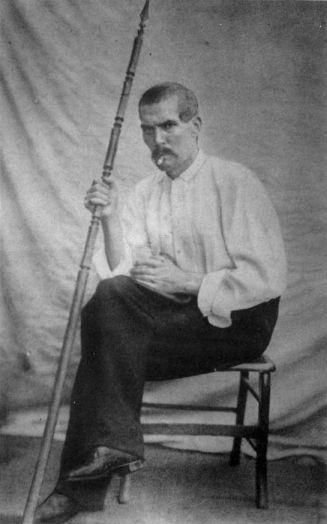

RICHARD BURTON IN HIS TENT IN AFRICA.

Whilst waiting to rejoin you, I leave as a message to the World we inhabited, the record of the Life into which both our lives were fused. Would that I could write as well as I can love, and do you that justice, that honour, which you deserve! I will do my best, and then I will leave it to more brilliant pens, whose wielders will feel less—and write better.

Meet me soon—I wait the signal!

ISABEL BURTON.

"No man can write a man down except himself."

In speaking of my husband, I shall not call him "Sir Richard," or "Burton," as many wives would; nor yet by the pet name I used for him at home, which for some reason which I cannot explain was "Jemmy;" nor yet what he was generally called at home, and what his friends called him, "Dick;" but I will call him Richard in speaking of him, and "I" where he speaks on his own account, as he does in his private journals. I always thought and told him that he destroyed much of the interest of his works by hardly ever alluding to himself, and now that I mention it, people may remark it, that in writing he seldom uses the pronoun I. I have therefore drawn, not from his books, but from his private journals. It was one of his asceticisms, an act of humility, which the world passed by, and probably only thought one of his eccentricities. In his works he would generally speak of himself as the Ensign, the Traveller, the Explorer, the Consul, and so on, so that I often think that people who are not earnest readers never understood who it was that did this, thought that, or saw the other. If I make him speak plainly for himself, as he does in his private journals, but never to the public, it will give twenty times the interest in relating events; so I shall throughout let him speak for himself where I can.

In early January, 1876, Richard and I were on our way to India for a six months' trip to visit the old haunts. We[Pg viii] divided our intended journey into two lots. We cut India down the middle, the long way on the map, from north to south, and took the western side, leaving the eastern side for a trip which was deferred, alas! for our old age and retirement. We utilized the voyage out (which occupied thirty-three days in an Austrian Lloyd, used as a Haj, or pilgrim-ship), and also the voyage back, in the part of the following pages which refers to his early life, he dictating and I writing.

In 1887, when my husband was beginning to be a real invalid, he lent some of these notes to Mr. Hitchman (who asked leave to write his biography), Richard promising not to tread upon his heels by his own Autobiography till he should be free from service in 1891. It will not, I think, do any harm to the reading public to reproduce it with more detail, because only seven hundred people got Mr. Hitchman's, who did not by any means use the whole of the material before he returned it, and what I give is the original just as Richard dictated it, and it is more needful, because it deals with a part of his life that was only known to himself, to me only by dictation; because everything that he wrote of himself is infinitely precious, and because to leave to the public a sketch of an early Richard Burton is desirable, otherwise readers would be obliged to purchase Mr. Hitchman's, as well as this work, in order to make a perfect whole.

I must take warning, however, that when Mr. Hitchman's book came out, part of the Press found this account of my husband's boyhood and youth charming, and another part of the Press said that I was too candid, and did nothing to gloss over the faults and foibles of the youthful Burtons; they doubted the accuracy of my information—I was informed that my style was too rough-and-ready, and of many others of my shortcomings. In short, I was considered rather as writing against my own husband, whilst both sides of the Press in their reviews assumed that I wrote it; this charmed Richard, and he would not let me refute. Not one word was mine—it was only dictation, and peremptory dictation when I objected to certain self-accusations. I beg leave to state that I did not write one single word; I could not, for I did not know it—and all that the family objected to, or considered[Pg ix] exaggerated, will not be repeated here. Before entering on these pages, I must warn the reader not to expect the goody-goody boy nor yet the precocious vicious youth of 1893. It is the recital of a high-spirited lad of the old school, full of animal spirits and manly notions, a lively sense of fun and humour, reckless of the consequences of playing tricks, but without a vestige of vice in the meaner or lower forms—a lad, in short, who would be a gentleman and a man of the world in his teens, and who, from his foreign travel, had seen more of life than boys do brought up at home.

I do not begin this work—the last important work of my life—without fear and trembling. If I can perform this sacred duty—this labour of love—well,—I shall be glad indeed, but I begin it with unfeigned humility. I have never needed any one to point out to me that my husband was on a pedestal far above me, or anybody else in the world. I have known it from 1850 to 1893, from a young girl to an old widow, i.e. for forty-three years. I feel that I cannot do justice to his scientific life, that I may miss points in travel that would have been more brilliantly treated by a clever man. My only comfort is, that his travels and services are already more or less known to the public, and that other books will be written about them. But if I am so unfortunate as to disappoint the public in this way, there is one thing that I feel I am fit for, and that is to lift the veil as to the inner man. He was misunderstood and unappreciated by the world at large, during his life. No one ever thought of looking for the real man beneath the cultivated mask that generally hid all feelings and belief—but now the world is beginning to know what it has lost. The old, old, sad story.

He shall tell his own tale till 1861, the first forty years, annotated by me. Whilst dictating to me I sometimes remarked, "Oh, do you think it would be well to write this?" and the answer always was, "Yes! I do not see the use of writing a biography at all, unless it is the exact truth, a very photograph of the man or woman in question." On this principle he taught me to write quite openly in the unconventional and personal style—being the only way to make a biography interesting, which we now class as the Marie[Pg x] Bashkirtcheff style. As you will see, he always makes the worst of himself, and offers no excuse. As a lad he does not know what to do to show his manliness, and all that a boy should, ought, and does think brave and honourable, be it wild or not, all that he does.

What appals me is, that the task is one of such magnitude—the enormous quantity of his books and writings that I have to look through, and, out of eighty or more publications, to ascertain what has seen the light and what has not, because it is impossible to carry the work of forty-eight years in one's head; and, again, the immense quantity of subjects he has studied and written upon, some in only a fragmentary state, is wonderful. My wish would be to produce this life, speaking only of him—and afterwards to reproduce everything he has written that has not been published. I propose putting all the heavier matter, such as pamphlets, essays, letters, correspondence, and the résumé of his works—that is, what portion shows his labours and works for the benefit of the human race—into two after-volumes, to be called "Labours and Wisdom of Richard Burton." After his biography I shall renew his "Arabian Nights" with his Forewords, Terminal Essay, and Biography of the book in such form that it can be copyrighted—it is now protected by my copyright. His "Catullus" and "Pentamerone" are now more or less in the Press, to be followed by degrees by all his unpublished works. His hitherto published works I shall bring out as a Uniform Library, so that not a word will be lost that he ever wrote for the public. Fortunately, I have kept all his books classified as he kept them himself, with a catalogue, and have separate shelves ticketed and numbered; for example, "Sword," "Gypsy," "Pentamerone," "Camoens," and so on.

If I were sure of life, I should have wished for six months to look through and sort our papers and materials before I began this work, because I have five rooms full. Our books, about eight thousand, only got housed in March, 1892, and they are sorted—but not the papers and correspondence; but I fancy that the public would rather have a spontaneous work sooner, than wait longer. If I live I shall always go on with them. I have no leisure to think of style[Pg xi] or of polish, or to select the best language, the best English,—no time to shine as an authoress. I must just think aloud, so as not to keep the public waiting.

From the time of my husband's becoming a real invalid—February, 1887—whilst my constant thoughts reviewed the dread To Come—the catastrophe of his death—and the subsequent suffering, I have been totally incapable, except writing his letters or attending to his business, of doing any good literary work until July, 1892, a period of five years, which was not improved by four attacks of influenza.

Richard was such a many-sided man, that he will have appeared different to every set of people who knew him. He was as a diamond with so many facets. The tender, the true, the brilliant, the scientific,—and to those who deserved it, the cynical, the hard, the severe. Loads of books will be written about him, and every one will be different; and though perhaps it is an unseemly boast, I venture to feel sure that mine will be the truest one, for I have no interest to serve, no notoriety to gain, belong to no party, have nothing to sway me, except the desire to let the world understand what it once possessed, what it has lost. With many it will mean I. With me it means HIM.

When this biography is out, the public will, theoretically, but not practically, know him as well as I can make them, and all of his friends will be able after that to put forth a work representing that particular facet of his character which he turned on to them, or which they drew from him. He was so great, so world-wide, he could turn a fresh facet and sympathy on to each world. I always think that a man is one character to his wife at his fireside corner, another man to his own family, another man to her family, a fourth to a mistress or an amourette—if he have one,—a fifth to his men friends, a sixth to his boon companions, and a seventh to his public, and so on ad infinitum; but I think the wife, if they are happy and love each other, gets the pearl out of the seven oyster-shells.

I fear that this work will be too long. I cannot help it. When I embarked on it I had no conception of the scope: it was a labour of love. I thought I could fly over it; but[Pg xii] I have found that the more I worked, the more it grew, and that the end receded from me like the mirage in the desert. I only aim at giving a simple, true recital without comment, and at fairness on all questions of whatever sort. I am very personal, because I believe the public like it. I want to give Richard as I knew him at home. I apologize in advance to my readers if I am sometimes obliged to mention myself oftener than they and I care about; but they will understand that our lives were so interwoven, so bound together, that I should very often spoil a good story or an anecdote or a dialogue were I to leave myself out. It would be an affectation that would spoil my work.

I am rather disheartened by being told by a literary friend that the present British public likes its reading "in sips." How can I give a life of seventy years, every moment of which was employed in a remarkable way, "in sips"? It is impossible. Though I must not detail much from his books, I want to convey to the public, at least, what they were about; striking points of travel, his schemes, wise warnings, advice, and plans for the benefit of England—then what about "sips"? It must not be dry, it must not be heavy, nor tedious, nor voluminous; so it shall be personal, full of traits of character, sentiments and opinions, brightened with cheerful anecdotes, and the more serious part shall go into the before-mentioned two volumes, the "Labours and Wisdom of Richard Burton."

I am not putting in many letters, because he generally said such personal things, that few would like them to be shown. His business letters would not interest. To economize time he used to get expressly made for him the smallest possible pieces of paper, into which he used to cram the greatest amount of news—telegram form. He only wrote much in detail, if he had any literary business to transact.

One of my greatest difficulties, which I scarcely know how to express, is, that which I think the most interesting, and which most of my intimates think well worth exploring; it is that of showing the dual man with, as it were, two natures in one person, diametrically opposed to each other, of which he was himself perfectly conscious. I had a party of literary[Pg xiii] friends to dinner one night, and I put my manuscript on the table before them after dinner, and I begged them each to take a part and look over it. Feeling as I do that the general public never understood him, and that his mantle after death seemed to descend upon my shoulders, that everything I say seems to be misunderstood, and that, in some few eyes, I can do nothing right, I said at the end of the evening, "If I endeavour to explain, will it not be throwing pearls to swine?" (not that I meant, dear readers, to compare you to swine—it is but an expression of thought well understood). And the answer was, "Oh, Lady Burton, do give the world the ins and outs of this remarkable and interesting character, and let the swine take care of themselves." "If you leave out by order" (said one) "religion and politics, the two touchstones of the British public, you leave out the great part of a man." "Mind you gloss over nothing to please anybody" (said a second). I think they are right—one set of people see one side, and another see another side, and neither of the two will comprehend (like St. Thomas) anything that they have not seen and felt; or, to quote one of Richard's favourite mottoes from St. Augustine, "Let them laugh at me for speaking of things which they do not understand, and I must pity them, whilst they laugh at me." So I must remain an unfortunate buffer amidst a cyclone of opinions. I can only avoid controversies and opinions of my own, and quote his and his actions.

These words are forced from me, because I have received my orders, if not exactly from the public, from a few of the friends who profess to know him best. I am ordered to describe Richard as a sort of Didérot (a disciple of Voltaire's), who wrote "that the world would never be quiet till the last king was strangled with the bowels of the last priest,"—whereas there was no one whom Richard delighted more to honour than a worthy King, or an honest straightforward Priest.

There are people who are ready to stone me, if I will not describe Richard as being absolutely without belief in anything; yet I really cannot oblige them, without being absolutely untruthful. He was a spade-truth man, and he honestly[Pg xiv] used to say that he examined every religion, and picked out its pearl to practise it. He did not scoff at them, he was perfectly sincere and honest in what he said; nor did he change, but he grew. He always said, and innumerable people could come forward, if they had the courage—I could name some—to say that they have heard him declare, that at the end of all things there were only two points to stand upon—NOTHING and CATHOLICISM; and many could, if they would, come forward and say, that when they asked him what religion he was, he answered Catholic.

He never was, what is called here and now in England, an Agnostic; he was a Master-Sufi, he practised Tasáwwuf or Sufi-ism, which combines the poetry and prose of religion, and is mystic. The Sufi is a profound student of the different branches of language and metaphysics, is gifted with a musical ear, indulges in luxuriant imagery and description. They have a simple sense—a double entendre understood amongst themselves—God in Nature,—Nature in God—a mystical affection for a Higher Life, dead to excitement, hope, fear, etc. He was fond of quoting Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn's motto, "It is better to restore one dead heart to Eternal Life, than Life to a thousand dead bodies."

I have seen him receive gratuitous copies of an Agnostic paper in England, and I remember one in particular—I do not know who wrote it,—it was very long, and all the verses ended with "Curse God the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost." I can see him now reading it—and stroking his long moustache, and muttering, "Poor devil! Vulgar beast!" He was quite satisfied, as his friends say, that we are not gifted with the senses to understand the origin of the Mysteries by which we are surrounded, and in this nobody agrees more thoroughly than I do. He likewise said he believed there was a God, but that he could not define Him; neither can I, neither can you, but I do not want to. Great minds tower above and see into little ones, but the little minds never climb sufficiently high to see into the Great Minds, and never did Lord Beaconsfield say a truer thing, speaking of religion than when he said, "Sensible men never tell." As I want to make this work both valuable and interesting, I am not going into the[Pg xv] unknown or the unknowable, only into what he knew—what I know; therefore I shall freely quote his early training, his politics, his Mohammedanism, his Sufi-ism, his Brahminical thread, his Spiritualism, and all the religions which he studied, and nobody can give me a sensible reason why I should leave out the Catholicism, except to point the Spanish proverb, "that no one pelts a tree, unless it has fruit on it," but were I to do so, the biography would be incomplete.

Let us suppose a person residing inside a house, and another person looking at the house from the opposite side of the street; you would not be unjust enough to expect the person on the outside to describe minutely its inner chambers and everything that was in it, because he would have to take it on trust from the person who resided inside, but you would take the report of the man living outside as to the exterior of the house. That is exactly the same as my writing my husband's history. Do you want an edition of the inside or an edition of the outside? If you do not want the truth, if you order me to describe a Darwin, a Spencer, a John Stuart Mill, I can do it; but it will not be the home-Richard, the fireside-Richard whom I knew, the two perfectly distinct Richards in one person; it will be the man as he was at lunch, at dinner, or when friends came in, or when he dined out, or when he paid visits; and if the world—or, let us say, a small portion of the world,—is so unjust and silly as to wish for untrue history, it must get somebody else to write it. To me there are only two courses: I must either tell the truth, and lay open the "inner life" of the man, by a faithful photograph, or I must let it alone, and leave his friends to misrepresent him, according to their lights.

It has been threatened to me that if I speak the truth I am to reap the whirlwind, because others, who claim to know my husband well, see him quite in a different light. (I know many people intimately, but I am quite incompetent to write their lives—I am only fit to do that for the man with whom I lived night and day for thirty years; there are three other people who could each write a small section of his life, and after those nobody; I do not accept the so-called general term "friend.") I shall be very happy indeed[Pg xvi] to answer anybody who attacks me, who is brave enough to put his or her name; but during the two years I have been in England I have hardly had anything but anonymous communications and paragraphs signed under the brave names of "Agnostic," or "One who knows," so I have no man or woman to deal with, but empty air, which is beneath my contempt. This is a very old game, perhaps even more ancient than "Prophesy, O Christ, who it was that struck Thee!" but it is cowardly and un-English—that is, if England "stands where she did." I would also remind you of the good old Arab proverb, that "a thousand curses never tore a shirt."

I would have you remember that I gain nothing by trying to describe my husband as belonging to any particular religion. If I would describe him as an English Agnostic—the last new popular word—the small band of people who call themselves his intimate friends, and who think to honour him by injuring me, would be perfectly satisfied. I should have all their sympathy, and my name would be at rest, both in Society and in the Press. I have no interest to serve in saying he was a Catholic more than anything else; I have no bigotry on the question at all. If he did something Catholic I shall say it, and if he did something Mohammedan or Agnostic I shall equally say it.

It is also a curious fact, that the people who are most vexed with me on this score, are men who, before their wives, mothers, sisters, are good Protestants, and who go twice to the Protestant church on Sundays, but who are quite scandalized that my husband should be allowed a religion, and are furious because I will not allow that Richard Burton was their Captain. No, thank you! it is not good enough: he was not, never was like any of you—nor can I see what it can possibly be to you what faith, or no faith, Richard Burton chose to die in, and why you threaten me if I speak the truth! We only knew two things—the beautiful mysticism of the East, which, until I lived here, I thought was Agnosticism, and I find it is not; and calm, liberal-minded Roman Catholicism. The difference between you and Richard is—you, I mean, who admired my husband—that you are not going anywhere,—according to your own Creed you have[Pg xvii] nowhere to go to,—whilst he had a God and a continuation, and said he would wait for me; he is only gone a long journey, and presently I shall join him; we shall take up where we left off, and we shall be very much happier even than we have been here.

Of the thousands that have written to me since his death, everybody writes, "What a marvellous brain your husband had! How modest about his learning and everything concerning himself! He was a man never understood by the world." It is no wonder he was not understood by the World; his friends hindered it, and when one who knew him thoroughly, offers to make him understood, it is resented.

The Press has recently circulated a paragraph saying that "I am not the fittest person to write my husband's life." After I have finished these two volumes, it will interest me very much to read those of the competent person, who will be so kind as to step to the front,—with a name, please, not anonymously,—and to learn all the things I do not know.

He, she, or it, will write what he said and wrote; I write what he thought and did.

ISABEL BURTON.

29th May, 1893.

Note.—I must beg the reader to note, that a word often has several different spellings, and my husband used to give them a turn all round. Indeed, I may say that during the latter years of his life he adopted quite a different spelling, which he judged to be correcter. In many cases it is caused by the English way of spelling a thing, and the real native way of spelling the same. For English Meeanee, native way Miani. The battle of Dabba (English) is spelt Dubba, Dubbah, by the natives. Fulailee river (English) is spelt Phuleli (native). Mecca and Medina have sometimes an h at the end of them. Karrachee is Karáchi. Sind is spelt Sind, Sindh, Scind, Scinde; and what the Anglo-Indians call Bóbagees are really Babárchis, and so on. I therefore beg that the spelling may not be criticized. In quoting letters, I write as the author does, since I must not change other people's spelling.—I. B.

[Transcriber's Note.—The page headings of the original edition have been converted into sidenotes in this digital edition. Typographical and other obvious errors have also been corrected, but the variations in the spelling of proper names, etc., mentioned above remain.]

Family history—The Napoleon Romance—The Louis XIVth Romance.

Richard Burton's early life—At Tours—His first school—Trips—Grandmammas

Baker and Burton—Aunt G.—They leave Tours.

School at Richmond—Measles disperse the school—Education at Blois—They

leave Blois for Italy—Pisa—Siena—Vetturino-travelling—Florence—Shooting—Rome

in Holy Week—Sorrento—Classical games—Chess—Naples—Cholera—Marseille—Pau—Bagnières

de Bigorres—Contrabandistas—Pau

education—Argélés—The boys fall in love—Drawing—Music—The

baths of Lucca—The boys get too old for home—Schinznach

and England—The family break up.

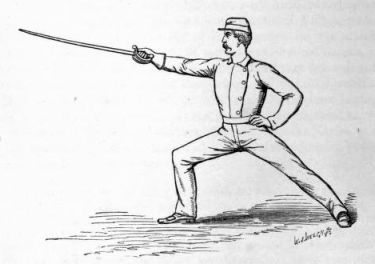

Practical jokes—Friends—Fencing-rooms—Manners and customs—Food

and smoking—Drs. Newman and Pusey—Began Arabic—Play—Town

life—College friends—Coaching and languages—Latin—Greek—Holidays—The

Rhine to Wiesbaden—The Nassau Brigade—The straws

that broke the camel's back—Rusticated.

He gets a commission and begins Hindostani—He goes to be sworn in at the

India Office.

The voyage and arrival—The sanitarium—His moonshee—Indian Navy—English

bigotry—Engages servants—Reaches Baroda—Brother

officers—Mess—Drill—Pig-sticking—Sport—Society—Feeding—Nautch—Reviews—Races—Cobden

and Indian history—Somnath gates—Outram

and Napier—He learns Indian riding and training—Passes exams. in

Hindostani—Receives the Brahminical thread—On the march—Embarks

for Sind—Karáchi, Sind—He passes in Maharátta.

A later chapter on same events differently told—His little autobiography—His

books on India—Burying a Sányasi—His Indian career practically

ends.

Boulogne—Bayonet exercise—Meets me at Boulogne at school—His famous

journey to Mecca and El Medinah—His start from Alexandria to Cairo—Twelve

days in an open Sambúk—Ten days' ride to Mecca—Moslem

Holy Week—The all-important crisis—His safe return—On board an

English ship—Interesting letters—The Kasîdah—The end of the

Kasîdah—Christian Poetry.

He starts for Harar in Somali-land—Preparations at Zayla—Desert journey—He

enters the city in triumph—Interview with the Amir—Has great

success—Damaging reports—He leaves Harar safely—A fearful desert

journey—Want of water—They reach Berberah—Join Speke, Herne,

Stroyan—He sails for Aden—Returns with forty men—They are attacked—A

desperate fight—Richard and Speke desperately wounded.

The Crimea—End of Crimea—Beatson's trial.

We become engaged—The story of Hagar Burton—Hagar Burton, the

Gipsy—Our strange parting.

Preliminary canter—Hippopotamus shooting—Our first fever.

A long march—Marsh fever—They ascend from Zungomero to a better

climate—From lovely scenery to fœtid marshes—Ants—The war-cry of

the Wahúmba—Evil reports—Game—Vermin—A hard jungle march—Description

of caravans and difficulties—Reptiles—Ill and attended by

a witch—Partial paralysis—Blindness—Elephants—The crossing of the

great river Malagarázi.

Scenery—In an Arab craft to Ujiji—More Scenery—After twenty-seven days Speke

returns—A fight—Are received with honour—A caravan arrives—Geographical

remarks—Troublesome following—Forest on fire—He

sends Speke to find the Nyanza—The Chief Suna—Richard collects a

vocabulary—Speke returns and the differences arose—Richard soliloquizes

on Speke's change of front—For geographers—The kindness of

Musa Mzuri and Snay bin Amir—Speke's illness—They cross the

"Fiery Field"—An official wigging—Christmas Day, 1858—Speke

leaves Richard ill, but apparently friendly.

We try to effect a reconciliation between Speke and Richard—My appeal to

my mother—My letter to my mother—Not a success—News of Richard

and subsequent return—A family council decides the matter—Our

wedding—We are received at home again—A delightful London season—Fire

at Grindlay's—Delightful days at country houses—Richard goes

to West Africa.

The West African negroes—The black man is raised above the white

man—Richard inaugurates a better state of things—Method of protecting the

negro—Teaching fair treatment for the negro—West African gold.

We sail for West Africa—We land at Madeira—Yellow fever—The peak of

Teneriffe—I return home—Richard sent as H.M.'s Commissioner to

Dahomè—Dahomè and Richard's travels—His travels, business, etc.,

on the West Coast.

Speke's death—Some lines I wrote on Richard and Speke—Richard's

"Stone Talk"—Gaiety—Winwood Reade—We go to Ireland—Richard

and Sir Bernard Burke—Bianconi—The anthropological farewell dinner—Lord

Derby's speech as chairman—Richard returns thanks—He speaks

his mind about the Nile.

We explore Portugal—I rejoin him at Rio de Janeiro—Arrival at Santos

and São Paulo—Life in Brazil—Brazilian life—Life at Rio—The Barra

for contrast—To the mines in Minas Gerães—We go down the big

mine—Below—Chico and I start on a fifteen days' ride alone—The landlord

of the hotel is mystified—Richard dangerously ill—Mesmerizing—Regatta—We

leave Brazil—Richard goes south—Lord Derby gives

Richard Damascus—His carbine pistol—Pleasant days in Vichy and

Auvergne—The Fell Railway—Geographical disagreeables—Work—The

Nile—Still the Nile—I sail for Damascus.

I find Richard has had a cordial reception—We go to Palmyra, or Tadmor

in the desert—We go without an escort—Tadmor—Camp life—Our

travelling day—Night camps—Return home after desert—Native life—The

Arabic library at Damascus—The library—The environs of

Damascus—How our days were passed—Our reception day—A most

interesting and remarkable woman—A romantic history—Richard's

love for children—Richard's notes on our wilder travels—The Tulúl el

Safá—Our home in the Anti-Lebanon—Our day—With Drake and

Palmer in the Lebanon—Religious disturbances—Holo Pasha gives us

a panther—The Druzes—Their stronghold—We camp at the Waters of

Merom—Richard is stung by a scorpion—Explorations of unknown

tracts—I prevent Rashíd Pasha's intentions taking effect—Rashíd's

intrigue about the Druzes—The manner in which we are received in

villages—Remarks on the journey—Kurdish dogs—Excursions to unknown

tracts—Troubles from a self-appointed zealot—Usurers very

troublesome—A Jehád threatened—Jews—Usurers try to remove

Richard—Letters of indignation and sympathy—Jews—Omar Bey's fine

mare—Horse-breeding—The Holy Land.

Shádilis—Sufis becoming Catholics—They are tried and condemned—And

persecuted—The Protestant converts—The Shádilis—Richard quotes

Mr. Gladstone—Letters approving his conduct—Richard's answer and

remarks—He leaves—I take a night ride across country—We were

stoned at Nazareth—General information—Salih's description of Richard—Letters

showing the state of Syria after his recall—The interval I

remained as a hostage—I leave the Anti-Lebanon—Wind up at

Damascus—I get fever—Eventually reach home—He gets an amende—We

become penniless—Small jottings—Death of my mother—Richard

accepts Trieste—The old story of shooting people, and a newer one—The

truth—Difficulty of English officials doing their duty—Conclusion of his Damascus career.

Lunge and Cut in Carte (inside).

Richard Burton, as Haji Abdullah, en route to Mecca.

Mecca and the Ka'abah, or the Holy Grail of the Moslems.

Burton's Sketch Map of Africa.

Richard Burton.

By Louis Desanges.

Isabel Burton.

By Louis Desanges.

The Chief Officer of Richard's Brigade of Amazons.

The Burtons' House in Salahíyyah, Damascus.

By Sir Frederick Leighton.

Salahíyyah, Damascus in the Oasis.

The Burtons' House-roof at Damascus and the Adjoining Mosque-Minaret.

The Burtons' House at Bludán, in Anti-Lebanon.

"He travels and expatriates; as the bee

From flower to flower, so he from land to land,

The manners, customs, policy of all

Pay contributions to the store he gleans;

He seeks intelligence from every clime,

And spreads the honey of his deep research

At his return—a rich repast for me!"

Autobiographers generally begin too late.

Elderly gentlemen of eminence sit down to compose memories, describe with fond minuteness babyhood, childhood, and boyhood, and drop the pen before reaching adolescence.

Physiologists say that a man's body changes totally every seven years. However that may be, I am certain that the moral man does, and I cannot imagine anything more trying than for a man to meet himself as he was. Conceive his entering a room, and finding a collection of himself at the several decades. First the puking squalling baby one year old, then the pert unpleasant schoolboy of ten, the collegian of twenty who, like Lothair, "knows everything and has nothing to learn." The homme fait of thirty in the full warmth and heyday of life, the reasonable man of forty, who first recognizes his ignorance and knows his own mind, of fifty with white teeth turned dark, and dark hair turned white, whose experience is mostly disappointment with regrets for lost time and vanished opportunities. Sixty when the man begins to die and mourns for[Pg 2] his past youth, at seventy when he ought to prepare for his long journey and never does. And at all these ages he is seven different beings not one of which he would wish to be again.

First I would make one or two notes on family history.

My grandfather was the Rev. Edward Burton, Rector of Tuam, in Galway (who with his brother, eventually Bishop Burton, of Killala, were the first of our branch to settle in Ireland). They were two of the Burtons of Barker Hill, near Shap, Westmoreland, who own a common ancestor with the Burtons of Yorkshire, of Carlow, and Northamptonshire. My grandfather married Maria Margaretta Campbell, daughter, by a Lejeune, of Dr. John Campbell, LL.D., Vicar-General of Tuam. Their son was my father, Lieut.-Colonel Joseph Netterville Burton, of the 36th Regiment, who married a Miss (Beckwith) Baker, of Nottinghamshire, a descendant, on her mother's side, of the Scotch Macgregors. The Lejeune above mentioned was related to the Montmorencys and Drelincourts, French Huguenots of the time of Louis XIV. To this hangs a story which will be told by-and-by. This Lejeune, whose real name was Louis Lejeune, is supposed to have been a son of Louis XIV. by the Huguenot Countess of Montmorency. He was secretly carried off to Ireland. His name was translated to Louis Young, and he eventually became a Doctor of Divinity. The royal, or rather morganatic, marriage contract was asserted to have existed, but has disappeared. The Lady Primrose of that date, who was a very remarkable personage, and a strong ally of the Jacobites, protected him and conveyed him to Ireland.

The Burtons of Shap derive themselves from the Burtons of Longnor, like Lord Conyngham and Sir Charles Burton of Pollacton, and the two above named were the collateral descendants of Francis Pierpoint Burton, first Marquis of Conyngham, who gave up the name of Burton. The notable man of the family was Sir Edward Burton, a desperate Yorkist who was made a Knight Banneret by Edward IV. after the second battle of St. Albans, and who added to his arms the Cross and four roses.

The Bishop of Killala's son was Admiral J. Ryder Burton, who entered the Navy in 1806. He served in the West Indies, and off the North Coast of Spain, when in an attack on the town of Castro, July, 1812, he received a gunshot wound in the left side, from which the ball was never extracted. From 1813 to 1816 he served in the Mediterranean and Adriatic, and was present at the bombardment of Algiers, when he volunteered to command one of the gunboats for destroying the shipping inside the Mole. His last appointment was in May, 1820, to the command of the Cornelian[Pg 3] brig, in which he proceeded in early 1824 to Algiers, where, in company with the Naiad frigate, he fell in with an Algerine corvette, the Tripoli, of eighteen guns and one hundred men, which, after a close and gallant action under the batteries of the place, he boarded and carried. This irascible veteran at his death was in receipt of a pension for wounds. He was Rear Admiral in 1853, Vice Admiral in 1858, and Admiral in 1863. He married, in 1822, Anna Maria, daughter of the thirteenth Lord Dunsany; she died in 1850, leaving one son, Francis Augustus Plunkett Burton, Colonel of the Coldstream Guards. He married the great heiress Sarah Drax, and died in 1865, leaving one daughter, Erulí, who married her cousin, John Plunkett, the future Lord Dunsany.

My father, Joseph Netterville Burton, was a lieutenant-colonel in the 36th Regiment. He must have been born in the latter quarter of the eighteenth century, but he had always a superstition about mentioning his birthday, which gave rise to a family joke that he was born in Leap Year. Although of very mixed blood, he was more of a Roman in appearance than anything else, of moderate height, dark hair, sallow skin, high nose, and piercing black eyes. He was considered a very handsome man, especially in uniform, and attracted attention even in the street. Even when past fifty he was considered the best-looking man at the Baths of Lucca. As handsome men generally do, he married a plain woman, and, "Just like Provy," the children favoured, as the saying is, the mother.[1]

In mind he was a thorough Irishman. When he received a commission in the army it was on condition of so many of his tenants accompanying him. Not a few of the younger sort volunteered to enlist, but when they joined the regiment and found that the "young master" was all right, they at once ran away.

The only service that he saw was in Sicily, under Sir John Moore, afterwards of Corunna, and there he fell in love with Italy. He was a duellist, and shot one brother officer twice, nursing him tenderly each time afterwards. When peace was concluded he came to England and visited Ireland. As that did not suit him he returned to his regiment in England. Then took place his marriage, which was favoured by his mother-in-law and opposed by his father-in-law. The latter, being a sharp old man of business, tied up every farthing of his daughter's property, £30,000, and it was well that he did so. My father, like too many of his cloth, developed a decided[Pg 4] taste for speculation. He was a highly moral man, who would have hated the idea of rouge et noir, but he gambled on the Stock Exchange, and when railways came out he bought shares. Happily he could not touch his wife's property, or it would speedily have melted away; yet it was one of his grievances to the end of his life that he could not use his wife's money to make a gigantic fortune. He was utterly reckless where others would be more prudent. Before his wedding tour, he passed through Windermere, and would not call upon an aunt who was settled near the Lakes, for fear that she might think he expected her property. She heard of it, and left every farthing to some more dutiful nephew.

He never went to Ireland after his marriage, but received occasional visits from his numerous brothers and sisters.

The eldest of the family was the Rev. Edward Burton, who had succeeded to the living. He wasted every farthing of his property, and at last had the sense to migrate to Canada, where he built a little Burtonville. In his younger days he intended to marry a girl who preferred another man. When she was a widow with three children, and he a widower with six children, they married, and the result was eventually a total of about a score. Such families do better than is supposed. The elder children are old enough to assist the younger ones, and they seem to hang together. My father's sisters, especially Mrs. Mathews, used to visit him when in England, and as it was known that he had married an heiress, they all hung to him, apparently, for themselves and their children. They managed to get hold of all the Irish land that fell to his share, and after his death they were incessant in their claims upon his children. My mother was Martha Baker, one of three sister co-heiresses, and was the second daughter. The third daughter married Robert Bagshaw, Esq., M.P. for Harwich, and died without issue. The eldest, Sarah, married Francis Burton, the youngest brother of my father. He had an especial ambition to enter the Church, but circumstances compelled him to become military surgeon in the 66th Regiment. There was only one remarkable event in his life, which is told in a few very interesting pages by Mrs. Ward, wife of General Ward, with a short comment by Alfred Bate Richards, late editor of the Morning Advertiser, who, together with Andrew Wilson, author of the "Abode of Snow," who took it up at his death, compiled and put together a short résumé of the principal features of my life, of which some three hundred copies were printed, in pamphlet form and circulated to private friends.

"Facts connected with the Last Hours of Napoleon.

"On the night of the 5th of May, 1821, a young ensign of the 66th Regiment, quartered at St. Helena, was wending his solitary way along the path leading from the plain of Deadwood to his barracks, situated on a patch of table-land called Francis Plain. The road was dreary, for to the left yawned a vast chasm, the remains of a crater, and known to the islanders as the 'Devil's Punchbowl;' although the weather had been perfectly calm, puffs of wind occasionally issued from the neighbouring valleys; and, at last, one of these puffs having got into a gully, had so much ado to get out of it, that it shrieked, and moaned, and gibbered, till it burst its bonds with a roar like thunder—and dragging up in its wrath, on its passage to the sea, a few shrubs, and one of those fair willows beneath which Napoleon, first Emperor of France, had passed many a peaceful, if not a happy, hour of repose, surrounded by his faithful friends in exile.

"This occurrence, not uncommon at St. Helena, has given rise to an idea, adopted even by Sir Walter Scott, that the soul of Napoleon had passed to another destiny on the wings of the Storm Spirit; but, so far from there being any tumult among the elements on that eventful night, the gust of wind I have alluded to was only heard by the few whose cottages dotted the green slopes of the neighbouring mountains. But as that fair tree dropped, a whisper fell among the islanders that Napoleon was dead! No need to dwell upon what abler pens than mine have recorded; the eagle's wings were folded, the dauntless eyes were closed, the last words, 'Tête d'armée,' had passed the faded lips, the proud heart had ceased to beat...!!

"They arrayed the illustrious corpse in the attire identified with Napoleon even at the present day; and among the jewelled honours of earth, so profusely scattered upon the breast, rested the symbol of the faith he had professed. They shaded the magnificent brow with the unsightly cocked hat,[2] and stretched down the beautiful hands in ungraceful fashion; every one, in fact, is familiar with the attitude I describe, as well as with a death-like cast of the imperial head, from which a fine engraving has been taken. The cast is true enough to Nature, but the character of the engraving is spoiled by the addition of a laurel-wreath on the lofty but insensate brow.

"About this cast there is a historiette with which it is time the public should become more intimately acquainted; it was the subject of litigation, the particulars of which are detailed in the Times newspaper of the 7th September, 1821, but to which I have now no opportunity of referring. Evidence, however, was unfortunately wanting at the necessary moment, and the complainant's case fell to the ground. The facts are these:—

"The day after Napoleon's decease, the young officer I have alluded[Pg 6] to, instigated by emotions which drew vast numbers to Longwood House, found himself within the very death-chamber of Napoleon. After the first thrill of awe had subsided, he sat down, and on the fly-leaf torn from a book, and given him by General Bertrand, he took a rapid but faithful sketch of the deceased Emperor. Earlier in the day, the officer had accompanied his friend, Mr. Burton, through certain paths in the island, in order to collect material for making a composition resembling plaster of Paris, for the purpose of taking the cast with as little delay after death as possible. Mr. Burton having prepared the composition, set to work and completed the task satisfactorily. The cast being moist, was not easy to remove; and, at Mr. Burton's request, a tray was brought from Madame Bertrand's apartments, Madame herself holding it to receive the precious deposit. Mr. Ward, the ensign alluded to, impressed with the value of such a memento, offered to take charge of it at his quarters till it was dry enough to be removed to Mr. Burton's; Madame Bertrand, however, pleaded so hard to have the care of it, that the two gentlemen, both Irishmen and soldiers, yielded to her entreaties, and she withdrew with the treasure, which she never afterwards would resign.

"There can scarcely, therefore, be a question that the casts and engravings of Napoleon, now sold as emanating from the skill and reverence of Antommarchi, are from the original taken by Mr. Burton. We can only rest on circumstantial evidence, which the reader will allow is most conclusive. It is to be regretted that Mr. Burton's cast and that supposed to have been taken by Antommarchi were not both demanded in evidence at the trial in 1821.

"The engraving I have spoken of has been Italianized by Antommarchi, the name inscribed beneath being Napoleone.

"So completely was the daily history of Napoleon's life at St. Helena a sealed record, that, on the arrival of papers from England, the first question asked by the islanders and the officers of the garrison was, 'What news of Buonaparte?' Under such circumstances it was natural that an intense curiosity should be felt concerning every movement of the mysterious and ill-starred exile. Our young soldier one night fairly risked his commission for the chance of a glimpse behind the curtain of the Longwood windows, and, after all, saw nothing but the imperial form from the knees downwards. Every night at sunset a cordon of sentries was drawn round the Longwood plantations. Passing between the sentinels, the venturesome youth crept, under cover of trees, to a lighted window of the mansion. The curtains were not drawn, but the blind was lowered. Between the latter, however, and the window-frame were two or three inches of space; so down knelt Mr. Ward! Some one was walking up and down the apartment, which was brilliantly illuminated.[3] The footsteps drew nearer, and Mr. Ward saw the diamond buckles of a pair of thin shoes, then two well-formed[Pg 7] lower limbs, encased in silk stockings; and, lastly, the edge of a coat, lined with white silk. On a sofa at a little distance was seated Madame Bertrand, with her boy leaning on her knee; and some one was probably writing under Napoleon's dictation, for the Emperor was speaking slowly and distinctly. Mr. Ward returned to his guard-house satisfied with having heard the voice of Napoleon Buonaparte.

"Mr. Ward had an opportunity of seeing the great captive at a distance on the very last occasion that Buonaparte breathed the outer air. It was a bright morning when the serjeant of the guard at Longwood Gate informed our ensign that 'General Buonaparte' was in the garden on to which the guard-room looked. Mr. Ward seized his spy-glass, and took a breathless survey of Napoleon, who was standing in front of his house with one of his Generals. Something on the ground attracted his notice; he stooped to examine (probably a colony of ants, whose movements he watched with interest), when the music of a band at a distance stirred the air on Deadwood Plain; and he who had once led multitudes forth at his slightest word now wended his melancholy way through the grounds of Longwood, to catch a distant glimpse of a British regiment under inspection.

"We have in our possession a small signal book which was used at St. Helena during the period of Napoleon's exile. The following passages will give some idea of the system of vigilance which it was thought necessary to exercise, lest the world should again be suddenly uproused by the appearance of the French Emperor on the battle-field of Europe. It is not for me to offer any opinion on such a system, but I take leave to say that I never yet heard any British officer acknowledge that he would have accepted the authority of Governor under the burden of the duties it entailed. In a word, although every one admits the difficulties and responsibilities of Sir Hudson Lowe's position, all deprecate the system to which he considered himself obliged to bend.

"But the signal-book! Here are some of the passages which passed from hill to valley while Napoleon took his daily ride within the boundary prescribed:—

"'General Buonaparte has left Longwood.'

"'General Buonaparte has passed the guards.'

"'General Buonaparte is at Hutt's Gate.'

"'General Buonaparte is missing.'

"The latter paragraph resulted from General Buonaparte having, in the course of his ride, turned an angle of a hill, or descended some valley beyond the ken, for a few minutes, of the men working the telegraphs on the hills!

"It was not permitted that the once Emperor of France should be designated by any other title than 'General Buonaparte;' and, alas! innumerable were the squabbles that arose between the Governor and his captive, because the British Ministry had made this puerile order peremptory. I have now no hesitation in making known the great Duke's opinion on this subject, which was transmitted[Pg 8] to me two years ago, by one who for some months every year held daily intercourse with his Grace, but who could not, while the Duke was living, permit me to publish what had been expressed in private conversation.

"'I would have taken care that he did not escape from St. Helena,' said Wellington: 'but he might have been addressed by any name he pleased.'

"I cannot close this paper without saying a word or two on the condition of the buildings once occupied by the most illustrious and most unfortunate of exiles.

"It is well known that Napoleon never would inhabit the house which was latterly erected at Longwood for his reception; that, he said, 'would serve for his tomb;' and that the slabs from the kitchen did actually form part of the vault in which he was placed in his favourite valley beneath the willows, and near the fountain whose crystal waters had so often refreshed him.

"This abode, therefore, is not invested with the same interest as his real residence, well named the 'Old House at Longwood;' for a more crazy, wretched, filthy barn, it would scarcely be possible to meet with; and many painful emotions have filled my heart during nearly a four years' sojourn on 'The Rock,' as I have seen French soldiers and sailors march gravely and decorously to the spot, hallowed in their eyes, of course, by its associations with their invisible but unforgotten idol, and degraded, it must be admitted, by the change it has undergone.

"Indeed, few French persons can be brought to believe that it ever was a decent abode; and no one can deny that it must outrage the feelings of a people like the French, so especially affected by associations, to see the bedchamber of their former Emperor a dirty stable, and the room in which he breathed his last sigh, appropriated to the purpose of winnowing and thrashing wheat! In the last-named room are two pathetic mementoes of affection. When Napoleon's remains were exhumed in 1846, Counts Bertrand and Las Casas carried off with them, the former a piece of the boarded floor on which the Emperor's bed had rested, the latter a stone from the wall pressed by the pillow of his dying Chief.

"Would that I had the influence to recommend to the British Government, that these ruined and, I must add, desecrated, buildings should be razed to the ground; and that on their site should be erected a convalescent hospital for the sick of all ranks, of both services, and of both nations. Were the British and French Governments to unite in this plan, how grand a sight would it be to behold the two nations shaking hands, so to speak, over the grave of Napoleon!

"On offering this suggestion, when in Paris lately, to one of the nephews of the first Emperor Napoleon, the Prince replied that 'the idea was nobly philanthropic, but that England would never listen to it.' I must add that his Highness said this 'rather in sorrow than in anger;' then, addressing Count L——, one of the faithful followers of Napoleon in exile, and asking him which mausoleum[Pg 9] he preferred,—the one in which we then stood, the dome of the Invalides, or the rock of St. Helena,—he answered, to my surprise, 'St. Helena; for no grander monument than that can ever be raised to the Emperor!'

"Circumstances made one little incident connected with this, our visit to the Invalides, most deeply interesting. Comte D'Orsay was of the party; indeed it was in his elegant atélier we had all assembled, ere starting, to survey the mausoleum then being prepared for the ashes of Napoleon. Suffering and debilitated as Comte D'Orsay was, precious, as critiques on art, were the words that fell from his lips during our progress through the work-rooms, as we stopped before the sculptures intended to adorn the vault wherein the sarcophagus is to rest. Ere leaving the works, the Director, in exhibiting the solidity of the granite which was finally to encase Napoleon, struck fire with a mallet from the magnificent block. 'See,' said Comte D'Orsay, 'though the dome of the Invalides may fall, France may yet light a torch at the tomb of her Emperor.' I cannot remember the exact words, but such was their import. Comte D'Orsay died a few weeks after this.

"Since the foregoing was written, members of the Burton family have told me, that, after taking the cast, Mr. Burton went to his regimental rounds, leaving the mask on the tray to dry; the back of the head was left on to await his return, not being dry enough to take off, and was thus overlooked by Madame Bertrand. When he returned he found that the mask was packed up and sent on board ship for France in Antommarchi's name. From a feeling of deep mortification he took the back part of the cast, reverently scraped off the hair now enclosed in a ring, and, overcome by his feelings, dashed it into a thousand pieces. He was afterwards offered by Messrs. Gall and Spurzheim (phrenologists), one thousand pounds sterling for that portion of the cast which was wanting to the cast so called Antommarchi's. Amongst family private papers there was a correspondence, read by most members of it, between Antommarchi and Mr. Burton, in which Antommarchi stated that he knew Burton had made the plaster and taken the cast. Mrs. Burton, after the death of her husband and Antommarchi, thought the correspondence useless and burnt it; but the hair was preserved under a glass watch-case in the family for forty years. There was an offer made about the year 1827 or 1828 by persons high in position in France who knew the truth to have the matter cleared up, but Mr. Burton was dying at the time, and was unable to take any part in it, so the affair dropped.

"The Bust of Buonaparte.

"Extract from the 'New Times' of September 7th, 1821.

"On Wednesday a case of a very singular nature occurred at the Bow Street Office.

"Count Bertrand, the companion of Buonaparte in his exile at[Pg 10] St. Helena (and the executor under his will), appeared before Richard Birnie, Esq., accompanied by Sir Robert Wilson, in consequence of a warrant having been issued to search the residence of the Count for a bust of his illustrious master, which, it was alleged, was the property of Mr. Burton, 66th Regiment, when at St. Helena.

"The following are the circumstances of the case:—

"Previous to the death of Buonaparte, he had given directions to his executors that his body should not be touched by any person after his death; however, Count Bertrand directed Dr. Antommarchi to take a bust of him; but not being able to find a material which he thought would answer the purpose, he mentioned the circumstances to Mr. Burton, who promised that he would procure some if possible.

"The Englishman, in pursuance of this promise, took a boat and picked up raw materials on the island, some distance from Longwood. He made a plaster, which he conceived would answer this purpose. When he showed it to Dr. Antommarchi he said it would not answer, and refused to have anything to do with it, in consequence of which Mr. Burton proceeded to take a bust himself, with the sanction of Madame Bertrand, who was in the room at the time. An agreement was entered into that copies should be made of the bust, and that Messieurs Burton and Antommarchi were to have each a copy.

"It was found, however, that the plaster was not sufficiently durable for the purpose, and it was proposed to send the original to England to have copies taken.

"When Mr. Burton, however, afterwards inquired for the bust, he was informed that it was packed and nailed up; but a promise was made, that upon its arrival in Europe, an application should be made to the family of Buonaparte for the copy required by Mr. Burton.

"On its arrival, Mr. Burton wrote to the Count to have his promised copy, but he was told, as before, that application would be made to the family of Buonaparte for it.

"Mr. Burton upon this applied to Bow Street for a search warrant in order to obtain the bust, as he conceived he had a right to it, he having furnished the materials and executed it.

"A warrant was issued, and Taunton and Salmon, two officers, went to the Count's residence in Leicester Square. When they arrived, and made known their errand, they were remonstrated with by Sir Robert Wilson and the Count, who begged they would not act till they had an interview with Mr. Birnie, as there must be some mistake. The officers politely acceded to the request, and waived their right of search.

"Count Bertrand had, it seems, offered a pecuniary compensation to Mr. Burton for his trouble, but it was indignantly refused by that officer, who persisted in the assertion of his right to the bust as his own property, and made application for the search warrant.

"Count Bertrand, in answer to the case stated by Mr. Burton, said that the bust was the property of the family of the deceased, to whom he was executor, and he thought he should not be authorized[Pg 11] in giving it up. If, however, the law of this country ordained it otherwise, he must submit; but he should protest earnestly against it.

"The worthy magistrate, having sworn the Count to the fact that he was executor under the will of Buonaparte, observed that it was a case out of his jurisdiction altogether, and if Mr. Burton chose to persist in his claim, he must seek a remedy before another tribunal.

"The case was dismissed, and the warrant was cancelled.

"The sequel to the Buonaparte story is short; Captain Burton (in 1861) thinking that the sketch, which was perfect, and the lock of hair which had been preserved in a family watch-case for forty years, would be great treasures to the Buonapartes, and should be given to them, begged the sketch of General and Mrs. Ward, and the hair from the Burtons; he had the hair set in a handsome ring, with a wreath of laurels and the Buonaparte bees. His wife had a complete set of her husband's works very handsomely bound, as a gift, and in January, 1862, Captain Burton sent his wife over to Paris, with the sketch, the ring, and the books, to request an audience with the Emperor and Empress, and offer them these things, simply as an act of civility—for Captain and Mrs. Burton in opinion and feeling were Legitimists. Captain Burton was away on a journey, and Mrs. Burton had to go alone. She was young and inexperienced, and had not a single friend in Paris to advise her. She left her letter and presents at the Tuileries. The audience was not granted. His Imperial Majesty declined the presents, and she never heard anything more of them. They were not returned. Frightened and disappointed at the failure of this, her first little mission at the outset of her married life, she returned to London directly, where she found the Burton family anything but pleased at her failure and her want of savoir faire in the matter, having unwittingly caused their treasure to be utterly unappreciated. She said to me on her return, 'I never felt so snubbed in my life, and I shall never like Paris again;' and I believe she has kept her word.

"Oxonian."

Francis Burton, alluded to in these pages, returned to England after the death of Napoleon, married one of the three co-heiress (Baker) sisters, and died early, leaving only two daughters. One died, and the other, Sarah, became Mrs. Pryce-Harrison.

Nor was this the only little romance in our Burton family, as the following story taken from family documents tends to show. Here is the Louis XIV. history—

"With regard to Louis XIV. there are one or two curious and interesting legends in the Burton family, well authenticated, which make Richard Burton great-great-great-grandson of Louis XIV. of France, by a morganatic marriage; and another which would entitle him to an English baronetcy, dating from 1622.

"One of the documents in the family is entitled, 'A Pedigree of the Young family, showing their descent from Louis XIV. of France,' and which runs as follows:—

"Louis XIV. of France took the beautiful Countess of Montmorency from her husband and shut him up in a fortress. After the death of (her husband) the Constable de Montmorency, Louis morganatically married the Countess. She had a son called Louis le Jeune, who 'was brought over to Ireland by Lady Primrose,' then a widow. This Lady Primrose's maiden name was Drelincourt, and the baby was named Drelincourt after his godfather and guardian, Dean Drelincourt (of Armagh), who was the father of Lady Primrose. He grew up, was educated at Armagh, and was known as Drelincourt Young. He married a daughter of Dean Drelincourt, and became the father of Hercules Drelincourt Young, and also of Miss (Sarah) Young, who married Dr. John Campbell, LL.D., Vicar-General of Tuam (ob. 1772). Sarah Young's brother, the above-mentioned Hercules Young, married and had a son George, a merchant in Dublin, who had some French deeds and various documents, which proved his right to property in France.

"The above-named Dr. John Campbell, by his marriage with Miss Sarah Young (rightly Lejeune, for they had changed the name from French to English), had a daughter, Maria Margaretta Campbell, who was Richard Burton's grandmother. The same Dr. John Campbell was a member of the Argyll family, and a first cousin of the 'three beautiful Gunnings,' and was Richard Burton's great-grandfather.

"These papers (for there are other documents) affect a host of families in Ireland—the Campbells, Nettervilles, Droughts, Graves, Burtons, Plunketts, Trimlestons, and many more.

"In 1875 Notes and Queries was full of this question and the various documents, but it has never been settled.

"The genealogy runs thus:—

"Louis XIV.

"Son, Louis le Jeune (known as Louis Drelincourt Young), by Countess Montmorency; adopted by Lady Primrose[4] (see Earl of Rosebery), and subsequently married to a daughter of Drelincourt, Dean of Armagh.

"Daughter, Sarah Young; married to Dr. John Campbell, LL.D., Vicar-General of Tuam, Galway.

"Daughter, Maria Margaretta Campbell; married to the Rev. Edward Burton, Rector of Tuam, Galway.

"Son, Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Netterville Burton, 36th Regiment.

"Son, Richard Burton, whose biography I am now relating.

"There was a Lady Primrose buried in the Rosebery vaults, by her express will, with a little casket in her hands, containing some secret, which was to die with her; many think that it might contain the missing link.

"The wife of Richard Burton received, in 1875, two very tantalizing anonymous letters, which she published in Notes and Queries, but which she has never been able to turn to account, through the writer declining to come forward, even secretly.

"One ran thus:—

"'Madam,—There is an old baronetcy in the Burton family to which you belong, dating from the reign of Edw. III.[5]—I rather believe now in abeyance—which it was thought Admiral Ryder Burton would have taken up, and which after his death can be taken up by your branch of the family. All particulars you will find by searching the Heralds' Office; but I am positive my information is correct.—From one who read your letter in N. and Q.

"She shortly after received and published the second anonymous letter; but, though she made several appeals to the writer in Notes and Queries, no answer was obtained, and Admiral Ryder Burton eventually died.

"'Madam,—I cannot help thinking that if you were to have the records of the Burton family searched carefully at Shap, in Westmoreland, you would be able to fill up the link wanting in your husband's descent, from 1712 to 1750, or thereabouts. As I am quite positive of a baronetcy being in abeyance in the Burton family, and that an old one, it would be worth your while getting all the information you can from Shap and Tuam—the Rev. Edward Burton, Dean of Killala and Rector of Tuam, whose niece he married was a Miss Ryder, of the Earl of Harrowby's family, by whom he had no children. His second wife, a Miss Judge, was a descendant of the Otways, of Castle Otway, and connected with many leading families in Ireland. Admiral James Ryder Burton could, if he would, supply you with information respecting the missing link in your husband's descent. I have always heard that de Burton was the proper family name, and I saw lately that a de Burton now lives in Lincolnshire.

"'Hoping, madam, that you will be able to establish your claim to the baronetcy,

"'I remain, yours truly,

"'A Reader of N. and Q.

"'P.S.—I rather think also, and advise your ascertaining the fact,[Pg 14] that the estate of Barker Hill, Shap, Westmoreland, by the law of entail, will devolve, at the death of Admiral Ryder Burton, on your husband, Captain Richard Burton.'

"From the Royal College of Heralds, however, the following information was forwarded to Mrs. Richard Burton:—

"'There was a baronetcy in the family of Burton. The first was Sir Thomas Burton, Knight, of Stokestone, Leicestershire; created July 22nd, 1622, a baronet, by King James I. Sir Charles was the last baronet. He appears to have been in great distress—a prisoner for debt, 1712. He is supposed to have died without issue, when the title became extinct—at least nobody has claimed it since. If your husband can prove his descent from a younger son of any of the baronets, he would have a right to the title. The few years must be filled up between 1712 and the birth of your husband's grandfather, which was about 1750; and you must prove that the Rev. Edward Burton, Rector of Tuam in Galway, your husband's grandfather (who came from Shap, in Westmoreland, with his brother, Bishop Burton, of Tuam), was descended from any of the sons of any of the baronets named.'"[6]

[1] N.B.—This I deny. Richard was the handsomest and most attractive man I have ever seen, and Edward, though smaller, was very good-looking, but there is no doubt that Richard grew handsomer every year of his life, and I can remember Maria exceedingly attractive so far back as 1857.—I. B.

[2] "The coffin being too short to admit this array in the order proposed, the hat was placed at the feet before interment."

[3] "Napoleon's dining-room lamp, from Longwood, is, I believe, still in the possession of the 91st Regiment, it having been purchased by the officers at St. Helena in 1836."

[4] "This Lady Primrose was a person of no small importance, and was the centre of the Jacobite Society in London, and the friend of several distinguished people; and as she was connected on her own side and her husband's with the French Calvinists, she may very likely have protected Lejeune from France to Ireland, and he would probably have, when grown up, married some younger Drelincourt—as such were undoubtedly the names of the parents of Sarah Young, who married Dr. John Campbell. We can only give the various documents as we have seen them."

[5] "This is an error of the anonymous writer. Baronetcies were first created in 1605."—I. B.

[6] N.B.—We never had the money to pursue these enquiries. But should they ever be sifted, the proper heir, since my husband is dead, will be Captain Richard St. George Burton, of the "Black Watch." We made out all the links, except twelve years from 1712. It is said that Admiral Ryder Burton himself was the author of those two anonymous letters to me. My husband often used to say there were only two titles he would care to have. Firstly, the old family baronetcy, and the other to be created Duke of Midian.—Isabel Burton.

I was born at 9.30 p.m., 19th March (Feast of St. Joseph in the calendar), 1821, at Barham House, Herts, and suppose I was baptized in due course at the parish church. My birth took place in the same year as, but the day before, the grand event of George IV. visiting the Opera for the first time after the Coronation, March 20th. I was the eldest of three children. The second was Maria Catherine Eliza, who married Henry, afterwards General Sir Henry Stisted, a very distinguished officer, who died, leaving only two daughters, one of whom, Georgina Martha, survives. Third, Edward Joseph Netterville, late Captain in the 37th Regiment, unmarried.

The first thing I remember, and it is always interesting to record a child's first memories, was being brought down after dinner at Barham House to eat white currants, seated upon the knee of a tall man with yellow hair and blue eyes; but whether the memory is composed of a miniature of my grandfather, and whether the white frock and blue sash with bows come from a miniature of myself and not from life, I can never make up my mind.

Barham House was a country place bought by my grandfather, Richard Baker, who determined to make me his heir because I had red hair, an unusual thing in the Burton family. The hair soon changed to black, which seems to justify the following remarks by Alfred Bate Richards in the pamphlet alluded to. They are as follows:—

"Richard Burton's talents for mixing with and assimilating natives of all countries, but especially Oriental characters, and of becoming as one of themselves without any one doubting or suspecting his origin; his perfect knowledge of their languages, manners, customs, habits, and religion; and last, but not least, his being gifted by nature with an Arab head and face, favoured this his first enterprise"[Pg 16] (the pilgrimage to Mecca). "One can learn from that versatile poet-traveller, the excellent Théophile Gautier, why Richard Burton is an Arab in appearance; and account for that incurable restlessness that is unable to wrest from fortune a spot on earth wherein to repose when weary of wandering like the desert sands.

"'There is a reason,' says Gautier, who had studied the Andalusian and the Moor, 'for the fantasy of nature which causes an Arab to be born in Paris, or a Greek in Auvergne; the mysterious voice of blood which is silent for generations, or only utters a confused murmur, speaks at rare intervals a more intelligible language. In the general confusion race claims its own, and some forgotten ancestor asserts his rights. Who knows what alien drops are mingled with our blood? The great migrations from the table-lands of India, the descents of the Northern races, the Roman and Arab invasions, have all left their marks. Instincts which seem bizarre spring from these confused recollections, these hints of distant country. The vague desire of this primitive Fatherland moves such minds as retain the more vivid memories of the past. Hence the wild unrest that wakens in certain spirits the need of flight, such as the cranes and the swallows feel when kept in bondage—the impulses that make a man leave his luxurious life to bury himself in the Steppes, the Desert, the Pampas, the Sahara. He goes to seek his brothers. It would be easy to point out the intellectual Fatherland of our greatest minds. Lamartine, De Musset, and De Vigny are English; Delacroix is an Anglo-Indian; Victor Hugo a Spaniard; Ingres belongs to the Italy of Florence and Rome.'

"Richard Burton has also some peculiarities which oblige one to suspect a drop of Oriental, perhaps gipsy, blood. By gipsy we must understand the pure Eastern."

My mother had a wild half-brother—Richard Baker, junior, a barrister-at-law, who refused a judgeship in Australia, and died a soap-boiler. To him she was madly attached, and delayed the signing of my grandfather's will as much as possible to the prejudice of her own babe. My grandfather Baker drove in his carriage to see Messrs. Dendy, his lawyers, with the object of signing the will, and dropped dead, on getting out of the carriage, of ossification of the heart; and, the document being unsigned, the property was divided. It would now be worth half a million of money.

When I was sent out to India as a cadet, in 1842, I ran down to see the old house for the last time, and started off in a sailing ship round the Cape for Bombay, in a frame of mind to lead any forlorn hope wherever it might be. Warren Hastings, Governor-General of India, under similar circumstances threw himself under a tree, and formed the fine resolution to come back and buy the old place; but he belonged to the eighteenth century. The nineteenth is far more cosmopolitan. I always acted upon the saying, Omne solum[Pg 17] forti patria, or, as I translated it, "For every region is a strong man's home."

Meantime my father had been obliged to go on half-pay by the Duke of Wellington for having refused to appear as a witness against Queen Caroline. He had been town mayor at Genoa when she lived there, and her kindness to the officers had greatly prepossessed them in her favour; so, when ordered by the War Office to turn Judas, he flatly refused. A great loss to himself, as Lord William Bentinck, Governor-General of India, was about to take him as aide-de-camp, and to his family, as he lost all connection with the army, and lived entirely abroad, and, eventually coming back, died with his wife at Bath in 1857. However, he behaved like a gentleman, and none of his family ever murmured at the step, though I began life as an East Indian cadet, and my brother in a marching regiment, whilst our cousins were in the Guards and the Rifles and other crack corps of the army.

The family went abroad when I was a few months old, and settled at Tours, the charming capital of Touraine, which then contained some two hundred English families (now reduced to a score or so), attracted by the beauty of the place, the healthy climate, the economy of living, the facilities of education, and the friendly feeling of the French inhabitants, who, despite Waterloo, associated freely with the strangers.

They had a chaplain, the Rev. Mr. Way (whose son afterwards entered the Indian army; I met him in India, and he died young); their schoolmaster was Mr. Clough, who bolted from his debts, and then Mr. Gilchrist, who, like the Rev. Edward Irving, Carlisle's friend (whom the butcher once asked if he couldn't assist him), caned his pupils to the utmost. The celebrated Dr. Brettoneau took charge of the invalids. They had their duellist, the Honourable Martin Hawke, their hounds that hunted the Forest of Amboise, and a select colony of Irishmen, Messrs. Hume and others, who added immensely to the fun and frolic of the place.

At that period a host of these little colonies were scattered over the Continent nearest England; in fact, an oasis of Anglo-Saxondom in a desert of continentalism, somewhat like the society of English country towns as it was in 1800, not as it is now, where society is confined to the parson, dentist, surgeon, general practitioners, the bankers, and the lawyers. And in those days it had this advantage, that there were no snobs, and one seldom noticed the aigre discorde, the maladie chronique des ménages bourgeoises. Knowing nothing of Mrs. Grundy, the difference of the foreign colonies was that the weight of English respectability appeared to be taken off them,[Pg 18] though their lives were respectable and respected. The Mrs. Gamps and Mrs. Grundys were not so rampant. The English of these little colonies were intensely patriotic, and cared comparatively little for party politics. They stuck to their own Church because it was their Church, and they knew as much about the Catholics at their very door, as the average Englishman does of the Hindú. Moreover, they honestly called themselves Protestants in those days, and the French called themselves Catholics. There was no quibble about "their being Anglo-Catholics, and the others Roman-Catholics." They subscribed liberally to the Church, and did not disdain to act as churchwardens. They kept a sharp look-out upon the parson, and one of your Modern High Church Protestants or Puseyites or Ritualists would have got the sack after the first sermon. They were intensely national. Any Englishman in those days who refused to fight a duel with a Frenchman was sent to Coventry, and bullied out of the place. English girls who flirted with foreigners, were looked upon very much as white women who permit the addresses of a nigger, are looked upon by those English who have lived in black countries. White women who do these things lose caste. Beauséjour, the château taken by the family, was inhabited by the Maréchale de Menon in 1778, and eventually became the property of her homme d'affaires, Monsieur Froguet. The dear old place stands on the right bank of the Loire, halfway up the heights that bound the stream, commanding a splendid view, and fronted by a French garden and vineyards now uprooted. In 1875 I paid it a last visit, and found a friend from Brazil, a Madame Izarié, widow of my friend the French Consul of Bahía, who had come to die in the house of his sister, Madame Froguet.