The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Trial of Peter Zenger, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Trial of Peter Zenger Author: Various Editor: Vincent Buranelli Release Date: June 3, 2017 [EBook #54836] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TRIAL OF PETER ZENGER *** Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, MFR and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The liberty of the press is a subject of the greatest importance, and in which every individual is as much concerned as he is in any other part of liberty.

New York Weekly Journal November 12, 1733

EDITED AND WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY

Vincent Buranelli

Washington Square

New York University Press

1957

© 1957 by New York University Press, Inc.

Library of Congress catalogue card number: 57-6370

Manufactured in the United States of America

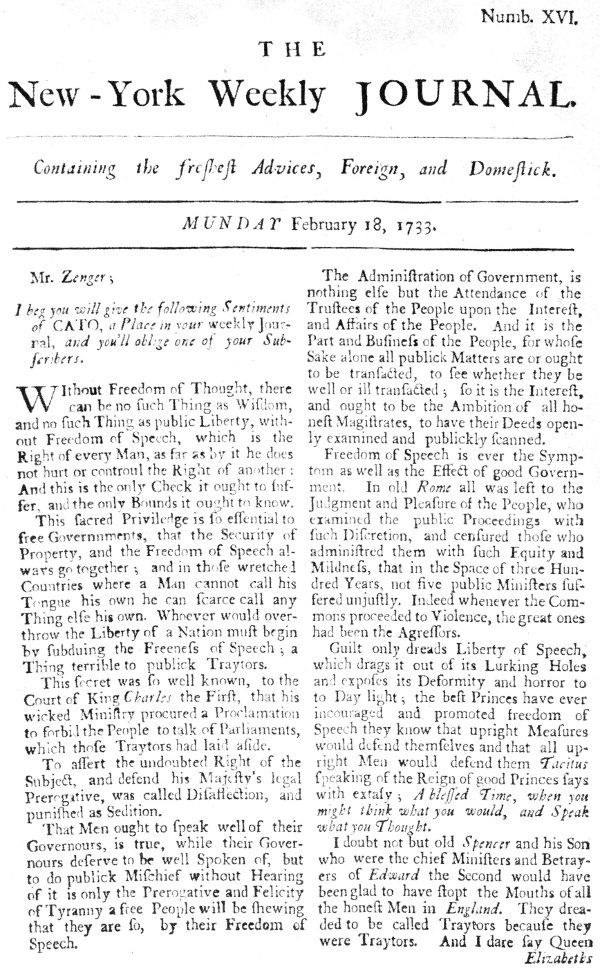

Numb. XVI.

THE

New-York Weekly JOURNAL.

Containing the freshest Advices, Foreign, and Domestick.

MUNDAY February 18, 1733.

Mr. Zenger;

I beg you will give the following Sentiments of CATO, a Place in your weekly Journal, and you’ll oblige one of your Subscribers.

Without Freedom of Thought, there can be no such Thing as Wisdom, and no such Thing as public Liberty, without Freedom of Speech, which is the Right of every Man, as far as by it he does not hurt or controul the Right of another: And this is the only Check it ought to suffer, and the only Bounds it ought to know.

This sacred Privilege is so essential to free Governnments, that the Security of Property, and the Freedom of Speech always go together; and in those wretched Countries where a Man cannot call his Tongue his own he can scarce call any Thing else his own. Whoever would overthrow the Liberty of a Nation must begin by subduing the Freeness of Speech; a Thing terrible to publick Traytors.

This secret was so well known, to the Court of King Charles the First, that his wicked Ministry procured a Proclamation to forbid the People to talk of Parliaments, which those Traytors had laid aside.

To assert the undoubted Right of the Subject, and defend his Majesty’s legal Prerogative, was called Disaffection, and punished as Sedition.

That Men ought to speak well of their Governours, is true, while their Governours deserve to be well Spoken of, but to do publick Mischief without Hearing of it is only the Prerogative and Felicity of Tyranny a free People will be shewing that they are so, by their Freedom of Speech.

The Administration of Government, is nothing else but the Attendance of the Trustees of the People upon the Interest, and Affairs of the People. And it is the Part and Business of the People, for whose Sake alone all publick Matters are or ought to be transacted, to see whether they be well or ill transacted; so it is the Interest, and ought to be the Ambition of all honest Magistrates, to have their Deeds openly examined and publickly scanned.

Freedom of Speech is ever the Symptom as well as the Effect of good Government. In old Rome all was left to the Judgment and Pleasure of the People, who examined the public Proceedings with such Discretion, and censured those who administred them with such Equity and Mildness, that in the Space of three Hundred Years, not five public Ministers suffered unjustly. Indeed whenever the Commons proceeded to Violence, the great ones had been the Agressors.

Guilt only dreads Liberty of Speech, which drags it out of its Lurking Holes and exposes its Deformity and horror to to[sic] Day light; the best Princes have ever incouraged and promoted freedom of Speech they know that upright Measures would defend themselves and that all upright Men would defend them. Tacitus speaking of the Reign of good Princes says with extasy; A blessed Time, when you might think what you would, and Speak what you Thought.

I doubt not but old Spencer and his Son who were the chief Ministers and Betrayers of Edward the Second would have been glad to have stopt the Mouths of all the honest Men in England. They dreaded to be called Traytors because they were Traytors. And I dare say Queen Elizabeths

In this book you will find the reasons for the fame of Peter Zenger and Andrew Hamilton. You will also find the reason why James Alexander deserves mention as the third member of a great trio. Zenger was the central figure of a colorful and influential historical event—his trial for seditious libel. Hamilton was the champion who won him his freedom. The place of Alexander in all this is virtually unknown, and yet without him Hamilton’s fame would be cut in half, while Zenger would not merit even a footnote in the histories of America, of democracy, or of journalism.

Alexander edited the New York Weekly Journal. That simple fact means that he was the first American editor to practice freedom of the press systematically and coherently, and the first to be justified legally. The defense of Zenger’s person was a defense of Alexander’s philosophy of journalism. The victory engineered by Hamilton was the result of a courtroom campaign along lines laid down by Alexander.

Perhaps it would be too strong to say that the genius behind the Journal was our greatest editor, but it would be hard to name one of equal importance. If we believe, as we do, that freedom of the press is essential to our civilization, surely we ought to give due recognition to the first American to say so and to act effectively. For this Scottish immigrant of the eighteenth century taught his adopted land the first law of sane journalism: that the news is to be reported on the basis of factual accuracy, and that censorship by the authorities is to be resisted as far as is consistent with national security and the interests of society.

The introduction to the text of the trial is based on a series of articles by the author, published in the following journals:

For permission to use material from these articles, thanks are due to the respective editors and to the following societies: American Studies Association, New York State Historical Association, Institute of Early American History and Culture, and National Council for the Social Studies. The author also wishes to thank Mr. H. V. Kaltenborn, without whose Fellowship the research would never have been undertaken, much less published.

My desk encyclopedia allots the subject of this book these two brief sentences: “Zenger, John Peter (1697-1749), American journalist, born Germany. His acquittal in libel trial helped further freedom of press in America.”

That represents a very sober acknowledgment of the fact that the Zenger case established highly important precedents and is a landmark in the history of the free press among the English-speaking peoples of the world. With all this it is something of an anomaly that Peter Zenger never learned to write good English. He was not a newspaper editor, but only a printer who published the writings of others in an effort to earn an honest living. It was the incidental cause he served, rather than his professional work, that brought him his enduring fame.

He began his career as a printer’s apprentice. He worked for William Bradford, the only printer in New York. Zenger became Bradford’s partner, but soon established a business of his own, and since Bradford published the weekly newspaper that supported the British governor, it was only natural that those prominent members of the colony who opposed the governor should contract with Peter Zenger to print and publish a weekly paper for the opposition. Governor Cosby, whose word was law in the British colony of New York, was an arbitrary individual. As a personal representative of the British king he ran things pretty much as he pleased. His arbitrary acts helped create an opposition known as the Popular Party. Zenger’s weekly became the organ for this party. Like other colonial newspapers of that day, it printed foreign news, literary essays, so called poetry, and a small amount of advertising. But its most interesting contents were the political articles attacking Governor Cosby and the actions of his administration. All these editorial comments were written by prominent members of the opposition party, but they were always signed with pen names.

Zenger’s was the only name associated with the new opposition journal. Governor Cosby knew very well that Zenger was only the printer and had nothing to do with the paper’s policy. He also knew that James Alexander, a brilliant leader of the political opposition, wrote or edited most of the articles that were critical of the Cosby administration. But the law, then as now, places responsibility on those who publish a libel—not upon those who write it. As a newspaper reporter, I myself once profited by that distinction. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle had to defend a one hundred thousand dollar libel suit for an article I had written. The leader of a religious sect that had its headquarters in Brooklyn was selling what it called Miracle Wheat. I exposed the one dollar a pound charge for this wheat as a fraud upon the public. That gave me the interesting task of helping the Eagle’s lawyers prove with the help of agricultural experts the truth of my printed assertion. For today, as in the days since Peter vi Zenger’s trial, the truth of the libelous allegations mitigates damages and justifies the libel.

It was not until the trial of Peter Zenger that his extremely able lawyer created the notable precedent that the truth must be accepted as justification for a libel and in mitigation of whatever damages might have been suffered by the plaintiff. In the Brooklyn Eagle Miracle Wheat case the libel was clear and the court so instructed the jury, which promptly brought in a verdict of six cents for the plaintiff. This justified the Eagle and humiliated the sellers of Miracle Wheat.

The Peter Zenger trial established one other notable precedent for libel cases. This was that the jury before which he was tried had the right not only to pass upon the fact but also the law in the case. The logic and eloquence of Zenger’s attorney persuaded the jury that it had the right to determine how and to what extent the letter and spirit of the law could and should be applied in the Zenger case.

It is an interesting fact that the entire preceding history of the freedom of the press among English-speaking peoples played its part in the Zenger trial. The writings of Milton, Locke, Swift, Steele, Addison, and Defoe were all quoted to justify the freedom with which Zenger’s newspaper voiced its criticism of Governor Cosby and the way he governed.

This willful executive first attempted to have Zenger indicted by a grand jury, but the jury refused to act. Then he ordered Zenger’s paper to be burned by the public hangman, and it was duly burned, though not by the hangman. Finally the Governor secured the issue of a warrant for Zenger’s arrest and the printer was put in jail on a charge of seditious libel. Zenger’s journal missed a single issue. Then, thanks to his wife, it appeared every Monday while Zenger was in jail. Zenger’s wife, Anna Catherine, took over the print shop and saw that the paper was published. She didn’t write the contents any more than her husband, but she never complained that the printer’s family was suffering for others.

Nowadays it is a Constitutional right that “Excessive bail shall not be required,” but in Zenger’s day there was no such rule. His bail was so high that neither he nor his friends could meet it. The fact that he was put in jail also helped sway public opinion in Zenger’s favor.

The record of the Zenger trial as it is developed in this book is one of the notable case histories of American jurisprudence. Andrew Hamilton, Zenger’s able attorney, made such a case for his client that it attracted attention not only in the colonies but in England. New York voted him the freedom of the city.

Governor Cosby did not long survive the rebuke he suffered by Zenger’s acquittal. And here is a curious fact worth recalling: Andrew Hamilton, whose notable defense of Peter Zenger has become an imperishable part of the history of our free press, was also the architect of Independence Hall in Philadelphia. The Hall still stands and so does the decision in the Zenger case, both symbolizing enduring monuments to freedom.

Of all the personalities involved in the Zenger case, none eludes investigation so much as the man who gave his name to it. There are irritating lacunae in the biography of John Peter Zenger, and no artist ever found him worthy of sketch or portrait (at least none has survived), so that we do not even know his face. But this lack of information is by no means crippling to the historian of the period. If we would prefer to know more about Peter Zenger, the plain truth is that half a dozen other men were of more consequence than he in the establishment of a free press in New York. He was neither the editor of his newspaper nor even a principal writer for it during its great days; his function hardly went beyond that of the mere printer. He became famous almost by accident, famous as a symbol rather than as a motivating force. We can, therefore, “place” him with the less difficulty, and the data to hand are sufficient for that.

He was a German immigrant, a native of the Rhenish Palatinate, where he was born in 1697. His family brought him to the New World in 1710, and that same year he was apprenticed to William Bradford, the only printer then at work in New York, and one of the top men of his trade in the Colonies. Bradford’s establishment was a good school for any apprentice, for it graduated a whole series of printers 4 who became famous in their own right, the best remembered of whom was the master’s son, Andrew Bradford, who competed with Benjamin Franklin for the publishing trade in Philadelphia.

Peter Zenger’s indentures were for eight years, during which time he toiled at the Bradford press, beginning at the bottom as a typical ink-stained printer’s devil and working his way up in the profession that Bradford liked to call “the art and mystery of printing.” Peter never became a refined practitioner, for one reason because his grasp of the English language remained defective, but he came out of his training as skilled as many others in the field, and he was obeying a sound instinct when, his indentures up, he decided to strike out for himself as an independent.

During the years 1719-22 he wandered through the Colonies looking for a place to set up a permanent business. He married Mary White of Philadelphia, and had a son, John Zenger, who was a printer after him. His most ambitious venture took him to Maryland, where he became a citizen and was granted the right to publish the Colony’s laws, proceedings, minutes, etc. What happened then is uncertain; perhaps it was just that his plans did not work out; perhaps the death of his wife was the crucial thing; for some reason he decided to abandon his Maryland career and return to New York. There he married his second wife, Anna Catherine Maulin, a native of Holland, and settled down for good.

In 1725 he joined William Bradford in a brief partnership, so brief that they published only one book jointly before splitting up, for what reason we do not know. The next year Peter Zenger went into business for himself, thus becoming the second printer in New York, and the first rival of his former master.

There was room for two. Bradford, the official printer, 5 worked for the Governor, the Council, and the Assembly. He was an honest man, but understandably reluctant to jeopardize his position by turning out anything of which his patrons might disapprove. That was where Zenger came in. Proprietor of a second-class printing shop, cut off from government work, he could keep his head above water in only one way, by taking the trade of New Yorkers who had some motive for avoiding the official press, especially those who were dissatisfied with the situation in either Church or State and wanted to say so. For six years he supplemented his staple output (mainly religious tracts) with critical pamphlets and open letters. Gradually the logic of his predicament pushed him into the position of “official” printer to those writers whose material Bradford could not, or would not, touch.

Such was Zenger’s status in the fall of 1732 when affairs in New York began to boil up into a political crisis that first involved him as a partisan in a duel of contending factions, and ultimately landed him in jail.

The powder train for the explosion had been laid during the previous decade in the form of a savage feud between two of the most powerful families in New York—the Morrises and the Delanceys, led by the patriarchs Lewis Morris and Stephen Delancey. Fundamentally, the conflict was the primordial one between landed gentry and business tycoons, and the occasion produced two perfect representatives to act as leaders.

Lewis Morris—territorial aristocrat, councillor, assemblyman, chief justice of the Supreme Court—was the model of the wealthy, influential, proud, and ambitious colonial magnate. 6 He made his family great, and handed on the tradition to his more famous grandsons, Gouverneur Morris and the Lewis Morris who signed the Declaration of Independence. He was a commanding figure in the politics of both New York and New Jersey, headstrong in defense of himself, his family, and his class, and a power for any governor to reckon with.

Stephen Delancey stood for the ever-increasing authority of money. He was New York’s leading merchant prince, a self-made man who accumulated a fortune in trade with Canada. French by birth, he was a Huguenot by religion, with all the tenacious acquisitiveness and flinty Puritan morality of his sect. In the Assembly he spoke for the powerful mercantile clique, and that alone would have made him—hardly less than Lewis Morris—a dangerous man to cross.

Now Morris crossed Delancey, and did it in two peculiarly galling ways. First of all, from the floor of the Assembly he led an attack on the trade in which the entrepreneur had made his money. Under this commercial system, New York businessmen sent their wares directly to the French in Canada, who used the manufactured articles they received to carry on their fur trade with the Indians. The system was a very profitable one for many New Yorkers, but Governor William Burnet was anxious to end it because it strengthened the hand of the French with the Indians, making the latter reliant on Quebec instead of Albany. Morris acted as his manager in the Assembly during the furious controversy that followed, while Stephen Delancey naturally commanded the opposition. The struggle developed into a fierce personal rivalry that continued to move with its own momentum long after Delancey had triumphed over Morris in this case of the Canada trade.

Secondly, Morris seems to have instigated Governor Burnet 7 to question Delancey’s right to sit in the Assembly on the ground that he was a foreigner, a purely personal attack of so little validity that the Governor had to back down and apologize to the Chamber for usurping one of its prerogatives, after which it put its seal of approval on Stephen Delancey.

There is no need to explain at length how the old plutocrat reacted to these insults. We simply note that the perspicacious Cadwallader Colden terms Delancey “a man of strong and lasting resentments” and adds that the Morris-Delancey clash gave rise to “violent party struggles.” Before long New York was disturbed by hostile groups known from their chiefs as the “Morris Interest” and the “Delancey Interest.” This is the background to the Zenger case. Party alignment was obviously dictated in many cases by motives other than personal allegiance—by political, social, and economic factors—but for our purposes the fundamental thing is the Morris-Delancey antithesis. During Burnet’s administration (1720-28) these embittered Interests were engaged in a constant struggle for power, with the Morrisites strong because they had the ear of the Governor, and the Delanceyites because the Assembly swung over to their side.

With the regime of Governor John Montgomerie (1728-31), the Delancey Interest definitely became paramount in New York because this executive made it the cornerstone of his policy to stay on good terms with the Assembly. Montgomerie maintained an uneasy peace (partly because he was himself a rather feckless individual), but the atmosphere in New York did not thereby cease to be explosive, for the Morris Interest, although temporarily checked, was still powerful, still ambitious, still hopeful, and still watching for the pendulum to swing its way.

Thus the scene was set for a violent climax whenever a sufficient cause should appear. It appeared on Montgomerie’s 8 death in the person of the new governor, Colonel William Cosby.

If you look into Burke’s Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland, you will find the following paragraph embedded in the genealogical history of “Cosby of Stradbally”:

William, brigadier-general, col. of the royal Irish, governor of New York and the Jersies, equerry to the Queen, and m. Grace, sister of George Montague Earl of Halifax, K.B., and left by that lady (who d. 25 Dec. 1767) at his decease, 10 March 1736, the following issue, William, an officer in the Army; Henry, R.N., d. 1753; Elizabeth, m. to Lord Augustus Fitzroy, 2nd son of Charles, Duke of Grafton; Anne, m. to —— Murray, Esq. of New York.

The entry enables us to form a pretty good idea of the background from which Governor Cosby came and explains much of his behavior as chief executive of New York. He was an Anglo-Irish aristocrat, sprung from the notorious Ascendancy class that maintained its position through a whole series of penal laws designed to keep the majority of Irishmen in subjection. He had all the craving for place and pension, the haughtiness, and the venal devotion to the status quo that were common in the worst section of his class, and these vices merely perverted a strong will and a certain resourcefulness in meeting obstacles.

With intelligence and decency William Cosby might have been a man of fair ability; instead he became a sycophant with his superiors, an intriguer with his equals, and a petty tyrant with those beneath him. We know from his correspondence that he could not abide opposition or even criticism.

How much of a soldier he was remains doubtful since, although he rose to the rank of general, it was a period in which office frequently enough went with bribery, conniving, and influence rather than with ability. William Cosby was in a position to resort to all of these because he enjoyed powerful contacts in England, being a close friend of the Duke of Newcastle, while his wife was a sister of the Earl of Halifax. These noblemen may both have been instrumental in furthering his rise in the army. His administrative career in the Colonies was certainly largely due to Newcastle, who controlled the Board of Trade and was able to send out whom he chose.

Cosby’s first governorship took him to the island of Minorca, where his high-handedness and cupidity exasperated the Minorcans, and they protested repeatedly to the Board of Trade. He committed one crime that London could not overlook or minimize: while England and Spain were at peace in 1718 Cosby ruthlessly seized the goods of a Spanish merchant, ordered them sold at auction, and then manipulated the records to cover his tracks. The whole thing was too flagrant. The Governor was ordered to reimburse his victim and removed from his post in Minorca.

Notwithstanding the incident, Cosby was able to wangle other appointments, of which the New York governorship was the most important. The feeling of the Colonials when they learned of the Minorca affair was expressed by Cadwallader Colden:

How such a man, after such a flagrant instance of tyranny and robbery, came to be intrusted with the government of an English colony and to be made Chancellor and keeper of the King’s conscience in that colony, is not easy for a common understanding to conceive without entertaining thoughts much to the disadvantage of the honor and integrity of the King’s Ministers, 10 otherwise than by thinking that the Ministry believed that what he had suffered by the complaints made against him from Minorca would make him for the future carefully avoid giving any occasion of complaint from his new government.[1]

However, there was no local prejudice against the new Governor when he arrived on August 1, 1732. His Minorca past was unknown. He had had the shrewdness to ingratiate himself with New Yorkers, while he lingered in England for over a year, by agitating against the pending sugar bill as detrimental to Colonial commercial interests; he was unable to bring news of success with him, but at least he was believed to have tried, and this alone would have created an atmosphere favorable to him. He had, moreover, personal attributes calculated to make him popular in Colonial society—a smooth charm, good birth, high military rank, familiar connections with the nobility at home, and a wife who was the sister of an earl. He was fond of playing the host on a lavish scale, and the parties and dances at the Governor’s mansion were soon noted as among the gayest ever seen in New York City.

Given all this popularity and good will on his arrival, what was it that went wrong? How did William Cosby’s become “one of the most disturbed administrations in New York Colonial history”? The transition was very rapid. Within three months of his arrival the new Governor wrote to the Duke of Newcastle:

I am sorry to inform your Grace that the example and spirit of the Boston people begin to spread amongst these colonies in a most prodigious manner. I had more trouble to manage these 11 people than I could have imagined; however for this time I have done pretty well with them; I wish I may come off as well with them of the Jersies.[2]

That old bugbear of Colonial governors, trouble with the Assembly, was not in question. Unlike many men better than himself, Cosby got along very well with his legislature, his differences with it being hardly more than the inevitable friction created by two forces in contact and working toward ends that did not always coincide. The harmony was striking because he insulted the Assembly after it had voted him a present for his opposition to the sugar bill: the sum did not satisfy him, and he snarled to Lewis Morris, “Damn them, why did they not add shillings and pence? Do they think that I came from England for money? I’ll make them know better.”[3]

This was a gratuitous affront, and typical of the small-minded avaricious man who offered it, but it did not raise any political issue that could cause a quarrel.

The quarrel began within the Governor’s Council, among the men who were supposed to be his close intimate advisers. The predisposing condition already existed there in the form of the Morris-Delancey feud, on the smoldering embers of which Cosby proceeded to pour oil. From the Council, ripples of animosity spread through the Colony, dividing the people into two factions—the Court party of the Governor (which absorbed the Delancey Interest), and the Popular party (formerly the Morris Interest) of his enemies. It happened like this.

During the year that Cosby stayed on in England after his appointment, the leadership of New York devolved on the president of the Council, the ranking member, who happened to be a veteran of the old New Amsterdam days named Rip Van Dam. He was a hard-headed, tight-fisted, honest 12 Dutchman, not very able, but extremely devoted to his duties and his rights. During his tenure of office he was voted, and drew, the stipend attached to it.

When Cosby finally arrived on the scene, he produced a royal decree ordering Van Dam to divide the sum with him. Van Dam’s answer was a shrewd reprisal. Knowing that Cosby had received many emoluments of the governorship while in England, he suggested a division that would include these, and he calculated that on this basis the Governor actually owed him a substantial amount. The dictatorial proconsul rejected the proposal with all the anger and contempt he usually displayed when thwarted. He decided to sue.

Determined to keep the case away from a jury because of local sentiment that favored a Colonial against a crown official, and unable to proceed in chancery since he would be presiding as chancellor over his own suit, Cosby hit on the idea of letting the justices of the Supreme Court handle it as Barons of the Exchequer. He therefore named the Supreme Court a court of equity, after which he brought suit against Van Dam.

The defendant’s lawyers were James Alexander and William Smith, two of the foremost members of the New York bar, who had been advising him throughout. When the suit began in the new court of equity, Alexander and Smith adopted the bold course of denying the validity of the court itself, arguing in particular that it was illegal for the Governor to establish it of his own free will and without the consent of the Assembly. This plea was more than an attack on the jurisdiction of a court: it was a direct accusation that the Governor had overstepped the limits of his authority and had violated the law.

The three justices of the Supreme Court were divided on the merits of the plea. Two of them, James Delancey and 13 Frederick Philipse, rejected it out of hand. They belonged to the Governor’s faction. But the Chief Justice was of another mind, and that was the critical thing, for he was Lewis Morris. (Notice the names. We are back in the familiar atmosphere of the Morris-Delancey feud, James being the son of old Stephen Delancey.) Morris had opposed obnoxious governors in the past, and he would not back down before Governor Cosby. There was this added point about Lewis Morris, that he had functioned in the New Jersey Council as did Van Dam in New York’s, so his pocketbook stood in the same kind of jeopardy if Van Dam should be condemned.

The Chief Justice therefore agreed with the counsel for the defense that the court of equity was no true court, and he openly defied the Governor with these words:

I take it the giving of a new jurisdiction in Equity by letters patent to an old Court that never had such jurisdiction before, or erecting a new Court of Equity by letters patent or ordinances of the Governor and Council, without assent of the legislature, are equally unlawful, and not a sufficient warrant to justify this Court to proceed in a course of Equity. And therefore by the grace of God, I, as Chief Justice of this Province, shall not pay any obedience to them in that point.[4]

The Governor was away in New Jersey at the time but, hearing what had happened, he wrote Morris a furious and insulting letter, and demanded a copy of the remarks he had made in court. The Chief Justice complied, at the same time publishing the remarks (through the Zenger press) as a gesture of studied contempt for all the Colony to see. This was more than Cosby was willing to stand. On May 3, 1733, he wrote to the Duke of Newcastle:

Things are now gone that length that I must either discipline Morris or suffer myself to be affronted, or, what is still worse, see the King’s authority trampled on and disrespect and irreverence 14 to it taught from the Bench to the people by him who, by his oath and his office, is obliged to support it. This is neither consistent with my duty nor my inclination to bear, and therefore when I return to New York I shall displace him and make Judge Delancey Chief Justice in his room.[5]

In August, Cosby made good his threat. At one Council meeting, and without notifying Morris in advance, he announced that henceforth Delancey was chief justice of the Supreme Court of New York, with Philipse advancing to the second place. Cadwallader Colden, who was present in his capacity of councillor, tells us that he disapproved of the Governor’s action, and that Cosby resented his saying so. Colden’s account of the episode is so revealing of Cosby’s character that it is worth quoting in full:

I had been sent for to town a few days before under pretense of some affairs in my office of Surveyor General. When I came into the Governor’s house he received me into his arms with, “My dear Colden, I am glad to see you.” I was caressed for two or three days by every one of the family. Just before I went to Council he took me upon the couch and seemed to entertain me in the most friendly manner, but spoke not one word of removing the Chief Justice and appointing another till we were sitting in Council, when he said that he had removed Mr Morris and appointed James Delancey in his room, and thought this the most proper place to give the first notice of it. Upon which I said, “Then Your Excellency only tells us what you have already done?” To which he answered, “Yes.” I replied, “It is not what I would have advised.” And he very briskly returned to it, “I do not ask your advice.” This put his having the consent of the Council out of the question and defeated the whole design he had been put upon of cajoling me (for I do not think he was capable of forming any design himself that had any reach). However he never forgave me.[6]

Morris soon learned what had taken place at the meeting, 15 and in a letter of protest he passed the information on to London:

I believe I am well informed that, on the delivery of the Commissions to the Judges in Council, Doctor Colden asked the Governor whether the Council was summoned to be advised on that head? If they were, he would advise against it as being prejudicial to His Majesty’s service. To which the Governor replied that he did not, nor ever intended to, consult them about it; he thought fit to do it, and was not accountable to them; or words to that effect.[7]

From this time on there was no mollifying Lewis Morris. Implacably revengeful, he never lowered his sights from two main goals, to regain the office of chief justice, and to get William Cosby removed from the governorship of New York. He achieved neither of these, but he did achieve the leadership of the antiadministration faction—the Popular party—that gave Cosby no peace.

The Governor had really stirred up a hornets’ nest. Not only was New York already disgusted with him as a man and an executive, his private arrogance and public avarice being notorious, but he had openly adopted the pattern of behavior that had made Colonial governors unpopular in the past. Before he finished he had insulted the Assembly, tampered with the courts, divided his Council into venomous cliques, frightened property owners with his claims to land, and treated leading citizens with cavalier disdain. He practiced nepotism, tried to rig elections, and violated his instructions from London.

He committed a blunder as well as a crime when he alienated some of the most powerful men in his Colony—especially Lewis Morris, Rip Van Dam, and James Alexander, the last of whom became the mastermind of the Popular party. Working with them were Colden, William Smith, 16 Lewis Morris, Junior, and many others down the scale into the anonymous mass of the population. The opposition to Governor Cosby soon turned from a matter of sporadic pinpricks into a concerted conspiracy bent on his political destruction.

The Governor’s friends rallied around him, led by Chief Justice James Delancey (the only man of real ability among them), but they suffered in the contest for public opinion because they had to defend Cosby at a time when New Yorkers generally had made up their minds that he was indefensible. However, the Court party was strong in this, that it possessed the governmental machinery that could be brought to bear at a dozen different points of the battlefield, for example in the magistracies and at the bar.

The Court party also possessed the only newspaper in the Colony, William Bradford’s New York Gazette. Bradford himself was hardly a party man, but (again as official printer) he was in no position to let his little two-page publication be used against those in power. He could not refuse to let them censor the Gazette. He could not even demur when Governor Cosby decided to put one of his own men in charge of editorial policy.

That decision introduces us to the most entertaining rascal of the Zenger case—Francis Harison, the dubious individual who functioned as editor-by-appointment and flatterer-in-chief to His Excellency the Governor. Since Harison was a censor in fact, if not in name, he merits some attention in any explanation of how freedom of the press was established for the first time on this side of the Atlantic. His career, more 17 than any except Governor Cosby’s, reveals why the Popular party of New York determined to throw down the gauntlet in the form of an opposition newspaper.

Francis Harison was notorious before Cosby was ever heard of in the Colony. Arriving more than twenty years earlier, he soon carved out a comfortable niche for himself. He had an enormous gift for wheedling jobs of some importance, and he did very well for himself, becoming among other things a member of the Governor’s Council, recorder for the City of New York, and a judge of the admiralty. He served as one of the commissioners in settling the boundary dispute with Connecticut. He must have been a real genius at wangling, for on more than one occasion he showed a dishonesty and a stupidity so startling as to rouse wonder that anyone ever trusted him with responsibility.

Take the matter of the Connecticut boundary, when he stumbled on the chance for his first really outrageous performance, an act as characteristic of the man as anything you could ask for. Knowing that 50,000 acres were to be turned over to New York in one place (the famous “Oblong”), he wrote clandestinely to friends in London, urging them to snap up the land before local people could get their hands on it. At the same time he maneuvered himself into the group of Colonials who were applying for a patent, apparently with the intention of undermining his trusting and unsuspecting colleagues, and of wresting control from them as agent for the London syndicate.

If such duplicity was second nature to him, its outcome was no less typical. The London patentees, after hurriedly obtaining a royal grant according to the advice of their mentor in New York, discovered that he (a boundary commissioner, be it remembered) had given them misplaced lines on the map, and that their claim was already occupied. How 18 they felt about him after that may easily be surmised, also how the New Yorkers reacted to his perfidy. From then on it was axiomatic that when dealing with Francis Harison you had to use extreme caution and circumspection.

If we judge by intent and motive rather than by accomplishment, he was as consummate a scoundrel as the Colonies ever produced. His only saving grace was a beguiling habit of being almost invariably hoist with his own petard. Stupid criminality followed by exposure and humiliation—that is the pattern; and wherever you find it on the banks of the Hudson during the early 1730’s, you may justifiably look for the imprint of Francis Harison’s fine Italian hand.

His big opportunity came with the arrival of Colonel Cosby. The two hit it off from the start. They were two of a kind, complementaries: the one found a willing tool, the other a powerful patron. Where the Governor was perforce hemmed in to a certain extent by the nature of his office, his lieutenant enjoyed a wide latitude where he could do almost as he pleased.

In the Cosby scheme of things Harison was allotted the dirty work, the low chicanery, and the brute force that the administration resorted to. In particular, he was given control of the Gazette, to which he fed weekly eulogies of the administration. His associates may have despised him privately (we know that James Delancey did), but in the governor’s mansion he received the appreciation due his special talents. Cosby, like many another tyrant, had a place near the top for an unprincipled adventurer. Francis Harison was his hatchetman.

They were so close that Cosby almost made Harison chief justice following the dismissal of Lewis Morris. Delancey, who got the post, was not at all happy about it, and Colden tells us:

19Mr Delancey excused his accepting of the commission at the expense of his predecessor by saying that the Governor could not be diverted from removing Mr Morris, and that if he did not accept it the Governor was resolved to put Mr Harison in the office, a man nowise acceptable to anybody. If that had been done it would certainly have been of great advantage to Mr Morris, for Mr Harison was of so bad a character, and so odious to the people, that they certainly would have pulled him from the Bench.[8]

Harison finally went too far in his shady deals and ruined himself. William Truesdale, one of the small fry who worked for him, owed a debt to a persistent creditor, Joseph Weldon of Boston. Somehow Harison got hold of a dunning letter from Weldon to Truesdale. Just what he had in mind is not clear—a pathetic lament that the historian has to make so often in dealing with what passed for ratiocination in this particular mind—but he caused a warrant to be sworn out against Truesdale in Weldon’s name. If you think he simply had his minion arrested without further ado, you do not know Francis Harison. His behavior is described thus by Colden:

Mr Harison met Truesdale at an ale house where, pretending not to like the beer, he invited Truesdale and his company to meet him two hours afterwards at another house. When Truesdale came to the other house he found the Under-Sheriff, who immediately arrested him. Truesdale sends to Mr Harison, as his friend, to help him in his distress. As soon as Mr Harison came, he, in a seeming great surprise, said to Truesdale, “In the name of God, what is this? I hear you are arrested for such a sum”—and blamed him for not informing of it that he might have kept him out of the Sheriff’s way.[9]

New York’s archvillain must have been very pleased with himself as his victim was carted off to jail. Did he whisper, “Honest Iago!” to himself?

The roguery was there, but as usual there was no intelligence to back it up and make it work. The intriguer had counted on a smooth explanation to fend off the man in whose name he was practicing on Truesdale. Instead, Joseph Weldon felt outraged when he learned what was going on, rushed down from Boston, swore that he never gave anyone any authority to act for him, and added that at the time he did not even know of Harison’s existence.

After this scandal there was no place in New York for Francis Harison. Even his protector in the governor’s mansion could not save him. A Grand Jury indicted him for using Weldon’s name, whereupon he fled from the Colony in May of 1735, made his way to England, and never came back. From then on his story is virtually a blank, the last word on him being that he was down-and-out when he died.

However, this melancholy denouement was in the future and unforeseen when Cosby put Harison in charge of the Gazette in 1732. The new editor began to ride very high indeed, for he was in the enviable position of one who could both flatter his own side and castigate its critics with impunity since there was no rival newspaper to contradict him. With Harison in command, the administration’s mouthpiece lavished on William Cosby the adulation that he loved and could get only from a trusted henchman, interspersing at the same time quick jabs at Morris, Van Dam, Alexander, and the rest.

Here is the way the Gazette covered one meeting between the Governor and the Assembly:

The harmony and good understanding between the several branches of the legislature—whereby nothing came to be demanded on the one side but what was for the public general good and welfare of His Majesty’s people, and everything done on the other which may recommend the honorable House to 21 His Majesty, to his representative and to their constituents—will, we hope, continue to us all those blessings which we enjoy under a government greatly envied, and too often disturbed by such as, instead thereof, are struggling to introduce discord and public confusion.[10]

The Gazette resorted to verse to make its case:

Cosby the mild, the happy, good and great,

The strongest guard of our little state;

Let malcontents in crabbed language write,

And the D...h H...s belch, tho’ they cannot bite.

He unconcerned will let the wretches roar,

And govern just, as others did before.[11]

It went to Pope’s translation of the Odyssey to find a suitable description of the opposing faction:

Thersites only clamored in the throng,

Loquacious, loud, and turbulent of tongue,

And by no shame, by no respect controlled;

In scandal busy, in reproaches bold;

But chief, he gloried with licentious style,

To lash the great, and rulers to revile.[12]

These passages epitomize the problem facing the Popular party. In fighting the Governor there was no hope of success unless he could be met at every critical spot, and one of the most critical was precisely that of journalism. Irregular pamphlets and open letters were of little use against a systematic weekly dose of administration propaganda in the Gazette. The passage of time only made the problem more acute.

Naturally we do not have minutes of the discussions that went on between the anti-Cosby conspirators, but we do not need such information to see the rationale of the strategy they worked out. Their behavior is most eloquent on that 22 score; it systematizes by practical example the disjointed notes, memoranda, and other documents that have come down to us.

First of all, they would do everything they could to sap the political strength of their hated enemy: they would support opposing candidates at elections, they would provide legal counsel for those whom he attacked through the courts, they would found a newspaper to bring their side of the controversy before the bar of public opinion. Secondly, they would wage their war on another front, in London, sending to the Board of Trade a steady barrage of propaganda designed to prove that William Cosby was no more fit to govern New York than he had been to govern Minorca. Eventually they would dispatch an emissary to make the situation clear in personal talks with the authorities.

With the lines thus drawn up, the first blows were struck on October 29, 1733. On that day was held the election of an assemblyman for Westchester, and the candidate of the Popular party was Lewis Morris. Governor Cosby, desperately anxious to defeat this formidable antagonist, threw everything he had to the support of his own man, William Forster. The result was the famous poll on the green of St. Paul’s Church, Eastchester.[1]

The two candidates, arriving with motley arrays of their followers behind them, were like commanding generals bound for battle. The image is not at all inexact, for Westchester was a stronghold of the Delancey-Philipse element of the Court party, and both sides were able to count on a disciplined mass of voters.

The sheriff presiding over the election was, like many officials, a creature of the Governor. Cosby evidently had ordered him to make sure, in one way or another, that the result went against Morris—in other words, to rig the election if necessary. When it became clear that Morris had a majority of the voters with him, the sheriff intervened and tried to snatch a victory by disfranchising one whole body of the population.

It had been customary to let Quakers vote without taking the oath, for by their religion they were forbidden to “swear.” Instead they were allowed to “affirm.” That custom gave Cosby’s sheriff a loophole. He decreed that no one who would not take the oath should be allowed to cast a ballot, and so he ruled the Friends out of the election, hoping that this maneuver would change the result. In fact it did not, for even without this group of his supporters Morris won a resounding victory.

The election was momentous beyond the fact that it returned to the Assembly a veteran of rough-and-tumble politics who was sure to throw his weight against the Governor wherever he could, and that it hardened the Quakers against the regime. It revealed Cosby as completely unscrupulous in dealing with his opponents, as a man who, occupying the position of chief upholder of the law, had no hesitation in playing fast and loose with it when he thought he could gain some advantage. Before the election he had been guilty of many questionable things, such as the legal attack on Van Dam and the removal of Lewis Morris from the Supreme Court, but these were at least debatable, with something to be said for him even if he could not be exculpated. Now his conduct was not debatable. It was plainly unethical, if not technically illegal.

The Westchester election was, in more ways than one, a triumph for the Popular party, which had impelled Cosby into a crime that was at once manifest and useless, revealing him as stupid as well as criminal.

The furor had hardly begun to die away before there burst upon the Governor the bombshell of an opposition newspaper. The New York Weekly Journal, edited by James Alexander and printed by Peter Zenger, was the first political independent ever published on this continent. The men behind it created a journalistic category new to American experience when they deliberately decided to make a continuing open battle with Governor Cosby the rationale of their editorial policy. They published a specifically political newspaper, no arm of the authorities or toady to headquarters, but the mouthpiece of those who were challenging the representative of the king in their Colony. There was nothing hesitant or sporadic about their undertaking. The paper came out every Monday, always truculent and always propagandizing one point of view in politics. The political issue was the only raison d’être of publication. Everything else—foreign news, essays, verses, squibs, advertisements—was filler.

Here was something original for this side of the ocean, an experiment in journalism as critical as ever was attempted by any members of our fourth estate; and successful, for the Journal lived and throve and became the ancestor of the great American political organs of modern times.

Now for all of this James Alexander was more responsible than any other man. From his literary remains we know that he was in full possession of the theory of a free press long before the occasion rose for him to implement it as a working editor, and that, the occasion having risen, he wrote much 25 of the copy for the opposition newspaper and blue-penciled virtually all the contributions bearing on the feud with the Governor.

This pivotal figure of American history was Scottish by birth, heir to the title of Earl of Stirling (a title his son made illustrious in the patriotic annals of the Revolution). He studied mathematics and science in Edinburgh, but compromised his future there by joining the Jacobite rising that attempted to place the Old Pretender on the British throne in 1715. After the fiasco, Alexander, like so many of his class, found Scotland too hot for him. He fled to America, studied law, went into politics, and eventually entered the Councils of both New York and New Jersey. Mathematician, scientist, lawyer, and politician, he was one of the most extraordinary men of his generation, a gentleman and a scholar, a charter member of Benjamin Franklin’s Philosophical Society, and the trusted confidant of more than one Governor.

The idea of founding the Journal was probably his. For one thing, he was already something of a journalist, having published various items in William Bradford’s Gazette when it was the only newspaper in town. Secondly, he was among the first overt opponents of Governor Cosby, the collision between them being remarkably quick and remarkably bitter, perhaps even more so than the Cosby-Morris and the Cosby-Van Dam conflicts. Only a few months after arriving the Governor wrote to his patron, the Duke of Newcastle:

There is one, James Alexander, whom I found here in both the New York and the New Jersey Councils, although very unfit to sit in either, or indeed to act in any other capacity where His Majesty’s honor and interest are concerned. He is the only man that has given me any uneasiness since my arrival.... In short, his known very bad character would be too long to 26 trouble Your Grace with particulars, and stuffed with such tricks and oppressions too gross for Your Grace to hear. In his room I desire the favor of Your Grace to appoint Joseph Warrell.[13]

Many more letters of a similar content passed between the governor’s mansion in New York and authoritative personages in England.

Alexander repaid the compliment in his own correspondence. To his old friend, former Governor Robert Hunter, he confided:

Our Governor, who came here but last year, has long ago given more distaste to the people than I believe any Governor that ever this Province had during his whole government. He was so unhappy before he came to have the character in England that he knew not the difference between power and right; and he has, by many imprudent actions since he came here, fully verified that character. It would be tedious to give a detail of them. He has raised such a spirit in the people of this Province that, if they cannot convince him, yet I believe they will give the world reason to believe that they are not easily to be made slaves of, nor to be governed by arbitrary power.... Nothing does give a greater luster to your and Mr Burnet’s administrations here than being succeeded by such a man.[14]

This letter is notable for giving Alexander’s own express statement about the reason for publishing the brand new Journal:

Inclosed is also the first of a newspaper designed to be continued weekly, chiefly to expose him [Cosby] and those ridiculous flatteries with which Mr Harison loads our other newspaper, which our Governor claims and has the privilege of suffering nothing to be in but what he and Mr Harison approve of.

27Mr Van Dam is resolved, and by far the greater part of the Province openly approve his resolution, of not yielding to the Governor’s demand. He has not as yet answered, nor will the Governor’s lawyers be able for one while to compel him unless they break over all law and persuade the new Judges [Delancey and Philipse] into a contradiction of themselves. Which if they do, the world shall know it from the press.[15]

The advent of the Journal did nothing to lessen the bitterness of Cosby’s condemnation of Alexander, for although it was known as “Zenger’s paper” (since it bore only the printer’s name), the Governor was in no doubt about who was the guiding genius of the enterprise. On December 6, 1734, he writes to the Board of Trade:

Mr James Alexander is the person whom I have too much occasion to mention.... No sooner did Van Dam and the late Chief Justice (the latter especially) begin to treat my administration with rudeness and ill-manners than I found Alexander to be at the head of a scheme to give all imaginable uneasiness to the government by infusing into, and making the worst impression on, the minds of the people. A press supported by him and his party began to swarm with the most virulent libels.[16]

Cosby realized further that Alexander was not the only one in New York who was playing at the new kind of journalism, and he said of Morris:

His open and implacable malice against me has appeared weekly in Zenger’s Journal. This man with the two others I have mentioned, Van Dam and Alexander, are the only men from whom I am to look for any opposition in the administration of the government, and they are so implacable in their malice that I am to look for all the insolent, false and scandalous aspersions that such bold and profligate wretches can invent.[17]

Cosby’s cries of rage and anguish are understandable enough. From the date of the Journal’s appearance (November 5, 1733) until his death more than two years later it constituted itself his most alert censor, critic, and judge. Every Monday the lash fell across his shoulders, the attacks varying through the gamut from airy satire to thundering condemnation. The opposition writers called him everything from an “idiot” to a “Nero,” and pointedly suggested that his London superiors should do something to alleviate the affliction they had imposed on their Colony.

The first issue started the ball rolling with a brilliant and biting story of the Westchester election and Morris’ victory in spite of the sheriff’s heavy-handed machinations; and from then on there was no letup. The fundamental idea being to convict Cosby of violating the rules of his governorship, the Journal never ceased to hammer at this theme. The best example of the technique is in the issues of the last two weeks of September, 1734, a continued essay that accuses Cosby of voting as a member of the Council during its legislative sessions, of demanding that bills from the Assembly be presented to him before the Council saw them, and of adjourning the Assembly in his own name instead of the king’s.

All three of these acts violated the rules by which the Governor was bound, and when the Journal carried the story to the Board of Trade, Cosby was warned about them. He could not, of course, be condemned out of hand on the basis of a newspaper story, but the significant thing is that the Board should have found the story sufficient basis for mentioning the subject.

Most of the Journal writing is lost irretrievably behind a veil of anonymity, which is not too important since whoever “Cato” and “Philo-Patriae” and “Thomas Standby” may have been, they were acting in concert. But every once in a 29 while individual personality peeps or glares through the writing, as in this reply to one argument for the prudence of obeying the government, no matter what. The text of the reply is saturated through and through with the pent-up gall and venom on which Lewis Morris had been feeding for so long:

Let this wiseacre (whoever he is) go to any country wife and tell her that the fox is a mischievous creature that can and does do her much hurt, that it is difficult if not impracticable to catch him, and that therefore she ought on any terms to keep in with him.

Why don’t we keep in with serpents and wolves on this foot? Animals much more innocent and less mischievous to the public than some Governors have proved.

A Governor turns rogue, does a thousand things for which a small rogue would have deserved a halter; and because it is difficult if not impracticable to obtain relief against him, therefore it is prudent to keep in with him and join in the roguery; and that on the principle of self-preservation. That is, a Governor does all he can to chain you, and it being difficult to prevent him, it is prudent in you (in order to preserve your liberty) to help him put them on and to rivet them fast.

No people in the world have contended for liberty with more boldness and greater success than the Dutch; are more tenacious in retaining it; or more jealous of any attempts upon it; yet in their plantations they seem to be lost to all the sense of it, and a fellow that is but one degree removed from an idiot shall, with a full-mouthed “Sacrament, Donder and Blixum!” govern as he pleases, dispose of them and their properties at his discretion, and their magistrates will keep in with him at any rate, and think his favor no mean purchase for the loss of their liberty.

There have been Nicholsons, Cornburys, Coots, Barringtons, Edens, Lowthers, Georges, Parks, Douglases, and many more, 30 as very Bashaws as ever were sent out from Constantinople; and there have not been wanting under each of their administrations persons, the dregs and scandals of human nature, who have kept in with them and used their endeavors to enslave their fellow-subjects, and persuaded others to do so.[18]

This was political independence with a vengeance. Never before had an American newspaper dared to treat an officer of the crown so. Other periodicals depended on official sanction to keep them going, or at least never strayed too far from the line laid down for them. The Journal had no sanction and toed no line. It was, depending on one’s political sympathies, either an outrageous innovation or else simply an unfamiliar experiment. In either case it needed to be legitimized in the eyes of its readers.

That was why Alexander, as editor, pushed the issue of freedom of the press so hard. New Yorkers who had been unaware of that freedom would come upon it every time they opened “Zenger’s paper.” Side by side they would find stories about the misdemeanors of the Governor and essays defending and defining a free press, an ingenious interplay of practice and theory, a journalistic dialectic shifting between independent news reporting and the theory that justifies such reporting. Under Alexander’s editing hand the contributors both pilloried their enemy in the executive mansion and claimed the right to do so.

Alexander did not, of course, invent the technique. It was already well known in Britain, and he took it over for his own purposes, just as our political philosophers such as Jefferson, Franklin, and Madison took over ideas already current in Britain and France. Like all our Colonial editors, he 31 was dependent on classics such as Milton, Locke, Swift, Steele, Addison, and Defoe. He used all of these at different times, quoting them as authorities for unfettered journalism and free speech.

Most of all he used the celebrated Cato’s Letters of Thomas Gordon and John Trenchard. They furnished him with an ideal model. The letters had appeared in the London Journal and the British Journal only a decade before, when, signing themselves “Cato,” Gordon and Trenchard castigated his majesty’s government, and particularly the men responsible for the scandal of the South Sea Bubble. They also larded their attacks with animadversions on freedom of the press, which they explicitly defended as intrinsic to liberty itself. They caused so much embarrassment to the Ministry that it was forced to counterattack: characteristically for the eighteenth century, it solved the problem by buying out the London Journal.

But that did not kill the argument, for Cato’s Letters were published in four volumes and enjoyed a tremendous popularity on both sides of the Atlantic. It took James Alexander to show just how much might be done with them over here. He manifestly had read and reread Gordon and Trenchard, soaking up their ideas as avidly as a sponge soaks up water, and, turning editor, he found in them a treasure trove of journalistic philosophy and invective. His policy is theirs adapted to the situation in Colonial New York.

He copied out extracts from the Letters both for his own private edification and guidance and for use in the Journal. There is extant in his handwriting part of the letter headed “Of the restraints which ought to be laid upon public rulers.” He thought it apropos of the Cosby administration, so it appeared in the Journal on May 27, 1734. Here are a few others that he selected, or else approved, for reprinting: “The right and capacity of the people to judge of government,” 32 “Of reverence true and false,” “Of freedom of speech: that the same is inseparable from public liberty,” “Reflections upon libelling,” “Cautions against the natural encroachments of power.”

To put his editorial credo in a nutshell, Alexander went to another classical source, the Craftsman, and printed this maxim on November 12, 1733:

The liberty of the press is a subject of the greatest importance, and in which every individual is as much concerned as he is in any other part of liberty.

Under the aegis of his text he adroitly maneuvered the opposition newspaper against all the power of the Governor—and against all the defenses thrown up by Francis Harison as editor of the Governor’s newspaper.

The Journal’s anti-Cosby campaign touched off the first of the many newspaper wars that have raged on the banks of the Hudson. As often as it attacked did the Gazette rush to the rescue amid an acrimonious exchange of accusations and insults. Thus, referring to the sentiments of the people of New York toward their Governor:

The Journal. They think, as matters now stand, that their liberties and properties are precarious, and that slavery is like to be entailed on them and their posterity if some past things be not amended.[19]

The Gazette. Now give me leave to say what I have reason to believe some of the people of this City and Province think in relation to that paragraph in Zenger’s paper. They think it is an aggravated libel.[20]

In such a tone did New York’s two newspapers carry on their duel, one which concedes nothing to the later age of yellow journalism in its furious charges and countercharges of deceit, ignorance, calumny, and slander. The above onset and riposte stand out because the passage from the Journal sounds like Alexander himself, while Governor Cosby agreed with the Gazette that it was “libelous” and made it part of the formal indictment of Peter Zenger.

Both sides went at it hammer and tongs. In the Journal, where Cosby is called a “Nero,” his kept journalist is his “spaniel.” The Gazette retorts with epithets like “seditious rogues” and “disaffected instigators of arson and riot,” and proposes that the name “Zenger” be turned into a common-noun synonym for “liar.”

The men behind the opposition newspaper made a point of referring to Harison obliquely in satirical mock “advertisements” like these:

A large spaniel of about five foot five inches high has lately strayed from his kennel with his mouth full of fulsome panegyrics, and in his ramble dropped them in the New York Gazette. When a puppy he was marked thus (FH), and a cross in the middle of his forehead; but the mark being worn out, he has taken upon him in a heathenish manner to abuse mankind by imposing a great many gross falsehoods on them. Whoever will strip the said panegyrics of their fulsomeness, and send the beast back to his kennel, shall have the thanks of all honest men, and all reasonable charges.[21]

The spaniel strayed away is of his own accord returned to his kennel, from whence he begs leave to assure the public that all those fulsome panegyrics were dropped in the New York Gazette by the express orders of his master; and that for the gross falsehoods he is charged with imposing upon mankind, he is willing to undergo any punishment the people will impose 34 on him if they can make full proof in any Court of Record that any one individual person in the Province (that knew him) believed any of them.[22]

The writers of these squibs had measured their man perfectly. They could become furious, caustic, ironic or insulting—that is, serious—with the Governor and the rest of the men around him; but the proper approach to Francis Harison was through satire. From the Journal he received a systematic dose of it.

For six months he absorbed the barbs of ridicule while maintaining an air of indifference. Finally, able to stand the badgering no longer, he whirled on his tormentors and attempted to repay them in their own coin:

Supposing another should turn the tables upon the authors of these infamous and fictitious advertisements, how easily might it be done? The real or imagined defects of the Amsterdam Crane, the Connecticut Mastiff, Phillip Baboon, Senior, Phillip Baboon, Junior, the Scythian Unicorn, and Wild Peter from the Banks of the Rhine might be enlarged upon, and placed in a most ludicrous light.[23]

Since the crass and clumsy Harison was devoid of the slightest capacity for satire, he inevitably suffered when he picked up the weapon that was wielded so devastatingly by his enemies. The only interesting thing about this paragraph is that it identifies the men of the Popular party who contributed most to the Journal: Rip Van Dam, William Smith, Lewis Morris, Senior, Lewis Morris, Junior, James Alexander, and Peter Zenger.

The honors of combat obviously went to “Zenger’s paper.” It was not always fair, by a long shot—nor has any newspaper ever been when fighting a war with a rival. But Cosby and Harison and the Court party in toto were too vulnerable for 35 all the Journal’s broadsides to go astray. The Governor was hit over and over again. So was his editor. So were his other cronies.

They fought back in the Gazette, but they were always on the defensive, always incapable of getting a real attack going. Finally Cosby, boiling with rage, determined on something more practical than a war of words.

The Governor paused long enough to see what could be done through the usual legal channels, with Chief Justice Delancey given the job of extracting a grand jury indictment for libel. That this attempt failed twice is indicative of the administration’s unpopularity. The jurors manifestly had determined from the start that they would do nothing, and though they were in no more doubt than Delancey about the identity of the principal men who wrote for the Journal, they used the “anonymity” of the affair as an excuse to avoid indicting anybody.

With the second grand jury failure, Cosby’s attention began to focus more intently on the newspaper and its printer. His next move was to order copies of the obnoxious periodical to be burned, which was done even though the Assembly and the magistrates refused to participate. Naturally the man in charge was the man maintained expressly for such purposes. Harison was all the more eager to perform the duty in that, besides the eternal ridicule the Journal heaped on him, in one issue it had run a letter from the freeholders of Orange County thanking their assemblyman, Vincent Matthews, for making a vitriolic attack on him from 36 the floor of the legislature. A copy from that issue was one of four earmarked for the flames.

The hatchetman’s first instinct was to adopt strong-arm methods. He therefore went around to Peter Zenger’s establishment, disburdened himself of some violent opinions (“more fit to be uttered by a drayman than a gentleman,” says Peter), and threatened to cane him on the street. That was why the printer took to wearing a sword whenever he went out—the sword that gave an excuse for much heavy sarcasm in the columns of the Gazette.

Harison did not overlook more indirect and devious methods of dealing with his critics. He sent a couple of his creatures, John Alsop and Edward Blagg, to Orange County to spread the story that the Journal with the freeholders’ letter commending Matthews had been burned by the common hangman, and that the signers were to be rounded up and thrown into jail—a rumor that caused some trepidation among the solid citizens of the county.

Unfortunately Harison, misjudging the situation in his usual fashion, had jumped the gun a little too smartly. He counted on the hangman to do the job because he himself, as recorder of New York City, was supposed to persuade the magistrates to throw their authority behind the ceremonial burning. But when he met with them, he found himself in an atmosphere of chilly distrust, for they knew that Cosby was trying to kill legitimate opposition. Harison started to argue that there were sound British precedents for dealing thus with the Journal; was quickly shown up as grossly ignorant on that score (he put up the defense that he did not carry his lawbooks around with him); was roundly snubbed; and departed in a spasm of fury. The magistrates then forbade anyone within their authority, including the hangman, to have anything to do with the affair.

The Journal was burned on schedule, with Harison presiding, but he had to bring in a slave to set the fire, and they were virtually alone in front of the City Hall as the flames rose. It was the most dismal fiasco of a career studded with fiascoes.

We can judge how heated the situation had become by reverting once more to that most percipient of contemporary witnesses, Cadwallader Colden:

One might think, after such aversion to this prosecution appeared from all sorts of people, that it would have been thought prudent to have desisted from farther proceedings. But the violent resentment of many in the administration who had been exposed in Zenger’s papers, together with the advantage they thought of gaining by his papers being found libels by a Jury, blinded their eyes so that they did not see what any man of common understanding would here have seen, and did see.[24]

Governor Cosby was indeed blind. He was blinded by a baffled fury that had grown increasingly unreasoning as his hopes crumbled into nothingness. Instead of bowing to his will, his enemies were causing him grave embarrassment with his superiors, compelling him to a perpetual defense of his right to remain in his office. And locally they had made him a laughingstock. With cool impudence Morris and Alexander (these two above any) tormented him from behind the safeguard of an “anonymity” that fooled nobody, and was intended to fool nobody—least of all the victim of their attacks, for the dagger was honed to a fine edge precisely by Cosby’s awareness of who held it. The commanders of the Popular party were all very much at large, hurling their invectives at him and satirizing his attempts to retaliate.

The hunters had fenced in the tiger, and were baiting him from a safe distance, prodding him into a frenzy—until with a 38 single bound he leaped on the one man who stood within reach.

Printer Peter Zenger had not even a specious “anonymity” between him and the Governor. The Journal was “his” newspaper. Accordingly a warrant for his arrest went out from the Governor and the Council, and the sheriff arrested Zenger on November 17, 1734, and held him for trial on a charge of “seditious libel.” Harison, needless to say, was one of the councillors who signed the warrant; in fact, he is the only person mentioned by name as having done so in the well-known “apology” that Zenger printed in his newspaper on November 25:

As you last week were disappointed of my Journal, I think it incumbent on me to publish my apology, which is this. On the Lord’s Day, the seventeenth, I was arrested, taken and imprisoned in the common jail of this City by virtue of a warrant from the Governor, the honorable Francis Harison, and others in the Council (of which, God willing, you will have a copy); whereupon I was put under such restraint that I had not the liberty of pen, ink or paper, or to see or speak with people, until upon my complaint to the honorable Chief Justice at my appearing before him upon my habeas corpus on the Wednesday following. He discountenanced that proceeding, and therefore I have had since that time the liberty of speaking thro’ the hole of the door to my wife and servants. By which I doubt not you will think me sufficiently excused for not sending my last week’s Journal, and hope for the future, by the liberty of speaking to my servants thro’ the hole of the door of the prison, to entertain you with my weekly Journal as formerly.

During all the printer’s imprisonment the Journal failed of but that one issue. The credit for its punctual appearance every Monday thereafter belongs to his wife, Anna Catherine Zenger, who stepped into his shoes back at the shop. Anna 39 Catherine has a real claim to fame for standing by her husband, a loyalty by no means insignificant in a woman with a family. She may have been emboldened by her ability to keep the press going in his absence, but even so it would have been a crushing blow if he had been given a harsh sentence as, for all she knew, might have been the outcome. The little evidence there is indicates that she never pressed him to give in and name the men who actually were responsible for the Journal. She must have known that the New York administration would gladly trade the printer for the editor, a comparatively minor figure for the archenemy—that is, Peter Zenger for James Alexander—but there is no record of her ever complaining that the Zenger family was suffering for someone else.

The Court party’s editor used the occasion for a show of mock sympathy with the Popular party’s printer. The Gazette for December 9, 1734, has a reference to

the pretended patriots of our days, the correspondents of John Peter Zenger, who are every hour undermining the credit and authority of the government by all the wicked methods and low artifices that can be devised, and which they flatter themselves are consistent with their own safety. I am sorry they are so tenacious of their own as to neglect that of their poor printer.

Harison had a fine time thinking up jibes like this. It would have been poetic justice if he had been around to suffer—with Governor Cosby and the rest of the Court party—through the acquittal Peter Zenger won so triumphantly on August 4, 1735. But by that time New York had become too hot for this particular member of the faction, and he was on the other side of the Atlantic.

The arrest of Peter Zenger was one of Cosby’s gross mistakes. No one in the Colony could miss the fact that he was 40 bent on revenge, for the public bodies—Assembly, Common Council, grand juries—had all refused to have anything to do with proceedings that they recognized as strictly the Governor’s private affair. Nor could there be any doubt that his purpose was to silence a critic who had been uttering unpalatable truths. Popular feeling was exacerbated by the fact that Cosby’s vindictive wrath fell, not upon the powerful men of the opposite faction, but upon an insignificant German immigrant who plied the trade of printer in the city.