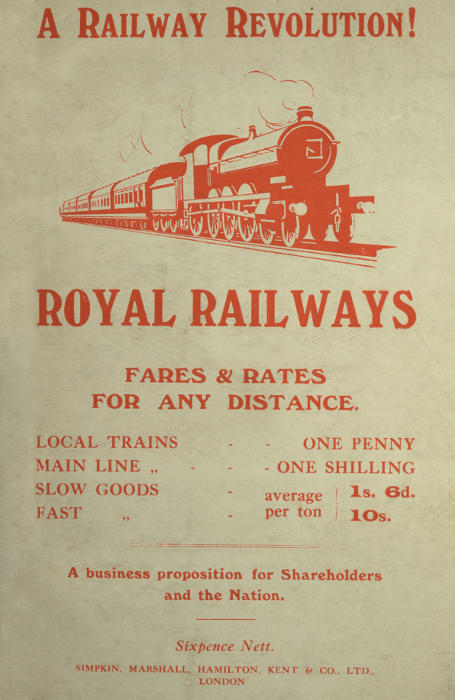

A Railway Revolution!

ROYAL RAILWAYS

FARES & RATES

FOR ANY DISTANCE.

| LOCAL TRAINS | ONE PENNY | |

| MAIN LINE ” | ONE SHILLING | |

| SLOW GOODS | average per ton } |

1s. 6d. |

| FAST ” | 10s. | |

A business proposition for Shareholders and the Nation.

Sixpence Nett.

SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, HAMILTON, KENT & CO., LTD.,

LONDON

ROYAL RAILWAYS

with Uniform Rates

by

Whately C. Arnold, LL.B. Lond.

A PROPOSAL

for amalgamation of Railways with the

General Post Office and adoption of

uniform fares and rates for any distance.

LONDON: SIMPKIN, MARSHALL,

HAMILTON, KENT & CO., LTD

1914

This pamphlet has been printed and published with the assistance of friends who share my opinion that the scheme proposed will solve the railway problem—now at an acute stage.

A rough outline of the Scheme has been submitted to Sir Charles Cameron, Bart. (on whose initiative sixpenny telegrams were adopted), and while reserving his opinion as to the advantages of State ownership and the difficulties of purchase, he has been good enough to write that this scheme is the boldest and best reasoned plea for the Nationalisation of Railways that he has come across.

The scheme has also been submitted to, among others, Mr. Emil Davies, Chairman of the Railway Nationalisation Society, to Mr. L. G. Chiozza Money, M.P., and to Mr. Philip Snowden, M.P., all of whom have expressed their approval subject to the figures and estimates being correct. These figures and estimates are based on the Official Board of Trade returns for Railways of 1911 and 1912.

I also had the temerity to submit my draft to Mr. W. M. Acworth, the well-known Railway expert, who very courteously gave me his views generally, although refraining from any detailed criticism. I deal with his remarks at the end of Chapter IV., but may here mention that Mr. Acworth called my attention to an article by himself on Railways in “Palgrave’s Encyclopædia of Political Economy” published in 1899. In such article he referred to a suggestion which had then been made for uniform fares on the Postal system, and he dismissed the idea in a sentence as impracticable, because no one would pay for a short journey as much as 8d., then the average fare for the whole country.

It is therefore evident that the principle of a flat rate is not novel; yet I can find no reference in any books or pamphlets on railways to any practical scheme for carrying it into effect. Apparently it has been assumed that there can be only one uniform rate, equivalent to the average rate, and that therefore the proposal is quite impossible. The simple expedient of dividing the traffic into the two kinds of “Fast” and “Slow,”[5] on the analogy of the Postal rate of one penny for letters and sixpence for telegrams, overcomes this difficulty. The scheme is in effect an extension to the Railway System of the principle upon which the existing Postal System is founded, and therefore involves Nationalisation.

As submitted to the above-named gentlemen, the draft did not include my remarks on the principles which in my opinion should govern all National and Municipal Trading, and which are now contained in Chapter IV. The attention of both opponents and advocates of Nationalisation is particularly called to these principles, which I have not found elsewhere, but which as laid down are believed to be absolutely sound, and of the highest importance, as removing most, if not all, of the objections of opponents, while retaining all the advantages claimed by advocates of National and Municipal Trading.

I do not pretend to be a railway expert, and have only been able to devote the small leisure time available from an exacting business to putting into writing the thoughts which have exercised my mind for many years past. But the well-known expert, Mr. Edwin A. Pratt, who is a strong opponent of Railway Nationalisation, admits in one of his books that “the greatest advances made by the Post Office have been due to the persistence of outside and far-seeing reformers, rather than to the Postal Officials themselves.” This admission and the conviction that the further advance now proposed is based upon sound principles and undisputed facts, encourages me to submit my scheme with confidence to the consideration of experts and the public.

W. C. A.

37, Norfolk Street,

Strand, London, W.C.

December, 1913.

PROPOSED UNIFORM FARES AND RATES:

| Passenger Fares: | Any Distance, so far as train travels. | |||

| Main Lines: | First Class | 5/-, | Third Class | 1/-. |

| Local Lines: | ” | 6d. | ” | 1d. |

| Goods Rates: | Any Distance. | |||

| Fast Service: | Average 10/- per ton. | |||

| Slow Service: | ” 1/6 ” | |||

The Royal Mail.—Letters carried for same price any distance. Why not passengers and goods? Object of pamphlet to prove that this is financially possible with small uniform fares and rates mentioned. A Business Proposition for Nation and Shareholders.

All Railways to be purchased by State and amalgamated with General Post Office. Trains of two kinds only, viz.:—

(1) Main Line Trains, i.e., non-stop for at least 30 miles.

(2) Local Trains, i.e., all trains other than Main Line.

Passenger tickets vary according to above fares only—no reference to stations or distance. Goods rates, payable by stamps vary only according to weight or size of goods, whether carried in bulk, in open or closed trucks, or with special packing, but irrespective of any other difference in nature or value of goods, or of distance, as now with parcel post.

All Railway Stations to be Post Offices. All Post Offices to sell Railway Tickets, and, where required, to be Railway Receiving Offices. Steamers to be regarded as trains.

1. Cheapness and regularity of transport.

2. Economy of service;—by unification of railways;—abolition of Railway Clearing House, of expenses of varying rates and fares, of multiplication of receiving offices, stations, &c.,—and by amalgamation with Post Office;—all railway land and buildings available for Government purposes—Postal, Civil, Military and Naval.

3. Progressive increase always follows adoption of small uniform fares (e.g., in Post Office); hence progressive increase of revenue available for working expenses, purchase money, extensions, improvements, and adoption of new safety appliances.

Present system founded on two principles, both mistaken and illogical, viz.:—(1) According to distance travelled. (2) According to “what the traffic will bear.”

(1) Although cost of building 200 miles, and hauling train that distance is more than for two miles, yet because regular train service required for whole distance, say, A to Z and back, passing intermediate places, therefore cost of travelling from A to B, or to N, identical with A to Z. For goods, cost of loading and unloading twice only, whether sent from A to B, or A to Z.

(2) Cost of hauling ton of coal exactly same as of bricks, sand, loaded van, in open truck, yet now different rates for each, according to “what the traffic will bear.”

True principle advocated by Sir Rowland Hill in Penny Post—whole country suffers by neglect or expense of transport to distant parts, and gains by including small districts with same rates as populous parts.

For a flat rate, three rules necessary.

(a) Must not exceed lowest in use prior to adoption.

(b) Increased traffic resulting must produce at least same net revenue.

(c) Variations of rate to be according to speed, not distance.

Hence:

(a) 1d. now lowest fare, fixed for Local Lines.

1s. now lowest fare, (e.g., 2s. 6d. return London to Brighton) fixed for Main Lines.

1s. 6d. per ton fixed for goods train or slow service, as the present average for minerals, and allowing present lowest rate for goods in open trucks, rising to, say, 6d. per cwt. (10s. per ton) for small consignments, in covered trucks.

10s. per ton, now lowest “per passenger train” (e.g., 6d. per cwt. for returned empties) fixed for fast service.

(b) The increased traffic dealt with under “Finance.”

(c) The two rates suggested for fast and slow trains solve the difficulty hitherto felt of charging lowest fare of 1d. as uniform fare—the 1s. fare and 10s. goods rate being double the present averages.

Writers for and against—All assume that on Nationalisation, system followed of charging according to distance, and to “what traffic will bear”—Fundamental differences between State Monopoly and Private Monopoly—Evils of applying profits of State monopolies in reductions of taxation—Strikes.

Four rules to be observed on Nationalisation:—

1. Natural monopolies only to be taken over.

2. When taken over, only to be worked for benefit of community and not for profit.

3. Competition of private enterprises not to be prohibited.

4. Monopoly to be worked by Department of State responsible to Parliament.

Chief grounds of objection to State ownership—

(1) Difficulty of Government in dealing with conflicting interests of traders and general public. (2) Difficulty of Railway servants (being also voters) using political pressure to obtain better wages, against interests of traders and general public. Both of these objections removed if scheme (which avoids all preferential or differential rates or treatment) adopted with above four rules.

Other grounds of objection, e.g., want of competition, officialism, &c., apply equally to present Company system, but may be remedied if owned by State. Suggested remedies:—Railway Council to deal with all matters of administration; Railway Courts to deal with questions of compensation, labour disputes, &c. Railways and Post Office being Department of State with Cabinet Minister at head subject to vote of censure in Parliament, provides better security for public than private Companies or Railway Trust.

Fear of Losses—

All existing staffs required for increased traffic—therefore no loss to them.

Traders, like newspapers more than make up for any losses by economy in rates and fares and increased circulation.

Mr. Acworth’s objections to “average” rates considered.

Present averages per annum in round figures taken from Board of Trade returns 1911 and 1912:—

| Receipts from Passengers | £45,000,000 |

| ” ” Goods per passenger train | 10,000,000 |

| ” ” Goods Train Traffic | 64,000,000 |

| ” (Miscellaneous) | 10,000,000 |

| Gross Revenue | £129,000,000 |

| Working Expenses | 81,000,000 |

| Net Receipts | £48,000,000 |

| Total Paid-up Capital and Debentures | £1,400,000,000 |

Net receipts show average income of 3½ per cent.

| Total passenger journeys (of which 10 per cent. were 1st and 2nd class) | 1,620,000,000 |

Average fare for each journey only 6½d.

| Total tonnage of goods:— | |

| Estimate per passenger trains | 20,000,000 |

| Actual per goods trains | 524,000,000 |

| 544,000,000 |

| Average rates per goods train:— | ||

| Minerals only | 1s. 6d. | per ton |

| General Merchandise | 6s. | ” |

| Both together | 2s. 4d. | ” |

Estimate under proposed scheme:—

I. Passengers.—Assuming Main Line passenger journeys are 300,000,000, i.e., under 20 per cent. of the total passenger journeys.

| 300,000,000 | at 1s. | = | £15,000,000 | |

| add | 30,000,000 | at 4s. for 1st class | = | 6,000,000 |

| 1,320,000,000 | at 1d. | = | 5,500,000 | |

| add | 132,000,000 | at 5d. for 1st class | = | 2,750,000 |

| Present No. | 1,620,000,000 | will produce | £29,250,000 |

Increased number of Main Line passengers required to make up deficiency:—

| 250,000,000 | at 1s | £12,500,000 | ||

| add | 25,000,000 | at 4s. extra | 5,000,000 | |

| £17,500,000 | ||||

| Estimated total | £46,750,000 | |||

This is £1,750,000 more than the present gross revenue from passengers and requires an increase of 250,000,000 = 15 per cent. on the total present number of passenger journeys.

II. Goods.

| Total tonnage by goods train as now, viz., 524,000,000, at 1s. 6d |

£39,300,000 |

| Ditto per passenger train, 20,000,000 at 10s | 10,000,000 |

| Live Stock, as now | 1,500,000 |

| £50,800,000 | |

| Increased tonnage required to make up present revenue, 48,000,000 tons at 10s. |

24,000,000 |

| £74,800,000 |

which is £800,000 more than present total receipts from goods per passenger and goods trains, and requires an increase of under 10 per cent. in tonnage.

Reasons for anticipating increase:—

(a) Of Passengers. Long distance journeys now restricted by expense.—Through tickets now counted as one journey will, under new scheme, be sometimes two or three, e.g., London to Londonderry would be three tickets—Every single journey taken, usually means also return journey home.

(b) Of Goods. Example of Post Office—Before Penny Post, average price per letter 7d., and letters carried 76,000,000. After Penny Post, first year number doubled; in twenty years, increased by eight times; about doubled every twenty years since. Before three letters per head of population, now 72 per head. Goods now sent by road motors will, with cheaper rates, go by rail—perishable articles, now not sent at all by fast train owing to expense, will be sent when rates cheaper.

If increase of traffic no more than above, increase of working expenses negligible, apart from economies made by unification. Expense of carrying 200 passengers no more than 20. If increase of traffic more, then revenue increases, but working expenses only by about 50 per cent., as expenses of permanent way, stations, signal boxes, and establishment charges but little affected. Expenses of Post Office and Railways to be lumped together.

| Present total market price of all | |

| Railway Stock and shares about | £1,350,000,000 |

| Debentures and Loans ” | 350,000,000 |

| Total about | £1,700,000,000 |

Estimate of annual sum required according to precedent of purchase of the East Indian Railway Company, namely, by annuities for 73 years, equal to 4¼ per cent. per annum on market value, plus liability for Loans and Debentures with interest at 3 per cent.

| 4¼ per cent. on £1,350,000,000 | £57,375,000 | ||||

| 3 ” ” 350,000,000 | 10,800,000 | ||||

| Total annual sum required for purchase | £68,175,000 | ||||

| Revenue available as per above estimates:— | |||||

| Passengers | £46,750,000 | ||||

| Goods | 74,800,000 | ||||

| Miscellaneous, as now | 10,000,000 | ||||

| £131,550,000 | |||||

| Less Working Expenses, with say, increase of £4,000,000 |

85,000,000 | ||||

| Net revenue available | £46,550,000 | ||||

| Balance required for purchase | £21,625,000 | ||||

| would be provided by following further increase of traffic, viz. | |||||

| 100,000,000 | passengers | at | 1s. | £5,000,000 | |

| 10,000,000 | ” | ” | 4s. | 2,000,000 | |

| 30,000,000 | tons | ” | 10s. | 15,000,000 | |

| £22,000,000 | |||||

This further traffic brings total increase of traffic to:—

| 350,000,000 | passengers | = about 21 per cent. |

| 78,000,000 | tons of goods | = about 15 per cent. |

Essential to purchase all Railways at same date—Railway Stock to be converted into Government Stock—Price to be fixed by average of market price of Stocks for three years prior to introduction of Bill.

Interested parties not prejudiced—Staff now employed in services to be discarded will be required for increased traffic—Facility of transport will increase trade, and open new markets, not only here but abroad—Foreign countries would adopt reform as they did Postal system—Advantages of inter-communication with Foreign Nations.

The Royal Mail! What scenes and memories are conjured up by these words! In the olden days, the Royal Mail coaches—in these modern days, the well-known scarlet Mail carts and motor vans arriving at all the larger railway stations from which the mail trains, always the fastest, convey the mails to every quarter of the United Kingdom, and over the whole world.

It is now a commonplace to post in the nearest pillar-box a batch of letters, some to addresses in the same town, others to provincial towns and villages, to Scotland, Ireland and far distant Colonies, each of them being conveyed to their destination, near or far, for the modest sum of one penny, by the speediest mode of locomotion that steam and electricity can provide. In order that travellers may have the advantage of that speed and regularity which is a feature of the Royal Mail, passengers and goods have always been carried by the Mail—formerly by the coach, now by the train. But whereas the mails are carried at the same price for any distance, the charges for passengers, and for goods which exceed the regulation size and weight permitted for the “Parcels Post,” vary according to the distance travelled, and as to goods also according to their nature or quality, with the result that for the greater part of our population long journeys are luxuries which can only be undertaken in cases of life and death, and not always then; the rates for carriage of goods by fast train are mostly prohibitive, and even by goods train for long distances are so great as to seriously restrict the traffic.

If mail trains can carry mails, with parcels up to 7 lbs. in weight at the same price for any distance, why cannot all trains carry passengers and goods of any size and weight at the same price for any distance? The answer is that they can, and it is the object of this pamphlet to prove not only that it is possible financially, but that, with the small uniform fares and rates indicated on the title page, sufficient revenue can be obtained to pay working expenses, and provide the sum required to purchase the whole of the existing railway undertakings at their full market price, or such a price as willing vendors would be ready to accept.

This, then, is “A Business Proposition” for all concerned; in other words, the magnificent net-work of railways in the United Kingdom, with all that is included in their undertakings, may be acquired by the nation at such a price as will make it worth the while of the present Companies and their shareholders to sell, and as the result to give the nation the benefit of speedy and efficient transport at the nominal fares and rates mentioned. It will, indeed, be a “Revolution,” but one of the most beneficial that can befall a nation.

The Royal Mail is an institution of which the nation is justly proud. How much more will it be so of an institution which will include the Royal Mail, namely, Royal Railways.

This is the scheme proposed:—

The whole of the existing undertakings of all the Railway Companies in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland will be acquired by purchase on some such terms as are set out at the end of this pamphlet and vested in the Government. The whole system will be amalgamated with the General Post Office and form one of the Departments of State, of which the Postmaster-General for the time being will be the head, and probably adopt the style of “Minister of Transport,” who will be a Member of the Cabinet. It will be expressly enacted that any profit made by the combined services shall be used only for increasing their efficiency, for payment of purchase money, or in reduction of fares and rates charged for the services, and in no case for general revenue of the country. There shall also be no prohibition of competition by private enterprise.[1]

All passenger trains will be regarded as consisting of two kinds, namely:—

(1) Main Line Trains, by which will be meant express trains running on the Main trunk lines between, and only stopping at, important towns.

A ticket for one shilling will entitle the holder to enter any Main Line train at any station, and to travel in it to any other station at which it stops, and a ticket for five shillings will entitle him to travel first class in such trains.

(2) Local Trains, by which will be meant all trains, other than Main Line trains as defined above, including all Metropolitan, Suburban and Branch Line trains throughout the Kingdom, as well as trains on Main lines which stop at all stations.

A ticket for one penny will entitle the holder to enter any Local train at any station, and to travel in it to any other station at which it stops, and a ticket for sixpence will entitle him to travel first class in such train if that accommodation is provided.

Steamers which form part of the railway undertakings will also be regarded as of two kinds, according to whether they form part of a Main Line, e.g., the Irish Packets or the Cross Channel steamers, in which case admission to them will be 1s. or 5s., according to class, or simply as part of a Branch line, e.g., the Isle of Wight steamers, to which admission would be 1d. or 6d. according to class.

In the case of Main Line trains and steamers, additional fixed charges (the same for any distance) will be made for the use of refreshment cars, sleeping cars, State cabins, reserved seats and any other special services.

In the case of Local trains, and possibly Main Line trains, Season Tickets may be issued, in each case available for any Main Line train or Local train as the case may be. For Local trains the following rates are suggested, viz.:—

| 3rd class | 1s. per week, | 4s. per month, | £2 per annum. |

| 1st class | 2s. 6d. ” | 10s. ” | £5 ” |

Passenger Tickets will not be issued to or from any particular stations, but like postage stamps will vary only according to the fares and special charges for the time being in force. The four denominations of 5s., 1s., 6d. and 1d. will, of course, be required, and 4s. and 5d. tickets could also be issued to make up the first class fares with the 1s. and 1d. tickets.

These tickets will be sold not only at every railway station, but also at every Post Office and in automatic machines. Every railway station will be, or will contain, a Post Office, with all postal, telegraphic and telephonic facilities, and every Post Office will sell not only passenger tickets but also railway stamps for parcels, goods and live stock.

Goods traffic will also consist of two services only, namely:—

(1) Fast Service, corresponding with the present service “per passenger train,” the charge for which will be an average of ten shillings per ton for any distance.

(2) Slow Service, corresponding with the present service “per goods train,” the charge for which will be an average of one shilling and sixpence per ton for any distance.

For both these services stamps will be issued of various denominations, and applied in manner now in use for the Parcels Post, with any necessary modification; for instance, the stamps might be affixed to consignment notes in the case of goods in bulk, or other suitable arrangements might be made for large quantities of goods.

For the slow goods traffic a regular service of goods trains will be organised so that at every town or village in the United[19] Kingdom served by rail there may be at least one delivery and one collection daily, more populous places, of course, having more frequent services.

For the fast goods traffic a similar regular service will be organised, and in cases where the traffic will warrant it special fast goods trains will be run; otherwise the goods will be carried by the passenger trains.

In course of time provision should be made for all trunk lines to have at least two double lines of rails, upon one of which fast trains for passengers and goods will run at uniform speeds, and at regular intervals, and upon the other the local trains and slow goods trains, also at uniform speed and at regular intervals.

The present complicated system of differential rates, which vary not only according to distance but also according to the nature, quality and value of goods, and involving different rates, amounting in number literally to millions, would be swept away, the only variations in rates being in respect of such obvious matters as weight, size, whether carried in bulk or in packages, in open trucks or closed, whether requiring special care or labour in packing or otherwise. The average rates proposed would, it is believed, admit of a uniform rate for any distance for minerals and other goods carried in bulk in open trucks, of no more than the lowest rate now in force, by charging higher rates for goods requiring closed trucks and more labour in handling, still higher rates for goods of abnormal size or weight, and higher rates still for single small parcels, on account of greater proportionate expense of handling. For the small single parcels the rate might be for slow service as much as 6d. for any weight up to 1cwt. (equal to 10s. per ton), and for fast service say 1s., or possibly more, for any weight up to 1cwt., the weight being graduated downwards for parcels of greater weight as are the rates now in force for letter and parcels post. The goods traffic would be in effect an extension of the present parcels post, the present rates for which would probably be capable of very substantial reduction.

These figures are put forward by way of suggestion only, and the question of terminal charges and fees for loading and unloading may have to be taken into account. Numerous details must necessarily be gone into in fixing an average uniform rate, and it is very likely that considerable modifications may be found necessary. Any such modifications, however, must be based upon the three rules set out on page 30 in order that the scheme may effect its object.

[1] For reasons of these modifications of the present practice in National and Municipal Trading see Chapter IV., pp. 33-41.

If this scheme is practicable financially (and one object of this pamphlet is to prove that this is so), then it seems almost superfluous to point out the great advantages of its adoption.

It has been well said that “transport is the life-blood of a nation.” If circulation is impeded or restricted the whole country must suffer, and, conversely, if all obstructions and restrictions are removed the whole country must benefit. This scheme will, in effect, remove the principal obstruction to free circulation of passengers and goods, namely, expense. Cheapness of transport is “twice blessed; it blesseth him that gives and him that takes”—in other words, it enables the producer, whether agriculturist, manufacturer or merchant, to increase his market for goods, and enables the consumer who requires those goods to purchase at a lower price. It is common knowledge that agriculture in particular in this country is hampered and restricted by heavy charges for freight.[2] Under our present system the carriage of goods from abroad to London is cheaper than from the Midlands, and the foreigner has a great preference (so far as freight is concerned) over our own farmers. Fruit and fish is often thrown away on account of the cost of carriage being more than the value of the goods. On the other hand, the price of food and every commodity has been gradually increasing. With the removal of this obstruction of expense of carriage there must be an increase in the supply of goods, and increased supply means lower prices.

As to passenger traffic, traders will appreciate the great benefit of nominal fares for themselves and their commercial travellers. So also will the greater part of the population, namely, those of very moderate means who are now prevented, solely on account of expense, from travelling any considerable distance, either on business or pleasure, or from visiting friends and relatives.

These are some of the general advantages attending cheapness of transport, but it may be as well to point out in detail some of the very substantial economies and other special advantages to be obtained by adopting the proposed scheme.

A few examples of the waste attending the present system, both of money and time will illustrate some of these advantages.

In the Strand, London, within a few yards of each other, are the following premises:—

No. 168, Strand.—The Strand Station of the Piccadilly and Finsbury Park Tube Railway.

No. 170, Strand.—Great Western Railway Receiving Office.

No. 173-4, Strand.—East Strand Post Office.

No. 179, Strand.—Great Northern Railway Receiving Office.

No. 4, Norfolk Street, Strand, almost adjoining No. 179, Strand.—Inland Revenue Office.

No. 183, Strand.—Midland Railway and London and North Western Railway Receiving Office.

Within sight, at the other end of Norfolk Street, is the Temple Station District Railway, and at 6, Catherine Street, about the same distance from the other side of the Strand, is a Labour Exchange.

It is assumed that the rents of shops in the Strand would average about £500 per annum. Under the proposed scheme, the whole of the business transacted at the above eight premises could, with greater convenience, be carried on at the two railway stations, possibly with some extensions, but with a saving not only of rent but also of rates, taxes and other outgoings.

At Bexhill-on-Sea, with a population of only about 15,500, there are two large railway stations, one belonging to the South Eastern & Chatham Railway Company, the other to the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway Company, and situate about a mile apart. Half a mile from each is the Head Post Office, within a few doors from one of the stations is a branch Post Office, and within a small radius are Government offices for Inland Revenue and other purposes.

Letters posted at a pillar box outside the station are collected there, taken to the Head Post Office for sorting, then returned with others to the railway for the Mail train leaving the same station. The majority of the passengers are for London, and go by the two different routes, but the fares are identical, and the time occupied is about the same, no advantage being gained by the public through the so-called competition.

If both stations were amalgamated one staff only would be required, there would be ample room on the premises to accommodate the Head Post Office with sorting rooms, etc. (the branch office now near the station would not be required), and there would be plenty of room also for the Government Offices. In addition[22] to the saving of expense, there would also be the great convenience and saving of time in the transport of, and dealing with, mails, passengers and goods.

These two examples with many others have come under my personal observation, and they may be multiplied ten thousand times throughout the United Kingdom. Where is there a railway station, whether a great London terminus, or small provincial station, where postal facilities are available; while just outside rents are paid, in some cases very heavy ones, for other premises, to and from which the mails have to be conveyed?

Other examples of waste under the present system, although not so apparent to the public, are well-known to the railway expert, and involve much greater expenditure of time and money.

I refer in particular to the waste of rolling stock, especially of goods wagons, occasioned by the multiplicity of goods stations, the transfer of rolling stock to and from the lines of different railway companies, the shunting of trains, and the large number of road vans used by the various companies. In London alone there are 74 goods stations, used for goods only, and 700 goods trains per day travel between these 74 stations, doing nothing but transferring goods from one of these stations to another! Goods consigned to one warehouse in London from places on, say, seven different railway companies’ lines are sent by seven different vans, one belonging to each company. Under my proposed scheme one or two central goods stations of large area would not only suffice, but would provide a far more efficient and speedy transport service, and yet with the nominal rates referred to.

Under the present system goods trains, having been unloaded, must be returned in order to clear the line, so that it is not uncommon to find goods trains belonging to the various companies returning empty for long distances on each line, on the G. W. R. as far as Bristol, on the S. W. R. to Basingstoke, on the G. C. R. to Banbury, and so on. It has been estimated that of the 1,400,000 goods wagons now on the railways of the United Kingdom, no more than 3 per cent. are actually in effective use at one time, the remaining 97 per cent. being either stationary or running empty![3] One reason for this, no doubt, is the use of merely hand labour for loading and unloading.

With a view to avoiding this waste the New Transport Company, Limited was registered in 1908, for the purpose of introducing new and ingenious machinery, invented by Mr. A. W. Gattie and Mr. A. G. Seaman, for handling goods, including the adoption of movable “containers” on trucks and wagons, and a scheme for a “Goods Clearing House” occupying a site of about 30 acres, in Clerkenwell, to be connected by rail with all the lines coming to London.

It is, of course, necessary, in order to carry so important a scheme into effect to negotiate with all the various railway companies interested, as well as to obtain an Act of Parliament. Besides this, a large amount of capital is required for the acquisition of the site, the construction of the connecting lines, installation of the machinery, etc.

Notwithstanding the large cost, estimated by Mr. Edgar Harper, F.S.S., late Statistical Officer of the London County Council, at £14,000,000, he shows that such a system would more than pay for itself in a year by the economies in transport which it would effect directly or indirectly.

No estimate, however, is given, nor probably can be given by anyone, of the time that will be occupied in carrying such a scheme into effect, so long as this present system of numerous companies and conflicting interests continues. Five years have already gone by since the Company was registered.

If, however, the scheme of nationalisation and amalgamation with the Post Office be adopted, there should be no difficulty in providing as part of such scheme for the system and machinery of the New Transport Company already referred to, not only in London but in every other traffic centre. It might also be possible to avoid the expense of acquiring a new site for a “Goods Clearing House” by utilising some portion of the large area occupied by the three large termini and approaches thereto of King’s Cross, St. Pancras and Euston.

There will then be no conflicting interests, no multiplicity of companies, and no difficulty in raising the necessary capital for establishing the system, and what is still more important, no difficulty, as will be shown hereafter under the heading of “Finance,” in producing the necessary revenue to repay the capital and interest, by reason of the progressively increasing traffic which will result from the adoption of the small uniform average rates advocated.

The following, then, are some of the very substantial economies which will be effected by my scheme:—

I. Expenditure which would be entirely abolished:—

(a) The Railway Clearing House, the sole object of which is to apportion receipts and payments between the various companies, about 217 in number, and requiring for its work a large and expensive staff, not only of clerks, but also of inspectors at every junction, and a large establishment at Seymour Street, Euston.

(b) The separate Boards of Directors, officers, and clerical staff of all the separate companies.

(c) The legal and parliamentary expenses incurred in disputes between the various companies, and in opposing rival companies’ new lines.

(d) Advertisements by rival companies of their own routes.

II. Expenditure and waste which would be diminished:—

1. By reason of unification of systems.

(a) Competing receiving offices and their staffs would be reduced to one in each locality.

(b) Rolling stock, which is now often idle because owned by different companies, could be used solely according to the requirements of the traffic.

(c) Competing trains now running on different lines at the same time between London and other large towns could be run at different times with largely increased numbers of passengers at same cost.

(d) Adjoining stations belonging to competing companies would be amalgamated.

2. By reason of the adoption of uniform rates and fares.

(a) The abolition of the elaborate book-keeping and staffs needful for the present complicated system of passengers’ fares and goods rates, especially the latter, with the waste not only of expense but also of time.

(b) The saving of the expense of printing and advertising various priced tickets and fare tables, also of the large staff of booking clerks, inspectors and others.

(c) The saving of the legal expenses now incurred by the Railway and Canal Commission Court in appeals and disputes between the companies and traders as to rates, etc.

3. By reason of the amalgamation of railways with the Post Office.

(a) The rent and expenses of numerous Post Offices in the neighbourhood of railway stations would be saved, all stations being used for postal purposes.

(b) All postal sorting and other offices could be situate on railway premises in or near the stations, and besides thus saving the rent would be in closer touch with the railway.

(c) The whole of the railway tracks would be available without rent for laying of telegraph and telephone wires, either over or underground.

(d) Surplus land of the railways, in particular where adjoining to stations, would be available for other Government purposes, such as Inland Revenue Offices, Labour Exchanges, Military, Naval or Civil Service purposes, Police Stations, Fire Stations, County Courts, Police Courts, Land Courts, as well as Courts for dealing with questions arising out of the railways themselves.

Unification enables each part of the country to have as good a service of trains as every other part, notwithstanding differences of population and resources. The Companies now operating on the South Coast cannot provide so good a service as the Northern Companies owing to the lack of the great mining and industrial centres which are served by the latter.

One of the most conspicuous examples of this is Ireland. A Royal Commission was sitting for many years on the question of Irish railways, and ultimately reported in favour of State acquisition. Even this, it is clear, would not entirely solve the difficulty, which arises from the natural causes of being an island with (compared to the rest of Great Britain) a small population, mostly agricultural. If, however, the Irish railways were amalgamated with all the others of the United Kingdom under the proposed scheme the problem is solved. In the estimate given in considering the finance of the scheme the Irish railways are included.

The conversion of the railway system into Government property will, apart from the question of economy already referred to, provide a most important advantage to the State. For example, the War Office can make use of the railway system, not only for the purposes of transport, but for the erection on surplus land throughout the country of barracks, stores, and other buildings, for wireless telegraph stations and for aviation purposes. The Admiralty will have the use of the great docks and wharves now owned by railways. The Civil Service will also find ample space for additional office accommodation, often in the most convenient spots both in town and country.

Still more important even than these advantages is the fact that by the removal of all money restrictions from transport, not only an immediate but a progressive increase of traffic will result. That this will be so is shown hereafter when considering the question of the finance of the scheme, but it is referred to here as one of the most important advantages of the scheme, apart from the benefits to the nation already referred to of free circulation of passengers and goods.

In the first place, the increase of traffic will require in all probability the whole of the staff now employed, who would otherwise be thrown out of employment by reason of the economies referred to above. It will be noticed that in the estimates given under the heading of “Finance of the Scheme” no decrease, but on the contrary, a slight increase has been estimated for in the working expenses, notwithstanding the enormous saving to be anticipated by the abolition and reduction of wasteful expenditure under the present system. My reason for so doing is partly to err on the side of caution in the estimates, but also to provide for the probability of having to retain the whole of the[26] existing staff, and possibly increasing their wages and reducing their hours of labour. Most of the economies referred to must necessarily be effected gradually; for instance, the clerical staffs of the various railway companies and of the Railway Clearing House would be required for some considerable time in the process of winding-up, and by the time this is finished the traffic will have still further increased and their work will then be required in the more necessary departments of, say, the Goods Clearing Houses throughout the country.

Secondly, the progressive increase of traffic will produce a corresponding increase of revenue which will be available for extensions and additions, for electrification of lines, and other improvements in means of transport, and ultimately even in still further reduction in charges, but last and by no means least in the adoption of appliances and inventions for the safety of life and limb both of passengers and railway servants.

Unlike the present companies, the Government will have no difficulty in raising the capital required for any such purposes, and in relying upon the inevitable increase of traffic, as now is the case of the Post Office, for repayment.

Take the case of automatic couplings. These were invented 40 years ago[4] and their adoption has been urged on the companies ever since, not only on the merciful ground of saving life and limb, but also on the financial ground of saving waste of time in shunting; but the initial expense of fitting these to every truck and carriage has been too much for the directors of the Companies to risk.

Many inventions for automatic signalling, instantaneous brakes, and other life-saving appliances have been from time to time submitted to railway companies, but the initial expense of installation throughout the many miles of railway of each company has been so great that one hardly wonders at the hesitation of directors in laying out money belonging to the shareholders, especially when, notwithstanding a small normal increase of traffic, the working expenses have increased to a greater degree.

[2] See “The Rural Problem,” by H. D. Harben (Constable & Co., 1913, 2s. 6d.). Mr. Balfour Browne, K.C., also, in addressing the London Chamber of Commerce, February, 1897, said, “I am not exaggerating when I say that the Agricultural question … is nothing else but a question of Railway Rates.”

[3] Lecture by A. W. Gattie, at London School of Economics, 11th March, 1913.

[4] “Mammon’s Victims,” by T. A. Brocklebank, published by C. W. Daniel, 1911—Price 6d.

At first sight it seems preposterous that the fare from London to Glasgow should be only one shilling, the same as from London to Brighton, or that the fare of one penny from Mansion House to Victoria should be the same as from Victoria to Croydon. To a railway expert it will doubtless appear still more preposterous that the rate for a ton of iron-ore should be the same as for a ton of manufactured iron, and that the rate for general merchandise should be as low as 1s. 6d. per ton for any distance; and yet it is now considered a matter of course that the rate of 1d. for 4 ozs. for a letter from London to Londonderry should be the same as from one part of London to another, or 3d. for 1 lb. should be the rate by parcel post for any distance great or small, and irrespective of what the contents of the parcel may be.

The system of charging for transport according to distance, which is still in force throughout the civilised world, except in the Postal Service, appears to me to be founded on a wrong principle. It has no doubt been adopted on the assumption that the greater the cost of production the greater should be the charge, and, therefore, that as it costs more to build 100 miles of railway than one mile, and takes more coal or electric current to haul a train for 100 miles than for one mile, it is necessary to charge more for the longer distance. Even the Post Office still clings to the same idea, in charging higher rates for the telephone trunk service according to distance, although the charges for telegrams are the same for any distance! It is significant that whereas the net profits from railways remain more or less stationary, that of the Post Office with uniform rates continually increases, and that the telephone system with charges according to distance is so far the least satisfactory branch of the Post Office.

It is no doubt a general rule that the price of an article depends upon the cost of production, but when dealing with transport the analogy fails. In the case of a national system of railways[28] the provision of a regular service of trains to and from all parts of the country is a necessity. Such a service requires that trains must run at stated intervals advertised beforehand from one terminus to another, say from A to Z, with various stopping places between those points, which may be represented by other letters of the alphabet. The cost of running each train will be the same, whether it contains 20 passengers or 200, whether some or all of the passengers alight from or board the train at any intermediate station or at either terminus. Therefore, the actual cost of carrying a passenger from A to Z is not, in fact, more than from A to B, or from M to Z.

The same consideration applies to goods with even greater force. With goods the cost of handling them has to be considered, as well as the cost of haulage. If goods are sent from A to B only they must be handled twice, and this is no more than if they are sent from A to Z, assuming there is no need for change of trucks.

In the case of goods under the present system there is a further principle acted upon, which is still more obviously a wrong one, viz., what is known as charging according to “what the traffic will bear.” This term is well known to all railway experts, and is a convenient way of explaining the reasons governing the various rates under the present system. For instance, if too high a rate is charged for goods of comparatively small value, traders prefer to send by the cheaper modes, namely, by sea or by road, and in many cases it would not be worth while to send at all, whereas in the case of an article like silk or bullion of considerable value the extra cost of carriage even at a high rate would not add appreciably to the price. Therefore, the railway companies are compelled to make lower charges for low-priced goods, otherwise they would lose the traffic altogether. Accordingly there are such anomalies as a higher rate for the carriage of manufactured iron than of iron-ore for the same distance, although the cost of trucks, of haulage, and of handling may be identical. Again, the rate for carriage of meat from the Midlands to London is greater than that from Liverpool to London, partly on account of the competition of the sea, and partly on account of the large consignments of foreign meat. Again, the rate for the carriage of bricks from one part of London to another is greater than from Peterborough to London, because Peterborough is in a brick-producing district. These inconsistencies and anomalies are intensified by the necessity of the goods having to be carried over the lines of several different railway companies, all of whom must receive some profit out of the carriage of the goods, in addition to the actual cost.

It is quite clear that the actual cost of haulage for the same distance of say a ton of coal is no more than that of a ton of bricks or of manufactured iron, or of sand, or of a pantechnicon full of[29] furniture, all of which can be carried in open trucks, yet the rates for all these various goods, even for the same distance, differ widely from each other under the present system, and differ again not only according to distance but actually according to the different towns between which the service is rendered. Many examples of the present anomalies are strikingly shown by Mr. Emil Davies in his book, “The Case for Railway Nationalisation,”[5] which should be read by all interested in the subject.

Now assume that the whole of the various existing railways are amalgamated; that Main line trains both for goods and passengers run at regular intervals to and from the principal towns; that Local trains run from station to station and on branch lines also at regular intervals, connecting at junctions with Main line trains; that just as there are now regular times for delivery and collections of letters and parcels by post, varying in number according to the population of each locality, so there are regular collections and deliveries of goods to and from every town and village in the United Kingdom; and that a uniform rate, no more than, or even less than, the smallest rate now charged, is all that has to be paid. It is true that with such a system at many of the smaller places the actual expense of collection and delivery may, indeed, be “more than the traffic would bear,” certainly much more than the Directors of a railway company would feel warranted in risking under the present system with their necessarily limited area, but when these smaller places are part of such a system as is here described, extending to every town in the United Kingdom, then the whole becomes self-supporting, and there is no advantage in charging, either according to distance, or according to “what the traffic will bear.”

Every little village Post Office in the United Kingdom is an object-lesson to us. Here we have all the resources of civilisation, letter and parcel post, telegraph, telephone, savings bank, money orders, all provided at exactly the same rate as in the largest Cities of the Empire. Although the actual expense of each village Post Office taken by itself is out of all proportion to the population of the district, the combination of all of them in one national unified system enables these remote villages to benefit, not only with no financial loss to the nation, but actually with a handsome net profit which has actually contributed to the general revenue of the nation. This was not contemplated when the Penny Post was established, and is a practice which, in my view, is a great mistake, as explained in Chapter IV.

The same principle has been applied to the ordinary roads of the country, which are now open free of charge to the whole population, although many of this generation can still remember the restrictions of the old toll-gates.

It is only applying the same principle to the nation which applies to the human body. “The body is not one member, but many.… Whether one member suffers, all the members suffer with it, or one member be honoured, all the members rejoice with it.”

If from any cause, such as a flood or other physical disturbance a small industrial or agricultural district were cut off from all communication with the rest of the Country, it is not only that district but also the whole of the Country which suffers loss, namely, the loss of trade with that district. And if by reason of high rates the remote towns, villages, and districts, as well as those nearer to great centres, are prevented from obtaining an outlet for their produce, the whole Country suffers. The converse is equally true: as soon as free circulation of passengers and goods is provided, the prosperity of the whole Country as well as of each district is increased.

This, then, is the principle upon which the scheme of uniform fares and rates is founded, as opposed to the existing system of charging according to distance and according to “what the traffic will bear.” There remains, however, to be considered the principle upon which the particular uniform fares and rates mentioned on the title page have been suggested for the proposed scheme. These have not been selected at haphazard, but in accordance with three rules which, I believe, are founded upon a sound principle, namely:—

(1) That any flat rate to be successful must not exceed the minimum rate in force prior to the adoption of the scheme;

(2) That there should result from the change a sufficient increase of traffic to produce at least the same net revenue as before;

(3) That in a system of transport the fares and rates should vary, not according to distance travelled, but according to speed of service.

In accordance with these rules I take for Passenger Traffic first the present minimum railway fare now charged, that is, 1d. for short distances of one mile or under. If the flat rate were fixed at say 2d., or, indeed, any sum over 1d., passengers who now pay that sum would have to pay at least double the existing fare; this would, of course, render the whole scheme impracticable. On the other hand, under a flat rate of 1d. throughout the whole country the receipts would not be sufficient to produce the present revenue unless and until the number of passengers carried should increase by as much as six or seven times. That this is so is clear when it is remembered that the present average[31] railway fare for the whole of the United Kingdom (allowing for season ticket holders), is 6½d. In other words, if all the passengers now travelling would pay 6½d. for every journey, both for short ones, as from Mansion House to Charing Cross, and long ones, as from London to Londonderry, then the same gross revenue from passengers would be obtained as now; or, on the other hand, if a flat rate of 1d. any distance were fixed, and the number of passenger journeys were increased by six-and-a-half times as a result of this great reduction, then, again, the same gross revenue would be obtained. The first of these alternatives is, of course, impracticable, and the second one is certainly not likely to be attained for some time to come, and even then account would have to be taken of the additional working expenses occasioned by so large an increase of traffic. It is on account of these difficulties that any system of uniform fares has hitherto been regarded as impracticable.

The solution of this problem was suggested to me by the practice of the Post Office of charging 3d. for express delivery, and 6d. for a telegram. Here we have the third rule before referred to of charging according to speed of service. Applying this to railways, and again searching for the lowest fares now charged for fast Main line trains, it will be observed that these are the regular cheap excursion fares of 2s. 6d. from London to Brighton or Southend and back, which amounts to 1s. 3d. each way. It is true that these are exceptionally cheap fares. Return tickets only are issued at this price, available by certain trains only, but on the principle already laid down that the flat rate must not exceed the lowest, this forms the basis of the proposed uniform fare of 1s. for Main line trains. Although this uniform fare is so exceptionally low, it is still nearly double the present average fare, and it is precisely on the Main line trains that increase of traffic (now restricted by expense) is sure to take place. These facts (as will appear in the chapter, “Finance of the Scheme”) enable me to estimate the increase of passenger traffic required to make up the present gross revenue at only 15 per cent. of the present number of passengers carried.

For goods traffic the uniform rates suggested have been ascertained in accordance with the same rules. It is more difficult to ascertain the present minimum owing to the enormous complication of goods rates.

Under the present system, goods are divided into eight different classes according to the rate charged, and a maximum rate is fixed by law for each class. In the lowest of these classes the rates vary from one penny and a fraction up to 4d. per ton per mile for any distance up to 20 miles, and smaller proportionate rates for distances over 20 miles. But although these are the greatest amounts that the companies may charge for this class of goods, they do make special rates of considerably lower amounts for[32] special kinds of goods. It is estimated that five-sevenths of all the goods carried are charged according to special rates not included in the eight classes mentioned.

The Board of Trade returns give the totals of two classes of goods only, namely, “minerals,” of which 410 million tons are carried, and “general merchandise,” of which only 116 million tons are carried. These returns are possibly misleading as, although derived from returns made by the several companies themselves, it may be that those returns include the same goods sent over different lines.

For the purposes of my estimates, however, I have assumed that the Board of Trade returns are correct, and if they are so, the average charge for “minerals” is now about 1s. 6d. per ton, and for “general merchandise” about 6s. per ton. Taking the two classes of goods traffic together, as representing what under my scheme will be the “slow goods traffic,” the average is only 2s. 4d. per ton.

The average rate of 1s. 6d. per ton has been suggested for the slow service because it is believed that this average will allow of a rate for all goods in open trucks as small as the lowest rate now charged for minerals for short distances, the average being maintained by higher rates chargeable for other kinds of goods as already described. If the actual tonnage of goods carried is really less than that mentioned in the official returns (it cannot be more), it may be found necessary to fix a somewhat higher uniform rate, and the estimates may be affected to a certain degree. The figures, especially those relating to goods traffic, are put forward by way of suggestion only, and there should be no difficulty in ascertaining a uniform rate in accordance with the rules already stated.

It is believed that any difficulty in this respect will be solved by the large accession of traffic by Fast service, which, as with Main line passengers, is sure to follow the adoption of the scheme.

The average rate for “fast” service has been obtained by ascertaining the lowest rate now charged for goods carried “per passenger train.” This appears to be the rate for returned empties for any distance up to 25 miles, namely, 6d. per cwt. (equals 10s. per ton). There is also a charge of £1 for a load not exceeding 2 1/2 tons on carriage trucks attached to a passenger train for a distance of 40 miles, and thereafter at 6d. a mile. It is evident that an average of 10s. per ton would allow of a still smaller rate than that amount for goods carried in bulk and in large consignments.

[5] “The Case for Railway Nationalisation” by Emil Davies, published by Collins, 1913—Price 1s.

I now propose to consider objections which may be raised to the proposed scheme.

I anticipate opposition from those who object to all forms of State Ownership or State Management.

The late Lord Avebury was one of the most prominent opponents of nationalisation, and his views are set out in his book “On Municipal and National Trading.”[6]

Mr. Edwin A. Pratt has written several books on the subject and has recently collected all the arguments up to date against State Ownership in his book, “The Case against Railway Nationalisation,”[7] In this book examples are given of the experience of foreign countries and the Colonies where railways have been taken over by the State.

Other writers who have advocated the retention of our present system, and are quoted with approval by Lord Avebury, are the following:—

Messrs. G. Foxwell and T. C. Farrer (now Lord Farrer), in “Express Trains, English and Foreign.” (1889);

Mr. W. M. Acworth, in “The Railways and the Traders”;

Mr. H. R. Meyer, in “Government Regulation of Railway Rates,” and in “Railway Rates”;

and Lord Farrer and Mr. Giffin, in “The State in its Relation to Trade.”

On the other side, the following, among other advocates of railway nationalisation have shown the great advantages to be anticipated by such a measure, and have given very cogent answers to the objections of the opponents, namely:—

Mr. William Cunningham, “Railway Nationalisation.” (Published by himself at Dunfermline, 1906, 2s. 6d.);

Mr. Clement Edwards, M.P., “Railway Nationalisation.” (Methuen & Co., 1907, 2s. 6d.);

and Mr. Emil Davies in several books, including his latest, already referred to, “The Case for Railway Nationalisation.” (Collins, 1913, 1s.)

But in all these books, and in other books and articles, both for and against nationalisation, it has been assumed that if, and when, the railways are acquired by the State, the same system will obtain as now, and as obtains in the case of all the foreign countries and colonies referred to, namely, to charge according to distance and according to “what the traffic will bear,” and with the primary object of making the most profit.

With very great deference to all these distinguished writers, it appears to me that they have one and all overlooked the fundamental principles which should be acted upon by a State or a Municipality first in deciding whether or not to acquire a monopoly, and secondly, in the administration of it when acquired. These principles depend upon the fundamental difference between the objects in view, and actuating a Company or individual on the one hand and a Nation or Municipality on the other in acquiring a monopoly. In the former case the sole object is that of pecuniary gain or profit; in the latter the sole object is, or ought to be, the benefit of the community. It may be said that these are not respectively the sole objects, but only the primary objects. My reply is that in the case of the company it is the duty of the directors, as trustees for the shareholders, to so carry on the business in question as to produce the most profit, irrespective of any benefit to the community, or, indeed, to any persons other than the shareholders. Railway companies, it is true, provide the benefit of transport, and various advantages held out by the companies as inducements to use their particular lines, but these are, of course, solely offered with the view of increasing the profits. Other advantages for the comfort, safety and benefit of the public are provided under compulsion from the Government, as a condition of the grant of privileges and compulsory powers conferred upon the companies, without which the railways could not have been made. I refer to such matters as rules and regulations for the safety and benefit of the public; workmen’s trains; maximum fares and rates allowed to be charged; provision for at least one train a day at all stations, etc.

Conversely, in the case of a Nation or Municipality taking over a monopoly, it is the duty of the Government Department or Town Council to so carry on the business as to render the most efficient service, at the lowest cost consistent with efficiency, with paying for the cost of acquisition and with paying the working expenses. Advocates of nationalisation urge that profits should be applied in reduction of taxation, and suggest that this is in itself one of the benefits to be derived therefrom. Opponents always assume that national and municipal trading must be carried on with a[35] view to profit, and some even ridicule the idea that any trading concern can be successfully carried on unless with this view and with a resulting profit. Acrimonious discussions have taken place as to whether profits which have been claimed by advocates of municipal trading to have been made by tramways, gas, water and electricity works, are only paper profits as alleged by the opponents. In Lord Avebury’s book already referred to,[8] one whole chapter, headed “Loss and Profit,” treats of the question whether municipal enterprises have been profitable or not, and he adduces many examples to prove that in most cases the alleged profits are imaginary.

It has, in fact, been the practice universally to apply profits made out of municipal trading in this Country in reduction of rates, and in foreign Countries, where railways are owned by the State, their revenues are made use of either as general revenue or, as in Prussia, for social or educational purposes, which would otherwise be provided for by direct taxation. The only instance of national trading in this Country is the General Post Office, and I think it is correct to say that the original intention when Penny Post was established was to so carry it on that working expenses only should be covered by the revenue. In practice, the gross revenue is entered with other items of revenue in the National Accounts, and the gross expenditure with other items of general and non-productive expenditure, with the result that the net profits of the Post Office, in effect, become a source of general revenue, and are therefore applied in reduction of general taxation. Until recent years this net profit has not been considerable, but last year it was as much as £5,000,000. Having regard to the continual and progressive increase in postal business, and the acquisition of the whole telephone system, there is every prospect of still further increase in net profits. What will be the result of a continuance of this practice of applying net profits of Municipal and National trading towards reduction of rates and taxes? It has not, so far, had any very serious result, simply on account of the fact that such net profits have not yet been of a very startling amount. But if these profits should increase, will not the result be the very evils which are the natural consequence of a private monopoly?

Once the principle is admitted that profits from such trading shall go in relief of taxation, the service will, and must, be worked more or less with the primary object of making as much profit as possible, with the inevitable result that the service in question will be starved for the sake of the profits. This has actually happened in the case of the Prussian State Railways, the one State Railway which has so far made the greatest net profit.

In addition to this difficulty there are others inherent in State or Municipal trading, if the principle of making profits be admitted, and if profits are actually made. In such a case the Chancellor of the Exchequer will be expected to budget for further profits, the general public will expect improvements in the service, traders will expect that the charges to them should be reduced, and the workers will expect that their wages should be increased.

This view is not a new one. It has been advocated in respect of the Post Office for many years by such well-known postal reformers as Lord Eversley (formerly Mr. Shaw Lefevre), and Sir Henniker Heaton, Bart. The latter, I believe, has several times moved resolutions in the House of Commons for the express purpose of having the postal profit applied to the use of the Post Office itself, instead of to general revenue.

It is well known that “strikes” are more likely to arise in a period of trade prosperity. It is the natural result of the workers seeing large profits made out of their industry, if they should have no benefit, by increase of wages, by sharing in such profits or otherwise. It makes but little difference to the workers that those profits go to ratepayers, instead of to shareholders, more especially as they usually inhabit houses let on weekly inclusive rentals, and are exempt from income-tax, so that they do not directly pay either rates or taxes. If, on the other hand, the profits are devoted to improving the efficiency of the service or cheapening the charges, then, not only are there no profits to excite the cupidity of various sections of the community, but the workers do, in fact, benefit by themselves and their families, as well as the whole of the public for whom the services are worked. No strike is ever successful which does not gain general public support, and even under existing conditions there is much less likelihood of strikes in the case of Civil Servants or postal or municipal employees, partly on account of the better wages paid, the certainty of continuing in employment except for misconduct, and the prospects of a pension, but still more on account of the practical certainty that public support would not be given to a strike which interferes with one of the most important of the public services.[9]

Another evil of ignoring the difference in principle of a public monopoly and a private monopoly has been the practice of applying to public monopolies the practice which all private monopolies endeavour to achieve (and properly so as their sole object is profit), namely, to put down all possible competition. If the[37] principle I advocate, namely, that the sole object of a public monopoly is the benefit of the community, then if some improvement in the service, the subject of such monopoly, shall be invented, which is proved to be practicable, the public should have the benefit of such improvement, and, instead of a prohibition of such private enterprise every encouragement should be given to it.

In our Navy, when new inventions are found which increase its efficiency, no time or money is lost in adopting them, even at the expense of discarding comparatively modern men-of-war or appliances. The risk to the nation of not doing so is too great to allow considerations of expense to stand in the way.

But what has happened in the case of so important a commercial matter as the Telephone? The Post Office are authorised by Act of Parliament to forbid any competition, a provision evidently enacted under the impression that a public monopoly must have Statutory protection against competition, which a private monopoly always seeks to obtain, but has to pay for. Having this monopoly, and having purchased the telegraphs, the Post Office from the first regarded telephones with the utmost jealousy, because it seemed likely to interfere with its “Profits”! Lord Avebury quotes from “The Times” of 13th June, 1884, as follows:—[10]

“… the action of the Post Office has been so directed as to throw every possible difficulty in the way of the development of the telephone, and of its constant employment by the public. We say advisedly, ‘every possible difficulty,’ because the regulations under which licences have been granted to the telephone companies are in many respects as completely prohibitory as an absolute refusal of them.” “… the effects of this claim are nearly as disastrous to the Country as to the inventors and owners of the instruments.”

When it is remembered that the Post Office insisted on being paid one-tenth, not of the profits, but of the gross receipts, the wonder is that our telephone system is not more backward than it is. Lord Avebury, of course, uses this and other instances, such as the opposition of municipalities owning tramway and gas undertakings, to tramway extensions in adjoining districts, and licences to motor omnibuses and also to the introduction of electricity for lighting and power, as an argument against nationalisation and municipal trading.[11] That these constitute a strong argument against public monopolies being worked for profit, I readily admit, but they do not weaken the argument that[38] all such concerns which must, in their very nature, be incapable of effective competition, should be taken over by the community, and be worked solely for its benefit. What possible chance is there of competition in a telephone system? It is, of course, an essential element to its success that each subscriber should be able to communicate with every other one. How, then, can it ever have been imagined that there could be any effective competition between rival systems? And yet competition was actually attempted between various municipalities and the National Telephone Company, and afterwards the Post Office itself was authorised to “compete” with that Company.

The ultimate purchase by the State was, of course, a foregone conclusion, but at what expense of both time and money has this at length been effected! The complaints which have been made since the completion of this purchase are evidently the result, not of nationalisation, but of the mistaken practice followed in a fruitless attempt at making or retaining so-called “profits” of the telegraph system, by at first putting “every possible difficulty” in the way of telephones, then attempting to compete with them, and then waiting a number of years before completing the purchase, with the result of being compelled to take over a large number of obsolete plant and instruments, and linking them up with a new system, thus producing a state of confusion and useless expenditure of time and money, which could all have been avoided by purchase of the patents and patent rights more than 30 years ago.

It is only right to say that Lord Avebury was still of opinion in 1907 that the resolution of the Government to buy up the National Telephone Company was “an extraordinary and most unfortunate policy.”[12]

Mr. Hanbury, who was the Minister mainly responsible in 1906 for the purchase of the telephones, had evidently changed his opinion since 1889, when, in answer to a deputation in favour of purchasing the telephones, he said, according to a report quoted by Lord Avebury from “The Times”:—

“If the telephone service was cast upon the Post Office it would be to the detriment of both the postal and telegraph services. Then, again, it would increase enormously the Government staff. He need only appeal to the Members of Parliament present to say whether they would like to have the weekly appeals for increase of wages from those State servants still further extended.”

Here we have exactly one of the arguments which is now being used against railway nationalisation, and by the very Minister who, 17 years after, did the very thing he had clearly condemned.

I admit the argument would hold good if the restriction be not imposed by an inflexible rule that there should be no attempt to work the concern, whether Post Office, telephone, railway or other monopoly for purposes of profit.

I have already referred to the mistake the Post Office are making in following the example of the private monopolist, the National Telephone Company, in charging for telephones according to distance, although between the very same towns in which different rates are charged the same department charges 6d. only for telegrams! This can only be with the strange, yet futile, intention of making more profit without regard to the benefit of the community. If the same rate were charged for Trunk calls as for local calls, many more provincial and country people would subscribe, and the wires being already laid and exchanges established, the additional expense would be but small.

It would seem, indeed, that the search after profits in the case of Government or municipal monopolies is as futile as the search by people after happiness, personified by Maeterlinck as “The Blue Bird,” and that when the only object is to benefit the community, the profits come, as does happiness, when the only object is that of benefiting other people.

Now, in considering the principle here laid down, it appears to me that there are four rules which should be observed when a nation or municipality undertakes anything in the nature of a trading concern:—

1. Only such concerns should be taken over as are, and must be, in the very nature of things, a monopoly, or, in other words, are not susceptible of effective competition.

2. Any such concern taken over should be worked with the sole object in view of benefiting the community and, therefore, the charges made should be so adjusted as to pay for the acquisition of the concern and for working expenses, and any surplus from time to time applied, only in improving the efficiency of the undertaking, or in reducing the charges made.

3. In the event of any invention or improvement being made, and proved to be commercially successful, whereby the benefit to the community can be increased, and provided the concern remains in its nature a monopoly, such improvements should be taken over and worked by the State or municipality, and meantime there should be no prohibition of any private enterprise carried on in competition apparent or real.

4. All such concerns, whether national or municipal, should be worked or directed by one or more Department of[40] State, having at its head a Minister, who should be a Member of the Cabinet, and responsible to the House of Commons, and as such liable to a vote of censure for any abuse or want of efficiency in the concern.

As to Rule No. 1, there appears sometimes to be a very thin line between what is, and is not, susceptible of effective competition. As a general rule, any concern which involves a right or easement over land, must be in the nature of a monopoly. Thus the supply of gas, water and electricity, all of which must be conveyed by pipes or wires into houses, are in the nature of a monopoly, but the fittings used in the houses are not, but are susceptible of very efficient competition, both as to workmanship, manufacture and design. All roads, including railroads and tramways, are, and must be, in the nature of a monopoly, but the manufacture of materials and rolling stock, the catering of hotels, forming part of the railway undertakings, or in the trains themselves, or in railway steamers, are all the subject of effective competition and should, therefore, be put up for competition with special supervision and restrictions against abuse of the privileges obtained by competition on Government property.

Now, I would ask any unprejudiced reader who has studied the writings of the eminent authors already quoted, and other opponents of nationalisation, to read those books again with these four rules in his mind, and consider whether all the objections so forcibly brought forward against nationalisation would not be very nearly, if not completely, answered, if such nationalisation were carried out with strict adherence to these rules.