|

A typographical error has been corrected; a list follows the text. List of Illustrations (etext transcriber's note) |

The Pilgrimage Series

| Agents— | |

| America: The Macmillan Company | |

| 64 and 66 Fifth Avenue, New York | |

| Australasia: The Oxford University Press | |

| 205 Flinders Lane, Melbourne | |

| Canada: The Macmillan Company of Canada, Ltd. | |

| St Martin’s House, 70 Bond Street, Toronto | |

| India: Macmillan & Company, Ltd. | |

| Macmillan Building, Bombay | |

| 309 Bow Bazaar Street, Calcutta | |

THE

Blackmore Country

BY

F. J. SNELL

AUTHOR OF “A BOOK OF EXMOOR,” ETC.

SECOND EDITION

WITH 32 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

FROM PHOTOGRAPHS BY

CATHARINE W. BARNES WARD

LONDON

ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK

First Edition, containing 50 illustrations, published 1906

This Edition published 1911

The Blackmore Country having achieved a second edition, it is proper to state that it is now presented to the public substantially in the same form as in the original issue. Advantage, however, has been taken of a friendly critique by Mr Arthur Smyth to effect some revision. Mr Smyth, who was well acquainted with the Blackmore family, and indeed a distant relation, is rather perplexed at the assertion that the novelist’s father was a poor man; but he certainly passed for such at Culmstock, and the fact that he took pupils, in addition to serving his poor cure, tends to show that he was by no means too well off.

In my Early Associations of Archbishop Temple it is stated with reference to the restoration of Culmstock Church: “Nobody knew from what source Mr Blackmore obtained the necessary funds, but it was supposed that his wife’s relations were rich.” This is, in a sense, confirmed by Mr Smyth, who says that Mr Turberville, R. D. Blackmore’s elder brother, inherited considerable property from his mother; but, when I wrote the passage above quoted, I was not aware that John Blackmore was married twice. His first wife, who died three years after their{viii} marriage, and before John Blackmore set foot in Culmstock, may not have been in possession of means, although Turberville’s estate—Mr Smyth says, “his will was proved for (I believe) £20,000”—may have been derived from his maternal connections. Mr Snowden Ward, in his Introduction to the Doone-land edition of Lorna Doone, informs us regarding R. D. Blackmore, also a son of this lady: “A bequest from the Rev. H. Hay Knight, his mother’s brother, put an end to his financial worries.”

Nevertheless, it may be doubted whether the novelist was ever in even “comparative affluence.” He himself publicly declared that he lost more than he gained from market-gardening—he was, by the way, a F.R.H.S.—and the late Rev. D. M. Owen, Blackmore’s old schoolfellow, with whom he maintained a lifelong correspondence, told me that he was constantly complaining of his pecuniary limitations. Mr Owen’s reply was that he had no excuse; he had only to write another Lorna Doone to replenish his treasury to the brim. When, also, he was asked for a subscription to the Culmstock flower show, Blackmore declined, assigning as the reason that he “couldn’t afford it.” This does not look like “comparative affluence.”

Mr Smyth says that he never saw or heard of any daughters of the Rev. John Blackmore. If he implies that there were none, he is certainly mistaken (see Prologue), but he raises a problem which, I confess, I am not able to solve. “In Charles Church there is a marble slab erected to the memory of the Rev. John Blackmore by his children, J. B., R. B., M. A. B. No allusion is{ix} made to M. A. B. in the pedigree either by the Rev. J. F. Chanter or Mr Snell.” The only explanation which occurs to me is that M. A. B. may represent the initials of their full sister, who died in infancy. The Rev. John Blackmore married in 1822. Three years later he sustained a terrible trial. “The novelist’s father,” says Mr Ward, “was a ‘coach’ for Oxford pupils, until, in 1825, a great outbreak of typhus fever swept away his wife, daughter, two pupils, the family physician, and all the servants, and almost broke John Blackmore’s heart.” R. D. Blackmore’s mother’s maiden name was Anne Basset Knight; and the A. in M. A. B. suggests that her daughter may have been called Anne—perhaps Mary Anne, if M. A. B. indicates that daughter. She had long been dead, but the brothers, as an act of piety, may have chosen to commemorate her in this way, whilst ignoring the daughters of the second family, whom Mr Smyth never saw or heard of.

In conclusion, the demand for a second edition of this work is a satisfactory answer to the disparaging remarks of the late Mr F. T. Elworthy in a presidential address to the members of the Devonshire Association for the Promotion of Literature, Science, and Art. It is a bad precedent that the title and contents of a new work should be officially censured on an occasion when it was by an accident that the author was not present to be lectured for his shortcomings, just as it was a pure accident that Mr Elworthy was not named in the book as accompanying Dr Murray and Professor Rhys in their visit to the Caractacus stone on Winsford{x} Hill (p. 109)! I now repair this omission, and at the same time express regret that the secretaries did not take steps to delete from the reports of a learned and very useful association criticism which, to say the least, was beside the mark.

F. J. SNELL.

The “Blackmore Country” is an expression requiring some amount of definition, as it clearly will not do to make it embrace the whole of the territory which he annexed, from time to time, in his various works of fiction, nor even every part of Devon in which he has laid the scenes of a romance. The latter point may perhaps be open to discussion in the sense that, ideally, the glamour of his writing ought to rest with its full might of memory on all the neighbourhoods of the West around which he drew his magic circle. As a fact, however, it is North Devon and a slice of the sister county that form his literary patrimony, while Dartmoor is a more general possession, which he failed to seal with the same staunch and archetypal impression. There have been many good Dartmoor stories, and one instinctively associates that region with the names of Baring-Gould and Eden Phillpotts; with Blackmore, hardly at all. But from Exmoor to Barnstaple, and from Lynton to Tiverton, he reigns supreme—and naturally, for this was his homeland, which, through all its length and breadth, he knew with an intimacy,{xii} and loved with a devotion, and portrayed with a skill, that will surely never again be the portion of any child of Devon.

Richard Doddridge Blackmore was born on June 7, 1825, at Longworth, in Berkshire—a circumstance which raises the delicate and important question whether, after all, he can be justly claimed as a Devonshire man. On the whole, I think, the question may be answered affirmatively, although it is evident that he cannot possibly be described as a native of the county. Who, however, would dream of depriving an Englishman of his nationality merely for the accident of his being born abroad, unless indeed he deliberately abandoned that proud title and threw in his lot with the country of his birth, to the exclusion of his ancestral home? And this practically represents the state of affairs as regards Blackmore. In one sense it must be admitted he did not remain constant to his Devonshire connections, inasmuch as he resided through a great part of his life, and to the day of his death, at Teddington, in Middlesex. But as against this must be set the facts that he descended from an old North Devon stock, a stock so old that it may fairly be termed indigenous, and that his boyish experiences were almost entirely confined within the county. To these weighty considerations may be added that he eventually became possessor of the ancient residence of his race, that he always manifested the warmest interest in county concerns, and that his great achievement in literature was inspired by West-country legend. That well-known authority, the Rev. J. F. Chanter, worthy son of{xiii} a worthy sire, would like to say “Devon” legend, and much may be urged in favour of his contention, notwithstanding that modern Exmoor is altogether in Somerset. He points out, for instance, that Bagworthy (or “Badgery”) Wood, the centre of the Doone traditions, is in Devon. Still it were better, perhaps, to consider Lorna Doone in the light of a border romance. Indeed, on an impartial survey, it seems almost necessary to adopt this view; and Blackmore himself was anything but unwilling to recognise, and even to emphasise, the Somerset element in his story.

Not long before the novelist’s death, a gentleman wrote to him from Taunton, calling attention to the widely prevalent idea that in the course of the tale he conveyed the impression of allocating this charming country to North Devon rather than West Somerset; and Mr Blackmore’s correspondent went on to mention that recently strenuous efforts had been made to procure the inclusion of Exmoor in Devon, but that the policy of plunder had been defeated by the vigilant action of the Somerset County Council. In reply to this communication the following letter was received:—

“My dear Sir,—Nowhere, to the best of my remembrance, have I said, or even implied, that Exmoor lies mainly in Devonshire. Having known that country from my boyhood—for my grandfather was the incumbent of Oare as well as of Combe Martin—I have always borne in mind the truth that by far the larger part of the moor is within the county of Somerset, and the very first sentence in Lorna Doone shows that{xiv} John Ridd lived in the latter county. Moreover, when application is made to Devon J.P.’s for a warrant against the Doones, does not one of them say that the crime was committed in Somerset, and therefore he cannot deal with it? See also p. 179 (6d. edition), which seems to me clear enough for anything. Moreover, the rivalry of the militia, both in Lorna Doone and Slain by the Doones—which title I dislike, and did not choose freely—shows that the Doone Valley was upon the county border. I think also that Cosgate, supposed to be ‘County’s Gate,’ is referred to in Lorna Doone, but I cannot stop to look.[1] The Warren where the Squire lived is on the westward of the line, as Lynmouth is—or, at least, I think so—and therefore North Devon is spoken of the heroine who lives there. All this being so very clear to me, I have been surprised more than once at finding myself accused in Somerset papers of describing Exmoor as mainly a district of Devonshire—a thing which I never did, even in haste of thought. And if you should hear such a charge repeated, I trust that your courtesy will induce you to contradict it, which I have never done publicly, as I thought the refutation was self-evident.”

It is certainly true that at Dulverton, which, if not Exmoor, is next door to it, visitors frequently imagine that they are in Devonshire, as I have myself proved, but, for my own part, I have never attributed this delusion to the influence of Lorna Doone. On the contrary, it{xv} has seemed to me that a river is the culprit. The Exe is universally esteemed a Devon stream, and lends its name to the metropolis of the West. That in these circumstances Exmoor should be anywhere but in Devonshire, may well appear a violation of the fitness of things, and as coloured maps seldom perhaps emerge from their impedimenta, these visitors revenge themselves on the makers of England by substituting for artificial delimitations their own easy beliefs and natural assumptions.

This, however, is somewhat of a digression. I return to the probably more interesting topic of Mr Blackmore’s Devonshire “havage,” which good old West-country term I once heard a good old West-country clergyman derive from the Latin avus—needless to say, a most unlikely etymon. In the above-quoted letter reference is made to the novelist’s grandfather as incumbent of Oare and Combe Martin, but, had the occasion required it, Blackmore could no doubt have furnished a much fuller account of his North Devon pedigree. It is extremely probable, but not absolutely certain, that one of his remote ancestors, sharing the same Christian name Richard, married a Wichehalse of Lynton. To have read Lorna Doone is to remember how John Ridd rudely disturbed young Squire Wichehalse in the act of kissing his sister Annie; and I shall have more to say of this half-foreign clan, their fortunes, and their eyry in a subsequent chapter. Meanwhile one may note that the first entry in the parish register of Parracombe relates to the marriage of Richard Blackmore and Margaret, daughter of Hugh Wichehalse, of Ley, Esq.;{xvi} and, further, that the bride’s father died on Christide, 1653, and the bride herself thirty years later. These dates are important, as they seem to preclude the possibility of the Richard Blackmore who wedded the Lady of Ley being the direct progenitor of the Richard Blackmore who wrote Lorna Doone, though it can scarcely be questioned that he was of the same kith and kin, and so, in the larger sense, an ancestor. In any case, the match cannot be accepted as a criterion of the standing of the family. Mésalliances are not unknown in North Devon, one such romantic union of erstwhile celebrity being the marriage of a small farmer’s son with a daughter of the resident rector, a gentleman of good descent and prebendary of Exeter Cathedral. From the time of John Ridd, and who shall say for how many ages antecedent thereto, love has laughed at locksmiths and gone its own wilful way.

Small farmers, however, the Blackmores were not. They were freeholders settled at East Bodley and Barton in the parish of Parracombe, and leaseholders of the neighbouring farm of Killington, or Kinwelton, in the parish of Martinhoe. Over the porch of the old farmstead at Parracombe may still be read the inscription, “R.B., J.B., 1638”; and as the Subsidy Rolls of 16 Charles I. for Parracombe and Martinhoe contain the names of Richard and John Blackmore, we may conjecture without difficulty to whom the initials belonged. The first of the yeomen on whom we can fasten as a certain ancestor of the novelist was a John Blackmore who died in 1689. His son Richard, and grandson John, and great-grandson John—{xvii}not to mention other members of the family whose names are duly recorded—suffered themselves to be absorbed with the peaceful and healthful pursuit of husbandry, which they practised, generation after generation, on their estate at Bodley. Then, towards the end of the eighteenth century there occurred a change; and the Blackmore name, in the person of another John, took what may be termed an upward turn. This John Blackmore, born in 1764, betrayed a taste for learning, and through Tiverton School found his way to Exeter College, Oxford, where he won the degree of B.A. He was soon after ordained, and entered on his duties as curate of High Bray, on the outskirts of Exmoor, and in his own country and county. An antiquary and a person of general cultivation, he was at the pains of copying the parish register, and in the new edition did what every parson should do, set down items of current interest, together with an informal history of the parish, so far as it could be learned. He did also what few parsons should attempt—adorned his copy of the register with original Latin verses. Such specimens of new Latin poetry as I have disinterred from parochial records are, for the most part, fearful and wonderful lucubrations as to both sentiment and technique, whereas it is frequently the case that voluntary jottings in the vulgar tongue gild and redeem, with their human touches, whole continents of inky wilderness.

Not long after his advent at High Bray Mr Blackmore appears to have married, and in process of time his wife bore him a first-born son, whom he named John. He was, however,{xviii} not quite content with his position as curate; and accordingly he bought the advowson of the adjacent living of Charles, in the confident expectation that it would shortly become void, pending which happy consummation he agreed to serve as curate-in-charge. No speculation could have been more disastrous, since, in point of fact, the hoped-for vacancy did not occur till quite half a century had passed over his head, and at that advanced age he did not think proper to enter upon possession. Instead of doing so, he presented his second son Richard to the rectory. During this protracted era of suspense John Blackmore, senior, as he must now be designated, did not lack preferment. In 1809 he was appointed rector of Oare, and in 1833 (pluralities being still admissible) he received in addition the valuable living of Combe Martin; and both these appointments he continued to hold till his death in 1842.

As has been intimated, the original Parson Blackmore had two sons, John and Richard, each of whom, following in his footsteps, entered the Church; and the elder at all events met with considerably worse luck than his father. Curiously enough, his early life was full of promise, for in 1816 he was elected Fellow of Exeter, his father’s old college, and this might well have proved the inception of a long and successful academic career, either in Oxford or at one of our public schools. But in 1822 he vacated his fellowship on his marriage with Anne Basset, daughter of the Rev. J. Knight, of Newton Nottage. Thirteen years later he had attained to no higher position than that of{xix} curate-in-charge of Culmstock, near Tiverton; and when he retired from that, it was only to proceed in a similar capacity to Ashford, near Barnstaple. He was always poor, but deserved a happier fate, since he was always good (see Maid of Sker, chapter xxxix.). He died in 1858.

By his wife Anne the Rev. John Blackmore had one daughter and two sons, Henry John, who afterwards took the name of Turberville, and Richard Doddridge. The former produced a bizarre poem entitled “The Two Colonels,” and was proficient in a number of sciences, notably in astronomy, but he was eccentric to such a degree that there was grave doubt, in spite of all his attainments, whether he was quite compos mentis. He resided at Bradiford, near Barnstaple, died at Yeovil under distressing circumstances, and was buried at Charles (in 1875). He assumed the name Turberville, so it is said, out of resentment at the sale of the family estates for the benefit of a half-brother, Frederick Platt Blackmore, an officer in the army and a spendthrift; and he notified his intention, as well as his reason, to all whom it might concern in a printed handbill. Anger was also the motive for his writing “The Two Colonels”; he conceived there had been discourtesy on the part of the members of the Ilfracombe Highway Board and others. The publication caused much excitement, and at one time an action for libel seemed imminent. Eventually, it is believed, the book was withdrawn.

Besides the son already mentioned, the Rev. John Blackmore had by his second wife two{xx} daughters, Charlotte Ellen, who married the Rev. J. P. Faunthorpe, of Whitelands College, Chelsea, and Jane Elizabeth, who was the wife of the Rev. Samuel Davis, for many years vicar of Barrington, Devon. He was for a year or two at Bude Haven, and won some reputation there as a preacher. Hence, his son, Mr A. H. Davis, thought he might possibly be the “Bude Light” of Tales from the Telling House, but my friend, the late Rev. D. M. Owen, who probably knew, gave me to understand that the “Bude Light” was the Rev. Goldsworthy Gurney.

Returning to the first family—the second son was Richard Doddridge Blackmore, the novelist. In his case, although great wit is proverbially allied to madness, the question of sanity is not likely to be raised; and probably the worst fault that the world will lay to his charge is that of undue secretiveness. It is common knowledge that he interdicted anything in the shape of a biography, and doubtless he took measures to prevent the survival of private papers and letters which might be used as material for the purpose. Whether or not he did this, his wish will assuredly be held sacred by his more intimate friends, who alone are qualified to undertake such a work. Meanwhile the novelist has to pay for his prohibition of an authentic Life, by the unrestricted play of ben trovare. Having myself been victimised by this insidious enemy of truth, I seize the opportunity to protest that any statements regarding the late Mr Blackmore to be found in the present work are made without prejudice and with all reserve,{xxi} as being, conceivably, the inventions of the Father of Lies. At the same time, as due caution has been observed and the evidence has, in various instances, been drawn from reputable and independent witnesses who, without knowing it, acted as a check on each other, I cannot seriously believe that these contributions to history are either gratuitous or garbled.

An illustration, pointed and germane, is not far to seek. I always understood from my late kind friend, the Rev. C. St Barbe, Sydenham, rector of Brushford, who, to the deep regret of a wide circle of acquaintance, passed away in the spring of 1904 at the age of 81, that R. D. Blackmore, as a boy, spent many of his vacations at the moorland village of Charles, to the rectory of which his uncle Richard had, as we have seen, been presented by his grandfather. Mr Sydenham even went so far as to use the expression “brought up” in this connection, which indicates at least the length and frequency of young Blackmore’s visits. Now the Rev. J. F. Chanter, in a paper written in 1903, shows that he also has gained a knowledge of the circumstance—certainly by some other means. As the rector of Charles did not die till 1880, and so lived to see his nephew and guest grown famous, it is not to be supposed that he allowed his share in the hero’s tirocinium to remain obscure. What more natural than that he should communicate it freely to his neighbours, with all the pride of a fond uncle with no children of his own? Would he not have related also, as the harvest of imparted wisdom, that in the rectory parlour, the scene of former instruction, great part of Lorna Doone was{xxii} written? Nor must we forget the old Blackmore property at Bodley, where the novelist’s grandfather, in order to adapt it to his requirements as an occasional residence, had added to the venerable homestead a new wing; and where, or at Oare rectory, the future romancer passed blissful holidays, roaming at will in the North Devon fields and lanes, and drinking in quaint lore, conveyed in the broad, kindly accents of the North Devon country-folk. The Bodley estates, consisting of East Bodley, West Hill, and Burnsley Mill, passed to the novelist’s father, by whom they were sold a few years before his death. Mr Arthur Smyth, referring to R. D. Blackmore’s college days, avers that even then he was very reserved. Mr Smyth’s father often went shooting with him. About this time a white hare was caught at Bodley, and, having been stuffed, was treasured by the Rev. R. Blackmore in his dining-room at Charles.

Thus the limits of the Blackmore country are definitely staked out by family tradition, as well as by literary interest, running from Culmstock to Ashford, and from Oare to Combe Martin, with the commons appurtenant. The confines are somewhat vague and irregular, and I must crave some indulgence for my method of configuration. Obviously, the novelist’s recollections of his youth with their accompanying sentiments and inspirations, cannot be taken as an absolute guide, for then it would be requisite to cross the Bristol Channel to Newton Nottage, his mother’s home, in the vicinity of which are laid the opening scenes of the charming Maid of Sker. Such a course would infringe too much on the popular{xxiii} conception of the phrase, and the attempt to link localities without any natural connection, and severed by an arm of the sea, however successfully accomplished in the romance, would in our case involve needless confusion. What little is said about Newton Nottage, therefore, may as well be said here.

A village in Glamorganshire, it had peculiarly sacred and solemn associations for R. D. Blackmore. Nottage Court, the seat of the Knight family, was his mother’s ancestral home, and it was also one of the homes of his own childhood. Here he wrote his first book, the above-named romance, which was ever his favourite, but the story was re-written, and not published till a later date. For Blackmore, however, the place had sad as well as pleasant memories, for it was here that his father, then curate of Ashford, was found dead in his bed on the morning of September 24, 1858, whilst on a visit to his wife’s people, and at Newton Nottage he lies buried.

If this is crossing the Bristol Channel, so be it; we are soon back again, and ready to discourse of Tiverton, and Southmolton, and Lynton, and Barnstaple, and their smaller neighbours, with the moors and commons appurtenant.[2]

Note.—For the Blackmore pedigree and other kindly assistance, the author is indebted to the Rev. J. F. Chanter, of Parracombe.

From Photographs by CATHARINE W. BARNES WARD.

| 1 | On the Lyn, below Brendon | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | ||

| 2 | Culmstock Vicarage and Church | 9 |

| 3 | Rectory House at Charles | 16 |

| 4 | Culmstock Church and River | 25 |

| 5 | Hemyock | 32 |

| 6 | Culmstock Bridge | 41 |

| 7 | Old Blundell’s School, Tiverton | 48 |

| 8 | Chapel, Greenway’s Almshouses, Tiverton | 73 |

| 9 | Combe, Dulverton | 80 |

| 10 | A Bit of Old Dulverton | 89 |

| 11 | Torr Steps, Hawkridge | 96 |

| 12 | Winsford | 121 |

| 13 | Landacre Bridge, Exmoor | 128 |

| 14 | Bagworthy Valley | 137 |

| 15 | Brendon, near Oare | 144 |

| 16 | Nicholas Snow’s Farmyard Gate | 153 |

| 17 | Oare Church | 160 |

| 18 | Junction of Lyn and Bagworthy Water | 169 |

| 19 | “The Waterslide,” Lancombe | 176 |

| 20 | The Cheesewring, Valley of Rocks | 174 |

| 21 | Ship Inn, Porlock | 185 |

| 22 | Minehead Church | 192 |

| 23 | Dunster Castle Gate, from the Outside | 201 |

| 24 | Square at Southmolton | 208 |

| 25 | Whitechapel Barton | 217 |

| 26 | Tom Faggus’s Forge, Northmolton{xxx} | 224 |

| 27 | Chancel, Northmolton Church | 233 |

| 28 | Ashford Church, near Barnstaple | 240 |

| 29 | Barnstaple Bridge | 249 |

| 30 | Tawstock Church, near Barnstaple | 256 |

| 31 | Towards Morte Point | 265 |

| 32 | Combmartin Church | 272 |

| Sketch Map of Blackmore Country | 288 | |

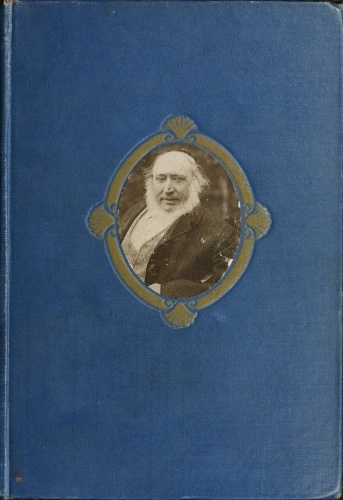

| R. D. Blackmore, from a Photograph by Frederick Jenkins | On the Cover | |

R. D. Blackmore was about ten years of age when his father took up his abode at Culmstock, a village in East Devon, at the foot of the Blackdowns. Notwithstanding an inclination to wander, evidence of which has been adduced in the previous section, the boy must have passed a fair amount of time at home; and wherever Blackmore tarried, he became imbued with the spirit of the place, wrested all its secrets, and acquired an intimate acquaintance with its arts and crafts such as would do credit to a committee of experts. Above all, he had the enviable gift of being able to distil from the rude realities their poetic essence—the prize of loving intelligence.

So far as Culmstock and the neighbourhood are concerned, the fruits of his observation are to be seen in Perlycross, and in a much lesser degree in Tales from the Telling House. The former, by no means so répandu as Lorna Doone, labours under the disadvantage, which is yet not all disadvantage, of fictitious names; consequently but few are aware that Perliton, Perlycross, and{2} Perlycombe are pretty, but deceptive aliases of Uffculme, Culmstock, and Hemyock. These little places—Uffculme, however, claims to be a town—are tapped by a light railway of serpentine construction, which branches from the main line at Tiverton Junction. The trains are appallingly slow, chiefly on account of the curves; and just outside the junction is a stiff gradient, the ascent of which, especially in frosty weather, is problematical. Often there is nothing for it but to drop back to the station and try again, or, as the French have it, se reculer pour mieux sauter.

The level champaign traversed by the caricature of locomotion is remarkable for its fertility, and for many other things redolent, I wot, to the ordinary resident of nothing but the meanest bathos—so deadly in use! It is otherwise with the stranger within the gates, to whom these items of every day unfold themselves as precious boons, creating a joyous sense of novelty and possession. A rapid but happy and accurate description of the vale by Mr Henry, who, I believe, is an Irishman, points the common lesson how much of beauty and wonder lies around us, had we but eyes to see. Impatient for the hills, and doubtless as purblind as my neighbours, I should scarce have lingered amid these pastoral scenes but for his restraining touch, so that I rest doubly indebted to his sage and kindly interpretation.

“I live in Uffculme. Its name might appropriately be Coleraine, for it is indeed a corner of ferns; every lane abounds with them, the hart’s tongue being specially abundant. Uffculme takes its name from the river Culm, and means simply{3} up Culm. It is noted for ‘zider’ and its grammar school. It is a quaint and quiet village. I love its charming thatched cottages, with their niched eaves, each niche the eyebrow of a little window. The inns too are quaint, with their suspended signs, each a symbolic gem. Some in the country around here bear such names as the ‘Merry Harriers,’ the ‘Honest Heart,’ the ‘Rising Sun,’ the ‘Half Moon,’ the ‘Hare and Hounds,’ etc.

“There are four streets in Uffculme, and a triangular ‘square,’ on which a market is held every two months. In the interval the grass has its own sweet will. Everything is still; the smoke rises like incense in the air. Here, as I write, looking into a garden, which even now, in October, has many flowers in bloom, I hear no sounds but the song of the robin enjoying the glory of the morning sun, a chanticleer crowing in the distance, and the clanging anvil of the village blacksmith.

“The narrowness of the lanes around adds greatly to the country’s charms, their high hedgerows being a mass of many kinds of flowers. Thoroughly to enjoy the beauties of the neighbourhood, however, it must be viewed from one of the hills or downs. Embowered in a wealth of greenery, Uffculme sleeps on a slope of the Culm valley. As far as the eye can reach, lies a most beautiful panorama of diversified hill and dale with rounded trees, every field hedged with them. The quiet herds of Devon cattle lie ruminating and adorning the green bosom of the country. The whole scene has a charming cultured aspect, as if some giant landscape-gardener had laid it{4} out. What peacefulness! How beautiful the cattle!

“And then the Devonshire clotted cream! It is delicious, yet simply made. The milk stands on the hob till the cream rises and attains almost the consistency of dough. Every son of Devon, native and adopted, enjoys this luxury to the full.

“The Culm is a little wandering river, abounding in trout. Otters are hunted at Hemyock. Foxes also are found in the neighbourhood, and on one occasion the noble wild red deer approached within five miles of us. Birds of all kinds are plentiful, and flowers abound. Bullfinches are a pest, even among the apple-trees. In my first walk, I saw a kingfisher and a jay. The country exudes vegetation at every pore. The mildness of the climate is evidenced by the fact that on Saturday last (October 17) I saw in bloom the foxglove, poppy, primrose, wild anthernum, and many other flowers. I ate a strawberry grown in the open; watched the bees on the mignonette beds, and saw a wood-pigeon’s nest with young. The{5} climax is reached when I say that a man of great agricultural faith, in the neighbouring parish of Halberton, is attempting a second crop of potatoes.

“The country is well-watered; little rills gush from every quarter. The natives reckon by the flowers—e.g., ‘He went to Canada last hyacinth time.’ The gentlemen’s seats are lovely in the extreme, and are surrounded by trees that would not grow ‘in the cold North’s unhallowed ground.’ Within a stone’s throw of the ‘square,’ and in a former Coleraine gentleman’s seat, grow Wellingtonia pines, the cypress, the breadfruit tree, the Spanish chestnut, and other exotic beauties. A house in the village has its walls adorned with passion-flowers, now in bloom.

“We are out of the tourist’s track here. The motor rarely invades our quiet life; indeed, the roads are not suited for motoring, as the streams cross them in several places, and a foot-bridge affords the only means of dry transit for the passengers.

“I need not dwell on the Devon dialect. It is familiar to every reader of Lorna Doone. Suffice it to say that it slides out with the maximum ease, and in defiance of every rule of grammar. Have I exhausted Devonian joys? Nay, I could mention the melodious church-bells, the beauty of the children, and many other matters; but I have fulfilled my intention, if I have conveyed the quaintness, the peace, and the good living of this part of rural Devon—a land ‘where the plain old men have rosy faces, and the simple maidens quiet eyes.’”

Hence it appears that all the glory did not{6} depart from Devon with fustian coats and brass buttons.

Mr Henry, it will be observed, speaks admiringly, as well he may, of the extreme loveliness of the country-seats. So far as the Culm valley is concerned, none will compare with Bradfield, the immemorial home of the Walrond family. Readers of Perlycross will recollect the brave veteran, Sir Thomas Waldron, and the wrong done to his honoured remains; and they may perchance note the different modes of spelling the name. Blackmore follows the local pronunciation, and the precedent of good old John Waldron, founder of an almshouse at Tiverton, of whom Harding remarks, “By his arms I judge his ancestors were branched from the ancient family at Bradfield, near Cullompton, where they were located in Henry II.’s time.”

According to Hutchins, the family of Walrond is descended from Walran Venator, to whom William I. gave eight manors in Dorsetshire. The name is indubitably of French origin, and apparently represents the old Latin patronymic Valerian.

To turn from names to things, an authentic note attests that, in 1332, John Walrond had a licence for an oratory. Presumably this was the ancient chapel of which Lysons speaks, and which probably stood on a site still known as the Chapel Yard, on the north side of the mansion. The present house does not go back to so remote a time. On the north wall are the words, “Vivat E. Rex”; and elsewhere may be seen the dates 1592 and 1604. It is considered that the house was rebuilt in sections{7} and at intervals, during the short reign of Edward VI., and towards the close of that of Elizabeth.

Apart from inevitable decay, the mansion remained practically unaltered until about the middle of the last century, when it was thoroughly restored by the late Sir John Walrond, who planted the fine avenues of oak and cedar. Sir John did nothing to destroy or impair the character of the place, and the changes he introduced were extremely judicious, as indeed was to be expected from a gentleman of his refined taste. Son of Mr Benjamin Bowden Dickinson, of Tiverton, who assumed his wife’s name on his marriage with the heiress of the last of the Bradfield line, he came into possession in 1845. At that time the house consisted of north and south gabled wings, united by the old hall, and in ruinous repair, roughcast and whitewashed. Low offices disfigured the west side, and the south wall was propped with timber. A farmyard and other buildings occupied the site of the present entrance.

Such was Bradfield. To-day it is one of the most charming and beautiful homes in the West. The most ancient and characteristic portion is the noble hall, which is forty-four feet long by twenty-one feet wide, and glories in a magnificent hammer-beam roof, adorned with carved angels, a rich cornice, carved pendants, and old oak plenishings. The napkin panelling is in excellent preservation, and the fine woodwork, once covered with many coats of paint, is now fully exposed. Quaint and delightful features of the apartment are the open fireplace, the minstrel gallery, and{8} a dog-gate which kept canine favourites below stairs. Just off the minstrel gallery is the state bedroom, containing a good sketch of the hall and gallery in days of yore, which gives one to see how rich the colouring must have been. Below the gallery is the “buttery hatch,” and beyond the “buttery hatch,” the old kitchen, now the library.

The drawing-room, communicating by a doorway with the hall dais, and one of the last rooms to be restored, has, in lieu of paint and whitewash, walls of moulded oakwork, a richly panelled and decorated ceiling, and a Jacobean mantelpiece. On the screen over the doorway are coloured figures of Adam and Eve; and among other curios are an embroidered silk sachet, in which is enclosed a love letter from Mr Walrond to Anne Courtenay, written on parchment, and dated October 27, 1659, and a prayer-book belonging to the old family chapel. Many other charming sights the interior affords, such as the oak panelling of the dining-room, its old chimney-piece, its pictures. And outside is a rare plesaunce, with clipped box-trees, and great clipped yews, and a lake, and an old bowling-green. Truly, an ideal country-house!

Another branch of the Walronds lived at Dulford House, which is also in the neighbourhood. Neither of these mansions can be exactly identified with the “Walderscourt” of the romance, which is represented as standing on a spot roughly indicated by Pitt Farm, in the parish of Culmstock, and not far from the village.{9}

There are coloured effigies of the Cavalier period in Uffculme Church, which, by the way, has a magnificent screen, sixty-seven feet in length, probably the longest in the county. Nothing authentic is known about the effigies, but many have the impression that they represent members of the Walrond family. It is possible, however, that the originals of the busts were Holways, of Leigh, since the oldest monuments in the church were erected in memory of their dead. Leigh Court is the name of the present mansion, but Goodleigh, as is shown by old deeds, was the description of the more ancient manorial residence, which did not stand on the same site. And thereby hangs a tale.

The late Mr William Wood, father of my kind friend, Mr William Taylor Wood, of Gaddon, owned and lived at Leigh, and, being of an economical turn of mind, he thought he would clear away the few mouldering ruins of the old manor house, which only cumbered the ground, and thus extend the area of one of his fields. Men were engaged for the work, and had already proceeded some way with their task, when suddenly a workman threw down his tools and vanished clean out of the neighbourhood. For years there were no tidings of him. Eventually he returned, but never vouchsafed the least explanation of his extraordinary conduct. The people of the place, by whom a new coat or pair of boots would have been scrutinised with suspicion, all decided that he had found a “pot of treasure,” whilst Mr Wood, who, with all his good qualities, was somewhat touched with{10} superstition, commanded the operation to be stayed.

Wandering about in this pleasant and hospitable region one gathers many a charming idyll of bygone times. Such, for instance, is the story of the young lady who arrived at Gaddon on a short visit and remained fourteen years. It seems that the old housekeeper was sitting on a box before the kitchen fire, preparing lamb’s tails for a pie (by dipping them in water brought to a certain temperature, in order to facilitate the removal of the wool), when all at once she fell back—dead.

The master of the house, Mr Richard Hurley, had relations living in another part of the parish, and, on learning the sad news, sent off to them for assistance. There were a lot of girls in the family, and they and their mother were sitting cosily round the hearth, when there came a knock at the door. In those days a knock at the door was enough to throw any country household into a ferment of excitement, which, in this instance, was not diminished when the messenger announced his errand.

“Please, master wants one of the young ladies to come over, because old Betty has dropped dead.”

Upon this a family council was held, and the following morning Mary Garnsey, a pretty, rosy-cheeked maiden of fourteen, mounted her horse, and with her impedimenta slung from the saddle-bow—there were no Gladstone bags in those days—rode over to Gaddon to aid her uncle in his difficulty. Pleased with her agreeable company, and more than satisfied with her{11} efficient services, Mr Hurley became loth to part with her, and, in fact, coaxed her to remain till she was twenty-eight, when she left to be married. Old inhabitants may, perchance, remember Mrs Pocock, of Rock House, Halberton. She was the lady.{12}

At Culmstock one finds oneself in a village of considerable beauty, to which the little stream with its border of aspens, and the fine old church on the knoll, are the principal contributors. Hence also are avenues leading up to the witching prospects of the Blackdown Hills, Culmstock Beacon, in particular, being a favourite spot for picnics. So far so good. But there are drawbacks. When one sets foot in any of these West-country villages, one is apt to be affected with a sense of half-melancholy. Stillness is, of course, to be expected; stillness, indeed, is one of the great charms of the country, and a happy contrast to the bustle and confusion of the town. But stillness, to be entirely welcome, must not be emblematic of decay.

Not that Culmstock is altogether in that parlous state; there are many signs of enterprise and activity. Witness the erection of tidy brick houses in lieu of crumbling, thatched cottages, so sweet to look upon, but not specially comfortable to live in. That, however, is not all. One reason why cob-cottages are no longer built is that this is, to a great extent, a lost art. A{13} friend of mine, who is not an architect, but is a pretty shrewd observer of things in general, has explained to me what he believes to have been the process. The angle of a roof is formed by “half-couples,” and in the case of cob-cottages my friend thinks that underneath the “half-couples,” at tolerably close intervals, were set upright posts. The whole of this scaffolding constituted the permanent frame of the building, and as soon as it was completed by the addition of horizontal timbers, the roof was thatched. Then the “cob,” which resembled mortar with a thickening of hair, etc., was erected in sections about two or three feet high, so as to envelop the posts, and each section was allowed to dry before the mud-wall was carried higher. This was a necessity, but, as the result, the work was slow and tedious, and nowadays would be more expensive than building with brick or stone.

Be that as it may, the fact cannot be gainsaid that at Culmstock, and not at Culmstock alone, the advent of the railway and the newspaper, and the general opening-up of communications with the outer world, have made a difference. So great indeed is the revolution that one is constrained to admit that here, though one is in Blackmore’s village, one is yet not properly in the village that Blackmore knew. True, there is the old church tower, the stone-screen (Mr Penniloe’s glorious “find”), and even the old yew-tree springing from the ledge below the battlements. The bridge, too, is much the same, save for a tasteless, if necessary, addition. The vicarage also stands, its back turned discourteously on the wayfarer; and I certify that it is the{14} identical structure which sheltered Blackmore as a boy, though his father was never the vicar, only curate-in-charge.

All this may be granted, but the man of feeling still mourns the loss—for loss he knows there has been—of local life and colour. As Pericles observed many centuries ago, a city is not an affair of walls only; and were the material village of seventy years since more intact than it is, the change in its social conditions would be none the less. In the old days, Culmstock was no mere geographical expression; it was a distinct entity, a separate organism, fully equipped for its own needs, and harbouring, as Perlycross testifies, a spirit of pride and independence. The warlike rivalry between rustic communities like Culmstock and Hemyock, though almost universal, may strike one as a trifle ridiculous; but if a “bold peasantry” could be retained at the cost of occasional horseplay, it was worth the price. What can be conceived more admirable than a strong and healthy, and in its heart of hearts, contented population, grouped into parishes, living on the land?

Old inhabitants with a tincture of education do not, I admit, see things quite in this light. They are all for modern improvements, and refer with bitter cynicism to the hardships experienced, and the low wages earned, in days of yore, for which they have usually not a particle of regret. But such people are not always right, and now and then one meets with a pleasing appreciation of the olden times. Not long ago there might have been seen, tottering about the village, a Culmstock veteran, who had been wont to ply{15} the flail. The staccato of the “broken stick,” however, had yielded place to the drone of the threshing-machine, which was not so agreeable. Suddenly he paused and cocked his ear—what was that? From the interior of a yeoman’s barn came a familiar sound. Bang! bang! bang! bang! ’Twas the flail; and the wrinkled old face beamed with delight as Hodge exclaimed, rubbing his hands, “Blest if Culmstock be dead yet!”

(Which demonstrates, by the way, the truth of Blackmore’s dictum—“There are very few noises that cannot find some ear to which they are congenial.”)

The task will not be easy, but let us endeavour to form some idea of Culmstock parish as it appeared to the veteran in his long-past youth. Most likely he was a parish apprentice, bound out at one of the triennial meetings of the local magistrates held for that purpose in a cottage near the church. Farmers generally appreciated the privilege of having poor boys assigned to them as apprentices, especially as they were not compelled to take any particular boy; but this was not invariably so, and sometimes they would pay a tailor or a shoemaker (say) five pounds to relieve them of the distasteful duty. We will suppose, however, that the farmer is willing to stand in loco parentis to the trembling little mortal—not more than ten years old, perhaps—and accordingly signs his name and sets his seal to the indenture.

Have you ever seen such a document? A more portentous agreement than “these presents,” seeing that the business itself was so simple, was{16} surely never devised by misplaced ingenuity. No less than six officials—to say nothing of the master—were parties to the deed, viz., two justices, two overseers, and two churchwardens; and their names were entered in the blank spaces of the form reserved for them. I will not inflict the whole of the rigmarole on the reader, but here is the cream of it:—

The instrument conveys that the churchwardens and overseers between them do put and place M. or N., a poor child of the parish, apprentice to John Doe or Richard Roe, yeoman, with him to dwell and serve until the said apprentice shall accomplish his full age of twenty-one years, according to the statute made and provided, during all which term the said apprentice the said master faithfully shall serve in all lawful business according to his power, wit, and ability; and honestly, orderly, and obediently, in all things demean and behave himself towards him. On the contrary part, the said master the said apprentice in husbandry work shall and will teach and instruct, and cause to be taught and instructed, in the best way and manner he can, during the said term; and shall and will, during all the term aforesaid, find, provide, and allow unto the said apprentice, meet, competent, and sufficient meat, drink, and apparel, lodging, washing, and all other things necessary and fit for an apprentice.

With such tautological, though no doubt impressive verbiage, was the poor child of the parish launched on the sea of life. Conducted to the farmhouse, he was speedily initiated into the habits of the occupants—rough people, but{17}

sometimes not unkindly. At dinner the “missus” usually presided, with the master on one side and the family on the other, and the servants in the lowest places. For the broth, which was an important item in the menu, wooden spoons were in favour, although an old fellow called Tinker Toogood came round from time to time and cast the lead that had been saved for him into a pewter spoon. In some farmhouses no real plates of any description were employed; instead of that, the table was carved throughout its length into a series of mock plates, and on these spaces the meat was placed. Every day the table was washed with hot water, and covers were set over the imitation plates to keep the dust off. It was the custom to serve the pudding and treacle first, so as to lessen the appetite and effect a saving in the meat—salt pork as a rule. Wheaten bread was unknown. It was always barley bread, nearly black, and cut up into chunks. These were placed in a wooden bowl.

In addition to Tinker Toogood, itinerant tailors, shoemakers, and harness-makers were regular visitors at the farmhouses, where they performed their tasks and were allowed free commons. Harness-menders were the best paid; they received two shillings a day. Commons, although free, were not always abundant; and a Mr Snip once complained, in the bitterness of his heart, that he had tea and fried potatoes for breakfast, fried potatoes and tea for dinner, and tea and fried potatoes for supper. With the blacksmith the farmer made a contract, agreeing to pay so much for the shoeing of horses, repairing of ploughshares, etc., and, as in the ploughing{18} season coulter and share required to be sharpened every night, the smithy on the hill was generally crowded.

At least fifty oxen were kept on the different farms for ploughing; and, in the opinion of some, these animals were better than horses. Young bullocks were stationed between the wheelers and the front oxen, but soon became used to the work, and placed themselves in the furrow as a matter of course. All the time a boy, armed with a goad, used to sing to them:

Wishing to encourage his team, the boy would say, not “Woog up!” as in the case of horses, but “Ur up!” Other cries were, “Broad, hither!” “Tender, hither!” and the like.

In reaping, when the time came for sharpening hooks, the foreman sang out:

whereupon the catchpoll asked,

To this the foreman replied,

and the catchpoll rejoined,

As the finale, all drank out of a horn cup.

In the first verse of an old Devonshire harvest-home song, convivial spirits were thus addressed:

In successive verses they were adjured to drink it out of the nipperkin, the quarter-pint, the half-pint, the quart, the pottle, the gallon, the half-anker, the anker, the half-hogshead, the hogshead, the pipe, the well, the river, and, finally, the ocean.

In the direction of Nicolashayne were three large barns (since converted into six cottages) in front of which was a broad area of road for the wagons to halt upon. The “Church of Exeter” has proprietary rights in the parish; and a proctor came up from Thorverton to receive tithes on behalf of the Dean and Chapter. Only the small tithes went to the vicar.

The grandson of Clerk Channing of Perlycross, a man over seventy, tells me that he can remember the introduction of the first wagon and the first spring-cart at Culmstock, pack-horses being used always before. This circumstance can be accounted for in two ways, partly from the intense conservation of rural Devonshire—at last, perhaps, broken up—and partly from the pose of the village, with its face towards the valley of the Culm and its back against the hills. In a rough country like the Blackdowns the pack-horse{20} would be certain to tarry longer than in more cultivated regions, and a large portion of the parish of Culmstock, though, according to Blackmore, it comprises some of the best land in East Devon, consists of hills and commons.

The wildest tract of all is Maidendown—a dreary waste compact of bog and scrub in the vicinity of the late Archbishop Temple’s paternal home, Axon, and reaching out to the main road between Wellington and Exeter. Its situation does not agree with that of the Black Marsh, or Forbidden Land, of Perlycross, which is described as lying a long way back among the Blackdown Hills, and “nobody knows in what parish”; otherwise one might have guessed that Maidendown was the prototype of that barren stretch with a curse upon it.

In the West country pack-horses are equally associated with moors and lanes. Nowadays a Devonshire lane—love is compared to a Devonshire lane—is regarded as essentially beautiful, with its beds of wild flowers and tracery of briars; but Vancouver’s impartial testimony compels one to think that in former days this domain of the pack-horse was not so attractive. He says:

“The height of the hedge-banks, often covered with a rank growth of coppice-wood, uniting and interlocking with each other overhead, completes the idea of exploring a labyrinth rather than that of passing through a much-frequented country. This first impression, however, will be at once removed on the traveller’s meeting with, or being overtaken by, a gang of pack-horses. The rapidity with which these animals descend the hills, when not loaded, and the utter impossibility{21} of passing loaded ones, require that the utmost caution should be used in keeping out of the way of the one, and exertion in keeping ahead of the other. A cross-way in the road or gateway is eagerly looked for as a retiring spot to the traveller, until the pursuing squadron, or heavily-loaded brigade, may have passed by.... As there are but few wheel-carriages to pass along them, the channel for the water and the path for the pack-horse are equally in the middle of the way, which is altogether occupied by an assemblage of such large and loose stones only as the force of the descending torrents have not been able to sweep away or remove.”

This was certainly not pleasant, although in most other respects Culmstock was then a more interesting place than now. I do not assert that it was more moral. About seventy years ago, a native of the village, one Tom Musgrove, was hanged for sheep-stealing, being the last man, it is said, to experience that fate in the county of Devon. We stand aghast at the barbarity of our forefathers; but if ever the penalty could be made to fit the crime, then it must be owned, Tom deserved the rope. He was a notorious thief, whose depredations were the common talk of the village, and, to make matters worse, his evil deeds were performed under the cloak of religion. Once a couple of ducks were missed, and, whilst every cottage was being searched in the hope of regaining the stolen property, Tom, secure in his pretensions to piety, stood complacently in his doorway, and the party of inquisitors passed on. Just inside were the ducks, feeding out of his platter.{22}

One night a huckster’s shop, kept by Betsy Collins, at Millmoor, was feloniously entered and robbed. Next morning, Tom, apprised of the event, ran off in his night-cap to condole with the poor woman in her misfortune, and succeeded so well as to be invited to share her morning repast. “There!” said he, “her’ve a-gied the old rogue a good breakfast.”

As a professor of religion Tom contracted a warm friendship with a baker named Potter, who was an ardent Methodist. Neither friendship nor religion, however, prevented Mr Musgrove from enriching himself at his neighbour’s expense. Profiting by an opportunity when Potter was at chapel, and closely engaged with pious exercises, Tom and his one-armed daughter broke into the bakehouse and carried off Potter’s bacon, the lady burglar aiding herself with her teeth.

These breaches of morality appear to have been condoned—at any rate, they did not land the culprit in any serious trouble. But at last Tom went a step too far. Down in the hams, or water-meadows, between Culmstock and Uffculme, he seized a large ram, which he slew, brought home, and buried in his garden. The crime was traced to his door, professions and protestations proved unavailing, and Musgrove, tried and convicted at the following Assizes, was publicly executed at Exeter Gaol. It will be remembered that Mrs Tremlett’s “dree buys was hanged, back in the time of Jarge the Third, to Exeter Jail for ship-staling” (Perlycross, chapter xxvi.)

Sheep-stealing was not the only excitement.{23} In Blackmore’s youth—and Perlycross is built on the circumstance—smuggling was carried on with spirit (in both senses) over the Blackdowns, and queer stories are told of fortunes made by “fair trade,” in the conduct of which a mysterious tower, out on the hills, is said to have played an important part. An octogenarian of my acquaintance admits that, as a boy, he shared in these illegal adventures, which did not receive that amount of social reprobation they may have deserved. He does not deny that he slept in a friend’s house over kegs of brandy which he knew to be contraband, nor does he disguise the fact that he was not a mere sleeping partner. He acknowledges being sent with a keg to meet a fellow-conspirator, who for the sake of appearances toiled in the local woollen factory, but out of business hours drove a lucrative trade with the farmers in the forbidden thing. Worst of all, on one occasion, when an excise officer was reported to be in the village, a cask was hastily transferred to his shoulders, which, as being youthful, were less likely to attract suspicion, and he actually walked past the Government man—barrel and brandy and all! Horses laden with the foreign stuff came up from Seaton. They had no halters, and were guided, says my friend, by the scent, the journey being naturally performed in the dark.

Smuggling, however, took various forms. Men from Upottery, Clayhidon, and elsewhere would halt a cart on the outskirts of the village, and go round with brandy or gin in bladders, which they carried in the pockets of their greatcoats.{24} One Giles, of Clayhidon, had a donkey and cart with a keg of brandy concealed in a furnace turned upside down. A Culmstock man called Townsend, landlord of the “Three Tuns,” is said to have been ruined by a smuggler, who sold him a gallon of brandy and demanded accommodation, as usual. The publican refused it on the ground that the house was already full, upon which the smuggler, stung with resentment, informed the police, and Townsend was fined £270.

By these instances, something, it may be hoped, has been done towards reconstructing the Culmstock in which Blackmore grew up, and which helped to make him what he was—essentially the prophet of the village and rural life. And here I must rectify a possible misunderstanding, Because stress has been laid on changes in the social conditions of the parish, as being of deeper significance, it must not be inferred that there have been no alterations, or none of any importance, in the face of things. The contrary is the truth, and, on a reckoning, one is tempted to say with Betty Muxworthy, “arl gone into churchyard.”

Culmstock churchyard has indeed swallowed up, not only successive generations of the inhabitants, but a goodly share of the village itself. This is the more regrettable, as the portions absorbed are precisely those which, being redolent of the olden times, one would have liked preserved. The shambles, a covered enclosure for butchers attending the weekly market, has gone the way of all flesh. So also has the stockhouse, which was, rather inconsequently, an open{25}

space where the stocks were kept. Hard by stood an inn, called the “Red Lion,” which either failed to draw sufficient custom, or having a handsome porch, was deemed too good for a common inn and metamorphosed into a school. A Mr Kelso arriving with wife and daughters three, accomplished the transformation, and, according to local tradition, he had the honour of instilling the rudiments of learning into the late Archbishop Temple. This, not the National School which was built in the Rev. John Blackmore’s time and mainly through his exertions, was the academy of Sergeant Jakes, the position of which is plainly defined in chapter xxxvi.[4]

There was formerly a considerable trade at Culmstock in combing and spinning wool. Thirty hands are now employed at the mill (no longer an independent concern, but a branch establishment of Messrs Fox Brothers, of Wellington); once four hundred were busy at home. Soap also throve. It was made on the right shoulder of the hill, and the manufacturer, a Mr Hellings, kept seven pack-horses to transport it to Exeter. Culmstock soap had a great vogue in the cathedral city, and it was a common observation that no one had a chance till Hellings was “sold out.” In the neighbouring village of Clayhidon was a silk factory, employing, I believe, a hundred hands, and run by a gentleman of the Methodist persuasion, whose house and chapel adjoined—the three together producing a combination of the earthly{26} and the heavenly which impressed my informant as the acme of convenience. A similar factory in Red Lion Court, Culmstock, met with speedy failure.

These industries are now extinct, and one is somewhat at a loss in seeking for “live” interests, although it is impossible to forget that Hemyock is a famous mart for pigs. The whole district is piggy, and the sleek black animal with the curly tail is as highly respected, in life and in death, as his congener in that porcine paradise, Erin. I was talking to an old fellow at Culmstock, it may have been two years ago, and the conversation turned on swine. Rather to my surprise, he spoke of a certain female of the breed as having been “brought up in house,” and with full appreciation of the fun, volunteered a local saw to the effect that “when a sow has had three litters, she is artful enough to open a door.”

Culmstock, it is not too much to say, is redolent of Waterloo. The beacon was often aflame during the Napoleonic wars, and, upon their conclusion, the famous Wellington Monument was erected at no great distance, in honour of the Iron Duke, who took his title from Wellington in Somerset, the Pumpington of Perlycross.

Thanks to the industry of Mr William Doble, who is, I believe, a descendant of more than one of the local heroes, it is possible to restore the atmosphere which brought about the creation, years afterwards, of Sir Thomas Waldron and Sergeant Jakes. When R. D. Blackmore was a boy, many were still living who could remember the incessant din of the joy-bells on the{27} announcement of the victory—a din continued for several days; and the scene in the Fore-street, the “grateful celebration,” when high and low, indiscriminately, turned out to share the feast. Naturally, however, the festivities were dashed with some amount of sorrow and anxiety, as it was not yet known what had been the fortunes of the gallant fellows who had gone forth to fight England’s battle. Two stanzas of a song, which an old lady of Culmstock sang as a girl, reflect with simple pathos the dreadful suspense of relations and friends.

A rough list of the Culmstock warriors comprises the following names:—

| Major Octavius Temple, (father of the late Archbishop). Dr Ayshford. Sergt. J. Mapledorham. Sergt. W. Doble. Sergt. Gregory. William Berry. William Sheers. Robert Wood. Thomas Scadding. |

Richard Fry. Abram Lake. William Gillard. John Jordan. Thomas Andrews. John Nethercott. John Tapscott. “Urchard” Penny. James Mapledorham, jun. Betty Milton. Betsy Mapledorham. |

Mapledorham, was too much of a mouthful for Culmstock people, so they consulted their own{28} convenience by calling the couple Maldrom. The excellent sergeant already possessed a long record of service when summoned to the final test of Waterloo, and in several campaigns he had been accompanied by his faithful Betsy. Equally adventurous, Betty Milton was full of reminiscences of her hard life in the Peninsula.

William Berry, too, was fond of story-telling. He related, with humorous glee, that he had once captured a mule with a sack of doubloons. Unfortunately a wine-shop proved seductive, and whilst he was regaling himself therein, an artful Spaniard made off with the booty. Robert, better known as “Robin,” Wood was literary, and published a penny history of his exploits, of which, alas! not a single copy is known to exist. William Sheers, figuratively speaking, turned his spear into a ploughshare, as he took to shopkeeping and became a pronounced Methodist and zealous supporter of the Smallbrook Chapel. I can just remember this bearded veteran, who in his last days was a victim to a severe form of cardiac asthma. Tapscott and “Urchard” Penny were both ex-marines. The former had been present at the Battle of Trafalgar and rejoiced in the nicknames “John Glory” and “Blue my Shirt.” As for Penny, he was sometimes called “Tenpenny Dick,” the reason being that he would never accept more than tenpence as his day’s wage. When his turn came to be buried, the bystanders observed that water had found its way into his last resting-place, so that, it was said, he remained constant to the element in which he had so long served.{29}

The foremost of the group of veterans is claimed to have been Doble, who, after starting in life as a parish apprentice, at the age of seven, took part in seven pitched battles in the Peninsula, and ended his military career at Waterloo. He retired from the service on a pension of twelve shillings a week, and was the proud owner of two medals and nine clasps. As a civilian, he was the trusted foreman of the silk factory in Red Lion Court, which, despite his probity, soon came to grief; and at his funeral his old comrades assembled, some from considerable distances, to pay a last tribute to the brave soldier who had rallied the waverers at Waterloo.

Dr Ayshford used to say that he had three sources of income—his pension, his practice, and his property. On the strength of these resources he kept a pack of hounds. He was naturally very intimate with the Temples, and I have been told by a descendant that it was thanks to his generosity that the late Archbishop Temple was enabled to proceed to Oxford. Mutatis mutandis, it seems not improbable that by Frank Gilham, Blackmore may have intended his schoolmate. Think of it. Major Temple was not only an officer of the army, but a practical farmer, and the late primate could plough and thresh with the best. Gilham is described as no clodhopper: he “had been at a Latin school, founded by a great high priest of the Muses in the woollen line,” i.e., Blundell. Again, his farm adjoins the main turnpike road from London to Devonport, at the north-west end of the parish; and where is Axon, the Temples’ old place? The name “White Post” is perhaps adapted from “Whitehall,{30}” a fine old-fashioned farmhouse between Culmstock and Hemyock.

Like Parson Penniloe (see Perlycross, chapter xxxiii.), Parson Blackmore kept pupils—a fact to which allusion is made in Tales from the Telling House. The Bude Light was the Rev. Goldsworthy Gurney. The existence of a wayside cross, from which and the fictitious description of the Culm was formed the name of both village and romance, is attributed to the public spirit of one Baker, who lived in the Commonwealth time, and usurped the manor; but whether it was anything more than a tradition in Blackmore’s youth, is perhaps doubtful. Priestwell is Prescott, Hagdon Hill Hackpen, and Susscott Northcott. Crang’s forge, had any such institution existed, would have been at Craddock.

The reader, however, may rest assured that Blackmore did not select these fanciful appellations without excellent reason. He desired for himself a large freedom, which, as we have seen, he used in transporting mansions, and other feats of imagination. One more illustration of this spiritual liberty may be cited. By the Foxes he evidently means the Wellington family. The dialogue between Mrs Fox of Foxden and Parson Penniloe, in chapter xliv., is sufficient to settle that. The name Foxdown, too, is evidently based on that of Mr Elworthy’s residence, Foxdene. Yet in chapter xii. Foxden is stated to be thirty miles from Perlycross by the nearest roads. On the other hand, Pumpington, as Wellington is called in Perlycross, is just where it should be (chapter xxiv.).

Turning to another matter, Blackmore has{31} idealised the bells, inasmuch as he states that on the front of one of them—the passing bell—was engraven,

“Time is over for one more”;

and on the back,

“Soon shall thy own life be o’er.”

The Culmstock set is an interesting collection of bells, but not one of them is adorned with mottoes such as those. One bears the inscription “Ave Maria Gracia Plena,” and this was cast by Roger Semson, a West-country founder of repute, who was dwelling at Ash Priors, in Somerset, in 1549, and who stamped his initials on the bell. Another of his bells, at Luppitt, is at once more and less explicit on this point, since the inscription runs “nosmes regoremib.” To make sense, this must be read backwards. Two modern bells, placed in the Culmstock belfry in 1852 and 1853 respectively, awaken proud or painful memories. The former was cast in memory of the Duke of Wellington, the cost being defrayed by subscription, while the latter was “the free gift of James Collier, of Furzehayes, and John Collier, of Bowhayes.” John Collier, who was killed by lightning at Bowhayes, was the sporting yeoman with the otter hounds, to whom Blackmore alludes. The old house, by the way, was reputed to be haunted, and for years no one would live in it.

Blackmore’s description of the vicarage is literally correct, save that he calls it “the rectory.” A long and rambling house it certainly is, and the dark, narrow passage, like{32} a tunnel, beneath the first-floor rooms, is a feature explained by the higher level of the front of the house “facing southwards upon a grass-plot and a flower-garden, and as pretty as the back was ugly” (Perlycross, chapter vi.).{33}

Although Culmstock and its immediate vicinity is somewhat deficient in what I have ventured to term “live” interests, it must not be inferred that the neighbourhood has nothing further to show; and among the objects that deserve to be scheduled as worthy of attention are the colossal stone quarries at Westleigh, which, whether viewed from the parallel line of railway or from the opposite height on which stands Burlescombe Church, present an imposing spectacle. For ages they have been the principal source of supply for the district, huge quantities of limestone having been drawn from them for building and agricultural purposes. Much of it was formerly conveyed to Tiverton in barges towed along the canal, the terminus of which was fitted with a number of kilns. These, in my boyhood, I have often seen burning, and regarded with no little awe, owing to stories that were circulated of persons having gone to sleep on the margin, fallen over into the glowing furnace, and been consumed to powder. They are now a picturesque ruin. Older men can recall a yet earlier time when pack-horses came to Westleigh from Tiverton and fetched lime in{34} boxes. In front was a man riding a pony, and the horses followed without compulsion.

The string of pack-horses mentioned in chapter ii. of Lorna Doone, as arriving from Sampford Peverell, may be a reminiscence of this traffic.

Not far from the entrance to the Whiteball tunnel, and in the neighbourhood of the great limestone quarries, in a pleasant meadow facing south, are the ruins of Canonsleigh Abbey. To a connoisseur like Mr F. T. Elworthy, these remains tell their own story, and it is thanks to that gentleman’s investigations and researches that we are able to furnish a concise account of the ancient nunnery. A gateway yet stands, though unhappily disfigured by the desecrating touch of modern man, and near it is a doorway of red sandstone leading to a staircase doubtless belonging to the porter. In the upper storey, square-headed windows—wrought, we may believe, in the fourteenth century—command the approach in either direction; other features are less easy to determine, since there are modern walls and a modern roof, which have been added for the purpose of turning the place into a shed, and incidentally obscure the older architecture.

Without spending more time here, let us pass to a quadrangular building of massive construction, and supported at two of its angles by solid buttresses. Situated at the east end of the convent, this is considered to have been a great flanking tower communicating, by means of strong walls (fragments of which yet remain), at the angles opposite to the buttresses, with the residential portions. The outer or enclosing wall of the abbey precincts started from the middle of{35} the east wall of the tower; and under the middle of the tower flowed a stream, which issued through a covered exit and continued its course outside the boundary wall, washing its base. The reason for this somewhat peculiar arrangement was a good one—the supply of the abbey stews; but its effect was to throw the tower out of line with the walls and the other buildings.

Inside the walls were two spaces, irregular in shape, and clearly open courtyards, from one of which a doorway led into the tower. The chief entrances seem to have been from the two or more floors of the domestic quarters. On the side next the convent, approached by a massive doorway, is a narrow chamber, conjectured to have been a “guard-room” for refractory nuns. Over this, but running the entire length of the building, and not, like the lower floor, divided by wall and doorway, is a floor supported by beams.

This tower, with the plaster clinging to its walls—how can we explain its survival when the rest of the once stately abbey has vanished? Probably the reason lies partly in its strength and partly in its plainness and the absence of wrought stone tempting human greed. As has been well said, “it still stands a picturesque and sturdy relic of an age of good lime-burners and honest masons.” The wrought stone of one or two windows in the adjacent walls has been removed, but what indications remain suggest the close of the twelfth century as that virtuous age.

The Priory of Leigh was founded, Dr Oliver says, in the latter half of the twelfth century, and Prebendary Hingeston-Randolph opines, before{36} 1173. In its infant days, it seems to have been a dependency of Plympton Priory—at any rate, in the estimation of the latter monastery, whose head claimed the right to appoint the superior of Leigh. This demand was resisted, and in 1219 the then Bishop of Exeter composed the quarrel by deciding, as a sort of compromise, that the Prior of Plympton might, if he chose, be present at the election.

In the second half of the thirteenth century there were scandals at Leigh calling for episcopal cognisance and visitation; and these disorders proving incurable, Bishop Quivil went the length of ejecting the prior and canons, and transferring the monastery, with all its belongings, to a body of canonesses of the same rule of St Augustine. And Matilda de Tablere became the first Prioress of Leigh. Next year, Matilda de Clare, Countess of Gloucester and Hertford, presented the convent with the (then) great sum of six hundred marks, in acknowledgment of which Bishop Quivil erected the priory into an abbey, and appointed the countess its abbess.

The patron saints, under the old régime, had been the Blessed Virgin Mary and St John the Evangelist. St Ethelreda the Virgin was now added, and practically displaced St Mary, whose name is omitted in later descriptions. Another change affected the name of the place, “Mynchen” being often substituted for “Canon”-leigh. “Mynchen” is the old English feminine of “monk,” and therefore equivalent to the modern “nun.”

The indignant canons did not take their extrusion meekly. They appealed to the archbishop,{37} and, through him, to the king, against the usurpation of the “little women,” but they appealed in vain.

Sad to relate, the ladies do not appear to have behaved much better than their predecessors. In 1314 Bishop Stapledon, Quivil’s successor, addressed a letter to his dear daughters in Christ, telling them in Norman-French that he had heard of many deshonestetes, and calling particular attention to the fact that there was an entrance into the cellar where a man brewed le braes, and another under the new chamber of the abbess! These he ordered to be closed by a stone wall before the following Easter.

The abbey was suppressed in February 1538, and at the end of the same year the king granted a lease of the site and precincts, with the tithes of sheaf and the rectories of Oakford and Burlescombe, to Thomas de Soulemont, of London. The inmates, however, were not turned adrift on the charity of the cold world. Each received a pension, and this, in the case of the abbess, Elisabeth Fowell, was considerable. There were eighteen sisters in all, and some of them, as is proved by their names—Fortescue, Coplestone, Sydenham, Carew, Pomeroy—were of good West-country extraction.

In course of time the property passed through various hands, and out of the spoils of the abbey a certain owner appears to have built a mansion, which was demolished in 1821.

From Canonsleigh let us away to Dunkeswell, about equidistant from Culmstock, but in another direction. On the journey we may look again at the grassy plateau which has Culmstock Beacon{38} at one extremity and the Wellington Monument, set up in honour of the Iron Duke and his victories, at the other. This stretch of moorland is yet in its primitive state, and the Dean and Chapter of Exeter, whose property it is, exercise zealous supervision over it. Time was when the villagers depastured their donkeys thereon, but of late years the privilege seems to have been withdrawn.