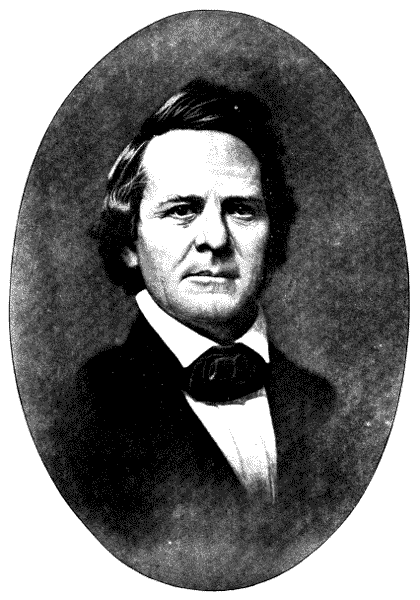

JOHN CHAMBERS.

About 1873.

WORKS OF WILLIAM ELLIOT GRIFFIS, D.D., L.H.D.

JAPAN.

The Mikado's Empire; History to 1902 and Personal Experiences. (Harpers.)

Matthew Calbraith Perry, a Typical American Naval Officer. (Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

Townsend Harris, First American Envoy in Japan. (Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

Verbeck of Japan; A Citizen of No Country. A Story of Foundation Work Inaugurated by Guido Fridolin Verbeck. (Fleming H. Revell Co.)

A Maker of the New Orient. Samuel Robbins Brown, Pioneer Educator in China, America, and Japan. (Fleming H. Revell Co.)

Japan, in History, Folk-lore, and Art. (Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

In the Mikado's Service. A Story of Two Battle Summers in China. (W. A. Wilde Co.)

Corea, the Hermit Nation. Part I. Ancient, Medieval and Modern History. Part II. Social Life, Literature, Art, Folk-lore, Proverbs, Recent Events, etc. (Charles Scribner's Sons.)

HOLLAND.

The American in Holland. Sentimental Rambles in the Eleven Provinces of the Netherlands. (Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

Brave Little Holland, and What She Taught Us. (Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

The Student's Motley, being "The Rise of the Dutch Republic", by J. R. Motley, condensed to 690 pages in six parts. Part VII: History of the Dutch Nation from 1584 to 1897. (Harpers.)

Young People's History of Holland. (Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

AMERICAN HISTORY.

The Romance of Discovery; A Thousand Years of Exploration and the Unveiling of Continents. (W. A. Wilde Co.)

The Romance of American Colonization. How the Foundations of Our History were Laid. (W. A. Wilde Co.)

The Romance of Conquest. The Story of American Expansion through Arms and Diplomacy. (W. A. Wilde Co.)

The Pilgrims in their Three Homes: England, Holland, and America. (Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

America in the East. A Glance at our History, Prospects, Problems, and Duties in the Pacific Ocean. (A. S. Barnes Co.)

The Pathfinders of the Revolution. A Story of the Great March into the Wilderness and Lake Region of New York in 1779. (W. A. Wilde Co.)

John Chambers, and His Ministry in Philadelphia. 1 vol. 8vo. Pp. 172, with two portraits, index, etc. Price, one dollar, postpaid. (Andrus & Church, Ithaca, N. Y.)

Sunny Memories of Three Pastorates, in (Schenectady, Boston, and Ithaca), with a Selection of Sermons and Essays. 1 vol. Illust. Price, $1. Ithaca, N. Y. (Andrus & Church.)

BIBLICAL.

The Lily Among Thorns. A Study of the Biblical Drama Entitled, "The Song of Songs." (Houghton, Mifflin & Co.)

JOHN CHAMBERS

SERVANT OF CHRIST AND MASTER OF HEARTS

AND

HIS MINISTRY IN PHILADELPHIA

JOHN CHAMBERS.

About 1873.

Servant of Christ and Master of Hearts

AND

HIS MINISTRY IN PHILADELPHIA

BY

Rev. Wm. Elliot Griffis, D.D., L.H.D.

Author of "THE MIKADO'S EMPIRE", "BRAVE LITTLE HOLLAND", "COREA,

THE HERMIT NATION", "THE PILGRIMS IN THEIR THREE

HOMES", "VERBECK OF JAPAN", Etc.

ITHACA, N. Y.

ANDRUS & CHURCH

1903

COPYRIGHT, 1903

BY

ANDRUS & CHURCH

(OCTOBER)

PRESS OF

ANDRUS & CHURCH

ITHACA, N. Y.

JOHN CHAMBERS'S FAVORITE PSALM

PSALM CXXXIII

TO

ALL MY FELLOW ALUMNI

MEMBERS OF

THE FIRST INDEPENDENT CHURCH

OF PHILADELPHIA

WHO IN HALLOWED MEMORY OF THE PAST

OR

IN HOPE OF REUNION IN THE ETERNAL HOME

GREET

JOHN CHAMBERS AS THEIR FATHER IN GOD

I DEDICATE THIS LITTLE BOOK

John Chambers was one of the first among popular preachers of the nineteenth century in Philadelphia, and the pastor for fifty years of one congregation.

Not alone to delight those with vivid memories, who knew, loved and honored John Chambers, have I undertaken this work of filial piety, but to tell to young men of to-day the story of a consecrated, strenuous, and successful life, the secret of which was self-conquest and strength in God.

One great purpose and benefit of biography is lost if it does not clearly reveal the growth of character, and, in the case of a beautiful and successful life, a personality worthy of being held up as an example. It ought to show also self-conquest, ripening in wisdom, the philosophic mind that comes with years, and the maturing and sweetening influences of honored old age. It would be of little help to young men, struggling against their own besetting weaknesses to gain self-mastery and attainment to true Christian manhood, to picture only the John Chambers, as we knew him,—in the serene evening of life, when passions had cooled and reason reigned, and the gray light of Heaven's morning had settled on his head. I have tried to show in the typical Irishman, the creature of heredity and the passionate patriot, the aspiring Christian and the child of God, educated by unseen but potent influences, winning steadfast victory over sin and self, becoming king of men and master of hearts, leading a host to triumph along the pathway to Heaven, able to do all things through Christ his helper.

The wonderful character and personality of John Chambers were not sudden creations. They were growths. He himself believed that while justification was instant, sanctification was gradual. He laughed at the man who professed never to have made mistakes. He had always patience with those who slipped and fell. He showed us how to neutralize the results of our missteps and gain new strength by painful and humiliating experiences.

I return my hearty thanks to one and all of the friends, fellow alumni of the old First Independent Church of Philadelphia, who have aided me with reminiscences, asking pardon for omissions and indulgence for possible errors.

W. E. G.

Ithaca, N. Y., July 20, 1903.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Philadelphia. The Historic Site | 1 |

| II. | Ireland. A Bonnie Bairn | 7 |

| III. | Ohio. Life in a Log Cabin | 14 |

| IV. | Maryland. Student Days in Baltimore | 19 |

| V. | Newtown. Rejected of Men | 25 |

| VI. | New England. Ordination at New Haven | 34 |

| VII. | Home and Church. Love and Work | 42 |

| VIII. | The War Horse of the Temperance Cause | 51 |

| IX. | The Master of Hearts | 61 |

| X. | Boyhood's Memories of the Old Church | 68 |

| XI. | The Master of Assemblies | 81 |

| XII. | True Yoke-fellows | 94 |

| XIII. | Church Life. Minor Personalities | 105 |

| XIV. | The Civil War | 111 |

| XV. | Light at Evening Time | 127 |

| XVI. | Transfer of the Church to the Presbytery | 135 |

| XVII. | The Semi-Centennial and Farewell | 139 |

| XVIII. | The Children of the Mother | 144 |

Throngs of people daily pass along two of Philadelphia's most imposing highways. Broad Street spans the entire city from north to south. Chestnut Street is the Quaker City's most brilliant thoroughfare, stretching between the Delaware and the Schuylkill. Those who traverse either may see the great twenty story building wherein is made and published the North American, the oldest daily newspaper on the continent. Northward from Broad and Chestnut, rise the imposing municipal buildings, on the crest of whose mountain of stone and peak of metal is visible the bronze statue of William Penn, founder of the City of Brotherly Love. Though this son of a Dutch mother was the beginner of the City of Homes, yet there have been many other makers of Philadelphia.

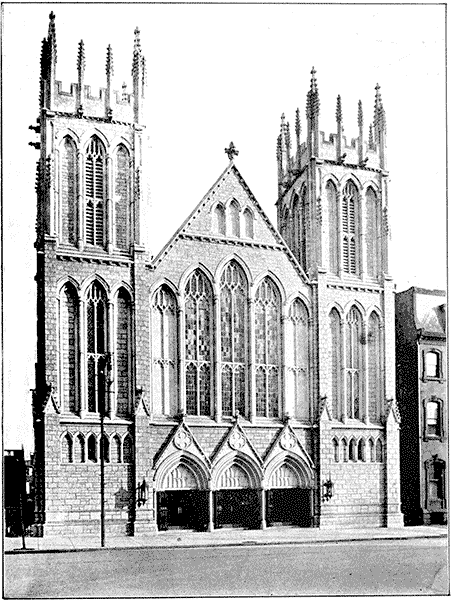

Not least among those who have builded the unseen but nobler city, and who have stamped their names indelibly upon human hearts and lives, even unto the third and fourth generation of its citizens, is John Chambers. During forty-eight years he was pastor of the First Independent Church, whose second edifice stood from 1831 to 1899 on the site of the twenty-storied "sky-scraper" at Broad and Sansom streets.

Happily, in the eternal fitness of things, history and sentiment were not ignored in the uprearing of the mighty structure, whose cornice is not far from the clouds. In the two lower stories of the façade is a happy reminder of the old brown stone church of pillared front. Most felicitously does memory find here a sermon in stone and a stimulus in architecture. Indeed, a former worshipper walking on the[2] other side of the street, who chanced to look no higher than the old familiar altitudes, might imagine that the house of prayer, with its Ionic columns, still stood to bless its worshippers. Even of the same hue and tint as in childhood's days, eight columns of fluted brown sandstone renew in verisimilitude the old architecture. Thus the mighty edifice enshrines upon its front, in imperishable masonry, suggestions, at least, of former history.

To be exact, whereas there were in old times six round fluted Ionic columns, resting on high square bases, supporting a simple but imposing pediment, there are to-day eight front columns supporting an architrave, with two mightier upholding pillars within.

At first thought, men might be tempted to see in this colossal structure, whose roof is so much nearer the sky a symbol of "the power of the press," which is alleged to be more influential than the pulpit. One political gentleman whom I knew well—even he who in 1893, raised the stars and stripes over Hawaii—affirmed in my hearing, that "one newspaper was equal to three pulpits". Yes, but that depends on which newspaper and which pulpit. It is certain that in the eyes of some, printing machinery and type, and daily square miles of inked paper, for which whole forests have been destroyed, have more moral potency than worship, prayer, and preaching. Yet against this modern parable of the mustard seed become a tree, phenomenal and imposing, we have happily also the Master's parable of the leaven, or of might unseen, of a kingdom coming "without observation". "Things seen", even when dazzling are not really as potent as those which transform the life. It could add little or nothing to the reputation of John Chambers, to put on paper with ink his words that kindled our souls. Yet, "did not our hearts burn within us" when we heard? Can[3] we forget them? Was not his a life unto life? "He being dead yet speaketh."

So then, whether standing in the shadow of the great edifice—typical of the soaring twentieth century—or setting foot on its roof high in air, many fathoms higher in the deeps of space than where once we sat or stood, and thence gazing upon the sea of humanity beneath, or over the great city set between the two silver streams, and ever fascinating and beautiful with boyhood's memories, let us stop to recall the past. Let us think of that busy and potent life of John Chambers (1797-1875), and of that First Independent Church (1825-1873), which, like a spiritual storage battery, still supplies the power that pulses in many thousand souls. Man and edifice, though vanished from earth, give by their visible potencies or inspiring memories, in churches and Sunday Schools, in hallowed homes and beautiful careers of men and women, even to the fourth generation, the shining and convincing evidence of an earthly immortality, of life unto life. In the ever widening circles of eternity, that unspent influence will be felt.

Let us now descend from the mountain to the plain. Until the first early autumn of the twentieth century, one could see also on the east side of Thirteenth Street, north of Market and within a few feet of Filbert Street, a four-sided, plain gray stone or marble post, in which even a casual passer-by could detect a survival. It was an old-timer, battered, rubbed, and chipped. Evidently it had once been a hitching post. Then, after sundry paintings and daubings, it had served for various advertising purposes, setting forth the changing business carried on in the dwelling place itself, in front of which it stood, or, in the cellar of the same. The Belgian block pavements, the flagstone sidewalks, the great Reading Railway Terminal, not far away, and the lofty business edifices of steel and stone, with a[4] thousand modern suggestions, all seem by their contrast to suggest antiquity in that horse post, and possibly its descent from once more noble uses.

When, however, to the evidence of eyesight, was added the play of memory and imagination, then there rose upon the mind's vision the little brick church, the Church of the Vow, that stood directly opposite, where John Chambers, master of hearts and transformer of human lives, wrought and taught. Within its now vanished walls the sunny pastor, the shining ornament in social life, the soul-stirring preacher, the unquailing soldier, who fought evil in every form, prayed, preached, and labored with men. Here he communicated quickening impulses not yet spent, but ever urging on to vaster issues. Yes, there is where the old church stood.

But this old battered horse-post,—so close by the curb stone as to wear ever fresh marks of tar and grease from passing wagon wheel hubs—what has it to do with John Chambers and the First Independent Church of Philadelphia, which is almost forgotten before a brood of lusty children and vigorous grandchildren that now train thousands in the ways of holiness? Especially may we ask the question, since the church and the post were on opposite sides of the street, here a few feet wide.

Well, hereto hangs not only a tale, but literally, there hung a chain, with associations. Before the First Independent Church—that church which, according to scripture and reality, though not in common parlance, is not an edifice, but a company of believers—was formed, in 1825, there stood at Thirteenth and Filbert streets, a comparatively new building. It had been reared in fulfilment of a vow made during a storm on the Atlantic by a holy woman of prayer, whose life was saved. Those who carried out her purpose were Irish refugees, seeking freedom in America.[5] Being intense Sabbatarians, they would have no sound of passing wheel or hoof on the Lord's Day, for theirs was the age, also, of Delaware river cobble stones, and of iron tires. No pneumatic or sound deadening rubber-swathed wheels existed then. Hence, to warn off all matutinal disturbers of the solemnity of worship, and evening passers on wheels, an iron chain was stretched across the street, guarding either side, north or south, of the holy edifice. Thus, in quiet, the people within could worship God. The same rule held in other neighborhoods as in this congregation, and in front of the Presbyterian church edifice at Fourth and Arch, as the pictures show, a similar stout iron chain was stretched. It was the rule in Sabbath-keeping Philadelphia, according to the vigorous law of 1798.

Philadelphia was, early in the last century, a little place, of only tens of thousands, and so long as there were but few churches, the chains seemed appropriate. As the city grew, the problem for the firemen, mail wagons, and ambulances increased. In time not a single street running north or south, even in case of a fire, was open to the firemen, who were apt to make quick work in removing obstacles. A snow storm of petitions, for and against the repeal of the Acts of 1798 and the removal of the street chains, fell on the legislature and the law ceased to be operative, March 15, 1830. The old stone posts remained and occasionally one may be recognized by the keen-eyed antiquarian in dear old Philadelphia.

Both the first and second edifices, in which John Chambers labored in the Gospel, have been levelled and their sites built upon. That old post, effective Sabbath guardian, has gone; the First Independent Church, in edifice or organization, is no more. Nevertheless, its spirit lives. Like Huldah's home, our old church in its "second quarter" was a "college," and, fellow alumni, we shall try to tell the story[6] of our Alma Mater, "mother of us all," and sketch the life and work of the great and good man, with whom the First Independent Church began, continued, and ended. Both church and pastor have become as leaven that transforms, and in leavening is itself transformed,—lost to form and view, while yet potent. "The eagle's cry is heard even after its form disappears behind the mountain," says the Chinese proverb.

The "three measures of meal" still abide. From them is still supplied the bread of life to thousands. To change from metaphor to facts that are as hard as stone, and as enduring as human character, there are, first in point of time, the Bethany Mission Sunday-school and the Bethany Presbyterian Church; the John Chambers Memorial Church, an offshoot and outgrowth from the Bethany Church; the Presbyterian Church at Rutledge, Pa.; the St. Paul's Presbyterian Church in West Philadelphia; and the magnificent edifice and active congregation of the Chambers-Wylie Memorial Church on Broad below Pine Street, which enshrines the name not only of John Chambers, but of T. W. J. Wylie—two noble preachers of the gospel, sons of thunder and also of consolation.

Shall we attempt to measure influence, by even suggesting how three churches, one Presbyterian, one Baptist, and one Lutheran grew up out of the early prayer meetings before 1840, sustained chiefly by John Chambers' young men? Shall we hint at the missionary and educational impulses given at "the ends of the earth" by missionaries, or of lives nourished or transformed in our home land by the forty or more ministers of the gospel, who call John Chambers their father in God?

Nay, our dear under-shepherd himself, were he with us, would say, "Not unto us O Lord, not unto us, but unto thy name give glory, for thy mercy and thy truth's sake."

Nisi Dominus Frustra.

Many a chairman, clerical or lay brother, in introducing John Chambers to an always delighted audience, referred to his "big Irish heart," and indeed he had in him all the winning and fascinating elements which make the jolly Irishman. He was emotional, clear-brained, rich in personal magnetism, and in general a "good fellow". He had in him also those traits which characterize the strong, clean, God-fearing and man-loving Puritan, whose career so often illustrates the highest type of manhood. Of superb and commanding figure, six feet high, and the most imposing individual known in the Chambers clan, he had an open illuminated face, and eyes that penetrated one's inmost nature. He was skilled in the handshake or shoulder pat, that warmed one's entire being into personal loyalty and were inspirations to friendship for the man and his Master. His face made you believe in the immortality of the soul. To these physical traits may be added an absolutely fearless mien and a flashing eye, that made his enemies fear him, even when they most hated his ways and words. With leonine countenance and majestic presence, was a tongue that beat the blarney stone, and yet was made, under God, a unerring instrument in winning souls. Some one has written of "The Pastor as Praiser". John Chambers by praising a boy made him a hero. Often a word from him came as Paul's clarion call, "Stand fast".

In brief, John Chambers possessed in person, bearing, and characteristics, the noble heritages of that Scottish race which settled in north Ireland, and which has shown itself, especially in America, one of the most distinctive of stocks,[8] rich in mental initiative and nervous energy, with power of manifold adaptation and persistency. In America the Scotch-Irish have certainly influenced, with power second to that of no other strain or nationality, the making of the American republic.

The people of north Ireland were noted for their Calvinism, which in practice is only another word for an inextinguishable love of freedom and democracy. Their faith fruited in free schools, popular education, family worship, familiarity with the Bible, hatred of priest-craft, Romanism, and British cruelty and oppression. In their Christianity, some Jewish notions in survival were perhaps put on a level with the teachings of Jesus, and their passionate devotion to Sabbath-keeping seemed sometimes to run into idolatry. They were not at all disinclined to controversy, and many of them were rather fond of a bit of a fight. Among the less sanctified, religion of a certain narrow sort and the contents of the whiskey bottle were very much in demand.

Naturally the British government with its aristocracy and political church, its absentee-landlordism and its corrupt parliament—which in the eighteenth century represented land rather than people—had much trouble with this insular people of many virtues and some glaring defects. The more oppressive measures of the first half and middle of the eighteenth century sent tens of thousands of emigrants to America, where they settled, especially in New Hampshire, the Carolinas, and western Pennsylvania. Only too glad to take up arms against the British, they furnished from their ranks for the Continental army and patriot partisan bodies, probably a larger proportion of soldiers than those of any other nationality among the colonists.[1] Many thousands of the "Yankees" of New England were Irishmen. In North Carolina they were the Regulators whom[9] "Bloody Billy" Tryon slaughtered. In Sullivan's Expedition of 1779, one of the most important campaigns of the Revolution, four of the five generals, and possibly a majority of the rank and file, were born in Ireland, or were of Irish stock. At the banquet held in the forest, on the Chemung River on the site of Elmira, N. Y., on Saturday September 25, 1779, in the pavilion of greenery, one of the thirteen toasts drunk was this,—"May Ireland merit a stripe in the American standard."[2]

[1] See Romance of American Colonization. Boston, 1898, p. 272.

[2] See the Pathfinders of the Revolution. Boston, 1900, p. 296.

The general dissatisfaction in Ireland, not only among the Catholics who suffered from oppressive penal statutes, but also among the Protestants, broke out in 1798 into a rebellion fomented by the numerous secret societies then in the island. To read this page of history brings us to the parentage and birth of John Chambers, who sprung not from "illiterate" folk, as some have ignorantly imagined, but from intelligent and educated as well as patriotic parentage and ancestry.

William Chambers, the father of our American John, was born in 1768 of fairly well-to-do parents, and had a good education. One of his ancestors was an officer in the British navy. When about twenty-seven years of age, he married a Miss Smythe, or Smith, who was traditionally descended from Robert the Bruce, being one of a family which has furnished a long succession of Presbyterian ministers in Scotland, Ireland, and the United States. Their first son and eldest child, they named James. Their second son, John, is the subject of our biography. John Chambers was born on September 19, 1797 in Stewartstown, Tyrone county, Ireland.

There are four towns of this name in the United States, settled probably by Irishmen, and the original place in Ireland, in 1880, contained 931 souls.

William Chambers was a hot-headed, impulsive man of great physical vigor, a superb horseman, and a leader in athletic sports. In early manhood he was powerfully influenced in his political opinions and action by the ideas exploited in both the American and the French Revolutions. A fierce patriot, he became a follower of the famous Wolf Tone, and in their ups and downs on the wheel of politics, both master and disciple found themselves in prison within a few days of each other. William Chambers by some means escaped, but was soon involved in trouble with the British authorities, and so engaged passage to America.

Theobald Wolf Tone (1763-1798), orator and advocate of the freedom of Ireland, was educated at Trinity College, Dublin. He wrote pamphlets exposing British misgovernment, joined Protestants and Catholics in political fraternity, and founded at Belfast the first Society of United Irishmen, which William Chambers promptly joined. It is believed that at this time the green flag of Ireland was adopted, by uniting the orange and the blue. It is certain that at this time, green became the national color, although an emerald green standard was used in the sixteenth century.

One of these United Irishmen was Samuel Brown Wylie, who became the celebrated pastor, preacher, and Doctor of Divinity in Philadelphia. He left Ireland in 1797. In God's providence, exactly one century afterwards, the names of Chambers and Wylie were united in Philadelphia in that of a memorial church.

Wolf Tone, as secretary of the Roman Catholic committee, had already entered into secret negotiations with France and had to fly to the United States in 1795. He was afterwards captured on one of the ships of the French squadron, which was to invade Ireland.

The French having occupied Holland, had had a great fleet built in the Zuyder Zee to co-operate with the United[11] Irishmen, but at the battle of Camperduin, off the coast of North Holland, October 11th, 1797, the British Admiral Duncan destroyed the French and Dutch fleet, and the high hopes of those who looked for Irish independence were dashed to the ground. Hundreds of them fled.

Tried and sentenced to death, Wolf Tone committed suicide in his cell, November 19th, 1798. His son afterwards served in the armies of France and the United States and wrote the biography of his father. Ever since 1797, the British navy has had a ship named "Camperdown".

In Scotland I have had the pleasure of visiting the Duncan estate near Dundee, and in Holland of seeing Camperduin and its vicinity, both of land and water.

The defeat of the French fleet and the imprisonment, trial, and sentence of their leader, Wolf Tone, drove the United Irishmen into an insurrection of despair. At the battle of Vinegar Hill, in May, 1798, the revolt was crushed and the French general Humbert surrendered. Forthwith the British constables began their hunt for each one and all of the United Irishmen to land them in prison.

William Chambers was, as we have seen, arrested and thrown into prison at Stewartstown. In some way he escaped and eluded those who were seeking him, until he made his way down to the ship, on which his family was leaving Ireland for America. Besides his wife with her little boys, James and John, the latter an infant of three months at the breast, were other emigrants on board. In the hold, there was a stock of cabbages and down among these vegetables the refugee father hid himself. The British officers came on board and searched the ship from stem to stern to find their man, but his wife had encouraged him to get so deeply under the material for sauerkraut, and had covered him up so well, that, unable to find him, they[12] imagined he must have fled elsewhere. It was not until the ship was well out at sea that William Chambers rose up from among the cabbages and made himself visible. In later years, John Chambers visited the Stewartstown prison in which his father had been incarcerated.

In the slow ship they were knocked about on the wintry Atlantic during a stormy voyage of fourteen weeks, but happily arrived in the Delaware Bay, just when the buds were bursting, and the landscape of spring time putting on its fresh mantle of green. After their sea weariness the peach-orchards of Delaware must have looked as "fair as a garden of the Lord."

The Mayflower, which in 1620 bore the Pilgrims to America, was bound for the same beautiful region, then vaguely called "Virginia" but these people in 1799 were pilgrims bound to the forests of Ohio, the first of the Pilgrim states beyond the Alleghenies.[3]

[3] See the Pilgrims in their Three Homes, Boston, 1898.

Landing at Newcastle, William Chambers and his little family soon joined a great party of emigrants who were turning their faces westward. Ohio was then, except for the river valleys and old maize lands of the Indians, an almost unbroken forest. In those days, when there was neither canal, railway nor trolley, such roads as existed, traversed chiefly the long stretches of dark woods. They were made of corduroy, or logs laid crosswise, with a surface covering of earth. Very few counties were as yet named or laid out in the Buckeye State, for it was only five years after General Anthony Wayne's great victory at Maumee Rapids over the Indians, and many of the red men were still in the land. Frontier life was still very rough, both as respects material comfort and the relations of the settlers with the Indians. The second stage of territorial life was entered upon in this[13] same year, 1799, and the State Legislature had met for the first time in Cincinnati.

Slowly and painfully the caravan of home seekers made its way through Pennsylvania over the great road through Harrisburg and the Juniata valley, Hollidaysburg and Pittsburg, where Scotchmen and Irishmen were still very numerous. Thence floating down the Ohio River, they reached the first county on the western side, which was later named after Thomas Jefferson, third president of the United States. The Irish pioneer from Stewartstown helped to lay out the original townships of the county, in which Warren Ridge was situated, often going ahead to blaze some trees along the future road. Later, in 1799, he settled at Smithfield, and ultimately at Mount Pleasant. It was to this last named place that the visits of John Chambers, notably in 1843 and 1861, were made.

The little baby boy John's first American home was a log cabin and his cradle was made of part of a hollowed-out tree trunk. When he began noticing things from the doorway, his eyes took in a great space filled with a multitude of stumps, the dark and lonely forest, the new and strange fields of Indian corn, the tender green of spring, the gold of autumn, and the great white landscape of winter. When he was but three years old, Ohio became a state.

Remembering the witticism, so common a generation ago, that "some men are born great, and some are born in Ohio", we may believe that John Chambers came very near a double inheritance, though failing in but one share; for, to the end of his days, he boasted that he was by birth an Irishman.

Among his earliest playthings were the "buckeyes", or horse-chestnuts, from the particular tree, so plentiful in the new land. As the Bible was then, besides being in supreme honor as the Word of God, the one familiar volume, library, reference, and text-book, source of literary and intellectual recreation, John, as he learned to read, was as much delighted to find the popular name of "Ohio" in the Bible, as American tourists in Japan are, to hear the sound of this good State's name, in the Japanese for "good morning".[4]

[4] See I. Chronicles VI:5, about Bukki, the father of Uzzi.

In after years, in the freshness of his metropolitan fame, John Chambers visited several times his old home, the log cabin in which he grew up. The house is now a weather-boarded dwelling place, but in the wooden walls is still to be seen the little hollow place or alcove, where were kept[15] the decanters or glasses, containing cherry brandy and whiskey, which were so popular and in such general use in those early days before teetotalism, or prohibition or no license was known. During the war of 1812, this house was used as a recruiting station for volunteers, and here the young soldiers pledged their glass in token of their patriotism and comradeship. Against this phase of social life, the boy John set his face from the first.

William Chambers lived the life of a pioneer in the American forest. He gained his bread by tilling the soil, and a little ready money by burning the timber and leaching the potash out of the ashes, and by other industries common to the forest. Indian cooking was soon learned and the food of the red man became popular. In fact there are very few purely American dishes, which are not evolutions from the Indian originals. Sugar was plentiful from the maple trees, but salt was very costly and hard to get. By boring wells, brine was found from which good salt could be made.

Life on the frontier was necessarily rude in some points, especially in moral relations with the Indians. As pretty much all Irishmen are very fond of religion and whiskey and a bit of a fight, there were often rough scenes. William Chambers was a strong character and his hot temper was easily roused, but his wife, an equally strong character, but with finer strength, was cool-headed and made a good balance for her husband. She was a noted nurse and especially skillful in the sickroom. Hence she was often called upon for help by both friends and strangers in time of pain and misfortune. Malaria and homesickness were common woes. Devoutly pious, she trained up her children in the fear and love of God, and by them and even by later generations her memory is treasured.

The religion of these pioneers may have been narrow, but it was strong and deep. It was based on a first-hand knowl[16]edge of the English Bible. Even in his early life, as I remember Mr. Chambers saying, he revolted against bigotry and the kind of religion that was not rich in love to one's neighbor. These were psalm-singers and not hymn-using Christians, but the Methodist preachers and Christians of other sorts than Scotch-Irish Presbyterians were in the land. The boy John once heard an old gentleman say that he would as soon sit down to the Lord's Supper with a horse-thief, as with a man who sang Dr. Watts' version of the Psalms.

Little John also refused to touch liquor, for he saw the awful effects of its use, and grew to have a hatred of it. On one occasion, the little fellow rebuked a crowd of men, including his own father, for their drinking habits whereby the parent, William Chambers was greatly affected. "The heart of the child three years old is in the heart of the sage of sixty," as says the Japanese proverb, was true of John Chambers, the metropolitan preacher, but it was in childhood that God began to shape this bonnie bairn for a long life of usefulness. The boy in the Ohio forests was a hearty hater of all bickering and squabbling. He was often called upon to settle differences. He came to be known among neighbors and friends as "the little peacemaker." "The child is father to the man," and all his life John Chambers was mighty as a reconciler.

John Chambers's boyhood was thus spent in the wilderness in continuous hard work, by which he toughened his thews and kept his cheeks rosy, rising into brave, pure, and clean manhood. He took his part in the hard work of the farm, even to clearing the forest. He knew what it was to "lift up axes against thick trees." With his other brothers and sisters, he enjoyed life to the full. Politically, in this Jeffersonian era, his parents took the Democratic view of[17] things, so that their offspring had the spirit of democracy in their veins. All his life the intensely patriotic John followed the faith of his father, and was, as he called himself, a Constitutional State-Rights Democrat.

He was taught to read and write at home, but with that true instinct for education, which is inborn with Calvinists and the Scotch-Irishmen, his parents wished to have him better educated. They sent him, therefore, when he was but fifteen years of age, to Baltimore, where lived some of their relatives. A journey over the mountains in the early nineteenth century was like a trip to the Philippines in our days, but John gladly set out on horseback, with a party, in the spring of 1813, to the city on the Patapsco.

It seems that he had no special purpose of remaining permanently there, but Providence made his a stay of twelve years. After some experience at school, he decided to learn the jeweler's trade. Thus with business, and later with love, and then a call to the ministry, Baltimore was to be the city in which his mind was shaped, and which all his life was to him, socially, as magnet and star.

Patriotism, too, had something to do with making the Monumental City his home. It was war time, and the second struggle with Great Britain was on. As a municipality, the young city, but sixteen years old, had already become a famous place for the building of ships, the timber being floated down from the heart of New York state and from northern Pennsylvania, along the old line of Sullivan's march of 1779, by way of the Susquehanna River. Immediately on the declaration of war by Congress, a swarm of privateers sailed out of the Patapsco and Chesapeake to prey on Great Britain's commerce, especially in the West Indies. Hence the British government early decided that one of the first places to be occupied was Baltimore. The[18] stalwart youth from Ohio arrived in good time to hold a shovel and dig earth to throw up entrenchments, over which waved "The Star-Spangled Banner". He worked several days in the trenches. In September, 1814, the British forces made their attack under Col. Ross, a veteran under Sir John Moore and Wellington. Their commander was killed and the assault given up. The next day Admiral Cockburn's fleet bombarded Fort McHenry in vain. The attack from ship by water was as ignominious a failure as was the attempt by land. The happy result was the deliverance of the city and the birth of America's national song, "The Star-Spangled Banner". Francis Scott Key, detained against his will on the deck of the British man-of-war Minden, was an indignant spectator of the bombardment, but in the morning of September 14th, saw his country's flag "in full glory reflected ... on the stream". In 1876 a bronze statue to his memory was erected and Old Defenders' Day keeps alive the stirring memories of September 11th, 1813.

Soon after coming to Baltimore John Chambers became a member of the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church, of which the Rev. John Mason Duncan was pastor. Under the preaching of this eminent prophet, the mind of the young man expanded. Indeed it was so shaped and moulded by Dr. Duncan, that we may consider him as the greatest of all John Chambers' teachers, and his direct influence as greater than all subsequent schools and teachings. "My honored father in Christ" was Mr. Chambers' designation. Dr. Duncan saw in the young Ohio lad "an eloquent man and mighty in the scriptures". He persuaded him to study for the ministry, which John, soon after uniting with the church, determined to do.

In pursuance of his plan, the lad entered the Classical Academy of the Rev. James Gray, D.D., formerly of Philadelphia, who had established in Baltimore one of the numerous first-class schools in the South, almost every one of which was founded by people of Scotch-Irish descent. When it came to the study of theology and practical training for the pastorate, John Chambers followed the method which was then the common one in America. Very few theological seminaries then existed in the country. That at New Brunswick, N. J., probably the oldest, was scarcely fifteen years of age; that at Princeton hardly over two years old. There were one or two in New England. For a young man having the ministry in view, it was the usual custom to study under his own pastor, a method not without great benefits, especially in this instance, as Dr. Duncan was one of the most eloquent ministers in the country. John Chambers learned how to preach by preaching. He was success[20]ful with human beings because he knew them so well. He was a master of the scriptures "in the original English". Only those who afterward sat for years under John Chambers' preaching so long as to be saturated with his ideas, to know the basic principles of his thought and the workings of his mind, and have also read and studied Dr. Duncan's works, can realize how greatly the pupil was indebted to his great master.

In fact it was John Mason Duncan who gave the keynote of the gospel message as to its form, and it was John Chambers who filled out the strain. The theme was set in Baltimore, the variations given in Philadelphia. The pupil followed the master very closely in practical organization and discipline also. Dr. Duncan was suspicious of all creeds and confessions of faith when made instruments of ecclesiastical power. His trust in the people was sincere, profound, intense, and practical. In theology he ever laid stress on "the mediatorial reign of Christ and his absolute ability and willingness to save all mankind", which willingness it was his delight to demonstrate from the Scriptures and "to rescue the Gospel call from false philosophy". Dr. Duncan was jealous, almost to hostility, of theological seminaries, and also of the growing usurpations of power by synods. He dubbed America "the land of synods". He wrote at the time when even the liberty of the presbyteries seemed endangered by the centralizing power of the synods: "To persevere in such a course is to raise up a class of men who, from the nature of the case, must be destitute of sympathy with the people; who will rise above the people as being their superiors and governors, and who will ultimately distract and divide the church by their philosophic subtleties and literary distinction".

Verily the writer of those words was a prophet.

Dr. Duncan's trust in the people was so great because, as[21] he believed and taught, "the Bible is addressed to the people".

All of this John Chambers believed, carrying out, even to a fuller logical conclusion, his teacher's doctrines.

In his book entitled "An Essay on the Origin, Character and the Tendency of Creeds and Confessions of Faith as Instruments of Ecclesiastical Power", Dr. Duncan showed in his first chapter that "the intention of this essay, strictly political in character, involves the great question of human liberty to think, speak, to write, to act". He delivered also a course of lectures on "The General Principles in Moral Government", as they are exhibited in the first three chapters of Genesis, in which the same ideas are more fully carried out.

Here is one of his passages:

"Supposing then a minister—blameless, faithful, apt to teach, believing in the great truths now defined, i.e. 'the Word made flesh'—should come to preach, who has a right to prevent him, or to refuse to recognize him as a true bishop and to stigmatize him as a heretic? The apostle John says he is of God, and any trial to which the statute in question would subject him must result in the equivocal recognition of that fact. Presbyteries, as they are now constructed, will not and cannot admit such a man to ministerial and church fellowship without violating the principles of their party. They will not and cannot ordain such a man without something more.... What mischief would the most extensive liberality produce?"

In a biography of John Chambers we shall see the pertinence of this quotation when we come to the story of his ordination.

The instructor of young Chambers was the Rev. James Gray, D.D., who published a book entitled "The Mediatorial Reign of the Son of God, or the Absolute Ability and[22] Willingness of Jesus Christ to Save all Mankind, Demonstrated from the Scriptures—an Attempt to Rescue the Gospel Call from False Philosophy", in which the grandeur, glory and all-embracing nature of the divine call to salvation is set forth.

This Dr. Gray, born in Ireland on Christmas day, 1770, had come to America in 1797, two years before his pupil, John Chambers. Probably he had been one of the United Irishmen. After preaching at Washington, N. Y., he settled, in 1808, in Philadelphia, over the Spruce Street Associate Reformed Church. In the Quaker City he became a very popular leader in many good things. He helped to found the Philadelphia Bible Society and received the degree of Doctor of Divinity from the University of Pennsylvania. With Rev. S. B. Wylie (father of the Dr. Wylie, whose name is embalmed in the title of the Chambers-Wylie Memorial Church), he opened a Classical Academy which became famous. After a few years he removed to Baltimore. Besides his study of theology and writing of the book on which his reputation rests—the Mediatorial Reign of the Son of God—(a favorite phrase of Mr. Chambers, even as the book was known by heart), he started a theological review which lived but a year. He died at Gettysburg, Pa., September 20, 1824.

It will be easily seen that under such teachers as Duncan and Gray, men of national repute, the Ohio boy received no mean training. On Garfield's theory, that a seat on a log, at the other end of which Mark Hopkins was teacher, might outrank the most showy university and apparatus, John Chambers was a college bred man. Under such direct, constant and personal influence as the Ohio boy in Baltimore received, the value of the quality of his education cannot be over estimated. It is very certain that no number of brick or stone edifices on a university campus, or profusion of apparatus in the laboratories, or comforts and luxuries in the[23] student's room of to-day, can take the place of the personal influence of great teachers. Nor can these turn out men who excel in character and abilities the leaders of men in the United States of America in the early nineteenth century, among whom the home-bred John Chambers was a characteristic specimen.

Yet, though favored with such acute, learned, and inspiring teachers, and kindled by fervor with ideas that made heat as well as light in his soul, John Chambers' idea of the religion of Jesus was, that first of all it must be practical. There was no special division of it called "applied Christianity." To him it was all application. How it could ever be printed in a catechism and exist apart from life, he refused to see. He scorned professions of orthodoxy or of doctrine that did not quickly and permanently bear fruit in holy living, and in service for souls. With five or six other young men, he started prayer meetings and evangelistic labors.

When ready for examination for the ministry Mr. Chambers made his appearance before the Second Presbytery of Philadelphia, and in May, 1824, received his license to preach the Gospel and to accept a call to the pastorate. This body of ministers and elders which licensed him was dissolved in the autumn of 1824, and Mr. Chambers was then received as a licentiate under the care of the Presbytery of Baltimore.

It was about ten months after his first visit to Philadelphia to receive license, that is in March, 1825, that Mr. Chambers was invited to preach in the Margaret Duncan (Associate Reformed) Church in Philadelphia. The little brick edifice had been erected in compliance with the will of, and as a gift from, the grandmother of Dr. John Mason Duncan, and the latter as well as Mr. Chambers' preceptor, Dr. James Mason Gray, had taken part in the dedicatory services in 1815.

The church itself at this time, 1825, was a struggling one. The edifice was in a poor and thinly inhabited part of the city. There was no fund for the support of the building, and the Associate Reformed denomination in the United States was weak and poor, with a scarcity of ministers. Happily other Presbyterians gave assistance and supplied the pulpit; otherwise, the building would have been often closed for long periods at a time. The first regular pastor was the Rev. Thomas Gilfillan McInnis, who was called to the service early in 1822. He died on the 26th of August, 1824, and the flock was left shepherdless. There was even better provision for the dead than for the living. On the 7th of October, 1824, Robert A. Caldcleugh and wife presented to the minister, elders, and fifty-two church members, a lot of ground, on the South side of Race street between what was the "Schuylkill Third" and "Schuylkill Fourth" streets, now Nineteenth and Twentieth, for a cemetery. This lot is eighteen feet six inches wide and one hundred and twenty-nine feet deep.

This was the situation, when Mr. Chambers was called, in March, 1825, to preach as a candidate. He came on from Baltimore and on two Sundays in April told the people of God's love in Christ Jesus. His sermons were as a mighty stack of fuel, with the breath of the Lord on the first Sabbath kindling it, and the wind of the Holy Spirit on the second Lord's Day turning it into vehement flame. A triple fire of love to God, of the people to the young pastor, and of his young heart to them began its glow, which paled not until after fifty years of beacon glory it was quenched by death.

Since out of the Margaret Duncan Church, or "Church of the Vow", have grown, it is believed, at least ten other churches, and since the tradition of her ocean experiences has taken varied shapes and forms in its transmission, we shall give a narrative which is probably the most in accordance with fact.

Mrs. Margaret Duncan, on the death of her husband, a prosperous merchant of Philadelphia, determined to visit old friends in Stewartstown, Tyrone County, Ireland, in which she had been born. She took with her her little grandson, who was to become the famous Dr. John Mason Duncan. Returning across the ocean in the autumn of 1798, the ship sailing from Belfast, Ireland, was loaded heavily with many passengers, most of them poor emigrants, but had little cargo in the hold. It is said that the captain had never crossed the Atlantic. The compass was out of order, and with head winds and wet and foggy weather, the voyage was dangerously prolonged. The passengers were put on short allowance and there was no water. It is even said that in a severe storm the captain and crew deserted the vessel. The people suffered from agonizing thirst. They even talked of drawing lots to see who should be put to death and give his own flesh as food to the others.

Mrs. Duncan was then a woman between seventy and eighty years of age. Late tradition says the lot was drawn and she drew it and expected to be a victim. Mr. Chambers, though often referring to her experiences on the sea, makes no mention of the lot or of this dire extremity. Going into her cabin she gave herself to prayer, and vowed be[26]fore God that if He would avert the impending blow and in mercy save her life and the ship's company she would forever consecrate herself and all that she had to His service; that she would erect a church edifice for the congregation of the Associate Reformed people in Philadelphia with whom she worshipped, and that she would give and educate her little grandson for the Gospel ministry.

Not long after this, rain fell, and the agonizing thirst of those in the ship was relieved. Soon the shout, "sail ho" was heard from the man aloft. A vessel hove in sight and rescued them all. The ship entered the Delaware river and all reached Philadelphia in safety.

True to her vows, Margaret Duncan educated her grandson John Mason Duncan to preach the good news of God. Dying Nov. 16th, 1802, she left her money by will for the erection of a house of worship, which she minutely described, specifying that it was to be of the Associate Reformed communion. By various names, the "Margaret Duncan Church," or "The Vow Church," or "Saint Margaret's Church," the brick edifice on Thirteenth street near Filbert on the west side, stood until some time in the fifties. I can remember as a little boy going to see the debris of the ruins, the piled up old brick partially cleaned of mortar, the dust and the broken bits of lime, and the great hollow place where the cellar had been. In 1875, Mr. Chambers spoke of "the little church where we worshipped so long.... It is a shame that the church was ever destroyed. However it was torn down, and we have nothing more to do with it".

His was the language of affection. As matter of cold fact, the "house was of plain brick, without the least trace of ornament and for many years was one of the gloomiest looking churches in the city. The dimensions were fifty by sixty feet." The edifice was opened for worship on the[27] 26th of November, 1815. The dedication sermon was preached by the son of the vow, and the grandson of her who made it, Rev. John Mason Duncan. As before stated, Rev. James Gray, D.D., then with Dr. Wylie at the head of a classical school in Philadelphia, also took part.

Having been called to be the pastor of this church, Mr. Chambers surveyed his field to see what resources there were for sustaining permanent gospel work. He found no organized effort. There was no prayer-meeting, no Sunday School, not a man to lead in public prayer, and the three elders were all superannuated. The congregation was made up of humble people, poor, hard-working, industrious, with only here and there one among them who might be called rich; nor was there a family in which family worship was held. It was necessary therefore that the young man from Baltimore, who did not know ten people in Philadelphia when he first arrived, should borrow two devout men, Presbyterians, Wilfrid Hall and Hiram Ayres, to help him in meetings for social prayer. He then made application to Mr. Hall for the use of a room on Market street near what is now Seventeenth, in a district of vacant lots. Very few people were then living west of Broad street, and most of the streets now well known were not yet "cut through". He knew not whether any one would come to the meeting called for prayer, but God gave him a gracious surprise. When he arrived near the hour, "there was scarcely a spot for a human being to stand on". There and then began the Holy Spirit's workings which resulted in a whole family of Christian churches.

These prayer meetings were begun, according to due announcement, on the fourth Sunday in May. Their good influences were seen in the immediate enlargement of the church audience. By the beginning of July, there were[28] four men ready to speak or lead in prayer. By August 1st, over forty persons, many of them young men and women, had declared their faith in Christ, and were ready for Christian work. Mr. Chambers found a friend in Rev. Dr. Stiles Ely, a New England man, the principal founder of the Jefferson Medical College, and editor of The Philadelphian. From 1801 he had been pastor of the old Pine street Church, and was at that time moderator of the Presbyterian General Assembly. As Mr. Chambers was not yet ordained, Dr. Ely preached the sermon and administered the Lord's Supper, when the new converts were received.

As Dr. Chambers told the story in 1875, "The next move was for a Sabbath School, and the marvel was with what eagerness they took hold of it ... and carried it on with vigor, procured rooms and Sabbath School scholars and teachers and entered their names, and we went on and on from that very day after the institution of the prayer meeting, and the consequence was that we very soon felt that God was with us".

When the people of the Ninth Presbyterian, or Margaret Duncan Church on Thirteenth street, met together to vote a call to John Chambers, it was under the care of the First Presbytery of Philadelphia. Of course, therefore, the call must be approved at the regular meeting of the presbytery, and only after the usual examination of the candidate. Mr. Chambers came on from Baltimore, having accepted the call, and began his work as pastor and preacher-elect on the 9th day, or second Sabbath, in May, 1825. The presbytery was to meet in October in its semi-annual gathering. By a strange coincidence this was at Newtown, near the Neshaminy stream, in Bucks county, Pa.—the field of the evangelical and revival labors of the ancestor of his betrothed, of whom more anon. Was the young preacher's imagination busy with the scenes of a century before?

The glories of autumn made lovely the landscape of this affluent agricultural county lying along the bend of the Delaware, rich in fruit, in Pennsylvania Germans, in English Quakers, and in Scotch-Irish people. Its name, that of Penn's county in England, is suggestive of the old world, and it is historically famous for being on the line of Washington's march to his great victory over the Hessians at Trenton, and through it part of Sullivan's men had moved for the chastisement of the Iroquois tribes at Newtown, near Elmira, N. Y., in 1779. Yet the historical associations uppermost in the mind of the young licentiate must have been those with the great-grandfather of his betrothed, who in this very region and near this very house of worship, had labored with Gilbert Tennant in the gospel.

The young minister's call and the letter announcing it, from the hands of the elders of the Ninth Church, Messrs. Ross, Hogg, and Reed, in the name of the congregation, was handed in to the assembled authorities. No doubt the document was on genuine honest rag paper, the only kind then known, and on a letter sheet, folded and dovetailed together and closed with sealing wax or wafer, without an envelope, directed on the outside and carried to him by stage coach. No doubt he himself had to go to the office in Baltimore to get it. In compliance with its request, the young licentiate's journey would be by stage through Elkton and Wilmington to Philadelphia. From Philadelphia to Newtown, twenty-seven miles northeast of Philadelphia, the route would probably be up the well-known road crossing the Neshaminy Creek.

The young licentiate, accustomed to do his own thinking, appeared with clean papers from the Presbytery of Baltimore, and asked that he might be taken under the care of the First Presbytery of Philadelphia, with a view to ordina[30]tion and installation as pastor of the Ninth Church. Nevertheless, although he might be punctual and his papers clean, Dame Rumor had arrived before him. Several of her thousand tongues had declared, and even asseverated vehemently, that John Chambers was that strange, curious, and ever-changing thing called a "heretic." Often that undefined thing is a babe thrust into the cradle, while the orthodoxy of yesterday is turned out. A "heretic," as Saint Paul was once called, even as Jesus was before him, is very apt to be crucified to-day and glorified to-morrow. Indeed, "heresy" is almost as protean and as undefinable as "orthodoxy" itself. We shall see what kind of a "heretic" John Chambers was. His life for fifty years revealed the reality.

Within that little company gathered at Newtown there was, in the language of old times many a "heresio-mastix" or scourger of heresy, and a majority of the ministers present were already pre-determined to "hereticate" the young licentiate, who had already made the bounds of the little brick church on Thirteenth street too small to hold his hearers. Nevertheless our sympathies go out to all church bishops, whose duty it is to show that sudden popularity is no proof of fitness or character.

It developed during the examination that the head and front of the young man's offending was his belief in the Bible as an all sufficient rule of faith and practice. In this position, he was confirmed by the fact that the Westminster standards, the Confession of Faith, the Larger and Shorter Catechisms, teach that the Bible is the only infallible rule of faith and obedience. These all unite in declaring that the Scriptures are "given by inspiration of God to be the rule of faith and life", "the rule of worship", the only rule of faith and obedience; which teach "what man is to[31] believe concerning God, and what duty God requires of man", and form "the rule given us of God to direct us how we may glorify and enjoy Him."

In a word, to an independent thinker, loyal to the Bible as the word of God, as John Chambers was, the Westminster standards contain their own reductio ad absurdum to any one who puts creed, catechism, or confession above the Holy Scriptures, or who makes certain parts, or even a collection of parts, greater than the whole. Mr. Chambers, using his own words, believed that nothing could exceed infallibility, and was therefore satisfied with the infallible rule of the Scriptures. There was not then the freedom of faith, and the liberty of private interpretation of Holy Scripture and the Westminster symbols that is now happily the rule in the Presbyterian churches. The fault, if fault it were, was not solely on the young man's part.

The eyes of the "fathers and brethren" were opened and the "heretic" stood revealed. One of the members, the Rev. Dr. Ely, then proposed that the moderator should ask Mr. Chambers whether at the time of his licensure he subscribed to the Confession of Faith. He answered that he did not. When the second question was proposed, "Are you prepared to do so now?" he answered firmly, "I am not".

A motion was then made by Dr. Ely that Mr. Chambers and his papers be referred back to the Presbytery of Baltimore, and that the pulpit of the Ninth Church be declared vacant. Rev. Messrs. Patterson and Hoff were appointed a committee to perform the duty.

On Thursday evening of the same week, which was the regular evening for the weekly lecture, the committee of the Presbytery, which had met at Newtown, appeared at the church.

Although there were no telegraphs in those days, it was quickly known in Philadelphia, and to all the people of the Ninth Church, that Mr. Chambers, the man whom they had learned to love, had been rejected by the Presbytery. The preaching of the young minister had already resulted, under God, in a deep and strong religious interest. Consequently there was a large attendance and not a little excitement in the little brick edifice, so much so, indeed, that some of the congregation had quietly resolved to put the committee out in the street should they attempt to go into the pulpit.

Punctuality with the young pastor had already settled into what proved to be a life-long habit. He was at the church in good season. Finding the committee already there, he explained to the two men the situation and told them what the consequences would be if they attempted to fulfil their mission. Happily, however, both gentlemen being more concerned with the coming of the kingdom of God than about obeying the letter of their orders, did indeed go into the pulpit, but it was at the request of Mr. Chambers, who made them his firm friends for life. When there they co-operated with him, assisting to conduct the services, and not a word was said about the pulpit being vacant. Thus God, through his servant, quieted the Irishmen, and then and there magnified this man who had a genius for friendship and was an expert peacemaker; all of which was for the coming of the kingdom and the good of souls.

As days passed by, the people of the congregation, realizing that if they wanted to have a minister they would have to be an independent church, took prompt action. After due notice had been given, a congregational meeting was held. By a vote of four to one the people declared themselves independent of all church courts, with only Christ as their Master. By another vote, equally large, they resolved to retain John Chambers as their minister.

The minority, led by Mr. Moses Reed, one of the elders, withdrew, and in a room on Race street organized themselves as the Ninth Presbyterian Church. In the law suit that followed, the seceders won their case. With the edifice, given up in 1830, went the possession of the small burying ground on Race street, above Nineteenth, in which sleeps the dust of the Ross family and the father of the renowned soldier's friend, Miss Anna Ross, whom defenders of the Union from 1861 to 1865, and the survivors of the Grand Army remember so well. In the writer's memory her name and face are not forgotten, for she was his Sunday School teacher.

In Nevins' Presbyterian Encyclopedia, which contains a brief sketch of the career of John Chambers and a wood-cut portrait of him in his prime, it is stated, that "When Mr. Duncan about this time renounced the jurisdiction of the Presbyterian Church into which the Associate Reformed, with Dr. Mason and others had been merged, Dr. Chambers followed his example, from sympathy with his teacher". Was the pupil's "sympathy" stronger than were the preacher's convictions?

Meanwhile the young minister, then twenty-seven years old, returned to Baltimore to meet the Presbytery and seek ordination. Here again another obstacle arose. The theologians on the Patapsco declared that Mr. Chambers was no longer a licentiate under their care, and handed him back his papers. Again was John Chambers preacher of the gospel rejected of men. Was ecclesiasticism good order in this case? Did the true cause of this rather rough treatment lie in this, that he had been a pupil of John Mason Duncan, the independent?

What should the young man do? Disowned of presbyteries and looked at suspiciously by the fathers and lords in the church, where should he go? As he himself wrote on his fiftieth anniversary, May 9th, 1875:

"The prospect, therefore, was rather chilly. I had left my home of many years in the city of Baltimore, where I received all the education that ever was bestowed upon me, and where I sat at the feet of that Gamaliel, the Reverend John Mason Duncan, to whom under God, I am indebted, entirely by His grace, for the position I occupy to-day. My[35] heart had been much interested in religious matters for two or three years before I left Baltimore. There were five or six of us young men, as students of Mr. Duncan, and we had organized some meetings through the city of Baltimore, and God was with us; and the warm heart—if I had any warm heart at all—that I brought to Philadelphia, was kindled at the altar of those dear young brethren. How much we are indebted to God for young men! How much, my brethren, are the eldership, are you, am I, indebted to young men!" Dr. Chambers's last words in this paragraph are especially appropriate, because it is the tendency of most theologians and elderly men to teach that God was, not that he is. With young men, God's existence is more likely to be in the present tense.

The ecclesiastical orphan, thus cast fatherless and friendless upon the wide world, began to inquire whither he should go to seek ordination. Happily there were other bodies of Christians and a living church of Christ, besides the one which had withheld its blessing. Happily too, there were men in the Presbyterian Churches of Philadelphia, warm friends, who were able to direct him wisely, one of them being the large-hearted scholar, James Patriot Wilson, D.D., pastor of the First Presbyterian Church, predecessor of Albert Barnes, and then fifty-six years old. The other was Rev. Thomas Harvey Skinner, D.D., pastor of the Fifth Presbyterian Church in Locust street, and who, twenty-six years afterwards, became the famous professor in Union Theological Seminary of New York City. Both of these men were in hearty sympathy with those views of truth afterwards called the "New School". These brethren with Dr. Duncan, advised Mr. Chambers to go into Yankee land and there be ordained by Congregational clergymen. They gave him letters of introduction to the[36] Rev. Nathaniel W. Taylor, the famous exponent of "the new divinity" and then of the theological department of Yale College.

It was not Presbyterianism only that was at this era being rocked on the waves of progress by the gales of the Spirit. About this time, or shortly afterwards, Connecticut Congregationalism was being excited and lifted out of torpor and routine by the breezy discussions of "Taylorism" and "Tylerism". The former expressed the views of Dr. Nathaniel William Taylor, the successor of Moses Stuart, and then holding the Dwight professorship in the Theological Department of Yale College. The young seminary opened in 1822 was therefore but three years old when Mr. Chambers appeared to be ordained. Whatever may be the true label we put upon Dr. N. W. Taylor, he was one of the greatest of America's theologians when the appeal was being taken from Calvin to Christ. He taught a modification of Hopkinsism which many Presbyterians regarded as hostile to Calvinism and many New Englanders as "unsound". As Mr. Chambers had already done, Dr. Taylor repudiated the words "predestinate" and "decreed" and used the word "purposed" concerning God's desire to save men. Before he died, in 1858, he had trained over seven hundred ministers. Ex-President Dwight, in his recent book on Men and Memories of Yale, presents him felicitously in word and picture.

About the time also of rising "Taylorism" the new methods of preaching and revival used by Rev. C. G. Finney, afterwards president of Oberlin College, excited much alarm among the men of the old school. How strange are the variations and how curious is the progress of orthodoxy! Most of the great revivalists of this country were nourished in the Congregational churches; and, from Finney to Moody, they were at first looked upon with suspicion. Later[37] they were welcomed and lauded as the saviors of orthodoxy. Verily the "earthen vessel" is sometimes more in evidence than the "heavenly treasure".

To combat the views of Dr. Taylor, Dr. Bennett Tyler, ex-president of Dartmouth College, and then pastor at Portland, Me., was hailed as the champion by all the leading spirits among the "conservatives", though both of these great teachers had modified the original Calvinism. Of Dr. Tyler it has been well said that "In forming his system he began not with mind, but with the Bible, and he looked for no advances in theology except such as come from a richer Christian experience". Dr. Tyler founded a theological institute at East Windsor, Conn., in 1834, so long and ably presided over by the cultured Philadelphian, Chester D. Hartranft, D.D., brother of Pennsylvania's soldier and governor.

The monuments of these controversies between "Taylorism" and "Tylerism", now forgotten, are seen in the superb theological seminaries of New Haven and Hartford, but the points of difference, as now discoverable only under the microscope of research, are of no practical importance. Hardly any one except the hair-splitting philosophers can state them. They have been forgotten in the larger vision of advancing Christianity. So will it be with most of the controversies of to-day, especially those centering in the "higher criticism".

It was to Dr. N. W. Taylor, that Mr. Chambers had letters, as well as to Dr. Leonard Bacon, afterwards the famous opponent of slavery, and author, in 1833 of the hymn,

For over twenty years Dr. Bacon was pastor of the First Congregational Church in New Haven, one of the professors in Yale Divinity School, and the progenitor of a remarkably intellectual family. Until his death, the day before Christmas of 1881, he was a commanding figure in American history. Of the council which ordained Mr. Chambers he was the scribe. It will be seen at a glance that the ecclesiastical exile from Philadelphia and Baltimore was to stand before giants. If these mighty men of God could give him ordination, why need he mourn the loss of clerical favor nearer home?

Thus armed with letters of commendation, the young Irish-American proceeded to the City of Elms, in the opening week of December, 1825. It was the first year of John Quincy Adams's administration, and the Erie Canal had joined the waters of the great lakes with the Atlantic. It was an era of mighty conquests over nature, and the heart of the young man who was thrilling with the spirit of the age and of the ages, beat high with hope. He, too, wanted to do great things for God and help in making the world better. He sought out those addressed, and handed to them his letters. Two days afterwards, the Association of Congregational ministers of the Western District of New Haven County was called together by the Moderator, and eight ministers were present in the assembly which was held in the Centre Church.

Of the meeting, the following official record was copied out for the biographer, at the request of Rev. Dr. T. T. Munger, author of The Freedom of Faith, and through the courtesy of Rev. Franklin Dexter, librarian of Yale University.

"At a Special Meeting of the Association of the Western District of New Haven County, convened by letters from the Moderator and holden in New Haven, December 7th, 1825.

Present—Messrs. S. W. Stebbins, J. Day, D.D., E. Scranton, S. Merwin, J. Allen, E. T. Fitch and L. Bacon.

Mr. Stebbins was chosen Moderator, and Mr. Bacon, Scribe. The session was opened with prayer.

Mr. John Chambers, a licentiate of the late second Presbytery of Philadelphia, now dissolved, being introduced to the Association by Mr. Merwin, requested to be ordained to the ministry of the Gospel, and producing proper testimonials of his standing as a member of the church of Christ; of his regular license to preach the Gospel, and of his having passed through a period of probation, with proper acceptance, the Association, after examining him as to his belief in the doctrines of the Gospel, his experimental acquaintance with religion, and his motives in desiring the work of the ministry,

Voted to proceed to his ordination this evening at half-past six o'clock.

Voted that the parts be performed as follows: The introductory prayer to be offered by Mr. Scranton; the sermon to be preached by Professor Fitch; the ordaining prayer to be offered by Mr. Merwin, during which Messrs. Stebbins, Fitch and Merwin to impose hands; the charge to be given by Mr. Stebbins; the right hand of fellowship by Mr. Bacon; the concluding prayer to be offered by Mr. Allen. Adjourned to meet in the Centre Meeting-house at half-past six o'clock.

Met according to adjournment. The ordination took place according to the preceding votes.

Mr. Chambers, at his request, was admitted a member of the Association.

The minutes were read and accepted.

Leonard Bacon, Scribe."

[Test]

The ordination sermon was duly preached in the evening by the Rev. Professor Eleazer T. Fitch, D.D., Livingstone[40] Professor of Divinity in Yale College, and then Mr. Chambers was ordained by the laying on of hands of the three appointed ministers of the Association.

According to Congregational usage an Association of ministers does not ordain to the ministry, but a Council does. The Association may transform itself into a Council for the time being. In Connecticut the Consociation, or standing council, performed this function. In any event, John Chambers was properly ordained to the Gospel ministry according to due Congregational call, form, and precedent.

Furthermore, by his own request, he became a member of the Association. This did not make him a "Congregationalist", but it showed his hearty sympathy with the principles and ideas of his fellow members. For forty-eight years, his only ministerial standing and connection was in the Congregational body as an independent minister, though his church was governed according to Presbyterian form and usage. So strong and deep was his faith in the validity of non-Episcopal and non-Presbyterian ordination that he showed it all his life by his works. He ordained during the course of his ministry several young men to the work of the gospel. One of these impressive ceremonies I myself witnessed, probably about 1859. After preaching a sermon and reading the papers or certificates of the candidate, Mr. Chambers called his elders, those grand men of God, Burtis, Luther, Steinmetz, and Walton around him. Then upon the head of the kneeling young man he and they laid their hands, solemnly ordaining him to the gospel in true apostolic style.

Years afterwards, in 1892, one of his own boys, even the biographer, delivered the Dudleian lecture at Harvard University in Appleton Chapel on "The Validity of non-Episcopal Ordination", or, more exactly, the validity of[41] ordination by the congregation, according to the method of the primitive Christian Churches[5]. By a strange coincidence, it was on the same night, Dec. 7, on which Mr. Chambers was ordained, and thus the sixty-seventh anniversary of his ordination.

[5] See the Bibliotheca Sacra, for October, 1893.

Mr. Chambers left New Haven the next morning, Dec. 8th, 1825. The elms were leafless, but his heart was happy and his face radiant with joy. Coming back to minister to his constantly increasing flock, he baptized on the first Sunday in January, 1826, several new communicants and administered for the first time the memorial supper of Jesus. It was a day long to be remembered, for between seventy and eighty souls were on this occasion added to the church, and the young pastor, in the joy of his initial service, baptized the first child that ever received the dedicating waters from his hands, John Chambers Arrison, the first of a mighty host.

In 1875, the white-haired pastor who had welcomed 3,585 members into his church, said: "Thus it seemed that the tide of God's favor was taken at the flood, and it has brought us to where we are to-day".

Let us now look into John Chambers's inner life,—of the heart as well as the intellect. We have seen how the vigorous and lusty twig which grew up in the classical academy of Baltimore began to bend away from certain statements and formulæ in the Westminster symbols, as then interpreted to him, which gave the afterwards robust and widespreading tree a tremendous inclination. "As a man thinketh in his heart, so is he." John Chambers's convictions shaped his message and colored all his preaching. There were probably reasons, other than those merely intellectual, for the young man's tremendous antipathy to the idea that the fullness of the Christian life and the message of Jesus could be compressed into the mathematical statements made at Westminster during the days of the British Commonwealth.

When I was a student at Rutgers College, New Brunswick, New Jersey, from 1865 to 1869, I was asked, as an incoming freshman, by the president, Rev. William H. Campbell, D.D., LL.D., concerning my religious training. I told him how much I owed to John Chambers in Philadelphia. A bland light overspread the full expanse of that face, so seamed with thought and studious toil and which nothing but warm affection could call handsome. Indeed, it seemed as though every wrinkle was smoothed out, as a prairie-like smile suffused its whole area. Then, laughing heartily, he said, "Well, I can remember when he had orthodoxy taught him with the sole of a slipper." Evidently then, according to the accepted and supposedly wholesome custom of the times, the future preacher received at intervals[43] what was expected to be a physical aid to faith, though in reality the result was the reverse of what was expected. Whether the slipper was applied to the lad before or after intellectual defection, its use induced reaction. Whether, as is probable, the correction by leather came from the employer to whom the apprentice was bound, or from the schoolmaster is not known. The boy would not accept Westminsterism whole, certainly not as then interpreted.