The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Modern Vikings, by Hjalmar Hjorth Boyesen

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Modern Vikings

Stories of Life and Sport in the Norseland

Author: Hjalmar Hjorth Boyesen

Release Date: September 17, 2016 [EBook #53070]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MODERN VIKINGS ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, John Campbell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

THE SCRIBNER SERIES

FOR YOUNG PEOPLE

EACH WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOR

| BOOKS FOR BOYS | |

| THE MODERN VIKINGS | By H. H. Boyesen |

| WILL SHAKESPEARE’S LITTLE LAD | By Imogen Clark |

| THE BOY SCOUT and Other Stories for Boys | |

| STORIES FOR BOYS | By Richard Harding Davis |

| HANS BRINKER, or, The Silver Skates | By Mary Mapes Dodge |

| THE HOOSIER SCHOOL-BOY | By Edward Eggleston |

| THE COURT OF KING ARTHUR | By William Henry Frost |

| WITH LEE IN VIRGINIA | |

| WITH WOLFE IN CANADA | |

| REDSKIN AND COWBOY | By G. A. Henty |

| AT WAR WITH PONTIAC | By Kirk Munroe |

| TOMMY TROT’S VISIT TO SANTA CLAUS and | |

| A CAPTURED SANTA CLAUS | By Thomas Nelson Page |

| BOYS OF ST. TIMOTHY’S | By Arthur Stanwood Pier |

| KIDNAPPED | |

| TREASURE ISLAND | |

| BLACK ARROW | By Robert Louis Stevenson |

| AROUND THE WORLD IN EIGHTY DAYS | |

| A JOURNEY TO THE CENTRE OF THE EARTH | |

| FROM THE EARTH TO THE MOON | |

| TWENTY THOUSAND LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA | By Jules Verne |

| ON THE OLD KEARSAGE | |

| IN THE WASP’S NEST | By Cyrus Townsend Brady |

| THE BOY SETTLERS | |

| THE BOYS OF FAIRPORT | By Noah Brooks |

| THE CONSCRIPT OF 1813 | By Erckmann-Chatrian |

| THE STEAM-SHOVEL MAN | By Ralph D. Paine |

| THE MOUNTAIN DIVIDE | By Frank H. Spearman |

| THE STRANGE GRAY CANOE | By Paul G. Tomlinson |

| THE ADVENTURES OF A FRESHMAN | By J. L. Williams |

| JACK HALL, or, The School Days of an American Boy | By Robert Grant |

| BOOKS FOR GIRLS | |

| SMITH COLLEGE STORIES | By Josephine Daskam |

| THE HALLOWELL PARTNERSHIP | By Katharine Holland Brown |

| MY WONDERFUL VISIT | By Elizabeth Hill |

| SARAH CREWE, or, What Happened at Miss Minchin’s | By Frances Hodgson Burnett |

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

THE MODERN VIKINGS

Stories of Life and Sport in the

Norseland

BY

HJALMAR HJORTH BOYESEN

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1921

Copyright, 1887, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Copyright, 1915, by

HJALMAR H. BOYESEN

ALGERNON BOYESEN

BAYARD H. BOYESEN

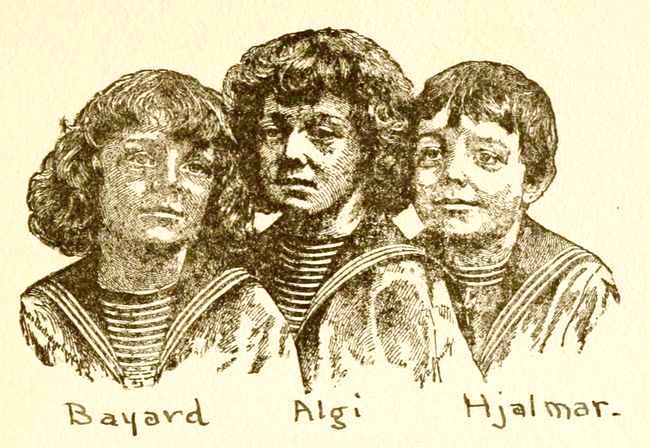

TO THE THREE VIKINGS:

HJALMAR, ALGERNON, AND BAYARD.

Three little lovely Vikings

Came sailing over the sea,

From a fair and distant country,

And put into port with me.

The first—how well I remember—

Sir Hjalmar was he hight.

With a lusty Norseland war-whoop,

He came in the dead of night.

He met my respectful greeting

With a kick and a threatening frown;

He pressed all the house in his service,

And turned it upside-down.

[vi]He thrust, when I meekly objected,

A clinched little fist in my face;

I had no choice but surrender,

And give him charge of the place.

He heeded no creature’s pleasure;

But oft, with a conqueror’s right,

He sang in the small hours of morning,

And dined in the middle of night.

And oft, to amuse his Highness—

For naught we feared as his frowns—

We bleated and barked and bellowed,

And danced like circus-clowns.

Then crowed with delight our despot;

So well he liked his home,

He summoned his brother, Algie,

From the realm beyond the foam.

And he is a laughing tyrant,

With dimples and golden curls;

He stole a march on our heart-gates,

And made us his subjects and churls.

He rules us gayly and lightly,

With smiles and cajoling arts;

He went into winter-quarters

In the innermost nooks of our hearts.

[vii]And Bayard, the last of my Vikings,

As chivalrous as your name!

With your sturdy and quaint little figure,

What havoc you wrought when you came!

There’s a chieftain in you—a leader

Of men in some glorious path—

For dauntless you are, and imperious,

And dignified in your wrath.

You vain and stubborn and tender

Fair son of the valiant North,

With a voice like the storm and the north-wind,

When it sweeps from the glaciers forth.

With the tawny sheen in your ringlets,

And the Norseland light in your eyes,

Where oft, when my tale is mournful,

The tears unbidden arise.

For my Vikings love song and saga,

Like their conquering fathers of old;

And these are some of the stories

To the three little tyrants I told.

| PAGE | |

| Tharald’s Otter, | 1 |

| Between Sea and Sky, | 17 |

| Mikkel, | 41 |

| The Famine among the Gnomes, | 71 |

| How Bernt Went Whaling, | 79 |

| The Cooper and the Wolves, | 91 |

| Magnie’s Dangerous Ride, | 102 |

| Thorwald and the Star-Children, | 128 |

| Big Hans and Little Hans, | 147 |

| A New Winter Sport, | 165 |

| The Skerry of Shrieks, | 182 |

| Fiddle-John’s Family, | 211 |

| Between sea and sky | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| The baron sprang up with an exclamation of fright | 76 |

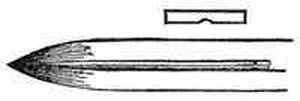

| Norwegian skee-runners | 178 |

| In Battery Park | 260 |

Tharald and his brother Anders were bathing one day in the lake. The water was deliciously warm, and the two boys lay quietly floating on their backs, paddling gently with their hands. All of a sudden Tharald gave a scream. A big trout leaped into the air, and almost in the same instant a black, shiny head rose out of the water right between his knees. The trout, in its descent, gave him a slap of its slimy tail across his face. The black head stared out at him, for a moment, with an air of surprise, then dived noiselessly into the deep.

Anders hurried to shore as rapidly as arms and legs would propel him.

“It was the sea-serpent,” said he.

He was so frightened that he grew almost numb; his breath stuck in his throat, and the blood throbbed in his ears.

“Oh, you sillibub!” shouted his brother after him, “it was an otter chasing a salmon-trout. The trout will always leap, when chased.”

He had scarcely spoken when, but a few rods from Anders, appeared the black, shiny head again, this time with the trout in its mouth.

“He has his lair somewhere around here,” said Tharald; “let us watch him, and see where he is going.”

The otter was nearing the shore. He swam rapidly, with a slightly undulating motion of the body, so that, at a distance, he might well have been mistaken for a large water-snake. When he had reached the shore, he dragged the fish up on the sand, spied cautiously about him, to see if he was watched, and again seizing the trout, slid into the underbrush. There was something so delightfully wild and wary about it that the boys felt the hunter’s passion aroused in them, and they could scarcely take the time to fling on their clothes before starting in pursuit. Like Indians, they crept on hands and feet over the mossy ground, bent aside the bushes, and peered cautiously between the leaves.

“Sh—sh—sh! we are on the track,” whispered Tharald, stooping to smell the moss. “He has been here within a minute.”

“Here is a drop of fish-blood,” answered Anders, pointing to a twig, over which the fish had evidently been dragged.

“Serves him right, the rascal,” murmured his elder brother.

“If we haven’t got him now, my name is not Anders,” whispered the younger.

They had advanced about fifty rods from the water, when their attention was arrested by two faint tracks among the stones—so faint, indeed, that no eyes but those of a hunter would have discovered them. A strange pungent odor, as of something wild, pervaded the[3] air; the whirring of the crickets in the tree-tops seemed hushed and timid, and little silent birds hopped about in the elder-bushes as if afraid to make a noise.

The boys lay down flat on the ground, and following the two tracks, discovered that they converged toward a frowsy-looking juniper-bush which grew among the roots of a big old pine. Very cautiously they bent the bush aside.

What was that? There stood the old otter, tearing away at his trout, and three of the prettiest little black things your eyes ever fell upon were gambolling about him, picking up bits of the fish, and slinging them about in their efforts to swallow.

The boys gave a cry of delight. But the otter—what do you think he did? He showed a set of very ugly teeth, and spat like an angry cat. It was evidently not advisable to molest him with bare hands.

In hot haste Tharald and Anders by their united weight broke off a young elder-tree and stripped off the leaves. Now they could venture a battle. Eagerly they pulled aside the juniper. But alas, Mr. Otter was gone, and had taken his family with him.

To track him through the tangled underbrush, where he probably knew a hundred hiding-places, would be a hopeless task. The boys were about to return, baffled and disappointed, to the lake, when it occurred to Tharald to explore the den.

There was a hole under the tree-root, just big enough to put a fist through, and, without thought of harm, the boy flung himself down and thrust his arm in to the very[4] elbow. He fumbled about for a moment—ah, what was that?—something soft and hairy, that slipped through his fingers. Tharald made a bold grab for it—then with a yell of pain pulled out his hand. The soft thing followed, but its teeth were not soft. As Tharald rose to his feet, there hung a tiny otter with its teeth locked through the fleshy part of his hand, at the base of the thumb.

“Look here, now,” cried his brother; “sit down quietly, and I will soon rid you of the little beast.”

Tharald, clinching his teeth, sat down on a bowlder. Anders drew his knife.

“No, I thank you,” shouted Tharald, as he saw the knife, “I can do that myself. I don’t want you to harm him.”

“I don’t intend to harm him,” said Anders. “I only want to force his mouth open.”

To this Tharald submitted. The knife was carefully inserted at the corner of the little monster’s mouth, when lo! he let the hand go, and snapped after the knife-blade. Anders quickly threw his hat over him, and held it down with his knees, while he tore a piece off the lining of his coat to bandage his brother’s wound. Then they trudged home together with the otter imprisoned in the hat.

You would scarcely have thought that “Mons”—for that became the otter’s name—would have made a pleasant companion; but strange as it may seem, he improved much, as soon as he got into civilized society. He soon learned that it was not good-manners to snarl and show[5] his teeth when politely addressed, and if occasionally he forgot himself, he got a little tap on the nose which quickened his memory. He was scarcely six inches long when he was caught, not reckoning the tail; and so sleek and nimble and glossy, that it was a delight to handle him His fur was of a very dark brown, and when it was wet looked black. It was so dense that you could not, by pulling the hair apart, get the slightest glimpse of the skin. But the most remarkable things about Mons were the webs he had between his toes, and his long glossy whiskers. Of the latter he was particularly proud; he would allow no one to touch them.

Tharald taught him a number of tricks, which Mons learned with astonishing ease. He was so intelligent that Sultan, the bull-terrier, grew quite jealous of him.

Inquisitiveness seemed to be the strongest trait in Mons’s character. His curiosity amounted to an overmastering passion. There was no crevice that he did not feel called upon to investigate, no hole which he did not suspect of hiding some interesting secret. Again and again he made explorations in the flour-barrel, and came out as white as a miller. Once, for the sake of variety, he put his nose into the inkstand, and in attempting to withdraw it, poured the contents over his head.

In the part of Norway where Tharald’s father lived, the people added largely to their income by salmon-fishing. Nay, those who had no land made their living entirely by fishing and shooting. Every spring the salmon migrated from the sea into the rivers, to deposit their spawn; you could see their young darting in large schools[6] over the pebbles in the shallows of the streams, pursued by the big fishes that preyed upon them. Then the perch and the trout grew fat, and the pike and the pickerel made royal meals out of the perch and trout. All along the coast lay English schooners, ready to buy up the salmon and carry it on ice to London. Everywhere there was life and traffic; everybody felt prosperous and in good-humor.

It was during this season that Tharald one day walked down to the lake to try his luck with a fly. It had been raining during the night; and the trees along the shore shivered and shook down showers of raindrops. The only trouble was that the water was so clear that you could see the bottom, which sloped gently outward for fifty or a hundred feet. Mons, who was now a year old, was sitting in his usual place on Tharald’s shoulder, and was gazing contentedly upon the smiling world which surrounded him. He was so fond of his master, now, that he followed him like a dog, and could not bear to be long away from him.

“Mons,” said Tharald, after having vainly thrown the alluring fly a dozen times into the river, “I think this is a bad day for fishing; or what do you think?”

At that very instant a big salmon-trout—a six-pounder at the very least—leaped for the fly, and with a splash of its tail sent a shower of spray shoreward. The line flew with a hum from the reel, and Tharald braced himself to “play” the fish, until he should tire him sufficiently to land him.

But the trout was evidently of a different mind. He[7] sprang out of the water, and his beautiful spotted sides gleamed in the sun.

That was a sight for Mons! Before his master could prevent him, he plunged from his shoulder into the lake, and shot through the clear tide like a black arrow. The trout saw him coming, and made a desperate leap!

The line snapped; the trout was free!

Free! It was delightful to see Mons’s supple body as it glided through the water, bending upward, downward, sideward, with amazing swiftness and ease. His two big eyes (which were conveniently situated so near the tip of his nose that he could see in every direction with scarcely a turn of the head) peered watchfully through the transparent tide, keeping ever in the wake of the fleeing fish. If the latter had had the sense to keep straight ahead, he might have made good his escape. But he relied upon strategy, and in this he was no match for Mons. He leaped out of the water, darted to the right and to the left, and made all sorts of foolish and flurried manœuvres. But with the calmness of a Von Moltke, Mons outgeneralled him. He headed him off whenever he turned, and finally by a brisk turn plunged his teeth into the trout’s neck, and brought him to land.

I need not tell you that Tharald made a hero of him. He hugged him and patted him and called him pet names, until Mons grew quite bashful. But this exploit of Mons’s gave Tharald an idea. He determined to train him as a salmon-fisher.

It was in the spring of 1880, when Mons was two years old and fully grown, that he landed his first salmon. And when he had landed the first, it cost him little trouble to secure the second and the third. Tharald felt like a rich man that day, as he carried home in his basket three silvery beauties, worth, at the very least, a dollar and a half apiece. He made haste to dispose of them to an English yachtsman at that figure, and went home in a radiant humor, dreaming of “gold and forests green,” as the Norwegians say.

“Now, Mons,” he said to his friend, whom he was leading after him by a chain, “if we do as well every day as we have done to-day, we shall soon be rich enough to go to school. What do you think of that, Mons?”

One day a big fish-tail splashed out of an eddy, and a black furry head and back rose for an instant and were whirled out of sight.

“Oh, dear, dear,” cried Tharald, “he will die! He will drown! How often have I told you, Mons,” he shouted, “that you shouldn’t attack fishes that are bigger than yourself.”

“Whom are you talking to?” asked a fisherman named John Bamle, who had come to look after his traps.

“To Mons,” answered the boy, anxiously.

“You don’t mean to say your brother is out there in the water!” shouted John Bamle, in amazement.

“Yes, Mons, my otter,” cried Tharald, piteously.

“Mons, your brother!” yelled the man, and seizing a boat-hook, he ran out on the beams from which the traps were suspended. The roar of the waters was so loud that[9] it was next to impossible to distinguish words, and “Mons, my otter,” and “Mons, my brother,” sounded so much alike that it was not wonderful that John mistook the former for the latter. For awhile he balanced himself by means of the boat-hook on the slippery beams, peering all the while anxiously into the rapids.

Suddenly he saw something struggling in the water; showers of spray whirled upward. Could it be possible that a fish had attacked the drowning child? Full of pity, he stretched himself forward, extending the boat-hook before him, when lo! he lost his balance, and tumbled headlong into the cataract.

Half a dozen other fishermen who were sauntering down the hill-sides saw their comrade fall, and rushed into the water to rescue him.

One man, bolder than the rest, sat astride a floating log and rode out into the seething current. Now he was thrown off; now he scrambled up again; at last, as his drowning comrade appeared for the third time, with an arm extended out of a whirling eddy, he caught him deftly with his boat-hook, and pulled him up toward the log.

As John Bamle lay there, more dead than alive, upon the bank, emitting streams of water through mouth and nostrils, the question was asked how he came to endanger his life in such a reckless manner. At that very instant the head of a black otter was seen emerging from the water, dragging a huge salmon up among the stones.

“Look, the otter, the otter!” cried the men; and a[10] shower of stones hailed down upon the bowlder upon which Mons had sought refuge.

“Let him alone, I tell you!” screamed Tharald; “he is mine.”

And with three leaps he was at Mons’s side, wringing wet from top to toe, but happy to have his friend once more in safety. He seized him in his arms, and would have borne him ashore, if the enormous salmon had not demanded all his strength.

As they again reached the bank, the fishermen gathered about them; but Mons slunk cautiously at his master’s heels. He understood the growling comments, as one man after the other lifted the big salmon and estimated its weight. John Bamle had now so far regained consciousness that he could speak, and he stared with no friendly eye at the boy who had come near causing his death.

“Come, now, Mons,” said Tharald, “come, and let us hurry home to breakfast.”

“Mons!” repeated John Bamle; “is that your Mons?”

“Yes, that is my Mons,” answered Tharald, innocently.

“Then you just wait till I am strong enough to stand on my legs, and I’ll promise to give you a thrashing that you’ll remember to your dying day,” said John, and shook his big fist.

Tharald was not anxious to wait under such circumstances, but betook himself homeward as rapidly as his legs would carry him.

During the next week Tharald did his best to avoid the fishermen. And yet, try as he might, he could not help meeting them on the road, or on the river-bank, as he carried home his heavy load of salmon.

“Hallo! How is your brother Mons?” they jeered, when they saw him.

Occasionally they stopped and glanced into his basket; and Tharald noticed that they glowered unpleasantly at him, whenever he had caught a fine fish. The fact was, he had had extraordinary luck this week; for Mons was getting to be such an expert, that he scarcely ever dived without bringing something or other ashore.

He had almost money enough now to pay for a year’s schooling, and he could scarcely sleep for joy when he thought of the bright future that stretched out before him. He saw himself in all manner of delightful situations. Mons, in the meanwhile, who was not troubled with this kind of ambition, snoozed peacefully in his box, at the foot of his master’s bed. He did not dream what a rude awakening was in store for him.

It had been a very bad week for John Bamle and his comrades. Morning after morning their traps were empty, or one solitary fish lay sprawling at the bottom of the box.

“I tell you, boys,” said John, spitting into his fist, and shaking it threateningly against the sky, “I am bewitched; that’s what I am. And so are you, boys—every mother’s son of you. It is that Gimlehaug boy that has bewitched us. Are you fools enough to suppose[12] that it is a natural beast—that black thing—that trots at his heels, and empties the river of its fish for his benefit? Not by a jugful, lads—not by a big jugful! The devil it is—the black Satan himself—or my name is not John Bamle. You never saw a beast act like that before, plunging into the yellow whirlpools, and coming back unscathed every time, and with a fish as big as himself dangling after him. Now, shall we stand that any longer, boys? We have wives and babies at home, crying for food! And here we come daily, and find empty traps. Now wake up, lads, and be men! There has come a day of reckoning for him who has sold himself to the devil. I, for my part, am just mad enough to venture on a tussle with old Nick himself.”

Every word that John uttered fell like a firebrand into the men’s hearts. They shouted wildly, shook their fists, and swung their long boat-hooks.

“We’ll kill him, the thief,” they cried, “the scoundrel! He has sold himself to the devil.”

Up they rushed from the river-bank, up the green hillsides, up the rocky slope, until they reached the gate at Gimlehaug. It was but a small turf-thatched cottage, with tiny lead-framed window-panes and a rude stone chimney. The father was out working by the day, and the two boys were at home alone. Tharald, who was sitting at the window reading, felt suddenly a paw tapping him on the cheek. It was Mons. In the same instant an angry murmur of many voices reached his ear, and he saw a crowd of excited fishermen, with boat-hooks in their hands, thronging through the gate. There were[13] twenty or thirty of them at the very least. Tharald sprang forward and bolted the door. He knew why they had come. Then he snatched Mons up in his arms, and hugged him tightly.

“Let them do their worst, Mons,” he said; “whatever happens, you and I will stand by each other.”

Anders, Tharald’s brother, came rushing in by the back door. He, too, had seen the men coming.

“Hide yourself, hide yourself, Tharald!” he cried in alarm; “it is you they are after.”

Hide yourself! That was more easily said than done. The hut was now surrounded, and there was no escape.

“Climb up the chimney,” begged Anders; “hurry, hurry! you have no time to lose.”

Happily there was no fire on the hearth, and Tharald, still hugging Mons tightly, allowed himself to be pushed by his brother up the sooty tunnel. Scarcely was Anders again out on the floor, when there was a tremendous thump at the door, so that the hut trembled.

“Open the door, I say!” shouted John Bamle without.

Anders, knowing how easily he could force the door, if he wished, drew the bolt and opened.

“I want the salmon-fisher,” said John, fiercely.

“Yes, we want the salmon-fisher,” echoed the crowd, wildly.

“What salmon-fisher?” asked Anders, with feigned surprise.

“Don’t you try your tricks on me, you rascal,” yelled John, furiously; and seizing the boy by the collar, flung him out through the door. The crowd stormed in after[14] him. They tore up the beds, and scattered the straw over the floor; upset the furniture, ransacked drawers and boxes. But no trace did they find of him whom they sought. Then finally it occurred to someone to look up the chimney, and a long boat-hook was thrust up to bring down whatever there might be hidden there. Tharald felt the sharp point in his thigh, and he knew that he was discovered. With the strength of despair he tore himself loose, leaving part of his trousers on the hook, and, climbing upward, sprang out upon the roof. His thigh was bleeding, but he scarcely noticed it. His eyes and hair were full of soot, and his face was as black as a chimney-sweep’s. The men, when they saw him, jeered and yelled with derisive laughter.

“Hand us down your devilish beast there, and we won’t hurt you!” cried John Bamle.

“No, I won’t,” answered Tharald.

“By the heavens, lad, if you don’t mind, it will go hard with you.”

“I am not afraid,” said Tharald.

“Then we’ll make you, you beastly brat,” yelled a furious voice in the crowd; and instantly a stone whistled past the boy’s ear, and fell with a thump on the turf below.

“Now, will you give up your beast?”

Tharald hesitated a moment. Should he give up Mons, who had been his friend and playmate for two years, and see him stoned to death by the cruel men? Mons fixed his black, liquid eyes upon him as if he would ask him that very question. No, no, he could not for[15]sake Mons. A second stone, bigger than the first, flew past him, and he had to dodge quickly behind the chimney, as the third and fourth followed.

“Tharald, Tharald!” cried Anders, imploringly; “do let the otter go, or they will kill both you and him.”

Before Tharald could answer, a shower of stones fell about him. One hit him in the forehead; the sparks danced before his eyes. A warm current rushed down his face; dizziness seized him; he fell, he did not know where or how. John Bamle with a yell sprang forward, climbed up the low wall to the roof, and saw the boy lying, as if dead, behind the chimney. He turned to call for his boat-hook, when suddenly something black shot toward him from the chimney-top, and a set of terrible teeth buried themselves in his throat. The mere force of the leap made him lose his balance, and he tumbled backward into the yard.

In the same instant Mons bounded forward, lighted on somebody’s shoulder, and made for the woods. Before anybody had time to think, he was out of sight.

Thus ended the famous battle of Gimlehaug, of which the salmon-fishers yet speak in the valley. Or rather, I should say, it did not end there, for John Bamle lay ill for several weeks, and had to have his wound sewed up by the doctor.

As for Tharald, he got well within a few days. But a strange uneasiness came over him, and he roamed through the woods early and late, seeking his lost friend. At the end of a week, as he was sitting, one night, on the rocks at the river, he suddenly felt something hairy rubbing[16] against his nose. He looked up, and with a scream of joy clasped Mons in his arms. Then he hurried home, and had a long talk with his father. And the end of it was, that with the money which Mons had earned by his salmon-fishing, tickets were bought for New York for the entire family. About a month later they landed at Castle Garden.

Tharald and Mons are now doing a large fish-business, without fear of harm, in one of the great lakes of Wisconsin. Some day, he hopes yet, it may lead to a parsonage. Since he learned that some of the apostles were fishermen, he feels that he is on the right road to the goal of his ambition.

“Iceland is the most beautiful land the sun doth shine upon,” said Sigurd Sigurdson to his two sons.

“How can you know that, father,” asked Thoralf, the elder of the two boys, “when you have never been anywhere else?”

“I know it in my heart,” said Sigurd, devoutly.

“It is, after all, a matter of taste,” observed the son. “I think if I were hard pressed, I might be induced to put up with some other country.”

“You ought to blush with shame,” his father rejoined warmly. “You do not deserve the name of an Icelander, when you fail to see how you have been blessed in having been born in so beautiful a country.”

“I wish it were less beautiful and had more things to eat in it,” muttered Thoralf. “Salted codfish, I have no doubt, is good for the soul, but it rests very heavily on the stomach, especially when you eat it three times a day.”

“You ought to thank God that you have codfish, and[18] are not a naked savage on some South Sea isle, who feeds, like an animal, on the herbs of the earth.”

“But I like codfish much better than smoked puffin,” remarked Jens, the younger brother, who was carving a pipe-bowl. “Smoked puffin always makes me sea-sick. It tastes like cod-liver oil.”

Sigurd smiled, and, patting the younger boy on the head, entered the cottage.

“You shouldn’t talk so to father, Thoralf,” said Jens, with superior dignity; for his father’s caress made him proud and happy. “Father works so hard, and he does not like to see anyone discontented.”

“That is just it,” replied the elder brother; “he works so hard, and yet barely manages to keep the wolf from the door. That is what makes me impatient with the country. If he worked so hard in any other country he would live in abundance, and in America he would become a rich man.”

This conversation took place one day, late in the autumn, outside of a fisherman’s cottage on the north-western coast of Iceland. The wind was blowing a gale down from the ice-engirdled pole, and it required a very genial temper to keep one from getting blue. The ocean, which was but a few hundred feet distant, roared like an angry beast, and shook its white mane of spray, flinging it up against the black clouds. With every fresh gust of wind, a shower of salt water would fly hissing through the air and whirl about the chimney-top, which was white on the windward side from dried deposits of brine. On the turf-thatched roof big pieces of drift-wood,[19] weighted down with stones, were laid lengthwise and crosswise, and along the walls fishing-nets hung in festoons from wooden pegs. Even the low door was draped, as with decorative intent, with the folds of a great drag-net, the clumsy cork-floats of which often dashed into the faces of those who attempted to enter. Under a driftwood shed which projected from the northern wall was seen a pile of peat, cut into square blocks, and a quantity of the same useful material might be observed down at the beach, in a boat which the boys had been unloading when the storm blew up. Trees no longer grow in the island, except the crippled and twisted dwarf-birch, which creeps along the ground like a snake, and, if it ever dares lift its head, rarely grows more than four or six feet high. In the olden time, which is described in the so-called sagas of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Iceland had very considerable forests of birch and probably also of pine. But they were cut down; and the climate has gradually been growing colder, until now even the hardiest tree, if it be induced to strike root in a sheltered place, never reaches maturity. The Icelanders therefore burn peat, and use for building their houses driftwood which is carried to them by the Gulf Stream from Cuba and the other well-wooded isles along the Mexican Gulf.

“If it keeps blowing like this,” said Thoralf, fixing his weather eye on the black horizon, “we shan’t be able to go a-fishing; and mother says the larder is very nearly empty.”

“I wish it would blow down an Englishman or some[20]thing on us,” remarked the younger brother; “Englishmen always have such lots of money, and they are willing to pay for everything they look at.”

“While you are a-wishing, why don’t you wish for an American? Americans have mountains and mountains of money, and they don’t mind a bit what they do with it. That’s the reason I should like to be an American.”

“Yes, let us wish for an American or two to make us comfortable for the winter. But I am afraid it is too late in the season to expect foreigners.”

The two boys chatted together in this strain, each working at some piece of wood-carving which he expected to sell to some foreign traveller. Thoralf was sixteen years old, tall of growth, but round-shouldered, from being obliged to work when he was too young. He was rather a handsome lad, though his features were square and weather-beaten, and he looked prematurely old. Jens, the younger boy, was fourteen years old, and was his mother’s darling. For even up under the North Pole mothers love their children tenderly, and sometimes they love one a little more than another; that is, of course, the merest wee bit of a fraction of a trifle more. Icelandic mothers are so constituted that when one child is a little weaker and sicklier than the rest, and thus seems to be more in need of petting, they are apt to love their little weakling above all their other children, and to lavish the tenderest care upon that one. It was because little Jens had so narrow a chest, and looked so small and slender by the side of his robust brother, that his mother always singled him out for favors and caresses.

All night long the storm danced wildly about the cottage, rattling the windows, shaking the walls, and making fierce assaults upon the door, as if it meant to burst in. Sometimes it bellowed hoarsely down the chimney, and whirled the ashes on the hearth, like a gray snowdrift, through the room. The fire had been put out, of course; but the dancing ashes kept up a fitful patter, like that of a pelting rainstorm, against the walls; they even penetrated into the sleeping alcoves and powdered the heads of their occupants. For in Iceland it is only well-to-do people who can afford to have separate sleeping-rooms; ordinary folk sleep in little closed alcoves, along the walls of the sitting-room; masters and servants, parents and children, guests and wayfarers, all retiring at night into square little holes in the walls, where they undress behind sliding trapdoors which may be opened again, when the lights have been put out, and the supply of air threatens to become exhausted. It was in a little closet of this sort that Thoralf and Jens were lying, listening to the roar of the storm. Thoralf dozed off occasionally, and tried gently to extricate himself from his frightened brother’s embrace; but Jens lay with wide-open eyes, staring into the dark, and now and then sliding the trapdoor aside and peeping out, until a blinding shower of ashes would again compel him to slip his head under the sheepskin coverlet. When at last he summoned courage[22] to peep out, he could not help shuddering. It was terribly cheerless and desolate. And all the time his father’s words kept ringing ironically in his ears: “Iceland is the most beautiful land the sun doth shine upon.” For the first time in his life he began to question whether his father might not possibly be mistaken, or, perhaps, blinded by his love for his country. But the boy immediately repented of this doubt, and, as if to convince himself in spite of everything, kept repeating the patriotic motto to himself until he fell asleep.

It was yet pitch dark in the room, when he was awakened by his father, who stood stooping over him.

“Sleep on, child,” said Sigurd; “it was your brother I wanted to wake up, not you.”

“What is the matter, father? What has happened?” cried Jens, rising up in bed, and rubbing the ashes from the corners of his eyes.

“We are snowed up,” said the father, quietly. “It is already nine o’clock, I should judge, or thereabouts, but not a ray of light comes through the windows. I want Thoralf to help me open the door.”

Thoralf was by this time awake, and finished his primitive toilet with much despatch. The darkness, the damp cold, and the unopened window-shutters impressed him ominously. He felt as if some calamity had happened or were about to happen. Sigurd lighted a piece of driftwood and stuck it into a crevice in the wall. The storm seemed to have ceased; a strange, tomb-like silence prevailed without and within. On the hearth lay a small[23] snowdrift which sparkled with a starlike glitter in the light.

“Bring the snow-shovels, Thoralf,” said Sigurd. “Be quick; lose no time.”

“They are in the shed outside,” answered Thoralf.

“That is very unlucky,” said the father; “now we shall have to use our fists.”

The door opened outward and it was only with the greatest difficulty that father and son succeeded in pushing it ajar. The storm had driven the snow with such force against it that their efforts seemed scarcely to make any impression upon the dense white wall which rose up before them.

“This is of no earthly use, father,” said the boy; “it is a day’s job at the very least. Let me rather try the chimney.”

“But you might stick in the snow and perish,” objected the father, anxiously.

“Weeds don’t perish so easily,” said Thoralf. “Stand up on the hearth, father, and I will climb up on your shoulders.”

Sigurd half reluctantly complied with his request. Thoralf crawled up his back, and soon planted his feet on the parental shoulders. He pulled his knitted woollen cap over his eyes and ears so as to protect them from the drizzling soot which descended in intermittent showers. Then groping with his toes for a little projection of the wall, he gained a securer foothold, and pushing boldly on, soon thrust his sooty head through the snow-crust. A chorus as of a thousand howling wolves burst[24] upon his bewildered sense; the storm raged, shrieked, roared, and nearly swept him off his feet. Its biting breath smote his face like a sharp whip-lash.

“Give me my sheepskin coat,” he cried down into the cottage; “the wind chills me to the bone.”

The sheepskin coat was handed to him on the end of a pole, and seated upon the edge of the chimney, he pulled it on and buttoned it securely. Then he rolled up the edges of his cap in front and cautiously exposed his eyes and the tip of his nose. It was not a pleasant experiment, but one dictated by necessity. As far as he could see, the world was white with snow, which the storm whirled madly around, and swept now earthward, now heavenward. Great funnel-shaped columns of snow danced up the hillsides and vanished against the black horizon. The prospect before the boy was by no means inviting, but he had been accustomed to battle with dangers since his earliest childhood, and he was not easily dismayed. With much deliberation, he climbed over the edge of the chimney, and rolled down the slope of the roof in the direction of the shed. He might have rolled a great deal farther, if he had not taken the precaution to roll against the wind. When he had made sure that he was in the right locality, he checked himself by spreading his legs and arms; then judging by the outline of the snow where the door of the shed was, he crept along the edge of the roof on the leeward side. He looked more like a small polar bear than a boy, covered, as he was, with snow from head to foot. He was prepared for a laborious descent, and raising himself up he[25] jumped with all his might, hoping that his weight would carry him a couple of feet down. To his utmost astonishment he accomplished considerably more. The snow yielded under his feet as if it had been eiderdown, and he tumbled headlong into a white cave right at the entrance to the shed. The storm, while it had packed the snow on the windward side, had naturally scattered it very loosely on the leeward, which left a considerable space unfilled under the projecting eaves.

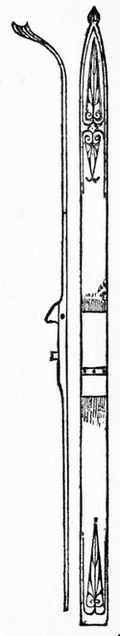

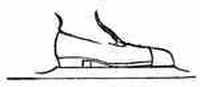

Thoralf picked himself up and entered the shed without difficulty. He made up a large bundle of peat, which he put into a basket which could be carried, by means of straps, upon his back. With a snow-shovel he then proceeded to dig a tunnel to the nearest window. This was not a very hard task, as the distance was not great. The window was opened and the basket of peat, a couple of shovels, and two pairs of skees[1] (to be used in case of emergency) were handed in. Thoralf himself, who was hungry as a wolf, made haste to avail himself of the same entrance. And it occurred to him as a happy afterthought that he might have saved himself much trouble, if he had selected the window instead of the chimney when he sallied forth on his expedition. He had erroneously taken it for granted that the snow would be packed as hard everywhere as it was at the front door. The mother, who had been spending this exciting half-hour in keeping little Jens warm, now lighted a fire and[26] made coffee; and Thoralf needed no coaxing to do justice to his breakfast, even though it had, like everything else in Iceland, a flavor of salted fish.

Five days had passed, and still the storm raged with unabated fury. The access to the ocean was cut off, and, with that, access to food. Already the last handful of flour had been made into bread, and of the dried cod which hung in rows under the ceiling only one small and skinny specimen remained. The father and the mother sat with mournful faces at the hearth, the former reading in his hymn-book, the latter stroking the hair of her youngest boy. Thoralf, who was carving at his everlasting pipe-bowl (a corpulent and short-legged Turk with an enormous mustache), looked up suddenly from his work and glanced questioningly at his father.

“Father,” he said, abruptly, “how would you like to starve to death?”

“God will preserve us from that, my son,” answered the father, devoutly.

“Not unless we try to preserve ourselves,” retorted the boy, earnestly. “We can’t tell how long this storm is going to last, and it is better for us to start out in search of food now, while we are yet strong, than to wait until later, when, as likely as not, we shall be weakened by hunger.”

“But what would you have me do, Thoralf?” asked the father, sadly. “To venture out on the ocean in this weather would be certain death.”

“True; but we can reach the Pope’s Nose on our skees, and there we might snare or shoot some auks and gulls. Though I am not partial to that kind of diet myself, it is always preferable to starvation.”

“Wait, my son, wait,” said Sigurd, earnestly. “We have food enough for to-day, and by to-morrow the storm will have ceased, and we may go fishing without endangering our lives.”

“As you wish, father,” the son replied, a trifle hurt at his father’s unresponsive manner; “but if you will take a look out of the chimney, you will find that it looks black enough to storm for another week.”

The father, instead of accepting this suggestion, went quietly to his book-case, took out a copy of Livy, in Latin, and sat down to read. Occasionally he looked up a word in the lexicon (which he had borrowed from the public library at Reykjavik), but read nevertheless with apparent fluency and pleasure. Though he was a fisherman, he was also a scholar, and during the long winter evenings he had taught himself Latin and even a smattering of Greek.[2] In Iceland the people have to spend their evenings at home; and especially since their millennial celebration in 1876, when American[28] scholars[3] presented them with a large library, books are their unfailing resource. In the case of Sigurd Sigurdson, however, books had become a kind of dissipation, and he had to be weaned gradually of his predilection for Homer and Livy. His oldest son especially looked upon Latin and Greek as a vicious indulgence, which no man with a family could afford to foster. Many a day when Sigurd ought to have been out in his boat casting his nets, he stayed at home reading. And this, in Thoralf’s opinion, was the chief reason why they would always remain poor, and run the risk of starvation, whenever a stretch of bad weather prevented them from going to sea.

The next morning—the sixth since the beginning of the storm—Thoralf climbed up to his post of observation on the chimney top, and saw, to his dismay, that his prediction was correct. It had ceased snowing, but the wind was blowing as fiercely as ever, and the cold was intense.

“Will you follow me, father, or will you not?” he asked, when he had accomplished his descent into the room. “Our last fish is now eaten, and our last loaf of bread will soon follow suit.”

“I will go with you, my son,” answered Sigurd, putting down his Livy reluctantly. He had just been reading for the hundredth time about the expulsion of the Tarquins from Rome, and his blood was aglow with sympathy and enthusiasm.

“Here is your coat, Sigurd,” said his wife, holding up the great sheepskin garment, and assisting him in putting it on.

“And here are your skees and your mittens and your cap,” cried Thoralf, eager to seize the moment, when his father was in the mood for action.

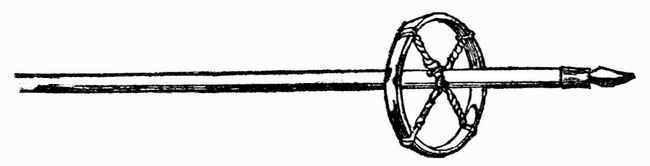

Muffled up like Esquimaux to their very eyes, armed with bows and arrows and long poles with nooses of horse-hair at the ends, they sallied forth on their skees. The wind blew straight into their faces, forcing their breath down their throats and compelling them to tack in zigzag lines like ships in a gale. The promontory called “The Pope’s Nose” was about a mile distant; but in spite of their knowledge of the land, they went twice astray, and had to lie down in the snow, every now and then, so as to draw breath and warm the exposed portions of their faces. At the end of nearly two hours they found themselves at their destination, but, to their unutterable astonishment, the ocean seemed to have vanished, and as far as their eyes could reach, a vast field of packed ice loomed up against the sky in fantastic bastions, turrets, and spires. The storm had driven down this enormous arctic wilderness from the frozen precincts of the pole; and now they were blockaded on all sides, and cut off from all intercourse with humanity.

“We are lost, Thoralf,” muttered his father, after having gazed for some time in speechless despair at the towering icebergs; “we might just as well have remained at home.”

“The wind, which has blown the ice down upon us[30] can blow it away again, too,” replied the son, with forced cheerfulness.

“I see no living thing here,” said Sigurd, spying anxiously seaward.

“Nor do I,” rejoined Thoralf; “but if we hunt, we shall. I have brought a rope, and I am going to pay a little visit to those auks and gulls that must be hiding in the sheltered nooks of the rocks.”

“Are you mad, boy?” cried the father in alarm. “I will never permit it!”

“There is no help for it, father,” said the boy resolutely. “Here, you take hold of one end of the rope; the other I will secure about my waist. Now, get a good strong hold, and brace your feet against the rock there.”

Sigurd, after some remonstrance, yielded, as was his wont, to his son’s resolution and courage. Stepping off his skees, which he stuck endwise into the snow, and burrowing his feet down until they reached the solid rock, he tied the rope around his waist and twisted it about his hands, and at last, with quaking heart, gave the signal for the perilous enterprise. The promontory, which rose abruptly to a height of two or three hundred feet from the sea, presented a jagged wall full of nooks and crevices glazed with frozen snow on the windward side, but black and partly bare to leeward.

“Now let go!” shouted Thoralf; “and stop when I give a slight pull at the rope.”

“All right,” replied his father.

And slowly, slowly, hovering in mid-air, now yielding to an irresistible impulse of dread, now brave, cautious,[31] and confident, Thoralf descended the cliff, which no human foot had ever trod before. He held in his hand the pole with the horse-hair noose, and over his shoulder hung a foxskin hunting-bag. With alert, wide-open eyes he spied about him, exploring every cranny of the rock, and thrusting his pole into the holes where he suspected the birds might have taken refuge. Sometimes a gust of wind would have flung him violently against the jagged wall if he had not, by means of his pole, warded off the collision. At last he caught sight of a bare ledge, where he might gain a secure foothold; for the rope cut him terribly about the waist, and made him anxious to relieve the strain, if only for a moment. He gave the signal to his father, and by the aid of the pole swung himself over to the projecting ledge. It was uncomfortably narrow, and, what was worse, the remnants of a dozen auks’ nests had made the place extremely slippery. Nevertheless, he seated himself, allowing his feet to dangle, and gazed out upon the vast ocean, which looked in its icy grandeur like a forest of shining towers and minarets. It struck him for the first time in his life that perhaps his father was right in his belief that Iceland was the fairest land the sun doth shine upon; but he could not help reflecting that it was a very unprofitable kind of beauty. The storm whistled and howled overhead, but under the lee of the sheltering rock it blew only in fitful gusts with intermissions of comparative calm. He knew that in fair weather this was the haunt of innumerable sea birds, and he concluded that even now they could not be far away. He pulled up his legs, and crept care[32]fully on hands and feet along the slippery ledge, peering intently into every nook and crevice. His eyes, which had been half-blinded by the glare of the snow, gradually recovered their power of vision. There! What was that? Something seemed to move on the ledge below. Yes, there sat a long row of auks, some erect as soldiers, as if determined to face it out; others huddled together in clusters, and comically woe-begone. Quite a number lay dead at the base of the rock, whether from starvation or as the victims of fierce fights for the possession of the sheltered ledges could scarcely be determined. Thoralf, delighted at the sight of anything eatable (even though it was poor eating), gently lowered the end of his pole, slipped the noose about the neck of a large, military-looking fellow, and, with a quick pull, swung him out over the ice-field. The auk gave a few ineffectual flaps with his useless wings,[4] and expired. His picking off apparently occasioned no comment whatever in his family, for his comrades never uttered a sound nor stirred an inch, except to take possession of the place he had vacated. Number two met his fate with the same listless resignation; and numbers three, four, and five were likewise removed in the same noiseless manner, without impressing their neighbors with the fact that their turn might come next. The birds were half-benumbed with hunger, and their usually alert senses were drowsy and stupefied. Nevertheless, number six, when it felt the noose about its neck, raised a hubbub that suddenly[33] aroused the whole colony, and, with a chorus of wild screams, the birds flung themselves down the cliffs or, in their bewilderment, dashed headlong down upon the ice, where they lay half stunned or helplessly sprawling. So, through all the caves and hiding-places of the promontory the commotion spread, and the noise of screams and confused chatter mingled with the storm and filled the vault of the sky. In an instant a great flock of gulls was on the wing, and circled with resentful shrieks about the head of the daring intruder who had disturbed their wintry peace. The wind whirled them about, but they still held their own, and almost brushed with their wings against his face, while he struck out at them with his pole. He had no intention of catching them; but, by chance, a huge burgomaster gull[5] got its foot into the noose. It made an ineffectual attempt to disentangle itself, then, with piercing screams, flapped its great wings, beating the air desperately. Thoralf, having packed three birds into his hunting-bag, tied the three others together by the legs, and flung them across his shoulders. Then, gradually trusting his weight to the rope, he slid off the rock, and was about to give his father the signal to hoist him up. But, greatly to his astonishment, his living captive, by the power of its mighty wings, pulling at the end of the pole, swung him considerably farther into space than he had calculated. He would have liked to let go both the gull and the pole, but he perceived[34] instantly that if he did, he would, by the mere force of his weight, be flung back against the rocky wall. He did not dare take that risk, as the blow might be hard enough to stun him. A strange, tingling sensation shot through his nerves, and the blood throbbed with a surging sound in his ears. There he hung suspended in mid-air, over a terrible precipice—and a hundred feet below was the jagged ice-field with its sharp, fiercely-shining steeples! With a powerful effort of will, he collected his senses, clinched his teeth, and strove to think clearly. The gull whirled wildly eastward and westward, and he swayed with its every motion like a living pendulum between sea and sky. He began to grow dizzy, but again his powerful will came to his rescue, and he gazed resolutely up against the brow of the precipice and down upon the projecting ledges below, in order to accustom his eye and his mind to the sight. By a strong effort he succeeded in giving a pull at the rope, and expected to feel himself raised upward by his father’s strong arms. But, to his amazement, there came no response to his signal. He repeated it once, twice, thrice; there was a slight tugging at the rope, but no upward movement. Then the brave lad’s heart stood still, and his courage wellnigh failed him.

“Father!” he cried, with a hoarse voice of despair; “why don’t you pull me up?”

His cry was lost in the roar of the wind, and there came no answer. Taking hold once more of the rope with one hand, he considered the possibility of climbing; but the miserable gull, seeming every moment to re[35]double its efforts at escape, deprived him of the use of his hands unless he chose to dash out his brains by collision with the rock. Something like a husky, choked scream seemed to float down from above, and staring again upward, he saw his father’s head projecting over the brink of the precipice.

“The rope will break,” screamed Sigurd. “I have tied it to the rock.”

Thoralf instantly took in the situation. By the swinging motion, occasioned both by the wind and his fight with the gull, the rope had become frayed against the sharp edge of the cliff, and his chances of life, he coolly concluded, were now not worth a sixpence. Curiously enough, his agitation suddenly left him, and a great calm came over him. He seemed to stand face to face with eternity; and as nothing else that he could do was of any avail, he could at least steel his heart to meet death like a man and an Icelander.

“I am trying to get hold of the rope below the place where it is frayed,” he heard his father shout during a momentary lull in the storm.

“Don’t try,” answered the boy; “you can’t do it alone. Rather, let me down on the lower ledge, and let me sit there until you can go and get someone to help you.”

His father, accustomed to take his son’s advice, reluctantly lowered him ten or twenty feet until he was on a level with the shelving ledge below, which was broader than the one upon which he had first gained foothold. But—oh, the misery of it!—the ledge did not project far[36] enough! He could not reach it with his feet! The rope, of which only a few strands remained, might break at any moment and—he dared not think what would be the result! He had scarcely had time to consider, when a brilliant device shot through his brain. With a sudden thrust he flung away the pole, and the impetus of his weight sent him inward with such force that he landed securely upon the broad shelf of rock.

The gull, surprised by the sudden weight of the pole, made a somersault, strove to rise again, and tumbled, with the pole still depending from its leg, down upon the ice-field.

It was well that Thoralf was warmly clad, or he could never have endured the terrible hours while he sat through the long afternoon, hearing the moaning and shrieking of the wind and seeing the darkness close about him. The storm was chilling him with its fierce breath. One of the birds he tied about his throat as a sort of scarf, using the feet and neck for making the knot, and the dense, downy feathers sent a glow of comfort through him, in spite of his consciousness that every hour might be his last. If he could only keep awake through the night, the chances were that he would survive to greet the morning. He hit upon an ingenious plan for accomplishing this purpose. He opened the bill of the auk which warmed his neck, cut off the lower mandible, and placed the upper one (which was as sharp as a knife) so that it would inevitably cut his chin in case he should nod. He leaned against the rock and thought of his mother and the warm, comfortable chimney-corner[37] at home. The wind probably resented this thought, for it suddenly sent a biting gust right into his face, and he buried his nose in the downy breast of the auk until the pain had subsided. The darkness had now settled upon sea and land; only here and there white steeples loomed out of the gloom. Thoralf, simply to occupy his thought, began to count them. But all of a sudden one of the steeples seemed to move, then another—and another.

The boy feared that the long strain of excitement was depriving him of his reason. The wind, too, after a few wild arctic howls, acquired a warmer breath and a gentler sound. It could not be possible that he was dreaming, for in that case he would soon be dead. Perhaps he was dead already, and was drifting through this strange icy vista to a better world. All these imaginings flitted through his mind, and were again dismissed as improbable. He scratched his face with the foot of an auk in order to convince himself that he was really awake. Yes, there could be no doubt of it; he was wide awake. Accordingly he once more fixed his eyes upon the ghostly steeples and towers, and—it sent cold shudders down his back—they were still moving. Then there came a fusillade as of heavy artillery, followed by a salvo of lighter musketry; then came a fierce grinding, and cracking, and creaking sound, as if the whole ocean were of glass and were breaking to pieces. “What,” thought Thoralf, “is the ice breaking up!” In an instant the explanation of the whole spectral panorama was clear as the day. The wind had veered round to the southeast,[38] and the whole enormous ice-floe was being driven out to sea. For several hours—he could not tell how many—he sat watching this superb spectacle by the pale light of the aurora borealis, which toward midnight began to flicker across the sky and illuminated the northern horizon. He found the sight so interesting that for a while he forgot to be sleepy. But toward morning, when the aurora began to fade and the clouds to cover the east, a terrible weariness was irresistibly stealing over him. He could see glimpses of the black water beneath him; and the shining spires of ice were vanishing in the dusk, drifting rapidly away upon the arctic currents with death and disaster to ships and crews that might happen to cross their paths.

It was terrible at what a snail’s pace the hours crept along! It seemed to Thoralf as if a week had passed since his father left him. He pinched himself in order to keep awake, but it was of no use; his eyelids would slowly droop and his head would incline—horrors! what was that? Oh, he had forgotten; it was the sharp mandible of the auk that cut his chin. He put his hand up to it, and felt something warm and clammy on his fingers. He was bleeding. It took Thoralf several minutes to stay the blood—the wound was deeper than he had bargained for; but it occupied him and kept him awake, which was of vital importance.

At last, after a long and desperate struggle with drowsiness, he saw the dawn break faintly in the east. It was a mere feeble promise of light, a remote sugges[39]tion that there was such a thing as day. But to the boy, worn out by the terrible strain of death and danger staring him in the face, it was a glorious assurance that rescue was at hand. The tears came into his eyes—not tears of weakness, but tears of gratitude that the terrible trial had been endured. Gradually the light spread like a pale, grayish veil over the eastern sky, and the ocean caught faint reflections of the presence of the unseen sun. The wind was mild, and thousands of birds that had been imprisoned by the ice in the crevices of the rocks whirled triumphantly into the air and plunged with wild screams into the tide below. It was hard to imagine where they all had been, for the air seemed alive with them, the cliffs teemed with them; and they fought, and shrieked, and chattered, like a howling mob in times of famine. It was owing to this unearthly tumult that Thoralf did not hear the voice which called to him from the top of the cliff. His senses were half-dazed by the noise and by the sudden relief from the excitement of the night. Then there came two voices floating down to him—then quite a chorus. He tried to look up, but the beetling brow of the rock prevented him from seeing anything but a stout rope, which was dangling in mid-air and slowly approaching him. With all the power of his lungs he responded to the call; and there came a wild cheer from above—a cheer full of triumph and joy. He recognized the voices of Hunding’s sons, who lived on the other side of the promontory; and he knew that even without their father they were strong enough to pull up a man three times his weight. The difficulty now was[40] only to get hold of the rope, which hung too far out for his hands to reach it.

“Shake the rope hard,” he called up; and immediately the rope was shaken into serpentine undulations; and after a few vain efforts, he succeeded in catching hold of the knot. To secure the rope about his waist and to give the signal for the ascent was but a moment’s work. They hauled vigorously, those sons of Hunding—for he rose, up, along the black walls—up—up—up—with no uncertain motion. At last, when he was at the very brink of the precipice, he saw his father’s pale and anxious face leaning out over the abyss. But there was another face too! Whose could it be? It was a woman’s face. It was his mother’s. Somebody swung him out into space; a strange, delicious dizziness came over him; his eyes were blinded with tears; he did not know where he was. He only knew that he was inexpressibly happy. There came a tremendous cheer from somewhere—for Icelanders know how to cheer—but it penetrated but faintly through his bewildered senses. Something cold touched his forehead; it seemed to be snow; then warm drops fell, which were tears. He opened his eyes; he was in his mother’s arms. Little Jens was crying over him and kissing him. His father and Hunding’s sons were standing, with folded arms, gazing joyously at him.

You may find it hard to believe what I am going to tell you, but it is, nevertheless, strictly true. I knew the boy who is the hero of this story. His name was Thor Larsson, and a very clever boy he was. Still I don’t think he would have amounted to much in the world, if it had not been for his friend Michael, or, as they write it in Norwegian, Mikkel. Mikkel, strange to say, was not a boy, but a fox. Thor caught him, when he was a very small lad, in a den under the roots of a huge tree. It happened in this way. Thor and his elder brother, Lars, and still another boy, named Ole Thomlemo, were up in the woods gathering faggots, which they tied together in large bundles to carry home on their backs; for their parents were poor people, and had no money to buy wood with. The boys rather liked to be sent on errands of this kind, because delicious raspberries and blueberries grew in great abundance in the woods, and gathering faggots was, after all, a much manlier occupation than staying at home minding the baby.

Thor’s brother Lars and Ole Thomlemo were great[42] friends, and they had a disagreeable way of always plotting and having secrets together and leaving Thor out of their councils. One of their favorite tricks, when they wished to get rid of him, was to pretend to play hide-and-seek; and when he had hidden himself, they would run away from him and make no effort to find him. It was this trick of theirs which led to the capture of Mikkel, and to many things besides.

It was on a glorious day in the early autumn that the three boys started out together, as frisky and gay as a company of squirrels. They had no luncheon-baskets with them, although they expected to be gone for the whole day; but they had hooks and lines in their pockets, and meant to have a famous dinner of brook-trout up in some mountain glen, where they could sit like pirates around a fire, conversing in mysterious language, while the fish was being fried upon a flat stone. Their tolle knives[6] were hanging, sheathed, from their girdles, and the two older ones carried, besides, little hatchets wherewith to cut off the dry twigs and branches. Lars and Ole Thomlemo, as usual, kept ahead and left Thor to pick his way over the steep and stony road as best he might; and when he caught up with them, they started to run, while he sat down panting on a stone. Thus several hours passed, until they came to a glen in which the blueberries grew so thickly that you couldn’t step without crushing a handful. The boys gave a shout of[43] delight and flung themselves down, heedless of their clothes, and began to eat with boyish greed. As far as their eyes could reach between the mossy pine trunks, the ground was blue with berries, except where bunches of ferns or clusters of wild flowers intercepted the view. When they had dulled the edge of their hunger, they began to cut the branches from the trees which the lumbermen had felled, and Ole Thomlemo, who was clever with his hands, twisted withes, which they used instead of ropes for tying their bundles together. They had one bundle well secured and another under way, when Ole, with a mischievous expression, ran over to Lars and whispered something in his ear.

“Let us play hide-and-seek,” said Lars aloud, glancing over toward his little brother, who was working like a Trojan, breaking the faggots so as to make them all the same length.

Thor, who in spite of many exasperating experiences had not yet learned to be suspicious, threw down an armful of dry boughs and answered: “Yes, let us, boys. I am in for anything.”

“I’ll blind first,” cried Ole Thomlemo; “now, be quick and get yourselves hidden.”

And off the two brothers ran, while Ole turned his face against a big tree and covered his eyes with his hands. But the very moment Thor was out of sight, Lars stole back again to his friend, and together they slipped away under cover of the bushes, until they reached the lower end of the glen. There, they pulled out their fish-lines, cut rods with their hatchets, and went[44] down to the tarn, or brook, which was only a short distance off; the fishing was excellent, and when the large speckled trout began to leap out of the water to catch their flies, the two boys soon ceased to trouble themselves about little Thor, who, they supposed, was hiding under some bush and waiting to be discovered.

In this supposition they were partly right and partly wrong.

No sooner had Ole Thomlemo given the signal for hiding, than Thor ran up the hill-side, stumbling over the moss-grown stones, pushing the underbrush aside with his hands, and looking eagerly for a place where he would be least likely to be found. He was full of the spirit of the game, and anticipated with joyous excitement the wonder of the boys when they should have to give up the search and call to him to reveal himself. While these thoughts were filling his brain, he caught sight of a huge old fir-tree, which was leaning down the mountain-side as if ready to fall. The wind had evidently given it a pull in the top, strong enough to loosen its hold on the ground, and yet not strong enough to overthrow it. On the upper side, for a dozen yards or more, the thick, twisted roots, with the soil and turf still clinging to them, had been lifted, so as to form a little den about two feet wide at the entrance. Here, thought Thor, was a wonderful hiding-place. Chuckling to himself at the discomfiture of his comrades, he threw himself down on his knees and thrust his head into the opening. To his surprise the bottom felt soft to his hands, as if it had been purposely covered with moss and a layer[45] of feathers and eider-down. He did not take heed of the peculiar wild smell which greeted his nostrils, but fearlessly pressed on, until nearly his whole figure, with the exception of the heels of his boots, was hidden. Then a sharp little bark startled him, and raising his head he saw eight luminous eyes staring at him from a dark recess, a few feet beyond his nose. It is not to be denied that he was a little frightened; for it instantly occurred to him that he had unwittingly entered the den of some wild beast, and that, in case the old ones were at home, there was small chance of his escaping with a whole skin. It could hardly be a bear’s den, for the entrance was not half big enough for a gentleman of Bruin’s size. It might possibly be a wolf’s premises he was trespassing upon, and the idea made his blood run cold. For Mr. Gray-legs, as the Norwegians call the wolf, is not to be trifled with; and a small boy armed only with a knife was hardly a match for such an antagonist. Thor concluded, without much reflection, that his safest plan would be to beat a hasty retreat. Digging his hands into the mossy ground, he tried to push himself backward, but, to his unutterable dismay, he could not budge an inch. The feathers, interspersed with the smooth pine-needles, slipped away under his fingers, and the roots caught in his clothes and held him as in a vice. He tried to force his way, but the more he wriggled the more he realized how small was his chance of escape. To turn was impossible, and to pull off his coat and trousers was a scarcely less difficult task. It was fortunate that the four inhabitants of the den, to whom the glaring eyes[46] belonged, seemed no less frightened than himself; for they remained huddled together in their corner, and showed no disposition to fight. They only stared wildly at the intruder, and seemed anxious to know what he intended to do next. And Thor stared at them in return, although the darkness was so dense that he could discern nothing except the eight luminous eyes, which were fixed upon him with an uncanny and highly uncomfortable expression. Unpleasant as the situation was, he began to grow accustomed to it, and he collected his scattered thoughts sufficiently to draw certain conclusions. The size of the den, as well as the feathers which everywhere met his fumbling hands, convinced him that his hosts were young foxes, and that probably their respected parents, for the moment, were on a raid in search of rabbits or stray poultry. That reflection comforted him, for he had never known a fox to use any other weapon of defence than its legs, unless it was caught in a trap and had to fight for bare life. He was just dismissing from his mind all thought of danger from that source, when a sudden sharp pain in his heel put an end to his reasoning. He gave a scream, at which the eight eyes leaped apart in pairs and distributed themselves in a row along the curving wall of the den. Another bite in his ankle convinced him that he was being attacked from behind, and he knew no other way of defence than to kick with all his might, screaming at the same time so as to attract the attention of the boys, who, he supposed, could hardly be far off. But his voice sounded choked and feeble in the close den, and he[47] feared that no one would be able to hear it ten yards away. The strong odor, too, began to stifle him, and a strange dizziness wrapped his senses, as it were, in a gray, translucent veil. He made three or four spasmodic efforts to rouse himself, screamed feebly, and kicked; but probably he struck his wounded ankle against a root or a stone, for the pain shot up his leg and made him clinch his teeth to keep the tears from starting. He thought of his poor mother, whom he feared he should never see again, and how she would watch for his return through the long night and cry for him, as it said in the Bible that Jacob cried over Joseph when he supposed that a wild beast had torn him to pieces and killed him. Curious lights, like shooting stars, began to move before his eyes; his tongue felt dry and parched, and his throat seemed burning hot. It occurred to him that certainly God saw his peril and might yet help him, if he only prayed for help; but the only prayer which he could remember was the one which the minister repeated every Sunday for “our most gracious sovereign, Oscar II., and the army and navy of the United Kingdoms.” Next he stumbled upon “the clergy, and the congregations committed to their charge;” and he was about to finish with “sailors in distress at sea,” when his words, like his thoughts, grew more and more hazy, and he drifted away into unconsciousness.

Lars and Ole Thomlemo in the meanwhile had enjoyed themselves to the top of their bent, and when they had caught a dozen trout, among which was one three-pounder, they reeled up their lines, threaded the fish on[48] withes, and began to trudge leisurely up the glen. When they came to the place where they had left their bundles of faggots, they stopped to shout for Thor, and when they received no reply, they imagined that, being tired of waiting, he had gone home alone, or fallen in with some one who was on his way down to the valley. The only thing that troubled them was that Thor’s bundle had not been touched since they left him, and they knew that the boy was not lazy, and that, moreover, he would be afraid to go home without the faggots. They therefore concluded to search the copse and the surrounding underbrush, as it was just possible that he might have fallen asleep in his hiding-place while waiting to be discovered.

“I think Thor is napping somewhere under the bushes,” cried Ole Thomlemo, swinging his hatchet over his head like an Indian tomahawk. “We shall have to halloo pretty loud, for you know he sleeps like a top.”

And they began scouring the underbrush, traversing it in all directions, and hallooing lustily, both singly and in chorus. They were just about giving up the quest, when Lars’s attention was attracted by two foxes which, undismayed by the noise, were running about a large fir-tree, barking in a way which betrayed anxiety, and stopping every minute to dig up the ground with their fore-paws. When the boys approached the tree, the foxes ran only a short distance, then stopped, ran back, and again fled, once more to return.

“Those fellows act very queerly,” remarked Lars, eying[49] the foxes curiously; “I’ll wager there are young un’s under the tree here, but”—Lars gasped for breath—“Ole—Ole—Oh, look! What is this?”

Lars had caught sight of a pair of heels, from which a little stream of blood had been trickling, coloring the stones and pine-needles. Ole Thomlemo, hearing his comrade’s exclamation of fright, was on the spot in an instant, and he comprehended at once how everything had happened.

“Look here, Lars,” he said, resolutely, “this is no time for crying. If Thor is dead, it is we who have killed him; but if he isn’t dead, we’ve got to save him.”

“Oh, what shall we do, Ole?” sobbed Lars, while the tears rolled down over his cheeks, “what shall we do? I shall never dare go home again if he is dead. We have been so very bad to him!”

“We have got to save him, I tell you,” repeated Ole, tearless and stern: “we must pull him out; and if we can’t do that, we must cut through the roots of this fir-tree; then it’ll plunge down the mountain-side, without hurting him. A few roots that have burrowed into the rocks are all that keep the tree standing. Now, act like a man. Take hold of him by one heel and I’ll take the other.”

Lars, who looked up to his friend as a kind of superior being, dried his tears and grasped his brother’s foot, while Ole carefully handled the wounded ankle. But their combined efforts had no perceptible effect, except to show how inextricably the poor lad’s clothes were inter[50]tangled with the tree-roots, which, growing all in one direction, made entrance easy, but exit impossible.

“That won’t do,” said Ole, after three vain trials. “We might injure him without knowing it, driving the sharp roots into his eyes and ears, as likely as not. We’ve got to use the hatchets. You cut that root and I’ll manage this one.”