By Natt N. Dodge

Drawings by Jeanne R. Janish

SOUTHWESTERN MONUMENTS ASSOCIATION

POPULAR SERIES NO. 4

Globe, Arizona

1954

Copyright 1951, 1952, 1954

by the Southwestern Monuments Association

U. S. Department of the Interior

National Park Service

Southwestern National Monuments

Gila Pueblo, Globe, Arizona

This booklet is published by the Southwestern Monuments Association in keeping with one of its objectives, to provide accurate and authentic information about the Southwest.

Other numbers of the Popular Series now in print are: (2) “Arizona’s National Monuments,” 1946; (3) “Poisonous Dwellers of the Desert,” in its fourth printing, 1951; (5) “Flowers of the Southwest Mesas,” 1951; (6) “Tumacacori’s Yesterdays,” 1951; (7) “Flowers of the Southwest Mountains,” 1952; and (8) “Animals of the Southwest Deserts,” April, 1954.

A Technical Series will embody results of research accomplished by the staff and friends of Southwestern National Monuments.

Notification of publications by the Association will be given upon date of release to such persons or institutions as submit their names to the Executive Secretary for this purpose.

Dale Stuart King, Executive Secretary

Harry B. Boatright, Treasurer

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

DALE STUART KING, Editor

Naturalist, Southwestern National Monuments

First Edition, 5,000 copies, published April 9, 1951

Second edition, revised, of 7,500 copies, January, 1952

Third edition, revised, of 10,000 copies, March, 1954

Printed in the United States of America by

Rydal Press, Santa Fe, N.M.

Desert Areas of the West—this booklet deals with the common plants of three of them: (1) the Chihuahua; (2) the Sonoran; and (3) the Mojave.

Plants of the higher plateau country of from 4,500 to 7,000-feet elevation are shown and described in “Flowers of the Southwest Mesas,” companion volume to this one, by Pauline M. Patraw and Jeanne R. Janish, 1951.

Mountain zone vegetation (from the Ponderosa Pine belt, or about 7,000 feet, on up) is the subject of “Flowers of the Southwest Mountains,” the third of the triad, by Leslie P. Arnberger and Jeanne R. Janish.

By Natt N. Dodge

Drawings by Jeanne R. Janish

In order that you may get full value from this booklet, it is important that you understand how to make the greatest use of it. The purpose of the booklet is double: (1) to introduce the common desert flowers to newcomers to the Southwest; and (2), to give a little background of information about the plants’ interesting habits and how they have been and are used by animals, by the native peoples, and by the settlers. Every effort has been made to present accurate, if not always complete, information.

Since there are more than 3,200 plants recorded from Arizona alone, and this booklet attempts to introduce you to the common plants of desert areas in Texas, New Mexico, and California in addition to Arizona, it is apparent that you will find an enormous number of flowers which are not included. Therefore, a painstaking effort has been made to select the commonest or most spectacular; that is, those which you will naturally stop to look at and say, “Who are you?”

For ease in identification, flowers are arranged in this booklet according to color of the flower petals. When you meet a flower to whom you would like an introduction, first note the color of its petals. Don’t jump too quickly to a conclusion, for what at first glance may seem to be pink, careful examination may prove to be lavender, violet, or purple. Once you feel reasonably sure of the color, turn to the section of the booklet in which flowers of that color are listed and examine the sketches. Find something that looks similar?

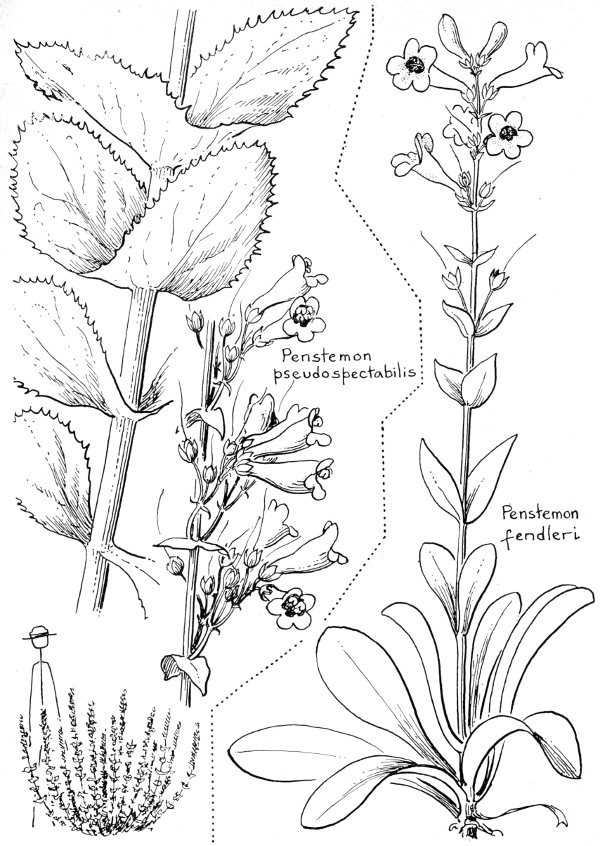

Now check the size of the plant as indicated in the sketch and text. Does the text list the flower as occurring in the particular desert area (see map on next page) where you are? Is the blossoming season correct? Do other details check? If so, the chances are that you have the right flower—or at least a close relative. Close enough, anyway, so that you may be reasonably safe in calling the flower by its common name. Of course if a botanist happens along, he may point out that you have Penstemon parryi whereas you thought you had struck up an acquaintance with Penstemon pseudospectabilis. However, it’s a penstemon, even tho’ a sister of the one you thought you were meeting. Perhaps you’ll run across a dozen other brothers and sisters before you happen onto the member of the genus common enough to be listed specifically in our Desert Who’s Who.

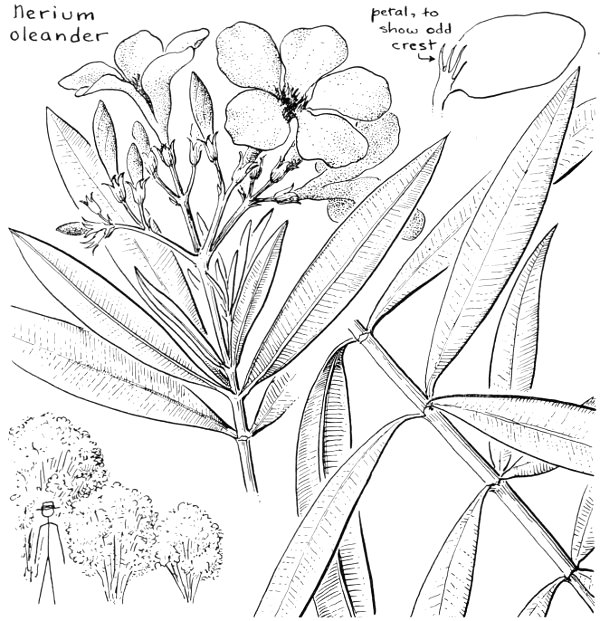

Certain of the desert flowers change color with age. Also, during off seasons, some of the really common flowers don’t show up in large numbers while a few of the rarer ones may take their turn at brightening up the desert. Furthermore, in a few cases such as the Oleander, the species comes in two colors, red flowers on one plant and white on another. The Bird-of-Paradise flower has yellow petals, but the rest of the flower is red, so it’s a toss-up which color you might call it. The Beavertail Cactus has magenta flowers while 4 those of its very close relative, Engelmann’s Prickly Pear, have yellow blossoms, yet in this booklet it has been necessary to put them both on the same page in the “yellow” section.

So, this booklet makes no claims to perfection, and these discrepancies add certain hazards to the game. You may strike out several times before getting to first base. As you become accustomed to using the booklet, home runs will come more frequently, and you will soon begin to have a lot of fun. If any particular species especially interests you, once you are certain of its identity you can readily find out more about it by following up in one or more of the publications listed in this booklet under the heading “References.”

A few of the common desert flowers have been left out of this booklet—purposely. The reason is that, although they are well represented among desert flowers, they are even more common throughout non-desert parts of the Southwest. You will find them all in a companion booklet: Polly Patraw’s “Flowers of the Southwest Mesas.” They belong principally to the following groups: Cottonwood, Rabbit-brush, Snakeweed, Saltbush, Apacheplume, Clematis, Squawbush, Blanketflower, Sunflower, Groundsel, Elder, Blazing Star and Morningglory.

It has often been said that “a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” Although the statement is literally true, we are often disappointed, perhaps offended, when we find some flower friend of long acquaintance called by another, and, to our minds, inferior name. Also, we dislike the attachment of a name which we have long associated with a certain plant to another, and perhaps less attractive, flower.

Common names are by no means standardized in their usage, and a well known plant in one part of the country may be called by an entirely different name somewhere else. Also, certain names are applied to a number of plants which more or less resemble one another. For instance, the name “Greasewood” is applied to almost any plant that has oily or highly inflammable leaves; and with the avid reading by eastern people of Zane Grey’s and other “westerns,” any shrubby plant with grayish foliage covering large areas of western land immediately becomes “Sagebrush.” This is particularly irritating to inhabitants of the desert areas treated in this booklet because true Sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata) rarely grows below elevations of 6,000 feet. The loose application of common names is a confusing annoyance to wildflower enthusiasts.

In an effort to avoid this confusion and to establish a method of naming that will be uniform throughout the world, botanists have developed a system using descriptive Latin names and grouping plants into genera and families based upon their relationships to one another as determined by their physical structure. Unfortunately for the layman, this system is so technical and the Latin names so unintelligible that he becomes completely bewildered. Furthermore, advanced botanical studies result in continual regroupings and changes in names so that the amateur botanist finds it impossible to keep up. Botanists who specialize in plant nomenclature have a tendency to 5 become so involved with the technicalities of naming that their writings bristle with minute descriptions of anatomical details and the reader searches in vain for such basic information as a simple statement of the color of the flowers.

The majority of common flowers have several to many common names. This is particularly true in the Southwest where some plants have names in English, Spanish, and one or more Indian languages. In addition, of course, each species has its scientific name. An effort has been made in this booklet to give as many of the names applied to each selected flower as are readily available. This not only aids in identifying the plant, but adds to its interest. The reader then finds himself in the enviable position of being able to scan the field and choose whichever name appeals to him with the reasonable assurance that he is right—at least in one locality.

Since this booklet was written by a layman for the use and enjoyment of other laymen, it violates a number of botanical, or taxonomic, principles. These violations have been committed with no spirit of disrespect, but in an effort to avoid confusion, conserve space, and keep a complicated and involved subject as simple as possible. The writer believes that the visitor to the desert who has a normal pleasure in nature is interested in the flowers because of their beauty and their relationships with other inhabitants of the desert, including mankind.

In this booklet we are dealing with DESERT flowers, so it seems logical to take a moment to check upon the desert itself. What is a desert, and how may we recognize one when we see it?

“A desert,” stated the late Dr. Forrest Shreve, “is a region of deficient and uncertain rainfall.” Where moisture is deficient and uncertain, only such plants survive as are able to endure long periods of extreme drought. Desert vegetation is, therefore, made up of plants which, through various specialized body structures, can survive conditions of severe drought. In general, the deserts of the world are fairly close to the equator, so they occur in climates that are hot as well as dry. Plants in the deserts of the Southwest must endure long periods of heat as well as drought.

In North America, major desert areas are located in the general vicinity of the international boundary between Mexico and the United States. Due to various differences in elevation, climatic conditions, and other factors, certain portions of this Great American Desert favor the growth of plants of certain types. Based on these general vegetative types, botanists have catalogued the Great American Desert into four divisions, as follows (see map):

It is of especial interest to note that certain plants such as Creosotebush (Larrea tridentata) seems to thrive in several of these desert areas while others are found in great abundance in only one. Plants that grow in profusion in only one desert are spoken of as “indicators” of that particular desert. Any person interested in desert vegetation soon learns the major indicators, not only of the different deserts, but of different sections or elevations in the same desert. Here are some of the better-known indicator plants:

This publication deals with the common plants and flowers of the Chihuahuan, Sonoran, and Mohave-Colorado Deserts. Since these names are strange to many visitors to the Southwest, the writer has taken the liberty of applying descriptive names as synonyms. In this booklet the Chihuahuan Desert is called the Texas Desert, the Sonoran Desert is referred to as the Arizona Desert, and the Colorado-Mohave Desert is considered as the California Desert.

Whenever possible, the desert in which a particular species of plant is most common is indicated; however, this should not be interpreted too rigidly as most of the plants in this book grow in more than one desert and some grow in all.

Because the Great Basin Desert is a region of higher elevation and is influenced by other factors which are not common to the three portions of the Great American Desert covered in this booklet, its vegetation is more like that of the plateaulands and foothills of the Southwest. Therefore, the flowers of the Great Basin Desert are included in a companion booklet, Polly Patraw’s “Flowers of the Southwest Mesas.”

Someone has called National Parks and Monuments “The Crown Jewels of America.” A part of their beauty and irreplaceable value is because the approximately 180 units of the National Park System which extends from Florida to Alaska and from Hawaii to Maine, are and have been wildflower sanctuaries. Not only do native plants live under natural conditions, but they are protected from picking, from grazing of domestic livestock, and from the competition of exotic species, and from other activities of mankind that would disrupt their normal habitat or disturb their native way of life.

Men in the uniform of the National Park Service feel complimented whenever visitors show an interest in the natural features of the areas they protect, and are happy to assist them in locating rare species or especially beautiful or spectacular specimens. Range and grazing specialists are more and more using the natural vegetation of National Parks and Monuments as “check plots” to aid them in studying ways and means of preserving the level of grazing value on the open ranges.

Within the desert areas of the Southwest there are a number of National Parks and Monuments. Three Monuments (Joshua Tree in 7 California, Organ Pipe Cactus and Saguaro in Arizona) have been created primarily to save from exploitation and destruction outstanding areas of typical desert vegetation. Although the others have been established to protect and preserve geologic, historic, or archeologic values of national significance, they are all wildflower sanctuaries. In California, Death Valley National Monument is outstanding in its variety of desert flowers. Lake Mead National Recreation Area, of which Hoover Dam is the center, has exceptional displays of various forms of desert plants. A great variety of desert vegetation will be shown and, if desired, explained to the interested visitor, by National Park Service rangers at Chiricahua, Tonto, Montezuma Castle, Casa Grande, and Tumacacori National Monuments in Arizona. Of course the really great displays of desert botany and ecology are featured at Organ Pipe Cactus and Saguaro National Monuments.

In New Mexico, Chihuahuan Desert vegetation is particularly abundant at Carlsbad Caverns National Park. A number of desert forms, especially interesting because of the effect upon them of the ever-moving gypsum dunes, are found at White Sands National Monument, near Alamogordo. Another outstanding Chihuahuan Desert wildflower sanctuary is Big Bend National Park in southwestern Texas.

Photography is encouraged in all of the National Parks and Monuments. By asking a ranger, you will be able to learn where the various flower displays may be found, the best time of day to obtain good results, and other suggestions helpful in obtaining photographs of desert wildflowers at their very best.

Each year the following magazine and radio program present bulletins on moisture and other pertinent conditions in the desert, spotlight areas in which outstanding wildflower displays are developing, and advance suggestions relative to areas in which spectacular displays may be expected.

Many people think of a desert as an area of shifting sand dunes without vegetation except in areas where springs provide moisture. This is by no means true of our Southwestern deserts which are characterized by a rich and diversified plant cover. However, the majority of true desert plants are equipped by Nature to meet conditions of high temperatures and deficient and uncertain precipitation. The way in which desert plants, closely related to common species found growing under normal temperature and moisture conditions, have adapted themselves to meet the severe requirements of desert life is truly remarkable and forms an absorbing and fascinating study.

Shreve groups desert plants into three categories based on the manner in which they have contrived to conquer the hazards of desert life.

These are:

Drought-escaping plants are the “desert quickies,” or ephemerals. Taking advantage of the two seasons of rainfall on the desert (midsummer showers and midwinter soakers) they develop rapidly, blossom, and mature their seeds which lie dormant in the soil during the rest of the year, thus escaping the season of heat and drought. There are two groups of these “quickies,” the summer ephemerals and the winter ephemerals. The former are hot-weather plants; the latter are species that thrive during the cool, moist weather of winter and early spring. These “quickies” present their spectacular floral displays only following seasons of above-average precipitation.

Drought-evading plants (in common with the deciduous plants of northern and colder climes which remain dormant while below-freezing temperatures prevail), meet the heat and drought by reducing the bodily processes to maintain life only, dropping their leaves, and remaining in a state of dormancy until temperature and moisture conditions, suitable to renewed activity, again prevail.

The drought-resisting plants are the bold spirits which take the worst that the desert has to offer without flinching, or resorting to evasive tactics. Chief among these are the cacti which store moisture in their spongy stem or root tissues during periods of rainfall, using it sparingly during drought. To reduce moisture loss to a minimum, they have done away with their leaves, the green skin of their stems taking over the function of foliage. Other plants, such as the Mesquite, develop deep or widespread root systems that extract every drop of moisture from a huge area of soil. The majority of the drought-resisters either cut down their leaf surface to an irreducible minimum, or coat the leaves with wax or varnish, thus restricting the loss of moisture.

Methods, techniques, devices, or body modifications which desert plants have developed or evolved to enable them to withstand the rigors of long-continued drought and heat are legion. Many of them are known and understood, but it is probable that there are many others which scientists have not yet discovered.

For numerous helpful suggestions, lists of common flowers, herbarium and fresh specimens for use in preparing illustrations, and for assistance in many other ways, the author and illustrator proffer sincere thanks to the following: Glen Bean, L. Floyd Keller, Walter B. McDougall, and William R. Supernaugh of the National Park Service; Dr. Norman C. Cooper, research associate, Allen Hancock Foundation; Mrs. Robert Gibbs, Isle Royale National Park, Mich.; Leslie M. Goodding, St. David, Arizona; Edmund C. Jaeger, Riverside Junior College, California; Thomas H. Kearney, California Academy of Sciences; Robert H. Peebles (who kindly reviewed the manuscript), director of the U. S. Field Service Station, Department of Agriculture, Sacaton, Arizona; Paul Ricker, president, Wildflower Preservation Society, Washington, D. C.; and Barton H. Warnock, head of biology department, Sul Ross State College, Alpine, Texas.

Largest of the U. S. cacti, this species occurs only in southern and western Arizona and adjoining northwestern Mexico and sparingly in extreme southeast California. It is an indicator of the Sonoran Desert.

This giant is such a spectacular example of desert vegetation that it is used as a trademark of the desert. It is the state flower of Arizona. Blossoms unfold at night, remaining open until late the following afternoon, attracting swarms of insects which in turn attract birds. Fruits mature in July, resembling small, egg-shaped cucumbers. When ripe, they burst open revealing a scarlet lining and deep red pulp filled with tiny black seeds. Fruits are eagerly sought by birds and rodents.

Because of its enormous capacity for storing water in its spongy stem tissue, the Saguaro (sah-WAR-oh) produces flowers and fruits even during droughts of long duration. When other foods failed, the Pima and Papago Indians could depend upon the Saguaro harvest.

Saguaros are believed to live to a maximum age of 200 years, usually succumbing to a necrosis disease transmitted by the larvæ of a small moth. Grazing cattle trample out the young plants and much of the desert occupied by Saguaros is being placed under cultivation. Both Saguaro National Monument and Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument preserve and protect spectacular stands of these desert behemoths.

WHITE

One of the most delicately beautiful of the flowers for which the desert is famous, “Queen of the Night” is waxy-white with thread-like stamens that give it the appearance of wearing a halo. The night on which the Cereus blooms is eagerly awaited by desert dwellers of long residence. All of the buds on a single plant, from two to six or seven in number, may open on the same night or may time their opening over a period of a week or more, usually in late June or early July, depending upon the season and other factors.

It is not unusual for nearly all of the plants in one locality to blossom on the same night. Buds unfold in the early evening, the flowers wilting permanently soon after sunrise the following morning. Fragrant, with a heavy, cloying perfume, they attract large numbers of night-flying insects.

The long, slender, fluted, lead-colored stems of the Nightblooming Cereus are inconspicuous and unattractive. Usually growing upward from beneath a Creosotebush or other desert shrub, they are partially supported and almost entirely hidden by the larger plant.

The beet-like root, which serves as a moisture-storage organ, may weigh from 5 to 85 pounds and is reportedly eaten by desert Indians. Fruits are podlike, pointed at the ends, and the size of a large pickle. They turn dull red when mature.

WHITE

All portions of this coarse, vine-like herb are poisonous, and are used by some Indians as a narcotic to induce visions.

Seeds are sometimes administered to prevent miscarriage.

The plants with their large, gray-green leaves and showy, white, sometimes lavender-tinted flowers which open at night and close soon after contact by rays of the morning sun, are a common and arresting sight along roadsides and washes at elevations from 1,000 to 6,500 feet in Texas, New Mexico, southern Utah, southern California, and Mexico.

WHITE

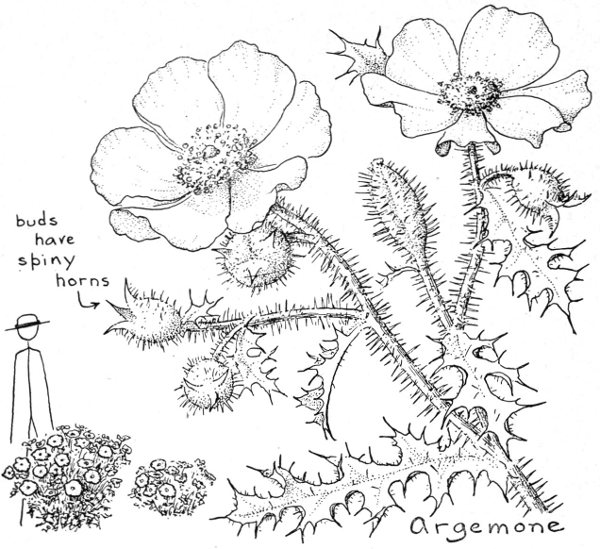

One of the commonest and most noticeable perennials of the Southwest, the Pricklypoppy ranges from South Dakota and Wyoming to Texas, Arizona, southern California, and northern Mexico. A coarse, prickly plant with large flowers and yellowish sap, it is easily recognized.

It is sometimes facetiously called “cowboys’ fried egg.”

Flowers are normally white with large, tissue-paper petals and yellow centers. In southern Arizona an occasional plant with pale yellow petals is found; and in Big Bend National Park, Texas, a form with rose-colored petals and a deep red center is occasionally encountered.

Plants are drought-resistant, unpalatable to livestock, and may be found in blossom during any month in the year, although much more prolific during the spring and summer. When abundant on cattle range, they are an indication of over-grazing. Seeds are reported to contain a narcotic more potent than opium.

WHITE

One of the showiest and most famous of the desert wildflowers, although limited in distribution to sandy areas below 2,000 feet elevation, the Desertlily greatly resembles the Easterlily of greenhouse habitat.

In some seasons, the blossoms are abundant and their delicate fragrance perfumes the surrounding atmosphere. During “off” seasons, visitors may scour the desert to find only a very few of the fragile blossoms.

Named “Ajo” by Spanish explorers because of the large, edible bulb resembling garlic, the Lily has passed on its name to a mountain range, a broad valley, and a thriving town in southwestern Arizona where it grows in profusion. Its range is limited to southwestern Arizona, southeastern California, and probably northern Sonora.

Papago Indians eat the bulbs which have an onion-like flavor. Bulbs are difficult to obtain because they grow at a depth of 18 inches to two feet beneath the surface of the hard-packed desert soil. Flowers remain open during the day, and propagation is principally by seeds.

WHITE

In early springs that follow winters of more than average rainfall the Desert-Dandelion is one of the conspicuous annuals helping to carpet the deserts with a ground-cover of flowers.

Although much more delicate, longer stemmed, and less coarse and robust than the common Dandelion, the flowers sufficiently resemble those of the better-known yellow Dandelion to stimulate recognition.

Desert-Dandelion is found below 4,000 feet in desert situations from western Texas to Lower California and northward to southern Utah.

WHITE

Well known and widely grown because of its large clusters of red or white blossoms and glossy, evergreen leaves, the Oleander is one of the handsomest shrubs found under cultivation in towns and cities of the desert. Requiring sub-tropical conditions, easily rooted from cuttings, and rapid in growth, the Oleander thrives in Southwestern desert areas if supplied with plenty of water. It is used individually and as hedgerows in ornamental plantings.

Although blossoms may be present at almost any time of year, the principal flowering season extends from early spring well through the summer. Both the red-flowered and the white-flowered plants are popular and may be grown separately or intermixed. Recently a yellow-flowered form has come into use.

These handsome shrubs immediately attract the attention of northerners visiting desert towns, and arouse their curiosity as to their identity.

WHITE

The tiny, slender-stemmed, profusely-branched Threadplant is so small that it is completely overlooked by the majority of visitors to the Southwest, yet it is one of the most common and most attractive of desert flowers. Under a magnifying glass, the shape and coloring of the minute, delicate flowers make them appear as beautiful as orchids. The white flowers are touched with tints of red, brown, yellow, or purple.

Plants are abundant below 1,800 feet elevation on dry, gravelly or rocky soils, frequently along the shoulders of highways from Nevada throughout western Arizona and southern California to Lower California. Be on the lookout for this small but interesting and beautiful plant.

WHITE

Rootless, leafless, and with pale yellow to brownish stems which twine in vine-like embrace about the host, the parasitic Dodders are immediately noticeable because of their strange appearance.

Frequently the automobile traveler’s attention is arrested by a pale yellowish blotch in the green of the roadside vegetation. Examination shows this to be caused by the matted yellowish stems and the white to pale yellow, fleshy blossoms. These flowers are attractive and often abundant enough to make a showy display.

Dodder is found widespread throughout the United States and is often a serious parasitic pest on crops of economic importance. Desert species are usually found infesting Mesquite, Goldenrod, Aster, Burrobush, Seepwillow, and Arrowweed. Although certain Dodders show a preference in choosing hosts (C. denticulata common on Creosotebush), most of them grow readily upon various plants.

WHITE

Because the presence of the grotesque Joshua-tree marks, more effectively than any other plant, the limits and extent of the Mohave Desert, this species is worthy of special recognition. This tree Yucca holds, in the Mohave Desert, similar status to the Saguaro in the Sonoran Desert. Strangely enough, in west-central Arizona, the Saguaro and Joshua-tree are found growing together and there the Sonoran and Mohave Deserts overlap.

And, just as in southern Arizona an area has been set aside as Saguaro National Monument to preserve and protect that species, so in southern California we find the Joshua Tree National Monument.

The Joshua-tree is outstanding among the many species of Yucca because of its short leaves growing in dense bunches or clusters, and because the plant has a definite trunk with numerous branches forming a crown. Great forests of these sturdy trees are found in parts of southern California, southern Nevada, southwestern Utah, and northwestern Arizona where rainfall averages 8 to 10 inches per year.

Flowers of this Yucca develop as tight clusters of greenish-white buds at the ends of the branches, but do not open wide as do the flowers of other Yuccas. Joshua-trees do not bloom every year, the interval apparently being determined by rainfall and temperature. Birds, a small lizard, wood rats, and several species of insects are closely associated with the Joshua-tree, making use of it for food, shelter, or nest-building materials. Indians use the smallest roots, which are red, for patterns in their baskets.

The name “Joshua-tree” was given by the Mormons because the tree seemed to be lifting its arms in supplication as did the Biblical Joshua.

WHITE

Although, in general, the Broad-leafed Yuccas do not reach tree size, 20 the Giant Dagger (Yucca carnerosana) of Big Bend National Park reaches a height of 20 feet. In dense stands or “forests” these Yuccas, with their huge clusters of creamy, wax-like, lightly scented, bell-shaped flowers produce a never-to-be-forgotten display in blooming season.

The Yucca is the state flower of New Mexico.

Yuccas are often confused by newcomers to the desert with three other groups of plants: the Agaves (Century Plant), Dasylirion (Sotol) and Nolinas (Beargrass).

The plate on the opposite page has been devoted to a comparison of the four groups, and by studying it carefully, the characteristics by which each may be identified can be determined.

Yucca leaf fibers have long been used by Indians for fabricating rope, matting, sandals, basketry, and coarse cloth. Indians also ate the buds, flowers, and emerging flower stalks. The large, pulpy fruits were eaten raw or roasted, and the seeds ground into meal.

Roots of the Yuccas have saponifying properties and are still gathered by some tribes and used as soap, especially for washing the hair. Flowers are browsed by livestock. (See Narrow-leaf Yuccas and Joshua-tree). Yucca baccata, a broad-leaf species found in the Southwest outside of the desert areas, is discussed in “Flowers of the Southwest Mesas.”

CREAM

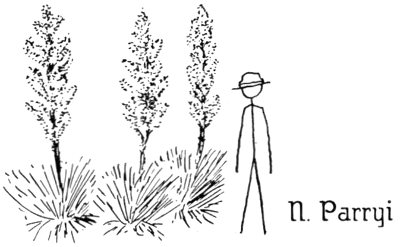

The Nolinas are sometimes confused with Sotol and the Yuccas and occasionally with the Agaves. However, the Nolinas resemble huge clumps of long-bladed grass, whereas Sotol leaves are ribbon-like and Yucca leaves taper to a sharp point. Flower stalks of the Nolinas are usually drooping and plume-like, and the numerous flowers are tiny. The many papery, dry-winged fruits often remain on the stalk until late autumn.

Beargrass does not grow on the flat mesas or sandy flats as do the Yuccas, but is confined to exposed locations on rocky slopes above the 3,000-foot elevation. The Parry Nolina of the California Desert is a larger and more spectacular plant than the species found in the Arizona and Texas-New Mexico Deserts. Indians are reported to use the very young flower stalks for food. Leaves are browsed by livestock in times of drought, sometimes with harmful results in the case of sheep or goats.

Nolina parryi

CREAM

At first glance, this plant may readily be mistaken for a Yucca, but its ribbon-like leaves (which are usually split at the tips instead of sharp-pointed) and tiny flowers instead of the bell-like blossoms of the Yucca, are distinguishing characteristics. The round heads of these plants grow close to the ground with the thick, woody stem beneath the soil. 22 Leaves, when stripped from the head, come away with a broad, curving blade.

When trimmed and polished, they are sold as curios called “desert spoons.” In some portions of the desert near large cities, exploitation of the plants for this purpose has endangered the species and aroused the ire of conservationists.

The cabbage-like base, after the leaves are removed, is split and fed to livestock as an emergency ration during periods of drought.

The rounded heads of these plants are high in sugar which is dissolved in the sap of the bud stalk. This sap, when gathered and fermented, produces a potent beverage called “sotol,” which is the “bootleg” of northern Mexico.

CREAM

CREAM

The Narrow-leaf Yuccas are frequently confused with the Agaves (Century plant), Dasylirion (Sotol), and Nolinas (Beargrass) but may readily be recognized by the fibers protruding from the margins of the leaves. To permit comparison and bring out the differences so that the four groups may be recognized and confusion avoided, sketches of all four appear on the same plate (p. 21).

In many grassland areas of western Texas and southern New Mexico, Y. elata dominates the landscape for miles. This species has been used as emergency rations for range stock during periods of drought, the chopped stems being mixed with concentrates such as cottonseed meal. A substitute for jute has been made from the leaf fibers. Indians eat the young flower stalks, which grow rapidly and are relatively tender.

In its relationship with a moth of the genus Pronuba, the Yucca illustrates one of Nature’s interesting partnerships. The moth, which visits the Yucca flowers at night, lays her eggs in the ovary of a flower where the larvae will feed upon the developing seeds. But to be sure that the seeds do develop, the moth must place pollen on the stigma of the flower. Dependent upon the moth for this vital act of pollenization, the Yucca repays its winged benefactor by sacrificing some of its developing seeds as food for the moth’s larvæ. Fruits of the Narrow-leaf are dry capsules in contrast to the fleshy fruits of the Broad-leaf Yuccas.

Yucca whipplei is a much smaller plant than Y. elata, but produces a stouter flower stalk with a great spreading plume of small, delicate flowers. These graceful plumes appear at night as if aglow with an inner light, hence the name “Our Lord’s Candle.” (See Broad-leaf Yucca [p. 19] and Joshua-tree [p. 18].)

By no means limited to the desert, Clematis is found throughout the Southwest. Several species are grown as ornamentals, foliage, flower clusters and the cotton-like masses of hairy fruits all being effective. Petals are absent or rudimentary, the sepals which furnish color to the blossoms being either creamy or purplish-brown. The name “Leatherflower” has been applied to the latter group.

CREAM

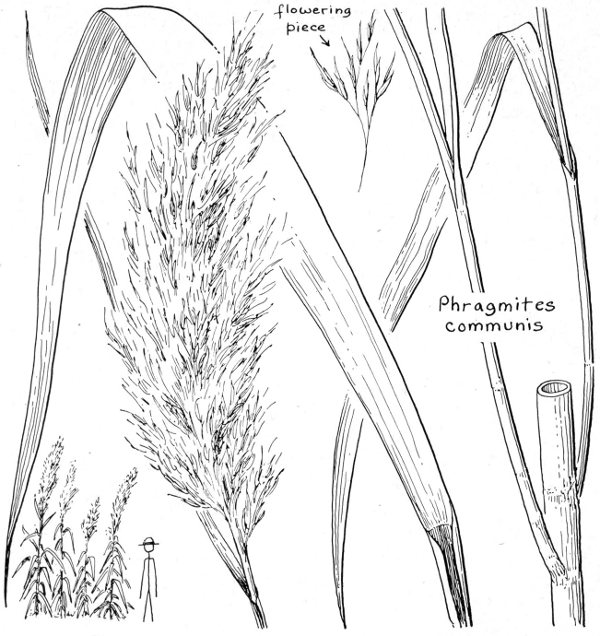

Among the largest of the grasses, the Common Reed and its close relative Giantreed (Arundo donax) with their jointed stems resembling Bamboo, are coarse perennials with broad, flat, grass-like leaves found in marshes and stock tanks, along irrigation canals, and on river banks throughout the desert country of the Southwest. Common Reed is found throughout the world where conditions are suitable. The flower stalks are long, tassel-like, and at the ends of the stems.

In Arizona and New Mexico, Common Reed is called Carrizo. The hollow stems were used by the Indians for making arrow shafts, prayer sticks, pipe stems, and loom rods. Mats, screens, nets, and cordage, as well as thatching, are made from the leaves. The plants are useful as windbreaks and in controlling soil erosion along streams.

CREAM

Genus Baccharis is composed, in the desert, of coarse shrubs with a number of common species. The flowers themselves are not beautiful, but the female plants with their flower heads that develop glaring-white pappus hairs, are spectacular and quite attractive.

B. glutinosa is a common shrub along watercourses, often forming dense thickets. The straight stems are used in native houses as matting across ceiling timbers to support the mud roof. B. sarathroides and several other species are often referred to as the Desert Brooms. They are common along desert washes and roadsides in sandy soil, their pale yellow, bristly flower heads, during the fall and winter months, appearing in sharp contrast to the vivid green branchlets and dark stems of the bushes. Among some Indians, the stems are chewed as a toothache remedy.

CREAM

Plantains are not noted for the beauty of their blossoms but the larger, coarser species are sufficiently noticeable to attract attention, both in their blossoming and fruiting stages. The smaller winter annuals known as Indianwheat carpet the desert floor, in January and February, in some places, producing a straw-colored “pile” of tiny blossom spikes.

CREAM

Flowers of these small, slender-stemmed, shrubby chollas (CHOH-yahs) are small, sparse, and so inconspicuous as to be rarely noticed. However, the fruits, particularly those of O. Leptocaulis, are scarlet, egg-shaped, about 1 inch in length, and occur in such profusion that they immediately attract attention to the plants during the late fall and winter months, giving these plants the appropriate name of Christmas Cholla.

A large Cholla, O. bigelovi, also has greenish to pale yellow flowers but inconspicuous fruits and short, heavy joints so densely covered with silvery spines as to give it the name Teddybear Cholla. Found in south central and southwestern Arizona and westward into southern California, southern Nevada, and south into Sonora and Lower California, the Silver Cholla is noticeable at any season. Propagation is chiefly by joints which drop from the plant and take root, the new plants forming dense thickets on desert hillsides. Because the joints are so easily detached, they actually seem to jump at a passerby, this characteristic giving the plant the name Jumping Cactus.

YELLOW

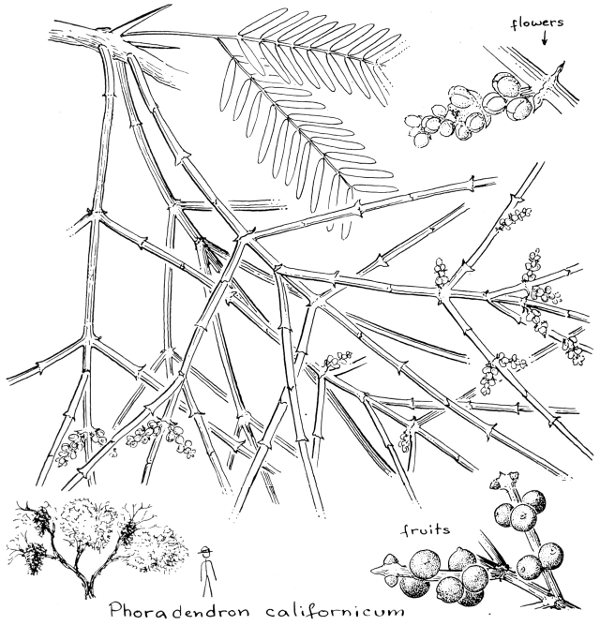

Because they form conspicuous, dense, shapeless masses in Mesquite, Ironwood, Acacia, Cottonwood, or other trees (depending upon the species of Mistletoe), these parasitic plants attract the attention and arouse the curiosity of persons unfamiliar with the desert. P. macrophyllum, which parasitizes Cottonwood trees, is widespread throughout the Southwest, and, because of its large gray-green leaves and glistening white berries is much in demand as a Christmas green. The Mistletoe is the state flower of Oklahoma.

The species of Mistletoe that parasitize such trees as Ironwood, Mesquite, and Catclaw have small, scale-like tawny-brown leaves and stems. The tiny yellow-green flowers which appear in spring are fragrant and secrete nectar which attracts Honeybees and other insects. The handsome coral-pink berries are a major food, during the winter months, for 29 Phainopeplas and other birds. The Arizona Verdin often builds its nest in the protected center of a clump of Mistletoe. Birds are believed to be instrumental in spreading this parasite from tree to tree.

Mistletoe saps the energy of the host tree and, where abundant, may cause considerable damage, killing branches and sometimes the entire tree. Papago Indians dry the berries in the sun and store them for winter food.

YELLOW

Several species of wild tobacco are found in the desert. Of these, Tree-tobacco is conspicuous because of its rank growth, its large leaves, and the spectacular clusters of tubular, yellow flowers. In addition to nicotine, Tree-tobacco contains an alkaloid, anabasine. This conspicuous plant occurs in moist locations below 3,000 feet elevation and bears flowers throughout the entire year. Although now thoroughly naturalized in the Southwest, it is a native of South America.

Desert-tobacco, sometimes perennial in southwestern Arizona, is a dark-green herb common and widespread throughout the desert areas of the Southwest. It is not nearly as noticeable as its larger relative although it, too, blossoms the year around. Flowers are a pale yellow, almost greenish-white. It provides dense ground cover in rocky canyons and along desert washes.

Leaves, which are somewhat bad smelling, were smoked (and still are during ceremonials) by the Yuma and Havasupai Indians who are reported to have cleared land, burned the brush, and scattered the seeds of Desert-tobacco in an effort to promote the growth of strong plants with many large leaves.

YELLOW

One of the handsomest of desert spring annuals, Calycoseris is common on plains, mesas, and rocky slopes at elevations between 1,200 and 4,000 feet from western Texas to southern Utah, southern California, and south into Mexico.

The name Tackstem comes from the presence of numerous tack-shaped glands which protrude from the stems.

Taking advantage of the cool, moist weather of winter, the Tackstems produce their beautiful rose, white, or yellow blossoms in early spring, and mature their seeds before the advent of hot, dry weather.

YELLOW

Intricately branched and brittle-stemmed, this shrub with blossom heads holding from 8 to 18 yellowish flowers is common throughout the Southwest from western Texas and Colorado to Nevada, Sonora and Lower California.

It grows among rocks and in rocky locations throughout much of the desert country from 3,000 up to 7,000 feet.

YELLOW

Closely related to the garden Zinnia, which is a native of Mexico, desert Zinnias are attractive herbs suitable for trial as ornamental border plantings.

Z. pumila prefers caliche soils and is found on dry mesas and slopes from Texas westward to southern Arizona and northern Mexico. It is often found blossoming in association with the Paperflower (Psilostrophe cooperi) which it superficially resembles. The pale yellow flowers of the Wild-zinnia turn white with age.

Z. pumila may be easily recognized by the single heavy rib running the length of each narrow leaf.

YELLOW

The numerous thorns, short and curved like a cat’s claw, serve readily to identify this common, often abundant, shrub or small tree.

There are several species, some with large, bright-yellow flowers, but A. greggi is the most common and occurs throughout all of the deserts of the Southwest, at elevations below 4,000 feet, often forming thickets along streams and washes.

Flowers, like pale yellow, fuzzy caterpillars, are one of the important sources of nectar for honeybees, the trees being alive with insects during the period of heaviest blooming in April and May.

In mid-August, the light green fruit pods begin to turn reddish and, if abundant, make a colorful display.

Seeds of the Catclaw were at one time widely used as food by the Indians of Arizona and Mexican tribes. They were ground into meal and eaten as mush or cakes.

Catclaw is one of the most heartily disliked plants in the Southwest, especially by riders and hikers, because of the strong thorns which tear clothing and lacerate the flesh.

YELLOW

Apparently leafless, these common Southwestern shrubs do have leaves, although they are reduced to tiny scales. The harsh, stringy stems are green to yellow-green and, when dried, were used with the flowers in making a palatable brew, particularly by the Utah pioneers; hence the names Mormon-tea and Brigham-tea. The beverage was also popular with Indians and settlers in treating syphilis and other afflictions, as it contains tannin and certain alkaloids. Flowers are small, pale yellow, and 35 appear in the spring at which time the plants are quite noticeable, and attract large numbers of insects.

YELLOW

The flowers are not particularly attractive, but become conspicuous as the seed-heads develop, because of the white, densely-haired tufts. Stems are tall and straight “like telegraph poles,” and the crushed leaves give off a slight camphor-like odor.

Although the plant occurs from the east coast across the southern portion of the United States, it is found in the desert at elevations between 1,000 and 5,000 feet.

Camphor-weed is a tall, coarse, robust, straight-stemmed plant which is abundant and conspicuous along roads and ditchbanks, and in the open desert following winters of heavy precipitation.

YELLOW

Arizona Paloverdes (meaning green stick) are large shrubs or small trees abundant along washes in the hotter, drier portions of the Sonoran Desert. When in blossom in the springtime, they appear as masses of pale yellow or golden bloom, and are a glorious sight, both as individual trees and massed as borders along the courses of washes which they mark with a line of color winding across the desert floor. During the dry season, they are without leaves, but are readily recognized by the bark, yellowish green in the case of C. microphyllum; blue green in C. floridum.

After the petals form, seeds form in bean-like pods which are not relished by livestock, but are eaten during periods of drought and when other forage is scarce. Indians ground the seeds into meal.

When the trees are in blossom, they attract myriads of insects, some of which, including Honeybees, seek the nectar. Wood is soft and the branches are brittle and easily broken. It is unsuited for fuel as it burns rapidly, leaves no coals, and gives off an unpleasant odor.

YELLOW

Clammyweed is not limited in its range to desert areas, but is found as far north as Saskatchewan and British Columbia. However, it is also a common annual in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona at elevations between 1,200 and 6,000 feet, and is usually found in abundance in the sandy channels of dry stream beds.

It somewhat resembles both Yellow Beeweed (Cleome lutea) and Jackass-clover (Wislizenia refracta.)

YELLOW

A troublesome annual vine-like weed naturalized from southern Europe, the Puncturevine has established itself throughout the Southwest below 7,000 feet. Although fairly readily controlled by cultivation, the plant spreads rapidly in sandy, dry wastelands, often taking over vacant lots in towns, and areas in the desert where it finds sufficient moisture.

The fruits, which are produced in quantities, are armed with strong spurs which become embedded in the feet and fur of animals and in automobile tires. Fruits are also carried by irrigation or flood waters. Although the spurs are too short to puncture automobile tires, they make bicycles almost useless in some localities, and are an aggravation to children who go barefoot—and to dogs.

Flowers and fruits in various stages of maturity may be found on this fast-growing plant at almost any time during the summer months. Botanically, Puncturevine is closely related to the Creosotebush and also to the Arizona-poppy.

YELLOW

Although superficially resembling in size, shape, and color the blossoms of the Goldpoppy, the blossoms of the large-flowered Caltrop have five petals instead of four, and the plant is a close relative of the Puncturevine and the Creosotebush. One of the most attractive of the desert’s summer annuals, Arizona-poppy is found at elevations below 5,000 feet in the drylands of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and northern Mexico.

Large-flowered Caltrop may be distinguished from Goldpoppy by (1) sprawling open habit of growth, (2) compound leaves, (3) season of blossoming, and (4) the fact that the plants grow singly rather than in masses.

YELLOW

No one could justifiably question the statement that Creosotebush is the most successful, widespread, and readily recognized desert plant of the hot, arid regions of North America. It often occurs over wide areas in such pure stands as to constitute true Larrea plains. Its common companion is the grayish Burrobush or Bur-sage.

Following winter rains, the Creosotebush may put out a few yellow blossoms in January, but usually bursts into full flower in April or May, to be followed in a short time with the equally spectacular fuzzy white seed balls making the bushes appear to be covered with a light frosting of snow. After a rain, the plants give off a musty, resinous odor which is the basis of the Mexican name Hediondilla (freely translated, “Little Stinker”). Lac occurs as a resinous incrustation on the branches, and was used by the Indians for mending pottery, making mosaics, and for fixing arrow points.

Leaves of the Creosotebush are covered with a “varnish” which often 41 glistens in the sunlight, and helps reduce evaporative moisture loss, thereby enabling the plant to resist the desiccating effect of hot, dry winds.

YELLOW

Conspicuous in late summer along roadsides and dry streambeds, the large number of yellow flowers and the widespread presence of these much branched, annual plants justify the inclusion of Jackass-clover in this booklet as one of the common flowers of the desert.

The plant ranges across the Southwest from western Texas to southern California at elevations between 1,000 and 6,500 feet. The flowers themselves are small, although the flower heads are quite conspicuous.

Since the leaves somewhat resemble the tri-foliate leaves of Clover, the plant is commonly called Jackass-clover. It is usually found in sandy locations.

YELLOW

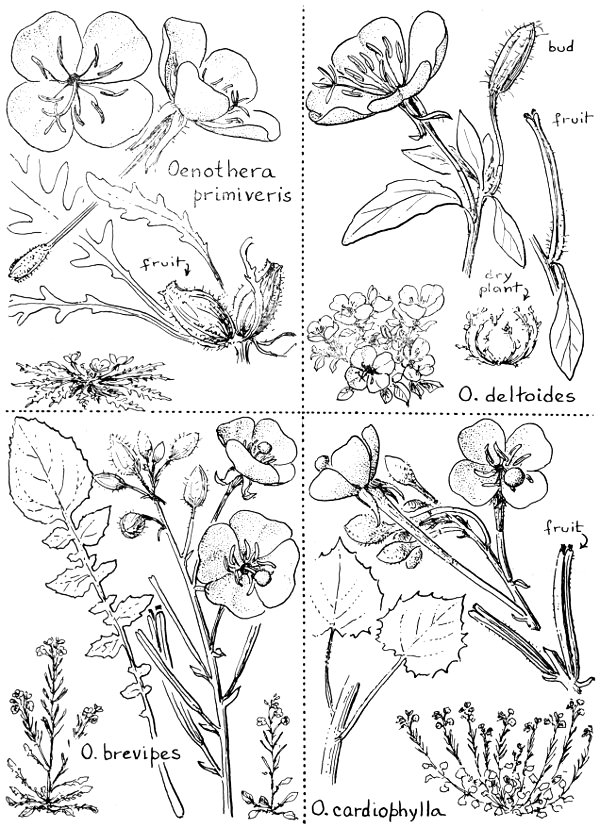

Among the commonest but most beautiful and delicate of the flowering plants of the desert are the Evening-primroses. Flowers are usually large, with the four petals either white or yellow, turning to red or pink with age. Many species are low-growing herbs with large, delicate petals; while others may be shrub-like, sometimes attaining a height of 5 feet. As the name implies, the flowers open in the evening and wilt soon after sunrise.

In the low, warmer sections of the desert, plants in blossom may be found as early as February.

YELLOW

The pendant clusters of golden blossoms are particularly noticeable because of their delightful fragrance, and the small purple berries are juicy and of pleasant flavor. They make excellent jelly and are readily eaten by birds and some of the small mammals. Due to the holly-like leaves and the fragrant blossoms and fruits, the plants would make attractive ornamentals for landscape and decorative plantings were it not for the fact that they are secondary hosts for the black stem rust of the cereals, hence cannot be used in communities where grains are grown. Indians use the root as a tonic, and obtain from it a brilliant yellow dye.

Some botanists prefer to use the generic name Mahonia or Odostemon for this group of plants.

YELLOW

Extensive sections of the desert are gilded in springtime with this low-growing annual herb which is one of the earliest of the desert flowers.

Following moist winters, it covers dry mesas and plains below 4,000 feet from Oklahoma west to Utah, and southward into northern Mexico. After the seed pods have matured, the plant is reported to furnish valuable forage for range stock.

YELLOW

Gourds are conspicuous, trailing, rank-growing plants common along roadsides and in the open desert. Leaves are grayish-green, and blossoms yellow and trumpet-shaped. The striped fruits are about the size and shape of a tennis ball, although some are egg-shaped.

The fruits which are very conspicuous after the vines and leaves have been winter-killed, are sometimes collected, painted in gay colors, and used as ornaments about the house.

Although Indians considered the fruits as inferior and suitable only for coyotes, they ate them either cooked or dried, and made the seeds into a mush. Pioneers used the crushed roots of these plants as a cleansing agent in washing clothes.

YELLOW

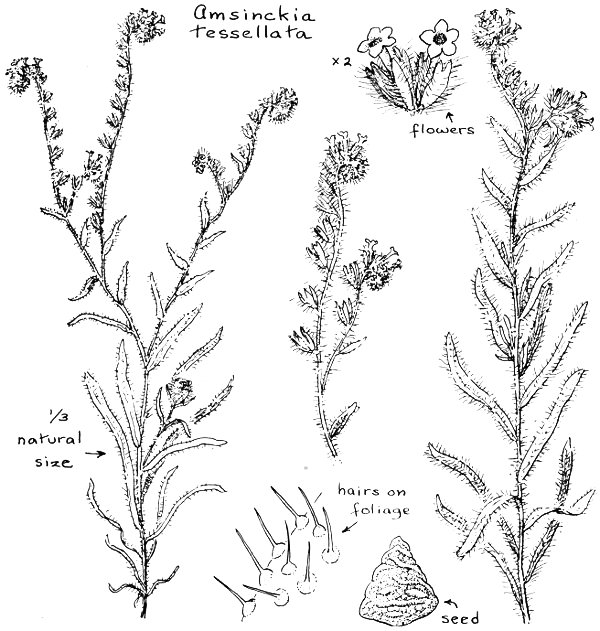

An annual of the Creosotebush belt, and very abundant on gravelly or sandy soils in dry, open places, Fiddleneck is found from western New Mexico to California and north to eastern Washington.

A. tessellata occurs also in Chile and Argentina. Plants are reported to make good spring forage where they grow in heavy stands, but indications have been found that cirrhosis of the liver may result in cattle, sheep and horses that eat the nutlets.

Following moist winters, Fiddleneck is often so abundant as to form vast fields of yellow or orange-yellow blossoms, especially on the Mohave Desert in southern California.

The curling habit of the opening flower heads somewhat resembles the neck of a violin, hence the name.

YELLOW

These resinous, much-branched, perennial shrubs are found on plains and mesas at elevations around 4,000 feet from western Texas to eastern Arizona and south into Mexico. The yellow, nodding flower heads are small, and the leaves have a hop-like odor and a bitter flavor unpalatable to cattle.

In northern Mexico the leaves and dried flower heads are sold in the drug markets under the name of hojase, recommended, in the form of a brew, as a remedy for indigestion.

YELLOW

Mesquite (mess-KEET) is one of the commonest and most widespread of desert trees, often growing in extensive thickets. It occurs at elevations below 5,000 feet, usually along streams, desert washes, or in locations where the water table is relatively high, from Kansas to California and south into Mexico. Roots are reported to penetrate to a depth of 60 feet with more wood below ground than above. In some parts of the desert, blowing sand settles around Mesquite clumps forming hummocks through which rodents tunnel.

The numerous branches are armed with sturdy, straight thorns. In the spring when covered with bright green leaves and laden with catkin-like clusters of greenish-yellow flowers, Mesquite is a particularly handsome shrub or tree. Blossoms are fragrant and attract myriads of insects, including Honeybees.

During pioneer days, Mesquite wood was of the utmost importance to settlers as fuel, and was also used extensively in building corrals and in making furniture and utensils. With the exception of Ironwood, Mesquite is the best firewood to be found in the desert, giving off a characteristic aroma and forming a long-lived bed of coals.

Fruits of the Mesquite, which resemble string beans, ripen in autumn and are eaten by domestic livestock and other animals. They are rich in sugar and still form a staple food among natives. Indians made wide use of Mesquite, the fruits often carrying them over periods when their crops failed. Pinole, a meal made by grinding the long, sweet pods, was served in many ways. When fermented, it formed a favorite intoxicating drink of the Pimas. The gum, which exudes through the bark, was eaten as candy, and was used as a pottery-mending cement, and as a black dye.

YELLOW

Although the Screwbean, so called because of the tight spiral curl formed by the seed pod, is not as common as Honey Mesquite, it is nearly as widespread, being found below 4,000 feet from western Texas to southern Nevada, and southern California to northern Mexico. The majority of the trees are small and shrubby.

Fruits, in common with those of Honey Mesquite, are used by Indians and livestock for food. Bark from the roots was used by the Pima Indians to treat wounds. Where abundant, the wood is used for fence posts, tool handles, and fuel. Birds, particularly the Crissal Thrasher, make use of the shreddy bark for nest-lining material.

Where Screwbean and Honey Mesquite grow together, they may be distinguished in the winter when trees are leafless and fruits have fallen or been removed by animals, by the gray-barked twigs of the Screwbean, those of the Honey Mesquite being brownish red.

Some botanists prefer to classify Screwbean as genus Strombocarpa.

YELLOW

After winters of particularly heavy precipitation, these small close-growing annuals with their sunflower-like blossoms cover large patches of desert with a carpet of gold. Individual flowers are so small and so inconspicuous among larger plants that they are easily passed unnoticed, but millions of the plants all in blossom at the same time make a spectacular display that attracts visitors from considerable distances.

They occur in Arizona below 3,600 feet, westward to California, Lower California, and north to Oregon. A plant of winter and early springtime, Goldfields takes advantage of winter moisture and cool spring weather to produce its flowers and mature its seeds. Thus it escapes the heat and drought of the desert by lying dormant in the seed stage until the moisture and cool temperatures of the following winter awaken it.

In common with Goldpoppy and other annuals that mature their seeds before the summer heat descends upon the desert, Goldfields cannot correctly be called a “desert plant.” Actually these are plants of cooler climes which have found winter conditions in the desert ideal for their needs and have established themselves.

These plants demonstrate effectively one method, that of escaping the heat and drought, by which plants have adapted themselves to survival in the desert. Like the winter tourist, they take advantage of ideal climatic conditions of winter and spring. Since, unlike the winter tourist, they cannot return north for the summer, they take the next best course and pass through the hot, dry period in the dormancy of the seed phase of their life cycles.

YELLOW

The large, solitary, coarse flower heads with their yellow petals make the Sunrays among the most impressive composites of the desert.

Flowers rise on stout stems above a luxuriant growth of leaves that make the plants appear almost egotistical in their elegant arrogance.

They are at their best in sandy washes and on dry slopes at elevations between 1,000 and 3,500 feet, often where other plants seem too hard pressed eking out an existence to produce the garish foliage and bloom achieved by the Sunray.

YELLOW

One of the showiest of the Sunflowers. Desert-sunflowers often form sweet-scented gardens of luxuriant bloom along roadsides and in sandy basins early in the spring.

Its seeds form a dependable source of food for small rodents, especially Pocket Mice, which store them in quantities. Wild bees and Hummingbird Moths are attracted to the fragrant flowers.

This species is common in areas of sandy soil below 1,500 feet in elevation from Utah and southeastern Colorado to southern Arizona and Sonora, Mexico. It is one of the showy roadside flowers of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument.

YELLOW

These low, branching shrubs with gray-green leaves are common on rocky slopes and benches where they lighten the winter landscape with their bright flower heads and create a spectacular mass of bloom during early spring. Flower stems rise several inches above the brittle leaf-covered branches, thus hiding the plant under a blanket of blossoms at the height of the blooming period.

Plants are abundant on rocky slopes below 3,000 feet from southern Nevada to Lower California and eastward through Arizona.

Stems exude a gum prized as incense by the early-day Catholic priests. Indians chewed this gum, and also heated it to smear on their bodies for the relief of pain.

YELLOW

This low-growing, woolly, annual herb with showy, yellow flowers on long, solitary stems is one of the commonest bloomers gracing the desert roadsides and making patches of bright color along otherwise drab and dry, sandy desert washes. It is particularly noticeable because of its luxurious crop of flowers and long period of bloom.

At first glance, Desert-marigold may be confused with Crownbeard, to which it is quite similar in color, size, and habit of growing in groups. However, the regular, circular shape of Marigold blooms and the considerable difference in leaf shape make the two readily distinguishable.

In California, Desert-marigold is cultivated for the flower trade.

Fatal poisoning of sheep on over-grazed ranges has been laid at the door of this plant, although horses crop the flower heads, apparently without harmful effect. Blossom petals become bleached and papery as the blossoms age, thus giving the plant in some localities the name Paperdaisy.

Desert-marigold, of which there are but few species, is common throughout desert areas of the Southwest from Utah and Nevada to Lower California, Sonora and Chihuahua.

YELLOW

The genus Aplopappus (sometimes spelled Haplopappus) is represented in the Southwest by a great many species, both annuals and perennials, which range from elevations of 2,000 feet up to 9,000 feet. Desert forms prefer open, dry canyon slopes and mesas.

A. linearifolius is conspicuous in the springtime, at elevations between 3,000 and 5,000 feet because of its many, showy flower heads.

A. heterophyllus often takes over heavily grazed rangeland since it is generally unpalatable to livestock and replaces vegetation destroyed by overgrazing.

YELLOW

One man of the writer’s acquaintance, confused by the great number of yellow flowers on the desert, refers to them all as “yellow composites.” The Paperflower is one of these.

It is noticeable because of the conspicuous, bright yellow flowers which sometimes cover the plants almost completely, often during periods of the year when bloom is quite scarce on the desert.

The flowers are persistent, petals become papery, fade to a pale yellow, and remain on the plants intact for weeks.

Although the Paperflower does not form great masses of color, the blossom-covered clumps are conspicuous among the Cactus, Mesquite, and Creosotebush of the desert.

It is common at elevations below 5,000 feet from southern Utah to Lower California, with similar species ranging eastward through southern New Mexico and northern Chihuahua.

Some species are reported to be poisonous to sheep.

YELLOW

Members of this large genus are chiefly tropical, the majority having golden to bronze flowers and brown, woody seed pods. They are quite common along desert roadsides, and a few species are cultivated as ornamentals.

In some localities, following moist winters, Desert-senna bursts into a riot of color in April and May adding a golden glory to the spring floral display.

Representatives of the several desert species occur at elevations between 2,000 and 5,000 feet from Texas westward to southern California and south into Mexico.

YELLOW

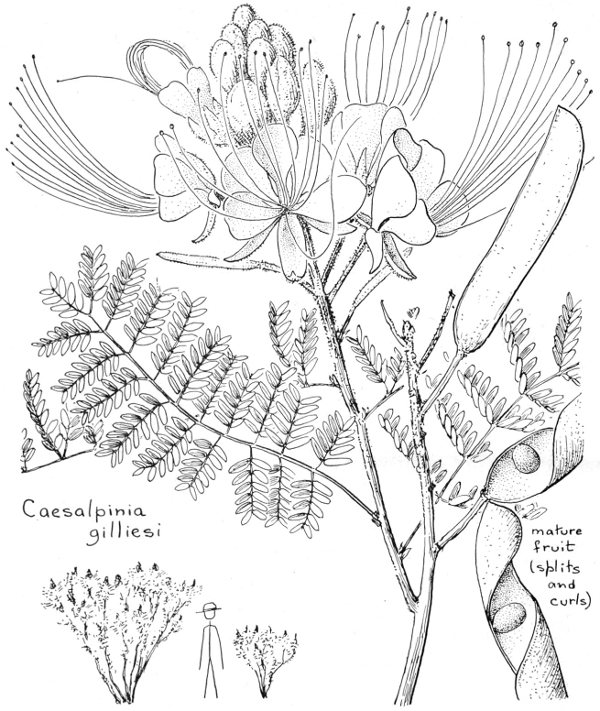

Widely grown as a decorative shrub by the people of Mexico, this spectacular import from South America is quite commonly used as an ornamental in yards and around houses in desert areas of the Southwest. Under suitable conditions, it may escape and grow wild. The very showy blossoms with yellow petals and long, thread-like, red filaments are certain to attract attention.

In contrast to the striking showiness of the blossoms, the plant itself is straggling and unsymmetrical, and gives off an unpleasant odor.

YELLOW

The flattened pods, or stem joints, of the Pricklypears growing, as they do, in huge clumps make them the best known of the Cacti throughout 60 the West. There are many species found throughout the United States, but the plants reach their greatest size and luxuriant growth in the desert areas of the Southwest. The large, red to purple and mahogany, juicy, pear-shaped fruits are known as tunas, and are eaten by many animals as well as by the native peoples. Flowers are large and spectacular.

Although a number of species of Pricklypears are found in all of the desert areas, O. engelmanni with its bright yellow flowers is the commonest form in both the Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts, while the Beavertail cactus with its magenta flowers and lack of large spines is the common and spectacular form of the Mohave Desert.

Pricklypears are increasing in parts of the desert where conditions are favorable, especially where heavy grazing has given them an advantage over plants that are favorable to livestock.

YELLOW

Well known among the desert figures are the heavy-bodied Barrel Cacti which are sometimes pointed out as sources of water for travelers suffering from thirst. Under extreme conditions, it is possible to hack off the tops of these tough, spine-protected plants and obtain, by squeezing the macerated tissues, enough juice to sustain life.

Growing faster on the shaded side, the taller-growing plants tend to lean toward the south, hence the name “Compass” cactus. Flowers range in color from yellow to orange and rose-pink, depending on the species, and the pale yellow, egg-shaped fruits which ripen early in the winter, are a favorite food of deer and rodents. Flowers, and the resulting fruits, form a ring around the crown of the plant.

The flesh of the Barrel cactus, cooked in sugar, forms the base of cactus candy.

YELLOW

Many species of Agave are found in various parts of the desert, hence it is difficult to settle on those which should be given particular recognition. Their blossoms, in general, are various shades of yellow. The larger species are called Centuryplant or Mescal (mess-KAHL), while the small ones are spoken of as Lechuguillas (letch-you-GHEE-ahs). The Lechuguilla, covering hundreds of square miles in Texas, New Mexico, and northern Mexico, is an indicator of the Chihuahuan Desert, holding the position in that desert which the Saguaro does in the Sonoran desert and the Joashua-tree in the Mohave Desert.

From its leaf fibers the Mexicans weave a coarse fabric. Its plumelike flower stalks, relished by deer and cattle, form one of the spectacular sights of the Chihuahuan Desert in springtime.

YELLOW

Agave plants require a number of years to store sufficient plant foods for the production of the huge flower stalk which grows with amazing rapidity to produce the many flowers and seeds, after which the plant dies. This long pre-blossom period of a dozen to 15 or more years is the basis for the name “Centuryplant.” If the young flower stalk is cut off, the sweet sap may be collected and fermented to form highly intoxicating beverages, some of which are distilled commercially. Among these are mescal, pulque (POOL-kay), and tequila (tay-KEEL-ah). Indians cut the young bud stalks, and roast them in rock-lined pits.

Under favorable weather conditions, this short-stemmed Mariposa presents a gorgeous display of spring color. Closely related to the white-flowered Twisted-stem Mariposa (C. flexuosus) and to the Sego-lily (state flower of Utah), the Desert-mariposa is found below 5,000 feet in Nevada, southern California, southern Arizona, and northern Sonora. When growing beneath taller shrubs, it forsakes its short-stemmed habit and forces its way up through the low branches, displaying its blossom above.

The Mariposas, of which there are several species, are among the most beautiful wildflowers of the Southwest.

ORANGE

Because of their abundance and dense growth, following winters of heavy precipitation, these annual poppies often cover portions of the desert with “a cloth of gold.” They are closely related to the well-known California Poppy, state flower of California, and a common border or bedding plant in home flower gardens. In the desert, Goldpoppies are sometimes mixed with Owlclover, Lupines, and other spring flowers forming a multi-colored carpet that attracts visitors from great distances. (See cover.)

ORANGE

The showy flowers, which are large enough to attract attention, are relatively few. Even more spectacular are the large, black, woody pods ending in two curved, prong-like appendages that hook about the fetlocks of burros or the fleece of sheep, thereby carrying the pod away from the mother plant and scattering the seeds. Young pods are sometimes eaten by desert Indians as a vegetable, and the mature fruits are gathered by the Pima and Papago Indians, who strip off the black outer covering and use it in weaving designs into basketry.

Blossoms of the small-flowered species are reddish purple to white streaked with orange and yellow, while the large-flowered species have coppery yellow blossoms, the throat spotted with purple and the edge of the cup streaked with orange.

COPPERY

Burrobush is another of the common desert shrubs whose fruits are much more conspicuous than the blossoms. The shrub itself is bright green in color, and somewhat resembles the common Russian-thistle. It is widespread, and abundant in sandy washes, where it tends to form thickets.

In some localities it is called “Cheeseweed” because of the cheesy odor of the crushed foliage.

It occurs throughout the Southwest at elevations below 4,000 feet, from western Texas to southern California and northern Mexico.

RED

One of the few flower families restricted to the desert, the unique Ocotillo (oh-koh-TEE-oh) with its long, unbranching stems is found on rocky hillsides below 5,000 feet from western Texas to southern California and south into Mexico. It is one of the commonest, queerest, and most spectacular of desert plants, especially when the tips of its long, slender stems seem afire with dense clusters of bright red blossoms. Following rains, leaves clothe the thorny stems with green, but after the soil becomes dry, the leaves turn brown and fall. The heavily thorned stems are covered with green bark which takes over the functions of leaves during periods of drought. The plant thus becomes semi-dormant during hot dry 67 periods and, in sections of the desert visited by showers, may go through this cycle several times during a year.

Because of its sharp thorns, strangers to the desert may think that the Ocotillo is one of the Cacti, but it is more closely related to both the Violet and the Tamarix than to the Cacti.

Stems of the Ocotillo are used by natives in building huts. They are sometimes cut and, when planted close together in rows, take root and form living fences and corrals.

RED

Slender, trailing stems up to 30 inches in length with clusters of three rose-purple to pink blossoms serve to identify the Trailing-four-o’clock which is a conspicuous plant of the open plains and mesas. The plants prefer dry, sandy benches where they are quite conspicuous with their 68 prostrate, somewhat sticky stems weighted with clinging grains of sand. Blossoms are usually showy and colorful, rarely pale rose to white.

Fruits of A. incarnata are conspicuously toothed.

PINK

Common throughout all of the Southwest, the Mallows range in size from small herbs 5 or 6 inches high to coarse, straggling, woody-stemmed plants with stems 4 or 5 feet long. Their flowers range in color from white and pale yellow to lavender, apricot, and red. Some species, including Ambigua, grow in large clumps with as many as 100 stems from a single root. The smaller species often cover the desert floor in early spring with a dense growth of flowers giving an apricot tinge to the landscape. Several species flower in spring and again after the summer rains.

A local belief that hairs of the plant are irritating to the eyes has given the name “Sore-eye Poppies,” an appellation carried out in the Mexican name Mal-de-ojos. In Lower California, Mallows are called Plantas Muy Malas, meaning very bad plants. In contrast, the Pima Indian name is translated to mean “a cure for sore eyes.”

PINK

This straggling, perennial shrub with fine, Mimosa-type leaves is common over much of the desert, lining banks of arroyos or dotting open hillsides. It is particularly conspicuous when in flower because of the spectacular tassel-like blossoms which are white and scarlet, or generally pink in appearance. The small leaves are nutritious and are highly palatable to deer and to livestock. The petite Fairyduster adds much to the color and springtime atmosphere of the desert. It is particularly noticeable along the base of the Tanque Verde hills in Saguaro National Monument.

PINK

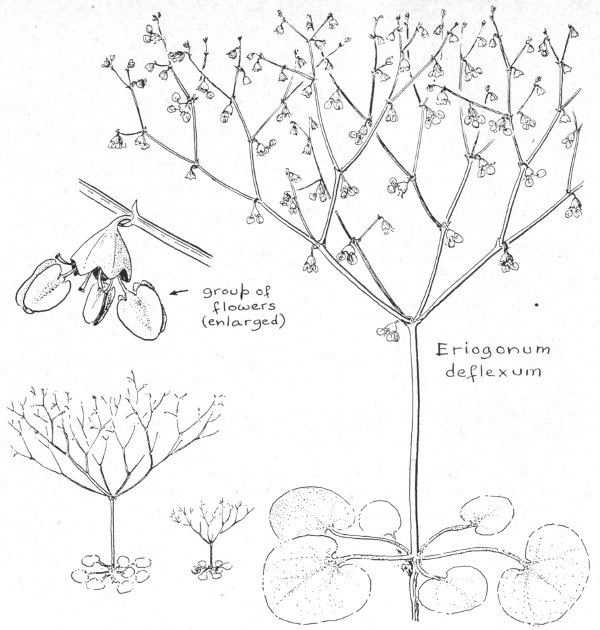

Eriogonum is a very large genus, many species of which are common, and contains both annuals and biennials. Although the flowers are small, they are usually numerous and conspicuous. E. densum is often very abundant in semi-desert areas, particularly along roadsides, where it is especially noticeable because it monopolizes the pavement edges for miles. It is extremely resistant to drought and flourishes when many other herbaceous plants have dried out completely. Although it bears flowers at almost any time throughout the year, during the autumn months the branches are loaded with myriads of pendant, pearly flowers the size of rice kernels. In winter, the stalks turn maroon in color and are quite conspicuous.

E. polycladon is often so common along roadsides and desert washes as to color the landscape with its greyish stems and pink flowers.

E. inflatum always attracts attention because of its swollen stems which resemble tall, slender bottles.

PINK

Purists could object to inclusion of the Saltcedar in this booklet because it is not native. However, due to a number of importations (eight species being introduced by the Department of Agriculture between 1899 and 1915) and to its ability to spread rapidly under suitable conditions, Saltcedar is now widespread throughout the Southwest.

It grows as a graceful shrub or small tree with drooping branches covered with small, scale-like leaves and is abundant in moist locations below 5,000 feet. It prefers a hot climate, low humidity, and saline soils. In river bottoms, it often forms dense thickets which require immense quantities of water, hence rob the few desert streams of a high percentage of their moisture.

Honeybees obtain nectar from the blossoms, which are particularly noticeable in the spring and early summer, as they completely cover the branches which appear as light pink, drooping plumes. The thickets are valuable as wind breaks and in erosion control, and once established, are very difficult to control and because of the deep shade cast by their dense growth and the heavy feeding of the shallow roots, they prevent cropping.

The name Tamarisk is often confused with the name of the Larch or Tamarack tree. There is little similarity except in the name.

The larger Tamarix aphylla is similar in appearance but much larger and suitable for cultivation as a shade and decorative tree. It is subject to winterkill, but does not have the bad habit of spreading, characteristic of T. pentandra.

PINK

Representatives of the Phlox genus are found from the hot desert lowlands to the mountain tops well above the timberline. Certain species are limited in their range to the desert areas of the Southwest, and it is in these that we are interested here. The plants sometimes present a mass of heavy bloom twice yearly: heaviest in the spring, and again following the summer rains. Several of the native species have been brought under cultivation, particularly P. tenuifolia, in desert gardens, as it grows naturally in a brushy habitat similar to that formed by the shrubs planted around a house. Other forms grow as low, creeping mats forming fragrant, colorful floral carpets.

LAVENDER

Although a close relative of the Catalpa, the willow-like foliage of this small tree has given it the name Desertwillow. A small and inconspicuous part of the desert vegetation when not in flower, unnoticed among the heavier growth of trees and shrubs that crowd the banks of desert washes, the tree’s beautiful orchid-like flowers of white to lavender mottled with dots and splotches of brown and purple bring exclamations of delight from persons viewing them for the first time. Because of the beauty of the tree when in bloom, it is sometimes cultivated as an ornamental.

Leaves are rarely browsed by livestock, and the durable, black-barked wood is used for fenceposts. In Mexico, a tea made by steeping the dried flowers is considered to be of medicinal value. By early autumn, the violet-scented flowers which appear after summer rains are replaced by the long, slender seed pods which remain dangling from the branches and serve to identify the tree long after the flowers are gone.

Although Desertwillows are never found in pure stands, growing singly and rather infrequently among other trees and shrubs lining desert washes, the species is quite common below 4,000 feet across the entire desert from western Texas to southern Nevada, southern California and southward into Mexico.

LAVENDER

Two somewhat similar, columnar cacti occur in the United States only in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and in its immediate vicinity. Both are fairly common in northwestern Mexico.

These two spectacular desert giants with their clumps of erect branches are sufficiently similar to be readily confused at first glance. However, the stems of the Organpipe (L. thurberi) are longer and contain more but much smaller ridges than do the stems of the Sinita or “Whisker cactus.” The name “Sinita” (meaning old age) refers to the long, gray, hair-like spines covering the upper ends of the Sinita stems.

Both species are night-blooming, the flowers, which appear along the sides and at the tips of the stems, closing soon after sunrise the following morning. Fruits of the Organpipe are harvested by the Papago Indians.

Although these two species of cactus are restricted to a very limited area, they are sufficiently spectacular and interesting to be considered worthy of inclusion in this booklet. It was to protect these species, threatened with extinction in the United States, and other rare and interesting forms of desert plants and animals, that Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument was established.

LAVENDER

Unlike blossoms of many of the Cacti, flowers of the little Mammallarias often last for several days. Blossoms are pink or lavender, occasionally yellow, while the fruits are finger- or club-shaped and red. Being small and forming low clumps, or with single pincushion-like stems, they often escape attention except when glorified with bright, comparatively large flowers, which often form a crown around the top of the plant. The long spines are curved at the tips giving the plant the appearance of being covered with unbarbed fishhooks.

The Pincushion cacti, of which there are a number of species throughout the Southwest, occur in dry, sandy hills from southern Utah to western Texas and in southern California and northern Mexico. The red fruits are bare, without scales, spines, or hairs.

LAVENDER