REVISED EDITION

BY Kenneth Macgowan

AND Joseph A. Hester, Jr.

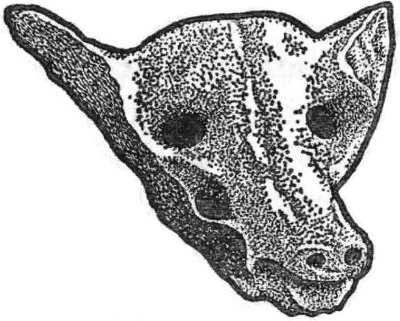

WITH DRAWINGS BY CAMPBELL GRANT

And these are ancient things.

CHRONICLES I, 4:22

PUBLISHED IN CO-OPERATION WITH

THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

THE NATURAL HISTORY LIBRARY

ANCHOR BOOKS

DOUBLEDAY & COMPANY, INC.

GARDEN CITY, NEW YORK

The Natural History Library Edition, 1962

Copyright © 1962 by The American Museum of Natural History

Copyright © 1950, 1962 by Kenneth Macgowan

For permission to quote passages from their respective publications grateful acknowledgment is made to the following authors, publishers, and literary executors:

J. B. Lippincott Company: Aleš Hrdlička, “Early Man in America: What Have the Bones to Say?” in Early Man, ed. George Grant MacCurdy (copyright, 1937, by The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia); The Macmillan Company: William B. Scott, History of Land Mammals in the Western Hemisphere, rev. ed. (copyright, 1937, by The American Philosophical Society); G. P. Putnam’s Sons: Earnest A. Hooton, Apes, Men, and Morons (copyright, 1937, by G. P. Putnam’s Sons); Rinehart & Company, Inc.: Robert H. Lowie, The History of Ethnological Theory (copyright, 1937, by Robert H. Lowie); Charles Scribner’s Sons: Roland B. Dixon, The Racial History of Man (copyright, 1923, by Charles Scribner’s Sons) and The Building of Cultures (copyright, 1928, by Charles Scribner’s Sons); Whittlesey House: Harold S. Gladwin, Men Out of Asia (copyright, 1947, by McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc.); University of Toronto Press: Earnest A. Hooton, “Racial Types in America and Their Relations to Old World Types” in The American Aborigines, ed. Diamond Jenness; Yale University Press: Earnest A. Hooton, The Indians of Pecos Pueblo (copyright, 1930, by Yale University Press).

Printed in the United States of America

TO

GEORGE C. VAILLANT

Since the time of Columbus, when the peoples of the New World were discovered by Europeans, there has been a continuous interest in knowing something about their origin and early history. This has been almost completely shrouded in the primitive past, unmentioned in any written records, and thus largely a matter of speculation of one kind or another. Only very slowly have the means of investigating this history come into being. Greater knowledge of all the world’s peoples has provided the means for solidly based comparative studies, and the developing techniques of archaeology have brought more factual evidence to hand. Gradually the true picture is taking shape as each new discovery is analyzed and discussed and takes its place in the total structure.

This is an exciting adventure in discovery and learning that many would like to share more completely with the archaeologist and anthropologist. Usually, however, the reports of the professionals are too technical to be meaningfully understood by the layman, and the brief accounts of “finds” and “digs” that appear in the press are far too fragmentary. Most fortunately, x we have the present book, which fills the need very nicely—far better than anything else in print.

Kenneth Macgowan professes to be an amateur in archaeological matters and, technically speaking, he is, although his competence in the extraordinarily involved subject he deals with is certainly of professional stature. In any event, he clearly discerns what is needed by the amateur and, without minimizing the complexities and involved problems of his subject, he provides the background to make them understandable. To incorporate the various discoveries and new formulations that have appeared in the twelve years since this book was first published, the text has been revised and brought up to date, largely by Professor Joseph A. Hester, Jr. This has been skillfully done in a way that does not alter the quality or coverage of the original.

I have been recommending this book for many years and now begin a new series of such recommendations. I am sure that it will be enjoyed and found most illuminating by all who want to know how the early history of man in the New World is being revealed.

GORDON F. EKHOLM Curator of Mexican Archaeology

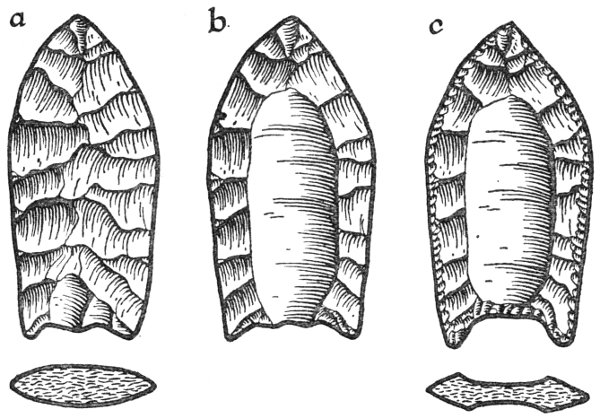

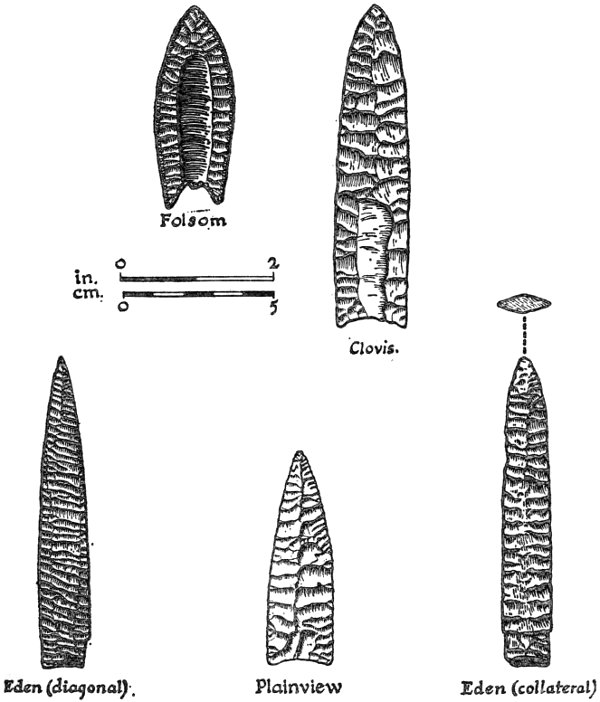

In the twelve years since Early Man in the New World appeared, in 1950, a good deal of archaeological water has passed under the bridge—or over the land-bridge that led the first immigrants into the Americas. Because I had given most of these years to the founding and development of the Department of Theater Arts at U.C.L.A., I was in no position to revise and add to that book without the collaboration of an able and willing anthropologist, a man who had followed far more closely than I the new findings in American prehistory, and the new theories, or guesses, about their meanings. I was fortunate indeed to find such a man in Professor Joseph A. Hester, Jr., of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, San Jose State College, California. To him must go the fullest credit for the updating and the correcting, too, of a twelve-year-old book. Through him, Early Man in the New World is now able to present a great deal of information that was not in existence in 1950. Then, for example, the dating of wood and charcoal, bone, horn, and shell, through radiocarbon was hardly more than a gleam in the eye of Willard F. Libby. As I was reading page proof when he xii announced his first pre-Columbian date, I could mention this invaluable time clock only at the end of three chapters. A change, rather than an addition to the text, is the use of the word “Clovis” instead of “Generalized Folsom,” and “Eden” instead of “Yuma,” thus bringing our terminology in line with today’s practice.

In its first form, the book came about almost by accident. During 1941 and 1942, my work in the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs included the preparation of some educational films upon archaeological work in Mexico and South America. As a result I came to know and esteem the Director of the University Museum, George C. Vaillant. To my surprise and pleasure, when he learned of my interest in American archaeology, he proposed that we collaborate on a prehistory of the New World. When the war prevented active work together by taking him to Peru, I prepared what would have been the first two chapters of our book—the place of early man in the story of pre-Columbian America. Upon Vaillant’s untimely death, I decided to study the subject more intensively, to add material on the Great Ice Age and early man in the Old World, and to expand the two chapters into a book that I might dedicate to the man who had done so much for American archaeology in the twenty years of his work—George C. Vaillant.

Since the book was not the result of personal work in the field, but rather the product of the kind of research that is nothing more than reading and talking, I was in the debt of many men and books, and a welter of papers, pamphlets, and periodicals. I found it hard to believe that in any other branch of science so many overworked men and women would be so ready to give their time to talk and correspondence with the amateur. I was deeply indebted to more than two score who had gone out of their way to answer questions, lend books, or give reprints of papers. In listing them xiii I was more than certain that I had inadvertently omitted some: Edgar Anderson, Ernst Antevs, Ralph L. Beals, Junius Bird, Robert J. Braidwood, Henry J. Bruman, Kirk Bryan, George F. Carter, R. A. Daly, Helmut de Terra, Loren C. Eiseley, Richard F. Flint, James Gilluly, Harold S. Gladwin, M. R. Harrington, Frank C. Hibben, Frederick W. Hodge, Harry Hoijer, Earnest A. Hooton, W. W. Howells, Frederick R. Johnson, Arthur R. Kelly, G. H. R. von Koenigswald, Alex D. Krieger, Alfred L. Kroeber, M. M. Leighton, Theodore D. McCown, George G. MacCurdy, P. C. Mangelsdorf, Paul S. Martin, Hallam L. Movius, Jr., Raymond W. Murray, N. C. Nelson, Charles W. Phillips, Cyrus N. Ray, E. B. Renaud, Frank H. H. Roberts, Jr., Alfred S. Romer, Irving Rouse, Curt Sachs, Carl O. Sauer, E. H. Sellards, Herbert J. Spinden, T. D. Stewart, Wm. Duncan Strong, Griffith Taylor, Bella Weitzner, H. M. Wormington, and Clark Wissler.

Next to the scientists who provide knowledge stand the librarians who help to preserve it and make it usable. I was peculiarly indebted to a number of these: Miss Margaret Currier, Librarian of the Peabody Museum, Cambridge; her assistant Miss Jessie Bell MacKenzie; Mrs. Ella L. Robinson, Librarian of the Southwest Museum; Dr. Lawrence C. Powell, Librarian of the University of California at Los Angeles; his most cooperative staff; and particularly one of its members, Miss Hilda M. Gray, whose expeditions into the equal mysteries of stacks and bibliographies saved me many hours of labor and I can’t guess how many blunders. Professor Hester and I add a warm word of thanks to Mrs. Alice De Lisle for assembling data, preparing charts, typing, filing, and research.

I was particularly indebted to Frank H. H. Roberts, Jr., of the Smithsonian Institution, the outstanding authority on early man in North America, for his reading, checking, and challenging of the manuscript, and to xiv M. R. Harrington, who read and criticized my first draft. I also owed much to a number of men and women who read various chapters on which they had special knowledge: Edgar Anderson, Ernst Antevs, Robert J. Braidwood, Henry J. Bruman, Loren C. Easeley, James Gilluly, Harold S. Gladwin, M. R. Harrington, Robert F. Heizer, Earnest A. Hooton, Alex Krieger, Alfred L. Kroeber, Theodore D. McCown, Ernest S. Macgowan, Hallam L. Movius, Jr., and H. M. Wormington.

Both Professor Hester and I are especially obliged to Campbell Grant, amateur of anthropology as well as artist, for the many illustrations.

Finally, in the typing of the original manuscript and the checking of the many references I was fortunate in having the aid of Miss Frankie Porter and of Joe Pavalko.

Since we are not adding a repetitive bibliography to the almost four hundred references that we cite, we should like to list a few of the sources which we have found most useful and which should prove so to any reader who may wish to pursue further various aspects of the subject:

Frank H. H. Roberts, Jr., “Developments in the Problem of the North-American Paleo-Indian,” Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 100:51-116 (1940), and “The New World Paleo-Indian,” Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution for 1944, 403-433.

H. M. Wormington, Ancient Man in North America, 4th edit. (1957).

E. H. Sellards, Early Man in America (1952).

Raymond W. Murray, Man’s Unknown Ancestors (1943).

Early Man, a symposium edited by George Grant MacCurdy (1937).

The American Aborigines, a symposium edited by Diamond Jenness (1933).

George Grant MacCurdy, Human Origins (1924).

Miles C. Burkitt, The Old Stone Age (1933).

W. J. Sollas, Ancient Hunters and Their Modern Representatives (1924).

W. B. Wright, Tools and the Man (1939).

André Vayson de Pradenne, Prehistory (1940).

Edith Plant, Man’s Unwritten Past (1942).

Hallam L. Movius, Jr., Early Man and Pleistocene Stratigraphy in Southern and Eastern Asia (1944).

Earnest A. Hooton, Up from the Ape (1946).

W. W. Howells, Mankind in the Making (1959).

Richard F. Flint, Glacial Geology and the Pleistocene Epoch (1947) and Glacial and Pleistocene Geology (1957).

Roland B. Dixon, Racial History of Man (1923).

R. A. Daly, The Changing World of the Ice Age (1934).

Frederick E. Zeuner, Dating the Past, 4th edit. (1958).

Robert H. Lowie, The History of Ethnological Theory (1937).

Marcellin Boule and Henri V. Vallois, Fossil Men, trans. by Michael Bullock (1957).

Robert J. Braidwood, Prehistoric Men, 4th edit. (1959).

K. M.

There are no footnotes in this book. A catch-all for the author’s afterthoughts and for the corrections provided by friends who have read manuscript or galley proof—as well as a place for legitimate references—they are often a nuisance and always a typographical eyesore. The reference numbers in this book direct attention only to the sources of quotations, facts, or theories. They do not lead the reader to supplementary text material. Therefore, he may ignore them unless he wants to pursue the subject further for himself, or to verify the authority for what may seem to him an implausible statement.

Of all animals, we men are the only ones who wonder where we came from and where we will go. —W. W. HOWELLS

By the end of World War II, Timbuctoo was surprisingly close to Keokuk. Boys from Brooklyn stared up at Roman columns in the African desert, and Marines swapped a package of cigarettes for the spear of a stone-age man in New Guinea. Physically ours was indeed one world.

In a different sense it was one world before Columbus sailed, but a very limited world. Europe, North Africa, and portions of Asia made up all that Columbus knew and all that he expected to know. He intended to find a new road to the Indies; that was all. It would be a road across his own one world.

Then suddenly this world of his was two worlds. A new hemisphere appeared like a comet from outer space. It was a land and a people utterly unknown, utterly different. It had lived and grown for thousands upon thousands of years, sealed off to itself, unique. We search for some fit comparison, and find nothing adequate to describe the discovery of this secret laboratory of experiment in human culture.

Perhaps we should not have said that the New World had been “sealed off to itself.” We might better 2 have said “sealed off from Europe.” The culture which the Spanish Conquistadores found in the Americas owed nothing to that world from which they had come. What the Americas owed to Asia is another matter—in fact, the matter of this book.

One thing is clear. The Americas were indebted to Asia for man himself. Man—even one type of man—did not originate here. A small primate, the extinct Notharctus, left his bones—but no descendants—in our Southwest. The New World has no great apes; there are no indications that it ever had any. Its monkeys are quite out of the running. They have four too many teeth, their nose is flat, and they are cursed with a prehensile tail.

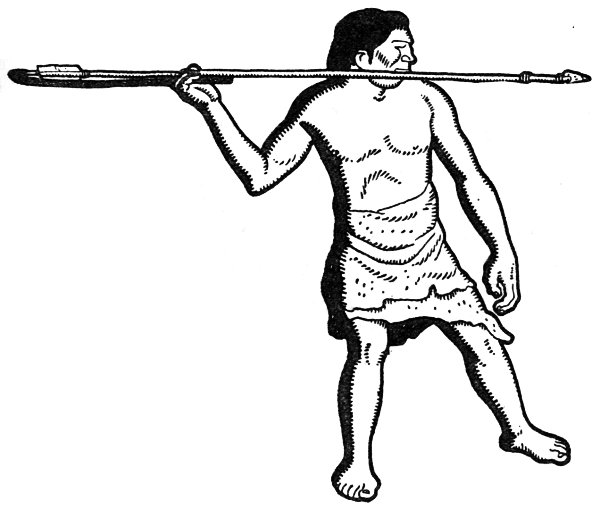

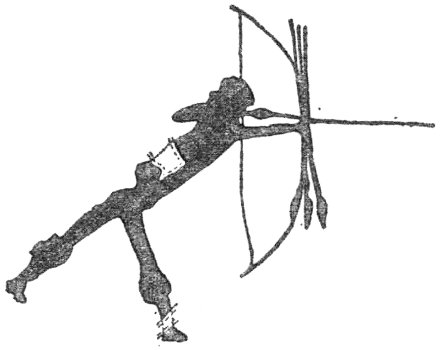

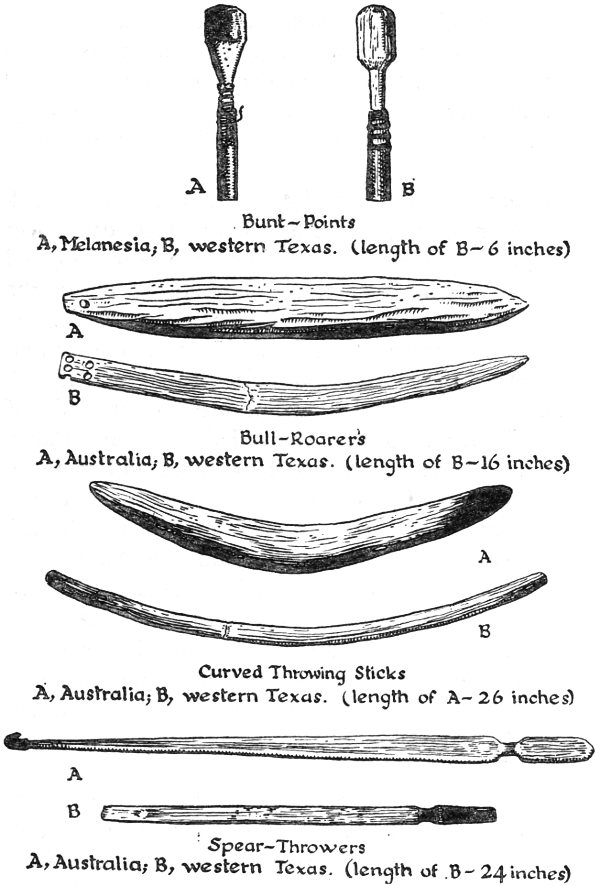

The New World owed something more to Asia, of course; but how much, is uncertain. Most anthropologists believe that man crossed Bering Strait with a very meager kit of material culture. He brought, at various times, the spear-thrower, the bow and arrow, the dog, the boat, the strike-a-light, some kind of clothing, but not a great deal more. Many other things—pottery, weaving, agriculture, masonry, metallurgy—he had to invent for himself in the New World; at least, that is the general opinion. A few anthropologists say that men out of Asia brought quite an array of culture traits; but these migrants were late comers, and some of them crossed the Pacific by boat.

Only a few students now deny that men had been crossing over from Asia through twenty or more millenniums before the birth of Christ. Some of them were what we call Indians—most of them, no doubt; but, before the Indians came, there seem to have been other immigrants. It is the purpose of this book to tell you what is known or believed or hazarded about these earliest men of the New World.

There are two chief problems: When did these men come? and What were they like?

It is a curious fact that, if we look at the rich variety of men and languages and cultures which was spread from end to end of two whole continents when the European came, we get some vague idea of how long man had been in the western hemisphere but no idea at all of what he was like when he anticipated Columbus by discovering the New World. Through the haze of time, we can see the general outline of Indian civilization, and many details. Much of this is clear and concrete, most of it is natural and understandable in terms of our Americas, and all of it is striking and extraordinary. But, for our present purposes, the best it does is to tell us that many millenniums of time must have been required for its development. It tells us nothing about the men who preceded the Indian, the primitive savages who discovered the New World. These men who first journeyed from Bering Strait to Cape Horn were not the men who made the Maya civilization, and they came long, long before. But by studying both the Indian and his predecessors we may gain some hint of how long ago this was.

Somehow or other, by this route or that, the migrants from Asia drifted across to the Americas, down the two continents, and out to their uttermost limits. Of the many possible tests of man’s age in the New World—some good, some not so good—one of the least accurate is a guess at how long it would take men and women, encumbered with children, to walk—and to eat their way—from Bering Strait to Cape Horn. It has been estimated that they might have covered the 4,000 miles from Harbin, Manchuria, to Vancouver Island in from 20 to 1,000 years; the time involved really depends on how fast and in what direction those wild animals moved upon which early man depended for food. As the country widened out, then narrowed in Central America, and widened out once more, there is no knowing how long the trip to Cape Horn may have taken. Our migrants would have had to camp and hunt as they went, and at first they would have moved only as the pursuit of game spurred them on. There would have had to be time, too, for increase in numbers—among themselves as well as among later invaders—to create pressure of population, and force the earlier men to the peripheries of northeastern America, Florida, and Lower California, and push them across jungled Panama and Amazonia and toward the bleaker and less desirable parts of South America. The various invaders multiplied as they moved, and it is anybody’s guess how many people were crowded into America by 1492; one authority says 8,400,000, another 50,000,000 to 75,000,000.[1] It took much time, of course—many millenniums—to breed so many men and cover so wide a space.

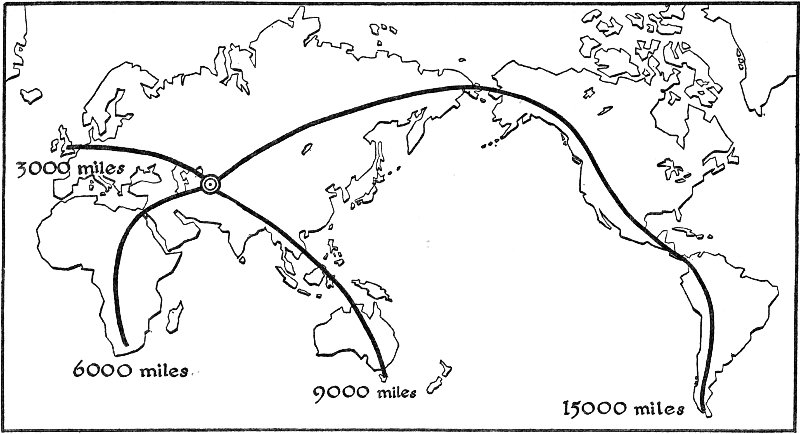

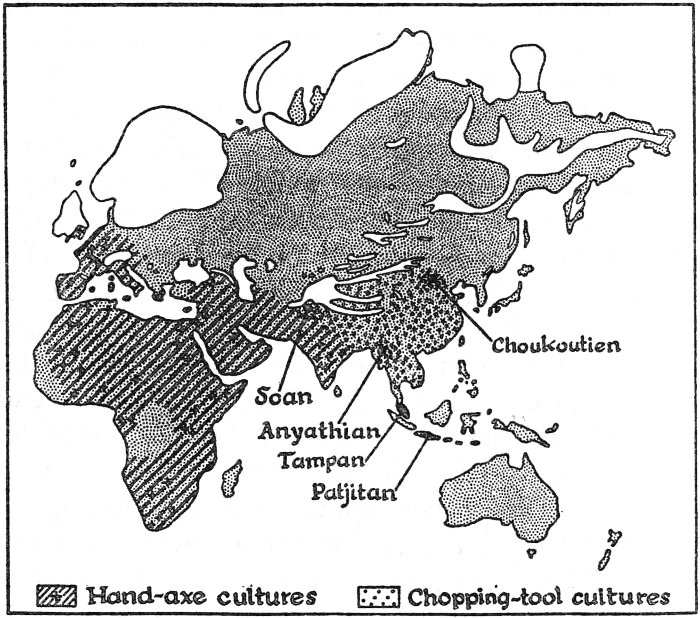

THE TREKS OF EARLY MAN

This map shows how far man would have had to walk from southern Africa to a spot just east of the Caspian Sea, where it used to be supposed that man originated, and it also shows the distance from that area to England, Australia, and Tierra del Fuego. The journey of early man from Bering Strait to the tip of Cape Horn was a matter of 10,000 miles.

Other things suggest a long sojourn for the Indian in the New World. Consider the matter of language—“the archives of history.” The Indian, writes N. C. Nelson, “had been at home in the New World long enough to have evolved about 160 linguistic stocks or language families, with 1,200 or more dialectic subdivisions.”[2] Alfred L. Kroeber says that North and South America “contain more native language families than all the remainder of the world.”[3] Some of this diversity could be due to migrations from different linguistic areas of 6 the Old World. It might also be accounted for by the theory of Franz Boas that among early primitive peoples there was great diversity of language, and that single tongues began to spread widely only when conquering and proselyting groups won a certain amount of power and dominion.[4] John Harrington, an American linguistic authority, believes that the diversity of Indian speech argues a very long residence in the New World—“at least 20,000 years, perhaps three times that.”[5] Edgar B. Howard states: “Considering that the languages of the New World lack evidence, outside of Eskimo, of any identification with Old World languages, the conclusion appears to be that human contact between the two continents was very remote.”[6] If there is no such identification, then even the last migrants came at a very early date indeed, or else all the tribal relatives who were left behind in the Old World perished without linguistic trace. It is possible, of course, that resemblances have merely not been recognized.

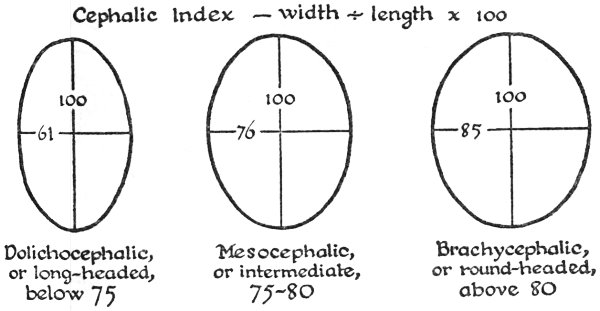

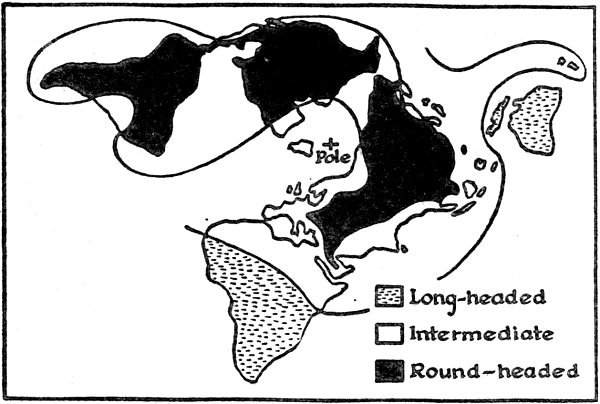

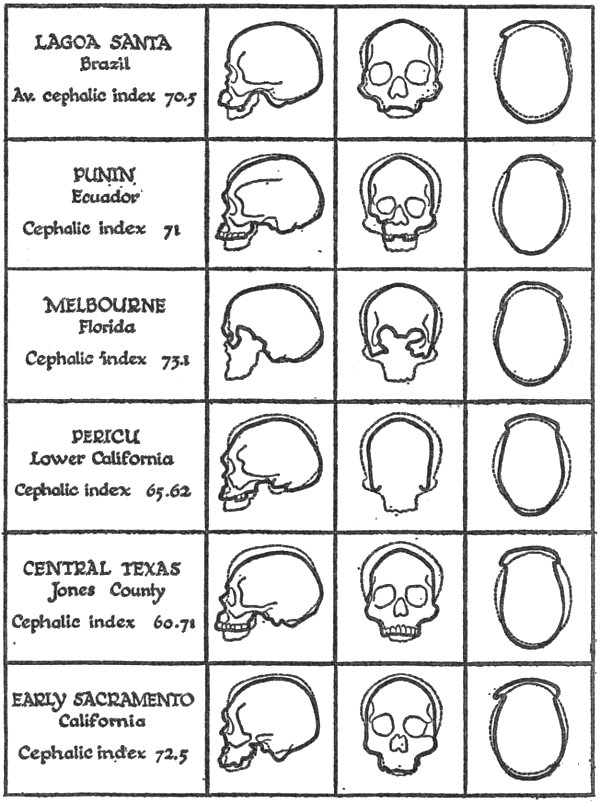

In addition to differentiation of language, there is differentiation of physique. When we in the United States think of the Indian, we think of a tall man with high cheekbones, a hawk-nose, and a bronze-red skin. Actually the American Indian is probably more varied in height, face, and color than the whole White racial stock.[7] More than that, his somatic constitution—the inner man in a physical sense—varies greatly. By 1492 the Indian had adapted himself to eight different climates from arctic to tropic, from arid to humid, from sea level to the 14,000-foot heights of Peru. This would take time, much time. Albrecht Penck, the great European glacialist, thinks 25,000 years hardly long enough.[8]

The civilizations which the Indian developed in the Americas—the Maya, Aztec, and Inca cultures—provide another test of how long man had been in the 7 New World before Columbus came. This test is no more exact than those we have already mentioned, but it suggests quite a long sojourn.

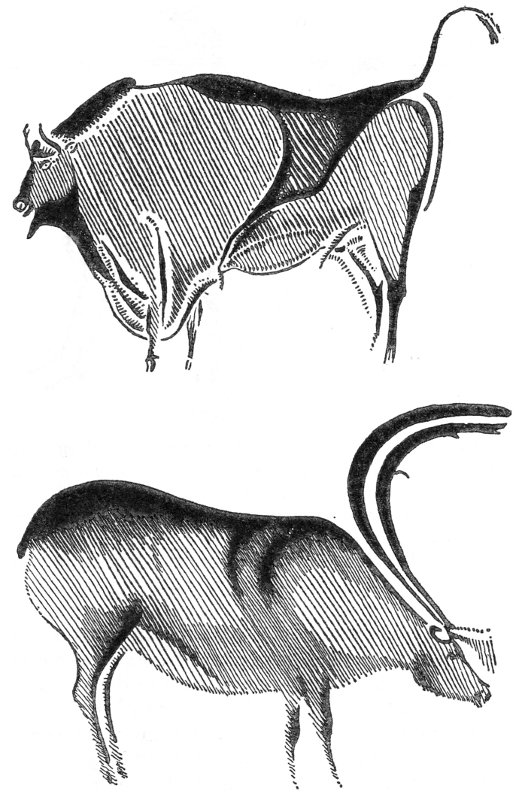

While the physical man was adapting himself to all manner of climates, the mental man dragged himself up from the hunting life of the Old Stone Age to the invention of writing and the perfecting of an accurate calendar. On the way—and as slow, necessary steps in his progress—he developed agriculture, and invented or perfected the arts and crafts of pottery, weaving, dyeing, metallurgy, sculpture, poetry, painting, architecture, city planning. In his agriculture he utilized irrigation, discovered fertilizers, and developed a great many exclusively American plants which now supply more than half of the world’s provender. He was probably the first to write numbers effectively through the use of zero and numerical position. He practiced trepanning—the removal of a piece of skull bone to relieve pressure on the brain—and he discovered how to use certain medicines and narcotics. In his textiles he employed all the weaves known to us today. He contrived efficient methods of government. He proliferated into 368 major tribal groups, and developed fifteen culture centers of distinct individuality.[9] In the United States he left 100,000 mounds as the product of one of his cultures; in Middle America, 4,000 ceremonial cities of stone. He practiced most types of religion except atheism. Certain things that he made resemble things of the Old World; most are peculiar to him and his life. Of Indian culture traits Clark Wissler remarks that “the range in variety and individuality seems even greater in aboriginal America than in the primitive Old World.”[10]

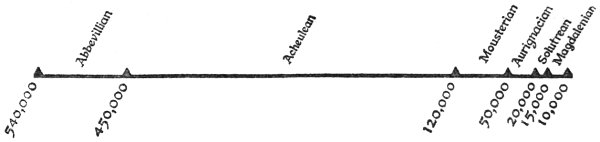

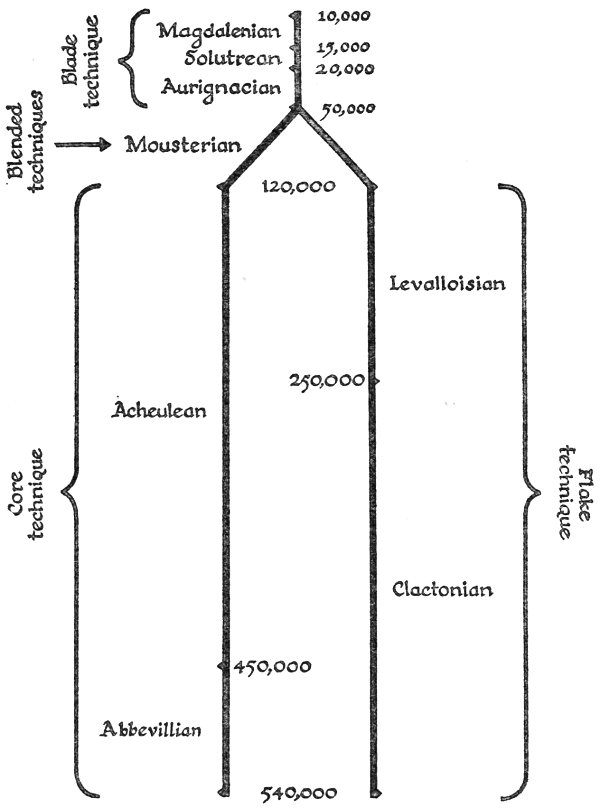

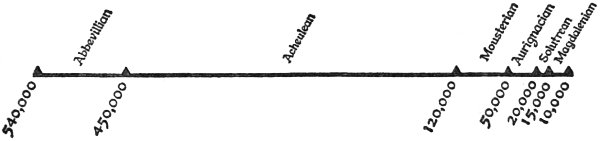

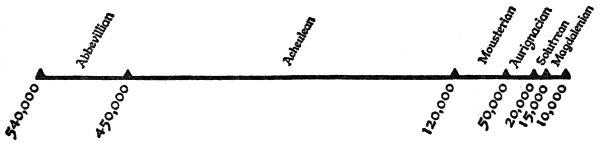

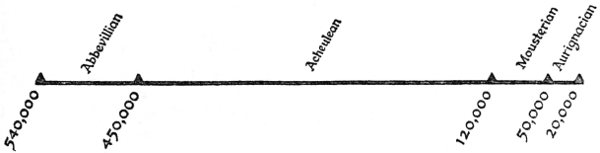

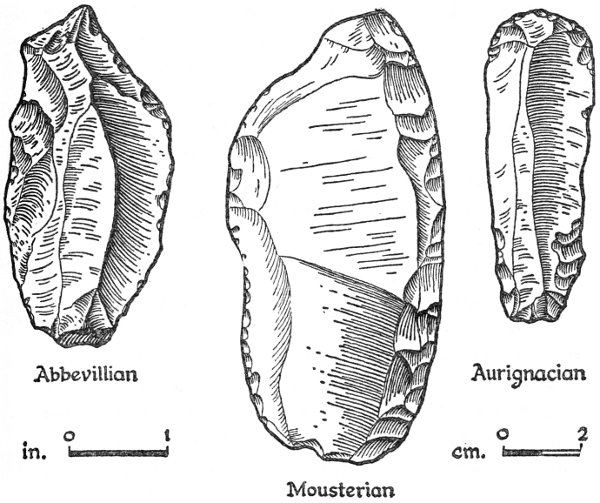

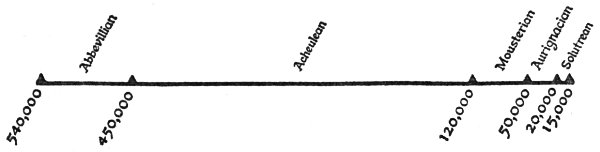

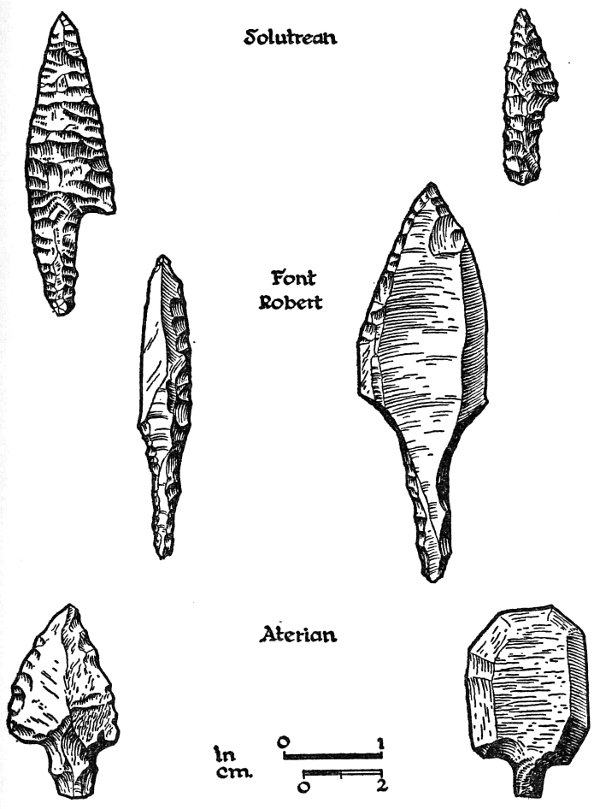

Progress is slow in the stone age. It seems to have been particularly slow in the Old Stone Age, or paleolithic period, when man spent half a million to a million 8 years learning to chip stone and hunt and gather food efficiently. Things went much faster in the New Stone Age, or neolithic period, when he was learning to cultivate plants and make pottery and polish stone tools. To move from the beginnings of agriculture to the beginnings of metallurgy, which superseded the neolithic, may have taken as little as 700 years in the Old World and certainly not much more than 4,000 or 5,000.

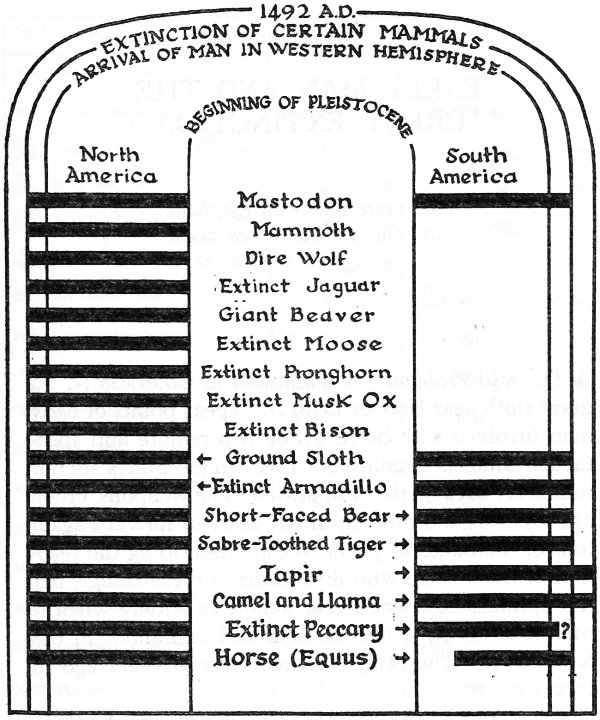

Progress was slower in the New World. The Indian reached the neolithic stage later, and he may have stayed in it longer than man did in the Old World. This can probably be blamed on the peculiar fauna of the western hemisphere. In all of the Americas there were no suitable animals to domesticate except the dog—which the Indian probably brought with him—and those dubious objects of husbandry, the turkey, the bee, the Muscovy duck, the llama, the alpaca, the vicuña, and the guinea pig. Because there were no sheep or cattle, the Indian had no pastoral life and no milk and butter. He had no beasts of burden except the dog and the llama; he invented no wheeled cart. It was not entirely his own fault that he remained essentially a man of the stone age even though, toward the last, he had perfected a metallurgy of copper, silver, gold, platinum, and bronze.

The story of the Indian’s spread through the Americas, his variation in language and physique, and his building of the civilizations of Peru, Central America, and Mexico argues that he came to the New World many millenniums before the birth of Christ. You may point out that the argument is too general, too inexact in outcome, but you must remember that behind the Indian lies an earlier migrant. We are on somewhat firmer ground when we turn to the evidence we have of this migrant’s tools, his hearths, and his bones. For sometimes they are related to the fossils of extinct 9 mammals and—more important—to certain kinds of earth, charcoal and rock that can be dated.

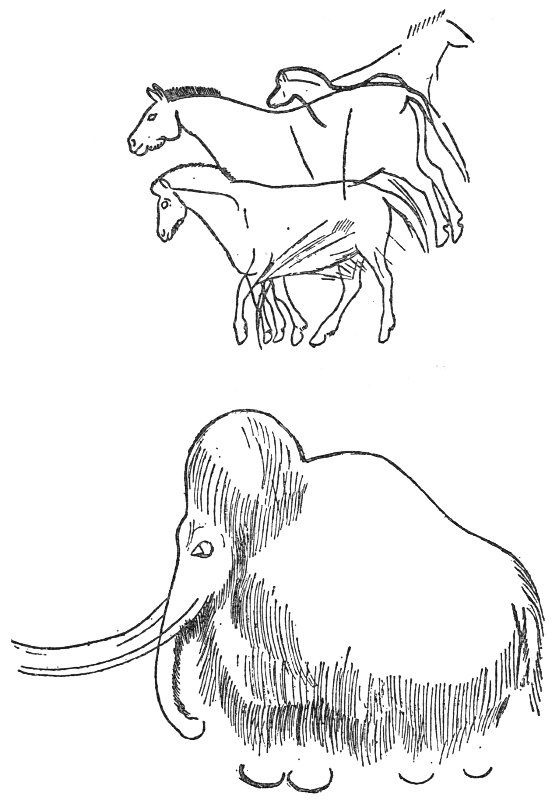

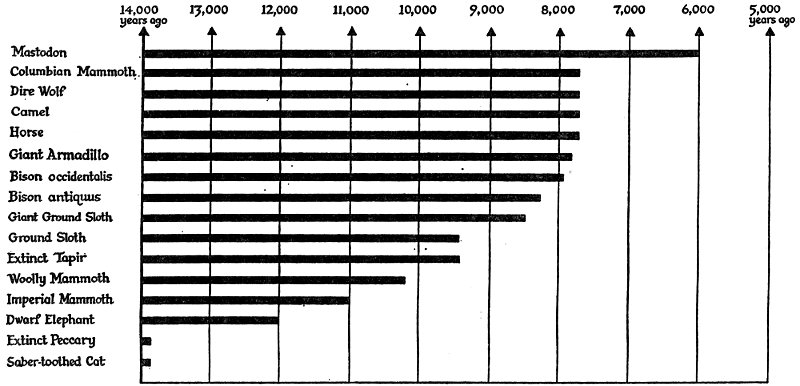

The tools and the hearths and the fossils are plentiful, and some years ago this proof of man’s antiquity seemed to be enough. The great and spectacular mammals whose remains were associated with early man in the Americas, as well as in Europe, were thought to have vanished with the glaciers of the Great Ice Age. Therefore, early man in the Americas must also have lived in that period. Now, however, a number of scientists believe that the American mastodon, along with a number of other animals that are now extinct in the New World, survived the Great Ice Age here. This would still leave us with an American whose antiquity is quite respectable.

The best proof of the age of early man was for a long time geological. Archaeologists dated man by the earth and rocks in which they found his tools or his bones. Unfortunately, they had not too much geological evidence in the Americas. In the past ten years, however, radiocarbon (of which you will learn more later) has made it possible to know much about when man reached the New World and where he lived.

I have been a stranger in a strange land. —EXODUS 2:22

We moderns were not the first to ask the question: Just how new was the New World on October 12, 1492? Or how old?

For a time, it was a very ancient world to the Spaniards. It was the Indies of the East, and they thought they had discovered nothing more than a new way of getting at them. Some years passed before they awoke to the fact that they had found a new continent. There may, of course, have been suspicions from the first. Certainly the tropical trees and plants were new; the animals, too, all except man. Man was an Indian—that is, an East Indian. Balboa may have had a “wild surmise,” but it remained for later Spaniards, as well as the Portuguese, to find in South America a land that could not be Asia. Columbus discovered the New World and thought it was India; the Italian Amerigo Vespucci did not discover the continent named for him, but at least he knew it was not India and gave it a name of its own—Mundus Novus.

Then, indeed, our world became a new world, and a world freighted with a problem. The problem was how to put its inhabitants into a proper theological—and 12 ethnological—pigeonhole. As a new and unknown being, the Indian presented a serious issue to the Catholic Church and its clerical and imperial pioneers. Here was a people of whom the Bible made no mention. Shem, Ham, and Japheth had filled three continents very handily, but they had somehow neglected this one. Established authority had no explanation for these new men. Were they, indeed, beings without souls? “While the New World with its gold and other riches was accepted as reality,” observes N. C. Nelson, “the truly human nature of its inhabitants was temporarily held in doubt.”[1]

Soon, however, the church found an explanation. The Bible mentioned no separate creation in an American Garden of Eden; therefore the forebears of the red man must have come from the Old World. As early as 1512 Pope Julius II declared officially that the Indians were descended from Adam and Eve. For many years thereafter they were considered as children of Babel driven back into the stone age because of their sins.

In 1590—not quite a hundred years after Columbus’s discovery—a Spanish cleric, José de Acosta, put on paper an ingenious theory for the populating of the Americas. In an English translation of 1604, it reads:

It is not likely that there was another Noes Arke, by the which men might be transported into the Indies, and much lesse any Angell to carie the first man to this new world, holding him by the haire of the head, like to the Prophet Abacuc.... I conclude then, that it is likely the first that came to the Indies was by ship-wracke and tempest of wether.[2]

But Acosta felt the need of a land route to take care of the animals. Noah had let them out of the Ark in western Asia, and they could hardly be expected to sail or even to swim to America. And so Acosta ventured 13 the opinion that somewhere in the north explorers would ultimately find a portion of America that joined with some corner of the Old World, or at any rate was “not altogether severed and disjoined” from it. In this way the animals—and man—had come to the New World.

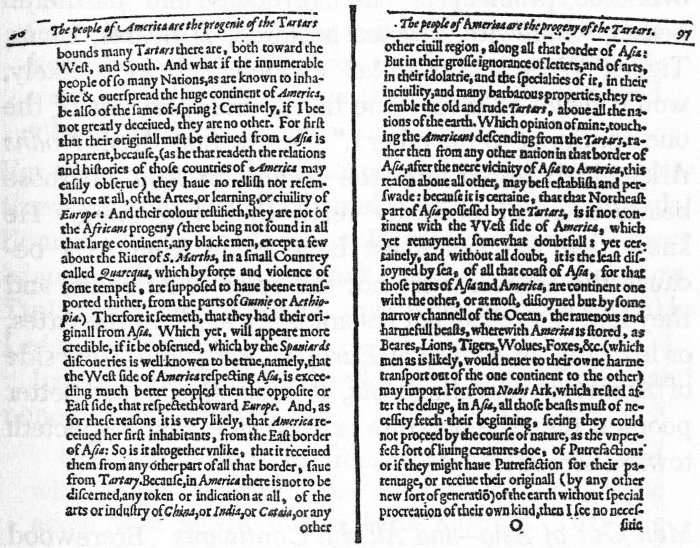

OUT OF NOAH’S ARK AND OVER BERING STRAIT

Two pages from Brerewood’s seventeenth-century book Enquiries Touching the Diversity of Languages, and Religions, Through the Chief Parts of the World, in which he pictures bears and Tartars crossing to the New World at a point where Asia and America “are continent one with the other, or at most, disioyned but by some narrow channell of the Ocean.” (Courtesy of the University of California, Los Angeles, Library.)

God-fearing Protestants from England joined clerics of the Roman church in bringing the American aborigine over from Asia. Long before any white man had stared across Bering Strait from the eastern tip of Asia and discovered Alaska, sixteenth and seventeenth century 14 men were envisioning the neighborliness of the two continents and an easy crossing. It had to be. There was no escaping this solution. Men from Eden could be trusted to force their way across the widest and wildest of oceans, but not animals from Ararat. In 1614 Edward Brerewood worried, like Father de Acosta, over the problem of “the ravenous and harmefull beasts, wherewith America is stored, as Beares, Lions, Tigers, Wolves, Foxes, &c. (which men as is likely, would never to their owne harme transport out of the one continent to the other).” He saw that “from Noahs Ark, which rested after the deluge, in Asia, all those beasts must of necessity fetch their beginning.” He knew that the men must have come from Asia because the Indians were not the color of Africans, and they had “no rellish nor resemblance at all, of the Artes, or learning, or civility of Europe.” Also, “the West side of America respecting Asia, is exceeding much better peopled then the opposite or East side, that respecteth toward Europe.”

Brerewood moved on from the questions of how and whence to who. With considerable hardihood, this learned Englishman picked a single Asiatic race to supply the Indian with a forebear. Looking askance at the inhabitants of America, he wrote: “In their grosse ignorance of letters, and of arts, in their idolatrie, and the specialties of it, in their incivility, and many barbarous properties, they resemble the old and rude Tartars, above all the nations of the earth.”[3]

Brerewood’s reasoning was logic itself and his conclusion inescapable compared with much of the theorizing of his day and much more that went on for three hundred years after the discovery of America. In 1607 15 Fray Gregorio Garcia published a book, The Origin of the Indians of the New World, in which appeared these words:

The Indians proceed neither from one nation or people, nor have they come from one part alone of the Old World, or by the same road, or at the same time, in the same way, or for the same reasons; some have probably descended from the Carthaginians, others from the Ten Lost Tribes and other Israelites, others from the lost Atlantis, from the Greeks, and Phoenicians, and still others from the Chinese, Tartars, and other groups.[4]

For good measure, Fray García and his fellow theorists threw in men of Ophir and Tarsus, old Spaniards, Romans, Japanese, Koreans, Egyptians, Moors, Canary Islanders, Ethiopians, French, English, Irish, Germans, Trojans, Danes, Frisians, and Norsemen—a veritable League of Nations.

Iconoclastic Voltaire would have none of this—and none of Eden, either:

Can it still be asked from whence came the men who people America? The same question might be asked with regard to the Terra Australis. They are much farther distant from the port which Columbus set out from, than the Antilles. Men and beasts have been found in all parts of the earth that are inhabitable. Who placed them there? We have already answered He that caused the grass to grow in the fields; and it is no more surprising to find men in America, than it is to find flies there.[5]

The more or less scientific minds of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were no less prodigal in theory than the clerics and the philosophers of the seventeenth and eighteenth. Sometime in the 1820’s Lord Kingsborough, son of an Irish peer of great wealth, got it into his head that the Lost Tribes of Israel were the ancestors of the Maya and the Aztecs—the same idea that animated Joseph Smith and The Book of Mormon; and 16 in 1830—the very year that Smith’s American supplement to the Bible appeared—Kingsborough began the publication of the nine monumental and handsomely illustrated volumes, Antiquities of Mexico, which cost him £25,000 and ultimately—like Smith—his life. Quite as eccentric theories followed. The otherwise sound and observant George Catlin thought the Mandan Indians the descendants of the Welsh. The “lost continent” of Mu—the Atlantis of the Pacific—reared its ugly head. Elliot Smith left the teaching of anatomy, and W. J. Perry cultural anthropology and comparative religions, to bring from Egypt all the culture of America—together with most of Eurasia’s and Africa’s—on the backs of those indefatigable travelers of their invention, the Children of the Sun.

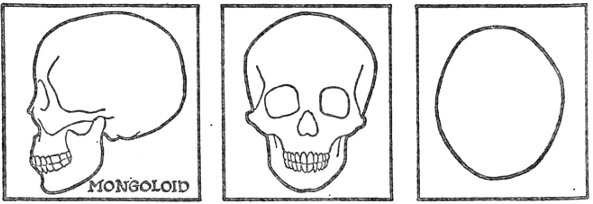

In the face of such wild theorizing it is comforting to recall that the great Humboldt recognized as early as 1811 a “striking analogy between the Americans and the Mongol race.” We must pardon him for clinging to some vague notion of a primordial American race and declaring that the Indians were “a mixture of Asiatic tribes and the aborigines of this vast continent.”[6]

Today science does not have all the answers to the anthropological problem which arose when Balboa discovered the Pacific and Magellan crossed it, thus dropping the world’s largest ocean in between the Americas and the Garden of Eden. So far as early man is concerned, we know a good deal about how he came, and whence, and a little about when.

Except for the passionate protagonists of Atlantis and of its “opposite number,” the mythical land of Mu lost in the depths of the Pacific, most students agree that early man came across what is now Bering Strait—not by way of the Aleutians, for their inhospitable western tip is separated from Asia by 225 miles of sea with one small island midway between. For a long time, the Bering Strait route was supported only by 17 a priori reasoning, but of late years the weapons of early man have been found either alone or with the fossils of extinct mammals in parts of Alaska and north-west Canada.

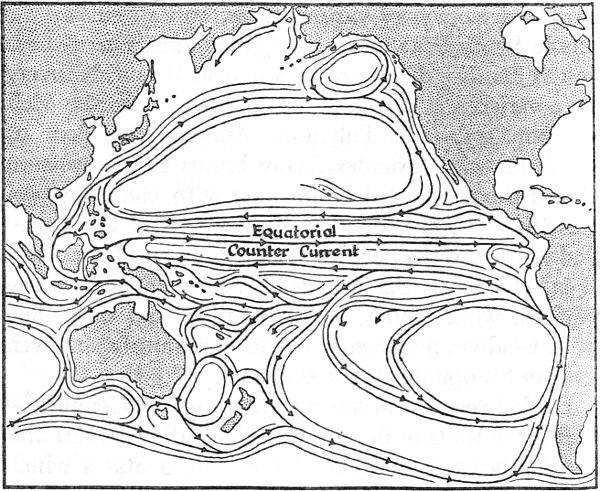

Though early man from northern Asia certainly crossed in one area and in one area only, he may have made the crossing by any one of three methods. That depends on when he came.

If he came rather late—say around 10,000 years ago—he had to negotiate Bering Strait, open water in summer, iced over in winter. If the migrants were a boating and fishing people voyaging north along the Asiatic shore, the 56-mile gap of Bering Strait, broken by the Diomede Islands, was a negligible barrier, since the greatest stretch of open water was only 23 miles across. If they found the strait frozen over, they would have followed the southern edge of the ice. Men of a more inland type, men less given to water travel, could have crossed to Alaska—as some do now—on the ice of winter.

If early man first came to the New World in the Great Ice Age or in the time when the glaciers were beginning to melt, he could have crossed dry-shod on a land-bridge. Geologists have calculated that the water withdrawn from the ocean to form the glaciers—which were half a mile to two miles thick over much of Canada and the northern portion of the United States—would have lowered the water level in the Bering Strait region by as much as 200 to 300 feet toward the end of the Great Ice Age.[7] In addition, the ocean floor of the strait—relieved of so much weight of water—would doubtless have risen to some extent. Since, at present, portions of the strait reaching from shore to shore are not more than 120 feet deep, a land-bridge is a perfectly plausible hypothesis. Of course the bridge 18 would have disappeared with the end of the glaciers, which means that, if man had to come over dry-shod in the summer, he must have invaded America while the glaciers were still fairly extensive.

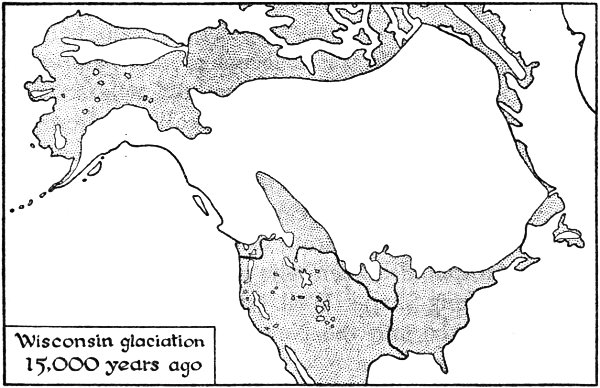

THE LAND-BRIDGE TO THE NEW WORLD

A conservative map of shorelines during the last glaciation, based on a drop in sea level of 180 feet. Geologists believe that the ice impounded in the great glaciers and ice fields of the world lowered the ocean 200 to 300 feet. The southern shore of Alaska during the last glaciation may have been much nearer its present position. (After Johnston, 1933.)

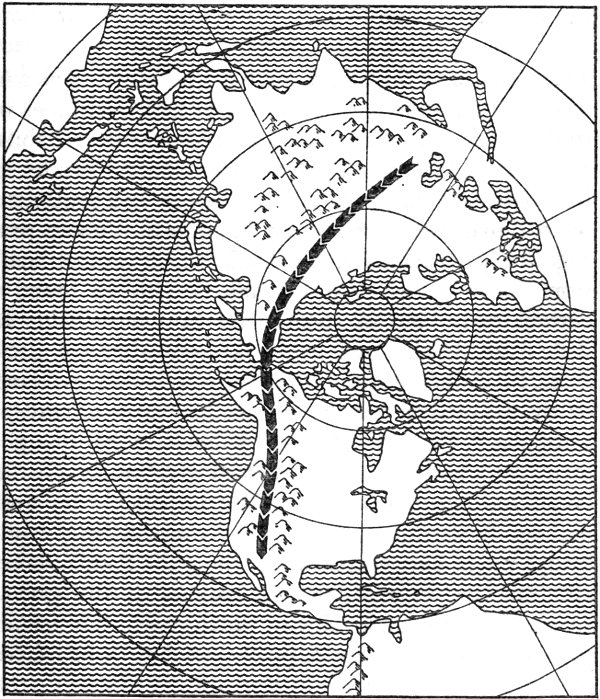

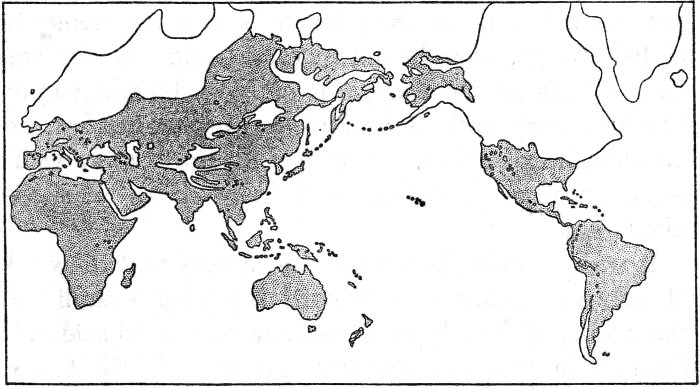

A GREAT-CIRCLE ROUTE TO NORTH AMERICA

On the flat, distorted map of Mercator, on page 4, the path of early man across Asia to the New World seems a roundabout curve. On a globe, it is very nearly a great circle. This is indicated on a map such as this, projected from a point above the North Pole. From above Bering Strait, the route would appear still straighter.

Aleš Hrdlička has said that not many men would have frequented northeastern Siberia because of its inhospitable climate, and so only a few would have “trickled over.”[8] The opposite seems to have been true in the time of the glaciers. Then northeastern Asia was an excellent jumping-off place for the Old World migrant. In the first place, there was not much glaciation in this area, certainly nothing to interfere with the passage of people along the coast. The last glaciation was “far less extensive than its predecessor,” say R. F. Flint and H. G. Dorsey, “and was confined to the higher parts of the higher mountain ranges.”[9] Secondly, the land-bridge, which made crossing easy, also altered the 20 climate of Siberia south of the bridge.[10] It cut off the arctic currents and therefore to some extent the arctic damp which now makes the Asiatic coast inhospitable. Hrdlička—one of the first and most violent opponents of early man in America—said that the land-bridge was not essential. Even if it had existed, “man would not have used it, but would have followed the much easier route over the water.”[11]

Once in Alaska, man—early or not so early—had a number of routes to choose from. If he was of maritime habits, and crossed by water, he would have tended to stick to his boats, and sail or paddle southward and southeastward down the coast and on through the inland passages of lower Alaska and Canada which protect boats from ocean storms. When Frank C. Hibben found a certain early kind of spear point in a curio shop in Ketchikan, Alaska, and on the far-away shore of Cook Inlet, he called attention to a route—whether overland or by sea—which hardly anyone had stressed except Hrdlička.[12] Hrdlička stressed it because he brought man over after the glaciers and in boats. But even in the Great Ice Age this route was not impossible for men without boats. Migrants who had crossed by a land-bridge might have turned south along the Pacific shore, climbing and crossing the ice barriers of the glacial rivers that still slide slowly down from the inland mountains. Philip S. Smith points out that “ice surfaces allow fully as easy travel by sled and on foot as do the ordinary land surfaces.”[13] But was there game, as well as fish, along the coast to lure the migrant on and to sustain him upon the journey?

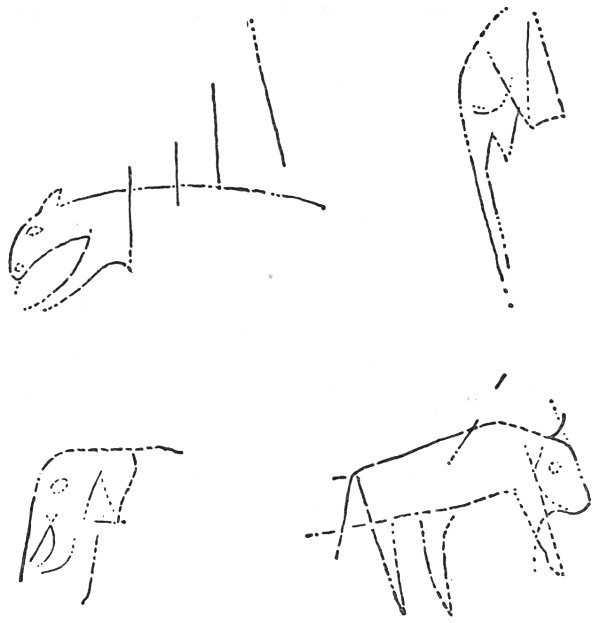

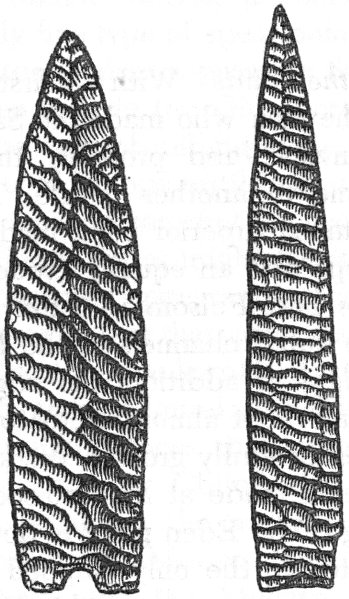

Other men seem to have chosen to tramp and hunt eastward and northeastward from the strait. In this direction there were two main routes open to men and game. One route led up the narrow lowlands of the 21 northwest coast to the mouth of the Mackenzie River and then south up its long valley. The other, and much more likely path for early man, was up the ice-free Yukon and its tributaries. These would have taken him eastward to the Mackenzie or southward through the plateau between the northern Rockies and the Coastal Range. Hrdlička thought the Yukon valley a most unpromising route because of the turbulent rivers and the noxious insects; but most students disagree with him and stress the abundance of fish and game. There can be no question that some parts of this route were used by early man—and extinct mammals, too. His ancient spear points have been found in the muck beds of Fairbanks mingled with the fossilized bones of elephant, bison, camel, horse, and an extinct jaguar once called the Alaskan lion.[14] Other early points have been discovered in western Canada in the area of the mountain plateau. In 1944 Frederick Johnson located fifteen camp sites in early soil levels along the route of the plateau corridor and found many varieties of artifacts. Among these were a few points, most of them fragmentary, the butts of which resembled those of an early type.[15] Following Johnson in 1945, Douglas Leechman found other sites and artifacts along this route in soils formed perhaps 9,000 years ago.[16]

The Yukon valley rivers could have taken early man to the Mackenzie and to the northern edge of the plateau; but during a large part of the Great Ice Age he still faced the gigantic fields of snow and ice that covered half of North America. Although ice journeys may not be so very difficult, and early man had learned to live in the chill of northern Siberia (the Eskimo of today proves that human existence is possible in a land of little sun and much cold), we cannot believe that he attempted to cross the icy wastes. A journey on foot across a thousand or two thousand miles of ice becomes a sheer impossibility if there is no provender to be found along the way. There was certainly no food for musk ox or mammoth, and therefore no food for man. Without game to hunt, he would not have felt the impulse to invade the ice fields.

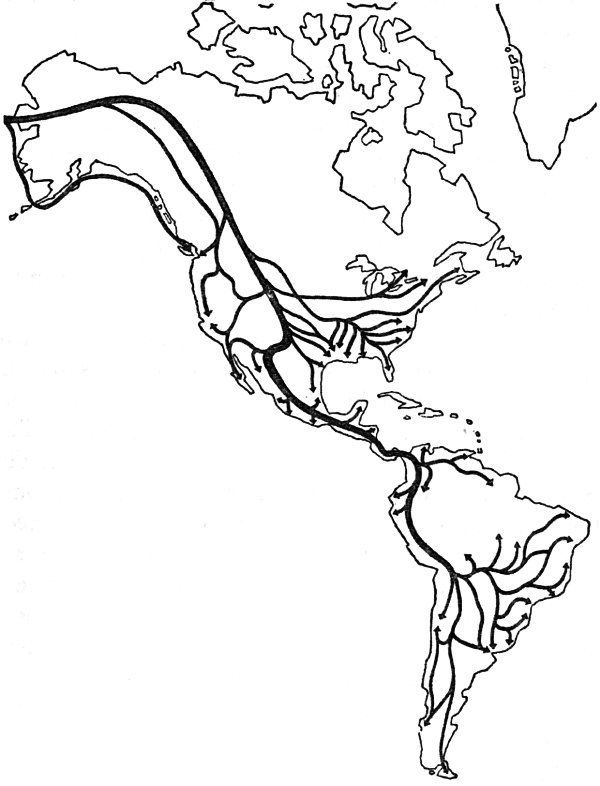

MIGRATION ROUTES

The pathways available to early man, as mapped by Carl Sauer—to which have been added a problematical route by sea along the southern coast of Alaska and another down the corridor between the eastern Rockies in Canada and the coastal range. (After Sauer, 1944.)

Too many authorities have written as if early man made a free choice of routes through Alaska and Canada. Actually, the animals he hunted chose his route for him—doubtless many routes. Unless he had learned to spear and net fish, the first invader probably pursued a herd of mammoth or musk ox across the land-bridge or over the frozen ice of later winters. You in your armchair are likely to suggest that, once man was in Alaska, he turned south of his own free will and intelligence in order to avoid the cold. The first trouble with that line of thought is that man had gone north in Asia. The second is that primitive man had no conception of where south lay or of the possibility of greater comfort there. At this point, you will probably say that, though he had no ideas about the nature of the south, he had brains enough to follow the sun. Unfortunately this would have spun him round like a slow-motion teetotum; for he entered North America in the neighborhood of the Arctic Circle where the summer sun moves in a great low circle, and sinks out of sight when winter sets in.

If you want to understand early man, and guess with some accuracy at why he came to the New World and how he happened to drift southward and eastward until he filled it, you must think of him as a wanderer looking for food. Game lured him on at random, and vegetation lured both beast and man. Man might eat his way through caribou country, and come upon the bison of another area. As he killed and wandered, he might go south or he might go east. But the animal—and the man who ate berries and roots and wild grains as well as meat—would move as the climate moved. The world has known many changes of climate and 24 shifts of rain belts. Some of these have been extreme—in the Great Ice Age, for example—and some have been less marked. But they have moved the forests and the grasslands, and animals and man have moved with the vegetation.

During the past 100,000 years, glacialists believe that there were three periods when the inland ice melted sufficiently to allow the southward passage of both animals and man. The first was more than 75,000 years ago in the Sangamon Interglacial period before the time when the last, or Wisconsin, glaciation had covered the plains of Canada (see pages 26 and 27). During the Wisconsin, a corridor probably opened about 50,000 years ago along the eastern foothills of the Rockies, and another, perhaps a little later, down the plateau between the northern Rockies and the Coast Range. The third opportunity for man to penetrate from the north came around 11,000 years ago, when the final retreat of the ice sheets began in those same regions.[17] Perhaps the land-bridge was still usable up to 10,000 years ago, but certainly later migrants had to cross Bering Strait by water or winter ice.

Bering Strait and the great glaciers were not the only obstacles to the peopling of the Americas. The Isthmus of Panama must have presented quite a problem to the pioneers who were to fill Amazonia and the Andean Highlands and to reach Cape Horn. Today nobody sets off blithely by foot through the jungle that separates Costa Rica from Colombia. The beach is the best pathway at low tide; but it is an intermittent one. It is better to hope that the shifts of climate which were involved with the glaciers made Panama a drier country than it is today.

Of course it was not only early man and his prey that used the routes from Siberia across Bering Strait and through Alaska and Canada. The later migrants—ancestors 25 of the Algonquins, the Athapascans, and others—undoubtedly came in the same way.

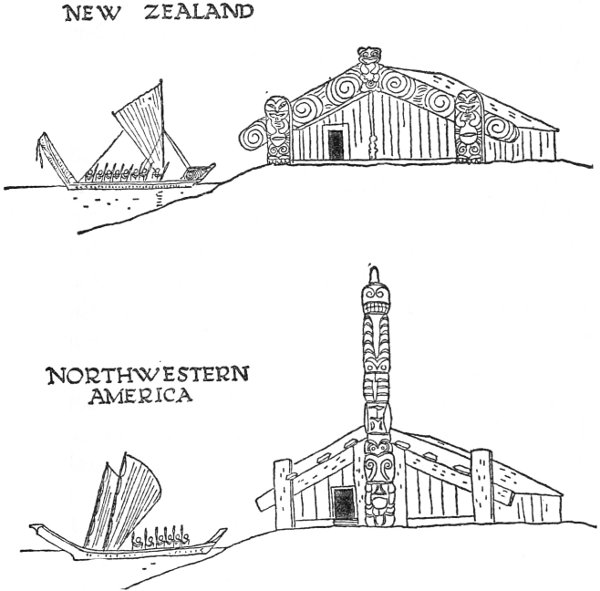

Other routes from other lands may have brought other migrants. These routes are not so fanciful as the paths from Atlantis and Mu, but they have had few advocates. M. R. Harrington has mentioned the possibility that Magdalenian man of Glacial or Postglacial Europe may have crossed from Europe to Canada by way of Iceland and Greenland and various ice- and land-bridges to father the Eskimo.[18] Ellsworth Huntington adds to the land-bridge over Bering Strait “wind-bridges” across the middle Atlantic.[19] Like Father de Acosta, he believes that storms may have blown occasional vessels to the New World. To suggest that unwilling mariners from the Mediterranean may thus have made oneway trips, he cites from Stansbury Hagar[20] striking resemblances between the zodiacs of Europeans and of the Mayas, Aztecs, and even Peruvians. Whether this matter of the zodiacs is fact or fancy, Huntington’s unwilling voyagers could not have come much earlier than the birth of Christ. More fantastic were the claims voiced some years ago that the men who left skulls of Australoid or Melanesian type in the caves of South America reached that continent by a southern route across an Antarctic bridge of land and ice. Of much more serious importance is the possibility that the long-voyaging Polynesians, having negotiated the 5,000 or 6,000 miles that lay between their home on the edge of Asia and the Marquesas or Easter Island, would have tried occasionally to continue their eastward course. If they had done so, they could scarcely have missed South America. But this was in our own era, not in the time of early man.

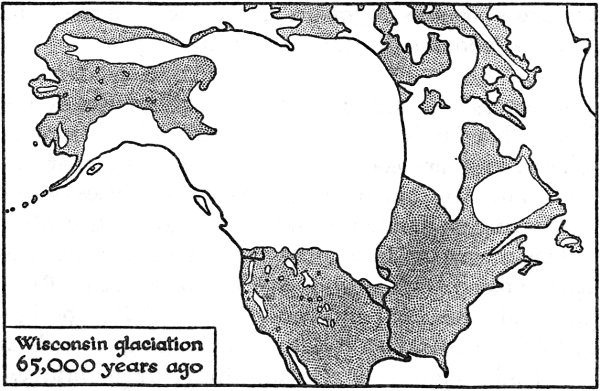

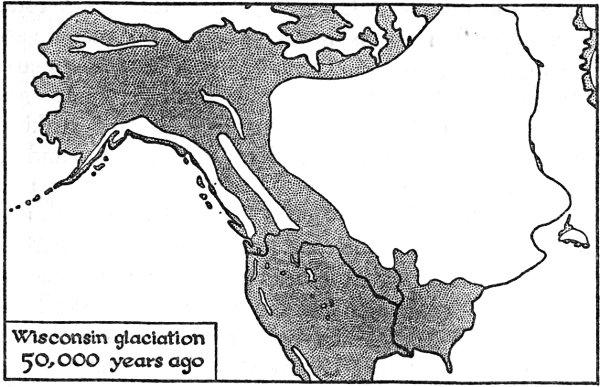

GLACIERS AND ICE FIELDS AS BARRIERS TO EARLY MAN

These maps follow the outlines of the continent today, and so do not show the land-bridge from Alaska to Siberia that existed in varying extent throughout the entire Wisconsin period. The maps indicate tentatively how the great white ice fields may have appeared to different areas at different times, producing an effect of shifting from west to east and then back across the continent. Drawn in 1936, the first three maps probably show too little ice in arctic Canada and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Newfoundland region. (After Antevs; the first three in Gladwin, 1937, the fourth from data furnished by Antevs.)

Wisconsin glaciation 65,000 years ago

Wisconsin glaciation 50,000 years ago

Wisconsin glaciation 15,000 years ago

Wisconsin glaciation 10,000 years ago

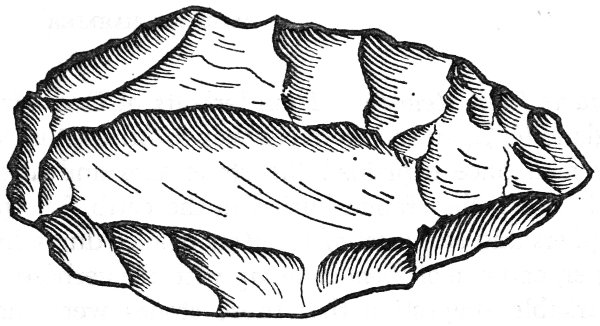

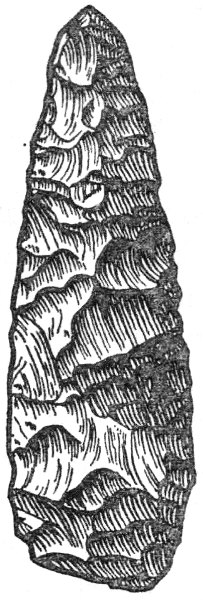

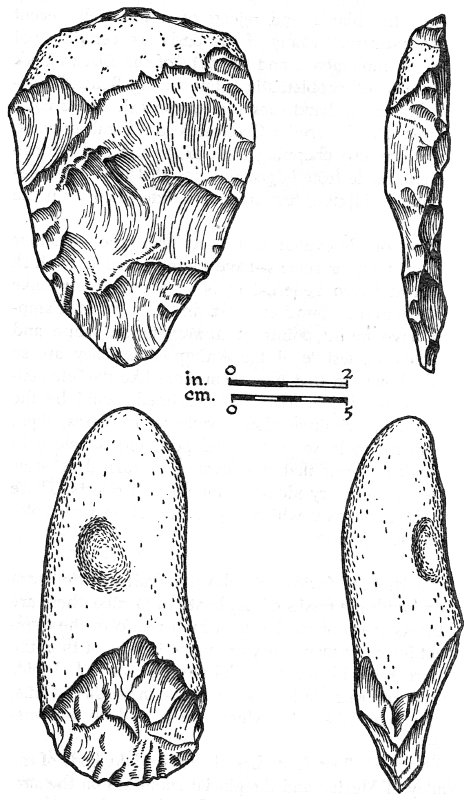

Today we have a few facts about early man and many guesses. Not so long ago there were a few reputable anthropologists who believed that the New World was innocent of man before 1000 B.C. Now most of them grant a foothold at least 10,000 years ago to an enterprising savage—called Folsom man—whose taste for travel was as great as his talent for making an exceptionally fine and original type of stone spear point. Some say he came to the New World 25,000 years ago. A few daring students find traces of an earlier Australoid human who may have seen the last glaciers taking shape. Well informed opinion places man’s entrance into the New World between 10,000 and 25,000 years ago.

Of course we must not expect early dates to be precise. Many of them must be intelligent guesses as we go deeper and deeper into the past and reach the time when the glaciers were waxing and waning. To gain a perspective upon such toying with time—as well as upon early man in the Americas—we must next consider the story of early man in the Old World. Incidentally, its contradictions and uncertainties—prefaced by a few in New World prehistory—may help you to look with a charitable as well as critical eye upon certain theories about the peopling of the Americas which may be suspect today yet respectable tomorrow.

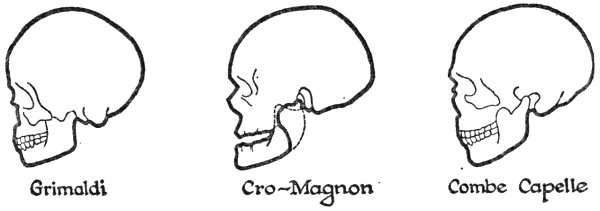

... systems into ruin hurl’d. —ALEXANDER POPE

The authors are afraid that it may be a little hard for you, dear reader, to shake yourself out of the late Victorianism of your schoolbooks and accept the idea that someone discovered America at least 14,092 years before Columbus. It may be still harder for you to believe that he was not that noble yet very vague red man whom you and your teachers called the American Indian. Certainly you will be shocked to hear that two or three anthropologists of note believe he had more than a touch of Negroid or Australoid blood. Your horror will be no greater, however, than that of a few of our archaeologists; such notions give them what might be called Victorian vapors. Some accept ideas like these; others keep an open mind, for they remember that many a scientific fact of today was sheer nonsense to earlier generations, and vice versa.

As late as 1900, the prehistory of Mexico was accounted for very neatly by three successive words, Toltec, Chichimec, and Aztec. Now we know other words, and we know that other peoples and other cultures—Olmec, Zapotec, Mixtec, Totonac, Tarascan, Teotihuacan—also 30 played an important part. We divided the Maya just as neatly into the Old Empire and the New, one south and the other north. Now we know that there were no empires, and that the Maya culture grew widely and steadily towards fruition and decay. Once we thought that the Itzá were the Maya that founded Chichén-Itzá in Yucatan. Now we give the name Itzá to the Toltec or Toltec-influenced invaders that came hundreds of years later. Once scientists disputed whether culture and agriculture began in the highlands of Mexico or in the highlands of Peru. Now certain of them believe that the American became a farmer in the lowlands east of the Andes, while others think he began to till the soil in many spots at the same time. Only a few years ago, we thought that a fairly recent Indian culture—which is called the Woodland Pattern of the eastern United States—had its roots in Middle America. Now its pottery is being traced back through northwestern Canada and northern Asia to the Baltic and even perhaps to Africa.[1] The Mound Builders were once thought an ancient people. Now some of them seem barely to antedate the discovery of America. Bernal Díaz del Castillo—best of the chroniclers of the conquest of Mexico—may have observed that the Mexicans, along with all the Indians of the New World, were ignorant of the principle of the wheel; certainly this has been repeated over and over again for many years. Yet in 1888 Désiré Charnay reported and pictured a Mexican pottery toy with wheels, and since then more of these toys have been found.[2] Throughout his life Roland B. Dixon denied the possibility of productive transpacific migration from Polynesia to South America; yet at the end he accepted the transfer of the sweet potato from South America to Polynesia. From important matters to trivia, the list is long; we have hardly touched it. Obviously, prehistory is not a field where truth is easily and 31 quickly come upon. The student, quite as much as the scientist, must keep an open mind. He must neither cherish dogma nor refuse speculation. Truth still lies afar off.

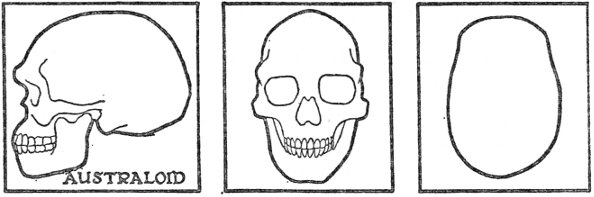

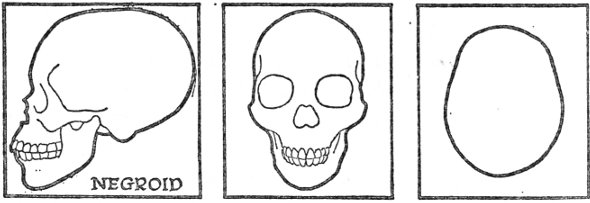

Doubts about early man in the Americas seem to have been an occupational disease with archaeologists. Geologists have found it much easier to accept him. Men like Ernst Antevs, M. M. Leighton, Kirk Bryan, and Albrecht Penck, perhaps because they are accustomed to dealing generously with time, seem to have little trouble in embracing early man as a Late Glacial interloper anywhere from 15,000 to 100,000 years ago. Physical anthropologists like Earnest A. Hooton and Sir Arthur Keith, and cultural anthropologists and ethnologists like Roland Dixon and A. C. Haddon are not at all afraid to recognize signs of Australoid or Negroid ancestry in the skulls of New World man. Perhaps it is easier for the geologists and the physical anthropologists to accept such ideas because they do not run counter to their own dogmas. Many archaeologists, at any rate, find it extraordinarily hard to adjust themselves to evidence which does not fit accepted theories. They may defend themselves by pointing out that the evidence is not too clear, or at best is merely suggestive; but the theories they cherish arose from no firmer evidence in many cases, and frequently continue quite as unclear or at best merely suggestive. Certainly such reluctance to accept new evidence held back archaeological research when Aleš Hrdlička, W. H. Holmes, and Daniel G. Brinton were in their heyday.

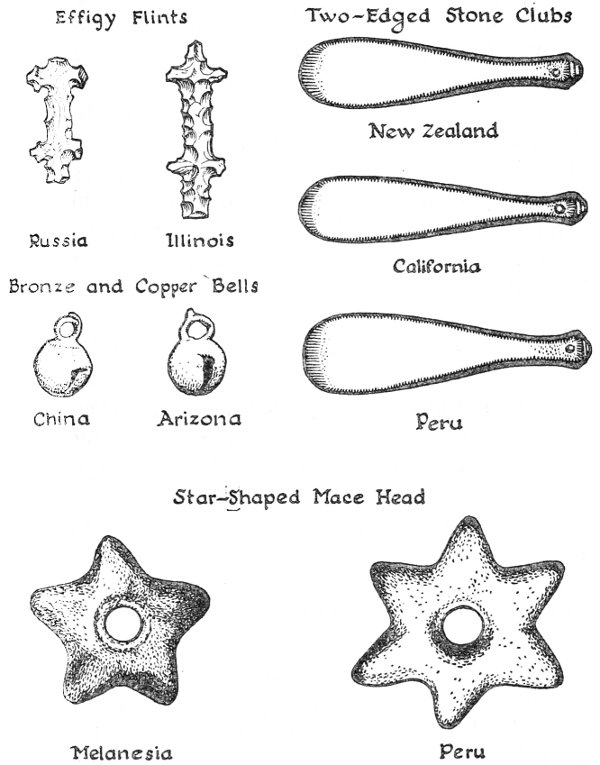

This reluctance to face facts permeated even so great and productive a man as Baron Erland Nordenskiöld. An example of such a Jovian nod may be salutary. Arguing in The Copper and Bronze Ages in South America against the theory that the craft of metallurgy may have been brought to the New World by migrants, instead of having been invented here, three times he 32 cites facts that contradict his thesis, and three times he offers a kind of self-conscious apology for blinking them. (The italics are ours.)

If we go through all our material of weapons and tools of bronze and copper from South America, we must confess that there is not much that is entirely original, and that to the majority of fundamental types there is something to correspond in the Old World.

It must be confessed that there is considerable similarity between the metal technique of the New World and that of the Old during the Bronze Age.

Bronze is, of course, also a very hard invention, and I must confess to finding it most remarkable that the art of alloying tin and copper should have been hit upon independently both in the Old World and the New.[3]

“Admissions,” said Charles John Darling, “are mostly made by those who do not know their importance.”

Unfortunately there are still a few archaeologists whose attitude resembles Nordenskiöld’s. Hooton writes of one of these:

One of our most brilliant and once progressive archaeologists naïvely expressed to me some years ago his sentiments on this question [evidences of early man in America]. He said it would be a pity to have new evidence come to light which would overthrow all the admirable scientific work of the past indicating the recent arrival in the New World of the American Indian.[4]

Of course early man is not a subject that can hope to be free from error and contradiction—even early man in the Old World. Perhaps an account of some of the errors and misconceptions about him that crept into the study of prehistory may be as good a means as any 33 of preparing your mind for new facts or new heresies in the Americas.

The first confusion that confronts the student of early man is one of nomenclature. It is a by-product of the human animal’s inveterate and estimable love of system. Give us some new subject, such as prehistoric relics, and we immediately set up a scheme of classification. The scheme works beautifully for a while, but presently new evidence accumulates which doesn’t fit the framework. By that time, unfortunately, it is too late to change the classification. In vulgar parlance, it is our story, and we are stuck with it.

An outstanding example of this tendency to set up a classification system prematurely is the division of the story of man into ages. As far back as A.D. 52 a Chinese with a scientific bent of mind suggested that man had passed through three periods: a stone age, a bronze age, and an iron age. A French magistrate named Goguet wrote a book in 1758 in which he expounded a similar order of ages, inserting copper ahead of bronze. In 1813 a Dutch historian named Vedel-Simonsen argued for stone, bronze, and iron periods in Scandinavian history. A Dane, Christian Jurgensen Thomsen, gave the system permanent and indeed international status in 1836 when he arranged on this basis the exhibits of the institution he directed, the National Museum in Copenhagen.

The scheme is neat but far from scientific. To begin with a small matter, but one that may confuse the layman, the ages overlap. Bronze did not wholly replace stone; neither did iron. The use of chipped flint and polished stone continued into the Iron Age.

“Bronze Age” itself is a misnomer and a phantasm. While “Stone Age” and 34 “Iron Age” do define important culture periods—though not the only periods of man’s early activity—the Bronze Age, says T. A. Rickard, “represents a minor phase in the use of copper.”[5] This alloy is merely an incident in the much longer history of the first metal used by man. At the start copper seemed to him to be merely a soft stone. He beat it into ornaments. When he began to melt and cast the native metal instead of pounding it, he took the first step in the true use of metals; but when he smelted copper ore—turning a hard rock into a soft metal—he made himself the master of metallurgy. Bronze—at first an accidental mixing of copper and tin—was merely an episode along the way. “The superiority of copper or bronze over flint and stone tools is, I think,” says Gordon Childe, “generally overestimated. Not only for tilling the land but also for the execution of monumental carvings and even for shaving, the Egyptians of the Old Kingdom were apparently content with stone.”[6]

The Bronze Age was very limited in area. Because of the rarity of tin, the primitive use of the alloy was confined to southern Europe, Asia Minor, and the Inca empire. Most of the world used iron before bronze. Furthermore, the Bronze Age is as delimited in time as it is in space. The earliest bronze in the Danube region is dated about 2300 B.C., and the earliest iron about 1350 B.C., at Gerar in Judea. “Thus,” said Rickard, “the so-called Bronze Age shrinks, at most, to a mere millennium ... the merest fraction of human existence.”[7]

The Iron Age is not so significant as it sounds. It was many centuries after the first use of iron and bronze that either played a really important part in the economic life of man. Like the domesticated horse, the trained elephant, and the wheeled vehicle, bronze and iron were first used chiefly in the making of war.

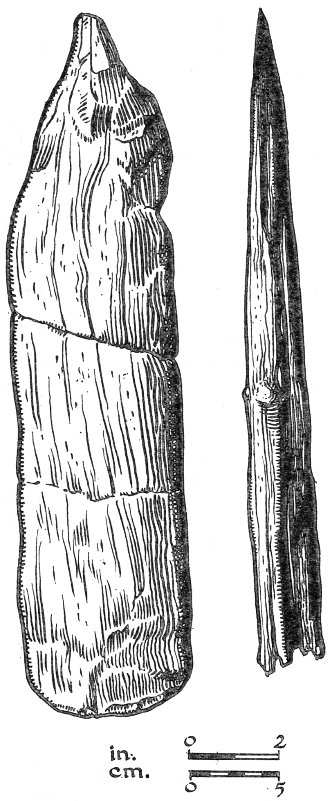

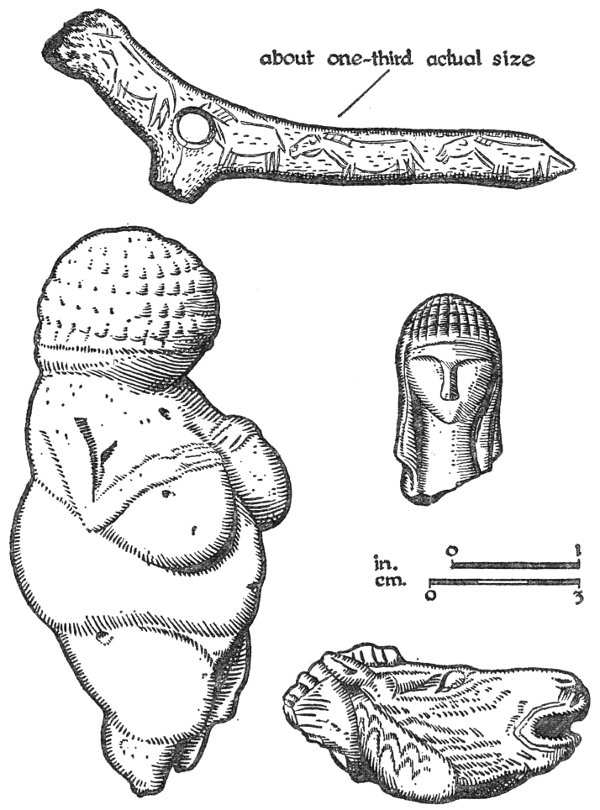

There is another serious 35 weakness in the Stone Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age sequence. It takes no account of the probability that man used wood, bone, and shell before he used stone. The ape swings a stick much as the first man must have done. The carcass of some bison or stag, picked clean by vultures, must have seemed to our earliest ancestors “a whole potential tool-shop”—as George R. Stewart writes in Man: An Autobiography—“thigh bones ready-made for clubs, horns or antlers for awls, shoulder-blades for scrapers.”[8] As early as 1864, a British student of anthropology, John Crawfurd, stood out against Thomsen’s Stone Age as the beginning of culture. At a meeting of the Ethnological Society, he said: “On man’s first appearance, the most obvious materials would consist of wood and bone.... This would constitute the wood and bone age, of which, from the perishable nature of the materials, we, of course, possess but slender records.”[9] Because the discovery of the stone artifacts of early man in Europe was then creating a scientific furore, Crawfurd’s sane observations went unnoticed. Today we have part of a wooden spear made, perhaps, far back in the Great Ice Age (see illustration, page 74).

Wood, bone, and shell not only antedated stone; they have continued in use until today. Certain primitive peoples—the Chukchi of Siberia, for example—retained the use of wood and bone after they were given iron.[10] Numerous tribes, when first encountered by explorers and navigators, had not yet begun to use stone; among these were the Aleuts, the Andaman Islanders, Malayans from the hills, and people of the upper Amazon.[11]

Rickard, from whom we have drawn liberally in this discussion, proposes a different scheme of classification for the cultures of man.[12] In the Primordial Age he would include the primary use of wood, bone, and shell. He would accept the Stone Age as the next stage. 36 For the Bronze and Iron ages he would substitute the Metallurgic Age, basing this on the discovery and use of smelting, whatever the metal involved. The dead hand of Thomsen, however, will probably continue to rule. The best we can do will be to take the Stone Age as including all materials except metal, and pay little attention to that illusion the Bronze Age.

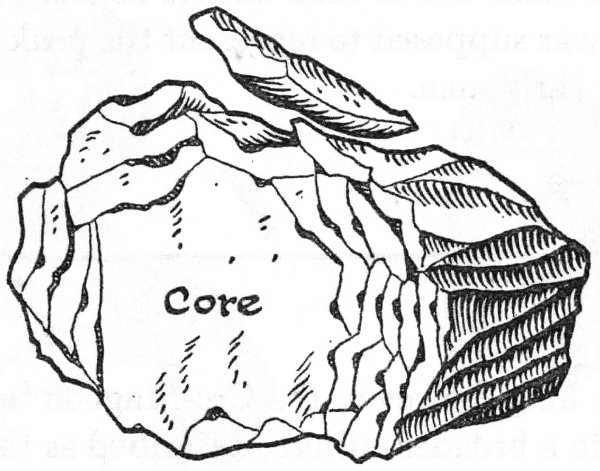

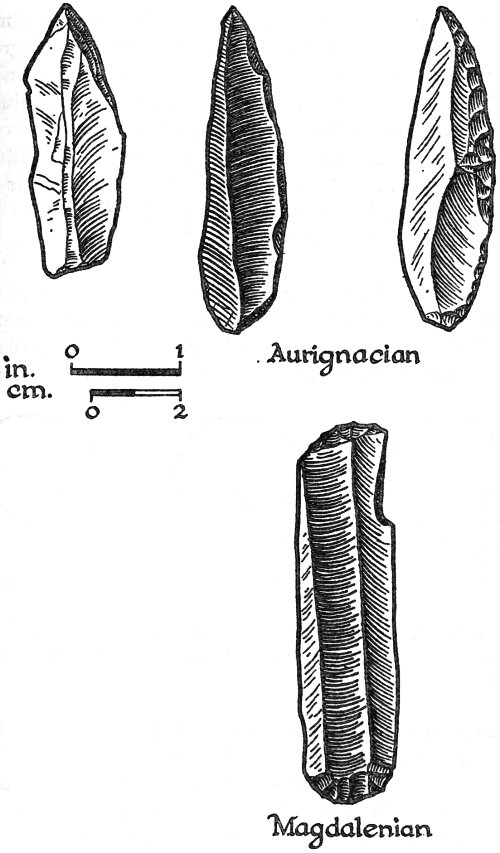

Still more conflict and confusion have resulted from attempts to divide the Stone Age into watertight compartments. In 1865 Sir John Lubbock proposed two divisions—the Paleolithic, or Old Stone Age—and the Neolithic, or New Stone Age.[13] The Paleolithic included objects found in caves and glacial gravels; the Neolithic, on the surface and in tombs. The first period ran from some vague beginning hundreds of thousands of years ago up to the advent of the Neolithic after the glaciers had melted. By definition, paleolithic man made chipped stone implements and no other kind. Neolithic man was supposed to be distinguished by the making of ground, or—as we usually say—polished, stone axes and of other tools shaped by rubbing instead of chipping; agriculture, pottery, and textiles came in as secondary traits.

After a time, however, archaeologists found some disturbing discrepancies. Before neolithic man grew grain and wove textiles, someone of an earlier age seems to have been making axes from antlers, turning out new artifacts called microliths—tiny chips of flint which were set in a row along a wooden or bone handle to make a kind of saw or a sickle—and also producing a partially polished ax with a ground edge, and making crude pots. This was all very upsetting to the old scheme of dividing prehistory into the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. So science inserted the Mesolithic, or 37 Middle Stone Age, between the two, in order to account for the appearance of the new tools.

The trouble with the system that Lubbock launched is that man’s behavior toward stone is a very poor basis for classifying him in culture or time. For a while it fitted our knowledge of the prehistory of Europe. Now it is out of line on that continent, and completely askew so far as the rest of the world is concerned. The kind of stone available often determines whether a man will chip or grind it. When first discovered, South Sea Islanders were still polishing stone because they had no flint.[14] Some Australian natives make chipped stone tools while their neighbors, who control a supply of diorite, go in for polishing; yet none of these Blackfellows can be considered as anything but paleolithic.

Like the Bronze Age, the Neolithic suffers from having shrunk in length. Rickard figures “that 700 years covers what was meant to be a major division of human chronology.”[15] To reach this figure he puts the end of the Paleolithic at 3000 B.C., which seems much too late, and the beginning of bronze at 2300. Even though we use the date of N. C. Nelson for the beginning of the Neolithic—5500 B.C.[16]—we have a New Stone Age of only 3,200 years.

Gordon Childe goes so far as to declare that “there is no such thing as a neolithic civilization.”[17] Different people, living under different climates and on different soils, have developed different elements of the culture of the New Stone Age and combined them with elements of other cultures.

If we are going to continue using the term Neolithic—as we certainly are—and if we want to limit it in some sensible way that may prove a bit more permanent, let us see what else than polished stone can be used to define it.

Three activities 38 stand out. They are the making of pots, the weaving of textiles, and the planting and harvesting of crops accompanied by the domestication of animals.

There can be no question that pottery is an important factor in neolithic life. It was in the New Stone Age that man fully wrought the miracle of “a sort of magic transubstantiation—the conversion of mud or dust into stone,” as Childe puts it. It was, as he says, “the earliest conscious utilization by man of a chemical change.”[18] But behind this miracle and this science must have lain many years of almost accidental, adventitious experiment. L. S. B. Leakey claims specimens of partially baked pottery sherds in paleolithic Africa.[19] One of these shows marks of basketry, rather thin support for the theory that the women who daubed the inside of the baskets to make them hold water must have discovered, when the baskets stood too near the fire, a little bit about how to bake clay. It was not until the invention of agriculture tied neolithic man more or less to the soil that true pottery could and did flourish widely. We have added many refinements to the craft of the potter—porcelain, cloisonné, and so forth—but basically it remains unchanged. Incidentally, all agriculturists did not have pottery—the Big Bend and Hueco cave dwellers of Texas, and certain people of the Virú valley in Peru, for example.[20]

The craft of textile weaving almost reached perfection at the hands of neolithic man—or, rather, woman. But it stemmed from basketry, and basketry undoubtedly began in the Paleolithic Age.

The first of two interesting facts suggested by the foregoing is that woman was the only true begetter of the Neolithic Age. She did the weaving—first of baskets and then of textiles—and she invented and practiced pottery making. More than that, she must be credited with the planting and harvesting of grain; for, while her lord and master enjoyed himself on the hunt, she 39 gathered fruits, nuts, and edible seeds, and sooner or later this led her to observe that seeds she carelessly dropped on the midden pile produced new and bigger plants. By so doing woman invented work; for early man was only an idler who gave himself intermittently to the pleasures of the chase. Woman also invented leisure—true, creative leisure—for out of agriculture rose a settled community and a surplus of provender which allowed the few to think and plan and build civilization.

The second fact is that agriculture seems to be the only sound test of the Neolithic. Pottery and weaving preceded agriculture, yet, without agriculture and its fixed communities and its leisure, pottery and weaving could not have reached perfection. As for the polished ax, it was handy enough in in-fighting; but it was of no practical social use until the farmer needed to cut down the trees which began to thrive all over the place when the glaciers disappeared. The Badarians of Egypt were farmers, yet they made no polished axes because there was almost no timber to cut.[21]

Speech was certainly the first great inventive triumph of primitive man. The making of fire ranks second. The third great invention, agriculture, was also the first industrial revolution; without it what we carelessly assume to be the industrial revolution would have been impossible.

Science feels sure that agriculture appeared in the Old World before it did in the New, but is not so certain as to where man first tilled the soil and when. James H. Breasted, Sr., put agriculture back to 18,000 B.C.; later writers push it up to 5000 B.C. There has been quite as much disagreement about the area where agriculture began. At first the valley of the Nile seemed to be the right spot, for every fall the flood 40 waters of the river brought not only automatic irrigation but also fresh, fertile soil to enrich the depleted farm lands. Soon, however, the birthplace of agriculture moved to the “fertile crescent” that stretched from Egypt to Mesopotamia. Later it shifted from the Tigris-Euphrates valley to the valley of the Indus. Now it seems to lie somewhere between these two, perhaps in the dry highlands of Iran and Iraq. In northern Iraq, 400 miles north of Ur, the wild ancestors of certain of our cultivated grains still grow, and excavators have come on evidences of farming communities which may be 8,000 to 11,000 years old.[22] There has always been hot argument between the supporters of denuded river valleys and the supporters of dry uplands as the natural site of early agriculture. Lately students have begun to argue for forested or jungle areas, and above all for mountain valleys; and they have plumped for tubers and melons, rather than grains, as the first crops cultivated by early man. These students see man as a gardener before he was a farmer.

Only the beginnings of agriculture are of any importance in a discussion of early man. Early man may invent agriculture, but thereupon he promptly ceases to be early man. With the food, leisure, and fixed abode that farming provides, he is soon inventing writing. He is then no longer even prehistoric.

It is important to realize and remember that early man ate seed grains, tubers, and fruit before he knew how to cultivate them. Probably he began to eat more and more of these natural products just before he became a farmer. Because archaeologists have found evidences that early man was quite a food gatherer at the end of his career, they have been inclined to set up another classification system which is faulty. They see man first as a hunter, then as a food gatherer who was still a 41 hunter, and then as a food producer. This ignores the very important fact that man began as a food gatherer and not as a hunter.

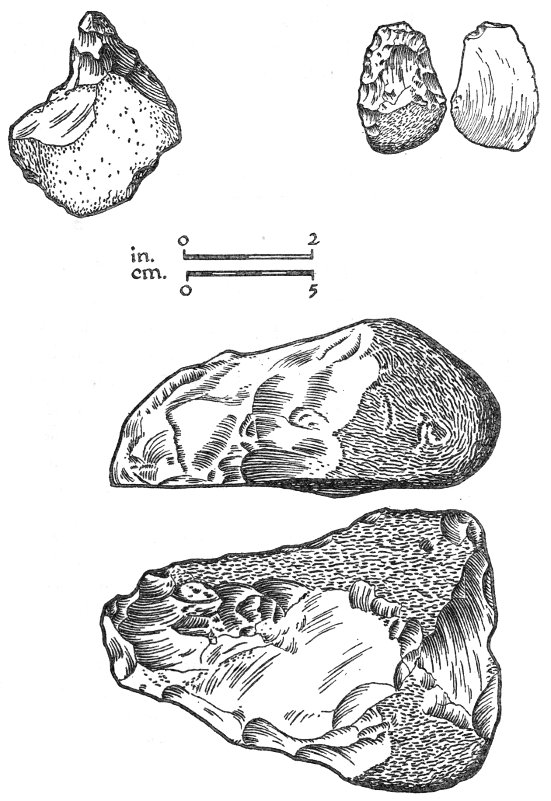

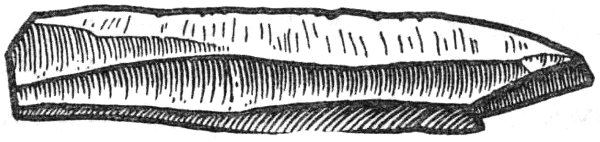

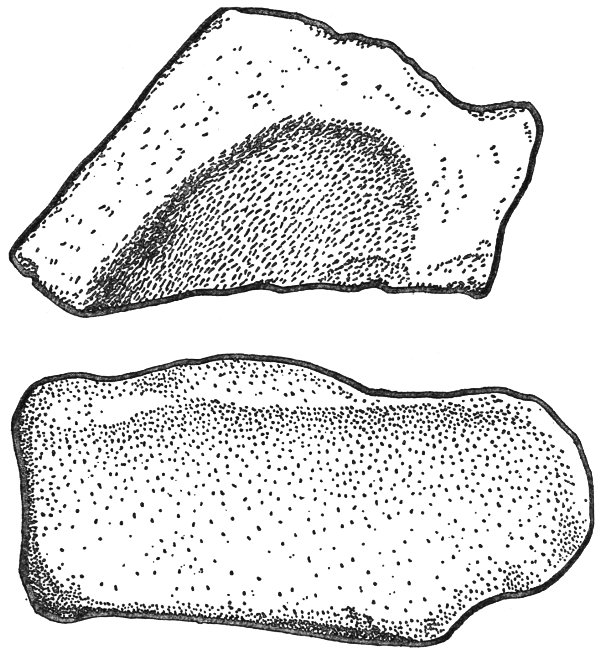

The first man probably ate the same food as the great ape—fruits, nuts, roots, and berries—and perhaps grubs and insects. Occasionally he may have varied his repast with birds’ eggs and fledglings. With a broken branch for a weapon, he improved his diet a bit. He knocked over small animals, and he may occasionally have got hold of the carcass of a large one, but, for thousands upon thousands of years, he was basically a vegetarian. His first well developed stone tool—the hand ax shaped rather like a flattened and pointed egg—was probably more useful for grubbing roots and tubers out of the ground than for killing animals. As early man learned to make more efficient weapons—first the curved throwing stick, then the spear and the spear-thrower, and finally the bow and arrow—hunting became his chief activity, and meat his chief diet. But his woman went right on gathering berries and nuts, tubers and seeds, and getting ready to invent agriculture. Certainly in the New World—perhaps in the Old World, too—she invented milling stones to grind seeds while her man was still a paleolithic. Perhaps when she watched the wearing away and the smoothing down of mortar and pestle, milling stone and mano, as she ground her seeds into flour between them, the idea may have occurred to her—or to her man who watched her labor—that it was possible to grind and polish stone into axes and other implements.

We feel that the life-story of prehistoric man can best be divided—certainly for the purposes of this book—into a Paleolithic, or Old Stone Age, which included the making of artifacts out of wood, bone, shell, and chipped and sometimes polished stone, and a Neolithic, or New Stone Age, which was defined by the invention of agriculture and the perfecting of pottery, 42 of weaving, and of the polishing of stone. This may reduce a little the confusions that are inevitable in the study of early man tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of years ago. Conflicts of evidence and opinion will remain, of course. We need not let them deter us from judging early man in the Americas. Indeed, they should free us from paying too much heed to the dogmas of scientific conservatism.

Speak to the earth, and it shall teach thee. —JOB 12:8

The dead hand of another system of classification lies across a still larger area than the Stone Age itself or the Age of Man. This area is the entire life of our earth since it took sufficient shape to support cellular life. As it is so large an area and much of it is so remote in time, changes in the definition of most of its various divisions do not much affect the present discussion.

Once upon a time there were four great divisions, neatly numbered in Latin as the Primary, the Secondary, the Tertiary, and the Quaternary. The first two went by the board when newer scientists found older ages and stretched the life of the earth a couple of billion years. The Tertiary is still a respected appellation, but the good name of the Quaternary—the area of time with which this book is mainly concerned—is seriously questioned. Defined as the Age of Man, it was supposed to harbor all evidence of his existence; but hints of his presence in the Tertiary have rather sullied the scientific standing of the later period.

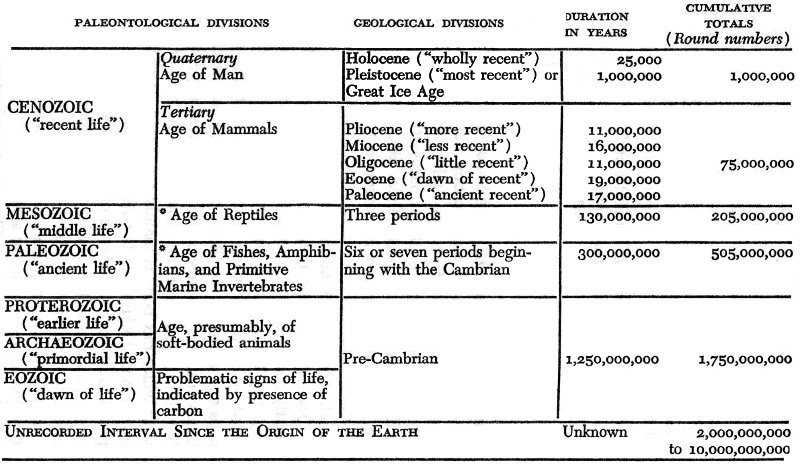

THE LIFE STORY OF THE EARTH

This summary of the story of the earth is a combination of charts in Arthur Holmes’ Principles of Physical Geology, Earnest A. Hooton’s Up from the Ape, and George Gaylord Simpson’s The Meaning of Evolution, with modifications by William C. Putnam and James Gilluly. *The divisions marked with an asterisk used to be called, respectively, Secondary and Primary.

| PALEONTOLOGICAL DIVISIONS | GEOLOGICAL DIVISIONS | DURATION IN YEARS | CUMULATIVE TOTALS (Round numbers) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CENOZOIC (“recent life”) | ||||

| Quaternary Age of Man | Holocene (“wholly recent”) | 25,000 | ||

| Pleistocene (“most recent”) or Great Ice Age | 1,000,000 | 1,000,000 | ||

| Tertiary Age of Mammals | Pliocene (“more recent”) | 11,000,000 | ||

| Miocene (“less recent”) | 16,000,000 | |||

| Oligocene (“little recent”) | 11,000,000 | 75,000,000 | ||

| Eocene (“dawn of recent”) | 19,000,000 | |||

| Paleocene (“ancient recent”) | 17,000,000 | |||

| MESOZOIC (“middle life”) | Three periods | 130,000,000 | 205,000,000 | |

| *Age of Reptiles | ||||

| PALEOZOIC (“ancient life”) | Six or seven periods beginning with the Cambrian | 300,000,000 | 505,000,000 | |

| *Age of Fishes, Amphibians, and Primitive Marine Invertebrates | ||||

| PROTEROZOIC (“earlier life”) | Pre-Cambrian | 1,250,000,000 | 1,750,000,000 | |

| Age, presumably, of soft-bodied animals | ||||

| ARCHAEOZOIC (“primordial life”) | ||||

| EOZOIC (“dawn of life”) | ||||

| Problematic signs of life, indicated by presence of carbon | ||||

| Unrecorded Interval Since the Origin of the Earth | Unknown | 2,000,000,000 to 10,000,000,000 | ||

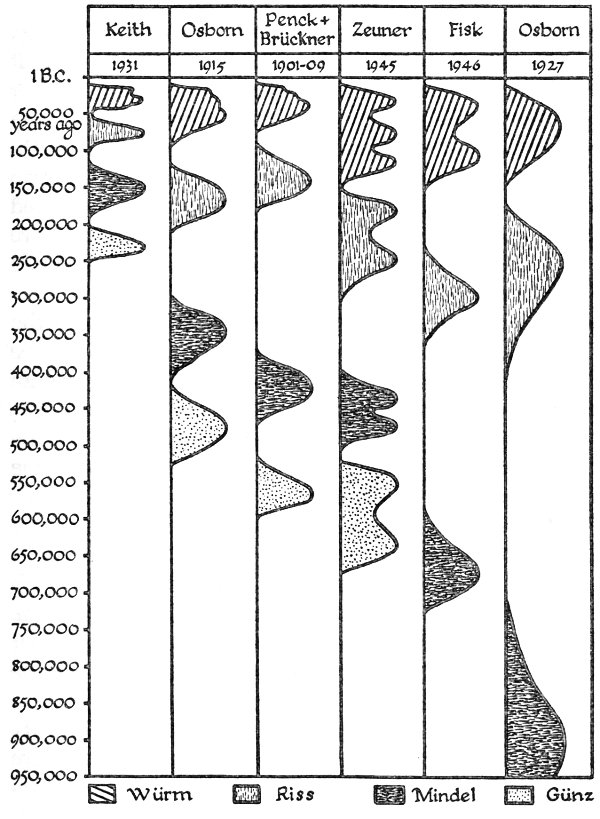

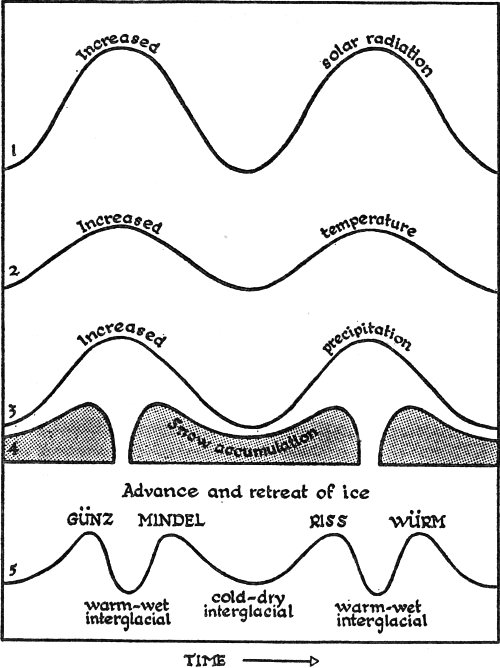

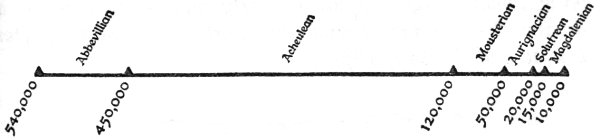

In this book we are concerned with two divisions of the Quaternary which are also growing vaguer in outline, less precise in time. They are the Pleistocene, or Glacial Period, or Great Ice Age, and the Holocene, Recent, or Postglacial Period in which we now live. (If your Greek is rusty, you will be amused to discover that those scientific-sounding terms are merely translations of “wholly recent” and “most recent.”) Most geologists believe that these two areas of time covered about 1,000,000 years; but some give them half a million more, and a few limit them to the 600,000 years, or even 300,000 years, of the last four glaciations. Some start the Postglacial 25,000 years ago, when the ice began to shrink toward its present limits; some start it 9,000 years ago, when a relatively modern climate appeared. Some geologists say we are still in the Pleistocene, and merely enjoying a warm spell before another glaciation.

By definition—or lack of it—the Pleistocene is rather vaguely bounded, and quite as much at its beginning as at its end. To the paleontologist, the Pleistocene is the time of certain large and picturesque mammals that are now extinct. To the geologist, it is the time of the waxing and waning of the great glaciers. The beginnings and the ends of these two definitions of the Pleistocene do not correspond too closely. We shall use the term as little as possible, substituting the Great Ice Age.