Popular Series No. 3

Southwest Parks and Monuments Association

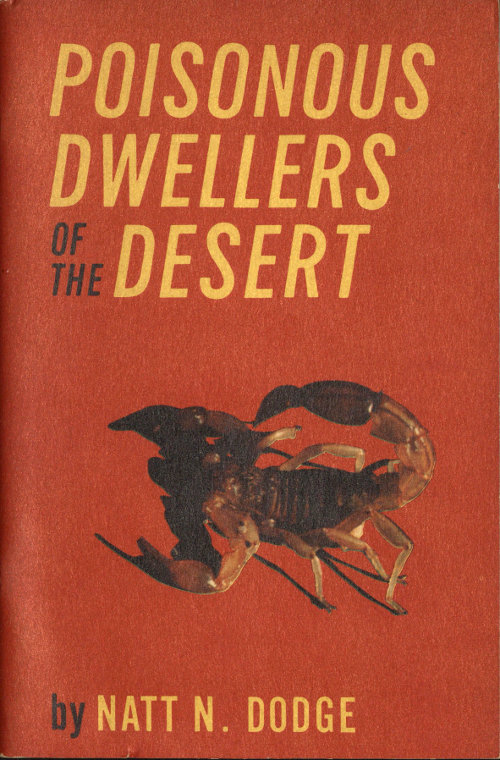

Deserts of the Southwest are not desolate expanses of sand as many persons believe. This photograph, showing vegetation in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona, is a typical illustration of the variety and density of plant growth in the Sonoran desert area of northwestern Mexico and southwestern Arizona.

by NATT N. DODGE

TWELFTH EDITION (revised), 1970

Published in co-operation with the National Park Service by the Southwest Parks and Monuments Association in keeping with one of its objectives, to provide accurate and authentic information about the Southwest.

Southwest Parks and Monuments Association Globe, Arizona (formerly Southwestern Monuments Association)

Copyright, 1952, by the Southwestern Monuments Association

Box 1562, Gila Pueblo, Globe, Arizona 85501

Published October 21, 1947

Second printing, revised, October, 1948

Third printing, revised, December, 1948

Fourth printing, revised, January, 1952

Fifth printing, June, 1953

Sixth printing, March, 1955

Seventh printing, December, 1957

Eighth printing, revised, January, 1961

Ninth printing, revised, March, 1964

Tenth printing, June, 1966

Eleventh printing, August, 1968

Twelfth printing, revised, August, 1970

Printed in the United States of America

by PABSCO Printing and Business Supply Co.

Globe, Arizona

Recommendations given in previous editions of this book regarding use of DDT and other “hard” pesticides are withdrawn in this 12th edition. We advise, until questions about merits and dangers of these products are resolved, that you contact a local agency before deciding what pesticides, if any, to use.

We believe that every citizen should make a real effort to become informed about pesticides and potential changes in them, for use or non-use will likely have great impact on mankind’s future use of this earth.

The author has conducted no original research, but has simply assembled information provided by others who have made painstaking scientific investigations into the lives, habits, and poisons of desert creatures. To these men all credit for the information contained herein is due.

The writer considers it a privilege to present partially herein the results of work conducted by Dr. Herbert L. Stahnke, Poisonous Animals Laboratory, Arizona State University, on scorpions and other poisonous creatures.

Valuable assistance has been obtained from Dr. Howard K. Gloyd, former director of the Chicago Academy of Sciences. To Laurence M. Klauber and the late C. B. Perkins, formerly of the San Diego Museum of Natural History, are expressed our thanks for much valuable information relative to poisonous snakes.

The help and cooperation of Dr. Sherwin F. Wood of Los Angeles City College has made possible inclusion of the section on the conenose bug.

The late Dr. Forest Shreve, for many years director of the Desert Laboratory in Tucson, and the late Dr. Charles Vorhies, zoologist at the University of Arizona, proved to be founts of knowledge regarding plant and animal life of the desert. The late Dr. C. P. Russell, of the National Park Service, checked many statements to assure accuracy.

We are indebted to Dr. W. Ray Jones, physician and hobby beekeeper in Seattle, Washington for his findings on, and treatment of, bee-sting poisoning. Also to Dr. F. A. Shannon of Wickenburg, Arizona for his especially helpful commentary. We take this opportunity to thank Dr. Paul Wehrle, entomologist, University of Arizona, and Dr. W. J. Gertsch of the American Museum of Natural History, for kindly checking the contents for authenticity.

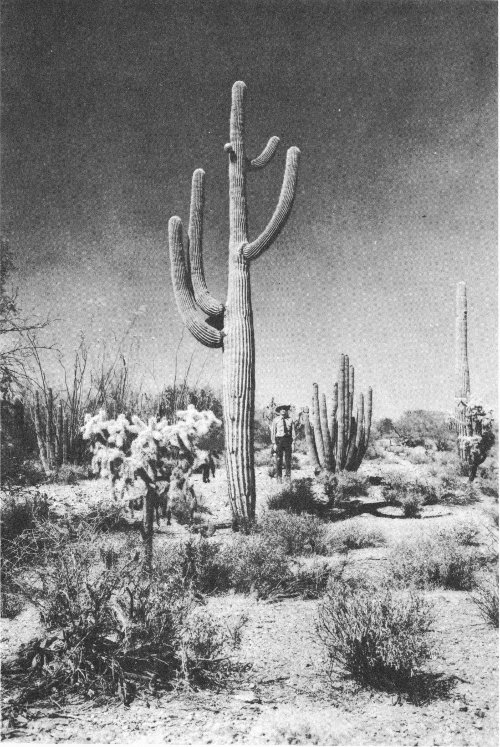

Map of western United States and Mexico showing location of deserts

The late Dr. Forrest Shreve of the Desert Laboratory in Tucson, Arizona, stated that the principal characteristic of a desert is “deficient and uncertain rainfall.” From our grammar school geographies we gained the impression that a desert is a great expanse of sand piled into dunes by the wind, without moisture or vegetation, a land of thirst, desolation, even death.

Although sand dunes devoid of vegetation are characteristic of the Sahara and some other deserts of the world, those of the United States support a variety of plant and animal life which, through generations of adaptation, are able to meet the conditions imposed by this environment (see frontispiece). Persons who misunderstand our deserts fear them, while others who have visited them become fascinated and return periodically or settle down and live in them.

Some of the creatures living in deserts are known to be poisonous to man. Western thriller fiction of press, screen, and TV has emphasized and exaggerated this fact, developing in many people a wholly mistaken fear of the desert and its inhabitants. In contrast, other persons may under-estimate the possibility of injury from these animals and become careless.

It is the purpose of this booklet to discuss accurately the various poisonous dwellers of the desert, as well as to debunk some of the superstitions and misunderstandings which have developed.

A majority of the poisonous creatures in the desert are by no means restricted to that environment. Rattlesnakes, for example, so often associated with the arid regions of the West, occur in nearly every section of the United States.

“A poison,” states Encyclopedia Brittanica, “is a substance which, by its direct action on the mucous membrane, tissues, or skin, or after absorption into the circulatory system can, in the way which it is administered, injuriously affect health or destroy life.” A poisonous creature may be defined as one which produces a poison for the administering of which it has developed a special mechanism.

Since, due to personal differences, the bite or sting of a poisonous creature may injuriously affect the health of one person and not that of another, and since the poison of one individual creature may be insufficient to cause an unpleasant reaction, while that from several hundred might produce severe illness or even death, it is difficult to determine which creature should be included in a publication of this nature. The writer, therefore, has exercised his judgment in discussing in the following pages such creatures as he feels may offer a menace to the welfare of a visitor to the desert. In addition, a few paragraphs are included for the defense of several harmless desert dwellers which are mistakenly believed poisonous and which, as a result, have been mercilessly persecuted.

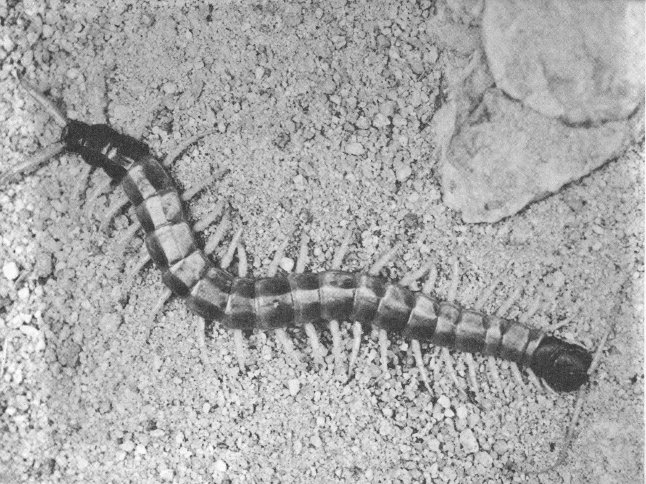

Giant desert centipede

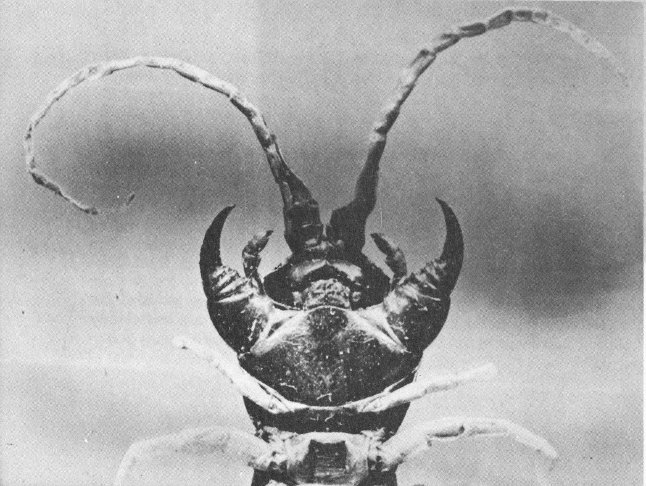

Enlarged view of underside of centipede’s head, showing the double pair of jaws.

(Photographs by Marvin H. Frost Sr.)

It should be understood that the author has not himself conducted scientific research among the desert animals regarding which he writes. The material in this book is a digest of the findings of various competent scientific and medical authorities, and has been carefully checked for accuracy and authenticity.

Don’t be frightened as a result of reading this booklet. The desert is just as safe—perhaps safer—for homemaking as many other parts of our country.

Many species of centipedes of various sizes and colors are found throughout the world. The majority are small, harmless, and not sufficiently numerous to be considered seriously, even as pests.

Usually they are found under boards, in cracks and crevices, in basements and closets, and in other moist locations where they hide during the day and venture forth at night in search of small insects for food.

The large, poisonous desert centipede attains a length of 6 or even 8 inches and has jaws of sufficient strength to inflict a painful bite. Glands at the base of the jaw produce poison which causes the area about the bite to swell and become feverish and painful. Persons who have been bitten report that the swelling and tenderness may persist for several weeks, that the bite sometimes suppurates and is difficult and slow to heal.

Because the bite of even a large centipede is usually a painful inconvenience rather than a serious injury, no specific treatment has been developed. Application of an antiseptic such as iodine immediately following receipt of the bite, working it well into the fang punctures, is advised. Bathing the site of the bite with strong ammonia will bring relief if done immediately, while soaking the area in a solution of hot Epsom salts may shorten the period of discomfort. Prompt treatment by a physician will reduce duration and intensity of pain.

Although the bite of a large centipede is no joke, it is not cause for fear or worry. Exaggerated stories of the deadly effects of the bite, and reports that the tip of each leg carries a poisonous spur, have caused many persons to be overly afraid of centipedes. Hysteria and shock resulting from this unfounded fear probably have been the cause of more suffering than the bites themselves.

The tip of each of the 42 legs of the giant desert centipede is equipped with a sharp claw. It is possible when the centipede scurries across a person’s arm or leg for these claws to make pin-point punctures. Infection introduced through these tiny openings readily leads to the belief that poison has been injected. Prompt application of an antiseptic will greatly reduce the possibility of infection.

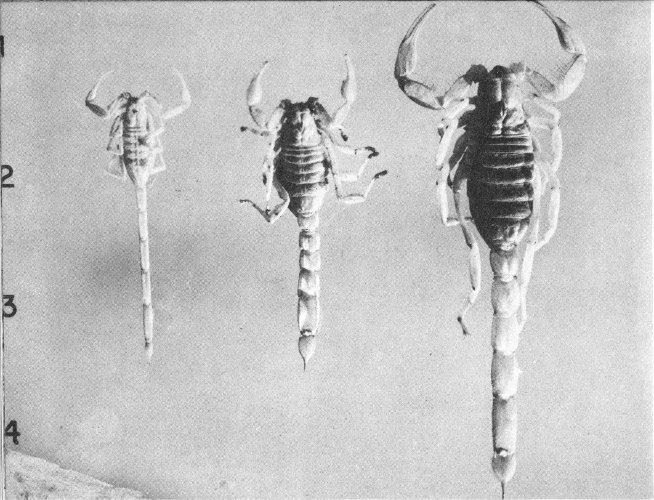

Left: Yellow, slender-tailed. Deadly species.

Centruroides sculpturatus

Center: Striped-tail. Not deadly.

Vejovis spinigeris

Right: Desert hairy. Large, not deadly.

Hadrurus hirsutus

More deaths have occurred in Arizona from scorpion sting than from the bites and stings of all other creatures combined. It is apparent that scorpions are dangerous, that all persons should be informed regarding them, and that details of first-aid treatment should be common knowledge.

In some parts of the South, scorpions are called “stinging lizards.” This is unfortunate because it has caused many people to think of lizards as poisonous and capable of stinging.

Not all scorpions are deadly. Danger from the two deadly species (one shown above) which look so much alike that only an expert can tell them apart, is greatest to children under 4 years of age. Unless prompt action is taken small children might succumb to the poison from a single sting from an individual of either of the deadly species. Older children may die from the effect of several stings, and adults, especially those in poor health, may suffer serious injuries.

Of the more than 20 species of scorpions recorded in Arizona where detailed studies have been made, the two deadly forms have been found only across the southern portion of the State and in the bottom of 5 Grand Canyon. As far as is now known, no other deadly species occur in the Southwest, except in Mexico where there are several.

It is important, then, that all persons should recognize the deadly species. Study the photograph. Note that the deadly species (left) is about 2 inches in length, is straw colored, and that its entire body, especially the joints of the legs, pincers, and “tail,” are long and slender. It has a streamlined appearance. This is in contrast with the stubby or chunky appearance of the many non-deadly species.

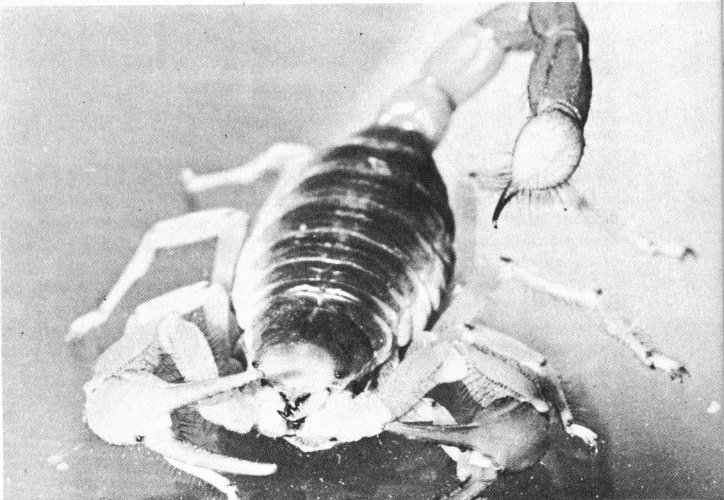

Scorpions sting, they do not bite. The pincers at the head end of the body are for the purpose of holding the prey, which consists primarily of soft-bodied insects, while the scorpion tears it to pieces with its jaws.

The sting is located at the extremity of the “tail” and consists of a very sharp, curved tip attached to a bulbous organ containing the poison-secreting glands and poison reservoir. The sting is driven into the flesh of the victim by means of a quick, spring-like flick of the “tail.” Muscular pressure forces the poison into the wound through two tiny openings very near the sting tip. Thus the poison is injected beneath the skin, making treatment difficult, as the impervious skin renders surface application ineffective.

Whereas the poison of non-deadly species of scorpions is local in effect, causing swelling and discoloration of the tissues in immediate proximity to the point of puncture, that of the deadly species is general over the entire body of the victim. There is intense pain at the site of the sting but very little inflammation or swelling.

Giant desert hairy scorpion in alert position.

According to Kent and Stahnke[1], “the victim soon becomes restless. This increases to a degree that, in cases of small children, the patient is entirely unable to cooperate with attendants. It turns, frets, and does 6 not remain quiet for an instant. The abdominal muscles may become rigid, and there may be contractions of the arms and legs. Drooling of saliva begins, and the heart rate increases. The temperature may reach 103 or 104 degrees. Cyanosis (skin turning blue) gradually appears, and respiration becomes increasingly difficult, causing a reaction not unlike that observed in a severe case of bronchial asthma. Involuntary urination and defecation may occur. In fatal cases the above symptoms may become so marked that apparently the child dies from exhaustion.

“In cases that recover, the acute symptoms subside in 12 hours or less. In the adult, symptoms as enumerated may be encountered, but as a rule they are less severe. Numbness is usually experienced at the site of the sting. If one of the appendages is stung, the member may become temporarily useless. Two cases of temporary blindness have been experienced. Some patients complain of malaise (discomfort) for many days following the sting. One patient developed a tachycardia (rapid heart) lasting two weeks.”

Dr. Stahnke recommends the following treatment for a person stung by one of the deadly scorpions:

“First, apply a tight tourniquet near the point of puncture and between it and the heart.... As soon as possible, place an ice pack on the site of the sting. Have a pack of finely crushed ice wrapped in as thin a cloth as possible. Cover and surround the area for about 10 to 12 inches. After the ice pack has been in place for approximately 5 minutes, remove the tourniquet.

“If a person is stung on the hand, foot, or other region that can be submerged completely, place the portion, as soon as possible, in an ice-and-water mixture made of small lumps of ice (about half the size of ice cubes) in a proportion of half ice and half water. Treatment should not be continued longer than 2 hours.

“NEVER put salt in the water. After the first 15 minutes, the hand or foot must be removed for relief for 1 minute every 10 minutes in the iced water.”

Dr. Stahnke continues: “If the patient is less than 3 years old, if the patient has been stung several times, or if the patient has been stung on the back of the neck, anywhere along the backbone, or on an area of deep flesh like the buttock, thigh, or trunk of the body, or especially on the genital organs, medical assistance should be obtained at once.”

Dr. F. A. Shannon advises that no person with disease involving the circulation of the extremities should use iced water. Morphine is a necessary tool in controlling pain, and barbiturates are useful for control of convulsions.

Several hospitals in southern Arizona keep a supply of scorpion antivenin and, in any case, the patient should be taken to a hospital as quickly as possible. In all cases the first-aid treatment should be applied and maintained until the patient is under the care of a physician.

With adults, in case a physician is not available, the iced-water treatment usually proves sufficient. Generally, after 2 hours of iced-water use, there is no longer any danger, but should symptoms reappear, treatment should be resumed.

Scorpion antivenin for stings of Centruroides sculpturatus and C. gertschi is available at the Poisonous Animals Research Laboratory, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona. The recommended method of treatment is the “L-C” method. The L stands for ligature and C for cryotherapy (tourniquet and ice pack treatment).

Treatment is as follows: “As soon as possible (after the sting has been received) inject intramuscularly or subcutaneously, 5 to 10 cc. of natural serum or 3 cc. of the concentrated. In serious cases, inject intravenously.” No immediate untoward results have been noted, but some cases of skin irritation develop later.

In cases of scorpion poisoning when antivenin is not available, the following treatment is recommended[12]:

“Use morphine with extreme caution. It has not been found effective in the usual doses. Barbiturates are more effective and less dangerous. Bromides in large doses are apparently of value. In those cases characterized by severe pulmonary edema (accumulation of fluid in the lungs) atropine is indicated along with general supportive measures. Compresses, using a fairly concentrated ammonium hydroxide solution, have been found helpful if applied within a few moments. If applied for the first time about 10 minutes after the sting, no apparent benefit is attained.”

Scorpions normally remain in hiding during the day, coming out in search of insects at night. The deadly species are commonly found under bark on old stumps, in lumber piles, or in firewood piled in dark corners. It is not unusual to find them in basements or in linen closets. Adults may find an unpleasant surprise in a shoe or a piece of clothing taken from a closet or dresser drawer. Legs of cribs or children’s beds may be placed in cans containing kerosene or in wide-mouthed jars.

Moral: Keep your garage, basement, and premises in general, clean, tidy, and free from insects on which scorpions feed. Screen children’s cribs, and pull the sheets clear back before putting the youngsters to bed. Shake out your shoes before putting them on, and inspect sheets, blankets, or clothing which have been in closets or drawers.

Although spiders in general produce venom with which to paralyze their prey, only a very few have fangs of sufficient length or power to 8 penetrate human skin, or venom of sufficient quantity or potency to affect human health.

There are two poisons present in spider venom: a toxin which cause local symptoms, and a toxalbumin producing general symptoms. In those spiders whose bites produce systematic disturbances it is believed that the latter poison predominates.

Black widows spin their webs in crevices between rocks, under logs or overhanging banks, in abandoned rodent holes, and in rock and wood piles. Indoors they are most frequently encountered in dark corners of garages, basements, and stables.

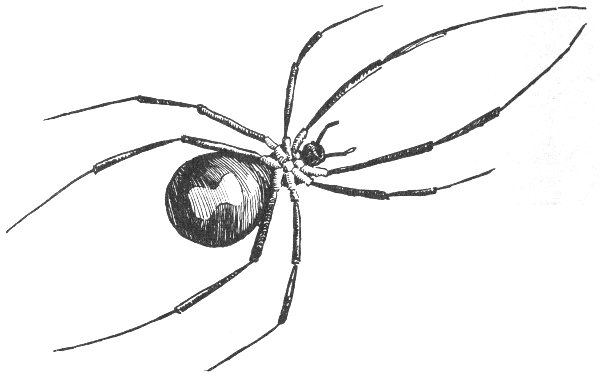

Underside of black widow spider showing characteristic red “hourglass” mark on the abdomen by which this species may be recognized.

A favorite and especially dangerous location in which a black widow establishes her home is beneath the seat of a pit toilet. Such a location is ideal for the spider because it is dark, is not usually disturbed, and insects, especially flies, upon which the spiders feed, are abundant. Humans using the toilet, unaware of the presence of the spider, arouse her by breaking or agitating her web, and offer especially tender and susceptible portions of their anatomies for her bite.

Pit toilets in warm climates should always be built with hinged seats which should be raised and inspected frequently. As a further precaution, the underside of the seats should be treated with creosote, an effective repellent.

Although the majority of people now recognize the black widow, some do not, hence they kill all dark-colored spiders on general principles. This is neither necessary nor desirable.

The female black widow is a medium-sized, glossy black, solitary spider with a globular abdomen spectacularly marked on the underside with a bright red spot roughly the shape of an hourglass. The normal position of the spider is hanging upside down in her web so that the “hourglass” is plainly visible if she is below the level of the eye. Her overall length is 1 to 1¼ inches.

The males are much smaller and, like the immature females, are grey in color and variously striped and spotted.

Adult females spin egg cocoons during the warm season; each cocoon contains approximately 300 to 500 eggs which hatch in about 30 days. As many as nine broods per year have been recorded. The young grow fast but do not mature until the following spring or summer.

Although black widows ferociously pounce upon insects or other spiders much larger than themselves which become entangled in their webs, they are by nature retiring and bite humans only when restrained from escape by contact with the body of man.

The fangs, which are about one-fiftieth of an inch in length, serve to inject from two large glands the venom which is reported to be much more virulent per unit than that of the rattlesnake.

There is some pain and swelling at the site of the bite. The pain spreads throughout the body, centering at the extremities, which become cramped, and over the abdomen, where the muscles become rigid. There is nausea and vomiting, difficulty in breathing, dizziness, ringing in the ears, and headache. Blood pressure is raised, eye pupils are dilated and the reflexes are overactive. Medical records, according to Bogen[2], show that “despite its severe symptoms, arachnidism (poisoning by spider, tick, or scorpion) is, in the majority of cases, a self-limiting condition, and generally clears up spontaneously within a few days,” although cases of death resulting from black widow bites are on record[3].

Since the venom of the black widow, among other properties, appears to affect the nervous system, its effect is almost instantaneous, and most first-aid measures are of little value.

Stahnke has found that the iced-water treatment (as described in detail in the scorpion section of this booklet) is beneficial. The points of puncture should be treated with iodine, the patient kept as quiet as possible, and an ice pack applied or the part submerged in iced-water, and a physician summoned immediately.

Baerg[4] recommends hot baths—as hot as the patient can endure. These should be used only in cases of advanced poisoning, never immediately after the bite is received.

Internal use of alcohol is dangerous, and a person bitten when intoxicated would have much less chance of recovery.

Professional treatment consists mostly in the use of opiates, hydrotherapy, and similar measures to alleviate the acute pain. Of more than 75 different remedies used, three seem to be outstanding as palliatives: spinal puncture, intravenous injections of Epsom salts, and intramuscular administration of convalescent serum when given within 8 hours. Dr. Charles Barton, of Los Angeles, recommends intramuscular or intravenous injection of calcium gluconate, 10 cc. in a 10 per cent solution. The patient should be encouraged to drink as much water as he will. He usually leaves the hospital on the fourth day. Recent experiments with an injection of neostigmine followed by one of atropine have had encouraging results, and the use of ACTH in several cases has had spectacular results, according to Readers’ Digest (Nov. 1951, p. 45).

Because of their wide distribution and secretive habits, black widows are difficult to control. Basements, outbuildings, and garages should be cleaned frequently, and black widow webs and eggs destroyed. If accessible, the spider may be dislodged from her web with a broom, and smashed. The use of a blowtorch, where there is no fire hazard, is effective for both spiders and egg cocoons. Insect sprays, in general, are ineffectual.

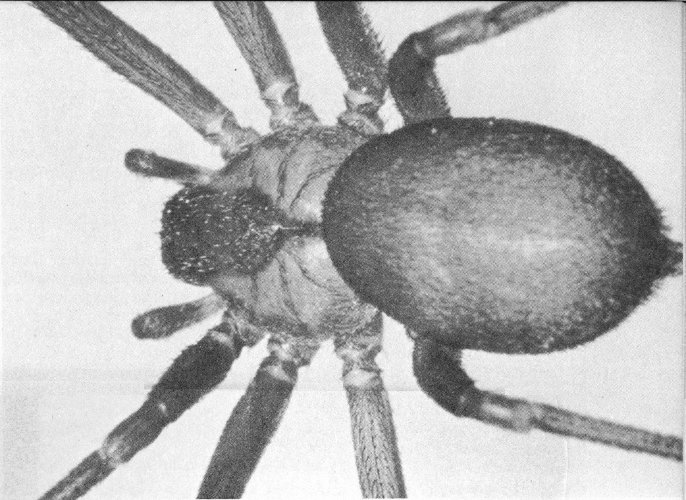

Until recently the black widow was considered the only spider in the United States dangerous to man. In 1955, physicians in Missouri and Arkansas began treating persons suffering from the bite of the brown recluse spider, whose poison caused serious damage to the skin at the site of the puncture and often produced a severe systemic reaction sometimes fatal to young children.

The spider is approximately ⁵/₁₆ inch in length, dark brown to fawn, with long legs. A violin-shaped spot on the upper side of the cephalothorax (head portion) is the only noticeable identification giving rise to another common name—fiddleback spider. It is also known as brown spider, or brown house spider.

Little has been published on its life history, but it has been reported from Kansas, Illinois, the Gulf Coast, and from Tennessee to Oklahoma. It is extending its territory westward and has recently been reported 11 from southeastern New Mexico and southern California. People are contributing to the rapid geographical spread of this species by unknowingly carrying it across state lines in their luggage. The brown recluse spider, according to Paul N. Morgan, research microbiologist at the Little Rock, Arkansas, Veterans Administration Hospital, “constitutes a hazard to the health of man, perhaps greater than the Black Widow.”

Brown recluse spider (Photo—Division of Dermatology Dept. of Medicine U. of Arkansas Medical Center)

It is found in open fields and rocky bluffs but thrives particularly well in outhouses, garages, dark closets, storerooms, and in piles of sacking or old clothing. Its web is large and irregular.

Because of the spider’s nocturnal and retiring habits few people are bitten, in spite of a large spider population. According to an article in the August, 1963 Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society, “there may be mild transitory stinging at the time of the bite, but there is little associated early pain. The patient may be completely unaware he has been bitten, and the spider is seldom seen. Only after 2 to 8 hours does pain, varying from mild to severe, begin. After several days an ulcer may form at the site of the bite. The venom appears to contain a 12 spreading factor resulting in a spread of the necrosis or tissue destruction. In some instances, the ulcer may be so large that skin grafting is required, but the graft may take poorly or not at all. “The bite may also produce serious systemic symptoms including fever, chills, weakness, vomiting, joint pain, and a spotty skin eruption, all occurring within 24-48 hours after the venom injection.”

Physicians at the University of Arkansas Medical Center, Little Rock, prefer the prompt administration of corticosteroids, stating, “Large doses given early may completely prevent the gangrenous response as well as the systemic reaction. The dosage schedule which we have found most effective is: 80 mg. of methylprednisolone (Deep-Medrol) intramuscularly immediately followed by one or two additional doses of same amount at 24-48 hour intervals. Subsequently, step wise decrease to 40, 20, 10 mg., every 24-48 hours, depending on the patient’s response, is carried out.”

Dr. Herbert L Stahnke, Director of the Arizona Poisonous Animals Research Laboratory, reports that an antivenin has been prepared in South America to control both the local and general symptoms from the bite of a closely related species of Loxosceles. He states, “locally there seems to be a favorable response to hydroxyzine, 100 mg. four times a day. I would say that cryotherapy, as we recommend it, would prevent all symptoms. I would recommend that the site of the bite be packed in crushed ice for 6 to 8 hours, after which the patient should be kept warm to the point of perspiration with the ice pack continuing for a total of 24 hours. In other words, treated like a pit viper bite, but over a much shorter period of time.” Avoid narcotics (morphine, demerol, dilaudid, codeine, etc.) since they enhance the systemic effects.

Although the brown recluse has not yet been reported in Arizona, it may be expected at any time, according to Dr. Mont A. Cazier, professor of zoology at Arizona State University at Tempe. In the meantime, studies are being made of the several close relatives of Loxosceles reclusa known to be present in the state. Among these is L. unicolor, first collected near Littlefield and Virgin Narrows in 1932. Equally poisonous with reclusa is the similar L. laeta, also found in Arizona. Other members of the genus, L. deserta and L. arizonica, have been known to live in Arizona and elsewhere in the Southwest for more than three decades, but no studies have been made of their venom. Dr. Willis J. Gertsch, world famous authority on spiders, believes that there may be as many as 20 species of Loxosceles in the Southwest. Several reports by persons who have been bitten by spiders describe reactions similar to those caused by the bite of the brown recluse.

According to Dr. Findley E. Russell, toxicology researcher of the University of Southern California Medical School, the “venom” injected by the brown spider is not really a toxin but a complete chemical that inhibits the normal action of infection-fighting antibodies in the human anatomy.

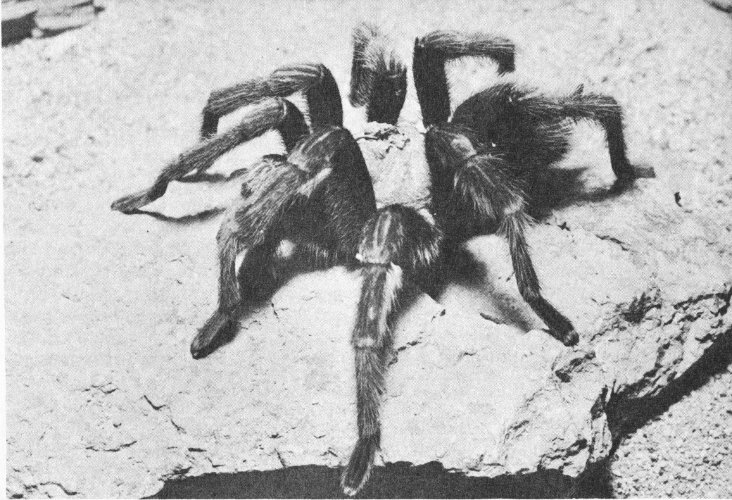

Known to naturalists as bird spiders, the large hairy members of the genera Avicularia, Dugesiella, and Aphonopelma of the arid Southwest are commonly called tarantulas.

Tarantula (Photo by Marvin H. Frost Sr.)

This name originated in southern Italy where, centuries ago, according to a story, in the little town of Tarantum (now Taranto) there developed an epidemic of “tarentism” supposedly resulting from the bite of a large wolf spider (Lycosa tarantula). Victims were affected with melancholy, stupor, and an irresistible desire to dance. Presumably, the Neapolitan folk dance, Tarentella, came about as a result of an effort to develop a cure for tarentism.

Early day immigrants brought to the western hemisphere both the unreasoning fear of spider bites and the name “tarantula,” which they applied to the large and fearsome-looking bird spider of the Southwest. Since that time this superstitious fear has become established among the uneducated and uninformed people of the southwestern United States, where the bird spiders are numerous.

It has been spread and aggravated by prolific writers of western thrillers, published in the pulp-paper magazines. Fantastic tales in which the big spiders followed their victims, sprang upon them from distances of from 6 to 10 feet, and inflicted painful bites resulting in 14 lingering, agonizing death have had wide circulation and have found a credulous audience.

Tarantulas are nearsighted, and their habit of pouncing upon grasshoppers and other large insects on which they prey is probably the basis for exaggerated stories of their jumping abilities. Their strong, sharp fangs can inflict a painful bite, but they use them only rarely in defense against human molestation. Stahnke states that any effects produced appear to be the result of bacterial infection rather than that of poison, although a mild poison is present. Treatment of tarantula bite with iodine or similar antiseptic is recommended.

One species of Avicularia and several of Aphonopelma range throughout the Southwest where they are active during spring, summer, and autumn months. They live in web-lined holes in the ground, usually located on south-facing slopes. The males are commonly encountered traveling across country, and are particularly noticeable as they cross a highway.

Preying upon insects, these large and interesting desert dwellers are beneficial rather than harmful to mankind, and deserve protection.

Unfortunately, many become the innocent victims of the wholly unwarranted fear in which they are held because of the fantastic stories regarding their purported poisonous characteristics.

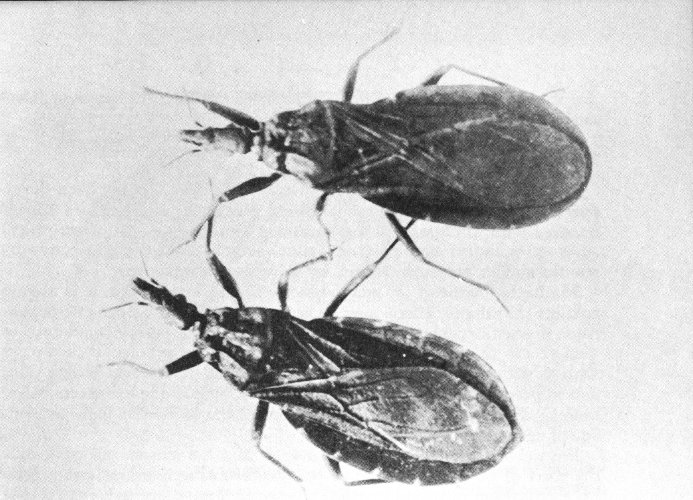

Although not limited to the deserts of the Southwest, conenose bugs, of which there are several species, are commonly associated with subtropical climates.

Certain South American species of the family Reduviidae are disease carrying and there is evidence the conenoses in San Diego County, California, are infected with a disease-producing flagellate. Lack of large bug populations in close contact with man and ineffective transmission habits protect man in the Southwest from disease contacts. However, the site of the bug’s bite becomes inflamed, and swelling may spread over an area up to a foot in diameter.

In general appearance, conenose bugs resemble assassin and squash bugs, with protruding eyes at the base of a cone-shaped snout and are about the same size. Some species are considerably smaller, while others attain a length of an inch or more.

Since conenose bugs subsist upon animal blood which they suck from the capillaries by inserting the stylets of the proboscis, they seek locations where there is a source of blood. These include livestock barns, poultry houses, and human habitations.

Conenose bugs—Triatoma protracta

Adult male (rounded abdomen); Adult female (pointed abdomen)

(Photo courtesy of Dr. Sherwin F. Wood)

Studies conducted by Wehrle[5] show that conenoses are parasitic on woodrats and breed in the dens of these rodents. They are also found in meadow vole (mouse) nests. Early in May the winged conenose adults begin dispersal flights, invading human habitations in the vicinity of woodrat dens. Although reported as most active in May and June, they may be expected throughout the summer until October, and are much more numerous in the country than in cities.

During the daytime, the insects remain hidden under rugs, between quilts, or even in bedding or behind drapes. They may be seen during the evening on ceiling beams, walls, curtains, and around windows. They are alert and difficult to catch.

Conenose bugs do not attack people until the victim is quiet or asleep, and may take blood without awakening the host. Immediately after being bitten, however, the victim is awakened by severe itching. The area about the puncture swells and becomes red and feverish. Welts at the point of puncture are hard, and may be 1 to 3 inches in diameter.

About 5% of the people repeatedly bitten develop severe allergic reactions with burning pain and itching at the site of the bite, itching on the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, neck, and groin; general body swelling, and a nettle-like rash over the body. Some persons feel ill, with light depression followed by quickening of the pulse. Others 16 are faint, weak, and nauseated. In very severe allergy these symptoms may lead to anaphylactic shock and unconsciousness.

Although a specific treatment for conenose bites has not been developed, some physicians use epinephrine. More promising results appear possible with antihistamine preparations (under doctor’s prescription) such as benadryl and pyribenzamine, which have been effective by mouth, and in severe reactions, by intravenous injections.

Matheson[6] writes: “When a blood-sucking insect bites, it is always possible that the proboscis may be contaminated with pathogenic organisms. If such organisms become localized near the point of puncture or gain access to the blood stream, results may be serious. It is always wise to use some disinfectant such as alcohol, tincture of iodine, etc., and to press out the blood, if possible, from bites made by insects.” Antibiotics are frequently necessary to control the extremely high percentage of secondary infections.

Physicians recommend the application of a hot Epsom salt pack over the point of puncture as soon as possible after the bite has been received. Application of antiphlogistine alleviates the severe itching. ACTH is recommended by some physicians. Hydrocortizone ointments reduce the skin eruptions and local pain.

Prevention is more satisfactory than treatment, and since conenoses live in woodrat dens, these rodents should be eliminated from the vicinity. Weatherstripping around all permanent doors and screen doors, tight-fitting, holeless screens in all windows, and fine screens in fireplace chimneys will help to keep the bugs out of houses. Occasionally they may be seen on walls and ceilings in the evening, and may be killed with a flyswatter.

If impossible to keep the insects out of the house, sleeping persons may be protected by the use of mosquito netting. It is especially important that the beds of babies and young children should be safe-guarded because of the danger from scorpions.

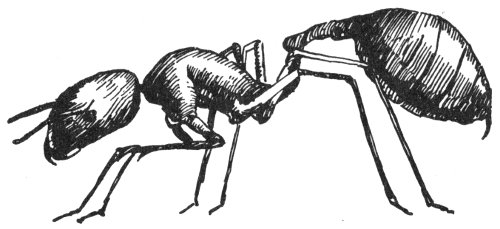

Common ant

Bedding should be shaken thoroughly just before children retire, because both scorpions and conenose bugs have a habit of concealing themselves in bedding during the daytime.

Stinging insects all belong to the group Hymenoptera and consist of the families Apidae (honeybee, etc.), Bombidae (bumblebee), Vespidae (wasps and hornets), Sphecidae (thread-waisted wasps), Mutillidae (velvet ants), and Formicidae (the ants).

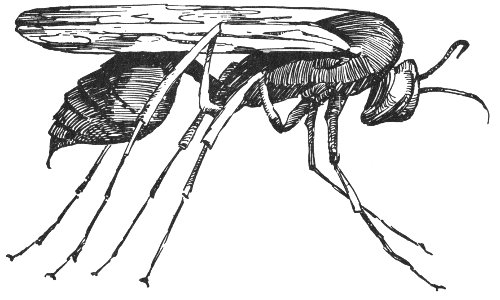

Wasp

In general, the only treatment recommended for insect stings is to bathe the parts with ordinary liquid household bluing just as soon as possible after the sting has been received, and apply hot compresses. However, certain specific treatments are advised, depending upon the particular species or condition.

Some persons are extremely susceptible to insect bites and stings, and preliminary work has been done in trying to immunize those sensitive individuals, but, in general, with very little success. The problem of immunizing or desensitizing persons who are allergic to insect bites and stings is one of considerable importance, as such unfortunate persons will testify.

Because of the fact that honeybees are of such great economic importance, not only as producers of an important food but also as pollenizers of fruit, vegetable, seed, and other crops, they will be discussed separately from the other stinging insects.

Everyone is familiar with ants, wasps, hornets, and bumblebees, and there are very few persons who have not had unpleasant experiences with one or more of these groups of insects.

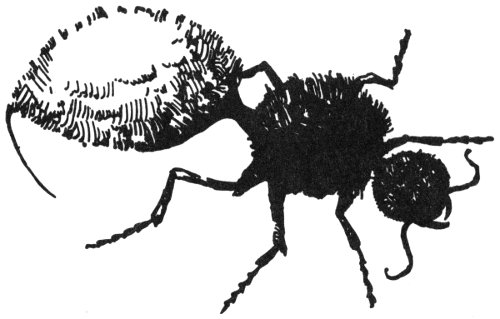

Velvet ants, which are in reality wingless wasps and not true ants, are not as well known as the others, although the little creatures that scurry about like brightly dyed bits of cotton are quite numerous in the desert.

The primary purpose of the sting is to paralyze or kill their prey, although it becomes more important as a weapon of defense with insects which do not prey upon or parasitize other creatures. Although the solitary insects use their poison as a means of personal defense if attacked or imposed upon, the social insects such as ants, social wasps and hornets, honeybees, and others, rally to the defense of their nests and in mass attacks against an intruder may cause painful and sometimes serious injury.

Although the small amount of poison introduced beneath the skin by the sting of one of these creatures usually causes only temporary discomfort, there are sometimes after effects which may be more intense and of longer duration with some persons than with others. In general, stinging insects may be considered more as a nuisance than a menace, although a person attacked by a large number, or subjected to their stings for some length of time, might receive serious and perhaps fatal injuries. Known deaths have been caused by the sting of imported fire ants in southeastern States. The species is believed to be spreading. Treatment by a physician may include the use of ACTH and calmitol.

Although ants and velvet ants are commonly considered as wingless, they are, actually, winged. Male velvet ants have wings whereas the females are normally without wings. The females have a very effective sting, and if picked up or pinched they make every effort to use it, at the same time emitting a peculiar faint squeaking sound.

True ants, of which there are hundreds of species, are social insects living in colonies containing the mother, or queen, which becomes wingless after fertilization; numerous workers, or non-fertile females; and young winged males and females.

Velvet ant

Ants of various species are numerous on the desert, some of them becoming serious household pests, difficult to control.

There are effective ant poisons on the market, but the surest method of control is to find the nest and destroy it. Ants that are household pests usually are either grease eaters or sweet eaters, and the proper poison for the specific type should be obtained in attempting to rid the house of these insects.

Wasps, hornets, yellowjackets, and bees of many species are common in the desert, some species being solitary in habit while others live in colonies or nests which they defend with great pugnacity.

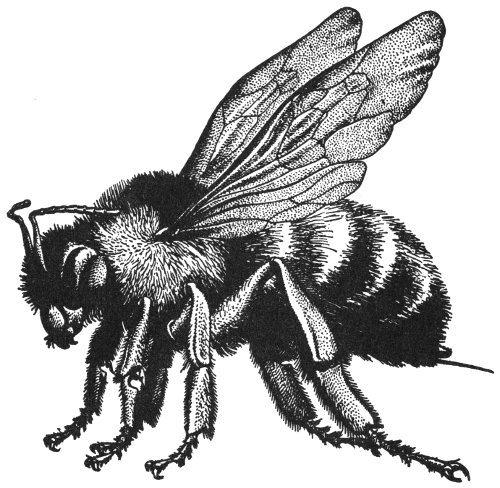

Bumblebee

Although humans have little to fear from these insects if they leave them strictly alone, some species select nest sites beneath overhanging eaves or in attics or lofts, thus becoming persistent pests. They are usually tolerated until one or more members of the family are stung.

Other species are attracted to human habitations by the presence of sweets or other edibles, and make persistent nuisances of themselves. They are capable of inflicting painful injuries, and are greatly feared by many persons.

Not usually serious, these injuries do not respond to any treatment that has yet been developed. Immediate application of strong ammonium hydroxide (household ammonia) is a home treatment which has 20 been found helpful for ant stings, and, in most cases, for the stings of other insects.

A piece of ice held at the point of puncture will relieve the pain and burning sensation in the majority of cases of insect sting.

In serious cases, of course, the services of a physician should be obtained immediately.

At first thought it may seem unjustified to include the common honeybee in a discussion of poisonous creatures of the desert. Although the honeybee is not a desert native, having been imported from Europe, it has established itself in the wild state throughout the Southwest in locations providing adequate moisture and sufficient nectar-producing flowers.

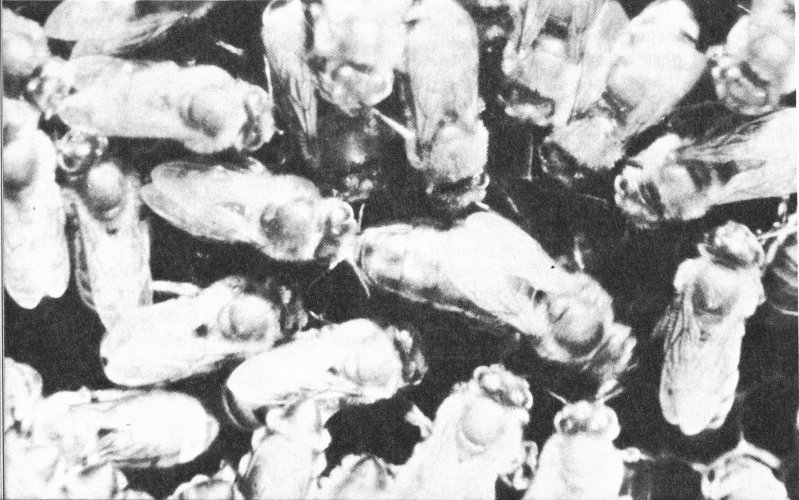

Honeybees on the honeycomb

Throughout much of the United States honeybees are encountered in numbers only in apiaries operated by beekeepers, or in bee trees where the insects have established themselves. In the desert climatic conditions are ideal for honeybees, and they have become widespread and well established.

They obtain water at springs, seeps, waterholes, cattle tanks, dripping faucets, and leaking water containers, often congregating in such numbers around sources of water that they become a distinct nuisance to men and to animals. Individual honeybees are frequently found in flowers, or may fly in through an open automobile window, and sting one of the car’s occupants. Small children sometimes receive stings while playing on white clover lawns or going barefoot. Farm boys may 21 be severely stung as a result of molesting beehives or throwing stones at bees’ nests in trees or caves.

Normally, poison introduced by the sting of a honeybee is local in effect and little more than a painful inconvenience to the person stung. There are many cases on record, however, of persons and domestic animals receiving stings from so many of the enraged insects that serious and even fatal results have followed.

During the past half century, medical records show a number of deaths each resulting from a single sting. Jones[7] made an intensive study of this problem and was able to show conclusively that occasional individuals become supersensitive to honeybee venom. If persons in such condition receive even the small amount of poison injected by a single sting, the resulting excessive susceptibility may be fatal unless proper treatment is administered immediately. To such persons the honeybee is definitely a poisonous and dangerous creature.

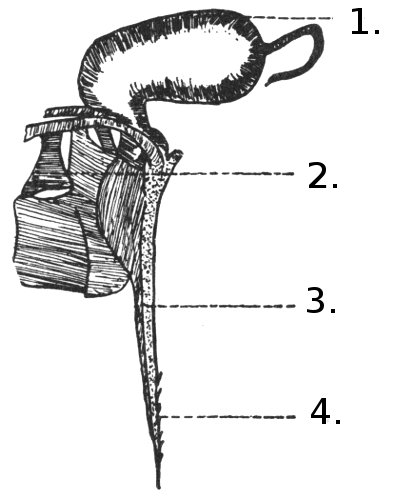

Poison mechanism of worker bee, greatly enlarged.

The poison-injecting mechanism of the worker bee is located within the extremity of the abdomen and consists of a barbed sting at the base of which is attached a sack, or reservoir, containing the poison. Male bees (drones) have no sting, and the queen reserves hers for possible use in battle with a rival queen.

In the act of stinging, the bee forces the tip of the sting through the skin of the victim, where it becomes imbedded, being held by the barbs. In escaping the bee tears away, leaving the sting, poison sack, and attached muscles and viscera. Incidentally, this rupture results in the death of the bee.

Capillarity and the spasmodic movement of the attached muscles force the poison from the sack through the hollow shaft of the sting into the wound.

To counteract this, the first thing that anyone should do when stung by a honeybee is to SCRAPE out the sting. This may be done with a knife blade or even with the fingernail, although the latter is far from sanitary. NEVER PULL OUT THE STING, because in grasping the protruding poison sack between the thumb and forefinger, the sack is certain to be pinched and the poison squeezed into the wound.

Since, under normal conditions, it takes several seconds for the contents of the sack to work into the puncture, prompt removal of the sting with the attached sack prevents much of the poison from being injected.

Application of strong household ammonia just as soon as the sting is scraped out is helpful in allaying the pain.

If a person receives a great number of stings, a physician should be summoned at once. The victim should be undressed, put in bed, and all of the sting scraped out. All parts of the body that have received stings should be covered with cloths soaked in hot water and wrung out. These applications should be as hot as the victim can endure.

Persons who are supersensitive to bee-sting venom show the following symptoms when stung: the skin over the entire body breaks out in lumpy welts, palms of the hands and soles of the feet itch. This is followed by headache, nausea, and vomiting. Breathing becomes labored and heart action is rapid and weak.

As soon as such symptoms are noted, a physician should be summoned or the victim taken to a hospital. Treatment consists of frequent, small, hypodermic injections of epinephrine in the ratio of one part of epinephrine to 1,000 parts of water. Dr. W. Ray Jones[7], who developed and perfected this treatment, reports that it is immediately effective and recommends that all commercial beekeepers provide themselves with hypodermic kits and a small supply of epinephrine.

Even persons who are apparently immune to bee-sting venom through having received bee stings during the course of many years of work in the apiary, may suddenly develop supersensitivity. The treatment is relatively simple, may be self-administered, and has already proved effective in treating serious cases of excessive susceptibility resulting from supersensitive persons receiving bee stings.

Experimental use of calcium lactate to counteract “sting shock” indicates a high degree of success. Physicians should investigate “Death by Sting Shock,” p 234, Science News Letter, April 9, 1955. Use of antihistamines or a hormone of the cortizone family has had some success.

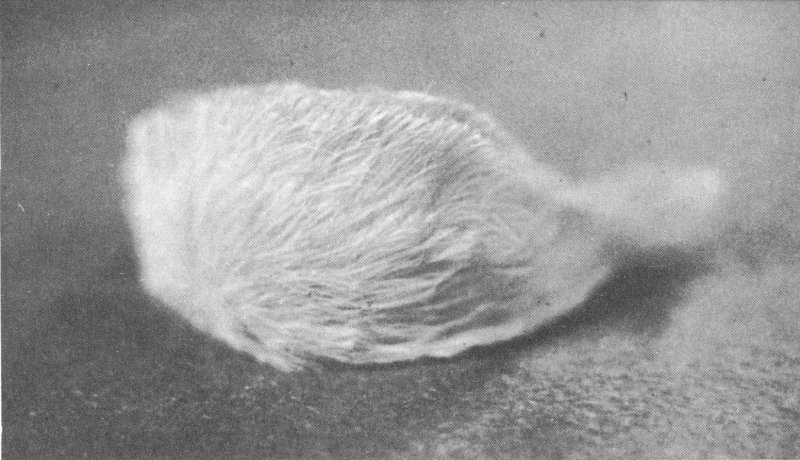

Superficially resembling a tiny, light, golden-yellow kitten, the puss caterpillar is a short, bushy larva of a small gray-brown moth with whitish underwings. When disturbed, the caterpillar rears back on its hind legs and “makes a face.” The species has long been widespread throughout the southern states feeding on the foliage of oak, elm, plum, and sycamore trees. They have been found also in truck gardens and orchards. Recently they have invaded the desert mountains of the Southwest, having been reported by Stahnke as especially numerous in the Globe-Miami area of Arizona, feeding on the foliage of oaks.

Puss caterpillar (Courtesy Dr. Herbert L. Stahnke)

Because of their long, silky hairs, children are tempted to touch them. Under the hairs are small protrusions, each bearing a circlet of very small spines resembling tiny porcupine quills. The venom is injected when these spines pierce the child’s skin and the tips break off, producing a burning, itching, irritated, inflamed area. The welts, ranging in size from a dime to a dollar, are sometimes followed by severe muscle cramps and headache. Not lethal, the toxin may cause enough sleeplessness in a child to reduce his resistance to other infections.

Treatment suggested by Dr. Bernard J. Collopy, Assistant Medical Director of the Miami-Inspiration Hospital of Miami, Arizona, consists of immersing the inflamed area in iced water for thirty minutes. Remove for one minute at ten minute intervals for relief from the cold. The skin may blister and peel at the site much as in the case of a first degree burn, but should heal completely in ten days. Some physicians suggest an opiate for relief of pain in severe cases. Cooling lotions may be applied to relieve the itching.

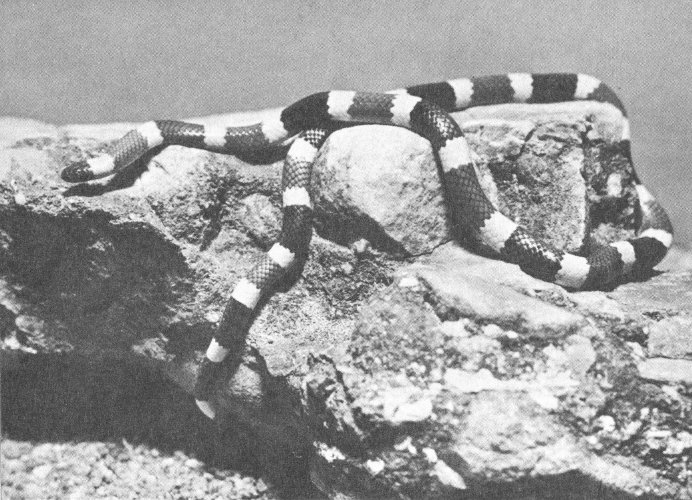

The coral snake, of which there are two species in the United States, belongs to the Elapine group, which is represented in the Old World by the cobras and other poisonous snakes. These two species, the coral snake of the Gulf States, and the smaller Arizona coral snake whose range extends into the desert lands of southern New Mexico and Arizona, are the only representatives of the Elapine group found in this country.

Arizona coral snake (Photo by Marvin H. Frost, Sr.)

The Arizona coral is shy and secretive in its habits, timid rather than pugnacious, and it is so rarely seen that little is known of its habits.

The poison mechanism of the coral snake is somewhat different from that of the pit viper group, to which the copperheads, cottonmouths, and rattlesnakes belong. The teeth of the coral are short, and to be effective the coral snake must chew rather than strike its victim.

The Arizona coral snake is so small—rarely reaching 2 feet in length—and its mouth is so tiny, that it would be very difficult for it to bite an adult human. It is conceivable that a small child playing with one might be bitten.

Because of its close resemblance to several ringed or banded snakes of the desert and also to the Arizona mountain kingsnake, or “coral” 25 kingsnake, of the ponderosa pine highlands of the Southwest, a brief description of the Arizona coral snake is indicated. One of the beautifully spectacular snakes of the desert, it is marked by bands of dark red, cream, and black, which encircle the body. Superficially the markings of the Arizona mountain kingsnake and other tricolored ringed snakes appear similar. However, the red of the kingsnake and of others is usually brighter, and the black bands narrower than those of the coral.

Definite identification is provided by the relationship of the colors to each other, the arrangement on the Arizona coral snake being red, cream, black, cream, red, cream, black, cream. The bands of the Arizona coral snake entirely circle the body and its snout is black.

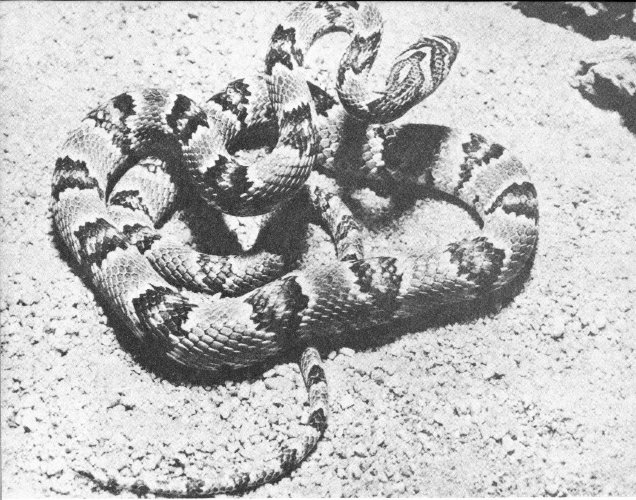

Thirty species and subspecies of rattlesnakes occur in the United States, more than half of this number being found in the Southwest. Because they have been killed on sight for years, their numbers have been considerably reduced in densely populated areas. For this reason, together with emphasis placed upon their poisonous characteristics by some writers of western thriller fiction, rattlesnakes are considered by many people to be a serious menace in the thinly populated portions of the arid West[8].

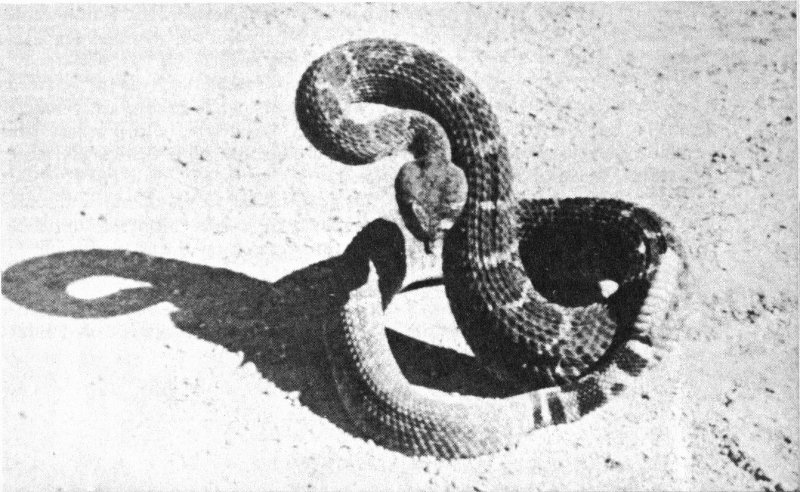

Western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox.) (Photo by Earl Jackson)

In the hot desert regions of the Southwest rattlesnakes are usually abroad at night during the summer months, as they have no controlling 26 system for body temperature and cannot endure the heat at ground surface during the hours of sunlight. In spring and autumn they may be encountered in the daytime but during December, January, and February they are in hibernation and are rarely or never seen.

Their food consists principally of lizards and small rodents such as ground squirrels, rats, mice, pocket gophers and young rabbits. They are sometimes found along irrigation canal banks where they go for water, and because they find rodents congregating there for the same reason. Unless surprised, cornered, teased, handled, or injured, a rattlesnake usually will try to remain hidden or will endeavor to crawl away rather than strike. Because they are attracted to places where small rodents abound, they are sometimes encountered around barns and outbuildings. They occasionally enter abandoned structures in search of food or to escape from the heat of the sun.

Because a rattlesnake may be met at almost any time, except during the winter months, by a person who lives, works, or visits in the desert, he should be ever alert. If hiking or climbing through country where rattlesnakes are known to be abundant, he should wear clothing that will protect him from a possible bite.

Pope[9] states that records kept during 1928 and 1929 show that 98 per cent of snake bites occurred below the knee or on the hand or forearm. When in snake country, the hiker should wear knee-high boots or leggings, and should never place his hand on a rock or ledge above the level of his eyes. In other words, watch your step, and look before you reach! Apparently rattlesnakes may strike at a quick movement and are very sensitive to the body warmth of a nearby warm-blooded creature.

Rattlesnakes belong to the group known as the pit vipers, which includes the cottonmouths and the copperheads. The latter do not occur in the desert, so they do not come within the province of this publication. Snakes of the pit viper group are characterized by a noticeable depression, or pit, found almost halfway between the eye and the nostril, but slightly lower, on each side of the head.

Of the several species found in the desert, some, such as the western diamondback rattlesnake have a wide range, while others are restricted to limited areas. Some species attain large size, while others are quite small; some are inclined to be pugnacious, while others are more or less docile. All are dangerous!

It is not within the scope of this publication to enter into a discussion of the many species, so the reader who wishes to pursue that subject further is referred to Klauber’s publication on the rattlesnakes[10].

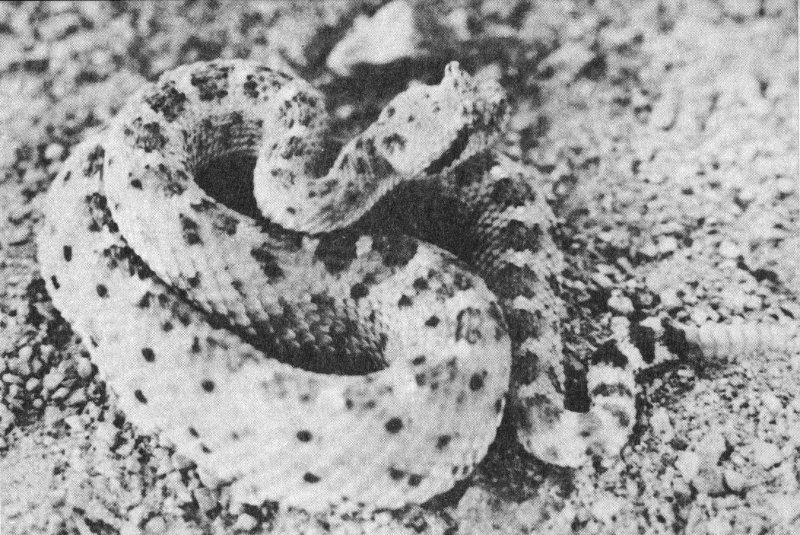

There is one rattlesnake of the desert that should be especially mentioned: the sidewinder, or the little horned rattlesnake. It is called sidewinder 27 because of the peculiar method of locomotion that enables it to progress in the sandy habitat which it frequents. Unable to get sufficient traction in loose sand by moving as other snakes do, it throws a portion of its body ahead as a loop, thus serving to anchor or pull the rest of the body ahead. Thus it progresses sideways in a looping, or winding, motion most interesting to observe.

Sidewinder or “horned” rattlesnake

Although the term sidewinder is often used loosely in referring to other species of rattlesnakes, it actually applies only to this particular species—Crotalus cerastes.

In snake country, it is important to take a flashlight along whenever there is occasion to go outside at night in summer to be sure that there are no rattlesnakes lying across your path. If you sleep out of doors. keep your bed off the ground if possible. The widely believed statement that, “a rattlesnake will not crawl across a hair rope” is not true, although such a statement will often precipitate an argument.

Persons much in the field should provide themselves with a suction-type snakebite kit, and should know how to use it. Although you stand 200 chances of being killed by an automobile to one of dying from snakebite, the price of a suction-type kit is cheap insurance against that possibility.

If, in spite of all precautions, you or some companion should be bitten by a rattlesnake, first-aid should be rendered at once. This is not 28 difficult if you have a snakebite kit, and it is possible even if you do not.

The following steps are quite universally accepted:

1. Apply a tourniquet a short distance above the bite (that is between it and the heart) but do not make it too tight. This prevents the blood and lymph carrying the poison from being spread rapidly through the body. The tourniquet should be loosened for a few seconds every 20 minutes.

2. Make a short cut about one-fourth inch deep and one-fourth inch long near each fang puncture with a sharp, sterile instrument. A knife or razor blade sterilized in the flame of a match will do.

3. Apply suction to the cuts. If no suction cup is available, the mouth will do if it contains no open sores.

4. If antivenin is available, administer it according to instructions, but, if possible, this should be left to a physician. (Recent experiments with antivenin indicate that, in some cases, its reaction may be harmful and that it should be administered only under the care of a physician.)

5. Get the patient to medical help as soon as possible, continuing the first-aid treatment enroute. Keep the patient quiet and do not let him get frightened or excited. Rather than require the patient to walk or otherwise exercise, medical aid should be brought to him.

6. If medical help is not available, and if Epsom salts can be obtained, apply cloths soaked in a strong, hot solution of Epsom salts over the cuts. The sucking, however, should be continued for at least half an hour, preferably for an hour or more. Never give alcoholic stimulants or use permanganate of potash. Snakebite kits give complete instructions; follow them carefully.

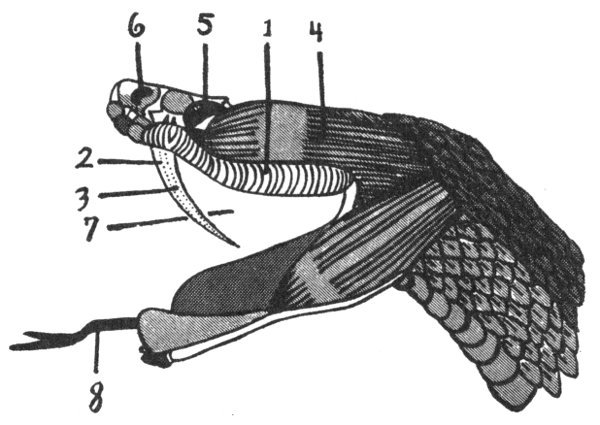

Poison mechanism of the rattlesnake Redrawn from Dr. Fox

Rattlesnake venom contains digestive enzymes which attack and destroy tissue, and because of this and the possibility of bacterial infection introduced by cutting the skin, another method of treatment—cryotherapy (treatment with cold)—advocated by Dr. Herbert L. Stahnke, Poisonous Animals Laboratory, Arizona State University, seems to be gaining more and more support. This technique is designed to prevent and control the chemical action of the venom and of bacteria, as well as minimizing stress. This latter action is extremely important, since recent research work has indicated that the physiological products produced by the body under stress may more than double the toxic effects of the venom. Cut-and-suction, or any similar treatment, tends to greatly increase stress.

The following description of treatment is excerpted from “American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene,” Volume 6, Number 2, March, 1957, The Treatment of Snake Bite, by Herbert L. Stahnke, Fredrick M. Allen, Robert V. Horan, and John H. Tenery:

1. Place a ligature (tight tourniquet) at once between the site of the bite and the body, but as near the point of entrance of the venom as possible.

2. Place a piece of ice on the site while preparing a suitable vessel of crushed ice and water.

3. Place the bitten hand or other member in the iced water well above the point of ligation.

4. After the envenomed member has been in the iced water for not less than 5 minutes (N.B. research has shown that the danger generally attributed to a ligature is not present when the member is refrigerated), remove the ligature, but keep the member in the iced water for at least 2 hours.

5. Pack the envenomed member in finely crushed ice. This hypothermia must continue for approximately 24 hours, and the patient must not be permitted to chill, since this increases body stress.

6. Change from hypothermia to cryotherapy. This is accomplished as follows: after the first 24 hours following the bite, the patient should be kept somewhat uncomfortably warm—that is, to the point of perspiration—and encouraged to drink much water. This step is exceedingly important. Unless the patient is kept uncomfortably warm the proteolytic portion of the venom will not leave the site of the bite. Consequently, when hypothermia is stopped, the concentration of this part of the venom is greater and the tissue destruction will be proportionately increased. Hypothermia should be avoided entirely if this step is not meticulously observed.

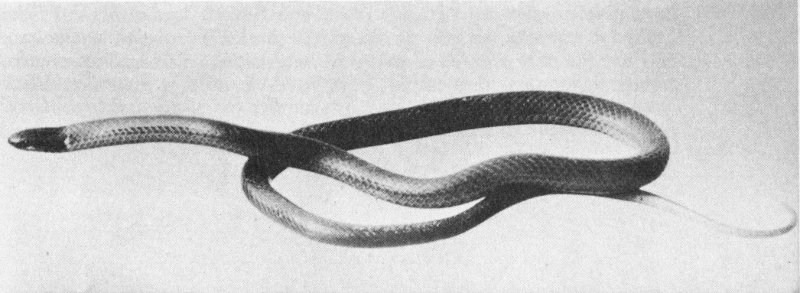

Western black-headed snake (Tantilla eiseni). (Courtesy San Diego Natural History Museum)

Sonora lyre snake (Trimorphodon lambda). (Photo by Marvin H. Frost, Sr.)

7. The warm-up period after Cryotherapy is important. This must be done gradually. Remove the member from the crushed ice and place it in ice water (without ice). Allow the water to warm to room temperature.

Dr. Walter C. Alvarez in the Santa Fe New Mexican, 8-18-57: “Recently, Dr. Wm. Deichmann, John E. Dees, M. L. Keplinger, John J. Farrell, and W. E. MacDonald Jr. reported that hydrocortizone is a life-saving drug when given to animals that have suffered poisoning from rattlesnake venom. Instead of only the 17% of the untreated animals that survived, 75% of treated animals were saved.”

The southwestern desert regions are credited with harboring several genera of snakes whose grooved back teeth indicate that they may have poisonous properties. Of these, the Sonora lyre snake[11] (Trimorphodon lambda) and the Mexican vine snake (Oxybelis aeneus auratus) are the only species of sufficient size to be considered as even remotely dangerous to mankind. Species of the genera Tantilla (black-headed snake), Hypsiglena, and Sonora are too small and too difficult for the amateur to identify to be considered in this publication.

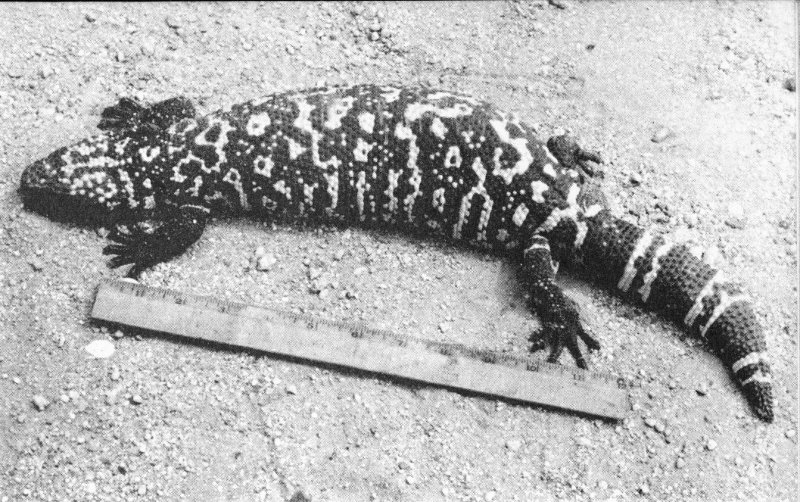

More conflicting statements are made about the Gila (HEE-lah) monster than about any other desert reptile. Some persons insist that it is not poisonous, others are sure that even its breath is poisonous: that it spits or blows its poison: that the animal has no anal opening, hence undigested fecal matter remains in the body, decays, and is the basis of its poison; and so on.

Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum).

Here are the facts. The lizard is poisonous and its bite may be serious, possibly fatal[13]. Its breath is not poisonous, and although the animal seems to have a chronic case of halitosis, this has nothing to do with its dangerous properties. It does not spit poison, but when angered it frequently hisses, the outcoming blast of air sometimes carrying droplets of saliva. It has a normal anal opening and voids fecal matter in a perfectly normal manner. It is not a walking septic tank as many persons believe.

Largest of the lizards native to the United States, and the only species found in this country which is poisonous, the Gila monster rarely attains a length of 2 feet. Average specimens are smaller. Its beady skin, heavy body, short legs, and waddling gait set it apart from all other lizards except its close relative, the also poisonous Heloderma horridum of Mexico. The Gila Monster is a spectacular black and corral color, while the other is black and yellow.

Gila monsters are found in southern Arizona, their range extending northwestward into the southern tip of Nevada and southwestern Utah.

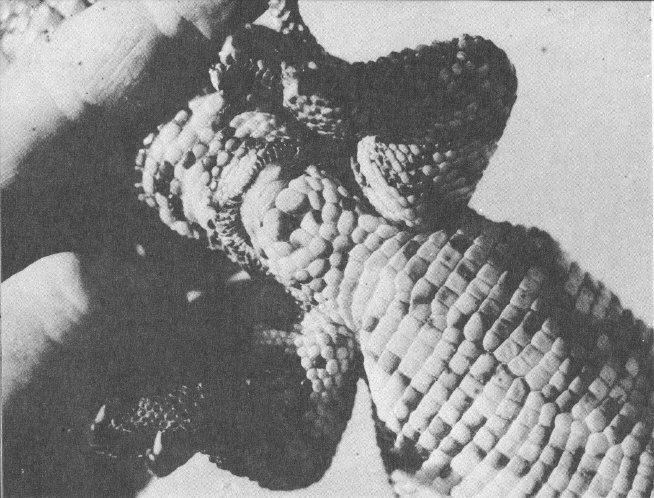

Underside of Gila monster showing anal opening. This photograph is advanced as proof that the Gila monster is a perfectly normal creature in this respect. (Photo courtesy of Poisonous Animals Research Laboratory, Tempe, Arizona)

Food consists chiefly of bird and reptile eggs, young rodents, and such small or juvenile creatures as it is able to capture. It is especially fond of hen eggs and may be kept in captivity for a long time without other food. It is also fond of clear water, which seems strange because of the scarcity of this liquid in the natural habitat of the lizard. If provided with a basin of water it may lie partly submerged for hours.

Occasionally encountered ambling across stretches of open desert, especially in the spring, the Gila monster is normally docile and bends every effort toward escape among the stiff stems of some bush or beneath the protecting spine-clad stems of a cactus plant. Sometimes an individual with a “chip on its shoulder” may be met, or one in a normal state of mind may be teased or prodded into anger, when it advances with open mouth, sputtering and hissing.

When aroused, the Gila monster is remarkably agile, making quick turns of its head to snap at nearby objects. If it secures a grip, it hangs on with bulldog-like tenacity, grinding the object between its teeth.

Gila monsters reproduce by means of eggs which are about 2½ inches long with a tough, parchment-like skin. From 5 to 13 eggs are deposited by the female in a hole which she scoops in moist sand in a 33 sunny location. After laying the eggs, she covers them with sand, and leaves them for the heat of the sun to hatch.

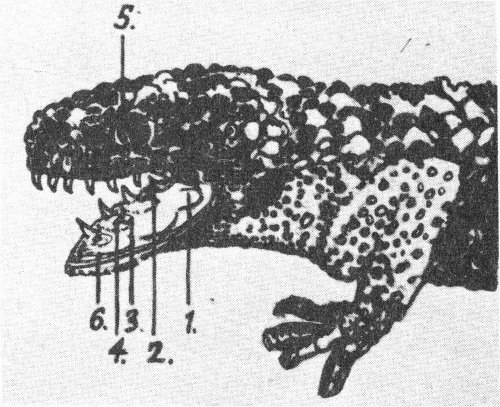

Poison mechanism of the Gila monster Redrawn from Dr. Fox

The Gila monster’s tail serves as a storehouse of nourishment, being thick and heavy in times of plenty, and thin and rope-like in the early spring when the reptile first appears after months of hibernation, during which time it has lived on the reservoir of fat stored in its tail.

The poison of the Gila monster is produced by glands in the lower jaw. To be most effective, the poison must be ground into the wound through action of the grooved teeth, the process taking a little time. Bitten persons who immediately have broken away sometimes show no effects of the venom, therein lying the basis for the widespread statement that Gila monsters are not poisonous.

Bitten persons who have been unable to release themselves show symptoms of poisoning similar to persons suffering from rattlesnake bite, although the poison is more neurotoxic in action. Breathing and heart action are speeded up, followed by a gradual paralysis of the heart and breathing muscles.

Treatment is essentially the same as that for rattlesnake bite, which is described earlier in this booklet. A physician should be summoned at once. Stimulants are dangerous, and no one should be permitted to give the patient any alcohol whatever.

Prevention is much simpler than cure, so Gila monsters should be allowed to mind their own affairs unmolested. Normally they are not pugnacious, and it would be very difficult for one to bite a human unless it were being teased or handled or were stepped upon by a bare-footed child. Please do not kill or capture Gila monsters. These interesting lizards are a unique feature of native desert wildlife threatened with extinction. Please leave them for other people to see and enjoy. Furthermore, the Gila monster is protected by State law.

Practically everyone is aware of the widespread fear of snakes exhibited by people of all races and in all walks of life. This fear although largely emotional, is rationalized by many persons with the statement “Well, it MIGHT be poisonous.” Other persons believe that there is some rule of thumb, such as a flat or triangular-shaped head, by which all poisonous snakes may be recognized. A great many persons kill all snakes, just on general principles. Thus the innocent suffer with the guilty, the harmless with the dangerous.

As scientists explore deeper and deeper into the intricacies of animal behavior and obtain more and more knowledge of the ecological relationships among animals and between animals and plants, it becomes increasingly clear that these relationships present a delicate balance or adjustment of nature. Epidemic diseases, disasters such as fires and floods, and radical climatic changes may upset or alter these relationships, sometimes with far-reaching effects.

But the greatest and most persistent disturber of the biological peace is MAN. Almost every time man reduces or destroys one phase of nature, he releases, in so doing, previously unrecognized forces which turn on him in a manner that he least expects. Snakes, in general, live on small rodents, thereby helping to maintain a balance whereby rodents are unable to increase to such a point that they get out of nature’s control. Kill all of the snakes in a given area, and some of the control on rodent population is removed with a resulting increase in the destruction of vegetation and consequent damage to farmers’ crops. So if you must kill snakes, by all means limit your activities to those which are known definitely to be poisonous.

One of the purposes of this booklet is to familiarize the desert dweller or visitor with the snakes that ARE poisonous. All the rest are harmless, in fact they are generally beneficial to mankind, even though their heads may be triangular in shape. A given territory is capable of supporting a rather definite number of snakes. Kill the harmless ones and those that come in to take their place may be poisonous species.

In all parts of the country certain creatures, particularly reptiles, are credited with supernatural powers for causing injury or aid to human beings. Among aboriginal peoples, these superstitions are a part of their religion and have a powerful effect upon their thinking. For example, among the Hopi Indians of northern Arizona, snakes may be messengers who, if properly indoctrinated, will convey to the rain gods expressions of the people’s need for moisture in order that their crops may mature.

Even among a people who for years have had the benefit of scientific knowledge, superstitions persist. The hoopsnake and the milksnake offer cases in point, and there will be readers of this booklet who will toss it aside in anger because it states that both of these myths are 35 without substantiation in fact.

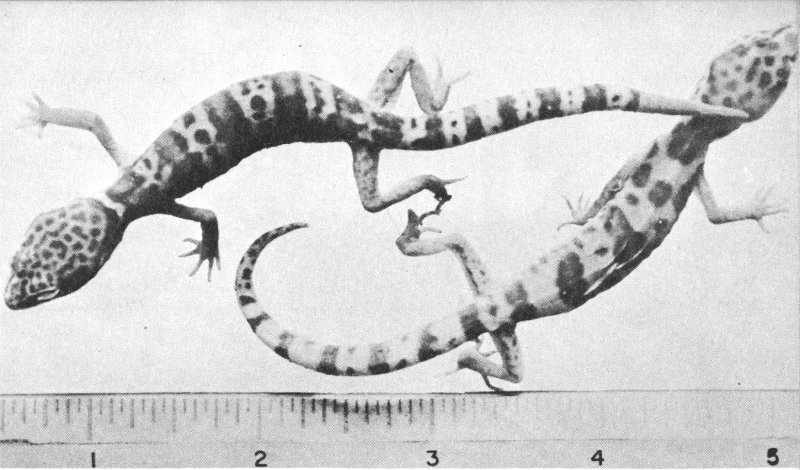

Two adult banded gecko lizards

These imaginary tales are passed from generation to generation and are the strongest in regions where the percentage of uneducated people is high. This situation exists in the South and Southwest. Many persons who have been denied educational opportunities are extremely credulous and have a long list of creatures to each of which they credit injurious or helpful powers. A majority of these creatures are perfectly harmless, but they are too numerous to be given space in this publication. However, it seems only fair to mention a few of the commonest of these persecuted species in the hope that they may be recognized as not only harmless, but in many cases actually beneficial to man. Thus may their unwarranted persecution be somewhat reduced.

Quite small, with velvety skin and delicate markings making it appear fragile and semitransparent, this lizard has little to inspire fear. Hiding away during daylight hours in dark and preferably moist retreats, it comes forth at night in search of insects for food.

It is rarely seen unless disturbed in its hiding place, which may be in the corner of a closet or cupboard beneath the sink. If captured, it struggles to escape, emitting a faint, high-pitched squeak.

Although the banded gecko is sometimes mistaken for the young of a Gila monster, in general the desert people accuse it of no definite crime, stating merely “we have heard that it is very poisonous,” and in consequence, kill it whenever they find it.

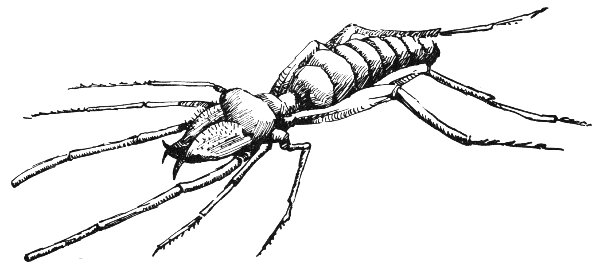

Probably because of its large and prominent jaws, the solpugid, Eremobates sp., which is closely related to the spiders, is greatly feared.

Solpugid or sun Spider

“Anything so ugly MUST be poisonous,” seems to be the principal basis for its unhappy reputation.

It is often found inside buildings where it has gone in search of insect prey, and Mexican families living in adobe houses with dirt floors are reported to be terrorized by it. In Mexico and in many parts of the Southwest it is known as niña de la tierra or child-of-the-earth.

The range of the solpugid or sun spider is by no means limited to the desert, but its reputation as a poisonous creature seems to be much worse in the Southwest than elsewhere.

The solpugid not only is perfectly harmless to man but does not rely on poison in capturing its prey, as it has no venom glands whatever.

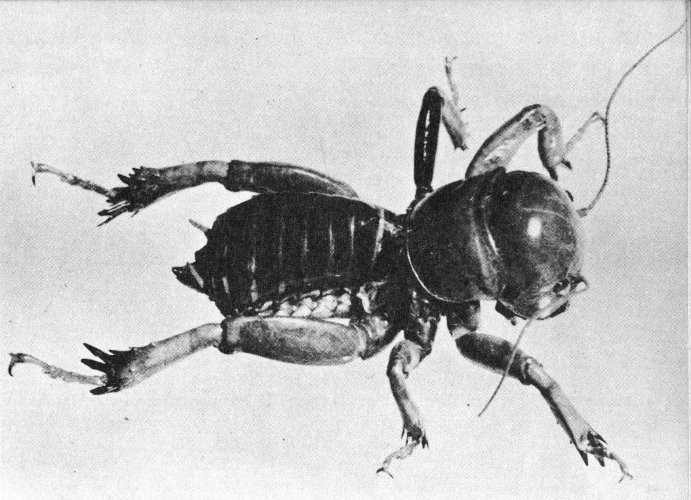

Whereas the solpugid is called child-of-the-earth in the southern portions of the Southwest, in the northern part of this territory another creature, the Jerusalem cricket, sand cricket, or chacho is reported as 37 imbued with the same dangerous qualities evidently credited to any creature to which this name has been applied.

Jerusalem cricket, sand cricket, or chacho (Photo by Marvin H. Frost, Sr.)

Although quite common, the Jerusalem cricket, Stenopelmatus sp., is shy and nocturnal in its habits. Its striking appearance is due to its head which is round, bald, and with markings on top that form, with the use of a little imagination, a simple, smiling face. It is this that suggests to the Spanish-speaking people of the Southwest, who occasionally dig it from its burrow, the name “niña de la tierra.” The Navajo Indians call it woh-seh-tsinni, meaning Old Man Bald-head.

By the superstitious natives, this creature is believed to be highly venomous and frequently the death of a horse or cow is blamed by the owner on a “chacho” that has crawled into the hay.

Actually, the Jerusalem cricket is harmless and may be handled with perfect impunity by anyone, although it may inflict a painful nip.

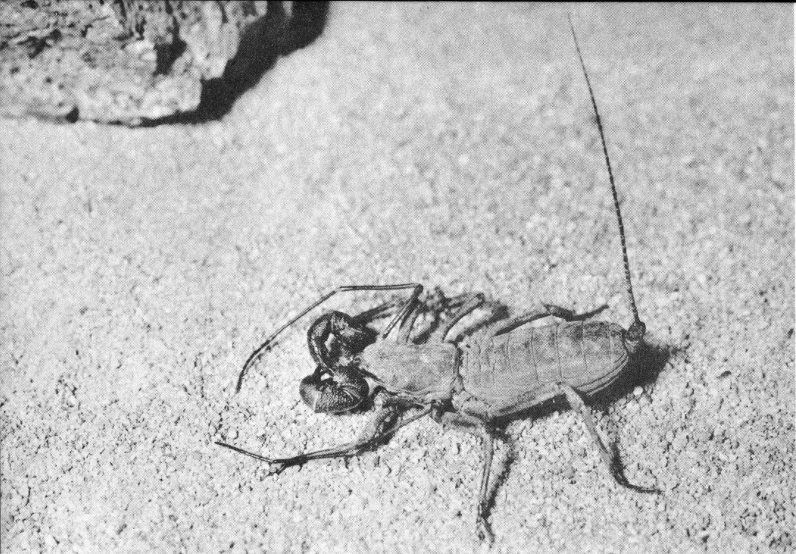

Since people coming from Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas bring the majority of tales regarding the deadly characteristics of the little vinegaroon or whip-tail scorpion, fear of it is apparently more widespread 38 over the cotton belt as a whole than within the desert regions of the Southwest.

Vinegaroon (Photo by Marvin H. Frost, Sr.)

The name vinegaroon stems from the fact that when the little creature is injured or smashed it gives off the odor of an acetate similar to that of acetic acid, the principal ingredient of vinegar.

Equipped with a massive pair of pincers, the vinegaroon, like the solpugid, gives an impression of fierceness which is probably the basis for much of its reputation as a dangerous criminal. However, the pincers are used in catching and holding prey and have no poison mechanism in connection.

The hairlike posterior appendage, or tail, is without any protective or offensive mechanism whatever, so that the creature is perfectly harmless insofar as human beings are concerned.

In fact, like the solpugid and the banded gecko, its food habits cause it to rid the world of a great many insects during the course of its life and many of its victims are certain to be noxious to the interests of mankind.

All of these creatures, then, are not only harmless, but are actually beneficial to man, and they deserve to be freed from the persecution resulting from ignorance and superstition, and to be permitted to live in their normal relationship with other creatures.

A B C D E F G H I J K L M

N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

This booklet is published in cooperation with the National Park Service by the

SOUTHWEST PARKS AND MONUMENTS ASSOCIATION

a non-profit distributing organization pledged to aid in preservation and interpretation of Southwestern features of outstanding national interest.

The Association lists for sale many excellent publications for adults and children and hundreds of color slides on Southwestern subjects. We recommend the following items for additional information on the Southwest and the National Park System:

YOUR NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM IN THE SOUTHWEST. IN WORDS AND COLOR. Jackson. 500 word articles on each National Park Service area in the huge Southwest Region, with full-color photograph for 54 of the 56 areas listed. Most authoritative treatment possible, by 32-year former career N.P.S. employee, with every text checked for accuracy by Regional Office and each area’s superintendent. Also contains “How to Get There” appendix. 64 pages, 56 full-color illustrations, color cover, paper.$1.95

100 DESERT WILDFLOWERS IN NATURAL COLOR. Dodge. Descriptions and full-color portraits of 100 of the most interesting desert wildflowers. Photographic hints. 64 pp., full-color cover, paper.$1.50

100 ROADSIDE WILDFLOWERS OF SOUTHWEST UPLANDS IN NATURAL COLOR. Dodge. Companion book to author’s 100 Desert Wildflowers in Natural Color, but for higher elevation flowers. 64 pages and full-color cover, paper.$1.50

FLOWERS OF THE SOUTHWEST DESERTS. Dodge and Janish. More than 140 of the most interesting and common desert plants beautifully drawn in 100 plates, with descriptive text. 112 pp., color cover, paper.$1.00

FLOWERS OF THE SOUTHWEST MESAS. Patraw and Janish. Companion volume to the Desert flowers booklet, but covering the plants of the plateau country of the Southwest. 112 pp., color cover, paper.$1.00

FLOWERS OF THE SOUTHWEST MOUNTAINS. Arnberger and Janish. Descriptions and illustrations of plants and trees of the southern Rocky Mountains and other Southwestern ranges above 7,000 feet elevation. 112 pp., color cover, paper.$1.00

MAMMALS OF THE SOUTHWEST DESERTS (formerly Animals of the Southwest Deserts). Olin and Cannon. Handsome illustrations, full descriptions, and life habits of the 42 most interesting and common mammals of the lower desert country of the Southwest below the 4,500-foot elevation. 112 pp., 60 illustrations, color cover, paper.$1.00

MAMMALS OF SOUTHWEST MOUNTAINS AND MESAS. Olin and Bierly. Companion volume to Mammals of Southwest Deserts. Fully illustrated in exquisitely done fine and scratchboard drawings, and written in Olin’s masterfully lucid style. Gives description, ranges, and life habits of the better known Southwestern mammals of the uplands. Color cover, paper$2.00

Cloth$3.25

Write For Catalog

SOUTHWEST PARKS AND MONUMENTS ASSOCIATION

Box 1562—Globe, Arizona 85501

12th Edition (Revised) 8-70—20M

On page 29, we regretfully acknowledge a typographical error. Step 3 of the cryotherapy treatment should read: