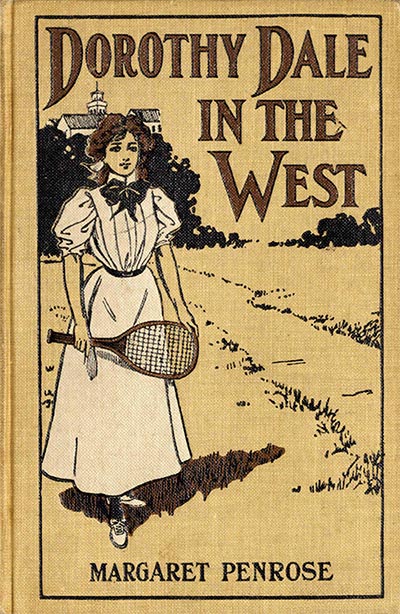

DOROTHY DALE

IN THE WEST

BY

MARGARET PENROSE

AUTHOR OF “DOROTHY DALE: A GIRL OF TO-DAY,” “DOROTHY

DALE AT GLENWOOD SCHOOL,” “THE MOTOR

GIRLS SERIES,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY

BOOKS BY MARGARET PENROSE

THE DOROTHY DALE SERIES

THE MOTOR GIRLS SERIES

12mo. Cloth. Illustrated.

Price per volume, 60 cents, postpaid.

Cupples & Leon Co., Publishers, New York

Copyright, 1915, by

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY

DOROTHY DALE IN THE WEST

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | A Surprise Is Coming | 1 |

| II. | “Hooray for the Wild West!” | 10 |

| III. | The “Two-Faced” Man | 17 |

| IV. | To Catch the Midnight Express | 24 |

| V. | The Old Lady With the Basket | 33 |

| VI. | “The Breath of the Night” | 44 |

| VII. | A Night With a Knight | 57 |

| VIII. | The Night Adventure Continued | 72 |

| IX. | What Followed an Elopement | 82 |

| X. | The Man Who Would Have Died Indoors | 91 |

| XI. | At Dugonne at Last | 101 |

| XII. | On the Road to Hardin’s | 109 |

| XIII. | At the Ranch-House | 123 |

| XIV. | “The Snake in the Grass” | 133 |

| XV. | Exploring | 141 |

| XVI. | In the Gorge | 147 |

| XVII. | Flores | 154 |

| XVIII. | Ophelia Comes Visiting | 162 |

| XIX. | “’Way Up in the Mountain-Top, Tip-Top!” | 172 |

| XX. | Two Eyes in the Dark | 182 |

| XXI. | Dorothy’s Courage | 192 |

| XXII. | Dorothy Hears Something Important | 199 |

| XXIII. | “Where Is Aunt Winnie?” | 207 |

| XXIV. | The Chase | 220 |

| XXV. | A Little More Excitement | 227 |

| XXVI. | Saying Good-Bye All Around | 238 |

1 DOROTHY DALE IN THE WEST

“He, he, he!” giggled Tavia.

“What is the matter now, child?” demanded Dorothy Dale, haughtily. “There are no ‘hes’ in this lane. The road is empty before us——”

“And the world would be, too, if it wasn’t for the possible ‘hes’ that are to come into our lives,” quoth Tavia, with shocking frankness.

“You talk like a cave girl,” declared her chum. “Is there nothing on your mind but boys?”

“Yes’m! More boys!” chuckled Tavia. “It is June. The bridal-wreath is in bloom. If ‘In spring the young man’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of love,’ can’t our girls’ fancies turn in June to thoughts of white lace veils, shoes that pinch your feet horribly—and can’t we dream of hobbling up to the altar to the sound of Mendelssohn’s march?”

“Hobble to the haltar, you mean,” sniffed Dorothy, with her best suffragette air.

“How smart!” crowed her chum. “But you2 mustn’t blame me for giggling this morning—you mustn’t!”

“Why not? What particular excuse have you?”

“That shad we had for breakfast. Shad is as full of bones as Cologne’s shoes are of feet. I always manage to swallow some of them—the bones, I mean, not dear Florida Water—Rosemary’s tootsies—and those said bones are tickling me right now.”

“How absurd,” said Dorothy Dale, as Tavia went off in another “spasm.” “Do you realize that you are growing up, Tavia—or, pretty near?”

“‘Pretty near,’ or ‘near pretty’?” asked Tavia, making a little face at her.

“Baiting your hook for a compliment, I see,” laughed Dorothy. “Well, you get none, Miss. I want you to behave. Think!”

Tavia immediately struck an attitude that seemed possible for only a jointed doll to get into. “Business of thinking,” she said.

“Suppose anybody should see you?” pursued Dorothy, admonishingly.

“Then you do expect the boys to motor in by this road?” cried Tavia. “Sly Puss!”

“No, Ma’am. I am not thinking of Ned and Nat—or even of Bob Niles.”

Tavia made another little face at mention of3 Bob’s name. “Poor Bob!” she sighed. “No fun for him this summer. His father says he must go to work and begin to learn the business—whatever that may mean. Bob wrote me a dreadfully mournful letter. It almost tempted me to go to the same town and get a job in his father’s office, and so alleviate the poor boy’s misery.”

“You wouldn’t!” gasped Dorothy.

“Got to go to work somewhere,” decided Tavia. “And I hate housework and cleaning up after a lot of children.”

“But just think! how proud your father will be to have you at the head of the household. And remember, too, how much your brothers and sisters need you.”

“Goodness, Doro! You talk like the back end of the spelling-book—where all the hard words are. And the hardest word in the whole vocabulary is ‘duty.’ Don’t remind me of it while I am here with you at North Birchlands.”

“And think!” cried Dorothy, giving a little skip as they walked on. “Think! we are not a week away from dear old Glenwood School yet, and to-day Aunt Winnie’s surprise is coming. Gracious, Tavia! I can scarcely wait for ten o’clock.”

“I know—I know,” said Tavia. “If your Aunt Winnie wasn’t the very dearest little gray-haired, pink-cheeked woman who ever lived, I’d4 have shaken the secret out of her long ago. I just would! And we can’t even guess what the surprise is going to be like.”

“Goodness! No!” gasped Dorothy. “I’ve given up guessing. I know it is something perfectly scrumptious, but nothing like anything we ever had before.”

“I hope, whatever it is, that I’ll be in it,” groaned Tavia.

“I am sure you will be, or Aunt Winnie wouldn’t have invited you here to her home at just this time,” declared Dorothy.

They were walking down the shady road toward the railroad station “killing time,” before the family conference which had been called for ten o’clock.

Nat and Ned White, Dorothy’s cousins, had gone off in their auto, the Fire Bird, on an errand, and the girls had an idea they might come home by this route, and so pick them up.

“Hush!” cried Tavia, suddenly. “Methinks I hear footsteps approaching on horseback.”

“That’s no horse you hear,” Dorothy said. “It is somebody walking on the bridge over the brook.”

There was a turn in the road just ahead and the girls could not see the bridge. But in a moment they could descry the figure of a man striding toward them.

5 “This must have been what you were he-heing for,” whispered Dorothy.

“How romantic!” was Tavia’s utterance.

“What is romantic about a man coming up from the station?”

“Don’t you see his long, silky black mustache? And his long hair and broad hat? Goodness! he’s a picture.”

“Yes. The stage picture of a villain—Simon Legree type,” scoffed Dorothy. “That red silk handkerchief sticking out of his pocket—and the big diamond in his shirt front—and another flashing on his finger——”

“My!” gasped Tavia, clasping her hands. “He might have stepped right out of Bret Harte. Ah-ha! ah-ha! Jack Dalton! unhand me!”

“Hush, Tavia!” begged her chum. “He will hear you.”

“Oh!” exclaimed Tavia, suddenly disturbed. “He’s looking at us—and he’s crossing over to this side of the road.”

“Well, don’t you look at him any more and—we’ll cross the road, too.”

“Do you suppose he eats little girls?” queried Tavia, with a most ridiculous air.

Dorothy felt as though she wanted to shake her chum. But then, she frequently felt that desire. The man was too near for her to speak again, but the girls crossed the road suddenly.

6 The man stopped, half turned as though to approach them, and leered at Dorothy and Tavia. He was not a large man, but he was remarkably dressed. His black suit was rather wrinkled, as though he had been traveling some time in it. The broad-brimmed hat gave him the air of a Westerner, or Southerner. And his flashy appearance made him very distasteful to Dorothy.

She made Tavia hurry on, and soon they reached the bridge themselves. Tavia was “raving” again:

“Those wonderful eyes! Did you see them? Deep brown pools of light—only one was green? Did you notice it, Doro?”

“No, I didn’t. I told you not to look at him again. You might have encouraged him to follow us.”

“I wonder how it would feel to be a gambler’s bride. I just feel that he’s from the West and is a gambler, or a cowpuncher—or a maverick—or——”

“You don’t even know what a maverick is,” scoffed Dorothy.

“Yes, I do! A maverick steals cattle,” declared Tavia, quite soberly.

“You ridiculous thing! It’s ‘rustlers’ that steal cattle—or used to. A ‘maverick’ is a stray calf without a brand.”

“Well! he looked as though he had strayed—— Oh,7 Doro!” gasped Tavia, suddenly. “He’s coming back.”

The girls had reached the bridge and had stopped upon it. The brown water was gurgling over the stones, the birds were twittering in the bushes, and the scent of the wild roses was wafted to them as they leaned upon the bridge-rail.

It was a lovely picture, and Dorothy and Tavia fitted right into it. But the picture did not suit Dorothy and Tavia at all when they saw the black-hatted man round the turn in the road.

They felt just as though the picture needed some action. An automobile with Ned and Nat in it, would have furnished just the life the girls thought would improve the scene.

“Come on!” whispered Dorothy. “Don’t let him speak.”

But it was too late to escape that. “Little ladies!” exclaimed the man. “You’re not going to run away from me, are you?”

Tavia would have run; only, as she confessed to Dorothy later, her skirt “was not built that way.” Now, however, Dorothy had to face the man.

“What do you want?” she asked, just as sternly as she could speak.

“Oh, now, little lady,” began the fellow, “you mustn’t be angry.”

Dorothy turned her back and seized Tavia’s arm. “Come on,” she said, with much more8 confidence in her voice than she actually felt.

“Ned and Nat will soon be along. Come!”

The girls began walking briskly. “Is—is he going to follow us?” whispered Tavia.

“Don’t you dare look back to see,” commanded Dorothy, fiercely.

Either the black-hatted man was not very bold and bad, after all, or Dorothy’s remark about expecting the boys fulfilled its duty. He did not follow them beyond the bridge.

“Oh, Doro! You can’t blame me this time,” urged Tavia, as they hurried on.

“I do not believe the fellow would have dared speak to us if you had not rolled your big eyes at him,” declared Dorothy, rather sharply.

“Oh, Doro! I didn’t!” Then she began giggling again. “It is your fatal beauty that gets us into such scrapes—you know it is.”

It was little use scolding Tavia. Dorothy was well aware of that. She had “summered and wintered” her chum too long not to know how incorrigible she was.

For fear the man might still follow them, Dorothy insisted upon taking the first side road and so walking back to Aunt Winnie White’s home, the Cedars, by another way. When they arrived the boys were there before them.

“Hi, girls! where were you?” shouted Nat. “We looked for you along the station road.”

9 “Did you come right up from the station?” demanded Tavia, eagerly.

“Sure!”

“Did you see a black-mustached pirate down there by the bridge, with a yellow diamond in his bosom——”

“In the bridge’s bosom?” demanded Nat.

“Of the pirate’s shirt,” finished Tavia. “Such a mustache! He looked deliciously villainous.”

“Another conquest?” grunted Nat, who never liked to see any fellow “tagging about after Tavia,” as he expressed it, unless it was a gallant of his own choosing.

“He followed Dorothy—and spoke to her,” declared Tavia, with effrontery. “And she spoke to him.”

“Soft pedal! soft pedal, there, Tavia!” urged Ned, who had overheard. “We know Dorothy.”

“And we know you,” added his brother. “You’ll have to unwind a better string than that, Tavia. There’s a ‘knot’ in it—Dorothy did not.”

“Ask her!” snapped Tavia, quite offended, and marched away toward the house.

Dorothy at that moment appeared on the side porch. “Come in, boys, do,” she urged. “It’s ten o’clock and everybody else is in the library. Your mother is all ready to unveil the Great Surprise.”

The family gathered in the library. Major Dale, Dorothy’s father, sat forward in his armchair, leaning his crossed hands and chin upon his cane. Joe and Roger, Dorothy’s brothers, fidgetted side by side upon the leather couch.

Mrs. Winnie White, Major Dale’s sister, and her two big sons, Ned and Nat, occupied chairs at the table. Dorothy and Tavia, their arms about each others’ waists, were on a narrow settee in the fireplace, that was banked with green, odorous Balsam boughs.

“Now, children, I have a great announcement to make—two, in fact,” said Aunt Winnie, playing with her lorgnette and smiling about at the expectant faces. “The Major tells me to ‘go ahead,’ and I am going to do so.

“First of all, the Dale and White families have come in for a considerable increase in this world’s goods. In other words, the Major and I have been left in partnership, the great Hardin Ranch and game park, in Colorado.”

11 “Game! Shooting! Wow!” ejaculated Nat.

“Ranch! Cattle! Ah!” added his brother.

“Sounds like a new college yell,” muttered Tavia in Dorothy’s ear.

“I was well aware,” continued Aunt Winnie, “that old Colonel Hardin contemplated making the Major a beneficiary of his will. The Colonel was my brother’s companion in arms during the war——”

“And a right good fellow, too,” interposed Dorothy’s father, heartily.

“When Colonel Hardin came East several years ago, he spoke to me about this intended disposition of his estate. He knew he could not live for long. The doctors had already pronounced upon his case, and he had no family, you will remember,” Aunt Winnie said. “I had no idea he proposed making me a legatee, as well. But he has done so. The Hardin property is a great estate—one of the largest in Colorado.”

“Hooray for the Wild West!” murmured Tavia, waving a handkerchief, yet evidently suffering under some emotion beside extravagant joy!

“The Hardin property was first of all a quarter section of Government land—one hundred and sixty acres—that the Colonel took up and proved upon when he obtained his discharge from the army. Then he bought up neighboring sections12 and finally obtained control of a vast, wild park in the foothills adjoining his cattle range.

“Of late years cattle have gone out and farming has come in. All between the Hardin land and Desert City are farms. They need irrigation for their developement.

“Colonel Hardin told me he held the water supply for the whole region in his hands. It would cost a large sum, he said, to make the water available for Desert City and the dry farming lands.”

“How is that, mother?” asked Ned, interested.

“I do not just know?”

“Can’t they dig wells and get water?” demanded Roger Dale.

“It strikes me,” said the Major, chuckling, “that in some of those desert lands, they say it is easier to pipe it in fifty miles than to dig for it. It’s just as far under the surface, or overhead, as it is latitudinally!”

“I suppose it must be something like that,” agreed Aunt Winnie. “I only know that Colonel Hardin said when the City and the farmers could raise the money necessary he stood ready to lease the water rights to them. Such lease would add vastly to the income from his property.

“Now, his lawyers have informed us that the will giving all this great estate to the Major and13 me, has been probated, and that somebody must come out there and look over the property and meet the people who want the water, and all that.”

“And somebody means us, mother?” cried Nat, joyfully.

“Us young folks—yes,” said Mrs. White, smiling. “That is my second announcement—and the larger part of the surprise, I warrant. We are going to celebrate Dorothy’s graduation by taking a trip West.

“The Major does not feel equal to the journey, because of his lameness; I am to take over the property jointly in our names. I shall need you four young people, of course, to advise me,” and she laughed.

“Say! Say! what four young people?” demanded Roger and Joe in chorus.

“Why,” said their Aunt, “you know somebody must remain to look after the Major. That duty, Joe, devolves upon you and Roger. Ned and Nat are going with me, and of course Dorothy can’t go without Tavia.”

“Hold me, somebody!” begged Tavia. “I am going to faint with joy,” and she fell weakly into Dorothy’s arms. “I was afraid I was going to be left out,” she muttered.

Nat ran with an ink bottle in lieu of smelling salts, but Tavia waved him away.

“Keep your distance, sir!” she cried. “This14 is a brand new frock—and they don’t grow on bushes; at least, they don’t in Dalton.”

“You bet they don’t,” commented Ned. “If the present-day girl’s frocks grew in the woods all the wild animals certainly would run wild. The bite of a chipmunk would give one hydrophobia.”

“Every knock’s a boost,” sniffed Tavia, who was very proud indeed of her narrow skirt. “I notice the boys are just as much interested in us as ever, no matter what we wear. Why! Dorothy and I had a perfectly scandalous adventure this morning——”

The maid appeared in the doorway at that moment and looked at Mrs. White. “What is it, Marie?” asked the lady.

“A—a gentleman, Madam,” said the maid. “At least, it’s a man, Mrs. White. And he wants to see you particular, so he says. He says he’s come all the way from Colorado about getting some water. I don’t understand what he means.”

“Crickey!” exclaimed the irreverent Nat. “What a long way to come for a drink.”

“It must be about this very thing we are speaking of,” said the Major, starting.

The two girls had risen and gone to a window. They could see out upon the porch.

“Goodness, Doro!” gasped Tavia, grabbing her chum tightly. “That’s the very man we met on the road this morning.”

15 We began to get acquainted with Dorothy Dale, and Tavia Travers, and their friends in the first volume of this series, entitled “Dorothy Dale: A Girl of To-day.” At that time Dorothy was more than three years younger than she is to-day. Nevertheless, when her father was taken ill, she undertook the regular publication of his weekly paper, The Dalton Bugle, which was the family’s main dependence at that time.

Later the family received an uplift in the world and went to live at the Cedars, Aunt Winnie’s beautiful home, while Dorothy and Tavia went to Glenwood School where, through “Dorothy Dale at Glenwood School,” “Dorothy Dale’s Great Secret,” “Dorothy Dale and Her Chums,” “Dorothy Dale’s Queer Holidays,” “Dorothy Dale’s Camping Days” and “Dorothy Dale’s School Rivals” our heroine and her friends enjoyed many pleasures, had adventures galore, worked hard at their studies, had many schoolgirl rivalries, troubles, secrets, and learned many things besides what was contained in their textbooks.

In the eighth volume of the series, entitled, “Dorothy Dale in the City,” Dorothy and Tavia spent the holidays with Aunt Winnie and her sons, in New York. Aunt Winnie had taken an apartment in the city, on Riverside Drive, and the girls had many gay times, likewise helping Mrs. White16 very materially in the untangling of a business matter that had troubled her.

“Dorothy Dale’s Promise,” the volume preceding our present story, deals with Dorothy’s last semester at Glenwood School, and her graduation. Tavia, who is a perfect flyaway, but one with a heart of gold, is close to her chum all the time, and the two inseparables had now, but the week before, bidden the beautiful old school good-bye.

Dorothy Dale was a bright and quick-witted girl; the impulsive Tavia was apt to get them both into little scrapes of which Dorothy was usually obliged to find the door of escape.

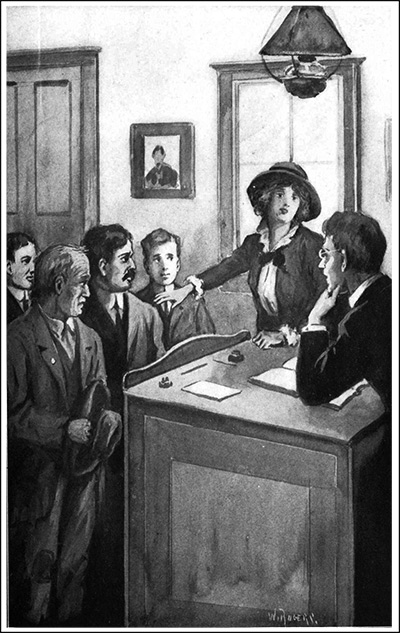

Now, when the maid announced the black-mustached man, and the boys departed by another door, Tavia drew Dorothy into the embrasure of a curtained window, whispering:

“Let’s wait. I’m crazy to know what has brought such a brigandish looking fellow here.”

“But it is not nice to listen,” objected Dorothy.

“But your aunt doesn’t mind.”

Mrs. White smiled at the two girls as she saw them pop behind the draperies. There was nothing private about the proposed interview.

The Major sat back in his chair while Aunt Winnie arose to meet the stranger as the maid ushered him into the library.

The boys were discussing the extent of Colonel Hardin’s great estate when Dorothy and Tavia joined them at the garage an hour later. The possibilities of the vast cattle pastures and game preserves, walled in by the natural boundary of the higher Rockies, appealed strongly to Ned and Nat, and even to Dorothy’s younger brothers.

“And it was all begun by Colonel Hardin taking advantage of the Homestead Law when he came out of the army. Too bad your father didn’t do that, Dorothy,” said Ned.

“What is the Homestead Law?” asked Dorothy.

“I can tell you,” interposed Nat, quickly. “Not just in the wording of the law—the legal phraseology, you know,” he added, his eyes twinkling. “But the upshot of it is, that the Government is willing to bet you one hundred and sixty acres of land against fourteen dollars that you can’t live on it five years without starving to death!”

18 “How ridiculous!” scoffed Dorothy.

“What is the use of asking these boys anything?” demanded Tavia, her nose in the air. “They’re like all other college freshmen.”

“Don’t say that, Miss,” urged Ned, easily. “Remember that we’re freshmen no longer, but sophs. Or, we will be so rated next fall.”

“Then perhaps you’ll know a little less than you have appeared to know this past year,” said the sharp-tongued Tavia. “As juniors you will know a little less. And when you’re seniors, you’ll probably be still more human—less like Olympic Joves, you know.”

“Compliments fly when quality meets,” quoth Dorothy. “Don’t let’s scrap, children. We can tell the boys something they don’t know. We’ve got to get a hustle on, to quote the provincialism of the locality for which we are bound—the wild and woolly West. A telegram has been already sent to Tavia’s folks. We start West to-morrow.”

“To-morrow!” cried Ned and Nat, in surprise.

“The Mater must have changed her mind mighty sudden,” added Ned.

“She did,” said Tavia, nodding. “Or, rather, we changed it for her.”

“How was that?” asked Nat. “And say! what did the fellow want who came so far for a drink?” and he grinned. “What’s his name?”

“Mr. Philo Marsh,” said Dorothy, gravely.19 “And a very shrewd, if not an out-and-out bad man.”

“Hul-lo!” exclaimed Ned. “What’s happened? Let’s hear about it.”

“You should have stayed and seen the visitor,” said Dorothy.

“He’s a two-faced scamp!” declared Tavia, with emphasis.

“Right out of Barnum & Bailey’s—eh?” asked Nat. “One of the greatest freaks of the age. Two faces, no less!”

But Ned saw that something serious had happened. “What is it, Dorothy?” he asked.

“I wish you had remained and seen that Philo Marsh,” said Dorothy Dale. “I—I think he is a bad man. I do not trust him at all.”

“And good reason!” broke in Tavia, forgetting that she had first exclaimed over the romantic appearance of the man with the silky black mustache and the yellow diamond.

Then, eagerly, she went on to tell the boys of what had happened to her and Dorothy on the road that morning.

“Why! the scamp!” ejaculated Nat, quite savagely.

“But that isn’t all the story?” queried Ned, turning to Dorothy. “What were you going to say about Philo Marsh?”

Dorothy at once told them how she and Tavia20 had hidden behind the window draperies when Mr. Philo Marsh was announced, having recognized him as he stood waiting on the porch.

“And you should have heard him talk!” interrupted Tavia.

“He is a very smooth talking man,” went on Dorothy, seriously, “and we could see father and Aunt Winnie were impressed.”

“But what did he want?” Ned demanded.

“He says he represents a committee of citizens of Desert City and the farmers on that side of the Hardin estate. He had papers all drawn up, ready to sign, leasing to him and his fellow-committeemen the water rights on the Hardin place, and he wants father and Aunt Winnie to sign up right now.”

“But they didn’t?” cried Ned and Nat.

“He urged them to. He claims haste is necessary.”

“Why?” asked the older cousin.

“He wasn’t just clear about that. I guess that is what made father doubtful. But he was very persuasive.”

“Say!” interrupted Nat. “What about this water? If there is so much of it on the Hardin place, doesn’t it flow somewhere?”

“That’s a curious thing,” Dorothy said, quickly. “It seems this water-supply is a stream called Lost River.”

21 “Lost River?” ejaculated Ned.

“Yes. There’s more than one like it out there, too. I guess this particular Lost River has its rise on the estate somewhere. And without flowing beyond the boundaries of the land Colonel Hardin has left to us, it dives right down into a crack in the earth again.”

“Crickey!” exclaimed Nat. “Some river! I want to see that.”

“I’ve read of such things,” said his brother.

“It must be wonderful,” Dorothy said. “You see, they want father and Aunt Winnie to let them turn the water into another channel. From that channel they will pipe water to Desert City, while the surplus will be carried by open ditches to the irrigated farms.”

“And how about the water supply for the cattle pastures?” demanded Ned, who, from the first, had shown a deep interest in the cattle end of the business in hand.

“Oh, they say there is water in abundance,” Dorothy answered.

“Well,” asked Ned, “did that fellow get mother to sign up? That’s the important question.”

“Do you think we would let her, after what we know about the fellow?” retorted Tavia, indignantly.

“I don’t see how you girls knew much about22 him,” chuckled Nat. “You simply did not like the cut of his jib, as the sailors say.”

“What did you do to stop them?” asked Joe Dale, round-eyed. “Walk right in and give him away?”

“That would have been melodramatic, wouldn’t it?” laughed Dorothy.

“But what did you do?” insisted Joe.

“Why,” said Tavia, “we climbed out of the window—and I ripped my skirt, of course!—and we ran around to the hall and sent the maid in to call Mrs. White out. Then we told her about Philo Marsh—the two-faced scamp! Why, to hear and see him in that library, you’d think butter wouldn’t melt in his mouth!”

“Well, wouldn’t it?” grunted Nat.

“I guess the Major was suspicious, anyway,” chuckled Tavia, ignoring Master Nat. “And Mrs. White declared she would have to look over the ground personally before she could make any decision.”

“He was in an awful hurry,” said Dorothy.

“Who’s in a hurry?” asked Ned, quickly.

“That Philo Marsh, as he calls himself. So we are going to start for the West to-morrow, instead of next week.”

“And what is this fellow who’s come East here going to do?” asked Ned.

“Going back. Says he’ll meet us at Dugonne.23 That is where we leave the train. Oh, Aunt Winnie has already looked up our route, and the time-tables, and all that,” Dorothy said.

“Well, we’ll be on hand to look out for Little Mum, and see that this fellow doesn’t ‘double cross’ her in any way,” said Nat, with assurance.

“We girls shall watch him, too,” Tavia declared. “I believe he’s a regular ‘bad man’—like you read about.”

“Shouldn’t read about such things,” advised Dorothy, laughing.

“I guess we four can hedge Little Mum about so that no wild and woolly Westerner will trouble her,” Ned said, with gravity.

But only time could prove whether that was so, or not.

The Fire Bird looked like an express truck—or so Nat said. They had loaded up the boys’ auto with more than a fair share of the baggage.

“But just the same, you girls have got to find room in here,” declared Ned. “Nat and I must have somebody to chin to while we’re driving over Hominy Ridge. They say there are ‘ha’nts’ in the woods, and we’d be afraid to go alone.”

“Poor ’ittle sing!” crooned Tavia. “Doro and I know just how scared you are. But we’ll go with you—providing you can find us room.”

“We’ll make room,” said Nat. “Mother will have to carry some of the baggage in her car. There is no use in putting the last camel on the straw’s back!”

“Joe and Roger have begged to go along,” Dorothy said.

“Well, they’re excess baggage, too,” answered Nat. “They’ll have to go in the other car.”

It was the evening following the June day on25 which Aunt Winnie had divulged her Great Surprise. The intervening hours had been very, very busy for the girls.

It was arranged that the party should go by auto to Portersburg to catch the midnight express on the P. B. & O.

Dorothy and Tavia—as well as Mrs. White—had made exceedingly swift preparations for this journey. Of course, Ned and Nat did not have much to get ready.

“Wish I were a boy,” groaned Tavia.

“I’ve heard you express that wish a thousand times,” declared Dorothy.

“This is the thousand-and-wunth time then! Look at how easy they have it, Doro! All they have to do is put a clean collar and a toothbrush in their pockets, and start for a tour of Europe!”

It was a long journey over the forest-covered ridge to Portersburg. They started at nine o’clock so as to be sure to be on time at the railway station. The chauffeur who drove Mrs. White’s machine would chain the cars together and bring them—with Joe and Roger—back to the Cedars, after seeing the tourists off for the West.

Dorothy kissed the Major good-bye. “My little Captain” he still called her. Major Dale was very proud of his daughter.

They got away at last, the Fire Bird in the lead. There would be no moon until after midnight, so26 they had to depend entirely upon the headlights for the discovery of any obstruction in the road.

Nat was under the wheel and he had insisted upon Tavia sitting beside him. Naturally Ned was glad to get Dorothy to himself in the tonneau. It was a tight squeeze for the latter couple, for the motor car was overburdened with baggage.

“Are you comfortable, Doro?” shouted Tavia, turning to look at her chum.

“Just as comfortable as I can be with the end of Nat’s dress-suit case poking me in the back, and a bundle of umbrellas right across my poor shins. Oh! I did not dream it would be so uncomfortable.”

“Our dreams seldom come true,” declared Tavia, sentimentally.

“Don’t know about that,” said Nat. “You know, a couple of tramps were talking about the same thing. One says: ‘Isn’t it strange how few of our youthful dreams come true?’ And the other fellow answers back: ‘Oh, I dunno. I remember when I used to dream of wearing long pants, and now I guess I wear ’em longer than anybody else in the country.’”

“Better ’tend to your business, boy, and stop cracking jokes,” advised Ned.

“I’ll see that he doesn’t run us up a tree,” promised Tavia, confidently.

The Fire Bird swiftly passed out of the neighborhood27 with which the young people were familiar and struck into the road leading to Portersburg. It was a fairly good auto track, but had never been oiled. Therefore, there were “hills and hummocks,” as Tavia said, “in great profusion.”

“Oh! oh! OH!” she gasped, in crescendo, as the car bounced and jarred over some of these “thank-you-ma’ams.” “Did you ever see such a hubbly road, Doro?”

“I don’t see much of this one,” confessed Dorothy.

The forest shut the road about so thickly that beyond the headlights’ glare the way looked like a tunnel. Occasionally, some small, night wandering animal, scurried across the track.

“There’s a rabbit!” ejaculated Tavia. “I wonder what he thinks this auto is?”

“The Car of Juggernaut,” said Dorothy. “Lucky he escaped.”

They were going down a hill. Suddenly Nat threw out the clutch and braked hard. The horn likewise uttered a stuttering warning.

A ray of light flickered upon some object directly in the path of the flying car. It was impossible to stop and the road was too narrow for Nat to swerve aside and in this way escape the collision.

“Low Bridge!” he shouted, and they all28 crouched down. The next instant the car struck the creature standing in its path.

“A deer!” yelled Ned, as the car came to a jarring stop, some yards beyond the point of collision.

He hopped out and ran back to see if the poor animal was really dead. His mother’s car meanwhile halted where the deer lay beside the road. The Fire Bird had thrown the creature some distance away, and it was quite dead, its neck being broken.

“Killing game out of season is a misdemeanor, Nat,” said his brother, returning to the automobile. “Lucky you are going to get out of the state to-night. The game warden might be after you.”

“I don’t think it is a thing to laugh over,” said Tavia. “The poor deer!”

“Thank you,” Nat said. “I never expected to hear you call me by such a tender name.——”

“Don’t flatter yourself, Mr. Nat!” snapped Tavia, scrambling out of the front seat and joining Dorothy in the tonneau. “I don’t want to risk being in front if you are going to run down all the livestock in the country.”

“It’s too bad to leave perfectly good venison behind,” Ned said. “I suppose he was dazzled by the lights. You must have a care how you drive, Nathaniel. Mother says so.”

29 “Huh! I couldn’t see the deer until we were right on top of it.”

“I know Nat didn’t mean to,” said Dorothy, the peacemaker. “It is awfully dark.”

Nat only grunted, but he drove more slowly. The deer had been actually hypnotized by the lamps; Nat did not want to play the same rough joke on another.

“Huh!” he muttered to his brother. “If the law had been off and we’d come up this way hunting deer, we wouldn’t have gotten within a mile of one!”

“Life is full of disappointments—just like that,” chuckled Ned, turning so that the two girls could hear him. “There was the old farmer who saw something in the clothing store window that kept him marching up and down before it for an hour, looking frequently at his watch.

“Finally he went inside and demanded of a salesman: ‘What’s your time?’ ‘Twenty minutes past five,’ says the salesman. ‘That’s what I make it,’ says the farmer, ‘and I’ll take them pants,’ and he pointed to a ticket in the window which read: ‘Given Away at 5.20.’ But he was disappointed, too.” concluded Ned.

“How ridiculous,” said Dorothy. “Oh! here’s the end of the woods. I’m so glad.”

“It’s the end of this piece,” said Ned. “But there’s more ahead.”

30 It was much lighter when they came out into the farming lands, and Nat could speed up his engine a little. Behind the Fire Bird coughed the other car. They met nobody, nor overtook any vehicle. This was a lonely road by night. They were still a long distance from Portersburg, and it was after eleven o’clock.

“You’d better get a wiggle on, boy,” declared Ned. “We don’t want to miss that train.”

“And I do want to miss any other deer that may be loafing about this right of way,” grumbled his brother.

They flew past a farmhouse where a dog tugged at his chain and almost barked his head off at the two automobiles. A wall of forest loomed up before them again. It was fortunate that the darkness beyond the lamplight made Nat reduce speed.

Up heaved a disturbing figure beside the road. Nat applied the brakes in a hurry once more. The beast stepped right into the radiance of the lamplight and then—the automobile struck it!

Everybody screamed—including the object battle-rammed! “Another deer!” shrieked Tavia. But the bellow that replied made her realize at once that she was wrong. No deer ever bawled like that!

“It’s a cow,” said Ned. “Crickey, boy! you’ll slaughter all the animals in the state.”

31 “That cow isn’t hurt,” growled Nat, “or she wouldn’t bawl so.”

The other automobile stopped in the rear and Aunt Winnie was anxious to know what had happened. Ned was already out of the Fire Bird, trying to discover the whereabouts of the cow and the extent of her injuries.

“Something doing back there at the farmhouse,” warned the chauffeur of Mrs. White’s car. “You boys will be deep in trouble in a minute.”

They could see lights in the windows, and now heard a banging of doors. A harsh voice began to shout commands, and a waggling lantern approached across the fields.

Ned had found the cow. She was leaning up against the roadside fence, and one horn was hanging by a thread of tissue, in a drunken looking manner over her eye. Otherwise she seemed to be unhurt—only surprised. The varnish of the car had suffered more than the cow.

When the farmer arrived he was very angry.

“I’ll fix you city fellers fer this. I’m a constable. Ye air all arrested!”

His dress was haphazard. Over his coarse nightshirt he had drawn his trousers, and he was barefooted. But he had not forgotten his star of office, and he carried a locust club as well as the lantern. He fixed himself in the road directly in front of the Fire Bird and demanded fifty dollars.

32 “I could buy cows like that skinny old thing for fifty dollars a dozen,” grumbled Ned.

“You’ll pay me fifty for this here caow, or th’ whole on ye will march ter jail at Hacktown.”

“Your cow is perfectly good,” suggested Tavia, “all except one horn. And that horn serves no good purpose on a domestic animal. Most farmers dehorn their cattle anyway. I think this man owes us about fifty cents.”

Nat began to chuckle at that, and the farmer was not at all pleased.

“Ye gotter fork over fifty dollars, or go to Hacktown an’ see the Jestice of the Peace.”

“But we’re in a hurry,” said Ned.

“That’s what they all say,” chuckled the farmer.

“You had no business to allow your cattle to run loose in the road,” cried Ned.

“Think not, eh, young man?” retorted the man. “You’d better read aour county ord’nance on cattle. Don’t hafter fence aour farms no more.”

“I bet,” growled Ned to the girls, “that the old scoundrel just set this crow-bait of a cow like a trap for any automobilist who might come by. Goodness! I hate to pay that fifty dollars.”

Time was flying and Mrs. White was becoming anxious. “Do pay the man, Ned, and let us go on. Of course, the cow is not worth so much——”

“Why, mother, it’s a miserable little thing,” began Nat; but the farmer burst in with a lot of threats as to what he would do if the money was not immediately forthcoming, and Nat subsided.

“It is an imposition, Mrs. White,” warned her chauffeur. “I’ll go with him, if he likes, and tell the judge about it.”

“I’ll pull you all,” threatened the farmer, boisterously, “if you don’t fork over the money for my caow—yes, I will, by Jo!”

“If he talks fresh to mother,” growled Nat to Ned, “we ought to take away his tin star and club and throw him into the ditch.”

“No use making a bad matter worse,” said Ned.

“It is unfair,” Dorothy said, warmly. “Fifty34 dollars is a lot of money. Can’t we postpone our trip and go to court with this man?”

“Goodness, Dot!” exclaimed her aunt, who heard this. “Our berths are engaged upon that train. We positively cannot wait here. Of course the cow isn’t worth so much as this man asks——”

At that moment a dilapidated figure shuffled into the radiance of the automobile lights. It was an ancient darkey, with kinky gray wool, and he took off his ragged hat as he asked:

“Ebenin’, genmen an’ ladies. Is yo’ seed anythin’ ob my cow? She done strayed erway ag’in, an’ I’s powerful anxious ter recover her—ya-as, suh!”

“Another cow!” groaned Nat. “The owner of that pet deer will be around next.”

“What kind of a cow was it?” asked Tavia, giggling.

“Jes’ a cow, Ma’am,” said the old darkey. “Jes’ a ord’nary ornery cow, Ma’am. Ebenin’, Mars’ Judson,” he added, seeing the farmer for the first time. “Has you seed my cow?”

“Naw, I ain’t,” snapped the farmer.

Here Dorothy Dale suddenly broke into the inquiry meeting. “Did your cow have a big white patch on her left shoulder, and is she otherwise a red cow?” asked the girl.

“Ya-as’m. That suah is my cow.”

35 “Turn your light on that one against the fence, Ned,” commanded Dorothy. “Now look, sir,” she added, to the old negro. “Is that your cow?”

“Suah is!” declared the darkey, gladly. “Das my Sookey-cow. Law-see! She done broke her horn. I wisht she bruk two on ’em; den she couldn’t hook herself t’rough de parstur fence no mo’.”

“Well! what do you know about that?” demanded Tavia.

“This constable ought to have his badge taken away,” grumbled Nat.

Aunt Winnie was a most timid lady, but she was angry now. “You shall be reported for this, sir, just as soon as I get back from the West,” she promised the farmer. “Give the colored man five dollars, Ned. He deserves something for showing us what this other man is.”

The old darkey was tickled enough to accept a five dollar note for the loss of the cow’s horn. The creature was not really hurt, and everybody was satisfied save the constable-farmer who had over-reached himself. He dared say nothing more about arresting the automobile party, and the two cars soon got under way again and shot off along the road to Portersburg station.

There was no further adventure on the way. They arrived at the station with five good minutes to spare. The town was asleep, but the agent was36 in his office with the tickets for Mrs. White’s party and the coupons for the Pullman berths.

They were to have a section to themselves, and an extra berth besides. Dorothy was to occupy this extra berth, which proved to be an upper.

Everybody else aboard the car was asleep and the porter made up their berths at once. “I do so hate to half undress in the corridor of a car,” grumbled Tavia. “It’s as bad as camping out.”

“But we pay good money for the privilege,” said Dorothy. “I wonder why we are always so easy—we Americans?”

“Our fatal good nature. That’s it!” cried Tavia.

Dorothy had a hazy idea that somebody in the berth beneath her was restless. Then she fell asleep, roused only now and then by the stopping and starting of the train. At seven she was wide awake, however, and as the train was still going at full speed, she crept down from her high perch and started for the ladies’ room at the end of the car.

But suddenly a hand was stretched out for her and the person in the lower berth whispered:

“I say, Miss! I say!”

Dorothy turned to see a little old lady, in a close, black bonnet with the strings untied, but otherwise fully dressed. It was plain she had gone to bed in all her clothing the night before.

37 “Can a body git up, Miss?” whispered the worried old creature. “My goodness me! I been useter gittin’ up when the fust rooster crows; this has been the longest night I ever remember.”

“Why, you poor dear!” returned Dorothy, warmly. “Of course you can get up. Come with me and I’ll help you tidy yourself for the day. You must feel all mussed up.”

“I do,” admitted the old lady, feelingly.

She came after Dorothy, but the latter saw that she bore with her a covered basket, the cover being tied close with bits of string.

“You need not be afraid of leaving your lunch basket in the berth. Nobody will take it,” Dorothy said.

“I—I guess I’ll keep it by me,” said the old lady, with a timid smile.

Dorothy was able to make the old lady comfortable, and she found out several things about her while the porter arranged their berths. She was a Mrs. Petterby, and had lived all her life long (she was over sixty) in the little mill town of Rand’s Falls, in Massachusetts.

This was the very first time the old lady had ever been ten miles from the house where she was born. She had lived alone in her own house for the last few years, her husband and all her children but one being dead.

“My baby, he’s out West. I’m a-going to see38 him,” declared Mrs. Petterby. “He sent me money for ticket and all, long ago; he told me to put it in the bottom of the old teapot, where I’d be sure to know where it was, and then I could start for Colorado any time the fit tuk me.

“Did seem day b’fore yisterday, as though I’d got to see my baby again. He was dif’rent from the other children—sort o’ wild and hard to manage. He had a flare-up with his dad and went West.

“But there ain’t a mite o’ harm in my baby—no, Ma’am! An’ so I tell ’em. His father said so himself b’fore he died. He warn’t like the rest o’ the children, so his father didn’t understand him.

“He’s doin’ well, he writes. Gets his forty-five dollars ev’ry month, and sends me part. Of course, I don’t need it; I got it all in the Rand’s Falls Bank. But I kep’ out this ticket money, like he said; and—here I be!” and she cackled a soft little laugh, and smiled a transfiguring smile as she thought of the surprise she was going to give “her baby.”

She was going to Dugonne, the very town where Dorothy and her friends were to leave the train. So the girls sort of adopted the little old lady. But they could not find out what was in her basket.

Tavia was enormously curious. “I saw her39 dropping something through a crack into the basket,” she whispered to Dorothy. “She was feeding it.”

“Nonsense!” exclaimed her chum.

“You see. It’s no lunch basket. It’s something alive.”

“A dog?” suggested Dorothy.

“Maybe a cat.”

“Or a parrot?” again said Dorothy.

“Or a rabbit.”

“It couldn’t be a canary, I s’pose?” asked Dorothy.

“Or a pet goldfish?” giggled Tavia.

“How ridiculous!” returned the other girl.

Everybody went to breakfast when it was announced, save Mrs. White. She had a “railroad headache,” and lay back in her seat with closed eyes and an ice-pack upon her forehead. But Dorothy thought she ought to have something to “stay her stomach.”

“You know,” she said to Tavia, “this car will be taken off and we will not be able to get even a glass of milk for her before noon.”

Mrs. Petterby overheard this, and she blushed and whispered: “I got one o’ them bottles that keeps things hot or cold, as you want ’em. You get some milk off the ice, and then it will be all ready to have the egg broke into and shaken up when your auntie wants it, by and by.”

40 “That’s nice of you!” cried Dorothy, and proceeded to call the waiter and order the cold milk.

“But where’ll you get an egg—a real fresh egg, I mean?” sniffed Tavia. “Not on a dining-car.”

“That’s so!” groaned Dorothy. “And Aunt Winnie is so particular about her eggs. She can always tell if an egg is the least bit stale.”

The old lady leaned forward again, and once more the pretty pink flush suffused her withered cheek. She was a keen-eyed, birdlike person, and her manner was timid like a bird’s.

“If—if you don’t mind waiting about an hour, I shouldn’t be surprised if I—I could supply the fresh egg,” she said.

“You?” gasped Tavia, amazed.

“You know where we can buy one, you mean?” queried Dorothy.

“Oh, you won’t have to buy one,” declared Mrs. Petterby. “I’d be glad enough to give it to you.”

“But who has fresh eggs on this train?” demanded Tavia.

“I guess nobody has them to sell, dearie,” said the little old lady, smiling. “But in about an hour I can get one.”

“Do—do you think she’s just right, Doro?” whispered Tavia, on the sly.

41 Dorothy did not know. It sounded very peculiar to her. But the little old lady seemed quite in her right mind, and she went back to the Pullman, still clinging to her basket.

That mystery furnished the girls and Ned and Nat with subject matter for an endless discussion. They guessed at its contents as everything from a white rat to a jewel-box, or a root of horseradish that Nat declared he believed she was taking with her from her garden, to transplant on her son’s ranch. “His horses will like it, you know,” said Nat, seriously.

“Yes,” agreed his brother, “on their oysters. Horseradish is very good as a relish with raw oysters.”

“And of course they rake oysters right out of the streams and ponds in Colorado,” sniffed Tavia, with a superior air. “Was anything ever crazier?”

Dorothy went to sit beside Mrs. Petterby again. The old lady was smiling contentedly. “I guess I’ll stay as much as a week with my baby,” she declared to Dorothy. “I hope I won’t be homesick before the week’s up.”

“But it will take you almost a week to get there, and a week to return—and you intend to stay in Colorado only a week?”

“I declare, child! I don’t believe I could stand it longer. I don’t think I could stand furrin’42 parts—not at all. Rand’s Falls, Massachusetts, is good enough for me.”

There was a movement in the basket. Dorothy was sure of it. And a sort of crooning noise. Dorothy looked her amazement and curiosity—she could not help it.

“There! there!” said the old lady, softly, and tapping the basket. Then she looked aside at the girl and whispered:

“Don’t you tell that conductor. They told me that I couldn’t take her with me unless I crated her and put her in the baggage car. But I’ll show ’em!”

“What is it?” breathed Dorothy. “Oh! I won’t tell.”

“There! your auntie can have her fresh egg in a minute or two now. I know Ophelia.”

“Ophelia?” gasped Dorothy.

“Yes. That’s her name. I gave it to her when she was a little bit of a chicken.”

“A hen!” exclaimed the amazed Dorothy.

“Yes. She’s a regular pet—and not much more than a year old. She was the only one left of a brood that my old Blackie brought off last May was a year ago,” said Mrs. Petterby.

“I couldn’t afford to have old Blackie nussin’ just one chicken,” she pursued, calmly. “So I brought Ophelia up by hand. She was just as cunning as she could be.

43 “She sat on my shoulder when I ate breakfast, and she’d eat her share of johnny-cake and sausages, too—yes, Ma’am! Then she’d take a nap sometimes, in my lap, when I sot down in my rocker by the kitchen window.

“And when she got to be a good sized pullet and I was lookin’ for her to begin to lay pretty quick, I declare if she didn’t hop up into my lap and lay her first egg.”

“My!” exclaimed Dorothy, in appreciative wonder.

“I left my flock in the care of my next door neighbor; but I knowed Ophelia would be lonesome for me.

“So,” concluded the little old lady, “I’m a-takin’ her through unbeknownst to the conductor. Don’t you tell! And now—there!”

She thrust her hand under one flap of the covered basket. There was a little rustling sound, a seemingly objecting croak, and out came the old lady’s hand with a white, clean and warm egg.

“I expect she’s gettin’ sort of broody,” said Mrs. Petterby, dropping the egg into Dorothy’s hand. “She’s beginnin’ to think of settin’ an’ tryin’ to raise a famb’ly. That’s all she knows about it—poor thing!

“Well, there’s your aunt’s egg, child.”

The girls and Mrs. White’s sons were vastly amused by the egg incident. Aunt Winnie thankfully drank her egg and milk, but her boys joked about the production of “Ophelia” being so quickly “swallowed up.”

“And why didn’t the old lady bring along Hamlet?” demanded Nat. “The Prince of Denmark would have found life in a Pullman endurable, I fancy. He was a philosophical old shark.”

“Speaking of eggs,” Ned said, ignoring his brother’s irreverent observation about the Melancholy Dane, “speaking of eggs——”

“Well! speak, I prithee!” said Tavia.

“Why, there was a chap performing tricks of legerdermain one night, and he took eggs from a high hat, as usual. In his ‘patter’ he interpolated a remark to a wide-eyed small boy who sat down front.

“‘Say, sonny, your mother can’t get eggs without hens, can she?’ he said to the kid.

“‘Yes, she can,’ replied the boy.

“‘How does she do it?’ chuckles the conjurer.

45 “‘She keeps ducks,’ says the kid.”

“Good! good!” quoth Nat, applauding. “If you hadn’t told it, Ned, I would.”

“Ah-ha!” cried Tavia. “You boys have been reading the same joke-book, and have gotten your wires crossed.”

“Goodness, Tavia! Don’t. Such slang as you use!”

The train was bearing them rapidly and smoothly toward the West. The girls and Ned and Nat enjoyed this sort of traveling immensely. At the rear of the train was a fine observation platform, and the four young folk got more benefit of the chairs there than any of the travelers.

The prospect in part was lovely. They liked, too, to sit there as the train roared through the smaller towns where there was no stop. And it was nice when they swept over the rolling prairies and crossed the mid-western rivers on the long bridges.

The stops at the larger cities were never long; then the train would fly on again, reeling off the miles at top-speed. The second night they did not mind sleeping in the berths. And Dorothy helped Mrs. Petterby get ready for bed so that she felt more comfortable.

“But it does seem awful resky,” she sighed. “Suppose there should be a smash-up—an’ me without my skirt on!”

46 There was a smash-up the next day, but fortunately the train in which Dorothy Dale rode was not in the accident. Two freight trains went into each other some ways ahead of the express, and spread themselves all over the right of way. It would take some time to clear the mess up so that the express could pass; therefore the latter was stopped at a very pleasant Illinois town and the conductor told the young folk they would have at least two hours to wait.

“Goody-good!” exclaimed Tavia. “Let’s run and see if we can get some candy at a decent price, Doro. The candy-butcher aboard this train is a highway-robber.”

“I can beat that for a suggestion,” Nat said. “Why not find a place where we can get something beside this buffet stuff to eat. I haven’t the heart to eat all I want to in the dining-car.”

“Why not?” asked Dorothy.

“It costs so much.”

“Come on,” agreed Ned. “We’ll go foraging.”

“Be sure you get back in time, children,” ordered Aunt Winnie.

But she expected Dorothy to keep her wits about her, whether the rest of them did or not. Near the railroad station there was nothing that appealed to Dorothy and Tavia—no restaurant, at least. But up a clean, bright little side street47 from the public square they saw a small, white painted house, with green doors and green window frames. Over the one big window beside the open door was a sign that read:

ORIENTAL LUNCH ROOM

“That looks nice,” said Dorothy.

“And look at that dear, old, clean colored Mammy!” gasped Tavia.

On the platform before the little restaurant was a large colored woman with a crimson bandana on her head, a spotless dress and white apron, and her sleeves rolled up to her fat elbows.

“I bet she can cook,” quoth Ned, with assurance.

“We’ll give the Oriental a whirl,” agreed Nat.

But just as they were crossing the street to go to the place, Tavia suddenly exclaimed: “Oh! there’s somebody in there.”

“Well, what of it?” asked Ned.

“It’s hardly big enough for us. Let’s wait till that man comes out. I don’t like his looks, anyway. He has his hat on,” declared Tavia.

They all saw the man in question. He was a black-browed and broad-hatted stranger, and he sat at a table in the little eating place, staring out through the window with a frown on his brow. He was not an attractive looking man at all.

48 “I bet he has a bad conscience!” exclaimed Nat.

“Or indigestion,” chimed in his brother.

“He won’t eat us,” said Dorothy, doubtfully. “If we do go in——”

“I say, Mammy!” cried Tavia, to the smiling colored woman. “Do you do the cooking?”

“’Deed an’ I do, Missie,” declared the woman. “An’ I got de freshes’ catfish dat eber come out o’ de ribber. An’ light beaten’ biscuit—an’ co’npone, an’ all de odder fixin’s.”

“Sounds good to me,” said Nat, smacking his lips.

“But can’t we have the place to ourselves?” complained Tavia. “If that man was only gone!”

“Yo’ mean Cunnel Pike?” whispered the colored woman. “He comes yere befo’. He’s er-gwine out on dat train wot’s stalled down yander——”

“That’s the train we’re going out on,” Tavia declared. “Like enough he’ll stay here till it goes.”

“But we can eat in there if he is present,” said Dorothy, again. She knew just how stubborn Tavia was when she got an idea in her head.

“We’ll get him out! I’ll tell you,” gasped Tavia, suddenly.

“How?” demanded the others, in chorus.

49 “No, I won’t. Only Nat. I’ll tell him. You can order the meal, Ned, and while it is being cooked we’ll fix it so that horrid man will leave. Come on, Nat.”

Nat went off with her. The others were doubtful of her scheme, but they were hungry. So Ned instructed the colored woman as to the repast and then he and Dorothy sat down on the steps to wait for developments.

Meanwhile Tavia led Nat back to the main square of the village. “Run, get me a telegraph blank from the station,” she ordered, and Nat, without question, did as he was bade.

Tavia quickly wrote a message and addressed it to “Colonel Pike, Oriental Lunch Room,” with the name of the town appended. “Now,” she said to Nat, “I dare you to send this message,” and her eyes danced.

Nat read it through once, looked puzzled, and then read it twice and grinned—the grin expanding as the full significance of the joke penetrated his mind.

“Crickey-Jiminy!” he exclaimed. “But if they tell him?”

“Telegraph operators are not supposed to tell. Instruct this one not to do so, Nat. Now, I dare you!”

“You can’t dare me,” boasted Nat, and hurried back to the station. When he returned they50 strolled on to the Oriental Lunch Room once more and rejoined Ned and Dorothy.

“Now! whatever have you been doing, Tavia?” demanded Dorothy.

Tavia could not help giggling. “Just you wait and see,” she said.

“I hope you didn’t let her do anything very bad,” Dorothy said to Nat.

“I helped her do something mighty smart,” returned her cousin, looking with admiration at pretty Tavia.

Just then a boy with a Western Union cap came up and went into the little restaurant. “Say!” he demanded of the black-browed man. “Are you Pike?”

“Am I what?” asked the man, in a hoarse voice.

“Cunnel Pike’s the name,” said the boy. “And right at this restaurant.”

“Oh! a telegram?” demanded the man, in surprise. “Well, that’s my name,” and he put his hand out for the envelope.

“Sign here,” said the boy, and after he had gotten the signature in his book he gave up the message and went out.

“Look!” gasped Tavia, clinging to Dorothy’s hand.

All four of the young people watched covertly the man behind the window. They saw him tear51 open the envelope and read the message curiously. Then his heavy, dark face changed and curiosity was blended first with amazement and then with something very like fear.

He started to tear the message up. Then he got to his feet and his face began to pale. Dorothy and the others watched him in wonder and some alarm.

Finally the man grabbed his hat brim and pulled it down over his eyes. He strode out of the place and down the steps, without looking at the boys and girls, and started straight for the railroad station.

As he went his trembling fingers relaxed and the telegraph message dropped at Dorothy’s feet.

“What do you know about that?” whispered Nat. “We sent him that message.”

“What?” demanded Dorothy, and snatched it up.

She uncrumpled the sheet of yellow paper and read in the crooked letters of the old typewriter which the local operator used:

“Come home at once. All is forgiven.”

“Tavia Travers!” cried Dorothy. Then she burst into laughter, and so did Ned when he had read the slip of paper.

“I believe I have done a very good thing,”52 claimed Tavia, quite seriously. “No wonder that old Colonel Pike looked like a ‘grouch.’ He had trouble on his mind, and now we’ve sent him home to get it all straightened out.”

“Oh, Tavia!” groaned Dorothy again.

“I’d give a good bit to be at his home—if he goes there—and see what happens,” Ned said, when he had ceased laughing.

“Anyway,” grinned Nat, “the ‘bogey man’ is gone and we can take possession of the Oriental Lunch Room.”

Which they forthwith proceeded to do. The old colored woman served them a delicious meal, and added to their enjoyment of it by her comments upon many things, not the least of which was her wonder as to “what tuk Cunnel Pike out o’ yere so suddent like.”

The gay little party left the restaurant in good season and rejoined Aunt Winnie aboard the train. They saw nothing more of the man called “Cunnel” Pike. Another train had just gotten away for the East and Tavia said:

“I tell you he has gone home. We did a very good action—probably have changed the current of his whole life.”

“Like to peek over the shoulder of the Recording Angel, Tavia, and see what’s marked down against you for that telegram—eh?” chuckled Ned.

53 “Well!” declared Dorothy, “I hope when he gets home they will be as glad to see him as that message intimated.”

“Well, I shouldn’t worry and get wrinkled!” shrugged Tavia.

“I guess we’ll never know about that,” said Ned.

“It’s like one of those serial stories in the papers, ‘continued in our next’—and you always miss your copy of the next number,” said Nat. “I’ve a dozen different plots ‘hanging fire’ in my mind that I never will get to know how they finish up.”

“Learn to read books, then,” advised his brother, “and stop littering up your mind with such useless stuff.”

“Wow!” exclaimed Nat. “You talk like Professor Grubber. Oh, I say! Did you hear of that one they had on Old Grubs in class one day? He was discussing organic and inorganic kingdoms. Says he:

“‘Now, if I should shut my eyes—so—and drop my head—so—and remain perfectly still, you would say I was a clod. But I move. I leap. Then what do you call me?’

“And Poley Gray says, quite solemnly, ‘A clodhopper, sir.’ It got them all,” concluded the slangy Nat. “Even Old Grubs himself had to laugh.”

54 After that two-hour hold-up of their train the party found that the speed at which they traveled was greatly increased. Each engineer in turn tried to make up a bit of that handicap, and the travelers were tossed about in their berths that night in rather a disturbing manner.

Mrs. Petterby would not have gone to bed at all had it not been for Dorothy’s encouragement; she would have sat up with her pullet in her lap, and her bonnet firmly tied under her chin.

“I’m ever expectin’ to have this train crash right into another,” said the old lady. “And I want to be ready for it.”

“Do you think you’ll be any more ready sitting up than you will be lying down, dear Mrs. Petterby?” Dorothy asked.

“Seems as if I would,” returned the old lady. “I tell you what! I sha’n’t come out to see my baby no more. I shall tell him that. And I dread the going back.”

“Perhaps you will like Colorado so much that you will want to stay.”

“What? And never see Rand’s Falls, Massachusetts, again?” exclaimed Mrs. Petterby, in horror. “I—guess—not.”

“I hope we shall see her baby when she meets him,” Doro said, tenderly. “And I hope he’s all she expects him to be.”

55 “A cow-puncher at forty-five a month,” sniffed Nat.

“Oh! but cowboys are awfully romantic,” said Tavia, quickly.

“Look out for her, Dot,” begged Ned. “You’ll have to blindfold her to get her past any cow-punching outfit we may meet. I can see that.”

On the following day when the train crossed the first ranges and they beheld little bunches of five hundred or a thousand head of “longhorns,” Tavia went into raptures.

The four young folk from the East remained upon the observation platform most of the time. Even after supper the girls went back there to view the prairies in the gloaming.

There was a distant light here and there, like a low-hung star; but there were few towns, or even settlements. Suddenly the train slowed down and they saw several switch-targets. Then they passed the ghostly fence of a large corral, and they ran by a barn-like, darkened station and freight sheds.

The train stopped altogether. The girls saw the flagman seize his lantern and run back to set his signal. “Come on!” exclaimed Tavia. “He’s left the gate open.”

She gave Dorothy no time to decide, but ran56 lightly down the steps herself and sprang onto the cinder path. Dorothy followed.

“Listen!” whispered Tavia, seizing her chum’s hand, tightly. “Hear the night breathe.”

There did seem to be a vast, curious sound to the inhalation of breath.

Dorothy listened to the sound with a wonder that grew. It was not the engine exhaust. It was a sound like nothing she had ever heard before.

“See! there’s another big corral beyond the station,” Tavia said. “Come on!”

She led Dorothy down the platform, and out upon the softly giving earth.

The headstrong Tavia went directly toward the high fence. The regular, rhythmic breathing seemed to surround them.

Of a sudden, something scrambled against the fence before them. There was a bump against the bars, and two shining eyes transfixed them.

The engine gave a single long-drawn shriek. Instantly the car wheels began to turn, while from the creature inside the corral fence came a bellow.

“Goodness me!” shrieked Tavia. “It’s cattle—the corral’s full of cattle.”

“That isn’t the worst of it!” returned Dorothy, grabbing her hand and starting to run. “We’re being left behind, Tavia Travers!”

“Well! I wouldn’t talk as though it had never happened before to anybody,” said Tavia, at last. “Why! even we, Doro, have been left behind before.

“Still, I grant you, we were never left before behind a fast express, which was speeding your aunt and the boys away from us so rapidly that we will be miles and miles behind before they discover our absence.”

“If, however, they learn that we are behind before they reach——”

“Stop!” commanded Dorothy, dropping down beside the track and covering her ears. “If you say that again, I’ll certainly do something to you.”

They had followed the train down the long platform, screaming to the flagman to pull the signal cord. He had not heard them. He had merely closed the gate and gone into the car.

Here Dorothy Dale and Tavia Travers were,58 deserted at this un-named prairie station, where—to all appearances—there was not a soul.

“And if anyone is here, I expect I shall be scared to death,” admitted Tavia, sitting down beside her chum.

It was so dark that only the vastness of the earth and sky was made known to them—and that but vaguely. Stars twinkled above their heads, but seemingly so high that, as Tavia complained, they did not seem like “the stars at home, back East!”

Sitting facing the railroad tracks, they saw no lights but the switch targets. There was no tower here, nor did there seem to be any life at all about the railroad property. Why the express train had stopped here, to tempt them to disembark, the girls could not imagine.

They were sitting close up against the great corral fence. The deep breathing of the herd was like the distant, low notes of an organ; the girls were not now interested in the manifestation of the presence of such a great number of cattle. But the cattle were curious.

Another came and snorted behind them, and Dorothy and Tavia scrambled up in a hurry. “They sound just as savage as bears,” declared Tavia.

“I don’t see why they have all deserted the cattle,” murmured Dorothy. “I should think there would be a night watch.”

59 “And all the railroad people have deserted, too.”

“Oh, dear!” said Dorothy. “We can’t even send a telegram after the train to tell Aunt Winnie we are all right.”

“But that wouldn’t be true,” said Tavia, shivering. “We are not all right.”

“We-ell,” said her friend, slowly. “I don’t expect there is anything here to hurt us.”

“That’s all right. Maybe there isn’t. But I never did like to be alone in a strange place. I want to be introduced to folks.”

“Maybe there is a cowboy camp near——”

“Bully! let’s find it!” ejaculated Tavia.

“But you wouldn’t know the cowboys. They’d all be strange men.”

“Well! Cowboys are so romantic,” urged Tavia. “Let’s look.”

“You can use your eyes as well as I can,” sighed Dorothy. “But I must say the prospect for finding anybody in this half darkness is not very alluring.”

They started, following the line of the corral fence away from the station. Dorothy was convinced there was no telegraph operator there, and the barn-like building looked more dreary and threatening than did the open prairie. So they were glad to get away from it.

The fence seemed unending. Occasionally a60 beast faced them, glaring with eyes like hot coals, and pawing the earth. But the fence looked strong.

They were not booted for walking, however, and the ground was uneven. So they hobbled on very slowly.

Tavia seized Dorothy’s arm. “Oh! what’s that?”

“Now, don’t you begin scaring me,” commanded Dorothy. “Oh!”

“Didn’t I tell you?”

“A man on horseback.”

They could see him between them and the skyline. He was riding slowly, and riding toward them. The girls hugged close to the fence and their dark traveling frocks were not noticeable.

The horseman drew nearer. The girls, clinging together, saw that he wore a wide hat and sheepskin chaps that looked like a woman’s divided skirt, they were so wide.

His pony pranced and snorted, doubtless scenting the girls. But the man spoke a soothing word and did not even gather up the reins that lay loose on the animal’s neck.

His voice had a pleasant, drawling tone to it. “Easy, there, Gaby—yuh shore ain’t gettin’ no thousand plunks er night for dancing yere—no, Ma’am! Stan’ still a moment, Gaby.”

Then a spark flared up and the girls knew the61 cowboy had been rolling a cigarette and was now lighting it.

“Sh!” breathed Dorothy. “Watch his face.”

The match flared up, held in the hollow of his hand. The yellow glare of it fell full upon the cowboy’s face.

That was what Dorothy had waited for. She wanted to see what manner of face it was before she spoke—if she spoke at all.

It was a bronzed, beardless, rather reckless countenance; but there was nothing bad in its expression, and if the features were not strikingly handsome they were pleasant. The mouth and eyes laughed too easily, perhaps; but Dorothy risked it. She walked right up to the pony’s surprised head.

“Please!” she said.

The match went out. So did the spark of the cigarette, as it dropped from the man’s fingers.

“Jerusha Juniper!” gasped the man. “I got ’em!”

“Will you please listen?” asked Dorothy.

“A gal—and a gal from back East—shore! Why, yes, Ma’am! I’ll listen tuh yuh,” said the amazed cowboy.

Just then Tavia joined her chum and the man muttered: “There’s two on ’em—Jerusha Juniper!”

“Please help us, sir,” pleaded Dorothy again.

62 “I shore will, Miss,” declared the cowboy. “But yuh did tee-totally sup-prise me—yes, Ma’am!”

Tavia began to giggle. “I guess you’re not used to meeting ladies around here?” she questioned, saucily.

“Jerusha Juniper! I reckon we ain’t; not around here.”

“I didn’t know, for sure,” said the wicked Tavia; “hearing you take a lady’s name in vain so frequently, you know. Is she a friend of yours?”

“Who, Ma’am?” asked the puzzled cowboy, while Dorothy tugged at Tavia’s sleeve.

“‘Miss Jerusha Juniper’—or is she a ‘Mrs.’?”

The man laughed heartily at that and urged his pony nearer to the two girls.

“We see so few females out here we hafter talk about ’em, and name critters after ’em, and all that.”

“I see,” said Tavia, quite assured of herself now.

“Oh, dear!” interrupted Dorothy, anxiously. “All this isn’t getting us anywhere.”

“Jeru—— Well!” said the man. “Where do yuh want tuh go?”

“Why, we’ve been left behind,” said Dorothy, and then she fully explained their predicament.

63 The cowboy, who was a young fellow, grasped the situation at once.

“You won’t git even a slow train out o’ yere before noon to-morrer,” he said. “And ’twixt now and then you’d be mighty uncomfortable, I reckon. There ain’t nawthin’ yere but a boardin’ shack, an’ there ain’t a woman ever stops thar only Miz’ Little, whose old man runs the shack and keeps the corral yere.”

“Goodness!” gasped Dorothy.

“Gracious!” gasped Tavia.

“Oh, they’re nice folks, but they ain’t fixed right to entertain ladies,” said the man.

“And we don’t want to be entertained,” wailed Dorothy. “We want to get on.”

“Shore you do,” granted the cowboy. “No other good train on this road, as I say. If you follered by slow trains you’d never catch that flyer—not in a dawg’s age.”

“What can we do, then?” demanded Dorothy. “Can’t we even telegraph?”

“Now, I’ll fix that for yuh, first of all,” declared the man. “The operator lives at Little’s shack. We’ll rout him out and make him tell your folks on that train that you’ll overtake ’em at Sessions.”

“But how can we?” asked Dorothy.

“Sessions is a junction of this line and the old D. & C. Yuh see, I know this country pretty well.64 I’m over yere for the Double Chain Outfit right now, shipping cows, and I was startin’ back to-morrer, anyway. I’ll git you ladies ponies, and we’ll start for Killock to-night.”

“Where’s Killock?” asked Dorothy, doubtfully.

The cowboy pointed vaguely across the prairie. “Right over thar—that-a-way,” he said. “It’s on the D. & C. There’s a fast train stops thar at five in the morning. If we make a pretty quick get-away we’ll easy make it in time, and you’ll ketch your folks at Sessions.”

“Oh, that will be jolly!” cried Tavia.

“But, Tavia!” gasped Dorothy. “How can we ride—in these frocks?”

“Side saddle?” queried her chum, doubtfully. “Why not?”

“We’d never be able to hang on,” groaned Dorothy, “without a proper riding habit!”

Here the cowboy interrupted. “There isn’t a lady’s saddle in this neck o’ woods. But I can find easy mounts and easy saddles for you. An’ Miz’ Little will let you have skirts. You can send them back with the ponies from Killock.”

“You think of everything!” exclaimed Tavia, gratefully.

Dorothy Dale was doubtful. She had trusted the man’s face and his manner, still——

“Come on, now, to Miz’ Little,” said the cowboy,65 frankly. “I’ll rout ’em out and we’ll be on the jog in half an hour, ladies.”

The man’s free and familiar way troubled Dorothy more than anything else. Yet, she knew that this was the West and that western ways were not eastern ways. And there was a woman they could talk to, at least!

So she and Tavia, hand in hand, followed behind the cowboy. He had dismounted, but the track would not allow of their walking abreast. And he made as slow progress in his high-heeled riding boots as the girls did, over the rough way.

Their eyes were more accustomed to the path now, or else it was not so dark. However, they could not have mistaken the bulk of the cowboy and that of the pony, before them.

It certainly was a strange experience. Two eastern girls thrown suddenly into a situation of this character! An unknown protector, an unknown locality, and unknown adventures before them.

“What an experience!” breathed the delighted Tavia. “And he’s a regular knight.”

“Is he?”

“A knight of the lariat,” whispered Tavia. “It’s so romantic.”

“I am glad you like it,” said Dorothy, grimly.

“Why! don’t you, Dorothy Dale?”

66 “I would give a good deal to be back aboard that train with Aunt Winnie.”

“Never!” cried Tavia.

“All right there, ladies?” threw back the “knight” over his shoulder. “There’s the light ahead.”

“Oh! we are perfectly all right,” said Tavia, with assurance.

Dorothy was not at all sure, so she said nothing.

In a few minutes they came to a long, low building. There was a dim light shining through a window in the end of the shack.

The cowboy dropped his pony’s bridle-rein upon the ground and the well-trained animal stood still. The “knight” knocked on the door and at once a fierce voice asked:

“Who’s thar?”

“Lance,” said the man.

“Well. I told you Number Eight was empty, Lance.”

“I ain’t goin’ to stay, Miz’ Little.”

“Aw-right,” pursued the same gruff voice, which the girls could scarcely believe was a woman’s. “I’ll let the nex’ pilgrim thet comes erlong have it.”

“I gotter see yuh,” said the cowboy. “Git up, will yuh?”

“What yuh want, Lance?”

67 “Come yere. Land’s sake! S’pose I’m talkin’ for pleasure?”

A couch squeaked. There was immediately a heavy footstep on the creaking plank floor. The girls were rather startled. They wondered if the savage sounding female was coming to the door just as she got out of bed?

But “Miz’ Little” had evidently been lying down dressed. When the door opened she was revealed in a shapeless dark gown. Only, her head and feet were bare.

She was a gigantic creature—a good deal bigger than the cowboy who had befriended the girls. Dorothy saw at once that she had a very kindly face, despite her masculine appearance.

“I vow!” she said, starting. “Ladies with you, Lance?”

“Yep. And they want to git on to Killock to-night. They’ll tell you all about it. I’m goin’ to rout out that thar key-pusher.”

“He’s in Number Six,” said Mrs. Little. Then to the girls: “Come in. Gals are yere erbout as often as angels—an’ I ain’t never hearn their wings yit.”

Dorothy and Tavia entered—yet not without some hesitancy. The room was large, and almost bare of furnishings. There was a broad bed, and on it Mrs. Little had been lying. But there was no other occupant of it, or of the room.

68 There was a small cookstove, a chest of drawers, a clock on the shelf, and a picture of Washington crossing the Delaware on the wall. One rocker had a tidy on the back of it, but the other plain deal chairs were entirely undecorated.

The woman herself, however, drew Dorothy Dale’s attention. She was very curious as to what manner of creature she could be—this masculine and gruff spoken female.

In the lamplight Dorothy had a better view of Mrs. Little’s face. Mrs. Little did not have a single pretty or attractive feature, but the girl from the East would have trusted her with anything she possessed!

Mrs. Little looked closely into the faces of both girls. She saw something shining in Dorothy’s eyes.

“Why, chile!” she gasped. “You ain’t re’lly afraid, be yuh?”