by

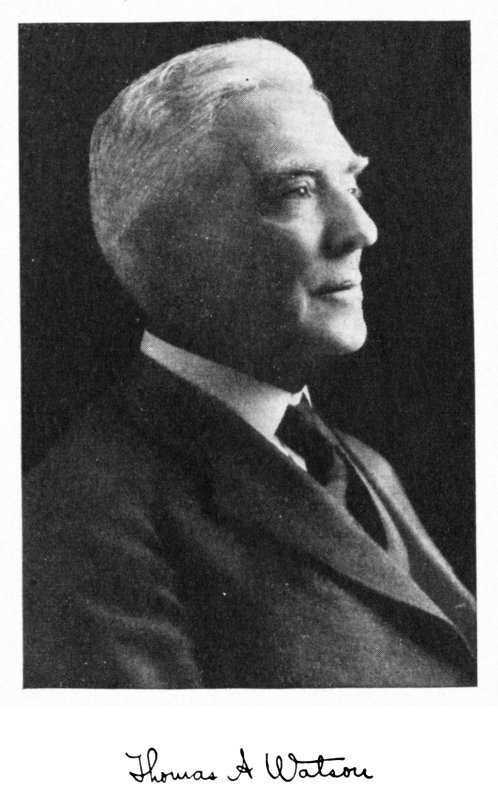

Thomas A. Watson

Assistant to Alexander Graham Bell

(An address delivered before the Third Annual Convention of the Telephone Pioneers of America at Chicago, October 17, 1913)

Information Department

AMERICAN TELEPHONE AND TELEGRAPH COMPANY

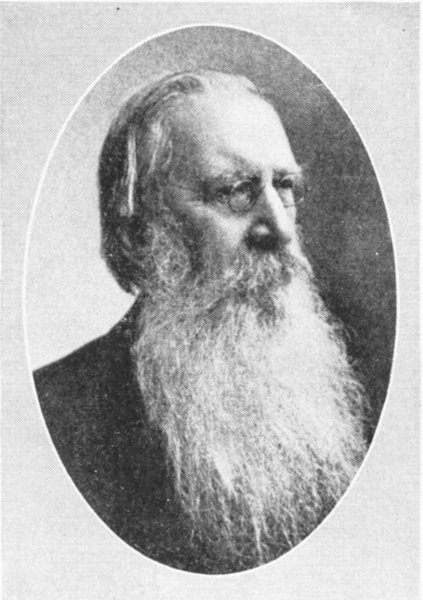

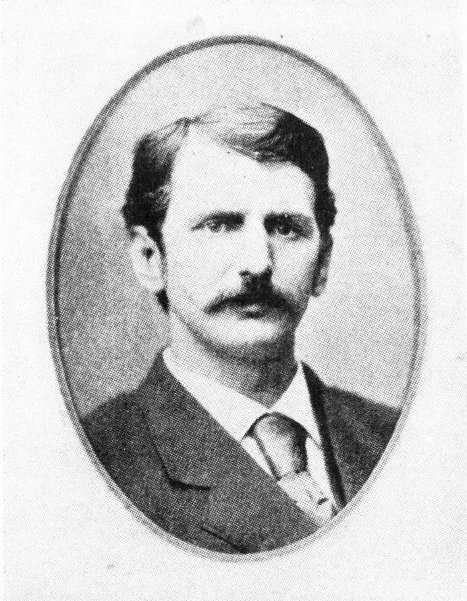

Thomas A. Watson

1854-1934

Thomas A. Watson was born on January 18, 1854, in Salem, Massachusetts, and died December 13, 1934, at more than four-score years. At the age of 13 he left school and went to work in a store. Always keenly interested in learning more and in making the most of all he learned, every new experience was to him, from his childhood on, an opening door into a larger, more beautiful and more wonderful world. This was the key to the continuous variety that gave interest to his life.

In 1874 he obtained employment in the electrical shop of Charles Williams, Jr., at 109 Court Street, Boston. Here he met Alexander Graham Bell, and the telephone chapter in his life began. This he has told in the little book herewith presented. In 1881, having well earned a rest from the unceasing struggle with the problems of early telephony, and being now a man of means, he resigned his position in the American Bell Telephone Company and spent a year in Europe. On his return he started a little machine shop for his own pleasure, at his place in East Braintree, Massachusetts. From this grew the Fore River Ship and Engine Company, which did its large share of building the U. S. Navy of the Spanish War. In 1904 he retired from active business.

When 40 years of age and widely known as a shipbuilder, he went to college, taking special courses in geology and biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. At the same time he specialized in literature. These studies dominated his later years, leading him in extensive travels all over the world, and at home extending to others the inspiration of a genial simplicity of life and of a love for science, literature and all that is fine in life.

By Thomas A. Watson

I am to speak to you of the birth and babyhood of the telephone, and something of the events which preceded that important occasion. These are matters that must seem to you ancient history; in fact, they seem so to me, although the events all happened less than 40 years ago, in the years 1874 to 1880.

The occurrences of which I shall speak, lie in my mind as a splendid drama, in which it was my great privilege to play a part. I shall try to put myself back into that wonderful play, and tell you its story from the same attitude of mind I had then—the point of view of a mere boy, just out of his apprenticeship as an electro-mechanician, intensely interested in his work, and full of boyish hope and enthusiasm. Therefore, as it must be largely a personal narrative, I shall ask you to excuse my many “I’s” and “my’s” and to be indulgent if I show how proud and glad I am that I was chosen by the fates to be the associate of Alexander Graham Bell, to work side by side with him day and night through all these wonderful happenings that have meant so much to the world.

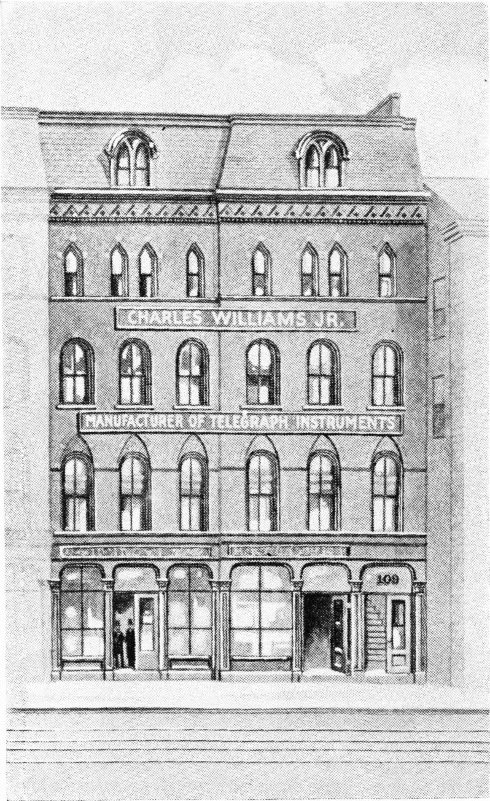

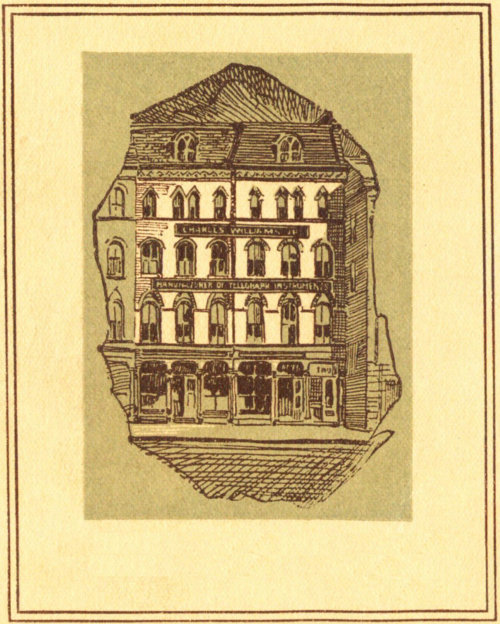

I realize now what a lucky boy I was, when at 13 years of age I had to leave school and go to work for my living, although I didn’t think so at that time. I am not advising my young friends to leave school at this age, for they may not have the opportunity to enter college as I did at 40. There’s a “tide in the affairs of men,” you know, and that was the beginning of its flood in my life, for after trying several vocations—clerking, bookkeeping, carpentering, etc.—and finding them all unattractive, I at last found just the job that 6 suited me in the electrical work-shop of Charles Williams, at 109 Court Street, Boston—one of the best men I have ever known. Better luck couldn’t befall a boy than to be brought so early in life under the influence of such a high-minded gentleman as Charles Williams.

I want to say a few words about my work there, not only to give you a picture of such a shop in the early ’70s, but also because in this shop the telephone had its birth and a good deal of its early development.

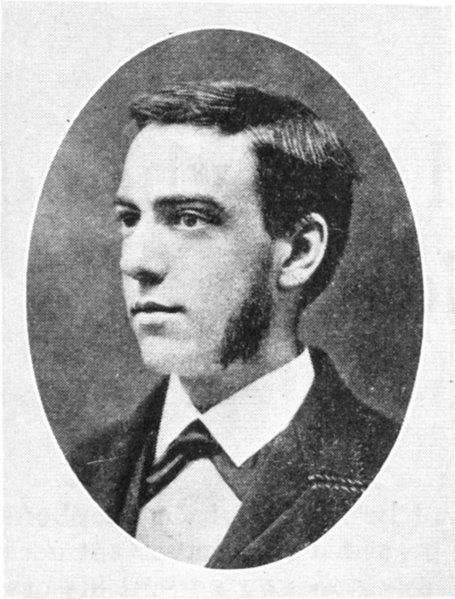

Thomas A. Watson in 1874

I was first set to work on a hand lathe turning binding posts for $5 a week. The mechanics of to-day with their automatic screw machines, hardly know what it is to turn little rough castings with a hand tool. How the hot chips used to fly into our eyes! One day I had a fine idea. I bought a pair of 25-cent goggles, thinking the others would hail me as a benefactor of mankind and adopt my plan. But they laughed at me for being such a sissy boy and public opinion forced me back to the old time-honored plan of winking when I saw a chip coming. It was not an efficient plan, for the chip usually got there first. There was a liberal education in it for me in manual dexterity. There was no specializing in these shops at that time. Each workman built everything there was in the shop to build, and an apprentice also had a great variety of jobs, which kept him interested all the time, for his tools were poor and simple and it required lots of thought to get a job done right.

There were few books on electricity published at that time. Williams had copies of most of them in his showcase, which we boys used to read noons, but the book that interested me most was Davis’ Manual of Magnetism, published in 1847, a copy of which I made mine for 25 cents. If you want to get a good idea of the state of the electrical art at that time, you should read that book. I found it very stimulating and that same old copy in all the dignity of its dilapidation has a place of honor on my book shelves to-day.

My promotion to higher work was rapid. Before two years had passed, I had tried my skill on about all the regular work of the establishment—call bells, annunciators, galvanometers, telegraph keys, sounders, relays, registers and printing telegraph instruments.

Individual initiative was the rule in Williams’ shop—we all did about as we pleased. Once I built a small steam engine for myself during working hours, when business was slack. No one objected. That steam engine, by the way, was the embryo of the biggest shipbuilding plant in the United States to-day, which I established some ten years later with telephone profits, and which now employs more than 4,000 men.

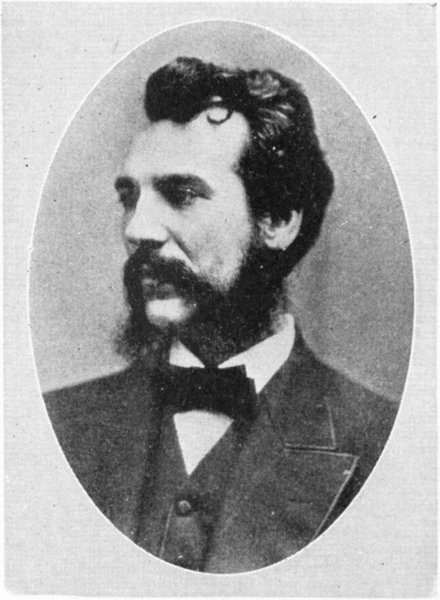

Alexander Graham Bell in 1876

Such were the electrical shops of that day. Crude and small as they were, they were the forerunners of the great electrical works of to-day. In them were being trained the men who were among the leaders in the wonderful development of applied electricity which began soon after the time of which I am to speak. Williams, although he never had at that time more than 30 or 40 men working for him, had one of the largest and best fitted shops in the country. I think the Western Electric shop at Chicago was the only larger one. That was also undoubtedly better organized and did better work than Williams’. When a piece of machinery built by the Western Electric came into our shop for repairs, we boys always used to admire the superlative excellence of the workmanship.

Besides the regular work at Williams’, there was a constant stream of wild-eyed inventors, with big ideas in their heads and little money in their pockets, coming to the shop to have their ideas tried out in brass and iron. Most of them had an “angel” whom they had hypnotized into paying the bills. My enthusiasm, and perhaps my sympathetic nature, made me a favorite workman with those men of visions, and in 1873-74 my work had become largely making 8 experimental apparatus for such men. Few of their ideas ever amounted to anything, but I liked to do the work, as it kept me roaming in fresh fields and pastures new all the time. Had it not been, however, for my youthful enthusiasm—always one of my chief assets—I fear this experience would have made me so skeptical and cynical as to the value of electrical inventions that my future prospects might have been injured.

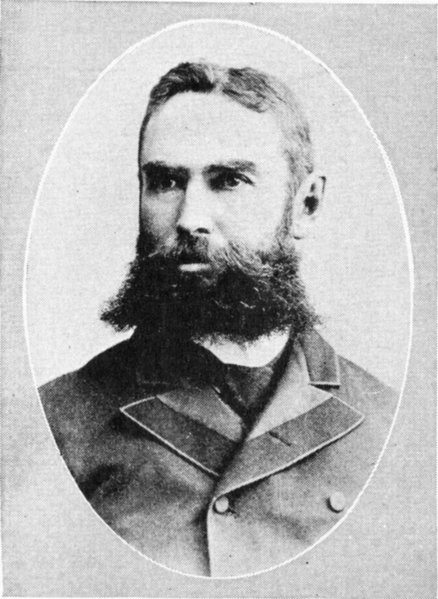

Thomas Sanders in 1878, at the Time He Was the Sole Financial Backer of the Telephone

I remember one limber-tongued patriarch who had induced some men to subscribe $1,000 to build what he claimed to be an entirely new electric engine. I had made much of it for him. There was nothing new in the engine, but he intended to generate his electric current in a series of iron tanks the size of trunks, to be filled with nitric acid with the usual zinc plates suspended therein. When the engine was finished and the acid poured into the tanks for the first time, no one waited to see the engine run, for inventor, “angel,” and workmen all tried to see who could get out of the shop quickest. I won the race as I had the best start.

I suppose there is just such a crowd of crude minds still besieging the work-shops, men who seem incapable of finding out what has been already done, and so keep on, year after year, threshing old straw.

All the men I worked for at that time were not of that type. There were a few very different. Among them, dear old Moses G. Farmer, perhaps the leading practical electrician of that day. He was full of good ideas, which he was constantly bringing to Williams to have worked out. I did much of his work and learned from him more about electricity than ever before or since. He was electrician at that time for the United States Torpedo Station at Newport, Rhode Island, and in the early winter of 1874 I was making for him some experimental torpedo exploding apparatus. That apparatus will always be 9 connected in my mind with the telephone, for one day when I was hard at work on it, a tall, slender, quick-motioned man with pale face, black side whiskers, and drooping mustache, big nose and high sloping forehead crowned with bushy, jet black hair, came rushing out of the office and over to my work bench. It was Alexander Graham Bell, whom I saw then for the first time. He was bringing to me a piece of mechanism which I had made for him under instructions from the office. It had not been made as he had directed and he had broken down the rudimentary discipline of the shop in coming directly to me to get it altered. It was a receiver and a transmitter of his “Harmonic Telegraph,” an invention of his with which he was then endeavoring to win fame and fortune. It was a simple affair by means of which, utilizing the law of sympathetic vibration, he expected to send six or eight Morse messages on a single wire at the same time, without interference.

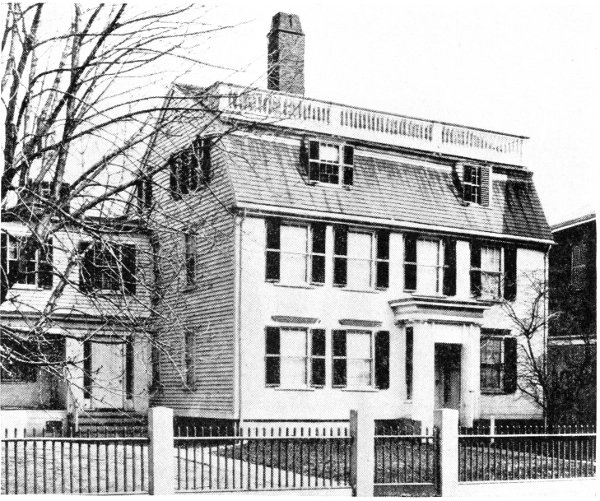

Home of Mrs. Mary Ann (Brown) Sanders, Salem, Mass., where Professor Bell carried on experiments for three years which led to the discovery of the principle of the telephone

Although most of you are probably familiar with the device, I must, to make my story clear, give you a brief description of the instruments, 10 for though Bell never succeeded in perfecting his telegraph, his experimenting on it led to a discovery of the highest importance.

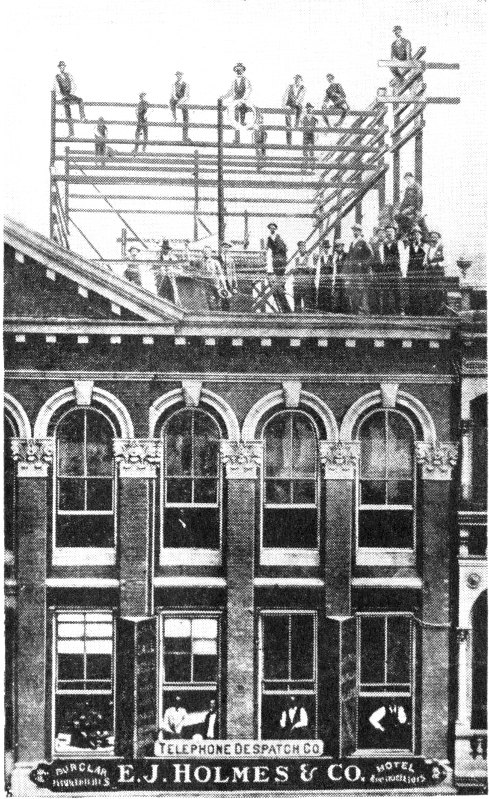

The Birthplace of the Telephone, 109 Court Street, Boston.—On the top floor of this building, in 1875, Prof. Bell carried on his experiments and first succeeded in transmitting speech by electricity

The essential parts of both transmitter and receiver were an electro-magnet and a flattened piece of steel clock spring. The spring was clamped by one end to one pole of the magnet, and had its other end free to vibrate over the other pole. The transmitter had, besides this, make-and-break points like an ordinary vibrating bell which, when the current was on, kept the spring vibrating in a sort of nasal whine, of a pitch corresponding to the pitch of the spring. When the signalling key was closed, an electrical copy of that whine passed through the wire and the distant receiver. There were, say, six transmitters with their springs tuned to six different pitches and six receivers with their springs tuned to correspond. Now, theoretically, when a transmitter sent its electrical whine into the line wire, its own faithful receiver spring at the distant station would wriggle sympathetically but all the others on the same line would remain coldly quiescent. Even when all the transmitters were whining at once through their entire gamut, making a row as if all the miseries this world of trouble ever produced were concentrated there, each receiver spring along the line would select its own from that sea of troubles and ignore all the others. Just see what a simple, sure-to-work invention this was; for just break up those various whines into the dots and dashes of Morse messages and one wire would do the work of six, and the “Duplex” telegraph that had just been invented would be beaten to a frazzle. Bell’s reward would be immediate and rich, for the “Duplex” had been bought by the Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph Company, 11 giving them a great advantage over their only competitor, the Western Union Company, and the latter would, of course, buy Bell’s invention and his financial problems would be solved.

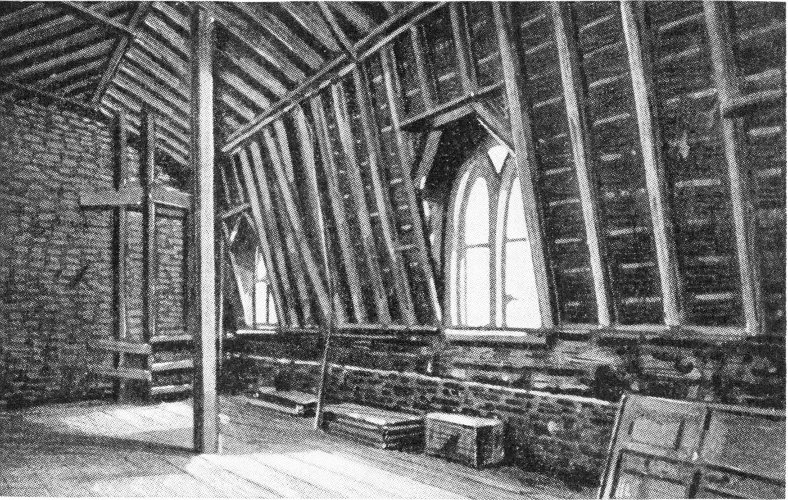

The Garret, 109 Court St., Boston, where Bell Verified the Principle of Electrical Speech Transmission

All this was, as I have said, theoretical, and it was mighty lucky for Graham Bell that it was, for had his harmonic telegraph been a well behaved apparatus that always did what its parent wanted it to do, the speaking telephone might never have emerged from a certain marvelous conception, that had even then been surging back of Bell’s high forehead for two or three years. What that conception was, I soon learned, for he couldn’t help speaking about it, although his friends tried to hush it up. They didn’t like to have him get the reputation of being visionary, or—something worse.

To go on with my story; after Mr. Farmer’s peace-making machines were finished, I made half a dozen pairs of the harmonic instruments for Bell. He was surprised, when he tried them, to find that they didn’t work as well as he expected. The cynical Watson wasn’t at all surprised for he had never seen anything electrical yet that worked at first the way the inventor thought it would. Bell wasn’t discouraged in the least and a long course of experiments followed which gave me a steady job that winter and brought me into close contact with a wonderful personality that did more to mould my life rightly than anything else that ever came into it.

I became mightily tired of those “whiners” that winter. I called 12 them by that name, perhaps, as an inadequate expression of my disgust with their persistent perversity, the struggle with which soon began to take all the joy out of my young life, not being endowed with the power of Macbeth’s weird sisters to

“Look into the seeds of time,

And say which grain will grow and which will not.”

Let me say here, that I have always had a feeling of respect for Elisha Gray, who, a few years later, made that harmonic telegraph work, and vibrate well-behaved messages, that would go where they were sent without fooling with every receiver on the line.

Most of Bell’s early experimenting on the harmonic telegraph was done in Salem, at the home of Mrs. George Sanders, where he resided for several years, having charge of the instruction of her deaf nephew. The present Y. M. C. A. building is on the site of that house. I would occasionally work with Bell there, but most of his experimenting in which I took part was done in Boston.

Mr. Bell was very apt to do his experimenting at night, for he was busy during the day at the Boston University, where he was Professor of Vocal Physiology, especially teaching his father’s system of visible speech, by which a deaf mute might learn to talk—quite significant of what Bell was soon to do in making mute metal talk. For this reason I would often remain at the shop during the evening to help him test some improvement he had had me make on the instruments.

One evening when we were resting from our struggles with the apparatus, Bell said to me: “Watson, I want to tell you of another idea I have, which I think will surprise you.” I listened, I suspect, somewhat languidly, for I must have been working that day about sixteen hours, with only a short nutritive interval, and Bell had already given me, during the weeks we had worked together, more new ideas on a great variety of subjects, including visible speech, elocution and flying machines, than my brain could assimilate, but when he went on to say that he had an idea by which he believed it would be possible to talk by telegraph, my nervous system got such a shock that the tired feeling vanished. I have never forgotten his exact words; they have run in my mind ever since like a mathematical formula. “If,” he said, “I could make a current of electricity vary in intensity, precisely as the air varies in density during the production of a sound, I should be able to transmit speech telegraphically.” He then sketched for me an instrument that he thought would do this, and we discussed the possibility of constructing one. I did not make it; it was altogether 13 too costly, and the chances of its working too uncertain to impress his financial backers—Mr. Gardiner G. Hubbard and Mr. Thomas Sanders—who were insisting that the wisest thing for Bell to do was to perfect the harmonic telegraph; then he would have money and leisure enough to build air castles like the telephone.

I must have done other work in the shop besides Bell’s during the winter and spring of 1875, but I cannot remember a single item of it. I do remember that when I was not working for Bell I was thinking of his ideas. All through my recollection of that period runs that nightmare—the harmonic telegraph, the ill working of which got on my conscience, for I blamed my lack of mechanical skill for the poor operation of an invention apparently so simple. Try our best, we could not make that thing work rightly, and Bell came as near to being discouraged as I ever knew him to be.

But this spring of 1875 was the dark hour just before the dawn.

If the exact time could be fixed, the date when the conception of the undulatory or speech-transmitting current took its perfect form in Bell’s mind would be the greatest day in the history of the telephone, but certainly June 2, 1875, must always rank next; for on that day the mocking fiend inhabiting that demonic telegraph apparatus, just as a now-you-see-it-and-now-you-don’t sort of satanic joke, opened the curtain that hides from man great Nature’s secrets and gave us a glimpse as quick as if it were through the shutter of a snap-shot camera, into that treasury of things not yet discovered. That imp didn’t do this in any kindly, helpful spirit—any inventor knows he isn’t that kind of a being—he just meant to tantalize and prove that a man is too stupid to grasp a secret, even if it is revealed to him. But he hadn’t properly estimated Bell, though he had probably sized me up all right. That glimpse was enough to let Bell see and seize the very thing he had been dreaming about and drag it out into the world of human affairs.

Gardiner G. Hubbard in 1876

Coming back to earth, I’ll try and tell you what happened that day. In the experiments on the harmonic telegraph, Bell had found that the reason why the messages got mixed up was inaccuracy in the adjustment of the pitches of the receiver springs to those of the transmitter. Bell always had to do this tuning himself, as my sense of pitch and knowledge of music were quite lacking—a faculty (or lackulty) which you will hear later became quite useful. Mr. Bell was in the habit of observing the pitch of a spring by pressing it against his ear while the corresponding transmitter in a distant room was sending its intermittent current through the magnet of that receiver. He would then manipulate the tuning screw until that spring was tuned to accord with the pitch of the whine coming from the transmitter. All this experimenting was carried on in the upper story of the Williams building, where we had a wire connecting two rooms perhaps sixty feet apart looking out on Court Street.

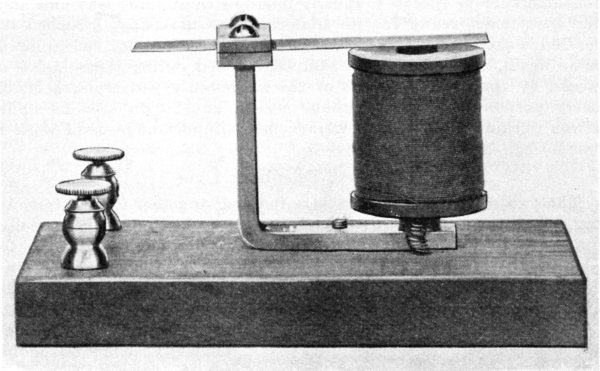

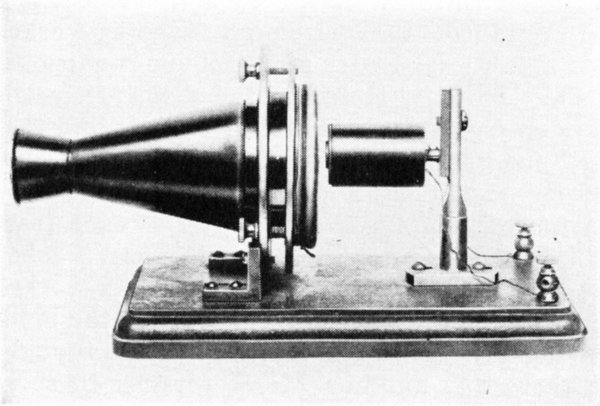

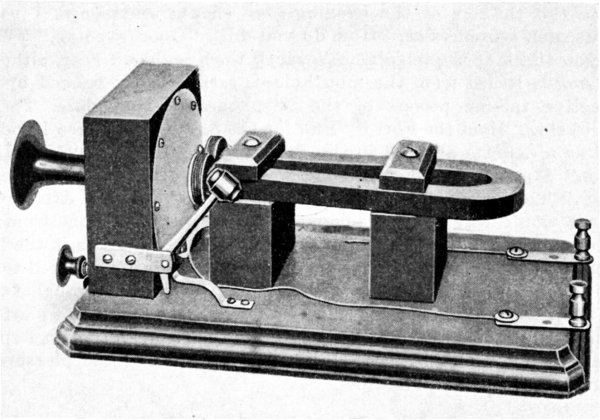

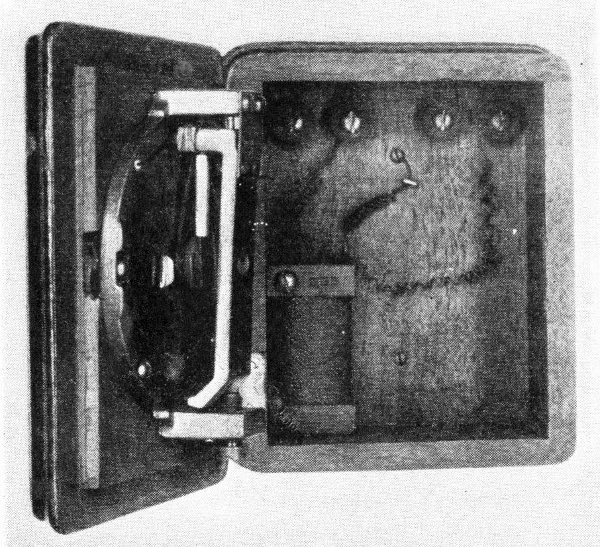

Prof. Bell’s Vibrating Reed—Used for a Receiver

On the afternoon of June 2, 1875, we were hard at work on the same old job, testing some modification of the instruments. Things were badly out of tune that afternoon in that hot garret, not only the instruments, but, I fancy, my enthusiasm and my temper, though Bell was as energetic as ever. I had charge of the transmitters as usual, setting them squealing one after the other, while Bell was retuning the receiver springs one by one, pressing them against his ear as I have described. One of the transmitter springs I was attending to stopped vibrating and I plucked it to start it again. It didn’t start and I kept on plucking it, when suddenly I heard a shout from Bell in the next room, and then out he came with a rush, demanding, “What did you do then? Don’t change anything. Let me see!” I showed him. It was very simple. The contact screw was screwed down so far that it made permanent contact with the spring, so that when I snapped the spring the circuit had remained unbroken while that strip of magnetized steel by its vibration over the pole of its magnet was generating that marvelous conception of Bell’s—a current of electricity that varied in intensity precisely as the air was varying in density within hearing distance of that spring. That undulatory current had passed through the connecting wire to the distant receiver which, fortunately, was a mechanism that could transform that current back into an extremely faint echo of the sound of the vibrating spring that had generated it, but what was still more 15 fortunate, the right man had that mechanism at his ear during that fleeting moment, and instantly recognized the transcendent importance of that faint sound thus electrically transmitted. The shout I heard and his excited rush into my room were the result of that recognition. The speaking telephone was born at that moment. Bell knew perfectly well that the mechanism that could transmit all the complex vibrations of one sound could do the same for any sound, even that of speech. That experiment showed him that the complex apparatus he had thought would be needed to accomplish that long dreamed result was not at all necessary, for here was an extremely simple mechanism operating in a perfectly obvious way, that could do it perfectly. All the experimenting that followed that discovery, up to the time the telephone was put into practical use, was largely a matter of working out the details. We spent a few hours verifying the discovery, repeating it with all the differently tuned springs we had, and before we parted that night Bell gave me directions for making the first electric speaking telephone. I was to mount a small drumhead of gold-beater’s skin over one of the receivers, join the center of the drumhead to the free end of the receiver spring and arrange a mouthpiece over the drumhead to talk into. His idea was to force the steel spring to follow the vocal vibrations and generate a current of electricity that would vary in intensity as the air varies in density during 16 the utterance of speech sounds. I followed these directions and had the instrument ready for its trial the very next day. I rushed it, for Bell’s excitement and enthusiasm over the discovery had aroused mine again, which had been sadly dampened during those last few weeks by the meagre results of the harmonic experiments. I made every part of that first telephone myself, but I didn’t realize while I was working on it what a tremendously important piece of work I was doing.

The two rooms in the attic were too near together for the test, as our voices would be heard through the air, so I ran a wire especially for the trial from one of the rooms in the attic down two flights to the third floor where Williams’ main shop was, ending it near my work bench at the back of the building. That was the first telephone line. You can well imagine that both our hearts were beating above the normal rate while we were getting ready for the trial of the new instrument that evening. I got more satisfaction from the experiment than Mr. Bell did, for shout my best I could not make him hear me, but I could hear his voice and almost catch the words. I rushed downstairs and told him what I had heard. It was enough to show him that he was on the right track, and before he left that night he gave me directions for several improvements in the telephones I was to have ready for the next trial.

Alexander Graham Bell’s First Telephone

I hope my pride in the fact that I made the first 17 telephone, put up the first telephone wire and heard the first words ever uttered through a telephone, has never been too ostentatious and offensive to my friends, but I am sure that you will grant that a reasonable amount of that human weakness is excusable in me. My pride has been tempered to quite a bearable degree by my realization that the reason why I heard Bell in that first trial of the telephone and he did not hear me, was the vast superiority of his strong vibratory tones over any sound my undeveloped voice was then able to utter. My sense of hearing, however, has always been unusually acute, and that might have helped to determine this result.

The building where these first telephone experiments were made is still in existence. It is now used as a theater. The lower stories have been much altered, but that attic is still quite unchanged and a few weeks ago I stood on the very spot where I snapped those springs and helped test the first telephone thirty-seven years and seven months before.

(Editor’s Note: The old building was finally replaced by new construction in 1931.)

Of course in our struggle to expel the imps from the invention, an immense amount of experimenting had to be done, but it wasn’t many days before we could talk back and forth and hear each other’s voice. It is, however, hard for me to realize now that it was not until the following March that I heard a complete and intelligible sentence. It made such an impression upon me that I wrote that first sentence in a book I have always preserved. The occasion had not been arranged and rehearsed as I suspect the sending of the first message over the Morse telegraph had been years before, for instead of that noble first telegraphic message—“What hath God wrought?” the first message of the telephone was: “Mr. Watson, come here, I want you.” Perhaps, if Mr. Bell had realized that he was about to make a bit of history, he would have been prepared with a more sounding and interesting sentence.

Soon after the first telephones were made, Bell hired two rooms on the top floor of an inexpensive boarding house at No. 5 Exeter Place, Boston, since demolished to make room for mercantile buildings. He slept in one room; the other he fitted up as a laboratory. I ran a wire for him between the two rooms and after that time practically all his experimenting was done there. It was here one evening when I had gone there to help him test some improvement and to spend the night 18 with him, that I heard the first complete sentence I have just told you about. Matters began to move more rapidly, and during the summer of 1876 the telephone was talking so well that one didn’t have to ask the other man to say it over again more than three or four times before one could understand quite well, if the sentences were simple.

This was the year of the Centennial Exposition at Philadelphia, and Bell decided to make an exhibit there. I was still working for Williams, and one of the jobs I did for Bell was to construct a telephone of each form that had been devised up to that time. These were the first nicely finished instruments that had been made. There had been no money nor time to waste on polish or non-essentials. But these Centennial telephones were done up in the highest style of the art. You could see your face in them. These aristocratic telephones worked finely, in spite of their glitter, when Sir William Thompson tried them at Philadelphia that summer. I was as proud as Bell himself, when I read Sir William’s report, wherein he said after giving an account of the tests: “I need hardly say I was astonished and delighted, so were the others who witnessed the experiment and verified with their own ears the electric transmission of speech. This, perhaps, the greatest marvel hitherto achieved by electric telegraph, has been obtained by appliances of quite a homespun and rudimentary character.” I have never forgiven Sir William for that last line. Homespun!

However, I recovered from this blow, and soon after Mr. Gardiner G. Hubbard, afterwards Mr. Bell’s father-in-law, offered me an interest in Bell’s patents if I would give up my work at Williams’ and devote my time to the telephone. I accepted, although I wasn’t altogether sure it was a wise thing to do from a financial standpoint. My contract stipulated that I was to work under Mr. Bell’s directions, on the harmonic telegraph as well as on the speaking telephone, for the two men who were paying the bills still thought there was something in the former invention, although very little attention had been given to its vagaries after the June 2nd discovery.

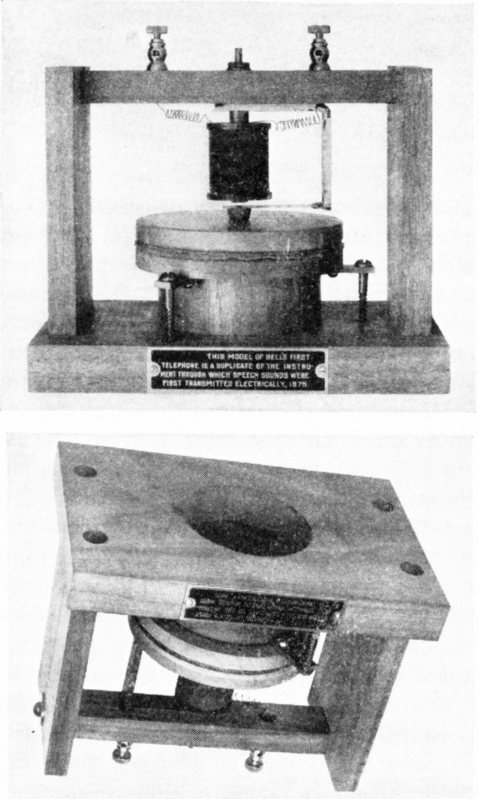

1876 BELL TELEPHONE

Telephone Apparatus Patented in 1876 by Prof. Bell, Models Made from Figure 7

in Bell’s Original Patent

I moved my domicile from Salem to another room on the top floor at 5 Exeter Place, giving us the entire floor, and as Mr. Bell had lost most of his pupils by wasting so much of his time on telephones, he could devote nearly all his time to the experimenting. Then followed a period of hard and continuous work on the invention. I made telephones with every modification and combination of their essential parts that either of us could think of. I made and we tested telephones with all sizes of diaphragms made of all kinds of materials—diaphragms of boiler iron several feet in diameter, down to a miniature affair made of the bones and drum of a human ear, and found that the best results came from an iron diaphragm of about the same size and thickness as is used to-day. We tested electro magnets and permanent magnets of a multitude of sizes and shapes, with long cores and short cores, fat cores and thin cores, solid cores and cores of wire, with coils of many sizes, shapes and resistances, and mouthpieces of an infinite variety. Out of the hundreds of experiments there emerged practically the same telephone you take off the hook and listen with to-day, although it was then transmitter as well as receiver.

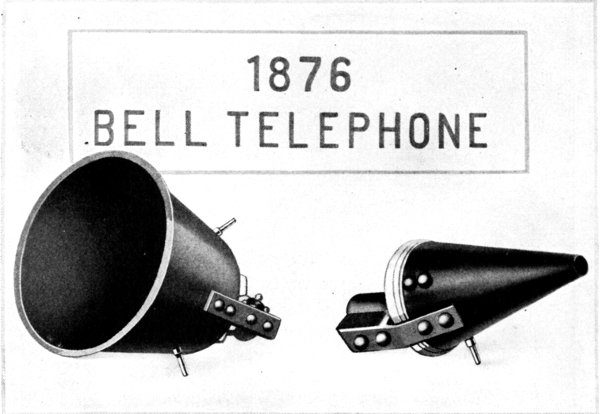

Reprint from the Boston Advertiser describing the Telephone Talk between Boston and Cambridgeport, October 9, 1876

TELEPHONY.

AUDIBLE SPEECH CONVEYED TWO MILES BY TELEGRAPH.

PROFESSOR A. GRAHAM BELL’S DISCOVERY—SUCCESSFUL AND INTERESTING EXPERIMENTS—THE RECORD OF A CONVERSATION CARRIED ON BETWEEN BOSTON AND CAMBRIDGEPORT.

The following account of an experiment made on the evening of October 9 by Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas A. Watson is interesting, as being the record of the first conversation ever carried on by word of mouth over a telegraph wire. Telephones placed at either end of a telegraph line owned by the Walworth Manufacturing Company, extending from their office in Boston to their factory in Cambridgeport, a distance of about two miles. The company’s battery, consisting of nine Daniels cells, was removed from the circuit and another of ten carbon elements substituted. Articulate conversation then took place through the wire. The sounds, at first faint and indistinct, became suddenly quite loud and intelligible. Mr. Bell in Boston and Mr. Watson in Cambridge then took notes of what was said and heard and the comparison of the two records is most interesting, as showing the accuracy of the electrical transmission:—

BOSTON RECORD.

Mr. Bell—What do you think was the matter with the instruments?

Mr. Watson—There was nothing the matter with

CAMBRIDGEPORT RECORD.

Mr. Bell—What do you think is the matter with the instruments?

Mr. Watson—There is nothing the matter with them.

Progress was rapid, and on October 9, 1876, we were ready to take the baby outdoors for the first time. We got permission from the Walworth Manufacturing Company to use their private wire running from Boston to Cambridge, about two miles long. I went to Cambridge that evening with one of our best telephones, and waited until Bell signalled from the Boston office on the Morse sounder. Then I 21 cut out the sounder and connected in the telephone and listened. Not a murmur came through! Could it be that, although the thing worked all right in the house, it wouldn’t work under practical line conditions? I knew that we were using the most complex and delicate electric current that had ever been employed for a practical purpose and that it was extremely “intense,” for Bell had talked through a circuit composed of 20 or 30 human beings joined hand to hand. Could it be, I thought, that these high tension vibrations leaking off at each insulator along the line, had vanished completely before they reached the Charles River? That fear passed through my mind as I worked over the instrument, adjusting it and tightening the wires in the binding posts, without improving matters in the least. Then the thought struck me that perhaps there was another Morse sounder in some other room. I traced the wires from the place they entered the building and sure enough I found a relay with a high resistance coil in the circuit. I cut it out with a piece of wire across the binding posts and rushed back to my telephone and listened. That was the trouble. Plainly as one could wish came Bell’s “ahoy,” “ahoy!”[1] I ahoyed back, and the first long distance telephone conversation began. Skeptics had been objecting that the telephone could never compete with the telegraph as its messages would not be accurate. For this reason Bell had arranged that we should make a record of all we said and heard that night, if we succeeded in talking at all. We carried out this plan and the entire conversation was published in parallel columns in the next morning’s Advertiser, as the latest startling scientific achievement. Infatuated with the joy of talking over an actual telegraph wire, we kept up our conversation until long after midnight. It was a very happy boy that traveled back to Boston in the small hours with the telephone under his arm done up in a newspaper. Bell had taken his record to the newspaper office and was not at the laboratory when I arrived there, but when he came in there ensued a jubilation and war dance that elicited next morning from our landlady, who wasn’t at all scientific in her tastes, the remark that we’d have to vacate if we didn’t make less noise nights.

Tests on still longer telegraph lines soon followed—the success of each experiment being in rather exact accordance with the condition of the poor, rusty-joined wires we had to use. Talk about imps that baffle inventors! There was one of an especially vicious and malignant type in every unsoldered joint of the old wires. The genial Tom Doolittle hadn’t even thought of his hard-drawn copper wire then, with which he later eased the lot of the struggling telephone men.

Meanwhile the fame of the invention had spread rapidly abroad and all sorts of people made pilgrimages to Bell’s laboratory to hear the telephone talk. A list of the scientists who came to the attic of that cheap boarding house to see the telephone would read like the roster of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. My old electrical mentor, Moses G. Farmer, called one day to see the latest improvements. He told me then with tears in his eyes when he first read a description of Bell’s telephone he couldn’t sleep for a week, he was so mad with himself for not discovering the thing years before. “Watson,” said he, “that thing has flaunted itself in my very face a dozen times within the last ten years and every time I was too blind to see it. But,” he continued, “if Bell had known anything about electricity he would never have invented the telephone.”

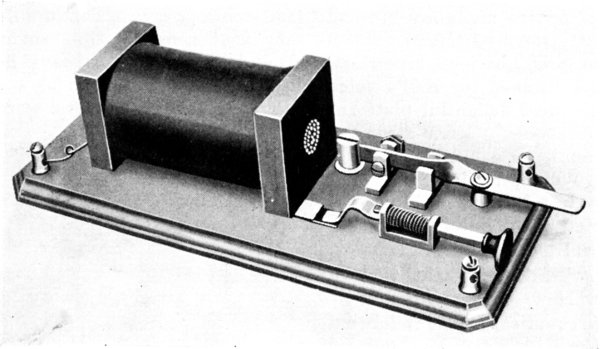

Prof. Bell’s Original Centennial Magneto Transmitter

Two of our regular visitors were young Japanese pupils of Professor Bell—very polite, deferential, quiet, bright-eyed little men, who saw everything and made cryptic notes. They took huge delight in proving that the telephone could talk Japanese. A curious effect of the telephone I noticed at that time was its power to paralyze the tongues of men otherwise fluent enough by nature and profession. I remember a prominent lawyer who, when he heard my voice in the telephone making some such profound remark to him as “How do you do?” could only reply, after a long pause, “Rig a jig jig and away we go.”

Men of quite another sort came occasionally. Mr. Hubbard received a letter one day from a man who wrote that he could put us on the track of a secret that would enable us to talk any distance without a wire. This interested Mr. Hubbard and he made an appointment for the man to meet me. At the appointed time, a stout, rather unkempt man made his appearance. He didn’t take the least interest in the telephone; he said that was already a back number, and if we 23 would hire him for a small sum per week we would soon learn how to telephone without any apparatus or any wires. He went on to tell in a most convincing way how two prominent theatrical men in New York, whom he had never seen, had got his brain so connected into their circuit that they could talk with him at any time, day or night, and make all sorts of fiendish suggestions to him. He didn’t know yet how they did it, but he was sure I could find out their secret, if I would just take the top off his head and examine his brain. It dawned on me then that I was dealing with an insane man. I got rid of him as soon as I could by promising to experiment on him when I could find time. The next I heard of the poor fellow he was in the violent ward of an insane asylum. Several similar cases of insanity attracted by the fame of Bell’s occult (!) invention called on us or wrote to us within a year of that time.

Prof. Bell’s Original Centennial Receiver

We began to get requests for telephone installations long before we were ready to supply them. In April, 1877, the first outdoor telephone line was run between Mr. Williams’ office at 109 Court Street and his house in Somerville. Professor Bell and I were present and participated in the important ceremony of opening the line and the event was a headliner in the next morning’s papers.

At about this time Professor Bell’s financial problems had begun to press hard for solution. We were very much disappointed because the President of the Western Union Telegraph Company had refused, somewhat contemptuously, Mr. Hubbard’s offer to sell him all the Bell patents for the exorbitant sum of $100,000. It was an especially hard blow to me, for while the negotiations were pending I had had visions of a sumptuous office in the Western Union Building in New York, which I was expecting to occupy as Superintendent of the Telephone Department of the great telegraph company. However, we 24 recovered even from that facer. Two years later the Western Union would gladly have bought those patents for $25,000,000.

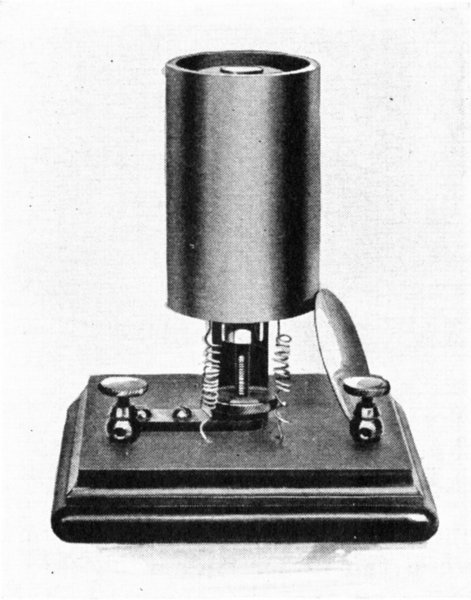

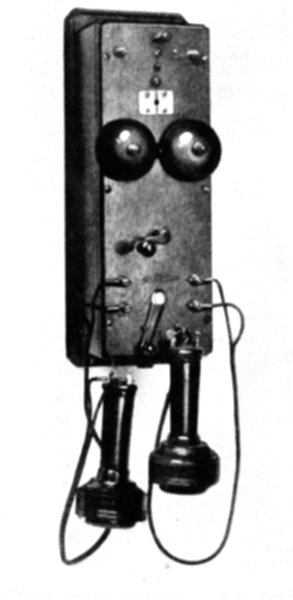

Original Box Telephone Introduced Commercially in 1877

But before that happy time there were lots of troubles of all the old and of several new varieties to be surmounted. Professor Bell’s particular trouble in the spring of 1877 arose from the fact that he had fallen in love with a most charming young lady. I had never been in love myself at that time and that was my first opportunity of observing what a serious matter it can be, especially when the father isn’t altogether enthusiastic. I rather suspected at that time that that shrewd but kind-hearted gentleman put obstacles in the course of that true love, in order to stimulate the young man to still greater exertion in perfecting his inventions. But he might have thought as Prospero did:

“They are both in either’s power; but this swift business

I must uneasy make, lest too light winning

Make the prize light.”

Bell’s immediate financial needs were solved, however, by the demand that began at this time for public lectures by him on the telephone. It is hard to realize to-day what an intense and widespread interest there was then in the telephone. I don’t believe any new invention could stir the public to-day as the telephone did then, surfeited as we are now with the wonderful things that have been invented since.

These lectures are important for another reason than that they solved a temporary money problem. They obviated the necessity of selling telephones outright, instead of leasing them so as to retain control—a policy Mr. Hubbard afterwards adopted which made possible the splendid universal service Mr. Vail with your help has given the Bell system to-day. Some of the ladies deeply interested in the immediate outcome were strenuously advocating at this critical juncture making and selling the telephones at once in the largest possible 25 quantities—imperfect as they were. Fortunately, for the future of the business the returns from the lectures that began at this very time obviated this danger.

Bell’s first lecture, as I have said, was given before a well-known scientific society—the Essex Institute—at Salem, Mass. They were especially interested in the telephone because Bell was living in Salem during the early telephone experiments. The first lecture was free to members of the society, but it packed the hall and created so much interest that Bell was requested to repeat it for an admission fee. This he did to an audience that again filled the house. Requests for lectures poured in upon Bell after that. Such men as Oliver Wendell Holmes and Henry W. Longfellow signed the request for the Boston lectures. The Salem lectures were soon followed by a lecture in Providence to an audience of 2,000, by a course of three lectures at the largest hall in Boston—all three packed—by three in Chickering Hall, New York, and by others in most of the large cities of New England. They all took place in the spring and early summer of 1877, during which time there was little opportunity for experimenting for either Bell or myself, which I think now was rather a good thing, for we had become quite stale and needed a change that would give us a new influx of ideas. My part in the lectures was important, although entirely invisible as far as the audience was concerned. I was always at the other end of the wire, generating and transmitting to the hall where Professor Bell was speaking, such telephonic phenomena as he needed to illustrate his lectures. I would have at my end circuit breakers—rheotomes, we called them—that would utter electric howls of various pitches, a lusty cornet player, sometimes a small brass band, and an electric organ with Edward Wilson to play on it, but the star performer was the young man who two years before didn’t have voice enough to let Bell hear his own telephone, but in whom that two years of strenuous shouting into mouthpieces of various sizes and shapes had developed a voice with the carrying capacity of a steam calliope. My special function in these lectures was to show the audience that the telephone could really talk. Not only that, I had to do all the singing, too, for which my musical deficiencies fitted me admirably.

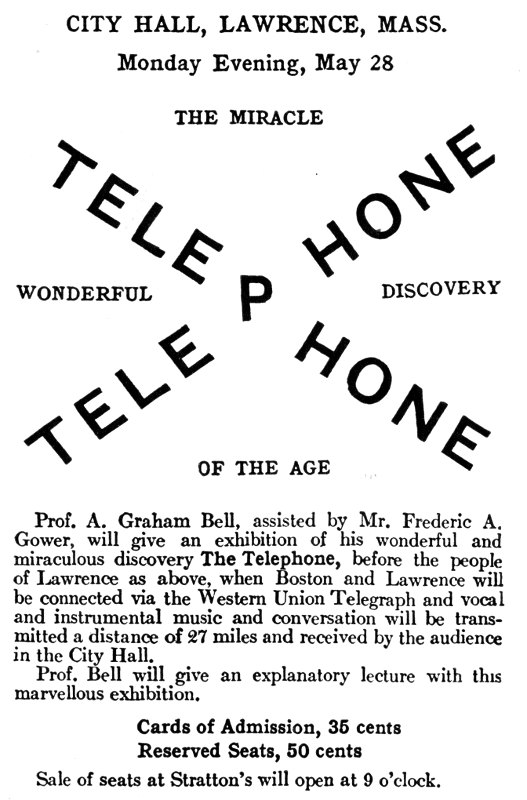

Facsimile of Flier Advertising Prof. Bell’s Lecture at Lawrence, Mass., Monday Evening, May 28, 1877

CITY HALL, LAWRENCE, MASS.

Monday Evening, May 28

THE MIRACLE

TELEPHONE

WONDERFUL DISCOVERY

OF THE AGE

Prof. A. Graham Bell, assisted by Mr. Frederic A. Gower, will give an exhibition of his wonderful and miraculous discovery The Telephone, before the people of Lawrence as above, when Boston and Lawrence will be connected via the Western Union Telegraph and vocal and instrumental music and conversation will be transmitted a distance of 27 miles and received by the audience in the City Hall.

Prof. Bell will give an explanatory lecture with this marvellous exhibition.

Cards of Admission, 35 cents

Reserved Seats, 50 cents

Sale of seats at Stratton’s will open at 9 o’clock.

Professor Bell would have one telephone by his side on the stage, where he was speaking, and three or four others of the big box variety we used at that time would be suspended about the hall, all connected by means of a hired telegraph wire with the place where I was stationed, from five to twenty-five miles away. Bell would give the audience, first, the commonplace parts of the show and then would 27 come the thrillers of the evening—my shouts and songs. I would shout such sentences as, “How do you do?” “Good evening,” “What do you think of the telephone?” which they could all hear, although the words issued from the mouthpieces rather badly marred by the defective talking powers of the telephones of that date. Then I would sing “Hold the Fort,” “Pull for the Shore,” “Yankee Doodle,” and as a delicate allusion to the Professor’s nationality, “Auld Lang Syne.” My sole sentimental song was “Do Not Trust Him, Gentle Lady.” This repertoire always brought down the house. After every song I would listen at my telephone for further directions from the lecturer, and always felt the artist’s joy when I heard in it the long applause that followed each of my efforts. I was always encored to the limit of my repertoire and sometimes had to sing it through twice.

I have always understood that Professor Bell was a fine platform speaker, but this is entirely hearsay on my part for, although I spoke at every one of his lectures, I have never yet had the pleasure of hearing him deliver an address.

In making the preparations for the New York lectures I incidentally invented the sound-proof booth, but as Mr. Lockwood was not then associated with us, and for other reasons, I never patented it. It happened thus: Bell thought he would like to astonish the New Yorkers by having his lecture illustrations sent all the way from Boston. To determine whether this was practicable, he made arrangements to test the telephone a few days before on one of the Atlantic and Pacific wires. The trial was to take place at midnight. Bell was at the New York end, I was in the Boston laboratory. Having vividly in mind the strained relations already existing with our landlady, and realizing the carrying power of my voice when I really let it go, as I knew I should have to that night, I cast about for some device to deaden the noise. Time was short and appliances scarce, so the best I could do was to take the blankets off our beds and arrange them in a sort of loose tunnel, with the telephone tied up in one end and the other end open for the operator to crawl into. Thus equipped I awaited the signal from New York announcing that Bell was ready. It came soon after midnight. Then I connected in the telephone, deposited myself in that cavity, and shouted and listened for two or three hours. It didn’t work as well as it might. It is a wonder some of my remarks didn’t burn holes in the blankets. We talked after a fashion but Bell decided it wasn’t safe to risk it with a New York audience. My sound-proof booth, however, was a 28 complete success, as far as stopping the sound was concerned, for I found by cautious inquiry next day that nobody had heard my row. Later inventors improved my booth, making it more comfortable for a pampered public but not a bit more sound-proof.

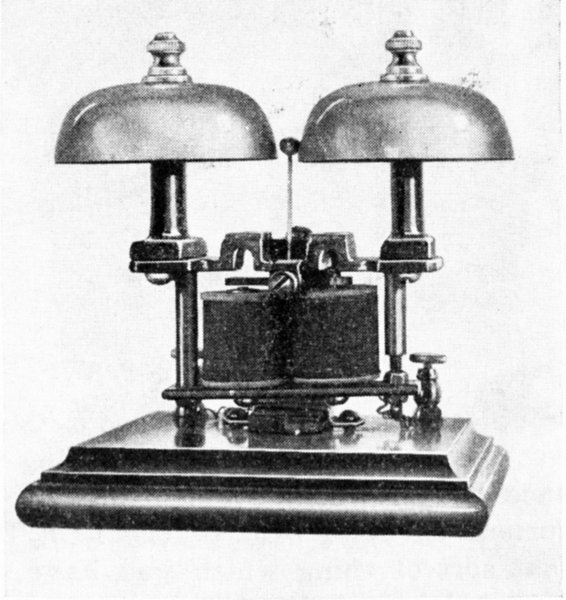

Box Telephone with Watson Hammer Signal

Watson Type of Ringer

One of those New York lectures looms large in my memory on account of a novel experience I had at my end of the wire. After hearing me sing, the manager of the lectures decided that while I might satisfy a Boston audience I would never do for a New York congregation, so he engaged a fine baritone soloist—a powerful negro, who was to assume the singing part of my program. Being much better acquainted with the telephone than that manager was, I had doubts about the advisability of this change in the cast. I didn’t say anything, as I didn’t want to be accused of professional jealousy, and I knew my repertoire would be on the spot in case things went wrong. I was stationed that night at the telegraph office at New Brunswick, New Jersey, and I and the rest of the usual appliances of that end of the lecture went down in the afternoon to get things ready. I rehearsed my rival and found him a fine singer, but had difficulty in getting him to crowd his lips into the mouthpiece. He was handicapped for the telephone business by being musical, and he didn’t like the sound of his voice jammed up in that way. However, he 29 promised to do what I wanted when it came to the actual work of the evening, and I went to supper. When I returned to the telegraph office, just before eight o’clock, I found to my horror that the young lady operator had invited six or eight of her dear friends to witness the interesting proceedings. Now, besides my musical deficiencies, I had another qualification as a telephone man—I was very modest; in fact, in the presence of ladies, extremely bashful. It didn’t trouble me in the least to talk or sing to a great audience, provided, of course, it was a few miles away, but when I saw those girls, the complacency with which I had been contemplating the probable failure of my fine singer was changed to painful apprehension. If he wasn’t successful a very bashful young man would have a new experience. I should be obliged to sing myself before those giggling, unscientific girls. This world would be a better place to live in if we all tried to help our fellow-men succeed, as I tried that night, when the first song was called for, to make my musical friend achieve a lyrical triumph on the Metropolitan stage. But he sang that song for the benefit of those girls, not for Chickering Hall, and it was with a heavy heart that I listened for Bell’s voice when he finished it. The blow fell. In his most delightful platform tones, Bell uttered the fatal words I had foreboded, “Mr. Watson, the audience could not hear that. Won’t you please sing?” Bell was always a kind-hearted man, but he didn’t know. However, I nerved myself with the thought that that New York audience, made skeptical by the failure of that song, might be thinking cynical things about my beloved leader and his telephone, so I turned my back on those girls and made that telephone rattle with the stirring strains of “Hold the Fort,” as it never had before. Then I listened again. Ah, the sweetness of appreciation! That New York audience was applauding vigorously. When it stopped, the same voice came with a new note of triumph in it. “Mr. Watson, the audience heard that perfectly and 30 call for an encore.” I sang through my entire repertoire and began again on “Hold the Fort,” before that audience was satisfied. That experience did me good, I have never had stage fright since. But the “supposititious Mr. Watson,” as they called me then, had to do the singing at all of Bell’s subsequent lectures. Nobody else had a chance at the job; one experience was enough for Mr. Bell.

My baritone had his hat on his head and a cynical expression on his face, when I finished working on those songs. “Is that what you wanted?” he asked. “Yes.” “Well, boss, I couldn’t do that.” Of course he couldn’t.

Another occasion is burnt into my memory that wasn’t such a triumph over difficulties. In these lectures we always had another trouble to contend with, besides the rusty joints in the wires; that was the operators cutting in, during the lectures, their highest resistance relays, which enabled them to hear some of the intermittent current effects I sent to the hall. Inductance, retardation, and all that sort of thing which you have so largely conquered since were invented long before the telephone was, and were awaiting her on earth all ready to slam it when Bell came along. Bell lectured at Lawrence, Massachusetts, one evening in May, and I prepared to furnish him with the usual program from the laboratory in Boston.

Watson’s “Buzzer”

But the wire the company assigned us was the worst yet. It worked 31 fairly well when we tried it in the afternoon, but in the evening every station on the line had evidently cut in its relay, and do my best I couldn’t get a sound through to the hall.

The local newspaper generally sent a reporter to my end of the wire to write up the occurrences there. This is the report of such an envoy as it appeared in the Lawrence paper the morning after Bell’s lecture there:

“Mr. Fisher returned this morning. He says that Watson, the organist and himself occupied the laboratory, sitting in their shirt sleeves with their collars off. Watson shouted his lungs into the telephone mouthpiece, ‘Hoy! Hoy! Hoy!’ and receiving no response, inquired of Fisher if he pardoned for a little ‘hamburg edging’ on his language. Mr. Fisher endeavored to transmit to his Lawrence townsman the tune of ‘Federal Street’ played upon the cornet, but the air was not distinguishable here. About 10 P.M., Watson discovered the ‘Northern Lights’ and found his wires alive with lightning, which was not included in the original scheme of the telephone. He says the loose electricity abroad in the world was too much for him.”

The next morning a poem appeared in the Lawrence paper. The writer must have sat up all night to write it. It was entitled “Waiting for Watson,” and as I am very proud of the only poem I ever had written about me, I am going to ask your permission to read it. Please notice the great variety of human feeling the poet put into it. It even suggests missiles, though it flings none.

Lawrence, Mass., Daily American, Tuesday, May 29, 1877.

To the great hall we strayed,

Fairly our fee we paid,

Seven hundred there delayed,

But, where was Watson?

Was he out on his beer?

Walked he off on his ear?

Something was wrong, ’tis clear.

What was it, Watson?

Seven hundred souls were there,

Waiting with stony stare,

In that expectant air—

Waiting for Watson.

Oh, how our ears we strained,

How our hopes waxed and waned,

Patience to dregs we drained,

Yes, we did, Watson!

Softly the bandmen played,

Rumbled the Night Brigade,

For this our stamps we paid,

Only this, Watson!

But, Hope’s by fruitage fed,

Promise and Act should wed,

Faith without works is dead,

Is it not, Watson?

Give but one lusty groan,

For bread we’ll take a stone,

Ring your old telephone!

Ring, brother Watson.

Doubtless ’tis very fine,

When, all along the line,

Things work most superfine—

Doubtless ’tis Watson.

Let’s hear the thrills and thrums,

That your skilled digit drums,

Striking our tympanums—

Music from Watson.

We know that, every day,

Schemes laid to work and pay,

Fail and “gang aft a-gley”—

Often, friend Watson.

And we’ll not curse, or fling,

But, next time, do the thing

And we’ll all rise and sing,

“Bully for Watson!”

Or, by the unseen powers,

Hope in our bosom sours,

No telephone in ours—

“Please, Mr. Watson.”

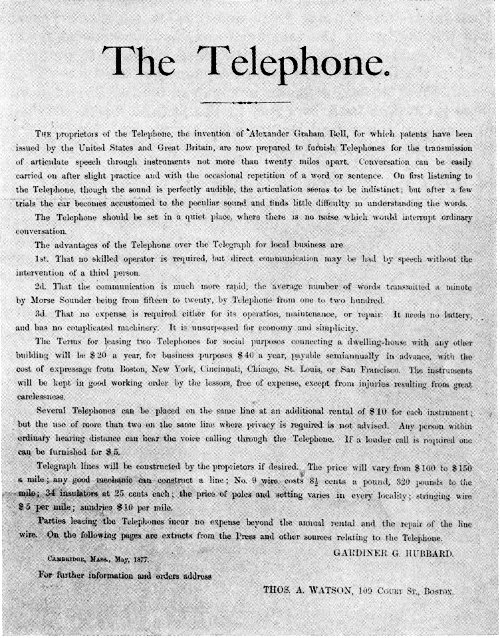

The First Telephone Advertisement, Used the Year Following the Issuance of the Original Patent, Offered to Furnish Telephones “for the Transmission of Articulate Speech Through Instruments Not More Than Twenty Miles Apart.”

The Telephone.

The proprietors of the Telephone, the invention of Alexander Graham Bell, for which patents have been issued by the United States and Great Britain, are now prepared to furnish Telephones for the transmission of articulate speech through instruments not more than twenty miles apart. Conversation can be easily carried on after slight practice and with the occasional repetition of a word or sentence. On first listening to the Telephone, though the sound is perfectly audible, the articulation seems to be indistinct; but after a few trials the ear becomes accustomed to the peculiar sound and finds little difficulty in understanding the words.

The Telephone should be set in a quiet place, where there is no noise which would interrupt ordinary conversation.

The advantages of the Telephone over the Telegraph for local business are

1st. That no skilled operator is required, but direct communication may be had by speech without the intervention of a third person.

2d. That the communication is much more rapid, the average number of words transmitted a minute by Morse Sounder being from fifteen to twenty, by Telephone from one to two hundred.

3d. That no expense is required either for its operation, maintenance, or repair. It needs no battery, and has no complicated machinery. It is unsurpassed for economy and simplicity.

The Terms for leasing two Telephones for social purposes connecting a dwelling-house with any other building will be $20 a year, for business purposes $40 a year, payable semiannually in advance, with the cost of expressage from Boston, New York, Cincinnati, Chicago, St. Louis, or San Francisco. The instruments will be kept in good working order by the lessors, free of expense, except from injuries resulting from great carelessness.

Several Telephones can be placed on the same line at an additional rental of $10 for each instrument; but the use of more than two on the some line where privacy is required is not advised. Any person within ordinary hearing distance can hear the voice calling through the Telephone. If a louder call is required one can be furnished for $5.

Telegraph lines will be constructed by the proprietors if desired. The price will vary from $100 to $150 a mile; any good mechanic can construct a line; No. 9 wire costs 8½ cents a pound, 320 pounds to the mile; 34 insulators at 25 cents each; the price of poles and setting varies in every locality; stringing wire $5 per mile; sundries $10 per mile.

Parties leasing the Telephones incur no expense beyond the annual rental and the repair of the line wire. On the following pages are extracts from the Press and other sources relating to the Telephone.

GARDINER G. HUBBARD.

Cambridge, Mass., May, 1877.

For further information and orders address

THOS. A. WATSON, 109 Court St., Boston.

But my vacation was about over. Besides raising the wind, the lectures had stirred up a great demand for telephone lines. The public was ready for the telephone long before we were ready for the public, and this pleasant artistic interlude had to stop; I was needed in the shop to build some telephones to satisfy the insistent demand. Fred Gower, a young newspaper man of Providence, had become interested with Mr. Bell in the lecture work. He had an unique scheme for a dual lecture with my illustrations sent from a central point to halls in two cities at the same time. I think my last appearance in public was one of these dualities. Bell lectured at New Haven and Gower gave the talk at Hartford, while I was in between at Middletown, Conn., with my apparatus, including my songs. It didn’t work very well. The two lecturers didn’t speak synchronously. Gower told me afterwards that I was giving him, “How do you do,” when he wanted “Hold the Fort,” and Bell said I made it awkward for him by singing “Do Not Trust Him, Gentle Lady,” when he needed the trombone solo.

In the following August, Professor Bell married and went to England, taking with him a complete set of up-to-date telephones, with which he intended to start the trouble in that country. Fred Gower became so fascinated with lecturing on the telephone that he gave up an exclusive right Mr. Hubbard had granted him for renting telephones all over New England, for the exclusive privilege of using the telephone for lecture purposes all over the United States. But it wasn’t remunerative after Bell and I gave it up. The discriminating public preferred Mr. Bell as speaker—and I always felt that the singing never reached the early heights.

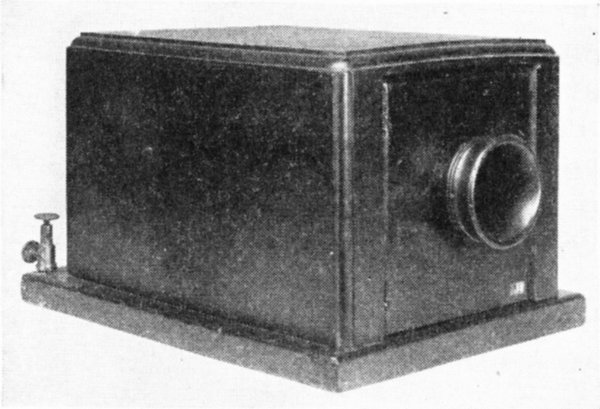

Magneto Wall Set (Williams’ Coffin)

Gower went to England later. There he made some small modification of Bell’s telephone, called it the “Gower-Bell” telephone, and made a fortune out of his hyphenated atrocity. Later he married Lillian Nordica, although she soon separated from him. He became interested in ballooning. The last scene in his life before the curtain dropped showed a balloon over the waters of the English Channel. A fishing boat hails him, “Where are you bound?” Gower’s voice replies, “To London.” Then the balloon and its pilot drifted into the mist forever.

Francis Blake

As I said, I went back to work, and my next two years was a continuous performance. It began to dawn on us that people engaged in getting their living in the ordinary walks of life couldn’t be expected to keep the telephone at their ear all the time waiting for a call, especially as it weighed about ten pounds then and was as big as a small packing case, so it devolved on me to get up some sort of a call signal. Williams on his line used to call by thumping the diaphragm through the mouthpiece with the butt of a lead pencil. If there was someone close to the telephone at the other end, and it was very still, it did pretty well, but it seriously damaged the vitals of the machine and therefore I decided it wasn’t really practical for the general public; besides, we might have to supply a pencil with every telephone and that would be expensive. Then I rigged a little hammer inside the box with a button on the outside. When the button was thumped the hammer would hit the side of the diaphragm where it could not be 36 damaged, the usual electrical transformation took place, and a much more modest but still unmistakable thump would issue from the telephone at the other end.

That was the first calling apparatus ever devised for use with the telephone, not counting Williams’ lead pencil, and several with that attachment were put into practical use. But the exacting public wanted something better, and I devised the Watson “Buzzer”—the only practical use we ever made of the harmonic telegraph relics. Many of these were sent out. It was a vast improvement on the Watson “Thumper,” but still it didn’t take the popular fancy. It made a sound quite like the horseradish grater automobile signal we are so familiar with nowadays, and aroused just the same feeling of resentment which that does. It brought me only a fleeting fame for I soon superseded it by a magneto-electric call bell that solved the problem, and was destined to make a long-suffering public turn cranks for the next fifteen years or so, as it never had before, or ever will hereafter.

The Blake Transmitter

Perhaps I didn’t have any trouble with the plaguy thing! The generator part of it was only an adaptation of a magneto shocking machine I found in Davis’ Manual of Magnetism and worked well enough, but I was guilty of the jingling part of it. At any rate, I felt guilty when letters began to come from our agents reciting their woes with the thing, which they said had a trick of sticking and failing on the most important occasions to tinkle in response to the frantic crankings of the man who wanted you. But I soon got it so it behaved itself and it has been good ever since, for Chief Engineer Carty told me the other day that nothing better has ever been invented, that they have been manufactured by the millions all over the world, and that identical jingler to-day does practically all the world’s telephone calling.

For some reason, my usual good luck I presume, the magneto call bells didn’t get my name attached to them. I never regretted this, for the agents, who bought them from Williams, impressed by the long and narrow box in which the mechanism was placed, promptly christened them “Williams’ Coffins.” I always thought that a narrow escape for me!

The first few hundreds of these call bells were a continuous shock to me for other reasons than their failure to respond. I used on them a switch, that had to be thrown one way by hand, when the telephone was being used, and then thrown back by hand to put the bell in circuit again. But the average man or woman wouldn’t do this more than half the time, and I was obliged to try a series of devices, which culminated in that remarkable achievement of the human brain—the automatic switch—that only demanded of the public that it should hang up the telephone after it got through talking. This the public learned to do quite well after a few years of practice.

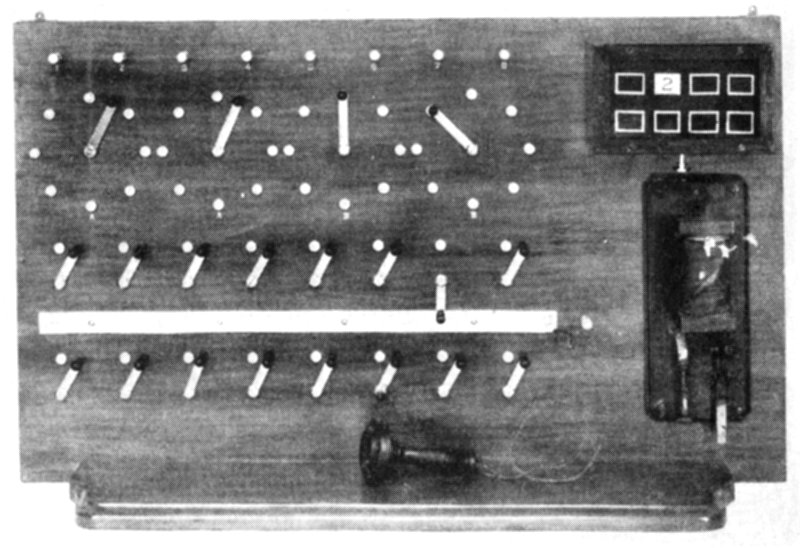

The First Commercial Telephone Switchboard, Used in New Haven, Conn., in 1878 with Eight Lines and Twenty-one Subscribers

You wouldn’t believe me if I should tell you a tithe of the difficulties we got into by flexible cords breaking inside the covering, when we first began to use hand telephones!

Then they began to clamor for switchboards for the first centrals, and individual call bells began to keep me awake nights. The latter were very important then, for such luxuries as one station lines were scarce. Six to twenty stations on a wire was the rule, and we were trying hard to get a signal that would call one station without disturbing the whole town. All of these and many other things had to be done at once, and, as if this was not enough, it suddenly became necessary for me to devise a battery transmitter. The Western Union people had discovered that the telephone was not such a toy as they had thought, and as our $100,000 offer was no longer open for acceptance, they decided to get a share of the business for themselves, and Edison evolved for them his carbon-button transmitter. This was the hardest blow yet.

Theodore N. Vail in 1878

We were still using the magneto transmitter, although Bell’s patent clearly covered the battery transmitter. Our transmitter was doing much to develop the American voice and lungs, making them powerful but not melodious. This was, by the way, the telephone epoch when they used to say that all the farmers waiting in a country grocery would rush out and hold their horses when they saw any one preparing to use the telephone. Edison’s transmitter talked louder than the magnetos we were using and our agents began to clamor for them, and I had to work nights to get up something just as good. Fortunately for my constitution, Frank Blake came along with his transmitter. We bought it and I got a little sleep for a few days. Then our little David of a corporation sued that big Goliath, the Western Union Company, for infringing the Bell patents, and I had to devote my leisure to testifying in that suit, and making reproductions of the earliest apparatus to prove to the court that they would 39 really talk and were not a bluff, as our opponents were asserting.

Then I put in the rest of my leisure making trips among our agents this side of the Mississippi to bring them up to date and see what the enemy were up to. I kept a diary of those trips. It reads rather funnily to-day, but I won’t go into that. It would detract from the seriousness of this discourse.

Nor must I forget an occasional diversion in the way of a sleet storm which, combining with our wires then beginning to fill the air with house top lines and pole lines along the sidewalks, would make things extremely interesting for all concerned. I don’t remember ever going out to erect new poles and run wires after such a catastrophe. I think I must have done so, but such a trifling matter naturally would have made but little impression upon me.

Is it any wonder that my memory of those two years seems like a combination of the Balkan war, the rush hours on the subway and a panic on the stock market?

Location of the First Telephone Switchboard in Boston—Holmes Burglar Alarm Building

I was always glad I was not treasurer of the company, although I filled about all the other offices during those two years. Tom Sanders was our treasurer, and a mighty good one he made. Had it not been for his pluck and optimism, we might all of us have failed to attain the prosperity that came to us later. The preparation of this paper has aroused in me many delightful memories, but with them have been mixed sad thoughts, too, for friends who have gone. Jovial Tom Sanders! How everybody loved him! No matter how discouraging the outlook 40 was the skies cleared whenever he came into the shop. I can hear his ringing laugh now!

It was a red-letter day for me when he hired the first bookkeeper the telephone business ever had—the keen, energetic, systematic Robert W. Devonshire. You must not forget “Dev.” I never shall, for after he came I didn’t have to keep the list of telephone leases in my head any more.

Then Thomas D. Lockwood was hired to take part of my engineering load, but he developed such an extraordinary faculty for comprehending the intricacies of patents and patent law, that our lawyers captured him very soon, and kept him at work until he practically captured their job. And how proud I was when the company could afford the extravagance of a clerk for me. He is still working for the company—Mr. George W. Pierce.

I suppose I did have some fun during this time, but the only diversion that lingers in my mind is arranging telephones in a diver’s helmet for the first time, and finding that the diver could not hear when he was under water, going down myself to see what the matter was. I still feel the pathos of the moment, when, arrayed for the descent, just before I disappeared beneath the limpid waters of Boston harbor, my usually undemonstrative assistant put his arm around my inflated neck and kissed me on the glass plate.

But matters soon began to straighten out—the clouds gradually cleared away. The Western Union tornado ceased to rage, and David found to his delight that he had hit Goliath squarely in the forehead with a rock labelled Patent No. 174465. Then for the first time stock in the Bell Company began to be worth something on the stock market.

Wooden Hand Telephone Used Commercially in 1877. It Resembles the Present Desk Telephone Receiver

Something else happened about that time fully as important. The Company awoke to the fact that the Watson generator was overloaded, 41 and that it ought to get a new dynamo. Watson could still hold up the engineering end perhaps, but we must have a business manager. President Hubbard said he knew just the man for us—a thousand horsepower steam engine wasting his abilities in the United States Railway Mail Service, and he sent me down to Washington to investigate and report.

I must have been impressed, for I telegraphed to Mr. Hubbard to hire the man if he could raise money enough to pay his salary. He did so. This was one of the best things I ever helped to do. When the new manager came to work a short time later, he said to me: “Watson, I want my desk alongside of yours for a few months until I learn the ropes.” But the balance of the conceit that previous two years had not knocked out of me vanished, when in about a fortnight, I found he knew all I had learned, and that at the end of a month I was toddling along in the rear trying to catch up, which I never did. He has still quite an important position in the business. His name is Theodore N. Vail. May his light never dim for many and many a year!

(Editor’s Note: Mr. Vail died Apr. 16, 1920.)

The needs of the new business attracted other men with good ideas who entered our service, such men as Emile Berliner and George L. Anders and many others. Every agency became a center of inventive activity, each with its special group of ingenious, thinking men—every one of whom contributed something, and sometimes a great deal to the improvement of apparatus or methods. I remember particularly Ed. Gilliland, of Indianapolis, an ingenious man and excellent mechanic, who improved the generator of my magneto call bell, shortening the box and making it less funereal.

He did much also for central office switchboards.

This was the beginning of the great wave of telephonic activity, not only in electrical and mechanical invention, but also in business and operative organization, which has been increasing in its force ever since, to which men in this audience have made and are making splendid contributions. To-day that wave has become a mighty flood on which the great Bell system floats majestically as it moves ever onward to new achievements.

My connection with the telephone business ceased in 1881. The strenuous years I had passed through had fixed in me a habit of not 42 sleeping nights as much as I should, and a doctor man told me I would better go abroad for a year or two for a change. There was not the least need of this, but as it coincided exactly with my desires, and as the telephone business had become, I thought, merely a matter of routine, with nothing more to do except pay dividends and fight infringers, I resigned my position as General Inspector of the Company, and went over the ocean for the first time.

When I returned to this country a year or so later, I found the telephone business had not suffered in the least from my absence, but there were so many better men doing the work that I had been doing, that I didn’t care to go into it again.

I was looking for more trouble in life and so I went into shipbuilding, where I found all I needed.

Before Mr. Bell went to England on his bridal trip, we agreed that as soon as the telephone became a matter of routine business he and I would begin experimenting on flying machines, on which subject he was full of ideas at that early time. I never carried out this agreement. Bell did some notable work on airships later, but I turned my attention to battleships.

Such is my very inadequate story of the earliest days of the telephone so far as they made part of my life. To-day when I go into a central office or talk over a long distance wire or read the annual report of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, filled with figures up in the millions and even billions, when I think of the growth of the business, and the marvelous improvements that have been made since the day I left it, thinking there was nothing more to do but routine, I must say that all that early work I have told you about seems to shrink into a very small measure, and, proud as I always shall be, that I had the opportunity of doing some of that earliest work myself, my greatest pride is that I am one of the great army of telephone men, every one of whom has played his part in making the Bell Telephone service what it is to-day.

I thank you.

| 1847, | March 3—Birth of Alexander Graham Bell at Edinburgh, Scotland. |

| 1854, | January 18—Birth of Thomas A. Watson at Salem, Mass. |

| 1870, | August 1—Bell moves to America with his parents, arriving in Canada on this date, and settling at Brantford, Ontario. |

| 1872, | October 1—Permanent residence in the United States taken up by Bell at 35 West Newton Street, Boston. |

| 1875, | February 27—Written agreement between Bell, Sanders, and Hubbard forming “Bell Patent Association” to promote inventor’s work in telegraph field. |

| June 2—Bell completes the invention of the Telephone, electrically transmitting overtones for the first time and verifying his principle of the electrical transmission of speech at 109 Court Street, Boston. | |

| June 3—First telephone instrument constructed by Watson according to Bell’s specifications. | |

| September—Bell at Brantford begins writing specifications for a telephone patent. | |

| 1876, | February 14—Application for telephone patent filed with U. S. Patent Office, Washington, D. C. |

| March 7—U. S. Patent 174,465 issued to Bell, covering fundamental principles of the Electric Speaking Telephone. | |

| March 10—First complete sentence transmitted by telephone by Bell to Watson, “Mr. Watson, come here; I want you.” Between two rooms at 5 Exeter Place, Boston. | |

| June 25—Bell exhibits his Telephone to the Judges of the Centennial Exhibition at Philadelphia, on which he is awarded the Exhibition’s medal. | |

| August 10—Experimental one-way talk—8 miles, Brantford to Paris, Ontario. | |

| September 1—Contract with Thomas A. Watson for one-half his time—the beginning of telephone research laboratories. | |

| October 9—First experimental two-way telephone conversation between different towns—2 miles, between Boston and Cambridgeport, Mass. | |

| November 26—Conversation over railroad telegraph wires—16 miles, Boston to Salem. | |

| 1877, | February 12—Bell’s first public lecture and demonstration of his new invention given before the Essex Institute in Salem, where he had lived and had done some of his experimenting. |

| April 4—First outdoor line for regular telephone use installed—Boston to Somerville. | |

| May 17—Telephone lines first interconnected by means of an experimental switchboard at 342 Washington Street, Boston. | |

| July 9—“Bell Telephone Co., Gardiner G. Hubbard, Trustee,” the first telephone organization, formed. | |

| 44 | |

| August 1—First stock issue—5,000 shares—dividing interest in the business between seven original stockholders: A. G. Bell, Mrs. Bell, G. G. Hubbard, Mrs. Hubbard, C. E. Hubbard, Thomas Sanders and Thomas A. Watson. | |

| August 10—First Bell telephone employee hired in Boston—Robert W. Devonshire. | |

| 1878, | January 28—Opening of first commercial telephone exchange at New Haven, Conn., serving 8 lines and 21 telephones. |

| May 22—Theodore N. Vail accepts General Managership of Bell Telephone Company. | |

| 1879, | March 13—Certificate of Incorporation filed in Boston for National Bell Telephone Company for purpose of unifying telephone development throughout the country. |

| November 10—Agreement signed by Western Union Telegraph Co. admitting validity of Bell’s basic telephone patents. | |

| 1880, | December 31—47,900 Bell telephones in the United States. |

| 1881, | January 1—First telephone dividend, inaugurating a continuous regular series of payments to stockholders. |

| January 10—Formal opening of telephone service by overhead wire between Boston and Providence—45 miles. A metallic circuit was first successfully tried out on this route by J. J. Carty. | |

| 1882, | April 16—Experimental laying of underground telephone cable—5 miles, Attleboro to West Mansfield, Mass. |

| 1884, | March 27—Telephone service opened experimentally between Boston and New York by overhead wires of hard-drawn copper—235 miles. |

| 1885, | March 3—Certificate of Incorporation filed in Albany, N. Y., for the American Telephone and Telegraph Company for the purpose of effecting intercommunication “with one or more points in each and every other city, town or place in said State, and in each and every other of the United States, and in Canada and Mexico—and also by cable and other appropriate means with the rest of the known world.” |

| 1892 | Service opened between New York and Chicago, 900 miles. |