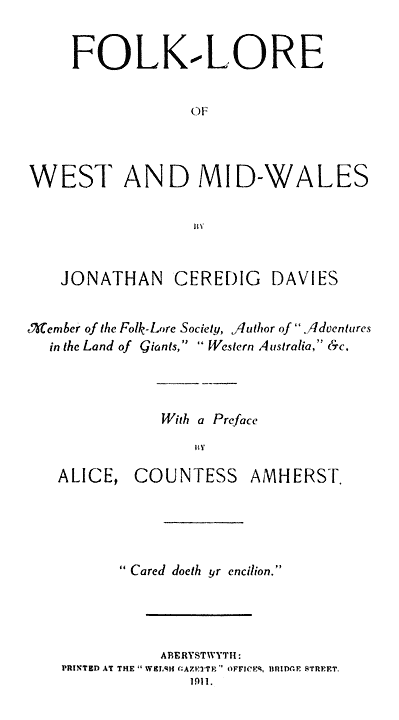

OF

WEST AND MID-WALES

ABERYSTWYTH:

PRINTED AT THE “WELSH GAZETTE” OFFICES, BRIDGE STREET.

1911.

This book is respectfully dedicated by the Author

to

COUNTESS OF LISBURNE, CROSSWOOD.

ALICE, COUNTESS AMHERST.

LADY ENID VAUGHAN.

LADY WEBLEY-PARRY-PRYSE, GOGERDDAN.

LADY HILLS-JOHNES OF DOLAUCOTHY.

MRS. HERBERT DAVIES-EVANS, HIGHMEAD.

MRS. WILLIAM BEAUCLERK POWELL, NANTEOS. [V]

PREFACE

The writer of this book lived for many years in the Welsh Colony, Patagonia, where he was the pioneer of the Anglican Church. He published a book dealing with that part of the world, which also contained a great deal of interesting matter regarding the little known Patagonian Indians, Ideas on Religion and Customs, etc. He returned to Wales in 1891; and after spending a few years in his native land, went out to a wild part of Western Australia, and was the pioneer Christian worker in a district called Colliefields, where he also built a church. (No one had ever conducted Divine Service in that place before.)

Here again, he found time to write his experiences, and his book contained a great deal of value to the Folklorist, regarding the aborigines of that country, quite apart from the ordinary account of Missionary enterprise, history and prospects of Western Australia, etc.

In 1901, Mr. Ceredig Davies came back to live in his native country, Wales.

In Cardiganshire, and the centre of Wales, generally, there still remains a great mass of unrecorded Celtic Folk Lore, Tradition, and Custom.

Thus it was suggested that if Mr. Ceredig Davies wished again to write a book—the material for a valuable one lay at his door if he cared to undertake it. His accurate knowledge of Welsh gave him great facility for the work. He took up the idea, and this book is the result of his labours. [VI]

The main object has been to collect “verbatim,” and render the Welsh idiom into English as nearly as possible these old stories still told of times gone by.

The book is in no way written to prove, or disprove, any of the numerous theories and speculations regarding the origin of the Celtic Race, its Religion or its Traditions. The fundamental object has been to commit to writing what still remains of the unwritten Welsh Folk Lore, before it is forgotten, and this is rapidly becoming the case.

The subjects are divided on the same lines as most of the books on Highland and Irish Folk Lore, so that the student will find little trouble in tracing the resemblance, or otherwise, of the Folk Lore in Wales with that of the two sister countries.

ALICE AMHERST.

Plas Amherst, Harlech,

North Wales, 1911. [VII]

INTRODUCTION.

Welsh folk-lore is almost inexhaustible, and of great importance to the historian and others. Indeed, without a knowledge of the past traditions, customs and superstitions of the people, the history of a country is not complete.

In this book I deal chiefly with the three counties of Cardiganshire, Carmarthenshire, and Pembrokeshire, technically known in the present day as “West Wales”; but as I have introduced so many things from the counties bordering on Cardigan and Carmarthen, such as Montgomery, Radnor, Brecon, etc., I thought proper that the work should be entitled, “The Folk-Lore of West and Mid-Wales.”

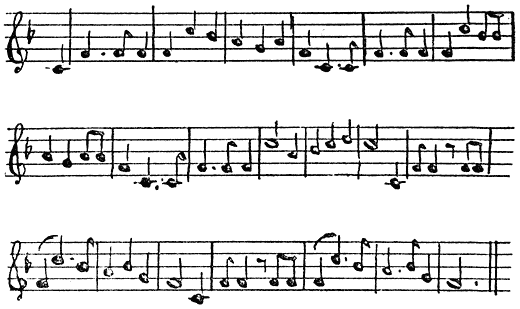

Although I have been for some years abroad, in Patagonia, and Australia, yet I know almost every county in my native land; and there is hardly a spot in the three counties of Carmarthen, Cardigan, and Pembroke that I have not visited during the last nine years, gathering materials for this book from old people and others who were interested in such subject, spending three or four months in some districts. All this took considerable time and trouble, not to mention of the expenses in going about; but I generally walked much, especially in the remote country districts, but I feel I have rescued from oblivion things which are dying out, and many things which have died out already. I have written very fully concerning the old Welsh Wedding and Funeral Customs, and obtained most interesting account of them from aged persons. The “Bidder’s Song,” by Daniel Ddu, which first appeared in the “Cambrian Briton” 1822, is of special interest. Mrs. Loxdale, of Castle Hill, showed me a fine silver cup which had been presented to this celebrated poet. I have also a chapter on Fairies; but as I found that Fairy Lore has almost died out in those districts which I visited, and the traditions concerning them already recorded, I was obliged to extract much of my information on this subject from books, though I found a few new fairy stories in Cardiganshire. But as to my chapters about Witches, Wizards, Death Omens, I am indebted for almost all my information to old men and old women whom I visited in remote country districts, and I may emphatically state that I have not embellished the stories, or added to anything I have heard; and care has been taken that no statement [VIII]be made conveying an idea different from what has been heard. Indeed, I have in nearly all instances given the names, and even the addresses of those from whom I obtained my information. If there are a few Welsh idioms in the work here and there, the English readers must remember that the information was given me in the Welsh language by the aged peasants, and that I have faithfully endeavoured to give a literal rendering of the narrative.

About 350 ladies and gentlemen have been pleased to give their names as subscribers to the book, and I have received kind and encouraging letters from distinguished and eminent persons from all parts of the kingdom, and I thank them all for their kind support.

I have always taken a keen interest in the History and traditions of my native land, which I love so well; and it is very gratifying that His Royal Highness, the young Prince of Wales, has so graciously accepted a genealogical table, in which I traced his descent from Cadwaladr the Blessed, the last Welsh prince who claimed the title of King of Britain.

I undertook to write this book at the suggestion and desire of Alice, Countess Amherst, to whom I am related, and who loves all Celtic things, especially Welsh traditions and legends; and about nine or ten years ago, in order to suggest the “lines of search,” her Ladyship cleverly put together for me the following interesting sketch or headings, which proved a good guide when I was beginning to gather Folk-Lore:—

(1) Traditions of Fairies. (2) Tales illustrative of Fairy Lore. (3) Tutelary Beings. (4) Mermaids and Mermen. (5) Traditions of Water Horses out of lakes, if any? (6) Superstitions about animals:—Sea Serpents, Magpie, Fish, Dog, Raven, Cuckoo, Cats, etc. (7) Miscellaneous:—Rising, Clothing, Baking, Hen’s first egg; Funerals; Corpse Candles; On first coming to a house on New Year’s Day; on going into a new house; Protection against Evil Spirits; ghosts haunting places, houses, hills and roads; Lucky times, unlucky actions. (8) Augury:—Starting on a journey; on seeing the New Moon. (9) Divination; Premonitions; Shoulder Blade Reading; Palmistry; Cup Reading. (10) Dreams and Prophecies; Prophecies of Merlin and local ones. (11) Spells and Black Art:—Spells, Black Art, Wizards, Witches. (12) Traditions of Strata Florida, King Edward burning the Abbey, etc. (13) Marriage Customs.—What the Bride brings to the house; The Bridegroom. (14) Birth Customs. (15) Death Customs. (16) Customs of the Inheritance of farms; and Sheep Shearing Customs.

[IX]

Another noble lady who was greatly interested in Welsh Antiquities, was the late Dowager Lady Kensington; and her Ladyship, had she lived, intended to write down for me a few Pembrokeshire local traditions that she knew in order to record them in this book.

In an interesting long letter written to me from Bothwell Castle, Lanarkshire, dated September 9th, 1909, her Ladyship, referring to Welsh Traditions and Folk-Lore, says:—“I always think that such things should be preserved and collected now, before the next generation lets them go! ... I am leaving home in October for India, for three months.” She did leave home for India in October, but sad to say, died there in January; but her remains were brought home and buried at St. Bride’s, Pembrokeshire. On the date of her death I had a remarkable dream, which I have recorded in this book, see page 277.

I tender my very best thanks to Evelyn, Countess of Lisburne, for so much kindness and respect, and of whom I think very highly as a noble lady who deserves to be specially mentioned; and also the young Earl of Lisburne, and Lady Enid Vaughan, who have been friends to me even from the time when they were children.

I am equally indebted to Colonel Davies-Evans, the esteemed Lord Lieutenant of Cardiganshire, and Mrs. Davies-Evans, in particular, whose kindness I shall never forget. I have on several occasions had the great pleasure and honour of being their guest at Highmead.

I am also very grateful to my warm friends the Powells of Nanteos, and also to Mrs. A. Crawley-Boevey, Birchgrove, Crosswood, sister of Countess Lisburne.

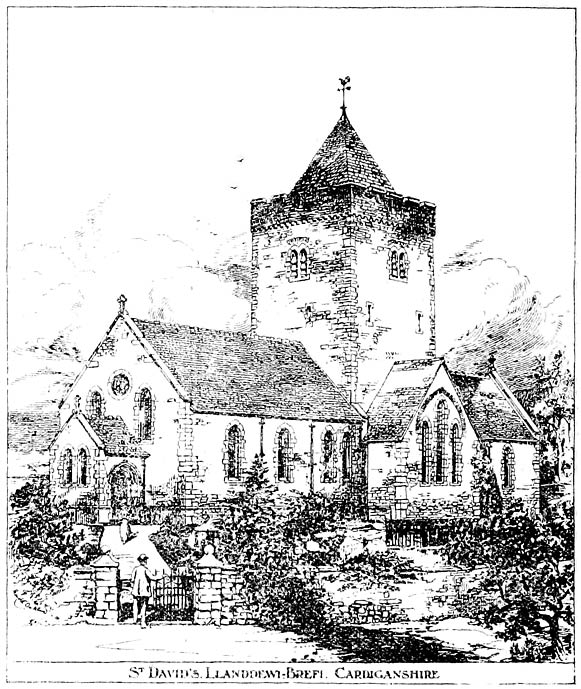

Other friends who deserve to be mentioned are, Sir Edward and Lady Webley-Parry-Pryse, of Gogerddan; Sir John and Lady Williams, Plas, Llanstephan (now of Aberystwyth); General Sir James and Lady Hills-Johnes, and Mrs. Johnes of Dolaucothy (who have been my friends for nearly twenty years); the late Sir Lewis Morris, Penbryn; Lady Evans, Lovesgrove; Colonel Lambton, Brownslade, Pem.; Colonel and Mrs. Gwynne-Hughes, of Glancothy; Mrs. Wilmot Inglis-Jones; Capt. and Mrs. Bertie Davies-Evans; Mr. and Mrs. Loxdale, Castle Hill, Llanilar; Mr. and Mrs. Lloyd, Waunifor; Mrs. Webley-Tyler, of Glanhelig; Archdeacon Williams, of Aberystwyth; Professor Tyrrell Green, Lampeter; Dr. Hughes, and Dr. Rees, of Llanilar; Rev. J. F. Lloyd, vicar of Llanilar, the energetic secretary of the Cardiganshire Antiquarian Society; Rev. Joseph [X]Evans, Rector of Jordanston, Fishguard; Rev. W. J. Williams, Vicar of Llanafan; Rev. H. M. Williams, Vicar of Lledrod; Rev. J. N. Evans, Vicar of Llangybi; Rev. T. Davies, Vicar of Llanddewi Brefi; Rev. Rhys Morgan, C. M. Minister, Llanddewi Brefi; Rev. J. Phillips, Vicar of Llancynfelyn; Rev. J. Morris, Vicar, Llanybyther; Rev. W. M. Morgan-Jones (late of Washington, U.S.A.); Rev. G. Eyre Evans, Aberystwyth; Rev. Z. M. Davies, Vicar of Llanfihangel Geneu’r Glyn; Rev. J. Jones, Curate of Nantgaredig; Rev. Prys Williams (Brythonydd) Baptist Minister in Carmarthenshire; Rev. D. G. Williams, Congregational Minister, St. Clears (winner of the prize at the National Eisteddfod, for the best essay on the Folk-Lore of Carmarthen); Mr. William Davies, Talybont (winner of the prize at the National Eisteddfod for the best essay on the Folk-Lore of Merioneth); Mr. Roderick Evans, J. P., Lampeter; Rev. G. Davies, Vicar of Blaenpenal; Mr. Stedman-Thomas (deceased), Carmarthen, and others in all parts of the country too numerous to be mentioned here. Many other names appear in the body of my book, more especially aged persons from whom I obtained information.

JONATHAN CEREDIG DAVIES.

Llanilar, Cardiganshire.

March 18th, 1911. [XI]

CONTENTS.

| PAGE. | ||||||||

| Dedication | III. | |||||||

| Preface | V. | |||||||

| Introduction | VII. | |||||||

| I. | Love Customs, etc. | 1 | ||||||

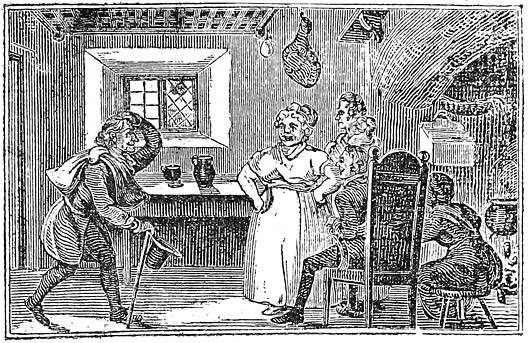

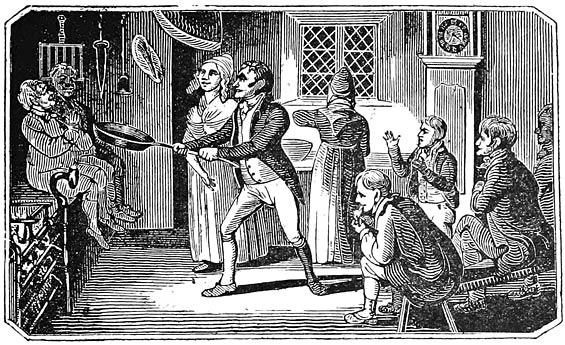

| II. | Wedding Customs | 16 | ||||||

| III. | Funeral Customs | 39 | ||||||

| IV. | Other Customs | 59 | ||||||

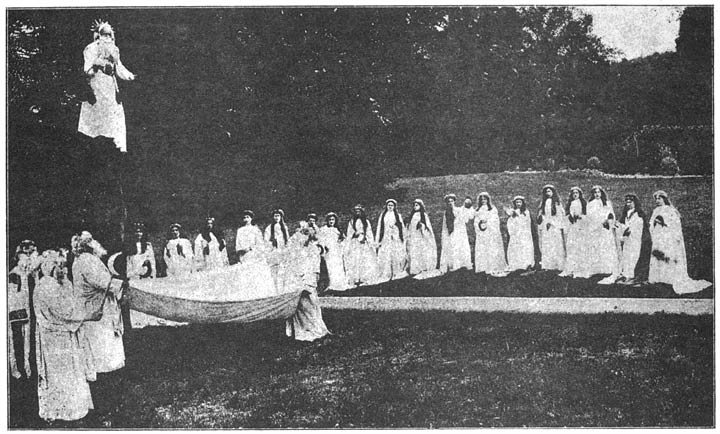

| V. | Fairies and Mermaids | 88 | ||||||

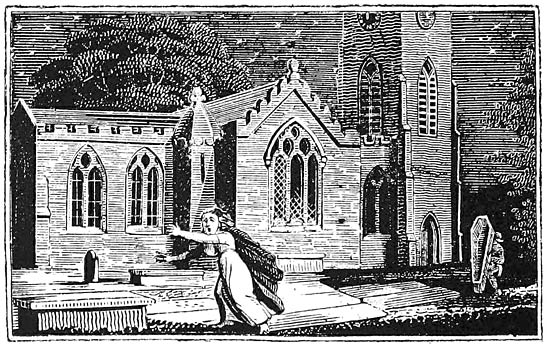

| VI. | Ghost Stories | 148 | ||||||

| VII. | Death Portents | 192 | ||||||

| VIII. | Miscellaneous Beliefs, Birds, etc. | 215 | ||||||

| IX. | Witches and Wizards, etc. | 230 | ||||||

| X. | Folk-Healing | 281 | ||||||

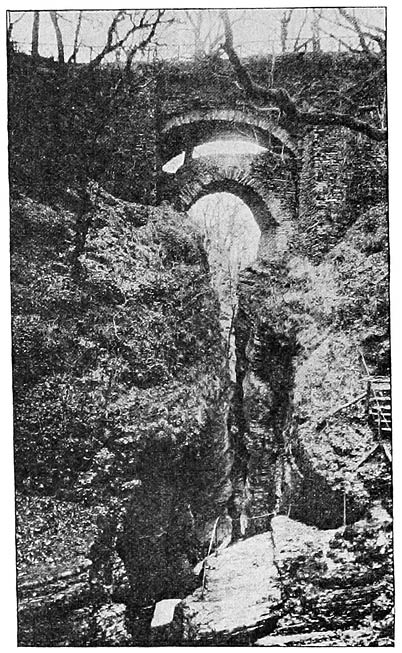

| XI. | Fountains, Lakes, and Caves ... | 298 | ||||||

| XII. | Local Traditions | 315 | ||||||

| Index | 335 | |||||||

[1]