THE RED FOX'S SON

This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Red Fox's Son

A Romance of Bharbazonia

Author: Edgar M. Dilley

Release Date: December 25, 2016 [EBook #53804]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE RED FOX'S SON ***

Produced by Al Haines.

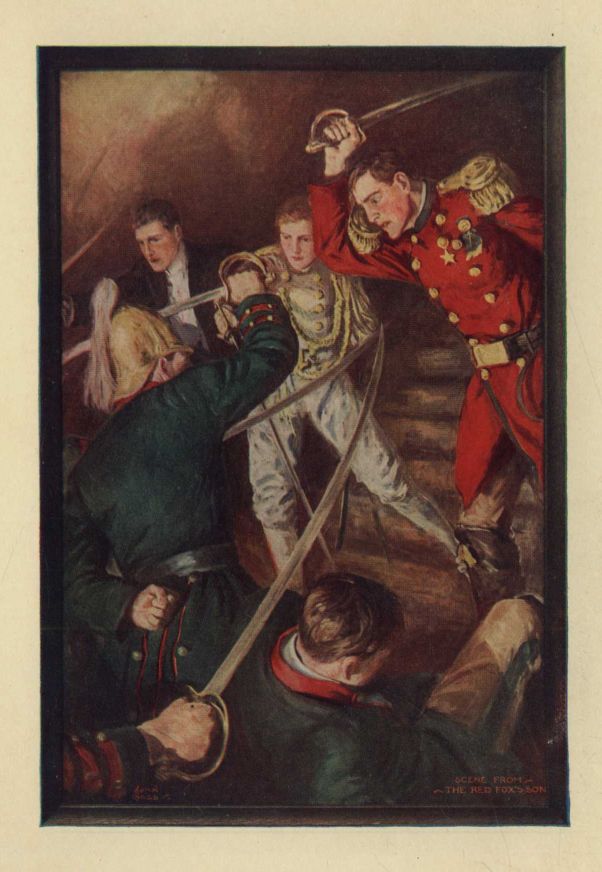

rank back upon its fellows, a new

set of swords took its place"

(See page 337)

From a Painting by John Goss

THE RED FOX'S SON

A Romance of Bharbazonia

By

Edgar M. Dilley

With a frontispiece in colour by

John Goss

Boston ::: L. C. Page &

Company ::: Mdccccxi

Copyright, 1911,

BY L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

(INCORPORATED)

Entered at Stationers' Hall, London

All rights reserved

First Impression, June, 1911

Electrotyped and Printed by

THE COLONIAL PRESS

C. H. Simonds & Co., Boston, U.S.A.

TO

MY MOTHER

THAT GENTLE LITTLE MENTOR OF MINE WHO HAS

GROWN MORE DEAR WITH ADVANCING YEARS,

WHOSE UNSHAKEN FAITH AND UNSWERVING

AFFECTION HAVE BEEN MY INSPIRATION

THIS BOOK IS

AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED

FOREWORD

A word with you, who lift me from my place among the Books,Before you take or leave me, pleased or displeased with my looks;If you are seeking knowledge of a scientific kind,If you would delve in pages full of wisdom for the mind,Although I stand a Slave Girl upon the Public Mart,Leave me! Leave me! Oh, my Masters! I can never reach your heart!But, if you love the glamour of the Palace of the King,And find your pulses quicken when intrigue is on the wing;If you would see the Lover and the Maiden he would wed,The flight, the fight upon the stair, the rich blood running red,The last despair, the rescue, hero acting well his part—Take me! Take me! Oh, my Masters! I can ever reach your heart!EDGAR M. DILLEY

CONTENTS

THE RED FOX'S SON

CHAPTER I

DAVID AND JONATHAN

We still have slept together,Rose at an instant, learn'd, play'd together,And wheresoe'er we went, like Juno's swans,Still we went coupled and inseparable.—Shakespeare: As You Like It.

As I write in my quiet library the history of those stirring events which began and ended while the bells of 19— were ringing in the New Year in the Kingdom of Bharbazonia, I am interrupted on my literary journey by the sound of a sweet voice singing, in the room below, the robust melody of "The King and the Pope," my favourite song.

The sweet music sets me dreaming of the day I first met Solonika in her quaint little Dhalmatian summerhouse; of the time when she would have killed me in the Red Fox's Castle; of the night of suffering when I was lost in the Forest of Zin; of the race for life with Marbosa's men; of the sacrilege in the Cathedral of Nischon; of that last awful scene at the Turk's Head Inn, when friendship was put to the test—and I marvel, not so much that a man may be placed in danger of death in this, the Twentieth Century, from the religious superstitions of a mediæval race; but that I should owe my life to that fortunate occurrence, years before, when Dame Fortune's handmaiden, "Chance," made Nicholas Fremsted my friend.

I often wonder at that friendship which came to mean so much to me. It began when Nick and I were seventeen years old, and, although we are past thirty now, it has but grown stronger with advancing years. We were first attracted to each other as a result of a college prank. Like most youngsters whose parents make great sacrifices that their children may be permitted in a class-room, my whole ambition in life was to absent myself from lectures as much as possible. Nor was I alone in my folly, for most of my fellow students joined with me, knowing that the dread day of reckoning, examination day, was far distant. It is difficult to be a faithful student when the football season is gathering momentum!

Our professor was old and almost blind; and we young rascals unfeelingly took advantage of his infirmities. Before we were Freshmen a week, grown wise under the evil counsel of our elders, the Sophomores and Juniors, we had become adepts in dodging all his lectures. Because he could not see, it was easy for us to answer to our names at roll call and slip out the rear door, leaving the kind old man to talk to empty chairs. Sometimes, when it was not convenient for us to leave the athletic field, growing bolder with success, we commissioned one "man" to answer "Here" for all of us. He was careful to use different tonal qualities for each name. When his mission was safely concluded he, too, would rejoin us, leaving a few of that despised set of boys known as "grinds" in the front seats to sustain the appearance of a full class. They, fearful of the wrath to come, diligently minded their own business.

It was on one of the occasions when I had been sent up to answer for the class, and was standing just inside the doorway impatient to be off, that I first heard Nick's name. The professor, his nose close to the sheet, lead pencil in hand, called it out and waited for the answer which did not come. I glanced hastily down the list I held, but Nick's name did not appear there. Again the professor called:

"Nicholas Fremsted."

"Here," I cried on the spur of the moment, and the roll call proceeded, keeping me in continual hot water running the scale of "Here, Here," until it was over. To this day I cannot tell why I befriended him then. He might have been a "grind" with a bona fide excuse for his absence which when presented later might lead to discovery. I hoped he would be one of the "good fellows" who were, I suppose, very bad fellows indeed.

The roll call over, I did not wait to see if he came late to lecture; but that same evening he visited me in my rooms. He was a tall, well made lad about my own height and build, with sleepy brown eyes and waving black hair. His skin was as dark as an Italian's, but when he spoke it was with a marked French accent mingled with something that smacked of a Russian or Slavonic flavour. There was the pride of ancestry in his easy bearing, and he spoke with the decision of one whom the habit of taking care of himself had rendered self-reliant.

"I am come to make my thanks to you, sir," he said, "for your kind offices this afternoon in replying to my name for the roll call."

"Do not mention it," I replied, bidding him be seated; "you came to class then after all?"

"Yes. Soon after the rest they are gone, I advance to the fine old professor to explain my lateness. He informs me I am not tardy."

"You didn't give the snap away?" I cried, realizing more fully the chances I had taken, for, if this foreigner were of the stripe of human beings who would rather be right than President, I should be made to suffer for my kindness. My classmates would never forgive me for breaking up the little deception which other classes had practised undetected for years.

"Snap?" he repeated, puzzled by the colloquialism.

"I mean you did not tell him some one answered to your name?"

"Oh, no, I did not; although it is peculiar to be told by inference that one lies. When the instructor he says you are here since the beginning of the hour, and shows me the mark on the roll beside my name I only thank him and say 'Ah.'"

"Good boy," I cried, knowing that our secret was safe in his hands; and I took him to my heart then and there.

In five minutes we were smoking our pipes in the easy chairs, engaged in the pleasant occupation of getting acquainted. I told him all about myself and learned that he was not a Frenchman nor yet a Russian. That much he told me, and a great deal more, but he did not volunteer any information as to his nationality. There was that about him, too, which discouraged familiarity and he remained a man of mystery, even to me with whom he came to dwell at the end of that week, and with whom he continued to live for eight years. After we passed through college, I persuaded him to study medicine, and we both graduated from the medical school at the age of twenty-five.

He was one of the most remarkable linguists I have ever met, and with good cause. From his own account, he was sent away from home by his father for political reasons, the import of which he himself did not know, when he was eleven years old. He spent two years in St. Petersburg at school, two in Berlin and one in Paris before he came to Philadelphia, and, as far as I could learn, had never been home in all that time. His ample quarterly remittances came through a Paris broker's office.

When first we knew him we called him "François Fremsted" because we believed him French. But, after he joined the football squad and finally won his place on the team, having developed into a great strong fellow, we nicknamed him "Lassie." because that was the most absurd name we could think of for a man who was as intensely masculine as he. Nicknames, like dreams, you know, usually go by contraries. Of course the appellation was derived from the last syllable of his first name. To unsympathetic ears it may at first have been misunderstood, but "Lassie" himself liked it best of all the names we gave him.

His knowledge of languages did not extend alone to Russian, German, French and English. I remember, on one occasion, when we were celebrating a football victory with the usual foolish college abandon and found ourselves among the docks on the Delaware River front, Nick spoke in a peculiar dialect to a Slav stevedore, who was much surprised to find an American so addressing him. For some reason Nick became angry, and hurled the jargon at him imperiously; whereupon the labouring man removed his cap and knelt on the Belgian blocks of the street. So great was his humility that he would have kissed Fremsted's hand had not Nick brushed him aside and walked away.

Again, I frequently accompanied him to the Italian and Russian quarter of the town, when he wished to transact some mysterious business with certain residents there, and found that he got on equally well with them. It was also true that the Bulgarian consul was, next to me, Nick's most intimate friend and adviser.

What Nick's business might be I could never determine, owing to the fact that his negotiations were always conducted in different dialects, while French was the only language I found time to learn—thanks to Nick's assistance. Whatever he was doing, he did not permit it to interfere with his college work, except on two occasions; once he was absent for a week in New York and once he made a flying trip to San Francisco.

Beyond leaving a note for me saying he would not be home for a week or so, he never volunteered any information about these journeys and I never questioned him. Had it not been that he was such a handsome fellow, not averse to the society of the ladies, I might yet be in ignorance as to his destinations; but on both occasions letters with illuminating post marks followed his return and told me that Nick had found time to make social calls after business hours. There was never anything serious about this sporadic feminine correspondence, and it soon fell away, possibly because he presently forgot to answer—a most reprehensible, though not unusual, fault in young men.

So the years went by and we became inseparable. The boys on the campus, whom nothing ever escapes, remarked the friendship and dubbed us "David and Jonathan." They eagerly watched for the advent of the woman, for they desired to know what would happen if the eternal feminine should come between David and Jonathan. But she never materialized and our lives went peacefully on.

After graduation Nick and I hung out our shingles together in Philadelphia. I persuaded my widowed mother to take a larger residence on West Spruce Street where there was ample room for all. Some of his clothing is still hanging on the hooks in his room and I suppose the key to the front door is still on his key-chain. We were scarcely comfortably fixed in our new quarters when Nick went away on one of his sudden and mysterious journeys. At first I thought he would soon be back, but he did not return for four years.

During that time I received an occasional letter from him, each one mailed from a different part of the globe. In one of his missives he told me his father had died, necessitating a change in his attitude toward life. In a letter from Paris he said he had been home for a season, but the country life of a gentleman did not appeal to him. He assured me he would soon return, and one morning, when I awoke, I found him in his bed-room next to mine. He had crept in quietly, while the house slept, and retired as if it were the most ordinary thing in the world for him to be home.

My joy at seeing him, as you can well believe, was great; but at the end of one short month he was suddenly away again, and his letters began arriving. This time he had a commission in the Russian army of the Far East, and was in Vladivostok when the war with Japan was declared. It was his misfortune to be transferred to Port Arthur, where he was captured when the stronghold was surrendered.

At the conclusion of hostilities he resigned his commission, but remained in Japan because he was interested in the country and the language. Then he drifted over to the Philippines in search of that will-o'-wisp called "Something New," and thence to California. In his last letter he said that he was coming eastward by easy stages and that there was a chance that I would soon see him in Philadelphia. In this hope I was not disappointed, for Nicholas shortly made his appearance. And here is where the story begins.

CHAPTER II

THE RETURN OF NICHOLAS

Returning he proclaims by many a grace,By shrugs and strange contortions of the face,How such a dunce that has been sent to roam,Excels the dunce that has been kept at home.—Cowper: Progress of Error.

It was on the evening of November 17, 19—, that Nicholas returned. I recall the date distinctly because it was the opening night of the Philadelphia Opera House. I was standing against the wall in the red carpeted promenade, marvelling at the magnificent display of gowns and the wonderful beauty of the women, both of which were a revelation to me, native born though I am, when I saw Nick sauntering through the crowd.

Older, a trifle heavier and more matured, I thought, than when I last saw him, but in all else the same old Nicholas. He was attired in the perfection of evening dress, for perfection was usual with him, and, although I least expected to find him here, I knew I could not be mistaken. There was the same mass of dark waving hair, soft, sleepy brown eyes and smooth olive skin; the same well-built athletic figure—proud heritage of the American college man—the same generous full rounded mouth and even white teeth enhanced by contrast with the darkness of his skin.

Waiting long enough to assure myself that he was alone, I made my way through the crowd, none too gently I fear, trampling on many beautiful, slow-moving trains in my eagerness to reach him.

"Lassie!" I called.

"Rude person," said the angry owner of a ruined dress; but I maintained my reputation for rudeness by ignoring the pouting beauty in my frantic effort to keep Nick in sight.

At the sound of the college name, which he had not heard for years, Nick turned and examined face after face within range of his vision until, over the undulating sea of the hair dresser's art—and artifice—our smiling eyes met and he recognized me. So effusive was our meeting, and so genuine the display of affection, that we became the centre of an interested circle of bare-shouldered observers who, mayhap, imagined that we were fighting. And not without reason, for we were alternately shaking hands and punching each other forcibly, but affectionately, upon our white shirt bosoms. As the lights were dimmed for the next act our audience scattered as silently as possible to recover their places in boxes and pit.

"Are you alone?" asked Nick.

"Yes."

"Good. Then you will spend the remainder of the evening with me, now that I have found you."

The blare of the orchestra drowned further talk until we emerged from the opera house, leaving the cigarette girl, Carmen, and her Spanish lovers to their fate.

A huge dark green automobile with some sort of a foreign monogram on the door, and a small Japanese boy enveloped in a great fur coat at the wheel, drew silently up at the curb. Nicholas pushed through the aisles of waiting carriages and the crowd of spectators that lined the street and sidewalk on that famous opening night.

"To the Bellevue?" I asked noting the direction.

"I would rather take you home. We can have more quiet in your back office, Dale. I want to hear you talk. The sound of your voice is the best music I have heard since I returned to old Philadelphia."

"Have you seen mother?"

"Yes; I got in just after you had gone to the opera. She told me where to find you."

When we arrived home the Jap boy put the car in a neighbouring garage and I got out my Scotch and seltzer in the back office. Nick fled upstairs and brought down a mandarin's coat of many colours which he had picked up in Japan for me. It was indeed a beauty and I was proud of it as I strutted around viewing myself in the mirrors. Nick made himself comfortable in my old smoking jacket, and threw himself into a chair, his glance wandering about the room.

"Just to think of it," he said; "all these years have gone by and everything here is unchanged. Not a piece of furniture, not an ornament has been moved. In the midst of it you sit, the very personification of immovability, working away, doing the same thing yesterday, to-day and for ever. While I have looked upon a new scene with every changing hour, have seen cities rise and fall, have watched men die by the hundreds. Doesn't the wanderlust ever grip you, Dale; don't you ever want to get out and see something of the world?"

"Some persons have to earn their living, you young gadabout," I said, smiling; "and, after all, what have you accomplished with the fleeing years?"

"Humph," said he, "nothing worth talking about. What have you done?"

"I have been practising my profession, distributing with a free hand my pills and physic to the residents of Philadelphia; I have written a medical book or two and I have extended the lives of a few men and women, bringing joy into the homes of their loved ones. That is more than you can say, perhaps."

"True," said Nick, "I have done nothing. Are you married, Dale?"

"No."

"Going to be?"

"Not that I am aware of."

"Nor I, either; but I never stayed long enough in one place. Why haven't you?"

"Been too busy with my work to think about it, I suppose. Besides, there's mother, you know. Nick, I wish you would write to me oftener; your letters were so few and far between that I sometimes felt you had forgotten me."

For answer he put his hand into the pocket of the mandarin coat I was wearing and handed me a leather case. I opened it and recognized the meerschaum pipe I had given him as a graduation present. Pure white it was then, but now it was stained a beautiful reddish black, showing the years of comfort it had given him since that time. Nicholas never wasted words and I knew by this silent action in handing me the relic of our old, happy days, that he was telling me in his characteristic way how often he had thought of me. I was much pleased.

He took back the meerschaum, filled and lit before he replied.

"I know you have never forgiven me, Dale, for giving up the practice of medicine. I wish I could make you understand that it was not entirely my fault, and that there is no place for the medical profession in my country."

"I never could understand that, Nick, for it always seemed to me that a young man could make his best start where he was known."

"It is difficult to make you Americans understand that tout le monde, as the French say, is not American. In the first place there is no city, town or hamlet near my home place; and in the second the people—although I say it who love them well—are not progressive. They still live under the laws of the middle ages and the wonders of modern medicine would appear as witchcraft in their eyes."

"Your country must be most peculiar," I said. Such was the rapport between us that Nick took my reply as I meant it, a gentle suggestion that he tell me more about his mysterious native land. Deep down in my heart I always resented his secrecy in the matter, and could never understand his reason for keeping anything from one who loved him like a brother.

A frown gathered upon his brow as he studied the carpet.

"If you still want to make a mystery of yourself," I said when he remained silent, "you need tell me nothing and I shall not be offended."

"When I first came to you, old friend," he said, "I kept my own counsel for various reasons. One was because I desired you, and all who knew me, to like me because I was just Nick Fremsted and not the descendant of an old and illustrious family. Another was because you Americans are inclined to smile at anything smaller than your own country and my Fatherland is not any larger than the state of Delaware."

"Let it pass," I replied, "and instead tell me what you have done since last we met."

"All right," said he. "Where shall I begin?"

"The last time you were here your father had died and you had arranged your estate and continued your travelling. You went to St. Petersburg on secret business for your government—the Turks were pressing you hard and you needed assistance from your guardian angel, the Bear of the North. After that you spent a month with me and then came the Russo-Japanese war. Tell me about that."

He took up the account from the day he left Philadelphia and held me spellbound with the tale of his experiences and the dangers he had escaped until I felt that my own quiet existence was a mean little life after all. The entrance of Teju Okio, returned from the garage, led the story in his direction.

"I found the Jap boy in front of Port Arthur," said Nick. "He was one of the little brown men who captured it. But, a month before they caused us to surrender, I captured him. It happened in this way. I was in command of one of the numerous defences which had to be taken before the city fell. The Japs, like little moles, burrowed in the ground, driving trenches toward us until they could win a position from which they could drive us out. We made frequent charges on their works, captured and put to death many of their soldiers pick and shovel in hand.

"One night, as I was accompanying an attacking party, the ground caved in beneath my feet and I fell on my back into a tunnel filled with Japanese within a hundred feet of the foundations of our redoubt. Before I could arise they recovered from their surprise and attacked me. I put up the best fight I could for my life but they were too numerous.

"The only light in the hole was a smoking oil torch which was soon kicked over, giving me the advantage of darkness. They were afraid to strike in the dark for fear of hitting friends, but I had no such compunctions. I fought my way to my feet, using both fists and feet, and escaped the crowd, leaving them fighting together.

"I knew that the open end of the tunnel must be opposite from the fort, so I went in that direction only to encounter more Japanese, running with lights to learn the cause of the disturbance. The top of the tunnel was so low that I had to stoop and there was no room to use my sword. I dashed the leader of the relief party back upon his comrades; three or four of them fell and the rest blocked up the passageway. Before I could fight my way through, the first party came up in the rear and I was knocked down by a blow on the head with a shovel.

"They tied me hand and foot and held a council of war. Most of them were naked to the waist, and, as they gathered around the torch, with the sweat running from them in streams, they looked like little demons to me. Most of them were for killing me at once and be done with it, and I suppose I should have died then and there with a pick in my brain if one of their number, little Lieutenant Teju Okio, the only officer among them, had not interceded for me. He stood over me with a revolver in each hand and ordered them back to work. And they went reluctantly.

"In the meanwhile the Russian attacking party went on without noticing my absence. As luck would have it, they stumbled upon the very ditch which communicated with the tunnel, found the opening and came through it, cautiously firing in front of them and feeling their way. Okio heard them coming and knew that his men were caught in their own trap. At his command the Japs attacked the side walls with their picks and shovels and blocked up the passage with soil. Then he retreated with his men, leaving me alone and bound beside the barrier. He had forgotten to gag me and, when my companions came to what they imagined was the end of the works, I shouted my orders to them to dig through. Willing hands fell upon that hastily constructed barrier and in five minutes I saw a Russian hand come through, followed by the face of one of my own lieutenants, who paused in surprise when he saw me lying on the ground with a torch burning beside me.

"'Heaven help me, captain,' he cried, 'what does this mean?'

"'Cut me loose. Hurry. They are in the far end of the tunnel. Get your men through and capture them.'

"Man after man crawled through the hole until we were in sufficient force to advance with assurance of success. I led the way at double quick, but, when we came to the end of the work, there was only one man there and that one was Teju Okio. He was squatting before his miner's lamp calmly lighting a cigarette, his uniform and hands covered with mud, as if an army had walked over him, his little chest heaving like a victorious runner's after a gruelling race, a smile of satisfaction upon his face. He knew it was not our habit to give or ask quarter, yet there the brave little fellow sat smiling into the eyes of death.

"But I had not forgotten what he had done for me and I repaid my debt of gratitude by interposing my body between his enemies, just as he, a short time before, had done for me.

"'Leave this man to me,' I cried; 'get the rest. They are not far away.'

"But, search as we would, we could not find them. Neither was there another tunnel and the one we were in ended right there. I was mystified and turned to my prisoner for the explanation. He was furtively watching the ceiling above his head. Looking in that direction I saw the starry sky twinkling down through the hole in the roof of the tunnel which I had made in falling. The heroism of Teju Okio was apparent. Obeying his instructions, every one of his unarmed companions had mounted Okio's shoulders and escaped through the opening, leaving him to face the fury of the Russians alone.

"But I saw to it that they did not harm him, making him my own personal prisoner. We retreated that night before the Japs finished their tunnel and blew up the fort and, when Port Arthur fell, Teju Okio got his freedom and I was taken with the rest of the survivors to Japan. Hostilities concluded, I resigned my commission and stayed in Japan to study the language. Teju Okio was only a poor farmer's boy and he gladly came with me as my servant.

"I wrote you from the Philippines and California," he concluded, "didn't you get my letters?"

"Oh, yes," I replied, "every one of them."

"Well, to bring it up to date, I arrived in New York last Saturday, a week ago to-day; I left there this morning and motored over here. So there, my friend, you have the record of my meagre years wherein you observe I have been seeking amusement all over the earth. Sometimes I found it and sometimes I was bored to death."

"Going to stay long, Nick?"

"As far as I now know I shall remain with you for some time."

My expressions of happiness were interrupted by the ringing of the front doorbell.

"Somebody requires a pill," said Nick, as I answered it in person. "My, what a practice we have built up!"

But the visitor was not one of my patients. He was a man of about five and fifty with snow white hair which he wore rather long. His heavy moustache, also white, was tightly waxed and turned up at the ends after the manner of the German Emperor. His eyebrows, in contradistinction to his hair and moustache, were black. They were heavy and overhung a fine pair of alert, far-seeing black eyes, giving to his face a distinction which made it cling to the most casual memory. His skin, like that of Fremsted, was dark and showed the effect of an outdoor life. He seemed to be a bluff, hearty old gentleman with whom Nature had dealt kindly. On the whole there was something most pleasing about him.

"I wish to see Nicholas Fremsted," he said.

I hesitated, wondering who he might be and how he knew of Nick's presence in my house. It was then nearly two o'clock in the morning, an unseemly hour for a call whether of business or pleasure.

"Tell him General Palmora is here," he continued, and the ring of command in his voice left me no alternative but to obey.

With some misgivings I ushered him into the reception room and called Nick, feeling somehow that Nick's promised visit with me was at an end before it was begun.

The General was evidently an old friend of Nick's, for when the two men saw each other they embraced, kissing each other on the cheek like foreigners and mingling their cries of delight. When their effusive greeting was over, Nick led the old man to a chair and they began a spirited conversation in a strange tongue, while I for the moment was forgotten.

I wandered about the room making a pretence of examining my own pictures and keeping my eye on the proceedings, but I could make little out of them. The General did most of the talking. He handed Nick an official looking document engrossed with a red seal from which was suspended blue and gold ribbons. Nick held it under the hanging lamp, and the black and the gray hair mingled as the two bent their heads together over it. The General frequently tapped the paper with his slender fingers and talked rapidly, combating every argument which Nicholas seemed to advance. Finally he produced from his overcoat pocket a chamois bag which he deposited upon the table. Judging from the jingle I concluded that it contained gold coins. The argument ended when the General won some sort of a promise from Nicholas. Then, having effected his purpose, he rose abruptly, bowed low over Nick's hand and made his way to the door, which I opened for him. He bade me "good night" politely in English, and went down the steps.

When I returned to the reception room, Nick was deeply absorbed in re-reading the parchment with the red seal. His face wore a troubled look. As I went around to his side and placed a hand on his shoulder, he started like a man suddenly awakened from a deep sleep. The message before him was written in a foreign language with peculiar characters the like of which I had never seen. They might have been Russian or Hebrew. From the arrangement of the seal I imagined the screed was intended to be read from right to left.

"Can you make anything of it?" asked Nick, noting my glance.

"All Greek to me," I replied; "Has it something to do with your country?"

"Yes. It is an official command to Grand Duke—that is, I should say it is a summons to Nicholas Fremsted "to be present at the Cathedral in Nischon on New Year's Day, January 1, 19—, to bear witness and attest to the legality of the coronation of Prince Raoul as King of Bharbazonia," said Nick, reading the scroll. "It is signed by Oloff Gregory, the present king, who is eighty-two years old, and desires to abdicate."

At last the secret of Nick's nationality was out, but I was not concerned with that so much as I was with the fear that I was to lose him so soon.

"Of course you are going?" I asked.

"Yes; I gave my word to the General."

"I have never heard of this country of Bharbazonia; where is it, Nick?"

"No, of course not," said he. "It is one of the many small provinces of southeastern Europe which is generally summed up and dismissed with the expression—one of the Balkan states. My country threw off the yoke of the Turks about the same time Bulgaria obtained her freedom at the Battle of Shipka Pass, thanks to Russian intervention and their great fighting chief Grand Duke Alexoff. During that struggle Bharbazonia sent her best fighting men and all her money to Bulgaria's aid and many of the fiercest battles for the extermination of the red fez were waged in the mountains which surround the Fatherland. When the treaty was signed Bulgaria and Bharbazonia were free. Gregory was made king and the nobles, banished by the Turks, returned from exile in friendly Russia and resumed control of the land of their forefathers."

"Was the General's news the first you had of the proposed abdication?"

"No, I knew of it; but did not feel called upon to be present. He convinced me that it was my duty."

"Who is General Palmora?"

"He is one of the first men of Bharbazonia, commander-in-chief of her army. Upon his shoulders fell the brunt of the fighting which resulted in our freedom. My father and he were like brothers; a friendship like ours existed between them, Dale, and, now that father is dead, Palmora loves me like a son. All my affairs are in his hands at home. He was visiting America on business of state. Bharbazonia's interests are in charge of the Bulgarian consul in Philadelphia and, since I always leave my address with him, General Palmora experienced no difficulty in locating me."

"When do you sail?"

"I must return with the General on the Koenig Albert from Hoboken next Tuesday."

"Just one week from to-day?"

"Yes. We will be in Naples, if all goes well, a week from the following Tuesday. There the General's yacht will meet us."

"What a beautiful trip you will have," I exclaimed, something of the wanderlust engendered by Nick's story getting into my blood. "How I should like to go with you."

"I wish you would, Dale. We could be back in a month or so, and you will see one of the prettiest little countries in the world. The coronation services, too, are well worth the journey. Come now, make up your mind and say you will go."

The more I thought about it the more feasible it became. I had arranged to take a month in Florida, my first extended vacation in eight years, and it would not be a difficult matter to rearrange the trip and go with Nick.

And so it was agreed that he should book passage for me. Had I been able to look into the future and see what was to befall in the Kingdom of Bharbazonia, and that Nick would never come back with me, I might not have taken my decision so lightly, nor have looked forward to the trip with so much pleasure.

And here is where the story really begins.

CHAPTER III

OFF FOR BHARBAZONIA!

See, what a ready tongue suspicion hath!He that but fears the thing he would not know,Hath, by instinct, knowledge from another's eyes,That what he feared is chanced.—Shakespeare: Henry IV.

When the big ocean liner swung clear of her dock the following Tuesday under the propelling influence of a pair of optimistic tugs which, undaunted by her huge bulk and their diminutive size, dragged her slowly into the current of the Hudson River, and set her face toward Europe, Nick and I were leaning over the guard rail watching the sea of upturned faces on the dock and the mass of waving handkerchiefs.

My preparations for the voyage had been quickly made. After expressing my steamer trunk to the boat, writing a few letters and turning my practice over to my hospital colleague, I was at liberty to accompany Nick in his swift trips about the city while he transacted the business which brought him to Philadelphia.

He first visited the Russian consul; then he held a long talk with a white-bearded black-robed priest of the Greek Church and an Armenian shoemaker in the Lombard Street district. Everywhere he was received with considerable show of respect, and I began to suspect that his early education in the languages had not been entirely a matter of taste or of chance.

During all this time I had no glimpse of General Palmora in Philadelphia, and he was not on board when we drove on the dock in Nicholas' automobile, having made the trip from home in it. Nick intended to take his car with him.

"It will be the first one they ever saw in Bharbazonia," he laughed, and, when I suggested that it might be cheaper to buy a car in Europe and so avoid the duties, he said that automobiles were unknown at the place where we would disembark from the General's yacht and that there would be no duties.

"Looks as if I had fallen in with a band of smugglers," I said banteringly.

"Worse, oh, much worse," he replied in the same spirit.

On the second night out General Palmora made his appearance on deck, and Nick introduced him. He paid me the compliment of saying that he had often heard Nicholas speak of his chum, Dale Wharton; and tried to communicate with me in several languages, much to Nick's amusement.

"Try English, General," he suggested. "Dale is an American and probably knows only one language.

"You mustn't forget my French," I reminded him.

"Why, of course," replied the General, resuming his beautiful London drawl, which revealed the source of his English education, "how stupid of me. I should have known as much."

But the probability that he was trying to determine what language to use with Nick in my presence, did not escape me.

"This is not the first time I have had the pleasure of seeing you, General," I reminded him, opening the conversation after we were comfortably seated in our steamer chairs, protected from the wind by our rugs, "I was present with Fremsted the night you called at my house to see him."

"Ah, indeed? I do not remember you. I must apologize for my seeming rudeness in thus interrupting you, but the meeting with Nicholas was of great importance. I could think of nothing else."

"I presume Nicholas would never have attended the coronation if you had not urged him. He tells me in that event his estates might have been confiscated."

"Although such is the law in Bharbazonia," said the General laughing, and regarding Nick with affection, "I do not believe it would have been enforced in his case. Nicholas has friends at court who are powerful."

"Then why drag me away from the work of the Order?" exclaimed Nick with so much sudden heat that even the General was astonished.

"Gently, gently, my son," he answered in a conciliating tone, "I wanted you in Bharbazonia because I fear that we will have need for you. The 'Red Fox of Dhalmatia' was never known to run straight, and all may not be right with the succession."

"You mean that you suspect some trick may be attempted in connection with Prince Raoul, who is to be king?" I asked, eager for news of this strange country.

"It is one of his hobbies, Dale," said Nick. "You will soon find that his suspicions have not a leg to stand upon."

"It is true, Dr. Wharton," said the old man sadly; "I have only the vaguest ideas on the subject, although I have been watching and waiting, and, I might add, hoping, these past twenty years. The boy Raoul I know to be a capable youth. Although he is but twenty-two, he takes an interest in the work of the Order, which his father the 'Red Fox' never did. For that I like the boy. It argues well for his independence of thought. But, because he is the son of his father, I—cordially dislike him."

"Yes, General," I said, "but what are your suspicions?"

"If you will bear with me, young man, I will tell you the story. It goes back to the time when the Prince was born. Nick was then a lad of eleven or twelve and he was not interested in affairs of state. It was the year I believe that his father, acting on my advice, sent him to school in St. Petersburg. We were then only nine years away from the consummation of the Treaty of Berlin by which Bulgaria, Eastern Roumelia, Thessaly and Bharbazonia achieved independence, protected by the Powers. Now in Bharbazonia, as in many Eastern countries, the succession to the throne falls only upon the first male child of the ruler. Oloff Gregory, the king, even then an old man, had no son, which grieved him much, for he feared the throne must go away from his immediate family. His only child was his daughter Teskla.

"On the other hand his younger brother, the Red Fox of Dhalmatia, was more than pleased with the condition of affairs. He knew that, if he should have a son, the boy would reign in Bharbazonia, not because of any rights of succession, but because there was no other. Although, he, too, was no longer young, the 'Red Fox' took unto himself a young wife and it was soon noised abroad that the stork was expected to visit his castle."

The point which the General made of the male succession in Bharbazonia did not strike me as unusual, because I recalled that in England during Queen Victoria's reign, her uncle, the Duke of Cumberland, was made King of Hanover by virtue of the law which excluded females from that throne.

Before continuing his story Palmora lit his cigar with a wind match, and, turning to me, said:

"I trust you will pardon the length of my tale. I do not wish to bore you."

"Please go on, General, I am much interested," I hastened to assure him.

"In our country, Dr. Wharton, it is still the custom to notify the peasantry of the birth of a castle child by ringing the tower bell, and, in the event of a male, to proclaim the sex by five strokes of the tongue, and in the event of a female by seven. The news is then carried by word of mouth and so spreads over the country.

"On the night the stork brought its precious burden to Dhalmatia I was playing chess, if I remember correctly, with my great friend, Nicholas' father, in his library, when we heard the brass bell of Dhalmatia give voice. With the fate of even more than the future king in the balance, we forgot our game in our intense interest, counting the strokes.

"'One; two; three; four; five; six—'tis a girl,' said Nick's father, much relieved, for he shared my dislike for the 'Red Fox,' and was pleased that the succession would not go to Dhalmatia. There were other reasons why we were delighted with the failure of the 'Red Fox's' hopes, but they were locked in our breasts by the events which followed. Scarcely had the bell completed its toll of seven, when to our astonishment it began again.

"'One; two; three; four; five,' we both counted aloud, looking into each other's eyes over the table between.

"'Five,' we shouted, springing to our feet and scattering the chessmen broadcast.

"'A boy at Dhalmatia?' I cried, scarcely believing my ears.

"'Is he playing with us?' said my friend. 'By the first ring he tells us it is a girl, and then he changes his mind and it is a boy?'

"'Let us solve this mystery at once,' I suggested.

"We took our lantern from the hooks and saddled our horses. It was about nine of the clock when the bell began ringing and I warrant it was not more than fifteen minutes later when we drew rein in front of Dhalmatia. It was as dark as the pit and not a light was shining from the windows, which on such a festive occasion should have been illuminated. From the direction of the servants' quarters came the sound of sobbing which grated horribly upon our ears.

"We pounded upon the heavy oak door with the hilts of our swords but only the echoes answered us; the weeping continued. Presently the door swung back a little way, slowly and it seemed to me cautiously, and the 'Fox' himself stood in the narrow opening, muffled to the eyes in his long black cloak. When he saw who his visitors were, he was not pleased and made as if to shut the door in our faces, but we placed our shoulders against it, defeating his purpose.

"'Well?' he growled ungraciously.

"'The bell; the bell!' cried Nicholas' father with some anger, out of breath with hard riding, 'what means this curious ringing of the tower bell?'

"'Curious?' he sneered; 'curious? I like not your words, Framkor. There is nothing unusual about it that I can discover.'

"'Did not you announce the birth of a daughter?'

"'The bell rang seven times,' returned the Fox.

"'Then Bharbazonia is without an heir in your house?'

"'Not so, my kind and most considerate neighbour,' he replied sarcastically, 'you must still wait a little longer. Did you not hear the bell ring also five times?'

"'The meaning! The meaning!' we both exclaimed.

"'It is perfectly clear, noble sirs,' he said. 'The house of Dhalmatia has been honoured this night with the advent of both a daughter and a son.'

"'Twins!' we cried, looking at each other and wondering why we had not thought of it before. We saw that we had been hoping against hope, and our worst fears were realized. I suppose our chagrin showed in our faces for the 'Red Fox' seemed to enjoy our discomfiture. It was not in our hearts to congratulate the old rogue. We could not lie for the sake of an empty courtesy. We mounted our horses and rode away with the discordant chuckle of the lord of Dhalmatia ringing in our ears."

"Nothing very suspicious in all that," drawled Nick, flicking his cigarette into the sea. He had probably heard the story so often that he had no interest in it.

"If I could only make you understand," sighed the General.

"But why were the servants crying?" I asked.

"That came out the next day," continued the old man, glad at least to find one willing listener; "it seems that the old midwife, who was the only person with the mother when the children were born, had fallen from the tower in some strange way when she was tugging at the bell rope to announce the birth of the girl. Her neck was broken."

"Who then rang the bell the second time?"

"The Red Fox."

"How great was the interval between the ringing?"

"There was scarcely a pause; it was almost immediate."

"Then the 'Red Fox' must have been very near the nurse in the tower."

"He must have been very near."

Both Nick and I smoked in silence, while the General took a turn around the deck to still his excitement caused by his narration. Below, the sea slipped swiftly, softly by as the liner throbbed her quiet course through a vacant ocean. Overhead, the wireless spit and sputtered as the operator talked to his fellow aboard an unseen ship possibly a hundred miles away. It was as if the mocking voice of modern times were laughing at the mysteries of the long dead past. If there was any hidden meaning in the General's story it was exceedingly vague at best. When he resumed his seat by our side I ventured to open the subject again.

"Have you ever seen the Twins of Dhalmatia, General?"

"Oh, yes; many times," he replied.

"They exist, then."

"Oh, yes," he said, and from his manner I judged he would have added "unfortunately" had he not hesitated to shock me.

"Well then, my dear General, be frank with us. What do you suspect?"

"My sentiments exactly," joined Nick lightly.

"I wish to Hercules I knew what I suspected," he answered with a sigh. "All I know is that I have the feeling that all was not as it should be the night we talked with Dhalmatia. It is with me still. Wait until you know the 'Red Fox' as I do and you will understand."

"Bah," exclaimed Nick, "you gossip like an old woman. Do not put much faith in what he says, Dale, about the master of Dhalmatia. Prejudice is like a disorder of the blood; it sometimes causes hallucinations."

"Wait and see," returned the General. "I still believe that murder will out."

"But even if your wild imaginings should prove true, why am I desired in Bharbazonia?"

"That," said the General, "is your father's secret. Some day you shall be told."

On different occasions during the voyage, I drew the General into a discussion concerning the birth of the heir to the Bharbazonian throne, but gleaned very little more information. The General described the various times he had met the Prince and Princess. He was present on both occasions when first one and then the other was christened at the Cathedral of Nischon. These two events happened a week apart. He entertained quite a friendship for the Prince, who was a great boar hunter and horseman. The Princess he scarcely knew.

"I have never seen them in each other's society," he said, "because when one was home on a vacation the other was usually away at school in England or France. Most nobles of our little kingdom believe in the boon of education for their children."

At Naples the General's yacht came alongside the liner at her dock and we were transferred to the cramped quarters of still smaller staterooms. Although it was midnight, and the passengers were not permitted to land, the General seemed to possess sufficient authority to have the automobile hoisted from the hold of the vessel and lashed securely to the deck of his little craft. In the morning when I awoke I found that we were well on our way toward the toe of the Italian peninsula.

For several days we steamed quietly along, the blue Mediterranean beneath and the bluer sky above, until we entered the Dardanelles and passed in front of the Turk's capital, the city of Constantinople. When we came in sight of the white, flatroofed town, the captain hauled down the white flag with the blue diagonals of the Russian navy and hoisted the stars and stripes. What he meant by the deception I could not imagine and, when I ventured to ask him, he laughed and said:

"What a man dinna' see he canna' forget."

A sunny old Scotchman was Captain MacPherson, and he took a great liking to me because I knew his friend Thomas Anderson, who had charge of the dissecting room at the University.

"Tamas was e'er a gude hand with those as could na answer him back," said the Captain. "His first occupation at hame was as an undertaker's assistant. He comes by it honestly."

He pointed out the fortresses on both shores of the narrow channel, which was only a mile wide in front of the city, and told me that the Turks had mounted them with the most improved modern guns.

"They could e'en blow us out of the water," he said, "had they a mind to."

Constantinople was like an open book to him and he showed me the Sultan's Palace, standing white and high like an office building, the Mosque of St. Sophia, and various points of interest as the city, thrusting its myriad minarets to the sky, slipped swiftly by like a beautiful panorama. Somewhere along these shores both Leander and Byron swam the Hellespont, and Xerxes, the Persian king, smote the waves in a rage because they, troubled by a storm, forbade for a time the passage of his Greek conquering army. I was awakened from my historic reverie by hearing the voice of Nicholas. He and the General were leaning over the railing with their eyes fixed on the Palace of the Sultan. There was an expression of intense hatred on the faces of both.

"Oh, Thou, who holdest the destinies of nations in thy hand; Oh, Thou, who gavest the land of Canaan to thy chosen people; how long must we wait the coming of that glad day when thou wilt send a Joshua to us, that we may become the humble instruments of destiny to drive the Turk from Europe back to the sands of Bagdad whence he sprang?"

"Amen," came the deep bass of the General.

"Amen," said the voice of Captain MacPherson at my elbow.

They watched the city in silence until distance and darkness swallowed it up as the yacht continued its way up the north coast of the Black Sea. So intent were the three in getting all the pleasure they could out of their mutual hate that they forgot my existence entirely.

"French became an accomplishment rather than a necessity in the English court in the fifteenth century," I said to Nick that evening at table.

"What do you mean?" he said with a frown.

"It is still the language of the Russian court. But why are you so interested in fighting Russia's battles, you a Bharbazonian?"

"Archaic though she may be, I love Russia, Dale," he said, "for without Russia there would have been no independent Bharbazonia to-day. Even now she is paying into our treasury 24,000 rubles a year, which we in turn must pay as tribute to the Turk."

"How soon shall we reach your little kingdom, Nick?"

"We should be there day after to-morrow."

Sure enough, on the day set the little yacht's engine came to a stop early in the morning while we were still in our berths. All the gloom had vanished and Nick was in high spirits when he came to get me up.

"All ashore for Bharbazonia. Change cars for the Belle of the Balkans. This train doesn't go any further. Come, come, out of bed, you lazy one. We are home at last!"

CHAPTER IV

AT THE TURK'S HEAD INN

Oh, Freedom! thou art not, as poets dream,A fair young girl, with light and delicate limbs,And wavy tresses gushing from the capWith which the Roman master crowned his slaveWhen he took off the gyves. A bearded man,Armed to the teeth, art thou; one mailed handGrasps the broad shield, and one the sword; thy brow,Glorious in beauty though it be, is scarredWith tokens of old wars.—Bryant: Antiquity of Freedom.

When I came on deck I found the Black Sea had disappeared and we were at rest in a deep, narrow river which ran swiftly and noiselessly through a sombre gorge between two high mountains that almost shut out the light of day and hid the ocean from our sight. The sudden change of scene from the hard white glare of the sea to the soft black sheen of the land was startling. The foliage was so close to the ship that it seemed one could almost reach out the hand and touch it, although the yacht was moored at the end of a long dock. I experienced a foolish fear that the high hills were about to fall upon the little vessel and crush it. That impression wore off in a short time as the motion of the ship left me.

At the other side of the dock, set down upon a narrow space of rocky level land between the mountains and the river, was the little fishing village of Bizzett. In the rear the houses rose on terraces along the edge of the mountain and in front the town extended into the river on piles. There were no windows in the houses looking upon the street. If windows existed at all, they opened upon an inner court.

All the women and children of the town were on the dock, curious to see the travellers, filling the air with the babel of strange voices. It was plain that the landing of the yacht was an event. A few of the fishermen, who had not gone seaward upon their daily toil, were watching us from their boats.

Some of the women, after the manner of Turkish women, wore veils over their faces, having nothing but the eyes exposed, but the girls went about uncovered, their long black hair braided and ornamented with coins. The few of the male peasantry in sight were dressed much alike, in brown sheepskin caps, jackets of undyed brown wool, which their women folk spin and make, white cloth trousers and sandals of raw leather.

The natives were lively and hospitable. They greeted General Palmora with loud cheers as soon as he stepped on the dock and several of the older men came forward to shake him by the hand. The General, in anticipation of his reception, had donned a splendid uniform richly embossed with sparkling shoulder epaulettes and much gold braid. Nick, on the other hand, stood beside me attired in a plain dark blue serge suit which he had purchased in America. The women, walking two by two with their arms around each other's waists, examined us curiously, but the men never glanced once in our direction. Two young girls, without the least timidity, stopped in front of us and examined us as if we were tailors' models. That is to say, our clothes appeared to interest them more than the men inside of them. They talked and laughed and even went so far as to feel the texture of the goods. Their remarks made Nicholas frown.

"What are they saying, Nick?" I asked.

"They are saying, 'The English dogs have well trained wives who weave such fine cloth,'" he replied.

"You seem to be a stranger in your own country. These people take you for a foreigner."

"They do not know me," he sighed. "The penalty one pays for being a nomad. How they love the General!"

But the General's popularity faded when the automobile was placed upon the dock, and Teju Okio became the centre of attraction. The townsfolk crowded around the Jap boy, honked the horn with all the delight of mischievous newsboys and watched each piece of baggage as it was stowed away in the tonneau. But they departed with much speed and many frightened cries when Okio started the engine, running in all directions as if a demon had fallen from the sky in their midst. In a twinkling the dock was vacant and the village apparently deserted. They only came to the doors of their houses to watch us leave the village in a cloud of dust. But our attention was brought to the front by an expression of surprise from Teju Okio.

"Very dam-fine," he said, referring to the hill which the machine had to climb. Teju's English vocabulary was limited to three words which he used to express every emotion. This time it was admiration and respect. And the road was worthy of both. It ran diagonally up the side of the mountain until it reached the top at a depression or gap caused by two mountains pressing their foreheads together. One could see the end from the beginning, for it was a singularly straight road laid out as if the builder had placed a schoolboy's ruler upon the mountainside, drawn a line from the village to the gap and said, "Build ye here the way as I have drawn it," just as the Tzar is said to have laid out his eighteen-day railroad across Siberia.

A perfect arbour of tall trees lined both sides of the way, interlocking their branches overhead. The foliage on the lower side of the mountain was trimmed so as to give a view of the sea; the early morning sun streamed gratefully in, taking the chill from the air and casting long shadows across the road in front. As we ascended we looked back and saw part of the village still in sight. The peasants were standing in the streets, marking the progress of the strange vehicle which had within itself the power to conquer the hill of Bizzett without the aid of oxen.

At the top was a stone fortress, called Castle Comada. It came in sight suddenly as we reached level ground and turned our back to the sea. Castle Comada was a spacious building completely filling up the gap and extending across the road as far as the eye could reach among the trees. The roadway ran through the centre of it in a sort of tunnel of solid masonry and over this archway the main part of the castle rose higher than the rest, supported on the four corners by square watch towers. A fifth tower, even more lofty, sprang from the centre, and from this tower snapping gaily in the wind was the flag of Bharbazonia, alternate stripes of light blue and gold.

Beneath the castle walls, lining both sides of the way, were five regiments of cavalry, their horses' heads forming a perfect line and each man sitting erect in the saddle. As we came in sight, the garrison band burst forth in the national air and, at the given order, hundreds of bared sabres flashed in the sun and came to rest in an upright position before each man's chin. The salute was for the General; the army of the kingdom was welcoming home its commander-in-chief, warned, possibly, the night before by the sharp-eyed watchman in the tower who had sighted the yacht.

It was sure that the defences of the government, ever watchful of the Turk, were in modern hands, and, if one noticed the look of pleasure on the old General's countenance at the visible signs of a well oiled system, one had not far to seek the master mind.

Nicholas preferred to remain in the car with me while the General paid his respects to Governor Noovgor of the Southern Province. I was very glad of that, because he was able to explain the country, whenever the band was stilled long enough to permit conversation.

"This road is known as the Highway of Bizzett," Nick said. "Sometimes it is called the 'King's Highway.' It traverses Bharbazonia from north to south almost in a straight line over several hundred miles of fertile, rolling country. The mountain range, running east and west as you see, gradually turns toward the north until both arms meet at the other end of the highway in a similar pass, guarded by a similar fortress. Thus Castle Comada, on the Black Sea, and Castle Novgorod, on the Russian border, are the Beersheba and Dan of Bharbazonia. No man may enter or leave the country unless he pass under the guns of one or the other; and let me tell you, Dale, there is no fortress in America, or in any other country, which is the peer of these for modern disappearing guns, garrison equipment, or perfection of discipline."

As the General seemed in no hurry, Nick and I killed time by strolling around the grounds and inspecting the castle from all sides. I found that its guns commanded not only the Black Sea and the harbour of Bizzett, but also the approaches from the inland side; for the mountain formed a precipitous wall at the castle foundations, which left us standing on a high promontory, viewing, like Moses, a land flowing with milk and honey. Below us lay a level country, which even in its winter garb showed evidences of being in an excellent state of cultivation. Here and there were villages clustered along the great limestone pike—the straight white way of Bharbazonia.

An army attacking the fortress from either side would be equally powerless. Nicholas had every reason to be proud of his country's war craft, but, in spite of the modern atmosphere of the cavalry, there was something about this Bharbazonia that smacked to me of the fourteenth century, when men slept at night behind the barred gates of their walled cities.

The General was already in his seat beside Teju Okio when we returned. He was impatient to be off; but, before we were able to enter the Kingdom, ten soldiers put their shoulders to a pair of solid iron gates that blocked the road through the Castle, and swung them open. The guns fired their salute to the commander-in-chief, the band struck up a lively air, and the Jap boy threw in his high speed clutch.

As we raced through the tunnel and down the hill on the other side, I looked back and saw the men close the gates, those relics of the hundred years' war against the terrible Turk, and knew that we were locked in the Kingdom of Bharbazonia. The sun shone warmly down upon us, the peaceful valley lay invitingly below, but somehow I felt as a mouse must feel as he peers between the wire openings of his trap and realizes that he cannot get out.

Once free of the mountain, we sped along through a country as beautiful as any in America. Farmers, working in the fields, paused at their labour to watch us go by. Teju made the most of a fine road and lifted us along at the rate of sixty miles an hour, leaving many slain chickens behind to mark his swift passage.

Fortunately there was little travel along the highway that morning, for we frightened every human being and every animal we met. Patient plodding horses, dragging creaking carts in the same direction in which we were going, were too surprised to continue their journey. They stood still in their tracks unable to move until we disappeared over the crest of the next hill. The drivers, open-mouthed, were too startled to urge them. But the horses we met coming toward us had more time to watch our approach and thrill with fear. All of them lowered their heads, pricked up their ears and, like the cows, showed signs of confusion as to which side of the road they should take; then, as we came opposite, they bolted across the front of the speeding machine into the adjoining field. Their frightened owners, slowly gathering courage in a ditch, shook their fists and hurled Bharbazonian epithets after us.

It is amusing to play havoc in a country where there are no license tags, no mounted policemen and no fines to pay.

At noontide we made our first stop at a fine old road-house called the Turk's Head Inn. It was a queer little brick and red stone structure approaching the colonial style of architecture in its small, leaded glass windows and white paint, with the curious addition of Byzantine doors and windows, the result of Turkish influence. The main doorway, with its huge circular top, was in the centre of the building and formed an imposing entrance, reaching to the second floor. On an iron arm, extending from the top of this doorway, hung the signboard after which the inn was named.

It presented no written words; only a terrible life-sized painting of a Turk's head, dripping with blood and resting on a spear point. A red fez sat jauntily over one ear, giving the head a gala appearance; but the eyes, wide open, staring eyes, speedily dispelled any such thought. They were filled with a terrible expression of pain and horror, as if the head still breathed and felt the agony of the spear piercing its inmost brain, while its lips moved in the throes of cursing its tormentors, even in the face of death. The frightful signboard sent a shudder through me which the General noticed.

"What a grewsome thing," I said.

"It is the head of Helmud Bey," he replied, looking into the suffering eyes without a show of compassion; "he ruled over my sad country for forty years, the creature of the Sultan. So great was his ferocity that even now the peasantry tremble at the mention of his name. He was killed in this Inn thirty years ago by Oloff Gregory, the king. Clad in suits of French mail, they fought on horseback with sword and spear, while the Turkish and Bharbazonian army looked on, drawn up out there on opposite sides of the road.

"It was agreed that whichever champion won, his forces would be declared victorious without further fighting. It was the Turks' last stand after Shipka Pass and, had Gregory lost, Bharbazonia might not now be free. At the first shock Gregory unhorsed Helmud Bey and was himself thrown to the ground. Then the fighting was continued with heavy swords until the Turk, badly wounded, fled within the inn where Bharbazonia's champion killed him by cutting off his head.

"For a long time the head was displayed on the victor's pike before the roadhouse door. The Turks surrendered and the war was over. By this feat of arms Gregory became king, for, when Russia tried to rehabilitate the kingdom, she found that the Turks had killed or driven into exile every member of the royal house of Bharbazonia which was reigning in the fifteenth century before the time of the conquering Salaman the Magnificent. Gregory, you know, was only a soldier and a noble. His house never laid claim to royalty. And that is why his brother, the 'Red Fox,' is still a Duke although his children by special grant of the King are Prince and Princess of the land."

At the inn were the usual number of idlers. They gathered around the car at a respectful distance and watched us dismount. The innkeeper, in white apron and with bared head, appeared in the high doorway, scattering the crowd to make a passageway for us. He was a jolly old Frenchman.

"Back, ye hounds," he shouted in his native tongue, "cannot ye give the gentry room to alight?"

If the Bharbazonians understood they made no sign; neither did they give back a pace, standing their ground like stolid cattle. The reign of the invader had left the common people in a condition little above the brute. Gone was the warlike spirit of their Slavonic ancestors who inhabited the banks of the Volga in the seventh century. I experienced a feeling of pity for them. Ignorance, poverty and suffering had been their birthright. I could scarcely bring myself to believe that Nick and the General were their countrymen.

"Welcome home, my General," exclaimed the Frenchman.

"Thank you, Marchaud," returned the General. "What news have you?"

"Ah, sir; such coming and going. The coronation is all the talk. The Grand Duke Marbosa was here yesterday with the young men. You know, General," he added, winking slyly.

"Yes, I understand," said Palmora. "What then?"

"He was impatient for your return. He has a plan which lacks only your approval."

"Humph. How goes the dinner?"

"You are just in time. Will you enter?"

Again he made a passageway through the peasants with angry shouting and waving of hands. They were all respect for the General; some bowed in the dust before him and others raised a feeble cheer. He paid no particular attention to them.

The innkeeper led the way to the interior of his hostelry. Once past the door, we were immediately in the large room of the inn. On one side was a broad stairway which communicated with a balcony which in turn had access to all the sleeping rooms on the second floor. Off from the main room were smaller rooms, like booths, where the dining tables, covered with snow white linen, were invitingly set. He placed us at one of these tables and, with the assistance of two of his waiters, soon had a splendid feast spread before us.

The General was the life of the party. He was hungry and, judging from the amount of native wine he indulged in, thirsty, too. The change in Nick was also remarkable. Ever since his eyes fell upon the flag of Bharbazonia, and the well set-up cavalrymen at the castle, he seemed to grow in stature. Usually lazy and indolent, he became alert and active, as if the sleeping tiger within arose at the call of the setting sun to go forth to the water runs. Here, indeed, was a new Nicholas. The American youth whom I knew was becoming a Bharbazonian.

"Everything goes well for the great event," said the General, when we arrived at the coffee and cigarette stage of the repast. "Governor Noovgor tells me that he and Governor Hasson of the Northern Province will have 25,000 men before the Cathedral, both infantry and cavalry. The Tzar will be represented by a regiment of Cossacks from Moscow, and the Grand Duke Alexoff will come from St. Petersburg as the Emperor's personal representative. The first day of the new year will be a great day for Bharbazonia, my boy."

"You couldn't be more interested in the crowning of the Red Fox's son than if it were I you were honouring," said Nick, a bit petulantly.

"My boy; my boy," said the old man, patting his favourite on the back with a show of affection, "little prejudices must fall before patriotism."

"I wish you knew how repulsive this incognito business is becoming to me," said Nick. "I could scarcely keep myself from swinging my hat in the air and shouting for the flag when I saw those splendid fellows drawn up in front of Comada."

"All in good time," purred the General, pleased at Nick's reference to the army; "for the present it is best that I should be entertaining two American travellers. I do not want the Red Fox or his following to know who you are. If they suspect you, your usefulness to Russia would come to an end. For what they know is soon talked of in Constantinople. You must not forget that you are more than a Bharbazonian. You are of the Order."

The General's words had their effect upon Nicholas.

"I shall be glad when the day arrives that I can fight in the open," he said, much mollified. "I never felt so weary of this secret work as I do to-day."

"Am I to understand, General," I said, "that Nick is supposed to be an American?"

"Such is the intention, Dr. Wharton," he replied. "Should occasion arise, we will appreciate it if you will tell your questioner that Nicholas is a countryman of yours."

"Come," said Nick, "let us get started."

"How much further do we have to go to-night?" I asked, as we arose from the table.

"We will not reach Framkor until to-morrow evening," put in the General, but Nick interrupted him with a laugh.

"Why, General, we are at the Turk's Head Inn now, and it is not yet two o'clock. We shall be home before nightfall."

"So it is," murmured the old man. "It is the machine. I cannot become used to it. We usually consume two days coming from Bizzett on horseback."

Leaving the inn, we struck off into the country roads to the right and the travelling was not as luxurious as on the smooth government pike. Nevertheless, Teju Okio made good time. Toward evening, when we were near enough to our journey's end for Nick to recognize the country and point out some of his childhood haunts, we met a horseman on the road. It was just after the Jap boy lighted his two gleaming headlights, for the day was almost done. It may have been the glare of the lamps or the suddenness of our approach around an unexpected corner that caused the accident; for, as soon as the horse caught sight of us, he reared on his hind feet, stood upright in the air a moment and toppled over backward, crushing his rider beneath him in the fall.

Teju Okio stopped the machine as soon as he saw the frightened horse and we all shouted directions to the horseman; when they fell, Nick and I leaped from the machine to render what aid we might. Before we could grasp his bridle the horse struggled to his feet and was off like the wind, the empty stirrups pounding his ribs at every jump; but the rider lay motionless.

He was a youth of about eighteen or twenty years. His wide riding breeches and neat fitting coat of black velvet were covered with dust; but they were not torn, neither did they show any evidence of blood which would have shown had the horse kicked and cut him. Although he lay crumpled in a heap, I was able to see that he was tall and slender and that one arm was either dislocated or broken. His eyes were closed and his face was exceedingly pale. His most distinguishing feature was the mass of red hair, which he wore as long as Nick's, and which was of a dark rich shade.

Nick tenderly raised the sufferer's head, while I tried to get some whiskey down his throat. But the boy showed no signs of returning consciousness.

"Better get him into the car, Nick, and take him to the nearest hospital," I advised.

"Hospital?" smiled Nick. "The nearest approach to one is at the Castle barracks. You are the best medico we have in Bharbazonia, Dale. Get busy yourself."

Teju Okio edged slowly up with the car until his white lights shone upon the scene in the road.

"Is he badly hurt?" called the General from his seat beside the driver.

"We do not know the extent of his injuries, General," I said, "he is unconscious."

"Who is he, Nick?"

"Haven't an idea."

The lamplight fell upon the boy's face.

"Good heavens," exclaimed the General, "get him into the machine as quickly as possible. We must procure medical assistance at once. On, on, to Dhalmatia Castle. This is the Red Fox's son, Prince Raoul, the future King of Bharbazonia. He must not die. Hurry! Hurry! for God's sake!"

CHAPTER V

THE RED FOX OF DHALMATIA

He entered in the house—his home no more;For without hearts there is no home;—and feltThe solitude of passing his own doorWithout a welcome.—Byron: Don Juan.

Castle Dhalmatia proved to be but a short distance ahead. I held the unconscious Prince in my arms while Nick leaned forward and called road directions into the Japanese driver's ear. General Palmora remembered a byway which was a short cut across the Red Fox's estate and we saved several minutes thereby. The walls of the Prince's home loomed up black and sombre against the sky line on the top of a hill vacant of trees. Like Castle Comada it was a fortress built for defence rather than for comfort. Its battlements and watchtowers were stern and forbidding.

Rapid as were our movements, the news of the accident preceded us, borne no doubt by the returning horse with the empty saddle. Stable grooms were coming down the road toward us carrying lanterns; house servants were arousing the master. Some were weeping aloud, running wildly about; others were shouting orders and talking, like persons who desired to do something but did not know what to do. Lights began to show in different rooms of the castle and, when we drew up with a rush and a grinding of brakes under the porte-cochère, a crowd of retainers were there to meet us.

As soon as they caught sight of the limp figure in my arms they imagined the Prince dead and their wailings broke out afresh. In the midst of the excitement, which even the commanding voice of the General failed to quell, a little, bent, old man with a weazen, wrinkled face, but with a certain virility of manner which proclaimed him master, appeared in the doorway. His voice vibrated through the air and forced obedience. He called to his servants in the Bharbazonian dialect and a silence fell upon them, in which there was more of fear than of love. I knew at once that I was in the presence of the Red Fox of Dhalmatia, the father of the Prince.

Standing in the lantern light he made a curious picture. He was attired in black from head to foot. On his head was a black fez that only partially concealed a mass of hair which, though darker in shade and streaked with gray, was the same colour as his son's. The first part of the Red Fox's name was derived no doubt from the colour of his hair.

Around his neck was a broad lace collar of white, extending to his narrow shoulders. He wore a close fitting coat buttoned up the front with a row of large ornamental buttons. Knee breeches with buckles at the side, silk stockings, and buckled shoes made up the rest of his costume. Over his shoulders hung a long Spanish cloak which partially concealed the hilt of a jewelled sword suspended from his left hip. There was that about him which suggested the stern, hard, old Pilgrim fathers who conquered the Massachusetts wilderness and burned witches three centuries ago.