OTHER WORKS BY GEORGE EYRE-TODD.

Byways of the Scottish Border.

Anne of Argyle.

Vignettes of the North.

Four Months of Bohemia.

Scotland Picturesque and Traditional.

Also, Edited by the same,

The Abbotsford Series of Scottish Poets. 7 Vols.

Ancient Scots Ballads, with their Traditional Airs.

SKETCH-BOOK

OF THE

NORTH

BY

GEORGE EYRE-TODD

ILLUSTRATED BY A. S. BOYD, A. MONRO, S. REID

AND HARRINGTON MANN

Fifth Thousand

EDINBURGH AND LONDON

OLIPHANT, ANDERSON & FERRIER

1903

| PAGE | |

| A Roman Road | 1 |

| The Black Douglas | 8 |

| In the Shadow of St Giles’ | 16 |

| A Weaving Village | 23 |

| Where the Clans Fell | 30 |

| Tam o’ Shanter’s Ride | 37 |

| An Old Tulip Garden | 45 |

| By the Blasted Heath | 52 |

| Among the Galloway Becks | 59 |

| In Kilt and Plaid | 66 |

| At the Foot of Ben Ledi | 74 |

| Cadzow Forest | 81 |

| A Fisher Town | 88 |

| A Loch-side Sunday | 95 |

| The Glen of Gloom | 103 |

| Across Bute | 110 |

| With a Cast of Flies | 118 |

| From a Field-Gate | 125vi |

| School-Days | 133 |

| A Loch-side Strath | 140 |

| A Highland Reel | 147 |

| An Arran Ride | 154 |

| By a Western Firth | 161 |

| An Island Picnic | 168 |

| Tennis in the North | 176 |

| Through the Pass | 183 |

| A Highland Morning | 190 |

| Till Death us Part | 198 |

| A Forest Wedding | 205 |

| Loch Lomond Ice-bound | 212 |

| Hallowmas Eve | 220 |

| Hogmanay | 228 |

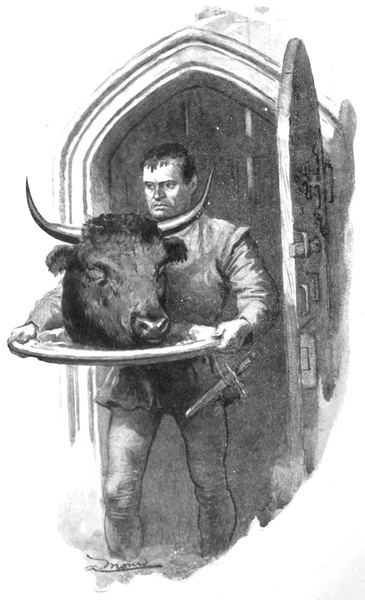

| Signal of Death (see p. 10) | A. Monro | Frontispiece |

| facing page | ||

| Thoughts of Home | A. Monro | 4 |

| The Web Returned | A. S. Boyd | 28 |

| The Death of Keppoch | Harrington Mann | 32 |

| On the Blasted Heath | A. Monro | 58 |

| Jeanie | A. S. Boyd | 60 |

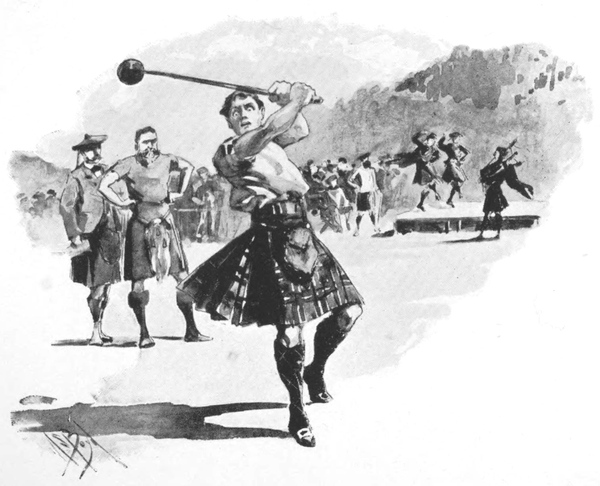

| Throwing the Hammer | A. S. Boyd | 72 |

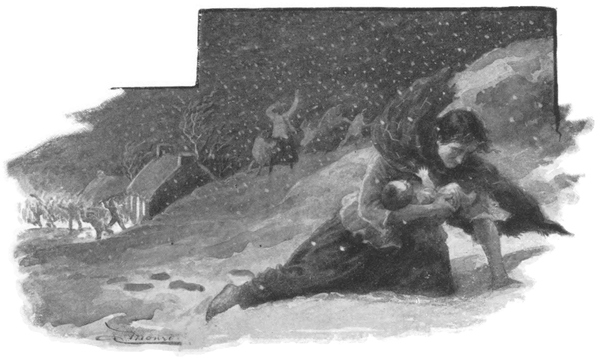

| Massacre of Glencoe | A. Monro | 108 |

| The Gentle Art | S. Reid | 120 |

| Forbidden Waters | S. Reid | 136 |

| Murray’s Curse | A. Monro | 144 |

| Archie | A. S. Boyd | 170 |

| “Serve!” | S. Reid | 180 |

| The Last Hour | A. S. Boyd | 204 |

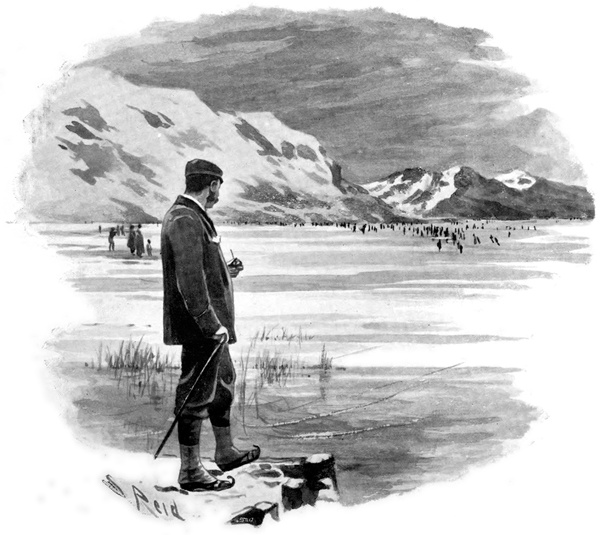

| Seven Miles of Ice | S. Reid | 216 |

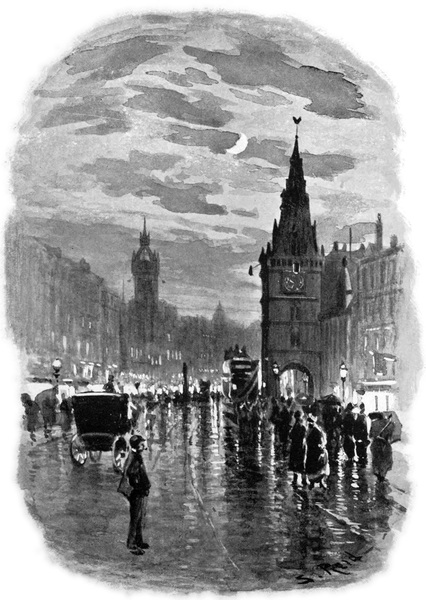

| Trongate of St Mungo | S. Reid | 232 |

Still and soft with the mild radiance of early spring the afternoon sunshine sleeps upon the rich country, moor and woodland and meadow, that stretches away southward towards the Border. The top of a ruined tower far off rises grey amid the shadowy woods, and a river, like a shining serpent, gleams in blue windings through the russet valley-land, while the smoke of an ancient Border town hangs in the distance, like an amber haze, above the side of its narrow strath. Northward, too, league upon league, sweep the rich pasture-lands of another river valley. The red roofs of more than one peaceful hamlet glow warm there among the bowering road-avenues of ancient trees. And afar at the foot of the purple mountain to the west lies the grey sequestered abbey of the Bruce.

North and south upon that rich landscape history marks with a crimson stain the field of many a battle; and though peace and silence2 sleep upon it to-day in the sunshine, hardly is there hamlet or meadow in sight whose name does not recall some struggle of bygone times. Across these hills a hundred and forty years ago Prince Charles Edward led the last raid of the clans, and before his time the battlefields of Douglas and Percy, of Cumberland and Liddesdale, carry the mind back into the mists of antiquity, out of which looms the sullen splendour of more classic arms.

Here, straight as a swan-flight along the ridge of the watershed, commanding the country for miles upon either side, still runs the ancient highway of Imperial Rome. From the golden milestone of Augustus in the Capitol, in a line scarce broken by the blue straits of the sea, ran hither the path of that ancient Power. Of old, along these far-stretching arteries came pulsing in tidal waves the iron blood of the stern heart beating far away in the south. From the wooded valleys below, the awed inhabitants doubtless long ago looked up and wondered, as the dark masses of the legions came rolling along these hills.

Tide after tide, like the rising sea, they rolled to break upon the Grampian barriers of the North. Here rode Agricola, his face set towards3 the dark and mist-wrapt mountains beyond the Forth, eager to add by their conquest the word “Britannicus” to his name. Here by his side, it is probable, rode the courtly Tacitus, his son-in-law, to describe to future ages the Scotland of that time, “lashed,” as he knew it, “by the billows of a prodigious sea.” Southward here, stern and intent, once sped the swift couriers bearing to Rome tidings of that great battle at Mons Grampus, where the bodies of ten thousand Caledonians slain barred the northward march of the Roman general. Southward, again, along this road it is almost certain has passed the majesty of a Roman Emperor himself. For in the year 211 the Emperor Severus, ill and angry, leaving fifty thousand dead among the unsubdued mountains of the North, was borne out of Scotland by the remnant of his army, to die of chagrin at York. And here, long ago, by his flickering watch-fire at night, the Roman sentinel, perhaps, has let his thoughts wander again sadly to his home by the yellow Tiber two thousand miles away, to the vine-clad cot where the dark-eyed sister of his boyhood, the little Livia or Tessa, would be ripening now like the olives, with no one to care for and protect her.

Fifteen hundred years ago, however, the last yellow-haired captives had been carried south to whet the wonder of the populace in the triumph of a Roman general. Fifteen hundred years ago the power of the Imperial city had begun to wane, and the tide of her conquest ebbed along these hills. The eagles of the empire swept southward to defend their own eyrie upon the Palatine, and here, along the highways they had made, died the tramp of the departing legions. The tides of later wars, it is true, have flowed and ebbed across the Border. Saxon and Norman, both in turn, have set their faces towards the North. But later nations kept lower paths, and, untrodden here along the hill-tops, like the great Roman Empire itself, this chariot-way of the Cæsars has looked down upon them all. Forsaken, indeed, and altogether lonely it is now. Torn by the rains of fifteen centuries, and overgrown with the tangle of a thousand years, the roadway that rang to the hoofs of Agricola is haunted to-day by the timid hare, while overhead, where the sun glittered once on the golden eagles of the legions, grey wood-doves flutter now among the trees. But, strongly marked by its moss-grown ramparts, it still bears witness to the5 might of its makers, and, affording no text for the sad Sic transit gloria mundi, it remains a Roman defiance to time, like the defiance of all true greatness—Non omnis moriar.

Greater benefits than these roads of stone did the Roman bring to the lands he conquered. The tread of the victorious legions it was that broke the dark slumber of Europe, and in the onward march of the western nations the footsteps of the Cæsars echo yet upon the earth. Rome, it is true, ploughed her empire with the sword, but in the furrows she sowed the seeds of her own greatness; and these seeds since then have grown to many a stately tree. Fallen, it may be, is the splendour of the “city upon seven hills”; but east and north and west of her rise the younger empires of her sons. Augustus from his gilded Capitol no longer rules the world, and the gleam of the steel-clad legions no longer flashes along these old forsaken highways among the hills; but the earth is listening yet, spell-bound, to the strains of the Latin lyre, and wherever to this hour there is eloquence in the west, there flourishes the living glory of the Roman tongue.

To-day, with the coming of spring in the air,6 there are symbols enough on every hand of the great Past that is not dead. The bole of the giant beech-tree here, it is true, has itself long since ceased to put forth leaves; but, springing upward from its strength, a hundred branches are spreading aloft the promise of the budding year. The dry brown spires of foxglove that stand six feet high in the coppice near, dropped months ago their purple splendours; but thick already about their roots the green tufts of their seedlings are pushing up through rich mould and warm leaf-drifts of bygone autumn to fill the place anon with tenfold glory. From the gnarled roots of the ancient thorn-hedge hangs many a yellow tress of withered fern; yet the life of the fallen fronds is, even now, stirring underground, and from the brown knobs there before long will rise the greenery of another year. Already, here and there, in sunny nooks, a spray of the prickly whin has burst into blossom of bright gold. A little longer, and the mossy crannies of the ruined dyke will be purple with the dim wood-violet. And soon, in the steep corner of the immemorial pasture that runs up there under the edge of the wood, the deep sward will be tufted with creamy clusters of the pale primrose.

7 A pleasant spot it is to linger in, even on this early spring day, for the sunshine falls warm in the mossy hollow of the road, and rampart and thicket overhead are a shelter from the wind. Resting on the dry branch of a fallen pine, one can gaze away southward over the landscape that the Romans saw; and, fingering through a pocket volume of some old Augustan singer, it is possible to realise something of the iron thought that stirred them to become masters of the world.

Under the great eastern oriel at Melrose, where the high altar of the abbey once stood, lies buried the heart of King Robert the Bruce. Elsewhere, far off at Dunfermline, in Fife, the body of the Scots King was entombed. Some seventy years ago, when workmen in that ancient Scottish capital were repairing the ruined church, they came upon a marble monument, broken and defaced. Digging below, amid the mould of the sepulchre, they found the skeleton of a tall man. Fragments of cloth-of-gold lay about it, and the breast-bone had been sawn through; and by these signs the workmen knew that they had found the resting-place of the King. There, as one who was present has said, after the silence and darkness of five centuries, was seen the head that had planned and changed the destinies of Scotland; there lay the dry bone of the arm that on the eve of Bannockburn had at one blow slain the fierce De Bohun.9 But the Bruce’s heart, embalmed and cased in silver, bearing its own strange romantic story, lies apart in the Border Abbey. Around the place of its rest, in that fallen and mouldering fane, lie the race that took from the heart their armorial cognisance—the lords of the great house of Douglas.

Hot and stirring was the Douglas blood, and hardly a battlefield of the Middle Ages in Scotland but was stained with some of its best. Derived far back amid the mists of antiquity, none could tell how the race arose, and it was wont to be a boast with the house that none could point to its “first mean man.” There is a tower in Yarrow by the Douglas (dhu glas, black water) Burn which is said to have been the stronghold of “the Good Lord James”; and amid the fastnesses of Cairntable in Lanark there is another Douglas Water and Douglas Castle. From one of these, no doubt, in ancient Scots fashion, the family took its name; but when that happened, and what the story was of its early days, must remain a tale untold. The house’s mediæval greatness began, however, with the rise of Robert the Bruce, and from that time onwards its deeds mark with stain or10 blazon every page of Scottish history. Lords of the broad Scottish Border, east and west, their hands were sometimes stronger than the King’s. At one time a Douglas could ride to the field with twenty thousand spears at his back, and the gallop of the Douglas steeds sometimes was terrible alike on the causeway of Edinburgh and on the moorland marches of Northumberland. Douglas Earls and Knights fought as leaders through all the wars of David Bruce. A dead Douglas in 1388 won the famous fight with Hotspur on the moonlit field of Otterbourne. At Shrewsbury, in the days of Robert III., Henry IV. of England himself ran close to being hewn in pieces by the Earl of Douglas; and for gallantry on the battlefields of France this same great Earl was invested by the French King with the Dukedom of Touraine. The fame of Scottish chivalry for three hundred years was blown abroad under the Douglas name; for courtesies and blows alike were exchanged by the race on many battlefields besides those of the northern Borderland. Not that dark deeds are lacking in their history. Dark deeds belonged to their times. But in the tilting-yard or on the tented field were to be met no fairer foes. Nor11 was their heroism all of the sword-and-buckler order, or confined to one sex. The finest thing recorded of the race, after all, was done by a woman. On that dark February night in 1437, when James I. was murdered in the Blackfriars Abbey at Perth, when the noise and clashing was heard as of men in armour, and the torches of the coming assassins in the garden below cast up great flashes of light against the windows of the King’s chamber, was it not a Catherine Douglas who, for lack of a bolt, thrust her own fair arm into the staples of the door?

The fortunes of the family culminated in the reign of James II. Whatever its origin had been, in that reign the race had attained an eminence more dazzling, perhaps, than that of any subject before or since. Earls of Douglas and Wigton, Lords of Bothwell, Galloway, and Annandale, Dukes of Touraine, Lords of Longueville, and Marshals of France, they had inter-married more than once with the Scottish Royal House itself. Members of the family also held the Earldoms of Angus, Ormond, and Moray. What wonder that they lifted haughty heads, and began to look askance at the Royal power? Then it was that the Stuart King stooped to12 treachery, and then was done the darkest deed that ever sullied the Stuart name.

Already, in the boyhood of James, a youthful Earl of Douglas and his brother had been betrayed and slain by the King’s Ministers. For this transaction, however, the King was in no way to blame. The young Earl was his guest in the Castle of Edinburgh, and when at the treacherous feast the black bull’s head, the sign of death, was placed upon their table, James had wept piteously and begged hard for the lives of his friends. It was later, when another Earl was lord upon the Border, that the King made murder his resource. For this act, it must be said, James had strong provocation. Douglas had been honoured by him, had been made Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom, and had abused that honour. He had flouted the King’s authority, and slain the King’s friends, and, having been commanded by letter to deliver up to James’s representative the person of a subject unjustly imprisoned by him, he delivered him up “wanting the head.” Finally, with two great Earls of the North, he had entered into an open league against the King. All this, however, cannot palliate the King’s resource, cannot absolve13 the tragic scene in that little supper-chamber in the Castle of Stirling. There the great Earl was under the protection of the King’s hospitality, when James, bursting into rage at his taunts and at his refusal to abandon the treasonous compact, suddenly cried, “By Heaven, my Lord, if you will not break the league, this shall!” and, drawing his dagger, stabbed Douglas to the heart.

This deed brought the family fortunes to a climax, and for three years Scotland was blackened by the raging of the Douglas Wars. From Berwick to Inverness the country was wasted by the struggles of the partisans. Stirling and Elgin were burned, and, amid famine and pestilence, the troubles of the wars of Edward seemed come again on Scotland: so great had grown the power of these Border lords. At last, however, the King and the Earl came face to face. Each led an army of forty thousand men, and only the small river Carron ran between them. By the combat of the morrow, it seemed, would be known whether James Stuart or James Douglas should wear the Scottish crown. But the Earl’s heart was seen to fail, and on the morrow, when he awoke, he found his camp14 deserted. Of all his host of the previous day not a hundred followers remained. Nothing was left him but flight; and, turning his back, as a Douglas had never done before, he made his way to England. Twenty years later, having been captured by one of his own vassals in a petty skirmish on the Border, he was sent to end his days as a monk in the Fifeshire Abbey of Lindores.

Thus ended the great line of the Earls of Douglas, a race whose history for three hundred years had been the history of Scotland, and whose foot had twice, at least, been set upon the step even of the throne. From the house’s latter days of turbulence and ambition there is pleasure in turning back to those earlier years when the Good Lord James rode at the Bruce’s saddle-bow, and the patriotism of groaning Scotland rallied round the coupled names of Douglas and the King. No later deed can dim the lustre of those years, and nothing in history can outshine the last scene in the life of the Knight who strove to carry the Bruce’s heart to the Holy Land. Himself hemmed round by the Moors on that Spanish plain, in his effort, it is said, to succour a friend, the Earl took from15 his neck the casket containing the King’s heart. “Pass first in fight,” he cried, “as thou wert wont to do! Douglas will follow thee, or die!” Then, throwing the casket far among the enemy, he rushed forward to the place where it fell, and was there slain. Well would it have been for the race of Douglas had they ever remained true as that ancestor to the service of their King!

Night in Edinburgh! The traveller may have seen the sun set over the lagoons of Venice; he may have watched the moon rise behind the Acropolis of Athens; but he has seen nothing finer or more inspiring than is shown him by the sparkle of the frosty stars in this grey metropolis of Scotland. From the terraced pavement of Princes Street, that unmatched boulevard of the modern city, looking across the dark chasm where once surged the waters of the North Loch, he sees the form of the Old Town rise, from Holyrood Palace low in the eastern meadows to the castled rock high at the western end, a dark mass all against the southern sky. Yellow lines of light mark the modern bridges spanning the abyss below, and windows still glowing—dim loopholes in the perilously high old houses beyond—bespeak the inhabitants there not yet all asleep. But these are forgotten in the witchery of the sight, when17 the clouds part, and the silvery starlight is shaken down upon the ancient city; when behind the broken sky-line of roofs and gables the clear moon comes up, and hangs, a lustrous jewel, among the pinnacles of St Giles’.

Nor is it only the magic of the sight that stirs strange pulses in the blood. Standing at night in the Roman Coliseum, it seems still possible to hear majestic echoes of an older world. But the Scotsman under the shadow of “high Dunedin” is moved, as nowhere else, by memories of old glory and old sorrow. Here to a Scottish heart the past comes back. Here sighed the fatal sweetness of Rizzio’s lute. Here rang the wild clan-music of Lochiel. Among these old walls, however, something more is to be remembered than the deeds of high fame. Ever and again, it is true, amid the gloom of half-forgotten centuries, there is caught the glitter of some historic pageant. Out of the silence about the Cathedral one seems to catch the chime of fuming censers and the roll of coronation litanies, with, perchance, the sonorous accents of a Gavin Douglas, poet-bishop of Dunkeld; and one thrills again to hear the boom of the Castle cannon as the Fourth James rides gallantly away18 to his death. But behind all this a more tender interest touches the heart. What of the real inner life of those centuries bygone—the loves and sorrows, burning once, and poignant as ours are to-day, which have passed out of sight among the years, and been forgotten? Of some of these, indeed, Sir Walter Scott has written the story on the dark curtain of the past with a pen of fire. But for countless others there is not even the poor consolation of a recorded name. Occasionally, however, amid the seething of history, or in some half-remembered old song, a reference occurs, and a glimpse all too brief is had into some tender and mournful story. And so one sees that, behind the glitter of a Stuart chivalry, of brave and splendid deeds before the world, sometimes there lay a shadow, the sigh of a breaking heart, the stain of unavailing tears.

Who knows the early history of that Lady of Loch Leven, mother of the Regent Murray? Grimly enough she is painted by Scott in her old age as the keeper of Queen Mary. Yet assuredly once she was lovely and young, and had strange beatings of heart as she listened to the whispers of her Royal lover, that all too gallant James V. What was their parting like,19 when the parting came? Was there the last touch of regretful hands, a remorseful caress from the royal lips, a passionate farewell? Or was there only the cruel news by alien mouths that her place was filled by another, that she had been forsaken? No one can tell us now.

Then what of the Lady Anne Campbell of Argyle, at one time betrothed to Charles II.? The youthful Prince, aged twenty, had been crowned gorgeously, after the ancient manner of the Scottish Kings, at Scone. But King only in name, with England still under the iron rule of Cromwell, and only a faction in Scotland devoted to his cause, his immediate fortunes were entirely in the hands of the Scottish leader, the crafty, covenanting Marquis of Argyle. Reaching ever higher in ambition, and dazzled by the weird vision of the race of MacCallum More mounting the throne, Argyle proposed that Charles should marry his daughter. Needy and reckless, and eager to attach Argyle to the Royalist cause by the golden bands of hope, the King pretended consent. Alas for the Lady Anne! What maiden could keep still her heart when wooed by so royal a lover? For wooing there must have been, to keep up the pretence of betrothal, and20 how was the maiden to know that those words and looks, and, it may have been, those warmer caresses, were all no more than a diplomacy? And when the crash came, with Cromwell’s defeat of the covenanting army at Dunbar, and the revelation that she had given up her all and had been deceived—how bitter, how cruel the discovery! The contemporary Kirkton relates circumstantially that “so grievous was the disappointment to the young lady, that of a gallant young gentlewoman, she lost her spirit, and turned absolutely distracted.”

Then there is a pitiful little song, unprinted and all but forgotten,A sung to a quavering, pathetic old tune, and relating in quaint ballad fashion something of the story of one Jeanie Cameron, an adherent of Prince Charles Edward in the rebellion of 1745. It narrates how the maiden, having fallen sick, not without a suspicion of its being heart-sickness, and all cures of the leeches failing, was prescribed “ae bricht blink o’ the Young Pretender.” So she sate her down and wrote the Prince “a very long letter, stating who were his friends and who were his 21foes.” This letter she had closed, and was just “sealing with a ring,” when, as used to happen in ballad story, “ope flew the door, and in came her King.” Poor young lady!—

Nor is this pretty romance merely an invention of the poet’s brain. One of the family by whom the song has been preserved happened, it seems, in the latter part of last century, to be buying snuff in a shop in Edinburgh, when a beggar came in. Nothing was said before the stranger; but the shopkeeper, as if it were an accustomed dole, handed the beggar a groat. Afterwards, in reply to a remark of his customer as to the delicacy of the beggar’s hand which had received the coin, the shopkeeper revealed the fact that the recipient of his charity was no man, but a woman, and no other than Jeanie Cameron, a follower of the Chevalier. Her story, so far as he knew it, was sad enough. She had followed the Prince to France, hoping, no doubt, poor thing! to resume there something of the place she had believed herself to hold in his affections. Alas! it was only to find herself, like so many22 others, forgotten, cast off, an encumbrance to a broken man. And then, with who can tell how heavy a heart, she made her way home, only to discover that her family had shut their door upon her, and cut her adrift. So, for these many years, she had wandered about forlorn and lonely, supported by a few charitable bourgeois in the streets of Edinburgh—she who could look back upon the day when she had loved and been loved by a Stuart Prince.B

A It has now been included in “Ancient Scots Ballads with their Traditional Airs.” Glasgow: Bayley & Ferguson, 1894.

B This account of the latter days of “Mrs Jean Cameron” finds corroboration in a footnote to the second volume of Chambers’s “Traditions of Edinburgh.”

Such are some of the stories which find no place in history, but whose consciousness sheds a tragic and tender interest about this grey old capital of the North. Who will say that they are not as well worth thought as the trumpetings of herald pursuivants and the clash of warlike arms?

Out of the way, in this quiet hollow of the Ayrshire hills, something remains yet of the life of a hundred years ago. Elsewhere the puffing of steam may have taken the place of toil by hand, but here in the long summer days, from morning till night, the click-clack of the looms is still to be heard, and within every second window up the length of the village street, the dusty frames are to be seen moving regularly to and fro. Pots of geranium and fuchsia are set sometimes in these windows, and through the narrow doorways the cottage gardens can be seen behind, carefully kept, and ablaze just now with wallflower borders and pansies. Sadly, however, is the place decayed from its prosperity of old. Little traffic comes now to the wide, empty street. The carrier’s waggon is an object of interest when it puts in an appearance. The baker’s van may be the only vehicle of an afternoon; and twice a week only comes the flesher’s cart. Butcher24 meat, it is to be feared, is but seldom seen on some of the village tables; and, when work is more than usually scarce, many must put up with but “muslin-broth.” Here and there a roofless ruin, breaking the regular line of dwellings, tells of a decaying industry. In the sunny inn-door at the head of the village the brown retriever may rouse himself, once in the afternoon, to inspect the credentials of some vagrant terrier; and, but for the faint click-clack of the looms all day, and the appearance, once in a while, of a woman with a pair of stoups to draw water at the village well, the place might seem asleep.

Yet a hearty trade once throve on the spot. Every house had its loom going, sometimes two; and there was always work in plenty. Weavers’ wives could go to kirk then in black-beaded bonnets and flowered Paisley shawls, and the Relief Kirk minister got his stipend of eighty pounds a year nearly always paid. In those times the carrier’s cart used to have business in the village every day; merchants from Glasgow came bidding against each other for work in a hurry; and four of the weavers at once have been known to have sons at college studying for the ministry. Those were the days when the25 village kept a watchful eye upon the religious and political movements of the country. Before the Stamp Duty was removed from newspapers, the weavers subscribed in clubs and took out their weekly sheet, which was passed from shop to shop, read and digested, and thoroughly threshed out in the door-step debates, when a knot of neighbours would gather between the spells of work. In this way the great Reform Bill was fully discussed and settled here long before it passed the House of Commons; and the absorbing question of the Disruption, which gave birth to the Free Church, was thoroughly argued and thought out on its merits.

True to the traditions of their craft, of course, most of the weavers were the reddest of Radicals, and the progress of the Chartist movement excited the keenest interest among them. The work at the looms was to a great extent mechanical, and while they pushed the treadles and pulled the shuttles to and fro, the weavers had time to think; and shrewd thinkers and able debaters many of them became, ready at the hustings with questions on the Corn Laws, the freeing of the slaves, and the Irish grievances, which were apt to put a political candidate to some trouble.26 He had not their advantage of the daily “argufying” and the Saturday night debates at the village inn. There was a tradition that in the room where this club met, the poet Burns had once spent an evening, and the fact lent an additional zest to his song, which they never tired of quoting,—“A man’s a man for a’ that.”

The industry of the village has died hard. Amid decaying trade the weavers kept to their looms, and many a pinch was suffered before one after another laid down his shuttle. Their feelings are not difficult to understand. As boys they had played about the village well. As young men they had wandered with their sweethearts—that delicious time—down the woodland roads around. Memories had grown about them and their old homes during the long years of work. In the kirkyard not far off lay the ashes of mother or wife or child. But the merchants had ceased to come to the village, and it was a weary walk for the poor weavers to carry their webs all the way to Glasgow, to hawk them27 from warehouse to warehouse, and sometimes to have the choice at last of accepting a ruinous price for them, or of taking them home again.

It was after a bootless errand of this sort that old John Gilmour was returning to the village one night in late October some forty-three years back. Honest soul, through all his straits he had never owed a neighbour a penny. That night, however, his affairs had come to a critical pass, and the morrow held a black look-out for him. His web was still on his back, not an offer having been got for it in town, though he knew the workmanship to be his best. Upon its sale he had depended to pay for the winter’s coals, and the necessaries of the morrow; for on the day previous the last of his carefully guarded savings had been spent. Moreover, his wife and he were growing old, and could hardly look forward to increased energy for work. And he was bringing home bad news. Their second son (the eldest had run away to sea eleven years before) had broken down in his attempt to teach, and, at the same time, push his way through the Divinity Hall, and had been ordered by the doctor to stop work for the winter altogether. How was the old man to break all this disastrous28 news to his wife? The web was heavy, but his heart was heavier.

He had reached the fork of the road close by the old disused graveyard of the parish, and was thinking a little bitterly of the reward that remained to him from his long life of hard work, and of how quiet and far from care those were who lay on the other side of the low dyke under the green sod, when a hackney carriage came up behind, and the driver stopped to ask the way to ——.

“Keep the left road,” said the old man, and was resuming his walk, when a bearded face appeared at the carriage window.

“That seems a heavy bundle you are carrying. Are you going my way?”

Once inside, the old weaver found his companion looking at him intently.

“You have had a long walk this day, surely? Have you no son to carry so heavy a load for you?”

Ay, he had two sons, Gilmour said: but one was lost at sea, and the other was struggling at college.

“You live alone, then?” asked the questioner, tremulously.

29 No, thank God! he had a kind wife at home, who had been his consolation through many a dark hour.

“Thank God!” echoed the younger man.

The carriage rolled on and entered the village. The weaver pointed to his house, and they stopped there. The stranger helped him out with his web, and entered the house with him.

“It’s just the web back, guidwife,” he said. “But dinna look sae queer like. I’se warrant I’ll sell it the morn. An’ here’s a gentleman has helpit me on the road. Hae ye onything i’ the hoose to offer him?”

But the wife was not thinking of the web or the distress of the morrow. Her eyes were on the stranger, and the corners of her lips were twitching curiously. He had not spoken, but as he removed his hat she sprang towards him.

“It’s Willie!” she cried; “it’s Willie!” And her arms were about his neck, and, half laughing and half crying, she buried her face on his breast.

It was Willie. He was the first who came back to the village from the gold-fields of Ballarat.

What richer picture could the eye desire than this sunlit glory of harvest colour amid the Highland mountains? The narrow sea-loch itself below gleams blue as melted sapphire under the radiant and stainless sky; around it, on the rising slopes, the corn-fields, rough with fruitful stooks, spread their yellow ripeness in the sun; amid them shine patches of fresh soft green where the second clover has been cut; while above hang the sheltering woods, like dark brown shadows; and, over all, the surrounding hills, bloom-spread as for a banquet of the gods, raise their purple stain against the blue. Only far off, above the dim mountains of amethyst in the North, lies a white argosy of clouds, like some convoy of home-bound India-men becalmed on a summer sea.

There has been no sound for an hour but the whisper of the warm autumn wind that the farmer loves for winnowing his grain, the drone of a31 velvety bee sometimes in the blue depth of a hare-bell, and the crackle of the black broom-pods bursting in the heat. The furry brown rabbits that pop prudently out of sight in the mossy bank are silent as shadows; the red squirrel that runs along the dyke top and disappears up a tree makes no chatter; and even the shy speckled mavis that bobs bright-eyed across the path is voiceless, for among the birds this is the silent month.

Less and less, as the narrow road rises through the fir woods, grows the bit of blue loch seen far behind under the branches, and the little clachan in the warm hollow over the brow of the hill is shut from the world on every side by the deep and silent forests of fragrant pine. Wayside flowers are seeding on the time-darkened thatch of these sequestered dwellings. There, with branches of narrow pods, the wallflower clings; and the spikes of the field-mustard ripen beside the golden bullets of the ox-eyed daisy. On a chair at the door of one of the cottages an ancient granny is sunning herself, counting with feeble fingers the stitches on her glancing knitting wires. A frail old body she is, set here, neat and comfortable, by some loving hand, to32 enjoy, it may be, the sunshine of her last autumn on earth. Withered and wrinkled are her old cheeks with the cares of many a winter, and it seems difficult to recall the day when she was a ripe-lipped, merry reaper in the corn-fields; but under her clean, white mutch the grey old eyes are undimmed yet as they watch, heedful and lovingly, the movements of the little maid tottering about her knee. Where are her thoughts as she sits there alone, hour after hour, in the silent sunshine? Is she back in the dusk among the sweet-scented hay-ricks, listening with fluttering heart to the whispers of her rustic lover? Is it a sunny doorway where she sits crooning for happiness over the baby on her knee? the little one that is all her own—and his. Or is it a winter night as she kneels in the flickering light by the bedside, feeling the rough, loving hand relax its grasp, while she sees the shadow pass across the wistful face, and knows with breaking heart that she is alone? These are the peaceful scenes of peasant life; alas, that they should ever be darkened by the shadow of the sword!

Granny can speak no English, or she might have something to say of the great disaster that befell the clans on the moor close by in her33 father’s time. For not far beyond the little clachan the road emerges on the open heath, and there, where the paths cross, lies the great, grey boulder on which the terrible duke stood to survey the field just before the battle. Not even then was he aware how nearly his birthday carousals of the night before, at Nairn, had been surprised and turned into another slaughter of Prestonpans. So perilously sometimes does the sword of Damocles tremble over an unconscious head. His troops, well rested and provisioned, were fresh as that April morning itself, while the poor clansmen in the boggy hollow to the right, divided in their councils, and famishing for treacherous lack of bread, were exhausted by the fruitless twenty-four mile surprise march of the night. Yet they came on, these clansmen, half an hour later, like lions; plunging through the bog, sword in hand, in the face of the regulars’ terrific blaze of musketry, cutting Cumberland’s first line to pieces, and rushing on the second line to be blown to atoms at sword’s length.

The yellow corn is being shorn to-day where the clans were mowed down then. Here was spilt the best blood of the Highlands. Close by, the brave Keppoch, crying out as he charged alone34 before the eyes of his immovable Macdonalds that the children of his tribe had forsaken him, threw his sword in the air as a bullet went into his heart. Wounded, at the tall tree to the west fell Cameron of Lochiel; and in the little valley beyond, the defeated Prince Charles, as he fled, paused a moment to bid his army a bitter farewell. The road here at the corn-field’s edge dips a little yet, where the fatal bog once lay, and ten yards to the left still springs the Dead Men’s Well, to which so many poor fellows crawled during the awful succeeding night to allay the tortures of their thirst before they died. Here the gigantic MacGillivray, leader that day of the clan M’Intosh, fell dead as, with his last strength, he bore to the spring a little wounded boy whom he had heard at his side moaning for water.

A better fate the bravery of these men deserved, misguided though they might be; for the victors gave no quarter to wounded or prisoners, and the soul shudders yet at thought of the horrors that followed the battle. It was not enough that disabled men should be clubbed and shot, and barns full of them burned to ashes; but to this day in many a quiet glen lie the remains of hamlets35 ruined in cold blood, and tales are told of the dark vengeance taken by the victorious soldiery upon defenceless women, little children, and old men. Well was it, perhaps, for those who had fallen that they lay here at rest under the heather—they could not know the cruel fate of wife or child. To other lips was left the wail for “Drummossie; oh, Drummossie!” At rest they were, these hot and valiant hearts, plaided and plumed as warriors wish to lie, in their long bivouac under the open heaven. Not the first nor the last of their race, either, were they to fall, scarred with the wounds of war; for, less than a mile away, under the lichened cairns of Clava, do not the ashes rest of the chiefs their ancestors, slain in some long-forgotten battle of the past, and waiting, like these, for the sound of the last réveille?

Here, on each side of the road, can still be made out the trenches where the dead were buried, according to their tartans it is said; and, while the rest of the moor is purple with heather, these sunken places alone are green. On the edge of the corn-field rises a stone, inscribed “Field of the English; they were buried here”; and at the end of each trench on the moor stands36 a rude slab bearing the name of its tribe. A singular pathos attends two of these stones, on which is written, not M’Intosh or Stewart or Fraser, but “Mixed Clans.”

Round the oval moorland of the battle rise thick fir-woods now, dark and mournful. Sometimes the winds of the equinox, as they roar through these, recall the deadly rolling musketry of long ago. But the air to-day scarcely whispers in the tree-tops, and sunshine and silence sleep upon the resting-place of the gallant dead. Only some fair, white-clad girls, who have come up from Inverness to read the battle inscription on the great boulder-cairn, are plucking a spray of heather from the Camerons’ grave.

Never is a man more conscious of his manhood than when, with bridle in hand and a good horse under him, he takes the road at a gallop. As his steed stretches out and the hoof-beats quicken, as the milestones fly past and the cool air rushes in his face, he casts care to the winds, his pulse beats stronger, he rejoices to breathe and to live. The pride and the pleasure of this experience have ever appealed to the poets, and the ringing of horse-hoofs echoes through the verse of all ages—in the warrior chants of Israel; through the sounding Virgilian lines; to the reverberating rhythm of the “Ride from Ghent to Aix.” But the maddest, most riotous gallop of all is, perhaps, that of the grey mare Meg and her master from Ayr to the Shanter farm.

Burns was never more fortunate in his subject than when thus fulfilling his promise of providing a legend for “Alloway’s auld haunted kirk.” He did not, it is true, with the nice precision38 of the Augustan laureate, trim his verse to a mechanical imitation of sound; but the wild rush and deftness of the movement of the poem, the quick succession of humour on pathos, scene upon scene, the ludicrous, the startling, the horrible, carry away the breath, and suggest more vividly than any mere measuring rhythm the mad daring of that midnight ride.

There is a little, old-fashioned, deep-thatched inn still standing where the street leads southwards out of Ayr. Under its low, brown-raftered roof it is yet easy to imagine how the veritable hero, Tam, may have sat with his cronies “fast by the ingle, bleezing finely,” while “the night drave on wi’ sangs and clatter,” and the storm outside hurled itself fruitlessly against the little deep-set window. It would need all the liquor he had imbibed to fortify the carouser for that fourteen-mile ride into Carrick. A midnight hurricane of rain and wind would be no pleasant encounter on that lonely road, to say nothing of the eerie spots to be passed, and at least one point more than a trifle dangerous. But Tam o’ Shanter was a stout Ayrshire farmer, and, moreover, he was accustomed to face worse ragings than those of the elements; so it may39 be supposed that, when he had hiccupped a last goodbye to his friends, and, leaving the warm lights of the inn streaming into the street behind him, galloped off into the blackness of the night, it was with no stronger regret than that he must go so soon. Half a mile to his right, as he bucketed southward along the narrow road, he could hear the ocean thundering its diapason on the broad beach of sand, and at the places where he crossed the open country its spray would strike his cheek and fly inland with the foam from Maggie’s bit. Sometimes, when the way lay through belts of beech and oak woods, the branches would roar and shriek overhead as they strove with maniac arms against the tempest.

The old road to Maybole, and that which Tam o’ Shanter took, ran a little nearer the sea than the one which did duty in Burns’ time, and still serves its purpose; and about a mile out of Ayr it crosses the small stream at the ford where “in the snaw the chapman smoored.” Here, on the newer road, a curious adventure is said to have befallen the poet’s father. There was formerly no bridge across this stream; and the legend runs that William Burnes, a few hours before the birth of his son,40 in riding to Ayr for an attendant, found the water much swollen, and was requested by an old woman on the farther side to carry her across. Notwithstanding his haste he did this; and a little later, on returning home with the attendant, he was surprised to find the woman seated by his own fireside. It is said that when the child was born it was placed in the gipsy’s lap, and she, glancing into its palm, made a prophecy which the poet has turned in one of his verses:—

If all gipsy predictions were as well fulfilled as this concerning the poet, the dark-skinned race assuredly would be far sought and courted.

A few strides beyond the stream his grey mare had to carry Tam past a dark, uncanny spot—“the cairn whare hunters fand the murdered bairn.” It was covered then with trees, and one of them still stands marking the place. To the left of the old road here, and hard by the newer highway, lies the humble cottage, of one storey, where Robert Burns was born. It has been41 considerably altered since then, having been used until recently as an alehouse, and further accommodation having been added at either end. But enough of the interior remains untouched to allow of its original aspect being realised. The house is the usual “but and ben,” built of natural stones and clay, and neatly whitewashed and thatched. In the “but,” the apartment to the left on entering from the road, there is little alteration; and it was here, in the recessed bed in the wall, that the poet first saw light. The plain deal dresser, with dish-rack above, remains the same, and the small, square, deep-set window still looks out behind, over the fields his father cultivated. An old mahogany press with drawers still stands next the bed; the floor is paved with irregular flags; and the open fireplace, with roomy, projecting chimney, occupies the gable. An extra door has been driven through the south-east corner to allow the profane crowd to pass through, and a larger window has been opened towards the road that they may see to scratch their names in the visitors’ book; but the rest of the apartment, towards the back, is little changed, if at all, since the eventful night when “Januar’ winds blew hansel in on Robin.”

42 The hour of his ride was too dark, however, for the galloping farmer to see so far over the fields. A weirder sight was in store for him.

A few hundred yards farther on, when, by a well which is still flowing, he had passed the thorn, now vanished, where “Mungo’s mither hanged hersel,” just as the road plunged down along the woody banks of Doon, there, a little to his left,

The grey walls of the little kirk are standing yet among the graves, though the last rafters of the ruined roof were carried off long since to be carved into mementos. The tombs of Lord Alloway’s family occupy one end of the interior, and a partition wall has been built dividing off that portion, but otherwise the place remains unchanged. The bell still hangs above the eastern gable, and under it remains the little window with a thick mullion, the “winnock bunker” in which the astonished farmer, sitting on his mare, and looking through another opening in the side wall, saw the queer musician ensconced.

A more eerie spot on a stormy night could43 hardly be imagined, the trees shrieking and groaning around, the Doon roaring in the darkness far below, while the thunder crashed overhead, and the lurid glare of lightning ever and again lit up the ruin. But with the unearthly accessories of warlocks and witches, corpse-lights and open coffins, with the screech of the pipes, and grotesque contortions of the dancers, the place must pass comparison in horror. Yet, inspired by “bold John Barleycorn,” the farmer stared eagerly in on the revels, till, fairly forgetting himself in the height of his admiration, he must shout out “Weel dune, Cutty Sark!” Then, in a moment, as every reader is aware, the lights went out, the pipes stopped, and the wrathful revellers streamed after him like angry bees. A few bounds of his mare down that narrow, winding, and rather dangerous road would carry Tam to the bridge, and the clatter of terrified Maggie’s hoofs as she plunged off desperately through the trees seems to echo in the hollow way yet. All the world knows how she carried her master in safety across the keystone of the bridge at the cost of her own grey tail. The feat was no easy one, for the single arch (still spanning the river there) was high and steep and narrow.

44 Beyond the Doon the old road rises inland, bowered high with ash and saugh trees, to the open country; and Tam, pale and sober no doubt, but breathing freer, had still twelve long miles before him to the far side of Kirkoswald in Carrick, where sat his wife—

A quiet, sunny nook in the hollow it is, this square old garden with its gravelled walks and high stone walls; a sheltered retreat left peaceful here, under the overhanging woods, when the stream of the world’s traffic turned off into another channel. The grey stone house, separated from the garden by a thick privet hedge and moss-grown court, is the last dwelling at this end of the quiet market-town, and, with its slate roof and substantial double storey, is of a class greatly superior to its neighbours, whose warm red tiles are just visible over the walls. It stands where the old road to Edinburgh dipped to cross a little stream, and, in the bygone driving days, the stage-coach, after rattling out of the town, and down the steep road here, between the white, tile-roofed houses, when it crossed the bridge opposite the door, began to ascend through deep, embowering woods. But a more direct46 highway to the capital was opened many a year ago; just beyond the bridge a wall was built across the road; and the grey house with its garden was left secluded in the sunny hollow. The rapid crescendo of the coach-guard’s horn no longer wakens the echoes of the place, and the striking of the clock every hour in the town steeple is the only sound that reaches the spot from the outside world.

The hot sun beats on the garden here all day, from the hour in the morning when it gets above the grand old beeches of the wood, till it sets away beyond the steeple of the town. But in the hottest hours it is always refreshing to look over the weather-stained tiles of the long low toolhouse at the mossy green of the hill that rises there, cool and shaded, under the trees. Now and then a bull, of the herd that feeds in the glades of the wood, comes down that shaded bank, whisking his tawny sides with an angry tail to keep off the pestering flies, and his deep bellow reverberates in the hollow. In the early morning, too, before the dewy freshness has left the air, the sweet mellow pipe of the mavis, and the fuller notes of the blackbird, float across from these green depths, and ever and again throughout47 the day the clear whistle of some chaffinch comes from behind the leaves.

Standing among the deep box edgings and gravelled paths, it is not difficult to recall the place’s glory of forty years ago—the glory upon which the ancient plum-trees, blossoming yet against the sunny walls, looked down. To the eye of Thought time and space obstruct no clouds, and in the atmosphere of Memory the gardens of the past bloom for us always.

Forty years ago! It is the day of the fashion for Dutch bulbs, when fabulous prices were paid for an unusually “fancy” specimen, and in this garden some of the finest of them are grown. The tulips are in flower, and the long narrow beds which, with scant space between, fill the entire middle of the garden, are ablaze with the glory of their bloom. Queenly flowers they are and tall, each one with a gentle pedigree—for nothing common or unknown has entrance here—and crimson, white, and yellow—the velvet petals of some almost black—striped with rare and exquisite markings, they raise to the sun their large chaste chalices. The perfection of shape is theirs, as they rise from the midst of their green, lance-like leaves; no amorous breeze ever48 invades the spot to dishevel their array or filch their treasures; and the precious golden dust lies in the deep heart of each, untouched as yet save by the sunshine and the bee. When the noonday heat becomes too strong, awnings will be spread above the beds, for with the fierce glare, the petals would open out and the pollen fall before the delicate task of crossing had been done.

But see! through the gate in the privet hedge there enters as fair a sight. Ladies in creamy flowered muslins and soft Indian silks, shading their eyes from the sun with tiny parasols, pink and white and green,—grand dames of the county, and grander from a distance; gentlemen in blue swallow-tailed coats and white pantaloons—gallants escorting their ladies, and connoisseurs to examine the flowers—all, conducted by the owner, list-book in hand, advance into the garden and move along the beds.

To that owner—an old man with white hair, clear grey eyes, and the memory of their youthful red remaining in his cheeks—this is the gala time of the year. Next month the beds of ranunculus will bloom, and pinks and carnations will follow; but the tulips are his most famous flowers, and, for the few days while they are in49 perfection, he leads about, with his old-world courtesy, replying to a question here, giving a name or a pedigree there, a constant succession of visitors. These are his hours of triumph. For eleven months he has gone about his beloved pursuit, mixing loams and leaf-moulds and earths, sorting, drying, and planting the bulbs, and tending their growth with his own hand—for to whose else could he trust the work?—and now his toil has blossomed, and its worth is acknowledged. Plants envied by peers, plants not to be bought, are there, and he looks into the heart of each tenderly, for he knows it a child of his own.

Presently he leads his visitors back into the house, across the mossy stones of the court where, under glass frames, thousands of auricula have just passed their bloom, and up the railed stair to the sunny door in the house-side. He leads them into the shady dining-room, with its furniture of dark old bees-waxed mahogany, where there is a slight refreshment of wine and cake—rare old Madeira, and cake, rich with eggs and Indian spice, made by his daughter’s own hand. Jars and glasses are filled with sweet-smelling flowers, and the breath of the new-blown summer comes in through the open doors.

50 The warm sunlight through the brown linen blind finds its way across the room, and falls with subdued radiance on the middle picture on the opposite wall. The dark eyes, bright cheeks, and cherry mouth were those of the old man’s wife—the wife of his youth. She died while the smile was yet on her lip, and the tear of sympathy in her eye; for she was the friend of all, and remains yet a tender memory among the neighbouring poor. The old man is never seen to look upon that picture; but on Sundays for hours he sits in reverie by his open Bible here in the room alone. In a velvet case in the corner press lies a silver medal. It was pinned to his breast by the Third George on a great day at Windsor long ago. For the old man, peacefully ending his years here among the flowers, in his youth served the king, and fought, as a naval officer, through the French and Spanish wars. As he goes quietly about, alone, among his garden beds, perchance he hears again sometimes the hoarse word of command, the quick tread of the men, and the deep roar of the heavy guns as his ship goes into action. The smoke of these battles rolled leeward long ago, and their glory and their wounds are alike51 forgotten. In that press, too, lies the wonderful ebony flute, with its marvellous confusion of silver keys, upon which he used to take pleasure in recalling the stirring airs of the fleet. It has played its last tune; the keys are untouched now, and it is laid past, warped by age, to be fingered by its old master no more.

But his guests rise to leave, and, receiving with antique grace their courtly acknowledgments, he attends the ladies across the stone-paved hall to their carriages.

Forty years ago! The old man since then has himself been carried across that hall to his long home, and no more do grand dames visit the high-walled garden. But the trees whisper yet above it; the warmth of summer beats on the gravelled walks; and the flowers, lovely as of old in their immortal youth, still open their stainless petals to the sun.

The barometer has fallen somewhat since last night, and there are ominous clouds looming here and there in the west; but the sky remains clear blue overhead, the white road is dry and dazzling, and the sun as hot as could be wished. Out to the eastward the way turns along the top of the quaint fisher town, with its narrow lanes and throng of low thatched roofs, till at a sudden dip the little bridge crosses the river. Sweet Nairn! The river has given its name to the town. A hundred and forty years have passed since these clear waters, wimpling now in the sun, brought down from the western moors the life-blood of many a wounded Highlander fallen on dark Culloden. The sunny waters keep a memory still of the flight of the last Prince Charles.

Like a crow-flight eastward the road runs straight, having on the left, beyond the rabbit warren, the silver sand-beach and the sea, and53 on the right the fertile farm-lands and the farther woods. The white line glistening on the horizon far along the coast to the east, is a glimpse of the treacherous hillocks of the Culbin shifting sands. They are shining now like silver in the calm forenoon; but, as if restless under an eternal ban, they keep for ever moving, and, when stirred by the strong sea-wind, they are wont yet to rise and rush and overwhelm, like the dust-storm of the Sahara. For two hundred years a goodly mansion and a broad estate have lain buried beneath those wastes, and what was once called the Garden of Moray is nothing now but a desolate sea of sand. They say that a few years ago an apple-tree of the ancient manor orchard was laid bare for some months by a drift, that it blossomed and bore fruit, and again mysteriously disappeared. Curious visitors, too, can still see, in the open spaces where the black earth of the ancient fields is exposed, the regular ridges and furrows as they were left by the flying farmers; and the ruts of cart-wheels two hundred years old are yet to be traced in the long-hidden soil. Flint arrowheads, bronze pins and ornaments, iron fish-hooks and spear-points, as well as numerous nails, and sometimes an ancient54 coin, are to be picked up about the mouldered sites of long-buried villages; but the mansion of Kinnaird, the only stone house on the estate, lies yet beneath a mighty sandhill, as it was hidden by the historic storm which in three days overwhelmed nineteen farms, altered by five miles the course of a river, and blotted out a prosperous country-side. Pray Heaven that yonder terrible white line by the sea may not rise again some night on its tempest wings to carry that ruin farther!

Over the firth, looking backward as the highway at lasts bends inland, the red cliffs of Cromarty show their long line in the sun, and, with the yellow harvest-fields above them, hardly fulfil sufficiently the ancient name of the “Black Isle.” Not a sail is to be seen on the open firth, only the far-stretching waters, under the sunny sky, bicker with the “many-twinkling smile of ocean.” Here, though, two miles out of Nairn, where the many-ricked farmhouses lie snug among their new-shorn fields, the road rises into the trim village of Auldearn.

Neat as possible are the little gardens before the cottages, bright yet with late autumn flowers. Yellow marigolds glisten within the low fences55 beside dark velvety calceolarias and creamy stocks; while the crimson flowers of tropeolum cover the cottage walls up to the thatch, and some pale monthly roses still bloom about the windows. A peaceful spot it is to-day, yet a spot with a past and a grim tale of a hundred years before Culloden. Here it was that in 1645 Montrose, fighting gallantly for the First Charles, drove back into utter rout the army of the covenanting Parliament. On the left, among sheepfolds and dry-dyke inclosures, lay his right wing with the royal standard; nearer, to the right, with their backs to the hill, stood the rest of his array with the cavalry; and here in the village street, between the two wings, his few guns deceived the enemy with a show of force. It was from the church tower, up there in front, that Montrose surveyed the position; and below, in the little churchyard and church itself, lie many of those who fell in the battle. They are all at peace now, the eastern Marquis and the western, Montrose and Argyle: long ago they fought out their last great feud, and departed.

The country about has always been a famous place for witches, and doubtless the three who fired Macbeth with his fatal ambition belonged56 to Auldearn. Three miles beyond the village the road runs across the Hardmuir, and there it was that the awful meeting took place. The moor is planted now with pines, and the railway runs at less than a mile’s distance; but even when the road is flooded with sunshine, there hangs a gloom among the trees, and a strange feeling of eeriness comes upon the intruder in the solitude. On the left a gate opens into the wood, and the witches’ hillock lies at some distance out of sight.

Utterly silent the place is! Not a breath of air is moving, and the atmosphere has become close and sultry. There is no path, for few people follow their curiosity so far. Dry ditches and stumps of old trees make the walking difficult; withered branches of pine crackle suddenly sometimes under tread; and here and there the fleshy finger of a fungus catches the eye at a tree root.

And here rises the hillock. On its bald and blasted summit, in the lurid corpse-light, according to the old story,

57 when Macbeth, approaching the spot with Banquo, after victory in the west over Macdonald of the Isles, exclaims:

and the hags, suddenly confronting the general, greet him with the triple hail of Glamis, Cawdor, and King.

The blasted hillock was indeed a fit spot for such a scene. Not a blade of grass grows upon it; the withered needles and cones of the pines lie about, wan and lifeless and yellow; and on one side, where the witches emptied their horrid caldron, and the contents ran down the slope, the earth remains bare, and scorched, and black. Even the trees themselves which grow on the hillock appear of a different sort from those on the heath around.

Antiquaries set the scene of fulfilment of the witches infernal promptings—Macbeth’s murder of King Duncan—variously at Inverness, Glamis, and Bothgofuane, a smithy near Forres. Popular tradition, however, points to Cawdor, and less than seven miles from the fatal heath the Thane’s great moated keep frowns yet among its woods.

58 But what is this? The air has grown suddenly dark; the gloom becomes oppressive; and in the close heat it is almost possible to imagine a smell of sulphur. A flash of lightning, a rush of wind among the tree-tops, and a terrible crash of thunder just overhead! A moment’s silence, a sound as if all the pines were shaking their branches together, a deluging downpour of rain, and the storm has burst. The spirits of the air are abroad, and the evil genius of the place is awake in demoniac fury. The tempest waxes terrific. The awful gloom among the trees is lit up by flash after flash of lightning; the cannon of thunder burst in all directions; and the rain pours in torrents. The ghastly hags might well revisit the scene of their orgies at such a moment.

It is enough. The powers of the air have conquered. It is hardly safe, and by no means pleasant, to remain among the pines in such a storm. So farewell to the deserted spot, and a bee-line for the open country. To make up for the wetting, it is consoling to think that few enthusiasts have beheld so realistic a representation of the third scene of Macbeth.

It rained heavily at intervals all night, and, though it has cleared a little since day-break, there is not a patch of blue to be seen yet in the sky, and the torn skirts of the clouds are still trailing low among the hills. The day can hardly brighten now before twelve o’clock, and as the woods, at anyrate, will be rain-laden and weeping for hours, the walk through “fair Kirkconnel Lea” is not to be thought of. The lawn, too, is out of condition for tennis. But see! the burn, brown with peat and flecked with foam, is running like ale under the bridge, and though the spate is too heavy for much hope of catching trout down here, there will be good sport for the trouble higher up among the moorland becks. Bring out the fishing-baskets, therefore, some small Stewart tacklings, and a canister of bait. Put up, too, a substantial sandwich and a flask; for the air among the hills is keen, and the mists are sometimes chilly.

60 Wet and heavy the roads are, and there will be more rain yet, for the pools in the ruts are not clear. The slender larch on the edge of the wood has put on a greener kirtle in the night, and stands forward like a young bride glad amid her tears. If a glint of sunshine came to kiss her there, she would glitter with a hundred rain-jewels. The still, heavy air is aromatic with the scent of the pines. By the wayside the ripening oats are bending their graceful heads after the rain, like Danae, with their golden burden, while the warrior hosts of the barley beyond hold their spiky crests white and erect.

The long, springing step natural on the heather shortens the road to the hills; and already a tempting burn or two have been crossed by the way. But nothing can be done without rods; and these have first to be called for at the shepherd’s.

A quiet, far-off place it is, this shieling upon the moors, with the drone of bees about, and the bleating of sheep. The shepherd himself is away to the “big house” about some “hogs,” but his wife, a weather-grey woman of sixty, with rough hospitable hands and kindly eyes, says that “maybe Jeanie will tak’ a rod to the becks.”61 Jeanie, by her dark glance, is pleased with the liberty; and indeed this lithe, handsome girl of fifteen will not be the least pleasant of guides, with her hair like the raven’s wing, and on her clear features the thoughtful look of the hills.

Here are the rods, straight ash saplings of convenient length, with thin brown lines.

“Ye’ll come back and tak’ a cup o’ tea; and dinna stay up there if it rains,” says the goodwife, by way of parting.

Jeanie is frank and interesting in speech, with a gentle breeding little to be expected in so lonely a place. She has the step of a deer, and seems to know every tuft of grass upon the hills. There is not so much heather in Galloway as in the West Highlands. A long grey bent takes its place, and on mossy ground the white tufts of the cotton grass appear.

But here is a chance for a trial cast. A small burn comes down a side glen, and, just before it joins the main stream, runs foaming into a deeper pool. Keep well back from the bank, impale a tempting worm on the hook, and drop it in just where the water runs over the stones. Let the line go: the current carries it at once into the pool. There! The bait is held. Strike quickly down62 stream: the trout all swim against the current. But it is not a fish; the hook has only caught on a stone. Disentangle it, and try again. This time there is no mistaking the wriggle at the end of the rod; with a jerk the hungry nibbler is whipped into the air, and alights among the grass, a dozen yards from his native pool. A plump little fish he proves, his pretty brown sides spotted with scarlet, as he gasps and kicks on terra firma.

Not another trout, however, can be tempted to bite in that eddy; the fish are too well fed by the spate, or too timid. “There will be more to catch,” says Jeanie, “higher up the becks.” She is right. Perhaps the trout in these narrow streamlets are less sophisticated than their kind lower down, for in rivulets so narrow as almost to be hidden by the bent-grass there seem plenty of fish eager to take the bait. These are darker in colour than the trout in the river, taking their shade from the peat, and though small, of course, averaging about a quarter of a pound in weight, are plump, and make merry enough rivalry in the whipping of them out.

But the mists droop lower overhead, and a small smirring rain has been falling for some time; so, as Jeanie, at least, has a fair basketful,63 it will be best to put up the lines, discuss a sandwich under the shelter of the birches close by, and hold a council of war.

Desolate and silent are these grey hillsides. Hardly a sheep is to be seen; the far-off cry of the curlew is the only sound heard; and as the white mists come down and shroud the mountains, there is an eerie, solemn feeling, as at the near presence of the Infinite. Something, however, must be done. The rain is every moment coming down more heavily, and the small leaves of the birches afford but scant protection. Off, then; home as fast as possible! The mountain maid knows a shorter way over the hill; and lightly and swiftly she leads the Indian file along the narrow sheep-path. On the moor, amid the grey mist and rain, appear the stone walls of a lonely sheepfold; and just below, in the channel of the beck, lies the deep pool, swirling now with peaty water and foam, where every year they wash the flocks.

The shepherd’s wife appears at her door. Her goodman is home. A great peat fire is glowing on the warm hearth, and she is “masking the tea.” “Ye’ll find a basin of soft water in the little bedroom there, and ye’ll change ye’re coats64 and socks, and get them dried,” says the kindly woman.

This is real hospitality. The rough coats and thick dry socks bespeak warm-hearted thoughtfulness; and a wash in clean water after the discomforts of fishing is no mean luxury. The small, low-raftered bedroom, with quaintly-papered walls, and little window looking out upon the moors, is comfortably furnished; and the stone-floored kitchen, clean and bright and warm, with geraniums flowering in the window, has as pleasant a fireside seat as could be desired. Why should ambition seek more than this, and why are so many hopeless hearts cooped up in the squalid city?

Here comes Jeanie down from the “loft,” looking fresher and prettier than ever in her dry wincey dress, with a little bit of blue ribbon at the throat. The tea is ready; her mother has fried some of the trout, and the snowy table is loaded with thick white scones, thin oatmeal cakes, home-made bramble jelly, and the freshest butter. Kings may be blest; but what hungry man needs more than this? The shepherd, too, is well-read, for does not Steele and Addison’s “Spectator” stand there on the shelf, along with Sir Walter65 Scott, Robert Burns, and the Bible? With fare like this for body and mind, man may indeed become “the noblest work of God.”

But an hour has passed, too quickly; the rain has cleared at last, and away to the south and west the clouds are lifting in the sunset. Yonder, under the clear green sky, glistens the treacherous silver of the Solway, and as far again beyond it in the evening light rises the dark side of Skiddaw, in Cumberland. The gravel at the door lies glistening after the shower, the yellow marigolds in the little plot are bright and opening, and the moorland air is perfumed with mint and bog-myrtle. A hearty handshake, then, from the shepherd, a warm pressing to return soon from his goodwife, a pleasant smile from Jeanie, and the road must be taken down hill with a swinging step.

All dust has been swept from the causeways by the clear wind from the firth, as if in preparation for this great gala-day of the North. Unusual stir and movement fill the streets of the quiet Highland town, and the bright sunshine glitters everywhere on jewelled dirk and brooch and skeandhu. The clean pavements are ringing far and near with the quick, light step of the Highlander, and, from the number of tartans to be seen, it might almost be thought that the Fiery Cross was abroad, as in days of old, for the gathering of the clans.

Sad enough are the memories here of the last war summons of the chiefs. High-hearted, indeed, was the town on the morning when the clans marched forth under “Bonnie Prince Charlie” to do battle for the Stuart cause. But before an April day had passed, the gates received again, flying from fatal Culloden, the remnants of the broken chivalry of the North, and the67 streets themselves shook under the thunder of the Lowland guns.

The wounds of the past, however, are healed, the feuds are forgotten, and the clouds of that bygone sorrow have been blown away by the winds of time. A lighter occasion now has brought gaiety to the town, and the heroes of the hour go decked with no ominous white cockade. Already in the distance the wild playing of the pipes can be heard, and at the sound the kilted clansmen hurry faster along the streets; for the business of the day is on the greensward, and the hill folk, gentle and simple, are gathering from far and near to witness the Highland games.

A fair and appropriate scene is the tourney-ground, with the mountains looking down upon it, purple and silent—the Olympus of the North. The eager crowd gathers thick already, like bees, round the barricade. Little knots of friends there, from glens among the hills, discuss the chances of their village hero. Many a swarthy mountaineer is to be seen, of pure Celtic blood, clear eyed and clean limbed, from far-off mountain clachan. Gamekeepers and ghillies there are, without number, in gala-day garb. And the68 townspeople themselves appear in crowds. On every side is to be heard the emotional Gaelic of the hills, beside the sweet English speech for which the town is famous, and only sometimes one catches the broader accent of a Lowland tongue.

The lists have just been cleared, and the “chieftain” of the day has gathered his henchmen around him. The games are about to begin.

Yonder go the pipers, half a dozen of them, their ribbons and tartans streaming on the wind. Featly they step together to the quick tune of the shrill mountain march they are playing. Deftly they turn in a body at the boundary, and brightly the cairngorms of their broad silver shoulder-brooches flash all at once in the sun. No wonder it is that the Highlander has the tread of a prince, accustomed as he is to the spring of the heather beneath his feet, and to music like that in the air. The Highland garb, too, can hardly fail to be picturesque when it is worn by stalwart fellows like these.

The programme of the games is very full, and several competitions are therefore carried on at the same time. Here a dozen fleet youths speed past on the half-mile racecourse. Some lithe69 ghillies yonder are doing hop, step, and leap to an astonishing distance. And, farther off, five brawny fellows are preparing to “put” the heavy ball. Out of the tent close by come some sinewy men, well stripped for the encounter, to try a bout of wrestling. A pair at a time, they wind their strong arms about each other, and each strains and heaves to give his rival a fall. One man scowls, and another smiles as he picks himself up after his overthrow—the sympathy of the crowd goes largely by these signs. Most, however, display the greatest good-humour, and every one must obey the ruling of the umpire. Gradually the two stoutest and heaviest men overcome the rest; and at last, the only champions remaining, they stand up to engage each other. The grey-headed man has some joke to make as he hitches up his belt before closing, and the bystanders laugh heartily at his pleasantry; but his opponent evidently looks upon the contest too seriously for that. Hither and thither they stagger in “the grips,” the back of each as rigid as a plank at an angle of forty-five degrees. More than once they loosen hold for a breath, and again grasp each other, till at last, by dint of sheer strength, the grey-headed wrestler draws the younger man to himself, and,70 with a sudden toss, throws him clear upon the ground.

The slim youths at the pole-vaulting look like white swallows as they swing high into the air on their long staves to clear the bar; and a roar of applause from the far end of the lists, where the dogged “tug of war” has been going on, tells that one of the teams of heavy fellows straining at the rope has been hauled over the brink into the dividing ditch. The brawny giants who were throwing the axle a little while ago are just now breathing themselves, and will be tossing the mighty caber by and by. And ever and anon throughout the day there float upon the breeze the wild strains of the competing pipers—pibrochs and strathspeys and “hurricanes of Highland reels.”

Meanwhile the grand pavilion has filled. Lord and lady, earl and marquis and duke are there. And beside these are others, heads of families, who count their chieftainship, it may be, through ten centuries, and who are to be called neither esquire nor lord, but just —— of that Ilk. Chiefs by right of blood, they need no other title than their name.

The presence of so much that is noble and71 illustrious lends a feudal interest to the games, and imports to the rivalry something of that desire to appear well in the eyes of the chief which was once so powerful an influence in the Highlands. The young ghillie here, who has out-stripped all but one competitor at throwing the hammer, feels the stimulus of this. He knows not only that his sweetheart’s eyes are bent eagerly upon him from the barrier at hand, but that he has a chance of distinguishing himself before his master and “her ladyship,” who are watching from under the awning yonder. So he breathes on his hands, takes a firm grasp of the long ash handle, and, vigorously whirling the heavy iron ball round his head, sends it with all his strength across the lists. How far has it gone? They chalk the distance up on a board—95½ feet. There is a clapping of hands from the crowd, and a waving of white kerchiefs from the pavilion. He is sure of winning now, and the shy, pretty face at the barrier flushes with innocent pride. Is he not her hero?

There, on the low platform before the judges, go the dancers, two after two. They are trimly dressed for the performance, and wear the thin,72 low-heeled Highland shoes, while the breasts of some of them are fairly panoplied in gold and silver medals won at former contests. Mostly young lads, it is wonderful how neatly they perform every step, turning featly with now one arm in the air and now the other. Cleverly they go through the famous sword dance over crossed claymores, and in the wild whirl of the Reel o’ Tulloch seem to reach the acme of the art.