BOOKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR

| Children of Fancy (Poems) | $2.00 |

| Jacopo Robusti, Called Tintoretto | (Out of print) |

| Architectures of European Religions | $2.00 |

| The Need for Art in Life | .75 |

G. ARNOLD SHAW

GRAND CENTRAL TERMINAL, NEW YORK

THE

CHILD OF THE MOAT

A STORY FOR GIRLS. 1557 A.D.

BY

IAN B. STOUGHTON HOLBORN

1916

G. ARNOLD SHAW

NEW YORK

COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY G. ARNOLD SHAW

COPYRIGHT IN GREAT BRITAIN AND COLONIES

DEDICATED

TO

AVIS DOLPHIN

On the analogy of the famous apple,—“there ain’t going to be no” preface, “not nohow.” Children do not read prefaces, so anything of a prefatory nature that might interest them is put at the beginning of chapter one.

As for the grown-ups the story is not written for grown-ups, and if they want to know why it begins with such a gruesome first chapter, let them ask the children. Children like the horrors first and the end all bright. Many grown-ups like the tragedy at the end. But perhaps the children are right and the grown-ups are standing on their heads. Besides they can skip the first chapter; it is only a prologue.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Hate | 1 |

| II | Secrets | 9 |

| III | Hate and Love | 29 |

| IV | The Prisoner | 55 |

| V | The Thief | 79 |

| VI | Bitterness | 94 |

| VII | Death | 104 |

| VIII | Remorse | 111 |

| IX | The Judgment | 115 |

| X | The Packman’s Visit | 126 |

| XI | Swords and Questionings | 140 |

| XII | “Moll o’ the Graves” | 156 |

| XIII | Coming Events Cast Shadows | 166 |

| XIV | Good-Bye | 182 |

| XV | The Terror of the Mist | 189 |

| XVI | A Desperate Task | 200 |

| XVII | Carlisle | 217 |

| XVIII | A Diplomatic Victory | 226 |

| XIX | The Loss | 247 |

| XX | Persecution | 253 |

| XXI | Torture | 259 |

| XXII | To the Rescue | 282 |

| XXIII | Duel to the Death | 296 |

| XXIV | A Ride in Vain | 317 |

| XXV | Amazing Discoveries | 329 |

| XXVI | The Battle of Liddisdale | 344 |

| XXVII | The Birthday Party | 354 |

| XXVIII | The Last Adventure | 378 |

| XXIX | A Tale of a Tub | 388 |

| XXX | The Great Iron Chest | 401 |

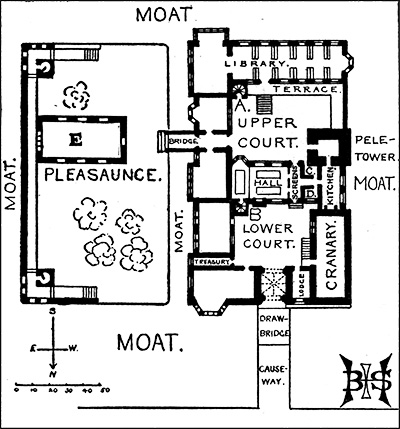

A, Staircase to Solar and Aline’s Room; B, Staircase to Solar and North Rooms; C, Buttery (the place where the drink was kept, Cf. French boire); D, Pantry (the place where the food was kept, Cf. French pain); E, Chapel.

Note.—The approach is from the north, therefore the usual position of the compass is inverted. The scale is a scale of feet.

PLAN OF THE HALL

HOLWICK, YORKSHIRE

THE CHILD OF THE MOAT

A STORY FOR GIRLS

Children of Fancy: The Guelder Roses.

THE great ship Lusitania was nearing Queenstown on May 7th, 1915, when a terrible explosion occurred, and in fifteen minutes she had sunk. Among some 1700 adults and 500 children were a lecturer on art and archaeology and a little girl, with whom he had made friends on board. About 700 people escaped and these two were both eventually picked up out of the water. When they reached the land there was no2 one left to look after her; so he first took her across to her relatives in England and then she went to live in the home of the archaeologist, in Scotland, who had three little boys of his own but no little girls.

Archaeologists do not know anything about girls’ story books, and he may have been misinformed when he was told that girls’ books were too tame and that most girls preferred to read the more exciting books of their brothers. However, this made him decide himself to write a story for the little girl, which should be full of adventures. It was frankly a melodramatic story, a story of love and hate, and he chose the period of the Reformation, so as to have two parties bitterly opposed to each other; but, except for dramatic purposes, religious problems were as far as possible left out.

One difficulty was as to whether the characters should speak in old English; but, as that might have made it hard to read, only a few old words and phrases were introduced here and there, just, as it were, to give a flavour.

Afterwards the author was asked to publish the story “for precocious girls of thirteen,” as it was delightfully phrased; that is to say, for girls of thirteen and upwards and perhaps for grown up people, but hardly for superior young ladies of about seventeen; and this is the story:

Father Laurence, the parish priest of Middleton, was returning home from Holwick on a dark night in the late spring. He had come from the bedside of a dying woman and the scene was unpleasantly impressed on his mind. Sarah Moulton had certainly not been a blessing3 to her neighbours, but, in spite of that, he felt sorry for the delicate child left behind, as he did not see what was to become of it. He felt very troubled, too, about the poor creature, herself, for was not his task the cure of souls? Not that Sarah Moulton was much of a mother; but perhaps any kind of a mother was better than nothing, and the poor child had loved her; yet, after she had received the viaticum, she had given vent to the most frightful curses on her neighbours. “If I cannot get the better of Janet Arnside in life,” she had screamed, “I will get the better of her when I am dead. I will haunt her and drive her down the path to Hell, I will never let her rest, I will....” and with these words on her lips the soul had fled from her body. He sighed a little wearily. He was famished and worn for he had previously been a long tramp nearly to Lunedale. “I do my best,” he said, “but I am afraid the task is too difficult for me. I wish there were some one better than myself in Upper Teesdale: poor Sarah!”

Father Laurence’ way led through the churchyard, but clear as his conscience was, he had never been able to free himself from a certain fear in passing through it on a dark night. Could it be true that the spirits of the departed could plague the living? Of course it could not; and yet, somehow, he was not able to rid himself of the unwelcome thought. As he passed through the village and drew nearer to the church, he half resolved to go round. No, that was cowardly and absurd. He would not allow idle superstitions to get the better of him.

But when he approached the gate he hesitated and his heart began to beat violently. What was that unearthly screech in the darkness of the night? He crossed himself4 devoutly, however, and said a Paternoster and stepped through the wicket gate. “‘Libera nos a malo,’ yes, deliver us from evil, indeed,” he said, as, dimly on the sky line he saw a shadowy figure with long gaunt arms stretched to the sky.

He crossed himself again, when a ghoulish laugh rang through the still night air. He turned a little to the left, but the figure came swiftly toward him. He wanted to run, but duty bade him refrain. His heart beat yet more violently as the figure approached and at length he stood still, unable to move.

The figure came closer, and closer still, stretching out its arms, and finally a harsh voice said: “Is that you, Father Laurence? Ha! Ha! I told you Sarah Moulton would die. You need not tell me about it.”

It was old Mary, “Moll o’ the graves,” as the folk used to call her. Father Laurence felt a little reassured, but she was not one whom anybody would wish to meet on a dark night, least of all in a churchyard.

“What is the matter, Mary? Why are you not in your bed,” he asked; “disturbing honest folk at this time of night?”

“You let me alone,” she replied, “with your saints and your prayers and your Holy Mother. I go where I please and do as I please. I knew Sarah would die. I like folk to die,” she said with horrible glee; “and she cursed Janet Arnside, did she? A curse on them all, every one of them. I wish she would die too; ay, and that slip of a girl that Sarah has left behind. What are you shaking for?” she added. “Do you think I do not know what is going on? You have nothing to tell me;5 I assure you the powers are on our side. There is nothing like the night and the dark.”

“You are a wicked woman, Mary,” said the old priest sorrowfully, “and God will punish you one day. See you—I am going home; you go home too.”

“You may go home if you like,” said the old hag as he moved on, “and my curses go with you; but I stay here;” and she stood and looked after him as he faded into the darkness.

“Silly old dotard,” she growled; “I saw him at her bedside or ever I came along here. The blessed sacrament indeed; and much may it profit her! I wish now I had waited and seen what he did after she had gone; comforted that child, I expect! Fancy loving a mother like that! Ha! Ha! No, I am glad I came here and scared the pious old fool.”

She moved among the tombs and sat down near an open grave that had just been dug. “Pah! I am sick of their nonsense. Why cannot they leave folk in peace? I want to go my own way; why should I not go my own way? All my life they have been at me, ever since I was a little girl. My foolish old mother began it. Why should I not please myself? Well, she’s dead anyway! I like people to die. And now Mother Church is at me. Why should I think of other people, why should I always be holding myself in control? No, I let myself go, I please myself.”

“I have no patience with any of them,” she muttered, “and now there is a new one to plague me,” and “Moll o’ the graves” saw in her mind’s eye a slim, graceful girl of twelve, endowed with an unparalleled refinement6 of beauty. “What do they mean by bringing that child to Holwick Hall,” she continued, “as if things were not bad enough already,—a-running round and waiting on folk, a-tending the sick and all the rest of it? Let them die! I like them to die. Self-sacrifice and self-control forsooth! They say she is clever and well-schooled and mistress of herself and withal sympathetic. What’s the good of unselfishness and self-control? No, liberty, liberty—that’s the thing for you, Moll. Self-control, indeed!” and again the ghastly laugh rang through the night air. “Yes, liberty, Moll,—liberty. Are you not worth more than all their church-ridden priests and docile unselfish children? What avails unselfishness and affection? Father Laurence and Aline Gillespie, there’s a pair of them! No, hate is the thing, hate is better than love. Scandal and spite and jealousy—that’s true joy, that’s the true woman, Moll,” and she rubbed her hands with unholy mirth.

As she talked to herself the moon rose and gradually the churchyard became light. “Love!” she went on, “love! Yes, Oswald, that’s where they laid you,” she said, as she looked at the next place to the open grave. “Ah, but hate got the better of your love, for all that, fine big man that you were, a head taller than the rest of the parish, and all the girls after you, too!”

She looked at the side of the open grave, where the end of a bone protruded. She pulled it out. It was a femur of unusual size. “Yes, Oswald,” she repeated, “and that’s yours. You did not think I would be holding your thigh-bone these forty years after!

“Ha! you loved me, did you? I was a pretty lass then. Yes, you loved me, I know you loved me. You7 would have died for me, and I loved you, too. But little Sarah loved you and you loved her. I know you loved me most, but I would not have that. ‘I should have controlled myself,’ you say; ha! I was jealous and I hated you. Self-control and love;—no, no, liberty and hate, liberty and hate; and when you were ill I came to see you and I saw the love-light in your eyes. They thought you would get well. Of course you would have got well; but there you were, great big, strong man, weak as a child,—a child! I hate children. Was that it? You tried to push my hands off, as I pressed the pillow on your face, you tried; oh, you tried hard, and I laugh to think of it even now. How I longed to bury my fingers in your throat, but I knew they would leave marks.

“Yes, liberty and hate, ha! ha! I would do it again. See, Oswald!” and she took the brittle bone and viciously snapped it across her knee. “Self-control! love! unselfishness! Never! And that child up at the Hall, Oswald, I must send her after you. I have just frightened Sarah down to you. You can have her now, and that child shall come next. Hate is stronger than love. Liberty, self-will and hate must win in the end.”

The abandoned old wretch stood up and took her stick—she could not stand quite straight—and hobbled with uncanny swiftness across to a newly made child’s grave and began to scrape with her hands; but at that moment she heard the night-watchman coming along the lane; so she rose and walked back to Newbiggin, where she lived.

She opened the door and found the tinder box and struck a light, and then went to a corner where there was8 an old chest. She unlocked it and peered in and lifted out a bag and shook it. It was full of gold. “Yes,” she said, “money is a good thing, too. How little they know what ‘old Moll o’ the graves’ has got,—old, indeed, Moll is not old! Ah, could not that money tell some strange tales? Love and learning and self-control! Leave all that to the priests. Hate will do for me,—money and liberty are my gods.

“Aha, Aline Gillespie, you little fool, what do you mean by crossing my path? I was a pretty little girl once and you are not going to win the love of Upper Teesdale folk for nothing, I’ll warrant you.”

“I AM so tired of this rain,” said Audry, as she rose and crossed the solar[1] and went to the tall bay window with its many mullions and sat down on the window seat. “It is three days since we have been able to get out and no one has seen the top of Mickle Fell for a week. The gale is enough to deafen one,” she added, “while the moat is like a stormy sea,—and just look at the mad dancers in the rain-rings on the water!”

[1] The predecessor of the withdrawing room or drawing room.

It was a terrible day, the river was in spate[2] indeed, carrying down great trees and broken fences and even, now and then, some unfortunate beast that had been swept away in the violence of the storm.

2 In torrent.

“The High Force must be a wonderful sight though,” she continued, “the two falls must be practically one in all this deluge.”

“I do not altogether mind the rain,” said her little friend; “there is something wonderful about it and I always rather like the sound of the wind; it has a nice eerie suggestion, and makes me think of delightful stories of fairies and goblins and strange adventures.”

“Well, that may be all right for you, Aline, because you can tell magnificent stories yourself; but I cannot,10 and it only makes me feel creepy and the rain annoys me because I cannot go out. I wish that we had adventures ourselves, but of course nothing exciting ever happens to us.”

“They probably would not really be nice if they did happen. These things are better to read about than to experience.”

“I don’t know,” said Audry; “anyway, the only exciting thing that ever happened to me was when you came to stay here. I really was excited when mother told me that a distant cousin of my own age was coming from Scotland to live with us; and I made all sorts of pictures of you in my mind. I thought that you would have a freckled face and be very big and strong and fond of climbing trees and jumping and good shouting noisy games and that kind of thing.”

“You must be very disappointed then.”

“No, not exactly; I never thought that you would be so pretty:—was your mother pretty, Aline?”

“I do not remember my mother,” and a momentary cloud seemed to pass over the child’s beautiful face, “but her portrait that Master Lindsay painted is very beautiful, and father always said that it did not do her justice. It is very young, not much older than I am; she was still very young when she died.”

“How old was she?”

“I do not know exactly,” Aline answered, moving over to the window-seat and sitting down by Audry, “but I remember there was once some talk about it. Her name was Margaret and she was named after her grandmother or her great grandmother, who was lady in waiting to Queen Margaret, and who not only had the11 same name as the Queen but was born on the same day and married on the same day.”

“What Queen Margaret,” asked Audry, “and how has it anything to do with your mother?”

“Well, that is just what I forget,” said Aline with a smile like April sunshine;—“I used to think it was your queen, Margaret of Anjou, who married Henry IV; but she seems to be rather far back, so I have thought it might be Margaret Tudor, who married our James IV.

“I expected their age would settle it,” she continued, stretching out her arms and putting her hands on Audry’s knees. “I looked it up; but they were almost the same, your queen was fourteen years and one month when she married and ours was thirteen years and nine months. But I know that mother was exactly six months older to a day when she married, and I know that she died before the year was out.”

“Then she was not nearly sixteen anyway,” said Audry; “how sad to die before one was sixteen!”

“Yes, Audry, it is terrible, but there is worse than that,—think of poor Lady Jane Grey who was barely sixteen when she and her husband were executed. Father used to tell me that I was something like the Lady Jane.”

“Had he seen her?”

“No, I do not think so; he was in France with our Queen Mary at the time of the Lady Jane’s death and your Queen Mary’s accession: for a short time he was a captain in the Scots Guard in France.”

“Were you with him and have you seen the Queen? She is about your age, is she not?”

“No, I have not seen her, but she is a little older than I12 am. She is fourteen and is extraordinarily beautiful. They say her wedding to the Dauphin is to take place very soon. If father had been alive I might have seen it.”

“Was your father good looking?” asked Audry.

“Yes, he was said to be the handsomest man in the Lothians.”

“That explains it, then,” she went on, looking somewhat enviously at her companion; “but I wish you cared more for games and horses and running and a good romp and were not so fond of old books. Fancy a girl of your age being able to read the Latin as well as a priest. Father says that you know far more Latin than he does and that you can even read the Greek.”

“But I can run,” Aline objected, “and I can swim, too.”

“Yes, you can run, though you do not look like it, you wee slender thing, but you do not love it as I do;” and Audry stood up to display her sturdy little form. “Now if we were to wrestle,” she said, “where would you be?”

Aline only laughed and said: “Well, there is one good thing in reading books, it gives one something to do in wet weather. Let us go down to the library and see if I cannot find something nice to read to you.”

“Come along, then, and read to me from that funny old book by Master Malory, with the pictures.”

“You mean the ‘Morte d’Arthur,’ I suppose, with the stories of King Arthur and the Round Table. That certainly is exciting and I am so fond of it. I often wish that there were knights going about now to fight for us in tourney and to rescue us from tyrants. It would be nice to have anybody care for one so much.”

“You silly little one, they would not trouble their heads about you, you are only twelve years old.”

“Perhaps not,” answered Aline with a half sigh, as she thought of her present condition.

“I do not believe there is anybody in the world that cares for me,” she said to herself, “except perhaps Audry, and I have only known her such a little time that she cannot care much. I don’t suppose there are many little girls who can be as lonely as I am. I have not even an aunt or uncle. Yes, I do want some one to love me, it is all so very hard; I wish I had a sister or a brother.”

In a way, doubtless, Audry’s mother did not mean to be altogether cruel; but she had no love for her small visitor and thought that it was unnecessary for Master Mowbray to bring her to Holwick Hall. So she always found plenty of heavy work for the child to do and often made excuses when Audry had some dainty or extra pleasure as to why Aline should not have her share. Aline thought of her father, Captain Angus Gillespie of Logan, and remembered his infinite care for her when she had been the apple of his eye. It had been a sad little life;—first she had been motherless from infancy and then had followed the long financial difficulties that she did not understand; but one thing after another had gone; and just before her father died they had had to leave Logan Tower and go and live in Edinburgh; and the little estate was sold.

Audry in her rough, kindly way, flung her arms round the slim form and kissed her. “Do not think melancholy things; come along to the library and see what we can find.” So they left the solar and went down14 through the hall and out into the upper court. They raced across the court, because of the rain, and up the little flight of nine steps, three at a time, till they were on the narrow terrace that ran along the front of the library.

Aline reached the door first, and, as she swung back the heavy oak with its finely carved panels, exclaimed: “There, I told you I could run.”

They shut the door and walked down the broad central space. The library had been built in the fifteenth century by Master James Mowbray, Audry’s great-great-grandfather, and was supposed to be the finest in the North of England. It was divided on each side into little alcoves, each lit by its own window and most of the books were chained to their places, being attached to a long rod that ran along the top of each shelf. At the end of each alcove was a lock with beautifully wrought iron tracery work that held the rod so that it could not be pulled out. The library was very dusty and was practically never used, as the present lord of Holwick was not a scholar; so for the last four years since he had succeeded to the estate it had been neglected and Aline was almost the only person who ever entered it.

The children walked down the room admiring the delicate iron work of the locks, for which Aline had a great fancy and she had paused at one, which was her particular favourite, and was fingering every part of it affectionately, when she noticed that a small sculptured figure was loose and could be made to slide upwards. This excited her curiosity and she pushed it to and fro to see if it was for any special purpose, till suddenly she discovered that, when the figure was pushed as high15 as it would go, the whole lock could be pulled forward like a little door on a hinge, revealing a small cavity behind. Both children started and peered eagerly into the space disclosed, where they found a very thin little leather book which was dropping to pieces with old age. They took it out and examined it and found that the cover had separated so as to lay open what had been a secret pocket in the cover, which contained a piece of stout parchment the same size as the pages of the book.

The book was written in black letter and was in Latin. “Now you see the use of knowing Latin,” said Aline triumphantly, with a twinkle in her dark blue eyes.

“That depends whether it is interesting,” Audry replied.

“It seems to be an account of the building of Holwick Hall; but what is the use of this curious piece of parchment with all these holes cut in it?”

“Perhaps you can find out if you read the book,” suggested Audry. “It certainly must be of some importance or they would not have taken all that trouble to hide the book and also the parchment in the book. Let us sit down and see what you can make of it.”

So they sat down and Aline was soon deeply interested in the account of the building, how the great dining hall was erected first, then the buttery, pantry and kitchen and afterwards the beautiful solar. Audry found her interest flag; although, when it came to the building of her room and the cost of the different items, she brightened up. “Still,” she said, “I do not see why all this should be kept so secret; any one might know all that we have read.”

There was one thing that seemed to promise interest,16 but apparently it led to nothing. At the beginning of the book was a dedication which could be translated thus: “To my heirs trusting that this may serve them as it has served me.” But in what way it was to serve them did not appear, and the evening was closing in and it was getting dark, but the children were as far as ever from discovering the meaning of the phrase or of the parchment with the holes.

“Let us take it to our room,” Aline said at last; “it is not chained like the others. We can hide it in the armoire and read with the little lamp when the others have gone to sleep and no one is likely to come in.”

So they put the piece of parchment to mark the place, ran to their room and hid the book and went to join the rest of the family.

It was nearly time for rere-supper[3] and Master Richard Mowbray had just come in. He was dripping wet and the water ran down in long streams across the floor. “Gramercy,” he exclaimed, “it is not a fit day for a dog let alone a horse or a man. Come and pull off my boots, wench,” he went on, catching sight of Aline.

3 A meal taken about 8 o’clock.

He sat down and Aline with her little white hands manfully struggled with the great boots. “You are not much good at it,” he said roughly, when at last she succeeded in tugging off the first one. “Ah, well, never mind,” he added, when he saw her wince at his words, and stooped and kissed her and called to one of the men to come and take off the other boot. “You cannot always live on a silk cushion, lassie,” he went on, not unkindly, “you must work like the rest of us.”

“It is a strange thing where that man can have got,” he continued; “in all this rain it is impossible that he can have gone far.”

“Let us hope he is drowned,” Mistress Mowbray remarked; “that would save us further trouble, but it is a pity that a man meant for the fire should finish in the water.”

“Some of the folk going to Middleton say that they saw a stranger early this morning, playing with a child, but he turned off toward the hills,” one of the serving men observed.

“That’s he, but it’s hard enough to find a man in a bog-hole, particularly on a day like this, yet Silas Morgan and William Nettleship have both taken over a score of men and there must easily be two score of others on the hills; you would think that they would find him. He cannot know the hills as we do,” said Master Mowbray.

There was silence for a time and then he spoke again,—“Of course those people might be mistaken; but he could not get over Middleton Bridge after the watch was set, and I do not see how any one could get over the river to-day, it is simply a boiling torrent. Well, they are on the look out on the Appleby side and he must come down somewhere.”

“What is he wanted for?” Audry ventured to ask.

“Wanted for?” almost shrieked Mistress Mowbray, “a heretic blaspheming Mother Church, whom the good priest said was a servant of the devil.”

“But what is a heretic and how does he blaspheme Mother Church?” Audry persisted.

“I do not know and I do not want to know,” said Mistress Mowbray.

“Then if you do not know, how can you tell that it is wrong? You must know what he says, Mother, before you can judge him.”

“I was brought up a good daughter of the church, and I know when I am right, and look here, you young hussie, what do you mean by talking to your mother like that? It’s that good for nothing baggage, that your father has brought from Scotland, that has been putting these notions into your head, with her book learning and nonsense. I assure you that I won’t have any more of it, you little skelpie,[4] you are not too old for a good beating yet, and I tell you what;—I will not have the two of you wasting your time in that library, I shall lock it up, and you are not to go in there without permission, and that will not be yet awhile, I can promise you.”

4 A girl young enough to be whipped (skelped).

After this outburst the meal was eaten in silence and every one felt very uncomfortable.

When supper was over the sky seemed to show signs of breaking and Master Mowbray ventured to express a hope that the next day would be fine, and that they would be able to find the heretic on the hills. “That man has done more mischief than any of the others,” he muttered; but when pressed to explain himself he changed the subject and said he must go and see if the water had done any damage in the lower court.

The children were not sorry to retire to their room when bedtime came. They had undressed and Audry was helping Aline to brush her great masses of long hair. What a picture she looked in her little white night-robe, with her large mysterious dark blue eyes that no one ever saw without being stirred, and her wonderful19 charm of figure! Her colouring was as remarkable as her form. The hair was of a deep dark red, somewhat of the colour beloved by Titian, but with more gloss and glow although a little lower in tone; that colour which one meets perhaps once in a lifetime, a full rich undoubted red, but without a suspicion of the garishness and harshness that belongs to most red hair. The eyes were of the dark ultramarine blue only found among the Keltic peoples and even then but rarely, like the darkest blue of the Mediterranean Sea, when the sapphire hue is touched with a hint of purple.

“What is a heretic?” Audry asked; “I am sure you know.”

“I do not know that I do, but I remember father saying something to me about it before he died. He said that they were people who were not satisfied with the way that things were going in the church and that in particular they denied that it was only through the priests of the church that God spoke to his people. They say that the priests are no better than any one else and indeed are sometimes even worse.”

“I do not know that they claim to be better than other people,” objected Audry.

“Well, dear, I am not defending the heretics. I only say what they think. They do feel, however, that if the priests really were the special channels of God that that fact itself would make them better. So, many of them say that God can and does speak directly to all of us himself, and they all think that it is in the Bible that we can best learn what he desires, and that the Bible should therefore be translated into the language of the people.

“‘This has been the cause of great troubles in the20 world for these many years,’ father said, ‘but, little maid, do not trouble your head about it now; when you are older we can talk about it.’”

“Are the heretics such very wicked people then, do you think, Aline?”

Aline put her little white hand to her chin and looked down. “I do not know what to think about it,” she said. “I suppose that they are, but they do not seem to be treated fairly.”

“I hate unfairness,” said Audry in her impulsive way.

“I do not see why they should not be allowed to speak for themselves, and I do not see how people can condemn them when they do not know what their reasons are for thinking what they do. Of course I am very young and do not know anything about it; but it sounds as though the priests were afraid that the truth can not take care of itself; but surely it cannot be the truth if it is afraid to hear the other side. I remember a motto on the chimney piece at home,—‘Magna veritas est et prevalebit,’ and it seems to me that it must be so. I wish that father were alive to talk to me. He was so clever and he understood things.”

“But you have not said what your motto means,” Audry interposed.

Aline laughed through the tears that were beginning to gather,—“Oh, that means, The truth is great and will prevail. If it is the truth it must win; and it can do it no harm to have objections raised against it, as it will only make their error more clear.”

“What about the book, Aline?” said Audry, changing the subject; “no one is likely to come up here now, they never do; so I think we could have another look at it.”

Aline picked up the book and opened it; she paused for a moment and then gave a little cry,—“I have found out what the parchment is for; come and look here.”

Audry came and looked. “I do not see anything,” she said.

“Look at the parchment; do you not see one or two letters showing through nearly all the little holes?”

“Yes.”

“What are they?”

“b. u. t. o. n. e. m. u. s. t. s. e. e. t. h. a. t. a. l. i. g. h. t. i. s. n. e. v. e. r. c. a. r. r. i. e. d. i. n. f. r. o. n. t. o. f. t. h. e. s. l. i. t. s. i. n. t. h. e.,” read Audry, a letter at a time.

“And what does that spell?” said Aline.

“Oh, I see,— It spells, ‘but one must see that a light is never carried in front of the slits in the.’ How clever of you to find it out!”

“Well, it was more or less accident; the parchment is exactly the size of the paper and as I shut the book I naturally made it all even. So, when I opened it in this room, it was lying even on the page and I could not help seeing the letters and what they spelt.”

“I should never have noticed it, Aline; why I did not even notice at once that the letters spelt anything after you had shown me.”

“Let us go back to the beginning and then,” said Aline, “we shall discover what it is all about.”

So she turned to the beginning of the book and placed the parchment over the page and found that it began like this;—“Having regard to the changes and misfortunes of this life and the dangers that we may incur, I have provided for myself and my heirs a place of refuge and a way of escape in the evil day. This book containeth22 a full account of the building of Holwick Hall; so that it will be easily possible to follow that which I now set down. Below the Library on the west side of the house just above the level of the moat, there is a secret chamber, which communicateth with a passage below the moat that hath an exit in the roof of the small cave in the gully that lieth some two hundred paces westward of the Hall of Holwick. The way of entrance thereto is threefold. There is an entrance from the library itself. There is also an entrance from the small Chamber that occupieth the southwest corner of the building on the topmost floor.”

“Why, that is our bedroom, the room that we are in now!” Audry exclaimed. “Do let us try and find it.”

“Wait a moment; the book will probably tell us all about it,” and Aline resumed her reading.

“‘There is a third method of approach from the store-chamber or closet on the ground floor in the southeast corner of the lower quadrangle.’”

“That is the treasury, where the silver and the other plate is kept,” said Audry; “go on.”

“‘In the corner of the library that goeth round behind the newel stair there is a great oaken coffer that is fastened to the floor, in the which are the charters and the license to crenellate[5] and sundry other parchments.’”

5 To make battlements or crenellations. A house could not be fortified without a royal license.

“Oh, I have often wondered what was in that kist,” said Audry; “how really exciting things have become at last, but I want to find out the way to get down from our room; do go on.”

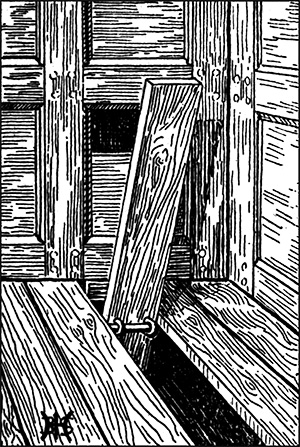

“You must not keep interrupting then,” said Aline and continued her reading. “‘Now the bottom of this kist can be lifted for half its breadth, if the nail head with the largest rosette below the central hinge be drawn forth. After so doing, the outer edge of the plank next the wall in the bottom of the chest can be pushed down slightly, which will cause the inner edge to rise a little. This can then be taken by the hand and lifted. In exactly the same manner the plank of the floor immediately underneath can be raised.’

“I hope you understand it all,” Aline remarked.

“I am not quite sure that I do,” said Audry. “Yes, I think it is quite clear; it’s very like the way the lid works on the old sword-kist.”

“But we cannot get into the library and, even if we could,” said Audry, “the kist might be locked.”

“Never mind that now; I expect that our room will come next,” said Aline. “Yes, listen to this:—‘In the topmost chamber a different device is adopted for greater safety by means of variety. If the ambry[6] nigh unto the door be opened it will be found that the shelf will pull forward an inch and a finger can be inserted behind it on the left hand side, and a small lever can be pushed backward. This enables the third plank near the newel-stair[7] wall to be lifted by pressing down the western end thereof, and a bolt may be found which, being withdrawn, one of the panels will fall somewhat and may be pushed right down by the hand. The newel-stair, though it appeareth not, is double and one may creep down thereby to the chamber itself.’”

6 A small cupboard made in the thickness of the wall.

7 A newel staircase is a spiral staircase circling round the newel, i.e., the centre shaft or post.

The fact was,—that what appeared to be simply the under side of the steps, to any one going up the staircase, was really a second staircase, leaving a space of nearly three feet between the two.

The children did not read further at that time, as they were eager at once to see if they could put their discovery to the test.

Aline put down the book and went to the ambry and opened the door. The single shelf came forward without difficulty. “Have you found anything?” Audry asked eagerly.

“Yes,” she replied, “but I cannot move it; it is too stiff.”

“Let me have a try,” and Audry stepped forward and put her fingers into the space. “My hands are25 stronger than yours,” she said. “Ah, that is it!” she exclaimed, as she felt the lever move to one side, and by working it backwards and forwards she soon made it quite loose.

Aline meanwhile had already put her little foot on the third board, at the end just against the wall, and felt it yield. The other end was now sufficiently raised to allow of the fingers being passed underneath. She lifted it up and found that it was simply attached to a bar about six inches from the wall-end. They both peeped into the opening disclosed and felt round it. Aline was the first to find the bolt and pulled it forward. But alas no panel moved. Audry looked ready to weep, but Aline exclaimed, “Oh, it must be all right as we have got so far; let us feel the panels and try and force them down. This is the one above the bolt,” and she put her fingers on it to try and make it slide down. She had no sooner spoken than the panel moved an inch and, slipping her hand inside, she pressed it down to the bottom. The panel tended to rise again when she let go,26 as the bottom rested on the arm of a weighted lever. It looked very gloomy inside but the children were determined to go on. They then found that there was just comfortable room for them to go backwards down the stairs and that there would have been room even for a big man to manage it without much difficulty. There were many cobwebs and once or twice their light threatened to go out; but at last they reached the bottom, crawling on hands and knees the whole way. There they found a long narrow passage, in the thickness of the wall, of immense length. They went along this for a great distance and then began to get frightened.

“Where ever can we have got to?” Audry said at length.

“It is quite clear that we are wrong,” said Aline, “as the library, we know, is just at the bottom of the newel-stair and the book said that the secret room was just underneath the library. We must go back.”

“What if we go wrong again and lose our way altogether, Aline, and never get out of this horrible place?”

It was a terrible thought; and the damp smell and forbidding looking narrow stone passage had a strange effect on the children’s nerves. Then another thought occurred to Aline that made them still more nervous. There were occasional slits along the wall for ventilation and she remembered the words that she had read by chance when she first discovered the use of the parchment. Supposing that their light should be seen; what would happen to them then? and yet they dare not put it out and be left in the dark.

“I wish that we had never come,” said Audry as they hurried along the difficult passage. They reached the27 bottom of the stair and felt a little reassured. They then saw that the passage turned sharply back on itself and led in a step or two to a door. It was of very stout oak and plated with iron. They opened it and found that it had eight great iron bolts that could be shut on that side. Within was a second door equally strong and, on opening that, they found themselves in the secret room itself. It was a long apartment only about eight feet high, and was panelled throughout with oak. There was a large and beautiful stone fireplace, above which was the inscription,—“Let there be no fire herein save that the fires above be lit.”

“That must be in case the smoke should show,” said Aline; “how careful they have been with every little thing!”

The room was thick with dust and obviously had not been entered for many many years. Even if the present occupants of Holwick knew of the secret room at all, which probably they did not, it was clear that they never made any use of their knowledge. There was a magnificent old oak bed in one corner but some of the bedding was moth-eaten and destroyed. There were also many little conveniences in the room, amongst other things a small book-case containing several books. On the whole it was a distinctly pleasant apartment despite the absence of any visible windows. There were even one or two pictures on the walls. In one corner on the outer wall was a door, which the children opened, and which clearly led to the underground passage below the moat; but they decided not to examine any more that night. So they made their way up the stairs again back to their room.

They were almost too excited to sleep and Aline, as her custom was, when she lay awake, amused herself by building castles in the air. Sometimes she would imagine herself as a great lady, sought after by all the noble knights of the land, but holding herself aloof with reserved dignity until one, by some deed of unusual distinction, should win her favour. As a rule, however, this seemed rather a dull part to play, though there was something naturally queenly in her nature, and she would therefore prefer something more active. She would take the old Scots romance of Burd Helen, or Burd Aline, as her own inspiration, and follow her knight in the disguise of a page over mountain and torrent and through every hardship. This better suited the romantic self-sacrifice of her usual moods and, by its imaginary deeds of heroism, ministered just as much to her sense of exaltation. To-night had opened vistas of new suggestion; and she pictured her knight and herself fleeing before a host of enemies and miraculously disappearing at the critical moment into the secret room. But at last she fell into a sound slumber and did not wake till it was nearly time for the morning meal.

ALINE certainly did not belong to any ordinary type and she would have puzzled the psychologist to classify. She was so many sided as to be in a class by herself. She had plenty of common sense and intelligence for her years and an outlook essentially fair minded and just. But she also had a quiet hauteur, curiously coupled with humility, and at the same time a winning manner that was irresistible; so that the strange thing was that she had only to ask and most people voluntarily submitted to her desires. This unusual power might have been very dangerous to her character and spoiled her, had it not been that what she wanted was almost always just and reasonable and moreover she never used her power for her own benefit. Further, her humble estimate of her own capacity for judgment caused her but rarely to exercise the power at all. In practice it was almost confined to those cases where a sweet minded child’s natural instinct for fair play sees further than the sophistries of the adult.

She was practically unaware of this power, which was destined to bring her into conflict with Eleanor Mowbray; nor did she take the least delight, as she might easily have done, in exercising power for power’s sake.

Eleanor Mowbray, on the other hand, like so many women, loved power. Masculine force has so largely monopolised the more obvious manifestations of power that it might be said to be almost a feminine instinct to snatch at all opportunities that offer themselves.

Be that as it may, Mistress Mowbray loved to use power for the sake of using it; she loved to make her household realise that she was mistress. She did not exactly mean to be unkind, but they were servants and they must feel that they were servants. Her attitude to them was that of the servant who has risen or the one so commonly exhibited toward servants by small girls, that puzzles and disgusts their small brothers.

She would address them contemptuously, or would impatiently lose her self-control and shout at them. She lacked consideration and would call them from their main duties to perform petty services, which she could perfectly well have done for herself. This was irritating to the servants and there was always a good deal of friction. The servants tended to lose their loyalty and, when once the bond of common interest was broken, what did it matter to Martha, the laundry-maid, that she one day scorched and destroyed the most cherished and valuable piece of lace that Mistress Mowbray possessed; or of what concern was it to Edward, the seneschal, that in cleaning the plate, he broke the lid off her pouncet box and not only did not trouble to tell her, but when charged with it, coolly remarked, after the manner of his kind,—“Oh, it came to pieces in my hands!”

On one occasion, before the discovery of the secret room, when Edward was away, Thomas, a sly unprincipled31 man, whose duties were with the horses, had taken his place for the day. The four silver goblets, which he had placed on the table, were all of them tarnished; and after the meal was over, Mistress Mowbray said to him sharply,—“Thomas, what do you mean by putting dirty goblets on the high table?”[8]

8 The table on the raised dais at which the family sat. The retainers sat at the two lower tables. See plan.

“I am sure I did my best, Mistress,” said Thomas; “I spent a great amount of pains in laying the table, but we all of us make mistakes sometimes.”

“Then go and clean them at once, you scullion, and bring them back to me to look at directly you have finished.”

“Please, Mistress, that is not my work,” replied Thomas, “and I have a great deal to do in the stables this afternoon.” As a matter of fact he had finished his work in the stables and was planning for an easy time.

“Do you dare to talk to me?” she said, her voice rising. “You are here to do as you are told; go and clean them at once, or it will be the worse for you.” She knew that this time the man was within his rights; but she was not going to be dictated to by a servant.

Thomas sulkily departed. When he reached the buttery he remembered that he had noticed Edward cleaning some of the goblets the day before. He soon found them, and then drew himself a measure of ale and sat down with a chuckle to enjoy himself over the liquor, while allowing for the time that would have been needed to clean the silver.

Meanwhile Mistress Mowbray began impatiently to32 walk up and down the hall. The children were generally allowed to go out after dinner and amuse themselves, but it was a wet day and Aline was looking disconsolately out of the window wondering whether she should go into the library or what she should do, when the angry dame thought that the child offered an object for the further exercise of her power. “Why are you idling there?” she said. “They are all short-handed to-day, go you and scour out the sink and then take out the pig-bucket and be quick about it.”

Aline gave a little gasp of surprise, but ran off at once. The buttery door was open and she saw Thomas drinking and offering a tankard to one of the other servants, and she heard him laugh loudly as he pointed to a row of goblets, four of them clean and the rest of them dirty, while he said,—“Edward cleaned those, and I am waiting here as long as it would take to clean them.” He caught sight of her and scowled, but she passed on.

Aline had soon finished the sink and ran quickly with the pig-bucket, after which she returned to the dining hall to tell Mistress Mowbray she had finished. Thomas had just come in, so she stood and waited.

He held up the four goblets on a tray for Mistress Mowbray to inspect.

“Yes, those are better, Thomas,” she said frigidly. Thomas could not conceal a faint smile and the lady became suspicious. “By the way, Thomas, there are a dozen of these goblets, bring me the others.”

“Yes, Mistress,” said Thomas, triumphantly, “but they were all dirty and I have just cleaned these.”

Mistress Mowbray saw that she could not catch him33 that way, but felt that the man was somehow getting the better of her, so she merely replied calmly,—“Then you can clean the whole set, Thomas, and bring me the dozen to look at.”

Aline nearly burst into a laugh, but put her hand to her mouth and smothered it without Mistress Mowbray seeing; but Thomas saw and as he departed, crest-fallen, he vowed vengeance in his heart.

“Have you done what I told you, child?” Mistress Mowbray said, turning to Aline. “Marry, but I trust you have done it well. It is too wet for you to go out; you can start carding a bag of wool that I will give you. That will keep you busy.”

Aline sighed, as she had hoped to get into the library and she wondered what Audry was doing, who had been shrewd enough to get away, but she said nothing and turned to her task.

At first Eleanor Mowbray’s treatment of Aline was merely the joy of ordering some one about, of compelling some one to do things whether they liked to or not, just because they were not in a position of power to say no; but what gave her a secret additional joy was that Aline was a lady and she herself was not. True, Aline’s father was only one of the lesser Lairds, but he was a gentleman of coat armour,[9] whereas Eleanor Mowbray was merely the beautiful daughter of the wealthy vintner of York. It caused Eleanor Mowbray great satisfaction to have the power to compel a gentleman’s daughter to serve her in what her plebeian mind34 considered degrading occupations. It was for this reason therefore that Aline was set to scour sinks, scrub floors and empty slops, with no deliberate attempt to be unkind, but simply to feed the love of power.

9 A gentleman is a man who has the right conferred by a royal grant to his ancestors or himself of bearing a coat of arms. It is not as high a rank as esquire with which it is often confused.

As a matter of fact, so long as the tasks remained within her physical strength, Aline was too much of a lady to mind and, if need had been, would have cleaned out a stable, a pigsty or a sewer itself, with grace and dignity and even have lent distinction to such occupations.

But these very qualities led to further antagonism on Eleanor Mowbray’s part. They were part of that power of the true lady that in Aline was developed to an almost superhuman faculty and which went entirely beyond any power of which Mistress Mowbray even dreamed and yet without the child making any effort to get it. Aline herself indeed was unconscious of her strength as anything exceptional. She had been brought up by her father, practically alone and had not as yet come to realise how different she was from other children.

It was the morning after the discovery of the secret room that Mistress Mowbray had the first indication that Aline had a power that might rival her own. It was a small incident, but it sank deeply and Eleanor Mowbray did not forget it.

She was expecting a number of guests to dinner and it looked as though nothing would be ready in time. She rushed to and fro from the hall to the kitchen upbraiding the servants and talking in a loud and domineering tone. But the servants, who were working as hard as the average of their class, became sullen and35 went about their labours with less rather than more effort.

Eleanor Mowbray was furious and finding Aline still at her spinning wheel, where she herself had put her, “’Sdeath child,” she exclaimed, “this is no time for spinning, what possesses you? I cannot get those varlets to work, everything is in confusion,—knaves!—hussies!—go you to the kitchen and lend a hand and that right speedily.”

Aline felt sorry for her hostess, who certainly was like enough to have her entertainment spoilt. She had already noticed that the servants in the hall were very half-hearted, so she said, “I will do what I can, Mistress Mowbray, perhaps I might help to get them to work.”

“You, indeed,” said the irate lady, “ridiculous child!—but go along and assist to carry the dishes.”

Aline rose and passed into the screens and down the central passage to the kitchen. The place was filled with loud grumbling, almost to the verge of mutiny.

As the queenly little figure stood in the doorway, the servants nudged each other and the voices straightway subsided.

“Hush, she will be telling tales,” said one of the maids quietly.

“Nonsense,” said Elspeth, Audry’s old nurse, who was assisting, “surely you know the child better than that.”

For a moment or two Aline did not speak and a strange feeling of shame seemed to pervade the place.

“Elspeth,” said Aline, while the flicker of a smile betrayed her, “if you run about so, you’ll wear out your36 shoon; you should sit on the table and swing your feet like Joseph there.”

“Now, hinnie, why for are you making fun of an old body?”

“I would not make fun of you for anything,” said Aline; “but look at his shoon; are they not fine,—and his beautiful lily-white hands?”

“Look as if you never did a day’s work, Joe,” said Silas, the reeve.

“Oh, no, he works with his brain, he’s thinking,” said Aline, putting her hand to her brow with mock gravity. “He’s reckoning up his fortune. How much is it, Joseph?”

“Methinks his fortune will all be reckonings,” said Silas, “for he’ll never get any other kind.”

“Well, we’ll change the subject; there’s going to be a funeral here to-night,” Aline observed.

“No, really?” exclaimed half a dozen voices.

“Yes, it’s a terrible story and it really ought not to be known; but you’ll keep it secret I know,” she said, lowering her voice to a whisper.

As they crowded round her she went on in mysterious tones, “You know John Darley and Philip Emberlin.”

“Yes,” said Joe, rousing himself to take in the situation, “they are coming here to-night.”

“They’ve a long way to come and they are not strong,” said Aline, “and they will arrive hungry and just have to be buried, because there was nothing to eat. Yes, it’s a sad story; I’m not surprised to see the tears in your eyes, Joseph, and, in fact, in a manner of speaking you might say that you will have killed them, you and your accomplices,” she added, looking round.

A good tempered laugh greeted this last sally.

“Marry, we have much to get through. How can I help? It would be a sorry thing that Holwick should be disgraced before its guests. Give me something to do.”

There was nothing in the words, but the tone was one of dignity combined with gentleness and sympathy.

The effect was peculiar;—no one felt reproved, but felt rather as though there was full sympathy with his own point of view; yet at the same time he was conscious that he would lose his own dignity if he became querulous and allowed the honour of the house to suffer.

Aline helped for a short time and then, leaving them for a moment all cheerful and joking but working with a will, she looked into the buttery, where she saw Thomas and Edward, the seneschal, a pompous but good hearted fellow, merely talking and doing nothing.

“You are not setting us a good example,” she said laughing; “everybody else is working so hard,” and then she added in a tone that combined something of jest, something of command and something of a coaxing quality, “do try to keep things going; Master Richard would be much put about if he failed in his hospitality.”

This time there was undoubtedly a very gentle sting in the tone that pricked Edward’s vanity; yet his own conscience smote him, so that he bore no ill will.

He said nothing, however, but Thomas remarked;—“Yes, Mistress Aline, the sin of idleness is apt to get hold of us, we must to our work as you say.”

Aline raised her eyebrows slightly, the ill-bred vulgarity of the remark was too much for her sensitive nature. Thomas was marked by that lack of refinement38 that cheapens all that is noble and good by ostentatious piety and sentimentality.

Aline gave a little shiver and passed on to do the same with the others. She also took her full share in the work, so that in fifteen minutes everything was moving smoothly. It was done entirely out of kindness, but Eleanor Mowbray felt that it was a triumph at her expense and although Aline had helped her out of a difficulty, she only bore a grudge against her.

Thomas also was nettled. Aline had got the better of him; he suspected her, too, of seeing through his hypocrisy; which, as a matter of fact, she had only partially done, as she was so completely disgusted at his vulgarity that she did not look further.

It was not till the afternoon that the children had any opportunity to pursue their own devices and they decided, as the day was fine and the storm had cleared away, that they would go down to the river near-by and see the waterfall before the water had had time greatly to abate.

They did not go straight across the moor, but went by way of the small hamlet of Holwick. Everything looked bright and green after the rain, varied by the grey stone walls, that ran across the country, separating the little holdings. The distance was brilliantly blue and the wide spaciousness that characterises the great rolling moorland scenery was enhanced by the beauty of the day.

The children turned into the second cottage which was even humbler than its neighbours. It was a long, low, thatched building, roughly built of stone with clay instead of mortar. Within, a portion was divided off39 at one end by a wooden partition. There was no window save one small opening under the low eaves which was less than six feet from the ground. It was about eight inches square and filled with a piece of oiled canvas on a rudely made movable frame instead of glass. In warm weather it often stood open.

The children stumbled as they entered the dark room and crossed the uneven floor of stamped earth. There was no movable furniture save one or two wooden kists or chests, a dilapidated spinning wheel and a couple of small stools. In the very middle of the floor was a fire of peats on a flat slab of stone in the ground and a simple hole in the roof allowed the choking smoke to escape after it had wandered round the whole building.

An old man, bent double with rheumatism, hastened forward as the children came to the door and, holding out both his hands, shook Audry’s and Aline’s at the same time. “I am right glad to see you,” he said, “and may the Mother of God watch over you.”

He quickly brought two stools and, carefully dusting them first, bade his young visitors sit down by the fire.

“How is Joan to-day, Peter,” asked Aline, “she isn’t out again is she?”

“No, Mistress Aline, she has been worse the last few days and is in bed, but maybe the brighter weather will soon see her out and about.”

He hobbled over toward a corner of the cottage, where a box-bed stood out from the wall. It was closed in all around like a great cupboard, with sliding shutters in the front. These were drawn back, but the interior was concealed by a curtain. He drew aside this curtain and within lay a little girl about eleven years old40 with thin wasted cheeks and hollow sunken eyes. She stretched out her small hand as the two children approached and a smile lit up the white drawn face.

Aline stooped and kissed her. “Oh, Joan,” she said, “I wish you would get well, but it is always the same, no sooner are you up than you are back in bed again. I have been asking Master Mowbray about you and he has promised that the leech from Barnard Castle shall come and see you as soon as he can get word to him.”

“It is good of you to think and plan about me, Mistress Aline, and I believe I am not quite so badly to-day, but I wish that horrid old ‘Moll o’ the graves’ would not come in here and look at me. She does frighten me so. Mother was always so frightened of Moll.”

“She is a wretched old thing,” said Audry, “but do not let us think about her.”

“You mustn’t thank us, anybody would do the same,” said Aline; “you cannot think how sorry we are to see you like this, and you must just call me Aline the same as I call you Joan. See! Audry and I have brought you a few flowers and some little things from the Hall that old Elspeth has put up for us, and when the leech comes, he will soon make you well again.”

“I sometimes wonder whether I shall ever get well any more; each time I have to go back to bed I seem to be worse. All my folk are gone now and I am the only one left. The flowers are right bonnie though and the smell of them does me good,” she added, as she lifted the bunch of early carnations that the children had brought.

After she had spoken she let her hand fall and lay41 quite still gazing at the two as though even the few words had been too great an effort.

The bed looked very uncomfortable and Aline and Audry did their best to smooth it a little, after which Joan closed her eyes and seemed inclined to sleep.

“I wish we could get her up to the Hall,” said Aline in a whisper, “the smoke is so terrible and I never saw such a dreadful place as that bed.”

“Mother would never hear of it; so it’s no use your thinking of such a thing.”

They returned to the fire and sat down on the stools for a few moments before leaving.

“Ay, the child is about right,” said the old man, “her poor mother brought her here from Kirkoswald when her man died last November. Sarah Moulton was a sort of cousin of my wife who has been lying down in Middleton churchyard this many a long year. She lived in this very house as a girl and seemed to think she would be happier here than in Kirkoswald. Well, it was not the end of March before she had gone too and the lassie is all that is left.”

The children bade farewell and went out. As they passed the end of the house they saw the black figure of an old woman creeping round the back as though not wishing to be seen.

“Oh, there’s that horrible old woman! ‘Moll o’ the graves,’” said Audry; “let us run. I wonder what she has been doing listening round the house; I hate her. You know, Aline, they say she does all manner of dreadful things, that it was she who made all old Benjamin Darley’s sheep die. Some people say she eats children and if she cannot get hold of them alive she42 digs them up from their graves at night. I do not believe it, but come along.”

“No, I want to see what she is doing,” said Aline; “I am sure she is up to no good. I believe that she has been spying outside waiting for us to depart, so that she can go in.”

“But you cannot prevent her,” said Audry.

“We must prevent her,” said Aline; “she might frighten Joan to death.”

Aline was right and the old woman came round from the other end of the house and approached the cottage door. Aline at once advanced and stood between the old woman and the door, while Audry followed and took up her position beside Aline.

“What do you want, mother?” said Aline.

“What business is that of yours?” said the old dame savagely; “you clear away from that door or I will make it the worse for you.”

She raised her stick as she spoke and glared at the children. It was not her physical strength that frightened them, as they were two in number, although she was armed with a stick, but something gruesome and unearthly about her manner. Aline took a step forward so as half to shelter Audry, but her breath came quickly and she was filled with an unspeakable dread.

“You must not go in there,” said the child firmly; “there is a little girl within who is sick and she must not be disturbed.”

“I shall do as I please and go in if I please,” she muttered, advancing to the door and laying her hand on the latch.

Aline at once seized her by the shoulders, saying, “I43 may want your help, Audry,” and gently but firmly turned her round and guided her on to the road. Moll made no resistance, as she feared the publicity of the road and moreover the girls were both strong and well built, though of different types. Aline then stepped so as to face her, and keeping one hand on her shoulder, she said, as she looked her full in the eyes,—“go home, Moll, Joan is not well enough to see any one else to-day,—go home.”

The old woman’s eyes dropped; she was cowed; she felt herself in the presence of something she had never met before, as she caught the fire in those intense blue eyes. “I will never forgive you,” she snarled, but she skulked down the road like a beaten dog.

The children stood and watched her, feeling a little shaken after their unpleasant experience.

“What a good thing you were there,” said Audry. “I am sure she would have frightened Joan terribly.”

“Come, let us forget it,” and they raced down to the waterfall.

It was a magnificent sight, one great seething mass of foam, cream-white as it boiled over the cliff; while below, the dark brown peat-coloured water swirled, mysteriously swift and deep, and rainbows danced in the flying spray. They walked down the stream a little way watching the rushing flood, when Aline suddenly cried out, “Audry, what is that on the other side?”

Just under the rock, partly concealed by the over-hanging foliage, could be made out with some difficulty the form of a man. He was lying quite still and although they watched for a long time he never moved at all.

“I wonder if he is hiding,” said Audry.

“I am sure he is not,” said Aline. “It would be a very poor place to hide, particularly when there are so many better ones quite close by. He may be drowned.”

“Possibly, but I think he is too high out of the water.”

“Then perhaps he is only hurt; I wonder if there is anything that we could do.”

“We might go up to the Hall and get help,” Audry suggested.

“Yes,” said Aline, doubtfully, as the thought crossed her mind that he might be the poor stranger whom the country-side was hunting like a beast of prey and although she could not explain her feelings she felt too much pity to do anything that might help the hunters and therefore it would not be wise to go to the Hall. It was partly the natural gentleness of her nature and partly her instinctive abhorrence of the vindictive way in which Mistress Mowbray had spoken on the previous night.

Then a shudder passed through her as she looked at the foaming torrent. Any help that could be given must be through that. Aline was only a child; but until she came to Holwick Hall she had lived entirely with older people and realised as children rarely do the full horror of death. It was so easy to stay where she was, she was not even absolutely certain that the stranger was in any real danger. It was not her concern. But Aline from long association with her brave father had a measure of masculine physical courage that will even court danger and that overcame her natural girlish timidity, and along with that she had in unusual degree the true feminine courage that can suffer in silence45 looking for no approval, no victory and no reward, the stuff of which martyrs are made. “He is obviously unfortunate,” she said to herself,—“Oh, if I could only help him, what does it matter about me, and yet how beautiful the day is, the rainbows, the clear air, the flowers and dear Audry; must I risk them all?”

She was not sure, however, what line her cousin might take and therefore did not like to express her thoughts aloud. On the other hand she could do nothing without Audry, but she thought it best to keep her own counsel and do as much as she could before Audry could possibly hinder her. So she only said;—“But if we went for help to the Hall it might be too late before any one came, if he is injured and still alive.”

At this moment both of them distinctly saw the figure move, and Aline at once said, “Oh, we must help him at once. I am sure we should not be in time if we went up to the Hall. We might find no one who could come and there might be all manner of delays.”

“But whatever can you do, Aline, he is on the other side?”

“I shall try and swim across,” she said, after thinking a moment.

“What, in all this flood! That is impossible.”

“I think I could manage it, if I went a little lower down the river where the torrent is not quite so bad.”

“Aline, you will be killed; you must not think of it.”

But Aline had already started down the bank to the spot that she had in her mind. Audry ran after her, horror struck and yet unable to offer further opposition.

“Well,” she said, “you are always astonishing me,” as Aline was taking off her shoes; “you seem too timid46 and quiet, and here you are doing what a man would not attempt.”

“My father would have attempted it,” was all that Aline vouchsafed in reply.

She took off her surcoat, her coat-hardie and her hose, and then turned and kissed Audry. “There is no one to care but you,” she said, “if I never come back.”

For a few moments the little slim figure stood looking at the black whirling of the treacherous water, her dainty bare feet on the hard rocks. Her white camise lifted and fluttered over her limbs like the draperies of some Greek maiden, the sunlight flushing the delicate texture of her skin, while her beautiful hair flew behind her in the breeze. It was but a passing hesitation and then she plunged in and headed diagonally up the river. She struck out hard and found that she could make some progress from the shore although she was being swiftly carried down the stream. If only she could reach the other side before she was swept down to the rapids below, where she must inevitably be smashed to pieces on the rocks! It was a terrible struggle and Audry sat down on the bank and watched her, overcome by tears. “Oh, Aline, little Aline,” she cried, “why did I ever let you go?” At last she could bear to look no longer. Aline had drawn nearer and nearer to the rapids, and although she was now close to the further bank there seemed not the slightest hope of her getting through.

She held on bravely, straining herself to the utmost, but it was no use;—she was in the rapids when only a couple of yards from the shore. Almost at once she struck a great rock, but, as it seemed by a miracle,47 although much bruised, she was carried over the smooth water-worn surface and by a desperate movement that taxed her strength to the uttermost, was able to force herself across it and the small intervening space of broken water and scramble on to the shore.

When Audry at length looked up, Aline was standing wringing the water out of her dripping hair, shaken and bruised and cut in several places, but alive. She took off the garment she had on and wrung it out before putting it on again. She then paused for a moment not knowing what to do. Blood was flowing freely from a deep cut below the right knee and also from a wound on the back of her right shoulder. She hesitated to tear her things for fear of the wrath of Mistress Mowbray, but at the same time was frightened at the loss of blood. Finally she tore off some strips of linen and bandaged herself as well as she could manage and made her way to where the man was lying.

Ian Menstrie had had a hard struggle. He had been working as a carpenter in Paris and had fallen in with some of his exiled countrymen and become for a time a servant to John Knox. It was three weeks since he had left France with the important documents that he was bearing from Knox and others; and only his iron determination had carried him through. Time and again nothing but the utmost daring and resourcefulness had enabled him to slip through his enemies’ hands. He had actually been searched twice unsuccessfully before he was finally arrested as a heretic at York. After extreme suffering he had escaped again and the precious papers were still with him. He had reached Aske Hall in Yorkshire, some twenty miles or so, over48 the hills, from Holwick, the home of Elizabeth of Aske, mother of Margaret Bowes, whom Knox had married, a lady with whom the reformer regularly corresponded.

But almost at once he again had to give his pursuers the slip, and he made his way up Teesdale with the precious papers still on him.

Although they were hot on his trail he had managed to get through Middleton in the night unobserved and would probably have reached the hills and got away North, unseen; but he met a little four-year-old boy on the road, who had fallen and hurt himself and was sitting in the rain and crying bitterly. There was nothing serious about it, but the child had a large bruise on his forehead. Ian had hesitated a moment, looking apprehensively behind, but stopped and bathed the bruise at a beck close by, comforted the child and carried him to his home and set him down just outside the little garden.

The delay, however, had cost him dear; the day was now fully up and two or three people noticed the stranger as he left the road to try and make for the steepest ground where pursuit would be less easy. Shortly afterwards he had seen men in the distance, both on foot and on horseback, setting out on his track and, with infinite difficulty, availing himself of every hollow, at the risk of being seen at any moment he had made his way to the river. If only he could get across, he argued, he might consider himself tolerably safe. They would never suspect that he was on that side and it was in any case the best road to the North. He knew little of the country, of course, or that there was a better place to attempt the feat lower down the stream. He leaped49 in where he found himself and being a strong swimmer he made his way over but was sucked down by an eddy and dashed against the cliff on the opposite side, but on coming to the surface again he had just sufficient strength to get out of the water and crawl along the ledge of rock to where the overhanging leaves afforded at least a partial concealment. Indeed, the place was such an unlikely one that anybody actually searching for him would probably have overlooked it.

He had lain there for hours, the pain in his head being intense. One ankle was badly sprained and much swollen and he felt sure that he had broken his left collar bone. He had had nothing to eat for days and the dizziness and the pain together caused him repeatedly to fall into a fitful doze from which he would wake trembling, with his heart beating violently. It was after one of these dozes that he woke and, on opening his eyes, saw a little figure in white bending over him, whose large dark blue eyes, filled with pity, were looking into his face. Her long hair fell down so as to touch him and her beautiful arms rested on the rock on either side of his head. At first he thought it was a water-sprite with dripping locks, of which many tales were told by the country folk, and then he noticed the blood oozing from below the bandage on the little arm. “Who are you?” he asked at last, as his senses gradually returned.

“My name is Aline and I have come to help you,” she said.

“But, sweet child, how can you do that?”

As his brain became clearer he became more able to face the situation. Who could this exquisite fairy-like50 little damsel possibly be, and how could she ever have heard of him and why should any family that wished to help him do it by the hands of any one so young? Then she was wet and wounded, which made the case still more extraordinary. “Little one,” he went on, “why have you come; do you know who I am?”

“No,” she said, “but I saw you lying on the rock and so I came across to try and do something for you.”

“You do not mean to say that you swam that raging river?”

“It was the only way to reach you.”

“And you are really a little girl and not a water fay?” he asked half playfully and half wondering if there really could be such things, as so many people seriously believed. It was almost easier to believe in fairies than to believe that a little girl had actually swum that flood.

“Of course I am; you have hurt your head and are talking nonsense.”

It seemed hard to tell her who he was; this charming little maiden would then hate him like the rest. It was not that he thought that she could possibly be of serious assistance to him; but it was a vision of delight and there was a music in the sound of her voice that to the exile reminded him of his own country. Yet he felt it was his duty and indeed the child might be running great risks and get herself into dire trouble even by speaking to him, so intense was the hatred of the heretics.

“Child, you must not help me. I am a heretic.”

“I guessed that you were,” she said, and the large eyes were full of pity, “but somehow I feel that it is right to aid any one in distress.”

“When you are older, little one, you will think differently. It is only your sweet natural child-heart that instinctively sees the right without prejudice or sophistry.”

“I am afraid that I do not understand you; but we must not stop talking here, we must get you to a place of safety.”

“Will your people help me?” he said, as a possible explanation occurred to him. “Are they of the reformed faith?”

“Are they heretics? you mean; no, indeed.” There was just the suspicion of a touch of scorn in her voice; it was true that to her a heretic was a member of a despised class, but there was also a slight, commingling of bitterness that gave the ring to her words, and which he did not detect, when she thought of the unreasoning and uncharitable prejudice that Mistress Mowbray had shown the day before.