The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine

(May 1913), by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine (May 1913)

Vol. LXXXVI. New Series: Vol. LXIV. May to October, 1913

Author: Various

Release Date: October 16, 2016 [EBook #53286]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CENTURY ILLUSTRATED ***

Produced by ane Robins, Reiner Ruf, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

This e-text is based on ‘The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine,’ from May 1913. Even though this edition includes an Index for the complete volume (May–October 1913), page links have been created for the May issue only.

Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation have been retained, but punctuation and typographical errors have been corrected. Passages in English dialect and in languages other than English have not been altered.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

VOL. LXXXVI

NEW SERIES: VOL. LXIV

MAY TO OCTOBER, 1913

THE CENTURY CO., NEW YORK

HODDER & STOUGHTON, LONDON

Copyright, 1913, by THE CENTURY CO.

THE DE VINNE PRESS

VOL. LXXXVI NEW SERIES: VOL. LXIV

| PAGE | ||

| ADAMS, JOHN QUINCY, IN RUSSIA. (Unpublished letters.) | ||

| Introduction and notes by Charles Francis Adams. Portraits of John Quincy Adams and Madame de Staël | 250 | |

| AFTER-DINNER STORIES. | ||

| An Anecdote of McKinley. | Silas Harrison | 319 |

| AFTER-THE-WAR SERIES, THE CENTURY’S. | ||

| The Hayes-Tilden Contest for the Presidency. | Henry Watterson | 3 |

| Pictures from photographs and cartoons. | ||

| Another View of “The Hayes-Tilden Contest”. | George F. Edmunds | 192 |

| Portrait of Ex-Senator Edmunds. | ||

| AMERICANS, NEW-MADE. Drawings by | W. T. Benda | |

| Facing page 894 | ||

| ARTISTS SERIES, AMERICAN, THE CENTURY’S. | ||

| John S. Sargent: Nonchalance. | 44 | |

| Carl Marr: The Landscape-Painter. | 110 | |

| Frank W. Benson: My Daughter. | 264 | |

| AUTO-COMRADE, THE. | Robert Haven Schauffler | 850 |

| AVOCATS, LES DEUX. From the painting by | Honoré Daumier | |

| Facing page 654 | ||

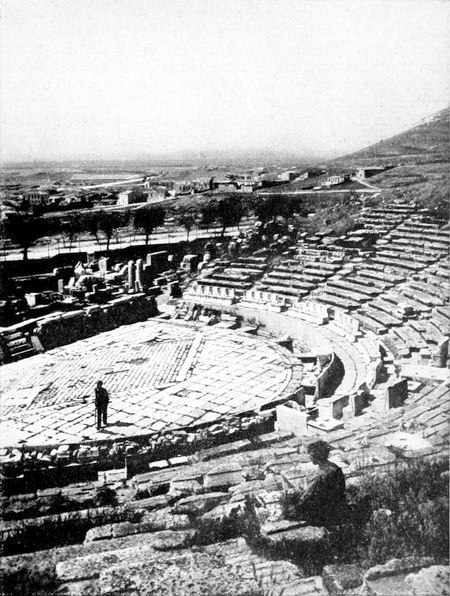

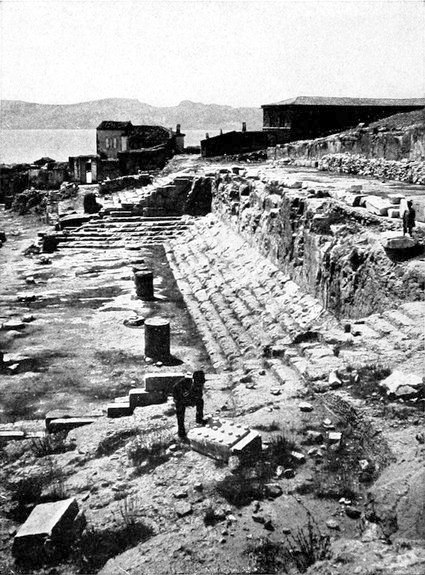

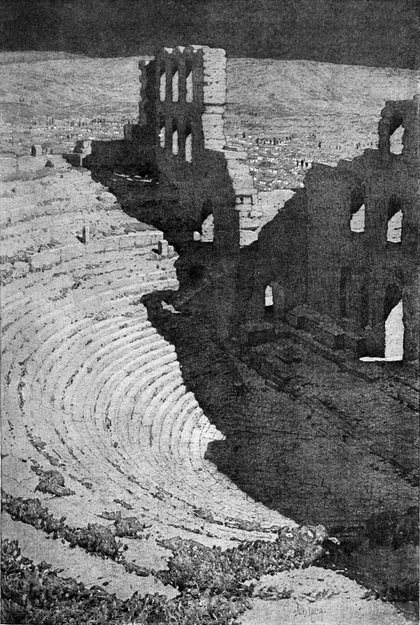

| BALKAN PENINSULA, SKIRTING THE | Robert Hichens | |

| III. The Environs of Athens. | 84 | |

| Pictures by Jules Guérin and from photographs. | ||

| IV. Delphi and Olympia. | 224 | |

| Pictures by Jules Guérin and from photographs. | ||

| V. In Constantinople. | 374 | |

| Pictures by Jules Guérin and from photographs. | ||

| VI. Stamboul, the City of Mosques. | 519 | |

| Pictures by Jules Guérin, two printed in color. | ||

| BEELZEBUB CAME TO THE CONVENT, HOW | Ethel Watts Mumford | 323 |

| Picture by N. C. Wyeth. | ||

| “BLACK BLOOD.” | Edward Lyell Fox | 213 |

| Pictures by William H. Foster. | ||

| BOOK OF HIS HEART, THE | Allan Updegraff | 701 |

| Picture by Herman Pfeifer. | ||

| BORROWED LOVER, THE | L. Frank Tooker | 348 |

| BRITISH UNCOMMUNICATIVENESS. | A. C. Benson | 567 |

| BROTHER LEO. | Phyllis Bottome | 181 |

| Pictures by W. T. Benda. | ||

| BUSINESS IN THE ORIENT. | Harry A. Franck | 475 |

| CAMILLA’S FIRST AFFAIR. | Gertrude Hall | 400 |

| Pictures by Emil Pollak-Ottendorff. | ||

| [Pg iv] CARTOONS. | ||

| Noise Extracted without Pain. | Oliver Herford | 155 |

| Foreign Labor. | Oliver Herford | 477 |

| Ninety Degrees in the Shade. | J. R. Shaver | 477 |

| A Boy’s Best Friend. | May Wilson Preston | 634 |

| “The Fifth Avenue Girl” and “A Bit of Gossip.” Sculpture by | Ethel Myers | 635 |

| The Child de Luxe. | Boardman Robinson | 636 |

| The “Elite” Bathing-Dress. | Reginald Birch | 797 |

| From Grave to Gay. | C. F. Peters | 798 |

| Died: Rondeau Rymbel. | Oliver Herford | 955 |

| A Triumph for the Fresh Air Fund. | F. R. Gruger | 957 |

| Newport Note. | Reginald Birch | 960 |

| CASUS BELLI. | 955 | |

| CENTURY, THE, THE SPIRIT OF | Editorial | 789 |

| CHOATE, JOSEPH H. From a charcoal portrait by | John S. Sargent | |

| Facing page 711 | ||

| CHRISTMAS, ON ALLOWING THE EDITOR TO SHOP EARLY FOR | Leonard Hatch | 473 |

| CLOWN’S RUE. | Hugh Johnson | 730 |

| Picture, printed in tint, by H. C. Dunn. | ||

| COLE’S (TIMOTHY) ENGRAVINGS OF MASTERPIECES IN AMERICAN GALLERIES. | ||

| Une Dame Espagnole. From the painting by | Fortuny | 2 |

| COMING SNEEZE, THE | Harry Stillwell Edwards | 368 |

| Picture by F. R. Gruger. | ||

| COMMON SENSE IN THE WHITE HOUSE. | Editorial | 149 |

| COUNTRY ROADS OF NEW ENGLAND. Drawings by | Walter King Stone | 668 |

| DEVIL, THE, HIS DUE | Philip Curtiss | 895 |

| DINNER OF HERBS,” “BETTER IS A. Picture by | Edmund Dulac | |

| Facing page 801 | ||

| DORMER-WINDOW, THE, THE COUNTRY OF | Henry Dwight Sedgwick | 720 |

| Pictures by W. T. Benda. | ||

| DOROTHY MCK——, PORTRAIT OF | Wilhelm Funk | 211 |

| DOWN-TOWN IN NEW YORK Drawings by | Herman Webster | 697 |

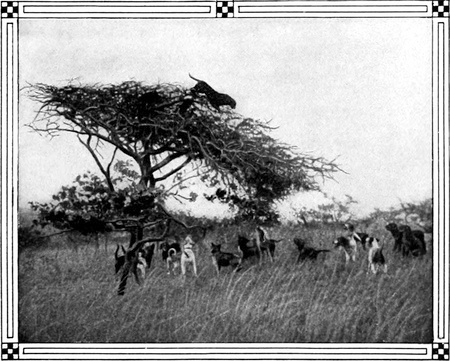

| ELEPHANT ROUND-UP, AN | D. P. B. Conkling | 236 |

| Pictures from photographs. | ||

| ELEPHANTS, WILD, NOOSING | Charles Moser | 240 |

| Pictures from photographs. | ||

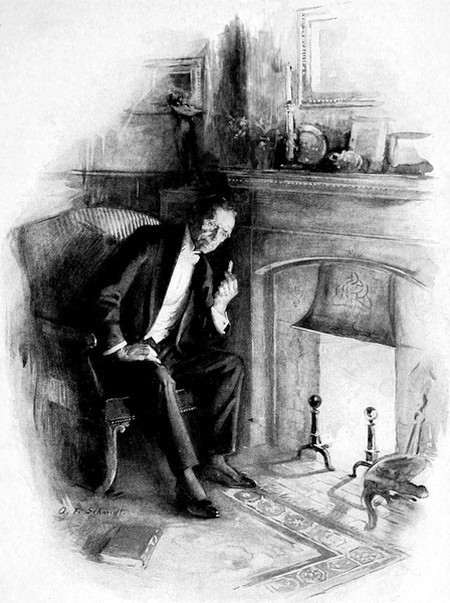

| ELIXIR OF YOUTH, THE | Albert Bigelow Paine | 21 |

| Picture by O. F. Schmidt. | ||

| FLOODS, THE GREAT, IN THE MIDDLE WEST | Editorial | 148 |

| FRENCH ART, EXAMPLES OF CONTEMPORARY. | ||

| A Corner of the Table. From the painting by | Charles Chabas | 83 |

| GARAGE IN THE SUNSHINE, A | Joseph Ernest | 921 |

| Picture by Harry Raleigh. | ||

| GET SOMETHING BY GIVING SOMETHING UP, ON HOW TO | Simeon Strunsky | 153 |

| GHOSTS,” “DEY AIN’T NO | Ellis Parker Butler | 837 |

| Pictures by Charles Sarka. | ||

| GOING UP. | Frederick Lewis Allen | 632 |

| Picture by Reginald Birch. | ||

| GOLF, MIND VERSUS MUSCLE IN | Marshall Whitlatch | 606 |

| GOVERNMENT, THE CHANGING VIEW OF | Editorial | 311 |

| GRAND CAÑON OF THE COLORADO, THE | Joseph Pennell | 202 |

| Six lithographs drawn from nature for “The Century.” | ||

| GUTTER-NICKEL, THE | Estelle Loomis | 570 |

| Picture by J. Montgomery Flagg. | ||

| HARD MONEY, THE RETURN TO | Charles A. Conant | 439 |

| Portraits, and cartoons by Thomas Nast. | ||

| HER OWN LIFE. | Allan Updegraff | 79 |

| HOME. I. AN ANONYMOUS NOVEL. | 801 | |

| Illustrations by Reginald Birch. | ||

| [Pg v] HOMER AND HUMBUG. | Stephen Leacock | 952 |

| HYPERBOLE IN ADVERTISING, ON THE USE OF | Agnes Repplier | 316 |

| ILLUSION OF PROGRESS, THE | Kenyon Cox | 39 |

| IMPRACTICAL MAN, THE | Elliott Flower | 549 |

| Pictures by F. R. Gruger. | ||

| INTERNATIONAL CLUB, THE, ON THE COLLAPSE OF | G. K. Chesterton | 151 |

| JAPANESE CHILD, A, THE TRAINING OF | Frances Little | 170 |

| Pictures from photographs. | ||

| JAPAN, THE NEW, AMERICAN MAKERS OF | William Elliot Griffis | 597 |

| Pictures from photographs. | ||

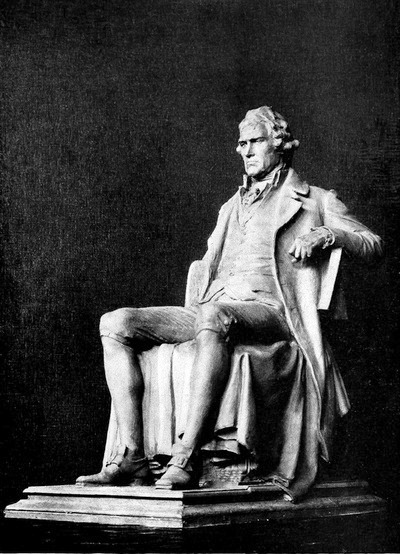

| JEFFERSON, THOMAS. From the statue for the Jefferson Memorial in St. Louis by | Karl Bitter | 27 |

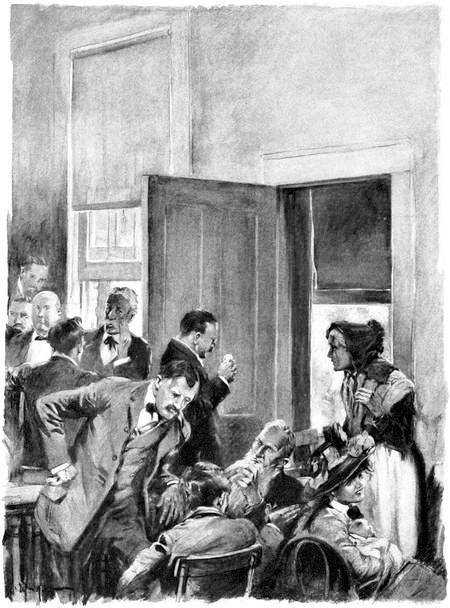

| JURYMAN, THE, THE MIND OF | Hugo Münsterberg | 711 |

| LADY AND HER BOOK, THE, ON | Helen Minturn Seymour | 315 |

| LAWLESSNESS IN ART. | Editorial | 150 |

| LIFE AFTER DEATH. | Maurice Maeterlinck | 655 |

| LITERATURE FACTORY. | E. P. Butler | 638 |

| LOUISE. Color-Tone, from the marble bust by | Evelyn Beatrice Longman | |

| Facing page 766 | ||

| LOVE BY LIGHTNING. | Maria Thompson Daviess | 641 |

| Pictures, printed in tint, by F. R. Gruger. | ||

| MANNERING’S MEN. | Marjorie L. C. Pickthall | 427 |

| MAN WHO DID NOT GO TO HEAVEN ON TUESDAY, THE | Ellis Parker Butler | 340 |

| MILLET’S RETURN TO HIS OLD HOME. | Truman H. Bartlett | 332 |

| Pictures from pastels by Millet. | ||

| MONEY BEHIND THE GUN, THE | Editorial | 470 |

| MORGAN’S, MR., PERSONALITY | Joseph B. Gilder | 459 |

| Picture from photograph. | ||

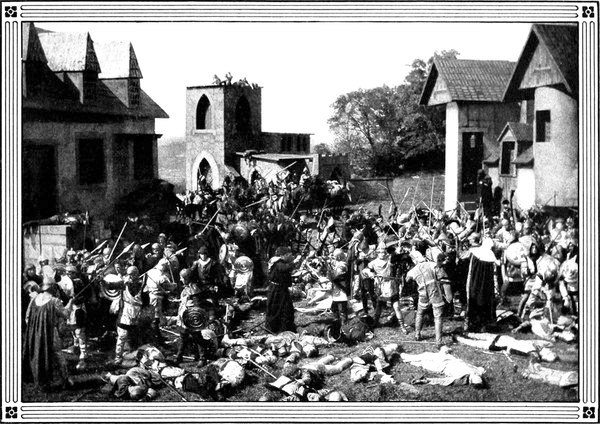

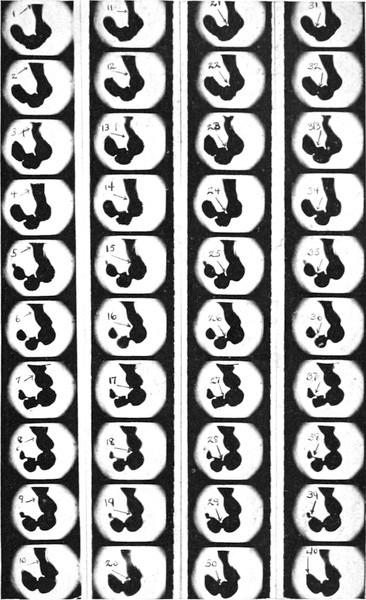

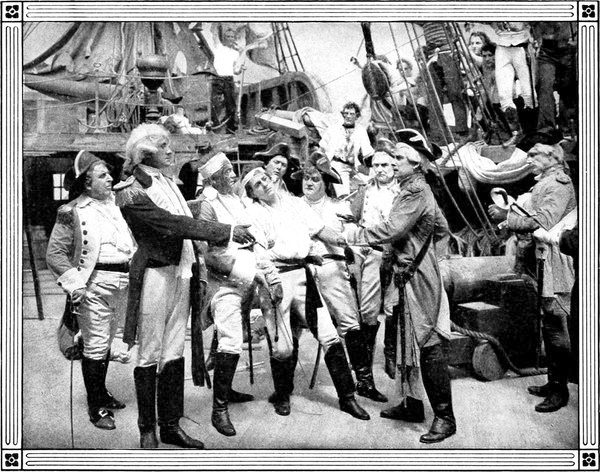

| MOVING-PICTURE, THE, THE WIDENING FIELD OF | Charles B. Brewer | 66 |

| Pictures from photographs. | ||

| MRS. LONGBOW’S BIOGRAPHY. | Gordon Hall Gerould | 56 |

| NEMOURS: A TYPICAL FRENCH PROVINCIAL TOWN. | Roger Boutet de Monvel | 844 |

| Pictures by Bernard Boutet de Monvel. | ||

| NEWSPAPER INVASION OF PRIVACY. | Editorial | 310 |

| NIAGARA AGAIN IN DANGER. | Editorial | 150 |

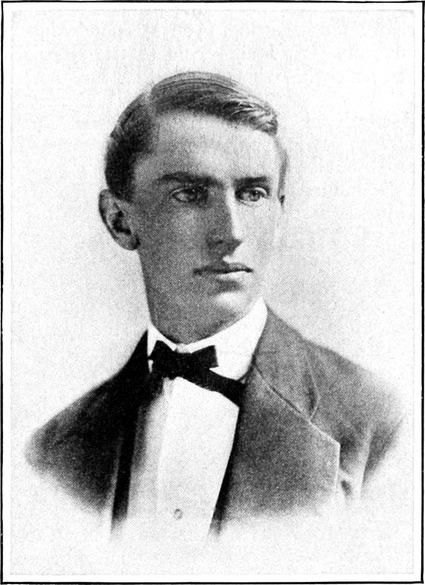

| NOTEWORTHY STORIES OF THE LAST GENERATION. | ||

| The Tachypomp. | Edward P. Mitchell | 99 |

| Portrait of the author, and drawings by Reginald Birch. | ||

| Belles Demoiselles Plantation. | George W. Cable | 273 |

| With portrait of the author, and new pictures by W. M. Berger. | ||

| The New Minister’s Great Opportunity. | C. H. White | 390 |

| With portrait of the author, and new picture by Harry Townsend. | ||

| ONE WAY TO MAKE THINGS BETTER. | Editorial | 471 |

| OREGON MUDDLE,” “THE | Victor Rosewater | 764 |

| PADEREWSKI AT HOME. | Abbie H. C. Finck | 900 |

| Picture from a portrait by Emil Fuchs. | ||

| PARIS. | Theodore Dreiser | 904 |

| Pictures by W. J. Glackens. | ||

| “PEGGY.” From the marble bust by | Evelyn Beatrice Longman | 362 |

| POLO TEAM, UNDEFEATED AMERICAN, BRONZE GROUP OF THE | Herbert Hazeltine | |

| Facing page 641 | ||

| PROGRESSIVE PARTY, THE | Theodore Roosevelt | 826 |

| Portrait of the author. | ||

| PUNS, A PAPER OF | Brander Matthews | 290 |

| Head-piece by Reginald Birch. | ||

| REMINGTON, FREDERIC, RECOLLECTIONS OF | Augustus Thomas | 354 |

| Pictures by Frederic Remington, and portrait. | ||

| ROMAIN ROLLAND. | Alvan F. Sanborn | 512 |

| Picture from portrait of Rolland from a drawing by Granié. | ||

| ST. BERNARD, THE GREAT | Ernst von Hesse-Wartegg | 161 |

| Pictures by André Castaigne. | ||

| [Pg vi] ST. ELIZABETH OF HUNGARY. By Francisco Zubarán. Engraved on wood by | Timothy Cole | 437 |

| SCARLET TANAGER, THE. Printed in color from the painting by | Alfred Brennan | 29 |

| “SCHEDULE K”. | N. I. Stone | 111 |

| “SCHEDULE K,” COMMENTS ON | Editorial | 472 |

| SCULPTURE. | Charles Keck | 917 |

| SENIOR WRANGLER THE | 958 | |

|

Snobbery—America vs. England. Our Tender Literary Celebrities. |

||

| SIGIRIYA, “THE LION’S ROCK” OF CEYLON. | Jennie Coker Gay | 265 |

| Pictures by Duncan Gay. | ||

| SOCIALISM IN THE COLLEGES. | Editorial | 468 |

| SPINSTER, AMERICAN, THE | Agnes Repplier | 363 |

| SUMMER HILLS,” THE, IN “THE CIRCUIT OF | John Burroughs | 878 |

| Portrait of the author by Alvin L. Coburn. | ||

| SUNSET ON THE MARSHES. From the painting by | George Inness | |

| Facing page 824 | ||

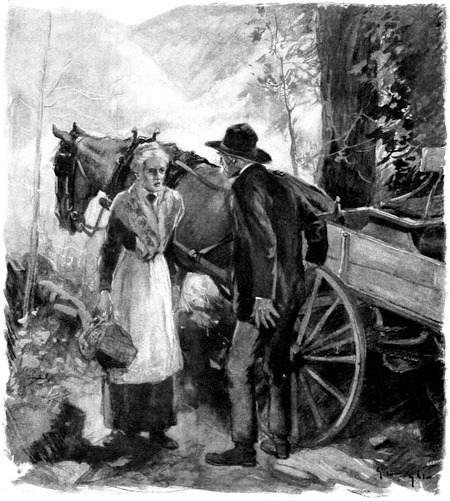

| “THEM OLD MOTH-EATEN LOVYERS”. | Charles Egbert Craddock | 120 |

| Pictures by George Wright. | ||

| TRADE OF THE WORLD PAPERS, THE | James Davenport Whelpley | |

| XVII. If Canada were to Annex the United States | 534 | |

| Pictures from photographs. | ||

| XVIII. The Foreign Trade of the United States | 886 | |

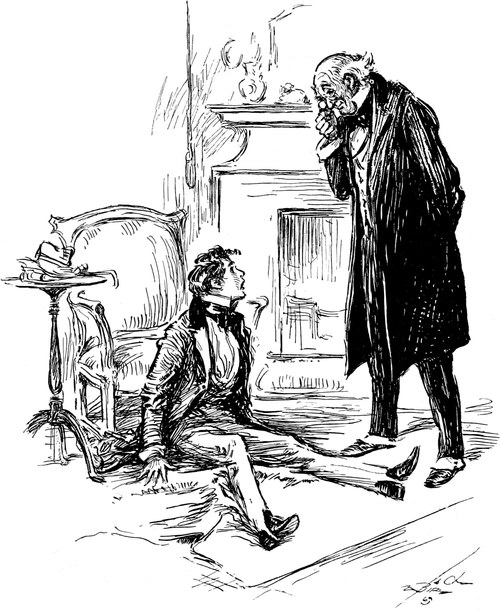

| T. TEMBAROM. | Frances Hodgson Burnett | 130 |

| Drawings by Charles S. Chapman. | 296, 413, 610, 767, 929 | |

| TWO-BILLION-DOLLAR CONGRESS, THE | Editorial | 313 |

| UNCOMMERCIAL TRAVELER, AN, IN LONDON | Theodore Dreiser | 736 |

| Pictures by W. J. Glackens. | ||

| UNDER WHICH FLAG, LADIES, ORDER OR ANARCHY? | Editorial | 309 |

| VENEZUELA DISPUTE, THE, THE MONROE DOCTRINE IN | Charles R. Miller | 750 |

| Cartoons from “Punch,” and a map. | ||

| VERITA’S STRATAGEM. | Anne Warner | 430 |

| VOYAGE OVER, THE FIRST | Theodore Dreiser | 586 |

| Pictures by W. J. Glackens. | ||

| WAGNER, RICHARD, IF, CAME BACK | Henry T. Finck | 208 |

| Portrait of Wagner from photograph. | ||

| WALL STREET, THE NEWS IN | James L. Ford | 794 |

| Pictures by Reginald Birch and May Wilson Preston. | ||

| WAR AGAINST WAR. | Editorial | 147 |

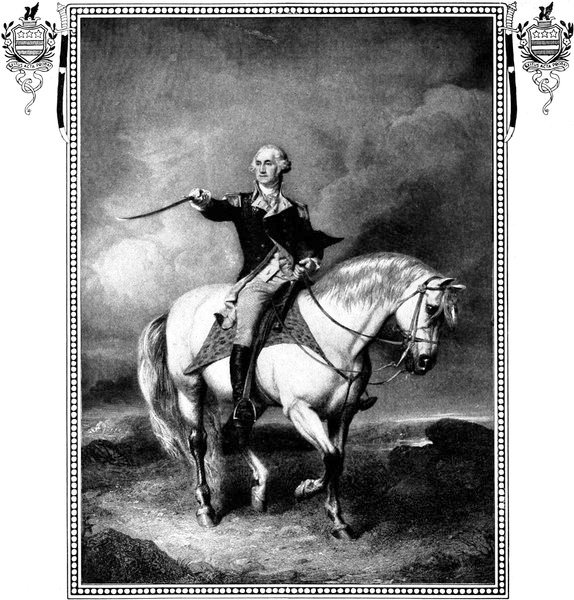

| WAR-HORSES OF FAMOUS GENERALS. | James Grant Wilson | 45 |

| Pictures from paintings and photographs. | ||

| WAR WORTH WAGING, A | Richard Barry | 31 |

| Picture by Jay Hambidge. | ||

| WASHINGTON, FRESH LIGHT ON | 635 | |

| WATTERSON’S, COLONEL, REJOINDER TO EX-SENATOR EDMUNDS | Henry Watterson | 285 |

| Comments on “Another View of ‘The Hayes-Tilden Contest.’” | ||

| WHISTLER, A VISIT TO | Maria Torrilhon Buel | 694 |

| WHITE LINEN NURSE, THE | Eleanor Hallowell Abbott | 483 |

| Pictures, printed in tint, by Herman Pfeifer. | 672, 857 | |

| WIDOW, THE. From the painting by | Couture | 457 |

| An example of French portraiture. | ||

| WORLD REFORMERS—AND DUSTERS. | The Senior Wrangler | 792 |

| Picture by Reginald Birch. | ||

| YEAR, THE MOST IMPORTANT | Editorial | 951 |

VERSE

| BALLADE OF PROTEST, A | Carolyn Wells | 476 |

| BEGGAR, THE | James W. Foley | 877 |

| BELLE DAME SANS MERCI, LA | John Keats | 388 |

| Republished with pictures by Stanley M. Arthurs. | ||

| BLANK PAGE, FOR A | Austin Dobson | 458 |

| BROTHER MINGO MILLENYUM’S ORDINATION. | Ruth McEnery Stuart | 475 |

| CONTINUED IN THE ADS. | Sarah Redington | 795 |

| CUBIST ROMANCE, A | Oliver Herford | 318 |

| Picture by Oliver Herford. | ||

| DADDY DO-FUNNY’S, OLD, WISDOM JINGLES | Ruth McEnery Stuart | 154 |

| 319, 478 | ||

| DOUBLE STAR, A | Leroy Titus Weeks | 511 |

| EMERGENCY. | William Rose Benét | 916 |

| EXPERIMENTERS, THE, TO | Charles Badger Clark, Jr. | 43 |

| FINIS. | William H. Hayne | 295 |

| GENTLE READER, THE | Arthur Davison Ficke | 692 |

| HOUSE-WITHOUT-ROOF. | Edith M. Thomas | 339 |

| HUSBAND SHOP, THE | Oliver Herford | 956 |

| Picture by Oliver Herford. | ||

| INVULNERABLE. | William Rose Benét | 308 |

| JUSTICE, AT THE CLOSED GATES OF | James D. Corrothers | 272 |

| LADY CLARA VERE DE VERE: NEW STYLE. | Anne O’Hagan | 793 |

| Picture by E. L. Blumenschein. | ||

| LAST FAUN, THE | Helen Minturn Seymour | 717 |

| Picture, printed in tint, by Charles A. Winter. | ||

| LAST MESSAGE, A | Grace Denio Litchfield | 26 |

| LIFE’S ASPIRATION. | Louis Untermeyer | 156 |

| Drawing by George Wolfe Plank. | ||

| LIMERICKS: | ||

| Text and pictures by Oliver Herford. | ||

| XXVII. The Somnolent Bivalve. | 157 | |

| XXVIII. The Ounce of Detention. | 158 | |

| XXIX. The Kind Armadillo. | 320 | |

| XXX. The Gnat and the Gnu. | 479 | |

| XXXI. The Sole-Hungering Camel. | 480 | |

| XXXII. The Eternal Feminine. | 639 | |

| XXXIII. Tra-la-Larceny. | 640 | |

| XXXIV. The Conservative Owl. | 799 | |

| XXXV. The Omnivorous Book-worm. | 800 | |

| LITTLE PEOPLE, THE | Amelia Josephine Burr | 387 |

| MAETERLINCK, MAURICE | Stephen Phillips | 467 |

| MARVELOUS MUNCHAUSEN, THE | William Rose Benét | 563 |

| Pictures by Oliver Herford. | ||

| MAY, FROM MY WINDOW. | Frances Rose Benét | 155 |

| Drawing by Oliver Herford. | ||

| MESSAGE FROM ITALY, A | Margaret Widdemer | 547 |

| Drawing printed in tint by W. T. Benda. | ||

| MOTHER, THE | Timothy Cole | 920 |

| Picture by Alpheus Cole. | ||

| MY CONSCIENCE. | James Whitcomb Riley | 331 |

| Decoration by Oliver Herford. | ||

| MYSELF,” “I SING OF | Louis Untermeyer | 960 |

| NEW ART, THE | Corinne Rockwell Swain | 156 |

| [Pg viii] NOYES, ALFRED, TO | Edwin Markham | 288 |

| OFF CAPRI. | Sara Teasdale | 223 |

| PARENTS, OUR | Charles Irvin Junkin | 959 |

| Pictures by Harry Raleigh. | ||

| PRAYERS FOR THE LIVING. | Mary W. Plummer | 367 |

| RITUAL. | William Rose Benét | 788 |

| ROYAL MUMMY, TO A | Anna Glen Stoddard | 631 |

| RYMBELS: | ||

| Pictures by Oliver Herford. | ||

| The Girl and the Raspberry Ice. | Oliver Herford | 637 |

| The Yellow Vase. | Charles Hanson Towne | 637 |

| Tragedy. | Theodosia Garrison | 638 |

| “On Revient toujours à Son Premier Amour”. | Oliver Herford | 638 |

| A Rymbel of Rhymers. | Carolyn Wells | 796 |

| The Prudent Lover. | L. Frank Tooker | 797 |

| On a Portrait of Nancy. | Carolyn Wells | 797 |

| SAME OLD LURE, THE | Berton Braley | 478 |

| SCARLET TANAGER, TO A | Grace Hazard Conkling | 28 |

| SIERRA MADRE. | Henry Van Dyke | 347 |

| SOCRATIC ARGUMENT. | John Carver Alden | 960 |

| SUBMARINE MOUNTAINS. | Cale Young Rice | 693 |

| TRIOLET, A | Leroy Titus Weeks | 636 |

| WINE OF NIGHT, THE | Louis Untermeyer | 119 |

| WINGÈD VICTORY. | Victor Whitlock | 596 |

| Photograph and decoration. | ||

| WISE SAINT, THE | Herman Da Costa | 798 |

| Picture by W. T. Benda. | ||

| YOUNG HEART IN AGE, THE | Edith M. Thomas | 78 |

UNE DAME ESPAGNOLE

BY

FORTUNY

Owned by the Metropolitan Museum, New York

UNE DAME ESPAGNOLE. BY FORTUNY

(TIMOTHY COLE’S WOOD ENGRAVINGS OF MASTERPIECES IN AMERICAN GALLERIES)

Copyright 1913, by THE CENTURY CO. All rights reserved.

THE CENTURY MAGAZINE

INSIDE HISTORY OF A GREAT POLITICAL CRISIS

(THE CENTURY’S AFTER-THE-WAR SERIES)

BY HENRY WATTERSON

Editor of the Louisville “Courier-Journal”

THE time is coming, if it has not already arrived, when among fair-minded and intelligent Americans there will not be two opinions touching the Hayes-Tilden contest for the Presidency in 1876–77—that both by the popular vote and a fair count of the electoral vote Tilden was elected and Hayes was defeated—but the whole truth underlying the determinate incidents which led to the rejection of Tilden and the seating of Hayes will never be known.

“All history is a lie,” observed Sir Robert Walpole, the corruptionist, mindful of what was likely to be written about himself, and, “What is history,” asked Napoleon, the conqueror, “but a fable agreed upon?”

In the first administration of Mr. Cleveland, there were present at a dinner-table in Washington, the President being of the party, two leading Democrats and two leading Republicans who had sustained confidential relations to the principals and played important parts in the drama of the Disputed Succession. These latter had been long upon terms of personal intimacy. The occasion was informal and joyous, the good-fellowship of the heartiest. Inevitably the conversation drifted to the Electoral Commission, which had counted Tilden out and Hayes in, and of which each of the four had some story to tell. Beginning in banter, with interchanges of badinage, it presently fell into reminiscence, deepening as the interest of the listeners rose to what under different conditions might have been described as unguarded gaiety, if not imprudent garrulity. The little audience[Pg 4] was rapt. Finally, Mr. Cleveland raised both hands and exclaimed, “What would the people of this country think if the roof could be lifted from this house and they could hear these men!” And then one of the four, a gentleman noted for his wealth both of money and humor, replied, “But the roof is not going to be lifted from this house, and if any one repeats what I have said I will denounce him as a liar.”

Once in a while the world is startled by some revelation of the unknown which alters the estimate of an historic event or figure; but it is measurably true, as Metternich declares, that those who make history rarely have time to write it.

It is not my wish in recurring to the events of five-and-thirty years ago to invoke and awaken any of the passions of that time, nor my purpose to assail the character or motives of any of the leading actors. Most of them, including the principals, I knew well; to many of their secrets I was privy. As I was serving, in a sense, as Mr. Tilden’s personal representative in the Lower House of the Forty-fourth Congress, and as a member of the joint Democratic Advisory or Steering Committee of the two Houses, all that passed came more or less, if not under my supervision, yet to my knowledge; and long ago I resolved that certain matters should remain a sealed book in my memory. I make no issue of veracity with the living; the dead should be sacred. The contradictory promptings, not always crooked; the double constructions possible to men’s actions; the intermingling of ambition and patriotism beneath the lash of party spirit; often wrong unconscious of itself; sometimes equivocation deceiving itself; in short, the tangled web of good and ill inseparable from great affairs of loss and gain, made debatable ground for every step of the Hayes-Tilden proceeding.

I shall bear sure testimony to the integrity of Mr. Tilden. I directly know that the Presidency was offered to him for a price and that he refused it; and I indirectly know and believe that two other offers came to him which also he declined. The accusation that he was willing to buy, and through the cipher despatches and other ways tried to buy, rests upon appearance supporting mistaken surmise. Mr. Tilden knew nothing of the cipher despatches until they appeared in the “New-York Tribune.” Neither did Mr. George W. Smith, his private secretary, and later one of the trustees to his will. It should be sufficient to say that, so far as they involved No. 15 Gramercy Park, they were the work solely of Colonel Pelton, acting on his own responsibility, and, as Mr. Tilden’s nephew, exceeding his authority to act; that it later developed that during this period Colonel Pelton had not been in his perfect mind, but was at least semi-irresponsible; and that on two occasions when the vote or votes sought seemed within reach, Mr. Tilden interposed to forbid. Directly and personally, I know this to be true.

The price, at least in patronage, which the Republicans actually paid for possession is of public record. Yet I not only do not question the integrity of Mr. Hayes, but I believe him, and most of those immediately about him, to have been high-minded men who thought they were doing for the best in a situation unparalleled and beset with perplexity. What they did tends to show that men will do for party and in concert what the same men never would be willing to do each on his own responsibility. In his “Life of Samuel J. Tilden,” John Bigelow says:

Why persons occupying the most exalted positions should have ventured to compromise their reputations by this deliberate consummation of a series of crimes which struck at the very foundations of the Republic, is a question which still puzzles many of all parties who have no charity for the crimes themselves. I have already referred to the terrors and desperation with which the prospect of Tilden’s election inspired the great army of office-holders at the close of Grant’s administration. That army, numerous and formidable as it was, was comparatively limited. There was a much larger and justly influential class who were apprehensive that the return of the Democratic party to power threatened a reactionary policy at Washington, to the undoing of some or all the important results of the war. These apprehensions were inflamed by the party press until they were confined to no class, but more or less pervaded all the Northern States. The Electoral Tribunal, consisting mainly of men appointed to their positions by Republican[Pg 5] Presidents, or elected from strong Republican States, felt the pressure of this feeling, and from motives compounded in more or less varying proportions of dread of the Democrats, personal ambition, zeal for their party, and respect for their constituents, reached the conclusion that the exclusion of Tilden from the White House was an end which justified whatever means were necessary to accomplish it. They regarded it like the emancipation of the slaves, as a war measure.

THE nomination of Horace Greeley in 1872 and the overwhelming defeat that followed left the Democratic party in an abyss of despair. The old Whig party, after the disaster that overtook it in 1852, had been not more demoralized. Yet in the general elections of 1874 the Democrats swept the country, carrying many Northern States and sending a great majority to the Forty-fourth Congress.

From a photograph owned by F. H. Meserve

SENATOR ZACHARIAH CHANDLER

Chairman of the Republican National Committee

in the Hayes-Tilden campaign.

Reconstruction was breaking down of its very weight and rottenness. The panic of 1873 reacted against the party in power. Dissatisfaction with Grant, which had not sufficed two years before to displace him, was growing apace. Favoritism bred corruption, and corruption grew more and more defiant. Succeeding, scandals cast their shadows before. Chickens of “carpet-baggery” let loose upon the South were coming home to roost at the North. There appeared everywhere a noticeable subsidence of the sectional spirit and a rising tide of the national spirit. Reform was needed alike in the State governments and the National government, and the cry for reform proved something other than an idle word. All things made for Democracy.

Yet there were many and serious handicaps. The light and leading of the historic Democratic party which had issued from the South were in obscurity and abeyance, while most of those surviving who had been distinguished in the party conduct and counsels were disabled by act of Congress. Of the few prominent Democrats left at the North, many were tainted by what was called Copperheadism (sympathy with the Confederacy). To find a chieftain wholly free from this contamination, Democracy, having failed of success in presidential campaigns not only with Greeley but with McClellan and Seymour, was turning to such disaffected Republicans as Chase, Field, and Davis of the Supreme Court. At last Heaven seemed to smile from the clouds[Pg 7] upon the disordered ranks and to summon thence a man meeting the requirements of the time. This was Samuel Jones Tilden.

From a photograph by Sherman & McHug

CONGRESSMAN ABRAM S. HEWITT

Chairman of the Democratic National Committee

in the Hayes-Tilden campaign.

To his familiars, Mr. Tilden was a dear old bachelor who lived in a fine old mansion in Gramercy Park. Though sixty years of age, he seemed in the prime of his manhood; a genial and overflowing scholar; a trained and earnest doctrinaire; a public-spirited, patriotic citizen, well known and highly esteemed, who had made fame and fortune at the bar and had always been interested in public affairs. He was a dreamer with a genius for business, a philosopher yet an organizer. He pursued the tenor of his life with measured tread. His domestic fabric was disfigured by none of the isolation and squalor which so often attend the confirmed celibate. His home life was a model of order and decorum, his home as unchallenged as a bishopric, its hospitality, though select, profuse and untiring. An elder sister presided at his board, as simple, kindly, and unostentatious, but as methodical as himself. He was a lover of books rather than music and art, but also of horses and dogs and out-of-door activity. He was fond of young people, particularly of young girls; he drew them about him, and was a veritable Sir Roger de Coverley in his gallantries toward them and his zeal in amusing them and making them happy. His tastes were frugal and their indulgence was sparing. He took his wine not plenteously, though he enjoyed it—especially his “blue seal” while it lasted—and sipped his whisky-and-water on occasion with a pleased composure redolent of discursive talk, of which, when he cared to lead the conversation, he was a master. He had early come into a great legal practice and held a commanding professional position. His judgment was believed to be infallible; and it is certain that after 1871 he rarely appeared in the courts of law except as counselor, settling in chambers most of the cases that came to him.

It was such a man whom, in 1874, the Democrats nominated for Governor of New York. To say truth, it was not thought by those making the nomination that he had much chance to win. He was himself so much better advised that months ahead he prefigured very near the[Pg 8] exact vote. The afternoon of the day of election one of the group of friends, who even thus early had the Presidency in mind, found him in his library confident and calm.

“What majority will you have?” he asked cheerily.

“Any,” replied the friend sententiously.

“How about fifteen thousand?”

“Quite enough.”

“Twenty-five thousand?”

“Still better.”

“The majority,” he said, “will be a little in excess of fifty thousand.” It was 53,315. His estimate was not guesswork. He had organized his campaign by school-districts. His canvass system was perfect, his canvassers were as penetrating and careful as census-takers. He had before him reports from every voting precinct in the State. They were corroborated by the official returns. He had defeated General John A. Dix, thought to be invincible, by a majority very nearly the same as that by which Governor Dix had been elected two years before.

THE time and the man had met. Although Mr. Tilden had not before held executive office, he was ripe and ready for the work. His experience in the pursuit and overthrow of the Tweed Ring in New York, the great metropolis, had prepared and fitted him to deal with the Canal Ring at Albany, the State Capital. Administrative Reform was now uppermost in the public mind, and here in the Empire State of the Union had come to the head of affairs a Chief Magistrate at once exact and exacting, deeply versed not only in legal lore but in a knowledge of the methods by which political power was being turned to private profit, and of the men—Democrats as well as Republicans—who were preying upon the substance of the people.

The story of the two years that followed relates to investigations that investigated, to prosecutions that convicted, to the overhauling of the civil fabric, to the rehabilitation of popular censorship, to reduced estimates and lower taxes.

The campaign for the presidential nomination began as early as the autumn of 1875. The Southern end of it was easy enough. A committee of Southerners residing in New York was formed. Never a leading Southern man came to town who was not “seen.” If of enough importance, he was taken to No. 15 Gramercy Park. Mr. Tilden measured to the Southern standard of the gentleman in politics. He impressed the disfranchised Southern leaders as a statesman of the old order and altogether after their own idea of what a President ought to be. The South came to St. Louis, the seat of the National Convention, represented by its foremost citizens and almost a unit for the Governor of New York. The main opposition sprang from Tammany Hall, of which John Kelly was then the Chief. Its very extravagance proved an advantage to Tilden. Two days before the meeting of the Convention I sent this message to Mr. Tilden: “Tell Blackstone [his favorite riding horse] that he wins in a walk.” The anti-Tilden men put up the Hon. S. S. (“Sunset”) Cox, for Temporary Chairman. It was a clever move. Mr. Cox, though sure for Tammany, was popular everywhere and especially at the South. His backers thought that with him they could count upon a majority of the National Committee.

The night before the assembling, Mr. Tilden’s two or three leading friends on the Committee came to me and said: “We can elect you Chairman over Cox, but no one else.” I demurred at once. “I don’t know one rule of parliamentary law from another,” I said. “We will have the best parliamentarian on the continent right by you all the time,” they said. “I can’t see to recognize a man on the floor of the convention,” I said. “We’ll have a dozen men to tell you,” they replied. So it was arranged, and thus at the last moment I was chosen.

I had barely time to write the required “key-note” speech, but not to commit it to memory, nor sight to read it, even had I been willing to adopt that mode of delivery. It would not do to trust to extemporization. A friend, Colonel Stoddard Johnston, who was familiar with my penmanship, came to the rescue. Concealing my manuscript behind his hat, he lined the words out to me between the cheering, I having mastered a few opening sentences.

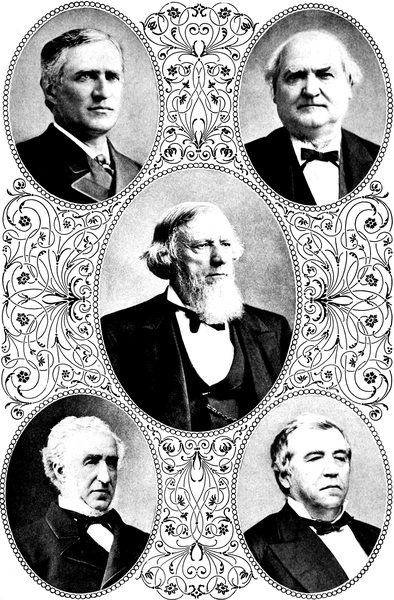

From a photograph owned by F. H. Meserve

THOMAS F. BAYARD

of Delaware

From a photograph by Brady

FRANCIS KERNAN

of New York

From a photograph, copyright by C. M. Bell

ALLEN G. THURMAN

of Ohio

From a photograph, copyright by C. M. Bell

JOSEPH E. MCDONALD

of Indiana

From a photograph by Brady

JOHN W. STEVENSON

of Kentucky

SENATORS OF THE DEMOCRATIC “ADVISORY COMMITTEE” IN THE HAYES-TILDEN CONTEST

Luck was with me. It went with a bang—not, however, wholly without [Pg 10]detection. The Indianians, devoted to Hendricks, were very wroth. “See that fat man behind the hat telling him what to say,” said one to his neighbor, who answered, “Yes, and wrote it for him, too, I’ll be bound.”

One might as well attempt to drive six horses by proxy as preside over a National Convention by hearsay. I lost my parliamentarian at once. I just made my parliamentary law as we went. Never before nor since did any deliberative body proceed under manual so startling and original. But I delivered each ruling with a resonance—it were better called an impudence—which had an air of authority. There was a good deal of quiet laughter on the floor among the knowing ones, though I knew the mass was as ignorant as I was myself; but, realizing that I meant to be just and was expediting business, the Convention soon warmed to me, and, feeling this, I began to be perfectly at home. I never had a better day’s sport in all my life.

One incident was particularly amusing. Much against my will and over my protest, I was brought to promise that Miss Phœbe Couzins, who bore a Woman’s Rights Memorial, should at some opportune moment be given the floor to present it. I foresaw what a row it was bound to occasion. Toward noon, when there was a lull in the proceedings, I said with an emphasis meant to carry conviction, “Gentlemen of the Convention, Miss Phœbe Couzins, a representative of the Woman’s Association of America, has a Memorial from that body and, in the absence of other business, the chair will now recognize her.”

Instantly, and from every part of the hall, arose cries of “No!” These put some heart into me. Many a time as a school-boy I had proudly declaimed the passage from John Home’s tragedy, “My name is Norval.” Again I stood upon “the Grampian hills.” The Committee was escorting Miss Couzins down the aisle. When she came within the radius of my poor vision I saw that she was a beauty and dressed to kill! That was reassurance. Gaining a little time while the hall fairly rocked with its thunder of negation, I laid the gavel down and stepped to the edge of the platform and gave Miss Couzins my hand. As she appeared above the throng there was a momentary “Ah!” and then a lull broken by a single voice: “Mr. Chairman, I rise to a point of order.” Leading Miss Couzins to the front of the stage, I took up the gavel and gave a gentle rap, saying, “The gentleman will take his seat.”

“But, Mr. Chairman, I rise to a point of order,” he vociferated.

“The gentleman will take his seat instantly,” I answered in a tone of one about to throw the gavel at his head. “No point of order is in order when a lady has the floor.”

After that Miss Couzins received a positive ovation, and having delivered her message retired in a blaze of glory.

Mr. Tilden was nominated on the second ballot. The campaign that followed proved one of the most memorable in our history. When it came to an end the result showed on the face of the returns 196 in the Electoral College, 11 more than a majority, and in the popular vote 4,300,316, a majority of 264,300 over Hayes.

How this came to be first contested and then complicated so as ultimately to be set aside has been minutely related by its authors. The newspapers, both Republican and Democratic, of November 8, 1876, the morning after the election, conceded an overwhelming victory for Tilden and Hendricks. There was, however, a single exception. “The New York Times” had gone to press with its first edition, leaving the result in doubt but inclining toward the success of the Democrats. In its later editions this tentative attitude was changed to the statement that Mr. Hayes lacked the vote only of Florida—“claimed by the Republicans”—to be sure of the required 185 votes in the Electoral College.

The story of this surprising discrepancy between midnight and daylight reads like a chapter of fiction.

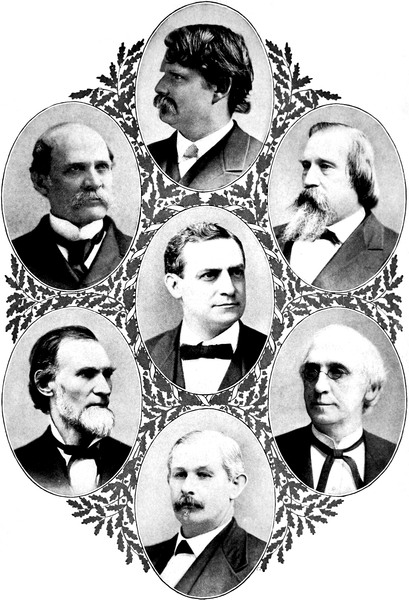

CONGRESSMEN OF THE DEMOCRATIC “ADVISORY

COMMITTEE” IN THE HAYES-TILDEN CONTEST

From a photograph, copyright by C. M. Bell

R. L. GIBSON

of Louisiana

From a photograph

WILLIAM S. HOLMAN

of Indiana

From a photograph by Sarony

HENRY WATTERSON

of Kentucky

From a photograph, copyright by C. M. Bell

SAMUEL J. RANDALL

of Pennsylvania (Speaker)

From a photograph, copyright by C. M. Bell

EPPA HUNTON

of Virginia

From a photograph, copyright by C. M. Bell

L. Q. C. LAMAR

of Mississippi

From a photograph, copyright by C. M. Bell

HENRY B. PAYNE

of Ohio

After the early edition of the “Times” had gone to press certain members of the editorial staff were at supper, very much cast down by the returns, when a messenger brought a telegram from Senator Barnum of Connecticut, financial head of the Democratic National Committee, asking for the “Times’s” latest news from Oregon, Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina. But for that unlucky telegram [Pg 12]Tilden would probably have been inaugurated President of the United States.

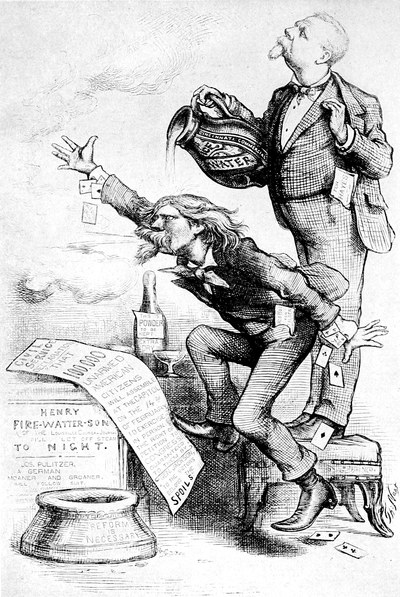

FIRE AND WATER MAKE VAPOR.

WHAT A COOLING OFF WILL BE THERE, MY COUNTRYMEN!

From “Harper’s Weekly” of February 3, 1877

THOMAS NAST’S CARTOON ON COLONEL WATTERSON’S

SUGGESTION OF A GATHERING OF ONE HUNDRED

THOUSAND DEMOCRATS IN WASHINGTON

The ice-water is being applied by Murat Halstead, editor of the

Cincinnati “Commercial,” which was opposed to Tilden; but in

the Greeley campaign of 1872 Halstead had worked with Watterson.

(See THE CENTURY for November, 1912.)

The “Times” people, intense Republican partizans, at once saw an opportunity. If Barnum did not know, why might not a doubt be raised? At once the editorial in the first edition was revised to take a decisive tone and declare the election of Hayes. One of the editorial council, Mr. John C. Reid, hurried to Republican[Pg 13] Headquarters in the Fifth Avenue Hotel, which he found deserted, the triumph of Tilden having long before sent everybody to bed. Mr. Reid then sought the room of Senator Zachariah Chandler, Chairman of the National Republican Committee. While upon this errand he encountered in the hotel corridor “a small man wearing an enormous pair of goggles, his hat drawn over his ears, a greatcoat with a heavy military cloak, and carrying a gripsack and newspaper in his hand. The newspaper was the ‘New-York Tribune,’” announcing the election of Tilden and the defeat of Hayes. The new-comer was Mr. William E. Chandler, even then a very prominent Republican politician, just arrived from New Hampshire and very much exasperated by what he had read.

Mr. Reid had another tale to tell. The two found Mr. Zachariah Chandler, who bade them leave him alone and do whatever they thought best. They did so consumingly, sending telegrams to Columbia, Tallahassee, and New Orleans, stating to each of the parties addressed that the result of the election depended upon his State. To these were appended the signature of Zachariah Chandler. Later in the day Senator Chandler, advised of what had been set on foot and its possibilities, issued from National Republican Headquarters this laconic message: “Hayes has 185 electoral votes and is elected.” Thus began and was put in motion the scheme to confuse the returns and make a disputed count of the vote.

THE day after the election I wired Mr. Tilden suggesting that, as Governor of New York, he propose to Mr. Hayes, the Governor of Ohio, that they unite upon a committee of eminent citizens, composed in equal numbers of the friends of each, who should proceed at once to Louisiana, which appeared to be the objective point of greatest moment to the already contested result. Pursuant to a telegraphic correspondence which followed, I left Louisville that night for New Orleans. I was joined en route by Mr. Lamar of Mississippi, and together we arrived in the Crescent City Friday morning.

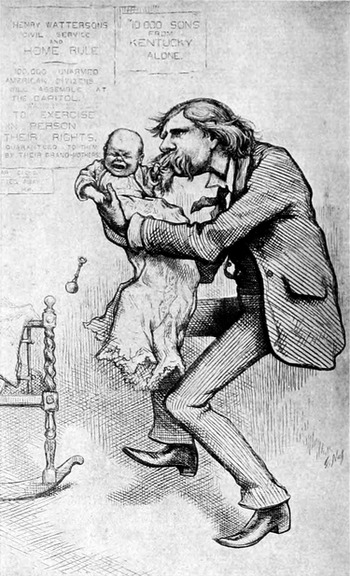

“ONE TOUCH OF NATURE MAKES”—EVEN HENRY

WATTERSON GIVE IN

“Let us have peace. I don’t care who is the next

President,” cries our bold Patriarch at the FIRST arrival.

“The Hon. Henry Watterson has just been presented with

son—weight, 11 pounds.”—Washington Correspondence.

This cartoon by Thomas Nast, with the above titles and

explanation, appeared in “Harper’s Weekly” of March 10, 1877, as

an apology for the lampoon on the opposite page. (See page 17.)

It has since transpired that the Republicans were promptly advised by the Western Union Telegraph Company of all that passed over its wires, my despatches to Mr. Tilden being read in Republican Headquarters at least as soon they reached Gramercy Park.

Mr. Tilden did not adopt the plan of a direct proposal to Mr. Hayes. Instead, he chose a body of Democrats to go to the “seat of war.” But before any of them had arrived General Grant, the actual President, anticipating what was about to happen, appointed a body of Republicans for the like purpose, and the advance guard of these appeared on the scene the following Monday.

Within a week the St. Charles Hotel might have been mistaken for a caravansary of the National Capital. Among the Republicans were John Sherman, Stanley Matthews, Garfield, Evarts, Logan, Kelley, Stoughton, and many others. Among the Democrats, besides Lamar and myself, came Lyman Trumbull, Samuel J. Randall, William R. Morrison, McDonald, of Indiana, and many others. A certain degree of personal intimacy existed between the members of the two groups, and the “entente” was quite as unrestrained as might have existed between rival athletic teams. A Kentucky friend sent me a demijohn of what was represented as very old Bourbon, and I divided it with “our friends the enemy.” New Orleans was new to most of the “visiting statesmen,” and we attended the places of amusement, lived in the restaurants, and “saw the sights,” as if we had been tourists in a foreign land and not partizans charged with the business of adjusting a presidential election from implacable points of view.

My own relations were especially friendly with John Sherman and James A. Garfield, a colleague on the Committee of Ways and Means, and with Stanley Matthews, a near kinsman by marriage, who had stood as an elder brother to me from my childhood.

Corruption was in the air. That the Returning Board was for sale and could be bought was the universal impression. Every day some one turned up with pretended authority and an offer. Most of these were of course the merest adventurers. It was my own belief that the Returning Board was playing for the best price it could get from the Republicans and that the only effect of any offer to buy on our part would be to assist this scheme of blackmail.

The Returning Board consisted of two white men, Wells and Anderson, and two Negroes, Kenner and Casanave. One and all they were without character. I was tempted through sheer curiosity to listen to a proposal which seemed to come direct from the Board itself, the messenger being a well-known State senator. As if he were proposing to dispose of a horse or a dog he stated his errand.

“You think you can deliver the goods?” said I.

“I am authorized to make the offer,” he answered.

“And for how much?” I asked.

“Two hundred and fifty thousand dollars,” he replied. “One hundred thousand each for Wells and Anderson and twenty-five thousand apiece for the niggers.”

To my mind it was a joke. “Senator,” said I, “the terms are as cheap as dirt. I don’t happen to have the amount about me at the moment, but I will communicate with my principal and see you later.”

Having no thought of entertaining the proposal, I had forgotten the incident, when two or three days later my man met me in the lobby of the hotel and pressed for a definite reply. I then told him I had found that I possessed no authority to act and advised him to go elsewhere.

It is asserted that Wells and Anderson did agree to sell and were turned down by Mr. Hewitt, and, being refused their demands for cash by the Democrats, took their final pay, at least in patronage, from their own party.[1]

I PASSED the Christmas week of 1876 in New York with Mr. Tilden. On Christmas day we dined alone. The outlook, on the whole, was cheering. With John Bigelow and Manton Marble Mr. Tilden had been busily engaged compiling the data for a constitutional battle to be fought by the Democrats in Congress, maintaining the right of the House of Representatives to concurrent jurisdiction with the Senate in the counting of the electoral vote, pursuant to an unbroken line of precedents established by the method of proceeding in every presidential election between 1793 and 1872.

There was very great perplexity in the public mind. Both parties appeared to be at sea. The dispute between the Democratic House and the Republican Senate made for thick weather. Contests of the vote of three States—Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida, not to mention single votes in Oregon and Vermont—which presently began to blow a gale, had already spread menacing clouds across the political sky. Except Mr. Tilden, the wisest among the leaders knew not precisely what to do.

From New Orleans, on the Saturday night succeeding the presidential election, I had telegraphed to Mr. Tilden, detailing the exact conditions there and urging active and immediate agitation. The chance had been lost. I thought then, and I still think, that the conspiracy of a few men to use the corrupt Returning Boards of Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida to upset the election and make confusion in Congress, might, by prompt exposure and popular appeal, have been thwarted. Be this as it may, my spirit was depressed and my confidence discouraged the intense quietude on our side, for I was sure that beneath the surface the Republicans, with resolute determination and multiplied resources, were as busy as bees.

Mr. Robert M. McLane, later Governor of Maryland and Minister to France—a man of rare ability and large experience, who had served in Congress and in diplomacy, and was an old friend of Mr. Tilden—had been at a Gramercy Park conference when my New Orleans report arrived, and had then and there urged the agitation recommended by me. He was now again in New York. When a lad he had been in England with his father, Lewis McLane, then American Minister to the Court of St. James’s, during the excitement over the Reform Bill of 1832. He had witnessed the popular demonstrations and had been impressed by the direct force of public opinion upon law-making and law-makers. An analogous situation had arrived in America. The Republican Senate was as the Tory House of Lords. We must organize a movement such as had been so effectual in England. Obviously something was going amiss with us and something had to be done.

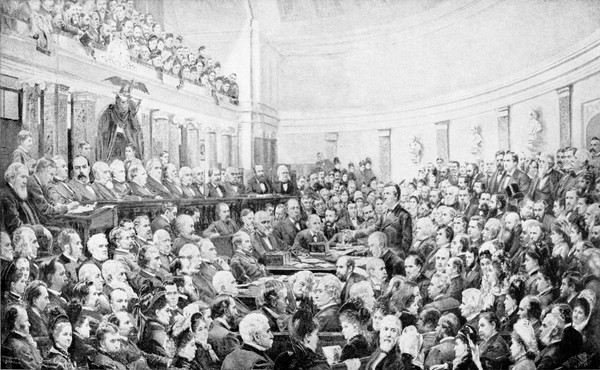

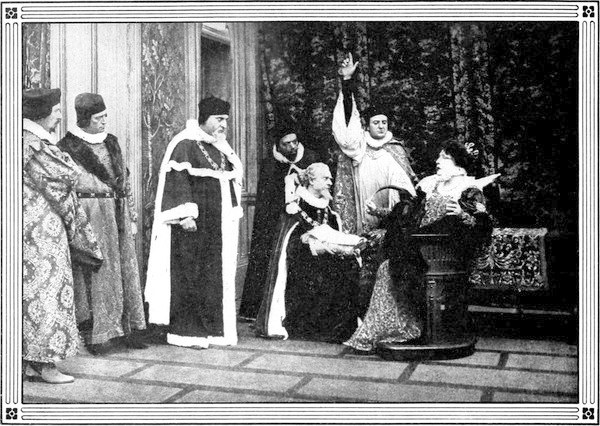

From the painting by Cordelia Adele Fassett, in

the Senate wing of the Capitol at Washington.

After a photograph, copyright, 1878, by Mrs. S. M. Fassett

THE SESSION OF THE ELECTORAL COMMISSION TO CONSIDER

THE CASE OF THE

FLORIDA RETURNS, IN THE SUPREME COURT ROOM, FEBRUARY 5, 1877

NOTE TO “THE SESSION OF THE ELECTORAL COMMISSION,” ETC. (SEE THE PREVIOUS PAGE)

With the purpose of making a picture typical of the sessions of the Electoral Commission, Mrs. Fassett included prominent people who were in Washington at the time, and who gave the artist sittings in the Supreme Court Room.

The Commissioners on the bench, from left to right are: Senators Thurman, Bayard (writing), Frelinghuysen, Morton, Edmunds; Supreme Court Justices Strong, Miller, Clifford, Field, Bradley; Members of the House, Payne, Hunton, Abbott, Garfield, and Hoar. At the left, below Thurman, is the head of Senator Kernan who acted as substitute for the former when ill.

William M. Evarts, counsel for Hayes, is addressing the Commission, and his associate, E. W. Stoughton (white-haired), sits behind him; Charles O’Conor, chief counsel for Tilden, sits at his left. Other members of counsel are grouped in the middle-ground. At the left is seen George Bancroft (with long white beard), and in the middle foreground (looking out), James G. Blaine.

It was agreed that I return to Washington and make a speech “feeling the pulse” of the country, with the suggestion that in the National Capital should assemble “a mass convention of at least one hundred thousand peaceful citizens,” exercising “the freeman’s right of petition.”

The idea was one of many proposals of a more drastic kind and was the merest venture. I, myself, had no great faith in it. But I prepared the speech, and after much reading and revising, it was held by Mr. Tilden and Mr. McLane to cover the case and meet the purpose, Mr. Tilden writing Mr. Randall, Speaker of the House of Representatives, a letter, carried to Washington by Mr. McLane, instructing him what to do in the event that the popular response should prove favorable.

Alack-the-day! The Democrats were equal to nothing affirmative. The Republicans were united and resolute. I delivered the speech, not in the House, as had been intended, but at a public meeting which seemed opportune. The Democrats at once set about denying the sinister and violent purpose ascribed to it by the Republicans, who, fully advised that it had emanated from Gramercy Park, and came by authority, started a counter agitation of their own.

I became the target for every kind of ridicule and abuse. Nast drew a grotesque cartoon of me, distorting my suggestion for the assembling of one hundred thousand citizens, which was both offensive and libelous.

Being on friendly terms with the Harpers, I made my displeasure so resonant in Franklin Square—Nast himself having no personal ill-will toward me—that a curious and pleasing opportunity which came to pass was taken to make amends. A son having been born to me, “Harper’s Weekly” contained an atoning cartoon representing the child in its father’s arms, and, above, the legend: “10,000 sons from Kentucky, alone.” Some wag said that the son in question, was “the only one of the hundred thousand in arms who came when he was called.”

For many years afterward I was pursued by this unlucky speech, or rather by the misinterpretation given to it alike by friend and foe. Nast’s first cartoon was accepted as a faithful portrait, and I was accordingly satirized and stigmatized, although no thought of violence ever had entered my mind, and in the final proceedings I had voted for the Electoral Commission Bill and faithfully stood by its decisions. Joseph Pulitzer, who immediately followed me on the occasion named, declared that he wanted my “one hundred thousand” to come fully armed and ready for business; yet he never was taken to task or reminded of his temerity.

THE Electoral Commission Bill was considered with great secrecy by the Joint Committees of the House and Senate. Its terms were in direct contravention of Mr. Tilden’s plan. This was simplicity itself. He was for asserting, by formal resolution, the conclusive right of the two Houses acting concurrently to count the electoral vote and determine what should be counted as electoral votes, and for denying, also by formal resolution, the pretension set up by the Republicans that the President of the Senate had lawful right to assume that function. He was for urging that issue in debate in both Houses and before the country. He thought that if the attempt should be made to usurp for the President of the Senate a power[Pg 18] to make the count, and thus practically to control the Presidential election, the scheme would break down in process of execution.

Strange to say, Mr. Tilden was not consulted by the party leaders in Congress until the fourteenth of January, and then only by Mr. Hewitt, the extra-constitutional features of the Electoral Tribunal measure having already received the assent of Mr. Bayard and Mr. Thurman, the Democratic members of the Senate Committee. Standing by his original plan, and answering Mr. Hewitt’s statement that Mr. Bayard and Mr. Thurman were fully committed, Mr. Tilden said: “Is it not, then, rather late to consult me?” to which Mr. Hewitt replied: “They do not consult you. They are public men, and have their own duties and responsibilities. I consult you.” In the course of the discussion with Mr. Hewitt which followed Mr. Tilden said, “If you go into conference with your adversary, and can’t break off because you feel you must agree to something, you cannot negotiate—you are not fit to negotiate. You will be beaten upon every detail.” Replying to the apprehension of a collision of force between the parties, Mr. Tilden thought it exaggerated, but said: “Why surrender now? You can always surrender. Why surrender before the battle, for fear you may have to surrender after the battle?”

In short, Mr. Tilden condemned the proceeding as precipitate. It was a month before the time for the count, and he saw no reason why opportunity should not be given for consideration and consultation by all the representatives of the people. He treated the state of mind of Bayard and Thurman as a panic in which they were liable to act in haste and repent at leisure. He stood for publicity and wider discussion, distrusting a scheme to submit such vast interests to a small body sitting in the Capitol, as likely to become the sport of intrigue and fraud.

Mr. Hewitt returned to Washington and, without communicating to Mr. Tilden’s immediate friends in the House his attitude and objection, united with Mr. Thurman and Mr. Bayard in completing the bill and reporting it to the Democratic Advisory Committee, as, by a caucus rule, had to be done with all measures relating to the great issue then before us. No intimation had preceded it. It fell like a bombshell upon the members of the Committee. In the debate that followed Mr. Bayard was very insistent, answering the objections at once offered by me, first aggressively and then angrily, going the length of saying, “If you do not accept this plan I shall wash my hands of the whole business, and you can go ahead and seat your President in your own way.”

Mr. Randall, the Speaker, said nothing, but he was with me, as was a majority of my colleagues. It was Mr. Hunton, of Virginia, who poured oil on the troubled waters, and, somewhat in doubt as to whether the changed situation had changed Mr. Tilden, I yielded my better judgment, declaring it as my opinion that the plan would seat Hayes, and there being no other protestant the Committee finally gave a reluctant assent.

In “open session” a majority of Democrats favored the bill. Many of them made it their own. They passed it. There was belief that justice David Davis, who was expected to become a member of the Commission, was sure for Tilden. If, under this surmise, he had been, the political complexion of “eight to seven” would have been reversed. Elected to the United States Senate from Illinois, Judge Davis declined to serve, and Mr. Justice Bradley was chosen for the Commission in his place. The day after the inauguration of Hayes my kinsman, Stanley Matthews, said to me, “You people wanted Judge Davis. So did we. I tell you what I know, that Judge Davis was as safe for us as Judge Bradley. We preferred him because he carried more weight.” The subsequent career of Judge Davis in the Senate gives conclusive proof that this was true.

When the consideration of the disputed votes before the Commission had proceeded far enough to demonstrate the likelihood that its final decision would be for Hayes, a movement of obstruction and delay, “a filibuster,” was organized by about forty Democratic members of the House. It proved rather turbulent than effective. The South stood very nearly solid for carrying out the agreement in good faith. “Toward the close the filibuster received what appeared formidable reinforcement from the Louisiana Delegation.” This was in reality merely a[Pg 19] “bluff,” intended to induce the Hayes people to make certain concessions touching their State government. It had the desired effect. Satisfactory assurances having been given, the count proceeded to the end—a very bitter end, indeed, for the Democrats.

The final conference between the Louisianians and the accredited representatives of Mr. Hayes was held at Wormley’s Hotel and came to be called “the Wormley Conference.” It was the subject of uncommon interest and heated controversy at the time and long afterward. Without knowing why or for what purpose, I was asked to be present by my colleague, Mr. Ellis, of Louisiana, and later in the day the same invitation came to me from the Republicans through Mr. Garfield. Something was said about my serving as “a referee.” Just before the appointed hour General M. C. Butler, of South Carolina, afterward so long a Senator in Congress, said to me: “This meeting is called to enable Louisiana to make terms with Hayes. South Carolina is as deeply concerned as Louisiana, but we have nobody to represent us in Congress and hence have not been invited. South Carolina puts herself in your hands and expects you to secure for her whatever terms are given to Louisiana.” So, of a sudden, I found myself invested with responsibility equally as an “agent” and a “referee.”

It is hardly worth while repeating in detail all that passed at this Wormley Conference, made public long ago by Congressional investigation. When I entered the apartment of Mr. Evarts at Wormley’s I found, besides Mr. Evarts, Mr. John Sherman, Mr. Garfield, Governor Dennison and Mr. Stanley Matthews, of the Republicans, and Mr. Ellis, Mr. Levy, and Mr. Burke, Democrats of Louisiana. Substantially, the terms had been agreed upon during previous conferences; that is, the promise that, if Hayes came in, the troops should be withdrawn and the people of Louisiana be left free to set their house in order to suit themselves. The actual order withdrawing the troops was issued by President Grant two or three days later, just as he was going out of office.

“Now, gentlemen,” said I, half in jest, “I am here to represent South Carolina, and if the terms given to Louisiana are not equally applied to South Carolina, I become a filibuster myself to-morrow morning.” There was some chaffing as to what right I had there and how I got in, when with great earnestness Governor Dennison, who had been the bearer of a letter from Mr. Hayes which he had read to us, put his hand on my shoulder and said, “As a matter of course, the Southern policy to which Mr. Hayes has here pledged himself embraces South Carolina as well as Louisiana.” Mr. Sherman, Mr. Garfield, and Mr. Evarts concurred warmly in this, and, immediately after we separated, I communicated the fact to General Butler.

In the acrimonious discussion which subsequently sought to make “bargain, intrigue, and corruption” of this Wormley Conference, and to involve certain Democratic members of the House who were nowise party to it, but had sympathized with the purpose of Louisiana and South Carolina to obtain some measure of relief from intolerable local conditions, I never was questioned or assailed. No one doubted my fidelity to Mr. Tilden, who had been promptly advised of all that passed and who justified what I had done. Though “conscripted,” as it were, and rather a passive agent, I could see no wrong in the proceeding. I had spoken and voted in favor of the Electoral Tribunal Bill and, losing, had no thought of repudiating its conclusions. Hayes was already as good as seated. If the States of Louisiana and South Carolina could save their local autonomy out of the general wreck, there seemed no good reason to forbid. On the other hand, the Republican leaders were glad of an opportunity to make an end of the corrupt and tragic farce of Reconstruction; to unload their party of a dead weight which had been burdensome and was growing dangerous; mayhap to punish their Southern agents who had demanded so much for doctoring the returns and making an exhibit in favor of Hayes.

MR. TILDEN accepted the result with equanimity. “I was at his house,” says John Bigelow,[Pg 20] “when his exclusion was announced to him, and also on the fourth of March when Mr. Hayes was inaugurated, and it was impossible to remark any change in his manner, except perhaps that he was less absorbed than usual and more interested in current affairs.” His was an intensely serious mind; and he had come to regard the Presidency as rather a burden to be borne—an opportunity for public usefulness—involving a life of constant toil and care, than as an occasion for personal exploitation and rejoicing.

However much of captivation the idea of the Presidency may have had for him when he was first named for the office, I cannot say, for he was as unexultant in the moment of victory as he was unsubdued in the hour of defeat; but it is certainly true that he gave no sign of disappointment to any of his friends. He lived nearly ten years longer, at Greystone, in a noble homestead he had purchased for himself overlooking the Hudson River, the same ideal life of the scholar and gentleman that he had passed in Gramercy Park.

Looking back over these untoward and sometimes mystifying events, I have often asked myself: Was it possible, with the elements what they were, and he himself what he was, to seat Mr. Tilden in the office to which he had been elected? The missing ingredient in a character intellectually and morally great, and a personality far from unimpressive, was the touch of the dramatic discoverable in most of the leaders of men: even in such leaders as William of Orange and Louis the XI, as Cromwell and Washington.

There was nothing spectacular about Mr. Tilden. Not wanting the sense of humor, he seldom indulged it. In spite of his positiveness of opinion and amplitude of knowledge, he was always courteous and deferential in debate. He had none of the audacious daring, let us say, of Mr. Blaine, the energetic self-assertion of Mr. Roosevelt. Either, in his place, would have carried all before him.

It would be hard to find a character farther from that of a subtle schemer—sitting behind his screen and pulling his wires—which his political and party enemies discovered him to be as soon as he began to get in the way of the Machine and obstruct the march of the self-elect. His confidences were not effusive nor their subjects numerous. His deliberation was unfailing, and sometimes it carried the idea of indecision, not to say actual love of procrastination. But in my experience with him I found that he usually ended where he began, and it was nowise difficult for those whom he trusted to divine the bias of his mind where he thought it best to reserve its conclusions. I do not think that in any great affair he ever hesitated longer than the gravity of the case required of a prudent man, or that he had a preference for delays, or that he clung over-tenaciously to both horns of the dilemma, as his professional training and instinct might lead him to do, and did certainly expose him to the accusation of doing.

He was a philosopher and took the world as he found it. He rarely complained and never inveighed. He had a discriminating way of balancing men’s good and bad qualities and of giving each the benefit of a generous accounting, and a just way of expecting no more of a man than it was in him to yield. As he got into deeper water his stature rose to its level, and, from his exclusion from the Presidency in 1877 to his renunciation of public affairs in 1884 and his death in 1886, his walks and ways might have been a study for all who would learn life’s truest lessons and know the real sources of honor, happiness, and fame.

BY ALBERT BIGELOW PAINE

Author of “The Bread-Line,” “Elizabeth,” “Mark Twain: A Biography,” etc.

THEN, it being no use to try, Carringford let the hand holding the book drop into his lap and from his lap to his side. His eyes stared grimly into the fire, which was dropping to embers.

“I suppose I’m getting old,” he said; “that’s the reason. The books are as good as ever they were—the old ones, at any rate. Only they don’t interest me any more. It’s because I don’t believe in them as I did. I see through them all. I begin taking them to pieces as soon as I begin to read, and of course romance and glamour won’t stand dissection. Yes, it’s because I’m getting old; that’s it. Those things go with youth. Why, I remember when I would give up a dinner for a new book, when a fresh magazine gave me a positive thrill. I lost that somewhere, somehow; I wonder why. It is a ghastly loss. If I had to live my life over, I would at least try not to destroy my faith in books. It seems to me now just about the one thing worth keeping for old age.”

The book slipped from the hand hanging at his side. The embers broke, and, falling together, sent up a tongue of renewed flame. Carringford’s mind was slipping into by-paths.

“If one only might live his life over!” he muttered. “If one might be young again!”

He was not thinking of books now. A procession of ifs had come filing out of the past—a sequence of opportunities where, with the privilege of choice, he had chosen the wrong, the irrevocable thing.

“If one only might try again!” he whispered. “If one only might! Good God!” Something like a soft footfall on the rug caused him to turn suddenly. “I beg your pardon,” he said, rising, “I did not hear you. I was dreaming, I suppose.”

A man stood before him, apparently a stranger.

“I came quietly,” he said. “I did not wish to break in upon your thought. It interested me, and I felt that I—might be of help.”

Carringford was trying to recall the man’s face,—a studious, clean-shaven face,—to associate it and the black-garbed, slender figure with a name. So many frequented his apartment, congenial, idle fellows who came and went, and brought their friends if they liked, that Carringford was not surprised to be confronted by one he could not place. He was about to extend his hand, confessing a lack of memory, when his visitor spoke again.

“No,” he said in a gentle, composed voice, “you would not know it if you heard it. I have never been here before. I should not have come now only that, as I was passing below, I heard you thinking you would like to be young again—to live your life over, as they say.”

Carringford stared a moment or two at the smooth, clean-cut features and slender, black figure of his visitor before replying. He was used to many curious things, and not many things surprised him.

“I beg your pardon,” he repeated,[Pg 22] “you mentioned, I believe, that you heard me thinking as you were passing on the street below?”

The slender man in black bowed.

“Wishing that you might be young again, that you might have another try at the game of life. I believe that was the exact thought.”

“And, may I ask, is it your habit to hear persons think?”

“When their thoughts interest me, yes, as one might overhear an interesting conversation.”

Carringford had slipped back into his chair and motioned his guest to another. Wizard or unbalanced, he was likely to prove a diversion. When the cigars were pushed in his direction, he took one, lighted it, and smoked silently. Carringford smoked, too, and looked into the fire.

“You were saying,” he began presently, “that you pick up interesting thought-currents as one might overhear bits of conversation. I suppose you find the process quite as simple as hearing in the ordinary way. Only it seems a little—well, unusual. Of course that is only my opinion.”

The slender man in black assented with a slight nod.

“The faculty is not unusual; it is universal. It is only undeveloped, uncontrolled, as yet. It was the same with electricity a generation ago. Now it has become our most useful servant.”

Carringford gave his visitor an intent look. This did not seem the inconsequential phrasing of an addled brain.

“You interest me,” he said. “Of course I have heard a good deal of such things, and all of us have had manifestations; but I think I have never before met any one who was able to control—to demonstrate, if you will—this particular force. It is a sort of mental wireless, I suppose—wordless, if you will permit the term.”

“Yes, the true wireless, the thing we are approaching—speech of mind to mind. Our minds are easily attuned to waves of mutual interest. When one vibrates, another in the same wave will answer to it. We are just musical instruments: a chord struck on the piano answers on the attuned harp. Any strong mutual interest forms the key-note of mental harmonic vibration. We need only develop the mental ear to hear, the mental eye to see.”

The look of weariness returned to Carringford’s face. These were trite, familiar phrases.

“I seem to have heard most of those things before,” he said. Then, as his guest smoked silently, he added, “I am only wondering how it came that my thought of the past and its hopelessness should have struck a chord or key-note which would send you up my stair.”

The slender, black figure rose and took a turn across the room, pausing in front of Carringford.

“You were saying as I passed your door that you would live your life over if you could. You were thinking: ‘If one might be young again! If one only might try again! If only one might!’ That was your thought, I believe.”

Carringford nodded.

“That was my thought,” he said, “through whatever magic you came by it.”

“And may I ask if there was a genuine desire behind that thought? Did you mean that you would indeed live your life over if you could? That, if the opportunity were given to tread the backward way to a new beginning, you would accept it?”

There was an intensity of interest in the man’s quiet voice, an eager gleam in his half-closed eyes, a hovering expectancy in the attitude of the slender, black figure. Carringford had the feeling of having been swept backward into a time of sorcery and incantation. He vaguely wondered if he had not fallen asleep. Well, he would follow the dream through.

“Yes, I would live my life over if I could,” he said. “I have made a poor mess of it this time. I could play the game better, I know, if the Fates would but deal me a new hand. If I could start young again, with all the opportunities of youth, I would not so often choose the poorer thing.”

The long, white fingers of Carringford’s guest had slipped into his waistcoat pocket. They now drew forth a small, bright object and held it to the light. Carringford saw that it was a vial, filled with a clear, golden liquid that shimmered and quivered in the light and was never still. Its possessor regarded it for a moment through half-closed lashes, then placed it on a table under the lamp, where it continued to glint and tremble.

Carringford watched it, fascinated, half hypnotized by the marvel of its gleam. Surely there was magic in this. The man was an alchemist, a sort of reincarnation from some forgotten day.

Carringford’s guest also watched the vial. The room seemed to have grown very still. Then after a time his thin lips parted.

“If you are really willing to admit failure,” he began slowly, carefully selecting each word, “if behind your wish there lies a sincere desire to go back to youth and begin life over, if that desire is strong enough to grow into a purpose, if you are ready to make the experiment, there you will find the means. That vial contains the very essence of vitality, the true elixir of youth. It is not a magic philter, as I see by your thought you believe. There is no magic. Whatever is, belongs to science. I am not a necromancer, but a scientist. From boyhood my study has been to solve the subtler secrets of life. I have solved many such. I have solved at last the secret of life itself. It is contained in that golden vial, an elixir to renew the tissues, to repair the cells, of the wasting body. Taken as I direct, you will no longer grow old, but young. The gray in your hair will vanish, the lines will smooth out of your face, your step will become buoyant, your pulses quick, your heart will sing with youth.” The speaker paused a moment, and his gray eyes rested on Carringford and seemed probing his very soul.

“It will take a little time,” he went on; “for as the natural processes of decay are not rapid, the natural restoration may not be hurried. You can go back to where you will, even to early youth, and so begin over, if it is your wish. Are you willing to make the experiment? If you are, I will place the means in your hands.”

While his visitor had been speaking, Carringford had been completely absorbed, filled with strange emotions, too amazed, too confused for utterance.

“I see a doubt in your mind as to the genuineness, the efficacy, of my discovery,” the even voice continued. “I will relieve that.” From an inner pocket he drew a card photograph and handed it to Carringford. “That was taken three years ago. I was then approaching eighty. I am now, I should say, about forty-five. I could be younger if I chose, but forty-five is the age of achievement—the ripe age. Mankind needs me at forty-five.”

Carringford stared at the photograph, then at the face before him, then again at the photograph. Yes, they were the same, certainly they were the same, but for the difference of years. The peculiar eyes, the clean, unusual outlines were unmistakable. Even a curious cast in the eye was there.

“An inheritance,” explained his visitor. “Is the identification enough?”

Carringford nodded in a dazed way and handed back the picture. Any lingering doubt of the genuineness of this strange being or his science had vanished. His one thought now was that growing old need be no more than a fiction, after all that one might grow young instead, might lay aside the wrinkles and the gray hairs, and walk once more the way of purposes and dreams. His pulses leaped, his blood surged up and smothered him.

The acceptance of such a boon seemed too wonderful a thing to be put into words. His eyes grew wide and deep with the very bigness of it, but he could not for the moment find speech.

“You are willing to make the experiment?” the man asked. “I see many emotions in your mind. Think—think clearly, and make your decision.”

Words of acceptance rushed to Carringford’s lips. They were upon the verge of utterance when suddenly he was gripped by an old and dearly acquired habit—the habit of forethought.

“But I should want to keep my knowledge of the world,” he said, “to profit by my experience, my wisdom, such as it is. I should want to live my life over, knowing what I know now.”

The look of weariness which Carringford’s face had worn earlier had found its way to the face of the visitor.

“I seem to have heard most of those things before,” he said, with a faint smile.

“But shall I not remember the life I have lived, with its shortcomings, its blunders?”

“Yes, you will remember as well as you do now—better, perhaps, for your faculties will be renewed; but whether you will profit by it—that is another matter.”

“You mean that I shall make the same mistakes, commit the same sins?”

“Let us consider to a moment. You will go back to youth. You will be young again. Perhaps you have forgotten what it is to be young. Let me remind you.” The man’s lashes met; his voice seemed to come from a great distance. “It is to be filled with the very ecstasy of living,” he breathed—“its impulses, its fevers, the things that have always belonged to youth, that have always made youth beautiful. Your experience? Yes, you will have that, too; but it will not be the experience of that same youth, but of another—the youth that you were.” The gray eyes gleamed, the voice hardened a little. “Did you ever profit by the experience of another in that earlier time?”

Carringford shook his head.

“No,” he whispered.

His guest pointed to the book-shelves.

“Did you ever, in a later time, profit by the wisdom set down in those?”

Carringford shook his head.

“No,” he whispered.

“Yet the story is all there, and you knew the record to be true. Have you always profited even by your own experience? Have you always avoided the same blunder a second, even a third, time? Do you always profit by your own experience even now?”

Carringford shook his head.

“No,” he whispered.

“And yet you think that if you could only live your life over, you would avoid the pitfalls and the temptations, remembering what they had cost you before. No, oh, no; I am not here to promise you that. I am not a magician; I am only a scientist, and I have not yet discovered the elixir of wisdom or of morals. I am not superhuman; I am only human, like yourself. I am not a god, and I cannot make you one. Going back to youth means that you will be young again—young! Don’t you see? It does not mean that you will drag back with you the strength and the wisdom and the sobered impulses of middle age. That would not be youth. Youth cares nothing for such things, and profits by no experience, not even its own.”