“HELENA”

“HELENA”

“Tranquilly, Lillian Gish sits, dressed in white organdie, her ash blond hair down her back, relaxed on the window seat, looking out for hours into the depths of the California night.

“‘What are you looking at, Lillian?’ Mrs. Gish has asked for years.

“‘Nothing, Mother, just looking.’”

“She is an extraordinarily difficult person to know, and if I hadn’t gone to live with her ... and been with her through some of the most trying times of her life, I doubt whether our casual contacts at the studio would have brought me any intimate knowledge of her. There seems to be a wall of reserve between her and the outside world, and very few people ever get through that wall.

“The little things of life simply don’t worry her at all. Gales of temperament can rage around her—she remains undisturbed.... I have seen her at a time when anyone else would have been distraught with anxiety, come quietly in from the set, eat her luncheon calmly and collectedly (for first of all, Lillian believes in keeping fit for her work), then pick up some little book of philosophy and read it steadily until they sent for her.

“She refuses to believe that there are people in the world who are jealous of her and want to harm her. I remember someone once remarking that a certain person was jealous of her and hated her, and I can still see the look of utter surprise on Lillian’s face. But it never made any difference in her treatment of that person. In fact, I doubt whether she remembered it when she met her again.

“She is intensely loyal to those who have helped her along the path of success. She likes to be alone. She has an inexhaustible fund of patience, and a quiet sense of humor.”

(Scene: Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya”—end of second act. Lillian Gish as Helena)

First Woman in Front of Me: “They say she’s been playing over twenty-five years.”

Second Woman in Front of Me: “Goodness! How old is she?”

“The piece I read said about thirty or so....”

“Oh, began as a child; is Gish her real name?”

“I believe so; the piece said....”

“Do you like these Russian plays?”

“I like her, in anything. I loved her in ‘Broken Blossoms,’ though it nearly killed me.”

“I wonder why she left the movies.”

“Oh, lots of ’em do; the piece said....”

“Do you suppose that is all her own hair?”

“Oh, I think so; the piece said....”

When Lillian was six, she found herself with a company (one night stands, mostly), “trouping” through the Middle West— ... the golden-haired child actress who supplied the beauty and pathos in a melodrama variously known as “The Red Schoolhouse” and “In Convict Stripes.” All of which had come about reasonably enough—as reasonably as anything is likely to happen, in a world where nothing seems at all reasonable until we begin taking it to pieces.

On an evening in October—the 14th, to be exact, 1896—in a very modest dwelling, in Springfield, Ohio, May Gish—Mary Robinson Gish (born McConnell)—waited for her first child. She was barely twenty, and it was hardly more than a year earlier that James Gish, a travelling salesman—young, handsome, winning—had found her at Urbana, and after a whirlwind wooing, had carried her off, a bride, to Springfield.

No one knew very much of Gish. From that mysterious “Dutch” region of Pennsylvania, he had drifted into Springfield, made friends easily, and found work there, with a wholesale grocery. He might be Dutch himself; “Gish” could easily have been “Gisch”; or French—a legend has it that the name had once been “Guise” or “de Guise” ... all rather indefinite, today.

On the other hand, everybody in Urbana knew about pretty May McConnell, whose Grandfather Robinson had been in the State Senate; who had a President, Zachary Taylor, and a poetess, Emily Ward, somewhere in her family; whose father was a very respectable dealer in saddlery and harness, with a spirited dapple-grey horse in his big show window.

Oh, well, it is all so “accidental” ... even though some of us do not believe in accidents, and talk knowingly of a Great Law ... of a Weaver who sits at the Loom of Circumstance....

Still, it was natural enough that now, within a year from her marriage, pretty May Gish should be looking up from her window at the thronging stars, wondering how a baby soul could find its way among them to her tiny room.

A girl child, born with a caul ... supposed to mean good fortune, even occult power. Mary Gish did not much concern herself with this superstition; she had been rather strictly raised; when she gave her daughter the name of Lillian, and added Diana—Lillian because she was so fair, and Diana because a big moon looked into her window—she thought it a happy combination and hoped well for it—no more than that.

The little household did not remain in Springfield. At the time of his marriage, or soon after, James Gish gave up his position as a salesman, and opened a small confectionery. Candy-making may have been his trade; at all events, he worked at it now, sometimes leaving “Maysie,” as he called her, to tend shop while he went to nearby fairs and celebrations. Had he persevered, he might have done well enough. As it was, when Lillian was about a year old, he gave up Springfield for Dayton, to which prosperous town Father McConnell had already taken his saddlery and harness business, including the smart dapple-grey horse for the show window. Dorothy Gish, who was born in Dayton, still remembers the impressive horse in Grandfather’s window. Lillian, a fair, sedate little lass, was delighted when Dorothy arrived—fat, rosy, red-haired—full of fun and mischief, almost from the beginning.

So different, these two. Lillian had been a pensive baby—one to lie quietly, looking at nothing, as one thinking long thoughts—possibly of a pleasanter land, so recently left behind. Dorothy’s arms and legs were perpetually in action ... impossible to keep the covers on her. When she could creep about, then walk, it was necessary to grab quickly for one’s possessions.

Lillian had a doll, probably a tidy rag-doll, or a very small china one, and a little rocker, which she sometimes sat in, holding her doll and singing to it. She never really cared for dolls. Ruddy-haired Dorothy was lovelier than any doll. When Lillian held her, as she did, often, they made a dainty picture: one doll rocking another.

A tragic thing happened. Lillian sat in her chair alone, one day, when a terrible object looked in the window. It was a workman, who had put on a false face, to frighten her. He succeeded. The terrified child screamed and went into spasms. Always, after that, she was subject to nightmares, from which she awoke, screaming. In later years they came during periods of prolonged rehearsal. Usually they took one of two forms: She was in a wood, at evening ... the trees became sinister, drew their roots from the ground and pursued her.... Or in a field, where there were many red poppies ... large ones ... the California kind. They became very tall, and threatening, like the trees.... They came up and slapped her in the face.

In summer time Mrs. Gish took her little girls to visit her sister Emily, who had married and lived at Massillon, in the eastern part of the state. It was a happy place for children. There was a green dooryard, with chickens, a cat asleep on the porch, a dog—a kindly dog who would not hurt a little girl and her baby sister.

And in the house was a wonderful cupboard, where a number of interesting things were kept, including a bottle of Castoria. Lillian was not meddlesome, but she had a complex for Castoria. She would even dose herself with it surreptitiously. Her aunt put the bottle on an upper shelf, but Lillian with a chair, a high-chair if necessary, would manage to reach it. It became a kind of game. Her aunt took a Castoria bottle and secretly half filled it with cod liver oil, which certainly was not playing the game fairly. There it stood, in plain view; even a low chair would reach it. A good swallow—saints above! What an explosion, what a spitting, what a grabbing at the poor punished tongue! Lillian was naturally very honest. Castoria had been the one temptation she could not resist. Her character was now perfect.

But she did love baked beans. She could almost never get enough of them. One day—this was in Dayton—her father took her for a walk. The drinking-saloons of Dayton, like those everywhere, had swinging doors, with free lunch inside, spread at the end of the high bar. Gish pushed open a pair of these swinging doors, perched the little girl on the high counter, close to a great platter of beans. A man wearing a white apron handed her a plate and a spoon: “Help yourself,” he said. Lillian did not know what became of her father, but by and by Grandfather McConnell appeared, rather frantic, and shocked, and took her away.

One other thing she loved—ice cream—her taste for it amounted to a passion. Her father did not sell it, but there was a place just down the street that did. When in funds, Lillian haunted the ice-cream counter. But one was so liable to be bankrupt. Reflecting on these things, she had a startling idea. One did not need money to buy things! More than once in her father’s shop she had seen a customer pick up a package, and with the magic words, “Charge it, please,” walk out. Why, of course—she could do that, too. Ten minutes later she was finishing her second dish of vanilla and chocolate mixed.

“Charge it, please.”

The young man regarded the slender little vision, who had just stowed away two saucers of his stock in trade.

“You’re Mr. Gish’s little girl, aren’t you?”

“Yes, thank you,” said Lillian, who was nothing if not polite.

“Oh, all right.”

Such a nice man, to know who she was.

On the way home, she noticed a little green cap in a window—just what she had wanted.... She stood on tiptoe, to look over the counter, at the grisly man who sold things.

“I want to buy that little green cap in the window—and charge it, please.”

“Oh—why, you’re Jim Gish’s little girl, ain’t you?”

“Yes, thank you.”

He held her up to the glass, the tiny cap a green jewel on her crown of gold. And presently at home she was explaining all the wonder of her system to Mama, who also did some explaining, very gently, which put the system in a new light. Lillian was then about three.

In the case and circumstance of James Gish, there is an element of mystery. He had the gift of friendship, of popularity, even of prosperity ... without material increase. It may be that the swinging doors were too handy to his confectionery ... a spoiled child ... and heredity is always to be reckoned with. It may be that he was not quite a reality ... a good many of us are like that.... He closed his business in Dayton and removed his family to Baltimore, where he arranged some sort of partnership with a man named Meixner. Did he put up his experience against Meixner’s capital? Grandfather McConnell probably helped.

The firm of Gish and Meixner must have prospered, in the beginning. Mary Gish allied herself with the church of her faith, the Episcopal, in which both she and her children had been baptized. Gentle and lovely, she made friends. The children, neatly dressed, went to Sunday School. Mary Gish was one of God’s fine souls. She had a beautiful spirit, and she had exquisite taste. Whatever her circumstances—and the time was coming when they would be hard enough—she would manage, through some sacrifice, to get a scrap of dainty material, a bit of real lace, for her children’s clothing. Lillian and Dorothy were much noticed—she must not fail them. In her husband’s shop, by day and often in the evening, she nevertheless made every garment with her own hands—those tiny, marvelous hands that could draw and embroider, could put up bonbons, and gift packages, as no one else could do it—mended and laundered and ironed when the others were long abed.

The Gish children found their Sunday School an interesting place. Sometimes there were entertainments, “exhibitions” they called them, and there was an Empty Stocking Club that filled stockings for the less fortunate, at Christmas time. Lillian’s first public appearance, at one of the exhibitions, was not an entire success.

She had been chosen to speak a piece, some verses of welcome, which daily she faithfully rehearsed at home, going over them time and again, just as in later years she would prepare for her rôles. Little Dorothy, playing about the room, apparently gave slight attention, perhaps not realizing herself how the lines were being drilled into her brain.

The afternoon of the performance came, and Lillian, all white and gold, rose and spoke the lines faultlessly. There was applause, of course—and something more. Dorothy, shining like a jewel, jumped up and waved her hand to the superintendent:

“May I speak a piece, please—may I speak a piece, too?”

“Why, of course, my dear, you may; come right along.”

And Dorothy, fair and undismayed, marched to the platform, and repeated Lillian’s poem of welcome, word for word.

Poor Lillian! The audience, at first puzzled, broke into applause. Her heart was broken. She thought she had failed—recited badly. She struggled a little, and found relief in a welter of tears. Which meant grief for Dorothy, who adored Lillian—set her up as a kind of queen.

The Empty Stocking distribution was quite another matter—a real event. It was held at Ford’s Theatre, where Nat Goodwin and Maxine Elliot were playing that week, on an afternoon when there was no matinée. The big tree was set up in the center of the stage, and the stars were invited to take part. Maxine Elliot offered to fill stockings; Nat Goodwin agreed to be Santa Claus. When a particularly angelic child was needed, to perch on Nat Goodwin’s shoulder and distribute the stockings, Lillian Gish was chosen, and so made her first stage appearance—rode into the drama—on the shoulder of one of the best-known actors of the day.

Dorothy and Lillian were near enough together to be playmates. Lillian was not so good at play as Dorothy. Long afterwards she wrote:

“I envy this dear, darling Dorothy with all my heart, for she is the side of me that God left out....

“All my life I have wanted to play happily, as she does, only to find myself bad at playing. As a little girl, I was not much good at playing, and I find that, try as I will, I don’t play very convincingly today.”

They were good little girls—Lillian especially so. They had been taught to say their prayers, and would as soon have omitted their little nightgowns as their prayers. If Dorothy made a scramble of hers, while Lillian offered her petition to the last word and syllable, and overborne by some ancient melancholy prayed regularly that she might wake up in Heaven, it was only as Nature had intended them to be from the beginning.

Different as they were, then and always, they had one great interest in common: their mother. They thought her the best and most beautiful person in the world. Dorothy loved to think that she looked like her, and cried when told that Lillian “looked more like Mama” than she did.

From the beginning, almost, Lillian was inclined to be orderly, tidy. Dorothy—well, Dorothy was different. Even in that early day, when Lillian was no more than five, she carefully removed her clothes and laid them neatly together. Dorothy did not remove hers. She dropped, or flung, them off, and where they fell they remained. It was said—this was much later—that you could at any time find Dorothy by following her clothes.

By day, Lillian was inclined to sit in her little chair and reflect, while Dorothy tore about the house, escaping to the street if not watched, and perpetually had her knees bruised and scratched, from falls. She also liked to sample any food or liquids that were in handy reach, and once went on a genuine debauch. Lillian had come down with an attack of croup, her medicine being a tasty toddy, which, upon experiment, Dorothy found that she liked. Lillian was dozing, and she continued her experiment. Then she laid aside the spoon and picked up the glass. Her mother found her, staggering down the hall, “making whoopee.” Mary Gish got a whiff of her breath, and sent for the doctor. Next day Dorothy went through the tortures that go with a bandaged head, and usually come later in life.

The world was not kind to James Gish. Perhaps those wise ones who know all about the world, and human nature, and the free-will to choose, will say that he was not kind to himself. One must admire those people; they know things with such a deadly certainty. I never in my life knew a thing so certainly as a man who once told me that I could always do the right thing, if I only wanted to. Apparently I didn’t want to.

Nor, as it seemed, did James Gish. When, after less than two years in Baltimore, he sold out to Meixner, he had very little left. Part of that little he gave to his wife; with the rest, he went to New York, where he would find employment and send remittances.

For a time the remittances came; then they dwindled, skipped, ceased. Mrs. Gish worked, but the money she earned was not enough for the little family. Meixner lent her small sums, then advised her to join her husband, advancing money for her fare and for immediate needs on arrival. Meixner appears to have been a good soul.

In New York, Mary Gish took an apartment—small, but large enough to accommodate two boarders. It faced West 39th Street, up one or two flights of stairs. She needed more furniture and bought it on installments. She also took a job—demonstrating, in a Brooklyn department store. She was twenty-five, handsome, capable, determined to make her way. Up at five, she set her house in order, got breakfast for her family and the two boarders—theatrical women, who had their luncheons outside. Leaving the children in the hands of a colored girl, she was off for the day. Back at night, she got the supper; then worked at the making and mending and laundering of the family clothing.

Gish was there, and may have been employed at times, but his help was negligible. Less than that. As she saved from her modest pay, she gave him sums, trusting soul, to pay on her furniture. But then, one day, when she came home from her job in distant Brooklyn, more distant then than now, the dealers who had sold it to her had come and taken it away. Her husband appears to have vanished about the same time. Later, she sought and obtained legal separation.

Kind-hearted, weak—James Gish was only one of thousands. That he loved his family is certain. When a year or two later, Mary Gish and little Dorothy were on a theatrical circuit, he was likely to turn up any time, appearing mysteriously in distant places. Hungry for the sight of them, he must have watched them enter and leave the theatre—perhaps went in to see the play. Sometimes he confronted them on a street in a far-off town. Always in Mary Gish’s heart was the dread that he would take one or both of her children from her. She knew he was a Freemason, and in her lack of knowledge, thought he might in some way invoke that secret agency. He seems never to have attempted anything of the sort, and if he secretly followed Lillian, she did not know it. Probably it was Mary Gish herself that he most wanted to see. Those wise ones who know all about the world will not fail to explain that he deserved his tragedy....

Night and day the Loom of Circumstance weaves its inevitable pattern. The filaments proceed from a million sources, stretching backward through eternity. Incredibly they unite, and once united the gods themselves cannot change the design.

Mary Gish’s fortunes were at low ebb. Her unfurnished room would presently be on her hands. The two actresses, who owed her money, were willing to bunk on the floor, but the theatrical season would open shortly, and what then? Such jewelry as she owned was pawned, even to the last piece—even to her wedding ring. The actresses had likewise parted with their valuables. One of them, who called herself Dolores Lorne, had taken a great fancy to little Dorothy. There came a momentous afternoon. Mary Gish, arriving from Brooklyn, was met by a startling proposal:

“I can get a good part in Rebecca Warren’s ‘East Lynne’ Company,” Dolores Lorne excitedly announced, “if I can get a child to play ‘Little Willie.’ Dorothy would do it, exactly. They will pay her fifteen dollars a week, and we’d have a week’s salary in advance. I could pay you; and I know a woman who can get a part for Lillian, too. A lovely woman, Alice Niles, in a ‘Convict Stripes’ Company.”

Mary Gish stared at her, dazed, staggered. She could not grasp it. Her little girls ... going away ... motherless.... Poor little Dot, hardly more than a baby ... and Lillian, barely six ... on the road with theatre people ... what would the folks at home say?

Theatre people! She had not even dared to confess that she had them in her house. Dolores was a good soul ... but little Dot ... and Alice Niles—who was Alice Niles? A stranger! And Lillian, so frail ... on the road ... with a stranger!!! James Gish’s wife, who had borne up in the face of everything, gave way, wept as if her heart would break.

Dolores Lorne comforted her ... later, Alice Niles. She believed them good women, both of them. They promised to take a mother’s care of her little girls. They painted life on the circuit as happy—just a long pleasure trip. If they forgot the broken nights on wretched trains, the scanty, stale food, the dragging weariness of delays ... oh, well, they were human. Lillian and Dorothy became excited. They had never been to a theatre, except to the Christmas-tree performance in Baltimore. That had been beautiful. Especially Maxine Elliot. Now, they were going to be beautiful, like Maxine. Tearfully Mary Gish began to assemble two little wardrobes—scanty little wardrobes, of a size to go into two cheap little telescope bags.

Also, there were the rehearsals. Mary Gish taught her children their brief lines, which they rehearsed at the theatre. Lillian went at her task in her obedient, thorough way, and became a favorite. Dorothy, who perhaps had ideas of her own, was invited to repeat, and repeat, until both Mr. William Dean, the kindly manager of her company, and herself, were a trifle worn and critical. Finally, when Mr. Dean became really quite fierce, and peremptory, Dorothy, aged four, whispered, her lips trembling a little:

“Please, Mr. Dean, if you let me alone for a few minutes, I know I’ll be able to do it.”

Mrs. Gish, meantime, had a new and quite definite plan. She would herself become an actress! Very likely her people would cast her out, but never mind. Acting could not be worse than the long hours in Brooklyn. She would equip herself to be with one or both of her children. Alice Niles introduced her at a theatrical agency, and Mary Gish—determined woman that she was—was rehearsing for a small part at Proctor’s almost as soon as the two real actresses of the family had said their heartbreaking good-byes.

Stage children of that day took whatever name was offered them, usually the name of the woman in whose charge they traveled. Dorothy readily learned to say “Aunt Dolores” and accepted the name of Lorne. Alice Niles became “Aunt Alice” to Lillian, and she herself “Florence Niles.”

It is not certain where Dorothy’s company opened, but “In Convict Stripes,” with “Little Florence Niles, the loveliest and most gifted child actress on the American stage,” opened at Risingsun, Ohio, in a barn. Barns and upstairs halls were often used by the one-night-stand companies, though a larger town sometimes had an “opera house,” with real seats, not just boards for benches.

Risingsun was accounted a very good town of the barn-and-board-seat variety. It had a stage with side slips, and something in the nature of scenic effects. After a long night ride on the train—a night when one did not undress and go properly to bed, but slept part of the time on a seat, part of the time leaning against Aunt Alice—a journey which was not altogether a pleasure trip—the “Convict Stripes” Company arrived at Risingsun in time for a rehearsal before the performance.

There was a stone quarry in the play, and some papier-maché rocks, probably carried by the company. At the climax of the third act, the villain—there was always a villain—places the child at the bottom of the stone quarry, then lights a fuse to explode a charge of dynamite which will hurl rocks, and the poor innocent child, into the air. Is the child killed? Dear, no! In the nick of time, the hero swings out upon a rope, swoops down into the pit, seizes the child and swings himself and his precious charge to safety, just as the dynamite explodes.

Inasmuch as a delicate, real flesh-and-blood, child might not stand the wear of being handled in that reckless way, a neatly made dummy-duplicate of Lillian was placed in the pit for the hero to grab. Lillian had been carefully taught to creep to safe hiding behind some of the papier-mâché rocks before the explosion, and knew just how to do it. They practiced now on the barn stage, and it went off perfectly. They forgot one thing, however: They forgot to tell the “lovely and gifted Florence Niles” that the explosion would make a sudden and very big noise. In the rehearsals, somebody had merely said “BOOM,” which wasn’t at all the same thing.

Evening came, and the big barn was filled with farmers and townspeople, a breathless audience. Florence Niles, aged six, lay safely behind a stout papier-mâché rock, waiting for somebody to say “Boom!” But then, just at the instant when the villain or somebody should have said “Boom!” something else, something very terrific and awful, happened: a real BOOM in fact—one that fairly shook the barn, and made the audience jump and say something. The gifted Florence Niles did not stop to see what became of her double, but with a shriek, shot out from behind the rock and across the stage as fast as her legs could carry her, while the audience shouted for joy.

Never again would the climax go off as well as that. When the curtain fell, and Lillian—that is to say, Florence Niles—on the hero’s shoulder, passed in the procession before it, they received a great ovation.

And this was not so far from that modest house in Springfield, Ohio, where just six years earlier Mary Gish had waited for her first-born.

I do not know what the next stop was, and it does not matter, any more. The family likeness among one-night-stands was strong. The child actress presently did not mind the explosion—not so much—she only stopped her ears for it, and always she took the curtain call on the shoulder of the big hero, who adored her, and would have swung, regardless of explosions, into any quarry, any time, night or day, to save her.

How kind they were, all of them! Aunt Alice especially. She had a round, smiling face, and a round, soft, motherly body. Just right for the character part she played ... just right for a little girl to snuggle up to, those nights on the train when there was no empty seat where one could really stretch out and sleep. Any of the company would gladly have given a shoulder to that golden head, and did, in turn, but no one except Aunt Alice had such a nice, soft shoulder, with such a good smell—no tobacco or anything—just Aunt Alice.

But the nights were quite hard, sometimes:—hard ... and strange. Even when she got a seat all to herself and was covered by somebody’s coat, and sound asleep, it did not last. At any station a crowd of noisy people might come in, and a fat woman, or a thin woman with a baby, or somebody, would need the seat; and struggling to get her eyes open, and almost dead, Lillian would shrink back into her corner, and start at the rest of the company, huddled into the unusual attitudes of sleep.

The train did queer things to people. Such remarkable people ... when one was awake to notice. Men—women, too—with funny faces. Country-jakes and their girls. Boys who stared at her, and if she turned on them suddenly, acted so crazily ... babies—that mostly cried ... fat people ... thin people ... dirty people ... even clean and pretty ones.

Sometimes faces and people were there very uncertainly—perhaps not really there at all—just a part of some dream. One dreamed and dreamed, especially if one was not very well. Sometimes she woke with a dry, feverish mouth, and staggered down the aisle for a drink. Sometimes she was awakened by being bumped and jerked, this way and that, switching, with engine bells that swept by with a watery sound.

Faces ... faces—one could even invent faces, especially just as one was going to sleep ... or they just came of themselves ... like the train boy, who brought a strong smell of oranges. Sometimes Aunt Alice would let her buy one, and a lemon stick to push into it. That was heaven. One could suck the lemon stick and dig into one’s corner and go to sleep. Or press one’s cheek against the glass and watch the snow or rain or solid dark go by, with sometimes a light ... far off, or perhaps quite near. Somebody would be where the light was—somebody lived there. On clear nights there were stars—even a moon that made the snow fields very white, and traveled with the train, no matter how fast or far it went.

So much snow: fields of snow, hills of snow; villages with snow on the roofs, and in the dooryards, looking white and deserted in the moonlight. And tunnels—long, terrible, gasping tunnels; and big towns where the train slowed down with a great clackety-clack of wheels, and there was confusion—shouting, and rumbling baggage trucks, and where probably one had to change and sit in a station, or work one’s way through the iron arms that divided up the seats, so one could stretch out, and really sleep a little, at last. Not long, of course, for the other train would soon come shrieking in, and Aunt Alice or the hero, or Corinne, the soubrette, or somebody, would drag her through the iron divisions, and maybe carry her onto it, and if she didn’t remember that she had gone to bed before, she was apt to say her “Now I lay me” over again, and “God bless Mama and Dorothy, and keep them safe and well, and please, God, let me wake up in Heaven,” which she always added. And then, if there were no more changes that night, almost right away it was morning, with coal-dust, and cinders, and gray outside at first ... with perhaps a streaky sky ... or dull and drowned with rain ... or caught up in a whirl of snow; and the train boy came through and sold her a sandwich for breakfast; or maybe they had reached the next show-town, and she went scurrying down the platform, holding Aunt Alice’s hand and lugging the little telescope bag, to a lunch counter where there might be something warm.... Not really a “pleasure excursion,” but long afterwards she did not regret it—she even found something “rather beautiful” in it.

They did not really “put up” at hotels. They merely “put in,” at a cheap one, for the day. Aunt Alice would get a room for fifty cents, until theatre time. Then the two soubrettes—good-hearted, even if rather tough, girls—would come to “call,” to share the room, each paying ten or fifteen cents. All stretched out on the bed, the sofa, anywhere, to catch up with their sleep. They only got up to eat—something they brought in, or at a restaurant, a cheap one (oh, worse in that day than now!)—or for a matinée.

If they were awake and there was nothing else to do, Aunt Alice taught her charge from a little book, and told her about a number of useful things. For one thing, it was quite wrong. Aunt Alice said, to kill animals, and not really healthy to eat their flesh. Vegetables, bread, milk and eggs had in them all that was good for human beings. Aunt Alice was a vegetarian, and advised Lillian to become one. Lillian liked the sound and size of the word, and could not bear the thought of killing anything—animals especially. Besides, at the places they ate, one could get more vegetables than meat for one’s money. One could get quite a lot of potatoes for a nickel, or a dime; other things, too—baked beans, which she still loved, and rice. They were not always good—sometimes greasy and tasteless, but they filled up. Often the butter was bad, especially. Still, if one could have a piece of pie at the end ... or a plate of ice cream—a five cent plate ... she became a vegetarian.

All the actors paid their own expenses, except train fares. Unlike Dorothy, Lillian received only ten dollars a week, but by close economy could send more than half of it to her mother. Perhaps the economy was too close, the physical foundation she was laying too slender.

And there was more than the need of food and sleep. A child—the wistful, heart-hungry child that she was—needed more than even the kind-hearted care of Aunt Alice: ... Companions, play ... the comfort of a mother’s arms.... Darkness gathering in a lonely hotel room—a little figure crouching at the window, staring into the night.

“What are you looking at, dear?”

“Nothing, Aunt Alice—just looking.”

Always her reply would be the same—always the same heart-hunger behind it. A dozen, twenty years later, a slender, white figure on a window seat, staring into the depths of the California night.

“What are you looking at, Lillian?” her mother asks.

“Nothing, Mother; just looking.”

Sometimes when the town was quite large and they played more than one night, she got to sleep in a real bed, could take off her clothes and have a bath—how splendid! Sometimes the paper in such a town had a piece in it about the play, even once or twice with her picture. The others thought this very fine, especially where their names were mentioned. They bought a lot of the papers, and cut out the pieces. Lillian did not value the notices very highly; what the paper said was not always true. The picture was of the same sad-faced little girl she saw every morning in the glass when Aunt Alice combed her hair. When one of the company gave her a clipping for herself, she politely said “Thank you,” and put it away in her little telescope, but she seldom looked at it.

One performance was like another; but then came one which brought her a special and rather wide publicity. In the play was a prison scene, where a guard, a lame guard, Cliff Dean, carried a rifle, loaded with a blank cartridge. During the performance at Fort Wayne, Indiana, the unfortunate guard dropped his gun, and it went off. Lillian, close by, received the charge in her leg, and was badly powder-burned. No burn hurts worse than that. She screamed and ran off the stage. The leading man, the hero, was going down some steps that led to the dressing-rooms. He picked her up and carried her down, soothing and comforting her. Others not in the scene gathered to help. The wounded leg was bathed and bandaged. The play upstairs did not stop. The audience may have thought the incident just a part of it.

The next act was the last one, and Lillian’s share in it important. She was suffering terribly, but she said she would go on, and did. Few, if any, of the spectators knew what had happened. When, after the show, the facts were known, they crowded the lobby of the hotel and watched the doctor pick the powder grains out of the tender flesh. It was torture, but Florence Niles, the child actress, refused to cry. Some of the powder had to stay under the skin and remain there permanently, like tattoo.

Alice Niles did not write to Mary Gish of the accident, but of course it got into the Western papers. Grandfather McConnell, in Dayton, saw it, and sent her a clipping. Certain of the family may have regarded it as a kind of retribution for permitting one of her own to follow such a calling. The biblical-minded can always identify punishment, even when it falls on the innocent child, or flocks, of the transgressor. The fact that her children and herself had become play-actors was for years not mentioned by Mary Gish’s family to their friends—nor discussed among themselves.

The company did not perform on Sundays—nor always travel—but stayed in a hotel room; shabby, but how luxurious! Aunt Alice mended their clothes—washed them. Florence Niles, the child actress, helped. All the others were doing the same. Sometimes they dropped in, to visit. Among them they taught her to read. The patter of the stage and much general information she picked up unconsciously. Nothing that was evil—certainly nothing that she recognized as such—neither then nor ever. More than twenty years later she wrote:

Stage children are in most cases more sheltered than those who go to school. They constantly associate with older people who are, as a rule, most careful what they say in front of them.

In after years, she remembered that once a stage hand had knocked another one down because he swore in front of her. Some of the company may have been a bit dissipated, even dissolute; if so, it was outside of her knowledge. There would come a day when she would realize that the soubrettes probably had been as “tough” off as on the stage—that some of the others were not saints. But to her, then, they were, and in her memory would always remain, the best people in the world.

And talented; they said so themselves. All, including Lillian, looked forward to playing New York. The others because it might mean a Broadway engagement where their talents would be appreciated. Lillian, because New York would mean her mother ... better meals ... a bed to sleep in at night. Considerately, she did not mention these things, but looked out of the window, thinking long thoughts. And this picture I am trying to present is not only of that first year, but of the years that followed it, one so nearly like another—except for the parts she took and the rapidly increasing length of her slim legs—that in later years she found it by no means easy to distinguish them.

Two events remembered from that first far-off engagement were particularly tragic, both connected with running for trains. Always they seemed to have been running for trains. Every night after the performance there was the same scramble, even though they had to wait for hours in a station that was too hot or too cold, with only those divided benches to sleep on, or the telegraph desk, when the station agent took pity on a tired little theatre-girl.

And often it seemed to be raining, or snowing, when they started for the train, and there were single-board-crossings over the ditches, where you could not hold to Aunt Alice’s hand and stay under her umbrella, and where it was not easy for someone to pick you up, because all the talented company carried their baggage, every fellow for himself.

So it happened that on one of those rainy nights, when she was running behind Aunt Alice, across a narrow foot-bridge, lugging her little telescope bag—there, right in the middle of the bridge—the treacherous strap gave way, and all her possessions—her little nightgown, her little extra stockings and underwears, her press-clippings, everything—disappeared in the black, rushing torrent below. She did not stop—no time for that, and no use, anyway—but raced on after Aunt Alice, holding fast to the useless little strap of the telescope, and crying—oh, crying. No money to send home that week—so many things to buy.

The other event, scarcely less tragic, was also of the night and rain. She was wearing the little white furs that once an uncle had bought for her, and that she so dearly loved. All about were mud puddles, and by some misstep she plunged into one, and the precious furs could never be the same again. Rain! Rain! Once in the South, on the Seaboard Air Line, it fairly poured, and the rickety old day-coach leaked. The whole company had to sit holding umbrellas, to keep from getting soaked. Lillian always remembered that, as something different.

Christmas that year she remembered, too. A little present had come from Mother—very precious—but there was still more to this Christmas than that—a good deal more. All day they were on a freight train, a train that lumbered and bumped along, and stopped for what seemed hours in the towns, and ran up and down, pulling and pushing all kinds of freight cars, in and out and around, sometimes slamming them into your part of the train, until it seemed your head must certainly come off. You had to ride in the caboose, not at all a nice place—just long, dirty benches on the side, and grimy train men coming in, leaving the doors open, to let in the cold.

But then came a stop at quite a big town, where there was certain to be a lot of switching and backing, which would take a good while. A good many of the company “went ashore,” and when by and by they came back they brought, of all things, a Christmas Tree! A little, green tree that they set up right in the old, dingy caboose; and then they opened packages and hung balls and candy canes on the little tree, and even presents. And all the rest of that day, the gay little tree rode and rode, and the old caboose wasn’t dingy any more, and one’s heart could almost break with happiness over a thing like that. Surely in all the world there was never such another Christmas Tree!

If Dorothy had a Tree that Christmas, there is no memory of it today. A very remarkable one was on its way to her, a little farther down the years, but “Little Willie of East Lynne” appears to have had other entertainments.

Life in Rebecca Warren’s “East Lynne” Company was probably less strenuous than in a “Convict Stripes” combination. They made larger towns, had fewer one-night stands. Sleep and food could be more regularly counted upon, and may easily have been of a better quality. Besides, Dorothy—light of heart, plump, dimpled—was fairly worshiped by Dolores Lorne, who lay awake nights planning how she might keep her always, and asked nothing better than to hold her and carry her and shield her from every possible trial of the road. She even planned to steal her, and might have done so, had she not been a devout Catholic.

She was rather rigid in the matter of Dorothy’s conduct. She took her to early Sunday morning Mass, and taught her to tell her beads, to pray with a rosary. It was something new, and Dorothy rather liked it. Especially as Aunt Dolores often had candy in her pockets. She was willing to adopt any new and profitable faith. She became a “rice Christian.”

Auntie Dolores could be severe. Dorothy had a queer habit of picking the stitching out of the hem of her dress. Miss Lorne had tried all sorts of ways to correct this, for it meant that she must sit down and restitch the little garment, by hand. Finally, she said:

“You know, Dorothy, you don’t like to wear the little trousers that go with your part.”

Dorothy didn’t. She hated them, and said so. She cried every night, when she had to put them on. Aunt Dolores regarded her very solemnly.

“Very well,” she said, “the next time you pick out the seam of your dress, you will have to wear the little trousers to the hotel.”

Dorothy didn’t believe her. A grown person couldn’t do a thing like that to a child—especially Aunt Dolores, who loved her so.

She did, though. Dorothy picked out the hem again, and that night when the play ended, the little trousers were not taken off. She wept, but it was of no use. Auntie Dolores hardened her heart. Dorothy set out for the hotel in the hated trousers. Her little coat nearly concealed them, and she scrooched as much as possible, but the disgrace was there—she could not forget it. It was a terrible punishment, but effective. Dorothy did not pick out the seam again.

One more correction she remembered in after years. The Company had reached Cleveland, where Miss Lorne had relatives. They stayed with them, and somebody made a pudding—a wonderful pudding, with raisins on the top. It was set out on the back porch, to cool. Dorothy, playing out there, found it interesting. Then fascinating. Then she picked off a raisin. Then all the raisins. Then Auntie Dolores came out and asked for an explanation.

Dorothy shook her head: She had seen some blackbirds about the yard ... perhaps they had picked off the raisins. “Perhaps,” agreed Aunt Dolores. There was a raisin in the ruffle of Dorothy’s little dress. Perhaps the blackbirds had left it there.

Aunt Dolores took Dorothy on her knee and explained in good, Catholic fashion what happened to little girls who did such things, and then told stories about it. Presently reduced to a freshet of tears, Dorothy confessed. She was forgiven; but Auntie Dolores found it necessary to wash out her mouth, with soap.

Dorothy as a “baby star” had been a success. It is true that her attention sometimes wandered during a rather long speech, when she was supposed to be listening, and Miss Warren devised a plan, something with a jelly-bean in it, plainly visible to Dorothy, who knew if she looked at it steadily, it would be slipped to her when the speech ended. Also, there had been a night that she went to sleep, when she was supposed only to be dead, and rolled off the narrow, improvised couch, nearly breaking up the performance.

Dorothy’s first season closed rather late, when Lillian was already with her mother, in New York. A telegram came that Dorothy, in care of the Pullman conductor, was on her way to them. Mrs. Gish, anxious at the thought of the little girl traveling alone, wild to see her, was at the station long before train time. With Lillian she waited ... then at last the train was there, and looking down the platform, they saw Dorothy—not walking in charge of the conductor, but riding high on the shoulder of a very large man, one of a delegation of Elks, who had been captured by the child actress with sunlit, red-gold hair. They had heaped riches upon her—her arms were full. A moment later, and her mother and Lillian had her in their embrace.

“Oh, Dorothy,” said Lillian, “I’m a vegetarian!”

“That’s nothing,” said Dorothy, “I’m a Roman Catholic!”

At the apartment, Dorothy found her family considerably increased. A very nice lady was there, also two girls, somewhat older than herself, named Gladys and Lottie, and a boy about her own age, named Jack, who fell in love with her at sight. Their names were Smith, some day to become Pickford, which is a later story.

It had come about in this wise: Lillian’s Aunt Alice Niles had severed her engagement with the “Convict Stripes” Company, and had written to say that she would leave it at Buffalo, and come to New York. The season was not ended, but Mrs. Gish, not wishing to leave Lillian with a stranger, wired Miss Niles to bring her in. The manager of the company, remembering that young Gladys Smith had played the part in Toronto, where the play had been called “The Little Red Schoolhouse,” promptly arranged to have Gladys join the company in Buffalo. Mrs. Smith decided to bring all the children to Buffalo, and after getting Gladys established, to keep on with the other two, to New York.

The meeting between the two little girls, destined to become world stars, was neither formal nor memorable. More than twenty years later, in an article in Photoplay, Mary Pickford wrote:

Neither of us, I am sure, remembers our first meeting. We were too young to be impressed by the event. I do recall a fleeting glimpse of Lillian when I went to Buffalo from Toronto to take the part of little Mabel Payne that she had been playing in Hal Reid’s famous old melodrama, “The Little Red Schoolhouse.” Lillian was just leaving the theatre as I came in, and we waved. She could not stop to talk, because she was being whisked away to catch a train for New York.

Lillian and Mary! How little either of them guessed, that day, that within no more than a dozen years, the names and faces of those little yellow-haired, waving girls would be familiar, and beloved, in the world’s far corners.

Alice Niles and Lillian rode with Mrs. Smith and Lottie and Jack to New York. Lillian’s mother, at the train to meet her, took them all to her apartment, established Mrs. Smith and her children there for as long as they would stay—a kindness which Mrs. Smith, a stranger in New York, never forgot. Mrs. Gish, by this time quite a professional, also introduced her to theatrical agencies, with a view to future engagements. In a word, they joined forces. And thus began an association which was to last many years, and become historic in the theatrical world.

Whether Lillian went out again that season may only be surmised. At some time in the days of her beginning, she had a “Little Willie” part in another “East Lynne” Company—Mabel Pennock’s, and long preserved the little trousers she wore. It was a brief engagement, and she had no clear picture of it, later. She seems to remember that, like Dorothy, she went to sleep one night and rolled off the little bench during Madame Vine’s long scene, but this is most likely a confusion. Lillian would be too conscientious and well-trained to do a thing like that, even in her sleep.

The end of the dramatic season found two mothers, four girls and a boy in the Gish flat, a combination that at times could produce something resembling a riot. They were a happy family. They went in for two things: peace, and economy. Lillian’s influence had much to do with the former—her unearthly beauty and gentleness. Mrs. Smith told her children that she looked “like an angel dropped out of Heaven,” and with the old Irish superstition that the good die young, they expected any moment to see a long arm reach out of the sky and take her home. Gladys, especially, refused to be left entirely alone with her, fearing it might happen at such a time. Certainly she was not always melancholy. Life was a serious matter—from the beginning, apparently, she had known that; also, that Heaven was indeed a desirable place to go to—to wake up in, some morning, quite soon. Yet she enjoyed the company of the others, especially when they went on little excursions. Once at least, they all went to the theatre. Mary, in her article, tells of this:

What fun we youngsters had! Never will I forget the day we went to the American Theatre on Eighth Avenue near 42nd Street. At that time, the American was one of the important legitimate theatres. Now it is a picture house, I think. A Shakesperian play was on; I cannot recall its name, but it seems to me that it was “King Lear.” At any rate, it was very heavy and tragic, and we all sat in a row, looking very important and pretending to understand every word. I remember how I went up to the manager in a very sober and dignified manner, and presented my card, saying: “Do you recognize the profession?” There we were, five of us—Lillian, Dorothy, Lottie, Jack and I—and to the manager we must have looked very much like the family of the old Mother Goose lady who lived in the shoe. He smiled amusedly, and assured us that he most certainly did recognize the profession, adding: “Have you got ten cents apiece for the Actors’ Fund?”

This threw us into a near panic, for a hasty survey of our resources disclosed that among all of us we had only eight pennies and one had a hole in it. The manager, however, finally relented and passed us in, telling us that we could give him the money for the Actors’ Fund some other time. What a task it was to pay that debt! For weeks and weeks, it seemed, we were running to that box office every time we had saved a few pennies.

The combined housekeeping made for economy, and here, too, Gladys Smith was a leader and a force. Even the mothers listened to her advice. On the kitchen table, at night, with a grubby little pencil and a scrap of paper, she audited the accounts.

Those were very meagre, but really very happy, days. When Mrs. Smith was called to Toronto by her mother’s failing health, Mary remained undisputed head of the Smith family, and dealt out counsel, rewards, even punishments, with a fair but firm hand.

With money saved from her own and the children’s earnings, Mary Gish opened a candy and popcorn stand at the Fort George amusement grounds. Her six or seven years of candy making and business experience came in very handy, now. She hired an assistant—one strong enough to pull the taffy she made—Don, a handsome, good-hearted boy, with whom Dorothy fell desperately in love. It was a joy to Dorothy to stand on the counter or on a chair and “ballyhoo” for Don’s taffy and popcorn. “This way for the best taffy and popcorn in New York! This way, this way!” Lillian would do it, too, but from a sense of duty, and much less riotously. Mary Pickford recently said:

“I can still hear Lillian’s timid little voice saying: ‘Would you like to buy some popcorn?!’”

To the Smith (Pickford) family, Mrs. Gish’s stand at Fort George was in the nature of a diversion. Often in high season, they went up there, to help. In the early morning, the two families rode up together on the streetcar, the two younger ones discussing their rights to the “outside seat.” Jack was dead in love with Dorothy, but there is a limit to love’s sacrifice.

Arriving at Fort George, everybody helped. The corn had to be popped and put in bags; the candy had to be wrapped in paraffined paper, a good deal of a chore. Mrs. Gish let them eat what candy they wanted, and in the beginning their by-word was “Wrap one and eat two.” Then presently they were just wrapping, for the charm of a candy diet is fleeting. There was a place “down the line” where one got marvelous German-fried-potatoes, at a nickel a dish. About noon, armed with a nickel apiece, they went down there. Those heavenly fried potatoes! If one might only get a job with the potato man. Or the milk-shake man....

An interesting place, the “line”: Stands of several sorts; a variety of shows, and a merry-go-round. The children found it fascinating. There was a place where they had ponies, and the man there on slack days let Lillian and Dorothy ride. They learned quickly, and went tearing up and down, their astonishing hair flying out behind. They really rode like mad—good training for those “picture” days ahead, when as Indians, or cowboys, they would go racing among the hills behind Los Angeles. The pony man declared that they rode like monkeys, and the lovely spectacle they made undoubtedly brought him business.

Dorothy came to grief. One day her pony swerved, or stopped, or something, and Dorothy didn’t. So she broke her arm, a thing so terrifying to Lillian that she scrambled quickly from her horse and hid behind the merry-go-round. The alarm reached the Gish taffy stand, and Dorothy’s beloved Don came on a dead run and bore her in his arms to her mother. Don, so noble and brave and beautiful—how heavenly—worth breaking one’s arm for. Then there was the ride to the hospital in the clanging ambulance, with everybody getting out of the way!

Nobody seems to have thought of Lillian; yet she needed comfort almost as much as Dorothy. Often she fainted at the sight of suffering. If anything was to be done that meant physical pain, like the drawing of a tooth, she was promptly sent from the room. Even then, the knowledge of the fact was almost too much for her.

She was more self-contained than Dorothy, who would do almost anything on the spur of the moment. One day at the apartment, two girls came along below the window, where Lillian and Dorothy looked out.

“Come down to us,” one of the girls called, holding out her arms—“Jump!”

And though the distance was several feet, Dorothy was ready to do that—the girl who called was so beautiful. Her name was Evelyn Nesbit.

There was not much time for cooking in the Gish flat, and anyway the weather was hot—too hot to bend over the kitchen stove after a day on the “line.” The younger members, the five of them, would go out foraging for cool things.

We used to love to buy our dinner in the delicatessen shops [Mary Pickford writes]. The five of us would troop in and order pickles and turkey to take home.

One can imagine that little row of future stars ranged along the fat delicatessen man’s showcase, coveting all the good things in it, agreeing at last on a modest purchase of pickles and turkey. Any one of them could have eaten every bit of it. Sometimes they extended themselves on a bit of dessert—ice-cream, always—who does not love ice-cream? They had an ice-cream complex. If they were in funds, they bought a little dab to take home, and had their own dessert in advance—ice-cream soda. The Greeks over there sold ice-cream soda for five cents. When, one day, they raised it to ten, it was the end of the world.

None of these children can be said to have had any real childhood. Those summers together (there appear to have been two of them) provided about all they ever had in the way of playmates of their own age. The opening of each amusement season found them back on the road, trouping, with grown-up players as companions. Naturally, they did not go to school—not during those earlier years—but picked up such rudiments of instruction as it was possible to acquire in stuffy, badly-lighted, dressing rooms, in jolting day coaches and in casual nooks and corners of the world’s worst hotels. I cannot speak for the others, but I am sure that Lillian and Dorothy had very little in the way of regular schooling until they were in, or near, their ’teens. Had it been otherwise, they would have been quite certain, I think, to remember.

It was during this period that the Gerry Society became their bogey man. They did not know what it was, but only that it was something likely to grab them in any strange city, in a dark hall or alley, as they entered or left the theatre. It would take them out of the theatre, they were told, so they would not be able to earn money any more, and maybe put them into an “Institution,” which was a terrible sounding word. To Mary Gish it was a very real menace, for she knew that she would have hard work convincing the Gerry officers that her children were getting proper care and education, playing six nights and two matinées a week, sleeping and eating in that sketchy fashion of the road. They did not linger on the street, they did not show themselves more than necessary, especially in the larger towns. Lillian, many years later, wrote:

Before I could understand what it was all about, I knew of subterfuges and evasions and tremendous plottings to keep myself and my sister acting, so that the very necessary money might be earned....

Their safety lay in their obscurity. Had they been with important companies, playing finer theatres, they would hardly have escaped.

The season of 1903-4 remains to Lillian and Dorothy the most memorable—for a very good reason: they were together, and their mother was with them. For the time, at least, Mary Gish’s dream had come true: she had secured parts for her little girls and herself in the same company. Her own part and Dorothy’s were small, but would more than pay expenses. Dorothy was a news-girl, who sold “Evenin’ pipers!” Lillian’s part was a very good one; their combined salaries were forty-five dollars per week!

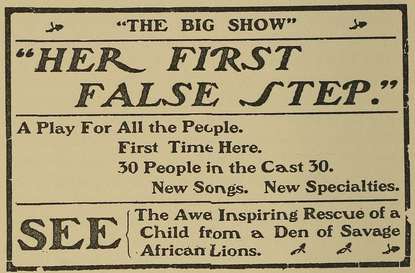

The play was “Her First False Step,” another fierce melodrama; only, in this one, Lillian, instead of being nearly blown up was within an ace of being devoured by savage African lions, being rescued by the brave hero, barely in the nick of time!

There were two of the lions, and they were really savage, for later when they were sold to a circus, one of them tore out a keeper’s arm. There was a provision, however, against accidents: The lions were in a cage in which there was a sliding division, so cunningly arranged that even those who sat in the front rows could not see it. At the instant when the noble hero leaps into the cage and drags out the little victim—child of the woman he loves—while every eye is riveted on this deed of daring, the invisible partition is drawn back from behind, the lions rush in, roaring and leaping about, wild at being deprived of their prey, for at that very instant, too, the cage door is slammed shut. It was truly a terrible spectacle. Women in the audience sometimes fainted.

Small “dodger” scattered about the towns before a performance.

Once, when the safety slide had not yet been slipped into place, one of the lions took up a position at the wrong end of the cage, and refused to budge. The villain, with Lillian in his arms, had twice vowed he would fling her to the beasts, and was ready to vow again, when somebody behind the scenes had an inspiration. Two men from the wings rushed upon the villain, and while the fierce struggle for the child held the audience, the stage-hands persuaded the lion to be reasonable.

The heroine in “Her First False Step” was a tall, handsome woman, Helen Ray. Lillian and Dorothy played her two little girls. In one scene Dorothy and her “mother” are out in the snow, as Lillian rushes in, to find them. She has a lollypop for Dorothy, who claps her hands with joy while Lillian kneels by Miss Ray, saying: “Oh, mother, what are you doing out here in the cold snow?” Often it was cold enough, too. The air, not the snow. The latter was swept up every night, to be used at the next performance. Sometimes other things were swept up with it, and were likely to hit them on the head—nails, bits of wood, a little dry mouse.

A real romance goes with the “False Step” season—one with a “happy-ever-after” ending. In one of the larger towns, a young actor from another company came to a matinée and was much struck by the beauty of Helen Ray, whom he had never met. That night he managed to come again, and next day at rehearsal time was lingering around the stage entrance. Dorothy, with a beloved Teddybear, was playing just outside. He struck up an acquaintance with her, and was invited in, to see her other possessions. A very few minutes later he had met Helen Ray. When the season had ended, they were married. At last accounts they were still married—and happy—after more than twenty-five years.

Lillian and Dorothy, at the theatre before the others, had diversions of their own. Both dearly loved lemon sticks, especially if oranges went with them. To suck orange juice through a lemon stick was pure delight. They would run across the dressing-room and jam their oranges against the wall.

In a corner of the first-act-set, they would set up a play-house. They did not play at “acting,” like other children. They would put on long dresses, and play at “keeping house”—having a home. When it came time for the performance, they hurried, not very eagerly, to change into the costumes required for their parts. They were not unhappy. They did not reflect much whether they liked what they were doing, or not. They just did it. The parts they played were always sad—pathetic, but not more so than their lives. They did not know that, but their mother did.

If one might have looked into Mary Gish’s heart at this time, just what would one have found there? Chiefly, of course, devotion to her children—thought of their immediate welfare and needs. After that? Was it to equip them for the career of actresses—a life which, unless they were at the top, was hardly to be called enviable, and even at its best was one of impermanent triumphs and fitful rewards? She knew pretty well that with their special kind of beauty, which each day she saw develop—their flair for subtle phases of human portrayal—given health, they could count on at least reasonable success. Did she greatly desire that? I think not. I think she considered it, but that her real purpose was to keep her children and herself on the stage only until by close, the very closest, economy, she had saved enough to establish herself in a permanent business which would give them a home, where they could go to school and grow into normal, or what she regarded as normal, womanhood. I think the old prejudice which she had shared with her family as to the theatre, did not die easily, and that for years she felt herself more or less “beyond the pale,” willing to stay there only because it meant a livelihood, with the possibility of something better, something with a home in it, not too far ahead. We shall see the effort she made in this direction, by and by, and what came of it—how the web of circumstance had its will with her, as with us all.

A SCENE FROM “HER FIRST FALSE STEP”

Whatever her plan, Mary Gish saw that she must educate her children. Herself reared in a town that rather specializes in education, she had known the advantage of excellent public schools. That her children should have less than herself was a distressing thought. From little books, at every spare moment, she taught them. In every town of importance, she made it her business to learn what she could of its history, its population, its industries, and of these she told them in as interesting a form as she could invent. In the South, she told them of the war; when it was possible, showed them landmarks, often taking them on little excursions.

In one city she had a special interest: Chattanooga, where an uncle, a Captain McConnell, had been killed in the battle above the clouds. When she found they had time there, she took the children for a drive up Lookout Mountain, telling them the story as they went along. And then a remarkable thing happened: they came to a tablet by the roadside, and paused to read the inscription. It was a tablet to Captain McConnell, commemorating his bravery.

She did not hold them to schoolbooks. She read them story books, or allowed an actor named Strickland—“Uncle High” in the play, because he was so tall—to read to them—from “Black Beauty,” which was their favorite, and Grimm’s and Andersen’s Fairy Tales. In a seat on the train, when all were awake at once, or during a wait in a station—oh, anywhere—Uncle High was faithful, and those little girls never ceased to remember it.

Uncle High was really very tall—“six feet six, and skinny as a blue-racer” according to one of the notices. In the play there was a house-warming, at which he was one of the guests. When Uncle High entered, Lillian, the “golden-haired grandchild,” was moved to examine him. They stood just at the footlights, and very deliberately she looked him up and down until the snickering audience was still. Then very gravely: “Grandpa, what is he standing on?” a line, according to Uncle High, that was “always a scream.”

“Uncle High” further remembers that “no matter what time of night Lillian and Dorothy had to get out of a warm, comfortable bed to catch a train, or how many times they had to be awakened to change cars, no one ever heard a whimper or complaint from either, and I cannot recall one instance where they ever found any fault with anything, and I never heard their mother speak a cross word to either of them. Lillian was just like a little mother to Dorothy, and looked after her all the time. Her whole life seemed to be to watch that nothing happened to her little sister. And Lillian only eight years old.” She was, in fact, considerably less.

Mrs. Gish’s skillful handicraft included drawing. She had received no art instruction but her pen sketches were exquisite. She thought them poor, and destroyed them. There remains only a water-color interior—subtle in tone, atmospheric—of a quality that commands immediate attention.

It seems curious that she should also have had a taste for mechanics. Delicate mechanics. She enjoyed taking a clock apart and putting it together again. A clock that did not go was her delight. Once that winter, when they were all together, a clock in their room had gone out of commission. Mary Gish examined it, then set to work. In a brief time she had it on the operating table, the pieces here and there. Dorothy’s deep interest may have had something to do with the fact that when she came to assemble them, two insignificant bits seemed to be missing. Never mind, the clock would go without them. It would go, but with a gay indifference to time, and every little while made queer noises in its inside. Lillian and Dorothy, in bed in that room, laughed themselves to sleep, listening to its complaints.

They found amusement where they could—the situation was so often barren enough. Once, remembering, Lillian said:

“Sometimes the theatre was very poor, and the dressing-rooms nearly always bad (even to this day they could be better). Some were worse than others. At a theatre in Chicago, a theatre of the second or third class, a good way out, the dressing-rooms were in a kind of cellar. There was water on the floor—we had to walk on boards. I remember the big, black water-bugs. Mother had to shake out our dresses, before we put them on.

“The Gerry Society was very strict in Chicago. We hardly dared to show ourselves outside the theatre and hotel. Four or five years later, when I was perhaps twelve, and we were there again, Mother put me into long skirts and high heels, so that I could look sixteen, and reduce the risk. I felt very proud to be grown-up in that sudden way.”

But the winter travel was hardest. One town they were to play could be reached only from a junction, six miles distant. That night a terrible blizzard came up, and the company, quite a large one, had to be driven cross-country in big farm sleighs, bedded with straw. It was terribly cold, their feet became ice. And when they arrived, the train was five hours late! The place was just a telegraph office; the little girls were allowed to stretch out on the desks, which were sloping;—members of the company took turns, holding them from rolling off.

The problem of food was a serious one, especially in the smaller towns of the Middle West. Dorothy was robust, and seemed to thrive on anything; Lillian needed better fare.

“Dorothy and I lived, when we could, on ice-cream and cake. Mother would give us fifteen cents, and we would spend ten cents for ice-cream, half vanilla and half chocolate. With the other five we bought lady-fingers. We mixed the cream, stirred the two kinds together, and made ‘mashed potatoes’; then we spread it on the lady-fingers.”

It does not seem very substantial, nor an over-plentiful allowance. They were being very economical, trying to get a little money ahead. At one wonderful restaurant—in some Western town—they were able to get a meal for ten cents! Just one place like that: soup, meat, potatoes, and a piece of pie! Perhaps it was not very good, but it seemed good, to them.

And two places in the South—good negro cooking:

“At Richmond and Norfolk, we went to boarding-houses, where we had chicken and ham at one meal, and sweet potatoes, and gingerbread! Nothing could be better than that. We were always happy when we were going to those places; and there was a park in one of those towns where there were squirrels. We bought peanuts, and they would hurry up to be fed.

“There was another place—it was in New Haven—that Dorothy and I looked forward to. In the hall next the dressing-rooms, was a small sliding door, or window, and beyond it an ice-cream salon. We could knock on the magic door and it would open, and a chocolate ice-cream soda be handed through. You can’t imagine how wonderful that seemed to us ... like something out of Fairyland. Then there was a place in Philadelphia—an automat—the only one we had ever seen. It was the delight of our hearts. We were willing to walk miles, to get to it.”

Philadelphia was remembered for another reason. A considerable number of newsboys attended a matinée of “Her First False Step,” and hissed the villain and cheered the brave hero and the two little heroines in good, orthodox fashion. At the end of the play, the delegation hurried out and assembled at the back. When Lillian and Dorothy, in velveteen hats and coats and patent leather shoes, stepped from the stage door, they were waited upon by a meek and almost speechless committee of two and presented with two rare bottles of perfume, the best “five-and-ten” that money could buy. The stars bowed and spoke their thanks. After which, there was something resembling a cheer, and an almost uncanny disappearance of their admirers.

A very serious thing happened: At Scranton, Dorothy awoke one morning with what proved to be scarlet fever. It was not a severe case, but the company, knowing the certainty of quarantine, fled at once, bag and baggage, taking Lillian with them. The hotel faced the station platform, a high one, almost on a level with the windows of Mrs. Gish’s room. Lillian, waiting for the train that would take her away from them, could see her mother and Dorothy at the window, waving a tearful good-bye. It seemed as if her heart must break.

How long they were separated is not remembered—possibly not more than a fortnight. Dorothy’s part was abandoned. Later, she was given the part that had been played by Lillian. And this is curious: Lillian herself had never been at all afraid when she was thrust into the lions’ cage, but now that Dorothy had the part, it made her almost frantic when she heard the lions roaring, and knew that her little sister was being put in there.

The season appears to have closed in Boston, and for whatever reason—possibly Dorothy was not yet over-strong—Mrs. Gish went by day-coach to New York, putting Dorothy and Lillian into an upper berth, in the sleeper. They had with them a small dog—a Boston bull puppy, which the stage-hands had given them—and all night long, they took turns sitting up with it. One slept while the other watched, with more or less success. Then, next morning, they were in New York, tired but triumphant. They were returning from a long season—forty weeks!—and on the whole, a successful one. Two little actresses! They were beginning to realize what their work meant.

It seems unnecessary to speak of the quality of their acting. We really know nothing of it; we can only assume that, like the majority of actors, old or young, they did just about what they were told, and through repetition, and because they were intelligent, learned to do it well.

LILLIAN AND DOROTHY GISH

They had begun too early to be either awkward, or frightened, after the first one or two performances. The people beyond the footlights did not bother them at all. They scarcely knew they were there. Lillian, later:

“I had very little consciousness of the audience, in those days. When they applauded or laughed, I hardly noticed it. I remember wondering what they were laughing about. To become an actress, one cannot begin too soon.”

Again that summer Mary Gish had a taffy and popcorn stand at Fort George. Probably not after that, though each summer found her busy. Alert, handsome, familiar with business, she never failed of employment. Lillian remembers that there were summers when she took a clerkship, and let the little girls go to their aunt, in Massillon, for the cleaner life there, and for schooling—a summer term. A teacher in Massillon recalls having Lillian in the Fourth Grade—year uncertain. Also, that she “never had a lovelier or sweeter pupil; wonderful in art, but could not get mathematics.” Poor Lillian! to her, as to another little girl a hundred years earlier—little Marjorie Fleming—“seven times six was an invention of the devil, and nine times eight more than human nature could bear.”

That she could write quite as well as the average child of her age is shown by a small pencilled note to Mell Faris, manager of the “False Step” Company when the little family had been together. She had been out a season “on her own” since then, and was with Dorothy, now, at Aunt Emily’s “having a fine time, playing in the yard. I do wish we could get into a ‘conpany’ with you next season.” But the spelling is for the most part perfect.

Another teacher remembers having her in the Seventh Grade, in 1907, so it appears that in spite of recurring theatrical seasons, she made progress. In the summer of 1907 she was not yet eleven years old. I do not know whether that is the right age in Massillon for the Seventh Grade, or not. The wonder is that she was able to maintain any grade, under the circumstances.

Dorothy was better off. Lillian had her mother but the one time; Dorothy, during five straight seasons: the one just ended; another “False Step” season, and three seasons with Fisk O’Hara, the Irish singing comedian, a happy soul, who gave her a broken heart, among other things, for she forgot the heroic Don, and fell in love with him. He promised to wait for her, and then, one day, in an absent-minded moment, married his leading lady.

Mrs. Gish kept her part during the second season of the “False Step” Company, and had something in each of the Fisk O’Hara plays. The company was a very good one, made good towns and played in good theatres. The papers paid a good deal of attention to Dorothy. Her dimpled face looked out from dramatic columns; the little scrapbook which her mother kept for her contains notices of the “dainty child actress, who risks her life nightly in a lions’ den,” or “ably supported Fisk O’Hara in ‘Dion O’Dare.’” False Fisk O’Hara! We hope he has been properly punished for not waiting for her.

It was during the second season in “Her First False Step” that Dorothy had her Christmas Tree. In the last act of the play, there was a Christmas scene—no tree, but Dorothy, looking into the wings, had to pretend to see one. In his book, “To Youth,” John V. A. Weaver,[1] gives this incident in verse better than anyone could hope to do it in prose. Here is the latter half of it:

It was a season or two later, when they were with the Fisk O’Hara Company, that Dorothy woke one night in a hotel in Toledo, to find her mother very ill indeed, with high fever and delirium. The day before, she had complained of a cold, and Dorothy had bought her a bottle of some mixture, chiefly persuaded by the picture on the label. Apparently it had not helped. The frightened child crept down the hall to summon help.

Mrs. Gish had intermittent fever, and Dorothy next day had to leave her and go on with the company. There was nobody to take her part. She was only too kindly treated, but during the days before her mother joined them, she was a sadly worried little girl.

Once—and this has to do with another Christmas—the Fisk O’Hara Company laid off in New Orleans, and went one night to see “The Lion and the Mouse,” at the theatre they would occupy the following week. On the way out, Dorothy noticed a purse in one of the back rows. She took it to the box office, to the manager, who knew them. He said: “If nobody calls for it, it will be yours.”

Nobody did call for it, and the next week he gave it to her. It contained $21.00, a sum which they could have used very handily, but instead they went out and spent it on a gold watch to send to Lillian, for Christmas.

1. Published by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.