Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

Merciless Monster of the Deep.

The murderous German submarine sighting its prey. Sinking under water it launched the fatal torpedo and its helpless victim, crowded with innocent men, women and children, was doomed.

A NEW KIND OF WARFARE

——COMPRISING——

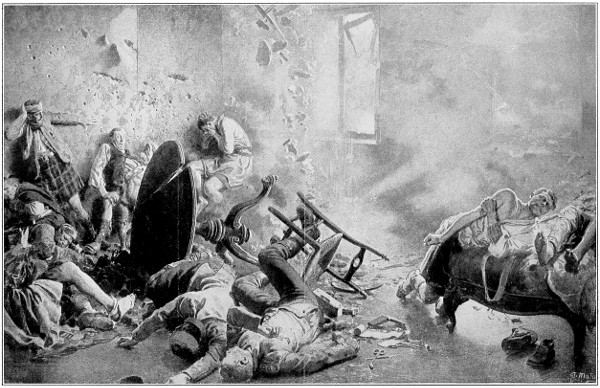

The Desolation of Belgium, the Sacking of Louvain, the Shelling of Defenseless Cities, the Wanton Destruction of Cathedrals and Works of Art, the Horrors of Bomb Dropping

——VIVIDLY PORTRAYING——

The Grim Awfulness of this Greatest of All Wars Fought on Land and Sea, in the Air and Under the Waves, Leaving in Its Wake a Dreadful Trail of Famine and Pestilence

By LOGAN MARSHALL

Author of “The Sinking of the Titanic,” “Myths and

Legends of All Nations,” etc.

With Special Chapters by

SIR GILBERT PARKER

Author of “The Right of Way”

VANCE THOMPSON

Author of “Spinners of Life”

PHILIP GIBBS

Author of “The Street of Adventure,” Special

Correspondent on The London Daily Chronicle.

Illustrated

Copyright 1915

By L. T. MYERS

“Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.”—Jesus of Nazareth

The sight of all Europe engaged in the most terrific conflict in the history of mankind is a heartrending spectacle. On the east, on the south and on the west the blood-lust leaders have flung their deluded millions upon unbending lines of steel, martyrs to the glorification of Mars.

We see millions of men taken from their homes, their shops and their factories; we see them equipped and organized and mobilized for the express purpose of devastating the homes of other men; we see them making wreckage of property; we see them wasting, with fire and sword, the accumulated efforts of generations in the field of things material; we see the commerce of the world brought to a standstill, all its transportation systems interrupted, and, still worse, the amenities of life so placed in jeopardy for long generations to come that the progress of the world is halted, its material and physical progress turned to retrogression.

“Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me!”

But this is not the worst. We see myriads of men banded together to practice open violation of the very[4] fundamental tenets of humanity; we see the worst passions of mankind, murder, theft, lust, arson, pillage—all the baser possibilities of human nature—coming to the surface. Outside of the natural killing of war, hundreds of men have been murdered, often with incidents of the most revolting brutality; children have been slaughtered; women have been outraged, killed and shamefully mutilated. And this we see among peoples who have no possible cause for personal quarrel.

“Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me!”

To all human beings of normal mentality it must have seemed that the destruction of the Lusitania marked the apex of horror. There is, indeed, nothing in modern history—nothing, at least, since the Black Hole of Calcutta and some of the indescribable atrocities of Kurdish fanatics—to supply the mind with a vantage ground from which to measure the causeless and profitless savagery of this black deed of murder.

To talk of “warning” having been given on the day the Lusitania sailed is puerile. So does the Black Hand send its warnings. So does Jack the Ripper write his defiant letters to the police. Nothing of this prevents us from regarding such miscreants as wild beasts, against whom society has to defend itself at all hazards.

There are many reasons but not a single excuse for the war. When a man, or a nation, wants what a rival holds and makes a violent effort to enter into possession thereof, right and conscience and duty before God and to one’s neighbor are forgotten in the struggle.[5] Man reverts to the brute. Loose rein is given to passion, and the worst appears. The fair edifice of sobriety and amity and just dealing between man and man, upreared by civilization in centuries of travail, is rent asunder, stone from stone. The inner shrine of the inalienable sense of human brotherhood is profaned. One cannot reconcile with any program for the lasting accomplishment of good and the victory of the truth, this fever of murder on a grand scale, this insensate madness of pillage and slaughter that goes from alarum and counter-alarum to overt acts of fiendish and sickening brutality, palliated because they are done by anonymous thousands instead of by one man who can be named.

“Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me!”

It is civilization that is being shot down by machine guns in Europe. That great German host is not made up of mercenaries, nor of the type of men that at one time composed armies. There are Ehrlichs serving as privates in the ranks and in the French corps are Rostands. A bullet does not kill a man; it destroys a generation of learning, annihilates the mentality which was about to be humanity’s instrument in unearthing another of nature’s secrets. The very vehicles of progress are the victims. It will take years to train their equals, decades perhaps to reproduce the intelligence that was ripe to do its work. The chances of the acquisition of knowledge are being sacrificed. Far more than half of the learning on which the world depends for progress is turned from laboratories[6] and workshops into the destructive arenas of battle.

It is indeed a war against civilization. The personnel of the armies makes it so. Every battle is the sacrifice of human assets that cannot be replaced. That is the real tragedy of this stupendous conflict.

Perhaps it is better that the inevitable has come so soon. The burden of preparation was beginning to stagger Europe. There may emerge from the whirlpool new dynasties, new methods, new purposes. This may be the furnace necessary to purge humanity of its brutal perspective. The French Revolution gave an impulse to democracy which it has never lost. This conflict may teach men the folly of dying for trade or avarice. But whatever it does, it is not too much to hope that the capital and energy of humanity will become again manifest in justice and moral achievement, until the place of a nation on the map becomes absolutely subordinate to the place it occupies in the uplift of humanity.

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction | 3 | |

| I. | The Supreme Crime Against Civilization: The Tragic Destruction of the Lusitania | 9 |

| II. | The Heroes of the Lusitania and Their Heroism | 22 |

| III. | Soul-Stirring Stories of Survivors of the Lusitania | 34 |

| IV. | A Canadian’s Account of the Lusitania Horror | 50 |

| V. | The Plot Against the Rescue Ships | 55 |

| VI. | British Jury Finds Kaiser a Murderer | 61 |

| VII. | The World-Wide Indictment of Germany for the Lusitania Atrocity | 69 |

| VIII. | America’s Protest Against Uncivilized Warfare | 81 |

| IX. | The German Defense for the Destruction of the Lusitania | 91 |

| X. | Swift Reversal to Barbarism |

101 |

| XI. | Belgium’s Bitter Need |

112 |

| XII. | James Bryce’s Report on Systematic Massacre in Belgium | 121 |

| XIII. | A Belgian Boy’s Story of the Ruin of Aerschot | 137 |

| XIV. | The Unspeakable Atrocities of “Civilized Warfare” | 144 |

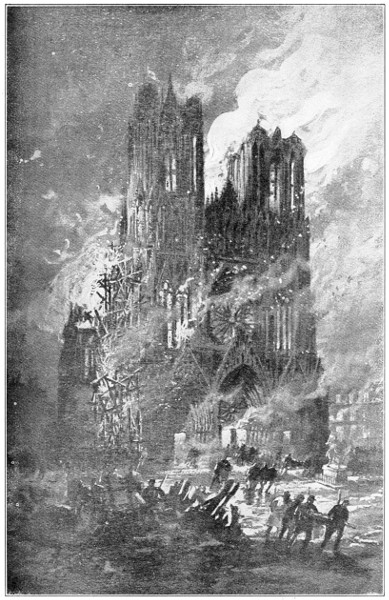

| XV. | Destroying the Priceless Monuments of Civilization[8] | 159 |

| XVI. | Wanton Destruction of the Beautiful Cathedral of Rheims | 169 |

| XVII. | Canadians’ Glorious Feat at Langemarck | 177 |

| XVIII. | Pitiful Flight of a Million Women |

195 |

| XIX. | Facing Death in the Trenches | 207 |

| XX. | A Vivid Picture of War | 221 |

| XXI. | Harrowing Scenes Along the Battle Lines | 228 |

| XXII. | What the Men in the Trenches Write Home | 234 |

| XXIII. | Bombarding Undefended Cities | 240 |

| XXIV. | Germany’s Fatal War Zone | 246 |

| XXV. | Multitudinous Tragedies at Sea | 251 |

| XXVI. | How “Neutral” Waters Are Violated | 255 |

| XXVII. | The Terrible Distress of Poland | 259 |

| XXVIII. | The Ghastly Havoc Wrought by the Air-Demons | 267 |

| XXIX. | The Deadly Submarine and Its Stealthy Destruction | 273 |

| XXX. | The Terrible Work of Artillery in War | 280 |

| XXXI. | Wholesale Slaughter by Poisonous Gases | 286 |

| XXXII. | “Usages of War on Land”: The Official German Manual | 294 |

| XXXIII. | The Sacrifice of the Horse in Warfare | 299 |

| XXXIV. | Scourges That Follow in the Wake of Battle | 303 |

| XXXV. | War’s Repair Shop: Caring for the Wounded | 308 |

| XXXVI. | What Will the Horrors and Atrocities of the Great War Lead to? | 314 |

The Giant Steamship “Lusitania” Torpedoed by the Germans off the Coast of Ireland.

The English Cunarder, “Lusitania,” one of the largest and fastest passenger vessels in the world, was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine in a few minutes with the loss of two-thirds of her passengers and crew, among whom were more than one hundred American citizens. The vessel was entirely unarmed and a noncombatant. (Copyright by Underwood and Underwood.)

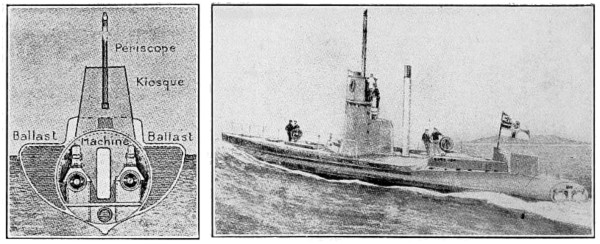

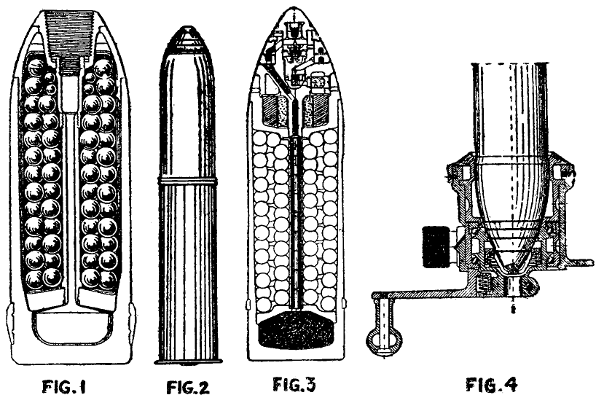

Top left: Persicope—Kiosque—Ballast—Machine—Ballast

The German Submarine and How it Works.

Upper left picture shows a section at center of the vessel. Upper right view shows the submarine at the surface with two torpedo tubes visible at the stern. The large picture illustrates how this monster attacks a vessel like the Lusitania by launching a torpedo beneath the water while securing its observation through the periscope, just above the waves.

AN UNPRECEDENTED CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY — THE LUSITANIA: BUILT FOR SAFETY—GERMANY’S ANNOUNCED INTENTION TO SINK THE VESSEL — LINER’S SPEED INCREASED AS DANGER NEARED — SUBMARINE’S PERISCOPE DIPS UNDER SURFACE — PASSENGERS OVERCOME BY POISONOUS FUMES — BOAT CAPSIZES WITH WOMEN AND CHILDREN — HUNDREDS JUMP INTO THE SEA — THE LUSITANIA GOES TO HER DOOM — INTERVIEW WITH CAPTAIN TURNER.

No thinking man—whether he believes or disbelieves in war—expects to have war without the horrors and atrocities which accompany it. That “war is hell” is as true now as when General Sherman so pronounced it. It seems, indeed, to be truer today. And yet we have always thought—perhaps because we hoped—that there was a limit at which even war, with all its lust of blood, with all its passion of hatred, with all its devilish zest for efficiency in the destruction of human life, would stop.

Now we know that there is no limit at which the makers of war, in their frenzy to pile horror on horror, and atrocity on atrocity, will stop. We have seen a nation despoiled and raped because it resisted an[10] invader, and we said that was war. But now out of the sun-lit waves has come a venomous instrument of destruction, and without warning, without respite for escape, has sent headlong to the bottom of the everlasting sea more than a thousand unarmed, unresisting, peace-bent men, women and children—even babes in arms. So the Lusitania was sunk. It may be war, but it is something incalculably more sobering than merely that. It is the difference between assassination and massacre. It is war’s supreme crime against civilization.

The horror of the deadly assault on the Lusitania does not lessen as the first shock of the disaster recedes into the past. The world is aghast. It had not taken the German threat at full value; it did not believe that any civilized nation would be so wanton in its lust and passion of war as to count a thousand non-combatant lives a mere unfortunate incidental of the carnage.

Nothing that can be said in mitigation of the destruction of the Lusitania can alter the fact that an outrage unknown heretofore in the warfare of civilized nations has been committed. Regardless of the technicalities which may be offered as a defense in international law, there are rights which must be asserted, must be defended and maintained. If international law can be torn to shreds and converted into scrap paper to serve the necessities of war, its obstructive letter can be disregarded when it is necessary to serve the rights of humanity.

HATE

CIVILIZATION--ART--RELIGION

The Triumph of Hate.

The irony of the situation lies in the fact that from the ghastly experience of great marine disasters the Lusitania was evolved as a vessel that was “safe.” No such calamity as the attack of a torpedo was foreseen by the builders of the giant ship, and yet, even after the outbreak of the European war, and when upon the eve of her last voyage the warning came that an attempt would be made to torpedo the Lusitania, her owners confidently assured the world that the ship was safe because her great speed would enable her to outstrip any submarine ever built.

Limitation of language makes adequate word description of this mammoth Cunarder impossible. The following figures show its immense dimensions: Length, 790 feet; breadth, 88 feet; depth, to boat deck, 80 feet; draught, fully loaded, 37 feet, 6 inches; displacement on load line, 45,000 tons; height to top of funnels, 155 feet; height to mastheads, 216 feet. The hull below draught line was divided into 175 water-tight compartments, which made it—so the owners claimed—“unsinkable.” With complete safety device equipment, including wireless telegraph, Mundy-Gray improved method of submarine signaling, and with officers and crew all trained and reliable men, the Lusitania was acclaimed as being unexcelled from a standpoint of safety, as in all other respects.

Size, however, was its least remarkable feature. The ship was propelled by four screws rotated by turbine engines of 68,000 horse-power, capable of developing a sea speed of more than twenty-five knots per hour regardless of weather conditions, and of[13] maintaining without driving a schedule with the regularity of a railroad train, and thus establishing its right to the title of “the fastest ocean greyhound.”

On Saturday May 1, 1915, the day on which the Cunard liner Lusitania, carrying 2,000 passengers and crew, sailed from New York for Liverpool, the following advertisement, over the name of the Imperial German Embassy, was published in the leading newspapers of the United States:

NOTICE!

TRAVELERS intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies; that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles; that, in accordance with formal notice given by the Imperial German Government, vessels flying the flag of Great Britain, or of any of her allies, are liable to destruction in those waters and that travelers sailing in the war zone on ships of Great Britain or her allies do so at their own risk.

IMPERIAL GERMAN EMBASSY.

Washington, D. C., April 22, 1915.

The advertisement was commented upon by the passengers of the Lusitania, but it did not cause any of them to cancel their bookings. No one took the[14] matter seriously. It was not conceivable that even the German military lords could seriously plot so dastardly an attack on non-combatants.

When the attention of Captain W. T. Turner, commander of the Lusitania, was called to the warning, he laughed and said: “It doesn’t seem as if they had scared many people from going on the ship by the looks of the passenger list.”

Agents of the Cunard Line said there was no truth in reports that several prominent passengers had received anonymous telegrams warning them not to sail on the Lusitania. Charles T. Bowring, president of the St. George’s Society, who was a passenger, said that it was a silly performance for the German Embassy to do.

Charles Klein, the American playwright, said he was going to devote his time on the voyage to thinking of his new play, “Potash and Perlmutter in Society,” and would not have time to worry about trifles.

Alfred G. Vanderbilt was one of the last to go on board.

Elbert Hubbard, publisher of the Philistine, who sailed with his wife, said he believed the German Emperor had ordered the advertisement to be placed in the newspapers, and added jokingly that if he was on board the liner when she was torpedoed, he would be able to do the Kaiser justice in the Philistine.

The early days of the voyage were unmarked by incidents other than those which have interested ocean passengers on countless previous trips, and little apprehension was felt by those on the Lusitania of the fate which lay ahead of the vessel.

The ship was proceeding at a moderate speed, on Friday, May 7, when she passed Fastnet Light, off Cape Clear, the extreme southwesterly point of Ireland that is first sighted by east-bound liners. Captain Turner was on the bridge, with his staff captain and other officers, maintaining a close lookout. Fastnet left behind, the Lusitania’s course was brought closer to shore, probably within twelve miles of the rock-bound coast.

Her speed was also increased to twenty knots or more, according to the more observant passengers, and some declare that she worked a sort of zigzag course, plainly ready to shift her helm whenever danger should appear. Captain Turner, it is known, was watching closely for any evidence of submarines.

One of the passengers, Dr. Daniel Moore, of Yankton, S. D., declared that before he went downstairs to luncheon shortly after one o’clock he and others with him noticed, through a pair of marine glasses, a curious object in the sea, possibly two miles or more away. What it was he could not determine, but he jokingly referred to it later at luncheon as a submarine.

While the first cabin passengers were chatting over their coffee cups they felt the ship give a great leap forward. Full speed ahead had suddenly been signaled from the bridge. This was a few minutes after two o’clock, and just about the time that Ellison Myers, of Stratford, Ontario, a boy on his way to join the British Navy, noticed the periscope of a submarine about a mile away to starboard. Myers and his[16] companions saw Captain Turner hurriedly give orders to the helmsman and ring for full speed to the engine room.

The Lusitania began to swerve to starboard, heading for the submarine, but before she could really answer her helm a torpedo was flashing through the water toward her at express speed. Myers and his companions, like many others of the passengers, saw the white wake of the torpedo and its metal casing gleaming in the bright sunlight. The weather was ideal, light winds and a clear sky making the surface of the ocean as calm and smooth as could be wished by any traveler.

The torpedo came on, aimed apparently at the bow of the ship, but nicely calculated to hit her amidships. Before its wake was seen the periscope of the submarine had vanished beneath the surface.

In far less time than it takes to tell, the torpedo had crashed into the Lusitania’s starboard side, just abaft the first funnel, and exploded with a dull boom in the forward stoke-hole.

Captain Turner at once ordered the helm put over and the prow of the ship headed for land, in the hope that she might strike shallow water while still under way. The boats were ordered out, and the signals calling the boat crews to their stations were flashed everywhere through the vessel.

Several of the life-boats were already swung out, according to some survivors, there having been a life-saving drill earlier in the day before the ship spoke Fastnet Light.

Down in the dining saloon the passengers felt the ship reel from the shock of the explosion and many were hurled from their chairs. Before they could recover themselves, another explosion occurred. There is a difference of opinion as to the number of torpedoes fired. Some say there were two; others say only one torpedo struck the vessel, and that the second explosion was internal.

In any event, the passengers now realized their danger. The ship, torn almost apart, was filled with fumes and smoke, the decks were covered with débris that fell from the sky, and the great Lusitania began to list quickly to starboard. Before the passengers below decks could make their way above, the decks were beginning to slant ominously, and the air was filled with the cries of terrified men and women, some of them already injured by being hurled against the sides of the saloons. Many passengers were stricken unconscious by the smoke and fumes from the exploding torpedoes.

The stewards and stewardesses, recognizing the too evident signs of a sinking ship, rushed about urging and helping the passengers to put on life-belts, of which more than 3,000 were aboard.

On the boat deck attempts were being made to lower the life-boats, but several causes combined to impede the efforts of the crew in this direction. The port side of the vessel was already so far up that the boats on that side were quite useless, and as the starboard boats were lowered the plunging vessel—she was[18] still under headway, for all efforts to reverse the engines proved useless—swung back and forth, and when they struck the water were dragged along through the sea, making it almost impossible to get them away.

The first life-boat that struck the water capsized with some sixty women and children aboard her, and all of these must have been drowned almost instantly. Ten more boats were lowered, the desperate expedient of cutting away the ropes being resorted to to prevent them from being dragged along by the now halting steamer.

The great ship was sinking by the bow, foot by foot, and in ten minutes after the first explosion she was already preparing to founder. Her stern rose high in the air, so that those in the boats that got away could see the whirring propellers, and even the boat deck was awash.

Captain Turner urged the men to be calm, to take care of the women and children, and megaphoned the passengers to seize life-belts, chairs—anything they could lay hands on to save themselves from drowning. There was never any question in the captain’s mind that the ship was about to sink, and if, as reported, some of the stewards ran about advising the passengers not to take to the boats, that there was no danger of the vessel going down till she reached shore, it was done without his orders. But many of the survivors have denied this, and declared that all the crew, officers, stewards and sailors, even the stokers, who dashed up from their flaming quarters below, showed the utmost[19] bravery and calmness in the face of the disaster, and sought in every way to aid the panic-stricken passengers to get off the ship.

When it was seen that most of the boats would be useless, hundreds of passengers donned life-belts and jumped into the sea. Others seized deck chairs, tubs, kegs, anything available, and hurled themselves into the water, clinging to these articles.

The first-cabin passengers fared worst, for the second- and third-cabin travelers had long before finished their midday meal and were on deck when the torpedo struck. But the first-cabin people on the D deck and in the balcony, at luncheon, were at a terrible disadvantage, and those who had already finished were in their staterooms resting or cleaning up preparatory to the after luncheon day.

The confusion on the stairways became terrible, and the great number of little children, more than 150 of them under two years, a great many of them infants in arms, made the plight of the women still more desperate.

After the life-boats had cut adrift it was plain that a few seconds would see the end of the great ship. With a great shiver she bent her bow down below the surface, and then her stern uprose, and with a horrible sough the liner that had been the pride of the Cunard Line, plunged down in sixty fathoms of water. In the last few seconds the hundreds of women and men,[20] a great many of them carrying children in their arms, leaped overboard, but hundreds of others, delaying the jump too long, were carried down in the suction that left a huge whirlpool swirling about the spot where the last of the vessel was seen.

Among these were Elbert Hubbard and his wife, Charles Frohman, who was crippled with rheumatism and unable to move quickly; Justus Miles Forman, Charles Klein, Alfred G. Vanderbilt and many others of the best-known Americans and Englishmen aboard.

Captain Turner stayed on the bridge as the ship went down, but before the last plunge he bade his staff officer and the helmsman, who were still with him, to save themselves. The helmsman leaped into the sea and was saved, but the staff officer would not desert his superior, and went down with the ship. He did not come to the surface again.

Captain Turner, however, a strong swimmer, rose after the eddying whirlpool had calmed down, and, seizing a couple of deck chairs, kept himself afloat for three hours. The master-at-arms of the Lusitania, named Williams, who was looking for survivors in a boat after he had been picked up, saw the flash of the captain’s gold-braided uniform, and rescued him, more dead than alive.

Despite the doubt as to whether two torpedoes exploded, or whether the first detonation caused the big liner’s boilers to let go, Captain Turner stated that there was no doubt that at least two torpedoes reached the ship.

“I am not certain whether the two explosions—and there were two—resulted from torpedoes, or whether one was a boiler explosion. I am sure, however, that I saw the first torpedo strike the vessel on her starboard side. I also saw a second torpedo apparently headed straight for the steamship’s hull, directly below the suite occupied by Alfred G. Vanderbilt.”

When asked if the second explosion had been caused by the blowing up of ammunition stored in the liner’s hull, Captain Turner said:

“No; if ammunition had exploded that would probably have torn the ship apart and the loss of life would have been much heavier than it was.”

Captain Turner declared that, from the bridge, he saw the torpedo streaking toward the Lusitania and tried to change the ship’s course to avoid the missile, but was unable to do so in time. The only thing left for him to do was to rush the liner ashore and beach her, and she was headed for the Irish coast when she foundered.

According to Captain Turner, the German submarine did not flee at once after torpedoing the liner.

“While I was swimming about after the ship had disappeared I saw the periscope of the submarine rise amidst the débris,” said he. “Instead of offering any help the submarine immediately submerged herself and I saw nothing more of her. I did everything possible for my passengers. That was all I could do.”

ALFRED G. VANDERBILT GAVE LIFE FOR A WOMAN — CHARLES FROHMAN DIED WITHOUT FEAR — SAVING THE BABIES — TORONTO GIRL OF FOURTEEN PROVES HEROINE — HEROISM OF CAPTAIN TURNER AND HIS CREW — WOMAN RESCUED WITH DEAD BABY AT HER BREAST — HEROIC WIRELESS OPERATORS — SAVED HIS WIFE AND HELPED IN RESCUE WORK — “SAVED ALL THE WOMEN AND CHILDREN WE COULD.”

Every great calamity produces its great heroes. Particularly is this true of marine disasters, where the opportunities of escape are limited, and where the heroism of the strong often impels them to stand back and give place to the weak. One cannot think of the Titanic disaster without remembering Major Archibald Butt, Colonel John Jacob Astor, Henry B. Harris, William T. Stead and others, nor of the sinking of the Empress of Ireland without calling to mind Dr. James F. Grant, the ship’s surgeon; Sir Henry Seton-Karr, Lawrence Irving, H. R. O’Hara of Toronto, and the rest of the noble company of heroes. So the destruction of the Lusitania brought uppermost in the breasts of many those qualities of fortitude and self-sacrifice which will forever mark them in the calendar of the world’s martyrs.

Among the Lusitania’s heroes, one of the foremost was Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, one of America’s wealthiest men. With everything to live for, Mr. Vanderbilt sacrificed his one chance for escape from the doomed Lusitania, in order that a woman might live. Details of the chivalry he displayed in those last moments when he tore off a life-belt as he was about to leap into the sea, and strapped it around a young woman, were told by three of the survivors.

Mr. Vanderbilt could not swim, and when he gave up his life-belt it was with the virtual certainty that he was surrendering his only chance for life.

Thomas Slidell, of New York, said he saw Mr. Vanderbilt on the deck as the Lusitania was sinking. He was equipped with a life-belt and was climbing over the rail, when a young woman rushed onto the deck. Mr. Vanderbilt saw her as he stood poised to leap into the sea. Without hesitating a moment he jumped back to the deck, tore off the life-belt, strapped it around the young woman and dropped her overboard.

The Lusitania plunged under the waves a few minutes later and Mr. Vanderbilt was seen to be drawn into the vortex.

Norman Ratcliffe, of Gillingham, Kent, and Wallace B. Phillips, a newspaper man, also saw Mr. Vanderbilt sink with the Lusitania. The coolness and heroism he showed were marvelous, they said.

Oliver P. Bernard, scenic artist at Covent Garden, saw Mr. Vanderbilt standing near the entrance to the grand saloon soon after the vessel was torpedoed.

“He was the personification of sportsmanlike coolness,[24]” Mr. Bernard said. “In his right hand was grasped what looked to me like a large purple leather jewel case. It may have belonged to Lady Mackworth, as Mr. Vanderbilt had been much in the company of the Thomas party during the trip and evidently had volunteered to do Lady Mackworth the service of saving her gems for her.”

Another touching incident was told of Mr. Vanderbilt by Mrs. Stanley L. B. Lines, a Canadian, who said: “Mr. Vanderbilt will in the future be remembered as the ‘children’s hero.’ I saw him standing outside the palm saloon on the starboard side, with Ronald Denit. He looked upon the scene before him, and then, turning to his valet, said:

“‘Find all the kiddies you can and bring them here.’ The servant rushed off and soon reappeared, herding a flock of little ones. Mr. Vanderbilt, catching a child under each arm, ran with them to a life-boat and dumped them in. He then threw in two more, and continued at his task until all the young ones were in the boat. Then he turned his attention to aiding the women into boats.”

“Why fear death? It is the most beautiful adventure in life,” were the last words of Charles Frohman before he went down with the Lusitania, according to Miss Rita Jolivet, an American actress, with whom he talked calmly just before the end came.

Miss Jolivet, who was among the survivors taken to Queenstown, said she and Mr. Frohman were standing on deck as the Lusitania heeled over. They decided not to trust themselves to life-boats, although Mr. Frohman believed the ship was doomed. It was after reaching this decision that he declared he had no fear of death.

Escaping a Torpedo by Rapid Maneuvering.

This British destroyer escaped a torpedo from a hunted submarine by quick turning. This incident took place at the naval fight off the island of Heligoland, in October. (Copyright, The Sun News Service.)

A New Weapon in Warfare.

One of the Belgian armored motor cars surprising a party of Uhlans. Several of the enemy were killed by the rapid fire from swivel machine gun and rifle, but the car driven at a furious pace was wrecked on a fallen horse.

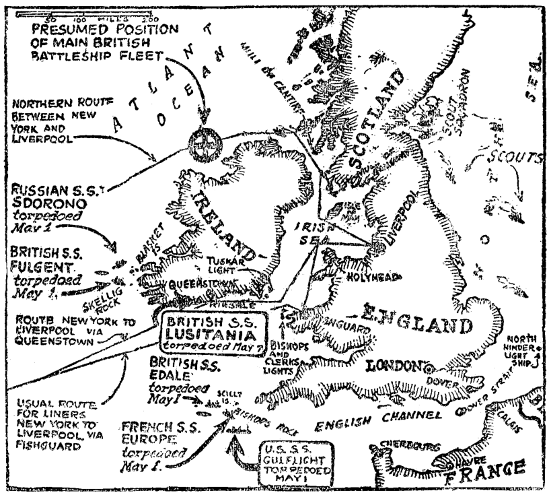

Germany’s Official Paid Advertisement Forewarning Americans Against Disaster; Map Showing Where It Took Place.

This advertisement was wired to forty American newspapers by Count von Bernstorff, German Ambassador at Washington. It was ordered inserted on the morning of the day the Lusitania sailed.

Dr. F. Warren Pearl, of New York, who was saved, with his wife and two of their four children, corroborated Miss Jolivet’s statement, saying:

“After the first shock, as I made my way to the deck, I saw Charles Frohman distributing life-belts. Mr. Frohman evidently did not expect to escape, as he[26] said to a woman passenger, ‘Why should we fear death? It is the greatest adventure man can have.’”

Sir James M. Barrie, in a tribute to Charles Frohman, published in the London Daily Mail, describes him as “the man who never broke his word.

“His companies were as children to him. He chided them as children, soothed them as children and forgave them and certainly loved them as children. He exulted in those who became great in that world, and gave them beautiful toys to play with; but great as was their devotion to him, it is not they who will miss him most, but rather the far greater number who never made a hit, but set off like all the rest, and fell by the way. He was of so sympathetic a nature; he understood so well the dismalness to them of being failures, that he saw them as children, with their knuckles to their eyes, and then he sat back cross-legged on his chair, with his knuckles, as it were, to his eyes, and life had lost its flavor for him until he invented a scheme for giving them another chance.

“Perhaps it is fitting that all those who only made for honest mirth and happiness should now go out of the world; because it is too wicked for them. It is strange to think that in America, Dernburg and Bernstorff, who we must believe were once good men, too, have an extra smile with their breakfast roll because they and theirs have drowned Charles Frohman.”

The presence of so many babies on board the Lusitania was due to the influx from Canada of the English-born[27] wives of Canadians at the battle front, who were coming to England to live with their own or their husband’s parents during the war.

No more pathetic loss has been recorded than that of F. G. Webster, a Toronto contractor, who was traveling second class with his wife, their six-year-old son Frederick and year-old twin sons William and Henry. They reached the deck with others who were in the dining saloon when the torpedo struck. Webster took his son by the hand and darted away to bring life-belts. When he returned his wife and babies were not to be seen, nor have they been since.

W. Harkless, an assistant purser, busied himself helping others until the Lusitania was about to founder. Then, seeing a life-boat striking the water that was not overcrowded, he made a rush for it. The only person he encountered was little Barbara Anderson, of Bridgeport, Conn., who was standing alone, clinging to the rail. Gathering her up in his arms he leaped over the rail and into the boat, doing this without injuring the child.

Francis J. Luker, a British subject, who had worked six years in the United States as a postal clerk, and was going home to enlist, saved two babies. He found the little passengers, bereft of their mother, in the shelter of a deck-house. The Lusitania was nearing her last plunge. A life-boat was swaying to the water below. Grabbing the babies he ran to the rail and made a flying leap into the craft, and those babies did not leave his arms until they were set safely ashore hours later.

One woman, a passenger on the Lusitania, lost all[28] three of her children in the disaster, and gave the bodies of two of them to the sea herself. When the ship went down she held up the three children in the water, shrieking for help. When rescued two were dead. Their room was required and the mother was brave enough to realize it.

“Give them to me!” she shrieked. “Give them to me, my bonnie wee things. I will bury them. They are mine to bury as they were mine to keep.”

With her form shaking with sorrow she took hold of each little one from the rescuers and reverently placed it in the water again, and the people in the boat wept with her as she murmured a little sobbing prayer.

Just as the rescuers were landing her third and only remaining child died.

Even the young girls and women on the Lusitania proved themselves heroines during the last few moments and met their fate calmly or rose to emergencies which called for great bravery and presence of mind.

Fourteen-year-old Kathleen Kaye was returning from Toronto, where she had been visiting relatives. With a merry smile on her lips and with a steady patter of reassurance, she aided the stewards who were filling one of the life-boats.

Soon after the girl took her own place in the boat one of the sailors fainted under the strain of the efforts to get the boat clear of the maelstrom that marked where the liner went down. Miss Kaye took the abandoned oar and rowed until the boat was out of danger. None among the survivors bore fewer signs[29] of their terrible experiences than Miss Kaye, who spent most of her time comforting and assisting her sisters in misfortune.

Ernest Cowper, a Toronto newspaper man, praised the work of the Lusitania’s crew in their efforts to get the passengers into the boats. Mr. Cowper told of having observed the ship watches keeping a strict lookout for submarines as soon as the ship began to near the coast.

“The crew proceeded to get the passengers into boats in an orderly, prompt and efficient manner. Helen Smith, a child, begged me to save her. I placed her in a boat and saw her safely away. I got into one of the last boats to leave.

“Some of the boats could not be launched, as the vessel was sinking. There was a large number of women and children in the second cabin. Forty of the children were less than a year old.”

R. J. Timmis, of Gainesville, Tex., a cotton buyer, who was saved after he had given his life-belt to a woman steerage passenger who carried a baby, told of the loss of his friend, R. T. Moodie, also of Gainesville. Moodie could not swim, but he took off his life-belt also and put it on a woman who had a six-months-old child in her arms. Timmis tried to help Moodie, and they both clung to some wreckage for a while, but presently Moodie could hold out no longer and sank. When Timmis was dragged into a boat[30] which he helped to right—it had been overturned in the suction of the sinking vessel—one of the first persons he assisted into the boat was the steerage woman to whom he had given his belt. She still carried her baby at her breast, but it was dead from exposure.

Oliver P. Brainard told of the bravery of the wireless operators who stuck to their work of summoning help even after it was evident that only a few minutes could elapse before the vessel must go down. He said:

“The wireless operators were working the emergency outfit, the main installation having been put out of gear instantaneously after the torpedo exploded. They were still awaiting a reply and were sending out the S. O. S. call.

“I looked out to sea and saw a man, undressed, floating quietly on his back in the water, evidently waiting to be picked up rather than to take the chance of getting away in a boat. He gave me an idea and I took off my jacket and waistcoat, put my money in my trousers pocket, unlaced my boots and then returned to the Marconi men.

“The assistant operator said, ‘Hush! we are still hoping for an answer. We don’t know yet whether the S. O. S. calls have been picked up or not.’

“At that moment the chief operator turned around, saying, ‘They’ve got it!’

“At that very second the emergency apparatus also broke down. The operator had left the room, but he dashed back and brought out a kodak. He[31] knelt on the deck, now listing at an angle of thirty-five degrees, and took a photograph looking forward.

“The assistant, a big, cheerful chap, lugged out the operator’s swivel chair and offered it to me with a laugh, saying: ‘Take a seat and make yourself comfortable.’ He let go the chair and it careened down the deck and over into the sea.”

F. J. Gauntlet, of New York and Washington, traveling in company with A. L. Hopkins, president of the Newport News Shipbuilding Company, and S. M. Knox, president of the New York Shipbuilding Company, of Philadelphia, unconsciously told the story of his own heroism. He said:

“I was lingering in the dining saloon chatting with friends when the first explosion occurred. Some of us went to our staterooms and put on life-belts. Going on deck we were informed that there was no danger, but the bow of the vessel was gradually sinking. The work of launching the boats was done in a few minutes. Fifty or sixty people entered the first boat. As it swung from the davits it fell suddenly and I think most of the occupants perished. The other boats were launched with the greatest difficulty.

“Swinging free from one of these as it descended, I grabbed what I supposed was a piece of wreckage. I found it to be a collapsible boat, however. I had great difficulty in getting it open, finally having to rip the canvas with my knife. Soon another passenger came alongside and entered the collapsible with me. We paddled around and between us we rescued thirty people from the water.”

George A. Kessler, of New York, said:

“A list to starboard had set in as we were climbing the stairs and it had so rapidly increased by the time we reached the deck, that we were falling against the taffrail. I managed to get my wife onto the first-class deck and there three boats were being got out.

“I placed her in the third, kissed her good-by and saw the boat lowered safely. Then I turned to look for a life-belt for myself. The ship now started to go down. I fell into the water, some kind soul throwing me a life-belt at the same time. Ten minutes later I found myself beside a raft on which were some survivors, who pulled me onto it. We cruised around looking for others and managed to pick up a few, making in all perhaps sixteen or seventeen persons who were on the raft. In all directions were scattered persons struggling for their lives and the boats gave what help they could.”

W. G. E. Meyers, of Stratford, Ont., a lad of sixteen years, who was on his way to join the British navy as a cadet, told this story:

“I went below to get a life-belt and met a woman who was frenzied with fear. I tried to calm her and helped her into a boat. Then I saw a boat which was nearly swamped. I got into it with other men and baled it out. Then a crowd of men clambered into it and nearly swamped it.

“We had got only two hundred yards away when the Lusitania sank, bow first. Many persons sank with[33] her, drawn down by the suction. Their shrieks were appalling. We had to pull hard to get away, and, as it was, we were almost dragged down. We saved all the women and children we could, but a great many of them went down.”

H. Smethhurst, a steerage passenger, put his wife into a life-boat, and in spite of her urging refused to accompany her, saying the women and children must go first. After the boat with his wife in it had pulled away Smethhurst put on a life-belt, slipped down a rope into the water and floated until he was picked up.

COULD NOT LAUNCH BOATS — SAYS SHIP SANK IN FIFTEEN MINUTES — SCREAMS INTENSIFY HORROR — ON HUNT FOR THE LIFE-BELTS — INJURED BOY SHOWS PLUCK — MANY CHILDREN DROWNED — WOMEN RUSHED FOR THE BOATS — PATERSON, N. J., GIRLS AMONG RESCUED — THREATENED SEAMEN WITH REVOLVER — RESCUED UNCONSCIOUS FROM THE WATER — LIFE-BOAT SMASHED — REASSURED BY SHIP’S OFFICER.

Among the stories of the Lusitania horror told by the survivors were a few that stand out from the rest for their clearness and vividness. One of the most interesting of these, notable for the prominence of the man who relates it as well as for its conciseness, was the description given by Samuel M. Knox, president of the New York Shipbuilding Company. Mr. Knox said:

“Shortly after two, while we were finishing luncheon in a calm sea, a heavy concussion was felt on the starboard side, throwing the vessel to port. She immediately swung back and proceeded to take on a list to starboard, which rapidly increased.

“The passengers rapidly, but in good form, left the dining room, proceeding mostly to the A or boat deck. There were preparations being made to launch the boats. Order among the passengers was well maintained, there being nothing approaching a panic.[35] Many of the passengers had gone to their staterooms and provided themselves with life-belts.

“The vessel reached an angle of about twenty-four degrees and at this point there seemed to be a cessation in the listing, the vessel maintaining this position for four or five minutes, when something apparently gave way, and the list started anew and increased rapidly until the end.

“The greater number of passengers were congregated on the high side of the ship, and when it became apparent that she was going to sink I made my way to the lower side, where there appeared to be several boats only partly filled and no passengers on that deck. At this juncture I found the outside of the boat deck practically even with the water and the ship was even farther down by the head.

“I stepped into a boat and a sailor in charge then attempted to cast her off, but it was found that the boat-falls had fouled the boat and she could not be released in the limited time available. I went overboard at once and attempted to get clear of the ship, which was coming over slowly. I was caught by one of the smokestacks and carried down a considerable distance before being released.

“On coming to the surface I floated about for a considerable time, when I was picked up by a life-raft. This raft, with others, had floated free when the vessel sank, and had been picked up and taken charge of by Mr. Gauntlet, of Washington, and Mr. Lauriat, of Boston, who picked up thirty-two persons in all.

“It was equipped with oars, and we made our way to a fishing smack, about five miles distant, which took us on board, although it was already overloaded. We were finally taken off this boat by the Cunard tender Flying Fish and brought to Queenstown at 9.30.”

Some of the passengers, notably David A. Thomas, told of panicky conditions on board the vessel before she sank, and one of the rescued declared that the loss of life was due to some extent to the assurances spread by the stewards among the passengers that there was no danger of the Lusitania sinking. But all united in praising the courage and steadiness of the officers and crew of the ship.

Mr. Thomas, a Cardiff, Wales, coal magnate, who was rescued with his daughter, Lady Mackworth, said that not more than fifteen minutes elapsed between the first explosion and the sinking of the ship. Lady Mackworth had put on a life-preserver and went down with the Lusitania. When she arose to the surface, Mr. Thomas said, she was unconscious, and floated around in the tumbling sea for three and a half hours before she was picked up.

“As soon as the explosions occurred,” said Mr. Thomas, “and the officers learned what had happened, the ship’s course was directed toward the shore, with the idea of beaching her. Captain Turner remained upon the bridge until the ship went down, and he was swallowed up in the maelstrom that followed. He wore a life-belt, which kept him afloat[37] when he arose to the surface, and remained in the water for three hours before he was picked up by a life-boat.

“During the last few minutes’ life of the Lusitania she was a ship of panic and tumult. Excited men and terrified women ran shouting and screaming about the decks. Lost children cried shrilly. Officers and seamen rushed among the panic-stricken passengers, shouting orders and helping the women and children into life-boats. Women clung desperately to their husbands or knelt on the deck and prayed. Life-preservers were distributed among the passengers, who hastily donned them and flung themselves into the water.

As Others See Us.

“In their haste and excitement the seamen overloaded one life-boat and the davit ropes broke while it was being lowered, the occupants being thrown into the water. The screams of these terrified women[38] and men intensified the fright of those still on the ship. Altogether I counted ten life-boats launched.”

A German submarine was seen for an hour before the liner was sunk, according to Dr. Daniel Moore, of Yankton, S. D., who said:

“About 1 P.M. we noticed that the Lusitania was steering a zigzag course. Land had been in sight for three hours, distinctly visible twelve miles away. Looking through my glasses, I could see on the port side of the Lusitania, between us and land, what appeared to be a black, oblong object, with four dome-like projections. It was moving along parallel to us, more than two miles away. At times it slowed down and disappeared. But always it reappeared. All this time the Lusitania was zigzagging along. Later the Lusitania kept a more even course, and we generally agreed then that it was a friendly submarine we were watching. We had seen no other vessels except one or two fishing boats.

“At 1.40 we sat down to luncheon in the second saloon. We talked of the curious object we had seen, but nobody seemed anxious or concerned. About two o’clock a muffled, drum-like noise sounded from the forward part of the Lusitania and she shivered and trembled. Almost immediately she began to list to starboard. She had been struck on the starboard side. Unless the first submarine seen had been speedy enough to make rings around the Lusitania, this torpedo must have come from a second submarine which had been lying hidden to starboard.

“We heard no sound of explosion. There was general excitement among the passengers at luncheon,[39] but the women were soon quieted by assurances that there was no danger and that the Lusitania had merely struck a small mine. The passengers left the saloon in good order.

“As I reached the deck above I had difficulty in walking owing to the tilt of the vessel. With most of the passengers I ran on to the promenade deck. There was no crushing. Although the deck was crowded, I looked over the side; but I could see no evidence of damage. I started to return to my cabin, but the list of the liner was so marked that I abandoned the idea and regained the deck. Looking over the starboard rail, I saw that the water was now only about twelve feet from the rail at one point. While searching for a life-belt I came upon a stewardess struggling with a pile of life-belts in a rack below deck and helped her put one on, afterward securing one for myself. I had tremendous difficulty in reaching the promenade deck again.

“The Lusitania now was on her side and sinking by the bow. I saw a woman clinging to the rail near where a boat was being lowered. I pushed her over the rail into the boat, afterward jumping down myself.

“The boat fell bodily into the sea, but kept afloat, although so heavily loaded that water was lapping in. We bailed with our hats, but could not keep pace with the water, and I realized we must soon sink.

“Seeing a keg, I threw it overboard and sprang after it. A young steward named Freeman also used the keg as a support. Looking back, I saw the[40] boat I had left swamped. We clung to the keg for about an hour and a half and then were picked up by a raft on which were twenty persons, including two women.

“We had oars and rowed toward land. At about four o’clock we were picked up by the patrol boat Brook. She took us aboard and then cruised out to where the Lusitania had gone down, picking up many survivors there, also taking aboard many from boats and rafts.

“A number of those picked up were injured, including a little boy, whose left thigh was broken. I improvised splints for him and set his leg. He was a plucky little chap, and was soon asking, ‘Is there a funny paper aboard?’

“At the scene of the catastrophe the surface of the water had seemed dotted with bodies. Only a few life-boats seemed to be doing good. Cries of ‘Save us! Help!’ gradually grew weaker from all sides. Finally low wailings made the heart sick. I saw many men die.

“There was no suction when the ship settled. It went down steadily. The life-boats were not in order and they were not manned. Weighing all the facts soberly convinces me that it was only through the mercy of God that any one was saved. Are there any bounds to this modern vandalism?”

L. Tonner, a County Dublin man, and a stoker on the Lusitania, who was one of the survivors landed at Kinsale, said:

“There must have been two submarines attacking the Lusitania. The liner was first torpedoed on the starboard side, and right through the engine room a few minutes afterward the Lusitania received a second torpedo on the port side. The Lusitania listed so heavily to starboard that it was impossible to lower the boats on the port side.”

Prominent American Victims of the Lusitania Horror.

Alfred G. Vanderbilt, New York Millionaire. (C. Underwood & Underwood.)

Elbert Hubbard, Editor and Lecturer. (C. Int. News Service.)

Charles Frohman, Theatrical Magnate. (C. Underwood & Underwood.)

Charles Klein, well-known Playwright. (C. Int. News Service.)

Sorrowful Burial of Some of the Lusitania Victims.

Sixty-six coffins were placed in one grave at the Queenstown graveyard. In the presence of a large crowd they were buried with full military honors. The view shows a few of the caskets in the grave. (C. Int. News Service.)

G. D. Lane, a youthful but cool-headed second-cabin passenger, who was returning to Wales from New York, was in a life-boat which was capsized by the davits as the Lusitania heeled over.

“I was on the B deck,” he said, “when I saw the wake of a torpedo. I hardly realized what it meant when the big ship seemed to stagger and almost immediately listed to starboard. I rushed to get a life-belt, but stopped to help get children on the boat deck. The second cabin was a veritable nursery.

“Many youngsters must have drowned, but I had the satisfaction of seeing one boat get away filled with women and children. When the water reached the deck I saw another life-boat with a vacant seat, which I took, as no one else was in sight, but we were too late. The Lusitania reeled so suddenly our boat was swamped, but we righted it again.

“We now witnessed the most horrible scene of human futility it is possible to imagine. When the Lusitania had turned almost over she suddenly plunged bow foremost into the water, leaving her stern high in the air. People on the aft deck were fighting with wild desperation to retain a footing on the almost[42] perpendicular deck while they fell over the slippery stern like crippled flies.

“Their cries and shrieks could be heard above the hiss of escaping steam and the crash of bursting boilers. Then the water mercifully closed over them and the big liner disappeared, leaving scarcely a ripple behind her.

“Twelve life-boats were all that were left of our floating home. In time which could be measured by seconds swimmers, bodies and wreckage appeared in the space where she went down. I was almost exhausted by the work of rescue when taken aboard the trawler. It seems like a horrible dream now.”

According to another American survivor, W. H. Brooks, “there was a scene of great confusion as women and children rushed for the boats which were launched with the greatest difficulty and danger, owing to the tilting of the ship.

“I heard the captain order that no more boats be launched, so I leaped into the sea. After I reached the water there was another explosion which sent up a shower of wreckage.”

Dr. J. T. Houghton, of Troy, N. Y., said: “It was believed there was no reason to fear any danger after the first explosion, as it was said the vessel would be headed for Queenstown and beached if necessary. Meanwhile boats were being got ready for any emergency.

“Just then the liner was again struck, evidently in a more vital spot, for it began to settle rapidly.[43] Orders then came from the bridge to lower all boats. A near panic took possession of the women. People were rushed into the boats, some of which were launched successfully, others not so successfully.”

Oscar F. Grab, of New York, said: “I was able to get hold of a life-preserver and I remained on the starboard side until the water was almost at my feet. Then I slid into the sea so easily that I did not even wet my hair. I was soon picked up by a boat in which were twenty women and some children.

“We had to keep the women lying in the bottom so as to get room to pull at the oars. The ship went down, as seen by me from the water, in this fashion:

“She had settled down well forward. She then listed to starboard, and rose to a perpendicular until the stern with the propellers was sticking straight out of the water.

“An explosion then occurred as the water reached the boilers; one of the funnels was blown clean out, and in half a minute there was nothing visible of the Lusitania but a lot of wreckage mingled with a number of dead bodies.”

The Misses Agnes and Evelyn Wilde, sisters, of Paterson, N. J., were at lunch when the torpedo struck the vessel. They rushed on deck. Miss Agnes Wilde said:

“We clung to each other, determined not to be separated, even if we went to the bottom. We were thrown into a boat, together with thirty-six others, and after several hours were picked up by a fishing[44] boat, which towed us for several hours, intending to take us to Kinsale. Before we arrived, however, a Government boat came along and took us to Queenstown.

“We were drenched to the skin, cold and penniless. We went into a shop, where they fitted us out from head to foot without charge. We are only beginning to realize what we have passed through.”

Mrs. Martha Anna Wyatt, sixty years old, of New Bedford, Mass., said: “I went down with the ship and spent four hours in a collapsible boat before being picked up. I was going to England to live.

“While the ship was sinking I found it impossible to get into any of the life-boats. There seemed no help about. I simply stood still, clinging to the rail, and went down. I seemed to go to the bottom. When I came to the surface again I was pulled into the collapsible boat which brought me to safety.”

Mrs. C. Stewart, who was traveling from Toronto to Glasgow, said:

“I was in my cabin with my eight-months-old baby, who was sleeping in the berth, when I heard the crash. I snatched my baby up and went on deck. A man yelled, ‘Come on with the baby.’ I handed him the infant and he said, ‘Now for yourself.’

“We were two and a half hours in the boat before we were picked up by a Greek steamer.”

Robert C. Wright, of Cleveland, O., gave what may be the last word of Elbert Hubbard. Mr. Wright said:

“I don’t know who was saved, but I know that Elbert Hubbard must have been drowned. He was a[45] conspicuous person on account of his long hair. I saw him and his wife start below, apparently for life-belts, but I never saw either again. I am certain they were drowned.”

Isaac Lehmann, of New York, a first-cabin passenger, who described himself as being engaged in the Department of Government Supplies, said that after having witnessed an accident to one of the boats through the snapping of the ropes while it was being lowered, he ran into his cabin and seizing a revolver and a life-belt, returned to the deck and mounted a collapsible boat and called to some of the crew to assist in launching it. One sailor, he said, replied that the captain’s orders were that no boats were to be put out.

“I drew my revolver, which was loaded with ball cartridges,” said Mr. Lehmann, “and shouted ‘I’ll shoot the first man who refuses to assist in launching.’ The boat was then lowered. At least sixty persons were in it. Unfortunately, the Lusitania lurched so badly that the boat repeatedly struck the side of the sinking ship, and I think at least twenty of its occupants were killed or injured.

“At that instant we heard an explosion on the right up forward, and within two minutes the liner disappeared. I was thrown clear of the wreckage, and went down twice, but the life-belt that I had on brought me up. I was in the water fully four hours and a half.”

Asked as to the probable speed of the Lusitania[46] when she was struck by the torpedo, Mr. Lehmann said the boat was probably going at about sixteen or seventeen knots.

Julian de Ayala, Consul General for Cuba at Liverpool, said that he was ill in his berth when the Lusitania was torpedoed. He was thrown against the partition of his berth by the explosion and suffered an injury to his head and had flesh torn off one of his legs.

The boat Mr. de Ayala got into capsized and he was thrown into the water, but later he was picked up.

“Captain Turner,” said Mr. de Ayala, “thought he could bring the crippled vessel into Queenstown, but she rapidly began to sink by the head.

“Her stern went up so high,” Mr. de Ayala added, “that we could see all of her propellers, and she went down with a headlong plunge, volumes of steam hissing from her funnels.”

The experience of two New York girls, Miss Mary Barrett and Miss Kate MacDonald, rescued at the last minute, may be taken as typical of the experience of many others. Miss Barrett gives the following account of her experiences:

“We had gone into the second saloon and were just finishing lunch. I heard a sound something like the smashing of big dishes and then there came a second and louder crash. Miss MacDonald and I started to go upstairs, but we were thrown back by the crowd when the ship stopped. But we managed to get to the second deck, where we found sailors trying to lower boats.

“There was no panic and the ship’s officers and crew went about their work quietly and steadily. I went to get two life-belts, but a man standing by told us to remain where we were and he would fetch them for us. He brought us two belts and we put them on. By this time the ship was leaning right over to starboard and we were both thrown down. We managed to scramble to the side of the liner.

“Near us I saw a rope attached to one of the life-boats. I thought I could catch it, so we murmured a few words of prayer and then jumped into the water. I missed the rope, but floated about in the water for some time. I did not lose consciousness at first, but the water got into my eyes and mouth and I began to lose hope of ever seeing my friends again. I could not see anybody near me. Then I must have lost consciousness, for I remember nothing more until one of the Lusitania’s life-boats came along. The crew was pulling on board another woman, who was unconscious, and they shouted to me, ‘You hold on a little longer!’

“After a time they lifted me out of the water. Then I remembered nothing more for a time. In the meantime our boat had picked up twenty others. It was getting late in the evening when we were transferred to a trawler and taken to Queenstown.

“Miss MacDonald floated about nearly four hours in a dazed state. She had little remembrance of what had passed until a boat saved her. She remembered somebody saying, ‘Oh, the poor girl is dead!’ She had just strength to raise her hand and they returned and pulled her on board.”

Miss Conner, a cousin of Henry L. Stimson, formerly Secretary of War of the United States, was standing beside Lady Mackworth when they were flung into the water as the ship keeled over. Both women were provided with life-belts and were picked up when at the point of exhaustion.

Doctor Howard Fisher of New York, who is a brother of Walter L. Fisher, formerly Secretary of the Interior of the United States, was on his way to Belgium for Red Cross duty. His story follows:

“It is not true that those on board were unconcerned over the possibility of being torpedoed. I took the big liner to save time and also because in case of a floating mine I felt she would have more chance of staying up. But like everybody else aboard, I felt sure in case of being torpedoed that we would have ample time to take to the boats.

“When I heard the crash I rushed to the port side. No officer was in sight. An effort was being made to lower the boat swinging just opposite the grand entrance. Women, children and men made a mad scramble about this boat, which was smashed against the side, throwing all the occupants into the sea.

“Then two big men, one a sailor and the other a passenger, succeeded in launching a second boat. Much to my surprise this amateur effort was successful. This boat got away and carried chiefly women and children. This boat was successfully launched on the port side.

“We then saw our first glimpse of an officer, who came along the deck and spoke to Lady Mackworth, Miss Conner and myself, who were standing in a group. He said:

“‘Don’t worry, the ship will right itself.’ He had hardly moved on before the ship turned sideways and then seemed to plunge head foremost into the sea.

“I came up after what seemed to be an interminable time under water and found myself surrounded by swimmers, dead bodies and wreckage. I got on an upturned yawl, where I found thirty other people, among them Lady Allan, whose collar-bone was broken while she was in the water.

“Another passenger on the yawl, a man whose name I did not learn, had his arm hanging by the skin. His injury probably was due to the explosion which followed. His arm was amputated successfully with a butcher knife by a little Italian surgeon aboard the tramp steamer which picked me up.”

PERCY ROGERS, OF CANADIAN NATIONAL EXHIBITION, TELLS GRAPHIC STORY — PASSENGERS WERE AGHAST — OCCUPANTS OF LIFE-BOATS THROWN INTO SEA — A HEART-BREAKING SCENE.

Percy Rogers, assistant manager and secretary of the Canadian National Exhibition, who went to England in connection with the Toronto Fair, told a graphic story of his experiences after the Lusitania was struck. He undoubtedly owed his life to the fact that he was a good swimmer.

“It had been a splendid crossing,” he said, “with a calm sea and fine weather contributing to a delightful trip. The Lusitania made nothing like her maximum pace. Her speed probably was about five hundred miles daily, which, as travelers know, is below her average.

“Early Friday morning we sighted the Irish coast. Then we entered a slight fog, and speed was reduced, but we soon came into a clear atmosphere again, and the pace of the boat increased. The morning passed and we went as usual down to lunch, although some were a little later than others in taking the meal. I should think it would be about ten minutes past two when I came from lunch. I immediately proceeded to[51] my stateroom, close to the dining-room, to get a letter which I had written. While in there I heard a tremendous thud, and I came out immediately.

“There was no panic where I was, but the people were aghast. It was realized that the boat had been struck, apparently on the side nearest the land. The passengers hastened to the boat deck above. The life-boats were hanging out, having been put into that position on the previous day. The Lusitania soon began to list badly with the result that the side on which I and several others were standing went up as the other side dropped. This seemed to cause difficulty in launching the boats, which seemed to get bound against the side of the liner.

“It was impossible, of course, for me to see what was happening in other places, but among the group where I was stationed there was no panic. The order was given, ‘Women and children first,’ and was followed implicitly. The first life-boat lowered with people at the spot where I stood smacked upon the water, and as it did so the stern of this life-boat seemed to part and the people were thrown into the sea. The other boats were lowered more successfully.

“We heard somebody say, ‘Get out of the boats; there is no danger,’ and some people actually did get out, but the direction was not generally acted upon. I entered a boat in which there were men, women and children, I should say between twenty and twenty-five. There were no other women or children standing on the liner where we were, our position, I should think,[52] being about the last boat but one from the stern of the ship.

“Our boat dropped into the water, and for a few minutes we were all right. Then the liner went over. We were not far from her. Whatever the cause may have been—perhaps the effect of suction—I don’t know, but we were thrown into the sea. Some of the occupants were wearing life-belts, but I was not. The only life-belts I knew about were in the cabins, and it had not appeared to me that there was time to risk going there. It must have been about 2.30 when I was thrown into the water. The watch I was wearing stopped at that time.

“What a terrible scene there was around me! It is harrowing to think about the men, women and children struggling in the water. I had the presence of mind to swim away from the boat and made towards a collapsible boat, upon which was the captain and a number of others. For this purpose I had to swim quite a distance.

“I noticed three children among the group. Our collapsible boat began rocking. Every moment it seemed we should be thrown again into the sea. The captain appealed to the people in it to be careful, but the boat continued to rock, and I came to the conclusion that it would be dangerous to remain in it if all were to have a chance. I said, ‘Good-by, Captain; I’m going to swim,’ and jumped into the water. I believe the captain did the same thing after me, although I did not see him, but I understand he was picked up.

“The scene was now terrible. Particularly do I remember a young child with a life-belt around her calling, ‘Mamma!’ She was not saved. I had seen her on the liner, and her sister was on the collapsible boat, but I could not reach her. I saw a cold-storage box or cupboard. I swam towards it and clung to it. This supported me for a long time. At last I saw a boat coming towards me and shouted. I was heard and taken in. From this I was transferred to what I think was a trawler, which also picked up three or four others. Eventually I was placed upon a ferry boat known as the Flying Fish, in which, with others, I was taken to Queenstown.

“It was quite possible that some people went down while in their cabins, because after lunch it was the custom with some to go for a rest. A friend of mine on the liner has told me he saw Alfred G. Vanderbilt on deck with a life-belt and observed him give it to a lady. It seemed to me the seriousness of the situation scarcely was realized when the boat was torpedoed. It was all so sudden and so unexpected, and the recollection of it all is terrible.”

GERMAN SUBMARINES PREVENTED RESCUE OF LUSITANIA PASSENGERS — STORY OF ETONIAN’S CAPTAIN — DODGED TWO SUBMARINES — NARRAGANSETT DRIVEN OFF — TORPEDO FIRED AT NARRAGANSETT.

From the lips of Captain Turner, of the Lusitania, and from several of the survivors the world has heard the story of the sudden appearance among the débris and the dead of the sunken liner, of the German submarine that had fired the torpedo which sent almost 1,200 non-combatants, hundreds of them helpless women and children, and among them more than a hundred American citizens, to their deaths. But it remained for the captain of the steamship Etonian, arriving at Boston on May 18, to add the crowning touch to the tragedy.

Captain William F. Wood, of the Etonian, specifically charged that two German submarines deliberately prevented him from going to the rescue of the Lusitania’s passengers after he had received the liner’s wireless S. O. S. call, and when he was but forty miles or so away, and might have rendered great assistance to the hundreds of victims.

Captain Wood charged further that two other ships, both within the same distance of the Lusitania when she sank, were warned off by submarines, and that[56] when the nearest one, the Narragansett, bound for New York, persisted in the attempt to proceed to the rescue of the Lusitania’s passengers, a submarine fired a torpedo at her, which missed the Narragansett by only a few feet.

The Etonian is a freight-carrying steamship, owned by the Wilson-Furness-Leyland lines, and under charter to the Cunard Line. She sailed from Liverpool on May 6. Captain Wood’s story, as he told it without embellishment and in the most positive terms, was as follows:

“We had left Liverpool without unusual incident, and it was two o’clock on the afternoon of Friday, May 7, that we received the S. O. S. call from the Lusitania. Her wireless operator sent this message: ‘We are ten miles south of Kinsale. Come at once.’

“I was then about forty-two miles from the position he gave me. Two other steamships were ahead of me, going in the same direction. They were the Narragansett and the City of Exeter. The Narragansett was closer to the Lusitania, and she answered the S. O. S. call.

“At 5 P.M. I observed the City of Exeter across our bow and she signaled, ‘Have you heard anything of the disaster?’

“At that very moment I saw the periscope of a submarine between the Etonian and the City of Exeter. The submarine was about a quarter of a mile directly ahead of us. She immediately dived as soon as she saw us coming for her. I distinctly saw the splash in the water caused by her submerging.

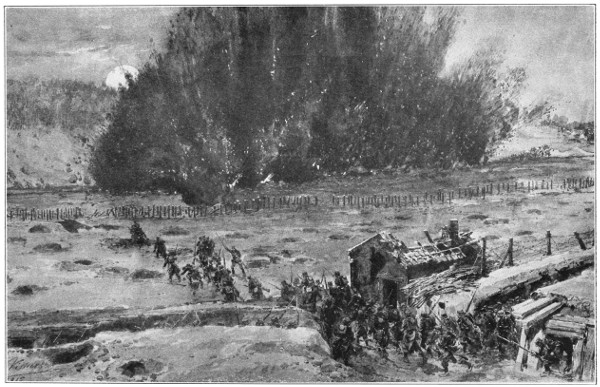

Charging Through Barbed-Wire Entanglements.

The King’s Regiment of the British Army suffered heavily while trying to penetrate the enemy’s wire entanglement at Givenchy. Three lines of a perfect thicket of barbed-wire lay between them and the enemy. Only one brave officer even managed to penetrate the wire. (Il. L. News copr.)

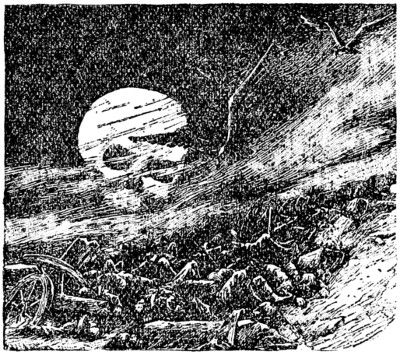

A Land Mine Exploded Underneath a Section of the Enemy’s Trenches.

A method which has been known to blow forty men to pieces at once. By sapping and mining the gallery was dug almost to the enemy’s trenches underground and explosives placed, which were then fired by electric wire. The explosion hurled a piece of railroad iron weighing twenty-five pounds a distance of over a mile. (Il. L. News copr.)

“I signaled to the engine room for every available inch of speed, and there was a prompt response. Then we saw the submarine come up astern of us with the periscope in line afterward. I now ordered full speed ahead, and we left the submarine slowly behind. The periscope remained in sight about twenty minutes. Our speed was perhaps two miles an hour better than the submarine could do.

“No sooner had we lost sight of the submarine astern than I made out another on the starboard bow. This one was directly ahead and on the surface, not submerged. I starboarded hard away from him, he swinging as we did. About eight minutes later he submerged. I continued at top speed for four hours, and saw no more of the submarines. It was the ship’s speed that saved her. That’s all.

“Both these submarines were long craft, and the second one had wireless masts. There is no question in my mind that these two submarines were acting in concert and were so placed as to torpedo any ship that might attempt to go to the rescue of the passengers of the Lusitania.

“As a matter of fact, the Narragansett, as soon as she heard the S. O. S. call, went to the assistance of the Lusitania. One of the submarines discharged a torpedo at her and missed her by a few feet. The Narragansett then warned us not to attempt to go to the rescue of the Lusitania, and I got her wireless call while I was dodging the two submarines. You can see that three ships would have gone to the assistance of the Lusitania had it not been for the two submarines.

“These German craft were, it seems to me, deliberately stationed off Old Head of Kinsale, at a point where all ships have got to pass, for the express purpose of preventing any assistance being given to the passengers of the Lusitania.”

That the British tank steamer Narragansett, one of the vessels that caught the distress signal of the Lusitania, was also driven off her rescue course by a torpedo from a submarine when she arrived within seven miles of the spot where the Lusitania went down, an hour and three-quarters after she caught the wireless call for help, was alleged by the officers of the tanker, which arrived at Bayonne, N. J., on the same day that the Etonian reached Boston.

The story told by the officers of the Narragansett corroborated the statements made by officers of the Etonian. They said that submarines were apparently scouting the sea to drive back rescue vessels when the Lusitania fell a victim to another undersea craft.

The Lusitania’s call for help was received by the Narragansett at two o’clock on the afternoon of May 7, according to wireless operator Talbot Smith, who said the message read: “Strong list. Come quick.”

When the Narragansett received the message she was thirty-five miles southeast of the Lusitania, having sailed from Liverpool the preceding afternoon at five o’clock for Bayonne. The message was delivered quickly to Captain Charles Harwood, and he ordered the vessel to put on full steam and increase her speed from eleven to fourteen knots. The Narragansett[59] changed her course and started in the direction of the sinking ship.

Second Officer John Letts, who was on the bridge, said he sighted the periscope of a submarine at 3.35 o’clock, and almost at the same instant he saw a torpedo shooting through the water. The torpedo, according to the second officer, was traveling at great speed.

It shot past the Narragansett, missing the stem by hardly thirty feet, and disappeared. The periscope of the submarine went out of sight at the same time, but the captain of the Narragansett decided not to take any chance, changed the course of his vessel so that the stern pointed directly toward the spot where the periscope was last sighted, and, after steering straight ahead for some distance, followed a somewhat zigzag course until he was out of the immediate submarine territories.

Captain Harwood abandoned all thought of the Lusitania’s call for help, because he thought it was a decoy message sent out to trap the Narragansett into the submarine’s path.

“My opinion,” said Second Officer Letts, “is that submarines were scattered around that territory to prevent any vessel that received the S. O. S. call of the Lusitania from going to her assistance.”

When attacked by the submarine the Narragansett had out her log, according to Second Officer Letts, and the torpedo passed under the line to which it was attached. The torpedo was fired from the submarine[60] when the undersea boat was within two hundred yards of the tanker.

The Narragansett when turned back had not sighted the wreck of the Lusitania, and her officers, who were led to believe the S. O. S. was a decoy, did not learn of the sinking of the Cunarder until the following morning at two o’clock.