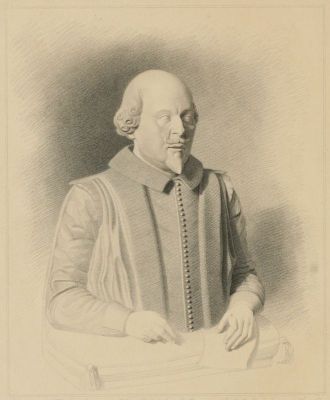

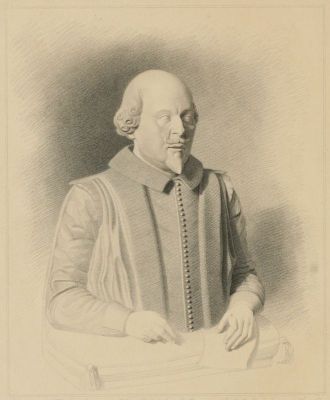

SHAKSPEARE.

Engraved by W. T. Fry after a Cast made by Mr. George Bullock from

the Monumental Bust at Stratford-upon-Avon.

Transcriber's Notes: In footnotes and attributions, commas and periods seem to be used interchangeably. They remain as printed. Variations in spelling, hyphenation, and accents remain as in the original unless noted. A complete list of corrections as well as other notes follows the text.

SHAKSPEARE.

Engraved by W. T. Fry after a Cast made by Mr. George Bullock from

the Monumental Bust at Stratford-upon-Avon.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR T. CADELL AND W. DAVIES, IN THE STRAND.

1817.

Printed by A. Strahan,

Printers-Street, London.

Though two centuries have now elapsed, since the death of Shakspeare, no attempt has hitherto been made to render him the medium for a comprehensive and connected view of the Times in which he lived.

Yet, if any man be allowed to fill a station thus conspicuous and important, Shakspeare has undoubtedly the best claim to the distinction; not only from his pre-eminence as a dramatic poet, but from the intimate relation which his works bear to the manners, customs, superstitions, and amusements of his age.

Struck with the interest which a work of this kind, if properly executed, might possess, the author was induced, several years ago, to commence the undertaking, with the express intention of blending with the detail of manners, &c. such a portion of criticism, biography, and literary history, as should render the whole still more attractive and complete.

In attempting this, it has been his aim to place Shakspeare in the fore-ground of the picture, and to throw around him, in groups more or [iv]less distinct and full, the various objects of his design; giving them prominency and light, according to their greater or smaller connection with the principal figure.

More especially has it been his wish, to infuse throughout the whole plan, whether considered in respect to its entire scope, or to the parts of which it is composed, that degree of unity and integrity, of relative proportion and just bearing, without which neither harmony, simplicity, nor effect, can be expected, or produced.

With a view, also, to distinctness and perspicuity of elucidation, the whole has been distributed into three parts or pictures, entitled,—"Shakspeare in Stratford;"—"Shakspeare in London;"—"Shakspeare in Retirement;"—which, though inseparably united, as forming but portions of the same story, and harmonized by the same means, have yet, both in subject and execution, a peculiar character to support.

The first represents our Poet in the days of his youth, on the banks of his native Avon, in the midst of rural imagery, occupations, and amusements; in the second, we behold him in the capital of his country, in the centre of rivalry and competition, in the active pursuit of reputation and glory; and in the third, we accompany the venerated bard to the shades of retirement, to the bosom of domestic peace, to the enjoyment of unsullied fame.

It has, therefore, been the business of the author, in accordancy with his plan, to connect these delineations[v] with their relative accompaniments; to incorporate, for instance, with the first, what he had to relate of the country, as it existed in the age of Shakspeare; its manners, customs, and characters; its festivals, diversions, and many of its superstitions; opening and closing the subject with the biography of the poet, and binding the intermediate parts, not only by a perpetual reference to his drama, but by their own constant and direct tendency towards the developement of the one object in view.

With the second, which commences with Shakspeare's introduction to the stage as an actor, is combined the poetic, dramatic, and general literature of the times, together with an account of metropolitan manners and diversions, and a full and continued criticism on the poems and plays of our bard.

After a survey, therefore, of the Literary world, under the heads of Bibliography, Philology, Criticism, History, Romantic, and Miscellaneous Literature, follows a View of the Poetry of the same period, succeeded by a critique on the juvenile productions of Shakspeare, and including a biographical sketch of Lord Southampton, and a new hypothesis on the origin and object of the Sonnets.

Of the immediately subsequent description of diversions, &c. the Economy of the Stage forms a leading feature, as preparatory to a History of Dramatic Poetry, previous to the year 1590; and this is again introductory to a discussion concerning the Period when Shakspeare[vi] commenced a writer for the theatre; to a new chronology of his plays, and to a criticism on each drama; a department which is interspersed with dissertations on the fairy mythology, the apparitions, the witchcraft, and the magic of Shakspeare; portions of popular credulity which had been, in reference to this distribution, omitted in detailing the superstitions of the country.

This second part is then terminated by a summary of Shakspeare's dramatic character, by a brief view of dramatic poetry during his connection with the stage, and by the biography of the poet to the close of his residence in London.

The third and last of these delineations is, unfortunately, but too short, being altogether occupied with the few circumstances which distinguish the last three years of the life of our bard, with a review of his disposition and moral character, and with some notice of the first tributes paid to his memory.

It will readily be admitted, that the materials for the greater part of this arduous task are abundant; but it must also be granted, that they are dispersed through a vast variety of distant and unconnected departments of literature; and that to draw forth, arrange, and give a luminous disposition to, these masses of scattered intelligence, is an achievement of no slight magnitude, especially when it is considered, that no step in the progress of such an undertaking can be made, independent of a constant recurrence to authorities.[vii]

How far the author is qualified for the due execution of his design, remains for the public to decide; but it may, without ostentation, be told, that his leisure, for the last thirty years, has been, in a great decree, devoted to a line of study immediately associated with the subject; and that his attachment to old English literature has led him to a familiarity with the only sources from which, on such a topic, authentic illustration is to be derived.

He will likewise venture to observe, that, in the style of criticism which he has pursued, it has been his object, an ambitious one it is true, to unfold, in a manner more distinct than has hitherto been effected, the peculiar character of the poet's drama; and, lastly, to produce a work, which, while it may satisfy the poetical antiquary, shall, from the variety, interest, and integrity of its component parts, be equally gratifying to the general reader.

Hadleigh, Suffolk,

April 7th, 1817.

| PART I. | |

| SHAKSPEARE IN STRATFORD. | |

| CHAP. I. | |

| Birth of Shakspeare—Account of his Family—Orthography of his Name. | Page 1 |

| CHAP. II. | |

| The House in which Shakspeare was born—Plague at Stratford, June 1564—Shakspeare educated at the Free-school of Stratford—State of Education, and of Juvenile Literature in the Country at this period—Extent of Shakspeare's acquirements as a Scholar. | 21 |

| CHAP. III. | |

| Shakspeare, after leaving School, follows his Father's Trade—Statement of Aubrey—Probably present in his Twelfth Year at Kenelworth, when Elizabeth visited the Earl of Leicester—Tradition of Aubrey concerning him—Whether there is reason to suppose that, after leaving his Father, he was placed in an Attorney's Office, who was likewise Seneschal or Steward of some Manor—Anecdotes of Shakspeare—Allusions in his Works to Barton, Wilnecotte, and Barston, Villages in Warwickshire—Earthquake in 1580 alluded to—Whether, after leaving School, he acquired any Knowledge of the French and Italian languages. | 34 |

| [x]CHAP. IV. | |

| Shakspeare married to Anne Hathaway—Account of the Hathaways—Cottage at Shottery—Birth of his eldest Child, Susanna—Hamnet and Judith baptized—Anecdote of Shakspeare—Shakspeare apparently settled in the Country. | 59 |

| CHAP. V. | |

| A View of Country-Life during the Age of Shakspeare—Its Manners and Customs—Rural Characters; the Country-Gentleman—the Country-Coxcomb—the Country-Clergyman—the Country-Schoolmaster—the Farmer or Yeoman, his Mode of Living—the Huswife, her Domestic Economy—the Farmer's Heir—the Poor Copyholder—the Downright Clown, or Plain Country-Boor. | 68 |

| CHAP. VI. | |

| A View of Country-Life during the Age of Shakspeare—Manners and Customs continued—Rural Holidays and Festivals; New-Year's Day—Twelfth Day—Rock-Day—Plough-Monday—Shrove-tide—Easter-tide—Hock-tide—May-Day—Whitsuntide—Ales; Leet-ale—Lamb-ale—Bride-ale—Clerk-ale—Church-ale—Whitsun-ale—Sheep-shearing Feast—Candlemas-Day—Harvest-Home—Seed-cake Feast—Martinmas—Christmas. | 123 |

| CHAP. VII. | |

| A View of Country-Life during the Age of Shakspeare—Manners and Customs, continued—Wakes—Fairs—Weddings—Christenings—Burials. | 209 |

| CHAP. VIII. | |

| View of Country-Life during the Age of Shakspeare, continued—Diversions—The Itinerant Stage—Cotswold Games—Hawking—Hunting—Fowling—Fishing—Horse-racing—The Quintaine—The Wild-goose Chase—Hurling—Shovel-board—Juvenile Sports—Barley-breake—Parish-Top. | 246 |

| [xi]CHAP. IX. | |

| View of Country-Life during the Age of Shakspeare, continued—An Account of some of its Superstitions; Winter-Night's Conversation—Peculiar Periods devoted to Superstition—St. Paul's Day—St. Swithen's Day—St. Mark's Day—Childermas—St. Valentine's Day—Midsummer-Eve—Michaelmas—All Hallow-Eve—St. Withold—Omens—Charms—Sympathies—Superstitious Cures—Miscellaneous Superstitions. | 314 |

| CHAP. X. | |

| Biography of Shakspeare resumed—His Irregularities—Deer-stealing in Sir Thomas Lucy's Park—Account of the Lucy family—Daisy-hill, the Keeper's Lodge, where Shakspeare was confined, on the Charge of stealing Deer—Shakspeare's Revenge—Ballad on Lucy—Severe Prosecution by Sir Thomas—never forgotten by Shakspeare—this Cause, and probably also Debt, as his Father was now in reduced Circumstances, induced him to leave the Country for London about 1586—Remarks on this Removal. | 401 |

| PART II. | |

| SHAKSPEARE IN LONDON. | |

| CHAP. I. | |

| Shakspeare's Arrival in London about the Year 1586, when twenty-two Years of Age—Leaves his Family at Stratford, visiting them occasionally—His Introduction to the Stage—His Merits as an Actor. | 413 |

| CHAP. II. | |

| Shakspeare commences a Writer of Poetry, probably about the year 1587, by the composition of his Venus and Adonis—Historical Outline of Polite Literature, during the Age of Shakspeare—General passion for Letters—Bibliography—Shakspeare's Attachment to Books—Philology—Criticism—Shakspeare's Progress in both—History, general, local, and personal, Shakspeare's Acquaintance with—Miscellaneous Literature. | 426 |

| [xii]CHAP. III. | |

| View of Romantic Literature during the Age of Shakspeare—Shakspeare's Attachment to, and Use of, Romances, Tales, and Ballads. | 518 |

| CHAP. IV. | |

| View of Miscellaneous Poetry during the same period. | 594 |

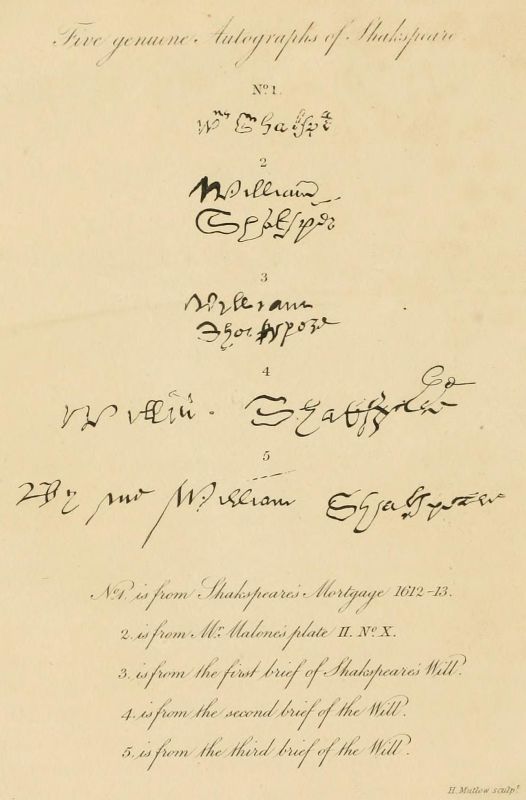

Five genuine Autographs of Shakspeare

No. 1 is from Shakspeare's Mortgage 1612-13.

2 is from Mr. Malone's plate II. No. X.

3 is from the first brief of Shakspeare's Will.

4 is from the second brief of the Will.

5 is from the third brief of the Will.

William Shakspeare, the object almost of our idolatry as a dramatic poet, was born at Stratford-upon-Avon, in Warwickshire, on the 23d of April, 1564, and he was baptized on the 26th of the same month.

Of his family, not much that is certain can be recorded; but it would appear, from an instrument in the College of Heralds, confirming the grant of a coat of arms to John Shakspeare in 1599, that his great grandfather had been rewarded by Henry the Seventh, "for his faithefull and approved service, with lands and tenements given to him in those parts of Warwickshire, where," proceeds this document, "they have continued by some descents in good reputation and credit." Notwithstanding this assertion, however, no such grant, after a minute examination, made by Mr. Malone in the chapel of the Rolls, has been discovered; whence we have reason to infer, that the heralds have been mistaken in their statement, and that the bounty of the monarch was directed through a different channel. From the language, indeed, of two rough draughts of a prior grant of[2] arms to John Shakspeare in 1596, it is probable that the service alluded to was of a military cast, for it is there expressly said, that he was rewarded "for his faithful and valiant service," a term, perhaps, implying the heroism of our poet's ancestor in the field of Bosworth.

That the property, thus bestowed upon the family of Shakspeare, descended to John, the father of the poet, and contributed to his influence and respectability, there is no reason to doubt. From the register, indeed, and public writings relating to Stratford, Mr. Rowe has justly inferred, that the Shakspeares were of good figure and fashion there, and were considered as gentlemen. We may presume, however, that the patrimony of Mr. John Shakspeare, the parent of our great dramatist, was not very considerable, as he found the profits of business necessary to his support. He was, in fact, a wool-stapler, and, there is reason to suppose, in a large way; for he was early chosen a member of the corporation of his town, a situation usually connected with respectable circumstances, and soon after, he filled the office of high bailiff or chief magistrate of that body. The record of these promotions has been thus given from the books of the corporation.

"Jan. 10, in the 6th year of the reign of our sovereign lady Queen Elizabeth, John Shakspeare passed his Chamberlain's accounts."

"At the Hall holden the eleventh day of September, in the eleventh year of the reign of our sovereign lady Elizabeth, 1569, were present Mr. John Shakspeare, High Bailiff."[2:A]

It was during the period of his filling this important office, that he first obtained a grant of arms; and, in a note annexed to the subsequent patent of 1596, now in the College of Arms[2:B], it is stated that he was likewise a justice of the peace, and possessed of lands and tenements to the amount of 500l. The final confirmation of this grant took place in 1599, in which his shield and coat are described to be, In a field of gould upon a bend sable, a speare of the first, the [3]poynt upward, hedded argent; and for his crest or cognisance, A falcon with his wyngs displayed, standing on a wrethe of his coullers, supporting a speare armed hedded, or steeled sylver.[3:A]

Mr. John Shakspeare married, though in what year is not accurately known, the daughter and heir of Robert Arden, of Wellingcote, in the county of Warwick, who is termed, in the Grant of Arms of 1596, "a gentleman of worship." The Arden, or Ardern family, appears to have been of considerable antiquity; for, in Fuller's Worthies, Rob. Arden de Bromwich, ar. is among the names of the gentry of this county returned by the commissioners in the twelfth year of King Henry the Sixth, 1433; and in the eleventh and sixteenth years of Elizabeth, A. D. 1562 and 1568, Sim. Ardern, ar. and Edw. Ardrn, ar. are enumerated, by the same author, among the sheriffs of Warwickshire.[3:B] It is well known that the woodland part of this county was formerly denominated Ardern, though, for the sake of euphony, frequently softened towards the close of the sixteenth century, into the smoother appellation of Arden; hence it is not improbable, that the supposition of Mr. Jacob, who reprinted, in 1770, the Tragedy of Arden of Feversham, a play which was originally published in 1592, may be correct; namely that Shakspeare, the poet, was descended by the female line from the unfortunate individual whose tragical death is the subject of this drama; for though the name of this gentleman was originally Ardern, he seems early to have experienced the fate of the county district, and to have had his surname harmonized by a similar omission. In consequence of this marriage, Mr. John Shakspeare and his posterity were allowed, by the College of Heralds, to impale their arms with the ancient arms of the Ardrns of Wellingcote.[3:C]

Of the issue of John Shakspeare by this connection, the accounts are contradictory and perplexed; nor is it absolutely ascertained, [4]whether he had only one wife, or whether he might not have had two, or even three. Mr. Rowe, whose narrative has been usually followed, has given him ten children, among whom he considers William the poet, as the eldest son.[4:A] The Register, however, of the parish of Stratford-upon-Avon, which commences in 1558, is incompatible with this statement; for, we there find eleven children ascribed to John Shakspeare, ten baptized, and one, the baptism of which had taken place before the commencement of the Register, buried.[4:B] The dates of these baptisms, and of two or three other events, recorded in this Register, it will be necessary, for the sake of elucidation, to transcribe:

[5]Now it is evident, that if the ten children which were baptized, according to this Register, between the years 1558 and 1591, are to be ascribed to the father of our poet, he must necessarily have had eleven, in consequence of the record of the decease of his daughter Margaret. He must also have had three wives, for we find his second wife, Margery, died in 1587, and the death of a third, Mary, a widow, is noticed in 1608.

It was suggested to Mr. Malone[5:A], that very probably, Mr. John Shakspeare had a son born to him, as well as a daughter, before the commencement of the Register, and that this his eldest son, was, as is customary, named after his father, John; a supposition which, (as no other child was baptized by the Christian name of the old gentleman,) carries some credibility with it, and was subsequently acquiesced in by Mr. Malone himself.

In this case, therefore, the marriage recorded in the Register, is that of John Shakspeare the younger with Margery Roberts, and the three children born between 1588 and 1591, Ursula, Humphrey, and Philip, the issue of this John, not by the first, but by a second marriage; for as Margery Shakspeare died in 1587, and Ursula was baptized in 1588-9, these children must have been by the Mary Shakspeare, whose death is mentioned as occurring in 1608, and as she is there denominated a widow; the younger John must consequently have died before that date.

The result of this arrangement will be, that the father of our poet had only nine children, and that William was not the eldest, but the second son.

On either plan, however, the account of Mr. Rowe is equally inaccurate; and as the introduction of an elder son involves a variety of suppositions, and at the same time nothing improbable is attached to the consideration of this part of the Register in the light in which it usually appears, that is, as allusive solely to the father, it will, we think, be the better and the safer mode, to rely upon it, according [6]to its more direct and literal import. This determination will be greatly strengthened by reflecting, that old Mr. Shakspeare was, on the authority of the last instrument granting him a coat of arms, living in 1599; that on the testimony of the Register, taken in the common acceptation, he was not buried until September 1601; and that in no part of the same document is the epithet younger annexed to the name of John Shakspeare, a mark of distinction which there is every reason to suppose would have been introduced, had the father and a son of the same Christian name been not only living at the same time in the same town, but the latter likewise a parent.

That the circumstances of Mr. John Shakspeare were, at the period of his marriage, and for several years afterwards, if not affluent, yet easy and respectable, there is every reason to suppose, from his having filled offices of the first trust and importance in his native town; but, from the same authority which has induced us to draw this inference, another of a very different kind, with regard to a subsequent portion of his life, may with equal confidence be taken. In the books of the corporation of Stratford it is stated, that—

"At the hall holden Nov. 19th, in the 21st year of the reign of our sovereign lady Queen Elizabeth, it is ordained, that every Alderman shall be taxed to pay weekly 4d., saving John Shakspeare and Robert Bruce, who shall not be taxed to pay any thing; and every burgess to pay 2d." Again,

"At the hall holden on the 6th day of September, in the 28th year of our sovereign lady Queen Elizabeth:

"At this hall William Smith and Richard Courte are chosen to be Aldermen in the places of John Wheler and John Shakspeare, for that Mr. Wheler doth desire to be put out of the company, and Mr. Shakspeare doth not come to the halls, when they be warned, nor hath not done of long time."[6:A]

The conclusion to be drawn from these memoranda must unavoidably be, that, in 1579, ten years after he had served the office [7]of High Bailiff, his situation, in a pecuniary light, was so much reduced, that, on this account, he was excused the weekly payment of 4d.; and that, in 1586, the same distress still subsisting, and perhaps in an aggravated degree, he was, on the plea of non-attendance, dismissed the corporation.

The causes of this unhappy change in his circumstances cannot now, with the exception of the burthen of a large and increasing family, be ascertained; but it is probable, that to this period is to be referred, if there be any truth in the tradition, the report of Aubrey, that "William Shakspeare's father was a butcher." This anecdote, he affirms, was received from the neighbours of the bard, and, on this account, merits some consideration.[7:A]

We are indebted to Mr. Howe for the first intimation concerning the trade of John Shakspeare; his declaration, derived also from tradition, that he was a "considerable dealer in wool," appears confirmed by subsequent research. From a window in a room of the premises which originally formed part of the house at Stratford, in which Shakspeare the poet was born, and a part of which premises has for many years been occupied as a public-house, with the sign of the Swan and Maidenhead, a pane of glass was taken, about five and forty years ago, by Mr. Peyton, the then master of the adjoining Inn called The White Lion. This pane, now in the possession of his son, is nearly six inches in diameter, and perfect, and on it are painted the arms of the merchants of the wool-staple—Nebule on a chief gules, a lion passant or. It appears, from the style in which it is finished, to have been executed about the time of Shakspeare, the father, and is undoubtedly a strong corroborative proof of the authenticity of Mr. Rowe's relation.[7:B]

[8]These traditionary anecdotes, though apparently contradictory, may easily admit of reconcilement, if we consider, that between the employment of a wool-dealer, and a butcher, there is no small affinity; "few occupations," observes Mr. Malone, "can be named which are more naturally connected with each other."[8:A] It is highly probable, therefore, that during the period of John Shakspeare's distress, which we know to have existed in 1579, when our poet was but fifteen years of age, he might have had recourse to this more humble trade, as in many circumstances connected with his customary business, and as a great additional means of supporting a very numerous family.

That the necessity for this union, however, did not exist towards the latter part of his life, there is much reason to imagine, both from the increasing reputation and affluence of his son William, and from the fact of his applying to the College of Heralds, in 1596 and 1599, for a grant of arms; events, of which the first, considering the character of the poet, must almost necessarily have led to, and the second directly pre-supposes, the possession of comparative competence and respectability.

The only remaining circumstance which time has spared us, relative to the personal conduct of John Shakspeare, is, that there appears some foundation to believe that, a short time previous to his death, he made a confession of his faith, or spiritual will; a document still in existence, the discovery and history of which, together with the declaration itself, will not improperly find a place at the close of this commencing chapter of our work.

About the year 1770, a master-bricklayer, of the name of Mosely, being employed by Mr. Thomas Hart, the fifth in descent, in a [9]direct line, from the poet's sister, Joan Hart, to new-tile the house in which he then lived, and which is supposed to be that under whose roof the bard was born, found hidden between the rafters and the tiling of the house, a manuscript, consisting of six leaves, stitched together, in the form of a small book. This manuscript Mosely, who bore the character of an honest and industrious man, gave (without asking or receiving any recompense) to Mr. Peyton, an alderman of Stratford; and this gentleman very kindly sent it to Mr. Malone, through the medium of the Rev. Mr. Davenport, vicar of Stratford. It had, however, previous to this transmission, unfortunately been deprived of the first leaf, a deficiency which was afterwards supplied by the discovery, that Mosely, who had now been dead about two years, had copied a great portion of it, and from his transcription the introductory parts were supplied.[9:A] The daughter of Mosely and Mr. Hart, who were both living in the year 1790, agreed in a perfect recollection of the circumstances attending the discovery of this curious document, which consists of the following fourteen articles.

1.

"In the name of God, the Father, Sonne and Holy Ghost, the most holy and blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of God, the holy host of archangels, angels, patriarchs, prophets, evangelists, apostles, saints, martyrs, and all the celestial court and company of heaven: I John Shakspear, an unworthy member of the holy Catholic religion, being at this my present writing in perfect health of body, and sound mind, memory, and understanding, but calling to mind the uncertainty of life and certainty of death, and that I may be possibly cut off in the blossome of my sins, and called to render an account of all my transgressions externally and internally, and that I may be unprepared for the dreadful trial either by sacrament, pennance, fasting, or prayer, or any other purgation whatever, do in the holy presence above specified, of my own free and voluntary accord, make [10]and ordaine this my last spiritual will, testament, confession, protestation, and confession of faith, hopinge hereby to receive pardon for all my sinnes and offences, and thereby to be made partaker of life everlasting, through the only merits of Jesus Christ my saviour and redeemer, who took upon himself the likeness of man, suffered death, and was crucified upon the crosse, for the redemption of sinners.

2.

"Item, I John Shakspear doe by this present protest, acknowledge, and confess, that in my past life I have been a most abominable and grievous sinner, and therefore unworthy to be forgiven without a true and sincere repentance for the same. But trusting in the manifold mercies of my blessed Saviour and Redeemer, I am encouraged by relying on his sacred word, to hope for salvation, and be made partaker of his heavenly kingdom, as a member of the celestial company of angels, saints, and martyrs, there to reside for ever and ever in the court of my God.

3.

"Item, I John Shakspear doe by this present protest and declare, that as I am certain I must passe out of this transitory life into another that will last to eternity, I do hereby most humbly implore and intreat my good and guardian angell to instruct me in this my solemn preparation, protestation, and confession of faith, at least spiritually, in will adoring and most humbly beseeching my Saviour, that he will be pleased to assist me in so dangerous a voyage, to defend me from the snares and deceites of my infernal enemies, and to conduct me to the secure haven of his eternal blisse.

4.

"Item, I John Shakspear doe protest that I will also passe out of this life, armed with the last sacrament of extreme unction: the which if through any let or hindrance I should not then be able to have, I doe now also for that time demand and crave the same;[11] beseeching his Divine Majesty that he will be pleased to anoynt my senses both internall and externall with the sacred oyle of his infinite mercy, and to pardon me all my sins committed by seeing, speaking, feeling, smelling, hearing, touching, or by any other way whatsoever.

5.

"Item, I John Shakspear doe by this present protest, that I will never through any temptation whatsoever despaire of the divine goodness, for the multitude and greatness of my sinnes; for which, although I confesse that I have deserved hell, yet will I steadfastly hope in God's infinite mercy, knowing that he hath heretofore pardoned many as great sinners as myself, whereof I have good warrant sealed with his sacred mouth, in holy writ, whereby he pronounceth that he is not come to call the just, but sinners.

6.

"Item, I John Shakspear do protest, that I do not know that I have ever done any good worke meritorious of life everlasting: and if I have done any, I do acknowledge that I have done it with a great deale of negligence and imperfection; neither should I have been able to have done the least without the assistance of his divine grace. Wherefore let the devill remain confounded: for I doe in no wise presume to merit heaven by such good workes alone, but through the merits and bloud of my Lord and Saviour Jesus, shed upon the cross for me most miserable sinner.

7.

"Item, I John Shakspear do protest by this present writing, that I will patiently endure and suffer all kind of infirmity, sickness, yea, and the paine of death itself: wherein if it should happen, which God forbid, that through violence of paine and agony, or by subtilty of the devill, I should fall into any impatience or temptation of blasphemy, or murmuration against God, or the Catholic faith, or give[12] any signe of bad example, I do henceforth, and for that present, repent me, and am most heartily sorry for the same: and I do renounce all the evill whatsoever, which I might have then done or said; beseeching his divine clemency that he will not forsake me in that grievous and paignefull agony.

8.

"Item, I John Shakspear, by virtue of this present testament, I do pardon all the injuries and offences that any one hath ever done unto me, either in my reputation, life, goods, or any other way whatsoever; beseeching sweet Jesus to pardon them for the same; and I do desire that they will doe the like by me whome I have offended or injured in any sort howsoever.

9.

"Item, I John Shakspear do here protest, that I do render infinite thanks to his Divine Majesty for all the benefits that I have received, as well secret as manifest, and in particular for the benefit of my creation, redemption, sanctification, conservation, and vocation to the holy knowledge of him and his true Catholic faith: but above all for his so great expectation of me to pennance, when he might most justly have taken me out of this life, when I least thought of it, yea, even then, when I was plunged in the durty puddle of my sinnes. Blessed be therefore and praised, for ever and ever, his infinite patience and charity.

10.

"Item, I John Shakspear do protest, that I am willing, yea, I do infinitely desire and humbly crave, that of this my last will and testament the glorious and ever Virgin Mary, mother of God, refuge and advocate of sinners, (whom I honour specially above all saints,) may be the chiefe executresse, togeather with these other saints, my patrons, (Saint Winefride,) all whome I invoke and beseech to be present at the hour of my death, that she and they comfort me with[13] their desired presence, and crave of sweet Jesus that he will receive my soul into peace.

11.

"Item, In virtue of this present writing, I John Shakspear do likewise most willingly and with all humility constitute and ordaine my good angell for defender and protector of my soul in the dreadfull day of judgment, when the finall sentence of eternall life or death shall be discussed and given: beseeching him that, as my soule was appointed to his custody and protection when I lived, even so he will vouchsafe to defend the same at that houre, and conduct it to eternall bliss.

12.

"Item, I John Shakspear do in like manner pray and beseech all my dear friends, parents, and kinsfolks, by the bowells of our Saviour Jesus Christ, that since it is uncertain what lot will befall me, for fear notwithstanding least by reason of my sinnes I be to pass and stay a long while in purgatory, they will vouchsafe to assist and succour me with their holy prayers and satisfactory workes, especially with the holy sacrifice of the masse, as being the most effectual means to deliver soules from their torments and paines; from the which, if I shall by God's gracious goodnesse, and by their vertuous workes, be delivered, I do promise that I will not be ungratefull unto them for so great a benefitt.

13.

"Item, I John Shakspear doe by this my last will and testament bequeath my soul, as soon as it shall be delivered and loosened from the prison of this my body, to be entombed in the sweet and amorous coffin of the side of Jesus Christ; and that in this life-giving sepulcher it may rest and live, perpetually enclosed in that eternall habitation of repose, there to blesse for ever and ever that direful iron of the launce, which, like a charge in a censore, formes so sweet[14] and pleasant a monument within the sacred breast of my Lord and Saviour.

14.

"Item, Lastly I John Shakspear doe protest, that I will willingly accept of death in what manner soever it may befall me, conforming my will unto the will of God; accepting of the same in satisfaction for my sinnes, and giving thanks unto his Divine Majesty for the life he hath bestowed upon me. And if it please him to prolong or shorten the same, blessed be he also a thousand thousand times; into whose most holy hands I commend my soul and body, my life and death: and I beseech him above all things, that he never permit any change to be made by me John Shakspear of this my aforesaid will and testament. Amen.

"I John Shakspeare have made this present writing of protestation, confession, and charter, in presence of the blessed Virgin Mary, my angell guardian, and all the celestial court, as witnesses hereunto: the which my meaning is, that it be of full value now presently and for ever, with the force and vertue of testament, codicill, and donation in course of death; confirming it anew, being in perfect health of soul and body, and signed with mine own hand; carrying also the same about me, and for the better declaration hereof, my will and intention is that it be finally buried with me after my death.

If the intention of the testator, as expressed in the close of this will, were carried into effect, then, of course, the manuscript which Mosely found, must necessarily have been a copy of that which was buried in the grave of John Shakspeare.

Mr. Malone, to whom, in his edition of Shakspeare, printed in 1790, we are indebted for this singular paper, and for the history [15]attached to it, observes, that he is unable to ascertain, whether it was drawn up by John Shakspeare the father, or by John his supposed eldest son; but he says, "I have taken some pains to ascertain the authenticity of this manuscript, and, after a very careful inquiry, am perfectly satisfied that it is genuine."[15:A] In the "Inquiry," however, which he published in 1796, relative to the Ireland papers, he has given us, though without assigning any reasons for his change of opinion, a very different result: "In my conjecture," he remarks, "concerning the writer of that paper, I certainly was mistaken; for I have since obtained documents that clearly prove it could not have been the composition of any one of our poet's family."[15:B]

In the "Apology" of Mr. George Chalmers "for the Believers in the Shakspeare-Papers," which appeared in the year subsequent to Mr. Malone's "Inquiry," a new light is thrown upon the origin of this confession. "From the sentiment, and the language, this confession appears to be," says this gentleman, "the effusion of a Roman Catholic mind, and was probably drawn up by some Roman Catholic priest.[15:C] If these premises be granted, it will follow, as a fair deduction, that the family of Shakspeare were Roman Catholics; a circumstance this, which is wholly consistent with what Mr. Malone is now studious to inculcate, viz. "that this confession could not have been the composition of any of our poet's family." The thoughts, the language, the orthography, all demonstrate the truth of my conjecture, though Mr. Malone did not perceive this truth, when he first published this paper in 1790. But, it was the performance of a clerke, the undoubted work of the family-priest. The conjecture, that Shakspeare's family were Roman Catholics, is strengthened by the fact, that his father declined to attend the [16]corporation meetings, and was at last removed from the corporate body."[16:A]

This conjecture of Mr. Chalmers appears to us in its leading points very plausible; for that the father of our poet might be a Roman Catholic is, if we consider the very unsettled state of his times with regard to religion, not only a possible but a probable supposition: in which case, it would undoubtedly have been the office of the spiritual director of the family to have drawn up such a paper as that which we have been perusing. It was the fashion also of the period, as Mr. Chalmers has subsequently observed, to draw up confessions of religious faith, a fashion honoured in the observance by the great names of Lord Bacon, Lord Burghley, and Archbishop Parker[16:B]. That he declined, however, attending the corporation-meetings of Stratford from religious motives, and that his removal from that body was the result of non-attendance from such a cause, cannot readily be admitted; for we have clearly seen that his defection was owing to pecuniary difficulties; nor is it, in the least degree, probable that, after having honourably filled the highest offices in the corporation without scruple, he should at length, and in a reign too popularly protestant, incur expulsion from an avowed motive of this kind; especially as we have reason to suppose, from the mode in which this profession was concealed, that the tenets of the person whose faith it declares, were cherished in secret.

From an accurate inspection of the hand-writing of this will, Mr. Malone infers that it cannot be attributed to an earlier period than the year 1600[16:C], whence it follows that, if dictated by, or drawn up at the desire of, John Shakspeare, his death soon sealed the confession of his faith; for, according to the register, he was buried on September 8th, 1601.

[17]Such are the very few circumstances which reiterated research has hitherto gleaned relative to the father of our poet; circumstances which, as being intimately connected with the history and character of his son, have acquired an interest of no common nature. Scanty as they must be pronounced, they lead to the conclusion that he was a moral and industrious man; that when fortune favoured him, he was not indolent, but performed the duties of a magistrate with respectability and effect, and that in the hour of adversity he exerted every nerve to support with decency a numerous family.

Before we close this chapter, it may be necessary to state, that the very orthography of the name of Shakspeare has occasioned much dispute. Of Shakspeare the father, no autograph exists; but the poet has left us several, and from these, and from the monumental inscriptions of his family, must the question be decided; the latter, as being of the least authority, we shall briefly mention, as exhibiting, in Dugdale, three varieties,—Shakespeare; Shakespere, and Shakspeare. The former present us with five specimens which, singular as it may appear, all vary, either in the mode of writing, or mode of spelling. The first is annexed to a mortgage executed by the poet in 1613, and appears thus, Wm Shakspea: the second is from a deed of bargain and sale, relative to the same transaction, and of the same period, and signed, William Shaksper̄: the third, fourth, and fifth are taken from the Will of Shakspeare executed in March 1616, consisting of three briefs or sheets, to each of which his name is subscribed. These signatures, it is remarkable, differ considerably, especially in the surnames; for in the first brief we find William Shackspere; in the second, Willm Shakspe re, and in the third, William Shakspeare. It has been supposed, however, that, according to the practice in Shakspeare's time, the name in the first sheet was written by the scrivener who drew the will.

In the year 1790, Mr. Malone, from an inspection of the mortgage, pronounced the genuine orthography to be Shakspeare[17:A]; in 1796, [18]from consulting the deed of sale, he altered his opinion, and declared that the poet's own mode of spelling his name was, beyond a possibility of doubt, that of Shakspere, though for reasons which he should assign in a subsequent publication, he should still continue to write the name Shakspeare.[18:A]

To this decision, relative to the genuine orthography, Mr. Chalmers cannot accede; and for this reason, that, "when the testator subscribed his name, for the last time, he plainly wrote Shakspeare."[18:B]

It is obvious, therefore, that the controversy turns upon, whether there be, or be not, an a introduced in the second syllable of the last signature of the poet. Mr. Malone, on the suggestion of an anonymous correspondent, thinks that there is not, this gentleman having clearly shown him, "that though there was a superfluous stroke when the poet came to write the letter r in his last signature, probably from the tremor of his hand, there was no a discoverable in that syllable; and that this name, like both the other, was written Shakspere."[18:C]

From the annexed plate of autographs, which is copied from Mr. Chalmers's Apology, and presents us with very perfect fac-similes of the signatures, it is at once evident, that the assertion of the anonymous correspondent, that the last signature, "like both the other, was written Shakspere," cannot be correct; for the surname in the first brief is written Shackspere, and, in the second, Shakspe re. Now the hiatus in this second signature is unaccounted for in the fac-simile given by Mr. Malone[18:D]; but in the plate of Mr. Chalmers it is found to have been occasioned by the intrusion of the word the of the preceding line, a circumstance which, very probably, might prevent the introduction of the controverted letter. It is likewise, we think, very evident that something more than a superfluous stroke exists between the e and r of the last signature, and that the variation [19]is, indeed, too material to have originated from any supposed tremor of the hand.

Upon the whole, it may, we imagine, be safely reposed on as a fact, that Shakspeare was not uniform in the orthography of his own name; that he sometimes spelt it Shakspere and sometimes Shakspeare; but that no other variation is extant which can claim a similar authority.[19:A] It is, therefore, nearly a matter of indifference which of these two modes [20]of spelling we adopt; yet, as his last signature appears to have included the letter a, it may, for the sake of consistency, be proper silently to acquiesce in its admission.

FOOTNOTES:

[2:A] Communicated to Mr. Malone by the Rev. Mr. Davenport, vicar of Stratford-upon-Avon.

[2:B] Vincent, vol. clvii. p. 24.

[3:A] See the instrument, at full length, Reed's Shakspeare, vol. i. p. 146, edit. of 1803.

[3:B] The History of the Worthies of England, part iii. fol. 131, 132.

[3:C] See Shakspeare's coat of arms, Reed's Shaksp. vol. i. p. 146.

[4:A] Reed's Shakspeare, vol. i. p. 58, 59.

[4:B] Reed's Shakspeare, vol. i. p. 133.

[4:C] "It was common in the age of Queen Elizabeth to give the same Christian name to two children successively. This was undoubtedly done in the present instance. The former Jone having probably died, (though I can find no entry of her burial in the Register, nor indeed of many of the other children of John Shakspeare) the name of Jone, a very favourite one in those days, was transferred to another new-born child."—Malone from Reed's Shakspeare, vol. i. p. 134.

[5:A] Reed's Shakspeare, vol. i. p. 136.

[6:A] Reed's Shakspeare, vol. i. p. 58.

[7:A] MS. Aubrey, Mus. Ashmol. Oxon. Lives, p. 1. fol. 78, a. (Inter Cod. Dugdal.) Vide Reed's Shakspeare, vol. iii. p. 213.

[7:B] Reed's Shakspeare, vol. iii. p. 214. and Ireland's Picturesque Views on the Upper or Warwickshire Avon, p. 190, 191. Since this passage was written, however, the proof which it was supposed to contain, has been completely annihilated. "If John Shakspeare's occupation in life," observes Mr. Wheeler, "want confirmation, this circumstance will unfortunately not answer such a purpose; for old Thomas Hart constantly declared that his great uncle, Shakspeare Hart, a glazier of this town, who had the new glazing of the chapel windows, where it is known, from Dugdale, that such a shield existed, brought it from thence, and introduced it into his own window."—Wheeler's Guide to Stratford, pp. 13, 14.

[8:A] Reed's Shakspeare, vol. iii. p. 214.

[9:A] Reed's Shakspeare, vol. iii. p. 197, 198.

[14:A] Reed's Shakspeare, vol. iii. p. 199. et seq.

[15:A] Reed's Shakspeare, vol. iii. p. 197.

[15:B] Malone's Inquiry, p. 198, 199.

[15:C] As a specimen, let us take the beginning of this declaration of faith, and see still stronger terms in the conclusion of this protestation, confession, and charter.

[16:A] "The place too, the roof of the house where this confession was found, proves, that it had been therein concealed, during times of persecution, for the holy Catholick religion." Apology, p. 198, 199.

[16:B] Chalmers's Apology, p. 200.

[16:C] Reed's Shakspeare, vol. iii. p. 198.

[17:A] Reed's Shakspeare, vol. i. p. 149.

[18:A] Malone's Inquiry, p. 120

[18:B] Chalmers's Apology, p. 235.

[18:C] Malone's Inquiry, p. 117, 118.

[18:D] Inquiry, Plate II. No. 12.

[19:A] A want of uniformity in the spelling of names, was a species of negligence very common in the time of Shakspeare, and may be observed, remarks Mr. Chalmers, "with regard to the principal poets of that age; as we may see in England's Parnassus, a collection of poetry which was published in 1600: thus,

| Sydney | Sidney. | ||

| Spenser | Spencer. | ||

| Jonson | Johnson | Jhonson. | |

| Dekker | Dekkar. | ||

| Markeham | Markham. | ||

| Sylvister | Sylvester | Silvester. | |

| Sackwill | Sackuil. | ||

| Fitz Geffrey | Fitzjeffry | Fitz Jeffray. | |

| France | Fraunce. | ||

| Midleton | Middleton. | ||

| Guilpin | Gilpin. | ||

| Achelly | Achely | Achilly | Achillye. |

| Drayton | Draiton. | ||

| Daniel | Daniell. | ||

| Davis | Davies. | ||

| Marlow | Marlowe. | ||

| Marston | Murston. | ||

| Fairefax | Fairfax. | ||

| Kid | Kyd. | ||

Yet, it is remarkable, that in this collection of diversities, our dramatist's name is uniformly spelt Shakespeare: in whatever manner this celebrated name may have been pronounced in Warwickshire, it certainly was spoken in London, with the e soft, thus, Shakespeare: in the registers of the Stationers' Company, it is written, Shakespere, and Shakespeare." Chalmers's Supplemental Apology, p. 129, 130.

A curious proof of the uncertain orthography of the poet's surname among his contemporaries and immediate successors, may be drawn from a pamphlet, entitled, "The great Assizes holden in Parnassus by Apollo and his Assessours: at which Sessions are arraigned, Mercurius Britannicus, &c. &c. London: Printed by Richard Cotes for Edward Husbands, and are to be sold at his shop in the Middle Temple. 1645. qto. 25 leaves."

In this rare tract, among the list of the jurors is found the name of our bard, written William Shakespeere; and in the body of the poem, it is given Shakespeare, and Shakespear. Vide British Bibliographer, vol. i. p. 513.

THE HOUSE IN WHICH SHAKSPEARE WAS BORN—PLAGUE AT STRATFORD, JUNE 1564—SHAKSPEARE EDUCATED AT THE FREE-SCHOOL OF STRATFORD—STATE OF EDUCATION, AND OF JUVENILE LITERATURE IN THE COUNTRY AT THIS PERIOD—EXTENT OF SHAKSPEARE'S ACQUIREMENTS AS A SCHOLAR.

The experience of the last half century has fully proved, that every thing relative to the history of our immortal dramatist has been received, and received justly too, by the public with an avidity proportional to his increasing fame. What, if recorded of a less celebrated character, might be deemed very uninteresting, immediately acquires, when attached to the mighty name of Shakspeare, an importance nearly unparalleled. No apology, therefore, can be necessary for the introduction of any fact or circumstance, however minute, which is, in the slightest degree, connected with his biography; tradition, indeed, has been so sparing of her communications on this subject, that every addition to her little store has been hitherto welcomed with the most lively sensation of pleasure, nor will the attempt to collect and embody these scattered fragments be unattended with its reward.

The birth-place of our poet, the spot where he drew the first breath of life, where Fancy

has been the object of laudable curiosity to thousands, and happily the very roof that sheltered his infant innocence can still be pointed out. It stands in Henley-street, and, though at present forming two separate tenements, was originally but one house.[21:A] The premises [22]are still in possession of the Hart family, now the seventh descendants, in a direct line, from Jone the sister of the poet. From the plate in Reed's Shakspeare, which is a correct representation of the existing state of this humble but interesting dwelling, it will appear, that one portion of it is occupied by the Swan and Maidenhead public-house, and the other by a butcher's shop, in which the son of old Mr. Thomas Hart, mentioned in the last chapter, still carries on his father's trade.[22:A] "The kitchen of this house," says Mr. Samuel Ireland, "has an appearance sufficiently interesting, abstracted from its claim to notice as relative to the Bard. It is a subject very similar to those that so frequently employed the rare talents of Ostade, and therefore cannot be deemed unworthy the pencil of an inferior artist. In the corner of the chimney stood an old oak-chair, which had for a number of years received nearly as many adorers as the celebrated shrine of the Lady of Loretto. This relic was purchased, in July 1790, by the Princess Czartoryska, who made a journey to this place, in order to [23]obtain intelligence relative to Shakspeare; and being told he had often sat in this chair, she placed herself in it, and expressed an ardent wish to become a purchaser; but being informed that it was not to be sold at any price, she left a handsome gratuity to old Mrs. Hart, and left the place with apparent regret. About four months after, the anxiety of the Princess could no longer be withheld, and her secretary was dispatched express, as the fit agent, to purchase this treasure at any rate: the sum of twenty guineas was the price fixed on, and the secretary and chair, with a proper certificate of its authenticity on stamped paper, set off in a chaise for London."[23:A] The elder Mr. Hart, who died about the year 1794, aged sixty-seven, informed Mr. Samuel Ireland, that he well remembered, when a boy, having dressed himself, with some of his playfellows, as Scaramouches (such was his phrase), in the wearing-apparel of Shakspeare; an anecdote of which, if we consider the lapse of time, it may be allowed us to doubt the credibility, and to conclude that the recollection of Mr. Hart had deceived him.

Little more than two months had passed over the head of the infant Shakspeare, when he became exposed to danger of such an imminent kind, that we have reason to rejoice he was not snatched from [24]us even while he lay in the cradle. He was born, as we have already recorded, on the 23d of April, 1564; and on the 30th of the June following, the plague broke out at Stratford, the ravages of which dreadful disease were so violent, that between this last date and the close of December, not less than two hundred and thirty-eight persons perished; "of which number," remarks Mr. Malone, "probably two hundred and sixteen died of that malignant distemper; and one only of the whole number resided, not in Stratford, but in the neighbouring town of Welcombe. From the two hundred and thirty-seven inhabitants of Stratford, whose names appear in the Register, twenty-one are to be subducted, who, it may be presumed, would have died in six months, in the ordinary course of nature; for in the five preceding years, reckoning, according to the style of that time, from March 25. 1559, to March 25. 1564, two hundred and twenty-one persons were buried at Stratford, of whom two hundred and ten were townsmen: that is, of these latter, forty-two died each year at an average. Supposing one in thirty-five to have died annually, the total number of the inhabitants of Stratford at that period was one thousand four hundred and seventy; and consequently the plague, in the last six months of the year 1564, carried off more than a seventh part of them. Fortunately for mankind it did not reach the house in which the infant Shakspeare lay; for not one of that name appears in the dead list. May we suppose, that, like Horace, he lay secure and fearless in the midst of contagion and death, protected by the Muses, to whom his future life was to be devoted, and covered over:—

It is now impossible to ascertain with any degree of certainty the mode which was adopted in the education of this aspiring genius; all that time has left us on the subject is, that he was sent, though but [25]for a short period, to the free-school of Stratford, a seminary founded in the reign of Henry the Sixth, by the Rev. —— Jolepe, M. A., a native of the town; and which, after sharing, at the general dissolution of chantries, religious houses, &c. the usual fate, was restored and patronised by Edward the Sixth, a short time previous to his death. Here it was, that he acquired the small Latin and less Greek, which Jonson has attributed to him, a mode of phraseology from which it must be inferred, that he was at least acquainted with both languages; and, perhaps, we may add, that he who has obtained some knowledge of Greek, however slight, may, with little hesitation, be supposed to have proceeded considerably beyond the limits of mere elementary instruction in Latin.

At the period when Shakspeare was sent to school, the study of the classical languages had made, since the era of the revival of literature, a very rapid progress. Grammars and Dictionaries, by various authors, had been published[25:A]; but the grammatical institute then in general use, both in town and country, was the Grammar of Henry [26]the Eighth, which, by the order of Queen Elizabeth, in her Injunctions of 1559, was admitted, to the exclusion of all others: "Every schoolmaster," says the thirty-ninth Injunction, "shall teach the grammar set forth by King Henrie the Eighth, of noble memorie, and continued in the time of Edward the Sixth, and none other;" and in the Booke of certain Cannons, 1571, it is again directed, "that no other grammar shall be taught, but only that which the Queen's Majestie hath commanded to be read in all schooles, through the whole realm."

With the exception of Wolsey's Rudimenta Grammatices, printed in 1536, and taught in his school at Ipswich, and a similar work of Collet's, established in his seminary in St. Paul's churchyard, this was the grammar publicly and universally adopted, and without doubt the instructor of Shakspeare in the language of Rome.

Another initiatory work, which we may almost confidently affirm him to have studied under the tuition of the master of the free-school at Stratford, was the production of one Ockland, and entitled ΕΙΡΗΝΑΡΧΙΑ, sive Elizabetha. The object of this book, which is written in Latin verse, is to panegyrise the characters and government of Elizabeth and her ministers, and it was, therefore, enjoined by authority to be read as a classic in every grammar-school, and to be indelibly impressed upon the memory of every young scholar in the kingdom; "a matchless contrivance," remarks Bishop Hurd, "to imprint a sense of loyalty on the minds of the people."[26:A]

To these school-books, to which, being introduced by compulsory edicts, there is no doubt Shakspeare was indebted for some learning and much loyalty, may be added, as another resource to which he was directed by his master, the Dictionary of Syr Thomas Elliot, declaring Latin by English, as greatly improved and enriched by Thomas Cooper in 1552. This lexicon, the most copious and celebrated of its day, was received into almost every school, and underwent numerous editions, namely, in 1559, and in 1565, under the title of Thesaurus Linguæ Romanæ et Britannicæ, and again in 1573, 1578, and [27]1584. Elizabeth not only recommended the lexicon of Cooper, and professed the highest esteem for him, in consequence of the great utility of his work toward the promotion of classical literature, but she more substantially expressed her opinion of his worth by promoting him to the deanery of Gloucester in 1569, and to the bishoprics of Lincoln and Winchester in 1570 and 1584, at which latter see he died on the 29th of April, 1594.[27:A]

Thus far we may be allowed, on good grounds, to trace the very books which were placed in the hands of Shakspeare, during his short noviciate in classical learning; to proceed farther, would be to indulge in mere conjecture, but we may add, and with every just reason for the inference, that from these productions, and from the few minor classics which he had time to study at this seminary, all that the most precocious genius, at such a period of life, and under so transient a direction of the mind to classic lore, could acquire, was obtained.[27:B]

[28]The universality of classical education about the era of 1575, when, it is probable, Shakspeare had not long entered on the acquisitions of the Latin elements, was such that no person of rank or property could be deemed accomplished who had not been thoroughly imbued with the learning and mythology of Greece and Rome. The knowledge which had been previously confined to the clergy or professed scholars, became now diffused among the nobility and gentry, and even influenced, in a considerable degree, the minds and manners of the softer sex. Elizabeth herself led the way in this career of erudition, and she was soon followed by the ladies of her court, who were taught, as Warton observes, not only to distil strong waters, but to construe Greek.[28:A]

The fashion of the court speedily became, to a certain extent, the fashion of the country, and every individual possessed of a decent competency, was solicitous that his children should acquire the literature in vogue. Had the father of our poet continued in prosperous circumstances, there is every reason to conclude that his son would have had the opportunity of acquiring the customary erudition of the times; but we have already seen, that in 1579 he was so reduced in fortune, as to be excused a weekly payment of 4d., a state of depression which had no doubt existed some time before it attracted the notice of the corporation of Stratford.

One result therefore of these pecuniary difficulties was the removal of young Shakspeare from the free-school, an event which has occasioned, among his biographers and numerous commentators, much controversy and conjecture as to the extent of his classical attainments.

From the short period which tradition allows us to suppose that our poet continued under the instruction of a master, we have a right [29]to conclude that, notwithstanding his genius and industry, he must necessarily have made a very superficial acquaintance with the learned languages. That he was called home to assist his father, we are told by Mr. Rowe; and consequently, as the family was numerous and under the pressure of poverty, it is not likely that he found much time to prosecute what he had commenced at school. The accounts, therefore, which have descended to us, on the authority of Ben Jonson, Drayton, Suckling, &c. that he had not much learning, that he depended almost exclusively on his native genius, (that his Latin was small and his Greek less,) ought to have been, without scruple, admitted. Fuller, who was a diligent and accurate enquirer, has given us in his Worthies, printed in 1662, the most full and express opinion on the subject. "He was an eminent instance," he remarks, "of the truth of that rule, Poeta non fit, sed nascitur; one is not made but born a poet. Indeed his learning was very little, so that as Cornish diamonds are not polished by any lapidary, but are pointed and smoothed even as they are taken out of the earth, so nature itself was all the art which was used upon him."[29:A]

Notwithstanding this uniform assertion of the contemporaries and immediate successors of Shakspeare, relative to his very imperfect knowledge of the languages of Greece and Rome, many of his modern commentators have strenuously insisted upon his intimacy with both, among whom may be enumerated, as the most zealous and decided on this point, the names of Gildon, Sewell, Pope, Upton, Grey, and Whalley. The dispute, however, has been nearly, if not altogether terminated, by the Essay of Dr. Farmer on the Learning of Shakspeare, who has, by a mode of research equally ingenious and convincing, clearly proved that all the passages which had been triumphantly brought forward as instances of the classical literature of Shakspeare, were taken from translations, or from original, and once popular, productions in his native tongue. Yet the conclusion drawn from this essay, so far as it respects the portion of latinity which our poet had [30]acquired and preserved, as the result of his school-education, appears to us greatly too restricted. "He remembered," says the Doctor, "perhaps enough of his school-boy learning to put the Hig, hag, hog, into the mouth of Sir Hugh Evans:" and might pick up in the writers of the time, or the course of his conversation, a familiar phrase or two of French or Italian: but his studies were most demonstratively confined to nature and his own language.[30:A]

A very late writer, in combating this part of the conclusion of Dr. Farmer, has advanced an opinion in several respects so similar to our own, that it will be necessary, in justice to him and previous to any further expansion of the idea which we have embraced, to quote his words. "Notwithstanding," says he, "Dr. Farmer's essay on the deficiency of Shakspeare in learning, I must acknowledge myself to be one who does not conceive that his proofs of that fact sufficiently warrant his conclusions from them: 'that his studies were demonstrably confined to nature and his own language' is, as Dr. Farmer concludes, true enough; but when it is added, 'that he only picked up in conversation a familiar phrase or two of French, or remembered enough of his school-boy's learning to put hig, hag, hog, in the mouths of others:' he seems to me to go beyond any evidence produced by him of so little knowledge of languages in Shakspeare. He proves indeed sufficiently, that Shakspeare chiefly read English books, by his copying sometimes minutely the very errors made in them, many of which he might have corrected, if he had consulted the original Latin books made use of by those writers: but this does not prove that he was not able to read Latin well enough to examine those originals if he chose; it only proves his indolence and indifference about accuracy in minute articles of no importance to the chief object in view of supplying himself with subjects for dramatic compositions. Do we not every day meet with numberless instances of similar and much greater oversights by persons well skilled in Greek as well as Latin, and professed critics also of the writings and abilities [31]of others? If Shakspeare made an ignorant man pronounce the French word bras like the English brass, and evidently on purpose, as being a probable mistake by such an unlearned speaker; has not one learned modern in writing Latin made Paginibus of Paginis, and another mentioned a person as being born in the reign of Charles the First, and yet as dying in 1600, full twenty-five years before the accession of that king? Such mistakes arise not from ignorance, but a heedless inattention, while their thoughts are better occupied with more important subjects; as those of Shakspeare were with forming his plots and his characters, instead of examining critically a great Greek volume to see whether he ought to write on this side of Tiber or on that side of Tiber; which however very possibly he might not be able to read; but Latin was more universally learnt in that age, and even by women, many of whom could both write and speak it; therefore it is not likely that he should be so very deficient in that language, as some would persuade us, by evidence which does not amount to sufficient proofs of the fact. Nay, even although he had a sufficiency of Latin to understand any Latin book, if he chose to do it, yet how many in modern times, under the same circumstances, are led by mere indolence to prefer translations of them, in case they cannot read Latin with such perfect ease, as never to be at a loss for the meaning of a word, so as to be forced to read some sentences twice over before they can understand them rightly. That Shakspeare was not an eminent Latin scholar may be very true, but that he was so totally ignorant as to know nothing more than hic, hæc, hoc, must have better proofs before I can be convinced."[31:A]

The truth seems to be, that Shakspeare, like most boys who have spent but two or three years at a grammar-school, acquired just as much Latin as would enable him, with the assistance of a lexicon, and no little share of assiduity, to construe a minor classic; a degree of acquisition which we every day see, unless forwarded by much leisure and much private industry, immediately becomes stationary, and [32]soon retrograde. Our poet, when taken from the free-school of Stratford, had not only to direct his attention to business, in order to assist in warding off from his father's family the menacing approach of poverty; but it is likewise probable that his leisure, as we shall notice more at large in the next chapter, was engaged in other acquisitions; and when at a subsequent period, and after he had become a married man, his efforts were thrown into a channel perfectly congenial to his taste and talents, still to procure subsistence for the day was the immediate stimulus to exertion. Under these circumstances, and when we likewise recollect that popular favour and applause were essential to his success, and that nearly to the last period of his life he was a prolific caterer for the public in a species of poetry which called for no recondite or learned resources, it is not probable, nay, it is, indeed, scarcely possible, that he should have had time to cultivate and increase his classical attainments, originally and necessarily superficial. To translations, therefore, and to popular and legendary lore, he was alike directed by policy, by inclination, and by want of leisure; yet must we still agree, that, had a proficiency in the learned languages been necessary to his career, the means resided within himself, and that, on the basis merely of his school-education, although limited as we have seen it, he might, had he early and steadily directed his attention to the subject, have built the reputation of a scholar.

That the powers, however, of his vast and capacious mind, especially if we consider the shortness of his life, were not expended on such an attempt, we have reason to rejoice; for though his attainments, as a linguist, were truly trifling, yet his knowledge was great, and his learning, in the best sense of the term, that is, as distinct from the mere acquisition of language, multifarious, and extensive beyond that of most of his contemporaries.[32:A] [33]

It is, therefore, to his English studies that we must have recourse for a due estimate of his reading and research; a subject which will be treated of in a future portion of the work.

FOOTNOTES:

[21:A] It is with some apprehension of imposition that I quote the following passage from Mr. Samuel Ireland's Picturesque Views on the River Avon. This gentleman, the father of the youth who endeavoured so grossly to deceive the public by the fabrication of a large mass of MSS. which he attributed to Shakspeare, was undoubtedly, at the time he wrote this book, the complete dupe of his son; and though, as a man of veracity and integrity, to be depended upon with regard to what originated from himself, it is possible, that the settlement which he quotes may have been derived from the same ample store-house of forgery which produced the folio volume of miscellaneous papers, &c. This settlement, in the possession of Mr. Ireland, is brought forward as a proof that the premises in Henley-street were certainly in the occupation of John Shakspeare, the father of the poet; it is dated August 14th, thirty-third of Elizabeth, 1591, and Mr. Ireland professes to give the substance of it in the subsequent terms:—"'That George Badger, senior, of Stratford upon Avon, conveys to John and William Courte, yeomen, and their heirs, in trust, &c. a messuage or tenement, with the appurtenances, in Stratford upon Avon, in a certain streete called Henley-streete, between the house of Robert Johnson on the one part, and the house of John Shakspeare on the other; and also two selions (i. e. ridges, or ground between furrows) of land lying between the land of Thomas Combe, Gent. on the one hand, and Thomas Reynolde, Gent. on the other.' It is regularly executed, and livery of seisin on the 29th of the same month and year indorsed." P. 195, 196.

[22:A] "In a lower room of this public house," says Mr. Samuel Ireland, "which is part of the premises wherein Shakspeare was born, is a curious antient ornament over the chimney, relieved in plaister, which, from the date, 1606, that was originally marked on it, was probably put up at the time, and possibly by the poet himself: although a rude attempt at historic representation, I have yet thought it worth copying, as it has, I believe, passed unnoticed by the multitude of visitors that have been on this spot, or at least has never been made public: and to me it was enough that it held a conspicuous place in the dwelling-house of one who is himself the ornament and pride of the island he inhabited. In 1759, it was repaired and painted in a variety of colours by the old Mr. Thomas Harte before-mentioned, who assured me the motto then round it had been in the old black letter, and dated 1606. The motto runs thus:

Picturesque Views, p. 192, 193.

[23:A] Picturesque Views, p. 189, 190. It is probable that Mr. Ireland, though, it appears, unconnected with the forgeries of his son, might, during his tour, be too eager in crediting the tales which were told him. One Jordan, a native of Alverton near Stratford, was for many years the usual cicerone to enquirers after Shakspeare, and was esteemed not very accurate in weighing the authenticity of the anecdotes which he related.

[24:A] Reed's Shakspeare, vol. i. p. 84, 85.

[25:A] It is possible also that the following grammars and dictionaries, independent of those mentioned in the text, may have contributed to the school-education of Shakspeare:—

1. Certain brief Rules of the Regiment or Construction of the Eight Partes of Speche, in English and Latin, 1537.

2. A short Introduction of Grammar, generallie to be used: compiled and set forth, for the bringyng up of all those that intend to attaine the knowledge of the Latin tongue, 1557.

3. The Scholemaster; or, Plaine and perfite Way of teaching Children to understand, write, and speak, the Latin Tong. By Roger Ascham. 1571.

4. Abecedarium Anglico-Latinum, pro tyrunculis, Ricardo Huloeto exscriptore, 1552.

5. The Short Dictionary, 1558.

6. A little Dictionary; compiled by J. Withals, 1559. Afterwards reprinted in 1568, 1572, 1579, and 1599; and entitled, A Shorte Dictionarie most profitable for young Beginners: and subsequently, A Shorte Dictionarie in Lat. and English.

7. The brefe Dyxcyonary, 1562.

8. Huloets Dictionary; newlye corrected, amended, and enlarged, by John Higgins, 1572.

9. Veron's Dictionary; Latin and English, 1575.

10. An Alvearie, or Quadruple Dictionarie; containing foure sundrie Tongues: namelie, English, Latine, Greeke, and Frenche. Newlie enriched with varietie of wordes, phrases, proverbs, and divers lightsome observations of grammar. By John Baret, 1580.

11. Rider's Dictionary, Latine, and English, 1589.

[26:A] Moral and Political Dialogues, vol. ii. p. 28. edit. 1788.

[27:A] That school-masters and lexicographers were not usually so well rewarded, notwithstanding the high value placed on classical literature at this period, may be drawn from the complaint of Ascham: "It is pitie," says he, "that commonlie more care is had, yea, and that amonge verie wise men, to find out rather a cunnynge man for their horse, than a cunnynge man for their children. They say nay in worde, but they do so in deede. For, to the one they will gladlie give a stipend of 200 crownes by yeare, and loth to offer to the other 200 shillings. God, that sitteth in heaven, laugheth their choice to skorne, and rewardeth their liberalitie as it should; for he suffereth them to have tame, and well ordered horse, but wilde and unfortunate children; and therefore, in the ende, they finde more pleasure in their horse than comforte in their children."—Ascham's Works, Bennet's edition, p. 212.

[27:B] It is more than possible that the Eclogues of Mantuanus the Carmelite may have been one of the school-books of Shakspeare. He is familiarly quoted and praised in the following passage from Love's Labour's Lost:—

"Hol. Fauste, precor gelidâ quando pecus omne sub umbrâ Ruminat,—and so forth. Ah, good old Mantua! I may speak of thee as the traveller doth of Venice:

Old Mantuan! old Mantuan! who understandeth thee not, loves thee not." Act iv. sc. 2. And his Eclogues, be it remembered, were translated and printed, together with the Latin on the opposite page, for the use of schools, before the commencement of our author's education; and from a passage quoted by Mr. Malone, from Nashe's Apologie of Pierce Penniless, 1593, appear to have continued in use long after its termination. "With the first and second leafe, he plaies very prettilie, and, in ordinarie terms of extenuating, verdits Pierce Pennilesse for a grammar-school wit; saies, his margine is as deeply learned as, Fauste, precor gelidâ." Mantuanus was translated by George Turberville in 1567, and reprinted in 1591.—Vide Reed's Shakspeare, vol. vii. p. 95.

[28:A] Warton's History of English Poetry, vol. iii. p. 491.

[29:A] Worthies, p. iii. p. 126.

[30:A] Reed's Shakspeare, vol. ii. p. 85.

[31:A] Censura Literaria, vol. ix. p. 285.

[32:A] "If it were asked from what sources," observes Mr. Capel Lofft, "Shakspeare drew these abundant streams of wisdom, carrying with their current the fairest and most unfading flowers of poetry, I should be tempted to say, he had what would be now considered a very reasonable portion of Latin; he was not wholly ignorant of Greek; he had a knowledge of the French, so as to read it with ease; and I believe not less of the Italian. He was habitually conversant in the chronicles of his country. He lived with wise and highly cultivated men; with Jonson, Essex, and Southampton, in familiar friendship. He had deeply imbibed the Scriptures. And his own most acute, profound, active, and original genius (for there never was a truly great poet, nor an aphoristic writer of excellence without these accompanying qualities) must take the lead in the solution." Aphorisms from Shakspeare: Introduction, pp. xii. and xiii.

Again, in speaking of his poems, he remarks—"Transcendent as his original and singular genius was, I think it is not easy, with due attention to these poems, to doubt of his having acquired, when a boy, no ordinary facility in the classic language of Rome; though his knowledge of it might be small, comparatively, to the knowledge of that great and indefatigable scholar, Ben Jonson. And when Jonson says he had 'less Greek,' had it been true that he had none, it would have been as easy for the verse as for the sentiment to have said 'no Greek.'"—Introduction, p. xxiv.

SHAKSPEARE, AFTER LEAVING SCHOOL, FOLLOWS HIS FATHER'S TRADE—STATEMENT OF AUBREY—PROBABLY PRESENT IN HIS TWELFTH YEAR, AT KENELWORTH, WHEN ELIZABETH VISITED THE EARL OF LEICESTER—TRADITION OF AUBREY CONCERNING HIM—WHETHER THERE IS REASON TO SUPPOSE THAT, AFTER LEAVING HIS FATHER, HE WAS PLACED IN AN ATTORNEY'S OFFICE WHO WAS LIKEWISE SENESCHAL OR STEWARD OF SOME MANOR—ANECDOTES OF SHAKSPEARE—ALLUSIONS IN HIS WORKS TO BARTON, WILNECOTTE AND BARSTON, VILLAGES IN WARWICKSHIRE—EARTHQUAKE IN 1580 ALLUDED TO—WHETHER, AFTER LEAVING SCHOOL, HE ACQUIRED ANY KNOWLEDGE OF THE FRENCH AND ITALIAN LANGUAGES.