CONTAINING

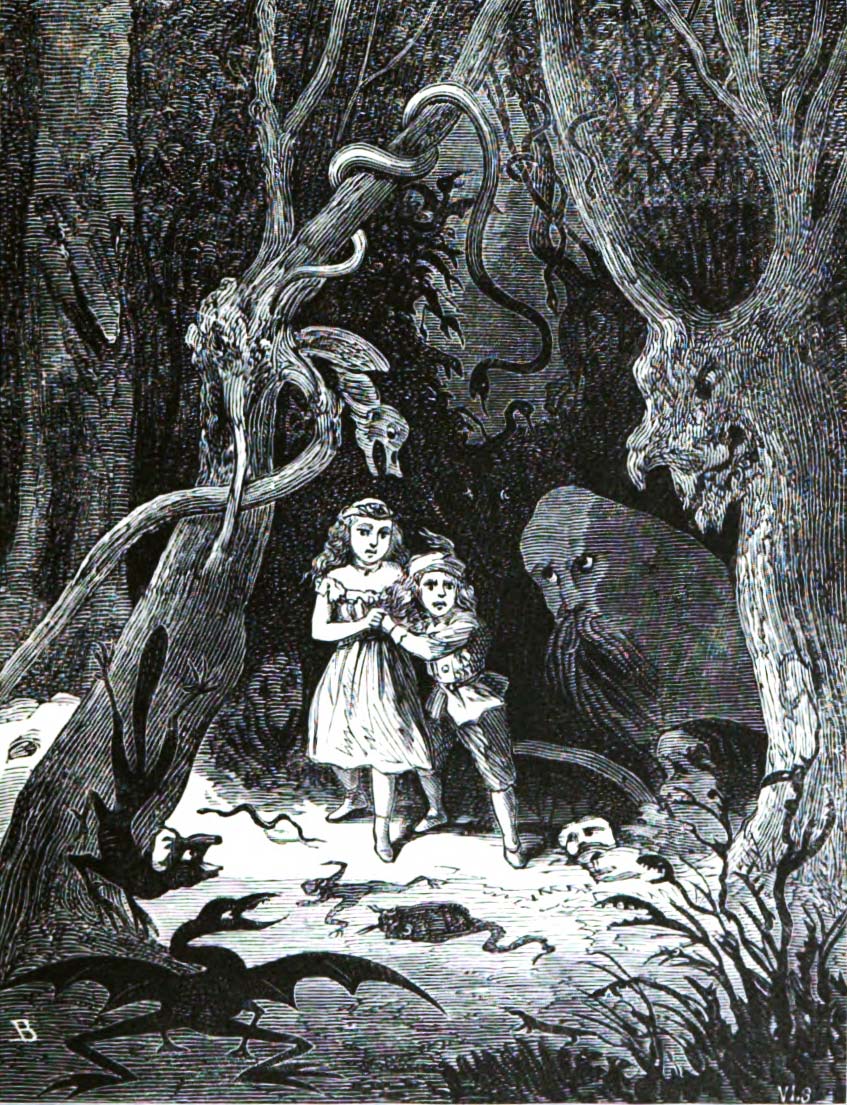

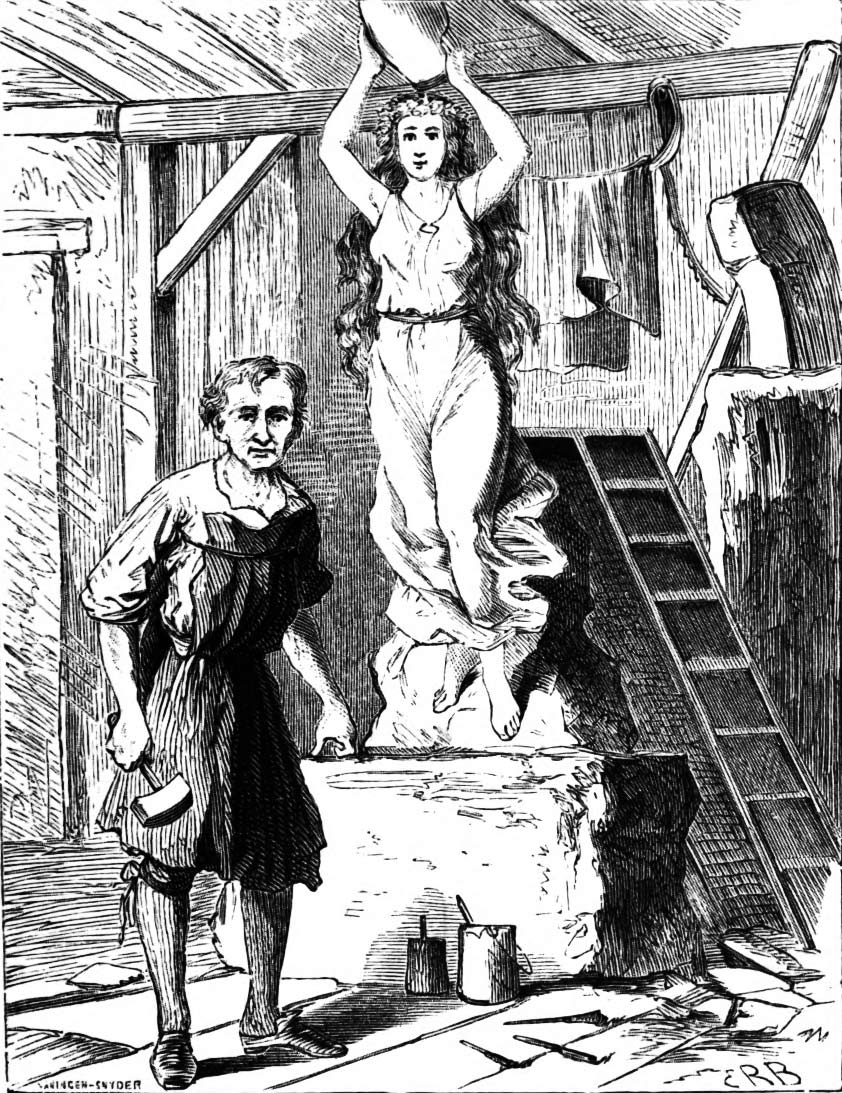

Eva’s Adventures in Shadow-land.

By Mary D. Nauman.

AND

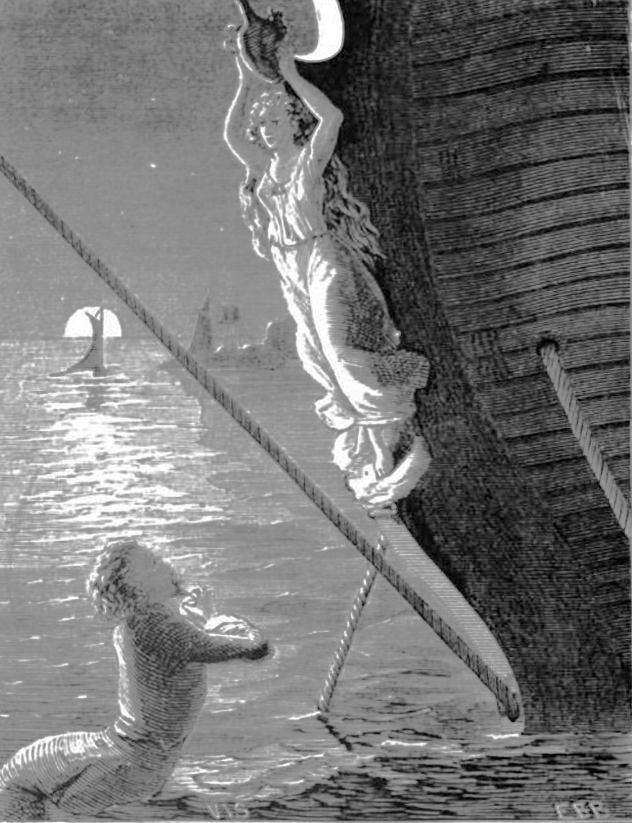

The Merman and the Figure-head.

By Clara F. Guernsey.

TWO VOLUMES IN ONE.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS.

PHILADELPHIA

J. B. LIPPINCOTT & CO.

1874.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1873, by

J. B. LIPPINCOTT & CO.,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Lippincott’s Press,

Philadelphia.

TO

MY FRIEND

E. W.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| What Eva saw in the Pond | 9 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Eva’s First Adventure | 15 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Gift of the Fountain | 23 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| The First Moonrise | 30 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| What Aster was | 36 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The Beginning of the Search | 45 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Aster’s Misfortunes | 52 |

| viii CHAPTER VIII. | |

| What Aster did | 63 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The Door in the Wall | 73 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| The Valley of Rest | 80 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| The Magic Boat | 92 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Down the Brook | 104 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Enchanted River | 119 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Green Frog | 130 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| In the Grotto | 145 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Aster’s Story | 151 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| The Last of Shadow-Land | 162 |

| THE MERMAN AND THE FIGURE-HEAD | |

| Contents | 5 |

EVA’S ADVENTURES

IN SHADOW-LAND.

SHE had been reading fairy-tales, after her lessons were done, all the morning; and now that dinner was over, her father gone to his office, the baby asleep, and her mother sitting quietly sewing in the cool parlor, Eva thought that she would go down across the field to the old mill-pond; and sit in the grass, and make a fairy-tale for herself.

There was nothing that Eva liked better than to go and sit in the tall grass; grass so tall that when the child, in her white dress, looped on her plump white shoulders with blue ribbons, her bright golden curls brushed back from her fair brow, and10 her blue eyes sparkling, sat down in it, you could not see her until you were near her, and then it was just as if you had found a picture of a little girl in a frame, or rather a nest of soft, green grass.

All through this tall, wavy grass, down to the very edge of the pond, grew many flowers,—violets, and buttercups, and dandelions, like little golden suns. And as Eva sat there in the grass, she filled her lap with the purple and yellow flowers; and all around her the bees buzzed as though they wished to light upon the flowers in her lap; on which, at last,—so quietly did she sit,—two black-and-golden butterflies alighted; while a great brown beetle, with long black feelers, climbed up a tall grass-stalk in front of her, which, bending slightly under his weight, swung to and fro in the gentle breeze which barely stirred Eva’s golden curls; and the field-crickets chirped, and even a snail put his horns out of his shell to look at the little girl, sitting so quietly in the grass among the flowers, for Eva was gentle, and neither bee, nor butterfly, beetle, cricket, or snail were afraid of her. And this is what Eva called making a fairy-tale for herself.

11 But sitting so quietly and watching the insects, and hearing their low hum around her, at last made Eva feel drowsy; and she would have gone to sleep, as she often did, if all of a sudden there had not sounded, just at her feet, so that it startled her, a loud

Croak! croak!

But it frightened the two butterflies; for away they went, floating off on their black-and-golden wings; and the brown beetle was in so much of a hurry to run away that he tumbled off the grass-stalk on which he had been swinging, and as soon as he could regain his legs, crept, as fast as they could carry him, under a friendly mullein-leaf which grew near, and hid himself; and the crickets were silent; and the bees all flew away to their hive; and the snail drew himself and his horns into his house, so that he looked like nothing in the world but a shell; for when beetles, and butterflies, and crickets, and bees, and snails hear this croak! croak! they know that it is time for them to get out of the way.

And when Eva looked down, there, just at her feet, sat a great green toad.

12 She gave him a little push with her foot to make him go away; but instead of that he only hopped the nearer, and again came—

Croak! croak!

He was entirely too near now for comfort, so the little girl jumped up, dropping all the flowers she had gathered; and as she stood still for a moment she thought that she heard the green toad say:

“Go to the pond! Go to the pond!”

It seemed so funny to Eva to hear a toad talk that she stood as still as a mouse looking at him; and as she looked at him, she heard him say again, as plain as possible:

“Go to the pond! Go to the pond!”

And then Eva did just exactly what either you or I would have done if we had heard a great green toad talking to us. She went slowly through the tall grass down to the very edge of the pond.

But instead of the fishes which used to swim about in the pretty clear water, and which would come to eat the crumbs of bread she always threw to them, and the funny, croaking frogs which used to jump and splash in the water, she saw nothing13 but the same great green toad, which had hopped down faster than she had walked, and which was now sitting on a mossy stone near the bank. And when Eva would have turned away he croaked again:

“Stay by the pond! Stay by the pond!”

And whether Eva wished it or not, she stood by the pond—for she really could not help it—and looked. And it seemed to her that the sky grew dark and the water black, as it always does before a rain; and then the child grew frightened, and would have run away, but that just then, in the very blackest part of the pond, she saw shining and looking up at her a little round full moon, with a face in it; and it seemed to her, strange though you may think it, that the eyes of the face in the moon winked at her; and then it was gone.

And again Eva would have left the pond, but the green toad, which she thought had suddenly grown larger, croaked more loudly:

“Stay by the pond! Stay by the pond!”

And Eva obeyed, as indeed she could not help doing; and then again, in the pond, there came and went the little moon-face, only that this time it was larger, and the eyes winked longer.

14 For the third time the child would have turned away, frightened at all these strange doings in the pond; but for the third time the green toad, larger than ever, croaked:

“Stay by the pond! Stay by the pond!”

So, for the third time, Eva looked at the pond; and there, for the third time, was the shining moon-face, as large now as a real full moon, though, when Eva looked up, there was no moon shining in the sky to be reflected in the pond; and then the eyes in the moon-face looked harder at her, and the toad winked at her; and then the toad was the moon and the moon was the toad, and both seemed to change places with each other; and at last both of them shone and winked so that Eva could not tell them apart; and before she knew what she was doing she lay down quietly in the tall grass, and the moon in the pond and the green toad winked at her until she fell asleep.

Then the moon-eyes closed and the shining face faded; and the green toad slipped quietly off his stone into the water; and still Eva slept soundly.

And that was what Eva saw in the pond.

HOW long she lay there asleep the child did not know. It might only have been for a few minutes; it might have been for hours. Yet, when she did awake, and think it was time for her to go home, she did not understand where she could be. The place seemed the same, yet not the same,—as though some wonderful change had come over it during her sleep. There was the pond, to be sure, but was it the same pond? Tall trees grew round it, yet their branches were bare and leafless. A little brook ran into the pond, which she was sure that she never had seen there before. Was she still asleep? No. She was wide awake. She sprang to her feet and looked around. The green toad was gone, so was the moon-face; her father’s house16 was nowhere to be seen; there was no sun, but it was not dark, for a light seemed to come from the earth, and yet the earth itself did not shine; mountains rose in the distance; but, strangest of all, these mountains sometimes bore one shape, sometimes another; at times they were like great crouching beasts, then again like castles or palaces, then, as you looked, they were mountains again. Strange shadows passed over the pond, stranger shapes flitted among the trees.

Eva did not know how the change had been made, still less did she guess that she was now in Shadow-Land.

Yet it was all so singular that, as she looked upon the changing mountain forms, and the quaint shadows, a sudden longing came over her, with a desire to go home, and she turned away from the pond. And as she did so, a little fragrant purple violet, the last that was left of all the flowers which she had gathered, and which had been tangled in her curls, fell to the ground, melting into fragrance as it did so; and as it fell, there passed from Eva’s mind all recollection of father, mother, home, and the little brother cooing17 in his cradle: the changing mountain forms seemed strange no longer; she forgot to wonder at the singular earth-light, and at the absence of the sun; and noticing for the first time that she was standing in a little path which ran along the pond, and then followed the course of the little brook, whose waters seemed singing the words, “Follow, follow me!” Eva wondered no longer, but first stooping to pick up a little stick, in shape like a boy’s cane, with a knob at one end, just like a roughly carved head, and which was lying just at her feet, she walked along the little path, which seemed made expressly for her to walk in.

She walked on and on, as she thought, for hours, yet there came neither sunset nor moonrise, and there were no stars in the sky, which seemed nearer the earth than she had ever seen it before. There were clouds, to be sure, of shapes as strange as those of the mountains, which passed and repassed each other, although there was no wind to move them. Everything was silent. Even the trees, swaying, as they did, to and fro, moved noiselessly; the only sound, save Eva’s light steps, which broke the stillness was the18 silvery ripple of the brook, which kept company with the path Eva trod, and whose waters murmured, gently, “Follow, follow me!”

And Eva followed the murmuring brook, which seemed to her like a pleasant companion in this silent land, where, even as there was no sound, there was no sign of life; nothing like the real world which the child had left, and of which, with the fall of the little violet from her curls, she had lost all recollection; even as though that world had never existed for her. Once or twice, as she went on, holding her little stick in her hand, she imagined that she saw child-figures beckoning to her; but, upon going up to them, she always found that either a rock, or a low, leafless shrub, or else a rising wreath of mist, had deceived her.

Yet, though she was alone, with no one near her, not even a bird to flit merrily from tree to tree, nor an insect to buzz across her path, Eva felt and knew no fear, and not for a moment did she care that she was alone. The silvery ripple of the little brook, along which her path lay, sounded like a pleasant voice in her ears; when19 thirsty, she drank of its waters, which seemed to serve alike as food and drink; when tired, she would lie fearlessly down upon its grassy margin, and sleep, as she would imagine, only for a few minutes, for there would be no change in the strange sky nor in the earth-light when she would awake from what it had been when she lay down; and yet in reality she would sleep as long as she would have done in her little bed at home.

For two whole days, which yet seemed as only a few hours, the child followed the brook. During this time she had felt no desire to leave the path; she had unhesitatingly obeyed the rippling voice of the brook, which seemed to say, “Follow, follow me!” But now there was a change: the water, at times, encroached upon the path, and rocks obstructed the current, around which little waves broke and dashed, while strange little flames, which yet did not burn, and gave no heat, started from the waves, dancing on them; and misty shapes, more definite than those she had first seen, beckoned to her to come to them. Now, Eva felt an irresistible longing to leave the brook,20 and wander away; far, far into the deep forest, away from the dancing flames and the beckoning shapes.

And once or twice she did leave the path, and turn her back upon the brook. But every time that she stepped off the beaten track, faint though it was, her feet grew heavy, and clung to the earth, so that she could scarcely move; and the waves of the brook leaped higher and higher; and the dancing flames grew brighter; and the silvery voice, louder and clearer than ever, would call, “Follow, follow me!” till the child was always glad to return to the path, and then once again the way would grow easy to her feet, and the water would resume its former tranquillity.

On, on she went, still following the course of the brook. But at last a new sound mingled, though but faintly, with its musical ripple,—the distant voice of falling waters. And when first this new tone reached Eva’s ears, a few signs of life began to show themselves,—a sad-colored moth flitted lazily across the path into the forest,—a slow-crawling worm or hairy caterpillar hid itself under a stone as Eva passed,—the bright21 eyes of a mouse would peep out at her from under the shelter of a leaf, or else a toad would leap hastily from the path into the waters of the brook.

Still Eva walked onward, more eagerly than ever, for though the “Follow, follow me!” of the brook was now silent, she heard the voice of the other waters, and at every turn in the path she looked forward eagerly for the little joyous cascade she expected to see. For it she looked, yet in vain: though the sound of the waters grew louder, she saw nothing, till at last a sudden gleam of golden light, from a long opening in the forest, fell across the now placid waters of the brook; and Eva looked up to see, far away in this opening, a fountain playing in clouds of golden spray, amid which danced sparkles of light; and the path, parting abruptly from the brook which it had followed so long, led down the opening in the forest directly to this play of waters, whose voice Eva had heard and followed.

And as she turned away from the little brook, whose course and her own had so long been the same, it seemed to her that even the silvery ripple22 of its waters died away into silence; and, looking back once more, after she had taken a few steps, upon the way by which she had come, lo! the brook and its waters had wholly disappeared, and an impenetrable forest had already closed up the path behind her.

I HAVE said that Eva wondered at nothing which came to pass in this land through which she was wandering; nothing surprised her, but the most singular occurrences appeared natural; and so it did not seem at all strange to her that the path and the brook should be swallowed up, as it were, by the dark, hungry, impenetrable forest; and it was almost with a feeling of pleasure at the change that after the one hurried glance she gave to the path by which she had come, and which was now no longer to be seen, that she went, still holding the little stick in her hand, up the opening between the trees to the beautiful fountain.

And as she drew near, the bright waters of the fountain played higher and higher, and sparkled24 and glistened in golden beauty; and rainbows of many colors surrounded it, so that Eva longed to dip her hands in its joyous flow, while the waters as they fell tinkled merrily like silvery fairy bells; and she came nearer and nearer, thinking she had never heard such sweet music as this water made, till she was within a few feet of the fountain.

But when there she paused. For, out of the earth,—all round and even under the dropping spray and the falling waters,—sprang myriads of little rainbow-colored flames, which danced to and fro among and under the water-drops,—like a circle of tiny, fiery sentinels, guarding the fountain. And Eva, afraid to cross this circle of flames, for which she was unprepared, would not have ventured nearer, but that at this very moment the little stick which she held turned in her hand, and pointed downward; and then Eva saw that it pointed to a little path, like that by which she had come, which ran around the fountain; and the child followed the path; until she had walked once, twice, thrice, around the playing waters, and yet, though she looked for it, found25 no spot where the little flame-sentinels, like faithful soldiers on duty, would permit her to pass. And then she would have turned away from the beautiful water,—her foot, indeed, had left the path,—when she heard a voice, even sweeter and more silvery than the voice of the brook, coming from the very midst of the fountain, and saying:

And hearing these words, Eva stood still in surprise, yet without obeying them. But, after a moment’s pause, the voice repeated the words.

Then, for the first time since her wanderings had begun, Eva spoke, and her voice sounded strange in her own ears, low though it was:

“How can I cross the fire?”

A little, low, melodious laugh, like that of a merry child, answered her; and when Eva looked to see whence it came, she saw that the little knot upon the end of her cane was a real head, that the lips were laughing, and that from the queer eyes came two funny little blue flames; and as26 Eva looked at it, very much tempted to throw it away, the head laughed again, and then the lips parted and said:

Then the voice was silent. But a thousand rainbow-colored bubbles glowed at once all over the waters of the fountain; and on each bubble there stood and danced a tiny elf, clad in bright colors; shapes so light and airy that their frail supports never failed them; and the tiny flames grew brighter, and then, as Eva still hesitated, fearing yet to cross them, the lips of the little head spoke once more:

Hearing this, Eva stepped forward. As she did so, the little stick dropped or slipped from her hand, and, rolling into the fountain, disappeared in its waters; and at every step she took she saw that the little flames died away, as the voice had said, under her feet; till, when she27 reached the fountain’s brink, they were all gone, and no trace of them was left. As she looked at the waters, they seemed to become solid, and shape themselves into an image carved as it were out of pure, shining gold, yet glowing with many colors; and then, slowly, slowly, with a sound like distant music, the beautiful, wonderful thing began to sink into the earth; and Eva, her tiny hands clasped, her fair cheeks flushed, her soft blue eyes sparkling, stood in silence and looked. And just as the magic fountain, which, when the child first came up to it, had been so high that its waters played far above her head, had sunk so low that Eva, had she wished, might have laid her hand upon its summit, she saw, cradled as it were, on the very crest of what had been the golden water, a tiny figure; not like one of the elves which had danced on the rainbow-bubbles, but like a sleeping child, which Eva thought, at first, was only a doll lying there, in its green-and-scarlet velvet dress; and for a moment the slow, descending motion of the fountain stopped, and Eva heard these words, in the same voice which had spoken before through the lips of the28 little head, though this time it came from the fountain:

Obedient to the voice, the child stretched forth her hand, and as her slight fingers closed upon the little, motionless form, a bright and dazzling crimson light seemed to flash everywhere, and the water, losing its solidity, began once more to gleam and sparkle, and to sink again into the earth; and in another moment it was gone, and in the place where the fountain had played there was now a bed of soft, green moss, through and around which was twined a vine, whose leaves were mingled with clusters of bright scarlet berries. Then for the first time she missed her little stick; and she looked for it, but it was nowhere to be found.

And then the sky grew dark, as the glorious crimson light slowly faded away, and one by one stars peeped out from the sky; and Eva, still clasping the little figure which had come so strangely to her, to her heart, lay down quietly upon the soft, green moss, which seemed to have29 sprung up there expressly as a bed for her, and before many minutes had passed she was asleep.

But while she slept, there hovered over her two fair white forms, who looked at her and smiled, and then one of them whispered to the other, in the silvery voice of the brook:

“The worst is over.”

“No,” the other replied. “Although the boy is safe, for a time, in the hands of his protector, his punishment is not yet over. Love must teach him obedience,—that alone can appease and work out the will of Fate.”

“And we can do no more for him!”

“We can only wait, and hope.”

A moment later, and the two bright forms were gone. And, watched by the twinkling stars, lulled by the low murmur of the gentle breeze playing among the trees of the great forest, the fair child slept, holding clasped to her innocent breast the helpless figure which had come to her as the gift of the fountain.

BUT sleep does not last forever, and after a time Eva awoke. And when she first sat up, and looked around her, she could not understand, for a moment, how it could be that everything was so changed; why the brook should be gone, and its voice silenced; the path no more to be seen; and how she should be sitting on this soft bed of velvety-green moss, with the little figure lying in her lap. Then, all at once, she remembered all that had happened the day before,—and as she thought it over, like a pleasant, yet indistinct dream, she recalled the two fair forms which had hovered over her sleep,—faintly conscious of their presence, though unaware of the words which they had spoken. Whether they were real, or only a dream, Eva did31 not know; she only recalled them mistily; for, in this strange, silent land, through which she was wandering, she never knew what was real or what unreal,—it was all alike to her.

And as nothing that happened astonished her, so never for one moment did her thoughts go back to the father and mother she had left, or to the little baby-brother cooing in his cradle. It was as though they never had existed, so completely were they forgotten. The Present, such as it was, had effaced all memory of that Past.

Sitting on her soft, mossy bed, still holding in her little hands the motionless little figure which the fountain had left her, and which, Eva knew,—though how she knew it she could not tell,—was something to be cared for and guarded, as being more helpless than herself. Eva thought over all the adventures of the day before, and while she wondered what would come next, she wished she could once more hear the pleasant murmur of the brook which had guided her, for what purpose she knew not, to this spot.

Only a few moments had passed since the child awoke, when a low, musical chime rang through32 the forest. It died away and then returned; and then came again and again, in tones so marvellously sweet that Eva, who had just taken the little figure into her hands, dropped him into her lap, and pushed her long golden curls away from her face, the better to listen to the melody.

Once more it came, and once more died away into silence. And then there was a low, rushing sound, and, far in the distance, Eva saw arise, as it were from out of the earth, among the trees, the tiny silver crescent of a young new moon,—and as she looked at it, it rose higher and higher, and faster and faster, till it reached, in a few minutes, the very centre of the sky, the child’s blue eyes still following it; and when once there it paused, and floated among the strange, gleaming clouds, which surrounded it, like a little shining boat.

With a sudden impulse Eva bent down and kissed the little figure lying in her lap; and then she looked up at the crescent of the moon, as upon the face of an old friend; and she would have sat there longer watching it, but that all at once a little, weak voice said:

“I am awake again, and there is my home.”

33 Then there came a hurried exclamation of surprise, and Eva looked down from the moon’s crescent to see that the little figure which she had taken from the crest of the fountain had suddenly, as it were, been gifted by her kiss, with life, motion, and speech, and that he was now standing in her lap, evidently as much astonished at seeing her as she was at the change which had come over him.

But their mutual surprise did not last; for the little mannikin began to laugh as Eva’s blue eyes grew larger and rounder, and when at last she asked, “Who are you?” he put his head to one side, in the most comical manner, and, taking off the plumed cap which he wore, he made her a very low bow.

“I know now who you are,” he said. “You are Eva, and you will have to take care of me,—that is all you were sent here for.”

Eva laughed. “Suppose I should not want to take care of such a little thing as you are?”

“You will not have any choice in the matter,—you cannot help yourself.”

“Why?”

34 “Because THEY have said it.”

“I may not choose to do it.”

“What is the use of talking,” the boy went on, “when you know that you will?”

And such were the answers that he persisted in giving to all her inquiries.

“You said you knew who I was,” Eva went on; “but how did you know it?”

“They told me.”

“Who are THEY?”

“They led you here to me, and for me. You must not ask so many questions.”

“May I not even ask your name?”

“You ought to know that without my telling you. But, as you don’t, I will answer you. It is Aster.”

“Aster? Aster?” Eva slowly repeated; “it seems to me that I have heard that name before.”

“You never did,” was the somewhat sullen answer; “for no one but myself has any right to it.”

“Yet I am very sure that I have heard it before, at——”

“Hush! hush! You must never say that here,” said the miniature boy, climbing up on Eva’s35 shoulder, and laying his hand upon her lips. “You know as well as I do that you never heard my name before.”

“I thought I had,” Eva said, looking lovingly at the little figure nestling among her golden curls; “but I now know that I never did. Still, I would like to know who you are. Are you a fairy?”

“I am not a fairy, but you are all mine,” Aster said, gayly. “But you must be careful with me, and never lose me, or else——”

“What?”

“I do not know. They are watching us.”

Who “THEY” were, Eva could not induce him to say. For even when he did try to explain, his words were all so confused that Eva could not understand at all what he meant, although he seemed to speak plainly; and the only thing that she could really learn from him was this,—that she must not ask questions, and that THEY were THEY.

Which is all very strange to us; but it appears that Eva was at last satisfied, because Aster seemed to think that she should understand it just as he did, and that nothing further need, consequently, be said on the subject.

FOR several days the two, Eva and Aster, wandered through the forest with no object in view, and returned every evening to rest upon the soft, mossy bed which now covered the place where the golden fountain had once played. The scarlet berries of the vine surrounding it gave them food. The young moon, floating in the sky, gave them light; for while she shone, it was their day; when, suddenly as she arose, she would drop from the centre of the sky, then came their night; and the hours of her absence were spent in sleep.

So, at stated intervals, the moon sprang suddenly from the earth, shone there, replacing the faint earth-light which, during her absence, had guided Eva, and which still shone when she was not to be seen; then, after her hours were over,37 she as suddenly descended; and her rising and her setting were alike accompanied by the same weird music which had heralded her first coming, though its notes were fainter than those which had hailed the rising of the young new moon.

But every time that the moon returned it seemed to Eva that she grew brighter and larger, and that she shed more light upon the earth. And as the light grew brighter, pale white flowers began here and there to bloom, flowers which drooped and closed their petals as soon as the moon fell from the sky; flowers which, as Eva thought, murmured a low song as she passed them, yet a song whose words she never could distinguish. And at last she noticed that, as the silver crescent of the moon broadened, the slight form of Aster seemed to grow and to expand; so that he was no longer the tiny doll-like figure which she had taken from the fountain’s crest, but more like a boy of four years old.

Yet this change, although it was singular, was only a source of pleasure to the child. It gave her a companion, not merely a plaything, for until now she had looked upon Aster in that light,—something38 which, though it could talk, walk, sleep, and eat, was only a new toy, to be taken care of and prized as such. She never had looked upon Aster otherwise.

At last, when the moon had reached her first quarter, and the two, enjoying her pure light, sat on their mossy bed, Eva asked the boy the same question she had asked him the day her first kiss had awakened him:

“Tell me who you are.”

“I am Aster.”

“I know that,” Eva said, laying her hand on the boy’s shoulder; “but that is only your name.”

“I shall be as large as you are, soon,” Aster said, raising his star-like eyes to the moon as he spoke. “When she is round, I shall be as tall as you are, Eva.”

Eva laughed. “How do you know?”

“It will be; because it must be.”

“You are Aster,” Eva said, slowly, “and I know how you came to me; but why did you come?”

“You will know then.”

“When?”

“Why not now?”

“They will not let you.”

And with this answer Eva was forced to be content. But every day they would stand side by side, and every day Aster grew taller and taller; and every day the moon grew broader and brighter.

At last she rose, a round, perfect orb, to her station in the sky; and as Eva, awakened by the loud music which told of her coming, sat up to see and wonder at the bright light she cast, Aster came quietly behind her, and, laying his hands on her shoulders, said:

“Look at me, Eva. The day has come, and I am as tall as you are.”

Eva sprang to her feet. As she did so, Aster put his arm around her, and she saw that there was now no difference in their height,—they were exactly the same size. And, strange to say, his clothes had grown with him, and their rich, soft velvet fitted him now as perfectly as it had done when Eva first took him, small and helpless, from the crest of the golden fountain.

“I can tell you now who I am,” the beautiful40 boy said, “for to-day THEY cannot silence me; this one day when I can be my own self again. You ought to know, Eva, without my telling you, and you would know, if you were like me; but you are not as I am.”

“Why not?” Eva asked, in surprise.

“Because you are only a little earth-maiden.”

Eva laughed, “What is that?” She had wholly, as we know, forgotten the past.

“I cannot tell you,” Aster said, slowly. “I only know what THEY have told me about you.”

“And that?”

“I do not know. But you are not like me, Eva. We are very different. Look at your dress, and then at mine.”

In truth, every here and there upon the rich velvet of Aster’s dress were soils and stains, while not a spot discolored the pure white Eva wore.

“Now do you see?” Aster asked. “You know that we are in Shadow-Land, and it can only affect things which are like itself; it cannot harm you or deceive you.”

“Do you belong here?”

“No,” Aster said, “I came from there,”41 pointing to the round full moon above their heads. “I wish I was there again.”

“Why don’t you go back, then?”

“I can’t, unless you help me. They who sent me here say so.”

“Why did they send you here?”

“Because up there,” pointing to the moon, “I lost my flower, and everything which is lost there falls into Shadow-Land, as everything which is lost in Fairy-Land falls into the Enchanted River; and so they sent me here to find it again, because a prince cannot live there without his flower; and I cannot find it unless you help me. Now you know who I am, Eva,—the moon-prince, Aster.”

“Then must I say Prince Aster?”

“No; to you I am only Aster. And I know that it will be hard for you to find the flower, for I cannot help you, or tell you what it is like. I know that the Green Frog has hidden it, and you are the only person who can help me to find it, and then you must give it to me. They say we shall have trouble.”

“But we will find it at last?”

42 “When my punishment for losing it is over. To-morrow we must leave this place, for after this moon the moss will be gone.”

“You know where to go, then?”

“No; I can only follow you. I have no power here; you will have to take care of me.”

And then Aster began to sing, and this was the song which he sung:

Then Aster threw himself down on the soft moss at Eva’s feet. But when she asked him where he had learned the words of his song, he43 could not tell her. Just then a cloud came over the face of the moon, hiding her from their sight; and as the darkness came over everything, only leaving for a moment the pale earth-light, it seemed to Eva that there were faces looking at her, peeping from behind every tree; and then a light breeze sprang up, just moving the flowers, and from the bell of one of them seemed to come these words, all in verse, for in Fairy-Land and in Shadow-Land people seldom speak in plain prose as we do:

Then the breeze died away, and the voice was silent; and Eva saw that Aster was asleep, and, frightened at the faces which made grimaces and mocked at her, more angrily, she thought, on account of the warning the flower had sung, she touched him to awaken him; and as she did so the cloud passed from the face of the moon, and as once more her pure, clear light returned, the ugly, threatening faces vanished, and Aster44 awoke. But when Eva tried to tell him of what she had seen and heard during his short sleep, she could only say these words:

Then Aster laughed, because Eva declared that these were not the words which the flower had spoken; yet every time that she tried to recollect and repeat them, she could only say the same thing over. Then she began to try and tell him about the faces, and when she began to speak of them, suddenly the full moon sank from the sky, and all was dark; and then a strange drowsiness came over the children, and Eva and Aster, nestled in each other’s arms, lay down to sleep upon the soft, green moss, knowing that with the next moonrise they must go forth in search of Aster’s lost flower.

WHEN the two children, after their sleep, awoke to see the moon rise to her station in the sky, they were not surprised to find that her fair, round proportions were already changed. But when Eva turned to Aster, she saw that he, too, was smaller than when they had lain down to rest; and she knew at once, almost as if she had been told, that the Moon-Prince would in future wax and wane as did the orb from which he had been banished; that this was part of his punishment; and now she understood why it was that Aster had said she would have to take care of him. But as she stood, thinking of this, Aster suddenly touched her hand, and directly over the mossy bed on which they had46 slept, and which had never been crushed by their weight, but was always fresh, Eva saw again the mocking faces which had disturbed her the night before; but only for a moment, and then they were gone. And even as she looked, she saw that the soft green moss began to shrivel, dry up, and crumble away, as though in a fire; and a moment later it was all gone, and in its place was a heap of rough sand and stone, instead of the velvety moss and the vine with its scarlet berries.

“The faces have done it,” Eva said, clasping Aster’s hand tightly, as she watched the rapid change.

“The faces!” Aster said, scornfully. “Eva, you are dreaming; there were no faces there.”

“I saw them,” Eva began; but Aster interrupted her.

“I tell you, Eva, you saw no faces, there was nothing there. I told you that the moss would be gone the next time that the moon rose; and you see I told you the truth. We must leave this place.”

“Where shall we go?”

47 “I don’t know. We cannot stay here. What did the flower say to you, Eva?

Even as Aster spoke, Eva saw a faint little path at her feet, like that which she had first followed. Looking back, wishing it might lead her again to the pleasant little brook, and that she might return to it, instead of going on into the forest, she saw that the sand and stone had grown into a huge wall, or rather a mound, over which she never could have climbed, and which would prevent her return. As if Aster had read her thoughts, he said to her,—

“There is no going back, Eva; we can only go forward.”

Aster’s words were true. The wall of stone, which a few moments had been enough to build up behind them, seemed to come closer and closer, as though to shut them out from the place where they had been; and, clasping Aster’s hand tightly, Eva and the boy walked slowly on, in the little path which lay before them.

48 For days the two went on, walking while the moon shone, and sleeping when her light was hid. At each moonrise they were awakened by the strains of music, which, as the moon waned, grew sadder and more mournful; while that accompanying her setting became at last a low, sad moaning, and each day she grew smaller, and, in sympathy with her, Aster seemed to dwindle and wane, and he became more and more helpless, till at last, when the moon was reduced to a thin crescent, the little prince was once more as small as he was when Eva first received him.

Yet, through all these changes, the two went slowly on through the dark forest, which opened on either side of the path to let them pass, and closed again behind them. Were they thirsty, they were sure to find some tiny spring, issuing as at a wish from the earth; were they hungry, some wild fruit or berry was always to be found. But not once did Eva leave the path. What it was that kept her in it, she could not tell,—except that every time she felt the slightest desire to go into the forest; she saw the same hateful faces which had peeped at her for the first time49 when the cloud had passed over the face of the full moon, and which had mocked at her from above the soft mossy bed when it had been turned into the stony wall which had forced them to go forward, and she thought they forbade her to go near them. But Aster, in spite of all her efforts to detain him in the path, would sometimes run away from her, saying he saw some beautiful flower which he must gather, or else some sweet child-face which smiled upon him; but each time that he did this, he was sure to hasten back to Eva, saying that either thorns had pierced or else nettles stung him; and then he would hide his face in the folds of Eva’s white dress, trembling, and saying that THEY were there, and had frightened him.

Still, Eva could never find out from the boy who THEY were. For Aster, though he sometimes tried, could not tell her; it seemed as if he was not allowed to speak, and the child began to think that the faces which haunted her, and THEY of whom Aster so often spoke, were only different manifestations of the same power, which seemed to follow them wherever they went, seeking an50 opportunity to hurt them, although as yet no harm had been done.

Once, before Aster grew so small, Eva asked him why it was that they were thus followed.

“It is not you that THEY are following; THEY would do me harm if I were to fall into their hands; but I am safe while you keep me. You are beyond their reach.”

But, though Aster knew this, it seemed to Eva that he dared, and tried, to put himself in the power of THEY, whom he seemed to dread,—for it was only when the faces looked at her from behind tree or shrub that Aster desired to leave her, and only then that he spoke of THEY who always frightened him back to her side. He never alluded to the flower they sought; only once, when Eva asked him what it was like, he said to her:

“I cannot describe it to you; you will know it when you see it.”

“How shall I know it?” Eva asked.

“You will know it when the time comes.”

But, though Eva looked carefully for the flower, she never saw it. There were flowers enough51 along the path, but the right one was not to be seen. She did not know—how could she?—that the search was only begun, and that not till after long wanderings and many troubles to Aster would she be able to find for him the flower which he had lost, and without which he could never regain his home.

AT last, even the thin crescent of the moon disappeared, and once more Aster lay motionless, and, as it were, without life, the same tiny, helpless thing which Eva had taken from the crest of the fountain. Once more she wandered, alone,—for what companionship could she find in the senseless little figure which she carried about with her?—through the strange, dream-like country in which she now found herself. But, wherever she went, a feeling she could not explain nor understand made her hold the helpless little prince close, never for a moment letting him pass from her loving clasp.

53 Once more, too, the faint earth-light shone, instead of the vanished moon. And Eva thought that while Aster lay helpless, there were fewer difficulties in her path; the faces no longer appeared to torment and harass her; the way seemed easier to her feet; more and brighter flowers bloomed along the path; and the misty, shadowy shapes which were to be seen at intervals passing among the close-set trunks of the trees were fair and lovely to look upon.

But this quiet was not to last. Again, after a time, the music rang triumphantly through the forest; and again, as the young moon sprang to her station overhead, Aster awoke, to all appearance unconscious of the time he had slept, and of the distance which Eva had carried him. As he grew, with the moon, it seemed to her that he was changed; that he was no longer the gentle, loving boy who had wandered with her when the first moon shone: something elfish, imp-like, and changeable had come over him.

Then, too, as day by day the path led them on into the forest, which seemed endless, the trees altered their shape. Sometimes they were circled with huge, twining snakes, which Eva thought seemed coiled there, ready to seize her as she passed, though when near them they proved to be54 nothing but huge vines climbing up the trees. Here and there in the path lay huge stones, which you might think at first sight were insurmountable, obstructing their further progress; yet, if either Eva’s foot touched them, or the hem of her white dress brushed ever so lightly against them, they would always fade away, like a shadow, into utter nothingness, or else would roll slowly away to one side, leaving the path clear. But when Aster saw the stones he would cry, and say that they would crush him if he passed them, and the only way in which Eva could soothe him was by taking him up in her arms and carrying him past the stones, while he hid his face, so as not to see them, in her long, golden curls.

Every now and then, in spite of what he had often told Eva,—that she, and she only, could find and give him the flower which he had lost,—Aster would declare to her that he saw it blooming in places where she saw nothing but nettles or ugly weeds, but which he would always insist were beds of the most beautiful flowers. These flowers, he said, called to him to come and gather them; while Eva thought that warning voices bade her55 pass them by, and that she saw over or else among them shadows of the same hateful faces which she dreaded. But it was useless to try and convince Aster of this; she soon learned that nothing ever presented the same appearance to him that it did to her.

In consequence, whenever Aster insisted upon leaving the path, as he often did, Eva watched him with a kind of terror, and never felt he was safe unless she led him by the hand. Placed, as he was, under her care, she felt sure that when with her no danger could come near him, nothing harm him. Still, if he had enemies in this great forest, he had friends, too; for once, when he stooped to gather a flower which bloomed near the path, she heard it say:

But Aster laughed joyfully, as he looked up without gathering the flower, and said:

“Did you hear what the flower told me, Eva? That was the reason why I did not pick it, for it said that I should have much pleasure to-day.”

56 Eva only smiled; she said nothing; she had learned that Aster would not bear being contradicted. But she quietly resolved to be more watchful than ever; for, from what she had heard the flower say, she thought that efforts would be made to take the little prince from her.

She was wrong, however, for the day passed, the moon disappeared, and, as nothing had happened to disturb them, she began to think that perhaps she had been mistaken, and that Aster had been right regarding the words which the flower had spoken; for he had, all that day, been cheerful and gentle. But, that night, she was awakened from her sleep by Aster’s talking, as though to himself, in a rambling, disconnected manner, of THEY whom he seemed to fear; and this being the first time for days—not since he had awakened from the stupor into which the disappearance of the moon had thrown him—that he had mentioned or even appeared to think of these nameless yet formidable beings, she guessed, seeing that Aster’s words were spoken, as it were, in a dream, and unconsciously to himself, that the coming day contained more danger to him than any of the preceding ones.

57 It was, notwithstanding, with a feeling of relief that Eva at last saw the moon arise, and once more she and Aster set out on their journey. He never referred to the words which had awakened her. No strange sights or sounds came to disturb them. There was utter stillness all around; and as hour after hour passed, and Aster walked quietly by her side, Eva began to think that her anxiety had all been for nothing, and she relaxed a little of her watchfulness.

At last they came to a place where every plant along the path was hung with filmy, gossamer, delicate webs, and in each web sat a spider. And every spider was different,—no two of them being alike. And, as they passed these patient spinners, Aster clung closely to Eva’s hand, saying that he was afraid of being entangled among their webs, or else stung by them; although to her it appeared as though the spiders did not even notice them as they passed. Then all of a sudden the webs and the insects were gone; and the children saw crawling slowly in the path, as if it was afraid of them and wanted to get out of their way, a spider larger than any of those they had seen; a spider whose58 body was ringed with scarlet and gold, whose long, slender black legs shone like polished jet, and whose eyes were like bright-green emeralds; a spider handsome enough to be the king of all the spiders.

And while Eva was admiring the beautiful colors of the insect, Aster let go her hand, and, stooping down, passed his finger gently over its gold and scarlet back. Then the spider raised its head, and looked at Eva with its bright-green eyes, which, as Eva gazed at them, appeared to grow larger and brighter, and dazzled her own; and then a mist seemed to come over them, and everything began to fade slowly away; and she never noticed how Aster went, slowly, nearer and nearer to the insect, crouching down into the path as he did so, nor how the spider, by degrees, began to grow larger, and moved towards the side of the path, till a sudden cry from Aster, “Eva! Eva! help me!” roused her from the trance in which she stood, in which she saw nothing but the emerald eyes, like two gleaming lights; and then she saw that the beautiful spider had enveloped Aster in a large web which it had spun around him, and was59 dragging him off the path, to carry him away with it.

But Eva was not going to lose her charge. Springing forward, she threw her arms around him. And as her dress touched the web, it fell off, releasing him; and the spider, unfolding a pair of blue wings, flew into the forest with a loud cry of disappointment; and as it flew away, its shape changed, and Eva, looking after it, with her arms still around Aster, saw that it had one of the terrible faces which she had seen so often before. Then it disappeared, and the two went on, or rather tried to go on, for Aster complained that his feet were fastened to the ground; and then Eva saw that they were still tangled in some of the spider’s web; and both Eva and Aster tried in vain to break it. But Eva was nearly in despair, when, as she stooped, one of her long golden curls brushed against the web, and then it melted away and vanished like smoke.

Then, and not till then, were they able to go on. But Aster walked forward unwillingly, and complained that he was tired, and began to insist upon Eva’s stopping to rest. But she felt that60 they would not be safe until after the moon was gone, and so they went on. At every mossy stone, every fair cluster of flowers, Aster would insist upon stopping, but Eva would not listen to him, for she always heard, at these places, a friendly voice which said, “Go on, go on;” and so they went on.

But at last Aster, who did nothing but complain of weariness, told Eva that he could and would go no farther. Seeing a great, velvety, green mushroom growing in the path, he ran and sat down upon it, saying that it was a seat which had been made and put there for him, and that Eva should not share it.

He had scarcely said this, had scarcely seated himself, when the mushroom changed into a great green frog, which, with Aster seated astride upon its back, began to hop nimbly away in the direction of the forest. But Eva, whose eyes had never for a moment left the boy, sprang forward, and before Aster—pleased at the motion of the frog—could say a word, she had dragged him off his strange steed, which turned and snapped at her, but, instead of touching her, caught the skirt of61 Aster’s coat in his mouth and held on to it till Eva’s efforts tore it from him, leaving, however, a small piece of the velvet in the frog’s mouth. Even then he tried to seize Aster again, and it was not till Eva’s dress touched him that he turned to leave them, still holding in his mouth the scrap torn from Aster’s coat, and as he hopped off the path he faded away just like a shadow.

Then, too, the moon sank from the sky, and the two children, completely worn out, lay down and slept, and Eva knew that for a little while, at least, Aster was safe, because as she lay down she heard a little song which said;

Then all was still. But though Eva, trusting to this song, was not afraid to lie down and sleep,62 she never knew that while they did sleep a circle of tiny shining lamps, like fairy-lamps, gleamed all around them,—a magic circle which nothing could pass. And although both the spider and the green frog returned, bringing with them the piece of Aster’s coat, by means of which they hoped to steal him away from Eva while he was asleep, they could not pass the circle which the Light Elves had drawn around the sleeping pair, and, after many vain efforts to cross it, they vanished.

And the grateful elves had watched and saved Aster because Eva, that morning, seeing a shapeless, helpless worm lying near a stone, which was about to fall and crush it, had tenderly picked up the worm, and laid it carefully on a cool, green leaf, out of danger. The grateful Light Elf,—for such she was,—being compelled to wear the form of a worm while the moonlight lasted, had come with her companions to return what service she could and give Eva a peaceful rest.

So, as ever, Good overcomes Evil, and no service, no matter how small or how trifling it may seem, is ever wasted or thrown away.

THE farther the progress which the children made into the forest, the wilder and more singular became the country through which they passed. Shadows cast by no visible forms went before them in the path,—shadows which shook, moved, and trembled; which seemed as if they might all at once become real forms; shadows which had something dreadful about them, so that Eva was glad they were always in advance of her, and that her foot never had to touch the ground on which they lay. The color of the moon’s light was changed. She shone with a pale greenish lustre. No green plants, no beautiful flowers, grew in the stony, rocky soil through which their path now lay. It produced things like sticks full of thorns. Under the stones lay hidden long, slender lizards,64 or coiled-up serpents with forked and fiery-red tongues; things like dry twigs, which would suddenly display many legs and run away. Slow-crawling, hairy caterpillars, and round, fat, slimy worms, lay everywhere. Things like insects, which yet had no life, grew, instead of flowers, on the thorny sticks which stood among the stones. One of these things, in shape like a dragon-fly, Aster picked; but he immediately dropped it, and said that it had stung him; and from that time Eva thought that he became more and more perverse, and that he was every day less like the gentle, affectionate boy she had been so glad to receive as a companion. She saw, too, that, while her own dress retained its spotless whiteness which nothing seemed to affect, his became every day more and more soiled and stained.

She missed, too, the low, sweet songs which had been sung by the flowers. To be sure, she had not always been able to distinguish their words; but they had been friendly, and had warned her of every danger before it came; but this was all over. Every night, as soon as the moon was gone, creatures like bats, with shining heads, came in65 great numbers, flying around, and moaning in a sad, mournful way which was most pitiful to hear.

As the moon neared the full, stranger shadows and shapes came near. Yet the two went on, following the path, though Eva sometimes imagined that the inhabitants of this strange country were opposed to their passing through it. The music which had been always heard at the rising and setting of the moon grew fainter and fainter, till at last her ascent and fall came in perfect silence. Then the strange shadows disappeared, but the path led through a stonier and more rocky country, where all was wild and barren, and where, after the moon was gone, little, dancing flames played on the stones. Sometimes it was hard, indeed almost impossible, for the two children to climb over the rough places in their path; and Aster was very often discouraged; but Eva persevered, for she felt that the flower they sought could never be found in this barren and dreary land.

I have said that Aster became every day more obstinate and perverse. Sometimes Eva thought that the strange flower, like a dragon-fly, which he had picked, and which he said stung him, had66 changed him, and that was the reason why he tried to annoy her in every possible way. He knew how uneasy she was when he was not with her; yet, knowing this, it was his greatest delight to hide himself behind some large stone, and after she had looked for him for a long time without finding him, afraid that his enemies had carried him off, he would jump out upon her with a loud mocking cry; he would pull her hair, he would try to soil her white dress, by throwing mud and dirt upon it, to make it, as he said, like his own, which was all stained and soiled, and then, when he found that he could not discolor its whiteness, he would throw himself down on the ground, and kick and scream, and tell Eva that he hated her, and that he wished THEY would come and carry her away.

One day, when Aster had been worse than ever, and the way had been stonier and harder than it had ever been before, Eva began to think that it was of no use to go on, or to look for the flower lost so long ago by the imp-like boy, whose powers of annoying her seemed to increase as he grew smaller with the moon. She sat down upon one67 of the rough stones, and great tears gathered in her eyes. And as, one by one, they rolled down her cheeks and fell to the ground, everything around her seemed to grow vague and dim; and at her feet, just where the tear-drops fell, there came a bed of round green leaves, under whose shelter bloomed and nodded a multitude of tiny purple flowers; violets, whose sweet fragrance, rising, made a misty cloud, through which Eva caught faint glimpses of a pond, and a house near it, and then the house seemed to change into a cosy parlor. And by the window of this parlor a lady was sitting sewing, and rocking a cradle with her foot, and singing to a baby boy who was kicking and crowing in the cradle; and then the child heard her mother’s voice calling, softly, “Eva, Eva!” But before these memories came fully back, Aster came up, and angrily crushed and trampled the sweet violets under his feet; and as he did so the cloud and its pictures disappeared, and Eva forgot them; only she was very sorry for the dear little flowers that Aster had killed.

Poor little flowers, which tried to do her good!68 For it seemed to her that with their last breath of perfume there came a low voice, which whispered. “Beware of the stones,”—and that was all. And then she asked Aster why he had destroyed the harmless flowers, which had only come to warn them.

“They only came to do me harm,” Aster said, angrily. “They would have taken you away from me, and I should never have seen you again. You shall not go away from me yet, for I can never get home without you; after I have done with you, why, then you may go.”

“Where?” Eva asked, pained at this selfish speech.

“Into what is to be,—out of Shadow-Land into what is to come, but is not yet.”

“I do not understand you.”

“You will know when the time comes. I crushed the flowers because they were part of what is to come; they had no right here.”

Nothing more was said; but Aster seemed restless and uneasy until they left the place where the violets had bloomed. Yet nothing disturbed them, and on they went, till Eva began to wonder69 where the stones could be of which the voice had said, “Beware!”

At last, when there was only a tiny crescent of the moon, like a faint silver line, floating in the sky, and Aster’s figure, like it, was once more reduced to its smallest dimensions, the forest through which they had wandered for so long ended; and as they passed from it, a low cry of surprise from Aster made Eva look down, as she saw that his eyes were fixed upon the earth; and then she saw with equal surprise that, while she walked along the rough, stony path without leaving any impression, every step that Aster took left a deep, plain track, and that in each of these tracks there was either a frog or a spider, which would disappear while she looked at them.

Then a sudden turn in the path brought them to a place where a huge pile of rocks, like an immense stone wall built by giants, rose up before them. A faint breath of violets seemed to come, and then pass away, and as it did, Eva knew that these were the stones of which she had been warned.

At that very moment there was a flash of70 light, and a star fell from the sky, near the moon.

“A falling star, how pretty it is!” Eva said, as she watched the bright thing, which seemed to fall behind the stone wall. “Did you see it, Aster?”

“You don’t know anything, Eva,” was his reply. “I told you once before that everything which was lost in the moon fell into Shadow-Land, and that was something bright which fell just now.”

But this had nothing to do with the wall, which must be climbed. How, Eva did not know. She was almost afraid to try it; and so she stood, looking at it, when Aster, who, ever since he had crushed the violets, had followed her in silence, except when he had spoken of the shooting star, with his eyes bent on the ground, suddenly ran forward to the wall, and began to look eagerly into every crevice between the stones.

“What are you looking for?” Eva asked him. “Come back to me, Aster; it is not safe for you there without me.”

“I will look,” Aster said. “The bright thing71 you called a star was my flower. It is here, and I am going to find it.”

“Don’t!” Eva said, imploringly, as the boy tried to creep into one of the crevices between the stones. “Remember Aster, that the moon is nearly gone, and if she should disappear, you will go to sleep, and then you will have to stay in there until she returns.”

“I don’t care!” Aster said, crossly, “If, as I know I shall, I find my flower in here, the moon will have no more power over me, for I shall then be myself; and you may go on alone into what will come. Besides, the piece which was torn off my coat is in there, and I am going to get it. If I do go to sleep, I can lie down in here, and rest; you can mark the place and wait for me, if you choose. I don’t intend to obey you any longer; you are nothing but a little girl, and I am a prince.”

Eva’s hand was on Aster’s shoulders and when he found she would not remove it, he raised his own, and struck her. Not till then did the child unwillingly release him, seeing that all her efforts to detain him would be in vain. Then, without72 saying another word, Aster crept slowly into the crevice. And Eva, picking up a white stone which lay at her feet; made a mark over the place with it. As she did this, the faint silver light of the moon faded from the sky; there was a loud croaking as of frogs, and then she heard the shrill cry of the spider which had spun the web around Aster; and then it grew very dark, and a sudden drowsiness came over her, which she could not resist; and, lying down upon a stone under the crevice into which Aster had crept, Eva fell asleep.

IT was with a start that, after the darkness had gone, Eva awoke from the dull, heavy sleep into which she had fallen; and for a moment she could not recollect how it was that she should be lying upon a stone at the foot of this huge rocky wall, or why she should be alone, without Aster near her. She looked for him, thinking that perhaps he might have hidden himself, only to tease her; but he was nowhere to be found. She called him, hoping that he might hear and answer her; but there was no reply,—only the rocks echoed back the sound of her own voice, which said, “Aster, Aster! where are you?” and then another echo seemed to answer, mockingly, “Where?”

74 But all this only lasted for a few moments. Then all at once Eva remembered the falling star; the warning which the violets had given her; the blow, which, coming as it did from Aster’s hand, had so deeply grieved her; her efforts to detain him at her side, which had all proved useless; and how, after the boy had crept into one of the crevices of the wall, declaring he went there in search of his flower, she had picked up a stone, which she now found she still held in her hand, and marked the place. Then she felt relieved, for she knew that this was the time when Aster would be asleep, as he always was when the moon was absent, and consequently he could not move from the place into which he had crept. She thought, therefore, that, whenever she chose, she would find him, and, taking him again under her care, carry him away from this barren and stony waste.

Encouraged and relieved by this thought, she did not look for Aster any longer, but went to a little spring bubbling up between two rough stones, and which was the only pleasant thing she could see in this rocky place. She knelt down75 by it, for she was thirsty, to drink from its cool and sparkling waters, and then to wash her face and hands in them; and as she dipped her hands in the spring, the little ripples they made whispered, softly, “Over yonder! over yonder!” but Eva was not sure if she really had heard these words; or only imagined them.

Refreshed by the cool waters she went back to the great, rough, stone wall, intending to secure her charge, and then try to go on. But what was her surprise, on returning, as she thought, to the same stone on which she had slept, to see that there were so many stones just exactly like it, that she could not find the one she wanted! and, what was still stranger, she saw that over every little hole, every tiny cavity in the stone, there was a white mark exactly like the one which she had made over the crevice into which Aster had crept, and she could not say which of them all was hers.

She was in despair for a moment. How was she to find, among all these holes, each with the same white mark over it, the one in which Aster was asleep? Then she remembered that standing still and looking at the wall would do no good;76 that if she wanted to find Aster she must look for him; and Eva determined to examine every hole she saw, in hopes that with patience and perseverance she might at last succeed in finding her lost charge, of whom, in spite of all the trouble he had given her, she had grown very fond.

But if she had been surprised at seeing a white mark over every hole, instead of the one she had made, she was still more astonished when she saw that in every cranny which she examined there sat either a large black-legged spider, with a gold and scarlet back, and eyes which shone in the dark like little bright stars, or else there squatted snugly in it a huge green frog, with a wide mouth and projecting black eyes; while just beyond her reach there would flutter every now and then a little green flag, like the scrap of velvet, as Eva thought, which the teeth of the frog had torn from Aster’s coat.

Yet the child climbed slowly up the wall, fearless of the spiders and the frogs, which she knew had no power to harm her, even if they had wished it. But seeing them, and knowing, as she did, that these two creatures, in the forest through77 which they had passed, had tried to get possession of Aster, Eva began to fear that by creeping into the hole he had put himself in their power, and that she would never be able to find him again.

She went on, however, looking carefully into every tiny cavity; but always with the same result. No Aster was to be seen: only huge spiders and squatting frogs stared at her from every cranny. And, as she climbed up higher and higher, she found that the rocky wall was like a giant staircase; and when she looked back, noticing that the stones she displaced, as she climbed up, only rolled a short time and then made no noise as they fell, and thinking that after her search was over she would return to the little spring and wait there patiently until the moon rose again, when, as she hoped, Aster, if she did not find him now, would wake up and come back to her, she saw that she could never return to the spring. For the steps by which she had come were gone, melting one by one into the face of the rock, changing into a steep precipice behind her; and at its foot were curling mists and vapors, among which she saw dimly the hateful, mocking faces78 she had seen before. Go back she could not, for every step, as she passed it, melted into the precipice; to look back made her dizzy. She must go upward.

For the first time since she had begun to climb the wall, which had changed, as she climbed, into steps, and then into a precipice, Eva was afraid. But there was no choice left for her; go on she must; and, accordingly, on she went, till she came to a place where the rock rose, so high that she could not see its top, in a smooth, unbroken wall, over which she could not possibly climb, and a narrow path ran along its base; and as yet she had not seen nor heard anything of the truant Aster.

She walked slowly along the foot of the great blank wall, tired and discouraged. What to do now, she did not know. She could not go back, for there was the frightful precipice; in front was the wall, along which she was walking. Poor Eva was almost ready to cry, when all of a sudden she saw a door, cut in the stone, and the door was shut. But she heard, behind this door, the silvery voices and ringing laughter of children, and then a great longing came over79 her to go in and join them, and she thought that perhaps Aster might be with them.

Yet, although she tried, she could not open the door. She heard the merry voices of the children, and, hearing them as plainly as she did, she thought it was strange that they did not hear her and open the door to her; for, try as she would, she could not open it. And then she grew tired of trying, and would have gone on, when, looking once more at the door to see if there was any way of opening it which she could possibly have neglected, she saw cut across the door, in deep, old-fashioned, moss-grown letters, the word

Then, gathering courage, Eva raised her tiny hand, and knocked. Once, and no answer came. Again, and with the same result. A third time, and then the merry voices of the children, and their gay laughter, ceased, and Eva hoped that her appeal was heard.

EVA waited for a moment, with as much patience as she could, in hopes that the door might now be opened for her. Vain hopes, for the ringing laughter and the merry voices began again; and once more Eva would have been discouraged, if the thought had not come that perhaps her gentle knocking had not been heard, and once more she tapped, louder this time, at the door.

A voice within immediately asked, “Who knocks?”

“I—Eva,” was the child’s reply.

“Eva may enter.”

Poor child! She thought the permission was useless, for the door remained as tightly shut as ever.

81 “Why do you not come in?” the same voice asked, after a pause, “You are permitted.”

“I cannot come in, because the door is shut,” Eva said.

“Take the key and unlock it.”

But Eva, after looking around carefully, could see no key, and so she said, “I do not know where the key can be.”

“Look under your right foot,” said the voice within; and Eva, stepping to one side, saw lying, just where her foot had been, a queer little key, which she picked up; and seeing a key-hole among the quaint letters of the inscription, she found the little key just fitted it; and on turning it, the door flew open, and, as it did, a band of beautiful children came forward to meet her, though not one of them crossed the threshold of the door, and they bade her welcome. But when Eva would have gone in, it seemed to her that invisible hands prevented her entrance; and then one of the children, seeing that she still held in her hand the white stone she had picked up near the spring, and with which she had made the mark over Aster’s hiding-place, told her to throw it away, for that82 nothing from Shadow-Land could be brought into their valley; and then to be careful and not touch the threshold of the door, but to step over it. And Eva did as they told her; but when she threw the white stone over the precipice, it changed into a large white moth as it left her hand; and Eva, watching it, saw one of the faces rise from out of the curling mists to meet it, and then the moth changed into a face like the one she had first seen, and then both disappeared among the mists and vapors. And the moment she passed through the door, it closed suddenly behind her, and could not be told from the solid rock; and Eva saw that she was in a place totally different from anything she had ever seen before in her wanderings.

She found that she was now in a large, grassy valley, in the midst of which was built a beautiful rose-colored palace, shining like a star. Flowers of the gayest hues bloomed all through the grass; fountains of musical water, surrounded with rainbows, played here and there; birds and butterflies of brilliant colors flew among the flowers, and were so tame that they would alight on the children’s83 hands, and the birds were so wise that they could talk, and tell the most interesting stories, which you never grew tired of hearing. A little brook ran sparkling through the valley, and groups of beautiful children were playing on its banks, among whom Eva looked—but looked in vain—for Aster.

The children gathered around her, asking where she came from, if she was the Queen who was to reign over them, and if she was not going to live always with them. And when Eva tried to explain how she had come, and asked them if they knew where Aster was, they joined hands and danced in a circle around her to their own singing, and then one of them gave her the leaves of a flower to eat. Now the leaves of this flower were delicious, and as sweet as honey to the taste, and one never wearied of eating them; and as Eva ate them, all memory of Shadow-Land and of Aster faded from her mind, and she was content to remain in the valley with the children.

It was a pleasant life that she led in this peaceful valley, surrounded, as it was, and shut in by high, insurmountable, and steep rocks, over which84 nothing without wings could go; in which the children dwelt, and where there was neither sun nor moon, but only a soft, rosy light, which never hurt or dazzled the eyes, and where nothing ever happened which could disturb the peace of the place. To chase the brilliant butterflies, to listen to the songs and stories of the birds, to dance on the soft green grass, and gather flowers to make fragrant wreaths and garlands with which to decorate the beautiful palace in which, when darkness came over the valley, they all assembled, and where tables, spread with the most delicious fruits, always stood ready for them,—such was the life that Eva and the children led in the Valley of Rest.

But at last a day came when the children told Eva that, as their custom was, they must leave the valley and carry baskets of flowers and fruit to the Queen for whom they had at first taken her. She could not go with them now, they said, but the next time that they went they would take her with them. They would be gone the next morning before she was awake, and she would be alone for that day in the valley; but then they would return;85 and the only favor they asked of her was this,—that she would not go near the brook, nor play upon its banks, while they were absent.

Eva willingly promised this. Such a little thing as it was to promise, when she would have the whole fair valley to herself, to go where she pleased, and to do what she pleased! It would be very easy to keep away from the brook.

But when once more the soft, rosy light came, and the darkness was gone, and Eva awoke to find herself lying, all alone, on her little bed in the palace, and to know that all the children were indeed gone, though only for a time, a strange restlessness came over her, and she felt that she could not stay all alone in the palace. She would go out of it into the valley. But she was no better off there. She gathered flowers and made beautiful wreaths and bouquets, but there was no one to admire them when they were made. The rainbows around the fountains were less brilliant; the birds were all gone with the children, so that she could not listen to their songs or the stories they might have told her. She might play and dance, but what fun was there in that, when she had no86 companions to dance and play with her? Eva thought she never had spent such a stupid, long, dull day in all her life; and she wished it was over. The only thing which seemed as merry as ever was the little brook, which she had promised to avoid, yet which rippled along so joyously that it was as much as Eva could do to keep away from it.

But she remembered her promise to the children, and turning her back upon the brook, she went and sat down near one of the fountains. She had only been there for a few moments, when she felt something pull her dress; and looking round to see what it was,—wondering if the children could possibly have returned,—she saw, to her great surprise, a huge green toad, which had hold of her dress, and which, when she looked at it, said:

“Croak! croak!”

Then Eva knew that she had seen the toad before, and she began to wonder how it had gotten into the Valley of Rest, where she never had seen anything like it. But she did not have much time for wonder; for the toad, giving her dress another pull, said to her, “Come to the87 brook! Come to the brook!” And then it began to hop towards the brook just as fast as it could go.

She forgot her promise to the children, and, just exactly as she had done once before, she obeyed the toad, and went down to the brook. And when she got there, she could not imagine why the toad wanted her to go there, for he was nowhere to be seen, and the brook looked just as it always did. But she sat down by it, and watched the merry water as it rippled along over its pebbly bed. Then, soothed by the low murmur it made, she lay down on the grass and fell asleep. And while she was asleep she had a dream; and this is what she dreamed:

She saw Aster, his dress torn, dirty, and ragged, his long curls tangled; tired and sad, and compelled to carry burdens of stone too heavy for him to lift. And when he wanted to rest, two figures, with the faces which Eva had seen in the forest and among the curling mists and vapors at the foot of the precipice, beat him with rods full of thorns. And then a huge red-and-black spider would sting him in the foot, or a great green frog,88 with prominent black eyes, would threaten to swallow him; and then the boy would cry, and call for Eva to come and help him.

Then the frog would say:

“Why did you let me tear your coat?”

And the faces would ask:

“Why did you lose your flower?”

And then the spider would say:

“Why did you creep into the rock?”

And to all this Aster would only answer with the cry, “Eva! Eva! help me!”

Then one of the faces said, angrily: