From a Sketch by Percy Anderson.

MISS CONSTANCE COLLIER AS PALLAS ATHENE IN “ULYSSES.”

Frontispiece.]

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/behindfootlights00twee |

BEHIND THE FOOTLIGHTS

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

MEXICO AS I SAW IT. Third Edition.

THROUGH FINLAND IN CARTS. Third Edition.

A WINTER JAUNT TO NORWAY. Second Edition.

THE OBERAMMERGAU PASSION PLAY. Out of print.

DANISH VERSUS ENGLISH BUTTER MAKING. Reprint from “Fortnightly.”

WILTON, Q.C. Second Edition.

A GIRL’S RIDE IN ICELAND. Third Edition.

GEORGE HARLEY, F.R.S.; or, the Life of a London Physician. Second Edition.

From a Sketch by Percy Anderson.

MISS CONSTANCE COLLIER AS PALLAS ATHENE IN “ULYSSES.”

Frontispiece.]

BY

AUTHOR OF

“MEXICO AS I SAW IT,” “GEORGE HARLEY, F.R.S.,” ETC.

WITH TWENTY ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW YORK

DODD MEAD AND COMPANY

1904

PRINTED BY

HAZELL, WATSON AND VINEY, LD.,

LONDON AND AYLESBURY,

ENGLAND.

| CHAPTER I | |

| THE GLAMOUR OF THE STAGE | |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

Girlish Dreams of Success—Golden Glitter—Overcrowding—Few Successful—Weedon Grossmith—Beerbohm Tree—How Mrs. Tree made Thousands for the War Fund—The Stage Door Reached—Glamour Fades—The Divorce Court and the Theatre—Childish Enthusiasm—Old Scotch Body’s Horror—Love Letters—Temptations—Emotions—How Women began to Act under Charles I.—Influence of the Theatre for Good or Ill |

1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| CRADLED IN THE THEATRE | |

Three Great Aristocracies—Born on the Stage—Inherited Talent—Interview with Mrs. Kendal—Her Opinions and Warning to Youthful Aspirants—Usual Salary—Starving in the Attempt to Live—No Dress Rehearsal—Overdressing—A Peep at Harley Street—Voice and Expression—American Friends—Mrs. Kendal’s Marriage—Forbes Robertson’s Romance—Why he Deserted Art for the Stage—Fine Elocutionist—Bad Enunciation and Noisy Music—Ellen Terry—Gillette—Expressionless Faces—Long Runs—Charles Warner—Abuse of Success |

21 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| THEATRICAL FOLK | |

Miss Winifred Emery—Amusing Criticism—An Actress’s Home Life—Cyril Maude’s first Theatrical Venture—First Performance—A Luncheon Party—A Bride as Leading Lady—No [Pg vi] Games, no Holidays—A Party at the Haymarket—Miss Ellaline Terriss and her First Appearance—Seymour Hicks—Ben Webster and Montagu Williams—The Sothern Family—Edward Sothern as a Fisherman—A Terrible Moment—Almost a Panic—Asleep as Dundreary—Frohman at Daly’s Theatre—English and American Alliance—Mummers |

46 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| PLAYS AND PLAYWRIGHTS | |

Interview with Ibsen—His Appearance—His Home—Plays Without Plots—His Writing-table—His Fetiches—Old at Seventy—A Real Tragedy and Comedy—Ibsen’s First Book—Winter in Norway—An Epilogue—Arthur Wing Pinero—Educated for the Law—As Caricaturist—An Entertaining Luncheon—How Pinero writes his Plays—A Hard Worker—First Night of Letty |

74 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| THE ARMY AND THE STAGE | |

Captain Robert Marshall—From the Ranks to the Stage—£10 for a Play—How Copyright is Retained—I. Zangwill as Actor—Copyright Performance—Three First Plays (Pinero, Grundy, Sims)—Cyril Maude at the Opera—Mice and Men—Sir Francis Burnand, Punch, Sir John Tenniel, and a Cartoon—Brandon Thomas and Charley’s Aunt—How that Play was Written—The Gaekwar of Baroda—Changes in London—Frederick Fenn at Clement’s Inn—James Welch on Audiences |

92 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| DESIGNING THE DRESSES | |

Sarah Bernhardt’s Dresses and Wigs—A Great Musician’s Hair—Expenses of Mounting—Percy Anderson—Ulysses—The Eternal City—A Dress Parade—Armour—Over-elaboration—An Understudy—Miss Fay Davis—A London Fog—The Difficulties of an Engagement [Pg vii] |

111 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| SUPPER ON THE STAGE | |

Reception on the St. James’s Stage—An Indian Prince—His Comments—The Audience—George Alexander’s Youth—How he missed a Fortune—How he learns a Part—A Scenic Garden—Love of the Country—Actors’ Pursuits—Strain of Theatrical Life—Life and Death—Fads—Mr. Maude’s Dressing-room—Sketches on Distempered Walls—Arthur Bourchier and his Dresser—John Hare—Early and late Theatres—A Solitary Dinner—An Hour’s Make-up—A Forgetful Actor—Bonne Camaraderie—Theatrical Salaries—Treasury Day—Thriftlessness—The Advent of Stalls—The Bancrofts—The Haymarket Photographs—A Dress Rehearsal |

125 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| MADAME SARAH BERNHARDT | |

Sarah Bernhardt and her Tomb—The Actress’s Holiday—Love of her Son—Sarah Bernhardt Shrimping—Why she left the Comédie Française—Life in Paris—A French Claque—Three Ominous Raps—Strike of the Orchestra—Parisian Theatre Customs—Programmes—Late Comers—The Matinée Hat—Advertisement Drop Scene—First Night of Hamlet— Madame Bernhardt’s own Reading of Hamlet—Yorick’s Skull—Dr. Horace Howard Furness—A Great Shakesperian Library |

151 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| AN HISTORICAL FIRST NIGHT | |

An Interesting Dinner—Peace in the Transvaal—Beerbohm Tree as a Seer—How he cajoled Ellen Terry and Mrs. Kendal to Act—First-nighters on Camp-stools—Different Styles of Mrs. Kendal and Miss Terry—The Fun of the Thing—Bows of the Dead—Falstaff’s Discomfort—Amusing Incidents—Nervousness behind the Curtain—An Author’s Feelings |

173 |

| CHAPTER X [Pg viii] | |

| OPERA COMIC | |

How W. S. Gilbert loves a Joke—A Brilliant Companion—Operas Reproduced without an Altered Line—Many Professions—A Lovely Home—Sir Arthur Sullivan’s Gift—A Rehearsal of Pinafore—Breaking up Crowds—Punctuality—Soldier or no Soldier—Iolanthe—Gilbert as an Actor—Gilbert as Audience—The Japanese Anthem—Amusement |

186 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| THE FIRST PANTOMIME REHEARSAL | |

Origin of Pantomime—Drury Lane in Darkness—One Thousand Persons—Rehearsing the Chorus—The Ballet—Dressing-rooms—Children on the Stage—Size of “The Lane”—A Trap-door—The Property-room—Made on the Premises—Wardrobe-woman—Dan Leno at Rehearsal—Herbert Campbell—A Fortnight Later—A Chat with the Principal Girl—Miss Madge Lessing |

200 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| SIR HENRY IRVING AND STAGE LIGHTING | |

Sir Henry Irving’s Position—Miss Geneviève Ward’s Dress—Reformations in Lighting—The most Costly Play ever Produced—Strong Individuality—Character Parts—Irving earned his Living at Thirteen—Actors and Applause—A Pathetic Story—No Shakespeare Traditions—Imitation is not Acting—Irving’s Appearance—His Generosity—The First Night of Dante—First Night of Faust—Two Terriss Stories—Sir Charles Wyndham |

222 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| WHY A NOVELIST BECOMES A DRAMATIST | |

Novels and Plays—Little Lord Fauntleroy and his Origin—Mr. Hall Caine—Preference for Books to Plays—John Oliver Hobbes—J. M. Barrie’s Diffidence—Anthony Hope—A [Pg ix] London Bachelor—A Pretty Wedding—A Tidy Author—A First Night—Dramatic Critics—How Notices are Written—The Critics Criticised—Distribution of Paper—“Stalls Full”—Black Monday—Do Royalty pay for their Seats?—Wild Pursuit of the Owner of the Royal Box—The Queen at the Opera |

240 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| SCENE-PAINTING AND CHOOSING A PLAY | |

Novelist—Dramatist—Scene-painter—An Amateur Scenic Artist—Weedon Grossmith to the Rescue—Mrs. Tree’s Children—Mr. Grossmith’s Start on the Stage—A Romantic Marriage—How a Scene is built up—English and American Theatres Compared—Choosing a Play—Theatrical Syndicate—Three Hundred and Fifteen Plays at the Haymarket |

263 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| THEATRICAL DRESSING-ROOMS | |

A Star’s Dressing-room—Long Flights of Stairs—Miss Ward at the Haymarket—A Wimple—An Awkward Predicament—How an Actress Dresses—Herbert Waring—An Actress’s Dressing-table—A Girl’s Photographs of Herself—A Greasepaint Box—Eyelashes—White Hands—Mrs. Langtry’s Dressing-room—Clara Morris on Make-up—Mrs. Tree as Author—“Resting”—Mary Anderson on the Stage—An Author’s Opinion—Actors in Society |

275 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| HOW DOES A MAN GET ON THE STAGE? | |

A Voice Trial—How it is Done—Anxious Faces—Singing into Cimmerian Darkness—A Call to Rehearsal—The Ecstasy of an Engagement—Proof Copy; Private—Arrival of the Principals—Chorus on the Stage—Rehearsing Twelve Hours a Day for Nine Weeks without Pay |

292 |

| CHAPTER XVII [Pg x] | |

| A GIRL IN THE PROVINCES | |

Why Women go on the Stage—How to prevent it—Miss Florence St. John—Provincial Company—Theatrical Basket—A Fit-up Tour—A Theatre Tour—Répertoire Tour—Strange Landladies—Bills—The Longed-for Joint—Second-hand Clothes—Buying a Part—Why Men Deteriorate—Oceans of Tea—E. S. Willard—Why he Prefers America—A Hunt for Rooms—A Kindly Clergyman—A Drunken Landlady—How the Dog Saved an Awkward Predicament |

302 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| PERILS OF THE STAGE | |

Easy to Make a Reputation—Difficult to Keep One—The Theatrical Agent—The Butler’s Letter—Mrs. Siddons’ Warning—Theatrical Aspirants—The Bogus Manager—The Actress of the Police Court—Ten Years of Success—Temptations—Late Hours—An Actress’s Advertisement—A Wicked Agreement—Rules Behind the Scenes—Edward Terry—Success a Bubble |

325 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| “CHORUS GIRL NUMBER II. ON THE LEFT” | |

| A Fantasy Founded on Fact | |

Plain but Fascinating—The Swell in the Stalls—Overtures—Persistence—Introduction at Last—Her Story—His Kindness—Happiness crept in—Love—An Ecstasy of Joy—His Story—A Rude Awakening—The Result of Deception—The Injustice of Silence—Back to Town—Illness—Sleep |

345 |

MISS CONSTANCE COLLIER AS PALLAS ATHENE IN “ULYSSES” |

Frontispiece | |

| From a sketch by Percy Anderson. | ||

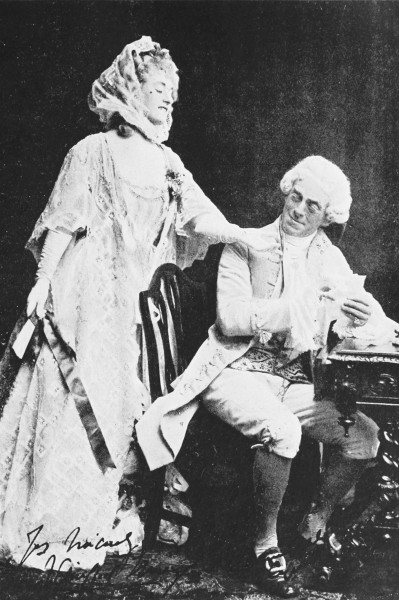

MRS. KENDAL AS MISTRESS FORD IN “MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR” |

To face p. | 20 |

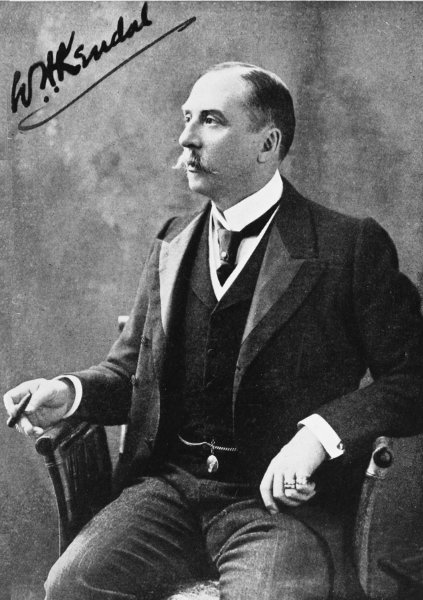

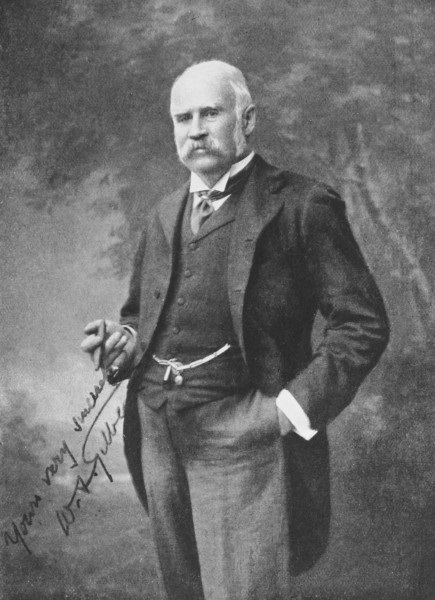

MR. W. H. KENDAL |

„ | 32 |

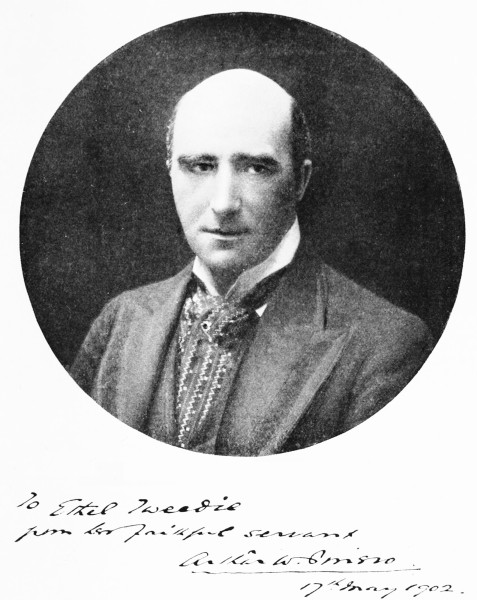

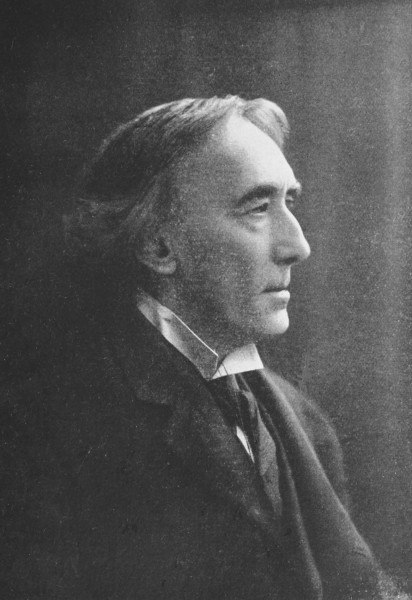

MR. J. FORBES-ROBERTSON |

„ | 36 |

| From a painting by Hugh de T. Glazebrook. | ||

MISS WINIFRED EMERY AND MR. CYRIL MAUDE IN “THE SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL” |

„ | 48 |

MR. AND MRS. SEYMOUR HICKS |

„ | 64 |

DR. HENRIK IBSEN |

„ | 76 |

MR. ARTHUR W. PINERO |

„ | 84 |

DRAWING OF COSTUME FOR JULIET |

„ | 112 |

| By Percy Anderson. | ||

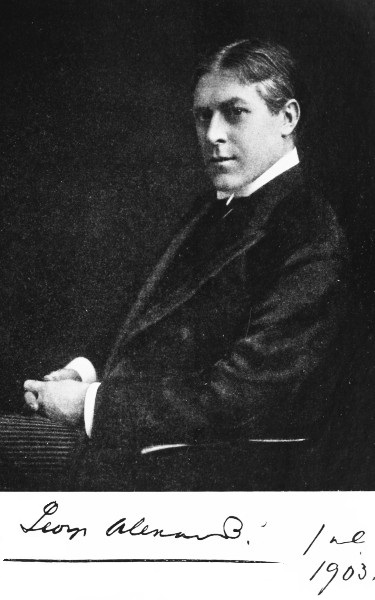

MR. GEORGE ALEXANDER |

„ | 128 |

MADAME SARAH BERNHARDT AS HAMLET |

„ | 152 |

MR. BEERBOHM TREE AS FALSTAFF |

„ | 176 |

MISS ELLEN TERRY AS QUEEN KATHERINE |

„ | 184 |

MR. W. S. GILBERT |

„ | 192 |

SIR HENRY IRVING |

„ | 224 |

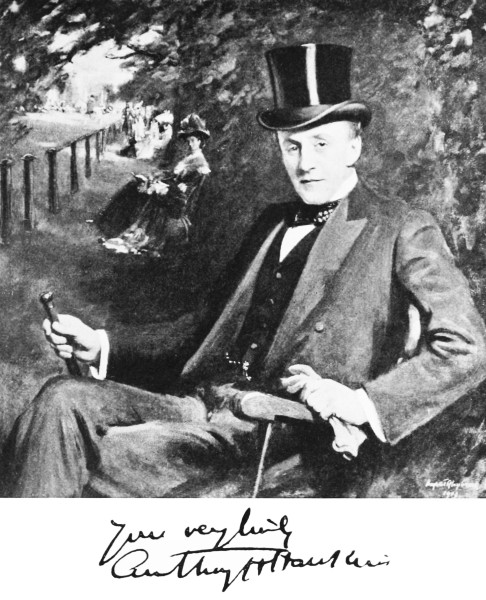

MR. ANTHONY HOPE |

„ | 248 |

| From a painting by Hugh de T. Glazebrook. | ||

MR. WEEDON GROSSMITH |

„ | 264 |

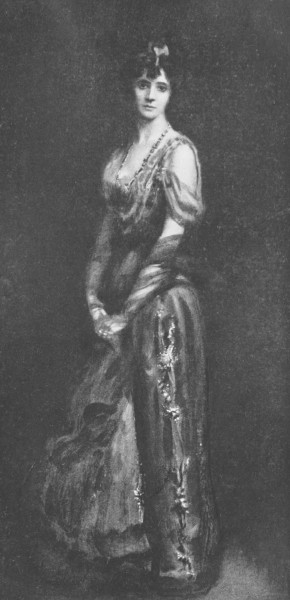

MRS. BEERBOHM TREE |

„ | 288 |

MRS. PATRICK CAMPBELL |

„ | 312 |

| From a painting by Hugh de T. Glazebrook. | ||

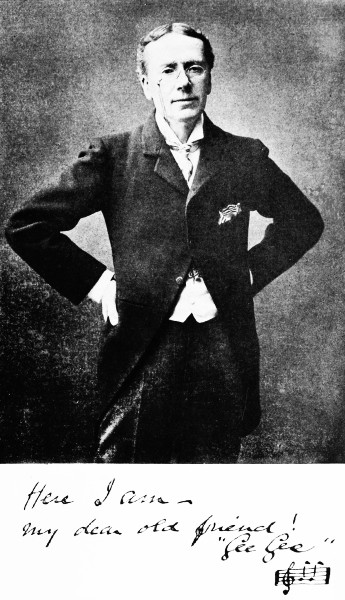

MR. GEORGE GROSSMITH |

„ | 336 |

BEHIND THE FOOTLIGHTS

“I WANT to go on the stage,” declared a girl as she sat one day opposite her father, a London physician, in his consulting-room.

The doctor looked up, amazed, deliberately put down his pen, cast a scrutinising glance at his daughter, then said tentatively:

“Want to go on the stage, eh?”

“Yes, I wish to be an actress. I have had an offer—oh, such a delightful offer—to play a girl’s part in the forthcoming production at one of our best theatres.”

Her father made no comment, only looked again[Pg 2] steadily at the girl in order to satisfy himself that she was speaking seriously. Then he took the letter she held out, read it most carefully, folded it up—in what the would-be actress thought an exasperatingly slow fashion—and after a pause observed:

“So this is the result of allowing you to play in private theatricals. What folly!”

The girl started up—fire flashed from her eyes, and her lips trembled as she retorted passionately:

“I don’t see any folly, I only see a great career opening before me. I want to go on the stage and make a name.”

The doctor looked more grave than ever, but replied calmly:

“You are very young—you have only just been to your first ball; you know nothing whatever about the world or work.”

“But I can learn, and intend to do so.”

“Ah yes, that is all very well; but what you really see at this moment is only the prospect of so many guineas a week, of applause and admiration, of notices in the papers, when at one jump you expect to gain the position already attained by some great actress. What you do not see, however, is the hard work, the dreary months, nay years, of waiting, the many disappointments that precede success—you do not realise the struggle of it all, or the many, many failures.”

She looked amazed. What possible struggle could there be on the stage? she wondered.

“Is this to be the end of my having worked for you,” he asked pathetically, “planned for you, given you the best education I could, done everything possible to make your surroundings happy, that at the moment when I hoped you were going to prove a companion and a comfort, you announce the fact that you wish to choose a career for yourself, to throw off the ties—I will not call them the pleasures—of home, and seek work which it is not necessary for you to undertake?”

“Yes,” murmured the girl, by this time almost sobbing, for the glamour seemed to be rolling away like mist before her eyes, while glorious visions of tragedy queens and comic soubrettes faded into space.

“I will not forbid you,” he went on sadly but firmly—“I will not forbid you, after you are twenty-one, for then you can do as you like; but nearly four years stretch between now and then, and during those four years I shall withhold my sanction.”

Tears welled up into her eyes. Moments come in the lives of all of us when our nearest and dearest appear to understand us least. Even in our youth we experience unreasoning sadness.

“I do not wish,” he continued, rising and patting her kindly on the back, “to see my daughter worn to a skeleton, working when she should be enjoying herself, taking upon her shoulders cares and worries which I have striven for years to avert—therefore I must save you from yourself. During the next four years I will try to show you what going[Pg 4] on the stage really means, and the labour it entails.”

She did not answer, exultation had given place to indignation, indignation to emotion, and the aspirant to histrionic fame felt sick at heart.

That girl was the present writer—her father the late Dr. George Harley, F.R.S., of Harley Street.

During those four years he showed me the work and anxiety connection with the stage involves, and as it was not necessary for me to earn my living at that time, I waited his pleasure, and, finally, of my own free will abandoned the girlish determination of becoming an actress. Wild dreams of glory and success eventually gave place to more rational ideas. The glamour of the footlights ceased to shine so alluringly—as I realised that the actor’s art, like the musician’s, is ephemeral, while the work and anxiety are great in both.

The restlessness of youth was upon me when I mooted the project, and an injudicious word then would have sent me forth at a tangent, probably to fail as many another has done before and since.

There may still be a few youthful people in the world who believe the streets of London are paved with gold—and there are certainly numbers of boys and girls who think the stage is strewn with pearls and diamonds. All the traditions of the theatre are founded in mystery and exaggeration; perhaps it is as well, for too much realism destroys illusion.

Boys and girls dream great dreams—they fancy[Pg 5] themselves leading actors and actresses, in imagination they dine off gold, wear jewels, laces, and furs, hear the applause of the multitude—and are happy. But all this, as said, is in their dreams, and dreams only last for seconds, while life lasts for years.

One in perhaps a thousand aspirants ever climbs to the top of the dramatic ladder, dozens remain struggling on the lower rung, while hundreds fall out weary and heart-sore before passing even the first step. Never has the theatrical profession been more overcrowded than at the present moment.

Many people with a wild desire to act prove failures on the stage, their inclinations are greater than their powers. Rarely is it the other way; nevertheless Fanny Kemble, in spite of her talent, hated the idea of going on the stage. At that time acting was considered barely respectable for a woman (1829). She was related to Sarah Siddons and John Kemble, a daughter of Charles and Fanny Kemble, and yet no dramatic fire burned in her veins. She was short and plain, with large feet and hands, her only charm her vivacity and expression. Ruin was imminent in the family when the girl was prevailed upon after much persuasion to play Juliet. Three weeks later she electrified London. Neither time nor success altered her repugnance for the stage, however. When dressed as Juliet her white satin train lying over the chair, she recalled the scene in the following words:

“There I sat, ready for execution, with the palms of my hands pressed convulsively together, and the tears I in vain endeavoured to repress welling up[Pg 6] into my eyes, brimming slowly over, down my rouged cheeks.”

There is a well-known actor upon the stage to-day who feels much as Fanny Kemble did.

“I hate it all,” he once said to me. “Would to Heaven I had another profession at my back. But I never really completed any studies in my youth, and in these days of keen competition I dare not leave an income on the stage for an uncertainty elsewhere.”

To some people the stage is an alluring goal, religion is a recreation, while to others money is a worship. The Church and the Stage cast their fascinating meshes around most folk some time during the course of their existences. It is scarcely strange that such should be the case, for both hold their mystery, both have their excitements, and man delights to rush into what he does not understand—this has been the case at all times and in all countries, and, like love and war, seems likely to continue to the end of time.

We all know the stage as seen from before the footlights—we have all sat breathless, waiting for the curtain to rise, and there are some who have longed for the “back cloth” to be lifted also, that they might peep behind. In these pages all hindrances shall be drawn away, and the theatre and its workings revealed from behind the footlights.

As every theatre has its own individuality, so every face has its own expression, therefore one can only generalise, for it is impossible to treat each theatrical house and its customs separately.

The strong personal interest I have always felt for the stage probably originated in the fact that from childhood I had heard stories of James Sheridan Knowles writing some of his plays, notably The Hunchback, at my grandfather’s house, Seaforth Hall, in Lancashire. Charles Dickens often stayed there when acting for some charity in Liverpool. Samuel Lover was a constant visitor at the house, as also the great American tragedian, Charlotte Cushman. Her beautiful sister Susan (the Juliet of her Romeo) married my uncle, Sheridan Muspratt, author of the Dictionary of Chemistry. From all of which it will be seen that theatrical stories were constantly retailed at home; therefore when I was about to “come out,” and my father asked if I would like a ball, I replied:

“No, I should prefer private theatricals.”

This was a surprise to the London physician; but there being no particular sin in private theatricals, consent was given, “provided,” as he said, “you paint the scenery, make your own dresses, generally run the show, and do the thing properly.”

A wise proviso, and one faithfully complied with. It gave an enormous amount of work but brought me a vast amount of pleasure.

Mr. L. F. Austin, a clever contributor to the Illustrated London News, wrote a most amusing account of those theatricals—in which he, Mr. Weedon Grossmith, and Mrs. Beerbohm Tree assisted—in his little volume At Random. Sir William Magnay, then a well-known amateur, and now a novelist,[Pg 8] was one of our tiny company. Sweethearts, Mr. W. S. Gilbert’s delightful little comedy, was chosen for the performance, but at the last moment the girl who should have played the maid was taken ill. Off to Queen’s College, where I was then a pupil, I rushed, dragged Maud Holt—who became Mrs Tree a few weeks later—back with me, and that same night she made her first appearance on any stage. Very shortly afterwards Mrs. Beerbohm Tree adopted acting as a profession, and appeared first at the Court Theatre. Subsequently, when her husband became a manager, she joined his company for many years.

We all adored her at College: she was tall and graceful, with a beautiful figure: she sang charmingly, and read voraciously. In those days she was a great disciple of Browning, and so was Mr. Tree; in fact, the poet was the leading-string to love and matrimony.

Mrs. Beerbohm Tree considers that almost the happiest moments of her life were spent in reciting The Absent-minded Beggar for the War Fund. It came about in this wise. She had arranged to give a recitation at St. James’s Hall on one particular Wednesday. On the Friday before that day she saw announced in the Daily Mail that a new poem by Rudyard Kipling on the Transvaal war theme would appear in the Tuesday issue. This she thought would be a splendid opportunity to declaim a topical song at the concert, so she wrote personally to the editor of the paper, and asked him if he could possibly let her have an advance copy of the poem, so that[Pg 9] she might learn and recite it on Wednesday, as the Tuesday issue would be too late for her purpose.

Through the courtesy of Mr. Harmsworth she received the proof of The Absent-minded Beggar on Friday evening, and sitting in her dining-room in Sloane Street with her elbows on the table she read and re-read it several times. This, she thought, might bring grist to the war mill. Into a hansom she jumped, and off to the Palace Theatre she drove, boldly asking for the manager. Her name was sufficient, and she was ushered into the august presence.

“This is a remarkable poem,” she said, “by Mr. Rudyard Kipling, so remarkable that I think if recited in your Hall nightly it would bring some money to the fund, and if you will give me £100 a week——”

Up went the manager’s hand in horror.

“One hundred pounds a week, Mrs. Tree?”

“Yes, £100 a week, I will come and recite it every evening, and hand over the cheque intact to the War Fund.”

It was a large sum, and the gentleman could not see his way to accepting the offer on his own responsibility, but said he would sound his directors in the morning.

Before lunch-time next day Mrs. Tree received a note requesting her to recite the poem nightly as suggested, and promising her £100 a week for herself or the fund in return. For ten weeks she stood alone every evening on that vast stage, and for ten minutes she recited “Pay, pay, pay.” There never have been such record houses at the Palace either before or since, and at the end of ten weeks she handed over[Pg 10] a cheque for £1,000 to the fund. Nor was this all, large sums were paid into the collecting boxes in the Palace Theatre. In addition Mrs. Tree made £1,700 at concerts, and £700 on one night at a Club. More than that, endless people followed her example, and the War Fund became some £20,000 richer for her inspiration in that dining-room in Sloane Street.

This was one of the plums of the theatrical cake; but how different is the performance and the gold and glitter as seen from the front of the curtain, to the real thing behind. How little the audience entering wide halls, proceeding up pile carpeted stairs, sweeping past stately palms, or pushing aside heavy plush curtains, realise the entrance to the playhouse on the other side of the footlights.

At the back of the theatre is the stage door. Generally up an alley, it is mean in appearance, more like an entrance to some cheap lodging-house than to fairyland. Rough men lounge about outside, those scene-shifters, carpenters, and that odd list of humanity who jostle each other “behind the scenes,” work among “flies,” and adjust “wings” in no ornithological sense, but merely as the side-pieces of the stage-setting.

Just inside this door is a little box-like office; nothing grand about it, oh dear no, whitewash is more often found there than mahogany, and stone stairs than Turkey carpets. Inside this little bureau sits that severe guardian of order, the stage door keeper. He is a Pope and a Czar in one. He is always busy, refuses to listen to explanations; even a card[Pg 11] is not sent in unless that important gentleman feels assured its owner means business.

At that door, which is dark and dreary, the glamour of the stage begins to wane. It is no portal to a palace. The folk hanging about are not arrayed in velvets and satins; quite the contrary; torn cashmeres and shiny coats are more en évidence.

Strange people are to be found both behind and upon the stage, as in every other walk through life; but there are plenty of good men and women in the profession, men and women whose friendship it is an honour to possess. Men and women whose kindness of heart is unbounded, and whose intellectual attainments soar far above the average.

Every girl who goes upon the stage need not enjoy the privilege of marrying titled imbecility, nor obtain the notoriety of the Divorce Court, neither being creditable nor essential to her calling, although both are chronicled with unfailing regularity by the press.

The Divorce Court is a sad theatre where terrible tragedies of human misery are acted out to the bitter end. Between seven and eight hundred cases are tried in England every year—not many, perhaps, when compared with the population of the country, which is over forty millions. But then of course the Divorce Court is only the foam; the surging billows of discontent and unhappiness lie beneath, and about six thousand judicial separations, all spelling human tragedy, are granted yearly by magistrates, the greater number of such cases being undefended. They[Pg 12] record the same sad story of disappointed, aching hearts year in year out.

Divorces are not more common amongst theatrical folk than any other class, so, whatever may be said for or against the morality of the stage, the Divorce Court does not prove theatrical life to be less virtuous than any other.

The fascination of the stage entraps all ages—all classes. Even children sometimes wax warm over theatrical folk. Once I chanced to be talking to a little girl concerning theatres.

“Do you know Mr. A. B. C.?” she asked excitedly, when the conversation turned on actors.

“Yes, he is a great friend of mine.”

“Oh, do tell me all about him,” she exclaimed, seizing my arm.

“Why do you want to know?”

“Because I adore him, and all the girls at school adore him, he is like a real prince; we save up our pocket-money to buy his photographs, and May Smith has actually got his autograph!”

“But tell me why you all adore him?” I asked.

“Because he is so lovely, so tall and handsome, has such a melodious voice, and oh! doesn’t he look too beautiful in his velvet suit as——? He is young and handsome, isn’t he? Oh, do say he is young and handsome,” implored the enthusiastic child.

“I am afraid I cannot, for it would not be true; Mr. A. B. C. is not tall—in fact, he is quite short.” She looked crestfallen. “He has a sallow complexion[Pg 13].”

“Sallow! Oh, not really sallow! but he is handsome and young, isn’t he?”

“I should think he is about fifty-two.”

“Fifty-two!” she almost shrieked. “My A. B. C. fifty-two. Oh no. You are chaffing me; he must be young and beautiful.”

“And his hair is grey,” I cruelly added.

“Grey?”—she sobbed. “Not grey? Oh, you hurt me.”

“You asked questions and I have answered them truthfully,” I replied. She stood silent for a moment, then in rather a subdued tone murmured:

“He is not married, is he?”

“Oh yes, he has been married for five-and-twenty years.”

The child looked so crestfallen I felt I had been unkind.

“Oh dear, oh dear,” she almost sobbed, “won’t the girls at school be surprised! Are you quite, quite sure he is not young and beautiful? he looks so lovely on the stage.”

“Quite, quite sure. You have only seen him from before the footlights. He is a good fellow, clever and charming, and he works hard, but he is no lover in velvet and jerkin, no hero of romance, and the less you worry your foolish little head about him the better, my dear.”

How many men and women believe like this child that there are only princes and princesses on the stage.

There was an old Scotch body—an educated,[Pg 14] puritanical person—who once informed me, “The the-a-ter is very bad, very wicked, ma’am.”

“Why?” I asked, amazed yet interested.

“It’s full of fire and lights like Hell. They just discuss emotions there, ma’am, and it’s morbid to discuss emotions and just silly conceit to think about them. I like deeds, and not talk—I do!”

“You seem to think the theatre a hotbed of iniquity?”

“Aye, indeed I do, ma’am. They even make thunder. Fancy daring to make thunder for amusement as the good God does to show His wrath—thunder with a machine—it’s just dreadful, it is.”

The grosser the exaggeration the more readily it provokes conversation. I was dying to argue, but fearing to hurt her feelings, I merely smiled, wondering what the old lady would say if she knew even prayers were made by a machine in countries where the prayer-wheel is used.

“Have you ever been to a theatre?” I ventured to ask, not wishing to disturb the good dame’s peace of mind.

“The Lord forbid!”

That settled the matter; but I subsequently found that the old body went to bazaars, and did not mind a little flutter over raffles, and on one occasion had even been to hear the inimitable George Grossmith in Inverness, when——

“He was not dressed-up-like, so it wasn’t a regular the-a-ter, and he was just alone, ma’am, wi’ a piano, so there was no harm in that,” added the[Pg 15] virtuous dame, complacently folding her hands across her portly form.

Wishing to change the subject, I asked her how her potatoes were doing.

“Bad, bad,” she replied, “they’re awfu’ bad, the Lord’s agin us the year; but we must jist make the best of it, ma’am.”

She was a thoroughly good woman, and this was her philosophy. She would make the best of the lack of potatoes, as that was a punishment from above; but she could not sanction play-acting any more than riding a bicycle on the Sabbath.

Her horror of the wickedness of the stage was as amusing as the absurd adoration of the enthusiastic child.

Every good-looking man or woman who “play acts” is the recipient of foolish love-letters. Pretty girls receive them from sentimental youth or sensual old age, and handsome men are pestered with them from old maids, or unhappily married women. Some curious epistles are sent across the footlights, even the most self-respecting woman cannot escape their advent, although she can, and, does, ignore them.

Here is a sample of one:

“For five nights I have been to the theatre to see you play in——. I was so struck by your performance last week that I have been back every night since. Vainly I hoped you would notice me, for I always occupy the same seat, and last night I really thought you did smile at me” (she had done nothing of the kind, and had never even seen the man), “so I went[Pg 16] home happy—oh so happy. I have sent you some roses the last two nights, and felt sorry you did not wear them. Is there any flower you like better? I hardly dare presume to ask you for a meeting, but if you only knew how much I admire you, perhaps you would grant me this great favour and make me the happiest man on earth. I cannot sleep for thinking of you. You are to me the embodiment of every womanly grace, and if you would take supper with me one night after the performance you would indeed confer a boon on a lonely man.”

No answer does not mean the end of the matter. Some men—and, alas! some women—write again and again, send flowers and presents, and literally pester the object of their so-called adoration.

For weeks and weeks a man sent a girl violets; one night a diamond ring was tied up in the bunch—those glittering stones began her ruin—she wrote to acknowledge them, a correspondence ensued.

That man proved her curse. She, the once beautiful and virtuous girl, who was earning a good income before she met her evil genius, died lately in poverty and obscurity. The world had scoffed at her and turned aside, while it still smiled upon the man, although he was the villain; but can he get away from his own conscience?

Every vice carries with it a sting, every virtue a balm.

There are many perils on the stage, to which of course only the weak succumb; but the temptations are necessarily greater than in other professions. Its[Pg 17] very publicity spells mischief. There is the horrid man in all audiences who tries to make love and ogle pretty women across the footlights, the class of creature who totally forgets that the best crown a man or woman can wear is a good reputation.

Temptations lie open on all sides for the actor and actress, and those who pass through the ordeal safely are doubly to be congratulated, for the man who meets temptation and holds aloof is surely a finer character than he who is merely “good” because he has never had a chance of being anything else.

Journalism, domestic service, and the stage probably require less knowledge and training for a beginning than any other occupations.

It costs money and time to learn to be a dressmaker, a doctor, an architect, even a shorthand writer; but given a certain amount of cleverness, experience is not necessary to do “scissor-and-paste” work in journalism, rough housework, or to “walk on” on the stage; but oh! what an amount of work and experience is necessary to ensure a satisfactory ending, more particularly upon the boards, where all is not gold that glitters. At best the crown is only brass, the shining silver merely tin, and in nine theatres out of every ten the regal ermine but a paltry rabbit-skin.

Glitter dazzles the eye. Nevertheless behind it beat good hearts and true; while hard work, patient endurance, and courage mark the path of the successful player.

Work does not degrade a man; but a man often degrades his work.

If, as the old body said, it be morbid to discuss emotions, and egotistical to feel them, it is still the actor’s art, and that is probably why he is such a sensitive creature, why he is generally in the highest spirits or deepest depths of woe, why he is full of moods and as varying as a weathercock. Still he is charming, and so is his companion in stageland—the actress. Both entertain us, and amusement is absolutely essential to a healthy existence.

When one considers the wonderful success of women upon the stage to-day, and their splendid position socially, it seems almost impossible to believe that they never acted in England until the reign of Charles I., when a French Company which numbered women among its players crossed the Channel, and craved a hearing from Queen Henrietta Maria. One critic of the time called them “unwomanish and graceless”; another said, “Glad am I they were hissed and hooted”; but still they had come to stay, and slowly, very slowly, women were allowed to take part in theatrical performances. We all know the high position they hold to-day.

In 1660 there were only two theatres in London, the King’s and the Duke of York’s, the dearest seats were the boxes at four shillings, the cheapest the gallery at one shilling. Ladies wore masks at the play, probably because of the coarse nature of the performances, which gradually improved with the advent of actresses.

In days gone by the playhouse was not the orderly place it is nowadays, and the unfortunate[Pg 19] “mummers” had to put up with every kind of nuisance until Colley Cibber protested, and Queen Anne issued a Proclamation (1704) against disturbances. In those days folk arrived in sedan chairs, and their noisy footmen were allowed free admission to the upper gallery to wait for their lords and ladies, added to which the orange girls called their wares and did a brisk trade in carrying love-missives from one part of the house to the other. Before the players could be heard they had to fight their way on to the boards, where gilded youth lolled in the wings and even crossed the stage during the rendering of a scene.

It was about this time that Queen Anne made a stand against the shocking immorality of the stage, and ordered the Master of the Revels (much the same post as the Lord Chamberlain now holds) to correct these abuses. All actors, mountebanks, etc., had to submit their plays or entertainments to the Master of the Revels in Somerset House from that day, and nothing could be performed without his permission.

The stage has a curious effect on people. Many a person has gone to see a play, and some line has altered the whole course of his life. Some idea has been put forth, some tender note played upon which has opened his eyes to his own selfishness, his own greed of wealth, his harshness to a child, or indifference to a wife. There is no doubt about it, the stage is a great power, and that is why it is so important the influence should be used for good, and that illicit love and demoralising thoughts should be kept out[Pg 20] of the theatre with its mixed audiences and susceptible youth. According to a recent report:

“The Berne authorities, holding that the theatre is a powerful instrument for the education of the masses, have decided that on two days of the week the seats in the theatre, without exception, shall be sold at a uniform price of fivepence. ‘Under the direction of the manager,’ writes a correspondent, ‘the tickets are enclosed in envelopes, and in this form are sold to the public. The scheme has proved a great success, especially among the working classes, whom it was meant to benefit. To prevent ticket speculators making a “corner,” the principle of one ticket for one person has been adopted, and the playgoer only knows the location of his seat after he enters the theatre. No intoxicants are sold and no passes are given. The expenses exceed the receipts, but a reserve fund and voluntary contributions are more than sufficient to meet the deficit.’”

Constantly seeing vice portrayed tends to make one cease to think it horrible. Love of gain should not induce a manager to put on a piece that is public poison. Some queer plays teach splendid moral lessons—well and good; but some strange dramas drag their audience through mire for no wise end whatever. The manager who puts such upon his stage is a destroyer of public morality.

Photo by Window & Grove, Baker Street, W.

MRS. KENDAL AS MISTRESS FORD IN “MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR.”

LONDON is a great world: it contains three aristocracies:

The aristocracy of blood, which is limited;

The aristocracy of brain, which is scattered;

And the aristocracy of wealth, which threatens to flood the other two.

The most powerful book in the world at the beginning of the twentieth century is the cheque-book. Foreigners are adored, vulgarity is sanctioned; indeed, all are welcomed so long as gold hangs round their skirts and diamonds and pearls adorn their bodies. Wealth, wealth, wealth, that is the modern cry, and there seems nothing it cannot buy, even a transient position upon the stage.

Many of our well-known actors and actresses have,[Pg 22] however, been “born on the stage”—that is to say, they were the children of theatrical folk, and have themselves taken part in the drama almost from babyhood.

The most successful members of the profession are those possessed of inherited talent, or that have gone on the stage from necessity rather than choice, men and women who since early life have had to fight for themselves and overcome difficulties. It is pleasant to give a prominent example of the triumph which may result from the blending of both influences in the person of one of our greatest actresses, Mrs. Kendal, who has led a marvellously interesting life.

She was born early in the fifties, and her grandfather, father, uncles, and brother (T. W. Robertson) were all intimately connected with the stage as actors and playwrights. When quite a child she began her theatrical career, and made her London début in 1865, when she appeared as Ophelia under her maiden name of Madge Robertson, Walter Montgomery playing the part of Hamlet. Little Madge was only three years old when she first trod the boards, whereon she was to portray a blind child, but when she espied her nurse in the distance, she rushed to the wings, exclaiming, “Oh, Nannie, look at my beautiful new shoes!”

Her bringing up was strict; she had no playfellows and never went to school, a governess and her father were her teachers. Every morning that father took her for a walk, explaining all sorts of things as they went along, or teaching her baby lips[Pg 23] to repeat Shelley’s “Ode to a Foxglove.” On their return home, he would read Shakespeare with her, so that the works of the bard were known to her almost before she learnt nursery rhymes.

“I was grown up at ten,” exclaimed Mrs. Kendal, “and first began to grow young at forty.”

When about fourteen, she was living with her parents in South Crescent, off Tottenham Court Road. One Sunday—a dreary heavy, dull, rainy London day—her father and mother had been talking together for hours, and she wearily went to the window to look out, the mere fact of watching a passer-by seeming at the moment to afford relaxation. Tears rolled down the girl’s cheeks—she was longing for companions of her own age, she was leaving the dolls of childhood behind and learning to be a woman. Her father noticed that she was crying, and exclaimed in surprise, “Why, Daisy, what’s the matter?”

“I feel dull,” she said.

“Dull, dear?—dull, with your mother and me?”

A pathetic little story, truly: the parents were so wrapped up in themselves, they never realised that sometimes the rising generation might feel lonely.

“My father and mother were then old,” said Mrs. Kendal, “I was their youngest child. All the others were out in the world, trying to find a place.”

Early struggles, hopes and fears, poverty and luxury, followed in quick succession in this remarkable woman’s life, but any one who knows her must[Pg 24] realise it was her indomitable will and pluck, coupled, of course, with good health and exceptional talent, which brought her the high position she holds to-day.

If Mrs. Kendal makes up her mind to do a thing, by hook or by crook that object is accomplished. She has great powers of organisation, and a capacity for choosing the right people to help her. “Never say die” is apparently her watchword.

She, like Miss Geneviève Ward, was originally intended for a singer, and songs were introduced into her parts in such plays as The Palace of Truth. Unfortunately she contracted diphtheria, which in those days was not controlled and arrested by antitoxin as it is now, and an operation had to be performed. All this tended to weaken her voice, which gradually left her. Consequently she gave up singing, or rather, singing gave her up, and she became a “play-actress.” She so thoroughly realises the disappointments and struggles of her profession that one of Mrs. Kendal’s pet hobbies is to try and counteract the evil arising from the wish of inexperienced girls to “go upon the stage.”

“If only the stage-struck young woman could realise all that an actress’ life means!” she said to me on one occasion. “To begin with, she is lucky if she gets a chance of ‘walking on’ at a pound a week. She has to attend rehearsals as numerous and as lengthy as the leading lady, who may be drawing £40 or £50 for the same period; though, mark you, there are very few leading ladies, while there are thousands and thousands of walkers-on who will never be anything[Pg 25] else. This ill-paid girl has not the interest of a big part, which stimulates the ‘star’ to work; she has only the dreariness of it all. Unless she be in a ballet, chorus, or pantomime, the girl has to find herself in shoes, stockings, and petticoats for the stage—no light matter to accomplish out of twenty shillings a week. Of course, in a character-part the entire costume is found, but in an ordinary case the girl has to board, lodge, dress herself, pay for her washing, and get backwards and forwards to the theatre in all weathers and at all hours on one pound a week, besides supplying those stage necessaries. Thousands of women are starving in the attempt.

“A girl has to dress at the theatre in the same room with others, she is thrown intimately amongst all sorts of women, and the result is not always desirable. For instance, some years ago, a girl was playing with us, and, mentioning another member of the company, she remarked, ‘She has real lace on her under-linen.’

“I said nothing, but sent for that lace-bedecked personage and had a little private talk with her, telling her that things must be different or she must go. I tried to show her the advantages of the straight path, but she preferred the other, and has since been lost in the sea of ultimate despair.”

So spoke Mrs. Kendal, the famous actress, in 1903, standing at the top of her profession; later we will see what a girl struggling at the bottom has to say on the same subject.

“Remember,” continued Mrs. Kendal, “patience,[Pg 26] courage, and talent may bring one to the winning-post, but few ever reach that line; by far the greater number fall out soon after the start—they find the pay inadequate, the hours too long; the back of a stage proves to be no enchanted land, only a dark, dreary, dusty, bustling place; and, disheartened, they wisely turn aside. Many of them drift aimlessly into stupid marriages for bread and butter’s sake, where discontent turns the bread sour and the butter rancid.

“The theatrical profession is not to blame—it is this terrible overcrowding. There are numbers of excellent men and women upon the stage who know that there is nothing so gross but what a good man or woman can elevate, nothing so lofty that vice cannot cause to totter.

“I entirely disapprove of a dress rehearsal,” continued Mrs. Kendal. “It exhausts the actors and takes off the excitement and bloom. One must have one’s real public, and play for them and to them, and not to empty benches. We rehearse in sections. Every one in turn in our company acts in costume, so that we know each individual get-up and make-up is right; but we never dress all the characters of the play at the same time until the night of production.”

Mrs. Kendal is very severe on the subject of overdressing a part.

“Feathers and diamonds,” she said “are not worn upon the river. Why, then, smother a woman with them when she is playing a boating scene?[Pg 27] The dress should be entirely subservient to the character. If one is supposed to be old and dowdy, one should look old and dowdy. I believe in clothing the character in character, and not striving after effect. Overdressing is as bad as over-elaboration of stage-setting: it dwarfs the acting and handicaps the performers.”

Mrs. Kendal is an abused, adored, and wonderful woman. Like all busy people, she finds time for everything, and has everything in its place. Her house is neatness exemplified, her table well arranged, the dishes dainty, and the attendance of spruce parlourmaids equally good. She believes in women and their work and employs them whenever possible.

There is an old-fashioned idea that women who earn their living are untidy in their dress and slovenly in their household arrangements, to say nothing of being unhappy in their home life. Those of us who know women workers can refute the charge: the busier they are, the more method they bring to bear; the more highly educated they are, the more capable in the management of their affairs. Mrs. Kendal is no exception to this rule, and in spite of her many labours, she lately encroached upon her time by undertaking another self-imposed task, namely, some charity work, which entailed endless correspondence, to say nothing of keeping books, and lists, and sorting cheques; but she managed all most successfully, and kept what she did out of the papers.

“Dissuade every one you know,” Mrs. Kendal entreated me one day, “from going on the stage. There are so few successes and so many failures! So many lives are shattered and hearts broken by that everlasting waiting for an opportunity which only comes to a few. In no profession is harder work necessary, the pay in the early stages more insignificant or less secure. To be a good actress it is essential to have many qualifications: first of all, health and herculean strength; the sweetest temper and most patient temperament, although my remark once made about having ‘the skin of a rhinoceros’ was delivered in pure sarcasm, which, however, was unfortunately taken seriously.

“I really feel very strongly about this rush to go on the stage. In the disorganisation of this democratic period we have all struggled to ascend one step, and many of us have tumbled down several in the attempt. Domestic servants all want to be shop-girls, and shop-girls want to be actresses—stars, mind you! Everything is upside-down, for are not the aristocracy themselves selling wine, coals, tea-cakes, and millinery?”

“Why have you succeeded?” I asked.

“Because I was born to it, cradled in the profession, my family have been upon the stage for some hundred years. To make a first-class actress, talent, luck, temperament, and opportunity must combine; but, mark you, the position of the stage does not depend upon her. It is those on the second and third rungs of the ladder who do the hardest of the work, and most firmly uphold the dignity of the stage, just as[Pg 29] it is the middle classes which rivet and hold together this vast Empire.”

Although married to an actor-manager, Mrs. Kendal has nothing whatever to do with the arrangements of the theatre. She does not interfere with anything.

“I never signed an agreement in all my life, either for myself or for anyone else. I never engage or dismiss a soul. Once everything is signed, sealed, and delivered, and all is ready, then, but not till then, my work begins, and I become stage-manager. On the stage I supervise everything, and attend to all the smallest details myself. To be stage-manager is not an enviable position, for one is held responsible for every fault.”

The Kendals lived for years in Harley Street, which is chiefly noted for its length, and being the home of doctors. Their house was at the end farthest from Cavendish Square, at the top on the left. I know the street well, for I was born in the house where Baroness Burdett-Coutts spent her girlhood, and have described in my father’s memoirs how, when he settled in Harley Street in 1860 as a young man, there was scarcely a doctor’s plate in that thoroughfare, or, indeed, in the whole neighbourhood. Sir William Jenner, Sir John Williams, Sir Alfred Garrod, Sir Richard Quain, and Sir Andrew Clark became his neighbours; and later Sir Francis Jeune, Lord Russell of Killowen, the present Speaker of the House of Commons (Mr. Gully), Sir William McCormac, Sir William Church, and[Pg 30] Mr. Gladstone settled quite near. Mr. Sothern (the original impersonator of Lord Dundreary and David Garrick) lived for some time in the street; but, so far as I know, he and the Kendals were the only representatives of the stage. A few years ago, not being able to add to the house they then occupied as they wished, the Kendals migrated to Portland Place, which is now their London residence, while Filey claims them for sea air and rest.

The Kendals spent five years in the United States. It was during those long and tedious journeys in Pullman-cars that Mrs. Kendal organised her “Unselfish Club.” It was an excellent idea for keeping every one in a good temper. At one end of the car the women used to meet to mend, make, and darn every afternoon, while one male member of the company was admitted to read aloud, each taking this duty in turn. Many pleasant and useful hours were spent in speeding over the dreary prairie in this manner. Only those who have traversed thousands of miles of desert can have any idea of the weariness of those days passed on the cars. The railway system is excellent, everything possible is done for one’s comfort, but the monotony is appalling.

Two things are particularly interesting about this great actress—her keen sense of humour and her love of soap. She is always merry and cheerful, has endless jokes to tell, has a quick appreciation of the ridiculous, and can be just as amusing off the stage as on it.

Her love of soap-and-water is apparent in all her surroundings; she is always most carefully groomed;[Pg 31] there is nothing whatever artificial about her—anything of that sort which is necessary upon the boards is left behind at the theatre. That is one of her greatest charms. She uses no “make-up,” and, consequently, she looks much younger off the stage than she does upon it.

Her expressions and her voice are probably Mrs. Kendal’s greatest attractions. Speaking of the first, she laughingly remarked, “My face was made that way, I suppose; and as for my acting voice, I have taken a little trouble to train it. We all start in a high key, but as we get older our voices often grow two or three notes lower, and generally more melodious, so that, while we have to keep them down in our youth, we must learn to get them up in our old age, for the head voice of comedy becomes a throat voice if not properly produced, and tends to grow hard and rasping.”

We had been discussing plays, good, bad, and indifferent.

“I have the greatest objection to the illicit love of the modern drama,” she remarked. “It is quite unnecessary. Every family has its tragedy, and many of these tragedies are far more thrilling, far more heart-breaking, than the unfortunate love-scenes put upon the stage.”

The charming impersonator of the “Elder Miss Blossom,” one of the most delightful touches of comedy-acting on record, almost invariably dresses in black. A strong, healthy-looking woman, untouched by art, and gently dealt with by years, Mrs.[Pg 32] Kendal wears her glorious auburn hair neatly parted in front and braided at the back. Fashion in this line does not disturb her; she has always worn it in the same way, and even upon the stage has rarely donned a wig. She tells a funny little story of how a dear friend teased and almost bullied her to be more fashionable about her head. Every one was wearing fringes at the time, and the lady begged her not to be so “odd,” but to adopt the new and becoming mode. Just to try the effect, Mrs. Kendal went off to a grand shop, told the man to dress her hair in the very latest style, paid a guinea for the performance, and went home. Her family and servants were amazed; but when she arrived at her friend’s house that evening her hostess failed to recognise her. So the fashionable hairdressing was never repeated.

“I worked the hardest,” said Mrs. Kendal, in reply to a question, “in America. For months we gave nine performances a week. The booking was so heavy in the different towns, and our time so limited, that we actually had to put in a third matinée, and as occasionally rehearsals were necessary, and long railway journeys always essential, it was really great labour.

Photo by Alfred Ellis, Upper Baker Street, W.

MR. W. H. KENDAL.

“As a rule I was dressed by ten, and managed to get in an hour’s walk before the matinée. Back to the hotel after the performance for a six o’clock meal, generally composed of a cutlet and coffee, quickly followed by a return to the theatre and another performance. To change one’s dress fourteen [Pg 33]times a day, as I did when playing The Ironmaster, becomes a little wearisome when it continues for months.”

“Did you not find that people in America were extraordinarily hospitable?” I inquired, remembering the great kindness I received in Canada and the States.

“Undoubtedly; but we had little time for anything of that sort, which has always been a great regret to me. It is hard lines to be in a place one wants to see, among people one wants to know, and never to have time for play, only everlasting work. We did make many friends on Sundays, however, and I have the happiest recollections of America.”

Pictures are a favourite hobby of the Kendals, and they have many beautiful canvases in their London home. Every corner is filled by something in the way of a picture, every one of which they love for itself, and for the memories of the way they came by it, more often than not as the result of some successful “run.” They have built their home about them bit by bit. Hard work and good management have slowly and gradually attained their ends, and they laugh over the savings necessary to buy such and such a treasure, and love it all the more for the little sacrifices made for its attainment. How much more we all appreciate some end or some thing we have had difficulty in acquiring. That which falls at our feet seems of little value compared with those objects and aims secured by self-denial.

“There is no doubt about it,” Mrs Kendal finished[Pg 34] by saying, “theatrical life is hard; hard in the beginning, and hard in the end.”

Such words from a woman in Mrs. Kendal’s position are of vast import. She knows what she is talking about; she realises the work, the drudgery, the small pay, and weary hours, and when she says, “Dissuade girls from rushing upon the stage,” those would-be aspirants for dramatic fame should listen to the advice of so experienced an actress and capable woman.

As said at the beginning of this chapter, Mrs. Kendal was cradled in the theatre: she was also married on the stage.

Madge Robertson and William Kendal Grimston were playing in Manchester when one fine day they were married by special licence. A friend of Mr. Kendal’s had the Town Hall bells rung in honour of the event, and the young couple were ready to start off for their honeymoon, when Henry Compton, the great actor, who was “billed” for the following nights, was telegraphed for to his brother’s deathbed.

At once the arrangements had to be altered. As You Like It was ordered, and Mr. and Mrs. Kendal were caught just as they were leaving the town, and bidden to play Orlando and Rosalind to the Touchstone of Buckstone. The honeymoon had to be postponed.

The young couple found the house unusually full on their wedding night, although they believed no one knew of their marriage until they came to the words, “Will you, Orlando, have to wife this Rosalind?[Pg 35]” when the burst of applause and prolonged cheering assured them of the good wishes of their public friends.

Another little romance of the stage happened to the Forbes Robertsons. Just before I sailed for Canada, in August, 1900, Mr. Johnston Forbes Robertson came to dinner. He had been away in Italy for some months recruiting after a severe illness, and was just starting forth on an autumn tour of his own.

“Have you a good leading lady?” I inquired.

“I think so,” he replied. “I met her for the first time this morning, and had never seen her before.”

“How indiscreet,” I exclaimed. “How do you know she can act?”

“While I was abroad I wrote to two separate friends in whose judgment I have much confidence, asking them to recommend me a leading lady. Both replied suggesting Miss Gertrude Elliott as suitable in every way. Their opinions being identical, and so strongly expressed, I considered she must be the lady for me, and telegraphed, offering her an engagement accordingly. She accepted by wire, and at our first rehearsal this morning promised very well.”

I left England almost immediately afterwards, and eight or ten weeks later, while in Chicago, saw a big newspaper headline announcing the engagement of a pretty American actress to a well-known English actor. Naturally I bought the paper at once to see who the actor might be, and lo! it was Mr. Forbes Robertson. It seemed almost impossible: but impossible things have a curious knack of being true,[Pg 36] and the signed photograph I had with me of Forbes Robertson, among those of other distinguished English friends, proved useful to the American press, who were glad of a copy for immediate reproduction. Almost as quickly as this handsome couple were engaged, they were married. Was not that a romance?

Mr. Forbes Robertson originally intended to be an artist, and his going on the stage came about by chance. He was a student at the Royal Academy, when his friend the late W. G. Wills was in need of an actor to play the part of Chastelard in his Mary Stuart, then being given at the Princess’s Theatre. It was difficult to procure exactly the type of face he wanted, for well-chiselled features are not so common as one might suppose. Young Forbes Robertson possessed those features, his clear-cut profile being exactly suitable for Chastelard. Consequently, after much talk with the would-be artist, who was loth to give up his cherished profession, W. G. Wills introduced his friend to the beautiful Mrs. Rousby, with the result that young Forbes Robertson undertook the part at four days’ notice.

Thus it was his face that decided his fate. From that moment the stage had been his profession and art his hobby; but a newer craze is rapidly driving paints and brushes out of the field, for, like many another, the actor has fallen a victim to golf.

There is no finer elocutionist on the stage than Forbes Robertson, and therefore it is interesting to know that he expresses it as his opinion that:

“Elocution can be taught.”

From a painting by Hugh de T. Glazebrook.

MR. J. FORBES-ROBERTSON.

Phelps was his master, and he attributes much of his success to that master’s careful training. What a pity Phelps cannot live among us again, to teach some of the younger generation to speak more clearly than they do.

Bad enunciation and noisy music often combine to make the words from the stage inaudible to the audience. Why an old farmer should arrive down a country lane to a blare of trumpets is unintelligible: why a man should plot murder to a valse, or a woman die to slow music, is a conundrum, but such is the fashion on the stage. One sometimes sits through a performance without hearing any of what ought to be the most thrilling lines.

Johnston Forbes Robertson has lived from the age of twenty-one in Bloomsbury. His father was a well-known art critic until blindness overtook him, and then the responsibility of the home fell on the eldest son’s shoulders. His father was born and bred in Aberdeen, and came as a young man to London, where he soon got work as a journalist, and wrote much on art for the Sunday Times, the Art Journal, etc. His most important work was The Great Painters of Christendom.

The West Central district of London, with its splendid houses, its Adams ceilings and overmantels, went quite out of fashion for more than a quarter of a century. With the dawn, however, of 1900, people began to realise that South Kensington stood on clay, was low and damp, and consequently they gradually migrated back to the Regent’s Park and those fine old[Pg 38] squares in Bloomsbury. One after another the houses were taken, and among Mr. Forbes Robertson’s neighbours are George Grossmith and his brother Weedon, Mr. and Mrs. Seymour Hicks, Lady Monckton, “Anthony Hope,” and many well-known judges, aldermen, solicitors, and architects.

In the old home in Bloomsbury the artistic family of Forbes Robertson was reared. Johnston, as we know, suddenly neglected his easel for the stage; his sister Frances took up literature as a profession; and his brothers, known as Ian Robertson and Norman Forbes, both adopted the theatrical profession. So the Robertsons may be classed among the theatrical families.

Who in the latter end of the nineteenth century did not weep with Miss Terry?—who did not laugh with her well-nigh to tears? A great personality, a wondrous charm of voice and manner, a magnetic influence on all her surroundings—all these are possessed by Ellen Terry.

In the days of their youth Mrs. Kendal and Miss Ellen Terry played together, but many years elapsed between then and the Coronation year of Edward VII., when they met again behind the footlights, in a remarkable performance which shall be duly chronicled in these pages.

Like Mrs. Kendal, Miss Ellen Terry began her theatrical life as a child. She was born in Coventry in 1848—not far from Shakespeare’s home, which later in life became such an attractive spot for her. Her parents had theatrical engagements at Coventry[Pg 39] at the time of her birth, so that verily she was cradled on the stage. She was one of four remarkable sisters, Kate, Ellen, Marion, and Florence, all clever actresses and sisters of Fred Terry; while another brother, although not himself an actor, was connected with the stage, Miss Minnie Terry being his daughter. Altogether ten or twelve members of the Terry family have been in the profession.

Ellen Terry, like Irving, Wyndham, Hare, Mrs. Kendal, and Lady Bancroft, learnt her art in stock companies.

Miss Ellen Terry has always had the greatest difficulty in learning her parts, and as years have gone on, even in remembering her lines in oft-acted plays; but every one knows how apt she is to be forgetful, and prompt her over her difficulties. Irving, on the other hand, is letter-perfect at the first rehearsal, and rarely wants help of any kind.

Ellen Terry is so clever that even when she has forgotten her words she knows how to “cover” herself by walking about the stage or some other pretty by-play until a friend comes to her aid. Theatrical people are extremely good to one another on these occasions. Somebody is always ready to come to the rescue. After the first week everything goes smoothly as a rule, until the strain of a long run begins to tell, and they all in turn forget their words, much to the discomfiture of the prompter.

Forgetting the words is a common thing during a long run. I remember Miss Geneviève Ward telling me that after playing Forget-Me-Not some five[Pg 40] hundred times she became perfectly dazed, and that Jefferson had experienced the same with Rip van Winkle, which he has to continually re-study. Miss Gertrude Elliott suffered considerably in the same way during the long run of Mice and Men.

Much has been said for and against a long run; but surely the “against” ought to have it. No one can be fresh and natural in a part played night after night—played until the words become hazy, and that dreadful condition “forgetting the lines” arrives.

At a charming luncheon given by Mr. Pinero for the American Gillette, when the latter was creating such a furore in England with Sherlock Holmes, I ventured to ask that actor how long he had played the part of the famous detective.

“For three years,” he replied.

“Then I wonder you are not insane.”

“So do I, ma’am, I often wonder myself, for the strain is terrible, and sometimes I feel as if I could never walk on to the stage at all; but when the theatre is full, go I must, and go I do; though I literally shun the name of Sherlock Holmes.”

We quickly turned to other subjects, and discussed the charm of American women, a theme on which it is easy for an English woman to wax eloquent.

If a man like Gillette, with all his success, all his monetary gain, and no anxiety—for he did not finance his own theatres—could feel like that about a long run, what horrors it must present to others less happily situated.

Long runs, which are now so much desired by[Pg 41] managers in England and America, are unknown on the Continent. In other countries, where theatres are more or less under State control, they never occur. Of course the “long run” is the outcome of the vast sums expended on the production. Managers cannot recoup themselves for the outlay unless the play draws for a considerable while. But is this the real end and aim of acting? Does it give opportunity for any individual actor to excel?

But to return to Ellen Terry. She has played many parts and won the love of a large public by her wonderful personality, for there is something in her that charms. She is not really beautiful, yet she can look lovely. She has not a strong voice, yet she can sway audiences at will to laughter or tears. She has not a fine figure, yet she can look a royal queen or simple maiden. Once asked whether she preferred comedy or tragedy, she replied:

“I prefer comedy, but I should be very sorry if there were no sad plays. I think the feminine predilection for a really good cry is one that should not be discouraged, inasmuch as there are few things that yield us a truer or a deeper pleasure; but I like comedy as the foundation, coping-stone, and pillar of a theatre. Not comedies for the mere verbal display of wit, but comedies of humour with both music and dancing.”

Miss Ellen Terry has a cheery disposition, invariably looks on the bright side of things, and not only knows how to work, but has actually done so almost continuously from the age of eight.

One of Miss Terry’s greatest charms is her mastery over expression. It is really strange how little facial and physical expression are understood in England. We are the most undemonstrative people. It is much easier for a Frenchman to act than for an Englishman; the former is always acting; the little shrug of the shoulders, the movement of the hand and the head, or a wink of the eye, accompany every sentence that falls from his lips. He is full of movement, he speaks as much with his body as with his mouth, and therefore it is far less difficult for him to give expression to his thoughts upon the stage than it is for the stolid Britisher, whose public school training has taught him to avoid showing feeling, and squeezed him into the same mould of unemotional conventionality as all his other hundreds of schoolfellows. There is no doubt about it that everything on the stage must be exaggerated to be effective. It is a world of unreality, and the more pronounced the facial and physical expression brought to bear, the more effective the representation of the character.

To realise the truth of these remarks, one should visit a small theatre in France, a theatre in some little provincial town, where a quite unimportant company is playing. They all seem to act, to be thoroughly enamoured of their parts, and to play them with their whole heart and soul. It is quite wonderful, indeed, to see the extraordinary capacity of the average French actor and actress for expressing emotion upon the stage. Of course it is their characteristic; but on the other hand, the German nation is[Pg 43] quite as stolid as our own, and yet the stage is held by them in high esteem, and the amount of drilling gone through is so wonderful that one is struck by the perfect playing of an ordinary provincial German. At home these Teutonic folk are hard and unemotional, but on the boards they expand. One has only to look at the German company that comes over to London every year to understand this remark. They play in a foreign tongue, the dresses are ordinary, one might say poor, the scenery is meagre, there is nothing, in fact, to help the acting in any way; and yet no one who goes to see one of their performances can fail to be impressed by the wonderful thoroughness and the general playing-in-unison of the entire company. Of course they do not aim so high as the Meiningen troupe, for they were a State company and the personal hobby of the Duke whose name they bore. We have no such band of players in England, although F. R. Benson has done much without State aid to accomplish the same result, and in many cases has succeeded admirably.

We have heard a great deal lately about the prospect of a State-Aided Theatre and Opera in London; and there is much to be said for and against the scheme. Municipal administration is often extravagant and not unknown to jobbery, neither of which would be advisable; but the present system leads to actor-managers and powerful syndicates, which likewise have their drawbacks. There is undoubtedly much to be said both for and against each system, and the British public has to decide. Meantime we learn that the six[Pg 44] Imperial theatres in Russia (three in St. Petersburg and three in Moscow), with their schools attached, cost the Emperor some £400,000 a year. “It is possible to visit the opera for 5d., to see Russian pieces for 3d., French and German for 9d.” These cheap seats are supposed to be a source of education to the populace, but there are expensive ones as well.

Some Englishmen understand the art of facial expression. A little piece was played for a short time by Mr. Charles Warner, under the management of Mrs. Beerbohm Tree. The chief scene took place in front of a telephone, through which instrument the actor heard his wife and child being murdered many miles away in the country, he being in Paris. It was a ghastly idea, but Charles Warner’s face was a study from the first moment to the last. He grew positively pale, he had very little to say, and yet he carried off an entire scene of unspeakable horror merely by his facial and physical expression.

Some of our actors are amusingly fond of posing off the stage as well as on. One well-known man was met by a friend who went forward to shake his hand.

“Ah, how do you do?” gushed the Thespian, striking an attitude, “how do you do, old chap? Delighted to see you,” then assuming a dramatic air, “but who the —— are you?”

And this was his usual form of greeting after an effusive handshake.

In a busy life it is of course impossible to remember every face, and the nonentities should surely forgive the celebrities, for it is so easy to recognise a well-known[Pg 45] person owing to the constant recurrence of his name or portrait in the press, and so easy to forget a nonentity whom nothing recalls, and whose face resembles dozens more of the same type.

One often hears actors and actresses abused—that is the penalty of success. Mediocrity is left alone, but, once successful, out come the knives to flay the genius to pieces; in fact, the more abused a man is, the more sure he may feel of his achievements. Abuse follows success in proportion to merit, just as foolish hopes make the disappointments of life.

ANOTHER striking instance of hereditary theatrical talent is Miss Winifred Emery, than whom there is no more popular actress in London. This pretty, agreeable little lady—who, like Mrs. Kendal and Miss Terry, may be said to have been born in the theatre—is the only daughter of Samuel Sanderson Emery, a well-known actor, and grand-daughter of John Emery, who was well known upon the stage. Her first appearance was at Liverpool, at the advanced age of eight.

The oldest theatrical names upon the stage to-day are William Farren and Winifred Emery. Miss Emery’s great-grandfather was also an actor, so she is really the fourth generation to adopt that profession, but her grandmother and herself are the[Pg 47] only two women of the name of Emery who have appeared on playbills.

As is well known, Miss Emery is the wife of Mr. Cyril Maude, lessee with Mr. Frederick Harrison—not the world-renowned Positivist writer—of the Haymarket Theatre.

Although Mrs. Maude finds her profession engrossing, she calls it a very hard one, and the necessity of being always up to the mark at a certain hour every day is, she owns, a great strain even when she is well, and quite impossible when she is ill.

Some years ago, when she was even younger than she is now, and not overburdened with this world’s gold, she was acting at the Vaudeville. It was her custom to go home every evening in an omnibus. One particularly cold night she jumped into the two-horse vehicle and huddled herself up in the farthest corner, thinking it would be warmer there than nearer the door in such bitter weather. She pulled her fur about her neck, and sat motionless and quiet. Presently two women at the other end arrested her attention; one was nudging the other, and saying:

“It is ’er, I tell yer; I know it’s ’er.”

“Nonsense, it ain’t ’er at all; she couldn’t have got out of the theayter so quick.”

“It is ’er, I tell yer; just look at ’er again.”

The other looked.

“No it ain’t; she was all laughing and fun, and that ’ere one looks quite sulky.”

The “sulky one,” though thoroughly tired and weary, smiled to herself.

I asked Miss Emery one day if she had ever been placed in any awkward predicament on the stage.

“I always remember one occasion,” she replied, “tragedy at the time, but a comedy now, perhaps. I was acting with Henry Irving in the States when I was about eighteen or nineteen, and felt very proud of the honour. We reached Chicago. Louis XI. was the play. In one act—I think it was the second—I went on as usual and did my part. Having finished, as I thought, I went to my room and began to wash my hands. It was a cold night, and my lovely white hands robbed of their paint were blue. The mixture was well off when the call boy shouted my name. Thinking he was having a joke I said:

“‘All right, I’m here.’

“‘But Mr. Irving is waiting for you.’

“‘Waiting for me? Why, the act isn’t half over.’

“‘Come, Miss Emery, come quick,’ gasped the boy, pushing open the door. ‘Mr. Irving’s on the stage and waiting for you.’

“Horrors! In a flash I remembered I had two small scenes as Marie in that act, and usually waited in the wing. Had I, could I have forgotten the second one?

Photo by Window & Grove, Baker Street, W.

MISS WINIFRED EMERY AND MR. CYRIL MAUDE IN “THE SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL.”

“With wet red hands, dry white arms, my dress not properly fastened at the back, towel in hand, along the passage I flew. On the stage was poor Mr. Irving walking about, talking—I know not what. On I rushed, said my lines, gave him my lobster-coloured wet hand to kiss—a pretty contrast to my[Pg 49] ashen cheeks, and when the curtain fell, I dissolved in tears.

“Mr. Irving sent for me to his room. In fear and trembling I went.

“‘This was terrible,’ he said. ‘How did it happen?’

“‘I forgot, I forgot, why I know not, but I forgot,’ I said, and my tears flowed again. He patted me on the back.