| Number 9. | SATURDAY, AUGUST 29, 1840. | Volume I. |

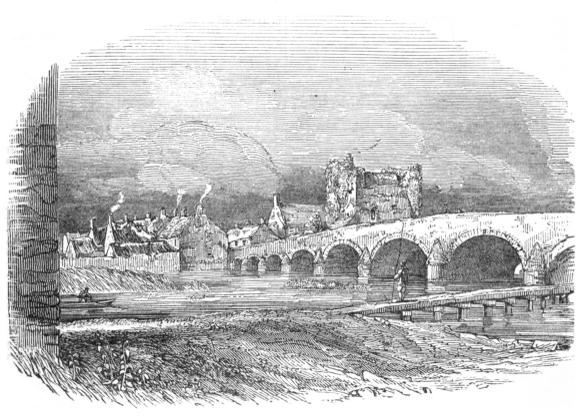

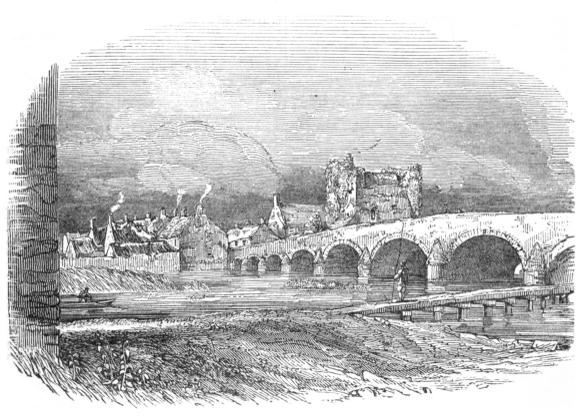

The ancient Bridge and Black Castle of Leighlin-Bridge, seated on “the goodly Barrow,” must be familiar to such of our readers as have ever travelled on the mail-coach road between Carlow and Kilkenny, for it is a scene of much picturesque beauty, and of a character very likely to impress itself on the memory.

These are the most striking features of the town called Leighlin-Bridge, a market and post town, situated partly in the parish of Augha and barony of Idrone-East, and partly in the parish of Wells and barony of Idrone-West, in the county of Carlow, six miles south from the town of that name, and forty-five miles S.S.W. from Dublin. This town contains about 2000 inhabitants, and is seated on both sides of the Barrow; the bridge, which contains nine arches, dividing it into nearly equal portions: that on the east side consists of 178 houses, and that on the west of 191, being 369 houses in all. The parish church of Wells, the Roman Catholic chapel, and a national school-house, are on the Wells side of the river, as is also the ruined castle represented in our illustration.

To the erection of this castle the town owes its origin. As a position of great military importance to the interests of the first Anglo-Norman settlers in Ireland, it was erected in 1181, either by the renowned Hugh de Lacy himself, or by John de Clahull, or De Claville, “to whom De Lacy gave the marshallshipp of all Leinster, and the land between Aghavoe and Leighlin.”

From a minute description of the remains of this castle given by Mr Ryan in his History and Antiquities of the County of Carlow, a work of much ability and research, it appears that it was constructed on the Norman plan, and consisted of a quadrangular enclosure, 315 feet in length and 234 feet in width, surrounded by a wall seven feet thick, with a fosse on the exterior of three sides of the enclosure, and the river on the fourth. Of this wall the western side only is now in existence. The keep or great tower of this fortress, represented in our sketch, is situated at the north-western angle of the square, and is of an oblong form, and about fifty feet in height. It is much dilapidated; but one floor, resting on an arch, remains, to which there is an ascent by stone steps, as there is to the top, which is completely covered over with ivy, planted by the present possessors of the castle. At the other, or south-west angle of the enclosure, are the remains of a lesser tower, which is of a rotund form and of great strength, the walls being ten feet thick. It is still more dilapidated than the great keep, and is only 24 feet high, having a flight of steps leading to its summit.

The present name of the town, however, is derived from the bridge, which was erected in 1320 to facilitate the intercourse between the religious houses of old and new Leighlin, by Maurice Jakis, a canon of the cathedral of Kildare, whose memory as a bridge-builder is deservedly preserved, having also erected the bridges of Kilcullen and St Woolstan’s over the Liffey,[Pg 66] both of which still exist. Previously to the erection of this bridge, the town was called New Leighlin, in contradistinction to the original Leighlin, a town of more ancient and ecclesiastical origin, which was situated about two miles to the west, and which was afterwards known by the appellation of Old Leighlin. The erection of this bridge, by giving a new direction to the great southern road, led rapidly to the increase of the new town and the decay of the old one, whose site is only marked at present by the remains of its venerable cathedral church.

In addition to the Black Castle and the bridge already noticed, Leighlin-Bridge had formerly a second castle, as well as a monastery, of which there are at present no remains. The former, which was called the White Castle, was erected in 1408 by Gerald, the fifth Earl of Kildare: its site, we believe, is now unknown. The monastery was erected for Carmelite or White Friars, under the invocation of the Virgin Mary, by one of the Carews, in the reign of Henry III., and was situated at the south side of the Black Castle. After the suppression of religious houses, this monastery, being in the hands of government, was in 1547 surrounded with a wall, and converted into a fort, by Sir Edward Bellingham, Lord Deputy of Ireland, who also established within it a stable of twenty or thirty horses, of a superior breed to that commonly used in Ireland, for the use of his own household, and for the public service. The dispersed friars did not, however, remove far from their original mansion when dispossessed of their tenements; they withdrew to a house on the same side of the river, about two hundred yards from the castle; and an establishment of the order was preserved till about the year 1827, when it became extinct, on the death of the last friar of the community.

As the English settlement here became very insecure towards the close of the fourteenth century, and was peculiarly exposed to the hostile attacks of the native Irish, who continued powerful in its immediate vicinity, a grant of ten marks annually was made by King Edward III. in 1371, to the Prior of this monastery, for the repairing and rebuilding of the house, which grant was renewed six years afterwards; and in 1378, Richard II., in consideration of the great labour, burden, and expense which the Priors had in supporting their house, and the bridge contiguous to it, against the king’s enemies, granted to the Priors an annual pension of twenty marks out of the rents of the town of Newcastle of Lyons, which grant he confirmed to them in 1394, and which was ratified by his successors Henry IV. and V. in the first years of their reigns (1399, 1412), the latter monarch ordering at the same time that all arrears of rent then due should be paid.

In the civil wars of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the possession of Leighlin-Bridge and its castle became an object of much importance to the combatants on both sides. In 1577, when the celebrated chieftain of Leix, Rory Oge O’More, rose in rebellion, among other depredations he burned a part of the town of Leighlin-Bridge, and endeavoured to get possession of its castle, which was then feebly garrisoned under the command of Sir George Carew, constable of the fort and town. With the slender force of seven horse, as it is stated by Hooker, but under the cover of night, Carew made a sally on his assailants, numbering two hundred and forty, who, being taken by surprise, lost many men, and the remainder for a time fled. Having soon however discovered the extremely small force by which they had been attacked, they rallied, and in turn became the assailants, pursuing Carew’s party to the gate of Leighlin-Bridge Castle, and some of them even entering within its walls; but by the bravery of the garrison they were soon expelled. Carew had two men and one horse killed, and every man of his party was wounded. The rebels lost sixteen men, among whom was one of their leaders, which so discomfited them that they retired, leaving one-half of the town uninjured.

In the great rebellion of O’Neil, at the close of the reign of Elizabeth, the castle of Leighlin-Bridge was repaired and garrisoned for the Queen, though the surrounding country was laid waste by the Kavanaghs. In the beginning of the succeeding reign (1604), the site of the castle, together with that of the monastery, &c. &c., were granted by the king to George Tutchett, Lord Awdeley, to be held of the crown for ever in common soccage.

In the great rebellion of 1641, the castle of Leighlin-Bridge was garrisoned for the confederate Catholics, in 1646, with one hundred men, under the command of Colonel Walter Bagnall; it was here also that in 1647 the Marquis of Ormond assembled his forces, to attack the republicans, who had got possession of Dublin; and he rested his forces here in 1649. It was, however, surrendered to the parliamentary forces under Colonel Hewson in the following year, soon after which the main army under Ireton sojourned here for a time, and plundered the surrounding country. Since this period, Leighlin-Bridge has enjoyed the blessings of peace, and has made those advances in prosperity which follow in its train. Its market is on Monday and Saturday amply supplied with corn and butter, &c., and it has four well-attended fairs, on Easter Monday, May 14th, September 25th, and December 27th. Much beautiful scenery and many interesting remains of antiquity exist in its immediate vicinity.

P.

The following song on the harp of our country has been sent to us by our friend Samuel Lover, the painter, poet, musician, dramatist, story-writer, and novelist of Ireland, for it is his pride to be in every thing Irish; and for this, no less than for his manly independence of character and sterling qualities of heart, we honour him. It cannot be said of him as of some of our countrymen at the other side of the water, that he is ashamed of us; and we are not, and we feel assured never shall be, ashamed of him.

We may remark that these verses owe their origin to an examination of Bunting’s delightful “Ancient Music of Ireland”—a work of which we have already expressed our opinion in our first number—and are adapted to be sung to the first melody in that collection, “Sit down under my protection.” We may also add, that it is the intention of the poet, when he prints the music and words together, to dedicate them to Mr Bunting, as a memorial of his gratitude for the services rendered to Ireland in the preservation of her national music—services which, as the author says, “will make his name be remembered amongst our bards.”

Poverty.—Poverty has in large cities very different appearances. It is often concealed in splendour, and often in extravagance. It is the care of a very great part of mankind to conceal their indigence from the rest. They support themselves by temporary expedients, and every day is lost in contriving for to-morrow.

When you intend to marry, look first at the heart, next at the mind, then at the person.

Pride is a vice, which pride itself inclines every man to find in others and to overlook in himself.—Johnson.

If the reader’s attention is now called to it for the first time, he will be rather surprised, we dare say, to find how much humbug is incorporated with our social system. It will rather surprise him to find, as a little reflection will certainly enable him to do, that humbug forms, in fact, the cement by which society is held together; that it pervades every department of it, fills up all its crevices and crannies, and, in truth, permeates its very substance. We, in short, all humbug one another; that’s beyond all manner of doubt.

Don’t we every day write cards and letters beginning with “My dear, or My very dear sir,” and ending with, “Yours sincerely, truly, &c. &c.,” knowing, in our conscience, that in ninety-nine instances out of the hundred—always excepting cases where a man’s interest is concerned—we do not care one straw for these very dear sirs—not one farthing although they were six feet below the ground to-morrow.

Suppose an intimation card of the death of one of these very dear sirs, or of some “good friend” or intimate acquaintance, waits us on our arrival home to dinner.

“Guess who’s dead?” says some member of our family, running towards us with joyful anticipation of our perplexity.

“Can’t say, indeed,” reply we. “Who is it?”

“Mr O’Madigan.”

“Ah, dear me, poor follow, is he dead? Very sudden, very unexpected.—Is dinner ready?”

What is the civility of the landlord and his waiters but humbug? What the smirking, smiling, ducking and bowing of the shopkeeper, but humbug? What his sweet and gentle “yes, sirs,” and “no, sirs,” and “proud to serve you, sirs,” but humbug? You are not goose enough to believe for a moment that he is serious, that he has either the least regard or respect for you. Not he; he would not care a twopence although you were hanged, drawn, and quartered before his shop-door to-morrow, except, perhaps, for the inconvenience of the thing.

What is the civility of the servant to his employer but humbug? Do you imagine for a moment that that man who, hat in hand, is looking up to you with such a respectful air—looking up to you as if you were a god—as if his very existence depended on your slightest breath—do you imagine for a moment, we ask, that he has in his heart that deference for you that he would make you believe? that he conceives you to be so very superior a being as his manner would imply? Not he, indeed. Depend upon it, it is all humbug; humbug all. And if you saw or heard him when he feels secure that you can do neither the one nor the other, you would speedily be convinced that it is.

But it is in the wheel-within-wheel of social life, the domestic circle, in what are called the friendly relations of life, that the system of humbug assumes, perhaps, its most deceptive character. See what a loving and friendly set of people are gathered together around that dinner table! See how blandly, how affectionately they look on each other! How delighted they are with one another—with mine host and hostess in particular! Why, they would die for them—die on the spot. They would go any length to serve one another. See that shake of the hand, how cordial it is! that smile, how affectionate! how winning! how full of kindly promise! Now, do these people in reality feel the smallest interest in each other’s welfare? Would they make the slightest sacrifice to serve one another? Not they, indeed. If you doubt it, try any one of them next day; try any of your “dear friends” if they will lend you a pound or five, as the case may be. Until you do this, or something like it, depend upon it you don’t know your men; no, nor your women either.

“Oh! but,” says the moralist, “mere civility, my good sir, mere civility; absurd idea to suppose that every man to whom you are civil should have a claim also on your purse.”

“But in the case of a ‘dear friend,’ Mr Moralist, or intimate acquaintance—eh?—for it is of them only that I speak. Surely they might do something for you.”

“Oh! that as it may be. But as a general rule”——

“Then all this cordiality of greeting, this affectionate shaking of hands, these sweet smiles and sweeter words, are all to go for nothing? They are to be understood as meaning nothing.”

“Certainly.”

“Then we are perfectly agreed—it is all deception.”

“Oh! you may call it what you please.”

“Thank you. Then with your leave I shall call it humbug. It is not a very elegant word, but it is pretty expressive.”

But, lo! here comes a funeral. See how grave and melancholy these sable-clad gentlemen look. Why, you would imagine that under that dismal pall lay all the earthly hopes of every individual present, that every heart in the solemn train was well-nigh broken. All this is very becoming no doubt, and it would scarcely be decorous to go either singing or laughing along the streets on such an occasion, when carrying the poor remains of mortality to its last resting-place. But it’s humbug, nevertheless—humbug all! Not one of these sorrowing mourners, excepting perhaps one or two of the nearest relations, cares one twopenny piece for the defunct. Not one of them would have given him sixpence to keep him from starving.

Notwithstanding, however, the very general diffusion of humbug, it may be classed under regular heads, and we rather think this would not be a bad way of illustrating it. We shall try; beginning with

My brave fellow soldiers, we are now on the eve of encountering the enemy. See, there he stands in hostile array against you. He thinks to terrify you by his formidable appearance. But you regard him with a steady and a fearless eye.

Soldiers! the world rings with the fame of your deeds. Your glory is imperishable: it will live for ever.

Regardless of wounds and death, you have ever been foremost where honour was to be won. Recollect, then, your ancient fame, and let your deeds this day show that you are still the same brave men who have so often chased your enemies from the field; the same brave men who have ever looked on death as a thing unworthy a moment’s consideration—on dishonour as the greatest of all evils.

Band of heroes, advance! On, on to victory, death, wounds, glory, honour, and immortality! (Hurra, hurra, General Fudge for ever!—lead us on, general, lead us on!) Lead ye on, my brave fellows! Would to heaven my duties would permit me that enviable honour! But it would be too much for one so unworthy. Alas! I dare not. My duties call me to another part of the field. I obey the call with reluctance. But my confidence in your courage, my brave fellows, enables me to trust you to advance yourselves. On, then, on, my band of heroes, and fear nothing! (General raises his hat gracefully, bows politely to his “band of heroes,” and rides off to a height at a safe distance, from which he views the battle comfortably through his telescope.)

In putting this work into the hands of the public, the author has not been influenced by any of those motives that usually urge writers to publication. Neither vanity, nor the desire of gaining what is called a name, has had the slightest share in inducing him to take this step; still less has he been influenced by any sordid love of gain; he looks for neither praise nor profit. His sole motive for writing and publishing this book has been to promote the general good, by contributing his mite to the stock of general information.

The author is but too well aware that the merits of his work, if indeed it have any at all, are of a very humble order; that it has, in short, many defects: but a liberal, discerning, and indulgent public, will make every allowance for one who makes no pretension to literary excellence.

The author may add, that part of the blame of his now obtruding himself on the public rests on the urgent entreaties of some perhaps too partial friends.

The publishers of this new undertaking have long been of opinion that a new and more efficient course of moral instruction was wanted, to raise the bulk of mankind to that standard of perfection which every Christian, every good member of society, must be desirous of seeing attained.

It is with the most poignant regret they have marked the almost total failure of all preceding attempts of this kind. How much it has pained them—how much they have grieved to see the inadequacy of the supplies of knowledge to the increasing wants of the community, especially alluding to the working and lower classes generally, whose interests they have deeply at heart, they need not say: but they may say, that they anticipate the most triumphant success in their present efforts to supply the desideratum alluded to.

The publishers may add, that as regards the undertaking they are now about to commence, profit is with them but a secondary consideration. Their great object is to promote the[Pg 68] general good by a wide diffusion of knowledge, and a liberal infusion of sound and healthy principle. If they effect this, their end is gained. The work, on which no expense will be spared, will be sold at a price so low as to leave but a bare remuneration for workmanship and material—so low, indeed, that a very large demand only can protect the publishers from positive loss. But it is not the dread of even the result that can deter them from commencing and carrying on a work undertaken from the purest and most disinterested motives.

A more delightful work than this, a work more rich and racy, more brilliant in style or more graphic in delineation, it has rarely been our good fortune to meet with. Every page bears the stamp of a master-mind, every sentence the impress of genius.

What a flow of ideas! What an outpouring of eloquence! What a knowledge of the human heart with all its nicer intricacies! What an intimacy with the springs of human action! What a mastery over the human passions! Ay, this is indeed the triumph of genius.

The author of this exquisite production writes with the pen of a Junius, and thinks with the intellect of a Bacon or a Locke. His language is forcible and epigrammatic, his reasoning clear and profound; yet can nothing be more racy than his pleasantry when he condescends to be playful—nothing more delicately cutting than his irony when he chooses to be satirical—nothing more striking or impressive than his ratiocination when he prefers being philosophical.

We confidently predict a wide and lasting popularity for this extraordinary production. Indeed, if we are not greatly mistaken, it will create quite a sensation in the literary circles of Europe.

My country, oh! my country! it is for thee, for thee alone, I live; and for thee, my country, will I at any time cheerfully die—(Who’s that calling out fudge?) Nearest my heart is the wish for thy welfare. To see thee happy is the one only desire of my soul, and that thou mayest be so, is my constant prayer.

Night and day dost thou engross my thoughts, and all, all would I sacrifice to thy welfare! My private interests are as dust in the balance—(Who’s that again calling fudge?—turn him out, turn him out)—My private interests are as dust in the balance; and shame, shame, oh! eternal shame to the sordid wretch, unworthy to live, who should for a moment prefer his individual aggrandisement to his country’s good. Perish his name—perish the name of the miserable miscreant!

Wealth! what is wealth to me, my country, compared to thy happiness? Station! what is station, unless thou, too, art advanced? Power! what is power, unless the power of doing thee good? Oh, my country! My country, oh!—(Oh! oh! oh! from various parts of the house.) The patriot sits down, wiping his patriotic forehead with a white handkerchief, amidst thunders of applause.

Before going farther with our Illustrations—indeed we don’t know whether we shall go any farther with them at all or not, as we rather think we have given quite enough of them—before going farther, then, with any thing in the more direct course of our subject, we may pause a moment to remark how carefully every one who comes before the public to claim its patronage, conceals the real object of his doing so. How remote he keeps from this very delicate point! He never whispers its name—never breathes it. How cautiously he avoids all allusion to his own particular interest in the matter! From the unction with which he speaks of the excellences of the thing he has to dispose of, be it what it may, a Dutch cheese or a treatise on philosophy, the enthusiasm with which he dwells on them, you would imagine that he spoke out of a pure feeling of admiration of these excellences. You would never dream—for this he carefully conceals from you—that his sole object is to get hold of as much of your cash as he can; the Dutch cheese or the treatise on philosophy being a mere instrument to accomplish the desired transfer.

It is rather a curious feature this in the social character: every thing offered for sale is so offered through a pure spirit of benevolence, either for the public good or individual benefit; nothing for the sake of mere filthy lucre, or the particular interest of the seller—not at all. He, good soul, has no such motive—not he, indeed.

We said a little while since that we doubted whether we would give any farther illustrations of the great science of humbug. We have now made up our minds that we shall not. Although we could easily give fifty more, it is unnecessary.

We confess, however, to be under strong temptations to give “the candidate’s humbug”—to exhibit that gentleman doing over the constituency, making them, whether he be whig or tory, swallow the grossest fudge that ever was thrust down an unsuspecting gullet; but we refrain. We refrain also, in the meantime, from giving what we would call “the liberty and equality humbug;” together with several other humbugs equally instructive and edifying.

And now we think we hear our readers exclaim of ourselves, what a humbug!

By no means, gentle readers; there are exceptions to every general rule. We have sketched the great mass of mankind, but we have no doubt that there are some truly sincere persons—few indeed—in all the classes we have sketched; and we trust that we ourselves shall be reckoned amongst the number.

C.

The ancient literature of Ireland is as yet but little known to the world, or even to ourselves. Existing for the most part only in its original Celtic form, and in manuscripts accessible only to the Irish scholar resident in our metropolis, but few even of those capable of understanding it have the opportunity to become acquainted with it, and from all others it is necessarily hidden. We therefore propose to ourselves, as a pleasing task, to make our literature more familiar, not only to the Irish scholar, but to our readers generally who do not possess this species of knowledge, by presenting them from time to time with such short poems or prose articles, accompanied with translations, as from their brevity, or the nature of their subjects, will render them suitable to our limited and necessarily varied pages—our selections being made without regard to chronological order as to the ages of their composition, but rather with a view to give a general idea of the several kinds of literature in which our ancestors of various classes found entertainment.

The specimen which we have chosen to commence with is of a homely cast, and was intended as a rebuke to the saucy pride of a woman in humble life, who assumed airs of consequence from being the possessor of three cows. Its author’s name is unknown, but its age may be determined, from its language, as belonging to the early part of the seventeenth century; and that it was formerly very popular in Munster, may be concluded from the fact, that the phrase, Easy, oh, woman of the three cows! [Go réiḋ a bhean na ttrí mbó] has become a saying in that province, on any occasion upon which it is desirable to lower the pretensions of proud or boastful persons.

P.

C.

[1] Forsooth.

M.

In those racy old times, when the manners and usages of Irishmen were more simple and pastoral than they are at present, dancing was cultivated as one of the chief amusements of life, and the dancing-master looked upon as a person essentially necessary to the proper enjoyment of our national recreation. Of all the amusements peculiar to our population, dancing is by far the most important, although certainly much less so now than it has been, even within our own memory. In Ireland it may be considered as a very just indication of the spirit and character of the people; so much so, that it would be extremely difficult to find any test so significant of the Irish heart, and its varied impulses, as the dance, when contemplated in its most comprehensive spirit. In the first place, no people dance so well as the Irish, and for the best reason in the world, as we shall show. Dancing, every one must admit, although a most delightful amusement, is not a simple, nor distinct, nor primary one. On the contrary, it is merely little else than a happy and agreeable method of enjoying music; and its whole spirit and character most necessarily depend upon the power of the heart to feel the melody to which the limbs and body move. Every nation, therefore, remarkable for a susceptibility of music, is also remarkable for a love of dancing, unless religion or some other adequate obstacle, arising from an anomalous condition of society, interposes to prevent it. Music and dancing being in fact as dependent the one on the other as cause and effect, it requires little argument to prove that the Irish, who are so sensitively alive to the one, should in a very high degree excel at the other; and accordingly it is so.

Nobody, unless one who has seen and also felt it, can conceive the incredible, nay, the inexplicable exhilaration of the heart, which a dance communicates to the peasantry of Ireland. Indeed, it resembles not so much enthusiasm as inspiration. Let a stranger take his place among those who are assembled at a dance in the country, and mark the change which takes place in Paddy’s whole temperament, physical and moral. He first rises up rather indolently, selects his own sweetheart, and assuming such a station on the floor as renders it necessary that both should “face the fiddler,” he commences. On the dance then goes, quietly at the outset; gradually he begins to move more sprightly; by and bye the right hand is up, and a crack of the fingers is heard; in a minute afterwards both hands are up and two cracks are heard, the hilarity and brightness of his eye all the time keeping pace with the growing enthusiasm that is coming over him, and which eye, by the way, is most lovingly fixed upon, or, we should rather say, into, that of his modest partner. From that partner he never receives an open gaze in return, but in lieu of this an occasional glance, quick as thought and brilliant as a meteor, seems to pour into him a delicious fury that is made up of love—sometimes a little of whisky, kindness, pride of his activity, and a reckless force of momentary happiness that defies description. Now commences the dance in earnest. Up he bounds in a fling or a caper—crack go the fingers—cut and treble go the feet, heel and toe, right and left. Then he flings the right heel up to the ham, up again the left, the whole face in a furnace-heat of ecstatic delight. “Whoo! whoo! your sowl! Move your elbow, Mickey (this to the fiddler). Quicker, quicker, man alive, or you’ll lose sight of me. Whoo! Judy, that’s the girl; handle your feet, avourneen; that’s it, acushla! stand to me! Hurroo for our side of the house!” And thus does he proceed with a vigour, and an agility, and a truth of time, that are incredible, especially when we consider the whirlwind of enjoyment which he has to direct. The conduct of his partner, whose face is lit up[Pg 70] into a modest blush, is evidently tinged with his enthusiasm—for who could resist it?—but it is exhibited with great natural grace, joined to a delicate vivacity that is equally gentle and animated, and in our opinion precisely what dancing in a female ought to be—a blending of healthful exercise and innocent enjoyment.

I have seen not long since an Irish dance by our talented countryman Mr M’Clise, and it is very good, with the exception of the girl who is dancing. That, however, is a sad blot upon what is otherwise a good picture. Instead of dancing with the native modesty so peculiar to our countrywomen, she dances with the unseemly movements of a tipsy virago, or a trull in Donnybrook; whilst her face has a leer upon it that reminds one of some painted drab on the outside of a booth between the periods of performance. This must neither be given to us, nor taken as a specimen of what Irishwomen are—the chastest and modestest females on the earth.

There are a considerable variety of dances in Ireland, from the simple “reel of two” up to the country-dance, all of which are mirthful. There are however, others which are serious, and may be looked upon as the exponents of the pathetic spirit of our country. Of the latter I fear several are altogether lost; and I question whether there be many persons now alive in Ireland who know much about the Horo Lhèig, which, from the word it begins with, must necessarily have been danced only on mournful occasions. It is only at wakes and funereal customs in those remote parts of the country where old usages are most pertinaciously clung to, that any elucidation of the Horo Lhèig and others of our forgotten dances could be obtained. At present, I believe, the only serious one we have is the cotillon, or, as they term it in the country, the cut-a-long. I myself have witnessed, when very young, a dance which, like the hornpipe, was performed but by one man. This, however, was the only point in which they bore to each other any resemblance. The one I allude to must in my opinion have been of Druidic or Magian descent. It was not necessarily performed to music, and could not be danced without the emblematic aids of a stick and handkerchief. It was addressed to an individual passion, and was unquestionably one of those symbolic dances that were used in pagan rites; and had the late Henry O’Brien seen it, there is no doubt but he would have seized upon it as a felicitous illustration of his system.

Having now said all we have to say here about Irish dances, it is time we should say something about the Irish dancing-master; and be it observed, that we mean him of the old school, and not the poor degenerate creature of the present day, who, unless in some remote parts of the country, is scarcely worth description, and has little of the national character about him.

Like most persons of the itinerant professions, the old Irish dancing-master was generally a bachelor, having no fixed residence, but living from place to place within his own walk, beyond which he seldom or never went. The farmers were his patrons, and his visits to their houses always brought a holiday spirit along with them. When he came, there was sure to be a dance in the evening after the hours of labour, he himself good-naturedly supplying them with the music. In return for this they would get up a little underhand collection for him, amounting probably to a couple of shillings or half-a-crown, which some of them, under pretence of taking the snuff-box out of his pocket to get a pinch, would delicately and ingeniously slip into it, lest he might feel the act as bringing down the dancing-master to the level of the mere fiddler. He on the other hand, not to be outdone in kindness, would at the conclusion of the little festivity desire them to lay down a door, on which he usually danced a few favourite hornpipes to the music of his own fiddle. This indeed was the great master-feat of his art, and was looked upon as such by himself as well as by the people.

Indeed, the old dancing-master had some very marked outlines of character peculiar to himself. His dress, for instance, was always far above the fiddler’s, and this was the pride of his heart. He also made it a point to wear a castor or Caroline hat, be the same “shocking bad” or otherwise; but above all things, his soul within him was set upon a watch, and no one could gratify him more than by asking him before company what o’clock it was. He also contrived to carry an ornamental staff, made of ebony, hiccory, mahogany, or some rare description of cane—which, if possible, had a silver head and a silk tassel. This the dancing-masters in general seemed to consider as a kind of baton or wand of office, without which I never yet knew one of them to go. But of all the parts of dress used to discriminate them from the fiddler, we must place as standing far before the rest the dancing-master’s pumps and stockings, for shoes he seldom wore. The utmost limit of their ambition appeared to be such a jaunty neatness about that part of them in which the genius of their business lay, as might indicate the extraordinary lightness and activity which were expected from them by the people, in whose opinion the finest stocking, the lightest shoe, and the most symmetrical leg, uniformly denoted the most accomplished teacher.

The Irish dancing-master was also a great hand at match-making, and indeed some of them were known to negociate as such between families as well as individual lovers, with all the ability of a first-rate diplomatist. Unlike the fiddler, the dancing-master had fortunately the use of his eyes; and as there is scarcely any scene in which to a keen observer the symptoms of the passion—to wit, blushings, glances, squeezes of the hand, and stealthy whisperings—are more frequent or significant, so is it no wonder indeed that a sagacious looker-on, such as he generally was, knew how to avail himself of them, and to become in many instances a necessary party to their successful issue.

In the times of our fathers it pretty frequently happened that the dancing-master professed another accomplishment, which in Ireland, at least, where it is born with us, might appear to be a superfluous one; we mean, that of fencing, or, to speak more correctly, cudgel-playing. Fencing-schools of this class were nearly as common in these times as dancing-schools, and it was not at all unusual for one man to teach both.

I have already stated that the Irish dancing-master was for the most part a bachelor. This, however, was one of those general rules which have very little to boast of over their exceptions. I have known two or three married dancing-masters, and remember to have witnessed on one occasion a very affecting circumstance, which I shall briefly mention. Scarlatina had been very rife and fatal during the spring of the year when this occurred, and the poor man was forced by the death of an only daughter, whom that treacherous disease had taken from him, to close his school during such a period as the natural sorrow for those whom we love usually requires. About a month had elapsed, and I happened to be present on the evening when he once more called his pupils together. His daughter had been a very handsome and interesting young creature of sixteen, and was, until cut down like a flower, attending her father’s school at the period I allude to. The business of the school went on much in the usual way, until a young man who had generally been her partner got up to dance. The father played a little, but the music was unsteady and capricious; he paused, and made a strong effort to be firm; the dancing for a moment ceased, and he wiped away a few hot tears from his eyes. Again he resumed, but his eye rested upon the partner of that beloved daughter, as he stood with the hand of another girl in his. “Don’t blame me,” said the poor fellow meekly, at the same time laying aside his fiddle and bursting into tears; “she was all I had, and my heart was in her; sure you are all here but her, and she—— Go home, boys and girls, oh, go home and pity me. You knew what she was. Give me another fortnight for Mary’s sake, for, oh, I am her father! I will meet you all again; but never, never will I see you here without feeling that I have a breaking heart. I miss the light sound of her foot, the sweetness of her voice, and the smile of the eye that said to me, ‘these are all your scholars, father, but I, sure I am your daughter.’” Although the occasion was joyous and mirthful, yet such is the sympathy with domestic sorrow entertained in Ireland, that there were few dry eyes present, and not a heart that did not feel deeply and sincerely for his melancholy and most afflicting loss.

After all, the old dancing-master, in spite of his most strenuous efforts to the contrary, bore, in simplicity of manners, in habits of life, and in the happy spirit which he received from and impressed upon society, a distant but not indistinct resemblance to the fiddler. Between these two, however, no good feeling subsisted. The one looked up at the other as a man who was unnecessarily and unjustly placed above him; whilst the other looked down upon him as a mere drudge, through whom those he taught practised their accomplishments. This petty rivalry was very amusing, and the “boys,” to do them justice, left nothing undone to keep it up. The fiddler had certainly the best of the argument, whilst the other had the advantage of a higher professional position. The one[Pg 71] was more loved, the other more respected. Perhaps very few things in humble life could be so amusing to a speculative mind, or at the same time capable of affording a better lesson to human pride, than the almost miraculous skill with which the dancing-master contrived, when travelling, to carry his fiddle about him, so as that it might not be seen, and he himself mistaken for nothing but a fiddler. This was the sorest blow his vanity could receive, and a source of endless vexation to all his tribe. Our manners, however, are changed, and neither the fiddler nor the dancing-master possesses the fine mellow tints nor that depth of colouring which formerly brought them and their rich household associations home at once to the heart.

One of the most amusing specimens of the dancing-master that I ever met, was the person alluded to at the close of my paper on the Irish Fiddler, under the nickname of Buckram-Back. This man had been a drummer in the army for some time, where he had learned to play the fiddle; but it appears that he possessed no relish whatever for a military life, as his abandonment of it without even the usual forms of a discharge or furlough, together with a back that had become cartilaginous from frequent flogging, could abundantly testify. It was from the latter circumstance that he had received his nickname.

Buckram-Back was a dapper light little fellow, with a rich Tipperary brogue, crossed by a lofty strain of illegitimate English, which he picked up whilst in the army. His habiliments sat as tight upon him as he could readily wear them, and were all of the shabby-genteel class. His crimped black coat was a closely worn second-hand, and his crimped face quite as much of a second-hand as the coat. I think I see his little pumps, little white stockings, his coaxed drab breeches, his hat, smart in its cock but brushed to a polish and standing upon three hairs, together with his tight questionably coloured gloves, all before me. Certainly he was the jauntiest little cock living—quite a blood, ready to fight any man, and a great defender of the fair sex, whom he never addressed except in that highflown bombastic style so agreeable to most of them, called by their flatterers the complimentary, and by their friends the fulsome. He was in fact a public man, and up to every thing. You met him at every fair, where he only had time to give you a wink as he passed, being just then engaged in a very particular affair; but he would tell you again. At cockfights he was a very busy personage, and an angry better from half-a-crown downwards. At races he was a knowing fellow, always shook hands with the winning jockey, and then looked pompously about, that folks might see that he was hand and glove with those who knew something.

The house where Buckram-Back kept his school, which was open only after the hours of labour, was an uninhabited cabin, the roof of which, at a particular spot, was supported by a post that stood upright from the floor. It was built upon an elevated situation, and commanded a fine view of the whole country for miles about it. A pleasant sight it was to see the modest and pretty girls, dressed in their best frocks and ribbons, radiating in little groups from all directions, accompanied by their partners or lovers, making way through the fragrant summer fields of a calm cloudless evening, to this happy scene of innocent amusement.

And yet what an epitome of general life, with its passions, jealousies, plots, calumnies, and contentions, did this little segment of society present! There was the shrew, the slattern, the coquette, and the prude, as sharply marked within this their humble sphere, as if they appeared on the world’s wider stage, with half its wealth and all its temptations to draw forth their prevailing foibles. There, too, was the bully, the rake, the liar, the coxcomb, and the coward, each as perfect and distinct in his kind as if he had run through a lengthened course of fashionable dissipation, or spent a fortune in acquiring his particular character. The elements of the human heart, however, and the passion that make up the general business of life, are the same in high and low, and exist with impulses as strong in the cabin as they have in the palace. The only difference is, that they have not equal room to play.

Buckram-Back’s system, in originality of design, in comic conception of decorum, and in the easy practical assurance with which he wrought it out, was never equalled, much less surpassed. Had the impudent little rascal confined himself to dancing as usually taught, there would have been nothing so ludicrous or uncommon in it; but no: he was such a stickler for example in every thing, that no other mode of instruction would satisfy him. Dancing! Why, it was the least part of what he taught or professed to teach.

In the first place, he undertook to teach every one of us—for I had the honour of being his pupil—how to enter a drawing-room “in the most fashionable manner alive,” as he said himself.

Secondly. He was the only man, he said, who could in the most agreeable and polite style taich a gintleman how to salute, or, as he termed it, how to shiloote, a leedy. This he taught, he said, wid great success.

Thirdly. He could taich every leedy and gintleman how to make the most beautiful bow or curchy on airth, by only imitating himself—one that, would cause a thousand people, if they were all present, to think that it was particularly intended only for aich o’ themselves!

Fourthly. He taught the whole art o’ courtship wid all peliteness and success, accordin’ as it was practised in Paris durin’ the last saison.

Fifthly. He could taich thim how to write love-letthers and valentines, accordin’ to the Great Macademy of compliments, which was supposed to be invinted by Bonaparte when he was writing love-letthers to both his wives.

Sixthly. He was the only person who could taich the famous dance called Sir Roger de Coverley, or the Helter-Skelter Drag, which comprehinded widin itself all the advantages and beauties of his whole system—in which every gintleman was at liberty to pull every leedy where he plaised, and every leedy was at liberty to go wherever he pulled her.

With such advantages in prospect, and a method of instruction so agreeable, it is not to be wondered at that his establishment was always in a most flourishing condition. The truth is, he had it so contrived that every gentleman should salute his lady as often as possible, and for this purpose actually invented dances, in which not only should every gentleman salute every lady, but every lady, by way of returning the compliment, should render a similar kindness to every gentleman. Nor had his male pupils all this prodigality of salutation to themselves, for the amorous little rascal always commenced first and ended last, in order, he said, that they might cotch the manner from himself. “I do this, leedies and gintlemen, as your moral (model), and because it’s part o’ my system—ahem!”

And then he would perk up his little hard face, that was too barren to produce more than an abortive smile, and twirl like a wagtail over the floor, in a manner that he thought irresistible.

Whether Buckram-Back was the only man who tried to reduce kissing to a system of education in this country, I do not know. It is certainly true that many others of his stamp made a knowledge of the arts and modes of courtship, like him, a part of the course. The forms of love-letters, valentines, &c. were taught their pupils of both sexes, with many other polite particulars, which it is to be hoped have disappeared for ever.

One thing, however, to the honour of our countrywomen we are bound to observe, which is, that we do not remember a single result incompatible with virtue to follow from the little fellow’s system, which by the way was in this respect peculiar only to himself, and not the general custom of the country. Several weddings, unquestionably, we had more than might otherwise have taken place, but in not one instance have we known any case in which a female was brought to unhappiness or shame.

We shall now give a brief sketch of Buckram-Back’s manner of tuition, begging our readers at the same time to rest assured that any sketch we could give would fall far short of the original.

“Paddy Corcoran, walk out an’ inther your drawin’-room; an’ let Miss Judy Hanratty go out along wid you, an’ come in as Mrs Corcoran.”

“Faith, I’m afeard, masther, I’ll make a bad hand of it; but, sure, it’s something to have Judy here to keep me in countenance.”

“Is that by way of compliment, Paddy? Mr Corcoran, you should ever an’ always spaik to a leedy in an alyblasther tone; for that’s the cut.”

[Paddy and Judy retire.

“Mickey Scanlan, come up here, now that we’re braithin’ a little; an’ you, Miss Grauna Mulholland, come up along wid him. Miss Mulholland, you are masther of your five positions and your fifteen attitudes, I believe?” “Yes, sir.” “Very well, Miss. Mickey Scanlan—ahem!—Misther Scanlan, can you perfome the positions also, Mickey?”

“Yes, sir; but you remimber I stuck at the eleventh altitude.”

“Attitude, sir—no matther. Well, Misther Scanlan, do you know how to shiloote a leedy, Mickey?”

“Faix, it’s hard to say, sir, till we thry; but I’m very willin’ to larn it. I’ll do my best, an’ the best can do no more.”

“Very well—ahem! Now merk me, Misther Scanlan; you approach your leedy in this style, bowin’ politely, as I do. Miss Mulholland, will you allow me the honour of a heavenly shiloote? Don’t bow, ma’am; you are to curchy, you know; a little lower eef you plaise. Now you say, ‘Wid the greatest pleasure in life, sir, an’ many thanks for the feevour.’ (Smack.) There, now, you are to make another curchy politely, an’ say, ‘Thank you, kind sir, I owe you one.’ Now, Misther Scanlan, proceed.”

“I’m to imitate you, masther, as well as I can, sir, I believe?”

“Yes, sir, you are to imiteet me. But hould, sir; did you see me lick my lips or pull up my breeches? Be gorra, that’s shockin’ unswintemintal. First make a curchy, a bow I mane, to Miss Grauna. Stop agin, sir; are you goin’ to sthrangle the leedy? Why, one would think that it’s about to teek laive of her for ever you are. Gently, Misther Scanlan; gently, Mickey. There:—well, that’s an improvement. Practice, Misther Scanlan, practice will do all, Mickey; but don’t smack so loud, though. Hilloo, gintlemen! where’s our drawin’-room folk? Go out, one of you, for Misther an’ Mrs Paddy Corcoran.”

Corcoran’s face now appears peeping in at the door, lit up with a comic expression of genuine fun, from whatever cause it may have proceeded.

“Aisy, Misther Corcoran; an’ where’s Mrs Corcoran, sir?”

“Are we both to come in together, masther?”

“Certainly. Turn out both your toeses—turn them out, I say.”

“Faix, sir, it’s aisier said than done wid some of us.”

“I know that, Misther Corcoran; but practice is every thing. The bow legs are strongly against you, I grant. Hut tut, Misther Corcoran—why, if your toes wor where your heels is, you’d be exactly in the first position, Paddy. Well, both of you turn out your toeses; look street forward; clap your caubeen—hem!—your castor undher your ome (arm), an’ walk into the middle of the flure, wid your head up. Stop, take care o’ the post. Now, take your caubeen, castor I mane, in your right hand; give it a flourish. Aisy, Mrs Hanratty—Corcoran I mane—it’s not you that’s to flourish. Well, flourish your castor, Paddy, and thin make a graceful bow to the company. Leedies and gintlemen”—

“Leedies and gintlemen”—

“I’m your most obadient sarvint”—

“I’m your most obadient sarwint.”

“Tuts, man alive! that’s not a bow. Look at this: there’s a bow for you. Why, instead of meeking a bow, you appear as if you wor goin’ to sit down wid an embargo (lumbago) in your back. Well, practice is every thing; an’ there’s luck in leisure.

“Dick Doorish, will you come up, and thry if you can meek any thing of that threblin’ step. You’re a purty lad, Dick; you’re a purty lad, Misther Doorish, wid a pair o’ left legs an you, to expect to larn to dance; but don’t despeer, man alive. I’m not afeard but I’ll meek a graceful slip o’ you yet. Can you meek a curchy?”

“Not right, sir. I doubt.”

“Well, sir, I know that; but, Misther Doorish, you ought to know bow to meek both a bow and a curchy. Whin you marry a wife, Misther Doorish, it mightn’t come wrong for you to know how to taich her a curchy. Have you the gad and suggaun wid you?” “Yes, sir.” “Very well, on wid them; the suggaun on the right foot, or what ought to be the right foot, an’ the gad upon what ought to be the left. Are you ready?” “Yes, sir.” “Come, thin, do as I bid you—Rise upon suggaun an’ sink upon gad; rise upon suggaun an’ sink upon gad; rise upon—— Hould, sir; you’re sinkin’ upon suggaun an’ risin’ upon gad, the very thing you ought not to do. But, God help you! sure you’re left-legged! Ah, Misther Doorish, it ’ud be long time before you’d be able to dance Jig Polthogue or the College Hornpipe upon a drum-head, as I often did. However, don’t despeer, Misther Doorish—if I could only get you to know your right leg—but, God help you! sure you hav’nt sich a thing—from your left, I’d make something of you yet, Dick.”

The Irish dancing-masters were eternally at daggers-drawn among themselves; but as they seldom met, they were forced to abuse each other at a distance, which they did with a virulence and scurrility proportioned to the space between them. Buckram-Back had a rival of this description, who was a sore thorn in his side. His name was Paddy Fitzpatrick, and from having been a horse-jockey, he gave up the turf, and took to the calling of a dancing-master. Buckram-Back sent a message to him to the effect that “if he could not dance Jig Polthogue on the drum-head, he had better hould his tongue for ever.” To this Paddy replied, by asking if he was the man to dance the Connaught Jockey upon the saddle of a blood-horse, and the animal at a three-quarter gallop.

At length the friends on each side, from a natural love of fun, prevailed upon them to decide their claims as follows:—Each master, with twelve of his pupils, was to dance against his rival with twelve of his; the match to come off on the top of Mallybeny Hill, which commanded a view of the whole parish. I have already mentioned that in Buckram-Back’s school there stood near the middle of the floor a post, which according to some new manœuvre of his own was very convenient as a guide to the dancers when going through the figure. Now, at the spot where this post stood it was necessary to make a curve, in order to form part of the figure of eight, which they were to follow; but as many of them were rather impenetrable to a due conception of the line of beauty, he forced them to turn round the post rather than make an acute angle of it, which several of them did. Having premised thus much, we proceed with our narrative.

At length they met, and it would have been a matter of much difficulty to determine their relative merits, each was such an admirable match for the other. When Buckram-Back’s pupils, however, came to perform, they found that the absence of the post was their ruin. To the post they had been trained—accustomed;—with it they could dance; but wanting that, they were like so many ships at sea without rudders or compasses. Of course a scene of ludicrous confusion ensued, which turned the laugh against poor Buckram-Back, who stood likely to explode with shame and venom. In fact he was in an agony.

“Gintlemen, turn the post!” he shouted, stamping upon the ground, and clenching his little hands with fury; “leedies, remimber the post! Oh, for the honour of Kilnahushogue don’t be bate. The post! gintlemen; leedies, the post if you love me! Murdher alive, the post!”

“Be gorra, masther, the jockey will distance us,” replied Bob Magawly; “it’s likely to be the winnin’-post to him anyhow.”

“Any money,” shouted the little fellow, “any money for long Sam Sallaghan; he’d do the post to the life. Mind it, boys dear, mind it or we’re lost. Divil a bit they heed me; it’s a flock o’ bees or sheep they’re like. Sam Sallaghan, where are you? The post, you blackguards!”

“Oh, masther dear, if we had even a fishin’-rod, or a crow-bar, or a poker, we might do yet. But, anyhow, we had better give in, for it’s only worse we’re gettin’.”

At this stage of the proceedings Paddy came over to him, and making a low bow, asked him, “Arra, how do you feel, Misther Dogherty?” for such was Buckram-Back’s name.

“Sir,” replied Buckram-Back, bowing low, however, in return, “I’ll take the shine out o’ you yet. Can you shiloote a leedy wid me?—that’s the chat! Come, gintlemen, show them what’s betther than fifty posts—shiloote your partners like Irishmen. Kilnahushogue for ever!”

The scene that ensued baffles all description. The fact is, the little fellow had them trained as it were to kiss in platoons, and the spectators were literally convulsed with laughter at this most novel and ludicrous character which Buckram-Back gave to his defeat, and the ceremony which he introduced. The truth is, he turned the laugh completely against his rival, and swaggered off the ground in high spirits, exclaiming, “He know how to shiloote a leedy! Why, the poor spalpeen never kissed any woman but his mother, an’ her only when she was dyin’. Hurra for Kilnahushogue!”

Such, reader, is a slight and very imperfect sketch of an Irish dancing-master, which if it possesses any merit at all, is to be ascribed to the circumstance that it is drawn from life, and combines, however faintly, most of the points essential to our conception of the character.

Printed and Published every Saturday by Gunn and Cameron at the Office of the General Advertiser, No. 6, Church Lane, College Green, Dublin.—Agents:—R. Groombridge, Panyer Alley, Paternoster Row, London; Simms and Dinham, Exchange Street, Manchester; C. Davies, North John Street, Liverpool; J. Drake. Birmingham; M. Bingham, Broad Street, Bristol; Fraser and Crawford, George Street, Edinburgh; and David Robertson, Trongate, Glasgow.