The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

THE OLD EAST INDIAMEN

Demy 8vo. Cloth Bindings. All fully Illustrated

THROUGH UNKNOWN NIGERIA

By John R. Raphael. 15s. net.

A WOMAN IN CHINA

By Mary Gaunt. 15s. net.

LIFE IN AN INDIAN OUTPOST

By Major Casserly. 12s. 6d. net.

CHINA REVOLUTIONISED

By J. S. Thompson. 12s. 6d. net.

NEW ZEALAND

By Dr Max Herz. 12s. 6d. net.

THE DIARY OF A SOLDIER OF FORTUNE

By Stanley Portal Hyatt. 12s. 6d. net.

OFF THE MAIN TRACK

By Stanley Portal Hyatt. 12s. 6d. net.

WITH THE LOST LEGION IN NEW ZEALAND

By Colonel G. Hamilton-Browne (“Maori Browne”). 12s. 6d. net.

A LOST LEGIONARY IN SOUTH AFRICA

By Colonel G. Hamilton-Browne (“Maori Browne”). 12s. 6d. net.

SIAM

By Pierre Loti. 7s. 6d. net.

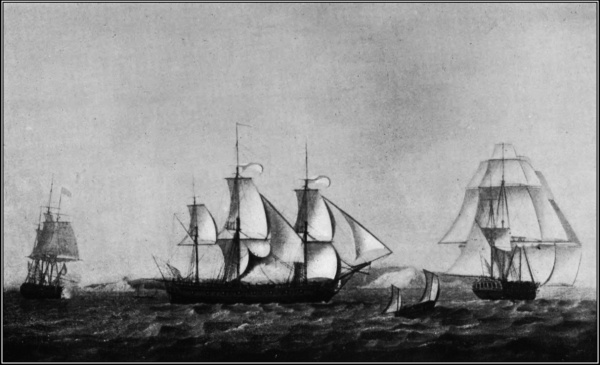

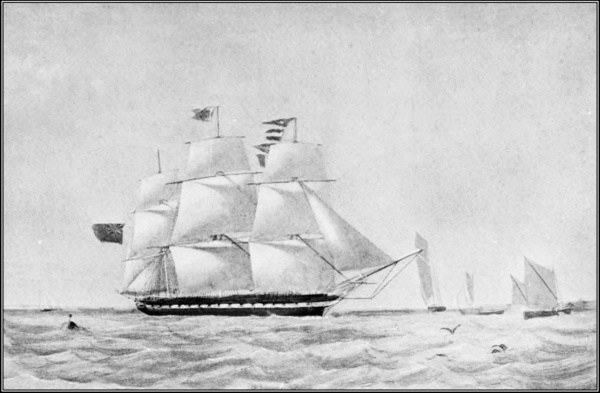

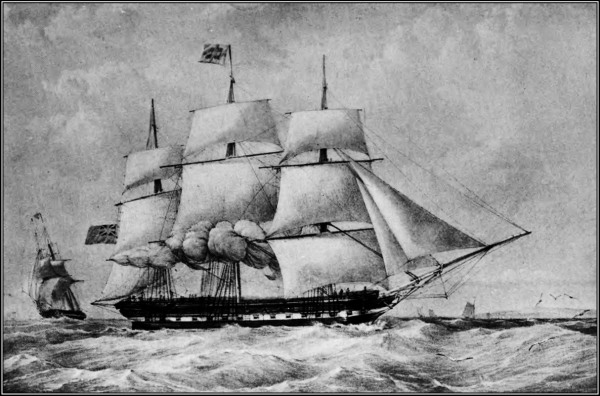

THE EAST INDIAMAN “THOMAS COUTTS,” AS SHE APPEARED IN THE YEAR 1826.

(By courtesy of Messrs. T. H. Parker Brothers)

Author of “Sailing-Ships and their Story,”

“Down Channel in the ‘Vivette,’”

“Through Holland in the ‘Vivette,’”

“Ships and Ways of Other Days,” etc.

ILLUSTRATED

LONDON

T. WERNER LAURIE LTD.

8 ESSEX STREET, STRAND

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Introduction |

1 |

| II. | The Magnetic East |

10 |

| III. | The Lure of Nations |

18 |

| IV. | The Route to the East |

31 |

| V. | The First East India Company |

46 |

| VI. | Captain Lancaster distinguishes Himself |

64 |

| VII. | The Building of the Company’s Ships |

77 |

| VIII. | Perils and Adventures |

91 |

| IX. | Ships and Trade |

106 |

| X. | Freighting the East Indiamen |

124 |

| XI. | East Indiamen and the Royal Navy |

138 |

| XII. | The Way they had in the Company’s Service |

152 |

| XIII. | The East Indiamen’s Enemies |

166 |

| XIV. | Ships and Men |

180 |

| XV. | At Sea in the East Indiamen |

198 |

| XVI. | Conditions of Service |

226 |

| XVII. | Ways and Means |

248 |

| XVIII. | Life on Board |

265 |

| XIX. | The Company’s Naval Service |

281 |

| XX. | Offence and Defence |

291vi |

| XXI. | The “Warren Hastings” and the “Piémontaise” |

305 |

| XXII. | Pirates and French Frigates |

316 |

| XXIII. | The Last of the Old East Indiamen |

329 |

The East Indiaman Thomas Coutts |

Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

The East India House |

4 |

The Hon. East India Co.’s Ship General Goddard with H.M.S. Sceptre and Swallow capturing Dutch East Indiamen off St Helena |

12 |

The Essex East Indiaman at anchor in Bombay Harbour |

24 |

The East Indiaman Kent |

42 |

Dutch East Indiamen |

54 |

The launch of the Hon. East India Co.’s Ship Edinburgh |

78 |

India House, the Sale Room |

88 |

The Hon. East India Co.’s Ship Bridgewater entering Madras Roads |

96 |

The Halsewell East Indiaman |

104 |

The Seringapatam East Indiaman |

120 |

A Barque Free-trader in the London Docks |

130 |

The Press-Gang at Work |

140 |

The East Indiaman Swallow |

182 |

Commodore Sir Nathaniel Dance |

190 |

Repulse of Admiral Linois by the China Fleet under Commodore Sir Nathaniel Dance |

196 |

A view of the East India Docks in the early 19th Century |

210 |

The Thames East Indiaman |

218 |

The Windham East Indiaman sailing from St Helena |

224 |

The Jessie and Eliza Jane in Table Bay, 1829 |

236 |

The Alfred East Indiaman |

242 |

The East Indiaman Cruiser Panther in Suez Harbour |

250 |

The East Indiaman Triton, rough sketch of stern |

256 |

The East Indiaman Earl Balcarres |

262 |

Deck scene of the East Indiaman Triton |

266 |

The West Indiaman Thetis |

272 |

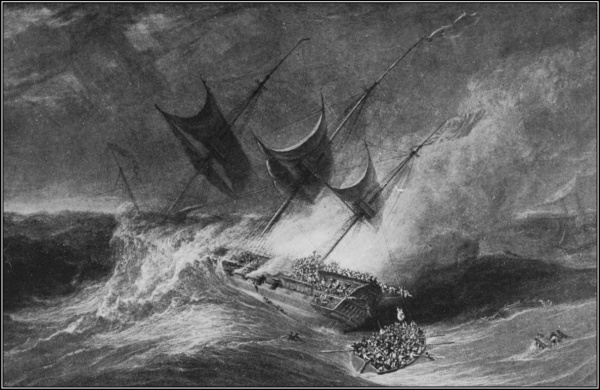

The Kent East Indiaman on fire in the Bay of Biscay |

276 |

The Cambria brig receiving the last boat-load from the Kent |

282 |

The Vernon East Indiaman |

294 |

The Sibella East Indiaman |

306 |

The East Indiaman Queen |

318 |

The East Indiaman Malabar, built of wood in 1860 |

330 |

The Blenheim East Indiaman |

340 |

The author desires to acknowledge the courtesy of Messrs T. H. Parker Brothers of Whitcomb Street, W.C., for allowing him to reproduce the illustrations mentioned on many of the pages of this book; as also the P. & O. Steam Navigation Company for permission to reproduce the old painting of the Swallow.

Owing to the fact that the author is now away at sea serving under the White Ensign, it is hoped that this may be deemed a sufficient apology for any errata which may have been allowed to creep into the text.

In this volume I have to invite the reader to consider a special epoch of the world’s progress, in which the sailing ship not only revolutionised British trade but laid the foundations of, and almost completed, that imposing structure which is to-day represented by the Indian Empire. It is a period brimful of romance, of adventures, travel and the exciting pursuit after wealth. It is a theme which, for all its deeply human aspect, is one for ever dominated by a grandeur and irresistible destiny.

With all its failings, the East India Company still remains in history as the most amazingly powerful trading concern which the world has ever seen. Like many other big propositions it began in a small way: but it acquired for us that vast continent which is the envy of all the great powers of the world to-day. And it is important and necessary to remember always that we owe this in the first place to the consummate courage, patience, skill and long-suffering of that race of beings, the intrepid seamen, who have never yet received their due from the landsmen whom they have made rich and comfortable.

Among the Harleian MSS. there is a delightful2 phrase written by a seventeenth-century writer, in which, treating of matters that are not immediately concerned with the present subject, he remarks very quaintly that “the first article of an Englishman’s Politicall Creed must be that he believeth in ye Sea etc. Without that there needeth no general Council to pronounce him uncapable of Salvation.” This somewhat sweeping statement none the less aptly sums up the whole matter of our colonisation and overseas development. The entire glamour of the Elizabethan period, marked as it unfortunately is with many deplorable errors, is derived from the sea. With the appreciation of what could be attained by a combination of stout ships, sturdy seamen, navigation, seamanship, gunnery and high hopes that refused persistently to be daunted, the most farsighted began to see that success was for them. Honours, wealth, the founding of families that should treasure their names in future generations, the acquisition of fine estates and the building of large houses with luxuries that exceeded the Tudor pattern—these were the pictures which were conjured up in the imaginations of those who vested their fortunes and often their lives in these ocean voyages. The call of the sea had in England fallen mostly on deaf ears until the late sixteenth century. It is only because there were some who listened to it, obeyed, and presently led others to do as they had done, that the British Empire has been built up at all.

Our task, however, is to treat of one particular way in which that call has influenced the minds and activities of men. We are to see how that, if it summoned some across the Atlantic to the Spanish3 Main, it sent others out to the Orient, yet always with the same object of acquiring wealth, establishing trade with strange peoples, and incidentally affording a fine opportunity for those of an adventurous spirit who were unable any longer to endure the cramped and confined limitations of the neighbourhood in which they had been born and bred. And though, as we proceed with our story, we shall be compelled to watch the gradual growth and the vicissitudes of the East Indian companies, yet our object is to obtain a clear knowledge not so much of the latter as of the ships which they employed, the manner in which they were built, sailed, navigated and fought. When we speak of the “Old East Indiamen” we mean of course the ships which used to carry the trade between India and Europe. And inasmuch as this trade was, till well on into the nineteenth century, the valuable and exclusive monopoly of the East India Company, carefully guarded against any interlopers, our consideration is practically that of the Company’s ships. After the Company lost their monopoly to India, their ships still possessed the monopoly of trading with China until the year 1833. After that date the Company sold the last of their fleet which had made them famous as a great commercial and political concern. In their place a number of new private firms sprang up, who bought the old ships from the East India Company, and even built new ones for the trade. These were very fine craft and acted as links between England and the East for a few years longer, reaching their greatest success between the years 1850 and 1870. But the opening of the Suez Canal and the enterprise of steamships sealed their fate, so that4 instead of the wealth which was obtained during those few years by carrying cargoes of rich merchandise between the East and the West, and transporting army officers, troops and private passengers, there was little or no money to be made by going round the Cape. Thus the last of the Indiamen sailing ships passed away—became coal-hulks, were broken up; or, changing their name and nationality, sailed under a Scandinavian flag.

The East India Company rose from being a private venture of a few enterprising merchants to become a gigantic corporation of immense political power, with its own governors, its own cavalry, artillery and infantry, its own navy, and yet with its trade-monopoly and its unsurpassed “regular service” of merchantmen. The latter were the largest, the best built, and the most powerfully armed vessels in the world, with the exception only of some warships. They were, so to speak, the crack liners of the day, but they were a great deal more besides. Their officers were the finest navigators afloat, their seamen were at times as able as any of the crews in the Royal Navy, and in time of war the Government showed how much it coveted them by impressing them into its service, to the great chagrin and inconvenience of the East India Company, as we shall see later on in our story.

THE EAST INDIA HOUSE.

(By courtesy of Messrs. T. H. Parker Brothers)

From being at first a small trading concern with a handful of factors and an occasional factory planted in the East in solitary places, the Company progressed till it had its own civil service with its training college in England for the cadets aspiring to be sent out to the East. It is due to the Company not only that India is now under the British flag,5 but that the wealth of our country has been largely increased and a new outlet was found for our manufactures. The factors who went out in the first Indiamen sailing ships sowed the seed which to-day we now reap. The commanders of these vessels made their “plots” (charts) and obtained by bitter experience the details which provided the first sailing directions. They were at once explorers, traders, fighters, surveyors. The conditions under which they voyaged were hard enough, as we shall see: and the loss of human life was a high price at which all this material trade-success was obtained. Notwithstanding all the quarrels, the jealousies, the murders, the deceits, the misrule and corruption, the bribery and extortion which stain the activities of the East India Company, yet during its existence it raised the condition of the natives from the lowest disorder and degradation: and if the Company found it not easy to separate its commercial from its political aspirations, yet the British Government in turn found it very convenient on occasions when this corporation’s funds could be squeezed, its men impressed; or even its ships employed for guarding the coasts of England or transporting troops out to India.

It is difficult to realise all that the East India Company stood for. It comprised under its head a large shipping line with many of the essential attributes of a ruling nation, and its merchant ships not only opened up to our traders India, but Japan and China as well. And bear in mind that the old East Indiamen set forth on their voyages not with the same light hearts that their modern successors, the steamships of the P. & O. line, begin their journey.6 Before the East India Company’s ships got to their destination, they had to sail right away round the Cape of Good Hope and then across the Indian Ocean, having no telegraphic communication with the world, and with none of the comforts of a modern liner—no preserved foods, no iced drinks or anything of that sort. Any moment they were liable to be plunged into an engagement: if not with the French or Dutch men-of-war, then with roving privateers or well-armed pirate ships manned by some of the most redoubtable rascals of the time, who stopped at no slaughter or brutality. There were the perils, too, of storms, and of other forms of shipwreck, and the almost monotonous safety of the modern liner was a thing that did not exist. Later on we shall see in what difficulties some of these ships became involved. It was because they were ever expectant of a fight that they were run practically naval fashion. They were heavily armed with guns, they had their special code of signals for day and night, they carried their gunners, who were well drilled and always prepared to fight: and we shall see more than one instance where these merchant ships were far too much for a French admiral and his squadron.

These East Indiamen sailing ships were really wonderful for what they did, the millions of miles over which they sailed, the millions of pounds’ worth of goods which they carried out and home: and this not merely for one generation, but for two and a half centuries. It is really surprising that such a unique monopoly should have been enjoyed for all this time, and that other ships should have been (with the exceptions we shall presently note) kept out7 of this benefit. The result was that an East Indiaman was spoken of with just as much respect as a man-of-war. She was built regardless of cost and kept in the best of conditions; and all the other merchantmen in the seven seas could not rival her for strength, beauty and equipment. It was a golden age, a glorious age: an epoch in which British seamanhood, British shipbuilding in wood, were capable of being improved upon only by the clipper ships that followed for a brief interval. They earned handsome dividends for the Company, they were always full of passengers, troops and valuable freight; and, although they were not as fine-lined as the clipper ships, yet they made some astounding passages. They carried crews that in number and quality would make the heart of a modern Scandinavian skipper break with envy. The result was that they were excellently handled and could carry on in a breeze till the last minute, when sail could be taken in smartly with the minimum of warning.

The country fully appreciated how invaluable was this East India service, and certainly no merchantmen were ever so regulated and controlled by Acts of Parliament. To-day you never hear of any merchant skipper buying or selling his command, nor retiring after a very few voyages with a nice little fortune for the rest of his life. But these things occurred in the old East Indiamen, when commanders received even knighthoods and a good income settled on them, for life, as a reward of their gallantry. Those were indeed the palmy days of the merchant service, and many an ill-paid mercantile officer to-day, wearied of receiving owners’ complaints and no thanks, must regret that his lot8 was not to be serving with the East India Company.

When we consider the two important centuries and a half, during which the East Indiamen ships were making history and trade for our country, helping in the most important manner to build up our Indian Empire, fighting the Portuguese, the Dutch and the French, privateers and pirates, and generally opening up the countries of the East, it is to me perfectly extraordinary that the history of these ships has never yet been written. I have searched in vain in our great national libraries—in the British Museum, the India Office, the Admiralty and elsewhere—but I have not been able to find one volume dealing exclusively with these craft. In an age that sees no end to the making of books there is therefore need for a volume that should long since have been written. Many of the story-books of our boyhood begin with the hero leaving England in an East Indiaman: but they say little or nothing as to how she was rigged, how she was manned, and what uniforms her officers wore.

I feel, then, that I may with confidence ask the reader who loves ships for themselves, or is fascinated by history, or is specially interested in the rise of our Indian Empire, to follow me in the following pages while the story of these old East Indiamen is narrated. In a little while we shall have passed entirely from the last of all surviving ocean-going sailing ships, but during the whole of their period none have left their mark so significantly on past and present affairs as the old East Indiamen. I can guarantee that while pursuing this story the reader will find much that will interest and even surprise him: but9 above all will be seen triumphant the true grit and pluck which have ever been the attributes of our national sailormen—the determination to carry out, in spite of all costs and hardships, the serious task imposed on them of getting the ship safely to port with all her valuable lives, and her rich cargoes, regardless of weather, pirates, privateers and the enemies of the nation whose flag they flew. And this fine spirit will be found to be confined to no special century nor to any particular ship: but rather to pervade the whole of the East India Company’s merchant service. The days of such a monopoly as this corporation’s trade and shipping are much more distant even than they seem in actual years: but happily it is our proud boast, as year after year demonstrates, that those qualities, which composed the magnificent seamanhood of the crews of these vessels, are no less existent and flourishing to-day in the other ships under the British flag that venture north, south, east and west. The only main difference is this:—Yesterday the sailor had a hundred chances, for every one opportunity which is afforded to-day to the sons of the sea, of showing that the grand, undying desire to do the right thing in the time of crisis is one of the greatest assets of our nation.

Within human experience it is a safe maxim, that if you keep on continuously thinking and longing for a certain object you are almost sure, eventually, to obtain that which you desire.

There is scarcely any better instance of this on a large scale than the longing to find a route to India by sea, and the attainment of this only after long years and years. As a study of perseverance it is remarkable: but the inspiration of the whole project was to get at the world’s great treasure-house, to find the way thereto and then unlock its doors. For centuries there had been trade routes between Europe and India overland. But the establishment of the Ottoman Empire in the fifteenth century placed a barrier across these routes. This suggested that there might possibly be—there was most probably—a route via the sea, and this would have the advantage of an easier method of transportation. It is very curious how throughout the ages a vague tradition survives and lingers on from century to century, finally to decide men’s minds on some momentous matter. It is not quite a literal inspiration, for often enough these ancient traditions had a modicum of truth therein contained.

In my last book, “Ships and Ways of Other Days,” I gave an instance of this which was remarkable enough to bear repeating. A reproduction was given of a fourteenth-century portolano, or chart, in which the shape of Southern Africa was seen to be extraordinarily accurate: and this, notwithstanding that it was sketched one hundred and thirty-five years before the Cape of Good Hope had been doubled. Some might suppose this knowledge to have been the result of second-sight, but my suggestion is that it was the result of an ancient tradition that the lower part of the African continent was shaped as depicted. For there is a well-founded belief that about the beginning of the sixth century B.C. the Phœnicians were sent by Neco, an Egyptian king, down the Red Sea; and that after circumnavigating the African continent they entered the Mediterranean from the westward.

The dim recollection of this voyage over a portion of the Indian Ocean, coupled with other knowledge derived from the Arabian seamen, doubtless left little hesitation in the minds of the seafaring peoples of the Mediterranean that the sea route to India existed if indeed it could be found. The various fruitless attempts, beginning with Vivaldi’s voyage from Genoa in 1281, are all evidence that this belief never died. For years nothing more successful was obtained than to get to Madeira or a little lower down the west coast of Africa, yet almost every effort was pushing on nearer the goal; even though that goal was still a very long way distant. The East was exercising a magnetic influence on the minds of men: India was bound to be discovered sooner or later, if they did not weary of the attempt.

Then comes on to the scene the famous Prince Henry the Navigator, who built the first observatory of Portugal, established a naval arsenal, gathered together at his Sagres headquarters the greatest pilots and navigators which could be collected, founded a school of navigation and chart-making, and then sent his trained, picked men forth to sail the seas, explore the unknown south with the hope ultimately of reaching the rich land of India. I have discussed this matter with such detail in the volume already alluded to that it will be enough if I here remark briefly that though Prince Henry died in the year 1460 without any of his ships or men attaining India, yet less than forty years were to elapse ere this was attained, and his was the influence which really brought this about. We must never forget that on the historical road to India through the long ages from the earliest times down to the fifteenth century the name of Prince Henry the Navigator represents one of the most important milestones.

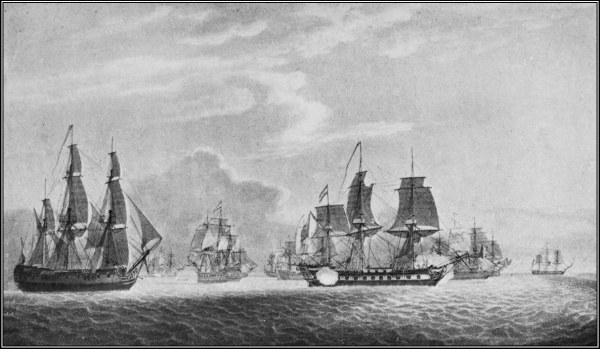

THE HONOURABLE EAST INDIA COMPANY’S SHIP “GENERAL

GODDARD,” COMMANDED BY WM. TAYLOR MONEY, WITH HIS MAJESTY’S SHIP

“SCEPTRE” AND “SWALLOW,” PACKET, CAPTURING SEVEN DUTCH EAST INDIAMEN

OFF ST. HELENA, ON 14th JUNE, 1795.

(By courtesy of Messrs. T. H. Parker Brothers)

You know so well how that thereafter, in the year 1486, the King of Portugal sent forth two expeditions with the desire to find an eastern route to India, and that one of these proceeded through Egypt, then down the Red Sea, across the Arabian Sea, and finally after some hardships reached Calicut, in the south-west of India. The other expedition consisted of a little squadron under Bartholomew Diaz, and although it did not get as far as India, yet it passed the Cape of Torments without knowing it—far out to sea—and even sighted Algoa Bay. The Cape of Torments he had called that promontory on his way back, remembering the bad weather which he here found: but the Cape of Good Hope his master,13 King John II., renamed it when Diaz reached home in safety. And then, finally, the last of these efforts was fraught with success when Vasco da Gama, in the year 1497, not only doubled the Cape of Good Hope, but discovered Mozambique, Melinda (a little north of Mombasa), and thence with the help of an Indian pilot crossed the ocean and reached Calicut by sea in twenty-three days—an absolutely unprecedented achievement for one who had sailed all the way from the Tagus.

This was the beginning of an entirely new era in the progress of the world, and till the crack of doom it will remain a memorable voyage, not merely for the fact that da Gama was able to succeed where so many others had failed, but because it unlocked the door of the East, first to the Portuguese, and subsequently to other nations of Europe. The twin arts of seamanship and navigation had made this possible, and it was only because the Portuguese, most especially Prince Henry, had believed “in ye sea” that the key had been found. As Columbus, by believing in the sea, was enabled in looking for India to open up the Western world, so was da Gama privileged to unlock the East. And since the sea connotes the ship we arrive at the standpoint that it is this long-suffering creature, fashioned by the hand of man, which has done more for the civilisation of the world than any other of those wonderful creations which the human mind has evolved from the things of the earth.

The first cargo which da Gama brought home was, so to speak, merely a small sample of those goods which were to be obtained by the ships that came after for generation after generation till the present14 day. It showed how great and priceless were the riches of the East—spices and perfumes, pearls and rubies, diamonds and cinnamon. The safe arrival of these, when da Gama got back home, made a profound impression. But it was no mere sentimental wonder, for the receipt of all these goods repaid the cost of the entire expedition sixty-fold. From this time forth the Portuguese were busily engaged in extracting wealth as men get it out from a gold mine. Their ships went backwards and forwards in their long voyages, sometimes narrowly escaping the attentions of the Moslem pirates anxious to relieve them of their valuable cargoes. Some Portuguese settled in India, and gradually there came into existence a fringe of Portuguese nationality extending from the Malabar coast right away to the Persian Gulf. Even as far as Japan was the East explored, and the vast fortunes which were brought back ever astonished the merchants of Europe. The first Portuguese factory was established at Calicut in the year 1500. For about a hundred years they were able to benefit, unrivalled, by their newly found treasure-house and to use their best endeavours, unfettered, to empty it.

In 1503 they erected their first fortress and strengthened their position. In their hands was the monopoly: theirs were the great and invaluable secrets of this amazing trade. And considering everything—the enterprise and training of Prince Henry, the far-sighted prudence in believing in the sea, the years and years of distressful voyages, the final attainment of the treasure-land only after many vicissitudes and the loss of ships and men—we cannot marvel that the Portuguese preserved these15 secrets, and held on to their monopoly, to the annoyance of the rest of civilised Europe. The fact was that Portugal was then the sovereign of the seas: she was far too strong afloat for any other country to think of wresting from her by force what she had obtained only by much study, skill and perseverance. What she had obtained she was going to hold. Those who wanted these Eastern goods must come to Lisbon, where the mart was held: and come they did, but they went back home envious that Portugal should enjoy this secret monopoly, and wondering all the time how India could be reached by a new route.

Curiosity and envy combined have been the means of the unravelling of many a secret. It was so now. Let us not fail to realise how greatly these human feelings influenced many of the voyages during the next hundred years. We justly admire the great daring of the Elizabethan seamen, but though the spirit of adventure and the hatred of Spain had a great deal to do with the cause of their setting forth to cross the ocean, yet there was another reason: and this explains much that is not otherwise quite clear. It is always fair to assume that men do not act except at the instigation of some clear motive. They do not persuade merchants to expend the whole of their small wealth in buying or building ships, victualling them and providing all the necessary inventories, without some rational cause. In the Elizabethan times, when wealth was much rarer than it is to-day, the prime motive of these expeditions was the pursuit of greater wealth.

But as England was not yet as expert at sea as the Portuguese, she could not hope to obtain the treasures of distant lands. Before she was ready16 there was, however, still Spain: and the latter was determined to do her best to obtain on her own what Portugal was enjoying. In a word, then, many of the sixteenth-century voyages which we have attributed, rashly, solely to a hope for adventurous exploration were in fact animated by the desire to find some new route to India. To this inspiration must be attributed many of those long sea journeys to the north, the north-east and the north-west. Men did not endeavour to find north-east or north-west passages merely for fun, but in order to discover a road to India. No one knew that it was impossible: if the Portuguese had been able to go one way, why should not they themselves go by another route? Remembering this, you must think of Spain sending Magellan to the west; of England sending Davis to the north-west; and of Holland sending Barentsz to the north-east to find a passage to the treasure-land of India or China.

The Spaniards discovered a way to India through the straits which are called after Magellan, and henceforth did their utmost to keep the ships of other countries out of their newly found waters, until the increase of English sea-power and the daring of our more experienced seamen showed that this Spanish sovereignty on sea could not be maintained by force. But still the English seamen had not yet reached India. We must turn for a moment to the Dutch, who were destined to become a great naval power. In the year 1580 the Spanish and Portuguese dominions had become united under the Spanish crown, and the Dutch were excluded from trading with Lisbon, their ships confiscated and their owners thrown into prison. Now, one of these captains17 while undergoing his imprisonment obtained from some Portuguese sailors a good deal of information concerning the Indian Seas, so that when he reached the Netherlands again he told the most wonderful accounts to his countrymen. The latter were so impressed by what was related that they decided to send an expedition to find the Indies themselves.

Presently, then, we shall see the Dutch not merely casting longing eyes towards India, but actually getting a footing therein, building up a very lucrative trade and employing great, well-built craft: but before we come to that stage we must note the gradual and persistent way in which the countries outside the Iberian Peninsula felt their way to this land of spices and precious stones, and after groping some time in the dark found that which they had been searching for during generations.

When once it was realised how wonderful was Portugal’s good fortune in the East, the nations of Europe one and all desired to enjoy some of these riches for themselves.

Even during the time of Henry VIII. one Master Robert Thorne, a London merchant, who had lived for a long time in Seville and had observed with envy the enterprise of the Portuguese, declared to his English sovereign a secret “which hitherto, as I suppose, hath beene hid”—viz. that “with a small number of ships there may bee discovered divers New lands and kingdoms ... to which places there is left one way to discover, which is into the North.... For out of Spaine they have discovered all the Indies and Seas Occidentall, and out of Portingall all the Indies and Seas Orientall.” His idea, then, was to seek a way to India via the north. The same Robert Thorne, writing in the year 1527 to Dr Ley, “Lord ambassadour for king Henry the eight,” concerning “the new trade of spicery” of the East, pointed out the wealth of the Moluccas (Malay Archipelago) abounding “with golde, Rubies, Diamondes, Balasses, Granates, Jacincts, and other stones and pearles, as all other lands, that are under19 and neere the Equinoctiall”; for just as “our mettalls be Lead, Tinne, and iron, so theirs be gold, silver and copper.”

Now Master Thorne was a very shrewd investor. “In a fleete of three shippes and a caravel,” he says, “that went from this citie armed by the marchants of it, which departed in Aprill last past, I and my partener have one thousand foure hundred duckets that we employed in the sayd fleete, principally for that two English men, friends of mine, which are somewhat learned in Cosmographie, should go in the same shippes, to bring me certaine relation of the situation of the countrey, and to be expert in the navigation of those seas, and there to have informations of many other things, and advise that I desire to know especially.” His idea was that our seamen should obtain some of the Portuguese “cardes” (i.e. charts) “by which they saile,” “learne how they understand them,” and thus, in plain language, crib some of the Portuguese secrets.

Thorne shows that he was no mean student of geography himself. Already he possessed “a little Mappe or Carde of the world” and pointed out that from Cape Verde “the coast goeth Southward to a Cape called Capo de buona speransa” (the Portuguese name for the Cape of Good Hope). “And by this Cape go the Portingals to their Spicerie. For from this Cape toward the Orient, is the land of Calicut.” “The coastes of the Sea throughout all the world I have coloured with yellow, for that it may appeare that all is within the line coloured yellow is to be imagined to be maine land or islands: and all without the line so coloured to bee Sea: whereby it is easie and light to know it.” Now20 Thorne had obtained this “carde” somehow by stealth: by rights he should not have possessed it, for the Portuguese, as already mentioned, were most anxious that their Indian secrets should not be divulged. He therefore begs his friend not to show anyone this chart else “it may be a cause of paine to the maker: as well for that none may make these cardes, but certaine appointed and allowed for masters, as for that peradventure it would not sound well to them, that a stranger should know or discover their secretes: and would appeare worst of all, if they understand that I write touching the short way to the spicerie by our Seas.”

We see, then, the determined desire to obtain the required information about a route to India obtained from the study of the very charts which the Portuguese made after some of their voyages, and by sending Englishmen out in their ships sufficiently expert in cosmography to learn all that could be known. It must not be forgotten, at the same time, that there were also land-travellers who journeyed to India and brought back alluring accounts of India. Cæsar Frederick, for instance, a Venetian merchant, set forth in the year 1563 with some merchandise bound for the East. From Venice he sailed in a vessel as far as Cyprus: from there he took passage in a smaller craft and landed in Syria, and then journeying to Aleppo got in touch with some Armenian and Moorish merchants whom he accompanied to Ormuz (on the Persian Gulf), where he found that the Portuguese had already established a factory and strengthened it, as the English East India Company’s servants were afterwards wont, with a fort. From Ormuz he went on to Goa and21 other places in India. Already, he pointed out, the Portuguese had a fleet or “Armada” of warships to guard their merchant craft in these parts from attack by pirates. Proceeding thence to Cochin, at the south-west of India, he found that the natives called all Christians coming from the West Portuguese, whether they were Italians, Frenchmen or whatever else: so powerful a hold had the first settlers from the Iberian Peninsula gained on the Indians. We need not follow this traveller on his way to Sumatra, to the Ganges and elsewhere, but it is enough to state that the accounts which he gave to his fellow-Europeans naturally whetted still more the appetites of the merchant traders anxious to get in touch with India by sea. He told them how rich the East was in pepper and ginger, nutmegs and sandalwood, aloes, pearls, rubies, sapphires, diamonds. It was a magnificent opportunity for an honest merchant to find wealth. “Now to finish that which I have begunne to write, I say that those parts of the Indies are very good, because that a man that hath little shall make a very great deale thereof: alwayes they must governe themselves that they be taken for honest men.”

When Magellan set forth from Seville to find a new route to India he had gone via the straits which now bear his name, and then striking north-west across the wide Pacific had arrived at the Philippine Islands, where he was killed. But his ships proceeded thence to the Moluccas, and one of his little squadron of five actually arrived back at Seville, having thus encircled the globe. Englishmen, however, were so determined that there was a nearer route than this that, in the year 1582, the Indian frenzy which enthralled our countrymen culminated22 in the voyage of Edward Fenton that set forth bound for Asia. This expedition consisted of four ships. It was customary in those days to speak of the Commodore or Admiral of the expedition as the “Generall,” thus indicating, by the way, that not yet had the English navy got away from the influence of the land army. The flagship was spoken of as the “Admirall.” These four ships, then, consisted, firstly, of the Leicester, the “Admirall” of the squadron. She was a vessel of 400 tons, her “generall” being Captain Edward Fenton, with William Hawkins (the younger) as “Lieutenant General,” or second in command of the expedition, the master of the ship being Christopher Hall. The second ship was the Edward Bonaventure, a well-known sixteenth-century craft of 300 tons, which was commanded by Captain Luke Ward, and the master was Thomas Perrie. The third ship was the Francis, a little craft of only 40 tons, whose captain was John Drake and her master was William Markham. The fourth was the Elizabeth, of 50 tons; captain, Thomas Skevington, and master, Ralph Crane.

Before we proceed any further it may be as well to explain a point that might otherwise cause confusion. In the ships of that time the captain was in supreme command, but he was not necessarily a seaman or navigator. He was the leader of the ship or expedition, but he was not a specialist in the arts of the sea. As we know from Monson, Elizabethan captains “were gentlemen of worth and means, maintaining there diet at their own charge.” “The Captaines charge,” says the famous Elizabethan Captain John Smith, the first president of Virginia, “is to commaund all, and tell the Maister to what port23 he will go, or to what height” (i.e. latitude). In a fight he is “to giue direction for the managing thereof, and the Maister is to see to the cunning [of] the ship, and trimming the sailes.” The master is also, with his mate, “to direct the course, commaund all the saylors, for steering, trimming, and sayling the ship”: and the pilot is he who, “when they make land, doth take the charge of the ship till he bring her to harbour.” And, finally, not to weary the reader too much, there is just one other word which is often used in these expeditions that we may explain. The “cape-merchant” was the man who had shipped on board to look after the cargo of merchandise carried in the hold.

On the 1st of April 1582 the Edward Bonaventure started from Blackwall in the Thames, and on the nineteenth of the same month arrived off Netley, in Southampton Water, where the Leicester was found waiting. On 1st May the four weighed anchor, but did not get clear of the land till the end of the month, “partly of businesse, and partly of contrary windes.” The complement of these ships numbered a couple of hundred, including the gentlemen adventurers with their servants, the factors (who were to open up trade), and the chaplains. In selecting crews, as many seamen as possible were obtained, but by this time these were not at all numerous in England: and even then great care had to be taken to avoid shipping “any disordered or mutinous person.”

The instructions given to Captain Fenton are so illustrative of these rules then so essential for the good government of overseas expeditions that it will not be out of place to notice them with some24 detail. As for the “Generall,” “if it should please God to take him away,” a number of names were “secretly set down to succeede in his place one after the other.” These names were inscribed on parchment and then sealed up in balls of wax with the Queen’s signet. They were then placed in two coffers, which were locked with three separate locks, one key being kept in the custody of the captain of the Edward Bonaventure, the second in the care of the Leicester’s captain, and the third in the keeping of Master Maddox, the chaplain. If the general were to die, these coffers were to be opened and the party named therein to succeed him.

Fenton’s instructions were to use all possible diligence to leave Southampton with his ships before the end of April, and then make for the Cape of Good Hope and so to the Moluccas. After leaving the English coast the general was to have special regard “so to order your course, as that your ships and vessels lose not one another, but keep companie together.” But lest by tempest or other cause the squadron should get separated, the captains and masters were to be advised previously of rendezvous, “wherein you will stay certaine dayes.” And every ship which reached her rendezvous and then passed on without knowing what had become of the other ships, was to “leave upon every promontorie or cape a token to stand in sight, with a writing lapped in leade to declare the day of their passage.” They were not to take anything from the Queen’s friends or allies, or any Christians, without paying therefor: and in all transactions they were to deal like good and honest merchants, “ware for ware.”

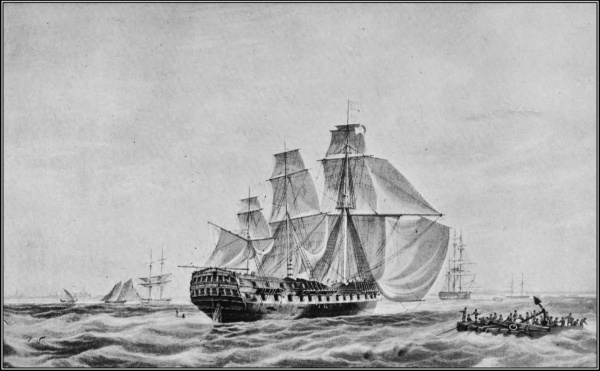

THE “ESSEX,” EAST INDIAMAN, AS SHE APPEARED WHEN

REFITTED AND AT ANCHOR IN BOMBAY HARBOUR.

(By courtesy of Messrs. T. H. Parker Brothers)

With a view to inaugurating a future trade they25 were if possible to bring home one or two of the natives, leaving behind some Englishmen as pledges, and in order to learn the language of the country. No person was to keep for his private use any precious stone or metal: otherwise he was to lose “all the recompense he is to have for his service in this voyage by share or otherwise.” A just account was to be kept of the merchandise taken out from England and what was brought home subsequently. And there is a strict order given which shows how slavishly the Portuguese example of secrecy was being copied. “You shall give straight order to restraine, that none shall make any charts or descriptions of the sayd voyage, but such as shall bee deputed by you the Generall, which sayd charts and descriptions, wee thinke meete that you the Generall shall take into your hands at your returne to this our coast of England, leaving with them no copie, and to present them unto us at your returne: the like to be done if they finde any charts or maps in those countreys.”

At the conclusion of the expedition the ships were to make for the Thames, and no one was to land any goods until the Lords of the Council had been informed of the ships’ arrival. As to the routine on board, Fenton was instructed to set down in writing the rules to be kept by the crew, so that in no case could ignorance be pleaded as excuse for delinquency. “And to the end God may blesse this voyage with happie and prosperous successe, you shall have an especiall care to see that reverence and respect bee had to the Ministers appointed to accompanie you in this voyage, as appertaineth to their place and calling, and to see such good order as by26 them shall be set downe for reformation of life and maners, duely obeyed and perfourmed, by causing the transgressours and contemners of the same to be severely punished, and the Ministers to remoove sometime from one vessell to another.”

But notwithstanding all these precautions this voyage was not the success which had been hoped for. After reaching the west coast of Africa and then stretching across to Brazil, where they watered ships, did some caulking, “scraped off the wormes” from the hulls, and learnt that the Spanish fleet were in the neighbourhood of the Magellan Straits, they determined to return to England. This they accordingly did. Before leaving England they had been instructed not to pass by these straits either going or returning, “except upon great occasion incident” with the consent of at least four of Fenton’s assistants. But a conference had decided that it were best to make for Brazil. And then the news which they received there of the Spanish fleet convinced them that it were futile to attempt to get to India that way.

But as the Italian whom we mentioned just now got to India by the overland route, so an Englishman named Ralph Fitch, a London merchant, being desirous to see the Orient, reached Goa in India via Syria and Ormuz. He set sail from Gravesend on 13th February 1582, left Falmouth on 11th March, and then never put in anywhere till the ship landed him at Tripoli in Syria on the following 30th April. After being absent from home nine years, Fitch came back in an English ship to London in April 1591. The reports which he brought were similar to the Italian’s verdict. India was rich in pepper, ginger, cloves, nutmegs, sandalwood, camphor, amber, sap27phires, rubies, diamonds, pearls, and so on. There was not the slightest doubt that it was the country to trade with. But, as yet, no English ship had found the way thither.

During the years 1585-1587 John Davis tried to find a way thither by the North-West Passage. Davis had a fine reputation as “a man very well grounded in the principles of the Arte of Navigation,” but none the less his efforts were unavailing. In 1588 the coming of the expected Armada turned the energies of the English seamen into another channel. But already, in the year 1586, Thomas Candish had set out from Plymouth with the Desire, 120 tons, the Content of 60 tons and the Hugh Gallant of 40 tons, victualled for two years and well found at his own expense. Journeying via Sierra Leone, Brazil and the Magellan Straits, he reached the Pacifice and China, and after touching at the Philippine Islands passed through the Straits of Java. From Java he crossed the ocean to the Cape of Good Hope, was able to correct the errors in the Portuguese sea “carts,” and in September 1588 reached Plymouth once more, having learnt from a Flemish craft bound from Lisbon that the Spanish Armada had been defeated, “to the singular rejoycing and comfort of us all.”A

The value of this voyage round the world was, from a navigator’s point of view, of inestimable advantage. For the benefit of those English navigators who were, a few years later, to begin the ceaseless voyages backwards and forwards round the Cape of 28 Good Hope, between England and India, Candish made the most elaborate notes and sailing directions, giving the latitudes (or, as the Elizabethans called them, “the heights”) of most of the places passed or visited. Very elaborate soundings were taken and recorded, giving the depth in fathoms and the nature of the sea-bed, wherever they went round the world, if the depth was not too great. In addition, he gave the courses from place to place, the distances, where to anchor, what dangers to avoid, providing warning of any difficult straits or channels, the variation of the compass at different places, the direction of the wind from certain dates to certain dates, and so on. But this, valuable as it undoubtedly was in many ways, did not exhaust the utility of the voyage. From China, whither the ships of the East India Company some years later were to trade, “I have brought such intelligence,” he wrote on his return to the Lord Chamberlain, “as hath not bene heard of in these parts. The stateliness and riches of which countrey I feare to make report of, least I should not be credited: for if I had not knowen sufficiently the incomparable wealth of that countrey, I should have bene as incredulous thereof, as others will be that have not had the like experience.”

And he showed in still further detail the fine opportunity which existed in the East and awaited only the coming of the English merchant. “I sailed along the Ilands of the Malucos, where among some of the heathen people I was well intreated, where our countrey men may have trade as freely as the Portugals if they will themselves.”

It is not therefore surprising that in the following year the English merchants began to stir themselves29 afresh. The East was calling loudly: and with the information brought back by Candish and some other knowledge, gained in a totally different manner, the time was now ripe for an expedition to succeed. For in the year 1587 Drake had left Plymouth, sailed across the Bay of Biscay, arrived at Cadiz Roads, where he did considerable harm to Spanish shipping, spoiled Philip’s plans for invading England that year, and then set a course for the Azores. It was not long before he sighted a big, tall ship, which was none other than the great carack, San Felipe, belonging to the King of Spain himself, whose name in fact she bore. This vessel was now homeward-bound from the East Indies and full of a rich cargo. Drake made it his duty to capture her in spite of her size, and very soon she was his and on her way to Plymouth.

Now the most wonderful feature of this incident was, historically, not the daring of Drake nor the value of the ship and cargo. The latter combined were found to be worth £114,000 in Elizabethan money, or in modern coinage about a million pounds sterling. But the most valuable of all were the ship’s papers found aboard, which disclosed the long-kept secrets of the East Indian trade. Therefore, this fact, taken in conjunction with the arrival of Candish the year following, and the wonderful incentive to English sea-daring given by the victory over the Spanish Armada—the fleet of the very nation whose ships had kept the English out of India—will prepare the reader for the memorial which the English merchants made to Queen Elizabeth, setting forth the great benefits which would arise through a direct trade with India. They there30fore prayed for a royal licence to send three ships thither. But Elizabeth was a procrastinating, uncertain woman. She had in that expedition of Drake in 1587 first given her permission and then had sent a messenger post haste all the way to Plymouth countermanding these orders. Luckily for the country, Drake had already got so far out to sea that it was impossible to deliver the message: and it was a good thing there was no such thing as wireless telegraphy in Elizabeth’s time.

So, in regard to these petitioning merchants, first she would and then she wouldn’t, and she kept the matter hanging indecisively until a few months before April 1591. By that time the necessary capital had been raised and the final preparations made, so that on the tenth of that month “three tall ships,” named respectively the Penelope (which was the “Admirall”), the Marchant Royall (which was the “Vice-Admirall”) and the Edward Bonaventure “Rear-Admirall”) were able to let loose their canvas and sailed out of Plymouth Sound.

I want in this chapter to call your attention to a very gallant English captain named James Lancaster, whose grit and endurance in the time of hard things, whose self-effacing loyalty to duty, show that there were giants afloat in those days in the ships which were to voyage to the East.

The account of the first of these voyages I have taken from Hakluyt, who in turn had obtained it by word of mouth from a man named Edmund Barker, of Ipswich. Hakluyt was known for his love of associating with seamen and obtaining from them first-hand accounts of their experiences afloat. And inasmuch as Barker is described as Lancaster’s lieutenant on the voyage, and the account was witnessed by James Lancaster’s signature, we may rely on the facts being true. Hakluyt was of course very closely connected with the subject of our inquiry. When the East India Company was started he was appointed its first historiographer, a post for which he was eminently fitted. He lectured on the subject of voyaging to the Orient, he made the maps and journals which came back in these ships useful to subsequent navigators and of the greatest interest to merchants and others. And when he died his work32 was in part carried on by Samuel Purchas of Pilgrimes fame. The second of these voyages, in which Lancaster again triumphs over what many would call sheer bad luck, has been taken from a letter which was sent to the East India Company by one of its servants, and is preserved in the archives of the India Office and will be dealt with in the following chapter. But for the present we will confine our attention to the voyage of those three ships mentioned at the end of the last chapter.

After leaving Devonshire the Penelope, Marchant Royall and Edward Bonaventure arrived at the Canary Isles in a fortnight, having the advantage of a fair north-east wind. Before reaching the Equator they were able to capture a Portuguese caravel bound from Lisbon for Brazil with a cargo of Portuguese merchandise consisting of 60 tuns of wine, 1200 jars of oil, about 100 jars of olives and other produce. This came as a veritable good fortune to the English ships, for the latter’s crews had already begun to be afflicted with bad health. “We had two men died before wee passed the line, and divers sicke, which tooke their sicknesse in those hote climates: for they be wonderful unholesome from 8 degrees of Northerly latitude unto the line, at that time of the yeere: for we had nothing but Ternados, with such thunder, lightning, and raine, that we could not keep our men drie 3 houres together, which was an occasion of the infection among them, and their eating of salt victuals, with lacke of clothes to shift them.” After crossing the Equator they had for a long time an east-south-east wind, which carried them to within a hundred leagues of the coast of Brazil, and then getting a33 northerly wind they were able to make for the Cape of Good Hope, which they sighted on 28th July. For three days they stood off and on with a contrary wind, unable to weather it. They had had a long voyage, and the health of the crew in those leaky, stinking ships had become bad. They therefore made for Table Bay, or, as it was then called, Saldanha, where they anchored on 1st August.

The men were able to go ashore and obtain exercise after being cramped for so many weeks afloat, and found the land inhabited by black savages, “very brutish.” They obtained fresh food by shooting fowl, though “there was no fish but muskles and other shel-fish, which we gathered on the rockes.” Later on a number of seals and penguins were killed and taken on board, and eventually, thanks to negro assistance, cattle and sheep were obtained by bartering. But when the time came to start off for the rest of the voyage it was very clear that the squadron, owing to the loss by sickness, was deficient in able-bodied men. It was therefore “thought good rather to proceed with two ships wel manned, then with three evill manned: for here wee had of sound and whole men but 198.” It was deemed best to send home the Marchant Royall with fifty men, many of whom were pretty well recovered from the devastating disease of scurvy. The extraordinary feature of the voyage was that the sailors suffered from this disease more than the soldiers. “Our souldiers which have not bene used to the Sea, have best held out, but our mariners dropt away, which (in my judgement) proceedeth of their evill diet at home.”

So the other two ships proceeded on their way towards India: but not long after rounding the Cape34 of Good Hope they encountered “a mighty storme and extreeme gusts of wind” off Cape Corrientes, during which the Edward Bonaventure lost sight of the Penelope. The latter, in fact, was never seen again, and there is no doubt that she foundered with all hands. The Edward, however, pluckily kept on, though four days later “we had a terrible clap of thunder, which slew foure of our men outright, their necks being wrung in sonder without speaking any word, and of 94 men there was not one untouched, whereof some were stricken blind, others were bruised in their legs and armes, and others in their brests, so that they voided blood two days after, others were drawn out at length as though they had bene racked. But (God be thanked) they all recovered saving onely the foure which were slaine out right.” The same electric storm had wrecked the mainmast “from the head to the decke” and “some of the spikes that were ten inches into the timber were melted with the extreme heate thereof.” Truly Lancaster’s command was a very trying one. What with a scurvy crew, an unhandy ship, now partially disabled, and both hurricanes and electric storms, there was all the trouble to break the spirit of many a man. Still, he held determinedly on his way whither he was bound.

But his troubles were now very nearly ended in one big disaster. After having proceeded along the south-east coast of Africa, and steering in a north-easterly direction, the ship was wallowing along her course over the sea when a dramatic incident occurred. It was night, and while some were below sleeping, one of the men on deck, peering through the moonlight, saw ahead what he took for breakers.35 He called the attention of his companions and inquired what it was, and they readily answered that it was the sea breaking on the shoals. It was the “Iland of S. Laurence.” “Whereupon in very good time we cast about to avoyd the danger which we were like to have incurred.” But it had been a close shave, and though Lancaster was to endure many other grievous hardships before his days were ended, yet but for the light of the kindly moon his ship, his crew and his own life would almost certainly have been lost that night.

But this was presently to be succeeded by the luck of falling in with three or four Arab craft, which were taken, their cargo of ducks and hens being very acceptable. They watered the ship at the Comoro Islands; a Portuguese boy, whom they had taken when the Arab craft were captured, being a useful acquisition as interpreter. But the master of the Edward Bonaventure, having gone ashore with thirty of his men to obtain a still further amount of fresh water, was treacherously taken and sixteen of his company slain. It was just one further source of discomfort for Lancaster now to have lost his ship’s master and more of his crew. So thence, “with heavie hearts,” the Edward sailed for Zanzibar, where they learnt that the Portuguese had already warned the natives of the character of Englishmen, in making out that the latter were “cruell people and men-eaters, and willed them if they loved safetie in no case to come neere us. Which they did onely to cut us off from all knowledge of the state and traffique of the countrey.”

The jealousy of the Portuguese was certainly very great: they were annoyed, and only naturally, that36 another nation should presume to burst into the seas which they had been the first of Europeans to open. Off this coast, from Melinda to Mozambique, a Portuguese admiral was cruising in a small “frigate”—that is to say, a big galley-type of craft propelled by sails and oars. And had this “frigate” been strong enough she would certainly have assailed Lancaster’s ship, for she came into Zanzibar to “view and to betray our boat if he could have taken at any time advantage.”

It was whilst riding at anchor here that another electric storm sprung the Edward’s foremast, which had to be repaired—“fished,” as sailors call it—with timber from the shore. And, to add still more to Lancaster’s bad luck, the ship’s surgeon, whilst ashore with the newly appointed master of the ship, looking for oxen, got a sunstroke and died. But the sojourn in that anchorage came to an end on 15th February. The progress of this voyage had been slow, but it had been sure. Relying on what charts he possessed, and then, after rounding the Cape of Good Hope, practically coasting up the African shore until reaching Zanzibar, he had wisely remained here some time. For this was the port whence the dhows traded backwards and forwards across the Indian Ocean and the East, and it must be remembered that the Arabs were skilled navigators and very fine seamen, who had been making these ocean voyages for centuries, whilst Englishmen were doing little more than coasting passages. Zanzibar was clearly the place where Lancaster could pick up a good deal of valuable knowledge regarding the voyage to India, and, incidentally, he took away from here a certain negro who had come37 from the East Indies and was possessed of knowledge of the country.

From Goa to Zanzibar the Arabian ships were wont to bring cargoes of pepper, and it was now Lancaster’s intention to cut straight across the Indian Ocean and make Cape Comorin—the southernmost point of the Indian peninsula—as his land-fall. He then meant to hang about this promontory, because it was to the traffic of the East what such places as Ushant and Dungeness to-day are to the shipping of the West. He knew that there was plenty of shipping bound from Bengal, the Malay Straits, from China and from Japan which would come round this cape well laden with all sorts of Eastern riches. He would therefore lie in wait off this headland and, attacking a suitable craft, would relieve her of her wealth. But the intention did not have the opportunity of being fulfilled as he had wished it. “In our course,” says Lancaster, “we were very much deceived by the currents that set into the Gulfe of the Red Sea along the coast of Melinde”—that is to say, from Zanzibar along the coast known to-day as British East Africa and Somaliland. “And the windes shortening upon us to the North-east and Easterly, kept us that we could not get off, and so with the putting in of the currents from the Westward, set us in further unto the Northward within fourescore leagues of” Socotra, which was “farre from our determined course and expectation.”

Therefore, as they had been brought so far to the northward of their course, Lancaster decided that it were best to run into Socotra or some port in the Red Sea for fresh supplies; but, luckily for him, the wind then came north-west, which was of course38 a fair wind from his present position to the south-west coast of India. Being a wise leader he of course now availed himself of this good fortune and sped over the Indian Ocean towards Cape Comorin, when the wind came southerly: but presently the wind came again more westerly, and so in the month of May 1592 the Cape was doubled, but without having sighted it, and then a course was laid for the Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal. But though they ran on for six days with a fair wind, and plenty of it, “these Ilands were missed through our masters default for want of due observation of the South starre.” It would be easy enough to criticise the lack of skill in the Elizabethan navigators, but it is much fairer to wonder rather that they were able to find their way as well as they did over strange seas, considering that until comparatively recently it was to them practically a new art. Excellent seamen they certainly had been for centuries: but it was not till long after Prince Henry the Navigator had taught his own countrymen, that this new sea-learning of navigation had reached England and “pilots-major” instructed our seamen in the higher branch of their profession. They were keen, they were adventurous, and they knew no fear: but these mariners were rude, unscientific men, who could not always be relied upon to make observations accurately. They did the best they could with their astrolabes and cross-staffs, but they lacked the perfection of the modern sextant. The most they could hope for was to make a land-fall not too distant from where they wanted to get, and then, having picked up the land, keep it aboard as far as possible. Thus they would approach their destined port, off which,39 by means of parleying with one of the native craft, they might persuade one of the crew to come aboard and so pilot them in.

As the Edward Bonaventure had missed the Nicobar Islands, it was decided to push on to the southward, which would bring them into the neighbourhood of Sumatra. There they lay two or three days, hoping for a pilot from Sumatra, which was only about six miles off. And subsequently, as the winter was approaching, they made for the Islands of Pulo Pinaou, which they reached in June, and there remained till the end of August. Many of the crew had again fallen sick, and though they put them ashore at this place, twenty-six more of them died. Nor were there many sources of supplies, but only oysters, shell-fish and the fish “which we tooke with our hookes.” But there was plenty of timber, and this came in very useful for repairing masts. When the winter passed and again they put to sea, the crew was now reduced to thirty-three men and one boy, but not more than twenty-two were fit for service, and of these not more than one-third were seamen: so the Edward was scarcely efficient.

But those which remained must have been of a resolute character, for in a little while they encountered a 60-ton ship, which they attacked and captured, and, shortly after, a second was also taken. Needless to say, the cargoes of pepper were discharged into the Edward, and even the sick men were soon reported as “being somewhat refreshed and lustie.” Lancaster had not by any means forgotten the fact that richly laden ships from China and Japan would pass through the Malacca Straits, and having arrived here he lay-to and waited. At40 the end of five days a Portuguese sail was descried, laden with rice, “and that night we tooke her being of 250 tunnes.” This was a big ship for those days, and so Lancaster determined to keep her as well as her cargo. He therefore put on board a prize crew of seven, under the command of Edmund Barker. The latter then came to anchor and hung out a riding-light so that the Edward could see her position. But the English ship was now so depleted of men that there were hardly enough men on board to handle her, and the prize had to send some of the men back to help her to make up the leeway. It was then decided to take out of the prize all that was worth having, and afterward, with the exception of the Portuguese pilot and four other men, she and her crew were allowed to go.

But it was not long before the Edward fell in with a much bigger ship, this time of 700 tons, which was on her way from India. She had left Goa with a most valuable cargo, and a smart engagement ended in her main-yard being shot through, whereupon she came to anchor and yielded, her people escaping ashore in the boats. Lancaster’s men found aboard her some brass guns, three hundred butts of wine, “as also all kind of Haberdasher wares, as hats, red caps knit of Spanish wooll, worsted stockings knit, shooes, velvets, taffataes, chamlets, and silkes, abundance of suckets, rice, Venice glasses,” playing-cards and much else. But trouble was brewing in the Edward, and a mutinous spirit was afoot. Lancaster’s men refused to obey his orders and bring the “excellent wines” into the Edward, so, after taking out of her all that he fancied, he then let the prize drift out to sea.

From there the Edward sailed to the Nicobar Islands, and afterwards proceeded to Punta del Galle (Point de Galle, Ceylon), where she anchored. Lancaster’s intention was again to lie in wait for shipping. He knew that more than one fleet of richly laden merchantmen would soon be due to pass that way. First of all he was expecting a fleet of seven or eight Bengal ships, and then two or three more from Pegu (to the north-west of Siam); and also there ought to be some Portuguese ships from Siam. These, he had learned, would pass that way in about a fortnight, bringing the produce of the country to Cochin (in the south-west of India), where the Portuguese caracks, or big merchantmen, would receive the goods and carry them home to Lisbon. It was a regular, yearly trade, the caracks being due to leave Cochin in the middle of January. A fine haul was certain, for these various fleets were bringing all sorts of commodities that were well worth having—cloth, rice, rubies, diamonds, wines and so on.

But Lancaster was again bound to bow to ill-luck. First of all, he had brought up where the bottom was foul, so he lost his anchor. He had on board two spare anchors, but they were unstocked and in the hold. This meant that a good deal of time was wasted, and meanwhile the ship was drifting about the whole night. In addition, to make matters worse, Lancaster himself fell ill. The current was carrying the ship to the southward, away from her required position, so in the morning the foresail was hoisted and preparations were being made to let loose the other sails, when the men mutinied and said they were determined they would remain there no longer42 but would take the ship to England direct. Lancaster, finding that persuasion was useless and that he could do nothing with them, had no other alternative but to give way to their demands: so on 8th December 1592 the Edward set sail for the Cape of Good Hope. On the way Lancaster recovered his health, and even amused himself fishing for bonitos. By February they had crossed the Indian Ocean and made the land by Algoa Bay, South Africa, where they had to remain a month owing to contrary winds. But in March they doubled the Cape of Good Hope once more, and on 3rd April reached St Helena. And here an extraordinary thing happened. When Edmund Barker went ashore he found an Englishman named Segar, like himself of Suffolk. He had been left here eighteen months before by the Marchant Royall, which you will remember had been sent home from Table Bay on the way out. On the way home he had fallen ill and would have died if he had remained on board, so it had been decided to put him ashore. When, however, the Edward’s men saw him this time, he was “as fresh in colour and in as good plight of body to our seeming as might be, but crazed in minde and halfe out of his wits, as afterward wee perceived: for whether he were put in fright of us, not knowing at first what we were, whether friends or foes, or of sudden joy when he understood we were his olde consorts and countreymen, hee became idel-headed, and for eight dayes space neither night nor day tooke any naturall rest, and so at length died for lacke of sleepe.”

On 12th April 1593 the Edward left St Helena, and the mutinous spirit was not yet dead on board. Lancaster’s intention was to cross the Atlantic to43 Pernambuco, Brazil, but the sailors were infuriated and wished to go straight home. So, the next day, whilst they were being told by the captain to finish a foresail which they had in hand, some of them asserted determinedly that, unless the ship were taken straight home, they would do nothing: and to this Lancaster was compelled to agree. But when they were about eight degrees north of the Equator the ship made little progress for six weeks owing to calms and flukey winds. Meanwhile the men’s victuals were running short, and the mutinous spirit reasserted itself strongly. They knew that the officers of the ship had their own provisions locked away in private chests—this had been done as a measure of precaution—and the men now threatened to break open these chests. Lancaster therefore determined, on the advice of one of the ship’s company, to make for the Island of Trinidad in the West Indies, where he would be able to obtain supplies. But, being ignorant of the currents of the Gulf of Paria, he was carried out of his course and eventually anchored off the Isle of Mona after a few days more.

After refreshing the stores and stopping a big leak, the Edward next put to sea bound for Newfoundland, but a heavy gale sent them back to Porto Rico, the wind being so fierce that even the furled sails of the ship were carried away, and the ship was leaking badly, with six feet of water in the hold. The victuals had run out, so that they were compelled to eat hides. Small provisions were obtained at Porto Rico, and then five of the crew deserted. From there the ship went to Mona again, and whilst a party of nineteen were on shore, including Lan44caster and Barker, to gather food, a gale of wind sprang up, which made such a heavy sea that the boat could not have taken them back to the Edward. It was therefore deemed wiser to wait till the next day: but during the night, about midnight, the carpenter cut the Edward’s cable, so that she drifted away to sea with only five men and a boy on board. At the end of twenty-nine days a French ship, afterwards found to be from Dieppe, was espied. In answer to a fire made on shore she dowsed her topsails, approached the land, hoisted out her ensign and came to anchor. Some of the Edward’s crew, including Barker and Lancaster, went aboard, but the rest of the party to the number of seven could not be found. Six more were taken on board another Dieppe ship and so reached San Domingo, where they traded with the people for hides. Here news reached them of their companions left in Mona. It was learnt that, of the seven men there left, two had broken their necks while chasing fowls on the cliffs, three were slain by Spaniards upon information given by the men who went away in the Edward, but the remaining two now joined Lancaster by a ship from another port.

Eventually Lancaster and his companions took passage aboard another Dieppe vessel, and arrived at the latter port after a voyage of forty-two days. They then crossed in a smaller craft to Rye, where they landed on 24th May 1594.

What good, then, had this expedition done? In spite of losing two out of the three ships, in spite of the losses of many men and the whole of the rich cargoes which had been obtained by capture, Lancaster and his companions had returned to England45 with something worth having. How had English trade with India been benefited? The answer is simple. If nothing tangible had been obtained, this expedition had been a great lesson. If it had brought back no spices or diamonds, it had brought much valuable information. Once again it showed to the English merchants that there was a fortune for all of them waiting in the Orient, and it showed by bitter experience the mistakes that must be avoided. The voyage had been begun at the wrong season of the year; it would have to be better thought out, and better provision would have to be taken to guard against scurvy. The route to India was now well understood, and it was no longer any Portuguese secret. England was just on the eve of sharing with the Portuguese their fortunate discovery, which eventually the latter were to lose utterly to the former.

Although the expedition of those three tall ships related in the previous chapter had been commercially such a dismal failure, it had shown that James Lancaster was the kind of man to whom there should be entrusted the leadership, not only of a single ship, but of an entire expedition. With the greatest difficulty he had prevented his unruly crew from excesses, he had taken his ship most of the way round the world, he had shown that he could put up a good fight when needs be, and that he possessed a capacity for finding out information—a most valuable ability in these the first days of Indian voyaging. He had obtained information about winds, tides, currents, places, peoples and trade. He had got to know where the Portuguese ships were usually to be found, where they started from and at what times of the year. Clearly he was just the man for the big expedition which was shortly to start from England, after but a few years’ interval.

We mentioned on an earlier page the travels of Ralph Fitch to India, though even prior to his setting forth another Englishman named Thomas Stevens had been to the East. This was in the year 1579, and although he was the first of our countrymen to47 reach India, yet he went out in a Portuguese ship, and is therefore entirely indebted to the Portuguese for having reached there at all. He had first proceeded from England to Italy, and then made his way from that country to Portugal. Having arrived in Lisbon, he went aboard and started eight days later when the Portuguese East Indian fleet sailed out. This was towards the beginning of April, which was very late for their sailing, but important business had detained them. Five ships proceeded together, bound for Goa, with many mariners, soldiers, women and children, the starting off being a solemn and impressive occasion, accompanied by the blowing of trumpets and the booming of artillery. Proceeding on their way via the Canaries and Cape Verde, they rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and afterwards steered to the north-east. And then occurred just that very incident which afterwards we have seen was to happen to Lancaster. Not knowing the set of the currents they got much too far to the northward and found themselves close to Socotra (at the entrance to the Gulf of Aden), whereas they imagined they were near to India. But eventually, having sailed many miles, and noticed birds in the sky which they knew came from their desired country, and then having seen floating branches of palm-trees they realised that they were now not far from their destination, and so on 24th October they arrived at Goa.

Stevens had watched the Portuguese navigators closely, and he had marvelled that these ships could find their way over the trackless ocean. “You know,” he wrote to his father in England, telling him all about the voyage, “you know that it is hard to48 saile from East to West, or contrary, because there is no fixed point in all the skie, whereby they may direct their course, wherefore I shall tell you what helps God provide for these men. There is not a fowle that appereth or signe in the aire, or in the sea, which they have not written, which have made the voyages heretofore. Wherefore, partly by their owne experience, and pondering withall what space the ship was able to make with such a winde, and such direction, and partly by the experience of others, whose books and navigations they have, they gesse whereabouts they be, touching degrees of longitude, for of latitude they be alwayes sure.”