Fig. 1.

Transcriber's Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

| VOL. I. | JANUARY, 1886. | No. 3. |

It may not be inappropriate to give in your journal a brief sketch of the history of medicine, by the consideration of which we may come to a better appreciation of our present standpoint as medical men. We may also the better understand how much we, as medical men, and the world at large, are indebted to the methodical, plodding workers of the past in the field of inquiry pertaining to the nature and cure of disease. Such review may have the effect of stimulating medical men to more careful observation and the recording the results of observations that they may be given to others for mutual benefit.

Science may be defined as “classified knowledge.” But all our knowledge is based on experience and observation. Medical science, like other sciences, taking the definition of Sir John Herschel, is “the knowledge of many, orderly and 98methodically digested and arranged so as to become attainable by one.”

In all cases art and observation precede and beget science, and give origin to its gradual construction. But soon science, so built up, begins to reflect new light upon its parents—observation and art—helps them onward, expands the range of vision, corrects their errors, improves their methods and suggests new ones. The stars were mapped out and counted by the shepherds watching their flocks by night, long before astronomy assumed any scientific form.

From the earliest ages the pains and disorders of the human body must have arrested men's anxious attention and claimed their succor. The facts observed, both as to hurts and diseases, and as to their attempted remedying, were handed down by tradition or by record from generation to generation in continually increasing abundance, and out of the repeated survey and comparison of these has grown the recognition of certain laws of events and rules of action, which together constitute “medical science.”

There is good reason for the belief that Egypt was the country in which the art of medicine, as well as the other arts of civilized life, was first cultivated with any degree of success, the offices of the priest and the physician being probably combined in the same person. In the writings of Moses there are various allusions to the practice of medicine amongst the Jews, especially with reference to the diagnosis and treatment of leprosy. The priests were the physicians, and their treatment mainly aimed at promoting cleanliness and preventing contagion. The same practice is approved by the light of latest science.

Chiron, the Centaur, is said to have introduced the art of medicine amongst the Greeks, but the early history of the art is entirely legendary. Æsculapius appears in Homer as an excellent physician of human origin; in the later legends he becomes the god of the healing art. His genealogy is obscure and altogether fabulous. He, however, soon surpassed his teacher, Chiron, and succeeded so far as to restore the dead to life (as the story goes). This offended Hades, who began to 99fear that his realm would not be sufficiently peopled; complained to Zeus (Jove) of the innovation, and Jove slew Æsculapius by a flash of lightning. After this he was deified by the gratitude of mankind, and was especially worshiped at Epidaurus, where a temple and a grove were consecrated to him. His statue in this temple was formed of gold and ivory, and represents him as a god seated on a throne, and holding in one hand a staff with a snake coiled around it, the other hand resting on the head of a snake; a dog, as an emblem of watchfulness, at his feet (an intimation very appropriate for the medical profession). The Asclepiades, the followers of Æsculapius, inherited and kept the secrets of the healing art; or, assuming that Æsculapius was merely a divine symbol, the Asclepiades must be regarded as a medical, priestly caste, who preserved as mysteries the doctrine of medicine. The members of the caste were bound by an oath—the Hippocratis jusjurandum—not to divulge the secrets of their profession.

In Rome, in the year 292 B. C., a pestilence (probably malarial fever) prevailed. The Sibyline books directed that Æsculapius (statue!) must be brought from Epidaurus. Accordingly, an embassy was sent to this place, and when they had made their request, a snake crept out of the temple into the ship. Regarding this as the god Æsculapius, they sailed to Italy, and as they entered the Tiber the snake sprang out upon an island, where afterwards a temple was erected to Æsculapius and a company of priests appointed to take charge of the service and practice the art of medicine. The name Æsculapius, then, is only an impersonation of medicine in the remote ages, or early ages of Grecian history.

Hippocrates is the first writer of medicine whose works have come down to us with anything like authority other than fable. Indeed, he was the most celebrated physician of antiquity. He was the son of Heracleides, also a physician, and belonged to the family of the Asclepiades, said to be about eighteen generations from Æsculapius. His mother was said to be descended from Hercules.

Hippocrates was born in the island of Cos (more anciently Meropis), an island of the Grecian archipelago of about one 100hundred square miles, probably about the year 460 B. C. Instructed in medicine by his father and other contemporary medical men, he traveled in various parts of Greece and Asia minor. He finally settled and practiced his profession at Cos, but died in Thessaly at the age of one hundred and four years (B. C. 357). Little is known of his personal history, other than that he was highly esteemed as a physician and an author, and that he raised the reputation of the medical school of Cos to a high degree. His works were studied and quoted by Plato. He was famous in his own time, and his works, some sixty in number, have in them many things that are not unworthy of consideration even after the lapse of twenty-two hundred years. Many of the works ascribed to Hippocrates are not well authenticated.

He divided the causes of diseases into two principal classes—the first consisting of the influence of seasons, climates, water, situations, etc.; the second of more personal causes, such as the food and exercise of the individual patient. His belief in the influence which different climates exert on the human constitution is very strongly expressed. He ascribes to this influence both the conformation of the body and the disposition of the mind, and hence accounts for the difference between the hardy Greek and the Asiatic.

The four humors of the body (blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile) were regarded by him as the primary seats of disease; health was the result of the due combination (or crasis) of these humors, and illness was the consequence of a disturbance of this crasis. When a disease was progressing favorably these humors underwent a certain change (coction), which was the sign of returning health, as preparing the way for the expulsion of morbid matters, or crisis, these crises having a tendency to occur at definite periods, which were hence called critical days.

His treatment of disease was cautious and what we now term expectant, i. e., it consisted chiefly, often solely, in attention to diet and regimen; and he was sometimes reproached with letting his patients die by doing nothing to keep them alive.

101His works written in Greek were at an early period translated into Arabic. They were first printed in Latin in 1525, at Rome. A complete edition in Greek bears a date a year later.

Several editions in Latin and other languages have appeared from time to time. An English translation of 'The Genuine Works of Hippocrates,' was published by the Sydenham society in 1848, in 2 vols., by Dr. Adams. The advance which Hippocrates made in the practice of medicine was so great that no attempts were made for some centuries to improve upon his views and precepts. His sons, Thessalus and Draco, and his son-in-law, Polybius, are regarded as the founders of the medical sect which was called the Hippocratean or Dogmatic school, because it professed to set out with certain theoretical principles, which were derived from the generalization of facts and observations, and to make these principles the basis of practice. The next epoch in the history of medicine is the establishment of the school at Alexandria, which was effected by the munificence of the Ptolemies, about B. C. 300. Indeed the whole race of Ptolemies (from Ptolemy I. to Ptolemy VII. B. C. 323 to 117) seem to have been patrons of learning and learned men. (Less so Ptolemy VIII. to XIII., B. C. 117 to 43. Ptolemy II., Philadelphius, was born in Cos about 150 years after Hippocrates.) It was by the patronage of these kings of Egypt that learning flourished in Alexandria during their reign.

In some of them this seems to have been the only redeeming feature of their character. Otherwise vicious, cruel, bloodthirsty in an extreme degree, they uniformly encouraged learning and learned men. (It seems to have been a hereditary trait.) Amongst the most famous of the medical professors of the School of Alexandria are Erasistratus and Herophilus.

The former of these was a pupil of Chrysippus, and probably imbibed from his master his prejudice against bleeding and against the use of active remedies, preferring to trust mainly to diet and to the vis medicatrix naturae.

Herophilus, born in Chalcedon, in Bythinia, flourished in the latter part of the fourth and the beginning of the third century 102B. C., and settled in Alexandria, especially was distinguished by his devotion to the study of anatomy. He is said to have pursued this to such an extent as to have dissected criminals alive. Several names which he gave to different parts of the body are still in use, as the torcular Herophili, calamus scriptorius, and duodenum. He located the seat of the soul in the ventricles of the brain. Only a few fragments remain of what he wrote.

About this time the Empirics formed themselves into a distinct sect and became the declared opponents of the Dogmatists. The controversy really consisted in the question, “How far we are to suffer theory to influence over practice.” While the Dogmatists, or as they were sometimes styled, the Rationalists, asserted that before attempting to treat any disease we ought to make ourselves fully acquainted with the structure and functions of the body generally, with the operation of medicinal agents upon it, and with the changes which it undergoes when under the operation of any morbid cause, the Empirics, on the contrary, contended that this knowledge is impossible to be obtained and if possible is not necessary; that our sole guide must be experience and that if we step beyond this, either as learned from our own observations or that of others on whose testimony we can rely, we are always liable to fall into dangerous and often fatal errors. According to Celsus, the founder of the Empirics was Serapion, who was said to be a pupil of Herophilus. At this period, and for some centuries later, all physicians were included in one or the other of these rival sects, and from the evidence of history the two sects or schools were about equal. From Phiny, who wrote about the middle and sixth, seventh and eighth decades of the first century, we learn that medicine was introduced into Rome at a later period than the other arts and sciences.

The first person who seems to have made it a distinct profession, separate from priestcraft, was Archagathus, a Peloponnesian, who settled at Rome about B. C. 200. His treatment of his patients was so severe and unsuccessful that he was finally banished, and no other mention is made of a physician at Rome for about a century, when Asclepiades of Bythinia, acquired a 103great reputation. His popularity depended upon his allowing his patients a liberal use of wine, and of their favorite dishes, and in all respects consulting their inclinations and flattering their prejudices; and hence it is easy to understand the eminence at which he arrived, for we see even in our own time men building up great reputations by similar practices.

This man with a long name—Archagathus—was succeeded by his pupil, Themison of Laodicea, the founder of a sect called Methodics, who adopted a middle course between the Dogmatists and Empirics. During the greater part of the first two centuries of our era the Methodics were the preponderating medical sect, and they included in their ranks C. Aurelianus, some of whose writings have come down to us.

They soon broke into various sects of which the chief were the Pneumatics, represented by Aretaeus of Cappadocia, whose works are still extant; and the Eclectics, who claimed as do the Eclectics of to-day, to select the best from all the other systems and to reject the hurtful. The most remarkable writer of this age is Celsus (about A. D.), whose work (De Medicina) gives a sketch of the history of medicine up to that time and the state in which it then was. He is remarkable in being the first native Roman physician whose name has come down to us.

Dioscorides of Cilicia flourished about the end of the first century. He accompanied the Roman army in their campaign through many countries and gathered a great store of information and observations on plants. In his great work 'De Materia Medica,' he treats of all the then known medicinal substances and their properties, real or reputed, on the principles of the so-called humoral pathology. Two other works are ascribed to him but their genuineness is questionable. For fifteen centuries the authority of Dioscorides, in botany and materia medica, was undisputed, and still holds among the Turks and Moors.

The following case came under my care during my term of service in the wards of Charity Hospital in this city. Mrs. D., age thirty-five, married, one child two years of age, was admitted to the hospital July 14, 1885, with the following history: She had always enjoyed good health, and there was no history of uterine disease. She menstruated about the first of April, 1885, did not menstruate in May, and supposed herself pregnant, as she had always been regular before, and during the latter part of May she had considerable nausea and other symptoms of pregnancy. About the first of June, while in church, she was taken with a severe hemorrhage. She was taken home and a physician called, who examined her and decided from the symptoms and history that she had had a miscarriage. There was very little hemorrhage after she arrived home, in fact very little at any subsequent time, but she did not recover well, had some pains in the abdomen, and she said had some fever all the time. Not getting on well, as she and her friends thought, it was decided to change physicians, which was done. The second physician concurred in the diagnosis of the first, and treated her evidently on the expectant plan, as any one would be compelled to do, owing to the difficulty of making a correct diagnosis at such an early stage. After a time, there being no improvement, she decided to go to the hospital. On admission she was quite emaciated and had an anaemic appearance; her temperature was about 99° to 100° in the morning and 100° to 102° in the evening. There was considerable tenderness in the right iliac region, extending into the hypogastric region. Uterus was not felt to be at all enlarged, but the os was patulous. There was an enlargement to the right of the uterus. This could be felt both externally and through the vagina; was of an irregular outline, and quite tense and tender upon pressure. A sound was introduced into the uterus and passed in about three inches and was deflected to the left quite perceptibly. It did not appear quite 105certain that there was nothing in the uterus, and in view of the history of the case it seemed justifiable to explore the cavity. Accordingly a good sized sponge tent was introduced and allowed to remain twenty-four hours, when it was removed and the uterine cavity explored with purely negative results. The patient had now been under observation over a week, and attempts made to improve her general condition with tonics and nutritious diet, but without success. Her temperature continued about 101° most of the time. A positive diagnosis had not been made, though it seemed that about everything could be excluded except extra-uterine pregnancy. At this juncture Dr. W. J. Scott was asked to see the patient. He did so and made a very careful examination, and gave it as his opinion the case was one of extra-uterine pregnancy. The next day Dr. Dudley P. Allen was called in consultation with Dr. Scott and myself. Dr. Allen's examination was careful and exhaustive, and at its close he gave it as his opinion that while there were some obscure points, the most probable conclusion was that the case was one of extra-uterine fœtation.

Having all arrived at this conclusion, independently of each other, it was agreed that as there was some obscurity in the case, and also that in the event of there being a fœtus outside of the uterus it had now advanced to about the fourth month of gestation; consequently the most favorable time for the employment of the electric current had passed. In view of these facts, and also of the fact that exploratory incisions are attended with comparatively little danger, it was decided to make an exploratory incision and determine what was the condition of things. If a fœtus was found remove it if possible. If the trouble was something that could not be removed, the incision could be closed and the patient probably in no wise injured. Dr. Allen was asked to operate, and on the sixth of August the operation was performed. There were present, Dr. Allen, Dr. Scott, Dr. Millikin and the house staff. The anæsthetic was administered, and before commencing the operation an aspirator needle of good size was introduced into the tumor through the vagina. Upon exhausting the air no fluid was obtained, but upon partially withdrawing the needle 106about a drachm of clear serum was obtained, which was thought to be peritoneal fluid. It was then decided to proceed with the operation. An incision was made about an inch above and parallel to Poupart's ligament, commencing at the anterior superior spinous process of the ilium, and terminating at the outer margin of the rectus muscle.

On opening the abdomen an adherent mass was found closely attached to the coecum. Strong bands also passed from the mass toward the symphysis pubis. In order to reach the mass more fully, and also the annexes of the uterus, the adhesions to the pubis were divided between ligatures. This having been done, it was still found to be impossible to detach the intestines which were closely adherent to the coecum, and nothing abnormal could be found in connection with the uterus. Failing to discover the cause of the adhesions about the coecum from the abdominal cavity, it was thought this might be accomplished by separating the peritoneum from the iliac fossa, and reaching the coecum from the outer and posterior side. This separation was continued until it could be carried no further without great danger of wounding the external iliac vessels, which were exposed for several inches. Although nothing further than a closely adherent mass of intestines had been found, an attempt to separate which had been carried to the limit of safety, and the cause of the malady had not been demonstrated with entire satisfaction, it was deemed best to close the abdominal incision, which was accordingly done.

The subsequent history of the cure was as favorable as could be desired. The wound united very readily. The temperature never rose above 103°, and was only at that point for a few hours; most of the time was 100° to 101.5°. Two weeks after the operation temperature was normal, a point it had not reached since her admission, and probably not for some time previous.

Patient was examined September 8; the tumor was found to be considerably diminished in size, and tenderness almost entirely disappeared. She had apparently gained in weight, and expressed herself as feeling well. She was discharged from the hospital September 9. On the tenth of October she again presented 107herself, according to agreement, and was examined by Dr. Scott, Dr. Allen and myself. The tumor had entirely disappeared, only a slight thickening of the tissues remaining, the uterus had resumed its normal position, and the patient, to all appearances, was as well as ever.

I have reported this case as one of extra-uterine pregnancy, and yet it will be seen by the report that the existence of that condition was not demonstrated at the operation, but it seems to me that the history of the case, both prior and subsequent to the operation, demonstrates pretty conclusively that it could be nothing else. Both the gentlemen who saw the case before operation were of the opinion that everything could be excluded except a collection of fluid, disease of the coecum and extra-uterine pregnancy, and to my mind (and the gentlemen who were called in consultation have expressed themselves in the same manner) the operation and the result of it excludes everything except the last mentioned condition. It may be said that in the treatment of the case less severe measures should first have been tried; that the electric current should have been employed before resorting to an operation. This subject was fully discussed, and the decision against the employment of electricity was unanimous, from the fact that the most favorable time for its employment had passed and the time had arrived when any further delay was dangerous. Then the danger from an exploratory incision is so small that it seemed to be more than counterbalanced by the knowledge that would be obtained by it. If an exploratory incision was made we would then be better able to tell what we had to deal with, and would also be in a position to deal with whatever was found in the most effectual manner, and it was thought that the most certain means of cure should be employed first and the patient not be subjected to the danger of delay in order that less certain methods might first be tried; also the high temperature seemed to render any delay more dangerous. The incision described was employed because it seemed that the tumor could be more easily reached and removed by means of it than by means of the central one. When, however, the mass was reached it was found to be so firmly attached to the cœcum by strong adhesions 108that it was absolutely immoveable. Under these circumstances it was decided that it would be unwise to attempt its removal, consequently the wound was closed and the operation desisted from. The subsequent history was all that could be desired, or could, under any circumstances, have been expected.

I think the most probable explanation of the disappearance of the tumor is this: The case was one of extra-uterine pregnancy of the abdominal variety, the ovum became attached to the peritoneum and a connective tissue proliferation was set up which surrounded it with a vascular sack, the walls of which kept pace with the growth of the ovum, and as they extended into the abdominal cavity formed adhesions to the cœcum, intestines, and other parts in the vicinity. During the operation these adhesions were ligated and divided, and in consequence the nutrition of the ovum was entirely cut off, and death and absorption was the result.

Since writing the report of this case the patient has been seen and examined. She seems to be in perfect health, and says she never felt better. There is not a vestige of the tumor remaining, except two or three small indurated spots that can be felt through the vagina.

Here is an universal and very strange infirmity, impeding speech, the origin of which must be anterior to the formation of languages. Hippocrates, the “Père de la Médecine,” Galen and Aristotle attributed it to an abnormal moisture of the brain and tongue and to a defective construction of the tongue, and their theories have been revived by modern writers. We find in Aristotle a double definition that stammering is an inability of articulating a certain letter, and stuttering an inability of joining one syllable to another. Notwithstanding the difference between the causes, the characteristics and the effects of both defects, several languages have but one word to express it; in 109French, for instance, “Bégaiement” means either stammering or stuttering. American dictionaries give the same definition for both; and in common talk no distinction is made, all stoppages in speech being called indiscriminately stammering or stuttering.

Speech being a combination of separate sounds produced by the expired air, it is certain that the first condition required for natural and correct speech is an undisturbed and normal action of the breathing apparatus.

The movements performed by the respiratory organs for the modification of the currents of air being produced by muscles owing their activity to nerves—motor and sensory—and the vocal organs being, like all parts of the organism, provided with nerves, it becomes evident that a general excitation of the nervous system, or any unusual excitement of the motor-nerves in action, will affect the muscles, cause irritation and create disturbances in inspiration, expiration and speech.

Normal inspiration is produced by a regular contraction of the diaphragm, and expiration is due to the elasticity of the tissue of the lungs. A spasmodic inspiration, during which a prolonged contracted spasm of the diaphragm takes place, produces stammering; such a convulsive contraction of the diaphragm can take place without attempting to speak, but any attempt to utter sounds during the spasm will result in stammering. At the end of the spasm, the air is then quickly expelled from the lungs. I have noticed stammering children that I have treated subject to frequent attacks of hiccough; in hiccough the expiration is quiet: an irritation of the nerves of the diaphragm brings about, with a violent inspiration, an attenuated convulsive contraction of the diaphragm, as in stammering.

In stuttering which is characterized by the presence of some spasm, in all articulations, labial, lingual, dental and guttural, although respiration is irregular and the respiratory organs do not work well, the inability to form and join the sounds comes from other sources than a spasmodic contraction of the diaphragm.

Stammering proper, when organic, might be called stammering 110of the diaphragm, and that distinction would be quite logical, as other organs wholly unconnected with speech show that peculiarity of being affected with stammering.

The influence exercised on the voice and speech by the respiratory mechanism is so considerable that a variety of theories on respiration have been advanced and discussed by physicians and specialists, not only with reference to speech impediments but specially for singing, elocution, acting and public speaking, and also in reference to general health. Writers and professors advocating exclusively so-called diaphragmatic, or costal, or abdominal respiration, are incorrect and perfectly deceived. The diaphragm, the ribs, and the muscles of the abdomen must all do more or less their special work, in order to carry on a normal and healthy respiratory act. An eminent physician, Dr. Ed. Fournié of Paris, says: “He who respires exclusively by one or the other of these alone (diaphragm, ribs or abdomen) must be indeed a sick man.” Costal or side-breathing is due to the elevation and depression of the ribs simultaneously with the contraction of the diaphragm. Abdominal breathing, the method taught to singers, is performed by the pressure of the abdominal muscles upon the anterior and lateral walls of the abdomen, forcing up the diaphragm, and thus expiring almost completely the air in the lungs.

Medical and scientific investigations concerning speech defects have been as considerable as it is contradictory. The observations of prominent doctors and specialists, some of them being afflicted themselves, have in the most argumentative thesis attributed stammering-stuttering to numerous and varied causes, the enumeration of which has a real historical and pathological interest:

Faulty action of the tongue, disorders of tongue-muscles, spasms of the glottis and epiglottis, troubles located in the larynx and in the hyoid-bone, abnormal depth of the palate, affections of the muscles of the lower jaw, spasm of the lips, abnormal dryness or moisture, or lesion of brain, nerves, muscles or tongue, nervous affection, intermittent necrosis, general debility or weakness, chorea, incomplete cerebral action, imperfect will-power, want of harmony between thought and 111speech, imitation and habit.—Such is the nomenclature of the principal ingenious theories exposed and upheld by those who have made a study or a business of the cure of speech defects. But some mistaken innovators, not satisfied with theories and investigations, gave to their ideas an experimental form. Forty and forty-five years ago a surgical craze, originating in Germany as a pretended cure of speech defects, was raging all over Europe. Stammerers and stutterers suffered a variety of operations, the horizontal section of the tongue, the division of the lingual muscles, the division of the genio-hyo-glossi muscles, the cutting of the tonsils and uvula, etc. Such suppression and mutilation of the vocal organs could not bring any cure, as it was proved, and some patients having died, the operating craze was put to an end forever. Since that it is by more gentle means that all attempts have been made to cure impediments of speech. The unfortunate stutterer has no longer to dread the misemployed zeal of surgical operators, and now it is even his own fault when he allows himself to fall into the hands of ignorant charlatans.

Without lessening the value of former discoveries, I will say that the specialist of to-day must disagree with the most eminent authors and the most prominent works on that question, including Velpeau, Amussat, Becquerel, Lenbuscher, Bèclard, Bristowe, etc., and arrive at the conclusion that their testimony was one-sided, being confined to their own or few cases, and limited to mere theory and speculation. For the treatment of vices of speech, with the indispensable knowledge, long and practical experience alone will instruct what is the right method to pursue. The various theories on the nature and causes of that infirmity, and the enumeration of the different responsible organs may be, at the same time, partly false and partially true; but they have proved powerless to cure or relieve.

In all varieties and forms of stammering-stuttering all the vocal organs can be blamed, and have, in each case, to be reformed and improved. In the majority of cases we find some traces of the organic peculiarities aimed at by authors, even if their influence is doubtful. Respiratory trouble is at the bottom of every case. The internal organs, and the tongue, the 112lips and jaws are to some extent in an abnormal condition, and suffer a convulsive spasm; they have to be treated, strengthened and made flexible. The nerve-function of the organs of speech is also disturbed. We notice in the majority of cases, to a certain degree, organic weakness, nervousness, lack of will-power, and above all, disregard of all natural rules and ignorance of the use and natural functions of the organs of speech.

As to prognosis, I will say that all stoppages in speech, accompanied by spasms, sometimes hardly perceptible, and which are not the result of paralysis or lesion, may be classified as stammering-stuttering, and can always be cured, whatever may be their origin or cause, or their intensity, and that it is only a question of time and perseverance even for the most stubborn cases.

The treatment of stammering-stuttering, which does not comport any operation nor drugs, is purely educational. It consists in remedying the defect and teaching properly the science of speech. Still, I think, that in many cases a strict attention ought to be paid to hygienic measures; some medical care and prescription would help the patient and the instructor. In the actual condition of things no regular practicing physician can afford to devote his ability and time to the treatment of speech defects. But doctors have to study the infirmity, to know that it can be cured, that it is an interesting and complex disease, in the treatment of which the progress of medical science can bring a revolution. Physicians the world over having wholly neglected to consider that question, the result has been to leave it in the hands of incompetent persons. In principle the question of speech impediments cannot be separated from medicine. Physicians cannot ignore an infirmity in which the organism itself is undoubtedly involved, at times in a very intricate manner and to a considerable extent. Every true physician feels that he has a sacred mission—to alleviate suffering; the tortures of a large class of people partially deprived of the faculty of speech are well worth his care and attention. Medical students ought to be provided with the means of becoming versed in an affection offering such a large 113field for study and work, where so much light is needed, and where the prospects of discovery and improvement from a scientific and medical standpoint are so legitimate. The family physician, often consulted, will do good work in advising his clients to try and get rid of such a terrible affliction, to be cured without delay, and in preventing them from falling into the hands of quacks.

Not long ago as a bottle was placed upon the counter of a pharmacist to be refilled, its inner walls were observed to be richly decorated with the active principles of the compound. A witch-hazel doctor standing by declared the decorated walls to be the secret of the patient's recovery, but upon inquiry it was found that the patient was no better. Still they had decided to try another bottle, and the apothecary was not the one to object. The investigation was carried no farther, but if it had been the same old story of incompatibles would have been retold. To the aqueous solutions containing oleoresinous tinctures or extracts (such as cannabis indica, guaiac, benzoin, lupulin, ginger, myrrh, cubeb, eucalyptus, sumbul, and many others) a sufficient quantity of carbonate or calcined magnesia should be added. A few grains (say three to twenty) to the prescribed dose will suffice for a good suspension, and will be found in most cases unobjectionable of course in an acid mixture.

There are many conflicting reports of this class of medicines, owing to unscientific prescribing as well as unreliable preparations. The activity of this class of medicines demands nothing short of strong alcohol for their extraction. Yet many weak and worthless preparations may be found in the market. If the unscientific observers would look more to the quality of their goods, these conflicting reports would begin to subside.

A physician once told an apothecary that he prescribed fluid 114extracts because he found them more reliable than the tinctures. This was not true, and could not be proven. Upon investigation it was found that his prescribed dose of fluid extract of digitalis was equivalent to fifty-five drops of the tincture, a dose larger than he intended to prescribe. With such science the witch-hazel doctor will ride a high horse, and come in on the home stretch with flying colors. No singer can sing well who sings too many songs, and no beginner will prescribe well who prescribes too many medicines. This song has been sung much but not half enough, for it is not borne in mind. Many fail with a remedy simply because they have failed to master it.

Mastering the few is said to be the key to success, and the writer believes it, for he has seen it proven. An eminent physician from New York was once called in consultation to a western city. His prescription was mercury iodide, potassium iodide, and infus. gentian. He stated (and the other physician said, “I see”) that the only object of the potassium was to dissolve the mercury iodide. But potassium's great affinity for iodide accepted it, at once dropped the free mercury to the bottom, likely to be taken all at the last dose, equal to fifteen or twenty grains of blue pill. He had failed to master this remedy.

The witch-hazel doctor could not declare this time that the untaken medicine saved the patient's life, for he died before taking it. But he could smile at the prescription appropriately, were none of his own to be found on file.

Another phase of fashion reminds one of the old saying “distance lends enchantment;” for there is just as good sense in going to New Brunswick to have a boil lanced as there is in bringing syrup hypophosphates from that place.

The present pharmacopœia contains a splendid formula for this syrup—one, too, with which phosphoric acid, quinine and strychnine are perfectly compatible. A pharmacist that will not exert himself to furnish the very best article for a physician's prescription is not entitled to the physician's respect. But for a physician to expect a pharmacist to send all over town for some foreign preparation that might, in almost all cases, be 115better made at home, affords a weapon to retard medical science and advance the nostrum manufacturer. The more scientific physicians well know and admit that a good pharmacist can better judge of a compound than a physician, who seldom stops to test it, but prescribes it a few times and, in many cases, never thinks of it again, or, perhaps, not until he presents his bill and finds the patient's money all gone for semi-proprietary medicines that cost from fifty to one hundred per cent. more than would have paid for better compounds. Physicians will only have to examine these medicines after they have stood a year or two, and in many cases a much less time, to see the force of this argument.

Among these nostrums are found numerous preparations we could mention, including many emulsions, elixirs, etc. It is comforting to see the better class of physicians giving these nostrums a “wide berth.” Others will follow their example if they investigate and master their remedies.

Having no time to continue this rehearsal, I close with a plea for more science, more investigation, that we may not have to send to Buffalo for syrups of Dover powder or farther east, west or south for nostrums, but master the remedies we have, saving to the physician and patient from fifty to one hundred per cent., thus mitigating the popular cry of the high price of medicine. There should be a table of incompatibles in every medical college as prominent as the multiplication table in the schools, or pharmacists should be allowed more freedom to prepare medicines properly, instead of being held to the letter.

The writer should not complain, for he has been liberally treated by the profession in this respect; but he does not feel at liberty to add magnesia to a mixture unless so ordered. A pharmacist did this at one time in a tar-and-water mixture, gaining great praise from the physician. (Making the tar quite thin with a little alcohol, then absorbing the whole with magnesia, and emulsifying by adding the water gradually.)

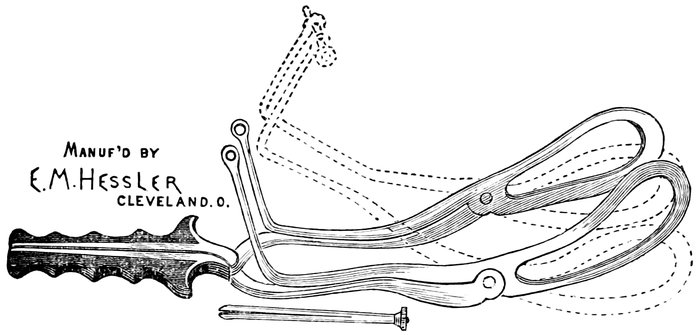

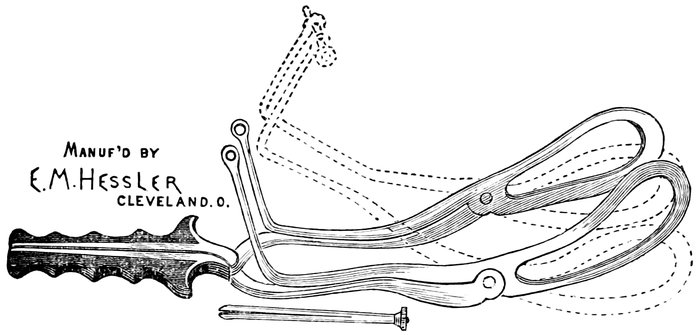

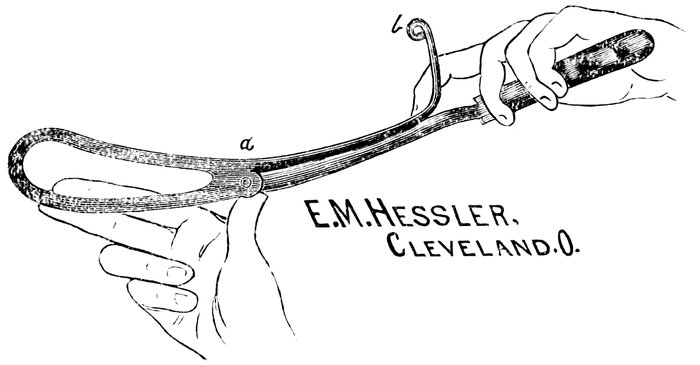

The accompanying wood-cuts represent the forceps recently introduced to the profession by Dr. Breus, formerly first assistant in the clinic of Prof. Carl Braun, Von Fernwald, in Vienna.[1]

1. Archiv für Gynäcologie XX Band 2 Heft.

It is the simplest in construction of the so-called axis traction forceps, and is specially designed for the extraction of the head presenting high above the pelvic brim. In size, shape, curves, handles, lock, etc., it is an exact model of the J. Y. Simpson forceps—the favorite instrument of the Vienna school.

Fig. 1.

Unlike the ordinary forceps, however, it is constructed with a hinge-joint (a Fig. 2) at the angle of the fenestrum with the shaft, which permits of a movement of the blades through an arc of about 40°. An elbow on the lower margin of the blade arrests the further movement in the downward direction, and a prolongation of the upper fenestrum of the blade, in the form of an arm (b), is continued backward parallel to the shafts. This arm turns at an angle of 100° in front of the lock and terminates in an eye, through which the split pin seen at the side of the 117instrument passes. The pin fits loosely in the eyes and restricts, while still permitting considerable latitude of movement to the blades. At the suggestion of several gentlemen to whom the instrument was shown, the shaft has been lengthened nearly one inch. In other respects the forceps is an exact counterpart of those now used in the lying-in department of the General Hospital in Vienna.

Fig. 2.

The principal advantages secured by these forceps are:

1. That they are best adapted to draw in the pelvic axis.

This was the special claim set up by Aveling for his Sigmoid forceps. Tarnier also, in introducing his axis traction forceps to the profession in 1877 (for an account of which see British Medical Journal, May 26, 1878), proves by means of diagrams and figures that, “in pulling on the classical forceps, it is impossible to make the traction exactly in the line of the pelvic curve,” and that two forces are actually exerted—one in the direction of the inferior straight, and the other at right angles to this in the direction of the pubes, while the head tends downward in the pelvic curve—the resultant of these two forces. This “vicious pressure” upon the pubes represents not only so much force lost, but also tends to injure the maternal soft parts, and can only be overcome by using the axis traction forceps. As the head descends, the pelvic curves of the blades become less and less, until, as the head arrives on the floor 118of the pelvis, the forceps are nearly straight. At the moment the head sweeps over the perineum the blades are still further deflected, until they form an angle with the shafts, as shown in the dotted lines of Fig. 1, thus forming the perineal curve of Herman's, Aveling's and Tarnier's forceps.

2. These forceps give the greatest permissible freedom of movement to the head during traction.

By the loose connection of the blades each possess a degree of independent movement, but always in a plane parallel to the other, so that the head may rotate during traction. The carrying out of this important principle is the chief advantage of this instrument over all other axis traction forceps.

3. An index is supplied by the arms and pin, which serves to indicate the advance and position of the head.

The application of Breus' forceps is in no wise more difficult than that of the ordinary instrument. Having disinfected, warmed and lubricated the blades, and the patient being prepared by an irrigation of a solution of bichloride, one part in 2,000, and placed in the lithotomy position, the handle of the left blade is taken up by the thumb and three fingers of the left hand (as one would hold a fiddle bow), the index finger pressing the projecting arm firmly against the shaft, as the thumb of the right hand guides the blade forward in the groove between the index and middle fingers introduced into the vagina. The right blade is then introduced in a similar manner and locked, and the pin inserted in the eyes of the projecting arms. The traction is made upon the handles in the axis of the brim, without changing its direction until the head presses on the perineum. Prof. Braun prefers, at this point, to remove the forceps and complete the delivery in the ordinary way.

The same precautions are necessary in using the axis traction as the ordinary forceps. Especially must it be remembered that, as the force is exerted directly in the axis of the pelvic curve, and none being lost, much less is required, and generally the force of one hand is quite sufficient. To avoid too great compression of the head, the compressing force should be removed by opening the lock in the interval of each traction.

Breus' forceps, after being tested successfully in all possible 119difficult cases—in many where the operator had failed with the ordinary forceps, as I myself have seen—is now recognized as the instrument best adapted to those cases where the head presents high above the pelvic brim.

It is said of Baltimore that socially it is different from other large cities in the freedom as well as the cordiality with which it extends its hospitality. The business men and their clerks are polite and attentive. They do not display the trait, so common in the metropolis, of incognizance—even to rudeness—if one chances to be on a tour of inspection instead of purchase. The impression is at once made, and very forcibly, that a Baltimorean has plenty of time, that he is not hurried. He will stop on the street and direct a discomfited stranger, and has been frequently known to turn aside from his duties and accompany the lost one to where he could take care of himself. This is a natural element in the entire populace, and is very prominent in the medical profession. A stranger is welcomed so heartily that he feels at home immediately, and can settle down among friends.

It occurs to me that this easy-going feeling has had much to do in keeping our city from occupying the prominent position in education and authorship that her opportunities, and conditions in general, would lead us to expect. I am glad to say that she is arousing from her lethargy, and recently her pen has been busy. Several works have emanated from the profession here which have attracted much attention, and have been quite extensively read. Notably among them is a 'Text-book of Hygiene,' by Dr. Rohe, and 'The Physician Himself,' by 120Dr. Cathell, which has reached a fifth edition and a sale of over fifteen thousand copies. I should like to say, concerning these two works, that no physician, especially if he be under thirty-five years of age, should be without them. Two other works, 'A Manual on Nervous Diseases,' by Dr. A. B. Arnold, an old, experienced and able teacher, and one on 'Practical Chemistry,' by Dr. Simon, have been much studied and commented upon. They are limited to special subjects and will not naturally obtain a large class of readers. These, like the long-delayed blade of corn, which pushes its emerald tip heavenward and bears upon its face the sparkling matin dew, give promise of a fertile soil and of abundant fruitage.

At the last meeting of the Medical and Surgical Society—which we had the pleasure of attending—there was an interesting discussion on cerebral troubles of syphilitic origin. A number of cases were related. The various symptoms of these maladies are familiar to your readers. The treatment which was successful in all but one of the cases here reported, was mercury and iodide of potassium. The plan preferred for the administration of mercury is by inunction. All the debaters insisted upon the full constitutional effects of the drugs. As one gentleman put it, “the system must be saturated before a cure is assured.”

I might mention among the symptoms, that those manifested by the eye were not regarded as reliable. In one case the only manifestation was a persistent and severe supra-orbital and occipital neuralgia, and for some time the man was in consequence wrongly treated.

One physician noted insomnia as a distinct and always present symptom. Also as a point of differential diagnosis between the convulsions of epilepsy and those of local lesion of the brain, that in the former there is no consciousness of having a convulsion, while in the latter such consciousness is very clear, at least at the beginning of the spasm.

A case of pelvic peritonitis of the chronic form, reported by the president of the society, elicited much discussion, especially upon the subject of exploratory abdominal incision as a means 121of diagnosis. He noticed that the younger surgeons favored the operation, but the older ones were more conservative.

A member reported one of those peculiarly (excruciatingly, I ought to say) interesting cases of labor, in which, by great exertion on his part, and the assistance of two physicians and three (I think is the number) midwifes or old ladies, he managed “to save the old man,” though the other parties concerned passed on into the mysterious future. (The society is expected to laugh a good deal just here, and of course we expect the readers to do the same.)

At a recent meeting of the Baltimore Medical Association a member related the following experience: In a family of three children, the oldest, who had scarlatina four years ago, contracted diphtheria; in a few days a younger one became ill with the same disease, but accompanied in forty-eight hours with a distinct eruption of scarlatina. A few days later the youngest was stricken with scarlatina, but had no symptom of the diphtheritic trouble.

The report brought out the thought of most of the members present. The two questions of “the identity of pseudomembranous croup and diphtheria,” and of “diphtheria a local or a constitutional disease” were again argued, and, as usual, no opinions were changed. Like the Scotchman, each was willing to be convinced, but he could not find any one able to convince him. Two points were fully agreed upon, namely, that the presence of membrane in the fauces, and of sequellæ, are not of importance in diagnosis; also that nearly all of the cases in which the posterior nares becomes seriously implicated are fatal. One gentleman advanced the opinion, supported by “statistics” (as accommodating a friend as “facts”), that when the submaxillary glands were enlarged in this disease recovery took place; when they were not enlarged, death occurred. The doctor did not say that death occurred at once or within a few days, so we shall be charitable and suppose that he meant sometime during the succeeding hundred years.

Notes of two very interesting cases of myelitis, followed by spastic paraplegia, were read and discussed. The author made special mention of the exaggerated tendon-reflex being always 122present in disease of the lateral tract of the cord, and that this symptom is diagnostic—if hysteria be first excluded. He also noted in these cases that the condition of the muscles of the posterior portion of the legs (lower) was very tense, producing an impression on grasping them similar to that noticed on grasping a piece of iron. Neither of these men were able to place the heel upon the floor when standing erect. No amount of effort on their part could enable them to accomplish it. Neither of them were improved by the use of the iodides.

If “K.” will send name, we will take pleasure in publishing his article in our next number.

White physicians in Oriental countries are asked almost daily whether they cannot prescribe for suffering women without seeing them. Oriental women, debarred by social custom from consulting male physicians, are the victims of great and unnecessary suffering. They are thus shut off from the aid of western medical skill, though they know its value and are desirous of availing themselves of it. The movement in China and Japan to introduce female physicians from Europe and America is conferring great benefit upon the women of those countries and making brilliant opportunities for skilled women who go there. The hospital for women recently opened at Shanghai, under the charge of American women, is already filled with patients. An association has also been formed in India for training native nurses.

The new college building of the Medical Department of the Western Reserve University is being pushed rapidly to completion. The stone-work is done and the roof is now being placed in position. When once inclosed, work upon the interior can proceed regardless of the weather. It is thought that 123it will be so far completed as to be used for commencement exercises the last week in February.

Four cases of trichiniasis were reported to the health officer of Cleveland, December 23d. All were members of one family and had partaken of the same uncooked ham. The physician reporting the cases, Dr. J. F. Armstrong, had his suspicions aroused by the symptoms presented, and at once examined the suspected meat. His fears were confirmed by finding trichinæ spirolis in the remaining portions of the ham, and his observations were verified by the health officer. None of those affected are as yet seriously ill. It appears necessary to sound a constant warning against eating uncooked pork.

“No Children Allowed.”—The “Solid Comfort” will answer for the occasion to designate an elegant apartment house opened about two years ago in a suburb of Boston. It was finished with all modern conveniences and inconveniences. There were electric bells in a row at the door, so that the afternoon caller could ring up nine different and peaceful maid servants before getting into communication with the family she came to see; there were fire escapes and telephones, and elevators and speaking tubes; and, in all probability, safety valves and submarine cables. But the crowning joy of all was the fact that no children were allowed within its walls. It was built for the accommodation of childless couples, and to ten childless couples were the suites let. How great was the quiet and calm of that sheltered retreat, until one ill-starred morning, when the cry of an infant, shrilly and piteously, broke the stillness! Horror and indignation upon the part of nine guiltless couples! And yet, so weak is humanity, that before the end of the second year there were children in seven of the ten families. The childless young couples were childless no more; and when the owner of the building complained to his friends of the unfair treatment he had received at the hands of his tenants, they all laughed in his face and advised him to let his apartments to bachelors.—Sanitarian for November, 1885.

| A. R. BAKER, M. D., Editor. | S. W. KELLEY, M. D., Associate Editor. |

Original communications, reports of cases and local news of general medical interest are solicited.

All communications should be accompanied by the name of the writer, not necessarily for publication.

Our subscription price remains at one dollar per annum in advance. Vol. I begins with November, 1885. Subscriptions can begin at any time.

Remittances when made by postal order or registered letter, are at the risk of the publishers.

It is reported that a Dr. Sax, of France, has discovered in all forms of beverages containing alcohol a “bacillus potumaniæ;” and it is claimed that this bacillus multiplies in the system of the drinker and circulates in his blood, and that when he gets delirium tremens he is not the subject of hallucinations but sees the reptilian forms that are inhabiting his own brain and optic apparatus.

While the microscopists and various ologists are discussing this, we will tell a story of a certain worthy practitioner of our acquaintance. The doctor's hobby was malaria. If a person 125came in with a headache it was “malarial headache;” backache, “malarial backache;” legs ache, “malaria.” One day a man came in with his arm hanging helpless. Our friend promptly began about malaria. The man said he had heard of break-bone fever, but that he had fallen off a street car and didn't think this was a malarial fracture.

Some of the best fellows we know ride hobbies, but let those who now bestride the bacillus beware where the creature carries them.

The subject of artificial butter continues to agitate the public mind and stomach. There are involved a few plain principles which, if applied, will elucidate the whole matter.

Good glycerine can be made from dogs or horse fat, sugar from rags; sea water or the most impure lake or river water can be changed to azua pura by distillation; good suet or tallow can be so treated as to make a nutritious and harmless article of diet. Now, if old grease can be so manipulated and modified as to give a pure and edible result, cheaper than old-fashioned butter, the latter will have to go out of fashion.

In that case, wrong would lie only in selling the article for what it is not, and not in the fact of its being also injurious to the user. Just as in many synthetically manufactured wines and cigars, which are not chemically essentially different from the article they imitate, but are fraudulent because they are sold as imported or genuine, which they are not.

If the goods are good, let them be sold for what they really are; and if the old-fashioned butter is higher priced, let those of us who like pay the difference for our fastidiousness. The manufacturers of the new butter should expend their efforts and their money in perfecting their process, so as to give an innocent and useful food, and in proving that it is so, instead of opposing the action of the Board of Health. The verdict of the health authorities should be regarded as final by every individual of the public, and until the new article is pronounced at least harmless, no one should think of using or handling it any more than they would measly pork or spoilt fish.

We have selected a few recent cases of suits for malpractice with the object of calling the attention of physicians to the importance of adopting some plan looking toward the suppression of quackery and the protection of professional rights when assailed by hostile influences.

“In April, 1884, Dr. Graves of Petaluma, California, was called to see Mrs. Winters, the wife of a laborer whose family he had attended gratuitously for nearly sixteen years. He found that the woman, who was fifty-eight years of age, had fallen from a height and injured her ankle. The limb was very much swollen, so as to interfere with examination, but no crepitus could be elicited, neither was there any displacement, or shortening; and as the swelling continued, the limb was placed in position and wrapped loosely in cloth saturated with anodyne lotions. The patient, we are told, received every attention from Dr. Graves, but there was left finally some stiffening of the joint and a very slight inversion of the foot. No complaints were made until a new doctor arrived in the town, who told the patient the limb had been badly treated and advised her to sue for malpractice. The case was examined by ten of the chief surgeons in the State, including Drs. Lane, McLean, Morse and Dennis, all of whom said that there might have been a sprain or an incomplete fracture of the external malleolus, but that the ends of the bones were in perfect apposition and never had been separated, and that the stiffening was probably due to inflammatory adhesions. Two other doctors, one of whom being he who advised the suit, testified that there was shortening of the limb, and that the lower fragment of the tibia had been driven up and behind the fibula. One of these would-be surgeons, Dr. Wells, is nearly eighty years of age, and had not read a work on surgery for thirty years; the other, Dr. Ivancovich, confessed he had no special experience in surgery. Their incompetence may be judged from the way they measured the patient's limb in court. This was done by taking a carpenter's rigid rectangular rule, and measuring the limb as she maintained 127the upright position. The result was that in the opinion of nine jurymen the testimony of two unknown, inexperienced general practitioners out-weighed that of ten specialists in surgery, all of whom possess a national reputation, so that a verdict was returned in favor of the plaintiff, awarding her eight thousand dollars damages.”

“Some three years ago Dr. Purdy, a well-known and esteemed physician, gave notice to the health department of New York City, in accordance with a regulation of the sanitary code which makes it the duty of physicians to notify this department of cases of infectious diseases, that in his opinion a young woman who was under his treatment was suffering with smallpox. The department sent one of its medical officers to investigate the case. The diagnosis made by Dr. Purdy was then confirmed and by the authority of the board of health the patient was transferred to the smallpox hospital. After a day or two the patient was discharged. This patient immediately brought suit against Dr. Purdy for $10,000 damages, on the ground of injury to her business and of the false diagnosis upon the part of her medical attendance. The jury which tried this case gave a verdict of $500 against the defendant. The singular injustice of this verdict resides in the fact that damages should have been brought against Dr. Purdy, when, in point of fact, the injury to the plaintiff was inflicted by the health department, which not only affirmed the diagnosis of the attending physician, but caused the removal of the patient to be made to the smallpox hospital. It appears that Dr. Purdy's sole error in the case was in informing the health authorities of the possible existence of smallpox. In the discharge of a duty imposed upon him by a city ordinance he has been subjected to the expense and annoyance of a legal case, and has been mulcted by a jury to the extent of $500.”

“Another suit of a blackmailing character has been brought against Dr. E. Williams and partners of Cincinnati, O. According to the Cincinnati Medical News, the charge was that they had permitted a small scale of iron, that had entered the eye of a boy, to remain, by which he eventually became blind—the 128sound eye becoming affected through sympathy with the injured one and losing the power of vision. It was proven on trial that the boy had visited the office of Dr. Williams but twice, and then had ceased calling because he was informed that, to preserve the sound eye and be saved from blindness, he must consent to have the eye that had been destroyed removed from its socket, to which his parents would not consent. For several months after declining the services of Dr. Williams and associates, he spent his time in going the rounds of the specialists of diseases of the eye, putting his case in charge, at different times, of both regular and homœopathic physicians. Every ophthalmologist by whom he was treated informed him that the only way by which he could avoid becoming blind was to have the injured eye removed. Finally, after losing sight in both eyes, he brought suit. The medical testimony, we are told, was uniformly in favor of Dr. Williams, but the jury disagreed.”

“The Boston correspondent of The Northwestern Lancet writes: 'Dr. A., a reputable practitioner living in a New England city, attended Mr. B. for a fractured thigh. The case did well, and the patient recovered without deformity. No measurements were recorded by the attending surgeon, but he was able to swear that the result was to him perfectly satisfactory. A year or two later the patient entered suit against Dr. A. for malpractice, and exhibited a leg considerably shortened and deformed. A jury at once found a verdict for the plaintiff, and awarded damages in some six or seven thousand dollars, a sum which seriously crippled the physician. He devoted his energies thereafter to discovering what he believed to be a fraud, and finally obtained evidence that B. had, subsequently to his recovery under A.'s attendance, again fractured the same thigh while in the Adirondack wilderness, and had, on that occasion, had no surgical attendance whatever. The physician was able to recover his money, but was at the expense of his detectives' and lawyers' fees, to say nothing of years of anxiety and of damage to his professional reputation.'”

The case of Drs. Reed and Ford of Norwalk, Ohio, will be remembered by many Cleveland physicians. Miss Pierce, a 129comely young lady, sustained a Colles fracture, and was attended by Drs. Reed and Ford. Suit was brought twice in county court and dismissed because plaintiff did not desire to try the case. A few days before the case was outlawed, suit was brought in the United States Court at Cleveland. Many physicians were called on both sides, and the testimony of all the physicians, with probably one exception, was that the treatment was good and the result better than is usual with such fractures. Flexion extension, pronation and supination were perfect. She had, however, the power, when the arm was midway between pronation and supination, of bending the wrist toward the radius, and by making the head of the ulna prominent she was able to make an apparent deformity. Her case, then, was her ability to make an apparent deformity by twisting her wrist. (She could do the same with the unfractured wrist.) She was a good-looking woman, and therefore entitled to sympathy. She followed up the case persistently for six years, therefore there must be some merit in the case. The doctors all testified against her, so there was a combination of the doctors which must not be countenanced. Upon this strong case twelve intelligent jurors awarded thirteen hundred dollars damages. The judge subsequently reduced this to five hundred. Is it any wonder, when such things can be done in the State of Ohio, in the name of justice, that physicians like old Dr. Kirtland refused to attend cases of fracture under any circumstances? or that it is not unusual to hear surgeons of recognized ability say they dare not possess property for fear of suits for damages?

Frequently physicians are accused of malpractice, and rather than undergo the expense and inconvenience of a suit they will submit to an extortion of money; or if a suit is lost in court through prejudice, unjust decisions, inability to secure good council or other unavoidable cause, rather than undertake to carry the case to a higher court, the physician will pay the damages, and thus establish a precedent which renders every physician under similar circumstances liable to a suit for damages. It is always observed whenever a large amount of damages is collected from a physician, numerous other suits on 130all sorts of cases are commenced. Such a condition of affairs ought not to exist. Physicians can not expect legislators to look after their interests until their grievances are made known. The testimony of physicians as individuals will not carry enough weight to accomplish anything. Moves have been made in this direction through the County and State societies and failed first, because the members of the societies are divided among themselves, second, because they represent only a fractional portion of the profession. Out of the thousands of physicians practicing in Ohio there are only about seven hundred members of the State society.

We believe the object of county, state and national medical societies are intended for purely scientific work, and the less of medical politics brought into them the better. But when there is some definite end to be accomplished, some gross wrong to be righted, some persecuted physician defended, there ought to be some organization including physicians of all schools, independent of the medical societies as now organized. When a physician is sued for damages, if his case is worthy of being defended, the entire profession ought to lend him their moral as well as financial support, and this could be rendered in no way better than by means of some organization similar to the Medical Defense Association of England.

Dr. John J. King, secretary of Trumbull County, O., Medical Society, saw our article in the last number of the Gazette, in which we urged the necessity of an elevation of the standard of preliminary education of medical students, and sends us the following resolutions which were unanimously adopted by the Trumbull County Medical Society, January 31, 1884, and Drs. Julian Harmon, J. R. Woods and T. H. Stewart appointed medical examiners. The requirements are about the same as 131adopted by the Pennsylvania State Society at their annual meeting in Norristown, Pa., May, 1883:

TO REGULATE THE STUDY OF MEDICINE.

Resolved, I.—That this Medical Society shall annually elect a board of medical examiners, to consist of three members, whose duty shall be to examine applicants for admission to the study of medicine.

Resolved, II.—All applicants for admission as students of medicine under the tuition of members of this society shall present themselves before the board of medical examiners and satisfactorily pass examination in the following requirements:

| “I.— | A written statement, previously prepared, setting forth the candidate's course of study. | |

| II.— | An essay. | |

| III.— | Writing from dictation. | |

| IV.— | Spelling—Oral and Written. | |

| V.— | Reading. | |

| VI.— | Geography—Descriptive, Physical. | |

| VII.— | Political Economy. | |

| VIII.— | History—Ancient, Modern. | |

| IX.— | Geology. | |

| X.— | Botany. | |

| XI.— | Chemistry. | |

| XII.— | Natural Philosophy. | |

| XIII.— | Mathematics— | Arithmetic complete; |

| Algebra, through quadratic equations; | ||

| Geometry, through plane geometry. | ||

| XIV.— | Languages— | English, standard school edition of English Grammar; |

| Latin, Cæsar's Com., 4; Virgil, 4; Cicero's Orations, 2. | ||

| Greek, the Reader; Gospels; Xenophon's Anabasis, 2.” | ||

Candidates for examination may elect in French, Keetle's Collegiate Course in French, Composition, Translation and Reading, and Lacomb's History of the French People, 132instead of Cæsar's Com., Virgil and Cicero's Orations; and in German, Whitney's German Grammar, Composition, Translation and Reading, Schiller's Willheim Tell and Goethe's Faust, but such elementary knowledge of Latin and Greek will be required as to enable the candidate to intelligently comprehend the etymology of medical terms derived therefrom.

Resolved, III.—No member of this society shall receive any person as a student of medicine unless he present a favorable certificate from the board of medical examiners.

Resolved, IV.—The time of study required by members of this society shall be five (5) years, including lectures.

Resolved, V.—Members of this society shall recommend their students to attend only such medical colleges as either require an examination for admission similar to the one required by this society, or make the full three-years' graded course of study obligatory for graduation therefrom, and otherwise endeavor to elevate the standard of medical education.

Resolved, VI.—That this society requests the Ohio State Medical society to adopt the foregoing schedule of requirements and to use its influence to secure legislation making the same obligatory upon persons entering their names as students of medicine in the State of Ohio.

Resolved, VII.—That these resolutions be printed and a copy sent to each medical society in this State with the request that they early report their action thereon.

“Pioneer Medicine on the Western Reserve” is the title of a series of articles which began in the November (1885) number of the Magazine of Western History (Williams & Co., Cleveland). They are written by Dr. Dudley P. Allen, which insures a warm interest in the subject as well as a capable handling of it. The series is historical and biographical, and the publisher promises several portraits before the last chapter in March or April. Probably none of the Magazine's various serials will be of more interest to the public, as well as to medical men generally. In the opening chapters we enjoyed the author's skillful joining into readable continuity of the broken facts that have been gathered from so long ago.

The president, Dr. Mitchell of Mansfield, called the meeting to order, and owing to the number of papers to be presented and the brief time for the session, ordered the omission of reading of minutes of last meeting and all miscellaneous business. E. H. Hyatt of Delaware, was first called, and excused on the ground that he could not do justice to his subject, “The Use and Abuse of Alcohol from a Professional Standpoint,” in so short a time.

Dr. R. Harvey Reed of Mansfield, the appointed lecturer, read a paper on Anæsthetics, in which he gave a brief review of the different general and local anæsthetics in use and the different compounds of the same.

He referred to the elaborate experiments of Dr. Watson of Jersey City, which showed the following mortality on rabbits:

| Sulphuric ether, | 16.66 |

| Chloroform, | 62.50 |

| Bromide of ethyl, | 50.00 |

| Alcohol, chloroform and ether, | 75.00 |

| Alcohol, chloroform and ethyl, | 66.66 |

And on dogs:

| Sulphuric ether, | 00.00 |

| Chloroform, | 00.00 |

| Bromide of ethyl, | 100.00 |

| Alcohol, chloroform and ether, | 60.00 |

| Alcohol, chloroform and ethyl, | 80.00 |

In these experiments the doctor found it necessary to resort to artificial respiration on dogs as follows:

| Sulphuric ether, | None at all. |

| Chloroform, | 2 times. |

| 134Alcohol, chloroform and ether, | 3 times. |

| Alcohol, chloroform and ethyl, | 5 times. |

The author referred to a number of experiments he had made on frogs, in which vivisection was made, and the heart exposed and chloroform applied direct, from which they died in from ten to twenty minutes, and when bromide of ethyl was used in fifteen to thirty minutes, but when ether was used, and even much freer than either of the others, they did not die at all.

In repeated experiments, he said, he had found the use of electricity unreliable in resuscitating the heart under these circumstances.

After referring to the mortality reports which showed 405 deaths from chloroform against seventeen from ether, he said: “I feel that every time I use chloroform as an anæsthetic I am trifling with a dangerous compound, and that it will only require time and perseverance in its use until I will share the fate of many others, whose misfortunes ought to be a timely warning to us against its dangerous effects; and if not heeded an accident will be all the more inexcusable.”

He condemned the use of so-called “vitalized air” as being an uncertain and unstable compound: being one of the nitro-oxygen series mixed with chloroform, its effects were uncertain and often very injurious, which, he said, “should be reason enough to deter any conscientious physician from using it or even recommending it.”

For administering anæsthetics the author recommended a clean folded towel as being more preferable than anything else, as it was just as efficient and decidedly better from a sanitary standpoint.

He recommended watching the pulse closely while administering chloroform, and the respirations when ether was administered, lest in the former the cardiac ganglia become affected and suddenly arrest the heart's action, or in the latter the nerve cells of the medulla from its toxic effects abruptly interfere with the breathing.

In closing the author said: “From the brief review of the anæsthetics most familiar to the profession from a practical 135standpoint we have arrived at the following conclusions:”

First—Of all general anæsthetics known pure sulphuric ether stands at the head for safety, efficiency and every day practical use.

Second—Hydrochlorate of cocaine stands at the head of all known local anæsthetics.

Third—Ethidene promises to rival ether and merits a more general and extended trial.

Fourth—No surgeon should give any anæsthetics without being prepared to resuscitate the patient on the shortest possible notice if necessary, among which preparations nitrite of amyl stands preëminent.

Fifth—No person should be entrusted with the administration of any anæsthetic who is not thoroughly familiar with its physiological action and practical administration.

Sixth—The indiscriminate use of anæsthetics should be strenuously guarded against, and especially the practice of leaving such dangerous compounds in the hands of the laity to be given ad libitum whenever they may deem it necessary.

Seventh—The judicious use of anæsthetics under all necessary circumstances should never be omitted, for when properly used by skilled hands they are a glorious haven of peace in the midst of a stormy sea.

Dr. J. Campbell of Galion reported a case of embolism, in which the diagnosis was uncertain, the symptoms grave and the disturbance of the circulation extremely severe, distinguished physicians differing widely as to the pathological conditions, and the autopsy revealed adhesions of the right lung and of the pericardum. Left lung compressed, left heart hypetrophied and stenosis of aortic orifice. On motion the case was referred to the committee on publication, and Drs. Hackendorn, Ridgway and Mitchell, who had seen the patient, were requested to give their views.

Dr. N. B. Ridgway reported a case of laceration of perinæum with operation within an hour, with complete success, on which remarks were made by Drs. Reed, Larimore and Kelley.

Dr. Kelley presented a clinical case of blindness in right eye 136of a girl, from the concussion of a snow ball striking the arch of the orbit.

The society adjourned to meet in Mansfield March 25, 1886.

In the summer of 1873 a few gentlemen met at Long Branch, New Jersey, and organized as the “American Public Health Association.” At that time there were but few state boards of health, and local boards were not generally efficient; and it was one of the chief objects of the American Public Health Association to aid in the establishment of health and sanitary organizations throughout the country. Prominent among the original members of the association were gentlemen from the Mississippi valley. For a long time the cities and towns of that valley had suffered from visitations of yellow fever, and men had become somewhat enlightened by the good results obtained from the course pursued by certain officers during the war. Especially was this true in New Orleans, and the question was fairly raised whether local conditions were not responsible for the disastrous outbreaks which had occurred so frequently.

From 1873 to the present time, there have been annual meetings of the association, with a greatly enlarged membership. A large result of the efforts of the association and its members is seen in the national, state and local boards of health, and other sanitary organizations throughout the country. But three of the states are now without state organizations. The recent meeting in Washington was its “thirteenth annual,” and was as well attended and its members as enthusiastic as at any. The members were “welcomed” on behalf the medical fraternity of Washington by the venerable Dr. J. M. Toner, and by the district authorities through the President of the Board of Commissioners, Judge Edmonds. These remarks were followed by the usual address by the president of the association, Dr. Reeves of West Virginia.