IN THE GRIP OF THE BASTILLE.

CHAPTER

| I. | Introduction |

| II. | The Conciergerie |

| III. | The Dungeon of Vincennes |

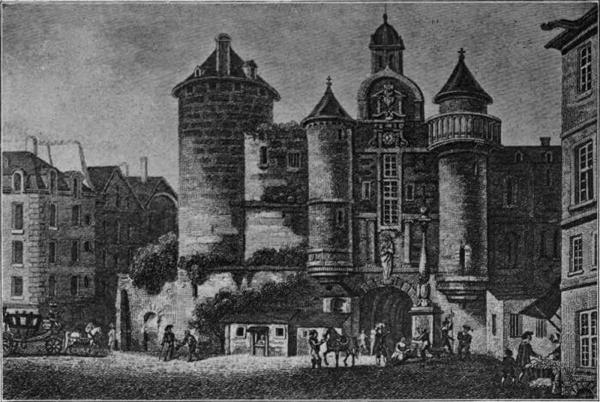

| IV. | The Great and Little Châtelet and the Fort-l'Évêque |

| V. | The Temple |

| VI. | Bicêtre |

| VII. | Sainte-Pélagie |

| VIII. | The Abbaye |

| IX. | The Luxembourg in '93 |

| X. | The Bastille |

| XI. | The Prisons of Aspasia |

| XII. | La Roquette |

Cell of Marie Antoinette in the Conciergerie

The Keep or Dungeon of Vincennes

Mirabeau on the Terrace of Vincennes

A Street Scene during the Massacres

Triste comme les portes d'une prison—Sad as the gates of Prison, is an old French proverb which must once have had an aching significance. To the citizen of Paris it must have been familiar above most other popular sayings, since he had the menace of a prison door at almost every turn! For the "Dungeons of Old Paris" were well-nigh as thick as its churches or its taverns. Up to the period, or very close upon the period, of the Revolution of 1789, everyone who exercised what was called with quite unconscious irony the "right of justice" (droit de justice), possessed his prison. The King was the great gaoler-in-chief of the State, but there were countless other gaolers. The terrible prisons of State—two of the most renowned of which, the Dungeon of Vincennes and the Bastille, have been partially restored in these pages—are almost hustled out of sight by the towers and ramparts of the host of lesser prisons. To every town in France there was its dungeon, to every puissant noble his dungeon, to every lord of the manor his dungeon, to every bishop and Abbé his dungeon. The dreaded cry of "Laissez passer la justice du Roi!" "Way for the King's justice!" was not oftener heard, nor more unwillingly, than "Way for the Duke's justice!" or "Way for the justice of my lord Bishop!" For indeed the mouldy records of those hidden dungeons and torture rooms of château and monastery, the carceres duri and the vade in pace, into which the hooded victim was lowered by torchlight, and out of which his bones were never raked, might shew us scenes yet more forbidding than the darkest which these chapters unfold. But they have crumbled and passed, and history itself no longer cares to trouble their infected dust.

Scenes harsh enough, though not wholly unrelieved (for romance is of the essence of their story), are at hand within the walls of certain prisons whose names and memories have survived. I have undone the bolts of nearly all the more celebrated prisons of historic Paris, few of which are standing at this day. One or two have been passed by, or but very briefly surveyed, for the reason that to include them would have been to commit myself to a certain amount of not very necessary repetition. I fear that even as the book stands I must have repeated myself more than once, but this has been for the most part in the attempt to enforce points which seemed not to have been brought out or emphasised with sufficient clearness elsewhere. Dealing with prisons which were in existence for centuries, and some of which were associated with almost every great and stirring epoch of French history, selection of periods and events was a paramount necessity. The endeavour has been to give back to each of these cruel old dungeons, Prison d'État, Conciergerie, or Maison de Justice, its special and distinctive character; to shew just what each was like at the most interesting or important dates in its career; and, as far as might be, to find the reason of that dreary proverb, "Sad as the gates of Prison." Light chequers the shades in some of these dim vaults, and the echoes of the dour days they witnessed are not all tears and lamentations. Something is shewn, it is hoped, of every kind of "justice" that was recognised in Paris until the days of '89, when everything that had been, fell with the terrific fall of the monarchy:—feudal justice, the justice of absolute kings and of ministers who were but less absolute, provosts' and bishops' justice, and the justice of prison governors and lieutenants of police. Often it is no more than a glimpse that is afforded; but the picture as a whole is, perhaps, not altogether lacking in completeness. Once inside a prison, the prisoner is the first study; and there are no more moving or pitiful objects in the annals of France than the victims of its criminal justice in every age. Slit the curtain of cobweb that has formed over the narrow grille of the dungeon, put back on their shrill hinges the double and triple doors of the cell, peer into the hole that ventilates the conical oubliette, and one may see once more under what conditions life was possible, and amid what surroundings death was a blessing, in the days when Paris was studded with prisons, when every abbot was free to wall-up his monks alive, and every seigneur to erect his gallows in his own courtyard.

For during all these days, dragging slowly into ages, justice has seldom more than one face to shew us: a face of cruelty and vengeance. The thing which we call the "theory of punishment" had really no existence. Punishment was not to chasten and reform; it was scarcely even to deter; it was mainly and almost solely to revenge. What the notion of prison was, I have tried briefly to explain in the chapters on "The Conciergerie," "The Dungeon of Vincennes," and, I think, elsewhere. We are strictly to remember, however, that the vindictive idea of punishment, and the idea of prison as a place in which (1) to hold and (2) to torment anyone who might be unfortunate enough to get in there, were not at all peculiar to France. The history of punishment in our own country leaves no room for boasting; and France has not more to reproach herself with in the memory of the Bastille, than we have in the actual and visible existence of Newgate. France has Archives de la Bastille; we have Howard's State of Prisons and Griffiths's Chronicles of Newgate. We are not to forget that, in the "age of chivalry" in England, it was unsafe for visitors in London to stroll a hundred yards from their inn after sunset; and that, in the reign of Elizabeth, Shakespeare might have penned his lines on "the quality of mercy" within earshot of the rabble on their way to gloat over the disembowelling of a "traitor," or flocking to surround the stake at which a woman was to die by fire. In a word, the sense of vengeance, and the thirst for vengeance, which underlay the old criminal law of France, and of all Europe, were not less the basis of our own criminal law until well on into the second quarter of this century. But the French, it would seem, have paid the cost of their quick dramatic sense. They have handed down to us, in history, drama, and romance, the picture of Louis XI. arm in arm with his torturer and hangman, Tristan; the spectacle of the noble whose sword was convertible into a headsman's axe; and of the abbot whose girdle was ever ready for use as a halter. Histories akin to these (and, at the root, there is more of history than of legend in all of them) are to be delved out of our own records; but the French have been more candid in the matter, and a good deal more skilled with the pen in chronicles of the sort.

On the other hand, England never had quite such bitter memories of her prisons as France had of hers. The struggle for freedom in England was never a struggle against the prisons; and it was not consciously a struggle against the prisons in France. But the destruction of a prison was the beginning of the French Revolution; and when the Revolution was over, its first historians took the prisons of France as the type and example of the immemorial tyranny of their kings. In one important respect, therefore, the dungeons of old Paris stand apart from the prisons of the rest of Europe.

I had proposed to myself, in beginning this introductory chapter, to attempt a comparison, more or less detailed, between these ruined and obliterated prisons of historic Paris and the French or English prisons of to-day. But a final glance at the chapters as they were going to press counselled me to abstain. There is no point to start from. The old and the new prisons have a space between them wider than divides the poles. The key that turned a lock of the Châtelet, Bicêtre, or the Bastille will open no cell of any modern prison, French or English. Punishment is systematised, and has its basis in two ideas,—the safety of peoples living in communities, and the cure of certain moral obliquities; or, it is quite without system, and means only the vengeance of the strong upon the weak. Between the prison which was intended either as a living tomb, or as a starting-place for the pillory, the whipping-post, or the scaffold; and the prison which proposes to punish, to deter, or to reform the bad, the diseased, the weak, or the luckless members of society, there is not a point at which comparison is possible.

If walls had tongues, those of the Conciergerie might rehearse a wretched story. This is, I believe, the oldest prison in Europe; it would speak with the twofold authority of age and black experience. Give these walls a voice, and they might say:

"Look at the buildings we enclose. There is a little of every style in our architecture, reflecting the many ages we have witnessed. Paris and France, in all the reigns of all the Kings, have been locked in here, starved here, tortured here, and sent from here to die by hanging, by beheading, by dismembering by horses, by fire, and by the guillotine. We have found chains and a bitter portion for the victims of all the tyrannies of France,—those of the Feudal Ages, those of the Absolute Monarchy, those of the Revolution, and those of the Restoration. There is no discord, trouble, passion, or revolution in France which is not recorded in our annals. Politics, religion, feuds of parties and of houses, private rancours and the enmities of queens, the vengeance of kings and the jealousies of their ministers, have filled in turn the vaults of this little city of the dead-in-life. We have seen the killing of the innocent; the torment of a Queen; the tears of a Dubarry and the stoicism of a hideous Cartouche; the collapse of a Marquise de Brinvilliers under torture and the silent heroism of a Charlotte Corday on her way to the guillotine; the bold immodesty of a La Voisin on the rack and the solemn abandon of the 'last supper' of the Girondins. We have seen the worst that France could shew of wickedness and the best that it could shew of patriotism; we have seen the beginning and the end of everything that makes the history of a prison."

Most French writers who have touched upon the Conciergerie seem to have felt the oppression of the place; their recollections or impressions are recorded in a spirit of melancholy or indignation.

"Ah, that Conciergerie!" exclaims Philarète Chasles; "there is a sense of suffocation in its buildings; one thinks of the prisoner, innocent or guilty, crushed beneath the weight of society. Here are the oldest dungeons of France; Paris has scarcely begun to be when those dungeons are opened."

The strain of Dulaure, the historian of Paris, is not less depressing:

"The Conciergerie, the most ancient and the most formidable of all our prisons, which forms a part of the buildings of the Palais de Justice, one time palace of the kings, has preserved to this day the hideous character of the feudal ages. Its towers, its courtyard, and the dim passage by which the prisoners are admitted, have tears in their very aspect. Pity on the wight who, condemned to sojourn there, has not the wherewithal to pay for the hire of a bed! For him a lodging on the straw in some dark and mouldy chamber, cheek by jowl with wretches penniless like himself."[1]

1. Histoire de Paris.

MADAME DUBARRY.

In the days when Paris had not so much as a gate to shut in the face of the invader, the citizen raftsmen of the Seine thought it well to have a prison, and "dug a hole in the middle of their isle." This, it seems, was the sorry beginning of the Conciergerie; but the details of that vanished epoch are scant. Palace and prison are thought to have been constructed at about the same date: the palace, which was principally a fortress, was the residence of the kings; the Conciergerie was their dungeon. Rebuilt by Saint Louis, the Conciergerie became in part—as its name implies—the dwelling of the Concierge of the palace. According to Larousse, the Concierge "was in some sort the governor of the royal house, and had the keeping of the King's prisoners, with the right of low and middle justice" (basse et moyenne justice). In 1348, the Concierge took the official title of bailli; the functions and privileges of the office were enlarged, and it was held by many persons of distinction, amongst whom was Jacques Coictier, the famous doctor of Louis XI. As the practice was, in an age when every gaoler "exploited" his prisoners, the concierge-bailli taxed the victuals he supplied them with, and charged what he pleased for the hire of beds and other cell-equipments; while it happened more than once, says Larousse, "that prisoners who were entitled to be released on a judge's order, were detained until they had paid all prison fees." On such a system were the old French gaols administered. The office of concierge-bailli, with its voluminous powers, and its manifold abuses, was in existence until the era of the Revolution.

Justice under the old régime counted sex as nothing. The physical weakness and finer nervous organisation of woman were allowed no claim upon its mercy. Primary or capital punishment, as to burning and beheading, was the same for women as for men, and the shocking apparatus of the torture chamber served for both sexes. The elaborate rules for the application of the Question published in Louis XIV.'s reign (and abolished only in the reign of Louis XVI.) specified the costume which women and girls should wear in the hands of the torturer.[2]

2. "Si c'est une femme ou fille, lui sera laissé une jupe avec sa chemise et sera sa jupe liée aux genoux."

The black walls of the torture chamber in the Conciergerie, with their ring-bolts and benches of stone, gave back the groans of many thousands of mutilated sufferers. There were the "Question ordinary" and the "Question extraordinary"; and if the first failed to extract a confession, the second seems almost always to have been applied. The extravagant cruelty of the age frequently added sentence of torture to the death sentence; and this was probably done in every case in which the condemned was thought to be withholding the name of an accomplice. Far on into the history of France these sentences were dealt out to, and executed upon, women as well as men; and with as artistic a disregard of human pain or shame in the one sex as in the other.

We are in the presence of a high civilisation, or at least a highly boasted one, in the days of Louis XIV.; but public sentiment is not offended by the knowledge that a woman is being tortured by the questionnaire and his assistants in the Conciergerie; nor are many persons shocked by seeing a woman on the scaffold semi-nude in the coarse hands of the headsman, or struggling amid blazing faggots in a Paris square. Nowadays, whether in France or in England, the mauvais quart d'heure (which, at the guillotine or on the gallows, is usually a half-minute at the utmost) pays the score of the worst of criminals; but in the advanced and cultured France of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries a Marquise de Brinvilliers must pass through the torture chamber on her way to the block, and a Ravaillac and a Damiens (after a like ordeal) are put to death in a manner which sends a thrill of horror through Europe, and which is not afterwards outdone in any camp of American Red Indians.

The extraordinary criminal drama of the Marquise de Brinvilliers has been vulgarised not a little by legend, by romance, and by the stage; but is there cause for wonder that a series of crimes which made Paris quake from its royal boudoirs to the extremities of its darkest alleys should have inspired writers to the fourth and fifth generations?

In the hands of De Brinvilliers and her lover and accomplice, the Gascon officer Sainte-Croix, poison became a polite art; and the accident of marriage associated the Marchioness with an industrial art which was of great renown in Paris,—I mean, the Gobelin Manufacture, or Royal Manufacture of Crown Tapestries. From the fourteenth century, in the Faubourg Saint-Marcel and on the Bièvre River—the water of which was considered specially good for dyeing purposes,—there were established certain drapers and wool-dyers; and amongst them, in 1450, was a wealthy dyer named Jean Gobelin, who had acquired large possessions on the banks of the river. His business, after his death, was continued by his son Philibert, who made it more than ever profitable, and who on his death-bed bequeathed handsome portions to his sons. The family divided between them, in 1510, ten mansions, gardens, orchards, and lands. Not less fruitful were the labours of their successors, and when the name of Gobelin had grown into celebrity, the popular voice bestowed it, says Dulaure, upon the district in which their establishment was situated.

Immensely enriched, the Gobelins ceased to occupy themselves with business, and took over various employments in the magistracy, army, and finance. Some of them succeeded in obtaining the rank and title of Marquis. From the middle of the sixteenth to the middle of the seventeenth century, the Gobelins held high offices, or married into office; and were notable amongst the merchant princes whose illustrious coffers and power to assert themselves won places for them amid the hereditary aristocracy of France. Into this family entered by marriage, in 1651, Marie Marguerite d'Aubrai, daughter of the Lieutenant Civil, or Civil Magistrate of Paris. Her husband, Antoine Gobelin, was the Marquis de Brinvilliers; a title which she was to cover with an infamy as great and enduring as the fame of the Gobelin Tapestries.

The Marquise's gallantries (a term which in the seventeenth century embraced a greater variety of moral eccentricities than the Decalogue has provided for) were quite eclipsed by her celebrity as a poisoner. With her performances in this art—in which she seems to have been trained by Sainte-Croix—began that incredible series of murders, and attempted murders, known as L'Affaire des Poisons, which both characterised and lent a special character to the morals of the age of the Grand Monarque.

It was the accidental death of her lover, in 1675, which exposed and brought the vengeance of the law on La Brinvilliers. Sainte-Croix was conducting some experiment with poisons in his laboratory, when the glass mask with which he had covered his face suddenly broke, and he fell dead on the spot. Letters of Mme. de Brinvilliers were amongst the suspicious objects found in the laboratory by the police, and she fled to London. One of Sainte-Croix' servants was put to the Question, and his confession did not improve the situation of the Marquise. Leaving London, she hid by turns in Brussels and Liège; and in a convent in the latter town she was discovered by the detective Desgrais, who got her out by a ruse, and brought her back to Paris. Her appearance in the torture chamber of the Conciergerie was not long delayed. All her fascinations failed her with those bloodless cross-examiners, and as she persisted in denying one charge after another, she saw the executioner and his attendants make ready the apparatus for the torture by water. She summoned a little shew of raillery: "Surely, gentlemen, you don't think that with a figure like mine I can swallow those three buckets of water! Do you mean to drown me? I simply cannot drink it." "Madame," replied the examiner-in-chief, "we shall see"; and the Marchioness was bound upon the trestle.

For a time her courage sustained her, but, as the torture grew sharper, avowals came slowly, which must have amazed the hardened ears that received them.

"Who was your first victim?"

"M. d'Aubrai—my father."

"You were very devout at this time, attending church and visiting hospitals?"

"I was testing the powers of our science on the patients. I gave poisoned biscuits to the sick."

"You had two brothers?"

"Yes ... we were two too many in my family. Lachaussée, Sainte-Croix' valet, had instructions to poison my brothers; they died in the country, with some of their friends, after eating a pigeon-pie which Lachaussée used to make to perfection."

"You poisoned one of your children?"

"Sainte-Croix hated it!"

"You wanted to poison your husband?"

"Sainte-Croix for some reason prevented it. After I had administered the poison, he would give my husband an antidote."

Before she was released from the trestle, Madame's confession was complete. Sainte-Croix, imprisoned in the Bastille, on a lettre-de-cachet obtained by M. de Brinvilliers, had there made the acquaintance of an Italian chemist, named Exili, who had taught him the whole art and mystery of poison. Exili's cell in the Bastille was the first laboratory of Sainte-Croix, who proved afterwards so apt a pupil that, as his mistress and accomplice avowed, he could conceal a deadly poison in a flower, an orange, a letter, a glove, "or in nothing at all."

After sentence of death had been passed on this most miserable woman, she was denied the consolations of the Church, but a priest found courage to give her absolution as she was carried to the scaffold. The Marchioness was followed to her death by the husband whom she had tried in vain to send to his death, and who, it is said, wept beside her the whole way from the Conciergerie to the Place de Grève. Conspicuous in the enormous crowd assembled in the square were women of fashion and rank, whom the noble murderess rallied on the spectacle she had provided for them. One of the ladies was that distinguished gossip, Madame de Sévigné, who wrote the whole scene down for her daughter on the following day. De Brinvilliers was beheaded, and her body burnt to ashes.

This signal example—the torture, beheading, and burning of a peeress of France—was signally void of effect.

The secrets of Sainte-Croix and La Brinvilliers had not been buried with the one, nor scattered with the ashes of the other. Four years later, Paris talked of nothing but poison and the revival of the "black art" which was associated with it; and, in 1680, the King established at the Arsenal a court specially charged to try cases of poisoning and magic. The notoriety of the widow Montvoisin, more commonly known as La Voisin, who dealt extensively in both arts, was inferior only to that of the Brinvilliers. Duchesses, marchionesses, countesses, and other high dames of the Court were concerned in this scandal, and Louis himself was active in seeking to bring the culprits of title to justice,—or to get them out of the way. He sent a private message to the Comtesse de Soissons, advising her that if she were innocent she should go to the Bastille for a time, in which case he would stand by her, and that if she were guilty, it would be well for her to quit Paris without delay. The Comtesse, who was "famous at the Court of Louis XIV. for her dissolute habits," fled and was exiled to Brussels; the Marquise d'Alluye or d'Allaye was banished to Amboise, Mme. de Bouillon to Nevers, and M. de Luxembourg was imprisoned for two years in the Bastille. A far more terrible expiation was prepared for La Voisin.

Outwardly, this was a woman of a grosser type than the Marchioness Brinvilliers. The Marchioness, is described as "gracieuse, élégante, spirituelle et polie." La Voisin was a repellent fat creature, as coarse in speech as in appearance. Yet she lived as a woman of society (en femme de qualitè); and composed and sold to the beauties and gallants of the Court, poisons, charms, philters, and secrets to procure lovers or to outwit rivals; she called up spirits for a fee, and would shew the Devil if one paid the tariff for a glimpse of that celebrity.[3]

3. Dulaure.

Her attitude in the Salle de la Question of the Conciergerie became her well. She cursed, flouted the examiners, and "swore that she would keep on swearing" if they racked her to pieces. "Here's your health!" she cried, when the first vessel of water was forced down her throat; and, as they fastened her on the rack,—"That 's right! One should always be growing. I have complained all my life of being too short." It is said that, having been made to drink fourteen pots of water during the water torture, she drank fourteen bottles of wine with the turnkeys in her cell at night. Her sentence was death at the stake, and on her way to the place of execution she jeered at the priest who accompanied her, refused to make the amende honorable at Notre-Dame, and fought like a tigress with the executioners on descending from the cart. Tied and fettered on the pile, she threw off five or six times the straw which was heaped on her. Sévigné, who looked on, detailed the scene with animation, and without a touch of feeling, in a letter to her daughter.

Confounding the real crimes with chimerical ones, the new court continued to prosecute poisoners and "sorcerers" together; and even at that credulous and superstitious date, when judges listened gravely to the most baseless and fantastic accusations, there were persons interrogated on charges of sorcery who had the spirit to laugh both judges and accusers in the face. Mme. de Bouillon said aloud, on the conclusion of her examination, that she had never in her life heard so much nonsense so solemnly spoken (n'avait jamais tant ouïdire de sottises d'un ton si grave); whereat, it is chronicled, his Majesty "was very angry." It was not until the bench itself began to treat as mere charlatans the wizards of both sexes who appeared before it, that trials for sorcery and "black magic" fell away and gradually ceased.

It was the Conciergerie which presided over the examination, torture, and atrocious punishment of Ravaillac, the assassin of Henri IV., and Damiens, who attempted the life of Louis XV. Ravaillac, the first to occupy it, left his name to a tower of the prison.

"You shiver even now in the Tower of Ravaillac," say MM. Alhoy and Lurine in Les Prisons de Paris,—"that cold and dreadful place. Thought conjures up a multitude of fearful images, and is aghast at all the tragedies and all the dramas which have culminated in the old Conciergerie, between the judge, the victim, and the executioner. What tears and lamentations, what cries and maledictions, what blasphemies and vain threats has it not heard, that pitiless doyenne of the prisons of Paris!"

Ravaillac, most fearless of fanatics and devotees, said, when interrogated before Parliament as to his estate and calling, "I teach children to read, write, and pray to God." At his third examination, he wrote beneath the signature which he had affixed to his testimony the following distich:

and a member of Parliament exclaimed on reading it, "Where the devil will religion lodge next!"

He was condemned by Parliament on the 2d of May, 1610, to a death so appalling that one wonders how the mere words of the sentence can have been pronounced. Our own ancient penalty for high treason was a mild infliction in comparison with this. Before being led to execution, Ravaillac did penance in the streets of Paris, wearing a shirt only and carrying a lighted torch or candle, two pounds in weight. Taken next to the Place de Grève, he was stripped for execution, and the dagger with which he had twice struck the King was placed in his right hand. He was then put to death in the following manner. His flesh was torn in eight places with red-hot pincers, and molten lead, pitch, brimstone, wax, and boiling oil were poured upon the wounds. This done, his body was torn asunder by four horses; the trunk and limbs were burned to ashes, and the ashes were scattered to the winds.

Eight assassins had preceded Ravaillac in attempts on the life of Henri IV., and six of them had paid this outrageous forfeit. The torments of the Conciergerie and the Place de Grève were bequeathed by these to the regicide of 1610, and Ravaillac left them a legacy to Robert François Damiens.

The Tower of Ravaillac was equally the Tower of Damiens. François Damiens, a bilious and pious creature of the Jesuits, not unfamiliar with crime, pricked Louis, as his Majesty was starting for a drive, with a weapon scarcely more formidable than a penknife. He was seized on the spot, and there were found on him another and a larger knife, thirty-seven louis d'or, some silver, and a book of devotions,—the assassins of the Kings of France were always pious men. "Horribly tortured," he confessed nothing at first, and it is by no means certain what was the nature or importance of his subsequent avowals. But, although there is little question that Damiens was merely the instrument of a conspiracy more or less redoubtable, no effort was made to arraign, arrest, or discover his supposed accomplices. The examination and trial, conducted with none of the publicity which such a crime demanded, were in the hands of persons chosen by the court, "persons suspected of partiality," says Dulaure, "and bidden to condemn the assassin without concerning themselves about those who had set him on—which gives colour to the belief, that they were too high to be touched" (que ces derniers étaient puissans).

One hundred and forty-seven years had passed since the Paris Parliament's inhuman sentence on Ravaillac, but not a detail of it was spared to Damiens on the 28th of March, 1757. Enough of such atrocities.

In the days of the Regency there was in one of the suburbs of Paris a tea-garden which was at once popular and fashionable under the name of La Courtille. In the groves of La Courtille, on summer evenings, amid lights and music, russet-coated burghers might almost touch elbows with "high-rouged dames of the palace"; and here one night Mesdames de Parabère and de Prie brought a party of elegant revellers. As one of the guests strolled apart, humming an air, he was approached softly from behind, and a hand was laid upon his shoulder.

"My gallant mask, I know you! So you have left Normandy, eh? Well, you have made us suffer much, but I fancy it will be our turn now. One of our cells has long been ready for you, and you shall sleep at the Conciergerie to-night. Cartouche!"

Yes, it was indeed the great Cartouche whom a deft detective had trapped on the sward of La Courtille. The capture was a notable one, and the next day and for many days to come Paris could not make enough of it,—Paris which had suffered beatings, plunderings, and assassinations at the hands of Cartouche and his band for ten years past. He lay three months at the Conciergerie, and every day his fame increased. The Regent's finances and the "ministerial rigours" of Dubois were disregarded; Cartouche was a godsend to rhymesters, journalists, wits, and diners-out; pretty lips repeated the dubious history of his amours, and a theatrical gentleman announced a "comedy" named after the distinguished cut-throat. Cartouche awaited stoically enough death by breaking on the wheel. It required a severe application of the Question to bring him to a betrayal of his band, but "his tongue once loosed, he passed an entire night in naming the companions of his crimes." The villain even denounced "three pretty women who had been his mistresses."

He consented one day to the visit of a person whose indiscreet candour was passing cruel. This was the dramatist Legrand who, with his Cartouche comedy in preparation, sought the "local colour" of the condemned cell. Cartouche had the vanity which characterises the great criminal, and willingly allowed himself to be "interviewed"; he answered all Legrand's questions, and then asked one himself: "When is your piece to be represented?" "On the day of your execution, my dear Monsieur Cartouche." "Ah, indeed! Then you had better interview the executioner also; he will come in at the climax, you see."

Having entertained the playwright with his wit, the murderer next essayed the part of patriot, and said to his Jesuit confessor, Guignard, in speaking of the assassination of Henri IV.:

"All the crimes that I have ever committed were the merest peccadilloes (de légères peccadilles) in comparison with those which your Order is stained with. Is there any crime more enormous than to take the life of your King, and such a King as that was? The noblest prince in the universe, the glory of France, the father of his country! I tell you that if a man whom I were pursuing had taken refuge at the foot of the statue of Henri IV., I should not have dared to kill him."

The condition of the Conciergerie at this date was at all events better than it had been two or three centuries earlier. No Mediæval prisons were fit to live in. Sanitation was a science as yet undreamed of in Europe, and even had there been such a science, it is improbable that the inmates of prisons would have tasted its advantages. In the Middle Ages, nothing was more remote from the official mind, from the minds of all judges, magistrates, governors, gaolers, and concierges, than the notion that prisoners should live in wholesome and decent surroundings. Two very definite ideas the Middle Ages had about prisons, and only two: the first was, that they should be impregnable, and the second was, that they should be "gey ill" to live in; and their one idea regarding the lot of all prisoners and captives was, that it should be beyond every other lot wretched and unendurable.

In the age we live in, civilised governments setting about the building of a new prison do not say to their architects, "You must build a fortress which prisoners cannot break, and you must put into it a certain quantity of conical cells below the level of the ground, in which prisoners may be suffocated within a given number of days," but, "You must build a prison of sufficient strength; and in planning your cells you must secure for every prisoner an ample provision of space, air, and light." Those are the supreme differences between ancient and modern gaols. Prison in the old days was of all places the least healthy to live in; nowadays, it is often the most healthy. Good control and strict surveillance confer security upon prisons which are not built as fortresses; but nothing gives such immense distinction to the new system, by contrast with all the earlier ones, as the elaborate and minute regard of everything which may make for the physical well-being of the prisoners.

Then comes the moral question; and from the standpoint of morals the situation tells even more in favour of the modern system. Imprisonment should never be cruel; but, when the prisoner is fairly tried and justly sentenced, it should always be both irksome and disgraceful. The disgrace of prison, however, depends upon the absolute impartiality of the tribunal and the soundness of public sentiment. Nobody is disgraced by being sent into prison in a society in which arrest is arbitrary, and in which arraignment at the bar is not followed by an honest examination of the facts. Princes of the blood, nobles, ministers, and judges and magistrates themselves were equally liable with the commonest offenders against the common law to be spirited into prison, and left there, without accusation and without trial, during many centuries of French history. Most tribunals were corrupt, and during many ages all were at the mercy of the Crown. A Daniel on the bench was rare, and in great danger of being hanged; and public sentiment was not yet articulate.

In such insecurity of justice, imprisonment could carry with it no social stigma, as it carries inevitably in these days. But, where there is no shame in imprisonment, there is no question of the reform of the prisoner, and this—one of the main endeavours of modern penal systems—was not only quite ignored by the old régime, but was an aspect of the matter to which it was entirely indifferent, and which had evidently no place whatever in its conceptions. In the progress of civilisation, no institution has been so completely transformed as the prison. It was an instrument of vengeance; it is seeking, not at present too successfully, to be an instrument of grace.

Prisons neglected or encumbered with filth are natural hotbeds of disease, and epidemic sicknesses were frequent. In 1548, the plague broke out in the Conciergerie, and then for the first time an infirmary was established in the prison, though I cannot find that it made greatly for the comfort of the sick. Doctor's work was grudgingly and carelessly done in the prisons of those days, and there was no great disposition to hinder the sick from yielding up the ghost; the bed or the share of a bed allotted to the patient was always wanted. The Conciergerie was devastated by fire in 1776, and this visitation resulted in a royal command to rehabilitate the whole interior of the prison. In this attempt to realise the generous thought of his minister Turgot, Louis XVI. did not imagine, we may be sure, that he was preparing a last lodging for Marie Antoinette!

Here then we stand on the threshold of the Conciergerie of the Revolution—the ante-chamber of the scaffold, in the fit words of Fouquier-Tinville.

It was at four o'clock on the morning of the 14th of October, 1793, at the close of the sitting of the revolutionary tribunal, that the dethroned and widowed Queen was brought to the Conciergerie. Poor, abandoned, outraged Queen, they thrust her into one of their common cells, and gave her for attendant a galley-slave named Barasin. This must have been a brave, good fellow, with a loyal heart under his galley-slave's vest, for at the risk of his life he waited devoutly and devotedly on the queenly woman, a queen no longer, who could in nothing reward his devotion. One should name also the concierge Richard, who shewed himself not less a man in his care of the "beautiful high-born," and who for his humanity to her was stripped of all his goods.

The gendarmes guarded her last hours, sat there in the cell with her, though republican modesty allowed the intervention of a screen.

It is known what a sublime dignity sustained her to the end; and indeed almost the worst was over when she had quitted Fouquier-Tinville's bar, after the "hideous indictment" and the condemnation. She withdrew to die, and she could die as became a Queen. Louis had gone before her, and all the mother's dying thoughts and prayers must have been for the children who were to live after her—how long, she knew not. She sat in the dingy cell, clasping her crucifix, waiting her call to the tumbril; "dim, dim, as if in disastrous eclipse; like the pale kingdoms of Dis!"

From this time on to the end of the Reign of Terror, the Conciergerie offered such a spectacle as was never seen before within the walls of any prison. The guillotine

The Revolution was eating not her enemies only but her children, and those victims and prospective victims, men and women, old and young, filled the cells of the Conciergerie, the chambers, the corridors, and the yards. They swarmed there in disorder, dirt, and disease, guarded and bullied by drunken turnkeys, who had a pack of savage dogs to assist them. They went out by batches in the tumbrils, to leave their heads in Samson's basket, and ever fresh parties of proscribed ones took the places of the dead. "I remained six months in the Conciergerie," says Nougaret, one of the historians of the period, "and saw there nobles, priests, merchants, bankers, men of letters, artisans, agriculturists, and honest sans-culottes." Often as this population was decimated, Fouquier-Tinville filled up the gap; and throughout the whole of the Terror the condemned and the untried proscribed ones, herded together, seldom had space enough for the common decencies of life.

Then some sort of classification was attempted, and three orders were established in the prison. The Pistoliers were those who could afford to pay for the privilege of sleeping two in a bed. The Pailleux lay huddled in parties, in dens or lairs, on piles of stale straw, "at the risk of being devoured by rats and vermin." Nougaret remarks that in some cells the prisoners on the floor at night had to protect their faces with their hands, and leave the rest of their persons to the rats. The Secrets were the third class of prisoners, who made what shift they could in black and reeking cells beneath the level of the Seine.

And the sick in the infirmary? Listen once more to Nougaret in his Histoire des Prisons de Paris et des Départemens:

"There were frightful fevers there, and you took your chance of catching them. The patients, lying in pairs in filthy beds, were in as wretched a plight as ever mortals found themselves in. The doctors hardly condescended to examine them. They had one or two potions which, as they said, were 'saddles for all horses,' and which they administered quite indiscriminately. It was curious to see with what an air of contempt they made their rounds. One day, the head doctor approached a bed and felt the patient's pulse. 'Ah,' said he to the hospital warder, 'the man's better than he was yesterday.' 'Yes, doctor, he's a good deal better,—but it's not the same man. Yesterday's patient is dead; this one has taken his place.' 'Really?' said the doctor, 'that makes the difference! Well, mix this fellow his draught.'"

When the prisoners were to be locked in for the night, there was always a great to-do in getting the roll called. Three or four tipsy turnkeys, with half-a-dozen dogs at their heels, passed from hand to hand an incorrect list, which none of them could read. A wrong name was spelled out, which no one answered to; the turnkeys swore in chorus, and spelled out another name. In the end, the prisoners had to come to the assistance of the guards and call their own roll. Then the numbers had to be told over and over again, and the prisoners to be marched in and marched out three or four times, before their muddled keepers could satisfy themselves that the count was correct.

One seeks to know what the feeding was like in the "ante-chamber of the guillotine." When, in the midst of the Terror, Paris was pinched with hunger, the pinch was felt severely in the Conciergerie. Rations ran desperately short, and a common table was instituted. The aristocrats had to pay scot for the penniless, and came in these strange circumstances to "estimate their fortunes by the number of sans-culottes whom they fed, as formerly they had done by the numbers of their horses, mistresses, dogs, and lackeys."

All histories, memoirs, chronicles, and legends are agreed that the Conciergerie of the Revolution was a frightful place. The political prisoners endured all the horrors, physical and mental, of an unparalleled régime. Sick and unattended, hungry and barely fed, cold and left to shiver in dark and naked cells—these were amongst the ills of the body. But greater by far than these must have been the pangs of the mind.

Nearly all of these prisoners, men and women both, regarded death as a certainty; before ever they were tried, from the moment that the outer door of the prison had closed behind them, the guillotine was as good as promised to them. They had no help to count on from without, they had not even the animating hope of a fair hearing by an upright judge. The judgment bar of Fouquier-Tinville did not pretend to be impartial.

Nevertheless, though the blade of the guillotine was suspended over all heads, and fell daily upon many, an air of mingled serenity and exaltation reigned throughout the gaol. There were few tears, and there was no weak repining. Morning and evening, the political prisoners chanted in chorus the hymns of the Revolution, and these were varied by witty verses on the guillotine, composed in some instances by prisoners on the eve of passing beneath the knife. Some had brought in with them their favourite books, and reading led to long discussions, of which literature, science, religion, and politics were alternately the themes. Devoted priests like the Abbé Emory went about making converts, and opposing their efforts to those of the militant atheist, Anacharsis Clootz, who styled himself the "personal enemy of Jesus Christ." For recreation, old games were played and new ones invented. Imagine a crowd of prisoners of both sexes, living in daily expectation of the scaffold, who played for hours together at the guillotine! A hall of the prison was transformed into Tinville's tribunal, a Tinville was placed on the bench who could parody the voice and manner of the terrible original, the prisoner was arraigned, there were eloquent counsel on both sides, and witnesses; and when the trial was finished, and the inevitable sentence had been pronounced, the guillotine of chairs and laths was set up, and amid a tumult of applause the wooden blade was loosed and the victim rolled into the basket. Sometimes the game was interrupted, and there was a general rush to the window to catch the voice of the crier in the street,—"Here's the list of the brigands who have won to-day at the lottery of the blessed guillotine!"

Famous figures, and a few sublime ones, detach themselves from the groups: a Duc d'Orléans, a Duc de Lauzun, a General Beauharnais (who writes to his wife Josephine that letter of farewell which she shewed to Bonaparte at her first interview with him), Charlotte Corday, the great chemist Lavoisier (on whose death Lagrange exclaimed, "It took but a moment to sever that head, and a hundred years will not produce one like it"), Danton the Titan of the Revolution, Camille Desmoulins, and Robespierre himself.

One evening, a few days after the death of Marie Antoinette, the twenty-two Girondins, condemned to die in twenty-four hours, passed into the keeping of Concierge Richard. These were some of the most heroic men of the Revolution, "the once flower of French patriotism," Carlyle calls them; tribunes, prelates, men of war, men of ancient and noble stock, poets, lawyers. One of their number had killed himself in court on receiving sentence, and the dead body was carried to the prison, and lay in a corner of the room in which the twenty-two spent their last night. They gathered at a long deal table for a farewell supper, at which, says Thiers, they were by turns, "gay, serious, and eloquent." They drank to the glory of France, and the happiness of all friends. They sang solemnly the great songs of the Revolution, and at five in the morning, when the turnkey came to call the last roll, one of them arose and declaimed the Marseillaise. A few hours later, the twenty-two went chanting to their death; and the chant was sustained until the last head had fallen.

These are amongst the loftier memories of those bloody days. It is impossible within the limits of a chapter to give a tithe even of the names that were written in the registers of the maison de justice of the Revolution. Well, indeed, might Fouquier-Tinville have named it the ante-chamber of the guillotine, for two thousand prisoners, drawn from all the other gaols of Paris, went to the scaffold from the Conciergerie. And they died, most of them, as children of a Revolution should die; virgin girls were no longer timid, women were weak no longer, when their turn came to mount the steps of the scaffold. A sense of patriotism so high and pure and penetrating as to resemble the spiritual exaltation and abandonment of the Christian martyrs seemed to extinguish in the frailest breasts the natural fear of death. "On meurt en riant, on meurt en chantant, on meurt en criant: Vive la France!"

The fierce political interests of the revolutionary period absorb all others; those who are not Fouquier-Tinville's victims languish obscurely in their cells, or travel towards the guillotine almost unnoticed. But who is this in a condemned cell of the Conciergerie in the year '94, not sent there by sentence of Tinville? It is honest, unfortunate Joseph Lesurques, unjustly convicted of the murder of a courier of Lyons,—one of the saddest miscarriages of justice. English play-goers are familiar with the dramatic version of the story, which gave Sir Henry Irving the material of one of his most remarkable creations. In the drama, playwright's justice snatches Lesurques from the tumbril within sight of the guillotine, but the Lesurques of real life fared otherwise. He died, innocent and ignorant of the crime, but the shade of the murdered courier had a double vengeance, for the actual assassin, Dubosc, was taken later, and duly stretched on the bascule.

In the Napoleonic era, the Conciergerie lost two-thirds of its lugubrious importance. It continued to receive prisoners of note, but their sojourn was brief; the prison of the Terror passed them on to Sainte-Pélagie, Bicêtre, the Temple, or the Bastille. With the return to France of the dynasty of Louis XVI., the old gaol went suddenly into mourning, as one may say, for Marie Antoinette. When Louis XVIII. commanded the erection of an "expiatory monument" in the Rue d'Anjou, the authorities of the Conciergerie made haste to blot out within its walls all traces of the Queen's captivity. They broke up the mean and meagre furniture of her cell, the wooden table, the two straw chairs, the shabby stump bedstead, the screen behind which her gaolers had gossiped in whispers; and the cell itself ceased its existence in that form, and was converted into a little chapel or sacristy. Some poor prisoner with a thought above his own distresses may be praying there to-day for the soul of Marie Antoinette.

CELL OF MARIE ANTOINETTE IN THE CONCIERGERIE.

A ghostly souvenir of 1815 may give us pause for a moment. There is no need to rehearse the story of Marshal Ney, bravest of the sons of France, Napoleon's le brave des braves, whose surpassing services in the field might have spared him a traitor's end. A few days after he had "gathered into his bosom" the bullets of a file of soldiers in the Avenue de l'Observatoire, behind the Luxembourg, the public prosecutor, M. Bellart, was entertaining at dinner the great men of the bar, the army, and society. At midnight, the door of the inner salon was suddenly thrown open, and a footman announced: Le Maréchal Ney!

M. Bellart and his guests, smitten to stone, looked dumbly towards the door. The talk stopped in every corner, the music stopped, the play at the card-tables stopped. In a moment, the tension passed. It was not the great Marshal, nor his astral. It was a blunder of the footman, who had confounded the name with that of a friend of the family, M. Maréchal Aîné.

Louis XI. strolled one day in the precincts of Vincennes, wrapped in his threadbare surtout edged with rusty fur, and plucking at the queer little peaked cap with the leaden image of the Virgin stuck in the band. There was a smile on the sallow and saturnine face.

At his Majesty's right walked a thick-set, squab man of scurvy countenance, wearing a close-fitting doublet, and armed like a hangman. On the King's left went a showy person, vulgar and mean of face, whose gait was a ridiculous strut.

Louis stopped against the dungeon and tapped the great wall with his finger.

"What's just the thickness of this?" he asked.

"Six feet in places, sire, eight in others," answered the squab man, Tristan, the executioner.

"Good!" said Louis. "But the place looks to me as if it were tumbling."

"It might, no doubt, be in better repair, sire," observed the showy person, Oliver, the barber; "but as it is no longer used——"

"Ah! but suppose I thought of using it, gossip?"

"Then, sire, your Majesty would have it repaired."

"To be sure!" chuckled the King—"If I were to shut you up in there, Oliver, you could get out, eh?"

"I think so, sire."

"But you, gossip," to his hangman, "you'd catch him and have him back to me, hein?"

"Trust me, sire!" said Tristan.

"Then I'll have my dungeon mended," said Louis. "I'm going to have company here, gossips."

"Sire!" exclaimed Oliver. "Prisoners so close to your Majesty's own apartments! But you might hear their groans."

"Ha! They groan, Oliver? The prisoners groan, do they? But there's no need why I should live in the château here. Hark you both, gossips, I'd like my guests to groan and cry at their pleasure, without the fear of inconveniencing their King."

And the King, and his hangman, and his barber fell a-laughing.

From that day, in a word, Louis ceased to inhabit the château of Vincennes, and the dungeon which appertained to it was made a terrible fastness for his Majesty's prisoners of State. It was already a place of some antiquity. The date of the original buildings is quite obscure. The immense foundations of the dungeon itself were laid by Philippe de Valois; his son, Jean le Bon, carried the fortress to its third story; and Charles V. finished the work which his fathers had begun.

All prisons are not alike in their origin. In the beginnings of states, force counts for more than legal prescripts, and ideas of vengeance go above the worthier idea of the repression of crime. Such-and-such a prison, renowned in history, is the expression in stone and mortar of the power or the hatred of its builders. Thus and thus did they plan and construct against their enemies. There was no mistaking, for example, the purpose of the architect of the Bastille,—it must be a fortress stout enough to resist the enemy outside, and a place fit and suitable to hold and to torture him when he had been carried a prisoner within its walls.

But Vincennes, in its origin, at all events, may be viewed under other and softer aspects. Those prodigious towers, for all the frightful menace of their frown, were not first reared to be a place of torment. The name of Vincennes came indeed, in the end, to be not less dreadful and only less abhorrent than that of the Bastille. A few revolutions of the vicious wheel of despotism, and the King's château was transformed into the King's prison, for the pain of the King's enemies, or of the King's too valiant subjects. But the infancy and youth of Vincennes were innocent enough, a reason, perhaps, why it was always less hated of the people than the Bastille. Vincennes lived and passed scathless through the terrors and hurtlings of the Revolution; and presently, from its cincture of flowers and verdant forest, looked down upon that high column of Liberty, which occupied the blood-stained site of the vanquished and obliterated Bastille.

THE KEEP OR DUNGEON OF VINCENNES.

King Louis lived no more in the château, and his masons made good the breaches in the dungeon which neglect, rather than age, had occasioned. When it stood again a solid mass of stone,—

"Gossip," said Louis to his executioner and torturer-in-chief, "if there were some little executions to be done here quietly and secretly—as you like to do them, Tristan—what place would you choose, hein?"

"I've chosen one, sire; a beautiful chamber on the first floor. The walls are thick enough to stifle the cries of an army; and if you lift the stones of the floor here and there, you find underneath the most exquisite oubliettes! Ah! sire, they understood high politics before your Majesty's time."

King Louis caressed his pointed chin, and laughed:

"I think it was Charles the Wise who built that chamber."

"No, sire; it was John the Good!"

"Ah, so! Go on, gossip. My dungeon is quite ready, eh?"

"Quite ready, sire."

"To-morrow, then, good Tristan, you will go to Montlhéry. In the château there you will find four guests of mine, masked, and very snug in one of our cosy iron cages. You will bring them here."

"Very good, sire."

"You will take care that no one sees you—or them."

"Yes, sire."

"And you will be tender of them, gossip. You are not to kill them on the way. When we have them here—we shall see. Start early to-morrow, Tristan. As for friend Oliver here, he shall be my governor of the dungeon of Vincennes, and devote himself to my prisoners. If a man of them escapes, my Oliver, Tristan will hang you; because you are not a nobleman, you know."

"Sire," murmured the barber, "you overwhelm me."

"Your Majesty owed that place to me, I think," said Tristan.

"Are you not my matchless hangman, gossip? No, no! Besides, I'm keeping you to hang Oliver. Go to Montlhéry."

Thus was Vincennes advanced to be a State prison, in 1473, when Louis XI. held the destinies of France. From that date to the beginning of the century we live in, those black jaws had neither sleep nor rest. As fast as they closed on one victim, they opened to receive another. At a certain stage of all despotic governments, the small few in power live mainly for two reasons—to amuse themselves and to revenge themselves. One amuses oneself at Court, and a State prison-controlled from the Court—is an ideal means of revenging oneself. The tedious machinery of the law is dispensed with. There is no trouble of prosecuting, beating up witnesses, or waiting in suspense for a verdict which may be given for the other side. The lettre de cachet, which a Court historian described as an ideal means of government, and which Mirabeau (in an essay penned in Vincennes itself) tore once for all into shreds, saved a world of tiresome procedure to the King, the King's favourites, and the King's ministers. For generations and for centuries, absolutism, persecution, party spirit, public and private hate used the lettre de cachet to fill and keep full the cells and dungeons of the Bastille and Vincennes. It was, to be sure, a two-edged weapon, cutting either way. He who used it one day might find it turned against him on another day. But, by whomsoever employed, it was the great weapon of its time; the most effective weapon ever forged by irresponsible authority, and the most unscrupulously availed of. It was this instrument which, during hundreds of years, consigned to captivity without a limit, in the oubliettes of all the State prisons of France, that "immense et déplorable contingent de prisonniers célèbres, de misères illustres."

Vincennes and the Bastille have been contrasted. They were worthy the one of the other; and at several points their histories touch. In both prisons the discipline (which was much an affair of the governor's whim) followed pretty nearly the same lines, and owed nothing in either place to any central, preconceived and ordered scheme of management. Prisoners might be transferred from Vincennes to the Bastille, and from the Bastille again to Vincennes. For the governor, Vincennes was generally the stepping-stone to the Bastille. At Vincennes he served his apprenticeship in the three branches of his calling—turnkey, torturer, and hangman. Like the callow barber-surgeon of the age, he bled at random, and used the knife at will; and his savage novitiate counted as so much zealous service to the State.

But Vincennes wears a greater colour than the Bastille. It stood to the larger and more famous fortress as the noblesse to the bourgeoisie. Vincennes was the great prison, and the prison of the great. Talent or genius might lodge itself in the Bastille, and often so did, very easily; nobility, with courage enough to face its sovereign on a grievance, or with power enough to be reckoned a thought too near the throne, tasted the honours of Vincennes. To be a wit, and polish an epigram against a minister or a madam of the Court; to be a rhymester, and turn a couplet against the Government; to be a philosopher, and hazard a new social theory, was to knock for admission at the wicket of the Bastille. But to be a stalwart noble, and look royalty in the eye, sword in hand; to be brother to the King, and chafe under the royal behest; to be a cardinal of the Church, and dare to jingle your breviary in the ranks of the Fronde; to be leader of a sect or party, or the head of some school of enterprise, this was to give with your own hand the signal to lower the drawbridge of Vincennes.

At seasons prisoners of all degrees jostled one another in both prisons; but in general the unwritten rule obtained that philosophy and unguarded wit went to the Bastille; whilst for strength of will that might prove troublesome to the Crown ... voilà le donjon de Vincennes!

Yes, Vincennes was the State prison, the prison for audacity in high places, for genius that could lead the general mind into paths of danger to the throne. The fetters fashioned there were for a Prince de Condé to wear, a Henri de Navarre, a Maréchal de Montmorency, a Bassompierre or a Cardinal de Retz, a Duc de Longueville or a Prince Charles Edward, a La Môle and a Coconas, a Rantzau or a Prince Casimir, a Fouquet or a Duc de Lauzun, a Louis-Joseph de Vendôme, a Diderot or a Mirabeau, a d'Enghien.

History, says a French historian, shews itself never at the Bastille but with manacles in one hand and headsman's axe in the other. At Vincennes, ever and anon, it appears in the rustling silks of a king's favourite, who finds within the circle of those cruel walls soft bosky nooks and bowers, for feasting and for love. Sometimes from the bosom of those perfumed solitudes, a death-cry escapes, and the flowers are spotted with blood: Messalina has dispensed with a lettre de cachet. At one epoch it is Isabeau de Bavière, it is Catherine de Médicis at another; what need to exhaust or to extend the list? Catherine made no sparing use of the towers of Vincennes. It was a spectacle of royal splendours on this side and of royal tyrannies on that; banquets and executions; the songs of her troubadours mingling with the sighs of her captives. Often some enemy of Catherine, quitting the dance at her pavilion of Vincennes, fell straightway into a cell of the dungeon, to die that night by stiletto, or twenty years later as nature willed. Yes, indeed, Vincennes and the Bastille were worthy of each other.

Two mysterious echoes of history still reach the ear from what were once the vaulted dungeons of Vincennes. The note of the first is gay and mocking, a cry with more of victory in it than of defeat, and one remembers the captivity of the Prince de Condé. The other is like the sudden detonation of musketry, and one recalls the bloody death of the young Duc d'Enghien, the last notable representative of the house of Condé.

The Prince de Condé's affair is of the seventeenth century. It was Anne of Austria, inspired by Mazarin, who had him arrested, along with his brother the Prince de Conti and their brother-in-law the Duc de Longueville. A lighter-hearted gallant than Condé never set foot on the drawbridge of Vincennes. On the night of his arrival with De Conti and the duke, no room had been prepared for his reception. He called for new-laid eggs for supper, and slept on a bundle of straw. De Conti cried, and De Longueville asked for a work on theology. The next day, and every day, Condé played tennis and shuttle-cock with his keepers; sang and began to learn music. He quizzed the governor perpetually, and laid out a garden in the grounds of the prison which became the talk of Paris. "He fasted three times a week and planted pinks," says a chronicler. "He studied strategy and sang the psalms," says another. When the governor threatened him for breaches of the rules, the Prince offered to strangle him. But not even Vincennes could hold a Condé for long, and he was liberated.

Briefer still was the sojourn of the Duc d'Enghien—one of the strangest, darkest, and most tragical events of history. In 1790, at the age of nineteen, he had quitted France with the chiefs of the royalist party. Twelve years later, in 1802, he was living quietly at the little town of Ettenheim, not far from Strasbourg; in touch with the forces of Condé, but not, as it seems, taking active part in the movement which was preparing against Napoleon. A mere police report lost him with the First Consul. He was denounced as having an understanding with the officers of Condé's army, and as holding himself in readiness to unite with them on the receipt of instructions from England. Napoleon issued orders for his arrest, and he was seized in his little German retreat on March 15, 1804. Five days later he was lodged in the dungeon of Vincennes.

Here the prison drama, one of the saddest enacted on the stage of history, commences. "Tout est mystérieux dans cette tragédie, dont le prologue même commence par un secret." (Everything is mysterious in this tragedy, the very prologue of which begins with a secret.)

The Duke had married secretly the Princess Charlotte de Rohan, who, by her husband's wish, continued to occupy her own house. The daily visits of the constant husband were a cause of suspicion to the agents of Napoleon. They said that he was framing plots; he was simply enjoying the society of his wife. He was engaged, they said, in a conspiracy with Georges and others against the life of Napoleon; he was but turning love phrases in the boudoir of the Princess.

The mystery accompanied the unfortunate prisoner from Ettenheim to Strasbourg, from Strasbourg to Paris, and went before him to Vincennes. Governor Harel was instructed to receive "an individual whose name is on no account to be disclosed. The orders of the Government are that the strictest secrecy is to be preserved respecting him. He is not to be questioned either as to his name or as to the cause of his detention. You yourself will remain ignorant of his identity."

As he was driven into Paris at five o'clock on the evening of March 20th, the Duke said with a fine assurance:

"If I may be permitted to see the First Consul, it will be settled in a moment."

That request never reached Napoleon, and the prisoner was hurried to Vincennes. His only thought on reaching the château was to ask that he might have leave to hunt next day in the forest. But the next day was not yet come.

The mystery does not cease. The military commission sent hot-foot from Paris to try the case were "dans l'ignorance la plus complète" both as to the name and the quality of the accused. An aide-de-camp of Murat gave the Duke's name to them as they gathered at the table in an ante-chamber of the prison to inquire what cause had summoned them. D'Enghien was abed and asleep.

"Bring in the prisoner," and Governor Harel fetched d'Enghien from his bed. He stood before his judges with a grave composure, and not a question shook him.

"Interrogated as to plots against the Emperor's life, taxed with projects of assassination, he answered quietly that insinuations such as these were insults to his birth, his character, and his rank."[4]

4. Histoire du Donjon de Vincennes.

The inquiry finished, the Duke demanded with insistence to see the First Consul. Savary, Napoleon's aide-de-camp, whispered the council that the Emperor wished no delay in the affair,[5] and the prisoner was withdrawn.

5. It is moderately certain at this day that everyone representing Napoleon in this miserable affair of d'Enghien mis-represented him from first to last.

Some twenty minutes later a gardener of the château, Bontemps by name, was turned out of bed in a hurry to dig a grave in the trenches against the Pavilion de la Reine; and the officer commanding the guard had orders to furnish a file of soldiers.

D'Enghien sat composedly in his room against the council-chamber, writing up his diary for his wife, and wondering whether leave would be given him to hunt on the morrow. Enters, once more, Governor Harel, a lantern in his hand. It was on the stroke of midnight.

"Would monsieur le duc have the kindness to follow?" It is still on record that the governor was pale, looked troubled, and spoke with much concern.

He led the way that conducted to the Devil's Tower. The stairs from that tower descended straight into the trenches. At the head of the staircase, looking into the blackness beyond, the Duke turned and said to his conductor: "Are you taking me to an oubliette? I should prefer, mon ami, to be shot."

"Monsieur," said Harel, "you must follow me,—and God grant you courage!"

"It is a prayer I never yet needed to put up," responded d'Enghien calmly, and he followed to the foot of the stairs.

"Shoulder arms!"

A lantern glimmering at either end of the file of soldiers shewed d'Enghien his fate. As the sentence of death was read, he wrote in pencil a message to his wife, folded and gave it to the officer in command of the file, and asked for a priest. There was no priest in residence at the château, he was told.

"And time presses!" said the Duke. He prayed a moment, covering his face with his hands. As he raised his head, the officer gave the word to fire.

Volumes have been written upon this tragedy, but to this day no one knows by whose precise word the blood of the last Condé was spilled in the trenches of Vincennes. That d'Enghien was assassinated seems beyond question—but by whom? Years after the event, General Hullin, president of the commission, asserted in writing that no order of death was ever signed; and that the members of the commission, still sitting at the council-table, heard with amazement the volley that made an end of the debate. Napoleon bore and still bears the opprobrium, but the proof lacks. Yet who, under the Consulate, dared shoot a d'Enghien, failing the Consul's word? The stones of Vincennes, wherein the mystery is locked, have kept their counsel.

Let the curtain be drawn for a moment on the last scene in the tragedy of La Môle and Coconas. It is a lurid picture of the manners of the time—the last quarter of the sixteenth century, Charles IX. on the throne. The tale, which space forbids to tell at length, is one of love and jealousy, with the wiles of a soi-disant magician in the background. The prime plotter in the affair was the Queen-Mother, Catherine de Médicis. La Môle was the lover of Marguerite de Navarre; Coconas, the lover of the Queen's friend, the Duchesse de Nevers. Arrested on a dull and senseless charge of conspiring by witchcraft against the life of the King, the two courtiers were thrown into Vincennes. The first stage of the trial yielding nothing, the accused were carried to the torture chamber, and there underwent all the torments of the Question. After that, being innocent of the charge, they were declared guilty, and sentenced to the axe.

"Justice" was done upon them in the presence of all Paris, wondering dumbly at the iniquity of the punishment.

Night had fallen, and the executioner was at supper with his family in his house in the tower of the pillory. All good citizens shunned that accursed dwelling, and those who had to pass the headsman's door after dark crossed themselves as they did so. All at once there was a knocking at the door.

On his dreadful days of office the "Red Man" sometimes received the stealthy visit of a friend, brother, wife, or sister, come to beg or purchase a lock of hair, a garment, or a jewel.

"There's money coming to us," said the headsman to his wife. He opened the door, and on the threshold stood a man, armed, and two women.

"These ladies would speak with you," said the man; and as the headsman stood aside, the two ladies, enveloped in enormous hoods, entered the house, their companion remaining without.

"You are the executioner?" said an imperious voice from behind an impenetrable veil.

"Yes, madame."

"You have here ... the bodies of two gentlemen."

The headsman hesitated. The lady drew out a purse, which she laid upon the table. "It is full of gold," she said.

"Madame," exclaimed the "Red Man," "what do you wish? I am at your service."

"Shew me the bodies," said the lady.

"Ah! madame, but consider. It is terrible!" said the headsman, not altogether unmoved. "You would scarcely support the sight."

"Shew them to me," said the lady.

Taking a lighted torch, the headsman pointed to a door in a corner of the room, dark and humid.

"In there!" he said.

The lady who had not yet spoken broke into an hysterical sob. "I dare not! I dare not! I am terrified!" she cried.

"Who loves should love unto death ... and in death," said she of the imperious voice.

The headsman pushed open the door of a cellar-like apartment, held the torch above his head, and from the black doorway the two ladies gazed in silent horror upon the mutilated spoils of the scaffold. In the red ooze upon the bare stone floor the bodies of La Môle and Coconas lay side by side. The severed heads were almost in their places, a circular black line dividing them from the white shoulders. The first of the two ladies, with heaving bosom, stooped over La Môle, and raised the pale right hand to her lips.

"Poor La Môle! Poor La Môle! I will avenge you!" she murmured.

Then to the executioner: "Give me the head! Here is the double of your gold."

"Ah! madame, I cannot. I dare not! Suppose the Provost——"

"If the Provost demands this head of you, tell him to whom you gave it!" and the lady swept the veil from her face.

The headsman bent to the earth: "Madame the Queen of Navarre!"

"And the head of Coconas to me, maître," said the Duchesse de Nevers.[6]

6. In effect, Margaret of Navarre bore away the head of La Môle, and the Duchesse de Nevers that of Coconas. It is said that La Môle on the scaffold bequeathed his head to the Queen.

Amongst Louis XV.'s State prisoners, a long and picturesque array, may be singled out for the present Prince Charles Edward, son of the Pretender. Under the wind of adversity, after Culloden, Prince Charles was blown at length upon French soil. Louis was gracious in his offer of an asylum, and courtly France was enthusiastic over the exploits and fantastic wanderings of the young hero. All went gaily with him in Paris until the signatures had been placed to the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. Then the wind began to blow from the east again.

One morning the visit was announced of MM. de Maurepas and the Duc de Gèvres.

"Gentlemen," said Prince Charles to his friends, "I know what this visit bodes. His Majesty proposes to withdraw his hospitality. We are to be driven out of France."

His handful of followers were stupefied, but the Prince was right. M. de Maurepas announced himself as commanded by the King to request Prince Charles Edward's immediate departure from France.

"Sir," returned the Prince, "your King has given me shelter, and the title of brother."

"Monseigneur," said M. de Maurepas, "circumstances have changed——"

"To my advantage, sir! For over and above the rights which Louis XV. has acknowledged in me, I have those more sacred ones of misfortune and persecution."

"His Majesty, monseigneur, is beyond doubt deeply touched by your misfortunes, but the treaty he has just signed for the welfare of his people compels him now to deny you his succour."

"Does your King indeed break his word and oath so lightly?" said Prince Charles. "Is the blood of a proscribed and exiled prince, to whom he has but just given his hand, so trifling a matter to him?"

"Monseigneur," said de Maurepas, "I am not here to sustain an argument with you. I am only the bearer of his Majesty's commands."

"Then tell the King from me that I shall yield only to his force."

This was on December 10, 1748.

When Louis's emissaries had retired, Prince Charles announced his intention of going to the Opera in the evening. His followers feared some public scandal, and did their utmost to dissuade him.

"The more public the better!" cried the Prince in a passion.

In effect, he drove to the Opera after dinner. De Maurepas had surrounded the building with twelve hundred soldiers, and as the Prince's carriage drew up at the steps, a troop of horse encircled it, and he himself was met with a brusque request for his sword.

"Come and take it!" said young Hotspur, flourishing the weapon.

In a moment he was seized from behind, his hands and arms bound, and the soldiers lifted him into another carriage, which was forthwith driven off at a gallop.

"Where are you taking me?" asked the Prince.

"Monseigneur, to the dungeon of Vincennes."

"Ah, indeed! Pray thank your King for having chosen for me the prison which was honoured by the great Condé. You may add that, whilst Condé was the subject of Louis XIV., I am only the guest of Louis XV."

M. du Châtelet, governor of Vincennes at that epoch, had received orders to make the Prince's imprisonment a rigorous one, and fifty men were specially appointed to watch him. But du Châtelet, a friend and admirer of the young hero, took his part, and counselled him to abandon a resistance which must be worse than futile, "You have had triumph enough," said the prudent du Châtelet, "in exposing the feebleness and cowardice of the King."

Prince Charlie's detention lasted but six days. He was liberated on December 16th, and left Paris in the keeping of an officer of musketeers to join his father in Rome.

Absolutism, l'arbitraire, all through this period was making hay while the sun shone, and playing rare tricks with the liberties of the subject. Vincennes was a witness of strange things done in the name of the King's justice. Take the curious case of the Abbé Prieur. The Abbé had invented a kind of shorthand, which he thought should be of some use to the ministry. But the ministry would none of it, and the Abbé made known his little invention to the King of Prussia, a patron of such profitable things. But one of his letters was opened at the post-office by the Cabinet Noir, and the next morning Monsieur l'Abbé Prieur awoke in the dungeon of Vincennes. He inquired the reason, and in the course of months his letter to the King of Prussia was shewn to him.

"But I can explain that in a moment," said the Abbé. "Look, here is the translation."

The hieroglyphs, in short, were as innocent as a verse of the Psalms, but the Abbé Prieur never quitted his dungeon.

A venerable and worthy nobleman, M. Pompignan de Mirabelle, was imprudent enough to repeat at a supper party some satirical verses he had heard touching Madame de Pompadour and De Sartines, the chief of police. Warned that De Sartines had filled in his name on a lettre de cachet, M. de Mirabelle called at the police office, and asked to what prison he should betake himself. "To Vincennes," said De Sartines.

"To Vincennes," repeated M. de Mirabelle to his coachman, and he arrived at the dungeon before the order for his detention.

Once a year, De Sartines made a formal visit to Vincennes, and once a year punctually he demanded of M. de Mirabelle the name of the author of the verses. "If I knew it I should not tell you," was the invariable reply; "but as a matter of fact I never heard it in my life." M. de Mirabelle died in Vincennes, a very old man.