CONTENTS

I. The Great Hanlon

II. A Trip To Newark

III. The Stunt

IV. The Emburys

V. The Explanation

VI. A Slammed Door

VII. A Vision

VIII. The Examiner

IX. Hamlet

X. A Confession

XI. Fifi

XII. In Hanlon’s Office

XIII. Fleming Stone

XIV. The Five Senses

XV. Marigny The Medium

XVI. Fibsy’s Busy Day

XVII. Hanlon’s Ambition

XVIII. The Guilty One

“You may contradict me as flat as a flounder, Eunice, but that won’t alter the facts. There is something in telepathy—there is something in mind-reading—”

“If you could read my mind, Aunt Abby, you’d drop that subject. For if you keep on, I may say what I think, and—”

“Oh, that won’t bother me in the least. I know what you think, but your thoughts are so chaotic—so ignorant of the whole matter—that they are worthless. Now, listen to this from the paper: ‘Hanlon will walk blindfolded—blindfolded, mind you—through the streets of Newark, and will find an article hidden by a representative of The Free Press.’ Of course, you know, Eunice, the newspaper people are on the square—why, there’d be no sense to the whole thing otherwise! I saw an exhibition once, you were a little girl then; I remember you flew into such a rage because you couldn’t go. Well, where was I? Let me see—oh, yes—’Hanlon—’ H’m—h’m—why, my goodness! it’s to-morrow! How I do want to go! Do you suppose Sanford would take us?”

“I do not, unless he loses his mind first. Aunt Abby, you’re crazy! What is the thing, anyway? Some common street show?”

“If you’d listen, Eunice, and pay a little attention, you might know what I’m talking about. But as soon as I say telepathy you begin to laugh and make fun of it all!”

“I haven’t heard anything yet to make fun of. What’s it all about?”

But as she spoke, Eunice Embury was moving about the room, the big living-room of their Park Avenue apartment, and in a preoccupied way was patting her household gods on their shoulders. A readjustment of the pink carnations in a tall glass vase, a turning round of a long-stemmed rose in a silver holder, a punch here and there to the pillows of the davenport and at last dropping down on her desk chair as a hovering butterfly settles on a chosen flower.

A moment more and she was engrossed in some letters, and Aunt Abby sighed resignedly, quite hopeless now of interesting her niece in her project.

“All the same, I’m going,” she remarked, nodding her head at the back of the graceful figure sitting at the desk. “Newark isn’t so far away; I could go alone—or maybe take Maggie—she’d love it—’Start from the Oberon Theatre—at 2 P.M.—’ ‘H’m, I could have an early lunch and—’hidden in any part of the city—only mentally directed—not a word spoken—’ Just think of that, Eunice! It doesn’t seem credible that—oh, my goodness! tomorrow is Red Cross day! Well, I can’t help it; such a chance as this doesn’t happen twice. I wish I could coax Sanford—”

“You can’t,” murmured Eunice, without looking up from her writing.

“Then I’ll go alone!” Aunt Abby spoke with spirit, and her bright black eyes snapped with determination as she nodded her white head. “You can’t monopolize the willpower of the whole family, Eunice Embury!”

“I don’t want to! But I can have a voice in the matters of my own house and family yes, and guests! I can’t spare Maggie to-morrow. You well know Sanford won’t go on any such wild goose chase with you, and I’m sure I won’t. You can’t go alone—and anyway, the whole thing is bosh and nonsense. Let me hear no more of it!”

Eunice picked up her pen, but she cast a sidelong glance at her aunt to see if she accepted the situation.

She did not. Miss Abby Ames was a lady of decision, and she had one hobby, for the pursuit of which she would attempt to overcome any obstacle.

“You needn’t hear any more of it, Eunice,” she said, curtly. “I am not a child to be allowed out or kept at home! I shall go to Newark to-morrow to see this performance, and I shall go alone, and—”

“You’ll do nothing of the sort! You’d look nice starting off alone on a railroad trip! Why, I don’t believe you’ve ever been to Newark in your life! Nobody has! It isn’t done!”

Eunice was half whimsical, half angry, but her stormy eyes presaged combat and her rising color indicated decided annoyance.

“Done!” cried her aunt. “Conventions mean nothing to me! Abby Ames makes social laws—she does not obey those made by others!”

“You can’t do that in New York, Aunt Abby. In your old Boston, perhaps you had a certain dictatorship, but it won’t do here. Moreover, I have rights as your hostess, and I forbid you to go skylarking about by yourself.”

“You amuse me, Eunice!”

“I had no intention of being funny, I assure you.”

“While not distinctly humorous, the idea of your forbidding me is, well—oh, my gracious, Eunice, listen to this: ‘The man chosen for Hanlon’s “guide” is the Hon. James L. Mortimer—’—h’m—’High Street—’ Why, Eunice, I’ve heard of Mortimer—he’s—”

“I don’t care who he is, Aunt Abby, and I wish you’d drop the subject.”

“I won’t drop it—it’s too interesting! Oh, my! I wish we could go out there in the big car—then we could follow him round—”

“Hush! Go out to Newark in the car! Trail round the streets and alleys after a fool mountebank! With a horde of gamins and low, horrid men crowding about—”

“They won’t be allowed to crowd about!”

“And yelling—”

“I admit the yelling—”

“Aunt Abby, you’re impossible!” Eunice rose, and scowled irately at her aunt. Her temper, always quick, was at times ungovernable, and was oftenest roused at the suggestion of any topic or proceeding that jarred on her taste. Exclusive to the point of absurdity, fastidious in all her ways, Mrs. Embury was, so far as possible, in the world but not of it.

Both she and her husband rejoiced in the smallness of their friendly circle, and shrank from any unnecessary association with hoi polloi.

And Aunt Abby Ames, their not entirely welcome guest, was of a different nature, and possessed of another scale of standards. Secure in her New England aristocracy, calmly conscious of her innate refinement, she permitted herself any lapses from conventional laws that recommended themselves to her inclination.

And it cannot be denied that the investigation of her pet subject, the satisfaction of her curiosity concerning occult matters and her diligent inquiries into the mysteries of the supernatural did lead her into places and scenes not at all in harmony with Eunice’s ideas of propriety.

“Not another word of that rubbish, Auntie; the subject is taboo,” and Eunice waved her hand with the air of one who dismisses a matter completely.

“Don’t you think you can come any of your high and mighty airs on me!” retorted the elder lady. “It doesn’t seem so very many years ago that I spanked you and shut you in the closet for impudence. The fact that you are now Mrs. Sanford Embury instead of little Eunice Ames hasn’t changed my attitude toward you!”

“Oh, Auntie, you are too ridiculous!” and Eunice laughed outright. “But the tables are turned, and I am not only Mrs. Sanford Embury but your hostess, and, as such, entitled to your polite regard for my wishes.”

“Tomfoolery talk, my dear; I’ll give you all the polite regard you are entitled to, but I shall carry out my own wishes, even though they run contrary to yours. And to-morrow I prance out to Newark, N.J., your orders to the contrary notwithstanding!”

The aristocratic old head went up and the aristocratic old nose sniffed disdainfully, for though Eunice Embury was strong-willed, her aunt was equally so, and in a clash of opinions Miss Ames not infrequently won out.

Eunice didn’t sulk, that was not her nature; she turned back to her writing desk with an offended air, but with a smile as of one who tolerates the vagaries of an inferior. This, she knew, would irritate her aunt more than further words could do.

And yet, Eunice Embury was neither mean nor spiteful of disposition. She had a furious temper, but she tried hard to control it, and when it did break loose, the spasm was but of short duration and she was sorry for it afterward. Her husband declared he had tamed her, and that since her marriage, about two years ago, his wise, calm influence had curbed her tendency to fly into a rage and had made her far more equable and placid of disposition.

His methods had been drastic—somewhat like those of Petruchio toward Katherine. When his wife grew angry, Sanford Embury grew more so and by harder words and more scathing sarcasms he—as he expressed it—took the wind out of her sails and rendered her helplessly vanquished.

And yet they were a congenial pair. Their tastes were similar; they liked the same people, the same books, the same plays. Eunice approved of Sanford’s correct ways and perfect intuitions and he admired her beauty and dainty grace.

Neither of them loved Aunt Abby—the sister of Eunice’s father—but her annual visit was customary and unavoidable.

The city apartment of the Sanfords had no guestroom, and therefore the visitor must needs occupy Eunice’s charming boudoir and dressing-room as a bedroom. This inconvenienced the Emburys, but they put up with it perforce.

Nor would they have so disliked to entertain the old lady had it not been for her predilection for occult matters. Her visit to their home coincided with her course of Clairvoyant Sittings and her class of Psychic Development.

These took place at houses in undesirable, sometimes unsavory localities and only Aunt Abby’s immovable determination made it possible for her to attend.

A large text-book, “The Voice of the Future,” was her inseparable companion, and one of her chief, though, as yet, unfulfilled, desires was to have a Reading given at the Embury home by the Swami Ramananda.

Eunice, by dint of stern disapproval, and Sanford, by his good-natured chaffing and ridicule had so far prevented this calamity, but both feared that Aunt Abby might yet outwit them and have her coveted séance after all.

Outside of this phase of her character, Miss Ames was not an undesirable guest. She had a good sense of humor, a kind and generous heart and was both perceptive and responsive in matters of household interest.

Owing to the early death of Eunice’s mother, Aunt Abby had brought up the child, and had done her duty by her as she saw it.

It was after Eunice had married that Miss Ames became interested in mystics and with a few of her friends in Boston had formed a circle for the pursuance of the cult.

Her life had otherwise been empty, indeed, for the girl had given her occupation a-plenty, and that removed, Miss Abby felt a vague want of interest.

Eunice Ames had not been easy to manage. Nor was Miss Abby Ames the best one to be her manager.

The girl was headstrong and wilful, yet possessed of such winsome, persuasive wiles that she twisted her aunt round her finger.

Then, too, her quick temper served as a rod and many times Miss Ames indulged the girl against her better judgment lest an unpleasant explosion of wrath should occur and shake her nervous system to its foundation. So Eunice grew up, an uncurbed, untamed, self-willed and self-reliant girl, making up her quarrels as fast as she picked them and winning friends everywhere in spite of her sharp tongue.

And so, on this occasion, neither of the combatants held rancor more than a few minutes. Eunice went on writing letters and Miss Abby went on reading her paper, until at five o’clock, Ferdinand the butler brought in the tea-things.

“Goody!” cried Eunice, jumping up. “I do want some tea, don’t you, Aunty?”

“Yes,” and Miss Ames crossed the room to sit beside her. “And I’ve an idea, Eunice; I’ll take Ferdinand with me to-morrow!”

The butler, who was also Embury’s valet and a general household steward, looked up quickly. He had been in Miss Ames’ employ for many years before Eunice’s marriage, and now, in the Embury’s city home was the indispensable major-domo of the establishment.

“Yes,” went on Aunt Abby, “that will make it all quite circumspect and correct. Ferdinand, tomorrow you accompany me to Newark, New Jersey.”

“I think not,” said Eunice quietly, and dismissing Ferdinand with a nod, she began serenely to make the tea.

“Don’t be silly, Aunt Abby,” she said; “you can’t go that way. It would be all right to go with Ferdinand, of course, but what could you do when you reached Newark? Race about on foot, following up this clown, or whoever is performing?”

“We could take a taxicab—”

“You might get one and you might not. Now, you will wait till San comes home, and see if he’ll let you have the big car.”

“Will you go then, Eunice?”

“No; of course not. I don’t go to such fool shows! There’s the door! Sanford’s coming.”

A step was heard in the hall, a cheery voice spoke to Ferdinand as he took his master’s coat and hat and then a big man entered the living-room.

“Hello, girls,” he said, gaily; “how’s things?”

He kissed Eunice, shook Aunt Abby’s hand and dropped into an easy chair.

“Things are whizzing,” he said, as he took the cup Eunice poured for him. “I’ve just come from the Club, and our outlook is rosy-posy. Old Hendricks is going to get, badly left.”

“It’s all safe for you, then, is it?” and Eunice smiled radiantly at her husband.

“Right as rain! The prize-fights did it! They upset old Hendrick’s apple-cart and spilled his beans. Lots of them object to the fights because of the expense—fighters are a high-priced bunch—but I’m down on them because I think it bad form—”

“I should say so!” put in Eunice, emphatically.

“Bad form for an Athletic Club of gentlemen to have brutal exhibitions for their entertainment.”

“And what about the Motion-Picture Theatre?”

“The same there! Frightful expense,—and also rotten taste! No, the Metropolitan Athletic Club can’t stoop to such entertainments. If it were a worth-while little playhouse, now, and if they had a high class of performances, that would be another story. Hey, Aunt Abby? What do you think?”

“I don’t know, Sanford, you know I’m ignorant on such matters. But I want to ask you something. Have you read the paper to-day?”

“Why, yes, being a normal American citizen, I did run through the Battle-Ax of Freedom. Why?”

“Did you read about Hanlon—the great Hanlon?”

“Musician, statesman or criminal? I can’t seem to place a really great Hanlon. By the way, Eunice, if Hendricks blows in, ask him to stay to dinner, will you? I want to talk to him, but I don’t want to seem unduly anxious for his company.”

“Very well,” and Eunice smiled; “if I can persuade him, I will.”

“If you can!” exclaimed Miss Abby, her sarcasm entirely unveiled. “Alvord Hendricks would walk the plank if you invited him to do so!”

“Who wouldn’t?” laughed Embury. “I have the same confidence in my wife’s powers of persuasion that you seem to have, Aunt Abby; and though I may impose on her, I do want her to use them upon me deadly r-rival!”

“You mean rival in your club election,” returned Miss Ames, “but he is also your rival in another way.”

“Don’t speak so cryptically, Aunt, dear. We all know of his infatuation for Eunice, but he’s only one of many. Think you he is more dangerous than, say, friend Elliott?”

“Mason Elliott? Oh, of course, he has been an admirer of Eunice since they made mud-pies together.”

“That’s two, then,” Embury laughed lightly. “And Jim Craft is three and Halliwell James is four and Guy Little—”

“Oh, don’t include him, I beg of you!” cried Eunice; “he flats when he sings!”

“Well, I could round up a round dozen, who would willingly cast sheeps’ eyes at my wife, but—well, they don’t!”

“They’d better not,” laughed Eunice, and Embury added, “Not if I see them first!”

“Isn’t it funny,” said Aunt Abby, reminiscently, “that Eunice did choose you out of that Cambridge bunch.”

“I chose her,” corrected Embury, “and don’t take that wrong! I mean that I swooped down and carried her off under their very noses! Didn’t I, Firebrand?”

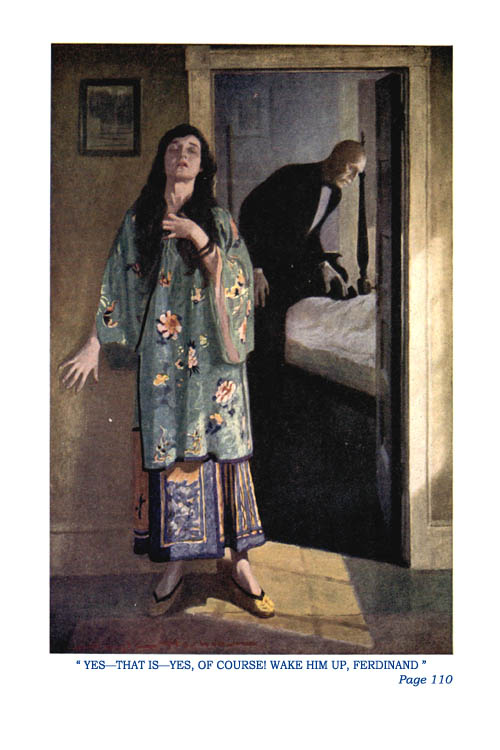

“The only way you could get me,” agreed Eunice, saucily.

“Oh, I don’t know!” and Embury smiled. “You weren’t so desperately opposed.”

“No; but she was undecided,” said Aunt Abby; “why, for weeks before your engagement was announced, Eunice couldn’t make up her mind for certain. There was Mason Elliott and Al Hendricks, both as determined as you were.”

“I know it, Aunt. Good Lord, I guess I knew those boys all my life, and I knew all their love affairs as well as they knew all mine.”

“You had others, then?” and Eunice opened her brown eyes in mock amazement.

“Rather! How could I know you were the dearest girl in the world if I had no one to compare you with?”

“Well, then I had a right to have other beaux.”

“Of course you did! I never objected. But now, you’re my wife, and though all the men in Christendom may admire you, you are not to give one of them a glance that belongs to me.”

“No, sir; I won’t,” and Eunice’s long lashes dropped on her cheeks as she assumed an absurdly overdone meekness.

“I was surprised, though,” pursued Aunt Abby, still reminiscent, “when Eunice married you, Sanford. Mr. Mason is so much more intellectual and Mr. Hendricks so much better looking.”

“Thank you, lady!” and Embury bowed gravely. “But you see, I have that—er—indescribable charm—that nobody can resist.”

“You have, you rascal!” and Miss Ames beamed on him. “And I think this a favorable moment to ask a favor of your Royal Highness.”

“Out with it. I’ll grant it, to the half of my kingdom, but don’t dip into the other half.”

“Well, it’s a simple little favor, after all. I want to go out to Newark to-morrow in the big car—”

“Newark, New Jersey?”

“Is there any other?”

“Yep; Ohio.”

“Well, the New Jersey one will do me, this time. Oh, Sanford, do let me go! A man is going to will another man—blindfolded, you know—to find a thingumbob that he hid—nobody knows where—and he can’t see a thing, and he doesn’t know anybody and the guide man is Mr. Mortimer—don’t you remember, his mother used to live in Cambridge? she was an Emmins—well, anyway, it’s the most marvelous exhibition of thought transference, or mind-reading, that has ever been shown—and I must go. Do let me?—please, Sanford!”

“My Lord, Aunt Abby, you’ve got me all mixed up! I remember the Mortimer boy, but what’s he doing blindfolded?”

“No; it’s the Hanlon man who’s blindfolded, and I can go with Ferdinand—and—”

“Go with Ferdinand! Is it a servants’ ball—or what?”

“No, no; oh, if you’d only listen, Sanford!”

“Well, I will, in a minute, Aunt Abby. But wait till I tell Eunice something. You see, dear, if Hendricks does show up, I can pump him judiciously and find out where the Meredith brothers stand. Then—”

“All right, San, I’ll see that he stays. Now do settle Aunt Abby on this crazy scheme of hers. She doesn’t want to go to Newark at all—”

“I do, I do!” cried the old lady.

“Between you and me, Eunice, I believe she does want to go,” and Embury chuckled. “Where’s the paper, Aunt? Let me see what it’s all about.”

“‘A Fair Test,’“ he read aloud. “‘Positive evidence for or against the theory of thought transference. The mysterious Hanlon to perform a seeming miracle. Sponsored by the Editor of the Newark Free Press, assisted by the prominent citizen, James L. Mortimer, done in broad daylight in the sight of crowds of people, tomorrow’s performance will be a revelation to doubters or a triumph indeed for those who believe in telepathy.’ H’m—h’m—but what’s he going to do?”

“Read on, read on, Sanford,” cried Aunt Abby, excitedly.

“‘Starting from the Oberon Theatre at two o’clock, Hanlon will undertake to find a penknife, previously hidden in a distant part of the city, its whereabouts known only to the Editor of the Free Press and to Mr. Mortimer. Hanlon is to be blindfolded by a committee of citizens and is to be followed, not preceded by Mr. Mortimer, who is to will Hanlon in the right direction, and to “guide” him merely by mental will-power. There is to be no word spoken between these two men, no personal contact, and no possibility of a confederate or trickery of any sort.

“ ‘Mr. Mortimer is not a psychic; indeed, he is not a student of the occult or even a believer in telepathy, but he has promised to obey the conditions laid down for him. These are merely and only that he is to follow Hanlon, keeping a few steps behind him, and mentally will the blindfolded man to go in the right direction to find the hidden knife.’ ”

“Isn’t it wonderful, Sanford,” breathed Miss Abby, her eyes shining with the delight of the mystery.

“Poppycock!” and Embury smiled at her as a gullible child. “You don’t mean to say, aunt, that you believe there is no trickery about this!”

“But how can there be? You know, Sanford, it’s easy enough to say ‘poppycock’ and ‘fiddle-dee-dee!’ and ‘gammon’ and ‘spinach!’ But just tell me how it’s done—how it can be done by trickery? Suggest a means however complicated or difficult—”

“Oh, of course, I can’t. I’m no charlatan or prestidigitateur! But you know as well as I do, that the thing is a trick—”

“I don’t! And anyway, that isn’t the point. I want to go to see it. I’m not asking your opinion of the performance, I’m asking you to let me go. May I?”

“No, indeed! Why, Aunt Abby, it will be a terrible crowd—a horde of ragamuffins and ruffians. You’d be torn to pieces—”

“But I want to, Sanford,” and the old lady was on the verge of tears. “I want to see Hanlon—”

“Hanlon! Who wants to see Hanlon?”

The expected Hendricks came into the room, and shaking hands as he talked, he repeated his question: “Who wants to see Hanlon? Because I do, and I’ll take any one here who is interested.”

“Oh, you angel man!” exclaimed Aunt Abby, her face beaming. “I want to go! Will you really take me, Alvord?”

“Sure I will! Anybody else? You want to see it, Eunice?”

“Why, I didn’t, but as Sanford just read it, it sounded interesting. How would we go?”

“I’ll run you out in my touring car. It won’t take more’n the afternoon, and it’ll be a jolly picnic. Go along, San?”

“No, not on your life! When did you go foolish, Alvord?”

“Oh, I always had a notion toward that sort of thing. I want to see how he does it. Don’t think I fall for the telepathy gag, but I want to see where the little joker is,—and then, too, I’m glad to please the ladies.”

“I’ll go,” said Eunice; “that is, if you’ll stay and dine now—and we can talk it over and plan the trip.”

“With all the pleasure in life,” returned Hendricks.

Perhaps no factor is more indicative of the type of a home life than its breakfast atmosphere. For, in America, it is only a small proportion, even among the wealthy who ‘breakfast in their rooms.’ And a knowledge of the appointments and customs of the breakfast are often data enough to stamp the status of the household.

In the Embury home, breakfast was a pleasant send-off for the day. Both Sanford and Eunice were of the sort who wake up wide-awake, and their appearance in the dining-room was always an occasion of merry banter and a leisurely enjoyment of the meal. Aunt Abby, too, was at her best in the morning, and breakfast was served sufficiently early to do away with any need for hurry on Sanford’s part.

The morning paper, save for its headlines, was not a component part of the routine, and it was an exceptionally interesting topic that caused it to be unfolded.

This morning, however, Miss Ames reached the dining-room before the others and eagerly scanned the pages for some further notes of the affair in Newark.

But with the total depravity of inanimate things and with the invariable disappointingness of a newspaper, the columns offered no other information than a mere announcement of the coming event.

“Hunting for details of your wild-goose chase?” asked Embury, as he paused on the way to his own chair to lean over Aunt Abby’s shoulder.

“Yes, and there’s almost nothing! Why do you take this paper?”

“You’ll see it all to-day, so why do you want to read about it?” laughed a gay voice, and Eunice came in, all fluttering chiffon and ribbon ends.

She took the chair Ferdinand placed for her, and picked up a spoon as the attentive man set grapefruit at her plate. The waitress was allowed to serve the others, but Ferdinand reserved to himself the privilege of waiting on his beloved mistress.

“Still of a mind to go?” she said, smiling at her aunt.

“More than ever! It’s a perfectly heavenly day, and we’ll have a good ride, if nothing more.”

“Good ride!” chaffed Embury. “Don’t you fool yourself, Aunt Abby! The ride from this burg to Newark, N.J., is just about the most Godforsaken bit of scenery you ever passed through!”

“I don’t mind that. Al Hendricks is good company, and, any way, I’d go through fire and water to see that Hanlon show. Eunice, can’t you and Mr. Hendricks pick me up? I want to go to my Psychic Class this morning, and there’s no use coming way back here again.”

“Yes, certainly; we’re going about noon, you know, and have lunch in Newark.”

“In Newark!” and Embury looked his amazement.

“Yes; Alvord said so last night. He says that new hotel there is quite all right. We’ll only have time for a bite, anyway.”

“Well, bite where you like. By the way, my Tiger girl, you didn’t get that information from our friend last evening.”

“No, San, I couldn’t, without making it too pointed. I thought I could bring it in more casually to-day—say, at luncheon.”

“Yes; that’s good. But find out, Eunice, just where the Merediths stand. They may swing the whole vote.”

“What vote?” asked Aunt Abby, who was interested in everything.

“Our club, Auntie,” and Embury explained. “You know Hendricks is president—has been for years—and we’re trying to oust him in favor of yours truly.”

“You, Sanford! Do you mean you want to put him out and put yourself in his place?”

“Exactly that, my lady.”

“But-how queer! Does he know it?”

“Rather! Yes—even on calm second thought, I should say Hendricks knows it!”

“But I shouldn’t think you two would be friends in such circumstances.”

“That’s the beauty of it, ma’am; we’re bosom friends, as you know; and yet, we’re fighting for that presidency like two cats of Kilkenny.”

“The New York Athletic Club, is it?”

“Oh, no, ma’am! Not so, but far otherwise. The Metropolitan Athletic Club if you please.”

“Yes, I know—I’d forgotten the name.”

“Don’t mix up the two—they’re deadly rivals.”

“Why do you want to be president, Sanford?”

“That’s a long tale, but in a nutshell, purely and solely for the good of the club.”

“And that’s the truth,” declared Eunice. “Sanford is getting himself disliked in some quarters, influential ones, too, and he’s making life-long enemies—not Alvord, but others—and it is all because he has the real interests of the club at heart. Al Hendricks is running it into—into a mud-puddle! Isn’t he, San?”

“Well, yes, though I shouldn’t have thought of using that word. But, he is bringing its gray hairs in sorrow to the grave—or will, if he remains in office, instead of turning it over to a well-balanced man of good judgment and unerring taste—say, like one Sanford Embury.”

“You certainly are not afflicted with false pride, Sanford,” and Aunt Abby bit into her crisp toast with a decided snap.

“Why, thank you,” and Embury smiled as he purposely misinterpreted her words. “I quite agree, Aunt, that my pride is by no means false. It is a just and righteous pride in my own merits, both natural and acquired.”

He winked at Eunice across the table, and she smiled back appreciatively. Aunt Abby gave him what was meant to be a scathing glance, but which turned to a nod of admiration.

“That’s so, Sanford,” she admitted. “Al Hendricks is a nice man, but he falls down on some things. Hasn’t he been a good president?”

“Until lately, Aunt Abby. Now, he’s all mixed up with a crowd of intractables—sporty chaps, who want a lot of innovations that the more conservative element won’t stand for.”

“Why, they want prize-fights and a movie theatre-right in the club!” informed Eunice. “And it means too much expense, besides being a horrid, low-down—”

“There, there, Tiger,” and Sanford shook his head at her. “Let us say those things are unpalatable to a lot of us old fogies—”

“Stop! I won’t have you call yourself old—or fogyish, either! You’re the farthest possible removed from that! Why, you’re no older than Al Hendricks.”

“You were all children together,” said Aunt Abby, as if imparting a bit of new information; “you three, and Mason Elliott. Why, when you were ten or eleven, Eunice, those three boys were eternally camping out in the front yard, waiting for you to get your hair curled and go out to play. And later, they all hung around to take you to parties, and then, later still—not so much later, either—they all wanted to marry you.”

“Why, Auntie, you’re telling the ‘whole story of my life and what’s my real name!’—Sanford knows all this, and knows that he cut out the other two—though I’m not saying they wanted to marry me.”

“It goes without saying,” and her husband gave her a gallant bow. “But, great heavens, Eunice, if you’d married those other two—I mean one of ‘em—either one—you’d have been decidedly out of your element. Hendricks, though a bully chap, is a man of impossible tastes, and Elliott is a prig—pure and simple! I, you see, strike a happy medium. And, speaking of such things, are your mediums always happy, Aunt Abby?”

“How you do rattle on, Sanford! A true medium is so absorbed in her endeavors, so wrapped up in her work, she is, of course, happy—I suppose. I never thought about it.”

“Well, don’t go out of your way to find out. It isn’t of vital importance that I should know. May I be excused, Madam Wife? I’m called to the busy marts—and all that sort of thing.” Embury rose from the table, a big, tall man, graceful in his every motion, as only a trained athlete can be. Devoted to athletics, he kept himself in the pink of condition physically, and this was no small aid to his vigorous mentality and splendid business acumen.

“Wait a minute, San,” and for the first time that morning there was a note of timidity in Eunice’s soft voice. “Please give me a little money, won’t you?”

“Money, you grasping young person! What do you want it for?”

“Why—I’m going to Newark, you know—”

“Going to Newark! Yes, but you’re going in Hendricks’ car—that doesn’t require a ticket, does it?”

“No—but I—I might want to give the chauffeur something when I get out—”

“Nonsense! Not Hendricks’ chauffeur. That’s all right when you’re with formal friends or Comparative strangers—but it would be ridiculous to tip Hendricks’ Gus!”

Embury swung into the light topcoat held by the faithful Ferdinand.

“But, dear,” and Eunice rose, and stood by her husband, “I do want a little money,” she fingered nervously the breakfast napkin she was still holding.

“What for?” was the repeated inquiry.

“Oh, you see—I might want to do a little shopping in Newark.”

“Shop in Newark! That’s a good one! Why, girlie, you never want to shop outside of little old New York, and you know it. Shop in Newark!”

Embury laughed at the very idea.

“But—I might see something in a window that’s just what I want.”

“Then make a note of it, and buy it in New York. You have an account at all the desirable shops here, and I never kick at the bills, do I, now?”

“No; but a woman does want a little cash with her—”

“Oh, that, of course! I quite subscribe to that. But I gave you a couple of dollars yesterday.”

“Yes, but I gave one to a Red Cross collector, and the other I had to pay out for a C.O.D. charge.”

“Why buy things C.O.D. when you have accounts everywhere?”

“Oh, this was something I saw advertised in the evening paper—”

“And you bought it because it was cheap! Oh, you women! Now, Eunice, that’s just a case in point. I want my wife to have everything she wants—everything in reason, but there’s no sense in throwing money away. Now, kiss me, sweetheart, for I’m due at a directors’ meeting in two shakes—or thereabouts.”

Embury snapped the fastening of his second glove, and, hat in hand, held out his arms to his wife.

She made one more appeal.

“You’re quite right, San, maybe I didn’t need that C.O.D. thing. But I do want a little chickenfeed in my purse when I go out to-day. Maybe they’ll take up a collection.”

“A silver offering for the Old Ladies’ Home,—eh? Well, tell ‘em to come to me and I’ll sign their subscription paper! Now, good-by, Dolly Gray! I’m off!”

With a hearty kiss on Eunice’s red lips, and a gay wave of his hand to Aunt Abby, Embury went away and Ferdinand closed the door behind him.

“I can’t stand it, Aunt Abby,” Eunice exclaimed, as the butler disappeared into the pantry; “if Sanford were a poor man it would be different. But he’s made more money this year than ever before, and yet, he won’t give me an allowance or even a little bit of ready money.”

“But you have accounts,” Aunt Abby said, absently, for she-was scanning the paper now.

“Accounts! Of course, I have! But there are a thousand things one wants cash for! You know that perfectly well. Why, when our car was out of commission last week and I had to use a taxicab, Sanford would give me just enough for the fare and not a cent over to fee the driver. And lots of times I need a few dollars for charities, or some odds and ends, and I can’t have a cent to call my own! Al Hendricks may be of coarser clay than Sanford Embury, but he wouldn’ treat a wife like that!”

“It is annoying, Eunice, but Sanford is so good to you—”

“Good to me! Why shouldn’t he be? It isn’t a question of goodness or of generosity—it’s just a fool whim of his, that I mustn’t ask for actual cash! I can have all the parties I want, buy all the clothes I want, get expensive hats or knick-knacks of any sort, and have them all charged. He’s never even questioned my bills—but has his secretary pay them. And I must have some money in my purse! And I will! I know ways to get it, without begging it from Sanford Embury!”

Eunice’s dark eyes flashed fire, and her cheeks burned scarlet, for she was furiously angry.

“Now, now, my dear, don’t take it so to heart,” soothed Aunt Abby; “I’ll give you some money. I was going to make you a present, but if you’d rather have the money that it would cost, say so.”

“I daren’t, Aunt Abby. Sanford would find it out and he’d be terribly annoyed. It’s one of his idiosyncrasies, and I have to bear it as long as I live with him!”

The gleam in the beautiful eyes gave a hint of desperate remedies that might be applied to the case, but Ferdinand returned to the room, and the two women quickly spoke of other things.

Hendricks’ perfectly appointed and smooth-running car made the trip to Newark in minimum time. Though the road was not a picturesque one, the party was in gay spirits and the host was indefatigable in his efforts to be entertaining.

“I’ve looked up this Hanlon person,” he said, “and his record is astonishing. I mean, he does astonishing feats. He’s a juggler, a sword swallower and a card sharp—that is, a card wizard. Of course, he’s a faker, but he’s a clever one, and I’m anxious to see what his game is this time. Of course, it’s, first of all, advertisement for the paper that’s backing him, but it’s a new game. At least, it’s new over here; they tell me it’s done to death in England.”

“Oh, no, Alvord, it isn’t a game,” insisted Miss Ames; “if the man is blindfolded, he can’t play any tricks on us. And he couldn’t play tricks on newspaper men anyway—they’re too bright for that!”

“I think they are, too; that’s why I’m interested. Warm enough, Eunice?”

“Yes, thank you,” and the beautiful face looked happily content as Eunice Embury nestled her chin deeper into her fur collar.

For, though late April, the day was crisply cool and there was a tang in the bright sunshiny air. Aunt Abby was almost as warmly wrapped up as in midwinter, and when, on reaching Newark, they encountered a raw East wind, she shrugged into her coat like a shivering Esquimau.

“Where do we go to see it?” asked Eunice, as later, after luncheon, she eagerly looked about at the crowds massed everywhere.

“We’ll have to reconnoiter,” Hendricks replied, smiling at her animated face. “Drive on to the Oberon, Gus.”

As they neared the theatre the surging waves of humanity barred their progress, and the big car was forced to come to a standstill.

“I’ll get out,” said Hendricks, “and make a few inquiries. The Free Press office is near here, and I know some of the people there.”

He strode off and was soon swallowed up in the crowd.

“I think I see a good opening,” said Gus, after a moment. “I’ll get out for a minute, Mrs. Embury. I must inquire where cars can be parked.”

“Go ahead, Gus,” said Eunice; “we’ll be all right here, but don’t go far. I’ll be nervous if you do.”

“No, ma’am; I won’t go a dozen steps.”

“Extry! Extry! All about the Great Magic! Hanlon the Wonderful and his Big Stunt! Extry!”

“Oh, get a paper, Eunice, do,” urged Aunt Abby from the depths of her fur coat. “Ask that boy for one! I must have it to read after I get home—I can’t look at it now, but get it! Here, you—Boy—say, Boy!”

The newsboy came running to them and flung a paper into Eunice’s lap.

“There y’are, lady,” he said, grinning; “there’s yer paper! Gimme a nickel, can’t yer? I ain’t got time hangin’ on me hands!”

His big black eyes stared at Eunice, as she made no move toward a purse, and he growled: “Hurry up lady; I gotta sell some papers yet. Think nobuddy wants one but you?”

Eunice flushed with annoyance.

“Please pay him, Aunt Abby,” she said, in a low voice; “I—haven’t any money.”

“Goodness gracious me! Haven’t five cents! Why, Eunice, you must have!”

“But I haven’t, I tell you! I can’t see Alvord, and Gus is too far to call to. Go over there, boy, to that chauffeur with the leather coat—he’ll pay you.”

“No, thanky mum! I’ve had that dodge tried afore! Pity a grand dame like you can’t scare up a nickel! Want to work a poor newsie! Shame for ya, lady!”

“Hush your impudence, you little wretch!” cried Aunt Abby. “Here, Eunice, help me get my purse. It’s in my inside coat pocket—under the rug—there, see if you can reach it now.”

Aunt Abby tried to extricate herself from the motor rug that had been tucked all too securely about her, and failing in that, endeavored to reach into her pocket with her gloved hand, and became hopelessly entangled in a mass of fur, chiffon scarf and eyeglass chain.

“I can’t get at my purse, Eunice; there’s no use trying,” she wailed, despairingly. “Let us have the paper, my boy, and come back here when the owner of this car comes and he’ll give you a quarter.”

“Yes—he will!” shouted the lad, “and he’ll give me a di’mon’ pin an’ a gold watch! I’d come back, willin’ enough, but me root lays the other way, an’ I must be scootin’ or I’ll miss the hull show. Sorry!” The boy, who had no trouble in finding customers for his papers, picked up the one he had laid on Eunice’s lap and made off.

“Never mind, Auntie,” she said, “we’ll get another. It’s too provoking—but I haven’t a cent, and I don’t blame the boy. Now, find your purse—or, never mind; here comes Alvord.”

“Just fell over Mortimer!” called out Hendricks as the two men came to the side of the car. “I made him come and speak to you ladies, though I believe its holding up the whole performance. Let me present the god in the machine!”

“Not that,” said Mr. Mortimer, smiling; “only a small mechanical part of to-day’s doings. I’ve a few minutes to spare, though but a few. How do you do, Miss Ames? Glad to see you again. And Mrs. Embury; this brings back childhood days!”

“Tell me about Hanlon,” begged Miss Ames. “Is he on the square?”

“So far as I know, and I know all there is to know, I think. I was present at a preliminary test this morning, and I’ll tell you what he did.” Mortimer looked at his watch and proceeded quickly. “In at the Free Press office one of the men took a piece of chalk and drew a line from where we were to a distant room of the building. The line went up and down stairs, in and out of various rooms, over chairs and under desks, and finally wound up in a small closet in the city editor’s office. Well—and I must jump away now—that wizard, Hanlon, being securely blindfolded—I did it myself—followed that line, almost without deviation, from start to finish. Through a building he had never seen before, and groping along in complete darkness.”

“How in the world could he do it?” Aunt Abby asked, breathlessly.

“The chap who drew the line was behind him—behind, mind you—and he willed him where to go. Of course, he did his best, kept his mind on the job, and earnestly used his mentality to will Hanlon along. And did! There, that’s all I know, until this afternoon’s stunt is pulled off. But what I’ve told you, I do know—I saw it, and I, for one, am a complete convert to telepathy!”

The busy man, hastily shaking hands, bustled away, and Hendricks told in glee how, through his acquaintance with Mortimer, he had secured a permit to drive his car among the front ones that were following the performance, which was to begin very soon now.

Gus returned, and they were about to start when Aunt Abby set up a plea for a copy of the paper that she wanted.

Good-natured Gus tried his best, Hendricks himself made endeavors, but all in vain. The papers were gone, the edition exhausted. Nor could any one whom they asked be induced to part with his copy even at a substantial premium.

“Sorry, Miss Ames,” said Hendricks, “but we can’t seem to nail one. Perhaps later we can get one. Now we must be starting or we’ll soon lose our advantage.”

The crowd was like a rolling sea by this time, and only the efficiency of the fine police work kept anything like order.

Cautiously the motor car edged along while the daring pedestrians seemed to scramble from beneath the very wheels.

And then a cheer arose which proclaimed the presence of Hanlon, the mysterious possessor of second sight, or the marvelous reader of another’s mind—nobody knew exactly which he was.

Bowing in response to the mighty cheer that greeted his appearance, Hanlon stood, smiling at the crowd.

A young fellow he seemed to be, slender, well-knit and with a frank, winning face. But he evidently meant business, for he turned at once to Mr. Mortimer, and asked that the test be begun.

A few words from one of the staff of the newspaper that was backing the enterprise informed the audience that the day before there had been hidden in a distant part of the city a penknife, and that only the hider thereof and the Hon. Mr. Mortimer knew where the hiding place was.

Hanlon would now undertake to go, blindfolded, to the spot and find the knife, although the distance, as the speaker was willing to disclose, was more than a mile. The blindfolding was to be done by a committee of prominent citizens and was to be looked after so carefully that there could be no possibility of Hanlon’s seeing anything.

After that, Hanlon engaged to go to the hiding place and find the knife, on condition that Mr. Mortimer would follow him, and concentrate all his willpower on mentally guiding or rather directing Hanlon’s footsteps.

The blindfolding, which was done in full view of the front ranks of spectators, was an elaborate proceeding. A heavy silk handkerchief had been prepared by folding it in eight thicknesses, which were then stitched to prevent Clipping. This bandage was four inches wide and completely covered the man’s eyes, but as an additional precaution pads of cotton wool were first placed over his closed eyelids and the bandage then tied over them.

Thus, completely blindfolded, Hanlon spoke earnestly to Mr. Mortimer.

“I must ask of you, sir, that you do your very best to guide me aright. The success of this enterprise depends quite as much on you as on myself. I am merely receptive, you are the acting agent. I strive to keep my mind a blank, that your will may sway it in the right direction. I trust you, and I beg that you will keep your whole mind on the quest. Think of the hidden article, keep it in your mind, look toward it. Follow me—not too closely—and mentally push me in the way I should go. If I go wrong, will me back to the right path, but in no case get near enough to touch me, and, of course, do not speak to me. This test is entirely that of the influence of your will upon mine. Call it telepathy, thought-transference, will-power—anything you choose, but grant my request that you devote all your attention to the work in hand. If your mind wanders, mine will; if your mind goes straight to the goal, mine will also be impelled there.”

With a slight bow, Hanlon stood motionless, ready to start.

The preliminaries had taken place on a platform, hastily built for the occasion, and now, with Mortimer behind him, Hanlon started down the steps to the street.

Reaching the pavement, he stood motionless for a few seconds and then, turning, walked toward Broad Street. Reaching it, he turned South, and walked along, at a fairly rapid gait. At the crossings he paused momentarily, sometimes as if uncertain which way to go, and again evidently assured of his direction.

The crowd surged about him, now impeding his progress and now almost pushing him along. He gave them no heed, but made his way here or there as he chose and Mortimer followed, always a few steps behind, but near enough to see that Hanlon was in no way interfered with by the throng.

Indeed, so anxious were the onlookers that fair play should obtain, the ones nearest to the performer served as a cordon of guards to keep his immediate surroundings cleared.

Hanlon’s actions, in all respects, were those that might be expected from a blindfolded man. He groped, sometimes with outstretched hands, again with arms folded or hands clasped and extended, but always with an expression, so far as his face could be seen, of earnest, concentrated endeavor to go the right way. Now and then he would half turn, as if impelled in one direction, and then hesitate, turn and march off the other way. One time, indeed, he went nearly half a block in a wrong street. Then he paused, groped, stumbled a little, and gradually returned to the vicinity of Mortimer, who had stood still at the corner. Apparently, Hanlon had no idea of his detour, for he went on in the right direction, and Mortimer, who was oblivious to all but his mission, followed interestedly.

One time Hanlon spoke to him. “You are a fine ‘guide,’ sir,” he said. “I seem impelled steadily, not in sudden thought waves, and I find my mind responds well to your will. If you will be so good as to keep the crowd away from us a little more carefully. I don’t want you any nearer me, but if too many people are between us, it interferes somewhat with the transference of your guiding thought.”

“Do you want to hear my footsteps?” asked Mortimer, thoughtfully.

“That doesn’t matter,” Hanlon smiled. “You are to follow me, sir, even if I go wrong. If I waited to hear you, that would be no test at all. Simply will me, and then follow, whether I am on the right track or not. But keep your mind on the goal, and look toward it—if convenient. Of course, the looking toward it is no help to me, save as it serves to fix your mind more firmly on the matter.”

And then Hanlon seemed to go more carefully. He stepped slowly, feeling with his foot for any curbstone, grating or irregularity in the pavement. And yet he failed in one instance to feel the edge of an open coalhole, and his right leg slipped down into it.

Some of the nearby watchers grabbed him, and pulled him back without his sustaining injury, for which he thanked them briefly and continued.

Several times some sceptical bystanders put themselves deliberately in front of the blindfolded man, to see if he would turn out for them.

On the contrary, Hanlon bumped into them, so innocently, that they were nearly thrown down.

He smiled good-naturedly, and said, “All right, fellows; I don’t mind, if you don’t. And I don’t blame you for wanting to make sure that I’m not playing ‘possum!”

Of course, Hanlon carried no light cane, such as blind men use, to tap on the stones, so he helped himself by feeling the way along shop windows and area gates, judging thus, when he was nearing a cross street, and sometimes hesitating whether to cross or turn the corner.

After a half-hour of this sort of progress he found himself in a vacant lot near the edge of the city. There had been a building in the middle of the plot of ground, but it had been burned down and only a pile of blackened debris marked the place.

Reaching the corner of the streets that bounded the lot, Hanlon made no pause, but started on a straight diagonal toward the center of the lot. He stepped into a tangle of charred logs and ashes, but forged ahead unhesitatingly, though slowly, and picked his way by thrusting the toe of his shoe tentatively forward.

Mortimer, about three paces behind him, followed, unheeding the rubbish he stalked through, and very evidently absorbed in doing his part to its conclusion.

For the knife was hidden in the very center of the burned-down house. A bit of flooring was left, on which Hanlon climbed, Mortimer getting up on it also.

Hanlon walked slowly round in a circle, the floor being several yards square. Mortimer stepped behind him, gravely looking toward the hiding-place, and exerting all his mentality toward “guiding” Hanlon to it. At no time was he nearer than two feet, though once, making a quick turn, Hanlon nearly bumped into him. Finally, Hanlon, poking about in the ashes with his right foot, kicked against something. He picked it up and it proved to be only a bit of wire. But the next moment he struck something else, and, stooping, brought up triumphantly the hidden penknife, which he waved exultantly at the crowd.

Loud and long they cheered him. Cordially Mr. Mortimer grasped the hands of the hero, and it was with some difficulty that Alvord Hendricks restrained Miss Abby Ames from getting out of his car and rushing to congratulate the successful treasure-seeker.

“Now,” she exclaimed; “no one can ever doubt the fact of telepathy after this! How else could that young man have done what he has done. Answer me that!”

“It’s all a fake,” asserted Hendricks, “but I’m ready to acknowledge I don’t know how it’s done. It’s the best game I ever saw put up, and I’d like to know how he does it.”

“Seems to me,” put in Eunice, a little dryly, “one oughtn’t to insist that it is a fake unless one has some notion, at least, of how it could be done. If the man could see—could even peep—there might be a chance for trickery. But with those thick cotton pads on his eyes and then covered with that big, thick, folded silk handkerchief—it’s really a muffle-there’s no chance for his faking.”

“And if he could see—if his eyes were wide open—how would he know where to go?” demanded Aunt Abby. “That blindfolding is only so he can’t see Mr. Mortimer’s face, if he turns round, and judge from its expression. And also, I daresay, to help him concentrate his mind, and not be diverted or distracted by the crowd and all.”

“All the same, I don’t believe in it,” and Hendricks shook his head obstinately. “There is no such thing as telepathy, and this ‘willing’ business has all been exposed years ago.”

“I remember,” and Aunt Abby nodded; “you mean that Bishop man and all that. But this affair it quite different. You don’t believe Mr. Mortimer was a party to deceit, do you?”

“No, I don’t. Mortimer is a judge and a most honest man, besides. He wouldn’t stoop to trickery in a thing of this sort. But he has been himself deceived.”

“Then how was it done?” cried Eunice, triumphantly; “for no one else knew where the knife was hidden, except that newspaper man who hid it, and he was sincere, of course, or there’d be no sense in the whole thing.”

“I know that. Yes, the newspaper people were hoodwinked, too.”

“Then what happened?” Eunice persisted. “There’s no possible explanation but telepathy. Is there, now?”

“I don’t know of any,” Hendricks was forced to admit. “After the excitement blows over a little, I’ll try to speak with Mortimer again. I’d like to know his opinion.”

They sat in the car, looking at the hilarious crowds of people, most of whom seemed imbued with a wild desire to get to the hero of the hour and demand his secret.

“There’s a man who looks like Tom Meredith,” said Eunice, suddenly. “By the way, Alvord, where do the Merediths stand in the matter of the club election?”

“Which of them?”

“Either—or both. I suppose they’re on your side—they never seemed to like Sanford much.”

“My dear Eunice, don’t be so narrow-minded. Club men don’t vote one way or another because of a personal like or dislike—they consider the good of the club—the welfare of the organization.”

“Well, then, which side do they favor as being for the good of the club?”

“Ask Sanford.”

“Oh—if you don’t want to tell me.”

Eunice looked provokingly pretty and her piquant face showed a petulant expression as she turned it to Hendricks.

“Smile on me again and I’ll tell you anything you want to know: if I know it myself.”

A dazzling smile answered this speech, and Hendricks’ gaze softened as he watched her.

“But you’ll have to ask me something else, for, alas, the brothers Meredith haven’t made a confidant of me.”

“Story-teller” and Eunice’s dark eyes assumed the look of a roguish little girl. “You can’t fool me, Alvord; now tell me, and I’ll invite you in to tea when we get home.”

“I’m going in, anyway.”

“Not unless you tell me what I ask. Why won’t you? Is it a secret? Pooh! I’d just as lief ask Mr. Tom Meredith myself, if I could see him. Never mind, don’t tell me, if you don’t want to. You’re not my only confidential friend; there are others.”

“Who are they, Euny? I flattered myself I was your only really, truly intimate friend—not even excepting your husband!”

“Oh, what a naughty speech! If you weren’t Sanford’s very good friend, I’d never speak to you again!”

“I don’t see how you two men can be friends,” put in Aunt Abby, “when you’re both after that same presidency.”

“That’s the answer!” Eunice laughed. “Alvord is San’s greatest friend, because it’s going to be an easy thing for Sanford to win the election from him! If there were a more popular candidate in Alvord’s place, or a less popular one in Sanford’s place, it wouldn’t be such a walkover!”

“You—you—” Hendricks looked at Eunice in speechless admiration. The dancing eyes were impudent, the red lips curved scornfully, and she made a daring little moue at him as she readjusted her black lace veil so that a heavy bit of its pattern covered her mouth.

“What do you do that for? Move that darned flower, so I can see you talk!”

She laughed then, and wrinkled her straight little nose until the veil billowed mischievously.

“I wish you’d take that thing off,” Hendricks said, irritatedly; “it annoys me.”

“And pray, sir, who are you, that I should shield you from annoyance? My veil is a necessary part of my costume.”

“Necessary nothing! Take it off, I tell you!”

“Merry Christmas!” and Eunice gave him such a scornful shrug of her furred shoulders that Hendricks laughed out, in sheer enjoyment of her audacity.

“Tell me about the Merediths, and I’ll take off the offending veil,” she urged, looking at him very coaxingly.

“All right; off with it.”

Slowly, and with careful deliberation, Eunice unpinned her veil, took it off and folded it in a small, compact parcel. This she put in her handbag, and then, with an adorable smile, said: “Now!”

“You beautiful idiot,” and Hendricks devoured her with his eyes. “All I can tell you about the Merediths is, that I don’t know anything about their stand on the election.”

“What do you guess, assume, surmise, imagine or predict?” she teased, still fascinating him with her magnetic charm.

“Well, I think this: they’re a little too old-timey to take up all my projects. But, on the other hand, they’re far from willing to subscribe to your husband’s views. They do not approve of the Sunday-school atmosphere he wants to bring about, nor do they shut their eyes to the fact that the younger element must be considered.”

“Younger element! Do you call Sanford old?”

“No; he’s only twenty-eight this minute. But there are a lot of new members even younger than that strange as it may seem! These boys want gayety—yea, even unto the scorned movies and the hilarious prize-fights—and as they are scions of the wealthy and aristocratic families of our little old town, I think we should consider them. And, since you insist on knowing, it is my firm belief, conviction and—I’m willing to add—my hope that the great and influential Meredith brothers agree with me! So there now, Madam Sanford Embury!”

“Thank you, Alvord; you’re clear, at least. Do you think I could persuade them to come over to Sanford’s side?”

“I think you could persuade the statue of Jupiter Ammon to climb down from his pedestal and take you to Coney Island, if you looked at him like that! But I also think that friend husband will not consent to your electioneering for him. It isn’t done, my dear Eunice.”

“As if I cared what is ‘done’ and what isn’t, if I want to help Sanford.”

“Go ahead, then, fair lady; but remember that Sanford Embury stands for the conservative element in our club, and anything you might try to do by virtue of your blandishments or fascinations would be frowned upon and would react against your cause instead of for it. If I might suggest, my supporters, the younger set, the—well—the gayer set, would more readily respond to such a plan. Why don’t you electioneer for me?”

Eunice disdained to reply, and Aunt Abby broke into the discussion by exclaiming: “Oh, Alvord, here comes Mr. Mortimer, and he has Mr. Hanlon with him!”

Sure enough the two heroes of the day were walking toward the Hendricks car, which, still standing near the scene of Hanlon’s triumph, awaited a good chance for a getaway.

“I wonder if you ladies wouldn’t like to meet this marvel,” began Mr. Mortimer, genially, and Aunt Abby’s delight was convincing, indeed.

Eunice, too, greeted Mr. Hanlon cordially, and Hendricks held out a welcoming hand.

“Tell us how you did it,” he said, smiling into the intelligent face of the mysterious “mind-reader.”

“You saw,” he returned, simply, with a slight gesture of out-turned palms, as if to disavow any secrets.

“Yes, I saw,” said Hendricks, “but with me, seeing is not believing.”

“Don’t listen, Hanlon,” Mr. Mortimer said, smiling a little resentfully. “That sort of talk would go before the test, but not now. What do you mean, Hendricks, by not believing? Do you suspect me of complicity?”

“I do not, Mortimer. I believe you have been taken in with the rest, by a very clever trick.” He looked sharply at Hanlon, who returned his gaze serenely. “I believe this young man is unusually apt as a trickster, and I believe he hoodwinked the whole community. The fact that I cannot comprehend, or even guess how he did it, in no way disturbs my conviction that he did do it by trickery. I will change this opinion, however, if Mr. Hanlon will look me in the eye and assure me, on his honor, that he found the penknife by no other means or with no other influence to guide him than Mr. Mortimer’s will-power.”

“I am not on trial,” he said. “I am not called upon to prove or disprove anything. I promised to perform a feat and I have done so. It was not nominated in the bond that I should defend my honor by asseverations.”

“Begging the question,” laughed Hendricks, but Mr. Mortimer said: “Not at all. Hanlon is right. If he has any secret means of guidance, it is up to us to discover it. But I hold that he cannot have, or it would have been discovered by some of the eager observers. We had thousands looking on to-day. There must have been some one clever enough to suspect the deceit, if deceit there were.”

“Thank you, Mr. Mortimer,” Hanlon spoke quietly. “I made no mystery of my performance; I had no confederate, no paraphernalia. All there was to see could be seen by all. You willed me; I followed your will. That is all.”

The simple manner and pleasant demeanor of the young man greatly attracted Eunice, who smiled at him kindly.

“I came here very sceptical,” she admitted; “and even now I can’t feel entirely convinced—”

“Well, I can!” declared Aunt Abby. “I am willing to own it, too. These people who really believe in your sincerity, Mr. Hanlon, and refuse to confess it, make me mad! I wish you’d give an exhibition in New York.”

“I’m sorry to disappoint you, madam, but this is my last performance.”

“Good gracious why?” Aunt Abby looked curiously at him.

“I have good reasons,” Hanlon smiled. “You may learn them later, if you care to.”

“I do. How can I learn them?”

“Read the Newark Free Press next Monday.”

“Oh!” and Eunice had an inspiration—a premonition of the truth. “May I speak to you alone a minute, Mr. Hanlon?”

She got out of the car and walked a few steps with the young man, who politely accompanied her.

They paused a short distance away, and held a brief but animated conversation. Eunice laughed gleefully, and it was plain to be seen her charming smiles played havoc with Hanlon’s reserved demeanor. Soon he was willingly agreeing to something she was proposing and finally they shook hands on it.

They returned to the car; he assisted Eunice in, and then he told Mr. Mortimer they had stayed as long as was permissible and were being eagerly called back to the committee in charge of the day’s programme.

“That’s so,” said Mortimer. “I begged off for a few minutes. Good-by, all.” He raised his hat and hurried away after Hanlon.

“Well,” said Hendricks as they started homeward, “what did you persuade him to do, Eunice? Give a parlor exhibition for you?”

“The boy guessed nearly right the very first time!” cried Eunice, gleefully; “it was all a fake, and he’s coming to our house Sunday afternoon to tell how he did it. It’s all coming out in the paper on Monday.”

“My good land!” and Aunt Abby sank back in her seat, utterly disgusted.

“And that’s my last word on the subject.”

Embury lighted one cigarette from the stub of another, and deposited the stub in the ash-tray at his elbow. It was Sunday afternoon, and the peculiar relaxedness of that day of rest and gladness had somewhat worn on the nerves of both Sanford and Eunice.

Aunt Abby was napping, and it was too early yet to look for their expected visitor, Hanlon.

Eunice had been once again endeavoring to persuade her husband to give her an allowance—a stated sum, however small, that she might depend upon regularly. The Emburys fulfilled every requirement of the condition known as “happily married” save for this one item. They were congenial, affectionate, good-natured, and quite ready to make allowances for each other’s idiosyncrasies or whims.

With this one exception. Eunice found it intolerable to be cramped and pinched for small amounts of ready cash, when her husband was a rich man. Nor was Embury mean, or even economical of nature. He was more than willing that his wife should have all the extravagant luxuries she desired. He was entirely ready to pay any and all bills that she might contract. Never had he chided her for buying expensive or unnecessary finery—even more, he had always admired her taste and shown pleasure at her purchases. He was proud of her beauty and willing it should be adorned. He was proud of her grace and charm and willing that the household appointments should provide an appropriate setting for her hospitality. They were both fond of entertaining and never was there a word of protest from him as to the amounts charged by florists and caterers.

And yet, by reason of some crank, crotchet or perverse notion, Embury was unwilling to give his wife what is known as “pin money.”

“Buy your pins at the best jewelers’,” he would laugh, “and send the bills to me; buy your hats and gowns from the Frenchiest shops—you can get credit anywhere on my name—Good Lord! Tiger, what more can a woman want?”

Nor would he agree to her oft-repeated explanations that there were a thousand and one occasions when some money was an absolute necessity. Or, if persuaded, he gave her a small amount and expected it to last indefinitely.

It is difficult to know just what was the reason for this attitude. Sanford Embury was not a miser. He was not penurious or stingy. He subscribed liberally to charities, many of them unknown to the public, or even to his wife, but some trick of nature, some twist in his brain, made this peculiarity of his persistent and ineradicable.

Now, Eunice Embury was possessed of a quick, sometimes ungovernable temper. It was because of this that her husband called her Tiger. And also, as he declared, because her beautiful, lithe grace was suggestive of “the fearful symmetry” of the forest tribe.

She had tried honestly to control her quick anger, but it would now and then assert itself in spite of her, and Embury delighted to liken her to Katherine, and declared that he must tame her as Petruchio tamed his shrew.

This annoyed Eunice far more than she let him know, for she was well aware that if he thought it teased her, he would more frequently try Petruchio’s methods.

So, when she flew into a rage, and he countered with a fiercer anger, she knew he was assuming it purposely, and she usually quieted down, as the better part of valor.

On this particular occasion Eunice had taken advantage of a quiet, pleasant tête-a-tête to bring up the subject.

Embury had heard her pleading, not unkindly, but with a bored air, and had finally remarked, as she paused in her arguments, “I refuse, Eunice, to give you a stated allowance. If you haven’t sufficient confidence in your husband’s generosity to trust him to give you all you want or need, and even more than that, then you are ungrateful for what I have given you. And that’s my last word on the subject.”

The rank injustice of this was like iron entering her soul. She knew his speech was illogical, unfair and even absurd, but she knew no words of hers could make him see it so.

And in utter exasperation at her own impotence, she flung her self-control to the winds, and let go of her temper.

“Well, it isn’t my last word on the subject!” she cried. “I have something further to say!”

“That is your woman’s privilege,” and Embury smiled irritatingly at her.

“Not only my privilege, but my duty! I owe it to my self-respect, to my social position, to my standing as your wife—the wife of a prominent man of affairs—to have at my command a sum of ready money when I need it. You know perfectly well, I do not want it for anything wrong—or for anything that I want to keep secret from you. You know I have never had a secret from you nor do I wish to have! I simply want to do as other women do—even the poorest, the meanest man, will give his wife an allowance, a little something that is absolutely her own. Why, most of the women of my set have a checking account at the bank—they all have a personal allowance!”

“So?” Embury took up another cigarette. “You may remember, Eunice, I have spoken my last word on the subject.”

“And you may remember that I have not! But I will—and right now. And it is simply that since you refuse me the pleasure and convenience of some money for everyday use, I shall get some from another source.”

Embury’s eyes narrowed, and he surveyed his wife with a calm scrutiny. Then he smiled.

“Stenography and typewriting?” he said; “or shall you take in plain sewing? Cut out the threats, Eunice; they won’t get you anywhere!”

“They’ll get me where I want to arrive! Don’t say I didn’t warn you—I repeat, I shall get money for my personal use, and you will have no right to criticize my methods, since you refuse me a paltry sum by way of allowance.”

Eunice was standing, her two hands tightly grasping a chair-back as she looked angrily at Embury, who still seated lazily, blew smoke rings toward her. She was magnificent in her anger, her cheeks burned crimson, her dark eyes had an ominous gleam in them and her curved lips straightened into a determined line of scarlet. Her muscles were strained and tense, her breath came quickly, yet she had full control of herself and her pose was that of a crouching, waiting tiger rather than a furious ode.

Embury was full of admiration at the beautiful picture she made, but pursuant of his inexorable plan, he rose to “tame” her.

“‘Tiger, tiger, burning bright,’“ he quoted, “you must take back that speech—it is neither pretty nor tactful—”

“I have no wish to be tactful! Why should I? I am not trying to coax or cajole you! You refuse my request—you have repeatedly refused me—now, I am at the end of my patience, and I shall take matters into my own hands!”

“Lovely hands!” he murmured, taking them in his own. “You have unusually pretty hands, Eunice; it would be a pity to use them to earn money.”

“Yet that is my intention. I shall get money by the work of these hands. It will be in a way that you will not approve, but you have forfeited your right to approve or disapprove.”

“That I have not! I am your husband—you have promised to obey me—”

“A mere form of words—it meant nothing!”

“Our marriage ceremony meant nothing?”

“If it did, remember that you endowed me with all your worldly goods—”

“And I give them to you, too! Do you know that nine-tenths of my yearly expenditures are for your pleasure and benefit! I enjoy our home, too, but it would not be the elaborate, luxurious establishment that it is, but that it suits your taste to have it so! And then, you whine and fret for what you yourself call a paltry matter! Ingrate!”

“Don’t you dare call me ingrate! I owe you no gratitude! Do you give me this home as a charity? As a gift, even! It is my right! And it is also my right to have a bank account of my own! It is my right to uphold my head among other women who laugh at me, who ridicule me, because, with all your wealth, I have no purse of my own! I will not stand it! I rebel! And you may rest assured things are going to be different hereafter. I will get money—”

“You shall not!” Embury grasped the wrists of the hands he still held, and his face was fiercely frowning. “You are my wife, and whatever you may or may not owe to me, you owe it to our position, to our standing in the community to do nothing beneath your dignity or mine!”

“You care nothing for my dignity, for my appearance before other women, so why should I consider your dignity? You force me to it, and it is therefore your fault if I—”

“What is it you propose to do? How are you going to get this absurd paltry sum you are making such a fuss about?”

“That I decline to tell you—”

“Don’t you dare to do needlework or anything that would make me look foolish. I forbid it!”

“And I scorn your forbidding! Make you look foolish, indeed! When you make me look foolish every day of my life, because I can’t do as other women do—can’t have what other wives have—”

“Now, now, Tiger, don’t make such a row over nothing—let’s talk it over seriously—”

“There’s nothing to talk over. I’ve asked you time and again for an allowance of money—real money, not charge accounts—and you always refuse—”

“And always shall, if you are so ugly about it! Why must you fly into a rage over it? Your temper is—”

“My temper is roused by your cruelty—”

“Cruelty!”

“Yes; it’s as much cruelty as if you struck me! You deny me my heart’s dearest wish for no reason whatever—”

“It’s enough that I don’t approve of an allowance—”

“It ought to be enough that I do!”

“No, no, my lady! I love you, I adore you, but I am not the sort of man to lie down and let you walk over me! I give you everything you want and if I reserve the privilege of paying for it myself, it does not seem to me a crime!”

“Oh, do hush up, Sanford! You drive me frantic! You prate the same foolishness, over and over! I don’t want to hear any more about it. You said you had spoken the last word on the subject, now stop it! I, too, have said my final say. I shall do as I please, and I shall not consider myself accountable to you for my actions.”

“Confound it! Do what you please, then! I wash my hands of your nonsense! But be careful how you carry the name I have given you!”

“If you keep on, I may decide not to carry it at all—”

Eunice was interrupted by the entrance of Ferdinand, announcing the arrival of Mason Elliott.

Trained in the school of convention, both the Emburys became at once the courteous, cordial host and hostess.

“Hello, Elliott,” sang out Sanford, “glad to see your bright and happy face. Come right along and chum in.”

Eunice offered her hand with a welcoming smile.

“Just the boy I was looking for,” she said, “we’ve the jolliest game on for the afternoon. Haven’t we, San?”

“Fool trick, if you ask me! Howsumever, everything goes. Interested in thought-transference bunk, Elliott?”

“I know what you’re getting at.” Mason Elliott nodded his head understandingly. “Hendricks put me wise. So, I says to myself, s’posin’ I hop along and listen in. Yes, I am interested, sufficiently so not to mind your jeers about bunk and that.”

“Oh, do you believe in it, Mason?” said Eunice, animatedly; “for this is a faked affair—or, rather, the explanation of one. It’s the Hanlon boy, you know—”

“Yes; I know. But what’s the racket with you two turtle-doves? I come in, and find Eunice wearing the pet expression of a tragedy queen and Sanford, here, doing the irate husband. Going into the movies?”

“Yes, that’s it,” and Eunice smiled bravely, although her lips still quivered from her recent turbulent quarrel, and a light, jaunty air was forced to conceal her lingering nervousness.

“Irate husband is good!” laughed Embury, “considering we are yet honeymooners.”

“Good dissemblers, both of you,” and Elliott settled himself in an easy chair, “but you don’t fool your old friend. Talk about thought-transference—it doesn’t take much of that commodity to read that you two were interrupted by my entrance in the middle of a real, honest-to-goodness, cats’-and-dogs’ quarrel.”

“All right, have it your own way,” and Embury laughed shortly; “but it wasn’t the middle of it, it was about over.”

“All but the making up! Shall I fade away for fifteen minutes?”

“No,” protested Eunice. “It was only one of the little tiffs that happen in the best families! Now, listen, Mason—”

“My dear lady, I live but on the chance of being permitted to listen to you—only in the hope that I may listen early and often—”

“Oh, hush! What a silly you are!”

“Silly, is it? Remember I was your childhood playmate. Would you have kept me on your string all these years if I were silly? And here’s another of my childhood friends! How do you do, most gracious lady?”

With courtly deference Elliott rose to greet Aunt Abby, who came into the living-room from Eunice’s bedroom.

Her black silk rustled and her old point lace fell yellowly round her slender old hands, for on Sunday afternoon Miss Ames dressed the part.

“How are you, Mason,” she said, but with a preoccupied air. “What time is Mr. Hanlon coming, Eunice?”

“Soon now, I think,” and Eunice spoke with entire composure, her angry excitement all subdued. It was characteristic of her that after a fit of temper, she was more than usually soft and gentle. More considerate of others and even, more roguishly merry.

“You know, Mason, that what we are to be told to-day is a most inviolable secret—that is, it is a secret until tomorrow.”

“Never put off till to-morrow what you can tell to-night,” returned Elliott, but he listened attentively while Eunice and Aunt Abby described the performance of the young man Hanlon.

“Of course,” Elliott observed, a little disappointedly, “if he says he hoaxed the crowd, of course he did; but in that case I’ve no interest in the thing. I’d like it better if he were honest.”

“Oh, he’s honest enough,” corrected Embury; “he owns right up that it was a trick. Why, good heavens, man! if it hadn’t been, he couldn’t have done it at all. I’m rather keen to know just how he managed, though, for the yarn of Eunice and Aunt Abby is a bit mystifying.”

“Don’t depend too much on the tale of interested spectators. They’re the worst possible witnesses! They see only what they wish to see.”

“Only what Hanlon wished us to see,” corrected Eunice, gaily. And then Hanlon, himself, and Alvord Hendricks arrived together.

“Met on the doorstep,” said Hendricks as he came in. “Mr. Hanlon is a little stage-struck, so it’s lucky I happened along.”

Willy Hanlon, as he was called in the papers, came shyly forward and Eunice, with her ready tact, proceeded to put him at once at his ease.

“You came just at the right minute to help me out,” she said, smiling at him. “They are saying women are no good at describing a scene! They say that we can’t be relied on for accuracy. So, now you’re here and you can tell what really happened.”

“Yes, ma’am,” and Hanlon swallowed, a little embarrassedly; “that’s what I came for, ma’am. But first, are you all straight goods? Will you all promise not to tell what I tell you before tomorrow morning?”

They all promised on their honor, and, satisfied, Hanlon began his tale.

“You see, it’s a game that can’t be played too often or too close together,” he said; “I mean, if I put it over around here, I can’t risk it again nearer than some several states away. And even then it’s likely to get caught on to.”

“Have you put it over often?” asked Hendricks, interestedly.