The Project Gutenberg eBook, Il nipotismo di Roma, or, The History of the

Popes Nephews, by Gregorio Leti, Translated by William Aglionby

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Il nipotismo di Roma, or, The History of the Popes Nephews

from the time of Sixtus IV. to the death of the last Pope, Alexander VII

Author: Gregorio Leti

Release Date: January 17, 2017 [eBook #54001]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII)

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IL NIPOTISMO DI ROMA, OR, THE

HISTORY OF THE POPES NEPHEWS***

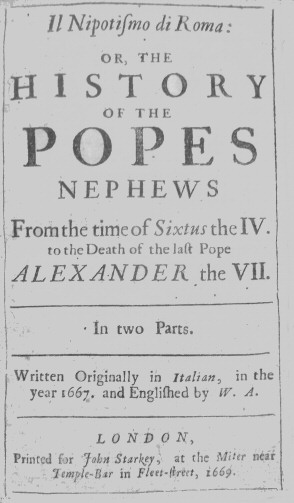

Transcribed from the 1669 John Starkey edition by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

Note: This book is from 1669 and hence the spelling, grammar and punctuation are not those of modern English: instead they are as they appear in the book.—DP.

OR,

THE

HISTORY

OF THE

POPES

NEPHEWS

From the time of Sixtus the

IV.

to the Death of the last Pope

ALEXANDER the VII.

In two Parts.

Written Originally in

Italian, in the

year 1667. and Englished by W. A.

LONDON,

Printed for John Starkey, at the Miter near

Temple-Bar in Fleet-street, 1669.

Kind Reader,

I should have much to say to thee, and not a few Ceremonies to Complement thee withall, if two Considerations did not make me resolve to hold my peace, and abstain from that courtship, which would become a Preface. The first is, because I will not (as the Proverb sayes) reckon without mine Hoste, and fill thy ears with excuses, before I know whether thy intention be to hear them or no. Secondly, because I think it will not be amiss to forbear Ceremonies in the presence of so many, whose business it hath been to be most accomplish’d in performing of them. What danger would there be for once, to let a Reader judge of a Book, without all those troublesome informations from the Author: For in a word, either the Reader hath parts and learning, and then his own judgment needs no instruction from the Authors; or he hath none, and is illiterate, and then the Author loses his time in p. viexcusing himself to one, whose abilities cannot reach his subject: But this our age being so far different from ancient times, wherein little notice was taken of the Author, though much of the thing written, it will be as just for him to inform his Reader, as for a Suppliant to inform his Judge, though never so learned, and to be recommended to him, though his case be never so just. A Friend of mine, calls the Advice to the Reader, the Sauce of the Book, because it is that part, which gives us a stomach to read the rest. I must confess, it is for his satisfaction that I give you mine; I know not how excellent it may prove to thy Palate: but my intention, is not, at least, to put too much Salt in it; and indeed, with what can I season it, or what Ingredients have I left to compound it withall? If I praise my own work, I shall incur the censure of an interested Judge; if I dispraise it, I shall do my self an injury. To tell thee that this Book comes from Rome is in vain, because the very Title of it discovers the place of its birth; and to entreat thee to read it, would be just the way to stifle thy curiosity; for now adayes, every body desires the reading of those Books which are prohibited; and I am certain, that it were a good way, to incite the publick curiosity of the world p. viifor any Books, to intreat them that they would be pleased to let them alone, for that, without doubt, would encrease their desire of seeing it. I think I had best do as those Hunters, who for fear of raising the Partridge too soon, talk to one another so softly, and so low, that they scarce hear themselves speak. Therefore, Reader, take notice, this is that famous Nipotismo di Roma, so much desired and wished for by all the ingenious of Europe, before it was brought forth by the Author. I give thee warning to read it in private, and keep it to thy self; for if the news of thy reading it come to the Inquisitors ears, without doubt thou runnest the hazard of an Excommunication; for they have sworn, to indure no Books in Italy, but those that shall flatter the Court of Rome. It is indeed a good policy for them, and for those Church men, who having pretensions to the highest Ecclesiastical Honours, stand all day before the Nipotismo with their Caps in their hands. I know, that in Rome this History will produce the same effect that our Nails do upon a Sore, that is, the more they scratch it, the worse they make it: Yet the itching pleases every body, and the more we scratch, the more we have a mind to scratch still. Neither do I doubt, but that there will be some p. viiiflatterers and false friends of the Nephews of the Popes, who will express their dislike of this Treatise; but it will be only in appearance, and not from their hearts, which may be forgiven them, for seldome in Rome do the Tongue and the Heart correspond.

In the dayes of Innocent the eighth, some body made a Book, intituled, The Abuses of the Churchmen, very satyrical, for in it were all the Ecclesiasticks Vices, but none of their Vertues, which indeed was somewhat severe: This Book was put into the Popes hands (who by judging things without passion, shewed himself to deserve his elevation to so great a dignity) for having read it in the presence of some Prelates of the holy Office, he turned to them, and said, This Book speaks truth; and if we have a mind that the Author should be found a lyar, we had best reform our selves first. I wish to God, that in this our Age, there were many such Innocents, and that all men were of so sound a judgment, as to profit by good things, and laugh only at ill ones, or rather avoid them: For my part, I think, that if ever there hath been a Book in this world free from a flattering design and interest, that this is one of those; for the Church of God will profit by it, the Romans will draw no small pleasure nor less p. ixadvantage from the reading of it; and, I hope, that it will be a kind of Looking-glass to the Nephews that are to come, whereby they may guide their actions, and steer their intentions to a better course then their Predecessors. There passed, not long ago, by this Town, a certain Prelate of Tuscany, to whom I gave a sight of this Manuscript before it was printed; he took such delight in perusing of it, that he entreated me to hasten the publication of it, with these words, For Gods sake, Sir, inrich Rome with so great a Treasure as this is; bestow so good an example upon Princes Politicks, and illustrate all Christendome with the demonstration of so much zeal: This was the opinion of a sincere Prelate. But besides, it is most certain, that the Nephews, as well those that now bear sway, as those that are out of date, and those that are to come, if they will judge without pre-occupation, will find, that this History is of no small concern to the promoting of their interest, considering, that the good which is said of them doth much surpass the ill, and, that it demonstrates how necessary a thing the Nipotismo is to the City of Rome. I do not pretend to any thanks or retribution for the good that shall happen to them; neither would I be content, that the harm, if there p. xbe any, should reflect upon me. As for the Book, Reader, it is in thy hands, and must stand or fall by thy verdict: I therefore only desire thee to pronounce sincerely, whether it be not as necessary for all Europe as for the City of Rome. I promise thee another Work, much more worthy thy curiosity, and fit for any body that hath a publick Employment, which is Il Cardinalismo, a Work, which speaking in general only of that Dignity, doth yet nevertheless now and then descend to particulars. In a word, I call the Cardinalismo, and the Nipotismo, Brothers; but the Cardinalismo is the eldest, because first conceived by me; in a moneth it will be Printed; if thou wilt have it, thou mayest, and I can assure you, it will please you infinitely.

Farewell.

In which is treated, of the difference that there is between the ancient and New Rome. Of the manner of Governing of the ancient Romans. And of the manner of the Popes governing. Of the murmurs of the Gentiles, Hereticks, and Catholicks, against the Church of Rome and the Popes. How to come to the knowledge of present state of Rome by the said murmurs. Of the time in which people began to talk ill of the Popes, and of the cause of this their libertie. Of the Popes first bringing their kindred into Rome. Of p. 2the Infallibility of the Popes in admitting their kindred to the Government of the State of the Church. Of the causes that ruin’d the old Roman Commonwealth: and of those that lessen the Honour and Grandeur of the Church of Rome. Why Christ chose to be Born in a time of Peace. Of the Succession of Peter to Christ. Of the Apostles to Peter; and of the Popes to the Apostles. Of the Holiness of Church-men in the primitive Church. Why the vertue of doing Miracles is failed in the Popes. Why for many Ages the Popes Kindred did not much care to own their Relation to him. How the Church came first to be so Rich. Of the Court of Rome. Of the Politick Wit of Church-men. Of the advantage that Politicians gain in frequenting Rome. And of some particular maximes of Innocent the Tenth, which were of utility to himself.

Rome alone amongst all the other Cities of the World can brag of the reputation, of having been alwayes esteemed the Mother of Nations, the whole Universe having almost alwayes taken a pride in paying to her a Tribute of filial Duties, in acknowledgment of which she has also opened her breasts, and pressed her Duggs for the nourishment of those who desired to encrease by their obedience to Her, and be free from those dangers to which they are subject that have not Parents or powerful Protectors.

The glories of Rome were never equalled, no more then Rome it self. Rome hath been seen in all the Cities of the World, not only commanding, p. 3but triumphing; and in Rome have been seen at divers times, not only Cities, but whole Provinces, nay, whole Kingdomes, obeying, and submitting. Rome seems to be born to rule the World, and with a great deal of reason, since not only it hath done, but doth still exerce its Empire over a great part of it.

It ruled while it was a Commonwealth; and not content with that Empire which nature, or to say better, the valour of its Citizens had purchased for it, it proposed to acquire all that it could think on, and still the acquisitions seemed small in comparison of that which remained to be acquired.

It rul’d in the time of the Roman Emperours, who made Lawes, and domineered over mankind as they pleased; nay, which was worse, tyranny it self came often from Rome to infect the rest of the Universe which was subject to this seat of Tyrants.

But why should we recall past Ages, and renew those wounds, which though not healed, are nevertheless worn out by the length of time; why should we praise Rome for having ruled the World, if now at this present it rules it more then ever, and domineers over it in a new manner.

In the time of the Commonwealth, in the time of the Emperours, Rome never pretended to command consciences, and exact from soules that Tribute which now they pay to the Vatican.

Every City had its Bishop, every Village its Curate, and every Church its Preacher, who in his Sermons did not make it his business to exalt Rome; neither did the Bishop, nor the Curate p. 4expect the rules of governing their flock from Rome.

But now quite contrary maximes have prevailed; for Rome, not content with the temporal power, hath perverted the order of Government, and made the temporal submit to the spiritual, contrary to the received custome of so many Ages.

If the Commonwealth subdued Nations, if the Roman Emperours commanded over kingdomes, they did it in such a manner, that those that obeyed seemed to have had more content then those that commanded; for they let them enjoy the liberty of their souls, and required only from them a Civil Obedience in compliance with the interest of the State.

But the Popes having confounded and mingled together the temporal and spiritual power, laying the stress upon the spiritual, do oblige Princes and people to so exact an obedience, that the only mention of it is able to scare our hearts and minds.

The Popes shutting of Paradise and Heaven when they please, their opening of Hell when they think good, are things that oblige whole Nations to forget the Obedience due to their natural Princes, and to prostrate themselves at his Holinesses his feet. The Commonwealth which ruled with so much wisdome and Policie, the Emperours who governed with the strength of Arms, and the Tyrants who domineered with cruelty, had they but known these secret maximes, might have humbled Nations and reduced Cities with a great deal less paines, and more security.

p. 5The Popes having being armed with the Soveraigne Authority over consciences, have so increased the glories of Rome, that there is scarce a corner in Europe, not a place in Asia, not a desart in Africa, nor a hidden solitude in America, where the name of the Pope hath not penetrated, and where there is not some discourse of Rome.

The Gentiles praise the Popes, and despise Rome; the Hereticks praise Rome, and despise the Popes; and the Catholicks despise both Rome and Popes with a greater, though secreter, disdain, then either the Gentiles or the Hereticks, of which I shall give the reasons.

The Pagans attribute all the mischief of Rome to that great number of Church-men with which this City is pestred. The Hereticks, on the other side, lay all the Church-mens disorders upon the Pope; and therefore the Hereticks are willing enough to be reconcil’d to Rome; but by no means will endure the Pope. The Pagans, on the contrary, are content to be friends with the Pope, but not with Rome.

This proceeds from the distinctions that the Heathens make in the person of the Popes, separating the spiritual from the temporal, and Religion from Civil Government; therefore in the time of Sixtus the V. and Gregory the XV. the Persians and Japponeses sent their Ambassador to Rome, taking no small pride in the Popes friendship, whom they esteemed as one of the powerfullest Princes of Italy, and for his greatness desired his Amity; their maxime being to make alliances with the most potent Princes of the World; they thought they could not better address themselves p. 6then to him, whom all the other Christian Princes did adore and reverence as their head.

The Hereticks destroy all this, being neither disposed to acknowledg the Pope as a temporal Prince, nor as a spiritual Pastor; so that with them, Popedome, Principality, Religion, Civil Government, all goes down, when they speak of the Pope.

Nay, I know a Gentleman of that Religion, who can by no means be perswaded that the Pope is master of Rome, and Prince of the Ecclesiastick State, though all the Princes of the world acknowledg him to be so, and for all this, the Protestant Gentleman cannot be brought to believe it, but stands firme upon the Negative.

Of the same humour was a great Lord in Spain, who could never be convinced, that Henry the fourth was King of France, though he knew that his own King did acknowledge him for such, and had sent an Embassadour to him, that all differences upon that subject were lay’d, and that all the Crowns in Europe did own him to be lawful King. And yet for all this the good Don could never believe that which all the world was sure of, and he died in this incredulous humour.

Now as for the murmurs that the Gentiles, the Hereticks, and the Catholicks have against Rome, there is this difference between them. The Heathens murmure upon what they hear; the Hereticks against those things that they do not believe; and the Catholicks against those things they see; and certainly of them all the Catholicks murmurs are the worst: for the eyes being as it were the p. 7treasurers of the heart, do furnish it so abundantly with the impressions which they receive, that it never is dispossessed of them afterwards; the Proverb being very true, which sayes, That in vain we fly from that which we carry in our hearts. Therefore the Catholicks, murmuring boldly, because they see the abuses of Rome, are much more believed then the others.

But indeed to speak truth, if we ballance the reasons that these three sorts of persons have to talke disadvantagiously of Rome, we shall find that the Hereticks have the greatest and most weighty arguments of their discontent.

But before I prove this, it is necessary to give notice that I make a distinction betwixt Hereticks and Protestants, though the Church of Rome does confound both these denominations; for they are Hereticks who deny the true Religion for a false one, which they set up without any foundation of reason, thinking that their own opinion is enough.

The Protestants are those that abhorre innovations, and do tie themselves to the sense of the Holy Scripture, denying every thing they find not in those Sacred Records: and for my part, I intend to speak only of the Protestants, not of the Hereticks.

Let us return to our subject; and say, that the Popes do neither good nor harme to the Heathens; to the Catholicks they do both good and evil; and to the Protestants alwayes ill, and never good. Looking upon the Heathens as neater, upon the Catholicks as their friends, and upon the Protestants as their greatest enemies.

p. 8From thence it proceeds that the Catholicks are more scandalized at the Popes errours; for they being friends are admitted to dive into the bottom of the disorders: The Protestants seeing that the Popes do not only suspect them, but openly profess enmity with them, do busie all their industry in penetrating into those hidden mysteries of the Court of Rome, that they may not be surprised, but have wherewith to defend themselves in their disputes: and therefore that which they report of the Court of Rome is most ordinarily true.

The Heathens let Rome alone as long as Rome lets them alone; and they talke according to the informations they receive from Catholicks and Protestants.

Whosoever therefore intends to draw a quintessence of truth out of so many different relations, must not give credit only to what the Catholicks say; for they being friends and dependants of the Pope, cannot do less for their own reputation, as well as for his, then to hide the abuses and palliate the disorders of his Court; neither ought he to take his informations from the Protestants alone, because they, being prepossessed with an aversion to the Pope, cannot chuse but be blinded by their pre-occupation, and say more then is true, in discredit of the proceedings of his Court.

The method of History would require a strict examination of the relations of both parties in matter of fact, and a ballance of their opinions in matter of policy, and upon so mature a discussion it were fit to frame the body of the History, and found the maximes of policy; for the History would then be true, and the maximes certain.

p. 9This hath alwayes been my way of writing, insomuch that many, both Protestants and Catholicks, have not been able to distinguish my Religion in my works, nor know whether the Author were Protestant or Catholick; and this because of the sincerity with which I praise, in both parties, that which deserves commendation, and blame vice, let it be where it will, and in what place and person soever.

But to say true, this present age hath so corrupted and perverted the art of writing, that some write only to flatter, and others to satyrize; and there is no ingenious Catholick but must confess, that there are publish’d every day more Libels by the Catholicks against Rome, then Satyres by the Protestants against the Popes; therefore now adayes the wiser sort of men give more credit to a Protestants relation, then to a Catholicks, meeting with less passion in the first then in the last, against the Popes and Rome.

I have been a great while in Protestant Countries, and have likewise made no small stay in Rome, where I have heard a thousand and a thousand times, both Romans and Protestants, discourse of the Popes Nephews, and their actions; but I must confess, that in Geneva it self I never heard any discourse so full of liberty, nor so satyrical, as those which the Romans, nay the Prelates themselves have vented in my presence, concerning the Popes and the Ecclesiastick authority.

Nay, I’le say more, and it is a thing I am very sure of, having heard it often said by persons of great understanding; the Protestant Gentlemen that travel to Rome are much more scandalized at p. 10the Romans proceedings towards the Popes, then the Catholick Gentlemen, who travel in Protestant Countries, are to hear the Pope defam’d and ill spoken of amongst them.

The Protestants, when they talk with Catholicks, because they cannot reasonably expect to be believed, do conceal the greatest part of the imperfections of the Popes kindred; but the Catholicks say a great deal more then becomes them, thinking thereby to show their aversion to vice.

More then all this, I say, that of all that is said in Rome concerning the Popes actions, and his kindred, there is none of it comes from the North, but from Rome it self; but on the contrary, even all that is said in the North, springs from Rome, and is not born in the Protestants Country.

The Romans make the Pasquins in Rome, and then to excuse themselves lay them upon the Protestants: thus the Pope is abused and deceived by the Romans themselves; so that then we may say with a great deal of reason, that out of Rome it self springs the source of all the harm it receives.

I wonder now no longer to see the change of stile which I have observed in Writers from age to age, since in the Court of Rome they change their way of living and speaking from day to day.

In the time that the Popes had golden consciences, and wooden walls, when with bare feet and clothed with sackcloth they went from door to door, accepting the charity of the faithful for p. 11their sustenance, and that full of zeal they administred themselves the Sacraments, exposing their lives for the safety of their flock. When the Popes applyed themselves only to their pastoral charge, without concerning themselves in Princes temporal interests: Rome in those dayes knew nothing of other Princes Courts, neither did the Courts of Princes concern themselves for Rome; there was so little mention made of the Popes, that the Church-men and Bishops did scarce know where to find them in their most important necessities.

It would have been indeed a great sacriledge to have spoken ill of a Pope, who from morning to evening did nothing but visit the sick, distribute the Sacraments, comfort the people, and serve the Altar with true zeal and piety.

But when once the face of things was changed, and that the Popes, weary of serving to the Altars, resolved to be served by the Altars themselves, when thinking it too low an employment to visit the sick, they pretended to be visited themselves by the greatest Princes, and have their feet kissed by them; these Popes, who were at first the edification of whole Nations, became a scandal to all the Kingdoms, for both Princes and people being surprised with this sudden change, and wondring at this new scene of grandeur, gave themselves up to seek into the reason of this alteration, and as it often happens, that in the Enquiries into one defect we discover another, so the world found out in the Popes change so many new subjects for murmuring and discontent, that from thence ensued Schismes and Heresies, p. 12with an infinite prejudice to the Church of Rome.

If the Popes would have been content to have been the heads of the Church in holiness and good life, and not in majesty and grandeur, the world would never have conceived so many sinister thoughts of their actions; therefore if there be murmurs in Rome, and the rest of Christendome, the Popes may thank themselves, for the fault is not in those that murmur, but in those that furnish them with a lawful subject for their complaints.

But let us speak truth: In the time that the Popes left to the Emperours the secular care of government, and all the interests of the temporal state, holiness and good life did shine in the Popes, as well as in the Church and Church-men; miracles were frequent, and Saints multiplied as fast as tyrant Emperours.

But as soon as the Popes usurped the civil power, and began to meddle with state matters, their holiness disappeared, miracles vanished, and by a strange mutation the Emperors became Saints, and the Popes as passionate for the temporal interest as the greatest Tyrants.

The Hereticks go further, and say, that the Popes are really Tyrants, as having introduced the Inquisition, which by constraining mens consciences to an exteriour worship of what they abhor, does more severely punish the breach of one of the Popes Orders, then it does the violation of one of Gods Commandements.

To this the Popes oppose, as a defence, the reason of policy, that obliges them to establish the p. 13Inquisition, leaving to their Divines the task of answering the other more sharp objection; who having no other way to extricate themselves from that difficulty, have written, to confute the Hereticks, such vast volumns of Controversie, that they being not able to read them, remain in their obstinacy, with no small dammage to the Pope and his Divines.

But this strange change of the Popes, from spiritual to temporal, and from holy Bishops to Politick Princes, is not so much to be attributed to the Popes themselves, as to their Nephews and kindred, there is the source and origin of the disease; for while the Popes lead a private life, and let their Nephews alone in their own homes, they were eminent for their zeal to the true Religion; but they had no sooner introduced them into Rome, but forgetting themselves, they fell to idolizing their Nephews, and for the increase of their greatness, employed not only the gold of the Church, but even all the pains and fatigues of the Popedom, nay even the consciences of their whole flock.

Experience teaches us, that many Popes, and particularly those of the greatest reputation, in the beginning of their Popedome did not only renounce their kindred, and refuse to own them, but with a solemn oath did protest to the Cardinals, that they would govern alone, and not admit their kindred upon any pretext whatsoever; so far they were from giving them a share in the government.

Alexander the seventh, who now lives, was one of those for a time, and from him we may conclude p. 14of the thoughts of the rest; for in the beginning of his Pontificat he shewed himself to be so averse from his kindred, that some thought him a Saint, or at least a man much above the frailties of humane nature.

Don Mario his Brother, Don Agostino his Nephew, and the Cardinal that now is, did every day offer up their prayers to Heaven, for a change in their Uncles inclination; the Ambassadors of Princes and the Cardinals, did nothing but weary themselves out in alledging to his Holiness the necessity of introducing his kindred, that it would be not only honourable, but of great advantage to the State and Church.

Yet the good Pope remaining unshaken in his opinion, was resolved to deny all their Instances, nay, often would be exceedingly scandalized at those that pressed him to it, saying, he could not in conscience condescend to their desires; as one day being importun’d upon the same occasion by Father Palavicino, a Jesuit, and his Confessor, who now is Cardinal, he answered him in these words, Your obligation, father, is to absolve from sins, and not invite to commit them.

Of this humour hath not been Alexander alone, but in the lives of the Popes there are many other such examples, as that of Adrian the sixth, and Pius the fifth, who were wont to say, that they would make it their task to perswade the world that they could live without kindred.

Now I would fain know, from whence proceeded in them this humour, so opposite to the others? if from an aversion and a kind of hatred to their relations, then certainly it was a sin, p. 15since we have as a Commandment from God, Despise not thy own flesh; if to make shew of an apparent zeal, that was worse, for they were guilty both before the world and God Almighty; if out of a design of first bestowing kindnesses on their Friends before they gave themselves up to their Nephews, it was a preposterous charity, which ought to have begun nearer home.

It remains then to conclude, that certainly these Popes, who made this profession of disowning their Relations, did it, because they were really perswaded, that the errors of their predecessors did proceed from this principle of admitting their kindred to a share in the government, and therefore they thought fit to free themselves from so great an imputation.

Therefore to save the reputation of the Papal dignity, I am forced to say, that those Popes, who at first did profess an aversion to their kindred, and yet afterwards admitted them, were certainly seised with some melancholy humors and capriciousness, which made them commit such errors. It must not seem strange if I call them errors, since reason it self must needs call them so; for first, to be perswaded that their predecessors had failed in admitting their kindred into Rome, and in giving up the government of the Church into their hands; then, to swear and protest to keep theirs at a distance, that they may be freed from the like miscarriages; and after all this, not onely to call them into Rome, give them the Keys of the treasure, and put all the administration of the temporal and spiritual into their hands, whereby to make themselves Princes, but also to give them p. 16an absolute authority over the Church, the Popedome, nay, the very person of the Pope; this is certainly to demonstrate, that the Pope hath the power of making that to be good and just, which he hath condemn’d for bad & mischievous; which if the people of Rome, or the Courtiers, do believe, certainly people of judgment and sound understanding do not.

As for me, I have not hitherto denyed that opinion of the Roman Divines, viz. that the Popes cannot erre; but when once I came to see the falsity of it proved in the person of Alexander the seventh, certainly I have had a mind to curse those Divines, that flatter thus the Popes, not out of a design to serve the Church, but to make themselves great; and we know very well, that there are now many of them living, who have been made Cardinals, meerly because they had writ to the advantage and honour of the Pope, which thing still stirs up others to do the same; but let them write what they will, all the world shall never perswade me, but that the proceeding of Alexander towards his kindred, in calling them to him, contrary to his oath, is as great an error as ever Pope committed.

Yet let us do them the favour to interpret their Doctrine their own way, and allow of their distinction, that is, that the Popes are infallible in matters of faith, but not in matters of policy; let it be so; but if we do them this kindness, I hope they will be so civil as to requite it with another: we desire them then to tell us a little; The Popes Nephews, have they not the same authority as the Popes themselves, who invest them p. 17with it as soon as they are admitted into the Vatican, they govern all affairs, politick, civil, Ecclesiastick, and in a word, sacred, prophane, divine, all things pass through their hands. Then with them sometimes the Popes may erre, even in matters of faith, since often in matters of faith they trust their Nephews, who being men subject to passions, are admitted by all to be capable of error.

I would fain ask you, whether Alexander the seventh, who had so great an aversion to his kindred at first, had the assistance of the holy Ghost, or whether he had it not?

If you answer he had it not, I am well pleased, and do profess with you, that I think that policy and humane reasons were the causes of his proceedings.

But if he had the holy Ghost, how then can you reconcile his first refusing to admit the calling his Nephews to his assistance? for either it was good or bad to admit them to his help in so great a charge; if good, then he failed at first in keeping them away, and shewing himself so alienated from them; if bad, then he failed at last, in repealing his first resolution, and betraying the Church and its riches into their hands.

The holy Ghost is infallible, and to believe the contrary is a high impiety; how is it then that the Popes have the holy Ghost, and yet cannot abstain from failing? certainly to me it appears a kind of Blasphemy and prophanation of the honour of the Divinity. We know that the holy Ghost inspires nothing but what is good, and yet we see that the Popes do commit ill. The Protestants p. 18do utterly deny this opinion, and demonstrate by good proofs, that the Pope neither hath, nor can have the holy Ghost in a more particular manner then other men; but for my part I believe that the holy Ghost is in the Popes when he pleases, and they receive him when they can.

So to save the reputation of Pope Alexander the seventh, I’le say, that in the beginning of his Pontificat he had not the holy Ghost, for if he had, he would have received his kindred; but the holy Ghost begun to take possession of the Pope, just at the same time that his kindred took possession of Rome, and of the Church; and therefore the good man was much to blame to keep the holy Ghost and his kindred out so long together, since by this means he deprived himself of the riches of the Spirit, and his Relations of the riches of this world: But now he hath mended his error, and made amends for all. Many believe that the Popes erre with their kindred, and their kindred with them; but for my part I believe that the Apostles did not erre, because that they received the holy Ghost from Jesus Christ himself; but the Popes do erre because they receive the holy Ghost from the Divines, who give it them, how and when they please: I know what I say.

Often Rome hath lost the order of its government, because it was become a prey to the ambition of its Subjects; and as often it hath been brought upon the brim of its ruine, by gold and riches.

Old Rome had much ado to preserve it self by an infinite number of severe Laws, and at last did p. 19make a shift betwixt good and bad times, to rub out some Ages, till new Rome came and took its place. By old Rome I mean that Rome that was founded by Romulus, and ended at the time of our Saviour: and by new Rome I understand Rome that was born in Christ, and lives even now in him. Now if the ancient City of Rome came to its ruine through ambition and covetousness, it will become us to consider what effects these very same things do produce in our new Rome.

When we speak of Rome, we speak of a City that desires to be acknowledged by all Nations, as the head of Christendom. Now let us see the difference between the Pagan and the Christian Rome, the old and the new.

In the time that our Saviour was born in Bethlehem, to destroy this old Rome of the Heathens, and give the foundation of this new Christian City, Augustus not only commanded, that all the Nations of the Roman Empire should be numbred, to shew, that with the coming of Christ there was a new Empire begun, but likewise he brought all the world into a calm peace and tranquility; so that our Saviour no sooner appeared, but peace was the joy and comfort of the whole Universe. Christ chose to be born in a time of peace, and not of war and misery, for two causes: First, to set a difference betwixt the new and old Rome; the old having been founded in blood and dissention, under the government of Romulus a Pagan, it was more then just, that the new should begin with peace, under the dominion of the King of Kings, the holy One of Israel. Secondly, to the end that the Successors of the p. 20Apostles, who were to reside in Rome, might not one day excuse their faults, with alledging the beginnings of the Christian Religion for example; and therefore our Saviour took possession of Rome in peace, and delivered it to those Popes, who were to govern Rome and Christendome.

To Christ succeeded Peter, to Peter the Popes, as the Divines of Rome teach, and do endeavour to prove, against the Protestants, as a principal point of Religion.

The Popes then took possession of this new Rome, with the holiness of life; and when first they established this Ecclesiastical Senate, they chose out men so holy, and of so good a life, that the Citizens willingly submitted to prostrate themselves at the feet of such Governours.

Ambition was then so far from the hearts of the Bishops, that not only many Prelates did renounce their Bishopricks, but also many retir’d from the Vatican, where they were adored, into deserts and solitudes, to serve God their Creator without trouble.

Gold had not yet found the way to Rome, because there was no hand that would receive it, no Treasurer to keep it, and all its glittering was much below that vertue, which did so eminently shine in those that were the Guardians of Rome. Woe would have been to that man, who should have opened himself a door to preferment in the Church with a golden Key; the Excommunications, the Laws, the pains of this and the next world, were fulminated against Simony, which was as much abhorred by all the Church-men ther, as it is now practised.

p. 21In one thing alone old Rome did not agree in its beginnings with the new; for one promoted to its highest honours, those Citizens who had shed their blood, and could produce noble scars received in the defence of their Country; but the other bestowed Offices and Ecclesiastical Dignities upon those, who in consideration of another world did despise this, and mortified their flesh and affections. The Roman Empire rise by Valours, the Roman Church by Holiness.

The Actions of those, that pretended to any place of publick employment in old Rome, were examined by the Senate; and the services, which the State had received from these Candidates, were as it were ballanced with the honour they ambitioned, and the weight of the place they stood for: and if those services were such, as to be able to weigh down these scales of equity, the Candidate was sure to obtain his desires; if they proved too light, he was forced to stay, and with new Endeavours encrease the obligation the publick had to him already.

Just in the same manner did the Popes at first proceed in the distribution of the charges of the Church; for having ballanced the holiness of life, and excellency of parts of him who was to be admitted, with the weightiness of the place; if the goodness of life was so eminent, as to surpass the exigency of the Office, the Demandant was without delay preferred, otherwise he was sent away with shame and confusion.

The Conquests of Kingdoms, and the subduing of Provinces, were the Keys, with which the p. 22Romans opened to themselves the door of honour, and an entrance into the Senate; but in new Rome, persecutions, martyrdoms, and mortifications, were the fore-runners of Christian Dignities, and the only way to Bishopricks and Popedoms.

While the Popes lived thus, and that this age of holiness lasted, it was with a great deal of reason, that the rest of the world called their Rome, Roma la Santa, Rome the holy: The Popes were looked upon to be more like Angels then Men, not only because their actions were altogether heavenly, but because that living in this world, without owning any of their kindred, they seemed rather sent from Heaven, then taken from the midst of mankind.

There hath been some Popes, who while they were Bishops and Cardinals did reckon an incredible number of Nephews and Cozens; and yet no sooner were they promoted to the highest Prelature, but all their kindred vanished and disappeared, as if they had never had any.

If in those times you had asked any of them if they were a-kin to the Pope, he would have denyed it openly, so little did the Popes care for their kindred, and their kindred for them: The cause of this was, that the Popes did not measure in their kindred their deserts, by any carnal affection they had for them, but compared their merits by the Standard of Christian perfection; so that if a Kinsman of a Pope should have happened to have had, for competitour in any place, one not much above him in learning and piety, yet without doubt he should have yielded to p. 23this his Competitour, and gone without his pretensions.

Hence it came, that the Popes kindred, that they might not receive affronts in Rome, did forbear to come at the City; and least the world should by their absence conclude of the meanness of their deserts, they would give it out, that they were in no wayes related to the Pope, whose kindred they were, saving thus their honour without honour.

In those times, the Popes did often resist the Emperours tyrannical proceedings, and withstood their injuries, not with Armies and Fleets, but with Zeal and Piety they did boldly oppose their vices and corruptions; as amongst others, Gregory the seventh excommunicated the Emperour Henry, and banished him from all commerce with the rest of his Christians, only because he had received I know not what sum of money from a Bishop, who us’d his favour to be preferr’d to a vacant Bishoprick.

Rome was then truly holy without ambition, and without gold; and glorious were the Popes, who with their zeal and good actions made barbarous Kings tremble, and Tyrants humble themselves to the yoak of Christian Religion; and indeed who would not obey that Pope, that should prefer true merit and deserts before Relations and Kindred, Vertue before Vice, Learning before Ignorance, Zeal before Ambition, Poverty before Riches, his flock before his Kindred, and Justice before Favour and Recommendations?

But if hitherto we have spoken of Rome without p. 24corruption, and of Popes full of zeal and holiness, so we must now consider Rome under another habit, that is, not holy, but wicked, not pure and innocent, but defiled and full of ambition and avarice.

While the Popes lived in this retired manner, devested of all earthly affections to their kindred, and inclin’d only to recompence deserts and goodness, Rome was happy and holy; but as soon as Christian modesty began to be banish’d by worldly pomps, that favour took place of merit, that ambition overpowered humility, and covetousness laughed at charity, the Popes began to lose their credit, Rome its goodness, the Church its Saints, and there started up another Church, another Rome, and other Popes.

And no sooner did the love of riches take possession of Rome, but Christendom was engaged in desperate Schisms, with no small affliction to the real and pious part of the Christian world.

Two hundred and twenty six years after the birth of Christ, the Popes began to change their poverty into riches, and with them introduced ambition into the Church; this was done in the time of Urban the first, who ordained, that the Church should possess land, riches, power, command, and all other conveniencies, to the end that Church-men might be rewarded out of the revenues of the Church it self.

Before Urban’s time, Ecclesiasticks were to trust to the alms of the faithful, and their charity; and whilst that lasted, they thought of nothing else then the conduct of Souls, having no care to take, either for the encrease or conservation of p. 25their Fortunes; but as soon as they saw the Church enriched with Abbyes, Canonicates, and other revenues, they fell to disputing among themselves, every one desiring the possession of the richest benefice.

Urban in doing this had neverthelesse no ill intention; and if his Successors had followed his steps, the revenues of the Church had certainly animated Romes greatness, and yet deminish’d nothing of the Churches riches.

When I speak of the riches of the Church, I mean, not the temporal, but the spiritual riches, as St. Laurence understood it, when being asked by the Emperour where were the riches of the Church, he produced before him a multitude of poor impotent beggars, but of a good life.

Therefore the Church became poor in Saints, and rich in ambitious Ecclesiasticks, who did now employ that time which they used to spend in the Churches, and at the feet of our Saviour, with the Popes and Bishops, in reckoning up the Revenues of their Abbies, and procuring preferments to themselves and others.

The bringing of temporal riches into the Church was a poison which infected the Church, and made the Church-men swell, ’till at last they were ready to burst with their own venome. As the Church encreased in revenues, Rome decreased in Holiness and Holy men, and Saints forsook it when once Courtiers and men of business came into it. I meane living Saints; for as for dead Saints there are too many in it still, it being a part of its Trade to doe now for Gold and Riches, that which before was done by poverty and self-denial, I mean, Canonising of Saints.

p. 26Before the Church enjoyed temporal revenues, there was modesty in the Church-mens Apparel, but with the introduction of riches, pride, pomp, and vanity took place; then were invented Mitets, Scarlet Robes with long Traines, Copes, and Tippets; so that with the expense that one is at now to cloath a Prelate or a Cardinal many poor might be fed and covered, and particularly poor Priests, who are faine to beg from Laicks that which their own Prelates should bestow upon them.

Though things were carryed on with this corruption, yet was it not come to that pass that the Popes durst bring their Nephewes to the Sterne, and Government of St. Peters Vessel; they were content to rule the temporal and spiritual without controle, but did not think of entayling the Popedome upon their kindred, which made their Nephews and Relations keep at a distance, being unwilling to be seen in Rome without command and power.

Nicholas the third in the year 1229, went about to make two of his Nephewes of the House of the Ursins Kings, one of Toscany, and the other Lumbardy, to the end that one should keep the Germans in awe, who have one part of the Alpes, and the other the French, who were then Masters of the Kingdomes of Naples and Sicily: and that he might compass his designe with lesse trouble, he perswaded Peter King of Arragon to undertake the recovery of the Kingdome of Sicily, to which he had a right by Constantine his Wife.

p. 27But all these designes soon vanished and were buried in the Tombe of the Popes brain, where they were first conceived. ’Tis true, that many say, that the Pope did this, only to satisfie the pressing instances of his Nephewes: but because he affected more the quiet of the Church, then the advancement of his kindred, he persisted not in his enterprise, but just as long as was necessary to make his Kindred believe he had once well resolved it; and thus the Ursins, who aspired to so much Grandeur, remained disappointed, and the Pope was pleased in the demonstration he had given them of His kindness.

The Popes were not yet perfect in the art of raising their kindred; the carnal love of their Relations did but begin a combat with the spiritual zeal for the Church, and as yet the last was too hard for the first, and in all occasions did carry it before their kindness for their Relations.

From Nicolas to Sixtus the Fourth, who was created in the year 1471, the Popes did by little and little humanise themselves, and lay aside that rude severity to themselves, and to their kindred, who now began to come very willingly to Rome, being sure to meet with kinder receptions then heretofore had been shewed to precedent Popes Relations; and when once they were in Rome and in sight of their Uncle, he to prevent them from leading an idle life, would give them entrance into the Vatican, and honour them with places of Honour and Profit.

Withall this things were carried so closely, that though the Church did receive some detriment, p. 28yet the people of Rome, and the other Christian Nations had no great occasion of scandal given them neither from the Nephews, nor from the Popes. The first of which were well pleased with any thing that was given them; and the last, that is, the Popes, were so provident as to be liberal only of what was superfluous, and not of that which the Church and Rome could not spare.

But in the time of Sixtus, Ambition and Covetousness introduced themselves so openly, with the utter destruction of the modesty and decorum of the Church, together with the subversion of Christian Piety, occasioned all by his filling the Vatican with such a company of Nephewes, that from that time forward we must reckon the birth and growth of the Nipotismo; in the History of which, before we engage any further, it will not be amiss to give a Character of the Court of Rome, which now at present is maintained by, and depends entirely upon the Nipotismo.

One of the greatest extravagancies that I meet withall in the World, is the error of those who are perpetually exclaiming against Courts; and generally ’tis observed, that few of those that are of this Humour, have been Courtiers, or if they have, yet have they not made any considerable stay in them. But for Gods sake, what kind of thing was the World, before there were any Courts? nothing but the refuge of baseness, the quintessence of ignorance, an apparent blindness, and in a word, a barbarous throne of Vices, and all sorts of ill actions.

Many complain of the Court, but few of themselves, for not having been able to maintain the p. 29ground, and keep the place they had once in it; as if the Court were bound to descend to a compliance with every particular mans humour, and not particular men rather frame themselves to a condescendency for the Court.

Who is it that frames and constitutes a Court? ’tis the Prince, without whom there is no such thing. But who brings Vices to the Court? The Courtiers; and yet though the Courtiers be bad, and the Prince good, all the fault is laid upon the Prince.

Princes seldome fayle to recompense those services which they receive from their Courtiers, and without this quality they would not long be Princes. ’Tis true, that some are more reserv’d, others more liberal in their rewards; but still the defect is not in the Prince, but in the courtier, whose ambition is not to be ruled by his Princes judgment, and against whom he exclaimes for not contenting him.

To the ambition or desire of honour is alwayes added an avidity or desire of riches in Courtiers: these two monsters being the natural production of Courts.

The Court is to the World, as a furnace to Gold, to purifie, and refine mens wits. Whensoever any bodies ingenuity is under a cloud, and not known, let him come to Court, for there without doubt he will be prest to an exact trial of his skill; and let him use it all in hiding himself, and drawing as it were a vayle over his designs, yet he shall find the Court to be the true Touch-stone of mens actions, and he shall be known, for what he is really, and not for what he would seem to be.

p. 30This general discourse is only, that we may descend with more light and instruction to particulars. All other Courts, are streams, and rivers; but the Court of Rome is the head and source of them all; and as ordinarily we find out the head by following the stream, so I thought it fit to say something in general of Courts, before I came to the description of the Court of Rome. Among all Nations in the World, the Italians are the most famous for managing State Affairs, and being naturally inclined to be good Politicians. Neither do the Princes of the North deny this advantage to the Courts of our Italian Princes, who in the Government of their States, are masters of so much conduct, and subtilty, that none but very excellent and experienced geniuses can penetrate the depth of their Counsels.

But those maximes and Court slights, which in Italy are ordinary, are as it were natural and inseparable from the Church-men of the Court of Rome; which City, upon this score, is become famous in all forreign Countries, not as a place that teaches, and instructs Church-men, but as one that is taught and perfected by them.

He that desires to see politick stratagems, and all that subtilty can compass, let him not forsake Rome, where he shall soon learn how State Affairs ought to be managed.

I alwayes had a great opinion of the cunning and abilities of Church-men in matter of Government; but when once I came to Rome, and began to know by experience something of their wayes, I must confess, that my imagination was far short of the reality of what I had conceived.

p. 31It was no hard matter for Rome, both the old, and the new, to be mistress of the World, and give Lawes to Nations, since it hath alwayes been the School of true policies, as having even in its birth drained all the rest of the world of its cunning, and impoverished, it in slights to enrich its self.

For the space of fifteen Ages, the Church-men have already demonstrated to the world their abilities, and subtilty; and that so much the more to the wonder of all, because their beginnings have been so different from the means they have us’d, shifting from one thing to another, and changing upon all occasions, as Seamen do their Sailes with the wind, so that they seem to be born entirely for their own profit.

In the first Ages of the Church, the Court of Rome thought it convenient to comply with the Courts of other Princes, and this slight had its effect, while the Emperours Tyrannised over Rome; but their Tyranny being destroyed, the Court of Rome chang’d its way, and desired a compliance from all other Courts to its self.

Yet this proceeding too, having by little and little, intricated, and perplex’d the Court, and Courtiers, they were fain to come back to their first complyance, and by all Arts appease the male-contents, and keep those that were affectionate from being alienated: but now the face of things is so changed, and the nature of transactions so perverted, that they which now command in the Court of Rome have invented new wayes how to carry themselves, and correspond with Princes, very intricate, and different from those that were us’d in past Ages.

p. 32Therefore there are very few who having resided in this Court, do at last forsake it to return home, but they have a great deal of reason to complaine and be ill satisfied of its proceedings; not only because they had not found so much favour as they had expected; but because they found that they had been meerly deluded with faire promises, and at last, as it were laughed at for their paines. For the Courtiers of Rome have a particular maxime, either of perplexing, or of jeering those that come to negotiate with them. The truth is, they have been so subtle in providing for their interest, and have brought things to that pass, that they seem to be able to be without those, who can by no means be without them; upon which score the Ministers of some Princes were wont to say; That Negotiations in the Court of Rome were a mischeif to those that were employed in them, but a very necessary one: And in a word; The Court of Rome cannot be better compared, then to a Labyrinth, out of which, many think they are going, when they do but just enter it.

Many have compared it to the Monky, that hugs its young ones to death; for just so do the Churchmen, who embrace every one with a paternal affection; but in those embraces, they that receive them, find their ruin. Therefore have a Care of Romes kindness. Others do compare it to a Tree laden with fruit, that to look upon, seems ripe and fair, which when you come to taste, you find soure and crabbed.

For my part, I think the Court of Rome is like those pills that Physitians give to their patients, p. 33which are all gold without, that they may not displease the sick person by exposing to his view Cassia, or Antimony, &c. and he, poor man, trusting to this glorious exteriour swallowes the Pill, and in the swallowing of it often perceives the bitterness.

So Rome, or rather the Church-men in Rome, cover every thing with the gold of their inventions and slights, giving thus to Princes and Nations most bitter medicines covered with the zeal of Religion, which they have no sooner swallowed, but they find that there was nothing but an appearance of good in it.

In the Court of Rome it often falls out, that he that makes as if he knew all mens intrigues is altogether ignorant, and he that feigns to know nothing, knowes all. The exterior shew of goodness runs like a stream in the sight of all, but it springs from a head of mischeif, which is seen by few, because there they seldome give the sting without the honey.

Nothing is done in Rome without the zeal of Religion; and yet the zeale of Religion is that which prevailes least in all things. For they make a great distinction between those things that they desire, and those that they ought to do. They employ all their resolution and their prudence towards the compassing of the first, but they seldome performe the last, as not being inclin’d to make their wills stoop to their duty.

These maximes, or the like, are common in all the Princes Courts, both within and without Italy; but Rome is the Seminary of these Arts, in which the Church-men are masters.

p. 34He that goes to negotiate in Rome as a publick Minister from some Prince or State, must first have made some stay in it as a private person; and for my part, I am perswaded, that to have good success in such an employment, one stands in need of that double spirit which Eliseus asked Elias for; since that Church-men are so double-souled, as to use nothing but slights and subtilties in their negotiations.

He that can live four or five years in the Court of Rome, without meeting with such impediments as shall make him stumble and go neer to fall, may live a whole Age in any other Princes Court without trouble.

We see every day by experience, that many excellent Politicians, Ministers of Princes, and States, who in other Courts had got a great deal of credit and reputation, by managing business to their Princes content, are no sooner come to Rome, but in an instant they lose all that honour that they had taken so much pains for. And indeed many are they that come to the Court of Rome with a great deal of credit, but few come off and leave it with honour and reputation.

In a Climate subject to so many sudden changes, they that live in it must expect thunder and lightning, as well as fair weather. There negotiations must needs be hard, where the face of things is changed every day.

Many publick Ministers lose themselves in Rome, because they know well where they are, but not with whom they are: for whilst they think they have to do with a Monarchy, of a sudden they meet with a Republick and a p. 35Senate; and when they imagine to be engaged with a commonwealth and a Senate, they find they have to do with a Monarchy: so that like a ball they are tossed from the Monarch to the Senate, and back again: Because indeed, the government of Rome is a Monarchy without a Head, and a Commonwealth without Counsellors. And thus even they that reside long in Rome are often puzzled in such sudden changes.

The Government of the Popes is much different from that of all other Princes; because that they that are raised to this eminent degree do often come to it, so raw and ignorant of Policies, that they are a great while before they can attain to any perfection in their charge, which when they have done at others expences, it is time for them to leave the world and their government to their Successours, who most commonly are of the same past fortune, introducing Church-men to this so high a command, and nature hurrying them away from the throne before they are fit for it.

I do not wonder, that in the Court of Rome, through a long experience, even the dullest and rawest Politicians do become at last most expert; since that from all the parts of the World, Rome receives none but the wisest and most able Statesmen to negotiate with her.

One of my friends compares this Court to the Sea; for as it receives in its bosome all the Rivers of the Earth, and being by them filled and swelled, fills them again from whom it received its plenty. So Rome doth as it were suck from the rest of the World, their purest milk of policies, and distributes it again, like a kind mother, to all those p. 36that are content with the appellation of its children.

Indeed as for the sucking part, I think my friend is much in the right; for Church-mens lips are so fit for this function, that they lose not one drop; but as for the distributive part, they make it a more difficult thing then he or others would imagine.

Neither do I wonder at it, for when they deal with others, they alwayes propose to them the zeal of Religion, and the interest of Christian Piety: While under the pretext of these, they hide their self-policy, to use it in time and place convenient: Which no body can discover but themselves. The truth is, that a good Politician may receive some benefit, by diving into that which they so much endeavour to hide; but he shall never be advantaged by any thing that they shall willingly reveal to him, their undoubtted maxime being never to discover any thing but such as they need not, or that cannot be beneficial to others.

To give a great proof of what I say; I remember, that an Embassadour of an Italian Prince, a wise and able man, being returned home after seven years stay in his imployment at Rome, could give to his master for all account of his Embassy, nothing but ambiguous words, equivocal enigmes, and uncertain answers; whereupon his Prince not understanding him, required a better information at his hands, and was thus answered by him.

Serenissime Prince: The School of Rome hath furnished me with no other Lectures, then what I p. 37have already layed open to your Highness: Therefore with all due submission, I beseech your Highness to have compassion of me, if I appear before you so barren and so empty; for in seven years time I have not been able to obtain from these Church-men any solid substance, to fill my self withal. This ’tis that befalls most Ambassadors and Agents in Rome.

Innocentius the Tenth had brought the Court into such a confusion; that in his time no body knew where to begin any business: For he did so little care to trouble himself with the important affairs of Christendome; that most commonly he refused to meddle, even in those which concerned his pastoral function. His troublesome houres were when he was forced to give audience to a forrain Embassadour, and to be rid of business; his maximes were, To deny all favours, to answer all requests with a negative, and never to come to a final resolution in any thing that might please his enemies; though the thing in its self was very beneficial to the Church and State. If he had any inclination to do good, it appeared only in what he did to his own family, and in the care he took to embellish the City of Rome. But the ill he did was not contained in such easie limits, it spread its self over all Christendome, which did lament to see the Church provided of so extravagant a Pastor.

In the beginning of his pontificat, he shewed himself much enclined to be well informed of the state of Rome, and the Church Territories; which vigilance of his, at last redounded to the prejudice of all his officers. For they thinking p. 38at first, that his proceeding came from the love of justice, and good order, came all to Rome with instructions and memorials, wherein their wants and the necessities of their places were set out: but all in vain; for when they expected answer and satisfaction, they found that the intention of the Pope was, to refuse all, and to resolve nothing; so that then every one avoided, not only the presence of the Pope, but Rome it self, and all business in it.

This is the general disposition of the Court of Rome, and of Church-men in common; though the Popes Nephews do often give it another face, according as their designs and thoughts are, which being as different as the humours of one Pope from another; fortune, not merit, raising both Popes and Nephews to this great command; we may say, that things in Rome are rather performed by masked and counterfit persons, then by natural ones: As one of my friends, who lives well, and is one of the best Church-men in the Court of Rome, is used to say, that when once he had put on the habit of a Priest, he could hardly discern his own nature, nor know himself with comparison to what he was before. Which shewes evidently, that Church-men have certain close wayes of treating, particular to themselves, that must make those that have to do with them, stand upon their guard, and use all their policy.

In which is discoursed, of the first bringing the Nipotismo into Rome, which happened under Sixtus the fourth, too much inclined to favour his kindred. Of the lascivious life, and of the death of Cardinal Peter his Nephew. Of the government of the Church transferred to Jerom Peter’s brother. Of the number of Sixtus his Nephews. Of the selling of many Jewels. Of the murmurs of the Romans against this Pope. Of the succession of Innocent the eighth to the Popedome. How he was naturally averse from his kindred. p. 40What he did for some of his Nephews. Of the assumption of Alexander the sixth to the Popedome. How he made his Bastards great. Of the crimes committed by him. Of the family of the Sforzas, being from Milan. Of the actions of Duke Valentine. How the Pope passed his time. Of his death, caused by poyson. How Duke Valentine carried himself after the death of his Father Pope Alexander. Of the succession of Pius the third to the Popedome, and of his short life. Of what happened to his kindred. Of Julius the second that succeeded Pius. Of his way of carrying himself towards his Nephews. Of the Popedome fallen to Leo the tenth. Of his mind entirely bent to favour the Family of the Medici. How Adrian the sixth succeeded to Leo the tenth. Of the severity he shewed to his kindred. Of the election of Clement the seventh for Pope. Of his great ambition to raise his Family. How Paul the third was chosen Pope. How he likewise was inclined to make his kindred great, and by what means. Of that which Julius the third did in favour of his Family: and how his life was inclined to pleasures and delight. Of the resolution of Marcellus the second, to give nothing to his kindred. How Paul the fourth was made Pope. Of his kindness to his kindred. How Pius the fifth was not naturally inclined to do his kindred good. How Gregory the thirteenth was of a quite contrary disposition. How Sixtus the fifth was made Pope, and how he was inclined to favour his kindred. Of the short life of Urban the seventh, Sixtus his successour. Of the election of Gregory the p. 41fourteenth. What was his inclination to his Nephews. Of the election of Innocent the ninth. Of his proceedings and death. Of the election of Clement the eighth: and of what he did for his kindred. Of the desire of Leo the eleventh, successour to Clement, to make his family great. Of the election of Paul the fifth. Of his life and actions, and how he advanced his kindred. How Gregory the fifteenth succeeded to Paul the fifth, and of his great affection to his kindred.

Now we must look back, and return to Sixtus the 4th, who first opened a door to the Nipotismo, and who by introducing his kindred, brought at the same time ambition and riches into Rome; the riches were for his Nephews, and the ambition he left as an inheritance to all Church-men; and it is now one of the greatest mischiefs that oppresseth the Church.

’Tis not to be wondred at, that I begin the History of the Nipotismo, from the time of Sixtus the fourth, since he was the first that delivered up Rome and the Popedom in prey to his Nephews, to the wonder and astonishment of the whole world.

He was then the first introducer of the Nipotismo, and so indulgent a one, that to favour his kindreds interest, he had forgot himself, and the Church, thinking of nothing, but of the means how to advance them to their satisfaction, from whence the murmurs of the people were so great in Rome, that many Confessors were fain to give p. 42over their Function, that they might not hear the peoples complaints against the Pope and his kindred: So that it was spread through Europe, that Rome had as many Popes as Sixtus had Nephews.

This Pope, immediately after his election, made two Cardinals; viz. Peter Riario, whom many suspected to be his Bastard, having alwayes been educated, with great care by him, in the same Monastery; the other was Julian, son of Raphad de la Rovere, brother to the Pope, and had been first Bishop of Carpentras, then was made Cardinal by his Brother, and at last came to be Pope, under the name of Julius the second, as we shall relate in due place.

Sixtus gave to the Cardinal, Peter Riario, all that was in his power to give, adding Abby upon Abby, and revenue upon revenue, till he had made him so rich in Church lands, that he lived most splendidly, and seemed to be born to waste a greater fortune; Plays, Balls, Dances, and such pastimes, were the ornament which he bestowed upon his Ecclesiastical dignity, being perswaded, that pomp and vanity were becoming the majesty of a Cardinal.

He lived but two years in this loose life; in which time ’tis thought he spent, in Treats, and Balls, and such like diversions, above two hundred thousand Duckats of gold, besides seventy thousand which he owed at his death, and which were never payed: He dyed at the age of 28 years, to the great regret of his Uncle, his disease having been caused by his debauchery, as the Physitians testified.

p. 43Six months before he dyed, the Pope, whose continual study it was, how to make him great, declared and proclaim’d him his Legat over all Italy; not that any urgent business did require such a Function, but only that he might give him an occasion of shewing his Grandeur, and receiving more pleasure in those triumphs and receptions, he was upon this score to have bestowed upon him by the Italian Princes; who to humour the Pope, forgot no honour they could think of, towards the person of his Legat; and could not indeed have done more to the Pope himself; particularly in Venice, Milan, and Padua, he was received with so extraordinary a pomp, that it was almost incredible.

Great was the delight which he took in these publick honours; but much greater were the pleasures, which he tasted in secret, having ordinarily, amongst his Attendants, five or six Russians, whose business it was to satisfie his appetite, though never so inordinate. Being at last come back to Rome, to the possession of his old Mistresses, he ended his dayes amongst them, and went to a new world, whether of pleasure or of pain, God knows.

But the Popes affection to his kindred was not buryed in his grave; for he made his Brother Jerome succeed in his favour and fortune, which he rather increased then diminished; for he made him Lord and Soveraign of Inola and Forli; and gave him the government of all the state of the Church, besides other important Offices.

This Jerome was a quite contrary disposition p. 44to his Brother; being naturally severe in words and deeds, and averse from all pleasures but hunting. He married Catharina, natural daughter to Galeazzo, Duke of Milan; and Sixtus made Ascanius, the son of the said Duke, Cardinal into the bargain, contrary to the young mans inclination, which was rather to marriage, then to a single life.

But the inordinate passion of this Pope did not rest in all this; for his ambition of having kindred to advance was such, that not being content with that great number of true Nephews that he had, he substituted and adopted some, that were no relation to him at all; to whom he gave an infinity of places and commands.

He gave to Leonard, his brothers son, a natural daughter of King Ferdinand in marriage, and made him Prefect of Rome: And he being dead, he immediately transferred that honour and place to another Nephew, called John de la Rovere, brother to the Cardinal Julian; giving him besides, the Propriety of the States of Sora and Sinigaglia.

This John had by Giovanna, daughter to Frederick, Duke of Urbin, a son, who was Francesco Maria della Rovere, who after the death of Guido Ubaldo, his Uncle, who dyed without male issue, succeeded by adoption, and in the right of his Wife, to the Dukedom of Urbin.

Besides these, Sixtus made Cardinals the two brothers, Christopher, and Dominic, de la Rovere, who lived in Turin, under the protection of the Duke of Savoy, though they were Soveraigns of Vico Nuovo, and other Estates in Italy.

p. 45Besides, he made Jerome Batto, his sisters Son, Cardinal, as likewise Raphael Samson, son to a sister of Pictro Riario, whom he promoted to that dignity, when he was but seventeen years old, upon condition, that he should change his name, and take that of the Popes Family.

This Pope had so much kindred, and was so inclined to advance them, that he often granted the same thing to two different persons, having forgot that he had granted it to the first.

But amongst all his inventions to enrich them, this was one of the best: In the beginning of his Pontificat, he made, as if he had a design to pay the debts, left upon the Church by the precedent Popes, Eugenius, Nicolas, Calistus, Pius, and Paul; but pretending want of money to do it, he compassed his design by this means.

Paul the second, his predecessour, had alwayes had a great inclination for the publick pomp and state of the Popedom, and therefore strove to make the Ornaments of the Popes person and head the richest that was possible for him; to which end, in the Miter, which serves at their Coronation, and other publick ceremonies, he had caused above the worth of a million in precious stones to be set, having bought up (all the world over) the best Diamonds, Saphires, Rubyes, Emeraulds, Chrysolites, &c. that could be had for money; so that afterwards, when he came out in publick, he looked like another Aaron, with a Majesty more divine then humane, being himself very tall, and of a comely port and presence.

Sixtus, who having been brought up in the p. 46severity of a Monastick life, did little esteem that outward pomp, which Paul, his predecessour, so much prized, caused these precious Stones to be sold, under pretence of discharging such debts, as the Church was lyable to for his predecessours.

The Jewels were soon sold, and the money consigned into the hands of his Nephews; but the debts were never payed, though the Jewels had been sold to that end: And that which is worth relating is, that the Pope answered every one, that came to demand any thing due to them; that he had already payed the others, that he was sorry it was not their fortune to come sooner, and that the money had proved short to discharge so many debts: So that the poor Creditors were fain to go away cheated, and yet knew not whom to complain of.

The Romans murmured strangely, against this greediness of the Pope and his kindred, and so much the more, because that they had not yet been accustomed to see a Popes passion; for his kindred make him rob and plunder the Church. They wondred what example Sixtus could have for his proceedings, for none of his predecessours had hitherto shewed so little moderation, but in providing for their kindred, had kept some measures. Neither could his education furnish him with this ambition and covetousness; for he had been brought up in a Convent, amongst Religious persons, who professed voluntary poverty, and to whose principles he seemed to be so inured, as not to be able to forsake them: for all the while he managed publick business, before he was a Cardinal, p. 47it was with a great deal of candour and disinteressment that he did it; and when he came to be made Cardinal, he was so far from keeping a Court, and living in that splendour, which others thought became that dignity, that his family and Retinue looked rather like a Convent, then like a train of Attendants. But as soon as he was Pope, he changed of a sudden, and lived like a Prince, never troubling himself at what the world said of him, but cared only to please himself, and make his kindred great.

Sixtus being dead, Innocentius the eighth was made Pope, in the year 1484. being of the noble Family of Cibo, which hath had many eminent persons in it. This Pope, remembring the complaints of the Romans against his predecessour, for being too indulgent to his kindred, resolved to be very cautious in that point, and give no occasion of scandal that way: Which he observed so well, that when any one of his kindred came to Rome, and that he had notice of it, he would say, Our kindred had much better stay in Geneva without us, then come to Rome for our sakes; and indeed he was very reserved to them: For to Mauritius Cibo, who was a very accomplish’d Gentleman, he gave nothing, but the Government of the Dutchy Spoleto, and made him President of the State of the Church Employments, which in those dayes were not of any great honour or profit, though now they are both rich and honourable.

So he made Lawrens Cibo, his Nephew, Cardinal, but with very little authority, forbidding him p. 48to meddle with publick business of importance, without being called to it. And yet was he forced, as it were, to honour him thus far; for many whispering about the Court, that he was a Bastard, he was fain to shew the world, that he did own him, as being lawfully born of one of his Cozens; which he proved by a process and strict examination before Cardinal Balbo, a Venetian, and one, who had no wayes interest to favour the family of Cibo.

The greatest advantage that this Pope procured his Family, was, that he married Francesco Cibo with Magdalen of Medicis, sister of Leo the tenth that was afterwards, giving him the County of Anguillara, which was not of any importance in those dayes, and making him Captain General of the Forces of the Church: And in this he ended all the favours that he ever shewed his Family, which was very noble besides.