OPEN FOR COMPETITION UNTIL JANUARY 15th, 1879.

In addition to the smaller premiums which we offer and which every body may get, there is a prize of a Lady's or Gentleman's Gold Watch, a Sewing Machine, Silver Watch, and a Small Patent Churn.

The person securing the largest sum in subscriptions to the Witness Publications before January 15th, 1879, will receive a Solid Gold Watch, suitable for either a lady or a gentleman.

The person sending in the second largest amount in subscriptions to the Witness Publications will receive a first-class Sewing Machine.

To the person third on the list, a magnificent Solid Silver watch will be sent.

To the person fourth on the list will be sent a small patent churn, suitable for a farmer who has a small number of cows.

The Churn is most simple in construction, and is therefore easily worked, and is not apt to get out of order.

Renewals, as well as new subscriptions count in for the above mentioned prizes.

JOHN DOUGALL & SON, Montreal.

PREMIUMS FOR THE MILLION.

In making up our Fall list of premiums we have tried to introduce as many new articles as possible, but owing to the request of many of our last year's workers who did not succeed in gaining all the prizes that they wished for, we again offer some of the articles which last year were most sought after. The Skates seem to have been the favorite of the Young Folks, as over 700 pairs have been sent away to successful competitors, and in every case, as far as we have learned, gave entire satisfaction; we, therefore, for a short time only, offer the skates as premiums on the following terms:

To any Boy or girl sending us $9 in new subscriptions to any of the Witness publications, we will send, securely packed and all charges paid, one pair of the CANADIAN CLUB SKATES, worth $2.75 per pair.

For $10 in new subscriptions we will send the all-steel EUREKA CLUB SKATE, which retails at $2.75. For $15 in new subscriptions we will send by express a pair of the celebrated steel and iron welded EUREKA CLUB SKATE, worth $4.

(Continued on Page 29.)

Re-printed from the "New Dominion Monthly."

MONTREAL:

JOHN DOUGALL AND SON, 33 TO 37 BONAVENTURE STREET.

1878.

| Page | |

| THE "WITNESS" BUILDING. | 2 |

| UPPER CASE. | 6 |

| LOWER CASE. | 6 |

| SETTING TYPE. | 6 |

| MAKING "PI." | 7 |

| BACKWARD WRITING. | 8 |

| TAKING A "PROOF." | 8 |

| PLACING "MATTER" IN "TURTLE." | 10 |

| HOISTING "TURTLE" ON THE PRESS. | 13 |

| A FELLOW LABORER. | 14 |

| The Press Room. | 15 |

| THE NEWSBOY'S FESTIVAL. | 15 |

| ADDRESSING MACHINE. | 17 |

| ANSWERING AN ADVERTISEMENT. | 18 |

| COUNTING ROOM. | 19 |

| GRAVERS' TOOLS. | 21 |

| WAITING FOR THE EDITOR. | 23 |

| THE LIBRARY. | 25 |

| JOHN DOUGALL. | 26 |

| LOCKING UP "DOMINION" FORM. | 27 |

Guttenberg and Faust were good printers. Their beautiful work still remains in proof that the moneyed partner was not in league with the Evil One, even were it not known that the first book which issued from their press was the Bible. Notwithstanding that it has often been asserted, and may be reiterated for centuries to come, that the fruit of the printing press is irreligion, the pages of the Mazarin Bible—the earliest printed book known—remain still perfect and bright as the morn that work issued complete from the press, four hundred years ago and more,—an evidence that in the minds of the pioneers of the art, good, and not evil, was the controlling influence. And the history of printing ever since, shows that the bright days of the art, in any part of the world whatsoever, have been ever contemporaneous with increasing prosperity, intelligence and progress in the more important things of life.

Time had not reached its greatest value in the anticipatory days of the art; the world had not then been scoured to find the materials wherewith [Pg 4] to make cheap ink and cheap paper. The early printers, in their work, had either to rival the exquisite manuscripts of the monkish transcribers of written knowledge, or be considered far behind in the "art preservative of all arts." Everything was done conscientiously in those days, and with the greatest care. The inventors were the printers, and their hearts were in their work. Printers then looked upon their productions as works of art. Their competition did not come in the shape of speed in production, nor lowness of price, but in that of excellence of material and beauty of execution; and when a man paid a fortune for a book, he expected that it would be an heirloom to be handed from generation to generation, to the end of time,—the same volume telling its story to grandfather, father, son, and grandson, gaining value with each generation and sanctity from the mere fact of age.

Now it is different. Rapidity of production, novelty, and above all cheapness, are the leading characteristics to be aimed at by the publisher who would reach the public. These latter attainments are found in highest combination in that wonder of the present age, the daily newspaper.

There is probably nothing so common of which so little is known, or about which there is so much curiosity, as the newspaper. Men read it every day; they abuse it, threaten to give it up, praise it, advertise their wants in it, write to it, search it to see if their letters are in it, call it hard names, pay for it year after year,—and still to ninety-nine out of a hundred of them its production is a complete mystery. To them it is a business office, a newsboy, or a post-office, who are simply carriers, and that is all. It is the exemplification of effect without cause,—an impersonal institution with plenty of vitality, and sometimes even with genius; but it is always mysterious even to those most intimately connected with it. The whole of its secrets are known to no single individual. Its personality is swallowed up in the editorial we, into whose depths no man penetrates, and even the inquisition of the law never gets behind the innermost curtain. The only name pertaining to it is that of the publisher, the accoucheur, who becomes responsible for its daily birth.

For the benefit of those who have no opportunity of visiting a city printing office and would know something of how such a one is arranged and regulated, and also for the further satisfaction of those who have visited an office of this description and learned only enough to make them desire to know more, we will endeavor to describe the process of making a daily newspaper, taking for a special subject the Witness Printing House, where this magazine is published.

The general appearance of a newspaper has no little to do with its success. It should be neatly and clearly printed, so that it may be read with ease and pleasure. This depends chiefly on the mechanical workmanship. Good paper is also a desideratum, but then it must not be expensive, and need not be made as if to last for all time, as from its nature the life of any single number of a newspaper is short, although in the continual succession of numbers, day after day, there is much of permanency about an established journal. A daily newspaper is the world's history of one day to be read on the same day or the next, and too often forgotten on the third; and to habitual news readers news forty-eight hours behind the date is almost as ancient history, and only interesting as a memorial of how the people lived so long ago.

There is hardly any portion of the world which has not been ransacked for material of which to make cheap paper. The "American Encyclopædia" gives the following extensive, though [Pg 5] incomplete, list of substances from which paper has been made: "Acacia, althæa, American aloe or maguey, artichoke, asparagus, aspen, bamboo, banana, basswood, bean vines, bluegrass, broom, buckwheat straw, bulrushes, cane, cattail, cedar, china grass, clematis, clover, cork, corn husks and stalks, cotton, couch grass, elder, elm, esparto grass, ferns, fir, flags, flax, grape vine, many grasses, hemp, hop vines, horse chestnut, indigo, jute, mulberry bark and wood; mummy cloth, oak, oakum and straw, osier, palm, palmetto, pampas grass, papyrus, pea vines, pine, plantain, poplar, potato vines, rags of all kinds, reeds, rice straw, ropes, rye straw, sedge grass, silk, silk cotton (bombax), sorghum, spruce, thistles, tobacco, wheat straw, waste paper, willow, and wool." The principal materials are: "1, cotton and linen rags; 2, waste paper; 3, straw; 4, esparto grass; 5, wood; 6, cane; 7, jute and manila." In Canada, the principal ingredients used in the newspaper are a mixture of cotton rags and basswood; although from a very prevalent habit amongst some of chewing paper, it might almost be presumed that tobacco was also commonly used. The process of converting these different ingredients into pure white paper is a most interesting one, but we shall pass on to other materials used in making the newspaper without further notice.

The central idea in the printing process is the movable type from which the impression, which we call printing, is made. Types are composed from an alloy known as type metal. Its chief ingredient is lead; antimony is added to make it more stiff, and tin to give it toughness. A very small quantity of copper is sometimes added to give it a still greater degree of tenacity, and in some cases the ordinary type is faced with copper through the agency of the galvanic battery,—an expensive operation, but one which adds greatly to the durability of the letters. A type has been described as a small bar of metal, with the letter in relief upon one end, as in the illustration, by which, also, it will be seen that the letter on the type is reversed, so that the impression will appear on the paper as we see it.

Types are of a uniform height, ninety-two hundredths of an inch being the invariable height of all types, and of everything used to print along with types all over the world. They are of various sizes, from the letters two or more feet across, used in posters, to the minute type only seen in the very smallest editions of the Bible, or in marginal notes. The largest size commonly used in the present day is "pica," of which 71.27 lines go to a foot. The next smaller is "small pica," with 80 lines to a foot; then "long primer" (with which this article is is printed), with 89.79 lines to a foot; then "bourgeois," 100.79 lines to a foot; "brevier," 113.13 lines to a foot; "minion" (with which the Witness is principally printed), 126.99 lines to a foot; "nonpareil," half the size of "pica;" and "agate" (with which the Witness advertisements are set), 160 lines to a foot.

Pearl.

Machinery now does nearly every part of labor, thus saving tim

Agate.

Machinery now does nearly every part of labor, thus sav

Nonpareil.

Machinery now does nearly every part of labor, thus

Minion.

Machinery now does nearly every part of labor,

Brevier.

Machinery now does nearly every part of

Long Primer.

Machinery now does nearly every part

Small Pica.

Machinery now does nearly every

Pica.

Machinery now does nearly

There are also several smaller sizes which are used for special purposes only, as for Bibles. These are "pearl," "diamond," and "brilliant," the last almost a microscopic type.

The different letters of the alphabet vary in thickness. The m, which, whether capital, lowercase, or italic, is nominally square in body,—that is, just as broad as the line is deep,—is taken in America as the basis of measuring the quantity of matter in a page, and, thus used, is written "em." The unit of measurement is a thousand "ems," which means an amount of matter equal to a thousand such square types. A line of this article measures seventeen ems, and there are fifty-five lines to a column, thus a full page contains 1,870 ems, for which a compositor would usually be paid forty-four cents. Every one who reads knows that some letters are used more frequently than others. For the ordinary class of English work, the relative ratios of the letters, as nearly as can be calculated, are as follows :—y, l, k, j, q, x—3; b, v—7; g, p, w, y—10; c, f, u, m—12; d, l—20; h, r—30; a, i, n, o, s—40; t—45; e—60; in all, 532. The "fonts," or supplies [Pg 7] of single styles of type, are made of all sizes, from two or three pounds to thousands of pounds, according to the quantity needed. Before the types are used they are placed in two "cases," called respectively the "upper" and "lower," which are placed on a stand or "frame." The upper case is divided into ninety-eight boxes of equal size, in which are placed the CAPITAL and SMALL CAPITAL letters, as in the plan given, by which the position of each letter and character may be seen. The lower case has fifty-four compartments of different sizes, in which are the "lowercase" letters, spaces, quadrats—commonly called "quads"—and other prime necessities for a printing office. The quadrats are pieces of metal lower than the type, and are used for filling out blank spaces, such as the incomplete lines at the end of a paragraph, while the "spaces," which vary from the thickness of a hair to the width of the letter n, make the spaces between words. The larger spaces are all multiples of the m, which is square, and are therefore called quadrats, or quads.

With a pair of these cases before him, the compositor begins his work. His "copy" (the reading matter to be set in type) lies before him on the right hand side of the upper case, which is very seldom used. He has in his mind a phrase of the article he is setting, and picks up the letters one by one, placing them in turn in a composing "stick," which he holds in his left hand. He does not pick the letters from their boxes at random, but, as a matter of habit, his eye searches out a particular letter that lies in a position to be grasped before his hand reaches it. He never looks at the face of a letter to be sure of what it is, but only at the notch, or "nick," at one side at the bottom, which must invariably be placed upward [Pg 8] or towards his thumb in the stick. With the nicks down the words would look as follows:

When a line is completed it is "justified,"—that is, the spaces between the words are increased or diminished, so that each line will end with a word or a syllable. An ordinary-sized stick will contain thirteen lines of the size of type in which this article is set; and when the stick is full, then comes one of the most unsatisfactory duties for novices—that of "emptying" it. There will be in the stick some two hundred different pieces of metal. Lifting them out of the stick in one piece is a precarious proceeding. The boy in the illustration has evidently failed in the attempt, as do most beginners.

The result of such a slip is "pi," which is made by no stated rules, but in numberless ways. A common work for beginners is setting up the "pi," which, when set up, looks like this:

heq ae tti d, mc cu bah, tchi ooh hi jz. vbcmwp;"—MKe 3 : - hx. i.r ta wsmt [fl]mcb2uo'zewlect 3o,gsu ,s—qvuke9oi?b [fi]y atim o irr ,h ae6 Ij gss off ieer xo a lpgt ro ,renc oc thd adeo sirt , ifofy

From the stick the type is transferred to a "galley," a long metal or wooden tray, against whose side and end the type rests. It is usually placed in an inclined position that there may be no danger of the type "pying," or becoming so mixed up as to be useless. When the galley becomes filled it is "locked up"—an operation made plain by our illustration—and "proofs" taken. This is done by "inking" the type by means of a roller, then placing a sheet of damped paper upon it and passing a heavy iron roller, surrounded by a "blanket," over it.

The proof is then sent to the proof-reader, who goes over it carefully, comparing it with the copy, which is read aloud to him by the "copy-holder." Any corrections to be made are indicated by certain hieroglyphical marks, which, with slight variations, are recognized by printers everywhere.

In daily papers, when great expedition is required, the proofs are read in "takes,"—which requires us to turn back for a moment in this description. Doubtless many of our readers have desired to know why it is that newspaper publishers are continually requiring correspondents to write only on one side of the paper, and thus encouraging so much waste and additional postage. It is this:—the copy is given out in "takes," or sections, of a dozen lines, more or less. To do this the sheets are often cut and renumbered. Thus, if the manuscript were written on both sides, endless confusion would ensue. The proofs are often read in these "takes," the impression being obtained from the type while in the stick. At times, when the news arrives immediately before the paper is sent to press, this reading is the only one it receives. Ordinarily they are read two or three times over, or oftener; first with the copy-holder, who reads the copy while the proof-reader compares it with the printed proof before him, then "revised" by the proof-reader, who compares the [Pg 9] second impression, or "revise" with the one on which the errors or omissions had been previously indicated, and glanced over a third time, to see that no mistakes have been overlooked in the previous reading and with more careful attention to the sense of the passage. Then a proof goes to the writer for further revision, if necessary.

The best proof-readers are usually those who have had some experience as compositors, and thus know from experience the errors most likely to be made, and the manner of correcting them so as to cause the least delay. Proof-reading requires a very unusual association of qualifications. The really good proof-reader must be perfectly acquainted with his own language, and have some general knowledge of almost all others, besides of the dialects of his own. He must have a general acquaintance with literature and be able to confirm every quotation, and have the dictionary and gazeteer at his fingers' ends. He must have an eye which nothing escapes (technically called a typographical eye), and be able to detect and correct the errors made by both author and compositor,—and the number by the former is usually not inconsiderable. And withal he must have a temper which nothing can ruffle, a power of centring his attention on the dryest matter read for the second and third time, and determination sufficient to see that every correction indicated is duly made—and this last is by no means the least of his necessary qualifications.

In the early days of printing, the proof-readers were eminent scholars, and it was no unusual thing for a proof to pass through the hands of several of the most learned men of the time and neighborhood before the sheets were printed. It is related of Raphelingus, a distinguished scholar who was engaged in reading proofs in Antwerp about 1558, that he declined the professorship of Greek at Cambridge, preferring to correct the text of the oriental languages. Plantin, of Antwerp, and Stephens, of Paris, used to expose publicly the sheets of their books, offering a reward to any who would discover errors in them. But it is very seldom, if ever, that a work is issued from the press absolutely typographically perfect. In this respect the Oxford edition of the Bible is said to be the most successful work published.

Many are the ludicrous and mortifying mistakes made in printing. Erasmus, rather unfortunately for himself, corrected his own proofs, with such a result that he declared that either the devil presided over typography or that there was diabolical malice on the part of the printers. Perhaps the most astonishing example of bad proofreading was the edition of the vulgate edited by Pope Sixtus V. His Holiness carefully supervised every sheet of this wonderful edition before it was sent to the press, and to stamp it with his authority fulminated a bull that any printer who, in reprinting the work, should make any alteration in the text would be excommunicated. This was printed as a preface to the first volume of the work. Isaac Disraeli, in his "Curiosities of Literature," says, in referring to this circumstance, that "To the amazement of the world, the work remained without a rival—it literally swarmed with errata. A multitude of scraps were printed to paste over the erroneous passages in order to give the true text. The book makes a whimsical appearance with these patches; and the heretics exulted in this demonstration of papal infallibility! The copies were called in, and violent attempts made to suppress it; a few still remain for the raptures of the Bible collectors. Not long ago the Bible of Sixtus V. fetched above sixty guineas—not too much for a mere book of blunders."

Another historical erratum was an intentional one made by a printer's widow in Germany, at whose house a [Pg 10] new edition of the Bible was being printed. At night she stole into the office and altered the passage—Genesis III., 16—which makes Eve subject to Adam, by taking out the two first letters of the word Herr, used in German, and substituting in their place Na. The passage thus improved read: "and he shall be thy fool," instead of, "and he shall be thy lord," as it should have been. It is said that this woman was punished by decapitation. Perhaps the most striking error of all in any edition of the Bible was the omission of the negation in the seventh commandment in one instance. This edition was very effectively suppressed.

In reporting Parliament some ten years ago, one of our morning papers contained a statement to the effect that the Hon. Mr. Holton said he had no doubt that Mr. Morris was tight (right), a single letter proving very derogatory both to the speaker and to the very highly respected gentleman to whom he referred.

When the proofs have been read and the errors corrected, or supposed to have been corrected, the "matter" is placed in the forms. Those, for the "rotary" press used in the Witness office, form segments of the central cylinder of the press, and from their resemblance to a turtle shell are called "turtles." The type is placed in the form piece by piece, the different kinds of matter each in its proper place. This is a matter requiring both skill, care and ability, so that paragraphs are all placed under their proper headings, and that two articles do not become "mixed up," as sometimes happens. There have been many illustrations of the evil effects of such a medley, but none hardly equal to that given by Max Adeler, which, we presume, has been subjected to some ingenious improvement. He says:

"The Argus is in complete disgrace with all the people who attend our church. Some of the admirers of Rev. Dr. Hopkins, the clergyman, gave him a gold-headed cane a few days ago, and a reporter of the Argus was invited to be present. Nobody knows whether the reporter was temporarily insane, or whether the foreman, in giving out the 'copy,' mixed it accidently with an account of a patent hog-killing machine which was tried in Wilmington on that same day, but the appalling result was that the Argus, next morning, contained the following obscure but very dreadful narrative:

"'Several of Rev. Dr. Hopkins friends called upon him yesterday, and after a brief conversation the unsuspicious hog was seized by the hind legs and slid along a beam until he reached the hot water tank. His friends explained the object of their visit, and presented him with a very handsome gold-headed butcher, who grabbed him by the tail, swung him round, slit his throat from ear to hear, and in less than a minute the carcass was in the water. Thereupon he came forward and said that there were times when the feelings overpowered one, and for that reason he would not attempt to do more than thank those around him, for the manner in which such a huge animal was cut into fragments was simply astonishing. The doctor concluded his remarks, when the machine seized him, and in less time than it takes to write it the hog was [Pg 11] cut into fragments and worked up into delicious sausage. The occasion will long be remembered by the doctor's friends as one of the most delightful of their lives. The best pieces can be procured for fifteen cents a pound, and we are sure that those who have sat so long under his ministry still rejoice that he has been treated so handsomely.'"

In the recent number of an English religious paper a somewhat similar mistake took place, the report of a meeting for the conversion of the Jews and an item on the advantages of phosphates as manure being pretty well shaken up together.

The matter all being properly placed in the "turtles," of which there are eight for the Daily Witness, the latter are "locked up" by means of screws at the ends, by tightening which pressure is brought to bear on all sides of the matter, and it becomes as one mass, so solid that it would not fall to pieces though it fell from one floor to another. It will be noticed that a section of the turtle forms the arc of a circle, while the sides of the type are parallel. How to make the matter close firmly under these circumstances was the subject of much study. One inventor made his type wedge-shaped, but that did not answer, and the difficulty was at length overcome by making the rules which divide the columns so much larger towards the top than the bottom that the column rule sits into the arch of types after the same fashion as a keystone in masonry.

The "turtles," when being made up, are placed on stands made for the purpose, which are wheeled along to the hoist and lowered to the press room.

The hoist used in the Witness office has some peculiarities which distinguish it from others. Where so many young people were working together, it was considered unsafe to have a a hole in the floor with no protection. The mechanical manager, Mr. John Beatty, therefore set his mind to work to invent attachments whereby the hoist would automatically open and close, as required. He was entirely successful, and now the machinery is so arranged that whenever the hoist is at any particular flat the gate opposite it is raised so that free access may be had to the platform; at all other times the gate is closed, so that no one can fall into what is, too often, little more than a man-trap.

Descending with the "turtles" to the ground floor, we arrive at the pressroom, where the forms are hoisted on to one of Hoe's mammoth eight-cylinder rotary presses. The turtles are fastened, or "locked," on to an immense cylinder and form a portion of its circumference, the rest of its surface being used for distributing the ink. Surrounding this cylinder, and acting in conjunction with it, are eight other cylinders, very much smaller than the one bearing the type. At each of them stands a man, whose duty it is to "feed" the press—that is, place the sheets, one by one, so that at the proper time they will be clutched by the automatic fingers by which they are drawn around the smaller cylinder, at the same time being pressed by the one bearing the type, so that a clear impression is made. The sheets are then carried away by means of tapes, and deposited evenly on tables at the rear of the press. This machine will print sixteen thousand copies an hour, and is often run beyond that speed in the Witness office. Its catalogue price is thirty thousand dollars.

A word may be said about the progress of the printing press towards perfection. The changes have all been from direct or reciprocating to rotary or revolving motion. At first the type was inked by "ink balls," and the paper was pressed on it by a flat platen brought down upon it with pressure by means of a spring or screw. Inking is now invariably done by rollers, but the direct action of a flat platen pressing against a flat bed is still preserved, not only in all the smaller and simpler [Pg 12] presses, but in those which do the very finest work. The first great step towards increased speed was made when the paper was pressed against the type by a cylinder or drum. This is the character of most newspaper presses, and of a good number in the Witness pressroom. In these presses the types still travel backwards and forwards on a flat bed, which has to stop and reverse its motion twice for every impression. The next step in advance was that which placed the types also on a cylinder, so that there might be for them only one continuous motion round and round in one direction. This is illustrated by the large rotary presses in the picture of the pressroom, one of which, the four-cylinder, has just been removed to make way for presses adapted to finer magazine work. There is still in the rotary press the necessity of feeding by hand. A number of machines have been invented to feed themselves from a roll of paper, thus introducing another rotary motion, and to "deliver" the paper by still another rotary process. None of these presses, so far, have come to such perfection as to print from type as well and as fast as the great rotary press now used by the Witness, but they are constantly improving in construction. Such presses [Pg 13] have, of course, to print one side of the paper and then the other before the sheet leaves the press, and would have to deliver these perfected sheets as fast from one exit as the rotary does from eight or ten. It is in these points where the difficulty is found, as one side has to be printed before the ink is dry on the other, and the rapid disposal of the finished papers requires very ingenious machinery. There are further improvements still in the future. We can imagine lithography completely supplanting type or stereotype printing,—as it has begun to do,—the impression of the type being transferred to stone, or some other lithographic surface. If lithographic surfaces could be made cylindrical they could, being smooth, work against each other, and so print both sides of the paper at the same time. The whole press would thus consist of two impression rollers and two more to ink them going round just as fast as the chemical character of the ink would permit. The Witness has had to purchase a new machine about every five years to keep up with the times, and it is not probable that it will be otherwise in the future.

As the sheets are printed they are gathered from each of the eight receiving tables and carried off to the folding machines, of which there are four on the same flat. These are unable to do all the work as quickly as required, so that some are sent up to the bindery above, and folded by hand.

Let us, for a moment, consider the amount of paper which goes through the presses on this floor in a year. There are, devoted to papers, an eight-cylinder rotary for the Daily, a two-cylinder for the Weekly Witness, and a single-feeder for the Messenger. There are also several presses for job work, one of which, however, prints L'Aurore, and another the New Dominion Monthly, which need not now be referred to in detail.

Some fourteen thousand five hundred copies of the Daily Witness are printed daily, or 4,509,500 a year, excluding from the calculation Sundays and legal holidays. The circulation of the Weekly Witness averages twenty-six thousand copies, or 1,412,000 in a year. Some fifty thousand copies of the Northern Messenger are issued semi-monthly, or 1,200,000 sheets a year. Thus the total mounts up to more than seven million papers which are printed on these premises during a year. A few statistics with this number as a basis would prove interesting. Piled in reams these papers would form a column 3,560 feet high, or more than two-thirds of a mile. Stretched out and pasted together they would [Pg 15] reach four thousand four hundred and twenty-one miles. But such figures as these simply daze one, and we will leave them and follow the papers a little farther.

These take two courses. Some go upstairs to the mailing room, while others are counted out to the newsboys for street sale and to the dealers throughout the city. The newsboys are a most unruly lot, and to be kept under control are compelled to wait in a room, built on purpose for them, until the papers are ready. This time they occupy in quarrelling, cutting their names on the sides of the deal partitions, and calling out to "Miss Gray," the traditional name given to every young lady who has had charge of that department for the last ten years or more. Should a gentleman take her place for the nonce, he is called Mr. Gray. As soon as the papers are ready they are counted out to the newsboys, each of whom has his particular beat or stand in the city. Some, with more enterprise or capital than others, buy by wholesale, and sell to others with less capital. A few, standing on the street corners, have regular customers who pay or not, as the case may be, each night; and as the business men pass, one after another, the papers are handed to them almost as rapidly as tickets at a crowded concert-room. Often they are snatched from under the boy's arm; but no matter, without any system of book-keeping, or even a book of original entry, each customer will be told the exact amount he owes at any time, and without a moment's hesitation. These newsboys sell from one to twenty dozen copies daily. They pay for the Witness eight cents a dozen, and sell them at a cent each. Thus the newsboy's income will average from four cents to eighty cents per day—the latter no inconsiderable sum in these hard times.

Although unkempt looking, rough in manner, boisterous and unmannerly in speech, there is often much that is good in the newsboy, and Mr. Beatty, of the Witness office, keeps a sharp eye after their character and interests. About once a year the office gives them a dinner, or something of the sort, which they attend as one man, or, more properly, as one boy or girl, for some of the "newsboys" are girls. It is one of these occasions which is shown in the picture. The boy standing with his arms full and legs crossed has just been informed that he could "pocket," and now wants to have his picture taken.

Much of the business once done by the newsboys has been taken away by the fruit dealers, grocers, and confectioners throughout the city, most of whom have regular customers to supply. To these the papers are sent by four carts built for the purpose. They are shown in the picture of the building, some of them in process of being laden and others departing with their loads. During the day the number of papers to be sent to each dealer is plainly marked on prepared labels, on which are printed the name and address. These are arranged in order according to the route they are to be taken. As soon as the papers are printed, they are rapidly and securely tied up in bundles, with the label exposed, for the carrier; and in a few minutes after the paper is sent to the press the four carts are swiftly carrying them to all corners of the city. Each driver has a shrill and peculiarly sounding whistle, which is blown immediately before each dealer's door is reached; the bundle is thrown on the sidewalk as the horse dashes by unchecked, and the contents distributed amongst the crowd of customers sure to be waiting for their Witness.

Again, some of the parcels have to be made up for the towns, to which they are sent by railway, through the agency of the Express office. Almost every town in Canada on the railway receives its bundle of papers, and as each new railroad is opened the demand for the Daily Witness to be sent in this manner increases. A large number also go by mail to the remote parts of the country, and in glancing over the mailing lists the person most conversant with the geography of Canada would be obliged to confess that a very large percentage of the names he would there meet was entirely unfamiliar to him.

The manner of addressing papers adopted in the Witness office is to print the names and addresses, with the date when the subscriptions expire, directly on the papers themselves, in red ink. This method has several disadvantages, but these are counterbalanced by the fact that when once the name is printed it can never come off, as is the case when addresses are printed on little slips of colored paper, and then pasted on. In either method the subscribers' names are first set up in columns, under their respective post-offices, these offices being arranged alphabetically for facility of reference. It will be noticed that the post-office is only printed once, and then in large heavy type, the subscribers' names following it in the column. Five of these columns, containing on an average two hundred names, are placed in a "chase" and locked up. There are altogether in the office some three hundred and fifty of these chases constantly in use. They have to be continually revised, at which from two to ten men are constantly engaged. When the mailing time comes the chase which is to be used is inked and placed in the mailing machine, which is shown in the engraving. The machine is worked by the operator's foot. A paper is put under the hammer, as shown, and the treadle being pressed the name in the chase beneath is plainly stamped on the paper. Only the [Pg 17] first paper of each parcel has the name of the post-office as well as that of the subscriber. When all the papers going to one post-office have been stamped, they are tied in one parcel and that with the name of the post-office being uppermost, the general address of the whole is known. When the parcel arrives there it is opened, and the postmaster makes the further distribution.

Those who read this account will understand how it is that sometimes papers go astray. It would be wonderful if, out of nearly a hundred thousand names always in type at the Witness office, while changes are constantly being made in the lists, there were not some mistakes, and it is creditable to the system adopted by newspaper publishers that the number is comparatively so small.

As will have been observed, the type from which the Witness is printed when in the turtles assumes a rounded shape. Readers of that paper know that on many occasions it is embellished with wood cuts, and that wood engravings are ordinarily cut on a flat surface. They may have wondered how the difficulty is got over. In the Witness all the engravings are electrotyped. To perform this operation an impression of the engraving is first made in a sheet of wax by means of a powerful press. The wax is so fine and the pressure so great that the finest lines are reproduced. The wax is then blackleaded with graphite, made especially fine for the purpose, and the waxen plate is inserted in an battery in which is a strong solution of copper. In a few hours a thin film of copper, the exact counterpart of the engraving, is formed. This is laid on its face in a hot iron pan and over the back a covering of tin foil is placed to give it consistency, the heat causing it to melt and fill all the finer interstices of the engraving. Over this again is poured a "backing" of lead or type metal, which is shaved down to the exact thickness required. This is again backed with wood, to raise it to the height necessary for printing. This wood has been curved to the shape of the press and the electrotype is bent to correspond. Some papers stereotype the whole form—a shorter process, but one impracticable for an afternoon paper in editions, as, in the latter case, even fifteen minutes' delay would be more than could be spared.

Thus having disposed of the mechanical branch of printing, we will next resort to another matter of the greatest importance to a daily newspaper—that of advertising. The Daily Witness is sold at a cent a number, a sum which hardly pays the cost of paper alone; so that out of the advertisements inserted must be met the expenses for printing, publishing, editing, etc. If an ordinary newspaper, published in a small city such as Montreal practically was twenty years ago, be examined, it will be found that nine-tenths of the advertisements, measured by the space occupied, come under one of the following categories: advertisements of liquors and tobacco, of groceries including [Pg 18] liquors and tobacco, or of places selling liquors; advertisements of theatres and other questionable amusements; advertisements of questionable medicines; advertisements of questionable reading matter; advertisements of other quackeries. To avoid all such was the firm determination of the Witness from the beginning, so that it had, as it were, to create its own advertising business. Another custom against which it set its face was that of using large and varied type in advertisements, seeing that when all do this they neutralize each other in point of prominence, and get much less value out of their space,—besides making a very ugly and vulgar looking paper. It was held that among advertisements printed in uniform type, a small number printed prominently would be worth a great deal to those who chose to pay for them, and more in proportion to the fewness of them. This end was gained by charging double to all who thought the prominence worth the price. Instead of putting difficulties in the way of making changes in advertisements, the Witness does its best to get the advertisers to put in new advertisements every day, believing that were this to become universal the advertising columns would be as much studied as the reading columns. Here are one or two points not understood by all advertisers: one, that it is of no advantage to draw attention to commodities that are not worth the money they are sold for. If purchasers are disappointed, the more attention drawn to the goods the worse for the business,—those swindling concerns that live on first transactions always excepted. Another thing is that it is better to have an advertisement where it will be looked for by those wanting the article than to have to draw the attention of everybody to it. To get people into the habit of looking into certain quarters for certain things should be the primary object of all advertisers and advertising mediums. Some Montreal men are proving adepts in the art of advertising and making it very profitable, while, on the other hand, there is no way of throwing away money faster than by unwise advertising.

Some idea of the amount of business which is done in advertising may be obtained from the fact that in 1877-78, one of the dull years, twenty-four thousand two hundred and ninety advertisements were received in the Witness office, a daily average of seventy-nine. This was obtained almost without any canvassing. A business that depends largely on canvassing must necessarily adopt prices that will cover canvassers' commission.

There are many traditions in the Witness office in regard to remarkable answers to advertisements. A gentleman, one bright summer's day, lost a favorite canary, and hurried to the Witness office to make his loss known. His advertisement was immediately sent up to the compositors' room to be set up, and while this was being done the bird flew in through the window and perched himself on the case immediately in front of the young man who was putting the advertisement into type. Birdie was caught, and soon the [Pg 19] owner was happy again. It is well that all lost articles do not, in a similar manner, find their way into printing offices, as the character of the profession might then be subject to suspicion.

The subject of curious advertisements is an endless one, and has been fully entered into in Sampson's "History of Advertising." There is the kind in which the sentences are, to say the least, ambiguous, as that of the lady who advertised for a husband "with a Roman nose having strong religious tendencies." Then there was "to be sold cheap, a splendid gray horse, calculated for a charger, or would carry a lady with a switch tail,"—hardly as curious an individual as the one spoken of in the following announcement: "To be sold cheap, a mail phaeton, the property of a gentleman with a movable head as good as new." A travelling companion to these would be the following: "To be sold an Erard grand piano, the property of a lady, about to travel in a walnut wood case with carved legs." But what can compare with the specimen of humanity referred to by a chemist in the request that "the gentleman who left his stomach for analysis will please call and get it, together with the result!"

The insertion of marriages is of early date, they first appearing as news, and in certain respects were much more satisfactory than those now given, as for instance, the one in the Daily Post Boy of February 21st, 1774:

"Married, yesterday at St. James' church, by the Right Rev. Dr. Hen. Egerton, Lord Bishop of Hereford, the Hon. Francis Godolphin, Esq., of Scotland Yard, to the third daughter of the Countess of Portland, a beautiful lady of £50,000 fortune."

Sometimes the papers in those days disputed as to the matters of marriages and deaths. The London Evening Post, in April, 1734, said:

"Married.—A few days since—Price, a Buckinghamshire gentleman of near £2,000 per annum, to Miss Robinson, of the Theatre Royal, Drury-lane."

At this the Daily Advertiser remarks, a few days later, "Mr. Price's marriage is entirely false and groundless"—a peculiar kind of marriage that. The Daily Journal about the same time asserts:

"Died.—On Tuesday, in Tavistock-street, Mr. Mooring, an eminent mercer, that kept Levy's warehouse, said to have died worth £60,000."

But the Daily Post informs the public that "this was five days before he did die, and £40,000 more than he died worth."

That the principle of protection was known in 1804 is clearly shown by the following important advertisement:

"To be disposed of, for the benefit of the poor widow, a Blind Man's Walk in a charitable neighborhood, the comings-in between twenty-five and twenty-six shillings a week, with a dog well drilled, and a staff in good repair. A handsome premium will be expected. For further particulars inquire at No. 40, Chiswell street."

We will conclude this branch of advertising by one of more recent date from a United States paper, whose frankness is charming:

"About two years and a half ago we took possession of this paper. It was then in the very act of pegging out, having neither friends, money, nor credit. We tried to breathe into it the breath of life; we put into it all our own money, and everybody else's we could get hold of; but it was no go; either the people of Keilhsburg don't appreciate our efforts, or we don't know how to run a paper. We went into the business with confidence, determined to run it or burst. We have busted. During our connection with the Observer we have made some friends and numerous enemies. The former will have our gratitude while life lasts."

This was inserted in the space reserved for death notices, and really deserved some obituary poetry.

During December and January the department in a newspaper office busy above all others is the one where the subscriptions are received and the lists attended to.

The immense amount of work which comes under this head has been previously referred to. A few statistics will render it more clear. During the [Pg 20] year ending February, 1877, twenty-two thousand seven hundred and seventy-three money letters passed through this department in the Witness office, while as many more, having reference to changes, instructions, giving advice, etc., were attended to. Some of these letters are of an extraordinary nature. In one instance, on a day when some eight hundred money letters poured into the department, the writer signed his name after the manner of an enigma. It was interesting, but out of place. People sometimes send letters with the statement, "Of course you know my name, as you sent me a circular," or something similar. Others sign their names without giving any post-office address, while many again give two addresses, one at the head and the other at the foot of their letters. Sometimes the amount required to be sent is enclosed with no other intimation; but more frequently still the letters, names and all, are sent without the money.

By an ingenious method all money letters which come into this department are numbered, the amount received and the page of cash book where entered marked upon them, and then filed away in books of one hundred, which are bound together, so that any particular letter can be turned up in an instant and referred to. The cash book is ruled so as to give a column for the Daily Witness, Weekly Witness, Northern Messenger, New Dominion Monthly, and Aurore, and the total amount; and sometimes one single letter contains a subscription for every one of the papers enumerated, while a very large proportion have at least two of them. There are a very large number of subscribers who, year after year, take these papers, and not satisfied with this evidence of goodwill, make a point of sending several other subscriptions along with their own. It is always pleasant to the publisher to hear from these, and their letters constantly [Pg 21] recurring, year by year, are like the visits of old friends.

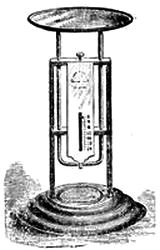

It would be impossible to leave this department without a reference to a minor one partially connected with it—that having charge of the premiums. It is desired, as far as possible, to give some return for all favors done. But here arises a difficulty. Most of these favors are simply because of the goodwill of the performers, and any direct return would be anything but pleasing to them. Thus the rule has been made that those who desire to work for prizes must, in some way, indicate their desire, and the manner considered most satisfactory is to have the words "In competition" written on the top of all letters containing money intended for the prizes. The names of those who send such letters are entered in a separate book ruled in columns, and the remittances are recorded one after the other, so that when the last is sent in the total can be checked in an instant. The number of prizes given in a year is nothing inconsiderable. The following is merely a partial list of what were sent out in the winter of 1877-78:—236 pairs of skates; 30 gold lockets; 125 gold rings; 40 photograph albums; 82 Pool's weather glass and thermometer combined; 6 magic lanterns; 4 McKinnon pens; 298 chromos of Lady Dufferin and 327 of the Earl of Dufferin.

A new and growing department in the Witness office, but quite unique as regards daily newspapers, is the one where the wood-engravings are made. Next to the reporter, whose materials, except those carried in the head, consist of a cedar lead-pencil, a few sheets of paper and a penknife, his are the least troublesome and expensive used in almost any line of business. To bring out all the beautiful effects obtainable in wood-engraving the only tools used are about thirty "gravers' tools," most of them triangular in shape, ground down to a sharp point. The material used is boxwood, cut across the log, joined in small pieces so perfectly that the place of junction cannot be distinguished, and polished to a perfect state. On this the design to be followed is drawn. The engraver may either be an artist or not. If an artist, he will, as he pursues his work, alter and improve an imperfect drawing in its minor and imperfect details, as may be necessary; putting in a little light here, darkening a shade there, and almost invariably turning out a pleasing picture. If not an artist, he will "follow his copy, even if it goes out of the window," as a compositor would say, copying beauties and defects with the same unconcern, and producing a picture even from a good drawing with as little spirit or soul as the block on which he works—a "wood-cut," not an "engraving." It will be understood that all wood-engravings are made in relief, that which is to be printed being allowed to remain, the lights being cut away. If this were merely all, the work would not be very difficult; but more is required. The block must be lowered at places to give very light and delicate shades and that the edges of the shades may not be harsh and coarse, for the press is not naturally a discriminating machine, and unless everything is very near perfection, little aid can be given by it. But, nevertheless, the pressman is required to assist the engraver, and to do this properly he also must be an artist. By placing small pieces of tissue paper, or, sometimes, something coarser, under the electrotype here and [Pg 22] there where needed, he will cause it to rise and greater pressure to come on some portions where greater distinctness is required than at others. This is called "underlaying." More perfect work than is possible in newspapers is obtained by "patches," as they are called, pasted on the "tympan," or the sheet which presses on the face of the engraving, a process called, in contradistinction to the other, "overlaying." There are now three engravers in the employ of the Witness office, and by one of these, Charles Wilson, a deaf-mute, the sketches which illustrate this article were made, with three exceptions, which the reader will have no difficulty in determining. Most of the pictures were engraved by him and his confrères, others being executed by an etching process on zinc without the use of wood at all, or, indeed, of any engraving process, which we cannot now further refer to.

All matters in regard to the newspaper are in interest subordinate to the editing, to which everything is in all ways subsidiary. Who or what is the mysterious "We" whose opinions have such weight, and who appears to be possessed of all knowledge? Sometimes there is little mystery about it, as when the public are informed that "yesterday we received the finest cucumbers we ever ate from Mr. Gardner;" or when it is announced that "the public must excuse the small quantity of editorial matter and the mistakes in our paper of last week, as we were laid up with rheumatism." There is no poetry about a "we" who eats cucumbers or is troubled with rheumatism. But the candid impersonal opinions of a newspaper are usually of great weight and value, and enhanced by the impersonality of the writer.

That this should be the case requires no discussion. A newspaper office is the centre of information on current topics. The news gravitates to this centre as naturally as riches to a wealthy man. Thus the writer should be well-informed and be the best able to give a correct judgment on matters of general interest. Then the fact that the argus-eyed press the country over is watching his utterances closely has a tendency to cause much greater care in the expression of views than is the case in ordinary conversation, or in public addresses which will be heard and forgotten. But let a writer in a paper which has the reputation of being impartial make a mistake of consequence, and he has many correctors before the day is over. On the other hand, there is a very great disadvantage under which many papers labor. They are the "organs" of some political party, and instead of being advocates of truth, are advocates of truth only when it suits the "party." It is strange that such papers are often blindly followed, although the followers generally imagine that they are the leaders.

Suffice it to say, while on this matter, that the editor of a metropolitan daily newspaper is an impersonal individual, or individuals, who never can be seen. His functions, however, are divided, and every one who visits a newspaper may find the person he wants. The reception of visitors is one of the most engrossing duties of the editorial chair. Almost daily they come in throngs, for business or for pleasure—to receive advice, but more often to give it—to compliment, but more frequently to complain—sometimes, but proportionately seldom, to give valuable information. But the last they do, sometimes, and all such visitors are gladly welcomed.

Usually the busiest looking man on the editorial staff in a newspaper office is the managing editor, on a morning paper known as the night editor. Every item which appears in the paper except the advertisements must pass through his hands. It is his duty to see that the copy is sent in in good form and grammatically correct. He prepares the telegrams for publication, [Pg 23] no inconsiderable duty, requiring an extended knowledge, exact and varied information, carefulness, tact and experience, to be properly done. No message, however ambiguous when he receives it, must be ambiguous when it leaves his hands. The contractions must be extended, the wrongly-spelled proper names put right and verified by means of atlas, directory or gazetteer, and on his zeal and ability in no slight measure depends the acceptability of the newspaper to the public.

A man of no little consequence in most daily papers is the commercial editor. He needs discretion, shrewdness, sound judgment, and above all to possess the highest sense of honor and responsibility. In these days when fortunes are made and lost in an hour, when farmers consult the newspapers as to the time to sell, and business is conducted at a feverish heat, it is necessary that all important commercial transactions be promptly and correctly reported in the daily papers. To do this properly is a matter of great difficulty. "Bulls" and "bears" are not over-scrupulous in playing a joke on a reporter sometimes, when they have an end in view, and unless the commercial editor of a paper is well up to his work he and his constituents will be often lead astray. He is supposed to be well versed in every topic of the commercial world, in stocks and produce, railroads, steamboats, dry-goods, hardware, and everything whereby men make gain.

The exchange editor of a newspaper is a man with an eye which just covers a page of print, no matter what the size. Through his hands pass all the newspapers received at the office, except, perhaps, those on special subjects, which may go to the different editors. He is usually armed with a huge pair of shears, and as he rapidly opens one paper after another, falling on something here and there of interest or probable interest, it is cut out for revision and perhaps republication. He is the "paste and scissors" editor so much talked and read about, but has no little responsibility in making a paper readable and "newsy." From the force of education or habit he knows exactly where to look for the kind of information he requires, and a single rapid glance over a page tells him at once if there is anything there for him. He is naturally well-informed in all matters interesting the country outside the city he is in, and thus becomes an authority on local politics.

The ubiquitous members of a daily newspaper staff are the city reporters. The education of habit can hardly go further than is shown in their lives. Unconsciously they are drawn to where some event is happening, or about to happen, and if the reporters are on the qui vive, but little need escape them. Gathering information is as much a matter of habit as the duties of the table. A reporter cannot stray along the street without finding something to make a note of, and the note is made in his mind if not in his book.

His perseverance is unmeasurable, his tact perfect, his courage undoubted, and his audacity—perhaps the least said of this the better! But it must be of a very peculiar nature—there must be no swagger about it. A reporter should not be what is best described by the vulgar term "cheeky." Such a one will never succeed. He must rather have a quiet determination which will overcome all obstacles, together with a modest demeanor and sufficient self-confidence "not to stand any nonsense;" be fluent of speech and speak with authority when he has anything to say; have a perfect knowledge of men and things of interest, and be an easy, rapid and fluent writer. It may be said that such a man would be a paragon of excellencies. However this may be, a first-class reporter is not often met, and seldom remains a reporter very long, except under specially favorable circumstances, for the opportunities to pursue other occupations, if he be a man of good character, are not few. But once a reporter, the reporting spirit never leaves him. The occupation is so full of variety and interest, that the mind constantly reverts to it. He has plenty of drudgery also. Sitting up till midnight or daylight to make a good resume of some dry speech is not pleasant work; digesting long and complicated reports, and many other duties, are mere drudgery, and form no small fraction of his duties. To these, however, are added the excitement belonging to the work of a detective who is employed in searching out hidden things; that of a lawyer examining and cross-examining a witness in order to arrive at the truth; of a judge weighing the evidence from all sides to come to something like a satisfactory decision on troublesome questions. It may be thought that this is an ideal view of a reporter, and that the reality is never met with in real life. But the ideal has often been reached, and during the comparatively short life of the Witness there have been connected with it in this and other capacities gentlemen whose names rank with the highest in commercial and professional life. The ranks of the press in England, France, and the United States, as well as Canada, are constantly being infringed on to fill those of legislators, business men and authors. There is one thing [Pg 25] connected with reporting which always has had a tendency to lower it in the public estimation. It has been considered a means of providing men of ability, but lax in morals and irregular in habits, a means of obtaining a precarious livelihood. This has made the dangers to be met with in this course of life very great, because of the associations surrounding those engaged in it, and at one time it was supposed to be almost impossible to be a reporter and a well-living man. But the days of "Bohemianism" have passed in Canada, and for years there has but very seldom been a reporter on the Witness who was not at the same time a total abstainer from all that intoxicates.

We might mention very many interesting instances, showing under what difficulties information is sometimes obtained, how "secret" meetings are reported in full, and how but very little that reporters want to know is hid, but space will not permit.

We will now rapidly run through the Witness office. It occupies two large, three-story buildings, one fronting on St. Bonaventure street, Montreal, and the other extending back almost to Craig street in the rear. These two buildings are united by an enclosed space, which is utilized as an engine-room and storehouse. This portion is covered with a glass roof to give light to both of the buildings, which are connected by bridges ornamented with flowers and musical with the songs of birds, as suggested by the engraving. Entering by the front door from St. Bonaventure street is the business office. Ascending the large staircase shown, the editorial and reporting rooms are reached. In the latter is the library for the use of the Witness employees, containing over one thousand volumes. These books are lent free to all engaged in the office desirous of reading them. The principal English, American and Canadian papers are also kept on file. On the same flat is the correspondence department,—in which young ladies do most of the work,—the engraving department, the editor of the Aurore, and the desk of the mechanical manager. Going up stairs still higher, the "news" room is reached, where the compositors of the Daily Witness perform their duties. The managing editor and the proof-readers monopolize a corner of this room. Crossing one of the bridges previously referred to, the electrotyping department is seen occupying a partitioned-off corner of the very large and airy "job" office, where are the compositors [Pg 26] of the Dominion Monthly, and where any amount of pamphlets, books, and of job work is turned out each year. Taking the hoist we descend to the next floor, which is occupied by the binding and folding room. Here also the mailing lists are kept and scores of "chases" full of names are to be seen, as well as the machines for mailing the papers. This room is the one shown in the illustration of the dinner to the newsboys, the tables, however being covered with something, to them, more attractive than sheets of pamphlets, while the walls are draped with the national flags. This room has been formally devoted to any reunions the employees may decide to hold for their own entertainment. Descending still another story, we reach the pressroom, where the huge eight feeder, nineteen feet high, thirty feet long and six broad, is turning out sixteen thousand printed sheets an hour. The double building occupies 7,300 feet of ground and 20,400 feet of flooring, besides cellarage.

In all there are one hundred and twenty-eight persons employed within these walls. In the business department there are ten; in the editorial and reporting thirteen; three engravers; four in the promotion and correspondence department; thirty-five compositors on the Daily Witness, including foremen; four proof-readers and copy-holders; two electrotypers; thirteen job printers; eighteen folders and binders; four despatchers; three compositors to keep the mailing lists in order; fifteen pressmen; one engineer, and four drivers for delivery to city dealers.

Besides these there are a host of others, a part of whose sustenance is obtained from the Witness. Newsboys, carriers, dealers, correspondents, telegraphic operators, writers, agents and others, all make a list of no little importance. Female labor is extensively used in the offices, there being no less than thirty-seven young women employed. Amongst all the employees there has grown up a commendable esprit de corps, which is much to be admired. There are but few changes in the personnel of any department, and the good feeling amongst all has much to do with the general efficiency of the establishment, and will conduce to make it still more prosperous and useful.

So much has been said about the Witness office that there is little room for the Witness itself. It will remain a lasting monument to the zeal of Mr. John Dougall, who is now in New[Pg 27] York, endeavoring to engineer the New York Witness to success. Its history has been one of trial, perseverance, but ultimate success all through. It was started in Montreal as a weekly in January, 1846, on a basis then entirely novel in Canada. It was devoted to the advance of religion, religious liberty, temperance, and of all moral and social reforms, and to the education of the people in matters affecting their moral or material wellbeing, standing entirely alone on many questions. The following, from the opening article in the first number, shows the object for which the paper was started, and the course marked out for it to pursue.

* * * "We say good papers, for assuredly the utmost of care should be exercised to keep such sheets as have a demoralizing tendency away from the hallowed precincts of the family circle.

"The Canadian field is comparatively unoccupied at present, and, therefore, the importance of sowing good seed early and plentifully can scarcely be over-rated, otherwise it will, doubtless, soon be filled with tares and thistles."

* * * "The power of the press is incalculable; it is, probably, the very first element, next to the living voice, of general influence; should not, then the Lord's people make every effort to wield it on His side, and not tamely abandon it to the god of this world." * * *

"By occupying the field for the Lord, we do not mean, however, the publication exclusively, or even chiefly, of what is called religious matter. We mean that every subject,—History, Science, Education, Agriculture, News, and in a word, all the affairs of life,—should be treated and illustrated as part and parcel of the Moral and Providential Government of an infinitely great, just, wise, and good God, whose crowning mercy is displayed on the cross of Christ.

"'I have never wanted articles on religious subjects half so much as articles on common subjects written with a decidedly religious tone,' were the words of Dr. Arnold, one of the master minds of the age, words which the Religious Tract Society of London has appropriately chosen as the motto of a series of volume publications intended to supply the Christian family, and in fact, the world, with the requisite information upon important secular subjects, tinged, or rather embued, with the spirit of pure, undefiled religion, instead of the spirit of infidelity or licentiousness which has too often pervaded popular publications hitherto. In fact, they seek to efface the brand of Satan from popular literature, and substitute the stamp of Christ; and is this not a worthy object of Christian ambition? For ourselves we would say, that our highest aim is to spend, and be spent, in humbly endeavoring to contribute to the attainment of such an object."

At the close of the year the following course was laid down:

"It is our intention to carry on the 'Witness' substantially as it has been carried on during the past year—testifying for great truths as occasions may arise; acknowledging no sect but Christianity, and regarding no politics but those of the kingdom of God; yet devoting much attention to everything that regards the physical welfare and social improvement of the people of Canada."

This was no idle expression of intention, as the history of the paper to the present time gives evidence. As it was instituted it remains to-day. It is amusing to read that in 1864 it began agitating for public baths—which it is agitating for now—and that it began working for a reduction in postage, which soon after it was successful in obtaining. It began publishing pictures in the second number issued, and still gives more space to them than other journals. For several of its early years appeals were made to subscribers to assist it so that it might be able to live and become a success. But the crisis once past it grew rapidly and firmly. It became a semi-weekly at the time it adopted first in Canada the cash system of payments, by which it was able to give just twice as much for the money. On the visit of the Prince of Wales in 1860, a daily was commenced experimentally. It was so popular from the first that it was continued. Its circulation, which began with hundreds, rapidly grew to thousands. As it became prosperous its production became expensive. First it was a very small sheet which might easily be sold for a cent with some profit. But as it grew older the necessity for improvement became more pressing until it now, in interest and the quantity and value of its contents, excels papers which attain to the proud dignity of selling fewer copies at three cents or more.

At first it was printed on a single feeder press in a back office; now it is printed on the gigantic eight feeder spoken of above. In 1860 the weekly pay list amounted to $80, which was paid to sixteen employees; now it amounts to $925, paid to one hundred and twenty-eight employees.

The Northern Messenger was commenced in 1865, as a four-paged semi-monthly, under the title, Canadian Messenger. Its circulation then was small, but now it has attained to nearly fifty thousand copies. The New Dominion Monthly began its existence contemporaneously with the Dominion of Canada, on July 1st, 1867. It has not had a very vigorous life until late years, but it seems to have overcome all its hinderances. It is now enjoying much popularity, and a long and useful career is looked forward to for it. The youngest of the Witness publications is L'Aurore, a child of adoption, which is published in French,—the only Protestant paper in America in that language. It is undergoing its struggle for existence and is weathering the storm bravely, and every day adds to its chance of ultimate success. All these publications are sent forth in the hope that they will be the instruments of good and blessing to many. Unless this object had been in some measure fulfilled, it is most likely that none of them would have lived any length of time. They were all, at starting, losing ventures in a monetary point of view, and in that respect have thus far little more than made ends meet; but in the higher reward sought—that of becoming engines of usefulness, they have exceeded all expectation.

G. H. F.

(Continued from second page of cover.)

WHAT KIND OF WEATHER WILL WE HAVE TO-MORROW?

This question can be solved by the possessor of one of

Pool's Signal Service Barometers

with thermometer attached. If not already the possessor of one of these valuable weather indicators, send us $6 in new subscriptions to any of the Witness publications and we will send you one by express with all charges paid.

MUSIC HATH CHARMS.

By sending us $10 in new subscriptions we will send a very good concertina by express, with all charges paid.

For $10 in new subscriptions we will send you

a first-class Opera Glass.

For $15 and $16 in new subscriptions we have two sizes of beautifully finished

WIRE BIRD CAGES;

prettily painted and fitted up with perches.

We still offer the

DOUBLE-EDGED LIGHTNING SAW

which, on account of its size and usefulness, is well adapted for household and general purposes. It is so arranged with holes in the handle that a pole can easily be attached with bolts, so that it may be used for sawing off the superfluous branches and twigs of a tree. Send us $7 in new subscriptions to the Witness publications and receive the above mentioned valuable implement.

A most necessary article in the kitchen is an Apple Corer. For one new subscriber to the Weekly Witness, at $1.10, or four new subscribers to the Messenger at 30c. each, we will send a

SOLID IVORY APPLE CORER.

FOR YOUR HOUSE WIVES AND

DAUGHTERS.

If you want to make your wife happy, send us $17 in new subscriptions, and we will send you by express a set of FLUTING, CRIMPING AND SMOOTHING IRONS.

WHO WOULD NOT HAVE A PHOTOGRAPH

ALBUM?

When you can get a magnificent one by sending in $7 in new subscriptions to the Witness publications, or for $6 you can get one not so finely bound.

For $7 we will send something new in the shape of a pretty little

ALBUM RESTING UPON AN EASEL.

Every boy has a longing for a box of tools, so that on a rainy day he can exercise his ingenuity in making or repairing some article of furniture. For such we now offer a

A NO. 1 FAMILY TOOL CHEST

which contains Gauges, Screw-drivers, Chisels, Gimlets, a small saw, Tack-lifter, Pruning Knife, an Inch Square, a Measure, &c., &c., all of which fit into one strong handle, and when packed in the box may be carried in the pocket. This valuable assortment of tools will be sent to any person sending us $20 in new subscriptions to the Witness publications.

DO YOU PAINT?

By this question we do not mean painting your cheeks, but do you paint pictures? If you do, and have not a good box of paints, send us $5 in new subscriptions to the Witness publications, and we will send you a

BOX OF PAINTS,

fitted up with all the necessary requirements to fit you to fill the position of head artist to the family. For $7 in new subscriptions we will send you a better box.

A handsome and most appropriate present for a birthday or New Year's gift is a gold ring. For $5 in new subscriptions to the Witness publications we will send a SOLID GOLD KEEPER, while for $10 in new subscriptions we will send a GOLD RING, with PEARLS and GARNETS, and which retails at $4. If the [Pg 30] competitors prefer they can obtain Rings of greater value on equally advantageous terms. A lady in sending for any of these Rings should send a piece of thread or paper the size of her finger, so that one to fit may be obtained.

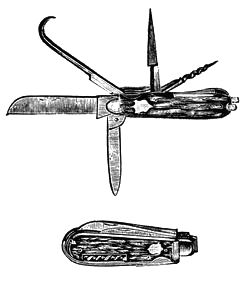

THE "EVER READY" POCKET KNIFE.

Fathers and Brothers Read This.

The desideratum of every living male is to become the possessor of a well stocked and thoroughly reliable pocket knife. The article which we now offer on such advantageous terms is not only a double bladed knife, but also contains several tools, which will be found to be very handy, and just the thing wanted in an emergency. The two engravings will show our readers the appearance and number of blades which the knife contains. The very effective and convenient SCREW DRIVER is hidden by the opened large blade, but is shown in the picture of the knife as closed. The HOOK can be made useful in sundry ways, such as to clean a horse's hoof, pull on the boots, lift a stove cover, &c. The back of the Hook makes a good tack hammer; while the inside of the Hook forms a small but strong nut cracker. The Punch makes holes in harness, wood, &c., which can be enlarged by its sharp corners. All close into a strong and compact handle. This POCKETFUL OF TOOLS will be sent to any person who sends us $5 in new subscriptions to the Witness publications.

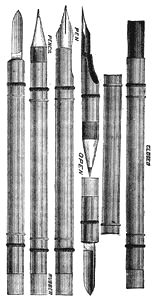

THE LLOYD COMBINATION PEN-HOLDER

is the best, and only practicable combination in the market. It is heavily nickel-plated, and with ordinary care will last a lifetime. It contains twelve articles in one. Pencil, pen-holder and a patent fountain pen, eraser, penknife, envelope opener, paper cutter, rubber and thread cutter. The knife is made of steel, firmly fastened in place, and can be used for ripping seams, cutting of hooks, eyes and buttons, for erasing blots, and many other purposes. The Combination has no open slots or ends, nor slides, to wear off the plating and get out of order. When not in use, the Lloyd may be so closed as to leave nothing but the rubber opened—even the point of the pencil may be turned in and protected; this could not be accomplished if the pen-holder was open at the ends or sides, as any opening would allow dust, dirt, moisture, &c., to enter. This handy Combination will be sent to any person sending us $2 in new subscriptions to any of the Witness publications.

THE AMERICAN HOUSEKEEPER'S SCALE

WEIGHS UP TO 24 LBS.

A pair of reliable scales is what every housekeeper should have. The Christian Union says of it: "American Housekeeper's Scale—the most convenient scale we have yet seen for housekeepers is that advertised in this week's issue. It is simple, accurate and cannot readily get out of order. The platform bears directly over the spring, and the nut is adjustable, so that the tare of the dish is had without the use of weights." To any one sending us $6 in new subscriptions to the Witness publications we will send one of the above described platform scales.

FOR THE LITTLE GIRLS ONLY.

Every little girl has an intense longing for a beautiful doll. Those little girls who desire a large and handsome wax doll to act as head of their doll family can easily earn one for themselves by canvassing for subscribers to our paper among their friends and relations.

SPECIAL OFFER.

To any little girl sending us $6 in new subscriptions to the Witness publications, we will send a large and

HANDSOME WAX DOLL.