The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Leopard's Spots, by Thomas Dixon, Jr.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Leopard's Spots

A Romance Of The White Man's Burden--1865-1900

Author: Thomas Dixon, Jr.

Illustrator: C. D. Williams

Release Date: May 23, 2017 [EBook #54765]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LEOPARD'S SPOTS ***

Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

LEADING CHARACTERS OF THE STORY

CHAPTER II—A LIGHT SHINING IN DARKNESS

CHAPTER IV—MR. LINCOLN’S DREAM

CHAPTER V—THE OLD AND THE NEW CHURCH

CHAPTER VI—THE PREACHER AND THE WOMAN OF BOSTON

CHAPTER VII—THE HEART OF A CHILD

CHAPTER VIII—AN EXPERIMENT IN MATRIMONY

CHAPTER X—THE MAN OR BRUTE IN EMBRYO

CHAPTER XIV—THE NEGRO UPRISING

CHAPTER XV—THE NEW CITIZEN KING

CHAPTER XVI—LEGREE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE

CHAPTER XVII—THE SECOND REIGN OF TERROR

CHAPTER XVIII—THE RED FLAG OF THE AUCTIONEER

CHAPTER XIX—THE RALLY OF THE CLANSMEN

CHAPTER XX—HOW CIVILISATION WAS SAVED

CHAPTER XXI—THE OLD AND THE NEW NEGRO

CHAPTER XXII—THE DANGER OF PLAYING WITH FIRE

CHAPTER XXIII—THE BIRTH OF A SCALAWAG

CHAPTER I—BLUE EYES AND BLACK HAIR

CHAPTER II—THE VOICE OF THE TEMPTER

CHAPTER VI—BESIDE BEAUTIFUL WATERS

CHAPTER VIII—THE UNSOLVED RIDDLE

CHAPTER IX—THE RHYTHM OF THE DANCE

CHAPTER X—THE HEART OF A VILLAIN

CHAPTER XII—THE MUSIC OF THE MILLS

CHAPTER XIV—A MYSTERIOUS LETTER

CHAPTER XVI—THE MYSTERY OF PAIN

CHAPTER XVII—IS GOD OMNIPOTENT?

CHAPTER XVIII—THE WAYS OF BOSTON

CHAPTER XIX—THE SHADOW OF A DOUBT

CHAPTER XX—A NEW LESSON IN LOVE

CHAPTER XXI—WHY THE PREACHER THREW HIS LIFE AWAY

CHAPTER XXII—THE FLESH AND THE SPIRIT

BOOK THREE—THE THE TRIAL BY FIRE

CHAPTER I—A GROWL BENEATH THE EARTH

CHAPTER II—FACE TO FACE WITH FATE

CHAPTER IV—THE UNSPOKEN TERROR

CHAPTER V—A THOUSAND-LEGGED BEAST

CHAPTER VII—EQUALITY WITH A RESERVATION

CHAPTER VIII—THE NEW SIMON LEGREE

CHAPTER X—ANOTHER DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE

CHAPTER XI—THE HEART OF A WOMAN

CHAPTER XII—THE SPLENDOUR OF SHAMELESS LOVE

CHAPTER XIII—A SPEECH THAT MADE HISTORY

CHAPTER XVI—THE END OF A MODERN VILLAIN

CHAPTER XVII—WEDDING BELLS IN THE GOVERNOR’S MANSION

In answer to hundreds of letters, I wish to say that all the incidents used in Book I., which is properly the prologue of my story, were selected from authentic records, or came within my personal knowledge.

The only serious liberty I have taken with history is to tone down the facts to make them credible in fiction. The village of “Hambright” is my birthplace, and is located near the center of “Military District No. 2,” comprising the Carolinas, which were destroyed as States by an Act of Congress in 1867. It will be a century yet before people outside the South can be made to believe a literal statement of the history of those times.

I tried to write this book with the utmost restraint.

Thomas Dixon, Jr.

May 9, 1902.

Elmington Manor, Dixondale, Va.

Scene: The Foothills of North Carolina-Boston-New York Time: From 1865 to 1900

Charles Gaston...........Who dreams of a Governor’s Mansion

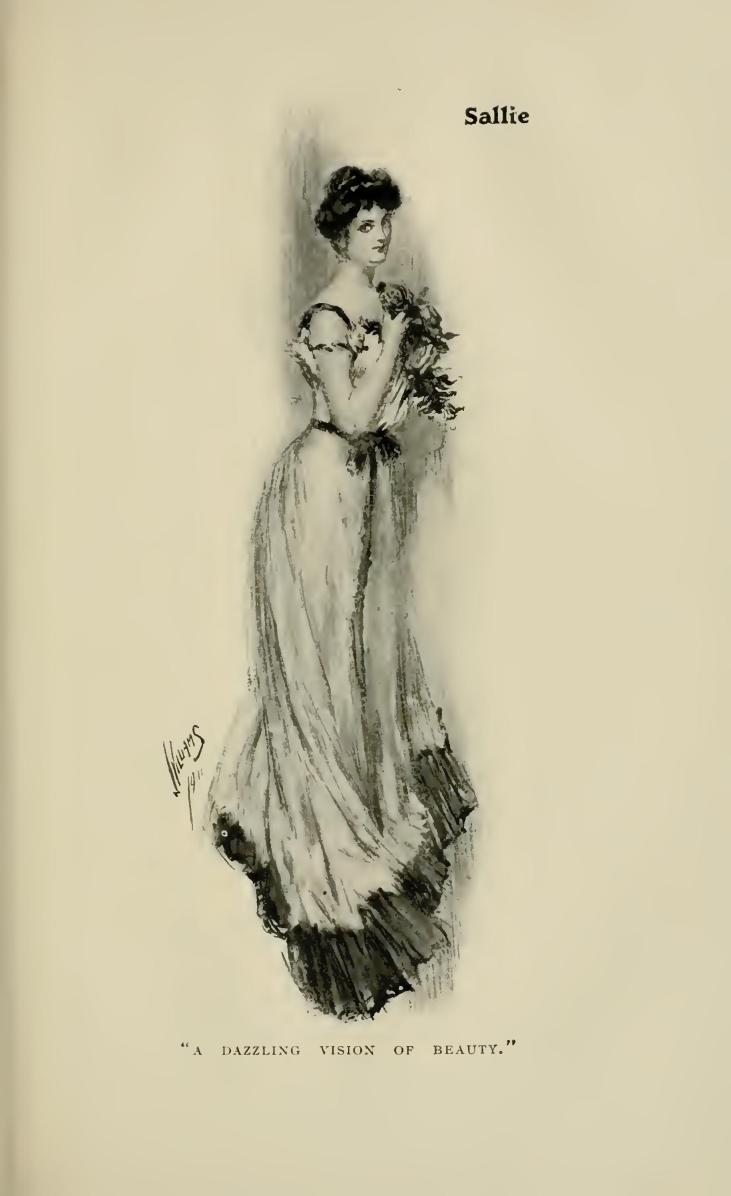

Sallie Worth.............A daughter of the old fashioned South

Gen. Daniel Worth..................................Her father

Mrs. Worth...........................................Sallie’s mother

The Rev. John Durham.........A preacher who threw his life away

Mrs. Durham........Of the Southern Army that never surrendered

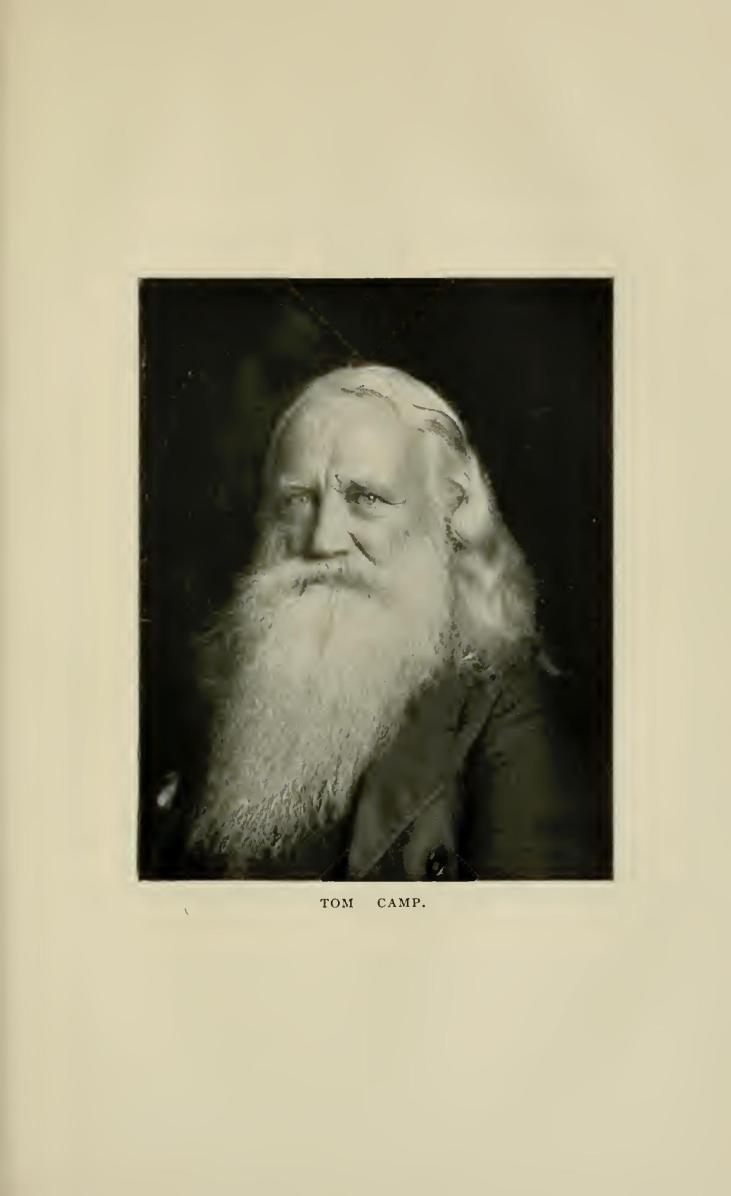

Tom Camp.....................A one-legged Confederate soldier

Flora....................................Tom’s little daughter

Simon Legree........Ex-slave driver and Reconstruction leader

Allan McLeod..............................A Scalawag

Hon. Everett Lowell..........Member of Congress from Boston

Helen Lowell........................His daughter

Miss Susan Walker.................A maiden of Boston

Major Stuart Dameron..............Chief of the Ku Klux Klan

Hose Norman.......................A dare-devil poor white man

Nelse........................A black hero of the old régime

Aunt Eve.....................His wife-“a respectable woman.”

Hon. Tim Shelby...................Political boss of the new era

Hon. Pete Sawyer.........Sold seven times, got the money once

George Harris, Jr............An Educated Negro, son of Eliza

Dick.......................................An unsolved riddle

ON the field of Appomattox General Lee was waiting the return of a courier. His handsome face was clouded by the deepening shadows of defeat. Rumours of surrender had spread like wildfire, and the ranks of his once invincible army were breaking into chaos.

Suddenly the measured tread of a brigade was heard marching into action, every movement quick with the perfect discipline, the fire, and the passion of the first days of the triumphant Confederacy.

“What brigade is that?” he sharply asked.

“Cox’s North Carolina,” an aid replied.

As the troops swept steadily past the General, his eyes filled with tears, he lifted his hat, and exclaimed, “God bless old North Carolina!”

The display of matchless discipline perhaps recalled to the great commander that awful day of Gettysburg when the Twenty-sixth North Carolina infantry had charged with 820 men rank and file and left 704 dead and wounded on the ground that night. Company F from Campbell county charged with 91 men and lost every man killed and wounded. Fourteen times their colours were shot down, and fourteen times raised again. The last time they fell from the hands of gallant Colonel Harry Burgwyn, twenty-one years old, commander of the regiment, who seized them and was holding them aloft when instantly killed.

The last act of the tragedy had closed. Johnston surrendered to Sherman at Greensboro on April 26th, 1865, and the Civil War ended,—the bloodiest, most destructive war the world ever saw. The earth had been baptized in the blood of five hundred thousand heroic soldiers, and a new map of the world had been made.

The ragged troops were straggling home from Greensboro and Appomattox along the country roads. There were no mails, telegraph lines or railroads. The men were telling the story of the surrender. White-faced women dressed in coarse homespun met them at their doors and with quivering lips heard the news.

Surrender!

A new word in the vocabulary of the South—a word so terrible in its meaning that the date of its birth was to be the landmark of time. Henceforth all events would be reckoned from this; “before the Surrender,” or “after the Surrender.”

Desolation everywhere marked the end of an era. Not a cow, a sheep, a horse, a fowl, or a sign of animal life save here and there a stray dog, to be seen. Grim chimneys marked the site of once fair homes. Hedgerows of tangled blackberry briar and bushes showed where a fence had stood before war breathed upon the land with its breath of fire and harrowed it with teeth of steel.

These tramping soldiers looked worn and dispirited. Their shoulders stooped, they were dirty and hungry. They looked worse than they felt, and they felt that the end of the world had come.

They had answered those awful commands to charge without a murmur; and then, rolled back upon a sea of blood, they charged again over the dead bodies of their comrades. When repulsed the second time and the mad cry for a third charge from some desperate commander had rung over the field, still without a word they pulled their old ragged hats down close over their eyes as though to shut out the hail of bullets, and, through level sheets of blinding flame, walked straight into the jaws of hell. This had been easy. Now their feet seemed to falter as though they were not sure of the road.

In every one of these soldier’s hearts, and over all the earth hung the shadow of the freed Negro, transformed by the exigency of war from a Chattel to be bought and sold into a possible Beast to be feared and guarded. Around this dusky figure every white man’s soul was keeping its grim vigil.

North Carolina, the typical American Democracy, had loved peace and sought in vain to stand between the mad passions of the Cavalier of the South and the Puritan fanatic of the North. She entered the war at last with a sorrowful heart but a soul clear in the sense of tragic duty. She sent more boys to the front than any other state of the Confederacy—and left more dead on the field. She made the last charge and fired the last volley for Lee’s army at Appomattox.

These were the ragged country boys who were slowly tramping homeward. The group whose fortunes we are to follow were marching toward the little village of Hambright that nestled in the foothills of the Blue Ridge under the shadows of King’s Mountain. They were the sons of the men who had first declared their independence of Great Britain in America and had made their country a hornet’s nest for Lord Cornwallis in the darkest days of the cause of Liberty. What tongue can tell the tragic story of their humble home coming?

In rich Northern cities could be heard the boom of guns, the scream of steam whistles, the shouts of surging hosts greeting returning regiments crowned with victory. From every flag-staff fluttered proudly the flag that our fathers had lifted in the sky—the flag that had never met defeat.

It is little wonder that in this hour of triumph the world should forget the defeated soldiers who without a dollar in their pockets were tramping to their ruined homes.

Yet Nature did not seem to know of sorrow or death. Birds were singing their love songs from the hedgerows, the fields were clothed in gorgeous robes of wild flowers beneath which forget-me-nots spread their contrasting hues of blue, while life was busy in bud and starting leaf reclothing the blood-stained earth in radiant beauty.

As the sun was setting behind the peaks of the Blue Ridge, a giant negro entered the village of Ham-bright. He walked rapidly down one of the principal streets, passed the court house square unobserved in the gathering twilight, and three blocks further along paused before a law-office that stood in the corner of a beautiful lawn filled with shrubbery and flowers.

“Dars de ole home, praise de Lawd! En now I’se erfeard ter see my Missy, en tell her Marse Charles’s daid. Hit’ll kill her! Lawd hab mussy on my po black soul! How kin I!”

He walked softly up the alley that led toward the kitchen past the “big” house, which after all was a modest cottage boarded up and down with weatherstrips nestling amid a labyrinth of climbing roses, honeysuckles, fruit bearing shrubbery and balsam trees. The negro had no difficulty in concealing his movements as he passed.

“Lordy, dars Missy watchin’ at de winder! How pale she look! En she wuz de purties’ bride in de two counties! God-der-mighty, I mus’ git somebody ter he’p me! I nebber tell her! She drap daid right ’fore my eyes, en liant me twell I die. I run fetch de Preacher, Marse John Durham, he kin tell her.”

A few moments later he was knocking at the door of the parsonage of the Baptist church.

“Nelse! At last! I knew you’d come!”

“Yassir, Marse John, I’se home. Hit’s me.”

“And your Master is dead. I was sure of it, but I never dared tell your Mistress. You came for me to help you tell her. People said you had gone over into the promised land of freedom and forgotten your people; but Nelse, I never believed it of you and I’m doubly glad to shake your hand to-night because you’ve brought a brave message from heroic lips and because you have brought a braver message in your honest black face of faith and duty and life and love.”

“Thankee Marse John, I wuz erbleeged ter come home.”

The Preacher stepped into the hall and called the servant from the kitchen.

“Aunt Mary, when your Mistress returns tell her I’ve received an urgent call and will not be at home for supper.”

“I’ll be ready in a minute, Nelse,” he said, as he disappeared into the study. When he reached his desk, he paused and looked about the room in a helpless way as though trying to find some half forgotten volume in the rows of books that lined the walls and lay in piles on his desk and tables. He knelt beside the desk and prayed. When he rose there was a soft light in his eyes that were half filled with tears.

Standing in the dim light of his study he was a striking man. He had a powerful figure of medium height, deep piercing eyes and a high intellectual forehead. His hair was black and thick. He was a man of culture, had graduated at the head of his class at Wake Forest College before the war, and was a profound student of men and books. He was now thirty-five years old and the acknowledged leader of the Baptist denomination in the state. He was eloquent, witty, and proverbially good natured. His voice in the pulpit was soft and clear, and full of a magnetic quality that gave him hypnotic power over an audience. He had the prophetic temperament and was more of poet than theologian.

The people of this village were proud of the man as a citizen and loved him passionately as their preacher. Great churches had called him, but he had never accepted. There was in his make-up an element of the missionary that gave his personality a peculiar force.

He had been the college mate of Colonel Charles Gaston whose faithful slave had come to him for help, and they had always been bosom friends. He had performed the marriage ceremony for the Colonel ten years before when he had led to the altar the beautiful daughter of the richest planter in the adjoining county. Durham’s own heart was profoundly moved by his friend’s happiness and he threw into the brief preliminary address so much of tenderness and earnest passion that the trembling bride and groom forgot their fright and were melted to tears. Thus began an association of their family life that was closer than their college days.

He closed his lips firmly for an instant, softly shut the door and was soon on the way with Nelse. On reaching the house, Nelse went directly to the kitchen, while the Preacher walking along the circular drive approached the front. His foot had scarcely touched the step when Mrs. Gaston opened the door.

“Oh, Dr. Durham, I am so glad you have come!” she exclaimed. “I’ve been depressed to-day, watching the soldiers go by. All day long the poor foot-sore fellows have been passing. I stopped some of them to ask about Colonel Gaston and I thought one of them knew something and would not tell me. I brought him in and gave him dinner, and tried to coax him, but he only looked wistfully at me, stammered and said he didn’t know. But some how I feel that he did. Come in Doctor, and say something to cheer me. If I only had your faith in God!”

“I have need of it all to-night, Madam!” he answered with bowed head.

“Then you have heard bad news?”

“I have heard news,—wonderful news of faith and love, of heroism and knightly valour, that will be a priceless heritage to you and yours. Nelse has returned—”

“God have mercy on me!”—she gasped covering her face and raising her arm as though cowering from a mortal blow.

“Here is Nelse, Madam. Hear his story. He has only told me a word or two.” Nelse had slipped quietly in the back door.

“Yassum. Missy, I’se home at las’.”

She looked at him strangely for a moment. “Nelse, I’ve dreamed and dreamed of your coming, but always with him. And now you come alone to tell me he is dead. Lord have pity! there is nothing left!” There was a far-away sound in her voice as though half dreaming.

“Yas, Missy, dey is, I jes seed him—my young Marster—dem bright eyes, de ve’y nose, de chin, de mouf! He walks des like Marse Charles, he talks like him, he de ve’y spit er him, en how he hez growed! He’ll be er man fo you knows it. En I’se got er letter fum his Pa fur him, an er letter fur you, Missy.”

At this moment Charlie entered the room, slipped past Nelse and climbed into his mother’s arms. He was a sturdy little fellow of eight years with big brown eyes and sensitive mouth.

“Yassir—Ole Grant wuz er pushin’ us dar afo’ Richmond Pear ter me lak Marse Robert been er fightin’ him ev’y day for six monts. But he des keep on pushin’ en pushin’ us. Marse Charles say ter me one night atter I been playin’ de banjer fur de boys, Come ter my tent Nelse fo turnin’ in—I wants ter see you.’ He talk so solemn like, I cut de banjer short, en go right er long wid him. He been er writin’ en done had two letters writ. He say, ‘Nelse, we gwine ter git outen dese trenches ter-morrer. It twell be my las’ charge. I feel it. Ef I falls, you take my swode, en watch en dese letters back home to your Mist’ess and young Marster, en you promise me, boy, to stan’ by em in life ez I stan’ by you.’ He know I lub him bettern any body in dis work, en dat I’d rudder be his slave dan be free if he’s daid! En I say, ‘Dat I will, Marse Charles.’

“De nex day we up en charge ole Grant. Pears ter me I nebber see so many dead Yankees on dis yearth ez we see layin’ on de groun’ whar we brake froo dem lines! But dey des kep fetchin’ up annudder army back er de one we breaks, twell bymeby, dey swing er whole millyon er Yankees right plum behin’ us, en five millyon er fresh uns come er swoopin’ down in front. Den yer otter see my Marster! He des kinder riz in de air—pear ter me like he wuz er foot taller en say to his men—’ ‘Bout face, en charge de line in de rear!’ Wall sar, we cut er hole clean froo dem Yankees en er minute, end den bout face ergin en begin ter walk backerds er fightin’ like wilecats ev’y inch. We git mos back ter de trenches, when Marse Charles drap des lak er flash! I runned up to him en dar wuz er big hole in his breas’ whar er bullet gone clean froo his heart. He nebber groan. I tuk his head up in my arms en cry en take on en call him! I pull back his close en listen at his heart. Hit wuz still. I takes de swode an de watch en de letters outen de pockets en start on—when bress God, yer cum dat whole Yankee army ten hundred millyons, en dey tromple all over us!

“Den I hear er Yankee say ter me ‘Now, my man, you’se free.’ ‘Yassir, sezzi, dats so,’ en den I see a hole ter run whar dey warn’t no Yankees, en I run spang into er millyon mo. De Yankees wuz ev’y whar. Pear ter me lak dey riz up outer de groun’. All dat day I try ter get away fum ’em. En long ’bout night dey ’rested me en fetch me up fo er Genr’l, en he say, ‘What you tryin’ ter get froo our lines fur, nigger? Doan yer know yer free now, en if you go back you’d be a slave ergin?’”

“Dats so, sah,” sezzi, “but I’se ’bleeged ter go home.”

“What fur?” sezze.

“Promise Marse Charles ter take dese letters en swode en watch back home to my Missus en young Marster, en dey waitin’ fur me—I’se ’bleeged ter go.”

“Den he tuk de letters en read er minute, en his eyes gin ter water en he choke up en say, ‘Go-long!’

“Den I skeedaddled ergin. Dey kep on ketchin’ me twell bimeby er nasty stinkin low-life slue-footed Yankee kotched me en say dat I wuz er dang’us nigger, en sont me wid er lot er our prisoners way up ter ole Jonson’s Islan’ whar I mos froze ter deaf. I stay dar twell one day er fine lady what say she from Boston cum er long, en I up en tells her all erbout Marse Charles and my Missus, en how dey all waitin’ fur me, en how bad I want ter go home, en de nex news I knowed I wuz on er train er whizzin’ down home wid my way all paid. I get wid our men at Greensboro en come right on fas’ ez my legs’d carry me.”

There was silence for a moment and then slowly Mrs. Gaston said, “May God reward you, Nelse!”

“Yassum, I’se free, Missy, but I gwine ter wuk for you en my young Marster.”

Mrs. Gaston had lived daily in a sort of trance through those four years of war, dreaming and planning for the great day when her lover would return a handsome bronzed and famous man. She had never conceived of the possibility of a world without his will and love to lean upon. The Preacher was both puzzled and alarmed by the strangely calm manner she now assumed. Before leaving the home he cautioned Aunt Eve to watch her Mistress closely and send for him if anything happened.

When the boy was asleep in the nursery adjoining her room, she quietly closed the door, took the sword of her dead lover-husband in her lap and looked long and tenderly at it. On the hilt she pressed her lips in a lingering kiss.

“Here his dear hand must have rested last!” she murmured. She sat motionless for an hour with eyes fixed without seeing. At last she rose and hung the sword beside his picture near her bed and drew from her bosom the crumpled, worn letters Nelse had brought. The first was addressed to her.

“In the Trenches Near Richmond, May 4, 1864.

“Sweet Wifie:—I have a presentiment to-night that I shall not live to see you again. I feel the shadows of defeat and ruin closing upon us. I am surer day by day that our cause is lost and surrender is a word I have never learned to speak. If I could only see you for one hour, that I might tell you all I have thought in the lone watches of the night in camp, or marching over desolate fields. Many tender things I have never said to you I have learned in these days. I write this last message to tell you how, more and more beyond the power of words to express, your love has grown upon me, until your spirit seems the breath I breathe. My heart is so full of love for you and my boy, that I can’t go into battle now without thinking how many hearts will ache and break in far away, homes because of the work I am about to do. I am sick of it all. I long to be at home again and walk with my sweet young bride among the flowers she loves so well, and hear the old mocking bird that builds each spring in those rose bushes at our window.

“If I am killed, you must live for our boy and rear him to a glorious manhood in the new nation that will be born in this agony. I love you,—I love you unto the uttermost, and beyond death I will live, if only to love you forever.

“Always in life or death your own,

“Charles.”

For two hours she held this letter open in her hands and seemed unable to move it. And then mechanically she opened the one addressed to “Charles Gaston, jr.”

“My Darling Boy:—I send you by Nelse my watch and sword. It will be all I can bequeath to you from the wreck that will follow the war. This sword was your great grandfather’s. He held it as he charged up the heights of King’s Mountain against Ferguson and helped to carve this nation out of a wilderness. It was a sorrowful day for me when I felt it my duty to draw that sword against the old flag in defence of my home and my people. You will live to see a reunited country. Hang this sword back beside the old flag of our fathers when the end has come, and always remember that it was never drawn from its scabbard by your father, or your grandfather who fought with Jackson at New Orleans, or your great grandfather in the Revolution, save in the cause of justice and right. I am not fighting to hold slaves in bondage. I am fighting for the inalienable rights of my people under the Constitution our fathers created. It may be we have outgrown this Constitution. But I calmly leave to God and history the question as to who is right in its interpretation. Whatever you do in life, first, last and always do what you believe to be right. Everything else is of little importance. With a heart full of love, Your father,

“Charles Gaston.”

This letter she must have held open for hours, for it was two o’clock in the morning when a wild peal of laughter rang from her feverish lips and brought Aunt Eve and Nelse hurrying into the room.

It took but a moment for them to discover that their Mistress was suffering from a violent delirium. They soothed her as best they could. The noise and confusion had awakened the boy. Running to the door leading into his mother’s room he found it bolted, and with his little heart fluttering in terror he pressed his ear close to the key-hole and heard her wild ravings. How strange her voice seemed! Her voice had always been so soft and low and full of soothing music. Now it was sharp and hoarse and seemed to rasp his flesh with needles. What could it all mean? Perhaps the end of the world, about which he had heard the Preacher talk on Sundays At last unable to bear the terrible suspense longer he cried through the key-hole, “Aunt Eve, what’s the matter? Open the door quick.”

“No, honey, you mustn’t come in. Yo Ma’s awful sick. You run out ter de barn, ketch de mare, en fly for de doctor while me en Nelse stay wid her. Run honey, day’s nuttin’ ter hurt yer.”

His little bare feet were soon pattering over the long stretch of the back porch toward the barn. The night was clear and sky studded with stars. There was no moon. He was a brave little fellow, but a fear greater than all the terrors of ghosts and the white sheeted dead with which Negro superstition had filled his imagination, now nerved his child’s soul. His mother was about to die! His very heart ceased to beat at the thought. He must bring the doctor and bring him quickly.

He flew to the stable not looking to the right or the left. The mare whinnied as he opened the door to get the bridle.

“It’s me Bessie. Mama’s sick. We must go for the doctor quick!”

The mare thrust her head obediently down to the child’s short arm for the bridle. She seemed to know by some instinct his quivering voice had roused that the home was in distress and her hour had come to bear a part.

In a moment he led her out through the gate, climbed on the fence, and sprang on her back.

“Now, Bess, fly for me!” he half whispered, half cried through the tears he could no longer keep back. The mare bounded forward in a swift gallop as she felt his trembling bare legs clasp her side, and the clatter of her hoofs echoed in the boy’s ears through the silent streets like the thunder of charging cavalry. How still the night! He saw shadows under the trees, shut his eyes and leaning low on the mare’s neck patted her shoulders with his hands and cried, “Faster. Bessie! Faster!” And then he tried to pray. “Lord don’t let her die! Please, dear God, and I will always be good. I am sorry I robbed the bird’s nests last summer—I’ll never do it again. Please, Lord I’m such a wee boy and I’m so lonely. I can’t lose my Mama!”—and the voice choked and became, a great sob. He looked across the square as he passed the court house in a gallop and saw a light in the window of the parsonage and felt its rays warm his soul like an answer to his prayer.

He reached the doctor’s house on the further side of the town, sprang from the mare’s back, bounded up the steps and knocked at the door. No one answered. He knocked again. How loud it rang through the hall! May be the doctor was gone! He had not thought of such a possibility before. He choked at the thought. Springing quickly from the steps to the ground he felt for a stone, bounded back and began to pound on the door with all his might.

The window was raised, and the old doctor thrust his head out calling, “What on earth’s the matter? Who is that?”

“It’s me, Charlie Gaston—my Mama’s sick—she’s awful sick, I’m afraid she’s dying—you must come quick!”

“All right, sonny, I’ll be ready in a minute.”

The boy waited and waited. It seemed to him hours, days, weeks, years! To every impatient call the doctor would answer, “In a minute, sonny, in a minute!”

At last he emerged with his lantern, to catch his horse. The doctor seemed so slow. He fumbled over the harness.

“Oh! Doctor you’re so slow! I tell you my Mama’s sick—!”

“Well, well, my boy, we’ll soon be there,” the old man kindly replied.

When the boy saw the doctor’s horse jogging quickly toward his home he turned the mare’s head aside as he reached the court house square, roused the Preacher, and between his sobs told the story of his mother’s illness. Mrs. Durham had lost her only boy two years before. Soon Charlie was sobbing in her arms.

“You poor little darling, out by yourself so late at night, were you not scared?” she asked as she kissed the tears from his eyes.

“Yessum, I was scared, but I had to go for the doctor. I want you and Dr. Durham to come as quick as you can. I’m afraid to go home. I’m afraid she’s dead, or I’ll hear her laugh that awful way I heard to-night.”

“Of course we will come, dear, right away. We will be there almost as soon as you can get to the house.”

He rode slowly along the silent street looking back now and then for the Preacher and his wife. As he was passing a small deserted house he saw to his horror a ragged man peering into the open window. Before he had time to run, the man stepped quickly up to the mare and said, “Who lived here last, little man?”

“Old Miss Spurlin,” answered the boy.

“Where is she now?”

“She’s dead.”

The man sighed, and the boy saw by his gray uniform that he was a soldier just back from the war, and he quickly added, “Folks said they had a hard time, but Preacher Durham helped them lots when they had nothing to eat.”

“So my poor old mother’s dead. I was afraid of it.” He seemed to be talking to himself. “And do you know where her gal is that lived with her?”

“She’s in a little house down in the woods below town. They say she’s a bad woman, and my Mama would never let me go near her.”

The man flinched as though struck with a knife, steadied himself for a moment with his hands on the mare’s neck and said, “You’re a brave little one to be out alone this time o’night,—what’s your name?”

“Charles Gaston.”

“Then you’re my Colonel’s boy—many a time I followed him where men were failin’ like leaves—I wish to God I was with him now in the ground! Don’t tell anybody you saw me,—them that knowed me will think I’m dead, and it’s better so.”

“Good-bye, sir,” said the child “I’m sorry for you if you’ve got no home. I’m after the doctor for my Mama,—she’s very sick. I’m afraid she’s going to die, and if you ever pray I wish you’d pray for her.”

The soldier came closer. “I wish I knew how to pray, my boy. But it seemed to me I forgot everything that was good in the war, and there’s nothin’ left but death and hell. But I’ll not forget you, good-bye!” When Charlie was in bed, he lay an hour with wide staring eyes, holding his breath now and then to catch the faintest sound from his mother’s room. All was quiet at last and he fell asleep. But he was no longer a child. The shadow of a great sorrow had enveloped his soul and clothed him with the dignity and fellowship of the mystery of pain.

IN the rear of Mrs. Gaston’s place, there stood in the midst of an orchard a log house of two rooms, with hallway between them. There was a mud-thatched wooden chimney at each end, and from the back of the hallway a kitchen extension of the same material with another mud chimney. The house stood in the middle of a ten acre lot, and a woman was busy in the garden with a little girl, planting seed.

“Hurry up Annie, less finish this in time to fix up a fine dinner er greens and turnips an’taters an a chicken. Yer Pappy’ll get home to-day sure. Colonel Gaston’s Nelse come last night. Yer Pappy was in the Colonel’s regiment an’ Nelse said he passed him on the road comin’ with two one-legged soldiers. He ain’t got but one leg, he says. But, Lord, if there’s a piece of him left we’ll praise God an’ be thankful for what we’ve got.”

“Maw, how did he look? I mos’ forgot—’s been so long sence I seed him?” asked the child.

“Look! Honey! He was the handsomest man in Campbell county! He had a tall fine figure, brown curly beard, and the sweetest mouth that was always smilin’ at me, an’ his eyes twinklin’ over somethin’ funny he’d seed or thought about. When he was young ev’ry gal around here was crazy about him. I got him all right, an’ he got me too. Oh me! I can’t help but cry, to think he’s been gone so long. But he’s comin’ to-day! I jes feel it in my bones.”

“Look a yonder, Maw, what a skeer-crow ridin’ er ole hoss!” cried the girl, looking suddenly toward the road.

“Glory to God! It’s Tom!” she shouted, snatching her old faded sun-bonnet off her head and fairly flying across the field to the gate, her cheeks aflame, her blond hair tumbling over her shoulders, her eyes wet with tears.

Tom was entering the gate of his modest home in as fine style as possible, seated proudly on a stack of bones that had once been a horse, an old piece of wool on his head that once had been a hat, and a wooden peg fitted into a stump where once was a leg. His face was pale and stained with the red dust of the hill roads, and his beard, now iron grey, and his ragged buttonless uniform were covered with dirt. He was truly a sight to scare crows, if not of interest to buzzards. But to the woman whose swift feet were hurrying to his side, and whose lips were muttering half articulate cries of love, he was the knightliest figure that ever rode in the lists before the assembled beauty of the world.

“Oh! Tom, Tom, Tom, my ole man! You’ve come at last!” she sobbed as she threw her arms around his neck, drew him from the horse and fairly smothered him with kisses.

“Look out, ole woman, you’ll break my new leg!” cried Tom when he could get breath.

“I don’t care,—I’ll get you another one,” she laughed through her tears.

“Look out there again you’re smashing my game shoulder. Got er Minie ball in that one.”

“Well your mouth’s all right I see,” cried the delighted woman, as she kissed and kissed him.

“Say, Annie, don’t be so greedy, give me a chance at my young one.” Tom’s eyes were devouring the excited girl who had drawn nearer.

“Come and kiss your Pappy and tell him how glad you are to see him!” said Tom, gathering her in his arms and attempting to carry her to the house.

He stumbled and fell. In a moment the strong arms of his wife were about him and she was helping him into the house.

She laid him tenderly on the bed, petted him and cried over him. “My poor old man, he’s all shot and cut to pieces. You’re so weak, Tom—I can’t believe it. You were so strong. But we’ll take care of you. Don’t you worry. You just sleep a week and then rest all summer and watch us work the garden for you!”

He lay still for a few moments with a smile playing around his lips.

“Lord, ole woman, you don’t know how nice it is to be petted like that, to hear a woman’s voice, feel her breath on your face and the touch of her hand, warm and soft after four years sleeping on dirt and living with men and mules, and fightin’ and runnin’ and diggin’ trenches like rats and moles, killin’ men, buryin’ the dead like carrion, holdin’ men while doctors sawed their legs off, till your turn came to be held and sawed! You can’t believe it, but this is the first feather bed I’ve touched in four years.”

“Well, well!—Bless God it’s over now,” she cried. “S’long as I’ve got two strong arms to slave for you—as long as there’s a piece of you left big enough to hold on to—I’ll work for you,” and again she bent low over his pale face, and crooned over him as she had so often done over his baby in those four lonely years of war and poverty.

Suddenly Tom pushed her aside and sprang up in bed.

“Geemimy, Annie, I forgot my pardners—there’s two more peg-legs out at the gate by this time waiting for us to get through huggin’ and carryin’ on before they come in. Run, fetch’em in quick!”

Tom struggled to his feet and met them at the door.

“Come right into my palace, boys. I’ve seen some fine places in my time, but this is the handsomest one I ever set eyes on. Now, Annie, put the big pot in the little one and don’t stand back for expenses. Let’s have a dinner these fellers’ll never forget.”

It was a feast they never forgot. Tom’s wife had raised a brood of early chickens, and managed to keep them from being stolen. She killed four of them and cooked them as only a Southern woman knows how. She had sweet potatoes carefully saved in the mound against the kitchen chimney. There were turnips and greens and radishes, young onions and lettuce and hot corn dodgers fit for a king; and in the centre of the table she deftly fixed a pot of wild flowers little Annie had gathered. She did not tell them that it was the last peck of potatoes and the last pound of meal. This belonged to the morrow. To-day they would live.

They laughed and joked over this splendid banquet, and told stories of days and nights of hunger and exhaustion, when they had filled their empty stomachs with dreams of home.

“Miss Camp, you’ve got the best husband in seven states, did you know that?” asked one of the soldiers, a mere boy.

“Of course she’ll agree to that, sonny,” laughed Tom.

“Well it’s so. If it hadn’t been for him, M’am, we’d a been peggin’ along somewhere way up in Virginny ‘stead o’ bein’ so close to home. You see he let us ride his hoss a mile and then he’d ride a mile. We took it turn about, and here we are.”

“Tom, how in this world did you get that horse?” asked his wife.

“Honey, I got him on my good looks,” said he with a wink. “You see I was a settin’ out there in the sun the day o’ the surrender. I was sorter cryin’ and wonderin’ how I’d get home with that stump of wood instead of a foot, when along come a chunky heavy set Yankee General, looking as glum as though his folks had surrendered instead of Marse Robert. He saw me, stopped, looked at me a minute right hard and says, ‘Where do you live?’”

“Way down in ole No’th Caliny,” I says, “at Ham-bright, not far from King’s Mountain.”

“How are you going to get home?” says he.

“God knows, I don’t, General. I got a wife and baby down there I ain’t seed fer nigh four years, and I want to see ’em so bad I can taste ’em. I was lookin’ the other way when I said that, fer I was purty well played out, and feelin’ weak and watery about the eyes, an’ I didn’t want no Yankee General to see water in my eyes.”

“He called a feller to him and sorter snapped out to him, ‘Go bring the best horse you can spare for this man and give it to him’.”

“Then he turns to me and seed I was all choked up and couldn’t say nothin’ and says:

“I’m General Grant. Give my love to your folks when you get home. I’ve known what it was to be a poor white man down South myself once for awhile.”

“God bless you, General. I thanks you from the bottom of my heart,” I says as quick as I could find my tongue, “if it had to be surrender I’m glad it was to such a man as you.”

“He never said another word, but just walked slow along smoking a big cigar. So ole woman, you know the reason I named that hoss, ‘General Grant.’ It may be I have seen finer hosses than that one, but I couldn’t recollect anything about ’em on the road home.”

Dinner over, Tom’s comrades rose and looked wistfully down the dusty road leading southward.

“Well, Tom, ole man, we gotter be er movin’,” said the older of the two soldiers. “We’re powerful obleeged to you fur helpin’ us along this fur.”

“All right, boys, you’ll find yer train standin’ on the side o’ the track eatin’ grass. Jes climb up, pull the lever and let her go.”

The men’s faces brightened, their lips twitched. They looked at Tom, and then at the old horse. They looked down the long dusty road stretching over hill and valley, hundreds of miles south, and then at Tom’s wife and child, whispered to one another a moment, and the elder said:

“No, pardner, you’ve been awful good to us, but we’ll get along somehow—we can’t take yer hoss. It’s all yer got now ter make a livin’ on yer place.”

“All I got?” shouted Tom, “man alive, ain’t you seed my ole woman, as fat and jolly and han’some as when I married her ’leven years ago? Didn’t you hear her cryin’ an’ shoutin’ like she’s crazy when I got home? Didn’t you see my little gal with eyes jes like her daddy’s? Don’t you see my cabin standin’ as purty as a ripe peach in the middle of the orchard when hundreds of fine houses are lyin’ in ashes? Ain’t I got ten acres of land? Ain’t I got God Almighty above me and all around me, the same God that watched over me on the battlefields? All I got? That old stack o’ bones that looks like er hoss? Well I reckon not!”

“Pardner, it ain’t right,” grumbled the soldier, with more of cheerful thanks than protest in his voice.

“Oh! Get off you fools,” said Tom good-naturedly, “ain’t it my hoss? Can’t I do what I please with him?” So with hearty hand-shakes they parted, the two astride the old horse’s back. One had lost his right leg, the other his left, and this gave them a good leg on each side to hold the cargo straight.

“Take keer yerself, Tom!” they both cried in the same breath as they moved away.

“Take keer yerselves, boys. I’m all right!” answered Tom, as he stumped his way back to the home. “It’s all right, it’s all right,” he muttered to himself. “He’d a come in handy, but I’d a never slept thinkin’ o’ them peggin’ along them rough roads.”

Before reaching the house he sat down on a wooden bench beneath a tree to rest. It was the first week in May and the leaves were not yet grown. The sun was pouring his hot rays down into the moist earth, and the heat began to feel like summer. As he drank in the beauty and glory of the spring his soul was melted with joy. The fruit trees were laden with the promise of the treasures of the summer and autumn, a cat-bird was singing softly to his mate in the tree over his head, and a mocking-bird seated in the topmost branch of an elm near his cabin home was leading the oratorio of feathered songsters. The wild plum and blackberry briars were in full bloom in the fence comers, and the sweet odour filled the air. He heard his wife singing in the house.

“It’s a fine old world after all!” he exclaimed leaning back and half closing his eyes, while a sense of ineffable peace filled his soul. “Peace at last! Thank God! May I never see a gun or a sword, or hear a drum or a fife’s scream on this earth again!”

A hound came close wagging his tail and whining for a word of love and recognition.

“Well. Bob, old boy, you’re the only one left. You’ll have to chase cotton-tails by yourself now.”

Bob’s eyes watered and he licked his master’s hand apparently understanding every word he said.

Breaking from his master’s hands the dog ran toward the gate barking, and Tom rose in haste as he recognised the sturdy tread of the Preacher, Rev. John Durham, walking rapidly toward the house.

Grasping him heartily by the hand the Preacher said, “Tom, you don’t know how it warms my soul to look into your face again. When you left, I felt like a man who had lost one hand. I’ve found it to-day. You’re the same stalwart Christian full of joy and love. Some men’s religion didn’t stand the wear and tear of war. You’ve come out with your soul like gold tried in the fire. Colonel Gaston wrote me you were the finest soldier in the regiment, and that you were the only Chaplain he had seen that he could consult for his own soul’s cheer. That’s the kind of a deacon to send to the front! I’m proud of you, and you’re still at your old tricks. I met two one-legged soldiers down the road riding your horse away as though you had a stable full at your command. You needn’t apologise or explain, they told me all about it.”

“Preacher, it’s good to have the Lord’s messenger speak words like them. I can’t tell you how glad I am to be home again and shake your hand. I tell you it was a comfort to me when I lay awake at night on them battlefields, a wonderin’ what had become of my ole woman and the baby, to recollect that you were here, and how often I’d heard you tell us how the Lord tempered the wind to the shorn lamb. Annie’s been telling me who watched out for her them dark days when there was nothin’ to eat. I reckon you and your wife knows the way to this house about as well as you do to the church.” Tom had pulled the Preacher down on the seat beside him while he said this.

“The dark days have only begun, Tom. I’ve come to see you to have you cheer me up. Somehow you always seemed to me to be closer to God than any man in the church. You will need all your faith now. It seems to me that every second woman I know is a widow. Hundreds of families have no seed even to plant, no horses to work crops, no men who will work if they had horses. What are we to do? I see hungry children in every house.”

“Preacher, the Lord is looking down here to-day and sees all this as plain as you and me. As long as He is in the sky everything will come all right on the earth.”

“How’s your pantry?” asked the Preacher.

“Don’t know. ‘Man shall not live by bread alone,’ you know. When I hear these birds in the trees an’ see this old dog waggin’ his tail at me, and smell the breath of them flowers, and it all comes over me that I’m done killin’ men, and I’m at home, with a bed to sleep on, a roof over my head, a woman to pet me and tell me I’m great and handsome, I don’t feel like I’ll ever need anything more to eat! I believe I could live a whole month here without eatin’ a bite.”

“Good. You come to the prayer meeting to-night and say a few things like that, and the folks will believe they have been eating three square meals every day.”

“I’ll be there. I ain’t asked Annie what she’s got, but I know she’s got greens and turnips, onions and col-lards, and strawberries in the garden. Irish taters’ll be big enough to eat in three weeks, and sweets comin’ right on. We’ve got a few chickens. The blackberries and plums and peaches and apples are all on the road. Ah! Preacher, it’s my soul that’s been starved away from my wife and child!”

“You don’t know how much I need help sometimes Tom. I am always giving, giving myself in sympathy and help to others, I’m famished now and then. I feel faint and worn out. You seem to fill me again with life.”

“I’m glad to hear you say that, Preacher. I get downhearted sometimes, when I recollect I’m nothin’ but a poor white man. I’ll remember your words. I’m goin’ to do my part in the church work. You know where to find me.”

“Well, that’s partly what brought me here this morning. I want you to help me look after Mrs. Gaston and her little boy. She is prostrated over the death of the Colonel and is hanging between life and death. She is in a delirious condition all the time and must be watched day and night. I want you to watch the first half of the night with Nelse, and Eve and Mary will watch the last half.”

“Of course, I’ll do anything in the world I can for my Colonel’s widder. He was the bravest man that ever led a regiment, and he was a father to us boys. I’ll be there. But I won’t set up with that nigger. He can go to bed.”

“Tom, it’s a funny thing to me that as good a Christian as you are should hate a nigger so. He’s a human being. It’s not right.”

“He may be human, Preacher, I don’t know. To tell you the truth, I have my doubts. Anyhow, I can’t help it. God knows I hate the sight of ’em like I do a rattlesnake. That nigger Nelse, they say is a good one. He was faithful to the Colonel, I know, but I couldn’t bear him no more than any of the rest of ’em. I always hated a nigger since I was knee high. My daddy and my mammy hated ’em before me. Somehow, we always felt like they was crowdin’ us to death on them big plantations, and the little ones too. And then I had to leave my wife and baby and fight four years, all on account of their stinkin’ hides, that never done nothin’ for me except make it harder to live. Every time I’d go into battle and hear them Minie balls begin to sing over us, it seemed to me I could see their black ape faces grinnin’ and makin’ fun of poor whites. At night when they’d detail me to help the ambulance corps carry off the dead and the wounded, there was a strange smell on the field that came from the blood and night damp and burnt powder. It always smelled like a nigger to me! It made me sick. Yes, Preacher, God forgive me, I hate ’em! I can’t help it any more than I can the color of my skin or my hair.”

“I’ll fix it with Nelse, then. You take the first part of the night ’till twelve o’clock. I’ll go down with you from the church to-night,” said the Preacher, as he shook Tom’s hand and took his leave.

ON the second day after Mrs. Gaston was stricken a forlorn little boy sat in the kitchen watching Aunt Eve get supper. He saw her nod while she worked the dough for the biscuits.

“Aunt Eve, I’m going to sit up to-night and every night with my Mama, ’till she gets well. I can’t sleep for hours and hours. I lie awake and cry when I hear her talking ’till I feel like I’ll die. I must do something to help her.”

“Laws, honey, you’se too little. You can’t keep ’wake ’tall. You get so lonesome and skeered all by yerself.”

“I don’t care, I’ve told Tom to wake me to-night if I’m asleep when he goes, and I’ll sit up from twelve ’till two o’clock and then call you.”

“All right, Mammy’s darlin’ boy, but you git tired en can’t stan’ it.”

So that night at midnight he took his place by the bedside. His mother was sleeping, at first. He sat and gazed with aching heart at her still, white face. She stirred, opened her eyes, saw him, and imagined he was his father.

“Dearie-, I knew you would come,” she murmured. “They told me you were dead; but I knew better. What a long, long time you have been away. How brown the sun has tanned your face, but it’s just as handsome. I think handsomer than ever. And how like you is little Charlie! I knew you would be proud of him!”

While she talked, her eyes had a glassy look, that seemed to take no note of anything in the room.

The child listened for ten minutes, and then the horror of her strange voice, and look and words overwhelmed him. He burst into tears and threw his arms around his mother’s neck and sobbed.

“Oh! Mama dear, it’s me, Charlie, your little boy, who loves you so much. Please, don’t talk that way. Please look at me like you used to. There! Let me kiss your eyes ’till they are soft and sweet again!”

He covered her eyes with kisses.

The mother seemed dazed for a moment, held him off at arm’s length, and then burst into laughter.

“Of course, you silly, I know you. You must run to bed now. Kiss me good night.”

“But you are sick, Mama, I am sitting up with you.” Again she ignored his presence. She was back in the old days with her Love. She was kissing her hand to him as he left her for his day’s work. Charlie looked at the clock. It was time to give her the soothing drops the doctor left. She took it, obedient as a child, and went on and on with interminable dreams of the past, now and then uttering strange things for a boy’s ears. But so terrible was the anguish with which he watched her, the words made little impression on his mind. It seemed to him some one was strangling him to death, and a great stone was piled on his little prostrate body.

When she grew quiet, at last, and dosed, how still the house seemed! How loud the tick of the clock! How slowly the hands moved! He had never noticed this before. He watched the hands for five minutes. It seemed each minute was an hour, and five minutes were as long as a day. What strange noises in the house! Suppose a ghost should walk into the room! Well, he wouldn’t run and leave his Mama; he made up his mind to that.

Some nights there were other sounds more ominous. The town was crowded with strange negroes, who were hanging around the camp of the garrison. One night a drunken gang came shouting and screaming up the alley close beside the house, firing pistols and muskets. They stopped at the house, and one of them yelled, “Burn the rebel’s house down! It’s our turn now!”

The terrified boy rushed to the kitchen and called Nelse. In a minute, Nelse was on the scene. There was no more trouble that night.

“De lazy black debbels,” said Nelse, as he mopped the perspiration from his brow, “I’ll teach ’em what freedom is.”

The next day when the Rev. John Durham had an interview with the Commandant of the troops, he succeeded in getting a consignment of corn for seed, and to meet the threat of starvation among some families whose condition he reported. This important matter settled, he said to the officer:

“Captain, we must look to you for protection. The town is swarming with vagrant negroes, bent on mischief. There are camp followers with you organizing them into some sort of Union League meetings, dealing out arms and ammunition to them, and what is worse, inflaming the worst passions against their former masters, teaching them insolence and training them for crime.”

“I’ll do the best I can for you Doctor, but I can’t control the camp followers who are organising the Union League. They live a charmed life.”

That night, as the Preacher walked home from a visit to a destitute family he encountered a burly negro on the sidewalk, dressed in an old suit of Federal uniform, evidently under the influence of whiskey. He wore a belt around his waist, in which he had thrust, conspicuously, an old horse pistol.

Standing squarely across the pathway, he said to the Preacher, “Git outer de road, white man, you’se er rebel, I’se er Loyal Union Leaguer!”

It was his first experience with Negro insolence since the emancipation of his slaves. Quick as a flash, his right arm was raised. But he took a second thought, stepped aside, and allowed the drunken fool to pass. He went home wondering in a hazy sort of way through his excited passions what the end of it all would be. Gradually in his mind for days this towering figure of the freed Negro had been growing more and more ominous, until its menace overshadowed the poverty, the hunger, the sorrows and the devastation of the South, throwing the blight of its shadow over future generations, a veritable Black Death for the land and its people.

EVERY morning before the Preacher could finish his breakfast, callers were knocking at the door—the negro, the poor white, the widow, the orphan, the wounded, the hungry, an endless procession.

The spirit of the returned soldiers was all that he could ask. There was nowhere a slumbering spark of war. There was not the slightest effort to continue the lawless habits of four years of strife. Everywhere the spirit of patience, self-restraint and hope marked the life of the men who had made the most terrible soldiery. They were glad to be done with war, and have the opportunity to rebuild their broken fortunes. They were glad, too, that the everlasting question of a divided Union was settled and settled forever. There was now to be one country and one flag, and deep down in their souls they were content with it.

The spectacle of this terrible army of the Confederacy, the memory of whose battle cry yet thrills the world, transformed in a month into patient and hopeful workmen, has never been paralleled in history.

Who destroyed this scene of peaceful rehabilitation? Hell has no pit dark enough, and no damnation deep enough for these conspirators when once history has fixed their guilt.

The task before the people of the South was one to tax the genius of the Anglo-Saxon race as never in its history, even had every friendly aid possible been extended by the victorious North. Four million negroes had suddenly been freed, and the foundations of economic order destroyed. Five billions of dollars worth of property were wiped out of existence, banks closed, every dollar of money worthless paper, the country plundered by victorious armies, its cities, mills and homes burned, and the flower of its manhood buried in nameless trenches, or worse still, flung upon the charity of poverty, maimed wrecks. The task of organising this wrecked society and marshalling into efficient citizenship this host of ignorant negroes, and yet to preserve the civilisation of the Anglo-Saxon race, the priceless heritage of two thousand years of struggle, was one to appal the wisdom of ages. Honestly and earnestly the white people of the South set about this work, and accepted the Thirteenth amendment to the Constitution abolishing slavery without a protesting vote.

The President issued his proclamation announcing the method of restoring the Union as it had been handed to him from the martyred Lincoln, and endorsed unanimously by Lincoln’s Cabinet. This plan was simple, broad and statesmanlike, and its spirit breathed Fraternity and Union with malice toward none and charity toward all. It declared what Lincoln had always taught, that the Union was indestructible, that the rebellious states had now only to repudiate Secession, abolish slavery, and resume their positions in the Union, to preserve which so many lives had been sacrificed.

The people of North Carolina accepted this plan in good faith. They elected a Legislature composed of the noblest men of the state, and chose an old Union man, Andrew Macon, Governor. Against Macon was pitted the man who was now the President and organiser of a federation of secret oath-bound societies, of which the Union League, destined to play so tragic a part in the drama about to follow was the type. This man, Amos Hogg, was a writer of brilliant and forceful style. Before the war, a virulent Secessionist leader, he had justified and upheld slavery, and had written a volume of poems dedicated to John C. Calhoun. He had led the movement for Secession in the Convention which passed the ordinance. But when he saw his ship was sinking, he turned his back upon the “errors” of the past, professed the most loyal Union sentiments, wormed himself into the confidence of the Federal Government, and actually succeeded in securing the position of Provisional Governor of the state! He loudly professed his loyalty, and with fury and malice demanded that Vance, the great war Governor, his predecessor, who, as a Union man had opposed Secession, should now be hanged, and with him his own former associates in the Secession Convention, whom he had misled with his brilliant pen.

But the people had a long memory. They saw through this hollow pretense, grieved for their great leader, who was now locked in a prison cell in Washington, and voted for Andrew Macon.

In the bitterness of defeat, Amos Hogg sharpened his wits and his pen, and began his schemes of revengeful ambition.

The fires of passion burned now in the hearts of hosts of cowards, North and South, who had not met their foe in battle. Their day had come. The times were ripe for the Apostles of Revenge and their breed of statesmen.

The Preacher threw the full weight of his character and influence to defeat Hogg and he succeeded in carrying the county for Macon by an overwhelming majority. At the election only the men who had voted under the old regime were allowed to vote. The Preacher had not appeared on the hustings as a speaker, but as an organizer and leader of opinion he was easily the most powerful man in the county, and one of the most powerful in the state.

IN the village of Hambright the church was the centre of gravity of the life of the people. There were but two churches, the Baptist and the Methodist. The Episcopalians had a building, but it was built by the generosity of one of their dead members. There were four Presbyterian families in town, and they were working desperately to build a church. The Baptists had really taken the county, and the Methodists were their only rivals. The Baptists had fifteen flourishing churches in the county, the Methodists six. There were no others.

The meetings at the Baptist church in the village of Hambright were the most important gatherings in the county. On Sunday mornings everybody who could walk, young and old, saint and sinner, went to church, and by far the larger number to the Baptist church.

You could tell by the stroke of the bells that the two were rivals. The sextons acquired a peculiar skill in ringing these bells with a snap and a jerk that smashed the clapper against the side in a stroke that spoke defiance to all rival bells, warning of everlasting fire to all sinners that should stay away, and due notice to the saints that even an apostle might become a castaway unless he made haste.

The men occupied one side of the house, the women the other. Only very small boys accompanying their mothers were to be seen on the woman’s side, together with a few young men who fearlessly escorted thither their sweethearts.

Before the services began, between the ringing of the first and second bells, the men gathered in groups in the church yard and discussed grave questions of politics and weather. The services over the men lingered in the yard to shake hands with neighbours, praise or criticise the sermon, and once more discuss great events. The boys gathered in quiet, wistful groups and watched the girls come slowly out of the other door, and now and then a daring youngster summoned courage to ask to see one of them home.

The services were of the simplest kind. The Singing of the old hymns of Zion, the Reading of the Bible, the Prayer, the Collection, the Sermon, the Benediction.

The Preacher never touched on politics, no matter what the event under whose world import his people gathered. War was declared, and fought for four terrible years. Lee surrendered, the slaves were freed, and society was torn from the foundations of centuries, but you would never have known it from the lips of the Rev. John Durham in his pulpit. These things were but passing events. When he ascended the pulpit he was the Messenger of Eternity. He spoke of God, of Truth, of Righteousness, of Judgment, the same yesterday, to-day and forever.

Only in his prayers did he come closer to the inner thoughts and perplexities of the daily life of the people. He was a man of remarkable power in the pulpit. His mastery of the Bible was profound. He could speak pages of direct discourse in its very language. To him it was a divine alphabet, from whose letters he could compose the most impassioned message to the individual hearer before him. Its literature, its poetic fire, the epic sweep of the Old Testament record of life, were inwrought into the very fibre of his soul. As a preacher he spoke with authority. He was narrow and dogmatic in his interpretations of the Bible, but his very narrowness and dogmatism were of his flesh and blood, elements of his power. He never stooped to controversy. He simply announced the Truth. The wise received it. The fools rejected it and were damned. That was all there was to it.

But it was in his public prayers that he was at his best. Here all the wealth of tenderness of a great soul was laid bare. In these prayers he had the subtle genius that could find the way direct into the hearts of the people before him, realise as his own their sins and sorrows, their burdens and hopes and dreams and fears, and then, when he had made them his own, he could give them the wings of deathless words and carry them up to the heart of God. He prayed in a low soft tone of voice; it was like an honest earnest child pleading with his father. What a hush fell on the people when these prayers began! With what breathless suspense every earnest soul followed him!

Before and during the war, the gallery of this church, which was built and reserved for the negroes, was always crowded with dusky listeners that hung spellbound on his words. Now there were only a few, perhaps a dozen, and they were growing fewer. Some new and mysterious power was at work among the negroes, sowing the seeds of distrust and suspicion. He wondered what it could be. He had always loved to preach to these simple hearted children of nature, and watch the flash of resistless emotion sweep their dark faces. He had baptised over five hundred of them into the fellowship of the churches in the village and the county during the ten years of his ministry.

He determined to find out the cause of this desertion of his church by the negroes to whom he had ministered so many years.

At the close of a Sunday morning’s service, Nelse was slowly descending the gallery stairs leading Charlie Gaston by the hand, after the church had been nearly emptied of the white people. The Preacher stopped him near the door.

“How’s your Mistress, Nelse?”

“She’s gettin’ better all de time now praise de Lawd. Eve she stay wid er dis mornin’, while I fetch dis boy ter church. He des so sot on goin’.”

“Where are all the other folks who used to fill that gallery, Nelse?”

“You doan tell me, you aint heard about dem?” he answered with a grin.

“Well, I haven’t heard, and I want to hear.”

“De laws-a-massy, dey done got er church er dey own! Dey has meetin’ now in de school house dat Yankee ’oman built. De teachers tell ’em ef dey aint good ernuf ter set wid de white folks in dere chu’ch, dey got ter hole up dey haids, and not ’low nobody ter push em up in er nigger gallery. So dey’s got ole Uncle Josh Miller to preach fur ’em. He ’low he got er call, en he stan’ up dar en holler fur ’em bout er hour ev’ry Sunday mawnin’ en night. En sech whoopin’, en yellin’, en bawlin’! Yer can hear ’em er mile. Dey tries ter git me ter go. I tell ’em, Marse John Durham’s preach-in’s good ernuf fur me, gall’ry er no gall’ry. I tell ’em dat I spec er gall’ry nigher heaven den de lower flo’ enyhow—en fuddermo’, dat when I goes ter church, I wants ter hear sumfin’ mo’ dan er ole fool nigger er bawlin’. I can holler myself. En dey low I gwine back on my colour. En den I tell ’em I spec I aint so proud dat I can’t larn fum white folks. En dey say dey gwine ter lay fur me yit.”

“I’m sorry to hear this,” said the Preacher thoughtfully.

“Yassir, hits des lak I tell yer. I spec dey gone fur good. Niggers aint got no sense nohow. I des wish I own ’em erbout er week! Dey gitten madder’n madder et me all de time case I stay at de ole place en wuk fer my po’ sick Mistus. Dey sen’ er Kermittee ter see me mos’ ev’ry day ter ’splain ter me I’se free. De las’ time dey come I lam one on de haid wid er stick er wood erfo dey leave me lone.”

“You must be careful, Nelse.”

“Yassir, I nebber hurt ’im. Des sorter crack his skull er little ter show ’im what I gwine do wid ’im nex’ time dey come pesterin’ me.”

“Have they been back to see you since?”

“Dat dey aint. But dey sont me word dey gwine git de Freeman’s Buro atter me. En I sont ’em back word ter sen Mr. Buro right on en I land ’im in de middle er a spell er sickness, des es sho es de Lawd gimme strenk.”

“You can’t resist the Freedman’s Bureau, Nelse.”

“What dat Buro got ter do wid me, Marse John?”

“They’ve got everything to do with you, my boy. They have absolute power over all questions between the Negro and the white man. They can prohibit you from working for a white person without their consent, and they can fix your wages and make your contracts.”

“Well, dey better lemme erlone, or dere’ll be trouble in dis town, sho’s my name’s Nelse.”

“Don’t you resist their officer. Come to me if you get into trouble with them,” was the Preacher’s parting injunction.

Nelse made his way out leading Charlie by the hand, and bowing his giant form in a quaint deferential way to the white people he knew. He seemed proud of his association in the church with the whites, and the position of inferiority assigned him in no sense disturbed his pride. He was muttering to himself as he walked slowly along looking down at the ground thoughtfully. There was infinite scorn and defiance in his voice.

“Bu-ro! Bu-ro! Des let ’em fool wid me! I’ll make ’em see de seben stars in de middle er de day!”

THE next day the Preacher had a call from Miss Susan Walker of Boston, whose liberality had built the new Negro school house and whose life and fortune was devoted to the education and elevation of the Negro race. She had been in the village often within the year, running up from Independence where she was building and endowing a magnificent classical college for negroes. He had often heard of her, but as she stopped with negroes when on her visits he had never met her. He was especially interested in her after hearing incidentally that she was a member of a Baptist church in Boston.

On entering the parlour the Preacher greeted his visitor with the deference the typical Southern man instinctively pays to woman.

“I am pleased to meet you, Madam,” he said with a graceful bow and kindly smile, as he led her to the most comfortable seat he could find.

She looked him squarely in the face for a moment as though surprised and smilingly replied, “I believe you Southern men are all alike, woman flatterers. You have a way of making every woman believe you think her a queen. It pleases me, I can’t help confessing it, though I sometimes despise myself for it. But I am not going to give you an opportunity to feed my vanity this morning. I’ve come for a plain face to face talk with you on the one subject that fills my heart, my work among the Freedmen. You are a Baptist minister. I have a right to your friendship and co-operation.”

A cloud overshadowed the Preacher’s face as he seated himself. He said nothing for a moment, looking curiously and thoughtfully at his visitor.

He seemed to be studying her character and to be puzzled by the problem. She was a woman of prepossessing appearance, well past thirty-five, with streaks of grey appearing in her smoothly brushed black hair. She was dressed plainly in rich brown material cut in tailor fashion, and her heavy hair was drawn straight up pompadour style from her forehead with apparent carelessness and yet in a way that heightened the impression of strength and beauty in her face. Her nose was the one feature that gave warning of trouble in an encounter. She was plump in figure, almost stout, and her nose seemed too small for the breadth of her face. It was broad enough, but too short, and was pug tipped slightly at the end. She fell just a little short of being handsome and this nose was responsible for the failure. It gave to her face when agitated, in spite of evident culture and refinement, the expression of a feminine bull dog.

Her eyes were flashing now, and her nostrils opened a little wider and began to push the tip of her nose upward. At last she snapped out suddenly, “Well, which is it, friend or foe? What do you honestly think of my work?”

“Pardon me, Miss Walker, I am not accustomed to speak rudely to a lady. If I am honest, I don’t know where to begin.”

“Bah! Lay aside your Don Quixote Southern chivalry this morning and talk to me in plain English. It doesn’t matter whether I am a woman or a man. I am an idea, a divine mission this morning. I mean to establish a high school in this village for the negroes, and to build a Baptist church for them. I learn from them that they have great faith in you. Many of them desire your approval and co-operation. Will you help me?”

“To be perfectly frank, I will not. You ask me for plain English. I will give it to you. Your presence in this village as a missionary to the heathen is an insult to our intelligence and Christian manhood. You come at this late day a missionary among the heathen, the heathen whose heart and brain created this Republic with civil and religious liberty for its foundations, a missionary among the heathen who gave the world Washington, whose giant personality three times saved the cause of American Liberty from ruin when his army had melted away. You are a missionary among the children of Washington, Jefferson, Monroe, Madison, Jackson, Clay and Calhoun! Madam, I have baptised into the fellowship of the church of Christ in this county more negroes than you ever saw in all your life before you left Boston.

“At the close of the war there were thousands of negro members of white Baptist churches in the state. Your mission is not to proclaim the gospel of Jesus Christ. Your mission is to teach crack-brained theories of social and political equality to four millions of ignorant negroes, some of whom are but fifty years removed from the savagery of African jungles. Your work is to separate and alienate the negroes from their former masters who can be their only real friends and guardians. Your work is to sow the dragon’s teeth of an impossible social order that will bring forth its harvest of blood for our children.”

He paused a moment, and, suddenly facing her continued, “I should like to help the cause you have at heart: and the most effective service I could render it now would be to box you up in a glass cage, such as are used for rattlesnakes, and ship you back to Boston.”

“Indeed! I suppose then it is still a crime in the South to teach the Negro?” she asked this in little gasps of fury, her eyes flashing defiance and her two rows of white teeth uncovering by the rising of her pugnacious nose.

“For you, yes. It is always a crime to teach a lie.”

“Thank you. Your frankness is all one could wish!”

“Pardon my apparent rudeness. You not only invited, you demanded it. While about it, let me make a clean breast of it. I do you personally the honour to acknowledge that you are honest and in dead earnest, and that you mean well. You are simply a fanatic.”

“Allow me again to thank you for your candour!”

“Don’t mention it, Madam. You will be canonised in due time. In the meantime let us understand one another. Our lives are now very far apart, though we read the same Bible, worship the same God and hold the same great faith. In the settlement of this Negro question you are an insolent interloper. You’re worse, you are a wilful spoiled child of rich and powerful parents playing with matches in a powder mill. I not only will not help you, I would, if I had the power seize you, and remove you to a place of safety. But I cannot oppose you. You are protected in your play by a million bayonets and back of these bayonets are banked the fires of passion in the North ready to burst into flame in a moment. The only thing I can do is to ignore your existence. You understand my position.”

“Certainly, Doctor,” she replied good naturedly.

She had recovered from the rush of her anger now and was herself again. A curious smile played round her lips as she quietly added:

“I must really thank you for your candour. You have helped me immensely. I understand the situation now perfectly. I shall go forward cheerfully in my work and never bother my brain again about you, or your people, or your point of view. You have aroused all the fighting blood in me. I feel toned up and ready for a life struggle. I assure you I shall cherish no ill feeling toward you. I am only sorry to see a man of your powers so blinded by prejudice. I will simply ignore you.”

“Then, Madam, it is quite clear we agree upon establishing and maintaining a great mutual ignorance. Let us hope, paradoxical as it may seem, that it may be for the enlightenment of future generations!”

She arose to go, smiling at his last speech.

“Before we part, perhaps never to meet again, let me ask you one question,” said the Preacher still looking thoughtfully at her.

“Certainly, as many as you like.”

“Why is it that you good people of the North are spending your millions here now to help only the negroes, who feel least of all the sufferings of this war? The poor white people of the South are your own flesh and blood. These Scotch Covenanters are of the same Puritan stock, these German, Huguenot and English people are all your kinsmen, who stood at the stake with your fathers in the old world. They are, many of them, homeless, without clothes, sick and hungry and broken hearted. But one in ten of them ever owned a slave. They had to fight this war because your armies invaded their soil. But for their sorrows, sufferings and burdens you have no ear to hear and no heart to pity. This is a strange thing to me.”

“The white people of the South can take care of themselves. If they suffer, it is God’s just punishment for their sins in owning slaves and fighting against the flag. Do I make myself clear?” she snapped.

“Perfectly, I haven’t another word to say.”

“My heart yearns for the poor dear black people who have suffered so many years in slavery and have been denied the rights of human beings. I am not only going to establish schools and colleges for them here, but I am conducting an experiment of thrilling interest to me which will prove that their intellectual, moral, and social capacity is equal to any white man’s.”

“Is it so?” asked the Preacher.

“Yes, I am collecting from every section of the South the most promising specimens of negro boys and sending them to our great Northern Universities where they will be educated among men who treat them as equals, and I expect from the boys reared in this atmosphere, men of transcendent genius, whose brilliant achievements in science, art and letters will forever silence the tongues of slander against their race. The most interesting of these students I have at Harvard now is young George Harris. His mother is Eliza Harris, the history of whose escape over the ice of the Ohio River fleeing from slavery thrilled the world. This boy is a genius, and if he lives he will shake this nation.”

“It may be, Miss Walker. There are more ways than one to shake a nation. And while I ignore your work, as a citizen and public man,—privately and personally, I shall watch this experiment with profound interest.”

“I know it will succeed. I believe God made us of one blood,” she said with enthusiasm.

“Is it true. Madam, that you once endowed a home for homeless cats before you became interested in the black people?” With a twinkle in his eye the Preacher softly asked this apparently irrelevant question.

“Yes, sir, I did,—I am proud of it. I love cats. There are over a thousand in the home now, and they are well cared for. Whose business is it?”

“I meant no offense by the question. I love cats too. But I wondered if you were collecting negroes only now, or, whether you were adding other specimens to your menagerie for experimental purposes.”

She bit her lips, and in spite of her efforts to restrain her anger, tears sprang to her eyes as she turned toward the Preacher whose face now looked calmly down upon her with ill-concealed pride.