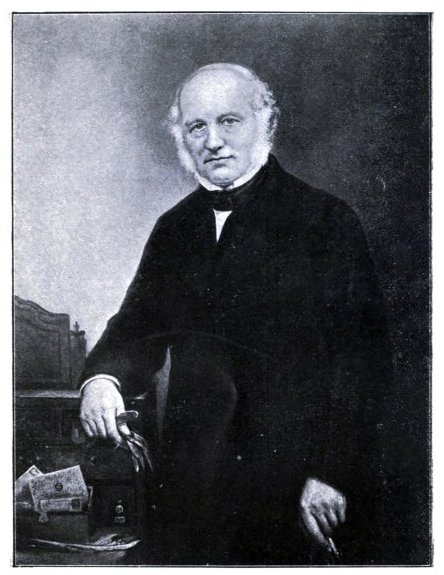

SIR ROWLAND HILL.

(From the painting by J. A. Vinter, R.A., in the National Portrait Gallery.)

Frontispiece.

BOOKS FOR COLLECTORS

With Frontispieces and many Illustrations

Large Crown 8vo, cloth.

CHATS ON ENGLISH CHINA.

By Arthur Hayden.

CHATS ON OLD FURNITURE.

By Arthur Hayden.

CHATS ON OLD PRINTS.

(How to collect and value Old Engravings.)

By Arthur Hayden.

CHATS ON COSTUME.

By G. Woolliscroft Rhead.

CHATS ON OLD LACE AND NEEDLEWORK.

By E. L. Lowes.

CHATS ON ORIENTAL CHINA.

By J. F. Blacker.

CHATS ON OLD MINIATURES.

By J. J. Foster, F.S.A.

CHATS ON ENGLISH EARTHENWARE.

By Arthur Hayden.

CHATS ON AUTOGRAPHS.

By A. M. Broadley.

CHATS ON PEWTER.

By H. J. L. J. Massé, M.A.

CHATS ON POSTAGE STAMPS.

By Fred. J. Melville.

CHATS ON OLD JEWELLERY AND TRINKETS.

By MacIver Percival.

CHATS ON COTTAGE AND FARMHOUSE FURNITURE.

By Arthur Hayden.

CHATS ON OLD COINS.

By Fred. W. Burgess.

CHATS ON OLD COPPER AND BRASS.

By Fred. W. Burgess.

CHATS ON HOUSEHOLD CURIOS.

By Fred. W. Burgess.

CHATS ON OLD SILVER.

By Arthur Hayden.

CHATS ON JAPANESE PRINTS.

By Arthur Davison Ficke.

CHATS ON MILITARY CURIOS.

By Stanley C. Johnson.

CHATS ON OLD CLOCKS AND WATCHES.

By Arthur Hayden.

CHATS ON ROYAL COPENHAGEN PORCELAIN.

By Arthur Hayden.

LONDON: T. FISHER UNWIN, LTD.

NEW YORK: F. A. STOKES COMPANY

SIR ROWLAND HILL.

(From the painting by J. A. Vinter, R.A., in the National Portrait Gallery.)

Frontispiece.

Chats on

Postage Stamps

BY

FRED J. MELVILLE

PRESIDENT OF THE JUNIOR PHILATELIC SOCIETY

WITH SEVENTY-FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW YORK

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

(All rights reserved.)

Come and chat in my stamp-den, that I may encircle you with fine-spun webs of curious and rare interest, and bind you for ever to Philately, by which name we designate the love of stamps. The "den" presents no features which would at first sight differentiate it from a snug well-filled library, but a close inspection will reveal that many of the books are not the products of Paternoster Row or of Grub Street. Yet in these stamp-albums we shall read, if you will have the kindness to be patient, many things which are writ upon the postage-stamps of all nations, as in a world of books.

It is not given to all collectors to know their postage-stamps. There is the collector who merely accumulates specimens without studying them. He has eyes, but he does not see more than that this stamp is red and that one is blue. He has ears, but they only hear that this stamp cost £1,000, and that this other can be purchased wholesale at sixpence the dozen. What shall it profit him if he collect many stamps, but never discover their significance as factors in the rapid spread of civilisation in the{8} nineteenth and twentieth centuries? The true student of stamps will extract from them all that they have to teach; he will read from them the development of arts and manufactures, social, commercial and political progress, and the rise and fall of nations.

To the young student our pleasant pastime of stamp-collecting has to offer an encouragement to habits of method and order, for without these collecting can be productive of but little pleasure or satisfaction. It will train him to be ever observant of the minutiæ that matter, and it will broaden his outlook as he surveys his stamps "from China to Peru."

The present volume is not intended as a complete guide to the postage-stamps of the world; it is rather a companion volume to the standard catalogues and numerous primers already available to the collector. It has been my endeavour to indicate what counts in modern collecting, and to emphasise those features of the higher Philately of to-day which have not yet been fully comprehended by the average collector. Some of my readers may consider that I have unduly appraised the value in a stamp collection of pairs and blocks, proofs and essays, of documental matter, and also that too much has been demanded in the matter of condition. But all these things are of greater importance than is realised by even the majority of members of the philatelic societies. Condition in particular is a factor which, if disregarded, will not only result in the formation of an unsatisfactory collection, but will lessen, if not{9} ruin, the collection as an investment. It has been thought that as time passed on the exacting requirements of condition would have to be relaxed through the gradual absorption of fine copies of old stamps in great collections. The effect has, however, been simply to raise the prices of old stamps in perfect condition. It may be taken as a general precept that a stamp in fine condition at a high price is a far better investment than a stamp in poor condition at any price.

In preparing the illustrations for this volume I am indebted to several collectors and dealers, chiefly to Mr. W. H. Peckitt, who has lent me some of the fine items from the "Avery" collection, to Messrs. Stanley Gibbons, Ltd., whose name is as a household word to stamp-collectors all over the world, and to Messrs. Charles Nissen, D. Field, and Herbert F. Johnson.

I should also be omitting a very important duty if I failed to acknowledge the general readiness of collectors, and especially of my colleagues the members of the Junior Philatelic Society both at home and abroad, in keeping me constantly au courant with new information connected with the pursuit of Philately. Without such assistance in the past, this work, and the score of others which have come from my pen, could never have been undertaken; and perhaps the best token of my appreciation of so many kindnesses will be to beg (as I now do) the favour of their continuance in the future.

FRED J. MELVILLE.

| PAGE | |

| PREFACE | 7 |

| PHILATELIC TERMS | 21 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| THE GENESIS OF THE POST | 55 |

| The earliest letter-carriers—The Roman posita—Princely Postmasters of Thurn and Taxis—Sir Brian Tuke—Hobson of "Hobson's Choice"—The General Letter Office of England—Dockwra's Penny Post of 1680—Povey's "Halfpenny Carriage"—The Edinburgh and other Penny Posts—Postal rates before 1840—Uniform Penny Postage—The Postage Stamp regarded as the royal diplomata—The growth of the postal business. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| THE DEVELOPMENT OF AN IDEA | 77 |

| Early instances of contrivances to denote prepayment of postage—The "Two-Sous" Post—Billets de port payé—A passage of wit between the French Sappho and M. Pellisson—Dockwra's letter-marks—Some fabulous stamped wrappers of the Dutch Indies—Letter-sheets used in Sardinia—Lieut. Treffenberg's proposals for "Postage Charts" in Sweden—The postage-stamp idea "in the air"—Early British reformers and their proposals—The Lords of the Treasury start {12}a competition—Mr. Cheverton's prize plan—A find of papers relating to the contest—A square inch of gummed paper—The Sydney embossed envelopes—The Mulready envelope—The Parliamentary envelopes—The adhesive stamp popularly preferred to the Mulready envelope. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| SOME EARLY PIONEERS OF PHILATELY | 113 |

| "Hobbyhorsical" collections—The application of the term "Foreign Stamp Collecting"—The Stamp Exchange in Birchin Lane—A celebrated lady stamp-dealer—The Saturday rendezvous at the All Hallows Staining Rectory—Prominent collectors of the first period—The first stamp catalogues—The words Philately and Timbrologie—Philatelic periodicals—Justin Lallier's albums—The Philatelic Society, London. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| ON FORMING A COLLECTION | 133 |

| The cost of packet collections—The beginner's album—Accessories—Preparation of stamps for mounting—The requirements of "condition"—The use of the stamp-hinge—A suggestion for the ideal mount—A handy gauge for use in arranging stamps—"Writing-up." | |

| CHAPTER V | |

| THE SCOPE OF A MODERN COLLECTION | 151 |

| The historical collection: literary and philatelic—The quest for rariora—The "grangerising" of philatelic monographs: its advantages and possibilities—Historic documents—Proposals and essays—Original drawings—Sources of stamp-engravings—Proofs and trials—Comparative rarity of some stamps in pairs, &c., or on original envelopes—Coloured postmarks—Portraits, maps, and contemporary records—A {13}lost opportunity. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| ON LIMITING A COLLECTION | 197 |

| The difficulties of a general collection—The unconscious trend to specialism—Technical limitations: Modes of production; Printers—Geographical groupings: Europe and divisions—Suggested groupings of British Colonies—United States, Protectorates and Spheres of Influence—Islands of the Pacific—The financial side of the "great" philatelic countries. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| STAMP-COLLECTING AS AN INVESTMENT | 209 |

| The collector, the dealer, and the combination—The factor of expense—Natural rise of cost—Past possibilities in British "Collector's Consols," in Barbados, in British Guiana, in Canada, in "Capes"—Modern speculations: Cayman Islands—Further investments: Ceylon, Cyprus, Fiji Times Express, Gambia, India, Labuan, West Indies—The "Post Office" Mauritius—The early Nevis, British North America, Sydney Views, New Zealand—Provisionals: bonâ fide and speculative—Some notable appreciations—"Booms." | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| FORGERIES, FAKES, AND FANCIES | 237 |

| Early counterfeits and their exposers—The "honest" facsimile—"Album Weeds"—Forgeries classified—Frauds on the British Post Office—Forgeries "paying" postage—The One Rupee, India—Fraudulent alteration of values—The British 10s. and £1 "Anchor"—A too-clever "fake"—Joined pairs—Drastic tests—New South Wales "Views" and "Registered"—The Swiss Cantonals—Government {14}"imitations"—"Bogus" stamps. | |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| FAMOUS COLLECTIONS | 261 |

| The "mania" in the 'sixties—Some wonderful early collections—The first auction sale—Judge Philbrick and his collection—The Image collection—Lord Crawford's "United States" and "Great Britain"—Other great modern collections—M. la Rénotière's "legions of stamps"—Synopsis of sales of collections. | |

| CHAPTER X | |

| ROYAL AND NATIONAL COLLECTIONS | 303 |

| The late Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha as a collector—King George's stamps: Great Britain, Mauritius, British Guiana, Barbados, Nevis—The "King of Spain Reprints"—The late Grand Duke Alexis Michaelovitch—Prince Doria Pamphilj—The "Tapling" Collection—The Berlin Postal Museum—The late Duke of Leinster's bequest to Ireland—Mr. Worthington's promised gift to the United States. | |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 333 |

| INDEX | 351 |

| PAGE | |

| Perforation Gauge | 43 |

| The Commemorative Letter Balance designed by Mr. S. King, of Bath (1840). A monument "which may be possessed by every family in the United Kingdom" | 72 |

| Mr. King's Letter Balance had a tripod base, as in the uppermost figure, thus affording three tablets on which the associations of J. Palmer, Rowland Hill, and Queen Victoria with postal reform are recorded | 73 |

| A Facsimile of the Address Side of a Penny Post Letter in 1686, showing the "Peny Post Payd" mark instituted by Dockwra and continued by the Government authorities | 83 |

| Facsimile of the Contents of the Penny Post Letter of 1686 | 84 |

| The Official Notification of December 3, 1818, relating to the use of the Sardinian Letter Sheets. Described in the records of the Schroeder collection as "the oldest official notification of any country in the world relating to postage-stamps" | 86 |

| (Continuation from previous page.) The models show the devices for the three denominations: 15, 25, and 50 centesimi respectively | 87 |

| Proof of the Mulready Envelope, signed by Rowland Hill. (From the "Peacock" Papers) | 111 |

| {16}Gauge for Arranging Stamps in a Blank Album | 144 |

| Autograph Letter from Rowland Hill to John Dickinson, the paper-maker, asking for six or eight sheets of the silk-thread paper for trial impressions of the adhesive stamps | 164 |

| Original Sketch for the "Canoe" Type of Fiji Stamps | 169 |

| A Postal Memento of New Zealand's "Universal Penny Postage," January 1, 1901 | 190 |

| The First Postage Stamp of the present reign, together with the Post Office notice concerning its issue on November 4, 1910 | 193 |

| The Official Notice of the Issue of the New Stamps of Great Britain for the reign of King George V. | 195 |

| Sir Rowland Hill. (From the painting by J. A. Vinter, R.A., in the National Portrait Gallery) | Frontispiece |

| Examples of some Philatelic Terms:—A Pair of Great Britain embossed Sixpence.—A Pair of Cape of Good Hope Triangular Shilling.—A Block of four Great Britain Penny Red.—A Strip of three Grenada "4d." on Two Shillings | 25 |

| Examples of some Philatelic Terms:—The figures "201" indicate the Plate Number, and "238" the Current Number. The Plate Number is also on each of these stamps in microscopic numerals.—Corner pair showing Current Number "575" in margin.—Corner pair showing Plate Number "15" in margin. The Plate Number is also seen in small figures on each stamp.—The above stamps are those of Great Britain overprinted for use in Cyprus | 29 |

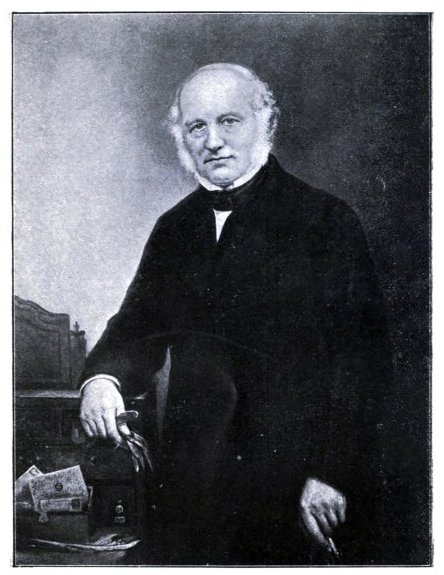

| Examples of some Philatelic Terms:—A sheet of stamps of Gambia, composed of two Panes of sixty stamps each.—The single "Crown and CA" watermark, as it appears looking from the back of the Gambia sheet illustrated above. The watermark is arranged in panes to coincide with the impressions from the plate | 33 |

| Examples of some Philatelic Terms:—A "Bisect," or "Bisected {17}Provisional." The One Penny stamp of Jamaica was in 1861 permitted to be cut in halves diagonally, and each half used as a halfpenny stamp | 37 |

| Examples of some Philatelic Terms:—Photograph of a flat steel die engraved in taille douce (i.e., with the lines of the design cut into the plate). The stamp is the 50 lepta of Greece, issue of 1901, showing Hermes adapted from the Mercury of Giovanni da Bologna | 51 |

| Scarce Pamphlet (first page) in which William Dockwra announces the Penny Post of 1680 | 65 |

| A Post Office in 1790 | 69 |

| Sardinian Letter Sheet of 1818: 15 centesimi.—The 25 centesimi Letter Sheet of Sardinia. Issued in Sardinia, 1818; the earliest use of Letter Sheets with embossed stamps | 89 |

| The highest denomination, 50 centesimi, of the Sardinian Letter Sheets.—One of the temporary envelopes issued for the use of members of the House of Lords, prior to the issue of stamps and covers to the public, 1840 | 93 |

| The "James Chalmers" Essay.—Rough sketches in water-colours submitted by Rowland Hill to the Chancellor of the Exchequer for the first postage stamps | 99 |

| Hitherto unpublished examples of the proposals submitted to the Lords of the Treasury in 1839 in competition for prizes offered in connection with the Penny Postage plan. (From the Author's Collection) | 103 |

| The address side of the model letter which has the stamp (shown below) affixed to the back as a seal.—Another of the unpublished essays submitted in the competition of 1839 for the Penny Postage plan. (From the Author's Collection) | 107 |

| A Postage Stamp "Chart"—one of the early forms of stamp-collecting | 119 |

| The small "experimental" plate from which impressions of the Two Pence, Great Britain, were made on "Dickinson" paper. Only two rows of four stamps were impressed on each piece of the paper. (Cf. next plate) | 157 |

| The Two Pence, Great Britain, on "Dickinson" paper. The upper block is in red (24 stamps printed in all, of which nine copies {18}are known), and the lower block in blue (16 stamps printed, of which twelve copies are known). The above blocks of six each are in the possession of Mr. Lewis Evans; the pairs cut from the left side of each block were in the collection of the late Mrs. John Evans | 161 |

| One of the rough pencil sketches by W. Mulready, R.A., for the envelope. The "flying" figures are not shown in this sketch | 165 |

| Engraver's proof of the Queen's head die for the first adhesive postage stamps, with note in the handwriting of Edward Henry Corbould attributing the engraving to Frederick Heath | 173 |

| An exceptional block of twenty unused One Penny black stamps, lettered "V R" in the upper corners for official use. (From the collection of the late Sir William Avery, Bart.) | 177 |

| An envelope bearing the rare stamp issued in 1846 by the Postmaster of Millbury, Massachusetts.—One of the stamps issued by the Postmaster of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, during the Civil War, 1861 | 181 |

| Another of the Confederate States rarities issued by the Postmaster of Goliad, Texas.—The stamp issued by the Postmaster of Livingston, Alabama. (From the "Avery" Collection) | 183 |

| The One Penny "Post Office" Mauritius on the original letter-cover. (From the "Duveen" Collection) | 187 |

| A roughly printed card showing the designs and colours for the Unified "Postage and Revenue" stamps of Great Britain, 1884 | 191 |

| The King's copy of the Two Pence "Post Office" Mauritius stamp.—The magnificent unused copies of the One Penny and Two Pence "Post Office" Mauritius stamps acquired by Henry J. Duveen, Esq., out of the collection formed by the late Sir William Avery, Bart. | 225 |

| The famous "Stock Exchange" Forgery of the One Shilling green stamp of Great Britain.—A Genuine "Plate 6."—One specimen was used on October 31, 1872, and the other on June 13 of the next year. The enlargements betray trifling differences in the details of the design, as compared with the {19}genuine stamp above | 245 |

| The unique envelope of Annapolis (Maryland, U.S.A.) in Lord Crawford's collection of stamps of the United States | 279 |

| Part sheet (175 stamps) of the ordinary One Penny black stamp of Great Britain, 1840. (From the collection of the Earl of Crawford, K.T.) | 283 |

| Nearly a complete sheet (219 stamps out of 240) of the highly valued One Penny black "V R" stamp, intended for official use. (From the collection of the Earl of Crawford, K.T.) | 285 |

| Part sheet (lacking but six horizontal rows) of the scarce Two Pence blue stamp "without white lines" issued in Great Britain, 1840. (From the collection of the Earl of Crawford, K.T.) | 287 |

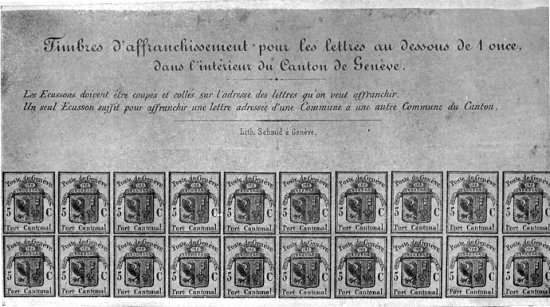

| The unique block of the "double Geneva" stamp, the rarest of the Swiss "Cantonals." (Formerly in the "Avery" Collection, now in the possession of Henry J. Duveen, Esq.) | 291 |

| Part sheet of the scarce 5c. "Large Eagle" stamp of Geneva, showing the marginal inscription at the top. (From the collection of Henry J. Duveen, Esq.) | 293 |

| A Page of the 5 cents. and 13 cents. Hawaiian "Missionary" stamps. (From the "Crocker" Collection) | 297 |

| Hawaiian Islands, 1851. The 5 cents "Missionary" stamp on original envelope. (From the "Crocker" Collection) | 299 |

| A Page from the King's historic collection of the stamps of Great Britain, showing the method of "writing up" | 307 |

| The three copies of the unissued 2d. "Tyrian-plum" stamp of Great Britain, in the collection of H.M. the King. The one on the envelope is the only specimen known to have passed through the post | 309 |

| Design for the King Edward One Penny stamp, approved and initialled by His late Majesty. (From the collection of H.M. King George V.) | 313 |

| The companion design to that on page 313, and showing the correct pose of the head, but in a different frame which was not adopted. (From the collection of H.M. the King) | 315 |

| A Page of the One Penny "Post Paid" stamps of Mauritius. (In {20}the collection of H.M. the King) | 319 |

| The Two Pence "Post Paid" stamp of Mauritius. Unique block showing the error (the first stamp in the illustration), lettered "Penoe" for "Pence". (In the collection of H.M. the King) | 323 |

| A specimen page from the "Tapling" Collection at the British Museum. Probably the most valuable page, showing the Hawaiian "Missionaries." The two stamps at the top have been removed from the cases and are now kept in a safe in the "Cracherode" Room | 327 |

PHILATELIC TERMS

Albino.—An impression made either from an uninked embossing die, or from a similar inked die, under which two pieces of paper have been simultaneously placed, only the upper one receiving the colour.

Aniline.—A term strictly applicable to coal-tar colours, but commonly used for brilliant tones very soluble in water.

Bâtonné.—See Paper.

Bisect.—A term applied to a moiety of a stamp, used as of half the value of the entire label.

Bleuté.—This word implies that the blueness of the paper has been acquired since the stamp was printed, as the result of chemical action.

Block.—An unsevered group of stamps, consisting of at least two horizontal rows of two each.

Bogus.—An expression applied to any stamp not designed for use.

Burelé.—A fine network forming part of design of stamp, or covering the front or back of entire sheet.

Cancelled to order.—Stamps which, though postmarked or otherwise obliterated, have not done postal or fiscal duty.

Centimetre (cm.).—The one-hundredth part of a metre = .3937 inch.

Chalky, or chalk-surfaced.—Before being used for printing, paper sometimes has its surface coated with a preparation largely composed of chalk or similar substance: this renders the print liable to rub off if wetted; and, in combination with a doubly-fugitive ink, renders fraudulent cleaning practically impossible.

Cliché.—The ultimate production from the die, and of a number of which the printing plate is composed.

Colour trials.—Impressions taken in various colours from a plate, so that a selection may be made.

Comb machine.—A variety of perforating machine, which produces, at each descent of the needles, a line of holes along a horizontal (or vertical) row of stamps, and a short line of holes down the two sides (or top and bottom) of each stamp in that horizontal (or vertical) row. And see Perforation.

Commemoratives.—A term applied to labels issued chiefly for sale to collectors, and commemorating the contemporaneous happening, or the anniversary, centenary, &c., of some often unimportant or almost forgotten event.

Compound.—See Perforation.

Control.—An arbitrary letter or number, or both, printed on the margin of a sheet of stamps, for facilitating a check on the supply. Also used to denote a design overprinted on a stamp (e.g. Persia, 1899) as a protection against forgery.

A Pair of Great Britain embossed Six Pence.

A Pair of Cape of Good Hope Triangular Shilling.

A Block of four Great Britain Penny Red.

A Strip of three Grenada "4d." on Two Shillings.

EXAMPLES OF SOME PHILATELIC TERMS.

Current number.—The consecutive number of a plate, irrespective of the denomination of the stamp.

Cut-outs.—A term used to denote the impressions, originally part of envelopes, postcards, &c., but cut off for use as ordinary stamps.

Cut-squares.—Stamps cut from envelopes, &c., with a rectangular margin of paper attached, are known as "cut-squares."

Dickinson paper.—See Paper.

Die.—The original engraving from which the printing plates are produced; or, sometimes, from which the stamps are printed direct. See Plate and Embossed.

Doubly-fugitive.—See Fugitive.

Double-print.—Strictly applicable to two similar impressions, more or less coincident, on the same piece of paper; though often, but erroneously, applied to instances where the paper, not being firmly held, has touched the plate, so receiving a partial impression, and then, resuming its correct position, has been properly printed.

Duty-plate.—Many modern stamps are printed from two plates, one being the same (key-plate, which see) for all the values, but the other differing for each denomination: this latter is the duty-plate.

Electro.—A reproduction of the original die, made by means of a galvanic battery from a secondary die. See Matrix.

Embossed.—Stamps produced from a die, or reproductions thereof, on which the design is cut to varying depths, are necessarily in relief, i.e., embossed. And see Printing.

Engraved.—The term is often used to denote stamps printed direct from a plate, on which the lines of the design are cut into the metal. And see Printing.

Entires.—This expression includes not only postal stationery (which see), but when used in describing an adhesive stamp, as being "on entire," implies that the stamp is on the envelope or letter as when posted.

Envelope stamp.—A stamp belonging to, and printed on, an envelope.

Error.—An incorrect stamp—either in design, colour, paper, &c.—which has been issued for use.

Essay.—A rejected design for a stamp; in the French sense also applied to proofs of accepted designs.

Facsimile.—A euphemism for a forgery.

Fake.—A genuine stamp, which has been manipulated in order to increase its philatelic or postal value.

Fiscal.—A stamp intended for payment of a duty or tax, as distinguished from postage.

Flap ornament.—This refers to the ornament (usually) embossed on the tip of the upper flap of envelopes, and variously termed Rosace or Tresse, or (incorrectly) Patte, which see.

Fugitive.—Colours printed in "singly-fugitive" ink suffer on an attempt to remove an ordinary ink cancellation; but if in "doubly-fugitive" ink it was thought that the removal of writing-ink would injure the appearance of the stamp. And see Chalky.

{29}

The figures "201" indicate the Plate Number, and "238" the Current Number. The Plate Number is also on each of these stamps in microscopic numerals.

Corner pair showing Current Number "575" in margin.

Corner pair showing Plate Number "15" in margin. The Plate Number is also seen in small figures on each stamp.

The above stamps are those of Great Britain overprinted for use in Cyprus.

EXAMPLES OF SOME PHILATELIC TERMS.

Generalising.—The collecting of all the postage-stamps of the world.

Government imitation.—Sometimes, when it is desired to reprint an obsolete issue, the original dies or plates are not forthcoming. New dies have, in these circumstances, been officially made, and the resulting labels are euphemistically called "Government imitations." "Forgeries" would be more candid.

Granite.—See Paper.

Grille.—Small plain dots, generally arranged in a small rectangle, but sometimes covering the entire stamp, embossed on certain issues of Peru and the United States. The idea of this was to so break up the fibre of the paper, as to allow the ink of the postmark to penetrate it and render cleaning impossible.

Guillotine.—The term used to define a perforating-machine which punches a single straight line of holes at each descent of the needles.

Gumpap.—A fancy term of opprobrium applied to a stamp issued purely for sale to collectors and not to meet a postal requirement.

Hair-line.—Originally used to indicate the fine line crossing the outer angles of the corner blocks of some British stamps, inserted to distinguish impressions from certain plates, this term is now often employed to denote any fine line, in white or in colour, and whether intentional or accidental, which may be found on a stamp.

Hand-made.—See Paper.

Harrow.—The form of perforating-machine which is capable of operating on an entire sheet of stamps at each descent of the needles. And see Perforation.

Head-plate.—See Key-plate.

Imperforate.—Stamps which have not been perforated or rouletted (both of which see) are thus described.

Imprimatur.—A word usually found in conjunction with "sheet," when it indicates the first impression from a plate endorsed with an official certificate to that effect, and a direction that the plate be used for printing stamps.

Imprint.—The name of the printer, whether below each stamp, or only on the margin of the sheet, is called the "imprint."

Inverted.—Simply upside-down. And see Reversed.

Irregular.—See Perforation.

"Jubilee" line.—Since 1887, the year of Queen Victoria's first Jubilee—whence the name—a line of "printer's rule" has been added round each pane, or plate, of most surface-printed British and British Colonial stamps, in order to protect the edges of the outer rows of clichés from undue wear and tear. The "rule" shows as a coloured line on the sheets of stamps.

Key-plate.—Stamps of the same design, when printed in two colours, require two plates for each value; that which prints the design (apart from the value, and sometimes the name of the country), and is common to and used for two or more stamps, is termed the head-plate or key-plate. And see Duty-plate.

A sheet of stamps of Gambia, composed of two Panes of sixty stamps each.

The single "Crown and CA" watermark as it appears looking from the back of the Gambia sheet illustrated above. The watermark is arranged in panes to coincide with the impressions from the plate.

EXAMPLES OF SOME PHILATELIC TERMS.

Knife.—This is a technical term for the cutter of the machine which cuts out the (unfolded) envelope blank, and is principally used in connection with the numerous varieties of shape in the United States envelopes, amongst which the same size may show several variations in the flap.

Laid.—See Paper.

Laid bâtonné.—See Paper.

Line-engraved.—Is properly applied to a print from a plate engraved in taille douce (which see) but is often applied to the plate itself.

Lithographed.—Stamps printed from a design laid down on a stone and neither raised nor depressed in the printing lines are denoted by this term. And see Printing.

Locals.—Stamps having a franking power within a definitely restricted area.

Manila.—See Paper.

Matrix.—A counterpart impression in metal or other material from an original die, and which in its turn is used to produce copies exactly similar to the original die.

Millimetre (mm.).—The one-thousandth part of a metre = .03937 inch.

Mill-sheet.—See Sheet.

Mint.—A term used to denote that a stamp or envelope, &c., is in exactly the same condition as when issued by the post-office—unused, clean, unmutilated in the slightest degree and with all the original gum undisturbed.

Mixed (Perforations).—In some of the 1901-7 stamps of New Zealand, the original perforation was to{36} some extent defective: such portions of the sheet were patched with strips of paper on the back and re-perforated, usually in a different gauge.

Mounted.—Usually applied to indicate that a stamp, which has been trimmed close to the design, has had new margins added. And see Fake.

Native-made paper.—See Paper.

Obliteration.—A general term used for any mark employed to cancel a stamp and so render it incapable of further use.

Obsolete.—Strictly, an obsolete stamp is one which has been withdrawn from circulation and is no longer available for postal use; but the term is often applied simply to old issues, no longer on sale at the post-office.

Original die.—The first engraved piece of metal, from which the printing plates are directly or indirectly produced.

Original gum.—Practically all stamps were, before issue, gummed on the back, and the actual gum so applied is known as "original": the usual abbreviation is "o.g.": it is also implied in the expression "mint", which see.

Overprint.—An inscription or device printed upon a stamp additional to its original design. Cf. Surcharge.

Pair.—Two stamps joined together as when originally printed. Without qualification, a pair is generally accepted as being of two stamps side by side: if a pair of two stamps joined top to bottom is intended, it is spoken of as a vertical pair.

EXAMPLES OF SOME PHILATELIC TERMS.

A "Bisect," or "Bisected Provisional." The One Penny stamp of Jamaica was in 1861 permitted to be cut in halves diagonally, and each half used as a halfpenny stamp.

Pane.—Entire sheets of stamps are frequently divided into sections by means of one or more spaces running horizontally or (and) vertically between similarly sized groups of stamps: each of these sections or groups is termed a pane.

Paper.—The two main divisions of paper are hand-made and machine-made: the former is manufactured, as its name indicates, by hand, sheet by sheet, by means of a special apparatus; the latter is made entirely by the aid of machinery and generally in long continuous rolls, which are afterwards cut up as required.

Each of these, apart from its substance, which may vary from the thinnest of tissue papers to almost thin card, is divisible according to its texture, distinguishable on being held up to the light, into—

Wove, of perfectly plain even texture, such as is generally used for books.

Laid: this shows lines close together, usually with other lines, an inch or so apart, crossing them—"cream laid" notepaper is an example.

Bâtonné is wove paper, with very distinct lines as wide apart as those on ordinary ruled paper.

Laid bâtonné: similar to bâtonné, but the spaces between the distinct lines are filled in with laid lines close together.

Quadrillé paper is marked with small squares or oblongs.

Rep is the term applied to wove paper which has been passed between ridged rollers, so that it becomes, to use a somewhat exaggerated description, corrugated: the small elevation or ridge on one side of the paper coincides with a depression or furrow on the other side—the thickness of the paper is the same throughout.

Ribbed paper, on the other hand, is different from rep, in that one side is smooth and the other is in alternate furrows and ridges—the paper is thinner in the furrows than it is on the ridges.

Native paper, so called, is yellowish or greyish, often with the feel and appearance of parchment; generally laid somewhat irregularly, but often wove. The early issues of Cashmere and some of the stamps and cards of Nepal are printed on native paper: it is always hand-made.

Pelure is a very thin, hard, tough paper, usually greyish in colour.

Manila is a strong, light, but coarse paper, and is used for wrappers, large envelopes, &c.; usually it is smooth on one side and rough on the other.

Safety paper contains ingredients which would make it very difficult, if not impossible, to remove an obliteration in writing-ink without at the same time destroying the impression of the stamp: usually this paper is more or less blued, owing to the use of{41} prussiate of potash, and its combination with impurities arising in the manufacture.

Granite paper is almost white, with short coloured fibres in it, sometimes very visible, but at others necessitating the use of a magnifying glass.

Dickinson paper, so called from its inventor, has a continuous thread, or parallel threads, of silk in the centre of its substance, embedded there in the pulp at an early stage of the manufacture.

Paraphe is the flourish which is sometimes added at the end of a signature: examples on stamps are found in the 1873-6 issues of Porto Rico.

Patte.—French for the loose flap of an envelope; it is sometimes (but incorrectly) used for Rosace or Tresse, the ornament on the flap.

Pelure.—See Paper.

Pen-cancelled denotes cancellation by pen-and-ink, as opposed to the more customary postmark; it usually implies fiscal use.

Percé is a French term denoting slits or pricks, no part of the paper being removed, in contradistinction to perforated, in which small discs of paper are punched out. There are several kinds of perçage, or, in English, rouletting:—

Percé en arc, the cuts being curved, so that, on severing a pair of stamps, the edge of one shows small arches, whilst the other has a series of small scallops, something like, but{42} more curved than, the perforations on the edges of an ordinary perforated stamp.

Percé en ligne: the cuts or slits are straight, as if a continuous line had been broken up into small sections. This variety usually goes by the English term rouletted.

Percé en pointe denotes that the slits are comparatively large and cut evenly in zigzag, so that the edges of a stamp show a series of equal-sided triangular projections.

Percé en points, usually expressed as pin-perforated, implies a pricking of holes with a sharp point, but without removal of paper, which is merely pushed aside.

Percé en scie is somewhat similar to percé en pointe, except that the slits are smaller and are cut in uneven zigzag (alternately long and short), so that the edge of a severed stamp is like that of a fine saw.

Percé en serpentin occurs when the paper is cut in comparatively large wavy curves of varying depth, with little breaks in the cutting which serve to hold the stamps together.

And see Perforated and Perforation.

Perforated—in French piqué. This word implies removal of small discs of paper, not simply slits or cuts. And see Percé.

Perforation is either "regular," where the number of holes within a similar space is constant along the entire row; or, where the number varies more or less, "irregular." The gauge of the perforations (or roulettes) of a stamp is measured{43} by a perforation-gauge, a piece of metal, card, or celluloid, on which is engraved or printed a long series of rows of dots, each row being two centimetres in length and containing a varying number of dots from, say, 6 to 17 or 18.

A stamp, the edge of which shows holes (perforated) corresponding in spacing and number to the row on the gauge marked, say "12," is said to be "perforated 12." If the stamp gauges the same on all four sides, it is simply "perforated ..."; if the top and bottom are of one gauge, say 12, and the sides, say, 14, the stamp would be perforated "12 × 14." If the gauge varies on each of the four sides—an unlikely combination—then the order of noting same is, top (say 12), right (say 11), bottom (say 13), and left (say 15)—"perforated 12 × 11 × 13 × 15." In the above the gauges are supposed to be regular.

PERFORATION GAUGE.

Should, however, the gauge be irregular, the extremes are noted even if not showing on the stamp: for instance, a stamp may be perforated{44} with a machine, which, in its entire length, gradually varies from 12 to 16 holes in the two centimetres, though the stamp itself does not show all those gauges. Such a stamp would be "perforated 12 to 16."

On the other hand, a row of perforations, instead of gradually altering in gauge, may do so abruptly; for instance, along a row of holes, part may gauge 14, the next part 16, and then 161/2, all quite distinct over a particular space. This would be termed "perforated 14, 16, 161/2," implying that the intermediate gauges did not exist.

The use of a regular machine, in conjunction with one of irregular gauge, might produce, say, "perforated 14" (horizontally) "× 12 to 15" (vertically); and so on.

Stamps perforated, horizontally and vertically, by differently gauged machines are sometimes said to be "perforated, compound of ... and ...". There are many difficulties in the way of obtaining a full knowledge of the combinations and vagaries of perforating-machines.

Perforation-gauge.—A means of measuring perforation or roulette, which see.

Philatelic.—The adjective of Philately.

Philatelist.—One who studies stamps.

Philately—from two Greek words, "φίλος" (= fond of) and "ἀτέλεια" (= exemption from tax)—signifies a fondness for things (viz., stamps) which denote an exemption from tax, i.e., that the tax, or postage, has been paid. The word{45} is a little far-fetched to imply the study of stamps, but as "Philately" has been the accepted term for over forty years, "Philately" it will doubtless remain, even if some one succeeds in finding a word which more accurately expresses the popular and scientific hobby.

Pin-perforated.—See Percé.

Plate is the term used, not always quite correctly, to describe the ultimate reproductions from the die which constitute the printing surface in the manufacture of stamps: the word covers not only a sheet of metal with stamps engraved on it, but also a group of clichés or a forme of printer's type and even a lithographic stone.

Plate number is the consecutive number of each plate of a particular value, appearing on the margin of the plates and (in some of the British series) on the stamps themselves.

Postal-fiscal is a fiscal stamp the use of which for postal purposes has been duly authorised, in contradistinction to a "fiscal postally used," a use which has been tacitly permitted in many countries.

Postal stationery, i.e., envelopes, postcards, letter-cards, wrappers, telegram forms, &c.: frequently termed entires.

Postmark.—The official obliteration applied to a stamp to prevent its further postal use.

Pre-cancelled.—Two or three countries have adopted the system, to save time in the post-office, of supplying sheets of stamps cancelled prior to use. This may be a convenience, but the{46} practice undoubtedly opens the door to possible fraud.

Print is an impression taken from any die, plate, forme, or stone.

Printing, in its fullest sense, is reproducing from a die, plate, stereotype, &c. (all of which see). There are, on this definition, four kinds of production: "Embossing," where the paper is impressed with a raised design, by pressure from a cut-out die (see Embossed); "Surface-printing" or "typography," where the portions of the plate which receive the ink and print the design are raised: this process causes a slight indentation on the surface of the paper and a corresponding elevation at the back; "Printing direct from plate" (so-called Line-engraved, which see), in which the portions to be inked are recessed: in this process, the printed design on the stamps is in very slight relief, due to the ink being taken from the recessed engraving. "Lithography" is printing from a stone, on which the design has been drawn or otherwise laid down: impressions from a stone are flat.

Proof.—An impression, properly in black, from the die, plate, or stone, taken in order to see if the design, &c., has been properly engraved or reproduced.

Provisional.—A make-shift intended to supply a temporary want of the proper stamp, which may have been unexpectedly sold out, or may not have been supplied owing to lack of time.

Quadrillé.—See Paper.

Re-issue denotes the bringing again into use of a stamp which has become obsolete, or at any rate has been long out of use at the post-office; it sometimes implies a new printing.

Remainders.—Stamps printed during the period of issue and left on hand when that issue has gone out of use.

Reprint.—Strictly a reprint is an impression taken from the identical original die, plate, stone, or block, after the stamps printed therefrom have gone out of use. The term is used to include printings from new plates or stones, made from the original die. And see Government imitations.

Rep.—See Paper.

Retouch, re-set, re-engraved, re-drawn, re-cut.—All these terms have a somewhat similar meaning, and imply repairs to, or alterations of, the die, plates, stones, or blocks: instances of most drastic re-engraving are known, e.g., that of the 1848 Two Pence ("Post Paid") of Mauritius, the plate of which was so altered as to produce a practically new stamp, the Two Pence, "large fillet," of 1859; and the Half Tornese "Arms" of Naples, which had the entire centre removed from each of the two hundred impressions on the plate and replaced by the Cross of Savoy. To differentiate—retouching is generally undertaken to remedy minor defects caused by wear and tear: re-setting suggests slight re-arrangement of stamps made up, wholly or partly, of printer's type; re-engraving, the replacing of parts of a design worn away by use or intention:{48} re-drawing rather leads one to infer that the original design has been reproduced in an improved form; and re-cutting implies going over the original die, &c., and strengthening the engraving, with, perhaps, slight accidental variations of the design.

Revenue.—This word indicates availability for fiscal use, as distinguished from postal use. A stamp may be available for either purpose, or for one only; the use is almost invariably indicated by the inscription.

Reversed.—Backwards-way; "as in a looking-glass." The term is often, but quite erroneously, used for inverted—which see—implying upside-down.

Ribbed.—See Paper.

Rosace.—The small ornament frequently found on the upper flap of old envelopes; known also as tresse.

Rough perforation.—When the holes in the lower plate of the perforating-machine get damaged or partly clogged up, or the punches are very worn, the perforation becomes very defective, the little discs of paper not being punched out, but (though generally distinct) left only partly cut through: this state is termed "rough," but must not be confused with percé en points (pin-perforated), which see.

Rouletted.—See Percé.

Rouletted in coloured lines is a variety of rouletting, and always so termed, in which the slits or cuts are made by means of type ("printer's rule") a little higher than the clichés or stereos{49} composing the plate, and which cut into the paper under the pressure of the printing-press.

Safety paper.—See Paper.

"Seebecks."—The late Mr. N. F. Seebeck, the contractor to various South American Republics had an arrangement under which there was a new issue of stamps every year, he to retain for his own benefit any demonetised remainders of the previous set: stamps provided under such conditions are called after their originator.

Se tenant.—A French expression signifying that the stamps referred to have not been separated: usually employed in reference to an error, or variety, when still forming a pair with a normal stamp.

Serpentine roulette.—See Percé en serpentin.

Sheet (of paper).—There are three "sheets": a mill-sheet, as manufactured; a sheet as printed, which may be, and often is, less than a mill-sheet; and a "post-office" sheet, either the whole or an arbitrary part of a printed sheet, so divided for convenience of reckoning.

Silk-thread paper.—See Paper (Dickinson).

Single-line perforation.—See Guillotine.

Spandrel is the term for the triangular space between a circle, oval, or curve, and the rectangular frame enclosing it.

Specialising.—To develop in a collection a complete record of the inception, history, and use of the stamps of a particular country, or group of countries, in the fullest and most detailed manner. In contradistinction to Generalising (which see).

Stationery.—See Entires.

Stereotype or stereo.—A reproduction of the original design, made by means of a papier-maché or other mould, in type-metal. And see Matrix.

Strip is the philatelic term for three or more stamps unsevered and in the same row, horizontal or vertical.

Surcharge.—An overprint (which see) which alters the face value of a stamp, or confirms it in the same or a new currency. The term is loosely used to mean any overprint, but it is desirable that its application be confined to inscriptions affecting the denomination of face-value.

Surface-printed, that is, printed by a process in which the parts of the plate, &c., which produce the coloured portions of the stamp are raised up. See Printing.

Taille douce.—When a design is cut into the substance of the plate it is said to be engraved in taille douce. A familiar example is a visiting-card plate.

Tête-bêche is a French expression signifying the inversion of one stamp of a pair (or more) in relation to the other stamp (or stamps): naturally, the peculiarity disappears on severance, and such varieties must necessarily be in a pair or more.

Toned, as applied to paper, implies a very slight buff tint.

Tresse.—See Rosace.

Trials.—These are impressions from die, plate, stone, &c., taken to ascertain if the design be correct, or to assist in the selection of a suitable colour.

EXAMPLES OF SOME PHILATELIC TERMS.

Photograph of a flat steel die engraved in taille douce (i.e., with the lines of the design cut into the plate). The stamp is the 50 lepta of Greece, issue of 1901, showing Hermes adapted from the Mercury of Giovanni da Bologna.

Type.—A representative common design, as distinguished from "variety," which indicates slight deviations therefrom.

Type-set.—Stamps—e.g., the 1862 issue of British Guiana—have sometimes been set up with ordinary printer's type, as used for books, and the ornamental type-metal designs to be found in a printing establishment.

Typographed.—See Surface-printed.

Used abroad.—Prior to certain countries and colonies having their own stamps, British post-offices were established in them, at which British stamps were to be purchased; such stamps, identified by their postmarks as having been so used, are termed "British used abroad." The stamps of other countries have been similarly "used abroad."

Variety.—A slight variation from the normal design, or type, which see.

Watermarks.—A thinning of the substance of the paper, in the form of letters, words, or designs, &c., during the manufacture. On the paper being held up to the light, or placed on a dark surface, the designs become more or less visible.

So-called "watermarks" are sometimes produced by impressing a design on the paper after manufacture; this has a somewhat similar effect, though the paper is only pressed, not thinned.

Wove.—See Paper.

Wove bâtonné.—See Paper.

THE GENESIS OF THE POST

The earliest letter carriers—The Roman posita—Princely Postmasters of Thurn and Taxis—Sir Brian Tuke—Hobson of "Hobson's Choice"—The General Letter Office of England—Dockwra's Penny Post of 1680—Povey's "Halfpenny Carriage"—The Edinburgh and other Penny Posts—Postal Rates before 1840—Uniform Penny Postage—The Postage Stamp regarded as the royal diplomata—The growth of the postal business.

Postage is so cheap and so easy to-day that we are apt to forget how, not very many years ago, it was a privilege of the rich. To-day the Post Office is no respecter of persons, and the "all swallowing orifice of the pillar-box" receives without favour or distinction the correspondence of the humble with the messages of the mighty. The Post Office treats everything confided to its charge with the same organised routine. In the palatial new edifice, King Edward the Seventh Building, a few days before Christmas, a letter was handed to me for inspection in the "Blind Division," where they deal with insufficiently addressed letters. The missive bore in the handwriting of a little child, "To Santa Claus, No. 1, Aerial Building, London."{58} That letter, I was informed, had to be passed through the Blind Division, thence to the Returned Letter Office, where it would be opened to discover if the enclosure contained any indication of the identity and whereabouts of the writer. If not returnable, the letter would be preserved for a period lest it should be claimed. The Department is as careful of the precocious petitions of a child as it is of the papers of State which it carries throughout the length and breadth of the land.

By all who would know the true love of stamps it must needs be understood how postal matters were before the birth of the Penny Black. Else we shall not fitly appreciate all the benefices that the "label with the glutinous wash" has brought to our present civilisation. Without this comparison of the old order with the new, we should be in peril of passing over the true significance of the postage-stamp in the surfeit of blessings it confers upon the world to-day. Postage to-day is as fecund of bounties as a fruitful garden, yet do we accept all as our rightful heritage, without giving much consideration to the little postage-stamp which was the seed which, planted in every civilised country of the earth, has yielded blessings in abundance.

So in our first chat, we would open up the book in which is told the history of things that are written from one to another. The first letter of which we have any particular knowledge was that by which David achieved his evil purpose of sending Uriah the Hittite to the forefront of the battle, that{59} he might be smitten and die. The unfortunate Uriah was himself the messenger, bearing the fatal letter to Joab with his own hand. The brazen-faced Jezebel forged her royal husband's name to letters, so our first meeting with letters in scriptural history shows that they could be used to evil as well as to good purpose.

As the Scythians made contracts one with another by mingling the warm blood of their bodies in a cup and drinking thereof, so the Persians used living letters in their early correspondence. Herodotus tells us how they shaved the heads of their messengers and impressed or branded the "writing" upon their scalps. Then they were shut up until the hair had grown again and concealed the message, when the runners were sent off upon their divers journeys. A messenger on reaching his destination was again shaved and the epistle was made plain to the eyes of the beholder.

This was a primitive method, one of many which had vogue amongst the ancients. Under Darius I. the Persians had a service of Government couriers, for whom were provided horses ready saddled at specified distances on their route, so that the Government could send and receive communications with the provinces. "Nothing in the world is borne so swiftly as messages by the Persian couriers," says Herodotus.

The word "post" descends to us from the Roman posita (positus = placed), and is a link between our posts of to-day and the cursus publicus of the time of Augustus. In those days of arms the roads were{60} laid for armies to traverse, not for traffic, and the organisation of the posita was military. Stations were established at intervals on the chief routes, where couriers and magistrates could be furnished with changes of horses (mutationes.) For the benefit of the travellers mansiones or night quarters were erected. These State posts were only for the use of the Government, and they were ridden by couriers who had, besides their own mount, a spare horse for carrying the letters. Individuals were at times permitted to use the posts, for which privilege they had to have the permits or diplomata of the Emperor. The Romans also had what may be compared with sea-posts, from Ostia and other ports.

Foot-runners and messengers on horseback have been organised for Government communications in most lands where civilisation has dawned, even in remote times. In the West the Incas and the Aztecs had runners from earliest times, and in the Orient carrier-pigeons provided an additional means of communication.

It is not until the fifteenth century that we find posts in operation on a more public scale, the first being a horse-post plying between the Tyrol and Italy, set up by Roger of Thurn and Taxis in 1460. From that modest beginning sprang the vast monopoly of the Counts of Thurn and Taxis, which dominated the posts of the Continent during five centuries, remaining into the early period of the postage-stamp system. By 1500, Franz von Taxis was Postmaster-General of Austria, the Low Countries, Spain, Burgundy, and Italy. In 1516{61} he connected up Brussels and Vienna, and his successor Leonard provided a link between Vienna and Nuremberg. In 1595, Leonard von Taxis was the Grand Postmaster of the Holy Roman Empire, and he established a post from the Netherlands to Italy by way of Trèves, Spire, Wurtemburg, Augsburg, and Tyrol. In the next century, Eugenius Alexander subscribes himself in a postal document as "Count of Thurn, Valsassina, Tassis and the Holy Empire, Chamberlain of His Majesty the Roman Emperor, Hereditary Postmaster-General of the Realm." The postal dominion of this princely house flourished until the wars of the French Revolution, from which period the power of the Counts began to dwindle. Some of the German States withdrew from their arrangements with the house of Thurn and Taxis, and others purchased their freedom and set up postal establishments of their own. By the middle of the nineteenth century Austria, Prussia, Bavaria, Hanover, Baden, Brunswick, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Holstein, Oldenburg, Lauenburg, Luxemburg and Saxony had independent posts, but the Thurn and Taxis administration still controlled an area of 25,000 square miles (with 3,750,000 inhabitants), under the direction of a head office at Frankfort-on-the-Maine. In 1851, however, Wurtemburg, at a cost of over £100,000, bought its freedom from the monopolists; and sixteen years later (1867) Prussia paved the way for the completion of the consolidation of the German Empire by purchasing for three million thalers (approximately £450,000) the last remaining rights of the{62} house of Thurn and Taxis in the postal affairs of Germany.

In England the royal Nuncii et Cursores were the forerunners of the King's Messengers of to-day, and were exclusively employed upon State affairs and for the correspondence of the Sovereign and of the Court. At what period the people were admitted to the privilege of the posts is obscure. The first Master of the Posts of whom we know was one Brian Tuke, Esq., afterwards Sir Brian Tuke, who is best remembered in Holbein's several portraits of him, and as the author of the preface to Thynne's "Chaucer." He was at one period secretary to Cardinal Wolsey, and it is in a letter (1533) to his successor in that office, Thomas Cromwell, that we find the one clue to the state of the posts at that time:

"By your letters of the twelfth of this moneth, I perceyve that there is grete defaulte in conveyance of letters, and of special men ordeyned to be sent in post; and that the Kinges pleasure is, that postes be better appointed, and laide in al places most expedient; with commaundement to al townshippes in al places, on payn of lyfe, to be in suche redynes, and to make suche provision of horses, at al tymes, as no tract or losse of tyme be had in that behalf."

In the sixteenth century, there were regular carriers licensed to take passengers, goods, and letters, and of these the most remarkable was Tobias Hobson, who was an innkeeper at Cambridge. His memory is perpetuated in the common expression of "Hobson's choice." The innkeeper{63} kept a stable of forty good cattle, but made it a rule that any who came to hire a horse was obliged to take the one nearest the stable door, "so that every customer was alike well served, according to his chance, and every horse ridden with the same justice." Milton, in one of his two punning epitaphs on Hobson, refers to his position as letter-carrier:—

From 1609, the Posts of Great Britain have been under the monopoly of the Crown, and at that time they were carried on at a loss. As the posts did not carry the correspondence of the public, there was no likelihood of their being made self-supporting until the facilities they offered were of utility to the people. The general admission of the public to these facilities dates from 1635, under the Postmastership of Thomas Witherings, and two years later was set up the "Letter Office of England." The cheapest rate under Withering's management was 2d. for a "single letter" (that is, one sheet of paper) conveyed a distance not exceeding 80 miles. If the letter weighed an ounce, the charge was 6d. A single letter to Scotland cost 8d. and to Ireland 9d.

For a number of years prior to 1667, the posts were farmed to various individuals, and during the Commonwealth, Parliament passed an Act settling the postage of the three kingdoms, which "pretended Act" was practically re-enacted at the Restoration. The profits on the Post Office were settled by Charles{64} II. upon his son, the Duke of York, afterwards James II., and the latter took care upon his accession to the throne to secure the continuance of his enjoyment of its revenues.

Private enterprise was responsible for putting a good deal of pressure on the Post Office in the early days. In 1659, a penny post was first proposed by one John Hill and certain other "Undertakers," but the most notable instance was the success that attended the efforts of William Dockwra in establishing the London Penny Post in 1680. By this penny post, Londoners had for three years an excellent and frequent service of postal collections and deliveries of their letters and parcels within the City and suburbs. The Government post had one office in London—the General Letter Office—up to 1680. Consequently, persons who had letters to send by post had either to take them, or procure messengers to take them, to the office in Lombard Street. Dockwra established between four and five hundred receiving offices for letters, and a good part of the business he did was in transmitting letters to and from the General Letter Office in Lombard Street.

The penny post made many friends, but also

a few enemies. Of the few there was one of powerful

influence, the Duke of York, who envied the

prospective income to be derived from a popular

post; there were others who were unscrupulous in

their attacks, led by the notorious Titus Oates, who

pretended to expose the whole of Dockwra's plan

as "a farther branch of the Popish plot," and the

porters of London, who, fearing to lose many of

{67}

their chances of employment, vented their spleen

in the manner of vulgar rioters.

SCARCE PAMPHLET (FIRST PAGE) IN WHICH WILLIAM DOCKWRA ANNOUNCES THE PENNY POST OF 1680.

Proceedings were taken against Dockwra for infringement of the Crown's monopoly, and the case being carried, the London Penny Post was shortly afterwards re-established and carried on under authority for nearly a hundred and twenty years, until 1801, when the penny rate was doubled and the Penny Post became the Twopenny Post.

Charles Povey's "halfpenny carriage" (1708) was a poor copy of Dockwra's post, covering a smaller area at the lower fee of one halfpenny. Its originator was fined £100 in 1760, and the incident of this post is only remarkable in postal history for its having originated the use of the "bellman" for collecting letters in the streets.

The Edinburgh Penny Post, set up by the keeper of a coffee-shop in the hall of Parliament House, Peter Williamson, in 1768, was also stopped by the authorities as a private enterprise; but its promoter was given a pension of £25 a year and the post was carried on by the General Post Office. Just three years previously, local Penny Posts had been legalised by the Act of 5 George III., c. 25, provided they were set up where adjudged to be necessary by the Postmaster-General. Such penny posts increased rapidly towards the end of the eighteenth century, and just before Uniform Penny Postage was introduced there were more than two thousand of them in operation in different parts of the country. In spite of the increase in these local posts, however, the general postage was high, the{68} tendency of the later changes in the rates being to increase rather than to lessen them.

In the early part of the nineteenth century, the rates were such that few but the rich could make frequent use of the luxury of postage, and these rates, coming close up to the period of the new régime of 1840, form an extraordinary series of contrasts. Here is an old post-office rate-book kept by the postmaster (or mistress) at Southampton in the 'thirties, which I like to show my friends when they sigh for the good old times. It is a printed list of the chief places to which letters could be sent, with columns to be filled in by the postal official after calculating distances and exercising simple arithmetic. In Great Britain the rates were for single letters:—

| From any post office in England or Wales to any place not exceeding 15 miles from such office | 4d. | ||||

| Between | 15 | and | 20 | miles | 5d. |

| " | 20 | " | 30 | " | 6d. |

| " | 30 | " | 50 | " | 7d. |

| " | 50 | " | 80 | " | 8d. |

| " | 80 | " | 120 | " | 9d. |

| " | 120 | " | 170 | " | 10d. |

| " | 170 | " | 230 | " | 11d. |

| " | 230 | " | 300 | " | 12d. |

and one penny in addition on each single letter for every 100 miles beyond 300. These rates did not include "1d. in addition to be taken for penny postage" and in certain cases toll-fees.

A Post-Office in 1790.

By permission of the Proprietors of the City Press.

Under these rates, a single letter to Kirkwall

from Southampton cost 1s. 7d.; to London 9d.,

{71}

plus the penny postage; Cork 1s. 3d., &c. These

rates were for a single-sheet letter, the charge being

multiplied by two for a double letter, by four for an

ounce, which is one-quarter of the weight at present

allowed on a letter which costs us a modest penny.

Letters for overseas were correspondingly high as the following comparisons will show:—

| Single-sheet Letter. | 1 oz. Letter. | ||

| 1830. | 1911. | ||

| Austria | 2s. 3d. | 2½d. | |

| Brazil | } | ||

| Buenos Aires | 3s. 5d. | 2½d. | |

| Chili, Peru, &c. | |||

| Canary Islands | 2s. 6d. | 2½d. | |

| Germany | 1s. 9d. | 2½d. | |

| Hayti | 2s. 11d. | 2½d. | |

| Honduras | 2s. 11d. | 2½d. | |

| Portugal | 2s. 2d. | 2½d. | |

| Russia | 2s. 3d. | 2½d. | |

| Spain | 2s. 2d. | 2½d. | |

| Sweden | 1s. 8d. | 2½d. | |

| Turkey | 2s. 2d. | 2½d. | |

| United States | 2s. 1d. | 1d. | |

| British West Indies and | } | ||

| British North America | 2s. 1d. | 1d. | |

| Malta, Gibraltar | 2s. 2d. | 1d. | |

| St. Helena | 1s. 8½d. | 1d. | |

The registration fee on foreign letters was, in the early nineteenth century, one guinea per letter; to-day it is twopence.

THE COMMEMORATIVE LETTER BALANCE DESIGNED BY MR. S. KING, OF BATH (1840).

A monument "which may be possessed by every family in the United Kingdom."

These are but a few examples showing what a mighty change was wrought with the introduction of the Uniform Penny Postage plan of Rowland Hill. The circumstances under which the new plan was introduced included several factors to which may{74} be attributed a share in the success of Hill's plan. First, the uniform and low minimum rate of one penny on inland letters, dispensing with tedious calculations of distance. By some it was feared that the necessity for calculating the weight would be more troublesome than examining the letter against a lighted candle to see if it were "single" or "double," and scores of "penny post letter balances" were placed upon the market at the outset. Next was the increased facility of transit provided by the then growing system of railways, and the subsequent development of steam-power at sea.

MR. KING'S LETTER BALANCE HAD A TRIPOD BASE, AS IN THE UPPERMOST FIGURE, THUS AFFORDING THREE TABLETS, ON WHICH THE ASSOCIATIONS OF J. PALMER, ROWLAND HILL, AND QUEEN VICTORIA WITH POSTAL REFORM ARE RECORDED.

But the one factor which to us is the most notable contribution to the success of the Penny Postage plan, was the square inch of paper with its backing of glutinous wash. This enabled the authorities to effect the introduction of prepayment, and save the long delays formerly occasioned by the postman having to await payment for each letter on delivery. It saved the complicated system by which the Post Office had to ensure that the postman did get paid, and in his turn accounted for the money to his office. It was to this simple contrivance of a small label, issued by authority, to indicate the prepayment of postage that the practical success of Hill's plan was greatly due. The little stamps are the royal diplomata which enable us all, at a modest fee, to use His Majesty's mails, a privilege enjoyed by great and small, by rich and poor. So stamp-collectors deem the objects of their interest to have achieved a vast reform in internal and universal communications, giving a powerful impetus to social{75} progress, international commerce, and the world's peace.

The year before the introduction of Uniform Penny Postage there were 75,907,572 letters dealt with by the Post Office. The number was more than doubled in the first year of the new system, and the subsequent growth of correspondence is outlined in the figures (letters only) for the following years:—

| 1840 | 168,768,344 |

| 1850 | 347,069,071 |

| 1860 | 564,002,000 |

| 1870 | 862,722,000 |

| 1880 | 1,176,423,600 |

| 1890 | 1,705,800,000 |

| 1900 | 2,323,600,000 |

| 1910 | 2,947,100,000 |

THE DEVELOPMENT OF AN IDEA

Early instances of contrivances to denote prepayment of postage—The "Two Sous" Post—Billets de port payé—A passage of wit between the French Sappho and M. Pellisson—Dockwra's letter-marks—Some fabulous stamped wrappers of the Dutch Indies—Letter-sheets used in Sardinia—Lieut. Treffenberg's proposals for "Postage Charts" in Sweden—The postage-stamp idea "in the air"—Early British reformers and their proposals—The Lords of the Treasury start a competition—Mr. Cheverton's prize plan—A find of papers relating to the contest—A square inch of gummed paper—The Sydney embossed envelopes—The Mulready envelope—The Parliamentary envelopes—The adhesive stamp popularly preferred to the Mulready envelope.

The simplest inventions are usually apt adaptations. The postage-stamp, as we know it to-day, can scarcely be said to have been invented, though much wild controversy has raged about the identity of its "inventor." The historian must prefer to regard the postage-stamp of to-day as the development of an idea.

It would not serve any purpose useful to the present subject to trace to its beginnings the use of stamped paper for the collection of Government revenues; but it is highly interesting to disentangle{80} from the web of history the facts which show this system to have been recognised as applicable to the collection of postages by the prototypes of the reformers of 1840.

The first known instance of special printed wrappers being sold for the convenience of users of a postal organisation occurred in Paris in 1653. At this time France had its General Post, just as England about the same time had set up a General Letter Office in the City of London; but in neither case did the General Post handle local letters. To despatch a letter to the country from Paris, or from London, there was no choice but to deliver it personally, or send it by private messenger, to the one solitary repository in either city for the conveyance of correspondence by the Government post.

The porters of London found no small part of the exercise of their trade in carrying letters to the General Letter Office, and in Paris, no doubt, a similar class of men enjoyed the benefit of catering at individual rates for what is now done on the vast co-operative plan of the State monopoly.

In 1653, a Frenchman, M. de Villayer, afterwards Comte de Villayer, set up as a private enterprise (but with royal authority) the petite poste in Paris, which had for its raison d'être the carrying of letters to the General Post, and also the delivery of local letters within the city. He distributed letter-boxes at prominent positions in the chief thoroughfares in Paris, into which his customers could drop their letters and from whence his laquais could collect them at regular intervals. At certain appointed{81} places M. de Villayer placed on sale letter-covers, or wrappers, which bore a marque particulier, and which, being sold at the rate of a penny each (two sous), were permitted to frank any letter deposited in the numerous letter-boxes of the Villayer post to any point within the city. The post is the one afterwards referred to by Voltaire as the "two-sous post."

These wrappers, then, were the first printed franks for the collection of postage from the public. The exact nature of the matter imprinted upon them is uncertain; but it probably included M. de Villayer's coat of arms, and it was on this hypothesis that the late M. Maury, the French philatelist, reconstructed an approximate imitation of the original form of cover. The covers, it should be stated, were wrapped around the letters by the senders, and were then dropped in the boxes. In the process of sorting for delivery, the servants of M. de Villayer removed the special cover, which removal was practically the equivalent of the cancellation of the stamps of to-day.

These covers undoubtedly represent the first known form of printed postage-stamps, being the forerunners of the impressed non-adhesive stamps of to-day. The Maury reconstruction is fanciful, but the inscriptions thereon are literally correct. Owing to the removal of the covers (which were probably broken in the process) during the postal operations no originals of these covers are now known to exist. Indeed, the only true relics of the billets de port payé of M. de Villayer are in the two fragments of correspondence between M. Pellisson and the French Sappho, Mlle.{82} Scudéri. Pellisson, who was not noted for his good looks, addressed "Mademoiselle Sapho, demeurant en la rue, au pays des Nouveaux Sansomates, à Paris, par billet de port payé." Signing himself "Pisandre," he inquired if the lady could give him a remedy for love. Her reply, sent by the same means, was, "My dear Pisandre, you have only to look at yourself in a mirror." It was of this correspondent that the lady once declared, "It is permissible to be ugly, but Pellisson has really abused the permission."

The London Penny Post of 1680, while it did not use special covers for the prepayment of letters, introduced the system of marking on letters, by means of hand-stamps, the time and place of posting and the intimation "Penny Post Payd." Dockwra, instead of setting up boxes in the public streets, organised a great circle of receiving houses to which the senders took their letters and paid their pennies over the counter. So the principle of the postage-stamp, as we know it to-day, was not represented in the triangular hand-stamps of Dockwra, or of his successors in the official Penny Post.

A device representing the arms of Castile and Leon was used in the eighteenth century as a kind of frank or stamp which passed official correspondence through the posts, and in the last quarter of that century the Chevalier Paris de l'Epinard proposed in Brussels the erection of a local post with a mark or stamp of some kind to denote postage prepaid—a plan which, however, was not adopted.

A FACSIMILE OF THE ADDRESS SIDE OF A PENNY POST LETTER IN 1686, SHOWING THE "PENY POST PAYD" MARK INSTITUTED BY DOCKWRA AND CONTINUED BY THE GOVERNMENT AUTHORITIES.

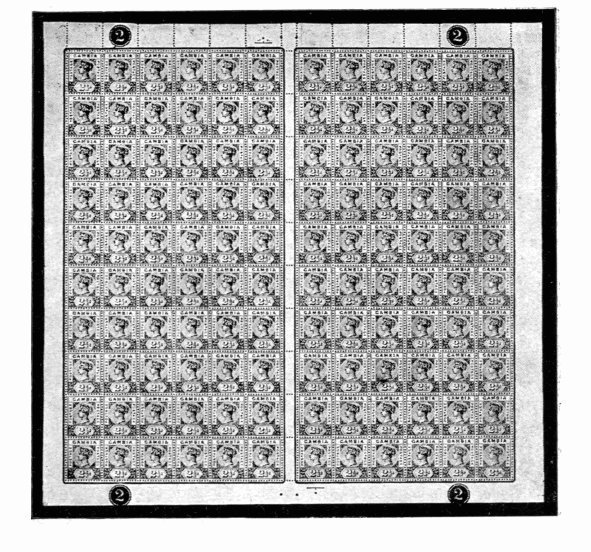

There is a curious account given by a correspondent in The Philatelic Record [xii. 138] of some{85} so-called stamps said to have been used in the Dutch Indies. The writer, whose account has never so far as I am aware received any definite confirmation, says:—

"At the beginning of this year [1890] were discovered amongst some old Government documents at Batavia some curious and hitherto—whether here or in Europe—unknown postally used envelopes, with value indicated.... In the time of Louis XIV. it is believed that postage-stamps existed; but nobody has been able to bring them to light, consequently we have in these hand-stamped envelopes of the Dutch East Indian Company absolutely the oldest documents of philatelic lore.

"The letter-sheets are all made from the same paper, and are all of the same size—namely, about 23 × 19 centimetres; whilst the side which is most interesting to us—the 'address' or 'stamp' side—is folded to a size of 103 × 88 mm. Up to the present the following values have been found:—

| 3 | stivers | black | |

| 5 | " | " | |

| 5 | " | red | |

| 6 | " | black | |

| 6 | " | " | double; that is to say, two stamps of 6 stivers side by side. |

| 10 | " | " | |

| 10 | " | red | |

| 15 | " | " |

"On the address-side is no date stamp, and no indication of the office of departure; also the figures denoting the year are only discernible on the seal{88} of each letter. On the specimens hitherto found are the dates from 1794 to 1809; but it is quite possible that other values may be unearthed. So far, of all the above values together, only about thirty specimens are known.... These envelopes came from various places in the Dutch Indian Archipelago."

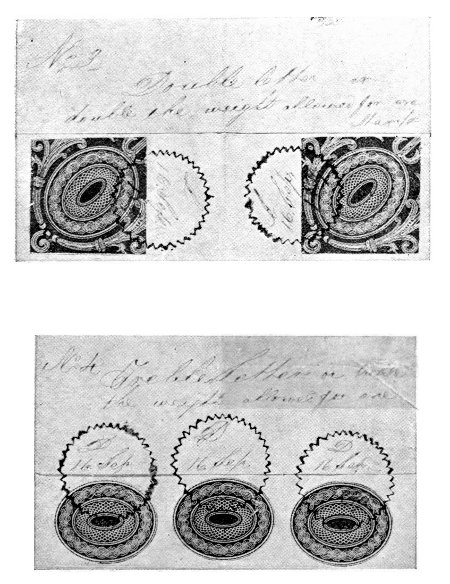

THE OFFICIAL NOTIFICATION OF DECEMBER 3, 1818, RELATING TO THE USE OF THE SARDINIAN LETTER SHEETS.

Described in the records of the Schroeder collection as "the oldest official notification of any country in the world relating to postage stamps."

(Continuation from previous page.)

THE MODELS SHOW THE DEVICES FOR THE THREE DENOMINATIONS: 15, 25, AND 50 CENTESIMI RESPECTIVELY.

The foregoing statement is open to much question, in view of the lapse of twenty years since the matter was first aired in The Philatelic Record. If authentic, these would be the earliest denominated stamps for the prepayment of postage, the Dutch stuiver in use in the colonies being a copper coin equal to about one penny. Perhaps the introduction of the matter in these Chats will, in the light of increased modern facilities for research, bring the subject before the notice of our Dutch philatelic confrères.