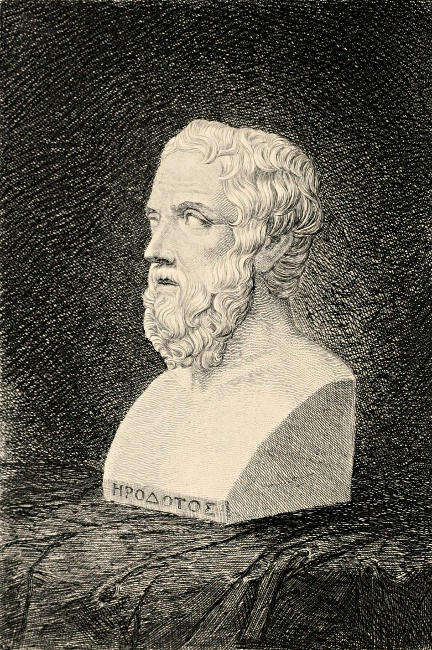

HERODOTUS

Transcriber’s Note: As a result of editorial shortcomings in the original, some reference letters in the text don’t have matching entries in the reference-lists, and vice versa.

HERODOTUS

THE HISTORIANS’

HISTORY

OF THE WORLD

A comprehensive narrative of the rise and development of nations

as recorded by over two thousand of the great writers of

all ages: edited, with the assistance of a distinguished

board of advisers and contributors,

by

HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS, LL.D.

IN TWENTY-FIVE VOLUMES

VOLUME III—GREECE TO THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR

The Outlook Company

New York

The History Association

London

1904

Copyright, 1904,

By HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS.

All rights reserved.

Press of J. J. Little & Co.

New York, U. S. A.

| VOLUME III | |

| GREECE | |

| PAGE | |

| Introductory Essay. The Scope and Development of Greek History. By Dr. Eduard Meyer | 1 |

| Greek History in Outline | 13 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Land and People | 26 |

| The land, 26. The name, 32. The origin of the Greeks, 33. Early conditions and movements, 36. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

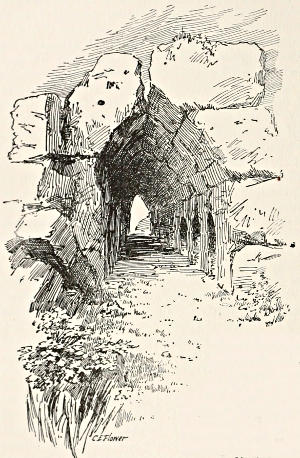

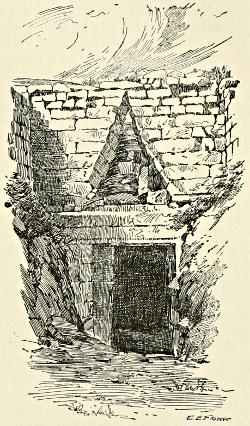

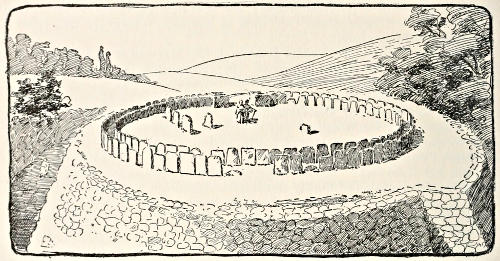

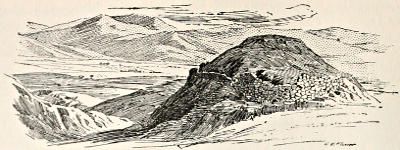

| The Mycenæan Age (ca. 1600-1000 B.C.) | 40 |

| Mycenæan civilisation, 40. The problem of Mycenæan chronology, 52. The testimony of art, 54. The problem of the Mycenæan race, 56. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

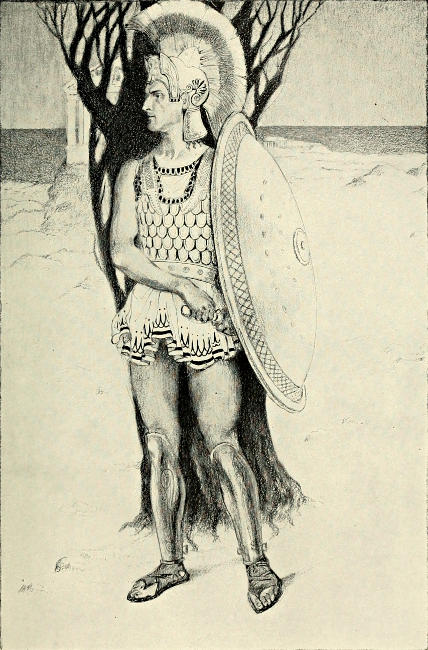

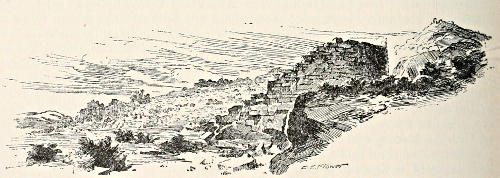

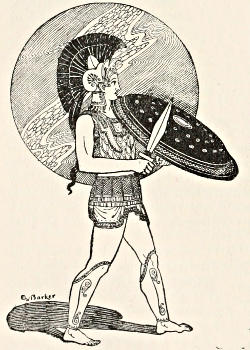

| The Heroic Age (1400-1200 B.C.) | 66 |

| The value of the myths, 67. The exploits of Perseus, 68. The labours of Hercules, 69. The feats of Theseus, 71. The Seven against Thebes, 72. The Argonauts, 73. The Trojan War, 76. The town of Troy, 78. Paris and Helen, 79. The siege of Troy, 80. Agamemnon’s sad home-coming, 81. Character and spirit of the Heroic Age, 82. Geographical knowledge, 86. Navigation and astronomy, 88. Commerce and the arts, 89. The graphic arts, 91. The art of war, 92. Treatment of orphans, criminals, and slaves, 94. Manners and customs, 97. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Transition to Secure History (ca. 1200-800 B.C.) | 99 |

| [x]Beloch’s view of the conventional primitive history, 99. | |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Dorians (ca. 1100-1000 B.C.) | 109 |

| The migration in the view of Curtius, 115. Messenia, 117. Argos, 118. Arcadia, 121. Dorians in Crete, 124. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Sparta and Lycurgus (ca. 885 B.C.) | 128 |

| Plutarch’s account of Lycurgus, 129. The institutions of Lycurgus, 131. Regulations regarding marriage and the conduct of women, 133. The rearing of children, 135. The famed Laconic discourse; Spartan discipline, 136. The senate; burial customs; home-staying; the ambuscade, 138. Lycurgus’ subterfuge to perpetuate his laws, 140. Effects of Lycurgus’ system, 141. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Messenian Wars of Sparta (ca. 764-580 B.C.) | 143 |

| First Messenian War, 144. The futile sacrifice of the daughter of Aristodemus, 146. The hero Aristomenes and the Second Messenian War, 147. The poet Tyrtæus, 149. | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Ionians (ca. 650-630 B.C.) | 152 |

| Origin and early history of Athens, 154. King Ægeus, 155. Theseus, 158. Rise of popular liberty, 162. Draco, the lawgiver, 164. | |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Some Characteristic Institutions (884-590 B.C.) | 167 |

| The oracle at Delphi, 170. National festivals, 170. The Olympian games, 172. Character of the games, 173. Monarchies and oligarchies, 175. Tyrannies, 177. Democracies, 179. | |

| CHAPTER X | |

| The Smaller Cities and States | 181 |

| Arcadia, Ellis, and Achaia, 181. Argos, Ægina, and Epidaurus, 182. Sicyon and Megara, 184. Bœotia, Locris, Phocis, and Eubœa, 187. Thessaly, 189. Corinth under Periander, 191. | |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Crete and the Colonies | 194 |

| [xi]Beloch’s account of Greek colonisation, 198. | |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Solon the Lawgiver (ca. 638-558 B.C.) | 207 |

| The life and laws of Solon according to Plutarch, 209. The law concerning debts, 213. Class legislation, 215. Miscellaneous laws; the rights of women, 216. Results of Solon’s legislation, 217. Solon’s journey and return; Pisistratus, 219. A modern view of Solonian laws and constitution, 220. | |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Pisistratus the Tyrant (550-527 B.C.) | 222 |

| The virtues of Pisistratus’ rule, 226. | |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Democracy Established at Athens (514-490 B.C.) | 231 |

| Clisthenes, the reformer, 236. Ostracism, 245. The democracy established, 251. Trouble with Thebes, 252. | |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| The First Foreign Invasion (506-490 B.C.) | 261 |

| The origin of animosity, 262. The Ionic revolt, 264. War with Ægina, 267. The first invasion, 268. Battle of Marathon, 272. On the courage of the Greeks, 277. If Darius had invaded Greece earlier, 279. | |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| Miltiades and the Alleged Fickleness of Republics (489 B.C.) | 280 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| The Plans of Xerxes (485-480 B.C.) | 285 |

| Xerxes bridges the Hellespont, 295. How the host marched, 297. The size of Xerxes’ army, 301. | |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| Proceedings in Greece from Marathon to Thermopylæ (489-480 B.C.) | 305 |

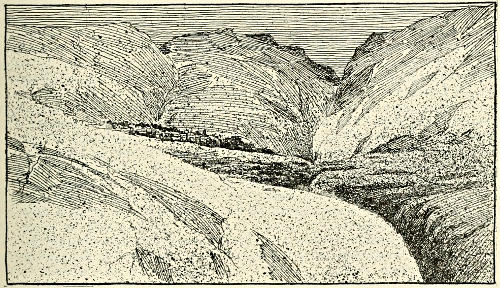

| Themistocles and Aristides, 306. Congress at Corinth, 308. The vale of Tempe, 313. Xerxes reviews his host, 314. | |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

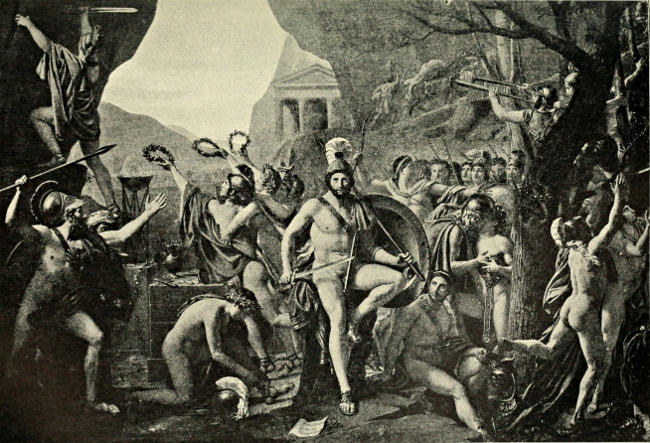

| Thermopylæ (480 B.C.) | 320 |

| The famous story as told by Herodotus, 320. Leonidas and his allies, 321. Xerxes assails the pass, 323. The treachery of Ephialtes, 323. The final assault, 325. Discrepant [xii]accounts of the death of Leonidas, 327. After Thermopylæ, 327. | |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| The Battles of Artemisium and Salamis (480 B.C.) | 330 |

| Battle of Artemisium, 331. Athens abandoned, 334. The fleet at Salamis, 337. Xerxes at Delphi, 338. Athens taken, 339. Xerxes inspects his fleet, 340. Schemes of Themistocles, 342. Battle of Salamis, 345. The retreat of Xerxes, 348. The spoils of victory, 351. Syracusan victory over Carthage, 352. | |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| From Salamis to Mycale (479 B.C.) | 353 |

| Mardonius makes overtures to Athens, 354. Mardonius moves on Athens, 356. Athens appeals to Sparta, 357. Mardonius destroys Athens and withdraws, 358. A preliminary skirmish, 360. Preparations for the battle of Platæa, 362. Battle of Platæa, 366. Mardonius falls and the day is won, 370. After the battle, 371. The Greeks attack Thebes, 373. The flight of the Persian remnant, 374. Contemporary affairs in Ionia, 374. Battle of Mycale, 376. After Mycale, 377. A review of results, 379. A glance forward, 379. | |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

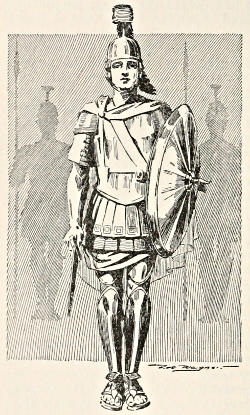

| The Aftermath of the War (478-468 B.C.) | 382 |

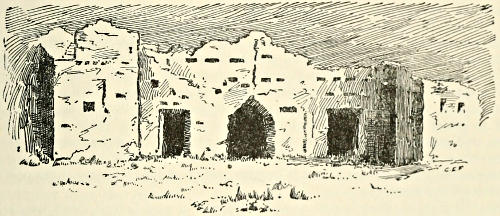

| Athens rebuilds her walls, 382. The new Athens, 384. The misconduct of Pausanias, 386. Athens takes the leadership, 388. The confederacy of Delos, 389. The treason of Pausanias, 391. Political changes at Athens, 394. The downfall of Themistocles, 396. | |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| The Growth of the Athenian Empire (479-462 B.C.) | 402 |

| The victories of Cimon, 408. Mitford’s view of the period, 409. | |

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

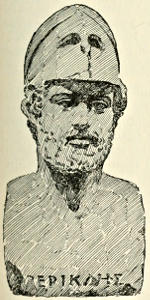

| The Rise of Pericles (462-440 B.C.) | 416 |

| The Areopagus, 420. Cimon exiled, 423. The war with Corinth, 424. The Long Walls, 425. Cimon recalled, 427. The Five-Years’ Truce, 430. The confederacy becomes an empire, 431. Commencement of decline, 432. The greatness of Pericles, 435. A Greek federation planned, 436. | |

| CHAPTER XXV | |

| Athens at War (440-432 B.C.) | 438 |

| The Samian War, 438. The war with Corcyra, 439. The war with Potidæa and [xiii]Macedonia, 444. | |

| CHAPTER XXVI | |

| Imperial Athens under Pericles (460-430 B.C.) | 448 |

| Judicial reforms of Pericles, 454. Rhetors and sophists, 459. Phidias accused, 461. Aspasia at the bar, 462. Anaxagoras also assailed, 463. | |

| CHAPTER XXVII | |

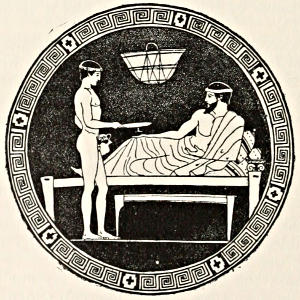

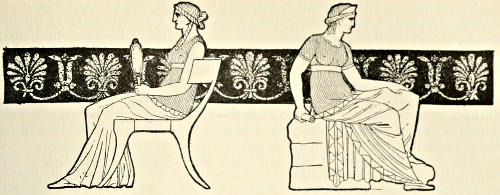

| Manners and Customs of the Age of Pericles (460-410 B.C.) | 465 |

| Cost of living and wages, 465. Schools, teachers, and books, 472. The position of a wife in Athens, 473. | |

| CHAPTER XXVIII | |

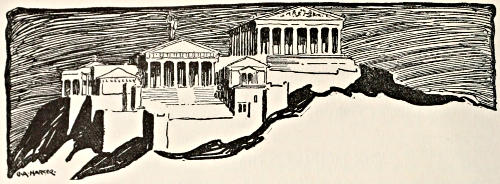

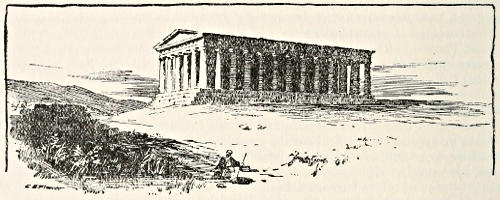

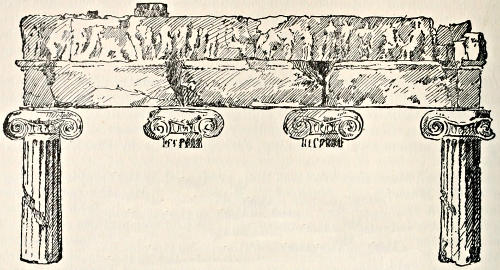

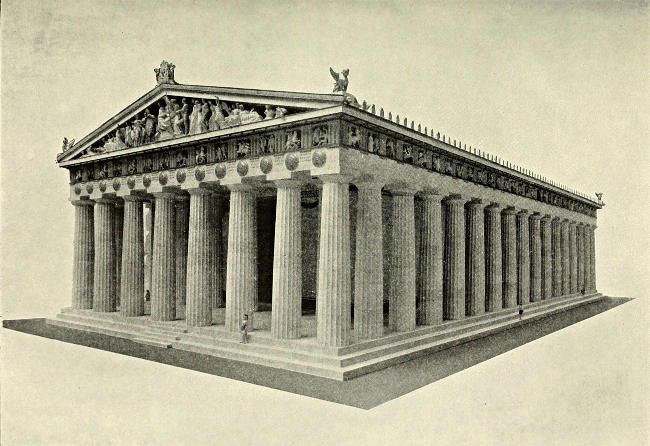

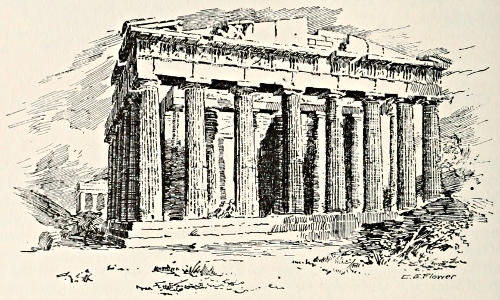

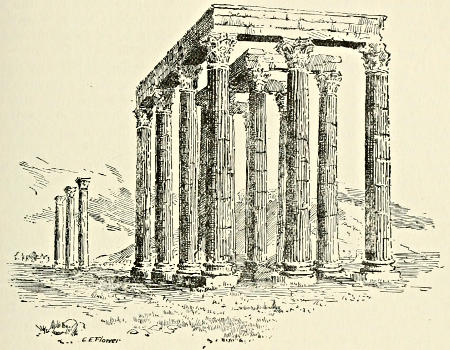

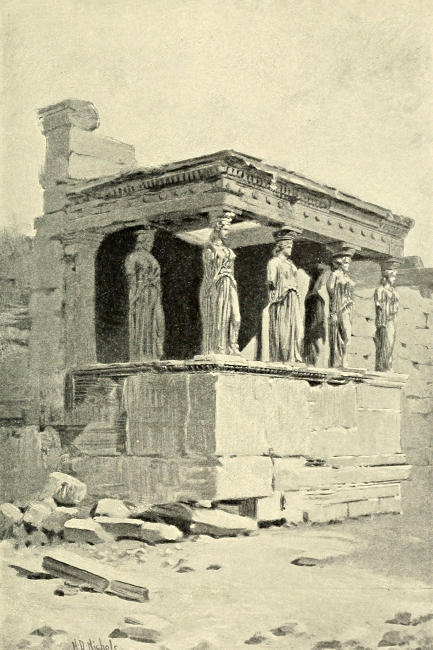

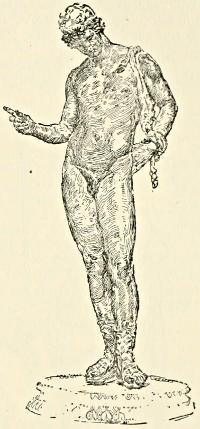

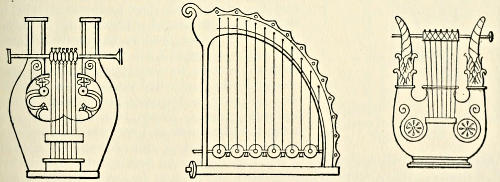

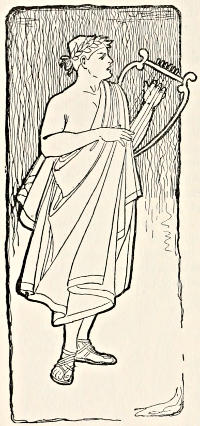

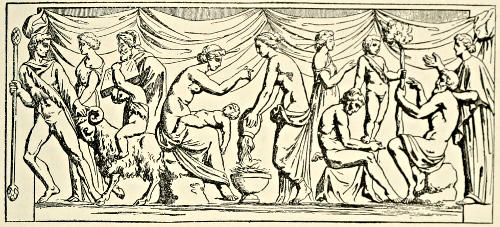

| Art of the Periclean Age (460-410 B.C.) | 477 |

| Architecture, 477. Sculpture, 483. Painting, music, etc., 487. The artists of the other cities of Hellas, 490. | |

| CHAPTER XXIX | |

| Greek Literature | 492 |

| Oratory and lyric poetry, 492. Tragedy, 497. Comedy, 504. The glory of Athens, 505. | |

| CHAPTER XXX | |

| The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (432-431 B.C.) | 508 |

| Our sources, 508. The origin of the war, 510. Preparations for the conflict, 517. The surprise of Platæa, 522. Pericles’ reconcentration policy, 526. The first year’s ravage, 527. | |

| CHAPTER XXXI | |

| The Plague; and the Death of Pericles (431-429 B.C.) | 535 |

| The oration of Pericles, 535. Thucydides’ account of the plague, 539. Last public speech of Pericles, 545. The end and glory of Pericles, 548. Wilhelm Oncken’s estimate of Pericles, 551. | |

| CHAPTER XXXII | |

| The Second and Third Years of the Peloponnesian War (429-428 B.C.) | 554 |

| The Spartans and Thebans attack Platæa, 556. Part of the Platæans escape; the [xiv]rest capitulate, 557. Naval and other combats, 560. | |

| CHAPTER XXXIII | |

| The Fourth to the Tenth Years—and Peace (428-421 B.C.) | 566 |

| The revolt of Mytilene, 566. Thucydides’ account of the revolt of Corcyra, 570. Demosthenes and Sphacteria, 575. Further Athenian successes, 579. A check to Athens; Brasidas becomes aggressive, 580. The banishment of Thucydides, 581. A truce declared; two treaties of peace, 582. | |

| CHAPTER XXXIV | |

| The Rise of Alcibiades (450-416 B.C.) | 584 |

| CHAPTER XXXV | |

| The Sicilian Expedition (481-413 B.C.) | 591 |

| Sicilian history, 591. The mutilation of the Hermæ, 596. The fleet sails, 599. Alcibiades takes flight, 601. Nicias tries strategy, 602. Spartan aid, 604. Alcibiades against Athens, 605. Athenian reinforcements, 606. Athenian disaster, 608. Thucydides’ famous account of the final disasters, 610. Demosthenes surrenders his detachment, 613. Nicias parleys, fights, and surrenders, 614. The fate of the captives, 615. | |

| CHAPTER XXXVI | |

| Close of the Peloponnesian War (425-404 B.C.) | 617 |

| Athens after the Sicilian débâcle, 617. Alcibiades again to the fore, 620. The overthrow of the democracy; the Four Hundred, 624. The revolt from the Four Hundred, 627. The triumphs of Alcibiades, 630. Alcibiades in disfavour again, 633. Conon wins at Arginusæ, 634. The trial of the generals, 636. Battle of Ægospotami, 638. The fall of Athens, 640. A review of the war, 642. Grote’s estimate of the Athenian Empire, 644. | |

| Brief Reference-List of Authorities by Chapters | 647 |

THE HISTORY OF GREECE

BASED CHIEFLY UPON THE FOLLOWING AUTHORITIES

ARRIAN, JULIUS BELOCH, A. BŒCKH, JOHN B. BURY, GEORG BUSOLT,

H. F. CLINTON, GEORGE W. COX, ERNST CURTIUS, HERMANN

DIELS, DIODORUS SICULUS, JOHANN G. DROYSEN,

GEORGE GROTE, HERODOTUS, GUSTAV F.

HERTZBERG, ADOLF HOLM,

JUSTIN, JOHN P. MAHAFFY, EDUARD MEYER, WILLIAM MITFORD, ULRICH VON

WILAMOWITZ-MÖLLENDORFF, KARL O. MÜLLER, CORNELIUS NEPOS,

PAUSANIAS, PLATO, PLUTARCH, QUINTUS CURTIUS,

HEINRICH SCHLIEMANN, STRABO, CONNOP

THIRLWALL, THUCYDIDES, XENOPHON

TOGETHER WITH AN INTRODUCTORY ESSAY ON

THE SCOPE AND DEVELOPMENT OF GREEK HISTORY

BY

EDUARD MEYER

A STUDY OF

THE EVOLUTION OF GREEK PHILOSOPHY

BY

HERMANN DIELS

AND A CHARACTERISATION OF

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE HELLENIC SPIRIT

BY

ULRICH VON WILAMOWITZ-MÖLLENDORFF

WITH ADDITIONAL CITATIONS FROM

CLAUDIUS ÆLIANUS, ANAXIMENES, APPIANUS ALEXANDRINUS, ARISTOBULUS, ARISTOPHANES, ARISTOTLE, W. ASSMANN, W. BELOE, E. G. E. L. BULWER-LYTTON, CALLISTHENES, CICERO, E. S. CREASY, CONSTANTINE VII (PORYPHYROGENITUS), DEMOSTHENES, W. DRUMANN, VICTOR DURUY, ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA, EUGAMON, EURIPIDES, EUTROPIUS, G. H. A. EWALD, J. L. F. F. FLATHE, E. A. FREEMAN, A. FURTWÄNGLER AND LÖSCHKE, P. GARDNER, J. GILLIES, W. E. GLADSTONE, O. GOLDSMITH, H. GOLL, J. DE LA GRAVIÈRE, G. B. GRUNDY, H. R. HALL, G. W. F. HEGEL, W. HELBIG, D. G. HOGARTH, ISOCRATES, R. C. JEBB, JOSEPHUS, F. C. R. KRUSE, P. H. LARCHER, W. M. LEAKE, E. LERMINIER, LIVY, LYSIAS, J. C. F. MANSO, L. MÉNARD, H. H. MILMAN, J. A. R. MUNRO, B. G. NIEBUHR, W. ONCKEN, L. A. PRÉVOST-PARADOL, GEORGE PERROT AND CHARLES CHIPIEZ, PHILOSTEPHANUS, PIGORINI, PHOTIUS, R. POHLMAN, POLYBIUS, J. POTTER, PTOLEMY LAGI, JAMES RENNEL, W. RIDGEWAY, K. RITTER, C. ROLLIN, J. RUSKIN, F. C. SCHLOSSER, W. SCHORN, C. SCHUCHARDT, S. SHARPE, G. SMITH, W. SMYTH, E. VON STERN, THEOGNIS, THEOPOMPUS, L. A. THIERS, C. TSOUNTAS AND J. IRVING MANATT, TYRTÆUS, W. H. WADDINGTON, G. WEBER, B. I. WHEELER, F. A. WOLF, XANTHUS

Copyright, 1904,

By HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS

All rights reserved

Written Specially for the Present Work

By Dr. EDUARD MEYER

Professor of Ancient History in the University of Berlin

The history of Greek civilisation forms the centre of the history of antiquity. In the East, advanced civilisations with settled states had existed for thousands of years; and as the populations of Western Asia and of Egypt gradually came into closer political relations, these civilisations, in spite of all local differences in customs, religion, and habits of thought, gradually grew together into a uniform sphere of culture. This development reached its culmination in the rise of the great Persian universal monarchy, the “kingdom of the lands,” i.e. “of the world.” But from the very beginning these oriental civilisations are so completely dominated by the effort to maintain what has been won that all progress beyond this point is prevented. And although we can distinguish an individual, active, and progressive intellectual movement among many nations,—as in Egypt, among the Iranians and Indians, while among the Babylonians and Phœnicians nothing of the sort is thus far known,—nevertheless the forces that represent tradition are in the end everywhere victorious over it and force it to bow to their yoke. Hence, all oriental civilisations culminate in the creation of a theological system which governs all the relations and the whole field of thought of man, and is everywhere recognised as having existed from all eternity and as being inviolable to all future time.

With the cessation of political life and the establishment of the universal monarchy, the nationality and the distinctive civilisation of the separate districts are restricted to religion, which has become theology. The development of oriental civilisation then subsides in the competition of these religions and the unavoidable coalescence consequent thereupon. This is true even of that nation which experienced the richest intellectual development, and did the most important work of all oriental peoples—the Israelites. When the great political storms from which the universal monarchy arose have spent their rage, Israel, the nation, has developed into Judaism; and under the Persian rule and with the help of the kingdom it organises itself as a church which seeks to put an end to all free individual movement, upon which the greatness of ancient Israel rests.

It was just the same with the ruling nation, the Persians, however vigorous their entrance into history under Cyrus. The Persian kingdom is, indeed, a civilised state, but the civilisations that it includes lack the highest that a civilisation can offer: an energetic, independent life, a combination of the firm institutions and permanent attainments of the past with the free, progressive, and creative movement of individuality. So the East, after the Persian period, was unable of its own force to create anything new. It stagnated, and, had it not received new elements from without, had it been left permanently to itself, would perhaps in the course of centuries have altered its external form again and again, but would hardly have produced anything new or have progressed a step beyond what had already been attained.

But when Cyrus and Darius founded the Persian kingdom, the East no longer stood alone. The nations and kingdoms of the East came into communication with the coast of the Mediterranean very early—not later than the beginning of the second millennium B.C.; and under their influence, about 1500 B.C., a civilisation arose among the Greeks bordering the Ægean. We call it the Mycenæan, and in spite of its formal dependence upon the East it could, in the field of art (where alone we have an exact knowledge of it), take an independent and equal place beside the great civilisations of the East.

How Greek civilisation continued to advance from step to step for many centuries in the field of politics and society as well as in that of the intellect; how it spread simultaneously over all the islands and coasts of the Mediterranean, from Massalia on the coast of the Ligurians and Cumæ in the land of the Oscans to the Crimea and the eastern coast of the Black Sea, and in the south as far as Cyprus and Cilicia; how Greek culture at the same time took root in much more remote districts, especially in Asia Minor; and how under its influence an energetic civilisation arose among the tribes of Italy, cannot be depicted here.

When the Persian kingdom was founded the Hellenes had developed from a group of linguistically related tribes into a nation possessing a completely independent culture whose equal the world had never yet seen, a culture whose mainspring was that very political and intellectual freedom of the individual which was completely lacking in the East.

Hence its character was purely human, its aim the complete and harmonious development of man; and if for that very reason it always strove to be moderate and to adapt itself to the moral and cosmical forces that govern human life, nevertheless it could accomplish this only in free subordination, by absorbing the moral commandment into its own will. Therefore it did not permit the opposing theological tendencies to gain control, strong as was their development in considerable districts of Greece in the sixth century. At that very period, on the other hand, it was stretching out to grasp the apples on the tree of knowledge; in the most advanced regions of Hellas science and philosophy were opposing theology. National as it was, this culture lacked but one thing: the political unity of the nation, the co-ordination of all its powers in the vigorous organism of a great state.

The instinct of freedom itself, upon which the greatness of this civilisation rested, favoured by the geographical conformation of the Greek soil, had caused a constantly increasing political disunion, which saw in the complete and unlimited autonomy of every individual community, even of the tiniest of the hundreds of city states into which Hellas was divided, the highest ideal of liberty, the only fit existence for a Hellene. And, internally,[3] every one of these dwarf states was eaten by the canker of political and social contrasts which could not be permanently suppressed by any attempt to introduce a just political order founded upon a codified law and a written constitution—whether the ideal were the rule of the “best,” the rule of the whole, i.e. of the actual masses, or that of a mixed constitution. The smaller the city and its territory, the more apt were these attempts to become bloody revolutions. Lively as was the public spirit, clearly as the justice of the demand for subordination to law was recognised, every individual and every party interpreted it according to its own conception and its own judgment, and at all times there were not a few who were ready to seize for themselves all that the moment offered.

To be sure, manifold and successful attempts to found a greater political power were brought about by the advancing growth of industry and culture, as well as by the development of the citizen army of hoplites, which had a firm tactical structure and was well schooled in the art of war. In the Peloponnesus Sparta brought the whole south under the rule of its citizens and not only effected the union of almost the whole peninsula into a league, but established its right, as the first military power of Hellas, to leadership in all common affairs.

In middle Greece, Thebes succeeded in uniting Bœotia into a federal state, while its neighbour Athens, which had maintained the unity of the Attic district since the beginning of history, began to annex the neighbouring districts of Megara, Bœotia, and Eubœa, and laid the foundation of a colonial power, as Corinth had formerly done. In the north the Thessalians acquired leadership over all surrounding tribes. In the west, in Sicily, usurpers had founded larger monarchical unified states, especially in Syracuse and Agrigentum.

But all these combinations were after all only of very limited extent and by no means firmly united; on the contrary, the weaker communities felt even the loosest kind of federation, to say nothing of dependence, as an oppressive fetter which impaired the ideal of the individual destiny of the autonomous state, and which at least one party,—generally the one that happened to be out of power,—felt justified in bursting at the first opportunity.

However, as things lay, the nation found itself forced, with this sort of constitution, to take up the struggle for its political independence. The Greeks of Asia Minor, formerly subjects of the kings of Sardis, had become subjects of the Persian kingdom under Cyrus; the free Hellenes had the most varied relations with the latter, and more than once gave him occasion to intervene in their affairs. The Persian kingdom, which under Darius no longer attempted conquests that were not necessary for the maintenance of its own existence, took no advantage of these provocations until the revolt of the Greeks of Asia Minor, supported by Athens, made war inevitable.

After the first attempt had failed Xerxes repeated it on the greatest scale. Against the Hellenic nation, whose alien character was everywhere a hindrance in its path, the Orient arose in the east and the west for a decisive struggle; the Phœnician city of Carthage, the great sea power of the west, was in alliance with the Persian kingdom. Only the minority of the Hellenes joined in the defence; in the west the princes of Syracuse and Agrigentum, in the east Sparta and the Peloponnesian league, Athens, the cities of Eubœa and a few smaller powers. But in both fields of operation the Hellenes won a complete victory; the Carthaginians were defeated on the Himera, in the east Themistocles broke the base of the Persian position by destroying their sea power with the Athenian fleet that he had created, and[4] on the battle-field of Platæa the Persian land forces were defeated by the superiority of the Greek armies of hoplites.

Thus the Hellenes had won the leading position in the world. For the moment there was no other power that could oppose them by land or sea; the Asiatic king never again ventured an attack on Greece. Her absolute military superiority was founded upon the national character, the energetic public spirit, the voluntary subordination to law and discipline and the capacity for conceiving and realising great political ideas. The Hellenes could gain and assert permanently the ascendency over the entire Mediterranean world, and impress upon it for all time the stamp of their nationality, provided only that they were united and saw the way to gather together all their resources into a single firmly knit great power.

But the Greeks were not able to meet this first and most urgent demand; though the days of particularism were irrevocably past, the idea which was so inseparably bound up with the very nature of Hellenism still exerted a powerful influence. As the individual communities were no longer able to maintain an independent existence, they gathered about the two powers that had gained the leadership, and each of which was striving for supremacy: the patriarchal military state of Sparta and the new progressive great power of Athens.

With the victory over the East it had been decided that the individuality of Hellenic culture, the intellectual liberty which gives free play to all vigorous powers in both material and intellectual life, had asserted itself; the future lay only along this way. Mighty was the advance that in all fields carried Greece along with gigantic strides; after only a few decades the time before the Persian wars seemed like a remote and long past antiquity.

But mighty as were the advancing strides of the nation in trade and industry, in wealth and all the luxury of civilisation, in art and science, all these attainments finally became factors of political disintegration. They furthered the unlimited development of individualism, which in custom and law and political life recognises no other rule than its own ego and its claims. The ideal world of the time of the sophists and the politics of an Alcibiades and a Lysander are the results of this development.

Athens perceived the political tasks that were set for the Hellenic people and ventured an attempt to perform them. They could be accomplished only by admitting the new ideas into the programme of democracy, by the foundation and extension of sea power, by an aggressive policy which aimed more and more at the subjection of the Greek world under the hegemony of one city. In consequence all opposing elements were forced under the banner of Sparta, which adopted the programme of conservatism and particularism, in order to strengthen its resistance, and restrict and, if possible, overcome its rival.

The conflict was inevitable, though both sides were reluctant to enter upon it; twenty years after the battle of Salamis it broke out. The fact that Athens was trying at the same time to continue the war against Persia and wrest Cyprus and Egypt from it gave her opponents the advantage; she had far overestimated her strength. After a struggle of eleven years (460-449 B.C.) Athens found herself compelled to make peace with Persia and free the Greek mainland, only retaining absolute control over the sea.

Under the rule of Pericles she consolidated her power, and the ideals that lived in her were embodied in splendid creations. She proved herself equal,[5] in spite of all internal instability and crises, to a second attack of her Greek opponents (431-421 B.C.). But it again became evident that the radical democracy, which was now at the helm, had no grasp of the realities of the political situation; for the second time it stretched out its hand for the hegemony over all Hellas, in unnatural alliance with Alcibiades, the conscienceless, ambitious man who was aiming at the crown of Athens and Hellas.

Mighty indeed was the plan to subdue the Western world, Sicily first of all; then with doubled power first to crush the opponents at home and then gain the supremacy over the whole Mediterranean world. But what a united Hellas might have accomplished was far beyond the resources of Athens, even if the democrats had not overthrown their dangerous ally at the first opportunity, and thus lamed the undertaking at the outset.

The catastrophe of the Athenians before Syracuse (413 B.C.) is the turning-point of Greek history. All the opponents of Athens united, and the Persian king, who saw that the hour had come to regain his former power without a struggle, made an alliance with them. Only through his subsidies was it possible for Sparta and her allies to reduce Athens—until she lay prostrate. And the gain fell to Persia alone, however feeble the kingdom had meanwhile become internally. Sparta, after overthrowing the despotism of Lysander, made an honest attempt to reorganise the Greek world after the conservative programme, and to fulfil the task laid upon the nation in the contest with Persia. But she only furnished her opponents at home, and particularism, which now immediately turned against its former ally, an occasion for a fresh uprising, which Sparta could master only by forming a new alliance with Persia. After the peace of 386 the king of Asia utters the decisive word even in the affairs of the Greek mother-country.

Here dissolution is going rapidly forward. Every power that has once more for a short time possessed some importance in Greece succumbs to it in turn; first Sparta, then Thebes and Athens. The attempts to establish permanent and assured conditions by local unions in small districts, as in Chalcidice under Olynthus, in Bœotia and Arcadia, were never able to hold out more than a short time. It was useless to look longer for the fulfilment of the national destiny. Feeble as the Persian kingdom was internally, every revolt against it, to say nothing of an attempt to make conquests and acquire a new field of colonisation in Asia,—the programme that Isocrates repeatedly urged upon the nation,—was made impossible by internal strife. Prosperity was ruined, the energy of the nation was exhausted in the wild feuds of brigands, the most desolate conditions prevailed in all communities. Greek history ends in chaos, in a hopeless struggle of all against all.

In this same period, to be sure, the positive, constructive criticism of Socrates and his school rose in opposition to the negative tendencies of sophistry; and made the attempt to put an end to the political misery, to create by a proper education the true citizen who looks only to the common welfare in place of the ignorant citizen of the existing states, who was governed only by self-interest. These efforts resulted in the development of science and the preservation for all future time of the highest achievements of the intellectual life of Hellas, but they could not produce an internal transformation of men and states, whose earthly life does not lie within the sphere of the problems of theoretical perception, but in that of the problems of will and power. So at the same time that Greek culture has reached the highest point of its development, prepared to become the culture of the world, the Greek nation is condemned to complete impotence.

For the development in the West, different as was its course, led to no other result. In the fifth century Greece controlled almost all Sicily except the western point, the whole south of Italy up to Tarentum, Elea and Posidonia and the coast of Campania. Nowhere was an enemy to be seen that might have become dangerous. The Carthaginians were repulsed, and the power of the Etruscans, who in the sixth century had striven for the hegemony in Italy, decayed, partly from internal weakness, partly in consequence of the revolt of their subjects, especially the Romans and the Sabines. The Cumæans under Aristodemus with the Sabines as their allies defeated Aruns, the son of Porsena of Clusium, at Aricia about 500 B.C., and in the year 474 the Etruscan sea power suffered defeat at Cumæ from the fleet of Hiero of Syracuse.

The cities of western Greece stood then as if founded for all eternity; they were adorned with splendid buildings, the gayest and most luxurious life developed in their streets; and they had leisure enough, after the Greek manner, to dissipate their energies, which were not claimed by external enemies, in internal strife and in struggles for the hegemony. Only the bold attempts which Phocæa made in the sixth century to turn the western basin of the Mediterranean likewise into a Greek sea, to get a firm footing in Corsica and southern Spain, had succumbed to the resistance of the Carthaginians, who were in alliance with the Etruscans. Only in the north, on the coast of Liguria from the Alps to the Pyrenees, Massalia maintained its independence. Southern Spain, Gades, and the coast of the land of Tarshish (Tartessus) were occupied by the Carthaginians about the middle of the fifth century; and the Greeks and all foreign mariners in general were cut off from the navigation of the ocean, as well as from the coasts of North Africa and Sardinia.

In the fourth century the political situation is totally changed in both east and west. The Greeks are reduced to the defensive and lose one position after the other. A few years after the destruction of the Athenian expedition the Carthaginians stretched out their hands for Sicily; in the years 409 and 406 they take and destroy Selinus, Himera, and Agrigentum; in the wars of the following years every other Greek city of the island except Syracuse was temporarily occupied and plundered by them.

In Italy after the middle of the fifth century a new people made their entrance into history, the Sabellian (Oscan) mountain tribes. From the valleys of the Abruzzi and the Samnitic Apennines they pressed forward towards the rich plains of the coast, and the land of civilisation with its inhabitants succumbed to them almost everywhere. To be sure, the Sabines under Rome defended themselves against the Æquians and Volscians, and so did the Apulians in the east against the Frentanians and Pentrians of Samnium. But the Etruscans of Capua and Nola and the Greeks of Cumæ were overcome (438 and 421 B.C.) by the Sabellian Campanians, and Naples alone in this district was able to preserve its independence. In the south the Lucanians advanced farther and farther, took Posidonia (Pæstum) in 400 B.C., Pyxus, Laos, and harassed the Greek cities of the east coast and the south.

From between these hostile powers, the Carthaginians and the Sabellians, an energetic ruler, Dionysius of Syracuse (405-367 B.C.), once more rescued Hellenism. In great battles, with heavy losses to be sure, and only by the employment of the military power of the Oscans, of Campanian mercenary troops and of the Lucanians, he succeeded in setting up once more a powerful Greek kingdom, including two-thirds of Sicily, the south of Italy as far as[7] Crotona and Terina; he held Carthage in restraint, scourged the Etruscans in the western sea, and at the same time occupied a number of important points on the Adriatic, Lissus and Pharos in Illyria, several Apulian towns, Ancona, and Hadria at the mouth of the Po in Italy. Dionysius had covered his rear by a close alliance with Sparta, which not only insured him against any republican uprising, but made possible an uninterrupted recruiting of mercenaries from the Peloponnesus. In return Dionysius supported the Spartans in carrying through the Kings’ Peace and against their enemies elsewhere.

The kingdom of Dionysius seemed to rest on a firm and permanent foundation. Had it continued to exist the whole course of the world’s history would have been different; Hellenism could have maintained its position in the West, which might even have received again a Greek impress instead of becoming Italic and Roman.

But the kingdom of Dionysius was in the most direct opposition to all that Greek political theory demanded; it was a despotic state which made the free self-government of communities an empty form in the capital Syracuse, and in the subject territories, for the most part, simply abolished the city-state, the polis. The necessity of a strong government that would protect Hellenism in the West against its external enemies was indeed recognised by the discerning, but internally it seemed possible to relax and to effect a more ideal political formation.

Under the successor of the old despot, Dionysius II, Plato’s pupil, Dion, and Plato himself, made an attempt at reform, first with the ruler’s support, and then in opposition to him. The result was, that the west Grecian kingdom was shattered (357-353 B.C.), while the establishment of the ideal state was not successful; instead anarchy appeared again, and the struggle of all against all. Only the enemies of the nation gained. In Sicily, to be sure, Timoleon (345-337) was able to establish a certain degree of order; he overthrew the tyrants, repulsed the Carthaginians, restored the cities and gave them a modified democratic constitution. But the federation of these republics had no permanence. On the death of Timoleon the internal and external strife began anew, and the final verdict was uttered by the governor of the Carthaginian province.

In Italy, on the other hand, the majority of the Greek cities were conquered by the Lucanians or the newly risen Bruttians. On the west coast only Naples and Elea were left, in the south Rhegium; in the east Locri, Crotona, and Thurii had great difficulty in defending themselves against the Bruttians. Tarentum alone (upon which Heraclea and Metapontum were dependent) possessed a considerable power, owing to its incomparable situation on a sea-girt peninsula and to the trade and wealth which furnished it the means again and again to enlist Greek chieftains and mercenaries in its service for the struggle against its enemies.

It was as Plato wrote to the Syracusans in the year 352 B.C. If matters go on in this way, no end can be foreseen “until the whole population, supporters of tyrants and democrats, alike, has been destroyed, the Greek language has disappeared from Sicily and the island fallen under the power and rule of the Phœnicians or Oscans” (Epist. 8, 353 e). In a century the prophecy was fulfilled. But its range extends a great deal farther than Plato dreamed; it is the fate not only of the western Greeks, but of the whole Hellenic nation, that he foretells here.

The Greek states were not equal to the task of maintaining the position of their nation as a world-power and gaining control of the world for their[8] civilisation. When they had completely failed, a half-Greek neighbouring people, the Macedonians, attempted to carry out this mission. The impotence of the Greek world gave King Philip (359-336) the opportunity, which he seized with the greatest skill and energy, of establishing a strong Macedonian kingdom, including all Thrace as far as the Danube, extending on the west to the Ionian Sea, and finally, on the basis of a general peace, of uniting the Hellenic world of the mother-country in a firm league under Macedonian hegemony (337 B.C.).

Philip adopted the national programme of the Hellenes proposed by Isocrates and began war in Asia against the Persians (336 B.C.). His youthful son Alexander then carried it out on a far greater scale than his father had ever intended. His aim was to subdue the whole known world, the οικουμένη, simultaneously to Macedonian rule and Hellenic civilisation. Moreover, as the descendant of Hercules and Achilles, as king of Macedonia and leader of the Hellenic league, imbued by education with Hellenic culture, the triumphs of which he had enthusiastically absorbed, he felt himself called as none other to this work. Darius III, after the victory of Issus (November 333 B.C.), offered him the surrender of Western Asia as far as the Euphrates; and the interests of his native state and also,—we must not fail to note,—the true interests of Hellenic culture would have been far better served by such self-restraint than by the ways that Alexander followed.

But he would go farther, out into the immeasurable; the attraction to the infinite, to the comprehension and mastery of the universe, both intellectual and material, that lies in the nature of the yet inchoate uniform world-culture, finds its most vivid expression in its champion. When, indeed, he would advance farther and farther, from the Punjab to the Ganges and to the ends of the world, his instrument, his army, failed him; he had to turn back. But the Persian kingdom, Asia as far as the Indus, he conquered, brought permanently under Macedonian rule, and laid the foundation for its Hellenisation. With this, however, only the smaller portion of his mission was fulfilled. The East everywhere offered further tasks which had in part been undertaken by the Persian kingdom at the height of its power under Darius I—the exploration of Arabia, of the Indian Ocean, and of the Caspian Sea, the subjugation of the predatory nomads of the great steppe that extends from the Danube through southern Russia and Turania as far as the Jaxartes.

It was of far more importance that Hellenism had a task in the West like that in the East; to save the Greeks of Italy and Sicily, to overcome the Carthaginians and the tribes of Italy, to turn the whole Mediterranean into a Greek sea, was just as urgently necessary as the conquest of Western Asia. It was the aim that Alcibiades had set himself and on which Athens had gone to wreck.

In the same years in which the Macedonian king was conquering the Persians, his brother-in-law, Alexander of Epirus, at the request of Tarentum, had devoted himself to this task. After some success at the beginning he had been overcome by the Lucanians and Bruttians and the opposition of Hellenic particularism (334-331 B.C.).

Now the Macedonian king made preparations to take up this work also and thus complete his conquest of the world. That the resources of Macedonia were inadequate for this purpose was perfectly clear to him. Since he had rejected the proposals of Darius he had employed the conquered Asiatics in the government of his empire, and above all had endeavoured to form an auxiliary force to his army out of the people that had previously[9] ruled Asia. In his naïve overvaluation of education, due to the Socratic belief in the omnipotence of the intellect, he thought he could make Macedonians out of the young Persians. But as ruler of the world he must no longer bear the fetters which the usage of his people and the terms of the Hellenic league put upon him. He must stand above all men and peoples, his will must be law to them, like the commandment of the gods. The march to Ammon (331 B.C.), which at the time enjoyed the highest regard in the Greek world, inaugurated this departure. This elevation of the kingship to divinity was not an outgrowth of oriental views, although it resembles them, but of political necessity and of the loftiest ideas of Greek culture—of the teaching of Greek philosophy, common to all Socratic schools, of the unlimited sovereignty of the true sage, whose judgment no commandment can fetter; he is no other than the true king.

Henceforth this view is inseparable from the idea of kingship among all occidental nations down to our own times. It returns in the absolute monarchy that Cæsar wished to found at Rome and which then gradually develops out of the principate of Augustus, until Diocletian and Constantine bring it to perfection; it returns, only apparently modified by Christian views, in the absolute monarchy of modern times, in kingship by the grace of God as well as in the universal monarchy of Napoleon, and in the divine foundation of the autocracy of the Czar.

But Alexander was not able to bring his state to completion. In the midst of his plans, in the full vigour of youth, just as a boundless future seemed to lie before him, he was carried off by death at Babylon, on the thirteenth of June, 323 B.C., in the thirty-third year of his age.

With the death of Alexander his plans were buried. He left no heir who could have held the empire together; his generals fought for the spoils. The result of the mighty struggles of the period of the Diadochi, which covers almost fifty years (323-277 B.C.), is, that the Macedonian empire is divided into three great powers; the kingdom of the Lagidæ, who from the seaport of Alexandria on the extreme western border of Egypt control the eastern Mediterranean with all its coasts, and the valley of the Nile; the kingdom of the Seleucidæ, who strive in continual wars to hold Asia together; and the kingdom of the Antigonidæ, who obtained possession of Macedonia, depopulated by the conquest of the world and again by the fearful Celtic invasion (280), and who, when they wish to assert themselves as a great power, must attempt to acquire an ascendency in some form or other over Greece and the Ægean Sea.

Of these three powers the kingdom of the Lagidæ is most firmly welded together, being in full possession of all the resources that trade and sea power, money and politics, afford. To re-establish the universal monarchy was never its aim, even when circumstances seemed to tempt to it. But as long as strong rulers wear the crown it always stands on the offensive against the other two; it harasses them continually, hinders them at every step from consolidating, wrests from the Seleucidæ almost all the coast towns of Palestine and Phœnicia as far as Thrace, temporarily gains control of the islands of the Ægean, and supports every hostile movement that is made in Greece against Macedonia. The Greek mother-country is thus continually forced anew into the struggle, the play of intrigue between the court of Alexandria and the Macedonian state never gives it an opportunity to become settled. All revolts of the Greek world received the support of Alexandria; the uprising of Athens and Sparta in the war of Chremonides (264), the attempt of Aratus to give the Peloponnesus an independent[10] organisation by means of the Achæan league (beginning in 252), and finally the uprising of Sparta under Cleomenes. The aim of giving the Greek world an independent form was never attained; finally, when at the end of the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes (221) the kingdom of the Lagidæ withdraws and lets Cleomenes fall, the peninsula comes anew under the supremacy of the Macedonians, whom Aratus the “liberator” had himself brought back to the citadel of Corinth. But neither can the Macedonian king attain the full power that Philip and Alexander had possessed a century earlier; in particular, its resources are insufficient, even in alliance with the Achæans, to overthrow the warlike, piratical Ætolian state, which is constantly increasing in power. So Greece never gets out of these hopeless conditions; on the contrary, indeed, through the emigration of the population to the Asiatic colonies, through the decay of a vigorous peasant population which began as early as in the fourth century, through the economic decline of commerce and industry caused by the shifting of the centre of gravity to the east, its situation becomes more and more wretched and the population constantly diminishes. It can never attain peace of itself, but only through an energetic and ruthlessly despotic foreign rule.

In the East, on the contrary, an active and hopeful life developed. The great kings of the Lagidæan kingdom, the first three Ptolemies, fully appreciated the importance of intellectual life to the position of their kingdom in the world. All that Greek culture offered they tried to attract to Alexandria, and they managed to win for their capital the leading position in literature and science. But in other respects the kingdom of the Lagidæ is by no means the state in which the life of the new time reaches its full development. However much, in opposition to the Greek world, in conflict with Macedonia, they coquette with the Hellenic idea of liberty, within their own jurisdiction they cannot endure the independence and the free constitution of the Greek polis, and their subjects are by no means initiated into the new world-culture, but are kept in complete subjugation, sharply distinguished from the ruling classes, the Macedonians and Greeks, to whom also no freedom of political movement whatever is granted.[1]

The development in Asia follows a very different course. Here, through the activity of the great founders of cities, Antigonus, Lysimachus, Seleucus I, and Antiochus I, one Greek city arises after another, from the Hellespont through Asia Minor, Syria, Mesopotamia, Babylonia, Media, as far as Bactria and India; and from them grow the great centres of culture, full of independent life, by which the Asiatic population is introduced to the modern world-civilisation and becomes Hellenised. Antigonus deliberately supported the independence of the cities within the great organic body of the kingdom, thus following on the lines of the Hellenic league under Philip and Alexander. By the pressure of political necessity and the fact that they could maintain their power only by winning the attachment and fidelity of their subjects, the Seleucidæ were forced into the same ways. And side by[11] side with the great kingdom the political struggle creates a great number of powers of the second rank, in part pure Greek communities, like Rhodes, Chios, Cyzicus, Byzantium, Heraclea, in part newly formed states of Greek origin, like the kingdom of Pergamus and later the Bactrian kingdom, in part fragments of the old Persian kingdom, like Bithynia, Pontus, Cappadocia, Armenia, Atropatene, and not much later the Parthian kingdom. Among these states the eastern retain their oriental character, while the western are forced to pass more and more into the culture of Hellenism.

Destructive as were the effects of the continual wars, and especially of the raids of the Celtic hordes in Asia Minor, nevertheless there pulsates here a fresh, progressive life, to which the future seems to belong. To be sure, there is no lack of counter disturbance; beneath the surface of Hellenism, the native population that is absorbed into the Greek life everywhere preserves its own character, not through active resistance, but through the passivity of its nature. When the orientals become Hellenised, Hellenism itself begins at the same time to take on an oriental impress.

But in this there lies no danger as yet. Hellenism everywhere retains the upper hand and seems to come nearer and nearer to the goal of its mission for the world. In all fields of intellectual life the cultured classes have undisputed control and can look down with absolute contempt on the currents that move the masses far beneath them; the exponents of philosophical enlightenment may imagine they have completely dominated them. When the great ideas upon which Hellenism is based have been created by the classical period and new ones can no longer be placed beside them, the new time sets to work to perfect what it has inherited. The third century is the culmination of ancient science.

However, this whole civilisation lacks one thing, and that is a state of natural growth. Of all the states that developed out of Alexander’s empire, the kingdom of the Antigonidæ in Macedonia was the only one that had a national basis; and therefore, in spite of the scantiness of its resources, it was also the most capable of resistance of them all. All others, on the contrary, were purely artificial political combinations, lacking that innate necessity vital to the full power of a state. They might have been altogether different, or they might not have been at all. The separation of state and nationality, which is the result of the development of the ancient East, exists in them also; they are not supported by the population, which, by the contingencies of political development, is for the moment included in them, and their subjects, so far as the individual man or community is not bound to them by personal advantage, have no further interest in their existence. To be sure, had they maintained their existence for centuries, the power of custom might have sufficed to give them a firmer constitution, such as many later similar political formations have acquired and such as the Austrian monarchy possesses to-day; and as a matter of fact we find the loyalty of subjects to the reigning dynasty already quite strongly developed in the kingdom of the Seleucidæ. But a national state can never arise on the basis of a universal, denationalised civilisation, and the unity is consequently only political, based only upon the dynasty and its political successes. Therefore, except in Macedonia, none of these states can, even in the struggle for existence, set in motion the full national force supplied by internal unity.

The resources at the command of the Macedonio-Hellenic states were consumed in the struggle with one another; nothing was left for the great task that was set them in the West. The remains of Greek nationality, still[12] maintaining their existence here, looked in vain for a deliverer to come from the East. An attempt made by the Spartan prince Cleonymus, in response to the appeal of Tarentum, to take up the struggle in Italy against the Lucanians and Romans, failed miserably through the incapacity of its leader (303-302 B.C.). In Sicily, to be sure, the gifted general and statesman Agathocles (317-289) had once more established, amid streams of blood, and by mighty and ruthless battles against both internal enemies and rivals and against Carthage, a strong Greek kingdom that reached even to Italy and the Ionian Sea. But he was never able to attain the position taken by Dionysius, and at his death his kingdom goes to pieces. At this point also the rôle of the Sicilian Greeks in the history of the world is played out; they disappear from the number of independent powers capable of maintaining themselves by their own resources.

[1] It is altogether wrong to regard the kingdom of the Lagidæ as the typical state of Hellenism. Through the mass of material that the Egyptian papyri afford a further shifting in its favour is threatened, which must certainly lead to a very incorrect conception of the whole of antiquity. It is frequently quite overlooked that we have to do here only with documents from a province of the kingdom of the Lagidæ (later of Rome) which had a quite peculiar constitution, and that these documents therefore show by no means typical, but in every respect exceptional, conditions. The investigators who have made this material accessible deserve great gratitude, but it must never be overlooked that even a small fragment of similar documents from Asia would have infinitely greater value for the interpretation of the whole history of antiquity and specially that of Hellenism.

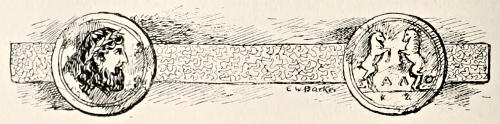

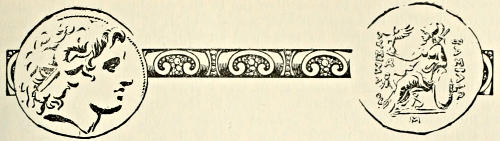

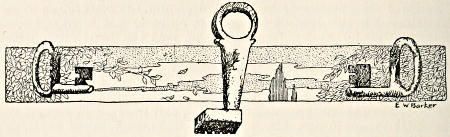

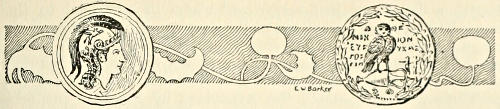

Greek City Seals

It is unnecessary in the summary of a country whose chief events are so accurately dated and so fully understood as in the case of Greece, to amplify the chronology. A synoptical view of these events will, however, prove useful. Questions of origins and of earliest history are obscure here as elsewhere. As to the earliest dates, it may be well to quote the dictum of Prof. Flinders Petrie, who, after commenting on the discovery in Greece, of pottery marked with the names of early Egyptian kings, states that “the grand age of prehistoric Greece, which can well compare with the art of classical Greece, began about 1600 B.C., was at its highest point about 1400 B.C. and became decadent about 1200 B.C., before its overthrow by the Dorian invasion.” The earlier phase of civilisation in the Ægean may therefore date from the third millennium B.C.

2000-1000. Later phase of civilisation in the Ægean (the Mycenæan Age). The Achæans and other Greeks spread themselves over Greece. Ionians settle in Asia Minor. The Pelopidæ reign at Mycenæ. Agamemnon, king of Mycenæ, commands the Greek forces at Troy. 1184. Fall of Troy (traditional date). 1124. First migration. Northern warriors drive out the population of Thessaly and occupy the country, causing many Achæans to migrate to the Peloponnesus. 1104. Dorian invasion. The Peloponnesus gradually brought under the Dorian sway. Dorian colonies sent out to Crete, Rhodes, and Asia Minor. Argos head of a Dorian hexapolis. 885. Lycurgus said to have given laws to Sparta. About this time (perhaps much earlier) Phœnician alphabet imported into Greece. 776. The first Olympic year. 750. First Messenian war.

683. Athens ruled by nine archons. 632. Attempt of Cylon to make himself supreme at Athens. 621. Draconian code drawn up. 611. Anaximander of Miletus, the constructor of the first map, born. End of seventh century. Second Messenian war. Spartans conquer the country. The Ephors win almost all the kingly power. Cypselus and his son Periander tyrants of Corinth. 600. The poets Alcæus and Sappho flourish at Lesbos. 594-593. Solon archon at Athens. 590-589. Sacred war of the Amphictyonic league against Crissa. Clisthenes tyrant of Sicyon. 585. Pythian games reorganised. Date of first Pythiad. 570. Pisistratus polemarch at Athens. Athenians conquer Salamis and Nisæa. 561. Pisistratus makes himself[14] supreme in Athens. He is twice exiled. 559-556. Miltiades tyrant of the Thracian Chersonesus. 556. Chilon’s reforms in Sparta. 549-548. Mycenæ and Tiryns go over to Sparta.

540. Pisistratus tyrant of Athens. 530. Pythagoras goes to Croton. 527. Pisistratus dies and is succeeded by his sons, Hippias and Hipparchus. Homeric poems collected. 514. Hipparchus slain by Harmodius and Aristogiton. 510. A Spartan army under Cleomenes blockades Hippias and forces him to quit Athens.

Clisthenes and Isagoras contend for the chief power in Athens. 507. Isagoras calls in Cleomenes who invades Attica. The Athenians overcome the Spartans, and Clisthenes, who had left Athens, returns. Clisthenes reforms the Athenian democracy. 506. Spartans, Bœotians, and Chalcidians allied against Athens. The Athenians allied with Platæa. Chalcidian territory annexed by Athens. Nearly the whole Peloponnesus forms a league under the hegemony of Sparta. Rivalry between Athens and Ægina. 504. The Athenians refuse to restore Hippias on the Persian demand. 498. Athens and Eretria send ships to aid the Milesians against the Persians. 496. Sophocles born at Athens. 494. Naval battle off Lade, the decisive struggle of the Ionian war, won by the Persians. Battle of Sepeia. The Spartans defeat the Argives. 493. Themistocles, archon at Athens, fortifies the Piræus.

492. Quarrel between the Spartan kings. King Demaratus flees to the Persian court, and King Cleomenes seizes hostages from Ægina. Thrace and Macedonia subdued by the Persians. 490. The Persians subdue Naxos and other islands, and destroy Eretria before landing in Attica. Battle of Marathon; the Greeks under Miltiades defeat the Persians, the latter losing six thousand men; the Persian fleet sets sail for Asia. 489. Miltiades’ expedition against Paros. Miltiades tried, and fined. His death. 487. War between Athens and Ægina. Themistocles begins to equip an Athenian fleet. 483. Aristides ostracised. 481. Xerxes musters an army to invade Greece. Greek congress at Corinth. 480. Xerxes at the Hellespont. The northern Greeks submit to Xerxes. The Greek army is defeated at the pass of Thermopylæ and Leonidas, the Spartan king, is slain. Battle of Artemisium. The Greek fleet retreats. Athens being evacuated, Xerxes occupies it. Battle of Salamis and complete victory of the Greeks. Retreat of Xerxes. The Greeks fail to follow up their victory. 479. Mardonius invades Bœotia; occupies Athens. Retreat of Mardonius. Battle of Platæa. Mardonius defeated and slain. Retreat of the Persian army. Battle of Mycale and defeat of the Persian fleet.

478. Athenians under Xanthippus capture Sestus in the Chersonesus. Confederacy of Delos. 477. Athenian walls rebuilt. Piræus fortified. Themistocles’ law providing for the annual increase of the navy. Pausanias[15] conquers Byzantium. He enters into treacherous relations with the Persians. 476. The Spartans endeavour to reorganise the Amphictyonic league. Their attempts defeated by Themistocles. 474. The poet Pindar flourishes. 473. Scyros conquered by the Athenian, Cimon. Argos defeated by the Spartans at the battle of Tegea. 472. Themistocles ostracised. Persæ of Æschylus performed. 471. The Arcadian league against Sparta crushed at the battle of Dipæa. 470-469. Naxos secedes from the confederacy of Delos, and is compelled to return. 470. Socrates born. 468. Cimon defeats the Persians at the Eurymedon. Argos recovers Tiryns. 465-463. Thasos revolts and is reduced by the fleet under Cimon. 464. Sparta stirred by terrible earthquake and a revolt of the helots. The Third Messenian war. 463-462. Cimon persuades Athens to send help to the Spartans, but the latter refuse the assistance. They are afraid of Athens’ revolutionary spirit. This incident puts an end to Cimon’s Laconian policy. It is the triumph of Ephialtes and his party.

463-461. Triumph of democracy at Athens under Ephialtes and Pericles. The Areopagus deprived of its powers. Cimon protests against the changes effected in his absence. He is ostracised, and Athens forms a connection with Argos, which captures and destroys Mycenæ. 460-459. Megara secedes from the Peloponnesian league to Athens. A fleet, sent by Athens to aid the Egyptian revolt against Persia, captures Memphis. 459. Ithome captured by the Spartans. 459-458. Athens at war with the northern states of the Peloponnesus. Athenian victories of Halieis, Cecryphalea, and Ægina. 458. Long walls of Athens completed. 457. Spartan expedition to Bœotia. Victory of Tanagra over the Athenians. Truce between Athens and Sparta. Battle of Œnophyta and conquest of Bœotia by the Athenians. The Phocians and Locrians make alliance with Athens. 456. Ægina surrenders to the Athenians. 454. Greek contingent in Egypt capitulates to the Persians; the Athenian fleet destroyed at the mouth of the Nile. 454-453. Treasury of the confederacy of Delos transferred from the island to Athens. 453. Pericles besieges Sicyon and Œniadæ without success. Achaia passes under the Athenian dominion. 452-451. Five years’ truce between Athens and the Peloponnesus. 450-449. Cimon leads an expedition against Cyprus. Death of Cimon. The fleet on its way home wins the battle of Salamis in Cyprus. 448. Peace of Callias concluded with Persia. Sacred war. The Phocians withdraw from the Athenian alliance. 447. Bœotia lost to Athens by the battle of Coronea. 447-446. Revolt of Eubœa and Megara from the Delian confederacy. Eubœa is subdued and annexed. Pericles plants colonies in the Thracian Chersonesus, Eubœa, Naxos, etc. 446-445. Thirty Years’ Peace between Athens and Sparta. 444. Aristophanes born. 442. Thucydides opposes Pericles; is ostracised, leaving Pericles without a rival in Athens, where he governs for fifteen years with absolute power. Sophocles’ Antigone produced. 440-439. Pericles subdues Samos. Corcyræans defeat Corinthians in a sea-fight. 433. Corcyra concludes alliance with Athens. Battle of Sybota between Corcyra and Corinth. King Perdiccas of Macedonia incites the revolt of Chalcidice against Athens. 432. “Megarian decree,” passed at Athens, excludes Megarians from all Athenian markets. Battle of Potidæa. Athenians defeat the Corinthians.

431. Sparta decides on war with Athens on the grounds of her having broken the Thirty Years’ Peace. Peloponnesian War. First period called the “Attic War.” Platæa surprised by Thebans. Thebans taken and executed in spite of a promise for their release. King Archidamus of Sparta invades Attica. The population crowd into Athens. Athens annexes Ægina. The fleet takes several important places. 430. The plague in Athens. Trial of Pericles for misappropriation of public money. Potidæa taken by the Athenians and the inhabitants expelled. 429. Archidamus besieges Platæa. Phormion, the Athenian, wins the victory of Naupactus. Death of Pericles. Rivalry between contending parties under Nicias and Cleon. 428. Archidamus invades Attica. Mytilene revolts and is blockaded by the Athenians. 427. Fourth invasion of Attica by the Spartans. Surrender of Mytilene. The Mytilenæan ringleaders executed. Surrender of Platæa to the Peloponnesians. Oligarchs in Corcyra conspire to overthrow the democrats. Civil war and naval engagement. Terrible slaughter. Athenian expedition to Sicily under Laches. Birth of Plato. 426. Athenians under Demosthenes defeated in Ætolia. Battle of Olpæ. Peloponnesians and Ambracians defeated by Demosthenes. Purification of Delos by the Athenians. The Delian festival revived under Athenian superintendence. 425. Athens increases the amount of tribute to be paid by the confederacy. The episode of Pylos, leading, after a long struggle, to the capture of Lacedæmonian forces in Sphacteria. 424. Defeat of Hippocrates at Delium. Thucydides, the historian, banished for not succouring Amphipolis in time. Brasidas takes towns of Chalcidice. 423. Truce between Athens and Sparta. Scione in Chalcidice revolts to Sparta and an Athenian expedition under Cleon is sent against it, notwithstanding the truce. 422. Battle of Amphipolis won by Brasidas, but both he and Cleon are slain. 421. Peace of Nicias ends the first period of the Peloponnesian War. Mutual restoration of conquests. Scione is taken and all the male inhabitants put to death. 420. Second period of the Peloponnesian War. Alcibiades becomes the chief opponent of Nicias. Expedition against Epidaurus. 418. Nicias recovers his power in Athens. The Spartans invade Argolis. Athenians take Orchomenus, but are defeated by the Spartans. Battle of Mantinea. Hyperbolus attempts to obtain the ostracism of Nicias. The decree is passed against himself, being the last instance of ostracism. Argive oligarchy overthrows the democratic government. A counter revolution restores the democrats. Athens concludes alliance with Argos. 416. Melos conquered by the Athenians. The Sicilian city of Segesta appeals to Athens for help against Selinus. Nicias opposes the sending of assistance, but is overruled and sent with Alcibiades in command of a Sicilian expedition. 415. Mysterious mutilation of the Hermæ statues regarded as an evil omen. Alcibiades accused of a plot. His trial postponed. The expedition sails. Fall of Alcibiades; his escape. 414. Siege of Syracuse. The Spartan Gylippus arrives with ships. 413. Nicias appeals for help to Athens and a second expedition is voted. Syracusans worsted in a sea battle. Syracusans capture an Athenian treasure fleet, and win a battle in the harbour of Syracuse. Arrival of the second Athenian expedition and its total defeat. The Athenians retreat by land. The rear guard is forced to surrender and the relics of the main body are captured after the defeat of the Asinarus. Tribute of the confederacy abolished and replaced by an import and export duty. 412. Third period of the Peloponnesian War, called the Decelean or Ionian War. The[17] allies of Athens take advantage of her misfortunes to revolt. Sparta makes a treaty with Persia. Athens wins several naval successes. 411. “Revolution of the Four Hundred.” The fleet and army at Samos place themselves under the leadership of Alcibiades. Spartans defeat the Athenian fleet at Eretria. Fall of the Four Hundred and partial restoration of Athenian democracy. Battle of Cynossema won by the Athenians. Alcibiades defeats the Peloponnesians at Abydos. 410. Battle of Cyzicus won by Alcibiades. Complete restoration of Athenian democracy. 408. Alcibiades conquers Byzantium. 407. Cyrus, viceroy of Sardis, furnishes the Spartan Lysander with money to raise the pay of the Spartan navy. Lysander begins to set up the oligarchical government of the decarchies in the cities conquered by him. Battle of Notium. Athenians defeated. Alcibiades’ downfall. 406. Battle of Arginusæ. Peloponnesians defeated by the Athenians. The victorious generals are blamed for not rescuing their wounded, and are illegally condemned and executed. The Spartans make overtures for peace, which are rejected. 405. Battle of Ægospotami. Most of the Athenian ships are taken and all the prisoners are put to death. The Athenian empire passes to Sparta. Lysander subdues the Hellespont and Thrace, and lays siege to Athens. 404. Surrender of Athens.

Return to Athens of exiles of the oligarchical party. Athens under the Thirty. Thrasybulus and other exiles gain Phyle. Theramenes opposes the violent rule of the Thirty and is put to death. 403. Battle of Munychia. Thrasybulus defeats the army of the Thirty. Death of Critias. The Thirty are deposed and replaced by the Ten. The Spartans under Lysander come to the aid of the Ten, but the intervention of the Spartan king, Pausanias, brings about the restoration of the Attic democracy. 401. Cyrus’ campaign and the battle of Cunaxa. Retreat of the Ten Thousand Greeks under Xenophon. 400. Spartan invasion of the Persian dominions. 399. Spartans under Dercyllidas occupy the Troad. Elis conquered and dismembered by the Spartans. Socrates put to death for denying the Athenian gods. 398. Agesilaus becomes king of Sparta. 397. Cinadon’s conspiracy. 396. Agesilaus invades Phrygia. 395. Agesilaus wins the victory of Sardis. Revolt of Rhodes. The Spartans invade Bœotia and are repelled with the assistance of the Athenians. Thebes, Athens, Argos, and Corinth allied against Sparta. 394. Agesilaus returns from Asia Minor. Battle of Nemea won by the Spartans. Battle of Cnidus. The Persian fleet under Conon destroys the Spartan fleet. Agesilaus wins the battle of Coronea and retreats from Bœotia. 393. Pharnabazus destroys the Spartan dominion in the eastern Ægean, and supplies Conon with funds to restore the long walls of Athens. Beginning of the “Corinthian War.” 392. Federation of Corinth and Argos. Fighting between the Spartans and the allies on the Isthmus of Corinth. Both sides send embassies to the Persians. 391. The Spartans begin fresh wars in Asia. 389. Successes of Thrasybulus in the northern Ægean. 388. Spartans dispute the supremacy of Athens on the Hellespont and are defeated at Cremaste. 387. Peace of Antalcidas between Persia and Sparta. Athens is compelled to accede. 386. Dissolution of the union of Corinth and Argos. Sparta compels the Mantineans to break down their city walls and separate into small villages. 384-382. The city of Olynthus, having united the Chalcidian towns under her hegemony[18] and increased her territory at the expense of Macedonia, makes alliance with Athens and Thebes. Sparta sends help to the towns which refuse to join. 384. Aristotle born. 382. Spartans seize the citadel of Thebes. 380. Panegyric of Isocrates, a plea for Greek unity. 381-379. Sparta forces Phlius to submit to her dictation. 379. Chalcidian league compelled by Sparta to dissolve. The power of Sparta at its height. Rising of Thebes under Pelopidas against Sparta. Sphodrias, the Spartan, invades Athenian territory. The Spartans decline to punish the aggression.

378. Athens makes alliance with Thebes. 378-377. Formation by the Athenians of a new maritime confederacy. 378-376. Three unsuccessful Spartan expeditions into Bœotia. 376. Great maritime victory of the Athenian Chabrias at Naxos. Successes of Timotheus of Athens in the Ionian Sea. 374. Brief peace between Sparta and Athens. 374-373. Corcyra unsuccessfully invested by the Spartans. 371. Peace of Callias, guaranteeing the independence of each individual Greek city. Thebes not included in the Peace. Jason of Pheræ, despot of Thessaly. Battle of Leuctra. Epaminondas of Thebes defeats the Spartans. Revolutionary outbreaks in Peloponnesus. 370. Arcadian union and restoration of Mantinea. Foundation of Megalopolis. Epaminondas and Pelopidas invade Laconia. 369. Messene restored by the Thebans as a menace to Sparta. Alliance between Sparta and Athens. The Thebans conquer Sicyon. Pelopidas sent to deliver the Thessalian cities from the rivals, Alexander of Macedon and Alexander of Pheræ. 368. The Spartans win the “tearless victory” of Midea over the Arcadians. Death of Alexander II of Macedon. Succession of his brother Perdiccas secured by Athenian intervention. Pelopidas captured by Alexander of Pheræ. 367. Epaminondas rescues him. Pelopidas obtains a Persian decree settling disputed questions in Peloponnesus. The decree disregarded in Greece. 366. The Thebans conquer Achaia, but fail to keep it. Athens makes alliance with Arcadia. 365. Athenians conquer and colonise Samos, and acquire Sestus and Crithote. Perdiccas III of Macedon assassinates the regent. Timotheus takes Potidæa and Torone for Athens. Elis invaded by the Arcadians. 364. Creation of a Bœotian navy encourages the allies of Athens to revolt. Battle of Cynoscephalæ. Alexander of Pheræ, defeated by the Bœotians and their Thessalian allies. Pelopidas falls in the battle. Orchomenus destroyed by the Thebans. Elis invaded by the Arcadians. Spartan operations fail. Battle in the Altis during the Olympic games. The Arcadians appropriate the sacred Olympian treasure. Praxiteles, the sculptor, flourished. 362. Unsuccessful attack on Sparta by Epaminondas. Battle of Mantinea and death of Epaminondas. 361. Agesilaus of Sparta goes to Egypt as a leader of mercenaries. Battle of Peparethus. Alexander of Pheræ defeats the Athenian fleet. He attacks the Piræus. 360. The Thracian Chersonesus lost to Athens.

359. Death of Perdiccas III of Macedon. Philip seizes the government as guardian for his nephew, Amyntas. 358. Brilliant victories of Philip over the Pæonians and Illyrians. 357. Thracian Chersonesus and Eubœa[19] recovered by Athens. Philip takes Amphipolis. Revolt of Athenian allies, Chios, Cos, and Rhodes. 356. Battle of Embata lost by the Athenians. Philip founds Philippi, takes Pydna and Potidæa, defeats the Illyrians and sets to work to organise his kingdom on a military basis. Birth of Alexander the Great. 355. Peace between Athens and her revolted allies. The Athenians abandon their schemes of a naval empire. Outbreak of the “Sacred war” against the Phocians who had seized the Delphic temple. 354. Battle of Neon. The Phocians defeated. Demosthenes begins his political activity. Phocian successes under Onomarchus. 353. Methone taken by Philip of Macedon. Philip and the Thessalian league opposed to Onomarchus and the tyrants of Pheræ. Onomarchus drives Philip from Thessaly. Philip crushes the Phocians in Magnesia and makes himself master of Thessaly. Phocis saved from him by help from Athens. 352. War in the Peloponnesus. Spartan schemes of aggression frustrated. Thrace subdued by Philip. 351. Demosthenes delivers his First Philippic. 349. Philip begins war against Olynthus which makes alliance with Athens. Athenian attempt to recover Eubœa fails. 348. Philip destroys Olynthus and the Chalcidian towns. 347. Death of Plato. 346. Peace of Philocrates between Philip and Athens. Phocis subdued by Philip. Philip presides at the Pythian games. Philip becomes archon of Thessaly. Demosthenes accuses Æschines of accepting bribes from Philip. 344. Demosthenes delivers The Second Philippic. 343. Megara, Chalcis, Ambracia, Acarnania, Achaia, and Corcyra ally themselves with Athens. 342-341. Philip annexes Thrace. He founds Philippopolis. 341. Demosthenes’ Third Philippic. 340. Diplomatic breach between Athens and Philip. 339. Perinthus and Byzantium unsuccessfully besieged by Philip. Philip’s campaign on the Danube. 338. The Amphictyonic league declares a “holy war” against Amphissa, and requests the aid of Philip. Philip destroys Amphissa and conquers Naupactus. Philip occupies Elatea. Athens makes alliance with Thebes. Battle of Chæronea. Philip defeats the Athenians and Thebans. The hegemony of Greece passes to Macedon. Philip invades the Peloponnesus which, with the exception of Sparta, acknowledges his supremacy. Philip establishes a Greek confederacy under the Macedonian hegemony. Lycurgus appointed to control the public revenues in Athens. 336. Attalus and Parmenion open the Macedonian war in Æolis.

Murder of Philip and succession of Alexander the Great. Alexander compels the Hellenes to recognise his hegemony. 335. Alexander conducts a successful campaign on the Danube and defeats the Illyrians at Pelium. Thebes revolts against him and is destroyed. 334. Alexander sets out for Asia. Battle of the Granicus. Alexander defeats the Persians. Lydia, Miletus, Caria, Halicarnassus, Lycia, Pamphylia, and Pisidia subdued. 333. Alexander goes to Gordium and cuts the Gordian knot. Death of his chief opponent, the Persian general, Memnon. Submission of Paphlagonia and Cilicia. Battle of Issus. Alexander puts the army of Darius to flight. Sidon and Byblos submit. 332. Tyre besieged and taken. He slaughters the inhabitants and marches southward, storming Gaza. Egypt conquered. He founds Alexandria. 331. Battle of Arbela and defeat of the Great King. Babylon opens its gates to Alexander. He enters Susa. The Spartans rise and are defeated at Megalopolis. 330. Alexander occupies[20] Persepolis. Alexander in Ecbatana, in Parthia, and on the Caspian. Philotas is accused of conspiring against Alexander’s life and is executed. His father, the general Parmenion, put to death on suspicion. Judicial contest between Demosthenes and Æschines ends in the latter’s quitting Athens. Part of Gedrosia (Beluchistan) submits to Alexander. 329. Arachosia conquered. 328. Alexander conquers Bactria and Sogdiana. 327. Alexander quells the rebellion of Sogdiana and Bactria. Clitus killed by Alexander at a banquet. Alexander marries the Sogdian Roxane. Callisthenes, the historian, is put to death under pretext of complicity in the conspiracy of the pages to assassinate Alexander. Beginning of the Indian war. 326. Alexander in the Punjab; he crosses the Indus, and is victorious at the Hydaspes. At the Hyphasis the army refuses to advance further. Alexander builds a fleet and sails to the mouth of the Indus. 325. Conquest of the Lower Punjab. March through Gedrosia (Mekran in Beluchistan) and Carmania. Nearchus makes a voyage of discovery in the Indian Ocean. 324. Alexander in Susa. He punishes treasonable conduct of officials during his absence. Alexander’s veterans discharged at Opis. Harpalus deposits at Athens the money stolen from Alexander. The trial respecting misappropriation of this money ends in Demosthenes being forced to quit Athens. Alexander’s last campaign against the Kossæans. 323. Alexander returns to Babylon and reorganises his army for the conquest of Arabia. Death of Alexander.