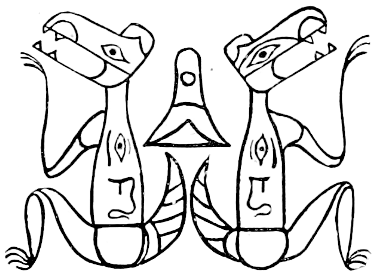

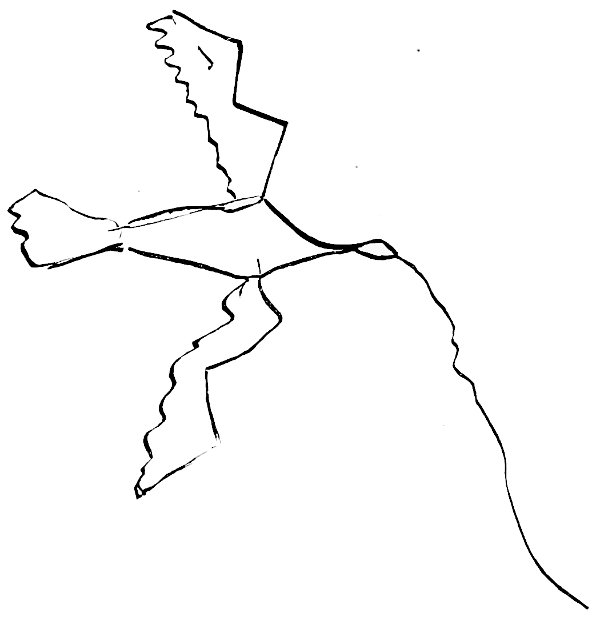

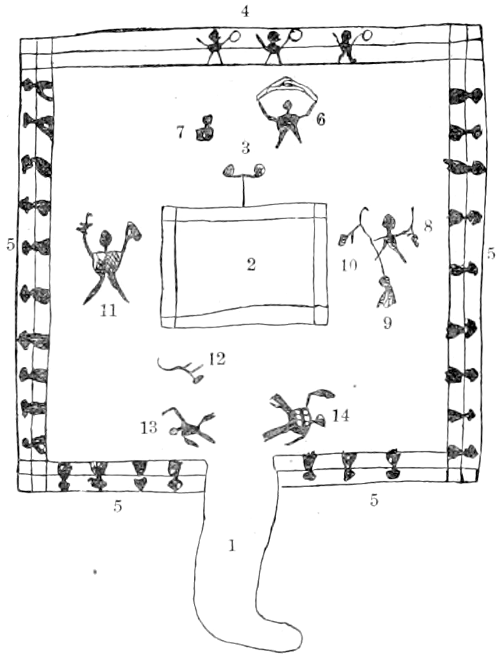

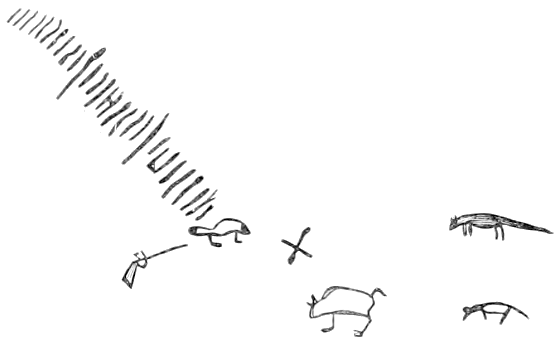

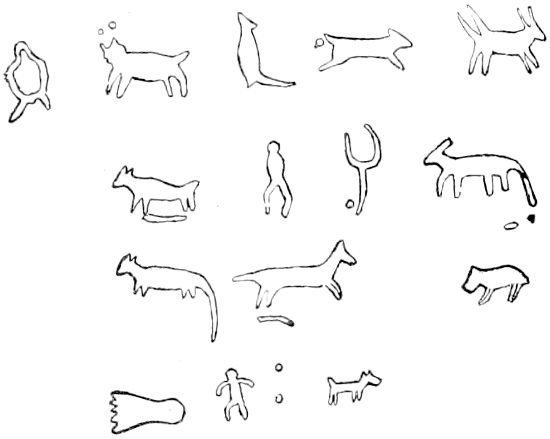

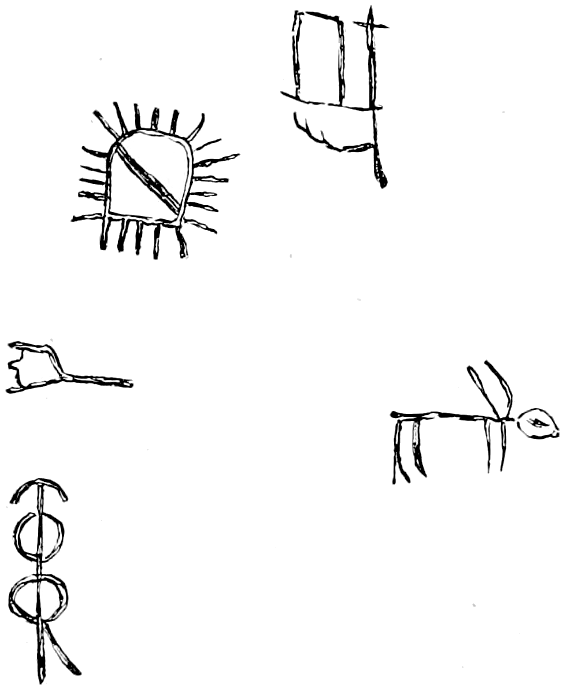

Fig. 1.—Petroglyphs at Oakley Springs, Arizona.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Pictographs of the North American Indians.

A preliminary paper, by Garrick Mallery

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Pictographs of the North American Indians. A preliminary paper

Fourth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the

Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1882-83,

Government Printing Office, Washington, 1886, pages 3-256

Author: Garrick Mallery

Release Date: May 2, 2017 [EBook #54643]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PICTOGRAPHS ***

Produced by Henry Flower, Carlo Traverso, The Internet

Archive (American Libraries). and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by the

Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF/Gallica) at

http://gallica.bnf.fr)

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION—BUREAU OF ETHNOLOGY.

A PRELIMINARY PAPER.

BY

GARRICK MALLERY.

| Page. | |

| List of illustrations | 7 |

| Introductory | 13 |

| Distribution of petroglyphs in North America | 19 |

| Northeastern rock-carvings | 19 |

| Rock-carvings in Pennsylvania | 20 |

| in Ohio | 21 |

| in West Virginia | 22 |

| in the Southern States | 22 |

| in Iowa | 23 |

| in Minnesota | 23 |

| in Wyoming and Idaho | 24 |

| in Nevada | 24 |

| in Oregon and Washington Territory | 25 |

| in Utah | 26 |

| in Colorado | 27 |

| in New Mexico | 28 |

| in Arizona | 28 |

| in California | 30 |

| in Colored pictographs on rocks | 33 |

| Foreign petroglyphs | 38 |

| Petroglyphs in South America | 38 |

| in British Guiana | 40 |

| in Brazil | 44 |

| Pictographs in Peru | 45 |

| Objects represented in pictographs | 46 |

| Instruments used in pictography | 48 |

| Instruments for carving | 48 |

| for drawing | 48 |

| for painting | 48 |

| for tattooing | 49 |

| Colors and methods of application | 50 |

| In the United States | 50 |

| In British Guiana | 53 |

| Significance of colors | 53 |

| Materials upon which pictographs are made | 58 |

| Natural objects | 58 |

| Bone | 59 |

| Living tree | 59 |

| Wood | 59 |

| Bark | 59 |

| Skins | 60 |

| Feathers | 60 |

| Gourds | 60 |

| Horse-hair | 60 |

| Shells, including wampum | 60 |

| Earth and sand | 60 |

| The human person | 61 |

| Paint on the human person | 61 |

| Tattooing | 63 |

| Tattoo marks of the Haida Indians | 66 |

| Tattooing in the Pacific Islands | 73 |

| Artificial objects | 78 |

| Mnemonic | 79 |

| The quipu of the Peruvians | 79 |

| Notched sticks | 81 |

| Order of songs | 82 |

| Traditions | 84 |

| Treaties | 86 |

| War | 87 |

| Time | 88 |

| The Dakota Winter Counts | 89 |

| The Corbusier Winter Counts | 127 |

| Notification | 147 |

| Notice of departure and direction | 147 |

| condition | 152 |

| Warning and guidance | 155 |

| Charts of geographic features | 157 |

| Claim or demand | 159 |

| Messages and communications | 160 |

| Record of expedition | 164 |

| Totemic | 165 |

| Tribal designations | 165 |

| Gentile or clan designations | 167 |

| Personal designations | 168 |

| Insignia or tokens of authority | 168 |

| Personal name | 169 |

| An Ogalala roster | 174 |

| Red-Cloud’s census | 176 |

| Property marks | 182 |

| Status of the individual | 183 |

| Signs of particular achievements | 183 |

| Religious | 188 |

| Mythic personages | 188 |

| Shamanism | 190 |

| Dances and ceremonies | 194 |

| Mortuary practices | 197 |

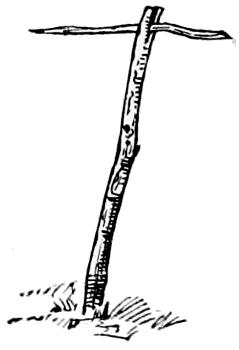

| Grave-posts | 198 |

| Charms and fetiches | 201 |

| Customs | 203 |

| Associations | 203 |

| Daily life and habits | 205 |

| Tribal history | 207 |

| Biographic | 208 |

| Continuous record of events in life | 208 |

| Particular exploits and events | 214 |

| Ideographs | 219 |

| Abstract ideas | 219 |

| Symbolism | 221 |

| Identification of the pictographers | 224 |

| General style or type | 225 |

| Presence of characteristic objects | 230 |

| Modes of interpretation | 233 |

| Homomorphs and symmorphs | 239 |

| Conventionalizing | 244 |

| Errors and frauds | 247 |

| Suggestions to collaborators | 254 |

| Plate | Page. |

| I.—Colored pictographs in Santa Barbara County, California | 34 |

| II.—Colored pictographs in Santa Barbara County, California | 35 |

| III.—New Zealand tattooed heads | 76 |

| IV.—Ojibwa Meda song | 82 |

| V.—Penn wampum belt | 87 |

| VI.—Winter count on buffalo robe | 89 |

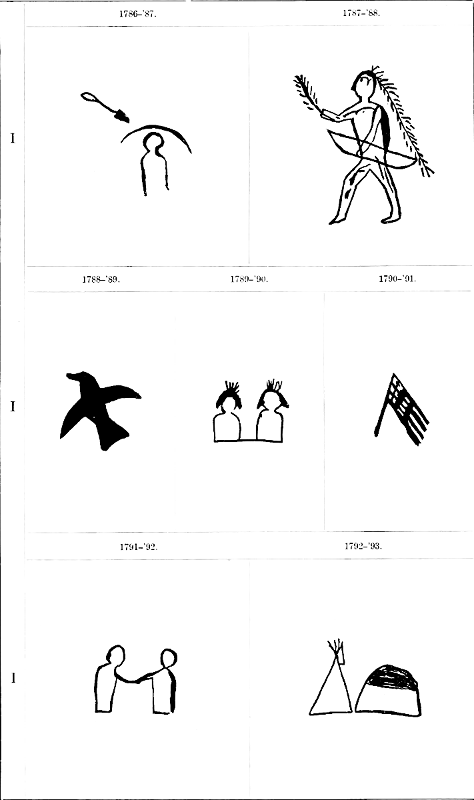

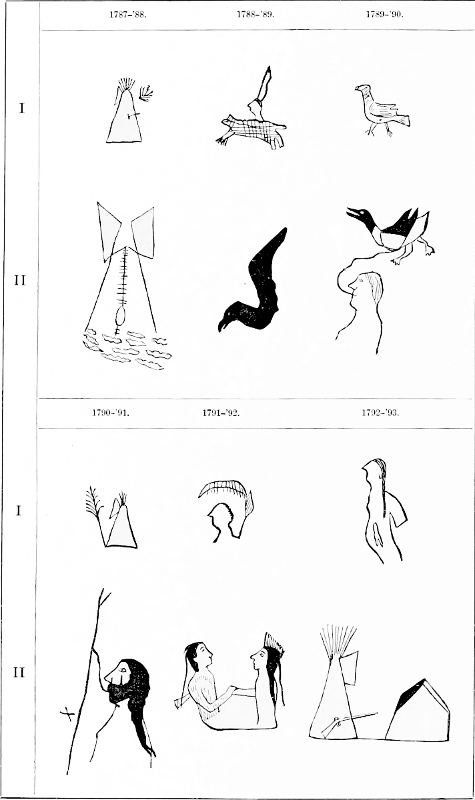

| VII.—Dakota winter counts: for 1786-’87 to 1792-’93 | 100 |

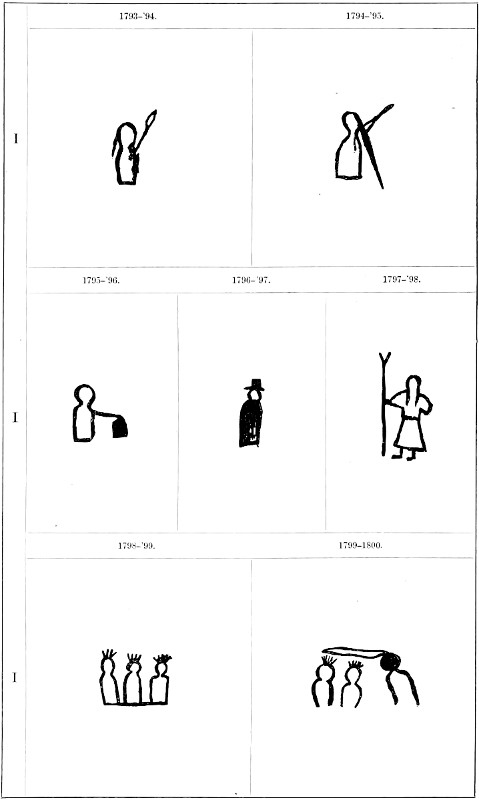

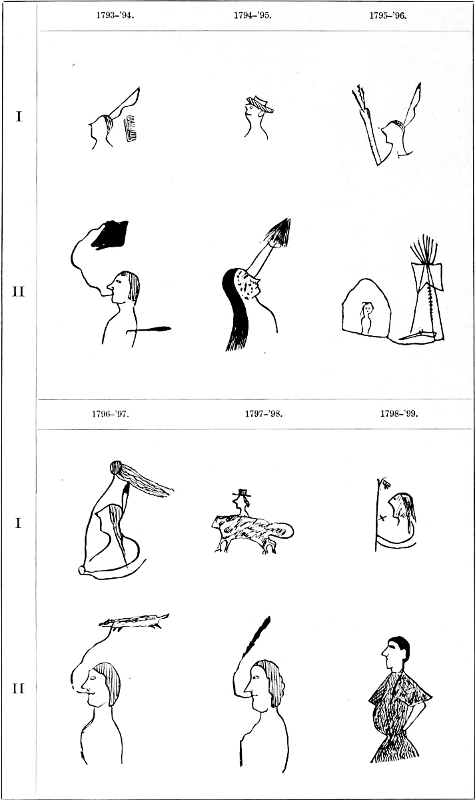

| VIII.—Dakota winter counts: for 1793-’94 to 1799-1800 | 101 |

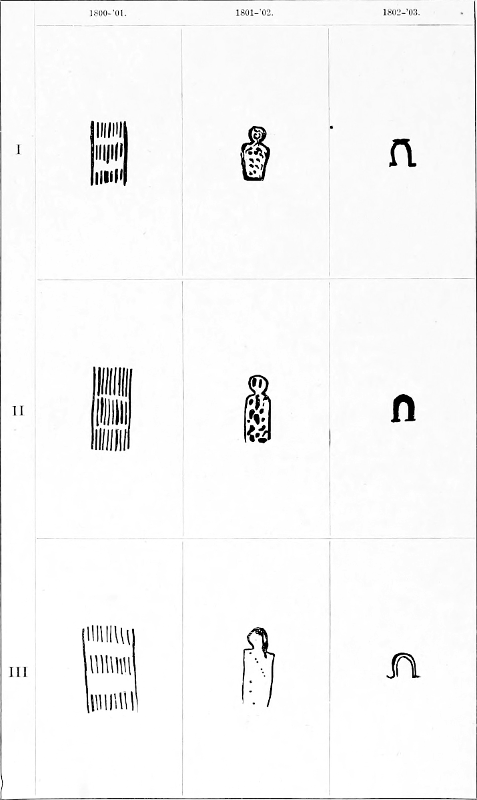

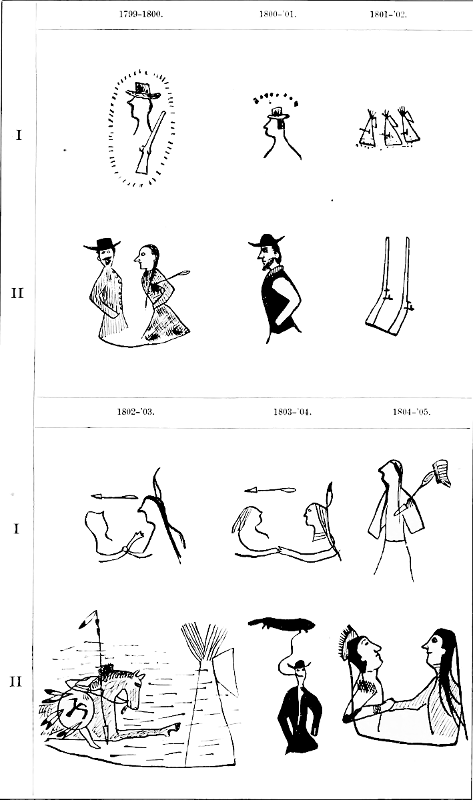

| IX.—Dakota winter counts: for 1800-’01 to 1802-’03 | 103 |

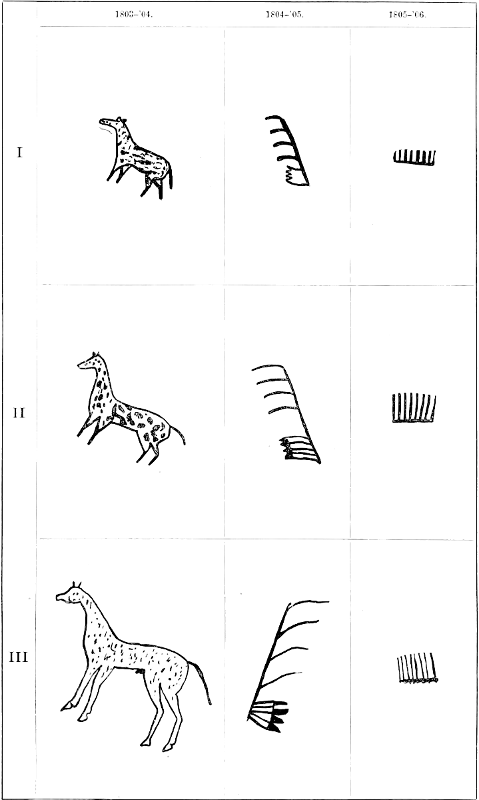

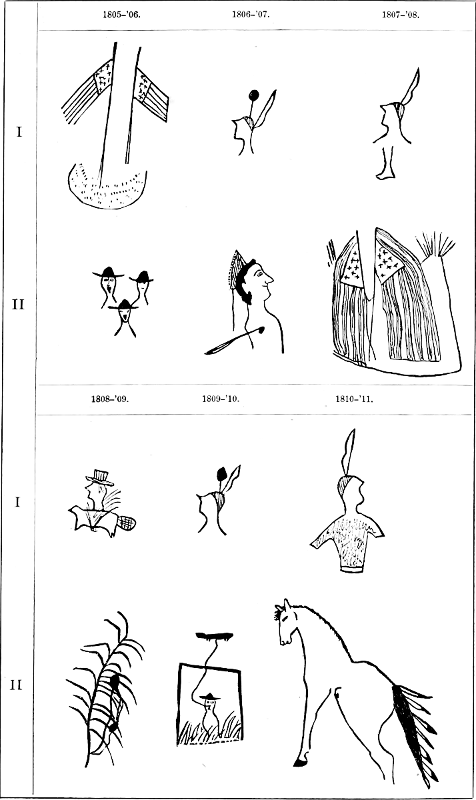

| X.—Dakota winter counts: for 1803-’04 to 1805-’06 | 104 |

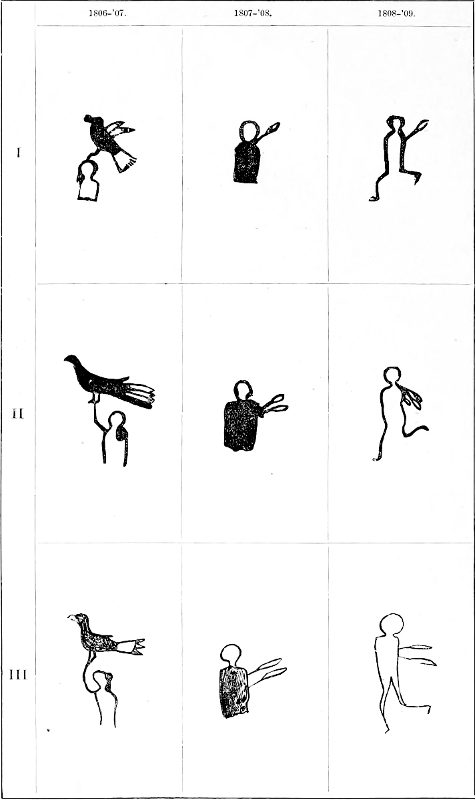

| XI.—Dakota winter counts: for 1806-’07 to 1808-’09 | 105 |

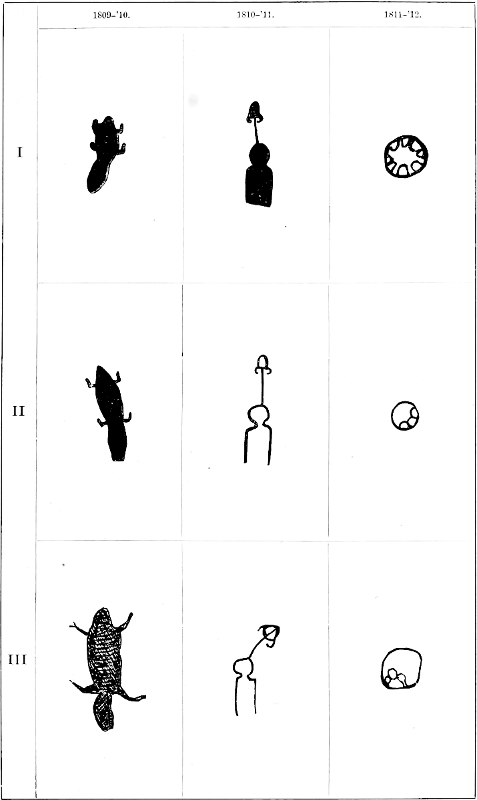

| XII.—Dakota winter counts: for 1809-’10 to 1811-’12 | 106 |

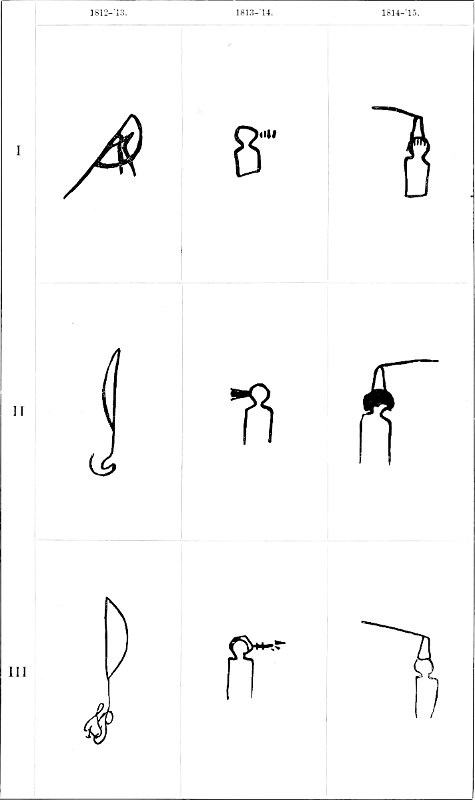

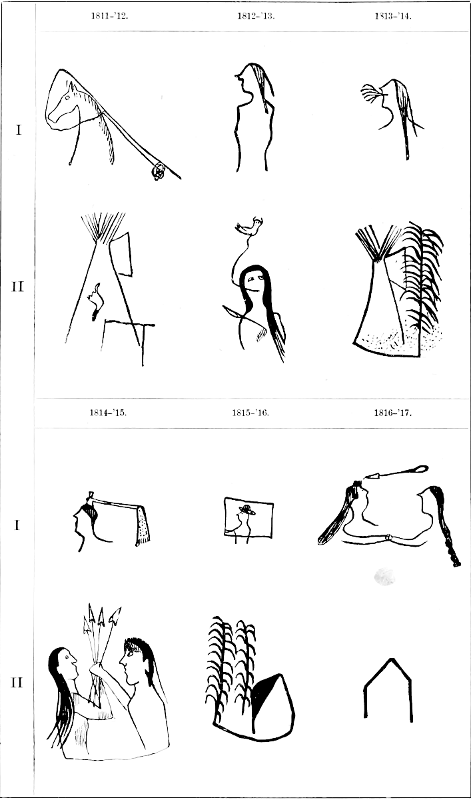

| XIII.—Dakota winter counts: for 1812-’13 to 1814-’15 | 108 |

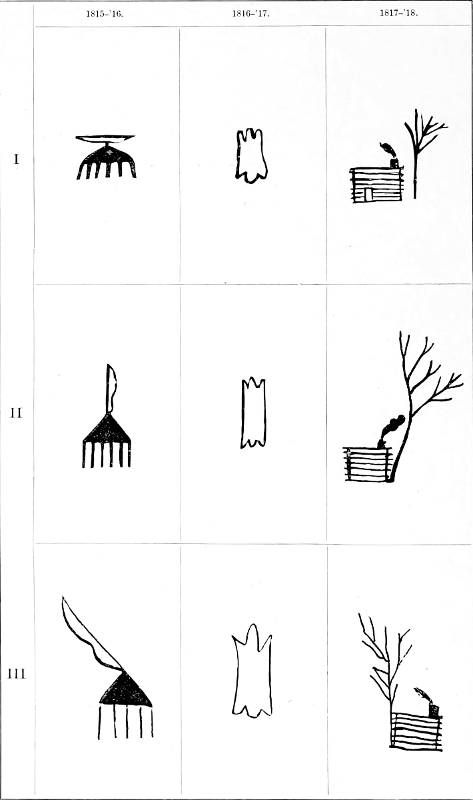

| XIV.—Dakota winter counts: for 1815-’16 to 1817-’18 | 109 |

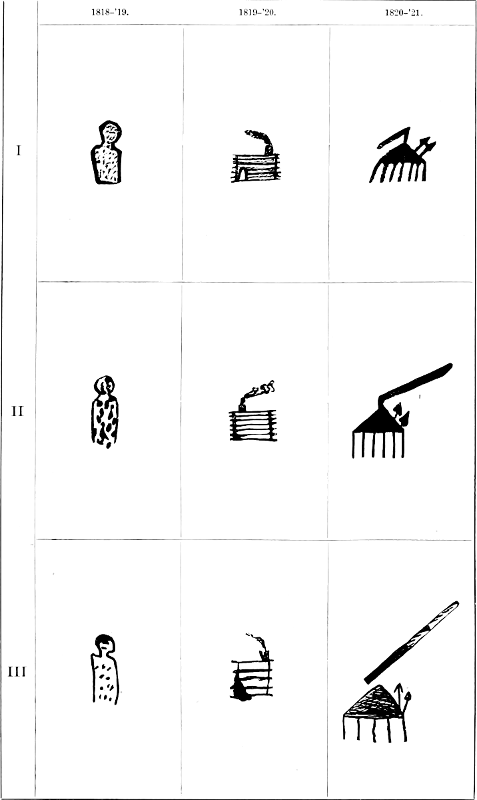

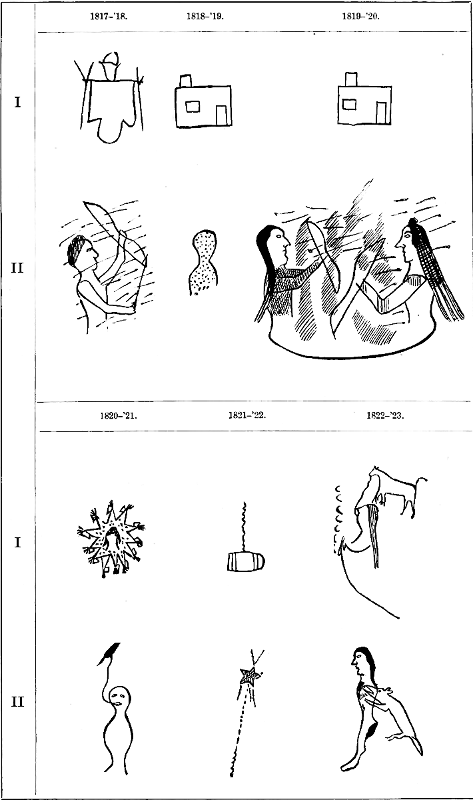

| XV.—Dakota winter counts: for 1818-’19 to 1820-’21 | 110 |

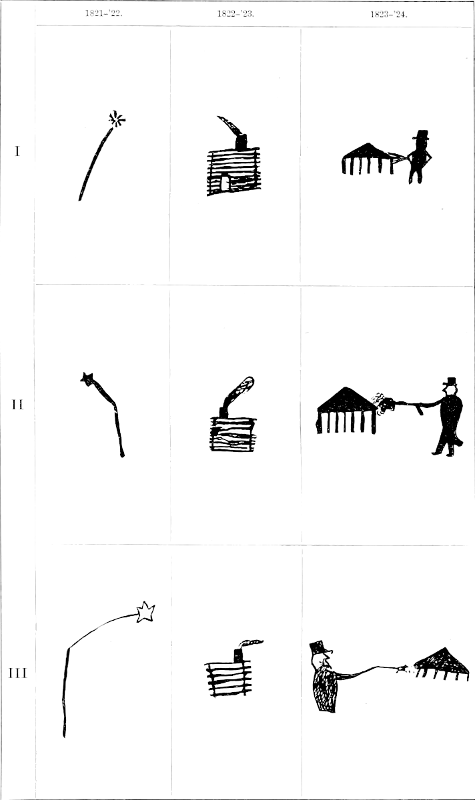

| XVI.—Dakota winter counts: for 1821-’22 to 1823-’24 | 111 |

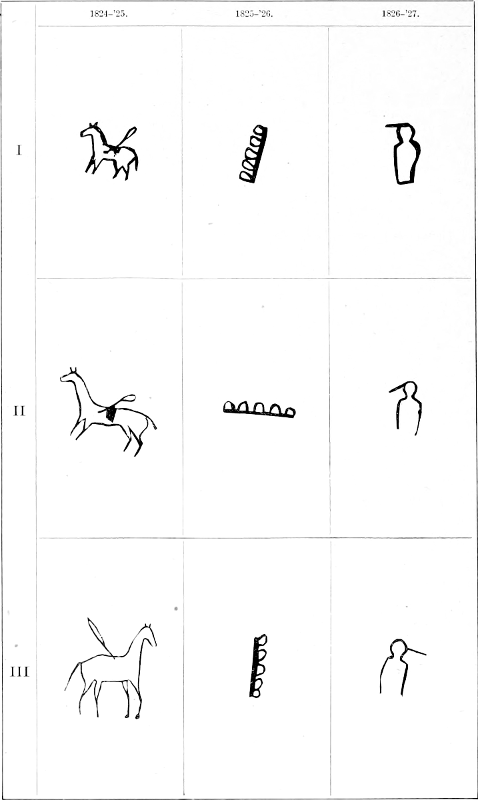

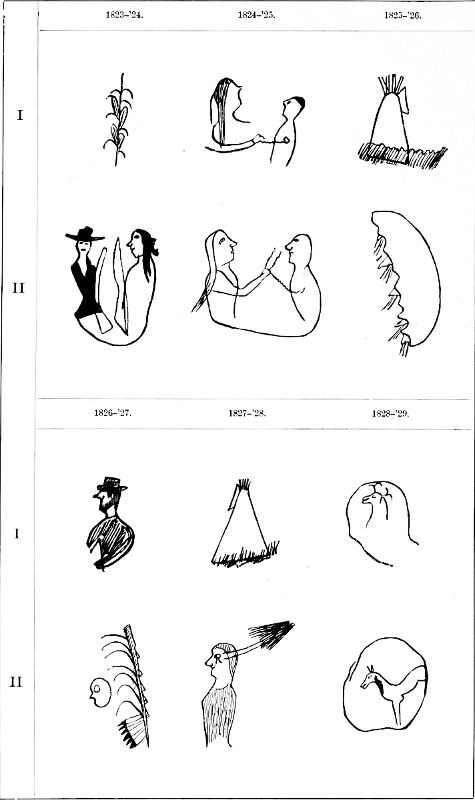

| XVII.—Dakota winter counts: for 1824-’25 to 1826-’27 | 113 |

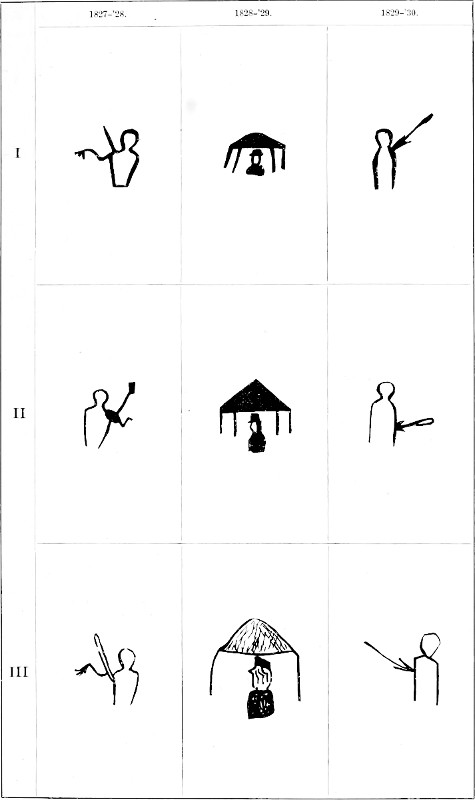

| XVIII.—Dakota winter counts: for 1827-’28 to 1829-’30 | 114 |

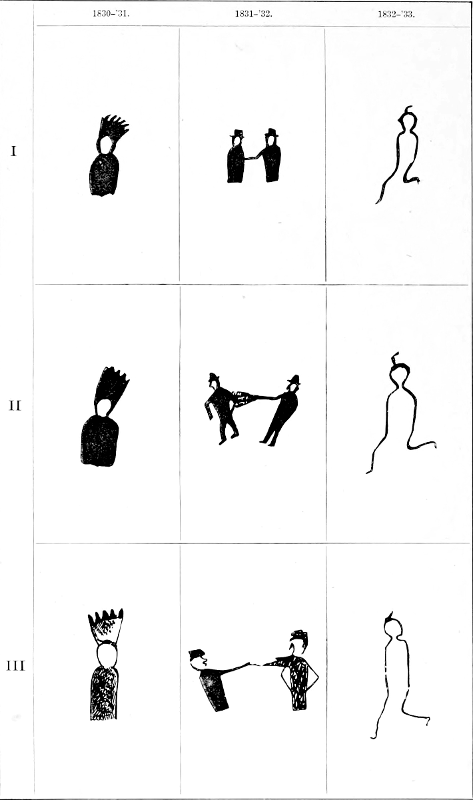

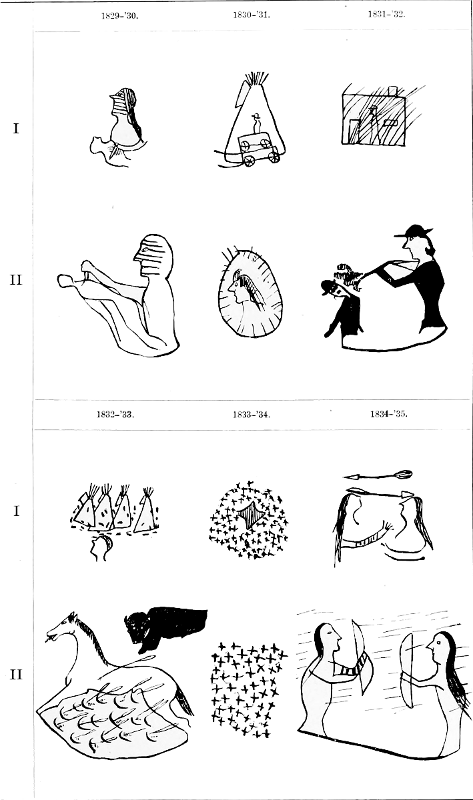

| XIX.—Dakota winter counts: for 1830-’31 to 1832-’33 | 115 |

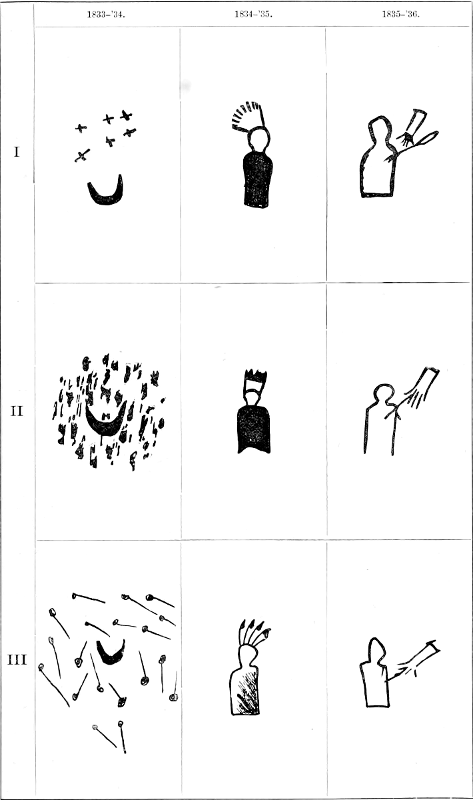

| XX.—Dakota winter counts: for 1833-’34 to 1835-’36 | 116 |

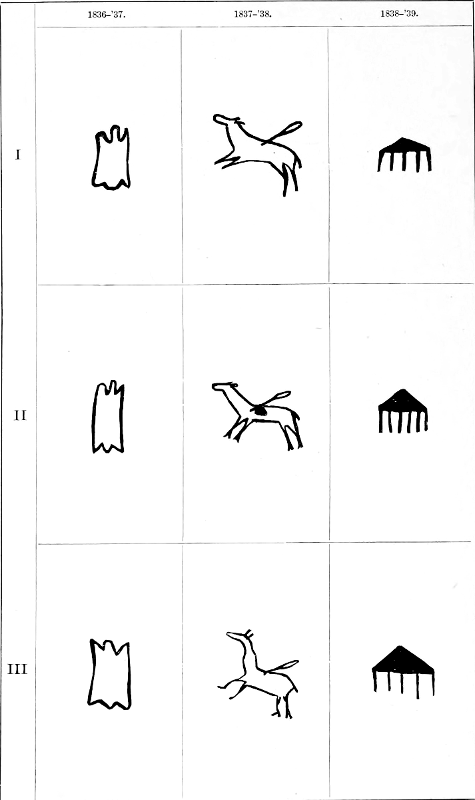

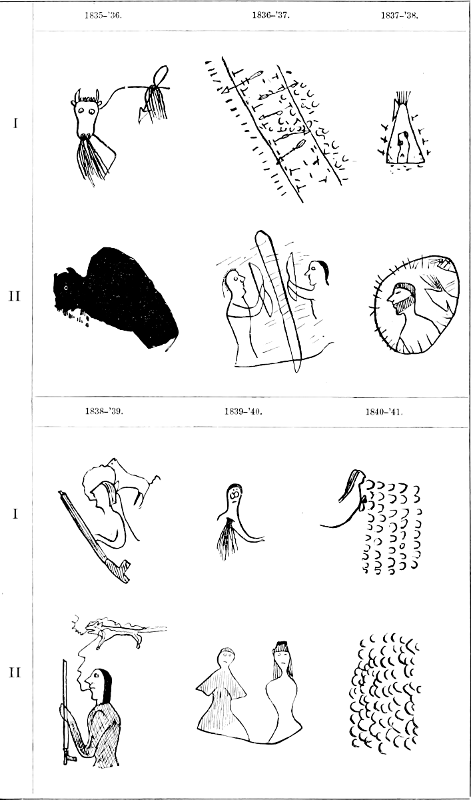

| XXI.—Dakota winter counts: for 1836-’37 to 1838-’39 | 117 |

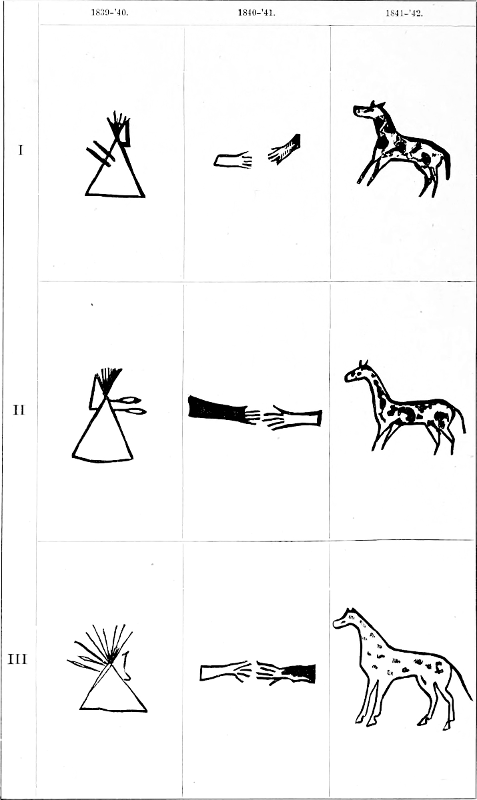

| XXII.—Dakota winter counts: for 1839-’40 to 1841-’42 | 117 |

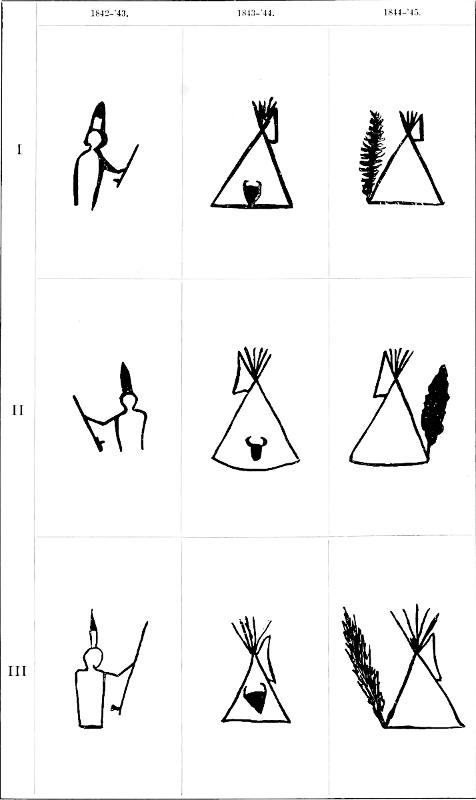

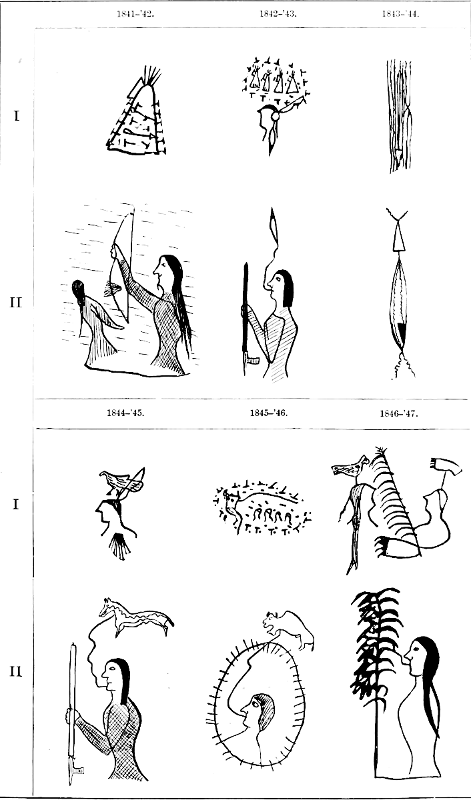

| XXIII.—Dakota winter counts: for 1842-’43 to 1844-’45 | 118 |

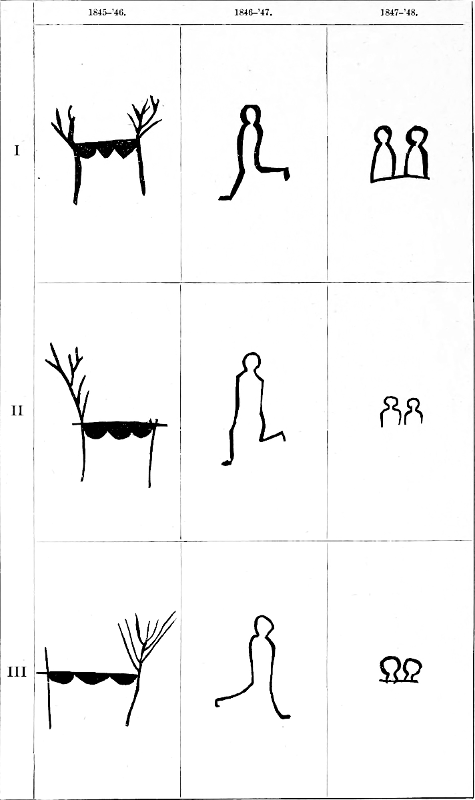

| XXIV.—Dakota winter counts: for 1845-’46 to 1847-’48 | 119 |

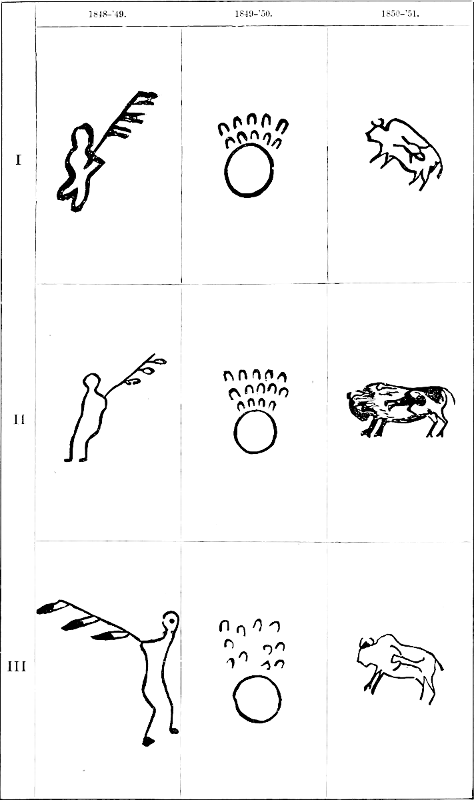

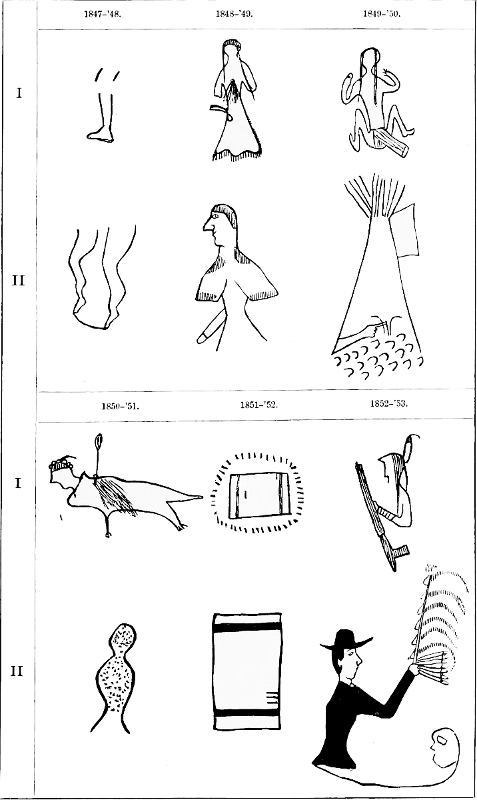

| XXV.—Dakota winter counts: for 1848-’49 to 1850-’51 | 120 |

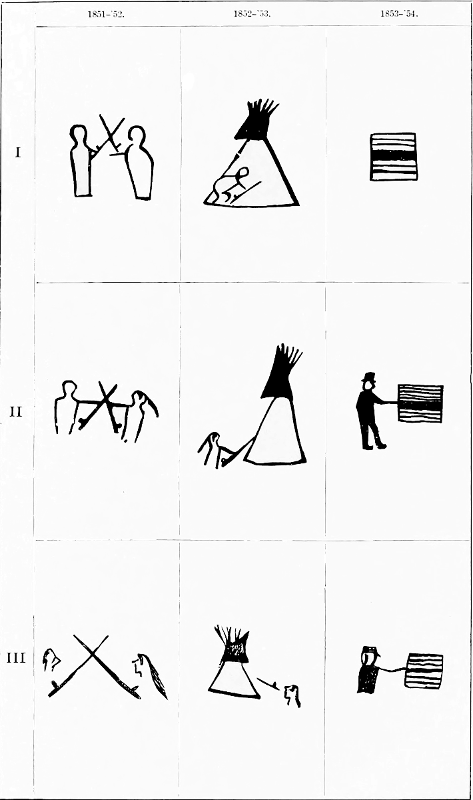

| XXVI.—Dakota winter counts: for 1851-’52 to 1853-’54 | 120 |

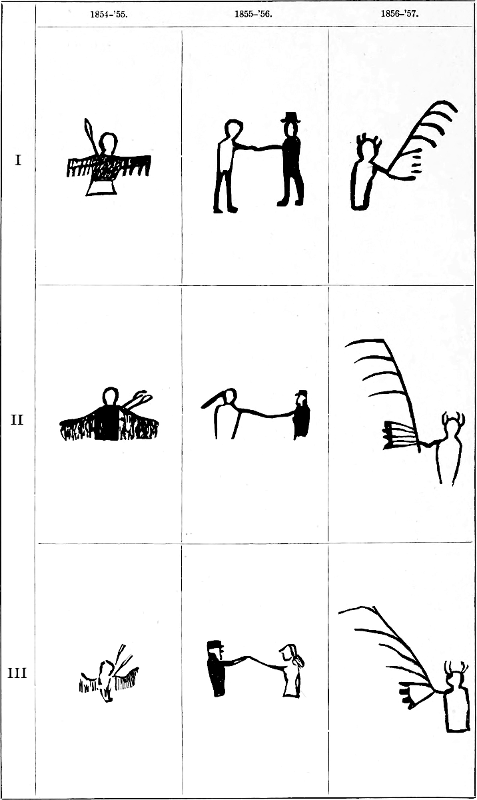

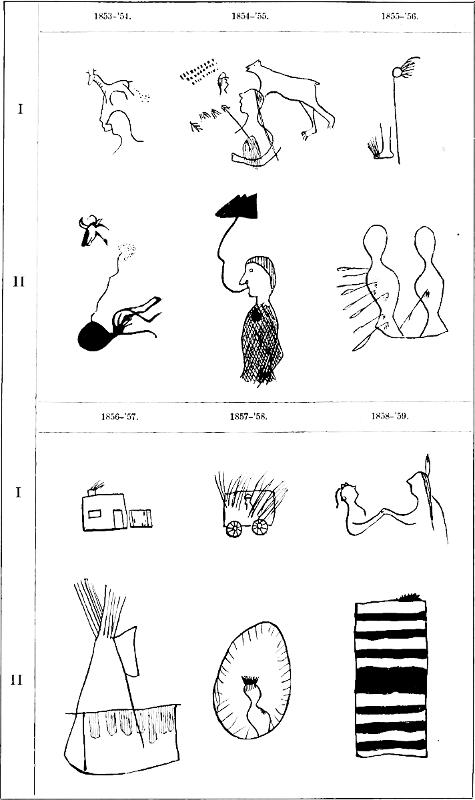

| XXVII.—Dakota winter counts: for 1854-’55 to 1856-’57 | 121 |

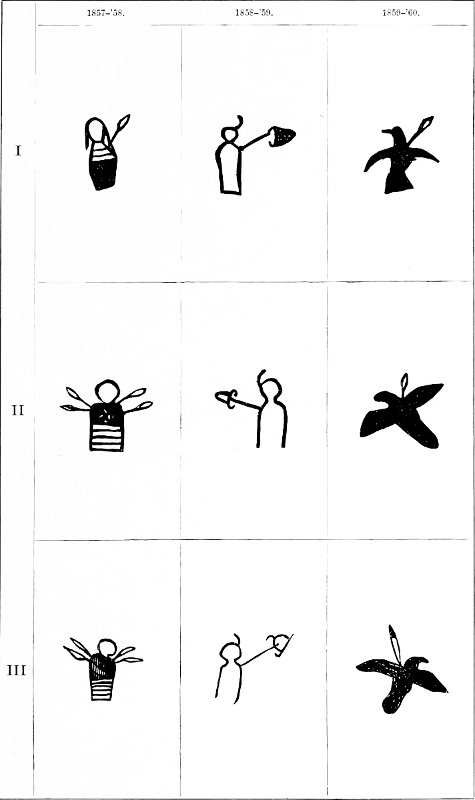

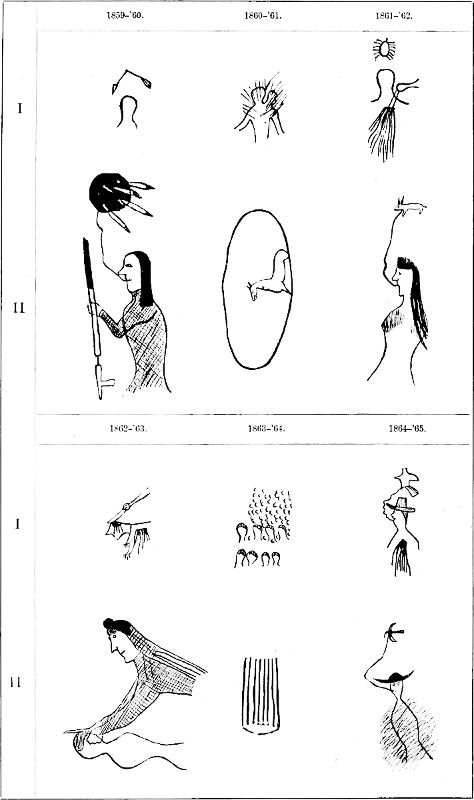

| XXVIII.—Dakota winter counts: for 1857-’58 to 1859-’60 | 122 |

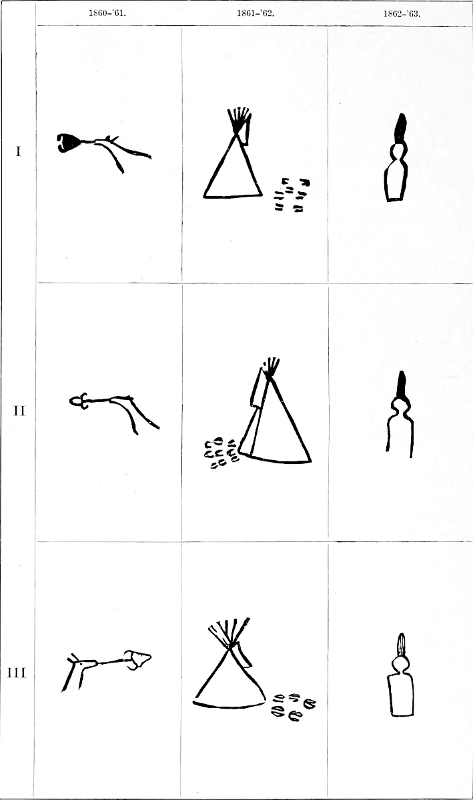

| XXIX.—Dakota winter counts: for 1860-’61 to 1862-’63 | 123 |

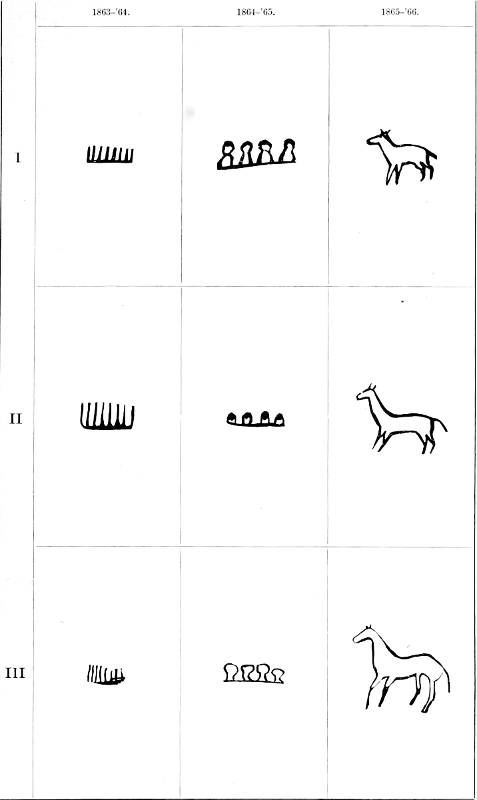

| XXX.—Dakota winter counts: for 1863-’64 to 1865-’66 | 124 |

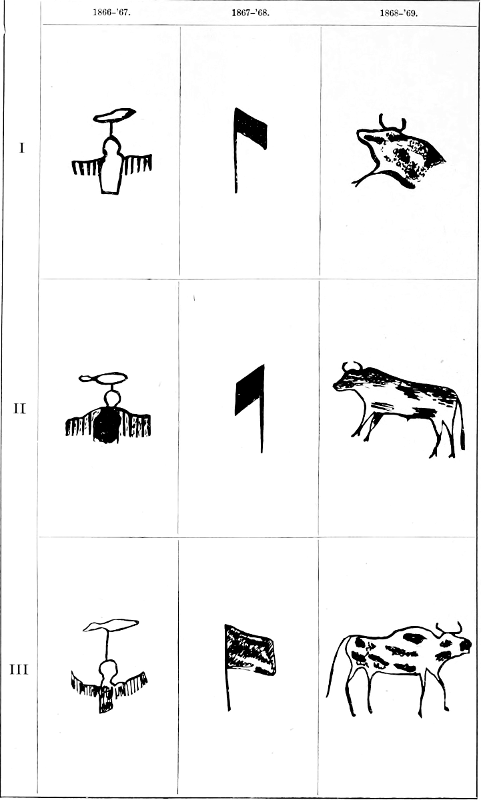

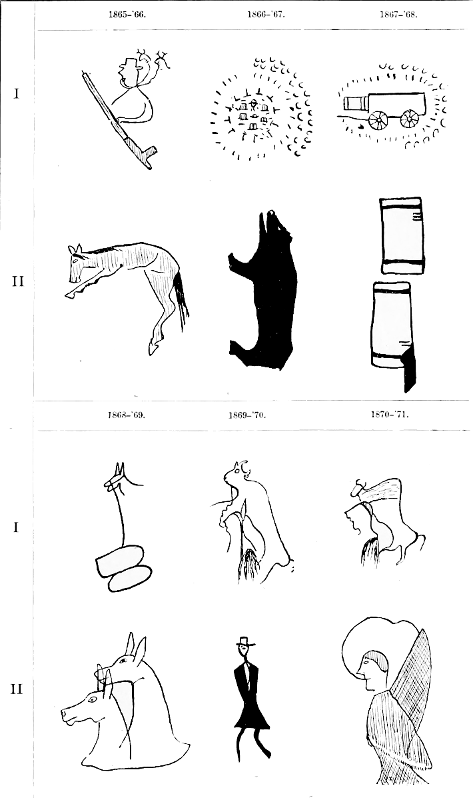

| XXXI.—Dakota winter counts: for 1866-’67 to 1868-’69 | 125 |

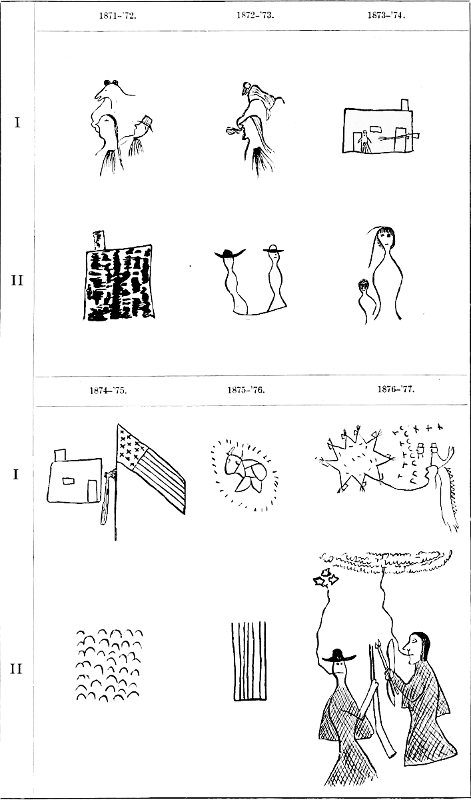

| XXXII.—Dakota winter counts: for 1869-’70 to 1870-’71 | 126 |

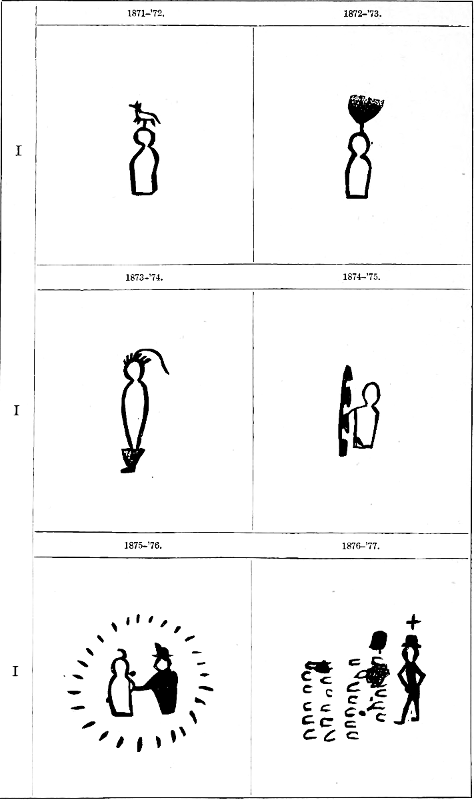

| XXXIII.—Dakota winter counts: for 1871-’72 to 1876-’77 | 127 |

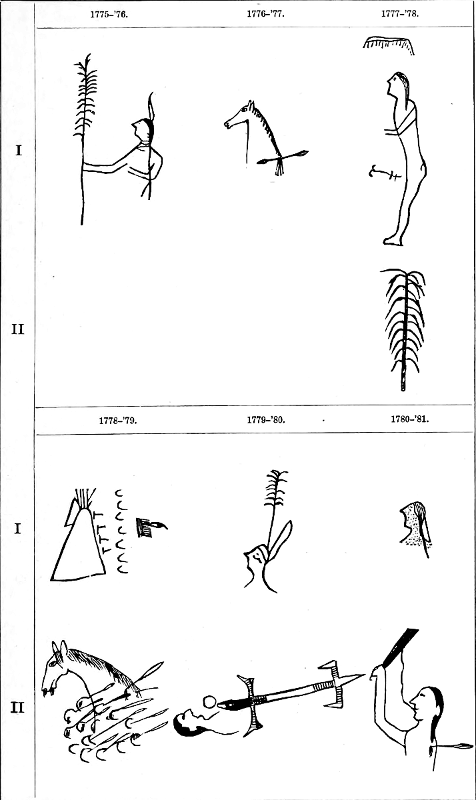

| XXXIV.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1775-’76 to 1780-’81 | 130 |

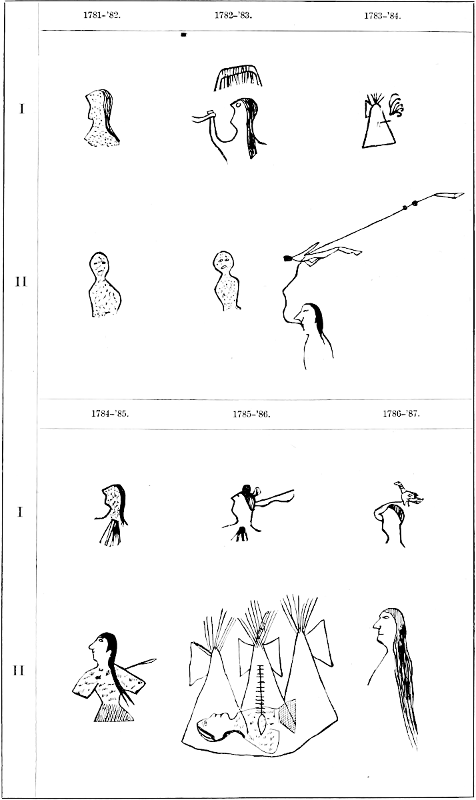

| XXXV.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1781-’82 to 1786-’87 | 131 |

| XXXVI.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1787-’88 to 1792-’93 | 132 |

| XXXVII.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1793-’94 to 1798-’99 | 133 |

| XXXVIII.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1799-1800 to 1804-’05 | 134 |

| XXXIX.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1805-’06 to 1810-’11 | 134 |

| XL.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1811-’12 to 1816-’17 | 135 |

| XLI.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1817-’18 to 1822-’23 | 136 |

| XLII.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1823-’24 to 1828-’29 | 137 |

| XLIII.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1829-’30 to 1834-’35 | 138 |

| [8]XLIV.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1835-’36 to 1840-’41 | 139 |

| XLV.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1841-’42 to 1846-’47 | 140 |

| XLVI.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1847-’48 to 1852-’53 | 142 |

| XLVII.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1853-’54 to 1858-’59 | 143 |

| XLVIII.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1859-’60 to 1864-’65 | 143 |

| XLIX.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1865-’66 to 1870-’71 | 144 |

| L.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1871-’72 to 1876-’77 | 145 |

| LI.—Corbusier winter counts: for 1877-’78 to 1878-’79 | 146 |

| LII.—An Ogalala roster: Big-Road and band | 174 |

| LIII.—An Ogalala roster: Low-Dog and band | 174 |

| LIV.—An Ogalala roster: The Bear Spares-him and band | 174 |

| LV.—An Ogalala roster: Has a War-club and band | 174 |

| LVI.—An Ogalala roster: Wall-Dog and band | 174 |

| LVII.—An Ogalala roster: Iron-Crow and band | 174 |

| LVIII.—An Ogalala roster: Little-Hawk and band | 174 |

| LIX.—Red-Cloud’s census: Red-Cloud’s band | 176 |

| LX.—Red-Cloud’s census: Red-Cloud’s band | 176 |

| LXI.—Red-Cloud’s census: Red-Cloud’s band | 176 |

| LXII.—Red-Cloud’s census: Red-Cloud’s band | 176 |

| LXIII.—Red-Cloud’s census: Red-Cloud’s band | 176 |

| LXIV.—Red-Cloud’s census: Red-Cloud’s band | 176 |

| LXV.—Red-Cloud’s census: Red-Cloud’s band | 176 |

| LXVI.—Red-Cloud’s census: Red-Cloud’s band | 176 |

| LXVII.—Red-Cloud’s census: Red-Shirt’s band | 176 |

| LXVIII.—Red-Cloud’s census: Red-Shirt’s band | 176 |

| LXIX.—Red-Cloud’s census: Red-Shirt’s band | 176 |

| LXX.—Red-Cloud’s census: Black-Deer’s band | 176 |

| LXXI.—Red-Cloud’s census: Black-Deer’s band | 176 |

| LXXII.—Red-Cloud’s census: Black-Deer’s band | 176 |

| LXXIII.—Red-Cloud’s census: Red-Hawk’s band | 176 |

| LXXIV.—Red-Cloud’s census: Red-Hawk’s hand | 176 |

| LXXV.—Red-Cloud’s census: High-Wolf’s band | 176 |

| LXXVI.—Red-Cloud’s census: High-Wolf’s band | 176 |

| LXXVII.—Red-Cloud’s census: Gun’s band | 176 |

| LXXVIII.—Red-Cloud’s census: Gun’s band | 176 |

| LXXIX.—Red-Cloud’s census: Second Black-Deer’s band | 176 |

| LXXX.—Rock Painting in Azuza Cañon, California | 156 |

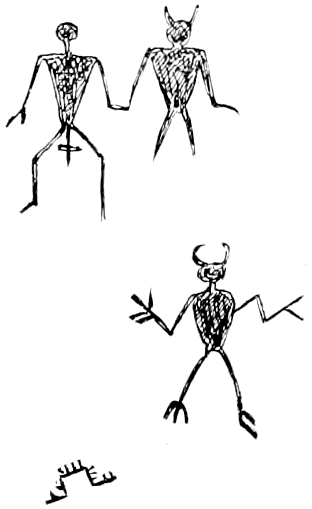

| LXXXI.—Moki masks etched on rocks. Arizona | 194 |

| LXXXII.—Buffalo-head monument | 195 |

| LXXXIII.—Ojibwa grave-posts | 199 |

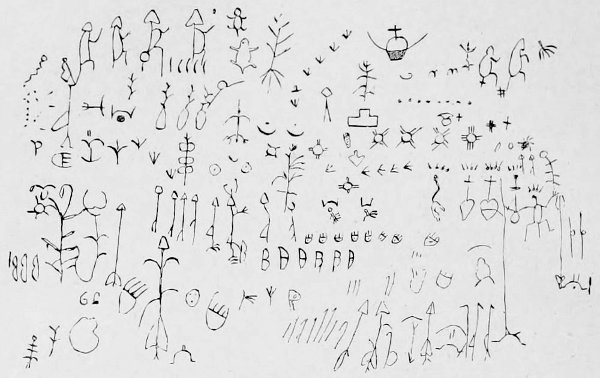

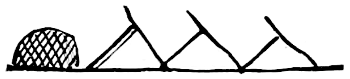

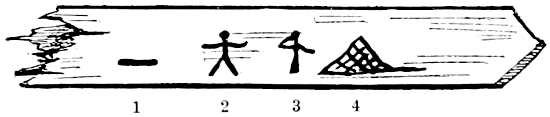

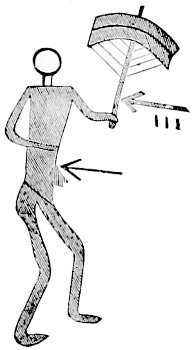

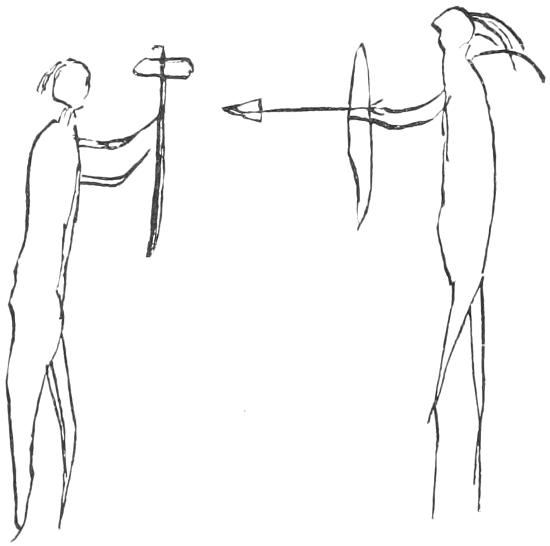

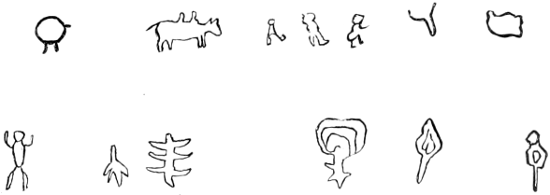

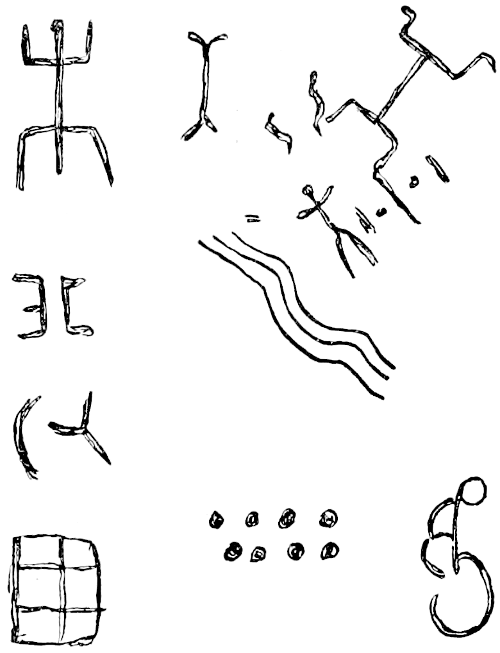

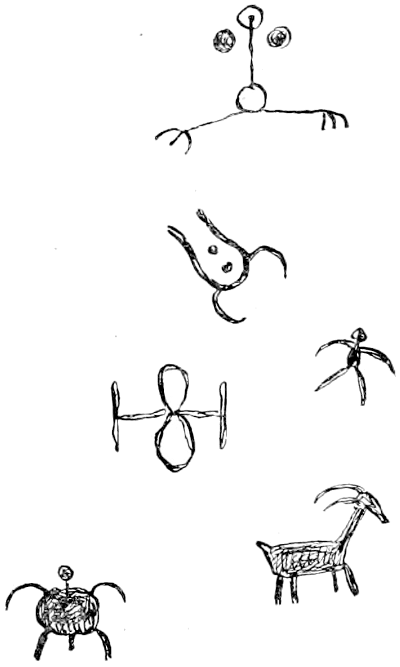

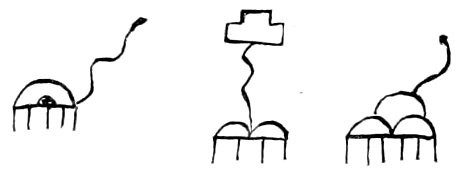

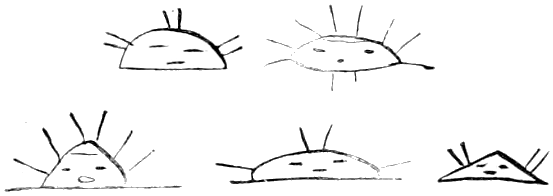

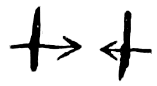

| Figure 1.—Petroglyphs at Oakley Springs, Arizona | 30 |

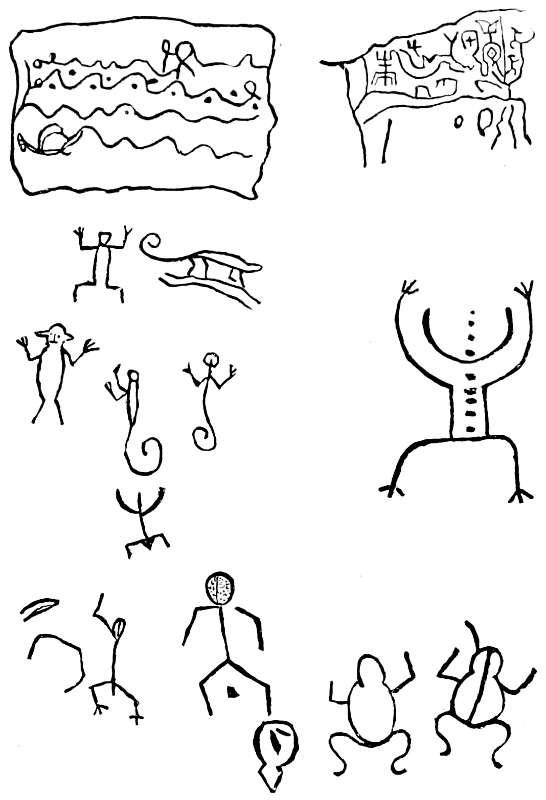

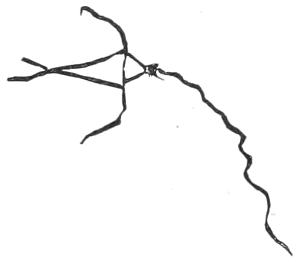

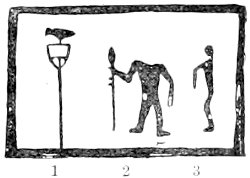

| 2.—Deep carvings in Guiana | 42 |

| 3.—Shallow carvings in Guiana | 43 |

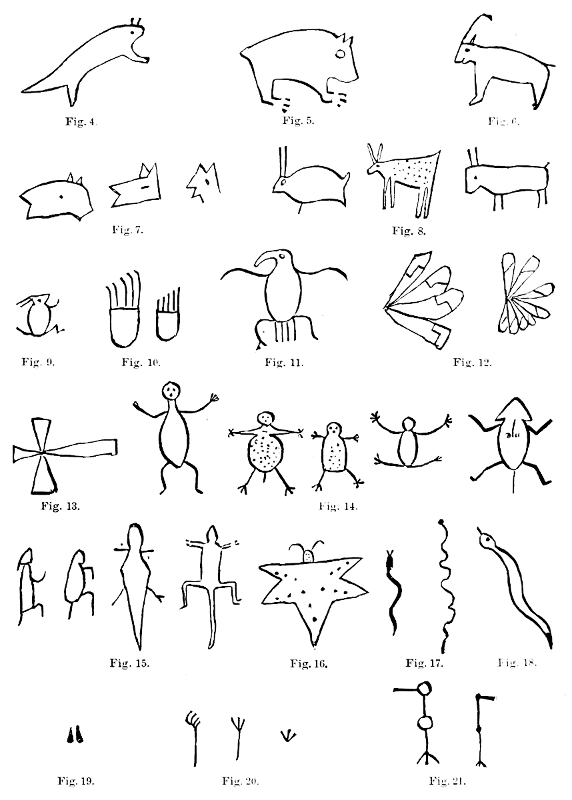

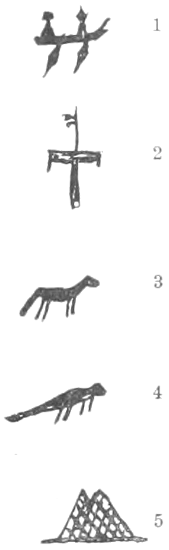

| 4.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Beaver | 47 |

| 5.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Bear | 47 |

| 6.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Mountain sheep | 47 |

| 7.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Three Wolf heads | 47 |

| 8.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Three Jackass rabbits | 47 |

| 9.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Cotton-tail rabbit | 47 |

| 10.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Bear tracks | 47 |

| 11.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Eagle | 47 |

| 12.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Eagle tails | 47 |

| 13.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Turkey tail | 47 |

| [9]14.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Horned toads | 47 |

| 15.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Lizards | 47 |

| 16.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Butterfly | 47 |

| 17.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Snakes | 47 |

| 18.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Rattlesnake | 47 |

| 19.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Deer track | 47 |

| 20.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Three Bird tracks | 47 |

| 21.—Rock etchings at Oakley Springs, Arizona: Bitterns | 47 |

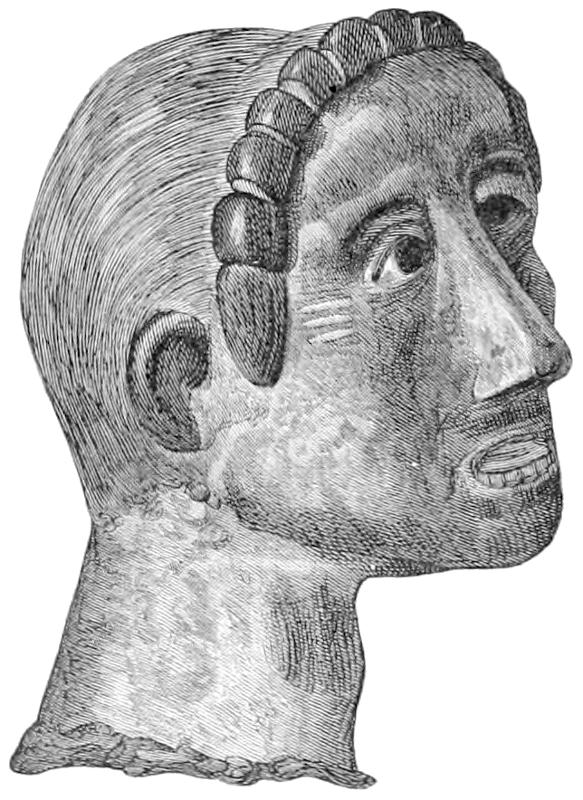

| 22.—Bronze head from the necropolis of Marzabotto, Italy | 62 |

| 23.—Fragment of bowl from Troja | 63 |

| 24.—Haida totem post, Queen Charlotte’s Island | 68 |

| 25.—Haida man, tattooed | 69 |

| 26.—Haida woman, tattooed | 69 |

| 27.—Haida woman, tattooed | 70 |

| 28.—Haida man, tattooed | 70 |

| 29.—Skulpin (right leg of Fig. 26) | 71 |

| 30.—Frog (left leg of Fig. 26) | 71 |

| 31.—Cod (breast of Fig. 25) | 71 |

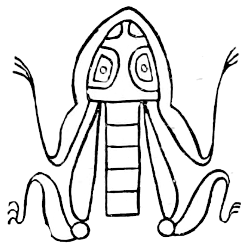

| 32.—Squid (Octopus), (thighs of Fig. 25) | 71 |

| 33.—Wolf, enlarged (back of Fig. 28) | 71 |

| 34.—Tattoo designs on bone, from New Zealand | 74 |

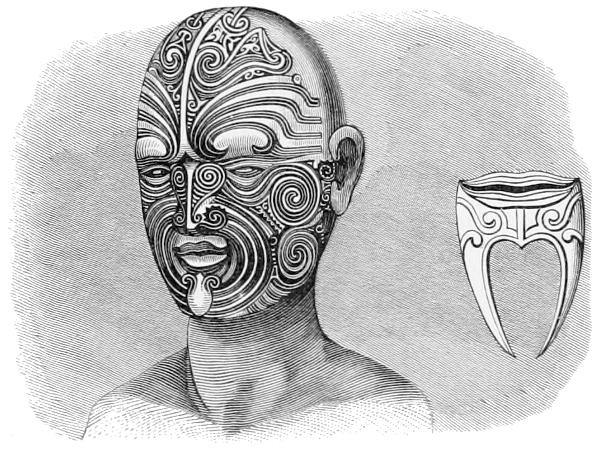

| 35.—New Zealand tattooed head and chin mark | 75 |

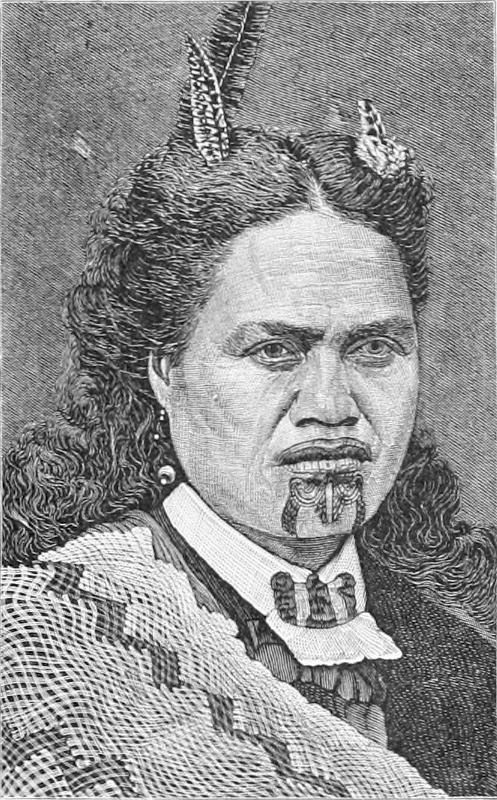

| 36.—New Zealand tattooed woman | 75 |

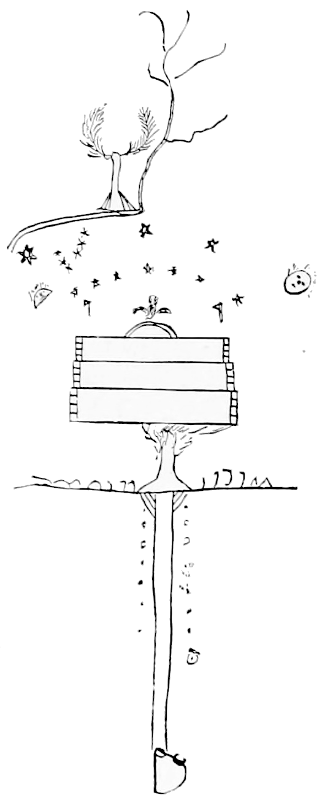

| 37.—Australian grave and carved trees | 76 |

| 38.—Osage chart | 86 |

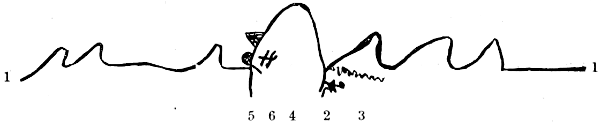

| 39.—Device denoting succession of time. Dakota | 88 |

| 40.—Device denoting succession of time. Dakota | 89 |

| 41.—Measles or Smallpox. Dakota | 110 |

| 42.—Meteor. Dakota | 111 |

| 43.—River freshet. Dakota | 113 |

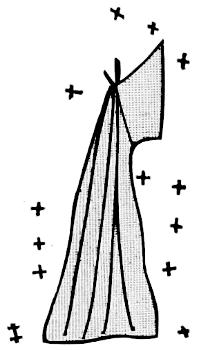

| 44.—Meteoric shower. Dakota | 116 |

| 45.—The-Teal-broke-his-leg. Dakota | 119 |

| 46.—Magic Arrow. Dakota | 141 |

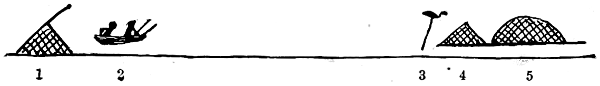

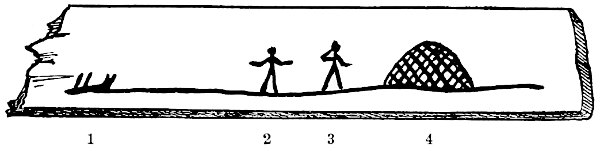

| 47.—Notice of hunt. Alaska | 147 |

| 48.—Notice of departure. Alaska | 148 |

| 49.—Notice of hunt. Alaska | 149 |

| 50.—Notice of direction. Alaska | 149 |

| 51.—Notice of direction. Alaska | 150 |

| 52.—Notice of direction. Alaska | 150 |

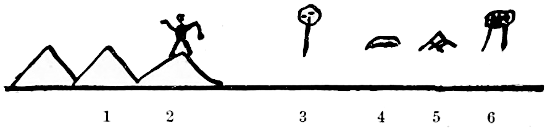

| 53.—Notice of distress. Alaska | 152 |

| 54.—Notice of departure and refuge. Alaska | 152 |

| 55.—Notice of departure to relieve distress. Alaska | 153 |

| 56.—Ammunition wanted. Alaska | 154 |

| 57.—Assistance wanted in hunt. Alaska | 154 |

| 58.—Starving hunters. Alaska | 154 |

| 59.—Starving hunters. Alaska | 155 |

| 60.—Lean Wolf’s map. Hidatsa | 158 |

| 61.—Letter to “Little-man” from his father. Cheyenne | 160 |

| 62.—Drawing of smoke signal. Alaska | 161 |

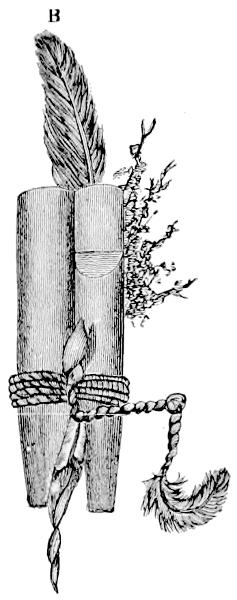

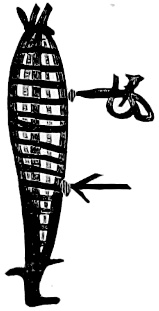

| 63.—Tesuque Diplomatic Packet | 162 |

| 64.—Tesuque Diplomatic Packet | 162 |

| 65.—Tesuque Diplomatic Packet | 162 |

| 66.—Tesuque Diplomatic Packet | 163 |

| 67.—Tesuque Diplomatic Packet | 163 |

| 68.—Dakota pictograph: for Kaiowa | 165 |

| [10]69.—Dakota pictograph: for Arikara | 166 |

| 70.—Dakota pictograph: for Omaha | 166 |

| 71.—Dakota pictograph: for Pawnee | 166 |

| 72.—Dakota pictograph: for Assiniboine | 166 |

| 73.—Dakota pictograph: for Gros Ventre | 166 |

| 74.—Lean-Wolf as “Partisan” | 168 |

| 75.—Two-Strike as “Partisan” | 169 |

| 76.—Lean-Wolf (personal name) | 172 |

| 77.—Pointer. Dakota | 172 |

| 78.—Shadow. Dakota | 173 |

| 79.—Loud-Talker. Dakota | 173 |

| 80.—Boat Paddle. Arikara | 182 |

| 81.—African property mark | 182 |

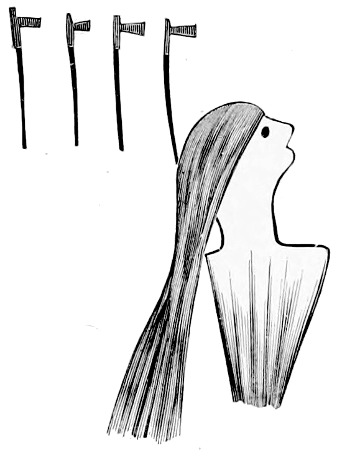

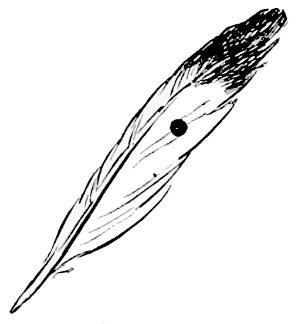

| 82.—Hidatsa feather marks: First to strike enemy | 184 |

| 83.—Hidatsa feather marks: Second to strike enemy | 184 |

| 84.—Hidatsa feather marks: Third to strike enemy | 184 |

| 85.—Hidatsa feather marks: Fourth to strike enemy | 184 |

| 86.—Hidatsa feather marks: Wounded by an enemy | 184 |

| 87.—Hidatsa feather marks: Killed a woman | 184 |

| 88.—Dakota feather marks: Killed an enemy | 185 |

| 89.—Dakota feather marks: Cut throat and scalped | 185 |

| 90.—Dakota feather marks: Cut enemy’s throat | 185 |

| 91.—Dakota feather marks: Third to strike | 185 |

| 92.—Dakota feather marks: Fourth to strike | 185 |

| 93.—Dakota feather marks: Fifth to strike | 185 |

| 94.—Dakota feather marks: Many wounds | 185 |

| 95.—Successful defense. Hidatsa, etc. | 186 |

| 96.—Two successful defenses. Hidatsa, etc. | 186 |

| 97.—Captured a horse. Hidatsa, etc. | 186 |

| 98.—First to strike an enemy. Hidatsa | 187 |

| 99.—Second to strike an enemy. Hidatsa | 187 |

| 100.—Third to strike an enemy. Hidatsa | 187 |

| 101.—Fourth to strike an enemy. Hidatsa | 187 |

| 102.—Fifth to strike an enemy. Arikara | 187 |

| 103.—Struck four enemies. Hidatsa | 187 |

| 104.—Thunder bird. Dakota | 188 |

| 105.—Thunder bird. Dakota | 188 |

| 106.—Thunder bird (wingless). Dakota | 189 |

| 107.—Thunder bird (in beads). Dakota | 189 |

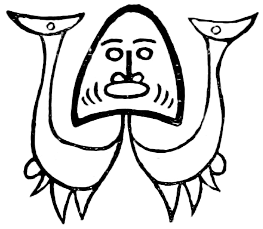

| 108.—Thunder bird. Haida | 190 |

| 109.—Thunder bird. Twana | 190 |

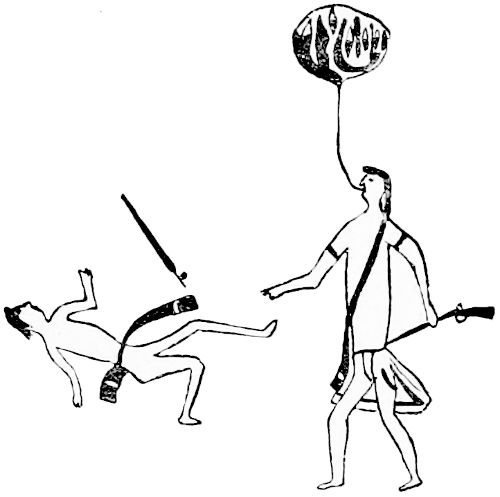

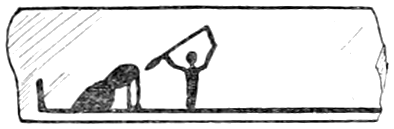

| 110.—Ivory record, Shaman exorcising demon. Alaska | 191 |

| 111.—Ivory record, Supplication for success. Alaska | 192 |

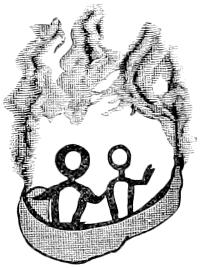

| 111a.—Shaman’s Lodge. Alaska | 196 |

| 112.—Alaska votive offering | 197 |

| 113.—Alaska grave-post | 198 |

| 114.—Alaska grave-post | 199 |

| 115.—Alaska village and burial grounds | 199 |

| 116.—New Zealand grave effigy | 200 |

| 117.—New Zealand grave-post | 201 |

| 118.—New Zealand house posts | 201 |

| 119.—Mdewakantawan fetich | 202 |

| 120.—Ottawa pipe-stem | 204 |

| 121.—Walrus hunter. Alaska | 205 |

| 122.—Alaska carving with records | 205 |

| [11]123.—Origin of Brulé. Dakota | 207 |

| 124.—Running Antelope: Killed one Arikara | 208 |

| 125.—Running Antelope: Shot and scalped an Arikara | 209 |

| 126.—Running Antelope: Shot an Arikara | 209 |

| 127.—Running Antelope: Killed two warriors | 210 |

| 128.—Running Antelope: Killed ten men and three women | 210 |

| 129.—Running Antelope: Killed two chiefs | 211 |

| 130.—Running Antelope: Killed one Arikara | 211 |

| 131.—Running Antelope: Killed one Arikara | 212 |

| 132.—Running Antelope: Killed two Arikara hunters | 212 |

| 133.—Running Antelope: Killed five Arikara | 213 |

| 134.—Running Antelope: Killed an Arikara | 213 |

| 135.—Record of hunt. Alaska | 214 |

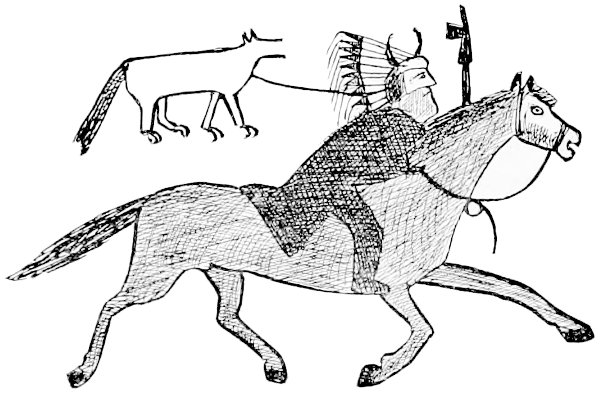

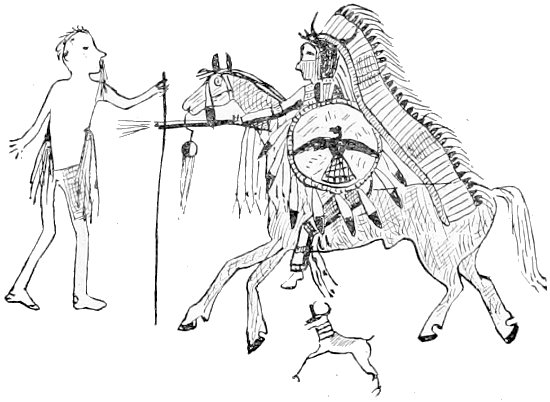

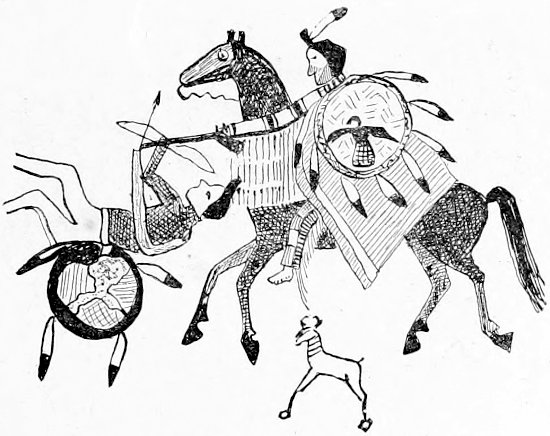

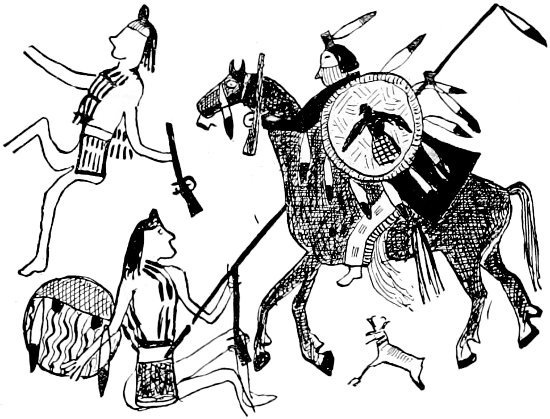

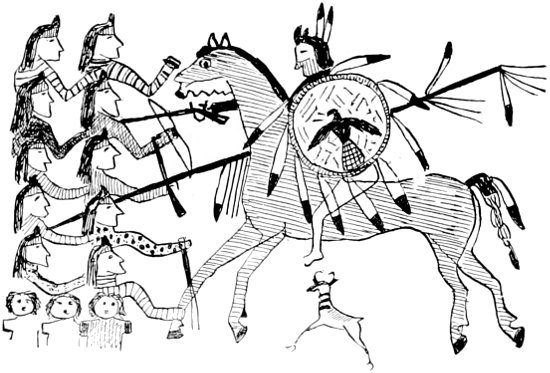

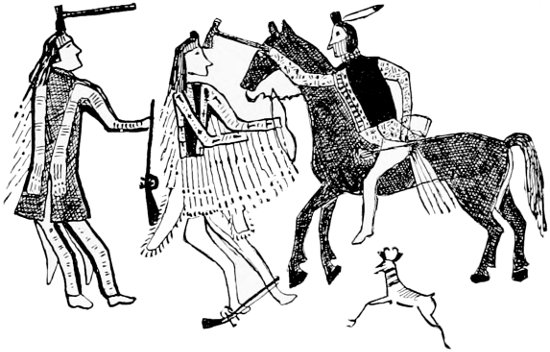

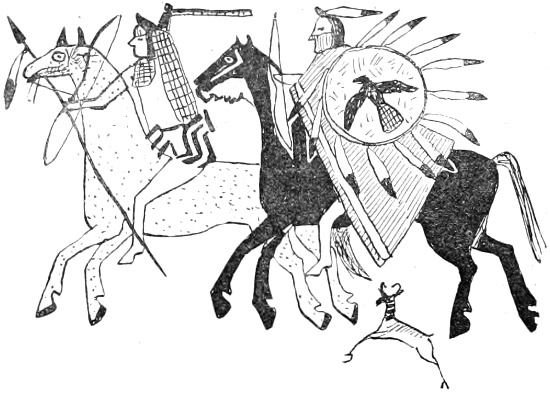

| 136.—Shoshoni horse raid | 215 |

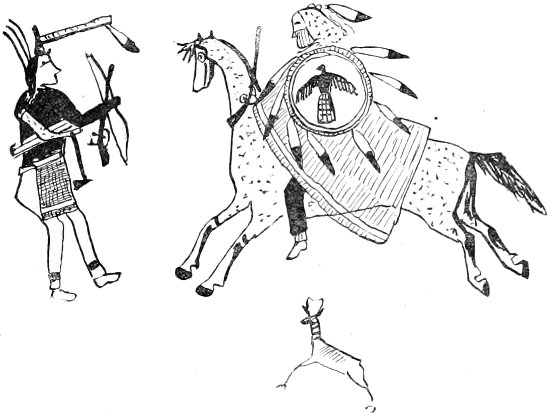

| 137.—Drawing on buffalo shoulder-blade. Camanche | 216 |

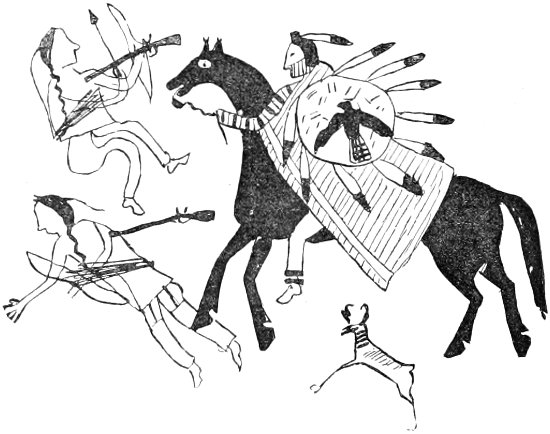

| 138.—Cross-Bear’s death | 217 |

| 139.—Bark record from Red Lake, Minnesota | 218 |

| 140.—Sign for pipe. Dakota | 219 |

| 141.—Plenty buffalo meat. Dakota | 219 |

| 142.—Plenty buffalo meat. Dakota | 220 |

| 143.—Pictograph for Trade. Dakota | 220 |

| 144.—Starvation. Dakota | 220 |

| 145.—Starvation. Ottawa and Pottawatomi | 221 |

| 146.—Pain. Died of “Whistle.” Dakota | 221 |

| 147.—Example of Algonkian petroglyphs, from Millsborough, Pennsylvania | 224 |

| 148.—Example of Algonkian petroglyphs, from Hamilton Farm, West Virginia | 225 |

| 149.—Example of Algonkian petroglyphs, from Safe Harbor, Pennsylvania | 226 |

| 150.—Example of Western Algonkian petroglyphs, from Wyoming | 227 |

| 151.—Example of Shoshonian petroglyphs, from Idaho | 228 |

| 152.—Example of Shoshonian petroglyphs, from Idaho | 229 |

| 153.—Example of Shoshonian petroglyphs, from Utah | 230 |

| 154.—Example of Shoshonian rock painting, from Utah | 230 |

| 155.—Rock painting, from Tule River, California | 235 |

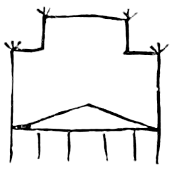

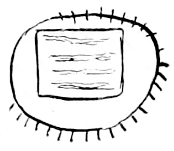

| 156.—Sacred inclosure from Arizona. Moki | 237 |

| 157.—Ceremonial head-dress. Moki | 237 |

| 158.—Houses. Moki | 237 |

| 159.—Burden-sticks. Moki | 238 |

| 160.—Arrows. Moki | 238 |

| 161.—Blossoms. Moki | 238 |

| 162.—Lightning. Moki | 238 |

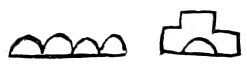

| 163.—Clouds. Moki | 238 |

| 164.—Clouds with rain. Moki | 238 |

| 165.—Stars, Moki | 238 |

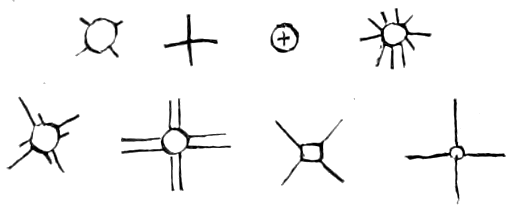

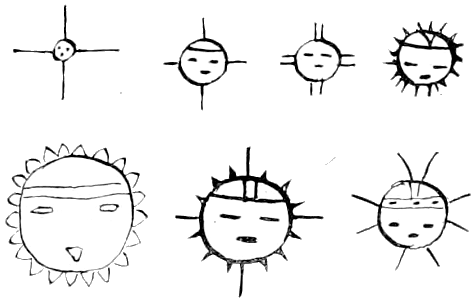

| 166.—Sun. Moki | 239 |

| 167.—Sunrise. Moki, | 239 |

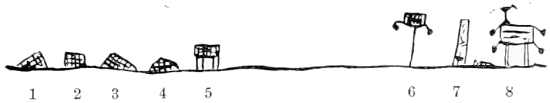

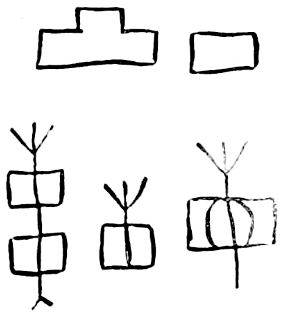

| 168.—Drawing of Dakota lodges, by Hidatsa | 240 |

| 169.—Drawing of earth lodges, by Hidatsa | 240 |

| 170.—Drawing of white man’s house, by Hidatsa | 240 |

| 171.—Hidatsati, the home of the Hidatsa | 240 |

| 172.—Horses and man. Arikara | 240 |

| 173.—Dead man. Arikara | 240 |

| 174.—Second to strike enemy. Hidatsa | 240 |

| 175.—Third to strike enemy. Hidatsa | 240 |

| 176.—Scalp taken. Hidatsa | 240 |

| [12]177.—Enemy struck and gun captured. Hidatsa | 240 |

| 178.—Mendota drawing. Dakota | 241 |

| 179.—Symbol of war. Dakota | 241 |

| 180.—Captives. Dakota | 242 |

| 181.—Circle of men. Dakota | 242 |

| 182.—Shooting from river banks. Dakota | 242 |

| 183.—Panther. Haida | 242 |

| 184.—Wolf head. Haida | 243 |

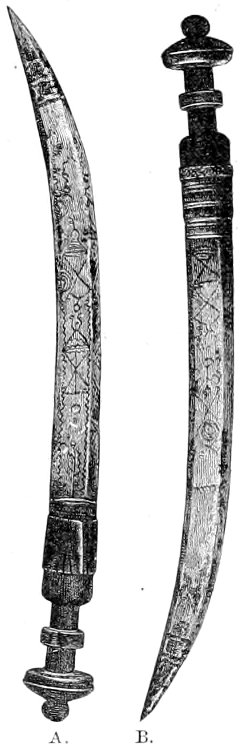

| 185.—Drawings on an African knife | 243 |

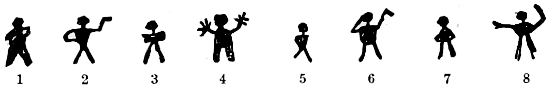

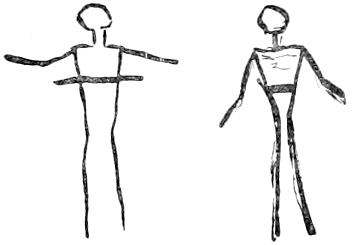

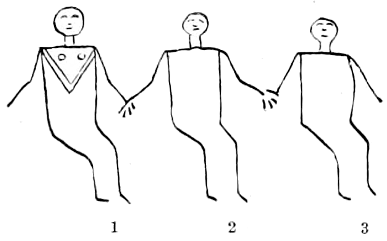

| 186.—Conventional characters: Men. Arikara | 244 |

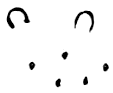

| 187.—Conventional characters: Man. Innuit | 244 |

| 188.—Conventional characters: Dead man. Satsika | 244 |

| 189.—Conventional characters: Man addressed. Innuit | 244 |

| 190.—Conventional characters: Man. Innuit | 244 |

| 191.—Conventional characters: Man. From Tule River, California | 244 |

| 192.—Conventional characters: Man. From Tule River, California | 244 |

| 193.—Conventional characters: Disabled man. Ojibwa | 244 |

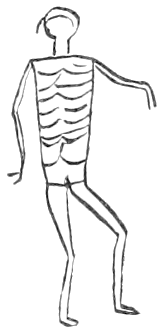

| 194.—Conventional characters: Shaman. Innuit | 245 |

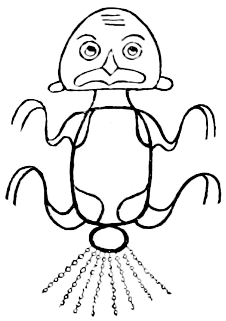

| 195.—Conventional characters: Supplication. Innuit | 245 |

| 196.—Conventional characters: Man. Ojibwa | 245 |

| 197.—Conventional characters: Spiritually enlightened man. Ojibwa | 245 |

| 198.—Conventional characters: A wabeno. Ojibwa | 245 |

| 199.—Conventional characters: An evil Meda. Ojibwa | 245 |

| 200.—Conventional characters: A Meda. Ojibwa | 245 |

| 201.—Conventional characters: Man. Hidatsa | 245 |

| 202.—Conventional characters: Headless body. Ojibwa | 245 |

| 203.—Conventional characters: Headless body. Ojibwa | 245 |

| 204.—Conventional characters: Man. Moki | 245 |

| 205.—Conventional characters: Man. From Siberia | 245 |

| 206.—Conventional characters: Superior knowledge. Ojibwa | 246 |

| 207.—Conventional characters: An American. Ojibwa | 246 |

| 208.—Specimen of imitated pictograph | 249 |

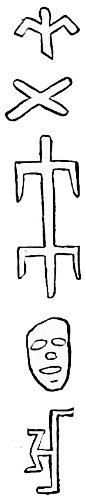

| 209.—Symbols of cross | 252 |

ON THE PICTOGRAPHS OF THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS.

By Garrick Mallery.

A pictograph is a writing by picture. It conveys and records an idea or occurrence by graphic means without the use of words or letters. The execution of the pictures of which it is composed often exhibits the first crude efforts of graphic art, and their study in that relation is of value. When pictures are employed as writing the conception intended to be presented is generally analyzed, and only its most essential points are indicated, with the result that the characters when frequently repeated become conventional, and in their later forms cease to be recognizable as objective portraitures. This exhibition of conventionalizing also has its own import in the history of art.

Pictographs are considered in the present paper chiefly in reference to their significance as one form of thought-writing directly addressed to the sight, gesture-language being the other and probably earlier form. So far as they are true ideographs they are the permanent, direct, visible expression of ideas of which gesture-language gives the transient expression. When adopted for syllabaries or alphabets, which is known to be the historical course of evolution in that regard, they have ceased to be the direct and have become the indirect expression of the ideas framed in oral speech. The writing common in civilization records sounds directly, not primarily thoughts, the latter having first been translated into sounds. The trace of pictographs in the latter use shows the earlier and predominant conceptions.

The importance of the study of pictographs depends upon their examination as a phase in the evolution of human culture, or as containing valuable information to be ascertained by interpretation.

The invention of alphabetic writing being by general admission the great step marking the change from barbarism into civilization, the history of its earlier development must be valuable. It is inferred from internal evidence that picture-writing preceded and originated the graphic systems of Egypt, Nineveh, and China, but in North America its use is still modern and current. It can be studied there, without any[14] requirement of inference or hypothesis, in actual existence as applied to records and communications. Furthermore, its transition into signs of sound is apparent in the Aztec and the Maya characters, in which stage it was only arrested by foreign conquest. The earliest lessons of the birth and growth of culture in this most important branch of investigation can therefore be best learned from the Western Hemisphere. In this connection it may be noticed that picture-writing is found in sustained vigor on the same continent where sign-language has prevailed or continued in active operation to an extent unknown in other parts of the world. These modes of expression, i. e., transient and permanent idea-writing, are so correlated in their origin and development that neither can be studied with advantage to the exclusion of the other.

The limits assigned to this paper allow only of its comprehending the Indians north of Mexico, except as the pictographs of other peoples are introduced for comparison. Among these no discovery has yet been made of any of the several devices, such as the rebus, or the initial, adopted elsewhere, by which the element of sound apart from significance has been introduced.

The first stage of picture-writing as recognized among the Egyptians was the representation of a material object in such style or connection as determined it not to be a mere portraiture of that object, but figurative of some other object or person. This stage is abundantly exhibited among the Indians. Indeed, their personal and tribal names thus objectively represented constitute the largest part of their picture-writing so far thoroughly understood.

The second step gained by the Egyptians was when the picture became used as a symbol of some quality or characteristic. It can be readily seen how a hawk with bright eye and lofty flight might be selected as a symbol of divinity and royalty, and that the crocodile should denote darkness, while a slightly further step in metaphysical symbolism made the ostrich feather, from the equality of its filaments, typical of truth. It is evident from examples given in the present paper that the North American tribes at the time of the Columbian discovery had entered upon this second step of picture-writing, though with marked inequality between tribes and regions in advance therein. None of them appear to have reached such proficiency in the expression of connected ideas by picture as is shown in the sign-language existing among some of them, in which even conjunctions and prepositions are indicated. Still many truly ideographic pictures are known.

A consideration relative to the antiquity of mystic symbolism, and its position in the several culture-periods, arises in this connection. It appears to have been an outgrowth of human thought, perhaps in the nature of an excrescence, useful for a time, but abandoned after a certain stage of advancement.

A criticism has been made on the whole subject of pictography by Dr. Richard Andree, who, in his work, Ethnographische Parallelen und Vergleiche, Stuttgart, 1878, has described and figured a large number of[15] examples of petroglyphs, a name given by him to rock-drawings and adopted by the present writer. His view appears to be that these figures are frequently the idle marks which, among civilized people, boys or ignorant persons cut with their pen-knives on the desks and walls of school-rooms, or scrawl on the walls of lanes and retired places. From this criticism, however, Dr. Andree carefully excludes the pictographs of the North American Indians, his conclusion being that those found in other parts of the world generally occupy a transition stage lower than that conceded for the Indians. It is possible that significance may yet be ascertained in many of the characters found in other regions, and perhaps this may be aided by the study of those in North America; but no doubt should exist that the latter have purpose and meaning. Any attempt at the relegation of such pictographs as are described in the present paper, and have been the subject of the study of the present writer, to any trivial origin can be met by a thorough knowledge of the labor and pains which were necessary in the production of some of the petroglyphs described.

All criticism in question with regard to the actual significance of North American pictographs is still better met by their practical use by historic Indians for important purposes, as important to them as the art of writing, of which the present paper presents a large number of conclusive examples. It is also known that when they now make pictographs it is generally done with intention and significance.

Even when this work is undertaken to supply the demand for painted robes as articles of trade it is a serious manufacture, though sometimes imitative in character and not intrinsically significant. All other instances known in which pictures are made without original design, as indicated under the several classifications of this paper, are when they are purely ornamental; but in such cases they are often elaborate and artistic, never the idle scrawls above mentioned. A main object of this paper is to call attention to the subject in other parts of the world, and to ascertain whether the practice of pictography does not still exist in some corresponding manner beyond what is now published.

A general deduction made after several years of study of pictographs of all kinds found among the North American Indians is that they exhibit very little trace of mysticism or of esotericism in any form. They are objective representations, and cannot be treated as ciphers or cryptographs in any attempt at their interpretation. A knowledge of the customs, costumes, including arrangement of hair, paint, and all tribal designations, and of their histories and traditions is essential to the understanding of their drawings, for which reason some of those particulars known to have influenced pictography are set forth in this paper, and others are suggested which possibly had a similar influence.

Comparatively few of their picture signs have become merely conventional. A still smaller proportion are either symbolical or emblematic, but some of these are noted. By far the larger part of them are merely[16] mnemonic records and are treated of in connection with material objects formerly and, perhaps, still used mnemonically.

It is believed that the interpretation of the ancient forms is to be obtained, if at all, not by the discovery of any hermeneutic key, but by an understanding of the modern forms, some of which fortunately can be interpreted by living men; and when this is not the case the more recent forms can be made intelligible at least in part by thorough knowledge of the historic tribes, including their sociology, philosophy, and arts, such as is now becoming acquired, and of their sign-language.

It is not believed that any considerable information of value in an historical point of view will be obtained directly from the interpretation of the pictographs in North America. The only pictures which can be of great antiquity are rock-carvings and those in shell or similar substances resisting the action of time, which have been or may be found in mounds. The greater part of those already known are simply peckings, etchings, or paintings delineating natural objects, very often animals, and illustrate the beginning of pictorial art. It is, however, probable that others were intended to commemorate events or to represent ideas entertained by their authors, but the events which to them were of moment are of little importance as history. They referred generally to some insignificant fight or some season of plenty or of famine, or to other circumstances the evident consequence of which has long ceased.

While, however, it is not supposed that old inscriptions exist directly recording substantively important events, it is hoped that some materials for history can be gathered from the characters in a manner similar to the triumph of comparative philology in resurrecting the life-history and culture of the ancient Aryans. The significance of the characters being granted, they exhibit what chiefly interested their authors, and those particulars may be of anthropologic consequence. The study has so far advanced that, independent of the significance of individual characters, several distinct types of execution are noted which may be expected to disclose data regarding priscan habitat and migration. In this connection it may be mentioned that recent discoveries render it probable that some of the pictographs were intended as guide-marks to point out trails, springs, and fords, and some others are supposed to indicate at least the locality of mounds and graves, and possibly to record specific statements concerning them. A comparison of typical forms may also usefully be made with the objects of art now exhumed in large numbers from the mounds.

Ample evidence exists that many of the pictographs, both ancient and modern, are connected with the mythology and religious practices of their makers. The interpretations obtained during the present year of some of those among the Moki, Zuñi, and Navajo, throw new and strong light on this subject. It is regretted that the most valuable and novel part of this information cannot be included in the present paper,[17] as it is in the possession of the Bureau of Ethnology in a shape not yet arranged for publication, or forms part of the forthcoming volume of the Transactions of the Anthropological Society of Washington, which may not be anticipated.

The following general remarks of Schoolcraft, Vol. I, p. 351, are of some value, though they apply with any accuracy only to the Ojibwa and are tinctured with a fondness for the mysterious:

For their pictographic devices the North American Indians have two terms, namely, Kekeewin, or such things as are generally understood by the tribe; and Kekeenowin, or teachings of the medas or priests, jossakeeds or prophets. The knowledge of the latter is chiefly confined to persons who are versed in their system of magic medicine, or their religion, and may be deemed hieratic. The former consists of the common figurative signs, such as are employed at places of sepulture, or by hunting or traveling parties. It is also employed in the muzzinábiks, or rock-writings. Many of the figures are common to both, and are seen in the drawings generally; but it is to be understood that this results from the figure-alphabet being precisely the same in both, while the devices of the nugamoons, or medicine, wabino, hunting, and war songs, are known solely to the initiates who have learned them, and who always pay high to the native professors for this knowledge.

It must, however, be admitted, as above suggested, that many of the pictographs found are not of the historic or mythologic significance once supposed. For instance, the examination of the rock carvings in several parts of the country has shown that some of them were mere records of the visits of individuals to important springs or to fords on regularly established trails. In this respect there seems to have been, in the intention of the Indians, very much the same spirit as induces the civilized man to record his initials upon objects in the neighborhood of places of general resort. At Oakley Springs, Arizona Territory, totemic marks have been found, evidently made by the same individual at successive visits, showing that on the number of occasions indicated he had passed by those springs, probably camping there, and such record was the habit of the neighboring Indians at that time. The same repetition of totemic names has been found in great numbers in the pipestone quarries of Dakota, and also at some old fords in West Virginia. But these totemic marks are so designed and executed as to have intrinsic significance and value, wholly different in this respect from vulgar names in alphabetic form. It should also be remembered that mere graffiti are recognized as of value by the historian, the anthropologist, and the artist.

One very marked peculiarity of the drawings of the Indians is that within each particular system, such as may be called a tribal system, of pictography, every Indian draws in precisely the same manner. The figures of a man, of a horse, and of every other object delineated, are made by every one who attempts to make any such figure with all the identity of which their mechanical skill is capable, thus showing their conception and motive to be the same.

The intention of the present work is not to present at this time a view of the whole subject of pictography, though the writer has been[18] preparing materials with a reference to that more ambitious project. The paper is limited to the presentation of the most important known pictographs of the North American Indians, with such classification as has been found convenient to the writer, and, for that reason, may be so to collaborators. The scheme of the paper has been to give very simply one or more examples, with illustrations, in connection with each one of the headings or titles of the classifications designated. This plan has involved a considerable amount of cross reference, because, in many cases, a character, or a group of characters, could be considered with reference to a number of noticeable characteristics, and it was a question of choice under which one of the headings it should be presented, involving reference to it from the other divisions of the paper. An amount of space disproportionate to the mere subdivision of Time under the class of Mnemonics, is occupied by the Dakota Winter Counts, but it is not believed that any apology is necessary for their full presentation, as they not only exhibit the device mentioned in reference to their use as calendars, but furnish a repertory for all points connected with the graphic portrayal of ideas.

Attention is invited to the employment of the heraldic scheme of designating colors by lines, dots, etc., in those instances in the illustrations where color appeared to have significance, while it was not practicable to produce the coloration of the originals. In many cases, however, the figures are too minute to permit the successful use of that scheme, and the text must be referred to for explanation.

Thanks are due and rendered for valuable assistance to correspondents and especially to officers of the Bureau of Ethnology and the United States Geological Survey, whose names are generally mentioned in connection with their several contributions. Acknowledgment is also made now and throughout the paper to Dr. W. J. Hoffman who has officially assisted the present writer during several years by researches in the field, and by drawing nearly all the illustrations presented.

Etchings or paintings on rocks in North America are distributed generally.

They are found throughout the extent of the continent, on bowlders formed by the sea waves or polished by ice of the glacial epoch; on the faces of rock ledges adjoining streams; on the high walls of cañons and cliffs; on the sides and roofs of caves; in short, wherever smooth surfaces of rock appear. Drawings have also been discovered on stones deposited in mounds and caves. Yet while these records are so frequent, there are localities to be distinguished in which they are especially abundant and noticeable. Also they differ markedly in character of execution and apparent subject-matter.

An obvious division can be made between characters etched or pecked and those painted without incision. This division in execution coincides to a certain extent with geographic areas. So far as ascertained, painted characters prevail perhaps exclusively throughout Southern California, west and southwest of the Sierra Nevada. Pictures, either painted or incised, are found in perhaps equal frequency in the area extending eastward from the Colorado River to Georgia, northward into West Virginia, and in general along the course of the Mississippi River. In some cases the glyphs are both incised and painted. The remaining parts of the United States show rock-etchings almost exclusive of paintings.

It is proposed with the accumulation of information to portray the localities of these records upon a chart accompanied by a full descriptive text. In such chart will be designated their relative frequency, size, height, position, color, age, and other particulars regarded as important. With such chart and list the classification and determination now merely indicated may become thorough.

In the present paper a few only of the more important localities will be mentioned; generally those which are referred to under several appropriate heads in various parts of the paper. Notices of some of these have been published; but many of them are publicly mentioned for the first time in this paper, knowledge respecting them having been obtained by the personal researches of the officers of the Bureau of Ethnology, or by their correspondents.

A large number of known and described pictographs on rocks occur in that portion of the United States and Canada at one time in the possession of the several tribes constituting the Algonkian linguistic stock.[20] This is particularly noticeable throughout the country of the great lakes, and the Northern, Middle, and New England States.

The voluminous discussion upon the Dighton Rock, Massachusetts, inscription, renders it impossible wholly to neglect it.

The following description, taken from Schoolcraft’s History, Condition, and Prospect of the Indian Tribes of the United States, Vol. IV, p. 119, which is accompanied with a plate, is, however, sufficient. It is merely a type of Algonkin rock-carving, not so interesting as many others:

The ancient inscription on a bowlder of greenstone rock lying in the margin of the Assonet, or Taunton River, in the area of ancient Vinland, was noticed by the New England colonists so early as 1680, when Dr. Danforth made a drawing of it. This outline, together with several subsequent copies of it, at different eras, reaching to 1830, all differing considerably in their details, but preserving a certain general resemblance, is presented in the Antiquatés Americanes [sic] (Tab. XI, XII) and referred to the same era of Scandinavian discovery. The imperfections of the drawings (including that executed under the auspices of the Rhode Island Historical Society, in 1830, Tab. XII) and the recognition of some characters bearing more or less resemblance to antique Roman letters and figures, may be considered to have misled Mr. Magnusen in his interpretation of it. From whatever cause, nothing could, it would seem, have been wider from the purport and true interpretation of it. It is of purely Indian origin, and is executed in the peculiar symbolic character of the Kekeewin.

Many of the rocks along the river courses in Northern and Western Pennsylvania bear traces of carvings, though, on account of the character of the geological formations, some of these records are almost, if not entirely, obliterated.

Mr. P. W. Shafer published in a historical map of Pennsylvania, in 1875, several groups of pictographs. (They had before appeared in a rude and crowded form in the Transactions of the Anthropological Institute of New York, N. Y., 1871-’72, p. 66, Figs. 25, 26, where the localities are mentioned as “Big” and “Little” Indian Rocks, respectively.) One of these is situated on the Susquehanna River, below the dam at Safe Harbor, and clearly shows its Algonkin origin. The characters are nearly all either animals or various forms of the human body. Birds, bird-tracks, and serpents also occur. A part of this pictograph is presented below, Figure 149, page 226.

On the same chart a group of pictures is also given, copied from the originals on the Allegheny River, in Venango County, 5 miles south of Franklin. There are but six characters furnished in this instance, three of which are variations of the human form, while the others are undetermined.

Mr. J. Sutton Wall, of Monongahela City, describes in correspondence a rock bearing pictographs opposite the town of Millsborough, in Fayette[21] County, Pennsylvania. This rock is about 390 feet above the level of Monongahela River, and belongs to the Waynesburg stratum of sandstone. It is detached, and rests somewhat below its true horizon. It is about 6 feet in thickness, and has vertical sides; only two figures are carved on the sides, the inscriptions being on the top, and are now considerably worn. Mr. Wall mentions the outlines of animals and some other figures, formed by grooves or channels cut from an inch to a mere trace in depth. No indications of tool marks were discovered. It is presented below as Figure 147, page 224.

The resemblance between this record and the drawings on Dighton Rock is to be noted, as well as that between both of them and some in Ohio.

Mr. J. Sutton Wall also contributes a group of etchings on what is known as the “Geneva Picture Rock,” in the Monongahela Valley, near Geneva. These are foot-prints and other characters similar to those mentioned from Hamilton Farm, West Virginia, which are shown in Figure 148, page 225.

Schoolcraft (Vol. IV, pp. 172, 173, Pll. 17, 18), describes also, presenting plates, a pictograph on the Allegheny River as follows:

One of the most often noticed of these inscriptions exists on the left bank of this river [the Allegheny], about six miles below Franklin (the ancient Venango), Pennsylvania. It is a prominent point of rocks, around which the river deflects, rendering this point a very conspicuous object. * The rock, which has been lodged here in some geological convulsion, is a species of hard sandstone, about twenty-two feet in length by fourteen in breadth. It has an inclination to the horizon of about fifty degrees. During freshets it is nearly overflown. The inscription is made upon the inclined face of the rock. The present inhabitants in the country call it the ‘Indian God.’ It is only in low stages of water that it can be examined. Captain Eastman has succeeded, by wading into the water, in making a perfect copy of this ancient record, rejecting from its borders the interpolations of modern names put there by boatmen, to whom it is known as a point of landing. The inscription itself appears distinctly to record, in symbols, the triumphs in hunting and war.

In the Final Report of the Ohio State Board of Centennial Managers, Columbus, 1877, many localities showing rock carvings are noted. The most important (besides those mentioned below) are as follows: Newark, Licking County, where human hands, many varieties of bird tracks, and a cross are noticed. Independence, Cuyahoga County, showing human hands and feet and serpents. Amherst, Lorain County, presenting similar objects. Wellsville, Columbiana County, where the characters are more elaborate and varied.

Mr. James W. Ward describes in the Journal of the Anthropological Institute of New York, Vol. I, 1871-’72, pp. 57-64, Figs. 14-22, some sculptured rocks. They are reported as occurring near Barnesville, Belmont County, and consist chiefly of the tracks of birds and animals. Serpentine forms also occur, together with concentric rings. The au[22]thor also quotes Mr. William A. Adams as describing, in a letter to Professor Silliman in 1842, some figures on the surface of a sandstone rock, lying on the bank of the Muskingum River. These figures are mentioned as being engraved in the rock and consist of tracks of the turkey, and of man.

Mr. P. W. Norris, of the Bureau of Ethnology, reports that he found numerous localities along the Kanawha River, West Virginia, bearing pictographs. Rock etchings are numerous upon smooth rocks, covered during high water, at the prominent fords of the river, as well as in the niches or long shallow caves high in the rocky cliffs of this region. Although rude representations of men, animals, and some deemed symbolic characters were found, none were observed superior to, or essentially differing from, those of modern Indians.

Mr. John Haywood mentions (The Natural and Aboriginal History of Tennessee, Nashville, 1823, pp. 332, 333) rock etchings four miles below the Burning Spring, near the mouth of Campbell’s Creek, Kanawha County, West Virginia. These consist of forms of various animals, as the deer, buffalo, fox, hare; of fish of various kinds; “infants scalped and scalps alone,” and men of natural size. The rock is said to be in the Kanawha River, near its northern shore, accessible only at low water, and then only by boat.

On the rocky walls of Little Coal River, near the mouth of Big Horse Creek, are cliffs upon which are many carvings. One of these measures 8 feet in length and 5 feet in height, and consists of a dense mass of characters.

About 2 miles above Mount Pleasant, Mason County, West Virginia, on the north side of the Kanawha River, are numbers of characters, apparently totemic. These are at the foot of the hills flanking the river.

On the cliffs near the mouth of the Kanawha River, opposite Mount Carbon, Nicholas County, West Virginia, are numerous pictographs. These appear to be cut into the sandstone rock.

See also page 225, Figure 148.

Charles C. Jones, jr., in his Antiquities of the Southern Indians, etc., New York, 1873, pp. 62, 63, gives some general remarks upon the pictographs of the southern Indians, as follows:

In painting and rock writing the efforts of the Southern Indians were confined to the fanciful and profuse ornamentation of their own persons with various colors, in[23] which red, yellow, and black predominated, and to marks, signs, and figures depicted on skins and scratched on wood, the shoulder blade of a buffalo, or on stone. The smooth bark of a standing tree or the face of a rock was used to commemorate some feat of arms, to indicate the direction and strength of a military expedition, or the solemnization of a treaty of peace. High up the perpendicular sides of mountain gorges, and at points apparently inaccessible save to the fowls of the air, are seen representations of the sun and moon, accompanied by rude characters, the significance of which is frequently unknown to the present observer. The motive which incited to the execution of work so perilous was, doubtless, religious in its character, and directly connected with the worship of the sun and his pale consort of the night.

The same author, page 377, particularly describes and illustrates one in Georgia, as follows:

In Forsyth County, Georgia, is a carved or incised bowlder of fine-grained granite, about 9 feet long, 4 feet 6 inches high, and 3 feet broad at its widest point. The figures are cut in the bowlder from one-half to three-fourths of an inch deep. * It is generally believed that they are the work of the Cherokees.

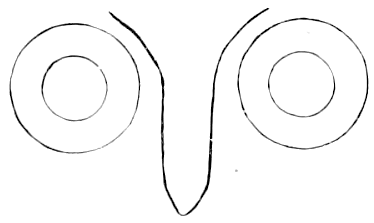

These figures are chiefly circles, both plain, nucleated, and concentric, sometimes two or more being joined by straight lines, forming what is now known as the “spectacle-shaped” figure.

Dr. M. F. Stephenson mentions, in Geology and Mineralogy of Georgia, Atlanta, 1871, p. 199, sculptures of human feet, various animals, bear tracks, etc., in Enchanted Mountain, Union County, Georgia. The whole number of etchings is reported as one hundred and forty-six.

Mr. P. W. Norris found numerous caves on the banks of the Mississippi River, in Northeastern Iowa, 4 miles south of New Albion, containing incised pictographs. Fifteen miles south of this locality paintings occur on the cliffs.

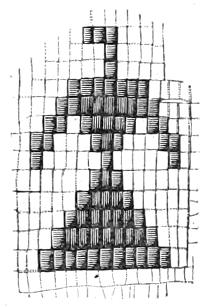

Mr. P. W. Norris has discovered large numbers of pecked totemic characters on the horizontal face of the ledges of rock at Pipe Stone Quarry, Minnesota, of which he has presented copies. The custom prevailed, it is stated, for each Indian who gathered stone (Catlinite) for pipes to inscribe his totem upon the rock before venturing to quarry upon this ground. Some of the cliffs in the immediate vicinity were of too hard a nature to admit of pecking or scratching, and upon these the characters were placed in colors.

A number of pictographs in Wyoming are described in the report on Northwestern Wyoming, including Yellowstone National Park, by Capt. William A. Jones, U. S. A., Washington, 1875, p. 268 et seq., Figures 50 to 53 in that work. The last three in order of these figures are reproduced in Sign Language among North American Indians, in the First Annual Report, Bureau of Ethnology, pages 378 and 379, to show their connection with gesture signs. The most important one was discovered on Little Popo-Agie, Northwestern Wyoming, by members of Captain Jones’s party in 1873. The etchings are upon a nearly vertical wall of the yellow sandstone in the rear of Murphy’s ranch, and appear to be of some antiquity.

Further remarks, with specimens of the figures, are presented in this paper as Figure 150, on page 227.

Dr. William H. Corbusier, U. S. Army, in a letter to the writer, mentions the discovery of rock etchings on a sandstone rock near the headwaters of Sage Creek, in the vicinity of Fort Washakie, Wyoming. Dr. Corbusier remarks that neither the Shoshoni nor the Arapaho Indians know who made the etchings. The two chief figures appear to be those of the human form, with the hands and arms partly uplifted, the whole being surrounded above and on either side by an irregular line.

The method of grouping, together with various accompanying appendages, as irregular lines, spirals, etc., observed in Dr. Corbusier’s drawing, show great similarity to the Algonkin type, and resemble some etchings found near the Wind River Mountains, which were the work of Blackfeet (Satsika) Indians, who, in comparatively recent times, occupied portions of the country in question, and probably also etched the designs near Fort Washakie.

A number of examples from Idaho appear infra, pages 228 and 229.

At the lower extremity of Pyramid Lake, Nevada, pictographs have been found by members of the United States Geological Survey, though no accurate reproductions are available. These characters are mentioned as incised upon the surface of basalt rocks.

On the western slope of Lone Butte, in the Carson Desert, Nevada, pictographs occur in considerable numbers. All of these appear to have been produced, on the faces of bowlders and rocks, by pecking and scratching with some hard mineral material like quartz. No copies have been obtained as yet.

Great numbers of incised characters of various kinds are found on the walls of rock flanking Walker River, near Walker Lake, Nevada.[25] Waving lines, rings, and what appear to be vegetable forms are of frequent occurrence. The human form and footprints are also depicted.

Among the copies of pictographs obtained in various portions of the Northwestern States and Territories, by Mr. G. K. Gilbert, is one referred as to as being on a block of basalt at Reveillé, Nevada, and is mentioned as being Shinumo or Moki. This suggestion is evidently based upon the general resemblance to drawings found in Arizona, and known to have been made by the Moki Indians. The locality is within the territory of the Shoshonian linguistic division, and the etchings are in all probability the work of one or more of the numerous tribes comprised within that division.

Numerous bowlders and rock escarpments at and near the Dalles of the Columbia River, Oregon, are covered with incised or pecked pictographs. Human figures occur, though characters of other forms predominate.

Mr. Albert S. Gatschet reports the discovery of rock etchings near Gaston, Oregon, in 1878, which are said to be near the ancient settlement of the Tuálati (or Atfálati) Indians, according to the statement of these people. These etchings are about 100 feet above the valley bottom, and occur on six rocks of soft sandstone, projecting from the grassy hillside of Patten’s Valley, opposite Darling Smith’s farm, and are surrounded with timber on two sides. The distance from Gaston is about 4 miles; from the old Tuálati settlement probably not more than 2½ miles in an air-line.

This sandstone ledge extends for one-eighth of a mile horizontally along the hillside, upon the projecting portions of which the inscriptions are found. These rocks differ greatly in size, and slant forward so that the inscribed portions are exposed to the frequent rains of that region. The first rock, or that one nearest the mouth of the cañon, consists of horizontal zigzag lines, and a detached straight line, also horizontal. On another side of the same rock is a series of oblique parallel lines. Some of the most striking characters found upon other exposed portions of the rock appear to be human figures, i. e., circles to which radiating lines are attached, and bearing indications of eyes and mouth, long vertical lines running downward as if to represent the body, and terminating in a bifurcation, as if intended for legs, toes, etc. To the right of one figure is an arm and three-fingered hand (similar to some of the Moki characters), bent downward from the elbow, the humerus extending at a right angle from the body. Horizontal rows of short vertical lines are placed below and between some of the figures, probably numerical marks of some kind.

Other characters occur of various forms, the most striking being an[26] arrow pointing upward, with two horizontal lines drawn across the shaft, vertical lines having short oblique lines attached thereto.

Mr. Gatschet, furthermore, remarks that the Tuálati attach a trivial story to the origin of these pictures, the substance of which is as follows: The Tillamuk warriors living on the Pacific coast were often at variance with the several Kalapuya tribes. One day, passing through Patten’s Valley to invade the country of the Tuálati, they inquired of a passing woman how far they were from their camp. The woman, desirous not to betray her own countrymen, said that they were yet at a distance of one (or two?) days’ travel. This made them reflect over the intended invasion, and holding a council they preferred to retire. In commemoration of this the inscription with its numeration marks, was incised by the Tuálati.

Capt. Charles Bendire, U. S. Army, states in a letter that Col. Henry C. Merriam, U. S. Army, discovered pictographs on a perpendicular cliff of granite at the lower end of Lake Chelan, lat. 48° N., near old Fort O’Kinakane, on the upper Columbia River. The etchings appear to have been made at widely different periods, and are evidently quite old. Those which appeared the earliest were from twenty-five to thirty feet above the present water level. Those appearing more recent are about ten feet above water level. The figures are in black and red colors, representing Indians with bows and arrows, elk, deer, bear, beaver, and fish. There are four or five rows of these figures, and quite a number in each row. The present native inhabitants know nothing whatever regarding the history of these paintings.

For another example of pictographs from Washington see Figure 109, p. 190.

A locality in the southern interior of Utah has been called Pictograph Rocks, on account of the numerous records of that character found there.

Mr. G. K. Gilbert, of the United States Geological Survey, in 1875 collected a number of copies of inscriptions in Temple Creek Cañon, Southeastern Utah, accompanied by the following notes: “The drawings were found only on the northeast wall of the cañon, where it cuts the Vermillion cliff sandstone. The chief part are etched, apparently by pounding with a sharp point. The outline of a figure is usually more deeply cut than the body. Other marks are produced by rubbing or scraping, and still other by laying on colors. Some, not all, of the colors are accompanied by a rubbed appearance, as though the material had been a dry chalk.

“I could discover no tools at the foot of the wall, only fragments of pottery, flints, and a metate.

“Several fallen blocks of sandstone have rubbed depressions that may have been ground out in the sharpening of tools. There have been many dates of inscriptions, and each new generation has unscrupulously run its lines over the pictures already made. Upon the best protected surfaces, as well as the most exposed, there are drawings dimmed beyond restoration and others distinct. The period during which the work accumulated was longer by far than the time which has passed since the last. Some fallen blocks cover etchings on the wall, and are themselves etched.

“Colors are preserved only where there is almost complete shelter from rain. In two places the holes worn in the rock by swaying branches impinge on etchings, but the trees themselves have disappeared. Some etchings are left high and dry by a diminishing talus (15-20 feet), but I saw none partly buried by an increasing talus (except in the case of the fallen block already mentioned).

“The painted circles are exceedingly accurate, and it seems incredible that they were made without the use of a radius.”

In the collection contributed by Mr. Gilbert there are at least fifteen series or groups of figures, most of which consist of the human form (from the simplest to the most complex style of drawing), animals, either singly or in long files, as if driven, bird tracks, human feet and hands, etc. There are also circles, parallel lines, and waving or undulating lines, spots, and other unintelligible characters.

Mr. Gilbert also reports the discovery, in 1883, of a great number of pictographs, chiefly in color, though some are etched, in a cañon of the Book Cliff, containing Thompson’s spring, about 4 miles north of Thompson’s station, on the Denver and Colorado Railroad, Utah.

Collections of drawings of pictographs at Black Rock spring, on Beaver Creek, north of Milford, Utah, have been furnished by Mr. Gilbert. A number of fallen blocks of basalt, at a low escarpment, are filled with etchings upon the vertical faces. The characters are generally of an “unintelligible” nature, though the human figure is drawn in complex forms. Foot-prints, circles, etc., also abound.

Mr. I. C. Russell, of the United States Geological Survey, furnished rude drawings of pictographs at Black Rock spring, Utah (see Figure 153). Mr. Gilbert Thompson, of the United States Geological Survey, also discovered pictographs at Fool Creek Cañon, Utah (see Figure 154). Both of those figures are on page 230.

Captain E. L. Berthoud furnished to the Kansas City Review of Science and Industry, VII, 1883, No. 8, pp. 489, 490, the following:

The place is 20 miles southeast of Rio Del Norte, at the entrance of the cañon of the Piedra Pintada (Painted Rock) Creek. The carvings are found on the right of the[28] cañon, or valley, and upon volcanic rocks. They bear the marks of age and are cut in, not painted, as is still done by the Utes everywhere. They are found for a quarter of a mile along the north wall of the cañon, on the ranches of W. M. Maguire and F. T. Hudson, and consist of all manner of pictures, symbols, and hieroglyphics done by artists whose memory even tradition does not now preserve. The fact that these are carvings, done upon such hard rock merits them with additional interest, as they are quite distinct from the carvings I saw in New Mexico and Arizona on soft sand-stone. Though some of them are evidently of much greater antiquity than others, yet all are ancient, the Utes admitting them to have been old when their fathers conquered the country.

On the north wall of Cañon de Chelly, one fourth of a mile east of the mouth of the cañon, are several groups of pictographs, consisting chiefly of various grotesque forms of the human figure, and also numbers of animals, circles, etc. A few of them are painted black, the greater portion consisting of rather shallow lines which are in some places considerably weathered.

Further up the cañon, in the vicinity of cliff-dwellings, are numerous small groups of pictographic characters, consisting of men and animals, waving or zigzag lines, and other odd and “unintelligible” figures.

Lieut. J. H. Simpson gives several illustrations of pictographs copied from rocks in the northwest part of New Mexico in his Report of an Expedition into the Navajo Country. (Sen. Ex. Doc. No. 64, 31st Cong., 1st sess., 1856, Pl. 23, 24, 25.)

Inscriptions have been mentioned as occurring at El Moro, consisting of etchings of human figures and other unintelligible characters. This locality is better known as Inscription Rock. Lieutenant Simpson’s remarks upon it, with illustrations, are given in the work last cited, on page 120. He states that most of the characters are no higher than a man’s head, and that some of them are undoubtedly of Indian origin.

At Arch Spring, near Zuñi, figures are cut upon a rock which Lieutenant Whipple thinks present some faint similarity to those at Rocky Dell Creek. (Rep. Pac. R. R, Exped., Vol. III, 1856, Pt. III, p. 39, Pl. 32.)

Near Ojo Pescado, in the vicinity of the ruins, are pictographs, reported in the last mentioned volume and page, Plate 31, which are very much weather-worn, and have “no trace of a modern hand about them.”

On a table land near the Gila Bend is a mound of granite bowlders, blackened by augite, and covered with unknown characters, the work of human hands. On the ground near by were also traces of some of[29] the figures, showing some of the pictographs, at least, to have been the work of modern Indians. Others were of undoubted antiquity, and the signs and symbols intended, doubtless, to commemorate some great event. (See Ex. Doc. No. 41, 30th Cong., 1st sess. (Emory’s Reconnaissance), 1848, p. 89; Ill. opposite p. 89, and on p. 90.)

Characters upon rocks, of questionable antiquity, are reported in the last-mentioned volume, Plate, p. 63, to occur on the Gila River, at 32° 38′ 13″ N. lat., and 109° 07′ 30″ long. [According to the plate, the figures are found upon bowlders and on the face of the cliff to the height of about 30 feet.]

The party under Lieutenant Whipple (see Rep. Pac. R. R. Exped., III, 1856, Pt. III, p. 42) also discovered pictographs at Yampais Spring, Williams River. “The spot is a secluded glen among the mountains. A high, shelving rock forms a cave, within which is a pool of water and a crystal stream flowing from it. The lower surface of the rock is covered with pictographs. None of the devices seem to be of recent date.”

Many of the country rocks lying on the Colorado plateau of Northern Arizona, east of Peach Springs, bear traces of considerable artistic workmanship. Some observed by Dr. W. J. Hoffman, in 1871, were rather elaborate and represented figures of the sun, human beings in various styles approaching the grotesque, and other characters not yet understood. All of those observed were made by pecking the surface of basalt with a harder variety of stone.

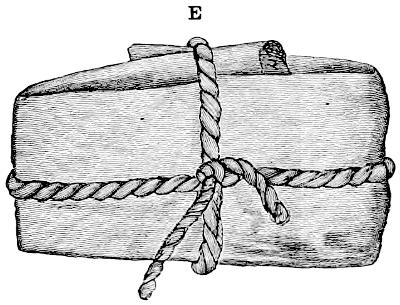

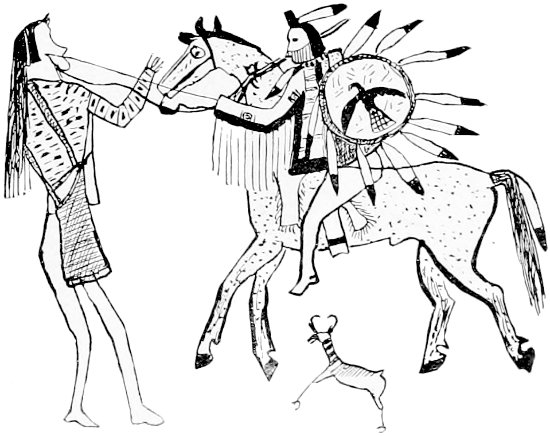

Mr. G. K. Gilbert discovered etchings at Oakley Spring, eastern Arizona, in 1878, relative to which he remarks that an Oraibi chief explained them to him and said that the “Mokis make excursions to a locality in the cañon of the Colorado Chiquito to get salt. On their return they stop at Oakley Spring and each Indian makes a picture on the rock. Each Indian draws his crest or totem, the symbol of his gens [(?)]. He draws it once, and once only, at each visit.” Mr. Gilbert adds, further, that “there are probably some exceptions to this, but the etchings show its general truth. There are a great many repetitions of the same sign, and from two to ten will often appear in a row. In several instances I saw the end drawings of a row quite fresh while the others were not so. Much of the work seems to have been performed by pounding with a hard point, but a few pictures are scratched on. Many drawings are weather-worn beyond recognition, and others are so fresh that the dust left by the tool has not been washed away by rain. Oakley Spring is at the base of the Vermillion Cliff, and the etchings are on fallen blocks of sandstone, a homogeneous, massive, soft sandstone. Tubi, the Oraibi chief above referred to, says his totem is the rain cloud but it will be made no more as he is the last survivor of the gens.”

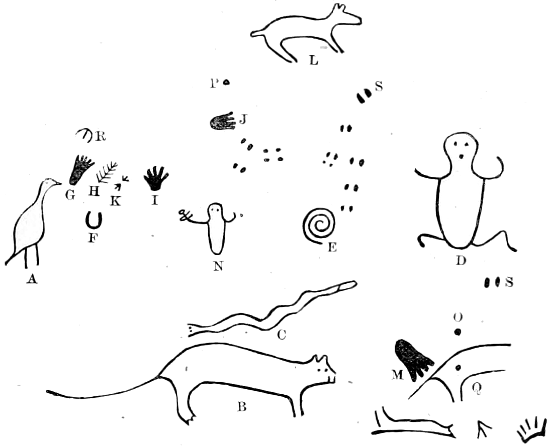

A group of the Oakley Spring etchings of which Figure 1 is a copy, measures six feet in length and four feet in height. Interpreta[30]tions of many of the separated characters of Figure 1 are presented on page 46 et seq., also in Figures 156 et seq., page 237.

Mr. Gilbert obtained sketches of etchings in November, 1878, on Partridge Creek, northern Arizona, at the point where the Beale wagon road comes to it from the east. “The rock is cross-laminated Aubrey sandstone and the surfaces used are faces of the laminæ. All the work is done by blows with a sharp point. (Obsidian is abundant in the vicinity.) Some inscriptions are so fresh as to indicate that the locality is still resorted to. No Indians live in the immediate vicinity, but the region is a hunting ground of the Wallapais and Avasupais (Cosninos).”

Notwithstanding the occasional visits of the above named tribes, the characters submitted more nearly resemble those of other localities known to have been made by the Moki Pueblos.

Rock etchings are of frequent occurrence along the entire extent of the valley of the Rio Verde, from a short distance below Camp Verde to the Gila River.

Mr. Thomas V. Keam reports etchings on the rocks in Cañon Segy, and in Keam’s Cañon, northeastern Arizona. Some forms occurring at the latter locality are found also upon Moki pottery.

From information received from Mr. Alphonse Pinart, pictographic records exist in the hills east of San Bernardino, somewhat resembling[31] those at Tule River in the southern spurs of the Sierra Nevada, Kern County.

These pictographic records are found at various localities along the hill tops, but to what distance is not positively known.

In the range of mountains forming the northeastern boundary of Owen Valley are extensive groups of petroglyphs, apparently dissimilar to those found west of the Sierra Nevada. Dr. Oscar Loew also mentions a singular inscription on basaltic rocks in Black Lake Valley, about 4 miles southwest of the town of Benton, Mono County. This is scratched in the basalt surface with some sharp instrument and is evidently of great age. (Ann. Report upon the Geog. Surveys west of the 100th meridian. Being Appendix J J, Ann. Report of Chief of Engineers for 1876. Plate facing p. 326.)

Dr. W. J. Hoffman, of the Bureau of Ethnology, reports the occurrence of a number of series of etchings scattered at intervals for over twenty miles in Owen’s Valley, California. Some of these records were hastily examined by him in 1871, but it was not until the autumn of 1884 that a thorough examination of them was made, when measurements, drawings, etc., were obtained for study and comparison. The country is generally of a sandy, desert, character, devoid of vegetation and water. The occasional bowlders and croppings of rock consist of vesicular basalt, upon the smooth vertical faces of which occur innumerable characters different from any hitherto reported from California, but bearing marked similarity to some figures found in the country now occupied by the Moki and Zuñi, in New Mexico and Arizona, respectively.

The southernmost group of etchings is eighteen miles south of the town of Benton; the next group, two miles almost due north, at the Chalk Grade; the third, about three miles farther north, near the stage road; the fourth, half a mile north of the preceding; then a fifth, five and a half miles above the last named and twelve and a half miles south of Benton. The northernmost group is about ten or twelve miles northwest of the last-mentioned locality and south west from Benton, at a place known as Watterson’s Ranch. The principal figures consist of various simple, complex, and ornamental circles, some of the simple circles varying as nucleated, concentric, and spectacle-shaped, zigzag, and serpentine lines, etc. Animal forms are not abundant, those readily identified being those of the deer, antelope, and jack-rabbits. Representations of snakes and huge sculpturings of grizzly-bear tracks occur on one horizontal surface, twelve and a half miles south of Benton. In connection with the latter, several carvings of human foot-prints appear, leading in the same direction, i. e., toward the south-southwest.

All of these figures are pecked into the vertical faces of the rocks, the depths varying from one-fourth of an inch to an inch and a quarter. A freshly broken surface of the rock presents various shades from a cream white to a Naples yellow color, though the sculptured lines are all blackened by exposure and oxidation of the iron contained therein. This fact has no importance toward the determination of the age of the work.

At the Chalk Grade is a large bowlder measuring about six feet in height and four feet either way in thickness, upon one side of which is one-half of what appears to have been an immense mortar. The sides of this cavity are vertical, and near the bottom turn abruptly and horizontally in toward the center, which is marked by a cone about three inches high and six inches across at its base. The interior diameter of the mortar is about twenty-four inches, and from the appearance of the surface, being considerably grooved laterally, it would appear as if a core had been used for grinding, similar in action to that of a millstone. No traces of such a core or corresponding form were visible. This instance is mentioned as it is the only indication that the authors of the etchings made any prolonged visit to this region, and perhaps only for grinding grass seed, though neither grass nor water is now found nearer than the remains at Watterson’s Ranch and at Benton.

The records at Watterson’s are pecked upon the surfaces of detached bowlders near the top of a mesa, about one hundred feet above the nearest spring, distant two hundred yards. These are also placed at the southeast corner of the mesa, or that nearest to the northern most of the main group across the Benton Range. At the base of the eastern and northeastern portion of this elevation of land, and but a stone’s throw from the etchings, are the remains of former camps, such as stone circles, marking the former sites of brush lodges, and a large number of obsidian flakes, arrowheads, knives, and some jasper remains of like character. Upon the flat granite bowlders are several mortar-holes, which perhaps were used for crushing the seed of the grass still growing abundantly in the immediate vicinity. Piñon nuts are also abundant in this locality.

Upon following the most convenient course across the Benton Range to reach Owen’s Valley proper, etchings are also found, though in limited numbers, and seem to partake of the character of “indicators as to course of travel.” By this trail the northernmost of the several groups of etchings above mentioned is the nearest and most easily reached.

The etchings upon the bowlders at Watterson’s are somewhat different from those found elsewhere. The number of specific designs is limited, many of them being reproduced from two to six or seven times, thus seeming to partake of the character of personal names.

One of the most frequent is that resembling a horseshoe within which is a vertical stroke. Sometimes the upper extremity of such stroke is attached to the upper inside curve of the broken ring, and frequently there are two or more parallel vertical strokes within one such curve. Bear-tracks and the outline of human feet also occur, besides several unique forms. A few of these forms are figured, though not accurately, in the Ann. Report upon the Geog. Surveys west of the 100th meridian last mentioned (1876), Plate facing p. 326.

Lieutenant Whipple reports (Rep. Pac. R. R. Exped. III, 1856, Pt. III,[33] p. 42, Pl. 36) the discovery of pictographs at Pai-Ute Creek, about 30 miles west of the Mojave villages. These are carved upon a rock, “are numerous, appear old, and are too confusedly obscure to be easily traceable.”

These bear great general resemblance to etchings scattered over Northeast Arizona, Southern Utah, and Western New Mexico.

Remarkable pictographs have also been found at Tule River Agency. See Figure 155, page 235.

Mr. Gilbert Thompson reports the occurrence of painted characters at Paint Lick Mountain, 3 miles north of Maiden Spring, Tazewell County, Virginia. These characters are painted in red, blue, and yellow. A brief description of this record is given in a work by Mr. Charles B. Coale, entitled “The Life and Adventures of Wilburn Waters,” etc., Richmond, 1878, p. 136.

Mr. John Haywood (The Natural and Aboriginal History of Tennessee, Nashville, 1823, p. 149) mentions painted figures of the sun, moon, a man, birds, etc., on the bluffs on the south bank of the Holston, 5 miles above the mouth of the French Broad. These are painted in red colors on a limestone bluff. He states that they were attributed to the Cherokee Indians, who made this a resting place when journeying through the region. This author furthermore remarks: “Wherever on the rivers of Tennessee are perpendicular bluffs on the sides, and especially if caves be near, are often found mounds near them, enclosed in intrenchments, with the sun and moon painted on the rocks,” etc.

Among the many colored etchings and paintings on rock discovered by the Pacific Railroad Expedition in 1853-’54 (Rep. Pac. R. R. Exped., III, 1856, Pt. III, pp. 36, 37, Pll. 28, 29, 30) may be mentioned those at Rocky Dell Creek, New Mexico, which were found between the edge of the Llano Estacado and the Canadian River. The stream flows through a gorge, upon one side of which a shelving sandstone rock forms a sort of cave. The roof is covered with paintings, some evidently ancient, and beneath are innumerable carvings of footprints, animals, and symmetrical lines.

Mr. James H. Blodgett, of the U. S. Geological Survey, calls attention to the paintings on the rocks of the bluffs of the Mississippi River, a short distance below the mouth of the Illinois River, in Illinois, which were observed by early French explorers, and have been the subject of discussion by much more recent observers.

Mr. P. W. Norris found numerous painted totemic characters upon the cliffs in the immediate vicinity of the pipestone quarry, Minnesota. These consisted, probably, of the totems or names of Indians who had[34] visited that locality for the purpose of obtaining catlinite for making pipes. These had been mentioned by early writers.

Mr. Norris also discovered painted characters upon the cliffs on the Mississippi River, 19 miles below New Albin, in northeastern Iowa.