeant Gray was now moving through the camp, notifying the men who were chosen for guard duty that night. But neither Hal nor Noll were warned for detail that night.

Not long after dark tattoo was sounded by one of the buglers. Fifteen minutes later taps sounded, and all but the guard turned in in their dog-tents.

Each soldier is provided with a warm blanket and a rubber poncho, which is a blanket with a slit in the middle so that the head may be thrust through and the poncho worn, at need, as a rain coat. But to-night Noll Terry spread his poncho on the ground, Hal laying his a-top. Then both young soldiers lay down, drawing up their combined stock of blankets over them, for the early night had turned out chilly.

"Rest enough, now, for to-morrow's hike," mumbled Hal drowsily.

"Yes; unless we're turned out to meet a night surprise," returned Noll dryly.

In another part of the camp Hooper and Dowley, both warned for the guard, but not yet on post, were whispering by themselves.

"To-morrow Kid Overton begins to get his," chuckled Hooper.

"Yes; he'll begin to see those corporal's chevrons fading in the distance."

"We ought to fix Terry with him."

"One at a time; that'll be surer," scowled Private Dowley.

Hal and Noll slept the night through. Hal dreamed he was chasing an elusive rascal, who performed wretchedly on the cornet. As the rascal fled he continued to play on the cornet.

Then young Private Overton opened his eyes. The cornet player turned out to be the bugler, who was blowing lustily, twice through, the first call to reveille. Hal sprang up from his blankets. After he had crawled out of the pup-house, Noll joined him.

Wood and water were quickly brought. The field breakfast was like the field supper of the night before. Then the bugler got busy without delay. The men fell in and roll-call was read. Immediately Captain Cortland's crisp voice gave the orders that opened up the ranks. An unexpected inspection was on.

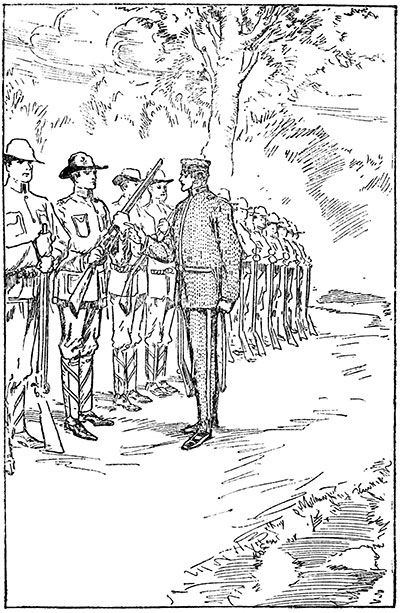

Lieutenant Hamilton stepped before the first platoon, Lieutenant Prescott before the second. Inspection of pieces was on.

Hal and Noll stood in the second platoon, about half way down the line.

Noll held his piece at port arms as soon as Lieutenant Prescott reached the man before him. By the time that the young West Pointer halted[Pg 45] before Noll, Hal, as the next man, threw his rifle over to port arms.

The inspection of Noll's rifle proved satisfactory. Then the lieutenant halted before Overton.

"Open your magazine," commanded Lieutenant Prescott.

Hal obeyed.

"Draw your bolt."

Hal did so, after a hard tug, holding the bolt in his hand.

"Let me look at that bolt," ordered Prescott, gazing at the piece of steel mechanism in astonishment. He took it from the young soldier's hand and looked thunderstruck.

"Don't replace your bolt until ordered, Private Overton. Fall out to the rear."

Overwhelmed with amazement, his face flushing hotly with shame, Private Hal Overton gave his officer the rifle salute, then obeyed.

Noll Terry's face went white with anxiety over his bunkie's misfortune.

When inspection had been completed, Lieutenant Prescott made his report to Captain Cortland, who immediately followed his young second lieutenant to where Hal stood.

"What's this, Overton?" asked the captain coldly. "I thought you were one of our model young soldiers. Why, your rifle-bolt must have[Pg 46] been in the fire. The end is out of shape, the temper is drawn—and here are file-marks on the bolt. It's unserviceable. I don't believe you could fire the piece."

"I'm afraid not, sir," Hal admitted.

"Load with a blank cartridge, my man, and try to fire the piece."

Returning the bolt, Hal slipped in a blank. But he could not drive the bolt home for firing.

"Ruined, my man," commented the captain stiffly. "Overton, this piece has been in your care. How did this happen?"

"I don't know, sir."

"Corporal Cotter!"

The corporal came over briskly.

"Corporal, Private Overton is in arrest until released. You will march him as a prisoner at the rear of the company and turn him over to the guard at night."

Corporal Cotter again saluted. Then, as the company officer and the young lieutenant started away, Cotter stationed himself beside Overton.

"Put your bolt back in the piece as far as it will go," ordered Cotter. "Tie it in place."

The men in ranks ahead had heard enough to realize that Private Hal Overton was in disgrace, and most of them were sorry.

Noll Terry was more than sorry.

THE company broke ranks under orders to strike camp at once.

Within six minutes the camp was down. Every enlisted man had his blanket roll made up and in place, and all his other equipment on.

Corporal Cotter stood over Hal even while he was making up his roll.

"How on earth did that thing happen?" murmured Noll wretchedly.

"Silence; no talking with the prisoner," rebuked Corporal Cotter crisply.

So Noll held his peace, though he was "boiling" inside.

Again the company was assembled.

"Fours right, march! By file, march!"

B Company again struck the trail, heading further up into the mountains, leaving the wagons to follow presently. Though B Company was now likely to be attacked at any time in sham battle, by C Company, it had been agreed that the respective wagon trains of the companies were to be immune from capture on this day.

"Overton, keep a distance of ten paces from[Pg 48] the rear man of the company, and march before me," commanded Cotter. "Keep the step carefully until the order for route step comes."

Never in his life had Hal Overton felt as heart-sick as he did now.

Marching to the rear, a prisoner!

It was, in every sense, as bad as being in the guard-house.

Up ahead in the line things were "doing," but to this Hal, in his new misery, was all but blind.

Sergeant Hupner, with six men, had been sent ahead as a "point" to discover any possible enemy who might be lurking in the way of the forward progress of B Company.

Scouts had been sent out on either flank. The line moved slowly, as though fearing the presence of an actual enemy. There were frequent halts. At one time, while the line waited, Lieutenant Prescott took a detachment of twelve men to explore the country ahead. When he returned, reporting no enemy developed, B Company moved forward, though never without point and flankers.

At noon B Company, still having stirred up no enemy, halted for dinner.

Captain Cortland and his two young officers got through their meal with soldierly despatch. Then the company commander called to Sergeant[Pg 49] Gray, who reported, saluting.

"Sergeant, direct Corporal Cotter to bring his prisoner here."

Seated on a small boulder, the captain eyed young Overton keenly as the latter was brought up.

"Private Overton," began Cortland, "have you yet discovered, or really suspected, how your rifle bolt came to be in such bad shape?"

"No, sir," replied Hal, again saluting.

"At first glance it looked like a case of sheer neglect on your part to care for your piece."

"Yes, sir."

"But those file marks?"

"I can't explain them, sir."

"It is forbidden for any man to use a file on the parts of his rifle, except by direct permission from one of the company officers."

"I know it, sir."

"Have you had any such permission?"

"No, sir."

"Have you a file?"

"Not a real one, sir. Only a manicure file."

"Let me see it."

Hal turned over the file, after finding it in his haversack.

"Now, let me have the bolt from your rifle."

Captain Cortland tried the file lightly in some of the nicks in the bolt. Then he passed file and[Pg 50] bolt over to Lieutenant Hampton.

"Mr. Hampton, don't these nicks seem to fit this file remarkably well?" queried the company commander.

"They appear to—very well, sir," replied Lieutenant Hampton, testing the file in the nicks.

"What do you say, Mr. Prescott?"

The young second lieutenant studied file and bolt attentively.

"I am obliged to agree, Captain, with yourself and Mr. Hampton."

"Private Overton, think again. Do you still care to deny that you employed the file on the bolt of your rifle?"

"I deny it, sir, with all the emphasis of which I am capable," was Hal's earnest retort. His face was flushed, his breath came quickly, but he looked straight and honestly into his commander's eyes. There was no cringing in his attitude. His high color was to be attributed only to the humiliation of the position in which he found himself.

"And this bolt has been in the fire," continued Captain Cortland. "Just such a fire, let us say, as you build three times a day for the preparation of your food. The temper of the end of the bolt is ruined."

"Yes, sir. May I speak, Captain?"

"Go on, Overton."

"Captain Cortland, I am aware how badly this looks for me. But I assure you, sir, on my honor as a soldier, that I have no guilty or other knowledge of how the bolt came to be in this fearful condition. I am entirely innocent, sir, of any act that could have put the bolt in such condition."

"You are not guilty even of negligence, Overton?"

"Not of any intentional negligence, sir."

"Then, Overton, you must have some sort of suspicion of how this thing happened."

"I have a suspicion, Captain, but it is not founded on anything that is yet very tangible, sir."

"You think it an enemy's work?"

"Yes, sir. None but an enemy could do such a thing as this to a comrade's rifle."

"Granted, but who is the enemy?"

"May I be excused, sir, from answering?" asked Private Overton very respectfully.

"Why?"

"Because it is quite possible that, in naming an enemy, I may do some honest soldier an injury."

"You need not answer, then, Overton. Wait here."

Captain Cortland stepped down from the small boulder on which he had been seated. At a sign[Pg 52] from him Lieutenant Hampton walked away with the company commander. The two remained for some moments in low conversation.

"Overton!" summoned Captain Cortland, returning.

Hal saluted.

"This affair looks badly for you, and I want it to be a lesson to you hereafter. You have had an excellent record, Overton, since you joined the regiment. For this time I am going to take your word that you are ignorant of how the accident to your rifle bolt happened. So you are now released from arrest, and will rejoin your company. If you suspect that any comrade is guilty of this outrage on your bolt, I recommend that you keep your eyes open for any further attempts against your record. Corporal Cotter, you will not repeat what has been said here. Overton, you are released from arrest. Corporal, report yourself to the first sergeant as being on regular duty again."

Corporal and private sainted, then turned back to the company.

"You got off easily," murmured Noll, when his bunkie, with face white and eyes flashing, joined him.

"That's because Captain Cortland decided to take my word for my innocence in the matter,"[Pg 53] Hal replied cautiously.

"Now, see here, old fellow, you've got to be up and doing," urged Noll earnestly in a whisper.

"What can I do, now?" Hal asked.

"Keep your eyes peeled. You can find out, by and by, who was responsible for that low trick. Hal, you'll have to make vengeance your watchword."

"Revenge is sweet," mimicked Hal dryly.

"It surely is—sometimes."

"But sweet things make one sick at his stomach," Hal uttered dryly.

"Well, if you're going to stand for having a job like that put over on you," uttered Noll disgustedly, "I'm not! The fellow who did that trick to you isn't fit to be in the service, and I'm going to get him out of it, whether you help or not."

Separated from the young soldiers by only a thin ledge of rock, eavesdropping Hooper and Dowley heard, and gazed keenly at each other.

"We've got to frame things up for young Terry, too, then!" whispered Bill Hooper, as the sulky pair stole away.

"CAN you see the enemy, Overton?"

"I can't see a thing, Corporal."

"Move forward cautiously. Don't make a sound. If you do you'll betray our position."

"How far shall I go, Corporal?"

"Move ahead until you run into signs of the enemy. Above all, bear in mind that you mustn't betray our presence to the enemy."

Private Hal Overton gripped his rifle tightly in the darkness as he all but wriggled forward over the ground.

It was all very real business to the soldiers engaged in this mimic warfare. If nothing more serious happened, any big mistake on the part of a soldier in this sham warfare would bring upon him the displeasure of his officers.

Late that same afternoon B Company had been attacked by lurking C Company. Some very clever manœuvring of the men under cover bad been done, and a good deal of blank ammunition had been fired. True, there had been no real casualties, but, under the rules of the game, B Company had made such a spirited and excellent defense that C Company had been[Pg 55] driven further back.

Now the position of C Company was unknown, but the "enemy" was believed to be lurking in the vicinity, bent upon a night surprise.

Two thirds of B Company slept back in the camp of pup-houses. The other third, under command of Lieutenant Prescott, was divided up among sentries, outposts and scouts.

To Corporal Cotter had been entrusted the problem of taking a scouting party consisting of three privates and trying to locate either the enemy's outpost or the main body.

Just a moment before Hal's orders to prowl forward a sound had been heard, evidently about four hundred yards ahead.

So now Hal stole forward, moving as softly as any cat could have done, this despite the fact that his advance must be over jagged rocks here and there.

The ground was ideal for ambush fighting.

Hal now had a new rifle, that had been issued to him when the wagons of B Company came up late that night. The damaged piece was now in the wagon, and Hal bore a rifle on whose efficient action he could depend.

"It's almost a mockery to have a gun, though, just now," Hal smiled grimly as he lifted the piece over a ledge of rock and followed.

"Wouldn't I get a clever roasting from Captain Cortland if I dared to fire it while scouting."

Now Private Overton came to an open space where he could walk more easily. He did not hasten, however, for there was no telling when, in the darkness, he might step on a stone and send it rolling, with a resulting racket that would warn the enemy, if any of them were within hearing.

Every step had to be taken as though the troops were in the midst of life and death war. The rules of the game were strict, and any bit of bad judgment was likely to count against the score of the company to which the man belonged.

Every now and then the sham young scout halted, peering backward, for it was going to be of prime importance to him to know how to get back when his scouting trip was done.

"Halt! Who's there?"

Overton did halt, flattening himself down against the rock.

The hail, though softly spoken, had been unmistakable.

"Halt! Who's there?"

"You'll have to come here and find out," thought Overton.

Then, as silence followed, Hal, holding his very breath, crawled some ten yards to the left. Again he halted, but this time there was no[Pg 57] faintly spoken challenge.

"I think I know where that fellow is," mused Hal. "Is he a lone sentry, or part of an outpost?"

It required fifteen minutes now of the most cautious procedure, but Private Overton at last found himself hugging the ground at a point from which he could just barely discern the dimly defined figure of an alert sentry against the skyline.

"I've got him between our camp and myself now," thought Hal swiftly. "Now I've got to be doubly careful. I don't care to have B Company laughing at me because I got captured while on scouting duty. But I'll settle the question of whether that sentry is alone, or part of an outpost."

Three minutes later, after some most careful manœuvring, Overton had solved the question. His grinning face was turned toward a corporal and two men who lay rolled in their blankets some ten yards behind the sentry.

"It's an outpost, all right," grinned Hal. "Whee! How I would like to bag the outpost and take them in as prisoners."

But that was out of the question—not to be thought of.

Private Hal Overton found himself seized by a spirit of mischief. It was the same type of[Pg 58] impulse which, carried to the point of reckless daring in real warfare, leads men on to swift promotion.

Almost before he realized what he was doing Hal had hidden his own rifle and was crawling stealthily toward the sleeping men.

Beside the corporal lay his rifle. Barely breathing, his body flattened against the ground. Hal crept closer and closer, then stealthily withdrew the rifle.

A moment or two later Hal had the captured rifle lying on the ground beside his own.

"That's a real find to take back to camp," laughed Hal silently.

He was about to make off with the captured piece when a new impulse seized him.

"Why not go back after more loot?" he asked himself, grinning. "Jupiter, I'll do it!"

Every such move as this was fraught with added danger. But Hal moved on his stomach, taking plenty of time, always with his watchful eyes on the dim figure of the sentry a few yards away. That soldier, however, appeared to be peering mostly in the direction where he believed the camp of B Company to lie.

After a short time Hal, back in safety again, gloated over the sight of three rifles beside his own.

"I'll be a hog, if I don't look out!" chuckled[Pg 59] the young scout of sham warfare.

Yet, though this was no life and death fighting, Private Overton had nevertheless a good deal at stake. It would result in his being set down as a rather stupid soldier should he be captured by the enemy's outpost while on scouting duty.

"I can't help it. I've got to have one more try, anyway," decided the mischievous soldier boy.

So back he crept. An instant later he tried to make himself flatter against the earth than he had been able yet to do.

For that sentry had now turned and was looking in his direction.

"I commit myself to the darkness," gasped Private Overton inwardly.

For, if his presence were detected, the sentry, with one call, could bring the other three sleeping men to their feet. Against such odds Hal would have but scant chance of getting away.

"And I'll have to leave my rifle behind if I duck from here," thought Hal, beginning to regret his rashness.

It was one thing to capture the rifles of the outpost; it was quite another thing to leave his own gun behind in their hands.

After a few moments of agony the dimly seen[Pg 60] sentry again turned his face in another direction.

"Now that I've started this trick, I'll put it through or die," thought the soldier boy, setting his teeth.

Again he crouched close to the corporal and the two other sleepers. This time there appeared to be no loot loose save a pair of canteens that lay upon the ground. Private Hal Overton made sure of these articles, then, as he lay there, took a last sweeping look.

The shoes of Corporal Raynes, of C Company, protruded under the foot of his blanket.

"I guess it would be too risky a stunt to try to unlace the corporal's shoes and carry 'em away," quivered mischievous Hal, eyeing the footgear longingly.

Then, as he gazed, it struck the soldier boy that there was something odd about the position of the corporal's shoes with regard to the line of Raynes body.

"I wonder if——" cogitated Private Overton, edging himself forward.

Hal made a cautious try.

His last guess proved to be correct. Corporal Raynes had taken off his shoes to ease his aching feet, and had tucked them in at the bottom of his blanket.

"It's a shabby trick to play on a good fellow," grinned the soldier boy, "but this is[Pg 61] war."

For the last time Hal crept back. Now an even greater task confronted him, and that was how to get away with all the outpost loot he had captured.

By making three stealthy trips, Private Overton at last succeeded in getting all the loot in safety to a point more than one hundred yards from the outpost.

"Now, it's time to drop nonsense for real business," decided the young scout.

Ten minutes later he had located the main camp, and that without falling into the hands of either of the two C Company sentries whom he was compelled to pass in the black night.

Then back to the hidden loot the young soldier returned.

"Whew, but that's going to be a pack!" muttered Hal, gazing at it almost ruefully. "However, I've got to take it. I won't leave a blessed thing behind."

The canteens Overton threw over his shoulders, so that he had one on each side, in addition to his own, which hung at his left hip. The corporal's shoes he tied to his belt. It was the bunching of the four service rifles, with their weight of more than forty pounds, that gave him his real trouble. But at last he had the[Pg 62] four pieces lashed together and started.

"I've yet got to look out that I don't run into any scouts of the enemy," thought the soldier boy half ruefully. "Whew, what a break it would be to be picked up with all this loot!"

It was a welcome sound indeed when, at last, the young scout heard, near the spot where he had left his own party, the almost whispered challenge:

"Halt! Who's there?"

"Friend," responded Hal Overton in a tone no louder.

"Halt where you are, friend, until a sentry advances to recognize you," returned cautious Corporal Cotter.

It was the corporal himself who came forward.

"Great Scott, Overton, what have you——"

"It's loot," returned Hal proudly.

"Where on earth did you——"

"From the enemy's outpost. And I located the camp, too. I could guide you right to either outpost or main camp. Will you take these guns, Corporal? My back feels broken."

"I should think it might," was Cotter's grinning response, as he reached out and took the lashed rifles. "Great Scott! What won't the lieutenant and Captain Cortland say!"

Just as they stepped softly back, Private Noll Terry challenged someone approaching softly[Pg 63] from the rear.

"Halt! Who's there?"

"Officer of the day," returned Lieutenant Prescott's low voice.

"Advance, officer of the day, to be recognized."

Lieutenant Prescott advanced into the group.

"Do you see all this stuff, Lieutenant?" asked Corporal Cotter, calling attention to Hal's loot as it lay on the ground. "Overton went forward as a scout, and located one of the enemy's outposts, also the main camp. And he brought back these souvenirs of the outpost."

"To whom do the shoes belong?" questioned Lieutenant Prescott after looking at the stuff.

"To Corporal Raynes, sir, in command of the outpost," returned the soldier boy, with a grin.

"How did you get hold of all this stuff, Overton?"

Hal told his story briefly.

"Great Scott! Bombshells and grenades, what a roaring joke on the enemy! Overton, you're a man worth having in B Company. Dark as the night is, your exploit would reflect credit on a trained Indian scout. Overton, I'm going to take you back to camp with me. I'll wake Captain Cortland to hear your report as[Pg 64] to the enemy's position. And the captain will surely want to see this loot of the outpost and to hear your tale of how you got it. Here, let me have a couple of those rifles to carry for you."

Lieutenant Prescott led the way hack to B Company's camp. And he shook with laughter all the way.

CAPTAIN Cortland heard the young scout's report without losing his gravity, though he decided against trying a night attack on the enemy beyond.

"Overton," he commented, "if you can do things like to-night's work very often there will be no doubt whatever that you have in you the making of a real genius for scouting. I commend you most heartily for this work."

It was only when he went back to his tent to lie down that Captain Cortland gave way to silent laughter.

At daybreak the camp was astir. The men who had been on guard duty and scouting through the night came in, somewhat heavy-eyed, after a relief had been marched out to take their places.

These returned soldiers, as soon as they had breakfasted, threw themselves on the ground, under such shade as they could find, and took an hour of solid sleep.

"The wagon train is approaching, sir," reported Sergeant Gray.

"Then pass the order for the men to report at the train and draw rations to last until to-morrow[Pg 66] night," directed Captain Cortland. "After to-morrow night the two companies will be together again for the balance of the field work."

Lieutenant Prescott was acting as commissary officer for B Company, and he went immediately to the trail. Captain Cortland, stepping into his tent, buckled on his sword and then sauntered down to the wagon train to see that all went smoothly.

As he reached the spot where the soldiers of B Company were drawing their rations, Captain Cortland caught sight of a corporal perched on the seat beside the driver of one of the wagons.

"You here, Corporal Haynes?" demanded Captain Cortland, striving hard to preserve his official gravity.

Grinning sheepishly, Corporal Haynes—in his stocking feet—sprang down into the trail and saluted.

"Yes, sir," he admitted.

"Ill?"

"No, sir."

"Were you captured, then?"

"No, sir," answered Haynes, the sheepish look in his face increasing. "But I'm a non-combatant, sir; ruled out of the manœuvres and ordered to stay with the wagon train, sir."

"How did that happen?" inquired the captain,[Pg 67] though he was able to make a very good guess.

"While I was on outpost during the night, sir, my shoes were taken from me. I suspect, sir, that one of your scouts got 'em."

"But we have quartermaster's supplies along. Why didn't you draw a new pair of shoes this morning?"

"No shoes of my size, sir, in the supplies," reported Raynes, once more saluting. "So Captain Freeman told me that I certainly couldn't fight in my stocking feet. Therefore, sir, he ordered me to join the wagon train and respect all the obligations of a non-combatant."

"Too bad, too bad, Corporal, for you are a valuable man," went on Captain Cortland.

"I don't feel like one this morning, sir, after having my shoes taken," grinned the C Company corporal in embarrassment.

"Well, since you've been ordered among the non-combatants," continued Cortland, after turning slightly and espying the grinning face of Private Hal Overton, "I think the scout who captured your shoes may as well return them. But hold on. I see two other men of your company on the wagons."

Again Corporal Raynes grinned sheepishly.

"Yes, sir! they had their rifles taken, and so are no longer combatants in a military sense.[Pg 68] My rifle is missing also, sir."

"My, my, my!" murmured Captain Cortland in a tone of mock commiseration. "Then the scout who plundered you all may as well return all the property. But of course, Corporal, you and the two other men will continue to be non-combatants as long as the sham fighting lasts."

"Those are Captain Freeman's orders, sir."

Again Captain Cortland turned toward Hal Overton, nodding a signal. Hal stepped away briskly, but came back bearing the pair of shoes, the rifles and the canteens.

"Private Overton is the scout who entered your lines alone and brought about the discomfiture of C Company," Captain Cortland announced, smilingly.

The captain walked away while Corporal Raynes, sitting on the ground, drew on his shoes and laced them, while a lot of B Company's men stood about and grinned over his discomfiture.

"Corporal, you're sure good sleepers over in C Company," laughed Private Hyman. "You fellows want to look out that, some night, you don't get taken in by a lot of amateur hunters from New York."

"Great guns, what's going to happen to the regular Army, when it's getting so that a whole company of infantry can't guard its own property?"[Pg 69] another B Company man wanted to know.

Corporal Raynes and his two comrades had to stand a lot of good-natured joshing from the crowding men of B Company.

When he stood up, Raynes turned to Hal Overton.

"Rookie," he growled, "you want to look out hard in the future. I'll pay you back for this in kind. Just remember, kid, that Corporal Raynes wasn't born yesterday!"

Hal laughed good-humoredly. He didn't know, at that moment, that not many hours would pass ere Corporal Raynes would find his opportunity.

Twenty minutes after the wagon train had pulled out, B Company started cautiously through the country ahead. It was B Company's task to advance through a supposedly hostile country; C Company's part in the under-taking was either to annihilate B, or to capture the company.

It was ten o'clock that morning ere B and C came in touch. The point and scouting squad ran into one platoon of C.

"Deploy your men and take cover," ordered Lieutenant Prescott, who was in charge of the advance. "Each corporal regulate the firing of his squad. Jam the fire in hard whenever[Pg 70] you are sure you locate the enemy."

Bang! Bang! Bang! As fast as the squads reached their places on the line, each man some nine feet from his nearest fellows, the firing of blank ammunition ripped out fast and hard. There was all the excitement of actual warfare, except that no soldier was actually hit.

B Company's men would have been driven back had not Lieutenant Hampton swiftly arrived on the scene with the entire first platoon of B Company.

"We'll advance by rushes, Mr. Prescott," announced Lieutenant Hampton as soon as he reached the younger officer, who saluted.

Prescott hastened, crouching low, down along the left wing of the little command.

Presently Hampton's voice rose, even over the firing as it ran low, and called:

"Rise! Charge!"

Uttering their battle yell, the little force of infantry rushed forward in its thin line, while the hidden men of C Company poured in a heavy fire.

"Halt! Lie down!" shouted Lieutenant Hampton. "Ready, load, aim!"

There came a brief pause, followed by the order:

"Fire!"

A single volley crashed out, with such unanimity[Pg 71] that it sounded as though one big piece had been fired.

"Ready! Open magazines! Load magazines! At will, commence firing!"

Fifteen rounds had been fired ere the bugler sounded furiously the order:

"Cease firing!"

The rush of feet sounded behind. Lieutenant Prescott rushed to the rear, but soon waved his sword reassuringly. It was the balance of B Company advancing on the run.

Captain Cortland now took command in person. He ordered another rush forward toward C Company's position.

Three volleys were fired after the rush. The fire was not answered. A cautious advance developed the fact that the force of C Company men had retired, nor could the line of their flight be discovered. B Company halted for a few moments, that the men might clean their sooty rifle chambers.

"We didn't really see the enemy," Hal remarked, as he worked his cleaning rod and a bit of waste through his gun barrel.

"In warfare nowadays you rarely do see the enemy," remarked Sergeant Hupner. "Attacking an enemy's position, nowadays, is a good deal like taking a gun and going into a dark room where some one is shooting at you. You can't[Pg 72] see the other fellow, but you have a mighty uncomfortable notion that he sees you and is shooting straight at you."

"Pleasant, when the game is real war," laughed Noll.

"Deadly, of course," commented Hupner.

Once again, late in the afternoon, C Company endeavored to ambush B Company. Captain Cortland's point and flankers, however, developed the enemy's position by drawing their fire. B Company, after a brisk fight of twenty minutes' duration, drove C Company back and continued to advance.

Despite the fact that no one had been really killed or wounded, most of the soldiers, who were serving their first enlistment, now found the game a wholly exciting one. When B Company halted, after the second engagement, the men fell into an eager discussion of the late engagement, the sergeants and other older men adding many comments out of their experiences in actual fighting.

"It leaves only real war to be desired," declared Hal, his cheeks glowing and his eyes snapping.

"Huh! If this was real war there'd be a lot of kids of the talky kind ducking to get away," growled Private Dowley as he slouched by.

"It isn't the kid soldiers who do the deserting[Pg 73] in war time," returned Sergeant Hupner quietly. "It's usually some of the older men, who have such a grouch with life that one wouldn't think they'd care about living much longer."

Dowley scowled, muttering something, but he did not venture to dispute with a man of Hupner's military experience.

"I guess that ought to hold Dowley for five minutes," laughed Noll.

"That fellow gives me a sense of fatigue," remarked Sergeant Hupner placidly. "He might turn out to be a good soldier under stress, but all I've got to say is that I wouldn't want to have to defend a position with only a squad or two of men of his type. I wonder how the recruiting officer ever came to let him into the service?"

"Perhaps he got in under somebody else's name on a stolen set of references," laughed Hal.

"Sergeant Hupner, I want two of your men to send back with a message," announced Captain Cortland, stepping up.

"Overton and Terry are in good condition, sir," reported Hupner, rising and saluting as soon as he saw his commander.

"Very good; come with me, Overton and Terry."

Captain Cortland led the two young soldiers[Pg 74] down the trail, drawing a local map from one of his pockets and spreading it on a flat table of rock.

"Study this map carefully, men, for I want you to be sure of the road you're to take. You will have to go back about four miles—two of it off this trail. You'll find a little telegraph station there. I want you to deliver, for transmission, this message to Colonel North, at Fort Clowdry."

"Yes, sir," Hal answered. "Shall we wait for the answer?"

"No; the answer will not be due until to-morrow. As soon as you have turned over your message, retrace your way to this point. B Company will have gone ahead. But a little way above here the trail broadens, and you'll find a house now and then. You can inquire for news of which way we've gone. You'll have to find us as best you can. And Overton!"

"Yes, sir."

"Remember that these are sham manœuvres, and that C Company stands for the enemy."

"Yes, sir."

"Either or both of you might be captured by a detachment from C Company."

"We'll do our level best to prevent that, sir," Hal promised, and Noll nodded with emphasis.

"Even worse than your own capture would[Pg 75] be the capture of this message," Captain Cortland added impressively. "This message, in effect, is my attempt to communicate with my base of supplies, represented by Fort Clowdry. If you fail to put the message through, and C Company captures it, then Captain Freeman and his men have scored heavily against us."