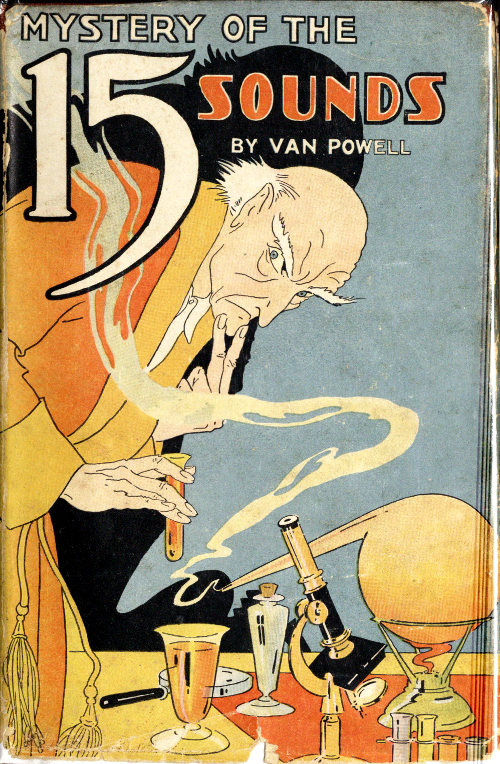

By Van Powell

The Goldsmith Publishing Company

CHICAGO

Copyright 1937 by

The Goldsmith Publishing Company

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

“No wonder I’m blue,” Roger told his father, “You’re packing to head a museum expedition into the heart of Borneo. You’ll have thrills.”

“Probably I will get my sort of excitement in plenty, Roger. It won’t be what you are always dreaming about—the ‘good old days’ of Pirates and Cowboys and Stage-Coach Bandits.”

“No,” Roger agreed, “the real thrills are all gone. But you can go on an expedition, instead of having school and——”

“There will be vacation time—baseball——”

“But I want real excitement. I’d like to be a Modern Pioneer. You are one, going off to Borneo for the museum just the way Columbus set out for Queen Isabella.”

His father looked up.

“You can be a Modern Pioneer. I will show you a House of Mystery, and once you step into its door you are in a land where there are more exciting activities packed into one day than you could get being a combination cow-hand, bad man, pirate and pony express rider. You may not be able to convoy an ox-team across a prairie, carry a squirrel gun and stand off scalping Sioux; but you will help battle against Pirate Fire, and Bad Man Erosion, and Bandit Microbe.”

“You mean—work in cousin Grover’s research lab?”

That was it, he found. And under the brilliant training of his older cousin, as he came to be the supply clerk and learned more about the work of the active place, Roger saw how truly his father had spoken.

There was fun, and mystery, and excitement, even in the work. Also, there was the feeling of being a Modern Pioneer, one who belonged to the band that had substituted electricity and wings for ox-wagon and candles, who gave the world instead of the pony rider carrying news, the radio and radio-telephone. Science was the Modern Pioneer.

Where their forefathers sought new borderlands, these modern way-showers explore the stratosphere. As their trail-blazing ancestors fought Indians and hardship and poor crops, these men battle against disease germs, and soil erosion, and eye-straining light and every other detriment to safer, happier existence.

As great as the feat of Columbus, Roger found the announcement that a cure had been found for a terrible disease.

On a par with Daniel Boone’s fame was the renown of the research worker who extended the range of compact radio receivers.

In such privately owned laboratories as that of his cousin, Grover Brown, and in those associated with universities and colleges and other institutions, the work of the Modern Pioneers went on.

They loved it, found adventure in it, and joy of achievement.

Not always was there the sort of mystery usually read about in detective stories; but when such problems did come up, Roger realized how the equipment of scientific research could be a useful aid to the clever deductive brain in solving the puzzle.

It is to show how much of adventure and thrill, excitement and romance can hide behind electrical transformers and tubes of germs, bags of sodium carbonate and humming motors that this experience of a boy in a scientific research laboratory is offered. Perhaps some boy, who has almost decided that the only “real” life involves guns and “rackets,” will be shown how the useful life of the fellow who fights for humanity and not against it brings more thrill and joy and contentment than any of the risky, falsely stimulating adventures that only lead to discredit, sorrow and punishment.

Van Powell

Names used in this story are purely fictitious and if any name is like that of a real person it is coincidence and no libel or aspersion on character is intended or implied. However, every scientific device, process and theory herein is based on electrical, chemical and other data of developed apparatus and procedure or on theories so far perfected as to be acceptable to Science.

Something was wrong at the laboratory! Ringing bells, long before dawn, awakened Roger Brown.

Dazed at first, he became alert as a strange, cold foreboding made him leap out of bed.

“Just the telephone,” his thirty year old cousin, head of the laboratory, called from his room beyond the adjoining bath. Roger, who was already on his way to the downstairs library of his cousin’s home, paused.

“No!” Well built and athletic, sharp-eyed, keen minded, a worthy student under his brilliant scientific cousin, Roger spoke earnestly, “It wasn’t just the protective beam system, or just the fire alarm, either. Grover, it was both!”

“Impossible! Why have they stopped ringing?” Tying his robe cord, the older cousin followed Roger. He knew that “Ear Detective’s” reputation for reading sounds, even if his own incisive reasoning made him feel that this time Roger had been too drowsy to live up to his nickname.

Just the same, he followed.

“As long as the beam was broken,” he insisted, “The bells ought to continue to ring. I think your fame as a sound interpreter is done.”

Roger did not try to defend himself.

“It was probably a wrong number on the telephone.” Grover was five steps behind his younger relative, “If you are so sure it was our alarm system, especially both bells, why aren’t you dressing to rush to the lab?”

“I’m getting down to be ready when Tip calls.”

Potiphar Potts, nicknamed Tip, was handy man at the scientific research plant. He slept there. In a moment Roger expected to have him call up to report the reason for the alarm.

“You will never hold your reputation now.” Grover turned at the library door as Roger, inside, stared, baffled, at the annunciator panel.

The reputation his cousin spoke about had come when a chemist, sent to them to help the laboratory develop a new series of dyes for a textile mill, had begun to “hear things.” Deaf, wearing an Amplivox, composed of a chest microphone, batteries and an ear piece, the man had been nearly crazed by a persecuting, accusing voice picked up, it seemed, by his device. Roger, by identifying an odd click he got in a makeshift imitation Amplivox set, gave Grover the clue through which a revengeful enemy who had sought to terrify the man had been discovered. As The Ear Detective, Roger, who was in charge of the laboratory stock-room, had really been the means of solving the mystery.

“I know I heard the laboratory bells,” Roger insisted.

“But the lights on our tell-tale are not lit.”

“I can’t help it. Both the fire alarm bell and the system that warns us if anybody enters——”

“But Potts has not called up, either. Go back to bed.”

Grover turned to leave the room. Roger, who was staying with his cousin while his own father headed an exploring expedition into Borneo for a museum, knew that his ears had not betrayed him.

His cousin, several years before, had secured capital with which to start a scientific research laboratory for the use of small companies unable to maintain equipment and an expensive staff.

Every form of research, electrical, chemical, industrial, and in one instance medical, had been successfully undertaken.

The “lab” prospered, and enjoyed a reputation for scientific and human thoroughness and dependability.

Priceless secrets, formulae, data and results were always in the laboratory, and its owner had devised seemingly perfect methods for safeguarding the secrets which rivals, or competing firms, might covet. A completed series of experiments to find a synthetic substitute for camphor gum, an industrial formula almost beyond price, was reposing in the safe on this early morning of Spring.

The safeguards comprised two:

There was a series of light-beams, interconnected with microphones and tiny speed cameras, at every possible entrance. Any broken beam, telling of wrongful entry, set off a laboratory bell in the room where Potts slept; and it also was wired to ring a bell at the owner’s home; and on a panel, numbered lights would show, by the one that glowed, which entrance had been used.

To protect the laboratory from fire, and warn of its existence, a bell of a higher tone with a thermostat connection in the laboratory, in each section, would give warning; and if the blaze was in the cellar, a green bulb would glow; if in the main floor, a red bulb, and for the upper section a blue bulb would be lit.

Naturally, Grover felt that his younger cousin had mistaken the sound that had awakened both.

Roger, still feeling his weird and unexplainable sense of hidden danger, picked up the telephone.

The laboratory, when he dialed repeatedly and waited long, did not respond. Tip, trusted, loyal, paid extra salary because he was counted on not to leave the mechanical devices to give the sole protection, should have answered his extension telephone.

“I tell you there is something wrong,” insisted Roger.

His cousin, partly convinced, taking on some of Roger’s concern, began to dress.

Just as he came down Roger knotted his tie.

In the car kept handy in the garage, they drove the several blocks to the two-story building.

Before they got near it, Grover put on speed.

Fire sirens and the scream of the warning signal on a police car made both cousins wonder what terrible situation they might face.

Had some one, entering the laboratory, set off the first alarm as fire broke out? Had Potts, fighting either fire or intruder, been rendered incapable of responding to their telephone call?

“Oh, I hope nothing has happened to Tip.”

Roger was very fond of the dull-witted, but dependable man, almost an Albino with his sandy hair and light eyes, who loved to use big words whether they fitted his idea or not, and who helped in the many mechanical, photographic and other activities involved in their work.

The car, racing forward, turned into the proper street and they saw fire apparatus gathering in front of the building. Roger, as the car slowed, leaped out, crouching and running to avoid being thrown down by the momentum.

“Don’t break in!” he shouted to firemen, “Our protective gas will prevent damage—and water would ruin our electrical things.”

The company captain paused as he saw, behind the youthful caller, the taller laboratory owner striding forward.

His men, with a battering ram, delayed.

The helmeted men, some with axes, others with scaling ladders, hose, or the rubber covers used by the emergency squad from the Fire Underwriters, paused.

“What-da-ya mean, nothing more won’t burn?” growled a policeman from the patrol car standing nearby.

His finger pointed toward the glass panel of the main door.

Roger, looking in, saw the curious orange glow and the weirdly bluish-violet splaying out across the office from the inner spaces.

“Who—what set off the flouroscope and the X-rays?” he gasped, while Grover reassured the gathered people.

Unobtrusively setting one foot well to the side on the top step, so that his toe, pressed forward, found the small protecting pin, he unlocked the door, careful to keep the knob turned toward the left, instead of in the natural hand-turn to the right.

That, Roger knew, cut out that particular light-beam system, so that they could enter without altering the present status of the tell-tale panel inside that would reveal where entry had been made, and by which magnetized plate the marauder would be held in trying to escape.

They rushed in. His first rush took Roger to the panel.

Not a bulb glowed! He stared, unable to accept the story it told—somebody had set off every light-beam-trip! That put out the lights.

Not one of the row connected-in with the magnetized plates was lit, either, and yet no living person should have walked or crept or climbed away through door, window, coal-chute or other exit without getting caught. But Roger did not pause. He ran to Tip’s room.

Tip, tied tightly to a bedpost, his lips taped shut, his eyes rolling as he sweated in his frantic effort to escape, saw him.

Roger first took the tape off as gently as haste allowed.

Just as soon as he was able to speak, Tip gasped:

“Tell Grover them mouses ain’t is.”

“Ain’t is?——”

He knew that Potts used queer phrases, trying to fit big words in, and this might be his way of leading up to some puzzling declaration.

“What happened? Stop being smart, and tell me!” ordered Roger.

“If mouses is here, you say they is here?”

“Well?——”

“They ain’t is.”

“Gone?” Roger stared, “The white rats. Gone?”

“They done extraverted.”

Roger had to study that out. He knew that the psychological word was used by analysts of human minds to indicate people whose outlook on life was normal, while introverts were shy, timid people who were afraid of life. “Extraverted” must mean that the animals had turned outward toward the world—run away, or escaped.

“But those white rats—Doctor Ryder’s—were in a cage with a trap door on top, and they’d been inoculated with cultures of a spinal disease,” cried Roger. “How do you know?”

“I was up lookin’ at ’em, and somethin’ with a hand like a ham hit me back of the ears, and when I come to, tied, them rats was evacuated. I was drug down here by a ape and tied. An’ there was somethin’ else I didn’t get a look at, behind the ape.”

Was the man crazed? It worried Roger.

But a call from Grover, upstairs, quickly told him that Potts had not been talking wildly.

“Roger,” called his cousin, “The white rats’ cage is empty!”

It took Roger a moment only to realize the enormous danger that was behind the loss of those inoculated rats.

When Doctor Ryder had been allotted space in which to conduct his experiments to see if he could perfect a cure for a horribly deadly spinal affliction, he had decided to experiment, first, on animals.

Such experiments had been gotten under way the night before.

The rats, inoculated, were carriers of the deadly germs. If some ignorant person had taken them, and the public was not warned to be careful, anything might happen!

One of Grover’s constantly repeated axioms about laboratory work was:

“Do the first thing first!”

All life, the scientific student always had insisted, was like the chemical compounds they handled. No matter what the problem might be, no matter how it looked, it could be analyzed the way compounds would be analyzed, the elements could be isolated, and the base—the guide to the whole condition—could be known. Sodium, a metal, very unstable, combined with chlorine, a gas, turned into sodium chloride, and that was a salt—common table salt, in fact. Yet the restrainer used in photography, a dissolved salt, was sodium bromide, another gas and the metal, and to find out what a compound held, one had to separate all parts by test and find the base or original element.

But first, one must do the first thing—and in this situation Roger knew that the first thing was to get busy on the telephone.

White rats had been inoculated with dangerous germs. A bite from such an animal was ten times more terrible than that of a plain rat, poisonous though that would be. Therefore, if those inoculated animals were now missing, Grover, up where their cage had been, would know it already; but the public, exposed to possible contamination, must be warned.

Roger plugged in the upstairs telephone so that the policeman could reach his headquarters and start a widespread search of all cars on the roads, all suspicious people carrying sacks or other possible packages or cases that could hide the rats. The Health Department and news and radio agencies must be asked to broadcast public warnings. And the owner of the rats, Doctor Ryder, should be called.

Therefore, when Roger went upstairs, his report made his cousin nod approvingly. Roger had done all he could to avert danger if the rats had been taken ignorantly by some idiot who might let one or more escape and spread disease germs.

With his story told, Potts was busy doing what Grover had ordered as one way to secure clues: a motion picture camera using non-flam film, flashbulbs of the latest type, tripod for time exposing, and both wide-angle and micrometric lenses, to give large views of big spaces or vastly magnified details of practically invisible things, formed the kit that the handy man worked with.

Because he had used his wit Grover had no orders for Roger as the firemen, police and officers departed.

Nothing could be done until Potts developed his “takes” so they could be run in the laboratory screening-room.

Grover, in his small, private “thinking den,” would want to be left to think out and separate all the mysteries, so that he could get to the heart of the affair and thus decide what to do about it.

Alone, wide-awake, with the dawn just beginning to lighten the skylight in the roof over his stock-room, Roger stood thinking.

He knew that if the small, partitioned space set aside for Doctor Ryder had held clues, Grover would have told him.

The germs supposed to have been injected into rats the night before could not have produced much effect that past night. The doctor had not felt that he had to observe, personally, as he would have done later.

Instead, automatic “observers” had been set up.

Inside the empty cage, a dictagraph microphone showed, fixed to the glass inside the cage top. That, Roger knew, led to a device like the seismograph which registers earthquake tremors. Its purpose was to show, by the vibration of a pen across a moving tape, when the rats developed any unusual excitement or stress, which was not expected but was provided for in that way.

A camera of the moving picture type, but set to snap one take at minute intervals, would check also; and if the seismograph got to zig-zagging sharply, it would make contact on one side with a relay, and throw on the “continuous” mechanism of the marvelous camera.

To discover by calculating how much of the tape had been unreeled when something had stopped it, was easy; and in that way Roger knew the time that the mechanism had stopped, although he did not dare fix that as the time the rats had vanished, because the tape had started at five in the afternoon, and had unreeled to the point to show that it had stopped at four in the morning; but the alarm had not sounded until half an hour or so later.

The tape showed excited swerves of the recording stylus, but not apparently enough to start the continuous takes, because Grover had left the magazine as it was until Potts should be ready to develop all prints at one time.

With his snapshots and time exposures of wide-angles of windows, doors, floors, air-conditioning intake, exhaust, cellar openings and floors, and his micrometric detail close-ups of parts of all these, Potts went to the dark-room adjoining Roger’s stock-room. The film he had taken would fill all tanks, so he left the other till later.

The authorities had been warned; and nothing more could be done.

Roger, as the sun rose, telephoned for light breakfast to be sent from a nearby restaurant, taking Potts his share in the dark-room.

As he ate, Roger tried to bring some sense into the baffling set of conditions:

The white rats, in their cage, with the observation apparatus and chart with notations, should have been recognized by anybody who could see and who could read, as dangerous to handle, much more to remove.

With the protecting system set, it should have been impossible to enter, at all, and more impossible to get out.

Yet the rats had not by any magic been evaporated into thin air.

Furthermore, Roger mused, why had the fluoroscope and X-ray machinery been put into operation?

The entire situation seemed to be too bizarre to be true: more than all the rest, the mad story of Potts that he had felt a hand as “big as a ham,” hit him before he had lost his senses!

Nothing fitted anything else.

Doctor Ryder, arriving, was as much a contrast to cold, unexcited Grover as could be imagined. He sputtered his fears for the public, his dismay that this should have brought discredit on the laboratory that had been known to safeguard its precious data.

Roger, watching the pudgy, stout little germ experimenter who excitedly mixed wild theories with wilder plans of procedure, thought to himself that if anybody or anything would upset his cousin, the man’s emotional excitement would be the thing.

Grover was not stirred out of his quiet manner.

The staff began to arrive. They had all seen in newspapers or had heard by radio the warnings and the brief story of the lost rats.

Mr. Millman, the electrical engineer, asked immediately of Dr. Ryder: “Have you any enemies?”

The experimenter thought that he might have antagonists among the scientists who disagreed with his theories; but they would not be men who would endanger the public for so small a revenge as could come from criticism of his laxness in not watching his experiment more closely.

Mr. Ellison, the laboratory’s electrical research specialist who worked with Mr. Millman, agreed; and so did the bio-chemist, Mr. Zendt; the analytical chemist, Mr. Hope, and Grover.

They were discussing the many contradictory and unexplainable points when Potts called, from the darkroom:

“Hi, Rog’—come quick!”

As soon as his eyes were accustomed to the dull rosy glow after he passed the light-trap, Roger saw Tip clipping non-flam film positives to drying drums.

“What have you got, Tip?”

“Look!”

Potts snapped a strip in place in a vision tunnel: Roger applied his eye to the lens, and saw, enlarged on the viewing-plate, what appeared to be the edge of a cellar step. With side-lighting, magnified ridges and depressions in dust looked like a range of hills and vales.

“It was a snake!”

“A—did you say ‘snake’?” Roger gasped, “How do you get that?”

Potts changed films under Roger’s gaze; an enlarged wide-angle of several steps was before his eyes, and the snake-slide of some body that had dragged across just the step-edges, and had made no track of hand or foot on the level of the steps showed!

“It certainly looks like something that creeps, Tip.”

“Well, a snake creeps. A snake! What else?”

Without waiting for the gelatin to harden, Roger summoned the staff and his cousin to the screening room. As soon as they had set their wrist watches with the observatory time signals, a routine part of the staff’s accuracy, they joined him.

He had the tender emulsion-covered celluloid threaded from the top magazine through film gate and take-up sprockets down to the lower magazine of the projector. In the small, compact theatre, with its platform for lecture and demonstration procedure, its large screen, easy chairs, loud speakers and apparatus, he showed Grover and the men what caused him to agree with Tip.

“It almost has to be a snake,” Roger declared.

No other than a creeping thing could drag over a step edge. Four footed creatures, he explained, did not disturb dust at the point indicated in close-up and wide-angle pictures, greatly enlarged by the projector.

The chief electrical specialist, Mr. Ellison, agreed. “It ends the mystery. A snake ate the rats.”

“Then there won’t be any disease epidemic,” Doctor Ryder was much relieved, “It will crawl somewhere and the germs may destroy the reptile.” To this Mr. Millman, electrical engineer; Mr. Zendt, bio-chemist; Mr. Hope, their analyst, and others, agreed.

Roger saw that his cousin reserved opinion. But routine had to go forward, and the staff men separated. Zendt went to resume experiments in the search for a dye of a certain desired shade and quality: the two electrical men were busy developing means to find a better way to insulate high-tension cable for carrying electricity from generators to distributing stations in small communities; the others had equally absorbing work in progress.

Grover, busy examining each picture projected and held on the screen without danger of the “cold” light igniting the protected film, gave Roger a dozen cellar views around the coal-chute to enlarge.

“Make ten-by-twelve bromide enlargement prints,” he ordered.

Roger, although it seemed impossible that anyone could have moved the stiff rusted bolt inside the trapdoor of the coal chute, a trap that lifted up and out onto the street, said no word of objection.

He felt that Grover would find nothing in the enlargements.

Expertly he adjusted paper on the camera-stand, extended the bellows to secure most perfect focus, made his exposures, developed, and fixed the large prints, and took them to his cousin’s own den.

“As I expected—nothing!” he reported.

“No abrasions of the bolt, or edge of the trap?”

“You mean, where someone inserted a ‘jimmy’ to shove back the bolt?”

Grover nodded.

“Not a thing shows.” Roger asserted. His cousin did not accept his statement; but his disappointed eyes told Roger that the examination he had made during developing work had been accurate, thorough, and had led to a correct decision.

They were at a standstill. Calls to the zoo, brought from its curator the declaration that no snake was absent from its cage, that no one of his keepers had tried to “train” snakes—as the laboratory head had half-laughingly suggested.

As he left the screening room, Roger met Potts.

“Tip,” he hailed, “Did you get anything on the ‘sound’ film in the one-snap-a-minute camera?”

“The one that took pictures of them mouses?”

“The one by the rats’ cage—yes.”

“You know about sound, Rog’. It ain’t just a lot of single pictures.” Potts wanted to air his knowledge. “Sound is a maintained concession of peaks an’ valleys on the sound track.”

“You always will use a .44 caliber word when a BB. size would hit what you aim at and not blow your idea to bits, Tip. You mean that sound is a ‘sustained succession’—I know that. And single frames, if they showed any sound impression at all, would give little pops.”

“So I didn’t bother.”

“But, Tip! There was a lot of wild zig-zag marking on the tape in the seismograph-like recorder; and it seemed as though the ‘continuous’ taking lever had been shifted before he—it—whatever was there, stopped the whole business by breaking off the wiring.”

“We can try.”

When they had developed the negative, made a print and fixed and washed it, Roger threaded the fifteen frames of continuous shots in place and projected with the speakers cut in.

Then he rushed to get Grover. The staff too!

He had a clue.

As nearly as he could have described the brief sound made and amplified with transformer-coupled, matched metal audio tubes of the most perfect type giving the speakers power, they had picked up a sound of hot grease sputtering, hissing and clicking, as it does if sausage is fried rapidly.

“Come on, Ear Detective,” chaffed Mr. Millman, “Who was frizzling sausages on the cage full of inoculated rats, so that the mike inside picked it up and took it on to the sound film?”

“That’s not sausage frying,” exclaimed the biochemist, “Someone had steam up and the mike picked up the sound the radiator valve made as air was expelled and steam arrived to close it spasmodically.”

“A microphone, inside of a glass cage top?” mocked Mr. Ellison. “How could a valve on a radiator across the room make all that noise?”

“Let the Ear Detective explain it,” urged Mr. Hope.

They all turned to Roger. He shook his head.

“It does sound most like the snick-snap, and sizzle, of sausage,” he admitted, “But——”

“It’s a snake, I say,” Potts defended his theory; “a snake, with hissing and his scales rattling on the glass when he was crawling up to dig his head in and grab breakfast.”

“What’s your idea, Grover?” asked Mr. Hope.

“Sounds as much like a snake as anything I can imagine, Sam.”

“So say I,” agreed Mr. Ellison.

“Are we right, interpreter?” Potts got the correct word, for once.

Roger hesitated. Not that he cared if he lost his reputation as a young person able to read correctly what his sensitive ears caught; Roger was not vain or self-satisfied. He was not the sort to make a statement just to hold up his reputation.

In some ways the sound might be such as a snake, with its hide striking or rubbing, as it hissed, could make; but, again, a lizard might make that sound—or a dog, scratching on a window.

He stood up, excited for the moment.

“Claws on glass!”

His sharp cry died into silence. They all considered it.

“A snake ain’t got pedicular exuberances,” objected Potts.

“Pedal protuberances, eh, Tip?” chuckled Mr. Hope, “What do you say, Grover?”

As Roger looked toward his cousin he saw what surprised him most of all that had so far happened.

Never in his stay at home or laboratory, intimately close to the scientifically brilliant, but poised, cousin, had Roger seen him lose his calm.

Now, Grover stood up, and in his eyes was the same sort of light of satisfaction and triumph that a boy would show when he had successfully smuggled in and hidden mother’s birthday present.

“Roger is absolutely right!”

“Claws on glass? A big dog?” asked Mr. Zendt.

“Remember the cellar step clue.”

“A lizard?” Mr. Ellison suggested.

“Remember Tip’s statement about how he was knocked senseless.”

“Oh—a man with a—a what?” Mr. Millman was not so confident of his deductive ability. He paused.

“I will leave you to work it out,” Grover beckoned to Roger; “I must run out to the zoo.” He was as eager and elated as a boy with a new football.

He beckoned to Roger who followed as his cousin got his hat.

“I want you to go to all the newspaper offices. Take a taxi. Get back issues for the past two weeks, maybe you’d better get them for three weeks back.”

“You know?——”

“I have two theories. I want to make sure which is right.”

“Do you really think I got the right meaning out of the hisses?”

“Precisely the correct meaning.”

“But it doesn’t tell me anything, cousin Grover.”

“Use my formula. Dig past appearances that can be falsified, to the truth. Marshal your facts, test each one, eliminate the impossible and what you have left is the truth.”

Telephoning to summon a taxi for Roger, the laboratory head was busy for a moment. Roger tried to employ the method just named.

Youth, inexperience in doing such consecutive and eliminative thinking, he knew, hampered him. With a mind trained, through solving chemical, electrical and other industrial experimental difficulties, Grover’s clever mind had skipped many of the links that Roger, slowly, had to take up and examine.

He was in the taxi, with bundles of back issues of the city papers, on his way back, and still his mind was a maze of unfitted details.

In the office, combing the papers for notes about snakes, or any other escaped reptile—he had to keep in mind that trail on the edge of the steps alone!—he got nowhere.

No news showed up about lost, stolen or escaped animals or any form of brute or reptile.

Grover, he saw, had returned, and was not joyful.

“One theory went to smash,” he said, “I verified your sound—claws on glass was the right deduction. But—that doesn’t bring what I want.”

“What do you want?” asked Roger, eagerly.

“To capture the culprit.”

“Won’t the police?——”

“We have no justification for calling them in. Nothing has been stolen. Nothing has been harmed.”

“The rats——the menace to the public!”

“Roger, you haven’t studied those films Potts took.”

Roger got them at once, projected, one at a time, examining the screen images carefully. The cellar views, only proving that some object left no other trace of progress than scraped dust on step-edges, he considered and discarded.

Those taken by windows, doors, intakes and outlets of the air-conditioning, and gas-exhausting roof, cellar and wall orifices gave no revealing clues.

When he got to the wide-angles of the lower floor and stairway, and found no reward for his long scrutiny, Roger was baffled.

Only the micrometric enlarged snaps and one time-exposure near the X-ray devices remained. He considered them ruefully. They gave no foreground evidence to help him.

Roger, with defeat creeping over his feelings, was about to give up.

He was fair, he told himself, when it came to interpreting sounds, but at the more important quality of being able to connect the clue with everything else, he was “stumped.”

What could those enlarged views hide from him?

The walls, with racks of test-tubes, some containing chemical solutions, others holding cultures of various forms of growth that Mr. Zendt had accumulated or was studying, told him——

He stared, bent closer, climbed up on a chair close to the screen!

After two minutes of close scrutiny, he jumped to the floor, and raced to find Grover.

“Just by chance, in taking the micro-lens pictures,” he gasped out, “Tip got in some of the test-tubes. Is that what you saw?”

Grover, smiling, agreed. “What did it tell you?”

“I arranged those racks yesterday. I have got a good memory.”

“I knew both those facts,” Grover admitted, “and I, too, helped in revising our arrangement of the racks. Go on!”

“The tubes that held the culture of the spinal disease germs—so dangerous that they had been delivered, personally, by the medical center bacteriologist, had blue labels!”

“You are ‘warm’ as the hide-and-seek game puts it.”

“I saw Doctor Ryder take them up, in his surgeon’s clothes to prevent infection.”

“So did I.” Grover acknowledged the fact.

“He actually took two tubes that must have had the right labels because he would have seen what they were marked.”

“Labels can be soaked off and transposed from one tube to another, Roger.”

“I think that happened. He took them, went up, and we both saw him use the hypodermic needle.”

“But—” Roger could hardly restrain his thrill at having made as clever a discovery as the coming one:

“Those two tubes—full!—are in back of others, right now. Not the two empty ones he incinerated to be sure the germs were all destroyed.”

“They are? How did you discover it?”

Roger told him: “Our chemical labels that are a green, photograph a darkish gray; and our culture labels, that are a buff, photograph lighter, but still grayer than white paper. The poisons are labeled red and come out in a picture almost black.

“But blue except very dark shades, will photograph nearly white! And those two labels, hidden in a dark corner, show up in the picture where they might not be noticed in the rack.”

“Can you go further and say why no culture was allowed to be given, although the inoculator evidently thought his serum was genuine?”

“Whoever was going to take the rats, did not want them to be dangerous to him.”

“Very nicely argued out, Roger,” his cousin complimented him. “Now, we must find a way to draw that criminal who trains animals to do his work, into the open where police can get him.”

Startling though Grover’s statement that a man trained animals to be criminals was, it gave Roger the one link to build what he knew into a chain.

Trained animals! That fitted in with claws on glass and made the rest of the puzzle fall into place.

To Roger, it seemed clear that a clever animal trainer could teach his beasts to obey criminally intended orders just as well as make them do the ordinary tricks.

What animal, he mused, would fit the conditions?

A monkey came to mind as the logical sort.

First of all, it was the one animal able to climb down a rope from the skylight on the roof, which it could have reached by being taken up the fire-escape on a candy factory next door, one story higher than Grover’s research laboratory.

Coming down in that fashion, it could have been made to do a trick taught for the purpose—take the white rats, put them in a sack, and fix it to the rope—or the sack could already be at the end of the rope. Then, unaware that it had set off an alarm, it could have wandered about, doing such tricks as getting into the light beams, pulling the switch to “on” for the X-ray and the other electrical devices.

Such an ape, too, with its master joining it during the time it wandered about, could have invaded Tip’s room, striking him with a huge paw, because it would be an ape; no smaller monkey could have reached down into the rats’ cage.

“How will you trap him?” Roger asked.

When his cousin outlined his plan, Roger was animated.

“It might work,” he exclaimed, “He will turn out to be the one who brought the white rats. They were trained, too, maybe.”

“I wondered that you did not see why I bought back issues of the newspapers,” Grover told him, “I had one idea that the thing might have been done by some zoo keeper; but the more possible notion was that some vaudeville act had trained animals. Now we do not need to comb through the advertisements of the theatre section. We know, by logical deduction, that we would find it.”

Roger, and Potts, carrying out instructions about which they said nothing to any member of the staff, assembled a mass of materials, apparatus and paraphernalia.

There were microphones; and they employed the laboratory’s device for producing infra-red rays, as well as a number of small cameras for taking motion pictures which Potts secured; to each one they applied a shutter-trip suggested by Grover, that would operate when a light-beam of the infra-red variety might be unknowingly broken by an intruder.

Other parts, and wiring by the yard, they connected up.

“But I don’t understand it,” Potts argued as they worked. “It’s all right to say a monkey climbed in through the skylight way; but how does that fit the snake-trail up the stairway?”

“I asked about that,” Roger told him, “Cousin Grover was more in a joking humor than I ever saw him, and he said I’d done so well, he would leave that for me to work out, too.”

“Did you?”

“I think so, Tip. How’s this? Monkey comes in. No alarm on the skylight, because the magnetic plate under it would be ‘on’ all night and would have caught anybody—anything but a monkey able to jump at a command while it swung clear—or the man above swung it.”

“So far, so good.” Potts waited expectantly.

“The ape wandered around, until it heard a call it recognized from outside, on the street. It was trained to open bolts, and the only other bolt that wouldn’t have a camera equipment and electric plate was our coal chute, that had the Chief stumped how to fix it.”

“And why would he have to go down there?”

“To let in his mate—another beast.”

“And what was it?”

“Well, what could leave a snake trail?”

“A boa-constrictor, or one of them bushmasters out of Australia?”

“What else—out of Australia?”

Potiphar stared, thinking hard.

“I don’t know.”

“Something that hops, and balances with its tail.”

“A—you mean a—kangaroo?”

Roger chuckled, nodding.

“But why did they go to all that trouble, when a man could of swarmed down a rope, and got the rats?”

“If he’d got caught—not knowing everything about the inside of our lab, maybe,” Roger responded, “He’d go to jail. But if we got a kangaroo, or an ape, the animal trainer could know it and have an ad. in next day’s papers, get back his animal that couldn’t tell what it was there for, and——”

“Well, what was it here for? What made all that compulsatory?”

“The motive made it compulsory, Tip.”

“You didn’t tell me about any motive. Or how all this wire and stuff will catch anything when we don’t know anything will come tonight, like you hint at.”

“The motive, Cousin Grover thinks, is to get into our safe, for our data and formula for synthetic camphor.”

“Well, come to think—one nation practically controls the camphor gum output, and if they want to raise the price——”

“Or forbid export to any other country, in war——”

“I can see how much it would be worth to have what we developed for one client. Maybe some foreign nation wants the secret.” Tip was alert. His pale blue eyes and almost albino-white hair made him seem, usually, washed-out and not very bright. But with this thrilling possibility of intrigue and excitement brewing, he was as alert and intelligent as anyone could be.

“We don’t know. But Cousin Grover thinks he will draw them on, and he publishes in the evening papers quite a write-up about the completion of the data. A friend, a newspaper fellow, will help us get it into good space.”

“And so the Chief thinks this fellow with the ape and the mouses and the kangaroo is a criminal and made them criminals?”

Roger nodded.

They waited until the staff checked up with Grover all results from the day’s experiments, and departed. Doctor Ryder, assured that his rats were not a menace, left with the rest.

Then, carrying from the doors, windows, coal-chute, skylight and all other available openings, wires from microphones set there, Roger and Potts led them all to a three-stage amplifier, having a delicately diaphragmed headset in circuit.

With that headset on, if a heart beat within a foot of any mike, a drum-beat could be heard in the headset.

Light-beams criss-crossed the entrances so that they must be interrupted by anybody or any thing that came along. Each was in circuit with one lamp of a number in a shadow-box, and the one that would stop glowing would show which beam had been broken.

Thus prepared to be warned well in advance of any intrusion, Roger sat wearing the headset as he monitored the volume controls.

Police hid inside and outside of the laboratory.

The safe, bathed in invisible rays, was provided with a new form of “capacity” protection so that anybody or anything touching the metal and standing with feet on the floor, would form a circuit and overload a sensitive and delicately balanced radio tube, that would operate a relay, putting into the circuit a criss-crossed series of small water-hoses, two playing along each side of a square around the safe, not easily observed when inactive.

And in that water would be an electric current strong enough to paralyze and chain, without permanently harming the invader!

He could not avoid it, because the water must fall and no one, even aware what would happen, could dodge or avoid the spray and the stream.

The precious, priceless synthetic camphor secret was protected.

As he sat, knowing that in the dark around him were Doctor Ryder, Potts, and his cousin, Roger felt a little thrill of expectancy and uneasiness.

Had he foreseen the outcome of the ruse, it is a question whether he would have danced for joy or shuddered in terror.

The trap caught something unexpected.

To Roger, the presence of Doctor Ryder showed that Grover suspected him. Of the whole staff only he had been told, included in this vigil.

The headset was shifted slightly away from his ears; Roger listened, as midnight approached, to his cousin’s chat with the experimenting medical man.

“Of course I know that I am under suspicion,” Dr. Ryder said. “The culture was hidden in my section. Other things look bad——”

“Of the whole staff you are the only man I need not suspect,” Grover saw deeper into things than had Roger. “It is an old trick, to turn suspicion toward an innocent man by ‘planting’ something.”

That, Roger decided, was sounder sense than he had used. He had forgotten to dig past appearances to the heart of truth!

“What do you expect will happen here?” asked the doctor.

“The miscreant will come, with his menagerie, for the priceless camphor secret.”

“Pretty smart stuff,” broke in Potts, “coagulating camphor with kangaroos.”

Coagulating was the wrong word, Roger knew; and the others saw through the meaning.

“Claws on glass implied something tall enough to reach up that high on top of the cage,” Grover explained. “The ‘snake’ trail and an animal with a dragging tail ‘coagulated.’”

“But why did the man take the white rats?” Potts was beaming, in the faint glow from the bulbs in the shadow box; tickled that his word had been so good; not dreaming that Grover was inwardly amused.

“With the same motive that makes a magician do meaningless movements with his left hand while he really palms cards in his other hand,” Dr. Ryder explained, “to make you look away from the real motive.”

“And he brought the kangaroo and the ape to confusicate us,” Potts was being clever, he felt.

“I’d say the ape came so he could be used to climb down a rope, and go and open the cellar trap that had no beam-alarm,” Roger spoke up. “I looked up notices in the theatre columns and there is an act that has a boxing kangaroo, and the critic called it ‘she.’ In the act, she ‘brings down the house’ when a fire is supposed to trap the trained rats on the roof of a little house, and ‘she’ makes everybody laugh by taking the rats and putting them in the pouch they have to carry their young in.”

“Oh, yes, that coagulates,” Potts agreed.

Although all the others realized that the word meant to clot or curdle, and wanted to smile when it was used to mean “connects up,” Potts, had they known it, was precisely correct—for they were to find that many deductions certainly coagulated, in a broad way of speaking, the real truth, instead of solving the mystery.

If clotting and curdling means to thicken and make lumpy, then as Potts said, Roger’s explanation did exactly that to their deductive cleverness.

Roger, as the slow minutes dragged along, picked up with his headset whispers of the policemen outside a window, exchanging ideas about their tedious watch; and even the slip and rattle of shifting coal in the cellar bin.

No invading menagerie, though, brought news to his intent ears.

A tiny, but sharp click broke a long silence. The oil-burner relays of heating plants in adjoining buildings made such “static” on his home radio, he knew, but the heat would not be used in the hour after midnight.

None of the apparatus or light was on the laboratory.

The interpretation Roger gave was that in moving he had jarred some poor connection that made loose contact in his circuits; and he began testing his wires at soldered points, seating tubes, and shaking headset binding posts.

He did not succeed in locating the source of the single sound, because things began to happen.

From the darkness, and apparently from the upper floor, in a hollow, grave-yard sort of tone, an unexpected voice spoke.

Roger, with power full-on, got a roar, and dashed aside the set to save his ear-drums, for a microphone had caught and had brought him what the others heard naturally.

The voice spoke in English, low, deep, mournful and yet, somehow, menacing, as it said:

“Hear me. I am the Voice of Doom!”

Roger felt his blood “coagulate” in very truth. Grover, never more calm, although the unforeseen and uncanny call galvanized and terrified Potts and made the Doctor’s face look absolutely horrified, leaped up, and vanished out of the small pool of dull light from the shadow-boxed panel. With the ease of familiarity, he got past their great transformers, and the storage batteries from which direct current was drawn for certain types of experimentation. He avoided, in the gloom, the new high-intensity-spark mechanism, and took the stairs two at a bound.

Roger, impulsively starting to follow, remembered his duty, and in spite of his shuddering nerves and the cold fear always coming from any uncanny and unexplained happening, he stuck to his post.

Doctor Ryder, attempting to follow, ran into the recording equipment and stopped, hesitating, as Grover, from above, threw on the lights. Roger got the switch-snap, but it differed from his other “click.”

“Nothing here,” Grover called down. “Strange!”

“Potts,” Doctor Ryder turned his head, half accusingly, “are you a ventriloquist?”

“A——”

“Ventriloquist! Able to throw your voice so that it sounds as if it came from somewhere else than where you are.”

“Are you?” asked Roger suddenly.

The other laughed.

Grover, leaving the lights going, came down, switching on illumination all over the building; while several policemen came from concealment, blinking and staring around uncertainly, the experimenter in the bright light walked over and sat beside Roger.

“Watch me closely,” he half-smiled, but kept his eyes glancing around half fearfully. “I did not dream—it would happen—again—and here!”

He spoke as if to himself.

“No, that is not ventriloquism,” he muttered. “It is some art of the Far East, known to the Lamas of Tibet——”

Again, and in the same hoarse, menacing, hollow way, the sound was repeated:

“Hear me! I am the Voice of Doom.”

Potts was shaking with fright. Uncanny and weird, the sound woke in the rather poorly educated man all the primitive fears and superstitions of his ancestors.

Grover, listening with his head on one side, his eyes on the Doctor, spoke:

“He isn’t a ventriloquist, Roger. The changes in muscular and other throat parts developed by constant ventriloquial practice, do not show. We took a film, remember, of just such throat development in connection with our research for the clue to our case when the deaf man ‘heard things.’”

Roger, recalling that in that case a tiny click had also come, when he had listened on a headset, jumped to the conclusion that he had before found correct.

“Somebody is using Mr. Ellison’s little radio test-sender,” he declared, confidently.

Grover nodded. “Possibly. Go and see.”

“His private locker needs a key that is in the safe.”

“Never mind, then. I think you have the explanation, Roger.”

Grover sat down again, relieved, as was Potts.

Dr. Ryder, though, seemed unconvinced.

“Sorry, but I must dispute your deduction,” he asserted. “I have heard that voice before, and it is sent by some Asiatic, wise in use of the hidden forces of Nature. It is a manifestation that is directly intended for me.”

Roger stared at him.

“‘Manifestation’? You mean—like thought transference or the ‘ghosts’ that spirit-mediums pretend to call on?”

“Only this is more sinister and terrible, because it is the way that the Far East makes known to some intended victim the fact that he is to be punished.”

He rose, and began to pace.

Roger, suddenly intent, caught at a passing “hunch.”

“Appearances” could be falsified. It appeared to be fact that something uncanny was happening. Might it not be the same sort of misleading use of one hand to distract attention while the other did some trick, as with the white rats that “appeared” to have been inoculated, were apparently “stolen” and so on?

Quickly the headset was put on. He cut the output strength to avoid having his ears blasted if the microphone upstairs picked up that booming, hollow voice again.

Grover, intently considering the Doctor’s last words, spoke:

“What do you mean by saying that you are being warned by some occult means that you are marked to be a victim?”

The man addressed held up a hand.

“It will tell you!” His face was set; he was listening.

Again Roger heard the inexplicable sound.

This time, no voice! Beginning in a low moan, faint and very much like the whine of a puppy that is hungry, it grew in volume, and its tone changed from a high falsetto, running down the scale and then up again, in cycles, constantly growing louder, while Grover, again rushing to the upper floor, stood looking around as, with a great grinding and rumble, following the last piercing roar of the sound, there fell silence.

Doctor Ryder, rising, walked around the recording machinery and Mr. Ellison’s newest camera, that worked with a stroboscopic lamp and ran its film so fast that no shutter was needed, as daylight did not act on it long enough in any spot to fog it.

“That,” he called upward, “was the real Voice of Doom.”

Grover, bidding Roger turn over the monitoring work to Potts, summoned his younger cousin.

“Roger,” as the hurrying figure came into the room with the vacant glass experiment-cage, “are you afraid to stay up here?”

“Not much—but if I am, I will stay, just the same.”

“Then set up that sound camera, with film, so you can take in every foot of this partitioned room. Be ready, and if the voice comes again, switch on, for continuous takes.”

“You think—anybody is hiding?”

“No. But a voice means something vibrating. I could not locate anything. The camera might do so.”

He went down, to give Potts some instructions and took over the monitor’s post while the handy man executed his order, which was to mix fresh developers and fixing baths, and to be ready for whatever Roger caught.

Doctor Ryder, helpful and desiring, as he made plain, to take away Roger’s sense of fear by explaining how the Far East made so uncanny a manifestation by mental powers, handed him the can of non-flam negative so that Roger lost no time in “threading up” and getting all ready for his duty.

Alert and steady, in spite of his chill of nervous uncertainty as to what might come next, Roger heard, seemingly from a corner of the small room, a thump.

“Start it!” gasped the man beside him.

But when two minutes of time had run out the film in his magazine and nothing more had come, Roger disappointedly took the film into the dark room and changed the magazines, hurrying back.

Half an hour later, with nothing to break the tedium, the next amazing development came. Potts, in the dark-room, shouted, and tore out into the light, waving a damp strip of film. He had developed the film on the chance that the thump had caused some change.

Instead, developing that film, he had brought, to wave before Roger’s startled eyes, an impossible thing.

On that film, in a different position on each Frame, or individual picture, a spectral monkey and an equally indistinct kangaroo hopped, bounced, and skipped, finally vanishing into thin air!

When that uncanny film was projected before him Grover seemed unwilling to believe the testimony of his eyes.

“It simply could not be,” he declared. “That film was taken from a brand new shipment, wasn’t it?”

“Yes,” Roger asserted.

“And there were no animals in the laboratory.”

“Not animals we could see,” said Doctor Ryder meaningly.

Grover, rather sharply, demanded his exact reason for saying that.

“I have heard the voices that seem to come out of nowhere,” the experimenter explained. “I have traveled in the Oriental countries. I have heard strange things; and I have seen things even more odd. In India, in China, and all the more in Tibet, there is what they call the sect of the Bon—Black Magicians.”

“Nonsense!” exclaimed Grover.

“To a scientific mind—yes. To an ignorant native of a country without educational facilities or communication such as our radio, telephone and so on—not so nonsensical. Besides, I have heard and I have seen curious things.”

“Like what?” Tip demanded.

“In India, a seed planted and an orange bush growing before my eyes. Or a rope flung into the air, staying aloft as if hooked to some invisible support, while a boy clambers up and seems to vanish.

“In Tibet, as well as in India, men who can apparently walk on water. Of course, our science explains it as hypnotism—the man who performs the feats is able to secure control over some part of the onlooker’s mind, impress his thoughts on the other mind, and make one believe the trick is a real occurrence.”

“I have read about men who can walk on pits of live coals,” Roger added.

“Those tricks or those marvels do not explain this film,” Grover was not satisfied, Roger knew by his tone.

“How about telepathy? Thought transference?”

“I believe,” Grover answered, “there is some ground for accepting that as possible. It might be reasonable to admit that if a man, by years of practice, can train himself and also treat his feet so that he can walk on fiery coals, a man might become able to impress a powerful idea on another without words. But—on a film!”

“In the sect of the Bon, or manipulators of the darker forces of Nature and of man’s superstition which is half of black magic,” the experimenter declared, “strange powers exist. I have read of a French scientist who has succeeded in developing a film so sensitive that a powerful thought, held by his trained mind, seemed to cause some changes in the film. This is a similar situation produced by some Oriental master mind, probably.”

“Or it could be that things like ghosts are true,” Potts volunteered. “What do we know about the unseen things? Even science is finding things like bacterions——”

“Bacteria,” Grover corrected, smiling.

“—In the air and water and blood. Well—I went to a spirit-meeting once. The woman threw a fit and talked awful funny about my ‘deceased aunt on the other side’ and told me things—now, if we brought in one of them there test mediators——”

“Test mediums,” Roger knew the right word. “They pretend to be able to communicate with spirits of people, but has it been verified?”

Potts was too eager to argue that. He stuck to his suggestion:

“All right. If we call in a trance medium, she’d tell us them spooks is around us, right now.”

“Just because the appearance seems to be that,” Grover stated, “is no basis for accepting the explanation of telepathy. In that case, Doctor, we would have seen the objects, the animals. We did not. You and Roger are sure you saw nothing. There are only two possible ways the phenomenon could happen.”

“How?” Potts was anxious, eager.

“First: the film had been exposed, previously. Second: some one hiding in the dark-room, while Potiphar was not closely observing the developing tank, changed for the original film in its rubber wrapping, this one.”

“I used a deep tray, full of pyro,” Potts stated, “wound the negative around in the rubber, but didn’t use a tank, on account of them bein’ stained, and you was so positive about fresh stuff, I got a deep tray, never used before, and watched every step of developin’. The second way of it happening is ‘out.’”

“Then we will test the possibility of the first,” Grover beckoned to Roger.

“Telephone downstairs for a taxi, and meanwhile, plug in the telephone in the screening room for me.”

When Roger had summoned a night-hawk car, his cousin reported his own activity.

“I got the night-watchman at the Bizarre Theatre, where the animal act finishes its engagement tonight,” he said. “The white rats and dogs, and several monkeys are quartered at a pet shop near the theatre. There is a kangaroo, and it stays in a stable. Here is the address, Roger. I want you to talk to the keeper, or some stable attendant who can say when the animal was taken out and when returned.”

Roger, when the taxi arrived, sped to his task.

He found a sleepy attendant, surprised at the time, so near dawn, for a visit from a young fellow who wanted details about the kangaroo.

“She ain’t been out this night,” the youth assured Roger.

“How about last night? Or the night before?”

“Neither time.”

“Oh, but she must have been.”

“Well, she wasn’t.”

“Well, then, was the ape?”

“What ape?”

“Doesn’t the man who has the trained animals use an ape?”

“Never saw nor heard of no ape.”

Roger was puzzled.

“Well—” He recalled a flash of inspiration that had been all his own. He pulled from his pocket the tiny, compact camera, small magnesium-flash gun, and tripod folding like a pocket ruler, very slender, but sturdy when unfurled.

“Can I snap her picture? Our laboratory wants it to study.”

“Cost you—how much you want to pay?”

“A quarter.”

“Go to it, buddy.”

Roger, with the hand of the youth clutching the coin, got a good snap just as the flash startled and almost stampeded the kangaroo and several horses and a few mules quartered there.

He returned by taxi as the East streaked rosily to the rising of the sun.

“There was the kangaroo, but she had not been out—at least, the attendant vowed she hadn’t,” he said. “But I’ve got her picture to compare with the ghost-one.”

“Clever head,” commended his older cousin. He went away, pleased, to develop, print and fix his prize.

While negative and contact print were being fixed and washed, he sat at the table in the adjoining room where the mysterious voice and roaring cry had been located, thinking hard.

“I wonder,” he mused, “if it could be that the film I used had some sort of emulsion that would be sensitive to rays we don’t see. You can take a picture through a quartz lens in a room that seems to be pitchy black. I’ve done it, with our special equipment. Maybe a film coating that has some light-sensitive ingredient sensitive to high-frequency vibrations of light, could catch what we don’t see, and—who can dispute this?—there may be in the air, all around us, forms of things that we can’t see.”

Science, he reflected, had managed to develop instruments so delicately adjusted that they caught earth tremors and recorded them, when the disturbance might be hundreds, thousands of miles away from the seismograph.

Their own Mr. Ellison, the cleverest and best informed man in the city, on electrical matters, was preparing a camera that ran its film at high speed past an aperture: a light more actinic than sunshine alternately lit and was out, but so rapidly that its flashes impressed pictures lit by it on the film, as many as a half million or more a minute, he believed. The papers had written it up as that many.

And scientific instruments pictured, in graphs, of course, such invisible things as electrical waves; yes, and radio made audible the inaudible electrical frequencies sent by an aerial, caught by another, transformed into sounds by other invisible agencies.

Grover, when appealed to, nodded.

“Anyone who has operated a modern laboratory knows better than to make fun of any theory,” he admitted. “What our Pilgrim ancestors would have called a witch talking to Satan, we see as an old crone listening to her radio.”

“They had their witches-on-broomsticks,” Roger chuckled. “We see airplanes. That’s so.”

“It doesn’t pay to scoff at your theory. It may be a scientific possibility to prove it correct, some day. But, just yet, let’s not take it as the only explanation of our ghosts. I realize that the film can was one of our last shipment, that you had to break the label, proving it had not been tampered with, apparently. Still, some test made at the film plant could have been inadvertently packed. We got it.”

“My snap of the kangaroo will prove or disprove that.” Roger went to get the force-dried bromide enlargement and the camera film taken in the haunted room. Comparison showed, apparently, the same animal, in one case sharply defined, a solid object; and in the other, just a shadowy specter. They looked to have the same proportions, though.

“My theory is that someone hired the animal trainer to send his rats here, so they could be removed. He could have read notes of the Doctor’s planned experiment in a science column of the papers.”

“Then where did the ape come from? The attendant was sure the act did not have any ape in it.” Roger was still unconvinced.

“That may have been the trainer, an agile man, in a masquerade costume of Tarzan-type.”

“It might.”

“I will admit that Doctor Ryder tells a story that makes wilder theories possible,” Grover added. “The policemen are gone, now. He gave me an outline that made me discard the theory about danger to our camphor substitute. Suppose you listen with me to the full recital.”

The narrative the man spun was amazing.

“Shortly after I left college,” Doctor Ryder began, “I became interested in study of medicinal herbs, because an old Indian in up-state New York, who had earned a reputation as an occult doctor, had made some astonishing cures of seemingly incurable cases. A friend and I got into an argument. I supported the Indian’s claims; and my chum argued it was impossible, that it was pure medication and not at all due to magical powers as the people claimed.

“I went to the Indian to study,” he went on. “He took a liking to me, and after a long time, teaching me secrets of wayside weeds and the properties of common plants in medication, he confided that in the Far East there were schools in which full knowledge of herbal medication could be learned by those qualified to share the secret—a dangerous one, because knowledge of it might enable some evil-doer to procure enough deadly poison among common wayside flowers and herbs to destroy a city’s populace.”

Skipping his explanations of how he finally secured the Indian’s help in reaching some one who knew more, and of how he finally found himself an accepted student journeying toward a Lamasery in far-away Tibet, Roger’s next intense interest came with the declaration:

“I learned something about what Ponce de Leon spent his time seeking, the secret of eternal youth. I learned much about marvelous properties of common plants—and then, through a desire to view with my own eyes the greatly revered Eye of Om—a precious jewel set in the forehead of a sacred statue of Buddha—I became a hunted man, suspected of a theft I never dreamed of committing, then. The Eye disappeared. I was suspected. My perils were many. I finally escaped from the land. But twice, since I began my private researches, I have been reached by that strange warning, the Voice of Doom—just as you, who have been my friends, heard it tonight.”

He bent forward in his chair, earnest, eager.

“I know who took the Eye of Om. If only you would help me to restore it—if only you could.”

When he heard Doctor Ryder’s startling plea, Roger’s clear, gray eyes lighted with a fire of hope and excitement.

To be involved in a mystery in the laboratory was thrilling; but to have a share in restoring the Eye of Om, evidently a priceless gem, would be more so.

His quick mind flashed over the fascinating prospect; but with equal quickness he saw the reason why Grover sat so silent and unimpressed.

A man accused, anxious to return a jewel, would merit help. A man who knew the real taker of the gem and wanted it restored meant possible trouble. He might want them to help him get the gem away from its possessor.

That was not their duty. It was police work.

“Please be more definite,” Grover said.

“I don’t want you to help me ‘steal’ the gem from anybody,” the medical experimenter declared. “I need financial help to buy it.”

“To buy it,” Roger exclaimed. “That would take a lot of money. Would the people in Tibet pay you?”

“They would pay a handsome profit, Roger. But it would not cost such a vast sum as you may think. You see, the one who has it is not aware of its value.”

“That is curious,” remarked Grover.

“What happened was this: I went to the temple with a native priest to see the marvel I had heard of. While we were entering, a figure slipped away out of another door to the sacred crypt. As we approached the great figure of Buddha, I saw a vacant hole in it and realized that the priceless jewel was gone. Terrified at the thought of being caught, suspected or in some way associated with the crime against their holiest treasure and venerated religious symbol, the priest and I hurried away just as other temple attendants discovered the situation.”

Without being certain, the rest of the gem’s history was assumed to be that the thief, terrified, had thrown away his loot. One of his camp staff, an ignorant, though strong pack-carrying youth from an American city, whose way the doctor had paid for his ability to obey orders without trying to improve on them, had found the gem, in a fissure of the great mountain pass they traversed in escaping.

He had evidently taken it to be only a beautiful native art object and had put it in his pack, apparently, without mentioning it, meaning to bring it back to America to “give to his sweetheart,” as the medical experimenter supposed.

“At any rate,” Doctor Ryder summed up, “he is living here in the city, his sweetheart had forgotten him, he has that treasure, put away, and I dare not go and talk to him about it. I know he has it because he has shown it, as a souvenir, to people who have recognized its worth without knowing just what it is. He would probably sell it for a fairly good sum, if approached by someone from a museum; but if he was told its history, and knew its real value, he might sell it to some gem dealer who would put it beyond my reach in some private collection. And my life would be forfeit, because I cannot prove, in the circumstances, my innocence to the Tibetan Dalai Lama and his vindictive, fanatical subordinates.”

Grover, as Roger watched him eagerly, anxiously, considered the situation thoughtfully.

“I suppose that there are complications,” he said, finally. “Some international jewel thieves must know the affair.”

“Exactly.” The other man nodded. “That accounts for the entry, here, night before last. From the use of a kangaroo I would assume that an Australian is interested——”

“An ape would mean somebody from Africa,” Roger argued.

“While the strange projection of the Voice of Doom implies that the Tibetans are preparing to strike at me,” Doctor Ryder added.

Grover sat considering the matter.

“With that all granted,” he said, finally, “it is easy to see what caused the queer ghost-figures in our film. I assume that the purpose of using the trained boxing kangaroo with a pouch to carry its young, also trained to ‘rescue’ from fire, was to furnish a novel way of hiding and removing the gem which evidently the thieves think, as do the Tibetans, that you have.”

“Certainly. In your safe.”

“And whoever came,” Roger was able to fill it all in, now, “with the kangaroo, meant to get into the safe, get the gem, put it in the animal’s pouch, and then, to make it go away safely, he had to turn on the fire alarm that rang a bell, the way it must ring in the act, for the kangaroo’s signal to rescue the rats. It rescued them, and hopped away, to its attendant, just the way it would in the theatre.”

“And what about the film?” asked Doctor Ryder.

“Some was probably in the ‘sound camera’ by the cage. Either in trying to shut it off or in an accidental knock against it by the animal, the ‘continuous’ lever was thrown. Focused with a diaphragm opening to catch the white rats’ movements under a vivid light, the lens got only an under-exposure in the light from the ceiling!”

“Logically,” Grover finished up for his younger cousin, “the man knew the camera had been running. He took out that magazine, took the blank film from the new can to replace it, making as many snaps as had been made of the rats, jarred the continuous-take lever on by accident, giving us the clue of claws-on-glass as his animal came to the cage, with the ringing of the alarm bell.”

“Science to the rescue!” Roger exclaimed. “Now we know it must be the animal trainer who is the key-man. If he did it for his own greed, we can protect ourselves from him in the future.”

“If he was a hired accomplice of others, as I assume to be most likely,” Grover added, “he can be compelled to tell us the facts.”

Declaring that he would interview the man in person, bidding Roger to add to the few hours of sleep secured before their midnight watch, the laboratory head, as the staff began to arrive, urged Doctor Ryder to say little, and to wait until consideration could be given to his plea that they help him get the Eye of Om.

On the emergency couch, in a small combination of rest-and-first-aid room, Roger stretched out without feeling the least bit drowsy.

The excitement was still keeping him alert.

“Science to the rescue,” he mused. “Modern apparatus is wonderful and understanding how it works and what can be done with it ought to help people solve many mysteries. They have developed instruments to measure nerve responses and other things. There is the lie-detector for one device to help fight crime.

“And if scientific appliances, and scientific understanding, both can be coupled with Cousin Grover’s axiom about ignoring appearances and digging to the heart of truth, analyzing down to the basic element of a complex combination, it will be even better.”

He thought back along the course of the many happenings, and of all the clues that scientific apparatus and wisdom had opened up.

He sat up suddenly.

“Science to the rescue!” he repeated to himself. “We don’t need to wait to see if the animal trainer will tell the truth. We can find out right away.”

In the files he found the enlargements made the day before, from the “routine” wide-angle and close-up views Potts had taken.

The folder full of pictures, and the rolls of film from the cabinet he studied carefully.

Roger’s study was concentrated on the close-up and magnified detail of door locks, window catches and all openings.

If any catch had been moved the picture should show to the screen-observing youth, some abrasion, or some disturbance of rust, or at least a displacement of the accumulated dust.

Nothing. Nothing in any picture, on any film!

“That tells me that the entry was made through the skylight, as we had thought,” he decided, but added:

“Or—does it tell more?”

An ape, he felt sure, could not have been trained, or have sense, to swing so as not to touch a magnetized and super-charged metal plate concealed by being painted the same color as the wooden floor under the skylight.

A man, dressed as an ape, might. But it seemed like a long way to go around to get through, when a more simple possibility was open.

Roger assumed that it might be possible that one of the people interested in securing that priceless treasure which could be supposed to be in their safe, could work there!

The fact that no pressure from outside had given its clue in the pictures, showed him that some “insider” might have opened the only possible place to get the kangaroo in—the coal chute.

His examination, with a high-powered, beam-focusing light and a magnifying lens, revealed that rust under the bolt had been scraped.

But the pictures had shown no sign of the use of “jimmy” or other implement for prying back bolts!

An “insider” was responsible for opening that chute trap.

It would be simple to associate kangaroos with Australians, apes with Africa, possibly India. It would be just as easy to narrow it down to whether any of the staff connected-in with either place.

A man from Australia would naturally think of a kangaroo and its peculiar qualities and usefulness for his plan. A man familiar with a country wherein apes were found might see the usefulness of that animal, or would resort to a costume for disguise that a man from the coal counties of Pennsylvania, for instance, would not have thought of.

To the office files Roger hurried. All the data concerning each employe, such as age, experience and so on, was there.

When he had looked, Roger put away the sheets of data carefully, and waited eagerly for Grover to return from interviewing the trainer.

Two sheets had told him much. One had given its maker’s experience on an expedition to India for a power-plant construction job. There was India, ape country. Roger knew that in many sections of India, apes were sacred.

The other sheet had told him that its maker had worked in Australia under Government chemists, studying the inroads of a destructive insect.

He had two names to give Grover.

Science, with brains, had come to the rescue.

“Admitting your cleverness,” Grover, informed by Roger, was more than surprised, “I still find it hard to accept your deductions.”

“I don’t deduce anything,” Roger argued, “I only got the facts. I think I would almost as soon suspect you as to suspect Mr. Zendt, or Mr. Ellison. But——”

“The appearances certainly look bad,” Grover agreed.

Zendt, quiet, calm, thorough, had been in Australia, his own record attested. Mr. Ellison, than whom no one was more clever in electrical matters, had built power plants for a big utility company, some of his work having been in Calcutta and Karachi, both Indian cities.

“I will watch them unobtrusively,” Grover stated, “while you do an errand for me.”

Roger waited for instructions.

“I went to the address given by Doctor Ryder, just to check up and see if his fantastic story had any basis of fact,” Grover told his cousin. “Sure enough, there was dull-witted Toby Smith, and when I represented myself as an attaché of a museum—I am, you remember, one of the sub-committee on Egyptian Embalming research—the young fellow, about twenty-two, promptly enough produced and let me study the memento of his adventurous trip into Tibet. He certainly does not realize its value, and to me, inexperienced as I am, it appears to be a marvel of Nature’s crystallizing stresses, as well as a credit to the Tibetan jeweler’s craftsmanship.”

Roger was all ears.

“To him it was a souvenir, with little other value—a bit of art-glass, he told me he supposed it was.

“I bought it. You are to go and get it.”

“Why wouldn’t he let you bring it?”

“I thought of the possibility of being watched——”

Oh, boy! was Roger’s mental comment.

“I satisfied myself that I had not been; however, I had arranged to have you take him, in return, a small moving-picture hand-camera that he had confided to be his heart’s desire. In exchange, he will surrender to you a large envelope which will contain, disguised in heavy documentary-looking papers, the art-glass.” Grover smiled amusedly.

“And if you have any matches or duplicates in your stamp collection, you might get intimate enough to trade for some of his foreign over-stock of stamps.”

“I’ll take a batch of duplicates,” agreed Roger.

His taxi, depositing him at the address given by Dr. Ryder, waited.

The Smith chap, he found, was intensely interested in collecting, and had a fine collection of stamps; in fact, he spent most of his small earnings as a dishwasher, on philatelic prizes.

He and Roger grew intimate and compared notes, exchanged stamps, and chatted about the Tibetan expedition Smith had joined as a young man, several years ago, he claimed.