| Number 20. | SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 1840. | Volume I. |

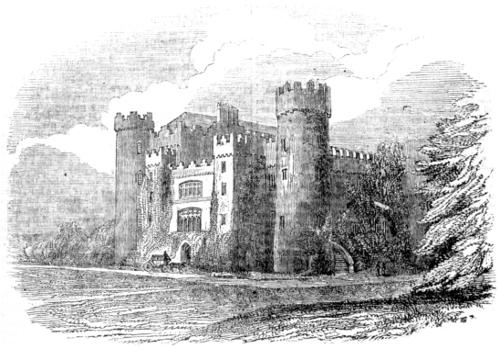

An ancient baronial castle, in good preservation and still inhabited by the lineal descendant of its original founder, is a rare object to find in Ireland; and the causes which have led to this circumstance are too obvious to require an explanation. In Malahide Castle we have, however, a highly interesting example of this kind; for though in its present state it owes much of its imposing effect to modern restorations and improvements, it still retains a considerable portion of very ancient date, and most probably even some parts of the original castle erected in the reign of King Henry II. Considered in this way, Malahide Castle is without a rival in interest, not only in our metropolitan county, but also perhaps within the boundary of the old English pale.

The Castle of Malahide is placed on a gently elevated situation on a limestone rock near the village or town from which it derives its name, and of which, with its picturesque bay, it commands a beautiful prospect. In its general form it is quadrangular and nearly approaching to a square, flanked on its south or principal front by circular towers, with a fine “Gothic” entrance porch in the centre. Its proportions are of considerable grandeur, and its picturesqueness is greatly heightened by the masses of luxuriant ivy which mantle its walls. For much of its present architectural magnificence it is however indebted to its present proprietor, and his father, the late Colonel Talbot. The structure, as it appeared in the commencement of the last century, was of contracted dimensions, and had wholly lost its original castellated character, though its ancient moat still remained. This moat is however now filled up, and its sloping surface is converted into a green-sward, and planted with Italian cypresses and other evergreens.

Interesting, however, as this ancient mansion is in its exterior appearance, it is perhaps still more so in its interior features. Its spacious hall, roofed with timber-work of oak, is of considerable antiquity; but its attraction is eclipsed by another apartment of equal age and vastly superior beauty, with which indeed in its way there is nothing, as far as we know, to be compared in Ireland. This unique apartment is wainscotted throughout with oak elaborately carved, in compartments, with subjects derived from scripture history, and though Gothic in their general character, some of them are executed with considerable skill; while the chimney-piece, which exhibits in its central division figures of the Virgin and Child, is carved with a singular degree of elegance and beauty. The whole is richly varnished, and from the blackness of tint which the wood has acquired from time, the apartment, as Mr Brewer well observes, assumes the resemblance of one vast cabinet of ebony.

The other apartments, of which there are ten on each floor, are of inferior architectural pretensions, though some of them are of lofty and spacious proportions. But they are not without attractions of a high order, being enriched with some costly specimens of porcelain, and their walls covered with the more valuable ornaments of a collection of original portraits[Pg 154] and paintings by the old masters. Among the former the most remarkable are portraits of Charles I. and Queen Henrietta Maria, by Vandyke; James II. and his queen, Anne Hyde, by Sir Peter Lely; Queen Anne, by Sir Godfrey Kneller; the Duchess of Portsmouth, mistress to Charles II.; the first Duke of Richmond (son of the above duchess) when a child; Richard Talbot, the celebrated Duke of Tirconnel, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, general and minister to James II., by Sir Peter Lely; the Ladies Catherine and Charlotte Talbot, daughters of the duke, by Sir P. Lely; with many other portraits of illustrious members of the Talbot family. The portraits of the Duchess of Portsmouth and her son were presented by herself to Mrs Wogan of Rathcoffy, from whom they were inherited by Colonel Talbot.

Among the pictures of more general interest, the most distinguished is a small altar piece divided into compartments, and representing the Nativity, Adoration, and Circumcision. This most valuable and interesting picture is the work of Albert Durer, and is said to have belonged to the unfortunate Mary Queen of Scots. It was purchased by Charles II. for £2000, and was given by him to the Duchess of Portsmouth, who presented it to the grandmother of the late Col. Talbot.

As already observed, the noble family of Talbot have been seated in their present locality for a period of nearly seven hundred years! According to the pedigree of the family, drawn up with every appearance of accuracy by Sir William Betham, Richard Talbot, the second son of Richard Talbot, Lord of Eccleswell and Linton, in Herefordshire, who was living in 1153, having accompanied King Henry II. into Ireland, obtained from that monarch the lordship of Malahide, being part of the two cantreds of Leinster, in the neighbourhood of Dublin, which King Henry had reserved, when he granted the rest of the province to Richard Earl of Strongbow, to be held as a noble fief of the crown of England. It is at all events certain, as appears from the chartulary or register of Mary’s Abbey, now in the British Museum, that this Richard Talbot granted to St Mary’s Abbey in Dublin certain lands called Venenbristen, which lie between Croscurry and the lands of Hamon Mac Kirkyl, in pure and perpetual alms, that the monks there might pray for the health of his soul and that of his brother Roger, and their ancestors; and that he also leased certain lands in Malahide and Portmarnoc to the monks of the same abbey. From this Richard Talbot the present Lord Talbot de Malahide descends in the twentieth generation, and in the twenty-fourth from Richard Talbot, a Norman baron who held Hereford Castle in the time of the Conqueror. The noble Earls of Shrewsbury and Talbot are of the same stock, but descend from Gilbert, the elder brother of Richard, who was Lord of Eccleswell and Linton, and was living in 1190.

There can be no question, therefore, of the noble origin of the Talbots de Malahide, nor can their title be considered as a mushroom one, though only conferred upon the mother of the present lord; for Sir William Betham shows that his ancestor, Thomas Talbot, knight and lord of Malahide, who had livery of his estate in 1349, was summoned by the sheriff of Dublin to the Magnum Concilium, or Great Council, held in Dublin in 1372, 46 Edward III., and again to the Magnum Concilium held on Saturday, in the vigils of the holy Trinity, 48 Edward III., 1374, by special writ directed to himself by the name of “Thome Talbot, Militis.” He was also summoned by writ to the Parliament of Ireland in the same year. If therefore it could be ascertained that this Thomas Talbot actually took his seat under that writ, it would be clear that his lineal heir-male and heir-general, the present baron, has a just claim to the honours and dignity which he has so recently acquired.

The manor of Malahide was created by charter as early as the reign of King Henry II., and its privileges were confirmed and enlarged by King Edward IV. in 1475. This, we believe, still remains in the possession of the chief of the family, but various other extensive possessions of his ancestors passed to junior branches of his house, and have been long alienated from his family.

Among the most memorable circumstances of general interest connected with the history of this castle and its possessors, should be mentioned what Mr Brewer properly calls “a lamentable instance of the ferocity with which quarrels of party rivalry were conducted in ages during which the internal polity of Ireland was injuriously neglected by the supreme head of government:—On Whitsun-eve, in the year 1329, as is recorded by Ware, John de Birmingham, Earl of Louth, Richard Talbot, styled Lord of Malahide, and many of their kindred, together with sixty of their English followers, were slain in a pitched battle at Balbriggan [Ballybragan] in this neighbourhood, by the Anglo-Norman faction of the De Verdons, De Gernons, and Savages: the cause of animosity being the election of the earl to the palatinate dignity of Louth, the county of the latter party.”

At a later period the Talbots of Malahide had a narrow escape from a calamity nearly as bad as death itself—the total loss of their rank and possessions. Involved of necessity by their political and religious principles in the troubles of the middle of the seventeenth century, they could hardly have escaped the persecution of the party assuming government in the name of the parliament. John Talbot of Malahide having been indicted and outlawed for acting in the Irish rebellion, his castle, with five hundred acres of arable land, was granted by lease, dated 21st December 1653, for seven years, to the regicide Miles Corbet, who resided here for several years after, till, being himself outlawed in turn at the period of the Restoration, he took shipping from its port for the continent. More fortunate, however, than the representatives of most other families implicated in the events of this unhappy period, Mr Talbot was by the act of explanation in 1665 restored to all his lands and estates in the county of Dublin, as he had held the same in 1641, only subject to quit rents. It is said that during the occupation of Malahide by Corbet it became for a short time the abode of Cromwell himself; but this statement, we believe, only rests on popular tradition—a chronicler which has been too fond of making similar statements respecting Irish castles generally, to merit attention and belief.

Our limits will not permit us on the present occasion to enter on any description of the picturesque ruins of the ancient chapel and tombs situated within the demesne, and immediately adjacent to the castle; and we shall only add in conclusion, that the grounds of the demesne, though of limited extent, and but little varied in elevation, are judiciously laid out, and present among its plantations many scenes of dignified character and beauty.

P.

Amongst the many extraordinary characters with which this country abounds, such as fools, madmen, onshochs, omadhauns, hair-brains, crack-brains, and naturals, I have particularly taken notice of one. His character is rather singular. He begs about Newbridge, county of Kildare: he will accept of any thing offered him, except money—that he scornfully refuses; which fulfils the old adage, “None but a fool will refuse money.” His habitation is the ruins of an old fort or ancient stronghold called Walshe’s Castle, on the road to Kilcullen, near Arthgarvan, and within a few yards of the river Liffey, far away from any dwelling. There he lies on a bundle of straw, with no other covering save the clothes he wears all day. Many is the evening I have seen this poor crazy creature plod along the road to his desolate lodging. There is another stamp of singularity on his character: his name is Pat Mowlds, but who dare attempt to call him Pat? It must be Mr Mowlds, or he will not only be offended himself, but will surely offend those who neglect this respect. In general he is of a downcast, melancholy disposition, boasts of being very learned, is much delighted when any one gives him a ballad or old newspaper. Sometimes he gets into a very good humour, and will relate many anecdotes in a droll style.

About two years ago, as I happened to be sauntering along the border of the Curragh, I overtook this solitary being.

“A fine morning, Mr Mowlds,” was my address.

“Yes, sur, thank God, a very fine morning; shure iv we don’t have fine weather in July, when will we have it?”

“What a great space of ground this is to lie waste—what a quantity of provisions it would produce—what a number of people it would employ and feed!” said I.

“Oh, that’s very thrue, sur; but was it all sown in pittaties, what would become ov the poor sheep? Shure we want mutton as well as pittaties—besides, all the devarshin we have every year.——Why, thin, maybe ye have e’er an ould newspaper or ballit about ye?”

I said I had not, but a couple of Penny Journals should be at his service which I had in my pocket.

“Och, any thing at all that will keep a body amused, though I have got a great many of them; but among them all I don’t see any picther or any account of the round tower[Pg 155] ferninst ye; nor any account ov the fire Saint Bridget kept in night an’ day for six hundred years; nor any thing about the raison why it was put out; nor any thing about how Saint Bridget came by this piece ov ground; nor any thing about the ould Earl ov Kildare, who rides round the Curragh every seventh year with silver spurs and silver reins to his horse—God bless ye, sur, have ye e’er a bit of tobacky?—there’s not a word about this poor counthry at all.”

My senses were now driven to anxiety—I gave him some tobacco. He then resumed:—

“Och, an’ faix it’s myself that can tell all about those things. Shure my grandfather was brother to one of the ould anshint bards who left him all his books, and he left them to my mother, who left them to me.”

“Well, Mr Mowlds,” I said, “you must have a perfect knowledge of those things—let us hear something of their contents.”

“Why, thin, shure, sur, I can’t do less. Now, you see, sur, it’s my fashion like the priests and ministhers goin’ to praich: they must give a bit ov a text out ov some larned book, and that’s the way with me. So here goes—mind the words:

He thus ended with a kick up of his heel which nearly touched the nape of his neck, and a flourish of his stick at the same time. Then turning to me he said,

“I am not going to tell you one word about the fire—I am going to tell you how Saint Bridget got all this ground. Bad luck to Black Noll (a name given to Cromwell) with his crew ov dirty Sasanachs that tore down the church; and if they could have got on the tower, that would be down also. No matther—every dog will have his day. Sit down on this hill till we have a shaugh ov the dhudheen. In this hill lie buried all the bones ov the poor fellows that Gefferds killed the time ov the throuble, peace an’ rest to their souls!”

“But to the story, Mr Mowlds,” I said, as I watched him with impatience while he readied his pipe with a large pin.

“Well, sur, here goes. Bad luck to this touch, it’s damp: the rain blew into my pocket t’other night an’ wetted it—ha, I have it.

Now, sur, you persave by the words ov my text that a great feast was kept up every year at the palace of Castledermot on Saint Pathrick’s day. Nothing was to be seen for many days before but slaughtering ov bullocks, skiverin’ ov pullets, rowlin’ in ov barrels, an’ invitin’ all the quolity about the counthry; nor did the roolocks and spalpeens lag behind—they never waited to be axt; all came to lind a frindly hand at the feast; nor war the kings ov those days above raisin’ the ax to slay a bullock. King O’Dermot was one ov those slaughtherin’ kings who wouldn’t cringe at the blood ov any baste.

’Twas on one ov those festival times that he sallied out with his ax in his hand to show his dexterity in the killin’ way. The butchers brought him the cattle one afther another, an’ he laid them down as fast as they could be dhrained ov their blood.

Afther layin’ down ninety-nine, the last ov a hundhred was brought to him. Just as he riz the ax to give it the clout, the ox with a sudden chuck drew the stake from the ground, and away with him over hill an’ dale, with the swingin’ block an’ a hundred spalpeens at his heels. At last he made into the river just below Kilcullen, when a little gossoon thought to get on his back; but his tail bein’ very long, gave a twitch an’ hitched itself in a black knot round the chap’s body, and so towed him across the river.

Away with him then across the Curragh, ever till he came to where Saint Bridget lived. He roared at the gate as if for marcy. Saint Bridget was just at the door when she saw the ox with his horns thrust through the bars.

‘Arrah, what ails ye, poor baste?’ sez she, not seein’ the boy at his tail.

‘Och,’ sez the boy, makin’ answer for the ox, ‘for marcy sake let me in. I’m the last ov a hundred that was goin’ to be kilt by King O’Dermot for his great feast to-morrow; but he little knows who I am.’

Begor, when she heard the ox spake, she was startled; but rousin’ herself, she said,

‘Why, thin, it ’ud be fitther for King O’Dermot to give me a few ov yees, than be feedin’ Budhavore: it’s well you come itself.’

‘Ah, but, shure, you won’t kill me, Biddy Darlin,’ sez the chap, takin’ the hint, as it was nigh dark, and Biddy couldn’t see him with her odd eye; for you must know, sur, that she was such a purty girl when she was young, that the boys used to be runnin’ in dozens afther her. At last she prayed for somethin’ to keep them from tormenting her. So you see, sur, she was seized with the small-pox at one side ov her face, which blinded up her eye, and left the whole side ov her face in furrows, while the other side remained as beautiful as ever.

‘In troth you needn’t fear me killin’ ye,’ sez she; ‘but where can I keep ye?’

‘Och,’ says the arch wag, ‘shure when I grow up to be a bull I can guard yer ground.’

‘Ground, in yeagh,’ sez the saint; ‘shure I havn’t as much as would sow a ridge ov pittaties, barrin’ the taste I have for the girls to walk on.’

‘And did you ax the king for nane?’ sed the supposed ox.

‘In troth I did, but the ould budhoch refused me twice’t.’

‘Well, Biddy honey,’ sez the chap, ‘the third offer’s lucky. Go to-morrow, when he’s at dinner, and you may come at the soft side ov him. But won’t you give some refreshment to this poor boy that I picked up on the road? I fear he is dead or smothered hanging at my tail.’

Well, to be sure, the chap hung his head (moryeah) when he sed this.

Out St Bridget called a dozen ov nuns, who untied the knot, and afther wipin’ the chap as clean as a new pin, brought him into the kitchen, and crammed him with the best of aitin’ and drinkin’; but while they wor doing this, away legged the ox. St Bridget went out to ax him some questions consarnin’ the king, but he was gone.

‘’Pon my sowkins,’ sed she, ‘but that was a mighty odd thing entirely. Faix, an it’s myself that will be off to Castledermot to-morrow, hit or miss.’

Well, sur, the next day she gother together about three dozen nuns.

‘Toss on yer mantles,’ sez she, ‘an’ let us be off to Castledermot.’

‘With all harts,’ sez they.

‘Come here, Norah,’ sez she to the sarvint maid. ‘Slack down the fire,’ sez she, ‘and be sure you have the kittle on. I couldn’t go to bed without my tay, was it ever so late.’

So afther givin’ her ordhers off they started.

Well, behould ye, sur, when she got within two miles ov the palace, word was brought to the king that St Bridget and above five hundred nuns were on the road, comin’ to dine with him.

‘O tundheranounthers,’ roared the king, ‘what’ll I do for their dinner? Why the dhoul didn’t she come an hour sooner, or sent word yestherday? Such a time for visithers! Do ye hear me, Paudeen Roorke?’ sez he, turnin’ to his chief butler: ‘run afther Rory Condaugh, and ax him did he give away the two hind quarthers that I sed was a little rare.’

‘Och, yer honor,’ sed Paudeen Roorke, ‘shure he gev them to a parcel of boccochs at the gate.’

‘The dhoul do them good with it! Oh, fire and faggots! what’ll become ov me?—shure she will say I have no hospitality, an’ lave me her curse. But, cooger, Paudeen: did the roolocks overtake the ox that ran away yestherday?’

‘Och, the dhoul a haugh ov him ever was got, yer honor.’

‘Well, it’s no matther; that’ll be a good excuse; do you go and meet her; I lave it all to you to get me out ov this hobble.’

‘Naboclish,’ said Paudeen Roorke, cracking his fingers, an’ out he started. Just as he got to the door he met her going to come in. Well become the king, but he shlipt behind the door to hear what ’ud be sed. ‘Bedhahusth,’ he roared to the guests that wor going to dhrink his health while his back was turned.

‘God save yer reverence!’ said St Bridget to the butler, takin’ him for the king’s chaplain, he had such a grummoch face on him; ‘can I see the king?’

‘God save you kindly!’ sed Paudeen, ‘to be shure ye can.[Pg 156] Who will I say wants him?’ eyeing the black army at her heels.

‘Tell him St Bridget called with a few friends to take pot luck.’

‘Oh, murther!’ sed Paudeen, ‘why didn’t you come an hour sooner? I’m afraid the meat is all cowld, we waited so long for ye.’

‘Och, don’t make any bones about it,’ sed St Bridget: ‘it’s a cowld stummock can’t warm its own mait.’

‘In troth that’s thrue enough,’ sed Paudeen; ‘but I fear there isn’t enough for so many.’

‘Why, ye set of cormorals,’ sed she, ‘have ye swallied the whole ninety-nine oxen that ye kilt yestherday?’

‘Oh, blessed hour!’ groaned the king to himself, ‘how did she know that? Och, I suppose she knows I’m here too.’

‘Oh, bad scran to me!’ said Paudeen, ‘but we had the best and fattest keepin’ for you, but he ran away.’

‘In troth you needn’t tell me that,’ sez she; ‘I know all about yer doings. If I’m sent away without my dinner itself, I must see the king.’

Just as she sed this, a hiccup seized the king, so loud that it reached the great hall. The guests, who war all silent by the king’s order, thought he sed hip, hip!—so. Such a shout, my jewel, as nearly frightened the saint away.

‘In troth,’ sez she, ‘I’d be very sorry to venthur among such a set of riff-raff, any way. But who’s this behind the door?’ sez she, cockin’ her eye. ‘Oh, I beg pardon!—I hope no inthrusion—there ye are—ye’ll save me the trouble ov goin’ in.’

‘Oh,’ sed the king (hic), ‘I tuck a little sick in my stummock, and came down to get fresh air. I beg pardon. Why didn’t you come in time to dinner?’

‘I want no dinner,’ said she; ‘I came to speak on affairs ov state.’

‘Why, thin,’ said the king, ‘before ye state them, ye must come in and take a bit in yer fingers, at any rate.’

‘In troth,’ sez she, ‘I was always used to full and plenty, and not any scrageen bits; and to think ov a king’s table not having a flaugooloch meal, is all nonsense: that’s like the taste ov ground I axt ye for some time ago.’

Begor, sur, when she sed that, she gev him such a start that the hiccough left him.

‘Ah, Biddy, honey,’ sez he, ‘shure ye wor only passin’ a joke to cure me: say no more—it’s all gone.’

Just as he sed this, he heard a great shout at a distance: out he pulled his specks, an’ put them on his nose; when to his joy he saw a whole crowd ov spalpeens dhrivin’ the ox before them. The king, forgettin’ who he was spaikin’ to, took off his caubeen, and began to wave it, as he ran off to meet them.

‘Oh! mahurpendhoul, but ye’re brave fellows,’ sez he; ‘who ever it was that cotch him shall have a commission in my life guards. I never wanted a joint more. Galong, every mother’s son ov yees, and horry all the gridirons and frying-pans ye can get. Hand me the axe, till I have some steaks tost up for a few friends.’

So, my jewel, while ye’d say thrap-stick, the ox was down, an’ on the gridirons before the life was half out ov him.

Well, to be shure, St Bridget got mighty hungry, as she had walked a long way. She then tould the king that the gentlemen should lave the room, as she could not sit with any one not in ordhers, and they being a little out ov ordher. So, to make themselves agreeable to her ordhers, they quit the hall, and went out to play at hurdles.

When the king recollected who he was goin’ to give dinner to, sez he to himself, ‘Shure no king ought to be above sarvin’ a saint.’ So over he goes to his wife the queen.

‘Dorah,’ sez he, ‘do ye know who’s within?’ ‘Why, to be shure I do,’ sez she; ‘ain’t it Bridheen na Keogue?’

‘Ye’re right,’ sez he, ‘and you know she’s a saint; an’ I think it will be for the good ov our sowls that she kem here to-day. Come, peel off yer muslins, and help me up wid the dinner.’

‘In troth I’ll not,’ sez the queen; ‘shure ye know I’m a black Prospitarian, an’ bleeve nun ov yer saints.’

‘Arrah, nun or yer quare ways,’ sez he; ‘don’t you wish my sowl happy, any how?—an’ if you help me, you will be only helpin’ my sowl to heaven.’

‘Oh, in that case,’ sez she, ‘here’s at ye, and the sooner the betther. But one charge I’d give ye: take care how ye open yer claub about ground: ye know she thought to come round ye twice before.’

So in the twinklin’ ov an eye she went down to the kitchen, an’ put on a prashkeen, an’ was first dish at the table.

The king saw every one lashin’ away at their dinner except Bridget.

‘Arrah, Biddy, honey,’ sez he, ‘why don’t ye help yerself?’

‘Why, thin,’ sez she, ‘the dhoul a bit, bite or sup, I’ll take undher yer roof until ye grant me one favour.’

‘And what is that?’ sez the king; ‘shure ye know a king must stand to his word was it half his kingdom, and how do I know but ye want to chouse me out ov it: let me know first what ye want.’

‘Well, thin, Mr King O’Dermot,’ sez she, ‘all I want is a taste ov ground to sow a few pays in.’

‘Well, an’ how much do ye want, yer reverence,’ sez he, all over ov a thrimble, betune his wife’s dark looks, and the curse he expected from Bridget if he refused.

‘Not much,’ sez she, ‘for the present. You don’t know how I’m situated. All the pilgrims going to Lough Dhearg are sent to me to put the pays in their brogues, an’ ye know I havn’t as much ground as would sow a pint; but if ye only give me about fifty acres, I’ll be contint.’

‘Fifty acres!’ roared the king, stretching his neck like a goose.

‘Fifty acres!’ roared the queen, knitting her brows; ‘shure that much ground would fill their pockets as well as their brogues.’

‘There ye’re out ov it,’ said the saint; ‘why, it wouldn’t be half enough if they got their dhue according to their sins; but I’ll lave it to yerself.’

‘How much will ye give?’

‘Not an acre,’ said the queen.

‘Oh, Dorah,’ sed the king, ‘let me give the crathur some.’

‘Not an inch,’ sed the queen, ‘if I’m to be misthress here.’

‘Oh, I beg pardon,’ sez the saint; ‘so, Mr King O’Dermot, you are undher petticoat government I see; but maybe I won’t match ye for all that. Now, take my word, you shall go on penance to Lough Dhearg before nine days is about; and instead ov pays ye shall have pebble stones and swan shot, in yer brogues. But it’s well for you, Mrs Queen, that ye’re out ov my reach, or I’d send you there barefooted, with nothing on but yer stockings.’

When the king heard this, he fell all ov a thrimble. ‘Oh, Dorah,’ sez he, ‘give the crathur a little taste ov ground to satisfy her.’

‘No, not as much as she could play ninepins on,’ sez she, shakin’ her fist and grindin’ her teeth together; ‘and I hope she may send you to Lough Dhearg, as she sed she would.’

‘Why, thin, have ye no feeling for one ov yer own sex?’ sez the saint. ‘I’ll go my way this minit, iv ye only give me as much as my shawl will cover.’

‘Oh, that’s a horse ov another colour,’ sez the queen; ‘you may have that, with a heart and a half. But you know very well if I didn’t watch that fool ov a man, he’d give the very nose off his face if a girl only axt him how he was.’

Well, sur, when the king heard this, he grew as merry as a cricket. ‘Come, Biddy,’ sez he, ‘we mustn’t have a dhry bargain, any how.’

‘Oh, ye’ll excuse me, Mr King O’Dermot,’ sez she; ‘I never drink stronger nor wather.’

‘Oh, son ov Fingal,’ exclaimed the king, ‘do ye hear this, and it Pathrick’s day!’

‘Oh, I intirely forgot that,’ sez she. ‘Well, then, for fear ye’d say I was a bad fellow, I’ll just taste. Shedhurdh.’

Well, sur, after the dhough-an-dheris she went home very well pleased that she was to get ever a taste ov ground at all, and she promised the king to make his pinance light, and that she would boil the pays for him, as she did with young men ov tendher conshinses; but as to ould hardened sinners, she’d keep the pays till they’d be as stale as a sailor’s bisket.

Well, to be shure, when she got home she set upwards ov a hundhred nuns at work to make her shawl, during which time she was never heard of. At last, afther six months’ hard labour, they got it finished.

‘Now,’ sez she, ‘it’s time I should go see the king, that he may come and see that I take no more than my right. So, taking no one with her barrin’ herself and one nun, off she set.

The king and queen were just sitting down to tay at the parlour window when she got there.

‘Whoo! talk of the dhoul and he’ll appear,’ sez he. ‘Why, thin, Biddy honey, it’s an ago since we saw ye. Sit down; we’re just on the first cup. Dorah and myself were afther talkin’ about ye, an’ thought ye forgot us intirely. Well, did ye take that bit ov ground?’

‘Indeed I’d be very sorry to do the likes behind any one’s back. You must come to-morrow and see it measured.’

‘Not I, ’pon my sowkins,’ sed the king: ‘do ye think me so mane as to doubt yer word?’

‘Pho! pho!’ sed the queen, ‘such a taste is not worth talkin’ ov; but, just to honour ye, we shall attind in state to-morrow. Sit down.’

She took up her station betune the king an’ queen: the purty side ov her face was next the king, an’ the ugly side next the queen.

‘I can’t be jealous ov you, at any rate,’ sed the queen to herself, as she never saw her veil off before.

‘Oh, murther!’ sez the king, ‘what a pity ye’re a saint, and Dorah to be alive. Such a beauty!’

Just as he was starin’, the queen happened to look over at a looking-glass, in which she saw Biddy’s pretty side.

‘Hem!’ sez she, sippin’ her cup. ‘Dermot,’ sez she, ‘it’s very much out ov manners to be stuck with ladies at their tay. Go take a shaugh ov the dhudheen, while we talk over some affairs ov state.’

Begor, sur, the king was glad ov the excuse to lave them together, in the hopes St Bridget would convart his wife.

Well, sur, whatever discoorse they had, I disremember, but the queen came down in great humour to wish the saint good night, an’ promised to be on the road the next day to Kildare.

‘Faix,’ sez the saint, ‘I was nigh forgettin’ my gentility to wish the king good night. Where is he?’

‘Augh, and shure myself doesn’t know, barrin’ he’s in the kitchen.’

‘In the kitchen!’ exclaimed the saint; ‘oh fie!’

‘Ay, indeed, just cock yer eye,’ sez the queen, ‘to the key-hole: that dhudheen is his excuse. I can’t keep a maid for him.’

‘Oh! is that the way with him?—never fear: I’ll make his pinance purty sharp for that. At any rate call him out an’ let us part in friends.’

So, sur, afther all the compliments wor passed, the king sed he should go see her a bit ov the road, as it was late: so off he went. The moon had just got up, an’ he walked alongside the saint at the ugly side; but when he looked round to praise her, an’ pay her a little compliment, he got sich a fright that he’d take his oath it wasn’t her at all, so he was glad to get back to the queen.

Well, sur, next morning the queen ordhered the long car to be got ready, with plenty ov clean straw in it, as in those times they had no coaches; then regulated her life guards, twelve to ride before and twelve behind, the king at one side and the chief butler at the other, for without the butler she couldn’t do at all, as every mile she had to stop the whole retinue till she’d get refreshment. In the meantime, St Bridget placed her nuns twenty-one miles round the Curragh. At last the thrumpet sounded, which gave notice that the king was coming. As soon as they halted, six men lifted the queen up on the throne, which they brought with them on the long car. The king ov coorse got up by her side.

‘Well, Dorah,’ sez he in a whisper, ‘what a laugh we’ll have at Biddy, with her shawl!’

‘I don’t know that neither,’ sez the queen. ‘It looks as thick as Finmocool’s boulsther, as it hangs over her shoulder.’

‘God save yer highness,’ sed the saint, as she kem up to them. ‘Why, ye sted mighty long. I had a snack ready for ye at one o’clock.’

‘Och, it’s no matther,’ sez the queen; ‘measure yer bit ov ground, and we then can have it in comfort.’

So with that St Bridget threw down her shawl, which she had cunningly folded up.

Now, sur, this shawl was made ov fine sewin’ silk, all network, each mesh six feet square, and tuck thirty-six pounds ov silk, and employed six hundred and sixty nuns for three months making it.

Well, sur, as I sed afore, she threw it on the ground.

‘Here, Judy Conway, run to Biddy Conroy with this corner, an’ let her make aff in the direckshin ov Kildare, an’ be shure she runs the corner into the mon’stery. Here, you, Nelly Murphy, make off to Kilcullen; an’ you, Katty Farrel, away with you to Ballysax; an’ you, Nelly Doye, away to Arthgarvan; an’ you, Rose Regan, in the direckshin of Connell; an’ you, Ellen Fogarty, away in the road to Maddenstown; an’ you, Jenny Purcel, away to Airfield. Just hand it from one to t’other.’

So givin’ three claps ov her hand, off they set like hounds, an’ in a minnit ye’d think a haul ov nuns wor cotched in the net.

‘Oh, millia murther!’ sez the queen, ‘she’s stretchin’ it over my daughter’s ground.’

‘Oh, blud-an’-turf!’ sez the king, ‘now she’s stretchin’ it over my son’s ground. Galong, ye set ov thaulabawns,’ sed he to his life-guards; ‘galong, I say, an’ stop her, else she’ll cover all my dominions.’

‘Oh fie, yer honour,’ sez the chief butler; ‘if you break yer word, I’m not shure ov my wages.’

Well behould ye, sur, in less than two hours Saint Bridget had the whole Curragh covered.

‘Now see what a purty kittle of fish you’ve made ov it!’ sez the queen.

‘No, but it’s you, Mrs Queen O’Dermot, ’twas you agreed to this.’

‘Ger out, ye ould bosthoon,’ sez the queen, ‘ye desarve it all: ye might aisy guess that she’d chouse ye. Shure iv ye had a grain ov sinse, ye might recollect how yer cousin King O’Toole was choused by Saint Kavin out ov all his ground, by the saint stuffin’ a lump ov a crow into the belly ov the ould goose.’

‘Well, Dorah, never mind; if she makes a hole, I have a peg for it. Now, Biddy,’ sez he, ‘though I gave ye the ground, I forgot to tell ye that I only give it for a certain time. I now tell ye from this day forward you shall only have it while ye keep yer fire in.’”

Here I lost the remainder of his discourse by my ill manners. I got so familiar with Mr Mowlds, and so interested with his story, that I forgot my politeness.

“And what about the fire, Pat?” said I, without consideration.

Before I could recollect the offence, he turned on me with the eyes of a maniac—

“The dhoul whishper nollege into your ear. Pat!—(hum)—Pat!—Pat!—this is freedom, with all my heart.”

So saying, he strode away, muttering something between his teeth. However, I hope again to meet him, when I shall be a little more cautious in my address.

An elaborate and very lucid article on the Electrotype and Daguerreotype, being a review of “An Account of Experiments in Electricity made by Thomas Spencer—Annals of Electricity, January 1840,” and of the account of M. Daguerre’s discovery of Photogenic Drawing as published by himself, has appeared in that excellent work “The Westminster Review” for September. Our space not allowing us to enter so fully into details as our admirable contemporary, we present our readers with as concise an article as the nature of the subject will permit, confining ourselves for the present to the Electrotype, as being less generally known, though not less curious.

The electrotype is another instance of the application of invisible elements to the uses of man, by which powers and influences, of whose nature he is as yet wholly ignorant, are made subservient to his purposes, and obedient to his rule.

To define accurately what electricity is, would be, as yet at least, impossible. Many conjectures have been, are, and will be hazarded, but the knowledge of its production, power, and effects, is only in its infancy, and so full of promise of a gigantic growth, that time will be better spent in its cultivation than in debating upon what it is.

The truth of this proposition is fully borne out by the subject of our present paper; for whilst many scientific men have been exhausting their energies in the production of plausible theories upon the nature of the electric fluid, other more matter-of-fact philosophers have addressed themselves to its application; and whilst some of these devote themselves to the developement of its motive powers, in the well-founded hope of its superseding steam, others press its services to far different uses. Amongst the last, Mr Spencer holds a foremost place.

Before entering into the description of the electrotype, we must say a few words on the subject of electricity to the less informed of our readers. The electric fluid, as it is called, may be produced in various ways: the most ordinary is by the friction of glass against silk, as exemplified in the electrical machine, which is familiar to almost every one. But galvanic and voltaic electricity is differently produced. In all cases its production is the consequence of combination,[Pg 158] but particularly in the galvanic battery and voltaic circle. The latter, being Mr Spencer’s apparatus, we shall briefly describe.

An ordinary voltaic circle is formed by a plate of zinc and another of copper being placed upright in a vessel containing acid or a saline solution. Zinc is more oxidisable than copper, that is, it has a greater affinity to, or inclination to unite itself with, the gas called oxygen, the combination of which with the particles of metal produces that appearance which is called “rust.” Whilst the zinc and copper are separate, the oxygen of the fluid operates upon both; but if they are united by means of a wire connected with each, the oxygen forsakes the copper altogether, and proceeds with increased force to unite with the zinc, and a current of electricity is immediately formed, which proceeds from the zinc plate through the fluid medium to the copper, thence along the connecting wire to the zinc, and thence round again in a constant circulating stream, until the zinc has been entirely decomposed, or oxidised.

Electricity being thus produced by combination, its progress and effects are marked by a wonderful power of separation or decomposition, which it exerts upon substances brought within the circle; and this is the power which Mr Spencer has turned to his use, the great object which he has at present in view being the multiplication of engraved plates of copper for the purpose of printing from.

Every person who has seen metal of any description in a state of fusion, must have remarked that it never forms a thin fluid such as water, capable of insinuating itself into the smallest interstices, but is what would be called thick even at the fiercest heat, consequently incapable of entering into such fine scratches as are necessary to be accurately and clearly defined upon an engraved plate. Again, the contraction and expansion of all metals by the application of heat and cold, would offer an almost insuperable bar to the utility of casting, even if the fusion could be rendered perfect. But the application of electricity removes all the inconveniences, and opens a new field of science.

Mr Spencer’s apparatus consists of an earthenware vessel, in which is suspended another, much smaller, of earthenware or wood, with a bottom formed of plaster-of-Paris. Into the larger vessel is poured a saturated solution of copper (the copper being dissolved in sulphuric acid) sufficient to rise up along the sides of the lesser one, which is filled with the acid or saline solution intended to operate upon the zinc. The plaster-of-Paris being very porous, allows the two liquids to meet in its cells, but prevents them from mixing; by permitting them to meet, however, the current of electricity is enabled to circulate through all. In the larger vessel, and beneath the bottom of the smaller one, is placed the copper plate from which the cast is to be taken, or upon which the pattern is to be raised. It is suspended by the wire, which is to connect it with the zinc, being fixed on the edge of the inner vessel, in which is the zinc plate, suspended by its connecting wire. The two wires are then brought into contact, fixed together by a screw, and the voltaic circle is complete. The acid in the upper vessel attacks the zinc, the electric current descends through the plaster bottom, thence through the solution of copper, where its separating or decomposing power is brought into operation, causing the infinitely minute particles of copper suspended in the solution to separate from the sulphuric acid, and descend upon the plate, through which itself proceeds to the wire, and so round again.

Now, here is probably the most wonderful part of the process. It is only on the copper plate that the particles of copper, disengaged from the solution, will descend and settle. If the copper be varnished, or covered with a coat of wax, they will not deposit themselves or go together at all; but where they find the clean surface of the metal, they at once not only settle, but fix and adjust themselves in their proper forms, building up as it were a metal structure, not eccentric or uneven, but forming a correct plate of new metal, so pure, so hard, and so free from defect or extraneous matter, that engravers prefer copper plates thus formed to any other for working upon. But the perfection of this operation consists in the wonderful accuracy with which the finest lines of the most beautiful engravings are copied: the particles which float in the solution are so indefinitely small, that they can enter into the finest cuts, the slightest scratches; and as they undergo no process of heating or cooling, their form is in nowise altered.

We have already observed, that if the plate of metal be covered, even with varnish, the particles will not descend or form upon it; nevertheless, if some slight substance be not interposed, the depositing particles adhere so firmly to it as to be inseparable, and it is upon this property that one of the processes—that of engraving in relief on a plate of copper—entirely depends for success. When a cast of an engraved plate is required, the plate must be coated with bee’s-wax, mixed with a little spirits of turpentine. It is laid on the plate in a lump and melted, and when just cooling is wiped off, when, although apparently clean, enough remains to interpose between the new and original plates, and prevent a too strong cohesion. It is not necessary that the engraved plate should be copper: it may be for instance lead or type metal, in which case it need not be waxed, as the application of heat, expanding the metals unequally, causes them at once to start asunder.

A piece of wire having been soldered to the back of the plate, its back and edges should be covered with a double coat of thick varnish, or it may be embedded in a box with plaster-of-Paris or Roman cement. This precaution is necessary, to prevent the plate from being inclosed, and to limit the deposition to a proper extent.

It may now be suspended in the apparatus, and the wires being placed in contact, the operation begins. Particle by particle the new metal is formed, until the plate is of sufficient thickness, when it is withdrawn, and heat being applied, the two plates are separated, one being the exact counterpart, in relief, of the other. Care must be taken in all cases to change the solution of copper frequently, for by merely adding, the separated particles of the sulphuric acid would accumulate to such extent as to mar or injure the operation.

From the plate thus formed in relief, as many casts as may be required can be obtained, by making it the mould.

To copy or multiply medals and coins the operation is very simple, for a mould can be easily obtained by compressing the medal or coin between two plates of milled sheet lead, and by varnishing the lead round the impression, the deposit will be formed in the hollow only; and for this purpose a very simple apparatus will suffice, and one that may be very easily made. For the outer vessel an ordinary glass tumbler or finger-bowl will answer; and for the inner, a cylindrical gas-glass, having a bottom made of plaster-of-Paris. The solution of copper being in the tumbler, and the acid with the zinc in the gas-glass, the mould should be suspended by its conducting wire between the bottoms, the wire of the zinc connected with it, and the operation will proceed. In all cases it must be observed that the edge of the mould should be up, as, if it be placed horizontally, extraneous substances, sinking by their own weight, may be deposited upon it.

To produce a raised design upon a plate of copper, or as it is rather erroneously styled, “Engraving in Relief,” the operation is thus performed:—

The plate upon which the design is to be raised having had the conducting wire soldered to it, is covered with a coat of wax about one-eighth of an inch or less in thickness, and upon the surface of this coat the design is drawn. With a graver, the end of which must be of the form of a thin parallelogram, so as to make grooves in the wax equally broad at the bottom as at the top, the lines of the drawing are to be carefully cut down to the plate; care being taken that the plate is perfectly cleaned throughout each line, and also that the grooves are not narrower at the bottom than at the top. In order to lay the surface of the copper at the bottom of the grooves perfectly bare, the plate must be immersed in diluted nitric acid (three parts of water to one of acid), and the particles of wax that may have escaped the graver are driven off by the fumes of the acid. The plate is then placed in the apparatus, the circle closed as before, and the operation commences. As the particles of copper require a metallic base, they avoid the wax and seek the metal in the grooves; they there attach themselves to it, and to each other, until the hollows are quite filled up, when the plate is removed. If the surfaces of the ridges thus built up be not perfectly smooth, a piece of pumice stone or smooth flag, with water, being rubbed to them, will soon reduce them, after which the wax can be melted and cleaned off with spirits of turpentine; and so firm is this formation of metal thus raised, both in the adherence of its particles to each other and to the original plate, that it may be printed from at any ordinary printing-press.

One general remark applies to the production of electrotype copper, and it is, that the strength and solidity of the formation depends upon the slowness and deliberation of the process. The more slowly and deliberately the particles separate from the solution and proceed to their places, the more[Pg 159] fitly they appear to take them up, and the more firmly they adhere; whilst on the contrary, if the operation be hurried, the metal is brittle, so much so as sometimes to powder under an ordinary pressure. The thicker and finer the partition of plaster between the two fluids, the more slightly are they connected, and consequently the slower is the circulation of the electricity. The proper length of time to be allowed for the process varies according to the nature of the work, and the strength or solidity required. Forty-eight hours seems to be the least time for forming a design in relief, and somewhat more than a week for a plate with sunk lines.

The laws which govern matter are mysterious. The entire of this process is so wonderful, that to descant upon it would be unnecessary; and, after all, it is but another step taken upon the path of science, each advance upon which, whilst disclosing new scenes and greater wonders, is only the needful preliminary to another which will display yet more!

N.

[1] A village near Frankfort on the Oder, in which Frederick the Great was defeated on the 12th August 1759, in one of the bloodiest battles of modern times.

[2] An allusion to Frederick’s literary pursuits.

[3] Death.

[4] The Grave.

[5] Bajazet II.

We have a mortal aversion to fine lads. And, wherefore, pray? Why, because in nine cases out of ten, if not positively in every case, they are the dullest and most insipid of all human beings: they are good, inoffensive creatures, certainly, but oh, they are dreadful bores! If you doubt it, just you take an hour of a fine lad’s company, with nobody present but yourselves. Shut yourself up in a room with him for that space of time, and if you don’t ever after, as long as you live, stand in dread and awe of the society of fine lads, you must be differently constituted from other men, and amongst other rare gifts must possess that of being bore-proof.

But, pray, what after all is a fine lad? To the possession of what quality or qualities is he indebted for this very amiable sort of character?

Why, these are questions which, like many others, are much more easily put than answered. But, speaking from our own knowledge and experience, we should say that it is not the presence, but the absence—the entire absence of every quality, good, bad, and indifferent, that constitutes the fine lad; and hence his intolerable insipidity.

The fine lad is a blank, a cipher, a vacuum, a nonentity, a ring without a circumference, a footless stocking without a leg. In disposition he is neither sweet, sour, nor bitter; in temper, neither hot nor cold; in spirit, neither merry nor sad. He is in fact, so far as any thing positive can be said of him, a mere concentration of negatives. In person he is neither long nor short, neither fat nor lean, neither stout nor slender. There must in short be a total absence of all meaning, all expression, all character, in the happy individual whom every body will agree in calling a fine lad.

Between the fine lad and the world the matter stands thus: the latter finding him destitute of all distinctive characteristics, is greatly at a loss what to make of him. It cannot in conscience call him clever, and it does not like to say he is an ass, so it good-naturedly calls him a fine lad, taking shelter in the vagueness and indefiniteness of the term, since nobody can say precisely what a fine lad really means. Unlike most other reputations, that of the fine lad is wholly undisputed: it is generally bestowed on him by universal consent—no dissentient voice—every body agrees in calling him a fine lad. This is well, and must be a source of great comfort and satisfaction to the fine lad himself.

We have stated that nobody can say precisely what a fine lad really is, and this is true, generally speaking. But there is notwithstanding some degree of meaning attached to the term: it means, so far as it means any thing, a soft, meek, simpering, unresisting creature, who will allow himself to be kicked and cuffed about by any body and every body without resenting it, and who will take quietly any given quantity of abuse you choose to heap upon him. This we imagine to be the true reason why people call him a fine lad, just because he offers them, whether right or wrong, no resistance; hence it is too, we have no doubt, that he is so general a favourite.

As most people have a great fancy for having as much of their own way as possible, and as they find themselves much jostled and opposed in the indulgence of this laudable propensity by those who are bent on having the same enjoyment, they are delighted when they meet with one who readily makes way for them, and reward his simplicity by clapping him on the head, and calling him a fine lad.

The fine lad is a goose, poor fellow—no doubt of it—a decided goose, but he cannot help that: it is no fault of his; he means well, and is a most civil and obliging creature—all smiles and good nature. Being in reality good for little or nothing, having no activity, no tact whatever of any kind, the fine lad would in most cases be rather ill off as regards his temporalities, but for his steadiness. He is generally steady, and of sober and regular habits; and this, together with his extremely civil demeanour and inoffensive disposition, helps him on, and secures him in comfortable and respectable bread. You will thus for the most part find the fine lad in a well-doing way—in a good situation probably, and with every prospect of advancement. His employer likes him for his integrity and docility. He confesses that he is by no means clever, in fact that he is rather stupid; but, then, he is a fine lad. This character he gives him to every body, and every body acknowledges its justice, and calls him a fine lad too.

Fine lads are in great favour with the ladies, and no wonder, for fine lads are remarkably attentive to them: they make the best of all beaus. Thus it is that you are sure to find at least one fine lad at every tea party you go to. You know him at once by his soft speech and maiden-like smile, and by the readiness with which he undertakes, and the quiet gentleness with which he performs, the task of handing about the tea-bread, and discharging the other little duties of the occasion. At all this sort of work the fine lad is unapproachable—it is his element—here, if nowhere else, he shines resplendent. High in favour, however, as fine lads are with the fair sex, we have sometimes thought that there was fully more of esteem than admiration in the feeling with which they contemplate his character. They like his society, and have at all times their softest words and blandest smiles ready for him; but we much doubt if he is just the sort of man they would choose for a husband. We rather think not. We suspect they see in his nature something too much akin to their own, to allow of their ever thinking of him in the light of a protector.

The fine lad, however, does get married sometimes, and in justice to him, we are bound to say, always makes an excellent husband. He is gentle, kind, and indulgent: for the fine lad generally remains, in spirit at least, a fine lad to the last. So the ladies had better take this into consideration, having our authority for so doing, and henceforth look on fine lads with more seriousness than they have hitherto done.

C.

Fidelity.—This virtue is displayed in the fulfilment of promises, whether expressed or implied, in the conscientious scrupulous discharge of the duties of friendship, and in the keeping of secrets. It is therefore a great virtue, and may be used as a decisive test of character. He who has it is entitled to confidence and respect; he who lacks it merits contempt. If a man carefully performs his promises, may we not confide in him? If he violates them, must we not despise him? If we find a person is true to friendship, we may be sure that he has just perceptions of virtue. If we find one who betrays a friend, or who is guilty of any species of treachery, we cannot doubt that he is essentially base and corrupt. To those who cannot keep a secret, we commend an anecdote of Charles II. of England, which ought to be engraved upon the heart of every man. When importuned to communicate something of a private nature, the subtle monarch said, “Can you keep a secret?” “Most faithfully,” returned the nobleman. “So can I,” was the laconic and severe answer of the king. Let parents, who desire that their children should possess the respect of the community and enjoy the pleasures of friendship, take care to imbue them with fidelity of character.—Fireside Education, by S. G. Goodrich.

Anecdote.—“Guzzling Pete,” a half-witted country wight, and the town’s jest, came home one rainy Saturday night so “darkly, deeply, beautifully blue,” that he went to bed with his hat and boots on, and his old cotton umbrella under his arm. He got up about two o’clock the next afternoon, drunk with last night, and took his way to the meeting-house. Rev. Dr B—— was at his “17thly” in the second of six divisions of a very comprehensive body of Hopkinsian divinity, when “Guzzling Pete” entered the church with an egg in each hand. He saw as through a glass darkly, and with evident commiseration, a man in black, very red in the face, for the day was oppressively warm, who seemed to utter something with a great deal of vehemence, while a considerable number of those underneath him were fast asleep—among them Deacon C——, with his shiny-bald head leaning against the wall. Pete, unobserved by the minister, balanced his egg, and with tolerable aim plastered its contents directly above the deacon’s pate! Hearing the concussion, the worthy divine paused in his discourse, and looked daggers at the maudlin visitor. “Never mind, uncle,” exclaimed the intruder: “jest you go on a-talkin’—I’ll keep ’em awake for you!” By this time the congregation were thoroughly aroused. “Mr L——,” said the reverend pastor, with a seeming charity, which in his mortification he could scarcely have felt, and addressing a “tiding-man” near the door, “Mr L——, won’t you have the kindness to remove that poor creature from the aisle? I fear that he is sick.” “Sick!” stammered our qualmish hero, as he began to confirm the fears of the clergyman by very active symptoms; “s-i-c-k!—yes, and it’s enough to make a dog sick to sit under such stupid preachin’ as your’n: it’s more’n I can stand under! Yes, take me out—the quicker the better!”

The Ass.—The ass performs so many useful duties besides his choragic functions in our community, that he cannot be respectfully omitted. He is called a bad vocalist, though some amateurs prefer him to the mule; but he is perhaps underrated. There are many notes which alone are shocking to the ear, that have in concert an agreeable harmony. The gabble of the goose is not unpleasant in the orchestra of the barn-yard, and there are many instances, no doubt, in which braying would improve harmony. If one looks close into nature, he will find nothing, not even the gargle of the frog-pond, created in vain. At Musard’s they often improve the spirit of a gallopade by the sudden clank and crash of a chain upon a hollow platform, with now and then a scream like the war-whoop of the Seminoles. What the Italians understand, and what most other nations do not, is the harmonious composition of discordant sounds. If a general concert of nature could be formed, the crow as well as the nightingale would be necessary to the perfect symphony; and it is likely even the file and hand-saw might be made to discourse excellent music. But even in a solo, the ass, according to Coleridge, has his merits. He has certainly the merit of execution. He commences with a few prelusive notes, gently, as if essaying his organs, rising in a progressive swell to enthusiasm, and then gradually dies away to a pathetic close; an exact prototype of the best German and Italian compositions, and a living sanction of the genuine and authentic instructions of the Academie de Musique.

Printed and published every Saturday by Gunn and Cameron, at the Office of the General Advertiser, No. 6, Church Lane, College Green, Dublin.—Agents:—R. Groombridge, Panyer Alley, Paternoster Row, London; Simms and Dinham, Exchange Street, Manchester; C. Davies, North John Street, Liverpool; J. Drake, Birmingham; Slocombe & Simms, Leeds; Frazer and Crawford, George Street, Edinburgh; and David Robertson, Trongate, Glasgow.