BORO MEDICINE MAN, WITH MY RIFLE

BORO MEDICINE MAN, WITH MY RIFLE

THE NORTH-WEST

AMAZONS

NOTES OF SOME MONTHS SPENT

AMONG CANNIBAL TRIBES

BY

THOMAS WHIFFEN

F.R.G.S., F.R.A.I.

Captain H.P. (14th Hussars)

NEW YORK

DUFFIELD AND COMPANY

1915

Printed in Great Britain

TO THE MEMORY OF THE LATE

Dr. ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE, O.M.

THESE NOTES ARE DEDICATED

In presenting to the public the results of my journey through the lands about the upper waters of the Amazon, I make no pretence of challenging conclusions drawn by such experienced scientists as Charles Waterton, Alfred Russel Wallace, Richard Spruce, and Henry Walter Bates, nor to compete with the indefatigable industry of those recent explorers Dr. Koch-Grünberg and Dr. Hamilton Rice.

Some months of the years 1908 and 1909 were passed by me travelling in regions between the River Issa and the River Apaporis where white men had scarcely penetrated previously. In the remoter parts of these districts the tribes of nomad Indians are frankly cannibal on occasion, and provide us with evidence of a condition of savagery that can hardly be found elsewhere in the world of the twentieth century. It will be noted that this area includes the Putumayo District.

With regard to the references in footnotes and appendices, I have inserted them to suggest where similarities of culture or variations of a given custom are to be found. These notes may be of some use to the student of such problems as the question of cultural contact with Pacific peoples, and at the least they represent the evidence on which I have based my own conclusions.

THOMAS WHIFFEN.

London, 1914.

| PAGE | ||

| CHAPTER I | ||

| Introductory | 1 | |

| CHAPTER II | ||

| Topography—Rivers—Floods and rainfall—Climate—Soil—Animal and vegetable life—Birds—Flowers—Forest scenery—Tracks—Bridges—Insect pests—Reptiles—Silence in the forest—Travelling in the bush—Depressing effects of the forest—Lost in the forest—Starvation the crowning horror | 17 | |

| CHAPTER III | ||

| The Indian homestead—Building—Site and plan of maloka—Furniture—Inhabitants of the house—Fire—Daily life—Insect inhabitants—Pets | 40 | |

| CHAPTER IV | ||

| Classification of Indian races—Difficulties of tabulating—Language-groups and tribes—Names—Sources of confusion—Witoto and Boro—Localities of language-groups—Population of districts—Intertribal strife—Tribal enemies and friends—Reasons for endless warfare—Intertribal trade and communications—Relationships—Tribal organisation—The chief, his position and powers—Law—Tribal council—Tobacco-drinking—Marriage system and regulations—Position of women—Slaves | 53 | |

| CHAPTER V | ||

| Dress and ornament—Geographical and tribal differentiations—Festal [x]attire—Feather ornaments—Hair-dressing—Combs—Dance girdles—Beads—Necklaces—Bracelets—Leg rattles—Ligatures—Ear-rings—Use of labret—Nose pins—Scarification—Tattoo—Tribal marks—Painting | 71 | |

| CHAPTER VI | ||

| Occupations—Sexual division and tabu—Tribal manufactures—Arts and crafts—Drawing—Carving—Metals—Tools and implements—No textile fabrics—Pottery—Basket-making—Hammocks—Cassava-squeezer and grater—Pestle and mortar—Wooden vessels—Stone axes—Methods of felling trees—Canoes—Rafts—Paddles | 90 | |

| CHAPTER VII | ||

| Agriculture—Plantations—Preparation of ground in the forest—Paucity of agricultural instruments—Need for diligence—Women’s incessant toil—No special harvest-time—Maize the only grain grown—No use for sugar—Manioc cultivation—Peppers—Tobacco—Coca cultivation—Tree-climbing methods—Indian wood-craft—Indian tracking—Exaggerated sporting yarns—Indian sense of locality and accuracy of observation—Blow-pipes—Method of making blow-pipes—Darts—Indian improvidence—Migration of game—Traps and snares—Javelins—Hunting and fishing rights—Fishing—Fish traps—Spearing and poisoning fish | 102 | |

| CHAPTER VIII | ||

| The Indian armoury—Spears—Bows and arrows—Indian strategy—Forest tactics and warfare—Defensive measures—Secrecy and safety—The Indian’s science of war—Prisoners—War and anthropophagy—Cannibal tribes—Reasons for cannibal practices—Ritual of vengeance—Other causes—No intra-tribal cannibalism—The anthropophagous feast—Human relics—Necklaces of teeth—Absence of salt—Geophagy | 115 | |

| CHAPTER IX | ||

| The food quest—Indians omnivorous eaters—Tapir and other animals used for food—Monkeys—The peccary—Feathered game—Vermin—Eggs, carrion, and intestines not eaten—Honey—Fish—Manioc—Preparation of cassava—Peppers—The Indian hot-pot—Lack of salt—Indian meals—Cooking—Fruits—Cow-tree [xi]milk | 126 | |

| CHAPTER X | ||

| Drinks, drugs, and poisons: their use and preparation—Unfermented drinks—Caapi—Fermented drinks—Cahuana—Coca: its preparation, use, and abuse—Parica—Tobacco—Poison and poison-makers | 138 | |

| CHAPTER XI | ||

| Small families—Birth tabu—Birth customs—Infant mortality—Infanticide—Couvade—Name-giving—Names—Tabu on names—Childhood—Lactation—Food restrictions—Child-life and training—Initiation | 146 | |

| CHAPTER XII | ||

| Marriage regulations—Monogamy—Wards and wives—Courtship—Qualifications for matrimony—Preparations for marriage—Child marriages—Exception to patrilocal custom—Marriage ceremonies—Choice of a mate—Divorce—Domestic quarrels—Widowhood | 159 | |

| CHAPTER XIII | ||

| Sickness—Death by poison—Infectious diseases—Cruel treatment of sick and aged—Homicide—Retaliation for murder—Tribal and personal quarrels—Diseases—Remedies—Death—Mourning—Burial | 168 | |

| CHAPTER XIV | ||

| The medicine-man, a shaman—Remedies and cures—Powers and duties of the medicine-man—Virtue of breath—Ceremonial healing—Hereditary office—Training—Medicine-man and tigers—Magic-working—Properties—Evil always due to bad magic—Influence of medicine-man—Method of magic-working—Magical cures | 178 | |

| CHAPTER XV | ||

| Indian dances—Songs without meaning—Elaborate preparations—The Chief’s invitation—Numbers assembled—Dance step—Reasons [xii]for dances—Special dances—Dance staves—Arrangement of dancers—Method of airing a grievance—Plaintiff’s song of complaint—The tribal “black list”—Manioc-gathering dance and song—Muenane Riddle Dance—A discomfited dancer—Indian riddles and mimicry—Dance intoxication—An unusual incident—A favourite dance—The cannibal dance—A mad festival of savagery—The strange fascination of the Amazon | 190 | |

| CHAPTER XVI | ||

| Songs the essential element of native dances—Indian imagination and poetry—Music entirely ceremonial—Indian singing—Simple melodies—Words without meaning—Sense of time—Limitations of songs—Instrumental music—Pan-pipes—Flutes and fifes—Trumpets—Jurupari music and ceremonial—Castanets—Rattles—Drums—The manguare—Method of fashioning drums—Drum language—Signal and conversation—Small hand-drums | 206 | |

| CHAPTER XVII | ||

| The Indians’ magico-religious system—The Good Spirit and the Bad Spirit—Names of deities—Character of Good Spirit—His visit to earth—Question of missionary influence—Lesser subordinate spirits—Child-lifting—No prayer or supplication—Classification of spirits—Immortality of the soul—Land of the After-Life—Ghosts and name tabu—Temporary disembodied spirits—Extra-mundane spirits—Spirits of particularised evils—Spirits of inanimate objects—The jaguar and anaconda magic beasts—Tiger folk—Fear of unknown—Suspicions about camera—Venerated objects—Charms—Magic against magic—Omens | 218 | |

| CHAPTER XVIII | ||

| Darkness feared by Indians—Story-telling—Interminable length of tales—Variants—Myths—Sun and moon—Deluge traditions—Tribal stories—Amazons—White Indians tradition—Boro tribal tale—Amazonian equivalents of many world-tales—Beast stories—Animal characteristics—Difference of animal characteristics in tale and tabu—No totems—Indian hatred of animal world | 236 | |

| CHAPTER XIX | ||

| Limitations of speech—Differences of dialect—Language-groups—Tribal names—Difficulties of languages—Method of transliteration—Need of a common medium—Ventral ejaculations—Construction—Pronouns [xiii]as suffix or prefix—Negatives—Gesture language—Numbers and reckoning—Indefinite measure—Time—No writing, signs, nor personal marks—Tribal calls—Drum-language code—Conversational repetitions—Noisy talkers—Ventriloquists—Falsetto voice—Conversational etiquette | 246 | |

| CHAPTER XX | ||

| No individualism—Effect of isolation—Extreme reserve of Indians—Cruelty—Dislike and fear of strangers—Indian hospitality—Treachery—Theft punished by death—Dualism of ethics—Vengeance—Moral sense and custom—Modesty of the women—Jealousy of the men—Hatred of white man—Ingratitude—Curiosity—Indians retarded but not degenerate—No evidence of reversion from higher culture—A neolithic people—Conclusion | 255 | |

| APPENDICES | ||

| I. | Physical Characteristics | 269 |

| II. | Mongoloid Origin | 280 |

| III. | Depilation | 282 |

| IV. | Colour Analysis and Measurements | 283 |

| V. | Articles noted by Wallace as in use among the Uaupes Indians that are found with the Issa-Japura Tribes | 291 |

| VI. | Names of Deities | 293 |

| VII. | Vocabularies and Lists of Names | 296 |

| VIII. | Poetry | 311 |

| LIST OF BOOKS REFERRED TO | 313 | |

| INDEX | 315 | |

| PLATE NO. | FACING PAGE | |

| Boro Medicine Man, with my Rifle | Frontispiece | |

| I. | Houses in the “Rubber Belt” of the Issa Valley | 4 |

| II. | A House in the “Rubber Belt,” Issa Valley | 16 |

| III. | 1. Typical River View below the Mouth of the Negro River 2. Bank of Main Amazon Stream in the Vicinity of the Mouth of the Japura River |

18 |

| IV. | 1. River View on Main Stream near Issa River 2. Landscape on Upper Amazon Main Stream |

20 |

| V. | The Bulge-stemmed Palm, Iriartea Venticosa, showing portion of Leaf and Fruit | 28 |

| VI. | Flowers and Section of Leaf of the Bussu Palm. The Leaf is used for Thatching | 44 |

| VII. | 1. Self, with Nonuya Tribe 2. Muenane Tribe | 46 |

| VIII. | 1. Group of Witoto 2. Group of Some of my Carriers |

70 |

| IX. | Medicine Man and his Wife (Andoke) | 72 |

| X. | Boro Tribesmen | 74 |

| XI. | Witoto Feather Head-dresses | 76 |

| XII. | Groups of Resigero Women | 78 |

| XIII. | Centre of Dancing Group—Muenane | 80 |

| XIV. | Boro Comb of Palm Spines set in Pitch and finished with Basketwork of Split Cane, Fibre Strings, and Tufts of Parrots’ Feathers | 78 |

| XV. | 1. Dukaiya (Okaina) Bead Dancing-girdle 2. Condor Claws, used by Andoke Medicine Man of the Upper Japura River |

80 |

| XVI. | Necklaces of Human and Tiger Teeth | 82 |

| XVII. | 1. Necklace of Polished Nutshells. 2. Leg Rattles of Beads and Nutshells. 3, 4, 5, and 6. Bead Necklaces. The Black “Beads” are Bits of Polished Nutshell, threaded between White Beads |

82 |

| [xvi]XVIII. | Boro Ligatures | 84 |

| XIX. | Boro Leg and Arm Ligatures. Witoto Leg Ligature | 84 |

| XX. | 1 and 3, Boro. 2, Witoto, Ligatures | 86 |

| XXI. | Andoke Girls | 88 |

| XXII. | Witoto Baskets of Split Cane and Fibre | 90 |

| XXIII. | Boro Necklace of Jaguars’ Teeth with Incised Patterns Necklace of Jaguar Teeth, Incised, and Flute made of Human Bone |

92 |

| XXIV. | Boro Cassava-squeezer. (A) Loop at End | 96 |

| XXV. | 1. Okaina Group 2. Group of Okaina Women |

98 |

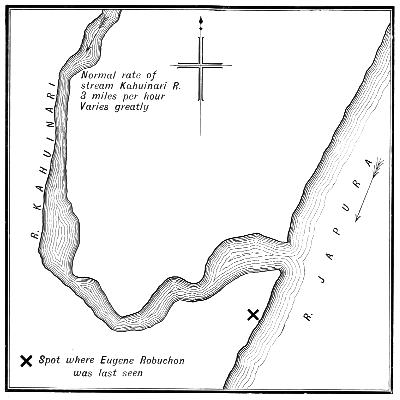

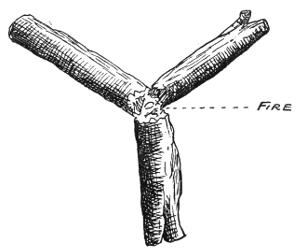

| XXVI. | 1. Indian Plantation cleared by Fire preparatory to Cultivation 2. View on Affluent of the Kahuinari River |

102 |

| XXVII. | Erythroxylon-Coca | 106 |

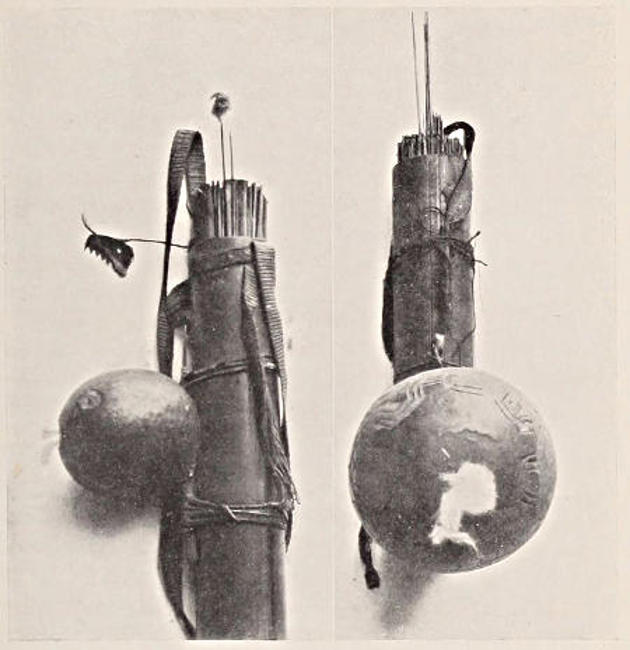

| XXVIII. | 1 and 2. Andoke Bamboo Cases with Darts and Cotton. 3. Dart with Cotton attached. 4. Blow-pipe with Dart. 5. Javelin. 6. Fishing Trident. 7. Spears in Bamboo Case. 8. Dance Staff |

108 |

| XXIX. | Andoke Bamboo Case with Darts for Blow-pipe and Gourd full of Cotton | 110 |

| XXX. | 1. Water Jar, Menimehe; (a) Witoto. 2. Drums (Witoto). 3. Pan-pipes, Witoto; (a) Boro. 4. Stone Axe (Andoke). 5. Paddle used on Main Amazon Stream. 6. Paddle used on Issa and Japura Rivers. 7. Menimehe Hand Club. 8. Wooden Sword (Boro). 9. Pestle—Coca, etc. (Boro) |

116 |

| XXXI. | Bamboo Cases, filled with Darts for Blow-pipe, showing Fish-jaw Scraper, and Gourd filled with Raw Cotton. One Dart has Tuft of Cotton placed ready for Use. These are Andoke Work | 118 |

| XXXII. | Witoto War Gathering | 120 |

| XXXIII. | 1. Boro Necklace made of Marmoset Teeth 2. Andoke Necklace of Human Teeth |

124 |

| XXXIV. | Boro Women making Cassava | 132 |

| XXXV. | Witoto Cassava-squeezer. Boro Manioc-grater with Palm-spine Points | 134 |

| XXXVI. | One of the Ingredients of the Famous Curare Poison | 138 |

| [xvii]XXXVII. | Incised Gourds | 144 |

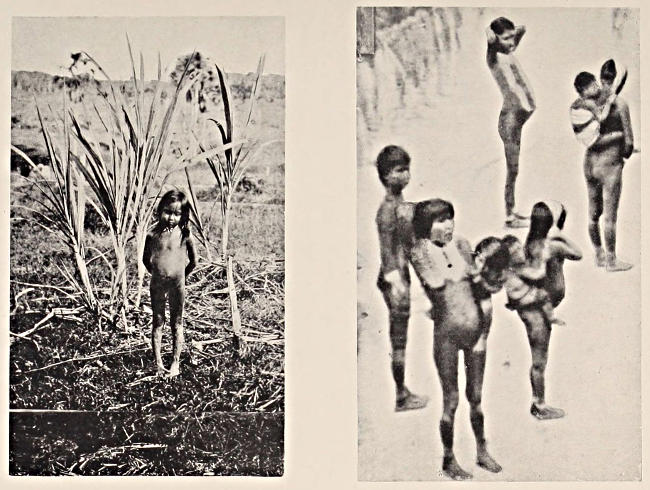

| XXXVIII. | Karahone Child. Boro Women carrying Children | 150 |

| XXXIX. | Boro Women carrying Children | 154 |

| XL. | Okaina Girls | 158 |

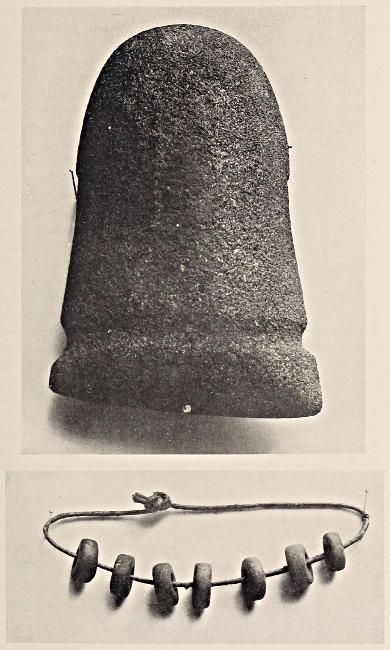

| XLI. | Stone Axe Head (Boro). String of Magic Stones (Andoke) | 184 |

| XLII. | Anatto, Bixa Orellana. A Red Dye, or Paint, is made from the Seed | 190 |

| XLIII. | Half Gourds decorated with Incised Patterns, made by Witoto near the Mouth of the Kara Parana River. Dukaiya (Okaina) Rattle made of Nutshells | 192 |

| XLIV. | Okaina Girls painted for Dance | 194 |

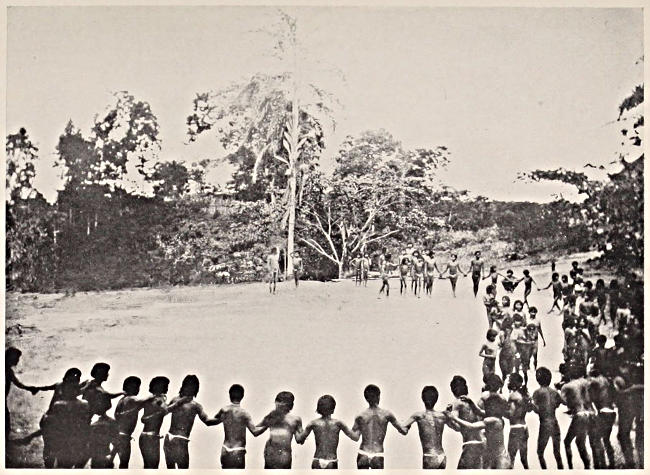

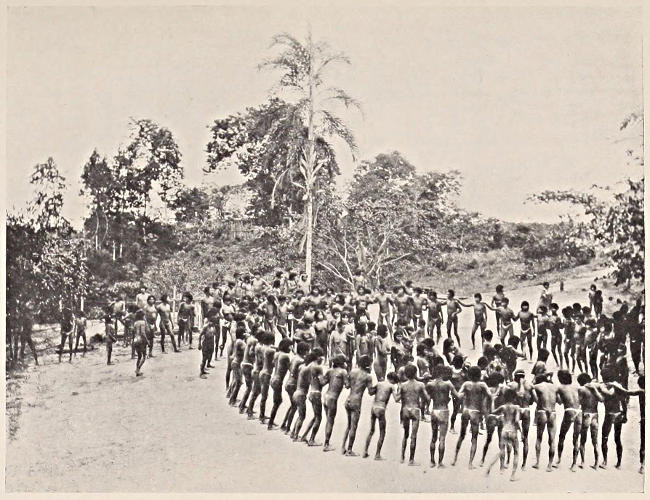

| XLV. | Boro Dancing. Group of Nonuya, Men and Women | 196 |

| XLVI. | Muenane Dance | 200 |

| XLVII. | Okaina Dance | 202 |

| XLVIII. | Okaina Dance | 204 |

| XLIX. | Pan-pipes | 210 |

| L. | Group of Witoto Women by Double-stemmed Palm Tree Group of Witoto Men by Double-stemmed Palm Tree |

232 |

| LI. | 1 and 2. Witoto Types. 3. Witoto from Kotue River | 270 |

| LII. | Combs. 1. Andoke Comb with Nutshell Cup for Rubber Latex. 2. Witoto Comb. 3. Boro Comb |

272 |

| LIII. | Boro Tribesman from the Pama River A Menimehe Captive |

274 |

| LIV. | Witoto Types. Witoto Woman with Leg Ligatures | 278 |

| MAPS | ||

| Map. 1. | Approximate Plan of Route | 2 |

| Map. 2. | Sketch Map | 10 |

| Map. 3. | Diagrammatic Map of the Issa-Japura Central Watershed, showing Language Groups | 58 |

| Sketch Map of the North-Western Affluents of the Amazon River | At end | |

| Sketch Map of the Amazon River with its Northern Affluents | At end | |

In the spring of 1908, having been among the Unemployed on the Active List for nearly two years on account of ill-health, and wearying not only of enforced inactivity but also perhaps of civilisation, I decided to go somewhere and see something of a comparatively unknown and unrecorded corner of the world. My mind reverted to pleasant days spent in the lesser known parts of East Africa, and at this moment I happened to come across Dr. Russel Wallace’s delightful Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro. His spirited adventures, and the unique character of the country through which he passed and the peoples he met, fascinated me. I thought of attempting to complete his unfinished journey up the Uaupes River, and imagined I would be able to secure in South America all the instruments and materials such an expedition required. There lay my initial error. My inability to obtain anything of the sort hampered me in scientific research, so that these chapters must simply be regarded as impressions and studies of native ways and doings, noted by a temporary dweller in their midst.

Difference of technique, industry, ability, and scientific knowledge may in the light of future investigations reveal errors or misapprehensions that must bring me into conflict with those who may go there better equipped and with greater understanding. But in any critical appraisement it must be remembered that these tribes are changing day by day, and every year that passes will increase the difference between the Amazonian native as I knew him and as he may be when studied by my successors. So far as in me[2] lies, I have here set forth an account of what he was when I travelled in his forest solitudes and fastnesses.

I left England towards the end of April 1908 and arrived at Manaos on the Negro River on May 27. Incidentally I arrived again at Manaos homeward bound on the same day and almost at the same hour the following year.[1] It may be taken, therefore, that my entire journey covered exactly twelve months.

On arrival at Manaos, I made inquiries as to the facilities for proceeding to S. Gabriel near the junction of the Negro and Uaupes Rivers, and thence up the latter stream.[2] My theory at the time was that it would be possible to ascend this river to its source, and from the vicinity to make a way across country via the Apaporis, Japura, Issa, and Napo Rivers to Iquitos. I soon found that the difficulty of obtaining the necessary men would be immense, and the ascent, in local opinion, impracticable without an expedition on a scale for which I possessed neither the influence nor the pecuniary resources. Persuaded that my line of least resistance, so far as the Uaupes was concerned, would be to reverse the contemplated journey and work from Iquitos to a point on the Uaupes and then descend to Manaos, I proceeded by the Navigation Company’s steamboat to the former town, where I arrived the second week in June.

APPROXIMATE PLAN OF ROUTE

In company with Mr. David Cazes, the British Consul, to whom I am indebted for many kindnesses, I made a trip up the Napo River. It was soon apparent, however, that it would be practically impossible to cross from that river to the Issa. This was not due to the difficulty of porterage, because there is a “recognised route” from a point some way above the mouth of the Curaray to Puerto Barros, but to the impossibility of obtaining men. Rumours were rife at this time of fighting between the Colombian and Peruvian rubber-gatherers on the Issa River, and the Napo Indians would not go in that direction on account[3] of a not unnatural dread lest they be treated as enemies by whichever party of combatants they might happen to meet.

Eventually, through the good offices of the British Consulate, I sailed from Iquitos by way of the main Amazon River and the Issa or Putumayo River to Encanto at the mouth of the Kara Parana, which I reached in the middle of August. It is from this point that my notes on the manners and customs of the Indians really commence.

I saw at once that it would be impossible to gain any insight into the ways and customs of the various tribes unless I spent some considerable time in what one might call a roving commission among them. I had with me at this time John Brown, a Barbadian negro. He had been for some three years previously in the Issa district in the employ of a Rubber Company, and I enlisted him as my personal servant at Iquitos. He had “married” a Witoto woman some two years before, and through this attachment I was able to derive much valuable information. In fact, he was invaluable throughout the whole expedition, and was more loyal and more devoted than a traveller with some experience of the African boy in his native haunts had reason to anticipate of any black servant.

On the 18th of August we started for the Igara Parana, having collected eight Indian carriers, two half-castes, and eight “rationales,” or semi-civilised Indians, armed with Winchesters, together with three Indian women, wives of three of the rationales.

It may here be mentioned that these armed Indians were to be obtained in the Rubber Belt by arrangement with their employers. It is the practice of the rubber-gatherers to train Indian boys and utilise them as escort, and to obtain rubber from the tribes hostile to those to which the boys belong. This is perhaps necessary to avoid collusion. In my experience there was never any question of fixed charge or price when hiring carriers. They expected to be given, at the conclusion of their service, a present of cloth, beads, a shot gun,[3] or such other item of trade as[4] their heart coveted. The line of argument was simple: “You do what I tell you, and when we part I will make you a rich man.” Wealth was represented by cloth, beads, and a knife. A boy I called Jim promised to go to the end of the earth if I would give him a shot gun. This was his sole ambition. He was one of my escort, and although carrying a Winchester, I do not think it ever entered into his head to make off with it. Such is the simple Indian nature. I do not mean that he would not have run away if such a plan suited him, but he would not have done so for the sake and value of the Winchester.

The two half-breeds were rubber-collectors. They were bound for the Igara Parana, and were only with me until we reached Chorrera.

The semi-civilised Indians are fairly trustworthy, although discipline must be strongly enforced to prevent looting if only because of the danger of reprisals on the part of the indigenous natives. During my wanderings the carriers were often changed, especially while passing through the Rubber Belt. Those men will always run if they get the chance, even if they are in the midst of hostile tribes, when to desert is more often death than not. In number the party remained approximately the same throughout my journey.

The carriers must be incessantly shepherded, kept from lagging behind or going ahead too quickly. They must not be allowed to stop for any length of time or a forced camp will be a necessity. It is the custom of all Indians to bathe whenever possible, however heated they may be, and this will have to be tolerated; but if progress is to be made they must not stop to eat. It was my custom to eat at daybreak and again at the end of the day’s march.

PLATE I.

HOUSES IN THE RUBBER BELT OF THE ISSA VALLEY

Treachery on the part of the native Indians it is always necessary to guard against—in the Rubber Belt because of the treatment they have received in the past; farther afield partly on account of the rumours of such treatment, and partly on the principle that it’s the nervous dog that bites. They ask but one question: “Why is the white man here?” They accord it but one answer: “We know not. It is best to kill.” And it is not, as is noted elsewhere,[5] the custom of the Indian to attack openly, but when he has the chance of succeeding with little or no danger to himself.

We reached Chorrera, or Big Falls, on the 22nd of August, and thence wended our way by land up the Igara Parana, arriving without much incident in the Andoke country on the 19th of September. Here, by arrangement with an Andoke chief, I managed to get a young Karahone lad, a slave who had been captured some years previously by the Andoke and who said he would take me to his own people across the great river. While we were encamped near the banks of the Japura River, and searching for the bulge-stemmed palm tree with which to make a canoe, we observed three canoes of Karahone on their way down the river, possibly after some warlike expedition. We tried to stop them, but in vain. When, eventually, we crossed the river, we found the occupants of the canoes had given the alarm. Every house we visited was abandoned, four in all, and the path was peppered with poisoned stakes sharpened to the finest point and exposed above ground for perhaps half to three-quarters of an inch. A carrier who trod on one had to be carried back as he was quite disabled for the march.

Returning to the Japura River, we made our way to the upper reaches of the Kahuinari River, visiting different tribes and collecting information. I was anxious at this time to descend this river and find out, if possible, the fate of Eugene Robuchon, the French explorer, who had been missing for some two years.

It may be pertinent here to give in full the story of Robuchon’s disappearance and my search for traces of his last expedition.

Eugene Robuchon, the adventurous French explorer whose notes on the Indians of the Putumayo are known to every investigator, left the Great Falls on the Igara Parana in November 1905. It was his intention to make for the head waters of the Japura and to explore that river on behalf of the Peruvian Government throughout its length for traces of rubber. He started with a party consisting of[6] three negroes, one half-breed, and five Indians with one Indian woman. He carried supplies barely sufficient for two months. I carefully examined all the survivors of the expedition that I encountered, and from them gathered the following account of the journey:—

Having left the Great Falls, Robuchon proceeded by canoe up the Igara Parana to a point some ten miles above the mouth of the Fue stream. He left the river there, struck northward through the Chepei country, and reached the Japura approximately at 74° W., some thirty miles above the Kuemani River. The Indians encountered at this spot belonged to a Witoto-speaking tribe, the Taikene. They were friendly, but either could not or would not provide Robuchon with a canoe. Three valuable weeks were spent in the search for a suitable tree and in the construction of a canoe.

When at length this was finished, the party started down-stream, and for a time progressed without incident. No natives were seen for several days. At last Robuchon’s Indians called his attention to a narrow path that led up from the river-bank on the right. Anxious about his food supply, he landed and followed the path until he came upon a clearing and an Indian house. Eventually Robuchon arranged with the inhabitants that four of them should come down to the canoe with food and receive presents in exchange. But when a larger number than he expected appeared upon the bank, the explorer feared treachery and at once pushed off without waiting for the much-needed provisions. The Indians thereupon manned their canoes and started in pursuit, shouting the while to him to stop. But with his small party Robuchon dared take no chances. He pushed on until the pursuers had been satisfactorily outdistanced.

The boy who told me the tale was convinced that these Indians were perfectly friendly in intention, and the incident appeared to be proof of the nervous state of the party. Some time after this, while shooting the rapids at the Igarape Falls, the canoe was upset and the greater part of the remaining stores was swept away.

The details of this misadventure I was never able to extract in a coherent fashion from the followers I interviewed, but they agreed that very little food of any kind was left, and what was rescued had been almost entirely destroyed by water.

Short of food, and without a canoe, the boys became mutinous. The three negroes and the half-breed deserted, and sought to cut a way through the bush backward in the direction whence they had come. This task was beyond them, and, a few days later, weary, disheartened, and starving, they returned to beg Robuchon’s forgiveness. The reunited party improvised a raft, and, after undergoing the customary hardships of an unequipped expedition in this hostile country, reached the mouth of the Kahuinari. The whole party was weak with hunger and fever, Robuchon himself prostrate and incapable of going farther. He determined to remain where he was with the Indian woman and the Great Dane hound, Othello. He ordered the negroes and the half-breed to push on up the Kahuanari to a rubber-gatherer’s house which he believed was situated somewhere between the Igara Parana and the Avio Parana. They were to send back relief at the earliest possible moment. The boys left Robuchon on February 3, 1906. He was never again seen by any one in touch with civilisation.

The boys had journeyed for but a few hours when they came across a herd of peccary. They killed more than they could possibly use, but made no attempt whatever to carry any meat back to the starving and abandoned Frenchman. Instead they wasted two valuable days in gorging themselves and smoking the flesh for their own journey.

For days they followed the course of the Kahuinari, hugging its right bank, and in this way happened across a Colombian half-breed, from whom they sought assistance. The Colombian took them to his house near the Avio Parana but would not grant them even food until they paid for it with the rifles they carried. The idea of succouring Robuchon was far removed from his philosophy. The boys, then, having surrendered their rifles in return for the stores they so much needed, made the narrow crossing[8] from the Avio Parana to the Papunya River, and followed that stream without deviation to its junction with the river Issa. Turning backward up the left bank of the Issa, they reached the military station at the mouth of the Igara Parana and there told their tale.

When at last a Relief Expedition was made up, it consisted of three negroes—John Brown and his comrades—and seventeen half-breeds. The party left on its search for Robuchon thirty-seven days after he had been abandoned at the mouth of the Kahuinari. It took ten days to reach the junction of the Avio Parana and the Kahuinari, and twenty-one days more to arrive at the camp on the Japura. It had taken ten weeks to bring help. The relief party found some tools, some clothes, a few tins of coffee, a little salt, and a camera. There was no trace of Robuchon, of the Indian woman, or of the dog. On a tree was nailed a paper, but the written message had been washed by the rain and bleached by the sun till it was illegible. Robuchon’s last message can never be known.

The relief party divided into two companies for the journey back—one section of twelve, the other of eight men. The larger party arrived in the rubber district six weeks later. The smaller party, with the three blacks, was lost in the bush. Five months and a half afterwards five survivors attained safety. The story of their misery is a chapter in the history of Amazonian travel that may never be written.

Two and a half years afterwards I was returning from a disappointing trip to the Karahone country. There were persistent rumours that Robuchon was held a prisoner by the Indians north of the Japura. I determined to see if any evidence could be found to settle his fate. I had in my party one of the negroes who had accompanied the French explorer. We journeyed overland southward through the Muenane-Resigero country till we reached the Kahuinari, thence by canoe to the Japura River. The Japura at this point is about a rifle-shot in width—2500 to 3000 yards across. Some three miles below this point on the right bank, a little way back from the river, was a small clearing.[9] In it were three poles marking the site of a deserted shelter. John Brown, my servant and formerly Robuchon’s, said it was the last camp of Eugene Robuchon.

We made camp in the clearing. A little way inland I found an abandoned Indian house, but all indications pointed to its having been deserted many years before. Half buried in the clearing I discovered eight broken photograph plates in a packet, and the eye-piece of a sextant. Other evidence of civilised occupation there was none. At some little distance my Indians detected traces of a path, and though to me it seemed only an old animal track, they maintained it was a man-made road. Cutting along the line of this path, at the end of a hard day’s work we emerged upon a second clearing and the ruins of a shelter. After careful searching we unearthed a rusty and much-hacked machete or trade knife. There our discoveries ended. The path went no farther.

We encountered no Indians in our search. On further investigation it appeared that there are none in the vicinity, and the nearest to the deserted camp on the south of the river are the Boro living on the Pama River, forty or fifty miles away.

Believing that the most probable route of escape was down the Japura, I journeyed slowly eastward almost to the mouth of the Apaporis. We then turned and came back, searching the right bank. Throughout this time we found no Indians and no signs of Indians. On the bank, about a mile and a half below Robuchon’s last camp, we found the remains of a broken and battered raft. It had evidently been carried down in full river, and left stranded on the fall of the waters. Brown recognised the wreck as that of the raft which the Frenchman’s party had built after the loss of the canoe. But it afforded no clue.

Much as I should have liked at this time to pursue my investigations among the Indians of the left, or north, bank of the river, I had perforce to give up further progress for the time being on account of the mutinous hostility of my boys. Nothing would persuade them that they would not be eaten up if they crossed the great river at this point.

Foiled, therefore, in my attempts to learn anything on the scene of Robuchon’s disappearance, I determined to prosecute inquiries among the Boro scattered about the peninsula bounded by the Pama, the Kahuinari, and the Japura. But here also no amount of examination could elicit any information as to the explorer, the woman, or the dog. I was particularly impressed by the fact that the existence of the Great Dane—an object of awe to the Indians—had left no legend among the natives. Robuchon himself wrote of his hound: “My dog, as always, entered the house first. The great size of Othello, his flashing teeth, and close inspection of strangers, his blood-shot eyes and bristling hair invariably inspired fear and respect among the Indians.” Had such an animal fallen into the hands of the Boro, I feel certain its fame would have outlived that of any chance European who might have become their prisoner, however much they desired to conceal their participation in his murder. My own Boro boys could find no record among their compatriots of the presence of Othello or his master.

After this we proceeded in a northerly direction, and, crossing the Japura, visited the Boro tribe located on the north bank of the river, between the Wama and the Ira tributaries. The chief of this tribe had married a Menimehe woman who, curiously enough, remained on terms of friendship with her parent tribe. The chief informed me that in the Long, Long Before—from reference to the size of his son at the time, I calculated about three years previously—the Menimehe had captured a white man with face hairy as a monkey’s. As Robuchon was wearing a beard at the time of his disappearance this seemed to present a clue, but as the Menimehe refused to confirm the statement, and there was no mention of the woman or of the dog, it added but little to the evidence of his fate.

Spot where Eugene Robuchon was last seen

The testimony was further weakened by the knowledge that about that time either the Menimehe or the Yahuna destroyed a Colombian settlement near the mouth of the Apaporis River, and made prisoners of white men. Whatever the truth of the bearded white man, there was certainly[11] no memory remaining of the Indian woman nor of Othello, the Great Dane.

On my return to the Rubber Belt I learned that Robuchon had been lost on a previous expedition for a considerable period, and had lived during that time with Indians. Although this had occurred in the regions south of the Amazon on the Peru-Brazil-Bolivian frontier, somewhere in the neighbourhood of the Acre River, the general haziness of natives with respect to place and time may have accounted for the rumours of captivity among the semi-civilised Indians of the Rubber Belt, which set me on a fruitless search among the Indians of the Kahuinari-Japura.

To sum up the evidence with respect to the fate of Robuchon, it seems to me that he did not die of starvation at the mouth of the Kahuinari, because a certain amount of food-stuff was found by the first Relief Expedition at the site of the camp, but no signs of human remains. The illegible message nailed to the tree suggests that he vacated the spot and endeavoured to leave information as to his route for those who might come to his relief.

Robuchon had five courses open to him once he decided on abandoning the camp:

1. He could retrace his steps up the Japura. With respect to this means of escape, I consider it extremely improbable that he would attempt to return against stream over the route which he had already traversed with such difficulty when aided by the current and the full strength of his party.

2. He could proceed across the Japura to the country of the Menimehe. He was unlikely, however, to cross that river, owing to the bad name enjoyed by the Menimehe. He could not count upon a relief expedition following him there.

3. He could journey up the Kahuinari. He could hardly negotiate the difficulties of the upstream journey though with the inadequate assistance of a single woman. He was aware of the existence of unfriendly tribes on the banks. My inquiries among the Pama Boro yielded no trace of his ever having been seen upon the river. If he had made his way along the right bank of that river, probably some evidence of him would have been found by the relief party.

4. He could have voyaged down the Japura in a canoe or upon a raft. It would have been very hazardous to have attempted this alone—practically hopeless. In any event, if he did make the attempt, he failed to reach the nearest rubber settlement.

5. There remains one means of escape—by an overland march. It would appear that he adopted this method, but only without any idea of permanent relief, in desperate search of temporary assistance. The line of the Kahuinari was the obvious route for a rescue party. Robuchon, however, was starving, and the native track promised a path to a native house and food.

I presume he was located by a band of visiting Indians, captured, and either murdered or carried away in captivity to their haunts on the north bank of the Japura. I suggest the probability of the Indians coming from the north bank up the Japura, because, so far as I could learn, it was not the custom of the Pama Boro to journey to the mouth of the Kahuinari, since they could obtain all they needed from the river at points more easily and more speedily accessible to them. There were no Indians resident in the vicinity, but Indians from across the Japura made excursions at low river in search of game or of turtles and their eggs.[4]

It is upon one of those chance bands that reluctantly I am forced to lay the responsibility for the death of Eugene Robuchon in March or April 1906.

This was little enough to add to the ascertained fact of Robuchon’s end, but such as it was it brushed aside some of the mystery, and proved of interest to the members of the French Geographical Society and to the relatives of the lost explorer.[5]

After concluding my investigations among the Boro in the vicinity of the Pama River, I again crossed the Japura River near the Boro settlement on the north of that river, and proceeded eastward into the country of the Menimehe. This country appears more sparsely populated than the[13] Kahuinari districts, and the manners and customs of these people vary considerably from the tribes inhabiting the country to the south.

From the most easterly point I decided to proceed in a north-westerly direction with a view to striking the upper waters of the Uaupes River eventually. It was in this neighbourhood that I developed beriberi; and, owing to the swelling of my legs, which were covered with wounds and sores, I was only able to walk with difficulty, although I had no pain. My brain was numbed as well as my legs. I slept at every opportunity, did not want to eat, and seemed to be under the effect of some delusive narcotic. Yet I never failed to take all necessary precautions—it was mechanical, a mere habit. Stores were running short, owing to their bad condition, and my boys and carriers were becoming mutinous. Game was scarce, and the few native houses we encountered were for the most part deserted; what Indians we came across were surly and sullen, and appeared latently hostile.

I decided to return, overcome by the argument of Brown that if I did not do so the boys would go, so we turned back to the east and south of the original line, and proceeded overland by way of the Kuhuinari River to the Igara Parana, and thence to the Kara Parana by river. Arriving at the latter river at the end of February, and finding that the steamer for Iquitos would not start for some time, I made a short trip among the tribes of this river.

By reference to the sketch-map it will be seen that from the time I left Encanto on my arrival from Iquitos to my arrival at the same place, bound for Iquitos, was approximately seven months.

The difficulties in the way of obtaining information are such that it is only those who sink for the nonce all inherited and acquired ideas of superiority, manners, and customs who can be successful. As a consequence, the stranger will have to journey with savages, eat with savages, sleep with savages, from the moment he seeks to penetrate their land. Watchfulness night and day must be the price of any desire to understand the native in his home. The field-worker[14] must subordinate every previous and personal conception. Native justice must be his justice. Almost necessarily native ethics must be his ethics. He is no missionary seeking to convert those he meets to ideas of his own; rather is he a learner, an inquirer, eager to understand the thoughts that inspire them, to analyse the beliefs they themselves have gathered. Then there is no common medium of language. Sometimes a native speaking a tongue with which the traveller has a passing acquaintance can make himself understood in another tribal language whereof the white man is blankly ignorant, and then some approximation of the truth sought to be conveyed is arrived at tortuously. For example, I had a Witoto Indian who understood a little Andoke, and by way of Brown the Barbadian carried to me much information of these little-known Indians. John Brown was here invaluable as he knew Witoto well and Boro to some purpose. But much of the appended vocabularies had to be gathered by the crude method of pointing to an object. Having noted the word phonetically, one had to get it confirmed by trial.

Travelling in the bush is a dreary monotony of discomfort and ever-present danger. There are weary stretches of inundated country, sweating swamp. You pass with an unexpected plunge from ankle-deep mire to unbottomed main stream. The eternal sludge, sludge of travel without a stone or honest yard of solid ground makes one long for the lesser strain of more definite dangers or of more obtrusive horrors. The horror of Amazonian travel is the horror of the unseen. It is not the presence of unfriendly natives that wears one down, it is the absence of all sign of human life. One happens upon an Indian house or settlement, but it is deserted, empty, in ruins. The natives have vanished, and it is only the silent message of a poisoned arrow or a leaf-roofed pitfall that tells of their existence somewhere in the tangled undergrowth of the neighbourhood.

On the trail one speedily learns the significance of the phrase “Indian file.” Here are none of the advance guards, flank guards, and rear guards that are needed to penetrate unfriendly country in other lands. The first man[15] hacks a way for those who follow, and the bush is left as a wall on either side that is as inscrutable to the possible enemy on the flank as to the advancing party. On account of such conditions I should say, from my experience of bush travel in these regions, that the whole party should rarely if ever exceed twenty-five in number. On this principle it will be seen that the smaller the quantity of baggage carried the greater will be the number of rifles available for the security of the expedition.

The difficulty of an efficient food supply is very great. Game is always hard to shoot on account of the density of the bush, and in many parts appears to be non-existent. Preserved goods in sealed cases, of convenient size for porterage, should be taken from Europe. My failure to carry out my original intentions was due more than anything else to the fact that my supplies were purchased in the country, and 50 per cent proved unfit for consumption. The country where supplies must be husbanded has little enough of food that is appetising to offer. Fish, if plentiful, are hard to catch for the uninitiated. One hungers for the occasional tapir or peccary, the joys of monkey-meat, and an incautious, though unpalatable, parrot, and in the days of real distress may be glad to fall back on frogs, snakes, and palm-heart. The real fear of starvation, after perhaps the ghastly dread of being lost, is the great cause of anxiety to the traveller in the Amazons.

As for shelter,—a tent is an encumbrance,—an open screen of rough palm thatch can be erected in a very short time, and is all that is necessary, although not all that is to be desired. The shelter is a poor one that does not prevent the dews and the inevitable rain from chilling one to the bone.

Clothes for the Amazons are not designed with a view to fashion or appearance. In the past, continental explorers have introduced some interesting fashions in ducks and khaki, but travelling through a country where one’s life is passed in a bath of perspiration, their distinction of appearance yields to the simple comfort of the native’s nudity. In search of a compromise, I have found that a thin flannel suit of pyjamas with the trouser-legs tucked into the socks,[16] and a pair of carpet slippers laced over the instep, best meet the requirements of the region. Ordinary boots are a positive danger on account of the narrow and sometimes slippery tree-trunks over which one clambers uneasily. A small towel round the neck to wipe away the perspiration is a great comfort. For head-gear a cloth cap or “smasher” hat suffices.

A long knife or cutlass must be carried, and, personally, I invariably carried a revolver, while the gun-bearer should always be at hand with a rifle or scatter-gun. A blanket, sleeping-bag, and waterproof sheet of course must be taken, with the other comforts, medical and hygienic, common to all expeditions.

The drawings that appear in this volume are either taken from photographs or from actual trophies and articles in my possession. The photographs are a record of industry and patience. Films I found useless in this climate, and plates alone materialised. It must be remembered, also, that every time plates have to be changed it is necessary to build a small house, and double thatch and treble thatch to prevent the entrance of any light. Even then the experienced do their work at night.

The difficulty of posing and overcoming the objection of the native subject will be at once realised. Too many groups have been draped by explorers in the unaccustomed decencies of camp equipment, though it has become an essential of the country—climatic and psychological—that the women walk abroad naked and the men unembarrassed by more than a loin-cloth.

The maps cannot pretend to be more than the roughest approximate sketch-maps. When absence of a horizon and the density of the bush are realised, it will be obvious that they can be nothing more. It is hoped that they will suffice to give some idea of the general trend of the country and the location of the various language-groups.

PLATE II.

A HOUSE IN THE ‘RUBBER BELT,’ ISSA VALLEY

Topography—Rivers—Floods and rainfall—Climate—Soil—Animal and vegetable life—Birds—Flowers—Forest scenery—Tracks—Bridges—Insect pests—Reptiles—Silence in the forest—Travelling in the bush—Depressing effects of the forest—Lost in the forest—Starvation.

Although the Amazons have been known to Europe for fully four hundred years, exploration has been confined almost entirely to the main river and its great tributaries. Little addition has been made to the information possessed by Sir Walter Raleigh in the three hundred years that have elapsed since his death. The rivers certainly are known and charted, yet the land beyond their banks is almost as much a land of mystery in the twentieth century as it was in the days of Queen Elizabeth. It is possible to spend a lifetime in navigating the Amazon,[6] and to know nothing more of its 2,722,000 square miles of basin than can be peered at through the curtain of vegetation which drapes the main streams. Behind that veil lies the fascination of Amazonian travel.

We are not here concerned with the scanty records history offers of these vast regions, nor, for our immediate purposes, is it needful to inquire into the conditions and features of the Amazon watershed as a whole, except in so far as they differ from or resemble those of my field of exploration, the tracts between the middle Issa and Japura Rivers, and in their vicinity. Roughly speaking, this lies in that debatable land where the frontiers of Brazil meet those of Peru, Colombia, and—perhaps—Ecuador, a country[18] claimed in part by the three latter, but administered by none. Here the dead level of the lower Amazonian plains imperceptibly acquires a more decided tilt, the trend of the land from the great Andean water-parting on the west and north-west being south-east to the mighty river on the south, consequently these north-western affluents of the Amazon flow in more or less parallel lines from the north-west to the south-east. It is the rivers that dominate this country, the mountains, those primal determinants, are only distant influences, snow-topped mysteries but dimly imagined on the far horizon from some upstanding outcrop, a savannah where momentarily a perspective may be gained over and beyond the illimitable forest.[7]

On the south of the tracks here dealt with the Amazon slowly sweeps its muddy yellow waters, 500,000 cubic feet per second, towards the ocean. On the north the Uaupes River flows to join the Rio Negro. Between the Uaupes and the Amazon the Rio Caqueta, or Japura River, runs south-east, due east, and south to the main stream, and almost parallel with it the Putumayo, or Issa, gathers the waters of the Kara Parana and the Igara Parana, both on its northern, that is to say its left bank, and joins the Amazon where the main river turns sharply south 471 miles below Iquitos. West again, the Napo drains down to join the great water-way 2300 miles from the sea. Of the Napo much has been written since Orellano sailed down it from Peru, homeward bound to Spain in 1521, and it may be left outside the bounds of our inquiry. With the Issa and Japura we must deal in some detail, but of the Uaupes and Rio Negro a few words will suffice.

Rapids and cataracts bar the navigation of the Uaupes, the chief tributary if not, as some would have it, the main stream of the Negro, until it is, according to Wallace, “perhaps unsurpassed for the difficulties and dangers of its navigation.”[8]

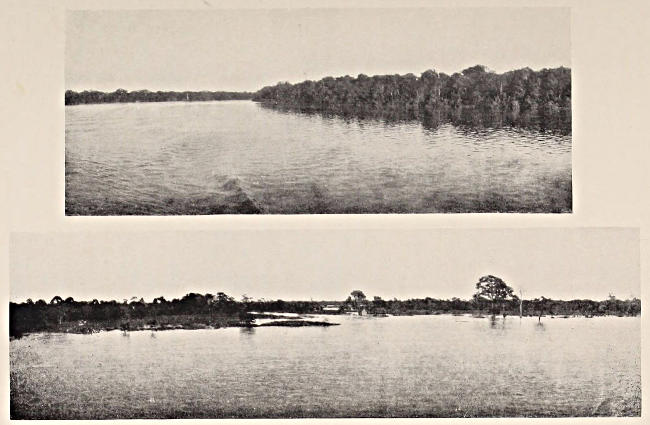

PLATE III.

TYPICAL RIVER VIEW BELOW THE MOUTH OF THE NEGRO RIVER

BANK OF MAIN AMAZON STREAM IN THE VICINITY OF THE MOUTH OF THE JAPURA RIVER

Wallace estimated the country to be not more than 1000 feet above sea-level. I should judge it to be considerably less, by the trend of the country to the south of it. But even here I may be mistaken, as my aneroid was useless, for undiscovered reasons, and my opinion is based simply on the force of the currents of the rivers, the number and depth of the rapids, and the distances to the main river and thence to the sea. The height above sea-level cannot be great, for the tides are felt at Obydos, more than half-way from the ocean to the mouth of the Rio Negro, and there is no abrupt rise from the Obydos levels; indeed the slope of the land is so slight that in the middle reaches of the main river during wet seasons the floods spread for twenty miles, and there is no visible current.

The Uaupes, though lighter than the majority of southern tributaries of the Negro, is what is known as a black water river, while most of the rivers flowing in on the northern bank are white water rivers. This peculiarity, which may be as marked as the difference between ink and milk, is due apparently to the variety of soil in the country drained by the rivers. The chief tributaries of the Uaupes, the Itiya and the Uniya, are both white water streams. Spruce notes that fish are scarcer in black than in white water streams,[9] and attributes it to the absence of vegetation. This may be true in part of the Negro, but it is not true, I think, of other rivers. Certainly these have some sort of fish, for I have seen them rise. One species is known to feed on a variety of laurel berry very plentiful on some of the river-banks.

The Rio Negro itself, the waters of which are dead black, is navigable for more than a third of its course to vessels of a 4 feet draught even in the dry season, and communication is possible from its upper waters with the great northern artery of the Orinoco, through the Casiquiari, the most important of the natural canals that abound throughout the Amazon regions.

The Issa, or Putumayo—the Peruvian name is perhaps better known than the Brazilian, the true geographical[20] one—is the first tributary of importance to join the Amazon after it has entered Brazilian territory. Of its 1028 miles only 93, according to the Brazilian Year-Book, are not navigable by steamers. This exceeds the truth, for there is practically no communication with Colombia or Ecuador by this route, as the statement would imply. In the upper reaches of the Issa rock and shingle are to be found, while 300 miles down stream hardly a stone is to be seen. The water is very muddy, and the current variable as the depth. Now it will be a swirling storm-fed torrent, the turbid water burdened with a wild flotsam of forest trees and matted vegetation, cutting into the soft layers of vegetable mould that form its banks, and rise above it as much as 25 feet in places; anon it is a sluggish stream that spreads oilily nowhither, with scarce a ripple over the deep alluvial deposits of its bed. This river is at its lowest in February and March. At its juncture with the Amazon looking upstream from the main water-way, the Issa is the more imposing of the two, for its course lies wide and fully exposed, while the Amazon bends sharply, and gives the impression that it and not its affluent is the tributary stream. Robuchon calculated that its breadth there was 600 metres, the depth 8, and the current 2½ miles an hour. He states very truly that landslides often occur on the banks of these rivers, and that such destruction of the bank, together with the quick rise and fall of the streams, may so alter the appearance of any stretch as to render it quite unrecognisable, even within a few hours. Special mention is made by him of the Papunya River, that enters on the left bank of the Issa. Forty miles from the Papunya is the Parana Miri,[10] a river with very black water and a large group of islands at its mouth. Many of the islands in these rivers are not stationary, they are floating masses of soil and vegetation, torn away from the banks when the river is in spate. They may be as much as a[21] hundred yards from bank to bank, and birds are to be found living upon them.

PLATE IV.

1. RIVER VIEW ON MAIN STREAM NEAR ISSA RIVER

2. LANDSCAPE ON UPPER AMAZON MAIN STREAM

The Igara Parana runs into the Issa where that river makes a horse-shoe bend,[11] the junction being on the inner side of the horse-shoe. The breadth of the stream at its mouth is 161 metres. The water is clearer than that of the Issa, and the current slower, never more than 3 miles an hour. Some 220 miles upstream there is an important waterfall, known as La Chorrera, or the Big Falls. The Igara Parana becomes vary narrow and most tortuous as it nears them, and is only 30 metres wide at its exit from Big Falls Bay. This is a huge pool almost as wide as it is long, with a narrow exit at one end, and a succession of cascades at the other. These falls are impassable in boats, and traffic with the upper river can only be carried on by land portage. Much debris of rocks and river-borne tree-trunks obstructs the narrow passage above the falls, which are given by Robuchon as having a total length of 120 metres and a width of 18 metres. The waters descend over a series of wide rocky steps, worn flat and smooth by the ceaseless friction. Masses of stone line the right bank, and rise perpendicularly from the water. This is the only part of the country where I have seen rocks and stones in any quantity.

The upper reaches of the river are distinctly more picturesque than its lower waters. The almost level banks, with their monotonous succession of forest trees, grow gradually steeper, till the sandstone cliffs rise like a fortification above the fringe of vegetation that encroaches on the high-water mark. Presently the river winds in and out between shelving hills, tree-clad to the very margin of the water. Between the Igara Parana and the Kara Parana the country is a perfect switchback of hills and ridges, with a stream in every gully. The steepness of these valleys, with a pitch perhaps of 25° or 30°, does not permit the surface water to lodge and form swamp or morass, in contrast to the waterlogged plains of the lower rivers. Immediately on the left bank of the Igara Parana, and in the vicinity of the Big[22] Falls, the country continues to be hilly, but to the north-east it is more open, and the bush is less obstructive, though its density varies immensely. Similar diversified scenery is to be found on the upper waters of the Japura.

The Kahuanari, a considerable tributary on the south bank of the Japura, drains the divide that intervenes between that river and the Igara Parana. It is subject to sudden floods, which wash down large quantities of forest debris. I have seen it rise twenty feet in a day, and afterwards subside as quickly.

The floods are not to be wondered at when the tremendous rainfall of these regions is considered. The question is never if it will rain, but when and for how long it will be fine. Rain is certain in a land which has but a few days clear of it in every twelve months. Five days, a fortnight, that, all told, is the extent of dry weather to be looked for in this country. The dry season is but a name. It is dry only in comparison with the wetter months from March to August. The upper valley of the Amazon has a three-day winter at our midsummer—June 24, 25, 26—so it is said, and certainly I noted a very decided drop in the temperature of these days in 1908. Snow is unknown, and hail not common. Despite the daily rain the turquoise blue of the sky is seldom long hidden, though from March to June leaden skies portend rain, and seldom fail to make good their portent. During the dry season the rain if it be frequent is never continuous. Almost every day, between three and four in the afternoon and two and five in the morning, heavy clouds will roll up, a preliminary breeze rustle through the leaves, shake the trees, and increase till suddenly there comes a deluge of big drops. Such storms last but half an hour, yet the rain will soak through everything, and the wet bushes drench the passer-by for hours afterwards. Nothing is ever really dry, things are in a constant state of saturation, and it is possible at all times to wring moisture out of any of one’s belongings. So great and incessant is the evaporation that at night the dew is as heavy as rain, while the marshy low-lying lands and the rivers are shrouded by mist both morning and[23] evening. With such humid air lichens and Hepaticæ flourish on all the tree-trunks, though I have never seen them, as described by Spruce, covering the very leaves of the trees.[12]

Electric disturbances are numerous, and a sharp and sudden thunder-shower often occurs about three in the afternoon, or in the night, though rain at night without thunder is common. These storms come up in the dry season especially, and the worst storms may be expected in February, at the breaking of the dry weather. Sometimes the electric storm will consist of an uninterrupted display of lightning with little or no thunder, and the sizzle of light makes the landscape appear as in a cinematograph picture. This continued on one occasion all through the night, and from the amount of interest the Indians evinced I judged it to be an unusual occurrence.

It is always possible to tell when rain will come because of the preliminary breeze, hardly felt below the tree-tops, followed by a dead calm that precedes the downpour. The prevailing wind for nine months of the year will be from the east or south-east, from June to August it will be north and north-west. In January the prevailing wind is from the Atlantic, north-east, veering to south-west; in July from the Pacific, south-west, round to north-east. Fitful and uncertain local whirlwinds will, without warning, swoop down on the clearings round the houses, play havoc in forest and plantation, uproot trees, and destroy habitations.

In spite of the continual rain, of the universal humidity; the climate is not unhealthy. The heat, though a damp heat, is never excessive, the enormously great evaporation brings in a succession of fresh breezes to moderate the temperature;[13] and so, despite apparently trying conditions,[24] the climate is not injurious. The low watersheds between the large rivers appear to be quite healthy, and if there be fever its prevalence varies locally to an extraordinary degree. It has been observed that where the soil is first turned up fever not infrequently follows, a fact noted in other parts of the world, and by no means a condition peculiar to the Amazons.

The soil of the vast Amazonian basin is mainly the alluvial deposit of decomposed vegetable life for centuries past. This sea of Pampean mud stretches from the ocean marshes up to the very heels of the mountains that stand outpost to hold the southern continent from the Pacific. Black and rich it lies in layer after layer twenty, thirty, forty feet beneath the great pall of vegetation that flourishes above during its little day, to die and drop for successive generations of arboreal life to thrive upon in their turn. And in all this vastness is never a stone. Vegetable mould and water-borne mud, but stone does not exist for thousands upon thousands of miles. Only in the upper waters of the Amazonian system are rock formations reached; in the particular district under consideration nothing is to be found harder than a soft, friable sandstone. On parts of the Issa, as on the Napo, the deep banks show strata of shingle, with perhaps red or white clay, that alternate with the dark humus and decaying wood.

It is the ceaseless activity of all vegetable life that renders these regions fit for human habitation at all. There is no period, as with us, of bare branches overhead and decaying matter below. Decomposition is there, but for every dead leaf a virent successor is ready to absorb the gases engendered by decay. The soil may be water-logged, but evaporation, combined with the constant rain, the frequent inundations, and the endless operations of an immeasurable insect world, militate against stagnation.[25] Dank it may be, but there is no iridescent scum upon the water, no fœtid smells to warn of lurking poisons. These natural danger-signals are unneeded, for the poisons are self-destructive. Processes of corruption are coexistent with those of purification. So extraordinary is this that I never hesitated to drink any water, nor is any evil resultant from water-drinking within my knowledge.

In this struggle it is the weak who go under, the feeble who support the strong. This holds good for vegetable and animal kingdom alike, and even with man there is no place for the helpless. Those who fail by the way, who cannot fulfil their functions in the toiling world, and have ceased to be of practical utility, must make way for the more capable. Altruism is not bred of the forest, it is a virtue born in cities. Here it would be suicide. The growing leaf must push off the fading leaf, or the latter will stunt and imperil its growth. In fact it does so, and growth is thus continual. There are no seasons to correspond with our spring nor with our fall of the leaf. From the lower Amazon’s maze of water-ways up to the foothills of the western mountains reigns perpetual summer; the same leafy veil hides the mysteries of the great expanse, eternally dying, eternally renewed.

As one passes onwards, however, nearer where the great cloud-banks gather over the mountain giants of the west, a perceptible change is to be noted, the scenery of the upper Amazon differs in certain essential particulars. It is not only that the great river thoroughfare, first spread on either side beyond the farthest horizon,[14] becomes a thin black line that grows nearer and deeper. Other features besides the river-surface contract. The majestic forest trees give way to timber not so towering. Plant life is not less prolific, but it is on a smaller scale. The bush has the air of being younger. It suggests that it has been dwarfed by perpetual inundations. Nor is the stunted growth limited to the vegetable world; the animals themselves, as if Nature insisted that all be in keeping, are on a lesser scale than their congeners of the eastern plains. No alligators of immense size lurk in the upper waters, even the fish and the turtles[26] are smaller, as though their inches were limited in proportion to the streams.

It is not easy to convey any true notion of the scenery of the Montaña, the vast forest regions spreading eastwards, down from the lower Andean slopes. Here and there the dense forest gives place to an open savannah, an outcrop of rock with but a shallow stratum of soil. These have none of the deep vegetable mould of the lower-lying forests, and the poorer and thinner soil harbours flora of many totally distinct varieties. Often the great fan leaves of the Aeta are matted into a dense roof over the black swamp of the valleys. Sometimes these water-loving palms are seen by the river-side, interlopers in the fringe of fern and thickets of feathery bamboo; or, again, they will grow in a regular belt with little or no other vegetation.

Life is more evident on the rivers than in the forest. Fish are there in plenty—eighteen hundred species are known in the Amazonian waters. Birds, often conspicuous by their apparent absence in the bush, flock on the sand-banks and marshes of the bank. Herons and ducks abound. Egrets haunt the sandy spits that rise from the water, and in the marshy swamps numbers of these beautiful creatures may commonly be seen hunting for the tiny fish, animals, and insects on which they feed. Another enemy of the small denizens of the stream and marsh is the kingfisher. More than one variety abound on all the Amazon water-ways, but none of them can compare with the English bird in brilliancy of colour. Probably this is an instance of protective colouring, one of Nature’s methods of defence, for on these dark waters the gorgeous blue of our Alcedo ispida would be even more conspicuous than it is on our clearer streams.

One pictures this tropical garden, this paradise of the naturalist, as a blaze of gorgeous colour, a profusion of exquisite forms. But, in proportion to one’s imaginative anticipation, I have never seen such a monotonous, flowerless wilderness as this bush appears. Still there are flowers, and flowers of showy colouring, the pinks and yellows of the bignonias, the white and crimson of the chocolate-tree, the[27] crimson of the hibiscus, the scarlet blaze of the passion-flower, the snowy beauty of the inga; all these and a thousand more are there, with the rarest blue and all the myriad shades of mauve and orange, yellow, pink, brown, violet of uncounted orchids. But orchids, though common, grow at the very top of the trees, and unless they are searched for they are not seen, except such varieties as are found on the savannahs.

The whole is on a scale so gigantic, the immense forest, the great rivers, that details are lost in the vast expanse, and the total effect is one of absolute sameness. Yet the individual variety is enormous. Though uniform in the mass, twenty-two thousand species of plants have been differentiated; thousands more remain undescribed. Only a botanist could attempt to deal with these even superficially. The uninitiated, like myself, can but look and wonder.

Many of the units of this mighty aggregate are of a surpassing loveliness; flowers unequalled for beauty, birds and insects that are living jewels, outrivalling inanimate gems. Such palms and ferns as would be rare treasures in a Kew Gardens hothouse riot unheeded in tangled profusion above the dark marshy soil, over a screen of parasites and epiphytes. Forest giants, those immense monarchs of the woods Californian advertisements depict for the edification of the populace, are not there; certainly they are never to be found in the Montaña. Nor, perhaps, in consequence of the lower growth, is there that intense gloom mentioned by writers on more easterly districts. The idea that you look up but can never see the sky is fiction to me. The foliage is certainly too dense for the sunlight to penetrate down to the damp soil and matted underbush, but patches of the sky are always more or less visible through the interlocked branches overhead. Light and air are to be had freely only on the tree-tops, and it is there that birds, insects, and flowers mass their glories out of human ken. Even the animals are climbers, and most of them spend more than half of their existence on the trees.

There are no long dark avenues beneath this leafy canopy[28] that hides all the life and colour of the forest world from the traveller, painfully cutting his path through the intricate confusion of roots and creepers below. These parasitic creepers are of many kinds, rooting down to the dark soil, intertwining with themselves, pushing boldly to the tree-tops, strong as withes, in wild festoons, knotted, tangled, of every thickness from a giant cable to a narrow thread. I have seen parasite on parasite. They loop from tree to tree, bind the underwood into impenetrable thickets, and trail over the track-way, ready to strangle or trip the heedless passer-by. But track-way is a misnomer. The only thoroughfares, where water is as abundant as dry land, are the water-ways. The bed of a stream is the only track. No other line of communication is intelligible to the Indian. Even in the vicinity of civilised centres, hundreds of miles away from these wild fastnesses of Nature, the exuberant vegetation rapidly encroaches upon a roadway. Paths in the forest there are none. A forest track consists in following the line of least resistance. If this should be stopped by any obstacle, a fallen tree, a sudden inundation, it would never be removed or surmounted. There is no choice but to climb over or go round. The ordinary Indian wayfarer would go round; and so the road deviates increasingly; it becomes inconceivably twisted, until the actual ground covered is enormous compared with the distance from point to point.

PLATE V.

THE BULGE-STEMMED PALM, IRIARTEA VENTICOSA, SHOWING PORTION OF LEAF AND FRUIT

Where a stream has to be crossed there is rarely any bridge more stable than a small tree cut down and thrown across just when and where it may be wanted. Frequently such impromptu bridges are under water. They are invariably of the slightest; a branch no thicker than a man’s hand suffices to span a deep chasm, and over this an Indian will pass more unconcernedly than an Englishman over London Bridge. The worst penance of all in forest journeyings is to cross a river or a gully full of great fallen trees, on such flimsy foothold. The drop at times may be 40 to 50 feet, and there will be but the one tree across without any attempt at a hand-rail to steady the traveller. Nor can you grasp an Indian’s shoulder for aid in the perilous[29] transit, for to do so is to lose once for all every trace of prestige and authority. The man who cannot get over a river unaided, the man who is not man enough to walk and must be carried in a hammock, is but a poor creature in the eyes of the South American Indian. Still it is more than a test of nerve. In the middle of such a bridge you feel yourself swaying, and it is only with a fearful concentration of will-power and a bitten lip that you arrive safely on the other side, having leapt the last three feet. In the first month of forest journeying I bit my lip through time and again. It is not the torrent below that frightens, it is the rotten trees in the gully. A fall may possibly be a broken neck, more probably it would be a broken leg. Of the two in country of this description a broken neck is preferable.

Where a stream has to be crossed that is too deep to be forded and cannot be bridged over in this elementary fashion, there is little difficulty in the construction of a raft or a temporary canoe. The bulging-stemmed palm furnishes an almost ready-made one. This palm, Iriartea ventricosa, is readily known by the peculiar swelling on the upper part of the trunk. It will attain the height of 100 feet, and the swollen portion is big enough to form the body of an improvised canoe.

Forest bridges are not the only terrors to confront the traveller; lurking dangers are many, and imagination is but too quick to multiply the risks. Peril from wild beasts does not loom largely in the picture, though the jaguar is a savage brute, and the experienced traveller will never sleep without a weapon at hand in case one of these daring creatures should venture to attack. But of animals more anon. There is one danger by no means imaginary, the danger of falling trees. A sudden crack, startlingly noisy in the all-pervading stillness, will give warning of a fall, but there is nothing to guide to safety. It may be the nearest tree that is coming down, or one at some distance; yet the deceptive noise will not determine which may be the doomed one, beyond the fact that a palm gives the sharpest crack. Indians when they hear such a sound are invariably frightened, and often will run backwards and forwards in terrified[30] uncertainty, to try and discover whence came the danger signal.

Then there are plants that injure more directly. One palm, an Astrocaryum, has spines six inches in length up its stem. These spines, black in colour, hard, unbreakable, fall in the bush and spike the foot of the unfortunate who may tread on them. On the palm-stem itself they will wound the unwary hand incautiously or involuntarily thrust in the thicket. Many of the climbing plants have thorns or hook-like prickles, and perhaps the worst are the many kinds of twining river-side palms, whose barbed leaves will tear both flesh and clothing.[15] But trying as these vegetable torments may be, they are outclassed in the eyes of the tyro by the more active evil of perils from snakes and insects. Creeping through dense bush is an agony at first. Poisonous reptiles may lie concealed all about one, virulent insects surround in their myriads. If imagination has painted a floral paradise it has also run riot over a profusion of deadly snakes, an uninterrupted purgatory from creeping things innumerable, and winged pests before which the plague of flies in ancient Egypt sinks to insignificance. And there is some excuse for imagination if it be fed on travellers’ tales. As a matter of fact, if these were true life would in all verity be insupportable. But the fear of snakes passes in two weeks, never to return, and mercifully the most pestilent creatures exist only in limited spheres, and seldom or never in the same. Places that are troubled with the pium will be found free of mosquitoes at night; in a belt of country where the mosquito abounds the pium will be absent, and in any case the two are never active together. The pium, a most vile little fly, comes out at sunrise. It is an intolerable pest, will attack any exposed part of the body, and draws blood every time. The traveller is forced, when journeying through a pium-infested country, to don guarded boots, gauntlets, and a veil. It is impossible to eat, drink, or smoke, till sunset puts a period to the troubling. Fortunately, piums are only found within a few hundred yards of the rivers. This is also the case as a rule with[31] mosquitoes. There is a bad belt of pium country on the Issa, at the Brazilian frontier. It takes two days to get through on a steamer, and during the forty-eight hours life is a long-drawn torture. But once through you are rid of them. Robuchon noted that the Culex mosquito disappears on entering this river: but there are others; one, a kind of Tabano in miniature, is called the Maringunios. I found piums on the Kahuanari at low river, but a light breeze would suffice to sweep them away, and both mosquitoes and piums are practically non-existent in the middle Issa-Japura valley, though mosquitoes are found in certain parts of tracts of flatter country, but are not bad enough to make a net a necessary adjunct for comfort. There is also a tiny sand-fly that occasionally appears at sunset, when the river is low, and though minute in size, causes a very painful wound. It is known in Brazil as the Maruim.

A most annoying little insect that is very common in the bush is a kind of harvest bug. This almost invisible “red tick” must not be confused with another parasite that is only obtained from contact with Indians. The forest tick lives on the leaves of plants and bushes, and when shaken off creeps everywhere, and will burrow under the skin, which gives rise to maddening irritation.