THE

SOMME

VOLUME 2.

THE SECOND BATTLE OF THE SOMME

(1918)

(AMIENS, MONTDIDIER, COMPIÈGNE)

MICHELIN & CIE —CLERMONT-FERRAND.

MICHELIN TYRE CO LTD —81, FULHAM ROAD, LONDON, S. W

MICHELIN TIRE CO —MILLTOWN. N.J. U.S.A.

AMIENS

Hôtel du Rhin, 4, rue de Noyon. Tel. 44.

Belfort-Hôtel, 42, rue de Noyon. Tel. 649.

Hôtel de l'Univers, 2, rue de Noyon. Tel. 2.51.

Hôtel de la Paix, 15, rue Duméril. Tel. 9.21.

Hôtel de l'Ecu de France, 51, place René-Goblet. Tel. 3.37.

COMPIÈGNE

Hôtel du Rond-Royal, av. Thiers. I Rond-Royal. Tel. 4.15.

Palace-Hôtel, place du Palais. I Palace, Tel. 1.15.

Hôtel de la Cloche, 27, place de l'Hôtel-de-Ville. Tel. 0.85.

Hôtel de Flandre, 2, rue d'Amiens. Tel. 36.

The above information, extracted from the MICHELIN TOURIST GUIDE (1920), may no longer be exact when it meets the reader's eye. Tourists are therefore recommended to consult the MICHELIN TOURING OFFICES, 81, Fulham Rd., London. S.W. 3, or 99, Boulevard Pereire, Paris, 17e.

AN INDISPENSABLE AUXILIARY:

The Michelin Map

On sale

at booksellers

and

MICHELIN

stockists.

For the

present

GUIDE,

take sheet

no 6.

MOTORISTS

this map

was made

specially

for you.

The "Michelin Wheel"

BEST of all detachable wheels

because the least complicated

Smart

It embellishes even the finest coachwork.

Simple

It is detachable at the hub and fixed by six bolts only.

Strong

The only wheel which held out on all fronts during the War.

Practical

Can be replaced in 3 minutes by anybody and cleaned still quicker.

It prolongs the life of tyres by cooling them.

AND THE CHEAPEST

In Memory

of the Michelin Workmen and Employees

who died gloriously for their Country.

THE

SOMME.

VOLUME II.

The Second Battle of the Somme

(1918)

AMIENS—MONTDIDIER—COMPIÈGNE.

Compiled and published by

MICHELIN & Cie., Clermont-Ferrand, France.

All rights of translation, adaptation or reproduction (in part or

whole) reserved in all countries

The Front Line,

March 21, 1918.

At different periods during the War, important events took place in the Plains of Picardy, in the region which extends between Amiens and St. Quentin, Bapaume and Noyon, between the valleys of the rivers Ancre, Avre and Oise.

The Franco-British Offensive of July-September 1916, and the German Retreat of March 1917, are described in the Michelin Guide "The First Battle of the Somme, 1916-1917", which includes carefully prepared itineraries, enabling the reader to cover the whole battlefield of that period.

The present guide describes the operations which took place in Picardy in March-April 1918 (The German Offensive), and in August 1918 (The Franco-British Offensive); in a Word, the ebb and flow of the German Armies in 1918, from St. Quentin to Montdidier.

Driven from the banks of the Somme by the Franco-British Offensive of 1916, the Germans were compelled, in March 1917, to retreat, before the menace of the Allied offensives on their flank.

They then established themselves on the Hindenburg Line, and in 1917, in consequence of British attacks in the Arras sector and before Cambrai, they unceasingly increased the number of their fortified lines. This redoubtable position stretched to the west of the Cambrai-La Fère road, via Le Catelet and St. Quentin, utilising a series of natural obstacles, the most important of which were the Escaut, the St. Quentin Canal and the marshy valley of the Oise. (See the Michelin Guide "The Hindenburg Line".)

But in the early days of 1918, having crushed Russia, Germany decided to assume the offensive, using the Hindenburg positions as a kind of spring-board, from which her mighty armies rushed forward to conquer France.

In February 1918, the British positions extended in front of the Hindenburg Line, as far as the village of Barisis, opposite the Forest of St. Gobain, to the south of the Oise. Three successive positions, widely separated from one another, had been actively strengthened. Moreover, the water-lines of the marshy valley of the Oise, the Crozat Canal, the loop in the Somme, and the North Canal, formed so many natural obstacles.

The Picardian Plain, with its broad and gentle undulations, dotted here and there with small woods, is closed, on the south, near the valley of the Oise, by the wooded hills of Genlis, Frières and La Cave, and to the west of the bend in the Oise, by the hills of Porquericourt and the wooded massif of Le Plémont, with its promontory, Mount Renaud, to the south of Noyon. Further west, the high ground of Boulogne-la-Grasse does not close the Plain of Santerre, which, between the slopes of Le Plémont and Montdidier, communicates freely with the Plain of Ile-de-France. The enclosed and wooded valleys of the rivers Avre, Trois-Doms and Luce intersect the tablelands of Santerre. Further north, stretches the old battlefield of 1916,—a chaotic waste of winding trenches and barbed wire entanglements.

In the Picardian Plain, beyond the bounds of the old battlefield, were numerous country villages, with their cottages grouped around the church. The long, straight roads, bordered with fine elms or fruit-trees, stretched as far as the eye could reach. This rich and prosperous region, with its vast fields of corn and beet, was completely ravaged by the War.

The Allied Offensive: Reducing the Pocket as far as the Hindenburg Line

(August 8-September 25.).

The Opposing Forces—Their Material and Moral Strength.

Towards the end of 1917, the abandonment of the Allies, by Russia, was consummated by the Russo-German Armistice of December 20, followed by the Peace of Brest-Litowsk, of February 9, 1918. As early as November 1917, Germany began to transfer her legions from the eastern to the western front. Arriving, via Belgium, in ever-increasing numbers, sixty-four new divisions were thus added to her Western Armies, already one hundred and forty-one divisions strong, giving a total strength of 205 German divisions against the Allies' 177 divisions.

The material resources, accumulated on the Russian front, were likewise transferred to the western front. The enemy's artillery was reinforced all along the line, the number of heavy batteries being doubled in many of the sectors.

Besides this numerical and material superiority, Germany possessed [Pg 7] the additional advantage of a unique commander: Ludendorff, master of the hour, at once absolute military chief and political dictator. On the other hand, whilst the Allies were closely united by cordial friendship, sealed on the field of battle, their armies were independant units, separately commanded, each having its own reserves concentrated behind its particular front.

On February 3, 1917, the United States of America ranged themselves on the side of the Allies, but their eventually powerful effort could not make itself seriously felt before the summer of 1918. In March 1918, four American divisions were in France, and a million more men were expected by the following Autumn, but the Germans were convinced that they would have the Allies beaten before then.

The moral strength of the opposing forces constituted one of the most important factors of victory.

During 1917, after the Allies' Spring Offensives, a wave of lassitude had lowered the fighting spirit of certain units of the French Army. However, the morale of the French Army had fully regained its former high level, when the great German offensive of March 1918 was launched.

The British Army had in the meantime perfected its training, and acquired, in addition to experience, splendid fighting qualities.

The Germans, badly shaken in 1916 by their failure at Verdun and by the Allies' Offensive on the Somme, had, in consequence of Russia's collapse, recovered all their former arrogant confidence and pride.

But the Allies' blockade, despite Germany's ruthless submarine warfare, tightened, and each day the menace of famine increased.

Triumphal announcements of victory, and promises of an early German peace appeared periodically in their press, yet still the war dragged on. Something had to be done to end it all, whatever the cost, and so the "Peace Offensive" was decided on.

Although inferior in numbers and equipment, the Allies had acquired moral superiority.

In all the previous offensives, especially that of the Somme in 1916, the artillery had been used, prior to the attack, to destroy the adversary's defences. The great number of fortified works and their ever increasing strength necessitated a proportionately longer and more intense artillery preparation. Thus warned, the enemy were able to make dispositions to counteract the effects of the attack, and to bring up reinforcements.

Moreover, the tremendous pounding of the ground greatly hampered the advance of the storming troops, who were hindered at every step by the enormous shell-holes and craters.

Breaking away from past errors, and adopting and perfecting the methods inaugurated the previous year before Riga, the German High Command attacked by surprise, in March 1918, thereby securing a crushing numerical superiority. The Allies were thrown into confusion, and all attempts at resistance were unavailing, until the arrival of the reserves. During this period of complete demoralisation, the enemy were able to exploit their initial success to the full.

The method employed was that of a sudden, violent shock, preceded by a short artillery preparation, mostly with smoke and gas shells, the aim of which was to put the men out of action, rather than to crush the defences. To this end, huge concentrations of troops were effected, in such wise that the masses of men could be thrown quickly and secretly at the presumed weak part of the Allies' front.

The semi-circular disposition of the front facilitated the enemy's task, as the German reserves, grouped in the Hirson-Mézières region, in the centre of the semi-circle, could be used with the same rapidity against any part of the front-line from Flanders to Champagne.

The point chosen by Ludendorff was the junction of the Franco-British Armies. To separate these two groups, by driving back the British, on the right, and the French, on the left; to exploit the initial success in the direction of the sea, isolating the British and forcing them back upon their naval bases of Calais and Dunkirk; then, having crushed the British, to concentrate the whole of his efforts against the French, who, unsupported and demoralized, would soon be driven to their knees,—such was apparently the strategical conception of the enemy's "Kaiserschlacht" or "Emperor's Battle".

The Opposing Forces.

On March 21, three German armies attacked along a 54-mile front, from the Scarpe to the Oise.

In the north, the XVIIth Army (von Below) and the IInd Army (von Marwitz) attacked on either side of the Cambrai salient, but the main effort was made by the XVIIIth Army (von Hutier), which stretched from the north of St. Quentin to the Oise.

Facing these armies were: the right of the British 3rd Army (Byng), extending from the Scarpe to Gouzeaucourt, and the British 5th. Army (Gough), from Gouzeaucourt to south of the Oise.

The British expected the brunt of the attack to fall between the river Sensée and the Bapaume-Cambrai road, i.e. on the right of Byng's Army, which was reinforced accordingly, whilst the sector in front of the Oise, south of St. Quentin, against which von Hutier's huge army had been concentrated, was only held by 4 divisions.

More than 500,000 Germans were about to attack the 160,000 British under Gough and Byng, whilst from the outset of the battle, large enemy reserves swelled the number of the attacking divisions to 64, i.e., more than the total number of British divisions in France. In all, no less than 1,150,000 Germans were engaged in these tremendous onslaughts.

During the five nights which preceded the attack, the German divisions had been brought up secretly, the artillery having previously taken up its positions and corrected its range, without augmenting the volume of firing, so that nothing revealed the increased number of the batteries.

The shock troops, after several weeks of intensive training, were brought up by night marches to the points of attack. During the day, they were kept out of sight in the woods or villages. At night, whether on the march or bivouacking, lights and fires were strictly forbidden. Aeroplanes hovered above the columns to see that these orders were carried out. The ammunition parks and convoys were concealed in the woods. Until the last moment, the troops and most of the officers were kept in ignorance of their destination.

These huge forces moving silently under the cover of night, symbolized the enemy's might and cunning. "It is strange", wrote a German officer in his note-book, "to think of these huge masses of troops—all Germany on the march—moving westward to-night".

On March 21, during this, the "Einbruch" or piercing stage, the enormous enemy mass crushed, in less than 48 hours, the three British positions situated in front of St. Quentin. Carrying the battle into the open country beyond, the enemy transformed the "piercing" into a break-through ("Durchbruch").

This sudden, powerful thrust was followed by a "tidal wave" of German infantry which at first submerged all before it, but which, dammed by degrees, finally spent itself, a week later, against the Allies' new front.

On March 21, at daybreak (4.40 a.m.) a violent cannonade broke out, and for five hours the intensity of this drum-fire steadily increased.

First, a deluge of shells, mostly gas, pounded the British batteries, some of which were silenced. Then the bombardment ploughed up the first positions, spreading dense clouds of gas and fumes over a wide zone.

"Michael" hour.

Under cover of the smoke and fog, the German Infantry speedily crossed No-Man's Land, and at 9.30 a.m. ("Michael" hour) penetrated the British defences.

The front assigned to each attacking division was only two kilometres wide, the troops being formed into two storm columns of one regiment each. The third regiment was kept as sector reserves, to develop initial successes.

The storm-troops, led by large numbers of non-commissioned officers, advanced in waves, shoulder-to-shoulder, preceded by a rolling barrage some 300 yards ahead of the first line. This barrage afterwards moved forward at the rate of about 200 yards every five minutes.

The waves advanced resolutely, protected first by the rolling barrage, then by the accompanying artillery and Minenwerfer. Wherever the resistance was too strong, a halt was made, allowing the neighbouring waves to outflank the obstacle on either side, and crush it.

The Germans straightway threw the greatest possible mass of infantry into the Allies' defences.

Amid clouds of gas, smoke and fog, the British in the advanced [Pg 11] positions were surrounded and overwhelmed, often before they had realized what was happening.

Nearly all their machine-guns, posted to sweep the first zone, were put out of action.

The First Day (March 21).

The first day of the attack, General Byng's Army from Fontaine-les-Croisilles to Demicourt, withstood the shock steadily, the Germans penetrating the first lines only.

In the centre, before St. Quentin, and to the south, in front of Moy and La Fère, General Gough's Army, overwhelmed by numbers, and notwithstanding the courage of the men, was broken early in the attack.

Opposite Le Catelet, the enemy storm divisions advanced 6 to 8 kilometres, penetrating at noon the second-line positions along the Epéhy-Le Verguier line. Further south, in front of Moy, they reached Essigny-Fargnières.

General Gough withdrew his right behind the water-line of the Crozat and Somme Canals.

The Second Day—March 22.

Tergnier fell, and the water-line was turned from the right. Still favoured by the fog, the Germans crossed the Crozat Canal. Fresh divisions harassed the British without respite, the losses, both in men and material, being very heavy.

Their reserves, greatly outnumbered, were quickly submerged, and the third positions were lost after a desperate but ineffectual resistance.

In spite of its stubborn resistance, the 3rd Army (Byng) was forced to fall back, pivoting on its left, to line up with the retreating 5th Army (Gough).

The enemy advance developed rapidly. Within forty-eight hours, over 60 German divisions (750,000 men) had been thrown into the battle, which now raged in the open.

The crushing of the right and centre of the British 5th Army opened a large breach north of the Oise, through which, as early as March 21, the Germans streamed south and west. The situation was critical, as the enemy hordes, having broken through the fortified zone, threatened to submerge all before them. Prompt intervention was imperative, in order to retard the enemy at all cost.

As early as the evening of the 21st, General Pétain made dispositions to support the British right. The 9th and 10th Div. (5th Corps) and the 1st Div. of unmounted Cuirassiers (Pellé), in reserve near Compiègne, received orders to hold themselves in readiness. At the same time, the staff of Gen. Fayolle's Army Group, and that of Gen. Humbert's Army, prepared to take over the direction of the operations.

The 125th Inf. Div. was pushed forward to the Oise, whilst the 22nd, 62nd, and 1st. Cavalry. Divn. (Robillot's Group) were rapidly despatched to the weak points of the battle line.

This newly formed group was placed under the command of Gen. Robillot of the 2nd Cavalry Corps.

Rushed up in lorries, the first French divisions were thrown into the thick of the battle without waiting for their artillery. Heroism often made good the lack of equipment and munitions.

Once the fortified zone crossed, the German armies pushed westward rapidly.

On March 23, the French Cavalry Divisions were engaged, with their armoured cars and groups of cyclists. Thanks to their great mobility, the situation was repeatedly saved. Galloping from breach to breach, the Cavalry, dismounting, stayed the enemy advance until the arrival of the infantry.

The armoured cars raided the enemy's lines unceasingly and harassed their troops with machine-gun fire. They were also used for bringing up supplies to the first-line troops and for maintaining the different liaisons. Their splendid work, with that of the Cyclist Corps, greatly helped to stay the enemy thrust.

The retreat of the British was also covered by detachments of cavalry, mounted artillery, armoured cars and tanks, which vigorously attacked the assaillants.

The Air Service likewise rendered invaluable aid.

On the evening of the 22nd, General Pétain gave orders for every available bombing plane to be used to retard the enemy advance, until reinforcements could be brought up. The air squadrons met a few hours later at the assigned point, some of them having flown ninety miles. On the way, they dropped their loads of bombs on German troops which were crossing the Somme, north of Ham, thereby retarding the advance of two enemy divisions which were preparing to outflank the British.

On the 23rd, at noon, a hundred aeroplanes, skimming just over the Germans' heads, wrought indescribable havoc and confusion in their ranks. Priceless hours were thus gained.

Whilst Byng's Army withstood the enemy's onslaughts, that commanded by Gough was dislocated by the powerful thrust of von Hutier's Army.

On the morning of the 23rd, the remnants of the British 3rd and 18th Corps were thrown back across the Crozat Canal, among the French divisions which were taking part in the battle between the Somme and Oise, and with which they were assimilated.

Further north, his divisions heavily depleted, and reinforcements coming up only slowly, General Gough abandoned the strong Somme-Tortille line, and continued his retreat westward, towards his reserves in the old battlefield of 1916.

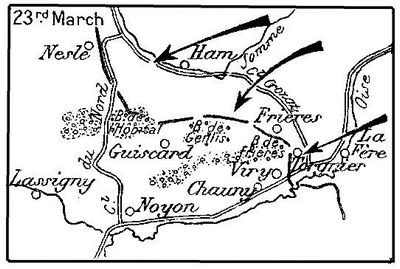

The same day, the first French units to arrive were thrown between Crozat Canal and the woods of Genlis and Frières, linking up, on their right, with the 125th Division, detached from the left of the 6th Army, and established astride of the Oise, in front of Viry. (Sketch below).

The 1st Division of dismounted Cuirassiers (Brécart) vigorously attacked the enemy, and succeeded in staying their thrust towards the Oise. The 9th Division (Gamelin) barred the Ham-Noyon road, along a ten mile front. On their left, the 10th Division (Valdant) held the zone north of Guiscard.

On the evening of the 23rd, the situation was critical. General Pellé's divisions retarded the German advance in front of the Chauny-Noyon region, which they were covering, but the enemy held Ham. In their retreat, the British constantly bore to the north-west.

The 1st Cavalry Division (Rascas), and the 22nd (Capdepont) and 62nd (Margot) Divisions arrived, and were thrown into the battle between Guiscard and Nesle, where they attempted to join hands with the [Pg 15] French 10th Division on their right and with the British on their left.

The same day, the German long range "Bertha" guns began to bombard Paris, in the hope of spreading panic and disorder there.

On March 24, the crushing effect of the German thrust was further accentuated by the arrival of new enemy divisions.

Favoured by the fog, which entirely hid the valleys of the Oise and Somme, their advance-guards swept the plain with machine-gun fire, in their search for gaps and weak places in the thin French line.

All the attacks converged towards Noyon. At 9 a.m., in the valley of the Oise, the capture of Viry-Noureuil threatened Chauny, whilst in the centre, Villequier-Aumont and Genlis Wood were taken. Overwhelmed by numbers, the Cuirassiers, after firing their last cartridges, fell back on Caillouel Hill. The divisions on the left took up positions south of Guiscard. In spite of the unequal struggle, the fighting spirit of the troops remained admirable.

On the left of General Pellé's group, between Nesle and Guiscard, the situation was still more desperate, as, having crossed the Somme, the Germans now greatly intensified their thrust. The depleted British units continued their retreat westward, leaving a gap north of Nesle. The French 22nd Div. was hurriedly despatched towards Nesle, and elements of the 1st Cav. Div. to the east of Chaulnes.

On March 24, south of Péronne, the German IInd Army crossed with difficulty the marshy valley of the Somme, then pushing on towards Chaulnes, opened a gap at Pargny.

North of Péronne, the enemy reached Sailly-Saillisel, Rancourt and Cléry in the morning, and pushed west with 3,000 cavalry. In danger of being turned, Byng's Army, which had abandoned the Havrincourt Salient during the night of the 22nd, evacuated Bertincourt and retreated westward.

One of the gravest consequences of the retreat of Gough's Army was the temporary severance of the French from the British. To restore and consolidate the liaison was the constant aim of the French General Staff.

These units coolly withdrew, whenever they found themselves outflanked and in danger of being cut off, often fighting furious rearguard actions, and repulsing the enemy with heavy loss, each time a frontal attack was attempted. (Field-Marshal Haig).

On the contrary, we read in Ludendorff's Memoirs that the German XVIIth Army was exhausted, having suffered too heavy losses before the Cambrai Salient on March 21 and 22.

During the night, the enemy continued to press forward in the fog, in an attempt to rout the precariously installed and ill-supplied French units, and to harass Gough's Army, in retreat towards the Santerre Plateau. On this, Palm Sunday evening, Holy Week opened tragically.

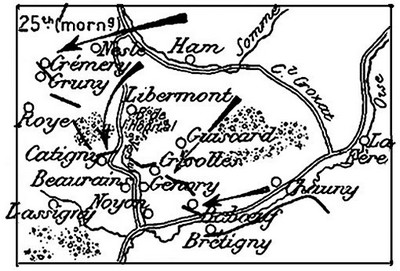

The 25th, at daybreak, fresh German divisions violently attacked the exhausted French units, seeking to turn their left wing, and at the same time crush General Pellé's group in the centre.

In face of the increasing danger, General Pellé received orders to "check the enemy advance, whatever the condition of the men might be".

The 1st Inf. Div. (Grégoire), hastily brought up and reinforced by the remnants of the British 18th Div. and of various French Divisions picked up on the way, established itself on the hills which cover Noyon to the north-east. They had scarcely taken up their positions, when the Germans attacked, only to be repulsed. Further to the left, the enemy were unable to debouch from Crisolles, but on the French right, the 55th and 125th Div., which had been fighting incessantly since the 22nd, were forced back across the Oise, near Brétigny. Pushing on, the Germans captured Babœuf, but a British counter-attack forced them to fall back slightly.

The battle continued to rage and the danger of being outflanked became more and more acute. Catigny and Beaurains fell, leaving Noyon unprotected on the north-west. In the course of a fierce counter-attack, the 144th Inf. Reg. succeeded in recapturing these villages, but the German hordes still pressed on, opening a gap between Beaurains and Genvry, through which they poured, following the little valley of the Verse which slopes down towards Noyon. The troops defending the northern and north-eastern approaches to that town were now threatened with being surrounded.

General Pellé endeavoured to stop this fresh gap with the few units left at his disposal, and organized a new line of support on Porquericourt Hill and Mont Renaud (sketch, p. 18), at the same time urging the troops which were fighting to the north of Noyon to "hold out a few hours longer, each hour being worth a day".

One French division, and units of a second division, comprising some British remnants, were now fighting against odds of four to one.

On the evening of the 25th, they fell back in good order, on Noyon. The 57th Inf. Reg. resisted all night in the town, to enable the final line of resistance to be organized.

At midnight, the front line passed in front of Porquericourt Hill and Mont Renaud, at Pont-l'Évêque, thence following the Oise. It was along this line that Gen. Pellé's Corps had orders to hold the German advance, and bar the road to Paris.

General Humbert declared on the evening of the 25th: The troops of the 5th A.C. and of the 2nd C. of unmounted Cavalry are defending the very heart of France. The consciousness of the grandeur of their task will point out the path of duty to them.

This day (25th) was still more tragical on General Humbert's left. At daybreak, a violent battle broke out around Nesle, the town being abandoned at 11 a.m.

Spread over a too wide front, from Nesle to Guiscard, the troops under Gen. Robillot had orders to maintain the liaison on their right with Gen. Pellé's forces (retreating southward) and on the left with the depleted British units which were falling back to the north-west. The gap widened, and the enemy pressed through. The situation was highly critical, the road to Montdidier being now open.

Despite their desperate resistance and the untiring activity of the 1st Cav. Div. and 2nd Corps—units of which galloped from breach to [Pg 19] breach to re-establish the liaison and retard the enemy onrush—General Robillot's group fell back towards Roye.

South of the Somme, the situation was still more critical. The remains of the British 18th and 19th Corps withdrew to the line Chaulnes-Frise, which they were, however, unable to hold.

Their retreat continued to the line Proyart-Rosières. No more reserves were expected for four days. Should the Germans succeed in crushing these exhausted units the road to Amiens would be open.

About six miles behind the Proyart-Rosières front, there was an old French line, partly filled in, on the Santerre Plateau, between the Somme (at Sailly-le-Sec) and the Luce (at Demuin).

A battalion of Canadian Engineers was ordered to restore it. However, there were no troops to hold it, and as its abandonment would have imperilled Amiens, Gen. Gough decided to muster an emergency detachment of engineers, miners, electricians, mechanics, staff personnel, pupils and instructors from the schools of the 3rd and 5th Armies, and American sappers, in all about 2,200 men. This detachment, under Maj.-Gen. Carey, was ordered to hold an eight-mile front and bar the road to Amiens.

North of the Somme, the Germans attacked from Ervillers to the river; the British left stood firm, whilst on the right, the hinge formed by Byng's Army, likewise resisted. Further south, the Germans captured Maricourt, and broke through the curtain of British troops, which lost contact with one another. The Ancre was crossed, and Byng's right, pivoting on Boyelles, fell back on the line Bucquoy, Albert, Bray-sur-Somme.

General Pétain issued a stirring appeal to the men:

The enemy is attacking in a supreme effort to separate us from the British, and open the road to Paris. At all cost, he must be held. Stick to the ground, stand firm, reinforcements are at hand. United, you will fling yourselves on the invader. Soldiers of the Marne, Yser and Verdun, the fate of France is in your hands.

From all parts of the front, French divisions poured in. Long lines of motor-lorries sped along all the roads converging towards Montdidier. The high spirits and fine bearing of the men reassured the anxious population, who, for several days past, had heard the guns drawing nearer, and seen the endless stream of refugees fleeing before the invader.

General Debeney arrived with his staff from Toul, to take command of the 1st Army (in formation), divisions of which arrived each day.

The 77th. Inf. Div. (d'Ambly) was added to the 3rd Army (Humbert). The operations of these two armies, whose task it was to bar the road to Paris and cover Amiens, were co-ordinated by Gen. Fayolle.

On the 26th, Gen. Pellé's group occupied Mont Renaud—a natural rampart protecting the valley of the Oise.

Determined to force a passage at all cost, the enemy attacked with fresh troops.

The present positions must be held at all cost. The honour of each commanding officer is at stake, proclaimed Gen. Pellé. Trenches were dug, and Mont Renaud organised. The road to Compiègne was barred and the hills to the south and south-west of Noyon became the pivot of the defences. Repeatedly attacked, Mont Renaud changed hands several times, finally resting with the French. The exhausted 10th Div. fell back on the massif of Le Plémont, where the 77th Div. had just taken up its positions.

However, although Gen. Humbert's right checked all enemy advance, Gen. Robillot's group and the first units of Gen. Debeney's Army, on the left, were unable to hold their ground in the Picardy Plain. Forming but a thin line, the enemy's powerful thrust opened gaps in places.

Units of the 56th and 133rd Inf. Divns. and of the 4th and 5th Cav. Divns. under Gen. de Mitry, were pushed forward, with orders to establish the liaison, on their right, with the 22nd Div., and on their left, with the British who were falling back on the Santerre Plateau. This liaison was necessarily weak, as the troops had to be deployed. Fighting day and night for every inch of ground given up, these splendid troops succeeded in retarding the enemy's advance until the arrival of reinforcements on the line of the Avre.

The exhausted 22nd Div. fell back, carrying with it the 62nd on its right. Roye, outflanked from the south and attacked on the north, was lost. A breach, opened between the 22nd and 62nd Div. was filled by an emergency detachment hastily got together on the spot by General Robillot.

On the evening of the 26th, the front was established on the line Echelle-St.-Aurin, Dancourt, Plessis-Cacheleux.

General Humbert made a strong appeal to his men: Let all commanding officers firmly resolve to accomplish their duty to the extreme limit of sacrifice, and imbue their men with the same spirit.

North of the Somme, the Germans took Albert—an important junction—but were checked further north, by the left wing of Byng's Army.

Events had forcibly demonstrated the urgent necessity for Allied unity of command. On March 26, a War Council, composed of M.M. Poincaré, Clemenceau, Lord Milner, Haig, Pétain and Foch, empowered the latter to coordinate the action of the Allied Armies on the Western Front.

"At the moment when Foch was to take precedence of Pétain and Haig, what was the position of the armies, as regards the directives of the High Command? In other words, how was the Anglo-French battle being directed? The position is defined in the General Orders of Pétain and Haig, the former of whom prescribed:

"To keep the French forces grouped, to protect the Capital; essential mission;

"To ensure the liaison with the British; secondary mission;

"The latter prescribed that everything possible should be done to avoid severance from the French;

"Should this be unavoidable, to fall back slowly, covering the Channel Ports.

"If we place these two orders side by side, their divergence strikes us painfully. It is patent that the instructions of the two great chiefs had not the same object in view, and did not tend towards the same end. One was thinking of Paris, the other of the Channel Ports. Each would evidently consecrate the bulk of his forces and resources to what he considered the essential task. To sum up: on the German side, there was only one battle; on the Allies' side, there were two: the battle for Paris, and the battle for the ports. Had this situation continued, our defeat was certain.

"Foch's first thought, from the moment he took over the direction, was to cause this disastrous divergence to cease. To the two commanders-in-chief he prescribed the maintenance, at all cost, of the liaison between their armies. The accessory thus became the essential. The vital point was to ensure the junction between the Allied Armies, and to that end, to cover neither Paris, nor Calais, but Amiens. The battle which, till then, had been double, became single, i. e. the Battle for Amiens.

"Such was the strategical idea which, during the following days, Foch strove to materialise. Motoring from G.H.Q. to G.H.Q., he impressed the same thing upon all; on Haig, Pétain, Gough, the latter's successor, Rawlinson, Fayolle, Debeney and Humbert. By dint of repetition, this idea was to be deeply impressed into the minds of the executants.

"To ensure liaison, to keep the troops where they were, to prevent voluntary retreat, above all, to avoid effecting relief during the battle, to throw the divisions into the line of fire, as they arrived—such were the orders which were constantly on his lips during the days which followed". (La bataille de Foch, by Raymond Recouly).

On March 28, General Pershing offered Foch the direct and immediate help of the American Forces: I come to tell you that the American people would consider it a great honour for our troops to take part in the present battle. I ask this of you in my name and theirs. At this time, the only question is to fight. Infantry, artillery, aviation, all we have is yours.

Henceforth, the battle was directed from Foch's headquarters, temporarily installed at Beauvais. Twice a day, couriers maintained communications between Foch and the British and French G.H.Q's.

By the 27th, the German attacks had lost much of their earlier sting. The French, whose resistance was stiffening steadily, harassed the enemy unceasingly.

Their infantry, now thirty-six miles from their base, could only be revictualled with great difficulty. The Allied airmen bombed their convoys and the railway stations incessantly.

Their artillery had difficulty in keeping up with the infantry, and the latter were not always efficiently supported.

Meanwhile, the Allies steadily organized their defences. Gen. Pellé's group, with strong positions on the bastions of the Île de France, repulsed the enemy's repeated assaults.

Five attacks on Mont Renaud were broken.

From Canny to the Oise, the Allies stood firm.

Held on this front, the enemy deviated towards Montdidier, overwhelming Gen. Robillot's forces, which fell back on Rollot. The Germans reached Montdidier, Piennes, Rubescourt and Rollot. [Pg 25] A wide breach was thus made between Gen. Humbert's left and the right of Gen. Debeney's Army, then taking up its positions on the tablelands before the valley of the Avre.

It was a tragic moment. Gen. Debeney telegraphed to Gen. Fayolle: There is a gap of nine miles between the two armies, with nobody to fill it. I ask General Fayolle to have troops brought up in motor-lorries and despatched north of Ployron, to resist at least the passing of the Cavalry.

A few hours later, two divisions of Humbert's Army filled the breach.

Exhausted by their terrible losses, the enemy were brought to a stand.

East of Rollot, the essential portions of the massif of Boulogne-la-Grasse were strongly held.

Behind the Avre, trains and lorries were bringing up the divisions of Debeney's Army.

The British received reinforcements, and stayed their retreat in the outskirts of Albert.

The thrust against their line was now less violent, the enemy forces converging towards Montdidier.

Gen. Rawlinson replaced Gen. Gough.

After the fall of Montdidier, the fourteen divisions of von Hutier's army converged towards the pocket to the south-west.

Seven other divisions, marching against the British front between the Somme and Arras, suddenly turned south. On the 28th, 80,000 Germans made for the gap, through which 160,000 men of von Hutier's army were already pressing. In all, 240,000 men were about to attack on a seventeen-mile front.

General Humbert's left maintained an aggressive defensive.

On March 28, they counter-attacked. The 4th Zouaves captured Orvillers and Boulogne-la-Grasse, threatening the enemy on the flank at Montdidier. Seeing the danger, the Germans retook part of the conquered positions. The moral effect was, however, considerable, indicative as it was of the Allies' determination to re-act.

On the 29th, these counter-attacks were continued, thus mobilising many enemy units on this front, which were preparing to attack on the Avre.

During these two days, General Debeney, further north, was concentrating his forces along the front of Le Quesnel, Hangest, Pierrepont, Mesnil-Saint-Georges, Rubescourt. There can be no question, he declared, of crossing to the left bank of the Avre.

The Germans attacked at dawn on the 28th. To the west of Montdidier, Mesnil-St.-Georges was captured. The 166th Division, which had just detrained, stayed the thrust at Grivesnes and Plessier. A battalion of the 5th Cav. Div. fighting on foot, recaptured Mesnil and Fontaine-sous-Montdidier.

At the junction with the British, the attack was more violent. Capturing Hangest, the Germans slipped along the valley of the Luce, driving back the British. The resistance of the latter stiffened, however, and they maintained their positions on the right bank of the Avre.

On the 29th, the enemy renewed the attack with fresh divisions, especially at Demuin and Mézières, where the defenders were driven back along the Avre. However, Gen. Debeney's Army was now completed by the arrival of the 127th, 29th and 163rd Divisions. Its junction with the British, was strongly reinforced.

Before Arras, astride the Scarpe, the British fell back into line with Byng's Army, repulsing several violent attacks. (Sketch, p. 26).

On the evening of March 29, the enemy were firmly held at the bottom of the pocket, the sides of which stood firm.

On March 30, the Germans launched a general attack along a thirty-mile front, from Moreuil to Noyon, against the armies of Humbert and Debeney. This was their last effort in the southward push.

In many places, the French heavy artillery had not yet taken up its new positions. The battle was therefore mainly one of infantry. To the Air Service fell the task of making good the deficiency, and throughout the battle, bombs were rained upon the railway-stations, columns of German infantry, and enemy supply convoys, whilst the fighting section, skimming over the enemy masses, riddled them with machine-gun fire.

In front of Humbert's Army, the French lines were practically intact. Homeric combats were delivered at Le Plémont, Plessis-de-Roye and before Orvillers.

In the region of Orvillers-Sorel, the 38th Div. repulsed four assaults delivered by the 4th Div. of the Prussian Guards.

The attack against the front of Debeney's Army was delivered with equal fury.

On its right, not an inch of ground was lost. All assaults on Mesnil-Saint-Georges were repulsed. The 6th Corps maintained practically all its positions intact, except before Hill 104, where a slight withdrawal was necessary.

On the left wing, the 36th Corps (Nollet) was forced to give way, and fell back on the Avre. Moreuil was lost in the evening of the 30th.

March 31 was marked by extremely violent local actions, especially at Mesnil-St-Georges and Grivesnes, without appreciable result for either side.

On the evening of the 31st, the French front, practically intact, passed west of Moreuil, skirted the high ground on the left bank of the Avre, running thence west of Cantigny, round Montdidier, along the suburbs of Orvillers, through Roye-sur-Matz, Le Plémont and the hills to the south of Noyon, where the Germans had been unable to gain a footing.

April 1st. The enemy sounded the French lines at Rollot, south-east of Montdidier, but were smartly checked by a vigorous counter-attack. Three attacks in front of Grivesnes were likewise repulsed.

April 2 and 3 were fairly quiet, being the prelude to the final effort against Debeney's Army.

April 4th. At daybreak, an intense artillery preparation began, extending from the north of Hangard to the south of Grivesnes. At 7.30 a.m., the attack was launched with unheard-of violence.

Against this front, only nine miles wide, fifteen divisions—seven of which were composed of fresh troops—attacked ten times in the course of the day.

Before Grivesnes, four attacks were repulsed, whilst all the enemy's efforts against Cantigny and Hill 104 broke down. Further north the Germans captured Mailly-Raineval, Morisel and Castel.

The next day (April 5th), counter-attacks checked the Germans, prevented them exploiting their success north of Montdidier, and drove them back into Mailly-Raineval and Cantigny.

On the following days, fighting took place at different points, which changed hands several times, but these actions were of a local nature only.

The great German attack was over. The roads to the south-west were barred, as those to the south, at Noyon, had been, and Gen. Debeney was able to address the following order to his troops:

Soldiers of the 1st Army,

You have carried out your arduous task well.Your tenacious resistance and vigorous counter-attacks have broken the onrush of the invader, and ensured the liaison with our brave Allies, the British. The great battle has begun. At this solemn hour, the whole country is with us. The soul of the Mother-land uplifts our hearts.

On April 4, the great battle—of which the battles for Amiens, Montdidier and Compiègne were only episodes—came virtually to an end.

For ten days, after breaking the Allies' front, the Germans were able to change the war of positions into one of movement, but by a tremendous effort the French Army threw itself across their path and, as at Verdun in 1916, checkmated them.

This warfare in the open did not give the results expected by the enemy, who failed either to separate the Allies, or to rout them. On the contrary, by bringing about Allied unity of command, they strengthened the hands of their adversaries, to their own undoing.

Although the Germans captured Montdidier, they failed to reach either Amiens or Compiègne, and whereas the British, at first severely shaken, fully recovered, whilst only a portion of the French reserves were engaged, the enemy used up a considerable part of their finest troops and shock divisions, mown down in tens of thousands along the road to Paris, by the Allies' machine-guns and field artillery.

By March 31, ninety enemy divisions had been engaged, twenty-five of which had to be withdrawn on account of excessive casualties, some of them (e. g. the 45th Reserve, certain units of the 2nd Guards and 5th Infantry) having lost 50% of their effective strength. The casualties of the 6th, 195th, 4th, and 119th divisions attained 75%. At the very lowest estimation, the Germans lost at least 250,000 men.

The Kronprinz had promised his men that the Easter bells would ring in the long-expected peace, but Easter Sunday found the Allies more closely united than ever, awaiting with confidence the end of the battle, and determined to win through to victory.

The check of April 4 saw the end of von Hutier's reserves. All the divisions of the XVIIIth Army had been engaged, most of them with heavy casualties. Unwilling to take any of the divisions from the army group under the Bavarian Crown Prince—reserved for the proposed offensive in Flanders—or the inferior and less trained troops on the Champagne and Lorraine fronts, the German High Command, realising that the struggle must develop into one of attrition, like the first battle of the Somme, gave up for the time being all idea of an offensive on the Somme-Oise front.

A document of the German XVIIIth Army refers to the operations prior to April 6 under the name of "The Battle of Disruption" and to those which followed, under the name of "The Fighting on the Avre and in the region of Montdidier-Noyon."

The divisions forming von Hutier's shock troops were withdrawn fairly quickly. By the end of May, only two out of the twenty-three divisions which, on March 21, had formed the XVIIIth Army, were still in line on the Moreuil-Oise front.

From April onwards, trench warfare began again. The Allied front was reformed, consisting of a continuous line of hastily dug trenches and rapidly constructed works, held by resolute troops, whose morale was intact and whose fighting spirit had never been better.

Once more the heavy artillery came into requisition, for the preparatory pounding of the adversaries' positions.

In April-May, sharp engagements frequently took place at certain points. On the Luce, in the region of Hangard, on the Avre, from Thennes to Mailly-Raineval, at Grivesnes, on the west bank of the Matz, and around Orvillers-Sorel. Of these, the attack of April 24, by its violence and scope, constituted a veritable offensive against Amiens.

See sketch below.

The plateau of Villers-Bretonneux dominates the ground between the Avre and the Somme.

It was held by the British. Slightly to the south, in Hangard Woods, close to Hill 99, was the point of junction of the Allied Armies.

The enemy's main effort was made at this point, as being the weakest.

The French line started at Anchin Farm, west of Moreuil, followed the western and northern outskirts of Castel, joined up with Hill 63 on the right bank of the Avre, took in Hangard, and linked up with the British near Hill 99, to the south of Hangard Wood. From this point the British line crossed the plateau between the Avre and the Somme, between Marcelcave and Villers-Bretonneux, and passed the eastern outskirts of Hamel.

At 5 a.m., after an artillery preparation lasting an hour, the German infantry attacked.

After a desperate struggle, the enemy captured Villers-Bretonneux. Hangard fell during the night and Cachy was threatened.

The next day, a Franco-British counter-attack won back the most important part of the lost ground. Villers-Bretonneux, Hangard and Hangard Wood were recaptured and held, in spite of all the subsequent efforts of the enemy, who finally abandoned this sector in favour of Flanders.

In his "Memoirs", Ludendorff wrote: The battle ended on April 4. It was a brilliant feat of arms and will always be so considered in history. What the British and French had been unable to do, we accomplished in the fourth year of the war.

Strategically, we did not attain what the events of March 23, 24 and 25 justified our hoping for.

That we failed to take Amiens, which would have rendered the communications of the enemy forces astride the Somme extremely difficult, was especially disappointing.

Long distance bombardment of the railways could not be considered an equivalent.

After the German Offensive of March.

After the check of their offensive in Picardy, the Germans attempted, by means of secondary offensives, to attain those results which they had failed to obtain in the first instance.

On April 9, they attacked in Flanders, from Béthune to the north of Ypres, in the direction of the Channel Ports, but failed to take Ypres, or to reach Hazebrouck. (See the Guide: Ypres.)

On May 27, the front of the Chemin des Dames was attacked by surprise, the enemy reaching the banks of the Marne. (See the Guide: The Second Battle of the Marne).

From June 9 to 18, their efforts were turned against the salients of the Aisne and Rheims. On June 11, they captured the massif of Thiescourt, but were held before Compiègne. In front of Rheims the road was barred by the French Colonial troops. (See the Guide: Rheims.)

Lastly, seeking a prompt decision at all cost, and hypnotised by Paris, the Germans planned a still more formidable offensive: the "Friedensturm" or Peace Battle. However, the French High Command were not taken unawares. The scope and time of the offensive were known, and the Germans failed.

The hour of the counter-offensive was about to strike. The Allies had overcome the crisis due to the shortage of men. The British Army had been reorganized. The American forces had greatly increased in numbers. The fighting spirit of the French was higher than ever. The material strength of the Allies was satisfactory, and included large numbers of the new offensive arm: the tank, destined to relieve and support the infantry, and combat the German shock troops.

Lastly, the Allies were now grouped under a single chief: Foch, who knew where and when to strike.

The Allied Armies, he declared, have arrived at the turning of the ways; in the thick of battle they have regained the initiative, and their strength enables them to retain it; the principles of war command them to do so. The time has come to abandon the defensive attitude necessitated till now by numerical inferiority, and to take the offensive.

The action of the Commander-in-chief of the Allied Armies will, in future, aim at maintaining his hold on the German Commandment, giving him no respite which would allow him to recover and reconstitute his forces. To that end, separate surprise attacks will be made successively, as rapidly as possible, so as to augment progressively the disorganization of the enemy's armies and the confusion of the German Commandment, until the day of the general offensive, and of the final attack which will crumble up the whole of the adversary's front.

A comparison of this conception of Foch's with that of Ludendorff brings out all its suppleness and power.

The counter-offensive by the armies of Mangin and Degoutte in the Château-Thierry pocket, begun on July 18, was scarcely over, when the Second Battle of the Somme broke out.

In this new battle of the Somme, the retreat of the German armies on the Hindenburg Line, in August-September 1918, was effected under the pressure of four successive thrusts:

I.—The operations carried out simultaneously by the British 4th Army and the French 1st and 3rd Armies against the Albert, Montdidier, Lassigny salient, to clear the Paris-Amiens railway. (Pages 38-45.)

II.—The British offensive north of the Somme, coinciding with the French offensive between the Oise and the Aisne. (Pages 46-49.)

III.—The British offensive on the Scarpe and the French offensive on the Ailette. (Page 50.)

IV.—The Franco-British offensive against the advanced defences of the Hindenburg line. (Page 51.)

Preliminary Operations of July.

Throughout July, the Allies carried out different local operations, in order to improve their positions and prepare for the coming offensive.

As early as July 4, Australians supported by Americans, had begun to advance between Villers-Bretonneux and the Somme, by capturing the village and wood of Hamel.

On July 9, after a brilliant attack between Castel and the north of Mailly-Raineval, the French captured Castel, and on the 23rd, Mailly-Raineval, which brought them nearer the Avre.

These different actions, and the flattening of the Cantigny salient by the American 1st Div. on May 28, had warned the enemy.

On August 2, the Germans fell back on the Ancre, and on the 3rd to the Avre. The bulk of their forces were withdrawn east of these rivers, leaving only light forces on the west bank.

On the Marne, Ludendorff had just suffered a severe defeat. From July 18 to August 4, his armies had been driven back from the Marne to the Vesle, where they organized new positions. (See the Guide: The Second Battle of the Marne.) In the belief that this effort had temporarily exhausted the Allies, Ludendorff was planning new operations in Flanders, when he was surprised by a new and powerful Allied Offensive. From that point, the initiative remained with Foch.

On August 8, the front line passed west of Albert, east of Villers-Bretonneux, then followed the left bank of the Avre, and the Doms stream, west of Montdidier, running thence towards the Matz and the Oise, via Assainvillers, west of Cuvilly and Chevincourt.

From north to south, the enemy front was held by the IInd Army (von Marwitz) (10 Divns. in line from Albert to Moreuil), and by the XVIIIth Army (von Hutier) (11 Divns. from Moreuil to the Oise).

These two armies, with 21 divisions in line, engaged 17 other divisions during the course of the battle, i. e. 38 divisions in all.

The undermentioned forces were grouped under the command of Field-Marshal Haig:

The British 4th Army (Rawlinson), comprising the 3rd Corps (3 divisions), the Australian Corps (4 divisions), the Canadian Corps (4 divisions), and 3 divisions of British Cavalry, 2 brigades of armoured cars and 1 battalion of Canadian Cyclists in reserve.

The French 1st Army (Debeney), comprising the 31st Corps (4 divisions), 9th Corps (2 divisions), 10th Corps (3 divisions), 35th Corps (4 divisions), and the 2nd Cavalry Corps in reserve.

These armies attacked on August 8, along a 15-mile front, from the Ancre to the Avre.

"At 4.20 a.m., after three formidable cannon-shots,—the signal for the opening of the attack,—the rolling barrage broke out before the Australian and Canadian troops, who immediately dashed forward. At the same time, the heavy and light tanks, armoured cars and motor-lorries, loaded with supplies and ammunition, set out. At certain points, the cavalry, followed by the artillery and the aeroplanes, guarded or speeded up the advance. The enemy were taken completely by surprise. The troops and staffs were taken prisoners before they realized what had happened. One after another, the villages were surrounded and captured. Forging ahead of the infantry, the cavalry and tanks spread panic everywhere."

The British advanced rapidly in the direction of Rosières, along both sides of the Amiens-Chaulnes railway.

Towards evening, the advanced line passed through Mézières, Caix and Cerisy. Everywhere, except at Morlancourt, north of the Somme, where the enemy resisted desperately, the Germans were routed.

More than 13,000 prisoners, a general and the staff of an army corps, and 300 guns had fallen into the hands of the British by 9 a.m.

Along the front of Debeney's Army, the artillery preparation was short but violent, (45 minutes). The infantry attacked about five o'clock i.e. after the British. The ground, divided for the greater part by the valley of the Avre, was more difficult, and General Debeney counted rather on manœuvering, than on surprise.

The attack began on a front of 2½ miles, south of the Amiens-Roye road, debouching from the valley of the Luce towards ground suitable for the tanks, the troops being gradually engaged on their right, along the Avre.

At 8 a.m., two divisions turned Moreuil Wood, from the north-east and south-west. On the Avre, another division captured Morisel, whilst to the south of Moreuil a battalion crossed the river. Moreuil, turned from the north and south, fell. South of Moreuil, two fresh divisions crossed the Avre, opposite Braches, opening up a way for the troops who had to fight on the plateaux.

At the end of the day, after an advance of about five miles, the French reached the line Braches, La Neuville-Sire-Bernard, and joined hands with the British near Mézières. 3,300 prisoners, including three regimental commandants, were taken.

"It was a black day for the German Army" wrote Ludendorff, "the blackest of all the war, except September 15, which saw the defection of Bulgaria, and sealed the destinies of the Quadruple Alliance".

On August 9-10, the British thrust and the French manœuvre developed.

The British Advance.

Between Albert and the Amiens-Roye road, the Canadians and Australians harassed the enemy without respite, and advanced several kilometres, capturing Bouchoir, Méharicourt, Rosières, Lihons and Proyart.

North of the Somme, in co-operation with American troops, they captured Morlancourt village and plateau to the south-east, where the enemy resisted desperately.

On the 11th, in spite of stubborn resistance, the British reached the Dernancourt crossroads, about a mile west of Bray, Chilly, Fouquescourt and the western suburbs of Villers-les-Roye.

On the 12th, they drove the enemy for good out of Proyart. On the 13th, they reached the suburbs of Bray-sur-Somme and the crossroads of Chuignolles. The front now ran along the old German lines of the Somme Battlefield of 1916, where the enemy, thanks to a number of strong points of support, succeeded in staying the advance. In five days, the British had scored a fine victory, their forces (13 infantry divisions, one regiment of the American 33rd Division, 3 divisions of cavalry, and 400 tanks) defeating 20 German divisions, advancing 12 miles, and capturing 22,000 prisoners and 400 guns.

Meanwhile, General Debeney, by a series of turning movements, brought about the fall of important sections of the German front, without frontal attacks.

Constantly extending his attacks along the Avre, the approaches to the river on the north and north-east, as far as the confluence with the Doms stream, were cleared, whilst his hold on Montdidier, from the north-east, gradually tightened.

On August 9, the French line was advanced as far as the station of Hangest-en-Santerre, on the Albert-Rosières-Montdidier railway.

In order to force the enemy to abandon Montdidier, without a frontal attack, General Debeney began a turning movement at about 4 p.m. A secondary attack was launched in the direction of Roye, between Domelieu and Le Ployron. The station of Montdidier and Faverolles Village on the Montdidier-Roye line, were reached that evening.

Throughout the day, the French airmen bombed Roye undisturbed by the enemy's planes or air-defence guns.

By evening, the 1st Army had taken 5,000 prisoners. From Faverolles, they threatened to join up with the men who had advanced north, via Davenescourt, and to cut off the Germans in Montdidier.

The latter was evacuated in great disorder the same night and on the following morning, only a few machine-gunners being left behind to retard the French advance as long as possible.

On August 10, at noon, the French entered the ruined town, and advanced rapidly eastward, beyond Fescamps, on both sides of the road to Roye. In the evening, they reached the line Villers-les-Roye (where they joined hands with the British) and Grivillers.

On the 11th, they captured the park and village of Tilloloy. By the evening of the 12th, the 1st Army had taken 8,500 prisoners (including 181 officers), 250 guns, numerous minenwerfer, 1,600 machines-guns, and huge quantities of stores.

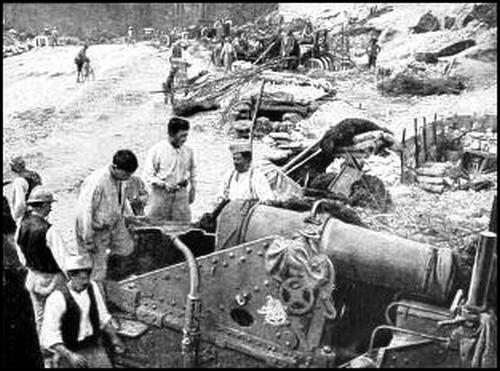

Photos, p. 44:

(1) Australian Sergeant examining a German Machine-gun captured by the 15th Brigade.

(2) Near Warfusée-Abancourt, August 8. Infantry of the Australian 1st Division advancing on Harbonnières, after a tank had cleaned up a line of German Machine-guns which was holding them.

(3) The Shelters of the above line of machine-guns— light constructions compared with the powerful trench organisations, yet strong enough to require tank treatment.

Photos above:

(1) Australians in German trench, with field-guns just captured (August 1918).

(2) British lorries in Villers-Bretonneux (August 17, 1918).

The first phase of the Battle of Picardy was ended, but a great new effort, between the Somme and the Scarpe, was being prepared.

Between the Aisne and the Oise, Mangin's Army attacked the plateaux on August 18th, advancing to the Ailette on the 23rd. (Sketch above).

Following up this advance, Humbert's Army continued its offensive vigorously on the 21st, conquered the northern slopes of Le Plémont, crossed the Divette, and occupied Lassigny. (Sketch above).

By their advance, these two armies threatened the right of the German XVIIIth Army, established on the Chaulnes-Roye line.

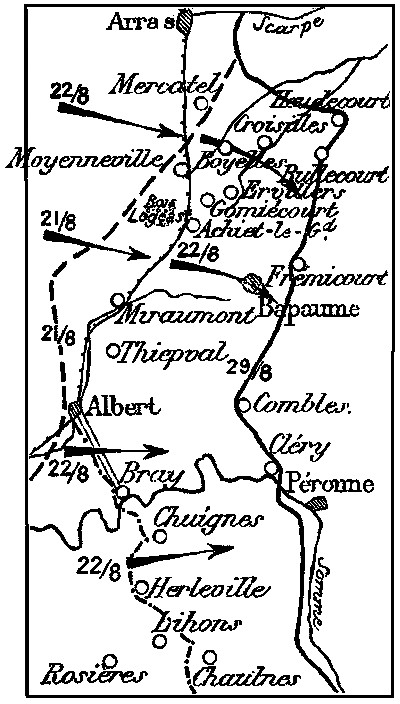

At the same time, Byng's Army attacked between the Ancre and Croisilles, whilst Rawlinson's left attacked north of the Somme. (Sketch above).

At dawn, on August 21, the 4th and 6th Corps of Byng's Army attacked between Miraumont and Moyenneville.

Supported by tanks, they captured the advance defences in brilliant style.

The fighting was particularly severe around Achiet-le-Grand and Logeast Wood, where, however, the advance continued steadily. The Arras-Albert railway which was the enemy's principal line of defence, was reached, 2,000 prisoners being taken.

After this preparatory attack, the offensive was launched on August 22, along a thirty-two mile front, between Lihons and Mercatel.

South of the Somme, the Australians captured Herleville and Chuignes, with 2,000 prisoners. Rawlinson's left crossed the Ancre, took Albert, and advanced its front to the hills east of the Albert-Braye road, capturing 2,400 prisoners.

But the hardest blow was struck further north by Byng's Army. Advancing beyond the principal line of defence (the Arras-Albert railway), [Pg 47] the 4th and 6th Corps took Gomiécourt, Ervillers, Boyelles, many guns, and more than 5,000 prisoners, then pushed on towards Bapaume and Croisilles. The 6th Corps, astride the Arras-Bapaume road, marched on Bapaume, threatening to cut off the Germans who were hanging on to the Heights of Thiepval. The latter, attacked at the same time further south, fell. Bray-sur-Somme was also captured.

The battle continued from the 25th to the 29th, the enemy's resistance stiffening steadily.

Counter-attacking, the Germans defended this old battlefield of 1916, strewn with obstacles, with great desperation.

On the 29th, Bapaume fell, and the Germans retreated from the north of that town to the Somme, on the line Cléry, Combles, Frémicourt, Bullecourt, and Heudecourt.

Threatened by the British to the north of the Somme, and by the French on the banks of the Oise, the Germans began their retreat in the bend of the Somme. Closely pursued by the British 4th Army and the French 1st and 3rd Armies, they withdrew to the river, from Péronne to Ham.

Chaulnes and Nesle were occupied by the Allies.

"On the same ground which had seen their stubborn defence, the British troops went up to the attack with untiring vigour and unshakeable determination, which neither the difficulty of the ground, nor the obstinate resistance of the enemy could break or diminish." (Haig).

Photo above:

Albert, seen from the interior of the Church, the day

the town was liberated

(Photo Imp. War Museum).

Pursuing his plan of offensive, Foch extended the field of operations. Writing to Field-Marshal Haig, he said: Continue your operations, leaving the enemy no respite, and developing the scope of your actions. It is this increasing breadth of the offensive, fed from the rear and strongly pressed in front, without limitation of objective, without consideration for the alignment and too close liaison, which will give us the greatest results with the least losses.... The armies of General Pétain are going forward again in the same manner.

At the time Mangin's Army was preparing to crush the enemy's front between the Aisne and St. Gobain, Horne's Army, on the Scarpe, attacked the salient east of Arras.

On August 25, the Canadians, astride the Scarpe, and the left of Byng's Army captured the difficult positions of Monchy-le-Preux, Guémappe and Rœux, bringing their line into contact with the redoubtable position of Quéant-Drocourt, a ramification of the Hindenburg Line.

On September 2, the Canadians attacked, progressing rapidly along the Arras-Cambrai road. Penetrating the German lines to a depth of 6 miles, they reached Buissy.

On the night of August 30, the Australians, in the centre, furiously attacked and captured the formidable bastion of Mont-St-Quentin. On September 1, they entered Péronne, after desperate fighting. To flank this attack on the north, Bouchavesnes and Frégicourt were captured.

Further south, on the Oise, Humbert's Army, in spite of the enemy's resistance, took Noyon and the high ground dominating the town. Advancing from the Ailette, towards Chauny, Mangin's left reached the outskirts of St. Gobain Forest, in the old lines of March 1918.

Outflanked on the north, towards Cambrai, and on the south along [Pg 51] the Oise, in the direction of La Fère, and violently attacked at the same time in the centre at Péronne, the Germans retreated towards the Hindenburg positions. The British and French forces drove back the enemy rear-guards, which were unable to hold the line of the Tortille and the Canal du Nord.

On Sept. 8, the Allied front ran west of Arleux and Marquion, through Havrincourt, Épéhy and Vermand, then followed the Crozat Canal.

The Germans had reached the advanced defences of their famous Hindenburg Line, consisting of the old British lines lost in March. These formidable positions protected the ramparts of the Hindenburg Line, said to be impregnable.

On September 10, the British 3rd and 4th Armies (Byng and Rawlinson) attacked between Havrincourt and Holnon.

The 4th Army took Vermand, the western outskirts of Holnon Woods, and gained a footing in Épéhy and Jeancourt. On the 13th, after desperate fighting, it captured the woods and village of Holnon.

The 3rd Army crossed the Canal du Nord, south of the Bapaume-Cambrai road, turned the positions from Havrincourt to Gouzeaucourt, and captured the greater part of them, the enemy resisting desperately.

The same day (Sept. 12), the American 1st Army captured the whole of the St. Mihiel Salient, with 15,000 prisoners and 200 guns. (See the Guide: The Battle of St. Mihiel.)

On the 18th, a general attack was launched by the British 3rd and 4th Armies, in liaison with the French 1st Army. All the enemy's positions between Gouzeaucourt and Holnon were captured, with 10,000 prisoners and 150 guns.

To the south, Debeney's Army took over the front of Humbert's Army—transferred to the sector of the 10th Army—the latter, due to the shortening of the front, being sent to Lorraine, for a new offensive.

Debeney's Army, extending south of the Oise, attacked, and after capturing Dallon Spur, Castres and Essigny-le-Grand, reached the valley of the Oise, from Vendeuil to La Fère.

Disorganized and exhausted, their ranks depleted, the enemy were now incapable of attempting a counter-offensive.

To avoid this continuous, exhaustive battle, the Germans sought refuge in positions which they believed to be impregnable, and where they hoped to rest, reorganize and reconstitute their reserves.

This was an imperious necessity, as from July 15 to September 25, 163 of their divisions had been engaged, 75 of them two or three times.

On September 26, despite a reduction of 120 miles in the length of the front, they were forced to maintain practically the same number of divisions in line as on July 15, owing to their decreased effective strength and fighting value.

Moreover, to keep these forces effective, ten divisions had to be dissolved, and the battalions of fifty others reduced from four to three companies. Large numbers of men were called up from the works, in order to husband their last resources—the 1920 recruits.

Everywhere, the Allied armies were in contact with the Hindenburg Line, ready for the grand assault against the formidable positions from which the enemy had set out on March 21 for Paris and victory.

The above photograph represents an assemblage of the maps on which the Staff of the French 20th Corps traced the front from day to day.

By bringing out the two lines of July 15 and November 2 (exactly reproduced), and by adding a few unimportant touches inside and the spike of the helmet, one of the Staff draughtsmen obtained this curious figure of Germania on her knees.

With the help of the inset sketch-map, it is easy to trace the salients of Ypres, Arras, Montdidier, Château-Thierry (crossed by the Vesle), Rheims, Verdun, and St. Mihiel.

In six weeks, by repeated, inter-related attacks, vigorously executed without respite, the Allies had flattened out the salient from St. Quentin to beyond Montdidier and Albert, produced by the German push.

The end was near. To avoid a military disaster without precedent in the world's history, the enemy soon afterwards sued for an armistice and peace.

To visit AMIENS,

centre of the itineraries for Bapaume and Péronne ("The First Battle of the Somme") and Montdidier and Compiègne ("The Second Battle of the Somme"), see the MICHELIN Illustrated Guide:

"AMIENS, before and during the War."

Lunch at Montdidier.

From Amiens to Villers-Bretonneux

via Longueau, Gentelles and Cachy.

Leave Amiens by Exit V (Michelin Tourist Guide) (Rue Jules-Barni, Chaussée Périgord and N. 35). Cross the railway twice (l.c.) or if preferred, take the road on the right under the railway. Longueau is soon reached.

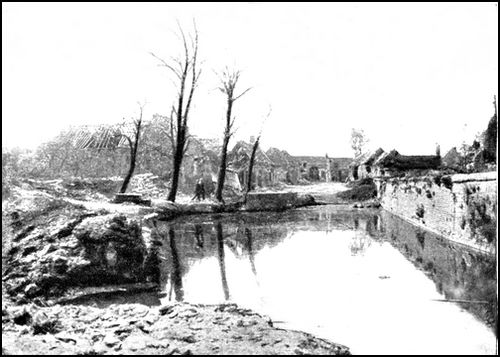

The road from Amiens to the crossing over the river Avre, before reaching Longueau, follows the left bank of the Somme. Market-gardens famous for their fertility and known locally as "hortillonnages" lie in the valley, especially around Camon. Formerly, the river-side seigneurs above Amiens, met once a year for wild swan-shooting in the valley of the Somme. The custom died out in the 18th century, poaching having by then exterminated the swans.

It was at Longueau that the Roman roads from Amiens to Rheims and to St. Quentin crossed the river Avre. Gallo-Roman tombstones were discovered in 1848, while excavating near the first bridge at Longueau. In 1590, the Leaguers held the village to ransom, and the Spaniards burnt it in 1636.

Beyond Longueau, leave the Montdidier road on the right, and keep straight along the road to Roye for 4½ kms. Take the second road on the left, to Gentelles. Gun emplacements, shelters and trenches are met with on both sides of the road. Gentelles Wood is on the right. (See sketch-map, p. 59).

Pass through Gentelles village, entirely destroyed. 1½ kms. beyond Gentelles stands a partly destroyed monument to the memory of the French who fell in the Franco-German War of 1870 (photo below).

Leave the monument on the right, and enter Cachy (completely ruined).

At the fork beyond Cachy, take the middle road, between the Woods of Aquenne and Abbé, in which are trenches, wire entanglements and shelters. Coming out into the main road from Amiens to Villers-Bretonneux (G.C. 201), take same on the right. (See sketch-map, p. 62).

After passing over the railway, Villers-Bretonneux is reached.

Formerly a country village, the cotton-spinning industry later transformed it into a small town. The war has left it in ruins. (See p. 61.)

Leave Villers-Bretonneux by the road to Demuin, on the right (G.C. 23).

See route-map, p. 62.

From Hill 98, 1 km. beyond the railway, near the junction with the road leading to Cachy, and close to a Franco-British cemetery, there is an extensive view of the battlefield around Villers-Bretonneux.

It was around Villers-Bretonneux that on November 27, 1870, part of the battle known as the "Battle of Amiens", was fought between the Prussians and the French Army of the North.

The French troops, about 10,000 in number, under the command of General Farre, were deployed from the railway (between Villers-Bretonneux and Marcelcave) to Cachy and Gentelles (on the Boves road), and on the high ground dominating the valleys of the Somme, Luce and Avre. The Prussians, under General Manteuffel, far more numerous and better equipped with artillery than the French, debouched from the valley of the Luce and the roads from Péronne and Roye to Amiens, the battle opening on the two wings.

The enemy partly took Cachy and approached Gentelles, but were driven back towards the river Luce, after the brilliant capture of Domart Wood by the French. Cachy, partly abandoned by the French after desperate resistance and heavy losses, was afterwards cleared of the enemy with great dash.

Unfortunately the French line from Cachy to Villers-Bretonneux was too weakly held to stay the Prussians, who got the upper hand in the afternoon and forced the French back. To the enemy's forty guns the French could only oppose sixteen (four batteries), and they were, moreover, short of ammunition.

A Prussian battery, which had succeeded in taking up a position near Cachy, enfiladed the French line. In Villers-Bretonneux, detachments of French Marines fought a violent engagement in the streets, giving ground only step-by-step. The enemy sustained heavy losses and were unable seriously to hamper the French withdrawal towards Corbie and Amiens.

A monument was erected at Villers-Bretonneux, south of the railway, to the memory of the French soldiers who fell in this battle.

Fierce fighting took place in 1918 around the monument, which was completely destroyed.

Prolonged and violent engagements were fought from March to August, 1918, in the vicinity of Villers-Bretonneux, for the possession of Amiens. The battlefield consisted of a plateau occupied, from north-east to south-west, by Villers-Bretonneux, Abbé Wood, Cachy and Gentelles. This plateau was the last dominating position in front of Amiens. From Villers-Bretonneux, situated on the main road from St. Quentin to Amiens, and ten miles from the latter, the ground slopes gradually down towards the great Picardian City and the confluence of the rivers Avre and Somme.

From March 28 onwards, this plateau was held by Australian divisions, the famous Anzacs, who covered themselves with glory there by staying the Germans. At the beginning of April, the latter attempted to outflank Villers from the north and south, with but little success. [Pg 64] On the 24th, after a bombardment with high explosive and gas shells, lasting the whole of the previous night, they threw four divisions (50,000 men), supported by five tanks each fitted with three guns and a central turret, against the Fouilloy-Cachy front, barely three miles wide. From 7 to 10 a.m., the attacking waves went forward unceasingly in the morning mists. At about 11 a.m., the British had to give way, under an intensely fierce onslaught, and the Germans entered Villers from the north and south.

Clinging to the western approaches of the village, the British, throughout the afternoon and night of the 24th, prevented the enemy from debouching, while their artillery fire made the position practically untenable. Two German battalions only were able to maintain themselves in the cellars and ruins of the houses. In the evening of the 25th, while troops of the Moroccan Division recaptured the [Pg 65] monument south of the Villers railway, British units debouched from Abbé Wood, and advancing via the ravine north of Villers, Aquenne Wood and the station to the south, surrounded and recaptured the village after a hand-to-hand fight lasting all night. A 3-gun tank and over 700 prisoners were taken. To the south-west, in the vicinity of Cachy and Gentelles, the enemy check was equally severe. On the 24th, a regular battle of tanks took place near Cachy, in which the Germans were routed and Cachy re-occupied. The four German divisions lost the battle, and left the ground covered with their dead.

On May 2, there was again sharp fighting near the Monument, but during the following weeks, the enemy ceased their attacks. The Australians, by local operations, enlarged their positions north-east of Villers-Bretonneux and between Villers and the Somme. On the night of May 23, the enemy violently bombarded Villers, and on the 25th made another powerful effort south of the village, but without success.

Follow G.C. 23, which runs close to Hangard Wood, the trees of which were devastated by the shells. (See map, p. 62.)

Descend from the plateau to Demuin, visible at the bottom of the valley of the Luce. There is a large British cemetery on the right. Tourists may here turn to the right as far as Hangard. (See p. 66.)

After visiting the village (completely devastated), return to Demuin. Take the main street, then the last street of the village and the uphill road indicated in the sketch-map above, to Hill 102, from which there is a fine view of Demuin, the valley of the Luce, Hangard, Domart and Gentelles Wood (photo above).

Return to Demuin, and take G.C. 23 to Hill 104 (See map, p. 62).

Hill 104, at the crossing of the Demuin-Moreuil road with the Roye-Amiens road, commands the valleys of the Luce and the Avre.

Hangard and Hangard Wood, seen to the north, were the scene of furious fighting in 1918. This vital position enabled the Germans to hold the river Luce, which they needed to consolidate the Montdidier-Moreuil salient, and for their advance south-east of Amiens.