The Project Gutenberg EBook of Ireland under the Stuarts and during the Interregnum, Vol. II (of 3), 1642-1660, by Richard Bagwell This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Ireland under the Stuarts and during the Interregnum, Vol. II (of 3), 1642-1660 Author: Richard Bagwell Release Date: January 7, 2017 [EBook #53916] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IRELAND UNDER THE STUARTS, VOL 2 *** Produced by Brownfox and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

By the same Author

IRELAND UNDER THE TUDORS

Vols. I. and II.—From the First Invasion of the

Northmen to the year 1578.

8vo. 32s.

Vol. III.—1578-1603. 8vo. 18s.

LONGMANS, GREEN, & CO.

London, New York, Bombay, and Calcutta

IRELAND

UNDER THE STUARTS

AND

DURING THE INTERREGNUM

BY

RICHARD BAGWELL, M.A.

AUTHOR OF ‘IRELAND UNDER THE TUDORS’

Vol. II. 1642-1660

WITH MAP

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

NEW YORK, BOMBAY, AND CALCUTTA

1909

All rights reserved

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| MUNSTER AND CONNAUGHT, 1641-1642 | |

| PAGE | |

| The rebellion spreads to Munster | 1 |

| The King’s proclamation | 3 |

| St. Leger, Cork, and Inchiquin | 3 |

| State of Connaught | 5 |

| Massacre at Shrule | 6 |

| Clanricarde at Galway | 7 |

| Weakness of the English party | 8 |

| State of Clare—Ballyallia | 10 |

| Cork and St. Leger | 12 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| THE WAR TO THE BATTLE OF ROSS, 1642-1643 | |

| Scots army in Ulster—Monro | 14 |

| Strongholds preserved in Ulster | 16 |

| Ormonde in the Pale | 17 |

| Battle of Kilrush | 18 |

| The Catholic Confederation | 19 |

| Owen Roe O’Neill | 20 |

| Thomas Preston | 21 |

| Loss of Limerick, St. Leger dies | 22 |

| Battle of Liscarrol | 23 |

| Fighting in Ulster | 23 |

| General Assembly at Kilkenny | 25 |

| The Supreme Council—foreign support | 27 |

| Fighting in Leinster—Timahoe | 29 |

| Parliamentary agents in Dublin | 29 |

| Siege of New Ross | 31 |

| Battle of Ross | 32 |

| [Pg vi]A papal nuncio talked of | 34 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| THE WAR TO THE FIRST CESSATION, 1642-1643 | |

| The Adventurers for land—Lord Forbes | 36 |

| Forbes at Galway and elsewhere | 38 |

| A pragmatic chaplain, Hugh Peters | 40 |

| Forbes repulsed from Galway | 41 |

| A useless expedition | 42 |

| Siege and capture of Galway fort | 43 |

| O’Neill, Leven, and Monro | 44 |

| The King will negotiate | 46 |

| Dismissal of Parsons | 47 |

| Vavasour and Castlehaven | 48 |

| The King presses for a truce | 48 |

| Scarampi and Bellings | 49 |

| A cessation of arms, but no peace | 50 |

| Ormonde made Lord Lieutenant | 51 |

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

| AFTER THE CESSATION, 1643-1644 | |

| The cessation condemned by Parliament | 53 |

| The rout at Nantwich | 54 |

| Monck advises the King | 55 |

| The Solemn League and Covenant | 55 |

| The Covenant taken in Ulster | 57 |

| Monro seizes Belfast | 59 |

| Dissensions between Leinster and Ulster | 60 |

| Failure of Castlehaven’s expedition | 60 |

| Antrim and Montrose | 61 |

| The Irish under Montrose—Alaster MacDonnell | 62 |

| Rival diplomatists at Oxford | 64 |

| Violence of both parties | 66 |

| Failure of the Oxford negotiations | 68 |

| Inchiquin supports the Parliament | 69 |

| CHAPTER XXV | |

| INCHIQUIN, ORMONDE, AND GLAMORGAN, 1644-1645 | |

| The no quarter ordinance | 72 |

| Roman Catholics expelled from Cork, Youghal, and Kinsale | 73 |

| The Covenant in Munster | 74 |

| Negotiations for peace | 75 |

| Bellings at Paris and Rome | 76 |

| Recruits for France and Spain | 77 |

| [Pg vii]Irish appeals for foreign help | 78 |

| Siege of Duncannon Fort | 80 |

| Mission of Glamorgan with extraordinary powers | 84 |

| Glamorgan in Ireland | 87 |

| The Glamorgan treaty | 88 |

| CHAPTER XXVI | |

| FIGHTING NORTH AND SOUTH—RINUCCINI, 1645 | |

| Castlehaven in Munster | 90 |

| Fall of Lismore, Youghal besieged | 93 |

| Relief of Youghal | 94 |

| Coote in Connaught | 95 |

| Rinuccini appointed nuncio | 96 |

| Scope of his mission | 97 |

| King and Queen distrusted at Rome | 98 |

| Rinuccini at Paris | 99 |

| His voyage to Ireland | 100 |

| Arrival in Kerry and welcome at Kilkenny | 102 |

| CHAPTER XXVII | |

| THE ORMONDE PEACE, 1646 | |

| Glamorgan and Rinuccini | 103 |

| Arrest of Glamorgan | 104 |

| Charles repudiates him | 106 |

| Mission of Sir Kenelm Digby | 107 |

| Ireland must be sacrificed | 108 |

| Sir Kenelm Digby’s treaty | 109 |

| Glamorgan swears fealty to the nuncio | 111 |

| Ormonde’s peace with the Confederacy | 112 |

| Lord Digby’s adventures | 114 |

| The peace proclaimed at Dublin | 115 |

| Siege of Bunratty | 115 |

| Battle of Benburb | 117 |

| Scots power in Ulster broken | 120 |

| Rejoicings in Ireland and at Rome | 121 |

| Rinuccini opposes the peace | 122 |

| Which the clergy reject | 123 |

| Riot at Limerick | 125 |

| Ormonde at Kilkenny | 126 |

| Triumph of Rinuccini | 129 |

| Quarrels of O’Neill and Preston | 130 |

| Lord Digby’s intrigues | 134 |

| Rinuccini loses his popularity | 136 |

| [Pg viii]Discords among the Confederates | 137 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII | |

| SURRENDER OF DUBLIN AND AFTER, 1647 | |

| Dublin between two fires | 140 |

| Mission of George Leyburn | 141 |

| Ormonde’s reasons for surrendering to Parliament | 143 |

| Digby’s last plots in Ireland | 144 |

| Glamorgan as general | 145 |

| His army adheres to Muskerry | 146 |

| Preston routed at Dungan Hill | 148 |

| Parliamentary neglect | 149 |

| Victories of Inchiquin | 150 |

| Lord Lisle’s abortive viceroyalty | 151 |

| Sack of Cashel | 153 |

| Mahony’s Disputatio Apologetica | 154 |

| Rinuccini and O’Neill | 155 |

| Battle of Knocknanuss | 157 |

| Declining fortunes of the Confederacy | 158 |

| Fresh appeals for foreign aid | 159 |

| Inchiquin distrusted by Parliament | 161 |

| Ormonde goes to England and France | 162 |

| CHAPTER XXIX | |

| INCHIQUIN, RINUCCINI, AND ORMONDE, 1648 | |

| Inchiquin deserts the Parliament | 164 |

| His truce with the Confederacy | 165 |

| Rinuccini dependent on O’Neill | 166 |

| Who threatens Kilkenny | 168 |

| O’Neill, Inchiquin, and Michael Jones | 170 |

| O’Neill proclaimed traitor at Kilkenny | 170 |

| Ormonde returns to Ireland | 171 |

| His reception at Kilkenny | 172 |

| Monck master in Ulster | 173 |

| The Prince of Wales expected | 174 |

| The Confederacy dissolved | 175 |

| Rinuccini driven from Ireland | 176 |

| CHAPTER XXX | |

| RINUCCINI TO CROMWELL, 1649 | |

| Ormonde’s commanding position | 179 |

| Charles II. proclaimed | 180 |

| Milton and the Ulster Presbyterians | 180 |

| Monck, O’Neill, and Coote in Ulster | 182 |

| Inchiquin takes Drogheda | 183 |

| [Pg ix]Ormonde defeated by Jones at Rathmines | 184 |

| Charles II. has thoughts of Ireland | 186 |

| Prince Rupert at Kinsale | 187 |

| Broghill consents to serve Parliament | 189 |

| Cromwell leaves London | 189 |

| CHAPTER XXXI | |

| CROMWELL IN IRELAND, 1649 | |

| Cromwell restores discipline in Dublin | 191 |

| Storm of Drogheda | 193 |

| Ormonde’s treaty with O’Neill | 196 |

| Death and character of Owen Roe O’Neill | 197 |

| Cromwell at Wexford | 198 |

| Storm of Wexford | 200 |

| Cromwell takes New Ross | 201 |

| Cork, Kinsale, and Youghal join Cromwell | 203 |

| Operations after New Ross | 204 |

| Siege of Waterford | 205 |

| Siege raised | 206 |

| Death of Michael Jones | 206 |

| Cromwell winters at Youghal | 208 |

| Broghill’s campaign | 208 |

| Carrickfergus taken | 209 |

| The Clonmacnoise decrees | 210 |

| CHAPTER XXXII | |

| CROMWELL IN IRELAND, 1650 | |

| Cromwell’s declaration | 212 |

| A lady’s experience at Cork | 213 |

| Cromwell’s southern campaign | 214 |

| Operations in Leinster—Castlehaven | 216 |

| Cromwell takes Kilkenny | 218 |

| Siege of Clonmel, assault repulsed | 220 |

| The town capitulates | 222 |

| Battle of Macroom, Cromwell leaves Ireland | 223 |

| Submission of Protestant Royalists | 225 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII | |

| ORMONDE’S LAST STRUGGLES, 1650 | |

| Dissensions among Irish Royalists | 226 |

| O’Neill succeeded by Bishop Macmahon | 227 |

| Englishmen turned out of the army | 228 |

| Battle of Scariffhollis | 230 |

| [Pg x]Assembly summoned to meet at Loughrea | 232 |

| Ormonde excluded from Limerick | 232 |

| Clanricarde excluded from Galway | 233 |

| Surrender of Tecroghan and Carlow | 234 |

| Waterford capitulates | 235 |

| Charlemont taken | 236 |

| Meeting of bishops at Jamestown | 237 |

| Ormonde’s adherents excommunicated | 238 |

| Charles II. repudiates the Irish | 239 |

| A conference at Galway | 241 |

| The excommunication maintained—no Protestant governor | 242 |

| The Loughrea assembly can do little | 243 |

| Ormonde leaves Ireland, Clanricarde Deputy | 243 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV | |

| CLANRICARDE AND IRETON, 1651 | |

| Plague and famine | 245 |

| A regicide government | 246 |

| Hugh O’Neill at Limerick | 247 |

| Charles IV., Duke of Lorraine | 249 |

| Taaffe’s mission to Charles II. | 251 |

| A Lorraine envoy in Ireland | 253 |

| Extent of Lorraine succours | 254 |

| Terms of agreement with the Duke | 256 |

| Condemned by Ormonde and Clanricarde | 257 |

| No help after Worcester | 258 |

| Ireton passes the Shannon | 261 |

| Coote and Reynolds elude Clanricarde | 262 |

| Desperate defence of Gort—Ludlow | 263 |

| Siege of Limerick | 263 |

| Ludlow in Clare | 266 |

| Broghill’s victory at Knockbrack | 268 |

| Capitulation of Limerick | 271 |

| Treatment of the besieged | 273 |

| Death and character of Ireton | 277 |

| CHAPTER XXXV | |

| LAST PHASE OF THE WAR, 1652 | |

| Galway holds out | 278 |

| The Irish in Scilly | 279 |

| Meeting of officers at Kilkenny | 280 |

| Horrors of guerrilla warfare | 280 |

| Capitulation of Galway | 283 |

| “Tame Tories” | 284 |

| Clanricarde’s last struggle | 285 |

| Castlehaven leaves Ireland—his memoirs | 286 |

| [Pg xi]Clanricarde goes to England—his character | 287 |

| Submission of Irish leaders | 289 |

| Siege of Ross Castle | 290 |

| The Parliament an avenger of blood | 292 |

| The Leinster articles | 293 |

| Richard Grace | 294 |

| Ludlow’s last service in the field | 295 |

| Arrival of Fleetwood | 298 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI | |

| END OF THE WAR, AND ITS PRICE | |

| Last stand at Innisbofin | 298 |

| Last stand in Ulster | 299 |

| Exhaustion of the country | 300 |

| Treatment of priests | 301 |

| Swordsmen sent abroad | 303 |

| Fleetwood commander-in-chief | 304 |

| Sir Phelim O’Neill tried and executed | 305 |

| Alleged commission from Charles I. | 307 |

| Lord Muskerry acquitted | 308 |

| Primate O’Reilly pardoned | 310 |

| Lord Mayo tried and shot | 311 |

| The Crown bound by the Adventurers’ Act | 312 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII | |

| PEACE, SETTLEMENT, AND TRANSPLANTATION, 1652-1654 | |

| Magnitude of the problem | 315 |

| Effect of the 1641 evidence | 317 |

| The Act of Settlement | 317 |

| Lambert’s abortive appointment as Deputy | 319 |

| Expulsion of the Long Parliament | 320 |

| Barebone’s Parliament—Irish members | 321 |

| Casting lots for Ireland | 322 |

| Claims of the army | 322 |

| The Act of Satisfaction | 324 |

| Transplantation proceeds slowly | 325 |

| The Protectorate established | 326 |

| Fleetwood Deputy | 327 |

| Cromwell’s first Parliament—Irish members | 328 |

| Transplantation—Gookin and Lawrence | 329 |

| Tories, name and thing | 330 |

| The Waldensian massacre | 332 |

| Difficulties of transplantation, Loughrea and Athlone | 333 |

| Worsley and Petty—the Down survey | 334 |

| Clarendon on the settlement | 338 |

| Desolation of the towns | 339 |

| [Pg xii]Proposed transplantation of Presbyterians | 341 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII | |

| HENRY CROMWELL, 1655-1659 | |

| Henry Cromwell supersedes Fleetwood | 343 |

| Deportation to the West Indies | 344 |

| Henry and the sectaries | 346 |

| Reduction of the army | 347 |

| Oliver and his son | 348 |

| Cromwell’s second Parliament—Irish members | 349 |

| The oath of abjuration | 350 |

| Henry Lord Deputy | 352 |

| Henry made Lord Lieutenant by his brother | 354 |

| Ireland in the Parliament of 1659 | 355 |

| Petty and his detractors | 356 |

| Henry recalled by the restored Rump | 359 |

| Attempted estimate of Henry Cromwell | 360 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX | |

| THE RESTORATION | |

| Provisional government, John Jones and Ludlow | 362 |

| Monck interferes | 363 |

| End of the revolutionary government | 364 |

| The Irish army proves Royalist | 365 |

| Monck gains Coote and Broghill | 366 |

| Ludlow’s last efforts | 366 |

| Impeachment of Ludlow and others | 368 |

| New commissioners of Government appointed | 369 |

| General convention and declarations of officers | 370 |

| Charles II. proclaimed in Dublin | 371 |

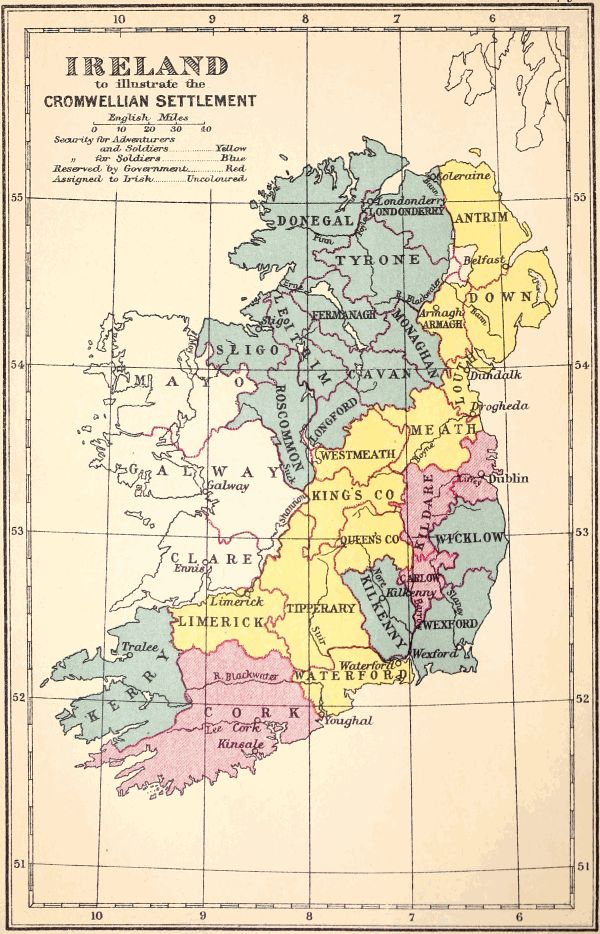

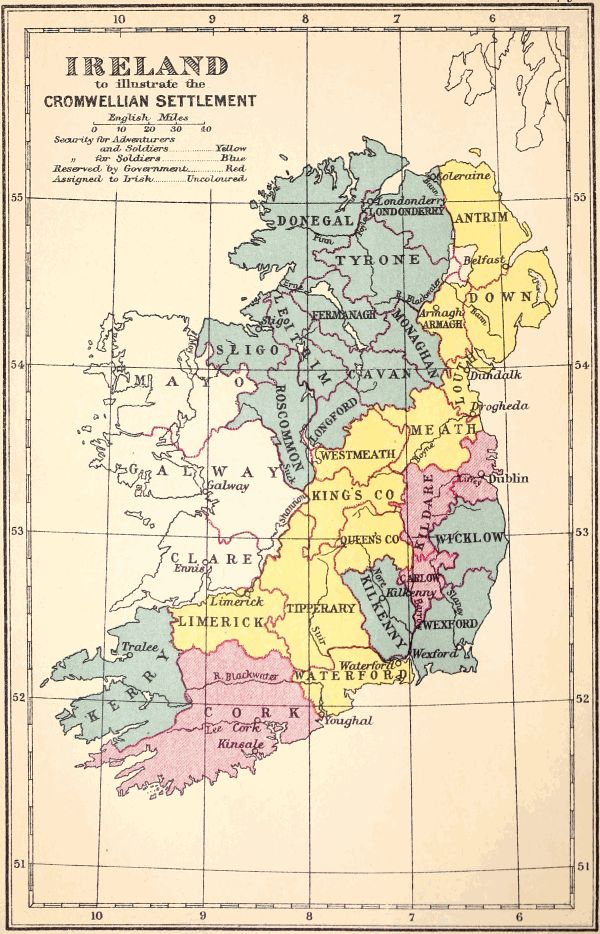

| Ireland, to illustrate the Cromwellian settlement | to face p. 1 |

IRELAND UNDER THE STUARTS

There was no outbreak in Munster during November, but Lord President St. Leger knew that he had no real means of resisting one. The Lords Justices had drawn off most of the soldiers, the rest were occupied as garrisons, and practically he had only his own troop of horse to depend on. Before the end of the month the Leinster rebels had come nearly to the Suir, and he repaired with what men he could collect to Clonmel lest Lady Ormonde, who was at Carrick, should fall into the invaders’ hands. The gentlemen of Tipperary came to meet him, but could or would do nothing. ‘Every man stands at gaze, and suffers the rascals to rob and pillage all the English about them.’ Ormonde’s own cattle were driven off. St. Leger’s brother-in-law having been pillaged, he took indiscriminate vengeance, and some innocent men were probably killed. He as good as told the Tipperary magnates that they were all rebels. In the meantime the Leinster insurgents had crossed the estuary of the Suir in boats, and ravaged the eastern part of Waterford. St. Leger rode rapidly through the intervening mountains, though there was snow on the ground, and fell upon a party of plunderers at Mothel, near Carrick. The main body were pursued to the river, and for the most part killed. About seventy prisoners were taken to Waterford and there hanged. He returned to Clonmel and thence back to Doneraile, for he could do no more. ‘My horses,’ he told Ormonde, ‘are[Pg 2] quite spent; their saddles have been scarce off these fourteen days; nor myself nor my friends have not had leisure to shift our shirts ... the like war was never heard of—no man makes head, one parish robs another, go home and share the goods, and there is an end of it, and this by a company of naked rogues.’[1]

St. Leger’s rough ways might furnish an excuse, but had no real effect upon events. The flame steadily spread over the whole island, and the contest fell more and more into the hands of extreme men. The Tipperary insurgents were soon enrolled in companies, the leading part being taken by Theobald Purcell, titular baron of Loughmoe, and Patrick Purcell, who rose to distinction during the war. At the end of January Mountgarret, who acted as general, invaded Munster with a heterogeneous force. He was assisted by Michael Wall, a professional soldier, and accompanied by Viscount Ikerrin, Lords Dunboyne and Cahir, all three Butlers, and the Baron of Loughmoe. Kilmallock was easily taken, and the Irish encamped at Redshard, near Kildorrery, at the entry to the county of Cork. Broghill reckoned them at 10,000, of whom half were unarmed. The President, who had 900 foot and 300 horse, thought it impossible to dispute the passage, and preferred to parley. Mountgarret demanded freedom of conscience, the preservation of the royal prerogative, and equal privileges for natives with the English. St. Leger answered that they had liberty of conscience already, that he was not likely to do anything against the Crown, from whom he held everything, and that he himself was a native. At last, on February 10, articles were agreed upon by which the President agreed to abstain from all further hostilities, both sides covenanting to do each other no harm for one month. St. Leger was induced to grant these terms mainly by the sight of a commission from Charles with[Pg 3] the Great Seal attached, but Broghill believed that this was a mere trick, and the document fabricated. The President withdrew to Cork and Mountgarret into Tipperary. The armistice was ill kept by the Irish, who were under the influence of Patrick Purcell. Mountgarret never showed any military ability.[2]

St. Leger had long cherished the belief that Donough MacCarthy, Viscount Muskerry, would remain staunch. Muskerry, who had great possessions, and who was married to Ormonde’s sister, seems to have tried the impossible part of neutral, but was soon drawn into the vortex, and it was to him that the supposed commission to raise 4000 men had been made out. He tried to stop plundering, and even hanged a few thieves, but the open country soon became untenable for English settlers. Many flocked to Bandon, which was held by Cork’s son Lord Kinalmeaky. Others fled to Cork, Kinsale, and Youghal, to which latter place Sir Charles Vavasour brought the first reinforcement of 1000 men. Vavasour carried over the King’s proclamation of January 1 against the rebels, of which only forty copies had been printed, and Cork immediately forwarded it to the Lord President. ‘I like it exceedingly well in all parts of it,’ said St. Leger, ‘save only that it is come so late to light ... it were very good that we had some store of them to disperse abroad, for of this one little notice can be taken.’ Cork maintained himself at Youghal and his sons in other places. St. Leger, as soon as he had received reinforcements, relieved Broghill at Lismore, and took Dungarvan from the Irish. Of all the old nobility Lord Barrymore, who had married Cork’s daughter, alone stood firm and refused all offers from the Irish. On March 12 St. Leger wrote that he was practically besieged in Cork by a ‘vast body of the enemy lying within four miles of the town, under my Lord of Muskerry, O’Sullivan Roe, MacCarthy Reagh, and all the western gentry and forces to the number of about 5000.’ The nominal chief of this army was Colonel Garret Barry, an experienced[Pg 4] soldier, but without originality, and more fit for a subordinate than for a chief command. On April 13, two days before Ormonde’s victory at Kilrush, Inchiquin—who was married to St. Leger’s daughter, and had studied war in the Spanish service—persuaded his father-in-law to let him make a sally. With only 300 foot and two troops of horse he surprised the Irish camp at Rochfordstown, routed the ill-disciplined host completely, and pursued them for some miles towards Ballincollig and Kilcrea. Muskerry’s own luggage fell into the victor’s hands, and a great stock of corn, which was very welcome. The only serious fighting was in the attack of a small enclosure desperately defended by Florence McDonnell, called Captain Sougane, perhaps in memory of the last Desmond rebel. Inchiquin’s loss was little or nothing, and he was soon able to ship guns and take castles which obstructed the navigation of Cork harbour. The southern capital was relieved from all immediate danger.[3]

Limerick did not at first take any decided part, but stood upon its defence. Clonmel and Dungarvan admitted the Leinster insurgents in December, a few days after St. Leger’s raid. A party commanded by Ormonde’s brother Richard came to the gate of Waterford on the day after Christmas, but the mayor, Francis Briver, refused to let him in. Two other attempts were made before Twelfth Day. The mob of the town and a majority of the corporation were opposed to the mayor, but he held his own for some time, received English fugitives within the walls, and kept them there till shipping could be had for themselves and such[Pg 5] property as they had been able to carry away. His own life was frequently in danger, and his hand was badly bitten by a rioter who resisted arrest. On another day, says Mrs. Briver, who took an active part, ‘when I heard so many swords were drawn at the market cross against my poor husband, I ran into the streets without either hat or mantle and laid my hands about his neck and brought him in whether he would or no ... This and much more the mayor has suffered seeking to let their goods go with the English.’ Mountgarret was excluded, but in April his son Edmund was admitted with 300 men, and the townsmen gave up their cannon.[4]

Roger Jones, created Viscount Ranelagh, was Lord President of Connaught, and lay at Athlone with only a troop of horse and two companies of foot. The government of the county of Galway was vested by special patent in the Earl of Clanricarde, who positively refused the request of the Roscommon gentlemen to take command of their county, and thus ignore the Lord President’s authority. Mayo was entrusted by the Lords Justices to Lord Mayo and to Dillon, Viscount Costello, who were both at this time professing Protestants. Sir Francis Willoughby, the governor of Galway fort, was in Dublin when the rebellion broke out, and his son Anthony, who was young and violent, commanded in his absence. Clanricarde was at Portumna when he heard of the outbreak, and he at once warned the mayor of Galway to be on his guard. The Lords Justices refused to send arms from Dublin on the ground that the passage was not safe, but told him to take what he could find at Galway. A hundred calivers, many of them unserviceable, and as many pikes were all that could be had. His own castles of Portumna, Loughrea, and Oranmore were in a defensible state, and he came to Galway on November 6. Richard Boyle, Archbishop of Tuam, took refuge in the fort, and Clanricarde’s castle of Aghenure, on the western shore of Lough Corrib, was seized by the O’Flahertys. On the 11th a town-meeting was held, and the citizens resolved to[Pg 6] hold Galway for the King. During the next three months there were frequent acts of violence on both sides, Willoughby treating the citizens as conquered, and they retorting by capturing and confining his stray soldiers. On December 29 the lords of the Pale invited the nobility and gentry of the county of Galway to join them, urging the legal grievances under which Roman Catholics laboured, and the severe measures of Coote and others. This did not make Clanricarde’s task easier, but he came to Galway on February 5, and patched up an accommodation. On the 11th he left the town for a fortnight, and during the interval an outrage was committed in the neighbourhood which rivalled the worst of the Ulster atrocities.[5]

According to the Rev. John Goldsmith, there were about 1000 English and Scotch Protestants in Mayo, many of whom tried to save themselves by going to mass. He had a brother a priest, and it was owing to the Jesuit Malone and an unnamed friar that he escaped with his life. Several Protestants, including one Buchanan of Strade, and John Maxwell, Bishop of Killala, sought the protection of Sir Henry Bingham at Castlebar, but he refused to admit Goldsmith, who was a convert from Rome, lest his presence should increase the animosity of the Irish. Lord Mayo promised to convoy the whole party safely to Galway fort, and they set out on February 13, Malachy O’Queely, Roman Catholic Archbishop of Tuam, ‘faithfully promising the Lord of Mayo to accompany them with his lordship and several priests and friars, to see them safely conveyed and delivered in Galway, or at the Fort of Galway.’ The first night was spent at Ballycarra, the second at Ballinrobe, the third at the Neale, and the fourth at Shrule, where a bridge joins the counties of Mayo and Galway. Lord Mayo seems to have declined all responsibility outside of his own county, and on Sunday the 17th he dismissed his followers except one[Pg 7] company commanded by Edmund Burke, who proposed to go with them a few miles, and hand them over to an escort of the county Galway. Burke’s men began to plunder the unarmed fugitives before they were out of Lord Mayo’s sight, and he sent his son Sir Theobald to keep order; according to Theobald’s own account he ran over the bridge with his sword drawn to help the English, but was fired at and afterwards ‘conveyed away for the safety of his life.’ The promised escort, consisting of two companies of the O’Flahertys, then came up and joined the Mayo people in an indiscriminate massacre of men, women, and children. The Bishop of Killala and a few others were saved by the exertions of Ulick Burke, of Castle Hacket, but those killed were not far short of a hundred, including Dean Forgie of Killala and five other clergymen, of whom John Corbet was one. Thomas Johnson, vicar of Turlough, escaped to the house of Walter Burke, who treated him kindly and defended him. Young priests and friars asked Stephen Lynch, prior of Strade, in his presence whether it was not lawful to kill him as a heretic, and Lynch answered that it was as lawful as to kill a sheep or a dog. The insurgents threatening to burn Burke’s house if he kept Johnson any longer, he managed to convey him to Clanricarde’s castle at Loughrea, and he ‘ever after that time lived by the noble and free charity of that good earl, until of late his lordship sent him and divers other Protestants away with a convoy.’[6]

Clanricarde returned to Galway on March 1. After a fortnight’s argument he succeeded in getting both town and fort to make declarations of loyalty and of peaceable intentions towards each other. As soon as his back was turned the flames fanned by the clergy broke out afresh. A party of armed townsmen disguised as boatmen seized an English ship, murdered some of the crew, and towed her off in spite[Pg 8] of Willoughby’s fire. When Galway surrendered to Coote in 1652 the perpetrators of the outrage were specially excepted from pardon. The malcontents then closed the gates, disarmed all the English within the walls, took an oath of union, and invited the O’Flahertys and the Mayo insurgents to join them. Willoughby burned some of the suburbs to prevent the O’Flahertys from occupying them, and this military precaution still further exasperated the citizens. But Clanricarde collected a quantity of provisions at Oranmore and relieved the fort. His castle of Tirellan, which commanded the river, enabled him to blockade the town, the neighbourhood being constantly patrolled by cavalry. Supplies ceased to reach the market, and before the end of April the leading citizens were tired of resisting. While negotiations were proceeding a man of war arrived with powder and provisions, and Clanricarde then took high ground. In vain did the warden Walter Lynch, whom Rinuccini afterwards made a bishop, fulminate the greater excommunication against all who agreed to Clanricarde’s articles. The mayor signed them nevertheless, agreeing that all soldiers harboured in the town should be sent away, that access to the town should be free and open, that the Anglican clergy should enjoy their legal rights, and that no arms or powder should be sold without Clanricarde’s orders. The gates were accordingly thrown open on May 13, the young men of the town laid down their arms, and Clanricarde received the keys publicly from the mayor’s hands. Ormonde approved of these proceedings, but the Lords Justices thought the rebellious town had been too leniently treated.[7]

Contrary to Ormonde’s own judgment, though he signed with the rest, the Lords Justices issued an order against holding any intercourse with the Irish living near garrisons and against giving protection to any of them. The soldiers were to prosecute the rebels with fire and sword, and whenever Ormonde established a garrison the order in council was to be sent to the commanders with directions for en[Pg 9]suring its observance. This order bound both Ranelagh and Clanricarde, but neither of them approved of it, and indeed it involved a censure upon the latter’s pacification at Galway. Athlone had since Christmas been beset on the Leinster side by a mixed multitude under the general direction of Sir James Dillon, who had made a truce with the Lord President so far as to allow free access to the market. The castle, which stands on the Connaught side of the Shannon, was thus provisioned and made safe against assailants who had no battering train. After a time the garrison began to make incursions into Westmeath, and this was regarded by Dillon as a breach of faith. He had been distrusted by the Irish for his moderation, but without gaining him the confidence of the Government, and he thought it would be better to have at least one side heartily with him. He accordingly seized the town on the Leinster side, and threw up a work which prevented the garrison from crossing the bridge. When he heard that Ormonde was coming to relieve the castle he withdrew into the county of Longford. Ormonde left Dublin on June 14, Mullingar and Ballymore being burnt at his approach, and on the 20th he was at the village of Kilkenny, about seven English miles from Athlone. There Ranelagh met him and took charge of the 2000 foot and two troops of horse provided to reinforce him under Sir Michael Earnley. Ormonde then returned to Dublin at once, though Clanricarde was most anxious to meet him. Ranelagh put the new troops into various castles, three hundred of them, under Captain Bertie, being assigned to a convent of Poor Clares on Lough Ree. The nuns had been hurriedly conveyed away by Dillon to an island in the lake, but the vestments remained and the cellar was full. The soldiers drank the wine, and were masquerading in the vestments when they were attacked by a party sent by Dillon. Bertie fought bravely, but he and most of his men were killed. The Lord President then concentrated his forces at Athlone and the open country was left at the mercy of the Irish.[8]

Ranelagh showed no energy, but he was in bad health and in want of money and supplies. He said Earnley’s men were rogues and gaol-birds, and that he longed for a commission to raise men of his own country. In the meantime he neglected to requisition the provisions available in the neighbourhood, and the soldiers died of want and neglect. Coote provided ten days’ bread, and pressed him to do something while a few men were left alive, whereupon he ordered an attack on Ballagh, which was not taken without loss, and which Earnley says was quite useless. Afterwards he joined his forces to those of Coote at Roscommon, and Sir James Dillon attacked Athlone in his absence with 1500 men, but was beaten off by the remnant left behind. A considerable Irish force under O’Connor Roe and others assembled after some skirmishing at Ballintober, where they were routed with a loss of six hundred men. Coote and Earnley were not allowed to follow up the victory, and Ranelagh refused to feed the latter’s men any longer. They were therefore dispersed among the garrisons which Coote commanded. Ranelagh made no further attempt to keep the field, and in October he made a truce for three months with the Irish. Clanricarde approved of this, and would have been glad to have its operation extended, for vengeance ‘need not be so sharp here, as where blood doth call for deserved punishment.’ But the Lords Justices were all for war to the knife, though they had not the means to wage it successfully, while Lord Forbes and Captain Willoughby did their best to prevent peace. The English Parliament were too busy at home to do much, while arms and ammunition from the Continent poured in through Wexford and the Ulster ports, with ‘most of the colonels, officers, and engineers that have served beyond seas for many years past ... which furnish all parts of the kingdom but those few that adhere to me for his Majesty’s service.’[9]

Strafford’s proposed settlement of Clare was never carried[Pg 11] out, but the Earls of Thomond were Protestants, and encouraged English tenants, so that a considerable colony had in fact been established. Inchiquin, who had agreed to the abortive plantation, threw his influence in the same direction; but the great mass of O’Briens, Macnamaras, and others favoured the insurgents. The outbreak in the north and the attempt on Dublin were known at the fair of Clare on November 1, but it was not till the end of the month that certain news came of the insurrection having spread to the part of Tipperary near the Shannon. Barnabas Earl of Thomond, who had an English wife, tried to keep the peace, and adopted a trimming policy, but soon lost all control over the country, though he held Bunratty and some other places. Robberies of the Protestants’ cattle soon began, and by Christmas the owners were generally on their guard in castles, of which thirty-one were in friendly hands. Three weeks later the troops raised by Thomond were siding openly with the rebels. Ballyallia Castle, on a lake near Ennis, belonged to Sir Valentine Blake, of Galway, who was a noted member of the Catholic confederacy, but was leased to a merchant named Maurice Cuffe, and became a place of refuge for at least a hundred Protestants. Others from the neighbourhood escaped to England in a Dutch vessel. About a thousand of the Irish encamped near the castle and built cabins, but without coming to close quarters. They captured Abraham Baker, an English carpenter apparently, and with his aid constructed a ‘sow,’ such as was frequently used during the war. It was a house 35 feet by 9 feet, built of beams upon four wheels, strengthened with iron and covered by a sharp ridge roof, and was moved by levers worked from inside. The whole was kept together by huge spike-nails, which cost 5l., ‘being intended for a house of correction which should have been built at Ennis.’ Captain Henry O’Grady summoned the castle, pretending to have his Majesty’s commission to banish all Protestants out of Ireland. Whereupon ‘a bullet was sent to examine his commission, which went through his thigh, but he made a shift to rumbel [sic] to the bushes and there fell down, but only lay by it sixteen weeks,[Pg 12] in which time unhappily it was cured.’ A girl who fell into the hands of the besiegers was tortured until she confessed that the shot was fired by the Rev. Andrew Chaplin. The Irish had no artillery, but devised a cannon made of half-tanned leather with a three-pound charge. The breech was blown out at the first fire, and the ball remained inside. The sow was soon taken and those within killed. A kind of loose blockade lasted from the beginning of February until near midsummer. The besieged often suffered much from want of water, but sometimes they ventured to skirmish in the open, joining with the garrison of Clare Castle and capturing cattle. Baker, who was taken in the sow, joined his captors, whereupon ‘the Irish immediately hewed in pieces his son, Thomas Baker, a proper young man, who was with them in their camp.’ After the fall of Limerick Castle one piece of artillery was brought against Ballyallia, but the gunner was at once shot, and little was done. After this the siege was much closer, famine and sickness reducing the garrison by one half. They got horseflesh at times, but were driven to eat salted hides, dried sheepskins and cats, all fried in tallow. At last they were forced to capitulate, and the terms were ill-kept, but in the end the survivors escaped to Bunratty, nearly all ill and stripped of everything.[10]

Cromwell is reported to have said that if there had been an Earl of Cork in every county the Irish could never have raised a rebellion. All his resources were expended in resisting it, and St. Leger, though he co-operated with him, could not but feel bitterly the inferiority of his own position. The Lords Justices never communicated with him, and though they allowed him to levy forces, sent no money to pay them; and indeed they had none to send. Earnest applications for cannon, ‘six drakes and two curtoes,’ were made in vain, and to take the field without guns was impossible. ‘If they have not wholly deserted me,’ he wrote[Pg 13] to Ormonde, ‘and bestowed the government on my Lord of Cork, persuade them to disburden themselves of so much artillery as they cannot themselves employ.’ He died a few weeks later, leaving the presidential authority in Inchiquin’s hands. In the meantime Cork himself had held Youghal, securing a landing-place for all succours from England. His son Broghill defended Lismore, and Kinalmeaky was governor of Bandon, which his father had walled and supplied with artillery. Clonakilty was an open place, and the Protestant settlers there and in the country round about escaped to Bandon, where the townsmen made them pay well for their quarters. ‘They were compelled,’ said Cork, ‘to give more rent for their chamber or corner than my tenants paid me for the whole house.’ After Kinalmeaky’s death at Liscarrol Sir Charles Vavasour became governor, and the town was never taken; the Bandonians making frequent sallies, like the Enniskilleners in a later age. Lord Cork, who had enjoyed a rental of 50l. a day, lost it all for the time, and was often in difficulties, but he saved the English interest in Munster from total destruction.[11]

[1] Carte’s Ormonde, with the letters in vol. iii. of November 8, 13, 16, 18 and 22, and December 11. Lismore Papers, 2nd series, vol. iv. St. Leger’s letters of November 7, 10, and 28, and December 2 and 17. Bellings says ‘some innocent labourers and husbandmen suffered by martial law for the transgression of others,’ and Carte gives instances. St. Leger’s letters from November 1 to December 11 in Egmont Papers, i. 142-154.

[2] The best account of this episode is Broghill’s letter printed in vol. ii. of Smith’s Hist. of Cork; Bellings.

[3] Bellings, i. 76; St. Leger’s letters of February 26, March 26, and April 18, 1641-2, in Lismore Papers, 2nd Series. Divers Remarkable Occurrences by Thomas Baron, Esq., who lived fifteen years six miles from Bandon and arrived in London July 2. This last contains a curious dirge on Captain Sougane, beginning, ‘O’Finnen McDonnell McFinnen a Cree’ which has these lines:—

[4] Lords Justices and Council to Leicester, Confederation and War, ii. 28; Letters from Mr. and Mrs. Briver, ib. 7-22.

[5] A good account in Hardiman’s Hist. of Galway. Clanricarde’s letters, November 14 to January 23, 1641-2, in Carte’s Ormonde, vol. iii., and the lords of the Pale to the Galway gentry, December 29, ib. Clanricarde’s correspondence with the Roscommon gentry is in Contemporary Hist. i. 380.

[6] Deposition of Goldsmith in 1643 in Hickson, i. 375. Other witnesses in 1653, ib. i. 387-399 and ii. 1-7. Henry Bringhurst’s evidence, as being rather favourable to Lord Mayo, has been chiefly followed for the massacre. See also Hardiman’s Hist. of Galway, p. 110, and the letters in Clanricarde’s Memoirs, 1757, pp. 77, 80. The Galway men tried to throw the blame on their Mayo neighbours, for fear of Clanricarde.

[7] Clanricarde to Essex, May 22, 1642; Ormonde to Clanricarde, June 13, in Carte’s Ormonde. Hardiman’s Hist. of Galway, p. 111.

[8] Order in Council, May 28, 1642, in Confederation and War, ii. 45. Earnley’s account, ib. 134; Bellings, i. 85. Carte’s Ormonde, i. 345.

[9] Sir Michael Earnley’s Relation (soon after July 20, 1642) in Confederation and War, ii. 134. Clanricarde’s letters of July 14 and 20, and October 26, in his Memoirs, pp. 190, 197, 281.

[10] Narrative of Maurice Cuffe, printed by T. Crofton Croker, Camden Society, 1841. Joseph Cuffe to H. Jones, November 12, 1658, MS. in Trinity College, 844, No. 37. Burnet says (i. 29) guns partly made of leather were used with effect by the Scots at Newburn.

[11] St. Leger to Ormonde, May 12, 1642, in Carte’s Ormonde, iii. Appx. No. 78. Inchiquin to Cork, November 24, 1642, with the answer, in Bennett’s History of Bandon, chap. vii.

When Charles received the news of the Irish insurrection, he at once called upon the Scottish Parliament to aid him in suppressing it. They replied that Ireland was dependent on England, that interference on their part would be misunderstood, and that they could only act as auxiliaries to the English people by agreement with them. Early in November the Parliament at Westminster resolved to send 12,000 men from England, and to ask the Scots to send 10,000 more. But Episcopalian jealousy was aroused, and the demand on Scotland was reduced to 1,000. Nothing was done for the moment, but on January 22, by which time some of the English troops had reached Ireland, both Houses agreed to ask for 2,500, and to this the Scots Commissioners in London assented. The King hesitated about giving up Carrickfergus to the Scotch regiments, but the Commissioners hoped that his Majesty, ‘being their native king, would not show less trust in them than their neighbour nation,’ and this appeal was successful. Money and military stores were stipulated for, and it was agreed that if any other troops in Ulster should join the Scots, their general was to command them as well as his own men, and he had also power to enlarge his quarters to make such expeditions as he might think fit. The Scottish estates had before offered 10,000 men, but nothing like that number ever went. A little later the command was given to Leven, who stayed but a short time and did nothing. The expeditionary force remained in the hands of Major-General Robert Monro, who had been employed to keep order at Aberdeen, and did so with no light hand. He set up, says Spalding, ‘ane timber mare, where[Pg 15]upon runagate knaves and runaway soldiers should ride. Uncouth to see sic discipline in Aberdeen, and more painful to the trespasser to suffer.’ Monro will live for ever in the form of Dugald Dalgetty, for whose portrait he was the chief model. Sir James Turner, who contributed some touches to the picture, says his great fault was a tendency to despise his enemy. Monro’s training was that of the Thirty Years’ War, and Turner, who belonged to the same school, thought he carried its lessons too far.[12]

Monro landed at Carrickfergus on April 15 with about 2500 men, Lord Conway and Colonel Chichester retiring with their regiments to Belfast. On the 28th he marched towards Newry, leaving a garrison behind him, and was joined by Conway and the rest, making up his army to near 4000 men. The Irish under Lord Iveagh were posted in a fort at Ennislaughlin near Moira, but were easily dislodged next day, and fled into the Kilwarlin woods. No quarter was given, to which Turner strongly objects. On the third day they marched through Dromore, where only the church was left standing, to Loughbrickland, where there was a garrison in an island. Monro bribed six Highlanders to swim across, and one of these succeeded in bringing away the only boat. The island was then occupied and all the Irish there killed. No attempt was made to defend the town of Newry, but the castle gave some trouble, and Monro was unwilling to assault or burn it, lest the prisoners confined there should suffer. The garrison were allowed to march out without arms on May 3, but over sixty townsmen, including a Cistercian monk and a secular priest, were hanged next day in cold blood. Turner criticises Monro’s conduct, and claims to have saved nearly 150 women whom the soldiers proposed to kill. At least a dozen women were shot or drowned, notwithstanding his interference. The natural result of Monro’s system was to make the Irish desperate, and O’Neill burned Armagh, ‘the cathedral with its steeple and with its bells, organ, and glass windows, and[Pg 16] the whole city, with the fine library, with all the learned books of the English on divinity, logic, and philosophy.’ Many lives were also taken by the Irish in revenge for Monro’s severities. After leaving a garrison at Newry the army marched through the Mourne mountains, and from one end of Down to the other. Turner mentions a frightful storm attributed by the superstitious to Irish witches, which if true he considered a good proof that their master was really prince of the air. Some of the soldiers died from sheer cold. On the twelfth day Monro returned to Carrickfergus. A detachment which he had left in the outskirts of Belfast had been attacked during his absence and driven off. A large number of cattle had been taken from the Magennises and Macartans, but the English soldiers everywhere complained that the Scots got most of the plunder.[13]

Sir Frederic Hamilton was at Londonderry on October 24. On hearing of the outbreak he rode hard with a dozen mounted servants, who made a great show by blowing trumpets and carrying two lighted matches each. The little party reached Donegal unmolested, succoured the English settlers there, and at Ballyshannon killed some rogues on the road, and reached Manor Hamilton in safety. Connor O’Rourke, sheriff of Leitrim, visited Hamilton on the 31st, but his professions of loyalty did not last long. The arrival of a few stray Scots soldiers, some from Carlisle direct, increased the garrison to fifty men. By December 4 twenty-four prisoners were taken, and to avenge the deaths of Englishmen at Sligo, eight of them were hanged upon a conspicuous gallows. Fifty-six persons, including one woman, died thus by martial law between December 3, 1641, and February 18, 1642-3. Hamilton complained bitterly that he was not supported by Sir William Cole, and their quarrels became the subject of an inquiry by the English Parliament. Cole held Enniskillen throughout, and without much difficulty,[Pg 17] while Captain Ffolliott maintained the important post at Ballyshannon. Meanwhile the brothers Sir William and Sir Robert Stewart, who were both professional soldiers, were active from Rathmelton in Donegal to Newtown Stewart in Tyrone. Their levies grew into an army which came to be known as the Laggan forces from a name locally given to the district. Londonderry and Coleraine also held out, and were never taken during the war.[14]

Ormonde returned to Dublin in the middle of March, and on April 2 set out again with 3000 foot, 500 horse, and five guns to waste the county of Kildare. Captain Yarner, with two troops, burned ten or twelve villages under the Wicklow mountains, and killed about the same number of armed men. A trumpeter was killed by a shot from Tipper Castle, near Naas, whereupon Coote blew up the house and put all to the sword. Ormonde garrisoned Naas, established a Protestant corporation there, and advanced to Maryborough, whence he sent most of his cavalry by forced marches to relieve Burris in Ossory and Birr, and to return by Portnahinch. The old men, women, and children of about sixty families were brought away safely and settled at Naas. Monck, who now appears for the first time in Ireland, was sent to secure their return passage over the Barrow. Other detachments were sent to relieve Ballinakill, Clogrennan and Carlow, and on the twelfth day Ormonde was back at Athy without any loss except of a few over-ridden horses. Great numbers of cattle were taken, and Coote gave 300 milch cows to the fugitives at Naas on condition of selling milk to the troops at a halfpenny a quart and making butter and cheese, and bread,[Pg 18] he supplying corn at ten shillings the Winchester barrel. Ormonde found that the enemy had concentrated in the meantime at the ford of Mageney on the Barrow with a view to intercept him on his return. Mountgarret and Roger O’More were both present, as well as Hugh MacPhelim O’Byrne, who was retreating from Drogheda to the Wicklow mountains, and they had more than 6000 men, but badly armed and with very little powder. Ormonde left Athy early in the morning of April 15, his force being considerably reduced by the garrisons left behind. The Irish were soon visible to the eastward trying to reach the pass at Ballyshannon before him. As they had no baggage they would probably have got there first, but Ormonde was superior in horse, and he sent on all that he had under Sir Thomas Lucas. The Irish finding themselves forestalled, had to fight in a less advantageous position at Kilrush. They had no real head, and the Munster and Leinster men disputed about the division of the spoil before the battle was won. The English cavalry had it all their own way, Coote charging like a man of thirty. He lost his cap, ‘but bare-headed scoured about the field, crying “Kill! kill!” and with his hand gave the example, while my Lord of Ormonde secured the cannon and victory with some divisions of foot, and beat their van into a speedy retreat.’ There was very little fighting, the Irish soon taking refuge in a bog near at hand. The number of killed on their side is uncertain, but it included some persons of rank, and the army simply ceased to exist. O’More and his brother fled to their home at Ballina near the Boyne, Mountgarret and others to Tullow, and the O’Byrnes to their Wicklow mountains. Ormonde lost some twenty men. That night he slept at Castlehaven’s house at Maddenstown, where Antrim and the Duchess of Buckingham were staying, and Coote ‘to pleasure the lady,’ fired a salute of artillery and musketry. According to an Irish writer Sir Charles boasted of the day’s victory. The men were silent, but the Duchess upbraided him as being less loyal than the Irish, and as ‘a poor mechanical fellow, raised by blind fortune, as informer and promoter against all that is just and godly, being chief instrument of the[Pg 19] shedding of many innocent blood [sic], and of the commencement of the new distempers.’ Coote, who was of a good old family, had served three sovereigns faithfully both in peace and war, and fell three weeks later fighting bravely against enormous odds.[15]

On June 22 that part of the House of Commons in Dublin which accepted the oath of supremacy expelled forty-one ‘rotten and unprofitable members’ who were either in open rebellion or indicted of high treason. Of these Richard Bellings, who sat for Callan, was the most important. Among the others were Rory Maguire the northern leader, Sir Valentine Blake of Galway, who was Clanricarde’s friend, and Sir James Dillon. In the meantime what claimed to be a new legislature was being gradually formed. On May 10, 11, 13, and 14 a congregation of the Roman Catholic hierarchy sat at Kilkenny. There were present three archbishops, six bishops and the procurators of four more, with several abbots and other dignitaries; and the plan of the proposed confederation was sketched out. The prelates declared that the war had been justly undertaken for religion and for the King, against sectaries and especially against Puritans. Any province, county, or city making separate terms with the enemy was to be held excommunicate. A number of lords and gentlemen joined the prelates, and out of their joint deliberations grew the Supreme Council in its first shape—two members out of each province with Mountgarret as president. An oath of association was framed binding the confederates to obey the council and to do nothing without their consent. The main object was the establishment of the Roman Catholic religion ‘in as full and ample a manner as the Roman Catholic secular clergy had or enjoyed the same within this realm at any time during the reign of Henry VII.’ Significantly, the regular clergy are not mentioned at all. The secular clergy were to enjoy all temporalities ‘in as[Pg 20] large and ample a manner as the late Protestant clergy respectively enjoyed the same on October 1, 1641.’ All laws to the contrary made since 20 Henry VIII. were void. Before a more regular assembly could meet Preston had landed in the south and O’Neill in the north, and their arrival gave events a new turn.[16]

Owen Roe O’Neill was son of Art MacBaron, the great Tyrone’s brother, whence he was often called Owen MacArt. In the Spanish service he was known as Don Eugenio O’Neill. He was a captain in Flanders in Henry O’Neill’s Irish regiment as early as 1607, and colonel of the regiment about 1633. With the rank of maître de camp he commanded the garrison of Arras during the siege in 1640, and marched out with the honours of war on August 9. For some time before the outbreak he had been in frequent communication with the Irish leaders, but perhaps without any well-formed intention of going over himself. When he heard that the plot to seize Dublin had been discovered ‘he was in a great rage against O’Connolly, and said he wondered how or where that villain should live, for if he were in Ireland, sure they would pull him in pieces there; and if he lived in England there were footmen and other Irishmen enough to kill him.’ It was less than eight years since another Irish colonel, Walter Butler, had murdered Wallenstein. O’Neill then asked his general Francis de Mello to let him go to Ireland, and the Spaniard answered that he should go and be well supplied for the enterprise if he could find a safe landing-place in his own country. It was, however, given out that he was in disgrace with the Spanish authorities, and years afterwards, when Hyde was at Madrid, Don Luis de Haro kept up the mystification and spoke of him as a deserter from his sovereign’s service. Where Spain was concerned there were always long delays, and the summer of 1642 was well advanced before O’Neill announced to Luke Wadding that he was about to start. Everything, he said, was going on well[Pg 21] in Ireland, but there was sad want of powder. If the Pope knew, he said, how fatal that powder would be to heresy and heretics he would make haste to procure a plentiful supply. O’Neill sailed from Dunkirk round Scotland, and landed in Lough Swilly about the last day of July. He captured two prizes at sea and detached a small vessel to Wexford with arms, which arrived safely. O’Neill brought to Ulster ‘ammunition, arms and a few low-country officers and soldiers of his own regiment,’ and he sent his ships back to Flanders for more. Sir Phelim sent 1500 men to join his kinsman, who went round by Ballyshannon to Charlemont, where he arrived without having met an enemy.[17]

Thomas Preston, a son of the fourth Viscount Gormanston, was fifty-six years old when the Irish rebellion broke out. He was a captain in the same regiment as Owen Roe O’Neill in 1607, but was never on good terms with him. They were rivals in recruiting during the reign of Strafford, who favoured the man of English descent as far as he could. In 1635 Preston distinguished himself in the defence of Louvain against the combined forces of France and Holland, and in 1641 in the defence of Genappe against Frederick Henry of Orange. In 1642 his nephew, Lord Gormanston, urged him to return to Ireland. In March of that year Mountgarret sent Geoffrey Barron, Wadding’s nephew, to Paris, and in July he met Preston there. Richelieu, who had not forgotten Rochelle, did not declare himself openly, but he discharged all the Irish soldiers in the French service, allowed war material to be purchased in France, and let it be understood that help would be forthcoming to the extent of a million of crowns. Preston sailed from Dunkirk, accompanied by several officers, and arrived in Wexford harbour at the beginning of August. Here he was joined by at least a dozen vessels laden with war material from St. Malo, Nantes, and Rochelle. He reconnoitred Duncannon fort, which he[Pg 22] thought could be taken in fifteen days, and then went to Kilkenny, where the confederates were still assembled. Public opinion quickly designated him as the fittest person to have military command in Leinster, and Mountgarret, who was no soldier, was very willing to yield the place to him.[18]

The army which Inchiquin had driven from before Cork came together again at Limerick, and St. Leger had no force to molest it there. After standing neutral for a time the city had joined the confederates, but the castle was held by Captain George Courtenay with sixty men and very little powder. Supplies were ordered by Parliament, but did not reach the garrison. The Irish stretched a boom across the river, which prevented any relief by water, and ran mines under the works, while the garrison were harassed by a continual fire from the walls of the cathedral. Courtenay capitulated on June 21, and Barry and Muskerry went south again with three pieces of cannon taken in the castle. Among these was a thirty-two pounder weighing about three tons, which was laid in the scooped-out trunk of a tree and dragged up hills and through bogs by twenty-five yoke of oxen. The whole county of Limerick was soon in Irish hands. St. Leger died on July 2, and the sole command then devolved on Inchiquin. His position as vice-president was confirmed by the Lords Justices, who associated Lord Barrymore with him for the civil government, but the latter died at Michaelmas. Patrick Purcell, acting as major-general under Barry, took up a strong position at Newtown near Charleville, but was beaten out of it by Inchiquin with very inferior numbers. This check caused a long delay, but at last Barry advanced with six thousand foot and five hundred horse and sat down on August 20 before the strong castle of Liscarrol. Here he was joined by Lord Dungarvan, who had just taken Ardmore Castle and hanged 117 men, leaving the women and children at liberty. A garrison of thirty men could do little against the fire of heavy guns, and Liscarrol surrendered on September 2. On the 3rd, Cromwell’s lucky day, Inchiquin[Pg 23] advanced, as he supposed, to their relief. His force of 3000 foot and 400 horse was about half of Barry’s, but much better armed and disciplined. The Irish, having a good position under the walls of the castle, were at first successful against the charge of a small division of horse consisting of Cork and Bandon men, without even helmets; but Lord Cork’s son Kinalmeaky, ‘who was clothed with armour of proof’ was shot dead. Though one else fell, his followers were driven back in confusion and the battle seemed lost, but the foot stood firm, and Inchiquin, coming up with some more regular cavalry, succeeded in rallying the fugitives. He killed Oliver Stephenson, the Irish cavalry leader, with his own hand, and had himself more than one narrow escape, being wounded in the head and hand. The Irish were routed and ‘recovered Sir William Pore’s bog near Kilbolaine,’ where they were out of reach. Inchiquin only lost some twelve men killed, and Barry is said to have lost seven hundred, but the victory was not of much use, for there were neither money nor provisions to follow it up. Liscarroll Castle was reoccupied, and three pieces of cannon brought from Limerick were taken. Inchiquin then fell back to Mallow, and dispersed his men in garrisons, while the Irish went to their several homes.[19]

There was perpetual fighting in Ulster during the summer of 1642. Monro marched on June 17, with about 2000 men, from Carrickfergus to Lisburn, where he was joined by Lord Montgomery and others with some 1100 foot and four troops of horse. Lord Conway brought his regiment and five troops of horse. Next morning the Scots general, with his[Pg 24] own foot and nearly all the horse, marched through the plain to Dromore, while Montgomery cleared the woods of Killultagh, most of the Irish flying across the Bann with their cattle and ‘burning the country all along.’ The fighting was not severe, and the two divisions coalesced somewhere near Banbridge. Monro, being short of provisions, decided not to follow the enemy into Tyrone, and went off with some troops of cavalry towards the Mourne mountains, leaving the other leaders to do the best they could. Three hundred cows were captured, and the bulk of the army came to Kinard. A priest was also taken, ‘Chanter of Armagh and a prime councillor to Sir Phelim O’Neill, who was since hanged, but would not confess or discover anything.’ The chief had gone to Charlemont, and his men ran away who ‘for haste did not kill any prisoners,’ so his house was burned, which was ‘built of free stone and strong enough to have kept out all the force we could make.’ Two hundred miserable captives were released, in rags and with faces like ghosts. The plunder was considerable, including Sir Phelim’s plate, which was on carts ready to carry off. News was heard of Lady Caulfield, who was ‘kept at a stone house near Braintree woods,’ and here Captain Rawdon found her with her children, just in time to prevent the rebels from taking her off into the forest. Rawdon was not so successful in the case of Lady Blaney, who had been carried away into the wilds of Monaghan the night before he came on the scene. As he rode through Kinard the second time there was ‘nothing left quick but angry dogs and embers.’ Charlemont had been strengthened with some skill, and there was no possibility of taking it without guns, though Sir Phelim was nearly captured trying to go there, and had to fly into Tyrone. Dungannon was afterwards taken and garrisoned, with the usual hangings, Sir William Brownlow and other prisoners there having overcome the rebel guard ‘with the help of some Irish that had formerly had relation to them.’ Two brass guns were taken, but they were not heavy enough to make the difference at Charlemont, and on the eighth and ninth days the army returned from Armagh through Loughbrick[Pg 25]land to Lisburn. A great many cattle had been taken, and all not eaten or stolen were divided among the men, one to every four foot soldiers and to every two troopers.[20]

On June 25 Clotworthy left Antrim with 600 men in twelve boats built for the service on Lough Neagh. On the flat Tyrone shore little resistance was made, and Mountjoy was taken with no loss. Here he entrenched himself strongly, and ‘notwithstanding the next was the Lord’s day’ spent it in building huts for his men. Before leaving it to be maintained by a garrison of 250 men he scoured the woods as well as he could, and lost very few men, though the pressure of hunger was severe, for he could not catch cows without cavalry, and there were 500 rescued British prisoners of both sexes and every age to feed along with the soldiers. The want of horse was partly supplied by making 200 men strip to their shirts for lightness, and they did not object, thinking it mean to wear armour against men that had none. Generally speaking the Irish would not stand against them, but they seemed to have ammunition enough, which was said to come from Limerick. One hundred cows were taken near Moneymore, after which the soldiers fared better, but there was much sickness from want of proper food, and from having to sleep on the ground.[21]

The provisional supreme council, which had been formed at Kilkenny in the early summer, did what they could to give their organisation something of a legal shape. ‘Letters,’ says Bellings, ‘in nature of writs were sent from this council to all the Lords spiritual and temporal, and all the counties, cities, and corporate towns that had right to send knights and burgesses to Parliament.’ The general assembly so constituted met on October 24, a year and a day after the first[Pg 26] outbreak in Ulster, at the house of Robert Shee, heir to Sir Richard Shee. The Lords spiritual and temporal and Commons sat in one room, Mr. Pat Darcy bareheaded upon a stool representing all or some that sat in Parliament upon the woolsack. Mr. Nicholas Plunket represented the Speaker of the Commons, and both Lords and Commons addressed their speech to him. The Lords had an upper room for a recess for private consultation, and upon resolutions taken the same were delivered to the Commons by Mr. Darcy. The name of Parliament was eschewed, and Plunket was called prolocutor or president, and not speaker. Burgesses were to be paid five shillings a day, and knights of the shire ten shillings during the session, and for ten days before and after. The first act of the assembly was to establish the Roman Catholic Church as it had been in the time of Henry VII., and the statute law was to be observed so far as it was ‘not against the Catholic Roman religion.’ Allegiance to King Charles came second. For the protection of the King’s subjects against murders, rapes and robberies ‘contrived and daily executed by the malignant party, and for the exaltation of the Holy Roman Catholic Church and the advancement of his Majesty’s service,’ a Supreme Council was appointed, with both executive and judicial authority; control over all officers, even generals, in the field; and power to hear and determine all matters capital, criminal or civil, ‘except the right or title of land.’ Owen Roe O’Neill was appointed general for Ulster, Preston for Leinster, and Colonel Gerald Barry for Munster. For Connaught, Colonel John Bourke was named lieutenant-general only, in the hope that Clanricarde would be induced to join. There were some bickerings between Owen Roe and Sir Phelim, who had just married Preston’s daughter, and who wished to be in command of his own province, and between Rory O’More and other Leinster gentlemen, but they were smoothed over for the time. All the generals had seen service on the Continent.[22]

The Supreme Council consisted of twenty-four persons, four taken from each province. Of these only four, an O’Neill and a Magennis from Ulster, an O’Brien from Munster and Lord Mayo, were not sworn in at the time. Lord Mountgarret was appointed president, Bellings secretary, and Richard Shee clerk. Of the whole twenty-four four were peers and five bishops. Provincial and county councils were also constituted, but they had no real existence, or a very shadowy one. That for Leinster was appointed, but was overshadowed by the Supreme Council, and events soon showed that military force and not new-fangled civil departments was the determining quantity during the revolutionary period.

The assembly decreed that lands taken from their owners since October 1, 1641, should be restored on pain of the new possessor being treated as an enemy; provided that if the old owner ‘be declared a neuter or enemy by the supreme or provincial,’ then the land should be surrendered not to him, but to the council, ‘to be disposed of towards the maintenance of the general cause.’ The war was a religious one, and thus the lands of all who were not prepared to espouse the Roman Catholic cause were to be forfeited, or at the least sequestered. English, Welsh and Scotch Roman Catholics were to be treated as well as natives of Ireland. All Church temporalities were at one stroke transferred from Protestants to Roman Catholics. It must have been from the first evident to all cool observers that no accommodation on these terms could ever be made with any settled English Government. After sitting for about a month the assembly adjourned till May 20 next. They had ordered 4000l. worth coin to be struck, and 5820 men to be raised as the Leinster contingent. The Kilkenny government never had any real authority, except in the south-east of Ireland.[23]

The Supreme Council assumed sovereign power, the King figuring largely in negotiations with Ormonde, but seldom appearing in documents intended for home consumption. Flags were devised with various religious emblems and mottoes; but in each case there was an Irish cross on a green[Pg 28] field, ‘Vivat Rex Carolus’ below, and C R with a crown imperial above. Francis Oliver, a Fleming, was appointed vice-admiral, and letters of marque to prey upon ‘enemies of the general Catholic cause’ were freely granted. Half-crowns and shillings and copper money were struck with Charles I. on one side and St. Patrick on the other, but this was not done without much opposition, for the coinage was unnecessary, and was an evident encroachment upon the Crown. Agents were accredited to the Emperor, the King of France, the Pope, the Duke of Bavaria, the Viceroy in Belgium, and the Governor of Biscay. The Franciscan Luke Wadding, a native of Waterford, was agent at Rome, and as this was emphatically the Pope’s war, the instructions to him are of special interest. The first thing asked for was a supply of indulgences for the confederates and of excommunications for all opponents and neutrals. The Pope was requested to send letters in their favour to the Queen of England, to the Catholic princes of Germany, Spain, France, Portugal, Poland, and Bavaria, to Genoa, and to the Catholics of Holland. Wadding was directed to impress upon his Holiness that the Catholic cause in Protestant countries would be much advanced by the success of the confederates. Free trade with France, Spain, and Holland was solicited through the Pope’s mediation. In general he was to be asked to give the council power over ecclesiastical patronage, and not to admit appeals during the war. In particular Thomas Dease, Bishop of Meath, had been suspended by the provincial synod of Armagh for refusing to approve of the war, and his appeal was to be rejected without trial. The Supreme Council thus engrossed to themselves all the chief prerogatives of the Crown which they professed to defend.[24]

Preston’s first service in the field did not augur well for his success as a general. Ormonde was anxious to relieve the garrison of Ballinakill on the borders of Queen’s County and Kilkenny, and in December he sent Monck with a convoy and enough men to guard it. This service was duly performed, but Preston and Castlehaven, with a thousand foot and three troops of horse, attempted to cut him off on his return to Dublin. Monck passed by Timahoe, where there was a confederate garrison, who lined the hedges by the roadside; but hearing that he was pursued, he avoided the snare by drawing aside to some level ground backed by a hill, where he placed his foot to serve as support in case the horse were worsted. The contrary happened, and after the first charge the whole of Preston’s force was driven under the shelter of Timahoe. The numbers engaged on each side were about equal, but a crowd of spectators on a distant hill were mistaken for reinforcements, and Monck prudently continued his journey to Dublin. Castlehaven thought most of the Irish foot would have been destroyed had the enemy pursued their advantage.[25]

‘The check at Timahoe,’ says Castlehaven, ‘made us pretty quiet till towards the spring following,’ when the Lords Justices resolved upon an expedition into Wexford. The sympathies of Parsons, who was the ruling spirit, were certainly with the Parliament, but the event was uncertain, and even after Edgehill it was hard to say whether the King would succeed or not. Since the end of October there had been a committee from the Parliament in Dublin consisting of Robert Reynolds and Robert Goodwin, members of the House of Commons, and of Captain William Tucker, agent for the English adventurers in Irish land. Part of their business was to induce soldiers to take debentures in lieu of pay. By the advice of the Chancellor Bolton these three were admitted to sit at the Council board. Tucker kept a journal of the proceedings, and it is clear that he was not much impressed by the wisdom of the Irish Government. The sittings were generally occupied in mere talk, and very little[Pg 30] was done in the field. Thus, when Sir Francis Willoughby took Maynooth Castle Tucker reports that the rebels ran away after one day’s siege, that four or five men were killed on each side, and ‘no service done at all, but only expectation and the gain of one ass.’ In the middle of January Lord Lisle, the Lord Lieutenant’s son, proposed to relieve the empty treasury by leading out fifteen hundred men to live upon the enemy’s country. Lisle was general of the horse, and Sir Richard Grenville major of Leicester’s own regiment, and it was intended that these two officers should command in the field. Grenville, according to Clarendon, was noted for his cruelty, but he had served with credit at Kilrush, and he was major of Leicester’s regiment of horse. In January came a commission from the King giving power to Ormonde, Clanricarde, and others to treat with the Irish, and the Lords Justices supposed that the field would thus be left clear for Lisle.[26]

When the King’s letter was read at the Council board Ormonde, according to his chaplain’s account, said he had no wish to be a commissioner to hear Irish grievances, ‘for I know that nothing grieves them more than that they could not cut all our throats,’ but that as general he would command in the field. His right could not be denied, and he had lately endeared himself to both officers and soldiers by his exertions to obtain their pay and other advantages for them. But the Lords Justices and the parliamentary commissioners, who had advanced money for Lord Lisle, were not at all pleased. Tucker, indeed, held that the money could not be decently denied to Ormonde, but his career and that of his colleagues in Ireland was cut short before the campaign actually began. In the middle of February came a letter from the King directing that the committee should no longer be admitted to the Council-chamber, and fearing arrest they returned to England before the end of the month. On[Pg 31] March 1 Ormonde set out with 2500 foot and 800 horse, and with two siege-guns and four field-pieces.[27]