The Twelfth Number of this work is now respectfully submitted to the attention of the public. This number, accompanied by the Title Page and Index, renders the first volume complete. The Subscribers, therefore, are now enabled to form a correct idea of the nature and object of the undertaking: and from the style in which it has been so far conducted, to form some conclusion of that in which it is likely for the future to be continued.

The general approbation that has been bestowed already upon this publication can be best appreciated from the extent of sale, which, to say the least, has been respectable from the commencement, notwithstanding that the undertaking was began under the manifest disadvantage of being little known, and the very knowledge of its existence being still in no small degree circumscribed. It is not, therefore, without a sense of grateful feeling that the author has observed that besides the incidental sale of the different detached or monthly parts selected by purchasers desirous of the plates and descriptions of some particular object of rarity, that the number of regular subscribers, instead of diminishing, has rapidly advanced with the publication of each number in succession, and as it seems to appear in proportion as the public became better acquainted with its merits, and the more assured of its uninterrupted continuance. While this testimony of approbation prevails, the author of this undertaking will be duly stimulated to exert his best means of rendering it deserving of their consideration. Nor has he any hesitation in believing that it will be in his power, under the auspices of public favour, to produce a work of much elegance, and no mean utility, either as a work of taste for the library of the general reader, or the admirer of nature; the folios of the amateur, or the professed Study of the experienced Naturalist.

The commencement of this work was necessarily preceded by a few observations upon the nature and object of the undertaking: those observations are no less appropriate on the present occasion than the former, and for this reason we shall again advert to them in restating the intention the author has in view. The Naturalist’s Repository, or Monthly Miscellany of Exotic Natural History, is designed to comprehend in the most commodious form, a miscellaneous assemblage of elegantly coloured plates, with appropriate scientific and general descriptions of the most curious, scarce, and beautiful productions of nature that have been recently discovered in various parts of the world or may hereafter occur to the notice of the author; and more especially of such novelties as from their extreme rarity remain entirely undescribed, or which have not been duly noticed by any preceding Naturalist.

Most readers, it is presumed, will be aware that the labours of the authors life, during a course of many years have been directed to the pursuits of natural science: labours not confined to any one particular branch or department of the varied face of nature, but extending generally to the whole. The endeavours of the author to elucidate the Natural History of the British Isles are sufficiently known from the various extensive works which have been produced by him during the course of the last thirty years, and the magnitude which those works have at length acquired in the progressive course of publication that had been adopted, is the best criterion of the approbation that has attended them. But it is not within the views of the author in this place to expatiate upon a subject which might be deemed irrelevant, the works alluded to being devoted solely to the productions of our native country, while the avowed object of the present undertaking is to comprehend a selection of those only which are peculiar to foreign, and with few exceptions, to extra European climates. The chief motive of the author in adverting to those works, is to point out a style and mode of execution for the present undertaking, which, from the very extensive patronage those former labours of the author have experienced, may be considered applicable in a very peculiar degree to every purpose of correct elucidation, and as one most likely to ensure by its elegance and perfection that same proportion of general approbation which the other productions of the author have obtained.

With respect to the means within the author’s power of rendering this work deserving of the public notice, either as to the novelty, variety, rarity, or beauty of the various objects it is destined to embrace, the author must rather trust to the favourable opinion which the world may entertain in its behalf, from the examples now submitted to consideration, than to any preliminary observations he can offer: he shall only presume respectfully that they are adequate to the purpose, and calculated to answer every moderate expectation his preliminary observations may have excited.

It will be readily conceived that the opportunities of the author’s life, so assiduously devoted to the Science of Nature, must have enabled him to enrich his port feuilles with a collection of Drawings, Manuscripts, and Memoranda of no mean importance in all its branches. This is perfectly correct. His own Museum confined chiefly, but not exclusively, to the productions of Great Britain, have afforded many rarities, the offspring of foreign climates, which could not elsewhere be procured. But independently of those resources which his own collection has afforded, his other means have been amply extensive. Through the kindness of his scientific friends, he has had unlimited access to many other collections of acknowledged moment, for the purpose of enriching his Collectanea with drawings and descriptions of the more interesting rarities which those cabinets respectively contained. Some of those collections exist no longer and are probably now forgotten, but the memory of others, even among the number of those which have passed away, will ever be cherished with regret in the mind of every man of science by whom their merits were understood. The preservation even of the memorials of some minor portion of the rarities which those collections once embodied can scarcely fail to prove of interest at the present day, while their total loss to the rising generation will be in some degree appreciated from the memoranda and occasional references that will appear respecting them in the progress of the present work: to enumerate the many collections of private individuals, the rarities of which have contributed to render this collection of the author’s drawings important, would extend our advertisement far beyond our intended limits. It may be sufficient to observe that the late Leverian Museum, rich in every branch of Natural History, has tended in an eminent degree to this effect; the author having been favoured with unreserved permission to take drawings and memoranda of whatever he deemed important, besides having subsequently enriched his own Museum with a very ample portion of that fine collection, by public purchase, at the time of its dispersion; particularly in the different tribes of the Mammiferous animals, in Ornithology, Ichthyology, and various others; and also with every object materially important among the extraneous fossils which that splendid museum originally contained. It will be also seen from many of our pages that through the kindness of the late worthy President of the Royal Society, Sir Joseph Banks, the rich and truly scientific collection of that munificent patron of the sciences was ever open to us for the furtherance of our pursuits in Natural History; and of the object of the present work among others. The collections of Mr. Drury, and also that of Mr. Francillon, in the particular branches of Entomology, are too considerable to be passed slightly over: the rarities of both these collections have in an eminent degree improved our means of rendering this work important. And lastly we may mention among other scientific acquisitions the Collectanea of drawings formed by the pencil of the late Mr. Jones of Chelsea, together with the manuscripts of Fabricius in elucidation, as a treasure which cannot be too highly appreciated when we recollect the importance of the Fabrician writings on the continent, and remember also that those drawings afford the only illustration of the most splendid portion of the insect race which that author exclusively describes, and by which very many of the species can alone be now determined.

In conclusion of these remarks it may be observed, however, that while in our elucidation of those rarities which the collections and museums above adverted to have so amply afforded, we render a deserved tribute of record to the liberality of those whose services in the cause of Natural History have so amply contributed to its advancement in former days, the author will not remain unmindful of those advantages which the many valuable collections of the present period offer. It will appear as this work proceeds that he is in no small degree indebted to the favor of many eminent scientific characters of our time, as well as those who have preceded them, for their permission to take drawings and descriptions of such rarities in their collections as really appear worthy of distinct consideration. And it may be added finally that he shall at all times avail himself with pleasure, and acknowledge with thanks, any further advantages of the same kind which the favours of others may be induced to allow for the purpose of enriching the present undertaking.

| Plate. | Fig. | |

|---|---|---|

| Acamas, Papilio; Acamas’s Butterfly | 18 | |

| Agave, Papilio; Agave’s Butterfly | 6 | 2 |

| Ageæa, Papilio; Ageæa’s Butterfly | 12 | |

| Alliacea, Peteveria, America | 24 | 1 |

| Ammiralis, Conus, var Amboinensis; Three-Banded High-Spired Admiral Shell | 1 | 1 |

| Ammiralis, Conus, var; Six-Banded High-Spired Admiral Shell | 1 | 2 |

| Ammiralis, Conus, var Cedonulli; Olive-Banded Nonpareil Cone | 1 | 3 |

| Ammiralis, Conus, var Fulvous Nonpareil Cone | 1 | 4 |

| Aurantiaea, Jacquinia, Sandwich Isles | 25 | |

| Aurora, Cypræa; Aurora, Morning Dawn, or Orange Cowry | 32 | |

| Belladonna, Papilio; Belladonna’s Butterfly | 35 | |

| Bengalus, Fringilla, Blue-Bellied Finch | 10 | |

| Camara Lantana, West Indies | 18 | |

| Cayana, Ampelis, Purple-Throated Chatterer | 14 | |

| Ciris, Emberiza, Painted Bunting | 7 | |

| Codomannus, Papilio, Codomannus’s Butterfly | 3 | 1, 1 |

| Dimas, Papilio, Dimas’s Butterfly | 27 | 2 |

| Foliatus, Murex, Tri-Foliated Murex, or Rock Shell | 15 | |

| Galgulus, Psittacus, Sapphire Crowned Parrakeet | 17 | |

| Harpa, Buccinum var testudo, Tortoise-Shell Harp | 8 | |

| Hippodamia, Papilio; Hippodamia’s Butterfly | 31 | |

| Homerus, Papilio; Homer’s Butterfly | 19 | |

| Imperialis, Trochus var Roseus; Roseate Imperial Sun Trochus | 11 | |

| Maculatus Psittacus; Spotted-Breasted Parrakeet | 33 | |

| Marcellina, Papilio; Marcellina’s Butterfly | 6 | 1, 1 |

| Melanopterus, Psittacus; Black-Winged Parrakeet | 30 | |

| Ornatus, Trochilus; Tufted-Necked Humming Bird | 25 | |

| Ovata, Goodenia; Ovate-Leaved Goodenia | 20 | |

| Palustre, Sedum, North America | 29 | |

| Parmentaria, Erica | 35 | |

| Pella, Trochilus, Topaz Humming Bird | 5 | |

| Polita, Nerita, var; Pink-Banded Variety of the Thick Polished Nerit | 36 | |

| Psamethe, Papilio, Psamethe’s Butterfly | 9 | |

| Punctata, Pipra, Punctata, or Speckled Manakin | 20 | |

| Pylades, Papilio, Pylades’s Butterfly | 13 | |

| Pyramus, Papilio, Pyramus’s Butterfly | 3 | 2, 2 |

| Pyrum, Voluta, Pear Volute, Front View | 21 | 1 |

| ---- Reversed Ditto, or Sacred Chank Shell, Front View | 21 | 2 |

| Pyrum, Voluta, Pear Volute, Back View | 22 | 1 |

| ---- Reversed Ditto, or Sacred Chank Shell, Back View | 22 | 2 |

| Sanguinea, Terebratulo, Sanguineous Lamp Anomia, or Lamp Cockle | 34 | |

| Scalaris, Turbo (Scalaria Pretiosa) Scarce Wentletrap | 26 | |

| Scapha, Volute var Nobilis, Noble Chinese Volute | 4 | |

| Scorpio, Murex, var Minor; Least Stag’s Horn Murex | 16 | |

| Thersites, Papilio, Thersites Butterfly | 24 | |

| Tricolor, Tanagra β, Tricoloured Tanager | 23 | |

| Tros, Papilio, Tros’s Butterfly | 29 | |

| Viridis, Trogon, Yellow-Bellied Green Trogon or Curucui | 2 | |

| Vulgaris, Malleus, Hound’s Tongue Hammer Shell | 28 | |

| Zacynthus, Papilio, Zacynthus’s Butterfly | 27 | 1 |

Is requested to observe that the Numbers have been transposed by mistake upon the Three following Plates.

| For Plate 27 | read 25. |

| Plate 25 | read 26. |

| Plate 26 | read 27. |

And place the plates with their respective descriptions according to this correction.

Animal a limax. Shell univalve, convolute and turbinate. Aperture effuse, longitudinal, linear, without teeth, entire at the base: pillar smooth.

Conus Ammiralis: testa basi punctato scabra.

Conus Ammiralis: testa basi punctato. Linn. Syst. Nat. 10 p. 714. n. 257.—Mus. Lud. Ulr. 553. n. 157. Gmel. Linn. Syst. Nat. 3378. 10.

Conus Ammiralis var Amboinensis. α. Spire high and tapering; shell pyriform, glossy, smooth, pale yellowish with two broad bands of testaceous marked with large subsaggitate oval spots of white, and a narrow band between composed of white spots and intermediate testaceous dots.

Were it within the contemplation of our present views to enter into the ancient history of the science of Conchology, we should be under little difficulty in demonstrating upon the authority of the best informed historians as well as ancient classics that it has a claim to very remote antiquity. The study of Shells prevailed, at least to some extent, in those early times when the generality of mankind believe the world to have been buried in the depths of ignorance. At periods, even when some among those of better information may be inclined to imagine that the ancients could have had no very accurate conceptions of the nature of these bodies, or of their classification, natural or artificial, and even when it might be supposed from the warlike temper of the age the collecting of shells would have been deemed an unworthy occupation, we discover sufficient indications to prove that their leisure hours were so employed. The productions of the sea were delineated in their manuscripts; Pliny speaks of the delight the artist took in painting the asterias, or sea stars. The spontaneous offerings of the ocean were depicted in their natural colours upon the walls of their dwellings, abundant evidence of which appears among the ancient paintings of Herculaneum and Pompeii; and that the shells themselves were sometimes collected by the ancients is placed beyond a doubt from those remains which have been found, at various times, among the relics of those celebrated ruins, and also among the ruins of the Roman town, perhaps no less ancient, denominated La Scava.

It is declared by Pliny, in the ninth book of his Natural History, that the Romans of his time were better acquainted with the productions of the sea than the animals of the land, a circumstance he attributes, and unquestionably with sufficient reason, to the extravagant excess to which the luxurious taste of those times was carried. This will excite the less surprise when we recollect the various useful results deduced from this investigation. Of these we have several very memorable examples; the exquisite dyes of green, the scarlet, and the imperial purple, which they possessed and prized so eminently, were all the produce of testaceous bodies. And so likewise the pearls gathered from the various perlaceous bivalve shells; and pearls we are assured were in those days valued at Rome, as in Egypt, at a price infinitely beyond that of gold and gems, the diamond alone excepted.

Pliny tells us, that, in his time, after the diamonds of India and Arabia, pearls were esteemed most precious, and that we may be under no error as to the application of the text to the pearls found in shells, he further adds, that he had before spoken of these pearls in his book that treats upon the productions of the sea[1]. The diamonds in those times were so scarce, and esteemed so highly, as to be little known, except among princes, the smaller and most inferior kinds alone excepted. The pearls were the most costly jewels employed in the ornaments for the ears, the neck, and fingers of the fair sex, and the shells themselves were converted into various articles of finery for their wardrobe and furniture.

But it is not, as before observed, within our province in this place, to enter into any such latitude of explanation as an ample illustration of these remarks may be conceived to merit. It is our object only to express ourselves in general terms: it may be sufficient therefore to observe, that among the luxuries of the great in the times of Pliny, Oppian, and Juvenal, it is certain they indulged their peculiar taste in the study of these productions of the deep. They not only amassed together the more curious among those shells whose beauty attracted their regard, they entered also to some extent into their history and manners, and were sufficiently informed as to their natural properties to render them subservient to the general purposes of luxury and life. They knew the distinctions between the land, the fresh-water, and the marine tribes of shells, and they proceeded with minuteness and sometimes fully into their history. No classic reader of the Halieutics of Oppian will doubt the general acquaintance of the ancients with those beings in their native element, nor will any one imagine, who is conversant with the lives of the philosophers of the infant ages of the world, that the study of Conchology, even as a science, was unknown. So many writings of the ancients, even of the classic ages of Greece and Rome, have disappeared, that it may be now impossible to form any very accurate conclusions, at the same time that enough remains to justify our persuasion that it was far from inconsiderable. Among others, the works of Aristotle, the preceptor of the Macedonian conqueror Alexander, have survived the ravages of time, and very happily, for the history of human knowledge unfolds to us the views which the ancients had then taken of natural science, and among the rest of the science of Conchology; and there is, moreover, every reason to believe that in the classification of the testaceous tribes, or shells, which the writings of this philosopher present us, we, in reality, possess the arrangement of the shells composing the Conchological collection of that most potent monarch, the conqueror of the world:—the classical distribution of the shells of the great Alexander, as they were disposed by the most celebrated naturalist of his age, and at a period more remote than three centuries before the commencement of the Christian æra.

The Science of Conchology, like that of all other branches of nature, has undergone its mutations at various periods. Generally, it has held a rank of some eminence, a circumstance attributable no doubt to the peculiar beauty of this interesting tribe. In speaking of the latter times, the period of the last and preceding centuries, it would be difficult to determine in which country of civilized Europe the science of Conchology has been most esteemed; at one time, the virtuosi of Holland, at another of France, and latterly of Britain, have endeavoured to produce the most extensive and costly cabinets of Conchology, and each in consequence may perhaps have excelled alternately; nor were other countries of Europe in this respect less emulous, or materially deficient in the number and excellence of their collections in this department of nature, during the same periods.

We have been unavoidably led into this train of digression and remark from a due consideration of the very interesting history connected with the shells which form the subject of the annexed Plate, the particulars of which, it is presumed, will be found to justify the general tendency of these observations, and these remarks may be considered also as a prelude to the introduction of many others among the number of those rarities which it is within our contemplation to produce progressively in the course of the present work; shells, to which the prevalence of general taste has assigned a value and importance scarcely less considerable than the nonpareil cones, or the eminently celebrated cedo nulli.

The first shell in the plate before us that invites attention from its magnitude is that superb cone delineated at figure I. This shell, which once held a distinguished place in the Leverian Museum, is two inches and six-eighths in length, its greatest breadth one inch and three-eighths. The general colour pale yellowish, with two bands of chesnut, marked with irregular arrow-headed spots of white, and an intermediate narrow band composed of white spots of the same form, each connected by means of an intervening dot of chesnut, which, together, form a catenated band of peculiar elegance. When very closely examined with the aid of a magnifier, the whole surface of the shell appears finely reticulated with yellow.

This shell was sold in one of the latter day’s sale of the Leverian Museum for the sum of five guineas and a half.

Spire high and tapering; shell subpyriform; smooth, pale yellowish, sprinkled with fulvous; body-wreath with six bands, the three uppermost linear, and composed of alternate white and chesnut-coloured dots, the three lower of two broad castaneous bands, marked with subsaggitate oval spots, and an intermediate narrow belt of alternate brown and white dots.

This shell, like the former, (fig. I) constituted part of the Leverian collection of exotic shells. Its length is an inch and half, its greatest breadth exceeding five-eighths of an inch.

Notwithstanding the inferiority of its size, this very elegant and curious shell is not less interesting than the preceding. The general tints in both are nearly the same, but in the present shell are rather deeper, the dots of fulvous brighter and more thickly sprinkled, and the bands more numerous. Like the former shell it has two broad bands of brown, checquered with subovate spots of white, and an intermediate dotted line, but these are placed rather nearer towards the narrower end of the shell, and the intervening space between the spire and the larger band, encompassed or girt round with two other linear bands, composed of white and brown dots, besides another still more conspicuous, and composed of larger spots along the base or body-wreath, contiguous to the spire or turban.

This little shell may be considered as affording an excellent type of one of the rarer kinds of Conus Ammiralis, the variety denominated the Six-banded high-spired Admiral Cone. During a period of some years that have now elapsed since the dispersion of that collection, no other example of this variety has occurred to our observation more perfect and characteristic in all its markings.

Spire high and tapering; marbled white, fulvous, and dusky; body-wreath with three subolivaceous bands, the broadest towards the spire, with four belts of whitish dots; the two others towards the narrow end each with a single row of dots.

If in the preceding instances we have produced some novelties worthy of particular attention, the present shell, in point of value as well as beauty, must also lay a distinguished claim to our consideration. This is one of those rare varieties of Conus Ammiralis denominated the Cedo Nulli, or Cedo Nulli pretiossissimus, in allusion to the incomparable value affixed to the varieties of this peculiar species. The importance attached to the shells of this kind may indeed be best conceived by stating that some of its varieties have been valued at twenty, fifty, and one hundred guineas; one, in almost every respect resembling that delineated at figure 4, the celebrated Cedo Nulli of Lyonet’s cabinet, was valued by Lyonet himself, about the year 1732, at three hundred guineas; and either this shell, or another very similar to it, actually realized a sum of 1200 florins.

As the shells of this kind may very justly be presumed to be of the first rarity, every trait of information that may appear calculated to elucidate their history, it is presumed, will not only be permitted but be deemed acceptable, and under this impression the ensuing observations are submitted.

Much about the æra of the first explosion of the French Revolution of 1789, and within the space of a few years after, it is perfectly well known that many of the choicest cabinets and collections of rarities that had before been the pride of France and Holland were consigned to this country for the sake of safety, and being in some instances afterwards dispersed, had tended, in no small degree, to enrich the cabinets of our own country. It was at this period that many very rare shells occurred to our observation which have since disappeared, and among others, several of those varieties of Cedo nulli which had been before held in other parts of Europe in considerable estimation. In the year 1797 we saw no less than five specimens of this rare shell, all varying a little from each other, in the cabinet of the French Minister of State, M. de Calonne; in one, the colour was pale, in another deeper, one was lineated, and another distinguished by having three distinct bands.

At the dispersion of the Calonnian Museum, which took place by public sale rather more than twenty years ago, the series of these valuable shells passed into the fine collection of the present Earl Tankerville, a collection his lordship was then forming for the pleasure of an amiable and beloved daughter since deceased, and these shells are still considered among the more choice rarities of that valuable cabinet.

The shell, however, more immediately under our consideration, the variety, delineated at figure 3, is from another source; it was among the spoils of rarities sent over to this country from Holland, at the time of the insurrection connected with the first inroads of the French into that country. The shell passed into the hands of a merchant of curiosities in London, and being afterwards sold, its destination is uncertain; the price affixed was twenty guineas.

This shell corresponded very nearly with the variety denominated Seba’s Cedo nulli, having once formed a part of the museum of the celebrated Seba, but it could not be the same, because the entire collection of Seba, which at the period of the French invasion constituted part of the Royal Museum of the Stadtholder, was carried into France and its contents distributed among the other objects of natural history in the French Museum[2]. The description which Favanne has left us of the Cedo nulli De Seba is in the following words, and will be found on a near comparison to accord pretty accurately with our present shell:—“Le Cedo nulli de Seba, à large bande citron foncé, chargée de quatre cordelettes de grains inégaux, blancs, bleus, rouges et orangés. Le reste de sa robe est fascié et marbré d’orangé-brun, de jaune, de rouge et bleu-pâle sur un fond blanc avec deux bandes grenues vers le bas.”

Spire high and tapering, fulvous reddish and orange, varied and marbled with white; two orange bands, each with four belts of white dots, and a single series near the tip.

The shell from which this drawing is taken fell also into the possession of the same individual as the last, and much about same period. This rarity was disposed of, as I have been informed, at a price exceeding that of the former, and passed shortly after, I believe, into the Imperial cabinet, at Vienna, or otherwise into one of the continental cabinets in the north of Europe, a circumstance we have not, at this distant period, any means whatever of determining.

The accordance between this shell and the celebrated Cedo nulli of Lyonet’s cabinet, which, as before intimated, was estimated at the value of three hundred guineas, will not escape the remark those who are acquainted with the description of Lyonet’s shell. According to Favanne there were two or more varieties of the Cedo nulli, in his time, in France, that bore a very near resemblance to the shell of Lyonet; he speaks of one in the cabinet of Madame La Presidente de Bandeville, which differed in its marbling of white: in being larger and more prolonged upon the top of the first whorl, ather larger, and interrupted with veins of orange, and the last of the two belts of white spots which follows this zone near the bottom of the first whorl, composed of rather larger spots; with these exceptions the two shells were precisely the same.

The Cedo nulli of Lyonet is described as being of a yellowish colour, divided into bands, the lower one and that in the middle marbled with white, the other two marked, the one with four little belts with white dots, the second with only three[3].

I ought not to close these remarks without observing, that these shells vary so considerably that no two specimens have yet occurred that agree precisely with each other. Some approach also, but are clouded instead of banded; these are the French Cedo nulli graphique, Conus mappa of Solander, and being held in less esteem from having their colours disposed in clouds instead of bands, have obtained the name of the false Cedo nulli. The transitions of these shells, it must be confessed are so various as to render it extremely difficult, if not unsafe, to determine where one species ends and another commences, the difference in the colours affords no sufficient data, neither is the form of the shell, nor the height of the spire so uniformly certain as to constitute a precise criterion.

Linnæus, in his description of the conchological cabinet of her majesty Ludovica Ulrica, the Queen of Sweden*, speaks of three different varieties of Conus Ammiralis α Ammiralis summus, β Ammiralis ordinarius, γ Ammiralis occidentalis, and these are again recited in his Systema Natura. But it will be seen from the last edition of that work, by Professor Gmelin, that the varieties discovered subsequently to the age of that inestimable naturalist are very considerable, amounting to no less than thirty different kinds, and these do not include the whole at present known. Gmelin, it should be added, admits only two or three kinds as the true Cedo nulli, which he characterizes essentially as being encompassed with dotted articulated belts, Cedo nulli cingulis punctato-articulatis; one he describes as being yellow, painted with red, and marked with eleven distinct belts of milk white; another, orange with crouded elevated interrupted chesnut lines.

These shells inhabit chiefly the South American Seas; the true Cedo nulli, as it is called, has been found at Grenada. Some of the varieties of Conus Ammiralis, are not very uncommon, and are in infinitely less esteem than others; for, as it has already appeared, it is in proportion to their rarity in addition to some peculiarity in the colours and markings, and most especially in their disposition into the form of bands, that taste and fancy has affixed a value so considerable as that which these shells are sometimes known to bear.

Bill shorter than the head, sharp edged, hooked margin of the mandibles serrated: feet scansorial or formed for climbing.

Green gold, beneath luteous; chin black; on the breast a green gold band.

Trogon viridis: viridi-aureus, subtus luteis, gula nigra, fascia pectorali viridi-aurea. Gmel. Linn. Syst. Nat. 2. 404. n. 3.

Trogon viridis, Linn. Syst. Nat. edit. 12. 1. p. 167. 3.

Trogon Cayanensis viridis. Briss. av. 4. p. 168. n. 2 t. 17.

Couroucou à ventre jaune. Buff. Ois. 6. p. 291. Pl. Enl. 195.

Trogon viridis: viridi-aureus subtus luteis, gula nigra, retricibus utrinque tribus extimis oblique et dentatim albis. Lath. Ind. Orn. t. 1. p. 199. 2.

Yellow-bellied Curucui. Lath. Gen. Syn. 2. p. 488. 2.

This curious and very elegant bird is about twelve inches in length; the bill an inch long and of a pale cinereous or ashen hue, and, like most other species of this remarkable genus, serrated along the margin. The legs are feathered to the toes, and with the toes and claws are of a pale brown.

The colour of the head and neck of this species is black, very richly glossed with blue, which appears, in different directions of the light, highly splendid upon its surface. Upon the crown of the head the blue verges into violet and purple, and in descending towards the neck becomes changeable into a fine green, glossed with gold; these brilliant hues appear also on the sides of the neck, and passing round as a kind of pectorial band forms in particular a rich zone of golden green upon the breast.

The pale ashen hue of the bill is singularly contrasted with the deep black and violet of the head and neck, and the sudden transition of the colours of the body is no less remarkable, the plumage in this part becoming abruptly of a fine yellow from the breast down to the thighs; these latter are black, but the vent feathers beyond are of a fine yellow, like the colour of the abdomen. The upper parts of the body are green glossed with yellowish and partaking of a golden lustre. The upper wing coverts and scapulars are dark fuscous, mottled with greyish; the quill feathers dark brown, quills from the base to the middle white. The tail is cuneated or wedge-formed, the middle feathers being longer than the outer ones. These feathers are most singularly contrasted with the rest, being of a fine dark green, glossed with gold, and at the tip black, while the three outer feathers on the contrary are white, and from the base downwards nearly to the tip very elegantly marked with oblique indented bars of black, leaving the tip of each feather immaculate; the inner one of these three exterior feathers are the same length as the dark ones, but the next outer feather is shorter, and the extreme exterior feather on each side shorter than the latter.

There is a variety of this bird in which the belly, instead of being yellow, is white; the whole bird is a trifle smaller than the example now before us, and may possibly prove hereafter to be the same species, in a less mature state of plumage. Buffon calls it Le Couroucou verd.

All the birds of this tribe at present known are inhabitants of the warmer climates of South America and India. Our present subject is a native of Cayenne, where it lives in damp and retired woods, building upon the lower branches of trees and feeding chiefly upon insects, with which the trees and herbage in those countries abound.

This truly interesting and very beautiful species is already known in our language by the epithet of the yellow-bellied Trogon or Curucui. There is, however, another bird of the same genus, which has the belly yellow, as in the present bird; we allude to the Rufous Curucui, the better therefore to define our species we have denominated it the yellow-bellied Green Trogon, or Curucui, as the least attention to the difference in the general colour of the plumage will thus enable the most cursory observer to discriminate the two species with facility and accuracy.

Antennæ thicker towards the tip and generally terminating in a knob: wings erect when at rest. Fly by day.

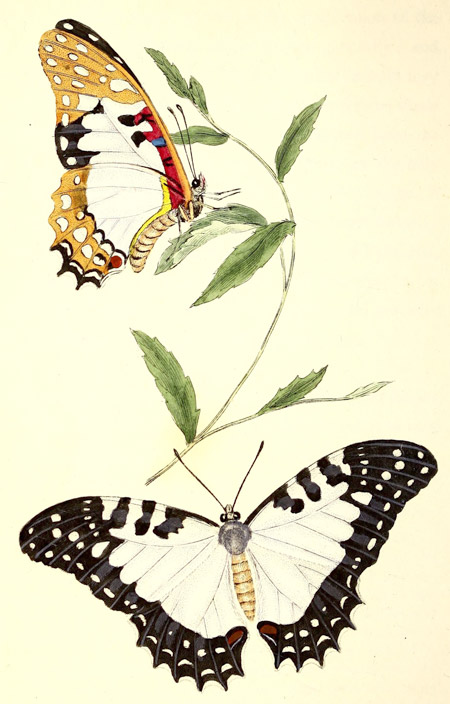

Wings entire, deep black with sanguineous bands: posterior ones beneath with annular yellow lines and dots of blue.

Papilio Codomannus: alis integerrimis atris sanguineo fasciatis: posticis subtus lineis annularibus flavis punctisque cœruleis. Fabr. Spec. Ins. t. 2. p. 57. n. 253.—Mant. Ins. 2. p. 28. n. 292.—Ent. Syst. t. 3. p. 1. p. 53. n. 165.

Alae anticæ supra atrae basi fasciaque, quæ margines haud attingit, sanguineis. Punctum fulvum transversum versus apicem et margo apicis albo punctatus. Subtus fere concolores fascia tantum flava et striga cœrulea apicis. Posticæ supra atræ vitta abbreviata fulva, subtus atræ lineis annularibus flavis punctisque cœrulescentibus. Pectus albo punctatum. Fabr.

Papilio Codomannus alis integerrimis atris sanguineo fasciatis: posterioribus subtus lineis annularibus flavis punctisque cœruleis. Gmel. Linn. Syst. t. 1. p. 5. 2280. n. 473.

The delineations of the very beautiful butterfly that appears in the annexed plate, are copied from a specimen in the cabinet of the late worthy president of the Royal Society, Sir Joseph Banks.

Fabricius had previously observed and made known throughout Europe the description of this species with many others of the Banksian Cabinet, but the figures of it now submitted to the amateur are the first that have appeared.—When we consider the celebrity which the entomological writings of Fabricius have acquired it may be satisfactory to learn that the delineation now before us is copied from the individual specimen which Fabricius had described, and that no other figure of this very interesting Papilio is extant.

The upper surface of the butterfly is of a dark brown colour of peculiar richness, crossed by stripes of deep scarlet. The insect with expanded wings displayed in a flying position in the lower part of the plate exemplifies this aspect of the upper surface. The lower surface is much more beautiful; the marks and colours on the anterior pair possess nearly the same character as those of the upper surface; the posterior pair are very different, being marked with large annular bands of bright yellow upon a fuscous ground, and inclosing a number of distinct spots of cœrulean blue, which in beauty emulate the brilliancy of the finest ultra marine: three of these blue spots are placed in the dark ground upon the disk, the remainder are disposed in a semi-circle upon a band of black towards the posterior extremity of the wings. This appearance is best perceived when the insect appears in a resting position as it is seen on one of the branches of the mimosa in the upper part of the plate.

This insect is a native of Brazil.

Antennæ thicker towards the tip, and generally terminating in a knob; wings erect when at rest. Fly by day.

Wings entire, fuscous glossed with blue, and marked with a fulvous spot; lower wings beneath grey.

Plebeji Rurales, Fabr. Sp. Ins.

Hesperia Rurales, Fabr. Ent. Syst.

Papilio Pyramus: alis integerrimis fuscis cœruleo micantibus, macula fulva, posticis subtus griseis. Fabr. Spec. Ins. 2 p. 130. n. 590.—Mant. Ins. 2 p. 83. n. 755.

Hesperia Pyramus: Fabr. Ent. Syst. t. 3. p. 1. 323. n. 223. Alæ omnes fuscæ, cœruleo micantibus: macula magna, in medio fulva. Anticæ, subtus concolores, posticæ griseæ sive cinereo fuscoque variæ. Fabr.

Fabricius describes Papilio Pyramus as a new species of the genus from the drawings of the late Mr. Jones, of Chelsea, a gentleman of fortune who had long devoted his attention to this peculiar tribe of insects, the Papiliones, and whose labours tended in a very eminent degree to aid those of Fabricius. In return for this assistance, Fabricius affixed to each of those insects the names under which they were destined afterwards to appear before the world, a circumstance that may explain sufficiently the frequent references of the Fabrician writings to those drawings, first in his Species Insectorum, and subsequently in his Entomologia Systematica. It may be further added, that the whole of these drawings, together with the manuscripts in the hand-writing of Fabricius were long in our own possession, during the life-time of the very amiable proprietor, Mr. Jones, for the very liberal purpose of copying and making known to the public whatever might appear likely to us to promote the interest and advantage of the Science of Nature; and that the insect now before us is one of those very rare species copied for this purpose.

The specimen from which the painting of Mr. Jones was taken formed originally part of the collection of the lamented Mr. Yates, the ingenious author of an English translation of the Linnæan Fundamenta Entomologia, that appeared about forty years ago, and who lost his life by bathing in the river some short time afterwards.

There was a variety of this insect, pretty nearly but not exactly according with this in the collection of an old and well-known entomologist, the late Mr. Drury, a figure of which appeared shortly after the publication of the Fabrician writings as the true Papilio Pyramus. It was not precisely the same as it appeared to us from an inspection of the specimen in the cabinet of Mr. Drury. This insect is to be found represented in the 23rd plate of the third volume of the Exotic Insects of that author, published in the year 1782.

Animal a limax. Shell uniocellar, spiral; aperture without a beak and sub-effuse: pillar twisted or plaited: generally without lips or perforation.

* Ventricose, spire papillary at the tip, or terminating in an obtuse rounded eminence.

Var Noble Chinese Volute: Shell smooth clouded with zig-zag brown lines, pillar blueish and four plaited: lip subulate.

Voluta Scapha (var, Nobilis) testa lævi nebulosa; lineis angularibus fuscis columella caerulescente quadruplicata, labro subulato.

Voluta Scapha: testa rudi nebulosa: lineis angularibus fuscis columella cærulescente quadruplicata, labro subulato.—Gmel. Linn. Syst. Nat. t. 1. p. 6. 3468. 121. Hist. Conch. t. 799. f. 6. Kircher 3. f. 10. Bonanni, c. 3. 113. f. 10. Klein Ostr. t. 5. f. 94.

The fine example from which our figure of this rare and interesting Volute is taken, once held a distinguished place in the Conchological department of the celebrated museum of Sir Ashton Lever. The length of this shell is four inches and one eighth, its greatest breadth two inches and three eighths; the colour a kind of buff with an olivaceous tint, and the whole surface traversed with a number of irregularly undulated or zig-zag lines of dark brown, disposed longitudinally throughout: the peculiar character of which will be conceived more readily from the delineation than from any explanation that can be conveyed by words. These longitudinal lines are numerous upon the back or superior surface of the first wreath of the shell, and extends also on the lower surface as far as the dilated space of the columella or pillar lip; which latter is of a pure white and destitute of any markings. The mouth or aperture with the interior of the shell is also white, and the plaits of the pillar, which constitutes one of the most essential characters of the genus Volute, are prominent and well defined.

This species of Voluta has long retained its reputation as a shell of distinguished rarity; it was very rare in the time of Kircher and Bonanni, and it has continued scarce even to the present period. At the sale of the Leverian collection, the example of which the delineation is now before us, produced the sum of five guineas and a half: since that time other specimens of the same species have occurred occasionally to observation, but which have still maintained an equal price in proportion to their excellence or perfection. The Leverian shell was a most select example, and has not been surpassed in point of beauty by any of the specimens we have since seen. At the dissolution of that inestimable museum, which happened in the year 1806, this admirable shell passed into the possession of the worthy secretary of the Linnæan Society, A. Mc. Leay, Esq. and it still constitutes a part of the fine Conchological collection of that very eminent naturalist.

The late Dr. Solander, as it appears from his manuscripts preserved in the library of the late worthy President of the Royal Society, Sir Joseph Banks, Bart. had designated this kind of Voluta by the name of Nobilis; it is a fine shell and not unworthy of that distinguished appellation. It is however certain, that it is no other than a variety of Voluta Scapha of the Linnæan school[4], and as the changing and transposition of names that are sufficiently explicit and well understood can only tend to create confusion instead of aiding the pursuits of science, we can have no hesitation in retaining it under its former designation. As a variety, we admit this shell to be distinct and well defined, and to be so far prominent as to merit a definitive appellation; and it is under this persuasion the term Nobilis, assigned but by Dr. Solander, is subjoined to the specific name Voluta Scapha.

This very rare kind of Voluta Scapha is from China, the variety more coarse in its general appearance that constitutes the type of this species, is a native of the Cape of Good Hope.

Among the older definitions by which this shell was known among the early writers, we may mention that of the learned Kircher, whose museum of curiosities, extant in the beginning of the last century, contained a shell of this kind, which Bonanni thus describes:—“Conchylium ea parte latius qua in turbinem desinit sine aculeis, et tuberculis, foramen non rotundum, ut in Purpura et Buccina, sed longum.” Musaei Kircheriani. classis iii. 10. 450. et Bonan. 113.

It may not be amiss to observe, in conclusion, that amidst all the improvements which modern naturalists have made in the science of Conchology, Voluta Scapha still remains a Volute among the most approved writers of the present day, while most of those species considered by Linnæus as appertaining to the same genus are removed to other newly-constituted genera.

The character of the true Volute, as it is at present laid down, consists in the shell being of an oval form, more or less ventricose, or swollen, the summit obtuse and ending in a kind of papilla, or teat, the base of the shell cut off or somewhat truncated: without canal, and the pillar charged with plaits or folds, of which the inferior ones are the largest and longest. The precise contrary of this is observable in the new genus Mitra, of which Voluta Episcopalis is considered as the type. In this last mentioned shell, the body instead of being ventricose is subfusiform, the spire pointed at the summit, and the lower plaits upon the pillar smaller instead of larger. The contrast between these two tribes will, it is conceived, sufficiently illustrate the characteristic peculiarities of the genus Volute, as it is at present constituted.

Bill subulate or awl-shaped; filiform, tubular at the tip and longer than the head; upper mandible forming a sheath for the lower. Tongue filiform, the two threads coalescing, and tubular feet formed for walking; tail composed of ten feathers, in general.

Red; middle tail feathers very long; body red; head brown; throat golden green; rump green.

Trochilus Pella: ruber rectricibus intermediis longissimis, capite fusca, gula aurata uropygioque viridi.—Linn. Syst. 1. p. 189. 2. Gmel. t. 1. p. 1. 485. 2.

Trochilus Pella: curvirostris ruber, rectricibus intermediis longissimis, corpore rubro, capite fusco, gula aurata uropygioque viridi. Lath. Orn. 1. p. 302. 2.

Polytmus Surinamensis longicaudus ruber.—Briss. 3. p. 690. 15.

Falcinellus gutture viridi.—Klein, Av. p. 108. 15.

Le Colibri topaze.—Buff. 6. p. 46.—Pl. Ent. 599.

Topaz Humming-Bird.—Lath Syn. 2. p. 746. 2.

There is not, throughout the very ample range of the creation which the feathered tribes present to our consideration, a race of beings more deservedly admired for their beauty than the Humming-Birds. Natives of the warmer climates of the globe: of countries where the fervour of a tropic sun calls forth the spontaneous productions of the earth bedecked in gaiety unexampled in other regions of the earth, these little beings seem to participate in all its genial influence. With forms the most pleasing for symmetry and elegance they combine a brilliancy of colours the most splendid; their golden hues, their sapphirine tints, the lustre of the emerald, the ruby, garnet, amethyst, and topaz, with which their plumage is adorned, is not surpassed in brightness by the valued gems whose hues they borrow, and whose splendours emulate; as though, in this much-favoured race we beheld the richest gems of earth inspired with life, and endowed with powers of activity and will. The flowers whose nectareous juices afford them sustenance, are moreover the liveliest and most luxuriant among those that adorn the surface of the teeming earth:—in a word, the Humming-Birds, poised and fluttering upon the wing, or flitting from flower to flower, in search of food beneath the fervid illumination of a cloudless tropic sun, present a spectacle of the works of nature upon a scale of miniature the most pleasing and most brilliant.

Owing to the slender structure of the bill, the Humming-Birds have some difficulty in obtaining their support; the luxuriant fruits of the tropic world afford them no repast: their bills are much too feeble to penetrate their rind to derive subsistence from their fluids. It is the rich juices of the flowers and not the fruits that afford them food; the fluids which they find secreted in the nectaria of flowers, the nectaria of those plants in particular which have the flowers long and tubular, and in which those repositories of mellifluous fluid lie in the bottom of the corolla are the favourite objects of their resort. About the flowers of this kind the Humming-Birds are seen hovering like bees, and like those industrious creatures extracting at the same time those juices of the flowers by means of their elongated tongue. The construction of the tongue in this tribe of birds is singular and deserving of explicit mention; it consists of two tubular filiform threads, which coalesce throughout their whole length, excepting at the tips, where they are divided, or bifid; this organ, which is remarkable for its extreme length, it inserts deeply down into the corolla of the flowers, and is thus enabled to obtain the nectar nearly in the same manner as the insects of the sphinx genus. The Humming-Birds, when on the wing, are observed to emit a humming noise, like that of the bee, and it is apparently from this circumstance that this class of the feathered race have derived the appellation of Humming-Birds.

As the different species of the Humming-Bird, though uniformly small, vary much in magnitude, from the bigness indeed of the wren and others of our smaller warblers to a size more diminutive than several of the larger kinds of the bee tribe, the nests of these birds, as may be conceived, are found to vary materially according to the size of the species to which they appertain. These little local habitations of the infant brood are all comparatively small, are usually of a roundish form, lined with the softest downy leaves, and each in general contains two little eggs, scarcely exceeding the size of peas, and of a pure white colour without any spots.

The slenderness of the bill and weakness of the legs in this tribe of birds sufficiently demonstrate that they are inadequate to any contests with other kinds of the feathered race; they are nevertheless observed among themselves to be rather of a pugnaceous disposition. Their usual contests are for their mates or for the possession of some favourite flower, and are observed to take place while on the wing. Their mode of attack is by striking with violence against each other, for they never attempt to assault each other with their bill and their feet are much too small and feeble for conflict.

The species of Humming-Bird now before us is one of the larger kinds, its length being about six inches from the tip of the bill to the extremity of the tail, exclusive of the two elongated feathers which extend beyond the true tail about two inches; the bill is long, slender, and slightly incurvated, and of a whitish colour with the tip black. The most characteristic peculiarity is the large space of topazine or golden green immediately beneath the chin, and which expands over the whole surface of the throat. The head is blackish purple, and the same colour descending along the sides of the neck passes in a kind of crescent round the breast, thus constituting an abrupt separation between the vivid green space of the chin and throat, and the vivid lustre of the abdomen, which is a fine crimson or ruby colour from the breast nearly to the vent, where it becomes interspersed with a few white feathers; the feathers of the thigh are white also. The back and wing coverts are brown with tints and shades of greenish, and glosses of a golden yellow. The greater quill feathers are fuscous, the tail coverts are fine green; the tail orange, except the two remarkable elongated candal feathers, which are black. The legs pale.

Notwithstanding the very decisive character which this species of Humming-Bird displays, and which considered individually can leave us little reason to distrust its identity as a species, we are not to overlook the very near approximation of this kind with some others that are described as specifically different, such as the Sapphire Humming-Bird, and that distinguished by the appellation of the Sapphire and Emerald Humming-Bird. The near approach of these and some others to the species now before us appears to be sufficiently obvious to induce a persuasion that in a less mature state one kind may sometimes have been mistaken for another, and this becomes the more probable when we recollect that the Humming-Birds in general, like many of the larger tribes of the feathered race, do not arrive at their full perfection of plumage till the second and more commonly till the third year.

Antennæ thicker towards the tip and generally terminating in a knob: wings erect when at rest. Fly by day.

Wings entire, rounded, yellow, each of them beneath with a geminous or double silver spot.

Papilio Marcellina: alis integris rotundatis flavis: singalis subtus puncto gemino argenteo.—Fabr. Spec. Ins. 2. 49. n. 214.—Ent. Syst. t. 3. p. 1. 209. 654.—Cram. 14. t. 165.

Papilio Marcellina is a butterfly of peculiar simplicity and beauty in its general effect. The upper surface is of a fine yellow with a singular subocellate spot or stigma of a reddish brown in the centre of the anterior wings, and a series of double spots of the same colour, disposed towards the exterior margin both of the anterior and the posterior pair. The lower surface, as we perceive from the Butterfly at rest, with the wings erect in the upper part of the plate, is rather more of an orange or fulvous hue, and instead of having the disk immaculate like the upper surface, except the stigma in the anterior wings, are sprinkled with reddish brown. The centre of the wings, as well the posterior as the anterior pair, are marked with two silver spots, and which, from their near approximation, may be denominated, according to the language of Fabricius, a geminous or double spot of silver.

This elegant insect is figured from a specimen in the collection of the celebrated Dr. Hunter, the individual example described and referred to by Fabricius in his Species Insectorum and Entomologia Systematica as expressed among the synonyms above recited.

The Papilio Marcellina has appeared already in the costly work of Cramer, upon the Papiliones tribe, we are nevertheless induced to present a figure of the species to our readers, in order to point out the very close affinity that prevails between this insect and another much more frequent species named Papilio Sennæ. This latter mentioned Butterfly is figured by Sloane, Merian, and Seba; Papilio Marcellina by Cramer only. These insects resemble each other, but are nevertheless distinct; the specific character of Papilio Sennæ consists chiefly, according to Linnæus, in having the double spot in the centre of each wing of a ferruginous colour, while in Papilio Marcellina that characteristic mark has the exact appearance of two approximating spots of molten silver. The tips of the wings in Papilio Sennæ are sometimes spotted as in Marcellina and are sometimes destitute of spots.

Both these analogous species are natives of Surinam; Sloane describes Papilio Sennæ, in his Natural History of Jamaica, as an inhabitant of that island.

Antennæ thicker towards the tip, and generally terminating in a knob; wings erect when at rest. Fly by day.

Wings entire rounded yellow; anterior pair at the tip black above, beneath sanguineous brown.

Papilio Agave: alis integerrimis rotundatis flavis: anticis apice supra nigris, subtus brunneis.—Fabr. Ent. Syst. t. 3. p. 1. 193. n. 599.

This very scarce and pretty species of the Papilio tribe is an inhabitant of Cayenne, and may possibly occur also in other parts of South America. It was unknown to Fabricius when he published the work entitled Species Insectorum; he afterwards observed a species of it in the cabinet of Von Rohr, and inserted a description of it between the two species P. Hecabe and P. Cardamines in his subsequent production Entomologia Systematica.

The upper surface of this Butterfly is entirely yellow, without any marks, excepting only the apex of the anterior wings, which are black in that portion of the tip which appears red on the lower surface, or as Fabricius terms it, somewhat erroneously brown.

This fly, so uniformly simple in the aspect of its superior surface, appears to peculiar advantage when in a resting position as it is depicted in the lower part of the plate.

Bill conic: mandibles receding from each other from the base downwards, the lower with the sides narrowed in; a hard knob within the upper mandible.

Head blue, abdomen fulvous, back green, feathers green brown.

Emberiza Ciris: capite cæruleo, abdomine fulvo, dorso-viridi, pennis viridi-fuscis Act. Stockh. 1750 p. 278 t. 7. f. 1.—Linn. Syst. Nat. 1. 179.—Gmel. Syst. 1. p. 885.

Friagilla Tricolor, Catesby Car. 1. p. 44. t. 44. Klein. Av. p. 97. 7.

Chloris ludoviciana, Papa, Briss. 3. p. 200. 58. t. 8. f. 3.

Fringilla Mariposa, Scop. Ann. 1. No. 222.

Le Pepe Buff. 4. p. 176. t. 9.—Pl. Enl. 139. f. 1.

China Bulfinch, Albin. 3. t. 68.

Painted Bunting, Lath. Gen. Syn. 3. p. 206. 54.—Supp. p. 159. Ind. Orn. T. 1. p. 416. 61.

The varieties of the very beautiful species now before us are rather numerous, as may be imagined from its moulting twice in a year, and not arriving, as it is pretty generally believed, at its full state of plumage till nearly the third year. These are the progressive changes of the male bird, and it may be also added, that the female undergoes several mutations of the same kind, as well as the male bird.

When its plumage has attained its full perfection, there are few birds of more striking beauty than the male of this species. Its size is scarcely inferior to that of our common Hedge Sparrow, the length between five and six inches. The head and neck of a fine blue purple, with a circle of red round the eyes. The whole of the underside, including the chin, throat, breast, and abdomen, is a fulvous, or rather a vivid scarlet; the back green, below which is a space of yellow, and the rump scarlet, like the abdomen. The wings are greenish, being shaded with brown, and having the edges of the feathers of a delicate green: the greater wing coverts in our specimen are of a pale rose colour, and which in the general conformation of the plumage constitutes a roseate band across the wings. The tail, like the wings, are brownish, having the edges of each feather green; the bill and legs dark.

In some of the varieties of this bird, occasioned as before observed, through the moulting of the feathers, the blue purple of the head and neck is more generally extended along the back, and sometimes appears in patches upon other parts of the plumage. Sometimes, also, the dark spots that appear upon the scarlet space of the chin, throat, breast, and abdomen, are more diffused, and in other states of moulting the abdomen becomes yellow or yellowish. The abdomen has also, in some instances, been known to change white, leaving only a rounded spot of red upon the breast.

Catesby describes this species as a native of Carolina. It is an inhabitant of all the warmer parts of America, extending from Mexico and Peru, as far as Canada, in the milder seasons of the year. It is rather a hardy bird, insomuch, that some attempts have been made by the Dutch to naturalize the species in Europe, like the Canary; but not, however, with the same success, although they may be kept alive for some time after being brought into the less genial climates of the Continent of Europe.

The celebrated Marmaduke Tunstall, Esq. a most indefatigable Naturalist, who lived towards the latter part of the preceding century, has stated, that two pair of these birds made their nests and laid eggs in the orange trees of a Menagery at Holderness, in Yorkshire, but observes at the same time, the eggs were unproductive. Mr. Tunstall, as a Collector, was the great rival of Sir Ashton Lever, and of authority unquestionable, and this circumstance tends to shew that it might be yet possible to rear these very beautiful birds in this country. Some authors have presumed upon the authority of Albin, that this species extends to China. There can be very little doubt that the figure in the third volume of Albin’s plate, denominated the China Bulfinch, is intended for this bird. Albin assures us that he saw the bird he figured in the possession of a curious gentlemen, who told him he had received it from China.

In the warmer parts of America, which these birds, as before observed, inhabit, they occur sometimes in vast flocks; it does not appear that they are of a shy or timid disposition, yet it is said they are seldom seen near habitable places, and never in any considerable numbers together.

Shell spiral, gibbous: aperture ovate, (generally) terminating in a short canal, leaning to the right, with a retuse beak or projection: pillar lip expanded.

Shell with equal longitudinal and distinct mucronate ribs: pillar lip smooth.

Buccinum Harpa: testa costis æquilibus longitudinalibus distinctis mucronatis, columella lævigata. Linn. Syst. Nat. 10. p. 7. 38. n. 400.—Mus. Lud. Ulr. 609. n. 261.

Buccinum Harpa: testa varicibus[5] æqualibus longitudinalibus distinctis mucronatis: columella lævigata. Gmel. Linn. Syst. Nat. T. 1. p. 6. 3482. n. 47.

Buccinum Testudo. Soland. MSS.

Harpa. Rumpf. Must. 32. f. K. L. M.

Harpa Nobilis Argenv. Conch. t. 17. f. D.

This superb shell, admitted to be the finest example of its kind, at present known, once constituted part of the Conchological Collection of Sir Ashton Lever; and continued to be a distinguished ornament of that Museum after it passed into the hands of Mr. Parkinson. At the dissolution of that Museum, which took place in the month of May, June, and the beginning of July, in the year 1806, the specimen became the property of a very celebrated amateur, the late Mr. Jennings: he purchased it at the sale for the sum of seven pounds.[6] Mr. Jennings is since dead, and his collection being, like the former, dispersed by public sale: we are no longer certain in whose possession this very beautiful rarity now remains.

Besides that this shell excels in magnitude every other known example of its kind, the formation of the shell itself is extremely fine, its perfection exquisite, the colouring of the richest and most decided hues, and the marks and lines throughout, which so eminently characterize the shell, definitely distinct; we shall dwell no further on the peculiar beauty of this shell, from a persuasion that the drawing will be found so explicit and so satisfactory, as to render a minute description needless: it was taken with peculiar care, by permission of its proprietor, while it remained in the Leverian Museum, and will not, we are convinced, be found defective in point of accuracy, upon the most attentive comparison with the original, should that ever be produced in competition with it.

In the Linnæan arrangement of Conchology, the shells of this kind constitute a species of the Genus Buccinum, the Buccinum Harpa of that author. Previous to the time of Linnæus, the best Conchologists had considered those particular shells that possess the essential characters of the Common Harp Shell, as a distinct genus. Rumpfius so adopts it under the name of Harpa; and Argenville subsequently regarding that particular kind called Buccinum Harpa, by Linnæus, as the type of the genus, denominates it, by way of eminence, Harpa Nobilis. By some inconceivable error it has been asserted that Lamarck was the first author who separated the family of Harps from the genus Buccinum; this is evidently a mistake, as we perceive from Rumpfius and Argenville, and as we are now proceeding to shew from the “Catalogue Systématique et Raisonné,” of the once celebrated cabinet of M. de Davilla; besides which, some others might be added, were it material to notice them.

As we have introduced the subject of Davilla’s Cabinet, it will, perhaps, afford some pleasure to many of our readers if we mention a few of those very beautiful varieties of this natural family of the Harps, which were once concentrated in that costly collection. These, collectively, appear to have presented a series of the most choice and interesting of the varieties at that time known. The distinctions are taken from the number of the prominent ridges with which these shells are longitudinally traversed, and these, it hence appears, varied from thirteen to fourteen and fifteen in number. One of these, a very fine shell, and deemed the type of the Harpe tribe, was the Harpa Nobilis of D’Argenville: it had fifteen ribs, was very regularly marked with alternate zic-zac lines of brown and white, or rather of brown lines disposed upon a white ground, with a small intermediate incurvate line of grey traversing the middle of each of the white lines, in the same, direction as those of brown; a disposition of marking, very similar to the zic-zac lineations upon the shell represented in the annexed plate. There were two other Harps, in which the number of ribs, or ridges, amounted to no more than fourteen, so that the sides were larger; and they were also more inclined than in the preceding. These were marbled, and marked with streaks and dashes of rose colour, yellow, white, and chesnut, a large intermediate and rather deeper coloured zone, or band, passed round the middle of the shell, and two large spots of brown appeared on the under surface of the shell. There were yet two other Harps, which differed in their colours and markings from the preceding; one of these had only twelve ribs, or ridges, the other thirteen. The colours in one of these were paler, in the other the zic-zac lines, were more contiguous, or placed closer, and the longitudinal striæ less distinct or prominent. And besides these, there were several others, all which differed in some peculiarities of inferior moment, principally in the paleness or intensity of their colours, and variations in the disposition of the dark and paler spaces with which the shells were marbled.

The above series of Davila presents us with a pretty ample elucidation of the presumed varieties of that beautiful species the Linnæan Buccinum Harpa. We say, only the presumed varieties, because in the present state of the Conchological Science there appears to be a very strong propensity among collectors to increase the number of the species, by considering every trivial variation, or accidental circumstance in the growth of shells, as so many characteristic indications of new species; a disposition that the best Conchologists cannot but disapprove. Experience teaches us that there is no class of beings in the creation, in which nature is more sportive, than the testaceous tribes; none in which a greater caution is required in the precise determination of what are species and what varieties only: and among other local causes the influence of climates in different regions are not the least powerful in producing those variations. With the best experience, and the advantage of many years assiduous application, the Conchologist may be sometimes in doubt, and hence it is not likely that a slight acquaintance, only, with the subject will be found sufficient to enable him to pronounce with definitive satisfaction the exact distinction between approximating species and the sportive varieties into which they sometimes divaricate. These remarks cannot be more forcibly exemplified than in the series of the presumed varieties of the Buccinum Harpa. Some of these are indeed so very dissimilar as to justify a persuasion that they may be specifically distinct, and yet again, these are blended so intimately with others, which are confessedly varieties, that it demands the utmost caution in pronouncing which are species, and which varieties or transitions only. This is the impression under which the best informed Conchologists have ever ventured to define the shells which constitute the natural family of the Harps, and may serve to afford us a sufficient explanation of the causes of those differences in opinion which so manifestly prevail among them.

It may not be very generally known, excepting only among Naturalists, that the late Dr. Solander had devoted much attention to this intricate science: his arrangement of shells was designed as an amendment upon that of Linnæus. This arrangement was never made public; it remained in manuscript in the library of the late Sir Joseph Banks. From a perusal of these MSS. it appears that Dr. Solander had conceived the necessity of a new disposition of the shells comprised in general as varieties of this species. Some he allows to remain varieties, while others constitute, in his ideas, species nearly analogous, but nevertheless distinct. He does not propose the formation of an independant genus of the Harp family, nor the removal of those shells from the genus Buccinum, in which Linnæus places the species Harpa: he proposes only to assemble together the least equivocal varieties of that shell, together with that which he considers as the type of the Linnæan species, the true Harpa Nobilis of preceding authors; and to allow the others to remain as species distinct from the Linnæan shell. It will be hence perceived that Dr. Solander’s constitutes several distinct species among the number of those Harps, which other writers, and Gmelin among the rest, regard as varieties only of the common kind. In the manuscripts of Dr. Solander the very beautiful Harp shell now before us stands as a distinct species from Buccinum Harpa, under the name of Buccinum testudo. Some of the French Naturalists have called it Harpa testudinaria: it was placed under that name, and its synonymous appellation L’ecaille de Tortue in the once celebrated Museum of Mons. de Colonne, the French Minister of State, under Louis the XVI: the definitive English name of Tortoiseshell Harp was assigned to it by Mr. George Humphrey, and from his known authority in the study of shells, this variety has been since distinguished among collectors in our country by that appropriate appellation. All these names, it will be scarcely necessary to add, are devised in allusion to that resemblance which its peculiarly beautiful variegations of colour are conceived to bear, to those of tortoiseshell, when transparent and exposed to light.

We have been at some pains in our endeavours to reconcile our mind to the idea of introducing this Tortoiseshell Harp as a species distinct from the Buccinum Harpa, in conformity with the opinion of Dr. Solander. We have compared our shell with the acknowledged type of the Linnæan species, with every attention, and are compelled, in truth, to allow, that however distinct it may appear upon the first glance of inspection, we cannot implicitly accede to the persuasion of its being specifically distinct. Placing this remarkable variety with that particular shell, the true Buccinum Harpa, the less informed Conchologist would assume as certain that the difference existing between the two removed them sufficiently from each other. Arrange these, however, with those varieties and transitions of the Common Harp that approach the nearest in appearance to both kinds, and we shall then perceive such a close analogy, such an intermediate catenation, as will induce a pause, and certainly under the impression with which we view them, an idea that these variations arise only from local causes, and are not specifical distinctions. As a marked and well distinguished variety we have retained the term testudo, which Dr. Solander had assigned to it; but as a distinctive appellation of it as a variety, and not as a shell altogether distinct.

That it may not be imagined we feel any disposition to object against those changes in the Science of Conchology, which the more advanced state of our present knowledge may demand, we have no hesitation in adding that in our own opinion the Harpa family should constitute a very distinct tribe from the other Buccini; we believe, also, that had Linnæus lived to reconsider them, he would have comprehended them together as a genus. The French writers have long since done so. De Monfort advances that Lamarck was the first who separated the Harps from the Linnæan Buccinum. This we have already shewn to be an error. Lamarck’s example in proposing them as a genus in his Système des Animaux sans Vertèbres, published in the year 1801, and his subsequent observations in other writings, has tended to establish them as a genus; he was not its first proposer.

It may not be amiss, in conclusion, to observe, that Lamarck has taken for the type of his genus, the variety figured by Lister, in his Conchology, tab. 992 f. 55, the shell which he denominates Harpa Ventricosa. The leading character of his genus consists in the shell being of an oval form, ventricose or swollen, and having the surface furnished or beset with longitudinal, parallel, and sharp or acutely edged ribs. The opening or mouth, oblong, ample, abbreviated or cut off below, and without canal. The pillar, or inner lip, smooth, or without plaits or tubercles, and terminating in a point at the base. The absence of a canal is one material character by which the Harpa genus, as thus laid down, is to be distinguished from the new genus Trophon, to which, in some respects, at least, it bears a general resemblance. The definition of the genus by De Montfort is rather different from that of Lamarck: according to De Montfort the shells of this family are globose; the first whorl very far surpassing the rest in size, and the spire obtuse. The mouth is very open. The pillar or inner lip smooth and rounded. The outer lip bordered by an acutely edged rib or ridge, running paralled to those with which the shell is traversed externally, and the base cut off. The spire in the true Harpa, according to this writer, forms a kind of little domes, one surmounting the other, and the spire, instead of ending in an acute point, terminates in a small mammillated knob.

All the known varieties of this natural family are inhabitants of the deep waters of the sea, and the animal inhabitants appear to have remained hitherto undescribed. They are confined chiefly to the Indian Seas. The variety known by the name of Nobilis is a native of Japan; there is another found in China, distinguished by the name of Chinensis: both these are considered by Dr. Solander as the Buccinum Harpa of Linnæus: there is one kind found at Ceylon, and another at Madagascar, which are to be esteemed distinct species. The sanguineous Harp, from the Coast of Guinea, is the Buccinum pandura of Solander. The Harp, distinguished by having a far greater number of elevated ribs than any of the preceding, is from the seas of the Phillippine Isles, and is certainly a distinct species. The very fine variety which constitutes the more immediate object of our present illustration, the Tortoiseshell Harp, is a native of Madagascar: its length is four inches, and its greatest breadth two inches and a half.

Antennæ elevated or thicker towards the tip, and generally terminating in a knob. Wings erect when at rest. Fly by day.

Wings entire, white; tip of the anterior pair black spotted with white, lower ones beneath greenish with two darker bands, the anterior one incurvate.

Papilio Psamathe: alis rotundatis integerrimis albis: anticis apice nigris albo maculatis; posticis subtus virescentibus; fasciis duabus obscurioribus; anteriore incurva. Fabr. Spec. Ins. T. 3. p. 1. 207.

A native of America and nearly allied to Papilio Phronima, represented in plate 153 of the work of Cramer. It differs in having only the tip, and not both the base and tip, black, as in Phronima. Our present species is also distinguished further by having two white spots on the black tip of the anterior wings, in the apex of the anterior wings being destitute of any black spot beneath, and in the anterior band on the lower wings beneath being incurvate.

This species has not been represented by any author. Fabricius described it from the drawings of the late Mr. Jones, and it is from that matchless series of designs and MSS. that the present figures are copied.

Fringilla Bengalus: dilute cærulea, capite dorsoque griseis, lateribus capitis purpureis. Gmel. Linn. Syst. Nat. 1. p. 920.

Fringilla Benghalus: Linn. Syst. Nat. 1. p. 323. 32. (mas.)

Fringilla Angolensis: Linn. Syst. Nat. 1. p. 323. 31. (fem.)

Fringilla Benghalus: dilute cærulea, capite dorsoque griseis, lateribus capitis purpureis. Lath. Ind. Orn. 2. p. 461. 91.—Lath. Syn. 111. p. 310. 81.

Le Bengali. Briss. Orn. 111. p. 303. 60. pl. 10. f. 1.—Buff. Ois. iv. p. 92.—Pl. Enl. 115. f. 1.

Blue Bellied Finch. Edw. pl. 131. (female)

A pretty species of the Fringilla tribe, about the size of our smaller Linnets. The bill and legs of this bird are of a pale flesh colour: the body above, together with the wings, of a greyish brown: the lower part of the back, rump, and whole of the underside, of a delicate azure blue; the tail blue, of a somewhat deeper tint, and rather cuneated or wedge-formed. This is the general appearance of the plumage in both sexes, excepting, only, that the colours are usually somewhat brighter in the male than the female bird; and that the male bird is distinguished further by having a dark red spot on each side of the head, beneath the eyes, a character altogether wanting in the female.

It should be observed that these birds vary occasionally in the colours of their plumage, particularly in the cærulean tints of the under surface, which sometimes inclines to a pale rufous grey, or to blue intermixed with rufous grey; and in some instances when the state of plumage is less mature, the latter colour predominates so entirely on the lower surface, that only a transition tint of the azure appears upon the breast and abdomen.