| Number 23. | SATURDAY, DECEMBER 5, 1840. | Volume I. |

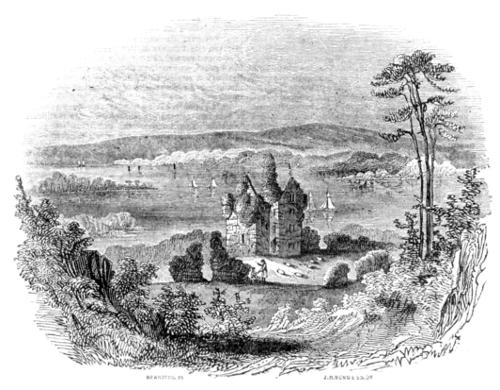

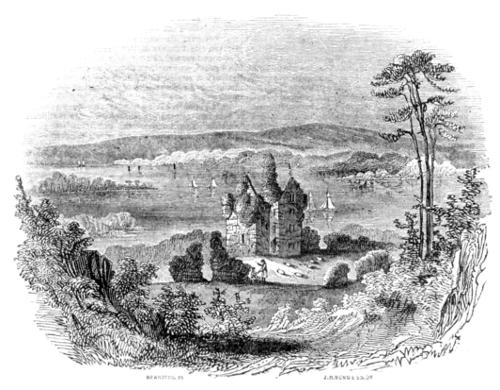

We have chosen the prefixed view of the Castle of Tully as a subject for illustration, less from any remarkable picturesqueness of character or historical interest connected with the castle itself, than for the opportunity which is thus afforded us of making a few remarks on the beautiful lake—the Windermere of Ireland, as Mr Inglis happily called it—on the bank of which it is situated. We cannot conceive any circumstance that better illustrates the truth of the general principle that, as Shakspeare expresses it, “what we have we prize not at its worth,” than the fact that Lough Erne—the admiration and delight of strangers, the most extensive and beautifully diversified sheet of water in Ireland—is scarcely known as an object of interest and beauty to the people of Ireland generally, and is rarely or never visited by them for pleasure. It is true that the nobility and gentry who reside upon its shores or in their vicinity, are not deficient in a feeling of pride in their charming locality, and even boast its superiority of beauty to the far-famed Lakes of Killarney; yet till very recently this admiration was almost exclusively confined to themselves, and the beauties of Lough Erne were as little known to the people of Ireland generally as those of the lakes and highlands of Connemara, neither of which have ever yet been included in the books concocted for the use of pleasure tourists in Ireland.

But Lough Erne will not be thus neglected or unappreciated much longer. Its beauties have been discovered and been eulogised by strangers, who have taught us to set a juster value on the landscape beauties which Providence has so bountifully given to our country; and it will soon be a reproach to us to be unfamiliar with them.

It would be utterly impossible, within the limits necessarily assigned to our topographical articles, to give any detailed account of a lake so extensive as Lough Erne, and whose attractive features are so numerous; but as these features shall from time to time be included among our subjects for illustration, it will be proper at least to give our readers a general idea of its extent, and the pervading character of its scenery, on this our first introduction of it to their notice; and with this view we shall commence with a description given of it by an author of a History of the County of Fermanagh, written in the seventeenth century, but not hitherto published.

“This lake is plentifully stocked with salmon, pike, bream, eel, trout, &c.

Seven miles broad in the broadest part. Said to contain[Pg 178] 365 islands, the land of which is excellent. The largest of the islands is Inismore, containing nine tates and a half of old plantation measure. Bally-Mac-Manus, now called Bell-isle, containing two large tates much improved by Sir Ralph Gore; Killygowan, Innis Granny, Blath-Ennis, Ennis-Liag, Ennis M’Knock, Cluan-Ennis, Ennis-keen, Ennis-M’Saint, and Babha.

These are the [islands] most notable, except the island of Devenish, of which I’ll speak in its proper place; however, by the bye, in Devenish is remembered the pious St Molaishe, who herein consecrated two churches and a large aspiring steeple [the round tower], and an abbey, which abbey was rebuilt A. D. 1430 very magnificently by Bartholomew O’Flanagan, son of a worthy baron of this county, and was one of the finest in the kingdom. In this island there is a house built by the Saint, to what use is not known, but it is as large as a small chapel-of-ease. It’s of great strength and cunning workmanship that may seem to stand for ever, having no wood in it; the inside lined and the outside covered with large flat hewn stone, walls and roof alike. On the east of this island runs an arm of the Lough called in Irish Cumhang-Devenish, which is of use to the inhabitants, viz, if cattle infected with murrain, black-leg, &c., be driven through the same, they are exempted from the same that season, as is often experienced. The said waters run northwards for twelve hours daily, and back again the same course for twelve hours more, to the admiration of the many.

Some authors write this Lough Erne to have been formerly a spring well, and being informed by their Druids or philosophers that the well would overflow the country to the North Sea, for the prevention of which they caused the well to be inclosed in a strong wall, and covered with a door having a lock and key, signifying no danger while the door was secured; but an unfortunate woman (as by them came more mischief to mankind) opening the door for water, heard her child cry, and running to its relief, forgot to secure the well, and ere she could return, she with her house and family were drowned, and many houses more betwixt that and Ballyshannon, and so continues a Lough unto this day. But how far this may pass for a reality, I am not to aver—however, it is in the ancient histories of the Irish. If true, it must be of a long standing, seeing this Lough is frequently mentioned in our chronicles amongst the ancientest of Loughs. Fintan calls it Samhir.”

We shall not, any more than our old author, “aver for the reality” of this legend, which by the way is related of many other Irish lakes; but we may remark, in passing, that the story would have more appearance of “reality” if it had been told of Lough Gawna—or the Lake of the Calf—in the county of Longford, which is the true source of the river Erne, of which Lough Erne is but an expansion. At Lough Gawna, however, they tell a different story, viz, that it was formed by a calf, which, emerging from a well in its immediate vicinity, still called Tobar-Gawna, or the Well of the Calf, was chased by its water till he entered the sea at Ballyshannon. The expansion of the Samhir or Erne thus miraculously formed, is no less than forty miles in extent from its north-west to its south-east extremities, being the length of the whole county of Fermanagh, through which it forms a great natural canal. Lough Erne, however, properly consists of two lakes connected by a deep and winding strait, of which the northern or lower is more than twenty miles in length, and seven and a half miles in its greatest breadth, and the southern or upper is twelve miles long by four and a half broad. Both lakes are richly studded with islands, mostly wooded, and in many places so thickly clustered together as to present the appearance of a country accidentally flooded; but these islands are not so numerous as they are stated to be by the old writer we have above quoted, or as popularly believed, as accurate investigation has ascertained that their number is but one hundred and ninety-nine, of which one hundred and nine are situated in the lower lake, and ninety in the upper. But these are in truth quite sufficient for picturesqueness, and it may be easily conceived that two sheets of water so enriched, and encircled by shores finely undulating, to a great extent richly wooded, and backed on most points by mountains of considerable elevation, must possess the elements of beauty to a remarkable degree; and the fact appears to be, that though the Killarney and other mountain lakes in Ireland possess more grandeur and sublimity of character, Lough Erne is not surpassed, or perhaps equalled, by any for exquisite pastoral beauty. Perhaps, indeed, we might add, that if it were further improved by planting and agricultural improvements, it might justly claim the rank assigned to it by Mr Inglis, that of “the most beautiful lake in the three kingdoms.”

Long anterior to the arrival of the English in Ireland, the beautiful district on each side of Lough Erne, now constituting the county of Fermanagh, was chiefly possessed by the powerful family of Maguire, from the senior branch of which the chiefs of the territory were elected. This territory, which was anciently known as “Maguire’s country,” was made shire ground in the 11th of Elizabeth, by the name which it still bears; but the family of its ancient chiefs still remained in possession till the plantation of Ulster by James I., when the lands were transferred to the English and Scottish undertakers, as they were called, with the exception of two thousand acres, left as a support to Brian Maguire, chief representative of the family. It is not for us to express any opinion on the justice or expediency of this great confiscation, but we may venture to remark, that it was a measure that could hardly have appeared proper to those who were so deprived of their patrimony, or that would have led to any other feeling than one of revenge and desire of retaliation, however reckless, if opportunity ever offered. Unhappily such opportunity did offer, by the breaking out of the great rebellion of 1641, a rebellion originating chiefly with the families of the disinherited Irish lords of the confiscated northern counties, and having for its paramount object the repossession of their estates.

Amongst the English and Scottish settlers in Fermanagh, the most largely endowed with lands was Sir John Humes, or Hume, the founder of Tully Castle, the subject of our prefixed wood-cut, and who was the second son of Patrick, the fifth Baron of Polwarth, in Scotland. The property thus obtained, consisting of four thousand five hundred acres, remained in the possession of his male descendants till the death of Sir Gustavus Hume, who dying without surviving male issue in 1731, it passed through the female line into the possession of the Loftus family, in which it now remains.

The Castle of Tully was for a time the principal residence of the Hume family; and on the breaking out of the rebellion in October 1641, it became the refuge of a considerable number of the English and Scottish settlers in the country. The discontented Irish of the county having, however, collected themselves together under the command of Rory, the brother of the Lord Maguire, they proceeded to the castle on the 24th of December, and having commanded the Lady Hume and the other persons within it to surrender, it was given up to them on a promise of quarter for their lives, protection for their goods, and free liberty and safe conduct to proceed either to Monea or Enniskillen, as they might choose. But what trust can be placed in the promises of men engaged in civil war, and excited by the demoniac feelings of revenge? With the exception of the Lady Hume, and the individuals immediately belonging to her family, the whole of the persons who had so surrendered, amounting to fifteen men, and, as it is said, sixty women and children, were on the following day stripped and deprived of their goods, and inhumanly massacred, when also the castle was pillaged, burnt, and left in ruins. Let us pray that Ireland may never again witness such frightful scenes!

The Castle of Tully does not appear to have been afterwards re-edified, or used as a residence. After the restoration of peace, the Hume family erected a more magnificent mansion, called Castle Hume, nearer Enniskillen, and which is now incorporated in the demesne of Ely lodge.

In its general character, as exhibited in its ruins, Tully Castle appears to have been a fortified residence of the usual class erected by the first Scottish settlers in the country—a keep or castle turreted at the angles, and surrounded by a bawn or outer wall, enclosing a court-yard. It is thus described by Pynnar in 1618:

“Sir John Humes hath two thousand acres called Carrynroe.

Upon this proportion there is a bawne of lime and stone, an hundred feet square, fourteen feet high, having four flankers for the defence. There is also a fair strong castle fifty feet long and twenty-one feet broad. He hath made a village near unto the bawne, in which is dwelling twenty-four families.”

The Castle of Tully is situated on the south-western shore of the lower lake of Lough Erne, about nine miles north-west of Enniskillen.

P.

“Arrah, Judy!” quoth Biddy Finnegan, running to a neighbour’s door.

“Arrah, why?” answered the party summoned.

“Arrah, did you hear the news?”

“No, then, what is it?”

“Sure there’s an Amerikey letter in the post-office.”

“Whisht!”

“Sorra a word of lie in it. Mickeen Dunn brought word from the town this morning; and he says more betoken that it’s from Dinny M’Daniel to his ould mother.”

“Oh, then, troth I’ll be bound that’s a lie, e’er-a-way: the born vagabond, there wasn’t that much good in him, egg or bird: the idle, worthless ruffian, that was the ruination of every one he kem near: the, the——”

“Softly, Judith, softly; don’t wrong the absent: it is from Dinny M’Daniel to his ould mother, and contains money moreover;” and she then proceeded to tell how the postmistress had desired the poor widow to bring some responsible person that might guarantee her identity, before such a weighty affair was given into her keeping, for who knew what might be inside of it? though a still greater puzzle was to discover by what means the much reprobated Dinny obtained even the price of the letter-paper; and how old Sibby had borrowed a cloak from one, and a “clane cap” from another, and the huxter had harnessed his ass and car to bring her in style, and Corney King the contingent man,[1] that knows all the quality, was going along with her to certify that she was the veritable Mrs Sybilla M’Daniel of Tullybawn; and how she would have for an escort every man, woman, and child in the village that could make a holiday—compliments cheerfully accorded by each and all, to do honour to the America letter, and the individual whose superscription it bore.

Dinny M’Daniel was the widow’s one son, born even in her widowhood, for his father had been killed by the fall of a tree before he had been six months married, and poor Sibby had nothing to lavish her fondness upon but her curly-headed gossoon, who very naturally grew up to be the greatest scapegrace in the parish. He had the most unlucky knack of throwing stones ever possessed by any wight for his sins; not a day passed over his head without a list of damages and disasters being furnished to his poor mother, in the shape of fowls killed and maimed, and children half murdered, or pitchers and occasionally windows made smithereens of; but to do him justice, his breakage in this latter article was not very considerable, there being but few opportunities for practice in Tullybawn. To all these the poor widow had but one reply, “Arrah, what would you have me do?—sorra a bit of harm in him; it’s all element, and what ’ud be the good of batin’ him?” At last the neighbours, utterly worn out by the pertinacity of his misdemeanours, hit upon an expedient to render him harmless for at least half the day, and enjoy that much of their lives in peace, with the ultimate chance of perhaps converting the parish nuisance into a useful character. A quarterly subscription of a penny for each house would just suffice to send Dinny to school to a neighbouring pedagogue, wonderful in the sciences of reading and writing, and, what was a much greater recommendation under the present circumstances, the “divil entirely at the taws.” To him accordingly Dinny was sent, and under his discipline spent some five or six years of comparative harmlessness, during which he mastered the Reading-made-Easy, the Seven Champions, Don Bellianis, and sundry other of those pleasing narratives whereby the pugnacity and gallantry of the Irish character used whilom to be formed, to which acquirement he added in process of time that of writing, or at least making pothooks and hangers, with a symmetry that delighted the heart of poor Sibby. The neighbours began to think better of him; but the “masther” swore he was a prodigy, and openly declared, that if he would but “turn the Vosther,” he’d be fit company for any lady in the land. Thus encouraged, Dinny attempted and succeeded, for he had some talent. But sure enough the turning of the Foster finished him.

It was now high time for Master Dinny to begin to earn his bread, and accordingly his mother sought and obtained for him a place in the garden of a nobleman who resided near the village, and was its landlord: but the dismay of the gossoon himself when this disparaging piece of good fortune was announced to him, was unbounded. He was speechless, and some moments elapsed before he could ejaculate,

“Fwhy, then, tare-an’-ages, mother, is that what you lay out for me, an’ me afther turnin’ the Vosther?”

Sibby expostulated, but in vain; his exploits in “the Vosther” had set him beside himself, and he boldly declared that nothing short of a dacint clerkship would ever satisfy his ambition. A man of one argument was Dinny M’Daniel, and that one he made serve all purposes—“Is it an’ me afther turnin’ the Vosther!”—so that people said it was turn about with him, for the Vosther had turned his brain. Be that as it may, there was one who agreed with Dinny that he could never think too highly of himself, for, like every other scapegrace on record, he had won the goodwill of the prettiest girl in the parish. Nelly Dolan’s friends, however, were both too snug and too prudent to leave her any hope of their acquiescing in her choice, so the lovers were driven to resort to secrecy. Dinny urged her to elope with him, knowing that her kin, when they had no remedy, would give her a fortune to set matters to rights; but she had not as yet reached that pitch of evil courage which would allow her to take such a step, nor, unfortunately, had she the good courage to discontinue such a hopeless connection, or the clandestine proceedings which its existence required. Alas, for poor Nelly! sorrow and shame were the consequence. The bright eyes, that used to pass for a very proverb through the whole barony, grew dim—the rosy cheeks, that more than one ballad-maker had celebrated, grew wan and sallow—and the slim and graceful figure——in a word, Dinny had played the ruffian, and had to fly the country to avoid the murderous indignation of her faction. It was to America he shaped his flight, though how he had obtained the means no one could divine; and now, after the lapse of nearly a year and a half, here was a letter from him to solve all speculations.

What a hubbub the arrival of “an America letter” causes in Ireland over the whole district blessed by its visit! It is quite a public concern—a joint property—being in fact always regarded as a general communication from all the neighbours abroad to all the neighbours at home, and its perusal a matter of intense and agonising interest to all who have a relative even in the degree of thirty-first cousin among the emigrants. Let us take for instance the letter in question, for the cavalcade has returned, and not only is the widow’s cabin full, but the very bawn before her door is crowded, and the door itself completely blocked up with an array of heads, poking forward in the vain attempt to catch a tone of the schoolmaster’s voice as he publishes the contents of the desired epistle, and absolutely smothering it by the uproar of their squabbles, as they endeavour each to obtain a better place.

“Tare-an’-eunties, Tom Bryan, fwhat are you pushing me away for, an’ me wanting to hear fwhat’s become of my own first cousin!”

“Arrah, don’t be talkin’, man—fwhy wouldn’t I thry to get in, an’ half the letther about my sisther-in-law?”

“Oh, boys, boys, agra, does any of yees hear e’er a word about my poor Paddy?”

The last speaker is a woman, poor Biddy Casey: for the last three years not a letter came from America that she could hear of, whether far or near, but she attended to hear it read, in the hope of getting some information about her husband, who, driven away by bad times and an injudicious agent, had made a last exertion to emigrate, and earn something for his family. Regularly every market-day from that event she called at the post-office, at first with the confident tone of assured expectation, to inquire for an America letter for one Biddy Casey; then when her heart began to sicken with apprehensions arising from the oft-repeated negative, her question was, “You haven’t e’er a letter for me to-day, ma’am?” and then when she could no longer trust herself to ask, she merely presented her well-known face at the window, and received the usual answer in heartbroken silence, now and then broken by the joyless ejaculation, “God in heaven help me!” But from that time to this not a syllable has she been able to learn of his fate, or even of his existence. Now, however, her labours and anxieties are to have an end—but what an end! This letter at last affords her the information that, tempted by the delusive promise of higher wages, her husband was induced to set out for the unwholesome south, and long since has found a grave among the deadly swamps of New Orleans.

But like every thing else in life, Dinny M’Daniel’s letter is a chequered matter. See, here comes a lusty, red-cheeked damsel, elbowing her way out of the cabin, her eyes bursting out of her head with joy.

“Well, Peggy—well—well!” is echoed on all sides as they[Pg 180] crowd around her; “any news from Bid?—though, troth, we needn’t ax you.”

“Oh, grand news!” is the delighted answer. “Bid has a wonderful fine place for herself an’ another for me, an’ my passage is ped, an’ I’m to be ready in five weeks, an’, widdy! widdy! I dunna what to do with myself.”

“And, Peggy agra, was there any thing about our Mick?”—“or our Sally, Peggy?”—“or Johnny Golloher, asthore?” are the questions with which she is inundated.

“Oh, I dunna, I dunna—I couldn’t listen with the joy, I tell ye.”

“But, Peggy alanna, what will Tom Feeny think of all this? and what is to become, pray, of all the vows and promises which, to our own certain knowledge, you made each other coming home from the dance the other night?”

Pooh! that difficulty is removed long ago—the very first money she earns in America is to be dispatched to the care of Father Cahill, to pay Tom’s passage over to her. “And will she do such a shameless thing?” some fair reader will probably ask. Ay will she; and think herself right well off, moreover, to have the shame to bear; for though Peggy can dig her ridge of potatoes beside the best man in the parish, her heart is soft and leal like nine hundred and ninety-nine out of the thousand of her countrywomen.

Another happy face—see, here comes old Malachi Tighe, clasping his hands, and looking up to heaven in silent thankfulness, for his “bouchal bawn, the glory of his heart,” is to be home with him before harvest, with as much money as would buy the bit o’ land out and out, and his daughter-in-law is fainting with gladness, and his grandchildren screaming with delight, and the neighbours wish him joy with all the earnestness of sympathy, for Johnny Tighe has been a favourite.

Woe, woe, woe!—Mick Finnegan has sent a message of fond encouragement to his sweetheart, which she never must hear, for typhus, the scourge of Ireland, has made her his victim, and the daisies have already rooted on her grave, and are blooming there as fresh and fair as she used to be herself; and the wounds of her kindred are opened anew, and the death-wail is raised again, as wild and vehement as if she died but yesterday, although six weeks have passed since they bore her to Saint John’s.

What comes next?—“Johnny Golloher has got married to a Munster girl with a stocking full of money;” and Nanny Mulry laughs at the news until you’d think her sides ought to ache, and won’t acknowledge that she cares one pin about it—on the contrary, wishes him the best of good luck, and hopes he may never be made a world’s wonder of; all which proceedings are viewed by the initiated as so many proofs positive of her intention, on the first convenient opportunity, to break her heart for the defaulting Mr Golloher.

But among the crowd of earnest listeners who thus attended to gratify their several curiosities by the perusal of Dinny’s unexpected letter, none failed to remark the absence of her who in the course of nature was, or should be, most deeply interested in the welfare of the departed swain. Nelly Dolan never came near them. In the hovel where the poor outcast had been permitted to take up her abode when turned out of doors by her justly incensed father, she sat during the busy recital, her head bowed down and resting upon the wheel from which she drew the support of herself and her infant. Now and then a sob, almost loud enough to awaken the baby sleeping in a cleave beside her, broke from her in spite of herself; while her mother, who had ventured to visit her on the occasion, sat crouched down on the hearth before her, and angrily upbraided her for her sorrow.

“Whisht, I tell you, whisht!” exclaimed the old crone, “an’ have a sperrit, what you never had, or it wouldn’t come to your day to be brought to trouble by the likes of him.”

“Och, mother darlint,” answered the sufferer, “don’t blame me—it’s a poor thing, God knows, that I must sit here quiet, an’ his letter readin’ within a few doors o’ me.”

“Arrah, you’d better go beg for a sight of it,” rejoined the angry parent with a sneer; “do, achorra, ontil you find out what little trouble you give him.”

“It’s not for myself, it’s not for myself,” answered the sobbing girl. “I can do without his thoughts or his favours; all I care to know is, what he says about the babby.”

“Pursuin’ to me!” exclaimed her mother, “but often as you tempted me to brain it, an’ that’s often enough, you never put the devil so strong into my heart as you do this minute. So be quiet, I tell you.”

“Och, mother, that’s the hard heart.”

“Musha, then, it well becomes you to talk that way,” replied her mother. “If your own wasn’t a taste too soft in its time, my darlint, your kith an’ kin wouldn’t have to skulk away as they do when your name’s spoken of.”

A fresh burst of tears was all the answer poor Nelly could give to this invective; an answer, however, as well calculated as any other to stimulate the wrath and arouse the eloquence of Mrs Dolan, the object of whose visit was to induce Nelly to assume an air of perfect coolness and nonchalance—in fine, to show she had a “sperrit.” In this it may be perceived she met with a signal failure; and now the full brunt of her indignation fell on the unfortunate recreant. Nelly’s sorrow of course became louder, and between both parties the child was wakened, and naturally added its small help to the clamour: nor did the united uproar of the three generations cease until a crowd unexpectedly appeared at the door of the hovel, and the voice of Sibby M’Daniel, half mad with joy, was heard through the din, internal and external.

“Well, if she won’t come to us,” spoke the elated Sibby, “we must only go to her, you know, though ye’ll allow the news was worth lookin’ afther;” and ere the sentence was well concluded, she with her whole train had made their way into the cabin.

“God save all here,” continued Sibby, “not excepting yourself, Mrs Dolan; for we must forgive and forget everything that was betune us, now.”

“An’ if I forgive an’ forget, what have you to swop for it?” asked the irate individual so addressed.

“Good news an’ the hoith of it,” was the answer of Sibby, as she displaced her letter; but Mrs Dolan was in no humour to listen to news or receive conciliation of any kind, and so she conducted herself like a woman of “sperrit;” and gathering her garments about her, rose slowly and stately from the undignified posture in which she was discovered, and so departed from amongst them.

“Musha, then, fair weather afther you,” was the exclamation of Sibby when she recovered from the surprise created by this exhibition of undisguised contempt. “Joy be with you, and if you never come back, it’ll be no great loss, for the never a word about you in it anyhow, you ould sarpint. But, Nelly, alanna, it’s you an’ me that ought to spend the livelong day down on our marrowbones with joy and thankfulness, though you didn’t think his letter worth lookin’ afther;” and down on her marrowbones poor Nelly sank to receive the welcome communication, her baby clasped to her bosom, her glazed eyes raised to heaven, all unconscious of the crowd by which she was surrounded, and her every nerve trembling with excess of joy and thankfulness, while the bustling Sibby placed a chair for the schoolmaster near the loophole that answered the purposes of a window, and loudly enjoining silence, gave into his hands the epistle of his favoured pupil to read to the assembled auditors for about the sixth time; and Mr Soolivan, squaring himself for the effort, proceeded to edify Nelly Dolan therewith.

The letter went on to state, in the peculiarly felicitous language of Dinny M’Daniel, that on his arrival in New York, and finding himself without either friends or money, and thus in some danger of starvation, he began to lower his opinions of his personal worth, and solicit any species of employment that could be given to him. After some difficulty he got to be porter to a large grocery establishment, in which he conducted himself pretty well, and secured the confidence of his employers, and a rate of wages moderate, but still sufficient to support him. The sense of his utter dependence upon his character compelled him to be most particularly cautious of doing anything to affect it in the slightest degree, and in process of time he became a changed gossoon altogether, an example of the blessed fruits of adversity. The thoughts of Nelly Dolan and his old mother never quitted him, his anxieties about the former clinging to him with such intensity that he began forthwith to lay by a little money every week to send her, but was ashamed to write until he should have it gathered. An unfortunate event, however, soon put a stop to his accumulation, and drove him to use it for his subsistence. This was no less than the sudden death of the head of the establishment in which he was employed, which, he being the entire manager of the concern, had the consequence of breaking it up completely. Thus Dinny was cast on the world again, and found employment as difficult to be got as ever. His little hoard was soon spent, and at last he had to turn his steps westward, where labour was more plentiful and hands fewer. After many journies and vicissitudes he at length[Pg 181] met a friend in the person of one of the partners in the grocery establishment which had first given him employment, and who, like himself, had sought a home in the wilderness. This man had some money, but, unfortunately for himself, never having “turned the Vosther” or learned anything in accounts, was unable to put it to any use that would require a knowledge of what a facetious alderman once called the three R’s, reading, writing, and ’rithmetic. Now, these happened to be Dinny’s forte. So when his quondam employer was one day lamenting to him the deficiency which forbade him to apply his capital to the lucrative uses which he otherwise might, Dinny modestly suggested a method whereby this desirable object might be effected: the other, after a little consideration, thought he might do worse than adopt it, and accordingly, before many days elapsed, a grand new store appeared in the township of Prishprashchawmanraw, in which Dinny was book-keeper and junior partner. Having brought him thus far by our assistance, we shall allow him to conclude his letter after his own way:—

“And so you see, dear mother, that notwithstanding all the neighbours said, it’s as lucky after all that I turned the Vosther, for it has made a man of me, and with the help of the holy St Patrick I am well able to spare the twenty pounds you will get inside, which is half for yourself to make your old days comfortable, or to come out to me, if you’d like that better, and the other half for my poor darling Nelly, the colleen dhas dhun, that I am afraid spent many a heavy hour on my account; but you may tell her that with the help of God I will live to make up for them all. I will expect her at New York by the next ship, and you may tell her that the first thing she is to buy with the money must be a grand goold ring, and let her put it on her finger at once, without waiting for either priest or parson, for I’m her sworn husband already, and will bring her straight to the priest the minute she puts her foot on America shore, and until then who dare sneeze at her? You must write to me to say where I am to meet her, and by what ship she will come out; and above all, whether she is to bring any thing out with her besides herself—you know what I mean. And, dear mother, when you write to me, you are to put on the back of the letter, Dennis M’Daniel, Esq. for that’s what I am now—not a word of lie in it. So wishing the best of good luck to all the neighbours, and to yourself and to Nelly, I remain, &c. &c. &c.”

“Glory to you, Dinny!” was ejaculated on every side, while they all rushed tumultuously forward to congratulate the unwedded bride. In their uproarious hands we leave her, drawing this moral from the whole thing, that it’s very hard to spoil an Irishman entirely, if there be any good at all in him originally.

A. M’C.

[1] Collector of county cess.

“It was with the good monks of old that sterling hospitality was to be found.”—Hansbrove’s Irish Gazetteer.

[2] Kilcrea Abbey, near Cork, was dedicated to Saint Bridget, and founded, A. D. 1494, by Cormac Lord Muskerry. Its monks belonged to the Franciscan order commonly called “the Grey Friars.”

It has not unfrequently occurred to us as a thing somewhat remarkable, that there is a vast difference in the comparative value of the black boys of America and those of Ireland; and this was very forcibly proved to us on a recent occasion. The American little blacks are, as we have been credibly informed, to be bought for forty dollars and upwards, according to their health, strength, and beauty; the Irish blackies for about a twentieth of that sum; and as everything is valued in proportion to its cost, it follows as a matter of course that the American urchins are vastly more prized and better taken care of than the Irish. It is not very easy to account for this, but perhaps it is only a consequence of difference of race. The American black boys are supposed to be the descendants of Cham—true woolly-headed chaps, with the colouring matter of their complexion deposited beneath their outer skin, and not washoffable by means of soap and water. The Irish black boys generally are believed to be of the true Caucasian breed—the descendants of Japhet; and their blackness is on the outer surface of the skin, and may, though we believe with difficulty, be removed. But we will not speak dogmatically on this point. In other respects they agree tolerably. They have both the power of bearing heat to a considerable degree, and of dispensing with the incumbrance of much clothing. But it is in their relative value that they most differ, and this is the point we desire to prove, and what we think we can do to the satisfaction of our readers by the following anecdote:—

Being naturally of a most humane and benevolent character, as all our readers are—for none others would support our pennyworth—we have often lamented the abject condition and sufferings of our black urchins, and have come to the resolution never to assist in encouraging their degradation, but on the contrary to do everything in our power to oppose it. With this praiseworthy intention we recently sent for a gentleman who professes the art of increasing our domestic comforts by the aid of modern science as developed in our improved machinery—or in other words, we sent for him to clean the chimney of our study, not with a little boy, but with a proper modern machine constructed for the purpose. The said professor came accordingly, but to our astonishment not merely with his sweeping machine, but also with one of the objects of our pity and commiseration—a little black boy! The use of this attendant we did not immediately comprehend, nor did we ask, but proceeded at once to inquire of the professor the price of his services in the way we desired.

“Three shillings,” was the answer.

“Three shillings!” we rejoined, with a look of astonishment; “why, we had no idea that your charge would be any thing like so much. What,” we asked, “is the cause of this unusual demand?”

“Why, sir, the price of my machine. But I’ll sweep the chimney with the boy there for a shilling.”

“And pray, sir, what did your machine cost?”

“Two pounds!”

“Indeed,” I replied; “and what was the cost of the boy?”

“Ten shillings; and do you think, sir, I could sweep with my machine, which cost me so much, at the same rate as I could charge for the boy, that cost me only ten shillings?”

There was no replying to logic so conclusive as this; and we think it right to give it publicity, in the hope that it may meet the eyes of some of our readers at the other side of the Atlantic, who may be induced to rid us of some of our superabundant population, by importing our black boys, which they can get, even including the expense of carriage, at so much cheaper a rate here than they can procure them at home!

G.

We have to express our thanks to the Westminster Review for the publication of two MS. letters to Leonard Horner, Esq. one of the factory inspectors, from the proprietor of a cotton mill in the north of England, whose modesty it is to be regretted prohibits the publication of his name, and has hitherto prevented the publication of these letters.

The introductory article in the Review contains some admirable strictures upon the radical defect of governments failing to perceive that the elevation of the people, in a moral and physical point of view, is not only one, but the fundamental duty of legislators. The writer points out that in all countries and ages to the present time, those who have been placed at the head of public affairs have had little or no leisure, if they possessed the inclination, to study schemes of human improvement; their time has been occupied in maintaining order, making war, and raising a revenue for these and similar objects, whereas the necessity for police and armies would be lessened by striking at the root of the evil, and elevating the “hewers of wood and drawers of water” in the scale of intelligence and happiness.

“Melancholy,” says the writer, “is the result of centuries of mischievous and often wicked legislation, in the impression it has left upon the mind of the public. Long after a government has ceased to do evil, it is left powerless for good by the universal distrust with which it is regarded. The people have yet to learn to place confidence in their own servants, and to support when needed in their persons their own authority, instead of seeking to overturn it as that of tyrants or masters. So numerous have been the evils which have arisen from unwise interference, that an opinion very widely prevails that a government can do nothing but mischief; and the almost universal prayer of the people is to be left alone.” Again he says, “Why should it not be borne in mind that there are higher objects for human exertion, whether for individuals or communities, than the greatest possible aggregate of wealth? And although the realization of those objects in our time may be but the visionary dream of the philanthropist, let no one say that good will not arise from keeping them steadily in view.”

And to explain his sentiments upon the subject of the elevation of the labouring classes, he quotes the following paragraph from Dr Channing’s first lecture, delivered at a meeting of the Mechanic Apprentices’ Library Association at Boston:

“By the elevation of the labourer I do not understand that he is to be raised above the need of labour. I do not expect a series of improvements by which he is to be released from his daily work. Still more, I have no desire to dismiss him from his workshop and farm, to take the spade and axe from his hand, and to make his life a long holiday. I have faith in labour, and I see the goodness of God in placing us in a world where labour alone can keep us alive. I would not change, if I could, our subjection to physical laws, our exposure to hunger and cold, and the necessity of constant conflicts with the material world. I would not, if I could, so temper the elements that they should infuse into us only grateful sensations, that they should make vegetation so exuberant as to anticipate every want, and the minerals so ductile as to offer no resistance to our strength or skill. Such a world would make a contemptible race. Man owes his growth, his energy, chiefly to that striving of the will, that conflict with difficulty, which we call effort. Easy, pleasant work does not make robust minds, does not give men a consciousness of their powers, does not train them to endurance, to perseverance, to steady force of will, that force without which all other acquisitions will avail nothing. Manual labour is a school in which men are placed to get energy of purpose and character—a vastly more important endowment than all the learning of all other schools. They are placed indeed under hard masters, physical sufferings and wants, the power of fearful elements, and the vicissitudes of all human things; but these stern teachers do a work which no compassionate indulgent friend could do for us, and true wisdom will bless Providence for their sharp ministry. I have great faith in hard work. The material world does much for the mind by its beauty and order; but it does more by the pains it inflicts; by its obstinate resistance, which nothing but patient toil can overcome; by its vast forces, which nothing but unremitting skill and effort can turn to our use; by its perils, which demand continual vigilance; and by its tendencies to decay. I believe that difficulties are more important to the human mind than what we call assistances. Work we all must, if we mean to bring out and perfect our nature. Even if we do not work with the hands, we must undergo equivalent toil in some other direction.… You will here see that to me labour has great dignity. Alas for the man who has not learned to work! He is a poor creature; he does not know himself.”

That the labouring classes can be greatly, immeasurably elevated in the social scale, without relieving them from the least portion of that labour entailed upon the race of Adam, is beautifully exemplified in the mill-owner’s letters which follow the article from which the foregoing has been extracted. We regret that their length far exceeds the utmost space which we could afford them, or we should present them to our readers in full. The account which they give of the social condition of the operatives employed in the writer’s factory, more resembles the details of a Utopian scheme than of one actually carried into effect by a single philanthropic individual.

The first letter describes the wretched and dilapidated state of the mill, and destitute condition of the few persons living about it, at the time (1832) that the writer and his brothers took it, and proceeded to rebuild and furnish it. This and the collection of the necessary hands occupied two years. In employing operatives they selected only the most respectable, such as were likely to settle down permanently wherever they should feel comfortably situated; and in order to hold out inducements, these gentlemen broke up three fields in front of the workmen’s cottages into gardens of about six roods each, separated by neat thorn hedges. Besides which, each house had a small flower-garden either in front or rear, and the houses themselves were made as comfortable as possible.

When the mill was completed and the population numerous, the proprietor called a meeting of all the workmen, and proposed the establishment of a Sunday school for the children. The proposal was gladly received, and some of the men were appointed teachers. He then built a schoolroom for the girls, and the boys had the use of a cellar; but he subsequently built a schoolroom for them also. In the girls’ school were 160 children, and in the boys’ 120. Each was placed under the management of a superintendent and a certain number of teachers, whose services were given gratuitously; and they relieved each other, so that each was obliged to attend only every third Sunday. They were all young men and women belonging to the mill, the proprietor taking no further part in the management than spending an hour or two in the room. As soon as the school was fairly established, the proprietor turned his attention to the establishment of games and gymnastic exercises amongst the people, and having set apart a field he called together some of the boys one fine afternoon, and commenced operations with quoits, trap and cricket balls, and leap-frog. The numbers quickly increased, regulations and rules were made, the girls got a portion of the field to themselves, and there were persons appointed to preserve order. The following summer he put up a swing, introduced the game called Les Graces, and bowls, a leaping-bar, a tight-rope, and a see-saw. Quoits became the favourite game of the men, hoops and tight-rope of the boys, and hoops and swing of the girls, the latter being in constant requisition. He at first found some difficulty in checking rudeness, but being constantly on the spot, it was soon corrected, and gradually quite wore away. The play-ground was only opened on Saturday evenings or holidays during the summer. He next got up drawing and[Pg 183] singing classes. The drawing-class, taught by himself, on Saturday evenings during the winter, from six to half past seven—half the time being spent in drawing, and the remainder with geography or natural history. To those pupils he lent drawings to copy during the evenings of the week, thereby giving them useful and agreeable employment for their leisure hours, and attracting them to their home fireside.

The breaking up of the drawing-class at half past seven gave room to the singing-class until nine. The superintendent of the Sunday school took charge of this class, which became at once very popular, especially with the girls. But what he seems to consider the most successful of his plans for the civilising of his people, was the establishment of regular evening parties during the winter, the number invited to each being about thirty, an equal number of boys and girls, and specially invited by a little printed card being sent to each. This afforded a mark of high distinction, only the best behaved and most respectable, or, as he calls them, “the aristocracy,” being invited. These parties are held in the schoolroom, which he fitted up handsomely, and furnished with pictures, busts, &c., and a piano-forte. When the party first assemble, they have books, magazines, and drawings, to amuse them. Tea and coffee are then handed round, and the proprietor walks about and converses with them, so as to render their manners and conversation unembarrassed; and after tea, games are introduced, such as dissected maps or pictures, spilicans, chess, draughts, card-houses, phantasmagoria, and others, whilst some prefer reading or chatting. Sometimes there is music and singing, and then a wind-up with Christmas games, such as tiercely, my lady’s toilet, blindman’s-buff, &c., previous to retiring, the party usually breaking up a little after nine. These parties are given to the grown-up boys and girls, but he sometimes also treats the juniors, when they have great diversion. The parties are given on Saturday evenings about once in three weeks, the drawing and singing bring given up for that day.

He next established warm baths at an expense of £80, and issued bathing tickets for 1d. each, or families subscribing 1s. per month were entitled to five baths weekly; and with an account of the arrangements of the baths, the receipts, &c., he concludes his first letter, which appears to have been written about the year 1835.

In the second letter, dated March 1838, he developes the principles upon which he acted, and the objects which he had in view, in answer to the request of Mr Horner. His object he avows to be “the elevation of the labouring classes,” or, to use his own language, “promoting the welfare of the manufacturing population, and raising them to that degree of intellectual and social advancement of which I believe them capable.” And amongst the matters which he considers necessary to the attainment of the object in view, he enumerates “fair wages, comfortable houses, gardens for their vegetables and flowers, schools and other means of improvement for their children, sundry little accommodations and conveniences in the mill, attention to them when sick or in distress, and interest taken in their general comfort and welfare.” He says that attention to these things, and gently preventing rather than chiding rudeness, ignorance, or immorality—treating people as though they were possessed of the virtues and manners which you wish them to acquire—is the best means of attaining the wished-for end; and that he has little faith in the efficacy of mere moral lectures. He established the order of the silver cross amongst the girls above the age of 17. It immediately became an object of great ambition, and a powerful means of forwarding the great object of refining the minds, tastes, and manners of the maidens, and through their influence, of softening and humanising the sterner part of the population. He says that he does not want to establish amongst the humbler classes the mere conventional forms of politeness as practised in the upper, but he would refine them considerably. He would have the most beautiful and tender forms of Christian charity exhibited in all their actions and habits, and mere preaching, rules, sermons, lectures, or legislation, can never change poor human nature if the people are not permitted to see what they are taught they should practise, and to hold intercourse with those whose manners are superior to their own. He points out the necessity of supplying innocent, pleasing, and profitable modes of filling up the leisure hours of the working-classes as the best mode of weaning them from drinking, and the vulgar amusements alone within their reach. He also points out that merely intellectual pursuits are not suited to uncultivated minds, and that resources should be provided of sufficient variety to supply the different tastes and capacities which are to be dealt with. It is with these views that he provided various objects of interesting pursuit or innocent amusement for his colony, and established prizes for their horticultural exhibitions; and to show how the taste for music had progressed, he mentions that a glee class had been established, and a more numerous one of sacred music that meets every Wednesday and Saturday during winter, and a band had been formed with clarionets, horns, and other wind instruments, which practised twice a-week, besides blowing nightly at home; and a few families had got pianos, besides which there were guitars, violins, violoncellos, serpents, flutes, and dulcimers, and he adds that it must be observed that they are all of their own purchasing. He goes on to observe that his object is “not to raise the manufacturing operative or labourer above his condition, but to make him an ornament to it, and thus elevate the condition itself—to make the labouring classes feel that they have within their reach all the elements of earthly happiness as abundantly as those to whose station their ambition sometimes leads them to aspire—that domestic happiness, real wealth, social pleasures, means of intellectual improvement, endless sources of rational amusement, all the freedom and independence possessed by any class of men, are all before them—that they are all within their reach, and that they are not enjoyed only because they have not been developed and pointed out, and therefore are not known. His object is to show them this, to show his own people and others that there is nothing in the nature of their employment, or in the condition of their humble lot, that condemns them to be rough, vulgar, ignorant, miserable, or poor—that there is nothing in either that forbids them to be well bred, well informed, well mannered, and surrounded by every comfort and enjoyment that can make life happy; in short, to ascertain and prove what the condition of this class of people might be made, what it ought to be made—what it is the interest of all parties that it should be made.”

In the name of our common humanity we thank him for the experiment which has so satisfactorily proved the truth of his propositions; and whilst wishing him God speed, we shall do what in our power lies to promote the benevolent object, by directing the attention of philanthropists to the good that may be effected by the unassisted efforts of a practical individual.

N.

During summer, when the weather is sultry, and the sky assumes that beautiful blue tinge so entirely its own, dew is formed in the greatest abundance, owing to the phenomena which are requisite for its deposition being then most favourably combined. It was long supposed by naturalists that this precipitation depended on the cooling of the atmosphere towards evening, when the solar rays began to decline; but it was not properly understood until M. Prevost published his theory of the radiation of caloric (which has since been generally adopted), which was as follows:—“That all bodies radiate caloric constantly, whether the objects that surround them be of the same temperature of themselves, or not.” According to this view, the temperature of a body falls whenever it radiates more caloric than it absorbs, and rises whenever it receives more than it radiates; which law serves to produce an equality of temperature. Such is exactly the case as regards the earth: during the day it receives a supply of heat from the sun’s rays, and as it is an excellent radiator of caloric, as soon as the shades of evening begin to fall, the earth imparts a portion of its caloric to the air, and the atmosphere having no means of imparting its caloric in turn, except by contact with the earth’s surface, the stratum nearest the earth becomes cooled, and consequently loses the property of holding so much moisture in the state of vapour, which becomes deposited in small globular drops. The stratum of air in immediate contact with the earth having thus precipitated its moisture, becomes specifically lighter than that immediately above it, which consequently rushes down and supplies its place; and in this manner the process is carried on until some physical cause puts a stop to it either partly or wholly. It is well known that dew is deposited sparingly, or not at all, in cloudy weather, the clouds preventing free radiation, which is so essential for its formation; that good radiators, as grass, leaves of plants, and filamentous substances in general, reduce their temperature in favourable states of the weather to an extent of ten or fifteen degrees below the circumambient air;[Pg 184] and whilst these substances are completely drenched with dew, others that are bad radiators, such as rocks, polished metal, sand, &c., are scarcely moistened. From the above remarks it will appear evident that dew is formed most abundantly in hot climates, and during summer in our own, which tends to renovate the vegetable kingdom by producing all the salubrious effects of rain without any of its injurious consequences, when all nature seems to languish under the scorching influence of a meridian sun.

Hoarfrost is formed when the temperature becomes so low as 32 degrees Fahrenheit; the dew being then frozen on falling, sometimes assuming very fantastic forms on the boughs and leaves of trees, &c., which sparkle in the sunshine like so many gems of purest ray.

M.

What makes men blow? “I’ll be blowed if I know.” Such might be the answer in nine hundred and ninety-nine cases out of a thousand; and the object of this paper is to invite that thousandth individual who is versed in the philosophy of blowing to come forth and settle the question.

Every body knows why butchers blow, and flute-players, and glass-blowers, &c., and why some men puff at auctions; but the question is, why, without any conceivable motive either of business or pleasure, certain men, while circulating through the streets of Dublin perhaps on a breezeless day, have been seen to distend their cheeks, and discharge a great volume of breath into the face of the serene and unoffending atmosphere.

One of the introductory chapters in Tom Jones is devoted to proving that authors always write the better for being acquainted with the subjects on which they write. If this position be true (as I believe it is), I may seem deserving of a blowing up for venturing on my present theme. However, my object (as I have already hinted) in this, as in my first sketch, is rather to court than to convey information. If my brief notices of Fox and Smut contained in said sketch could at all serve to promote the study of catoptrics, I would not consider the time it cost me misspent. (And, by the bye, Mr Editor, I know somebody who, if he chose, could inform your readers how he once saw one of his own cats actually assisting at a surgical operation!) In like manner, if the following meagre result of my attempt towards developing the philosophy of blowing should excite inquiry on a subject never, I believe, broached before, I would feel very thankful for any information anent it that might reach me through the medium of the Irish Penny Journal.

Blowing men form a small, a very small, part of the community. During some forty years’ experience of the Dublin flags, I have met with only four specimens of this genus. Yet limited as is the number of my specimens, I am constrained to distribute them into two classes—one consisting of three individuals, the other, of the remaining one. My first-class men blew all alike—right “ahead,” as the Americans say; my fourth man protruded his chin, and breathed rather than blew somewhat upwards, as if he wanted to treat the tip of his nose to a vapour-bath.

What characteristics, then, did my triad of blowers possess in common, and from what community of idiosyncrasy did they agree in a practice unknown to the generality of mankind? The latter question I avow my inability to answer: on the former I can perhaps throw a little twilight. The principal man among them in point of rank—a late noble and facetious judge—was by far the most inveterate blower in the class: his puff was perpetual, like the mahogany dye of his boot-tops. One point of resemblance I have traced between the peer and his two compeers: he was a proud man. In proof of this allegation I have the evidence of his own avowal:—“I’m the first peer of my family, but I’m as proud as the old nobility of England.” Of the other pair, one I know to be proud, the other I believe to be so. Here then is one element—PRIDE: another I conceive to be WEALTH. My first-class blowers were all rich men: nay, the youngest among them never ventured on blowing, to the best of my belief, till he had gotten a good slice of a quarter of a million whereof his uncle died possessed. I was standing one day at the door of a bookseller’s shop in Suffolk Street, deeply intent upon nothing, when my gentleman passed by on the opposite side. My eyes, ready for any new object, idly followed him, and as he crossed to Nassau Street he blew. The offer was fair enough for a beginner, but it would not do—he wanted fat. No man much under the episcopal standard of girth should think of blowing: of this I feel a perfect conviction.

As for my solitary second-class man, the unique character of his blowing, or breathing, may have been but an emanation of his unique mind. He was, as the song says, “werry pecooliar”—an extensive medical practitioner among the poor, though not a medical man—the editor of an agricultural journal, though unacquainted with farming—a moral man, yet the avowed admirer of the lady of an invalid whose expected death was to be the signal for their union: the death came, but the union was never effected.

Groping then, as I do, in the dark, I would with great diffidence submit, that certain individuals, being encumbered with PRIDE, WEALTH, and FAT, are hence, somehow, under both a mental and physical necessity of blowing: why all individuals thus encumbered do not adopt the practice, is matter for consideration. As a further clue to investigation I may add, that although the union of the above three qualifications in one individual is by no means peculiar to Dublin, yet in Dublin alone have I ever seen men blow, and that none of my quaternion of blowing men was of Milesian descent: one was of Saxon, another of Scottish race, and the remaining two were sprung from Huguenots.

I now conclude, submissively craving “a word and a blow” from any of the readers or writers of the Irish Penny Journal who may be able to give them to me in the shape of facts or fancies likely to lend to the full solution of a question which has been for years my torment, namely—“What makes men blow?”

G. D.

Heaping up Wealth.—It is often ludicrous as well as pitiable to witness the miserable ends in which the heaping up of wealth not unusually terminates. A life spent in the drudgery of the counting-house, warehouse, or factory, is exchanged for the dignified ease of a suburban villa; but what a joyless seclusion it mostly proves! Retirement has been postponed until all the faculties of enjoyment have become effete or paralysed. “Sans eyes, sans teeth, sans taste, sans everything,” scarcely any inlet or pulsation remains for old, much less new pleasures and associations. Nature is not to be won by such superannuated suitors. She is not intelligible to them; and the language of fields and woods, of murmuring brooks, mountain tops, and tumbling torrents, cannot be understood by men familiar only with the noise of crowded streets, loaded vans, bustling taverns, and postmen’s knocks. The chief provincial towns are environed with luckless pyrites of this description, who, dropped from their accustomed sphere, become lumps and dross in a new element. Happily their race is mostly short; death kindly comes to terminate their weariness, and, like plants too late transplanted, they perish from the sudden change in long-established habits, air, and diet.

An Old Newspaper.—There is nothing more beneficial to the reflecting mind than the perusal of an old newspaper. Though a silent preacher, it is one which conveys a moral more palpable and forcible than the most elaborate discourse. As the eye runs down its diminutive and old-fashioned columns, and peruses its quaint advertisements and bygone paragraphs, the question forces itself on the mind—where are now the busy multitudes whose names appear on these pages?—where is the puffing auctioneer, the pushing tradesman, the bustling merchant, the calculating lawyer, who each occupies a space in this chronicle of departed time? Alas! their names are now only to be read on the sculptured marble which covers their ashes! They have passed away like their forefathers, and are no more seen! From these considerations the mind naturally turns to the period when we, who now enjoy our little span of existence in this chequered scene, shall have gone down into the dust, and shall furnish the same moral to our children that our fathers do to us! The sun will then shine as bright, the flowers will bloom as fair, the face of nature will be as pleasing as ever, while we are reposing in our narrow cell, heedless of every thing that once charmed and delighted us!

Printed and published every Saturday by Gunn and Cameron, at the Office of the General Advertiser, No. 6, Church Lane, College Green, Dublin.—Agents:—R. Groombridge, Panyer Alley, Paternoster Row, London; Simms and Dinham, Exchange Street, Manchester; C. Davies, North John Street, Liverpool; J. Drake, Birmingham; Slocombe & Simms, Leeds; Frazer and Crawford, George Street, Edinburgh; and David Robertson, Trongate, Glasgow.