BARBARA WINSLOW, REBEL

This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Barbara Winslow, Rebel

Author: Elizabeth Ellis

Release Date: August 30, 2017 [EBook #55464]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BARBARA WINSLOW, REBEL ***

Produced by Al Haines.

BARBARA WINSLOW

REBEL

By ELIZABETH ELLIS

ILLUSTRATED BY JOHN RAE

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

COPYRIGHT, 1906, BY

DODD, MEAD & COMPANY

Published January, 1906

Preface

Whether James, Duke of Monmouth, would have succeeded in his enterprise had a different fortune attended his army at Sedgemoor, is a favourite subject for speculation among historians and others who interest themselves in the consideration of such strange chances as have not infrequently led to the downfall of great hopes. Certainly, had victory attended the invader's troops in their first battle, many waverers would have thereby been drawn to his standard, and the ranks of his supporters might have been swelled by that large class of politicians who measure the righteousness of a cause by its success.

But it was not ordained that Monmouth should free England from the abuses and injustice under which she struggled during the latter days of the Stuart dynasty; not into the hands of such men as this are entrusted the destinies of nations. This slight man, torn by weak hopes, weak fears, weak ambitions, small throughout his life, exceeding small and pitiful in his death, was not the instrument to overthrow the power of even so insecurely throned a monarch as James II. The history of the world is the history of individuals, and proclaims in all its pages the inexorable justice of God. A cause may be righteous, its vitality may be fanned by the devotion of thousands and watered by the heart's blood of heroes, but if the man in whom are centred the hopes of its supporters be unworthy, if his life be undisciplined, his aims selfish, his own faith weak, the glory of the struggle is clouded by the shadow of his personality, and failure is preordained to wait upon the enterprise.

James Monmouth, like his grandfather before him, like his cousin after him, inspired in the hearts of his followers an enthusiastic devotion that recked not of consequences, that gave all and asked nothing with unquestioning loyalty. In him his followers saw the man sent by Heaven to protect their religion and to purify the government of their country, the defender of their faith and freedom, and they were ready to lay down their lives at his bidding. But God, who reads the hearts of men, saw in the pretender a man of petty vices, of pitiful ambitions, weak, and selfish as the King he strove to dethrone, and though Monmouth offered at the altar of destiny many hundreds of devoted hearts, God refused the sacrifice and scattered his armies like the ashes of the offering of Cain.

So Duke Monmouth failed. The history of the world's triumphs is the history of individuals, but the world's failures are written in blood upon the hearts and lives of thousands; for though the reward of success may be the glory of one man, the suffering of many is the penalty demanded for failure. Duke Monmouth failed and the story of this abortive rebellion of the west is the story of the suffering of the innocent for the sins of the guilty. Many of those who prompted and led the invasion escaped in safety, to win pardon later from William of Orange and to live out their lives in peace and prosperity. Monmouth indeed died on the scaffold; but his worthless life was not to pay the price of rebellion. It was for the poor misguided peasants who had left their homes to fight for a religion dearer to them than life and happiness; it was for them, by cruel torture and death, or by weary years of suffering in the Plantations, to expiate their misplaced trust in a leader unworthy of the cause they cherished.

And where are we to look in this to find the infallible Justice that regulates the chances of this life?

Not indeed in the fair west country given over to pillage and the sword, her towns shambles, her countryside a waste of ruined crops and deserted farms; not in the attendant heartbreak and despair are the workings of justice transparent to our eyes. But looking across the years that followed is seen the reassuring ray of promise. The sacrifice offered at the hands of Monmouth was indeed rejected, but the sacrifice was not therefore vain. The wretched peasants had offered their lives for the establishment of religion and truth, and the offering was accepted. Their lives were indeed demanded of them on the battlefield, on the scaffold, in the slave cabins of the Plantations—who shall say that they did not receive their reward; and who, having regard to the wonderful growth of religious tolerance, of justice and national honour in England during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, will deny that the seeds sown with blood and tears in that short-lived rebellion of the west have blossomed in fadeless flowers? Here is a tale of two who threw in their lot with those who followed Monmouth; not for love of the Duke, but impelled thereto by an unexpected chain of circumstances. Two whose lives drifted together on the fierce tide of war and in whose hearts love was awakened by hatred of tyranny. It is a tale of dangers, of sorrow and of suffering, yet of some merriment, of courage and of great happiness withal, for she who inspired it was not one to let fear of the future darken the present, or present suffering weaken the spirit to endure. Rather she accepted whatsoever the Fates might send with a quiet courage, laughing in the face of frowning fortune, and found among the ashes of suffering and seeming desolation an exceeding great treasure. If the memory of Barbara Winslow inspire any to face the monotony of life with the same blithe courage with which she faced the horrors of death, her story will not have been told in vain, but will prove a seed bearing fruit in the life of a brave woman.

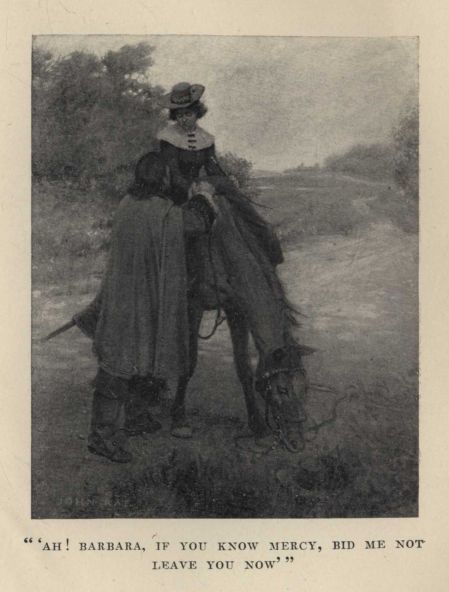

ILLUSTRATIONS

Mistress Barbara . . . . . . Frontispiece

"He Dropped the Point of His Rapier and Turned Away"

"Thus They Talked, These Two, Cut Off From All Their World"

"'Ah! Barbara, If You Know Mercy, Bid Me Not Leave You Now'"

Barbara Winslow, Rebel

CHAPTER I

"Truly, Sir Peter; 'tis a great honour you do me. Yet bethink you; if every fugitive felt it a duty to offer his hand to each maid who had favoured his escape, there would be busy doings in these troublous times."

"Duty, Mistress Barbara, i' faith! 'Tis no thought of duty your presence inspires."

There was an ominous glint in the speaker's eyes which caused his companion to interrupt him quickly with a nervous laugh.

"In that case, sir, 'twere best I should leave you; 'twere small good urging upon you the duty of saving your life by instant departure, if my presence play traitor to my words by bidding you stay. So fare thee well; I wish you a safe journey."

"Alas, madame, and will you indeed send me away without one word of hope? I will die an you do. What is life to me without your favour? I entreat you, have pity."

Sir Peter's protestations were eager, nay ardent, but they tripped too glibly from his tongue, they smacked too much of experience in the art of wooing and moved Mistress Barbara to naught save amusement.

"Nay, but listen to me, sir," she answered with mock solemnity. "As you well know, there are many who since the rising have been in hiding like yourself. For Rupert's sake, I will give help and shelter to all who need it, but it were too much to expect me to give to all such unfortunates what now you seek. Bethink you what complications might arise hereafter."

"But, madame, 'tis possible all will not adore you as devotedly as do I."

"'Twere scarcely worth my while to consider such a remote possibility, sir," she answered demurely. "Nor do I see reason why you should prove an exception."

A man and a maid seated together on a bank of moss in the moonlight have been seen oft in England; nor, if the maid were fair and not unwilling to listen (and what maid ever refused?), was it ever matter for surprise if the man has made wise use of the opportunities the Fates had given to him to perfect a romantic harmony of time and place by pouring forth protestations of undying devotion and of admiration for the incomparable charms of his companion; for moonlight is in truth a marvellous loosener of tongues; the greatest matchmaker of the universe is the pale witch queen of the night.

But natural though the affair may at first sight appear, in the present case it was attended by certain untoward circumstances which would have rendered the conventional occupation of Sir Peter and the lady productive of astonishment to an onlooker.

For it was but a week since the disastrous engagement at Sedgemoor where Sir Peter had commanded one of the foot regiments in Monmouth's ill-fated army. And though the ardour of his wooing for a time almost led him to forget the fact, he was nevertheless a condemned rebel with a price upon his head and little hope of life unless by some means he could reach the coast and so compass his escape from the country. Within a mile of where he sat there were those who were seeking high and low to take his person, dead or alive; yet despite his danger he seemed oblivious to everything beyond his immediate surroundings. He devoted himself to the wooing of his companion's favour with the same passionate assiduity which he had ever displayed in more peaceful days in the calm precincts of Whitehall, or even in the perhaps less reputable regions of Old Drury.

Three days after the rout at Sedgemoor, after experiencing the miseries of starvation and despair which fall to the lot of a hunted man, Sir Peter Dare had reached the village of Durford, hoping thence to escape to the coast. Driven by hunger and distress to desperate ventures, he had presented himself at the Manor House, trusting to his ready tongue, his handsome face and his large experience in the management of the sex to gain the sympathy and assistance at least of the women of the household. He met with a welcome even more kindly than he had dared to hope for. Mistress Barbara Winslow had a tender heart for all rebels, her own brother, Rupert, having also ridden with Monmouth, and being himself even then in hiding, she knew not where. Therefore, she and her cousin Lady Cicely gave shelter to Sir Peter gladly, and for some days he remained at the Manor House, lauding the Fates for directing him to such a pleasant haven, and employing his time, having nought else to do, in losing his heart to his fair hostess, who, being a woman, thought no worse of him for his obvious admiration, which, to do her justice, she considered but her due.

But not many days could the wanderer remain in safety at Durford. The country was closely patrolled by those searching every hole and corner for fugitives from Monmouth's army, and a small search party had their headquarters in the village itself. The Manor House was suspected, and the Winslows could not hope longer to conceal the presence of their guest, especially as their household consisted exclusively of women—creatures of unquestioned loyalty but irresponsible tongues.

In the meantime, however, news had been received of a fishing vessel lying off the coast, some three miles from Listoke, and with the help of one Peter Drew, a smith by trade, and a devoted admirer of Mistress Barbara, arrangements had been made with the skipper to take the fugitive on board.

Four days, therefore, after his arrival, Sir Peter reluctantly bade farewell to his hostess, and prepared to ride away once more upon his wanderings.

But ere he started finally on his journey, Mistress Barbara, moved either by the beauty of the evening, or by pity for his somewhat forlorn condition, proposed to accompany him to the end of the narrow lane, leading from the Manor House to the high road, and so set him on his way.

Now at the side of this lane ran a mossy bank, and the night being warm, and the moonlight inspiring, it befell that an hour after his departure from the house, Sir Peter was still seated on the bank at the feet of Mistress Barbara, oblivious alike to her repeated assertions that if he would not depart she at least could remain no longer, and to her warning that each moment's delay meant additional danger.

Still they sat there, until Sir Peter, moved by the sweet tones of his companion's voice, by the gleam of her eyes in the moonlight, and by gloomy reflections on their approaching separation, threw prudence to the winds, and burst forth into desperate, and for the time being heartfelt, protestations of devotion, mingled with entreaties that she would at least give him hope of one day winning her favour.

But Mistress Barbara, though she had found satisfaction in Sir Peter's open admiration, was in no wise pleased at so serious a turn to the conversation. She shrewdly suspected that it was by no means the first time such vows had passed his lips, and was consequently quite unmoved by his despair; but this unexpected change from moonlight dreams in the present to practical discussions of the future brought back her mind to realities with a sudden shock. She had no inclination to enter into a serious discussion of the matter, so she put a sudden end to the affair by springing to her feet and insisting upon her companion taking his departure forthwith, lest he miss the tide.

Sir Peter, recognising that further pleading would be useless, heaved a forlorn sigh, at which Mistress Barbara smiled under cover of the darkness and they walked to the end of the lane in silence. Here they paused and Barbara gave her final directions.

"I can go with you no further. I would we could have kept you with us longer, but indeed it is not safe; they have traced you here and are hunting high and low for you. Your only hope is to cross the water. I have told you the road; two hours' riding should bring you to the place. Pray Heaven you fall not in with Captain Protheroe and his men. But if you do you should soon outstrip them, for their horses will be weary; they have been out seeking you since daylight, though thanks to their belief in their own intelligence they have sought diligently in the wrong direction. But they will come back to quarters presently and you must be gone. Farewell, my friend, and a pleasant ride."

Sir Peter stooped to kiss her hand and mounted his horse reluctantly.

"Farewell, madame. It were useless to try to thank you. But at least I shall hope for some future occasion of repaying my debt."

"I shall deem it well repaid if you can contrive to send me word of Rupert's safety," answered the girl with a sigh. "That he will escape I am assured; Rupert could never come to harm; but the waiting for news is weary, and on some days hope is only a duty, not a consolation."

"See what it is to be a brother," exclaimed Sir Peter mournfully. "You care more for his little finger than you do for the offer of my heart."

"Well, sir, and is not the rarer commodity ever the more precious?" she answered saucily. "Rupert hath but two little fingers, whereas——"

"I have but one heart, madame."

"True, sir; but what limit to the times it may be offered?"

"Ah! Mistress Barbara, you know naught of the matter, for you yourself have no heart at all."

"And I marvel that you should still have one, considering how frequently you have lost it."

"I vow——"

"Hush!"

The jingle of accoutrements sounded round the corner of the road, and at the same moment they became aware of horses slowly approaching, a sound which hitherto they had been too much engrossed in their conversation to heed.

"Alack! 'Tis the troopers," whispered Barbara. "Back, ere it be too late."

But the time for escape had passed; for even as she spoke, and before Sir Peter had fully grasped the situation, the troopers had rounded the corner of the road, and were face to face with the fugitive.

They could scarcely be described as an imposing-looking force. Since daybreak they had been out scouring the country for rebels, beating the woods, ransacking the barns, following a wild-goose chase after false information extracted from the sullen country-folk, and were now returning to the village, worn out, dejected, and mud-stained. It would have been difficult to find a more forlorn-looking crew, even among the unfortunate men whom they hunted.

But at sight of the couple before them their dejection instantly vanished. The man's rich dress, handsome still, despite its draggled appearance, his presence on the road at this hour, and the horrified exclamation of the girl, all tended to prove that this was the man whom they sought. With a quick exclamation, the leader sprang from his horse and striding up to Sir Peter seized his horse's bridle, crying sharply, "I arrest you in the King's name. Surrender like a wise man, or take the consequences."

Sir Peter reined his horse back abruptly, and glanced round at his enemies with a muttered curse. But in Mistress Barbara the danger only roused a spirit of excitement and mischief. She flung up her head and laughed.

"Cock-a-doodle-do! Who is afraid of you?" she sang saucily.

Captain Protheroe was somewhat discomfited by this unexpected answer. He threw an angry glance in the direction of the girl, and otherwise ignoring her presence, turned again to his prisoner.

"Come, sir, I ask you again, do you surrender, or must I order my men to seize you?"

"And I repeat," remarked the girl again, "that you crow too loudly, noble sir."

One of the troopers in the background laughed, and the captain turned furiously on Barbara.

"Peace, wench," he began sharply. But at that moment, when all eyes were turned on the girl, Sir Peter dealt a furious blow in the captain's chest, driving him back against the bank, and at the same time wrenched the reins from his grasp and dug his spurs into the horse's flanks. The animal leaped forward suddenly, and before the men could recover from the confusion and make a further move to stop him, the prisoner was clear of the surrounding circle and galloping rapidly down the road, while Mistress Barbara clapped her hands and laughed delightedly at their discomfiture.

Captain Protheroe sprang to his feet in an instant, furious with rage, but quickly realising that it would be vain with their wearied horses to attempt to overtake the fugitive, he opened his lips to give the order to fire, that the man might be stopped, dead or alive. But ere he could speak the word, two arms were flung round his neck, and two soft hands were pressed tightly over his lips, while again the girl's mischievous laugh rang in his ears.

For a moment the captain was too much astonished to move, then astonishment gave place to anger.

Roughly seizing the girl's wrists, he pulled away her hands and shouted to the men to fire at once. But it was already too late, the fugitive was out of sight, and though several troopers presently set out in pursuit, it was obvious that the hope of recapture was very slight, seeing he rode a fresh horse, and the moon, already low in the sky, promised soon to give the pursued the protection of darkness.

Then, balked of his prisoner, Captain Protheroe turned furiously upon the cause of his failure.

"You hussy," he exclaimed harshly, "I will teach you——"

He stopped abruptly, for the girl's hood had fallen back, and he found himself gazing into the most wonderful eyes he had ever beheld.

Then a soft voice drawled in sympathetic tones, "'Deed, captain, hath he really escaped thee? How vastly annoying. For, an I mistake not, the orders were to take him at all costs, dead or alive, and now, being but few miles from the coast, and being well mounted, 'tis very like he may be altogether quit of the country by to-morrow morn. I vow 'tis too bad. But sure, you are eager to pursue him, so I will no longer delay you. I wish you a very good even."

She dropped him a sedate curtsey and turned to walk back to the house.

But by this time Captain Protheroe had recovered from the effect of her eyes. He seized her roughly by the wrist and dragged her back.

"Not so fast, my girl. I must have some information from you first concerning this same rebel."

Barbara eyed him in grave astonishment.

"You are hurting my wrist," she complained reproachfully.

The captain dropped her wrist instantly, and she held it out to him gravely, that he might see the red marks of his fingers on the white flesh.

"Come," he began, somewhat abashed, "tell me but this: Was that Sir Peter Dare who hath escaped us, and if so, where and how did you fall in with him?"

"Indeed, sir," answered the girl demurely, "you are surely forgetful of the place and hour. Bethink you, 'tis scarce meet that I remain here alone, parleying thus with strangers."

"Tut! girl," answered the captain, laughing, "that excuse will not avail. You thought it no shame ten minutes since to remain here parleying with one man. There is safety in numbers."

"Ah! That is a different matter, sir," she answered with a most innocent glance. "He was a gentleman."

"A gentleman! Well! What then?"

"Such do not mishandle women, sir," she said and pointed again reproachfully to her injured wrist.

"Peste!" muttered the captain angrily. In truth he was somewhat puzzled as to whom the girl might be. She wore a rough scarlet cloak and hood common to all the country maids, and he could not see her dress beneath. Furthermore she spoke with a slight Somersetshire accent, and this, together with her saucy manner, had at first led him to suppose her to be merely a simple country wench. But now the suspicion grew that she was but masquerading in the part.

The only thing of which he felt certain was that she had the sweetest voice and the most bewitching dimple in the corner of her mouth of any woman he had ever met.

"Come now," he continued more gently, "I am sorry I hurt thee, girl, but an answer I must have. Who was the fellow?"

She looked at him gravely.

"Well, sir, an you will have it, he was—he was a certain Captain Miles Protheroe."

Captain Protheroe laughed unwillingly at her coolness.

"Come, you must give a better account of him than that, mistress."

"Nay, is that no good account?" she exclaimed with elaborate astonishment. "Marry! How one may be deceived. I have ever heard Captain Protheroe spoken of as passably honest, though perchance not overwise, and decidedly hard-featured."

But this was too much, and Captain Protheroe lost all patience. Yet if the girl persisted in her saucy masquerade, he resolved at least to play up to her, and let her see how she enjoyed the part.

"A truce of this fooling, girl," he began harshly.

"Faith, sir, an my conversation please you not, I will e'en take my leave," she interposed quickly, and again turned to leave him.

But Captain Protheroe seized her cloak and held her fast.

"Listen to me, my girl," he said sharply, "and bridle your saucy tongue. Give me the information I require or, by Heaven, I'll march you back to the village and keep you prisoner till you learn to obey. Make up your mind. Which shall it be?"

Barbara turned and regarded him gravely from head to foot.

"I like you not," she remarked coolly, as the result of her critical survey.

"That may well be," he answered, smiling scornfully. "But an you answer not my questions, and that speedily, I must find means to make you do so. Now speak; which shall it be?"

Barbara glanced round eagerly for a way of escape, her mouth drooped, her eyes opened wide with fear, her hands were clasped convulsively at her throat, the fingers fidgeting with the ribbons of her cloak. She shook her head once or twice helplessly, casting at the captain glances of indignation, pleading, and reproach.

But he remained resolute. Then she began in a trembling voice:

"Well, sir, if there be no other way of escape, I must—I must e'en——I must run!" And as she spoke the word, with a quick movement she twisted herself free from the cloak which she had previously unfastened, leaving it in the captain's hands, and darting up the bank by the roadside, disappeared into the plantation beyond.

One or two of the troopers made a motion to pursue her, but the captain called them back.

"Let her go. You would never find her in the dark." And added, laughing, "The wench deserves her freedom. Fall in, men, and back to quarters; we can do no more to-night."

Nothing loth, the troopers resumed their way back to the village; but ere he departed, Captain Protheroe stooped and tore a ribbon from the discarded cloak, and with a short, half-shamed laugh twisted it round his wrist.

CHAPTER II

A man might journey far afield and find no sweeter spot than the village of Durford as it appeared on a certain sunny September afternoon in the year of grace 1685. The low white houses with their heavy overhanging thatched roofs were bowered in roses; while in each miniature garden the riot of colour and perfume intoxicated the senses. The low sun spread the long, cool shadows of the trees across the brilliant emerald and gold of the meadows, and lighted up each leaf and flower distinct from its fellows. The square tower of the old grey church and the grey-green clump of the yew trees behind it were silhouetted against a golden haze like the head of a haloed saint. The summits of the distant hills faded in golden mist like the mystic scopes of Paradise. In the neighbouring orchards the trees bent beneath the weight of their russet burdens, the fields spread golden with the harvest, and the wooded hills burned with the bright, burnished tints of early autumn. It was as though in this, the evening of the year, mother earth were moved in emulation of the sky to deck herself in all the varied colours of the autumn sunset.

In the woods the birds were practising for their autumn chorus, voicing the ecstatic joy of life in little unexpected trills and bursts of song, while the heavy drone of the bees and the occasional cry of the grasshoppers denoted a more sober contentment. The soft, warm air was heavy with a myriad delicate scents; breathing over the imagination faint, suggestive memories of a happy past and formless dreams of a golden future.

But as the heart of man is still untamed by the sweet influences of nature, so, on the afternoon in question, a scene was being enacted on the green before the Inn, as foul as the surrounding picture was fair, as though heaven and hell, God's love and tenderness to man, and man's brutality and cruelty to his fellows, were here met side by side.

In the centre of the green stood a tall whipping-post, and tied to this was a small boy of some nine years of age. His back was bare, his eyes were wide with fear, and his teeth were resolutely clenched to repress the sobs which ever and anon forced their way through his lips.

Over the boy, whip in hand, stood a man dressed in the uniform of a corporal of the 2d Tangiers Regiment, a stout, purple-faced fellow, with scrubby black hair and beard, near-set cunning eyes, a cruel mouth, and over all an air of supreme importance and self-satisfaction. This was Corporal Crutch, a man whose life was alternately glorified by his own assurance of his remarkable ability and embittered by the world's blindness towards the same.

Some half dozen troopers stood around watching the scene, and on the edge of the group were three or four sobbing women and a crowd of wide-eyed, terrified children.

"Now, my lad," cried the corporal, with a gleeful chuckle, "let us have no more of this obstinacy. Nay, an thou wilt not speak, I warrant me a taste of this whip will help me to the finding of thy tongue, and doubtless of thy father into the bargain. An thou beest a wise lad thou'lt speak now, once my arm gets to work on thee 'twill not be so ready to stop, maybe."

Some of the troopers laughed, and the women's sobs increased, but the boy remained resolutely silent.

"So thou wilt have it then," cried the corporal; and the whip descended with a sickening swish on to the boy's bare back.

Once! Twice! Thrice! The boy shuddered and sobbed, but no word came from his lips, and the corporal, angered by this unexpected determination on the part of his victim, doubled the weight of his blows.

Suddenly a shout interrupted the proceedings and a loud, clear voice rang out imperiously:

"Hold, fellow! What art thou doing to the child? Loose him instantly."

The crowd round the corporal fell back hurriedly, and he himself paused and slowly turned his head in the direction whence the voice came.

The speaker was a tall, slender girl, with a face of such exquisite beauty as men may hope to see but once or twice in a lifetime, and having seen, may never hope to forget. The beautiful oval face, clear-skinned and glowing with colour, was outlined by soft dark hair, shading to black in the shadows, waving back from the low white brow in soft rippling curls. The clear-cut perfection of her features was relieved from coldness by the unmanageable dimple at one corner of her mouth, and by the frank directness of the deep blue eyes, which looked out upon the world from beneath their dark lashes with habitual fearlessness. The expression of her face was habitually happy and friendly, only the firm lines of her mouth and chin belying the general expression of good-tempered recklessness.

She was mounted on a rough pony, and had drawn rein at the top of the hill leading down to the village, moved by an idle curiosity to learn the cause of the crowd before the Inn.

The faces of the sobbing women brightened when they saw the girl, and the men glanced at each other sheepishly.

"'Tis Mistress Barbara Winslow from the Manor House," muttered one. "Thou hadst best send the lad about his business, corporal."

But Corporal Crutch was an obstinate man, and one moreover who was imbued with a strong sense of his own importance; he had no mind to allow any woman, whether of high or low degree, to interfere with his chosen occupation. Moreover the Manor House was suspected of harbouring rebels, and its occupants were judged little better than rebels themselves. So paying no heed either to the command or the advice, he turned his back upon the advancing figure and raised his whip for another blow on the back of his trembling victim.

"Hold! I tell thee, fellow," cried the girl again angrily. "Dost thou not hear me? Nay, an thou wilt not, by Heaven I'll make thee obey."

Without further ado she galloped straight at the group on the green which scattered to right and left as she passed, then with a sudden quick movement cracked out the long lash of her riding whip, curling it lasso-like around the corporal's neck, and not checking her pace dragged him stumbling and stuttering backwards till he fell to the ground. Then releasing the whip handle and reining back her pony to admire her handiwork she burst into a peal of laughter. And indeed 'twas a fit subject for merriment, for the corporal was stout and angry and the lash was exceedingly long and heavy. The corporal alternately swore and struggled, and the lash became every minute more tightly entangled round his neck.

Presently Mistress Barbara checked her laughter, slipped from her pony and crossed to the whipping-post where the sobbing boy stood watching the scene with eager eyes in which hope and fear still strove for the mastery.

"Loose him," she cried imperiously, and the troopers hastened to obey her.

"My poor brave laddie," she murmured, bending over him tenderly. "Ah! but they have hurt thee cruelly. Get away to thy mother and fear not. They shall not touch thee again."

Then drawing herself up to her full height, and she was more than common tall, she faced round upon the group of men.

"Brutes," she cried. "Brutes ye are, and no men to treat a poor helpless laddie thus. What! Have ye no manhood? Think shame of yourselves to stand by and let such work go on. An I were but a man I'd teach you a lesson you would not soon forget."

"'Tis well enough to talk," grumbled one of the troopers angrily; "but the lad's father is in hiding and we must know where he is, The boy could tell us well enough an he would speak. We caught him slipping thro' the wood an hour back. Yon basket of food he carried was for him, I warrant."

"'Tis very like," answered Barbara coldly. "What then?"

"What then? Why the fellow is a rebel."

"And what of that, pray? An his father be a rebel to King James, is that reason why the lad should be traitor to his own father? Shame on you! You who are fathers yourselves; would you have your sons cast such a teaching in your teeth?"

By this time the corporal had freed his neck from the lash and recovered his equanimity. Now he bustled to the front with an air of importance.

"Best beware, mistress," he cried roughly. "Best beware. 'Tis ill work to interfere wi' the just punishment of traitors."

Barbara turned to him and laughed softly.

"Ha! Sir Gallows-Bird. So thou hast escaped the hemp; welcome on thy return to this wicked world."

"I tell thee, madame," stuttered the corporal angrily, "'tis ill work jesting——"

"Peace, fool!" she cried imperiously. "I marvel thou art not ashamed to show thy face after this day's work. I knew already you and your masters think it no shame to fight against women, but at least methought children might go unharmed. They can do but little harm to King James."

"Pshaw! Ye know nought of the matter," blustered the corporal. "I brook no interference in the exercise of my duty. Bring back the boy, Sam Perry, and proceed with the interrogation."

"Do not attempt it," answered the girl quietly, "for I will not permit it."

Sam Perry hesitated.

"What!" roared the corporal, "are ye afraid of a chit of a girl? Why do you not obey?"

"At your peril," cried Barbara sharply, moving before the men.

How the matter would eventually have terminated is doubtful had not a second interruption occurred.

The door of the Inn opened, and a figure emerged at sight of which the troopers shrank back sheepishly, and the corporal's air of importance vanished pitifully.

"What is the meaning of this disturbance?" sharply demanded the new arrival.

Barbara turned eagerly towards him.

"Are you the leader of these butchers, sir?" she enquired haughtily.

Though somewhat astonished at this unexpected mode of address, Captain Protheroe, for he it was, smiled slightly and answered politely enough:

"I am the captain of these men, if that is what you would ask, madame. Are all soldiers butchers in your estimation?"

"Soldiers!" she cried scornfully. "Call ye them soldiers? But perhaps you are even as they, and 'tis by your orders they torture women and children and make a veritable hell of God's earth. I wish you joy of such work."

"Pardon my dulness, madame," answered the captain calmly, "but I have not the least idea to what you are alluding or how I have incurred your displeasure."

"No? Then hearken, sir." And in burning words she described the cause of her indignation.

The captain listened with a gathering frown to her story, and at the conclusion turned on the corporal with a look that boded ill for that self-satisfied mortal.

"So, sirrah! Is this the way you carry out my orders? Have I not said I will have no violence to the village folk? And by Heaven I will be obeyed. I have long known thee for a knave. Art fool and coward, too, that you must needs force children to help thee with thy work? Is this thy notion of a soldier's work? I'll teach thee better knowledge of thy duty ere I've done with thee. 'Tis not the first time I've heard such complaints; see to it it be the last, or by the saints 'twill be the end of thy service. I'll have no bullies in my troop. Go, sirrah!"

The discomfited corporal slunk off down the street casting an ugly glance over his shoulder at the girl who had brought such a rating upon him. But for her part Barbara laughed and waved her hand after the retreating figure.

"Fare thee well, Sir Knight of the whipcord," she cried gaily.

When the corporal had vanished, followed by other troopers, the captain turned towards Barbara with a bow and said coldly:

"I trust you are satisfied with these orders, madame."

"I shall be satisfied, sir, when I know that the orders are executed," she answered coolly.

"Madame, I command here. Where I command I am obeyed."

"'Twere easy to believe it, sir," she answered with a half-smile and a glance at his resolute face. "But I have heard there be many orders delivered thus readily in public which privately are never intended to be performed."

The captain flushed hotly, but gave no further sign of anger at this insinuation.

"Indeed, I know not wherein I have deserved your distrust, madame."

"In such troublous times as these my distrust is given before my confidence, sir; and pray what have you done to prove that distrust is misplaced? You claim to be a gentleman, but by Heaven 'tis no gentle's work to hunt down poor wretches led astray by others who should have known a wiser path; 'tis no gentle's work to harry helpless women and children; 'tis no gentle's work to listen behind doors and spy through keyholes. By my faith, sir," she continued, her temper increasing at the remembrance of her many grievances; "By my faith, sir, this poor wretch of a corporal whom you have so rated is virtue itself compared with you. He but executes the orders which you conceive, hiding yourself behind the name of gentleman."

The last words were delivered with biting scorn, and having concluded her tirade, Barbara turned her back upon him and stepped towards her pony.

Captain Protheroe had remained politely silent during this harangue. When her back was turned he smiled slightly and followed the indignant lady.

"Permit me to assist you to mount, madame," he said with grave politeness.

Barbara drew her skirts around her and answered with as much haughty dignity as her rising anger would permit:

"No, sir. When you have shown yourself capable of a gentleman's work you may be worthy of a gentleman's privileges. Until that time I prefer to mount alone and keep myself from the pollution of your touch."

But instead of being crushed as she had intended he should be, Captain Protheroe merely smiled again and stood politely aside to watch her mount. The pony was restless, two or three attempts were necessary before the feat was accomplished, and during the struggle both Barbara's dignity and temper suffered considerably. Captain Protheroe wisely made no further offer of assistance, but watched her efforts with an amused twinkle in his eyes.

Suddenly an idea struck him. He laughed softly, and placing a detaining hand upon the pony's bridle he turned once more to the lady, an ironical smile playing about his lips.

"Madame, since I am unworthy to touch your foot, I fear I am equally unworthy to retain this small token of remembrance which you so obligingly bestowed upon me that evening some weeks ago when you did me the honour to embrace me." So speaking he placed his hand in the pocket of his coat and drew forth the scarlet ribbon of the cloak which she had left in his hands when she fled from him at their first meeting.

Had there been magic in the small piece of ribbon it could not well have wrought a greater change in Barbara. Her attempt at dignity vanished. A wave of crimson passed over her face, her eyes blazed, and when she spoke it was in a voice choked with passion.

"How dare you, sir! 'Tis a most cowardly lie. 'Twas no embrace, as you might know well. 'Twas—'Twas—an assault."

Her persecutor was as unmoved by her passion as he had been by her rating.

"No embrace?" he drawled in polite astonishment. "Nay, then I pray you pardon my mistake, which you will grant me was a natural one. Truly an that be your manner of assaulting your enemies, I forgive the Fates for having ranked me among their number, and shall desire of them nothing better than continuous battery at your hands."

"Have your desire then," cried Barbara furiously, and doubling up her first she dealt him a fierce blow on the side of his face.

With a quiet smile he turned his head.

"The other cheek, madame?"

Barbara gasped and for a moment stared down into the cool face raised to hers. Then suddenly her eyes twinkled, her mouth dimpled, and she broke into a soft, half-angry laugh which, however, she as quickly repressed.

"By Heaven, sir, an you be not the most aggravating man in the kingdom, Heaven grant I may never meet him. How dare you detain me thus? Loose my pony instantly."

He drew back with a low bow.

"Your pardon, madame, your way is free. In the meantime I will keep this token till ye redeem it by another embrace—I should say, assault."

"Then you will keep it forever, sir."

"It is nought but the alternative that I should desire more," answered the captain still with the same quiet smile. But Barbara was too furious to answer, and whipping up her pony she galloped away.

The captain stood silently watching her till she disappeared from the narrow village street, then he turned and walked into the Inn.

In the taproom sat the corporal, his wounded pride somewhat soothed by generous potations, holding forth upon the subject of his grievances to the half-dozen troopers collected there.

"'Tis a fine state of things when any blue-eyed wench is to be allowed to interfere in the administration of justice and say this ye shall and this ye shall not do, for all the world like the general himself. 'Tis no sort of work. 'Twas very different in the old days wi' Captain Carrington. Then an a lad would not speak we had ways to teach him. But now——" He paused cautiously and confided his criticism of his superior officer to the depths of his tankard.

"This Mistress Barbara is a bold wench," ventured Sam Perry cautiously.

The corporal's face darkened.

"Mistress Winslow had best be careful," he muttered. "Her brother is attainted as a rebel, and lieth somewhere in hiding, and I warrant yon haughty wench knows where. Zounds! I'll keep a careful watch of her—and I doubt not soon to surprise her secret. 'Twere a sweet revenge," he muttered, rubbing his fingers gleefully; "and 'twould teach her 'tis scant wisdom to bandy words wi' them in authority and fling whips i' an honest man's face."

Meanwhile Barbara rode home slowly, talking to herself as was her wont.

"Odd's bodikin! as Rupert would say, but how the fat corporal did puff and splutter. Poor Cicely would say 'twere wicked folly thus to anger our enemies against us, but sure such a prank can do no harm. The corporal is patently a fool, I fear him not; and as for the other——" Here she paused and laughed half-angrily. "He surely would not venge his quarrel with me on Rupert. But what an immovable fellow it is. How I would love to see him angry. 'Twere perchance a dangerous experiment, but I were no true woman did I not long to try. Ah! well, an he remain here much longer I fear he may have many chances to taste of my temper. 'Tis a brutal world." And so alternately laughing and frowning, she rode home to the Manor House.

CHAPTER III

The Durford Manor House, which for many generations had been the home of the Winslows, was a low, rambling structure of grey stone, full of strange nooks and corners and curious hiding places. Part of the house dated back to the fifteenth century, and had sheltered fugitives from Bosworth field. It had witnessed many strange scenes during the years of the Civil War; many a Royalist had found refuge there, and it had been twice besieged. Here, in the great oak-panelled hall, Lady Elizabeth Winslow, grandmother of the present Sir Rupert, had entertained the Parliamentarian officers to supper while her husband was held prisoner in the neighbouring room, and after disarming their suspicions by her wit and gaiety, had eluded their vigilance and slipped out of her window when her guests had retired for the night, and ridden through the darkness to Taunton. Here she roused the townsfolk, and herself riding at their head had surprised the small force conducting her husband to Gloucester and rescued him just when all hope of escape seemed dead. Here Mistress Penelope Winslow, the proud beauty of the House, whose portrait, a stiff, lifeless shadow of the beauty which had set fire to all the hearts in the countryside, still hung above the stairs, had refused her twenty suitors and finally given her hand to a nameless Scotch soldier and ridden away with him to the wilds of his Highland home. Here Richard Winslow, that renowned soldier, had been brought after the battle of Worcester, the very remnant of a man, spared by the clemency of Parliament to drag out a weary existence in the house of his fathers, and dream what his life might have been had not a fatal shot left him at once blind, deaf and paralysed. Here Stephen Winslow, after impoverishing his house and risking his life for his sovereign, had eaten his heart out through long years of baffled ambition and bitter disappointment, learning the gratitude of kings.

The Winslows had ever been loyal to the Stuarts, giving all and asking little in return, and, though she would not for the world confess it, it had been a sore trouble to Mistress Barbara that her twin brother Rupert, the last representative of his line, should have chosen to cast in his lot with the usurper Monmouth and rebel against his lawful sovereign.

She had acquiesced, as she acquiesced in all he proposed, but her heart boded no good of the matter, and when the fatal battle of Sedgemoor had sent Monmouth to captivity and the block, and had made of her own brother a fugitive from home, in hiding she knew not where, she experienced anxiety and misery indeed, so far as her sunny hopeful nature would allow, but no surprise.

More than two weary months had passed since that fatal morning, but no news of the wanderer had reached the Manor House. From time to time her more humble neighbours crept back in secret to the village they had left so hopefully that bright morning in June when they went out to join one whom they believed to be the Heaven-sent defender of their faith and freedom. But they came back, alas! only to creep away again to some dreary hiding-place in moor or wood, for the village was watched by the soldiers and home could no longer offer safe refuge to the weary, despairing men. From time to time came rumours of the escape or capture of this or that follower of the Duke and terrible stories of punishment meted out by brutal judges; still no news of young Sir Rupert Winslow came to allay the anxiety of his sister or soften the hopeless misery of his young cousin Cicely, to whom he had been betrothed but three short weeks before his departure. But no suspense, however terrible, can last forever, and at length, early in September, the longed-for news arrived.

Mistress Barbara and her cousin were at breakfast in the sunny parlour of the Manor House, and the former had just sought to win a smile from the sad face of her companion by relating her adventure with Corporal Crutch in the village on the previous afternoon. When she ended her story Cicely looked up fearfully and shook her head.

"Indeed, Barbara, thou art too rash. Thou hast but made an enemy of the man, and God wot we have enemies enough already."

"Nay, prithee do not chide me," answered her cousin coaxingly; "the fellow can do us no harm. And indeed, Cicely, I must be merry sometimes, or I verily believe I should die."

"Merry!" exclaimed Cicely somewhat bitterly. "Ay, perchance thou canst be merry, Rupert is but thy brother; yet to me——"

"He is thy betrothed. Then truly by all showing I should be more distressed than thou. New lovers may be gotten by the score, but by no power could I win me another brother. Nay, dear, I did but jest, I meant not to vex thee," she added contritely, seeing her cousin's lip quiver unsteadily; "thou knowest my tongue runs ever faster than my brain, plague on it."

"Thou hast not vexed me, Barbara, only—— I would I had the secret of thy courage."

"Nay, thou hast courage enough, only somewhat too much thought. Were I to sit and dream all day of what evils might befall Rupert I should be as sad-eyed as thou art. But indeed no news is good news. The world is a good place, and I see not why one may not hope for happy days until sad ones befall us, eh!"

They were interrupted by the entrance of the waiting-maid. "I were loath to trouble ye, Mistress Barbara," she began, "but 'tis a zertain tiresome vellow, Simon the pedlar, who asks to show you his wares. To my thinking he hath nought worth a glance, and I had zent un about his bizness speedily; but a be a mozt stubborn fellow and will not depart until a zee ye. A zays a hath zomething of great value but a be a vellow will say aught to gain a hearing, I know un well."

Barbara's face brightened suddenly and she sprang eagerly from her seat.

"'Tis well, Phoebe, take the fellow in; I will come on the instant."

"Why, Barbara!" exclaimed Cicely in astonishment; "what would you with the man? Would'st plenish thy store of linsey or tapes that thou art so ready to see him?"

"An I dream not, Cis, he will have wares more precious than those."

"What!" cried Cicely with awakened interest. "Is it possible the fellow hath stuffs from London with him? I would willingly buy, an it be so."

Barbara laughed and pinched her cousin's chin. "Thou little vanity! Thou worshipper of gauds and ribbons!" she cried with much solemnity; "I verily believe thou would'st sell thy soul for two dozen yards of Genoa velvet. But come; we will see what he has to show us."

On entering the large wainscotted hall the girls found the pedlar standing in the embrasure of one of the windows, his pack tying unopened at his feet. He was an aged, wizened-looking creature upon whose face greed and cunning had laid their stamp.

Cicely eagerly eyeing the pack addressed herself to him with a slight air of hauteur.

"Well, fellow, where are your wares? Have you aught of rarity or value to show us?"

"Ay, that have I, mistress," he answered in a high-pitched grating voice, with an air of impertinent familiarity. "I have that here which will bring light to the dullest eye, a blush to the palest cheek, and joy to the saddest heart. 'Tis not over rare neither, yet 'tis ever held to be of the greatest value."

"Why what mean you? What should this be?"

"A letter, mistress! a love-letter I doubt not."

"A letter! From whom?"

"From one of whom your ladyship hath long wished to hear, and hath well-nigh heard from no more," he answered with a brutal laugh.

Cicely's eyes flashed, her whole body trembled with eagerness.

"Ah! give it me, give it me, my good man; why hast thou delayed so foolishly?"

"Softly, softly mistress," answered the fellow coolly. "Here is the letter sure enow," drawing a small white packet from his valise—"And 'tis from Sir Rupert." Here he showed the direction. "But first give me my price."

"Oh yes, thou shalt be paid, never fear," cried Cicely with increasing impatience. "Now give me the packet."

"Not so fast, mistress," he answered curtly; "I yield not up this packet before I see my reward."

"Oh! you foolish fellow! name your price then."

"Five hundred crowns," he answered coolly.

"Five hundred crowns," cried Cicely in horror; "why, man, thou art mad, I have not such a sum."

"Mad or no, that is my price."

"But I could not pay thee such a sum; you are a very extortioner, you wicked fellow."

"Listen to me, mistress," interrupted the pedlar roughly; "and be not so glib with thy tongue; hard words win no favours. I know nought of politics, and Sir Rupert may hang twenty times for all I care. All I know is that this letter is worth my price, and if ye will not pay it there be others not a mile away who will be right willing to buy the information it contains."

"Ah, sure you could not be so cruel," began Cicely piteously, but Barbara intervened.

"Peace, Cicely, let me deal with the fellow. Now, my man," she continued, turning on him sharply, "we will give thee twenty crowns for that letter and not a penny more, dost hear me?"

"Oh, ay, mistress, I hear thee," drawled the pedlar jeeringly. "Well, 'tis but a small matter after all, 'tis but one more job for Tom Boilman. I doubt not your ladyship hath heard the sentence of these rebels," he continued turning to Cicely; "'Tis hanging, drawing and quartering for them all. Oh, I warrant me they'll spare no toil to give Sir Rupert a worthy death. He'll have music in plenty for his last dance, and in case he find the hanging wearisome they'll cut him down and cut him up before he chokes." He laughed brutally at his joke and added coolly, "Maybe he'll live long enough to feel the boiling pitch, they say some of them have done so, and Sir Rupert is hardy enow."

Cicely covered her face with her hands and sank shuddering to the ground.

"Oh! Barbara, Barbara, what can we do?" she sobbed, while the pedlar laughed once more.

"Plague take the man," muttered Barbara in desperation; "what could Rupert be doing to trust in such a rogue! Well, something must be done, but what?"

She looked round for inspiration and her glance rested on a long rapier which lay on the central table. She turned again to the pedlar and her eyes gleamed with excitement and triumph.

"He is but a poor creature," she muttered, "and by his face he should be but a coward. I can but try it."

"Well, mistress," continued the fellow harshly, "am I to offer the letter for sale down at the Winslow Arms yonder?"

"No, my man," answered Barbara calmly, "for an ye will not deliver it fairly I purpose to take it myself." So saying she stepped aside, picked up the rapier and raised the point full at the breast of the pedlar.

The cunning smile died from the man's face and he looked doubtfully from the shining blade to the resolute face of the girl.

Barbara watched him with a cheerful smile. "I fear me, fellow, you have made a sad mistake," she remarked coolly, "an you deemed you could act the bully undisturbed. We be two women, 'tis true, but not defenceless, as you will soon learn an you try to resist, for I can wield a rapier as well as any man; Cicely, reach me hither yonder pistol; 'tis loaded? Yes. Now my man, the letter, if you please."

This turn of events was totally unexpected by the pedlar. He half-doubted the girl's threat, but few such men as he would care to risk a rush against a loaded pistol and a rapier wielded by a resolute hand. He made an attempt to snatch the rapier but the girl easily fenced his attempt, and the rapidity of her disengagement showed him that her boast of skill had been no idle threat. Barbara stood betwixt him and the door, the window was closed, he could see no way of escape.

After a moment or two of hesitation during which Barbara watched him breathlessly, he decided on a prudent course; placed the letter on the window-seat and answered sulkily:

"There is the packet then, give me the twenty crowns and let me go."

"Not so, friend," answered Barbara sweetly. "The Winslow Arms is still conveniently near, and I have not so low an estimate of your cunning as to doubt your knowledge of the contents of yonder letter. We must keep you here a little space. Oblige me by mounting those stairs."

The hawker made a step forward, only to find the point of the rapier against his breast, and seeing resistance to be useless he turned with a muttered curse and commenced to climb the wide staircase. Barbara followed him, the sword in her right hand, the pistol in her left, for being thoroughly skilled in the use of the rapier she felt more confidence in that weapon than in the pistol, which latter aroused in her as in many of her sex feelings rather of doubt and suspicion than of confidence, in fact she carried it but to give an air of greater resolution to her action.

"What a grace it is to be firm of countenance," she chuckled to herself as she slowly followed her victim. "The poor fool! and he did but know how my heart trembles, for in truth, if he resists, I could not hurt him. If I did pink him with my rapier 'tis very like I should but faint at sight of his blood, but he is too great a coward to attempt it. What a tale this will be for Rupert."

Now when either man or woman is embarked upon any hazardous undertaking 'tis but scant wisdom to indulge in triumphant rejoicing before the success of the enterprise be thoroughly assured. Had Barbara borne this in mind and given less rein to her hopeful imagination she had doubtless been better prepared for what followed. For as they approached the top of the stairway and she was hugging herself over the success of her bravado, the pedlar suddenly stumbled forward upon his face, slipped down two steps, striking his boots against the girl's ankles, and before she rightly realised what was happening had twisted himself backwards under the guard of her rapier, knocked up her arm and flinging her roughly aside he started down the stairs.

Barbara clutched at the balustrade to save herself from falling headlong, and in so doing dropped the pistol. The suddenness of the attack had completely shattered her nerve, she could do nothing save cling to the oak railing and gaze helplessly after the retreating figure of the pedlar.

As for Simon, he paused neither for his pack nor his letter, but made all speed to reach the open door of the hall, and he would assuredly have escaped unopposed but for the sudden intervention of an unexpected enemy.

He had already reached the threshold, and in another minute would have been free, when Cicely, with a sudden thought born of the very nearness of the danger, sprang to her feet and gave a shrill whistle. There was a low, fierce growl, a quick rush of feet.

"Down with him, Butcher, at him! at him!" cried Cicely, and the next moment the pedlar was pulled to the ground and struggling wildly with the enormous wolfhound which had answered his mistress's eager summons and now stood over Simon shaking and worrying him as if he had been a rat.

If the man's life were to be saved there was clearly no time to be lost, and the two girls hurried to the spot to interpose between the dog and his victim.

It was no easy task, for the dog was savage with fury, but at length Cicely succeeded in dragging him away, while Barbara fell on her knees beside the man anxiously inquiring of his injuries.

"Oh! I can trust thou art not greatly hurt," she gasped; "tho' in truth 'twere but thy deserts. Canst not speak, fellow? Nay, prithee what ails thee? Alack! I fear me Butcher has hurt thee sorely, and yet truly I would it were more. Indeed the dog should be chained, tho' I am right thankful he was free."

So she continued, torn between a woman's compassion for his overthrow and a deep sense of relief at their escape.

Meanwhile Cicely having somewhat pacified the indignant Butcher returned to the pedlar's side. She could not repress a smile as she listened to her cousin's contradictory outburst. She had no pity to spare for the man who had so threatened the life of her lover.

"Tut, Barbara! 'tis my belief the fellow is but little injured save in the loss of his garments," for the pedlar's coat was in rags. "Come," she continued, turning sharply to the man, "be thankful the dog has dealt so gently with you, 'twould not be so the next time an ye attempt to escape again. Up with you, fellow."

With many groans and heartfelt curses Simon struggled to his feet. As Cicely had suspected he was rather terrified than hurt, but the dog had shaken out of him what little courage he possessed. He turned without further attempt at resistance, and slowly mounted the stairs, followed once more by Barbara, who, having well-nigh paid dearly for her experience, did not relax her wariness until she had safely secured him in one of the upper chambers whence there was no possibility of escape.

This done she hurried down into the hall, where Cicely sat engrossed already in her letter, and burst into a merry laugh.

"Well done, Cis, well done," she cried, flinging herself down beside her cousin. "I vow thou art a very virago, but for thee he would have escaped. Alack! 'tis small use to have the wrist, eye, and skill of a man when one has but a woman's nerve. But what news, coz; what says the letter?"

"He is safe, he has reached the coast, and to-morrow will take sail in a vessel bound for Holland. He—— But I will tell thee the rest anon," answered Cicely somewhat hurriedly, and then passed into the garden still reading her letter.

"Plague take these lovers!" exclaimed Barbara, looking after her whimsically, "they are not too generous with their news. But now, how to rid me of yon same discontented gentle upstairs." She paused and bit her lip thoughtfully. "Ah! well, there is time for that; he is safe enough now, and belike a plan will suggest itself later."

Then she stretched her arms as though a great load were lifted from her shoulders, and laughed again softly.

"'Tis selfish to be happy when there be so many still in sorrow," she murmured. "But with Rupert safe again I cannot feel a care. All! 'tis a good world, a good world, and therefore," she cried, springing to her feet with a laugh, "I will go out and rejoice in it."

CHAPTER IV

The old-fashioned garden was the glory of the Manor House. Generations of flower-lovers had tended it year by year, and every nook and corner bore testimony to the loving care of its owners. As Barbara tripped along the trim box-edged paths between banks of hollyhocks and proud-faced dahlias and sweet clusters of late roses, she looked, in her soft blue gown, with her happy face and shining eyes like the very spirit of Hope just escaped from the box of Pandora, and meet to face and vanquish all the evils of the world. But when she emerged upon the lawn and came in sight of the grey stone sun-dial she stopped short, for on the steps of the dial sat Sorrow herself in the person of Cicely, her head leaning forlornly against the stone pillar, her eyes streaming with tears, her hands clasped and her breast convulsed with bitter sobs.

The laughter died out of Barbara's face, and was replaced by a look of the utmost astonishment and desperation.

"Now may I be forgiven, Cicely, an thou beest not the most ungrateful girl in Christendom," she exclaimed reproachfully. "Shame on you to sit there weeping like a very fountain, when thou shouldest be glad and thankful at Rupert's escape."

"Ah, indeed, Barbara! I am thankful, but——"

"Nay, then Heaven preserve me from such a melancholy display of thankfulness," responded Barbara drily. Then seating herself beside her sobbing cousin she continued coaxingly, "Come, tell me what ails thee, Cicely. Thou sayest Rupert has reached the coast in safety and to-morrow will take ship for Holland where he will wait until we can make his peace with the King. Is it not so? I confess I see no great cause for tears in news such as this."

"Ah, Barbara, 'tis different with thee, Rupert is only thy brother."

"Well, and were he ten thousand times thy sweetheart, I still cannot see why thou shouldest weep at his escape."

"Thou dost not listen, Barbara," answered Cicely somewhat petulantly. "I thank Heaven for his safety, but, oh, Barbara! I cannot let him go without seeing him once more, just once; and he says likewise he will not go without seeing me. Bethink you, we may not meet for years, and so he being but ten miles distant, he purposes to ride over to-night and bid farewell; and so I must weep, Barbara, for if he comes he will assuredly be taken, and if he comes not I shall assuredly die."

Barbara sprang to her feet with a gesture of despair.

"Now a plague on you both for a pair of mad lovers. He cannot come here, 'tis madness. Thou knowest, Cicely, the house and roads are watched night and day by these scarlet-coated, scarlet-faced troopers, and they say yonder dark-visaged captain of theirs is a very dragon of vigilance. 'Tis clear they deem such a visit likely, seeing how closely they watch our movements; 'twere fair courting capture if Rupert came."

"I know the risk well enow. But, oh, Barbara, I cannot live another day without seeing him. Ah, to feel he is so near, so near, and I may not see him, feel his hand, hear his voice. Oh! I cannot endure it," and leaning her head once more against the cold stone pillar of the dial, she burst into a passion of sobs.

Barbara regarded her with an expression of helpless bewilderment.

"'Tis passing strange," she murmured. "Come, Cis, I am Rupert's self in face and figure. I will kiss and cozen thee and call thee pretty names to thy heart's content; why may not that suffice thee?"

In spite of her tears Cicely could not repress a smile at this strange offer of a substitute.

"'Tis very clear, Barbara, thou hast never loved."

"Truly no," was the frank rejoinder. "I know nought of the matter; it passeth my understanding altogether and indeed methinks it is but nonsense. Rupert is very well where he is and you shall see him in a year or two at most. What more can you wish tho' you were a thousand times in love. Come, Cis, dry thine eyes, and we will send to forbid him to come."

But Cicely only wept the more persistently.

"Ah! Barbara, thou hast no heart, I must see him once again, indeed I must. I must let him hold me in his arms, and feel him near me. Barbara, you do not understand, but I shall die if I may not see him. Sure thou couldst help me an thou wouldst. My heart will break else. Oh, Barbara! try to understand."

Barbara gave a sigh of sheer desperation, then yielded to her cousin's plea.

"'Tis stark madness, Cis," she cried; "but thou shalt have thy way. Only look cheerily and Rupert shall come. But now how to devise it." She clasped her chin in her hands and bent her brows in thought. "What said he in the letter?"

"Thou mayest read it, an thou wilt not laugh."

Barbara took the note and turned away to pace up and down the lawn lest her cousin should see the involuntary twitching of her lips as she read the tender epistle; it was so strange to her to think of Rupert writing thus—Rupert, who to her seemed the personification of boyish gaiety.

As she raised her head from perusing the note her attention was momentarily arrested by a rustling sound from within one of the large laurel bushes bordering the lawn and a strange shimmer behind the leaves. She stared at the bush a moment in surprise and then passed on towards the foot of the garden still deep in thought. Here she paused long, gazing into the stream which there flowed by the garden, her face wrinkled with anxiety and bewilderment as she puzzled her brain over the situation, her eyes darkened with a shadow, of fear.

Suddenly with a flash the inspiration came. Her bent brows relaxed, her eyes glanced mischievously, she gave a gasp at the very magnificence of the idea, and breaking into the gayest laughter she fairly danced back to her cousin, clapping her hands with delight.

"Cicely, Cicely," she cried, "never let it be said again that Barbara is a brainless madcap. I have conceived the properest plot, a very prince of plots. Thou shalt see thy Romeo to-night, my poor lovelorn Juliet, and I——faith! I will have the maddest prank that ever woman played." And flinging herself on to the grass, she laughed till the tears ran down her cheeks.

Cicely stared at her in undisguised astonishment.

"Barbara," she remarked solemnly, "I verily believe thou art mad."

"Thou wouldest say so indeed an thou knewest my plan."

"Come then, tell me."

"Not I," laughed Barbara. "Be thou content with thy beloved Romeo, and leave me my jest to myself."

"But, Barbara, I am afraid. What if the plan should fail!"

"Talk not to me of failure, Cis. There is a risk, I do not deny it; but," she continued, laughing, "if danger befall can we not fight our way out? Butcher is a mighty ally; I am well nigh as handy as Rupert with the rapier, and thou mightest perchance discharge a pistol or so, if it were possible to do so and cover thine ears at the same moment."

"In Heaven's name, Barbara, what have you in your mind?" cried Cicely in dismay.

"Fear nothing, coz; leave all to me. Listen, Peter the smith can always be trusted; he or little Jacky Marlow would carry our message to Rupert. If he start at twilight he should be here before ten. We can hide him——"

"Whist, Barbara!" interrupted Cicely softly, "didst not hear a rustle in yonder bush? Can anyone be in hiding there?"

"Tut, tut! thou trembler! Thou wouldest see a spy in every pansy face. 'Twas but a rat or a rabbit. Get thee in and send for Peter; I will write my note to Rupert."

"I know not why I trust you, Barbara," said Cicely doubtfully, "for thou art ever a madcap. But I must see him."

"Well so thou shalt, so thou shalt; now leave me alone to think."

Left alone by the sun-dial Barbara resumed her favourite attitude for thought, one foot tucked beneath her, her head bent, her chin resting upon her clasped hands.

She thought deeply. Twice or thrice she raised her head and laughed aloud suddenly, as though catching some new and entertaining idea. Once indeed her face grew grave and her eyes fearful, and she shuddered as she weighed the dangers before her, but presently with a laugh she banished the thought. Was she not a Winslow? and whenever was Winslow yet who let fear turn him from the path he chose to tread?

At length she drew paper and pencil from her reticule, and wrote a short note. Then gathering up her flowers she rose and walked towards the house.

As she passed the clump of laurel she paused and plucked a few sprigs, glancing sharply through the leaves the while; then with a laugh and a shake of the head she passed on.

But having passed, there lay behind her in the centre of the path two roses and the little white note which had slipped from her fingers to the ground.

No sooner had Barbara vanished from sight than the branches of the laurel were parted and a purple face peered cautiously out. The face was followed by the stout figure of Corporal Crutch, who crawled from behind the bush, pounced upon the paper, and with a low chuckle of delight disappeared with his prize, leaving the garden once again deserted.

CHAPTER V.

Corporal Crutch, having obtained possession of the coveted note, and seeing nothing more to be gained by remaining at his uncomfortable post, withdrew softly from the garden. Stealing into the adjoining coppice, he seated himself beneath the shady trees, mopped his brow and proceeded to decipher the letter, pausing occasionally to chuckle slyly and congratulate himself upon the unexpected success of his espionage.

The letter was written in a bold round hand, and ran as follows:

DEAR RUPERT.—Thou art indeed the very apostle of rashness, but seeing thou art resolved to venture here to bid Cicely farewell, 'twere waste of words to attempt to dissuade thee. Yet prithee think no shame to be cautious, for the risk is great; we are much suspected and the house and lanes are closely watched. But to-day I will convey a message to this worthy captain, as from a trusted informant, that it is thine intention to meet me at the Lady Farm. These troopers swallow any bait; 'twill go hard an they ride not thither on a wild goose chase. As for you, an you come with caution over the hill and down the stream (the boat is moored among the willows at the old place) you will surely escape them. Once in the garden thou art safe enough; they dare not show their faces there and they love not the copse at night, deeming it damp,—as assuredly it is,—and haunted,—as doubtless it may be. We will be on the watch for thee, and the old hiding place is ready, an it should be needed. Farewell, thou rash and lovelorn fool. Thy sister,

BARBARA.

"Ods zooks! here's a prize!" chuckled the corporal, tossing the paper in the air and catching it again in the very ecstacy of delight. "Ha, Ha! my pretty mistress, thou'lt sing a different tune ere I've done with thee to-night. Now what to do? What were best? The captain (curse him) is away to Spaxton wi' three o' the men, to search the Squire's papers; he'll not be back till nightfall. The better fortune that; I'll see to this business myself, and 'twill go hard an I have not this same 'rash and lovelorn fool' in my safe keeping ere day dawns. Now how to work it?" he mused. "It were easier had they but said where the fellow lies. Should I set one to follow her messenger, and so discover his hiding-place? Yet that were difficult, perchance dangerous; 'tis very like we would but be led astray; these peasants are cursedly untrustworthy, and monstrous shrewd. Or post men up the stream, and take him on the road? That, too, were risky. Perchance 'twere wiser to watch him into the house, and there trap him. Yes, by Jupiter!" he muttered excitedly, "trap him and trap them all. Two traitors are better than one, and if she be not judged traitor for thus harbouring rebels, may I dance to Kirke's music myself. Why, 'tis no less than Mistress Lisle lost her head for last week. Yes, it must be so. Ah! the pretty fool, wi' her prince of plots. She may plot, ay, and counter-plot, but she'll not out-plot Jonathan Crutch, I warrant me. But soft, who comes here?"

It was Peter Drew, the smith, from the village, who strode through the coppice on his way to the Manor House. He greeted the Corporal with a scowl.

"Good-day, fellow," began that worthy. "What do you up here?"

"My lawful business, which is more than you can say," growled the smith, and passed on towards the house.

"Hum! So yonder is her messenger," mused the corporal. "Well, let him pass, he'll lime our bird for us."

Then he arose, and cautiously resuming his post of observation within the laurel bush he tossed the note back into the garden. Scarcely had he done so when Barbara came down the garden, searching eagerly for the missing paper. Presently she espied it where it lay on the lawn, and picking it up she placed it carefully in her pocket and returned to the house, while the corporal chuckled again over his success.

Ten minutes later Peter Drew came into sight round a corner of the building. He led a sturdy pony by the bridle, and his right arm was firmly linked in the arm of the unfortunate hawker, who was helpless in the grip of the powerful smith, and with rage in his heart was forced to walk along apparently on terms of the greatest friendship with his companion. For behind them marched the wolfhound, and the hawker knew that at the least attempt to escape he would be given over at once to the mercy of this relentless foe. They turned in the direction of the smithy and soon disappeared from sight. Then all was quiet once more and the corporal, again extricating himself from the sheltering laurel, set off for the village to collect his men and make his dispositions for the evening.

He proceeded with the utmost caution. Two of his men he posted on the main road to Cannington, where a path turned off over the hill to the river, and two more some distance up the stream, that they might watch and follow Sir Rupert should he by chance elect not to visit the Manor House itself. These he instructed not to interfere with Sir Rupert, unless he showed signs of scenting a trap, but to allow him to reach his house unmolested. The remainder he ordered to conceal themselves in the plantation near the house, and after dusk at a signal from him quietly to surround the building. He enjoined on all the greatest caution in concealing themselves, and bade them take good note of all who entered or left the mansion, but not to prevent any or show themselves until he gave the signal.

This done he returned to the Winslow Arms and proceeded to fortify his spirits and strengthen his wits by a hearty meal, thanking his stars the while that Captain Protheroe's absence gave him the opportunity to direct the operations in his own way.

"If the matter were but left to the captain, there would be but little fear for Sir Rupert; he hath neither wit nor stomach for such a job. Like as not he would have left the women alone, to harbour what rebels they choose. I marvel how he hath already risen so high in favour, save that the general is always easy tempered. If the business had been in my hands alone, the fellow had been laid by the heels long since."

So mused the worthy corporal, as he devoured his dinner and complacently reviewed his crafty proceedings of the morning.

His meal and his meditations were alike presently cut short by the entrance of the host, who announced that a man stood without clamouring for instant permission to speak with the captain, or if that might not be, with the corporal of the troop.

"'Tis a most persistent fellow. He saith he hath information of great moment for your honour, but I'll not vouch for the truth of it; he is a pedlar by trade, and such have ever glib tongues," continued the host with some scorn.

The corporal started on hearing the man's message; but remembering that a part of Mistress Barbara's plan was to send a messenger to the captain he smiled cunningly and ordered that the pedlar be instantly admitted.

"'Tis some traitorous rogue she hath employed, I doubt not," he muttered, "and a daring fellow withal to venture thus into the net. 'Twere well that such an one be speedily laid by the heels."

Then the door opened and in hurried Simon, the Pedlar.

Breathless and eager, and glancing nervously over his shoulder the while, he ignored the curt greeting of the corporal and broke at once roughly into his story.