The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Life of Captain Sir Richard F. Burton,

volume 2 (of 2), by Isabel Burton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Life of Captain Sir Richard F. Burton, volume 2 (of 2)

By his Wife Isabel Burton

Author: Isabel Burton

Release Date: June 5, 2017 [EBook #54846]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LIFE OF SIR RICHARD F BURTON, VOL 2 ***

Produced by Clare Graham & Marc D'Hooghe at Free Literature

(online soon in an extended version, also linking to free

sources for education worldwide ... MOOC's, educational

materials,...) Images generously made available by the

Internet Archive.

We meet by accident in Venice and go to Trieste—Richard as a

"Celebrity at Home"—Articles by Alfred Bates Richards—Cicci—A wild

race—Opçina—Trieste life—And environs—Rome and the Tiber—Vienna—The

Imperial family—Fiume—Castellieri—Duino—Venice—Good-bye

to Charley Drake—Excursions—Proselytizing—Richard is very ill—Charley

Drake's death—Travelling for his health—The Nile on the

tapis again—My Arab girl goes home to be married—Gordon—Winwood

Reade's death—K.C.B.—Meeting Mr. Gladstone—Incidents of London

life—Excursions—More London life—Leave England.

Jeddah—Bazars of Jeddah—Experiences on a crowded

pilgrim-ship—Bombay—Sind—Travelling in Sind—Richard's remarks

on changes in Indian army—The Indian army—And Sind—The

Muhárram—Richard's old Persian moonshee—Mátherán—Karla Caves.

Hyderabad in the Deccan—Elephant riding—Ostrich

race—Hospitality—Eastern hospitality at Hyderabad—Golconda—The

famous Koh-i-noor—Regret at leaving the Deccan—Towers of

Silence—Sects—The Hindu Smáshán—The Pinjrapole—Bhendi

Bazar—Máhábáleshwar—Goa and West India—Life there—What to see—The

Inquisition—Xavier's death—The Inquisition perishes—Sea journey to

Suez—After a stay in Egypt, to Trieste.

Delightful Trieste life—Henri V. of

France—Bertoldstein—Midian—Akkas—Waiting and working—I go out

to join him—Richard's triumphant return—We go home—The British

Association for Science—Society and amusement.

Spiritualism—A memorable meeting on the subject—Richard's lecture—Some

very amusing and instructive speeches—Interesting discussions—And

letters.

A remarkable visit—On leave in London—We leave London—I

get a bad fall—The Austrian Scientific Congress—A ghost

story—Excursions—Richard sends me home to a bone-setter—Richard

meets with foul play—Camoens—A little anecdote about a

Capuchin—The Passion Play—Ober-Ammergau—Celebrating a Vice-Consul's

jubilee—Monfalcone—Richard's metal and colour.

Richard's three letters to Lord Granville—His application to be made

Slave-Commissioner—How to deal with the slave scandal in Egypt.

Duino—Our Squadron—Our Squadron leaves—We go to Veldes—We part

company—I am sent to Maríenbad—The Scientific Congress at Venice—Life

and incidents of Trieste—Gold in West Africa—Mining—African

mines.

London and back—The Great Trieste Exhibition—Émeute at Trieste—We

lose an old Vice-Consul—Lord Wolseley—Richard is sent to find

Palmer—Trieste life—Count Mattei's cure—Count Mattei—We get the

house we wanted—Scorpions—"Gup".

Miscellaneous traits of character and opinions—Descriptions from other

sources.

Richard's first bad attack of gout—His leave of absence—We return to

Trieste—Streams of visitors—Richard's second attack of gout—Gordon's

death—Colonel Primrose's death—Leave to England—"Arabian Nights"—London

again—Richard's programme for Egypt—He asks for

Tangier—Parts with my father—Goes to Marocco—What the world said—He

waits for me at Tangier.

Diet for Ireland—Another postscript—Treatment of Catholics and

loyalty—We winter in Marocco—Richard made a K.C.M.G.—A bad hurricane

at sea—I have another fall—Naples—The great Chinese move—We get

leave again to England—Oxford—His last appeal to Government—What the

world thought about it—Chow-chow—His third bad attack of gout without

danger.

Cannes and Society—The earthquakes—Riviera—Richard becomes an

invalid—His own account of it—Our journey with Dr. Leslie—Drains—The

Queen's Jubilee—Richard's speech—Ally Sloper—We think of a

caravan—He gets much better—We go for our summer trip—Some of our

Royalties come to Trieste—We lose Dr. Leslie, and Dr. Baker comes to

us.

Programme of our day—Abbazia—We return to Trieste—His notes on his

Swiss summer—Aigle—Our last visit to England—Richard leaves it for

ever—His advice about Suákin—Discussing about Ludlow—Richard's

remarks on Lausanne.

M. Elisée Réclus—Our Swiss outing—Trieste again—Maria-Zell—Austrian

Lourdes—Semmering—Home

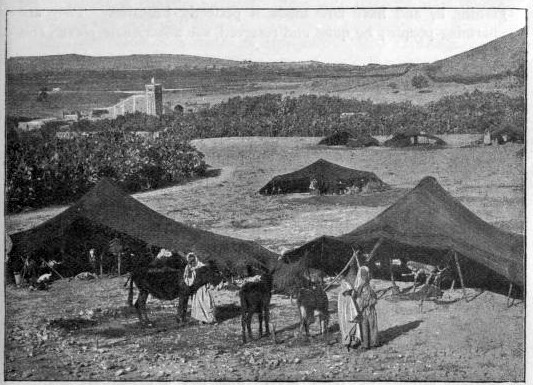

again—Malta—Tunis—Carthage—Constantine—Sétif—Bouira—Algiers—Hammam

R'irha—Things one would rather have left

unsaid—Marseilles—Hyères—Nice—Home—Our last

trip—Switzerland—Davos-Platz—Ragatz—St. Moritz—Maloja—We

descend into Italy homewards.

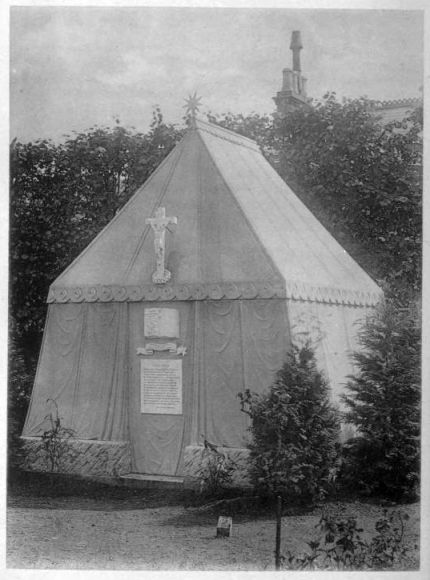

Our last happy day—The sword falls—He is called away—The sixty hours

between death and funeral—The funeral at Trieste—The dreadful time

that followed—Colonel Grant attacks Richard after his death—I answer

directly to the Graphic in two parts—My answer—The beloved remains

are removed to England—I leave Trieste and go to Liverpool—I fall

ill—The mausoleum tent complete—The funeral in England at Mortlake—"It"

confesses: too late.

My defence about the burnt MS.—To the Echo—And to the New

Review—Religion—I take my leave—Good-bye.

A.—List of Captain Sir Richard F. Burton's Works.

D.—Visit to the Village of Meer Ibrahim Khan Talpur, a Beloch Chief.

G.—Description of African Character—The Raw Material in 1856-59.

H.—Report after going to search for Palmer.

I.—Opinions of the Press and of Scholars on the "Arabian Nights."

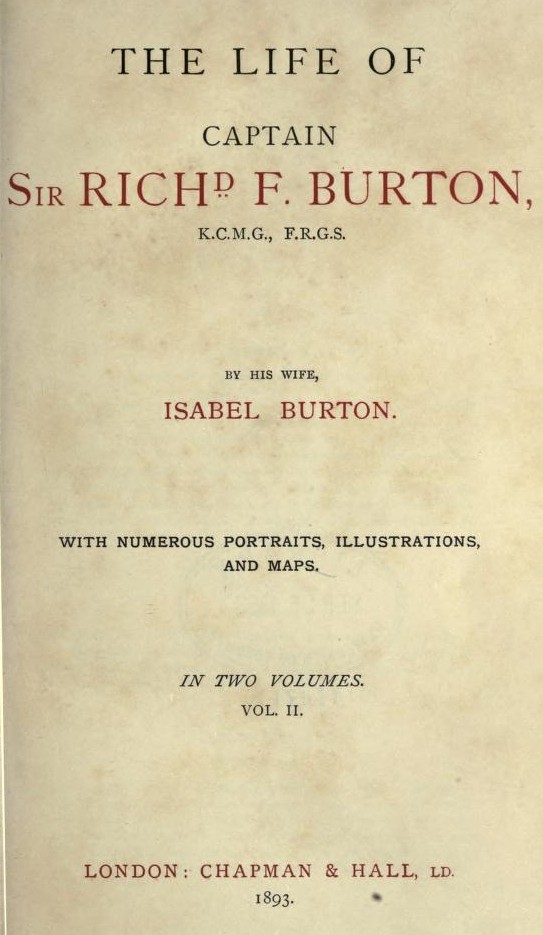

Daneu's Inn, Opçina, in the Karso.

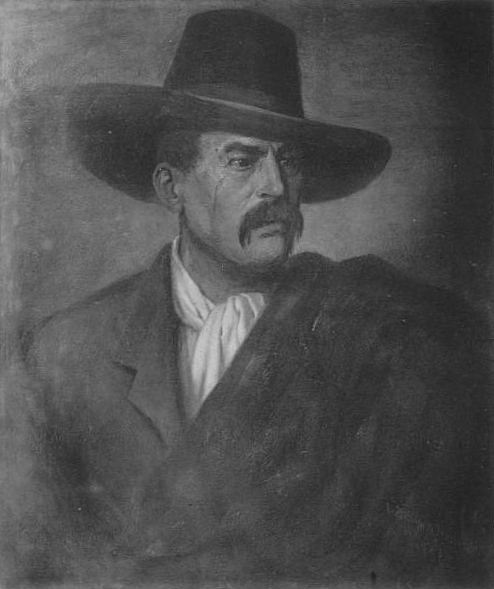

Sir Richard Burton, 1879.

By Madame Gutmansthal de Benvenuti, Trieste.

House at Trieste, where Burton died.

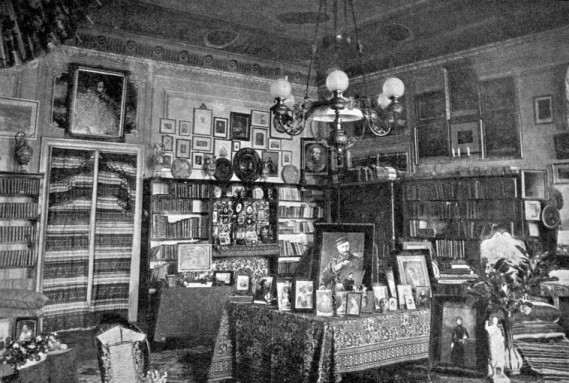

A Corner of the Burtons' Drawing-room at Trieste.

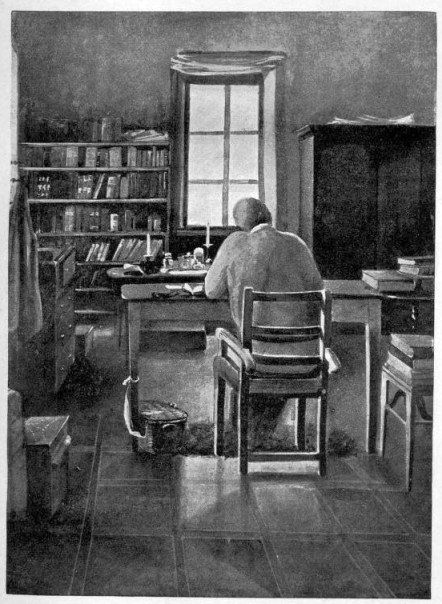

Richard Burton in his Bedroom at Trieste.

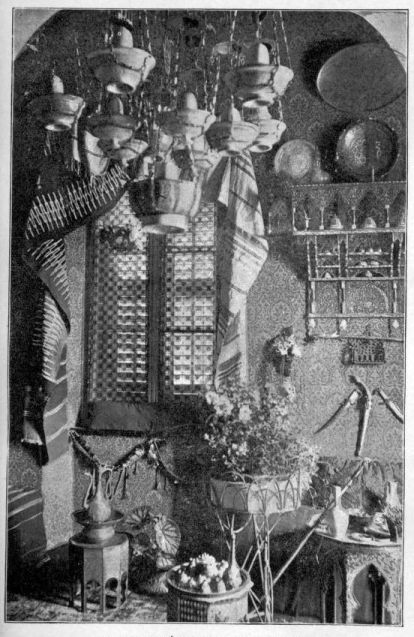

The Burtons' Smoking Divan, Trieste.

The View from the Burtons' Bedroom and Study over the Sea at Trieste.

The Mausoleum at Mortlake, where Sir Richard Burton is laid at rest.

On the 24th of October, 1872, Richard left England for Trieste, to pass, though we little thought it then, the last eighteen years of his life. He was recommended to go to Trieste by sea, which always did him so much good. He was to go on and look for a house, hire servants, etc.; and I was to lay in the usual stock of everything a Consul could want, and follow as soon as might be by land. We all went down to Southampton to see him off, but, as the gale and fog were awful, they were only able to steam out and anchor in the Yarmouth Roads.[1]

On the 18th of November I went down to Folkestone to cross, en route to Trieste, and ran through straight to Brussels, where I slept, and next day got to Cologne.

Of course, I stopped and looked at the Cathedral, and went to Johann M. Farina's (4, Jülichs Platz), and the Museum, top of Cathedral, for view, stained glass, and all that; and then I sauntered on to Bonn, Coblenz, Bingen, Castel, Mayence, until I got to Frankfort. I enjoyed the Rhine very much, but my perception for scenery had been a little blunted by the magnificence of South America, and for antiquities by ancient Syria. I thought the finest things in Frankfort were Dannecker's Ariadne, belonging to Mr. Bethmann, a private collection of pictures; and Huss before the Council of Constance, by Lessing; and another of four priests at the throne of the Virgin, by Moretto; and I thought how pretty the place must be in summer.

From here I went quietly on to Würzburg, and thence to Munich, where I was enchanted with the Hôtel des Quatres Saisons. I[Pg 2] enjoyed the winding river, and the Forest of Spessart (the remnant of the great primeval Hercynian Forest described by Cæsar and Tacitus), the Spessart range of hills wooded to the top, the wild country with a few villages. I thought the rail along the river-side ascending amongst the wooded hills, crossing the stream of the Laufach, very beautiful, and the entrance to Würzburg reminded me of Damascus and its minarets. Here I called on the famous Dr. Döllinger. I went to see Steigenwald's Bavarian glass, and the porcelain with the Old Masters painted on it, ascended to the top of the Cathedral tower to see the view, and went to every museum and picture-gallery in the place, and thought, as most people do, I imagine, that the City was very pretty, but the Art was very new.

I then went on quietly to Innsbrück. The scenery is magnificent along the banks of the river Inn, through the Tyrolese mountains, capped with snow, wooded, dotted with villages, and with cattle on the mounds, and churches and chapels with delicate spires. I liked the exhilarating air, and especially the valley of Zillerthal, and seeing the fine Tyrolean peasants. The best thing to see at Innsbrück is the Hof-Kirche, or Court Church. There are statues in bronze of all the great Emperors of Austria, and one or two Empresses; they stand in two lines down the church, all in armour and coats of mail. The moment I went into the centre, between these imperial lines, I singled out one of them, exclaiming, "There is a gentleman and a knight, from the top of his head to the sole of his foot;" and I ran up to see who he was. He was labelled, "King Arthur of England." All that day we were crossing the Brenner Pass. The scenery is splendid, with snowy peaks, wooded mountains, waterfalls, and rivers (the Eisach and Adige), torrents and boulders, porphyry rocks, villages, fortresses, convents and castles, churches and chapels with slender red or green steeples. I arrived at Trent, where I found nothing to stay for; so went on to Verona, Vicenza, Padua, and Venice, and landed at the Hôtel Europa—which I had inhabited long ago, in 1858, when I was a girl,—in time for table d'hôte. It was fourteen years since I had seen Venice, and it was like a dream to come back again. It was all to a hair as I left it, even, I believe, to the artificial flowers on the table d'hôte table. It was just the same, only less gay and brilliant—it had lost the Austrians and Henri V.'s Court; and I was older, and all the friends I knew were dispersed.

My first action was to send telegram and letter to Trieste (which was only six hours away), to announce my arrival, then the next day to gondola all over Venice, and to visit all old haunts. Towards late afternoon I thought it would be only civil to call on my Consul,[Pg 3] Sir William Perry. Lucky that I did so. After greeting me kindly, he said something about "Captain Burton." I said, "Oh, he is at Trieste; I am just going to join him." "No; he has just left me." Seeing that he was rather old, and seemed a little deaf and short-sighted, I thought he did not understand, so I explained for the third time that "I was Mrs. Burton (not Captain Burton), just arrived from London, on my way to join my husband at Trieste." "I know all that," he said, rather impatiently; "you had better come with me in my gondola. I am going to the 'Morocco' now—the ship that will sail for Trieste." I said, "Certainly;" and, very much puzzled, got into the gondola, chatted gaily, and went on board. As soon as I got down into the saloon, lo, and behold, there was my husband, quietly seated at the table, writing. "Hallo!" he said, "what the devil are you doing here?" So I said, "Ditto;" and we sat down and began to explain, Sir William looking intensely amused.

I had thought when Richard left me on the 24th October, that he had sailed straight for Trieste, and he thought I had also started by land straight for Trieste; so we had gone on writing and telegraphing to each other at Trieste, neither of us ever receiving anything, and Mr. Brock, our dear old Vice-Consul, who had been there for about forty years, thought what a funny couple he was going to have to deal with, who kept writing and telegraphing to each other, evidently knowing nothing of each other's movements. Stories never lose anything in the recital, and consequently this one grew thusly: "That the Burtons had been wandering separately all over Europe, amusing themselves, without knowing where each other were; that they had met quite by accident in the Piazza at Venice, shaking hands with each other like a pair of brothers who had met but yesterday, and then walked off to their hotel, sat down to their writing, as if nothing was the matter."

The ship was detained for cargo and enabled us to stay several days in Venice, amusing ourselves, and on the 6th of December, 1872, we crossed over to Trieste in the Cunard s.s. Morocco, Captain Ferguson, steaming out at 8 a.m., and getting to Trieste at 5.15 p.m. There came on board Mr. Brock, our Vice-Consul, and Mr. O'Callaghan, our Consular Chaplain. It was remarked "that Captain and Mrs. Burton (the new Consul) took up their quarters at the Hôtel de la Ville, he walking along with his game-cock under his arm, and she with her bull-terrier," and it was thought that we must be very funny. We dined at table d'hôte, and we did not like the place at all.

When Richard left England I had entrusted him with the care of two boxes containing all my best clothes, and part of my jewellery, wherewith to open my Trieste campaign. He contrived to lose them[Pg 4] on the road (value about £130), so when I arrived I had nothing to wear. We wrote and complained, but the Peninsular and Oriental would give us no redress; and when the boxes did arrive they were empty, but had been so cleverly robbed that we had to get the canvas covers off, before we perceived that they had been opened by running the pin out of the hinges at the back. I never recovered anything. The Peninsular laid the blame on Lloyd's, and Lloyd's on the Peninsular, and Richard said, "Of course I believe them both."

We stayed for the first six months in the hotel. The chief Israelitish family, our local Rothschilds, Chief Banker, and afterwards Director of Austrian-Lloyd's, Baron Morpurgo, called upon us, and opened their house to us; and this introduced us to all that was the best of Trieste, and everybody called. This family have always deserved to be placed on a pedestal for their princely hospitality, their enormous charities, and their innate nobleness of nature. They made Trieste what it was, and every one was glad to be asked to their house. We made our debut at the marriage of Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Sassoon. She was the belle of our little society; he was a British subject; and Richard, being his Consul, had to be sort of "best man." It was very interesting. I had not got used at that time to telegraphs, and when I saw innumerable telegrams flying about at the breakfast, I innocently asked if there was any great political crisis. They laughed, and they said, "Oh no; we only telegraphed to Madame Froufrou, to tell her how much Louise's dress was admired, and she telegraphs back her pleasure at hearing it," and so forth. I think in those days telegrams caused more surprise in England than they did abroad. I shall never forget the rage of my family the first time I came home from Trieste, who were thrown into violent palpitations at a telegram from me, which was only to ask them to send me a big goose for Michaelmas.

As I said, we stayed the first six months at the hotel, and we disliked the place very much, until we got thoroughly used to it; and, when we got used to it, I cannot give a better description of our lives than to cut out from the World the "Celebrity at Home, Captain R. F. Burton at Trieste," 1877, with Alfred Bates Richards's comments on the same; and that was the life we led from 1872 to 1882-83.

"CAPTAIN RICHARD F. BURTON AT TRIESTE.

"It is not given to every man to go to Trieste. The fact need not cause universal regret, inasmuch as the chief Austrian port on the Adriatic shares with Oriental towns the disagreeable character of presenting a fair appearance from a distance, and afflicting the[Pg 5] traveller who has become for the time a denizen, with a painful sense of disenchantment. Perhaps the first glimpse of Trieste owes something to contrast, as it is obtained after passing through a desolate stony wilderness called the Karso. As the train glides from these inhospitable heights towards Trieste, the head of the Adriatic presents a scene of unrivalled beauty. On the one side rise high, rugged, wooded mountains, on a ledge of which the rails are laid; on the other is a deep precipice, at whose base rolls the blue sea, dotted with lateen sails, painted in every shade of colour, and adorned with figures of saints and other popular devices. The white town staring out of the corner covers a considerable space, and places its villa-outposts high up the neighbouring hills, covered with verdure to the water's edge.

"Trieste is a polyglot settlement of Austrians, Italians, Slavs, Jews, and Greeks, of whom the two latter monopolize the commerce. It is a City dear and unhealthy to live in, over-ventilated and ill-drained. It might advantageously be called the City of Three Winds. One of these, the Bora, blows the people almost into the sea with its fury, rising suddenly, like a cyclone, and sweeping all before it; the second is named the Scirocco, which blows the drainage back into the town; and the third is the Contraste, formed by the two first-named winds blowing at once against each other. Alternating atmospherically between extremes of heat and cold, Trieste is, from a political point of view, perpetually pushing the principles of independence to the verge of disorder.

"Arrived at the railway station, there is no need to call a cab and ask to be driven to the British Consul's, since, just opposite the station and close to the sea, rises the tall block of building in which the Consulate is situated. Somewhat puzzled to choose between three entrances, the stranger proceeds to mount the long series of steps lying beyond the particular portal to which he is directed. There is a superstition, prevalent in the building and in the neighbourhood, that there are but four stories, including but one hundred and twenty steps. Whoso, after a protracted climb, finally succeeds in reaching Captain Burton's landing, will entertain considerable doubts as to the correctness of the estimate. A German damsel opens the door, and inquires whether the visitor wants to see the Gräfin or the Herr Consul.

"Captain and Mrs. Burton are well, if airily, lodged on a flat composed of ten rooms, separated by a corridor adorned with a picture of our Saviour, a statuette of St. Joseph with a lamp, and a Madonna with another lamp burning before it.[2] Thus far the belongings are all of the Cross; but no sooner are we landed in the little drawing-rooms than signs of the Crescent appear. Small but artistically arranged, the rooms, opening into one another, are bright[Pg 6] with Oriental hangings, with trays and dishes of gold and silver, brass trays and goblets, chibouques with great amber mouthpieces, and all kinds of Eastern treasures mingled with family souvenirs. There is no carpet, but a Bedouin rug occupies the middle of the floor, and vies in brilliancy of colour with Persian enamels and bits of good old china. There are no sofas, but plenty of divans covered with Damascus stuffs. Thus far the interior is as Mussulman as the exterior is Christian; but a curious effect is produced among the Oriental mise en scène by the presence of a pianoforte and a compact library of well-chosen books. There is, too, another library here, greatly treasured by Mrs. Burton, to wit, a collection of her husband's works in about fifty volumes. On the walls are many interesting relics, models, and diplomas of honour, one of which is especially prized by Captain Burton. It is the brevet de pointe earned in France for swordsmanship. Near this hangs a picture of the Damascus home of the Burtons, by Frederick Leighton.

"As the guest is inspecting this bright bit of colour, he will be roused by the full strident tones of a voice skilled in many languages, but never so full and hearty as when bidding a friend welcome. The speaker, Richard Burton, is a living proof that intense work, mental and physical, sojourn in torrid and frozen climes, danger from dagger and from pestilence, 'age' a person of good sound constitution far less than may be supposed. A Hertfordshire man, a soldier and the son of a soldier, of mingled Scotch, Irish, and French descent, his iron frame shows in its twelfth lustre no sign of decay. Arme blanche and more insidious fever have neither dimmed his eye nor wasted his sinews.

"Standing about five feet eleven, his broad deep chest and square shoulders reduce his apparent height very considerably, and the illusion is intensified by hands and feet of Oriental smallness. The Eastern, and indeed distinctly Arab, look of the man is made more pronounced by prominent cheek-bones (across one of which is the scar of a sabre-cut), by closely cropped black hair just tinged with grey, and a pair of piercing black, gipsy-looking eyes. A short straight nose, a determined mouth partly hidden by a black moustache, and a deeply bronzed complexion, complete the remarkable physiognomy so wonderfully rendered on canvas by Leighton only a couple of seasons ago. It is not to be wondered at that this stern Arab face, and a tongue marvellously rich in Oriental idiom and Mohammedan lore, should have deceived the doctors learned in the Korán, among whom Richard Burton risked his life during that memorable pilgrimage to Mecca and Medinah, on which the slightest gesture or accent betraying the Frank would have unsheathed a hundred khanjars.

"This celebrated journey, the result of an adventurous spirit worthy of a descendant of Rob Roy Macgregor, has never been surpassed in audacity or in perfect execution, and would suffice to immortalize its hero if he had not, in addition, explored Harar and Somali-land, organized a body of irregular cavalry in the Crimea, pushed (accompanied by Speke) into Eastern Africa from Zanzibar, visited the Mormons, explored the Cameroon Mountains, visited the[Pg 7] King of Dahomey, traversed the interior of Brazil, made a voyage to Iceland, and last but not least, discovered and described the Land of Midian.

"Leading the way from the drawing-rooms or divans, he takes us through bedrooms and dressing-rooms, furnished in Spartan simplicity with little iron bedsteads covered with bearskins, and supplied with reading-tables and lamps, beside which repose the Bible, the Shakespeare, the Euclid and the Breviary, which go with Captain and Mrs. Burton on all their wanderings. His gifted wife, one of the Arundells of Wardour, is, as becomes a scion of an ancient Anglo-Saxon and Norman Catholic house, strongly attached to the Church of Rome; but religious opinion is never allowed to disturb the peace of the Burton household, the head of which is laughingly accused of Mohammedanism by his friends. The little rooms are completely lined with rough deal shelves, containing, perhaps, eight thousand or more volumes in every Western language, as well as in Arabic, Persian, and Hindustani. Every odd corner is piled with weapons, guns, pistols, boar-spears, swords of every shape and make, foils and masks, chronometers, barometers, and all kinds of scientific instruments. One cupboard is full of medicines necessary for Oriental expeditions or for Mrs. Burton's Trieste poor, and on it is written, 'The Pharmacy.' Idols are not wanting, for elephant-nosed Gunpati is there cheek by jowl with Vishnu.

"The most remarkable objects in the rooms just alluded to are the rough deal tables, which occupy most of the floor-space. They are almost like kitchen or ironing tables. There may be eleven of them, each covered with writing materials. At one of them sits Mrs. Burton, in morning négligé, a grey choga—the long loose Indian dressing-gown of soft camel's hair—topped by a smoking-cap of the same material. She rises and greets her husband's old friend with the cheeriest voice in the world. 'I see you are looking at our tables. Every one does. Dick likes a separate table for every book, and when he is tired of one he goes to another. There are no tables of any size in Trieste, so I had these made as soon as I came. They are so nice. We may upset the ink-bottle as often as we like without anybody being put out of the way. These three little rooms are our "den," where we live, work, and receive our intimes, and we leave the doors open that we may consult over our work. Look at our view!' From the windows, looking landward, one may see an expanse of country extending for thirty or forty miles, the hills covered with foliage, through which peep trim villas, and beyond the hills higher mountains dotted with villages, a bit of the wild Karso peering from above. On the other side lies spread the Adriatic, with Miramar, poor Maximilian's home and hobby, lying on a rock projecting into the blue water, and on the opposite coast are the Carnian Alps capped with snow.

"'Why we live so high up,' explains Captain Burton, 'is easily explained. To begin with, we are in good condition, and run up and down the stairs like squirrels. We live on the fourth story because there is no fifth. If I had a campagna and gardens and servants,[Pg 8] horses and carriages, I should feel tied, weighted down, in fact. With a flat, and two or three maidservants, one has only to lock the door and go. It feels like "light marching order," as if we were always ready for an expedition; and it is a comfortable place to come back to. Look at our land-and-sea-scape: we have air, light, and tranquillity; no dust, no noise, no street smells. Here my wife receives something like seventy very intimate friends every Friday—an exercise of hospitality to which I have no objection, save one, and that is met by the height we live at. There is in every town a lot of old women of both sexes, who sit for hours talking about the weather and the cancans of the place, and this contingent cannot face the stairs.'

"In spite of all this, and perhaps because of it—for the famous Oriental traveller, whose quarter of a hundred languages are hardly needed for the entry of cargoes at a third-rate seaport, seems to protest too much—one is impelled to ask what anybody can find to do at Trieste, an inquiry simply answered by a 'Stay and see,' with a slap on the shoulder to enforce the invitation. The ménage Burton is conducted on the early-rising principle. About four or five o'clock our hosts are astir, and already in their 'den,' drinking tea made over a spirit-lamp, and eating bread and fruit, reading and studying languages. By noon the morning's work is got over, including the consumption of a cup of soup, the ablution without which no true believer is happy, and the obligations of Frankish toilette. Then comes a stroll to the fencing-school, kept by an excellent broadswordsman, an old German trooper. For an hour Captain and Mrs. Burton fence in the school, if the weather be cold; if it is warm, they make for the water, and often swim for a couple of hours.

"Then comes a spell of work at the Consulate. 'I have my Consulate,' the Chief explains, 'in the heart of the town. I don't want my Jack-tar in my sanctum; and when he wants me, he has usually been on the spree and got into trouble.' While the husband is engaged in his official duties, the wife is abroad promoting a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, a necessary institution in Southern countries, where—on the purely gratuitous hypothesis that the so-called lower animals have no souls—the uttermost brutality is shown in the treatment of them. 'You see,' remarks our host, 'that my wife and I are like an elder and younger brother living en garçon. We divide the work. I take all the hard and scientific part, and make her do all the rest. When we have worked all day, and said all we have to say to each other, we want relaxation. To that end we have formed a little "Mess," with fifteen friends at the table d'hôte of the Hôtel de la Ville, where we get a good dinner and a pint of the country wine made on the hillside for a florin and a half. By this plan we escape the bore of housekeeping, and are relieved from the curse of domesticity, which we both hate. At dinner we hear the news, if any, take our coffee, cigarettes, and kirsch outside the hotel, then go homewards to read ourselves to sleep; and to-morrow da capo.'

"To the remark that this existence, unless varied by journeys to Midian and elsewhere, would be apt to kindle desires for fresher woods and newer pastures, Captain Burton replies, 'The existence you deprecate is varied by excursions. We know every stick and stone for a hundred miles round, and all the pre-historic remains of the country-side. Our Austrian Governor-General, Baron Pino de Friedenthal, is a first-rate man, and often gives us a cruise in the Government yacht. It is, as you say, an odd place for me to be in; but recollect, it is not every place that would suit me' (1877).

"The man, who, with his wife, has made this pied à terre in Trieste is a man unlike anybody else—a very extraordinary man, who has toiled every hour and minute for forty-four and a half years, distinguishing himself in every possible way. He has done more than any other six men in her Majesty's dominions, and is one of the best, noblest, and truest that breathes.

"While not on active service or on sick leave, he has been serving his country, humanity, science, and civilization in other ways, by opening up lands hitherto unknown, and trying to do good wherever he went. He was the pioneer for all other living African travellers. He first attempted to open up the Sources of the Nile. He 'opened the oyster for the rest to take the pearl'—his Lake Tanganyika is the head basin of the Nile.

"He has made several great expeditions under the Royal Geographical Society and the Foreign Office, most of them at the risk of his life. His languages, knowledge, and experience upon every subject, or any single act of his life, of which he has concentrated so many into forty-four and a half years, would have raised any other man to the top of the ladder of honour and fortune.

"We may sum up his career by their principal heads.

"Nineteen years in the Bombay Army, the first ten in active service, principally in the Sindh Survey on Sir Charles Napier's staff. In the Crimea, Chief of the Staff to General Beatson, and the chief organizer of the Irregular Cavalry.

"Several remarkable and dangerous expeditions in unknown lands. He is the discoverer and opener of the Lake Regions of Central Africa, and perhaps the Senior Explorer of England.

"He has been nearly twenty-six years in the Consular service in the four quarters of the globe (always in bad climates—Africa, Asia, South America, and Europe), doing good service everywhere. It would be impossible to enumerate all that Captain Burton has done in the last forty-four years; but we cannot pass over his knowledge of twenty-nine languages, European and Oriental—not counting dialects—and now that Mezzofante is dead, we may call him the Senior Linguist. Nor can we omit the fact that he has written about fifty standard works, a list of which will appear at the end of this Memoir. (See Appendix A.)

"He is a man incapable of an untruth or of truckling to what finds favour. His wife tells us in her 'Inner Life of Syria' that 'humbug stands abashed before him,' that he lives sixty years before[Pg 10] his time, and that, 'born of Low Church and bigoted parents, as soon as he could reason he began to cast off prejudice and follow a natural law.' Grace aiding the reason of man—upright, honourable, manly, and gentlemanly, but professing no direct form of belief, except in one Almighty Being, God—the belief that says, 'I do that because it is right—not for hell nor heaven, nor for religion, but because it is right—a natural law of Divine grace, which such men unconsciously ignore as Divine intelligence: yet such it is.'

"Perhaps this is the secret of our finding so distinguished a soldier, Government envoy, Foreign Office commissioner, author, linguist, benefactor to science, explorer, discoverer, and organizer of benefits to his country and mankind at large, standing before the world on a pedestal as a plain unadorned hero, sitting by his distant fireside in a strange land, bearing England's neglect, and seeing men who have not done a tithe of his service reaping the credit and reward of his deeds—nay, of the very ideas and words that he has spoken and written. For years he has thought, studied, and written, and in all the four quarters of the globe has been a credit to his country. For years he has braved hunger, thirst, heat, and cold, wild beasts, savage tribes; has fought and suffered, carrying his life in his hand, for England's honour and credit, and his country's praise and approbation, and done it nobly and successfully. But, like many of the greatest heroes that have ever lived, his country will deny him the meed of success whilst he lives, and erect marble statues and write odes to his memory when he can no longer see and hear them—when God, who knows all, will be his reward."

"Burton's lamented college friend, Alfred Bates Richards, the author of this biography, also wrote two leading articles expressing his opinions in the following outspoken and manly words, and, if I quote them here, it is not by way of advertising any claim Burton may have, or of intoning any grumble against any Government, for to the best of my belief the Burtons have taken up a line of their own. I quote them merely to show the estimation in which I believe him to be held by the whole Press of England, since every article is more or less written in the same tone, with scarcely a dissentient pen, and I have selected these as two of the best specimens:—

"'The best men in this world, in point of those qualities which are of service to mankind, are seldom gifted with powers of self-assertion in regard to personal claims, rewards, and emoluments. Pioneers, originators, and inventors are frequently shunted and pushed aside by those who manage, by means of arts and subtleties (utterly unknown to men of true genius and greatness of character), to reap benefits and honours to which they are not in the slightest degree entitled. Sometimes a reaction sets in and the truth is discovered—when it is too late. There is no country which neglects real merit so frequently and so absolutely as England—none which so liberally bestows its bounties upon second and third rate men, and sometimes absolute pretenders. The most daring explorer cannot find his way up official back-stairs; the most heroic soldier[Pg 11] cannot take a salon or a bureau by storm. There are lucky as well as persevering individuals who succeed in the most marvellous way in obtaining far more than their deserts. We have heard of a certain foreigner, now dead, who held a lucrative position for many years in this country, that he so pestered and followed up the late Lord Brougham that he at last obtained the post he sought by simple force of boredom and annoyance. Some men think they ought not to be put in the position of postulants; but that recognition of their services should be spontaneous on the part of the authorities. They are too proud to ask for that which they consider it is patent they have so eminently deserved, that it is a violation of common decency to withhold it; and so they 'eat their hearts' in silence, and accept neglect with dignity, if not indifference.

"'We do not intend to apply these remarks strictly to the occasion which has suggested them. If we did not state this, we should possibly injure the cause which we are anxious to maintain. We have watched the career of an individual for some thirty-five years with interest and admiration, and we frankly own that we now think it time to express our opinion upon the neglect with which the object of that interest and admiration has been treated. We alone are responsible for the manner in which we record our sentiments. Captain Richard Burton, now her Majesty's Consul at Trieste, is, in our judgment, the foremost traveller of the age. We shall not compare his services or exploits with those of any of the distinguished men who have occupied a more or less prominent position, and whose services have been recognized by the nation.

"'He has been upwards of thirty years actively engaged in enterprises, many of them of the most hazardous description. We pass over his career in the Bombay army for nearly twenty years, during which time he acquired that wonderful knowledge of Eastern languages, which is probably unequalled by any living linguist. We shall not give even the catalogue of his varied and interesting works, which have been of equal service to philology and geography. His system of Bayonet Exercise, published in 1855, is, we may observe, en passant, the one now in use in the British army. He suffered the fate of too many of his brother officers of the Indian army when it was reduced, on changing hands, and when he was left without pension or pay.

"'He was emphatically the first great African pioneer of recent times. It is not our intention to speak disparagingly of the late Captain Speke—far from it; but it should be remembered that Speke was Burton's lieutenant, chosen by him to accompany him in his Nile researches, and that when Burton was stricken down by illness that threatened to prove fatal, Speke pushed on a little way ahead, and reaped nearly the whole credit of the discovery. Lake Tanganyika was Burton's discovery, and it was his original theory that it contained the Sources of the Nile. Never was man more cruelly robbed by fate of his just reward. Could Speke have arrived where he did without even the requisite knowledge of languages, manners of the people, etc., save under Burton's guidance? Burton's pilgrimage to Mecca and Medinah was one of the most extraordinary on record.

"'In the expedition to Somali-land, as well as that to the Lake regions of Central Africa, Speke was second in command. In the former, both were severely wounded, and cut their way out of surrounding numbers of natives with singular dash and gallantry, one of the party—Lieutenant Stroyan—being killed. Nor should the wonderful expedition, undertaken alone, to the walled town of Harar, where no European had even been known to penetrate before, be forgotten. On this occasion Captain Burton actually added a grammar and vocabulary of a language to the stores of the philologists. His journey and work on California and the Mormon country preceded that of Mr. Hepworth Dixon. He explored the West Coast of Africa from Bathurst, on the Gambia, to St. Paulo de Loanda in Angola, and the Congo River, visiting the Fans. But his visit to Dahomey was still more important, as he exposed the customs of that blood-stained kingdom, and gave information valuable to humanity as well as to civilization and science. This alone ought to have obtained for him some high honorary distinction; but he got nothing beyond a private expression of satisfaction from the Government then in power. During his four years' Consulship in Brazil his work was simply Herculean. He navigated the river San Francisco fifteen hundred miles in a canoe, visited the gold and diamond mines, crossed the Andes, and explored the Pacific Coast, affording a vast fund of information, political, geographical, and scientific, to the Foreign Office. Next we find him Consul at Damascus, where he did good work in raising English influence and credit. Here he narrowly escaped assassination, receiving a severe wound. He explored Syria, Palestine, and the Holy Land, protected the Christian population from a massacre, and was recalled by the effete Liberal Government because he was too good a man, Damascus being reduced to a Vice-Consulate in accordance with their policy of effacement. He is now shelved at Trieste, but has still managed to embellish his stay here by some valuable antiquarian discoveries.

"'If a Consulate is thought a sufficient reward for such a man and such services, we have no more to say. If he has been fairly treated in reference to his Nile explorations, we have no knowledge of the affair—which we narrowly watched at the time—no discernment, and no true sense of justice. When the war with Ashanti broke out, we expressed our opinion that Captain Burton should have been attached to the expedition. During the Crimean War he showed his powers of organization under General Beatson, whose Chief of the Staff he was, in training four thousand irregular cavalry, fit, when he left them, to do anything and go anywhere. In short, he has done enough for half a dozen men, and to merit half a dozen K.C.B.'s. We sincerely trust that the present Government will not fail, amidst other acts of justice and good works, to bestow some signal mark of her Majesty's favour upon Captain Richard Burton, one of the most remarkable men of the age, who has displayed an intellectual power and a bodily endurance through a series of adventures, explorations, and daring feats of travel, which have never been surpassed in variety and interest by any one man, and whose further[Pg 13] neglectful treatment, should it take place, will be a future source of indignant regret to the people of England.'

"The following article appeared when Burton wrote his 'Nile Basin.' I quote that part of it which refers to Burton, and expunge that which does not regard my immediate subject:—

"'About a quarter of a century ago Richard Burton, who had gained only a reputation for eccentricity at Oxford, left that University for India and entered the Bombay army. There he devoted his spare time to the acquisition of Oriental languages, science, and falconry, in company with the Chiefs of Sind, and, amongst other things, wrote works on the language, manners, and sports of that country. We cannot trace his career, but it is well known that he has become one of the greatest linguists of the age, gifted with the rare if not unique capacity of passing for a native in various Oriental countries. In addition to this, he is a good classical scholar, an accomplished swordsman, and a crack shot. His "Pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina" was a wonderful record of successful daring and wonderful impersonation of Oriental character.

"'As an Afghan, and under the name of Mirza Abdullah, he left Southampton on his mission, after undergoing circumcision, and during the voyage on board the P. and O. steamer was only known to be a European to the captain and attaché of the Turkish Embassy returning to Constantinople. His pilgrimage was successful, and he is the only European ever known to have performed it. Perhaps, however, the story of the most remarkable of his performances is contained in his 'First Footsteps in Eastern Africa,' telling how, alone and unaccompanied, during the latter stages, even by his attendants, he penetrated the hitherto almost fabulous walled city of Harar, hobnobbed with its ferocious and exclusive Sultan, and bestowed on philologists a grammar of a new language. The description of his lying down to sleep the first night in that walled city of barbaric strangers, ignorant of the reception he might receive at the Sultan's levée in the morning, is well worth perusal.

"'Then came the episode which first gave the name of Speke to the world—the expedition in the country of the Somali, on the coast of the Red Sea, when the cords of the tent of Burton, Speke, Herne, and the hapless Stroyan were cut by a band of a hundred and fifty armed Somali during the night, after the desertion of their Eastern followers. The escape of Burton was characteristic of the man. Snatching up an Eastern sabre, the first weapon he could grasp, he cut his way by sheer swordsmanship through the crowd, escaping with a javelin thrust through both cheeks. Speke, after receiving seventeen wounds, was captured, and also subsequently escaped, and Stroyan was killed. At this time Burton had taken Speke under his especial patronage, and made him lieutenant of his expeditions. Subsequently came the search after the Sources of the Nile, in which both Burton and Speke figured; next, Burton's expedition to Utah; his Consulship at Fernando Po, and the exploration of the Cameroon Mountains;[Pg 14] and, finally, his world-famed mission to the blood-stained Court of Dahomey. Such is Captain Richard Burton, and such his work, briefly and imperfectly described.

"'It is known, at least to the geographical world, that between Burton and his quondam lieutenant, Speke, a feud existed after the latter had proclaimed himself the discoverer of the Sources of the Nile. The outline of the story is this. On the exploring expedition under Burton's command he was seized with a violent and apparently fatal illness which compelled him to pause on the path of discovery at an advanced point. Speke went on, and, returning first to England, succeeded in getting the ear of the Geographical Society and the Foreign Office, and organized another expedition independently of Burton. On his return from this he proclaimed at once to the world that he had solved the great mystery, and the news was received with universal congratulation and belief. In the race for fame—if 'honor est à Nilo' be deemed, as it must be, the common motto of our daring travellers—Burton, shaken to the backbone by fever, disgusted, desponding, and left behind, both in the spirit and the flesh, was, in racing parlance, 'nowhere.' He had the sense to retire from the contest during the first burst of excitement, and let judgment go by default. He went to visit the Mormons, and thence, by an ascending scale in respect to the objects of his search, to leave a card or two in the forest residences of the Gorillas. In the mean time Speke became one of the lions of the day, and ignored the services of his able Chief and Pioneer. To him the good fortune, the honour, the success—to Burton, nothing. The very name and existence of the latter were, as far as possible, ignored. Yet he had commenced all, organized all, arranged all, and discovered Tanganyika. His Oriental acquirements and experiences had paved the way to at least within the last few stages of the discovery of the Nyanza. This is a matter to be regretted. Much more to be regretted was the sad and singular catastrophe of Captain Speke's untimely death. On that very day a great passage, not of Arms, but of intellect and knowledge, was fixed to take place. Burton had challenged Speke to a discussion before a select public tribunal. The subject was the Nile, its sources, and Speke's claim to their discovery.

"'On the fatal afternoon of the 16th of September, 1864, when Speke perished, Burton had met him at 1.30 p.m. in the rooms of Section E of the Bath Association. Their meeting was silent and ominous. Speke, who, as we are informed, had been suffering for some time from nervousness and depression of spirits, probably arising from the trials to his health in an Eastern climate, left the room to go out shooting, and never returned alive! Much cause had Richard Burton to lament that untimely end. His lips were, to a great extent, immediately sealed. Humanity, feeling, and decency—nay, imperious necessity—demanded this. What he has written is argumentative and moderate. He speaks of his deceased rival with commendation for those good qualities which he allows him to have possessed. Burton is as dignified in his style as if he[Pg 15] were a true Oriental. Unhappily, Speke is now no more, but Burton has maintained throughout a chivalrous tone towards his deceased adversary.'"

There is a very peculiar and wild race of men who in Trieste are called Cicci; they are Wallachians of the old Danube, and they dress in the Danubian dress, and live in Inner Istria. They are wild people, and have their own breed of wild dogs, which are of a very savage nature. A real Cicci dog costs what is for Trieste a good sum of money, if he is of pure breed; he is secured as a house-guard, and has to be tied up except at night, and, in a general way, only the person who feeds him is able to go near him. These Cicci do not live in Trieste; they live up in the Karso, or Karst, in a remote spot, in their own separate wild villages, where they have the bare necessities of life, and their occupation is charcoal-burning. Richard determined he would become acquainted with this unruly and isolated race, and he made his way to their villages alone, and stayed with them for five days, leading naturally a perfectly comfortless life, sleeping on the floor, and eating their black bread and olives. They were very pleased with him, and very civil to him; but when he came back no man in Trieste would believe that he had done it, till accidentally they saw a party of Cicci coming down to sell their charcoal, and rushing up and claiming him as an old friend. He never could resist seeing a curious and, so to speak, Ishmaelitic race, i.e. severed away from the whole world, without going to live with it, and learn it.

The first thing Richard always did when he arrived in a new place, was to look for a sanitarium to which he might go for change in case of being seedy. There is a Slav village, one hour from and twelve hundred feet above Trieste, called Opçina. You can drive up on a good road by zigzag wooded ways in an hour, or you may climb also in an hour by five other different rugged paths up the cliff. Once arrived at the top, Trieste, the Adriatic, and all the separate points of land, with their villages, churches, towers, villas, and objects of interest, lies before you like a raised map. There are ranges of wooded hills, cliffs dotted with churches and villages, which seem to cling to them. Sometimes banks of clouds cover the whole scene, and you can imagine yourself isolated at the north pole, the white, woolly clouds representing the snow and ice. You see nothing below you, but in the distance you see the Carnian Alps topped with snow.[Pg 16] The house you inhabit is Daneu's old-fashioned rural country inn, on the edge of the declivity, and is a sort of outpost to the village of Opçina; and its terrace commands all this lovely view—the finest in the world. The back of the inn has shrubberies and fields, and a view of the Karso, backed by mountains. The air is splendid. We used to take the most delightful walks when up here, or make excursions in little country carts called gripizzas.

It is exceedingly pretty on festival days. Every house in the village, from the big house, the school, and Daneu's inn, to the smallest shed, hangs out its gayest drapery from the windows, and is decorated with flowers and flags. The poorest have at least a jug of large white lilies. All the villages around pour in—the Slav peasant men, in their big boots and knickerbocker-trousers, slouch hat, brown velveteen jacket, one ear-ring, and one flower jauntily cocked behind the ear.

Women with straight features, tow-coloured hair, and blue eyes, dress very like a glorified Sister of Charity, only of all the colours of the rainbow, and a white head-dress deep with lace. In short, fine linen, fine lace, white head-dress, embroidered bodice, stout shoes, and ribbons round waist and down the petticoat of all different colours, one shorter than the other, and the last a big sash, over a final petticoat, opening behind like an all-round apron, a kerchief over the shoulders, real massive gold ornaments, and flowers form the costume. The dresses are most expensive, of all colours, but nothing in bad taste.

On procession days the whole village would turn out, perhaps six priests holding a canopy over the Blessed Sacrament, the villagers with banners, flambeaux, and bells, and every one a lighted candle and a bunch of flowers; they would walk through the village and fields and lanes. There were three altars erected out of doors, before which they would stop and recite the Gospels, and then to the church for High Mass and solemn benediction; fine voices rose in hymns, taking first, second, third, and fourths, nature taught, far better than many an oratorio. On one occasion I remember a little ragged urchin, two feet high, with bare feet, one little white garment, a straw hat with a hundred holes and rents in it, and his little bit of flower, kneeling near the altar. Educated visitors from Trieste would come in, but not even salute or kneel, to show their superiority; and this is the way that Faith gets stamped out of the world. The peasants, when the fête is over, steal the flowers to dry, and they burn them in a storm for protection, which is rather a pretty, though superstitious, idea.

Here we took rooms, and put in them all in which they were[Pg 17] deficient; and our delight was to come up alone, without servants, from Saturday to Monday, and get away from everything, wait upon ourselves more or less, and keep some literary work here. We sometimes stayed a fortnight or six weeks if we had a great work on hand.

DANEU'S INN, OPÇINA, IN THE KARSO.

The Trieste life was, of course, varied by many journeys and excursions; but we lived absolutely the jolly life of two bachelors, as it might be an elder and a younger brother. When we wanted to go, we just turned the key and left. We began our house with six rooms, and were intensely happy; but after some years I became ambitious, and I stupidly went on spreading our domain until I ran round the large block of building, and had got twenty-seven rooms. The joke in Trieste was that I should eventually build a bridge across to the next house, and run round that; but as soon as I had just got everything to perfection, in 1883, Richard took a dislike to it, and we went off to the most beautiful house in Trieste, where he eventually died, 1890.

Our first thought as soon as we were settled in Trieste was to scour every part of the country on foot, and we often used to lose[Pg 18] our way, and on the 1st of January, 1873, we were out from 10 a.m. till 7.50 p.m. in this manner. The thing that astonished us most at first was the Bora, the north-easterly wind, which sweeps down the mountains, at a moment's notice. There are only two places in the world that have it—Trieste and the Caucasus. Its force is so great, that it blows people into the sea; it occasionally blows over a train; or a cab and horse into the sea. When there is a bad Bora, ropes are put up; if any house is exposed to the full fury of it, a new-comer would suppose that the house would also be carried away. It makes all new buildings tremble and rock; in fact, I have been told that if one tried to describe it in England, one would not be understood.

A blizzard is the nearest thing to it, but that is short and sharp, whereas the Bora always lasts three days, and I have known it, in 1890, to last forty days, more or less severe. The Borino is the little Bora; the white Bora is still bearable, but the black Bora is frightening, especially when it has "ciappá," as the dialect goes, i.e. "gripped," or "taken hold." At first Richard got thrown down by it, and was badly cut. In my strongest days, I could never breast a hill with the Bora facing me. I used to have to turn round, sit down, and be blown back again. Shocks of earthquake were very common affairs. They made one feel sick and uncomfortable; but they did not shake the houses down, only made the pictures dangle towards the middle of the room, and the cupboards nod and move. They were always the tag-end of the great earthquakes at Agram, in Croatia, which is a hundred miles away on a direct line.

The chief thing that spoils Trieste is politics. The City is composed of Italians, Austrians, and Slavs, which three languages are spoken. Greeks and Jews monopolize the trade. The few foreigners are the Consular corps; the English are the engineers of Austrian-Lloyd steamers, with a very small sprinkling of merchants, and might number three hundred all told, including British protections. When we went there, an Austrian would hardly give his hand to an Italian in a dance. An Italian would not sing in the concert where an Austrian sang. If an Austrian gave a ball, the Italian threw a bomb into it; and the Imperial family were always received with a chorus of bombs—bombs on the railway, bombs in the gardens, bombs in the sausages; in fact, it was not at such times pleasant. The Slavs also form a decided party. With Richard's usual good sense, he at once desired me to form a neutral house—a neutral salon—where politics and religion should never be mentioned, and where all would meet on neutral ground; and this was done the whole time of our Triestine career.

Here we made the acquaintance of the Count and Countess di Ferraris-Occhieppo, their son and two daughters. They were at this time charming children. He was in the Austrian service. They were of noble family, but not rich, and she had the romantic idea of bringing her daughters up to a musical profession, of travelling all over the world for the purpose of seeing and studying, and leading an interesting life, paying their way with concerts and entertainments as they went. She nobly succeeded in her mission, and must be rewarded by looking down upon her two clever daughters carrying out her idea in perfection. The little boy—he must be a man, and possibly an officer now—used to rebel against the constant drill; but I dare say, though I have lost sight of him for the present, that he is very glad of it now.

Venice was our happy hunting-ground. Whenever we were a little bit tired of Trieste, we had only to run over there, and I know nothing so resting. If you have been living at too high pressure, you order your gondola, closing the door, lie down in the middle of it, put your head on a cushion, tell them to row you anywhere, and doze and dream until you come round.

Miramar, the sea-palace of poor Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, was a great resource to Trieste people, being an hour's drive from Trieste, built on a rock-promontory out to sea, and backed by beautiful grounds and woods of his own designs. Most people know—but some may not—the touching little history of the Emperor of Austria's brother, married to Princess Charlotte of Belgium, who lived in this palace. They built and made this home themselves, and they lived in a little cottage close by whilst they were so engaged. The lower rooms, occupied by the Archduke himself, were built and arranged exactly like the Admiral's quarters of his ship. The grounds are most romantic and fanciful, full of covered terraces, shady walks, secluded places for reading, the ruins of a very old chapel, Italian gardens, and so on.

They were perfectly adored in Trieste, and he was worshipped by the Navy. Nothing could be happier than their lives. In an evil hour the Imperial Crown of Mexico was offered to him under the protection of Louis Napoleon. The Emperor of Austria approved of it, but Maximilian long hung back. Finally Princess Charlotte, who was ambitious, urged him to accept; he did so, and they departed. There is a picture in Miramar showing their departure in the ship's gig, and crowds from Trieste to see them off, of which most are real portraits. That was their last happy day. Everybody knows how ill that Imperial Mexican crown succeeded, Maximilian's unhappy death, Empress Charlotte's coming[Pg 20] over to claim the promised protection of Napoleon, and how the not getting it affected her brain. At one time they took her to Miramar to see if it would cure her, but it only made her worse. The Emperor keeps up his brother's place exactly as if he was living there, and, with exquisite taste and benevolence, throws it open to the people who loved him so much.

Monsieur and Madame Léon Favre, brother to Jules Favre, were our French Consul and Consuless General, and their house was the rendezvous for Spiritualism, where we had frequent séances.

One of their guests at these séances had a very curious faculty. He would sit opposite you, his eyes would glaze, and your face and features changed in his sight, and he saw all the evil in you and all the good, just as if you were a pane of glass. When this fit passed off, his face, and yours also, resumed its natural expression, but he knew you perfectly well, better than if you had told him all your life. I was fortunate enough to please him. He sent for me on his death-bed, but I was away, and did not know it till after; but a year or two after his death, one of his disciples swam up to me in the sea and said that the deceased wanted me to translate and bring out his writings on religion, which were inspired. I have, however, up to the present never had the time nor the money to do so.

Richard sent the following, thinking it might be useful:—

"To the Editor of the Pall Mall Gazette.

"Precaution in fighting the Ashantees.

"Sir,—During the last Franco-Prussian War several of my friends escaped severe wounds by wearing in action a strip of hard leather with a rib or angle to the fore. It must be large enough to cover heart, lungs, and stomach-pit, and it should be sewn inside the blouse or tunic; of course the looser the better. Such a defence will be especially valuable for those who must often expose themselves in 'the bush' to Anglo-Ashanti trade-guns, loaded with pebbles and bits of iron. The sabre is hardly likely to play any part in the present campaign, or I should recommend my system of curb-chains worn across the cap, along the shoulders, and down the arms and legs.

"I am, sir, your obedient,

"Richard F. Burton.

"November 25th, 1873."

When we had been there a little while, Richard took it into his head to make a pilgrimage to Loretto, and from there we went on to Rome, seeing twenty-six towns on our way. Here we made acquaintance[Pg 21] with our Ambassador, Sir Augustus, and clever, beautiful, charming Lady Paget; also we saw much of Cardinal Howard (who was a connection of mine, and was one of my favourite dancing partners when he was in the Life Guards, and I was a girl), and Mgr. Stonor, Archbishop of Trebizond, between whom and Lady Ashburton we had a delightful time in Rome.

Richard, who had passed a good deal of time here in his boyhood, liked visiting the old places and showing them to me. It would take three months of high pressure and six quiet months to see everything in Rome; but during our short stay, under his guidance, I saw and enjoyed all the principal and best things, and he amused himself with writing long articles on Rome, which came out in Macmillan's Magazine, 1874-5. Religiously speaking, what I enjoyed most was the Ara Cœli, the church built on the site of the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus (I wish I knew all the things that have taken place on that site). The other place was the Scala Santa. His Holiness Pius IX., unfortunately for me, went to bed ill the day before I arrived, and got up well the day after I left, so that I did not see him. We also much enjoyed the Catacombs and the Baths of Caracalla; but it was a wet and miserable day that we went to the Baths, and the smells in this last place from the little interstices of the pavement were awful. We dined at some cousins' who had gone with us, and their little bulldog, which had had its nose close to the ground all day, went mad, and died that night, and we found them next day in shocking grief. I got Roman fever. Richard had written the following letter to the Tablet in October, 1872:—

"The Overflow of the Tiber.

"To the Editor of the Tablet.

"Sir,—The very able review in the Times supplement (Oct. 21) of Signor Raffaelle Pareto's report to the Minister of Agriculture, encourages me to address you upon a subject so deeply interesting to the Catholic world, indeed to the whole world, as Rome is.

"That eminent engineer, Mr. Thomas Page (acting engineer of the Thames Tunnel, under Brunel, and the engineer of Westminster Bridge), whose works in England are known to all, has been for some time engaged in a plan for preventing the inundations of the Tiber, and for the assainissement of the Campagna di Roma, undertakings more urgently required every year. He purposes gigantic measures, but measures of no difficulty, and the sooner they are begun and the more promptly they are erected, the more satisfactory will be their results and the more economical their execution.

"Your space will hardly allow me to enter into details concerning[Pg 22] his scheme, whose broadest outlines are as follows: Provide a new channel for the Tiber, which, during floods, shall conduct all its waters in a free and uninterrupted course. For the sake of crossing, the line must be governed by the levels of the valley through which it runs. It may be constructed at the junction of the Teverone with the Tiber, be carried along the line of the Fossa della Maranella, and, passing through the higher ground in the line of the second milestone on the Via Tusculana da Roma, it would enter the depression of the Fiume Alarone, and finally anastomose with the old bed near the Ponto della Moletta, about a kilometre and a quarter outside the Porta San Paolo. Mr. Page would continue his new channel so as to cut off the reach of the Prati di S. Paolo, passing to the west of the celebrated Basilica, so called, and, by an embankment with gates and sluices at the sharp bend near the Porta della Puzzolana, he would convert the old channel into the Port of Rome. At the embouchure of the Teverone he would throw a similar embankment; and thus the Tiber, cleansed of all mud and deposits, would become an ornamental stream, or rather lake whose banks, about three miles long, would be the most pleasant of promenades. I need hardly remark that this insulation of Rome, and this replacement by drainage and irrigation of the fatal Campagna atmosphere, would amazingly increase the value of the land, and make the profits of its sale pay for the expenses of the works.

"The Times review of Signor Pareto's labours has sketched for the benefit of the general reader all the interesting features of pasturage and tillage in the large towns known as the Agro Romano. Mr. Page's plan would give the opportunity and the means of training the Campagna into one of the most productive and salubrious districts in Italy. With an extent of 311,550 hectares of valuable land, with a new channel for drainage, and with improved means of irrigation, the suburban district of Rome will soon become worthy of her greatness, past and present.

"I only hope that Mr. Page will soon be permitted to publish in detail this sketch, whose outlines you have allowed me to make public. The Holy City, I need hardly say, is not so much the capital of Italy as the capital of Europe, and consequently the capital of the world.

"I am, sir, yours truly,

"Richard F. Burton, F.R.G.S.

"Southampton, October 24th, 1872."

The Tiber business after this was brought out as a brand-new-idea by another man in 1874, so I had to write the following:—

"The Tiber.

"To the Editor of the Pall Mall Gazette.

"Sir,—I venture to draw your attention to the fact that as early as October, 1872, my husband, Captain Burton, proposed the very[Pg 23] same measures for relieving the Tiber and for draining the Campagna which are now being taken up by General Garibaldi. Also the paper by Captain Burton, 'Notes on Rome,' published by Macmillan's Magazine in 1873, concluded as follows: 'At the present moment Anglo-Italian companies are out of favour in England and in Italy. It would be an invidious task to explain the reason and to register the complaints on both sides. But there should be no difficulty in raising a "City of Rome Improvements Company," directed by a board which would combine southern thrift with northern energy and capital, a combination hitherto found wanting. Nor do I think that the Municipality of Rome, in whose hands lies acceptance or refusal, would object to the influx of foreign funds, especially if the management were in part confided to their own countrymen—to persons of name and position.'

"These last sentences were the very gist of the whole of the 'Notes on Rome,' but, unhappily, Macmillan's, being an uncommercial magazine, thought proper to omit them, with that unfortunate instinct which taboos one's best bits, and crushes down one's originality until one's work is cut out exactly on the regulation pattern of former writers. This makes author's work in England rather disheartening; for, as in this case, one man sows and another reaps; one invents and originates, and another gets the whole benefit and credit of the idea.

"Captain Burton has had all his plans for the benefit of Rome laid down ever since 1872.

"Yours obediently,

"Isabel Burton.

"March 17th, 1874."

We took my fever on to Assisi, Perugia, Cortona, and to Lake Thrasimene, which is lovely, and to Florence. How flat and ugly is Roman country, the valley of the Tiber, and the Sabine Hills, but after an hour and a half express it becomes beautiful. In Florence we had the pleasure of seeing a great deal of "Ouida" and Lady Orford, who was the Queen of Florence. Thence we went on to Pistojia and Bologna, thence to Venice, and, after a while, back to Trieste in a night of terrible gales.

We only stayed here just to change baggage, as Richard was engaged as reporter to a newspaper for the Great Exhibition of Vienna. I will only say en passant that the journey from Trieste to Vienna by express (fifteen hours) is stupendously lovely for the first six hours, and likewise all round Graz, halfway to Vienna; and the passage over the Semmering is a dream, at any rate for the first and second time. We were three weeks at Vienna. The Exhibition was very fine; the buildings were beautiful; there were royalties from every Court in the world, so that the mob could feast their eyes on them thirty at a time—not that a foreign[Pg 24] mob ever stares rudely at royalties. But the Exhibition was spoilt by one or two things. Firstly, the hotels made everything so dear that few people could afford to go there. It is told of Richard, that while travelling on a steamboat he seated himself at the table and called for a beefsteak. The waiter furnished him with a small strip of that article. Taking it upon his fork, and turning it over and examining it with one of his peculiar looks, he coolly remarked, "Yes, that's it. Bring me some."

As a pendant to that, it was during the Viennese Exhibition when supplies at the hotels were charged enormous prices, and all portions were most homœopathic. A waiter brought Richard a cup of coffee, not Turkish coffee, but a doll's cup with the chestnut water which Europeans presume to call coffee. "What is that?" asked Richard, looking at it curiously, with his head on one side. "Coffee for one, sir." "Oh! is it indeed?" inspecting it still more curiously. "H'm! bring me coffee for ten!" "Yes, sir," said the waiter, looking as if he thought it a capital joke, and presently returned with a common-sized cup of coffee.

People waited until the end, hoping things would get cheaper, and by that time the great "Krach," or money failures, had come, followed by the cholera, so that Vienna was huge sums to the bad, instead of gaining. We had a very gay time. Whilst we were there we went to the Viennese Court. There was a great difficulty about Richard, because Consuls are not admissible at the Vienna Court; but upon the Emperor being told this, he said, "Fancy being obliged to exclude such a man as Burton because he is a Consul! Has he no other profession?" And they said, "Yes, your Majesty; he has been in the Army." So he said, "Oh, tell him to come as a military man, and not as a Consul."

It was three weeks of incessant Society and gaiety. I do not know when I have met so many delightful people. I was very much dazzled by the Court; I thought everything so beautifully done, so arranged to give every one pleasure, and somehow it was a graciousness that was in itself a welcome. I shall never forget the first night that I saw the Empress, a vision of beauty clothed in silver, crowned with water-lilies, with large roses of diamonds and emeralds round her small head, in her beautiful hair, and descending all down her dress in festoons. The throne-room is immense, with marble columns down each side. All the men are ranged on one side, all the women on the other, and the new presentations, with their Ambassadors and Ambassadresses, nearest the throne. When the Empress and Emperor come in they walk up the middle, the Emperor bowing, and the Empress curtsying most[Pg 25] gracefully and smiling a general gracious greeting. They then ascended the throne, and presently she turned to our side. The presentations first took place, and she spoke to each one in their own language and on their own particular subject. I was quite entranced with her beauty, her cleverness, and her conversation. She passed down the ladies' side, and then came up that of the men, the Emperor doing exactly the same as she had done. He also spoke to us. Then some few of us, whose families the Empress knew about, were asked to sit down, and refreshments were handed round, the present Dowager Lady Dudley sitting by her. It is a thing never to be forgotten to have seen these two beautiful women sitting side by side. The Empress Frederick of Germany was also there, and sent for some of us on another day, which was, in many ways, another memorable event, and the Crown Prince, as he was then, also came in.

It is not to be wondered at that the Austrians are so loyal and wrapped up in their Imperial family. Everything they do is so gracious, and the Emperor enters so keenly into all the events that occur to his people. He is such a thoroughly good man. If they called him their "father," as the Russians do their Czar, it would not be wondered at. At the time that I write of, and for many, many years later, poor Prince Rudolph was literally adored by the people; he had such a charming way of speaking to them. I remember when he came to Trieste from Vienna in early days, an old woman of the people knew he would arrive cold and uncomfortable after fifteen hours' express, and she prepared a nice cup of coffee and hot milk, and rolls and butter, and the moment the train came in she ran up to the carriage with her tray and offered it him, and he received it with such hearty good will and thanks that she was quite overcome, and he put forty florins on her tray. He did many unknown acts of good to the people during his short life, and one could so well understand the enthusiasm felt by the people—not much danger of a republic there. It does not matter where you go in Austria; you might be looking at the oldest church, or the most antique ruin, and your guide will say to you, "On that particular spot stood our Emperor ten years ago;" "Last August the Empress admired that view;" "Prince Rudolph went up those stairs when he was a child;" "He sat on that chair, and we never allow anybody to touch it;" and so on.

To return to the dearness of the hotels which choked strangers off: our humble bill—and we had had nothing but absolute necessaries—was £163 for three weeks. The landlord having assured us that it would be very small, and as the Embassy had taken the rooms for us at fifteen florins a day, we did not think it was good taste[Pg 26] to make a fuss about it, so we paid it; and on examining it we found the rooms were charged twenty-five florins a day; single cups of tea in one's bedroom, ten and sixpence apiece; a carriage to convey and set one down at the Exhibition, and to pick one up in the evening back to the hotel, £5 a day for the first few days, and so on. I heard one of the Rothschilds making an awful to-do about £100 for a month, but I thought we, far smaller fry, were much worse off. These things were bruited about, and very few people dared to come. I was taken to one of the great dressmakers' establishments, and what they showed me for £30 I am sure my maid would not have worn, and it was only when they began to show me things from £70 to £90 that they were good enough for me. In England one would have paid £15 or £20 for these last-named dresses.

Charley Drake now arrived on a visit to us, and we went up to see the great Government fête at the Adelsberg Caves. On that one day the Government lights this ninth wonder of the world with a million candles. The remarkable stalactite caverns and grottoes are of the most curious and fantastic shapes, and about seven miles of them are open; then the torrent that rushes into them plunges underground, and comes up again in another part of the Karso, that wild and desolate stony tract of land above Trieste, which is about seventy-five miles each way, and contains some seventy-two Slav villages. It is a mysterious, unnatural, weird land, full of pot-holes, varying from two hundred to two thousand feet deep, abounding in castellieri—prehistoric ruins—waters that disappear and reappear, that bound into the earth at one spot and rush out again some miles distant; and this is supposed to be the safeguard of Trieste against disastrous earthquakes.