A READING FROM HOMER

BY

WILLIAM H. ELSON

AUTHOR ELSON READERS AND GOOD ENGLISH SERIES

AND

CHRISTINE M. KECK

HEAD UNION JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH, GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN

SCOTT, FORESMAN AND COMPANY

CHICAGO ATLANTA NEW YORK

Copyright 1919

By Scott, Foresman and Company

For permission to use copyrighted material grateful acknowledgment is made to The London Times for “The Guards Came Through” by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle; to Thomas Hardy for “Men Who March Away” from The London Times; to John Galsworthy for “England to Free Men” from The Westminster Gazette; to John Masefield for “Spanish Waters”; to Hamlin Garland for “The Great Blizzard” from Boy Life on the Prairie; to Doubleday Page & Co. for “The Gift of the Magi” by O. Henry; to G. P. Putnam’s Sons for “Old Ephraim, the Grizzly Bear,” from The Wilderness Hunter by Theodore Roosevelt; to the George H. Doran Company for “Trees” from Trees and Other Poems by Joyce Kilmer; to Mr. R. W. Lillard for “America’s Answer” from The New York Evening Post; to Horace Traubel for “Pioneers! O Pioneers!”, “I Hear America Singing”, “O Captain! My Captain!” by Walt Whitman; to Charles Scribner’s Sons for “On a Florida River” by Sidney Lanier, from The Lanier Book, copyright 1904; and to Frederick A. Stokes Company for “Kilmeny—A Song of the Trawlers” by Alfred Noyes from The New Morning, copyright 1919.

ROBERT O. LAW COMPANY

EDITION BOOK MANUFACTURERS

CHICAGO, U. S. A.

The Junior High School offers exceptional opportunity for relating literature to life. In addition to the aesthetic and ethical purposes, long recognized in the study of literature, the World War emphasized the need for an extension of aims to include the teaching of certain fundamental American ideals. To marshal the available material, setting it to work in the service of social and civic ideals, is to give to literature the “central place in a new humanism.” When we organize reading in the schools with reference to the teaching of ideals—personal, social, national, and patriotic—we “put the stress on literature as one of the chief means through which the child enters on his intellectual and spiritual inheritance.” Outstanding among these ideals are: freedom, love of home and country, service, loyalty, courage, thrift, humane treatment of animals, a sense of humor, love of Nature, and an appreciation of the dignity of honest work. In a word, to provide a course in the history and development of civilization, particularly stressing America’s part in it, is the present-day demand on the school.

The Junior High School Literature Series, of which the present volume is intended for use in the first year, provides such a course. The literature brought together in this book is organized with reference to the social ideal. Nature in its varied relations to human life, particularly child life, is presented in stories and poems of animals, birds, flowers, trees, and winter, all abounding in beauty and charm. Interest in Nature leads to interest in the deeds of men filled with the spirit of adventure. The heroism of brave men and women from the age of chivalry to the days of self-sacrifice on Flanders Fields is told in ballad and romance, thus stimulating qualities of courage, loyalty, and devotion. Akin to these are the deeds of men who won freedom for their fellows and gave meaning to the words, “our inheritance of freedom.” Their heroism is told in story and song, from the time of the Great Charter and Robert the Bruce to the Declaration[iv] of Independence and the recent treaty of Versailles. The whole culminates in the literature and life in the homeland, interpreting America’s part in these great enterprises of the human spirit. Through legend and history the spirit and thoughts of our developing nation are portrayed in a literature of compelling interest, distinctively American.

This book supplies material in such generous quantity as to provide in one volume a complete one-year course of literature. There is material suited to all the purposes that a collection of literature for this grade should supply: reading for the story element, silent reading, reading for expression, intensive reading, memorizing, dramatization, public reading and recitation, plot study, etc. Moreover, the book offers a wide variety of literature, representing various types: ballads, lyrics, short stories, tales, biographies, and the rest. The selections comprise not only those that have stood the test of time, but also some of the choicest treasures of the modern creative period. They are given in complete units, not mere excerpts or garbled “cross-sections.”

The helps to study are more than mere notes; they take into account the larger purposes of the literature. Especially illuminating are the selection “The Three Joys of Reading,” pages 9-14, and the Introductions to Parts II, III, and IV; these should be read by pupils before beginning the study of the selections in the several groups, for they interpret and give greater significance to the units. The biographical and historical notes provide helpful data for interpreting the stories and poems. A comprehensive glossary, pages 592-626, contains the words and phrases of the text that offer valuable vocabulary training, either of pronunciation or meaning. An additional feature that will appeal to many teachers is the list of common words frequently mispronounced given in connection with the helps to study. See pages 14, 26, etc.

The Authors.

| PAGE | ||

| Preface | iii | |

| The Three Joys of Reading | ix | |

| PART I Stories and Poems of Nature |

||

| ANIMALS | ||

| The Buffalo | Francis Parkman | 1 |

| Old Ephraim, the Grizzly Bear | Theodore Roosevelt | 15 |

| Moti Guj—Mutineer | Rudyard Kipling | 27 |

| The Elephants That Struck | Samuel White Baker | 35 |

| BIRDS | ||

| Robert of Lincoln | William Cullen Bryant | 39 |

| The Maryland Yellow-Throat | Henry van Dyke | 43 |

| The Belfry Pigeon | Nathaniel Parker Willis | 45 |

| The Sandpiper | Celia Thaxter | 47 |

| The Throstle | Alfred, Lord Tennyson | 49 |

| To the Cuckoo | William Wordsworth | 50 |

| The Birds’ Orchestra | Celia Thaxter | 52 |

| FLOWERS AND TREES | ||

| To the Fringed Gentian | William Cullen Bryant | 53 |

| Violet! Sweet Violet! | James Russell Lowell | 54 |

| To the Dandelion | James Russell Lowell | 56 |

| The Daffodils | William Wordsworth | 59 |

| The Trailing Arbutus | John Greenleaf Whittier | 60 |

| To a Mountain Daisy | Robert Burns | 61 |

| Sweet Peas | John Keats | 63 |

| Chorus of Flowers | Leigh Hunt | 64 |

| Trees | Joyce Kilmer | 68 |

| WINTER | ||

| The Great Blizzard | Hamlin Garland | 69 |

| The Frost | Hannah F. Gould | 75 |

| The Frost Spirit | John Greenleaf Whittier | 76 |

| The Snow Storm | Ralph Waldo Emerson | 78 |

| Snowflakes | Henry W. Longfellow | 80 |

| Midwinter | John T. Trowbridge | 82 |

| Blow, Blow, Thou Winter Wind | William Shakespeare | 84 |

| [vi]When Icicles Hang by the Wall | William Shakespeare | 85 |

| PART II Adventures Old and New |

||

| Introduction | 89 | |

| THE DAYS OF CHIVALRY | ||

| King Arthur Stories Adapted from | Sir Thomas Malory | |

| The Coming of Arthur | 91 | |

| The Story of Gareth | 105 | |

| The Peerless Knight Lancelot | 126 | |

| The Passing of Arthur | 149 | |

| NARRATIVES IN VERSE | ||

| Sir Patrick Spens | Folk Ballad | 168 |

| The Skeleton in Armor | Henry W. Longfellow | 171 |

| The Three Fishers | Charles Kingsley | 177 |

| Lord Ullin’s Daughter | Thomas Campbell | 178 |

| The Pipes at Lucknow | John Greenleaf Whittier | 181 |

| Spanish Waters | John Masefield | 184 |

| Kilmeny—a Song of the Trawlers | Alfred Noyes | 186 |

| The Guards Came Through | Sir Arthur Conan Doyle | 188 |

| STORIES OF THE SEA | ||

| A Descent Into the Maelstrom | Edgar Allan Poe | 191 |

| The Wreck of the Golden Mary | Charles Dickens | 210 |

| TALES FROM SHAKESPEARE | ||

| As You Like It | Charles and Mary Lamb | 259 |

| The Tempest | Charles and Mary Lamb | 275 |

| PART III Ideals and Heroes of Freedom |

||

| Introduction | 289 | |

| SCOTLAND’S STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE | ||

| Tales of a Grandfather | Sir Walter Scott | 293 |

| The Story of Sir William Wallace | 293 | |

| Robert the Bruce | 301 | |

| The Battle of Bannockburn | 311 | |

| Exploits of Douglas and Randolph | 318 | |

| The Parting of Marmion and Douglas | Sir Walter Scott | 325 |

| Bruce’s Address at Bannockburn | Robert Burns | 328 |

| ENGLAND AND FREEDOM | ||

| The Last Fight of the Revenge | Sir Walter Raleigh | 330 |

| Ye Mariners of England | Thomas Campbell | 336 |

| England and America Natural Allies | John Richard Green | 338 |

| England and America in 1782 | Alfred, Lord Tennyson | 340 |

| England To Free Men | John Galsworthy | 341 |

| [vii]Men Who March Away | Thomas Hardy | 343 |

| EARLY AMERICAN SPIRIT OF FREEDOM | ||

| Grandfather’s Chair | Nathaniel Hawthorne | 345 |

| How New England Was Governed | 345 | |

| The Pine-tree Shillings | 349 | |

| The Stamp Act | 354 | |

| British Soldiers Stationed in Boston | 359 | |

| The Boston Massacre | 364 | |

| Some Famous Portraits | 370 | |

| The Gray Champion | Nathaniel Hawthorne | 376 |

| Warren’s Address at Bunker Hill | John Pierpont | 385 |

| Liberty Or Death | Patrick Henry | 386 |

| George Washington To His Wife | 390 | |

| George Washington To Governor Clinton | 393 | |

| Song of Marion’s Men | William Cullen Bryant | 395 |

| Times That Try Men’s Souls | Thomas Paine | 397 |

| PART IV Literature and Life in the Homeland |

||

| Introduction | 403 | |

| EARLY AMERICA | ||

| The Character of Columbus | Archbishop Corrigan | 405 |

| The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers | Felicia Hemans | 407 |

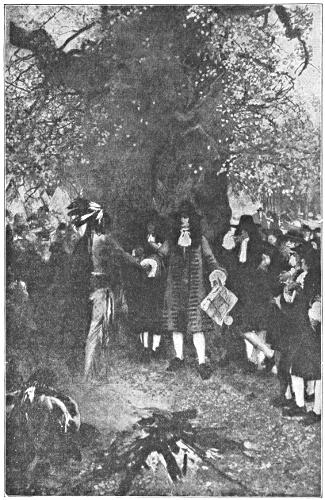

| Philip of Pokanoket | Washington Irving | 409 |

| The Courtship of Miles Standish | Henry W. Longfellow | 427 |

| AMERICAN SCENES AND LEGENDS | ||

| My Visit To Niagara | Nathaniel Hawthorne | 466 |

| On a Florida River | Sidney Lanier | 473 |

| I Sigh for the Land of the Cypress | Samuel Henry Dickson | 477 |

| The Legend of Sleepy Hollow | Washington Irving | 479 |

| The Great Stone Face | Nathaniel Hawthorne | 510 |

| AMERICAN LITERATURE OF LIGHTER VEIN | ||

| The Celebrated Jumping Frog | Mark Twain | 531 |

| The Height of the Ridiculous | Oliver Wendell Holmes | 538 |

| The Gift of the Magi | O. Henry | 541 |

| The Renowned Wouter van Twiller | Washington Irving | 547 |

| AMERICAN WORKERS AND THEIR WORK | ||

| Makers of the Flag | Franklin K. Lane | 553 |

| I Hear America Singing | Walt Whitman | 556 |

| Pioneers! O Pioneers! | Walt Whitman | 557 |

| The Beanfield | Henry David Thoreau | 559 |

| Ship-builders | John Greenleaf Whittier | 562 |

| [viii]The Builders | Henry W. Longfellow | 566 |

| LOVE OF COUNTRY | ||

| The Flower of Liberty | Oliver Wendell Holmes | 568 |

| Old Ironsides | Oliver Wendell Holmes | 570 |

| The American Flag | Henry Ward Beecher | 572 |

| The American Flag | Joseph Rodman Drake | 574 |

| The Flag Goes By | Henry H. Bennett | 577 |

| The Star-spangled Banner | Francis Scott Key | 578 |

| Citizenship | William Pierce Frye | 580 |

| The Character of Washington | Thomas Jefferson | 583 |

| The Twenty-second of February | William Cullen Bryant | 586 |

| Abraham Lincoln | Richard H. Stoddard | 587 |

| O Captain! My Captain! | Walt Whitman | 588 |

| In Flanders Fields | John D. McCrae | 590 |

| America’s Answer | R. W. Lillard | 591 |

| Glossary | 592 | |

THE LITERATURE SERIES

for the Junior High School

The complete series includes:

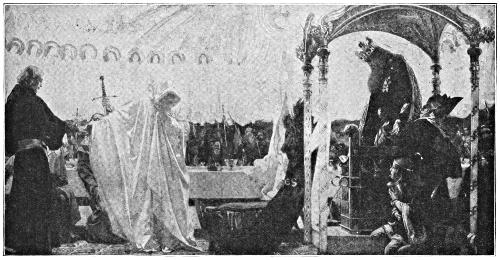

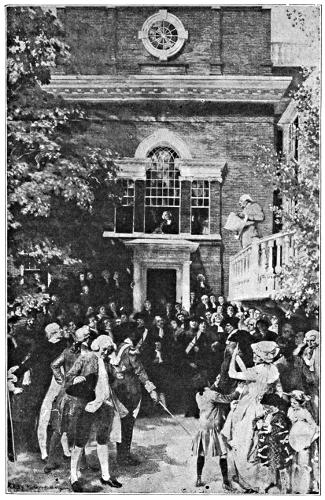

The picture on this page is called “A Reading from Homer.” Study each of the people who form the group. Judging from their dress and appearance, do you think they are people of the present time or of the ancient world? From what sort of book is the poet reading? Should you think such “books” could be owned by all sorts of people, or only by a few? Study the reader’s expression. What sort of story do you think he is reading? Can you decide anything about the listeners, who they are and what they are thinking about? Who is most deeply interested in the story, and why?

A READING FROM HOMER

Men do brave deeds on the sea, in far-off lands, or in war, and these deeds are the subject of song and story. Youths who are looking forward to heroic careers, and men and women to whom life has brought few thrilling experiences, like to hear these tales. A well-told story opens the door to a new pleasure in living. An animal knows only the present. He is hungry, or tired, or his life is in danger, or he is well fed and sleepy. But boys and girls,[x] and grown-ups, too, have not only their daily experience to draw upon, but through books and magazines and papers they can enter into the experience of others, so that they may live many lives in one.

Aladdin had a wonderful lamp. By rubbing it he could be anywhere he chose or could possess anything he desired. Such a lamp the reader of good books possesses. You come in from work or play, curl yourself up in a big chair before the fire, open your book, and in a twinkling you are whisked away to a new world. Your body is there, curled up before the fire, but enchantment has come upon you. In imagination you are with Sindbad the Sailor, or with Robinson Crusoe, or with King Arthur, or you are in the Indian Jungle, or on a ship sailing the South Seas, or you are hunting for Treasure Island. And you have it in your power to take these wonderful trips instantly; no railway tickets are required, no long delays. You may go on a journey to the other side of the world or into the South Polar ice or out on a western ranch. What is more wonderful, you may go back a century, or ten centuries; through this Aladdin’s lamp of reading you are master not only of space, but also of time. Thus the first joy of reading is the privilege of taking part in the experiences of men of every time and every portion of the world. You multiply your life, and the product is richness and joy.

The second joy of reading is even greater. Not only the world of adventure is open to you by means of books, but also a life enriched by the wisdom that has been gathered from a thousand poets and historians as bees gather honey from a thousand flowers. There is a story of a great Italian of the sixteenth century who found himself in the prime of life without a position, without money, and even compelled to become an exile because of a revolution. He retired to a farm remote from all the scenes in which his previous life had been passed. All day he worked hard, for only by hard work could he live. But in the evenings, when work was done, when horses and oxen and the laborers who had toiled with them all the day had gone to sleep, this man put on the splendid court dress he had worn in the days of his prosperity, days when he had associated with princes and the great ones of the[xi] earth, and so garbed he went into his library and shut the door. And then, he tells us, for four hours he lived amid the scenes that his books called up before him. He found in books an Aladdin’s lamp that transported him to past times, that revealed the secrets of nature, that showed him what men had accomplished. Through history, he re-created the past. He could call on the wisest of men for counsel, and he forgot during these hours his weariness and pain.

This story of the great Italian has been paralleled many times. There was once a boy in a frontier cabin who had no such experience as this man passed through centuries ago, but who was eager to know all that could be learned about life. His days were long and hard, but he was dreaming of things to come. At night by the light of the pine logs blazing in the fireplace, this boy read and studied. Books were hard to get; sometimes he tramped for miles to borrow one that he had heard a distant farmer possessed. Thus Lincoln found the second of the joys of reading, the stored-up wisdom of the race that he appropriated against the day when he was to be not merely a student of history but a maker of history as well.

THE SONG OF THE LARK

The third joy of reading is that through books our eyes are opened to the beauty of the world in which we live. There is a famous painting called “The Song of the Lark.” A peasant girl is on her way to work in the fields, sickle in hand, in early morning. She has stopped to listen to the flood of melody that pours from the sky above her, and is trying in vain to see the bird which is singing the glorious song. Her dull, unexpressive face is lighted up for the moment in the presence of a beauty that she feels but does not comprehend. So the painter interprets[xii] for us the effect of beauty upon even a dull intelligence. But the poet translates the song into beautiful language, and we read and are happy.

Thousands of people pass unthinkingly by a field filled with the common daisies. They know the name of the flower; they may even say, or think, that the flowers make a pretty sight. But a poor young poet plows one up on his farm and tells us of his sympathy for the little flower he has destroyed; tells us, too, how the fate of the daisy suggests to him his own fate, so that all who read the poem by Robert Burns no longer see in the daisy a common flower, but see instead a symbol of beauty.

Bird-song and flower, the west wind as it drives the dead leaves before it or hurries the clouds across the sky or piles up in great masses the waters of the sea; the mountain that rises stark and stern above the plain, the ocean over which men’s ships pass in safety or into whose depths they plunge to their grave—all these things the poet helps us to see and to feel. So once more our Aladdin’s lamp brings us into scenes of enchantment, multiplies our lives, opens our eyes to things that the fairy-folk know right well, but which are forbidden to mortal eye and ear until the spell has worked its will.

These, then, are the three joys of reading: First, to be able to travel at will in any country and in any period of time and to taste the salt of adventure; to hear the great stories that the human race has garnered through centuries of living; to know earth’s heroes and to become a part of the company that surrounds them. Second, to enter into the inheritance of wisdom that has come down from ancient times or that animates those who are the builders of our present world. “Histories make men wise,” said one of the wisest of men, by which he meant that history records the experience of men in their attempts to make the world a place where people may dwell together in safety, and that as men reflect on this experience they become wiser. And poets and prose writers, too, have told in books what they have thought to be the meaning of life. They are like the wise old hermits, dwelling in little cabins by the edge of the enchanted forest, who told Sir Galahad or Sir Gawain or Sir Lancelot about the perils of the forest[xiii] and how to win their way to the enchanted castle where dwelt the Queen.

And the third joy of reading is that which brings us knowledge of this enchanted world. For it is a world of wonder in which we live as truly as that fairy world which so delighted you when Mother told you stories or when you read your fairy books. The journey of Captain Scott in search of the South Pole was as thrilling as the voyage of Sinbad. Those brave men who made the first flight in an airplane across the ocean the other day were as venturesome as Columbus, and their journey was as wonderful as that journey in 1492. But Captain Scott did not leave his comfortable and safe life at home merely to seek adventure. It was an expedition planned in order that he might bring back exact information about parts of the earth where men had never been before. And the flight across the Atlantic was just one more step in the development of a new form of transportation. So science contributes in many ways to our happiness and safety. What men do to develop the resources of the earth, what they do to conquer disease, the inventions and discoveries that give us greater power than if we possessed the open sesame of our fairy stories—these also you learn about in your reading.

The book to which you are here introduced is planned in such a way as to help you find these three joys of reading. It is a big generous book, filled with good things. It is an Aladdin’s lamp. Take it to your favorite big chair or to your favorite corner and test it. Do you wish to get into the Enchanted Forest? The very first selections, about animals and birds and growing things, take you there where you will find friends old and new. Do you wish to go on a long journey back to King Arthur’s time and meet the knights of the Round Table? The power is yours for the asking. Or if you prefer songs and stories of the sea, here is a ballad that has been sung for centuries, or you may have ballads about battles in the war that ended the other day. And no one knew the secrets of the Enchanted Forest better than William Shakespeare—here are two stories that he loved.

At some other time your book will take you back to the days of Wallace and Bruce, or will bring before you some of the things[xiv] England has done for Freedom, or will show you what Americans of the old time did and thought when they were building their free land for you to dwell in and to protect. And, last of all, there are stories of life in our America—old legends and stories that will make you smile, and stories of workers and their work. When you have finished the last section you will be happier and a better citizen, ready to do your share every chance you get.

One word more. You know that, in order to work enchantment, people have had to do certain things. There was the fern-seed, you know, or the charm like “open sesame,” or you have to rub the wonderful lamp. Now to use this book rightly, you must not think of it as a lesson book, containing tasks. If you do that, it will be no Aladdin’s lamp at all but just a dull old smoky lamp that would not even guide you to the cellar. You must do these things: First, get that chair or that corner and make yourself comfortable. Second, look at the program. What is that? Why, the “Table of Contents,” of course. You must know where you are going and what you are to see. In this book everything is arranged in such a way as to help the charm to work. Third, you will find little questions and studies every now and then, and a glossary, guide-posts so that you will not lose your way. And, last of all, you are to try to see the book as a whole and not as a sort of scrapbook about all sorts of things. For it all deals, in one way or another, with the Enchanted Forest and the Castle of Life.

From a Thistle Print, Copyright Detroit Publishing Co.

AUTUMN WOODS—PAINTING BY GEORGE INNESS

Four days on the Platte, and yet no buffalo! The wagons one morning had left the camp; Shaw and I were already on horseback, but Henry Chatillon still sat cross-legged by the dead embers of the fire, playing pensively with the lock of his rifle, while his sturdy Wyandot pony stood quietly behind him, looking over his head. At last he got up, patted the neck of the pony (whom, from an exaggerated appreciation of his merits, he had christened “Five Hundred Dollar”), and then mounted with a melancholy air.

“What is it, Henry?”

“Ah, I feel lonesome; I never been here before; but I see away yonder over the buttes, and down there on the prairie, black—all black with buffalo!”

In the afternoon he and I left the party in search of an antelope; until, at the distance of a mile or two on the right, the tall white wagons and the little black specks of horsemen were just visible, so slowly advancing that they seemed motionless; and far on the left rose the broken line of scorched, desolate sand-hills.[2] The vast plain waved with tall rank grass that swept our horses’ bellies; it swayed to and fro in billows with the light breeze, and far and near, antelope and wolves were moving through it, the hairy backs of the latter alternately appearing and disappearing as they bounded awkwardly along; while the antelope, with the simple curiosity peculiar to them, would often approach us closely, their little horns and white throats just visible above the grass tops as they gazed eagerly at us with their round, black eyes.

I dismounted, and amused myself with firing at the wolves. Henry attentively scrutinized the surrounding landscape; at length he gave a shout, and called on me to mount again, pointing in the direction of the sand-hills. A mile and a half from us, two minute black specks slowly traversed the face of one of the bare, glaring declivities, and disappeared behind the summit. “Let us go!” cried Henry, belaboring the sides of Five Hundred Dollar; and I following in his wake, we galloped rapidly through the rank grass toward the base of the hills.

From one of their openings descended a deep ravine, widening as it issued on the prairie. We entered it, and galloping up, in a moment were surrounded by the bleak sand-hills. Half of their steep sides were bare; the rest were scantily clothed with clumps of grass and various uncouth plants, conspicuous among which appeared the reptile-like prickly-pear. They were gashed with numberless ravines; and as the sky had suddenly darkened and a cold gusty wind arisen, the strange shrubs and the dreary hills looked doubly wild and desolate. But Henry’s face was all eagerness. He tore off a little hair from the piece of buffalo robe under his saddle, and threw it up, to show the course of the wind. It blew directly before us. The game were therefore to windward, and it was necessary to make our best speed to get round them.

We scrambled from this ravine, and galloping away through the hollows, soon found another, winding like a snake among the hills, and so deep that it completely concealed us. We rode up the bottom of it, glancing through the shrubbery at its edge, till Henry abruptly jerked his rein and slid out of his saddle. Full a quarter of a mile distant, on the outline of the farthest[3] hill, a long procession of buffalo were walking, in Indian file, with the utmost gravity and deliberation; then more appeared, clambering from a hollow not far off, and ascending, one behind the other, the grassy slope of another hill; then a shaggy head and a pair of short, broken horns appeared, issuing out of a ravine close at hand, and with a slow, stately step, one by one, the enormous brutes came into view, taking their way across the valley, wholly unconscious of an enemy. In a moment Henry was worming his way, lying flat on the ground, through grass and prickly-pears, toward his unsuspecting victims. He had with him both my rifle and his own. He was soon out of sight, and still the buffalo kept issuing into the valley. For a long time all was silent; I sat holding his horse, and wondering what he was about, when suddenly, in rapid succession, came the sharp reports of the two rifles, and the whole line of buffalo, quickening their pace into a clumsy trot, gradually disappeared over the ridge of the hill. Henry rose to his feet, and stood looking after them.

“You have missed them,” said I.

“Yes,” said Henry; “let us go.” He descended into the ravine, loaded the rifles, and mounted his horse.

We rode up the hill after the buffalo. The herd was out of sight when we reached the top, but lying on the grass not far off was one quite lifeless, and another violently struggling in the death agony.

“You see I miss him!” remarked Henry. He had fired from a distance of more than a hundred and fifty yards, and both balls had passed through the lungs—the true mark in shooting buffalo.

The darkness increased, and a driving storm came on. Tying our horses to the horns of the victims, Henry began the bloody work of dissection, slashing away with the science of a connoisseur, while I vainly endeavored to imitate him. Old Hendrick recoiled with horror and indignation when I endeavored to tie the meat to the strings of rawhide, always carried for this purpose, dangling at the back of the saddle. After some difficulty we overcame his scruples; and heavily burdened with the more eligible portions of the buffalo, we set out on our return. Scarcely had we emerged from the labyrinth of gorges and ravines, and[4] issued upon the open prairie, when the pricking sleet came driving, gust upon gust, directly in our faces. It was strangely dark, though wanting still an hour of sunset. The freezing storm soon penetrated to the skin, but the uneasy trot of our heavy-gaited horses kept us warm enough, as we forced them unwillingly in the teeth of the sleet and rain by the powerful suasion of our Indian whips. The prairie in this place was hard and level. A flourishing colony of prairie dogs had burrowed into it in every direction, and the little mounds of fresh earth around their holes were about as numerous as the hills in a cornfield; but not a yelp was to be heard; not the nose of a single citizen was visible; all had retired to the depths of their burrows, and we envied them their dry and comfortable habitations. An hour’s hard riding showed us our tent dimly looming through the storm, one side puffed out by the force of the wind, and the other collapsed in proportion, while the disconsolate horses stood shivering close around, and the wind kept up a dismal whistling in the boughs of three old, half-dead trees above. Shaw, like a patriarch, sat on his saddle in the entrance, with a pipe in his mouth and his arms folded, contemplating with cool satisfaction the piles of meat that we flung on the ground before him. A dark and dreary night succeeded; but the sun rose with a heat so sultry and languid that the captain excused himself on that account from waylaying an old buffalo bull, who with stupid gravity was walking over the prairie to drink at the river. So much for the climate of the Platte!

But it was not the weather alone that had produced this sudden abatement of the sportsmanlike zeal which the captain had always professed. He had been out on the afternoon before, together with several members of his party; but their hunting was attended with no other result than the loss of one of their best horses, severely injured by Sorel in vainly chasing a wounded bull. The captain, whose ideas of hard riding were all derived from transatlantic sources, expressed the utmost amazement at the feats of Sorel, who went leaping ravines and dashing at full speed up and down the sides of precipitous hills, lashing his horse[5] with the recklessness of a Rocky Mountain rider. Unfortunately for the poor animal, he was the property of R., against whom Sorel entertained an unbounded aversion. The captain himself, it seemed, had also attempted to “run” a buffalo, but though a good and practiced horseman, he had soon given over the attempt, being astonished and utterly disgusted at the nature of the ground he was required to ride over.

Nothing unusual occurred on that day; but on the following morning Henry Chatillon, looking over the ocean-like expanse, saw near the foot of the distant hills something that looked like a band of buffalo. He was not sure, he said, but at all events, if they were buffalo there was a fine chance for a race. Shaw and I at once determined to try the speed of our horses.

“Come, captain; we’ll see which can ride hardest, a Yankee or an Irishman.”

But the captain maintained a grave and austere countenance. He mounted his led horse, however, though very slowly, and we set out at a trot. The game appeared about three miles distant. As we proceeded, the captain made various remarks of doubt and indecision, and at length declared he would have nothing to do with such a breakneck business; protesting that he had ridden plenty of steeple-chases in his day, but he never knew what riding was till he found himself behind a band of buffalo the day before yesterday. “I am convinced,” said the captain, “that ‘running’ is out of the question. Take my advice now and don’t attempt it. It’s dangerous, and of no use at all.”

“Then why did you come out with us? What do you mean to do?”

“I shall ‘approach,’” replied the captain.

“You don’t mean to ‘approach’ with your pistols, do you? We have all of us left our rifles in the wagons.”

The captain seemed staggered at the suggestion. In his characteristic indecision, at setting out, pistols, rifles, “running,” and “approaching” were mingled in an inextricable medley in his brain. He trotted on in silence between us for a while; but at length he dropped behind, and slowly walked his horse back to rejoin the party. Shaw and I kept on; when lo! as we advanced,[6] the band of buffalo were transformed into certain clumps of tall bushes, dotting the prairie for a considerable distance. At this ludicrous termination of our chase, we followed the example of our late ally and turned back toward the party. We were skirting the brink of a deep ravine, when we saw Henry and the broad-chested pony coming toward us at a gallop.

“Here’s old Papin and Frederic, down from Fort Laramie!” shouted Henry, long before he came up. We had for some days expected this encounter. Papin was the bourgeois of Fort Laramie. He had come down the river with the buffalo robes and the beaver, the produce of the last winter’s trading. I had among our baggage a letter which I wished to commit to their hands; so, requesting Henry to detain the boats if he could until my return, I set out after the wagons. They were about four miles in advance. In half an hour I overtook them, got the letter, trotted back upon the trail, and looking carefully as I rode, saw a patch of broken, storm-blasted trees, and moving near them some little black specks like men and horses. Arriving at the place, I found a strange assembly. The boats, eleven in number, deep-laden with the skins, hugged close to the shore to escape being borne down by the swift current. The rowers, swarthy, ignoble Mexicans, turned their brutish faces upward to look as I reached the bank. Papin sat in the middle of one of the boats upon the canvas covering that protected the robes. He was a stout, robust fellow, with a little gray eye that had a peculiarly sly twinkle. “Frederic” also stretched his tall, rawboned proportions close by the bourgeois, and “mountain-men” completed the group; some lounging in the boats, some strolling on shore; some attired in gayly painted buffalo robes like Indian dandies; some with hair saturated with red paint, and beplastered with glue to their temples; and one bedaubed with vermilion upon his forehead and each cheek. They were a mongrel race, yet the French blood seemed to predominate; in a few, indeed, might be seen the black, snaky eye of the Indian half-breed; and one and all, they seemed to aim at assimilating themselves to their savage associates.

I shook hands with the bourgeois and delivered the letter;[7] then the boats swung around into the stream and floated away. They had reason for haste, for already the voyage from Fort Laramie had occupied a full month, and the river was growing daily more shallow. Fifty times a day the boats had been aground; indeed, those who navigate the Platte invariably spend half their time upon sand-bars. Two of these boats, the property of private traders, afterward separating from the rest, got hopelessly involved in the shallows, not very far from the Pawnee villages, and were soon surrounded by a swarm of the inhabitants. They carried off everything that they considered valuable, including most of the robes; and amused themselves by tying up the men left on guard, and soundly whipping them with sticks.

We encamped that night upon the bank of the river. Among the emigrants there was an overgrown boy, some eighteen years old, with a head as round and about as large as a pumpkin, and fever-and-ague fits had dyed his face of a corresponding color. He wore an old white hat, tied under his chin with a handkerchief; his body was short and stout, but his legs of disproportioned and appalling length. I observed him at sunset breasting the hill with gigantic strides, and standing against the sky on the summit like a colossal pair of tongs. In a moment after, we heard him screaming frantically behind the ridge, and nothing doubting that he was in the clutches of Indians or grizzly bears, some of the party caught up their rifles and ran to the rescue. His outcries, however, proved but an ebullition of joyous excitement; he had chased two little wolf pups to their burrow, and he was on his knees, grubbing away like a dog at the mouth of the hole, to get at them.

Before morning he caused more serious disquiet in the camp. It was his turn to hold the middle guard; but no sooner was he called up than he coolly arranged a pair of saddle-bags under a wagon, laid his head upon them, closed his eyes, opened his mouth, and fell asleep. The guard on our side of the camp, thinking it no part of his duty to look after the cattle of the emigrants, contented himself with watching our own horses and mules; the wolves, he said, were unusually noisy; but still no mischief was[8] anticipated, until the sun rose, and not a hoof or horn was in sight! The cattle were gone! While Tom was quietly slumbering, the wolves had driven them away.

Then we reaped the fruits of R.’s precious plan of traveling in company with emigrants. To leave them in their distress was not to be thought of, and we felt bound to wait until the cattle could be searched for, and, if possible, recovered. But the reader may be curious to know what punishment awaited the faithless Tom. By the wholesome law of the prairie, he who falls asleep on guard is condemned to walk all day, leading his horse by the bridle, and we found much fault with our companions for not enforcing such a sentence on the offender. Nevertheless, had he been of our own party, I have no doubt he would in like manner have escaped scot-free. But the emigrants went further than mere forbearance; they decreed that since Tom couldn’t stand guard without falling asleep, he shouldn’t stand guard at all, and henceforward his slumbers were unbroken. Establishing such a premium on drowsiness could have no very beneficial effect upon the vigilance of our sentinels; for it is far from agreeable, after riding from sunrise to sunset, to feel your slumbers interrupted by the butt of a rifle nudging your side, and a sleepy voice growling in your ear that you must get up, to shiver and freeze for three weary hours at midnight.

“Buffalo! buffalo!” It was but a grim old bull, roaming the prairie by himself in misanthropic seclusion; but there might be more behind the hills. Dreading the monotony and languor of the camp, Shaw and I saddled our horses, buckled our holsters in their places, and set out with Henry Chatillon in search of the game. Henry, not intending to take part in the chase, but merely conducting us, carried his rifle with him, while we left ours behind as incumbrances. We rode for some five or six miles, and saw no living thing but wolves, snakes, and prairie dogs.

“This won’t do at all,” said Shaw.

“What won’t do?”

“There’s no wood about here to make a litter for the wounded[9] man; I have an idea that one of us will need something of the sort before the day is over.”

There was some foundation for such an apprehension, for the ground was none of the best for a race, and grew worse continually as we proceeded; indeed it soon became desperately bad, consisting of abrupt hills and deep hollows, cut by frequent ravines not easy to pass. At length, a mile in advance, we saw a band of bulls. Some were scattered grazing over a green declivity, while the rest were crowded more densely together in the wide hollow below. Making a circuit to keep out of sight, we rode toward them until we ascended a hill within a furlong of them, beyond which nothing intervened that could possibly screen us from their view. We dismounted behind the ridge just out of sight, drew our saddle-girths, examined our pistols, and mounting again rode over the hill and descended at a canter toward them, bending close to our horses’ necks. Instantly they took the alarm; those on the hill descended; those below gathered into a mass, and the whole got in motion, shouldering each other along at a clumsy gallop. We followed, spurring our horses to full speed; and as the herd rushed, crowding and trampling in terror through an opening in the hills, we were close at their heels, half suffocated by the clouds of dust. But as we drew near, their alarm and speed increased; our horses showed signs of the utmost fear, bounding violently aside as we approached, and refusing to enter among the herd. The buffalo now broke into several small bodies, scampering over the hills in different directions, and I lost sight of Shaw; neither of us knew where the other had gone. Old Pontiac ran like a frantic elephant up hill and down hill, his ponderous hoofs striking the prairie like sledge-hammers. He showed a curious mixture of eagerness and terror, straining to overtake the panic-stricken herd, but constantly recoiling in dismay as we drew near. The fugitives, indeed, offered no very attractive spectacle, with their enormous size and weight, their shaggy manes and the tattered remnants of their last winter’s hair covering their backs in irregular shreds and patches, and flying off in the wind as they ran. At length I urged my horse close behind a bull, and after trying in vain, by blows and spurring, to[10] bring him alongside, I shot a bullet into the buffalo from this disadvantageous position. At the report, Pontiac swerved so much that I was again thrown a little behind the game. The bullet, entering too much in the rear, failed to disable the bull, for a buffalo requires to be shot at particular points or he will certainly escape. The herd ran up a hill, and I followed in pursuit. As Pontiac rushed headlong down on the other side, I saw Shaw and Henry descending the hollow on the right at a leisurely gallop; and in front, the buffalo were just disappearing behind the crest of the next hill, their short tails erect and their hoofs twinkling through a cloud of dust.

At that moment I heard Shaw and Henry shouting to me; but the muscles of a stronger arm than mine could not have checked at once the furious course of Pontiac, whose mouth was as insensible as leather. Added to this, I rode him that morning with a common snaffle, having the day before, for the benefit of my other horse, unbuckled from my bridle the curb which I ordinarily used. A stronger and hardier brute never trod the prairie; but the novel sight of the buffalo filled him with terror, and when at full speed he was almost incontrollable. Gaining the top of the ridge, I saw nothing of the buffalo; they had all vanished amid the intricacies of the hills and hollows. Reloading my pistols in the best way I could, I galloped on until I saw them again scuttling along at the base of the hill, their panic somewhat abated. Down went old Pontiac among them, scattering them to the right and left, and then we had another long chase. About a dozen bulls were before us, scouring over the hills, rushing down the declivities with tremendous weight and impetuosity, and then laboring with a weary gallop upward. Still Pontiac, in spite of spurring and beating, would not close with them. One bull at length fell a little behind the rest, and by dint of much effort I urged my horse within six or eight yards of his side. His back was darkened with sweat, and he was panting heavily, while his tongue lolled out a foot from his jaws. Gradually I came up abreast of him, urging Pontiac with leg and rein nearer to his side, when suddenly he did what buffalo in such circumstances will always do: he slackened his gallop, and turning toward us with an aspect of[11] mingled rage and distress, lowered his huge shaggy head for a charge. Pontiac, with a snort, leaped aside in terror, nearly throwing me to the ground, as I was wholly unprepared for such an evolution. I raised my pistol in a passion to strike him on the head, but thinking better of it, fired the bullet after the bull, who had resumed his flight; then drew rein, and determined to rejoin my companions. It was high time. The breath blew hard from Pontiac’s nostrils, and the sweat rolled in big drops down his sides; I myself felt as if drenched in warm water. Pledging myself (and I redeemed the pledge) to take my revenge at a future opportunity, I looked round for some indications to show me where I was, and what course I ought to pursue. I might as well have looked for landmarks in the midst of the ocean. How many miles I had run or in what direction, I had no idea; and around me the prairie was rolling in steep swells and pitches, without a single distinctive feature to guide me. I had a little compass hung at my neck; and ignorant that the Platte at this point diverged considerably from its easterly course, I thought that by keeping to the northward I should certainly reach it. So I turned and rode about two hours in that direction. The prairie changed as I advanced, softening away into easier undulations, but nothing like the Platte appeared, nor any sign of a human being; the same wild endless expanse lay around me still; and to all appearance I was as far from my object as ever. I began now to consider myself in danger of being lost; and therefore, reining in my horse, summoned the scanty share of woodcraft that I possessed (if that term be applicable upon the prairie) to extricate me. Looking round, it occurred to me that the buffalo might prove my best guides. I soon found one of the paths made by them in their passage to the river; it ran nearly at right angles to my course; but turning my horse’s head in the direction it indicated, his freer gait and erected ears assured me that I was right.

But in the meantime my ride had been by no means a solitary one. The whole face of the country was dotted far and wide with countless hundreds of buffalo. They trooped along in files and columns, bulls, cows, and calves, on the green faces of the[12] declivities in front. They scrambled away over the hills to the right and left; and far off, the pale blue swells in the extreme distance were dotted with innumerable specks. Sometimes I surprised shaggy old bulls grazing alone, or sleeping behind the ridges I ascended. They would leap up at my approach, stare stupidly at me through their tangled manes, and then gallop heavily away. The antelope were very numerous; and as they are always bold when in the neighborhood of buffalo, they would approach quite near to look at me, gazing intently with their great round eyes, then suddenly leap aside and stretch lightly away over the prairie as swiftly as a racehorse. Squalid, ruffian-like wolves sneaked through the hollows and sandy ravines. Several times I passed through villages of prairie dogs, who sat, each at the mouth of his burrow, holding his paws before him in a supplicating attitude and yelping away most vehemently, energetically whisking his little tail with every squeaking cry he uttered. Prairie dogs are not fastidious in their choice of companions; various long, checkered snakes were sunning themselves in the midst of the village, and demure little gray owls, with a large white ring around each eye, were perched side by side with the rightful inhabitants. The prairie teemed with life. Again and again I looked toward the crowded hillsides, and was sure I saw horsemen; and riding near, with a mixture of hope and dread, for Indians were abroad, I found them transformed into a group of buffalo. There was nothing in human shape amid all this vast congregation of brute forms.

When I turned down the buffalo path, the prairie seemed changed; only a wolf or two glided past at intervals, like conscious felons, never looking to the right or left. Being now free from anxiety, I was at leisure to observe minutely the objects around me; and here, for the first time, I noticed insects wholly different from any of the varieties found farther to the eastward. Gaudy butterflies fluttered about my horse’s head; strangely formed beetles, glittering with metallic luster, were crawling upon plants that I had never seen before; multitudes of lizards, too, were darting like lightning over the sand.

I had run to a great distance from the river. It cost me a long[13] ride on the buffalo path before I saw from the ridge of a sand-hill the pale surface of the Platte glistening in the midst of its desert valleys, and the faint outline of the hills beyond waving along the sky. From where I stood, not a tree nor a bush nor a living thing was visible throughout the whole extent of the sun-scorched landscape. In half an hour I came upon the trail, not far from the river; and seeing that the party had not yet passed, I turned eastward to meet them, old Pontiac’s long, swinging trot again assuring me that I was right in doing so. Having been slightly ill on leaving camp in the morning, six or seven hours of rough riding had fatigued me extremely. I soon stopped, therefore; flung my saddle on the ground, and with my head resting on it, and my horse’s trail-rope tied loosely to my arm, lay waiting the arrival of the party, speculating meanwhile on the extent of the injuries Pontiac had received. At length the white wagon coverings rose from the verge of the plain. By a singular coincidence, almost at the same moment two horsemen appeared coming down from the hills. They were Shaw and Henry, who had searched for me a while in the morning, but well knowing the futility of the attempt in such a broken country, had placed themselves on the top of the highest hill they could find, and picketing their horses near them, as a signal to me, had lain down and fallen asleep.

Biographical and Historical Note. Francis Parkman (1823-1893) was an American writer, born in Boston, where his father was a well-known clergyman. At the age of eight years he went to live with his grandfather on a wild tract of land near Boston, and there developed the fondness for outdoor life which is shown in all his writings. Parkman was graduated from Harvard College in 1844, and from the Harvard Law School two years later, but he never practiced law. The journey related in his book, The Oregon Trail, from which “The Buffalo” is taken, was made immediately after Parkman completed his law studies. His purpose was to gain an intimate knowledge of Indian life. From the Missouri River two great overland routes led across the country to the Pacific. One, the Santa Fe trail, carried a large overland trade with northern Mexico and southern California; the other, the Oregon trail, was commonly used by emigrants on their way to the northwest coast. Parkman’s journey occupied about five months.[14] He left Boston in April, 1846, accompanied by Quincy Adams Shaw, a relative, and went first to St. Louis, the trip by railroad, steamboat, and stage requiring about two weeks. Here they engaged two guides and procured an outfit, including a supply of presents for the Indians. After eight days on a river steamboat they arrived at Independence, Missouri, where the land journey began.

In a newspaper item of March tenth, 1919, the following appeared: “For the first time in half a century bisons are on sale in Omaha. A herd of thirty-three, raised on a Colorado ranch, arrived at the stock yards yesterday. The meat will sell for around $1.00 a pound.”

Discussion. 1. Locate on a map the Platte River and the region mentioned in the story. 2. What picture do you see as you read the fourth paragraph? 3. Briefly relate the incident of the first afternoon’s hunting trip. 4. What objections to traveling with emigrants did the party find? 5. What do you learn of prairie animals from this story? 6. Read the description of the prairie dog found on page 12; why is this description a good one? 7. What insects that differ from those found farther east does the author mention? 8. Point out lines that show Parkman to be excellent in description. 9. Compare travel at the time the author made this trip with travel at the present time. 10. Pronounce the following: alternately; minute; reptile; patriarch; inextricably; ally; robust; squalid; pumpkin; lolled; applicable; vehemently; buttes; gorges; circuit.

Phrases

(The numbers in heavy type refer to pages; numbers in light type to lines.)

Transcriber’s Note: This notation has not been reproduced in this e-text. The first number refers to the page, the second to the line. Links are provided to each phrase.

The king of the game beasts of temperate North America, because the most dangerous to the hunter, is the grizzly bear; known to the few remaining old-time trappers of the Rockies and the Great Plains, sometimes as “Old Ephraim” and sometimes as “Moccasin Joe”—the last in allusion to his queer, half-human footprints, which look as if made by some misshapen giant, walking in moccasins.

Bear vary greatly in size and color, no less than in temper and habits. Old hunters speak much of them in their endless talks over the camp-fires and in the snow-bound winter huts. They insist on many species; not merely the black and the grizzly, but the brown, the cinnamon, the gray, the silver-tip, and others with names known only in certain localities, such as the range bear, the roach-back, and the smut-face. But, in spite of popular opinion to the contrary, most old hunters are very untrustworthy in dealing with points of natural history. They usually know only so much about any given game animal as will enable them to kill it. They study its habits solely with this end in view; and once slain they only examine it to see about its condition and fur. With rare exceptions they are quite incapable of passing judgment upon questions of specific identity or difference. When questioned, they not only advance perfectly impossible theories and facts in support of their views, but they rarely even agree as to the views themselves. One hunter will assert that the true grizzly is only found in California, heedless of the fact that the name was first used by Lewis and Clark as one of the titles they applied to the large bears of the plains country round the Upper Missouri, a quarter of a century before the California grizzly was known to fame. Another hunter will call any big brindled bear a grizzly no matter where it is found; and he and his companions[16] will dispute by the hour as to whether a bear of large, but not extreme, size is a grizzly or a silver-tip. In Oregon the cinnamon bear is a phase of the small black bear; in Montana it is the plains variety of the large mountain silver-tip. I have myself seen the skins of two bears killed on the upper waters of Tongue River; one was that of a male, one of a female, and they had evidently just mated; yet one was distinctly a “silver-tip” and the other a “cinnamon.” The skin of one very big bear which I killed in the Bighorn has proved a standing puzzle to almost all the old hunters to whom I have shown it; rarely do any two of them agree as to whether it is a grizzly, a silver-tip, a cinnamon, or a “smut-face.” Any bear with unusually long hair on the spine and shoulders, especially if killed in the spring, when the fur is shaggy, is forthwith dubbed a “roach-back.” The average sporting writer, moreover, joins with the more imaginative members of the “old hunter” variety in ascribing wildly various traits to these different bears. One comments on the superior prowess of the roach-back; the explanation being that a bear in early spring is apt to be ravenous from hunger. The next insists that the California grizzly is the only really dangerous bear; while another stoutly maintains that it does not compare in ferocity with what he calls the “smaller” silver-tip or cinnamon. And so on, and so on, without end. All of which is mere nonsense.

Nevertheless, it is no easy task to determine how many species or varieties of bear actually do exist in the United States, and I cannot even say without doubt that a very large set of skins and skulls would not show a nearly complete intergradation between the most widely separated individuals. However, there are certainly two very distinct types, which differ almost as widely from each other as a wapiti does from a mule deer, and which exist in the same localities in most heavily timbered portions of the Rockies. One is the small black bear, a bear which will average about two hundred pounds weight, with fine, glossy, black fur, and the foreclaws but little longer than the hinder ones; in fact, the hairs of the forepaw often reach to their tips. This bear is a tree climber. It is the only kind found east of the great plains, and it is also plentiful in the forest-clad portions of the Rockies,[17] being common in most heavily timbered tracts throughout the United States. The other is the grizzly, which weighs three or four times as much as the black, and has a pelt of coarse hair, which is in color gray, grizzled, or brown of various shades. It is not a tree climber, and the foreclaws are very long, much longer than the hinder ones. It is found from the great plains west of the Mississippi to the Pacific coast. This bear inhabits indifferently lowland and mountain; the deep woods and the barren plains where the only cover is the stunted growth fringing the streams. These two types are very distinct in every way, and their differences are not at all dependent upon mere geographical considerations; for they are often found in the same district. Thus I found them both in the Bighorn Mountains, each type being in extreme form, while the specimens I shot showed no trace of intergradation. The huge, grizzled, long-clawed beast, and its little, glossy-coated, short-clawed, tree-climbing brother roamed over exactly the same country in those mountains; but they were as distinct in habits, and mixed as little together as moose and caribou.

On the other hand, when a sufficient number of bears from widely separated regions are examined, the various distinguishing marks are found to be inconstant and to show a tendency—exactly how strong I cannot say—to fade into one another. The differentiation of the two species seems to be as yet scarcely completed; there are more or less imperfect connecting links, and as regards the grizzly it almost seems as if the specific characters were still unstable. In the far Northwest, in the basin of the Columbia, the “black” bear is as often brown as any other color; and I have seen the skins of two cubs, one black and one brown, which were shot when following the same dam. When these brown bears have coarser hair than usual their skins are with difficulty to be distinguished from those of certain varieties of the grizzly. Moreover, all bears vary greatly in size; and I have seen the bodies of very large black or brown bears with short foreclaws which were fully as heavy as, or perhaps heavier than, some small but full-grown grizzlies with long foreclaws. These very large bears with short claws are very reluctant to climb a tree; and are[18] almost as clumsy about it as is a young grizzly. Among the grizzlies the fur varies much in color and texture even among bears of the same locality; it is of course richest in the deep forest, while the bears of the dry plains and mountains are of a lighter, more washed-out hue.

A full-grown grizzly will usually weigh from five to seven hundred pounds; but exceptional individuals undoubtedly reach more than twelve hundredweight. The California bears are said to be much the largest. This I think is so, but I cannot say it with certainty—at any rate, I have examined several skins of full-grown Californian bears which were no larger than those of many I have seen from the northern Rockies. The Alaskan bears, particularly those of the peninsula, are even bigger beasts; the skin of one which I saw in the possession of Mr. Webster, the taxidermist, was a good deal larger than the average polar bear skin; and the animal when alive, if in good condition, could hardly have weighed less than 1400 pounds. Bears vary wonderfully in weight, even to the extent of becoming half as heavy again, according as they are fat or lean; in this respect they are more like hogs than like any other animals.

The grizzly is now chiefly a beast of the high hills and heavy timber; but this is merely because he has learned that he must rely on cover to guard him from man, and has forsaken the open ground accordingly. In old days, and in one or two very out-of-the-way places almost to the present time, he wandered at will over the plains. It is only the wariness born of fear which nowadays causes him to cling to the thick brush of the large river bottoms throughout the plains country. When there were no rifle-bearing hunters in the land, to harass him and make him afraid, he roved hither and thither at will, in burly self-confidence. Then he cared little for cover, unless as a weather-break, or because it happened to contain food he liked. If the humor seized him he would roam for days over the rolling or broken prairie, searching for roots, digging up gophers, or perhaps following the great buffalo herds either to prey on some unwary[19] straggler which he was able to catch at a disadvantage in a washout, or else to feast on the carcasses of those which died by accident. Old hunters, survivors of the long-vanished ages when the vast herds thronged the high plains and were followed by the wild red tribes, and by bands of whites who were scarcely less savage, have told me that they often met bears under such circumstances; and these bears were accustomed to sleep in a patch of rank sage bush, in the niche of a washout, or under the lee of a bowlder, seeking their food abroad even in full daylight. The bears of the Upper Missouri basin—which were so light in color that the early explorers often alluded to them as gray or even as “white”—were particularly given to this life in the open. To this day that close kinsman of the grizzly known as the bear of the barren grounds continues to lead this same kind of life, in the far north. My friend, Mr. Rockhill, of Maryland, who was the first white man to explore eastern Tibet, describes the large grizzly-like bear of those desolate uplands as having similar habits.

However, the grizzly is a shrewd beast and shows the usual bear-like capacity for adapting himself to changed conditions. He has in most places become a cover-haunting animal, sly in his ways, wary to a degree, and clinging to the shelter of the deepest forests in the mountains and of the most tangled thickets in the plains. Hence he has held his own far better than such game as the bison and elk. He is much less common than formerly, but he is still to be found throughout most of his former range; save, of course, in the immediate neighborhood of the large towns.

In most places the grizzly hibernates, or, as old hunters say, “holes up,” during the cold season, precisely as does the black bear; but, as with the latter species, those animals which live farthest south spend the whole year abroad in mild seasons. The grizzly rarely chooses that favorite den of his little black brother, a hollow tree or log, for his winter sleep, seeking or making some cavernous hole in the ground instead. The hole is sometimes in a slight hillock in a river bottom, but more often on a hill-side, and may be either shallow or deep. In the mountains it is generally a natural cave in the rock, but among the foot-hills and on the plains the bear usually has to take some hollow or opening,[20] and then fashion it into a burrow to his liking with his big digging claws.

Before the cold weather sets in, the bear begins to grow restless, and to roam about seeking for a good place in which to hole up. One will often try and abandon several caves or partially dug-out burrows in succession before finding a place to its taste. It always endeavors to choose a spot where there is little chance of discovery or molestation, taking great care to avoid leaving too evident trace of its work. Hence it is not often that the dens are found.

Once in its den the bear passes the cold months in lethargic sleep; yet, in all but the coldest weather, and sometimes even then, its slumber is but light, and if disturbed it will promptly leave its den, prepared for fight or flight as the occasion may require. Many times when a hunter has stumbled on the winter resting-place of a bear and has left it, as he thought, without his presence being discovered, he has returned only to find that the crafty old fellow was aware of the danger all the time, and sneaked off as soon as the coast was clear. But in very cold weather hibernating bears can hardly be wakened from their torpid lethargy.

The length of time a bear stays in its den depends of course upon the severity of the season and the latitude and altitude of the country.

When the bear first leaves its den the fur is in very fine order, but it speedily becomes thin and poor, and does not recover its condition until the fall. Sometimes the bear does not betray any great hunger for a few days after its appearance; but in a short while it becomes ravenous. During the early spring, when the woods are still entirely barren and lifeless, while the snow yet lies in deep drifts, the lean, hungry brute, both maddened and weakened by long fasting, is more of a flesh eater than at any other time. It is at this period that it is most apt to turn true beast of prey, and show its prowess either at the expense of the wild game, or of the flocks of the settler and the herds of the ranchman. Bears are very capricious in this respect, however. Some are confirmed game and cattle killers; others are not; while[21] yet others either are or are not, accordingly as the freak seizes them, and their ravages vary almost unaccountably, both with the season and the locality.

I spent much of the fall of 1889 hunting on the head-waters of the Salmon and Snake in Idaho, and along the Montana boundary line from the Big Hole Basin and the head of the Wisdom River to the neighborhood of Red Rock Pass and to the north and west of Henry’s Lake. During the last fortnight my companion was the old mountain man named Griffeth or Griffin—I cannot tell which, as he was always called either “Hank” or “Griff.” He was a crabbedly honest old fellow, and a very skillful hunter; but he was worn out with age and rheumatism, and his temper had failed even faster than his bodily strength. He showed me a greater variety of game than I had ever seen before in so short a time; nor did I ever before or after make so successful a hunt. But he was an exceedingly disagreeable companion on account of his surly, moody ways. I generally had to get up first, to kindle the fire and make ready breakfast, and he was very quarrelsome. Finally, during my absence from camp one day, while not very far from Red Rock Pass, he found my whiskey-flask, which I kept purely for emergencies, and drank all the contents. When I came back he was quite drunk. This was unbearable, and after some high words I left him, and struck off homeward through the woods on my own account. We had with us four pack and saddle horses; and of these I took a very intelligent and gentle little bronco mare, which possessed the invaluable trait of always staying near camp, even when not hobbled. I was not hampered with much of an outfit, having only my buffalo sleeping-bag, a fur coat, and my washing-kit, with a couple of spare pairs of socks and some handkerchiefs. A frying-pan, some salt, flour, baking-powder, a small chunk of salt pork, and a hatchet made up a light pack, which, with the bedding, I fastened across the stock saddle by means of a rope and a spare packing cinch. My cartridges and knife were in my belt; my compass and matches, as always, in my pocket. I walked, while[22] the little mare followed almost like a dog, often without my having to hold the lariat which served as halter.

The country was for the most part fairly open, as I kept near the foot-hills where glades and little prairies broke the pine forest. The trees were of small size. There was no regular trail, but the course was easy to keep, and I had no trouble of any kind save on the second day. That afternoon I was following a stream which at last “canyoned up”—that is, sank to the bottom of a canyon-like ravine impassable for a horse. I started up a side valley, intending to cross from its head coulies to those of another valley which would lead in below the canyon.

However, I got enmeshed in the tangle of winding valleys at the foot of the steep mountains, and as dusk was coming on I halted and camped in a little open spot by the side of a small, noisy brook, with crystal water. The place was carpeted with soft, wet, green moss, dotted red with the kinnikinnic berries, and at its edge, under the trees where the ground was dry, I threw down the buffalo bed on the mat of sweet-smelling pine needles. Making camp took but a moment. I opened the pack, tossed the bedding on a smooth spot, knee-haltered the little mare, dragged up a few dry logs, and then strolled off, rifle on shoulder, through the frosty gloaming, to see if I could pick up a grouse for supper.

For half a mile I walked quickly and silently over the pine needles, across a succession of slight ridges separated by narrow, shallow valleys. The forest here was composed of lodge-pole pines, which on the ridges grew close together, with tall slender trunks, while in the valleys the growth was more open. Though the sun was behind the mountains there was yet plenty of light by which to shoot, but it was fading rapidly.

At last, as I was thinking of turning toward camp, I stole up to the crest of one of the ridges, and looked over into the valley some sixty yards off. Immediately I caught the loom of some large, dark object; and another glance showed me a big grizzly walking slowly off with his head down. He was quartering to me, and I fired into his flank, the bullet, as I afterward found, ranging forward and piercing one lung. At the shot he uttered a loud, moaning grunt and plunged forward at a heavy gallop, while[23] I raced obliquely down the hill to cut him off. After going a few hundred feet he reached a laurel thicket, some thirty yards broad, and two or three times as long, which he did not leave. I ran up to the edge and there halted, not liking to venture into the mass of twisted, close-growing stems and glossy foliage. Moreover, as I halted, I heard him utter a peculiar, savage kind of whine from the heart of the brush. Accordingly, I began to skirt the edge, standing on tiptoe and gazing earnestly to see if I could not catch a glimpse of his hide. When I was at the narrowest part of the thicket, he suddenly left it directly opposite, and then wheeled and stood broadside to me on the hill-side, a little above. He turned his head stiffly toward me; scarlet strings of froth hung from his lips; his eyes burned like embers in the gloom.

I held true, aiming behind the shoulder, and my bullet shattered the point or lower end of his heart, taking out a big nick. Instantly the great bear turned with a harsh roar of fury and challenge, blowing the bloody foam from his mouth, so that I saw the gleam of his white fangs; and then he charged straight at me, crashing and bounding through the laurel bushes, so that it was hard to aim. I waited until he came to a fallen tree, raking him as he topped it with a ball which entered his chest and went through the cavity of his body, but he neither swerved nor flinched, and at the moment I did not know that I had struck him. He came steadily on, and in another second was almost upon me. I fired for his forehead, but my bullet went low, entering his open mouth, smashing his lower jaw and going into the neck. I leaped to one side almost as I pulled trigger; and through the hanging smoke the first thing I saw was his paw as he made a vicious side blow at me. The rush of his charge carried him past. As he struck he lurched forward, leaving a pool of bright blood where his muzzle hit the ground; but he recovered himself and made two or three jumps onward, while I hurriedly jammed a couple of cartridges into the magazine, my rifle holding only four, all of which I had fired. Then he tried to pull up, but as he did so his muscles seemed suddenly to give way, his head drooped, and he rolled over and over like a shot rabbit. Each of my first three bullets had inflicted a mortal wound.

It was already twilight, and I merely opened the carcass, and then trotted back to camp. Next morning I returned and with much labor took off the skin. The fur was very fine, the animal being in excellent trim, and unusually bright-colored. Unfortunately, in packing it out I lost the skull, and had to supply its place with one of plaster. The beauty of the trophy, and the memory of the circumstances under which I procured it, make me value it perhaps more highly than any other in my house.

This is the only instance in which I have been regularly charged by a grizzly. On the whole, the danger of hunting these great bears has been much exaggerated. At the beginning of the present century, when white hunters first encountered the grizzly, he was doubtless an exceedingly savage beast, prone to attack without provocation, and a redoubtable foe to persons armed with the clumsy, small-bore, muzzle-loading rifles of the day. But at present, bitter experience has taught him caution. He has been hunted for sport, and hunted for his pelt, and hunted for the bounty, and hunted as a dangerous enemy to stock, until, save in the very wildest districts, he has learned to be more wary than a deer, and to avoid man’s presence almost as carefully as the most timid kind of game. Except in rare cases he will not attack of his own accord, and, as a rule, even when wounded his object is escape rather than battle.

Still, when fairly brought to bay, or when moved by a sudden fit of ungovernable anger, the grizzly is beyond peradventure a very dangerous antagonist. The first shot, if taken at a bear a good distance off and previously unwounded and unharried, is not usually fraught with much danger, the startled animal being at the outset bent merely on flight. It is always hazardous, however, to track a wounded and worried grizzly into thick cover, and the man who habitually follows and kills this chief of American game in dense timber, never abandoning the bloody trail whithersoever it leads, must show no small degree of skill and hardihood, and must not too closely count the risk to life or limb. Bears differ widely in temper, and occasionally one may be found who will not show fight, no matter how much he is bullied; but, as a rule, a hunter must be cautious in meddling with a wounded[25] animal which has retreated into a dense thicket, and has been once or twice roused; and such a beast, when it does turn, will usually charge again and again, and fight to the last with unconquerable ferocity. The short distance at which the bear can be seen through the underbrush, the fury of its charge, and its tenacity of life make it necessary for the hunter on such occasions to have steady nerves and a fairly quick and accurate aim. It is always well to have two men in following a wounded bear under such conditions. This is not necessary, however, and a good hunter, rather than lose his quarry, will, under ordinary circumstances, follow and attack it, no matter how tangled the fastness in which it has sought refuge; but he must act warily and with the utmost caution and resolution, if he wishes to escape a terrible and probably fatal mauling. An experienced hunter is rarely rash, and never heedless; he will not, when alone, follow a wounded bear into a thicket, if by the exercise of patience, skill, and knowledge of the game’s habits he can avoid the necessity; but it is idle to talk of the feat as something which ought in no case to be attempted. While danger ought never to be needlessly incurred, it is yet true that the keenest zest in sport comes from its presence, and from the consequent exercise of the qualities necessary to overcome it. The most thrilling moments of an American hunter’s life are those in which, with every sense on the alert, and with nerves strung to the highest point, he is following alone into the heart of its forest fastness the fresh and bloody footprints of an angered grizzly; and no other triumph of American hunting can compare with the victory to be thus gained.

Biography. Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), twenty-sixth President of the United States, was born in New York City. As a boy he was of frail physique, but overcame this handicap by systematic exercise and outdoor life. He was always interested in natural history, and at the age of fourteen, when he accompanied his father on a tour up the Nile, he made a collection of the Egyptian birds to be found in the Nile valley. This collection is now in the Smithsonian Museum, Washington, D. C. In 1884, Roosevelt bought two cattle ranches near Medora, in North Dakota, where for two years he lived and entered actively into western life and spirit.

In 1909, at the close of his presidency, he conducted an expedition to Africa, to make a collection of tropical animals and plants. Expert naturalists accompanied the party, which remained in the wilderness for a year, and returned with a collection which scientists pronounce of unusual value for students of natural history. Most of the specimens are now in the Smithsonian Museum. Some of the books in which he has recorded his hunting experiences are: African Game Trails, The Deer Family, and The Wilderness Hunter, from which “Old Ephraim, the Grizzly Bear” is taken.

Mr. Roosevelt’s last work as an explorer was his journey to South America. On this journey he penetrated wildernesses rarely explored by white men, and made many discoveries in the field of South American animal and vegetable life and in geography.

The vigorous personality of this great American found expression not only in the life of men and their political and social relations, but also in his love of the great outdoors and the unbeaten tracks where life is an adventure, primitive in surroundings, such a life as was lived by Sir Walter Raleigh and other great seamen and explorers who were not content with the tameness of the commonplace.