VOLUNTEERS.

From the Painting by Arthur J. Black.

Exhibited in the Royal Academy, 1904.

Transcriber's Notes:

1. Page scan source: https://books.google.com/books?id=vapMAAAAMAAJ

The Quiver, Annual Volume, 1905;

Published by Cassell and Company, Limited;

London, Paris, New York & Melbourne: which includes

THE SWORD OF GIDEON, a Serial Story By J. Bloundelle-Burton

pp. 1, 114, 317, 363, 502, 552, 698, 744, 840, 993, 1031, 1175,

1226. Copyright, 1904, by John Bloundelle-Burton in the

United States of America. All rights reserved.

VOLUNTEERS.

From the Painting by Arthur J. Black.

Exhibited in the Royal Academy, 1904.

Principal Contributors

Elizabeth Banks

Katharine Tynan

The Rev. John Watson, D.D. ("Ian Maclaren")

The Rev. R. F. Horton, D.D.

D. L. Wookmer

The Rev. Principal Forsyth, M.A., D.D.

The Duke of Argyll

The Rev. High Black, M.A.

The Dean of Worcester

The Bishop of Derry

The Rev. J. H. Jowett, M.A.

Raymond Blathwayt

Fred E. Weatherly

J. Bloundelle-Burton

Richard Mudie-Smith, F.S.S.

The Rev. F. B. Meyer, B.A.

The Rev. Arthur Finlayson

Guy Thorne

Pastor Thomas Spurgeon

Morice Gerard

Dr. T. J. Macnamara, M.P.

The Rev. H. B. Freeman, M.A.

The Rev. R. J. Campbell, M.A.

Ethel F. Heddle

Sir Robert Anderson, K.C.B.

The Rev. Mark Guy Pearse

May Crommelin

The Lord Bishop of Manchester

Scott Graham

Amy Le Feuvre

The Venerable Archdeacon Sinclair,

etc. etc.

London, Paris, New York & Melbourne

SWORD OF GIDEON. THE Serial Story By J. Bloundelle-Burton pp. 1, 114, 317, 363, 502, 552, 698, 744, 840, 993, 1031, 1175, 1223. Illustrated by W. H. Margetson. Copyright, 1904, by John Bloundelle-Burton in the United States. All rights reserved.

I.

II.

III.

I.

II.

III.

I.

II.

III.

IV.

V.

VI.

VII.

VIII.

IX.

X.

XI.

XII.

XIII.

XIV.

XV.

XVI.

XVII.

XVIII.

XIX.

XX.

XXI.

XXII.

XXIII.

XXIV.

XXV.

XXVI.

XXVII.

XXVIII.

XXIX.

XXX.

XXXI.

XXXII.

XXXIII.

XXXIV.

XXXV.

XXXVI.

To north and south and east and west horsemen were spurring fast on the evening of May 15th, 1702 (N.S.), while, as they rode through hamlets and villages, they heard behind them the bells of the churches beginning to ring many a joyous peal. Also, on looking back over their shoulders, they saw that already bonfires were being lit, and observed the smoke from them curling up into the soft evening air of the springtime.

For these splashed and muddy couriers had called out as they passed through the main streets of the villages that the long expected war with France was declared at last by England, by Austria--or Germany, as Austria was then called--and the States-General of the United Netherlands.

Wherefore, it was no wonder that the bonfires were instantly set blazing and the bells ringing, since now, all said to the others, the great, splendid tyrant who for sixty years had given orders from his throne for battles, for spoliation and aggrandisement, for the humbling of all other countries beneath the heel of France, would meet his match. He--he! this superb arbiter of others' fate, who had in his younger days been called Le Dieudonné and in his older Le Roi Soleil--he who had driven forth from their homes countless Protestants and had cruelly entreated those who had remained by their hearths, while desiring only to worship God in their own way and without molestation, must surely be beaten down at last.

"And--'tis good news!--Corporal John goes, they say," exclaimed several of these horsemen as they drew bridle now and again at some village inn, "as Captain-General of all Her Majesty's forces and chief in command of the allied armies. He has been there before and hates Louis; Louis who, although he gave him command of his English regiment, would not give him command of a French one when he would have served France. Let us see how he will serve him now."

"I pity his generals and his armies when my lord the Earl of Marlborough crushes them between his ranks of steel," said one who stood by; "the more so that Lewis"--as they called him in this country--"has insulted us by espousing the claims of James's son, by acknowledging him as King of England. He acknowledges him who is barred for ever from our throne by the Act of Succession, and also because his father forswore the oath he took in the Abbey."

"He acknowledges the babe who, as I did hear Bishop Burnet say in Salisbury Cathedral," a Wiltshire rustic remarked, "was no child at all of the Queen, but brought into the palace in a warming pan, so that an heir should not be wanting."

"He persecutes all of our faith," a grave and reverend clergyman remarked now; "a faith that has never harmed him; that, in truth, has provided him with many faithful subjects who have served him loyally. And now he seeks to grasp another mighty country in his own hands, another great stronghold of Papistry--Spain. And wrongfully seeks, since, long ago, he renounced all claims to the Spanish throne for himself and his."

A thousand such talks as this were taking place on that night of May 15th as gradually the horsemen rode farther and farther away from the capital; the horsemen who, in many cases, were themselves soldiers, or had been so. For they carried orders to commanders of regiments, to Lord-Lieutenants, to mayors of country towns, and, in some cases, to admirals and sea captains, bidding all put themselves and those under them in readiness for immediate war service. Orders to the admirals and captains to have their ships ready for sailing at a moment's notice; to the commanders of regiments to stop all furlough and summon back every man who was absent; to the Lord-Lieutenants to warn the country gentlemen and the yeomanry. Orders, also, to the mayors to see to the militia--the oldest of all our English forces, the army of our freemen and our State--being called together to protect the country during the absence of a large part of the regular troops. Beside all of which, these couriers carried orders for food and forage to be provided at the great agricultural centres; for horses to be purchased in large quantities; for, indeed, every precaution to be taken and no necessary omitted which should contribute towards the chance of our destroying at last the power of the man who had for so long held the destiny of countless thousands in his hand.

Meanwhile, as all the bells of London were still ringing as they had been ringing from before midday, a young man was riding through the roads that lay by the side of the Thames, on the Middlesex side of it. A young man, well-built and as good-looking as a man should be; his eyes grey, his features good, his hair long and dark, as was plainly to be seen since he wore no wig. One well-apparelled, too, in a dark, blue cloth coat passemented with silver lace, and having long riding-boots reaching above his knees, long mousquetaire riding-gloves to his elbows, and, in his three-cornered hat, the white cockade.

He passed now the old church at Chelsea on the river's brink, and smiled softly to himself at the tintamarre made by the bells, while, as he drew rein the better to guide his horse betwixt the old waterside houses and all the confusion of wherries and cordage that lumbered the road, or, rather, the rutty passage, he said to himself:

"The torch is lighted. At last! 'Tis a grand day for England. And, though I say it not selfishly, for me. Oh!" he went on, as now his left hand fell gently to the hilt of his sword and played lovingly with its curled quillon; "if I may draw you once again for England and the Queen, and for all you represent for us," glancing at the old church, wherein lay the bodies of such men as Sir Thomas More, who, in his self-written epitaph, described himself in the bitterness wrung from his heart as "hereticisque" John Larke, an old rector of Chelsea, executed at Tyburn for his Protestantism; and many other staunch reformers. "Ah, yes," he continued, "if I may draw you against Spain and her hateful Inquisition, against France and the tyrant who persecutes all who love the faith you testify to; if I may but once more get back to where I stood before, then at last shall I be happy. Ah, well! I pray God it may be so. Let me see what cousin Mordaunt can do."

He was free now of the encumbered road betwixt the river and the old houses: the way before him lay through open fields in some of which there grew a vast profusion of many kinds of vegetables and orchard fruits, while, in others, the lavender scented all the afternoon air; whereupon, putting his horse to the canter, he rode on until he came to an open common and, next, to a kind of village green--a green on two sides of which were antique houses of substance, and in which was a pond where ducks disported themselves.

On the east side of the green, facing the pond, there stood embowered in trees an old mansion, known as the Villa Carey. In after days, when this old house had given place to a new one, the latter became known as Peterborough House, doubtless to perpetuate the memory of the dauntless and intrepid man who now inhabited it.

Arrived at the old, weather-beaten oak gate, against which the storms that the southwesterly gales brought up had beaten for more than two centuries, the young man summoned forth an aged woman and, on her arrival, asked if Lord Peterborough were within.

"Ay, ay," the old rosy-cheeked lodge-keeper murmured; "and so in truth he is. And to you always, Master Bracton. Always, always. Yet what brings you here? Is't anything to do with the pother the bells are making at Fulham and Putney and all around? And what is it all about?"

"You do not know? You have not heard?" Bevill Bracton answered, as he asked questions that were almost answers. "You have not heard, even though my lord is at home. For sure he knows, at least."

"If he knows he has said nothing--leastways to me. After midday he sat beneath the great tulip tree, with maps and charts on the carpet spread at his feet above the grass, and twice he has sent off messengers to Whitehall and once to Kensington, but still none come anigh us in this quiet spot. But, Master Bevill," the old woman went on, laying a knotted finger on the young man's arm--she had known him from boyhood--"those two or three who have passed by say that great things are a brewing--that we are going to war again as we went in the late King's reign, and with France as ever; and that--and that--the bells are all a-ringing because 'tis so."

"And so it is, good dame Sumner. We are going to see if we cannot at least check the King of France, who seeks now to make Spain a second half of France. But come; we must not trifle with time. Let me hook my bridle rein here, and you may give my horse a drink of water when he is cool, and tell me where my lord is now. Great deeds are afoot!"

"He is in the long room now. There shall you find him. Ay, lord! what will he be doing now that war is in the air again? He who is never still and in a dozen different cities and countries in a month."

With a laugh at the old woman's reflections on her master's habits--which reflections were true enough--Bevill Bracton went on towards the house itself and, entering it by the great front door, crossed a stone-flagged hall, and so reached a polished walnut-wood door that faced the one at the entrance. Arrived at it, he tapped with his knuckle on the panel, and a moment later heard a voice from inside call out:

"Who's there?"

"'Tis I--Bevill."

"Ha!" the voice called out again, though not before it had bidden the young man come in, "and so I would have sworn it was. Why, Bevill," the occupant of the room exclaimed, as now the young man stood before him, and when the two had exchanged handshakes, "I expected you hours before. When first the news came to me this morning----"

"Your lordship knows?"

"Know? Why, i' faith, of course I know. Is there anything Charles Mordaunt does not know when mischief is in the wind?--Mordanto, as Swift calls me; Sir Tristram, as others describe me; I, whose 'birth was under Venus, Mercury, and Mars,' and who, like those planets, am ever wandering and unfixed. Be sure I know it. As, also, I knew you would come. Yet, kinsman, one thing I do not know--that one thing being, what it is you expect to gain by coming, unless it is the hope of finding the chance to see those Catholics, amongst whom you lived as a youth, beaten down by sturdy Protestants like yourself."

"For that, and to be in the fray. To help in the good cause--the cause we love and venerate. Through you. By you--a kinsman, as you say."

"You to be in the fray--and by me? Yet how is that to be? You are----"

"Ah, yes! I know well. A broken soldier--one at odds with fortune. Yet----"

"Yet?"

"Not disgraced. Not that--never that, God be thanked."

"I say so, too. But still broken, though never disgraced. What you did you did well. That fellow, that Dutchman, that Colonel Sparmann, whom you ran through from breast to back--he may thank his lucky stars your spadroon was an inch to the left of his heart--deserved his fate."

"He insulted England," Bracton exclaimed. "He said that without King William to teach us the art of war we knew not how to combat our enemies. For that I challenged him, and ran him through. Pity 'twas I did not----"

"Nay; disable thine enemy--there is no need to kill him. All the same," Lord Peterborough continued drily, "King William broke you for challenging and almost killing a superior officer."

"King William is dead. Death pays all debts."

"I would it did! There are a-many who will not forgive me when I am dead."

"Queen Anne reigns, the Earl of Marlborough is at the head of the army. My lord, I want employment; I want to be in this campaign. Oh, cousin Mordaunt," Bevill Bracton said, with a break in his voice, "you cannot know how I desire to be a soldier once again, and fighting for my religion, my country, and the Queen. To be moving, to be a living man--not an idler. I have never parted with this," and he touched the hilt of the sword by his side, "help me; give me the right; find me the way to draw it once more as a soldier."

"How to find the way! There's the rub. Marlborough and I are none too much of cater-cousins now. We do not saddle our horses together. And he is--will be--supreme. If you would get a fresh guidon you had best apply to him."

"Even though I may have no guidon nor have any commission, still there will surely be volunteers, and I may go as one."

"There will be volunteers," Lord Peterborough said, still drily, "and I, too, shall go as one."

"You!"

"Yes, I. Only it will be later. When," and he smiled his caustic smile, "the others are in trouble. If Marlborough, if Athlone, or Ormond, who goes too, finds things going criss-cross and contrary, then 'twill be the stormy petrel, Mordanto, who will be looked to."

"But when--when?" Bevill Bracton asked eagerly.

"When they have had time to flounder in the mire; when Ginkell--I mean my Lord Athlone--has, good honest Dutchman as he is, fuddled himself with his continual schnapps drinking; or when Jack Churchill, sweet as his temper is and well under control, can bear no more contradictions and cavillings from his brother commanders. Then--then Charles Mordaunt will be looked to again; then--for I can cast my own horoscope as well as any hag can do it for me--I shall be invited to put my hand in my pocket, to stake my life on some almost impossible venture, to give them the advice that, when I attempt to offer it, they never care to take."

"But--but," Bevill said, "the time! The time!"

"'Twill come. Only you are young, impatient, hot-headed. I am almost old, yet I am the same sometimes--but you will not wait. What's to do, therefore?"

"I cannot think nor dream--oh, that I could!"

"Then listen to me. 'Tis not the way of the world to do so until it is too late; in your case you may be willing. Do you know Marlborough?"

"As the subaltern knows the general, not being known by him. But no more."

"'Tis pity. Yet--yet if you could bring yourself before his notice; if--if--you could do something that should come under his eyes--some deed of daring----"

"I must be there to do it--not here. At St. James's or Whitehall I can do nought. The watch can do as much as I."

"That's very true; you must be there. There! there! Let me see for it. Where are the charts?" and Lord Peterborough went towards a great table near the window, which was all littered with maps and plans that made the whole heterogeneous mass look more like a battlefield itself after a battle than aught else.

"Bah!" his lordship went on, picking up first a plan and then a chart, and throwing them down again. "Catalonia, Madrid, Barcelona, Cadiz. No good! no good! Marlborough will not be there. The war may roll, must roll, towards Spain, yet 'tis not in Spain that he will be. But Holland--Brabant--Flanders. Ha!" he cried at the two latter names. "Brabant--Flanders. And--why did I not think of it?--she is there, and there's the chance, and--and, fool that I am! for the moment I had forgotten it."

"She! The chance! Brabant! Flanders!" Bevill Bracton repeated, the words stumbling over each other in his excitement. "She! Who? And what have I to do with women--with any woman? I, who wish to do all a man may do in the eyes of men?"

"Sit down," Lord Peterborough said now, in a marvellously calm, a suddenly calm, voice. "Sit down. I had forgotten my manners when I failed to ask you to do so earlier."

"Ah, cousin Mordaunt, no matter for the manners at such a moment as this. Alas! you set my blood on fire when you speak of where the war will be, of where it must be, and then--then--you pour a douche of chill cold water over me by talking of women--of a woman."

"Do I so, indeed? Well, hearken unto me," and his lordship leant forward impressively and looked into the young man's eyes. "Hearken, I say. This woman of whom I speak may be the guiding star that shall light you along the path that leads to Marlborough, and all that he can do for you. This woman, who may, in very truth, be your own guiding star or----"

"Or?"

"She may lead to your undoing. Listen again."

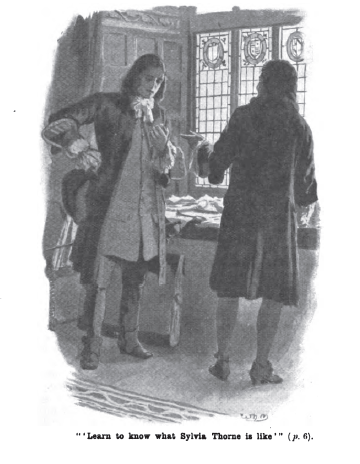

"'Learn to know what Sylvia Thorne is like.'" (p.

6).

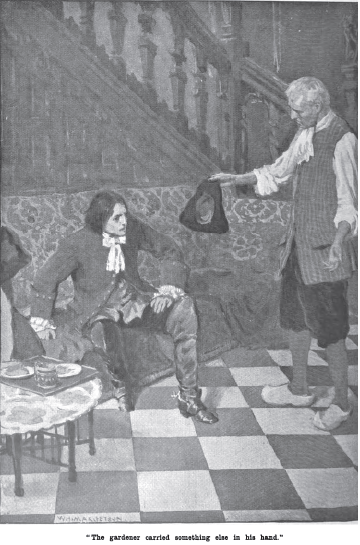

Had there been any onlooker or any listener at that interview now taking place in the old house at Parson's Green, either the eyes of the one or the ears of the other could not have failed to be impressed by what they saw or heard.

Above all, no observer could have failed to be impressed by the character of the elder man, Charles Mordaunt, Earl of Peterborough and Monmouth, who, although so outwardly calm, was in truth all fire within.

For this man, who was now forty-seven years of age, had led--and was still to lead for another thirty years--a life more wild and stirring than are the dreams of ordinary men. As a boy he had seen service at sea against the Tripoli corsairs, he had next fought at Tangiers, and, on the death of Charles II., had been the most violent antagonist of the Papist King James. An exile next in Holland, he had proposed to the Prince of Orange the very scheme which, when eventually adopted, placed that ungracious personage on the English throne, yet, at the time, he had received nothing but snubs for his pains. He had, after this, escaped shipwreck by a miracle, and, later, lay a political prisoner in the Tower, from which he emerged to become not long afterwards Governor of Jamaica. In days still to come he was to capture Barcelona by a scheme which his allies considered to be, when it was first proposed to them, the dream of a maniac; he was to rescue beautiful duchesses and interesting nuns and other religieuses from the violence of the people, to be then sent back to England as a man haunted by chimeras, next to be given the command of a regiment, to be made a Knight of the Garter, and to be appointed an Ambassador. Nor was this all. He flew from capital to capital as other men made trips from Middlesex to Surrey; one of his principal amusements was planting the seeds and pruning the trees in his garden with his own hands; he would buy his own provisions and cook them himself in his beautiful villa, and he was for many years married to a young and lovely wife, who had been a public singer, and whom he never acknowledged until his death was close at hand.

As still Lord Peterborough foraged among the mass of papers on the table, turning over one after the other, and sometimes half a dozen together, Bevill Bracton recognised that he was seeking for some particular scroll or document amidst the confused heap.

"What is it, my lord?" the young man asked. "Can I assist you?"

"Nay. If I cannot find what I want for myself, 'tis very certain none can do it for me. Ah!" he suddenly exclaimed, pouncing down like an eagle on a large, square piece of paper which was undoubtedly a letter. "Ah! here 'tis. A letter from the woman who is to give you your chance."

"I protest I do not comprehend----"

"You will do so in time. Bevill," his lordship went on, "do you remember some ten years ago, before you got your colours in the Cuirassiers and, consequently, before you lost them, a little child who played about out there?" and the Earl's eyes were directed towards the great tulip tree on the lawn.

"Why, yes, in very truth I do. I played with her oft, though being several years older than she. A child with large, grey eyes fringed with dark lashes; a girl who promised to be more than ordinary tall some day; one well-favoured too. I do recall her very well. She was the child of a friend of yours, and her name was--was--Sophia, was it now?--or Susan? Or----"

"Neither; her name was Sylvia, and is so still--Sylvia Thorne."

"Sylvia Thorne--ay, that is it. She promised to become passing fair."

"She is passing fair--or was, when I saw her last, two years ago. She is not vastly altered if I may judge by this," and Lord Peterborough went to a cabinet standing by one of the windows and, after opening a drawer, came back holding in his hand a miniature.

"Regard her," he said to Bracton, as he handed him the miniature; "learn to know what Sylvia Thorne is like. Learn to know the form and features of the woman who may lead to restoring you to all you would have, or--you are brave, so I may say it--send you to your doom."

"Why," Bracton exclaimed while looking at the miniature and, in actual fact, scarce hearing Lord Peterborough's words, so occupied was he, "she is beautiful. Tall, stately, queen-like, lovely. Can that little child have grown to this in ten years?"

In absolute fact the encomiums the young man passed upon the form and features that met his eye were well deserved.

The miniature, a large one, displayed a full, or almost full length portrait of a young woman of striking beauty. It depicted a young woman whose head was not yet disfigured by any wig, so that the dark chestnut hair, in which there was now and again a glint of that ruddy gold such as the old Venetians loved to paint, waved free and unconfined above her forehead. And the eyes were as Bevill Bracton recalled them, grey, and shrouded with long dark lashes. Only, now, they were the eyes of a woman, or one who was close on the threshold of womanhood, and not those of a little child; while a straight, small nose and a small mouth on which there lurked a smile that had in it something of gravity, if not of sadness, completed the picture. As for her form, she was indeed "more than common tall," and, since there was no suspicion of hoop beneath the rich black velvet dress she wore, Bracton supposed that it was donned for some ball or festival.

"She is beautiful!" he exclaimed again. "Beautiful!"

"Ay, and good and true," Lord Peterborough said. "Look deep into those eyes and see if any lie is hidden therein; look on those lips and ponder if they are highroads through which falsehood is like to pass."

"It is impossible. If the eyes are the windows of the soul, as poets say, then truth, and naught but truth, shelters behind them. And this is Sylvia Thorne But still--still--I do not comprehend. How shall she bring me before my Lord Marlborough? How advance my hopes and desires? Stands she so high that she has power with him?"

"She is a prisoner of France."

"What? She, this beautiful girl, she a prisoner of France, of chivalrous France, for chivalrous France is, though our eternal foe?"

"Yes, in company with some thousands of others, mostly Walloons--muddy Hollanders all--and mighty few English, if any. She is shut up in Liége, and the whole bishopric of Liége is in the hands of France under the command of De Boufflers."

"What does she there--she, this handsome English girl, in a town of Flanders now possessed by the French--she whom, I take it, since now I begin to comprehend--and very well I do!--I am to rescue?"

"One question is best answered at a time. Martin Thorne, her father, was my oldest friend. When James mounted the throne of England he, like your father and myself, was one of those honest adherents of the Stuarts who could not abide the practices James put in motion. He himself had been in exile with Charles and James while Cromwell lived, and he, again like your father, went into exile when James became a Papist."

"My father never returned from abroad," Bevill remarked.

"I know--I know. But Thorne returned only to go abroad again. Your father was, however, well to do. Thorne was not so. When a young exile during Cromwell's rule he had been in Liége, in a great merchant's house, since it was necessary he should find the means whereby to live. When he returned to Liége twenty-six years afterwards he had some means, and he became on this second occasion a merchant himself."

"I begin to understand."

"He thrived exceedingly. 'Tis true England was almost always at war with France, but war is good for commerce. Thorne profited by this state of affairs, and so grew rich. Sylvia is rich now, but the French hold Liége. She would escape from that city."

"Will they not let her go? She is a woman. What harm can she do either by going or staying?"

"They will let none go now who are strangers. Ere long this war, which the claims of Louis to the Spanish succession on behalf of his grandson have aroused, will have two principal seats--Flanders and Spain. There are such things as hostages; there are such things as rich people buying their liberty dearly. And Sylvia is rich, and they know it. Much of her wealth is placed in England, 'tis true, but much also is there, in Liége. Short of one chance, the chance that, in the course of this campaign Liége should fall into the hands of one of our allies, she may have to remain there until peace is made--and that will not be yet. Not for months--perhaps years."

"But if she should escape--what of her wealth then?"

"She will be free, and still she will be rich; while if, as I say, Liége falls into the allies' hands she will not even lose her property there. But, at the moment, she desires only one thing; and that desire, being a rich woman, she is anxious to gratify. She is anxious to return to England."

"And I--I am to be the man to help her to do so--to aid her to escape from Liége. I'll do it if 'tis to be done."

"Well spoken; especially those last words. 'If 'tis to be done.' Yet pause--reflect."

"I have reflected."

Though, however, Bevill had said, "I have reflected," it would scarcely seem as if Lord Peterborough placed much confidence in his statement, since, either ignoring what his young kinsman had said or regarding his words as of little worth, he now proceeded to tell the latter what difficulties, what dangers, would lie in his path.

"I would not send you to that which may, in truth, lead to your doom without giving you fair warning of what lies before you," his lordship commenced, while, as he spoke, his eyes were fixed on Bevill Bracton--fixed thus, perhaps, because he who, in this world, had never been known to flinch at or fear aught, was now anxious to see if the solemn speech he had just uttered could cause the other to blench. Observing, however, that, far from such being the case, Bracton simply received that speech with an indifferent smile, Peterborough went on.

"From the very instant you set foot on foreign ground, every step your feet take will be environed with difficulty and danger. For, since you could by no possibility go as an Englishman, it follows that you must be a Frenchman."

"Am I not already half a Frenchman?" the young man asked. "From the day my father took me to France until I got my colours, I spoke, I read--almost thought--in French. I learnt my lessons in French; I had French comrades, as every follower of the Stuarts had, since we were welcome enough in France; I was French in everything except my religion and my heart. They were always English."

"Therefore," Lord Peterborough continued, for all the world as though Bracton had not interrupted him or uttered one word, "if you, passing as a Frenchman, fell into the hands of the French and were discovered to be an Englishman, your shrift would be short."

"I shall never be discovered."

"While," his lordship continued imperturbably, "if the English, or the Dutch, or the Austrians, or the Hanoverians, or the troops of Hesse-Cassel--for all are in this Grand Alliance, as well as the Prussians and the Danes, who do not count for much, though even they will be powerful enough to string a supposed spy up to the branch of a tree--if any of these get hold of you, thinking you a spy of one or t'other side, well! your life will not be worth many hours' purchase."

"I shall soon prove to the English that I am not a Frenchman, and to the others that I am not a spy. I presume your lordship can provide me with a passport?"

"I can do so, but it will be that of a Frenchman. Bolingbroke, who is now, as you know, Secretary-of-War--oh! la-la! he Secretary-of-War!--has some already prepared. His French hangers-on have provided him with those. All Frenchmen are not loyalists. You will not be the first or only English spy abroad."

"Yet I shall not be a spy."

"Not on the passport, but if you are limed you will be treated as one. I disguise nothing from you."

"And terrify me not at all. As soon as I have that passport I am gone. I shall not return until I bring Mistress Sylvia Thorne with me."

"Fore 'gad, you are a bold fellow! I am proud to have you of my kith and kin. Yet you will want something else. What money have you?"

"I had forgotten that. Money, of course, I have, yet--yet----"

"Not enough. Is that it? Hey? Well, you shall have enough--enough to help you bravely; to bring you, if Providence watches over you, safely to Liége and before the glances of Sylvia's grey eyes. And, then, Heaven grant you may both get back safely."

"I have no fear. What a man may do I will do. Yet, my lord, one thing alone stands not clearly before my eyes. God, He knows, I go willingly enough to obey your behests, your desires; to, if it may be, help a young maiden to quit a town which may soon be ravaged by war; a town to be, perhaps, held by our enemies for months or even years. From my heart I do so. Yet--ah!--how shall I by this do that on which I have set my heart? How get back again to the calling I have loved and forfeited--though forfeited unjustly? How will this commend me to my Lord Marlborough?"

"What! How? Why, heart alive! if Marlborough but hears you have done such a thing as this, your new commission will be as good as signed by Queen Anne. He hath ever an eye for a quick brain, a ready hand. 'Tis thus that great men rise or, being risen, help to maintain their eminence. The workman who chooses good tools does ever the best of work."

"Therefore I need not fear?"

"Fear! Fear nothing; above all, fear not that you shall go unrewarded. Moreover, remember Jack Churchill has ever been a valiant cavalier of le beau sexe, un preux chevalier; remember his devotion to his wife, handsome shrew though she be. Great commander though he is, he is not above advancing those soldiers who can help beauty in distress.

"Now," Lord Peterborough concluded, "go and hold yourself in readiness, remembering always that she whom you go to succour is the child of a man I loved--of my dearest, my dead, friend. Remember, too, that she is young and good and pure and honest. Now go, remembering this; and when I send for you--'twill not be long--return. Then, when you have my last instructions, as also the money and the passport, with, too, a letter for Sylvia Thorne, I will bid you God speed. Go--farewell!"

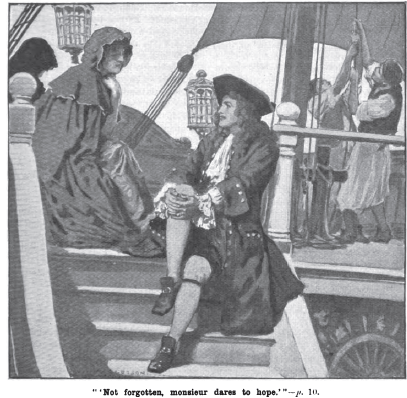

"'Not forgotten, monsieur dares to hope.'"--p. 10.

The bilander Le Grand Roi, flying French colours, was making her way slowly up the Scheldt to Antwerp, as she had been doing for five hours, namely, from the time she had entered the river. Two days before this time she had left Harwich, while, since the proclamation had been made in London and the principal cities of England that all French and Spanish subjects were to quit the country, and that they would be permitted to depart without molestation and also would not be interfered with while proceeding on the high seas to their destination, she had arrived safely. She was close to Antwerp now; the spire of the cathedral had long since become visible as Le Grand Roi passed between the flat, marshy plains that bordered the river; she would be moored, the sailors said, within another hour--moored in Antwerp, which, since the death of Charles II. of Spain, eighteen months before this time, had been seized by the French. For the whole of this region, the whole of Flanders, was now no longer the vast barrier of Western Europe against the power and ambition of the Great King, but was absolutely his own outworks and barrier against his foes.

On board the old-fashioned craft--which had brought away from England Frenchmen and Frenchwomen of all classes, from secretaries of the Embassy and ladies attached to the suite of the ambassadress, down to the croupiers of the faro banks and the women employed by the French milliners in London, as well as a choice collection of French spies who had been earning their living in the capital--all was now excitement. For, ere anyone on board would be permitted to land, their passports would have to be examined, their features, height, and other details of their appearance compared with those passports, and any baggage they might possess would be scrupulously inspected. If all were ashore and housed by the afternoon, or were enabled to set out on their further journey, the sailors told the travellers they might indeed consider themselves lucky.

"Nevertheless," said a young man who sat on the small raised deck on which the wheelhouse stood, while he addressed a young French lady who sat by his side, "it troubles me but very little. So that I reach Louvain in two days, or three, for the matter of that, or even four, I shall be well content."

"Monsieur is not pressed?" this young lady said, after looking at her mother who sat asleep on the other side of her, and then glancing at the young man. And, in truth, the object of her second glance was worthy of observation, since he was good-looking enough to merit scrutiny. His dark features were well set off by his wig, his manly form was none the worse for the gallooned, dark blue travelling coat and deep vest he wore. A handsome young man this, many had said in the last two days on board; a credit to France, the land, as they, told each other often--perhaps because they feared the fact might be overlooked even by themselves--of handsome men and lovely women. Even his mouches on the cheeks, his extremely fine lace and his sparkling rings were forgiven by his fellow-passengers, since, after all, were not patches and lace of the best, and jewels, the appanage of a true French gentleman? And a gentleman M. de Belleville was--a gentleman worthy of the greatest country in the universe, they modestly added.

"Not the least in all the world," this graceful, airified young man answered the young lady now in an easy manner; "not the least, I do assure you, mademoiselle. In truth, I am so happy to have left England behind that now I am out of it I care not where else I am."

"Monsieur has seemed happy since he has been on board. He has played with the children, given his arm to the elderly ladies, assisted the older men as they staggered about with the roll of the ship, played cards with the younger. Monsieur will be missed by all when we part at Antwerp."

"But not forgotten, monsieur dares to hope," the graceful M. de Belleville said.

"Agreeable persons are never forgotten," his companion of the moment replied, she being evidently accustomed to the riposte. "But, monsieur, this war, this Grand Alliance, as our enemies term it--tell me, it surely cannot last long? This Malbrouck of whom they speak, this fierce English general--he cannot--undoubtedly he cannot--prevail against King Louis' marshals!"

"Impossible, mademoiselle!" the young man exclaimed, while his eyes laughed as he answered. "Impossible! What? Against De Boufflers, Tallard, Villeroy, and the others? Yet there is one thing in his favour, too. He served France once."

"He! This Malbrouck. He! Yet now he fights against her!"

"In truth he did, and so learnt the art of war. He was colonel of the English regiment in the Palatinate under Turenne. That should have taught him something. Also----"

But there came an interruption at this moment. The side of the bilander grated against the great timbers of the dock, the hawsers were thrown out; Le Grand Roi had arrived at the end of her journey. A moment later the douaniers were swarming into the vessel, hoarse cries were heard, the passengers were ordered to prepare their necessaries for inspection, and to have their papers ready.

Among some of the first, though not absolutely one of the first, M. de Belleville was subjected to inspection. His passport was perused by the douanier, who mumbled out as he did so, "Height, five feet ten. Hein!" raising his eyes to the young man's face. "I should have said an inch more."

"I should have said two more," M. de Belleville replied with a laugh. "Mais, que voulez vous? The monsieur at our embassy would have it so, in spite of my pardonable remonstrances. Therefore five feet ten I have to be. And he was short himself. Let us forgive him."

"Monsieur is gay and debonair. Bon! That is the way to live long. Eyes, dark. Bon! Hair," putting up a forefinger and lifting M. de Belleville's peruke an inch or so, "dark. Bon! Age, twenty-nine."

"Another affront. I assure you, monsieur, I told the gentleman I am but twenty-eight and four months."

"Ohé! Monsieur has a light vein. When a man has passed twenty-eight he is twenty-nine in the eyes of the law. Monsieur's vanity need not be offended. Now, monsieur, the pockets. 'Tis but a ceremony, I assure monsieur."

The pockets were soon done with. The man saw a purse through which glistened many pistoles and louis d'or and gold crowns, several bills drawn by the great French banker Bernard, which could be changed almost anywhere, and--a portrait.

"Hein!" the man said, though not rudely. "A beautiful young lady. Handsome as monsieur himself, doubtless one whom----"

"Precisely. There is nothing more?"

"Except the baggage."

"I have none. By to-night, or to-morrow, or the next day, I hope to be in Marshal de Boufflers' lines."

"Monsieur must ride then. The Marshal's lines stretch from----"

"I know. I shall reach them as soon as horse can carry me."

After which the young man was permitted to walk ashore.

"So," 'Monsieur de Belleville' said to himself, as now, with his large cloak over his arm, he made his way to the vicinity of the cathedral, "I am here. So far so good. Yet this is but the first step. I must be wary. Vengeance confound the vagabond!" he went on as his thought changed. "I wish he had not looked on that sweet face and stately form of Sylvia Thorne. Almost it seems a sacrilege. Cousin Mordaunt gave me that as my passport to her. I wonder if he dreams of how many times I have gazed on it since I parted from him? Still, it had to be shown."

Consoled with this reflection, the young man continued on his way until the carillons sounding above his head told him that the cathedral was close at hand. Then, emerging suddenly from a narrow street full of lofty houses, he found himself on the cathedral place, and looked around for some hostelry where he might rest for the day and part of the night.

His first necessity was a horse. This it was important he should obtain at once, directly after he had procured a room and a meal. Yet, he thought, there should be no difficulty in that. The French, who never neglected the art of possessing themselves of the spoils of war, were reported to have laid all the country round under such contributions of food, cattle, forage, and other things, that he had read in the Flying Post ere he left London how, in spite of their large armies scattered over Flanders, they were now selling back at very small prices the things they had plundered.

"But first for an inn," said Bevill Bracton (the soi-disant M. de Belleville) to himself. Directing his steps, therefore, across the wide place and towards a deep archway, over which was announced the name of an inn, he entered the house and stated that he wanted a room for the night.

"A room?" the surly Dutch landlord repeated, looking up as he heard himself addressed in the French language--doubtless he had good reason to be surly! "A room? Two dollars a night, payable in advance."

"'Tis very well. You do not refuse French money?"

"No, 'specially as we see little enough of it. Hans," addressing a boy in the courtyard after he had received the equivalent of two dollars, "show the French gentleman to No. 89. All food and wine," he added, "is also payable in advance."

"That can also be accomplished. Likewise the price of a horse, if I can purchase one."

"Ja, ja! Very well!" the man said, brisking up at this. "If monsieur desires a horse, and will pay for it, I have many from which he may choose."

"So be it; when I descend I will inspect them. Now," to the boy, "show me to the room."

Arrived at No. 89, which, like all Dutch rooms, was scrupulously clean if bare of aught but the most necessary furniture, Bevill, after having made some sort of toilette, and one which would have to suffice until he had bought a haversack and some brushes and other necessaries, was ready for his meal.

He went downstairs now to where the surly Dutch landlord still sat in his little bureau, and asked him if the horses were ready for inspection. Receiving, however, the information that two or three had been sent for from some stables that were in another street, he decided to proceed to the long, low room where repasts were partaken of. Before he did so, however, the landlord told him that it was necessary to inscribe his name and calling in a register that was kept of all guests staying at the inn.

Knowing this to be an invariable custom, as it had always been for many long years--for centuries, indeed--on the Continent, Bevill made no demur, but, taking a pen, he dipped it in the inkhorn and wrote down, "André de Belleville, Français, Secrétaire d'Embassade récemment à Londres," since thus ran the passport which had been procured for him by Lord Peterborough.

After which, on the landlord having stated that this information was all that the Lieutenant of Police would require, Bevill proceeded to the room where a meal could be obtained--a meal which, as he had already been warned, he would have to pay for in advance. For now--and it was not to be marvelled at--there was no Dutchman in all Holland who would trust any Frenchman a sol for bite, or sup, or bed.

By the time this repast was finished, the horses from which Bevill was to select one were in the courtyard, and, being informed of this, he went out to see them. One glance from his accustomed eye, the eye of an ex-cuirassier who had followed William of Orange and fought under his command, was enough to show him that any one of them was sufficient for his purpose of reaching Liége by ordinary stages. Therefore the bargain was soon struck, six pistoles[1] being paid for the stoutest of the animals, a strong, good-looking black horse, and the one that seemed as if, at an emergency, it could attain a good speed--an emergency which, Bevill thought, might well occur at any moment on his route through roads and towns bristling with French soldiers.

As, however, the landlord and he returned to the bureau to complete the transaction, Bevill saw, somewhat to his surprise, a man leave the bureau--a man elderly and cadaverous--one who wore a bushy beard that was almost grey, and who looked as though he was far advanced in a decline. A man whose face appeared familiar to Bracton, yet one which, while being thus familiar, did not at first recall to him the moment or place where he had once seen or known him.

"Fore 'gad!" he said to himself. "Where have I seen that fellow?" And Bevill Bracton glanced down the passage as though desiring that the man would return. Not seeing him, however, he stepped back from the gloom of the passage into the sunshine of the courtyard and counted out into his hand the six pistoles he was to pay. Then, as he did so, he heard a step behind him--a step which he imagined to be that of the landlord as he came forth with the receipt, and, looking round, saw that the strange man was now in the bureau, and bending over the register. A moment later he heard him say to the landlord, while speaking in a husky, soddened voice:

"There was no secretary named André de Belleville at the French Embassy. The statement is false. I shall communicate with the Lieutenant of Police at once. I warn you not to let him depart."

Then, in an instant, the man was gone, he passing down the passage and out into the Dutch kitchen garden.

But Bevill had heard enough, had learnt enough.

The voice of the man, added to what he had already seen of him, aided his wandering recollection--it told him who the man was.

"'Tis Sparmann," he said to himself. "Sparmann, who, two years ago, had my sword through him from front to back. It is enough. There is no rest here for me. To-night I must be far from Antwerp. My lord said well. It is death if I am discovered."

The great high road that runs almost in a straight line from Antwerp to Cologne passes through many an ancient town and village, each and all of which have owned the sway of numerous masters. For Spain once had its grip fast on them, as also did Austria, Spain's half-sister; dukes, reigning over the provinces, fierce, cruel, and tyrannical, have sweated the blood from out the pores of the back-bowed peasants; prince-bishops, such as those of Liége and Antwerp and Cologne, have also held all the land in their iron grasp; even the Inquisition once heaped its ferocious brutalities on the dwellers therein. Also, France has sacked the towns and cities of the land, while armies composed of men who drew their existence from English soil have besieged and taken, and then lost and taken again, those very towns and cities and villages.

Among the cities, at this period garrisoned and environed by one of the armies of Louis le Grand, none was more fair and stately than Louvain, though over her now there hangs, as there has hung for two hundred years, an air of desolation. For she who once numbered within her walls a hundred and fifty thousand inhabitants has, since the War of the Spanish Succession, been gradually becoming more and more desolate; her great University, consisting once of forty colleges, exists only in a very inferior degree; where streets full of stately Spanish houses stood are meadows, vineyards, gardens, and orchards now.

But Louvain was still stately, as, at sunset in the latter part of May in the year of our Lord 1702, a horseman drew up at the western porte of the city walls, and, hammering on the great storm-beaten gate, clamoured for admission to the city. A horseman mounted on a bright bay--one that had a shifty eye, yet, judging by its lean flanks and thin wiry legs, gave promise of speed and endurance. A rider to whose shoulders fell dark, slightly curling hair, and whose complexion was bronzed and swarthy as though from long exposure to the sun and wind and rain.

"Cease! Cease!" a voice in French growled out from the inner side of the great gate. "Cease, in the name of all the fiends! The gate has had enough blows dealt on it in the centuries that are gone since it first grew a tree. Thy sword hilt will neither do it good nor batter it down. Also, I come. I do but swallow the last mouthful of my supper."

"I do beseech thee, bon ami," the traveller called back with a mocking laugh, "not to hurry thyself. My lady can wait thy time. The air is fresh and sweet outside, the wild flowers grow about the gate, and I am by no means whatever pressed. Eat and drink thy fill."

"Um--um!" the voice from inside grunted. "Whoe'er you are, you have a lightsome humour, a jocund tongue. I, too, do love my jest. Peste! These sorry Hollanders know not what wit and mirth are--therefore I will open the gate. Ugh! ugh! ugh!"

"Hast choked thyself in thine eager courtesy? Wash it down, man--wash it down with a flask of Rhine wine."

But as the traveller thus jeered the great gate grunted and squeaked on its huge hinges; then slowly, with many more rasping sounds, one half of it opened wide.

"A flask of Rhine wine," muttered the warder, an elderly man clad in a soldierlike-looking dress, and one who looked as if not only the Rhine wines, but those of Burgundy and Bordeaux, were well known to him. "A flask of Rhine wine. Where should I, a poor soldier of the Régiment de Beaume, and a wounded one at that, get flasks of wine?"

"Where? Why, camarade, from a friend. From me. Here," and, putting his hand to his vest pocket, the cavalier tossed down a silver crown to the warder.

"Monsieur is an officer," the soldier said, stiffening himself to the salute, while his eye roamed over the points of the bright bay, and observed the handsome, workman-like sword that lay against its flanks, and also the good apparel of the rider. "He calls me camarade, and is lavish."

"Aye, an officer. Now, also disabled by a cruel blow. One who is still weak, yet who hopes ere long to draw this again," touching his quillon. "Of the cavalry. Now, see to my papers, and then let me on my way."

"To the lady who awaits monsieur," the man said with a respectful smile.

"Tush! I did but jest. There is no lady fair for me. I ride towards--towards--the Rhine, there to take part against the Hollanders who cluster thick, waiting to join Malbrouck." As the horseman spoke, he drew forth a paper from his pocket, and, bending over his horse's neck, handed it to the man.

"Le Capitaine Le Blond," the latter read out respectfully, "capitaine des Mousquetaires Gris. Travelling to Cologne. Bon, monsieur le capitaine," saluting as he spoke. "Pass, mon capitaine."

"Tell me first a good inn where I may rest for the night."

"There are but two, 'L'Ours' and 'Le Duc de Brabant.' The first, monsieur le capitaine, is the best. The wine is--o--hé--superb, adorable. Also it is full of officers. Some mousquetaires are of them. Monsieur should go there. There are none at the other."

"I will," the captain of mousquetaires said aloud as he rode on, though to himself he muttered, "Not I. 'Le Duc de Brabant' will suffice for me."

When Bevill Bracton recognised Sparmann in the inn at Antwerp he knew, as has been told, that he already stood in deadly peril. Already, though he had scarce been ashore two hours! Nevertheless, while he recognised this and understood that at once, without wasting a moment, he must form some plans for quitting Antwerp, and also, if possible, assuming a fresh disguise, he could by no means comprehend the presence of Sparmann in the city. Nor could he conceive what this man, a Dutchman, could have to do with the French Lieutenant of Police, an official who must surely be hated by the townspeople as much as, if not more than, the rest of their conquerors.

Re-entering the passage now, and approaching the bureau with the determination of discovering something in connection with his old enemy, if it were possible to do so, Bevill observed that the landlord's eyes were fixed upon him with a glance that was half menacing and half derisive, while, as he perceived this, he reflected, "Doubtless the man is rejoiced to see one of the hated French, as he supposes me to be, outwitted by his own countryman." After which he addressed the other, saying:

"Who is that man who throws doubt upon my identity and the passport I carry, issued by the French Embassy in London?"

"He! ach he! One who is a disgrace to the country that bore him-- to this city, for of Antwerp he is. He was once an officer in the Stadtholder's bodyguard, the Stadtholder who was made King of England; yet now he serves the French, your countrymen. Bah!" and the landlord spat on the floor. "Now he is a spy on his own. A--a--a mouchard."

"But why? Why?"

"He has been disgraced. He was always in trouble. A soldier--a young one, too; an English officer, as it is said--ran him through for jeering at the English soldiers; then, since he was despised by his own brother-officers for being beaten, he took to drinking. At last, he was broken. Then he joined the French, your countrymen. Only, since he had been beaten by an Englishman, they would not have him for a soldier. So he became un espion. For my part, I would that the English officer had slain him. To think of it! A Hollander to serve the French!"

"I fear you do not love the French," Bevill said quietly, a sudden thought, an inspiration, flashing to his brain even as the landlord poured out his contempt on his own compatriot. "The English appear to have your sympathy."

"Does the lamb love the tiger that crushes it between its jaws? Does the hare love the spring in which it is caught? Yet--yet they say," the landlord went on, casting a venomous glance at Bevill, "your country will not triumph over us long. Malbrouck is coming, forty thousand more English soldiers are coming; so, too, are the soldiers of every Protestant country in Europe Then, look out for yourselves, my French friends."

"So you love the English?"

"We love those who pull us out of the mire. And they have been our allies for years."

For a moment after hearing these words Bevill stood regarding this man while pondering deeply; then, making up his mind at once, he said:

"If I told you that at this present time that young English officer who ran Sparmann through--this renegade countryman of yours, this espion, this spy of the French, your conquerors--stands in imminent deadly danger in Antwerp--here, here, in your own city--would you help and succour him? Would you strive to save him--from Sparmann, the spy?"

"What!" the landlord exclaimed, his fishlike eyes extending as he stared at Bracton. "What!" while in a lower tone he repeated to himself the words Sparmann had uttered a quarter of an hour ago: "There was no secretary named André de Belleville at the French Embassy. 'The statement is false.'"

"Aye," replied Bevill Bracton, hearing his muttered words, and understanding them too, since he had learnt some Dutch when in Holland under King William. "Aye, the statement is false, but his is true. There was no secretary of that name. The passport was procured to help that young officer to reach Liége and assist a countrywoman. Also, if the day should haply come, to assist, to join Protestant Holland against Catholic France and Spain."

"And," the man said, still staring at him, "you are he? You are an Englishman--a Protestant?"

"I am, God be praised. I trust in you. It is in your power to help me to escape, or you can give me up to the Lieutenant. It is in your power to enable me to quit Antwerp ere the alarm is given at the gates. If it be already given, my chance is gone! You hate France; you look to England for rescue and preservation. Speak. What will you do?"

"The spy saw," the landlord said, still muttering to himself, "that you had bought the black horse. Therefore you cannot ride that, though it is the best. But in my stable is a bay----"

"Ah!"

"A bay! Ja wohl, a bay! Tricky, ill-tempered, but swift as the wind. Once outside the city----"

"Heaven above bless you!"

"----You are safe. You speak French like a Frenchman. You have passed before as one, it seems; you can do so again. The bay belonged to a mousquetaire who died here of a fever when first the accursed French seized on the city. I would not give it up since his bill was large."

"One thing only! My passport will betray, ruin me."

"Nein. I have the mousquetaire's papers; his French pass. He was a captain named Le Blond. With those, and with that thing off your head," nodding at the peruke Bevill wore, "you will surely pass the gate. But you must be quick. Quick! Time is money, as you English say. With you it may be more. It may be life or death."

Even as the landlord spoke Bevill had torn off his wig and shaken out his own dark hair, after which the former said:

"I will go get the papers. Then will I saddle the bay myself. She is in the stable in the back of the garden. You can pass out that way and through a back street. If you have luck, you are saved. If not----"

"I shall be saved. I know it--feel it. But you--you--he warned you of what might befall----"

"Bah! You will have escaped unknown to me. For proof, I can show that you even left the black horse behind in your haste. How shall they know that I gave you another in its place?" And the landlord left his bureau and ran up the stairs, saying he would be back with the papers of Captain Le Blond ere many moments had passed.

Thus it was that the supposed captain of mousquetaires escaped the first peril he encountered on the road towards Liége, towards assisting Sylvia Thorne to quit that city. He had escaped, yet he had done so by means that were abhorrent to him--by a false passport, the papers of a man now in his grave. He who--Heaven pardon him!--could he have had matters as he desired, would have ridden boldly and openly to every barrier, have faced every soldier of the enemy, and, announcing himself as what he was, have got through or finished his mission almost ere it was begun.

Yet that escape was indeed perilous, and, though Bevill Bracton knew it not, he had, even with the aid of the landlord, only missed discovery by a hair's breadth.

For, but a quarter of an hour before he rode towards the city barrier, the guard had been changed; a troop of the Régiment d'Orléans had relieved a troop of the Mousquetaires Gris. Had Bevill, therefore, arrived before this took place, he would at once have been discovered and his fate sealed, since all would have known that le Capitaine Le Blond had been dead for months. But with the men of the Régiment d'Orléans it was different, since they had but marched in a week or so before, and probably--though it need by no means have been so--knew not the name or appearance of the officers of the mousquetaires.

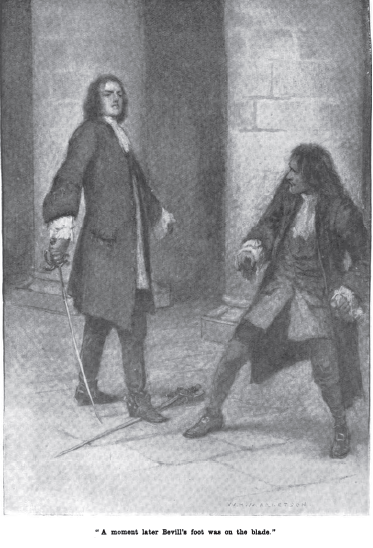

"'Would you strive to save him--from Sparmann,

the spy?'"

Bevill soon learnt, however, that Sparmann had wasted no time. Had he not acquired those papers, his undertaking must have ended here. The sergeant at the barrier, who came forward to inspect the paper he presented, carried in his hand another, which he read as Bevill rode up; and the latter divined, by the swift glance the trooper cast at his horse, and divined it with a feeling of actual certainty, that on that paper was a description of the black horse and his own appearance. But the horse was not the same, the peruke was wanting, and his riding cloak hid all that was beneath. Consequently, with a muttered "Bon voyage, M. le capitaine," and a salute, the sergeant stood back as Bevill rode through on the bay mare, who justified the character her recent owner had given her by lashing out with her hind legs and prancing from one side of the road to the other in her endeavour to unseat her rider. Soon finding, however, that she had her master on her back, she settled down into a swinging stride and bore him swiftly along the great, white east road.

And now he was in Louvain, after having passed by numberless implements of warfare collected by the roadside and watched over by French soldiery, as well as having passed also two French regiments marching swiftly towards Antwerp, there to reinforce the garrison, since, as war was declared, none knew how soon the forces of the redoubtable Marlborough, or Malbrouck, as they called him, might appear.

He was in Louvain, riding up an old, quiet street full of Spanish houses with pointed roofs that almost touched those of the opposite side, and allowed only a glimpse of the roseate hue of the early summer sunset to be seen between them. And soon, following the directions given him by the soldier at the gate, he reached the hostelry "Le Duc de Brabant," a house that looked almost as old as Time itself. One that, to each of its numerous windows, had huge projecting balconies of dark discoloured stone, of which the house itself was composed; an old, dark mansion, on whose walls were painted innumerable frescoes, most of which represented sacred subjects but some of which also depicted arrogantly the great deeds and triumphs of the Dukes of Brabant. A house having, too, a huge pointed gateway, the summit of which extended higher than the top of the windows of the first floor, and down one side of which there trailed a coiled rope carved in the stone, while, on the other side, was carved in the same way an axe, a block, and a miniature gibbet.

"Ominous signs for those who enter here," Bevill thought to himself, while the mare's hoofs clattered on the cobblestones as he rode under the archway. "Ominous once in far-off days for those who entered here, if this was some hall of justice, or the residence of their, doubtless, tyrannical rulers. Yet will I not believe that they are ominous for me. I have no superstitions, and, I thank Heaven devoutly, I have no fear. Yet," he muttered to himself as he prepared to dismount, "I would I had not to resort to so many subterfuges. Rather would I be passing for what I should be--a soldier belonging to those who have sworn to break down the power of this great ambitious king, this champion of the bigotry that we despise." Then, in an easier vein he added, as though to console himself, "No matter! What I do I do to help, perhaps to save, a helpless woman; to reinstate myself in the calling I love, the calling from which I was unjustly cast forth. And," he concluded, as he cast the reins to the servitors who had run into the courtyard at the clatter made by the mare's hoofs, "it is war time, and so--à la guerre, comme à la guerre!"

As Bevill dismounted in the great courtyard, and, addressing a man who was evidently the innkeeper, told him that he desired accommodation for the night, he recognised that, whatever might be the inferiority of this house to its rival, "L'Ours," it had at least some traveller, or travellers, of importance staying in it.

In one corner of the yard, round which ran a railed platform level with the ground floor and having four openings with steps leading up to that floor, there stood, horseless now, a large travelling coach, of the kind which, later, came to be called a berline. This construction was a massive one, since inside it were to be seen not only the front and back seats--the latter so deep and vast that one person might have made a bed of it by lying crosswise--but also a small table, which was firmly fixed into the floor in the middle of the vehicle. The body of the coach was slung on to huge leathern braces, which also served as springs, and was a considerable height from the ground--so high, indeed, that the steps outside the doors were four in number, though, when the vehicle was in progress, they were folded into one. On the panels were a count's coronet, a coat-of-arms beneath it, and above it the word and letter "De V." On the roof, and fitted into the grooves constructed for them, were some travelling boxes of black leather, with others piled on top of them. For the rest, there were on each side of the coach, in front, and at the back, long receptacles for musketoons as well as another for a horn, the weapons and instrument being visible.

"A fine carriage," Bevill said to the landlord, who seemed equally as surly and ungracious, if not more so, than the man at Antwerp had been while he supposed that the traveller was a Frenchman. "Some great personage, I should suppose."

"A compatriot of yours," the man said. "Mein Gott! Who travels thus in our land but your countrymen--and women? Yet," he added still more morosely, "it may not be ever thus."

Ignoring this remark, which naturally did not arouse Bevill's ire, since he imagined that the state of things the man suggested might most probably come to pass, he exclaimed:

"And women, you say? Pardie! Are ladies travelling about during such times as these, when war is in the air?"

"Aye, war is in the air," the landlord said, ignoring the first part of the other's remark. "In the air, and more than in the air. Soon it will be in the land and on the sea." After which, a waiting woman having arrived to conduct Bevill to his room, and a stableman having led the horse to a stall, the man turned away. Yet, as he went, he muttered, "Then we shall see. England and Holland are stronger than France on the sea, and on the land they are as good as France."

It was no part of Bevill's to assume indignation, even if he could have done so successfully, at these contemptuous remarks about his supposed country and countrymen; therefore he followed the woman to the room to which she led him. On this occasion, doubtless because he possessed a horse, and that horse was at the present moment in the landlord's custody, no demand was made for payment in advance.

"And now," he said to himself, "a supper, the purchase of a few necessaries in this town, and to bed. To-morrow I must be off and away again. The sooner I am in Liége the better."

In the old streets of that old city, Bevill found a shop in which he was able to provide himself with the few requisites that travellers carried with them in such distracted times. Amongst the accoutrements of the late Captain Le Blond's charger was his wallet-haversack for fastening behind the cantle, or in front of the pommel; but it required filling, and this was soon done. A change of linen was easily procured, which, with a comb, generally completed a horseman's outfit, and then Bevill set out on his return to "Le Duc de Brabant." But as he passed along the street he came across an armourer's shop, and, glancing into it, was thereby reminded that he was without pistols.

"And," he thought to himself, "good as my blade is, a firearm is no bad accessory to a sword. It may chance, and well it may, that ere I reach Liége, as in God's grace I hope to do, I may have need of such a thing. So be it. Cousin Mordaunt has well replenished my purse; I will enter and see if the armourer has any such toys."

Suiting the action to the thought, Bevill entered the shop, and, seeing an elderly man engaged on polishing up a breastplate, asked him if he had any pistols to dispose of.

"Ja!" the man replied. "And some good ones, too. Only they are dear. Also the mynheer may not like them. Most of them were taken from the French after Namur, and sold to me by an English soldier."

"Bah! What matters how I come by them so that 'tis honestly, and that they will serve their purpose? Produce them."

Upon this the armourer dragged forth a drawer in which were several weapons of the kind, some lying loose and some folded in the leather or buckskin wrappings in which the man had enveloped them. At first, those which met Bevill's eyes did not commend themselves much to him; some were too old, some too clumsy, and some too rusty.

"Mynheer is difficult to please," the armourer remarked with a grunt; "perhaps these will suit him better. Only they are dear," while, as he spoke, he unfolded two of the buckskin wrappers and exhibited a pair of pistols of a totally different nature from the others. These weapons were indeed handsome ones, well mounted on ivory and with long, unbrowned barrels worked with filigree. The triggers sprang easily back and fell equally as easily to the light touch of a finger, the flints flashing sparks bravely as they did so. On one was engraved "Dernier espoir," on the other "Mon meilleur ami."

"How much for these?" Bevill asked, looking at the armourer.

"Two pistoles, with powder flask and bullet-box. Also the flask well filled and two score balls."

"So be it. They are mine." And Bevill dropped one into each of the great pockets of his riding-coat. "Now for the flask and bullets."

"With these," he said to himself, as he walked back to the inn, "my sword, and the swift heels of the mare, I can give a good account of myself if danger threatens."

The supper for the guests was prepared when he reached "Le Duc de Brabant," and Bevill, taking his place at the table, glanced round to see who his fellow-travellers might be, yet soon observed that, for the present at least, there were none.

"So," he thought to himself, "the fellow at the gate spoke truly. 'Tis very apparent that 'The Duke' is not in such high favour as his rival, 'The Bear.' However, the eating proves the pudding and the drinking proves the wine. Let us see to it."

Whereupon he bade the drawer bring him a flask of good Coindrieux--the list of wines hanging on a wall so that all the guests might see and read. Then, ere the wine came, Bevill commenced to attack the course set before him, though before he had eaten two mouthfuls an interruption occurred.

Preceded by a servitor, whom Bevill supposed--and supposed truly, as he eventually knew--to be a private servant and not one attached to the inn, a lady came down the room towards the table at which the Englishman sat: a lady still young, of about thirty years of age, tall, and delicate-looking. Also she was extremely well favoured, her blue-grey eyes being shielded by long dark lashes, and her features refined and well cut. As for her hair, Bevill, who on her approach had risen from his seat and bowed gravely, and then remained standing till she was seated, could form no opinion, since it was disguised by her wig. But he observed that she was clad all in black, even to her lace; while, thrown over her wig, was the small coif, or hood, which widows wore. Therefore he understood the solemnity of her attire--a solemnity still more enhanced and typified by the look of sadness which her face wore.

"He had hastened to the door to hold

it open for her."--p. 122.

This lady, who had returned Bevill's courtesy by a slight inclination of her head, was now served by the elderly manservant, who took the dishes from the ordinary inn server, and, placing each before her who was undoubtedly his mistress, then retired behind her chair until the next dish was ready. But, as would indeed have been contrary to all etiquette, neither Bevill nor the lady addressed a word to the other.

When, however, the drawer returned with the flask of Coindrieux, and Bevill spoke some word to the man on the subject of not filling his glass too full, he observed for one moment that the lady lifted her eyes and looked at him somewhat curiously, and as though some tone or intonation of his had attracted her attention. A moment later her eyes were dropped to her plate again, though more than once during the serving of the next dish he observed that she was again regarding him.

"Has my accent betrayed me?" Bevill mused. "When I spoke to the man, did she recognise that I am no Frenchman? Has my tongue grown rusty?"

Yet, even as he so pondered, he told himself that there was no reason that such should be the case. The lady might herself be no Frenchwoman, but, instead, one belonging to this war-worn land.

"She may not be capable of judging who or what I am," he reflected.

Yet in another moment he had learnt that her powers of judging whether he was a Frenchman or not were undoubtedly sufficient.

In a voice, an accent, which no other than a Frenchman or Frenchwoman ever possessed, an intonation which none but those who had learnt to lisp that language at their mother's knee could have acquired, the lady spoke now to her elderly servant, saying:

"Ambroise, retire, and bid Jeanne prepare the valises. I have resolved to go forward an hour after dawn."

The manservant bowed, then said:

"But the supper, Madame la Comtesse? Who shall serve, madame? The remainder is not----"

"The server will do very well. Go and commence to assist Jeanne."

"Madame la Comtesse," Bevill thought to himself when the man had departed. "So this is doubtless the owner of the grand coach. And she is a Frenchwoman. It may well be that she understands I am no countryman of hers, though I know not, in solemn truth, why she should suppose I pretend to be one--unless the landlord or servants have told her, or she has looked in the register of guests." For here, as everywhere, all travellers had to give their names to the landlords, and Bevill was now registered as "Le Capitaine Le Blond, of the Mousquetaires Gris."

The supper went on still in silence, however, and the server attended both to the lady who had been styled "La Comtesse" and to Bevill. But he was nothing more than a raw Flemish boor, little accustomed to waiting on ladies and gentlemen, and gave Bevill the idea that he was not occupied in his usual vocations. Once he dropped a dish with such a clatter that the lady started, and once he handed another to Bevill before offering it to the countess.

"Serve madame!" Bevill said sternly, looking at the hobbledehoy and covering him with confusion, while, as he did so, the lady lifted her eyes to him and bowed stiffly, though graciously. Then, as if feeling it necessary that some word of acknowledgment, some small token of his civility, should be testified, the lady said:

"Monsieur is extremely polite. He is doubtless not native here?"

"No, madame. I am a stranger passing through the land on my way towards the Rhine," while, as Bevill spoke, he was glad that, in this case, there was no need for deception, since Liége was truly on the road towards the Rhine.

"As am I. I set out to-morrow for Liége."

"For Liége? Madame will scarcely find that town a pleasant place of sojourn. Yet I do forget--madame is French."

"As is monsieur," the Countess said, with a swift glance at her companion, speaking more as though stating a fact than asking a question.

Bevill shrugged his shoulders ever so slightly, but as much as good breeding would allow. Then he said:

"Monsieur de Boufflers commands there. Madame will be at perfect ease."

"Doubtless," the other said, with a slight shrug on her part now. "Doubtless. Yet," and again she shrugged her shoulders, "war is declared. The English and the Dutch will soon be near these barrier towns. They say that the Earl of Marlborough will come himself in person, that he will command all the armies directed against us. Would it be possible that monsieur should know--that he might by chance have heard--when the Earl will be in this neighbourhood?"

"I know nothing, madame," Bevill replied, while as he did so two thoughts forced themselves into his mind. One was that this lady had discovered easily enough that he was no Frenchman; the other, that she was endeavouring to extract some of the forthcoming movements of the enemy--the enemy of France--from him.

"What is she?" he mused to himself when the conversation had ceased, or, at least, come to a pause. "What? Some spy passing through the land and endeavouring to discover what the English plans may be; some woman who, under an appearance of calm and haughty dignity, seeks for information which she may convey to de Boufflers or Tallard. Yet--how to believe it! Spies look not as she looks; their eyes do not glance into the eyes of those they seek to entrap as hers look into mine when she speaks. It is hard to credit that she should be one, and yet--she is on her road to Liége--Liége that, at present, is in the grasp of France, as so much of all Flanders is now."

Suddenly, however, as still these reflections held the mind of Bevill Bracton, there came another, which seemed to furnish the solution of who and what this self-contained, well-bred woman might chance to be.

"There are," he reflected, "there must be, innumerable officers of high rank at Liége under Marshal de Boufflers; it may be that it is to one of these she goes. Not a husband, since she is widowed; nor a son, since, at her age, that is impossible; but a father, a brother. Heaven only grant that, if she and I both reach that city safely, she may not unfold her doubts of what I am. For doubt me she does, though it may be that she does not suppose I am an Englishman. If she should do so, 'twill be bad for Sylvia Thorne and doubly bad for me."

As Bevill reached this stage in his musings, the Countess rose from the table, and, when he had risen also and hastened o the door to hold it open for her, passed through, after acknowledging his attention and also his politely expressed hope that her journey to Liége would be easily made.

After which, as he still stood at the door until she should have passed the turn made by the great stone staircase, Bevill observed this lady look round at him, though not doing so either curiously or coquettishly. Instead, it appeared to the young man standing there deferentially that the look on her face seemed to testify more of bewilderment, of doubt, than aught else.