TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

A detailed transcriber's note can be found at the end of the book.

CONTAINING

AN ACCOUNT OF THE FORMATION OF THE

REGIMENT IN 1685,

AND OF ITS SUBSEQUENT SERVICES

TO 1847.

COMPILED BY

RICHARD CANNON, Esq.

ADJUTANT-GENERAL'S OFFICE, HORSE GUARDS.

ILLUSTRATED WITH PLATES.

LONDON:

PARKER, FURNIVALL & PARKER,

30 CHARING CROSS.

M DCCC XLVIII.

London: Printed by W. Clowes & Sons, Stamford Street,

for Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

HORSE-GUARDS,

1st January, 1836.

His Majesty has been pleased to command that, with a view of doing the fullest justice to Regiments, as well as to Individuals who have distinguished themselves by their Bravery in Action with the Enemy, an Account of the Services of every Regiment in the British Army shall be published under the superintendence and direction of the Adjutant-General; and that this Account shall contain the following particulars, viz.:—

—— The Period and Circumstances of the Original Formation of the Regiment; The Stations at which it has been from time to time employed; The Battles, Sieges, and other Military Operations in which it has been engaged, particularly specifying any Achievement it may have performed, and the Colours, Trophies, &c., it may have captured from the Enemy.

—— The Names of the Officers and the number of Non-Commissioned Officers and Privates Killed or Wounded by the Enemy, specifying the Place and Date of the Action.

—— The Names of those Officers who, in consideration of their Gallant Services and Meritorious Conduct in Engagements with the Enemy, have been distinguished with Titles, Medals, or other Marks of His Majesty's gracious favour.

—— The Names of all such Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers, and Privates, as may have specially signalized themselves in Action.

And,

—— The Badges and Devices which the Regiment may have been permitted to bear, and the Causes on account of which such Badges or Devices, or any other Marks of Distinction, have been granted.

By Command of the Right Honourable

GENERAL LORD HILL,

Commanding-in-Chief.

John Macdonald,

Adjutant-General.

The character and credit of the British Army must chiefly depend upon the zeal and ardour by which all who enter into its service are animated, and consequently it is of the highest importance that any measure calculated to excite the spirit of emulation, by which alone great and gallant actions are achieved, should be adopted.

Nothing can more fully tend to the accomplishment of this desirable object than a full display of the noble deeds with which the Military History of our country abounds. To hold forth these bright examples to the imitation of the youthful soldier, and thus to incite him to emulate the meritorious conduct of those who have preceded him in their honourable career, are among the motives that have given rise to the present publication.

The operations of the British Troops are, indeed, announced in the "London Gazette," from whence they are transferred into the public prints: the achievements of our armies are thus made known at the time of their occurrence, and receive the tribute[iv] of praise and admiration to which they are entitled. On extraordinary occasions, the Houses of Parliament have been in the habit of conferring on the Commanders, and the Officers and Troops acting under their orders, expressions of approbation and of thanks for their skill and bravery; and these testimonials, confirmed by the high honour of their Sovereign's approbation, constitute the reward which the soldier most highly prizes.

It has not, however, until late years, been the practice (which appears to have long prevailed in some of the Continental armies) for British Regiments to keep regular records of their services and achievements. Hence some difficulty has been experienced in obtaining, particularly from the old Regiments, an authentic account of their origin and subsequent services.

This defect will now be remedied, in consequence of His Majesty having been pleased to command that every Regiment shall, in future, keep a full and ample record of its services at home and abroad.

From the materials thus collected, the country will henceforth derive information as to the difficulties and privations which chequer the career of those who embrace the military profession. In Great Britain, where so large a number of persons are devoted to the active concerns of agriculture, manufactures, and commerce, and where these pursuits have, for so[v] long a period, been undisturbed by the presence of war, which few other countries have escaped, comparatively little is known of the vicissitudes of active service, and of the casualties of climate, to which, even during peace, the British Troops are exposed in every part of the globe, with little or no interval of repose.

In their tranquil enjoyment of the blessings which the country derives from the industry and the enterprise of the agriculturist and the trader, its happy inhabitants may be supposed not often to reflect on the perilous duties of the soldier and the sailor,—on their sufferings,—and on the sacrifice of valuable life, by which so many national benefits are obtained and preserved.

The conduct of the British Troops, their valour, and endurance, have shone conspicuously under great and trying difficulties; and their character has been established in Continental warfare by the irresistible spirit with which they have effected debarkations in spite of the most formidable opposition, and by the gallantry and steadiness with which they have maintained their advantages against superior numbers.

In the official Reports made by the respective Commanders, ample justice has generally been done to the gallant exertions of the Corps employed; but the details of their services and of acts of individual[vi] bravery, can only be fully given in the Annals of the various Regiments.

These Records are now preparing for publication, under His Majesty's special authority, by Mr. Richard Cannon, Principal Clerk of the Adjutant General's Office; and while the perusal of them cannot fail to be useful and interesting to military men of every rank, it is considered that they will also afford entertainment and information to the general reader, particularly to those who may have served in the Army, or who have relatives in the Service.

There exists in the breasts of most of those who have served, or are serving, in the Army, an Esprit de Corps—an attachment to everything belonging to their Regiment; to such persons a narrative of the services of their own Corps cannot fail to prove interesting. Authentic accounts of the actions of the great, the valiant, the loyal, have always been of paramount interest with a brave and civilized people. Great Britain has produced a race of heroes who, in moments of danger and terror, have stood "firm as the rocks of their native shore;" and when half the World has been arrayed against them, they have fought the battles of their Country with unshaken fortitude. It is presumed that a record of achievements in war,—victories so complete and surprising, gained by our countrymen, our brothers,[vii] our fellow-citizens in arms,—a record which revives the memory of the brave, and brings their gallant deeds before us, will certainly prove acceptable to the public.

Biographical memoirs of the Colonels and other distinguished Officers will be introduced in the Records of their respective Regiments, and the Honorary Distinctions which have, from time to time, been conferred upon each Regiment, as testifying the value and importance of its services, will be faithfully set forth.

As a convenient mode of Publication, the Record of each Regiment will be printed in a distinct number, so that when the whole shall be completed, the Parts may be bound up in numerical succession.

The natives of Britain have, at all periods, been celebrated for innate courage and unshaken firmness, and the national superiority of the British troops over those of other countries has been evinced in the midst of the most imminent perils. History contains so many proofs of extraordinary acts of bravery, that no doubts can be raised upon the facts which are recorded. It must therefore be admitted, that the distinguishing feature of the British soldier is Intrepidity. This quality was evinced by the inhabitants of England when their country was invaded by Julius Cæsar with a Roman army, on which occasion the undaunted Britons rushed into the sea to attack the Roman soldiers as they descended from their ships; and, although their discipline and arms were inferior to those of their adversaries, yet their fierce and dauntless bearing intimidated the flower of the Roman troops, including Cæsar's favourite tenth legion. Their arms consisted of spears, short swords, and other weapons of rude construction. They had chariots, to the[x] axles of which were fastened sharp pieces of iron resembling scythe-blades, and infantry in long chariots resembling waggons, who alighted and fought on foot, and for change of ground, pursuit, or retreat, sprang into the chariot and drove off with the speed of cavalry. These inventions were, however, unavailing against Cæsar's legions: in the course of time a military system, with discipline and subordination, was introduced, and British courage, being thus regulated, was exerted to the greatest advantage; a full development of the national character followed, and it shone forth in all its native brilliancy.

The military force of the Anglo-Saxons consisted principally of infantry: Thanes, and other men of property, however, fought on horseback. The infantry were of two classes, heavy and light. The former carried large shields armed with spikes, long broad swords and spears; and the latter were armed with swords or spears only. They had also men armed with clubs, others with battle-axes and javelins.

The feudal troops established by William the Conqueror consisted (as already stated in the Introduction to the Cavalry) almost entirely of horse; but when the warlike barons and knights, with their trains of tenants and vassals, took the field, a proportion of men appeared on foot, and, although these were of inferior degree, they proved stout-hearted Britons of stanch fidelity. When stipendiary troops were employed, infantry always constituted a considerable portion of the military force;[xi] and this arme has since acquired, in every quarter of the globe, a celebrity never exceeded by the armies of any nation at any period.

The weapons carried by the infantry, during the several reigns succeeding the Conquest, were bows and arrows, half-pikes, lances, halberds, various kinds of battle-axes, swords, and daggers. Armour was worn on the head and body, and in course of time the practice became general for military men to be so completely cased in steel, that it was almost impossible to slay them.

The introduction of the use of gunpowder in the destructive purposes of war, in the early part of the fourteenth century, produced a change in the arms and equipment of the infantry-soldier. Bows and arrows gave place to various kinds of fire-arms, but British archers continued formidable adversaries; and owing to the inconvenient construction and imperfect bore of the fire-arms when first introduced, a body of men, well trained in the use of the bow from their youth, was considered a valuable acquisition to every army, even as late as the sixteenth century.

During a great part of the reign of Queen Elizabeth each company of infantry usually consisted of men armed five different ways; in every hundred men forty were "men-at-arms," and sixty "shot;" the "men-at-arms" were ten halberdiers, or battle-axe men, and thirty pikemen; and the "shot" were twenty archers, twenty musketeers, and twenty harquebusiers, and each man carried, besides his principal weapon, a sword and dagger.

Companies of infantry varied at this period in numbers from 150 to 300 men; each company had a colour or ensign, and the mode of formation recommended by an English military writer (Sir John Smithe) in 1590 was:—the colour in the centre of the company guarded by the halberdiers; the pikemen in equal proportions, on each flank of the halberdiers; half the musketeers on each flank of the pikes; half the archers on each flank of the musketeers; and the harquebusiers (whose arms were much lighter than the muskets then in use) in equal proportions on each flank of the company for skirmishing.[1] It was customary to unite a number of companies into one body, called a Regiment, which frequently amounted to three thousand men; but each company continued to carry a colour. Numerous improvements were eventually introduced in the construction of fire-arms, and, it having been found impossible to make armour proof against the muskets then in use (which carried a very heavy ball) without its being too weighty for the soldier, armour was gradually laid aside by the infantry in the seventeenth century: bows and arrows also fell into disuse, and the infantry were reduced to two classes, viz.: musketeers, armed with matchlock muskets, [xiii]swords, and daggers; and pikemen, armed with pikes from fourteen to eighteen feet long, and swords.

In the early part of the seventeenth century Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, reduced the strength of regiments to 1000 men; he caused the gunpowder, which had heretofore been carried in flasks, or in small wooden bandoliers, each containing a charge, to be made up into cartridges, and carried in pouches; and he formed each regiment into two wings of musketeers, and a centre division of pikemen. He also adopted the practice of forming four regiments into a brigade; and the number of colours was afterwards reduced to three in each regiment. He formed his columns so compactly that his infantry could resist the charge of the celebrated Polish horsemen and Austrian cuirassiers; and his armies became the admiration of other nations. His mode of formation was copied by the English, French, and other European states; but so great was the prejudice in favour of ancient customs, that all his improvements were not adopted until near a century afterwards.

In 1664 King Charles II. raised a corps for sea-service, styled the Admiral's regiment. In 1678 each company of 100 men usually consisted of 30 pikemen, 60 musketeers, and 10 men armed with light firelocks. In this year the king added a company of men armed with hand-grenades to each of the old British regiments, which was designated the "grenadier company." Daggers were so contrived as to fit in the muzzles of the muskets, and bayonets[xiv] similar to those at present in use were adopted about twenty years afterwards.

An Ordnance regiment was raised in 1685, by order of King James II., to guard the artillery, and was designated the Royal Fusiliers (now 7th Foot). This corps, and the companies of grenadiers, did not carry pikes.

King William III. incorporated the Admiral's regiment in the Second Foot Guards, and raised two Marine regiments for sea-service. During the war in this reign, each company of infantry (excepting the fusiliers and grenadiers) consisted of 14 pikemen and 46 musketeers; the captains carried pikes; lieutenants, partisans; ensigns, half-pikes; and serjeants, halberds. After the peace in 1697 the Marine regiments were disbanded, but were again formed on the breaking out of the war in 1702.[2]

During the reign of Queen Anne the pikes were laid aside, and every infantry soldier was armed with a musket, bayonet, and sword; the grenadiers ceased, about the same period, to carry hand-grenades; and the regiments were directed to lay aside their third colour: the corps of Royal Artillery was first added to the army in this reign.

About the year 1745, the men of the battalion companies of infantry ceased to carry swords; [xv]during the reign of George II. light companies were added to infantry regiments; and in 1764 a Board of General Officers recommended that the grenadiers should lay aside their swords, as that weapon had never been used during the seven years' war. Since that period the arms of the infantry soldier have been limited to the musket and bayonet.

The arms and equipment of the British troops have seldom differed materially, since the Conquest, from those of other European states; and in some respects the arming has, at certain periods, been allowed to be inferior to that of the nations with whom they have had to contend; yet, under this disadvantage, the bravery and superiority of the British infantry have been evinced on very many and most trying occasions, and splendid victories have been gained over very superior numbers.

Great Britain has produced a race of lion-like champions who have dared to confront a host of foes, and have proved themselves valiant with any arms. At Creçy, King Edward III., at the head of about 30,000 men, defeated, on the 26th of August, 1346, Philip King of France, whose army is said to have amounted to 100,000 men; here British valour encountered veterans of renown:—the King of Bohemia, the King of Majorca, and many princes and nobles were slain, and the French army was routed and cut to pieces. Ten years afterwards, Edward Prince of Wales, who was designated the Black Prince, defeated, at Poictiers, with 14,000 men, a French army of 60,000 horse, besides infantry, and took John I., King of France, and his son[xvi] Philip, prisoners. On the 25th of October, 1415, King Henry V., with an army of about 13,000 men, although greatly exhausted by marches, privations, and sickness, defeated, at Agincourt, the Constable of France, at the head of the flower of the French nobility and an army said to amount to 60,000 men, and gained a complete victory.

During the seventy years' war between the United Provinces of the Netherlands and the Spanish monarchy, which commenced in 1578 and terminated in 1648, the British infantry in the service of the States-General were celebrated for their unconquerable spirit and firmness;[3] and in the thirty years' war between the Protestant Princes and the Emperor of Germany, the British troops in the service of Sweden and other states were celebrated for deeds of heroism.[4] In the wars of Queen Anne, the fame of the British army under the great Marlborough was spread throughout the world; and if we glance at the achievements performed within the memory of persons now living, there is abundant proof that the Britons of the present age are not inferior to their ancestors in the qualities [xvii]which constitute good soldiers. Witness the deeds of the brave men, of whom there are many now surviving, who fought in Egypt in 1801, under the brave Abercromby, and compelled the French army, which had been vainly styled Invincible, to evacuate that country; also the services of the gallant Troops during the arduous campaigns in the Peninsula, under the immortal Wellington; and the determined stand made by the British Army at Waterloo, where Napoleon Bonaparte, who had long been the inveterate enemy of Great Britain, and had sought and planned her destruction by every means he could devise, was compelled to leave his vanquished legions to their fate, and to place himself at the disposal of the British Government. These achievements, with others of recent dates in the distant climes of India, prove that the same valour and constancy which glowed in the breasts of the heroes of Creçy, Poictiers, Agincourt, Blenheim, and Ramilies, continue to animate the Britons of the nineteenth century.

The British Soldier is distinguished for a robust and muscular frame,—intrepidity which no danger can appal,—unconquerable spirit and resolution,—patience in fatigue and privation, and cheerful obedience to his superiors. These qualities, united with an excellent system of order and discipline to regulate and give a skilful direction to the energies and adventurous spirit of the hero, and a wise selection of officers of superior talent to command, whose presence inspires confidence,—have been the leading causes of the splendid victories gained by the British[xviii] arms.[5] The fame of the deeds of the past and present generations in the various battle-fields where the robust sons of Albion have fought and conquered, surrounds the British arms with a halo of glory; these achievements will live in the page of history to the end of time.

The records of the several regiments will be found to contain a detail of facts of an interesting character, connected with the hardships, sufferings, and gallant exploits of British soldiers in the various parts of the world where the calls of their Country and the commands of their Sovereign have required them to proceed in the execution of their duty, whether in active continental operations, or in maintaining colonial territories in distant and unfavourable climes.

The superiority of the British infantry has been pre-eminently set forth in the wars of six centuries, and admitted by the greatest commanders which Europe has produced. The formations and movements of this arme, as at present practised, while they are adapted to every species of warfare, and to all probable situations and circumstances of service, are calculated to show forth the brilliancy of military tactics calculated upon mathematical and scientific principles. Although the movements and evolutions have been copied from the continental armies, yet various improvements have from time to time been introduced, to insure that simplicity and celerity by which the superiority of the national military character is maintained. The rank and influence which Great Britain has attained among the nations of the world, have in a great measure been purchased by the valour of the Army, and to persons who have the welfare of their country at heart, the records of the several regiments cannot fail to prove interesting.

[1] A company of 200 men would appear thus:—

| | |||||||||

| 20 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| Harquebuses. | Muskets. | Halberds. | Muskets. | Harquebuses. | |||||

| Archers. | Pikes. | Pikes. | Archers. | ||||||

[2] The 30th, 31st, and 32nd Regiments were formed as Marine corps in 1702, and were employed as such during the wars in the reign of Queen Anne. The Marine corps were embarked in the Fleet under Admiral Sir George Rooke, and were at the taking of Gibraltar, and in its subsequent defence in 1704; they were afterwards employed at the siege of Barcelona in 1705.

[3] The brave Sir Roger Williams, in his Discourse on War, printed in 1590, observes:—"I persuade myself ten thousand of our nation would beat thirty thousand of theirs (the Spaniards) out of the field, let them be chosen where they list." Yet at this time the Spanish infantry was allowed to be the best disciplined in Europe. For instances of valour displayed by the British Infantry during the Seventy Years' War, see the Historical Record of the Third Foot, or Buffs.

[4] Vide the Historical Record of the First, or Royal Regiment of Foot.

[5] "Under the blessing of Divine Providence, His Majesty ascribes the successes which have attended the exertions of his troops in Egypt to that determined bravery which is inherent in Britons; but His Majesty desires it may be most solemnly and forcibly impressed on the consideration of every part of the army, that it has been a strict observance of order, discipline, and military system, which has given the full energy to the native valour of the troops, and has enabled them proudly to assert the superiority of the national military character, in situations uncommonly arduous, and under circumstances of peculiar difficulty."—General Orders in 1801.

In the General Orders issued by Lieut.-General Sir John Hope (afterwards Lord Hopetoun), congratulating the army upon the successful result of the Battle of Corunna, on the 16th of January, 1809, it is stated:—"On no occasion has the undaunted valour of British troops ever been more manifest. At the termination of a severe and harassing march, rendered necessary by the superiority which the enemy had acquired, and which had materially impaired the efficiency of the troops, many disadvantages were to be encountered. These have all been surmounted by the conduct of the troops themselves; and the enemy has been taught, that whatever advantages of position or of numbers he may possess, there is inherent in the British officers and soldiers a bravery that knows not how to yield,—that no circumstances can appal,—and that will ensure victory, when it is to be obtained by the exertion of any human means."

HISTORICAL RECORD

OF

THE TWELFTH, OR THE EAST SUFFOLK,

REGIMENT OF FOOT,

CONTAINING

AN ACCOUNT OF THE FORMATION OF THE

REGIMENT IN 1685,

AND OF ITS SUBSEQUENT SERVICES

TO 1847.

COMPILED BY

RICHARD CANNON, Esq.

ADJUTANT-GENERAL'S OFFICE, HORSE GUARDS.

ILLUSTRATED WITH PLATES.

LONDON:

PARKER, FURNIVALL, & PARKER,

30 CHARING CROSS.

M DCCC XLVIII.

London: Printed by W. Clowes & Sons, Stamford Street,

for Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

THE TWELFTH, OR THE EAST SUFFOLK,

REGIMENT OF FOOT

BEARS ON ITS REGIMENTAL COLOUR

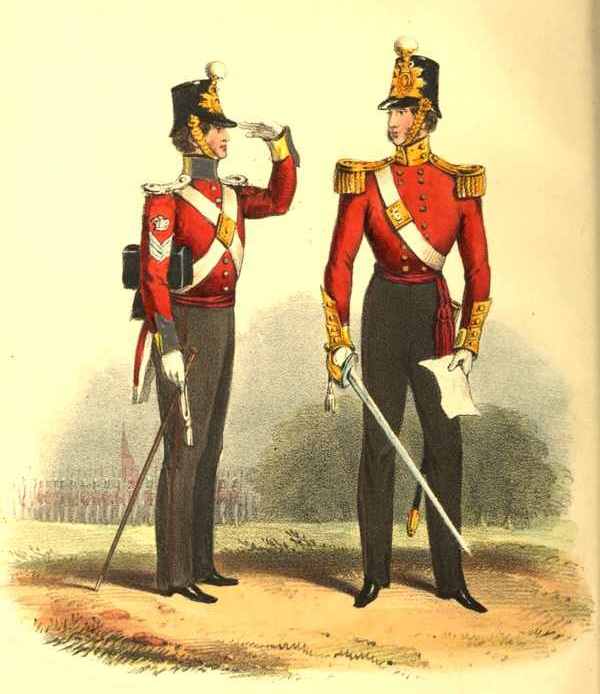

THE WORD MINDEN; THE WORD GIBRALTAR,

With the Castle and Key and the Motto, Montis Insignia Calpé;

AND THE WORDS

"SERINGAPATAM" and "INDIA;"

IN COMMEMORATION OF ITS DISTINGUISHED SERVICES

AT THE BATTLE OF MINDEN

ON THE 1st AUGUST, 1759;

IN THE GLORIOUS DEFENCE OF GIBRALTAR

FROM THE YEAR 1779 TO 1782;

AT THE STORMING AND CAPTURE OF SERINGAPATAM

ON THE 4th MAY, 1799;

and of its Gallant Conduct on many arduous Duties in INDIA

from the Year 1798 to 1807.

| Year | Page | |

| 1685 | Formation of the Regiment | 1 |

| 1686 | Station and Establishment | 2 |

| —— | Arms and Uniform | 3 |

| 1687 | Names of the Officers | 4 |

| 1688 | Assembled on Hounslow-heath | – |

| 1689 | Inspected at Hull after the Revolution | 5 |

| —— | Embarked for Ireland | 6 |

| —— | Engaged at the Siege of Carrickfergus | – |

| —— | Advanced to Dundalk | – |

| —— | Death of its Colonel, Henry Wharton, and of many soldiers by disease | 7 |

| 1690 | Engaged at Cavan | 8 |

| —— | ————– the battle of the Boyne | 9 |

| —— | ————– the siege of Waterford | – |

| —— | ————– the first siege of Limerick | – |

| —— | ————– Lanesborough | – |

| 1691 | Marched to Mullingar | 10 |

| —— | Engaged with the Rapparees | — |

| —— | ———– at the siege of Ballymore | 11 |

| —— | ———– at the storming of Athlone | — |

| —— | ———– at the battle of Aghrim | — |

| —— | ———– at the siege of Galway | 12 |

| —— | Surrender of Limerick, and termination of the war in Ireland | — |

| —— | Embarked from Kinsale for Plymouth | 13 |

| 1692 | ———— for the coast of France | — |

| —— | Proceeded to Ostend, and took possession of Furnes and Dixmude | — |

| —— | Returned to England | — |

| 1693 | Remained in England | — |

| [xxvi] 1694 | Embarked for Flanders | 13 |

| —— | Engaged at the siege of Huy | 14 |

| 1695 | —————— attack on Fort Kenoque | — |

| —— | —————— defence of Dixmude | — |

| —— | Surrender of Dixmude to the French | 15 |

| —— | Released from Prisoners of War and placed in garrison at Malines | — |

| 1696 | Marched to Ostend and Bruges | 16 |

| —— | Encamped and stationed in and near Bruges | — |

| 1697 | Marched to Brabant | — |

| —— | Encamped before Brussels | 17 |

| —— | Peace of Ryswick | — |

| —— | Returned to England | — |

| 1699 | Proceeded to Ireland | — |

| 1702 | War with France and Spain | — |

| 1703 | Embarked for the West Indies | 18 |

| 1704 | Proceeded to Jamaica | — |

| 1705 | Returned to England | — |

| 1708 | Embarked as Marines | 19 |

| —— | Landed at Ostend | — |

| —— | Employed to escort ammunition, &c. to the army besieging Lisle | 20 |

| —— | Surrender of Lisle | 21 |

| 1709 | Returned to England | — |

| 1710 | Reviewed at Portsmouth | — |

| 1712 | Embarked for Spain | — |

| 1713 | Peace of Utrecht | — |

| —— | Proceeded to Minorca | 22 |

| 1719 | Returned to England from Minorca | — |

| 1722 | Reviewed by King George I. | — |

| 1739 | Remained in England twenty years | — |

| 1740 | Embarked as Marines | — |

| 1742 | ———— for Flanders | 23 |

| 1743 | Marched to Germany | — |

| —— | Engaged at the battle of Dettingen | — |

| [xxvii] 1743 | Returned to Flanders | 24 |

| 1744 | Engaged in operations on the Scheldt | — |

| 1745 | Advanced to the relief of Tournay | — |

| —— | Engaged at the battle of Fontenoy | 25 |

| —— | Casualties at the battle of Fontenoy | 26 |

| —— | Returned to England | 27 |

| —— | Engaged in suppressing the Rebellion | — |

| 1746 | Proceeded to Scotland | — |

| 1747 | Returned to England | 28 |

| 1748 | Embarked for Holland | — |

| —— | Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle | — |

| —— | Returned to England | — |

| 1749 | Embarked for Minorca | — |

| 1751 | Royal Warrant issued for regulating Clothing, Colours, &c. | — |

| 1752 | Returned to England | 29 |

| 1755 | Commencement of the Seven years' War with France | — |

| 1757 | Second Battalion added to establishment | — |

| 1758 | Second Battalion constituted the 65th Regiment | — |

| —— | Embarked for Germany | 30 |

| —— | Marched into quarters at Munster | — |

| 1759 | Battle of Minden | 31 |

| —— | Royal Authority to bear the word "Minden" on the colours and appointments | 33 |

| —— | Entered cantonments at Osnaburg | 34 |

| 1760 | Arrived at Paderborn | — |

| —— | Encamped at Fritzlar | 34 |

| —— | ————— Kalle | — |

| —— | Marched to engage the French at Warbourg | — |

| —— | Went into quarters at Paderborn | 35 |

| 1761 | Advanced into Hesse | — |

| —— | Engaged at Kirch Denkern, &c. | — |

| 1762 | ————– Groebenstein and Wilhelmsthal | 36 |

| —— | ————– Lutterberg | — |

| [xxviii] 1762 | Engaged at Homburg | 37 |

| —— | ————– the siege of Cassel | — |

| 1763 | Peace of Fontainbleau | — |

| —— | Returned to England | — |

| 1764 | Proceeded to Scotland | — |

| 1769 | Embarked for Gibraltar | 38 |

| 1779 | Attack of Gibraltar by the Spaniards | — |

| 1780} | {39 | |

| 1781} | Siege and Defence continued | { to |

| 1782} | {47 | |

| 1783 | Returned to England | 48 |

| —— | Styled the East Suffolk Regiment | — |

| 1784 | Reviewed at Windsor by King George III. | — |

| 1788 | Proceeded to Jersey and Guernsey | 49 |

| 1790 | Embarked as Marines | — |

| —— | Returned to Portsmouth | — |

| 1791 | Embarked for Ireland | — |

| 1793 | Flank companies embarked for the West Indies | — |

| 1794 | ——————— engaged at Martinico | 50 |

| —— | ———————————– St. Lucia | — |

| —— | ———————————– Guadaloupe | — |

| —— | Battalion companies embarked for Flanders | 51 |

| —— | Engaged at Werwick, and on the Lys | — |

| —— | ———– in the relief of Ypres | 52 |

| —— | ———– near Boxtel | 53 |

| —— | Retired beyond the river Maese | 54 |

| 1795 | Returned from Holland | 55 |

| —— | Flank companies returned from the West Indies | — |

| —— | Embarked on an expedition for the coast of France | — |

| 1796 | Embarked for the East Indies | 56 |

| 1797 | Arrived at Madras | — |

| —— | Embarked for Manilla | — |

| —— | Returned to Madras | 57 |

| 1798 | Proceeded to Tanjore in the Carnatic | 58 |

| [xxix] 1799 | Engaged in operations against Tippoo Saib | 59 |

| —— | Advanced against Seringapatam | 60 |

| —— | Action near Malleville | — |

| —— | Storming and Capture of Seringapatam | 65 |

| —— | Received the Royal Authority to bear the word "Seringapatam" on the colours and appointments | 70 |

| 1800 | Proceeded against the tribes of the Wynaad country | 71 |

| 1801 | Returned to Seringapatam | — |

| —— | Proceeded to Trichinopoly | — |

| 1802 | Two companies returned from Java | 72 |

| —— | Three companies employed against the Polygans | — |

| 1805 | Marched to Seringapatam | — |

| 1807 | Proceeded to Cannanore | — |

| 1808 | Embarked for the port of Coulan in the Travancore country | 73 |

| —— | Serjeant Tilsey and 33 men destroyed by the Natives | 74 |

| —— | Operations in the Travancore country | 75 |

| —— | Returned to Seringapatam | 81 |

| —— | Proceeded to Trichinopoly | — |

| 1810 | Flank companies proceeded against the Isle of Bourbon | 81 |

| —— | Embarked against the Mauritius, or the Isle of France | 82 |

| —— | Capture of the Mauritius | 83 |

| 1811 | Stationed at the Mauritius | 85 |

| 1812 | Second Battalion added to the Establishment and embarked for Ireland | — |

| 1813 | First Battalion proceeded from the Mauritius to the Isle of Bourbon | — |

| 1814 | Island of Bourbon restored to France | 86 |

| 1815 | Proceeded to the Island of Mauritius on its being retained as a Colony of Great Britain | — |

| [xxx] 1815 | Second Battalion returned to England, and embarked for Flanders | 86 |

| —— | ——————— advanced to Paris | — |

| 1816 | ——————— returned to England, and proceeded to Ireland | 87 |

| —— | First Battalion continued at the Mauritius | — |

| 1817 | —————— returned to England | — |

| —— | —————— proceeded to Ireland | — |

| 1818 | Second Battalion reduced, and incorporated with the First Battalion | 88 |

| 1820 | Embarked for England | — |

| 1821 | Proceeded to Portsmouth, and thence to Jersey and Guernsey | — |

| 1823 | Returned to England | 89 |

| —— | Embarked for Gibraltar | — |

| 1825 | Augmented to ten Companies, six Service, and four Depôt Companies | — |

| 1827 | Presentation of new colours with the authorised Inscriptions conferred as Honourable Distinctions | — |

| 1828 | Casualties from an epidemic disease at Gibraltar | 90 |

| 1834 | Returned to England | 91 |

| 1835 | Embarked for Ireland | — |

| 1837 | Formed into six Service, and four Depôt Companies, and embarked for the Mauritius | — |

| 1838 | Depôt Companies remained in Ireland | — |

| 1839 | Augmentation of the Establishment | — |

| —— | Depôt Companies embarked for Wales | — |

| 1840 | ——————— proceeded to Scotland | — |

| 1841 | ——————— returned to South Britain | — |

| 1842 | Augmentation to two Battalions | 92 |

| 1843 | Reserve Battalion arrived at the Mauritius | — |

| 1847 | First Battalion Embarked for England | — |

| 1848 | The Conclusion | — |

SUCCESSION OF COLONELS.

| Year | Page | |

| 1685 | Henry Duke of Norfolk | 93 |

| 1686 | Edward Earl of Lichfield | 94 |

| 1688 | Robert Lord Hunsdon | 95 |

| —— | Henry Wharton | — |

| 1689 | Richard Brewer | 96 |

| 1702 | John Livesay | — |

| 1712 | Richard Phillips | 97 |

| 1717 | Thomas Stanwix | — |

| 1725 | Thomas Whetham | 98 |

| 1741 | Scipio Duroure | 99 |

| 1745 | Henry Skelton | — |

| 1757 | Robert Napier | — |

| 1766 | Henry Clinton | 100 |

| 1779 | William Picton | 101 |

| 1811 | Charles Hastings, Bart. | 102 |

| 1823 | Hon. Robert Meade | 103 |

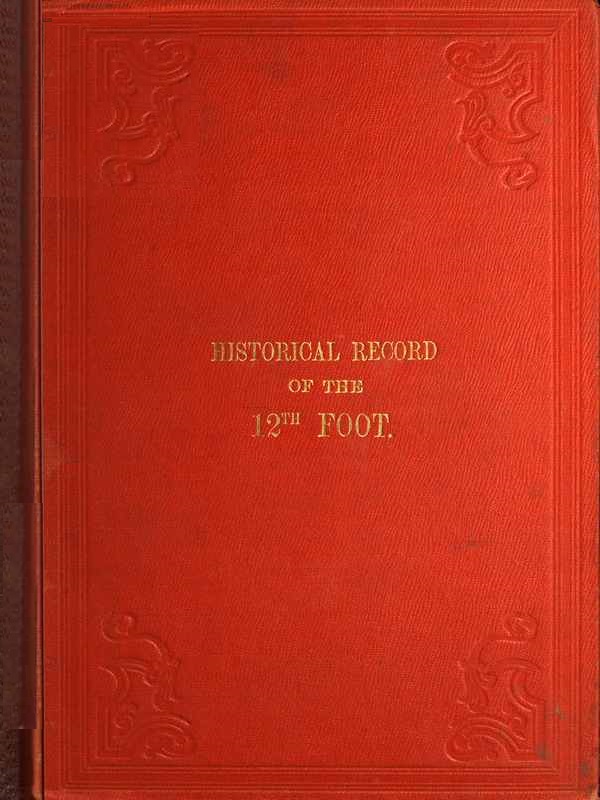

PLATES.

| Costume of the Regiment | to face | 1 |

| Colours of the Regiment | " | 28 |

| Attack of Gibraltar in 1782 | " | 48 |

| Storming and Capture of Seringapatam in 1799 | " | 70 |

Madelay Lith. 3 Wellington St Strand.

OF

THE TWELFTH, OR THE EAST SUFFOLK

REGIMENT OF FOOT.

After the Restoration in 1660, when King Charles II. had disbanded the army of the commonwealth, a number of non-regimented companies of foot were embodied for garrisoning the fortified towns, and one company was constantly stationed at Windsor, to furnish a guard at the castle. This company sent a detachment to Virginia in 1676. It was commanded by Henry Duke of Norfolk, Governor and Constable of Windsor Castle, and was united to several companies raised in the summer of 1685, and constituted a regiment, of which the Duke of Norfolk was appointed Colonel, by commission dated the 20th of June, 1685. This regiment having been retained in the service to the present time, now bears the title of the Twelfth, or the East Suffolk, regiment of foot.

The formation of this regiment was occasioned by the rebellion of James Duke of Monmouth, who assembled an army in the west of England to support his pretensions to the throne; and King James II. found it necessary to make a considerable augmentation[2] to the regular army. The companies, of which the regiment was composed, were raised in Norfolk, Suffolk, and the adjoining counties, by Henry Duke of Norfolk, Captains Henry Wharton, Charles Macartney, Dominick Trant, Jasper Patson, Charles Howard, Francis Blathwayt, Sir Alphonso de Mottetts, and George Trapp: the general rendezvous of the regiment was at Norwich, and as the several companies were formed, they were quartered at Norwich, Yarmouth, and Lynn.

The formation of the regiment was not completed when the rebel army was defeated at Sedgemoor, and the Duke of Monmouth was captured soon afterwards, and beheaded; but King James resolved to retain the newly raised corps in his service, and the Duke of Norfolk's regiment was ordered to march to London. It was quartered a few days, in the beginning of August, in the Tower Hamlets, and afterwards encamped on Hounslow-heath, where it was reviewed by the King. In the beginning of September the regiment marched into garrison at Portsmouth.

On the 1st January, 1686, the establishment was fixed at the numbers and rates of pay as shown in the next page.

Leaving Portsmouth in May, 1686, the regiment proceeded to Hounslow, and pitched its tents on the heath, where a numerous army was assembled; and while at this camp the colonelcy was conferred on Edward Earl of Lichfield, by commission dated the 14th of June, 1686.

At the camp on Hounslow-heath, the Earl of Lichfield's regiment was stationed in the centre of the line of infantry; it was distinguished by its white colours bearing the red cross of St. George; the soldiers wore broad-brimmed hats, with the brim turned up on one[3] side, and ornamented with white ribands; scarlet coats lined with white; blue breeches, blue stockings, and high shoes with square toes; and the pikemen, of whom there were twelve in each company, wore white sashes round their waists.

| The Duke of Norfolk's Regiment of Foot. | Pay per Day. | ||

| Staff. | £. | s. | d. |

| The Colonel, as Colonel | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| Lieut.-Colonel, as Lieut.-Colonel | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| Major, as Major | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Chaplain | 0 | 6 | 8 |

| Chirurgeon 4s. and 1 Mate 2s. 6d. | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Adjutant | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Quarter-Master and Marshal | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Total Staff | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| The Colonel's Company. | |||

| The Colonel, as Captain | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Lieutenant | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Ensign | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Two Sergeants, 1s. 6d. each | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Three Corporals, 1s. each | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| One Drummer | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Fifty Soldiers, 8d. each | 1 | 13 | 4 |

| Total for one Company | 2 | 15 | 4 |

| Nine Companies more at the same rate | 24 | 18 | 0 |

| Total | 29 | 18 | 6 |

| Per Annum £10,922 12s. 6d. | |||

After passing in review before the King several times, and receiving the expressions of His Majesty's approbation, the regiment struck its tents on the 10th of August, when two companies proceeded to Windsor, three to Tilbury-fort, and the remainder to Jersey and Guernsey.

A grenadier company was added to the regiment when it pitched its tents on Hounslow-heath in the summer of 1687, at which period the following officers were holding commissions, viz.:—

| Captains. | Lieutenants. | Ensigns. | |

| ——— | ——— | ——— | |

| Edward Earl of Lichfield (col). | Charles Potts. | James Carlisle. | |

| Thomas Salisbury (lieut.-col). | Charles Houston. | Henry Bows. | |

| George Trapp (major). | Edward Rupert. | John Beverly. | |

| Dominick Trant. | Robert Doughty. | Ferdinand Paris. | |

| Charles Macartney. | John Cuthbert. | Valentine Saunders. | |

| Sir A. de Mottetts. | William Fisher. | Isaac Foxley. | |

| Francis Blathwayt. | Alexander Waugh. | Daniel Mahony. | |

| Henry Wharton. | Robert Stourson. | Richard Waldegrave. | |

| John Berners. | James Seppens. | William Timperly. | |

| Thomas Dowcett. | John Broder. | Miles Bourk. | |

| Thomas Lord Jermyn. | George Raleigh. | } | Grenadier company. |

| Elric Le Mountay. | } |

| William Denny, Chaplain. | John Blakes, Adjutant. |

| John Ross, Chirurgeon. | James Healy, Quarter-Master. |

The frequent assembling of a numerous army, admired for its perfect equipment, discipline, and formidable appearance, on Hounslow-heath, was calculated to impress the English nation with a sense of the King's power, and to facilitate the overthrow of the religion and laws of the kingdom, which His Majesty had determined to accomplish. His Majesty resolved to make a trial of the disposition of his soldiers, to gain them over to the support of his measures; thinking, if one regiment could be induced to give a promise of implicit obedience, its example would be followed by the other corps. Accordingly in the summer of 1688, soon after the Earl of Lichfield's regiment had pitched its tents on the heath, it was formed on parade in presence of His Majesty; a short speech was made to the officers and soldiers to induce them to give an unreserved[5] pledge, and the major was directed to call upon all who would not support the repeal of the test and penal laws, to lay down their muskets; when the King was surprised and disappointed at seeing the whole ground their arms, excepting two officers and a very few soldiers, who were Roman Catholics. After some pause His Majesty commanded them to take up their arms, telling them that for the future he would not do them the honour of asking their opinions.

The conduct of the King occasioned the nobility and gentry to solicit the Prince of Orange to come to England with a Dutch army, and when the crisis arrived, His Majesty discovered that his soldiers had as much aversion to papacy and an arbitrary government, as his other subjects.

Soon after the Prince of Orange had landed, the Earl of Lichfield was removed to the first foot guards, and was succeeded in the colonelcy by Robert Lord Hunsdon, whose commission was dated the 30th of November, 1688.

After the flight of King James to France, Lord Hunsdon refused to take the required oath to the Prince of Orange, and His Highness conferred the colonelcy of the regiment on Henry Wharton, a gallant officer and a zealous protestant, who raised one of the companies of the regiment at its formation, and possessed the confidence and affection of the officers and soldiers: at the same time Captain Richard Brewer, from the fourteenth regiment of foot, was promoted to the lieut-colonelcy.

In the beginning of 1689 the regiment was stationed in Oxfordshire: it afterwards proceeded to Hull, where it was inspected, on the 28th of May, by the commissioners for remodelling the army.

The elevation of the Prince and Princess of Orange to the throne, under the title of King William and Queen Mary, was resisted in Ireland; and King James arrived in that country, with a body of troops, from France. King William sent an army thither, under Marshal Duke Schomberg, to rescue that part of his dominions from the power of the Roman Catholics, and the Twelfth regiment, commanded by Colonel Henry Wharton, was selected to take part in this service.

Embarking from England in the early part of August, the regiment arrived in Ireland in the middle of that month; it landed near Bangor, in the county of Down, without opposition, and encamped on the beach. The fortress of Carrickfergus was garrisoned by King James's troops, who were summoned, but refused to surrender; and the first service performed by the regiment, in the field, was the siege of that place.

A practicable breach having been made in the works, the regiment was under arms at six o'clock on the morning of the 27th of August, to take part in storming the town. The soldiers had arrived at the trenches, and Colonel Wharton stood with a pike in his hand ready to give the signal for the attack, when the Irish displayed a white flag on the walls, and agreed to surrender. Story states, in his History of the Wars in Ireland, 'Colonel Wharton lay before the breach with his regiment, and was ready to enter, when the Duke sent to command his men to forbear, which, with some difficulty, they were induced to do, for they had a great mind to enter by force.'

After the surrender of Carrickfergus, the regiment advanced with the army to Dundalk, and the Duke Schomberg, believing King James's forces were more than double his own in numbers, formed an entrenched[7] camp. The situation of this camp was particularly unfavourable; the ground was low, and the weather proving wet, the infantry regiments lost many men from disease. The Twelfth sustained a very serious loss in non-commissioned officers and soldiers; and on the morning of the 28th of October their commanding officer, the gallant Colonel Henry Wharton, died. This officer is represented by historians as possessing a noble disposition, refined understanding, and lofty sentiments of honour, which, added to a tall graceful person, and a gallant bearing, occasioned him to be admired and beloved by the officers and soldiers of his regiment. Story states,—'Colonel Wharton was a brisk, bold man, and had a regiment that would have followed him anywhere, for the officers and soldiers loved him, and this made him ready to push on upon all occasions.... He was of a comely handsome person, gifted with a rare understanding.' Colonel Sir Thomas Gower died on the preceding day, and the remains of these two officers were interred, on the 30th of October, in a vault in Dundalk church, their regiments attending and firing three volleys.

King William promoted the lieutenant-colonel of the regiment, Richard Brewer, to the colonelcy, by commission dated the 1st of November, 1689.

On the 7th of November the regiment struck its tents and marched towards Armagh; and it was employed on various services during the winter.

In February, 1690, the regiment was stationed at Belturbet, with the Inniskilling horse and dragoons (now sixth), and the Queen Dowager's foot (now second); and information having been received that the enemy was assembling a body of troops at Cavan, Colonel Wolseley left Belturbet on the night of the 10th[8] of February, with three hundred horse and dragoons, and seven hundred foot of the second and Twelfth regiments, to surprise the enemy in his quarters. Encountering difficulties on the march, the day had dawned before the Colonel came in sight of Cavan, when he was surprised at discovering four thousand Irish soldiers, commanded by the Duke of Berwick, formed on a rising ground to oppose him. The Colonel had only one thousand tired soldiers[6] to attack four thousand fresh opponents with, but trusting to the valour of his men, he sent the cavalry forward to commence the action. The enemy's cavalry drove back the Inniskilling dragoons; but a volley from the English musketeers, brought down ten Irish horsemen, and the survivors fell back. Wolseley's infantry formed line and advanced: arriving within pistol-shot of their opponents, they opened a sharp fire with good effect, and after a few volleys, drew their swords to charge, but on the smoke clearing, they discovered that their opponents had fled. Pursuing the fugitives, they entered the town, and finding stores of necessaries and provisions, they halted to possess themselves of the booty; when the Irish rallied and resumed the fight, but were repulsed by the reserve. After the action the troops returned to Belturbet.

A numerous body of recruits from England replaced the losses of the regiment, and in June it brought five hundred musketeers, one hundred and sixty pikemen, and sixty grenadiers into the field, to serve under King William III., who commanded the army in Ireland in person.

The Twelfth regiment, commanded by Colonel [9]Brewer, had the honour of taking part at the forcing of the passage of the Boyne on the 1st of July: it formed part of the main body under King William III., and after fording the river, engaged King James's army, and contributed to the gaining of a decisive victory. After the loss of this battle, King James fled to France; but the Irish Roman Catholics, aided by the French troops, adhered to his interest.

From the field of battle the regiment accompanied King William to Dublin; it afterwards proceeded to Limerick, but on arriving at Carrick-on-Suir, it was detached, under Major General Kirke, to besiege Waterford: the garrison of this place surrendered without waiting for an attack.

King William afterwards besieged Limerick; but King James's soldiers made a more resolute defence than appears to have been expected, and His Majesty was induced to raise the siege, and send the troops into quarters.

The Twelfth regiment was employed in various services during the winter, and detached parties of the corps had several rencounters with the bands of armed peasantry called Rapparees. Towards the end of December, the regiment was in motion against the enemy, and on the 31st of that month it approached the town of Lanesborough, when it encountered some opposition from a body of Irish troops formed up to oppose its advance. Colonel Brewer led the regiment forward with great gallantry; some sharp fighting ensued, and the enemy was driven from the trenches cut across the road, through the town, and across the river. The Twelfth were unable to follow their opponents for want of boats or other means to cross the stream.

From Lanesborough the regiment marched to Mullingar, of which place its commanding officer, Colonel Brewer, was appointed governor. The quarters of the regiment were infested with parties of armed Roman Catholic peasantry, called rapparees, and on the 28th of April, Colonel Brewer advanced with six hundred men of the Twelfth and eighteenth regiments, and twenty dragoons, towards the castle of Donore, beyond which place two thousand rapparees had taken post and occupied a number of huts. At daybreak the following morning the soldiers arrived at the quarters of the rapparees, who formed for battle on the hills; but when the musketeers of the Twelfth and eighteenth advanced to commence the action, the enemy fled; the soldiers pursued some distance, and killed fifty of the fugitives.

Parties of rapparees continued to hover round Mullingar, and on the 2nd of May, they intercepted a serjeant and four soldiers of the Twelfth regiment between that place and Kinnegad; they put the serjeant and three of the soldiers to death, and put out the eyes of the fourth soldier. Three of the perpetrators of this cruelty were captured; two of them were hanged on the spot, and the third, to save his life, guided Captain Poynes and a hundred soldiers of the regiment, to one of the lurking-places of the rapparees, where the men of the Twelfth fell suddenly upon a large company of these marauders, killed forty, dispersed the remainder, and recovered a quantity of property, which had been taken from the Protestants.

Towards the end of May, one division of the army encamped at Mullingar, where General De Ginkell arrived and assumed the command.

From Mullingar the army advanced to the fort of[11] Ballymore, which was besieged, and surrendered on the 8th of June.

After repairing the breaches of Ballymore, and putting the place in a state of defence, the army advanced to Athlone, and on the 20th of June, the regiment was ordered to support the storming party at the attack of the Westmeath side of the town. Major-General Mackay commanded the troops employed on this service, and after making the necessary arrangements for the attack, took his post on the battery to see the issue, when he observed that the advanced party had missed its way and halted. He instantly hastened to the Twelfth regiment, and taking the first captain he came to by the hand, pointed the way to the breach. The regiment immediately rushed forward, stormed the breach in gallant style, and overcoming the resistance of the Irish, drove them across the bridge to the Connaught side of the town.

Several batteries were raised against the works on the Connaught side of the river, and the grenadier company of the Twelfth was engaged in forcing the passage of the Shannon, and in capturing the town by storm, on the 30th of June, which was a most desperate service, and was performed with distinguished valour and intrepidity.

The Irish army, commanded by a French officer of talent and reputation, General St. Ruth, took up a position near Aghrim, where it was attacked on the 12th of July. During the action, Major-General Mackay ordered the Twelfth, and three other regiments, to pass a difficult bog, ford a rivulet, and drive the Irish from behind the hedges of the nearest enclosures. The soldiers waded through the bog and rivulet, which was waist deep, and drove the Irish out[12] of the first enclosures in gallant style. They afterwards pressed forward with too much ardour, before the troops designed to support them had arrived, and becoming insulated, they were attacked in front and on both flanks by very superior numbers, and driven back to the edge of the bog. The Irish followed, shouting and plying them with musketry; but a support arriving under Major-General Talmash, the four regiments faced about, repulsed their pursuers, and by a spirited effort recovered their lost ground; the cavalry passed the bog near the castle of Aghrim, and by a determined charge completed the overthrow of the Irish army: the French general, St. Ruth, was killed towards the close of the action by a cannon-ball.

The Twelfth regiment had one major, one captain, one ensign, and a number of private soldiers killed, one lieutenant, and seven rank and file wounded.

The regiment afterwards marched with the army to Galway, and formed part of the force employed in the siege of that place, which surrendered on the 21st, and was delivered up on the 26th of July. Major-General Bellasis was appointed governor of Galway, and the Twelfth, twenty-second, and twenty-third regiments were selected to form the garrison of that fortress.

During the remainder of the campaign, the Twelfth regiment was stationed at Galway; and in the autumn, the war in Ireland was terminated by the surrender of Limerick, which delivered that country from the power of King James the Second.

The conquest of Ireland enabled King William to withdraw several regiments from thence to strengthen the allied army in the Netherlands, assembled to oppose the progress of the French conquests in that country. The Twelfth regiment marched from Gal[13]way on the 23rd of November, embarked at Kinsale towards the end of that month, and sailed to Plymouth, where it landed in the beginning of December.

During the summer of 1692, the regiment was selected to form part of an expedition against the coast of France, under the command of the Duke of Leinster: it embarked at Southampton, and the expedition menaced the French coast at several places, occasioning much alarm; but the French had assembled so great a number of regiments to oppose the descent, that a council of war decided against landing. The troops afterwards sailed to Ostend, where they landed, and being joined by a detachment from the confederate army under King William III., they took possession of the towns of Furnes and Dixmude, which they fortified, to be occupied as frontier posts during the winter. After these places were put in a state of defence, the regiment returned to England.

During the year 1693, the regiment remained in Great Britain; but the loss of the battle of Landen, by King William, rendered it necessary for the confederate army in Flanders to be augmented, and Colonel Brewer's was one of the regiments selected to proceed on service.

The regiment embarked for Flanders in the spring of 1694; it was stationed at Malines a short time, and afterwards formed part of the escort which accompanied the train of artillery to the army at Tirlemont, where it arrived on the 6th of June; on the 10th the regiment was reviewed by the King, who expressed his approbation of its appearance and discipline. It was formed in brigade with a battalion of the Royal, the third, fourth, seventh, and nineteenth regiments, under Brigadier-General Erle, and was engaged in[14] the toilsome operations of the campaign, which was passed in manœuvring, without a general engagement. The regiment formed part of the covering army during the siege of Huy, and after the capture of this fortress it was stationed at Bruges.

The progress of the French conquests had been arrested, and in 1694 the current of success flowed in favour of the Confederates. In 1695, King William resolved to undertake the siege of Namur. As a preparative measure, the Twelfth, and several other regiments, marched to Dixmude, in May; in June an attack was made on the fort of Kenoque,—a strong post situate at the junction of the Loo and Dixmude canals, to draw the French forces to that part of their line of fortifications. The Twelfth were engaged in this attack; and they were formed in brigade with the fourteenth, fifteenth, and seventeenth regiments, under Colonel Leslie; they had several men killed and wounded. The French troops having taken post behind their lines, leaving Namur exposed, the King seized the favourable moment and invested the town. The attack on fort Kenoque was then discontinued, and the Twelfth marched into garrison at Dixmude, where three British and five Dutch regiments of foot, and the Queen's (now third) dragoons, were stationed under a Dutch officer,—Major-General Ellemberg.

A powerful French army, commanded by Marshal Villeroy, approached the town of Dixmude, and on the 15th of July the place was invested by a strong division under General de Montal. The trenches were opened on the same night, and on the following day a battery of eight guns and three mortars commenced a heavy fire. The works beginning to crumble under fire, Major-General Ellemberg called a council[15] of war of the commanding officers of regiments, and suggested the necessity of surrendering, using, at the same time, various arguments to induce the other officers to agree to his proposal. Colonel Brewer, of the Twelfth foot, remonstrated against this measure, and recommended a resolute defence of the town to the last extremity; but a majority in the council of war voted for surrendering. The garrison expected to march out with the honors of war; but the French King sent orders to make the whole prisoners of war. The soldiers in garrison were anxious to be permitted to defend the town; many of them broke their arms sooner than deliver them up to the French, and several stands of regimental colours were destroyed by the men, that they might not become trophies in the hands of the enemy. The regiments in garrison were all made prisoners of war, and were marched into the territory subject to France, Louis XIV. refusing to deliver them up on the conditions of the cartel previously agreed upon.

In the mean time King William was carrying on the siege of Namur, and when the citadel was surrendered, he permitted the garrison to march out with the honors of war, but ordered Marshal Boufflers to be arrested, and detained, until the regiments made prisoners by the French at Dixmude, and detained contrary to the cartel, were delivered up.

This produced the desired effect—the Twelfth, and other corps in prison, were liberated, and rejoined the army, and the necessary arms, equipments, and clothing, were procured as speedily as possible, to enable the regiment to resume its duties; it was afterwards placed in garrison at Malines.

A general court-martial assembled for the trial of[16] the officers who delivered up Dixmude and its garrison to the enemy; Major-General Ellemberg was sentenced to be beheaded, and executed at Ghent on the 20th of November; Colonels Graham, Leslie, and the Dutch Colonel Aüer were cashiered; Colonel Brewer of the Twelfth foot, and the other commanding officers, who remonstrated against the surrender of the town, were acquitted.

The French monarch made preparations for the invasion of England in favour of King James, and in the spring of 1696, several regiments were withdrawn from Flanders, when the Twelfth marched from Malines to Ostend and Bruges; but the enemy did not venture to put to sea, and the regiment was not required to embark for England.

On the 28th of May, the regiment joined the troops encamped between Ghent and Bruges; it was formed in brigade with the first battalion of the royals, the fifteenth, and Collingwood's (afterwards disbanded) regiments, under Brigadier-General the Earl of Orkney, and served the campaign of this year with the army of Flanders, under the Prince of Vaudemont. The troops of that army were encamped behind the Bruges canal, nearly all the summer, to cover Ghent, Bruges, and the maritime towns of Flanders: in the autumn the regiment was ordered to occupy quarters in the town of Bruges.

In the spring of 1697, the English regiments were ordered to proceed to Brabant, to join the army commanded by King William in person; the Twelfth foot were, however, detained in Flanders until the Brandenburg troops arrived, when they marched to Brabant, and served under the King during the remainder of the campaign. They were formed in[17] brigade with a battalion of the first royals, and the fifth, Collier's and Lauder's (afterwards disbanded) regiments, commanded by the Earl of Orkney.

The regiment was encamped before Brussels, when the war was terminated by the treaty of Ryswick, and King William saw his efforts, to prevent the aggrandizement of France by conquest, attended with complete success. During the winter the regiment returned to England.

Considerable reductions were made in the establishment of the army in 1698 and 1699, and the Twelfth were ordered to proceed to Ireland.

While the regiment was stationed in Ireland, the death of Charles II., King of Spain, occurred, and he was succeeded by Philip, Duke of Anjou, grandson of Louis XIV., in violation of existing treaties, which rekindled the war in Europe.

Various circumstances occurred to induce Great Britain to take part in the contest, and Queen Anne declared war against France and Spain, in May, 1702.

The establishment of the Twelfth regiment was augmented, and it was held in readiness to proceed on foreign service; but it was detained in Ireland several months, during which period Colonel Brewer was succeeded in the colonelcy by Lieut.-Colonel Livesay, by commission, dated the 28th of September 1702.

As soon as hostilities were commenced, Vice-Admiral Benbow, commanding the British naval force in the West Indies, began an active warfare against the commerce of the enemy, with some success. Soon afterwards the Twelfth regiment was ordered to form part of a powerful armament, designed to be sent to the West Indies, under Charles Earl of Peterborough who was promoted to the local rank of General, and a[18] Dutch naval and land force arrived at Spithead, to accompany the British fleet; but this joint expedition was laid aside.

The Twelfth regiment embarked for the West Indies during the winter. In the early part of March, 1703, an unsuccessful attack was made on the island of Guadaloupe, by the troops under Colonel Codrington; two regiments landed and gained some advantages, but the expedition was not of sufficient strength to capture the island.

Additional regiments were afterwards sent to the West Indies:[7] but nothing of importance took place, and the Twelfth were sent to the island of Jamaica, where they were stationed during the year 1704.

The regiment sustained very serious losses from the effects of the climate, and, in 1705, it transferred the non-commissioned officers and soldiers fit for service, to the twenty-second foot, and the officers and a few of the serjeants returned to England to recruit.

During the years 1706 and 1707, the regiment was employed in recruiting, training, and disciplining its ranks, and having attained a state of efficiency, it was reported fit for service, and in the spring of 1708, it was held in readiness to serve on board the fleet as marines.

During the summer, the regiment was encamped in the Isle of Wight, where it was reviewed, on the 19th of July, by Major-General Erle, and afterwards embarked on an expedition against the coast of France, [19]the fleet being under the orders of Admiral Sir George Byng, and the land forces under Major-General Erle.[8] The fleet sailed from Spithead on the 27th of July, and menaced the coast of Picardy with a descent, creating considerable alarm and consternation; a landing was afterwards effected a few miles from Boulogne, but nothing of importance was accomplished.

In the mean time, the allied army, commanded by the great Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene of Savoy, was carrying on the siege of the celebrated city of Lisle, the capital of French Flanders, which was defended by fifteen thousand men, under Marshal Boufflers. The French and Spaniards, thinking to prevent the allied army receiving supplies from the coast, detached a body of troops, under General Count de la Motte, towards Ostend; and the troops employed in alarming the French coast, were suddenly ordered to proceed to that port, where they arrived on the 21st of September. The Twelfth, and other regiments of the expedition, having landed at Ostend, the French general retired; first cutting the dykes, to lay the country between Ostend and Nieuport under water, and to prevent the troops, under Major-General Erle, communicating with the grand army under the Duke of Marlborough. A strong detachment from the Twelfth, and two other regiments, seized on Leffinghen, constructed [20]some works, and established a post at that village.

At this period, the army before Lisle was deficient in ammunition for carrying on the siege, and the Duke of Marlborough, having heard of the arrival of the troops at Ostend, and of their having established a post at Leffinghen, sent seven hundred waggons thither, under a strong guard, for supplies. The soldiers of the Twelfth, and other corps at Ostend, were employed in draining the inundations; they built a bridge over the canal of Leffinghen, opened a communication with the grand army, and assisted in loading the seven hundred waggons with ammunition and other necessaries.

The waggons left Ostend on the 27th of September; the troops employed to guard the convoy, under Major-General Webb, were attacked on the following day in the wood of Wynendale, by twenty-two thousand French and Spaniards, under Count de la Motte, who was repulsed, and the convoy arrived in safety at the head-quarters of the army. Major-General Webb received the thanks of Parliament for his conduct on this occasion.

The Duke of Vendôme was so chagrined at this success, that he advanced with a numerous army to Oudenburg, posted his men along the canal between Plassendael and Nieuport, and caused the dykes to be cut in several places, in order to let in the sea, and lay a great extent of country under water. The Twelfth, and other corps under Major-General Erle, were encamped on the high grounds of Raversein, and watched the enemy's movements; at length, the Duke of Marlborough put the covering army in motion, to attack the enemy, when the Duke of Vendôme made a precipi[21]tate retreat. The Twelfth were afterwards employed in conveying another supply of ammunition and other necessaries, for the besieging army, across the inundations in boats, which enabled the generals of the allied army to continue the siege of Lisle, and insured the reduction of that fortress. The Duke of Vendôme sent a body of troops to besiege Leffinghen, which was captured after a short resistance; the enemy also menaced the camp at Raversein, when the Twelfth, and other regiments under Major-General Erle, retired into the outworks of Ostend. The supplies furnished to the army, however, proved sufficient, and the citadel of Lisle surrendered on the 9th of December.

The service, for which the regiment was sent to Flanders having been accomplished, it returned to England in the early part of 1709, and was stationed in garrison at Portsmouth.

On the 4th of July, 1710, the regiments of Livesay (Twelfth), and of Montandre, Lord Mark Kerr, and Windsor (afterwards disbanded), were reviewed at Portsmouth by Lieut.-General Erle.

The regiment was detained on home service in 1711.

Colonel Livesay was succeeded in the colonelcy of the regiment by Lieut.-Col. Richard Phillips, whose commission was dated the 16th of March, 1712.

Being in an efficient state, the regiment was embarked for Spain, to reinforce the allied army in that country. In the summer of 1712, preliminary articles for a treaty of peace were agreed upon, which was followed by a cessation of hostilities, and the Twelfth regiment proceeded to the island of Minorca, which had been captured by a body of troops under Major-General Stanhope in 1708.

Minorca was ceded to Great Britain by the treaty of[22] Utrecht in 1713, and the Twelfth regiment was one of the corps selected to form part of the garrison of that island.

Colonel Phillips was appointed to the command of the fortieth foot, on the formation of that regiment from non-regimented companies in America, and was succeeded in the colonelcy of the Twelfth by Colonel Thomas Stanwix, from the thirtieth foot, whose commission was dated the 25th of August, 1717.

Having been relieved from duty at Minorca, in 1719, the regiment returned to England, where it arrived in October of that year.

In the summer of 1722, the regiment was encamped on Salisbury Plain, and it was reviewed on the 30th of August by King George I., and His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, afterwards King George II.

On the 14th of March, 1725, Brigadier-General Thomas Stanwix died, and King George I. conferred the colonelcy of the regiment on Major-General Thomas Whetham, from the twenty-seventh foot.

The regiment was employed on home service for several years; and on the breaking out of the war with Spain, in 1739, its establishment was augmented to nine hundred officers and soldiers.

In the summer of 1740, the regiment pitched its tents near Newbury, where an encampment was formed of two regiments of horse, three of dragoons, and four of infantry, under Lieut.-General Wade. It afterwards served on board the fleet as marines.

In the autumn of this year, Charles VI., Emperor of Germany, died, and the succession of his daughter Maria Theresa, as Queen of Hungary and Bohemia, was disputed by the Elector of Bavaria, who was aided by a French army.

King George II. resolved to support the house of Austria, and the Twelfth was one of the regiments selected to proceed on foreign service. It was encamped, in the summer of 1741, on Lexden Heath, and was held in readiness to embark; in the autumn it went into cantonments.

General Whetham died on the 28th of April; and the colonelcy remained vacant until August, when His Majesty conferred that appointment on the lieut.-colonel of the regiment, Scipio Duroure, who had performed the duties of commanding officer with reputation during the preceding seven years.

During the summer of 1742, King George II. sent an army to Flanders under Field-Marshal the Earl of Stair, to support the house of Austria, and the Twelfth foot embarked on this service under Colonel Duroure.

The regiment passed several months in Flanders, and in February 1743 it commenced its march for Germany. It was encamped a short period near the forest d'Armstadt, and afterwards at Aschaffenburg, where the King and His Royal Highness the Duke of Cumberland joined the army.

On the 27th of June, as the forces commanded by His Majesty were marching along the bank of the river Maine, the French under Marshal Noailles crossed the stream and took post near Dettingen, to intercept the march. The allied army formed for battle and a severe engagement took place, in which the Twelfth had an opportunity of distinguishing themselves under the eye of their Sovereign. On one occasion they repulsed a charge of the French cavalry, and afterwards engaged the enemy's infantry with signal intrepidity and determination. The opposing army was forced to give way before the steady valour of the infantry of the[24] allied army, and the charges of the British cavalry completed the overthrow of the French host, which was driven across the river Maine with severe loss.

The Twelfth regiment had Captain Phillips, Lieutenant Monro, and twenty-seven rank and file killed; Captain Campbell, Lieutenant Williams, Ensign Townshend, three serjeants, two drummers, and sixty rank and file wounded, on this occasion.

After passing the night on the field of battle, the regiment marched to Hanau; it was encamped several weeks on the banks of the Kinzig, and in August marched towards the Rhine. It crossed that river above Mentz, and was employed in various services until October, when the army marched in divisions back to Flanders. The Twelfth formed part of the fifth division, under Major-General the Earl of Rothes, and arrived on the 22nd of November, at Brussels, from whence they proceeded to Ostend for winter quarters.

The Twelfth regiment served the campaign of 1744 under Field-Marshal Wade: it was encamped some time on the banks of the Scheldt, and took part in several operations, but no general engagement occurred: in the autumn it was again stationed in Flanders.

In the spring of 1745, a very powerful French army appeared in the Austrian provinces of the Netherlands, and commenced the siege of Tournay. His Royal Highness the Duke of Cumberland assumed the command of the allied army, and advanced to the relief of the besieged fortress; and the Twelfth regiment of foot was withdrawn from garrison to take part in the enterprise. The French army took up a position at the village of Fontenoy; and the allies, though much inferior to the enemy in numbers, resolved to hazard a general engagement.

At two o'clock on the morning of the 11th of May, the allied army advanced to attack the formidable position occupied by the enemy, and the Twelfth regiment, commanded by Colonel Duroure, was detached with several other corps, under Brigadier-General Ingoldsby, to attack a large fort, mounted with cannon, in the wood of Barri. Against this post the regiment advanced, but the fort was found too formidable to be attacked without artillery, and some delay occurred. Brigadier-General Ingoldsby did not clearly understand his orders, and the regiment was detained a long time in a state of inactivity exposed to a heavy cannonade; during which time the British infantry had forced the enemy's centre, but were obliged to retire in consequence of the Dutch having failed on Fontenoy, and Brigadier-General Ingoldsby having lost the opportunity of attacking the batteries in the wood of Barri. A second attack was, however, determined on, in the hope that the Dutch would make a more determined effort, and the Twelfth were brought into action; Brigadier-General Ingoldsby was wounded at the head of the regiment, and removed to the rear. Impatient of the state of inactivity in which they had been detained, the soldiers of the Twelfth rushed into action with distinguished ardour, and were conspicuous for their gallant bearing throughout the remainder of the contest. They were exposed to a heavy fire, and had to contend against very superior numbers. Their commanding officer, Colonel Duroure, fell mortally wounded; Lieut.-Colonel Whitmore was killed; Major Cosseley was wounded, and the command devolved on Captain Rainsford, who was also wounded: but the regiment preserved its firm array, and when more than half the non-commissioned officers and soldiers had fallen, the[26] survivors continued the fight, advancing over the killed and wounded of both armies. The Dutch, however, failed a second time; the British who had penetrated the enemy's line became insulated, and constantly exposed to the attack of fresh troops, and a retreat was ordered; the army withdrawing from the field of battle to Aeth.

The conduct of the Twelfth regiment was commended in the Duke of Cumberland's public despatch; its loss was greater than any other corps in the army, and amounted to three hundred and twenty-one officers and soldiers: viz., Lieut.-Colonel Whitmore, Captain Campbell, Lieutenants Bockland and Lane, Ensigns Cannon and Clifton, five serjeants, and one hundred and forty-eight rank and file killed; Colonel Duroure, Major Cosseley, Captains Rainsford and Robinson, Lieutenants Murray, Townshend, Millington, and Delgaire, Ensigns Dagers and Pearce, seven serjeants, and one hundred and forty-two private soldiers wounded; Captain de Cosne, Captain-Lieut. Goulston, and Lieut. Salt, missing.

Colonel Duroure died of his wounds, and was succeeded by Brigadier-General Henry Skelton, from the thirty-second regiment of foot. Major Cosseley recovered of his wounds, and was promoted to the lieut.-colonelcy, and Captain Rainsford was appointed Major.

The regiment was encamped with the army on the plain of Lessines, and afterwards near Brussels; and the French, by their superior numbers, were enabled to capture several fortified towns.

In the meantime a rebellion had broken out in Scotland, headed by Charles Edward, eldest son of the Pretender. This adventurer, being guided by desperate and designing men,—urged on by the wily politics[27] of France,—personally sanguine in his disposition, and disposed to listen to every representation that flattered his views, embarked on his expedition in a style little adequate to the extent of his designs, which were to dethrone the reigning monarch, and to overturn the constitution of a brave and free people. Arriving in Scotland, he was joined by several of the Highland clans, and the King's troops being in Flanders, success attended his efforts for a short period.